User login

SGLT2 inhibitors: No benefit or harm in hospitalized COVID-19

A new meta-analysis has shown that SGLT2 inhibitors do not lead to lower 28-day all-cause mortality, compared with usual care or placebo, in patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

However, no major safety issues were identified with the use of SGLT2 inhibitors in these acutely ill patients, the researchers report.

“While these findings do not support the use of SGLT2-inhibitors as standard of care for patients hospitalized with COVID-19, I think the most important take home message here is that the use of these medications appears to be safe even in really acutely ill hospitalized patients,” lead investigator of the meta-analysis, Mikhail Kosiborod, MD, Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute, Kansas City, Mo., concluded.

He said this was important because the list of indications for SGLT2 inhibitors is rapidly growing.

“These medications are being used in more and more patients. And we know that when we discontinue medications in the hospital they frequently don’t get restarted, which can lead to real risks if SGLT2 inhibitors are stopped in patients with heart failure, chronic kidney disease, or diabetes. So, ,” he added.

The new meta-analysis was presented at the recent annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, held in Amsterdam.

Discussant of the presentation at the ESC Hotline session, Muthiah Vaduganathan, MD, MPH, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, agreed with Dr. Kosiborod’s interpretation.

“Until today we have had very limited information on the safety of SGLT2-inhibitors in acute illness, as the pivotal trials which established the use of these drugs in diabetes and chronic kidney disease largely excluded patients who were hospitalized,” Dr. Vaduganathan said.

“While the overall results of this meta-analysis are neutral and SGLT2 inhibitors will not be added as drugs to be used in the primary care of patients with COVID-19, it certainly sends a strong message of safety in acutely ill patients,” he added.

Dr. Vaduganathan explained that from the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, there was great interest in repurposing established therapies for alternative indications for their use in the management of COVID-19.

“Conditions that strongly predispose to adverse COVID outcomes strongly overlap with established indications for SGLT2-inhibitors. So many wondered whether these drugs may be an ideal treatment candidate for the management of COVID-19. However, there have been many safety concerns about the use of SGLT2-inhibitors in this acute setting, with worries that they may induce hemodynamic changes such an excessive lowering of blood pressure, or metabolic changes such as ketoacidosis in acutely ill patients,” he noted.

The initial DARE-19 study investigating SGLT2-inhibitors in COVID-19, with 1,250 participants, found a 20% reduction in the primary outcome of organ dysfunction or death, but this did not reach statistical significance, and no safety issues were seen. This “intriguing” result led to two further larger trials – the ACTIV-4a and RECOVERY trials, Dr. Vaduganathan reported.

“Those early signals of benefit seen in DARE-19 were largely not substantiated in the ACTIV-4A and RECOVERY trials, or in this new meta-analysis, and now we have this much larger body of evidence and more stable estimates about the efficacy of these drugs in acutely ill COVID-19 patients,” he said.

“But the story that we will all take forward is one of safety. This set of trials was arguably conducted in some of the sickest patients we’ve seen who have been exposed to SGLT2-inhibitors, and they strongly affirm that these agents can be safely continued in the setting of acute illness, with very low rates of ketoacidosis and kidney injury, and there was no prolongation of hospital stay,” he commented.

In his presentation, Dr. Kosiborod explained that treatments targeting COVID-19 pathobiology such as dysregulated immune responses, endothelial damage, microvascular thrombosis, and inflammation have been shown to improve the key outcomes in this patient group.

SGLT2 inhibitors, which modulate similar pathobiology, provide cardiovascular protection and prevent the progression of kidney disease in patients at risk for these events, including those with type 2 diabetes, heart failure, and kidney disease, and may also lead to organ protection in a setting of acute illness such as COVID-19, he noted. However, the role of SGLT2 inhibitors in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 remains uncertain.

To address the need for more definitive efficacy data, the World Health Organization Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies (REACT) Working Group conducted a prospective meta-analysis using data from the three randomized controlled trials, DARE-19, RECOVERY, and ACTIV-4a, evaluating SGLT2 inhibitors in patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

Overall, these trials randomized 6,096 participants: 3,025 to SGLT2 inhibitors and 3,071 to usual care or placebo. The average age of participants ranged between 62 and 73 years across the trials, 39% were women, and 25% had type 2 diabetes.

By 28 days after randomization, all-cause mortality, the primary endpoint, had occurred in 11.6% of the SGLT2-inhibitor patients, compared with 12.4% of those randomized to usual care or placebo, giving an odds ratio of 0.93 (95% confidence interval, 0.79-1.08; P = .33) for SGLT2 inhibitors, with consistency across trials.

Data on in-hospital and 90-day all-cause mortality were only available for two out of three trials (DARE-19 and ACTIV-4a), but the results were similar to the primary endpoint showing nonsignificant trends toward a possible benefit in the SGLT2-inhibitor group.

The results were also similar for the secondary outcomes of progression to acute kidney injury or requirement for dialysis or death, and progression to invasive mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or death, both assessed at 28 days.

The primary safety outcome of ketoacidosis by 28 days was observed in seven and two patients allocated to SGLT2 inhibitors and usual care or placebo, respectively, and overall, the incidence of reported serious adverse events was balanced between treatment groups.

The RECOVERY trial was supported by grants to the University of Oxford from UK Research and Innovation, the National Institute for Health and Care Research, and Wellcome. The ACTIV-4a platform was sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. DARE-19 was an investigator-initiated collaborative trial supported by AstraZeneca. Dr. Kosiborod reported numerous conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new meta-analysis has shown that SGLT2 inhibitors do not lead to lower 28-day all-cause mortality, compared with usual care or placebo, in patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

However, no major safety issues were identified with the use of SGLT2 inhibitors in these acutely ill patients, the researchers report.

“While these findings do not support the use of SGLT2-inhibitors as standard of care for patients hospitalized with COVID-19, I think the most important take home message here is that the use of these medications appears to be safe even in really acutely ill hospitalized patients,” lead investigator of the meta-analysis, Mikhail Kosiborod, MD, Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute, Kansas City, Mo., concluded.

He said this was important because the list of indications for SGLT2 inhibitors is rapidly growing.

“These medications are being used in more and more patients. And we know that when we discontinue medications in the hospital they frequently don’t get restarted, which can lead to real risks if SGLT2 inhibitors are stopped in patients with heart failure, chronic kidney disease, or diabetes. So, ,” he added.

The new meta-analysis was presented at the recent annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, held in Amsterdam.

Discussant of the presentation at the ESC Hotline session, Muthiah Vaduganathan, MD, MPH, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, agreed with Dr. Kosiborod’s interpretation.

“Until today we have had very limited information on the safety of SGLT2-inhibitors in acute illness, as the pivotal trials which established the use of these drugs in diabetes and chronic kidney disease largely excluded patients who were hospitalized,” Dr. Vaduganathan said.

“While the overall results of this meta-analysis are neutral and SGLT2 inhibitors will not be added as drugs to be used in the primary care of patients with COVID-19, it certainly sends a strong message of safety in acutely ill patients,” he added.

Dr. Vaduganathan explained that from the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, there was great interest in repurposing established therapies for alternative indications for their use in the management of COVID-19.

“Conditions that strongly predispose to adverse COVID outcomes strongly overlap with established indications for SGLT2-inhibitors. So many wondered whether these drugs may be an ideal treatment candidate for the management of COVID-19. However, there have been many safety concerns about the use of SGLT2-inhibitors in this acute setting, with worries that they may induce hemodynamic changes such an excessive lowering of blood pressure, or metabolic changes such as ketoacidosis in acutely ill patients,” he noted.

The initial DARE-19 study investigating SGLT2-inhibitors in COVID-19, with 1,250 participants, found a 20% reduction in the primary outcome of organ dysfunction or death, but this did not reach statistical significance, and no safety issues were seen. This “intriguing” result led to two further larger trials – the ACTIV-4a and RECOVERY trials, Dr. Vaduganathan reported.

