User login

Paradoxical Reaction to TNF-α Inhibitor Therapy in a Patient With Hidradenitis Suppurativa

To the Editor:

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory condition of the pilosebaceous unit that occurs in concert with elevations of various cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), IL-1β, IL-10, and IL-17.1,2 Adalimumab is a TNF-α inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of HS. Although TNF-α inhibitors are effective for many immune-mediated inflammatory disorders, paradoxical drug reactions have been reported following treatment with these agents.3-6 True paradoxical drug reactions likely are immune mediated and directly lead to new onset of a pathologic condition that would otherwise respond to that drug. For example, there are reports of rheumatoid arthritis patients who were treated with a TNF-α inhibitor and developed psoriatic skin lesions.3,6 Paradoxical drug reactions also have been reported with acute-onset inflammatory bowel disease and HS or less commonly pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), uveitis, granulomatous reactions, and vasculitis.4,5 We present the case of a patient with HS who was treated with a TNF-α inhibitor and developed 2 distinct paradoxical drug reactions. We also provide an overview of paradoxical drug reactions associated with TNF-α inhibitors.

A 38-year-old woman developed a painful “boil” on the right leg that was previously treated in the emergency department with incision and drainage as well as oral clindamycin for 7 days, but the lesion spread and continued to worsen. She had a history of HS in the axillae and groin region that had been present since 12 years of age. The condition was poorly controlled despite multiple courses of oral antibiotics and surgical resections. An oral contraceptive also was attempted, but the patient discontinued treatment when liver enzyme levels became elevated. The patient had no other notable medical history, including skin disease. There was a family history of HS in her father and a sibling. Seeking more effective treatment, the patient was offered adalimumab approximately 4 months prior to clinical presentation and agreed to start a course of the drug. She received a loading dose of 160 mg on day 1 and 80 mg on day 15 followed by a maintenance dosage of 40 mg weekly. She experienced improvement in HS symptoms after 3 months on adalimumab; however, she developed scaly pruritic patches on the scalp, arms, and legs that were consistent with psoriasis. Because of the absence of a personal or family history of psoriasis, the patient was informed of the probability of paradoxical psoriasis resulting from adalimumab. She elected to continue adalimumab because of the improvement in HS symptoms, and the psoriatic lesions were mild and adequately controlled with a topical steroid.

At the current presentation 1 month later, physical examination revealed a large indurated and ulcerated area with jagged edges at the incision and drainage site (Figure 1). Pyoderma gangrenosum was clinically suspected; a biopsy was performed, and the patient was started on oral prednisone. At 2-week follow-up, the ulcer was found to be rapidly resolving with prednisone and healing with cribriform scarring (Figure 2). Histopathology revealed an undermining neutrophilic inflammatory process that was consistent with PG. A diagnosis of PG was made based on previously published criteria7 and the following major/minor criteria in the patient: pathology; absence of infection on histologic analysis; history of pathergy related to worsening ulceration at the site of incision and drainage of the initial boil; clinical findings of an ulcer with peripheral violaceous erythema; undermined borders and tenderness at the site; and rapid resolution of the ulcer with prednisone.

Cessation of adalimumab gradually led to clearance of both psoriasiform lesions and PG; however, HS lesions persisted.

Although the precise pathogenesis of HS is unclear, both genetic abnormalities of the pilosebaceous unit and a dysregulated immune reaction appear to lead to the clinical characteristics of chronic inflammation and scarring seen in HS. A key effector appears to be helper T-cell (TH17) lymphocyte activation, with increased secretion of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-17.1,2 In turn, IL-17 induces higher expression of TNF-α, leading to a persistent cycle of inflammation. Peripheral recruitment of IL-17–producing neutrophils also may contribute to chronic inflammation.8

Adalimumab is the only US Food and Drug Administration–approved biologic indicated for the treatment of HS. Our patient initially responded to adalimumab with improvement of HS; however, treatment had to be discontinued because of the unusual occurrence of 2 distinct paradoxical reactions in a short span of time. Psoriasis and PG are both considered true paradoxical reactions because primary occurrences of both diseases usually are responsive to treatment with adalimumab.

Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced psoriasis arises de novo and is estimated to occur in approximately 5% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis.3,6 Palmoplantar pustular psoriasiform reactions are the most common form of paradoxical psoriasis. Topical medications can be used to treat skin lesions, but systemic treatment is required in many cases. Switching to an alternate class of a biologic, such as an IL-17, IL-12/23, or IL-23 inhibitor, can improve the skin reaction; however, such treatment is inconsistently successful, and paradoxical drug reactions also have been seen with these other classes of biologics.4,9

Recent studies support distinct immune causes for classical and paradoxical psoriasis. In classical psoriasis, plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) produce IFN-α, which stimulates conventional dendritic cells to produce TNF-α. However, TNF-α matures both pDCs and conventional dendritic cells; upon maturation, both types of dendritic cells lose the ability to produce IFN-α, thus allowing TNF-α to become dominant.10 The blockade of TNF-α prevents pDC maturation, leading to uninhibited IFN-α, which appears to drive inflammation in paradoxical psoriasis. In classical psoriasis, oligoclonal dermal CD4+ T cells and epidermal CD8+ T cells remain, even in resolved skin lesions, and can cause disease recurrence through reactivation of skin-resident memory T cells.11 No relapse of paradoxical psoriasis occurs with discontinuation of anti-TNF-α therapy, which supports the notion of an absence of memory T cells.

The incidence of paradoxical psoriasis in patients receiving a TNF-α inhibitor for HS is unclear.12 There are case series in which patients who had concurrent psoriasis and HS were successfully treated with a TNF-α inhibitor.13 A recently recognized condition—PASH syndrome—encompasses the clinical triad of PG, acne, and HS.10

Our patient had no history of acne or PG, only a long-standing history of HS. New-onset PG occurred only after a TNF-α inhibitor was initiated. Notably, PASH syndrome has been successfully treated with TNF-α inhibitors, highlighting the shared inflammatory etiology of HS and PG.14 In patients with concurrent PG and HS, TNF-α inhibitors were more effective for treating PG than for HS.

Pyoderma gangrenosum is an inflammatory disorder that often occurs concomitantly with other conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease. The exact underlying cause of PG is unclear, but there appears to be both neutrophil and T-cell dysfunction in PG, with excess inflammatory cytokine production (eg, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-17).15

The mainstay of treatment of PG is systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressives, such as cyclosporine. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors as well as other interleukin inhibitors are increasingly utilized as potential therapeutic alternatives for PG.16,17

Unlike paradoxical psoriasis, the underlying cause of paradoxical PG is unclear.18,19 A similar mechanism may be postulated whereby inhibition of TNF-α leads to excessive activation of alternative inflammatory pathways that result in paradoxical PG. In one study, the prevalence of PG among 68,232 patients with HS was 0.18% compared with 0.01% among those without HS; therefore, patients with HS appear to be more predisposed to PG.20

This case illustrates the complex, often conflicting effects of cytokine inhibition in the paradoxical elicitation of alternative inflammatory disorders as an unintended consequence of the initial cytokine blockade. It is likely that genetic predisposition allows for paradoxical reactions in some patients when there is predominant inhibition of one cytokine in the inflammatory pathway. In rare cases, multiple paradoxical reactions are possible.

1. Vossen ARJV, van der Zee HH, Prens EP. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review integrating inflammatory pathways into a cohesive pathogenic model. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2965. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02965

2. Goldburg SR, Strober BE, Payette MJ. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology, clinical presentation and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020; 82:1045-1058. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.090

3. Brown G, Wang E, Leon A, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor-induced psoriasis: systematic review of clinical features, histopathological findings, and management experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:334-341. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.08.012

4. Puig L. Paradoxical reactions: anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha agents, ustekinumab, secukinumab, ixekizumab and others. Curr Prob Dermatol. 2018;53:49-63. doi:10.1159/000479475

5. Faivre C, Villani AP, Aubin F, et al; . Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS): an unrecognized paradoxical effect of biologic agents (BA) used in chronic inflammatory diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1153-1159. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.01.018

6. Ko JM, Gottlieb AB, Kerbleski JF. Induction and exacerbation of psoriasis with TNF-blockade therapy: a review and analysis of 127 cases. J Dermatolog Treat. 2009;20:100-108. doi:10.1080/09546630802441234

7. Maverakis E, Ma C, Shinkai K, et al. Diagnostic criteria of ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum: a delphi consensus of international experts. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:461-466. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5980

8. Lima AL, Karl I, Giner T, et al. Keratinocytes and neutrophils are important sources of proinflammatory molecules in hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:514-521. doi:10.1111/bjd.14214

