User login

Anecdote Increases Patient Willingness to Take a Biologic Medication for Psoriasis

Biologic medications are highly effective in treating moderate to severe psoriasis, yet many patients are apprehensive about taking a biologic medication for a variety of reasons, such as hearing negative information about the drug from friends or family, being nervous about injection, or seeing the drug or its side effects negatively portrayed in the media.1-3 Because biologic medications are costly, many patients may fear needing to discontinue use of the medication owing to lack of affordability, which may result in subsequent rebound of psoriasis. Because patients’ fear of a drug is inherently subjective, it can be modified with appropriate reassurance and presentation of evidence. By understanding what information increases patients’ confidence in their willingness to take a biologic medication, patients may be more willing to initiate use of the drug and improve treatment outcomes.

There are mixed findings about whether statistical evidence or an anecdote is more effective in persuasion.4-6 The specific context in which the persuasion takes place may be important in determining which method is superior. In most nonthreatening situations, people appear to be more easily persuaded by statistical evidence rather than an anecdote. However, in circumstances where emotional engagement is high, such as regarding one’s own health, an anecdote tends to be more persuasive compared to statistical evidence.7 The purpose of this study was to evaluate patients’ willingness to take a biologic medication for the management of their psoriasis if presented with either clinical trial evidence of the agent’s efficacy and safety, an anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience, or both.

Methods

Patient Inclusion Criteria

Following Wake Forest School of Medicine institutional review board approval, a prospective parallel-arm survey study was performed on eligible patients 18 years or older with a self-reported diagnosis of psoriasis. Patients were required to have a working knowledge of English and not have been previously prescribed a biologic medication for their psoriasis. If patients did not meet inclusion criteria after answering the survey eligibility screening questions, then they were unable to complete the remainder of the survey and were excluded from the analysis.

Survey Administration

A total of 222 patients were recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk, an online crowdsourcing platform. (Amazon Mechanical Turk is a validated tool in conducting research in psychology and other social sciences and is considered as diverse as and perhaps more representative than traditional samples.8,9) Patients received a fact sheet and were taken to the survey hosted on Qualtrics, a secure web-based survey software that supports data collection for research studies. Amazon Mechanical Turk requires some amount of compensation to patients; therefore, recruited patients were compensated $0.03.

Statistical Analysis

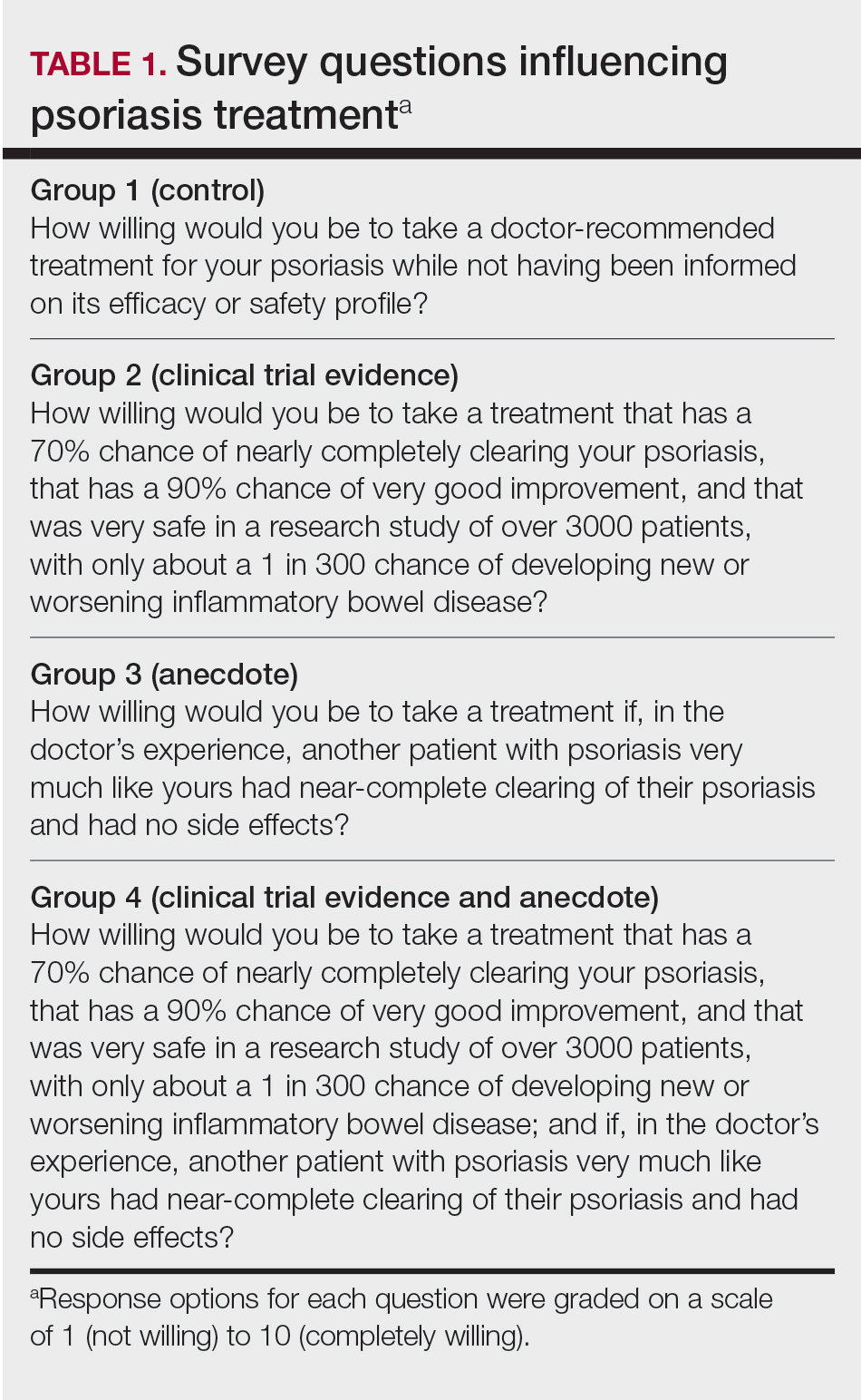

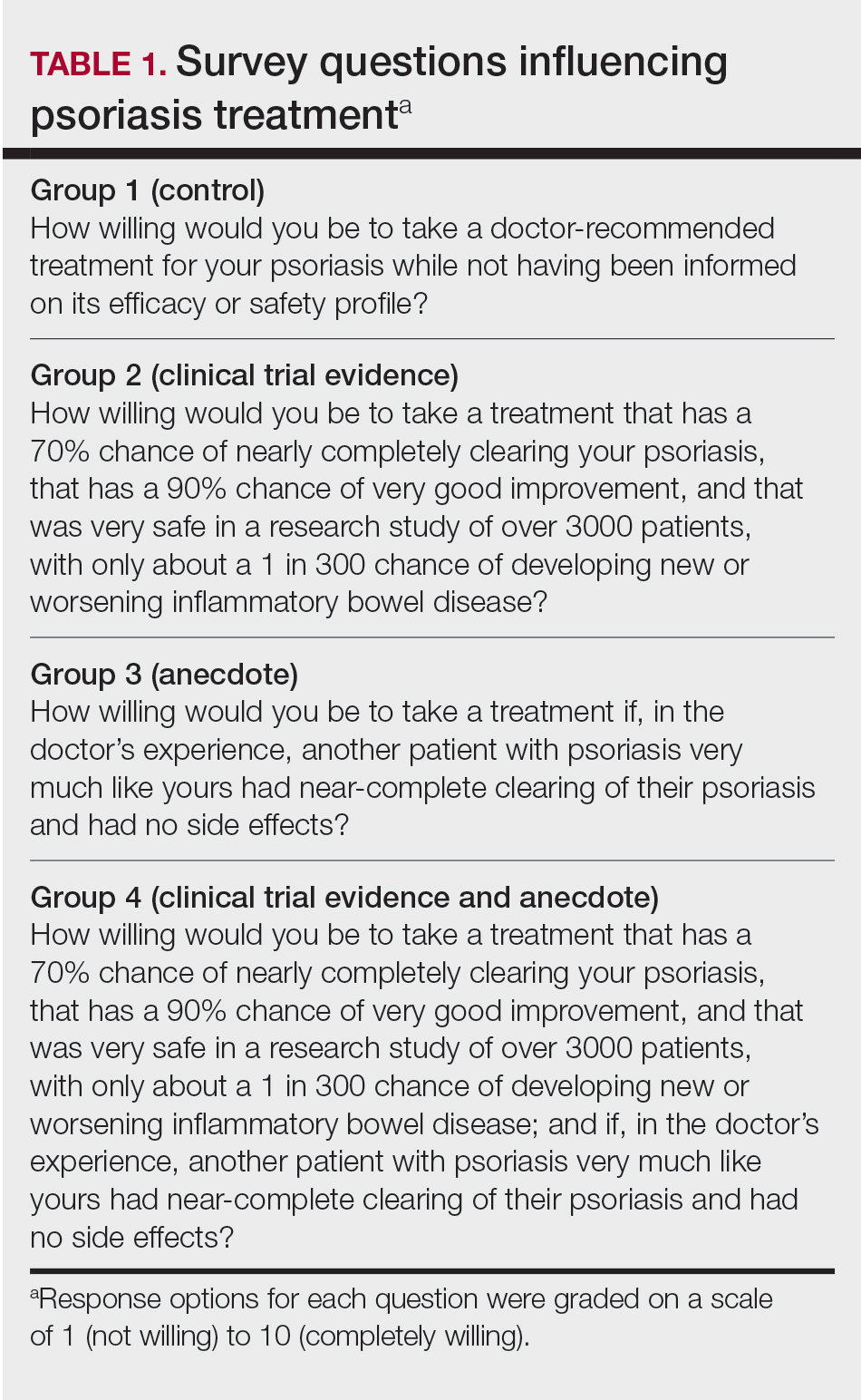

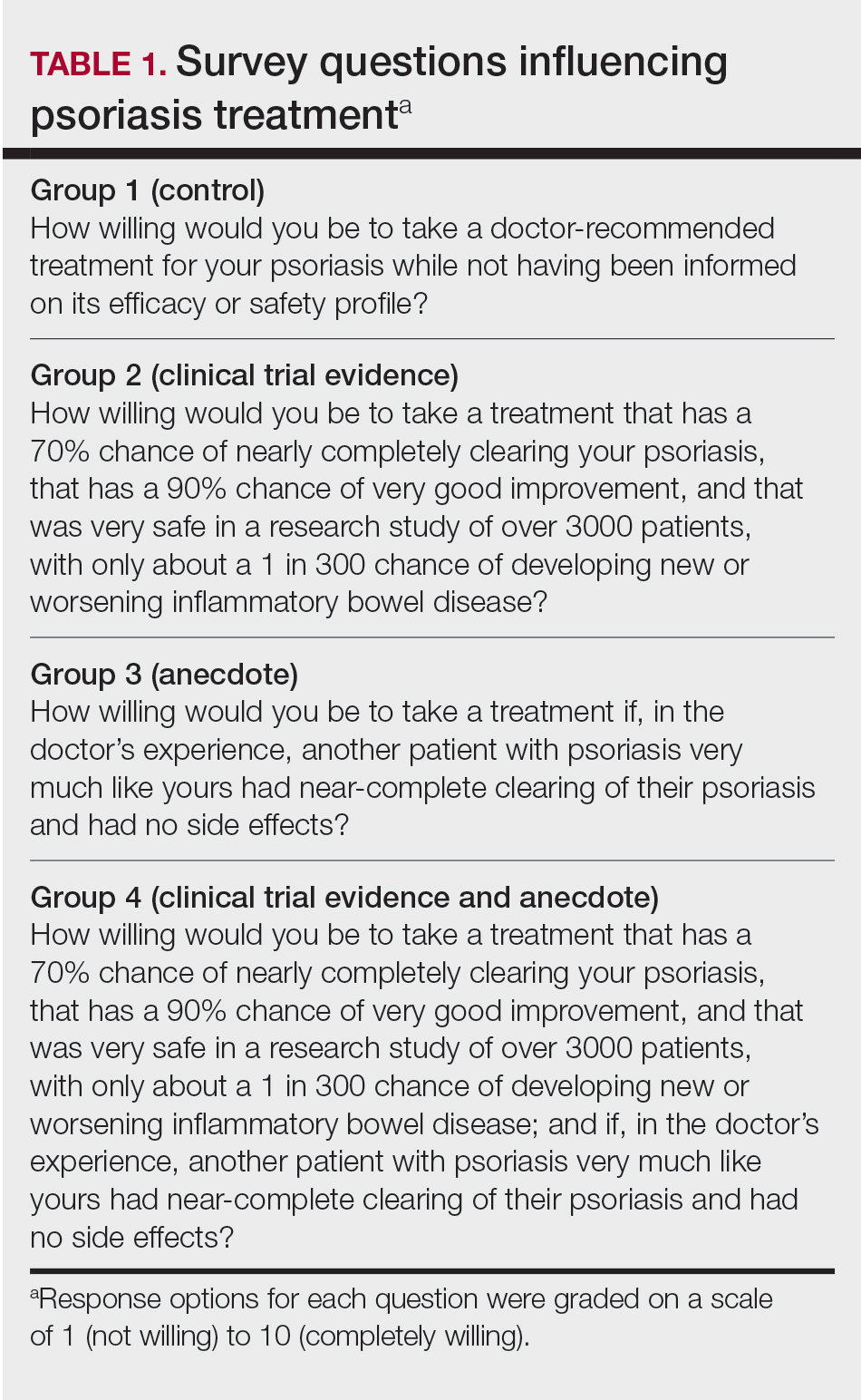

Patients were randomized using SPSS Statistics version 23.0 (IBM) in a 1:1 ratio to assess how willing they would be to take a biologic medication for their psoriasis if presented with one of the following: (1) a control that queried patients about their willingness to take treatment without having been informed on its efficacy or safety, (2) clinical trial evidence of the agent’s efficacy and safety, (3) an anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience, or (4) both clinical trial evidence of the agent’s efficacy and safety and an anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience (Table 1). Demographic information including sex, age, ethnicity, and education level was collected, in addition to other baseline characteristics such as having friends or family with a history of psoriasis, history of participation in a clinical trial with use of an experimental drug, and the number of years since clinical diagnosis of psoriasis.

Outcome measures were recorded as patients’ responses regarding their willingness to take a biologic medication on a 10-point Likert scale (1=not willing; 10=completely willing). Scores were treated as ordinal data and evaluated using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Dunn test. Descriptive statistics were tabulated on all variables. Baseline characteristics were analyzed using a 2-tailed, unpaired t test for continuous variables and the χ2 and Fisher exact tests for categorical variables. Ordinal linear regression analysis was performed to determine whether reported willingness to take a biologic medication was related to patients’ demographics, including age, sex, having family or friends with a history of psoriasis, history of participation in a clinical trial with use of an experimental drug, and the number of years since clinical diagnosis of psoriasis. Answers on the ordinal scale were binarized. The data were analyzed with SPSS Statistics version 23.0.

