User login

Clinical Case-Viewing Sessions in Dermatology: The Patient Perspective

To the Editor:

Dermatology clinical case-viewing (CCV) sessions, commonly referred to as Grand Rounds, are of core educational importance in teaching residents, fellows, and medical students. The traditional format includes the viewing of patient cases followed by resident- and faculty-led group discussions. Clinical case-viewing sessions often involve several health professionals simultaneously observing and interacting with a patient. Although these sessions are highly academically enriching, they may be ill-perceived by patients. The objective of this study was to evaluate patients’ perception of CCV sessions.

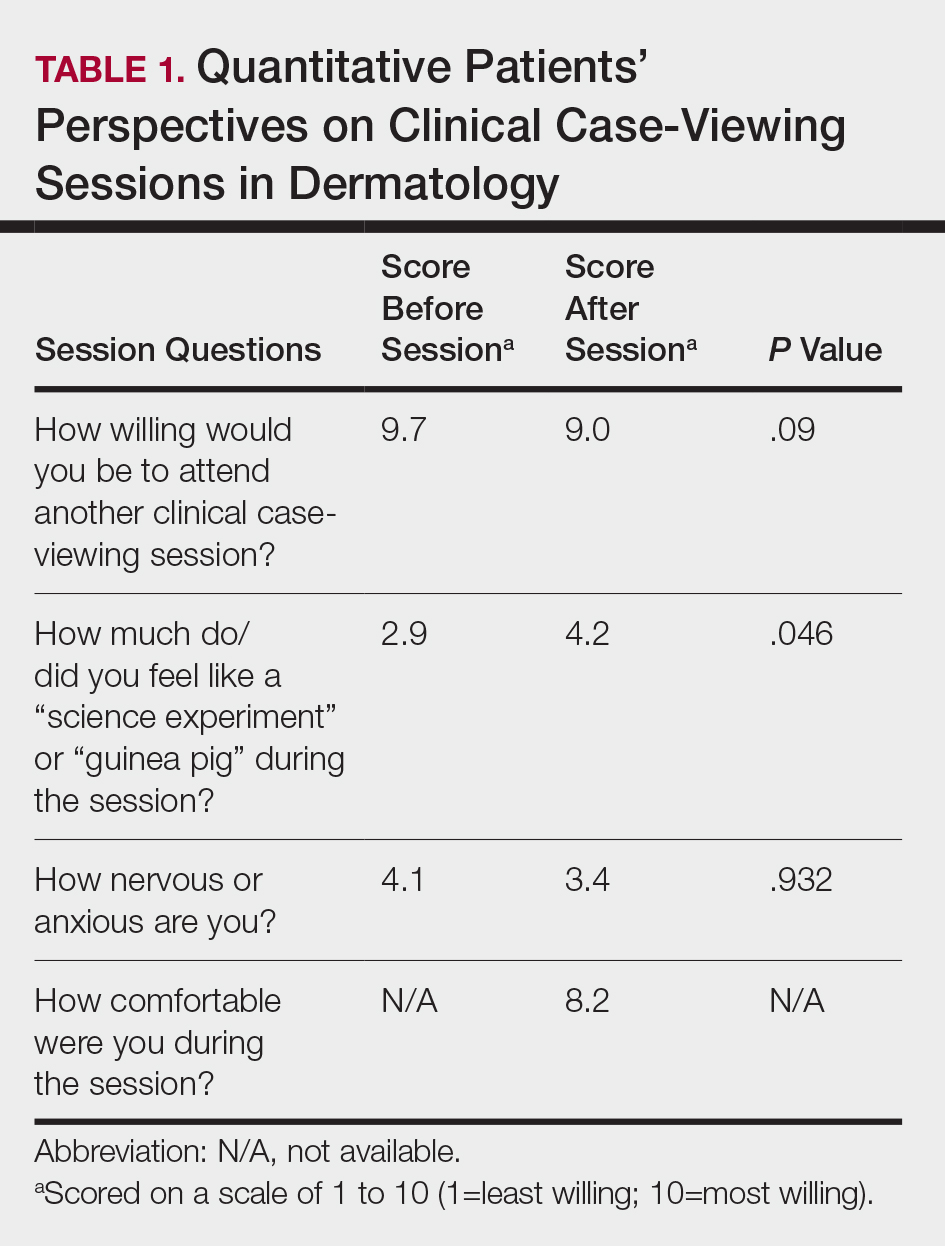

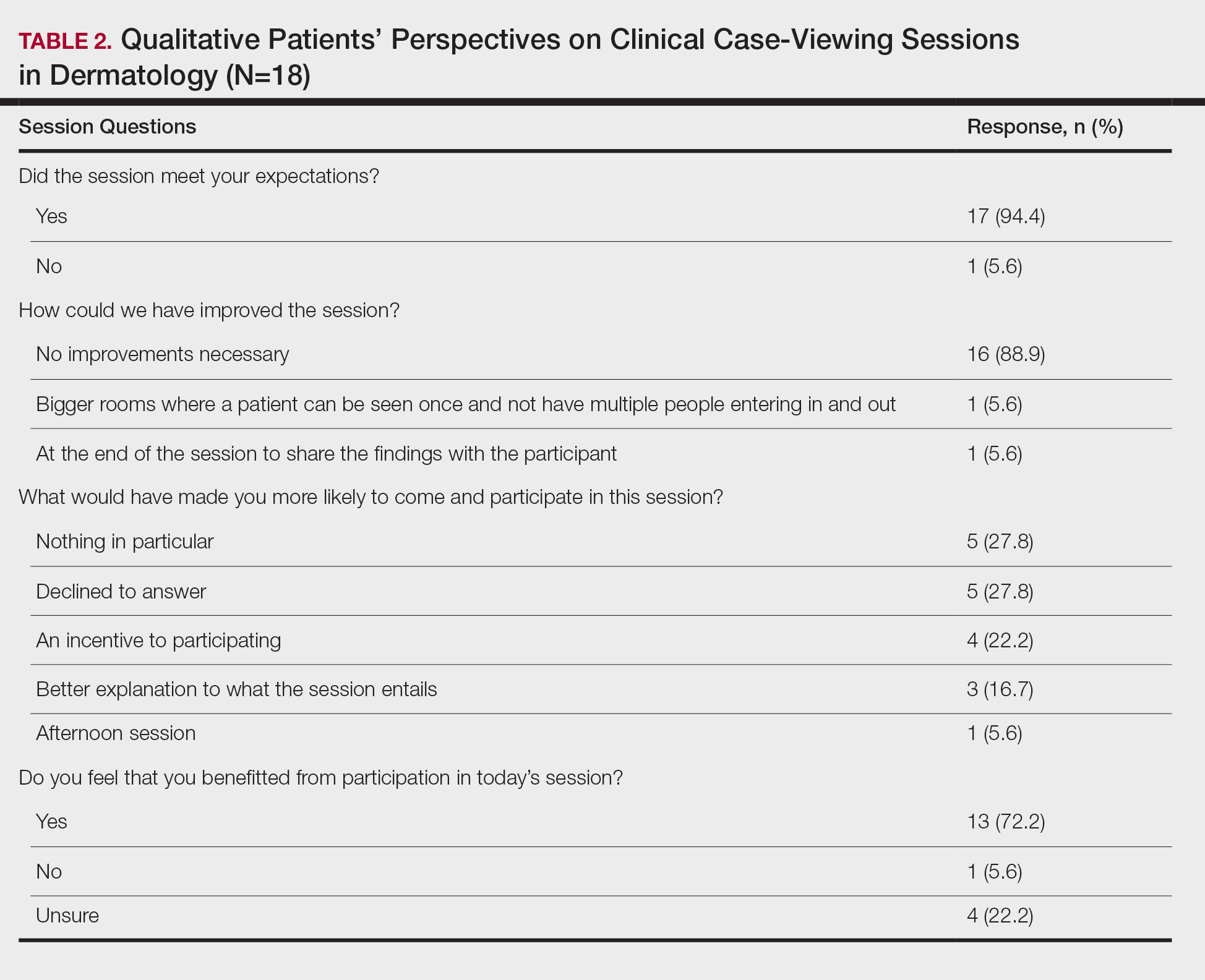

This study was approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) institutional review board and was conducted from February 2017 to August 2017. Following informed consent, 18 patients older than 18 years who were present at the Wake Forest Department of Dermatology CCV sessions were recruited. Patients were each assigned to a private clinical examination room, and CCV attendees briefly visited each room to assess the pathologic findings of interest. Patients received written quantitative surveys before and after the CCV sessions assessing their perspectives on the session (Table 1). Quantitative surveys were assessed using a 10-point Likert scale (1=least willing; 10=most willing). Patients also received qualitative surveys following the session (Table 2). Scores on a 10-item Likert scale were evaluated using a 2-tailed t test.

The mean age of patients was 57.6 years, and women comprised 66.7% (12/18). Patient willingness to attend CCV sessions was relatively unchanged before and after the session, with a mean willingness of 9.7 before the session and 9.0 after the session (P=.09). There was a significant difference in the extent to which patients perceived themselves as experimental subjects prior to the session compared to after the session (2.9 vs 4.2)(P=.046). Following the session, 94.4% (17/18) of patients had the impression that the session met their expectations, and 72.2% (13/18) of patients felt they directly benefitted from the session.

Clinical case-viewing sessions are the foundation of any dermatology residency program1-3; however, characterizing the sessions’ psychosocial implications on patients is important too. Although some patients did feel part of a “science experiment,” this finding may be of less importance, as patients generally considered the sessions to be a positive experience and were willing to take part again.

Limitations of the study were typical of survey-based research. All participants were patients at a single center, which may limit the generalization of the results, in addition to the small sample size. Clinical case-viewing sessions also are conducted slightly differently between dermatology programs, which may further limit the generalization of the results. Future studies may aim to assess varying CCV formats to optimize both medical education as well as patient satisfaction.