9. Li SJ, Perez-Chada LM, Merola JF. TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis: proposed algorithm for treatment and management. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2019;4:70-80. doi:10.1177/2475530318810851

10. Conrad C, Di Domizio J, Mylonas A, et al. TNF blockade induces a dysregulated type I interferon response without autoimmunity in paradoxical psoriasis. Nat Commun. 2018;9:25. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-02466-4

11. Matos TR, O’Malley JT, Lowry EL, et al. Clinically resolved psoriatic lesions contain psoriasis-specific IL-17-producing αβ T cell clones. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:4031-4041. doi:10.1172/JCI93396

12. Faivre C, Villani AP, Aubin F, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS): an unrecognized paradoxical effect of biologic agents (BA) used in chronic inflammatory diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1153-1159. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.01.018

13. Marzano AV, Damiani G, Ceccherini I, et al. Autoinflammation in pyoderma gangrenosum and its syndromic form (pyoderma gangrenosum, acne and suppurative hidradenitis). Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:1588-1598. doi:10.1111/bjd.15226

14. Cugno M, Borghi A, Marzano AV. PAPA, PASH, PAPASH syndromes: pathophysiology, presentation and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:555-562. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0265-1

15. Wang EA, Steel A, Luxardi G, et al. Classic ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum is a T cell-mediated disease targeting follicular adnexal structures: a hypothesis based on molecular and clinicopathologic studies. Front Immunol. 2018;8:1980. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.01980

16. Patel F, Fitzmaurice S, Duong C, et al. Effective strategies for the management of pyoderma gangrenosum: a comprehensive review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:525-531. doi:10.2340/00015555-2008

17. Partridge ACR, Bai JW, Rosen CF, et al. Effectiveness of systemic treatments for pyoderma gangrenosum: a systematic review of observational studies and clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:290-295. doi:10.1111/bjd.16485

18. Benzaquen M, Monnier J, Beaussault Y, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum arising during treatment of psoriasis with adalimumab: effectiveness of ustekinumab. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:e270-e271. doi:10.1111/ajd.12545

19. Fujimoto N, Yamasaki Y, Watanabe RJ. Paradoxical uveitis and pyoderma gangrenosum in a patient with psoriatic arthritis under infliximab treatment. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:1139-1140. doi:10.1111/ddg.13632

20. Tannenbaum R, Strunk A, Garg A. Overall and subgroup prevalence of pyoderma gangrenosum among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a population-based analysis in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1533-1537. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.004

To the Editor:

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory condition of the pilosebaceous unit that occurs in concert with elevations of various cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), IL-1β, IL-10, and IL-17.1,2 Adalimumab is a TNF-α inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of HS. Although TNF-α inhibitors are effective for many immune-mediated inflammatory disorders, paradoxical drug reactions have been reported following treatment with these agents.3-6 True paradoxical drug reactions likely are immune mediated and directly lead to new onset of a pathologic condition that would otherwise respond to that drug. For example, there are reports of rheumatoid arthritis patients who were treated with a TNF-α inhibitor and developed psoriatic skin lesions.3,6 Paradoxical drug reactions also have been reported with acute-onset inflammatory bowel disease and HS or less commonly pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), uveitis, granulomatous reactions, and vasculitis.4,5 We present the case of a patient with HS who was treated with a TNF-α inhibitor and developed 2 distinct paradoxical drug reactions. We also provide an overview of paradoxical drug reactions associated with TNF-α inhibitors.

A 38-year-old woman developed a painful “boil” on the right leg that was previously treated in the emergency department with incision and drainage as well as oral clindamycin for 7 days, but the lesion spread and continued to worsen. She had a history of HS in the axillae and groin region that had been present since 12 years of age. The condition was poorly controlled despite multiple courses of oral antibiotics and surgical resections. An oral contraceptive also was attempted, but the patient discontinued treatment when liver enzyme levels became elevated. The patient had no other notable medical history, including skin disease. There was a family history of HS in her father and a sibling. Seeking more effective treatment, the patient was offered adalimumab approximately 4 months prior to clinical presentation and agreed to start a course of the drug. She received a loading dose of 160 mg on day 1 and 80 mg on day 15 followed by a maintenance dosage of 40 mg weekly. She experienced improvement in HS symptoms after 3 months on adalimumab; however, she developed scaly pruritic patches on the scalp, arms, and legs that were consistent with psoriasis. Because of the absence of a personal or family history of psoriasis, the patient was informed of the probability of paradoxical psoriasis resulting from adalimumab. She elected to continue adalimumab because of the improvement in HS symptoms, and the psoriatic lesions were mild and adequately controlled with a topical steroid.

At the current presentation 1 month later, physical examination revealed a large indurated and ulcerated area with jagged edges at the incision and drainage site (Figure 1). Pyoderma gangrenosum was clinically suspected; a biopsy was performed, and the patient was started on oral prednisone. At 2-week follow-up, the ulcer was found to be rapidly resolving with prednisone and healing with cribriform scarring (Figure 2). Histopathology revealed an undermining neutrophilic inflammatory process that was consistent with PG. A diagnosis of PG was made based on previously published criteria7 and the following major/minor criteria in the patient: pathology; absence of infection on histologic analysis; history of pathergy related to worsening ulceration at the site of incision and drainage of the initial boil; clinical findings of an ulcer with peripheral violaceous erythema; undermined borders and tenderness at the site; and rapid resolution of the ulcer with prednisone.

Cessation of adalimumab gradually led to clearance of both psoriasiform lesions and PG; however, HS lesions persisted.

Although the precise pathogenesis of HS is unclear, both genetic abnormalities of the pilosebaceous unit and a dysregulated immune reaction appear to lead to the clinical characteristics of chronic inflammation and scarring seen in HS. A key effector appears to be helper T-cell (TH17) lymphocyte activation, with increased secretion of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-17.1,2 In turn, IL-17 induces higher expression of TNF-α, leading to a persistent cycle of inflammation. Peripheral recruitment of IL-17–producing neutrophils also may contribute to chronic inflammation.8

Adalimumab is the only US Food and Drug Administration–approved biologic indicated for the treatment of HS. Our patient initially responded to adalimumab with improvement of HS; however, treatment had to be discontinued because of the unusual occurrence of 2 distinct paradoxical reactions in a short span of time. Psoriasis and PG are both considered true paradoxical reactions because primary occurrences of both diseases usually are responsive to treatment with adalimumab.

Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced psoriasis arises de novo and is estimated to occur in approximately 5% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis.3,6 Palmoplantar pustular psoriasiform reactions are the most common form of paradoxical psoriasis. Topical medications can be used to treat skin lesions, but systemic treatment is required in many cases. Switching to an alternate class of a biologic, such as an IL-17, IL-12/23, or IL-23 inhibitor, can improve the skin reaction; however, such treatment is inconsistently successful, and paradoxical drug reactions also have been seen with these other classes of biologics.4,9

Recent studies support distinct immune causes for classical and paradoxical psoriasis. In classical psoriasis, plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) produce IFN-α, which stimulates conventional dendritic cells to produce TNF-α. However, TNF-α matures both pDCs and conventional dendritic cells; upon maturation, both types of dendritic cells lose the ability to produce IFN-α, thus allowing TNF-α to become dominant.10 The blockade of TNF-α prevents pDC maturation, leading to uninhibited IFN-α, which appears to drive inflammation in paradoxical psoriasis. In classical psoriasis, oligoclonal dermal CD4+ T cells and epidermal CD8+ T cells remain, even in resolved skin lesions, and can cause disease recurrence through reactivation of skin-resident memory T cells.11 No relapse of paradoxical psoriasis occurs with discontinuation of anti-TNF-α therapy, which supports the notion of an absence of memory T cells.

The incidence of paradoxical psoriasis in patients receiving a TNF-α inhibitor for HS is unclear.12 There are case series in which patients who had concurrent psoriasis and HS were successfully treated with a TNF-α inhibitor.13 A recently recognized condition—PASH syndrome—encompasses the clinical triad of PG, acne, and HS.10

Our patient had no history of acne or PG, only a long-standing history of HS. New-onset PG occurred only after a TNF-α inhibitor was initiated. Notably, PASH syndrome has been successfully treated with TNF-α inhibitors, highlighting the shared inflammatory etiology of HS and PG.14 In patients with concurrent PG and HS, TNF-α inhibitors were more effective for treating PG than for HS.