Results

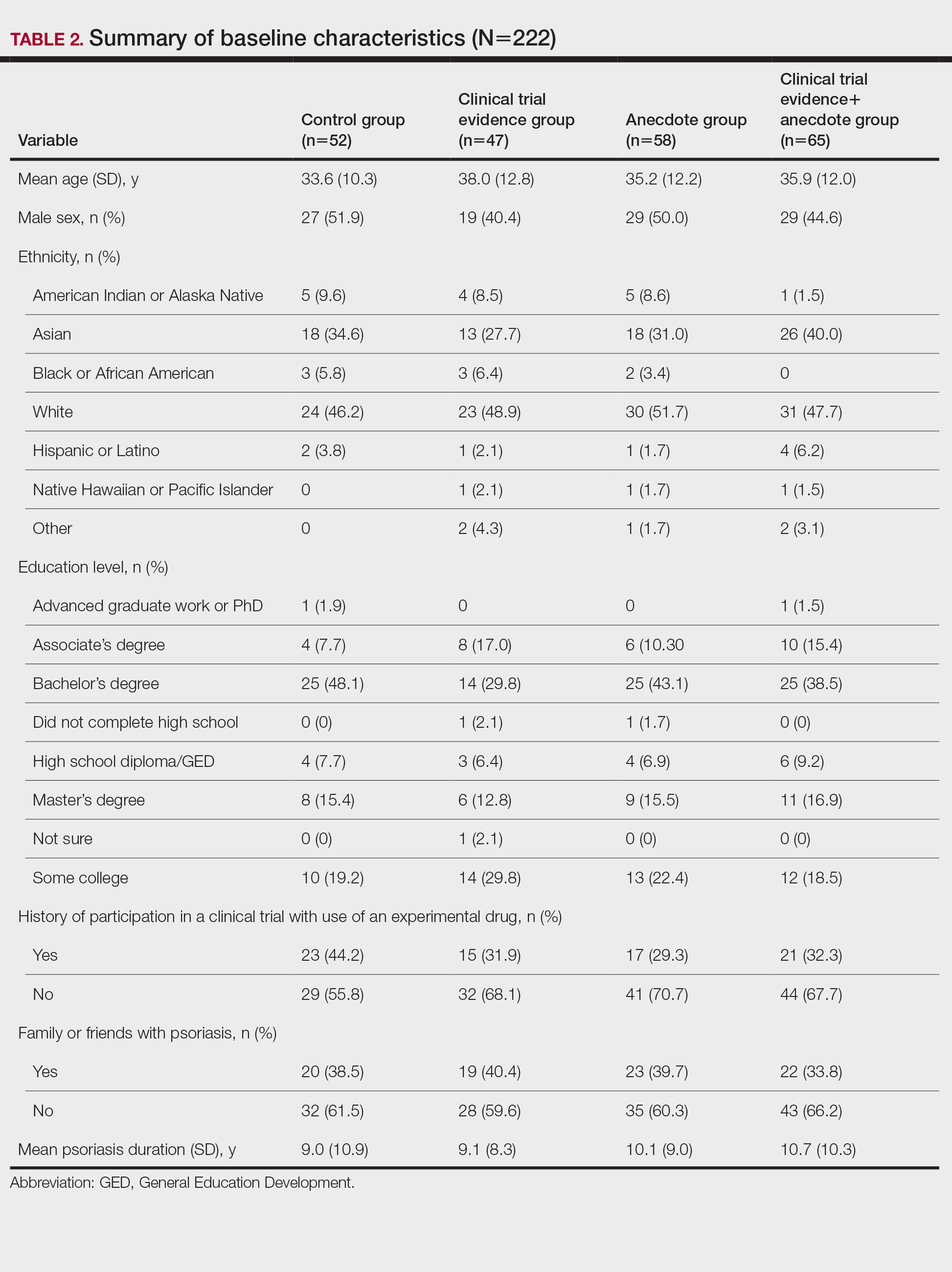

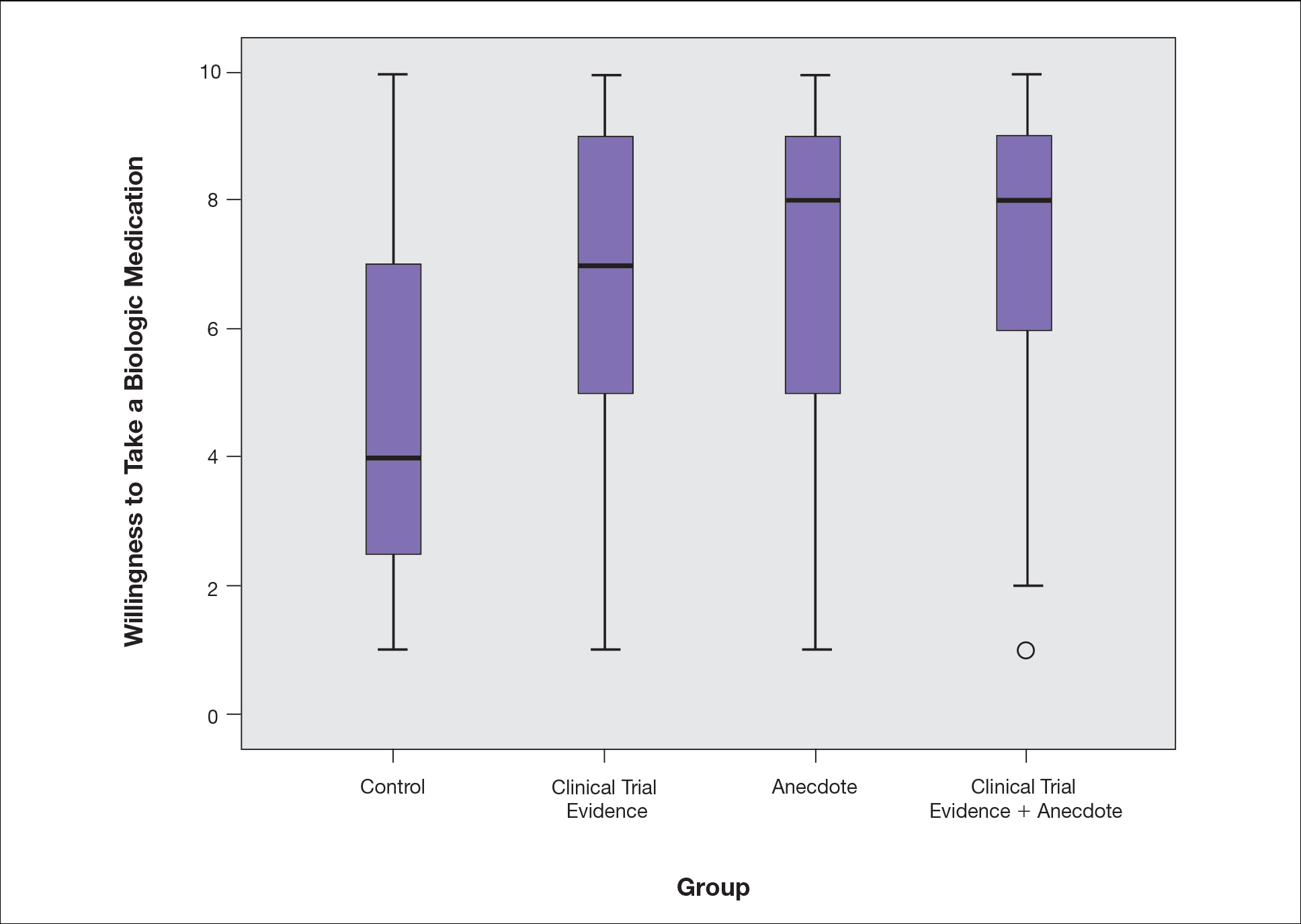

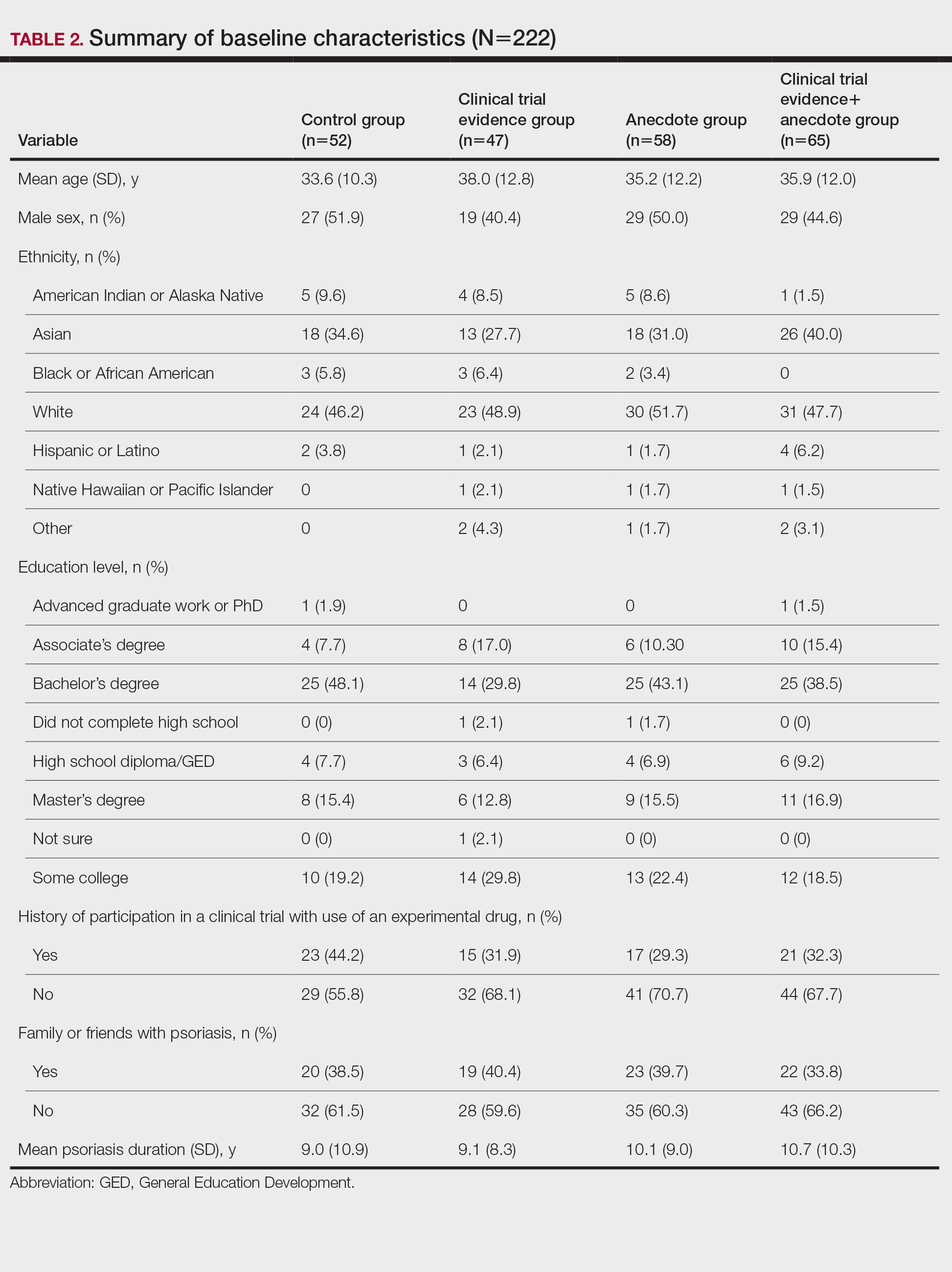

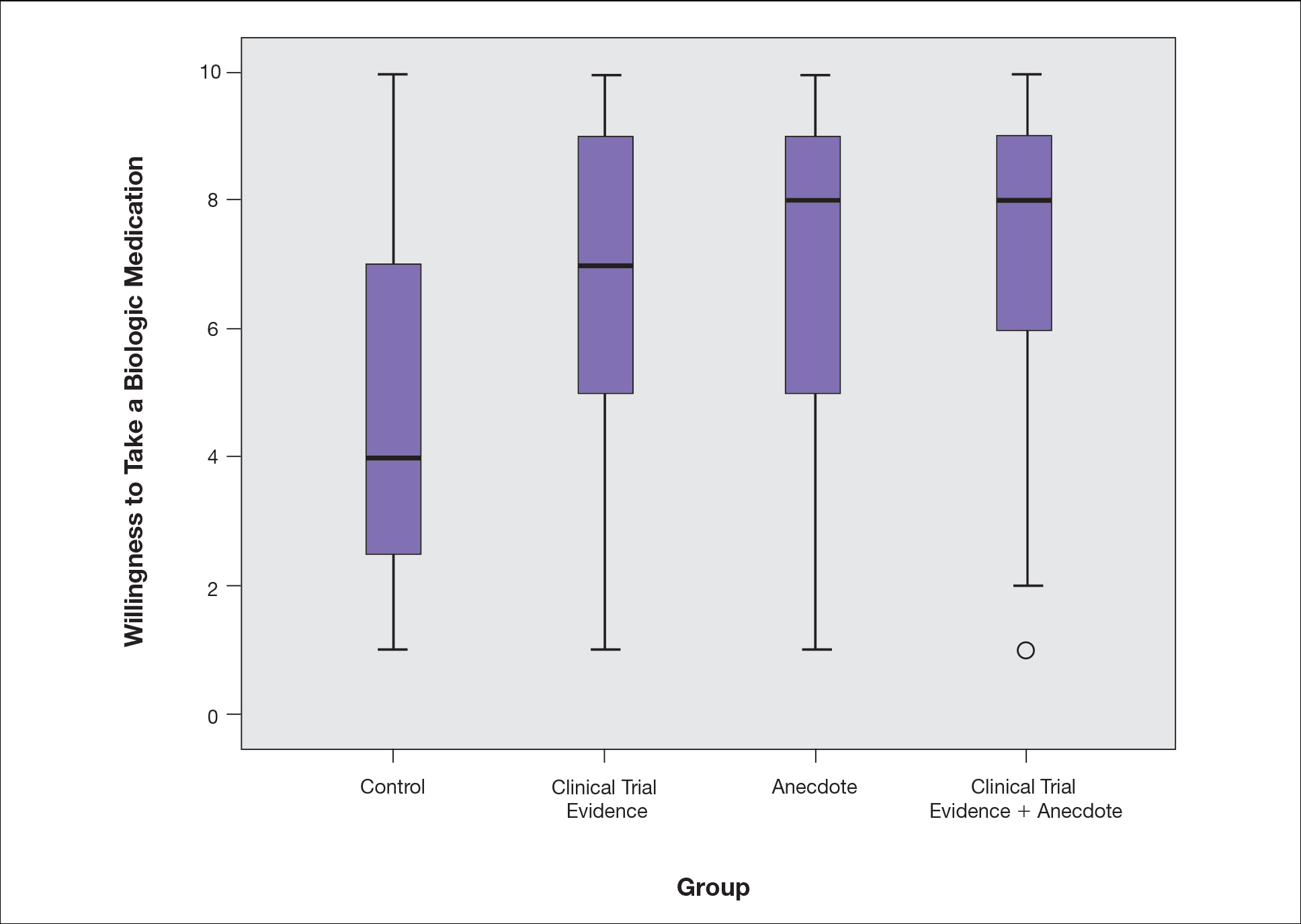

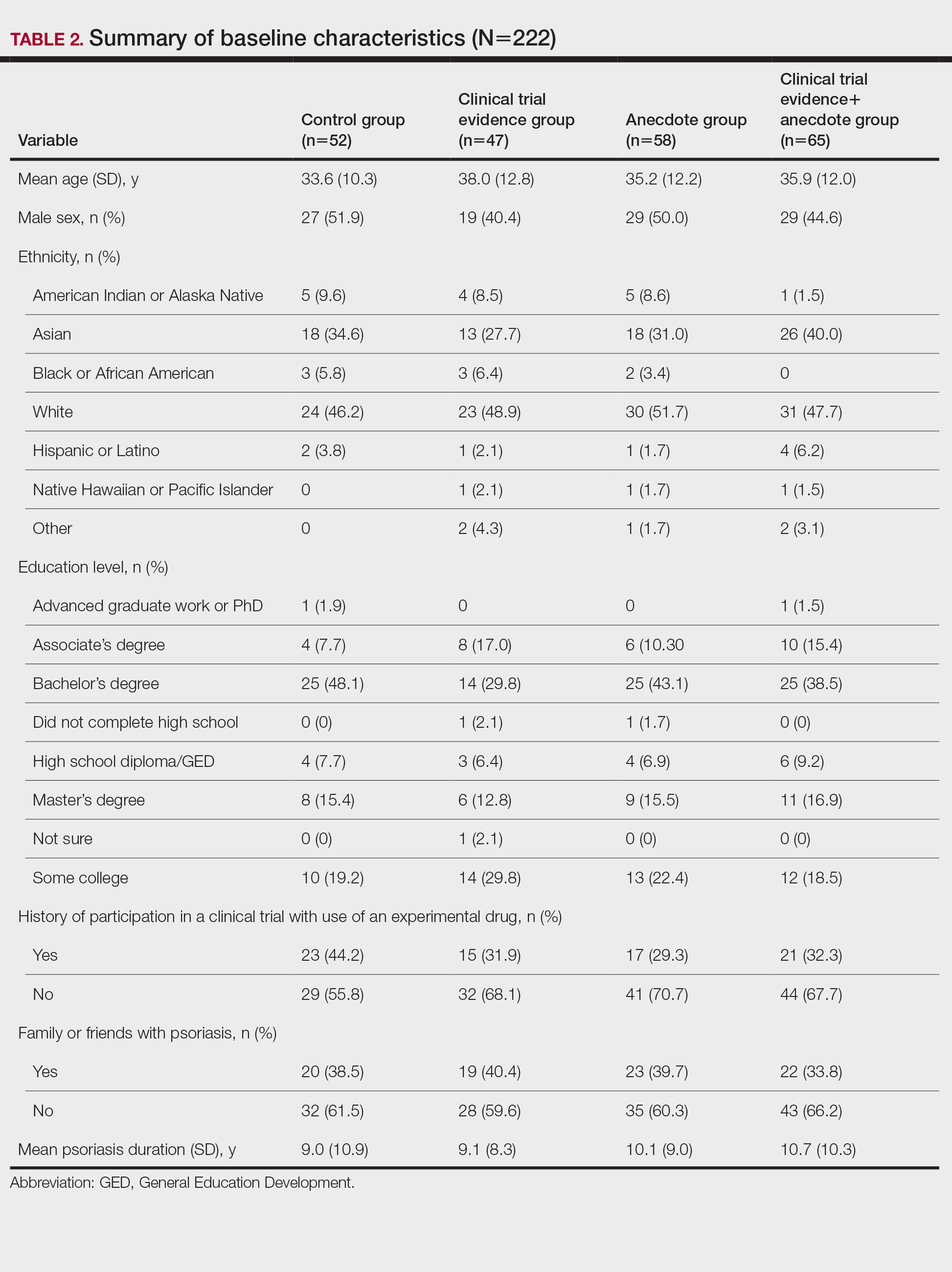

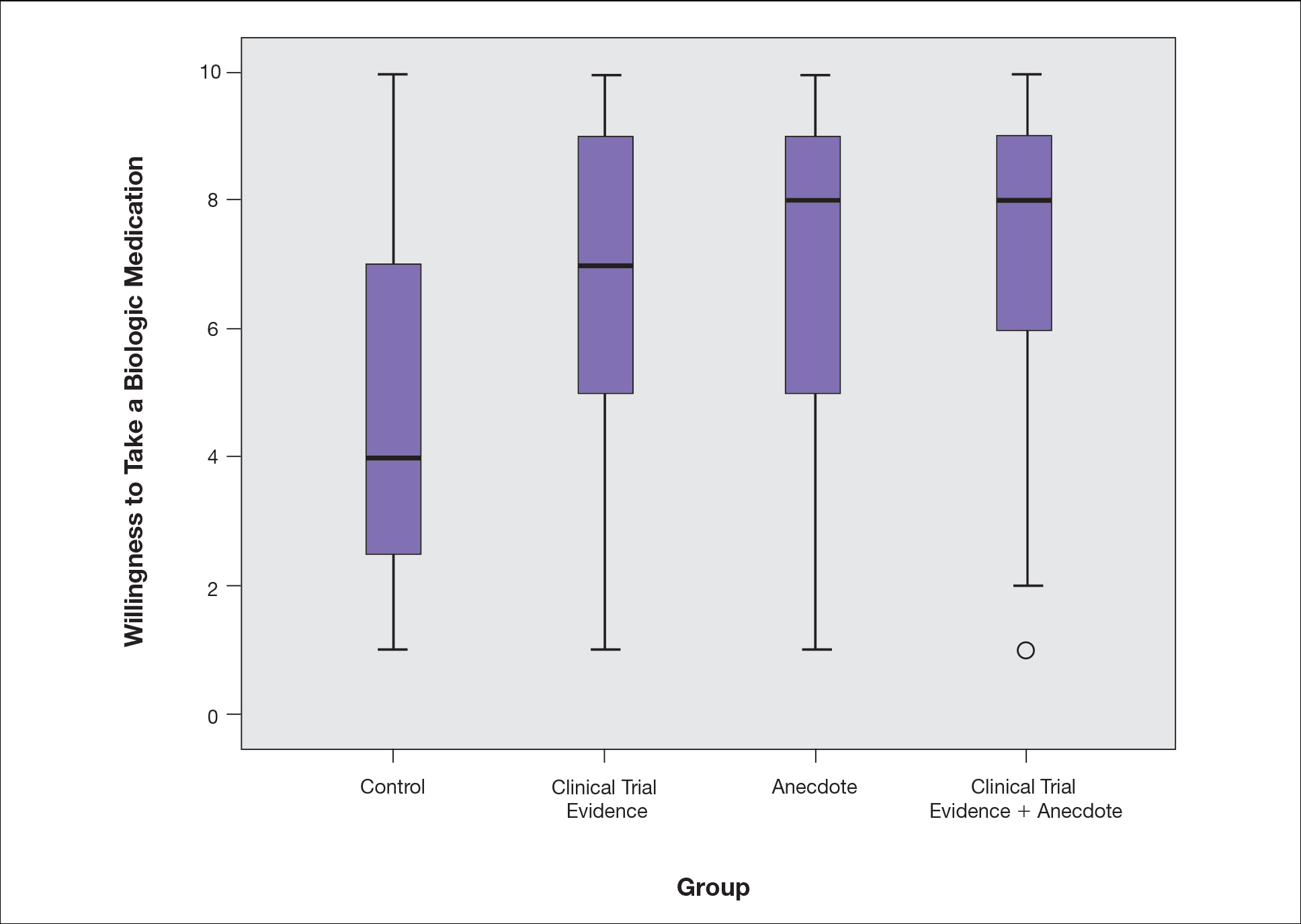

There were no statistically significant differences among the baseline characteristics of the 4 information assignment groups (Table 2). Patients in the control group not given either clinical trial evidence of a biologic medication’s efficacy and safety or anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience had the lowest reported willingness to take treatment (median, 4.0)(Figure).

