User login

Association Between Pruritus and Fibromyalgia: Results of a Population-Based, Cross-Sectional Study

Pruritus, which is defined as an itching sensation that elicits a desire to scratch, is the most common cutaneous condition. Pruritus is considered chronic when it lasts for more than 6 weeks.1 Etiologies implicated in chronic pruritus include but are not limited to primary skin diseases such as atopic dermatitis, systemic causes, neuropathic disorders, and psychogenic reasons.2 In approximately 8% to 35% of patients, the cause of pruritus remains elusive despite intensive investigation.3 The mechanisms of itch are multifaceted and include complex neural pathways.4 Although itch and pain share many similarities, they have distinct pathways based on their spinal connections.5 Nevertheless, both conditions show a wide overlap of receptors on peripheral nerve endings and activated brain parts.6,7 Fibromyalgia, the third most common musculoskeletal condition, affects 2% to 3% of the population worldwide and is at least 7 times more common in females.8,9 Its pathogenesis is not entirely clear but is thought to involve neurogenic inflammation, aberrations in peripheral nerves, and central pain mechanisms. Fibromyalgia is characterized by a plethora of symptoms including chronic widespread pain, autonomic disturbances, persistent fatigue and sleep disturbances, and hyperalgesia, as well as somatic and psychiatric symptoms.10

Fibromyalgia is accompanied by altered skin features including increased counts of mast cells and excessive degranulation,11 neurogenic inflammation with elevated cytokine expression,12 disrupted collagen metabolism,13 and microcirculation abnormalities.14 There has been limited research exploring the dermatologic manifestations of fibromyalgia. One retrospective study that included 845 patients with fibromyalgia reported increased occurrence of “neurodermatoses,” including pruritus, neurotic excoriations, prurigo nodules, and lichen simplex chronicus (LSC), among other cutaneous comorbidities.15 Another small study demonstrated an increased incidence of xerosis and neurotic excoriations in females with fibromyalgia.16 A paucity of large epidemiologic studies demonstrating the fibromyalgia-pruritus connection may lead to misdiagnosis, misinterpretation, and undertreatment of these patients.

Up to 49% of fibromyalgia patients experience small-fiber neuropathy.17 Electrophysiologic measurements, quantitative sensory testing, pain-related evoked potentials, and skin biopsies showed that patients with fibromyalgia have compromised small-fiber function, impaired pathways carrying fiber pain signals, and reduced skin innervation and regenerating fibers.18,19 Accordingly, pruritus that has been reported in fibromyalgia is believed to be of neuropathic origin.15 Overall, it is suspected that the same mechanism that causes hypersensitivity and pain in fibromyalgia patients also predisposes them to pruritus. Similar systemic treatments (eg, analgesics, antidepressants, anticonvulsants) prescribed for both conditions support this theory.20-25

Our large cross-sectional study sought to establish the association between fibromyalgia and pruritus as well as related pruritic conditions.

Methods

Study Design and Setting—We conducted a cross-sectional retrospective study using data-mining techniques to access information from the Clalit Health Services (CHS) database. Clalit Health Services is the largest health maintenance organization in Israel. It encompasses an extensive database with continuous real-time input from medical, administrative, and pharmaceutical computerized operating systems, which helps facilitate data collection for epidemiologic studies. A chronic disease register is gathered from these data sources and continuously updated and validated through logistic checks. The current study was approved by the institutional review board of the CHS (approval #0212-17-com2). Informed consent was not required because the data were de-identified and this was a noninterventional observational study.

Study Population and Covariates—Medical records of CHS enrollees were screened for the diagnosis of fibromyalgia, and data on prevalent cases of fibromyalgia were retrieved. The diagnosis of fibromyalgia was based on the documentation of a fibromyalgia-specific diagnostic code registered by a board-certified rheumatologist. A control group of individuals without fibromyalgia was selected through 1:2 matching based on age, sex, and primary care clinic. The control group was randomly selected from the list of CHS members frequency-matched to cases, excluding case patients with fibromyalgia. Age matching was grounded on the exact year of birth (1-year strata).

Other covariates in the analysis included pruritus-related skin disorders, including prurigo nodularis, neurotic excoriations, and LSC. There were 3 socioeconomic status categories according to patients' poverty index: low, intermediate, and high.26

Statistical Analysis—The distribution of sociodemographic and clinical features was compared between patients with fibromyalgia and controls using the χ2 test for sex and socioeconomic status and the t test for age. Conditional logistic regression then was used to calculate adjusted odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI to compare patients with fibromyalgia and controls with respect to the presence of pruritic comorbidities. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 26). P<.05 was considered statistically significant in all tests.

Results

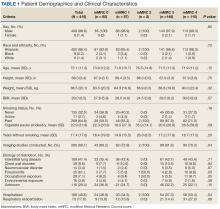

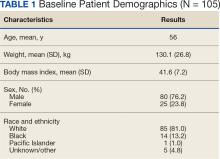

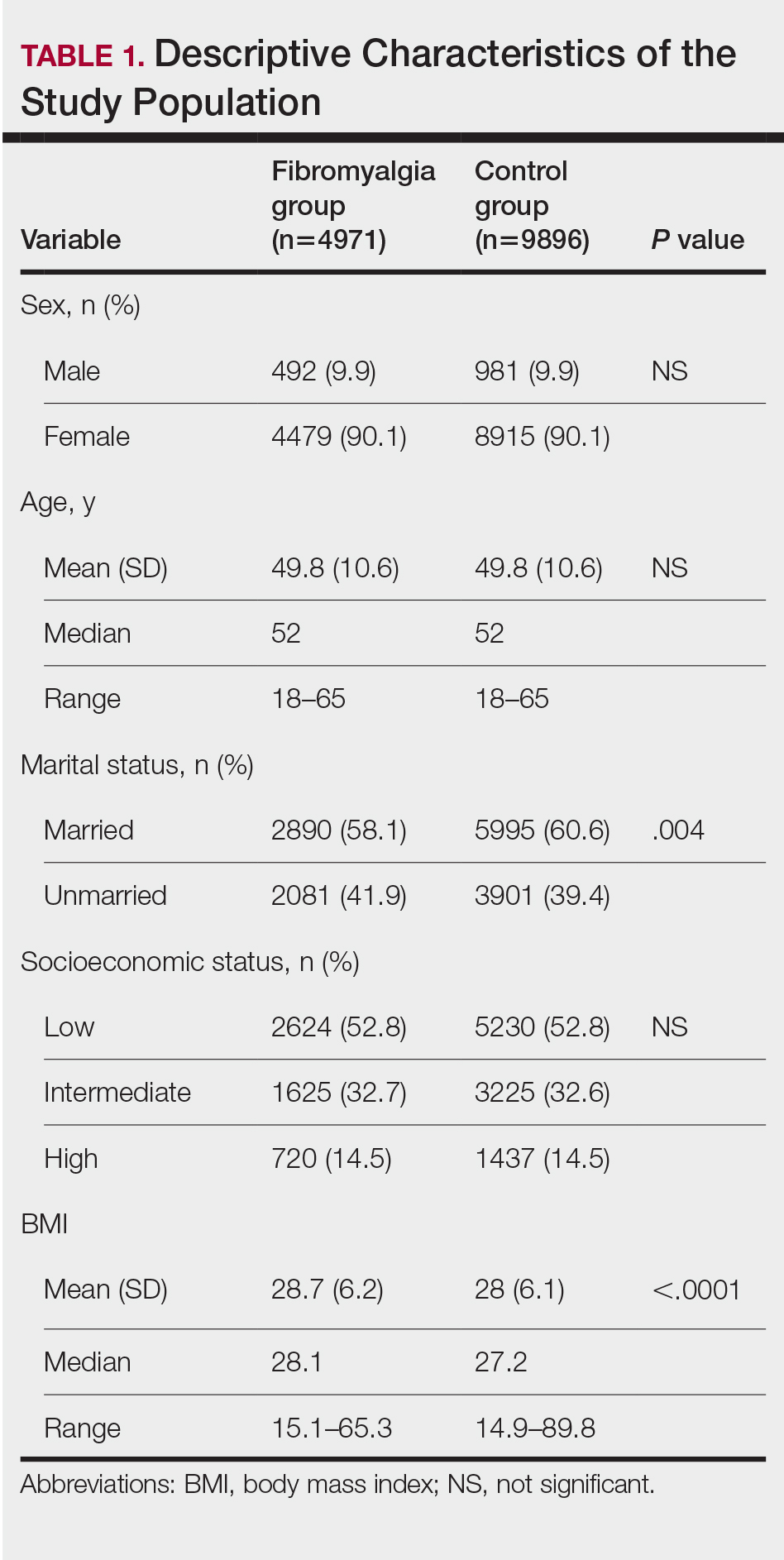

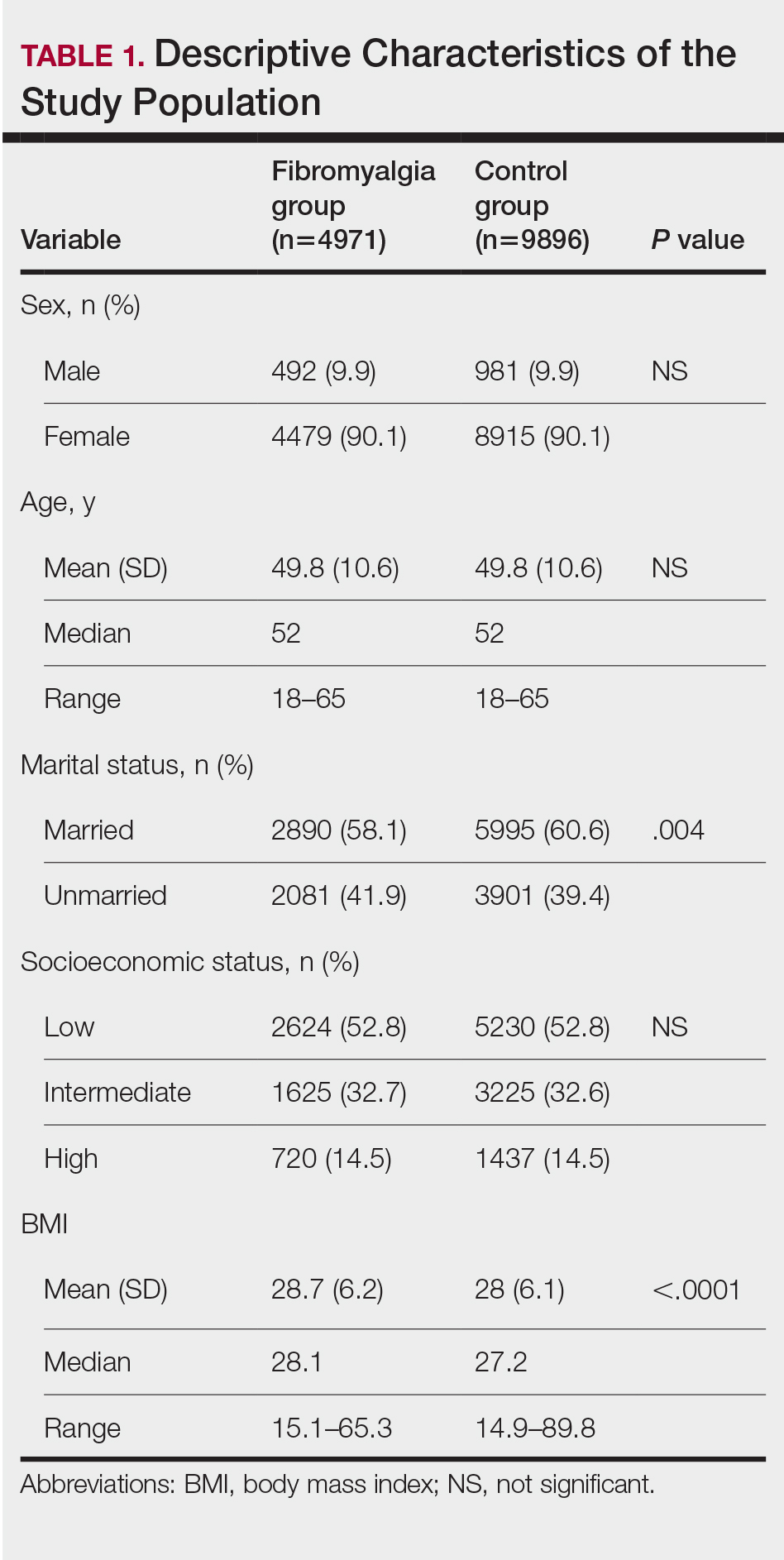

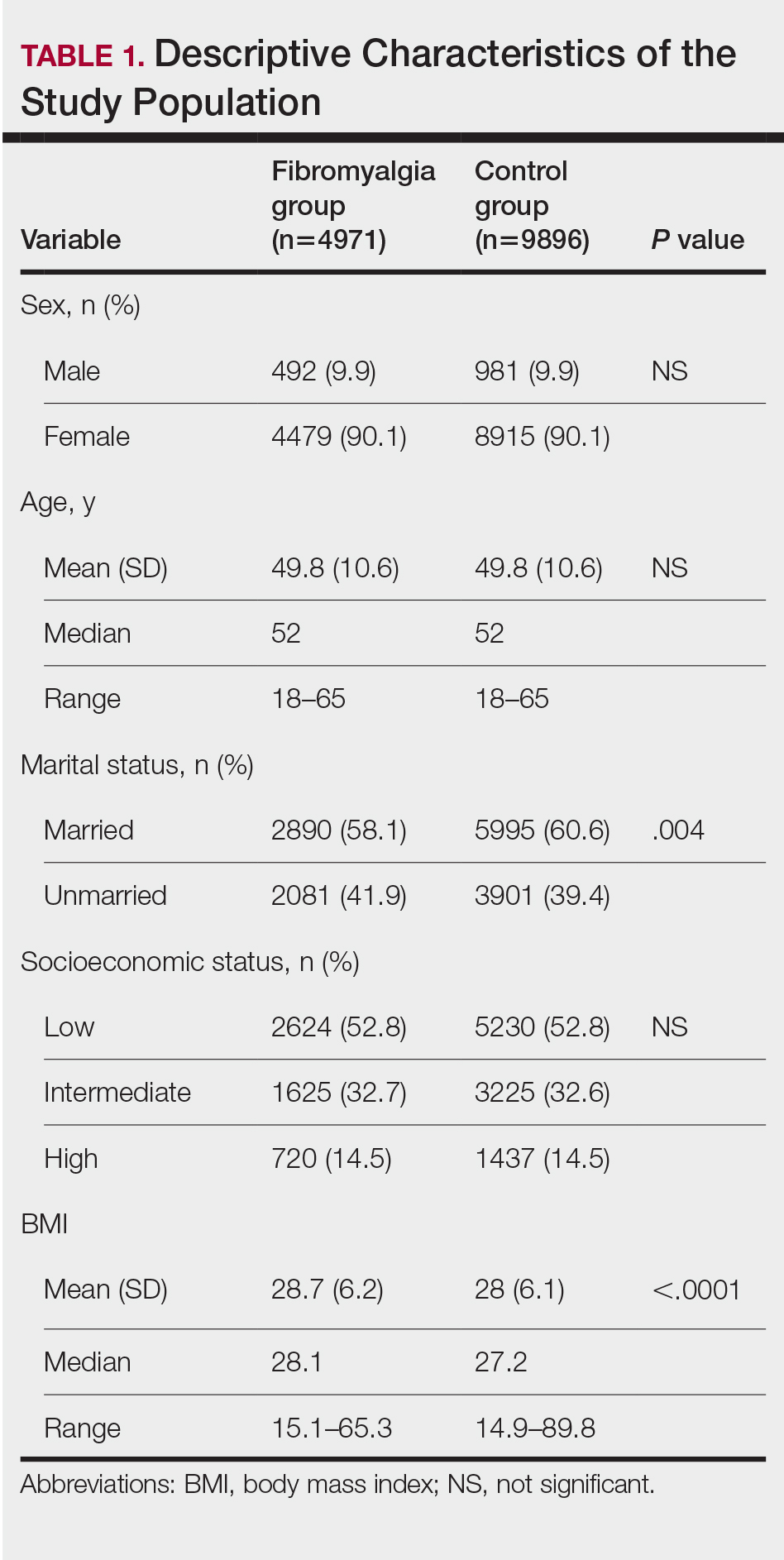

Our study population comprised 4971 patients with fibromyalgia and 9896 age- and sex-matched controls. Proportional to the reported female predominance among patients with fibromyalgia,27 4479 (90.1%) patients with fibromyalgia were females and a similar proportion was documented among controls (P=.99). There was a slightly higher proportion of unmarried patients among those with fibromyalgia compared with controls (41.9% vs 39.4%; P=.004). Socioeconomic status was matched between patients and controls (P=.99). Descriptive characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1.

