User login

Colorectal Cancer: New Primary Care Method Predicts Onset Within Next 2 Years

TOPLINE:

Up to 16% of primary care patients are non-compliant with FIT, which is the gold standard for predicting CRC.

METHODOLOGY:

- This study was retrospective cohort of 50,387 UK Biobank participants reporting a CRC symptom in primary care at age ≥ 40 years.

- The novel method, called an integrated risk model, used a combination of a polygenic risk score from genetic testing, symptoms, and patient characteristics to identify patients likely to develop CRC in the next 2 years.

- The primary outcome was the risk model’s performance in classifying a CRC case according to a statistical metric, the receiver operating characteristic area under the curve. Values range from 0 to 1, where 1 indicates perfect discriminative power and 0.5 indicates no discriminative power.

TAKEAWAY:

- The cohort of 50,387 participants was found to have 438 cases of CRC and 49,949 controls without CRC within 2 years of symptom reporting. CRC cases were diagnosed by hospital records, cancer registries, or death records.

- Increased risk of a CRC diagnosis was identified by a combination of six variables: older age at index date of symptom, higher polygenic risk score, which included 201 variants, male sex, previous smoking, rectal bleeding, and change in bowel habit.

- The polygenic risk score alone had good ability to distinguish cases from controls because 1.45% of participants in the highest quintile and 0.42% in the lowest quintile were later diagnosed with CRC.

- The variables were used to calculate an integrated risk model, which estimated the cross-sectional risk (in 80% of the final cohort) of a subsequent CRC diagnosis within 2 years. The highest scoring integrated risk model in this study was found to have a receiver operating characteristic area under the curve value of 0.76 with a 95% CI of 0.71-0.81. (A value of this magnitude indicates moderate discriminative ability to distinguish cases from controls because it falls between 0.7 and 0.8. A higher value [above 0.8] is considered strong and a lower value [< 0.7] is considered weak.)

IN PRACTICE:

The authors concluded, “The [integrated risk model] developed in this study predicts, with good accuracy, which patients presenting with CRC symptoms in a primary care setting are likely to be diagnosed with CRC within the next 2 years.”

The integrated risk model has “potential to be immediately actionable in the clinical setting … [by] inform[ing] patient triage, improving early diagnostic rates and health outcomes and reducing pressure on diagnostic secondary care services.”

SOURCE:

The corresponding author is Harry D. Green of the University of Exeter, England. The study (2024 Aug 1. doi: 10.1038/s41431-024-01654-3) appeared in the European Journal of Human Genetics.

LIMITATIONS:

Limitations included an observational design and the inability of the integrated risk model to outperform FIT, which has a receiver operating characteristic area under the curve of 0.95.

DISCLOSURES:

None of the authors reported competing interests. The funding sources included the National Institute for Health and Care Research and others.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Up to 16% of primary care patients are non-compliant with FIT, which is the gold standard for predicting CRC.

METHODOLOGY:

- This study was retrospective cohort of 50,387 UK Biobank participants reporting a CRC symptom in primary care at age ≥ 40 years.

- The novel method, called an integrated risk model, used a combination of a polygenic risk score from genetic testing, symptoms, and patient characteristics to identify patients likely to develop CRC in the next 2 years.

- The primary outcome was the risk model’s performance in classifying a CRC case according to a statistical metric, the receiver operating characteristic area under the curve. Values range from 0 to 1, where 1 indicates perfect discriminative power and 0.5 indicates no discriminative power.

TAKEAWAY:

- The cohort of 50,387 participants was found to have 438 cases of CRC and 49,949 controls without CRC within 2 years of symptom reporting. CRC cases were diagnosed by hospital records, cancer registries, or death records.

- Increased risk of a CRC diagnosis was identified by a combination of six variables: older age at index date of symptom, higher polygenic risk score, which included 201 variants, male sex, previous smoking, rectal bleeding, and change in bowel habit.

- The polygenic risk score alone had good ability to distinguish cases from controls because 1.45% of participants in the highest quintile and 0.42% in the lowest quintile were later diagnosed with CRC.

- The variables were used to calculate an integrated risk model, which estimated the cross-sectional risk (in 80% of the final cohort) of a subsequent CRC diagnosis within 2 years. The highest scoring integrated risk model in this study was found to have a receiver operating characteristic area under the curve value of 0.76 with a 95% CI of 0.71-0.81. (A value of this magnitude indicates moderate discriminative ability to distinguish cases from controls because it falls between 0.7 and 0.8. A higher value [above 0.8] is considered strong and a lower value [< 0.7] is considered weak.)

IN PRACTICE:

The authors concluded, “The [integrated risk model] developed in this study predicts, with good accuracy, which patients presenting with CRC symptoms in a primary care setting are likely to be diagnosed with CRC within the next 2 years.”

The integrated risk model has “potential to be immediately actionable in the clinical setting … [by] inform[ing] patient triage, improving early diagnostic rates and health outcomes and reducing pressure on diagnostic secondary care services.”

SOURCE:

The corresponding author is Harry D. Green of the University of Exeter, England. The study (2024 Aug 1. doi: 10.1038/s41431-024-01654-3) appeared in the European Journal of Human Genetics.

LIMITATIONS:

Limitations included an observational design and the inability of the integrated risk model to outperform FIT, which has a receiver operating characteristic area under the curve of 0.95.

DISCLOSURES:

None of the authors reported competing interests. The funding sources included the National Institute for Health and Care Research and others.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Up to 16% of primary care patients are non-compliant with FIT, which is the gold standard for predicting CRC.

METHODOLOGY:

- This study was retrospective cohort of 50,387 UK Biobank participants reporting a CRC symptom in primary care at age ≥ 40 years.

- The novel method, called an integrated risk model, used a combination of a polygenic risk score from genetic testing, symptoms, and patient characteristics to identify patients likely to develop CRC in the next 2 years.

- The primary outcome was the risk model’s performance in classifying a CRC case according to a statistical metric, the receiver operating characteristic area under the curve. Values range from 0 to 1, where 1 indicates perfect discriminative power and 0.5 indicates no discriminative power.

TAKEAWAY:

- The cohort of 50,387 participants was found to have 438 cases of CRC and 49,949 controls without CRC within 2 years of symptom reporting. CRC cases were diagnosed by hospital records, cancer registries, or death records.

- Increased risk of a CRC diagnosis was identified by a combination of six variables: older age at index date of symptom, higher polygenic risk score, which included 201 variants, male sex, previous smoking, rectal bleeding, and change in bowel habit.

- The polygenic risk score alone had good ability to distinguish cases from controls because 1.45% of participants in the highest quintile and 0.42% in the lowest quintile were later diagnosed with CRC.

- The variables were used to calculate an integrated risk model, which estimated the cross-sectional risk (in 80% of the final cohort) of a subsequent CRC diagnosis within 2 years. The highest scoring integrated risk model in this study was found to have a receiver operating characteristic area under the curve value of 0.76 with a 95% CI of 0.71-0.81. (A value of this magnitude indicates moderate discriminative ability to distinguish cases from controls because it falls between 0.7 and 0.8. A higher value [above 0.8] is considered strong and a lower value [< 0.7] is considered weak.)

IN PRACTICE:

The authors concluded, “The [integrated risk model] developed in this study predicts, with good accuracy, which patients presenting with CRC symptoms in a primary care setting are likely to be diagnosed with CRC within the next 2 years.”

The integrated risk model has “potential to be immediately actionable in the clinical setting … [by] inform[ing] patient triage, improving early diagnostic rates and health outcomes and reducing pressure on diagnostic secondary care services.”

SOURCE:

The corresponding author is Harry D. Green of the University of Exeter, England. The study (2024 Aug 1. doi: 10.1038/s41431-024-01654-3) appeared in the European Journal of Human Genetics.

LIMITATIONS:

Limitations included an observational design and the inability of the integrated risk model to outperform FIT, which has a receiver operating characteristic area under the curve of 0.95.

DISCLOSURES:

None of the authors reported competing interests. The funding sources included the National Institute for Health and Care Research and others.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Is Buprenorphine/Naloxone Safer Than Buprenorphine Alone During Pregnancy?

TOPLINE:

Buprenorphine combined with naloxone during pregnancy is associated with lower risks for neonatal abstinence syndrome and neonatal intensive care unit admission than buprenorphine alone. The study also found no significant differences in major congenital malformations between the two treatments.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a population-based cohort study using healthcare utilization data of people who were insured by Medicaid between 2000 and 2018.

- A total of 8695 pregnant individuals were included, with 3369 exposed to buprenorphine/naloxone and 5326 exposed to buprenorphine alone during the first trimester.

- Outcome measures included major congenital malformations, low birth weight, neonatal abstinence syndrome, neonatal intensive care unit admission, preterm birth, respiratory symptoms, small for gestational age, cesarean delivery, and maternal morbidity.

- The study excluded pregnancies with chromosomal anomalies, first-trimester exposure to known teratogens, or methadone use during baseline or the first trimester.

TAKEAWAY:

- According to the authors, buprenorphine/naloxone exposure during pregnancy was associated with a lower risk for neonatal abstinence syndrome (weighted risk ratio [RR], 0.77; 95% CI, 0.70-0.84) than buprenorphine alone.

- The researchers found a modestly lower risk for neonatal intensive care unit admission (weighted RR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.85-0.98) and small risk for gestational age (weighted RR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.75-0.98) in the buprenorphine/naloxone group.

- No significant differences were observed between the two groups in major congenital malformations, low birth weight, preterm birth, respiratory symptoms, or cesarean delivery.

IN PRACTICE:

“For the outcomes assessed, compared with buprenorphine alone, buprenorphine combined with naloxone during pregnancy appears to be a safe treatment option. This supports the view that both formulations are reasonable options for treatment of OUD in pregnancy, affirming flexibility in collaborative treatment decision-making,” the study authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Loreen Straub, MD, MS, of the Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston. It was published online in JAMA.

LIMITATIONS:

Some potential confounders, such as alcohol use and cigarette smoking, may not have been recorded in claims data. The findings for many of the neonatal and maternal outcomes suggest that confounding by unmeasured factors is an unlikely explanation for the associations observed. Individuals identified as exposed based on filled prescriptions might not have used the medication. The study used outcome algorithms with relatively high positive predictive values to minimize outcome misclassification. The cohort was restricted to live births to enable linkage to infants and to assess neonatal outcomes.

DISCLOSURES:

Various authors reported receiving grants and personal fees from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Roche, Moderna, Takeda, and Janssen Global, among others.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Buprenorphine combined with naloxone during pregnancy is associated with lower risks for neonatal abstinence syndrome and neonatal intensive care unit admission than buprenorphine alone. The study also found no significant differences in major congenital malformations between the two treatments.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a population-based cohort study using healthcare utilization data of people who were insured by Medicaid between 2000 and 2018.

- A total of 8695 pregnant individuals were included, with 3369 exposed to buprenorphine/naloxone and 5326 exposed to buprenorphine alone during the first trimester.

- Outcome measures included major congenital malformations, low birth weight, neonatal abstinence syndrome, neonatal intensive care unit admission, preterm birth, respiratory symptoms, small for gestational age, cesarean delivery, and maternal morbidity.

- The study excluded pregnancies with chromosomal anomalies, first-trimester exposure to known teratogens, or methadone use during baseline or the first trimester.

TAKEAWAY:

- According to the authors, buprenorphine/naloxone exposure during pregnancy was associated with a lower risk for neonatal abstinence syndrome (weighted risk ratio [RR], 0.77; 95% CI, 0.70-0.84) than buprenorphine alone.

- The researchers found a modestly lower risk for neonatal intensive care unit admission (weighted RR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.85-0.98) and small risk for gestational age (weighted RR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.75-0.98) in the buprenorphine/naloxone group.

- No significant differences were observed between the two groups in major congenital malformations, low birth weight, preterm birth, respiratory symptoms, or cesarean delivery.

IN PRACTICE:

“For the outcomes assessed, compared with buprenorphine alone, buprenorphine combined with naloxone during pregnancy appears to be a safe treatment option. This supports the view that both formulations are reasonable options for treatment of OUD in pregnancy, affirming flexibility in collaborative treatment decision-making,” the study authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Loreen Straub, MD, MS, of the Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston. It was published online in JAMA.

LIMITATIONS:

Some potential confounders, such as alcohol use and cigarette smoking, may not have been recorded in claims data. The findings for many of the neonatal and maternal outcomes suggest that confounding by unmeasured factors is an unlikely explanation for the associations observed. Individuals identified as exposed based on filled prescriptions might not have used the medication. The study used outcome algorithms with relatively high positive predictive values to minimize outcome misclassification. The cohort was restricted to live births to enable linkage to infants and to assess neonatal outcomes.

DISCLOSURES:

Various authors reported receiving grants and personal fees from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Roche, Moderna, Takeda, and Janssen Global, among others.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Buprenorphine combined with naloxone during pregnancy is associated with lower risks for neonatal abstinence syndrome and neonatal intensive care unit admission than buprenorphine alone. The study also found no significant differences in major congenital malformations between the two treatments.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a population-based cohort study using healthcare utilization data of people who were insured by Medicaid between 2000 and 2018.

- A total of 8695 pregnant individuals were included, with 3369 exposed to buprenorphine/naloxone and 5326 exposed to buprenorphine alone during the first trimester.

- Outcome measures included major congenital malformations, low birth weight, neonatal abstinence syndrome, neonatal intensive care unit admission, preterm birth, respiratory symptoms, small for gestational age, cesarean delivery, and maternal morbidity.

- The study excluded pregnancies with chromosomal anomalies, first-trimester exposure to known teratogens, or methadone use during baseline or the first trimester.

TAKEAWAY:

- According to the authors, buprenorphine/naloxone exposure during pregnancy was associated with a lower risk for neonatal abstinence syndrome (weighted risk ratio [RR], 0.77; 95% CI, 0.70-0.84) than buprenorphine alone.

- The researchers found a modestly lower risk for neonatal intensive care unit admission (weighted RR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.85-0.98) and small risk for gestational age (weighted RR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.75-0.98) in the buprenorphine/naloxone group.

- No significant differences were observed between the two groups in major congenital malformations, low birth weight, preterm birth, respiratory symptoms, or cesarean delivery.

IN PRACTICE:

“For the outcomes assessed, compared with buprenorphine alone, buprenorphine combined with naloxone during pregnancy appears to be a safe treatment option. This supports the view that both formulations are reasonable options for treatment of OUD in pregnancy, affirming flexibility in collaborative treatment decision-making,” the study authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Loreen Straub, MD, MS, of the Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston. It was published online in JAMA.

LIMITATIONS:

Some potential confounders, such as alcohol use and cigarette smoking, may not have been recorded in claims data. The findings for many of the neonatal and maternal outcomes suggest that confounding by unmeasured factors is an unlikely explanation for the associations observed. Individuals identified as exposed based on filled prescriptions might not have used the medication. The study used outcome algorithms with relatively high positive predictive values to minimize outcome misclassification. The cohort was restricted to live births to enable linkage to infants and to assess neonatal outcomes.

DISCLOSURES:

Various authors reported receiving grants and personal fees from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Roche, Moderna, Takeda, and Janssen Global, among others.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Viral Season 2024-2025: Try for An Ounce of Prevention

We are quickly approaching the typical cold and flu season. But can we call anything typical since 2020? Since 2020, there have been different recommendations for prevention, testing, return to work, and treatment since our world was rocked by the pandemic. Now that we are in the “post-pandemic” era, family physicians and other primary care professionals are the front line for discussions on prevention, evaluation, and treatment of the typical upper-respiratory infections, influenza, and COVID-19.

Let’s start with prevention. We have all heard the old adage, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. In primary care, we need to focus on prevention. Vaccination is often one of our best tools against the myriad of infections we are hoping to help patients prevent during cold and flu season. Most recently, we have fall vaccinations aimed to prevent COVID-19, influenza, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

The number and timing of each of these vaccinations has different recommendations based on a variety of factors including age, pregnancy status, and whether or not the patient is immunocompromised. For the 2024-2025 season, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended updated vaccines for both influenza and COVID-19.1 They have also updated the RSV vaccine recommendations to “People 75 or older, or between 60-74 with certain chronic health conditions or living in a nursing home should get one dose of the RSV vaccine to provide an extra layer of protection.”2

In addition to vaccines as prevention, there is also hygiene, staying home when sick and away from others who are sick, following guidelines for where and when to wear a face mask, and the general tools of eating well, and getting sufficient sleep and exercise to help maintain the healthiest immune system.

Despite the best of intentions, there will still be many who experience viral infections in this upcoming season. The CDC is currently recommending persons to stay away from others for at least 24 hours after their symptoms improve and they are fever-free without antipyretics. In addition to isolation while sick, general symptom management is something that we can recommend for all of these illnesses.

There is more to consider, though, as our patients face these illnesses. The first question is how to determine the diagnosis — and if that diagnosis is even necessary. Unfortunately, many of these viral illnesses can look the same. They can all cause fevers, chills, and other upper respiratory symptoms. They are all fairly contagious. All of these viruses can cause serious illness associated with additional complications. It is not truly possible to determine which virus someone has by symptoms alone, our patients can have multiple viruses at the same time and diagnosis of one does not preclude having another.3

Instead, we truly do need a test for diagnosis. In-office testing is available for RSV, influenza, and COVID-19. Additionally, despite not being as freely available as they were during the pandemic, patients are able to do home COVID tests and then call in with their results. At the time of writing this, at-home rapid influenza tests have also been approved by the FDA but are not yet readily available to the public. These tests are important for determining if the patient is eligible for treatment. Both influenza and COVID-19 have antiviral treatments available to help decrease the severity of the illness and potentially the length of illness and time contagious. According to the CDC, both treatments are underutilized.

This could be because of a lack of testing and diagnosis. It may also be because of a lack of familiarity with the available treatments.4,5Influenza treatment is recommended as soon as possible for those with suspected or confirmed diagnosis, immediately for anyone hospitalized, anyone with severe, complicated, or progressing illness, and for those at high risk of severe illness including but not limited to those under 2 years old, those over 65, those who are pregnant, and those with many chronic conditions.

Treatment can also be used for those who are not high risk when diagnosed within 48 hours. In the United States, four antivirals are recommended to treat influenza: oseltamivir phosphate, zanamivir, peramivir, and baloxavir marboxil. For COVID-19, treatments are also available for mild or moderate disease in those at risk for severe disease. Both remdesivir and nimatrelvir with ritonavir are treatment options that can be used for COVID-19 infection. Unfortunately, no specific antiviral is available for the other viral illnesses we see often during this season.

In primary care, we have some important roles to play. We need to continue to discuss all methods of prevention. Not only do vaccine recommendations change at least annually, our patients’ situations change and we have to reassess them. Additionally, people often need to hear things more than once before committing — so it never hurts to continue having those conversations. Combining the conversation about vaccines with other prevention measures is also important so that it does not seem like we are only recommending one thing. We should also start talking about treatment options before our patients are sick. We can communicate what is available as long as they let us know they are sick early. We can also be there to help our patients determine when they are at risk for severe illness and when they should consider a higher level of care.

The availability of home testing gives us the opportunity to provide these treatments via telehealth and even potentially in times when these illnesses are everywhere — with standing orders with our clinical teams. Although it is a busy time for us in the clinic, “cold and flu” season is definitely one of those times when our primary care relationship can truly help our patients.

References

1. CDC Recommends Updated 2024-2025 COVID-19 and Flu Vaccines for Fall/Winter Virus Season. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2024/s-t0627-vaccine-recommendations.html. Accessed August 8, 2024. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

2. CDC Updates RSV Vaccination Recommendation for Adults. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2024/s-0626-vaccination-adults.html. Accessed August 8, 2024. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

3. Similarities and Differences between Flu and COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/symptoms/flu-vs-covid19.htm. Accessed August 8, 2024. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

4. Respiratory Virus Guidance. https://www.cdc.gov/respiratory-viruses/guidance/index.html. Accessed August 9, 2024. Source: National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

5. Provider Toolkit: Preparing Patients for the Fall and Winter Virus Season. https://www.cdc.gov/respiratory-viruses/hcp/tools-resources/index.html. Accessed August 9, 2024. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

We are quickly approaching the typical cold and flu season. But can we call anything typical since 2020? Since 2020, there have been different recommendations for prevention, testing, return to work, and treatment since our world was rocked by the pandemic. Now that we are in the “post-pandemic” era, family physicians and other primary care professionals are the front line for discussions on prevention, evaluation, and treatment of the typical upper-respiratory infections, influenza, and COVID-19.

Let’s start with prevention. We have all heard the old adage, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. In primary care, we need to focus on prevention. Vaccination is often one of our best tools against the myriad of infections we are hoping to help patients prevent during cold and flu season. Most recently, we have fall vaccinations aimed to prevent COVID-19, influenza, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

The number and timing of each of these vaccinations has different recommendations based on a variety of factors including age, pregnancy status, and whether or not the patient is immunocompromised. For the 2024-2025 season, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended updated vaccines for both influenza and COVID-19.1 They have also updated the RSV vaccine recommendations to “People 75 or older, or between 60-74 with certain chronic health conditions or living in a nursing home should get one dose of the RSV vaccine to provide an extra layer of protection.”2

In addition to vaccines as prevention, there is also hygiene, staying home when sick and away from others who are sick, following guidelines for where and when to wear a face mask, and the general tools of eating well, and getting sufficient sleep and exercise to help maintain the healthiest immune system.

Despite the best of intentions, there will still be many who experience viral infections in this upcoming season. The CDC is currently recommending persons to stay away from others for at least 24 hours after their symptoms improve and they are fever-free without antipyretics. In addition to isolation while sick, general symptom management is something that we can recommend for all of these illnesses.

There is more to consider, though, as our patients face these illnesses. The first question is how to determine the diagnosis — and if that diagnosis is even necessary. Unfortunately, many of these viral illnesses can look the same. They can all cause fevers, chills, and other upper respiratory symptoms. They are all fairly contagious. All of these viruses can cause serious illness associated with additional complications. It is not truly possible to determine which virus someone has by symptoms alone, our patients can have multiple viruses at the same time and diagnosis of one does not preclude having another.3

Instead, we truly do need a test for diagnosis. In-office testing is available for RSV, influenza, and COVID-19. Additionally, despite not being as freely available as they were during the pandemic, patients are able to do home COVID tests and then call in with their results. At the time of writing this, at-home rapid influenza tests have also been approved by the FDA but are not yet readily available to the public. These tests are important for determining if the patient is eligible for treatment. Both influenza and COVID-19 have antiviral treatments available to help decrease the severity of the illness and potentially the length of illness and time contagious. According to the CDC, both treatments are underutilized.

This could be because of a lack of testing and diagnosis. It may also be because of a lack of familiarity with the available treatments.4,5Influenza treatment is recommended as soon as possible for those with suspected or confirmed diagnosis, immediately for anyone hospitalized, anyone with severe, complicated, or progressing illness, and for those at high risk of severe illness including but not limited to those under 2 years old, those over 65, those who are pregnant, and those with many chronic conditions.

Treatment can also be used for those who are not high risk when diagnosed within 48 hours. In the United States, four antivirals are recommended to treat influenza: oseltamivir phosphate, zanamivir, peramivir, and baloxavir marboxil. For COVID-19, treatments are also available for mild or moderate disease in those at risk for severe disease. Both remdesivir and nimatrelvir with ritonavir are treatment options that can be used for COVID-19 infection. Unfortunately, no specific antiviral is available for the other viral illnesses we see often during this season.

In primary care, we have some important roles to play. We need to continue to discuss all methods of prevention. Not only do vaccine recommendations change at least annually, our patients’ situations change and we have to reassess them. Additionally, people often need to hear things more than once before committing — so it never hurts to continue having those conversations. Combining the conversation about vaccines with other prevention measures is also important so that it does not seem like we are only recommending one thing. We should also start talking about treatment options before our patients are sick. We can communicate what is available as long as they let us know they are sick early. We can also be there to help our patients determine when they are at risk for severe illness and when they should consider a higher level of care.

The availability of home testing gives us the opportunity to provide these treatments via telehealth and even potentially in times when these illnesses are everywhere — with standing orders with our clinical teams. Although it is a busy time for us in the clinic, “cold and flu” season is definitely one of those times when our primary care relationship can truly help our patients.

References

1. CDC Recommends Updated 2024-2025 COVID-19 and Flu Vaccines for Fall/Winter Virus Season. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2024/s-t0627-vaccine-recommendations.html. Accessed August 8, 2024. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

2. CDC Updates RSV Vaccination Recommendation for Adults. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2024/s-0626-vaccination-adults.html. Accessed August 8, 2024. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

3. Similarities and Differences between Flu and COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/symptoms/flu-vs-covid19.htm. Accessed August 8, 2024. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

4. Respiratory Virus Guidance. https://www.cdc.gov/respiratory-viruses/guidance/index.html. Accessed August 9, 2024. Source: National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

5. Provider Toolkit: Preparing Patients for the Fall and Winter Virus Season. https://www.cdc.gov/respiratory-viruses/hcp/tools-resources/index.html. Accessed August 9, 2024. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

We are quickly approaching the typical cold and flu season. But can we call anything typical since 2020? Since 2020, there have been different recommendations for prevention, testing, return to work, and treatment since our world was rocked by the pandemic. Now that we are in the “post-pandemic” era, family physicians and other primary care professionals are the front line for discussions on prevention, evaluation, and treatment of the typical upper-respiratory infections, influenza, and COVID-19.

Let’s start with prevention. We have all heard the old adage, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. In primary care, we need to focus on prevention. Vaccination is often one of our best tools against the myriad of infections we are hoping to help patients prevent during cold and flu season. Most recently, we have fall vaccinations aimed to prevent COVID-19, influenza, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

The number and timing of each of these vaccinations has different recommendations based on a variety of factors including age, pregnancy status, and whether or not the patient is immunocompromised. For the 2024-2025 season, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended updated vaccines for both influenza and COVID-19.1 They have also updated the RSV vaccine recommendations to “People 75 or older, or between 60-74 with certain chronic health conditions or living in a nursing home should get one dose of the RSV vaccine to provide an extra layer of protection.”2

In addition to vaccines as prevention, there is also hygiene, staying home when sick and away from others who are sick, following guidelines for where and when to wear a face mask, and the general tools of eating well, and getting sufficient sleep and exercise to help maintain the healthiest immune system.

Despite the best of intentions, there will still be many who experience viral infections in this upcoming season. The CDC is currently recommending persons to stay away from others for at least 24 hours after their symptoms improve and they are fever-free without antipyretics. In addition to isolation while sick, general symptom management is something that we can recommend for all of these illnesses.

There is more to consider, though, as our patients face these illnesses. The first question is how to determine the diagnosis — and if that diagnosis is even necessary. Unfortunately, many of these viral illnesses can look the same. They can all cause fevers, chills, and other upper respiratory symptoms. They are all fairly contagious. All of these viruses can cause serious illness associated with additional complications. It is not truly possible to determine which virus someone has by symptoms alone, our patients can have multiple viruses at the same time and diagnosis of one does not preclude having another.3

Instead, we truly do need a test for diagnosis. In-office testing is available for RSV, influenza, and COVID-19. Additionally, despite not being as freely available as they were during the pandemic, patients are able to do home COVID tests and then call in with their results. At the time of writing this, at-home rapid influenza tests have also been approved by the FDA but are not yet readily available to the public. These tests are important for determining if the patient is eligible for treatment. Both influenza and COVID-19 have antiviral treatments available to help decrease the severity of the illness and potentially the length of illness and time contagious. According to the CDC, both treatments are underutilized.

This could be because of a lack of testing and diagnosis. It may also be because of a lack of familiarity with the available treatments.4,5Influenza treatment is recommended as soon as possible for those with suspected or confirmed diagnosis, immediately for anyone hospitalized, anyone with severe, complicated, or progressing illness, and for those at high risk of severe illness including but not limited to those under 2 years old, those over 65, those who are pregnant, and those with many chronic conditions.

Treatment can also be used for those who are not high risk when diagnosed within 48 hours. In the United States, four antivirals are recommended to treat influenza: oseltamivir phosphate, zanamivir, peramivir, and baloxavir marboxil. For COVID-19, treatments are also available for mild or moderate disease in those at risk for severe disease. Both remdesivir and nimatrelvir with ritonavir are treatment options that can be used for COVID-19 infection. Unfortunately, no specific antiviral is available for the other viral illnesses we see often during this season.

In primary care, we have some important roles to play. We need to continue to discuss all methods of prevention. Not only do vaccine recommendations change at least annually, our patients’ situations change and we have to reassess them. Additionally, people often need to hear things more than once before committing — so it never hurts to continue having those conversations. Combining the conversation about vaccines with other prevention measures is also important so that it does not seem like we are only recommending one thing. We should also start talking about treatment options before our patients are sick. We can communicate what is available as long as they let us know they are sick early. We can also be there to help our patients determine when they are at risk for severe illness and when they should consider a higher level of care.

The availability of home testing gives us the opportunity to provide these treatments via telehealth and even potentially in times when these illnesses are everywhere — with standing orders with our clinical teams. Although it is a busy time for us in the clinic, “cold and flu” season is definitely one of those times when our primary care relationship can truly help our patients.

References

1. CDC Recommends Updated 2024-2025 COVID-19 and Flu Vaccines for Fall/Winter Virus Season. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2024/s-t0627-vaccine-recommendations.html. Accessed August 8, 2024. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

2. CDC Updates RSV Vaccination Recommendation for Adults. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2024/s-0626-vaccination-adults.html. Accessed August 8, 2024. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

3. Similarities and Differences between Flu and COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/symptoms/flu-vs-covid19.htm. Accessed August 8, 2024. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

4. Respiratory Virus Guidance. https://www.cdc.gov/respiratory-viruses/guidance/index.html. Accessed August 9, 2024. Source: National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

5. Provider Toolkit: Preparing Patients for the Fall and Winter Virus Season. https://www.cdc.gov/respiratory-viruses/hcp/tools-resources/index.html. Accessed August 9, 2024. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Remission or Not, Biologics May Mitigate Cardiovascular Risks of RA

TOPLINE:

, suggesting that biologics may reduce cardiovascular risk in RA even if remission is not achieved.

METHODOLOGY:

- Studies reported reduced cardiovascular risk in patients with RA who respond to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors but not in nonresponders, highlighting the importance of controlling inflammation for cardiovascular protection.

- Researchers assessed whether bDMARDs modify the impact of disease activity and systemic inflammation on cardiovascular risk in 4370 patients (mean age, 55 years) with RA without cardiovascular disease from a 10-country observational cohort.

- The severity of RA disease activity was assessed using C-reactive protein (CRP) levels and 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on CRP (DAS28-CRP).

- Endpoints were time to first MACE — a composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke — and time to first ischemic cardiovascular event (iCVE) — a composite of MACE plus revascularization, angina, transient ischemic attack, and peripheral arterial disease.

TAKEAWAY:

- The interaction between use of bDMARD and DAS28-CRP (P = .017) or CRP (P = .011) was significant for MACE.

- Each unit increase in DAS28-CRP increased the risk for MACE in bDMARD nonusers (hazard ratio [HR], 1.21; P = .002) but not in users.

- The per log unit increase in CRP was associated with a risk for MACE in bDMARD nonusers (HR, 1.16; P = .009) but not in users.

- No interaction was observed between bDMARD use and DAS28-CRP or CRP for the iCVE risk.

IN PRACTICE:

“This may indicate additional bDMARD-specific benefits directly on arterial wall inflammation and atherosclerotic plaque anatomy, stability, and biology, independently of systemic inflammation,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by George Athanasios Karpouzas, MD, The Lundquist Institute, Torrance, California, was published online in RMD Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Patients with a particular interest in RA-associated cardiovascular disease were included, which may have introduced referral bias and affected the generalizability of the findings. Standard definitions were used for selected outcomes; however, differences in the reporting of outcomes may be plausible. Some patients were evaluated prospectively, while others were evaluated retrospectively, leading to differences in surveillance.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by Pfizer. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, suggesting that biologics may reduce cardiovascular risk in RA even if remission is not achieved.

METHODOLOGY:

- Studies reported reduced cardiovascular risk in patients with RA who respond to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors but not in nonresponders, highlighting the importance of controlling inflammation for cardiovascular protection.

- Researchers assessed whether bDMARDs modify the impact of disease activity and systemic inflammation on cardiovascular risk in 4370 patients (mean age, 55 years) with RA without cardiovascular disease from a 10-country observational cohort.

- The severity of RA disease activity was assessed using C-reactive protein (CRP) levels and 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on CRP (DAS28-CRP).

- Endpoints were time to first MACE — a composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke — and time to first ischemic cardiovascular event (iCVE) — a composite of MACE plus revascularization, angina, transient ischemic attack, and peripheral arterial disease.

TAKEAWAY:

- The interaction between use of bDMARD and DAS28-CRP (P = .017) or CRP (P = .011) was significant for MACE.

- Each unit increase in DAS28-CRP increased the risk for MACE in bDMARD nonusers (hazard ratio [HR], 1.21; P = .002) but not in users.

- The per log unit increase in CRP was associated with a risk for MACE in bDMARD nonusers (HR, 1.16; P = .009) but not in users.

- No interaction was observed between bDMARD use and DAS28-CRP or CRP for the iCVE risk.

IN PRACTICE:

“This may indicate additional bDMARD-specific benefits directly on arterial wall inflammation and atherosclerotic plaque anatomy, stability, and biology, independently of systemic inflammation,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by George Athanasios Karpouzas, MD, The Lundquist Institute, Torrance, California, was published online in RMD Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Patients with a particular interest in RA-associated cardiovascular disease were included, which may have introduced referral bias and affected the generalizability of the findings. Standard definitions were used for selected outcomes; however, differences in the reporting of outcomes may be plausible. Some patients were evaluated prospectively, while others were evaluated retrospectively, leading to differences in surveillance.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by Pfizer. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, suggesting that biologics may reduce cardiovascular risk in RA even if remission is not achieved.

METHODOLOGY:

- Studies reported reduced cardiovascular risk in patients with RA who respond to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors but not in nonresponders, highlighting the importance of controlling inflammation for cardiovascular protection.

- Researchers assessed whether bDMARDs modify the impact of disease activity and systemic inflammation on cardiovascular risk in 4370 patients (mean age, 55 years) with RA without cardiovascular disease from a 10-country observational cohort.

- The severity of RA disease activity was assessed using C-reactive protein (CRP) levels and 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on CRP (DAS28-CRP).

- Endpoints were time to first MACE — a composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke — and time to first ischemic cardiovascular event (iCVE) — a composite of MACE plus revascularization, angina, transient ischemic attack, and peripheral arterial disease.

TAKEAWAY:

- The interaction between use of bDMARD and DAS28-CRP (P = .017) or CRP (P = .011) was significant for MACE.

- Each unit increase in DAS28-CRP increased the risk for MACE in bDMARD nonusers (hazard ratio [HR], 1.21; P = .002) but not in users.

- The per log unit increase in CRP was associated with a risk for MACE in bDMARD nonusers (HR, 1.16; P = .009) but not in users.

- No interaction was observed between bDMARD use and DAS28-CRP or CRP for the iCVE risk.

IN PRACTICE:

“This may indicate additional bDMARD-specific benefits directly on arterial wall inflammation and atherosclerotic plaque anatomy, stability, and biology, independently of systemic inflammation,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by George Athanasios Karpouzas, MD, The Lundquist Institute, Torrance, California, was published online in RMD Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Patients with a particular interest in RA-associated cardiovascular disease were included, which may have introduced referral bias and affected the generalizability of the findings. Standard definitions were used for selected outcomes; however, differences in the reporting of outcomes may be plausible. Some patients were evaluated prospectively, while others were evaluated retrospectively, leading to differences in surveillance.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by Pfizer. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

These Four Factors Account for 18 Years of Life Expectancy

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Two individuals in the United States are celebrating their 30th birthdays. It’s a good day. They are entering the prime of their lives. One is a married White woman with a university degree. The other is a never-married White man with a high school diploma.

How many more years of life can these two individuals look forward to?

There’s a fairly dramatic difference. The man can expect 37.1 more years of life on average, living to be about 67. The woman can expect to live to age 85. That’s a life-expectancy discrepancy of 18 years based solely on gender, education, and marital status.

I’m using these cases to illustrate the extremes of life expectancy across four key social determinants of health: sex, race, marital status, and education. We all have some sense of how these factors play out in terms of health, but a new study suggests that it’s actually quite a bit more complicated than we thought.

Let me start by acknowledging my own bias here. As a clinical researcher, I sometimes find it hard to appreciate the value of actuarial-type studies that look at life expectancy (or any metric, really) between groups defined by marital status, for example. I’m never quite sure what to do with the conclusion. Married people live longer, the headline says. Okay, but as a doctor, what am I supposed to do about that? Encourage my patients to settle down and commit? Studies showing that women live longer than men or that White people live longer than Black people are also hard for me to incorporate into my practice. These are not easily changeable states.

But studies examining these groups are a reasonable starting point to ask more relevant questions. Why do women live longer than men? Is it behavioral (men take more risks and are less likely to see doctors)? Or is it hormonal (estrogen has a lot of protective effects that testosterone does not)? Or is it something else?

Integrating these social determinants of health into a cohesive story is a bit harder than it might seem, as this study, appearing in BMJ Open, illustrates.

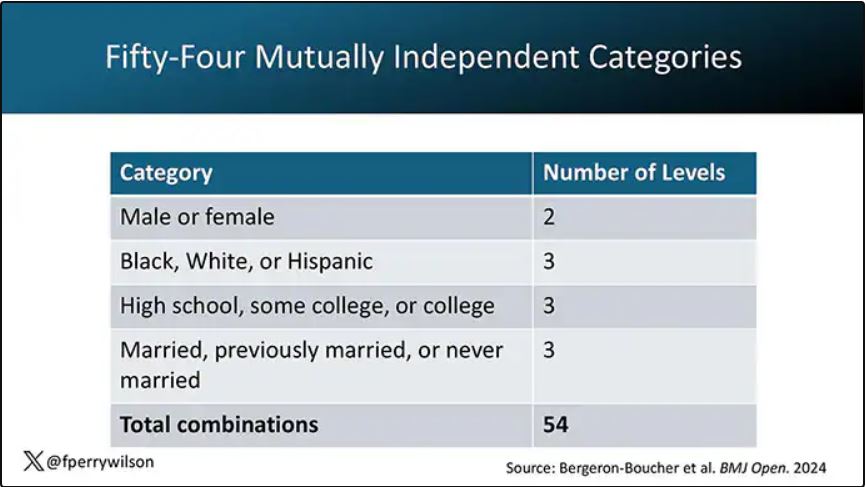

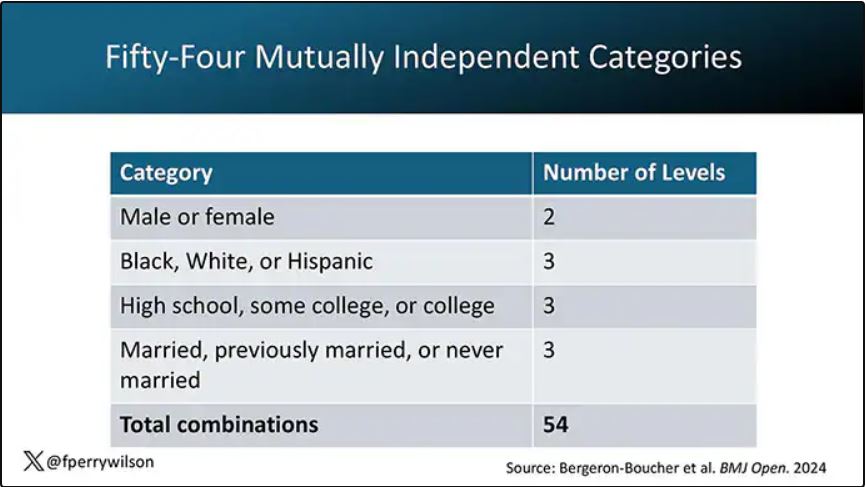

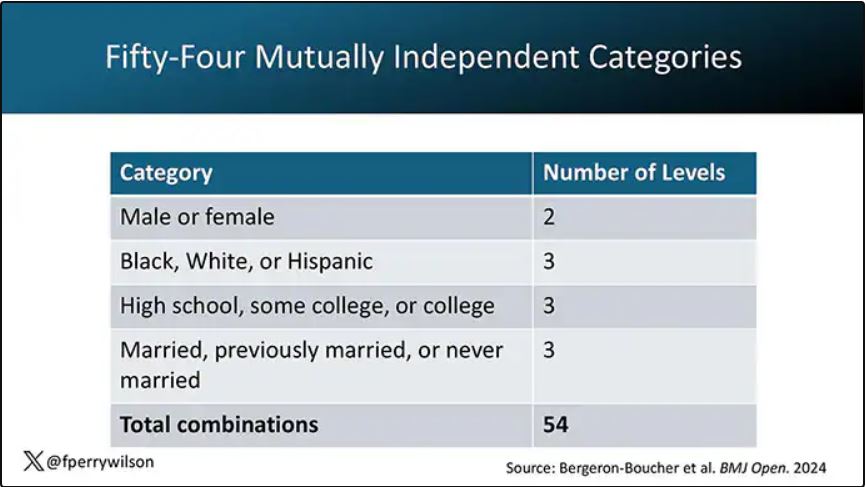

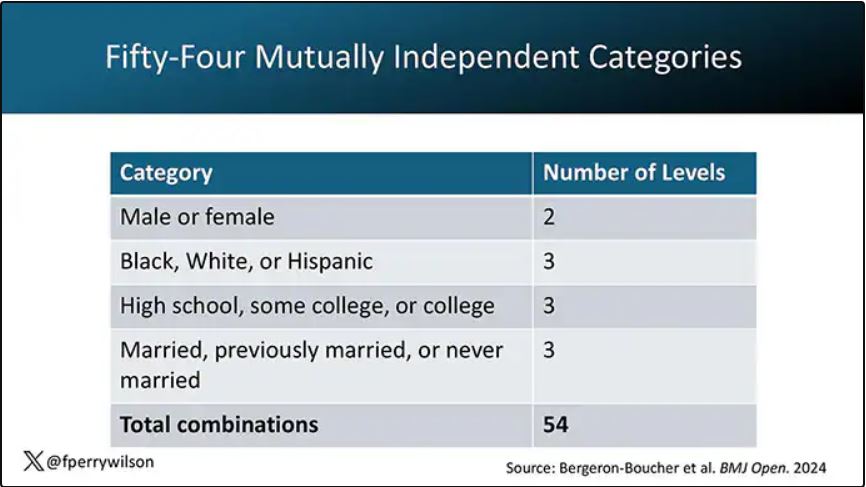

In the context of this study, every person in America can be placed into one of 54 mutually exclusive groups. You can be male or female. You can be Black, White, or Hispanic. You can have a high school diploma or less, an associate degree, or a college degree; and you can be married, previously married, or never married.

Of course, this does not capture the beautiful tapestry that is American life, but let’s give them a pass. They are working with data from the American Community Survey, which contains 8634 people — the statistics would run into trouble with more granular divisions. This survey can be population weighted, so you can scale up the results to reasonably represent the population of the United States.

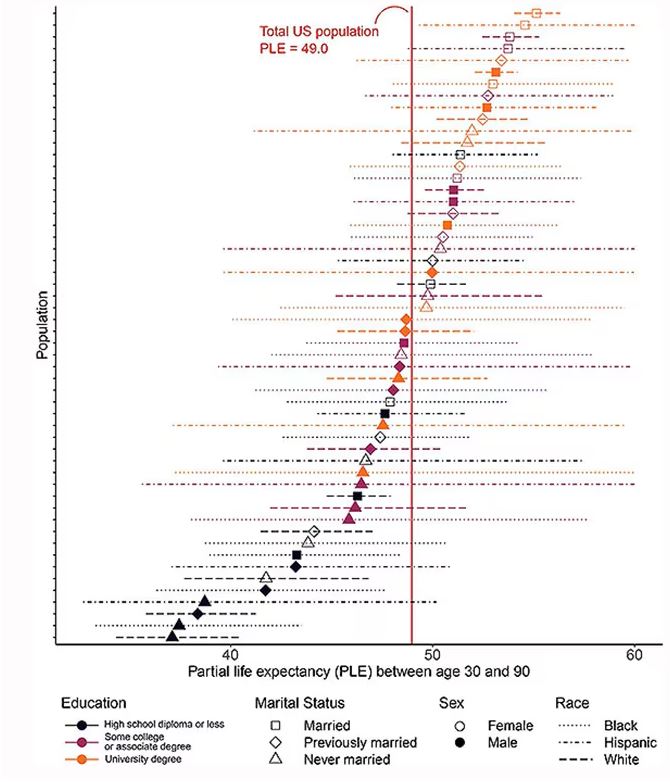

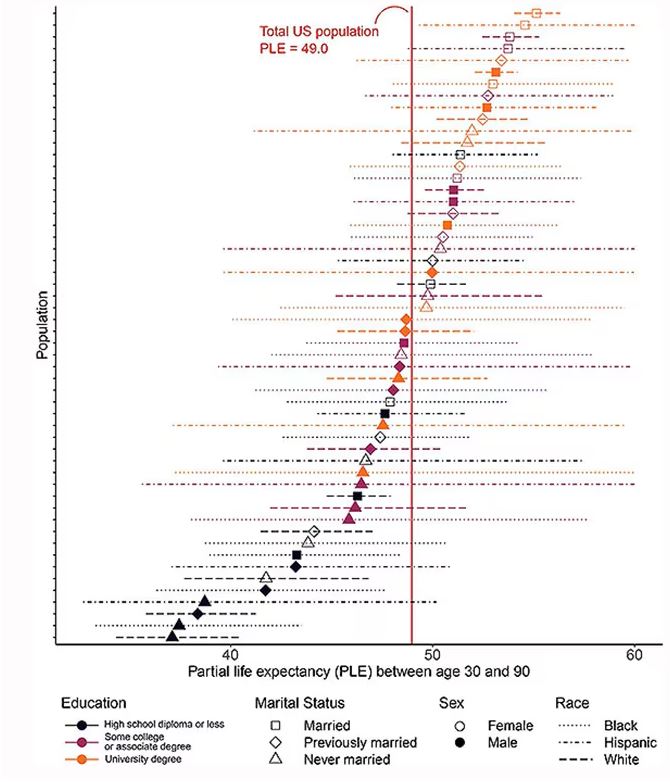

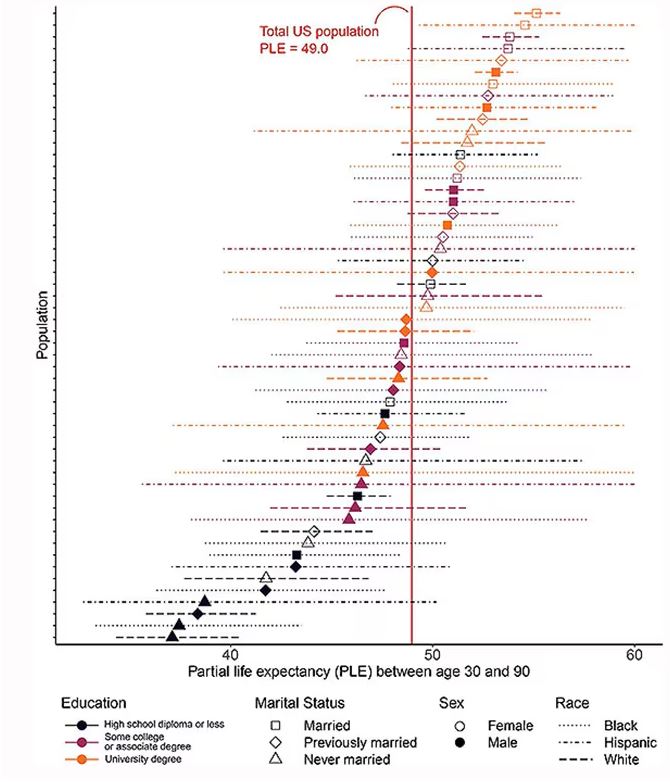

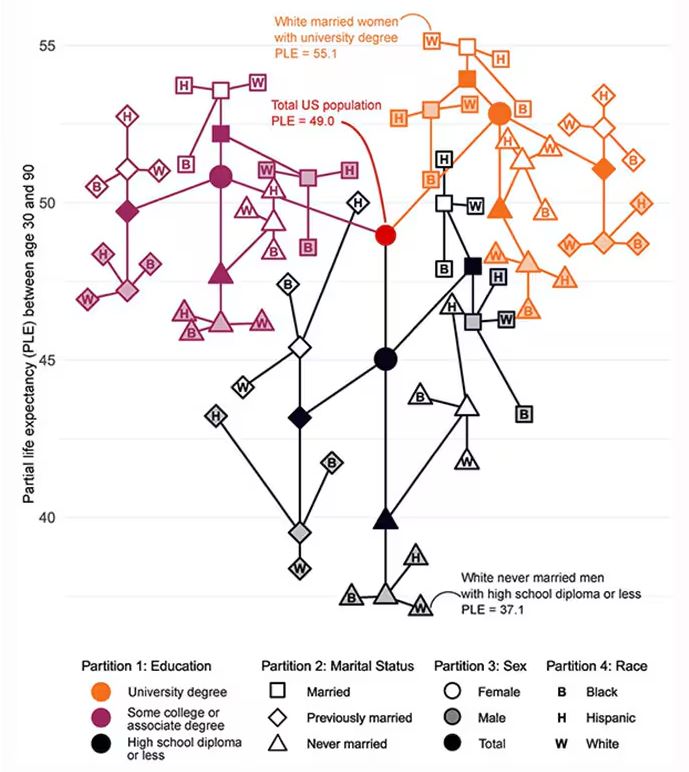

The survey collected data on the four broad categories of sex, race, education, and marital status and linked those survey results to the Multiple Cause of Death dataset from the CDC. From there, it’s a pretty simple task to rank the 54 categories in order from longest to shortest life expectancy, as you can see here.

But that’s not really the interesting part of this study. Sure, there is a lot of variation; it’s interesting that these four factors explain about 18 years’ difference in life expectancy in this country. What strikes me here, actually, is the lack of an entirely consistent message across this spectrum.

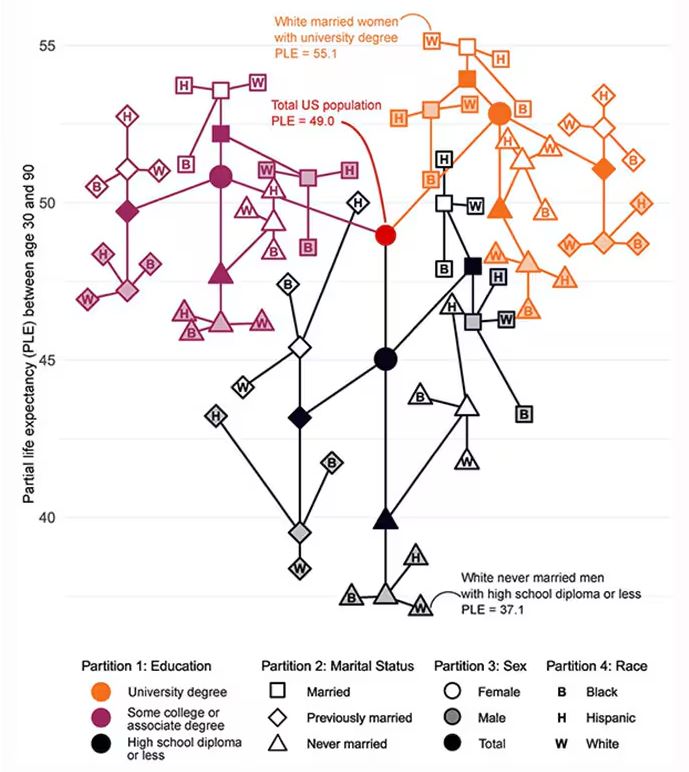

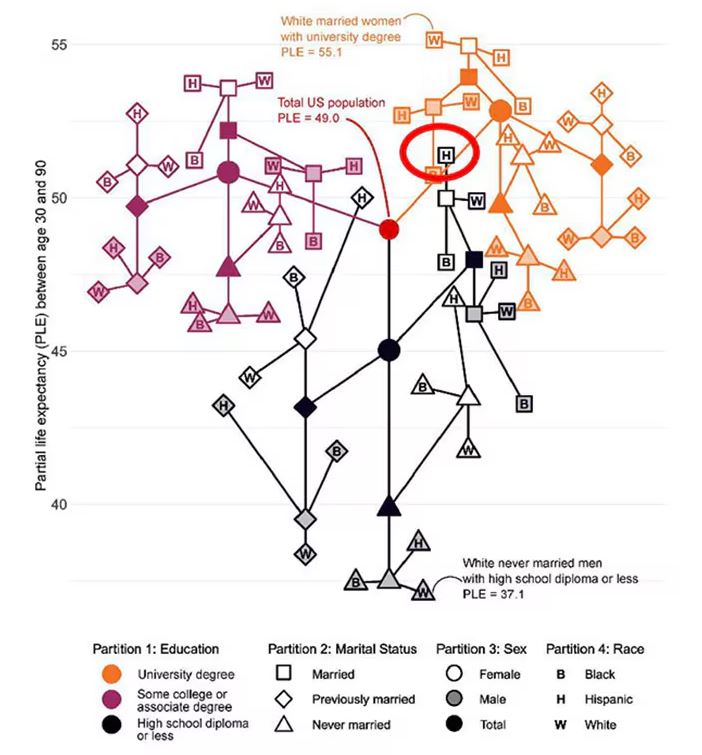

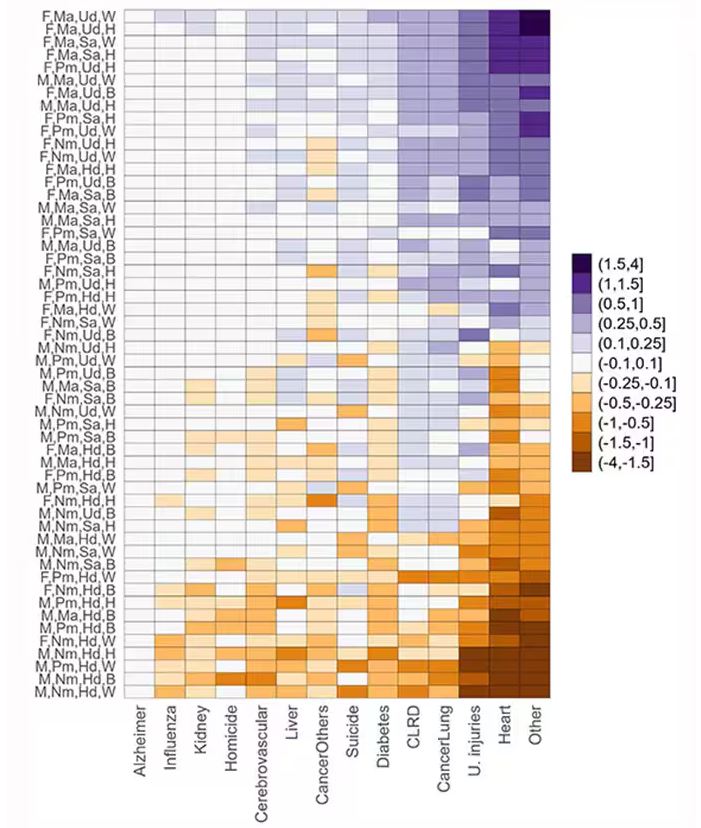

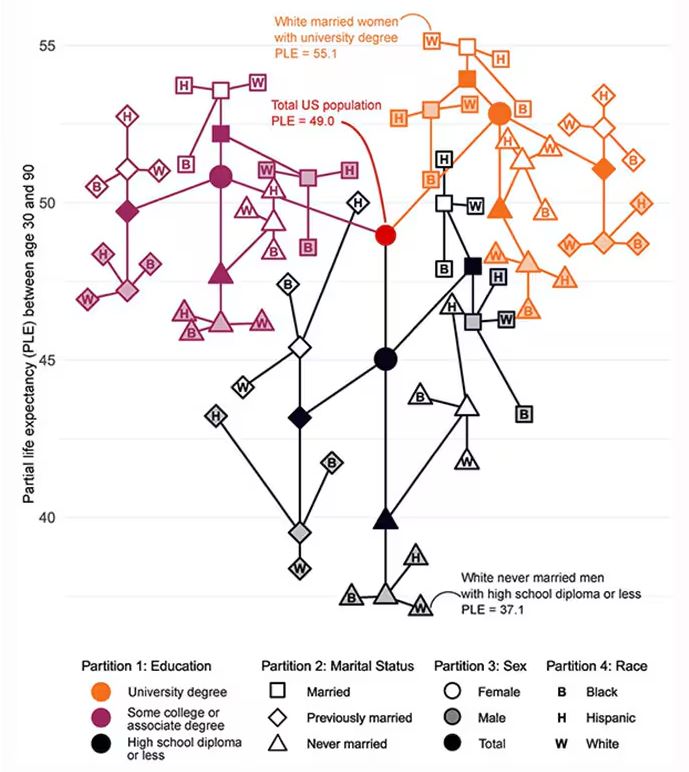

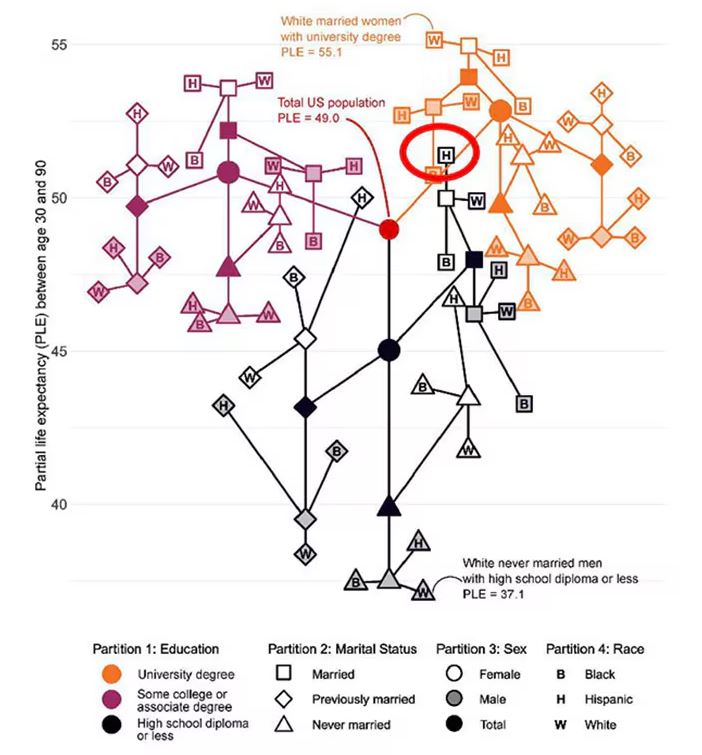

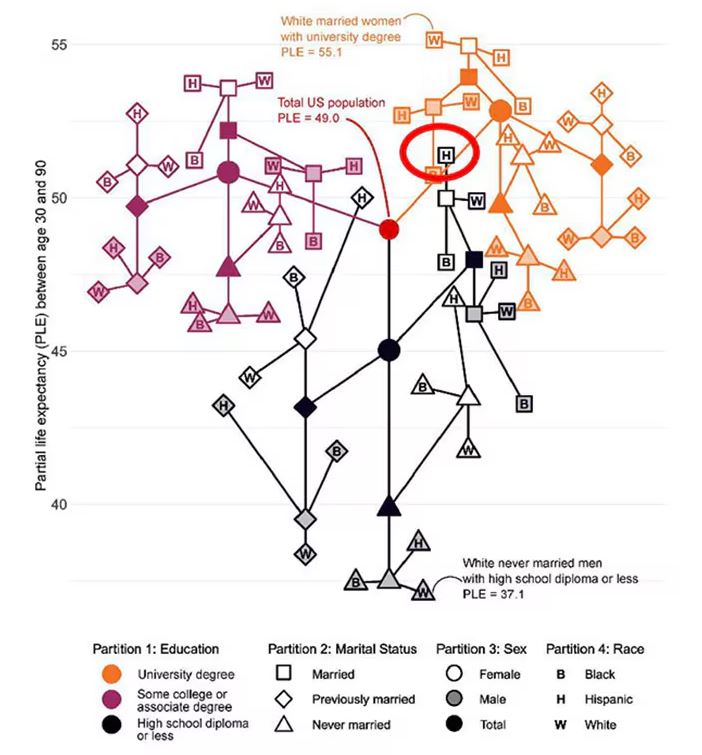

Let me walk you through the second figure in this paper, because this nicely illustrates the surprising heterogeneity that exists here.

This may seem overwhelming, but basically, shapes that are higher up on the Y-axis represent the groups with longer life expectancy.

You can tell, for example, that shapes that are black in color (groups with high school educations or less) are generally lower. But not universally so. This box represents married, Hispanic females who do quite well in terms of life expectancy, even at that lower educational level.

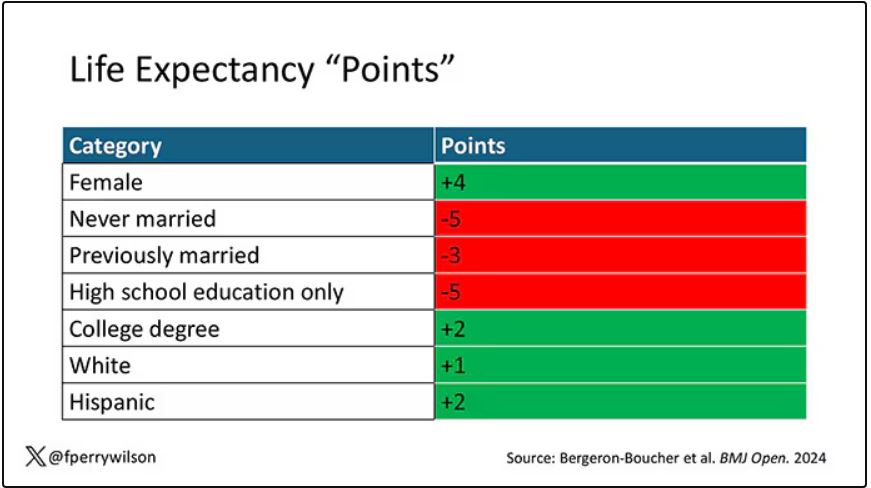

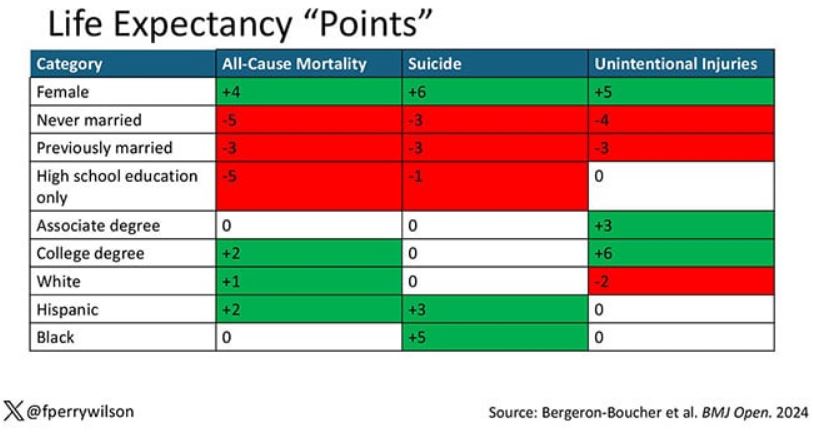

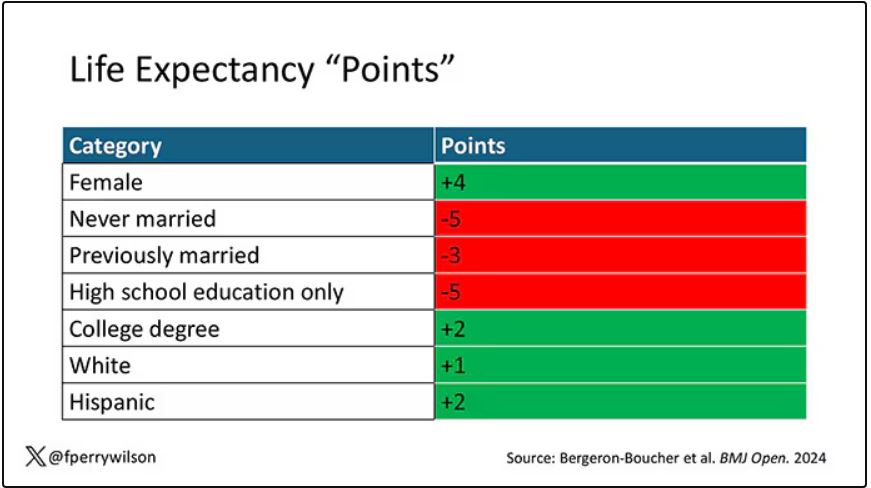

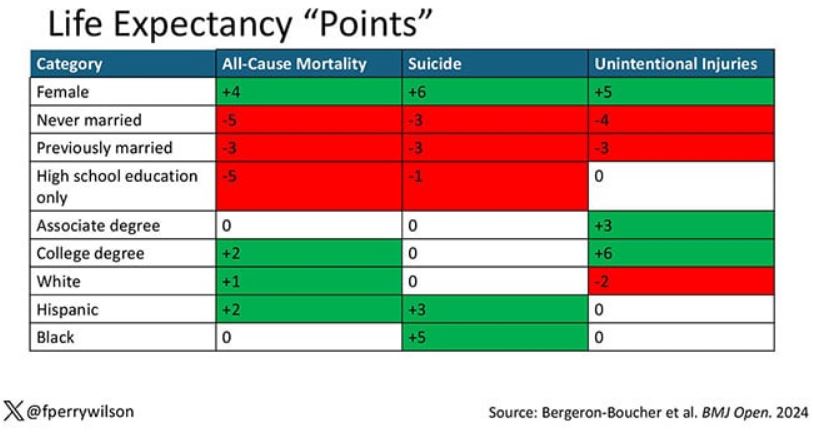

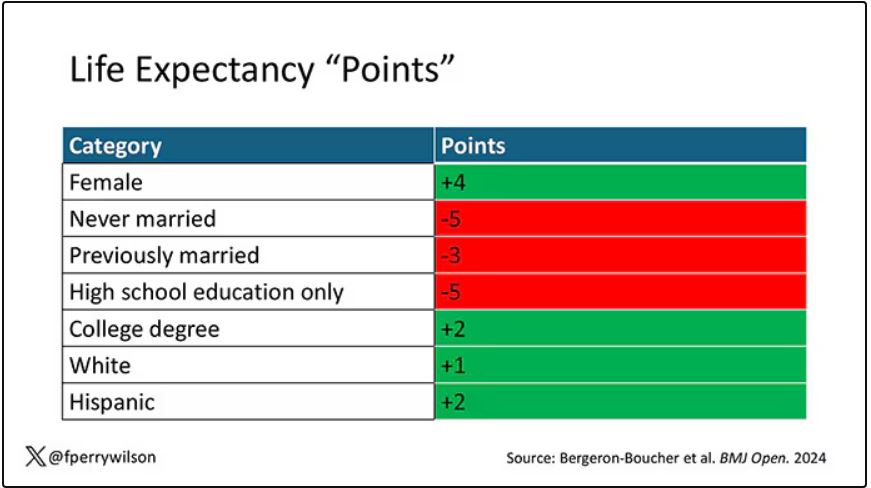

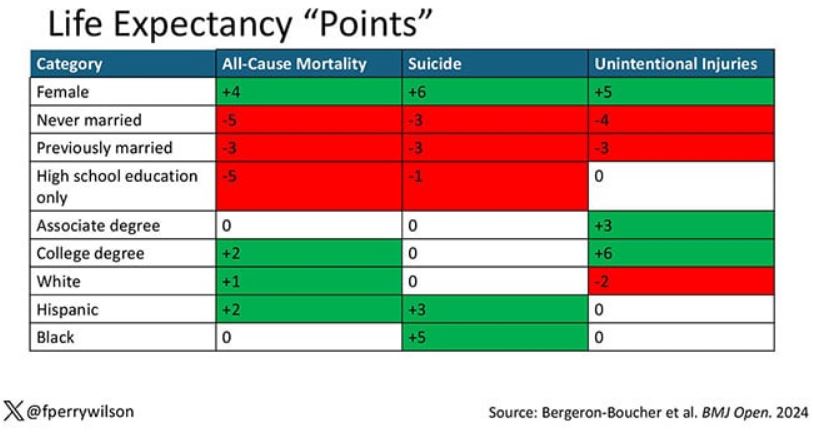

The authors quantify this phenomenon by creating a mortality risk score that integrates these findings. It looks something like this, with 0 being average morality for the United States.

As you can see, you get a bunch of points for being female, but you lose a bunch for not being married. Education plays a large role, with a big hit for those who have a high school diploma or less, and a bonus for those with a college degree. Race plays a relatively more minor role.

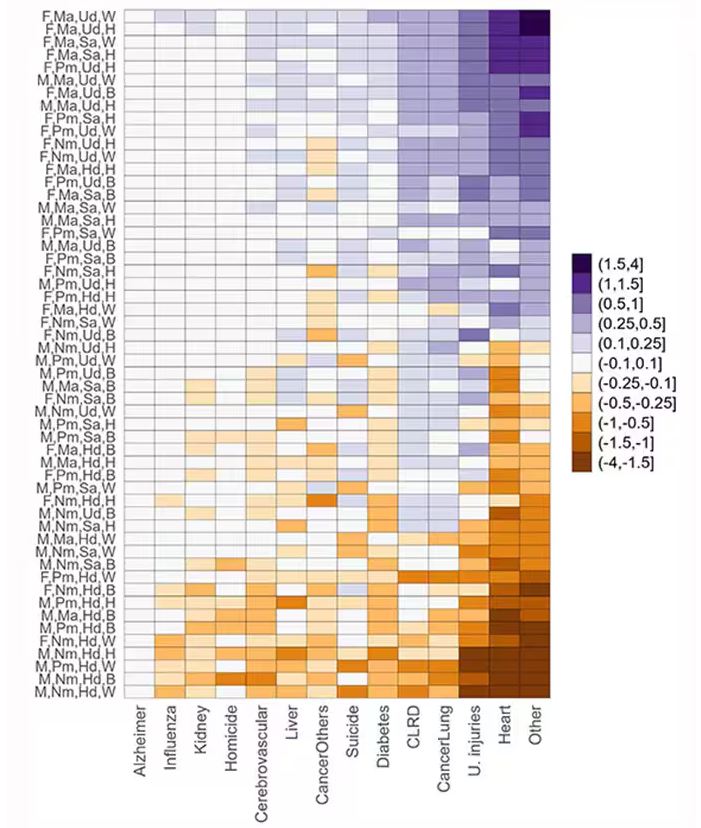

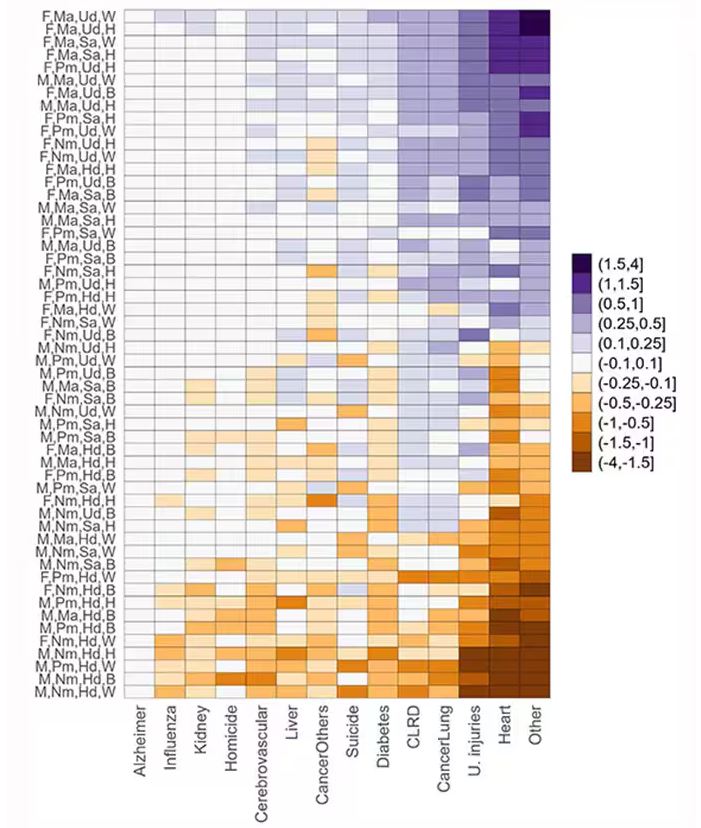

This is all very interesting, but as I said at the beginning, this isn’t terribly useful to me as a physician. More important is figuring out why these differences exist. And there are some clues in the study data, particularly when we examine causes of death. This figure ranks those 54 groups again, from the married, White, college-educated females down to the never-married, White, high school–educated males. The boxes show how much more or less likely this group is to die of a given condition than the general population.

Looking at the bottom groups, you can see a dramatically increased risk for death from unintentional injuries, heart disease, and lung cancer. You see an increased risk for suicide as well. In the upper tiers, the only place where risk seems higher than expected is for the category of “other cancers,” reminding us that many types of cancer do not respect definitions of socioeconomic status.

You can even update the risk-scoring system to reflect the risk for different causes of death. You can see here how White people, for example, are at higher risk for death from unintentional injuries relative to other populations, despite having a lower mortality overall.

So maybe, through cause of death, we get a little closer to the answer of why. But this paper is really just a start. Its primary effect should be to surprise us — that in a country as wealthy as the United States, such dramatic variation exists based on factors that, with the exception of sex, I suppose, are not really biological. Which means that to find the why, we may need to turn from physiology to sociology.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Two individuals in the United States are celebrating their 30th birthdays. It’s a good day. They are entering the prime of their lives. One is a married White woman with a university degree. The other is a never-married White man with a high school diploma.

How many more years of life can these two individuals look forward to?

There’s a fairly dramatic difference. The man can expect 37.1 more years of life on average, living to be about 67. The woman can expect to live to age 85. That’s a life-expectancy discrepancy of 18 years based solely on gender, education, and marital status.

I’m using these cases to illustrate the extremes of life expectancy across four key social determinants of health: sex, race, marital status, and education. We all have some sense of how these factors play out in terms of health, but a new study suggests that it’s actually quite a bit more complicated than we thought.

Let me start by acknowledging my own bias here. As a clinical researcher, I sometimes find it hard to appreciate the value of actuarial-type studies that look at life expectancy (or any metric, really) between groups defined by marital status, for example. I’m never quite sure what to do with the conclusion. Married people live longer, the headline says. Okay, but as a doctor, what am I supposed to do about that? Encourage my patients to settle down and commit? Studies showing that women live longer than men or that White people live longer than Black people are also hard for me to incorporate into my practice. These are not easily changeable states.

But studies examining these groups are a reasonable starting point to ask more relevant questions. Why do women live longer than men? Is it behavioral (men take more risks and are less likely to see doctors)? Or is it hormonal (estrogen has a lot of protective effects that testosterone does not)? Or is it something else?

Integrating these social determinants of health into a cohesive story is a bit harder than it might seem, as this study, appearing in BMJ Open, illustrates.

In the context of this study, every person in America can be placed into one of 54 mutually exclusive groups. You can be male or female. You can be Black, White, or Hispanic. You can have a high school diploma or less, an associate degree, or a college degree; and you can be married, previously married, or never married.

Of course, this does not capture the beautiful tapestry that is American life, but let’s give them a pass. They are working with data from the American Community Survey, which contains 8634 people — the statistics would run into trouble with more granular divisions. This survey can be population weighted, so you can scale up the results to reasonably represent the population of the United States.

The survey collected data on the four broad categories of sex, race, education, and marital status and linked those survey results to the Multiple Cause of Death dataset from the CDC. From there, it’s a pretty simple task to rank the 54 categories in order from longest to shortest life expectancy, as you can see here.

But that’s not really the interesting part of this study. Sure, there is a lot of variation; it’s interesting that these four factors explain about 18 years’ difference in life expectancy in this country. What strikes me here, actually, is the lack of an entirely consistent message across this spectrum.

Let me walk you through the second figure in this paper, because this nicely illustrates the surprising heterogeneity that exists here.

This may seem overwhelming, but basically, shapes that are higher up on the Y-axis represent the groups with longer life expectancy.

You can tell, for example, that shapes that are black in color (groups with high school educations or less) are generally lower. But not universally so. This box represents married, Hispanic females who do quite well in terms of life expectancy, even at that lower educational level.

The authors quantify this phenomenon by creating a mortality risk score that integrates these findings. It looks something like this, with 0 being average morality for the United States.

As you can see, you get a bunch of points for being female, but you lose a bunch for not being married. Education plays a large role, with a big hit for those who have a high school diploma or less, and a bonus for those with a college degree. Race plays a relatively more minor role.

This is all very interesting, but as I said at the beginning, this isn’t terribly useful to me as a physician. More important is figuring out why these differences exist. And there are some clues in the study data, particularly when we examine causes of death. This figure ranks those 54 groups again, from the married, White, college-educated females down to the never-married, White, high school–educated males. The boxes show how much more or less likely this group is to die of a given condition than the general population.

Looking at the bottom groups, you can see a dramatically increased risk for death from unintentional injuries, heart disease, and lung cancer. You see an increased risk for suicide as well. In the upper tiers, the only place where risk seems higher than expected is for the category of “other cancers,” reminding us that many types of cancer do not respect definitions of socioeconomic status.

You can even update the risk-scoring system to reflect the risk for different causes of death. You can see here how White people, for example, are at higher risk for death from unintentional injuries relative to other populations, despite having a lower mortality overall.

So maybe, through cause of death, we get a little closer to the answer of why. But this paper is really just a start. Its primary effect should be to surprise us — that in a country as wealthy as the United States, such dramatic variation exists based on factors that, with the exception of sex, I suppose, are not really biological. Which means that to find the why, we may need to turn from physiology to sociology.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Two individuals in the United States are celebrating their 30th birthdays. It’s a good day. They are entering the prime of their lives. One is a married White woman with a university degree. The other is a never-married White man with a high school diploma.

How many more years of life can these two individuals look forward to?

There’s a fairly dramatic difference. The man can expect 37.1 more years of life on average, living to be about 67. The woman can expect to live to age 85. That’s a life-expectancy discrepancy of 18 years based solely on gender, education, and marital status.

I’m using these cases to illustrate the extremes of life expectancy across four key social determinants of health: sex, race, marital status, and education. We all have some sense of how these factors play out in terms of health, but a new study suggests that it’s actually quite a bit more complicated than we thought.

Let me start by acknowledging my own bias here. As a clinical researcher, I sometimes find it hard to appreciate the value of actuarial-type studies that look at life expectancy (or any metric, really) between groups defined by marital status, for example. I’m never quite sure what to do with the conclusion. Married people live longer, the headline says. Okay, but as a doctor, what am I supposed to do about that? Encourage my patients to settle down and commit? Studies showing that women live longer than men or that White people live longer than Black people are also hard for me to incorporate into my practice. These are not easily changeable states.

But studies examining these groups are a reasonable starting point to ask more relevant questions. Why do women live longer than men? Is it behavioral (men take more risks and are less likely to see doctors)? Or is it hormonal (estrogen has a lot of protective effects that testosterone does not)? Or is it something else?

Integrating these social determinants of health into a cohesive story is a bit harder than it might seem, as this study, appearing in BMJ Open, illustrates.

In the context of this study, every person in America can be placed into one of 54 mutually exclusive groups. You can be male or female. You can be Black, White, or Hispanic. You can have a high school diploma or less, an associate degree, or a college degree; and you can be married, previously married, or never married.

Of course, this does not capture the beautiful tapestry that is American life, but let’s give them a pass. They are working with data from the American Community Survey, which contains 8634 people — the statistics would run into trouble with more granular divisions. This survey can be population weighted, so you can scale up the results to reasonably represent the population of the United States.

The survey collected data on the four broad categories of sex, race, education, and marital status and linked those survey results to the Multiple Cause of Death dataset from the CDC. From there, it’s a pretty simple task to rank the 54 categories in order from longest to shortest life expectancy, as you can see here.

But that’s not really the interesting part of this study. Sure, there is a lot of variation; it’s interesting that these four factors explain about 18 years’ difference in life expectancy in this country. What strikes me here, actually, is the lack of an entirely consistent message across this spectrum.

Let me walk you through the second figure in this paper, because this nicely illustrates the surprising heterogeneity that exists here.

This may seem overwhelming, but basically, shapes that are higher up on the Y-axis represent the groups with longer life expectancy.

You can tell, for example, that shapes that are black in color (groups with high school educations or less) are generally lower. But not universally so. This box represents married, Hispanic females who do quite well in terms of life expectancy, even at that lower educational level.

The authors quantify this phenomenon by creating a mortality risk score that integrates these findings. It looks something like this, with 0 being average morality for the United States.

As you can see, you get a bunch of points for being female, but you lose a bunch for not being married. Education plays a large role, with a big hit for those who have a high school diploma or less, and a bonus for those with a college degree. Race plays a relatively more minor role.

This is all very interesting, but as I said at the beginning, this isn’t terribly useful to me as a physician. More important is figuring out why these differences exist. And there are some clues in the study data, particularly when we examine causes of death. This figure ranks those 54 groups again, from the married, White, college-educated females down to the never-married, White, high school–educated males. The boxes show how much more or less likely this group is to die of a given condition than the general population.

Looking at the bottom groups, you can see a dramatically increased risk for death from unintentional injuries, heart disease, and lung cancer. You see an increased risk for suicide as well. In the upper tiers, the only place where risk seems higher than expected is for the category of “other cancers,” reminding us that many types of cancer do not respect definitions of socioeconomic status.

You can even update the risk-scoring system to reflect the risk for different causes of death. You can see here how White people, for example, are at higher risk for death from unintentional injuries relative to other populations, despite having a lower mortality overall.

So maybe, through cause of death, we get a little closer to the answer of why. But this paper is really just a start. Its primary effect should be to surprise us — that in a country as wealthy as the United States, such dramatic variation exists based on factors that, with the exception of sex, I suppose, are not really biological. Which means that to find the why, we may need to turn from physiology to sociology.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Are Your Patients Using Any of These Six Potentially Hepatotoxic Botanicals?

TOPLINE:

The estimated number of US adults who consumed at least one of the six most frequently reported hepatotoxic botanicals in the last 30 days is similar to the number of patients prescribed potentially hepatotoxic drugs, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and simvastatin.

METHODOLOGY:

- Herbal and dietary supplements (HDS) are an increasingly common source of drug hepatotoxicity cases, but their prevalence and the reasons for their use among the general population are uncertain.

- This survey study evaluated nationally representative data from 9685 adults (mean age, 47.5 years; 51.8% women) enrolled in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) between January 2017 and March 2020.

- Participants reported their use of HDS and prescription drugs through personal interviews for a 30-day period prior to the survey date.

- Researchers compared the clinical features and baseline demographic characteristics of users of six potentially hepatotoxic botanicals (ie, turmeric, green tea, Garcinia cambogia, black cohosh, red yeast rice, and ashwagandha) with those of nonusers.

- The prevalence of use of these at-risk botanicals was compared with that of widely prescribed potentially hepatotoxic medications, including NSAIDs, simvastatin, and sertraline.

TAKEAWAY:

- In the cohort of 9685 participants, 4.7% of individuals reported consumption of at least one of the six potentially hepatotoxic botanicals in the past 30 days, with turmeric being the most common, followed by green tea.

- Extrapolating the survey data, researchers estimated that 15.6 million US adults use at least one of these six botanicals, which is comparable to the number of those prescribed potentially hepatotoxic drugs, including NSAIDs (14.8 million) and simvastatin (14.0 million). Sertraline use was lower (7.7 million).

- Most individuals used these botanicals without the recommendation of their healthcare provider.

- Those using botanicals were more likely to be older (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.36; P = .04 for 40-59 years; aOR, 3.96; P = .001 for ≥ 60 years), to have some college education (aOR, 4.78; P < .001), and to have arthritis (aOR, 2.27; P < .001) than nonusers.

- The most common reasons for using any of these six potential hepatotoxic botanicals were to improve or maintain health or to prevent health problems or boost immunity.

IN PRACTICE:

“In light of the lack of regulatory oversight on the manufacturing and testing of botanical products, it is recommended that clinicians obtain a full medication and HDS use history when evaluating patients with unexplained symptoms or liver test abnormalities,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Alisa Likhitsup, MD, MPH, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The survey response rate was low at 43.9% for adults aged ≥ 20 years. As NHANES is a cross-sectional study, the causal relationship between consumption of the six botanicals of interest and the development of liver injury could not be determined. The use of HDS products and medications was self-reported in NHANES and not independently verified using source documents.

DISCLOSURES:

This study did not report any source of funding. Two authors declared receiving grants from pharmaceutical companies outside the submitted work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

The estimated number of US adults who consumed at least one of the six most frequently reported hepatotoxic botanicals in the last 30 days is similar to the number of patients prescribed potentially hepatotoxic drugs, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and simvastatin.

METHODOLOGY:

- Herbal and dietary supplements (HDS) are an increasingly common source of drug hepatotoxicity cases, but their prevalence and the reasons for their use among the general population are uncertain.

- This survey study evaluated nationally representative data from 9685 adults (mean age, 47.5 years; 51.8% women) enrolled in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) between January 2017 and March 2020.

- Participants reported their use of HDS and prescription drugs through personal interviews for a 30-day period prior to the survey date.

- Researchers compared the clinical features and baseline demographic characteristics of users of six potentially hepatotoxic botanicals (ie, turmeric, green tea, Garcinia cambogia, black cohosh, red yeast rice, and ashwagandha) with those of nonusers.

- The prevalence of use of these at-risk botanicals was compared with that of widely prescribed potentially hepatotoxic medications, including NSAIDs, simvastatin, and sertraline.

TAKEAWAY:

- In the cohort of 9685 participants, 4.7% of individuals reported consumption of at least one of the six potentially hepatotoxic botanicals in the past 30 days, with turmeric being the most common, followed by green tea.

- Extrapolating the survey data, researchers estimated that 15.6 million US adults use at least one of these six botanicals, which is comparable to the number of those prescribed potentially hepatotoxic drugs, including NSAIDs (14.8 million) and simvastatin (14.0 million). Sertraline use was lower (7.7 million).

- Most individuals used these botanicals without the recommendation of their healthcare provider.

- Those using botanicals were more likely to be older (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.36; P = .04 for 40-59 years; aOR, 3.96; P = .001 for ≥ 60 years), to have some college education (aOR, 4.78; P < .001), and to have arthritis (aOR, 2.27; P < .001) than nonusers.

- The most common reasons for using any of these six potential hepatotoxic botanicals were to improve or maintain health or to prevent health problems or boost immunity.

IN PRACTICE:

“In light of the lack of regulatory oversight on the manufacturing and testing of botanical products, it is recommended that clinicians obtain a full medication and HDS use history when evaluating patients with unexplained symptoms or liver test abnormalities,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Alisa Likhitsup, MD, MPH, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The survey response rate was low at 43.9% for adults aged ≥ 20 years. As NHANES is a cross-sectional study, the causal relationship between consumption of the six botanicals of interest and the development of liver injury could not be determined. The use of HDS products and medications was self-reported in NHANES and not independently verified using source documents.

DISCLOSURES:

This study did not report any source of funding. Two authors declared receiving grants from pharmaceutical companies outside the submitted work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

The estimated number of US adults who consumed at least one of the six most frequently reported hepatotoxic botanicals in the last 30 days is similar to the number of patients prescribed potentially hepatotoxic drugs, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and simvastatin.

METHODOLOGY:

- Herbal and dietary supplements (HDS) are an increasingly common source of drug hepatotoxicity cases, but their prevalence and the reasons for their use among the general population are uncertain.

- This survey study evaluated nationally representative data from 9685 adults (mean age, 47.5 years; 51.8% women) enrolled in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) between January 2017 and March 2020.

- Participants reported their use of HDS and prescription drugs through personal interviews for a 30-day period prior to the survey date.

- Researchers compared the clinical features and baseline demographic characteristics of users of six potentially hepatotoxic botanicals (ie, turmeric, green tea, Garcinia cambogia, black cohosh, red yeast rice, and ashwagandha) with those of nonusers.

- The prevalence of use of these at-risk botanicals was compared with that of widely prescribed potentially hepatotoxic medications, including NSAIDs, simvastatin, and sertraline.

TAKEAWAY:

- In the cohort of 9685 participants, 4.7% of individuals reported consumption of at least one of the six potentially hepatotoxic botanicals in the past 30 days, with turmeric being the most common, followed by green tea.

- Extrapolating the survey data, researchers estimated that 15.6 million US adults use at least one of these six botanicals, which is comparable to the number of those prescribed potentially hepatotoxic drugs, including NSAIDs (14.8 million) and simvastatin (14.0 million). Sertraline use was lower (7.7 million).

- Most individuals used these botanicals without the recommendation of their healthcare provider.

- Those using botanicals were more likely to be older (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.36; P = .04 for 40-59 years; aOR, 3.96; P = .001 for ≥ 60 years), to have some college education (aOR, 4.78; P < .001), and to have arthritis (aOR, 2.27; P < .001) than nonusers.

- The most common reasons for using any of these six potential hepatotoxic botanicals were to improve or maintain health or to prevent health problems or boost immunity.

IN PRACTICE:

“In light of the lack of regulatory oversight on the manufacturing and testing of botanical products, it is recommended that clinicians obtain a full medication and HDS use history when evaluating patients with unexplained symptoms or liver test abnormalities,” the authors wrote.