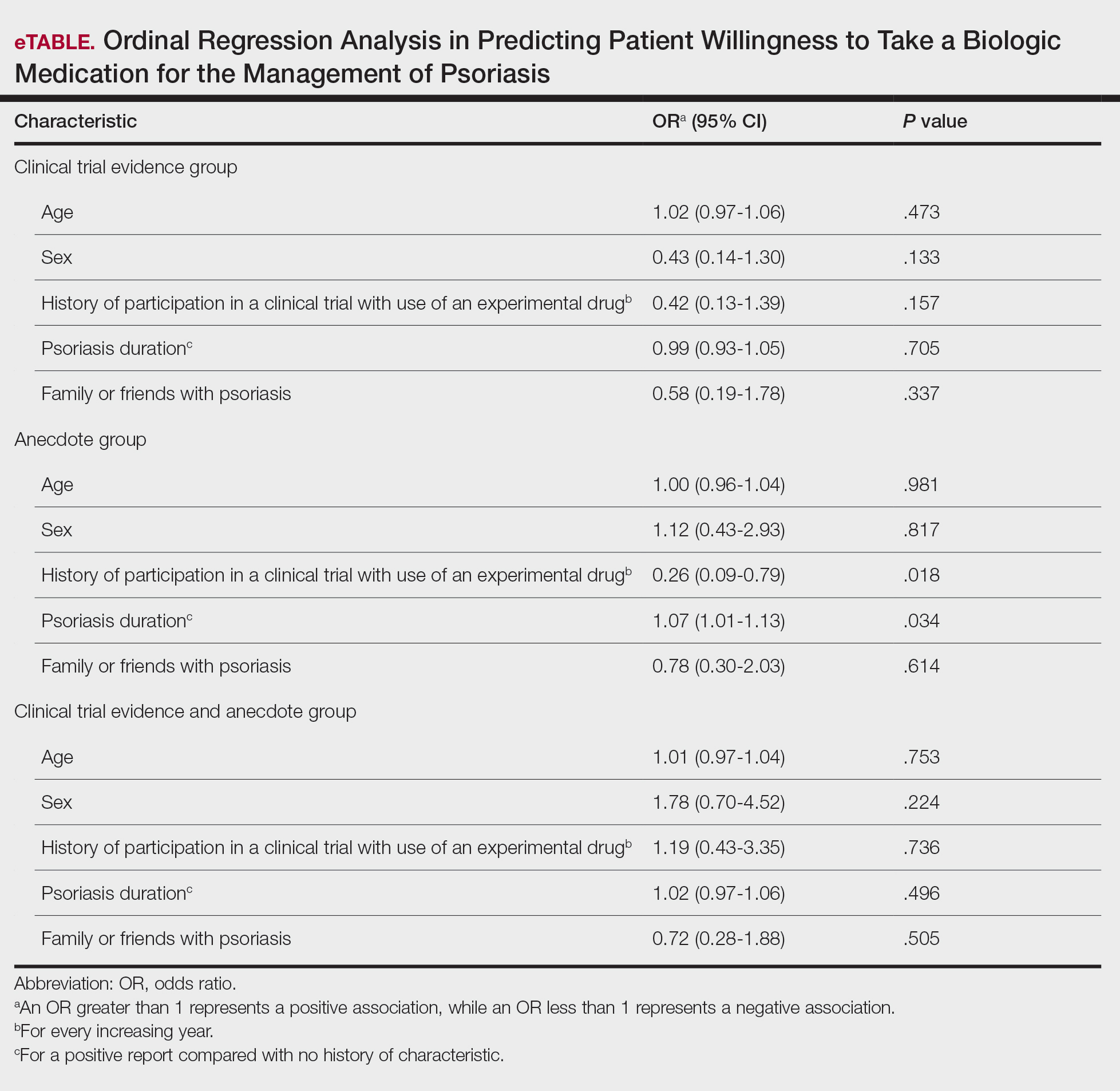

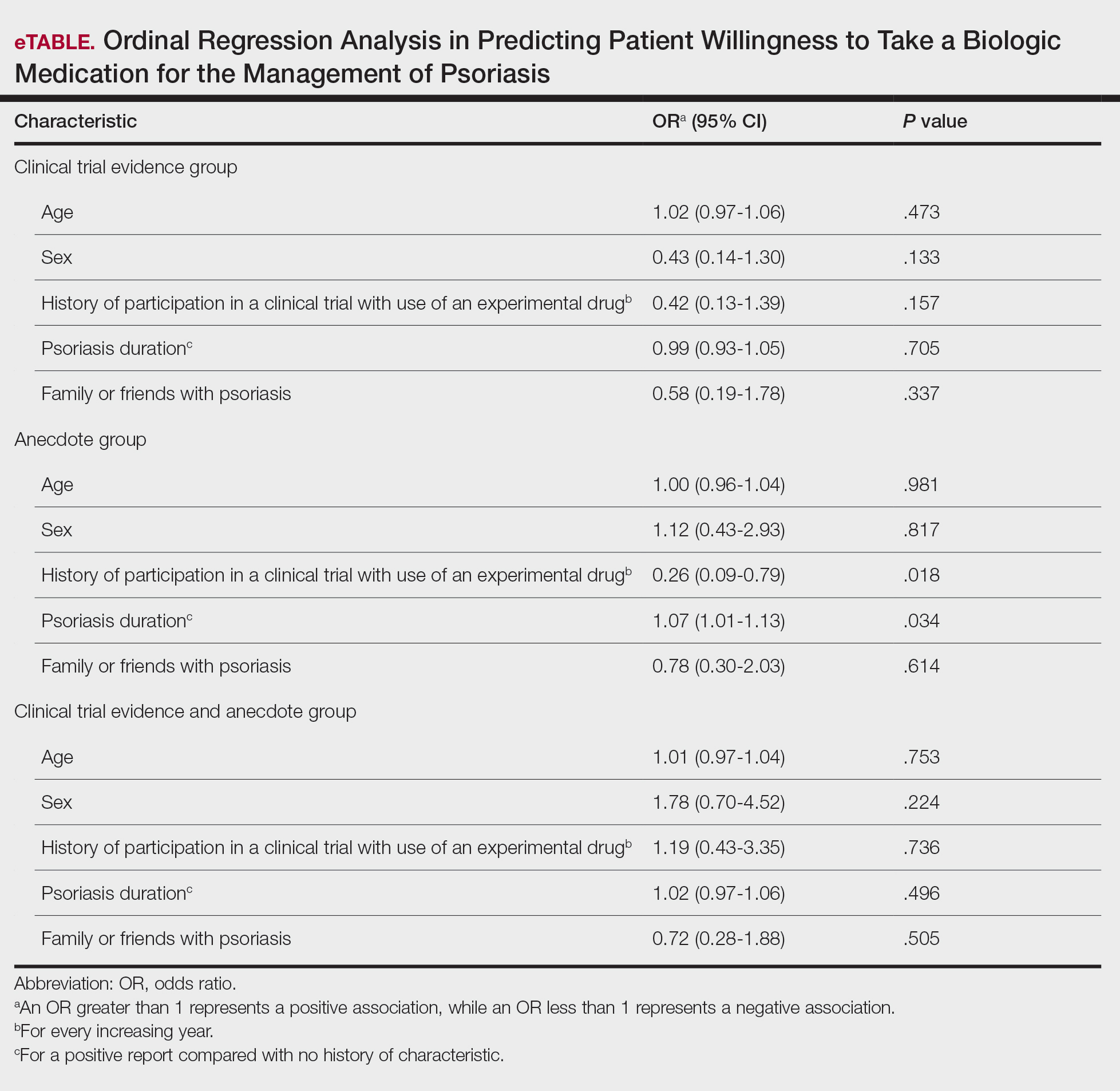

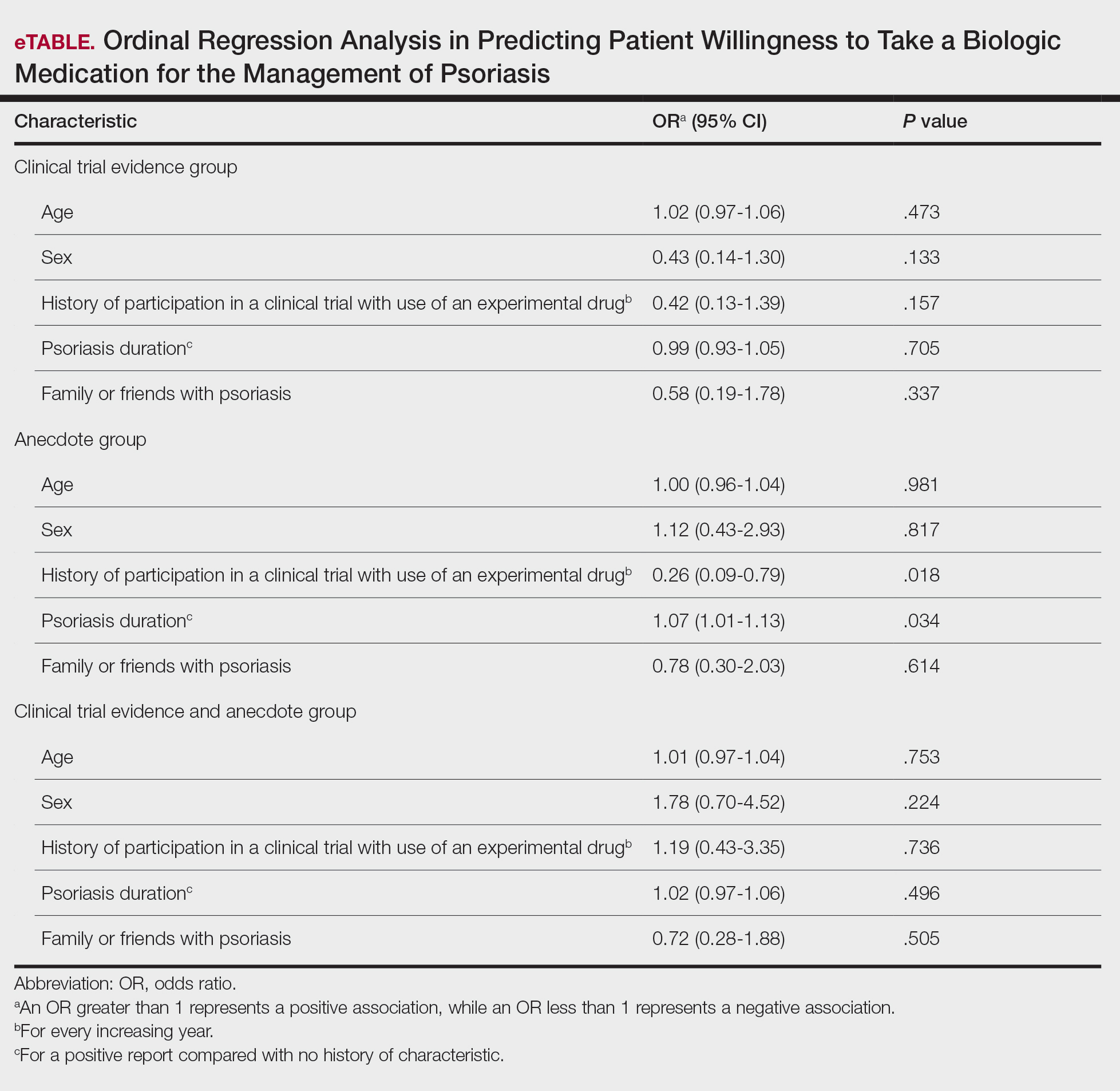

Based on regression analysis, age, sex, and having friends or family with a history of psoriasis were not significantly associated with patients’ responses (eTable). The number of years since clinical diagnosis of psoriasis (P=.034) and history of participation in a clinical trial with use of an experimental drug (P=.018) were significantly associated with the willingness of patients presented with an anecdote to take a biologic medication.