Pyoderma gangrenosum is an inflammatory disorder that often occurs concomitantly with other conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease. The exact underlying cause of PG is unclear, but there appears to be both neutrophil and T-cell dysfunction in PG, with excess inflammatory cytokine production (eg, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-17).15

The mainstay of treatment of PG is systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressives, such as cyclosporine. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors as well as other interleukin inhibitors are increasingly utilized as potential therapeutic alternatives for PG.16,17

Unlike paradoxical psoriasis, the underlying cause of paradoxical PG is unclear.18,19 A similar mechanism may be postulated whereby inhibition of TNF-α leads to excessive activation of alternative inflammatory pathways that result in paradoxical PG. In one study, the prevalence of PG among 68,232 patients with HS was 0.18% compared with 0.01% among those without HS; therefore, patients with HS appear to be more predisposed to PG.20

This case illustrates the complex, often conflicting effects of cytokine inhibition in the paradoxical elicitation of alternative inflammatory disorders as an unintended consequence of the initial cytokine blockade. It is likely that genetic predisposition allows for paradoxical reactions in some patients when there is predominant inhibition of one cytokine in the inflammatory pathway. In rare cases, multiple paradoxical reactions are possible.

To the Editor:

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory condition of the pilosebaceous unit that occurs in concert with elevations of various cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), IL-1β, IL-10, and IL-17.1,2 Adalimumab is a TNF-α inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of HS. Although TNF-α inhibitors are effective for many immune-mediated inflammatory disorders, paradoxical drug reactions have been reported following treatment with these agents.3-6 True paradoxical drug reactions likely are immune mediated and directly lead to new onset of a pathologic condition that would otherwise respond to that drug. For example, there are reports of rheumatoid arthritis patients who were treated with a TNF-α inhibitor and developed psoriatic skin lesions.3,6 Paradoxical drug reactions also have been reported with acute-onset inflammatory bowel disease and HS or less commonly pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), uveitis, granulomatous reactions, and vasculitis.4,5 We present the case of a patient with HS who was treated with a TNF-α inhibitor and developed 2 distinct paradoxical drug reactions. We also provide an overview of paradoxical drug reactions associated with TNF-α inhibitors.

A 38-year-old woman developed a painful “boil” on the right leg that was previously treated in the emergency department with incision and drainage as well as oral clindamycin for 7 days, but the lesion spread and continued to worsen. She had a history of HS in the axillae and groin region that had been present since 12 years of age. The condition was poorly controlled despite multiple courses of oral antibiotics and surgical resections. An oral contraceptive also was attempted, but the patient discontinued treatment when liver enzyme levels became elevated. The patient had no other notable medical history, including skin disease. There was a family history of HS in her father and a sibling. Seeking more effective treatment, the patient was offered adalimumab approximately 4 months prior to clinical presentation and agreed to start a course of the drug. She received a loading dose of 160 mg on day 1 and 80 mg on day 15 followed by a maintenance dosage of 40 mg weekly. She experienced improvement in HS symptoms after 3 months on adalimumab; however, she developed scaly pruritic patches on the scalp, arms, and legs that were consistent with psoriasis. Because of the absence of a personal or family history of psoriasis, the patient was informed of the probability of paradoxical psoriasis resulting from adalimumab. She elected to continue adalimumab because of the improvement in HS symptoms, and the psoriatic lesions were mild and adequately controlled with a topical steroid.

At the current presentation 1 month later, physical examination revealed a large indurated and ulcerated area with jagged edges at the incision and drainage site (Figure 1). Pyoderma gangrenosum was clinically suspected; a biopsy was performed, and the patient was started on oral prednisone. At 2-week follow-up, the ulcer was found to be rapidly resolving with prednisone and healing with cribriform scarring (Figure 2). Histopathology revealed an undermining neutrophilic inflammatory process that was consistent with PG. A diagnosis of PG was made based on previously published criteria7 and the following major/minor criteria in the patient: pathology; absence of infection on histologic analysis; history of pathergy related to worsening ulceration at the site of incision and drainage of the initial boil; clinical findings of an ulcer with peripheral violaceous erythema; undermined borders and tenderness at the site; and rapid resolution of the ulcer with prednisone.

Cessation of adalimumab gradually led to clearance of both psoriasiform lesions and PG; however, HS lesions persisted.

Although the precise pathogenesis of HS is unclear, both genetic abnormalities of the pilosebaceous unit and a dysregulated immune reaction appear to lead to the clinical characteristics of chronic inflammation and scarring seen in HS. A key effector appears to be helper T-cell (TH17) lymphocyte activation, with increased secretion of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-17.1,2 In turn, IL-17 induces higher expression of TNF-α, leading to a persistent cycle of inflammation. Peripheral recruitment of IL-17–producing neutrophils also may contribute to chronic inflammation.8

Adalimumab is the only US Food and Drug Administration–approved biologic indicated for the treatment of HS. Our patient initially responded to adalimumab with improvement of HS; however, treatment had to be discontinued because of the unusual occurrence of 2 distinct paradoxical reactions in a short span of time. Psoriasis and PG are both considered true paradoxical reactions because primary occurrences of both diseases usually are responsive to treatment with adalimumab.

Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced psoriasis arises de novo and is estimated to occur in approximately 5% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis.3,6 Palmoplantar pustular psoriasiform reactions are the most common form of paradoxical psoriasis. Topical medications can be used to treat skin lesions, but systemic treatment is required in many cases. Switching to an alternate class of a biologic, such as an IL-17, IL-12/23, or IL-23 inhibitor, can improve the skin reaction; however, such treatment is inconsistently successful, and paradoxical drug reactions also have been seen with these other classes of biologics.4,9

Recent studies support distinct immune causes for classical and paradoxical psoriasis. In classical psoriasis, plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) produce IFN-α, which stimulates conventional dendritic cells to produce TNF-α. However, TNF-α matures both pDCs and conventional dendritic cells; upon maturation, both types of dendritic cells lose the ability to produce IFN-α, thus allowing TNF-α to become dominant.10 The blockade of TNF-α prevents pDC maturation, leading to uninhibited IFN-α, which appears to drive inflammation in paradoxical psoriasis. In classical psoriasis, oligoclonal dermal CD4+ T cells and epidermal CD8+ T cells remain, even in resolved skin lesions, and can cause disease recurrence through reactivation of skin-resident memory T cells.11 No relapse of paradoxical psoriasis occurs with discontinuation of anti-TNF-α therapy, which supports the notion of an absence of memory T cells.

The incidence of paradoxical psoriasis in patients receiving a TNF-α inhibitor for HS is unclear.12 There are case series in which patients who had concurrent psoriasis and HS were successfully treated with a TNF-α inhibitor.13 A recently recognized condition—PASH syndrome—encompasses the clinical triad of PG, acne, and HS.10

Our patient had no history of acne or PG, only a long-standing history of HS. New-onset PG occurred only after a TNF-α inhibitor was initiated. Notably, PASH syndrome has been successfully treated with TNF-α inhibitors, highlighting the shared inflammatory etiology of HS and PG.14 In patients with concurrent PG and HS, TNF-α inhibitors were more effective for treating PG than for HS.

Pyoderma gangrenosum is an inflammatory disorder that often occurs concomitantly with other conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease. The exact underlying cause of PG is unclear, but there appears to be both neutrophil and T-cell dysfunction in PG, with excess inflammatory cytokine production (eg, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-17).15

The mainstay of treatment of PG is systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressives, such as cyclosporine. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors as well as other interleukin inhibitors are increasingly utilized as potential therapeutic alternatives for PG.16,17

Unlike paradoxical psoriasis, the underlying cause of paradoxical PG is unclear.18,19 A similar mechanism may be postulated whereby inhibition of TNF-α leads to excessive activation of alternative inflammatory pathways that result in paradoxical PG. In one study, the prevalence of PG among 68,232 patients with HS was 0.18% compared with 0.01% among those without HS; therefore, patients with HS appear to be more predisposed to PG.20

This case illustrates the complex, often conflicting effects of cytokine inhibition in the paradoxical elicitation of alternative inflammatory disorders as an unintended consequence of the initial cytokine blockade. It is likely that genetic predisposition allows for paradoxical reactions in some patients when there is predominant inhibition of one cytokine in the inflammatory pathway. In rare cases, multiple paradoxical reactions are possible.