- Mehrabi D, Cruz PD Jr. Educational conferences in dermatology residency programs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:523-524.

- Hull AL, Cullen RJ, Hekelman FP. A retrospective analysis of grand rounds in continuing medical education. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 1989;9:257-266.

- Cruz PD Jr, Chaker MB. Teaching conferences in dermatology residency programs revisited. J Am Acad of Dermatol. 1995;32:675-677.

To the Editor:

Dermatology clinical case-viewing (CCV) sessions, commonly referred to as Grand Rounds, are of core educational importance in teaching residents, fellows, and medical students. The traditional format includes the viewing of patient cases followed by resident- and faculty-led group discussions. Clinical case-viewing sessions often involve several health professionals simultaneously observing and interacting with a patient. Although these sessions are highly academically enriching, they may be ill-perceived by patients. The objective of this study was to evaluate patients’ perception of CCV sessions.

This study was approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) institutional review board and was conducted from February 2017 to August 2017. Following informed consent, 18 patients older than 18 years who were present at the Wake Forest Department of Dermatology CCV sessions were recruited. Patients were each assigned to a private clinical examination room, and CCV attendees briefly visited each room to assess the pathologic findings of interest. Patients received written quantitative surveys before and after the CCV sessions assessing their perspectives on the session (Table 1). Quantitative surveys were assessed using a 10-point Likert scale (1=least willing; 10=most willing). Patients also received qualitative surveys following the session (Table 2). Scores on a 10-item Likert scale were evaluated using a 2-tailed t test.

The mean age of patients was 57.6 years, and women comprised 66.7% (12/18). Patient willingness to attend CCV sessions was relatively unchanged before and after the session, with a mean willingness of 9.7 before the session and 9.0 after the session (P=.09). There was a significant difference in the extent to which patients perceived themselves as experimental subjects prior to the session compared to after the session (2.9 vs 4.2)(P=.046). Following the session, 94.4% (17/18) of patients had the impression that the session met their expectations, and 72.2% (13/18) of patients felt they directly benefitted from the session.

Clinical case-viewing sessions are the foundation of any dermatology residency program1-3; however, characterizing the sessions’ psychosocial implications on patients is important too. Although some patients did feel part of a “science experiment,” this finding may be of less importance, as patients generally considered the sessions to be a positive experience and were willing to take part again.

Limitations of the study were typical of survey-based research. All participants were patients at a single center, which may limit the generalization of the results, in addition to the small sample size. Clinical case-viewing sessions also are conducted slightly differently between dermatology programs, which may further limit the generalization of the results. Future studies may aim to assess varying CCV formats to optimize both medical education as well as patient satisfaction.

To the Editor:

Dermatology clinical case-viewing (CCV) sessions, commonly referred to as Grand Rounds, are of core educational importance in teaching residents, fellows, and medical students. The traditional format includes the viewing of patient cases followed by resident- and faculty-led group discussions. Clinical case-viewing sessions often involve several health professionals simultaneously observing and interacting with a patient. Although these sessions are highly academically enriching, they may be ill-perceived by patients. The objective of this study was to evaluate patients’ perception of CCV sessions.

This study was approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) institutional review board and was conducted from February 2017 to August 2017. Following informed consent, 18 patients older than 18 years who were present at the Wake Forest Department of Dermatology CCV sessions were recruited. Patients were each assigned to a private clinical examination room, and CCV attendees briefly visited each room to assess the pathologic findings of interest. Patients received written quantitative surveys before and after the CCV sessions assessing their perspectives on the session (Table 1). Quantitative surveys were assessed using a 10-point Likert scale (1=least willing; 10=most willing). Patients also received qualitative surveys following the session (Table 2). Scores on a 10-item Likert scale were evaluated using a 2-tailed t test.

The mean age of patients was 57.6 years, and women comprised 66.7% (12/18). Patient willingness to attend CCV sessions was relatively unchanged before and after the session, with a mean willingness of 9.7 before the session and 9.0 after the session (P=.09). There was a significant difference in the extent to which patients perceived themselves as experimental subjects prior to the session compared to after the session (2.9 vs 4.2)(P=.046). Following the session, 94.4% (17/18) of patients had the impression that the session met their expectations, and 72.2% (13/18) of patients felt they directly benefitted from the session.

Clinical case-viewing sessions are the foundation of any dermatology residency program1-3; however, characterizing the sessions’ psychosocial implications on patients is important too. Although some patients did feel part of a “science experiment,” this finding may be of less importance, as patients generally considered the sessions to be a positive experience and were willing to take part again.

Limitations of the study were typical of survey-based research. All participants were patients at a single center, which may limit the generalization of the results, in addition to the small sample size. Clinical case-viewing sessions also are conducted slightly differently between dermatology programs, which may further limit the generalization of the results. Future studies may aim to assess varying CCV formats to optimize both medical education as well as patient satisfaction.

- Mehrabi D, Cruz PD Jr. Educational conferences in dermatology residency programs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:523-524.

- Hull AL, Cullen RJ, Hekelman FP. A retrospective analysis of grand rounds in continuing medical education. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 1989;9:257-266.

- Cruz PD Jr, Chaker MB. Teaching conferences in dermatology residency programs revisited. J Am Acad of Dermatol. 1995;32:675-677.

- Mehrabi D, Cruz PD Jr. Educational conferences in dermatology residency programs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:523-524.

- Hull AL, Cullen RJ, Hekelman FP. A retrospective analysis of grand rounds in continuing medical education. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 1989;9:257-266.

- Cruz PD Jr, Chaker MB. Teaching conferences in dermatology residency programs revisited. J Am Acad of Dermatol. 1995;32:675-677.

Practice Points

- Patient willingness to attend dermatology clinical case-viewing (CCV) sessions is relatively unchanged before and after the session.

- Participants generally consider CCV sessions to be a positive experience.

Asboe-Hansen Sign in Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

To the Editor:

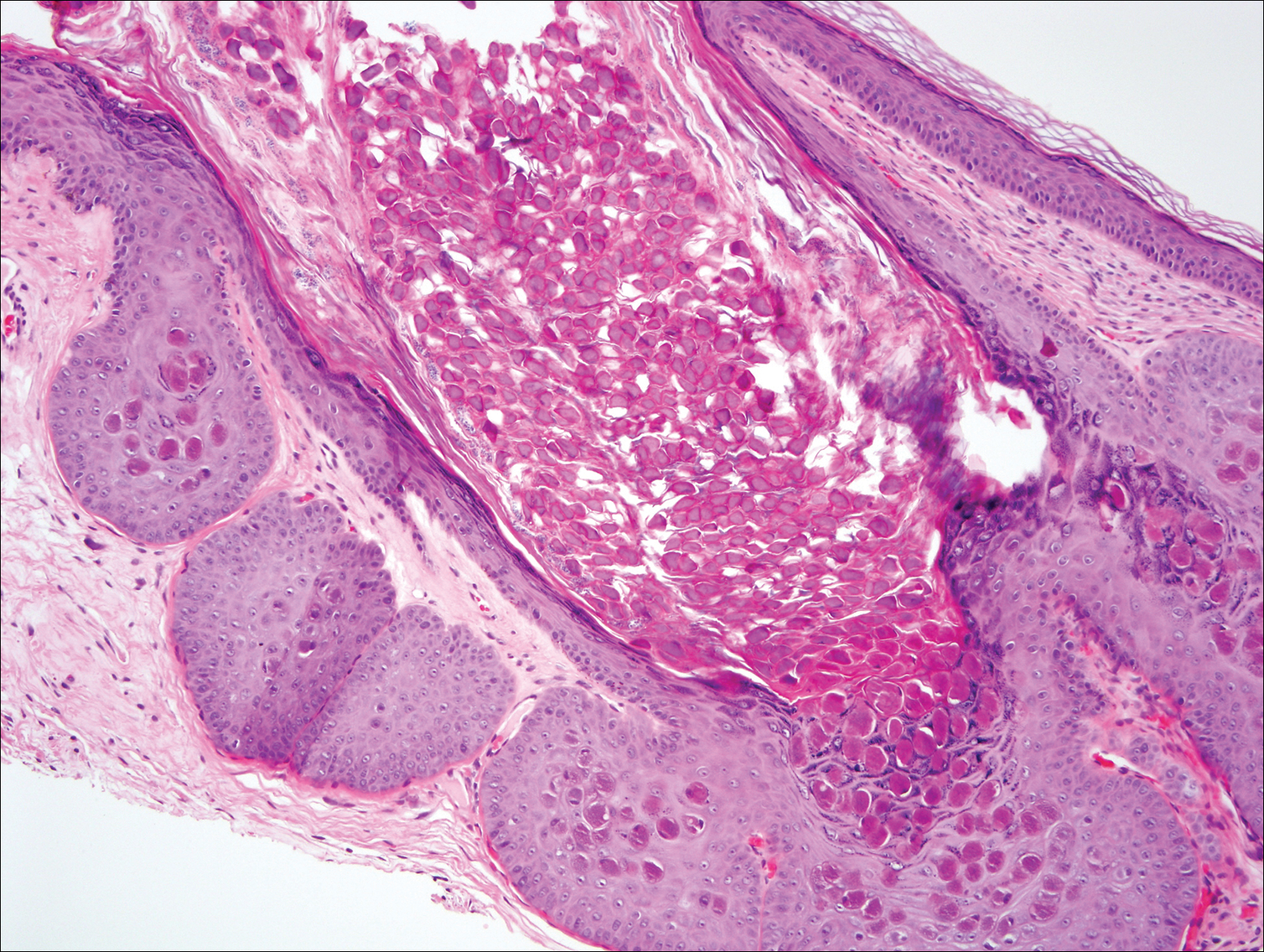

A 25-year-old woman with no notable medical history was admitted to the hospital for suspected Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS). The patient was started on amoxicillin 7 days prior to the skin eruption for prophylaxis before removal of an intrauterine device. On the day of admission, she reported ocular discomfort, dysphagia, and dysuria. She developed erythema of the conjunctivae, face, chest, and proximal upper extremities, as well as erosions of the vermilion lips. She presented to the local emergency department and was transferred to our institution for urgent dermatologic consultation. On physical examination by the dermatology service, the patient had erythematous macules coalescing into patches with overlying flaccid bullae, some denuded, involving the face, chest, abdomen, back (Figure 1), bilateral upper extremities, bilateral thighs, and labia majora and minora. Additionally, she had conjunctivitis, superficial erosions of the vermilion lips, and tense bullae of the palms and soles. On palpation of the flaccid bullae, the Asboe-Hansen sign was elicited (Figure 2 and video). A shave biopsy of the newly elicited bullae was performed. Pathology showed a subepidermal bulla with confluent necrosis of the epidermis and minimal inflammatory infiltrate. An additional shave biopsy of perilesional skin was obtained for direct immunofluorescence, which was negative for IgG, C3, IgM, and IgA. Based on the clinical presentation involving more than 30% of the patient’s body surface area (BSA) and the pathology findings, a diagnosis of toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) was made. The patient remained in the intensive care unit with a multidisciplinary team consisting of dermatology, ophthalmology, gynecology, gastroenterology, and the general surgery burn group. Following treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin, systemic corticosteroids, and aggressive wound care, the patient made a full recovery.

applied to an intact bulla.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis is a rare, acute, life-threatening mucocutaneous disease within a spectrum of adverse cutaneous drug reactions. The estimated worldwide incidence of TEN is 0.4 to 1.9 per million individuals annually.1 Toxic epidermal necrolysis is clinically characterized by diffuse exfoliation of the skin and mucosae with flaccid bullae. These clinical features are a consequence of extensive keratinocyte death, leading to dermoepidermal junction dissociation. Commonly, there is a prodrome of fever, pharyngitis, and painful skin preceding the diffuse erythema and sloughing of skin and mucous membranes. Lesions typically first appear on the trunk and then follow a centrifugal spread, often sparing the distal aspects of the arms and legs.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis is part of a continuous spectrum with SJS. Less than 10% BSA involvement is considered SJS, 10% to 30% BSA involvement is SJS/TEN overlap, and more than 30% BSA detachment is TEN. Stevens-Johnson syndrome can progress to TEN. In TEN, the distribution of cutaneous lesions is more confluent, and mucosal involvement is more severe.2 The differential diagnosis may include staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, drug-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis, severe acute graft-vs-host disease, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, and invasive fungal dermatitis. An accurate diagnosis of TEN is imperative, as the management and morbidity of these diseases are vastly different. Toxic epidermal necrolysis has an estimated mortality rate of 25% to 30%, with sepsis leading to multiorgan failure being the most common cause of death.3

Although the pathophysiology of TEN has yet to be fully elucidated, it is thought to be a T cell–mediated process with CD8+ cells acting as the primary means of keratinocyte death. An estimated 80% to 95% of cases are due to drug reactions.3 The medications that are most commonly associated with TEN include allopurinol, antibiotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and anticonvulsants. Symptoms typically begin 7 to 21 days after starting the drug. Less commonly, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, dengue virus, cytomegalovirus, and contrast medium have been reported as inciting factors for TEN.2

The diagnosis of TEN is established by correlating clinical features with a histopathologic examination obtained from a lesional skin biopsy. The classic cutaneous features of TEN begin as erythematous, flesh-colored, dusky to violaceous macules and/or morbilliform or targetoid lesions. These early lesions have the tendency to coalesce. The cutaneous findings will eventually progress into flaccid bullae, diffuse epidermal sloughing, and full-thickness skin necrosis.2,3 The evolution of skin lesions may be rapid or may take several days to develop. On palpation, the Nikolsky (lateral shearing of epidermis with minimal pressure) and Asboe-Hansen sign will be positive in patients with SJS/TEN, demonstrating that the associated blisters are flaccid and may be displaced peripherally.4 For an accurate diagnosis, the biopsy must contain full-thickness epidermis. It is imperative to choose a biopsy site from an acute blister, as old lesions of other diseases, such as erythema multiforme, will eventually become necrotic and mimic the histopathologic appearance of SJS/TEN, potentially leading to an incorrect diagnosis.4 Full-thickness epidermal necrosis has a high sensitivity but low specificity for TEN.3 The histologic features of TEN vary depending on the stage of the disease. Classic histologic findings include satellite necrosis of keratinocytes followed by full-thickness necrosis of keratinocytes and perivascular lymphoid infiltrates. The stratum corneum retains its original structure.4

The Asboe-Hansen sign, also known as the bulla spread sign, was originally described in 1960 as a diagnostic sign for pemphigus vulgaris.5 A positive Asboe-Hansen sign demonstrates the ability to enlarge a bulla in the lateral direction by applying perpendicular mechanical pressure to the roof of an intact bulla. The bulla is extended to adjacent nonblistered skin.6 A positive sign demonstrates decreased adhesion between keratinocytes or between the basal epidermal cells and the dermal connective tissue.5 In addition to pemphigus vulgaris, the Asboe-Hansen sign may be positive in TEN and SJS, as well as other diseases affecting the dermoepidermal junction including pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vegetans, and bullous pemphigoid. Asboe-Hansen5 made the argument that a fresh bulla should be biopsied if histopathologic diagnosis is necessary, as older bullae may exhibit epithelial cell regeneration and disturb an accurate diagnosis.

Accurate and early diagnosis of TEN is imperative, as prognosis is strongly correlated with the speed at which the offending drug is discontinued and appropriate medical treatment is initiated. Prompt withdrawal of the offending drug has been reported to reduce the risk for morbidity by 30% per day.7 Although classically associated with the pemphigus group of diseases, the Asboe-Hansen sign is of diagnostic value to the pathologist in diagnosing TEN by reproducing the same microscopic appearance of a fresh spontaneous blister. Due to the notable morbidity and mortality in SJS and TEN, the Asboe-Hansen sign should be attempted for the site of a lesional biopsy, as an accurate diagnosis relies on clinicopathologic correlation.

- Schwartz RA, McDonough PH, Lee BW, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: part I. introduction, history, classification, clinical features, systemic manifestations, etiology, and immunopathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:173.e1-173.e13.

- Frech LE, Prins C. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Schaffer J, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2012:332-347.

- Schwartz RA, McDonough PH, Lee BW, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: part II. prognosis, sequelae, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:187.e1–187.e16.

- Elston D, Stratman E, Miller S. Skin biopsy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1-16.

- Asboe-Hansen G. Blister-spread induced by finger-pressure, a diagnostic sign in pemphigus. J Invest Dermatol. 1960;34:5-9.

- Ganapati S. Eponymous dermatological signs in bullous dermatoses. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:21-23.

- Garcia-Doval I, Lecleach L, Bocquet H, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome: does early withdrawal of causative drugs decrease the risk of death? Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:323-327.

To the Editor:

A 25-year-old woman with no notable medical history was admitted to the hospital for suspected Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS). The patient was started on amoxicillin 7 days prior to the skin eruption for prophylaxis before removal of an intrauterine device. On the day of admission, she reported ocular discomfort, dysphagia, and dysuria. She developed erythema of the conjunctivae, face, chest, and proximal upper extremities, as well as erosions of the vermilion lips. She presented to the local emergency department and was transferred to our institution for urgent dermatologic consultation. On physical examination by the dermatology service, the patient had erythematous macules coalescing into patches with overlying flaccid bullae, some denuded, involving the face, chest, abdomen, back (Figure 1), bilateral upper extremities, bilateral thighs, and labia majora and minora. Additionally, she had conjunctivitis, superficial erosions of the vermilion lips, and tense bullae of the palms and soles. On palpation of the flaccid bullae, the Asboe-Hansen sign was elicited (Figure 2 and video). A shave biopsy of the newly elicited bullae was performed. Pathology showed a subepidermal bulla with confluent necrosis of the epidermis and minimal inflammatory infiltrate. An additional shave biopsy of perilesional skin was obtained for direct immunofluorescence, which was negative for IgG, C3, IgM, and IgA. Based on the clinical presentation involving more than 30% of the patient’s body surface area (BSA) and the pathology findings, a diagnosis of toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) was made. The patient remained in the intensive care unit with a multidisciplinary team consisting of dermatology, ophthalmology, gynecology, gastroenterology, and the general surgery burn group. Following treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin, systemic corticosteroids, and aggressive wound care, the patient made a full recovery.

applied to an intact bulla.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis is a rare, acute, life-threatening mucocutaneous disease within a spectrum of adverse cutaneous drug reactions. The estimated worldwide incidence of TEN is 0.4 to 1.9 per million individuals annually.1 Toxic epidermal necrolysis is clinically characterized by diffuse exfoliation of the skin and mucosae with flaccid bullae. These clinical features are a consequence of extensive keratinocyte death, leading to dermoepidermal junction dissociation. Commonly, there is a prodrome of fever, pharyngitis, and painful skin preceding the diffuse erythema and sloughing of skin and mucous membranes. Lesions typically first appear on the trunk and then follow a centrifugal spread, often sparing the distal aspects of the arms and legs.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis is part of a continuous spectrum with SJS. Less than 10% BSA involvement is considered SJS, 10% to 30% BSA involvement is SJS/TEN overlap, and more than 30% BSA detachment is TEN. Stevens-Johnson syndrome can progress to TEN. In TEN, the distribution of cutaneous lesions is more confluent, and mucosal involvement is more severe.2 The differential diagnosis may include staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, drug-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis, severe acute graft-vs-host disease, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, and invasive fungal dermatitis. An accurate diagnosis of TEN is imperative, as the management and morbidity of these diseases are vastly different. Toxic epidermal necrolysis has an estimated mortality rate of 25% to 30%, with sepsis leading to multiorgan failure being the most common cause of death.3