Comment

Anecdotal Reassurance

The presentation of clinical trial and/or anecdotal evidence had a strong effect on patients’ willingness to take a biologic medication for their psoriasis. Human perception of a treatment is inherently subjective, and such perceptions can be modified with appropriate reassurance and presentation of evidence.1 Across the population we studied, presenting a brief anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience is a quick and efficient means—and as or more effective as giving details on efficacy and safety—to help patients decide to take a treatment for their psoriasis.

Anecdotal reassurance is powerful. Both health care providers and patients have a natural tendency to focus on anecdotal experiences rather than statistical reasoning when making treatment decisions.10-12 Although negative anecdotal experiences may make patients unwilling to take a medication (or may make them overly desirous of an inappropriate treatment), clinicians can harness this psychological phenomenon to both increase patient willingness to take potentially beneficial treatments or to deter them from engaging in activities that can be harmful to their health, such as tanning and smoking.

Psoriasis Duration and Willingness to Take a Biologic Medication

In general, patient demographics did not appear to have an association with reported willingness to take a biologic medication for psoriasis. However, the number of years since clinical diagnosis of psoriasis had an effect on willingness to take a biologic medication, with patients with a longer personal history of psoriasis showing a higher willingness to take a treatment after being presented with an anecdote than patients with a shorter personal history of psoriasis. We can only speculate on the reasons why. Patients with a longer personal history of psoriasis may have tried and failed more treatments and therefore have a distrust in the validity of clinical trial evidence. These patients may feel their psoriasis is different than that of other clinical trial participants and thus may be more willing to rely on the success stories of individual patients.

Prior participation in a clinical trial with use of an experimental drug was associated with a lower willingness to choose treatment after being presented with anecdotal reassurance. This finding may be attributable to these patients understanding the subjective nature of anecdotes and preferring more objective information in the form of randomized clinical trials in making treatment decisions. Overall, the presentation of evidence about the efficacy and safety of biologic medications in the treatment of psoriasis has a greater impact on patient decision-making than patients’ age, sex, and having friends or family with a history of psoriasis.

Limitations

Limitations of the study were typical of survey-based research. With closed-ended questions, patients were not able to explain their responses. In addition, hypothetical informational statements of a biologic’s efficacy and safety may not always imitate clinical reality. However, we believe the study is valid in exploring the power of an anecdote in influencing patients’ willingness to take biologic medications for psoriasis. Furthermore, educational level and ethnicity were excluded from the ordinal regression analysis because the assumption of parallel lines was not met.

Ethics Behind an Anecdote

An important consideration is the ethical implications of sharing an anecdote to guide patients’ perceptions of treatment and behavior. Although clinicians rely heavily on the available data to determine the best course of treatment, providing patients with comprehensive information on all risks and benefits is rarely, if ever, feasible. Moreover, even objective clinical data will inevitably be subjectively interpreted by patients. For example, describing a medication side effect as occurring in 1 in 100 patients may discourage patients from pursuing treatment, whereas describing that risk as not occurring in 99 in 100 patients may encourage patients, despite these 2 choices being mathematically identical.13 Because the subjective interpretation of data is inevitable, presenting patients with subjective information in the form of an anecdote to help them overcome fears of starting treatment and achieve their desired clinical outcomes may be one of the appropriate approaches to present what is objectively the best option, particularly if the anecdote is representative of the expected treatment response. Clinicians can harness this understanding of human psychology to better educate patients about their treatment options while fulfilling their ethical duty to act in their patients’ best interest.

Conclusion

Using an anecdote to help patients overcome fears of starting a biologic medication may be appropriate if the anecdote is reasonably representative of an expected treatment outcome. Patients should have an accurate understanding of the common risks and benefits of a medication for purposes of shared decision-making.

- Oussedik E, Cardwell LA, Patel NU, et al. An anchoring-based intervention to increase patient willingness to use injectable medication in psoriasis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:932-934. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.1271

- Brown KK, Rehmus WE, Kimball AB. Determining the relative importance of patient motivations for nonadherence to topical corticosteroid therapy in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:607-613. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.12.021

- Im H, Huh J. Does health information in mass media help or hurt patients? Investigation of potential negative influence of mass media health information on patients’ beliefs and medication regimen adherence. J Health Commun. 2017;22:214-222. doi:10.1080/10810730.2016.1261970

- Hornikx J. A review of experimental research on the relative persuasiveness of anecdotal, statistical, causal, and expert evidence. Studies Commun Sci. 2005;5:205-216.

- Allen M, Preiss RW. Comparing the persuasiveness of narrative and statistical evidence using meta-analysis. Int J Phytoremediation Commun Res Rep. 1997;14:125-131. doi:10.1080/08824099709388654

- Shen F, Sheer VC, Li R. Impact of narratives on persuasion in health communication: a meta-analysis. J Advert. 2015;44:105-113. doi:10.1080/00913367.2015.1018467

- Freling TH, Yang Z, Saini R, et al. When poignant stories outweigh cold hard facts: a meta-analysis of the anecdotal bias. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2020;160:51-67. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2020.01.006

- Buhrmester M, Kwang T, Gosling SD. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011;6:3-5. doi:10.1177/1745691610393980

- Berry K, Butt M, Kirby JS. Influence of information framing on patient decisions to treat actinic keratosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:421-426. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.5245

- Landon BE, Reschovsky J, Reed M, et al. Personal, organizational, and market level influences on physicians’ practice patterns: results of a national survey of primary care physicians. Med Care. 2001;39:889-905. doi:10.1097/00005650-200108000-00014

- Borgida E, Nisbett RE. The differential impact of abstract vs. concrete information on decisions. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1977;7:258-271. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1977.tb00750.x

- Fagerlin A, Wang C, Ubel PA. Reducing the influence of anecdotal reasoning on people’s health care decisions: is a picture worth a thousand statistics? Med Decis Making. 2005;25:398-405. doi:10.1177/0272989X05278931

- Gurm HS, Litaker DG. Framing procedural risks to patients: Is 99% safe the same as a risk of 1 in 100? Acad Med. 2000;75:840-842. doi:10.1097/00001888-200008000-00018

Biologic medications are highly effective in treating moderate to severe psoriasis, yet many patients are apprehensive about taking a biologic medication for a variety of reasons, such as hearing negative information about the drug from friends or family, being nervous about injection, or seeing the drug or its side effects negatively portrayed in the media.1-3 Because biologic medications are costly, many patients may fear needing to discontinue use of the medication owing to lack of affordability, which may result in subsequent rebound of psoriasis. Because patients’ fear of a drug is inherently subjective, it can be modified with appropriate reassurance and presentation of evidence. By understanding what information increases patients’ confidence in their willingness to take a biologic medication, patients may be more willing to initiate use of the drug and improve treatment outcomes.

There are mixed findings about whether statistical evidence or an anecdote is more effective in persuasion.4-6 The specific context in which the persuasion takes place may be important in determining which method is superior. In most nonthreatening situations, people appear to be more easily persuaded by statistical evidence rather than an anecdote. However, in circumstances where emotional engagement is high, such as regarding one’s own health, an anecdote tends to be more persuasive compared to statistical evidence.7 The purpose of this study was to evaluate patients’ willingness to take a biologic medication for the management of their psoriasis if presented with either clinical trial evidence of the agent’s efficacy and safety, an anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience, or both.

Methods

Patient Inclusion Criteria

Following Wake Forest School of Medicine institutional review board approval, a prospective parallel-arm survey study was performed on eligible patients 18 years or older with a self-reported diagnosis of psoriasis. Patients were required to have a working knowledge of English and not have been previously prescribed a biologic medication for their psoriasis. If patients did not meet inclusion criteria after answering the survey eligibility screening questions, then they were unable to complete the remainder of the survey and were excluded from the analysis.

Survey Administration

A total of 222 patients were recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk, an online crowdsourcing platform. (Amazon Mechanical Turk is a validated tool in conducting research in psychology and other social sciences and is considered as diverse as and perhaps more representative than traditional samples.8,9) Patients received a fact sheet and were taken to the survey hosted on Qualtrics, a secure web-based survey software that supports data collection for research studies. Amazon Mechanical Turk requires some amount of compensation to patients; therefore, recruited patients were compensated $0.03.

Statistical Analysis

Patients were randomized using SPSS Statistics version 23.0 (IBM) in a 1:1 ratio to assess how willing they would be to take a biologic medication for their psoriasis if presented with one of the following: (1) a control that queried patients about their willingness to take treatment without having been informed on its efficacy or safety, (2) clinical trial evidence of the agent’s efficacy and safety, (3) an anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience, or (4) both clinical trial evidence of the agent’s efficacy and safety and an anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience (Table 1). Demographic information including sex, age, ethnicity, and education level was collected, in addition to other baseline characteristics such as having friends or family with a history of psoriasis, history of participation in a clinical trial with use of an experimental drug, and the number of years since clinical diagnosis of psoriasis.

Outcome measures were recorded as patients’ responses regarding their willingness to take a biologic medication on a 10-point Likert scale (1=not willing; 10=completely willing). Scores were treated as ordinal data and evaluated using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Dunn test. Descriptive statistics were tabulated on all variables. Baseline characteristics were analyzed using a 2-tailed, unpaired t test for continuous variables and the χ2 and Fisher exact tests for categorical variables. Ordinal linear regression analysis was performed to determine whether reported willingness to take a biologic medication was related to patients’ demographics, including age, sex, having family or friends with a history of psoriasis, history of participation in a clinical trial with use of an experimental drug, and the number of years since clinical diagnosis of psoriasis. Answers on the ordinal scale were binarized. The data were analyzed with SPSS Statistics version 23.0.

Results

There were no statistically significant differences among the baseline characteristics of the 4 information assignment groups (Table 2). Patients in the control group not given either clinical trial evidence of a biologic medication’s efficacy and safety or anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience had the lowest reported willingness to take treatment (median, 4.0)(Figure).

Based on regression analysis, age, sex, and having friends or family with a history of psoriasis were not significantly associated with patients’ responses (eTable). The number of years since clinical diagnosis of psoriasis (P=.034) and history of participation in a clinical trial with use of an experimental drug (P=.018) were significantly associated with the willingness of patients presented with an anecdote to take a biologic medication.

Comment

Anecdotal Reassurance

The presentation of clinical trial and/or anecdotal evidence had a strong effect on patients’ willingness to take a biologic medication for their psoriasis. Human perception of a treatment is inherently subjective, and such perceptions can be modified with appropriate reassurance and presentation of evidence.1 Across the population we studied, presenting a brief anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience is a quick and efficient means—and as or more effective as giving details on efficacy and safety—to help patients decide to take a treatment for their psoriasis.

Anecdotal reassurance is powerful. Both health care providers and patients have a natural tendency to focus on anecdotal experiences rather than statistical reasoning when making treatment decisions.10-12 Although negative anecdotal experiences may make patients unwilling to take a medication (or may make them overly desirous of an inappropriate treatment), clinicians can harness this psychological phenomenon to both increase patient willingness to take potentially beneficial treatments or to deter them from engaging in activities that can be harmful to their health, such as tanning and smoking.

Psoriasis Duration and Willingness to Take a Biologic Medication

In general, patient demographics did not appear to have an association with reported willingness to take a biologic medication for psoriasis. However, the number of years since clinical diagnosis of psoriasis had an effect on willingness to take a biologic medication, with patients with a longer personal history of psoriasis showing a higher willingness to take a treatment after being presented with an anecdote than patients with a shorter personal history of psoriasis. We can only speculate on the reasons why. Patients with a longer personal history of psoriasis may have tried and failed more treatments and therefore have a distrust in the validity of clinical trial evidence. These patients may feel their psoriasis is different than that of other clinical trial participants and thus may be more willing to rely on the success stories of individual patients.

Prior participation in a clinical trial with use of an experimental drug was associated with a lower willingness to choose treatment after being presented with anecdotal reassurance. This finding may be attributable to these patients understanding the subjective nature of anecdotes and preferring more objective information in the form of randomized clinical trials in making treatment decisions. Overall, the presentation of evidence about the efficacy and safety of biologic medications in the treatment of psoriasis has a greater impact on patient decision-making than patients’ age, sex, and having friends or family with a history of psoriasis.

Limitations

Limitations of the study were typical of survey-based research. With closed-ended questions, patients were not able to explain their responses. In addition, hypothetical informational statements of a biologic’s efficacy and safety may not always imitate clinical reality. However, we believe the study is valid in exploring the power of an anecdote in influencing patients’ willingness to take biologic medications for psoriasis. Furthermore, educational level and ethnicity were excluded from the ordinal regression analysis because the assumption of parallel lines was not met.

Ethics Behind an Anecdote

An important consideration is the ethical implications of sharing an anecdote to guide patients’ perceptions of treatment and behavior. Although clinicians rely heavily on the available data to determine the best course of treatment, providing patients with comprehensive information on all risks and benefits is rarely, if ever, feasible. Moreover, even objective clinical data will inevitably be subjectively interpreted by patients. For example, describing a medication side effect as occurring in 1 in 100 patients may discourage patients from pursuing treatment, whereas describing that risk as not occurring in 99 in 100 patients may encourage patients, despite these 2 choices being mathematically identical.13 Because the subjective interpretation of data is inevitable, presenting patients with subjective information in the form of an anecdote to help them overcome fears of starting treatment and achieve their desired clinical outcomes may be one of the appropriate approaches to present what is objectively the best option, particularly if the anecdote is representative of the expected treatment response. Clinicians can harness this understanding of human psychology to better educate patients about their treatment options while fulfilling their ethical duty to act in their patients’ best interest.

Conclusion

Using an anecdote to help patients overcome fears of starting a biologic medication may be appropriate if the anecdote is reasonably representative of an expected treatment outcome. Patients should have an accurate understanding of the common risks and benefits of a medication for purposes of shared decision-making.

Biologic medications are highly effective in treating moderate to severe psoriasis, yet many patients are apprehensive about taking a biologic medication for a variety of reasons, such as hearing negative information about the drug from friends or family, being nervous about injection, or seeing the drug or its side effects negatively portrayed in the media.1-3 Because biologic medications are costly, many patients may fear needing to discontinue use of the medication owing to lack of affordability, which may result in subsequent rebound of psoriasis. Because patients’ fear of a drug is inherently subjective, it can be modified with appropriate reassurance and presentation of evidence. By understanding what information increases patients’ confidence in their willingness to take a biologic medication, patients may be more willing to initiate use of the drug and improve treatment outcomes.

There are mixed findings about whether statistical evidence or an anecdote is more effective in persuasion.4-6 The specific context in which the persuasion takes place may be important in determining which method is superior. In most nonthreatening situations, people appear to be more easily persuaded by statistical evidence rather than an anecdote. However, in circumstances where emotional engagement is high, such as regarding one’s own health, an anecdote tends to be more persuasive compared to statistical evidence.7 The purpose of this study was to evaluate patients’ willingness to take a biologic medication for the management of their psoriasis if presented with either clinical trial evidence of the agent’s efficacy and safety, an anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience, or both.

