User login

Special Report II: Tackling Burnout

Last month, we introduced the epidemic of burnout and the adverse consequences for both our vascular surgery patients and ourselves. Today we will outline a framework for addressing these issues. The foundation of this framework is informed by the social and neurosciences.

From the perspective of the social scientist: Christina Maslach, the originator of the widely used Maslach Burnout Inventory, theorized that burnout arises from a chronic mismatch between people and their work setting in some or all of the following domains: Workload (too much, wrong kind); control (lack of autonomy, or insufficient control over resources); reward (insufficient financial or social rewards commensurate with achievements); community (loss of positive connection with others); fairness (lack of perceived fairness, inequity of work, pay, or promotion); and values (conflict of personal and organizational values). The reality of practicing medicine in today’s business milieu – of achieving service efficiencies by meeting performance targets – brings many of these mismatches into sharp focus.

From the perspective of the neuroscientist: Recent advances, including functional MRI, have demonstrated that the human brain is hard wired for compassion. Compassion is the deep feeling that arises when confronted with another’s suffering, coupled with a strong desire to alleviate that suffering. There are at least two neural pathways: one activated during empathy, having us experience another’s pain; and the other activated during compassion, resulting in our sense of reward. Thus, burnout is thought to occur when you know what your patient needs but you are unable to deliver it. Compassionate medical care is purposeful work, which promotes a sense of reward and mitigates burnout.

Because burnout affects all caregivers (anyone who touches the patient), a successful program addressing workforce well-being must be comprehensive and organization wide, similar to successful patient safety, CPI [continuous process improvement] and LEAN [Six Sigma] initiatives.

There are no shortcuts. Creating a culture of compassionate, collaborative care requires an understanding of the interrelationships between the individual provider, the unit or team, and organizational leadership.

1) The individual provider: There is evidence to support the use of programs that build personal resilience. A recently published meta-analysis by West and colleagues concluded that while no specific physician burnout intervention has been shown to be better than other types of interventions, mindfulness, stress management, and small-group discussions can be effective approaches to reducing burnout scores. Strategies to build individual resilience, such as mindfulness and meditation, are easy to teach but place the burden for success on the individual. No amount of resilience can withstand an unsupportive or toxic workplace environment, so both individual and organizational strategies in combination are necessary.

2) The unit or team: Scheduling time for open and honest discussion of social and emotional issues that arise in caring for patients helps nourish caregiver to caregiver compassion. The Schwartz Center for Compassionate Healthcare is a national nonprofit leading the movement to bring compassion to every patient-caregiver interaction. More than 425 health care organization are Schwartz Center members and conduct Schwartz Rounds™ to bring doctors, nurses, and other caregivers together to discuss the human side of health care. (www.theschwartzcenter.org). Team member to team member support is essential for navigating the stressors of practice. With having lunch in front of your computer being the norm, and the disappearance of traditional spaces for colleagues to connect (for example, nurses’ lounge, physician dining rooms), the opportunity for caregivers to have a safe place to escape, a place to have their own humanity reaffirmed, a place to offer support to their peers, has been eliminated.

3) Organizational Leadership: Making compassion a core value, articulating it, and establishing metrics whereby it can be measured, is a good start. The barriers to a culture of compassion are related to our systems of care. There are burgeoning administrative and documentation tasks to be performed, and productivity expectations that turn our clinics and hospitals into assembly lines. No, we cannot expect the EMR [electronic medical records] to be eliminated, but workforce well-being cannot be sustainable in the context of inadequate resources. A culture of compassionate collaborative care requires programs and policies that are implemented by the organization itself. Examples of organization-wide initiatives that support workforce well-being and provider engagement include: screening for caregiver burnout, establishing policies for managing adverse events with an eye toward the second victim, and most importantly, supporting systems that preserve work control autonomy of physicians and nurses in clinical settings. The business sector has long recognized that workplace stress is a function of how demanding a person’s job is and how much control that person has over his or her responsibilities. The business community has also recognized that the experience of the worker (provider) drives the experience of the customer (patient). In a study of hospital compassionate practices and HCAHPS [the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems], McClelland and Vogus reported that how well a hospital compassionately supports it employees and rewards compassionate acts is significantly and positively is associated with that hospital’s ratings and likelihood of patients recommending it.

How does the Society of Vascular Surgery, or any professional medical/nursing society for that matter, fit into this model?

We propose that the SVS find ways to empower their members to be agents for culture change within their own health care organizations. How might this be done:

- Teach organizational leadership skills, starting with the SVS Board of Directors, the presidential line, and the chairs of committees. Offer leadership courses at the Annual Meeting.

- Develop a community of caregivers committed to creating a compassionate collaborative culture. The SVS is a founding member of the Schwartz Center Healthcare Society Leadership Council, and you, as members of the SVS benefit from reduced registration at the Annual Compassion in Action Healthcare Conference, June 24-27, 2017 in Boston. (http://compassioninactionconference.org) This conference is designed to be highly experiential, using a hands-on “how to do it” model.

- The SVS should make improving the overall wellness of its members a specific goal and find specific metrics to monitor our progress towards this goal. Members can be provided with the tools to identify, monitor, and measure burnout and compassion. Each committee and council of the SVS can reexamine their objectives through the lens of reducing burnout and improving the wellness of vascular surgeons.

- Provide members with evidence-based programs that build personal resilience. This will not be a successful initiative unless our surgeons recognize and acknowledge the symptoms of burnout, and are willing to admit vulnerability. Without doing so, it is difficult to reach out for help.

- Redesign postgraduate resident and fellowship education. Standardizing clinical care may reduce variation and promote efficiency. However, when processes such as time-limited appointment scheduling, EMR templates, and protocols that drive physician-patient interactions are embedded in Resident and Fellowship education, the result may well be inflexibility in practice, reduced face time with patients, and interactions that lack compassion; all leading to burnout. Graduate Medical Education leaders must develop programs that support the learner’s ability to connect with patients and families, cultivate and role-model skills and behaviors that strengthen compassionate interactions, and strive to develop clinical practice models that increase Resident and Fellow work control autonomy.

The SVS should work proactively to optimize workload, fairness, and reward on a larger scale for its members as it relates to the EMR, reimbursement, and systems coverage. While we may be relatively small in size, as leaders, we are perfectly poised to address these larger, global issues. Perhaps working within the current system (i.e., PAC and APM task force) and considering innovative solutions at a national leadership scale, the SVS can direct real change!

Changing culture is not easy, nor quick, nor does it have an easy-to-follow blueprint. The first step is recognizing the need. The second is taking a leadership role. The third is thinking deeply about implementation.

*The authors extend their thanks and appreciation for the guidance, resources and support of Michael Goldberg, MD, scholar in residence, Schwartz Center for Compassionate Care, Boston and clinical professor of orthopedics at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

REFERENCES

1. J Managerial Psychol. (2007) 22:309-28

2. Annu Rev Neurosci. (2012) 35:1-23

3. Medicine. (2016) 44:583-5

4. J Health Organization Manag. (2015) 29:973-87

5. De Zulueta P Developing compassionate leadership in health care: an integrative review. J Healthcare Leadership. (2016) 8:1-10

6. Dolan ED, Morh D, Lempa M et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: A psychometry evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. (2015) 30:582-7

7. Karasek RA Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job design. Administrative Sciences Quarterly (1979) 24: 285-308

8. Lee VS, Miller T, Daniels C, et al. Creating the exceptional patient experience in one academic health system. Acad Med. (2016) 91:338-44

9. Linzer M, Levine R, Meltzer D, et al. 10 bold steps to prevent burnout in general internal medicine. J Gen Intern Med. (2013) 29:18-20

10. Lown BA, Manning CF The Schwartz Center Rounds: Evaluation of an interdisciplinary approach to enhancing patient-centered communication, teamwork, and provider support. Acad Med. (2010) 85:1073-81

11. Lown BA, Muncer SJ, Chadwick R Can compassionate healthcare be measured? The Schwartz Center Compassionate Care Scale. Patient Education and Counseling (2015) 98:1005-10

12. Lown BA, McIntosh S, Gaines ME, et. al. Integrating compassionate collaborative care (“the Triple C”) into health professional education to advance the triple aim of health care. Acad Med (2016) 91:1-7

13. Lown BA A social neuroscience-informed model for teaching and practicing compassion in health care. Medical Education (2016) 50: 332-342

14. Maslach C, Schaufeli WG, Leiter MP Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol (2001) 52:397-422

15. McClelland LE, Vogus TJ Compassion practices and HCAHPS: Does rewarding and supporting workplace compassion influence patient perceptions? HSR: Health Serv Res. (2014) 49:1670-83

16. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH Executive leadership and physician well-being: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. (2016) 6:1-18

17. Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP Addressing physician burnout: the way forward. JAMA (2017) 317:901-2

18. Singer T, Klimecki OM Empathy and compassion Curr Biol. (2014) 24: R875-8

19. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Satele DV et. al. Concurrent validity of single-item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in burnout assessment. J Gen Intern Med. (2012) 27:1445-52

20. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, et al. Interventions to address and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. (2016) 388:2272-81

21. Wuest TK, Goldberg MJ, Kelly JD Clinical faceoff: Physician burnout-Fact, fantasy, or the fourth component of the triple aim? Clin Orthop Relat Res. (2016) doi: 10.1007/5-11999-016-5193-5

Last month, we introduced the epidemic of burnout and the adverse consequences for both our vascular surgery patients and ourselves. Today we will outline a framework for addressing these issues. The foundation of this framework is informed by the social and neurosciences.

From the perspective of the social scientist: Christina Maslach, the originator of the widely used Maslach Burnout Inventory, theorized that burnout arises from a chronic mismatch between people and their work setting in some or all of the following domains: Workload (too much, wrong kind); control (lack of autonomy, or insufficient control over resources); reward (insufficient financial or social rewards commensurate with achievements); community (loss of positive connection with others); fairness (lack of perceived fairness, inequity of work, pay, or promotion); and values (conflict of personal and organizational values). The reality of practicing medicine in today’s business milieu – of achieving service efficiencies by meeting performance targets – brings many of these mismatches into sharp focus.

From the perspective of the neuroscientist: Recent advances, including functional MRI, have demonstrated that the human brain is hard wired for compassion. Compassion is the deep feeling that arises when confronted with another’s suffering, coupled with a strong desire to alleviate that suffering. There are at least two neural pathways: one activated during empathy, having us experience another’s pain; and the other activated during compassion, resulting in our sense of reward. Thus, burnout is thought to occur when you know what your patient needs but you are unable to deliver it. Compassionate medical care is purposeful work, which promotes a sense of reward and mitigates burnout.

Because burnout affects all caregivers (anyone who touches the patient), a successful program addressing workforce well-being must be comprehensive and organization wide, similar to successful patient safety, CPI [continuous process improvement] and LEAN [Six Sigma] initiatives.

There are no shortcuts. Creating a culture of compassionate, collaborative care requires an understanding of the interrelationships between the individual provider, the unit or team, and organizational leadership.