1. Vossen ARJV, van der Zee HH, Prens EP. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review integrating inflammatory pathways into a cohesive pathogenic model. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2965. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02965

2. Goldburg SR, Strober BE, Payette MJ. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology, clinical presentation and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020; 82:1045-1058. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.090

3. Brown G, Wang E, Leon A, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor-induced psoriasis: systematic review of clinical features, histopathological findings, and management experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:334-341. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.08.012

4. Puig L. Paradoxical reactions: anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha agents, ustekinumab, secukinumab, ixekizumab and others. Curr Prob Dermatol. 2018;53:49-63. doi:10.1159/000479475

5. Faivre C, Villani AP, Aubin F, et al; . Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS): an unrecognized paradoxical effect of biologic agents (BA) used in chronic inflammatory diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1153-1159. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.01.018

6. Ko JM, Gottlieb AB, Kerbleski JF. Induction and exacerbation of psoriasis with TNF-blockade therapy: a review and analysis of 127 cases. J Dermatolog Treat. 2009;20:100-108. doi:10.1080/09546630802441234

7. Maverakis E, Ma C, Shinkai K, et al. Diagnostic criteria of ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum: a delphi consensus of international experts. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:461-466. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5980

8. Lima AL, Karl I, Giner T, et al. Keratinocytes and neutrophils are important sources of proinflammatory molecules in hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:514-521. doi:10.1111/bjd.14214

9. Li SJ, Perez-Chada LM, Merola JF. TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis: proposed algorithm for treatment and management. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2019;4:70-80. doi:10.1177/2475530318810851

10. Conrad C, Di Domizio J, Mylonas A, et al. TNF blockade induces a dysregulated type I interferon response without autoimmunity in paradoxical psoriasis. Nat Commun. 2018;9:25. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-02466-4

11. Matos TR, O’Malley JT, Lowry EL, et al. Clinically resolved psoriatic lesions contain psoriasis-specific IL-17-producing αβ T cell clones. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:4031-4041. doi:10.1172/JCI93396

12. Faivre C, Villani AP, Aubin F, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS): an unrecognized paradoxical effect of biologic agents (BA) used in chronic inflammatory diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1153-1159. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.01.018

13. Marzano AV, Damiani G, Ceccherini I, et al. Autoinflammation in pyoderma gangrenosum and its syndromic form (pyoderma gangrenosum, acne and suppurative hidradenitis). Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:1588-1598. doi:10.1111/bjd.15226

14. Cugno M, Borghi A, Marzano AV. PAPA, PASH, PAPASH syndromes: pathophysiology, presentation and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:555-562. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0265-1

15. Wang EA, Steel A, Luxardi G, et al. Classic ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum is a T cell-mediated disease targeting follicular adnexal structures: a hypothesis based on molecular and clinicopathologic studies. Front Immunol. 2018;8:1980. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.01980

16. Patel F, Fitzmaurice S, Duong C, et al. Effective strategies for the management of pyoderma gangrenosum: a comprehensive review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:525-531. doi:10.2340/00015555-2008

17. Partridge ACR, Bai JW, Rosen CF, et al. Effectiveness of systemic treatments for pyoderma gangrenosum: a systematic review of observational studies and clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:290-295. doi:10.1111/bjd.16485

18. Benzaquen M, Monnier J, Beaussault Y, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum arising during treatment of psoriasis with adalimumab: effectiveness of ustekinumab. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:e270-e271. doi:10.1111/ajd.12545

19. Fujimoto N, Yamasaki Y, Watanabe RJ. Paradoxical uveitis and pyoderma gangrenosum in a patient with psoriatic arthritis under infliximab treatment. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:1139-1140. doi:10.1111/ddg.13632

20. Tannenbaum R, Strunk A, Garg A. Overall and subgroup prevalence of pyoderma gangrenosum among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a population-based analysis in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1533-1537. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.004

1. Vossen ARJV, van der Zee HH, Prens EP. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review integrating inflammatory pathways into a cohesive pathogenic model. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2965. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02965

2. Goldburg SR, Strober BE, Payette MJ. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology, clinical presentation and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020; 82:1045-1058. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.090

3. Brown G, Wang E, Leon A, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor-induced psoriasis: systematic review of clinical features, histopathological findings, and management experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:334-341. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.08.012

4. Puig L. Paradoxical reactions: anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha agents, ustekinumab, secukinumab, ixekizumab and others. Curr Prob Dermatol. 2018;53:49-63. doi:10.1159/000479475

5. Faivre C, Villani AP, Aubin F, et al; . Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS): an unrecognized paradoxical effect of biologic agents (BA) used in chronic inflammatory diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1153-1159. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.01.018

6. Ko JM, Gottlieb AB, Kerbleski JF. Induction and exacerbation of psoriasis with TNF-blockade therapy: a review and analysis of 127 cases. J Dermatolog Treat. 2009;20:100-108. doi:10.1080/09546630802441234

7. Maverakis E, Ma C, Shinkai K, et al. Diagnostic criteria of ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum: a delphi consensus of international experts. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:461-466. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5980

8. Lima AL, Karl I, Giner T, et al. Keratinocytes and neutrophils are important sources of proinflammatory molecules in hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:514-521. doi:10.1111/bjd.14214

9. Li SJ, Perez-Chada LM, Merola JF. TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis: proposed algorithm for treatment and management. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2019;4:70-80. doi:10.1177/2475530318810851

10. Conrad C, Di Domizio J, Mylonas A, et al. TNF blockade induces a dysregulated type I interferon response without autoimmunity in paradoxical psoriasis. Nat Commun. 2018;9:25. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-02466-4

11. Matos TR, O’Malley JT, Lowry EL, et al. Clinically resolved psoriatic lesions contain psoriasis-specific IL-17-producing αβ T cell clones. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:4031-4041. doi:10.1172/JCI93396

12. Faivre C, Villani AP, Aubin F, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS): an unrecognized paradoxical effect of biologic agents (BA) used in chronic inflammatory diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1153-1159. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.01.018

13. Marzano AV, Damiani G, Ceccherini I, et al. Autoinflammation in pyoderma gangrenosum and its syndromic form (pyoderma gangrenosum, acne and suppurative hidradenitis). Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:1588-1598. doi:10.1111/bjd.15226

14. Cugno M, Borghi A, Marzano AV. PAPA, PASH, PAPASH syndromes: pathophysiology, presentation and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:555-562. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0265-1

15. Wang EA, Steel A, Luxardi G, et al. Classic ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum is a T cell-mediated disease targeting follicular adnexal structures: a hypothesis based on molecular and clinicopathologic studies. Front Immunol. 2018;8:1980. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.01980

16. Patel F, Fitzmaurice S, Duong C, et al. Effective strategies for the management of pyoderma gangrenosum: a comprehensive review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:525-531. doi:10.2340/00015555-2008

17. Partridge ACR, Bai JW, Rosen CF, et al. Effectiveness of systemic treatments for pyoderma gangrenosum: a systematic review of observational studies and clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:290-295. doi:10.1111/bjd.16485

18. Benzaquen M, Monnier J, Beaussault Y, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum arising during treatment of psoriasis with adalimumab: effectiveness of ustekinumab. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:e270-e271. doi:10.1111/ajd.12545

19. Fujimoto N, Yamasaki Y, Watanabe RJ. Paradoxical uveitis and pyoderma gangrenosum in a patient with psoriatic arthritis under infliximab treatment. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:1139-1140. doi:10.1111/ddg.13632

20. Tannenbaum R, Strunk A, Garg A. Overall and subgroup prevalence of pyoderma gangrenosum among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a population-based analysis in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1533-1537. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.004

Practice Points

- Clinicians need to be aware of the potential risk for a paradoxical reaction in patients receiving a tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitor for hidradenitis suppurativa.

- Although uncommon, developing more than 1 type of paradoxical skin reaction is possible with a TNF-α inhibitor.

- Early recognition and appropriate management of these paradoxical reactions are critical.