Methods

Patient Inclusion Criteria

Following Wake Forest School of Medicine institutional review board approval, a prospective parallel-arm survey study was performed on eligible patients 18 years or older with a self-reported diagnosis of psoriasis. Patients were required to have a working knowledge of English and not have been previously prescribed a biologic medication for their psoriasis. If patients did not meet inclusion criteria after answering the survey eligibility screening questions, then they were unable to complete the remainder of the survey and were excluded from the analysis.

Survey Administration

A total of 222 patients were recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk, an online crowdsourcing platform. (Amazon Mechanical Turk is a validated tool in conducting research in psychology and other social sciences and is considered as diverse as and perhaps more representative than traditional samples.8,9) Patients received a fact sheet and were taken to the survey hosted on Qualtrics, a secure web-based survey software that supports data collection for research studies. Amazon Mechanical Turk requires some amount of compensation to patients; therefore, recruited patients were compensated $0.03.

Statistical Analysis

Patients were randomized using SPSS Statistics version 23.0 (IBM) in a 1:1 ratio to assess how willing they would be to take a biologic medication for their psoriasis if presented with one of the following: (1) a control that queried patients about their willingness to take treatment without having been informed on its efficacy or safety, (2) clinical trial evidence of the agent’s efficacy and safety, (3) an anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience, or (4) both clinical trial evidence of the agent’s efficacy and safety and an anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience (Table 1). Demographic information including sex, age, ethnicity, and education level was collected, in addition to other baseline characteristics such as having friends or family with a history of psoriasis, history of participation in a clinical trial with use of an experimental drug, and the number of years since clinical diagnosis of psoriasis.

Outcome measures were recorded as patients’ responses regarding their willingness to take a biologic medication on a 10-point Likert scale (1=not willing; 10=completely willing). Scores were treated as ordinal data and evaluated using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Dunn test. Descriptive statistics were tabulated on all variables. Baseline characteristics were analyzed using a 2-tailed, unpaired t test for continuous variables and the χ2 and Fisher exact tests for categorical variables. Ordinal linear regression analysis was performed to determine whether reported willingness to take a biologic medication was related to patients’ demographics, including age, sex, having family or friends with a history of psoriasis, history of participation in a clinical trial with use of an experimental drug, and the number of years since clinical diagnosis of psoriasis. Answers on the ordinal scale were binarized. The data were analyzed with SPSS Statistics version 23.0.

Results

There were no statistically significant differences among the baseline characteristics of the 4 information assignment groups (Table 2). Patients in the control group not given either clinical trial evidence of a biologic medication’s efficacy and safety or anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience had the lowest reported willingness to take treatment (median, 4.0)(Figure).

Based on regression analysis, age, sex, and having friends or family with a history of psoriasis were not significantly associated with patients’ responses (eTable). The number of years since clinical diagnosis of psoriasis (P=.034) and history of participation in a clinical trial with use of an experimental drug (P=.018) were significantly associated with the willingness of patients presented with an anecdote to take a biologic medication.

Comment

Anecdotal Reassurance

The presentation of clinical trial and/or anecdotal evidence had a strong effect on patients’ willingness to take a biologic medication for their psoriasis. Human perception of a treatment is inherently subjective, and such perceptions can be modified with appropriate reassurance and presentation of evidence.1 Across the population we studied, presenting a brief anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience is a quick and efficient means—and as or more effective as giving details on efficacy and safety—to help patients decide to take a treatment for their psoriasis.

Anecdotal reassurance is powerful. Both health care providers and patients have a natural tendency to focus on anecdotal experiences rather than statistical reasoning when making treatment decisions.10-12 Although negative anecdotal experiences may make patients unwilling to take a medication (or may make them overly desirous of an inappropriate treatment), clinicians can harness this psychological phenomenon to both increase patient willingness to take potentially beneficial treatments or to deter them from engaging in activities that can be harmful to their health, such as tanning and smoking.

Psoriasis Duration and Willingness to Take a Biologic Medication

In general, patient demographics did not appear to have an association with reported willingness to take a biologic medication for psoriasis. However, the number of years since clinical diagnosis of psoriasis had an effect on willingness to take a biologic medication, with patients with a longer personal history of psoriasis showing a higher willingness to take a treatment after being presented with an anecdote than patients with a shorter personal history of psoriasis. We can only speculate on the reasons why. Patients with a longer personal history of psoriasis may have tried and failed more treatments and therefore have a distrust in the validity of clinical trial evidence. These patients may feel their psoriasis is different than that of other clinical trial participants and thus may be more willing to rely on the success stories of individual patients.

Prior participation in a clinical trial with use of an experimental drug was associated with a lower willingness to choose treatment after being presented with anecdotal reassurance. This finding may be attributable to these patients understanding the subjective nature of anecdotes and preferring more objective information in the form of randomized clinical trials in making treatment decisions. Overall, the presentation of evidence about the efficacy and safety of biologic medications in the treatment of psoriasis has a greater impact on patient decision-making than patients’ age, sex, and having friends or family with a history of psoriasis.

Limitations

Limitations of the study were typical of survey-based research. With closed-ended questions, patients were not able to explain their responses. In addition, hypothetical informational statements of a biologic’s efficacy and safety may not always imitate clinical reality. However, we believe the study is valid in exploring the power of an anecdote in influencing patients’ willingness to take biologic medications for psoriasis. Furthermore, educational level and ethnicity were excluded from the ordinal regression analysis because the assumption of parallel lines was not met.

Ethics Behind an Anecdote

An important consideration is the ethical implications of sharing an anecdote to guide patients’ perceptions of treatment and behavior. Although clinicians rely heavily on the available data to determine the best course of treatment, providing patients with comprehensive information on all risks and benefits is rarely, if ever, feasible. Moreover, even objective clinical data will inevitably be subjectively interpreted by patients. For example, describing a medication side effect as occurring in 1 in 100 patients may discourage patients from pursuing treatment, whereas describing that risk as not occurring in 99 in 100 patients may encourage patients, despite these 2 choices being mathematically identical.13 Because the subjective interpretation of data is inevitable, presenting patients with subjective information in the form of an anecdote to help them overcome fears of starting treatment and achieve their desired clinical outcomes may be one of the appropriate approaches to present what is objectively the best option, particularly if the anecdote is representative of the expected treatment response. Clinicians can harness this understanding of human psychology to better educate patients about their treatment options while fulfilling their ethical duty to act in their patients’ best interest.

Conclusion

Using an anecdote to help patients overcome fears of starting a biologic medication may be appropriate if the anecdote is reasonably representative of an expected treatment outcome. Patients should have an accurate understanding of the common risks and benefits of a medication for purposes of shared decision-making.

- Oussedik E, Cardwell LA, Patel NU, et al. An anchoring-based intervention to increase patient willingness to use injectable medication in psoriasis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:932-934. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.1271

- Brown KK, Rehmus WE, Kimball AB. Determining the relative importance of patient motivations for nonadherence to topical corticosteroid therapy in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:607-613. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.12.021

- Im H, Huh J. Does health information in mass media help or hurt patients? Investigation of potential negative influence of mass media health information on patients’ beliefs and medication regimen adherence. J Health Commun. 2017;22:214-222. doi:10.1080/10810730.2016.1261970

- Hornikx J. A review of experimental research on the relative persuasiveness of anecdotal, statistical, causal, and expert evidence. Studies Commun Sci. 2005;5:205-216.

- Allen M, Preiss RW. Comparing the persuasiveness of narrative and statistical evidence using meta-analysis. Int J Phytoremediation Commun Res Rep. 1997;14:125-131. doi:10.1080/08824099709388654

- Shen F, Sheer VC, Li R. Impact of narratives on persuasion in health communication: a meta-analysis. J Advert. 2015;44:105-113. doi:10.1080/00913367.2015.1018467

- Freling TH, Yang Z, Saini R, et al. When poignant stories outweigh cold hard facts: a meta-analysis of the anecdotal bias. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2020;160:51-67. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2020.01.006

- Buhrmester M, Kwang T, Gosling SD. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011;6:3-5. doi:10.1177/1745691610393980

- Berry K, Butt M, Kirby JS. Influence of information framing on patient decisions to treat actinic keratosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:421-426. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.5245

- Landon BE, Reschovsky J, Reed M, et al. Personal, organizational, and market level influences on physicians’ practice patterns: results of a national survey of primary care physicians. Med Care. 2001;39:889-905. doi:10.1097/00005650-200108000-00014

- Borgida E, Nisbett RE. The differential impact of abstract vs. concrete information on decisions. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1977;7:258-271. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1977.tb00750.x

- Fagerlin A, Wang C, Ubel PA. Reducing the influence of anecdotal reasoning on people’s health care decisions: is a picture worth a thousand statistics? Med Decis Making. 2005;25:398-405. doi:10.1177/0272989X05278931

- Gurm HS, Litaker DG. Framing procedural risks to patients: Is 99% safe the same as a risk of 1 in 100? Acad Med. 2000;75:840-842. doi:10.1097/00001888-200008000-00018

- Oussedik E, Cardwell LA, Patel NU, et al. An anchoring-based intervention to increase patient willingness to use injectable medication in psoriasis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:932-934. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.1271

- Brown KK, Rehmus WE, Kimball AB. Determining the relative importance of patient motivations for nonadherence to topical corticosteroid therapy in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:607-613. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.12.021

- Im H, Huh J. Does health information in mass media help or hurt patients? Investigation of potential negative influence of mass media health information on patients’ beliefs and medication regimen adherence. J Health Commun. 2017;22:214-222. doi:10.1080/10810730.2016.1261970

- Hornikx J. A review of experimental research on the relative persuasiveness of anecdotal, statistical, causal, and expert evidence. Studies Commun Sci. 2005;5:205-216.

- Allen M, Preiss RW. Comparing the persuasiveness of narrative and statistical evidence using meta-analysis. Int J Phytoremediation Commun Res Rep. 1997;14:125-131. doi:10.1080/08824099709388654

- Shen F, Sheer VC, Li R. Impact of narratives on persuasion in health communication: a meta-analysis. J Advert. 2015;44:105-113. doi:10.1080/00913367.2015.1018467

- Freling TH, Yang Z, Saini R, et al. When poignant stories outweigh cold hard facts: a meta-analysis of the anecdotal bias. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2020;160:51-67. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2020.01.006

- Buhrmester M, Kwang T, Gosling SD. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011;6:3-5. doi:10.1177/1745691610393980

- Berry K, Butt M, Kirby JS. Influence of information framing on patient decisions to treat actinic keratosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:421-426. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.5245

- Landon BE, Reschovsky J, Reed M, et al. Personal, organizational, and market level influences on physicians’ practice patterns: results of a national survey of primary care physicians. Med Care. 2001;39:889-905. doi:10.1097/00005650-200108000-00014

- Borgida E, Nisbett RE. The differential impact of abstract vs. concrete information on decisions. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1977;7:258-271. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1977.tb00750.x

- Fagerlin A, Wang C, Ubel PA. Reducing the influence of anecdotal reasoning on people’s health care decisions: is a picture worth a thousand statistics? Med Decis Making. 2005;25:398-405. doi:10.1177/0272989X05278931

- Gurm HS, Litaker DG. Framing procedural risks to patients: Is 99% safe the same as a risk of 1 in 100? Acad Med. 2000;75:840-842. doi:10.1097/00001888-200008000-00018

Practice Points

- Patients often are apprehensive to start biologic medications for their psoriasis.

- Clinical trial evidence of a biologic medication’s efficacy and safety as well as anecdotes of patient experiences appear to be important factors for patients when considering taking a medication.

- The use of an anecdote—alone or in combination with clinical trial evidence—to help patients overcome fears of starting a biologic medication for their psoriasis may be an effective way to improve patients’ willingness to take treatment.

Clinical Case-Viewing Sessions in Dermatology: The Patient Perspective

To the Editor:

Dermatology clinical case-viewing (CCV) sessions, commonly referred to as Grand Rounds, are of core educational importance in teaching residents, fellows, and medical students. The traditional format includes the viewing of patient cases followed by resident- and faculty-led group discussions. Clinical case-viewing sessions often involve several health professionals simultaneously observing and interacting with a patient. Although these sessions are highly academically enriching, they may be ill-perceived by patients. The objective of this study was to evaluate patients’ perception of CCV sessions.