“Those early signals of benefit seen in DARE-19 were largely not substantiated in the ACTIV-4A and RECOVERY trials, or in this new meta-analysis, and now we have this much larger body of evidence and more stable estimates about the efficacy of these drugs in acutely ill COVID-19 patients,” he said.

“But the story that we will all take forward is one of safety. This set of trials was arguably conducted in some of the sickest patients we’ve seen who have been exposed to SGLT2-inhibitors, and they strongly affirm that these agents can be safely continued in the setting of acute illness, with very low rates of ketoacidosis and kidney injury, and there was no prolongation of hospital stay,” he commented.

In his presentation, Dr. Kosiborod explained that treatments targeting COVID-19 pathobiology such as dysregulated immune responses, endothelial damage, microvascular thrombosis, and inflammation have been shown to improve the key outcomes in this patient group.

SGLT2 inhibitors, which modulate similar pathobiology, provide cardiovascular protection and prevent the progression of kidney disease in patients at risk for these events, including those with type 2 diabetes, heart failure, and kidney disease, and may also lead to organ protection in a setting of acute illness such as COVID-19, he noted. However, the role of SGLT2 inhibitors in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 remains uncertain.

To address the need for more definitive efficacy data, the World Health Organization Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies (REACT) Working Group conducted a prospective meta-analysis using data from the three randomized controlled trials, DARE-19, RECOVERY, and ACTIV-4a, evaluating SGLT2 inhibitors in patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

Overall, these trials randomized 6,096 participants: 3,025 to SGLT2 inhibitors and 3,071 to usual care or placebo. The average age of participants ranged between 62 and 73 years across the trials, 39% were women, and 25% had type 2 diabetes.

By 28 days after randomization, all-cause mortality, the primary endpoint, had occurred in 11.6% of the SGLT2-inhibitor patients, compared with 12.4% of those randomized to usual care or placebo, giving an odds ratio of 0.93 (95% confidence interval, 0.79-1.08; P = .33) for SGLT2 inhibitors, with consistency across trials.

Data on in-hospital and 90-day all-cause mortality were only available for two out of three trials (DARE-19 and ACTIV-4a), but the results were similar to the primary endpoint showing nonsignificant trends toward a possible benefit in the SGLT2-inhibitor group.

The results were also similar for the secondary outcomes of progression to acute kidney injury or requirement for dialysis or death, and progression to invasive mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or death, both assessed at 28 days.

The primary safety outcome of ketoacidosis by 28 days was observed in seven and two patients allocated to SGLT2 inhibitors and usual care or placebo, respectively, and overall, the incidence of reported serious adverse events was balanced between treatment groups.

The RECOVERY trial was supported by grants to the University of Oxford from UK Research and Innovation, the National Institute for Health and Care Research, and Wellcome. The ACTIV-4a platform was sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. DARE-19 was an investigator-initiated collaborative trial supported by AstraZeneca. Dr. Kosiborod reported numerous conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new meta-analysis has shown that SGLT2 inhibitors do not lead to lower 28-day all-cause mortality, compared with usual care or placebo, in patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

However, no major safety issues were identified with the use of SGLT2 inhibitors in these acutely ill patients, the researchers report.

“While these findings do not support the use of SGLT2-inhibitors as standard of care for patients hospitalized with COVID-19, I think the most important take home message here is that the use of these medications appears to be safe even in really acutely ill hospitalized patients,” lead investigator of the meta-analysis, Mikhail Kosiborod, MD, Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute, Kansas City, Mo., concluded.

He said this was important because the list of indications for SGLT2 inhibitors is rapidly growing.

“These medications are being used in more and more patients. And we know that when we discontinue medications in the hospital they frequently don’t get restarted, which can lead to real risks if SGLT2 inhibitors are stopped in patients with heart failure, chronic kidney disease, or diabetes. So, ,” he added.

The new meta-analysis was presented at the recent annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, held in Amsterdam.

Discussant of the presentation at the ESC Hotline session, Muthiah Vaduganathan, MD, MPH, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, agreed with Dr. Kosiborod’s interpretation.

“Until today we have had very limited information on the safety of SGLT2-inhibitors in acute illness, as the pivotal trials which established the use of these drugs in diabetes and chronic kidney disease largely excluded patients who were hospitalized,” Dr. Vaduganathan said.

“While the overall results of this meta-analysis are neutral and SGLT2 inhibitors will not be added as drugs to be used in the primary care of patients with COVID-19, it certainly sends a strong message of safety in acutely ill patients,” he added.

Dr. Vaduganathan explained that from the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, there was great interest in repurposing established therapies for alternative indications for their use in the management of COVID-19.

“Conditions that strongly predispose to adverse COVID outcomes strongly overlap with established indications for SGLT2-inhibitors. So many wondered whether these drugs may be an ideal treatment candidate for the management of COVID-19. However, there have been many safety concerns about the use of SGLT2-inhibitors in this acute setting, with worries that they may induce hemodynamic changes such an excessive lowering of blood pressure, or metabolic changes such as ketoacidosis in acutely ill patients,” he noted.

The initial DARE-19 study investigating SGLT2-inhibitors in COVID-19, with 1,250 participants, found a 20% reduction in the primary outcome of organ dysfunction or death, but this did not reach statistical significance, and no safety issues were seen. This “intriguing” result led to two further larger trials – the ACTIV-4a and RECOVERY trials, Dr. Vaduganathan reported.

“Those early signals of benefit seen in DARE-19 were largely not substantiated in the ACTIV-4A and RECOVERY trials, or in this new meta-analysis, and now we have this much larger body of evidence and more stable estimates about the efficacy of these drugs in acutely ill COVID-19 patients,” he said.

“But the story that we will all take forward is one of safety. This set of trials was arguably conducted in some of the sickest patients we’ve seen who have been exposed to SGLT2-inhibitors, and they strongly affirm that these agents can be safely continued in the setting of acute illness, with very low rates of ketoacidosis and kidney injury, and there was no prolongation of hospital stay,” he commented.

In his presentation, Dr. Kosiborod explained that treatments targeting COVID-19 pathobiology such as dysregulated immune responses, endothelial damage, microvascular thrombosis, and inflammation have been shown to improve the key outcomes in this patient group.

SGLT2 inhibitors, which modulate similar pathobiology, provide cardiovascular protection and prevent the progression of kidney disease in patients at risk for these events, including those with type 2 diabetes, heart failure, and kidney disease, and may also lead to organ protection in a setting of acute illness such as COVID-19, he noted. However, the role of SGLT2 inhibitors in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 remains uncertain.

To address the need for more definitive efficacy data, the World Health Organization Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies (REACT) Working Group conducted a prospective meta-analysis using data from the three randomized controlled trials, DARE-19, RECOVERY, and ACTIV-4a, evaluating SGLT2 inhibitors in patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

Overall, these trials randomized 6,096 participants: 3,025 to SGLT2 inhibitors and 3,071 to usual care or placebo. The average age of participants ranged between 62 and 73 years across the trials, 39% were women, and 25% had type 2 diabetes.

By 28 days after randomization, all-cause mortality, the primary endpoint, had occurred in 11.6% of the SGLT2-inhibitor patients, compared with 12.4% of those randomized to usual care or placebo, giving an odds ratio of 0.93 (95% confidence interval, 0.79-1.08; P = .33) for SGLT2 inhibitors, with consistency across trials.

Data on in-hospital and 90-day all-cause mortality were only available for two out of three trials (DARE-19 and ACTIV-4a), but the results were similar to the primary endpoint showing nonsignificant trends toward a possible benefit in the SGLT2-inhibitor group.

The results were also similar for the secondary outcomes of progression to acute kidney injury or requirement for dialysis or death, and progression to invasive mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or death, both assessed at 28 days.

The primary safety outcome of ketoacidosis by 28 days was observed in seven and two patients allocated to SGLT2 inhibitors and usual care or placebo, respectively, and overall, the incidence of reported serious adverse events was balanced between treatment groups.