TNF blockers not associated with poorer pregnancy outcomes

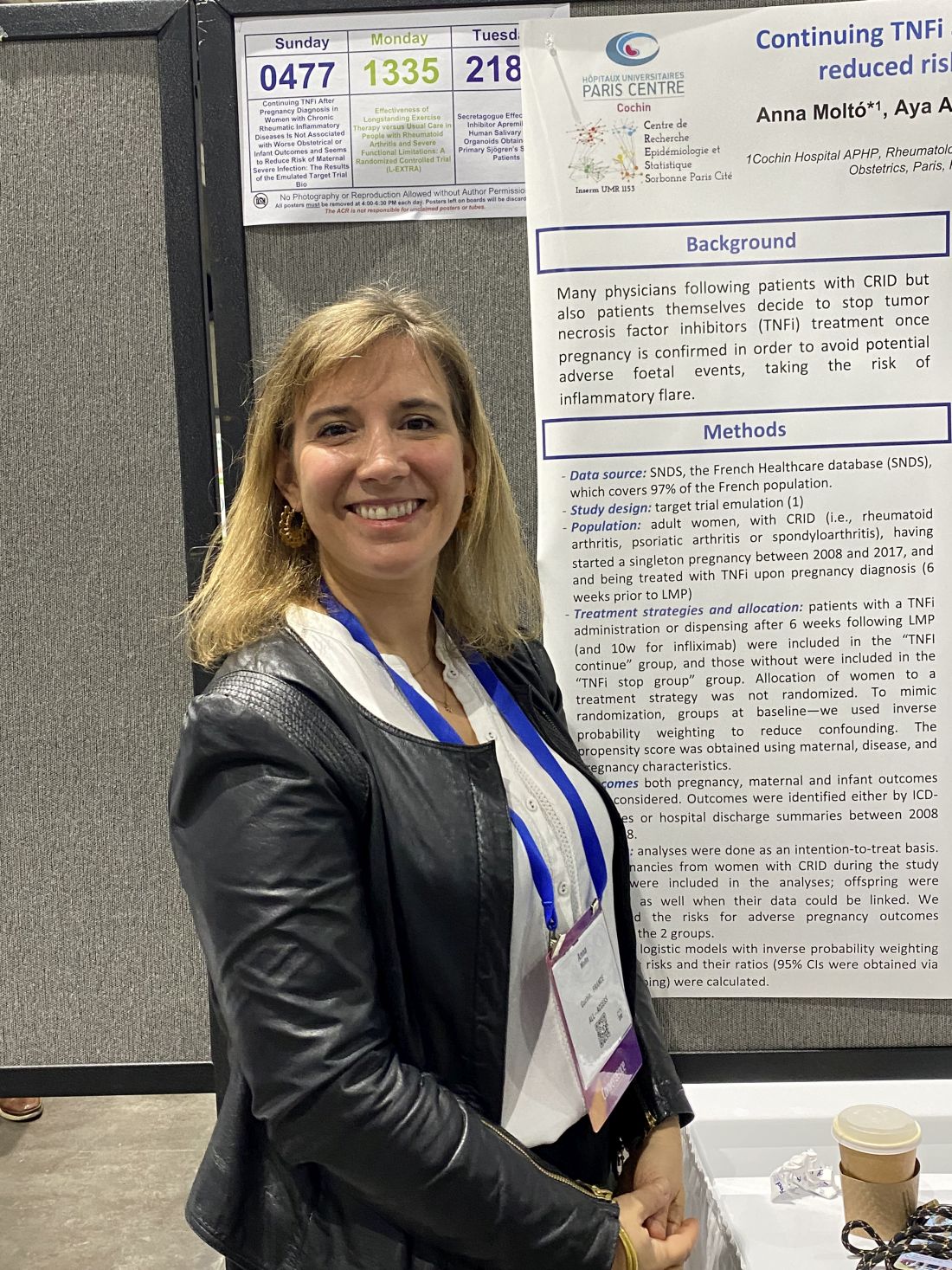

SAN DIEGO – Continuing a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) during pregnancy does not increase risk of worse fetal or obstetric outcomes, according to new research presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Patients who continued a TNFi also had fewer severe infections requiring hospitalization, compared with those who stopped taking the medication during their pregnancy.

“The main message is that patients continuing were not doing worse than the patients stopping. It’s an important clinical message for rheumatologists who are not really confident in dealing with these drugs during pregnancy,” said Anna Moltó, MD, PhD, a rheumatologist at Cochin Hospital, Paris, who led the research. “It adds to the data that it seems to be safe,” she added in an interview.

Previous research, largely from pregnant patients with inflammatory bowel disease, suggests that taking a TNFi during pregnancy is safe, and 2020 ACR guidelines conditionally recommend continuing therapy prior to and during pregnancy; however, many people still stop taking the drugs during pregnancy for fear of potentially harming the fetus.

To better understand how TNFi use affected pregnancy outcomes, Dr. Moltó and colleagues analyzed data from a French nationwide health insurance database to identify adult women with chronic rheumatic inflammatory disease. All women included in the cohort had a singleton pregnancy between 2008 and 2017 and were taking a TNFi upon pregnancy diagnosis.

Patients who restarted TNFi after initially pausing because of pregnancy were included in the continuation group.

Researchers identified more than 2,000 pregnancies, including 1,503 in individuals with spondyloarthritis and 579 individuals with rheumatoid arthritis. Patients were, on average, 31 years old and were diagnosed with a rheumatic disease 4 years prior to their pregnancy.

About 72% (n = 1,497) discontinued TNFi after learning they were pregnant, and 584 individuals continued treatment. Dr. Moltó noted that data from more recent years might have captured lower discontinuation rates among pregnant individuals, but those data were not available for the study.

There was no difference in unfavorable obstetrical or infant outcomes, including spontaneous abortion, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, major congenital malformation, and severe infection of the infant requiring hospitalization. Somewhat surprisingly, the data showed that women who discontinued a TNFi were more likely to be hospitalized for infection either during their pregnancy or up to 6 weeks after delivery, compared with those who continued therapy (1.3% vs. 0.2%, respectively).

Dr. Moltó is currently looking into what could be behind this counterintuitive result, but she hypothesizes that patients who had stopped TNFi may have been taking more glucocorticoids.

“At our institution, there is generally a comfort level with continuing TNF inhibitors during pregnancy, at least until about 36 weeks,” said Sara K. Tedeschi, MD, MPH, a rheumatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. Sometimes, there is concern for risk of infection to the infant, depending on the type of TNFi being used, she added during a press conference.

“I think that these are really informative and supportive data to let women know that they probably have a really good chance of doing very well during the pregnancy if they continue” their TNFi, said Dr. Tedeschi, who was not involved with the study.

TNF discontinuation on the decline

In a related study, researchers at McGill University, Montreal, found that TNFi discontinuation prior to pregnancy had decreased over time in individuals with chronic inflammatory diseases.

Using a database of U.S. insurance claims, they identified 3,372 women with RA, ankylosing spondylitis (AS), psoriasis/psoriatic arthritis (PsA), and/or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) who previously used a TNFi and gave birth between 2011 and 2019. A patient was considered to have used a TNFi if she had filled a prescription or had an infusion procedure insurance claim within 12 weeks before the gestational period or anytime during pregnancy. Researchers did not have time-specific data to account for women who stopped treatment at pregnancy diagnosis.

Nearly half (47%) of all identified pregnancies were in individuals with IBD, and the rest included patients with RA (24%), psoriasis or PsA (16%), AS (3%), or more than one diagnosis (10%).

In total, 14% of women discontinued TNFi use in the 12 weeks before becoming pregnant and did not restart. From 2011 to 2013, 19% of patients stopped their TNFi, but this proportion decreased overtime, with 10% of patients stopping therapy from 2017 to 2019 (P < .0001).

This decline “possibly reflects the increase in real-world evidence about the safety of TNFi in pregnancy. That research, in turn, led to new guidelines recommending the continuation of TNFi during pregnancy,” first author Leah Flatman, a PhD candidate in epidemiology at McGill, said in an interview. “I think we can see this potentially as good news.”

More patients with RA, psoriasis/PsA, and AS discontinued TNFi therapy prior to conception (23%-25%), compared with those with IBD (5%).

Ms. Flatman noted that her study and Moltó’s study complement each other by providing data on individuals stopping TNFi prior to conception versus those stopping treatment after pregnancy diagnosis.

“These findings demonstrate that continuing TNFi during pregnancy appears not to be associated with an increase in adverse obstetrical or infant outcomes,” Ms. Flatman said of Dr. Moltó’s study. “As guidelines currently recommend continuing TNFi, studies like this help demonstrate that the guideline changes do not appear to be associated with an increase in adverse events.”

Dr. Moltó and Ms. Flatman disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Tedeschi has worked as a consultant for Novartis.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO – Continuing a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) during pregnancy does not increase risk of worse fetal or obstetric outcomes, according to new research presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Patients who continued a TNFi also had fewer severe infections requiring hospitalization, compared with those who stopped taking the medication during their pregnancy.

“The main message is that patients continuing were not doing worse than the patients stopping. It’s an important clinical message for rheumatologists who are not really confident in dealing with these drugs during pregnancy,” said Anna Moltó, MD, PhD, a rheumatologist at Cochin Hospital, Paris, who led the research. “It adds to the data that it seems to be safe,” she added in an interview.

Previous research, largely from pregnant patients with inflammatory bowel disease, suggests that taking a TNFi during pregnancy is safe, and 2020 ACR guidelines conditionally recommend continuing therapy prior to and during pregnancy; however, many people still stop taking the drugs during pregnancy for fear of potentially harming the fetus.

To better understand how TNFi use affected pregnancy outcomes, Dr. Moltó and colleagues analyzed data from a French nationwide health insurance database to identify adult women with chronic rheumatic inflammatory disease. All women included in the cohort had a singleton pregnancy between 2008 and 2017 and were taking a TNFi upon pregnancy diagnosis.