Although the pathophysiology of TEN has yet to be fully elucidated, it is thought to be a T cell–mediated process with CD8+ cells acting as the primary means of keratinocyte death. An estimated 80% to 95% of cases are due to drug reactions.3 The medications that are most commonly associated with TEN include allopurinol, antibiotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and anticonvulsants. Symptoms typically begin 7 to 21 days after starting the drug. Less commonly, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, dengue virus, cytomegalovirus, and contrast medium have been reported as inciting factors for TEN.2

The diagnosis of TEN is established by correlating clinical features with a histopathologic examination obtained from a lesional skin biopsy. The classic cutaneous features of TEN begin as erythematous, flesh-colored, dusky to violaceous macules and/or morbilliform or targetoid lesions. These early lesions have the tendency to coalesce. The cutaneous findings will eventually progress into flaccid bullae, diffuse epidermal sloughing, and full-thickness skin necrosis.2,3 The evolution of skin lesions may be rapid or may take several days to develop. On palpation, the Nikolsky (lateral shearing of epidermis with minimal pressure) and Asboe-Hansen sign will be positive in patients with SJS/TEN, demonstrating that the associated blisters are flaccid and may be displaced peripherally.4 For an accurate diagnosis, the biopsy must contain full-thickness epidermis. It is imperative to choose a biopsy site from an acute blister, as old lesions of other diseases, such as erythema multiforme, will eventually become necrotic and mimic the histopathologic appearance of SJS/TEN, potentially leading to an incorrect diagnosis.4 Full-thickness epidermal necrosis has a high sensitivity but low specificity for TEN.3 The histologic features of TEN vary depending on the stage of the disease. Classic histologic findings include satellite necrosis of keratinocytes followed by full-thickness necrosis of keratinocytes and perivascular lymphoid infiltrates. The stratum corneum retains its original structure.4

The Asboe-Hansen sign, also known as the bulla spread sign, was originally described in 1960 as a diagnostic sign for pemphigus vulgaris.5 A positive Asboe-Hansen sign demonstrates the ability to enlarge a bulla in the lateral direction by applying perpendicular mechanical pressure to the roof of an intact bulla. The bulla is extended to adjacent nonblistered skin.6 A positive sign demonstrates decreased adhesion between keratinocytes or between the basal epidermal cells and the dermal connective tissue.5 In addition to pemphigus vulgaris, the Asboe-Hansen sign may be positive in TEN and SJS, as well as other diseases affecting the dermoepidermal junction including pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vegetans, and bullous pemphigoid. Asboe-Hansen5 made the argument that a fresh bulla should be biopsied if histopathologic diagnosis is necessary, as older bullae may exhibit epithelial cell regeneration and disturb an accurate diagnosis.

Accurate and early diagnosis of TEN is imperative, as prognosis is strongly correlated with the speed at which the offending drug is discontinued and appropriate medical treatment is initiated. Prompt withdrawal of the offending drug has been reported to reduce the risk for morbidity by 30% per day.7 Although classically associated with the pemphigus group of diseases, the Asboe-Hansen sign is of diagnostic value to the pathologist in diagnosing TEN by reproducing the same microscopic appearance of a fresh spontaneous blister. Due to the notable morbidity and mortality in SJS and TEN, the Asboe-Hansen sign should be attempted for the site of a lesional biopsy, as an accurate diagnosis relies on clinicopathologic correlation.

To the Editor:

A 25-year-old woman with no notable medical history was admitted to the hospital for suspected Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS). The patient was started on amoxicillin 7 days prior to the skin eruption for prophylaxis before removal of an intrauterine device. On the day of admission, she reported ocular discomfort, dysphagia, and dysuria. She developed erythema of the conjunctivae, face, chest, and proximal upper extremities, as well as erosions of the vermilion lips. She presented to the local emergency department and was transferred to our institution for urgent dermatologic consultation. On physical examination by the dermatology service, the patient had erythematous macules coalescing into patches with overlying flaccid bullae, some denuded, involving the face, chest, abdomen, back (Figure 1), bilateral upper extremities, bilateral thighs, and labia majora and minora. Additionally, she had conjunctivitis, superficial erosions of the vermilion lips, and tense bullae of the palms and soles. On palpation of the flaccid bullae, the Asboe-Hansen sign was elicited (Figure 2 and video). A shave biopsy of the newly elicited bullae was performed. Pathology showed a subepidermal bulla with confluent necrosis of the epidermis and minimal inflammatory infiltrate. An additional shave biopsy of perilesional skin was obtained for direct immunofluorescence, which was negative for IgG, C3, IgM, and IgA. Based on the clinical presentation involving more than 30% of the patient’s body surface area (BSA) and the pathology findings, a diagnosis of toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) was made. The patient remained in the intensive care unit with a multidisciplinary team consisting of dermatology, ophthalmology, gynecology, gastroenterology, and the general surgery burn group. Following treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin, systemic corticosteroids, and aggressive wound care, the patient made a full recovery.

applied to an intact bulla.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis is a rare, acute, life-threatening mucocutaneous disease within a spectrum of adverse cutaneous drug reactions. The estimated worldwide incidence of TEN is 0.4 to 1.9 per million individuals annually.1 Toxic epidermal necrolysis is clinically characterized by diffuse exfoliation of the skin and mucosae with flaccid bullae. These clinical features are a consequence of extensive keratinocyte death, leading to dermoepidermal junction dissociation. Commonly, there is a prodrome of fever, pharyngitis, and painful skin preceding the diffuse erythema and sloughing of skin and mucous membranes. Lesions typically first appear on the trunk and then follow a centrifugal spread, often sparing the distal aspects of the arms and legs.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis is part of a continuous spectrum with SJS. Less than 10% BSA involvement is considered SJS, 10% to 30% BSA involvement is SJS/TEN overlap, and more than 30% BSA detachment is TEN. Stevens-Johnson syndrome can progress to TEN. In TEN, the distribution of cutaneous lesions is more confluent, and mucosal involvement is more severe.2 The differential diagnosis may include staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, drug-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis, severe acute graft-vs-host disease, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, and invasive fungal dermatitis. An accurate diagnosis of TEN is imperative, as the management and morbidity of these diseases are vastly different. Toxic epidermal necrolysis has an estimated mortality rate of 25% to 30%, with sepsis leading to multiorgan failure being the most common cause of death.3

Although the pathophysiology of TEN has yet to be fully elucidated, it is thought to be a T cell–mediated process with CD8+ cells acting as the primary means of keratinocyte death. An estimated 80% to 95% of cases are due to drug reactions.3 The medications that are most commonly associated with TEN include allopurinol, antibiotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and anticonvulsants. Symptoms typically begin 7 to 21 days after starting the drug. Less commonly, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, dengue virus, cytomegalovirus, and contrast medium have been reported as inciting factors for TEN.2

The diagnosis of TEN is established by correlating clinical features with a histopathologic examination obtained from a lesional skin biopsy. The classic cutaneous features of TEN begin as erythematous, flesh-colored, dusky to violaceous macules and/or morbilliform or targetoid lesions. These early lesions have the tendency to coalesce. The cutaneous findings will eventually progress into flaccid bullae, diffuse epidermal sloughing, and full-thickness skin necrosis.2,3 The evolution of skin lesions may be rapid or may take several days to develop. On palpation, the Nikolsky (lateral shearing of epidermis with minimal pressure) and Asboe-Hansen sign will be positive in patients with SJS/TEN, demonstrating that the associated blisters are flaccid and may be displaced peripherally.4 For an accurate diagnosis, the biopsy must contain full-thickness epidermis. It is imperative to choose a biopsy site from an acute blister, as old lesions of other diseases, such as erythema multiforme, will eventually become necrotic and mimic the histopathologic appearance of SJS/TEN, potentially leading to an incorrect diagnosis.4 Full-thickness epidermal necrosis has a high sensitivity but low specificity for TEN.3 The histologic features of TEN vary depending on the stage of the disease. Classic histologic findings include satellite necrosis of keratinocytes followed by full-thickness necrosis of keratinocytes and perivascular lymphoid infiltrates. The stratum corneum retains its original structure.4

The Asboe-Hansen sign, also known as the bulla spread sign, was originally described in 1960 as a diagnostic sign for pemphigus vulgaris.5 A positive Asboe-Hansen sign demonstrates the ability to enlarge a bulla in the lateral direction by applying perpendicular mechanical pressure to the roof of an intact bulla. The bulla is extended to adjacent nonblistered skin.6 A positive sign demonstrates decreased adhesion between keratinocytes or between the basal epidermal cells and the dermal connective tissue.5 In addition to pemphigus vulgaris, the Asboe-Hansen sign may be positive in TEN and SJS, as well as other diseases affecting the dermoepidermal junction including pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vegetans, and bullous pemphigoid. Asboe-Hansen5 made the argument that a fresh bulla should be biopsied if histopathologic diagnosis is necessary, as older bullae may exhibit epithelial cell regeneration and disturb an accurate diagnosis.

Accurate and early diagnosis of TEN is imperative, as prognosis is strongly correlated with the speed at which the offending drug is discontinued and appropriate medical treatment is initiated. Prompt withdrawal of the offending drug has been reported to reduce the risk for morbidity by 30% per day.7 Although classically associated with the pemphigus group of diseases, the Asboe-Hansen sign is of diagnostic value to the pathologist in diagnosing TEN by reproducing the same microscopic appearance of a fresh spontaneous blister. Due to the notable morbidity and mortality in SJS and TEN, the Asboe-Hansen sign should be attempted for the site of a lesional biopsy, as an accurate diagnosis relies on clinicopathologic correlation.