1) The individual provider: There is evidence to support the use of programs that build personal resilience. A recently published meta-analysis by West and colleagues concluded that while no specific physician burnout intervention has been shown to be better than other types of interventions, mindfulness, stress management, and small-group discussions can be effective approaches to reducing burnout scores. Strategies to build individual resilience, such as mindfulness and meditation, are easy to teach but place the burden for success on the individual. No amount of resilience can withstand an unsupportive or toxic workplace environment, so both individual and organizational strategies in combination are necessary.

2) The unit or team: Scheduling time for open and honest discussion of social and emotional issues that arise in caring for patients helps nourish caregiver to caregiver compassion. The Schwartz Center for Compassionate Healthcare is a national nonprofit leading the movement to bring compassion to every patient-caregiver interaction. More than 425 health care organization are Schwartz Center members and conduct Schwartz Rounds™ to bring doctors, nurses, and other caregivers together to discuss the human side of health care. (www.theschwartzcenter.org). Team member to team member support is essential for navigating the stressors of practice. With having lunch in front of your computer being the norm, and the disappearance of traditional spaces for colleagues to connect (for example, nurses’ lounge, physician dining rooms), the opportunity for caregivers to have a safe place to escape, a place to have their own humanity reaffirmed, a place to offer support to their peers, has been eliminated.

3) Organizational Leadership: Making compassion a core value, articulating it, and establishing metrics whereby it can be measured, is a good start. The barriers to a culture of compassion are related to our systems of care. There are burgeoning administrative and documentation tasks to be performed, and productivity expectations that turn our clinics and hospitals into assembly lines. No, we cannot expect the EMR [electronic medical records] to be eliminated, but workforce well-being cannot be sustainable in the context of inadequate resources. A culture of compassionate collaborative care requires programs and policies that are implemented by the organization itself. Examples of organization-wide initiatives that support workforce well-being and provider engagement include: screening for caregiver burnout, establishing policies for managing adverse events with an eye toward the second victim, and most importantly, supporting systems that preserve work control autonomy of physicians and nurses in clinical settings. The business sector has long recognized that workplace stress is a function of how demanding a person’s job is and how much control that person has over his or her responsibilities. The business community has also recognized that the experience of the worker (provider) drives the experience of the customer (patient). In a study of hospital compassionate practices and HCAHPS [the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems], McClelland and Vogus reported that how well a hospital compassionately supports it employees and rewards compassionate acts is significantly and positively is associated with that hospital’s ratings and likelihood of patients recommending it.

How does the Society of Vascular Surgery, or any professional medical/nursing society for that matter, fit into this model?

We propose that the SVS find ways to empower their members to be agents for culture change within their own health care organizations. How might this be done:

- Teach organizational leadership skills, starting with the SVS Board of Directors, the presidential line, and the chairs of committees. Offer leadership courses at the Annual Meeting.

- Develop a community of caregivers committed to creating a compassionate collaborative culture. The SVS is a founding member of the Schwartz Center Healthcare Society Leadership Council, and you, as members of the SVS benefit from reduced registration at the Annual Compassion in Action Healthcare Conference, June 24-27, 2017 in Boston. (http://compassioninactionconference.org) This conference is designed to be highly experiential, using a hands-on “how to do it” model.

- The SVS should make improving the overall wellness of its members a specific goal and find specific metrics to monitor our progress towards this goal. Members can be provided with the tools to identify, monitor, and measure burnout and compassion. Each committee and council of the SVS can reexamine their objectives through the lens of reducing burnout and improving the wellness of vascular surgeons.

- Provide members with evidence-based programs that build personal resilience. This will not be a successful initiative unless our surgeons recognize and acknowledge the symptoms of burnout, and are willing to admit vulnerability. Without doing so, it is difficult to reach out for help.

- Redesign postgraduate resident and fellowship education. Standardizing clinical care may reduce variation and promote efficiency. However, when processes such as time-limited appointment scheduling, EMR templates, and protocols that drive physician-patient interactions are embedded in Resident and Fellowship education, the result may well be inflexibility in practice, reduced face time with patients, and interactions that lack compassion; all leading to burnout. Graduate Medical Education leaders must develop programs that support the learner’s ability to connect with patients and families, cultivate and role-model skills and behaviors that strengthen compassionate interactions, and strive to develop clinical practice models that increase Resident and Fellow work control autonomy.

The SVS should work proactively to optimize workload, fairness, and reward on a larger scale for its members as it relates to the EMR, reimbursement, and systems coverage. While we may be relatively small in size, as leaders, we are perfectly poised to address these larger, global issues. Perhaps working within the current system (i.e., PAC and APM task force) and considering innovative solutions at a national leadership scale, the SVS can direct real change!

Changing culture is not easy, nor quick, nor does it have an easy-to-follow blueprint. The first step is recognizing the need. The second is taking a leadership role. The third is thinking deeply about implementation.

*The authors extend their thanks and appreciation for the guidance, resources and support of Michael Goldberg, MD, scholar in residence, Schwartz Center for Compassionate Care, Boston and clinical professor of orthopedics at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

REFERENCES

1. J Managerial Psychol. (2007) 22:309-28

2. Annu Rev Neurosci. (2012) 35:1-23

3. Medicine. (2016) 44:583-5

4. J Health Organization Manag. (2015) 29:973-87

5. De Zulueta P Developing compassionate leadership in health care: an integrative review. J Healthcare Leadership. (2016) 8:1-10

6. Dolan ED, Morh D, Lempa M et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: A psychometry evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. (2015) 30:582-7

7. Karasek RA Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job design. Administrative Sciences Quarterly (1979) 24: 285-308

8. Lee VS, Miller T, Daniels C, et al. Creating the exceptional patient experience in one academic health system. Acad Med. (2016) 91:338-44

9. Linzer M, Levine R, Meltzer D, et al. 10 bold steps to prevent burnout in general internal medicine. J Gen Intern Med. (2013) 29:18-20

10. Lown BA, Manning CF The Schwartz Center Rounds: Evaluation of an interdisciplinary approach to enhancing patient-centered communication, teamwork, and provider support. Acad Med. (2010) 85:1073-81

11. Lown BA, Muncer SJ, Chadwick R Can compassionate healthcare be measured? The Schwartz Center Compassionate Care Scale. Patient Education and Counseling (2015) 98:1005-10

12. Lown BA, McIntosh S, Gaines ME, et. al. Integrating compassionate collaborative care (“the Triple C”) into health professional education to advance the triple aim of health care. Acad Med (2016) 91:1-7

13. Lown BA A social neuroscience-informed model for teaching and practicing compassion in health care. Medical Education (2016) 50: 332-342

14. Maslach C, Schaufeli WG, Leiter MP Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol (2001) 52:397-422

15. McClelland LE, Vogus TJ Compassion practices and HCAHPS: Does rewarding and supporting workplace compassion influence patient perceptions? HSR: Health Serv Res. (2014) 49:1670-83

16. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH Executive leadership and physician well-being: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. (2016) 6:1-18

17. Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP Addressing physician burnout: the way forward. JAMA (2017) 317:901-2

18. Singer T, Klimecki OM Empathy and compassion Curr Biol. (2014) 24: R875-8

19. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Satele DV et. al. Concurrent validity of single-item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in burnout assessment. J Gen Intern Med. (2012) 27:1445-52

20. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, et al. Interventions to address and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. (2016) 388:2272-81

21. Wuest TK, Goldberg MJ, Kelly JD Clinical faceoff: Physician burnout-Fact, fantasy, or the fourth component of the triple aim? Clin Orthop Relat Res. (2016) doi: 10.1007/5-11999-016-5193-5

Last month, we introduced the epidemic of burnout and the adverse consequences for both our vascular surgery patients and ourselves. Today we will outline a framework for addressing these issues. The foundation of this framework is informed by the social and neurosciences.

From the perspective of the social scientist: Christina Maslach, the originator of the widely used Maslach Burnout Inventory, theorized that burnout arises from a chronic mismatch between people and their work setting in some or all of the following domains: Workload (too much, wrong kind); control (lack of autonomy, or insufficient control over resources); reward (insufficient financial or social rewards commensurate with achievements); community (loss of positive connection with others); fairness (lack of perceived fairness, inequity of work, pay, or promotion); and values (conflict of personal and organizational values). The reality of practicing medicine in today’s business milieu – of achieving service efficiencies by meeting performance targets – brings many of these mismatches into sharp focus.

From the perspective of the neuroscientist: Recent advances, including functional MRI, have demonstrated that the human brain is hard wired for compassion. Compassion is the deep feeling that arises when confronted with another’s suffering, coupled with a strong desire to alleviate that suffering. There are at least two neural pathways: one activated during empathy, having us experience another’s pain; and the other activated during compassion, resulting in our sense of reward. Thus, burnout is thought to occur when you know what your patient needs but you are unable to deliver it. Compassionate medical care is purposeful work, which promotes a sense of reward and mitigates burnout.

Because burnout affects all caregivers (anyone who touches the patient), a successful program addressing workforce well-being must be comprehensive and organization wide, similar to successful patient safety, CPI [continuous process improvement] and LEAN [Six Sigma] initiatives.

There are no shortcuts. Creating a culture of compassionate, collaborative care requires an understanding of the interrelationships between the individual provider, the unit or team, and organizational leadership.

1) The individual provider: There is evidence to support the use of programs that build personal resilience. A recently published meta-analysis by West and colleagues concluded that while no specific physician burnout intervention has been shown to be better than other types of interventions, mindfulness, stress management, and small-group discussions can be effective approaches to reducing burnout scores. Strategies to build individual resilience, such as mindfulness and meditation, are easy to teach but place the burden for success on the individual. No amount of resilience can withstand an unsupportive or toxic workplace environment, so both individual and organizational strategies in combination are necessary.

2) The unit or team: Scheduling time for open and honest discussion of social and emotional issues that arise in caring for patients helps nourish caregiver to caregiver compassion. The Schwartz Center for Compassionate Healthcare is a national nonprofit leading the movement to bring compassion to every patient-caregiver interaction. More than 425 health care organization are Schwartz Center members and conduct Schwartz Rounds™ to bring doctors, nurses, and other caregivers together to discuss the human side of health care. (www.theschwartzcenter.org). Team member to team member support is essential for navigating the stressors of practice. With having lunch in front of your computer being the norm, and the disappearance of traditional spaces for colleagues to connect (for example, nurses’ lounge, physician dining rooms), the opportunity for caregivers to have a safe place to escape, a place to have their own humanity reaffirmed, a place to offer support to their peers, has been eliminated.