The RECOVERY trial was supported by grants to the University of Oxford from UK Research and Innovation, the National Institute for Health and Care Research, and Wellcome. The ACTIV-4a platform was sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. DARE-19 was an investigator-initiated collaborative trial supported by AstraZeneca. Dr. Kosiborod reported numerous conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ESC CONGRESS 2023

Recent leaps in heart failure therapy spur ESC guideline–focused update

Two years is a long time in the world of heart failure (HF) management, enough to see publication of more than a dozen studies with insights that would supplant and expand key sections of a far-reaching European Society of Cardiology (ESC) clinical practice guideline on HF unveiled in 2021.

“Back in 2021, we had three and a half decades of data to consider,” but recent years have seen “an amazing amount of progress” that has necessitated some adjustments and key additions, including several Class I recommendations, observed Roy S. Gardner, MBChB, MD, Golden Jubilee National Hospital, Clydebank, United Kingdom.

, which Dr. Gardner helped unveil over several days at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, held in Amsterdam.

The new document was also published in the European Heart Journal during the ESC sessions. Dr. Gardner is a co-author on both the 2021 and 2023 documents.

The task force that was charged with the focused update’s development “considered a large number of trials across the spectrum of acute chronic heart failure and the comorbidities associated with it,” Ultimately, it considered only those with “results that would lead to new or changed Class I or Class IIa recommendations,” noted Theresa A. McDonagh, MD, during the ESC sessions.

Dr. McDonagh, of King’s College Hospital, London, chaired the task force and led the document’s list of authors along with Marco Metra, MD, University of Brescia (Italy).

Chronic HF management

The 2021 document’s “beautiful algorithm” on managing HF with reduced ejection fraction, that is HF with an LVEF less than 40%, had helped enshrine the expeditious uptitration of the “four pillars” of drug therapy as a top management goal. That remains unchanged in the focused update, Dr. Gardner noted.

But the new document gives a boost to recommendations for HF with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF), characterized by an LVEF greater than 40% to less than 50%. For that, the 2021 document recommended three of the four pillars of HF medical therapy: beta blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA), renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors.

The focused update, however, adds the fourth pillar – SGLT2 inhibitors – to core therapy for both HFmrEF and HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), the latter defined by an LVEF greater than 50%. Publication of trials supporting those new recommendations had narrowly missed availability for the 2021 document.

EMPEROR-Preserved, for example, was published during the same ESC 2021 sessions that introduced the 2021 guidelines. Its patients with HFpEF (which at the time included patients meeting the current definition of HFmrEF) assigned to the SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin (Jardiance) showed a 21% reduction in risk for a composite primary endpoint that was driven by the HF-hospitalization component.

“This wasn’t a fluke finding,” Dr. Gardner said, as the following year saw publication of the DELIVER trial, which resembled EMPEROR-Preserved in design and outcomes using the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin (Farxiga).

The two trials, backed up by meta-analyses that also included DAPA-HF and other studies, suggested as well that the two SGLT2 inhibitors “work across the spectrum of ejection fraction,” Dr. Gardner said.

The 2023 focused update indicates an SGLT2 inhibitor, either empagliflozin or dapagliflozin, for patients with either HFmrEF or HFpEF to reduce the risk of HF hospitalization or cardiovascular death. Both recommendations are of Class I, level of evidence A.

The new indications make SGLT2 inhibitors and diuretics (as needed for fluid retention) the only drugs for HFmrEF or HFpEF with a Class I recommendation. Previously established “rather weaker” Class IIb recommendation for RAS inhibitors, MRAs, and beta blockers that had been “based on subgroup analyses of neutral trials” remained unchanged in the focused update, Dr. McDonagh noted.

Patients hospitalized with HF

The 2021 guidelines had recommended that patients hospitalized with acute HF be started on evidence-based meds before discharge and that they return for evaluation 1 to 2 weeks after discharge. But the recommendation was unsupported by randomized trials.

That changed with the 2022 publication of STRONG-HF, in which a strategy of early and rapid uptitration of guideline-directed meds, initiated predischarge regardless of LVEF, led to a one-third reduced 6-month risk for death or HF readmission.

Based primarily on STRONG-HF, the focused update recommends “an intensive strategy of initiation and rapid up-titration of evidence-based treatment before discharge and during frequent and careful follow-up visits in the first 6 weeks after hospitalization” to reduce readmission and mortality: Class I, level of evidence B.

“There was a large consensus around this recommendation,” said STRONG-HF principal investigator Alexandre Mebazaa, MD, PhD, a co-author of both the 2021 and 2023 documents. Conducted before the advent of the four pillars of drug therapy, sometimes called quartet therapy, the trial’s requirement for evidence-based meds didn’t include SGLT2 inhibitors.

The new focused update considers the new status of those agents, especially with regard to their benefits independent of LVEF. So, it completed the quartet by adding empagliflozin or dapagliflozin to the agents that should be initiated predischarge, observed Dr. Mebazaa, University Hospitals Saint Louis‐Lariboisière, Paris, at the focused-update’s ESC 2023 sessions.

The new document also follows STRONG-HF with its emphasis on “frequent and careful follow-up” by recommending certain clinical and laboratory evaluations known to be prognostic in HF. They include congestion status, blood pressure, heart rate, natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and potassium levels and estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Dr. Mebazaa stressed the importance of monitoring NT-proBNP after discharge. “What we saw in STRONG-HF is that sometimes the clinical signs do not necessarily tell you that the patient is still congested.”

After discharge, he said, NT-proBNP levels “should only go down.” So, knowing whether NT-proBNP levels “are stable or increasing” during the med optimization process can help guide diuretic dosing.

HF with comorbidities

The new document includes two new Class I recommendations for patients with HF and both type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease based on several recent randomized trials and meta-analyses.

The focused update recommends SGLT2 inhibitors as well as the selective, non-steroidal MRA finerenone (Kerendia) in HF patients with CKD and type-2 diabetes. Both Class I recommendations are supported by a level of evidence A.

The SGLT2 indication is based on DAPA-CKD and EMPA-KIDNEY plus meta-analyses that included those trials along with others. The recommendation for finerenone derives from the FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD trials and a pooled analysis of the two studies.

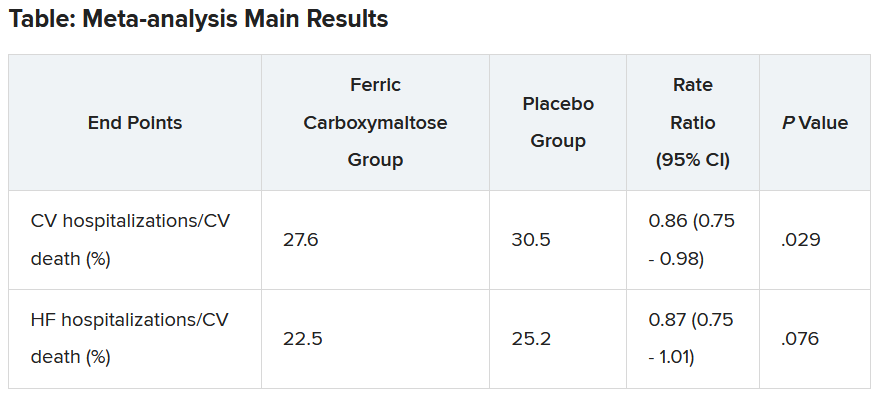

The 2023 focused update also accounts for new clinical-trial insights for patients with HF and iron deficiency. The 2021 document featured recommendations for the diagnosis and iron-repletion therapy in such cases, but only as Class IIa or at lower low levels of evidence. The focused update considers more recent studies, especially IRONMAN and some meta-analyses.

The 2023 document indicates intravenous iron supplementation for symptomatic patients with iron deficiency and either HFrEF or HFmrEF to improve symptoms and quality of life (Class I, level of evidence A), and says it should be considered (Class IIa, level of evidence A) to reduce risk for HF hospitalization.

When the task force assembled to plan the 2023 focused update, Dr. Gardner observed, “the first thing we thought about was the nomenclature around the phenotyping of heart failure.”