Patients who restarted TNFi after initially pausing because of pregnancy were included in the continuation group.

Researchers identified more than 2,000 pregnancies, including 1,503 in individuals with spondyloarthritis and 579 individuals with rheumatoid arthritis. Patients were, on average, 31 years old and were diagnosed with a rheumatic disease 4 years prior to their pregnancy.

About 72% (n = 1,497) discontinued TNFi after learning they were pregnant, and 584 individuals continued treatment. Dr. Moltó noted that data from more recent years might have captured lower discontinuation rates among pregnant individuals, but those data were not available for the study.

There was no difference in unfavorable obstetrical or infant outcomes, including spontaneous abortion, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, major congenital malformation, and severe infection of the infant requiring hospitalization. Somewhat surprisingly, the data showed that women who discontinued a TNFi were more likely to be hospitalized for infection either during their pregnancy or up to 6 weeks after delivery, compared with those who continued therapy (1.3% vs. 0.2%, respectively).

Dr. Moltó is currently looking into what could be behind this counterintuitive result, but she hypothesizes that patients who had stopped TNFi may have been taking more glucocorticoids.

“At our institution, there is generally a comfort level with continuing TNF inhibitors during pregnancy, at least until about 36 weeks,” said Sara K. Tedeschi, MD, MPH, a rheumatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. Sometimes, there is concern for risk of infection to the infant, depending on the type of TNFi being used, she added during a press conference.

“I think that these are really informative and supportive data to let women know that they probably have a really good chance of doing very well during the pregnancy if they continue” their TNFi, said Dr. Tedeschi, who was not involved with the study.

TNF discontinuation on the decline

In a related study, researchers at McGill University, Montreal, found that TNFi discontinuation prior to pregnancy had decreased over time in individuals with chronic inflammatory diseases.

Using a database of U.S. insurance claims, they identified 3,372 women with RA, ankylosing spondylitis (AS), psoriasis/psoriatic arthritis (PsA), and/or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) who previously used a TNFi and gave birth between 2011 and 2019. A patient was considered to have used a TNFi if she had filled a prescription or had an infusion procedure insurance claim within 12 weeks before the gestational period or anytime during pregnancy. Researchers did not have time-specific data to account for women who stopped treatment at pregnancy diagnosis.

Nearly half (47%) of all identified pregnancies were in individuals with IBD, and the rest included patients with RA (24%), psoriasis or PsA (16%), AS (3%), or more than one diagnosis (10%).

In total, 14% of women discontinued TNFi use in the 12 weeks before becoming pregnant and did not restart. From 2011 to 2013, 19% of patients stopped their TNFi, but this proportion decreased overtime, with 10% of patients stopping therapy from 2017 to 2019 (P < .0001).

This decline “possibly reflects the increase in real-world evidence about the safety of TNFi in pregnancy. That research, in turn, led to new guidelines recommending the continuation of TNFi during pregnancy,” first author Leah Flatman, a PhD candidate in epidemiology at McGill, said in an interview. “I think we can see this potentially as good news.”

More patients with RA, psoriasis/PsA, and AS discontinued TNFi therapy prior to conception (23%-25%), compared with those with IBD (5%).

Ms. Flatman noted that her study and Moltó’s study complement each other by providing data on individuals stopping TNFi prior to conception versus those stopping treatment after pregnancy diagnosis.

“These findings demonstrate that continuing TNFi during pregnancy appears not to be associated with an increase in adverse obstetrical or infant outcomes,” Ms. Flatman said of Dr. Moltó’s study. “As guidelines currently recommend continuing TNFi, studies like this help demonstrate that the guideline changes do not appear to be associated with an increase in adverse events.”

Dr. Moltó and Ms. Flatman disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Tedeschi has worked as a consultant for Novartis.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO – Continuing a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) during pregnancy does not increase risk of worse fetal or obstetric outcomes, according to new research presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Patients who continued a TNFi also had fewer severe infections requiring hospitalization, compared with those who stopped taking the medication during their pregnancy.

“The main message is that patients continuing were not doing worse than the patients stopping. It’s an important clinical message for rheumatologists who are not really confident in dealing with these drugs during pregnancy,” said Anna Moltó, MD, PhD, a rheumatologist at Cochin Hospital, Paris, who led the research. “It adds to the data that it seems to be safe,” she added in an interview.

Previous research, largely from pregnant patients with inflammatory bowel disease, suggests that taking a TNFi during pregnancy is safe, and 2020 ACR guidelines conditionally recommend continuing therapy prior to and during pregnancy; however, many people still stop taking the drugs during pregnancy for fear of potentially harming the fetus.

To better understand how TNFi use affected pregnancy outcomes, Dr. Moltó and colleagues analyzed data from a French nationwide health insurance database to identify adult women with chronic rheumatic inflammatory disease. All women included in the cohort had a singleton pregnancy between 2008 and 2017 and were taking a TNFi upon pregnancy diagnosis.

Patients who restarted TNFi after initially pausing because of pregnancy were included in the continuation group.

Researchers identified more than 2,000 pregnancies, including 1,503 in individuals with spondyloarthritis and 579 individuals with rheumatoid arthritis. Patients were, on average, 31 years old and were diagnosed with a rheumatic disease 4 years prior to their pregnancy.

About 72% (n = 1,497) discontinued TNFi after learning they were pregnant, and 584 individuals continued treatment. Dr. Moltó noted that data from more recent years might have captured lower discontinuation rates among pregnant individuals, but those data were not available for the study.

There was no difference in unfavorable obstetrical or infant outcomes, including spontaneous abortion, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, major congenital malformation, and severe infection of the infant requiring hospitalization. Somewhat surprisingly, the data showed that women who discontinued a TNFi were more likely to be hospitalized for infection either during their pregnancy or up to 6 weeks after delivery, compared with those who continued therapy (1.3% vs. 0.2%, respectively).

Dr. Moltó is currently looking into what could be behind this counterintuitive result, but she hypothesizes that patients who had stopped TNFi may have been taking more glucocorticoids.

“At our institution, there is generally a comfort level with continuing TNF inhibitors during pregnancy, at least until about 36 weeks,” said Sara K. Tedeschi, MD, MPH, a rheumatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. Sometimes, there is concern for risk of infection to the infant, depending on the type of TNFi being used, she added during a press conference.

“I think that these are really informative and supportive data to let women know that they probably have a really good chance of doing very well during the pregnancy if they continue” their TNFi, said Dr. Tedeschi, who was not involved with the study.

TNF discontinuation on the decline

In a related study, researchers at McGill University, Montreal, found that TNFi discontinuation prior to pregnancy had decreased over time in individuals with chronic inflammatory diseases.

Using a database of U.S. insurance claims, they identified 3,372 women with RA, ankylosing spondylitis (AS), psoriasis/psoriatic arthritis (PsA), and/or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) who previously used a TNFi and gave birth between 2011 and 2019. A patient was considered to have used a TNFi if she had filled a prescription or had an infusion procedure insurance claim within 12 weeks before the gestational period or anytime during pregnancy. Researchers did not have time-specific data to account for women who stopped treatment at pregnancy diagnosis.

Nearly half (47%) of all identified pregnancies were in individuals with IBD, and the rest included patients with RA (24%), psoriasis or PsA (16%), AS (3%), or more than one diagnosis (10%).

In total, 14% of women discontinued TNFi use in the 12 weeks before becoming pregnant and did not restart. From 2011 to 2013, 19% of patients stopped their TNFi, but this proportion decreased overtime, with 10% of patients stopping therapy from 2017 to 2019 (P < .0001).

This decline “possibly reflects the increase in real-world evidence about the safety of TNFi in pregnancy. That research, in turn, led to new guidelines recommending the continuation of TNFi during pregnancy,” first author Leah Flatman, a PhD candidate in epidemiology at McGill, said in an interview. “I think we can see this potentially as good news.”

More patients with RA, psoriasis/PsA, and AS discontinued TNFi therapy prior to conception (23%-25%), compared with those with IBD (5%).

Ms. Flatman noted that her study and Moltó’s study complement each other by providing data on individuals stopping TNFi prior to conception versus those stopping treatment after pregnancy diagnosis.

“These findings demonstrate that continuing TNFi during pregnancy appears not to be associated with an increase in adverse obstetrical or infant outcomes,” Ms. Flatman said of Dr. Moltó’s study. “As guidelines currently recommend continuing TNFi, studies like this help demonstrate that the guideline changes do not appear to be associated with an increase in adverse events.”