- Schwartz RA, McDonough PH, Lee BW, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: part I. introduction, history, classification, clinical features, systemic manifestations, etiology, and immunopathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:173.e1-173.e13.

- Frech LE, Prins C. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Schaffer J, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2012:332-347.

- Schwartz RA, McDonough PH, Lee BW, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: part II. prognosis, sequelae, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:187.e1–187.e16.

- Elston D, Stratman E, Miller S. Skin biopsy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1-16.

- Asboe-Hansen G. Blister-spread induced by finger-pressure, a diagnostic sign in pemphigus. J Invest Dermatol. 1960;34:5-9.

- Ganapati S. Eponymous dermatological signs in bullous dermatoses. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:21-23.

- Garcia-Doval I, Lecleach L, Bocquet H, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome: does early withdrawal of causative drugs decrease the risk of death? Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:323-327.

- Schwartz RA, McDonough PH, Lee BW, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: part I. introduction, history, classification, clinical features, systemic manifestations, etiology, and immunopathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:173.e1-173.e13.

- Frech LE, Prins C. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Schaffer J, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2012:332-347.

- Schwartz RA, McDonough PH, Lee BW, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: part II. prognosis, sequelae, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:187.e1–187.e16.

- Elston D, Stratman E, Miller S. Skin biopsy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1-16.

- Asboe-Hansen G. Blister-spread induced by finger-pressure, a diagnostic sign in pemphigus. J Invest Dermatol. 1960;34:5-9.

- Ganapati S. Eponymous dermatological signs in bullous dermatoses. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:21-23.

- Garcia-Doval I, Lecleach L, Bocquet H, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome: does early withdrawal of causative drugs decrease the risk of death? Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:323-327.

Practice Points

- Asboe-Hansen sign is a useful clinical tool for diagnosing toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN).

- Asboe-Hansen sign can be employed to generate a fresh bulla for lesional skin biopsy in the evaluation of TEN.

Molluscum Contagiosum in Immunocompromised Patients: AIDS Presenting as Molluscum Contagiosum in a Patient With Psoriasis on Biologic Therapy

Molluscum contagiosum (MC) is a double-stranded DNA virus of the Poxviridae family, which commonly infects human keratinocytes resulting in small, umbilicated, flesh-colored papules. The greatest incidence of MC is seen in the pediatric population and sexually active young adults, and it is considered a self-limited disease in immunocompetent individuals.1 With the emergence of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and subsequent AIDS epidemic in the 1980s, a new population of immunocompromised individuals has been observed to be increasingly susceptible to MC with an atypical clinical presentation and a recalcitrant disease course.2 Although the increased prevalence of MC in the HIV population has been well-documented, it has been observed in other disease states or iatrogenically induced immunosuppression due to a deficiency in function or absolute number of T lymphocytes.

We present a case of a patient with long-standing psoriasis on biologic therapy who presented with MC with a subsequent workup that revealed AIDS. This case reiterates the importance of MC as a potential indicator of underlying immunosuppression. We review the literature to evaluate the occurrence of MC in immunosuppressed patients.

Case Report

A 33-year-old man initially presented for evaluation of severe plaque-type psoriasis associated with pain, erythema, and swelling of the joints of the hands of 10 years’ duration. He was started on methotrexate 5 mg weekly and topical corticosteroids but was unable to tolerate methotrexate due to headaches. He also had difficulty affording topical medications and adjunctive phototherapy. The patient was sporadically seen in follow-up with persistence of psoriatic plaques involving up to 60% body surface area (BSA) with the only treatment consisting of occasional topical steroids. Five years later, the patient was restarted on methotrexate 5 to 7.5 mg weekly, which resulted in moderate improvement. However, because of persistent elevation of liver enzymes, this treatment was stopped. Several months later he was evaluated for treatment with a biologic agent, and after a negative tuberculin skin test, he began treatment with etanercept 50 mg subcutaneous injection twice weekly, which provided notable improvement and allowed for reduction of dose frequency to once weekly.

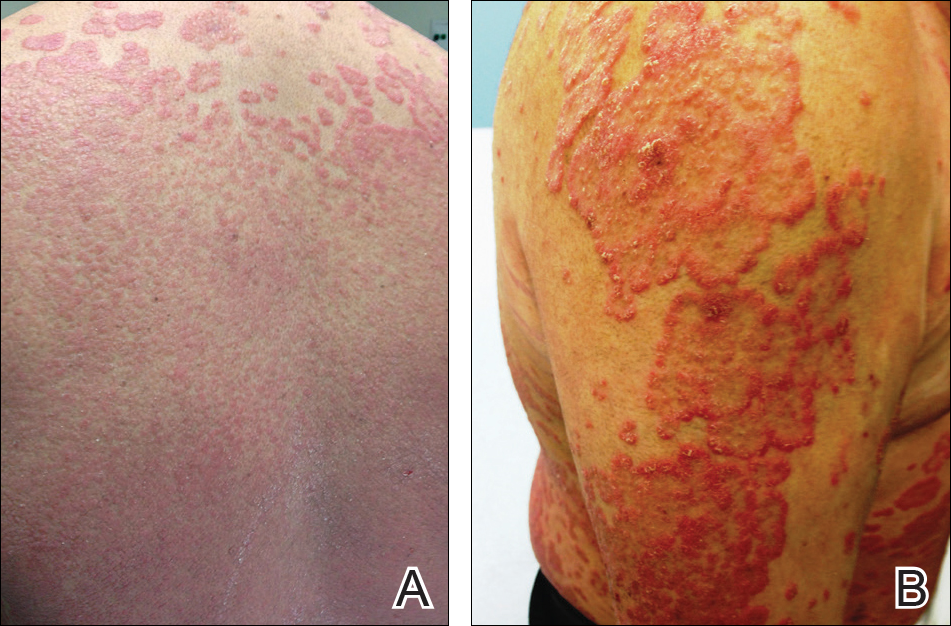

At follow-up 1 year later, the patient had continued improvement of psoriasis with approximately 30% BSA on a treatment regimen of etanercept 50 mg weekly injection and topical corticosteroids. However, on physical examination, there were multiple small semitranslucent papules with telangiectases on the chest and upper back (Figure 1). Biopsy of a representative papule on the chest revealed MC (Figure 2). The patient was subsequently advised to stop etanercept and to return immediately to the clinic for HIV testing. He returned for follow-up 3 months later with pronounced worsening of disease and a new onset of blurred vision of the right eye. Cutaneous examination revealed numerous large erythematous plaques with superficial scale and cerebriform surface on the chest, back, abdomen, and upper and lower extremities involving 80% BSA (Figure 3). Biopsy of a plaque demonstrated psoriasiform dermatitis with neutrophils and parakeratosis consistent with psoriasis. Extensive blood work was notable for reactive HIV antibody and lymphopenia, CD4 lymphocyte count of 60 cells/mm3, and an HIV viral load of 247,000 copies/mL, meeting diagnostic criteria for AIDS. Additionally, ophthalmologic evaluation revealed toxoplasma retinitis. Upon initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and continued use of topical corticosteroids, the patient experienced notable improvement of disease severity with approximately 20% BSA.

Comment

Molluscum contagiosum is a common skin infection. Among patients with HIV and other types of impaired cellular immunity, the prevalence of MC is estimated to be as high as 20%.3 The MC poxvirus survives and proliferates within the epidermis by interfering with tumor necrosis factor–induced apoptosis of virally infected cells; therefore, intact cell-mediated immunity is an important component of prevention and clearance of poxvirus infections. In immunocompromised patients, the presentation of MC varies widely, and the disease is often difficult to eradicate. This review will highlight the prevalence, presentation, and treatment of MC in the context of immunosuppressed states.

HIV/AIDS

Molluscum contagiosum in HIV-positive patients was first recognized in 1983,2 and its prevalence is estimated to range from 5% to 18% in AIDS patients.3 Molluscum contagiosum is a clinical sign of HIV progression, and its incidence appears to increase with reduced immune function (ie, a CD4 cell count <200/mm3).3 In a study of 456 patients with HIV-associated skin disorders, the majority of patients with MC had notable immunosuppression with a median survival time of 12 months. Thus, MC was not an independent prognostic marker but a clinical indicator of markedly reduced immune status.4

Molluscum contagiosum is transmitted in both sexual and nonsexual patterns in HIV-positive individuals, with the distribution of the latter involving primarily the face and neck. Although it may present with typical umbilicated papules, MC has a wide range of atypical clinical presentations in patients with AIDS that can make it difficult to diagnose. Complicated cases of eyelid MC have been reported in advanced HIV in both adults and children, resulting in obstruction of vision due to large lesions (up to 2 cm) or hundreds of confluent lesions.5 Giant MC, which appears as large exophytic nodules, is another presentation that has been frequently described in patients with advanced HIV. In these patients, the lesions often are too voluminous for conservative therapy and require excision.6 Atypical MC lesions also can resemble other dermatologic conditions, including condyloma acuminatum,7 nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn, ecthyma,8 and cutaneous horns,9,10 as well as other bacterial and fungal infections in HIV-positive patients, such as cutaneous Cryptococcus neoformans,11,12 disseminated histoplasmosis,13 and infections caused by Penicillium marneffei14 and Bartonella henselae.15 In most cases of MC in HIV-positive patients, diagnosis is dependent on the examination of biopsy specimens, which maintain the same histopathologic features regardless of immune status.