Although the 2021 guidelines relied fundamentally on the distinctions between HFrEF, HFmrEF, and HFpEF, it had become apparent to some in the field that some meds, especially the SGLT2 inhibitors, were obscuring their LVEF-based boundaries, at least with respect to drug therapy.

The 2023 document’s developers, Dr. Gardner said, seriously considered changing the three categories to two, that is HFrEF and – to account for all other heart failure – HF with normal ejection fraction (HFnEF).

That didn’t happen, although the proposal was popular within the task force. Any changes to the 2021 document would require a 75% consensus on the matter, Dr. Gardner explained. When the task force took a vote on whether to change the nomenclature, he said, 71% favored the proposal.

Disclosures for members of the task force can be found in a supplement to the published 2023 Focused Update.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two years is a long time in the world of heart failure (HF) management, enough to see publication of more than a dozen studies with insights that would supplant and expand key sections of a far-reaching European Society of Cardiology (ESC) clinical practice guideline on HF unveiled in 2021.

“Back in 2021, we had three and a half decades of data to consider,” but recent years have seen “an amazing amount of progress” that has necessitated some adjustments and key additions, including several Class I recommendations, observed Roy S. Gardner, MBChB, MD, Golden Jubilee National Hospital, Clydebank, United Kingdom.

, which Dr. Gardner helped unveil over several days at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, held in Amsterdam.

The new document was also published in the European Heart Journal during the ESC sessions. Dr. Gardner is a co-author on both the 2021 and 2023 documents.

The task force that was charged with the focused update’s development “considered a large number of trials across the spectrum of acute chronic heart failure and the comorbidities associated with it,” Ultimately, it considered only those with “results that would lead to new or changed Class I or Class IIa recommendations,” noted Theresa A. McDonagh, MD, during the ESC sessions.

Dr. McDonagh, of King’s College Hospital, London, chaired the task force and led the document’s list of authors along with Marco Metra, MD, University of Brescia (Italy).

Chronic HF management

The 2021 document’s “beautiful algorithm” on managing HF with reduced ejection fraction, that is HF with an LVEF less than 40%, had helped enshrine the expeditious uptitration of the “four pillars” of drug therapy as a top management goal. That remains unchanged in the focused update, Dr. Gardner noted.

But the new document gives a boost to recommendations for HF with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF), characterized by an LVEF greater than 40% to less than 50%. For that, the 2021 document recommended three of the four pillars of HF medical therapy: beta blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA), renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors.

The focused update, however, adds the fourth pillar – SGLT2 inhibitors – to core therapy for both HFmrEF and HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), the latter defined by an LVEF greater than 50%. Publication of trials supporting those new recommendations had narrowly missed availability for the 2021 document.

EMPEROR-Preserved, for example, was published during the same ESC 2021 sessions that introduced the 2021 guidelines. Its patients with HFpEF (which at the time included patients meeting the current definition of HFmrEF) assigned to the SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin (Jardiance) showed a 21% reduction in risk for a composite primary endpoint that was driven by the HF-hospitalization component.

“This wasn’t a fluke finding,” Dr. Gardner said, as the following year saw publication of the DELIVER trial, which resembled EMPEROR-Preserved in design and outcomes using the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin (Farxiga).

The two trials, backed up by meta-analyses that also included DAPA-HF and other studies, suggested as well that the two SGLT2 inhibitors “work across the spectrum of ejection fraction,” Dr. Gardner said.

The 2023 focused update indicates an SGLT2 inhibitor, either empagliflozin or dapagliflozin, for patients with either HFmrEF or HFpEF to reduce the risk of HF hospitalization or cardiovascular death. Both recommendations are of Class I, level of evidence A.

The new indications make SGLT2 inhibitors and diuretics (as needed for fluid retention) the only drugs for HFmrEF or HFpEF with a Class I recommendation. Previously established “rather weaker” Class IIb recommendation for RAS inhibitors, MRAs, and beta blockers that had been “based on subgroup analyses of neutral trials” remained unchanged in the focused update, Dr. McDonagh noted.

Patients hospitalized with HF

The 2021 guidelines had recommended that patients hospitalized with acute HF be started on evidence-based meds before discharge and that they return for evaluation 1 to 2 weeks after discharge. But the recommendation was unsupported by randomized trials.

That changed with the 2022 publication of STRONG-HF, in which a strategy of early and rapid uptitration of guideline-directed meds, initiated predischarge regardless of LVEF, led to a one-third reduced 6-month risk for death or HF readmission.

Based primarily on STRONG-HF, the focused update recommends “an intensive strategy of initiation and rapid up-titration of evidence-based treatment before discharge and during frequent and careful follow-up visits in the first 6 weeks after hospitalization” to reduce readmission and mortality: Class I, level of evidence B.

“There was a large consensus around this recommendation,” said STRONG-HF principal investigator Alexandre Mebazaa, MD, PhD, a co-author of both the 2021 and 2023 documents. Conducted before the advent of the four pillars of drug therapy, sometimes called quartet therapy, the trial’s requirement for evidence-based meds didn’t include SGLT2 inhibitors.

The new focused update considers the new status of those agents, especially with regard to their benefits independent of LVEF. So, it completed the quartet by adding empagliflozin or dapagliflozin to the agents that should be initiated predischarge, observed Dr. Mebazaa, University Hospitals Saint Louis‐Lariboisière, Paris, at the focused-update’s ESC 2023 sessions.

The new document also follows STRONG-HF with its emphasis on “frequent and careful follow-up” by recommending certain clinical and laboratory evaluations known to be prognostic in HF. They include congestion status, blood pressure, heart rate, natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and potassium levels and estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Dr. Mebazaa stressed the importance of monitoring NT-proBNP after discharge. “What we saw in STRONG-HF is that sometimes the clinical signs do not necessarily tell you that the patient is still congested.”

After discharge, he said, NT-proBNP levels “should only go down.” So, knowing whether NT-proBNP levels “are stable or increasing” during the med optimization process can help guide diuretic dosing.

HF with comorbidities

The new document includes two new Class I recommendations for patients with HF and both type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease based on several recent randomized trials and meta-analyses.

The focused update recommends SGLT2 inhibitors as well as the selective, non-steroidal MRA finerenone (Kerendia) in HF patients with CKD and type-2 diabetes. Both Class I recommendations are supported by a level of evidence A.

The SGLT2 indication is based on DAPA-CKD and EMPA-KIDNEY plus meta-analyses that included those trials along with others. The recommendation for finerenone derives from the FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD trials and a pooled analysis of the two studies.

The 2023 focused update also accounts for new clinical-trial insights for patients with HF and iron deficiency. The 2021 document featured recommendations for the diagnosis and iron-repletion therapy in such cases, but only as Class IIa or at lower low levels of evidence. The focused update considers more recent studies, especially IRONMAN and some meta-analyses.

The 2023 document indicates intravenous iron supplementation for symptomatic patients with iron deficiency and either HFrEF or HFmrEF to improve symptoms and quality of life (Class I, level of evidence A), and says it should be considered (Class IIa, level of evidence A) to reduce risk for HF hospitalization.

When the task force assembled to plan the 2023 focused update, Dr. Gardner observed, “the first thing we thought about was the nomenclature around the phenotyping of heart failure.”

Although the 2021 guidelines relied fundamentally on the distinctions between HFrEF, HFmrEF, and HFpEF, it had become apparent to some in the field that some meds, especially the SGLT2 inhibitors, were obscuring their LVEF-based boundaries, at least with respect to drug therapy.

The 2023 document’s developers, Dr. Gardner said, seriously considered changing the three categories to two, that is HFrEF and – to account for all other heart failure – HF with normal ejection fraction (HFnEF).

That didn’t happen, although the proposal was popular within the task force. Any changes to the 2021 document would require a 75% consensus on the matter, Dr. Gardner explained. When the task force took a vote on whether to change the nomenclature, he said, 71% favored the proposal.

Disclosures for members of the task force can be found in a supplement to the published 2023 Focused Update.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two years is a long time in the world of heart failure (HF) management, enough to see publication of more than a dozen studies with insights that would supplant and expand key sections of a far-reaching European Society of Cardiology (ESC) clinical practice guideline on HF unveiled in 2021.

“Back in 2021, we had three and a half decades of data to consider,” but recent years have seen “an amazing amount of progress” that has necessitated some adjustments and key additions, including several Class I recommendations, observed Roy S. Gardner, MBChB, MD, Golden Jubilee National Hospital, Clydebank, United Kingdom.

, which Dr. Gardner helped unveil over several days at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, held in Amsterdam.

The new document was also published in the European Heart Journal during the ESC sessions. Dr. Gardner is a co-author on both the 2021 and 2023 documents.

The task force that was charged with the focused update’s development “considered a large number of trials across the spectrum of acute chronic heart failure and the comorbidities associated with it,” Ultimately, it considered only those with “results that would lead to new or changed Class I or Class IIa recommendations,” noted Theresa A. McDonagh, MD, during the ESC sessions.

Dr. McDonagh, of King’s College Hospital, London, chaired the task force and led the document’s list of authors along with Marco Metra, MD, University of Brescia (Italy).

Chronic HF management

The 2021 document’s “beautiful algorithm” on managing HF with reduced ejection fraction, that is HF with an LVEF less than 40%, had helped enshrine the expeditious uptitration of the “four pillars” of drug therapy as a top management goal. That remains unchanged in the focused update, Dr. Gardner noted.

But the new document gives a boost to recommendations for HF with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF), characterized by an LVEF greater than 40% to less than 50%. For that, the 2021 document recommended three of the four pillars of HF medical therapy: beta blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA), renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors.

The focused update, however, adds the fourth pillar – SGLT2 inhibitors – to core therapy for both HFmrEF and HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), the latter defined by an LVEF greater than 50%. Publication of trials supporting those new recommendations had narrowly missed availability for the 2021 document.

EMPEROR-Preserved, for example, was published during the same ESC 2021 sessions that introduced the 2021 guidelines. Its patients with HFpEF (which at the time included patients meeting the current definition of HFmrEF) assigned to the SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin (Jardiance) showed a 21% reduction in risk for a composite primary endpoint that was driven by the HF-hospitalization component.

“This wasn’t a fluke finding,” Dr. Gardner said, as the following year saw publication of the DELIVER trial, which resembled EMPEROR-Preserved in design and outcomes using the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin (Farxiga).

The two trials, backed up by meta-analyses that also included DAPA-HF and other studies, suggested as well that the two SGLT2 inhibitors “work across the spectrum of ejection fraction,” Dr. Gardner said.

The 2023 focused update indicates an SGLT2 inhibitor, either empagliflozin or dapagliflozin, for patients with either HFmrEF or HFpEF to reduce the risk of HF hospitalization or cardiovascular death. Both recommendations are of Class I, level of evidence A.

The new indications make SGLT2 inhibitors and diuretics (as needed for fluid retention) the only drugs for HFmrEF or HFpEF with a Class I recommendation. Previously established “rather weaker” Class IIb recommendation for RAS inhibitors, MRAs, and beta blockers that had been “based on subgroup analyses of neutral trials” remained unchanged in the focused update, Dr. McDonagh noted.

Patients hospitalized with HF

The 2021 guidelines had recommended that patients hospitalized with acute HF be started on evidence-based meds before discharge and that they return for evaluation 1 to 2 weeks after discharge. But the recommendation was unsupported by randomized trials.

That changed with the 2022 publication of STRONG-HF, in which a strategy of early and rapid uptitration of guideline-directed meds, initiated predischarge regardless of LVEF, led to a one-third reduced 6-month risk for death or HF readmission.

Based primarily on STRONG-HF, the focused update recommends “an intensive strategy of initiation and rapid up-titration of evidence-based treatment before discharge and during frequent and careful follow-up visits in the first 6 weeks after hospitalization” to reduce readmission and mortality: Class I, level of evidence B.

“There was a large consensus around this recommendation,” said STRONG-HF principal investigator Alexandre Mebazaa, MD, PhD, a co-author of both the 2021 and 2023 documents. Conducted before the advent of the four pillars of drug therapy, sometimes called quartet therapy, the trial’s requirement for evidence-based meds didn’t include SGLT2 inhibitors.

The new focused update considers the new status of those agents, especially with regard to their benefits independent of LVEF. So, it completed the quartet by adding empagliflozin or dapagliflozin to the agents that should be initiated predischarge, observed Dr. Mebazaa, University Hospitals Saint Louis‐Lariboisière, Paris, at the focused-update’s ESC 2023 sessions.

The new document also follows STRONG-HF with its emphasis on “frequent and careful follow-up” by recommending certain clinical and laboratory evaluations known to be prognostic in HF. They include congestion status, blood pressure, heart rate, natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and potassium levels and estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Dr. Mebazaa stressed the importance of monitoring NT-proBNP after discharge. “What we saw in STRONG-HF is that sometimes the clinical signs do not necessarily tell you that the patient is still congested.”

After discharge, he said, NT-proBNP levels “should only go down.” So, knowing whether NT-proBNP levels “are stable or increasing” during the med optimization process can help guide diuretic dosing.

HF with comorbidities

The new document includes two new Class I recommendations for patients with HF and both type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease based on several recent randomized trials and meta-analyses.

The focused update recommends SGLT2 inhibitors as well as the selective, non-steroidal MRA finerenone (Kerendia) in HF patients with CKD and type-2 diabetes. Both Class I recommendations are supported by a level of evidence A.

The SGLT2 indication is based on DAPA-CKD and EMPA-KIDNEY plus meta-analyses that included those trials along with others. The recommendation for finerenone derives from the FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD trials and a pooled analysis of the two studies.

The 2023 focused update also accounts for new clinical-trial insights for patients with HF and iron deficiency. The 2021 document featured recommendations for the diagnosis and iron-repletion therapy in such cases, but only as Class IIa or at lower low levels of evidence. The focused update considers more recent studies, especially IRONMAN and some meta-analyses.

The 2023 document indicates intravenous iron supplementation for symptomatic patients with iron deficiency and either HFrEF or HFmrEF to improve symptoms and quality of life (Class I, level of evidence A), and says it should be considered (Class IIa, level of evidence A) to reduce risk for HF hospitalization.

When the task force assembled to plan the 2023 focused update, Dr. Gardner observed, “the first thing we thought about was the nomenclature around the phenotyping of heart failure.”

Although the 2021 guidelines relied fundamentally on the distinctions between HFrEF, HFmrEF, and HFpEF, it had become apparent to some in the field that some meds, especially the SGLT2 inhibitors, were obscuring their LVEF-based boundaries, at least with respect to drug therapy.

The 2023 document’s developers, Dr. Gardner said, seriously considered changing the three categories to two, that is HFrEF and – to account for all other heart failure – HF with normal ejection fraction (HFnEF).

That didn’t happen, although the proposal was popular within the task force. Any changes to the 2021 document would require a 75% consensus on the matter, Dr. Gardner explained. When the task force took a vote on whether to change the nomenclature, he said, 71% favored the proposal.

Disclosures for members of the task force can be found in a supplement to the published 2023 Focused Update.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE ESC CONGRESS 2023

Is AFib ablation the fifth pillar in heart failure care? CASTLE-HTx

Recorded Aug. 28, 2023. This transcript has been edited for clarity.

John M. Mandrola, MD: I’m here at the European Society of Cardiology meeting, and I’m very excited to have two colleagues whom I met at the Western Atrial Fibrillation Symposium (Western AFib) and who presented the CASTLE-HTx study. This is Christian Sohns and Philipp Sommer, and the CASTLE-HTx study is very exciting.

Before I get into that, I really want to introduce the concept of atrial fibrillation in heart failure. I like to say that there are two big populations of patients with atrial fibrillation, and the vast majority can be treated slowly with reassurance and education. There is a group of patients who have heart failure who, when they develop atrial fibrillation, can degenerate rapidly. The CASTLE-HTx study looked at catheter ablation versus medical therapy in patients with advanced heart failure.

Christian, why don’t you tell us the top-line results and what you found.

CASTLE-HTx key findings

Christian Sohns, MD, PhD: Thanks, first of all, for mentioning this special cohort of patients in end-stage heart failure, which is very important. The endpoint of the study was a composite of death from any cause or left ventricular assist device (LVAD) implantation and heart transplantation. These are very hard, strong clinical endpoints, not the rate of rehospitalization or something like that.

Catheter ablation was superior to medical therapy alone in terms of this composite endpoint. That was driven by cardiovascular death and all-cause mortality, which highlights the fact that you should always consider atrial fibrillation ablation in the end-stage heart failure cohort. The findings were driven by the fact that we saw left ventricular reverse remodeling and the reduction of atrial fibrillation in these patients.

Dr. Mandrola: Tell me about how it came about. It was conducted at your center. Who were these patients?

Philipp Sommer, MD: As one of the biggest centers for heart transplantations all over Europe, with roughly 100 transplants per year, we had many patients being referred to our center with the questions of whether those patients are eligible for a heart transplantation. Not all of the patients in our study were listed for a transplant, but all of them were admitted in that end-stage heart failure status to evaluate their eligibility for transplant.

If we look at the baseline data of those patients, they had an ejection fraction of 29%. They had a 6-minute walk test as a functional capacity parameter of around 300 m. Approximately two thirds of them were New York Heart Association class III and IV, which is significantly worse than what we saw in the previous studies dealing with heart failure patients.

I think overall, if you also look at NT-proBNP levels, this is a really sick patient population where some people might doubt if they should admit and refer those patients for an ablation procedure. Therefore, it’s really interesting and fascinating to see the results.

Dr. Mandrola: I did read in the manuscript, and I heard from you, that these were recruited as outpatients. So they were stable outpatients who were referred to the center for consideration of an LVAD or transplant?

Dr. Sohns: The definition of stability is very difficult in these patients because they have hospital stays, they have a history of drug therapy, and they have a history of interventions also behind them – not atrial fibrillation ablation, but others. I think these patients are referred because the referring physicians are done with the case. They can no longer offer any option to the patients other than surgical treatment, assist device, pump implantation, or transplantation.

If you look at the guidelines, they do not comment on atrial fibrillation ablation in this cohort of patients. Also, they have different recommendations between the American societies and the European societies regarding what is end-stage heart failure and how to treat these patients. Therefore, it was a big benefit of CASTLE-HTx that we randomized a cohort of patients with advanced end-stage heart failure.

How can AFib ablation have such big, early effects?

Dr. Mandrola: These are very clinically significant findings, with large effect sizes and very early separation of the Kaplan-Meier curves. How do you explain how dramatic an effect that is, and how early of an effect?

Dr. Sommer: That’s one of the key questions at the end of the day. I think our job basically was to provide the data and to ensure that the data are clean and that it’s all perfectly done. The interpretation of these data is really kind of difficult, although we do not have the 100% perfect and obvious explanation why the curves separated so early. Our view on that is that we are talking about a pretty fragile patient population, so little differences like having a tachyarrhythmia of 110 day in, day out or being in sinus rhythm of 60 can make a huge difference. That’s obviously pretty early.

The one that remains in tachyarrhythmia will deteriorate and will require an LVAD after a couple of months, and the one that you may keep in sinus rhythm, even with reduced atrial fibrillation burden – not zero, but reduced atrial fibrillation burden – and improved LV function, all of a sudden this patient will still remain on a low level of being stable, but he or she will remain stable and will not require any surgical interventions for the next 1.5-2 years. If we can manage to do this, just postponing the natural cause of the disease, I think that is a great benefit for the patient.

Dr. Mandrola: One of the things that comes up in our center is that I look at some of these patients and think, there’s no way I can put this patient under general anesthetic and do all of this. Your ablation procedure wasn’t that extensive, was it?

Dr. Sohns: On the one hand, no. On the other hand, yes. You need to take into consideration that it has been performed by experienced physicians with experience in heart failure treatment and atrial fibrillation in heart transplantation centers, though it›s not sure that we can transfer these results one-to-one to all other centers in the world.

It is very clear that we have almost no major complications in these patients. We were able to do these ablation procedures without general anesthesia. We have 60% of patients who had pulmonary vein isolation only and 40% of patients who have PVI and additional therapy. We have a procedure duration of almost 90 minutes during radiofrequency ablation.

We have different categories. When you talk about the different patient cohorts, we also see different stages of myocardial tissue damage, which will be part of another publication for sure. It is, in part, surprising how normal some of the atria were despite having a volume of 180 mL, but they had no fibrosis. That was very interesting.

Dr. Mandrola: How did the persistent vs paroxysmal atrial fibrillation sort out? Were these mostly patients with persistent atrial fibrillation?

Dr. Sommer: Two-thirds were persistent. It would be expected in this patient population that you would not find so many paroxysmal cases. I think it›s very important what Christian was just mentioning that when we discussed the trial design, we were anticipating problems with the sedation, for example. With the follow-up of those procedures, would they decompensate because of the fluid that you have to deliver during such a procedure.

We were quite surprised at the end of the day that the procedures were quite straightforward. Fortunately, we had no major complications. I think there were four complications in the 100 ablated patients. I think we were really positive about how the procedures turned out.

I should mention that one of the exclusion criteria was a left atrial diameter of about 60 mm. The huge ones may be very diseased, and maybe the hopeless ones were excluded from the study. Below 60 mm, we did the ablation.

Rhythm control

Dr. Mandrola: One of my colleagues, who is even more skeptical than me, wanted me to ask you, why wouldn’t you take a patient with persistent atrial fibrillation who had heart failure and just cardiovert and use amiodarone and try and maintain sinus rhythm that way?

Dr. Sohns: It is important to mention that 50% of the patients have already had amiodarone before they were randomized and enrolled for the trial. It might bring you a couple of minutes or a couple of hours [of relief], but the patients would get recurrence.

It was very interesting also, and this is in line with the data from Jason Andrade, who demonstrated that we were able to reduce the percentage of patients with persistent atrial fibrillation to paroxysmal. We did a down-staging of the underlying disease. This is not possible with cardioversion or drugs, for example.

Dr. Sommer: What I really like about that question and that comment is the idea that rhythm control in this subset of patients obviously has a role and an importance. It may be a cardioversion initially, giving amiodarone if they didn’t have that before, and you can keep the patient in sinus rhythm with this therapy, I think we’re reaching the same goal.

I think the critical point to get into the mind of physicians who treat heart failure is that sinus rhythm is beneficial, however you get there. Ablation, of course, as in other studies, is the most powerful tool to get there. Cardioversion can be a really good thing to do; you just have to think about it and consider it.

Dr. Mandrola: I do want to say to everybody that there is a tension sometimes between the heart failure community and the electrophysiology community. I think the ideal situation is that we work together, because I think that we can help with the maintenance of sinus rhythm. The control group mortality at 1 year was 20%, and I’ve heard people say that that’s not advanced heart failure. Advanced heart failure patients have much higher mortality than that. My colleague who is a heart failure specialist was criticizing a selection bias in picking the best patients. How would you answer that?

Dr. Sohns: There are data available from Eurotransplant, for example, that the waiting list mortality is 18%, so I think we are almost in line with this 20% mortality in this conservative group. You cannot generalize it. All these patients have different histories. We have 60% dilated cardiomyopathy and 40% ischemic cardiomyopathy. I think it is a very representative group in contrast to your friend who suggests that it is not.

Dr. Sommer: What I like about the discussion is that some approach us to say that the mortality in the control group is much too high – like, what are you doing with those patients that you create so many endpoints? Then others say that it’s not high enough because that is not end-stage heart failure. Come on! We have a patient cohort that is very well described and very well characterized.

If the label is end-stage heart failure, advanced heart failure, or whatever, they are sicker than the patients that we had in earlier trials. The patients that we treated were mostly excluded from all other trials. We opened the door. We found a clear result. I think everyone can see whatever you like to see.

Dr. Mandrola: What would your take-home message be after having done this trial design, the trial was conducted in your single center, and you come up with these amazing results? What would your message be to the whole community?

Dr. Sohns: Taking into consideration how severely sick these patients are, I can just repeat it: They are one step away from death, more or less, or from surgical intervention that can prolong their life. You should also consider that there are options like atrial fibrillation ablation that can buy time, postpone the natural course, or even in some patients replace the destination therapy. Therefore, in my opinion the next guidelines should recommend that every patient should carefully be checked for sinus rhythm before bringing these patients into the environment of transplantation.

Dr. Sommer: My interpretation is that we have to try to bring into physicians’ minds that besides a well-established and well-documented effect of drug therapy with the fabulous four, we may now have the fabulous five, including an ablation option for patients with atrial fibrillation.

Dr. Mandrola is a clinical electrophysiologist at Baptist Medical Associates, Louisville, Ky. Dr. Sohns is deputy director of the Heart and Diabetes Center NRW, Ruhr University Bochum, Bad Oeynhausen, Germany. Dr. Sommer is professor of cardiology at the Heart and Diabetes Center NRW. Dr. Mandrola reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Sohns reported receiving research funding from Else Kröner–Fresenius–Stiftung. Dr. Sommer reported consulting with Abbott, Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic USA.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Recorded Aug. 28, 2023. This transcript has been edited for clarity.

John M. Mandrola, MD: I’m here at the European Society of Cardiology meeting, and I’m very excited to have two colleagues whom I met at the Western Atrial Fibrillation Symposium (Western AFib) and who presented the CASTLE-HTx study. This is Christian Sohns and Philipp Sommer, and the CASTLE-HTx study is very exciting.

Before I get into that, I really want to introduce the concept of atrial fibrillation in heart failure. I like to say that there are two big populations of patients with atrial fibrillation, and the vast majority can be treated slowly with reassurance and education. There is a group of patients who have heart failure who, when they develop atrial fibrillation, can degenerate rapidly. The CASTLE-HTx study looked at catheter ablation versus medical therapy in patients with advanced heart failure.

Christian, why don’t you tell us the top-line results and what you found.

CASTLE-HTx key findings

Christian Sohns, MD, PhD: Thanks, first of all, for mentioning this special cohort of patients in end-stage heart failure, which is very important. The endpoint of the study was a composite of death from any cause or left ventricular assist device (LVAD) implantation and heart transplantation. These are very hard, strong clinical endpoints, not the rate of rehospitalization or something like that.

Catheter ablation was superior to medical therapy alone in terms of this composite endpoint. That was driven by cardiovascular death and all-cause mortality, which highlights the fact that you should always consider atrial fibrillation ablation in the end-stage heart failure cohort. The findings were driven by the fact that we saw left ventricular reverse remodeling and the reduction of atrial fibrillation in these patients.

Dr. Mandrola: Tell me about how it came about. It was conducted at your center. Who were these patients?

Philipp Sommer, MD: As one of the biggest centers for heart transplantations all over Europe, with roughly 100 transplants per year, we had many patients being referred to our center with the questions of whether those patients are eligible for a heart transplantation. Not all of the patients in our study were listed for a transplant, but all of them were admitted in that end-stage heart failure status to evaluate their eligibility for transplant.

If we look at the baseline data of those patients, they had an ejection fraction of 29%. They had a 6-minute walk test as a functional capacity parameter of around 300 m. Approximately two thirds of them were New York Heart Association class III and IV, which is significantly worse than what we saw in the previous studies dealing with heart failure patients.

I think overall, if you also look at NT-proBNP levels, this is a really sick patient population where some people might doubt if they should admit and refer those patients for an ablation procedure. Therefore, it’s really interesting and fascinating to see the results.

Dr. Mandrola: I did read in the manuscript, and I heard from you, that these were recruited as outpatients. So they were stable outpatients who were referred to the center for consideration of an LVAD or transplant?

Dr. Sohns: The definition of stability is very difficult in these patients because they have hospital stays, they have a history of drug therapy, and they have a history of interventions also behind them – not atrial fibrillation ablation, but others. I think these patients are referred because the referring physicians are done with the case. They can no longer offer any option to the patients other than surgical treatment, assist device, pump implantation, or transplantation.

If you look at the guidelines, they do not comment on atrial fibrillation ablation in this cohort of patients. Also, they have different recommendations between the American societies and the European societies regarding what is end-stage heart failure and how to treat these patients. Therefore, it was a big benefit of CASTLE-HTx that we randomized a cohort of patients with advanced end-stage heart failure.

How can AFib ablation have such big, early effects?

Dr. Mandrola: These are very clinically significant findings, with large effect sizes and very early separation of the Kaplan-Meier curves. How do you explain how dramatic an effect that is, and how early of an effect?

Dr. Sommer: That’s one of the key questions at the end of the day. I think our job basically was to provide the data and to ensure that the data are clean and that it’s all perfectly done. The interpretation of these data is really kind of difficult, although we do not have the 100% perfect and obvious explanation why the curves separated so early. Our view on that is that we are talking about a pretty fragile patient population, so little differences like having a tachyarrhythmia of 110 day in, day out or being in sinus rhythm of 60 can make a huge difference. That’s obviously pretty early.

The one that remains in tachyarrhythmia will deteriorate and will require an LVAD after a couple of months, and the one that you may keep in sinus rhythm, even with reduced atrial fibrillation burden – not zero, but reduced atrial fibrillation burden – and improved LV function, all of a sudden this patient will still remain on a low level of being stable, but he or she will remain stable and will not require any surgical interventions for the next 1.5-2 years. If we can manage to do this, just postponing the natural cause of the disease, I think that is a great benefit for the patient.

Dr. Mandrola: One of the things that comes up in our center is that I look at some of these patients and think, there’s no way I can put this patient under general anesthetic and do all of this. Your ablation procedure wasn’t that extensive, was it?

Dr. Sohns: On the one hand, no. On the other hand, yes. You need to take into consideration that it has been performed by experienced physicians with experience in heart failure treatment and atrial fibrillation in heart transplantation centers, though it›s not sure that we can transfer these results one-to-one to all other centers in the world.

It is very clear that we have almost no major complications in these patients. We were able to do these ablation procedures without general anesthesia. We have 60% of patients who had pulmonary vein isolation only and 40% of patients who have PVI and additional therapy. We have a procedure duration of almost 90 minutes during radiofrequency ablation.

We have different categories. When you talk about the different patient cohorts, we also see different stages of myocardial tissue damage, which will be part of another publication for sure. It is, in part, surprising how normal some of the atria were despite having a volume of 180 mL, but they had no fibrosis. That was very interesting.

Dr. Mandrola: How did the persistent vs paroxysmal atrial fibrillation sort out? Were these mostly patients with persistent atrial fibrillation?

Dr. Sommer: Two-thirds were persistent. It would be expected in this patient population that you would not find so many paroxysmal cases. I think it›s very important what Christian was just mentioning that when we discussed the trial design, we were anticipating problems with the sedation, for example. With the follow-up of those procedures, would they decompensate because of the fluid that you have to deliver during such a procedure.

We were quite surprised at the end of the day that the procedures were quite straightforward. Fortunately, we had no major complications. I think there were four complications in the 100 ablated patients. I think we were really positive about how the procedures turned out.

I should mention that one of the exclusion criteria was a left atrial diameter of about 60 mm. The huge ones may be very diseased, and maybe the hopeless ones were excluded from the study. Below 60 mm, we did the ablation.

Rhythm control

Dr. Mandrola: One of my colleagues, who is even more skeptical than me, wanted me to ask you, why wouldn’t you take a patient with persistent atrial fibrillation who had heart failure and just cardiovert and use amiodarone and try and maintain sinus rhythm that way?

Dr. Sohns: It is important to mention that 50% of the patients have already had amiodarone before they were randomized and enrolled for the trial. It might bring you a couple of minutes or a couple of hours [of relief], but the patients would get recurrence.

It was very interesting also, and this is in line with the data from Jason Andrade, who demonstrated that we were able to reduce the percentage of patients with persistent atrial fibrillation to paroxysmal. We did a down-staging of the underlying disease. This is not possible with cardioversion or drugs, for example.