3) Organizational Leadership: Making compassion a core value, articulating it, and establishing metrics whereby it can be measured, is a good start. The barriers to a culture of compassion are related to our systems of care. There are burgeoning administrative and documentation tasks to be performed, and productivity expectations that turn our clinics and hospitals into assembly lines. No, we cannot expect the EMR [electronic medical records] to be eliminated, but workforce well-being cannot be sustainable in the context of inadequate resources. A culture of compassionate collaborative care requires programs and policies that are implemented by the organization itself. Examples of organization-wide initiatives that support workforce well-being and provider engagement include: screening for caregiver burnout, establishing policies for managing adverse events with an eye toward the second victim, and most importantly, supporting systems that preserve work control autonomy of physicians and nurses in clinical settings. The business sector has long recognized that workplace stress is a function of how demanding a person’s job is and how much control that person has over his or her responsibilities. The business community has also recognized that the experience of the worker (provider) drives the experience of the customer (patient). In a study of hospital compassionate practices and HCAHPS [the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems], McClelland and Vogus reported that how well a hospital compassionately supports it employees and rewards compassionate acts is significantly and positively is associated with that hospital’s ratings and likelihood of patients recommending it.

How does the Society of Vascular Surgery, or any professional medical/nursing society for that matter, fit into this model?

We propose that the SVS find ways to empower their members to be agents for culture change within their own health care organizations. How might this be done:

- Teach organizational leadership skills, starting with the SVS Board of Directors, the presidential line, and the chairs of committees. Offer leadership courses at the Annual Meeting.

- Develop a community of caregivers committed to creating a compassionate collaborative culture. The SVS is a founding member of the Schwartz Center Healthcare Society Leadership Council, and you, as members of the SVS benefit from reduced registration at the Annual Compassion in Action Healthcare Conference, June 24-27, 2017 in Boston. (http://compassioninactionconference.org) This conference is designed to be highly experiential, using a hands-on “how to do it” model.

- The SVS should make improving the overall wellness of its members a specific goal and find specific metrics to monitor our progress towards this goal. Members can be provided with the tools to identify, monitor, and measure burnout and compassion. Each committee and council of the SVS can reexamine their objectives through the lens of reducing burnout and improving the wellness of vascular surgeons.

- Provide members with evidence-based programs that build personal resilience. This will not be a successful initiative unless our surgeons recognize and acknowledge the symptoms of burnout, and are willing to admit vulnerability. Without doing so, it is difficult to reach out for help.

- Redesign postgraduate resident and fellowship education. Standardizing clinical care may reduce variation and promote efficiency. However, when processes such as time-limited appointment scheduling, EMR templates, and protocols that drive physician-patient interactions are embedded in Resident and Fellowship education, the result may well be inflexibility in practice, reduced face time with patients, and interactions that lack compassion; all leading to burnout. Graduate Medical Education leaders must develop programs that support the learner’s ability to connect with patients and families, cultivate and role-model skills and behaviors that strengthen compassionate interactions, and strive to develop clinical practice models that increase Resident and Fellow work control autonomy.

The SVS should work proactively to optimize workload, fairness, and reward on a larger scale for its members as it relates to the EMR, reimbursement, and systems coverage. While we may be relatively small in size, as leaders, we are perfectly poised to address these larger, global issues. Perhaps working within the current system (i.e., PAC and APM task force) and considering innovative solutions at a national leadership scale, the SVS can direct real change!

Changing culture is not easy, nor quick, nor does it have an easy-to-follow blueprint. The first step is recognizing the need. The second is taking a leadership role. The third is thinking deeply about implementation.

*The authors extend their thanks and appreciation for the guidance, resources and support of Michael Goldberg, MD, scholar in residence, Schwartz Center for Compassionate Care, Boston and clinical professor of orthopedics at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

REFERENCES

1. J Managerial Psychol. (2007) 22:309-28

2. Annu Rev Neurosci. (2012) 35:1-23

3. Medicine. (2016) 44:583-5

4. J Health Organization Manag. (2015) 29:973-87

5. De Zulueta P Developing compassionate leadership in health care: an integrative review. J Healthcare Leadership. (2016) 8:1-10

6. Dolan ED, Morh D, Lempa M et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: A psychometry evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. (2015) 30:582-7

7. Karasek RA Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job design. Administrative Sciences Quarterly (1979) 24: 285-308

8. Lee VS, Miller T, Daniels C, et al. Creating the exceptional patient experience in one academic health system. Acad Med. (2016) 91:338-44

9. Linzer M, Levine R, Meltzer D, et al. 10 bold steps to prevent burnout in general internal medicine. J Gen Intern Med. (2013) 29:18-20

10. Lown BA, Manning CF The Schwartz Center Rounds: Evaluation of an interdisciplinary approach to enhancing patient-centered communication, teamwork, and provider support. Acad Med. (2010) 85:1073-81

11. Lown BA, Muncer SJ, Chadwick R Can compassionate healthcare be measured? The Schwartz Center Compassionate Care Scale. Patient Education and Counseling (2015) 98:1005-10

12. Lown BA, McIntosh S, Gaines ME, et. al. Integrating compassionate collaborative care (“the Triple C”) into health professional education to advance the triple aim of health care. Acad Med (2016) 91:1-7

13. Lown BA A social neuroscience-informed model for teaching and practicing compassion in health care. Medical Education (2016) 50: 332-342

14. Maslach C, Schaufeli WG, Leiter MP Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol (2001) 52:397-422

15. McClelland LE, Vogus TJ Compassion practices and HCAHPS: Does rewarding and supporting workplace compassion influence patient perceptions? HSR: Health Serv Res. (2014) 49:1670-83

16. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH Executive leadership and physician well-being: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. (2016) 6:1-18

17. Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP Addressing physician burnout: the way forward. JAMA (2017) 317:901-2

18. Singer T, Klimecki OM Empathy and compassion Curr Biol. (2014) 24: R875-8

19. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Satele DV et. al. Concurrent validity of single-item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in burnout assessment. J Gen Intern Med. (2012) 27:1445-52

20. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, et al. Interventions to address and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. (2016) 388:2272-81

21. Wuest TK, Goldberg MJ, Kelly JD Clinical faceoff: Physician burnout-Fact, fantasy, or the fourth component of the triple aim? Clin Orthop Relat Res. (2016) doi: 10.1007/5-11999-016-5193-5

Ready for post-acute care?

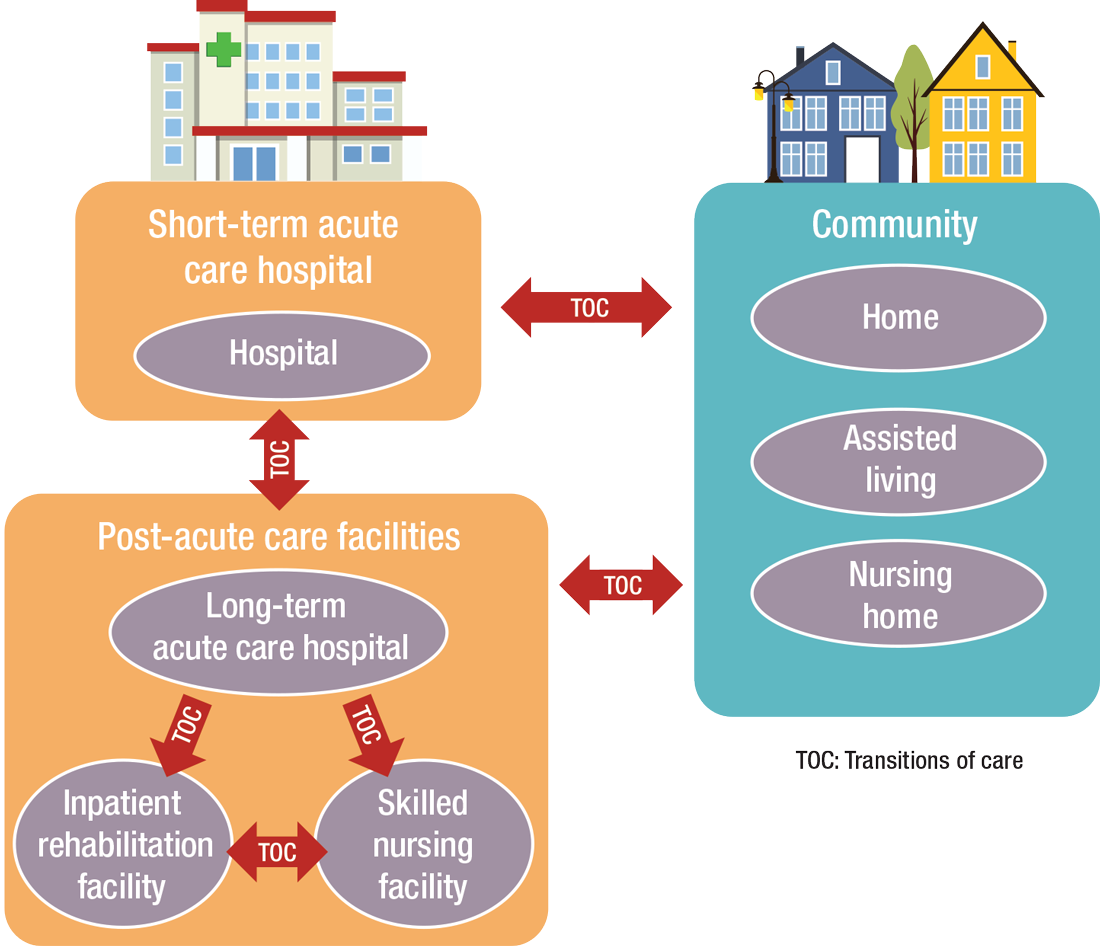

The definition of “hospitalist,” according to the SHM website, is a clinician “dedicated to delivering comprehensive medical care to hospitalized patients.” For years, the hospital setting was the specialties’ identifier. But as hospitalists’ scope has expanded, and post-acute care (PAC) in the United States has grown, more hospitalists are extending their roles into this space.

PAC today is more than the traditional nursing home, according to Manoj K. Mathew, MD, SFHM, national medical director of Agilon Health in Los Angeles.

Many of those expanded settings Dr. Mathew describes emerged as a result of the Affordable Care Act. Since its enactment in 2010, the ACA has heightened providers’ focus on the “Triple Aim” of improving the patient experience (including quality and satisfaction), improving the health of populations, and reducing the per capita cost of healthcare.1 Vishal Kuchaculla, MD, New England regional post-acute medical director of Knoxville,Tenn.-based TeamHealth, says new service lines also developed as Medicare clamped down on long-term inpatient hospital stays by giving financial impetus to discharge patients as soon as possible.

“Over the last few years, there’s been a major shift from fee-for-service to risk-based payment models,” Dr. Kuchaculla says. “The government’s financial incentives are driving outcomes to improve performance initiatives.”

“Today, LTACHs can be used as substitutes for short-term acute care,” says Sean R. Muldoon, MD, MPH, FCCP, chief medical officer of Kindred Healthcare in Louisville, Ky., and former chair of SHM’s Post-Acute Care Committee. “This means that a patient can be directly admitted from their home to an LTACH. In fact, many hospice and home-care patients are referred from physicians’ offices without a preceding hospitalization.”

Hospitalists can fill a need

More hospitalists are working in PACs for a number of reasons. Dr. Mathew says PAC facilities and services have “typically lacked the clinical structure and processes to obtain the results that patients and payors expect.

“These deficits needed to be quickly remedied as patients discharged from hospitals have increased acuity and higher disease burdens,” he adds. “Hospitalists were the natural choice to fill roles requiring their expertise and experience.”

Dr. Muldoon considers the expanded scope of practice into PACs an additional layer to hospital medicine’s value proposition to the healthcare system.

“As experts in the management of inpatient populations, it’s natural for hospitalists to expand to other facilities with inpatient-like populations,” he says, noting SNFs are the most popular choice, with IRFs and LTACHs also being common places to work. Few hospitalists work in home care or hospice.

PAC settings are designed to help patients who are transitioning from an inpatient setting back to their home or other setting.

“Many patients go home after a SNF stay, while others will move to a nursing home or other longer-term care setting for the first time,” says Tiffany Radcliff, PhD, a health economist in the department of health policy and management at Texas A&M University School of Public Health in College Station. “With this in mind, hospitalists working in PAC have the opportunity to address each patient’s ongoing care needs and prepare them for their next setting. Hospitalists can manage medication or other care regimen changes that resulted from an inpatient stay, reinforce discharge instructions to the patient and their caregivers, and identify any other issues with continuing care that need to be addressed before discharge to the next care setting.”

Transitioning Care

Even if a hospitalist is not employed at a PAC, it’s important that they know something about them.

“As patients are moved downstream earlier, hospitalists are being asked to help make a judgment regarding when and where an inpatient is transitioned,” Dr. Muldoon says. As organizations move toward becoming fully risk capable, it is necessary to develop referral networks of high-quality PAC providers to achieve the best clinical outcomes, reduce readmissions, and lower costs.2“Therefore, hospitalists should have a working knowledge of the different sites of service as well as some opinion on the suitability of available options in their community,” Dr. Muldoon says. “The hospitalist can also help to educate the hospitalized patient on what to expect at a PAC.”

If a patient is inappropriately prepared for the PAC setting, it could lead to incomplete management of their condition, which ultimately could lead to readmission.

“When hospitalists know how care is provided in a PAC setting, they are better able to ensure a smoother transition of care between settings,” says Tochi Iroku-Malize, MD, MPH, MBA, FAAFP, SFHM, chair of family medicine at Northwell Health in Long Island, N.Y. “This will ultimately prevent unnecessary readmissions.”

Further, the quality metrics that hospitals and thereby hospitalists are judged by no longer end at the hospital’s exit.

“The ownership of acute-care outcomes requires extending the accountability to outside of the institution’s four walls,” Dr. Mathew says. “The inpatient team needs to place great importance on the transition of care and the subsequent quality of that care when the patient is discharged.”

Robert W. Harrington Jr., MD, SFHM, chief medical officer of Plano, Texas–based Reliant Post-Acute Care Solutions and former SHM president, says the health system landscapes are pushing HM beyond the hospitals’ walls.

How PAC settings differ from hospitals

Practicing in PAC has some important nuances that hospitalists from short-term acute care need to get accustomed to, Dr. Muldoon says. Primarily, the diagnostic capabilities are much more limited, as is the presence of high-level staffing. Further, patients are less resilient to medication changes and interventions, so changes need to be done gradually.

“Hospitalists who try to practice acute-care medicine in a PAC setting may become frustrated by the length of time it takes to do a work-up, get a consultation, and respond to a patient’s change of condition,” Dr. Muldoon says. “Nonetheless, hospitalists can overcome this once recognizing this mind shift.”

According to Dr. Harrington, another challenge hospitalists may face is the inability of the hospital’s and PAC facility’s IT platforms to exchange electronic information.

“The major vendors on both sides need to figure out an interoperability strategy,” he says. “Currently, it often takes 1-3 days to receive a new patient’s discharge summary. The summary may consist of a stack of paper that takes significant time to sort through and requires the PAC facility to perform duplicate data entry. It’s a very highly inefficient process that opens up the doors to mistakes and errors of omission and commission that can result in bad patient outcomes.”

Arif Nazir, MD, CMD, FACP, AGSF, chief medical officer of Signature HealthCARE and president of SHC Medical Partners, both in Louisville, Ky., cites additional reasons the lack of seamless communication between a hospital and PAC facility is problematic. “I see physicians order laboratory tests and investigations that were already done in the hospital because they didn’t know they were already performed or never received the results,” he says. “Similarly, I see patients continue to take medications prescribed in the hospital long term even though they were only supposed to take them short term. I’ve also seen patients come to a PAC setting from a hospital without any formal understanding of their rehabilitative period and expectations for recovery.”

What’s ahead?

Looking to the future, Surafel Tsega, MD, clinical instructor at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, says he thinks there will be a move toward greater collaboration among inpatient and PAC facilities, particularly in the discharge process, given that hospitals have an added incentive to ensure safe transitions because reimbursement from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is tied to readmissions and there are penalties for readmission. This involves more comprehensive planning regarding “warm handoffs” (e.g., real-time discussions with PAC providers about a patient’s hospital course and plan of care upon discharge), transferring of information, and so forth.

And while it can still be challenging to identify high-risk patients or determine the intensity and duration of their care, Dr. Mathew says risk-stratification tools and care pathways are continually being refined to maximize value with the limited resources available. In addition, with an increased emphasis on employing a team approach to care, there will be better integration of non-medical services to address the social determinants of health, which play significant roles in overall health and healing.

“Working with community-based organizations for this purpose will be a valuable tool for any of the population health–based initiatives,” he says.

Dr. Muldoon says he believes healthcare reform will increasingly view an inpatient admission as something to be avoided.

“If hospitalization can’t be avoided, then it should be shortened as much as possible,” he says. “This will shift inpatient care into LTACHs, SNFs, and IRFs. Hospitalists would be wise to follow patients into those settings as traditional inpatient census is reduced. This will take a few years, so hospitalists should start now in preparing for that downstream transition of individuals who were previously inpatients.”

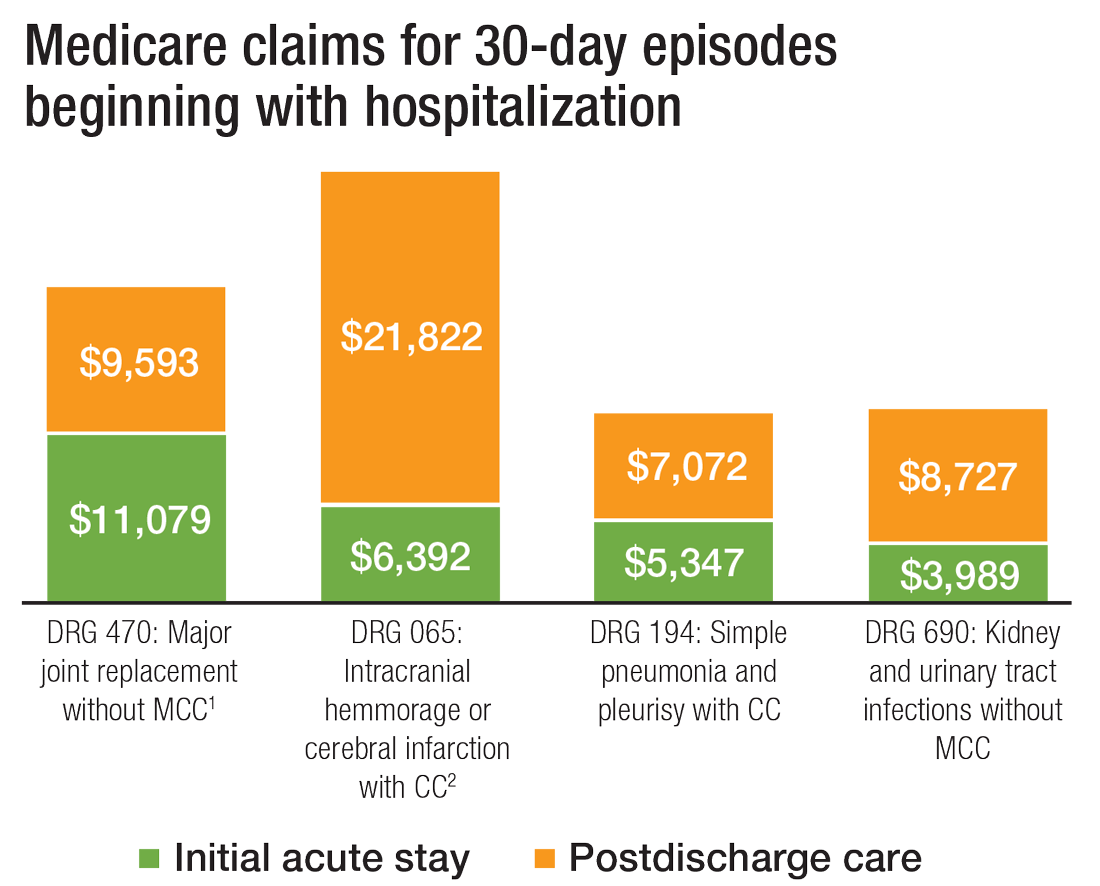

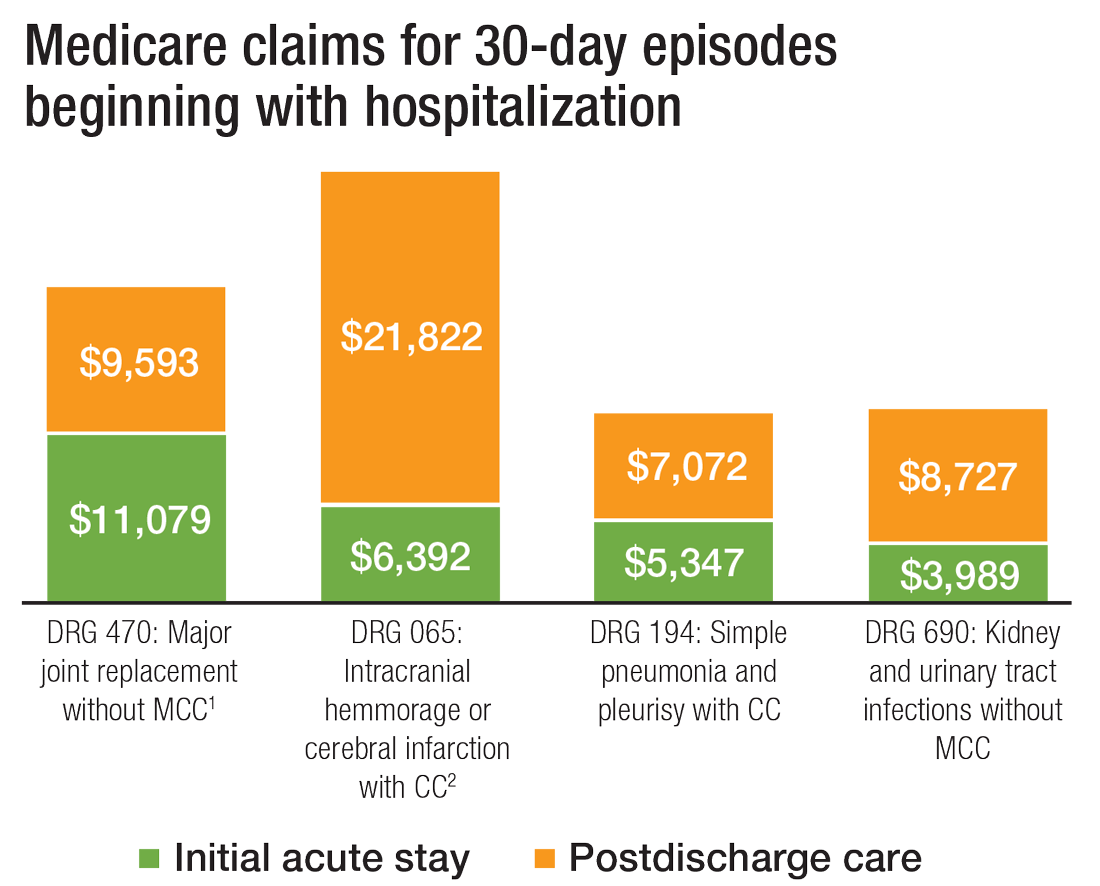

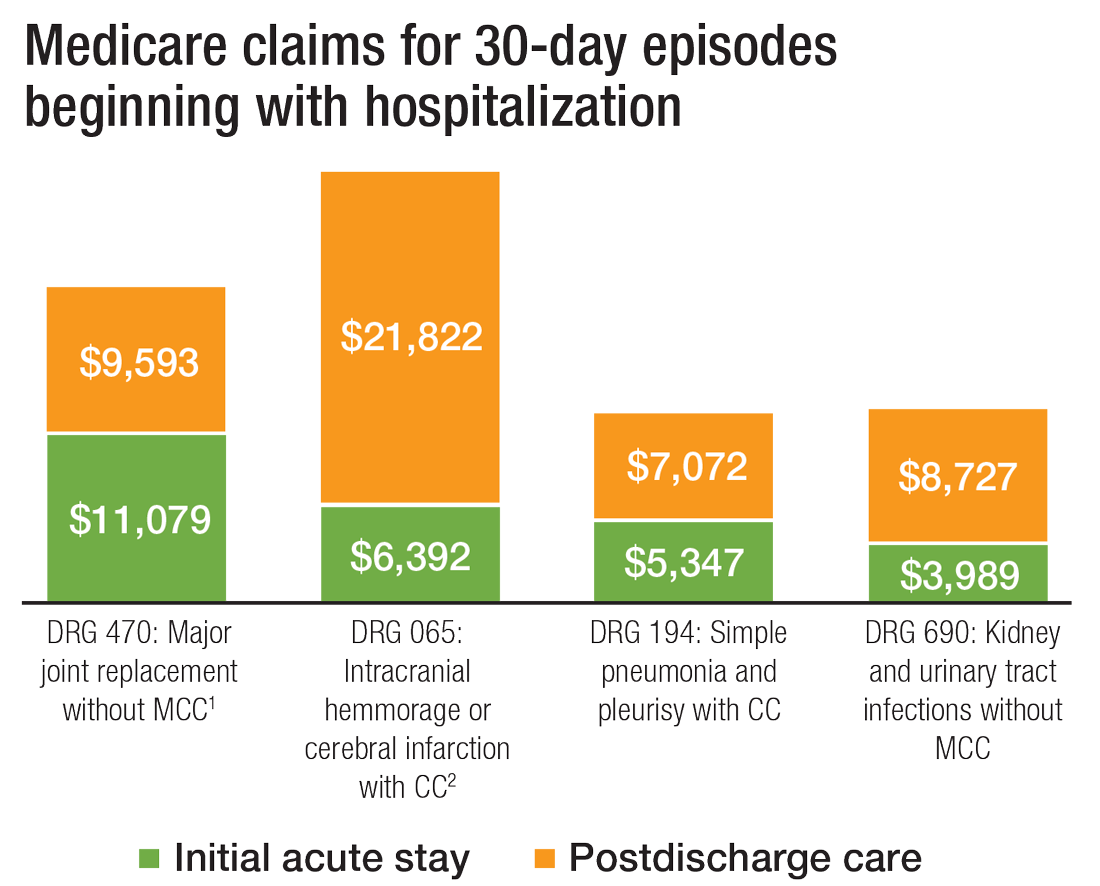

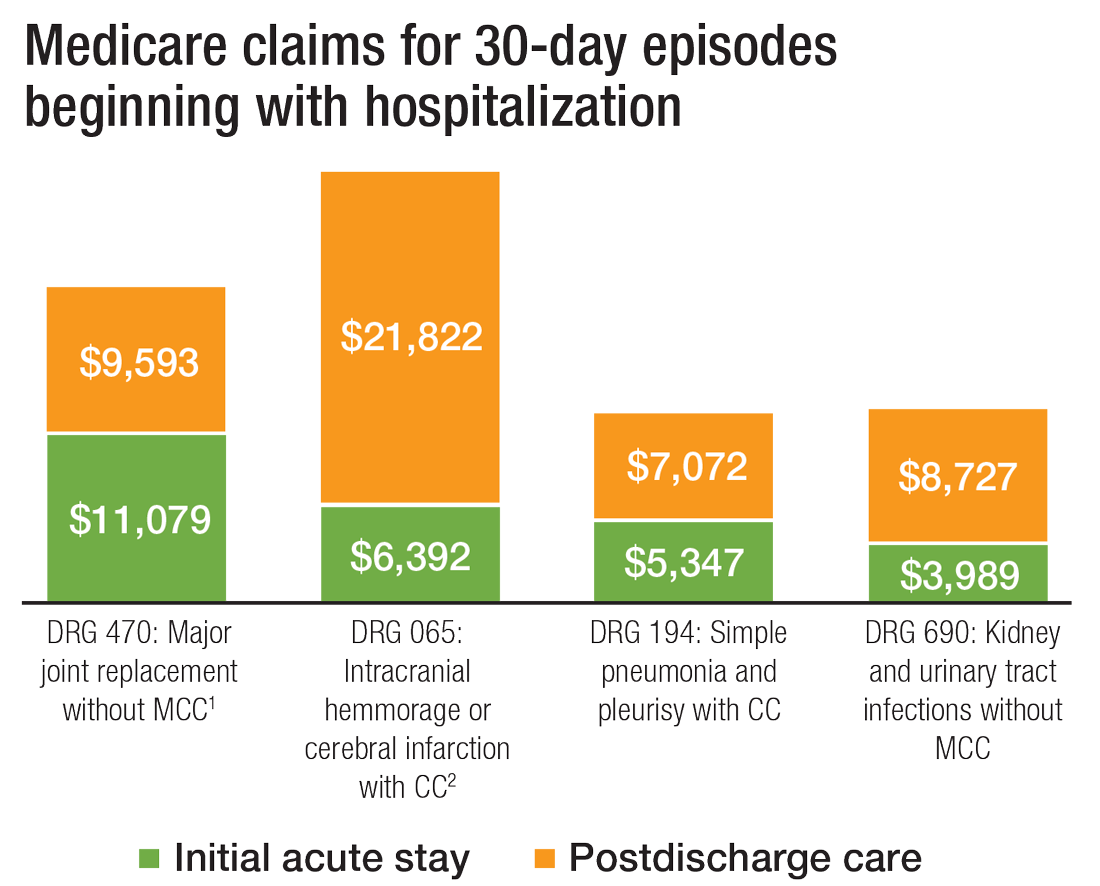

The cost of care, and other PAC facts and figures

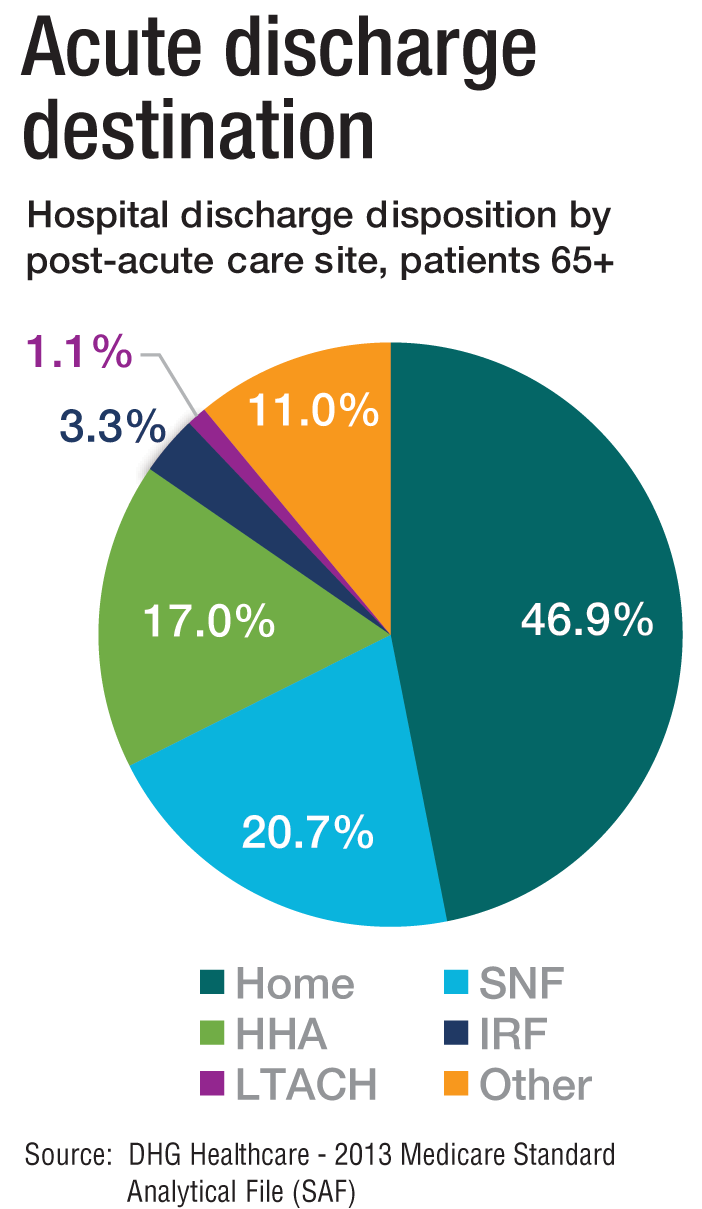

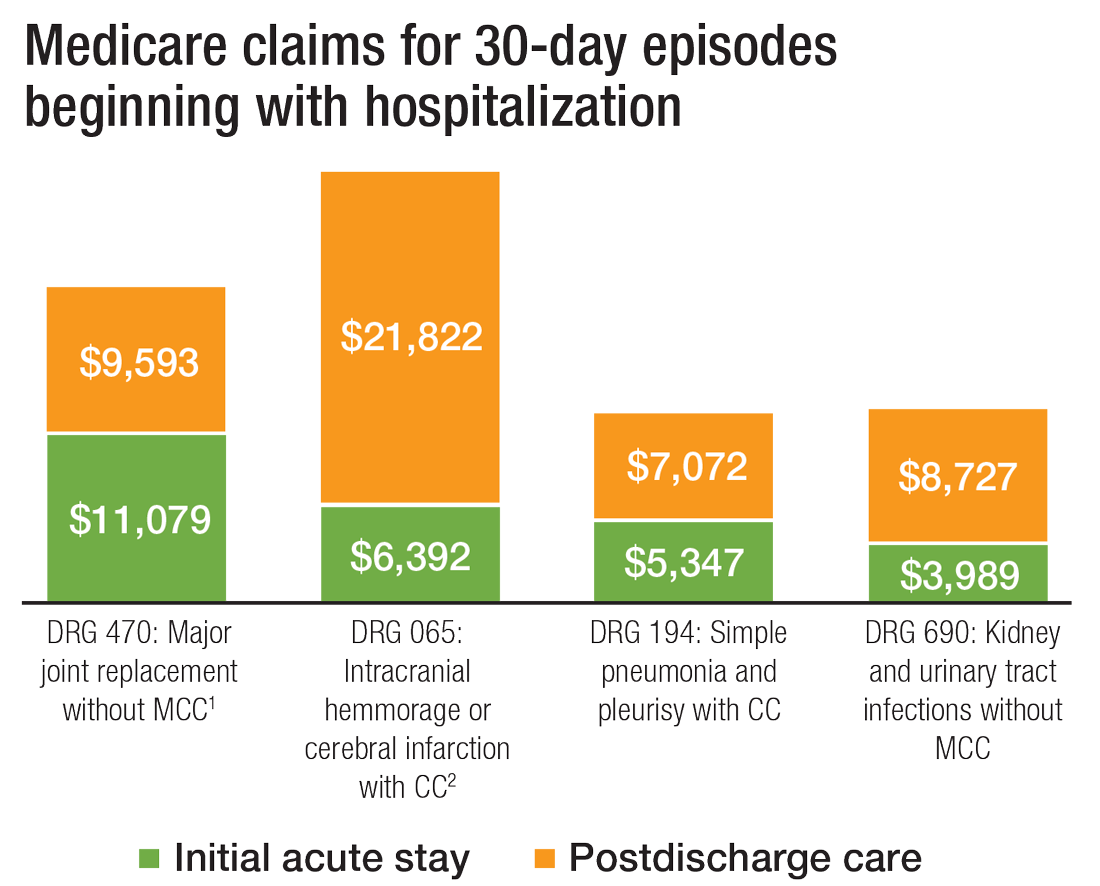

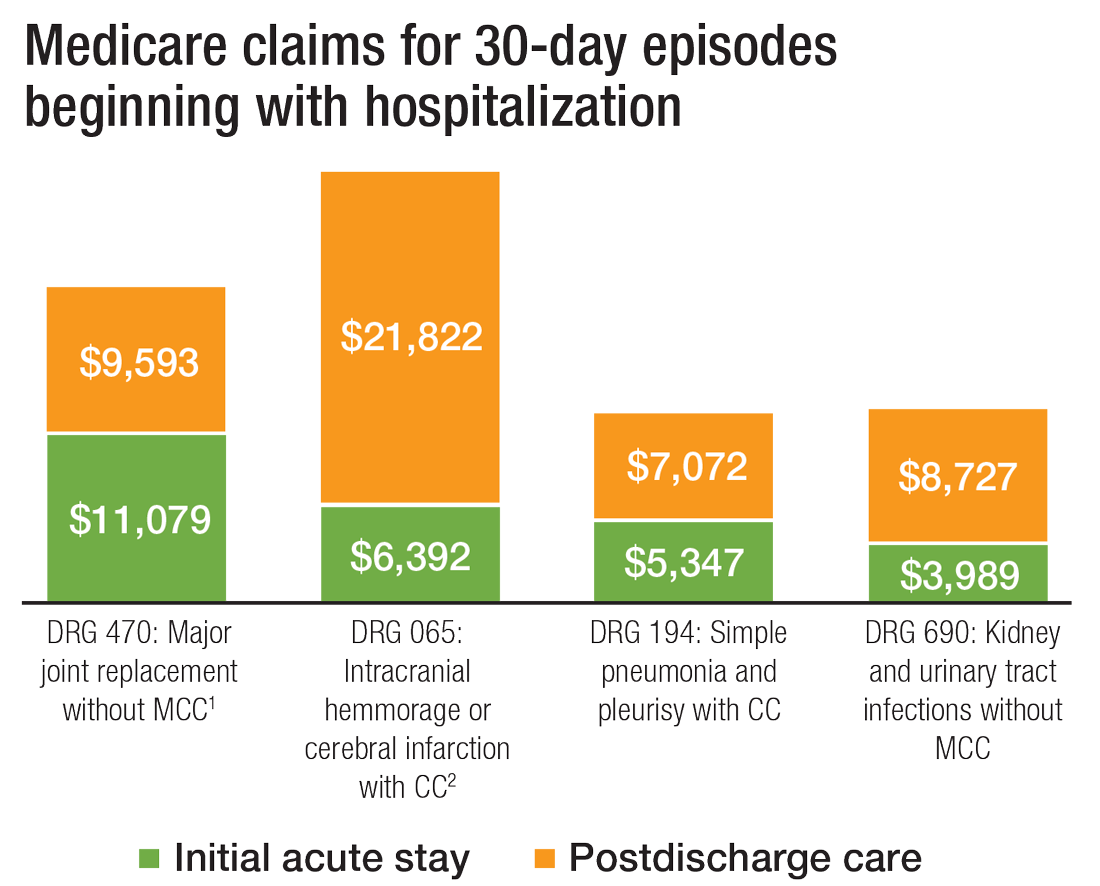

The amount of money that Medicare spends on post-acute care (PAC) has been increasing. In 2012, 12.6% of Medicare beneficiaries used some form of PAC, costing $62 billion.2 That amounts to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services spending close to 25% of Medicare beneficiary expenses on PAC, a 133% increase from 2001 to 2012. Among the different types, $30.4 billion was spent on skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), $18.6 billion on home health, and $13.1 billion on long-term acute care (LTAC) and acute-care rehabilitation.2

It’s also been reported that after short-term acute-care hospitalization, about one in five Medicare beneficiaries requires continued specialized treatment in one of the three typical Medicare PAC settings: inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs), LTAC hospitals, and SNFs.3

What’s more, hospital readmission nearly doubles the cost of an episode, so the financial implications for organizations operating in risk-bearing arrangements are significant. In 2013, 2,213 hospitals were charged $280 million in readmission penalties.2

References

1. The role of post-acute care in new care delivery models. American Hospital Association website. Available at: http://www.aha.org/research/reports/tw/15dec-tw-postacute.pdf. Accessed Nov. 7, 2016.

2. Post-acute care integration: Today and in the future. DHG Healthcare website. Available at: http://www2.dhgllp.com/res_pubs/HCG-Post-Acute-Care-Integration.pdf. Accessed Nov. 7, 2016.

3. Overview: Post-acute care transitions toolkit. Society for Hospital Medicine website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Web/Quality___Innovation/Implementation_Toolkit/pact/Overview_PACT.aspx?hkey=dea3da3c-8620-46db-a00f-89f07f021958. Accessed Nov. 10, 2016.

The definition of “hospitalist,” according to the SHM website, is a clinician “dedicated to delivering comprehensive medical care to hospitalized patients.” For years, the hospital setting was the specialties’ identifier. But as hospitalists’ scope has expanded, and post-acute care (PAC) in the United States has grown, more hospitalists are extending their roles into this space.

PAC today is more than the traditional nursing home, according to Manoj K. Mathew, MD, SFHM, national medical director of Agilon Health in Los Angeles.

Many of those expanded settings Dr. Mathew describes emerged as a result of the Affordable Care Act. Since its enactment in 2010, the ACA has heightened providers’ focus on the “Triple Aim” of improving the patient experience (including quality and satisfaction), improving the health of populations, and reducing the per capita cost of healthcare.1 Vishal Kuchaculla, MD, New England regional post-acute medical director of Knoxville,Tenn.-based TeamHealth, says new service lines also developed as Medicare clamped down on long-term inpatient hospital stays by giving financial impetus to discharge patients as soon as possible.

