User login

Risk for Appendicitis, Cholecystitis, or Diverticulitis in Patients With Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a chronic skin condition affecting approximately 2% to 3% of the population.1,2 Beyond cutaneous manifestations, psoriasis is a systemic inflammatory state that is associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease, including obesity,3,4 type 2 diabetes mellitus,5,6 hypertension,5 dyslipidemia,3,7 metabolic syndrome,7 atherosclerosis,8 peripheral vascular disease,9 coronary artery calcification,10 myocardial infarction,11-13 stroke,9,14 and cardiac death.15,16

Psoriasis also has been associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), possibly because of similar autoimmune mechanisms in the pathogenesis of both diseases.17,18 However, there is no literature regarding the risk for acute gastrointestinal pathologies such as appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis in patients with psoriasis.

The primary objective of this study was to examine if patients with psoriasis are at increased risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis compared to the general population. The secondary objective was to determine if patients with severe psoriasis (ie, patients treated with phototherapy or systemic therapy) are at a higher risk for these conditions compared to patients with mild psoriasis.

Methods

Patients and Tools

A descriptive, population-based cohort study design with controls from a matched cohort was used to ascertain the effect of psoriasis status on patients’ risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis. Our cohort was selected using administrative data from Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) during the study period (January 1, 2004, through December 31, 2016).

Kaiser Permanente Southern California is a large integrated health maintenance organization that includes approximately 4 million patients as of December 31, 2016, and includes roughly 20% of the region’s population. The geographic area served extends from Bakersfield in the lower California Central Valley to San Diego on the border with Mexico. Membership demographics, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity composition are representative of California.

Patients were included if they had a diagnosis of psoriasis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code 696.1; International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] codes L40.0, L40.4, L40.8, or L40.9) for at least 3 visits between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2016. Patients were not excluded if they also had a diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis (ICD-9-CM code 696.0; ICD-10-CM code L40.5x). Patients also must have been continuously enrolled for at least 1 year before and 1 year after the index date, which was defined as the date of the third psoriasis diagnosis.

Each patient with psoriasis was assigned to 1 of 2 cohorts: (1) severe psoriasis: patients who received UVB phototherapy, psoralen plus UVA phototherapy, methotrexate, acitretin, cyclosporine, apremilast, etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, ustekinumab, efalizumab, alefacept, secukinumab, or ixekizumab during the study period; and (2) mild psoriasis: patients who had a diagnosis of psoriasis who did not receive one of these therapies during the study period.

Patients were excluded if they had a history of appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis at any time before the index date. Only patients older than 18 years were included.

Patients with psoriasis were frequency matched (1:5) with healthy patients, also from the KPSC network. Individuals were matched by age, sex, and ethnicity.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were described with means and SD for continuous variables as well as percentages for categorical variables. Chi-square tests for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney U Test for continuous variables were used to compare the patients’ characteristics by psoriasis status. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to examine the risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis among patients with and without psoriasis and among patients with mild and severe psoriasis. Proportionality assumption was validated using Pearson product moment correlation between the scaled Schoenfeld residuals and log transformed time for each covariate.

Results were presented as crude (unadjusted) hazard ratios (HRs) and adjusted HRs, where confounding factors (ie, age, sex, ethnicity, body mass index [BMI], alcohol use, smoking status, income, education, and membership length) were adjusted. All tests were performed with SAS EG 5.1 and R software. P<.05 was considered statistically significant. Results are reported with the 95% confidence interval (CI), when appropriate.

Results

A total of 1,690,214 KPSC patients were eligible for the study; 10,307 (0.6%) met diagnostic and inclusion criteria for the psoriasis cohort. Patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher mean BMI (29.9 vs 28.7; P<.0001) as well as higher mean rates of alcohol use (56% vs 53%; P<.0001) and smoking (47% vs 38%; P<.01) compared to controls. Psoriasis patients had a shorter average duration of membership within the Kaiser network (P=.0001) compared to controls.

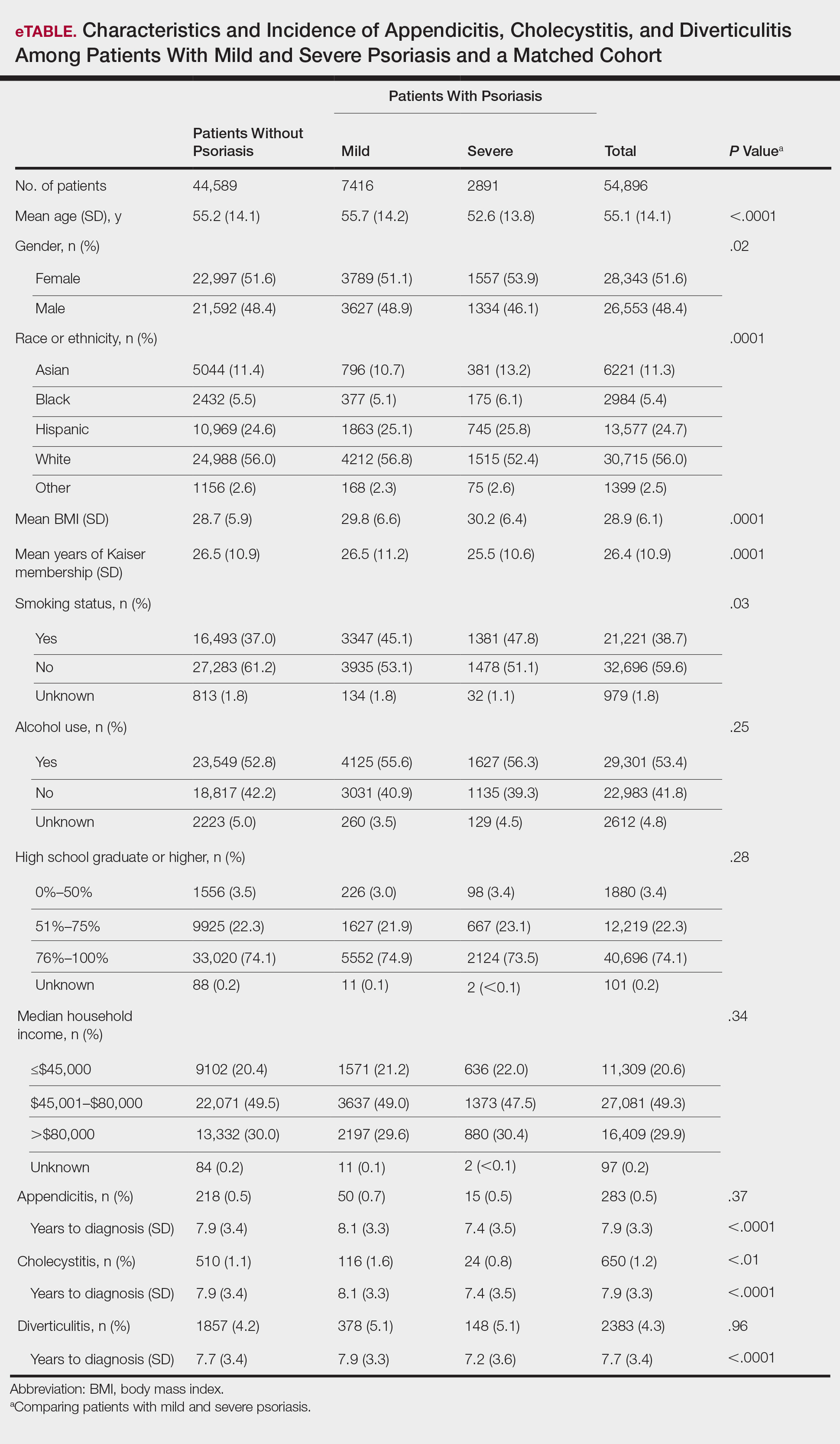

A total of 7416 patients met criteria for mild psoriasis and 2891 patients met criteria for severe psoriasis (eTable). Patients with severe psoriasis were significantly younger and had significantly higher mean BMI compared to patients with mild psoriasis (P<.0001 and P=.0001, respectively). No significant difference in rates of alcohol or tobacco use was detected among patients with mild and severe psoriasis.

Appendicitis

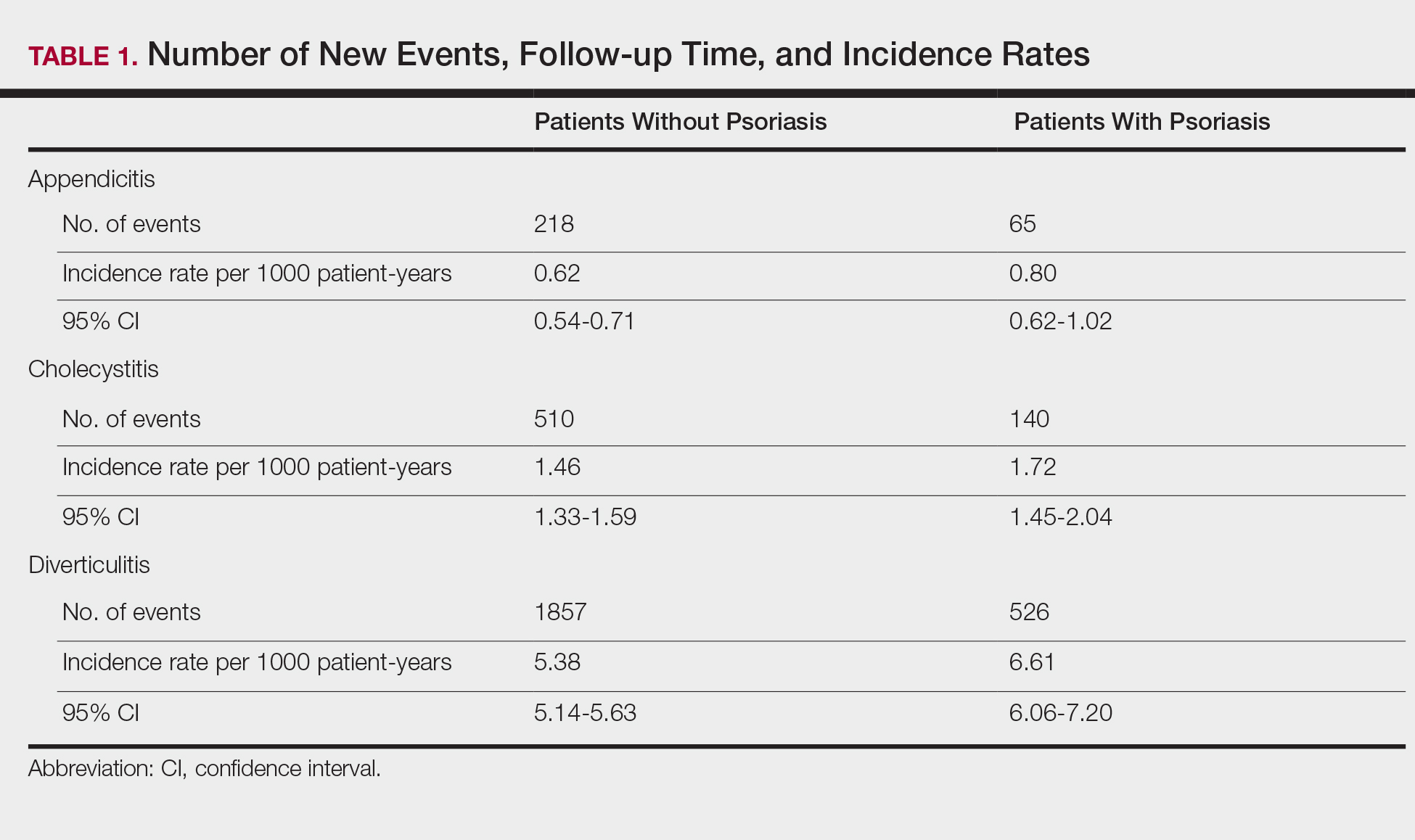

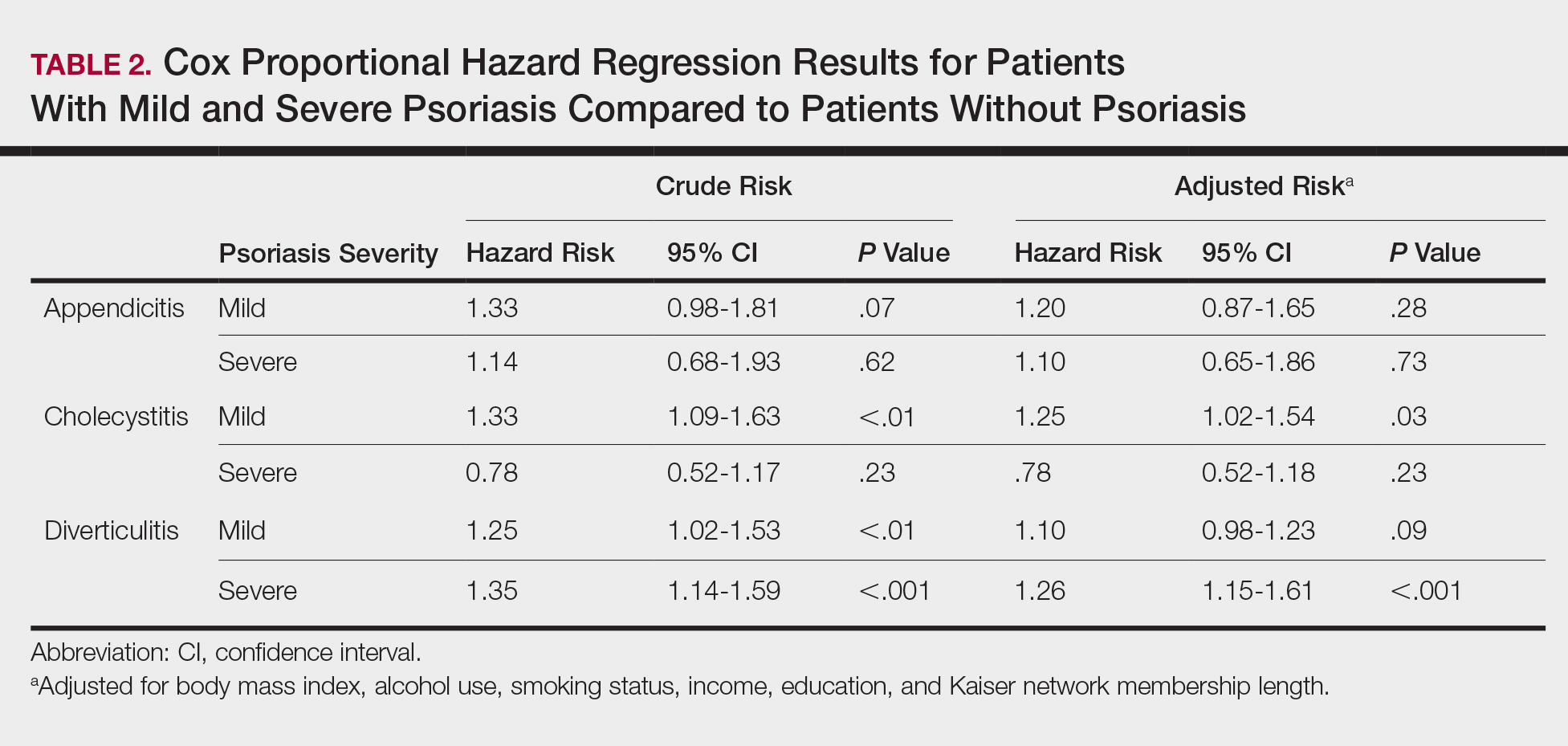

The prevalence of appendicitis was not significantly different between patients with and without psoriasis or between patients with mild and severe psoriasis, though the incidence rate was slightly higher among patients with psoriasis (0.80 per 1000 patient-years compared to 0.62 per 1000 patient-years among patients without psoriasis)(Table 1). However, there was not a significant difference in risk for appendicitis between healthy patients, patients with severe psoriasis, and patients with mild psoriasis after adjusting for potential confounding factors (Table 2). Interestingly, patients with severe psoriasis who had a diagnosis of appendicitis had a significantly shorter time to diagnosis of appendicitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis (7.4 years vs 8.1 years; P<.0001).