Dr. Sommer: What I really like about that question and that comment is the idea that rhythm control in this subset of patients obviously has a role and an importance. It may be a cardioversion initially, giving amiodarone if they didn’t have that before, and you can keep the patient in sinus rhythm with this therapy, I think we’re reaching the same goal.

I think the critical point to get into the mind of physicians who treat heart failure is that sinus rhythm is beneficial, however you get there. Ablation, of course, as in other studies, is the most powerful tool to get there. Cardioversion can be a really good thing to do; you just have to think about it and consider it.

Dr. Mandrola: I do want to say to everybody that there is a tension sometimes between the heart failure community and the electrophysiology community. I think the ideal situation is that we work together, because I think that we can help with the maintenance of sinus rhythm. The control group mortality at 1 year was 20%, and I’ve heard people say that that’s not advanced heart failure. Advanced heart failure patients have much higher mortality than that. My colleague who is a heart failure specialist was criticizing a selection bias in picking the best patients. How would you answer that?

Dr. Sohns: There are data available from Eurotransplant, for example, that the waiting list mortality is 18%, so I think we are almost in line with this 20% mortality in this conservative group. You cannot generalize it. All these patients have different histories. We have 60% dilated cardiomyopathy and 40% ischemic cardiomyopathy. I think it is a very representative group in contrast to your friend who suggests that it is not.

Dr. Sommer: What I like about the discussion is that some approach us to say that the mortality in the control group is much too high – like, what are you doing with those patients that you create so many endpoints? Then others say that it’s not high enough because that is not end-stage heart failure. Come on! We have a patient cohort that is very well described and very well characterized.

If the label is end-stage heart failure, advanced heart failure, or whatever, they are sicker than the patients that we had in earlier trials. The patients that we treated were mostly excluded from all other trials. We opened the door. We found a clear result. I think everyone can see whatever you like to see.

Dr. Mandrola: What would your take-home message be after having done this trial design, the trial was conducted in your single center, and you come up with these amazing results? What would your message be to the whole community?

Dr. Sohns: Taking into consideration how severely sick these patients are, I can just repeat it: They are one step away from death, more or less, or from surgical intervention that can prolong their life. You should also consider that there are options like atrial fibrillation ablation that can buy time, postpone the natural course, or even in some patients replace the destination therapy. Therefore, in my opinion the next guidelines should recommend that every patient should carefully be checked for sinus rhythm before bringing these patients into the environment of transplantation.

Dr. Sommer: My interpretation is that we have to try to bring into physicians’ minds that besides a well-established and well-documented effect of drug therapy with the fabulous four, we may now have the fabulous five, including an ablation option for patients with atrial fibrillation.

Dr. Mandrola is a clinical electrophysiologist at Baptist Medical Associates, Louisville, Ky. Dr. Sohns is deputy director of the Heart and Diabetes Center NRW, Ruhr University Bochum, Bad Oeynhausen, Germany. Dr. Sommer is professor of cardiology at the Heart and Diabetes Center NRW. Dr. Mandrola reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Sohns reported receiving research funding from Else Kröner–Fresenius–Stiftung. Dr. Sommer reported consulting with Abbott, Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic USA.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Recorded Aug. 28, 2023. This transcript has been edited for clarity.

John M. Mandrola, MD: I’m here at the European Society of Cardiology meeting, and I’m very excited to have two colleagues whom I met at the Western Atrial Fibrillation Symposium (Western AFib) and who presented the CASTLE-HTx study. This is Christian Sohns and Philipp Sommer, and the CASTLE-HTx study is very exciting.

Before I get into that, I really want to introduce the concept of atrial fibrillation in heart failure. I like to say that there are two big populations of patients with atrial fibrillation, and the vast majority can be treated slowly with reassurance and education. There is a group of patients who have heart failure who, when they develop atrial fibrillation, can degenerate rapidly. The CASTLE-HTx study looked at catheter ablation versus medical therapy in patients with advanced heart failure.

Christian, why don’t you tell us the top-line results and what you found.

CASTLE-HTx key findings

Christian Sohns, MD, PhD: Thanks, first of all, for mentioning this special cohort of patients in end-stage heart failure, which is very important. The endpoint of the study was a composite of death from any cause or left ventricular assist device (LVAD) implantation and heart transplantation. These are very hard, strong clinical endpoints, not the rate of rehospitalization or something like that.

Catheter ablation was superior to medical therapy alone in terms of this composite endpoint. That was driven by cardiovascular death and all-cause mortality, which highlights the fact that you should always consider atrial fibrillation ablation in the end-stage heart failure cohort. The findings were driven by the fact that we saw left ventricular reverse remodeling and the reduction of atrial fibrillation in these patients.

Dr. Mandrola: Tell me about how it came about. It was conducted at your center. Who were these patients?

Philipp Sommer, MD: As one of the biggest centers for heart transplantations all over Europe, with roughly 100 transplants per year, we had many patients being referred to our center with the questions of whether those patients are eligible for a heart transplantation. Not all of the patients in our study were listed for a transplant, but all of them were admitted in that end-stage heart failure status to evaluate their eligibility for transplant.

If we look at the baseline data of those patients, they had an ejection fraction of 29%. They had a 6-minute walk test as a functional capacity parameter of around 300 m. Approximately two thirds of them were New York Heart Association class III and IV, which is significantly worse than what we saw in the previous studies dealing with heart failure patients.

I think overall, if you also look at NT-proBNP levels, this is a really sick patient population where some people might doubt if they should admit and refer those patients for an ablation procedure. Therefore, it’s really interesting and fascinating to see the results.

Dr. Mandrola: I did read in the manuscript, and I heard from you, that these were recruited as outpatients. So they were stable outpatients who were referred to the center for consideration of an LVAD or transplant?

Dr. Sohns: The definition of stability is very difficult in these patients because they have hospital stays, they have a history of drug therapy, and they have a history of interventions also behind them – not atrial fibrillation ablation, but others. I think these patients are referred because the referring physicians are done with the case. They can no longer offer any option to the patients other than surgical treatment, assist device, pump implantation, or transplantation.

If you look at the guidelines, they do not comment on atrial fibrillation ablation in this cohort of patients. Also, they have different recommendations between the American societies and the European societies regarding what is end-stage heart failure and how to treat these patients. Therefore, it was a big benefit of CASTLE-HTx that we randomized a cohort of patients with advanced end-stage heart failure.

How can AFib ablation have such big, early effects?

Dr. Mandrola: These are very clinically significant findings, with large effect sizes and very early separation of the Kaplan-Meier curves. How do you explain how dramatic an effect that is, and how early of an effect?

Dr. Sommer: That’s one of the key questions at the end of the day. I think our job basically was to provide the data and to ensure that the data are clean and that it’s all perfectly done. The interpretation of these data is really kind of difficult, although we do not have the 100% perfect and obvious explanation why the curves separated so early. Our view on that is that we are talking about a pretty fragile patient population, so little differences like having a tachyarrhythmia of 110 day in, day out or being in sinus rhythm of 60 can make a huge difference. That’s obviously pretty early.

The one that remains in tachyarrhythmia will deteriorate and will require an LVAD after a couple of months, and the one that you may keep in sinus rhythm, even with reduced atrial fibrillation burden – not zero, but reduced atrial fibrillation burden – and improved LV function, all of a sudden this patient will still remain on a low level of being stable, but he or she will remain stable and will not require any surgical interventions for the next 1.5-2 years. If we can manage to do this, just postponing the natural cause of the disease, I think that is a great benefit for the patient.

Dr. Mandrola: One of the things that comes up in our center is that I look at some of these patients and think, there’s no way I can put this patient under general anesthetic and do all of this. Your ablation procedure wasn’t that extensive, was it?

Dr. Sohns: On the one hand, no. On the other hand, yes. You need to take into consideration that it has been performed by experienced physicians with experience in heart failure treatment and atrial fibrillation in heart transplantation centers, though it›s not sure that we can transfer these results one-to-one to all other centers in the world.