The management of MC in patients with HIV/AIDS is difficult. Molluscum contagiosum has shown no evidence of spontaneous resolution in patients with HIV, and treatment with one modality is often insufficient. Treatment is most successful when a combination approach is utilized with destructive procedures (eg, curettage, cryosurgery) and adjunctive agents (eg, retinoids, cantharidin, trichloroacetic acid). Imiquimod and cidofovir have been used off label for MC in AIDS patients.16 Imiquimod, which is used to treat genital warts, another cutaneous viral infection seen in patients with HIV, has demonstrated efficacy in treating MC.16 In a randomized controlled trial comparing imiquimod cream 5% to cryotherapy for MC in healthy children, imiquimod was slow acting but better suited than cryotherapy for patients with eruptions of many small lesions.17 For HIV patients, numerous reports have described successful treatment of disseminated or recalcitrant MC with topical imiquimod.18-20 Cidofovir, an antiviral used to treat cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients with AIDS, is a promising antiviral agent against the poxvirus family. In a study of viral DNA polymerase genes of MC virus, cidofovir inhibited MC virus DNA polymerase activity.21 It has been used in both topical (1% to 3%) and intravenous form to successfully treat recalcitrant and exuberant giant MC.6,22 However, the use of cidofovir is limited by its high costs, especially when compounded into a topical formulation.23

From a systemic standpoint, numerous reports have shown that treating the underlying HIV by optimizing HAART is the most important first step in clearing MC.24-27 However, a special concern regarding the initiation of HAART in patients with MC as well as a markedly impaired immune function is the development of an inflammatory reaction called immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS). This reaction is thought to be a result of immune recovery in severely immunosuppressed patients. During the initial phase of reconstitution when CD4 lymphocyte counts rise and viral load decreases, IRIS occurs due to an inflammatory reaction to microbial and autoimmune antigens, leading to temporary clinical deterioration.28 The incidence has been reported in up to 25% of patients starting HAART, and 52% to 78% of IRIS cases involve dermatologic manifestations such as varicella-zoster virus, cytomegalovirus infections, genital warts, and MC.29,30 In a cohort study of 199 patients, 2% of patients developed MC within 6 months of initiating HAART.31 In a case of exuberant MC lesions after beginning HAART, the lesions spontaneously resolved with the progression of immune reconstitution.28

Malignancies

Patients with hematologic malignancies such as lymphoma and leukemia comprise another subset of patients at risk for atypical presentations of MC. Molluscum contagiosum has been described in patients with hematologic malignancies such as adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, multiple myeloma, chronic myeloid leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, lymphomatoid papulosis, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. In a review of MC in children with cancer, 0.5% were diagnosed with MC.32,33 Reports also have documented eruptive MC in the presence of solid organ cancers, including lung cancer.34

In patients with malignancies, the differential diagnosis should include other common dermatologic conditions such as varicella, herpes simplex, papillomas, pyoderma, and cutaneous cryptococcosis, as well as MC. Similar to HIV-positive patients, the lesions of MC described in patients with malignancies do not tend to spontaneously resolve. In a report of a pediatric patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, MC presented as an ulcerated lesion without any classic features, requiring biopsy for definitive diagnosis. Only partial resolution was achieved with cryotherapy and crusting of the lesion in an attempt to slow the progression.35 In a series of 5 children with hematologic malignancies and MC, little improvement was noted after treatment with surgical scraping, liquid nitrogen, and salicylic acid ointment 5%. Similar to patients with HIV, improvement of immune status and function help clear the disease, and patients who reach remission and discontinue chemotherapeutic agents have a higher rate of spontaneous resolution of previously recalcitrant MC lesions.36

Transplant Patients

Molluscum contagiosum in transplant patients has features similar to patients with HIV/AIDS. In organ transplant recipients, there is an increased risk for cutaneous disease from iatrogenic immunosuppression or immunosuppression through infectious or neoplastic processes.37 As in other immunocompromised populations, MC often has an atypical presentation in transplant patients with more extensive involvement and recalcitrant, rapidly recurring lesions.

In a review of 145 pediatric organ transplant recipients, MC was the fourth most common skin infection after verruca vulgaris, tinea versicolor, and herpes simplex/zoster. Affecting 7% of patients, the majority of patients demonstrated clinically typical lesions; however, the disease was difficult to eradicate if multiple lesions were present.37 In other reports in adults, fulminant and giant MC have been described after renal and other solid organ transplants.38,39 Molluscum contagiosum also has been reported to mimic other skin diseases in transplant patients including tinea barbae40 and nodular basal cell carcinomas.41

The standard treatments are identical to those used in patients with HIV, including ablative methods via liquid nitrogen, electrocautery, cantharidin, trichloroacetic acid, and topical retinoids. Similar to MC in other immunocompromised states, treatment can be difficult and usually requires multiple modalities. For children, imiquimod cream 5% has been recommended due to high clearance rates (up to 92%) and the painless nature of the treatment.42,43

Other Iatrogenic Immunosuppressive States

Immunosuppression through the use of steroids, chemotherapeutic agents, and biologic drugs often is the result of treatment of various diseases. In patients with psoriasis treated with systemic immunosuppressive agents, there are numerous reports that describe the appearance of eruptive MC in association with methotrexate, cyclosporine, and biologics. Methotrexate acts as an immunosuppressive agent by binding to dihydrofolate reductase, which inhibits DNA synthesis in immunologically competent cells.44 It also may block host defense mechanisms against MC by suppressing the expression of serum inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and IFN-γ and suppressing the activity of TNF-α inducing apoptosis of virus-infected cells. Cyclosporine used in conjunction with methotrexate may exacerbate the insult to the immune system by inhibiting the production of IFN-γ.45 Biologics are an emerging class of drugs that have demonstrated efficacy in moderate to severe psoriasis by inhibiting TNF-α or other inflammatory molecules. Several published reports have described eruptive or atypical MC in patients on biologic medications. In one case, within 2 weeks after initiation of infliximab, a monoclonal antibody against TNF-α, a patient developed an eruption of MC involving the entire body.46 In another report, an anti–TNF-α agent for rheumatoid arthritis was associated with atypical MC with eyelid lesions.47

There are other skin disorders treated with immunosuppressive agents that also have been associated with MC. In a patient with pemphigus vulgaris treated with prednisolone, pimecrolimus, and azathioprine, MC lesions were observed on the face and within healed pemphigus vulgaris sites.48 Pimecrolimus and tacrolimus, corticosteroid-sparing agents, suppress cell-mediated immunity and inhibit inflammatory cytokines such as IL-2. The infection resolved with a gradual tapering of immunosuppressive therapy and 10 sessions of cryotherapy.48 In a case of topical pimecrolimus for pityriasis alba, the patient developed biopsy-proven MC within 2 weeks of initiating treatment in the areas that were treated with tacrolimus.49

In nontransplant patients with iatrogenic immunosuppression, MC treatment has not been documented to be as challenging as in patients with inherent immunosuppression. Most patients respond to either withdrawal of the drug alone or to simple ablative treatments such as cryotherapy.45,46,48 This important difference is most likely due to the presence of an otherwise intact immune system.

Conclusion

This case describes the appearance of MC in a patient with psoriasis treated with a TNF-α inhibitor who was ultimately diagnosed with AIDS. Although atypical MC infections have been documented in patients with psoriasis undergoing treatment with biologics, it is thought to be more common for MC to occur in more remarkably immunocompromised states such as AIDS. Thus, the persistence and progression of MC in our patient despite discontinuation of etanercept suggested a separate underlying process. Subsequent workup led to the diagnosis of AIDS along with the opportunistic ocular infection of toxoplasmosis retinitis. This clinical sequence consisting of psoriasis treated with a biologic agent, development of MC, and subsequent diagnosis of AIDS is unique and clinically significant to dermatologists. The presentation of psoriasis in patients with HIV can be diverse with different levels of severity and atypical clinical features. In many cases, HIV is known to exacerbate the classic clinical presentation of psoriasis. However, there are other particular presentations of psoriasis in HIV patients that have been observed, which include a predilection for scalp lesions, palmoplantar keratoderma, flexural involvement, and higher levels of immunodeficiency.50 Although tuberculin skin tests are required prior to initiating biologic therapy due to the potential for disease reactivation, there are no requirements for HIV antibody testing. In cases of severe recalcitrant psoriasis, an HIV test should be ordered during the workup to establish an early diagnosis so that an HIV-positive patient can avoid poor outcomes from either the disease processes, the use of certain therapeutic agents, or both. Furthermore, the benefit of avoiding possible harm to the patient and potential legal action outweighs the cost of performing surveillance HIV testing in this subset of patients. Thus, due to the potential additive immunosuppressive effect of HIV with biologic therapy, providers should always assess for risk factors and consider testing for HIV in all patients before initiating treatment with immunosuppressive agents such as biologics.

- Dohil MA, Lin P, Lee J, et al. The epidemiology of molluscum contagiosum in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:47-54.

- Reichert CM, O’Leary TJ, Levens DL, et al. Autopsy pathology in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Am J Pathol. 1983;112:357-382.

- Czelusta A, Yen-Moore A, Van der Straten M, et al. An overview of sexually transmitted diseases. Part III. Sexually transmitted diseases in HIV-infected patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:409-432.

- Husak R, Garbe C, Orfanos CE. Mollusca contagiosa in HIV infection. Clinical manifestation, relation to immune status and prognostic value in 39 patients [in German]. Hautarzt. 1997;48:103-109.

- Averbuch D, Jaouni T, Pe’er J, et al. Confluent molluscum contagiosum covering the eyelids of an HIV-positive child. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;37:525-527.

- Erickson C, Driscoll M, Gaspari A. Efficacy of intravenous cidofovir in the treatment of giant molluscum contagiosum in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:652-654.