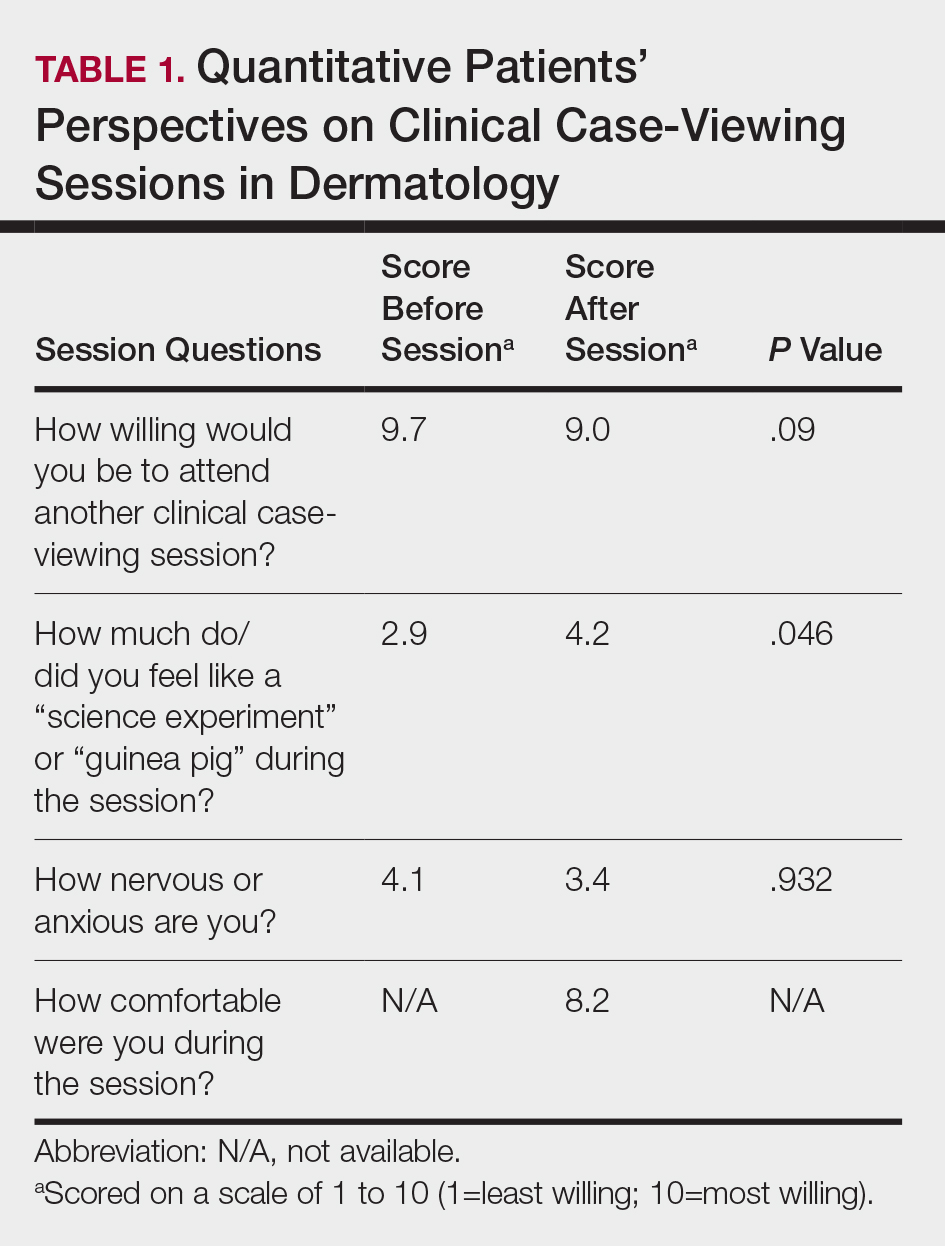

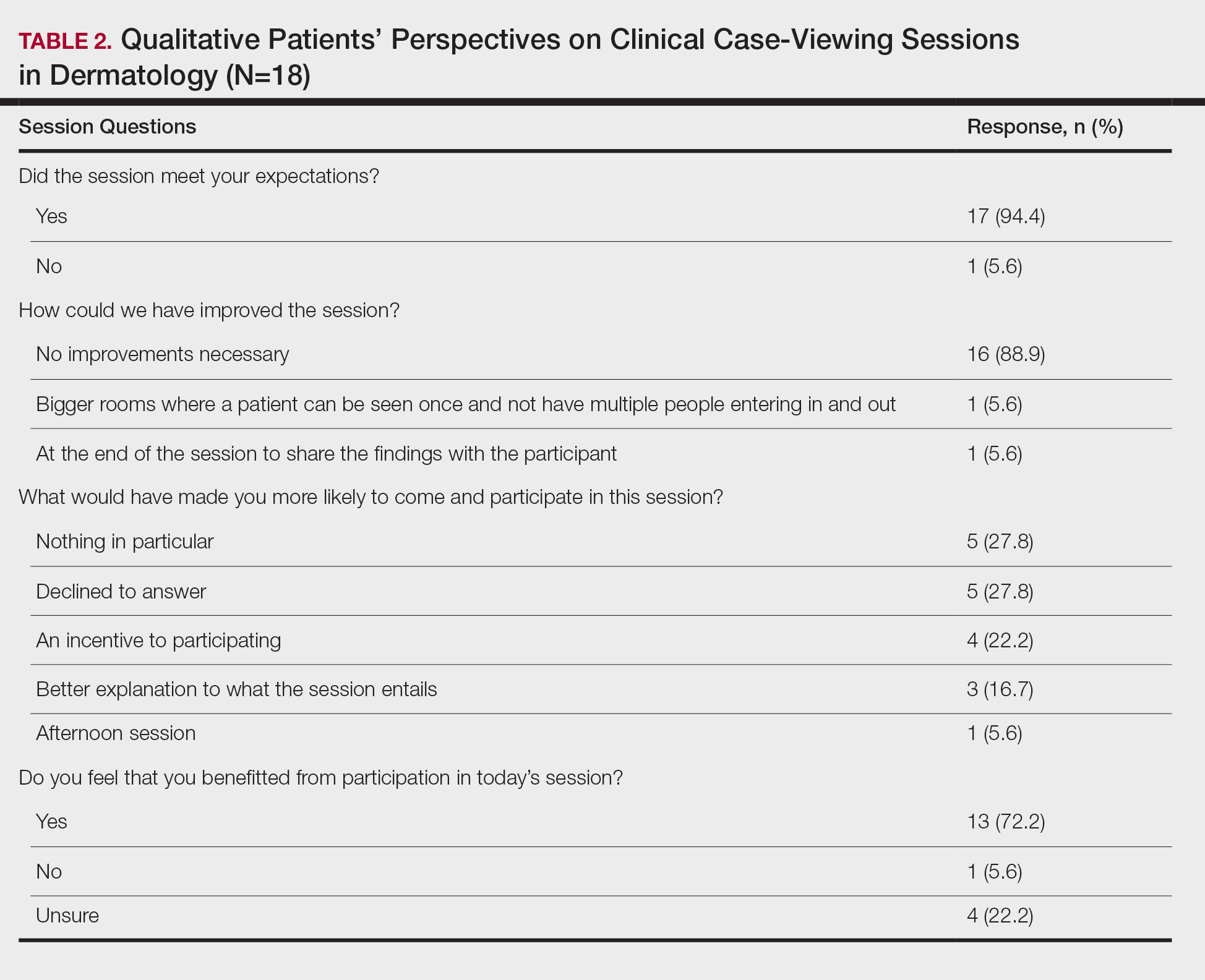

This study was approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) institutional review board and was conducted from February 2017 to August 2017. Following informed consent, 18 patients older than 18 years who were present at the Wake Forest Department of Dermatology CCV sessions were recruited. Patients were each assigned to a private clinical examination room, and CCV attendees briefly visited each room to assess the pathologic findings of interest. Patients received written quantitative surveys before and after the CCV sessions assessing their perspectives on the session (Table 1). Quantitative surveys were assessed using a 10-point Likert scale (1=least willing; 10=most willing). Patients also received qualitative surveys following the session (Table 2). Scores on a 10-item Likert scale were evaluated using a 2-tailed t test.

The mean age of patients was 57.6 years, and women comprised 66.7% (12/18). Patient willingness to attend CCV sessions was relatively unchanged before and after the session, with a mean willingness of 9.7 before the session and 9.0 after the session (P=.09). There was a significant difference in the extent to which patients perceived themselves as experimental subjects prior to the session compared to after the session (2.9 vs 4.2)(P=.046). Following the session, 94.4% (17/18) of patients had the impression that the session met their expectations, and 72.2% (13/18) of patients felt they directly benefitted from the session.

Clinical case-viewing sessions are the foundation of any dermatology residency program1-3; however, characterizing the sessions’ psychosocial implications on patients is important too. Although some patients did feel part of a “science experiment,” this finding may be of less importance, as patients generally considered the sessions to be a positive experience and were willing to take part again.

Limitations of the study were typical of survey-based research. All participants were patients at a single center, which may limit the generalization of the results, in addition to the small sample size. Clinical case-viewing sessions also are conducted slightly differently between dermatology programs, which may further limit the generalization of the results. Future studies may aim to assess varying CCV formats to optimize both medical education as well as patient satisfaction.

- Mehrabi D, Cruz PD Jr. Educational conferences in dermatology residency programs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:523-524.

- Hull AL, Cullen RJ, Hekelman FP. A retrospective analysis of grand rounds in continuing medical education. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 1989;9:257-266.

- Cruz PD Jr, Chaker MB. Teaching conferences in dermatology residency programs revisited. J Am Acad of Dermatol. 1995;32:675-677.

To the Editor:

Dermatology clinical case-viewing (CCV) sessions, commonly referred to as Grand Rounds, are of core educational importance in teaching residents, fellows, and medical students. The traditional format includes the viewing of patient cases followed by resident- and faculty-led group discussions. Clinical case-viewing sessions often involve several health professionals simultaneously observing and interacting with a patient. Although these sessions are highly academically enriching, they may be ill-perceived by patients. The objective of this study was to evaluate patients’ perception of CCV sessions.

This study was approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) institutional review board and was conducted from February 2017 to August 2017. Following informed consent, 18 patients older than 18 years who were present at the Wake Forest Department of Dermatology CCV sessions were recruited. Patients were each assigned to a private clinical examination room, and CCV attendees briefly visited each room to assess the pathologic findings of interest. Patients received written quantitative surveys before and after the CCV sessions assessing their perspectives on the session (Table 1). Quantitative surveys were assessed using a 10-point Likert scale (1=least willing; 10=most willing). Patients also received qualitative surveys following the session (Table 2). Scores on a 10-item Likert scale were evaluated using a 2-tailed t test.

The mean age of patients was 57.6 years, and women comprised 66.7% (12/18). Patient willingness to attend CCV sessions was relatively unchanged before and after the session, with a mean willingness of 9.7 before the session and 9.0 after the session (P=.09). There was a significant difference in the extent to which patients perceived themselves as experimental subjects prior to the session compared to after the session (2.9 vs 4.2)(P=.046). Following the session, 94.4% (17/18) of patients had the impression that the session met their expectations, and 72.2% (13/18) of patients felt they directly benefitted from the session.

Clinical case-viewing sessions are the foundation of any dermatology residency program1-3; however, characterizing the sessions’ psychosocial implications on patients is important too. Although some patients did feel part of a “science experiment,” this finding may be of less importance, as patients generally considered the sessions to be a positive experience and were willing to take part again.

Limitations of the study were typical of survey-based research. All participants were patients at a single center, which may limit the generalization of the results, in addition to the small sample size. Clinical case-viewing sessions also are conducted slightly differently between dermatology programs, which may further limit the generalization of the results. Future studies may aim to assess varying CCV formats to optimize both medical education as well as patient satisfaction.

To the Editor:

Dermatology clinical case-viewing (CCV) sessions, commonly referred to as Grand Rounds, are of core educational importance in teaching residents, fellows, and medical students. The traditional format includes the viewing of patient cases followed by resident- and faculty-led group discussions. Clinical case-viewing sessions often involve several health professionals simultaneously observing and interacting with a patient. Although these sessions are highly academically enriching, they may be ill-perceived by patients. The objective of this study was to evaluate patients’ perception of CCV sessions.

This study was approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) institutional review board and was conducted from February 2017 to August 2017. Following informed consent, 18 patients older than 18 years who were present at the Wake Forest Department of Dermatology CCV sessions were recruited. Patients were each assigned to a private clinical examination room, and CCV attendees briefly visited each room to assess the pathologic findings of interest. Patients received written quantitative surveys before and after the CCV sessions assessing their perspectives on the session (Table 1). Quantitative surveys were assessed using a 10-point Likert scale (1=least willing; 10=most willing). Patients also received qualitative surveys following the session (Table 2). Scores on a 10-item Likert scale were evaluated using a 2-tailed t test.

The mean age of patients was 57.6 years, and women comprised 66.7% (12/18). Patient willingness to attend CCV sessions was relatively unchanged before and after the session, with a mean willingness of 9.7 before the session and 9.0 after the session (P=.09). There was a significant difference in the extent to which patients perceived themselves as experimental subjects prior to the session compared to after the session (2.9 vs 4.2)(P=.046). Following the session, 94.4% (17/18) of patients had the impression that the session met their expectations, and 72.2% (13/18) of patients felt they directly benefitted from the session.

Clinical case-viewing sessions are the foundation of any dermatology residency program1-3; however, characterizing the sessions’ psychosocial implications on patients is important too. Although some patients did feel part of a “science experiment,” this finding may be of less importance, as patients generally considered the sessions to be a positive experience and were willing to take part again.

Limitations of the study were typical of survey-based research. All participants were patients at a single center, which may limit the generalization of the results, in addition to the small sample size. Clinical case-viewing sessions also are conducted slightly differently between dermatology programs, which may further limit the generalization of the results. Future studies may aim to assess varying CCV formats to optimize both medical education as well as patient satisfaction.

- Mehrabi D, Cruz PD Jr. Educational conferences in dermatology residency programs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:523-524.

- Hull AL, Cullen RJ, Hekelman FP. A retrospective analysis of grand rounds in continuing medical education. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 1989;9:257-266.

- Cruz PD Jr, Chaker MB. Teaching conferences in dermatology residency programs revisited. J Am Acad of Dermatol. 1995;32:675-677.

- Mehrabi D, Cruz PD Jr. Educational conferences in dermatology residency programs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:523-524.

- Hull AL, Cullen RJ, Hekelman FP. A retrospective analysis of grand rounds in continuing medical education. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 1989;9:257-266.

- Cruz PD Jr, Chaker MB. Teaching conferences in dermatology residency programs revisited. J Am Acad of Dermatol. 1995;32:675-677.

Practice Points

- Patient willingness to attend dermatology clinical case-viewing (CCV) sessions is relatively unchanged before and after the session.

- Participants generally consider CCV sessions to be a positive experience.

Automobile Injury: A Common Familiar Risk for Presenting and Comparing Risks in Dermatology

Numerous highly efficacious treatment modalities exist in dermatology, yet patients may be highly wary of their possible adverse events, even when those risks are rare.1,2 Such fears can lead to poor medication adherence and treatment refusal. A key determinant in successful patient-provider care is to effectively communicate risk. The communication of risk is hampered by the lack of any common currency for comparing risks. The development of a standardized unit of risk could help facilitate risk comparisons, allowing physicians and patients to put risk levels into better perspective.

One easily relatable event is the risk of injury in an automobile crash. Driving, whether to the dermatology clinic for a monitoring visit or to the supermarket for weekly groceries, is associated with risk of injury and death. The risk of automobile-related injury warranting a visit to the emergency department could provide a comparator that physicians can use to give patients a more objective sense of treatment risks or to introduce the justification of a monitoring visit. The objective of this study was to develop a standard risk unit based on the lifetime risk (LTR) of automobile injury and to compare this unit of risk to various risks of dermatologic treatments.

Methods

Literature Review

We first identified common risks in dermatology that would be illustrative and then identified keywords. PubMed searches for articles indexed for MEDLINE from November 1996 to February 2017 were performed combining the following terms: (relative risk, odds ratio, lifetime risk) and (isotretinoin, IBD; melanoma, SCC, transplantation; indoor tanning, BCC, SCC; transplant and SCC; biologics and tuberculosis; hydroxychloroquine retinal toxicity; psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis). An additional search was performed in June 2018 including the term blindness and injectable fillers. Our search combined these terms in numerous ways. Results were focused on meta-analyses and observational studies.

The references of relevant studies were included. Articles not focused on meta-analyses but rather on observational studies were individually analyzed for quality and bias using the 9-point Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, with a score of 7 or more as a cutoff for inclusion.

Determination of Risk Comparators

Data from the 2016 National Safety Council’s Injury Facts report were searched for nonmedical-related risk comparators, such as the risk of death by dog attack, by lightning, and by fire or smoke.3 Data from the 2015 US Department of Transportation Traffic Safety Facts were searched for relatable risk comparators, such as the LTR of automobile death and injury.4

Definitions

Automobile injury was defined as an injury warranting a visit to the emergency department.5 Automobile was defined as a road vehicle with 4 wheels and powered by an internal combustion engine or electric motor.6 This definition excluded light trucks, large trucks, and motorcycles.

LTR Calculation

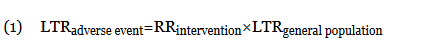

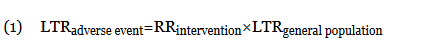

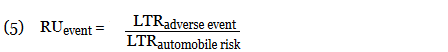

Lifetime risk was used as the comparative measure. Lifetime risk is a type of absolute risk that depicts the probability that a specific disease or event will occur in an individual’s lifespan. The LTRof developing a disease or adverse event due to a dermatologic therapy or interventionwas denoted as LTRadverse event and calculated by the following equation7,8:

In this equation, LTRgeneral population is the LTR of developing the disease or adverse event without being subject to the therapy or intervention, and RRintervention is the relative risk (RR) from previously published RR data (relating to the development of the disease in question or an adverse event of the intervention). The use of equation (1) holds true only when the absolute risk of developing the disease or adverse event (LTRgeneral population) is low.7 Although the calculation of an LTR using a constant lifetime RR may require major approximations, studies evaluating the variation of RR over time are sparse.7,9 The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was used to control such variance; only high-quality, nonrandomized studies were included. Although the use of residual LTR would be preferable, as LTR depends on age, such epidemiological data do not exist for complex diseases.

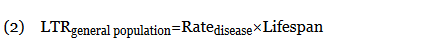

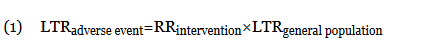

When not available, the LTRgeneral population was calculated from the rate of disease (cases per 100,000 individuals per year) multiplied by the average lifespan of an American (78.8 years)10:

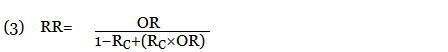

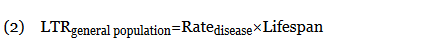

When an odds ratio (OR) was presented, its conversion to RR followed11:

In this equation, RC is the absolute risk in the unexposed group. If the prevalence of the disease was considered low, the rare disease assumption was implemented as the following11,12:

The use of this approximation overestimates the LTR of an event. From a patient perspective, this approach is conservative. If prior LTR values were available, such as the LTR of automobile injury, automobile death, or other intervention, they were used without the need for calculation.

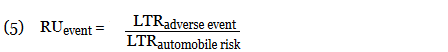

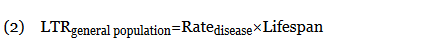

Unit Comparator

The LTRs of all adverse events were normalized to a unit comparator, using the LTR of an automobile injury as reference point, denoted as 1 risk unit (RU):

This equation allows for quick comparison of the magnitude of LTRs between events. Events with an RU less than 1 are less likely to occur than the risk of automobile injury; events with an RU greater than 1 are more likely than the risk of automobile injury. All RR, LTR, and unit comparators were presented as a single pooled estimate of their respective upper-limit CIs. The use of the upper-limit CI conservatively overestimates the LTR of an event.