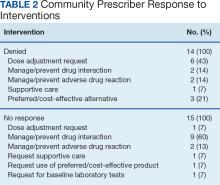

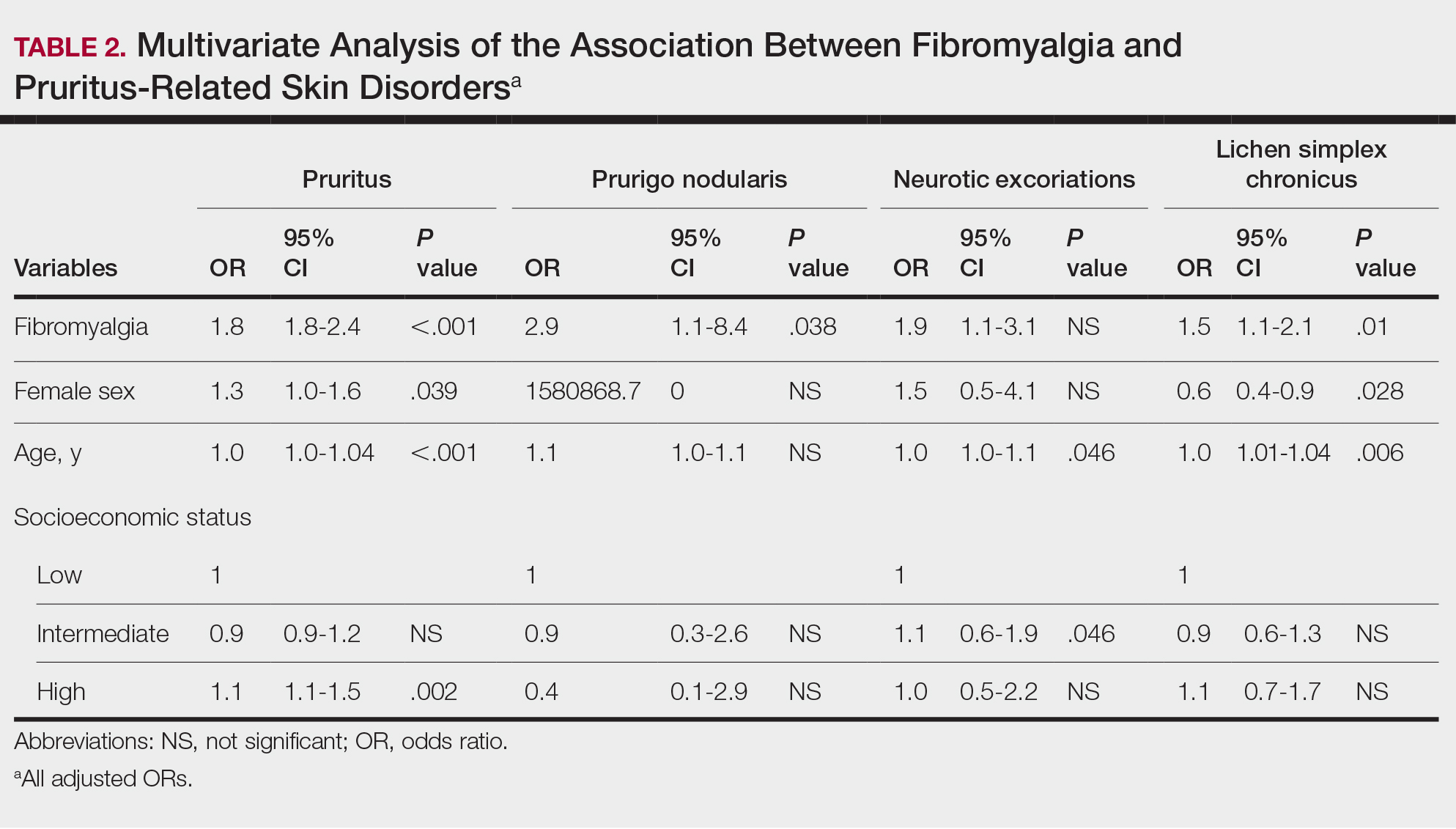

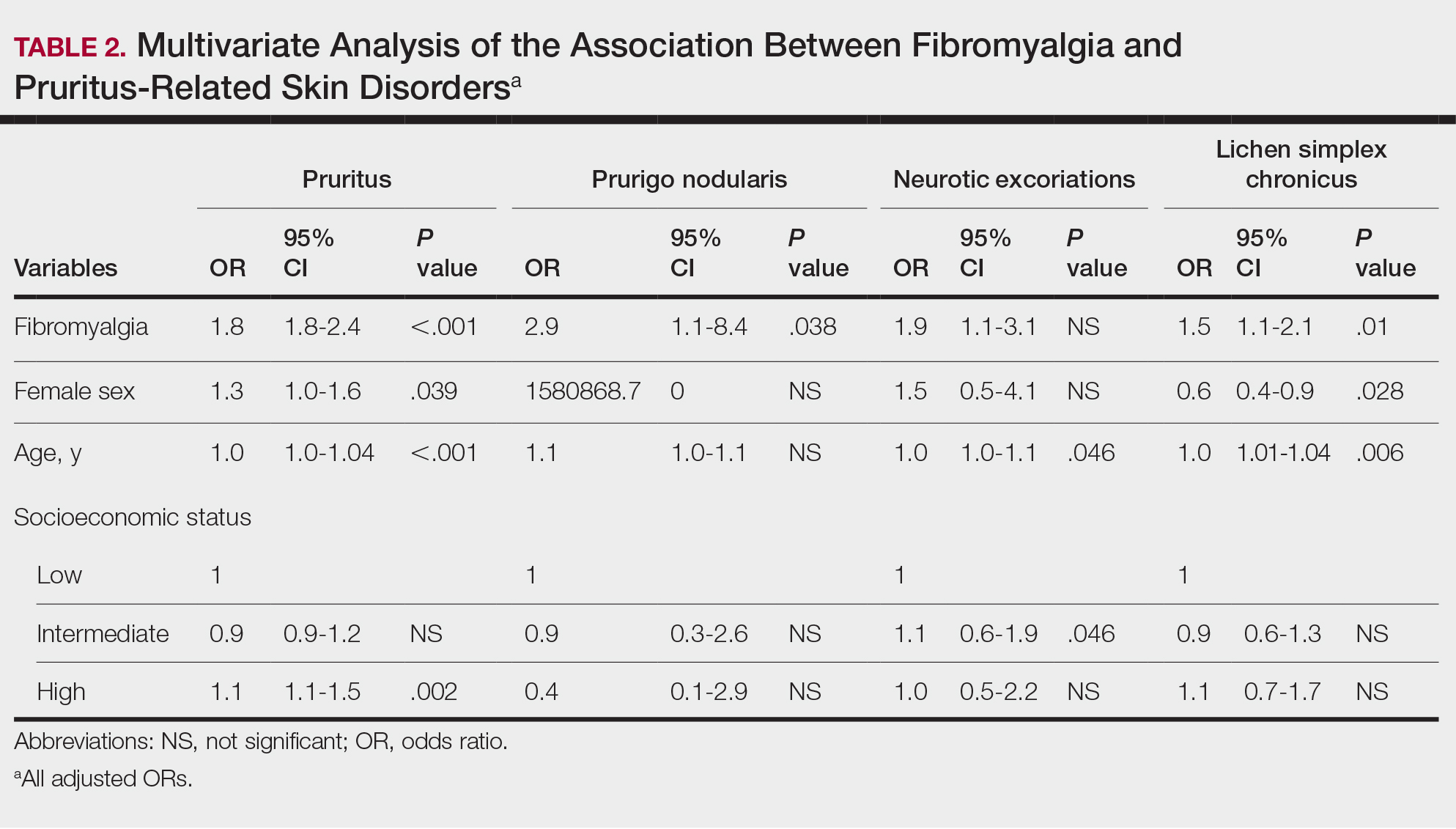

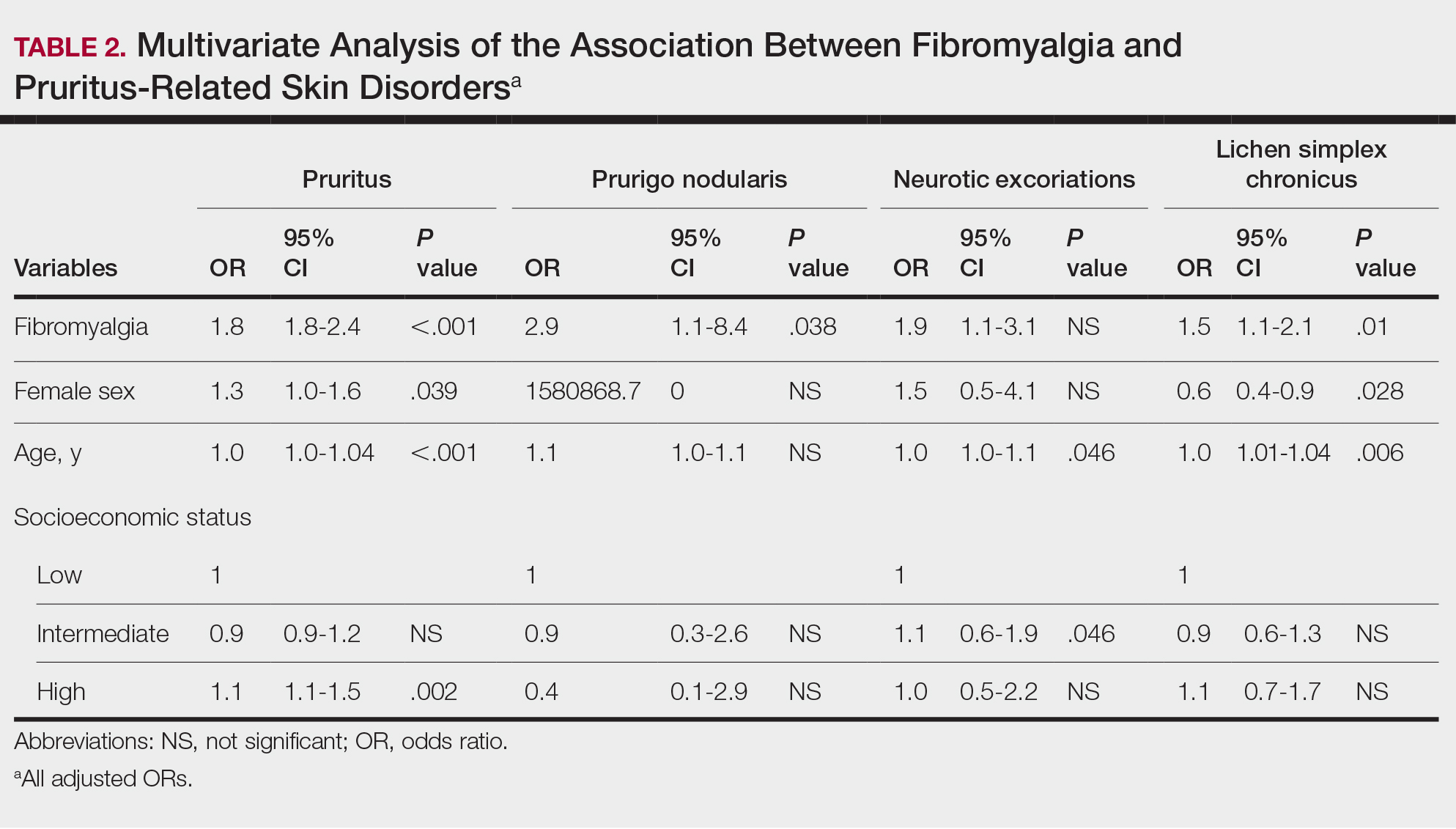

We assessed the presence of pruritus as well as 3 other pruritus-related skin disorders—prurigo nodularis, neurotic excoriations, and LSC—among patients with fibromyalgia and controls. Logistic regression was used to evaluate the independent association between fibromyalgia and pruritus. Table 2 presents the results of multivariate logistic regression models and summarizes the adjusted ORs for pruritic conditions in patients with fibromyalgia and different demographic features across the entire study sample. Fibromyalgia demonstrated strong independent associations with pruritus (OR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.8-2.4; P<.001), prurigo nodularis (OR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.1-8.4; P=.038), and LSC (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-2.1; P=.01); the association with neurotic excoriations was not significant. Female sex significantly increased the risk for pruritus (OR 1.3; 95% CI, 1.0-1.6; P=.039), while age slightly increased the odds for pruritus (OR, 1.0; 95% CI, 1.0-1.04; P<.001), neurotic excoriations (OR, 1.0; 95% CI, 1.0-1.1; P=.046), and LSC (OR, 1.0; 95% CI, 1.01-1.04; P=.006). Finally, socioeconomic status was inversely correlated with pruritus (OR, 1.1; 95% CI, 1.1-1.5; P=.002).