“Over the last few years, there’s been a major shift from fee-for-service to risk-based payment models,” Dr. Kuchaculla says. “The government’s financial incentives are driving outcomes to improve performance initiatives.”

“Today, LTACHs can be used as substitutes for short-term acute care,” says Sean R. Muldoon, MD, MPH, FCCP, chief medical officer of Kindred Healthcare in Louisville, Ky., and former chair of SHM’s Post-Acute Care Committee. “This means that a patient can be directly admitted from their home to an LTACH. In fact, many hospice and home-care patients are referred from physicians’ offices without a preceding hospitalization.”

Hospitalists can fill a need

More hospitalists are working in PACs for a number of reasons. Dr. Mathew says PAC facilities and services have “typically lacked the clinical structure and processes to obtain the results that patients and payors expect.

“These deficits needed to be quickly remedied as patients discharged from hospitals have increased acuity and higher disease burdens,” he adds. “Hospitalists were the natural choice to fill roles requiring their expertise and experience.”

Dr. Muldoon considers the expanded scope of practice into PACs an additional layer to hospital medicine’s value proposition to the healthcare system.

“As experts in the management of inpatient populations, it’s natural for hospitalists to expand to other facilities with inpatient-like populations,” he says, noting SNFs are the most popular choice, with IRFs and LTACHs also being common places to work. Few hospitalists work in home care or hospice.

PAC settings are designed to help patients who are transitioning from an inpatient setting back to their home or other setting.

“Many patients go home after a SNF stay, while others will move to a nursing home or other longer-term care setting for the first time,” says Tiffany Radcliff, PhD, a health economist in the department of health policy and management at Texas A&M University School of Public Health in College Station. “With this in mind, hospitalists working in PAC have the opportunity to address each patient’s ongoing care needs and prepare them for their next setting. Hospitalists can manage medication or other care regimen changes that resulted from an inpatient stay, reinforce discharge instructions to the patient and their caregivers, and identify any other issues with continuing care that need to be addressed before discharge to the next care setting.”

Transitioning Care

Even if a hospitalist is not employed at a PAC, it’s important that they know something about them.

“As patients are moved downstream earlier, hospitalists are being asked to help make a judgment regarding when and where an inpatient is transitioned,” Dr. Muldoon says. As organizations move toward becoming fully risk capable, it is necessary to develop referral networks of high-quality PAC providers to achieve the best clinical outcomes, reduce readmissions, and lower costs.2“Therefore, hospitalists should have a working knowledge of the different sites of service as well as some opinion on the suitability of available options in their community,” Dr. Muldoon says. “The hospitalist can also help to educate the hospitalized patient on what to expect at a PAC.”