Results

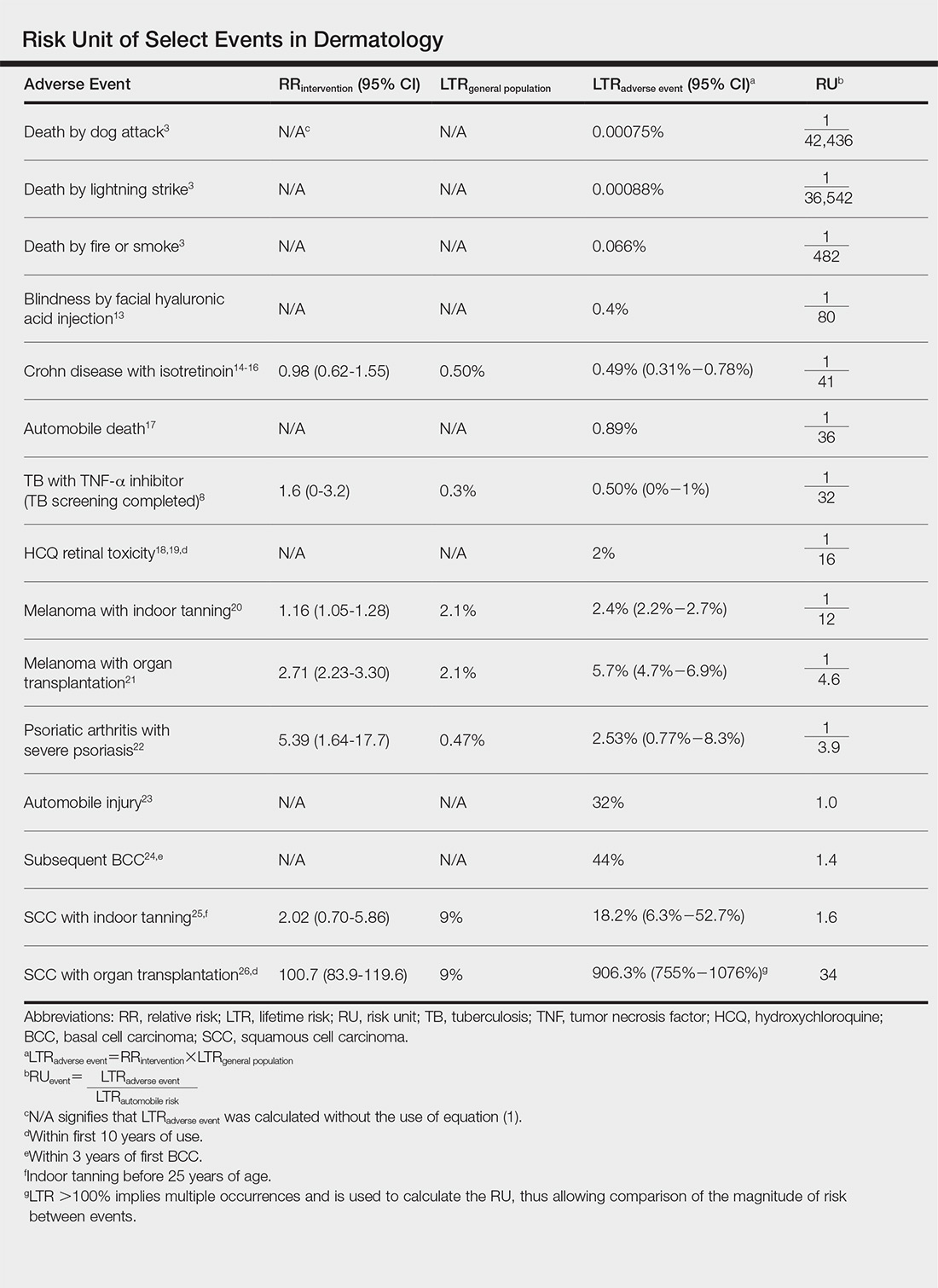

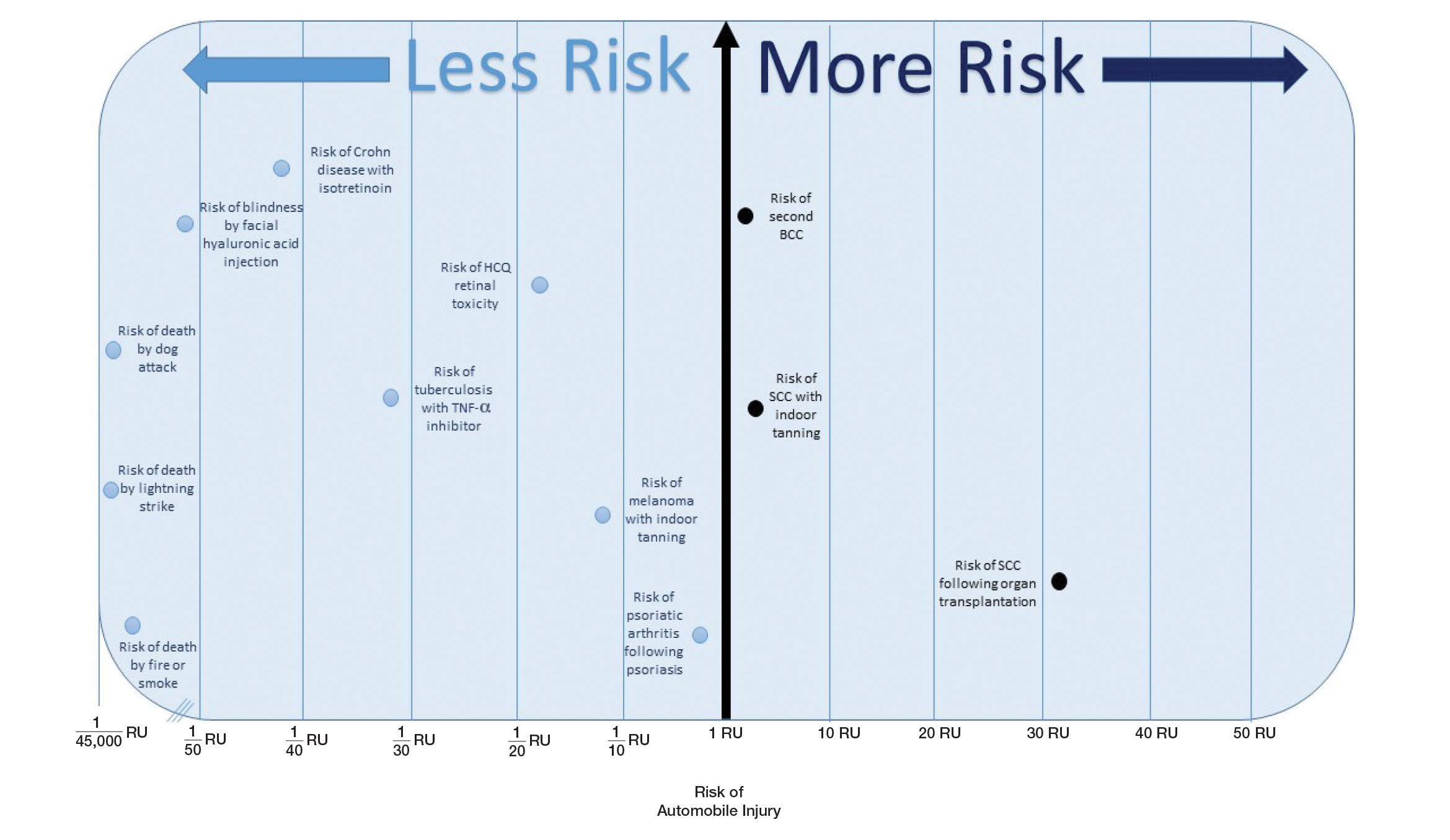

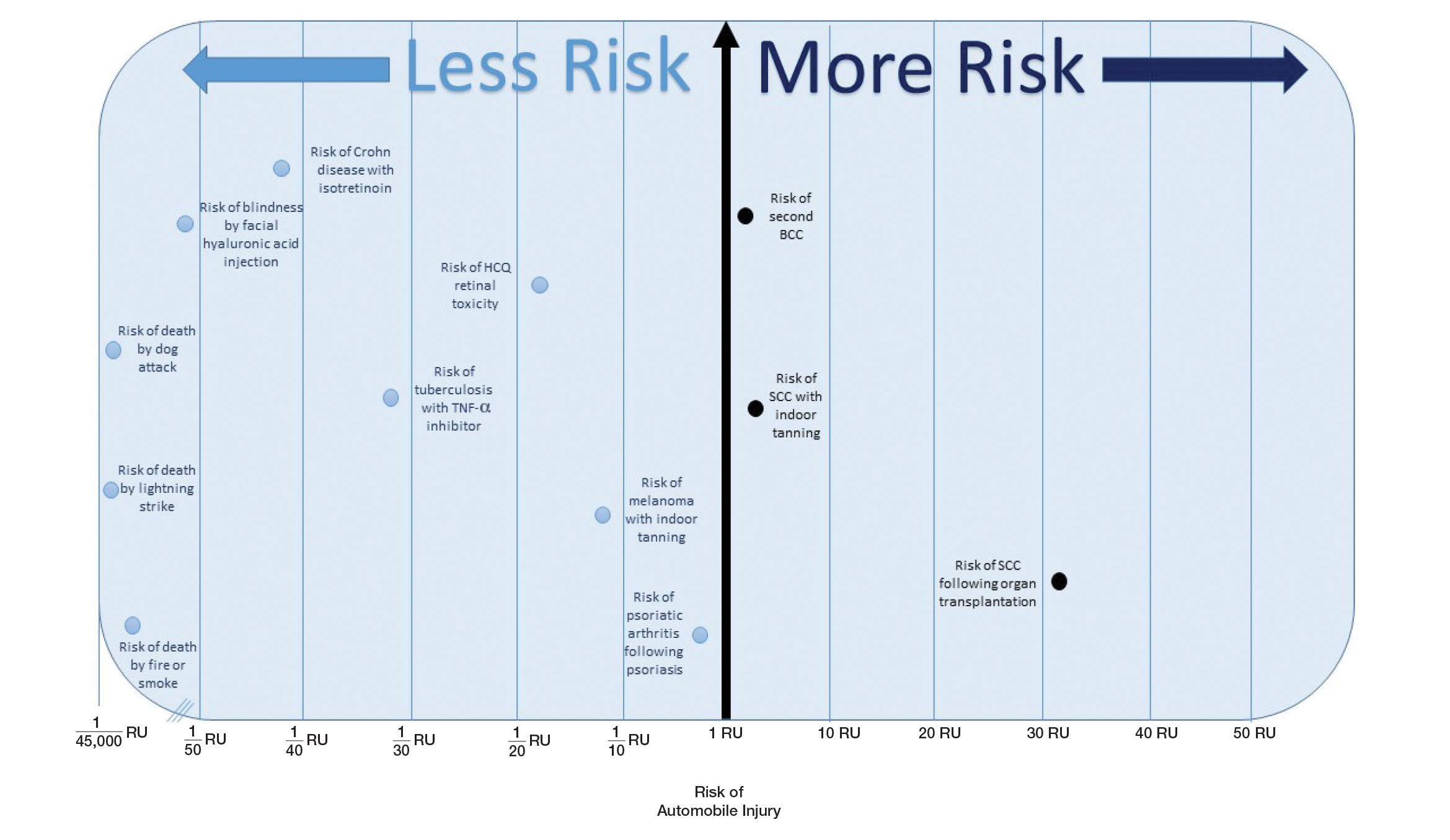

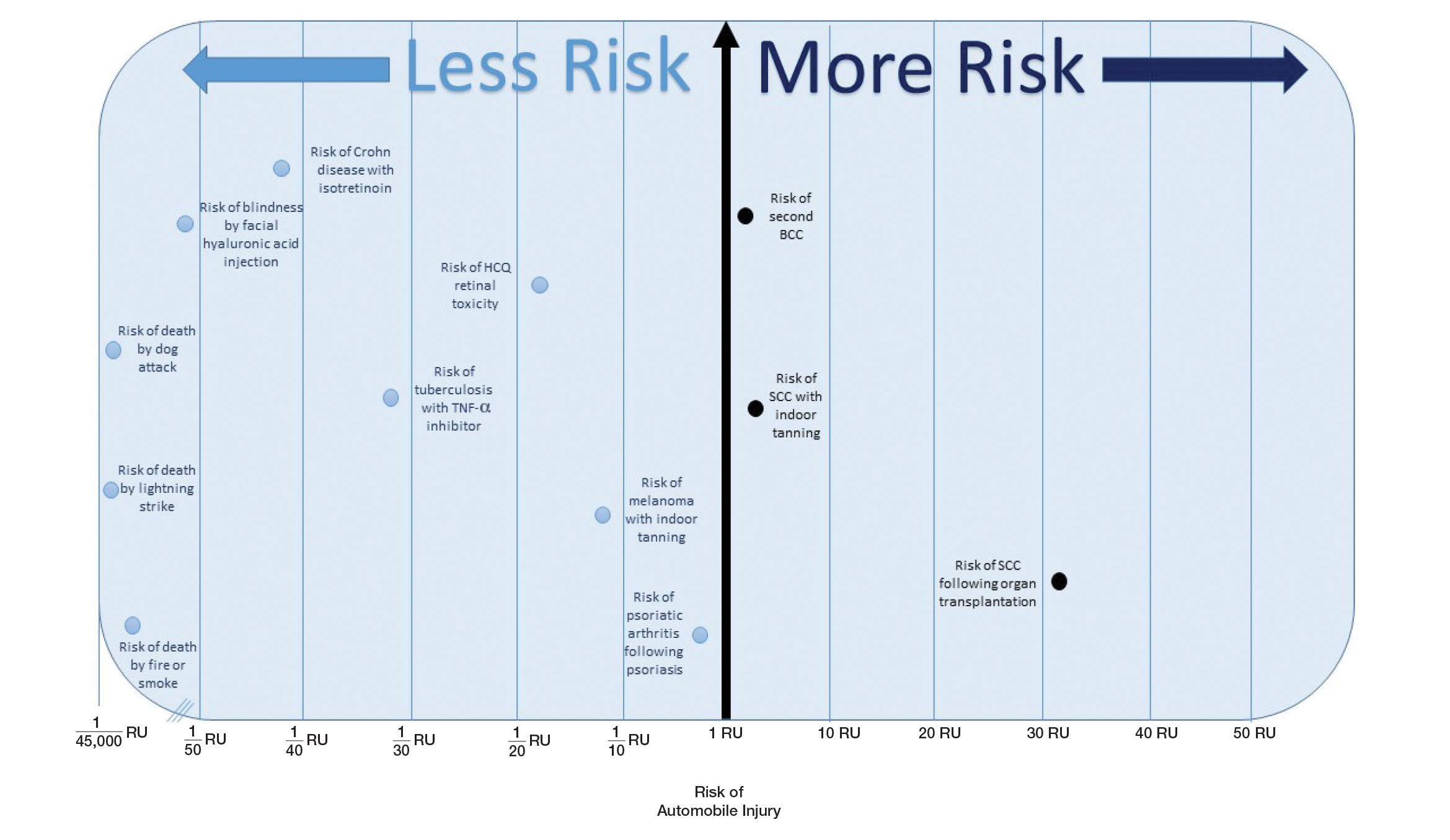

Ten dermatologic interventions were identified as illustrative, to be presented alongside the risk of automobile injury and death. The LTR of automobile injury was 32%, defined as 1.0 RU. The LTR of automobile death was 0.89% (1/36 RU).

Two events had LTRs roughly similar to automobile injury: development of a subsequent basal cell carcinoma within 3 years (1.4 RU) and development of a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) secondary to indoor tanning (1.6 RU). Development of SCC following organ transplantation (34 RU) was considerably more likely than automobile injury. All other identified events had lower RUs than automobile injury (Table). Three events with small RUs included tuberculosis development with a tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor (1/32 RU), Crohn disease development with isotretinoin (1/41 RU), and blindness following facial hyaluronic acid injection (1/80 RU). The LTR of death by dog attack (1/42,436 RU) and death by lightning strike (1/36,542 RU) also had small RUs.