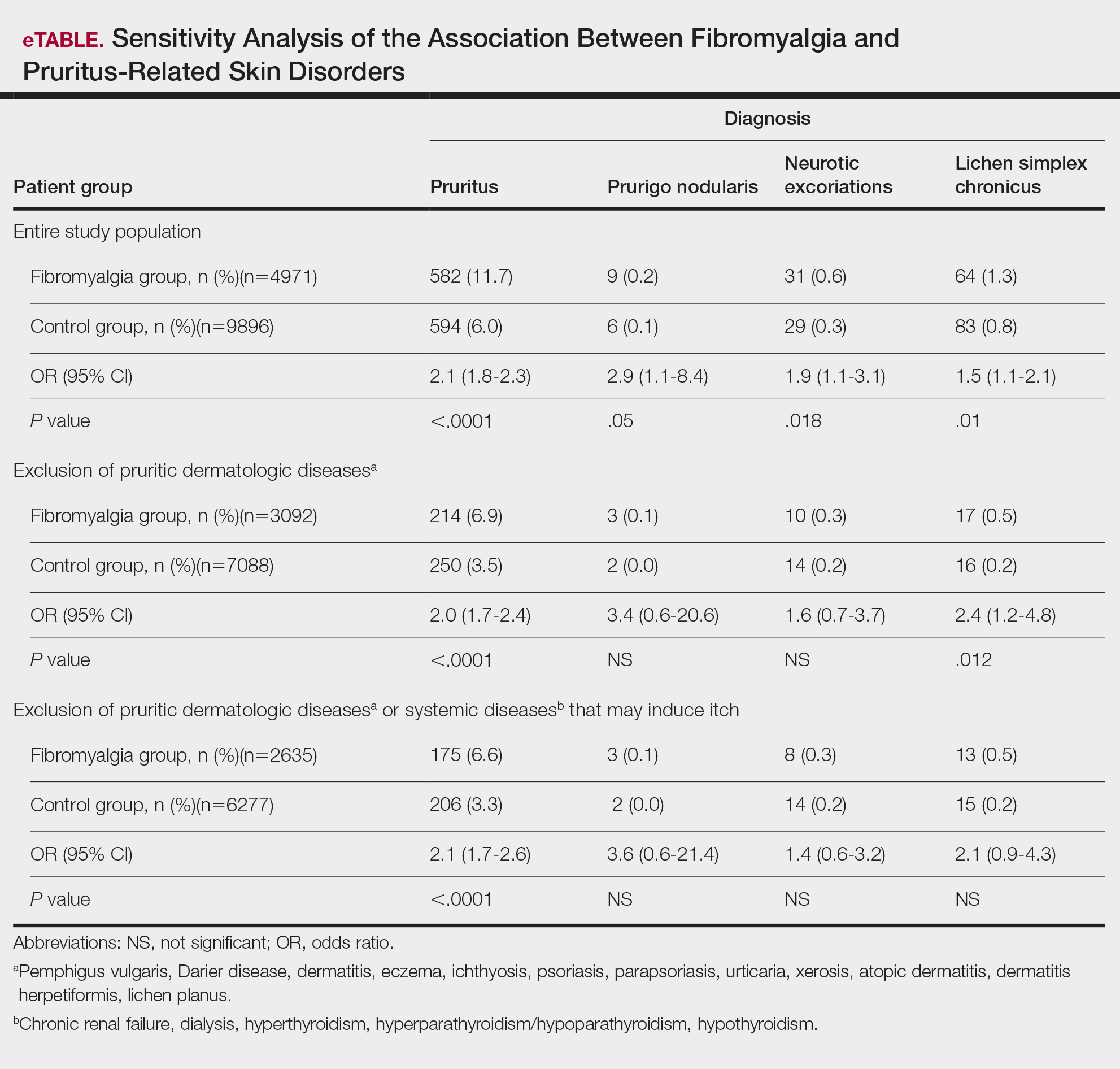

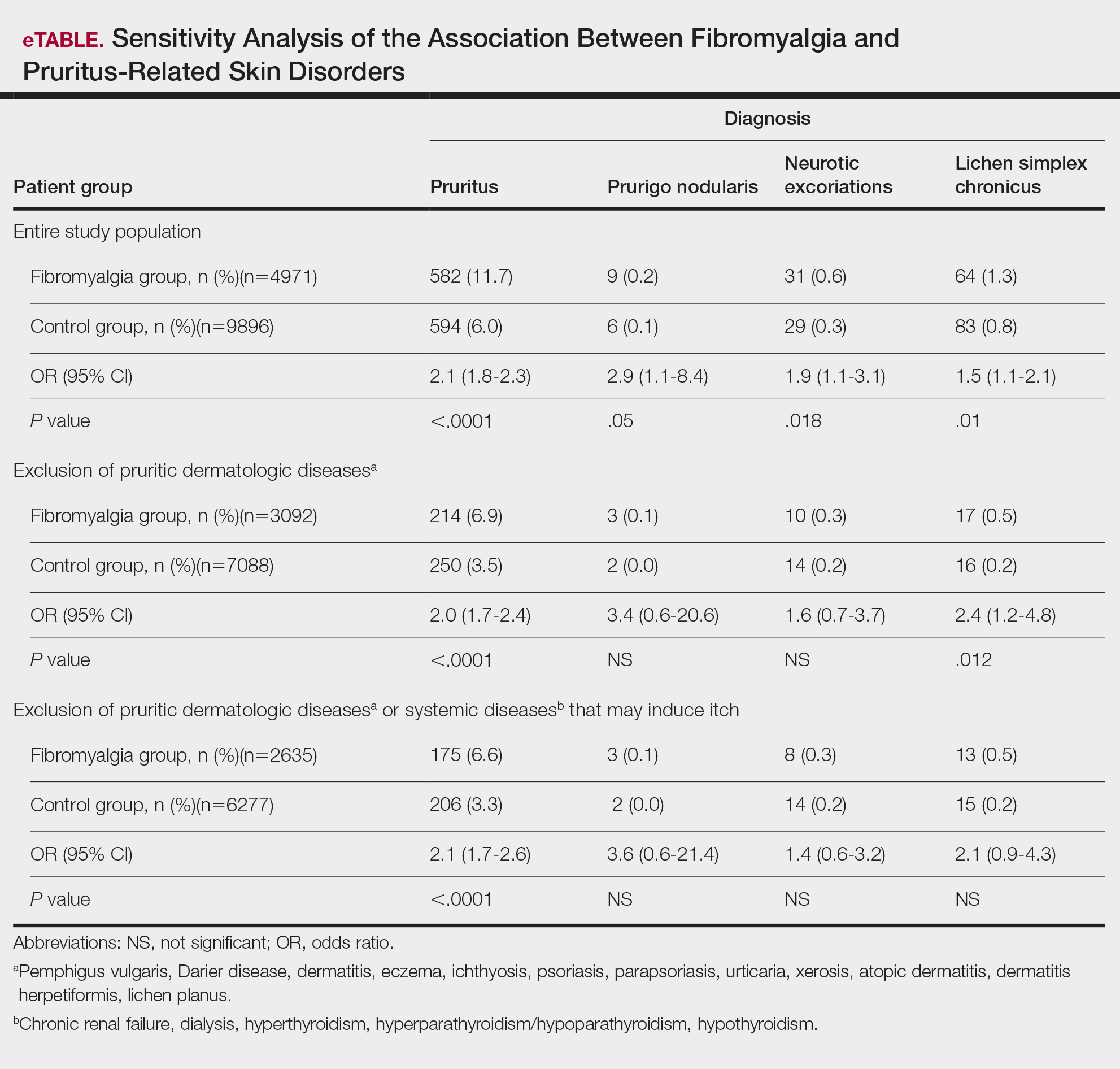

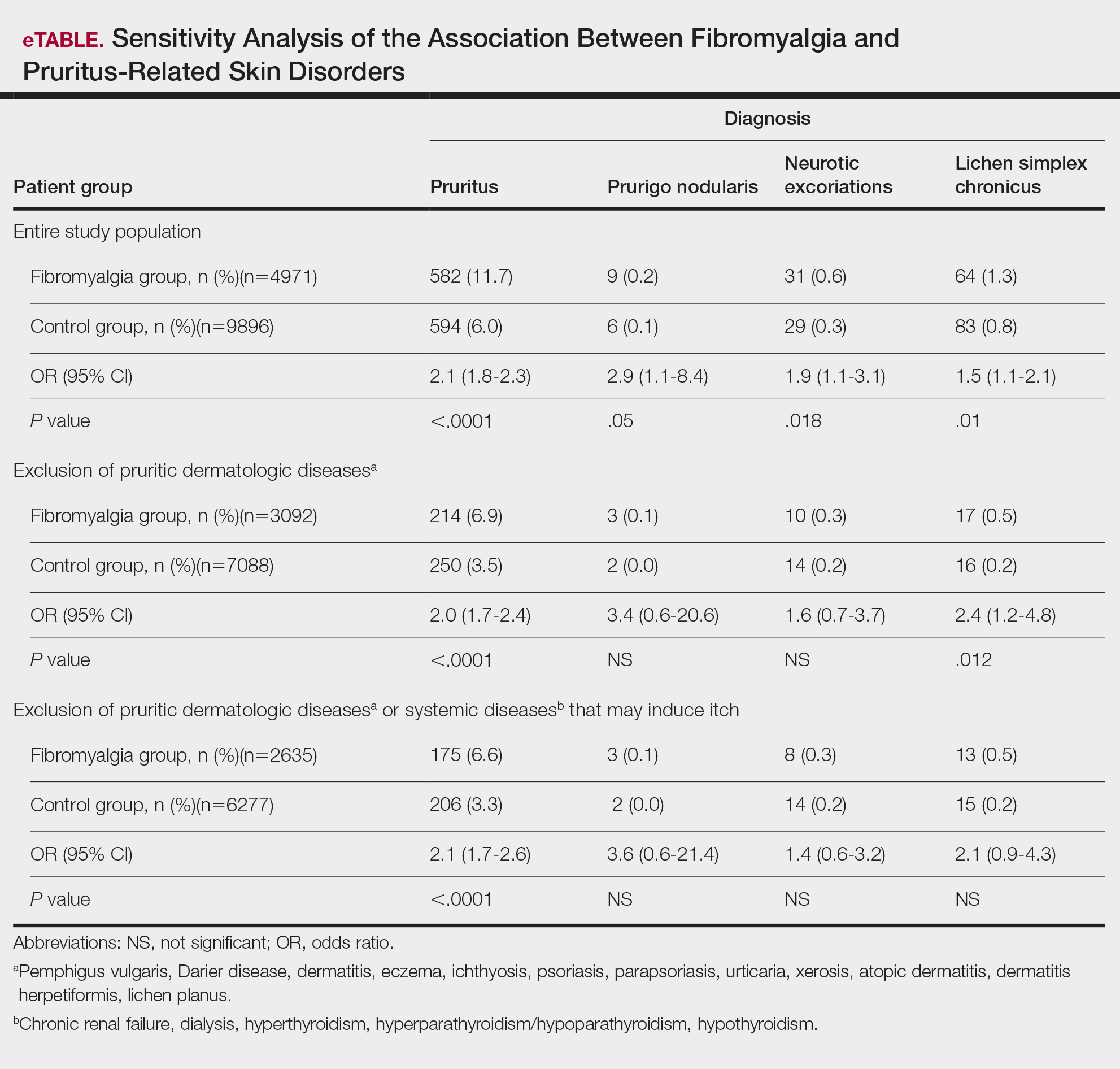

Frequencies and ORs for the association between fibromyalgia and pruritus with associated pruritic disorders stratified by exclusion of pruritic dermatologic and/or systemic diseases that may induce itch are presented in the eTable. Analyzing the entire study cohort, significant increases were observed in the odds of all 4 pruritic disorders analyzed. The frequency of pruritus was almost double in patients with fibromyalgia compared with controls (11.7% vs 6.0%; OR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.8-2.3; P<.0001). Prurigo nodularis (0.2% vs 0.1%; OR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.1-8.4; P=.05), neurotic excoriations (0.6% vs 0.3%; OR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.1-3.1; P=.018), and LSC (1.3% vs 0.8%; OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-2.1; P=.01) frequencies were all higher in patients with fibromyalgia than controls. When primary skin disorders that may cause itch (eg, pemphigus vulgaris, Darier disease, dermatitis, eczema, ichthyosis, psoriasis, parapsoriasis, urticaria, xerosis, atopic dermatitis, dermatitis herpetiformis, lichen planus) were excluded, the prevalence of pruritus in patients with fibromyalgia was still 1.97 times greater than in the controls (6.9% vs. 3.5%; OR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.7-2.4; P<.0001). These results remained unchanged even when excluding pruritic dermatologic disorders as well as systemic diseases associated with pruritus (eg, chronic renal failure, dialysis, hyperthyroidism, hyperparathyroidism/hypoparathyroidism, hypothyroidism). Patients with fibromyalgia still displayed a significantly higher prevalence of pruritus compared with the control group (6.6% vs 3.3%; OR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.7-2.6; P<.0001).

Comment

A wide range of skin manifestations have been associated with fibromyalgia, but the exact mechanisms remain unclear. Nevertheless, it is conceivable that autonomic nervous system dysfunction,28-31 amplified cutaneous opioid receptor activity,32 and an elevated presence of cutaneous mast cells with excessive degranulation may partially explain the frequent occurrence of pruritus and related skin disorders such as neurotic excoriations, prurigo nodularis, and LSC in individuals with fibromyalgia.15,16 In line with these findings, our study—which was based on data from the largest health maintenance organization in Israel—demonstrated an increased prevalence of pruritus and related pruritic disorders among individuals diagnosed with fibromyalgia.

This cross-sectional study links pruritus with fibromyalgia. Few preliminary epidemiologic studies have shown an increased occurrence of cutaneous manifestations in patients with fibromyalgia. One chart review that looked at skin findings in patients with fibromyalgia revealed 32 distinct cutaneous manifestations, and pruritus was the major concern in 3.3% of 845 patients.15

A focused cross-sectional study involving only women (66 with fibromyalgia and 79 healthy controls) discovered 14 skin conditions that were more common in those with fibromyalgia. Notably, xerosis and neurotic excoriations were more prevalent compared to the control group.16

The brain and the skin—both derivatives of the embryonic ectoderm33,34—are linked by pruritus. Although itch has its dedicated neurons, there is a wide-ranging overlap of brain-activated areas between pain and itch,6 and the neural anatomy of pain and itch are closely related in both the peripheral and central nervous systems35-37; for example, diseases of the central nervous system are accompanied by pruritus in as many as 15% of cases, while postherpetic neuralgia can result in chronic pain, itching, or a combination of both.38,39 Other instances include notalgia paresthetica and brachioradial pruritus.38 Additionally, there is a noteworthy psychologic impact associated with both itch and pain,40,41 with both psychosomatic and psychologic factors implicated in chronic pruritus and in fibromyalgia.42 Lastly, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the sympathetic nervous system are altered in both fibromyalgia and pruritus.43-45

Tey et al45 characterized the itch experienced in fibromyalgia as functional, which is described as pruritus associated with a somatoform disorder. In our study, we found a higher prevalence of pruritus among patients with fibromyalgia, and this association remained significant (P<.05) even when excluding other pruritic skin conditions and systemic diseases that can trigger itching. In addition, our logistic regression analyses revealed independent associations between fibromyalgia and pruritus, prurigo nodularis, and LSC.

According to Twycross et al,46 there are 4 clinical categories of itch, which may coexist7: pruritoceptive (originating in the skin), neuropathic (originating in pathology located along the afferent pathway), neurogenic (central origin but lacks a neural pathology), and psychogenic.47 Skin biopsy findings in patients with fibromyalgia include increased mast cell counts11 and degranulation,48 increased expression of δ and κ opioid receptors,32 vasoconstriction within tender points,49 and elevated IL-1β, IL-6, or tumor necrosis factor α by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction.12 A case recently was presented by Görg et al50 involving a female patient with fibromyalgia who had been experiencing chronic pruritus, which the authors attributed to small-fiber neuropathy based on evidence from a skin biopsy indicating a reduced number of intraepidermal nerves and the fact that the itching originated around tender points. Altogether, the observed alterations may work together to make patients with fibromyalgia more susceptible to various skin-related comorbidities in general, especially those related to pruritus. Eventually, it might be the case that several itch categories and related pathomechanisms are involved in the pruritus phenotype of patients with fibromyalgia.

Age-related alterations in nerve fibers, lower immune function, xerosis, polypharmacy, and increased frequency of systemic diseases with age are just a few of the factors that may predispose older individuals to pruritus.51,52 Indeed, our logistic regression model showed that age was significantly and independently associated with pruritus (P<.001), neurotic excoriations (P=.046), and LSC (P=.006). Female sex also was significantly linked with pruritus (P=.039). Intriguingly, high socioeconomic status was significantly associated with the diagnosis of pruritus (P=.002), possibly due to easier access to medical care.