Cholecystitis

Psoriasis patients also did not have an increased prevalence of cholecystitis compared to healthy patients. However, patients with severe psoriasis had a significantly higher prevalence of cholecystitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis (P=.0038). Overall, patients with psoriasis had a slightly higher incidence rate (1.72 per 1000 patient-years) compared to healthy patients (1.46 per 1000 patient-years). Moreover, the time to diagnosis of cholecystitis was significantly shorter for patients with severe psoriasis than for patients with mild psoriasis (7.4 years vs 8.1 years; P<.0001). Mild psoriasis was associated with a significantly increased risk (HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.09-1.63; P<.01) for cholecystitis compared to individuals without psoriasis in both the crude and adjusted models (Table 2). There was no difference between mild psoriasis patients and severe psoriasis patients in risk for cholecystitis.

Diverticulitis

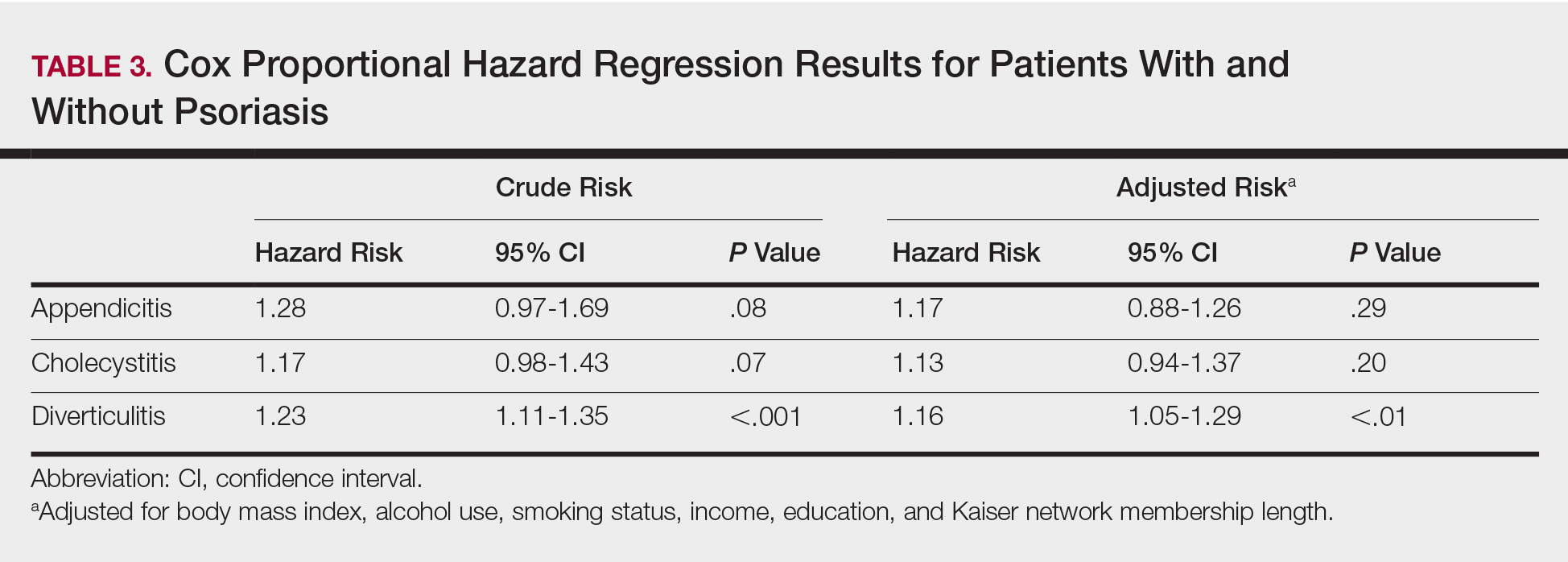

Patients with psoriasis had a significantly greater prevalence of diverticulitis compared to the control cohort (5.1% vs 4.2%; P<.0001). There was no difference in prevalence between the severe psoriasis group and the mild psoriasis group (P=.96), but the time to diagnosis of diverticulitis was shorter in the severe psoriasis group than in the mild psoriasis group (7.2 years vs 7.9 years; P<.0001). Psoriasis patients had an incidence rate of diverticulitis of 6.61 per 1000 patient-years compared to 5.38 per 1000 patient-years in the control group. Psoriasis conferred a higher risk for diverticulitis in both the crude and adjusted models (HR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.11-1.35 [P<.001] and HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.05-1.29; [P<.01], respectively)(Table 3); however, when stratified by disease severity, only patients with severe psoriasis were found to be at higher risk (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.15-1.61; P<.001 for the adjusted model).

Comment

The objective of this study was to examine the background risks for specific gastrointestinal pathologies in a large cohort of patients with psoriasis compared to the general population. After adjusting for measured confounders, patients with severe psoriasis had a significantly higher risk of diverticulitis compared to the general population. Although more patients with severe psoriasis developed appendicitis or cholecystitis, the difference was not significant.

The pathogenesis of diverticulosis and diverticulitis has been thought to be related to increased intracolonic pressure and decreased dietary fiber intake, leading to formation of diverticula in the colon.19 Our study did not correct for differences in diet between the 2 groups, making it a possible confounding variable. Studies evaluating dietary habits of psoriatic patients have found that adult males with psoriasis might consume less fiber compared to healthy patients,20 and psoriasis patients also might consume less whole-grain fiber.21 Furthermore, fiber deficiency also might affect gut flora, causing low-grade chronic inflammation,18 which also has been supported by response to anti-inflammatory medications such as mesalazine.22 Given the autoimmune association between psoriasis and IBD, it is possible that psoriasis also might create an environment of chronic inflammation in the gut, predisposing patients with psoriasis to diverticulitis. However, further research is needed to better evaluate this possibility.

Our study also does not address any potential effects on outcomes of specific treatments for psoriasis. Brandl et al23 found that patients on immunosuppressive therapy for autoimmune diseases had longer hospital and intensive care unit stays, higher rates of emergency operations, and higher mortality while hospitalized. Because our results suggest that patients with severe psoriasis, who are therefore more likely to require treatment with an immunomodulator, are at higher risk for diverticulitis, these patients also might be at risk for poorer outcomes.

There is no literature evaluating the relationship between psoriasis and appendicitis. Our study found a slightly lower incidence rate compared to the national trend (9.38 per 10,000 patient-years in the United States in 2008) in both healthy patients and psoriasis patients.24 Of note, this statistic includes children, whereas our study did not, which might in part account for the lower rate. However, Cheluvappa et al25 hypothesized a relationship between appendicitis and subsequent appendectomy at a young age and protection against IBD. They also found that the mechanism for protection involves downregulation of the helper T cell (TH17) pathway,25 which also has been found to play a role in psoriasis pathogenesis.26,27 Although our results suggest that the risk for appendicitis is not increased for patients with psoriasis, further research might be able to determine if appendicitis and subsequent appendectomy also can offer protection against development of psoriasis.

We found that patients with severe psoriasis had a higher incidence rate of cholecystitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis. Egeberg et al28 found an increased risk for cholelithiasis among patients with psoriasis, which may contribute to a higher rate of cholecystitis. Although both acute and chronic cholecystitis were incorporated in this study, a Russian study found that chronic cholecystitis may be a predictor of progression of psoriasis.29 Moreover, patients with severe psoriasis had a shorter duration to diagnosis of cholecystitis than patients with mild psoriasis. It is possible that patients with severe psoriasis are in a state of greater chronic inflammation than those with mild psoriasis, and therefore, when combined with other risk factors for cholecystitis, may progress to disease more quickly. Alternatively, this finding could be treatment related, as there have been reported cases of cholecystitis related to etanercept use in patients treated for psoriasis and juvenile polyarticular rheumatoid arthritis.30,31 The relationship is not yet well defined, however, and further research is necessary to evaluate this association.

Study Strengths

Key strengths of this study include the large sample size and diversity of the patient population. Kaiser Permanente Southern California membership generally is representative of the broader community, making our results fairly generalizable to populations with health insurance. Use of a matched control cohort allows the results to be more specific to the disease of interest, and the population-based design minimizes bias.

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. Although the cohorts were categorized based on type of treatment received, exact therapies were not specified. As a retrospective study, it is difficult to control for potential confounding variables that are not included in the electronic medical record. The results of this study also demonstrated significantly shorter durations to diagnosis of all 3 conditions, indicating that surveillance bias may be present.

Conclusion

Patients with psoriasis may be at an increased risk for diverticulitis compared to patients without psoriasis, which could be due to the chronic inflammatory state induced by psoriasis. Therefore, it may be beneficial for clinicians to evaluate psoriasis patients for other risk factors for diverticulitis and subsequently provide counseling to these patients to minimize their risk for diverticulitis. Psoriasis patients do not appear to be at an increased risk for appendicitis or cholecystitis compared to controls; however, further research is needed for confirmation.

- Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, et al; Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377-385.

- Channual J, Wu JJ, Dann FJ. Effects of tumor necrosis factor-α blockade on metabolic syndrome in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and additional lessons learned from rheumatoid arthritis. Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:61-73.

- Koebnick C, Black MH, Smith N, et al. The association of psoriasis and elevated blood lipids in overweight and obese children. J Pediatr. 2011;159:577-583.

- Herron MD, Hinckley M, Hoffman MS, et al. Impact of obesity and smoking on psoriasis presentation and management. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1527-1534.

- Qureshi AA, Choi HK, Setty AR, et al. Psoriasis and the risk of diabetes and hypertension: a prospective study of US female nurses. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:379-382.

- Shapiro J, Cohen AD, David M, et al. The association between psoriasis, diabetes mellitus, and atherosclerosis in Israel: a case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:629-634.

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:419-424.

- El-Mongy S, Fathy H, Abdelaziz A, et al. Subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with chronic psoriasis: a potential association. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:661-666.

- Prodanovich S, Kirsner RS, Kravetz JD, et al. Association of psoriasis with coronary artery, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular diseases and mortality. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:700-703.

- Ludwig RJ, Herzog C, Rostock A, et al. Psoriasis: a possible risk factor for development of coronary artery calcification. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:271-276.

- Kaye JA, Li L, Jick SS. Incidence of risk factors for myocardial infarction and other vascular diseases in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:895-902.

- Kimball AB, Robinson D Jr, Wu Y, et al. Cardiovascular disease and risk factors among psoriasis patients in two US healthcare databases, 2001-2002. Dermatology. 2008;217:27-37.

- Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA. 2006;296:1735-1741.

- Gelfand JM, Dommasch ED, Shin DB, et al. The risk of stroke in patients with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2411-2418.

- Mehta NN, Azfar RS, Shin DB, et al. Patients with severe psoriasis are at increased risk of cardiovascular mortality: cohort study using the General Practice Research Database. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1000-1006.

- Abuabara K, Azfar RS, Shin DB, et al. Cause-specific mortality in patients with severe psoriasis: a population-based cohort study in the United Kingdom. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:586-592.

- Christophers E. Comorbidities in psoriasis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:529-534.

- Wu JJ, Nguyen TU, Poon KY, et al. The association of psoriasis with autoimmune diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:924-930.

- Floch MH, Bina I. The natural history of diverticulitis: fact and theory. Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38(5, suppl 1):S2-S7.

- Barrea L, Macchia PE, Tarantino G, et al. Nutrition: a key environmental dietary factor in clinical severity and cardio-metabolic risk in psoriatic male patients evaluated by 7-day food-frequency questionnaire. J Transl Med. 2015;13:303.

- Afifi L, Danesh MJ, Lee KM, et al. Dietary behaviors in psoriasis: patient-reported outcomes from a U.S. National Survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7:227-242.

- Matrana MR, Margolin DA. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of diverticular disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22:141-146.

- Brandl A, Kratzer T, Kafka-Ritsch R, et al. Diverticulitis in immunosuppressed patients: a fatal outcome requiring a new approach? Can J Surg. 2016;59:254-261.

- Buckius MT, McGrath B, Monk J, et al. Changing epidemiology of acute appendicitis in the United States: study period 1993-2008. J Surg Res. 2012;175:185-190.

- Cheluvappa R, Luo AS, Grimm MC. T helper type 17 pathway suppression by appendicitis and appendectomy protects against colitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;175:316-322.

- Lynde CW, Poulin Y, Vender R, et al. Interleukin 17A: toward a new understanding of psoriasis pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:141-150.

- Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Serum levels of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005:2005;273-279.

- Egeberg A, Anderson YMF, Gislason GH, et al. Gallstone risk in adult patients with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis: possible effect of overweight and obesity. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:627-631.

- Smirnova SV, Barilo AA, Smolnikova MV. Hepatobiliary system diseases as the predictors of psoriasis progression [in Russian]. Vestn Ross Akad Med Nauk. 2016:102-108.

- Bagel J, Lynde C, Tyring S, et al. Moderate to severe plaque psoriasis with scalp involvement: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of etanercept. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:86-92.

- Foeldvari I, Krüger E, Schneider T. Acute, non-obstructive, sterile cholecystitis associated with etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of juvenile polyarticular rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:908-909.

Psoriasis is a chronic skin condition affecting approximately 2% to 3% of the population.1,2 Beyond cutaneous manifestations, psoriasis is a systemic inflammatory state that is associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease, including obesity,3,4 type 2 diabetes mellitus,5,6 hypertension,5 dyslipidemia,3,7 metabolic syndrome,7 atherosclerosis,8 peripheral vascular disease,9 coronary artery calcification,10 myocardial infarction,11-13 stroke,9,14 and cardiac death.15,16

Psoriasis also has been associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), possibly because of similar autoimmune mechanisms in the pathogenesis of both diseases.17,18 However, there is no literature regarding the risk for acute gastrointestinal pathologies such as appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis in patients with psoriasis.

The primary objective of this study was to examine if patients with psoriasis are at increased risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis compared to the general population. The secondary objective was to determine if patients with severe psoriasis (ie, patients treated with phototherapy or systemic therapy) are at a higher risk for these conditions compared to patients with mild psoriasis.

Methods

Patients and Tools

A descriptive, population-based cohort study design with controls from a matched cohort was used to ascertain the effect of psoriasis status on patients’ risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis. Our cohort was selected using administrative data from Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) during the study period (January 1, 2004, through December 31, 2016).

Kaiser Permanente Southern California is a large integrated health maintenance organization that includes approximately 4 million patients as of December 31, 2016, and includes roughly 20% of the region’s population. The geographic area served extends from Bakersfield in the lower California Central Valley to San Diego on the border with Mexico. Membership demographics, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity composition are representative of California.

Patients were included if they had a diagnosis of psoriasis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code 696.1; International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] codes L40.0, L40.4, L40.8, or L40.9) for at least 3 visits between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2016. Patients were not excluded if they also had a diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis (ICD-9-CM code 696.0; ICD-10-CM code L40.5x). Patients also must have been continuously enrolled for at least 1 year before and 1 year after the index date, which was defined as the date of the third psoriasis diagnosis.

Each patient with psoriasis was assigned to 1 of 2 cohorts: (1) severe psoriasis: patients who received UVB phototherapy, psoralen plus UVA phototherapy, methotrexate, acitretin, cyclosporine, apremilast, etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, ustekinumab, efalizumab, alefacept, secukinumab, or ixekizumab during the study period; and (2) mild psoriasis: patients who had a diagnosis of psoriasis who did not receive one of these therapies during the study period.

Patients were excluded if they had a history of appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis at any time before the index date. Only patients older than 18 years were included.

Patients with psoriasis were frequency matched (1:5) with healthy patients, also from the KPSC network. Individuals were matched by age, sex, and ethnicity.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were described with means and SD for continuous variables as well as percentages for categorical variables. Chi-square tests for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney U Test for continuous variables were used to compare the patients’ characteristics by psoriasis status. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to examine the risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis among patients with and without psoriasis and among patients with mild and severe psoriasis. Proportionality assumption was validated using Pearson product moment correlation between the scaled Schoenfeld residuals and log transformed time for each covariate.

Results were presented as crude (unadjusted) hazard ratios (HRs) and adjusted HRs, where confounding factors (ie, age, sex, ethnicity, body mass index [BMI], alcohol use, smoking status, income, education, and membership length) were adjusted. All tests were performed with SAS EG 5.1 and R software. P<.05 was considered statistically significant. Results are reported with the 95% confidence interval (CI), when appropriate.

Results

A total of 1,690,214 KPSC patients were eligible for the study; 10,307 (0.6%) met diagnostic and inclusion criteria for the psoriasis cohort. Patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher mean BMI (29.9 vs 28.7; P<.0001) as well as higher mean rates of alcohol use (56% vs 53%; P<.0001) and smoking (47% vs 38%; P<.01) compared to controls. Psoriasis patients had a shorter average duration of membership within the Kaiser network (P=.0001) compared to controls.

A total of 7416 patients met criteria for mild psoriasis and 2891 patients met criteria for severe psoriasis (eTable). Patients with severe psoriasis were significantly younger and had significantly higher mean BMI compared to patients with mild psoriasis (P<.0001 and P=.0001, respectively). No significant difference in rates of alcohol or tobacco use was detected among patients with mild and severe psoriasis.

Appendicitis

The prevalence of appendicitis was not significantly different between patients with and without psoriasis or between patients with mild and severe psoriasis, though the incidence rate was slightly higher among patients with psoriasis (0.80 per 1000 patient-years compared to 0.62 per 1000 patient-years among patients without psoriasis)(Table 1). However, there was not a significant difference in risk for appendicitis between healthy patients, patients with severe psoriasis, and patients with mild psoriasis after adjusting for potential confounding factors (Table 2). Interestingly, patients with severe psoriasis who had a diagnosis of appendicitis had a significantly shorter time to diagnosis of appendicitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis (7.4 years vs 8.1 years; P<.0001).

Cholecystitis

Psoriasis patients also did not have an increased prevalence of cholecystitis compared to healthy patients. However, patients with severe psoriasis had a significantly higher prevalence of cholecystitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis (P=.0038). Overall, patients with psoriasis had a slightly higher incidence rate (1.72 per 1000 patient-years) compared to healthy patients (1.46 per 1000 patient-years). Moreover, the time to diagnosis of cholecystitis was significantly shorter for patients with severe psoriasis than for patients with mild psoriasis (7.4 years vs 8.1 years; P<.0001). Mild psoriasis was associated with a significantly increased risk (HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.09-1.63; P<.01) for cholecystitis compared to individuals without psoriasis in both the crude and adjusted models (Table 2). There was no difference between mild psoriasis patients and severe psoriasis patients in risk for cholecystitis.

Diverticulitis

Patients with psoriasis had a significantly greater prevalence of diverticulitis compared to the control cohort (5.1% vs 4.2%; P<.0001). There was no difference in prevalence between the severe psoriasis group and the mild psoriasis group (P=.96), but the time to diagnosis of diverticulitis was shorter in the severe psoriasis group than in the mild psoriasis group (7.2 years vs 7.9 years; P<.0001). Psoriasis patients had an incidence rate of diverticulitis of 6.61 per 1000 patient-years compared to 5.38 per 1000 patient-years in the control group. Psoriasis conferred a higher risk for diverticulitis in both the crude and adjusted models (HR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.11-1.35 [P<.001] and HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.05-1.29; [P<.01], respectively)(Table 3); however, when stratified by disease severity, only patients with severe psoriasis were found to be at higher risk (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.15-1.61; P<.001 for the adjusted model).

Comment

The objective of this study was to examine the background risks for specific gastrointestinal pathologies in a large cohort of patients with psoriasis compared to the general population. After adjusting for measured confounders, patients with severe psoriasis had a significantly higher risk of diverticulitis compared to the general population. Although more patients with severe psoriasis developed appendicitis or cholecystitis, the difference was not significant.

The pathogenesis of diverticulosis and diverticulitis has been thought to be related to increased intracolonic pressure and decreased dietary fiber intake, leading to formation of diverticula in the colon.19 Our study did not correct for differences in diet between the 2 groups, making it a possible confounding variable. Studies evaluating dietary habits of psoriatic patients have found that adult males with psoriasis might consume less fiber compared to healthy patients,20 and psoriasis patients also might consume less whole-grain fiber.21 Furthermore, fiber deficiency also might affect gut flora, causing low-grade chronic inflammation,18 which also has been supported by response to anti-inflammatory medications such as mesalazine.22 Given the autoimmune association between psoriasis and IBD, it is possible that psoriasis also might create an environment of chronic inflammation in the gut, predisposing patients with psoriasis to diverticulitis. However, further research is needed to better evaluate this possibility.

Our study also does not address any potential effects on outcomes of specific treatments for psoriasis. Brandl et al23 found that patients on immunosuppressive therapy for autoimmune diseases had longer hospital and intensive care unit stays, higher rates of emergency operations, and higher mortality while hospitalized. Because our results suggest that patients with severe psoriasis, who are therefore more likely to require treatment with an immunomodulator, are at higher risk for diverticulitis, these patients also might be at risk for poorer outcomes.

There is no literature evaluating the relationship between psoriasis and appendicitis. Our study found a slightly lower incidence rate compared to the national trend (9.38 per 10,000 patient-years in the United States in 2008) in both healthy patients and psoriasis patients.24 Of note, this statistic includes children, whereas our study did not, which might in part account for the lower rate. However, Cheluvappa et al25 hypothesized a relationship between appendicitis and subsequent appendectomy at a young age and protection against IBD. They also found that the mechanism for protection involves downregulation of the helper T cell (TH17) pathway,25 which also has been found to play a role in psoriasis pathogenesis.26,27 Although our results suggest that the risk for appendicitis is not increased for patients with psoriasis, further research might be able to determine if appendicitis and subsequent appendectomy also can offer protection against development of psoriasis.

We found that patients with severe psoriasis had a higher incidence rate of cholecystitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis. Egeberg et al28 found an increased risk for cholelithiasis among patients with psoriasis, which may contribute to a higher rate of cholecystitis. Although both acute and chronic cholecystitis were incorporated in this study, a Russian study found that chronic cholecystitis may be a predictor of progression of psoriasis.29 Moreover, patients with severe psoriasis had a shorter duration to diagnosis of cholecystitis than patients with mild psoriasis. It is possible that patients with severe psoriasis are in a state of greater chronic inflammation than those with mild psoriasis, and therefore, when combined with other risk factors for cholecystitis, may progress to disease more quickly. Alternatively, this finding could be treatment related, as there have been reported cases of cholecystitis related to etanercept use in patients treated for psoriasis and juvenile polyarticular rheumatoid arthritis.30,31 The relationship is not yet well defined, however, and further research is necessary to evaluate this association.

Study Strengths

Key strengths of this study include the large sample size and diversity of the patient population. Kaiser Permanente Southern California membership generally is representative of the broader community, making our results fairly generalizable to populations with health insurance. Use of a matched control cohort allows the results to be more specific to the disease of interest, and the population-based design minimizes bias.

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. Although the cohorts were categorized based on type of treatment received, exact therapies were not specified. As a retrospective study, it is difficult to control for potential confounding variables that are not included in the electronic medical record. The results of this study also demonstrated significantly shorter durations to diagnosis of all 3 conditions, indicating that surveillance bias may be present.

Conclusion

Patients with psoriasis may be at an increased risk for diverticulitis compared to patients without psoriasis, which could be due to the chronic inflammatory state induced by psoriasis. Therefore, it may be beneficial for clinicians to evaluate psoriasis patients for other risk factors for diverticulitis and subsequently provide counseling to these patients to minimize their risk for diverticulitis. Psoriasis patients do not appear to be at an increased risk for appendicitis or cholecystitis compared to controls; however, further research is needed for confirmation.

Psoriasis is a chronic skin condition affecting approximately 2% to 3% of the population.1,2 Beyond cutaneous manifestations, psoriasis is a systemic inflammatory state that is associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease, including obesity,3,4 type 2 diabetes mellitus,5,6 hypertension,5 dyslipidemia,3,7 metabolic syndrome,7 atherosclerosis,8 peripheral vascular disease,9 coronary artery calcification,10 myocardial infarction,11-13 stroke,9,14 and cardiac death.15,16

Psoriasis also has been associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), possibly because of similar autoimmune mechanisms in the pathogenesis of both diseases.17,18 However, there is no literature regarding the risk for acute gastrointestinal pathologies such as appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis in patients with psoriasis.

The primary objective of this study was to examine if patients with psoriasis are at increased risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis compared to the general population. The secondary objective was to determine if patients with severe psoriasis (ie, patients treated with phototherapy or systemic therapy) are at a higher risk for these conditions compared to patients with mild psoriasis.

Methods

Patients and Tools

A descriptive, population-based cohort study design with controls from a matched cohort was used to ascertain the effect of psoriasis status on patients’ risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis. Our cohort was selected using administrative data from Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) during the study period (January 1, 2004, through December 31, 2016).

Kaiser Permanente Southern California is a large integrated health maintenance organization that includes approximately 4 million patients as of December 31, 2016, and includes roughly 20% of the region’s population. The geographic area served extends from Bakersfield in the lower California Central Valley to San Diego on the border with Mexico. Membership demographics, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity composition are representative of California.

Patients were included if they had a diagnosis of psoriasis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code 696.1; International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] codes L40.0, L40.4, L40.8, or L40.9) for at least 3 visits between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2016. Patients were not excluded if they also had a diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis (ICD-9-CM code 696.0; ICD-10-CM code L40.5x). Patients also must have been continuously enrolled for at least 1 year before and 1 year after the index date, which was defined as the date of the third psoriasis diagnosis.

Each patient with psoriasis was assigned to 1 of 2 cohorts: (1) severe psoriasis: patients who received UVB phototherapy, psoralen plus UVA phototherapy, methotrexate, acitretin, cyclosporine, apremilast, etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, ustekinumab, efalizumab, alefacept, secukinumab, or ixekizumab during the study period; and (2) mild psoriasis: patients who had a diagnosis of psoriasis who did not receive one of these therapies during the study period.

Patients were excluded if they had a history of appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis at any time before the index date. Only patients older than 18 years were included.

Patients with psoriasis were frequency matched (1:5) with healthy patients, also from the KPSC network. Individuals were matched by age, sex, and ethnicity.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were described with means and SD for continuous variables as well as percentages for categorical variables. Chi-square tests for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney U Test for continuous variables were used to compare the patients’ characteristics by psoriasis status. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to examine the risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis among patients with and without psoriasis and among patients with mild and severe psoriasis. Proportionality assumption was validated using Pearson product moment correlation between the scaled Schoenfeld residuals and log transformed time for each covariate.

Results were presented as crude (unadjusted) hazard ratios (HRs) and adjusted HRs, where confounding factors (ie, age, sex, ethnicity, body mass index [BMI], alcohol use, smoking status, income, education, and membership length) were adjusted. All tests were performed with SAS EG 5.1 and R software. P<.05 was considered statistically significant. Results are reported with the 95% confidence interval (CI), when appropriate.

Results

A total of 1,690,214 KPSC patients were eligible for the study; 10,307 (0.6%) met diagnostic and inclusion criteria for the psoriasis cohort. Patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher mean BMI (29.9 vs 28.7; P<.0001) as well as higher mean rates of alcohol use (56% vs 53%; P<.0001) and smoking (47% vs 38%; P<.01) compared to controls. Psoriasis patients had a shorter average duration of membership within the Kaiser network (P=.0001) compared to controls.

A total of 7416 patients met criteria for mild psoriasis and 2891 patients met criteria for severe psoriasis (eTable). Patients with severe psoriasis were significantly younger and had significantly higher mean BMI compared to patients with mild psoriasis (P<.0001 and P=.0001, respectively). No significant difference in rates of alcohol or tobacco use was detected among patients with mild and severe psoriasis.

Appendicitis

The prevalence of appendicitis was not significantly different between patients with and without psoriasis or between patients with mild and severe psoriasis, though the incidence rate was slightly higher among patients with psoriasis (0.80 per 1000 patient-years compared to 0.62 per 1000 patient-years among patients without psoriasis)(Table 1). However, there was not a significant difference in risk for appendicitis between healthy patients, patients with severe psoriasis, and patients with mild psoriasis after adjusting for potential confounding factors (Table 2). Interestingly, patients with severe psoriasis who had a diagnosis of appendicitis had a significantly shorter time to diagnosis of appendicitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis (7.4 years vs 8.1 years; P<.0001).

Cholecystitis

Psoriasis patients also did not have an increased prevalence of cholecystitis compared to healthy patients. However, patients with severe psoriasis had a significantly higher prevalence of cholecystitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis (P=.0038). Overall, patients with psoriasis had a slightly higher incidence rate (1.72 per 1000 patient-years) compared to healthy patients (1.46 per 1000 patient-years). Moreover, the time to diagnosis of cholecystitis was significantly shorter for patients with severe psoriasis than for patients with mild psoriasis (7.4 years vs 8.1 years; P<.0001). Mild psoriasis was associated with a significantly increased risk (HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.09-1.63; P<.01) for cholecystitis compared to individuals without psoriasis in both the crude and adjusted models (Table 2). There was no difference between mild psoriasis patients and severe psoriasis patients in risk for cholecystitis.

Diverticulitis

Patients with psoriasis had a significantly greater prevalence of diverticulitis compared to the control cohort (5.1% vs 4.2%; P<.0001). There was no difference in prevalence between the severe psoriasis group and the mild psoriasis group (P=.96), but the time to diagnosis of diverticulitis was shorter in the severe psoriasis group than in the mild psoriasis group (7.2 years vs 7.9 years; P<.0001). Psoriasis patients had an incidence rate of diverticulitis of 6.61 per 1000 patient-years compared to 5.38 per 1000 patient-years in the control group. Psoriasis conferred a higher risk for diverticulitis in both the crude and adjusted models (HR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.11-1.35 [P<.001] and HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.05-1.29; [P<.01], respectively)(Table 3); however, when stratified by disease severity, only patients with severe psoriasis were found to be at higher risk (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.15-1.61; P<.001 for the adjusted model).

Comment

The objective of this study was to examine the background risks for specific gastrointestinal pathologies in a large cohort of patients with psoriasis compared to the general population. After adjusting for measured confounders, patients with severe psoriasis had a significantly higher risk of diverticulitis compared to the general population. Although more patients with severe psoriasis developed appendicitis or cholecystitis, the difference was not significant.

The pathogenesis of diverticulosis and diverticulitis has been thought to be related to increased intracolonic pressure and decreased dietary fiber intake, leading to formation of diverticula in the colon.19 Our study did not correct for differences in diet between the 2 groups, making it a possible confounding variable. Studies evaluating dietary habits of psoriatic patients have found that adult males with psoriasis might consume less fiber compared to healthy patients,20 and psoriasis patients also might consume less whole-grain fiber.21 Furthermore, fiber deficiency also might affect gut flora, causing low-grade chronic inflammation,18 which also has been supported by response to anti-inflammatory medications such as mesalazine.22 Given the autoimmune association between psoriasis and IBD, it is possible that psoriasis also might create an environment of chronic inflammation in the gut, predisposing patients with psoriasis to diverticulitis. However, further research is needed to better evaluate this possibility.

Our study also does not address any potential effects on outcomes of specific treatments for psoriasis. Brandl et al23 found that patients on immunosuppressive therapy for autoimmune diseases had longer hospital and intensive care unit stays, higher rates of emergency operations, and higher mortality while hospitalized. Because our results suggest that patients with severe psoriasis, who are therefore more likely to require treatment with an immunomodulator, are at higher risk for diverticulitis, these patients also might be at risk for poorer outcomes.

There is no literature evaluating the relationship between psoriasis and appendicitis. Our study found a slightly lower incidence rate compared to the national trend (9.38 per 10,000 patient-years in the United States in 2008) in both healthy patients and psoriasis patients.24 Of note, this statistic includes children, whereas our study did not, which might in part account for the lower rate. However, Cheluvappa et al25 hypothesized a relationship between appendicitis and subsequent appendectomy at a young age and protection against IBD. They also found that the mechanism for protection involves downregulation of the helper T cell (TH17) pathway,25 which also has been found to play a role in psoriasis pathogenesis.26,27 Although our results suggest that the risk for appendicitis is not increased for patients with psoriasis, further research might be able to determine if appendicitis and subsequent appendectomy also can offer protection against development of psoriasis.

We found that patients with severe psoriasis had a higher incidence rate of cholecystitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis. Egeberg et al28 found an increased risk for cholelithiasis among patients with psoriasis, which may contribute to a higher rate of cholecystitis. Although both acute and chronic cholecystitis were incorporated in this study, a Russian study found that chronic cholecystitis may be a predictor of progression of psoriasis.29 Moreover, patients with severe psoriasis had a shorter duration to diagnosis of cholecystitis than patients with mild psoriasis. It is possible that patients with severe psoriasis are in a state of greater chronic inflammation than those with mild psoriasis, and therefore, when combined with other risk factors for cholecystitis, may progress to disease more quickly. Alternatively, this finding could be treatment related, as there have been reported cases of cholecystitis related to etanercept use in patients treated for psoriasis and juvenile polyarticular rheumatoid arthritis.30,31 The relationship is not yet well defined, however, and further research is necessary to evaluate this association.

Study Strengths

Key strengths of this study include the large sample size and diversity of the patient population. Kaiser Permanente Southern California membership generally is representative of the broader community, making our results fairly generalizable to populations with health insurance. Use of a matched control cohort allows the results to be more specific to the disease of interest, and the population-based design minimizes bias.

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. Although the cohorts were categorized based on type of treatment received, exact therapies were not specified. As a retrospective study, it is difficult to control for potential confounding variables that are not included in the electronic medical record. The results of this study also demonstrated significantly shorter durations to diagnosis of all 3 conditions, indicating that surveillance bias may be present.

Conclusion

Patients with psoriasis may be at an increased risk for diverticulitis compared to patients without psoriasis, which could be due to the chronic inflammatory state induced by psoriasis. Therefore, it may be beneficial for clinicians to evaluate psoriasis patients for other risk factors for diverticulitis and subsequently provide counseling to these patients to minimize their risk for diverticulitis. Psoriasis patients do not appear to be at an increased risk for appendicitis or cholecystitis compared to controls; however, further research is needed for confirmation.

- Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, et al; Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377-385.

- Channual J, Wu JJ, Dann FJ. Effects of tumor necrosis factor-α blockade on metabolic syndrome in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and additional lessons learned from rheumatoid arthritis. Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:61-73.

- Koebnick C, Black MH, Smith N, et al. The association of psoriasis and elevated blood lipids in overweight and obese children. J Pediatr. 2011;159:577-583.

- Herron MD, Hinckley M, Hoffman MS, et al. Impact of obesity and smoking on psoriasis presentation and management. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1527-1534.

- Qureshi AA, Choi HK, Setty AR, et al. Psoriasis and the risk of diabetes and hypertension: a prospective study of US female nurses. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:379-382.

- Shapiro J, Cohen AD, David M, et al. The association between psoriasis, diabetes mellitus, and atherosclerosis in Israel: a case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:629-634.

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:419-424.

- El-Mongy S, Fathy H, Abdelaziz A, et al. Subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with chronic psoriasis: a potential association. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:661-666.

- Prodanovich S, Kirsner RS, Kravetz JD, et al. Association of psoriasis with coronary artery, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular diseases and mortality. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:700-703.

- Ludwig RJ, Herzog C, Rostock A, et al. Psoriasis: a possible risk factor for development of coronary artery calcification. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:271-276.

- Kaye JA, Li L, Jick SS. Incidence of risk factors for myocardial infarction and other vascular diseases in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:895-902.

- Kimball AB, Robinson D Jr, Wu Y, et al. Cardiovascular disease and risk factors among psoriasis patients in two US healthcare databases, 2001-2002. Dermatology. 2008;217:27-37.

- Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA. 2006;296:1735-1741.

- Gelfand JM, Dommasch ED, Shin DB, et al. The risk of stroke in patients with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2411-2418.

- Mehta NN, Azfar RS, Shin DB, et al. Patients with severe psoriasis are at increased risk of cardiovascular mortality: cohort study using the General Practice Research Database. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1000-1006.

- Abuabara K, Azfar RS, Shin DB, et al. Cause-specific mortality in patients with severe psoriasis: a population-based cohort study in the United Kingdom. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:586-592.

- Christophers E. Comorbidities in psoriasis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:529-534.

- Wu JJ, Nguyen TU, Poon KY, et al. The association of psoriasis with autoimmune diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:924-930.

- Floch MH, Bina I. The natural history of diverticulitis: fact and theory. Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38(5, suppl 1):S2-S7.

- Barrea L, Macchia PE, Tarantino G, et al. Nutrition: a key environmental dietary factor in clinical severity and cardio-metabolic risk in psoriatic male patients evaluated by 7-day food-frequency questionnaire. J Transl Med. 2015;13:303.

- Afifi L, Danesh MJ, Lee KM, et al. Dietary behaviors in psoriasis: patient-reported outcomes from a U.S. National Survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7:227-242.

- Matrana MR, Margolin DA. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of diverticular disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22:141-146.

- Brandl A, Kratzer T, Kafka-Ritsch R, et al. Diverticulitis in immunosuppressed patients: a fatal outcome requiring a new approach? Can J Surg. 2016;59:254-261.

- Buckius MT, McGrath B, Monk J, et al. Changing epidemiology of acute appendicitis in the United States: study period 1993-2008. J Surg Res. 2012;175:185-190.

- Cheluvappa R, Luo AS, Grimm MC. T helper type 17 pathway suppression by appendicitis and appendectomy protects against colitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;175:316-322.

- Lynde CW, Poulin Y, Vender R, et al. Interleukin 17A: toward a new understanding of psoriasis pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:141-150.

- Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Serum levels of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005:2005;273-279.

- Egeberg A, Anderson YMF, Gislason GH, et al. Gallstone risk in adult patients with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis: possible effect of overweight and obesity. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:627-631.

- Smirnova SV, Barilo AA, Smolnikova MV. Hepatobiliary system diseases as the predictors of psoriasis progression [in Russian]. Vestn Ross Akad Med Nauk. 2016:102-108.

- Bagel J, Lynde C, Tyring S, et al. Moderate to severe plaque psoriasis with scalp involvement: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of etanercept. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:86-92.

- Foeldvari I, Krüger E, Schneider T. Acute, non-obstructive, sterile cholecystitis associated with etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of juvenile polyarticular rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:908-909.

- Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, et al; Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377-385.

- Channual J, Wu JJ, Dann FJ. Effects of tumor necrosis factor-α blockade on metabolic syndrome in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and additional lessons learned from rheumatoid arthritis. Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:61-73.

- Koebnick C, Black MH, Smith N, et al. The association of psoriasis and elevated blood lipids in overweight and obese children. J Pediatr. 2011;159:577-583.

- Herron MD, Hinckley M, Hoffman MS, et al. Impact of obesity and smoking on psoriasis presentation and management. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1527-1534.

- Qureshi AA, Choi HK, Setty AR, et al. Psoriasis and the risk of diabetes and hypertension: a prospective study of US female nurses. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:379-382.

- Shapiro J, Cohen AD, David M, et al. The association between psoriasis, diabetes mellitus, and atherosclerosis in Israel: a case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:629-634.

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:419-424.

- El-Mongy S, Fathy H, Abdelaziz A, et al. Subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with chronic psoriasis: a potential association. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:661-666.

- Prodanovich S, Kirsner RS, Kravetz JD, et al. Association of psoriasis with coronary artery, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular diseases and mortality. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:700-703.

- Ludwig RJ, Herzog C, Rostock A, et al. Psoriasis: a possible risk factor for development of coronary artery calcification. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:271-276.

- Kaye JA, Li L, Jick SS. Incidence of risk factors for myocardial infarction and other vascular diseases in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:895-902.

- Kimball AB, Robinson D Jr, Wu Y, et al. Cardiovascular disease and risk factors among psoriasis patients in two US healthcare databases, 2001-2002. Dermatology. 2008;217:27-37.

- Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA. 2006;296:1735-1741.

- Gelfand JM, Dommasch ED, Shin DB, et al. The risk of stroke in patients with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2411-2418.

- Mehta NN, Azfar RS, Shin DB, et al. Patients with severe psoriasis are at increased risk of cardiovascular mortality: cohort study using the General Practice Research Database. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1000-1006.

- Abuabara K, Azfar RS, Shin DB, et al. Cause-specific mortality in patients with severe psoriasis: a population-based cohort study in the United Kingdom. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:586-592.

- Christophers E. Comorbidities in psoriasis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:529-534.

- Wu JJ, Nguyen TU, Poon KY, et al. The association of psoriasis with autoimmune diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:924-930.

- Floch MH, Bina I. The natural history of diverticulitis: fact and theory. Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38(5, suppl 1):S2-S7.

- Barrea L, Macchia PE, Tarantino G, et al. Nutrition: a key environmental dietary factor in clinical severity and cardio-metabolic risk in psoriatic male patients evaluated by 7-day food-frequency questionnaire. J Transl Med. 2015;13:303.

- Afifi L, Danesh MJ, Lee KM, et al. Dietary behaviors in psoriasis: patient-reported outcomes from a U.S. National Survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7:227-242.

- Matrana MR, Margolin DA. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of diverticular disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22:141-146.

- Brandl A, Kratzer T, Kafka-Ritsch R, et al. Diverticulitis in immunosuppressed patients: a fatal outcome requiring a new approach? Can J Surg. 2016;59:254-261.

- Buckius MT, McGrath B, Monk J, et al. Changing epidemiology of acute appendicitis in the United States: study period 1993-2008. J Surg Res. 2012;175:185-190.

- Cheluvappa R, Luo AS, Grimm MC. T helper type 17 pathway suppression by appendicitis and appendectomy protects against colitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;175:316-322.

- Lynde CW, Poulin Y, Vender R, et al. Interleukin 17A: toward a new understanding of psoriasis pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:141-150.

- Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Serum levels of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005:2005;273-279.

- Egeberg A, Anderson YMF, Gislason GH, et al. Gallstone risk in adult patients with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis: possible effect of overweight and obesity. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:627-631.

- Smirnova SV, Barilo AA, Smolnikova MV. Hepatobiliary system diseases as the predictors of psoriasis progression [in Russian]. Vestn Ross Akad Med Nauk. 2016:102-108.

- Bagel J, Lynde C, Tyring S, et al. Moderate to severe plaque psoriasis with scalp involvement: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of etanercept. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:86-92.

- Foeldvari I, Krüger E, Schneider T. Acute, non-obstructive, sterile cholecystitis associated with etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of juvenile polyarticular rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:908-909.

Practice Points

- Patients with psoriasis may have elevated risk of diverticulitis compared to healthy patients. However, psoriasis patients do not appear to have increased risk of appendicitis or cholecystitis.

- Clinicians treating psoriasis patients should consider assessing for other risk factors of diverticulitis at regular intervals.

Emerging Therapies In Psoriasis: A Systematic Review

Psoriasis is a chronic, autoimmune-mediated disease estimated to affect 2.8% of the US population.1 The pathogenesis of psoriasis is thought to involve a complex process triggered by a combination of genetic and environmental factors that induce tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α secretion by keratinocytes, which in turn activates dendritic cells. Activated dendritic cells produce IL-23, leading to helper T cell (TH17) differentiation.2,3 TH17 cells secrete IL-17A, which has been shown to promote psoriatic skin changes.4 Therefore, TNF-α, IL-23, and IL-17A have been recognized as key targets for psoriasis therapy.

The newest biologic agents targeting IL-17–mediated pathways include ixekizumab, brodalumab, and bimekizumab. Secukinumab, the first US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved IL-17 inhibitor, has been available since 2015 and therefore is not included in this review. IL-23 inhibitors that are FDA approved or being evaluated in clinical trials include guselkumab, tildrakizumab, and risankizumab. In addition, certolizumab pegol, a TNF-α inhibitor, is being studied for use in psoriasis.

METHODS

We reviewed the published results of phase 3 clinical trials for ixekizumab, brodalumab, bimekizumab, guselkumab, tildrakizumab, risankizumab, and certolizumab pegol. We performed an English-language literature search (January 1, 2012 to October 15, 2017) of articles indexed for PubMed/MEDLINE using the following combinations of keywords: IL-23 and psoriasis; IL-17 and psoriasis; tumor necrosis factor and psoriasis; [drug name] and psoriasis. If data from phase 3 clinical trials were not yet available, data from phase 2 clinical trials were incorporated in our analysis. We also reviewed citations within articles to identify relevant sources.

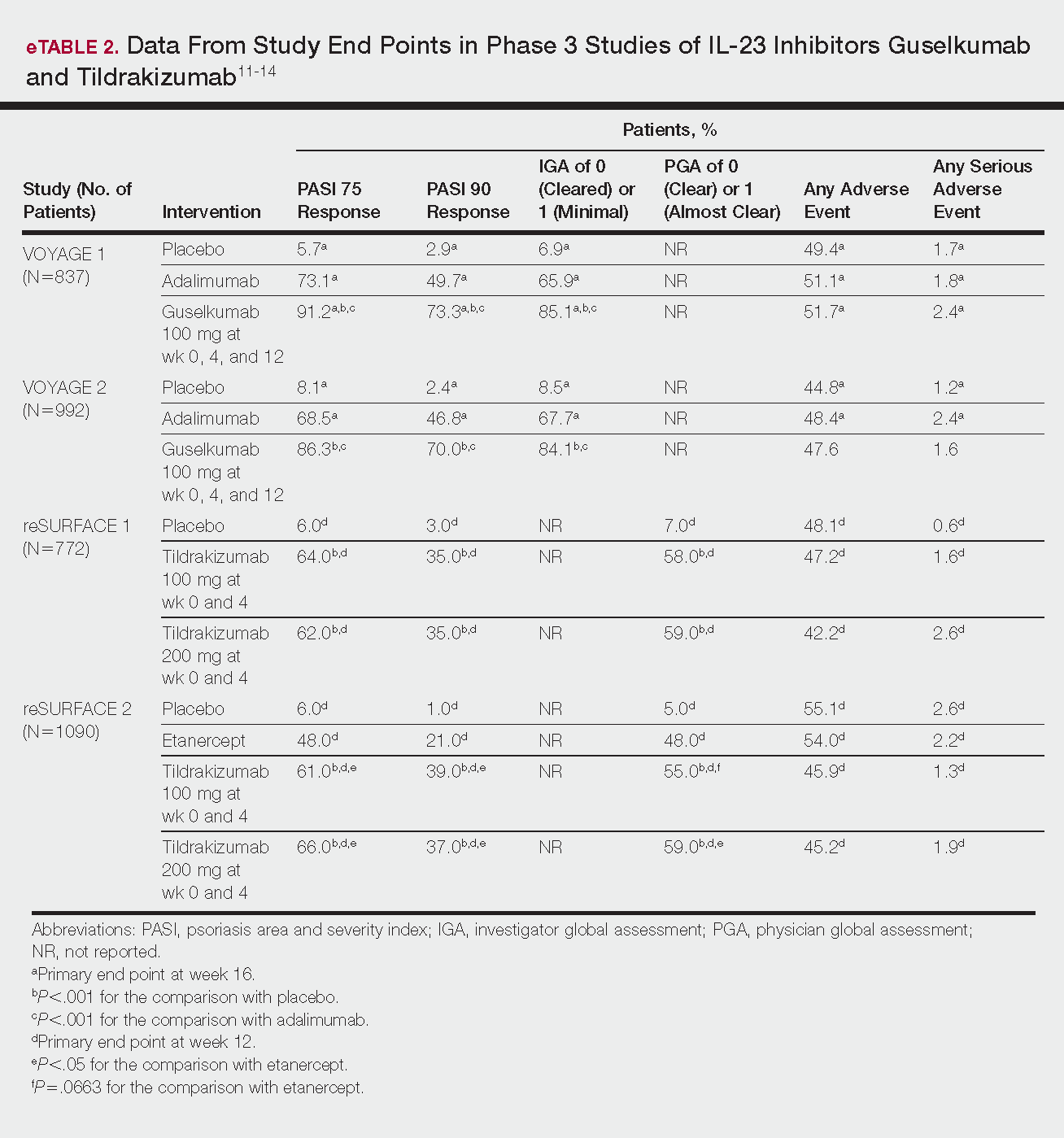

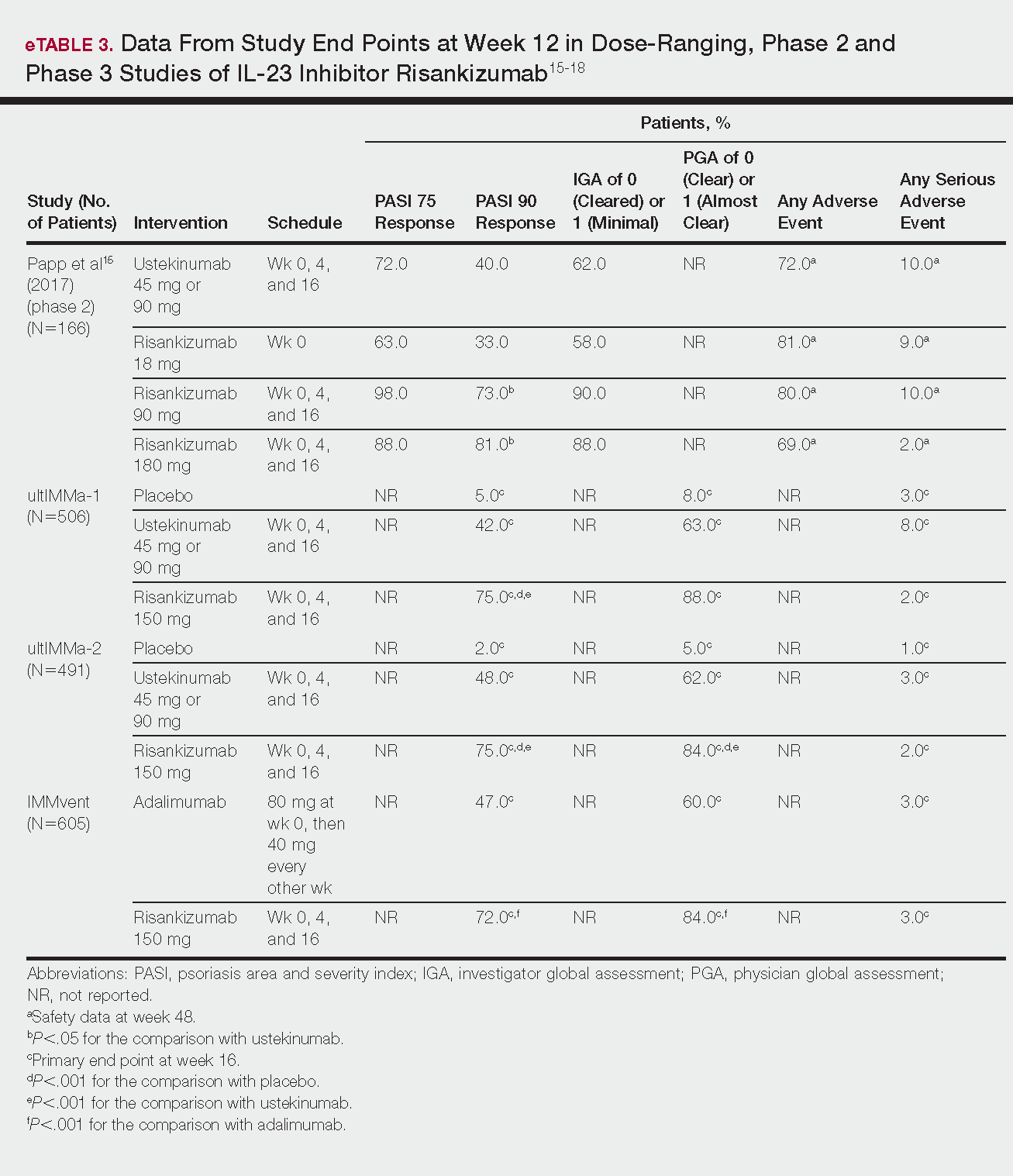

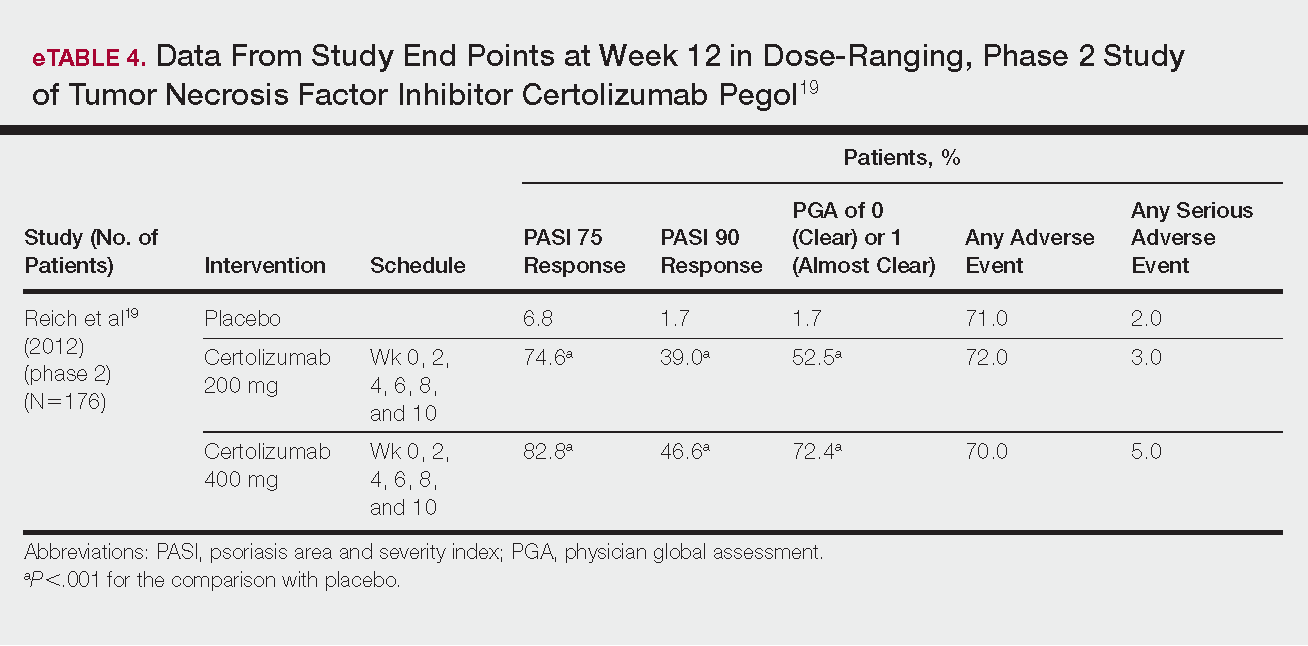

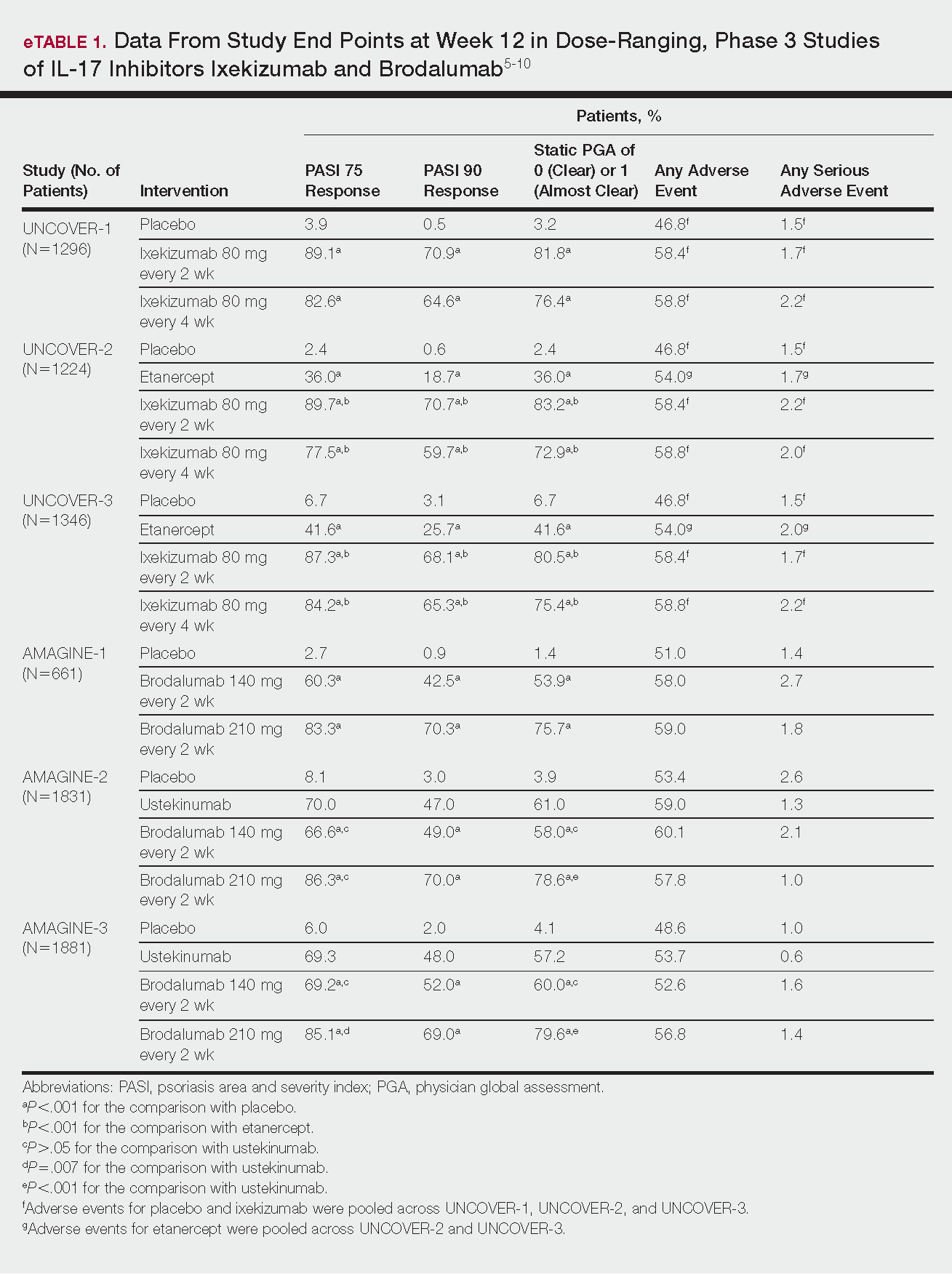

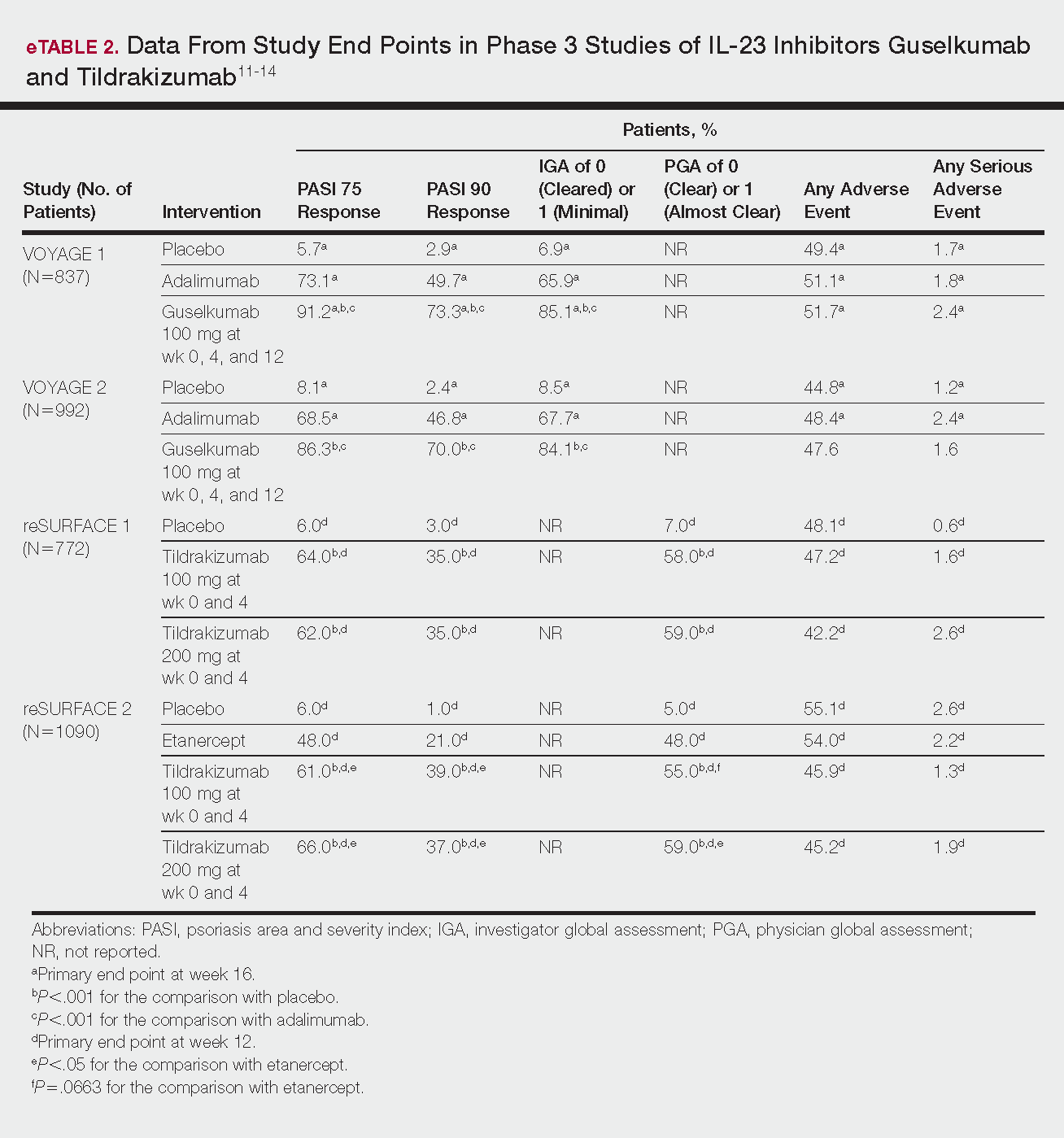

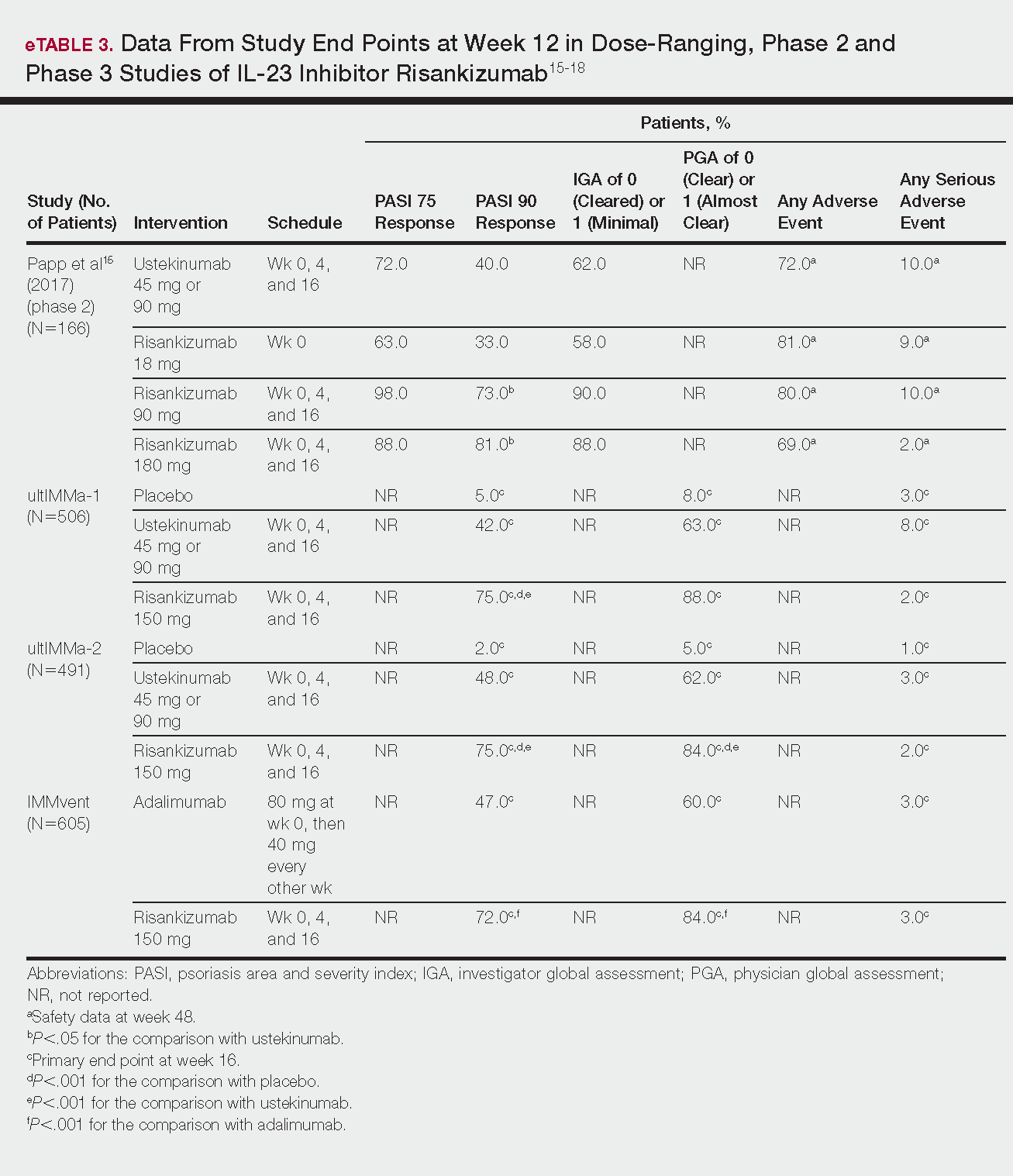

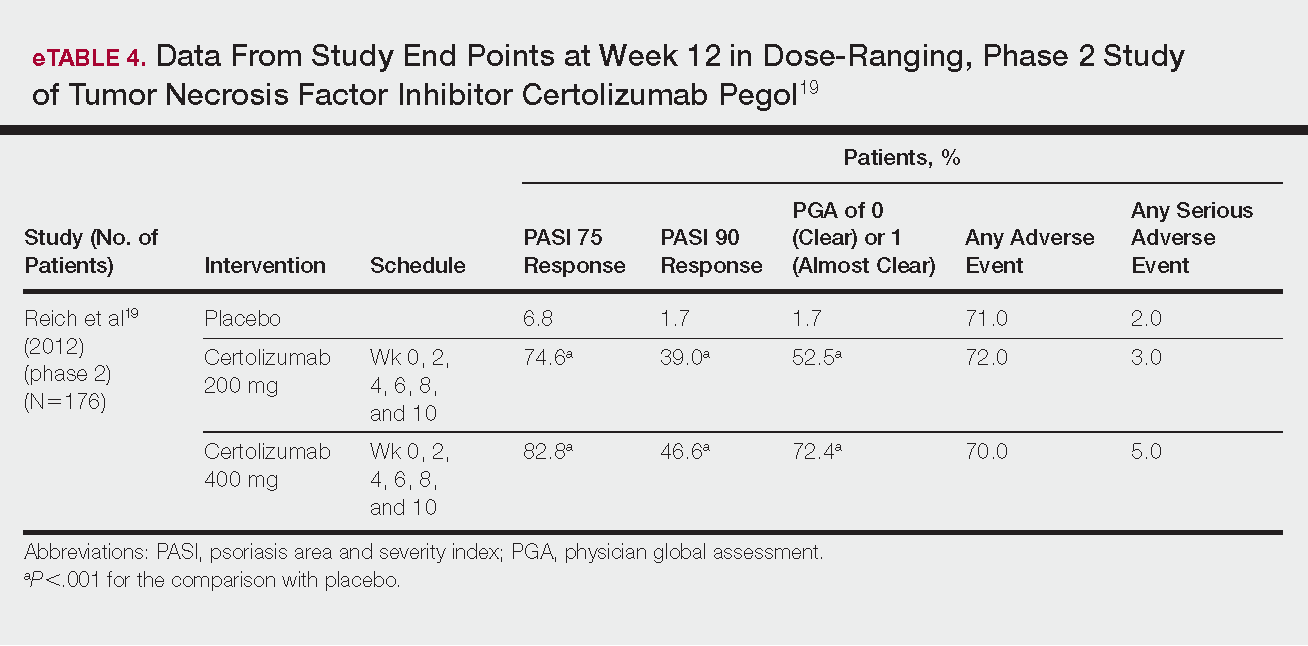

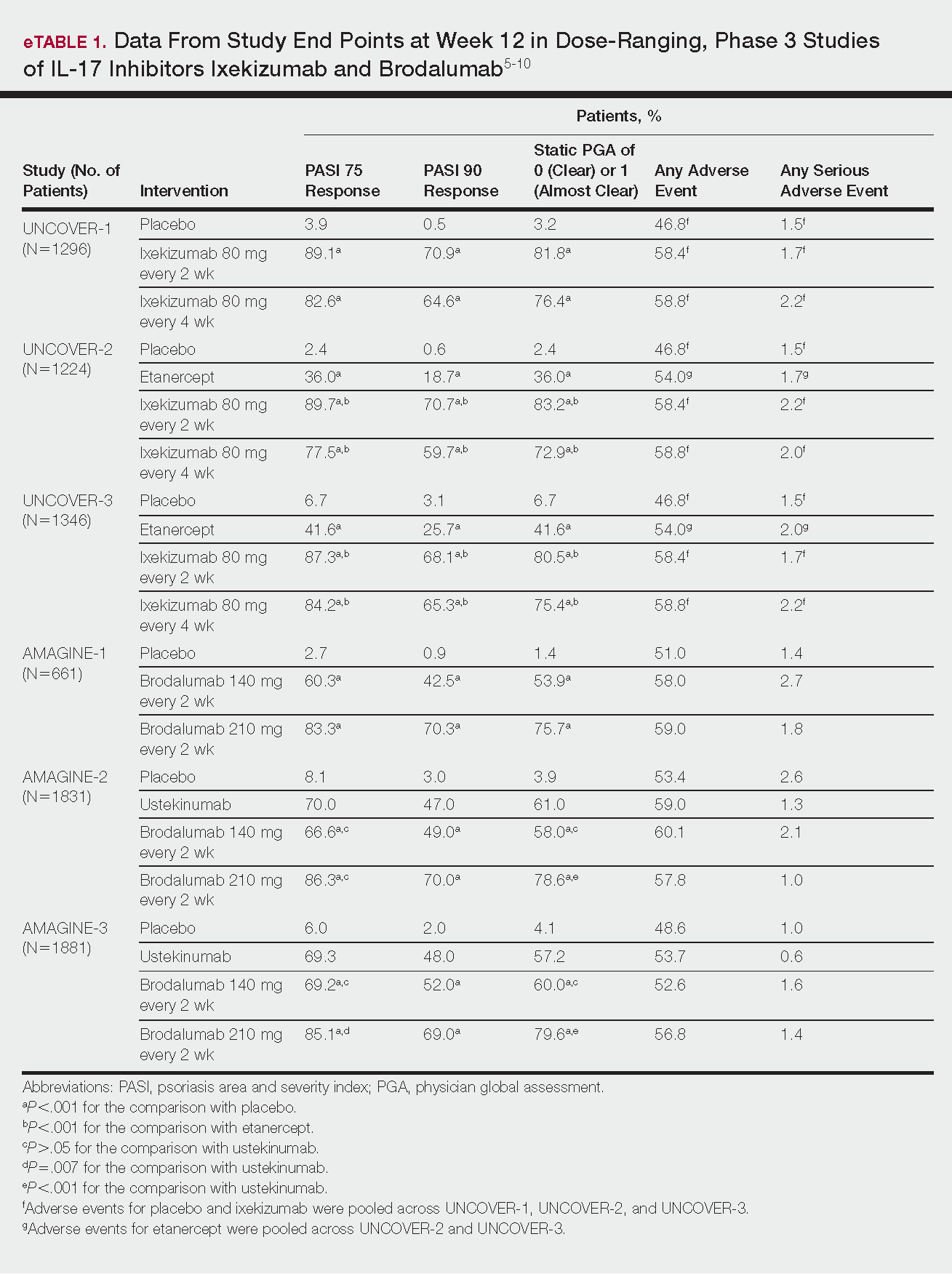

RESULTS

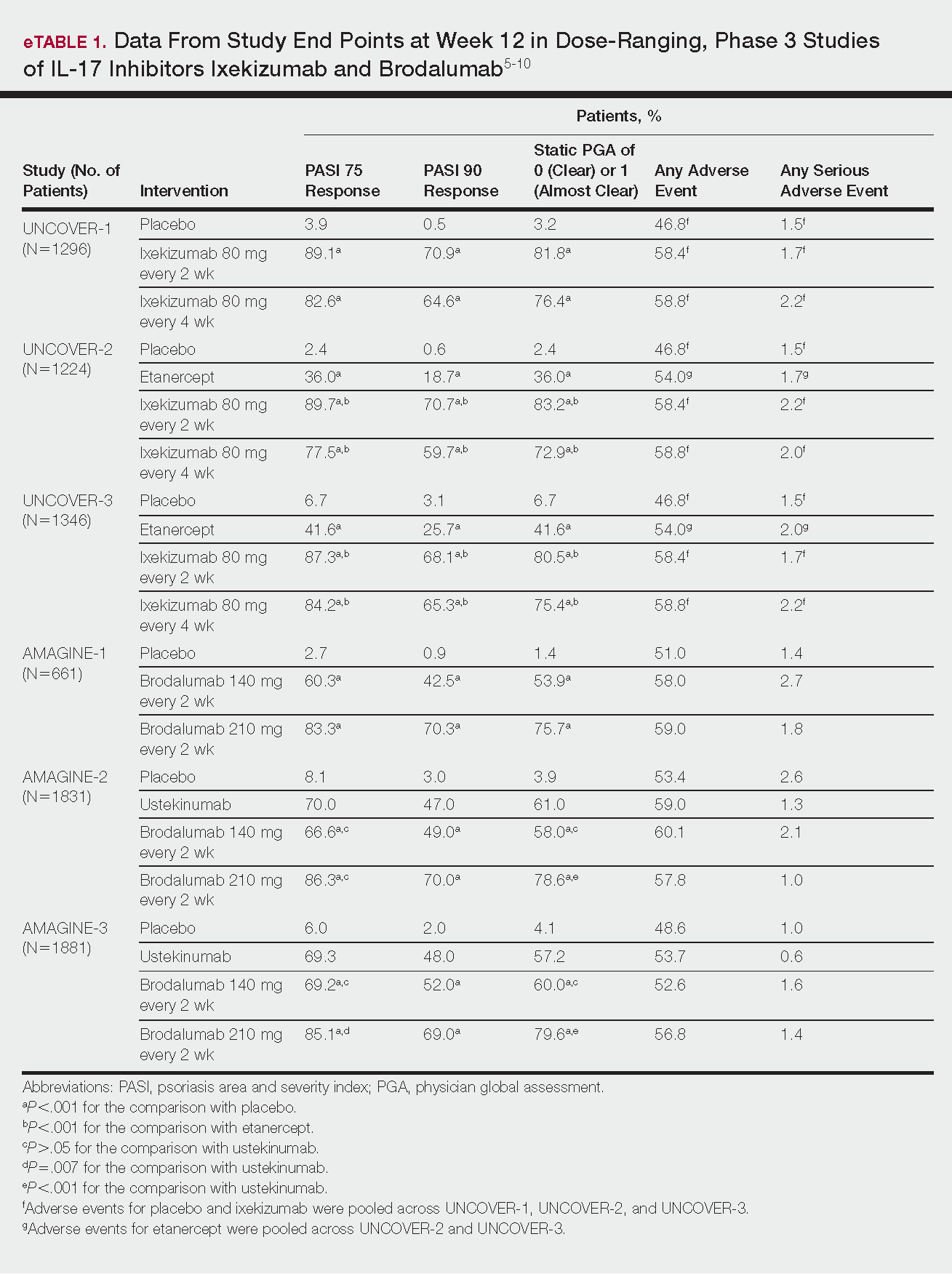

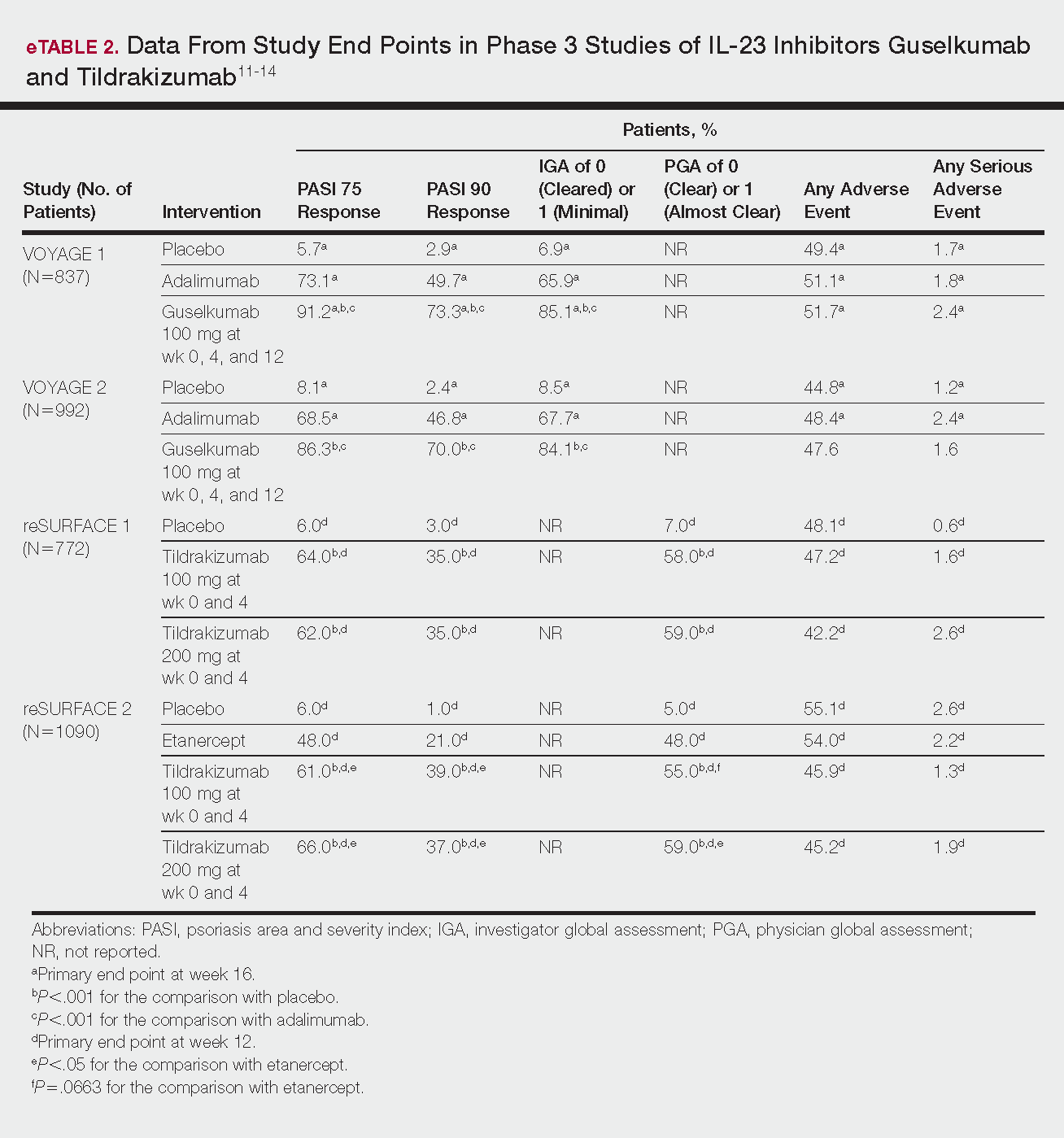

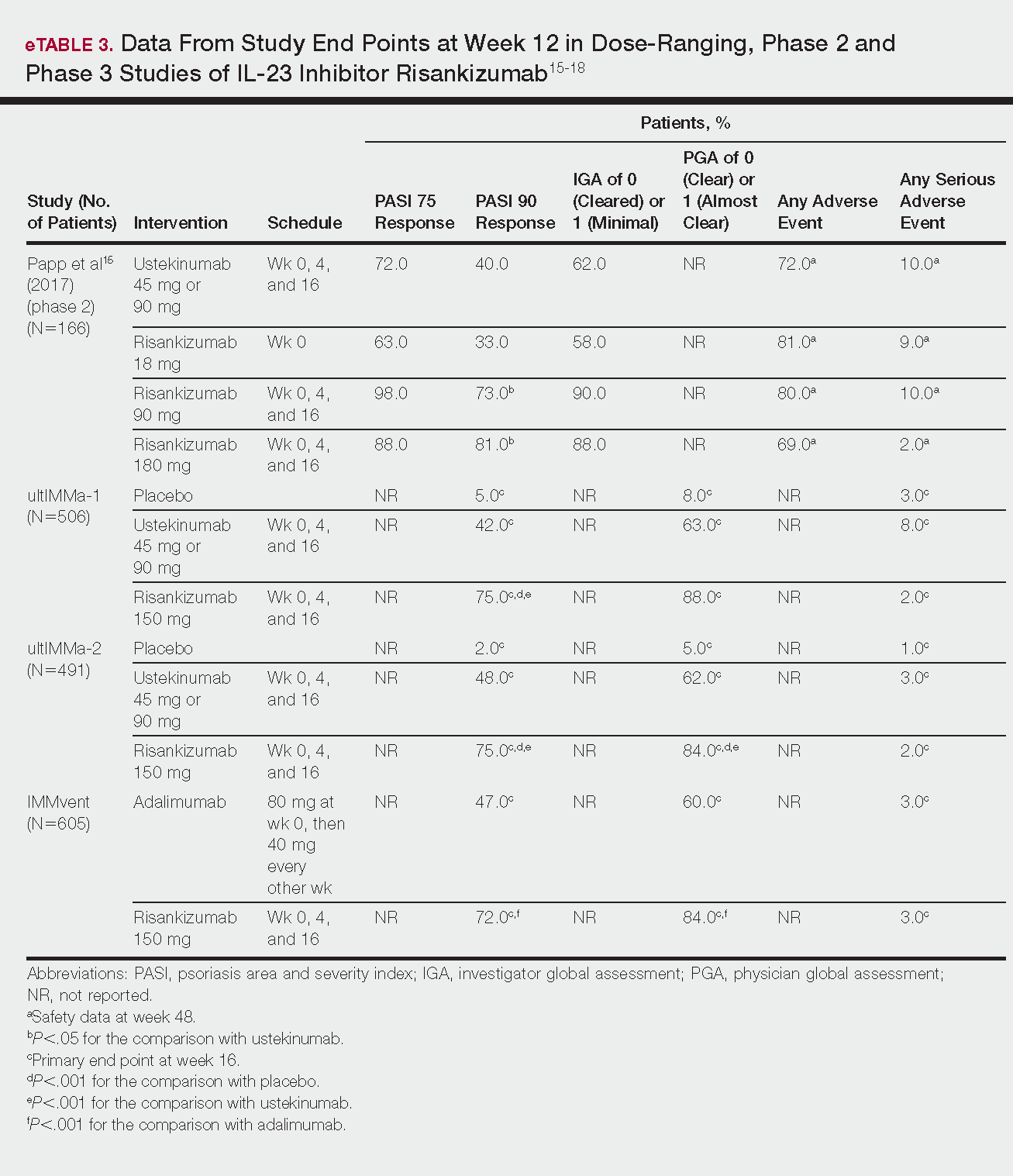

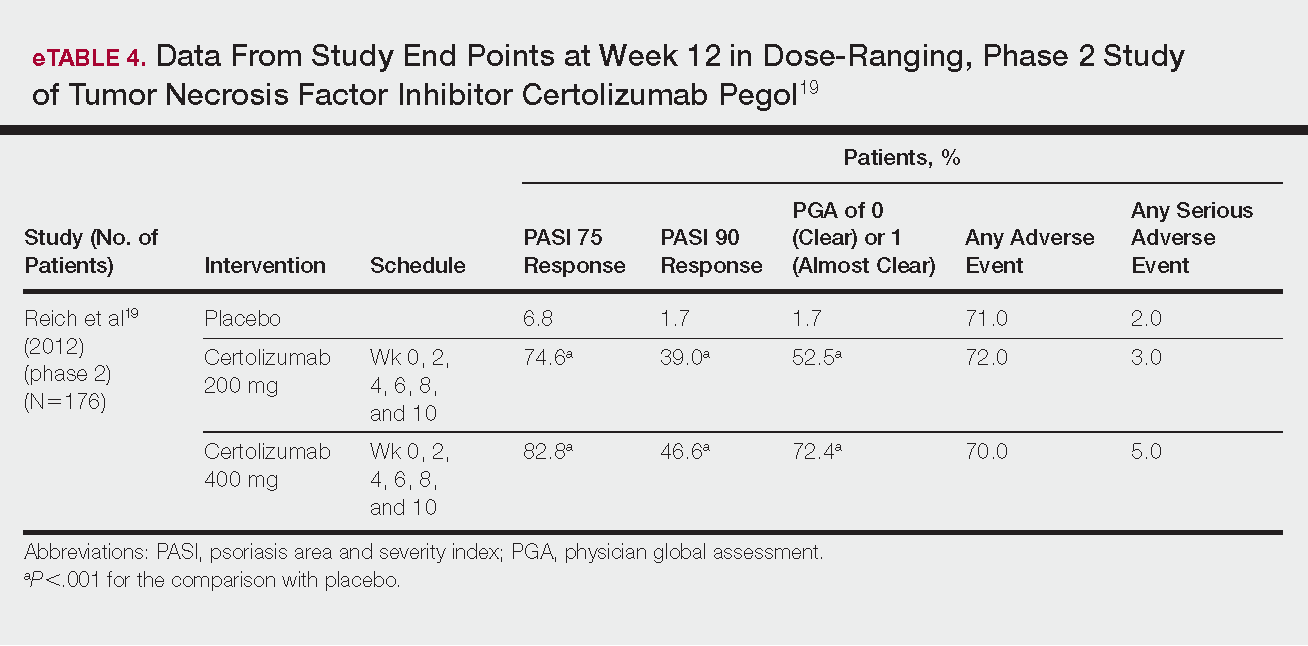

Phase 3 clinical trial design, efficacy, and adverse events (AEs) for ixekizumab and brodalumab are reported in eTable 15-10 and for guselkumab and tildrakizumab in eTable 2.11-14 Phase 2 clinical trial design, efficacy, and AEs are presented for risankizumab in eTable 315-18 and for certolizumab pegol in eTable 4.17,19 No published clinical trial data were found for bimekizumab.

IL-17 Inhibitors

Ixekizumab

This recombinant, high-affinity IgG4κ antibody selectively binds and neutralizes IL-17A.5,6 Three phase 3 clinical trials—UNCOVER-1, UNCOVER-2, and UNCOVER-3—evaluated ixekizumab for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.7

The 3 UNCOVER trials were randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trials of 1296, 1224, and 1346 patients, respectively, assigned to a placebo group; a group treated with ixekizumab 80 mg every 2 weeks; and a group treated with ixekizumab 80 mg every 4 weeks. Both ixekizumab groups received a loading dose of 160 mg at week 0.5,6 UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3 also included a comparator group of patients on etanercept 50 mg.5 Co-primary end points included the percentage of patients reaching a psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) of 75 and with a static physician global assessment (PGA) score of clear (0) or almost clear (1) at week 12.5,6

Ixekizumab achieved greater efficacy than placebo: 89.1%, 89.7%, and 87.3% of patients achieved PASI 75 in the every 2-week dosing group, and 82.6%, 77.5% and 84.2% achieved PASI 75 in the every 4-week dosing group in UNCOVER-1, UNCOVER-2, and UNCOVER-3, respectively (P<.001 for both treatment arms compared to placebo in all trials). The percentage of patients achieving a static PGA score of 0 or 1 also was higher in the ixekizumab groups in the 2-week and 4-week dosing groups in all UNCOVER trials—81.8% and 76.4% in UNCOVER-1, 83.2% and 72.9% in UNCOVER-2, and 80.5% and 75.4% in UNCOVER-3—compared to 3.2%, 2.4%, and 6.7% in the placebo groups of the 3 trials (P<.001 for both ixekizumab groups compared to placebo in all trials).5,6 Ixekizumab also was found to be more effective than etanercept for both co-primary end points in both UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3 (eTable 1).5

Safety data for all UNCOVER trials were pooled and reported.6 At week 12 the rate of at least 1 AE was 58.4% in patients on ixekizumab every 2 weeks and 58.8% in patients on ixekizumab every 4 weeks compared to 54.0% in the etanercept group in UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3 and 46.8% in the placebo group. At week 12, 72 nonfatal serious AEs were reported: 12 in the placebo group, 14 in the etanercept group, 20 in the ixekizumab every 2 weeks group, and 26 in the ixekizumab every 4 weeks group.6

The most common AE across all groups was nasopharyngitis. Overall, infections were more frequent in patients treated with ixekizumab than in patients treated with placebo or etanercept. Specifically, oral candidiasis occurred more frequently in the ixekizumab groups, with a higher rate in the 2-week dosing group than in the 4-week dosing group.6 Two myocardial infarctions (MIs) occurred: 1 in the etanercept group and 1 in the placebo group.5

Brodalumab

This human monoclonal antibody binds to IL-17ra.8,9 Three double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials—AMAGINE-1, AMAGINE-2, and AMAGINE-3—evaluated its use for plaque psoriasis.10

In AMAGINE-1 (N=661), patients were randomized to receive brodalumab 140 mg or 210 mg (every 2 weeks for 12 weeks), or placebo.8 In AMAGINE-2 (N=1831) and AMAGINE-3 (N=1881), patients were randomized to receive brodalumab 140 mg or 210 mg (every 2 weeks for 12 weeks), ustekinumab 45 mg or 90 mg by weight (at weeks 0 and 4, then every 12 weeks thereafter), or placebo. In all trials, patients on brodalumab received a dose at week 0 and week 1. Co-primary end points were PASI 75 and a static PGA score of 0 or 1 at 12 weeks compared to placebo and to ustekinumab (in AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 only).8

At week 12, 83.3%, 86.3%, and 85.1% of patients on brodalumab 210 mg, and 60.3%, 66.6%, and 69.2% of patients on brodalumab 140 mg, achieved PASI 75 in AMAGINE-1, AMAGINE-2, and AMAGINE-3, respectively, compared to 2.7%, 8.1%, and 6.0% in the placebo groups (P<.001 between both brodalumab groups and placebo in all trials).8 Both brodalumab groups were noninferior but not significantly superior to ustekinumab, which achieved a PASI 75 of 70.0% in AMAGINE-2 and 69.3% in AMAGINE-3. The PASI 90 rate was higher, however, in both brodalumab groups compared to ustekinumab but significance was not reported (eTable 1).9 For both brodalumab groups, significantly more patients achieved a static PGA value of 0 or 1 compared to placebo (P<.001 across all trials). However, only the brodalumab 210-mg group achieved a significantly higher rate of static PGA 0 or 1 compared to ustekinumab in AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 (P<.001).9

After 12 weeks, the percentage of patients reporting at least 1 AE was 59.0%, 57.8%, and 56.8% in the brodalumab 210-mg group in AMAGINE-1, AMAGINE-2, and AMAGINE-3, respectively; 58.0%, 60.1%, and 52.6% in the brodalumab 140-mg group; and 51.0%, 53.4%, and 48.6% in the placebo group. Patients taking ustekinumab had an AE rate of 59.0% in AMAGINE-2 and 53.7% in AMAGINE-3. The most common AE was nasopharyngitis, followed by upper respiratory infection (URI) and headache across all trials.8,9 Serious AEs were rare: 10 in AMAGINE-1, 31 in AMAGINE-2, and 24 in AMAGINE-3 across all groups. One death occurred from stroke in the brodalumab 210-mg group in AMAGINE-2.9

IL-23 Inhibitors

Guselkumab

This drug is a human IgG1κ antibody that binds to the p19 subunit of IL-23, thereby inhibiting IL-23 signaling.11,12 Guselkumab was approved by the FDA in July 2017 for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.13

VOYAGE 1 and VOYAGE 2 were phase 3, double-blind, placebo- and active comparator–controlled trials of 837 and 992 patients, respectively, randomized to receive adalimumab (80 mg at week 0 and 40 mg at week 1, then at 40 mg every 2 weeks thereafter), guselkumab 100 mg at weeks 0, 4, and 12, or placebo.11 Co-primary end points for both trials were the percentage of patients reaching PASI 90 and an investigator global assessment (IGA) score of cleared (0) or minimal (1) at week 16.11

By week 16 of both trials, PASI 90 values were statistically superior for guselkumab (VOYAGE 1, 73.3%; VOYAGE 2, 70.0%) compared to adalimumab (VOYAGE 1, 49.7%; VOYAGE 2, 46.8%) and placebo (VOYAGE 1, 2.9%; VOYAGE 2, 2.4%)(P<.001). Moreover, patients on guselkumab achieved a higher rate of IGA values of 0 and 1 at week 12 (85.1% in VOYAGE 1 and 84.1% in VOYAGE 2) than patients on adalimumab (65.9% in VOYAGE 1 and 67.7% in VOYAGE 2) and placebo (6.9% in VOYAGE 1 and 8.5% in VOYAGE 2)(P<.001).11,12

The frequency of AEs was comparable across all groups in both trials.11,12 During the 16-week treatment period, 51.7% and 47.6% of the guselkumab groups in VOYAGE 1 and VOYAGE 2, respectively; 51.1% and 48.4% of the adalimumab groups; and 49.4% and 44.8% of the placebo groups reported at least 1 AE. The most common AEs in all groups were nasopharyngitis, headache, and URI.11,12

Serious AEs also occurred at similar rates: 2.4% and 1.6% in the guselkumab group in VOYAGE 1 and VOYAGE 2, respectively; 2.4% and 1.8% in the adalimumab group; and 1.7% and 1.2% in the placebo group.11,12 One case of malignancy occurred in the VOYAGE 1 trial: basal cell carcinoma in the guselkumab group.11 Three major cardiovascular events occurred across both trials: 1 MI in the guselkumab group in each trial and 1 MI in the adalimumab group in VOYAGE 1.11,12

Tildrakizumab

A high-affinity, humanized IgG1κ antibody, tildrakizumab targets the p19 subunit of IL-23. As of February 2018, 2 double-blind, randomized phase 3 trials have studied tildrakizumab with published results: reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2.14

reSURFACE 1 (N=772) and reSURFACE 2 (N=1090) randomized patients to receive tildrakizumab 100 or 200 mg (at weeks 0 and 4), etanercept 50 mg (twice weekly) for 12 weeks (reSURFACE 2 only), or placebo. Co-primary end points were the percentage of patients achieving PASI 75 and the percentage of patients achieving a PGA score of 0 or 1 at week 12.14

In reSURFACE 1, significantly more patients receiving tildrakizumab attained PASI 75 at week 12 compared to placebo: 200 mg, 62.0%; 100 mg, 64.0%; and placebo, 6.0% (P<.001 for tildrakizumab groups compared to placebo). Moreover, significantly proportionally more patients received a PGA score of 0 or 1 compared to placebo: 100 mg, 59%; 200 mg, 58.0%; placebo, 7.0% (P<.001 for both tildrakizumab groups compared to placebo).14

In reSURFACE 2, significantly more patients receiving tildrakizumab achieved PASI 75 compared to etanercept and placebo at week 12: 200 mg, 66.0%; 100mg, 61.0%; etanercept, 48.0%; placebo, 6.0% (P<.001 for both tildrakizumab groups compared to placebo; P<.05 for both tildrakizumab groups compared to etanercept). Additionally, significantly more patients in the tildrakizumab groups experienced a PGA score of 0 or 1 at week 12 compared to placebo: 200 mg, 59%; 100 mg, 55.0%; placebo, 5% (P<.001 for both tildrakizumab groups compared to placebo).14

Adverse events were reported at a similar rate across all groups. For reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2, at least 1 AE by week 12 was reported by 42.2% and 45.2% of patients in the 200-mg group; 47.2% and 45.9% in the 100-mg group; and 48.1% and 55.1% in the placebo groups.14The most common AEs were nasopharyngitis, URI (reSURFACE 1), and erythema at the injection site (reSURFACE 2). One case of serious infection was reported in each of the tildrakizumab groups: 1 case of drug-related hypersensitivity reaction in the 200-mg group, and 1 major cardiovascular event in the 100-mg group of reSURFACE 1. There was 1 serious AE in reSURFACE 2 that led to death in which the cause was undetermined.14

Risankizumab

This humanized IgG1 antibody binds the p19 unit of IL-23.15,16 The drug is undergoing 3 phase 3 trials—ultIMMa-1, ultIMMa-2, and IMMvent—for which only preliminary data have been published and are reported here.16,17 There is 1 phase 2 randomized, dose-ranging trial with published data.15

ultIMMa-1 and ultIMMa-2 comprised 506 and 491 patients, respectively, randomized to receive risankizumab (150 mg at weeks 0, 4, and 16), ustekinumab (45 mg or 90 mg, by weight, at weeks 0, 4, and 16), or placebo. Co-primary end points were PASI 90 and a PGA score of 0 or 1 at week 16.17

In ultIMMa-1 and ultIMMa-2, 75.0% and 75.0% of patients on risankizumab 150 mg achieved PASI 90 compared to 42.0% and 48.0% on ustekinumab and 5.0% and 2.0% on placebo at 16 weeks (P<.001 between both placebo and ustekinumab in both trials).17 In both trials, patients receiving risankizumab achieved higher rates of a static PGA score of 0 or 1 (88.0% and 84.0%) compared to ustekinumab (63.0% and 62.0%) and placebo (8.0% and 5.0%) at 16 weeks (P<.001 for both trials).18

At week 16, 2.0% of patients on risankizumab reported a serious AE in both trials, compared to 8.0% and 3.0% of patients on ustekinumab and 3.0% and 1.0% on placebo. No new safety concerns were noted.17

In the phase 3 IMMvent trial, 605 patients were randomized to receive risankizumab (150 mg at weeks 0, 4, and 16) or adalimumab (80 mg at week 0, 40 mg at week 1, then 40 mg every 2 weeks). Co-primary end points were PASI 90 and a static PGA score of 0 or 1 at week 16.17

In IMMvent, risankizumab was significantly more effective than adalimumab for PASI 75 (risankizumab, 72.0%; adalimumab, 47.0%) and a static PGA score of 0 or 1 (risankizumab 84.0%; adalimumab, 60.0%) (P<.001 risankizumab compared to adalimumab for both end points).17

At week 16, serious AEs were reported in 3.0% of patients on risankizumab and 3.0% of patients on adalimumab. One patient receiving risankizumab died of an acute MI during the treatment phase.17

TNF Inhibitor

Certolizumab Pegol

Certolizumab pegol is a human PEGylated anti-TNF agent. In vitro studies have shown that certolizumab binds to soluble and membrane-bound TNF.19 Unlike other TNF inhibitors, certolizumab pegol is a Fab‘ portion of anti-TNF conjugated to a molecule of polyethylene glycol.19 The drug is approved in the United States for treating psoriatic arthritis, Crohn disease, and rheumatoid arthritis; its potential for treating psoriasis has been confirmed. Results of 1 phase 2 trial have been published19; data from 3 phase 3 trials are forthcoming.

This randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase 2 study comprised 176 patients who received certolizumab 200 mg, certolizumab 400 mg, or placebo. The dosing schedule was 400 mg at week 0, followed by either 200 or 400 mg every other week until week 10. Co-primary end points were PASI 75 and a PGA score of 0 or 1 at week 12.19

Certolizumab was significantly more effective than placebo at week 12: 74.6% of the 200-mg group and 82.8% of the 400-mg group achieved PASI 75 compared to 6.8% of the placebo group (P<.001). Certolizumab also performed better for the PGA score: 52.5% and 72.4% of patients attained a score of 0 or 1 in the 200-mg and 400-mg groups compared to 1.7% in the placebo group.19

Adverse events were reported equally across all groups: 72% of patients in the 200-mg group, 70% in the 400-mg group, and 71% in the placebo group reported at least 1 AE, most commonly nasopharyngitis, headache, and pruritis.19

COMMENT

With the development of new insights into the pathogenesis of psoriasis, therapies that are targeted toward key cytokines may contribute to improved management of the disease. The results of these clinical trials demonstrate numerous promising options for psoriatic patients.

IL-17 Inhibitors Ixekizumab and Brodalumab

When comparing these 2 biologics, it is important to consider that these studies were not performed head to head, thereby inhibiting direct comparisons. Moreover, dosage ranges of the investigative drugs were not identical, which also makes comparisons challenging. However, when looking at the highest dosages of ixekizumab and brodalumab, results indicate that ixekizumab may be slightly more effective than brodalumab based on the percentage of patients who achieved a PASI 75 and a static PGA score of 0 or 1 (eTable 1).

Phase 3 trials have shown ixekizumab to maintain efficacy over 60 weeks of treatment.6 Ixekizumab also has been shown to alleviate other symptoms of psoriasis, such as itching, pain, and nail involvement.20,21 Furthermore, ixekizumab appears to be equally effective in patients with or without prior exposure to biologics22; therefore, ixekizumab may benefit patients who have not experienced success with other biologics.

Across the UNCOVER trials, 11 cases of inflammatory bowel disease were reported in patients receiving ixekizumab (ulcerative colitis in 7; Crohn disease in 4)6; it appears that at least 3 of these cases were new diagnoses. In light of a study suggesting that IL-17A might have a protective function in the intestine,23 these findings may have important clinical implications and require follow-up studies.

Brodalumab also has been shown to maintain efficacy and acceptable safety for as long as 120 weeks.24 In the extension period of the AMAGINE-1 trial, patients who experienced a return of disease during a withdrawal period recaptured static PGA success with re-treatment for 12 weeks (re-treatment was successful in 97% of those given a dosage of 210 mg and in 84% of those given 140 mg).8

Furthermore, phase 2 trials also have shown that brodalumab is effective in patients with a history of biologic use.25 Across all AMAGINE trials, only 1 case of Crohn disease was reported in a patient taking brodalumab.9 There are concerns about depression, despite data from AMAGINE-1 stating patients on brodalumab actually had greater improvements in Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale scores after 12 weeks of treatment (P<.001) for both brodalumab 140 mg and 210 mg compared to placebo.8 Regardless, brodalumab has a black-box warning for suicidal ideation and behavior, and availability is restricted through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program.26

Bimekizumab

Although no phase 2 or phase 3 clinical trial data have been published for bimekizumab (phase 2 trials are underway), it has been shown in a phase 1 trial to be effective for psoriasis. Bimekizumab also is unique; it is the first dual inhibitor of IL-17A and IL-17F.18

IL-23 Inhibitors Guselkumab, Tildrakizumab, and Risankizumab

Making comparisons among the IL-23 inhibitors also is difficult; studies were not head-to-head comparison trials, and the VOYAGE and reSURFACE studies used different time points for primary end points. Furthermore, only phase 2 trial data are available for risankizumab. Despite these limitations, results of these trials suggest that guselkumab and risankizumab may be slightly more efficacious than tildrakizumab. However, future studies, including head-to-head studies, would ultimately provide further information on how these agents compare.

Guselkumab was shown to remain efficacious at 48 weeks, though patients on maintenance dosing had better results than those who were re-treated.12 Moreover, guselkumab was found to be effective in hard-to-treat areas, such as the scalp,11 and in patients who did not respond to adalimumab. Guselkumab may therefore benefit patients who have experienced limited clinical improvement on other biologics.12

Tildrakizumab was shown to improve PASI 75 and PGA scores through week 28 of treatment. Moreover, a higher percentage of patients taking tildrakizumab scored 0 or 1 on the dermatology life quality index, suggesting that the drug improves quality of life.14 No specific safety concerns arose in either reSURFACE trial; however, long-term studies are needed for further evaluation.