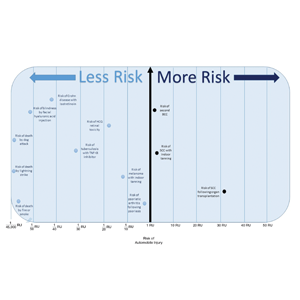

The unit comparators from the Table were adapted into graphic form to depict risk relative to the risk of automobile injury (Figure).

Comment

Numerous interventions in dermatology offer much less risk of an adverse event than the LTR of automobile injury. However, this concept of risk includes only the likelihood of development of an event, not the severity of the measured event, as our numerical and visual tool objectively captures the related risks using an RU comparator. Such use of a standardized RU demonstrates the essence of risk; “zero risk” does not exist, and each intervention or treatment, albeit how small, must be justified in concordance with other types of risk, such as the automobile.

The development of adverse events secondary to dermatologic intervention or therapy, for which monitoring visits are utilized, were used as important comparators to the risk of automobile injury. The continuous practice of monitoring visits may increase patient’s fears regarding possible adverse events secondary to therapy. Hydroxychloroquine retinal toxicity (1/16 RU) and psoriatic arthritis development following severe psoriasis (1/3.9 RU) were less likely to occur than automobile injury. The development of abnormal blood counts or blood tests secondary to therapy or intervention could not be formatted into an RU. The use of equation (1) for the calculation of LTRadverse eventholds true only when the absolute risk of developing the adverse event in the general population—in this case, abnormal blood counts or blood tests—is low.7

Although the unit comparator allows for the comparison of different dermatologic risk, a limitation of the RU model and its visual tool are a dependence on RR, a value that changes following publication of new studies. A solution was the use of a single pooled estimate to represent the upper-limit CIs of LTR. This practice overestimates risk. As with RR, new automobile injury rates are published annually.10 In the last 5 years, the LTR of automobile injury has stayed relatively constant: between 32% and 33%.4 Although the RU calculations and Figure included a wide variety of interventions in dermatology, select clinical situations were not included. It is beyond the scope of this article to systematically review all risk in dermatology but rather introduce the concept of the RU founded on automobile-associated risks. With the introduction of a methodical framework, the reader is invited to calculate RUs pertinent to their clinical interests.

Any intervention or treatment in dermatology is accompanied by risk. The use of a unit comparator using an easily relatable event—the LTR of automobile injury—allows the patient to easily compare risk and internally justify the practice of monitoring visits. Inclusion of a visual tool, such as the Figure, might alleviate many irrational fears that accompany some of the highly effective treatments and interventions used in dermatology and thus lead to better patient outcomes.

Acknowledgment

We thank Taranjeet Singh, MS (Dunn, North Carolina), for her comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

- Rosen AB, Tsai JS, Downs SM. Variations in risk attitude across race, gender, and education. Med Decis Making. 2003;23:511-517.

- Sandoval LF, Pierce A, Feldman SR. Systemic therapies for psoriasis: an evidence-based update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:165-180.

- National Safety Council. Odds of dying. Injury Facts website. http://injuryfacts.nsc.org/all-injuries/preventable-death-overview/odds-of-dying/. Accessed November 4, 2018.

- National Center for Statistics and Analysis (NCSA) motor vehicle traffic crash data resource page. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration website. https://crashstats.nhtsa.dot.gov/#/. Accessed November 4, 2018.

- CDC report shows motor vehicle crash injuries are frequent and costly. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2014/p1007-crash-injuries.html. Published October 7, 2014. Accessed November 4, 2018.

- Automobile. Business Dictionary website. http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/automobile.html. Accessed November 4, 2018.

- Dupont WD, Plummer WD Jr. Understanding the relationship between relative and absolute risk. Cancer. 1996;77:2193-2199.

- Kaminska E, Patel I, Dabade TS, et al. Comparing the lifetime risks of TNF-alpha inhibitor use to common benchmarks of risk. J Dermatolog Treat. 2011;24:101-106.

- Dupont WD. Converting relative risks to absolute risks: a graphical approach. Stat Med. 1989;8:641-651.

- Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu J, et al. Deaths: final data for 2014. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2016;65:1-122.

- Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration website. http://handbook.cochrane.org. Updated March 2011. Accessed November 15, 2018.

- Katz KA. The (relative) risks of using odds ratios. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:761-764.

- Rayess HM, Svider PF, Hanba C, et al. A cross-sectional analysis of adverse events and litigation for injectable fillers. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2018;20:207-214.

- Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, et al. The prevalence and geographic distribution of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1424-1429.

- Loftus EV Jr. Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: incidence, prevalence, and environmental influences. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1504-1517.

- Lee SY, Jamal MM, Nguyen ET, et al. Does exposure to isotretinoin increase the risk for the development of inflammatory bowel disease? A meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28:210-216.

- Injury Facts, 2017. Itasca, IL: National Safety Council; 2017.

- Marmor MF, Kellner U, Lai TY, et al. Recommendations on screening for chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine retinopathy (2016 revision). Ophthalmology. 2016;123:1386-1394.

- Melles RB, Marmor MF. The risk of toxic retinopathy in patients on long-term hydroxychloroquine therapy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132:1453-1460.

- Colantonio S, Bracken MB, Beecker J. The association of indoor tanning and melanoma in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:847-857.e1-18.

- Green AC, Olsen CM. Increased risk of melanoma in organ transplant recipients: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:923-927.

- Eder L, Haddad A, Rosen CF, et al. The incidence and risk factors for psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:915-923.

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). Traffic Safety Facts 2015. Washington, DC: US Department of Transportation; 2015.

- Marcil I, Stern RS. Risk of developing a subsequent nonmelanoma skin cancer in patients with a history of nonmelanoma skin cancer: a critical review of the literature and meta-analysis. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1524-1530.

- Wehner MR, Shive ML, Chren MM, et al. Indoor tanning and non-melanoma skin cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:E5909.

- Lindelöf B, Sigurgeirsson B, Gäbel H, et al. Incidence of skin cancer in 5356 patients following organ transplantation. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:513-519.

Numerous highly efficacious treatment modalities exist in dermatology, yet patients may be highly wary of their possible adverse events, even when those risks are rare.1,2 Such fears can lead to poor medication adherence and treatment refusal. A key determinant in successful patient-provider care is to effectively communicate risk. The communication of risk is hampered by the lack of any common currency for comparing risks. The development of a standardized unit of risk could help facilitate risk comparisons, allowing physicians and patients to put risk levels into better perspective.

One easily relatable event is the risk of injury in an automobile crash. Driving, whether to the dermatology clinic for a monitoring visit or to the supermarket for weekly groceries, is associated with risk of injury and death. The risk of automobile-related injury warranting a visit to the emergency department could provide a comparator that physicians can use to give patients a more objective sense of treatment risks or to introduce the justification of a monitoring visit. The objective of this study was to develop a standard risk unit based on the lifetime risk (LTR) of automobile injury and to compare this unit of risk to various risks of dermatologic treatments.

Methods

Literature Review

We first identified common risks in dermatology that would be illustrative and then identified keywords. PubMed searches for articles indexed for MEDLINE from November 1996 to February 2017 were performed combining the following terms: (relative risk, odds ratio, lifetime risk) and (isotretinoin, IBD; melanoma, SCC, transplantation; indoor tanning, BCC, SCC; transplant and SCC; biologics and tuberculosis; hydroxychloroquine retinal toxicity; psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis). An additional search was performed in June 2018 including the term blindness and injectable fillers. Our search combined these terms in numerous ways. Results were focused on meta-analyses and observational studies.

The references of relevant studies were included. Articles not focused on meta-analyses but rather on observational studies were individually analyzed for quality and bias using the 9-point Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, with a score of 7 or more as a cutoff for inclusion.

Determination of Risk Comparators

Data from the 2016 National Safety Council’s Injury Facts report were searched for nonmedical-related risk comparators, such as the risk of death by dog attack, by lightning, and by fire or smoke.3 Data from the 2015 US Department of Transportation Traffic Safety Facts were searched for relatable risk comparators, such as the LTR of automobile death and injury.4

Definitions

Automobile injury was defined as an injury warranting a visit to the emergency department.5 Automobile was defined as a road vehicle with 4 wheels and powered by an internal combustion engine or electric motor.6 This definition excluded light trucks, large trucks, and motorcycles.

LTR Calculation

Lifetime risk was used as the comparative measure. Lifetime risk is a type of absolute risk that depicts the probability that a specific disease or event will occur in an individual’s lifespan. The LTRof developing a disease or adverse event due to a dermatologic therapy or interventionwas denoted as LTRadverse event and calculated by the following equation7,8:

In this equation, LTRgeneral population is the LTR of developing the disease or adverse event without being subject to the therapy or intervention, and RRintervention is the relative risk (RR) from previously published RR data (relating to the development of the disease in question or an adverse event of the intervention). The use of equation (1) holds true only when the absolute risk of developing the disease or adverse event (LTRgeneral population) is low.7 Although the calculation of an LTR using a constant lifetime RR may require major approximations, studies evaluating the variation of RR over time are sparse.7,9 The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was used to control such variance; only high-quality, nonrandomized studies were included. Although the use of residual LTR would be preferable, as LTR depends on age, such epidemiological data do not exist for complex diseases.

When not available, the LTRgeneral population was calculated from the rate of disease (cases per 100,000 individuals per year) multiplied by the average lifespan of an American (78.8 years)10:

When an odds ratio (OR) was presented, its conversion to RR followed11:

In this equation, RC is the absolute risk in the unexposed group. If the prevalence of the disease was considered low, the rare disease assumption was implemented as the following11,12:

The use of this approximation overestimates the LTR of an event. From a patient perspective, this approach is conservative. If prior LTR values were available, such as the LTR of automobile injury, automobile death, or other intervention, they were used without the need for calculation.

Unit Comparator

The LTRs of all adverse events were normalized to a unit comparator, using the LTR of an automobile injury as reference point, denoted as 1 risk unit (RU):

This equation allows for quick comparison of the magnitude of LTRs between events. Events with an RU less than 1 are less likely to occur than the risk of automobile injury; events with an RU greater than 1 are more likely than the risk of automobile injury. All RR, LTR, and unit comparators were presented as a single pooled estimate of their respective upper-limit CIs. The use of the upper-limit CI conservatively overestimates the LTR of an event.

Results

Ten dermatologic interventions were identified as illustrative, to be presented alongside the risk of automobile injury and death. The LTR of automobile injury was 32%, defined as 1.0 RU. The LTR of automobile death was 0.89% (1/36 RU).

Two events had LTRs roughly similar to automobile injury: development of a subsequent basal cell carcinoma within 3 years (1.4 RU) and development of a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) secondary to indoor tanning (1.6 RU). Development of SCC following organ transplantation (34 RU) was considerably more likely than automobile injury. All other identified events had lower RUs than automobile injury (Table). Three events with small RUs included tuberculosis development with a tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor (1/32 RU), Crohn disease development with isotretinoin (1/41 RU), and blindness following facial hyaluronic acid injection (1/80 RU). The LTR of death by dog attack (1/42,436 RU) and death by lightning strike (1/36,542 RU) also had small RUs.

The unit comparators from the Table were adapted into graphic form to depict risk relative to the risk of automobile injury (Figure).

Comment

Numerous interventions in dermatology offer much less risk of an adverse event than the LTR of automobile injury. However, this concept of risk includes only the likelihood of development of an event, not the severity of the measured event, as our numerical and visual tool objectively captures the related risks using an RU comparator. Such use of a standardized RU demonstrates the essence of risk; “zero risk” does not exist, and each intervention or treatment, albeit how small, must be justified in concordance with other types of risk, such as the automobile.

The development of adverse events secondary to dermatologic intervention or therapy, for which monitoring visits are utilized, were used as important comparators to the risk of automobile injury. The continuous practice of monitoring visits may increase patient’s fears regarding possible adverse events secondary to therapy. Hydroxychloroquine retinal toxicity (1/16 RU) and psoriatic arthritis development following severe psoriasis (1/3.9 RU) were less likely to occur than automobile injury. The development of abnormal blood counts or blood tests secondary to therapy or intervention could not be formatted into an RU. The use of equation (1) for the calculation of LTRadverse eventholds true only when the absolute risk of developing the adverse event in the general population—in this case, abnormal blood counts or blood tests—is low.7

Although the unit comparator allows for the comparison of different dermatologic risk, a limitation of the RU model and its visual tool are a dependence on RR, a value that changes following publication of new studies. A solution was the use of a single pooled estimate to represent the upper-limit CIs of LTR. This practice overestimates risk. As with RR, new automobile injury rates are published annually.10 In the last 5 years, the LTR of automobile injury has stayed relatively constant: between 32% and 33%.4 Although the RU calculations and Figure included a wide variety of interventions in dermatology, select clinical situations were not included. It is beyond the scope of this article to systematically review all risk in dermatology but rather introduce the concept of the RU founded on automobile-associated risks. With the introduction of a methodical framework, the reader is invited to calculate RUs pertinent to their clinical interests.

Any intervention or treatment in dermatology is accompanied by risk. The use of a unit comparator using an easily relatable event—the LTR of automobile injury—allows the patient to easily compare risk and internally justify the practice of monitoring visits. Inclusion of a visual tool, such as the Figure, might alleviate many irrational fears that accompany some of the highly effective treatments and interventions used in dermatology and thus lead to better patient outcomes.

Acknowledgment

We thank Taranjeet Singh, MS (Dunn, North Carolina), for her comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Numerous highly efficacious treatment modalities exist in dermatology, yet patients may be highly wary of their possible adverse events, even when those risks are rare.1,2 Such fears can lead to poor medication adherence and treatment refusal. A key determinant in successful patient-provider care is to effectively communicate risk. The communication of risk is hampered by the lack of any common currency for comparing risks. The development of a standardized unit of risk could help facilitate risk comparisons, allowing physicians and patients to put risk levels into better perspective.

One easily relatable event is the risk of injury in an automobile crash. Driving, whether to the dermatology clinic for a monitoring visit or to the supermarket for weekly groceries, is associated with risk of injury and death. The risk of automobile-related injury warranting a visit to the emergency department could provide a comparator that physicians can use to give patients a more objective sense of treatment risks or to introduce the justification of a monitoring visit. The objective of this study was to develop a standard risk unit based on the lifetime risk (LTR) of automobile injury and to compare this unit of risk to various risks of dermatologic treatments.

Methods

Literature Review

We first identified common risks in dermatology that would be illustrative and then identified keywords. PubMed searches for articles indexed for MEDLINE from November 1996 to February 2017 were performed combining the following terms: (relative risk, odds ratio, lifetime risk) and (isotretinoin, IBD; melanoma, SCC, transplantation; indoor tanning, BCC, SCC; transplant and SCC; biologics and tuberculosis; hydroxychloroquine retinal toxicity; psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis). An additional search was performed in June 2018 including the term blindness and injectable fillers. Our search combined these terms in numerous ways. Results were focused on meta-analyses and observational studies.

The references of relevant studies were included. Articles not focused on meta-analyses but rather on observational studies were individually analyzed for quality and bias using the 9-point Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, with a score of 7 or more as a cutoff for inclusion.

Determination of Risk Comparators

Data from the 2016 National Safety Council’s Injury Facts report were searched for nonmedical-related risk comparators, such as the risk of death by dog attack, by lightning, and by fire or smoke.3 Data from the 2015 US Department of Transportation Traffic Safety Facts were searched for relatable risk comparators, such as the LTR of automobile death and injury.4

Definitions

Automobile injury was defined as an injury warranting a visit to the emergency department.5 Automobile was defined as a road vehicle with 4 wheels and powered by an internal combustion engine or electric motor.6 This definition excluded light trucks, large trucks, and motorcycles.

LTR Calculation

Lifetime risk was used as the comparative measure. Lifetime risk is a type of absolute risk that depicts the probability that a specific disease or event will occur in an individual’s lifespan. The LTRof developing a disease or adverse event due to a dermatologic therapy or interventionwas denoted as LTRadverse event and calculated by the following equation7,8: