User login

Eczema Herpeticum in a Patient With Hailey-Hailey Disease Confounded by Coexistent Psoriasis

To the Editor:

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD), also known as benign familial pemphigus, is an uncommon autosomal-dominant skin disease.1 Defects in the ATPase type 2C member 1 gene, ATP2C1, result in abnormal intracellular epidermal adherence, and patients experience recurring blisters in skin folds. Longitudinal white streaks of the fingernails also may be present.1 The illness does not appear until puberty and is heightened by the second or third decade of life. Family history often suggests the presence of disease.2 Misdiagnosis of HHD occurs because of a wide spectrum of presentations. The presence of superimposed infections and carcinomas may both obscure and exacerbate this disease.2

Herpes simplex viruse types 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and HSV-2) are DNA viruses that cause common recurrent diseases. Usually, HSV-1 is associated with infection of the mouth and HSV-2 is associated with infection of the genitalia.3 Longitudinal cutaneous lesions manifest as grouped vesicles on an erythematous base. Tzanck smear of herpetic vesicles will reveal the presence of multinucleated giant cells. A direct fluorescent antibody technique also may be used to confirm the diagnosis.3

Erythrodermic HHD disease is a rare condition; moreover, there are only a few reported cases with coexistence of HHD and HSV in the literature.3-6 We report a rare presentation of erythrodermic HHD and coexistent psoriasis with HSV superinfection.

A 69-year-old man presented to an outpatient dermatology clinic for evaluation and treatment of a rash on the scalp, face, back, and lower legs. The patient confirmed a dandruff diagnosis on the scalp and face as well as psoriasis on the trunk and extremities for the last 45 years. He described a history of successful treatment with topical agents and UV light therapy. A family history revealed that the patient’s father and 1 of 2 siblings had a similar rash and “skin problems.” The patient had a medical history of thyroid cancer treated with radiation treatment and a partial thyroidectomy 35 years prior to the current presentation as well as incompletely treated chronic hepatitis C.

A search of medical records revealed a punch biopsy from the posterior neck that demonstrated an acantholytic dyskeratosis with suprabasal acantholysis. Clinicians were unable to differentiate if it was Darier disease (DAR) or HHD. Treatment of the patient’s seborrheic dermatitis and acantholytic disorder was successful at that time with ketoconazole shampoo, ketoconazole cream, desonide cream, and triamcinolone cream. The patient remained stable for 5 years before presenting again to the dermatology clinic for worsening rash despite topical therapies.

At the current presentation, physical examination at the outpatient dermatology clinic revealed few scaly, erythematous, eroded papules distributed on the mid-back; erythematous greasy scaling on the scalp, face, and chest; and pink scaly plaques with white-silvery scale on the anterior lower legs. Histopathology of a specimen from the right mid-back demonstrated acantholysis with suprabasal clefting, hyperkeratosis, and parakeratosis with no dyskeratotic cells identified. The pathologic differential diagnosis included primary acantholytic processes including Grover disease, DAR, HHD, and pemphigus. Pathology from the right shin demonstrated acanthosis, confluent parakeratosis with associated decreased granular cell layer and collections of neutrophils within the stratum corneum, spongiosis, and superficial dermal perivascular chronic inflammation with focal exocytosis and dilated blood vessels in the papillary dermis. The clinical and pathological diagnosis on the lower legs was consistent with psoriasis. Diagnoses of seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis on the lower legs, and HHD vs DAR on the back and chest were made. The patient was instructed to continue ketoconazole shampoo, ketoconazole cream, and desonide for seborrheic dermatitis; fluocinonide ointment 0.05% to the lower legs for psoriasis; and triamcinolone cream and a bland moisturizer to the back and chest for HHD.

Over the ensuing months, the rash worsened with erythema and scaling affecting more than half of the body surface area. Topical corticosteroids and bland emollients resulted in minimal success. Biologics and acitretin were considered for the psoriasiform dermatitis but avoided due to the patient’s medical history of thyroid cancer and chronic hepatitis C infection. Because the patient described prior success with UV light therapy for psoriasis, he requested light therapy. A subsequent trial of narrowband UVB light therapy initially improved some of the psoriasiform dermatitis on the trunk and extremities; however, after 4 weeks of treatment, the patient described pain in some of the skin and felt he was burned by minimal exposure to light therapy on one particular visit, which caused him to stop light therapy.

Approximately 2 weeks later, the patient presented to the emergency department stating his psoriasis was infected; he was diagnosed with psoriasis with secondary cellulitis and received intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam, with bacterial cultures demonstrating Corynebacterium and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Some improvement was noted in the patient’s skin after antibiotics were initiated, but he continued to describe worsening “burning and pain” throughout the psoriasis lesions. The patient’s care was transferred to the Veterans Affairs hospital where a dermatology inpatient consultation was placed.

Our initial dermatologic examination revealed generalized scaly erythroderma on the neck, trunk, and extremities, sparing the face, palms, and soles (Figure 1). Multiple crusted and intact vesicles also were present overlying the erythematous plaques on the chest, back, and proximal extremities, most grouped in clusters. The patient endorsed new symptoms of pain and burning. Tzanck smear from the abdomen along with shave biopsies from the left flank and right abdomen were performed, and intravenous acyclovir was initiated immediately after these procedures.

Viral cultures were taken but were incorrectly processed by the laboratory. Tzanck smear showed severe acute inflammation with numerous neutrophils, multinucleated giant cells with viral nuclear changes, and positive immunostaining for HSV and negative immunostaining for herpes zoster. Both pathology specimens revealed an intense acute mixed, mainly neutrophilic, inflammatory infiltrate extending into the deeper dermis as well as distorted and necrotic hair follicles, some of which displayed multinucleated epithelial cells with margination of chromatin that were positive for both HSV-1 and HSV-2 and negative for herpes zoster (Figure 2). The positivity of both HSV strains might represent co-infection or could be a cross-reaction of antibodies used in immunohistochemistry to the HSV antigens. There was acantholysis surrounding the ulceration and extending through the full thickness of the epidermis with a dilapidated brick wall pattern (Figure 3) as well as negative immunohistochemical staining for HSV-1 and HSV-2 antigens. The clinical and histological picture together, along with prior clinical and pathological reports, confirmed the diagnoses of acute erythrodermic HHD with HSV superinfection.

The patient’s condition and pain improved within 24 hours on intravenous acyclovir. On the third day, his lesions were resolving and symptoms improved, so he was transitioned to oral acyclovir and discharged from the hospital. Follow-up in the dermatology outpatient clinic 1 week later revealed that all vesicles and papules had cleared, but the patient was still erythrodermic. Because HHD cannot always be distinguished histologically from other forms of pemphigus but yields a negative immunofluorescence, direct immunofluorescence and indirect immunofluorescence were obtained upon patient follow-up in the clinic and were both negative. Hepatitis C viral loads were undetectable. Consultations to gastroenterology and oncology teams were placed for consideration of systemic agents, and the patient was initiated on oral acitretin 25 mg daily, along with clobetasol as adjuvant therapy for any residual skin plaques. The laboratory results were closely monitored. Within 4 weeks after starting acitretin, the patient’s erythroderma had completely resolved. The patient has remained stable since then, except for one episode of secondary Staphylococcus infection that cleared on oral antibiotics. The patient remains stable and clear on oral acitretin 25 mg daily, with concomitant desonide cream and fluocinonide ointment as needed.

Hailey-Hailey disease is characterized by recurrent episodes of erythema, blisters, and plaques localized to intertriginous and perianal areas.1,2 Patients display a spectrum of lesions that vary in severity.8 Typical histologic examination reveals a dilapidated brick wall appearance. Pathology of well-developed lesions will show suprabasal acantholysis with minimal dyskeratosis.2

The generalized form of HHD is an extremely rare variant of the disease.10 Generalized HHD may resemble acute hypersensitivity reaction, erythema multiforme, and toxic epidermal necrolysis.1 Chronic diseases, such as psoriasis (as in this patient), also may contribute to a clinically confusing picture.8 Hailey-Hailey disease and psoriasis are thought to occasionally koebnerize (isomorphic response) to areas of trauma.16 Our patient experienced widespread erythematous papules and plaques not restricted to skin folds. His skin lesions continued to worsen over several months progressing to erythroderma. The presence of suprabasal acantholysis in a dilapidated brick wall pattern, along with the patient’s history, prior pathology reports, clinical picture, and negative direct immunofluorescence and indirect immunofluorescence studies helped to confirm the diagnosis of erythrodermic HHD.

Hailey-Hailey disease is caused by heterozygous mutations in the ATP2C1 gene on chromosome 3q21-24 coding for a Golgi ATPase called SPCA1 (secretory pathway calcium/manganese-ATPase).9 Subsequent disturbances in cytosolic-Golgi calcium concentrations interfere with epidermal keratinocyte adherence resulting in acantholytic disease. Studies of interfamilial and intrafamilial mutations fail to pinpoint a common mutation pattern among patients with generalized phenotypes,9 which further supports theories that intrinsic or extrinsic factors such as friction, heat, radiation, contact allergens, and infection affect the severity of HHD disease and not the type of mutation.3,9

Generalization of HHD is likely caused by nonspecific triggers in an already genetically disturbed epidermis.10 Interrupted epithelial function exposes skin to infections that exacerbate the underlying disease. Superimposing bacterial infections are commonly reported in HHD. Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Candida species colonize the skin and aggravate the disease.11 Much less commonly, HSV superinfection can complicate HHD.3-7 No data are currently available about the frequency or incidence of Herpesviridae in HHD.7 Some studies suggest that UVB light therapy can be an exacerbating factor in DAR and some but not all HHD patients,12,13 while other case reports14,15 document clinically improved responses using phototherapy for patients with HHD. Clinicians should remain suspicious and evaluate for HSV infection in refractory or sudden exacerbation of HHD.7 Furthermore, coexistent psoriasis and HHD also is a rare entity but has been described,8 which illustrates the importance of not attributing all skin manifestations to a previously diagnosed disorder but instead keeping an open mind in case new dermatologic conditions present themselves at a later time.

We present a rare case of erythrodermic HHD and coexistent psoriasis with HSV superinfection. We hope to draw awareness to this association of generalized HHD with both HSV and psoriasis to help clinicians make the correct diagnosis promptly in similar cases in the future.

- Chave TA, Milligan A. Acute generalized Hailey-Hailey disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:290-292.

- Mohr MR, Erdag G, Shada Al, et al. Two patients with Hailey-Hailey disease, multiple primary melanomas, and other cancers. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:211-215.

- Lee GM, Kim YM, Lee SY, et al. A case of eczema herpeticum with Hailey-Hailey Disease. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:311-314.

- Zaim MT, Bickers DR. Herpes simplex associated with Hailey-Hailey disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:701-702.

- Peppiatt T, Keefe M, White JE. Hailey-Hailey disease-exacerbation by herpes simplex virus and patch tests. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;17:201-202.

- Almeida L, Grossman ME. Benign familial pemphigus complicated by herpes simplex virus. Cutis. 1989;44:261-262.

- Nikkels AF, Delvenne P, Herfs M, et al. Occult herpes simplex virus colonization of bullous dermatitides. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:163-168.

- Chao SC, Lee JY, Wu MC, et al. A novel splice mutation in the ATP2C1 gene in a woman with concomitant psoriasis vulgaris and disseminated Hailey-Hailey disease. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:947-951.

- Ikeda S, Shigihara T, Mayuzumi N, et al. Mutations of ATP2C1 in Japanese patients with Hailey-Hailey disease: intrafamilial and interfamilial phenotype variations and lack of correlation with mutation patterns. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:1654-1656.

- Marsch W, Stuttgen G. Generalized Hailey-Hailey disease. Br J Dermatol. 1978;99:553-559.

- Friedman-Birnbaum R, Haim S, Marcus S. Generalized familial benign chronic pemphigus. Dermatologica. 1980;161:112-115.

- Richard G, Linse R, Harth W. Hailey-Hailey disease. early detection of heterozygotes by an ultraviolet provocation tests—clinical relevance of the method. Hautarzt. 1993;44:376-379.

- Mayuzumi N, Ikeda S, Kawada H, et al. Effects of ultraviolet B irradiation, proinflammatory cytokines and raised extracellular calcium concentration on the expression of ATP2A2 and ATP2C1. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:697-701.

- Vanderbeck KA, Giroux L, Murugan NJ, et al. Combined therapeutic use of oral alitretinoin and narrowband ultraviolet-B therapy in the treatment of Hailey-Hailey disease. Dermatol Rep. 2014;6:5604.

- Mizuno K, Hamada T, Hasimoto T, et al. Successful treatment with narrow-band UVB therapy for a case of generalized Hailey-Hailey disease with a novel splice-site mutation in ATP2C1 gene. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:233-235.

- Thappa DM. The isomorphic phenomenon of Koebner. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2004;70:187-189.

To the Editor:

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD), also known as benign familial pemphigus, is an uncommon autosomal-dominant skin disease.1 Defects in the ATPase type 2C member 1 gene, ATP2C1, result in abnormal intracellular epidermal adherence, and patients experience recurring blisters in skin folds. Longitudinal white streaks of the fingernails also may be present.1 The illness does not appear until puberty and is heightened by the second or third decade of life. Family history often suggests the presence of disease.2 Misdiagnosis of HHD occurs because of a wide spectrum of presentations. The presence of superimposed infections and carcinomas may both obscure and exacerbate this disease.2

Herpes simplex viruse types 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and HSV-2) are DNA viruses that cause common recurrent diseases. Usually, HSV-1 is associated with infection of the mouth and HSV-2 is associated with infection of the genitalia.3 Longitudinal cutaneous lesions manifest as grouped vesicles on an erythematous base. Tzanck smear of herpetic vesicles will reveal the presence of multinucleated giant cells. A direct fluorescent antibody technique also may be used to confirm the diagnosis.3

Erythrodermic HHD disease is a rare condition; moreover, there are only a few reported cases with coexistence of HHD and HSV in the literature.3-6 We report a rare presentation of erythrodermic HHD and coexistent psoriasis with HSV superinfection.

A 69-year-old man presented to an outpatient dermatology clinic for evaluation and treatment of a rash on the scalp, face, back, and lower legs. The patient confirmed a dandruff diagnosis on the scalp and face as well as psoriasis on the trunk and extremities for the last 45 years. He described a history of successful treatment with topical agents and UV light therapy. A family history revealed that the patient’s father and 1 of 2 siblings had a similar rash and “skin problems.” The patient had a medical history of thyroid cancer treated with radiation treatment and a partial thyroidectomy 35 years prior to the current presentation as well as incompletely treated chronic hepatitis C.

A search of medical records revealed a punch biopsy from the posterior neck that demonstrated an acantholytic dyskeratosis with suprabasal acantholysis. Clinicians were unable to differentiate if it was Darier disease (DAR) or HHD. Treatment of the patient’s seborrheic dermatitis and acantholytic disorder was successful at that time with ketoconazole shampoo, ketoconazole cream, desonide cream, and triamcinolone cream. The patient remained stable for 5 years before presenting again to the dermatology clinic for worsening rash despite topical therapies.

At the current presentation, physical examination at the outpatient dermatology clinic revealed few scaly, erythematous, eroded papules distributed on the mid-back; erythematous greasy scaling on the scalp, face, and chest; and pink scaly plaques with white-silvery scale on the anterior lower legs. Histopathology of a specimen from the right mid-back demonstrated acantholysis with suprabasal clefting, hyperkeratosis, and parakeratosis with no dyskeratotic cells identified. The pathologic differential diagnosis included primary acantholytic processes including Grover disease, DAR, HHD, and pemphigus. Pathology from the right shin demonstrated acanthosis, confluent parakeratosis with associated decreased granular cell layer and collections of neutrophils within the stratum corneum, spongiosis, and superficial dermal perivascular chronic inflammation with focal exocytosis and dilated blood vessels in the papillary dermis. The clinical and pathological diagnosis on the lower legs was consistent with psoriasis. Diagnoses of seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis on the lower legs, and HHD vs DAR on the back and chest were made. The patient was instructed to continue ketoconazole shampoo, ketoconazole cream, and desonide for seborrheic dermatitis; fluocinonide ointment 0.05% to the lower legs for psoriasis; and triamcinolone cream and a bland moisturizer to the back and chest for HHD.

Over the ensuing months, the rash worsened with erythema and scaling affecting more than half of the body surface area. Topical corticosteroids and bland emollients resulted in minimal success. Biologics and acitretin were considered for the psoriasiform dermatitis but avoided due to the patient’s medical history of thyroid cancer and chronic hepatitis C infection. Because the patient described prior success with UV light therapy for psoriasis, he requested light therapy. A subsequent trial of narrowband UVB light therapy initially improved some of the psoriasiform dermatitis on the trunk and extremities; however, after 4 weeks of treatment, the patient described pain in some of the skin and felt he was burned by minimal exposure to light therapy on one particular visit, which caused him to stop light therapy.

Approximately 2 weeks later, the patient presented to the emergency department stating his psoriasis was infected; he was diagnosed with psoriasis with secondary cellulitis and received intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam, with bacterial cultures demonstrating Corynebacterium and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Some improvement was noted in the patient’s skin after antibiotics were initiated, but he continued to describe worsening “burning and pain” throughout the psoriasis lesions. The patient’s care was transferred to the Veterans Affairs hospital where a dermatology inpatient consultation was placed.

Our initial dermatologic examination revealed generalized scaly erythroderma on the neck, trunk, and extremities, sparing the face, palms, and soles (Figure 1). Multiple crusted and intact vesicles also were present overlying the erythematous plaques on the chest, back, and proximal extremities, most grouped in clusters. The patient endorsed new symptoms of pain and burning. Tzanck smear from the abdomen along with shave biopsies from the left flank and right abdomen were performed, and intravenous acyclovir was initiated immediately after these procedures.

Viral cultures were taken but were incorrectly processed by the laboratory. Tzanck smear showed severe acute inflammation with numerous neutrophils, multinucleated giant cells with viral nuclear changes, and positive immunostaining for HSV and negative immunostaining for herpes zoster. Both pathology specimens revealed an intense acute mixed, mainly neutrophilic, inflammatory infiltrate extending into the deeper dermis as well as distorted and necrotic hair follicles, some of which displayed multinucleated epithelial cells with margination of chromatin that were positive for both HSV-1 and HSV-2 and negative for herpes zoster (Figure 2). The positivity of both HSV strains might represent co-infection or could be a cross-reaction of antibodies used in immunohistochemistry to the HSV antigens. There was acantholysis surrounding the ulceration and extending through the full thickness of the epidermis with a dilapidated brick wall pattern (Figure 3) as well as negative immunohistochemical staining for HSV-1 and HSV-2 antigens. The clinical and histological picture together, along with prior clinical and pathological reports, confirmed the diagnoses of acute erythrodermic HHD with HSV superinfection.

The patient’s condition and pain improved within 24 hours on intravenous acyclovir. On the third day, his lesions were resolving and symptoms improved, so he was transitioned to oral acyclovir and discharged from the hospital. Follow-up in the dermatology outpatient clinic 1 week later revealed that all vesicles and papules had cleared, but the patient was still erythrodermic. Because HHD cannot always be distinguished histologically from other forms of pemphigus but yields a negative immunofluorescence, direct immunofluorescence and indirect immunofluorescence were obtained upon patient follow-up in the clinic and were both negative. Hepatitis C viral loads were undetectable. Consultations to gastroenterology and oncology teams were placed for consideration of systemic agents, and the patient was initiated on oral acitretin 25 mg daily, along with clobetasol as adjuvant therapy for any residual skin plaques. The laboratory results were closely monitored. Within 4 weeks after starting acitretin, the patient’s erythroderma had completely resolved. The patient has remained stable since then, except for one episode of secondary Staphylococcus infection that cleared on oral antibiotics. The patient remains stable and clear on oral acitretin 25 mg daily, with concomitant desonide cream and fluocinonide ointment as needed.

Hailey-Hailey disease is characterized by recurrent episodes of erythema, blisters, and plaques localized to intertriginous and perianal areas.1,2 Patients display a spectrum of lesions that vary in severity.8 Typical histologic examination reveals a dilapidated brick wall appearance. Pathology of well-developed lesions will show suprabasal acantholysis with minimal dyskeratosis.2

The generalized form of HHD is an extremely rare variant of the disease.10 Generalized HHD may resemble acute hypersensitivity reaction, erythema multiforme, and toxic epidermal necrolysis.1 Chronic diseases, such as psoriasis (as in this patient), also may contribute to a clinically confusing picture.8 Hailey-Hailey disease and psoriasis are thought to occasionally koebnerize (isomorphic response) to areas of trauma.16 Our patient experienced widespread erythematous papules and plaques not restricted to skin folds. His skin lesions continued to worsen over several months progressing to erythroderma. The presence of suprabasal acantholysis in a dilapidated brick wall pattern, along with the patient’s history, prior pathology reports, clinical picture, and negative direct immunofluorescence and indirect immunofluorescence studies helped to confirm the diagnosis of erythrodermic HHD.

Hailey-Hailey disease is caused by heterozygous mutations in the ATP2C1 gene on chromosome 3q21-24 coding for a Golgi ATPase called SPCA1 (secretory pathway calcium/manganese-ATPase).9 Subsequent disturbances in cytosolic-Golgi calcium concentrations interfere with epidermal keratinocyte adherence resulting in acantholytic disease. Studies of interfamilial and intrafamilial mutations fail to pinpoint a common mutation pattern among patients with generalized phenotypes,9 which further supports theories that intrinsic or extrinsic factors such as friction, heat, radiation, contact allergens, and infection affect the severity of HHD disease and not the type of mutation.3,9

Generalization of HHD is likely caused by nonspecific triggers in an already genetically disturbed epidermis.10 Interrupted epithelial function exposes skin to infections that exacerbate the underlying disease. Superimposing bacterial infections are commonly reported in HHD. Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Candida species colonize the skin and aggravate the disease.11 Much less commonly, HSV superinfection can complicate HHD.3-7 No data are currently available about the frequency or incidence of Herpesviridae in HHD.7 Some studies suggest that UVB light therapy can be an exacerbating factor in DAR and some but not all HHD patients,12,13 while other case reports14,15 document clinically improved responses using phototherapy for patients with HHD. Clinicians should remain suspicious and evaluate for HSV infection in refractory or sudden exacerbation of HHD.7 Furthermore, coexistent psoriasis and HHD also is a rare entity but has been described,8 which illustrates the importance of not attributing all skin manifestations to a previously diagnosed disorder but instead keeping an open mind in case new dermatologic conditions present themselves at a later time.

We present a rare case of erythrodermic HHD and coexistent psoriasis with HSV superinfection. We hope to draw awareness to this association of generalized HHD with both HSV and psoriasis to help clinicians make the correct diagnosis promptly in similar cases in the future.

To the Editor:

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD), also known as benign familial pemphigus, is an uncommon autosomal-dominant skin disease.1 Defects in the ATPase type 2C member 1 gene, ATP2C1, result in abnormal intracellular epidermal adherence, and patients experience recurring blisters in skin folds. Longitudinal white streaks of the fingernails also may be present.1 The illness does not appear until puberty and is heightened by the second or third decade of life. Family history often suggests the presence of disease.2 Misdiagnosis of HHD occurs because of a wide spectrum of presentations. The presence of superimposed infections and carcinomas may both obscure and exacerbate this disease.2

Herpes simplex viruse types 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and HSV-2) are DNA viruses that cause common recurrent diseases. Usually, HSV-1 is associated with infection of the mouth and HSV-2 is associated with infection of the genitalia.3 Longitudinal cutaneous lesions manifest as grouped vesicles on an erythematous base. Tzanck smear of herpetic vesicles will reveal the presence of multinucleated giant cells. A direct fluorescent antibody technique also may be used to confirm the diagnosis.3

Erythrodermic HHD disease is a rare condition; moreover, there are only a few reported cases with coexistence of HHD and HSV in the literature.3-6 We report a rare presentation of erythrodermic HHD and coexistent psoriasis with HSV superinfection.

A 69-year-old man presented to an outpatient dermatology clinic for evaluation and treatment of a rash on the scalp, face, back, and lower legs. The patient confirmed a dandruff diagnosis on the scalp and face as well as psoriasis on the trunk and extremities for the last 45 years. He described a history of successful treatment with topical agents and UV light therapy. A family history revealed that the patient’s father and 1 of 2 siblings had a similar rash and “skin problems.” The patient had a medical history of thyroid cancer treated with radiation treatment and a partial thyroidectomy 35 years prior to the current presentation as well as incompletely treated chronic hepatitis C.

A search of medical records revealed a punch biopsy from the posterior neck that demonstrated an acantholytic dyskeratosis with suprabasal acantholysis. Clinicians were unable to differentiate if it was Darier disease (DAR) or HHD. Treatment of the patient’s seborrheic dermatitis and acantholytic disorder was successful at that time with ketoconazole shampoo, ketoconazole cream, desonide cream, and triamcinolone cream. The patient remained stable for 5 years before presenting again to the dermatology clinic for worsening rash despite topical therapies.

At the current presentation, physical examination at the outpatient dermatology clinic revealed few scaly, erythematous, eroded papules distributed on the mid-back; erythematous greasy scaling on the scalp, face, and chest; and pink scaly plaques with white-silvery scale on the anterior lower legs. Histopathology of a specimen from the right mid-back demonstrated acantholysis with suprabasal clefting, hyperkeratosis, and parakeratosis with no dyskeratotic cells identified. The pathologic differential diagnosis included primary acantholytic processes including Grover disease, DAR, HHD, and pemphigus. Pathology from the right shin demonstrated acanthosis, confluent parakeratosis with associated decreased granular cell layer and collections of neutrophils within the stratum corneum, spongiosis, and superficial dermal perivascular chronic inflammation with focal exocytosis and dilated blood vessels in the papillary dermis. The clinical and pathological diagnosis on the lower legs was consistent with psoriasis. Diagnoses of seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis on the lower legs, and HHD vs DAR on the back and chest were made. The patient was instructed to continue ketoconazole shampoo, ketoconazole cream, and desonide for seborrheic dermatitis; fluocinonide ointment 0.05% to the lower legs for psoriasis; and triamcinolone cream and a bland moisturizer to the back and chest for HHD.

Over the ensuing months, the rash worsened with erythema and scaling affecting more than half of the body surface area. Topical corticosteroids and bland emollients resulted in minimal success. Biologics and acitretin were considered for the psoriasiform dermatitis but avoided due to the patient’s medical history of thyroid cancer and chronic hepatitis C infection. Because the patient described prior success with UV light therapy for psoriasis, he requested light therapy. A subsequent trial of narrowband UVB light therapy initially improved some of the psoriasiform dermatitis on the trunk and extremities; however, after 4 weeks of treatment, the patient described pain in some of the skin and felt he was burned by minimal exposure to light therapy on one particular visit, which caused him to stop light therapy.

Approximately 2 weeks later, the patient presented to the emergency department stating his psoriasis was infected; he was diagnosed with psoriasis with secondary cellulitis and received intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam, with bacterial cultures demonstrating Corynebacterium and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Some improvement was noted in the patient’s skin after antibiotics were initiated, but he continued to describe worsening “burning and pain” throughout the psoriasis lesions. The patient’s care was transferred to the Veterans Affairs hospital where a dermatology inpatient consultation was placed.

Our initial dermatologic examination revealed generalized scaly erythroderma on the neck, trunk, and extremities, sparing the face, palms, and soles (Figure 1). Multiple crusted and intact vesicles also were present overlying the erythematous plaques on the chest, back, and proximal extremities, most grouped in clusters. The patient endorsed new symptoms of pain and burning. Tzanck smear from the abdomen along with shave biopsies from the left flank and right abdomen were performed, and intravenous acyclovir was initiated immediately after these procedures.

Viral cultures were taken but were incorrectly processed by the laboratory. Tzanck smear showed severe acute inflammation with numerous neutrophils, multinucleated giant cells with viral nuclear changes, and positive immunostaining for HSV and negative immunostaining for herpes zoster. Both pathology specimens revealed an intense acute mixed, mainly neutrophilic, inflammatory infiltrate extending into the deeper dermis as well as distorted and necrotic hair follicles, some of which displayed multinucleated epithelial cells with margination of chromatin that were positive for both HSV-1 and HSV-2 and negative for herpes zoster (Figure 2). The positivity of both HSV strains might represent co-infection or could be a cross-reaction of antibodies used in immunohistochemistry to the HSV antigens. There was acantholysis surrounding the ulceration and extending through the full thickness of the epidermis with a dilapidated brick wall pattern (Figure 3) as well as negative immunohistochemical staining for HSV-1 and HSV-2 antigens. The clinical and histological picture together, along with prior clinical and pathological reports, confirmed the diagnoses of acute erythrodermic HHD with HSV superinfection.

The patient’s condition and pain improved within 24 hours on intravenous acyclovir. On the third day, his lesions were resolving and symptoms improved, so he was transitioned to oral acyclovir and discharged from the hospital. Follow-up in the dermatology outpatient clinic 1 week later revealed that all vesicles and papules had cleared, but the patient was still erythrodermic. Because HHD cannot always be distinguished histologically from other forms of pemphigus but yields a negative immunofluorescence, direct immunofluorescence and indirect immunofluorescence were obtained upon patient follow-up in the clinic and were both negative. Hepatitis C viral loads were undetectable. Consultations to gastroenterology and oncology teams were placed for consideration of systemic agents, and the patient was initiated on oral acitretin 25 mg daily, along with clobetasol as adjuvant therapy for any residual skin plaques. The laboratory results were closely monitored. Within 4 weeks after starting acitretin, the patient’s erythroderma had completely resolved. The patient has remained stable since then, except for one episode of secondary Staphylococcus infection that cleared on oral antibiotics. The patient remains stable and clear on oral acitretin 25 mg daily, with concomitant desonide cream and fluocinonide ointment as needed.

Hailey-Hailey disease is characterized by recurrent episodes of erythema, blisters, and plaques localized to intertriginous and perianal areas.1,2 Patients display a spectrum of lesions that vary in severity.8 Typical histologic examination reveals a dilapidated brick wall appearance. Pathology of well-developed lesions will show suprabasal acantholysis with minimal dyskeratosis.2

The generalized form of HHD is an extremely rare variant of the disease.10 Generalized HHD may resemble acute hypersensitivity reaction, erythema multiforme, and toxic epidermal necrolysis.1 Chronic diseases, such as psoriasis (as in this patient), also may contribute to a clinically confusing picture.8 Hailey-Hailey disease and psoriasis are thought to occasionally koebnerize (isomorphic response) to areas of trauma.16 Our patient experienced widespread erythematous papules and plaques not restricted to skin folds. His skin lesions continued to worsen over several months progressing to erythroderma. The presence of suprabasal acantholysis in a dilapidated brick wall pattern, along with the patient’s history, prior pathology reports, clinical picture, and negative direct immunofluorescence and indirect immunofluorescence studies helped to confirm the diagnosis of erythrodermic HHD.

Hailey-Hailey disease is caused by heterozygous mutations in the ATP2C1 gene on chromosome 3q21-24 coding for a Golgi ATPase called SPCA1 (secretory pathway calcium/manganese-ATPase).9 Subsequent disturbances in cytosolic-Golgi calcium concentrations interfere with epidermal keratinocyte adherence resulting in acantholytic disease. Studies of interfamilial and intrafamilial mutations fail to pinpoint a common mutation pattern among patients with generalized phenotypes,9 which further supports theories that intrinsic or extrinsic factors such as friction, heat, radiation, contact allergens, and infection affect the severity of HHD disease and not the type of mutation.3,9

Generalization of HHD is likely caused by nonspecific triggers in an already genetically disturbed epidermis.10 Interrupted epithelial function exposes skin to infections that exacerbate the underlying disease. Superimposing bacterial infections are commonly reported in HHD. Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Candida species colonize the skin and aggravate the disease.11 Much less commonly, HSV superinfection can complicate HHD.3-7 No data are currently available about the frequency or incidence of Herpesviridae in HHD.7 Some studies suggest that UVB light therapy can be an exacerbating factor in DAR and some but not all HHD patients,12,13 while other case reports14,15 document clinically improved responses using phototherapy for patients with HHD. Clinicians should remain suspicious and evaluate for HSV infection in refractory or sudden exacerbation of HHD.7 Furthermore, coexistent psoriasis and HHD also is a rare entity but has been described,8 which illustrates the importance of not attributing all skin manifestations to a previously diagnosed disorder but instead keeping an open mind in case new dermatologic conditions present themselves at a later time.

We present a rare case of erythrodermic HHD and coexistent psoriasis with HSV superinfection. We hope to draw awareness to this association of generalized HHD with both HSV and psoriasis to help clinicians make the correct diagnosis promptly in similar cases in the future.

- Chave TA, Milligan A. Acute generalized Hailey-Hailey disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:290-292.

- Mohr MR, Erdag G, Shada Al, et al. Two patients with Hailey-Hailey disease, multiple primary melanomas, and other cancers. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:211-215.

- Lee GM, Kim YM, Lee SY, et al. A case of eczema herpeticum with Hailey-Hailey Disease. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:311-314.

- Zaim MT, Bickers DR. Herpes simplex associated with Hailey-Hailey disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:701-702.

- Peppiatt T, Keefe M, White JE. Hailey-Hailey disease-exacerbation by herpes simplex virus and patch tests. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;17:201-202.

- Almeida L, Grossman ME. Benign familial pemphigus complicated by herpes simplex virus. Cutis. 1989;44:261-262.

- Nikkels AF, Delvenne P, Herfs M, et al. Occult herpes simplex virus colonization of bullous dermatitides. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:163-168.

- Chao SC, Lee JY, Wu MC, et al. A novel splice mutation in the ATP2C1 gene in a woman with concomitant psoriasis vulgaris and disseminated Hailey-Hailey disease. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:947-951.

- Ikeda S, Shigihara T, Mayuzumi N, et al. Mutations of ATP2C1 in Japanese patients with Hailey-Hailey disease: intrafamilial and interfamilial phenotype variations and lack of correlation with mutation patterns. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:1654-1656.

- Marsch W, Stuttgen G. Generalized Hailey-Hailey disease. Br J Dermatol. 1978;99:553-559.

- Friedman-Birnbaum R, Haim S, Marcus S. Generalized familial benign chronic pemphigus. Dermatologica. 1980;161:112-115.

- Richard G, Linse R, Harth W. Hailey-Hailey disease. early detection of heterozygotes by an ultraviolet provocation tests—clinical relevance of the method. Hautarzt. 1993;44:376-379.

- Mayuzumi N, Ikeda S, Kawada H, et al. Effects of ultraviolet B irradiation, proinflammatory cytokines and raised extracellular calcium concentration on the expression of ATP2A2 and ATP2C1. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:697-701.

- Vanderbeck KA, Giroux L, Murugan NJ, et al. Combined therapeutic use of oral alitretinoin and narrowband ultraviolet-B therapy in the treatment of Hailey-Hailey disease. Dermatol Rep. 2014;6:5604.

- Mizuno K, Hamada T, Hasimoto T, et al. Successful treatment with narrow-band UVB therapy for a case of generalized Hailey-Hailey disease with a novel splice-site mutation in ATP2C1 gene. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:233-235.

- Thappa DM. The isomorphic phenomenon of Koebner. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2004;70:187-189.

- Chave TA, Milligan A. Acute generalized Hailey-Hailey disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:290-292.

- Mohr MR, Erdag G, Shada Al, et al. Two patients with Hailey-Hailey disease, multiple primary melanomas, and other cancers. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:211-215.

- Lee GM, Kim YM, Lee SY, et al. A case of eczema herpeticum with Hailey-Hailey Disease. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:311-314.

- Zaim MT, Bickers DR. Herpes simplex associated with Hailey-Hailey disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:701-702.

- Peppiatt T, Keefe M, White JE. Hailey-Hailey disease-exacerbation by herpes simplex virus and patch tests. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;17:201-202.

- Almeida L, Grossman ME. Benign familial pemphigus complicated by herpes simplex virus. Cutis. 1989;44:261-262.

- Nikkels AF, Delvenne P, Herfs M, et al. Occult herpes simplex virus colonization of bullous dermatitides. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:163-168.

- Chao SC, Lee JY, Wu MC, et al. A novel splice mutation in the ATP2C1 gene in a woman with concomitant psoriasis vulgaris and disseminated Hailey-Hailey disease. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:947-951.

- Ikeda S, Shigihara T, Mayuzumi N, et al. Mutations of ATP2C1 in Japanese patients with Hailey-Hailey disease: intrafamilial and interfamilial phenotype variations and lack of correlation with mutation patterns. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:1654-1656.

- Marsch W, Stuttgen G. Generalized Hailey-Hailey disease. Br J Dermatol. 1978;99:553-559.

- Friedman-Birnbaum R, Haim S, Marcus S. Generalized familial benign chronic pemphigus. Dermatologica. 1980;161:112-115.

- Richard G, Linse R, Harth W. Hailey-Hailey disease. early detection of heterozygotes by an ultraviolet provocation tests—clinical relevance of the method. Hautarzt. 1993;44:376-379.

- Mayuzumi N, Ikeda S, Kawada H, et al. Effects of ultraviolet B irradiation, proinflammatory cytokines and raised extracellular calcium concentration on the expression of ATP2A2 and ATP2C1. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:697-701.

- Vanderbeck KA, Giroux L, Murugan NJ, et al. Combined therapeutic use of oral alitretinoin and narrowband ultraviolet-B therapy in the treatment of Hailey-Hailey disease. Dermatol Rep. 2014;6:5604.

- Mizuno K, Hamada T, Hasimoto T, et al. Successful treatment with narrow-band UVB therapy for a case of generalized Hailey-Hailey disease with a novel splice-site mutation in ATP2C1 gene. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:233-235.

- Thappa DM. The isomorphic phenomenon of Koebner. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2004;70:187-189.

Practice Points

- Misdiagnosis of Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD) occurs because of a wide spectrum of presentations.

- Hailey-Hailey disease and psoriasis are thought to occasionally koebnerize (isomorphic response) to areas of trauma.

- Clinicians should remain suspicious and evaluate for herpes simplex virus infection in refractory or sudden exacerbation of HHD.

Scalp Psoriasis With Increased Hair Density

Case Report

A 19-year-old man first presented to our outpatient dermatology clinic for evaluation of a rash on the elbows and knees of 2 to 3 months’ duration. The lesions were asymptomatic. A review of symptoms including joint pain was largely negative. His medical history was remarkable for terminal ileitis, Crohn disease, anal fissure, rhabdomyolysis, and viral gastroenteritis. Physical examination revealed a well-nourished man with red, scaly, indurated papules and plaques involving approximately 0.5% of the body surface area. A diagnosis of plaque psoriasis was made, and he was treated with topical corticosteroids for 2 weeks and as needed thereafter.

The patient remained stable for 5 years before presenting again to the dermatology clinic for psoriasis that had now spread to the scalp. Clinical examination revealed a very thin, faintly erythematous, scaly patch associated with increased hair density of the right frontal and parietal scalp (Figure). The patient denied any trauma or injury to the area or application of hair dye. We prescribed clobetasol solution 0.05% twice daily to the affected area of the scalp for 2 weeks, which resulted in minimal resolution of the psoriatic scalp lesion.

Comment

The scalp is a site of predilection in psoriasis, as approximately 80% of psoriasis patients report involvement of the scalp.1 Scalp involvement can dramatically affect a patient’s quality of life and often poses considerable therapeutic challenges for dermatologists.1 Alopecia in the setting of scalp psoriasis is common but is not well understood.2 First described by Shuster3 in 1972, psoriatic alopecia is associated with diminished hair density, follicular miniaturization, sebaceous gland atrophy, and an increased number of dystrophic bulbs in psoriatic plaques.4 It clinically presents as pink scaly plaques consistent with psoriasis with overlying alopecia. There are few instances of psoriatic alopecia reported as cicatricial hair loss and generalized telogen effluvium.2 It is known that a higher proportion of telogen and catagen hairs exist in patients with psoriatic alopecia.5 Additionally, psoriasis patients have more dystrophic hairs in affected and unaffected skin despite no differences in skin when compared to unaffected patients. Many patients achieve hair regrowth following treatment of psoriasis.2

We described a patient with scalp psoriasis who had increased and preserved hair density. Our case suggests that while most patients with scalp psoriasis experience psoriatic alopecia of the lesional skin, some may unconventionally experience increased hair density, which is contradictory to propositions that the friction associated with the application of topical treatments results in breakage of telogen hairs.2 Additionally, the presence of increased hair density in scalp psoriasis can further complicate antipsoriatic treatment by making the scalp inaccessible and topical therapies even more difficult to apply.

- Krueger G, Koo J, Lebwohl M, et al. The impact of psoriasis on quality of life: results of a 1998 National Psoriasis Foundation patient-membership survey. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:280-284.

- George SM, Taylor MR, Farrant PB. Psoriatic alopecia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:717-721.

- Shuster S. Psoriatic alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 1972;87:73-77.

- Wyatt E, Bottoms E, Comaish S. Abnormal hair shafts in psoriasis on scanning electron microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 1972;87:368-373.

- Schoorl WJ, van Baar HJ, van de Kerkhof PC. The hair root pattern in psoriasis of the scalp. Acta Derm Venereol. 1992;72:141-142.

Case Report

A 19-year-old man first presented to our outpatient dermatology clinic for evaluation of a rash on the elbows and knees of 2 to 3 months’ duration. The lesions were asymptomatic. A review of symptoms including joint pain was largely negative. His medical history was remarkable for terminal ileitis, Crohn disease, anal fissure, rhabdomyolysis, and viral gastroenteritis. Physical examination revealed a well-nourished man with red, scaly, indurated papules and plaques involving approximately 0.5% of the body surface area. A diagnosis of plaque psoriasis was made, and he was treated with topical corticosteroids for 2 weeks and as needed thereafter.

The patient remained stable for 5 years before presenting again to the dermatology clinic for psoriasis that had now spread to the scalp. Clinical examination revealed a very thin, faintly erythematous, scaly patch associated with increased hair density of the right frontal and parietal scalp (Figure). The patient denied any trauma or injury to the area or application of hair dye. We prescribed clobetasol solution 0.05% twice daily to the affected area of the scalp for 2 weeks, which resulted in minimal resolution of the psoriatic scalp lesion.

Comment

The scalp is a site of predilection in psoriasis, as approximately 80% of psoriasis patients report involvement of the scalp.1 Scalp involvement can dramatically affect a patient’s quality of life and often poses considerable therapeutic challenges for dermatologists.1 Alopecia in the setting of scalp psoriasis is common but is not well understood.2 First described by Shuster3 in 1972, psoriatic alopecia is associated with diminished hair density, follicular miniaturization, sebaceous gland atrophy, and an increased number of dystrophic bulbs in psoriatic plaques.4 It clinically presents as pink scaly plaques consistent with psoriasis with overlying alopecia. There are few instances of psoriatic alopecia reported as cicatricial hair loss and generalized telogen effluvium.2 It is known that a higher proportion of telogen and catagen hairs exist in patients with psoriatic alopecia.5 Additionally, psoriasis patients have more dystrophic hairs in affected and unaffected skin despite no differences in skin when compared to unaffected patients. Many patients achieve hair regrowth following treatment of psoriasis.2

We described a patient with scalp psoriasis who had increased and preserved hair density. Our case suggests that while most patients with scalp psoriasis experience psoriatic alopecia of the lesional skin, some may unconventionally experience increased hair density, which is contradictory to propositions that the friction associated with the application of topical treatments results in breakage of telogen hairs.2 Additionally, the presence of increased hair density in scalp psoriasis can further complicate antipsoriatic treatment by making the scalp inaccessible and topical therapies even more difficult to apply.

Case Report

A 19-year-old man first presented to our outpatient dermatology clinic for evaluation of a rash on the elbows and knees of 2 to 3 months’ duration. The lesions were asymptomatic. A review of symptoms including joint pain was largely negative. His medical history was remarkable for terminal ileitis, Crohn disease, anal fissure, rhabdomyolysis, and viral gastroenteritis. Physical examination revealed a well-nourished man with red, scaly, indurated papules and plaques involving approximately 0.5% of the body surface area. A diagnosis of plaque psoriasis was made, and he was treated with topical corticosteroids for 2 weeks and as needed thereafter.

The patient remained stable for 5 years before presenting again to the dermatology clinic for psoriasis that had now spread to the scalp. Clinical examination revealed a very thin, faintly erythematous, scaly patch associated with increased hair density of the right frontal and parietal scalp (Figure). The patient denied any trauma or injury to the area or application of hair dye. We prescribed clobetasol solution 0.05% twice daily to the affected area of the scalp for 2 weeks, which resulted in minimal resolution of the psoriatic scalp lesion.

Comment

The scalp is a site of predilection in psoriasis, as approximately 80% of psoriasis patients report involvement of the scalp.1 Scalp involvement can dramatically affect a patient’s quality of life and often poses considerable therapeutic challenges for dermatologists.1 Alopecia in the setting of scalp psoriasis is common but is not well understood.2 First described by Shuster3 in 1972, psoriatic alopecia is associated with diminished hair density, follicular miniaturization, sebaceous gland atrophy, and an increased number of dystrophic bulbs in psoriatic plaques.4 It clinically presents as pink scaly plaques consistent with psoriasis with overlying alopecia. There are few instances of psoriatic alopecia reported as cicatricial hair loss and generalized telogen effluvium.2 It is known that a higher proportion of telogen and catagen hairs exist in patients with psoriatic alopecia.5 Additionally, psoriasis patients have more dystrophic hairs in affected and unaffected skin despite no differences in skin when compared to unaffected patients. Many patients achieve hair regrowth following treatment of psoriasis.2

We described a patient with scalp psoriasis who had increased and preserved hair density. Our case suggests that while most patients with scalp psoriasis experience psoriatic alopecia of the lesional skin, some may unconventionally experience increased hair density, which is contradictory to propositions that the friction associated with the application of topical treatments results in breakage of telogen hairs.2 Additionally, the presence of increased hair density in scalp psoriasis can further complicate antipsoriatic treatment by making the scalp inaccessible and topical therapies even more difficult to apply.

- Krueger G, Koo J, Lebwohl M, et al. The impact of psoriasis on quality of life: results of a 1998 National Psoriasis Foundation patient-membership survey. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:280-284.

- George SM, Taylor MR, Farrant PB. Psoriatic alopecia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:717-721.

- Shuster S. Psoriatic alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 1972;87:73-77.

- Wyatt E, Bottoms E, Comaish S. Abnormal hair shafts in psoriasis on scanning electron microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 1972;87:368-373.

- Schoorl WJ, van Baar HJ, van de Kerkhof PC. The hair root pattern in psoriasis of the scalp. Acta Derm Venereol. 1992;72:141-142.

- Krueger G, Koo J, Lebwohl M, et al. The impact of psoriasis on quality of life: results of a 1998 National Psoriasis Foundation patient-membership survey. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:280-284.

- George SM, Taylor MR, Farrant PB. Psoriatic alopecia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:717-721.

- Shuster S. Psoriatic alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 1972;87:73-77.

- Wyatt E, Bottoms E, Comaish S. Abnormal hair shafts in psoriasis on scanning electron microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 1972;87:368-373.

- Schoorl WJ, van Baar HJ, van de Kerkhof PC. The hair root pattern in psoriasis of the scalp. Acta Derm Venereol. 1992;72:141-142.

Practice Points

- Scalp psoriasis may present with hair loss or increased hair density.

- Psoriasis with increased hair density may make topical medications more difficult to apply.

A Review of Neurologic Complications of Biologic Therapy in Plaque Psoriasis

Biologic agents have provided patients with moderate to severe psoriasis with treatment alternatives that have improved systemic safety profiles and disease control1; however, case reports of associated neurologic complications have been emerging. Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitors have been associated with central and peripheral demyelinating disorders. Notably, efalizumab was withdrawn from the market for its association with fatal cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML).2,3 It is imperative for dermatologists to be familiar with the clinical presentation, evaluation, and diagnostic criteria of neurologic complications of biologic agents used in the treatment of psoriasis.

Leukoencephalopathy

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy is a fatal demyelinating neurodegenerative disease caused by reactivation of the ubiquitous John Cunningham virus. Primary asymptomatic infection is thought to occur during childhood, then the virus remains latent. Reactivation usually occurs during severe immunosuppression and is classically described in human immunodeficiency virus infection, lymphoproliferative disorders, and other forms of cancer.4 A summary of PML and its association with biologics is found in Table 1.5-13 Few case reports of TNF-α inhibitor–associated PML exist, mostly in the presence of confounding factors such as immunosuppression or underlying autoimmune disease.10-13 Presenting symptoms of PML often are subacute, rapidly progressive, and can be focal or multifocal and include motor, cognitive, and visual deficits. Of note, there are 2 reported cases of ustekinumab associated with reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome, which is a hypertensive encephalopathy characterized by headache, altered mental status, vision abnormalities, and seizures.14,15 Fortunately, this disease is reversible with blood pressure control and removal of the immunosuppressive agent.16

Demyelinating Disorders

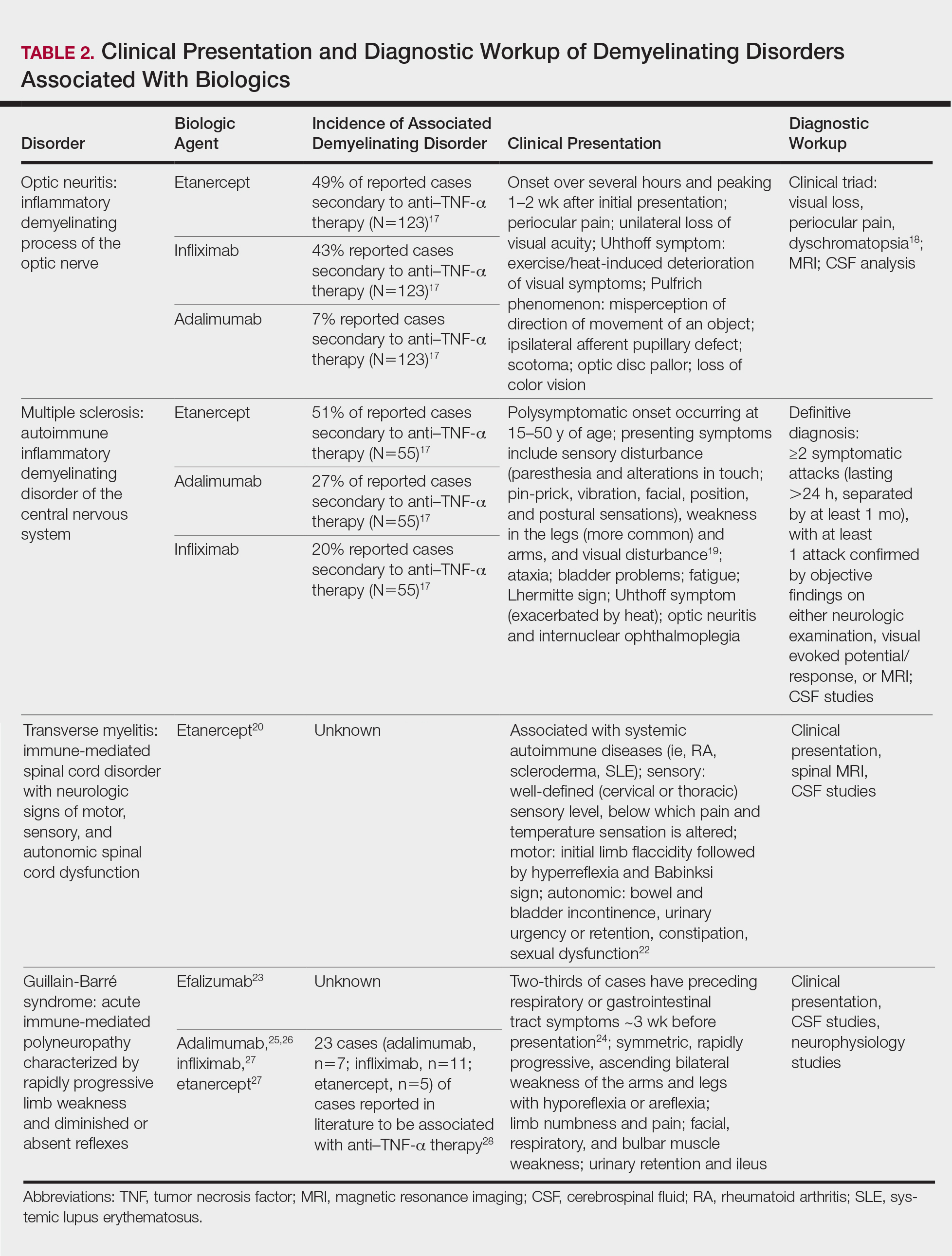

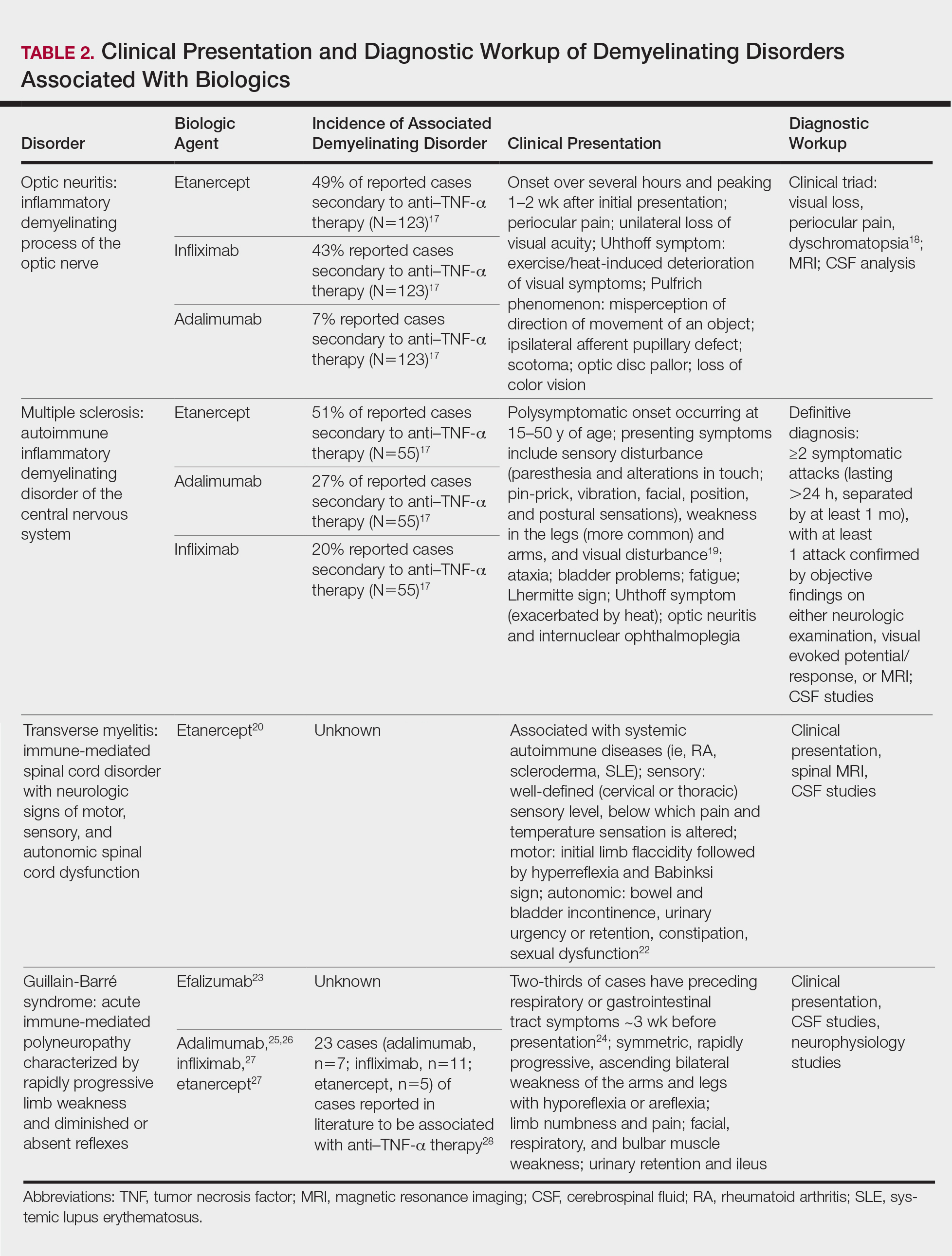

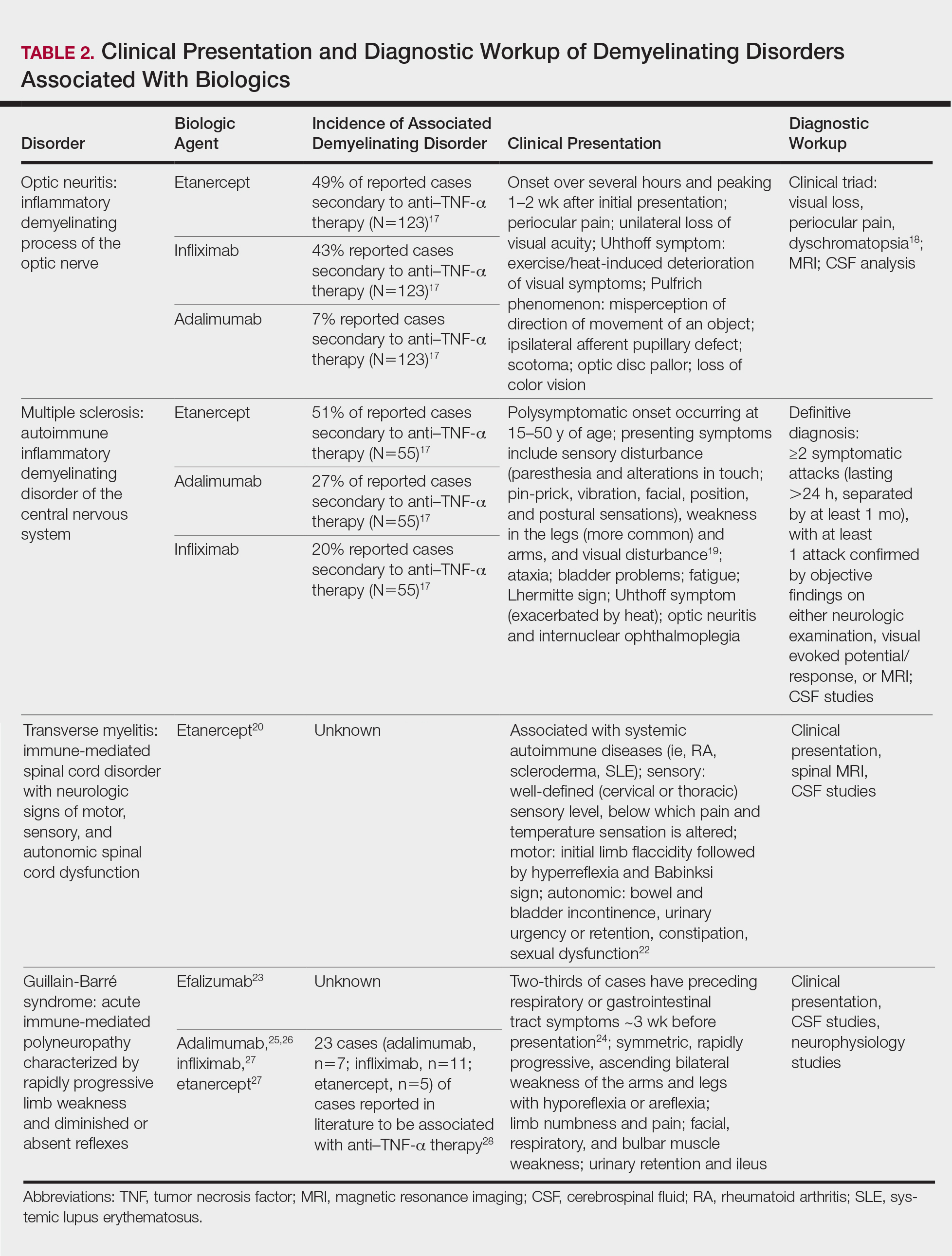

Clinical presentation of demyelinating events associated with biologic agents are varied but include optic neuritis, multiple sclerosis, transverse myelitis, and Guillain-Barré syndrome, among others.17-28 These demyelinating disorders with their salient features and associated biologics are summarized in Table 2.17-20,22-28 Patients on biologic agents, especially TNF-α inhibitors, with new-onset visual, motor, or sensory changes warrant closer inspection. Currently, there are no data on any neurologic side effects occurring with the new biologic secukinumab.29

Conclusion

Biologic agents are effective in treating moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, but awareness of associated neurological adverse effects, though rare, is important to consider. Physicians need to be able to counsel patients concerning these risks and promote informed decision-making prior to initiating biologics. Patients with a personal or strong family history of demyelinating disease should be considered for alternative treatment options before initiating anti–TNF-α therapy. Since the withdrawal of efalizumab, no new cases of PML have been reported in patients who were previously on a long-term course. Dermatologists should be vigilant in detecting signs of neurological complications so that an expedited evaluation and neurology referral may prevent progression of disease.

- Menter A, Gottlieb A, Feldman SR, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 1. overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:826-850.

- FDA Statement on the Voluntary Withdrawal of Raptiva From the U.S. Market. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrug-SafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm143347.htm. Published April 8, 2009. Accessed December 21, 2017.

- Kothary N, Diak IL, Brinker A, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy associated with efalizumab use in psoriasis patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:546-551.

- Tavazzi E, Ferrante P, Khalili K. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: an unexpected complication of modern therapeutic monoclonal antibody therapies. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:1776-1780.

- Korman BD, Tyler KL, Korman NJ. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, efalizumab, and immunosuppression: a cautionary tale for dermatologists. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:937-942.

- Sudhakar P, Bachman DM, Mark AS, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: recent advances and a neuro-ophthalmological review. J Neuroophthalmol. 2015;35:296-305.

- Berger JR, Aksamit AJ, Clifford DB, et al. PML diagnostic criteria: consensus statement from the AAN Neuroinfectious Disease Section. Neurology. 2013;80:1430-1438.

- Koralnik IJ, Boden D, Mai VX, et al. JC virus DNA load in patients with and without progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Neurology. 1999;52:253-260.

- Clifford DB, Ances B, Costello C, et al. Rituximab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:1156-1164.

- Babi MA, Pendlebury W, Braff S, et al. JC virus PCR detection is not infallible: a fulminant case of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy with false-negative cerebrospinal fluid studies despite progressive clinical course and radiological findings [published online March 12, 2015]. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2015;2015:643216.

- Ray M, Curtis JR, Baddley JW. A case report of progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy (PML) associated with adalimumab. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1429-1430.

- Kumar D, Bouldin TW, Berger RG. A case of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient treated with infliximab. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3191-3195.

- Graff-Radford J, Robinson MT, Warsame RM, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient treated with etanercept. Neurologist. 2012;18:85-87.

- Dickson L, Menter A. Reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome (RPLS) in a psoriasis patient treated with ustekinumab. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:177-179.

- Gratton D, Szapary P, Goyal K, et al. Reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome in a patient treated with ustekinumab: case report and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1197-1202.

- Hinchey J, Chaves C, Appignani B, et al. A reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:494-500.

- Ramos-Casals M, Roberto-Perez A, Diaz-Lagares C, et al. Autoimmune diseases induced by biological agents: a double-edged sword? Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:188-193.

- Hoorbakht H, Bagherkashi F. Optic neuritis, its differential diagnosis and management. Open Ophthalmol J. 2012;6:65-72.

- Richards RG, Sampson FC, Beard SM, et al. A review of the natural history and epidemiology of multiple sclerosis: implications for resource allocation and health economic models. Health Technol Assess. 2002;6:1-73.

- Caracseghi F, Izquierdo-Blasco J, Sanchez-Montanez A, et al. Etanercept-induced myelopathy in a pediatric case of blau syndrome [published online January 15, 2012]. Case Rep Rheumatol. 2011;2011:134106.

- Fromont A, De Seze J, Fleury MC, et al. Inflammatory demyelinating events following treatment with anti-tumor necrosis factor. Cytokine. 2009;45:55-57.

- Sellner J, Lüthi N, Schüpbach WM, et al. Diagnostic workup of patients with acute transverse myelitis: spectrum of clinical presentation, neuroimaging and laboratory findings. Spinal Cord. 2009;47:312-317.

- Turatti M, Tamburin S, Idone D, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome after short-course efalizumab treatment. J Neurol. 2010;257:1404-1405.

- Koga M, Yuki N, Hirata K. Antecedent symptoms in Guillain-Barré syndrome: an important indicator for clinical and serological subgroups. Acta Neurol Scand. 2001;103:278-287.

- Cesarini M, Angelucci E, Foglietta T, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome after treatment with human anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (adalimumab) in a Crohn’s disease patient: case report and literature review [published online July 28, 2011]. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:619-622.

- Soto-Cabrera E, Hernández-Martínez A, Yañez H, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome. Its association with alpha tumor necrosis factor [in Spanish]. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2012;50:565-567.

- Shin IS, Baer AN, Kwon HJ, et al. Guillain-Barré and Miller Fisher syndromes occurring with tumor necrosis factor alpha antagonist therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1429-1434.

- Alvarez-Lario B, Prieto-Tejedo R, Colazo-Burlato M, et al. Severe Guillain-Barré syndrome in a patient receiving anti-TNF therapy. consequence or coincidence. a case-based review. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:1407-1412.

- Garnock-Jones KP. Secukinumab: a review in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:323-330.

Biologic agents have provided patients with moderate to severe psoriasis with treatment alternatives that have improved systemic safety profiles and disease control1; however, case reports of associated neurologic complications have been emerging. Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitors have been associated with central and peripheral demyelinating disorders. Notably, efalizumab was withdrawn from the market for its association with fatal cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML).2,3 It is imperative for dermatologists to be familiar with the clinical presentation, evaluation, and diagnostic criteria of neurologic complications of biologic agents used in the treatment of psoriasis.

Leukoencephalopathy

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy is a fatal demyelinating neurodegenerative disease caused by reactivation of the ubiquitous John Cunningham virus. Primary asymptomatic infection is thought to occur during childhood, then the virus remains latent. Reactivation usually occurs during severe immunosuppression and is classically described in human immunodeficiency virus infection, lymphoproliferative disorders, and other forms of cancer.4 A summary of PML and its association with biologics is found in Table 1.5-13 Few case reports of TNF-α inhibitor–associated PML exist, mostly in the presence of confounding factors such as immunosuppression or underlying autoimmune disease.10-13 Presenting symptoms of PML often are subacute, rapidly progressive, and can be focal or multifocal and include motor, cognitive, and visual deficits. Of note, there are 2 reported cases of ustekinumab associated with reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome, which is a hypertensive encephalopathy characterized by headache, altered mental status, vision abnormalities, and seizures.14,15 Fortunately, this disease is reversible with blood pressure control and removal of the immunosuppressive agent.16

Demyelinating Disorders

Clinical presentation of demyelinating events associated with biologic agents are varied but include optic neuritis, multiple sclerosis, transverse myelitis, and Guillain-Barré syndrome, among others.17-28 These demyelinating disorders with their salient features and associated biologics are summarized in Table 2.17-20,22-28 Patients on biologic agents, especially TNF-α inhibitors, with new-onset visual, motor, or sensory changes warrant closer inspection. Currently, there are no data on any neurologic side effects occurring with the new biologic secukinumab.29

Conclusion

Biologic agents are effective in treating moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, but awareness of associated neurological adverse effects, though rare, is important to consider. Physicians need to be able to counsel patients concerning these risks and promote informed decision-making prior to initiating biologics. Patients with a personal or strong family history of demyelinating disease should be considered for alternative treatment options before initiating anti–TNF-α therapy. Since the withdrawal of efalizumab, no new cases of PML have been reported in patients who were previously on a long-term course. Dermatologists should be vigilant in detecting signs of neurological complications so that an expedited evaluation and neurology referral may prevent progression of disease.

Biologic agents have provided patients with moderate to severe psoriasis with treatment alternatives that have improved systemic safety profiles and disease control1; however, case reports of associated neurologic complications have been emerging. Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitors have been associated with central and peripheral demyelinating disorders. Notably, efalizumab was withdrawn from the market for its association with fatal cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML).2,3 It is imperative for dermatologists to be familiar with the clinical presentation, evaluation, and diagnostic criteria of neurologic complications of biologic agents used in the treatment of psoriasis.

Leukoencephalopathy

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy is a fatal demyelinating neurodegenerative disease caused by reactivation of the ubiquitous John Cunningham virus. Primary asymptomatic infection is thought to occur during childhood, then the virus remains latent. Reactivation usually occurs during severe immunosuppression and is classically described in human immunodeficiency virus infection, lymphoproliferative disorders, and other forms of cancer.4 A summary of PML and its association with biologics is found in Table 1.5-13 Few case reports of TNF-α inhibitor–associated PML exist, mostly in the presence of confounding factors such as immunosuppression or underlying autoimmune disease.10-13 Presenting symptoms of PML often are subacute, rapidly progressive, and can be focal or multifocal and include motor, cognitive, and visual deficits. Of note, there are 2 reported cases of ustekinumab associated with reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome, which is a hypertensive encephalopathy characterized by headache, altered mental status, vision abnormalities, and seizures.14,15 Fortunately, this disease is reversible with blood pressure control and removal of the immunosuppressive agent.16

Demyelinating Disorders

Clinical presentation of demyelinating events associated with biologic agents are varied but include optic neuritis, multiple sclerosis, transverse myelitis, and Guillain-Barré syndrome, among others.17-28 These demyelinating disorders with their salient features and associated biologics are summarized in Table 2.17-20,22-28 Patients on biologic agents, especially TNF-α inhibitors, with new-onset visual, motor, or sensory changes warrant closer inspection. Currently, there are no data on any neurologic side effects occurring with the new biologic secukinumab.29

Conclusion

Biologic agents are effective in treating moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, but awareness of associated neurological adverse effects, though rare, is important to consider. Physicians need to be able to counsel patients concerning these risks and promote informed decision-making prior to initiating biologics. Patients with a personal or strong family history of demyelinating disease should be considered for alternative treatment options before initiating anti–TNF-α therapy. Since the withdrawal of efalizumab, no new cases of PML have been reported in patients who were previously on a long-term course. Dermatologists should be vigilant in detecting signs of neurological complications so that an expedited evaluation and neurology referral may prevent progression of disease.

- Menter A, Gottlieb A, Feldman SR, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 1. overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:826-850.

- FDA Statement on the Voluntary Withdrawal of Raptiva From the U.S. Market. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrug-SafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm143347.htm. Published April 8, 2009. Accessed December 21, 2017.

- Kothary N, Diak IL, Brinker A, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy associated with efalizumab use in psoriasis patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:546-551.

- Tavazzi E, Ferrante P, Khalili K. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: an unexpected complication of modern therapeutic monoclonal antibody therapies. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:1776-1780.

- Korman BD, Tyler KL, Korman NJ. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, efalizumab, and immunosuppression: a cautionary tale for dermatologists. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:937-942.

- Sudhakar P, Bachman DM, Mark AS, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: recent advances and a neuro-ophthalmological review. J Neuroophthalmol. 2015;35:296-305.

- Berger JR, Aksamit AJ, Clifford DB, et al. PML diagnostic criteria: consensus statement from the AAN Neuroinfectious Disease Section. Neurology. 2013;80:1430-1438.

- Koralnik IJ, Boden D, Mai VX, et al. JC virus DNA load in patients with and without progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Neurology. 1999;52:253-260.

- Clifford DB, Ances B, Costello C, et al. Rituximab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:1156-1164.

- Babi MA, Pendlebury W, Braff S, et al. JC virus PCR detection is not infallible: a fulminant case of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy with false-negative cerebrospinal fluid studies despite progressive clinical course and radiological findings [published online March 12, 2015]. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2015;2015:643216.

- Ray M, Curtis JR, Baddley JW. A case report of progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy (PML) associated with adalimumab. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1429-1430.

- Kumar D, Bouldin TW, Berger RG. A case of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient treated with infliximab. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3191-3195.

- Graff-Radford J, Robinson MT, Warsame RM, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient treated with etanercept. Neurologist. 2012;18:85-87.

- Dickson L, Menter A. Reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome (RPLS) in a psoriasis patient treated with ustekinumab. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:177-179.

- Gratton D, Szapary P, Goyal K, et al. Reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome in a patient treated with ustekinumab: case report and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1197-1202.

- Hinchey J, Chaves C, Appignani B, et al. A reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:494-500.

- Ramos-Casals M, Roberto-Perez A, Diaz-Lagares C, et al. Autoimmune diseases induced by biological agents: a double-edged sword? Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:188-193.

- Hoorbakht H, Bagherkashi F. Optic neuritis, its differential diagnosis and management. Open Ophthalmol J. 2012;6:65-72.

- Richards RG, Sampson FC, Beard SM, et al. A review of the natural history and epidemiology of multiple sclerosis: implications for resource allocation and health economic models. Health Technol Assess. 2002;6:1-73.

- Caracseghi F, Izquierdo-Blasco J, Sanchez-Montanez A, et al. Etanercept-induced myelopathy in a pediatric case of blau syndrome [published online January 15, 2012]. Case Rep Rheumatol. 2011;2011:134106.

- Fromont A, De Seze J, Fleury MC, et al. Inflammatory demyelinating events following treatment with anti-tumor necrosis factor. Cytokine. 2009;45:55-57.

- Sellner J, Lüthi N, Schüpbach WM, et al. Diagnostic workup of patients with acute transverse myelitis: spectrum of clinical presentation, neuroimaging and laboratory findings. Spinal Cord. 2009;47:312-317.

- Turatti M, Tamburin S, Idone D, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome after short-course efalizumab treatment. J Neurol. 2010;257:1404-1405.

- Koga M, Yuki N, Hirata K. Antecedent symptoms in Guillain-Barré syndrome: an important indicator for clinical and serological subgroups. Acta Neurol Scand. 2001;103:278-287.

- Cesarini M, Angelucci E, Foglietta T, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome after treatment with human anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (adalimumab) in a Crohn’s disease patient: case report and literature review [published online July 28, 2011]. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:619-622.

- Soto-Cabrera E, Hernández-Martínez A, Yañez H, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome. Its association with alpha tumor necrosis factor [in Spanish]. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2012;50:565-567.

- Shin IS, Baer AN, Kwon HJ, et al. Guillain-Barré and Miller Fisher syndromes occurring with tumor necrosis factor alpha antagonist therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1429-1434.

- Alvarez-Lario B, Prieto-Tejedo R, Colazo-Burlato M, et al. Severe Guillain-Barré syndrome in a patient receiving anti-TNF therapy. consequence or coincidence. a case-based review. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:1407-1412.

- Garnock-Jones KP. Secukinumab: a review in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:323-330.

- Menter A, Gottlieb A, Feldman SR, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 1. overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:826-850.

- FDA Statement on the Voluntary Withdrawal of Raptiva From the U.S. Market. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrug-SafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm143347.htm. Published April 8, 2009. Accessed December 21, 2017.

- Kothary N, Diak IL, Brinker A, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy associated with efalizumab use in psoriasis patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:546-551.

- Tavazzi E, Ferrante P, Khalili K. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: an unexpected complication of modern therapeutic monoclonal antibody therapies. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:1776-1780.

- Korman BD, Tyler KL, Korman NJ. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, efalizumab, and immunosuppression: a cautionary tale for dermatologists. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:937-942.

- Sudhakar P, Bachman DM, Mark AS, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: recent advances and a neuro-ophthalmological review. J Neuroophthalmol. 2015;35:296-305.

- Berger JR, Aksamit AJ, Clifford DB, et al. PML diagnostic criteria: consensus statement from the AAN Neuroinfectious Disease Section. Neurology. 2013;80:1430-1438.

- Koralnik IJ, Boden D, Mai VX, et al. JC virus DNA load in patients with and without progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Neurology. 1999;52:253-260.

- Clifford DB, Ances B, Costello C, et al. Rituximab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:1156-1164.

- Babi MA, Pendlebury W, Braff S, et al. JC virus PCR detection is not infallible: a fulminant case of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy with false-negative cerebrospinal fluid studies despite progressive clinical course and radiological findings [published online March 12, 2015]. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2015;2015:643216.

- Ray M, Curtis JR, Baddley JW. A case report of progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy (PML) associated with adalimumab. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1429-1430.

- Kumar D, Bouldin TW, Berger RG. A case of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient treated with infliximab. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3191-3195.

- Graff-Radford J, Robinson MT, Warsame RM, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient treated with etanercept. Neurologist. 2012;18:85-87.