Dr. Moltó and Ms. Flatman disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Tedeschi has worked as a consultant for Novartis.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ACR 2023

The challenges of palmoplantar pustulosis and other acral psoriatic disease

WASHINGTON – The approval last year of the interleukin (IL)-36 receptor antagonist spesolimab for treating generalized pustular psoriasis flares brightened the treatment landscape for this rare condition, and a recently published phase 2 study suggests a potential role of spesolimab for flare prevention. , according to speakers at the annual research symposium of the National Psoriasis Foundation.

“The IL-36 receptor antagonists don’t seem to be quite the answer for [palmoplantar pustulosis] that they are for generalized pustular psoriasis [GPP],” Megan H. Noe, MD, MPH, assistant professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School and a dermatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said at the meeting.

Psoriasis affecting the hands and feet – both pustular and nonpustular – has a higher impact on quality of life and higher functional disability than does non-acral psoriasis, is less responsive to treatment, and has a “very confusing nomenclature” that complicates research and thus management, said Jason Ezra Hawkes, MD, a dermatologist in Rocklin, Calif., and former faculty member of several departments of dermatology. Both he and Dr. Noe spoke during a tough-to-treat session at the NPF meeting.

IL-17 and IL-23 blockade, as well as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibition, are effective overall for palmoplantar psoriasis (nonpustular), but in general, responses are lower than for plaque psoriasis. Apremilast (Otezla), a phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor, has some efficacy for pustular variants, but for hyperkeratotic variants it “does not perform as well as more selective inhibition of IL-17 and IL-23 blockade,” he said.

In general, ”what’s happening in the acral sites is different from an immune perspective than what’s happening in the non-acral sites,” and more research utilizing a clearer, descriptive nomenclature is needed to tease out differing immunophenotypes, explained Dr. Hawkes, who has led multiple clinical trials of treatments for psoriasis and other inflammatory skin conditions.

Palmoplantar pustulosis, and a word on generalized disease

Dermatologists are using a variety of treatments for palmoplantar pustulosis, with no clear first-line choices, Dr. Noe said. In a case series of almost 200 patients with palmoplantar pustulosis across 20 dermatology practices, published in JAMA Dermatology, 35% of patients received a systemic therapy prescription at their initial encounter – most commonly acitretin, followed by methotrexate and phototherapy. “Biologics were used, but use was varied and not as often as with oral agents,” said Dr. Noe, a coauthor of the study.

TNF blockers led to improvements ranging from 57% to 84%, depending on the agent, in a 2020 retrospective study of patients with palmoplantar pustulosis or acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau, Dr. Noe noted. However, rates of complete clearance were only 20%-29%.

Apremilast showed modest efficacy after 5 months of treatment, with 62% of patients achieving at least a 50% improvement in the Palmoplantar Pustulosis Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PPPASI) in a 2021 open-label, phase 2 study involving 21 patients. “This may represent a potential treatment option,” Dr. Noe said. “It’s something, but not what we’re used to seeing in our plaque psoriasis patients.”

A 2021 phase 2a, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of spesolimab in patients with palmoplantar pustulosis, meanwhile, failed to meet its primary endpoint, with only 32% of patients achieving a 50% improvement at 16 weeks, compared with 24% of patients in the placebo arm. And a recently published network meta-analysis found that none of the five drugs studied in seven randomized controlled trials – biologic or oral – was more effective than placebo for clearance or improvement of palmoplantar pustulosis.

The spesolimab (Spevigo) results have been disappointing considering the biologic’s newfound efficacy and role as the first Food and Drug Administration–approved therapy for generalized pustular disease, according to Dr. Noe. The ability of a single 900-mg intravenous dose of the IL-36 receptor antagonist to completely clear pustules at 1 week in 54% of patients with generalized disease, compared with 6% of the placebo group, was “groundbreaking,” she said, referring to results of the pivotal trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

And given that “preventing GPP flares is ultimately what we want,” she said, more good news was reported this year in The Lancet: The finding from an international, randomized, placebo-controlled study that high-dose subcutaneous spesolimab significantly reduced the risk of a flare over 48 weeks. “There are lots of ongoing studies right now to understand the best way to dose spesolimab,” she said.

Moreover, another IL-36 receptor antagonist, imsidolimab, is being investigated in a phase 3 trial for generalized pustular disease, she noted. A phase 2, open-label study of patients with GPP found that “more than half of patients were very much improved at 4 weeks, and some patients started showing improvement at day 3,” Dr. Noe said.

An area of research she is interested in is the potential for Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors as a treatment for palmoplantar pustulosis. For pustulosis on the hands and feet, recent case reports describing the efficacy of JAK inhibitors have caught her eye. “Right now, all we have is this case report data, mostly with tofacitinib, but I think it’s exciting,” she said, noting a recently published report in the British Journal of Dermatology.

Palmoplantar psoriasis

Pustular psoriatic disease can be localized to the hand and/or feet only, or can co-occur with generalized pustular disease, just as palmoplantar psoriasis can be localized to the hands and/or feet or, more commonly, can co-occur with widespread plaque psoriasis. Research has shown, Dr. Hawkes said, that with both types of acral disease, many patients have or have had plaque psoriasis outside of acral sites.

The nomenclature and acronyms for palmoplantar psoriatic disease have complicated patient education, communication, and research, Dr. Hawkes said. Does PPP refer to palmoplantar psoriasis, or palmoplantar pustulosis, for instance? What is the difference between palmoplantar pustulosis (coined PPP) and palmoplantar pustular psoriasis (referred to as PPPP)?

What if disease is only on the hands, only on the feet, or only on the backs of the hands? And at what point is disease not classified as palmoplantar psoriasis, but plaque psoriasis with involvement of the hands and feet? Inconsistencies and lack of clarification lead to “confusing” literature, he said.

Heterogeneity in populations across trials resulting from “inconsistent categorization and phenotype inclusion” may partly account for the recalcitrance to treatment reported in the literature, he said. Misdiagnosis as psoriasis in cases of localized disease (confusion with eczema, for instance), and the fact that hands and feet are subject to increased trauma and injury, compared with non-acral sites, are also at play.

Trials may also allow insufficient time for improvement, compared with non-acral sites. “What we’ve learned about the hands and feet is that it takes a much longer time for disease to improve,” Dr. Hawkes said, so primary endpoints must take this into account.

There is unique immunologic signaling in palmoplantar disease that differs from the predominant signaling in traditional plaque psoriasis, he emphasized, and “mixed immunophenotypes” that need to be unraveled.

Dr. Hawkes disclosed ties with AbbVie, Arcutis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, LEO, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, Sun Pharma, and UCB. Dr. Noe disclosed ties to Bristol-Myers Squibb and Boehringer Ingelheim.

WASHINGTON – The approval last year of the interleukin (IL)-36 receptor antagonist spesolimab for treating generalized pustular psoriasis flares brightened the treatment landscape for this rare condition, and a recently published phase 2 study suggests a potential role of spesolimab for flare prevention. , according to speakers at the annual research symposium of the National Psoriasis Foundation.

“The IL-36 receptor antagonists don’t seem to be quite the answer for [palmoplantar pustulosis] that they are for generalized pustular psoriasis [GPP],” Megan H. Noe, MD, MPH, assistant professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School and a dermatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said at the meeting.

Psoriasis affecting the hands and feet – both pustular and nonpustular – has a higher impact on quality of life and higher functional disability than does non-acral psoriasis, is less responsive to treatment, and has a “very confusing nomenclature” that complicates research and thus management, said Jason Ezra Hawkes, MD, a dermatologist in Rocklin, Calif., and former faculty member of several departments of dermatology. Both he and Dr. Noe spoke during a tough-to-treat session at the NPF meeting.

IL-17 and IL-23 blockade, as well as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibition, are effective overall for palmoplantar psoriasis (nonpustular), but in general, responses are lower than for plaque psoriasis. Apremilast (Otezla), a phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor, has some efficacy for pustular variants, but for hyperkeratotic variants it “does not perform as well as more selective inhibition of IL-17 and IL-23 blockade,” he said.

In general, ”what’s happening in the acral sites is different from an immune perspective than what’s happening in the non-acral sites,” and more research utilizing a clearer, descriptive nomenclature is needed to tease out differing immunophenotypes, explained Dr. Hawkes, who has led multiple clinical trials of treatments for psoriasis and other inflammatory skin conditions.

Palmoplantar pustulosis, and a word on generalized disease

Dermatologists are using a variety of treatments for palmoplantar pustulosis, with no clear first-line choices, Dr. Noe said. In a case series of almost 200 patients with palmoplantar pustulosis across 20 dermatology practices, published in JAMA Dermatology, 35% of patients received a systemic therapy prescription at their initial encounter – most commonly acitretin, followed by methotrexate and phototherapy. “Biologics were used, but use was varied and not as often as with oral agents,” said Dr. Noe, a coauthor of the study.