- Mastrolorenzo A, Urbano FG, Salimbeni L, et al. Atypical molluscum contagiosum infection in an HIV-infected patient. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:378-380.

- Itin PH, Gilli L. Molluscum contagiosum mimicking sebaceous nevus of Jadassohn, ecthyma and giant condylomata acuminata in HIV-infected patients. Dermatology. 1994;189:396-398.

- Sim JH, Lee ES. Molluscum contagiosum presenting as a cutaneous horn. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:262-263.

- Manchanda Y, Sethuraman G, Paderwani PP, et al. Molluscum contagiosum presenting as penile horn in an HIV positive patient. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81:183-184.

- Miller SJ. Cutaneous cryptococcus resembling molluscum contagiosum in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Cutis. 1988;41:411-412.

- Sornum A. A mistaken diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum in a HIV-positive patient in rural South Africa. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;14.

- Corti M, Villafañe MF, Palmieri O, et al. Rupioid histoplasmosis: first case reported in an AIDS patient in Argentina. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2010;52:279-280.

- Saikia L, Nath R, Hazarika D, et al. Atypical cutaneous lesions of Penicillium marneffei infection as a manifestation of the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome after highly active antiretroviral therapy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:45-48.

- de Souza JA. Molluscum or a mimic? Am J Med. 2006;119:927-929.

- Conant MA. Immunomodulatory therapy in the management of viral infections in patients with HIV infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:S27-S30.

- Gamble RG, Echols KF, Dellavalle RP. Imiquimod vs cryotherapy for molluscum contagiosum: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:109-112.

- Brown CW Jr, O’Donoghue M, Moore J, et al. Recalcitrant molluscum contagiosum in an HIV-afflicted male treated successfully with topical imiquimod. Cutis. 2000;65:363-366.

- Strauss RM, Doyle EL, Mohsen AH, et al. Successful treatment of molluscum contagiosum with topical imiquimod in a severely immunocompromised HIV-positive patient. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12:264-266.

- Theiler M, Kempf W, Kerl K, et al. Disseminated molluscum contagiosum in a HIV-positive child. improvement after therapy with 5% imiquimod. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2011;5:19-23.

- Watanabe T, Tamaki K. Cidofovir diphosphate inhibits molluscum contagiosum virus DNA polymerase activity. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1327-1329.

- Calista D. Topical cidofovir for severe cutaneous human papillomavirus and molluscum contagiosum infections in patients with HIV/AIDS. a pilot study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:484-488.

- Toro JR, Sanchez S, Turiansky G, et al. Topical cidofovir for the treatment of dermatologic conditions: verruca, condyloma, intraepithelial neoplasia, herpes simplex and its potential use in smallpox. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:301-309.

- Calista D, Boschini A, Landi G. Resolution of disseminated molluscum contagiosum with highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) in patients with AIDS. Eur J Dermatol. 1999;9:211-213.

- Cattelan AM, Sasset L, Corti L, et al. A complete remission of recalcitrant molluscum contagiosum in an AIDS patient following highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). J Infect. 1999;38:58-60.

- Sen S, Bhaumik P. Resolution of giant molluscum contagiosum with antiretroviral therapy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:267-268.

- Sen S, Goswami BK, Karjyi N, et al. Disfiguring molluscum contagiosum in a HIV-positive patient responding to antiretroviral therapy. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54:180-182.

- Pereira B, Fernandes C, Nachiambo E, et al. Exuberant molluscum contagiosum as a manifestation of the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:6.

- Osei-Sekyere B, Karstaedt AS. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome involving the skin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:477-481.

- Sung KU, Lee HE, Choi WR, et al. Molluscum contagiosum as a skin manifestation of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in an AIDS patient who is receiving HAART. Korean J Fam Med. 2012;33:182-185.

- Ratnam I, Chiu C, Kandala NB, et al. Incidence and risk factors for immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in an ethnically diverse HIV type 1-infected cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:418-427.

- Chen KW, Yang CF, Huang CT, et al. Molluscum contagiosum in a patient with adult T-cell leukaemia/lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2011;155:286.

- Fernandez KH, Bream M, Ali MA, et al. Investigation of molluscum contagiosum virus, orf and other parapoxviruses in lymphomatoid papulosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:1046-1047.

- Nakamura-Wakatsuki T, Kato Y, Miura T, et al. Eruptive molluscum contagiosums in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis and lung cancer. Rheumatol Int. 2011;31:1117-1118.

- Ozyürek E, Sentürk N, Kefeli M, et al. Ulcerating molluscum contagiosum in a boy with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33:E114-E116.

- Hughes WT, Parham DM. Molluscum contagiosum in children with cancer or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1991;10:152-156.

- Euvrard S, Kanitakis J, Cochat P, et al. Skin diseases in children with organ transplants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:932-939.

- Gardner LS, Ormond PJ. Treatment of multiple giant molluscum contagiosum in a renal transplant patient with imiquimod 5% cream. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:452-453.

- Mansur AT, Göktay F, Gündüz S, et al. Multiple giant molluscum contagiosum in a renal transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2004;6:120-123.

- Feldmeyer L, Kamarashev J, Boehler A, et al. Molluscum contagiosum folliculitis mimicking tinea barbae in a lung transplant recipient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:169-171.

- Tas¸kapan O, Yenicesu M, Aksu A. A giant solitary molluscum contagiosum, resembling nodular basal cell carcinoma, in a renal transplant recipient. Acta Derm Venereol. 1996;76:247-248.

- Tan HH, Goh CL. Viral infections affecting the skin in organ transplant recipients: epidemiology and current management strategies. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:13-29.

- Al-Mutairi N, Al-Doukhi A, Al-Farag S, et al. Comparative study on the efficacy, safety, and acceptability of imiquimod 5% cream versus cryotherapy for molluscum contagiosum in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:388-394.

- Lim KS, Foo CC. Disseminated molluscum contagiosum in a patient with chronic plaque psoriasis taking methotrexate. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:591-593.

- Fotiadou C, Lazaridou E, Lekkas D, et al. Disseminated, eruptive molluscum contagiosum lesions in a psoriasis patient under treatment with methotrexate and cyclosporine. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:147-148.

- Antoniou C, Kosmadaki MG, Stratigos AJ, et al. Genital HPV lesions and molluscum contagiosum occurring in patients receiving anti-TNF-alpha therapy. Dermatology. 2008;216:364-365.

- Cursiefen C, Grunke M, Dechant C, et al. Multiple bilateral eyelid molluscum contagiosum lesions associated with TNFalpha-antibody and methotrexate therapy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134:270-271.

- Heng YK, Lee JS, Neoh CY. Verrucous plaques in a pemphigus vulgaris patient on immunosuppressive therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1044-1046.

- Goksugur N, Ozbostanci B, Goksugur SB. Molluscum contagiosum infection associated with pimecrolimus use in pityriasis alba. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:E63-E65.

- Fernandes S, Pinto GM, Cardoso J. Particular clinical presentations of psoriasis in HIV patients. Int J STD AIDS. 2011;22:653-654.

Molluscum contagiosum (MC) is a double-stranded DNA virus of the Poxviridae family, which commonly infects human keratinocytes resulting in small, umbilicated, flesh-colored papules. The greatest incidence of MC is seen in the pediatric population and sexually active young adults, and it is considered a self-limited disease in immunocompetent individuals.1 With the emergence of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and subsequent AIDS epidemic in the 1980s, a new population of immunocompromised individuals has been observed to be increasingly susceptible to MC with an atypical clinical presentation and a recalcitrant disease course.2 Although the increased prevalence of MC in the HIV population has been well-documented, it has been observed in other disease states or iatrogenically induced immunosuppression due to a deficiency in function or absolute number of T lymphocytes.

We present a case of a patient with long-standing psoriasis on biologic therapy who presented with MC with a subsequent workup that revealed AIDS. This case reiterates the importance of MC as a potential indicator of underlying immunosuppression. We review the literature to evaluate the occurrence of MC in immunosuppressed patients.

Case Report

A 33-year-old man initially presented for evaluation of severe plaque-type psoriasis associated with pain, erythema, and swelling of the joints of the hands of 10 years’ duration. He was started on methotrexate 5 mg weekly and topical corticosteroids but was unable to tolerate methotrexate due to headaches. He also had difficulty affording topical medications and adjunctive phototherapy. The patient was sporadically seen in follow-up with persistence of psoriatic plaques involving up to 60% body surface area (BSA) with the only treatment consisting of occasional topical steroids. Five years later, the patient was restarted on methotrexate 5 to 7.5 mg weekly, which resulted in moderate improvement. However, because of persistent elevation of liver enzymes, this treatment was stopped. Several months later he was evaluated for treatment with a biologic agent, and after a negative tuberculin skin test, he began treatment with etanercept 50 mg subcutaneous injection twice weekly, which provided notable improvement and allowed for reduction of dose frequency to once weekly.

At follow-up 1 year later, the patient had continued improvement of psoriasis with approximately 30% BSA on a treatment regimen of etanercept 50 mg weekly injection and topical corticosteroids. However, on physical examination, there were multiple small semitranslucent papules with telangiectases on the chest and upper back (Figure 1). Biopsy of a representative papule on the chest revealed MC (Figure 2). The patient was subsequently advised to stop etanercept and to return immediately to the clinic for HIV testing. He returned for follow-up 3 months later with pronounced worsening of disease and a new onset of blurred vision of the right eye. Cutaneous examination revealed numerous large erythematous plaques with superficial scale and cerebriform surface on the chest, back, abdomen, and upper and lower extremities involving 80% BSA (Figure 3). Biopsy of a plaque demonstrated psoriasiform dermatitis with neutrophils and parakeratosis consistent with psoriasis. Extensive blood work was notable for reactive HIV antibody and lymphopenia, CD4 lymphocyte count of 60 cells/mm3, and an HIV viral load of 247,000 copies/mL, meeting diagnostic criteria for AIDS. Additionally, ophthalmologic evaluation revealed toxoplasma retinitis. Upon initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and continued use of topical corticosteroids, the patient experienced notable improvement of disease severity with approximately 20% BSA.