There is a considerable overlap between the therapeutic approaches used in pruritus, pruritus-related skin disorders, and fibromyalgia. Antidepressants, anxiolytics, analgesics, and antiepileptics have been used to address both conditions.45 The association between these conditions advocates for a multidisciplinary approach in patients with fibromyalgia and potentially supports the rationale for unified therapeutics for both conditions.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate an association between fibromyalgia and pruritus as well as associated pruritic skin disorders. Given the convoluted and largely undiscovered mechanisms underlying fibromyalgia, managing patients with this condition may present substantial challenges.53 The data presented here support the implementation of a multidisciplinary treatment approach for patients with fibromyalgia. This approach should focus on managing fibromyalgia pain as well as addressing its concurrent skin-related conditions. It is advisable to consider treatments such as antiepileptics (eg, pregabalin, gabapentin) that specifically target neuropathic disorders in affected patients. These treatments may hold promise for alleviating fibromyalgia-related pain54 and mitigating its related cutaneous comorbidities, especially pruritus.

- Stander S, Weisshaar E, Mettang T, et al. Clinical classification of itch: a position paper of the International Forum for the Study of Itch. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007; 87:291-294.

- Yosipovitch G, Bernhard JD. Clinical practice. chronic pruritus. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1625-1634.

- Song J, Xian D, Yang L, et al. Pruritus: progress toward pathogenesis and treatment. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:9625936.

- Potenzieri C, Undem BJ. Basic mechanisms of itch. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42:8-19.

- McMahon SB, Koltzenburg M. Itching for an explanation. Trends Neurosci. 1992;15:497-501.

- Drzezga A, Darsow U, Treede RD, et al. Central activation by histamine-induced itch: analogies to pain processing: a correlational analysis of O-15 H2O positron emission tomography studies. Pain. 2001; 92:295-305.

- Yosipovitch G, Greaves MW, Schmelz M. Itch. Lancet. 2003;361:690-694.

- Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008; 58:15-25.

- Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008; 58:26-35.

- Sarzi-Puttini P, Giorgi V, Marotto D, et al. Fibromyalgia: an update on clinical characteristics, aetiopathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020;16:645-660.

- Blanco I, Beritze N, Arguelles M, et al. Abnormal overexpression of mastocytes in skin biopsies of fibromyalgia patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29:1403-1412.

- Salemi S, Rethage J, Wollina U, et al. Detection of interleukin 1beta (IL-1beta), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in skin of patients with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:146-150.

- Sprott H, Muller A, Heine H. Collagen cross-links in fibromyalgia syndrome. Z Rheumatol. 1998;57(suppl 2):52-55.

- Morf S, Amann-Vesti B, Forster A, et al. Microcirculation abnormalities in patients with fibromyalgia—measured by capillary microscopy and laser fluxmetry. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R209-R216.

- Laniosz V, Wetter DA, Godar DA. Dermatologic manifestations of fibromyalgia. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33:1009-1013.

- Dogramaci AC, Yalcinkaya EY. Skin problems in fibromyalgia. Nobel Med. 2009;5:50-52.

- Grayston R, Czanner G, Elhadd K, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of small fiber pathology in fibromyalgia: implications for a new paradigm in fibromyalgia etiopathogenesis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;48:933-940.

- Uceyler N, Zeller D, Kahn AK, et al. Small fibre pathology in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Brain. 2013;136:1857-1867.

- Devigili G, Tugnoli V, Penza P, et al. The diagnostic criteria for small fibre neuropathy: from symptoms to neuropathology. Brain. 2008; 131:1912- 1925.

- Reed C, Birnbaum HG, Ivanova JI, et al. Real-world role of tricyclic antidepressants in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Pain Pract. 2012; 12:533-540.

- Moret C, Briley M. Antidepressants in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2006;2:537-548.

- Arnold LM, Keck PE Jr, Welge JA. Antidepressant treatment of fibromyalgia. a meta-analysis and review. Psychosomatics. 2000;41:104-113.

- Moore A, Wiffen P, Kalso E. Antiepileptic drugs for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia. JAMA. 2014;312:182-183.

- Shevchenko A, Valdes-Rodriguez R, Yosipovitch G. Causes, pathophysiology, and treatment of pruritus in the mature patient. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:140-151.

- Scheinfeld N. The role of gabapentin in treating diseases with cutaneous manifestations and pain. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:491-495.

- Points Location Intelligence. Accessed July 30, 2024. https://points.co.il/en/points-location-intelligence/

- Yunus MB. The role of gender in fibromyalgia syndrome. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2001;3:128-134.

- Cakir T, Evcik D, Dundar U, et al. Evaluation of sympathetic skin response and f wave in fibromyalgia syndrome patients. Turk J Rheumatol. 2011;26:38-43.

- Ozkan O, Yildiz M, Koklukaya E. The correlation of laboratory tests and sympathetic skin response parameters by using artificial neural networks in fibromyalgia patients. J Med Syst. 2012;36:1841-1848.

- Ozkan O, Yildiz M, Arslan E, et al. A study on the effects of sympathetic skin response parameters in diagnosis of fibromyalgia using artificial neural networks. J Med Syst. 2016;40:54.

- Ulas UH, Unlu E, Hamamcioglu K, et al. Dysautonomia in fibromyalgia syndrome: sympathetic skin responses and RR interval analysis. Rheumatol Int. 2006;26:383-387.

- Salemi S, Aeschlimann A, Wollina U, et al. Up-regulation of delta-opioid receptors and kappa-opioid receptors in the skin of fibromyalgia patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2464-2466.

- Elshazzly M, Lopez MJ, Reddy V, et al. Central nervous system. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Hu MS, Borrelli MR, Hong WX, et al. Embryonic skin development and repair. Organogenesis. 2018;14:46-63.

- Davidson S, Zhang X, Yoon CH, et al. The itch-producing agents histamine and cowhage activate separate populations of primate spinothalamic tract neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10007-10014.

- Sikand P, Shimada SG, Green BG, et al. Similar itch and nociceptive sensations evoked by punctate cutaneous application of capsaicin, histamine and cowhage. Pain. 2009;144:66-75.

- Davidson S, Giesler GJ. The multiple pathways for itch and their interactions with pain. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:550-558.

- Dhand A, Aminoff MJ. The neurology of itch. Brain. 2014;137:313-322.

- Binder A, Koroschetz J, Baron R. Disease mechanisms in neuropathic itch. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2008;4:329-337.

- Fjellner B, Arnetz BB. Psychological predictors of pruritus during mental stress. Acta Derm Venereol. 1985;65:504-508.

- Papoiu AD, Wang H, Coghill RC, et al. Contagious itch in humans: a study of visual ‘transmission’ of itch in atopic dermatitis and healthy subjects. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:1299-1303.

- Stumpf A, Schneider G, Stander S. Psychosomatic and psychiatric disorders and psychologic factors in pruritus. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:704-708.

- Herman JP, McKlveen JM, Ghosal S, et al. Regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical stress response. Compr Physiol. 2016;6:603-621.

- Brown ED, Micozzi MS, Craft NE, et al. Plasma carotenoids in normal men after a single ingestion of vegetables or purified beta-carotene. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;49:1258-1265.

- Tey HL, Wallengren J, Yosipovitch G. Psychosomatic factors in pruritus. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:31-40.

- Twycross R, Greaves MW, Handwerker H, et al. Itch: scratching more than the surface. QJM. 2003;96:7-26.

- Bernhard JD. Itch and pruritus: what are they, and how should itches be classified? Dermatol Ther. 2005;18:288-291.

- Enestrom S, Bengtsson A, Frodin T. Dermal IgG deposits and increase of mast cells in patients with fibromyalgia—relevant findings or epiphenomena? Scand J Rheumatol. 1997;26:308-313.

- Jeschonneck M, Grohmann G, Hein G, et al. Abnormal microcirculation and temperature in skin above tender points in patients with fibromyalgia. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000;39:917-921.

- Görg M, Zeidler C, Pereira MP, et al. Generalized chronic pruritus with fibromyalgia. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2021;19:909-911.

- Garibyan L, Chiou AS, Elmariah SB. Advanced aging skin and itch: addressing an unmet need. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:92-103.

- Cohen KR, Frank J, Salbu RL, et al. Pruritus in the elderly: clinical approaches to the improvement of quality of life. P T. 2012;37:227-239.

- Tzadok R, Ablin JN. Current and emerging pharmacotherapy for fibromyalgia. Pain Res Manag. 2020; 2020:6541798.

- Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Moore RA, et al. Antiepileptic drugs for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia—an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013:CD010567.

Pruritus, which is defined as an itching sensation that elicits a desire to scratch, is the most common cutaneous condition. Pruritus is considered chronic when it lasts for more than 6 weeks.1 Etiologies implicated in chronic pruritus include but are not limited to primary skin diseases such as atopic dermatitis, systemic causes, neuropathic disorders, and psychogenic reasons.2 In approximately 8% to 35% of patients, the cause of pruritus remains elusive despite intensive investigation.3 The mechanisms of itch are multifaceted and include complex neural pathways.4 Although itch and pain share many similarities, they have distinct pathways based on their spinal connections.5 Nevertheless, both conditions show a wide overlap of receptors on peripheral nerve endings and activated brain parts.6,7 Fibromyalgia, the third most common musculoskeletal condition, affects 2% to 3% of the population worldwide and is at least 7 times more common in females.8,9 Its pathogenesis is not entirely clear but is thought to involve neurogenic inflammation, aberrations in peripheral nerves, and central pain mechanisms. Fibromyalgia is characterized by a plethora of symptoms including chronic widespread pain, autonomic disturbances, persistent fatigue and sleep disturbances, and hyperalgesia, as well as somatic and psychiatric symptoms.10

Fibromyalgia is accompanied by altered skin features including increased counts of mast cells and excessive degranulation,11 neurogenic inflammation with elevated cytokine expression,12 disrupted collagen metabolism,13 and microcirculation abnormalities.14 There has been limited research exploring the dermatologic manifestations of fibromyalgia. One retrospective study that included 845 patients with fibromyalgia reported increased occurrence of “neurodermatoses,” including pruritus, neurotic excoriations, prurigo nodules, and lichen simplex chronicus (LSC), among other cutaneous comorbidities.15 Another small study demonstrated an increased incidence of xerosis and neurotic excoriations in females with fibromyalgia.16 A paucity of large epidemiologic studies demonstrating the fibromyalgia-pruritus connection may lead to misdiagnosis, misinterpretation, and undertreatment of these patients.

Up to 49% of fibromyalgia patients experience small-fiber neuropathy.17 Electrophysiologic measurements, quantitative sensory testing, pain-related evoked potentials, and skin biopsies showed that patients with fibromyalgia have compromised small-fiber function, impaired pathways carrying fiber pain signals, and reduced skin innervation and regenerating fibers.18,19 Accordingly, pruritus that has been reported in fibromyalgia is believed to be of neuropathic origin.15 Overall, it is suspected that the same mechanism that causes hypersensitivity and pain in fibromyalgia patients also predisposes them to pruritus. Similar systemic treatments (eg, analgesics, antidepressants, anticonvulsants) prescribed for both conditions support this theory.20-25

Our large cross-sectional study sought to establish the association between fibromyalgia and pruritus as well as related pruritic conditions.

Methods

Study Design and Setting—We conducted a cross-sectional retrospective study using data-mining techniques to access information from the Clalit Health Services (CHS) database. Clalit Health Services is the largest health maintenance organization in Israel. It encompasses an extensive database with continuous real-time input from medical, administrative, and pharmaceutical computerized operating systems, which helps facilitate data collection for epidemiologic studies. A chronic disease register is gathered from these data sources and continuously updated and validated through logistic checks. The current study was approved by the institutional review board of the CHS (approval #0212-17-com2). Informed consent was not required because the data were de-identified and this was a noninterventional observational study.

Study Population and Covariates—Medical records of CHS enrollees were screened for the diagnosis of fibromyalgia, and data on prevalent cases of fibromyalgia were retrieved. The diagnosis of fibromyalgia was based on the documentation of a fibromyalgia-specific diagnostic code registered by a board-certified rheumatologist. A control group of individuals without fibromyalgia was selected through 1:2 matching based on age, sex, and primary care clinic. The control group was randomly selected from the list of CHS members frequency-matched to cases, excluding case patients with fibromyalgia. Age matching was grounded on the exact year of birth (1-year strata).

Other covariates in the analysis included pruritus-related skin disorders, including prurigo nodularis, neurotic excoriations, and LSC. There were 3 socioeconomic status categories according to patients' poverty index: low, intermediate, and high.26

Statistical Analysis—The distribution of sociodemographic and clinical features was compared between patients with fibromyalgia and controls using the χ2 test for sex and socioeconomic status and the t test for age. Conditional logistic regression then was used to calculate adjusted odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI to compare patients with fibromyalgia and controls with respect to the presence of pruritic comorbidities. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 26). P<.05 was considered statistically significant in all tests.

Results

Our study population comprised 4971 patients with fibromyalgia and 9896 age- and sex-matched controls. Proportional to the reported female predominance among patients with fibromyalgia,27 4479 (90.1%) patients with fibromyalgia were females and a similar proportion was documented among controls (P=.99). There was a slightly higher proportion of unmarried patients among those with fibromyalgia compared with controls (41.9% vs 39.4%; P=.004). Socioeconomic status was matched between patients and controls (P=.99). Descriptive characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1.

We assessed the presence of pruritus as well as 3 other pruritus-related skin disorders—prurigo nodularis, neurotic excoriations, and LSC—among patients with fibromyalgia and controls. Logistic regression was used to evaluate the independent association between fibromyalgia and pruritus. Table 2 presents the results of multivariate logistic regression models and summarizes the adjusted ORs for pruritic conditions in patients with fibromyalgia and different demographic features across the entire study sample. Fibromyalgia demonstrated strong independent associations with pruritus (OR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.8-2.4; P<.001), prurigo nodularis (OR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.1-8.4; P=.038), and LSC (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-2.1; P=.01); the association with neurotic excoriations was not significant. Female sex significantly increased the risk for pruritus (OR 1.3; 95% CI, 1.0-1.6; P=.039), while age slightly increased the odds for pruritus (OR, 1.0; 95% CI, 1.0-1.04; P<.001), neurotic excoriations (OR, 1.0; 95% CI, 1.0-1.1; P=.046), and LSC (OR, 1.0; 95% CI, 1.01-1.04; P=.006). Finally, socioeconomic status was inversely correlated with pruritus (OR, 1.1; 95% CI, 1.1-1.5; P=.002).

Frequencies and ORs for the association between fibromyalgia and pruritus with associated pruritic disorders stratified by exclusion of pruritic dermatologic and/or systemic diseases that may induce itch are presented in the eTable. Analyzing the entire study cohort, significant increases were observed in the odds of all 4 pruritic disorders analyzed. The frequency of pruritus was almost double in patients with fibromyalgia compared with controls (11.7% vs 6.0%; OR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.8-2.3; P<.0001). Prurigo nodularis (0.2% vs 0.1%; OR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.1-8.4; P=.05), neurotic excoriations (0.6% vs 0.3%; OR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.1-3.1; P=.018), and LSC (1.3% vs 0.8%; OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-2.1; P=.01) frequencies were all higher in patients with fibromyalgia than controls. When primary skin disorders that may cause itch (eg, pemphigus vulgaris, Darier disease, dermatitis, eczema, ichthyosis, psoriasis, parapsoriasis, urticaria, xerosis, atopic dermatitis, dermatitis herpetiformis, lichen planus) were excluded, the prevalence of pruritus in patients with fibromyalgia was still 1.97 times greater than in the controls (6.9% vs. 3.5%; OR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.7-2.4; P<.0001). These results remained unchanged even when excluding pruritic dermatologic disorders as well as systemic diseases associated with pruritus (eg, chronic renal failure, dialysis, hyperthyroidism, hyperparathyroidism/hypoparathyroidism, hypothyroidism). Patients with fibromyalgia still displayed a significantly higher prevalence of pruritus compared with the control group (6.6% vs 3.3%; OR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.7-2.6; P<.0001).

Comment

A wide range of skin manifestations have been associated with fibromyalgia, but the exact mechanisms remain unclear. Nevertheless, it is conceivable that autonomic nervous system dysfunction,28-31 amplified cutaneous opioid receptor activity,32 and an elevated presence of cutaneous mast cells with excessive degranulation may partially explain the frequent occurrence of pruritus and related skin disorders such as neurotic excoriations, prurigo nodularis, and LSC in individuals with fibromyalgia.15,16 In line with these findings, our study—which was based on data from the largest health maintenance organization in Israel—demonstrated an increased prevalence of pruritus and related pruritic disorders among individuals diagnosed with fibromyalgia.

This cross-sectional study links pruritus with fibromyalgia. Few preliminary epidemiologic studies have shown an increased occurrence of cutaneous manifestations in patients with fibromyalgia. One chart review that looked at skin findings in patients with fibromyalgia revealed 32 distinct cutaneous manifestations, and pruritus was the major concern in 3.3% of 845 patients.15

A focused cross-sectional study involving only women (66 with fibromyalgia and 79 healthy controls) discovered 14 skin conditions that were more common in those with fibromyalgia. Notably, xerosis and neurotic excoriations were more prevalent compared to the control group.16

The brain and the skin—both derivatives of the embryonic ectoderm33,34—are linked by pruritus. Although itch has its dedicated neurons, there is a wide-ranging overlap of brain-activated areas between pain and itch,6 and the neural anatomy of pain and itch are closely related in both the peripheral and central nervous systems35-37; for example, diseases of the central nervous system are accompanied by pruritus in as many as 15% of cases, while postherpetic neuralgia can result in chronic pain, itching, or a combination of both.38,39 Other instances include notalgia paresthetica and brachioradial pruritus.38 Additionally, there is a noteworthy psychologic impact associated with both itch and pain,40,41 with both psychosomatic and psychologic factors implicated in chronic pruritus and in fibromyalgia.42 Lastly, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the sympathetic nervous system are altered in both fibromyalgia and pruritus.43-45

Tey et al45 characterized the itch experienced in fibromyalgia as functional, which is described as pruritus associated with a somatoform disorder. In our study, we found a higher prevalence of pruritus among patients with fibromyalgia, and this association remained significant (P<.05) even when excluding other pruritic skin conditions and systemic diseases that can trigger itching. In addition, our logistic regression analyses revealed independent associations between fibromyalgia and pruritus, prurigo nodularis, and LSC.

According to Twycross et al,46 there are 4 clinical categories of itch, which may coexist7: pruritoceptive (originating in the skin), neuropathic (originating in pathology located along the afferent pathway), neurogenic (central origin but lacks a neural pathology), and psychogenic.47 Skin biopsy findings in patients with fibromyalgia include increased mast cell counts11 and degranulation,48 increased expression of δ and κ opioid receptors,32 vasoconstriction within tender points,49 and elevated IL-1β, IL-6, or tumor necrosis factor α by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction.12 A case recently was presented by Görg et al50 involving a female patient with fibromyalgia who had been experiencing chronic pruritus, which the authors attributed to small-fiber neuropathy based on evidence from a skin biopsy indicating a reduced number of intraepidermal nerves and the fact that the itching originated around tender points. Altogether, the observed alterations may work together to make patients with fibromyalgia more susceptible to various skin-related comorbidities in general, especially those related to pruritus. Eventually, it might be the case that several itch categories and related pathomechanisms are involved in the pruritus phenotype of patients with fibromyalgia.

Age-related alterations in nerve fibers, lower immune function, xerosis, polypharmacy, and increased frequency of systemic diseases with age are just a few of the factors that may predispose older individuals to pruritus.51,52 Indeed, our logistic regression model showed that age was significantly and independently associated with pruritus (P<.001), neurotic excoriations (P=.046), and LSC (P=.006). Female sex also was significantly linked with pruritus (P=.039). Intriguingly, high socioeconomic status was significantly associated with the diagnosis of pruritus (P=.002), possibly due to easier access to medical care.

There is a considerable overlap between the therapeutic approaches used in pruritus, pruritus-related skin disorders, and fibromyalgia. Antidepressants, anxiolytics, analgesics, and antiepileptics have been used to address both conditions.45 The association between these conditions advocates for a multidisciplinary approach in patients with fibromyalgia and potentially supports the rationale for unified therapeutics for both conditions.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate an association between fibromyalgia and pruritus as well as associated pruritic skin disorders. Given the convoluted and largely undiscovered mechanisms underlying fibromyalgia, managing patients with this condition may present substantial challenges.53 The data presented here support the implementation of a multidisciplinary treatment approach for patients with fibromyalgia. This approach should focus on managing fibromyalgia pain as well as addressing its concurrent skin-related conditions. It is advisable to consider treatments such as antiepileptics (eg, pregabalin, gabapentin) that specifically target neuropathic disorders in affected patients. These treatments may hold promise for alleviating fibromyalgia-related pain54 and mitigating its related cutaneous comorbidities, especially pruritus.

Pruritus, which is defined as an itching sensation that elicits a desire to scratch, is the most common cutaneous condition. Pruritus is considered chronic when it lasts for more than 6 weeks.1 Etiologies implicated in chronic pruritus include but are not limited to primary skin diseases such as atopic dermatitis, systemic causes, neuropathic disorders, and psychogenic reasons.2 In approximately 8% to 35% of patients, the cause of pruritus remains elusive despite intensive investigation.3 The mechanisms of itch are multifaceted and include complex neural pathways.4 Although itch and pain share many similarities, they have distinct pathways based on their spinal connections.5 Nevertheless, both conditions show a wide overlap of receptors on peripheral nerve endings and activated brain parts.6,7 Fibromyalgia, the third most common musculoskeletal condition, affects 2% to 3% of the population worldwide and is at least 7 times more common in females.8,9 Its pathogenesis is not entirely clear but is thought to involve neurogenic inflammation, aberrations in peripheral nerves, and central pain mechanisms. Fibromyalgia is characterized by a plethora of symptoms including chronic widespread pain, autonomic disturbances, persistent fatigue and sleep disturbances, and hyperalgesia, as well as somatic and psychiatric symptoms.10

Fibromyalgia is accompanied by altered skin features including increased counts of mast cells and excessive degranulation,11 neurogenic inflammation with elevated cytokine expression,12 disrupted collagen metabolism,13 and microcirculation abnormalities.14 There has been limited research exploring the dermatologic manifestations of fibromyalgia. One retrospective study that included 845 patients with fibromyalgia reported increased occurrence of “neurodermatoses,” including pruritus, neurotic excoriations, prurigo nodules, and lichen simplex chronicus (LSC), among other cutaneous comorbidities.15 Another small study demonstrated an increased incidence of xerosis and neurotic excoriations in females with fibromyalgia.16 A paucity of large epidemiologic studies demonstrating the fibromyalgia-pruritus connection may lead to misdiagnosis, misinterpretation, and undertreatment of these patients.

Up to 49% of fibromyalgia patients experience small-fiber neuropathy.17 Electrophysiologic measurements, quantitative sensory testing, pain-related evoked potentials, and skin biopsies showed that patients with fibromyalgia have compromised small-fiber function, impaired pathways carrying fiber pain signals, and reduced skin innervation and regenerating fibers.18,19 Accordingly, pruritus that has been reported in fibromyalgia is believed to be of neuropathic origin.15 Overall, it is suspected that the same mechanism that causes hypersensitivity and pain in fibromyalgia patients also predisposes them to pruritus. Similar systemic treatments (eg, analgesics, antidepressants, anticonvulsants) prescribed for both conditions support this theory.20-25

Our large cross-sectional study sought to establish the association between fibromyalgia and pruritus as well as related pruritic conditions.

Methods

Study Design and Setting—We conducted a cross-sectional retrospective study using data-mining techniques to access information from the Clalit Health Services (CHS) database. Clalit Health Services is the largest health maintenance organization in Israel. It encompasses an extensive database with continuous real-time input from medical, administrative, and pharmaceutical computerized operating systems, which helps facilitate data collection for epidemiologic studies. A chronic disease register is gathered from these data sources and continuously updated and validated through logistic checks. The current study was approved by the institutional review board of the CHS (approval #0212-17-com2). Informed consent was not required because the data were de-identified and this was a noninterventional observational study.

Study Population and Covariates—Medical records of CHS enrollees were screened for the diagnosis of fibromyalgia, and data on prevalent cases of fibromyalgia were retrieved. The diagnosis of fibromyalgia was based on the documentation of a fibromyalgia-specific diagnostic code registered by a board-certified rheumatologist. A control group of individuals without fibromyalgia was selected through 1:2 matching based on age, sex, and primary care clinic. The control group was randomly selected from the list of CHS members frequency-matched to cases, excluding case patients with fibromyalgia. Age matching was grounded on the exact year of birth (1-year strata).

Other covariates in the analysis included pruritus-related skin disorders, including prurigo nodularis, neurotic excoriations, and LSC. There were 3 socioeconomic status categories according to patients' poverty index: low, intermediate, and high.26

Statistical Analysis—The distribution of sociodemographic and clinical features was compared between patients with fibromyalgia and controls using the χ2 test for sex and socioeconomic status and the t test for age. Conditional logistic regression then was used to calculate adjusted odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI to compare patients with fibromyalgia and controls with respect to the presence of pruritic comorbidities. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 26). P<.05 was considered statistically significant in all tests.

Results

Our study population comprised 4971 patients with fibromyalgia and 9896 age- and sex-matched controls. Proportional to the reported female predominance among patients with fibromyalgia,27 4479 (90.1%) patients with fibromyalgia were females and a similar proportion was documented among controls (P=.99). There was a slightly higher proportion of unmarried patients among those with fibromyalgia compared with controls (41.9% vs 39.4%; P=.004). Socioeconomic status was matched between patients and controls (P=.99). Descriptive characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1.

We assessed the presence of pruritus as well as 3 other pruritus-related skin disorders—prurigo nodularis, neurotic excoriations, and LSC—among patients with fibromyalgia and controls. Logistic regression was used to evaluate the independent association between fibromyalgia and pruritus. Table 2 presents the results of multivariate logistic regression models and summarizes the adjusted ORs for pruritic conditions in patients with fibromyalgia and different demographic features across the entire study sample. Fibromyalgia demonstrated strong independent associations with pruritus (OR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.8-2.4; P<.001), prurigo nodularis (OR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.1-8.4; P=.038), and LSC (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-2.1; P=.01); the association with neurotic excoriations was not significant. Female sex significantly increased the risk for pruritus (OR 1.3; 95% CI, 1.0-1.6; P=.039), while age slightly increased the odds for pruritus (OR, 1.0; 95% CI, 1.0-1.04; P<.001), neurotic excoriations (OR, 1.0; 95% CI, 1.0-1.1; P=.046), and LSC (OR, 1.0; 95% CI, 1.01-1.04; P=.006). Finally, socioeconomic status was inversely correlated with pruritus (OR, 1.1; 95% CI, 1.1-1.5; P=.002).

Frequencies and ORs for the association between fibromyalgia and pruritus with associated pruritic disorders stratified by exclusion of pruritic dermatologic and/or systemic diseases that may induce itch are presented in the eTable. Analyzing the entire study cohort, significant increases were observed in the odds of all 4 pruritic disorders analyzed. The frequency of pruritus was almost double in patients with fibromyalgia compared with controls (11.7% vs 6.0%; OR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.8-2.3; P<.0001). Prurigo nodularis (0.2% vs 0.1%; OR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.1-8.4; P=.05), neurotic excoriations (0.6% vs 0.3%; OR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.1-3.1; P=.018), and LSC (1.3% vs 0.8%; OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-2.1; P=.01) frequencies were all higher in patients with fibromyalgia than controls. When primary skin disorders that may cause itch (eg, pemphigus vulgaris, Darier disease, dermatitis, eczema, ichthyosis, psoriasis, parapsoriasis, urticaria, xerosis, atopic dermatitis, dermatitis herpetiformis, lichen planus) were excluded, the prevalence of pruritus in patients with fibromyalgia was still 1.97 times greater than in the controls (6.9% vs. 3.5%; OR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.7-2.4; P<.0001). These results remained unchanged even when excluding pruritic dermatologic disorders as well as systemic diseases associated with pruritus (eg, chronic renal failure, dialysis, hyperthyroidism, hyperparathyroidism/hypoparathyroidism, hypothyroidism). Patients with fibromyalgia still displayed a significantly higher prevalence of pruritus compared with the control group (6.6% vs 3.3%; OR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.7-2.6; P<.0001).

Comment

A wide range of skin manifestations have been associated with fibromyalgia, but the exact mechanisms remain unclear. Nevertheless, it is conceivable that autonomic nervous system dysfunction,28-31 amplified cutaneous opioid receptor activity,32 and an elevated presence of cutaneous mast cells with excessive degranulation may partially explain the frequent occurrence of pruritus and related skin disorders such as neurotic excoriations, prurigo nodularis, and LSC in individuals with fibromyalgia.15,16 In line with these findings, our study—which was based on data from the largest health maintenance organization in Israel—demonstrated an increased prevalence of pruritus and related pruritic disorders among individuals diagnosed with fibromyalgia.

This cross-sectional study links pruritus with fibromyalgia. Few preliminary epidemiologic studies have shown an increased occurrence of cutaneous manifestations in patients with fibromyalgia. One chart review that looked at skin findings in patients with fibromyalgia revealed 32 distinct cutaneous manifestations, and pruritus was the major concern in 3.3% of 845 patients.15

A focused cross-sectional study involving only women (66 with fibromyalgia and 79 healthy controls) discovered 14 skin conditions that were more common in those with fibromyalgia. Notably, xerosis and neurotic excoriations were more prevalent compared to the control group.16

The brain and the skin—both derivatives of the embryonic ectoderm33,34—are linked by pruritus. Although itch has its dedicated neurons, there is a wide-ranging overlap of brain-activated areas between pain and itch,6 and the neural anatomy of pain and itch are closely related in both the peripheral and central nervous systems35-37; for example, diseases of the central nervous system are accompanied by pruritus in as many as 15% of cases, while postherpetic neuralgia can result in chronic pain, itching, or a combination of both.38,39 Other instances include notalgia paresthetica and brachioradial pruritus.38 Additionally, there is a noteworthy psychologic impact associated with both itch and pain,40,41 with both psychosomatic and psychologic factors implicated in chronic pruritus and in fibromyalgia.42 Lastly, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the sympathetic nervous system are altered in both fibromyalgia and pruritus.43-45

Tey et al45 characterized the itch experienced in fibromyalgia as functional, which is described as pruritus associated with a somatoform disorder. In our study, we found a higher prevalence of pruritus among patients with fibromyalgia, and this association remained significant (P<.05) even when excluding other pruritic skin conditions and systemic diseases that can trigger itching. In addition, our logistic regression analyses revealed independent associations between fibromyalgia and pruritus, prurigo nodularis, and LSC.

According to Twycross et al,46 there are 4 clinical categories of itch, which may coexist7: pruritoceptive (originating in the skin), neuropathic (originating in pathology located along the afferent pathway), neurogenic (central origin but lacks a neural pathology), and psychogenic.47 Skin biopsy findings in patients with fibromyalgia include increased mast cell counts11 and degranulation,48 increased expression of δ and κ opioid receptors,32 vasoconstriction within tender points,49 and elevated IL-1β, IL-6, or tumor necrosis factor α by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction.12 A case recently was presented by Görg et al50 involving a female patient with fibromyalgia who had been experiencing chronic pruritus, which the authors attributed to small-fiber neuropathy based on evidence from a skin biopsy indicating a reduced number of intraepidermal nerves and the fact that the itching originated around tender points. Altogether, the observed alterations may work together to make patients with fibromyalgia more susceptible to various skin-related comorbidities in general, especially those related to pruritus. Eventually, it might be the case that several itch categories and related pathomechanisms are involved in the pruritus phenotype of patients with fibromyalgia.

Age-related alterations in nerve fibers, lower immune function, xerosis, polypharmacy, and increased frequency of systemic diseases with age are just a few of the factors that may predispose older individuals to pruritus.51,52 Indeed, our logistic regression model showed that age was significantly and independently associated with pruritus (P<.001), neurotic excoriations (P=.046), and LSC (P=.006). Female sex also was significantly linked with pruritus (P=.039). Intriguingly, high socioeconomic status was significantly associated with the diagnosis of pruritus (P=.002), possibly due to easier access to medical care.

There is a considerable overlap between the therapeutic approaches used in pruritus, pruritus-related skin disorders, and fibromyalgia. Antidepressants, anxiolytics, analgesics, and antiepileptics have been used to address both conditions.45 The association between these conditions advocates for a multidisciplinary approach in patients with fibromyalgia and potentially supports the rationale for unified therapeutics for both conditions.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate an association between fibromyalgia and pruritus as well as associated pruritic skin disorders. Given the convoluted and largely undiscovered mechanisms underlying fibromyalgia, managing patients with this condition may present substantial challenges.53 The data presented here support the implementation of a multidisciplinary treatment approach for patients with fibromyalgia. This approach should focus on managing fibromyalgia pain as well as addressing its concurrent skin-related conditions. It is advisable to consider treatments such as antiepileptics (eg, pregabalin, gabapentin) that specifically target neuropathic disorders in affected patients. These treatments may hold promise for alleviating fibromyalgia-related pain54 and mitigating its related cutaneous comorbidities, especially pruritus.

- Stander S, Weisshaar E, Mettang T, et al. Clinical classification of itch: a position paper of the International Forum for the Study of Itch. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007; 87:291-294.

- Yosipovitch G, Bernhard JD. Clinical practice. chronic pruritus. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1625-1634.

- Song J, Xian D, Yang L, et al. Pruritus: progress toward pathogenesis and treatment. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:9625936.

- Potenzieri C, Undem BJ. Basic mechanisms of itch. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42:8-19.

- McMahon SB, Koltzenburg M. Itching for an explanation. Trends Neurosci. 1992;15:497-501.

- Drzezga A, Darsow U, Treede RD, et al. Central activation by histamine-induced itch: analogies to pain processing: a correlational analysis of O-15 H2O positron emission tomography studies. Pain. 2001; 92:295-305.

- Yosipovitch G, Greaves MW, Schmelz M. Itch. Lancet. 2003;361:690-694.

- Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008; 58:15-25.

- Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008; 58:26-35.

- Sarzi-Puttini P, Giorgi V, Marotto D, et al. Fibromyalgia: an update on clinical characteristics, aetiopathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020;16:645-660.

- Blanco I, Beritze N, Arguelles M, et al. Abnormal overexpression of mastocytes in skin biopsies of fibromyalgia patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29:1403-1412.

- Salemi S, Rethage J, Wollina U, et al. Detection of interleukin 1beta (IL-1beta), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in skin of patients with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:146-150.

- Sprott H, Muller A, Heine H. Collagen cross-links in fibromyalgia syndrome. Z Rheumatol. 1998;57(suppl 2):52-55.

- Morf S, Amann-Vesti B, Forster A, et al. Microcirculation abnormalities in patients with fibromyalgia—measured by capillary microscopy and laser fluxmetry. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R209-R216.

- Laniosz V, Wetter DA, Godar DA. Dermatologic manifestations of fibromyalgia. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33:1009-1013.

- Dogramaci AC, Yalcinkaya EY. Skin problems in fibromyalgia. Nobel Med. 2009;5:50-52.

- Grayston R, Czanner G, Elhadd K, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of small fiber pathology in fibromyalgia: implications for a new paradigm in fibromyalgia etiopathogenesis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;48:933-940.

- Uceyler N, Zeller D, Kahn AK, et al. Small fibre pathology in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Brain. 2013;136:1857-1867.

- Devigili G, Tugnoli V, Penza P, et al. The diagnostic criteria for small fibre neuropathy: from symptoms to neuropathology. Brain. 2008; 131:1912- 1925.

- Reed C, Birnbaum HG, Ivanova JI, et al. Real-world role of tricyclic antidepressants in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Pain Pract. 2012; 12:533-540.

- Moret C, Briley M. Antidepressants in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2006;2:537-548.

- Arnold LM, Keck PE Jr, Welge JA. Antidepressant treatment of fibromyalgia. a meta-analysis and review. Psychosomatics. 2000;41:104-113.

- Moore A, Wiffen P, Kalso E. Antiepileptic drugs for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia. JAMA. 2014;312:182-183.

- Shevchenko A, Valdes-Rodriguez R, Yosipovitch G. Causes, pathophysiology, and treatment of pruritus in the mature patient. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:140-151.

- Scheinfeld N. The role of gabapentin in treating diseases with cutaneous manifestations and pain. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:491-495.

- Points Location Intelligence. Accessed July 30, 2024. https://points.co.il/en/points-location-intelligence/

- Yunus MB. The role of gender in fibromyalgia syndrome. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2001;3:128-134.

- Cakir T, Evcik D, Dundar U, et al. Evaluation of sympathetic skin response and f wave in fibromyalgia syndrome patients. Turk J Rheumatol. 2011;26:38-43.

- Ozkan O, Yildiz M, Koklukaya E. The correlation of laboratory tests and sympathetic skin response parameters by using artificial neural networks in fibromyalgia patients. J Med Syst. 2012;36:1841-1848.

- Ozkan O, Yildiz M, Arslan E, et al. A study on the effects of sympathetic skin response parameters in diagnosis of fibromyalgia using artificial neural networks. J Med Syst. 2016;40:54.

- Ulas UH, Unlu E, Hamamcioglu K, et al. Dysautonomia in fibromyalgia syndrome: sympathetic skin responses and RR interval analysis. Rheumatol Int. 2006;26:383-387.

- Salemi S, Aeschlimann A, Wollina U, et al. Up-regulation of delta-opioid receptors and kappa-opioid receptors in the skin of fibromyalgia patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2464-2466.

- Elshazzly M, Lopez MJ, Reddy V, et al. Central nervous system. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Hu MS, Borrelli MR, Hong WX, et al. Embryonic skin development and repair. Organogenesis. 2018;14:46-63.

- Davidson S, Zhang X, Yoon CH, et al. The itch-producing agents histamine and cowhage activate separate populations of primate spinothalamic tract neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10007-10014.

- Sikand P, Shimada SG, Green BG, et al. Similar itch and nociceptive sensations evoked by punctate cutaneous application of capsaicin, histamine and cowhage. Pain. 2009;144:66-75.

- Davidson S, Giesler GJ. The multiple pathways for itch and their interactions with pain. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:550-558.

- Dhand A, Aminoff MJ. The neurology of itch. Brain. 2014;137:313-322.

- Binder A, Koroschetz J, Baron R. Disease mechanisms in neuropathic itch. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2008;4:329-337.

- Fjellner B, Arnetz BB. Psychological predictors of pruritus during mental stress. Acta Derm Venereol. 1985;65:504-508.

- Papoiu AD, Wang H, Coghill RC, et al. Contagious itch in humans: a study of visual ‘transmission’ of itch in atopic dermatitis and healthy subjects. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:1299-1303.

- Stumpf A, Schneider G, Stander S. Psychosomatic and psychiatric disorders and psychologic factors in pruritus. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:704-708.

- Herman JP, McKlveen JM, Ghosal S, et al. Regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical stress response. Compr Physiol. 2016;6:603-621.

- Brown ED, Micozzi MS, Craft NE, et al. Plasma carotenoids in normal men after a single ingestion of vegetables or purified beta-carotene. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;49:1258-1265.

- Tey HL, Wallengren J, Yosipovitch G. Psychosomatic factors in pruritus. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:31-40.

- Twycross R, Greaves MW, Handwerker H, et al. Itch: scratching more than the surface. QJM. 2003;96:7-26.

- Bernhard JD. Itch and pruritus: what are they, and how should itches be classified? Dermatol Ther. 2005;18:288-291.

- Enestrom S, Bengtsson A, Frodin T. Dermal IgG deposits and increase of mast cells in patients with fibromyalgia—relevant findings or epiphenomena? Scand J Rheumatol. 1997;26:308-313.

- Jeschonneck M, Grohmann G, Hein G, et al. Abnormal microcirculation and temperature in skin above tender points in patients with fibromyalgia. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000;39:917-921.

- Görg M, Zeidler C, Pereira MP, et al. Generalized chronic pruritus with fibromyalgia. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2021;19:909-911.

- Garibyan L, Chiou AS, Elmariah SB. Advanced aging skin and itch: addressing an unmet need. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:92-103.

- Cohen KR, Frank J, Salbu RL, et al. Pruritus in the elderly: clinical approaches to the improvement of quality of life. P T. 2012;37:227-239.

- Tzadok R, Ablin JN. Current and emerging pharmacotherapy for fibromyalgia. Pain Res Manag. 2020; 2020:6541798.

- Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Moore RA, et al. Antiepileptic drugs for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia—an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013:CD010567.

- Stander S, Weisshaar E, Mettang T, et al. Clinical classification of itch: a position paper of the International Forum for the Study of Itch. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007; 87:291-294.

- Yosipovitch G, Bernhard JD. Clinical practice. chronic pruritus. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1625-1634.

- Song J, Xian D, Yang L, et al. Pruritus: progress toward pathogenesis and treatment. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:9625936.

- Potenzieri C, Undem BJ. Basic mechanisms of itch. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42:8-19.

- McMahon SB, Koltzenburg M. Itching for an explanation. Trends Neurosci. 1992;15:497-501.

- Drzezga A, Darsow U, Treede RD, et al. Central activation by histamine-induced itch: analogies to pain processing: a correlational analysis of O-15 H2O positron emission tomography studies. Pain. 2001; 92:295-305.

- Yosipovitch G, Greaves MW, Schmelz M. Itch. Lancet. 2003;361:690-694.

- Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008; 58:15-25.

- Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008; 58:26-35.

- Sarzi-Puttini P, Giorgi V, Marotto D, et al. Fibromyalgia: an update on clinical characteristics, aetiopathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020;16:645-660.

- Blanco I, Beritze N, Arguelles M, et al. Abnormal overexpression of mastocytes in skin biopsies of fibromyalgia patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29:1403-1412.

- Salemi S, Rethage J, Wollina U, et al. Detection of interleukin 1beta (IL-1beta), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in skin of patients with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:146-150.

- Sprott H, Muller A, Heine H. Collagen cross-links in fibromyalgia syndrome. Z Rheumatol. 1998;57(suppl 2):52-55.

- Morf S, Amann-Vesti B, Forster A, et al. Microcirculation abnormalities in patients with fibromyalgia—measured by capillary microscopy and laser fluxmetry. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R209-R216.

- Laniosz V, Wetter DA, Godar DA. Dermatologic manifestations of fibromyalgia. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33:1009-1013.

- Dogramaci AC, Yalcinkaya EY. Skin problems in fibromyalgia. Nobel Med. 2009;5:50-52.

- Grayston R, Czanner G, Elhadd K, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of small fiber pathology in fibromyalgia: implications for a new paradigm in fibromyalgia etiopathogenesis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;48:933-940.

- Uceyler N, Zeller D, Kahn AK, et al. Small fibre pathology in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Brain. 2013;136:1857-1867.

- Devigili G, Tugnoli V, Penza P, et al. The diagnostic criteria for small fibre neuropathy: from symptoms to neuropathology. Brain. 2008; 131:1912- 1925.

- Reed C, Birnbaum HG, Ivanova JI, et al. Real-world role of tricyclic antidepressants in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Pain Pract. 2012; 12:533-540.

- Moret C, Briley M. Antidepressants in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2006;2:537-548.

- Arnold LM, Keck PE Jr, Welge JA. Antidepressant treatment of fibromyalgia. a meta-analysis and review. Psychosomatics. 2000;41:104-113.

- Moore A, Wiffen P, Kalso E. Antiepileptic drugs for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia. JAMA. 2014;312:182-183.

- Shevchenko A, Valdes-Rodriguez R, Yosipovitch G. Causes, pathophysiology, and treatment of pruritus in the mature patient. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:140-151.

- Scheinfeld N. The role of gabapentin in treating diseases with cutaneous manifestations and pain. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:491-495.

- Points Location Intelligence. Accessed July 30, 2024. https://points.co.il/en/points-location-intelligence/

- Yunus MB. The role of gender in fibromyalgia syndrome. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2001;3:128-134.

- Cakir T, Evcik D, Dundar U, et al. Evaluation of sympathetic skin response and f wave in fibromyalgia syndrome patients. Turk J Rheumatol. 2011;26:38-43.

- Ozkan O, Yildiz M, Koklukaya E. The correlation of laboratory tests and sympathetic skin response parameters by using artificial neural networks in fibromyalgia patients. J Med Syst. 2012;36:1841-1848.

- Ozkan O, Yildiz M, Arslan E, et al. A study on the effects of sympathetic skin response parameters in diagnosis of fibromyalgia using artificial neural networks. J Med Syst. 2016;40:54.

- Ulas UH, Unlu E, Hamamcioglu K, et al. Dysautonomia in fibromyalgia syndrome: sympathetic skin responses and RR interval analysis. Rheumatol Int. 2006;26:383-387.

- Salemi S, Aeschlimann A, Wollina U, et al. Up-regulation of delta-opioid receptors and kappa-opioid receptors in the skin of fibromyalgia patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2464-2466.

- Elshazzly M, Lopez MJ, Reddy V, et al. Central nervous system. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Hu MS, Borrelli MR, Hong WX, et al. Embryonic skin development and repair. Organogenesis. 2018;14:46-63.

- Davidson S, Zhang X, Yoon CH, et al. The itch-producing agents histamine and cowhage activate separate populations of primate spinothalamic tract neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10007-10014.

- Sikand P, Shimada SG, Green BG, et al. Similar itch and nociceptive sensations evoked by punctate cutaneous application of capsaicin, histamine and cowhage. Pain. 2009;144:66-75.

- Davidson S, Giesler GJ. The multiple pathways for itch and their interactions with pain. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:550-558.

- Dhand A, Aminoff MJ. The neurology of itch. Brain. 2014;137:313-322.

- Binder A, Koroschetz J, Baron R. Disease mechanisms in neuropathic itch. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2008;4:329-337.

- Fjellner B, Arnetz BB. Psychological predictors of pruritus during mental stress. Acta Derm Venereol. 1985;65:504-508.

- Papoiu AD, Wang H, Coghill RC, et al. Contagious itch in humans: a study of visual ‘transmission’ of itch in atopic dermatitis and healthy subjects. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:1299-1303.

- Stumpf A, Schneider G, Stander S. Psychosomatic and psychiatric disorders and psychologic factors in pruritus. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:704-708.

- Herman JP, McKlveen JM, Ghosal S, et al. Regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical stress response. Compr Physiol. 2016;6:603-621.

- Brown ED, Micozzi MS, Craft NE, et al. Plasma carotenoids in normal men after a single ingestion of vegetables or purified beta-carotene. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;49:1258-1265.

- Tey HL, Wallengren J, Yosipovitch G. Psychosomatic factors in pruritus. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:31-40.

- Twycross R, Greaves MW, Handwerker H, et al. Itch: scratching more than the surface. QJM. 2003;96:7-26.

- Bernhard JD. Itch and pruritus: what are they, and how should itches be classified? Dermatol Ther. 2005;18:288-291.

- Enestrom S, Bengtsson A, Frodin T. Dermal IgG deposits and increase of mast cells in patients with fibromyalgia—relevant findings or epiphenomena? Scand J Rheumatol. 1997;26:308-313.

- Jeschonneck M, Grohmann G, Hein G, et al. Abnormal microcirculation and temperature in skin above tender points in patients with fibromyalgia. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000;39:917-921.

- Görg M, Zeidler C, Pereira MP, et al. Generalized chronic pruritus with fibromyalgia. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2021;19:909-911.

- Garibyan L, Chiou AS, Elmariah SB. Advanced aging skin and itch: addressing an unmet need. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:92-103.

- Cohen KR, Frank J, Salbu RL, et al. Pruritus in the elderly: clinical approaches to the improvement of quality of life. P T. 2012;37:227-239.

- Tzadok R, Ablin JN. Current and emerging pharmacotherapy for fibromyalgia. Pain Res Manag. 2020; 2020:6541798.

- Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Moore RA, et al. Antiepileptic drugs for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia—an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013:CD010567.

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should be aware of the connection between fibromyalgia, pruritus, and related conditions to improve patient care.

- The association between fibromyalgia and pruritus underscores the importance of employing multidisciplinary treatment strategies for managing these conditions.

Distinguishing Generalized Bullous Fixed Drug Eruption From SJS/TEN: A Retrospective Study on Clinical and Demographic Features

To the Editor:

Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption (GBFDE) is a rare subtype of fixed drug eruption (FDE) that manifests as widespread blisters and erosions following exposure to a causative drug.1 Diagnostic criteria include involvement of at least 3 to 6 anatomic sites—head and neck, anterior trunk, posterior trunk, upper extremities, lower extremities, or genitalia—and more than 10% of the body surface area. It can be challenging to differentiate GBFDE from severe drug rashes such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN) due to extensive body surface area involvement of blisters and erosions. Specific features distinguishing GBFDE from SJS/TEN include primary lesions consisting of larger erythematous to dusky, circular plaques that progress to bullae and coalesce into widespread erosions; history of FDE; lack of severe mucosal involvement; and better overall prognosis.2 Treatment typically involves discontinuation of the culprit medication and supportive care; evidence for systemic therapies is not well established.

Our study aimed to characterize the clinical and demographic features of GBFDE in our institution to highlight potential key differences between this diagnosis and SJS/TEN. An electronic medical record search was performed to identify patients who were clinically diagnosed with GBFDE at New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center (New York, New York) in both outpatient and inpatient settings from January 2015 to December 2022. This retrospective study was approved by the Weill Cornell Medicine institutional review board (#22-05024777).

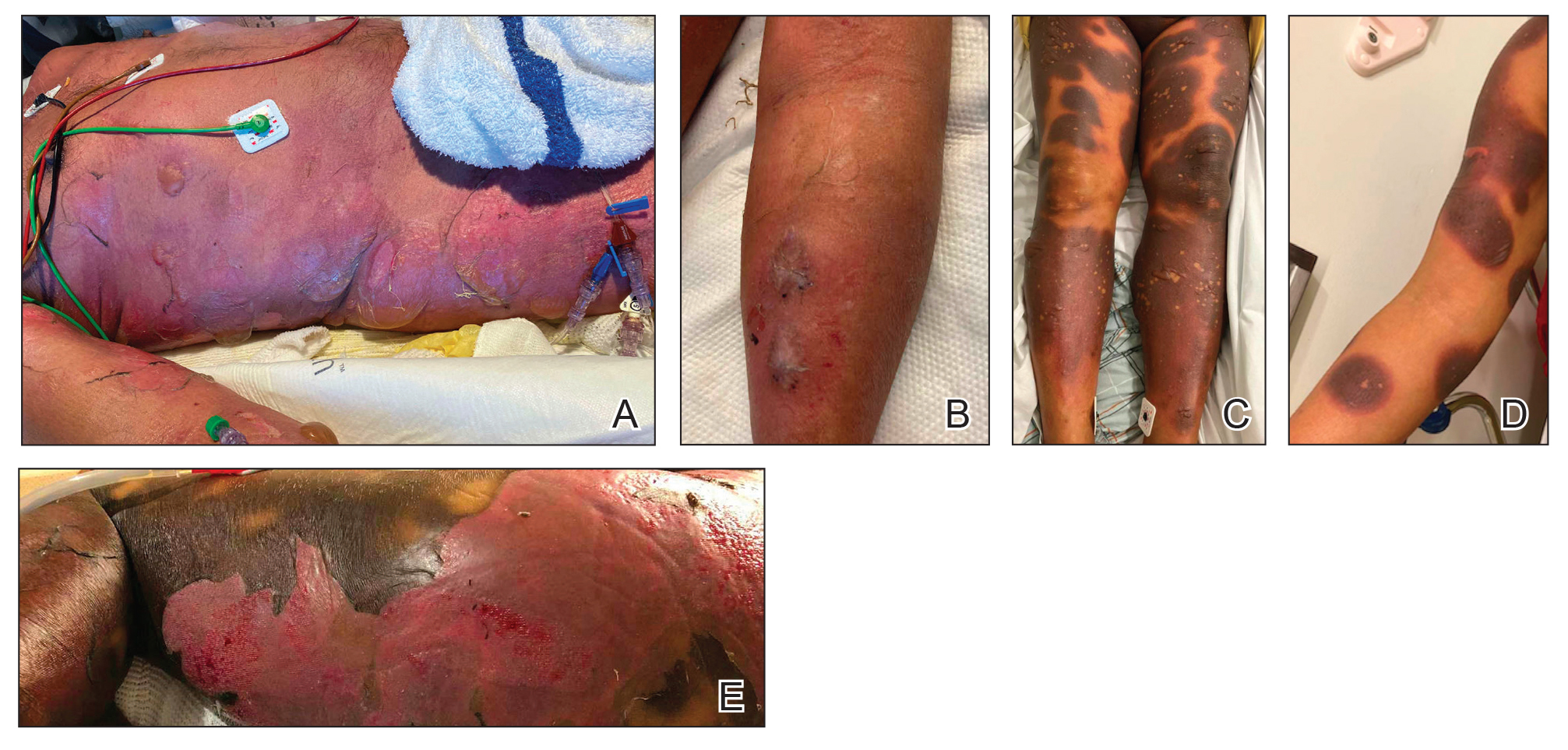

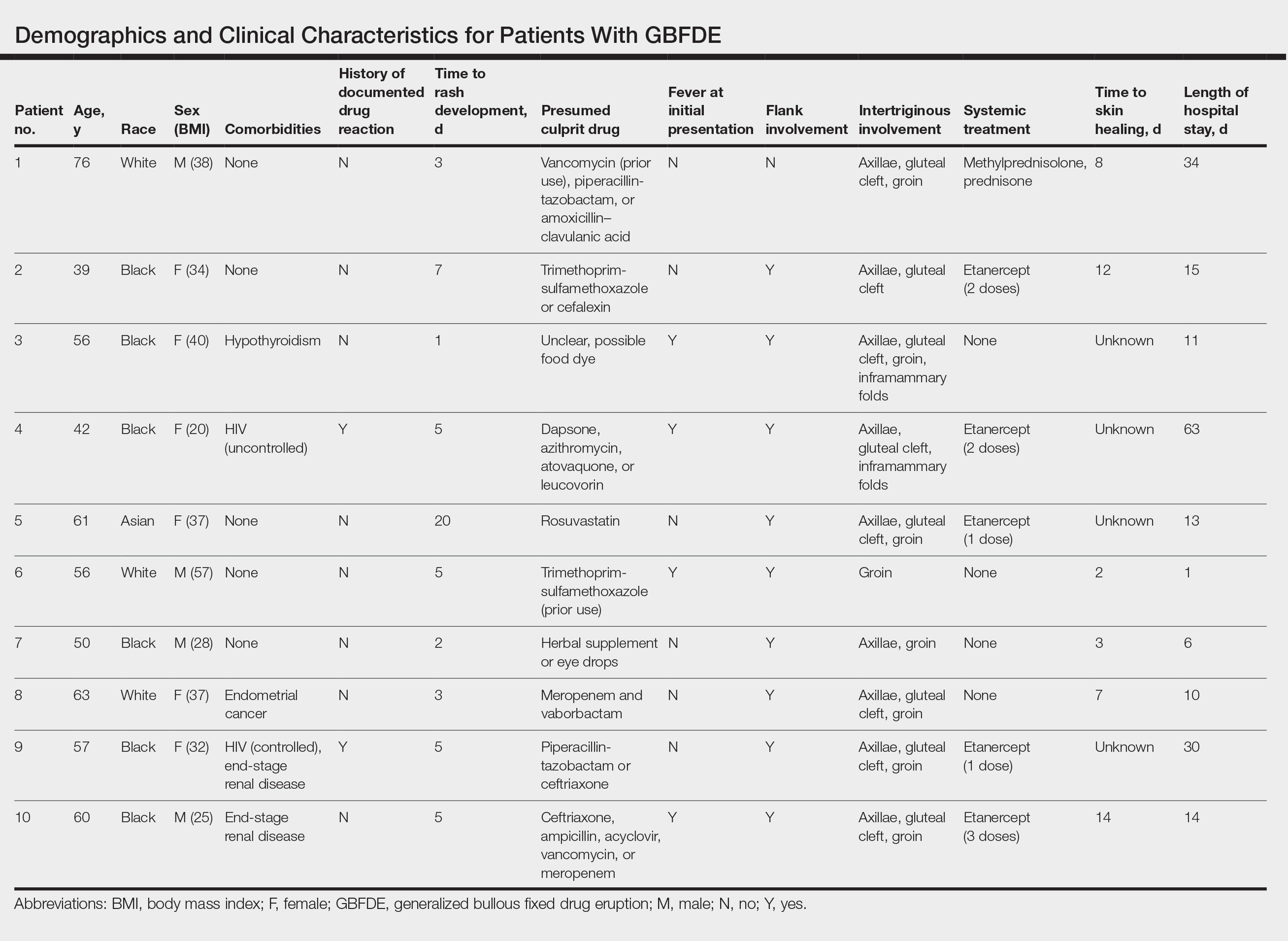

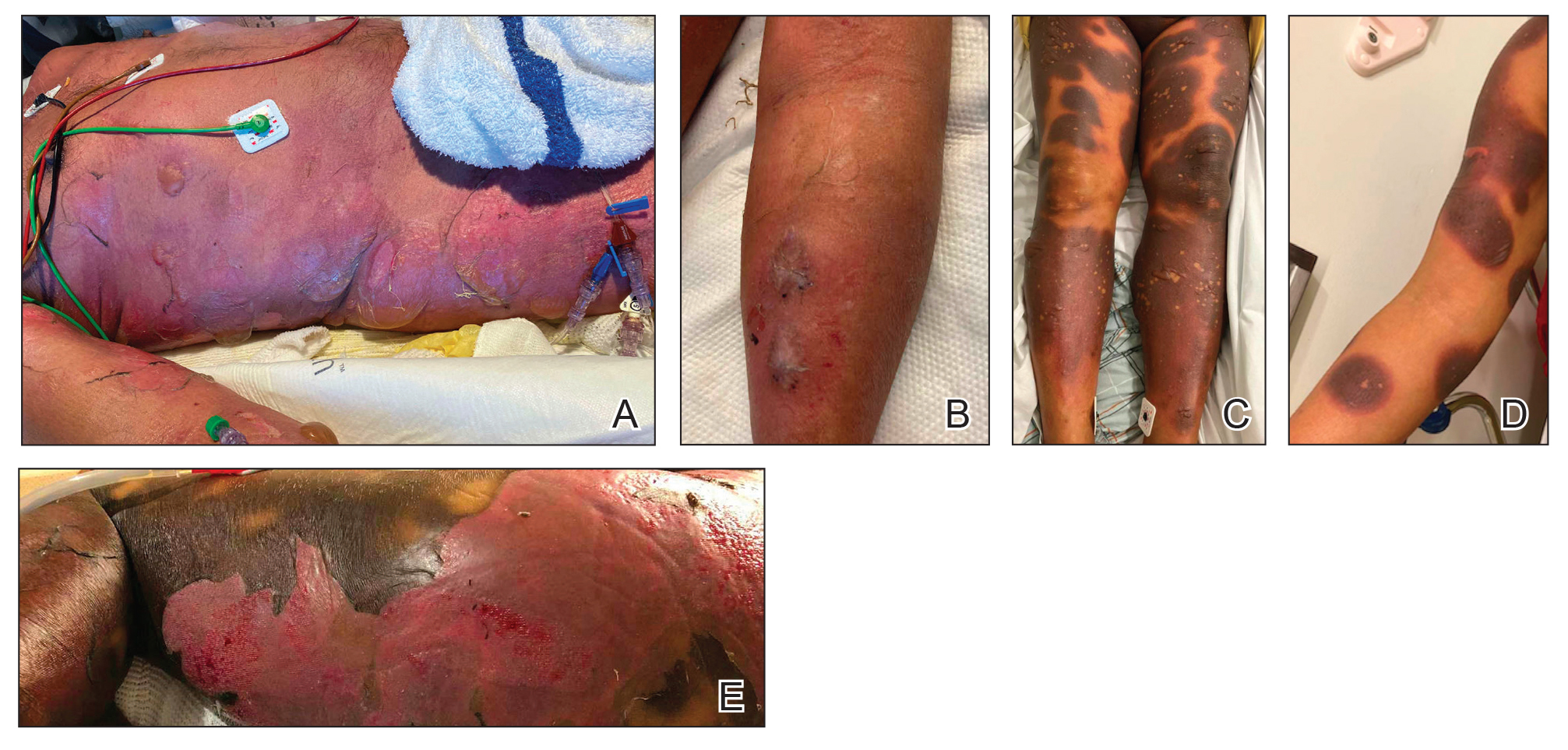

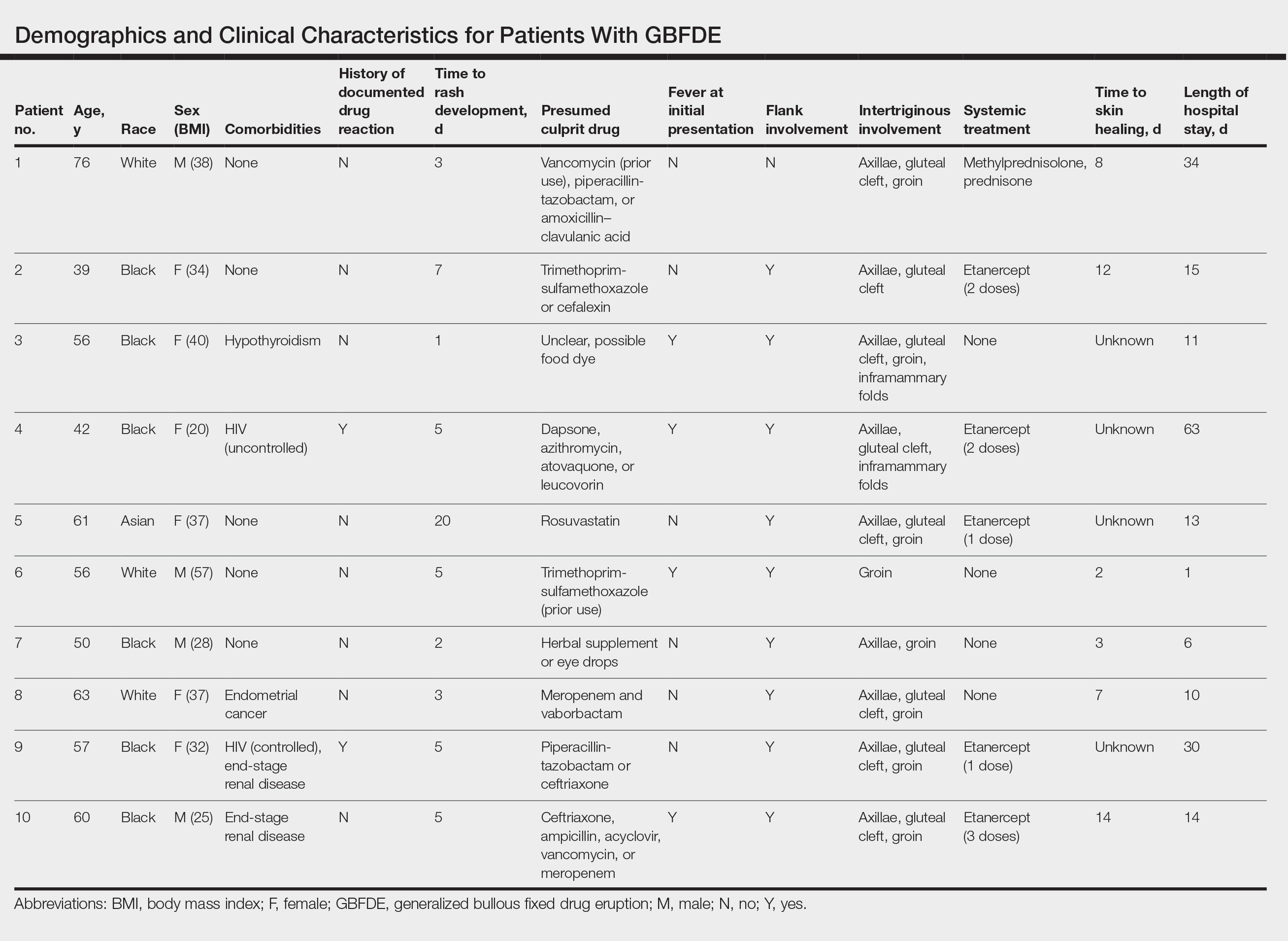

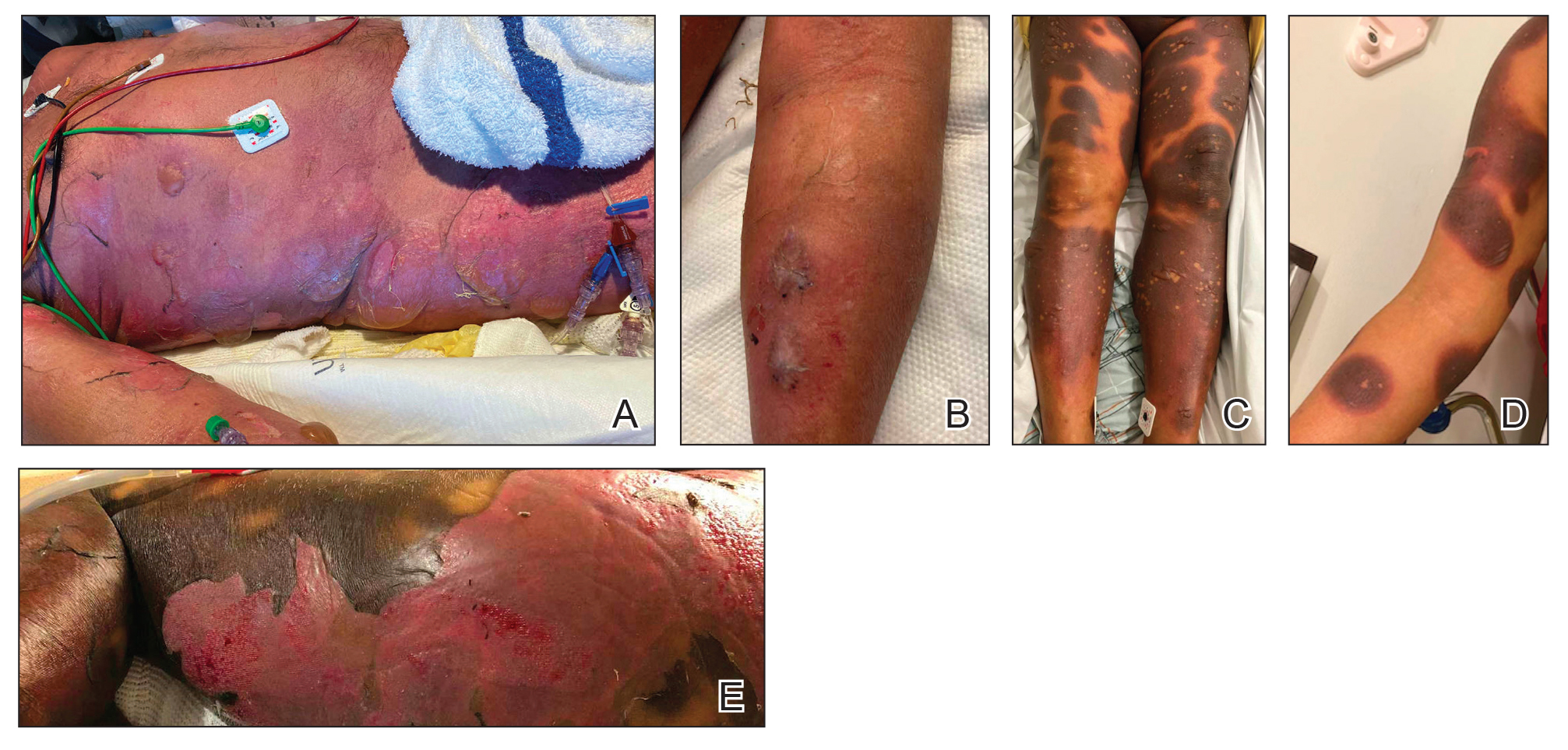

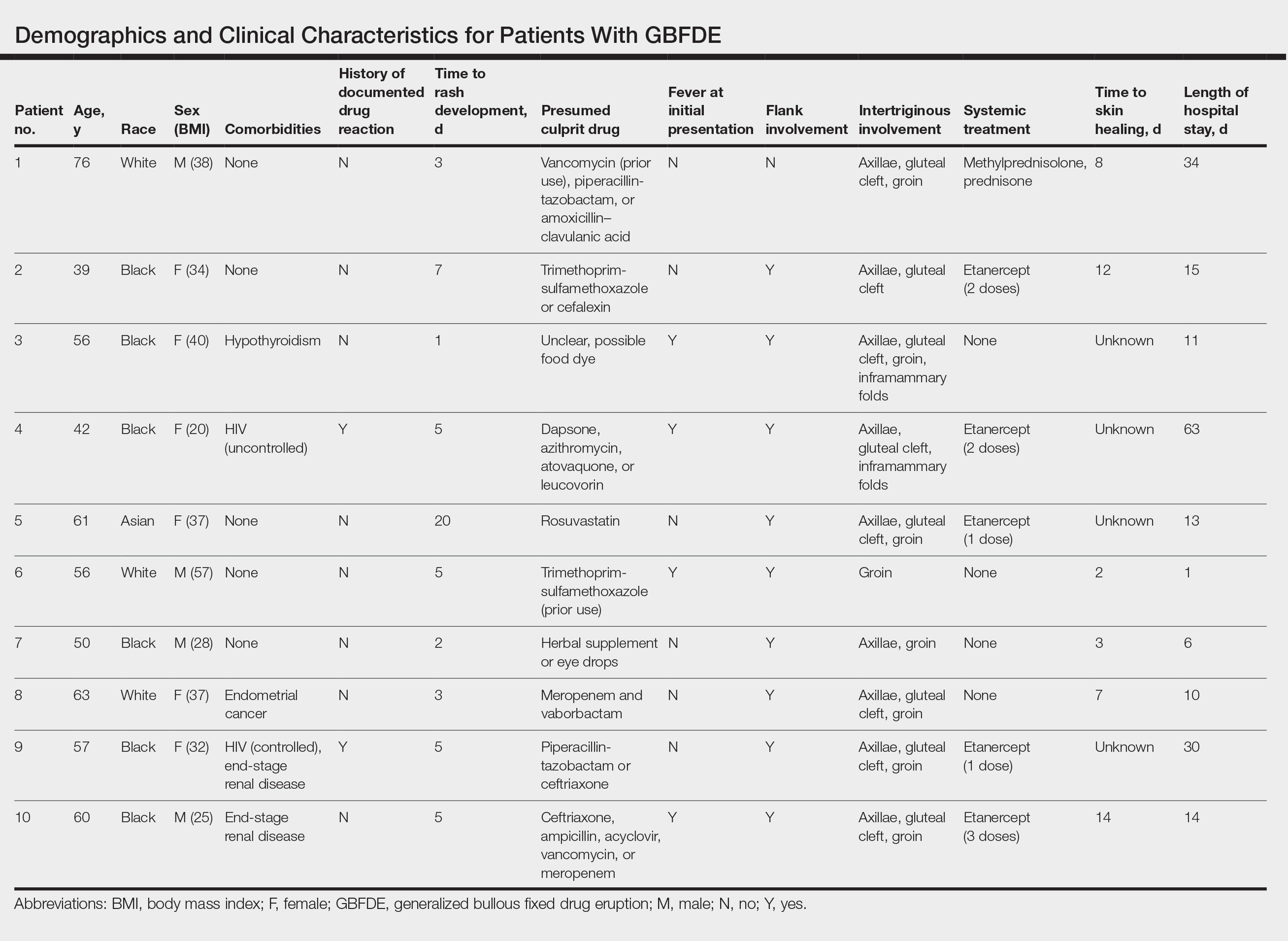

Ten patients were identified and included in the analysis (eTable). The mean age of the patients was 56 years (range, 39–76 years). Seven (70%) patients had skin of color (non-White) and 6 (60%) were female. The mean body mass index was 35 (range, 20–57), and 7 (70%) patients were clinically obese (body mass index >30). Only 2 (20%) patients had a history of a documented drug eruption (hives and erythema multiforme), and no patients had a history of FDE. Erythematous dusky patches followed by rapid development of blisters were noted within 3 days of drug initiation in 40% (4/10) and within 5 days in 80% (8/10) of patients. Antibiotics were identified as likely inciting agents in 8 (80%) patients. Biopsies were obtained in 3 (30%) patients and all 3 demonstrated cytotoxic CD8+ interface dermatitis with marked epithelial necrosis, neutrophilia, eosinophilia, and melanophage accumulation. Fever was present at initial presentation in only 4 (40%) patients, and only 1 (10%) patient had oral mucosal involvement. All 10 patients had intertriginous involvement (axillae, 90% [9/10]; gluteal cleft, 80% [8/10]; groin, 80% [8/10]; inframammary folds, 20% [2/10]), and there was considerable flank involvement in 9 (90%) patients. All 10 patients had initial erythematous to dusky, circular patches on the trunk and proximal extremities that then denuded most dramatically in the intertriginous areas (Figure). Six (60%) patients received systemic therapy, including 5 patients treated with a single dose of etanercept 50 mg. In patients with continued progression, 1 or 2 additional doses of etanercept 50 mg were administered at 48- to 72-hour intervals until blistering halted. Treatment with etanercept resulted in clinical improvement in all 5 patients, and there were no identifiable adverse events. The mean hospital stay was 19.7 days (range, 1–63 days).

This study highlights notable demographic and clinical features of GBFDE that have not been widely described in the literature. Large erythematous and dusky patches with broad zones of blistering with particular localization to the neck, intertriginous areas, and flanks typically are not described in SJS/TEN and may be helpful in distinguishing these conditions from GBFDE. Mild or complete lack of mucosal and facial involvement as well as more rapid time from drug initiation to rash (as rapid as 1 day) were key factors that aided in distinguishing GBFDE from SJS/TEN in our patients. Although a history of FDE is considered a key characteristic in the diagnosis of GBFDE, none of our patients had a known history of FDE, suggesting GBFDE may be the initial manifestation of FDE in some patients. Histopathology showed similar findings consistent with FDE in the 3 patients in whom a biopsy was performed. The remaining patients were diagnosed clinically based on the presence of distinctive, perfectly circular, dusky plaques present at the periphery of larger denuded areas, which are characteristic of GBFDE. Lower levels of serum granulysin3 have been shown to help distinguish GBFDE from SJS/TEN, but this test is not readily available with time-sensitive results at most institutions, and exact diagnostic ranges for GBFDE vs SJS/TEN are not yet known.

Our study was limited by a small number of patients at a single institution. Another limitation was the retrospective design.

Interestingly, a high proportion of our patients were non-White and clinically obese, which are factors that should be considered for future research. Sixty percent (6/10) of the patients in our study were Black, which is a notable difference from our hospital’s general admission demographics with Black individuals constituting 12% of patients.4 Our study also highlighted the utility of etanercept, which has reported mortality benefits and decreased time to re-epithelialization in other severe blistering cutaneous drug reactions including SJS/TEN,5 as a potential therapeutic option in GBFDE.

It is imperative that clinicians recognize the differences between GBFDE and SJS/TEN, as correct diagnosis is crucial for identifying the most likely causative drug as well as providing accurate prognostic information and may have future therapeutic implications as we further understand the immunologic profiles of these severe blistering drug reactions.

- Patel S, John AM, Handler MZ, et al. Fixed drug eruptions: an update, emphasizing the potentially lethal generalized bullous fixed drug eruption. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:393-399. doi:10.1007/s40257-020-00505-3

- Anderson HJ, Lee JB. A review of fixed drug eruption with a special focus on generalized bullous fixed drug eruption. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57:925. doi:10.3390/medicina57090925

- Cho YT, Lin JW, Chen YC, et al. Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption is distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis by immunohistopathological features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:539-548. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.015

- Tran T, Shapiro A. New York-Presbyterian 2022 Health Equity Report. New York-Presbyterian; 2023. Accessed July 22, 2024. https://nyp.widen.net/s/jqfbrvrf9p/dalio-center-2022-health-equity-report

- Dreyer SD, Torres J, Stoddard M, et al. Efficacy of etanercept in the treatment of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Cutis. 2021;107:E22-E28. doi:10.12788/cutis.0288

To the Editor:

Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption (GBFDE) is a rare subtype of fixed drug eruption (FDE) that manifests as widespread blisters and erosions following exposure to a causative drug.1 Diagnostic criteria include involvement of at least 3 to 6 anatomic sites—head and neck, anterior trunk, posterior trunk, upper extremities, lower extremities, or genitalia—and more than 10% of the body surface area. It can be challenging to differentiate GBFDE from severe drug rashes such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN) due to extensive body surface area involvement of blisters and erosions. Specific features distinguishing GBFDE from SJS/TEN include primary lesions consisting of larger erythematous to dusky, circular plaques that progress to bullae and coalesce into widespread erosions; history of FDE; lack of severe mucosal involvement; and better overall prognosis.2 Treatment typically involves discontinuation of the culprit medication and supportive care; evidence for systemic therapies is not well established.

Our study aimed to characterize the clinical and demographic features of GBFDE in our institution to highlight potential key differences between this diagnosis and SJS/TEN. An electronic medical record search was performed to identify patients who were clinically diagnosed with GBFDE at New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center (New York, New York) in both outpatient and inpatient settings from January 2015 to December 2022. This retrospective study was approved by the Weill Cornell Medicine institutional review board (#22-05024777).