TNF blockers led to improvements ranging from 57% to 84%, depending on the agent, in a 2020 retrospective study of patients with palmoplantar pustulosis or acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau, Dr. Noe noted. However, rates of complete clearance were only 20%-29%.

Apremilast showed modest efficacy after 5 months of treatment, with 62% of patients achieving at least a 50% improvement in the Palmoplantar Pustulosis Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PPPASI) in a 2021 open-label, phase 2 study involving 21 patients. “This may represent a potential treatment option,” Dr. Noe said. “It’s something, but not what we’re used to seeing in our plaque psoriasis patients.”

A 2021 phase 2a, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of spesolimab in patients with palmoplantar pustulosis, meanwhile, failed to meet its primary endpoint, with only 32% of patients achieving a 50% improvement at 16 weeks, compared with 24% of patients in the placebo arm. And a recently published network meta-analysis found that none of the five drugs studied in seven randomized controlled trials – biologic or oral – was more effective than placebo for clearance or improvement of palmoplantar pustulosis.

The spesolimab (Spevigo) results have been disappointing considering the biologic’s newfound efficacy and role as the first Food and Drug Administration–approved therapy for generalized pustular disease, according to Dr. Noe. The ability of a single 900-mg intravenous dose of the IL-36 receptor antagonist to completely clear pustules at 1 week in 54% of patients with generalized disease, compared with 6% of the placebo group, was “groundbreaking,” she said, referring to results of the pivotal trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

And given that “preventing GPP flares is ultimately what we want,” she said, more good news was reported this year in The Lancet: The finding from an international, randomized, placebo-controlled study that high-dose subcutaneous spesolimab significantly reduced the risk of a flare over 48 weeks. “There are lots of ongoing studies right now to understand the best way to dose spesolimab,” she said.

Moreover, another IL-36 receptor antagonist, imsidolimab, is being investigated in a phase 3 trial for generalized pustular disease, she noted. A phase 2, open-label study of patients with GPP found that “more than half of patients were very much improved at 4 weeks, and some patients started showing improvement at day 3,” Dr. Noe said.

An area of research she is interested in is the potential for Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors as a treatment for palmoplantar pustulosis. For pustulosis on the hands and feet, recent case reports describing the efficacy of JAK inhibitors have caught her eye. “Right now, all we have is this case report data, mostly with tofacitinib, but I think it’s exciting,” she said, noting a recently published report in the British Journal of Dermatology.

Palmoplantar psoriasis

Pustular psoriatic disease can be localized to the hand and/or feet only, or can co-occur with generalized pustular disease, just as palmoplantar psoriasis can be localized to the hands and/or feet or, more commonly, can co-occur with widespread plaque psoriasis. Research has shown, Dr. Hawkes said, that with both types of acral disease, many patients have or have had plaque psoriasis outside of acral sites.

The nomenclature and acronyms for palmoplantar psoriatic disease have complicated patient education, communication, and research, Dr. Hawkes said. Does PPP refer to palmoplantar psoriasis, or palmoplantar pustulosis, for instance? What is the difference between palmoplantar pustulosis (coined PPP) and palmoplantar pustular psoriasis (referred to as PPPP)?

What if disease is only on the hands, only on the feet, or only on the backs of the hands? And at what point is disease not classified as palmoplantar psoriasis, but plaque psoriasis with involvement of the hands and feet? Inconsistencies and lack of clarification lead to “confusing” literature, he said.

Heterogeneity in populations across trials resulting from “inconsistent categorization and phenotype inclusion” may partly account for the recalcitrance to treatment reported in the literature, he said. Misdiagnosis as psoriasis in cases of localized disease (confusion with eczema, for instance), and the fact that hands and feet are subject to increased trauma and injury, compared with non-acral sites, are also at play.

Trials may also allow insufficient time for improvement, compared with non-acral sites. “What we’ve learned about the hands and feet is that it takes a much longer time for disease to improve,” Dr. Hawkes said, so primary endpoints must take this into account.

There is unique immunologic signaling in palmoplantar disease that differs from the predominant signaling in traditional plaque psoriasis, he emphasized, and “mixed immunophenotypes” that need to be unraveled.

Dr. Hawkes disclosed ties with AbbVie, Arcutis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, LEO, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, Sun Pharma, and UCB. Dr. Noe disclosed ties to Bristol-Myers Squibb and Boehringer Ingelheim.

WASHINGTON – The approval last year of the interleukin (IL)-36 receptor antagonist spesolimab for treating generalized pustular psoriasis flares brightened the treatment landscape for this rare condition, and a recently published phase 2 study suggests a potential role of spesolimab for flare prevention. , according to speakers at the annual research symposium of the National Psoriasis Foundation.

“The IL-36 receptor antagonists don’t seem to be quite the answer for [palmoplantar pustulosis] that they are for generalized pustular psoriasis [GPP],” Megan H. Noe, MD, MPH, assistant professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School and a dermatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said at the meeting.

Psoriasis affecting the hands and feet – both pustular and nonpustular – has a higher impact on quality of life and higher functional disability than does non-acral psoriasis, is less responsive to treatment, and has a “very confusing nomenclature” that complicates research and thus management, said Jason Ezra Hawkes, MD, a dermatologist in Rocklin, Calif., and former faculty member of several departments of dermatology. Both he and Dr. Noe spoke during a tough-to-treat session at the NPF meeting.

IL-17 and IL-23 blockade, as well as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibition, are effective overall for palmoplantar psoriasis (nonpustular), but in general, responses are lower than for plaque psoriasis. Apremilast (Otezla), a phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor, has some efficacy for pustular variants, but for hyperkeratotic variants it “does not perform as well as more selective inhibition of IL-17 and IL-23 blockade,” he said.

In general, ”what’s happening in the acral sites is different from an immune perspective than what’s happening in the non-acral sites,” and more research utilizing a clearer, descriptive nomenclature is needed to tease out differing immunophenotypes, explained Dr. Hawkes, who has led multiple clinical trials of treatments for psoriasis and other inflammatory skin conditions.

Palmoplantar pustulosis, and a word on generalized disease

Dermatologists are using a variety of treatments for palmoplantar pustulosis, with no clear first-line choices, Dr. Noe said. In a case series of almost 200 patients with palmoplantar pustulosis across 20 dermatology practices, published in JAMA Dermatology, 35% of patients received a systemic therapy prescription at their initial encounter – most commonly acitretin, followed by methotrexate and phototherapy. “Biologics were used, but use was varied and not as often as with oral agents,” said Dr. Noe, a coauthor of the study.

TNF blockers led to improvements ranging from 57% to 84%, depending on the agent, in a 2020 retrospective study of patients with palmoplantar pustulosis or acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau, Dr. Noe noted. However, rates of complete clearance were only 20%-29%.

Apremilast showed modest efficacy after 5 months of treatment, with 62% of patients achieving at least a 50% improvement in the Palmoplantar Pustulosis Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PPPASI) in a 2021 open-label, phase 2 study involving 21 patients. “This may represent a potential treatment option,” Dr. Noe said. “It’s something, but not what we’re used to seeing in our plaque psoriasis patients.”

A 2021 phase 2a, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of spesolimab in patients with palmoplantar pustulosis, meanwhile, failed to meet its primary endpoint, with only 32% of patients achieving a 50% improvement at 16 weeks, compared with 24% of patients in the placebo arm. And a recently published network meta-analysis found that none of the five drugs studied in seven randomized controlled trials – biologic or oral – was more effective than placebo for clearance or improvement of palmoplantar pustulosis.

The spesolimab (Spevigo) results have been disappointing considering the biologic’s newfound efficacy and role as the first Food and Drug Administration–approved therapy for generalized pustular disease, according to Dr. Noe. The ability of a single 900-mg intravenous dose of the IL-36 receptor antagonist to completely clear pustules at 1 week in 54% of patients with generalized disease, compared with 6% of the placebo group, was “groundbreaking,” she said, referring to results of the pivotal trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

And given that “preventing GPP flares is ultimately what we want,” she said, more good news was reported this year in The Lancet: The finding from an international, randomized, placebo-controlled study that high-dose subcutaneous spesolimab significantly reduced the risk of a flare over 48 weeks. “There are lots of ongoing studies right now to understand the best way to dose spesolimab,” she said.

Moreover, another IL-36 receptor antagonist, imsidolimab, is being investigated in a phase 3 trial for generalized pustular disease, she noted. A phase 2, open-label study of patients with GPP found that “more than half of patients were very much improved at 4 weeks, and some patients started showing improvement at day 3,” Dr. Noe said.