If a patient is inappropriately prepared for the PAC setting, it could lead to incomplete management of their condition, which ultimately could lead to readmission.

“When hospitalists know how care is provided in a PAC setting, they are better able to ensure a smoother transition of care between settings,” says Tochi Iroku-Malize, MD, MPH, MBA, FAAFP, SFHM, chair of family medicine at Northwell Health in Long Island, N.Y. “This will ultimately prevent unnecessary readmissions.”

Further, the quality metrics that hospitals and thereby hospitalists are judged by no longer end at the hospital’s exit.

“The ownership of acute-care outcomes requires extending the accountability to outside of the institution’s four walls,” Dr. Mathew says. “The inpatient team needs to place great importance on the transition of care and the subsequent quality of that care when the patient is discharged.”

Robert W. Harrington Jr., MD, SFHM, chief medical officer of Plano, Texas–based Reliant Post-Acute Care Solutions and former SHM president, says the health system landscapes are pushing HM beyond the hospitals’ walls.

How PAC settings differ from hospitals

Practicing in PAC has some important nuances that hospitalists from short-term acute care need to get accustomed to, Dr. Muldoon says. Primarily, the diagnostic capabilities are much more limited, as is the presence of high-level staffing. Further, patients are less resilient to medication changes and interventions, so changes need to be done gradually.

“Hospitalists who try to practice acute-care medicine in a PAC setting may become frustrated by the length of time it takes to do a work-up, get a consultation, and respond to a patient’s change of condition,” Dr. Muldoon says. “Nonetheless, hospitalists can overcome this once recognizing this mind shift.”

According to Dr. Harrington, another challenge hospitalists may face is the inability of the hospital’s and PAC facility’s IT platforms to exchange electronic information.

“The major vendors on both sides need to figure out an interoperability strategy,” he says. “Currently, it often takes 1-3 days to receive a new patient’s discharge summary. The summary may consist of a stack of paper that takes significant time to sort through and requires the PAC facility to perform duplicate data entry. It’s a very highly inefficient process that opens up the doors to mistakes and errors of omission and commission that can result in bad patient outcomes.”

Arif Nazir, MD, CMD, FACP, AGSF, chief medical officer of Signature HealthCARE and president of SHC Medical Partners, both in Louisville, Ky., cites additional reasons the lack of seamless communication between a hospital and PAC facility is problematic. “I see physicians order laboratory tests and investigations that were already done in the hospital because they didn’t know they were already performed or never received the results,” he says. “Similarly, I see patients continue to take medications prescribed in the hospital long term even though they were only supposed to take them short term. I’ve also seen patients come to a PAC setting from a hospital without any formal understanding of their rehabilitative period and expectations for recovery.”

What’s ahead?

Looking to the future, Surafel Tsega, MD, clinical instructor at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, says he thinks there will be a move toward greater collaboration among inpatient and PAC facilities, particularly in the discharge process, given that hospitals have an added incentive to ensure safe transitions because reimbursement from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is tied to readmissions and there are penalties for readmission. This involves more comprehensive planning regarding “warm handoffs” (e.g., real-time discussions with PAC providers about a patient’s hospital course and plan of care upon discharge), transferring of information, and so forth.

And while it can still be challenging to identify high-risk patients or determine the intensity and duration of their care, Dr. Mathew says risk-stratification tools and care pathways are continually being refined to maximize value with the limited resources available. In addition, with an increased emphasis on employing a team approach to care, there will be better integration of non-medical services to address the social determinants of health, which play significant roles in overall health and healing.

“Working with community-based organizations for this purpose will be a valuable tool for any of the population health–based initiatives,” he says.

Dr. Muldoon says he believes healthcare reform will increasingly view an inpatient admission as something to be avoided.

“If hospitalization can’t be avoided, then it should be shortened as much as possible,” he says. “This will shift inpatient care into LTACHs, SNFs, and IRFs. Hospitalists would be wise to follow patients into those settings as traditional inpatient census is reduced. This will take a few years, so hospitalists should start now in preparing for that downstream transition of individuals who were previously inpatients.”

The cost of care, and other PAC facts and figures

The amount of money that Medicare spends on post-acute care (PAC) has been increasing. In 2012, 12.6% of Medicare beneficiaries used some form of PAC, costing $62 billion.2 That amounts to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services spending close to 25% of Medicare beneficiary expenses on PAC, a 133% increase from 2001 to 2012. Among the different types, $30.4 billion was spent on skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), $18.6 billion on home health, and $13.1 billion on long-term acute care (LTAC) and acute-care rehabilitation.2

It’s also been reported that after short-term acute-care hospitalization, about one in five Medicare beneficiaries requires continued specialized treatment in one of the three typical Medicare PAC settings: inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs), LTAC hospitals, and SNFs.3

What’s more, hospital readmission nearly doubles the cost of an episode, so the financial implications for organizations operating in risk-bearing arrangements are significant. In 2013, 2,213 hospitals were charged $280 million in readmission penalties.2

References

1. The role of post-acute care in new care delivery models. American Hospital Association website. Available at: http://www.aha.org/research/reports/tw/15dec-tw-postacute.pdf. Accessed Nov. 7, 2016.

2. Post-acute care integration: Today and in the future. DHG Healthcare website. Available at: http://www2.dhgllp.com/res_pubs/HCG-Post-Acute-Care-Integration.pdf. Accessed Nov. 7, 2016.

3. Overview: Post-acute care transitions toolkit. Society for Hospital Medicine website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Web/Quality___Innovation/Implementation_Toolkit/pact/Overview_PACT.aspx?hkey=dea3da3c-8620-46db-a00f-89f07f021958. Accessed Nov. 10, 2016.

The definition of “hospitalist,” according to the SHM website, is a clinician “dedicated to delivering comprehensive medical care to hospitalized patients.” For years, the hospital setting was the specialties’ identifier. But as hospitalists’ scope has expanded, and post-acute care (PAC) in the United States has grown, more hospitalists are extending their roles into this space.

PAC today is more than the traditional nursing home, according to Manoj K. Mathew, MD, SFHM, national medical director of Agilon Health in Los Angeles.

Many of those expanded settings Dr. Mathew describes emerged as a result of the Affordable Care Act. Since its enactment in 2010, the ACA has heightened providers’ focus on the “Triple Aim” of improving the patient experience (including quality and satisfaction), improving the health of populations, and reducing the per capita cost of healthcare.1 Vishal Kuchaculla, MD, New England regional post-acute medical director of Knoxville,Tenn.-based TeamHealth, says new service lines also developed as Medicare clamped down on long-term inpatient hospital stays by giving financial impetus to discharge patients as soon as possible.

“Over the last few years, there’s been a major shift from fee-for-service to risk-based payment models,” Dr. Kuchaculla says. “The government’s financial incentives are driving outcomes to improve performance initiatives.”

“Today, LTACHs can be used as substitutes for short-term acute care,” says Sean R. Muldoon, MD, MPH, FCCP, chief medical officer of Kindred Healthcare in Louisville, Ky., and former chair of SHM’s Post-Acute Care Committee. “This means that a patient can be directly admitted from their home to an LTACH. In fact, many hospice and home-care patients are referred from physicians’ offices without a preceding hospitalization.”

Hospitalists can fill a need

More hospitalists are working in PACs for a number of reasons. Dr. Mathew says PAC facilities and services have “typically lacked the clinical structure and processes to obtain the results that patients and payors expect.

“These deficits needed to be quickly remedied as patients discharged from hospitals have increased acuity and higher disease burdens,” he adds. “Hospitalists were the natural choice to fill roles requiring their expertise and experience.”

Dr. Muldoon considers the expanded scope of practice into PACs an additional layer to hospital medicine’s value proposition to the healthcare system.

“As experts in the management of inpatient populations, it’s natural for hospitalists to expand to other facilities with inpatient-like populations,” he says, noting SNFs are the most popular choice, with IRFs and LTACHs also being common places to work. Few hospitalists work in home care or hospice.

PAC settings are designed to help patients who are transitioning from an inpatient setting back to their home or other setting.

“Many patients go home after a SNF stay, while others will move to a nursing home or other longer-term care setting for the first time,” says Tiffany Radcliff, PhD, a health economist in the department of health policy and management at Texas A&M University School of Public Health in College Station. “With this in mind, hospitalists working in PAC have the opportunity to address each patient’s ongoing care needs and prepare them for their next setting. Hospitalists can manage medication or other care regimen changes that resulted from an inpatient stay, reinforce discharge instructions to the patient and their caregivers, and identify any other issues with continuing care that need to be addressed before discharge to the next care setting.”

Transitioning Care

Even if a hospitalist is not employed at a PAC, it’s important that they know something about them.

“As patients are moved downstream earlier, hospitalists are being asked to help make a judgment regarding when and where an inpatient is transitioned,” Dr. Muldoon says. As organizations move toward becoming fully risk capable, it is necessary to develop referral networks of high-quality PAC providers to achieve the best clinical outcomes, reduce readmissions, and lower costs.2“Therefore, hospitalists should have a working knowledge of the different sites of service as well as some opinion on the suitability of available options in their community,” Dr. Muldoon says. “The hospitalist can also help to educate the hospitalized patient on what to expect at a PAC.”

If a patient is inappropriately prepared for the PAC setting, it could lead to incomplete management of their condition, which ultimately could lead to readmission.

“When hospitalists know how care is provided in a PAC setting, they are better able to ensure a smoother transition of care between settings,” says Tochi Iroku-Malize, MD, MPH, MBA, FAAFP, SFHM, chair of family medicine at Northwell Health in Long Island, N.Y. “This will ultimately prevent unnecessary readmissions.”

Further, the quality metrics that hospitals and thereby hospitalists are judged by no longer end at the hospital’s exit.

“The ownership of acute-care outcomes requires extending the accountability to outside of the institution’s four walls,” Dr. Mathew says. “The inpatient team needs to place great importance on the transition of care and the subsequent quality of that care when the patient is discharged.”

Robert W. Harrington Jr., MD, SFHM, chief medical officer of Plano, Texas–based Reliant Post-Acute Care Solutions and former SHM president, says the health system landscapes are pushing HM beyond the hospitals’ walls.

How PAC settings differ from hospitals

Practicing in PAC has some important nuances that hospitalists from short-term acute care need to get accustomed to, Dr. Muldoon says. Primarily, the diagnostic capabilities are much more limited, as is the presence of high-level staffing. Further, patients are less resilient to medication changes and interventions, so changes need to be done gradually.

“Hospitalists who try to practice acute-care medicine in a PAC setting may become frustrated by the length of time it takes to do a work-up, get a consultation, and respond to a patient’s change of condition,” Dr. Muldoon says. “Nonetheless, hospitalists can overcome this once recognizing this mind shift.”