Comment

Molluscum contagiosum is a common skin infection. Among patients with HIV and other types of impaired cellular immunity, the prevalence of MC is estimated to be as high as 20%.3 The MC poxvirus survives and proliferates within the epidermis by interfering with tumor necrosis factor–induced apoptosis of virally infected cells; therefore, intact cell-mediated immunity is an important component of prevention and clearance of poxvirus infections. In immunocompromised patients, the presentation of MC varies widely, and the disease is often difficult to eradicate. This review will highlight the prevalence, presentation, and treatment of MC in the context of immunosuppressed states.

HIV/AIDS

Molluscum contagiosum in HIV-positive patients was first recognized in 1983,2 and its prevalence is estimated to range from 5% to 18% in AIDS patients.3 Molluscum contagiosum is a clinical sign of HIV progression, and its incidence appears to increase with reduced immune function (ie, a CD4 cell count <200/mm3).3 In a study of 456 patients with HIV-associated skin disorders, the majority of patients with MC had notable immunosuppression with a median survival time of 12 months. Thus, MC was not an independent prognostic marker but a clinical indicator of markedly reduced immune status.4

Molluscum contagiosum is transmitted in both sexual and nonsexual patterns in HIV-positive individuals, with the distribution of the latter involving primarily the face and neck. Although it may present with typical umbilicated papules, MC has a wide range of atypical clinical presentations in patients with AIDS that can make it difficult to diagnose. Complicated cases of eyelid MC have been reported in advanced HIV in both adults and children, resulting in obstruction of vision due to large lesions (up to 2 cm) or hundreds of confluent lesions.5 Giant MC, which appears as large exophytic nodules, is another presentation that has been frequently described in patients with advanced HIV. In these patients, the lesions often are too voluminous for conservative therapy and require excision.6 Atypical MC lesions also can resemble other dermatologic conditions, including condyloma acuminatum,7 nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn, ecthyma,8 and cutaneous horns,9,10 as well as other bacterial and fungal infections in HIV-positive patients, such as cutaneous Cryptococcus neoformans,11,12 disseminated histoplasmosis,13 and infections caused by Penicillium marneffei14 and Bartonella henselae.15 In most cases of MC in HIV-positive patients, diagnosis is dependent on the examination of biopsy specimens, which maintain the same histopathologic features regardless of immune status.

The management of MC in patients with HIV/AIDS is difficult. Molluscum contagiosum has shown no evidence of spontaneous resolution in patients with HIV, and treatment with one modality is often insufficient. Treatment is most successful when a combination approach is utilized with destructive procedures (eg, curettage, cryosurgery) and adjunctive agents (eg, retinoids, cantharidin, trichloroacetic acid). Imiquimod and cidofovir have been used off label for MC in AIDS patients.16 Imiquimod, which is used to treat genital warts, another cutaneous viral infection seen in patients with HIV, has demonstrated efficacy in treating MC.16 In a randomized controlled trial comparing imiquimod cream 5% to cryotherapy for MC in healthy children, imiquimod was slow acting but better suited than cryotherapy for patients with eruptions of many small lesions.17 For HIV patients, numerous reports have described successful treatment of disseminated or recalcitrant MC with topical imiquimod.18-20 Cidofovir, an antiviral used to treat cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients with AIDS, is a promising antiviral agent against the poxvirus family. In a study of viral DNA polymerase genes of MC virus, cidofovir inhibited MC virus DNA polymerase activity.21 It has been used in both topical (1% to 3%) and intravenous form to successfully treat recalcitrant and exuberant giant MC.6,22 However, the use of cidofovir is limited by its high costs, especially when compounded into a topical formulation.23

From a systemic standpoint, numerous reports have shown that treating the underlying HIV by optimizing HAART is the most important first step in clearing MC.24-27 However, a special concern regarding the initiation of HAART in patients with MC as well as a markedly impaired immune function is the development of an inflammatory reaction called immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS). This reaction is thought to be a result of immune recovery in severely immunosuppressed patients. During the initial phase of reconstitution when CD4 lymphocyte counts rise and viral load decreases, IRIS occurs due to an inflammatory reaction to microbial and autoimmune antigens, leading to temporary clinical deterioration.28 The incidence has been reported in up to 25% of patients starting HAART, and 52% to 78% of IRIS cases involve dermatologic manifestations such as varicella-zoster virus, cytomegalovirus infections, genital warts, and MC.29,30 In a cohort study of 199 patients, 2% of patients developed MC within 6 months of initiating HAART.31 In a case of exuberant MC lesions after beginning HAART, the lesions spontaneously resolved with the progression of immune reconstitution.28

Malignancies

Patients with hematologic malignancies such as lymphoma and leukemia comprise another subset of patients at risk for atypical presentations of MC. Molluscum contagiosum has been described in patients with hematologic malignancies such as adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, multiple myeloma, chronic myeloid leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, lymphomatoid papulosis, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. In a review of MC in children with cancer, 0.5% were diagnosed with MC.32,33 Reports also have documented eruptive MC in the presence of solid organ cancers, including lung cancer.34

In patients with malignancies, the differential diagnosis should include other common dermatologic conditions such as varicella, herpes simplex, papillomas, pyoderma, and cutaneous cryptococcosis, as well as MC. Similar to HIV-positive patients, the lesions of MC described in patients with malignancies do not tend to spontaneously resolve. In a report of a pediatric patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, MC presented as an ulcerated lesion without any classic features, requiring biopsy for definitive diagnosis. Only partial resolution was achieved with cryotherapy and crusting of the lesion in an attempt to slow the progression.35 In a series of 5 children with hematologic malignancies and MC, little improvement was noted after treatment with surgical scraping, liquid nitrogen, and salicylic acid ointment 5%. Similar to patients with HIV, improvement of immune status and function help clear the disease, and patients who reach remission and discontinue chemotherapeutic agents have a higher rate of spontaneous resolution of previously recalcitrant MC lesions.36

Transplant Patients

Molluscum contagiosum in transplant patients has features similar to patients with HIV/AIDS. In organ transplant recipients, there is an increased risk for cutaneous disease from iatrogenic immunosuppression or immunosuppression through infectious or neoplastic processes.37 As in other immunocompromised populations, MC often has an atypical presentation in transplant patients with more extensive involvement and recalcitrant, rapidly recurring lesions.

In a review of 145 pediatric organ transplant recipients, MC was the fourth most common skin infection after verruca vulgaris, tinea versicolor, and herpes simplex/zoster. Affecting 7% of patients, the majority of patients demonstrated clinically typical lesions; however, the disease was difficult to eradicate if multiple lesions were present.37 In other reports in adults, fulminant and giant MC have been described after renal and other solid organ transplants.38,39 Molluscum contagiosum also has been reported to mimic other skin diseases in transplant patients including tinea barbae40 and nodular basal cell carcinomas.41

The standard treatments are identical to those used in patients with HIV, including ablative methods via liquid nitrogen, electrocautery, cantharidin, trichloroacetic acid, and topical retinoids. Similar to MC in other immunocompromised states, treatment can be difficult and usually requires multiple modalities. For children, imiquimod cream 5% has been recommended due to high clearance rates (up to 92%) and the painless nature of the treatment.42,43

Other Iatrogenic Immunosuppressive States

Immunosuppression through the use of steroids, chemotherapeutic agents, and biologic drugs often is the result of treatment of various diseases. In patients with psoriasis treated with systemic immunosuppressive agents, there are numerous reports that describe the appearance of eruptive MC in association with methotrexate, cyclosporine, and biologics. Methotrexate acts as an immunosuppressive agent by binding to dihydrofolate reductase, which inhibits DNA synthesis in immunologically competent cells.44 It also may block host defense mechanisms against MC by suppressing the expression of serum inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and IFN-γ and suppressing the activity of TNF-α inducing apoptosis of virus-infected cells. Cyclosporine used in conjunction with methotrexate may exacerbate the insult to the immune system by inhibiting the production of IFN-γ.45 Biologics are an emerging class of drugs that have demonstrated efficacy in moderate to severe psoriasis by inhibiting TNF-α or other inflammatory molecules. Several published reports have described eruptive or atypical MC in patients on biologic medications. In one case, within 2 weeks after initiation of infliximab, a monoclonal antibody against TNF-α, a patient developed an eruption of MC involving the entire body.46 In another report, an anti–TNF-α agent for rheumatoid arthritis was associated with atypical MC with eyelid lesions.47

There are other skin disorders treated with immunosuppressive agents that also have been associated with MC. In a patient with pemphigus vulgaris treated with prednisolone, pimecrolimus, and azathioprine, MC lesions were observed on the face and within healed pemphigus vulgaris sites.48 Pimecrolimus and tacrolimus, corticosteroid-sparing agents, suppress cell-mediated immunity and inhibit inflammatory cytokines such as IL-2. The infection resolved with a gradual tapering of immunosuppressive therapy and 10 sessions of cryotherapy.48 In a case of topical pimecrolimus for pityriasis alba, the patient developed biopsy-proven MC within 2 weeks of initiating treatment in the areas that were treated with tacrolimus.49

In nontransplant patients with iatrogenic immunosuppression, MC treatment has not been documented to be as challenging as in patients with inherent immunosuppression. Most patients respond to either withdrawal of the drug alone or to simple ablative treatments such as cryotherapy.45,46,48 This important difference is most likely due to the presence of an otherwise intact immune system.

Conclusion