According to Dr. Harrington, another challenge hospitalists may face is the inability of the hospital’s and PAC facility’s IT platforms to exchange electronic information.

“The major vendors on both sides need to figure out an interoperability strategy,” he says. “Currently, it often takes 1-3 days to receive a new patient’s discharge summary. The summary may consist of a stack of paper that takes significant time to sort through and requires the PAC facility to perform duplicate data entry. It’s a very highly inefficient process that opens up the doors to mistakes and errors of omission and commission that can result in bad patient outcomes.”

Arif Nazir, MD, CMD, FACP, AGSF, chief medical officer of Signature HealthCARE and president of SHC Medical Partners, both in Louisville, Ky., cites additional reasons the lack of seamless communication between a hospital and PAC facility is problematic. “I see physicians order laboratory tests and investigations that were already done in the hospital because they didn’t know they were already performed or never received the results,” he says. “Similarly, I see patients continue to take medications prescribed in the hospital long term even though they were only supposed to take them short term. I’ve also seen patients come to a PAC setting from a hospital without any formal understanding of their rehabilitative period and expectations for recovery.”

What’s ahead?

Looking to the future, Surafel Tsega, MD, clinical instructor at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, says he thinks there will be a move toward greater collaboration among inpatient and PAC facilities, particularly in the discharge process, given that hospitals have an added incentive to ensure safe transitions because reimbursement from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is tied to readmissions and there are penalties for readmission. This involves more comprehensive planning regarding “warm handoffs” (e.g., real-time discussions with PAC providers about a patient’s hospital course and plan of care upon discharge), transferring of information, and so forth.

And while it can still be challenging to identify high-risk patients or determine the intensity and duration of their care, Dr. Mathew says risk-stratification tools and care pathways are continually being refined to maximize value with the limited resources available. In addition, with an increased emphasis on employing a team approach to care, there will be better integration of non-medical services to address the social determinants of health, which play significant roles in overall health and healing.

“Working with community-based organizations for this purpose will be a valuable tool for any of the population health–based initiatives,” he says.

Dr. Muldoon says he believes healthcare reform will increasingly view an inpatient admission as something to be avoided.

“If hospitalization can’t be avoided, then it should be shortened as much as possible,” he says. “This will shift inpatient care into LTACHs, SNFs, and IRFs. Hospitalists would be wise to follow patients into those settings as traditional inpatient census is reduced. This will take a few years, so hospitalists should start now in preparing for that downstream transition of individuals who were previously inpatients.”

The cost of care, and other PAC facts and figures

The amount of money that Medicare spends on post-acute care (PAC) has been increasing. In 2012, 12.6% of Medicare beneficiaries used some form of PAC, costing $62 billion.2 That amounts to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services spending close to 25% of Medicare beneficiary expenses on PAC, a 133% increase from 2001 to 2012. Among the different types, $30.4 billion was spent on skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), $18.6 billion on home health, and $13.1 billion on long-term acute care (LTAC) and acute-care rehabilitation.2

It’s also been reported that after short-term acute-care hospitalization, about one in five Medicare beneficiaries requires continued specialized treatment in one of the three typical Medicare PAC settings: inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs), LTAC hospitals, and SNFs.3

What’s more, hospital readmission nearly doubles the cost of an episode, so the financial implications for organizations operating in risk-bearing arrangements are significant. In 2013, 2,213 hospitals were charged $280 million in readmission penalties.2

References

1. The role of post-acute care in new care delivery models. American Hospital Association website. Available at: http://www.aha.org/research/reports/tw/15dec-tw-postacute.pdf. Accessed Nov. 7, 2016.

2. Post-acute care integration: Today and in the future. DHG Healthcare website. Available at: http://www2.dhgllp.com/res_pubs/HCG-Post-Acute-Care-Integration.pdf. Accessed Nov. 7, 2016.

3. Overview: Post-acute care transitions toolkit. Society for Hospital Medicine website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Web/Quality___Innovation/Implementation_Toolkit/pact/Overview_PACT.aspx?hkey=dea3da3c-8620-46db-a00f-89f07f021958. Accessed Nov. 10, 2016.

FDA Approves Lymphir for R/R Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma

The immunotherapy is a reformulation of denileukin diftitox (Ontak), initially approved in 1999 for certain patients with persistent or recurrent cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In 2014, the original formulation was voluntarily withdrawn from the US market. Citius acquired rights to market a reformulated product outside of Asia in 2021.

This is the first indication for Lymphir, which targets interleukin-2 receptors on malignant T cells.

This approval marks “a significant milestone” for patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, a rare cancer, company CEO Leonard Mazur said in a press release announcing the approval. “The introduction of Lymphir, with its potential to rapidly reduce skin disease and control symptomatic itching without cumulative toxicity, is expected to expand the [cutaneous T-cell lymphoma] treatment landscape and grow the overall market, currently estimated to be $300-$400 million.”

Approval was based on the single-arm, open-label 302 study in 69 patients who had a median of four prior anticancer therapies. Patients received 9 mcg/kg daily from day 1 to day 5 of 21-day cycles until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

The objective response rate was 36.2%, including complete responses in 8.7% of patients. Responses lasted 6 months or longer in 52% of patients. Over 80% of subjects had a decrease in skin tumor burden, and almost a third had clinically significant improvements in pruritus.

Adverse events occurring in 20% or more of patients include increased transaminases, decreased albumin, decreased hemoglobin, nausea, edema, fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, rash, chills, constipation, pyrexia, and capillary leak syndrome.

Labeling carries a boxed warning of capillary leak syndrome. Other warnings include visual impairment, infusion reactions, hepatotoxicity, and embryo-fetal toxicity. Citius is under a postmarketing requirement to characterize the risk for visual impairment.

The company expects to launch the agent within 5 months.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The immunotherapy is a reformulation of denileukin diftitox (Ontak), initially approved in 1999 for certain patients with persistent or recurrent cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In 2014, the original formulation was voluntarily withdrawn from the US market. Citius acquired rights to market a reformulated product outside of Asia in 2021.

This is the first indication for Lymphir, which targets interleukin-2 receptors on malignant T cells.

This approval marks “a significant milestone” for patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, a rare cancer, company CEO Leonard Mazur said in a press release announcing the approval. “The introduction of Lymphir, with its potential to rapidly reduce skin disease and control symptomatic itching without cumulative toxicity, is expected to expand the [cutaneous T-cell lymphoma] treatment landscape and grow the overall market, currently estimated to be $300-$400 million.”

Approval was based on the single-arm, open-label 302 study in 69 patients who had a median of four prior anticancer therapies. Patients received 9 mcg/kg daily from day 1 to day 5 of 21-day cycles until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

The objective response rate was 36.2%, including complete responses in 8.7% of patients. Responses lasted 6 months or longer in 52% of patients. Over 80% of subjects had a decrease in skin tumor burden, and almost a third had clinically significant improvements in pruritus.

Adverse events occurring in 20% or more of patients include increased transaminases, decreased albumin, decreased hemoglobin, nausea, edema, fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, rash, chills, constipation, pyrexia, and capillary leak syndrome.

Labeling carries a boxed warning of capillary leak syndrome. Other warnings include visual impairment, infusion reactions, hepatotoxicity, and embryo-fetal toxicity. Citius is under a postmarketing requirement to characterize the risk for visual impairment.

The company expects to launch the agent within 5 months.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The immunotherapy is a reformulation of denileukin diftitox (Ontak), initially approved in 1999 for certain patients with persistent or recurrent cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In 2014, the original formulation was voluntarily withdrawn from the US market. Citius acquired rights to market a reformulated product outside of Asia in 2021.

This is the first indication for Lymphir, which targets interleukin-2 receptors on malignant T cells.

This approval marks “a significant milestone” for patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, a rare cancer, company CEO Leonard Mazur said in a press release announcing the approval. “The introduction of Lymphir, with its potential to rapidly reduce skin disease and control symptomatic itching without cumulative toxicity, is expected to expand the [cutaneous T-cell lymphoma] treatment landscape and grow the overall market, currently estimated to be $300-$400 million.”

Approval was based on the single-arm, open-label 302 study in 69 patients who had a median of four prior anticancer therapies. Patients received 9 mcg/kg daily from day 1 to day 5 of 21-day cycles until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

The objective response rate was 36.2%, including complete responses in 8.7% of patients. Responses lasted 6 months or longer in 52% of patients. Over 80% of subjects had a decrease in skin tumor burden, and almost a third had clinically significant improvements in pruritus.

Adverse events occurring in 20% or more of patients include increased transaminases, decreased albumin, decreased hemoglobin, nausea, edema, fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, rash, chills, constipation, pyrexia, and capillary leak syndrome.

Labeling carries a boxed warning of capillary leak syndrome. Other warnings include visual impairment, infusion reactions, hepatotoxicity, and embryo-fetal toxicity. Citius is under a postmarketing requirement to characterize the risk for visual impairment.

The company expects to launch the agent within 5 months.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Immunotherapy May Be Overused in Dying Patients With Cancer

Chemotherapy has fallen out of favor for treating cancer toward the end of life. The toxicity is too high, and the benefit, if any, is often too low.

Immunotherapy, however, has been taking its place.

This means “there are patients who are getting immunotherapy who shouldn’t,” said Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, surgical oncologist Sajid Khan, MD, senior investigator on a recent study that highlighted the growing use of these agents in patients’ last month of life.

What’s driving this trend, and how can oncologists avoid overtreatment with immunotherapy at the end of life?

The N-of-1 Patient

With immunotherapy at the end of life, “each of us has had our N-of-1” where a patient bounces back with a remarkable and durable response, said Don Dizon, MD, a gynecologic oncologist at Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island.

He recalled a patient with sarcoma who did not respond to chemotherapy. But after Dr. Dizon started her on immunotherapy, everything turned around. She has now been in remission for 8 years and counting.

The possibility of an unexpected or remarkable responder is seductive. And the improved safety of immunotherapy over chemotherapy adds to the allure.

Meanwhile, patients are often desperate. It’s rare for someone to be ready to stop treatment, Dr. Dizon said. Everybody “hopes that they’re going to be the exceptional responder.”

At the end of the day, the question often becomes: “Why not try immunotherapy? What’s there to lose?”

This thinking may be prompting broader use of immunotherapy in late-stage disease, even in instances with no Food and Drug Administration indication and virtually no supportive data, such as for metastatic ovarian cancer, Dr. Dizon said.

Back to Earth

The problem with the hopeful approach is that end-of-life turnarounds with immunotherapy are rare, and there’s no way at the moment to predict who will have one, said Laura Petrillo, MD, a palliative care physician at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Even though immunotherapy generally comes with fewer adverse events than chemotherapy, catastrophic side effects are still possible.

Dr. Petrillo recalled a 95-year-old woman with metastatic cancer who was largely asymptomatic.

She had a qualifying mutation for a checkpoint inhibitor, so her oncologist started her on one. The patient never bounced back from the severe colitis the agent caused, and she died of complications in the hospital.