User login

American College of Surgeons (ACS): Annual Clinical Congress

How to slash colorectal surgery infection rates

BOSTON – driven mostly by a reduction in deep organ space infections from 5.5% to 1.7%.

It was a remarkable finding that got the attention of attendees at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons. The Cleveland Clinic had been an outlier, in the wrong direction, compared with other centers, and administrators wanted a solution.

I. Emre Gorgun, MD, FACS, a colorectal surgeon and quality improvement officer at Cleveland Clinic, led the search for evidence-based interventions. Eventually, big changes were made to perioperative antibiotics, mechanical bowel prep, preop shower routines, and intraoperative procedures. The efforts paid off (Dis Colon Rectum. 2018 Jan;61[1]:89-98).

To help surgeons lower their own infection rates, Dr. Gorgun agreed to an interview at the meeting to explain exactly what was done.

There was resistance at first from surgeons who wanted to stick with their routines, but they came around once they were shown the data backing the changes. Eventually, “everyone was on board. We believe in this,” Dr. Gorgun said.

BOSTON – driven mostly by a reduction in deep organ space infections from 5.5% to 1.7%.

It was a remarkable finding that got the attention of attendees at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons. The Cleveland Clinic had been an outlier, in the wrong direction, compared with other centers, and administrators wanted a solution.

I. Emre Gorgun, MD, FACS, a colorectal surgeon and quality improvement officer at Cleveland Clinic, led the search for evidence-based interventions. Eventually, big changes were made to perioperative antibiotics, mechanical bowel prep, preop shower routines, and intraoperative procedures. The efforts paid off (Dis Colon Rectum. 2018 Jan;61[1]:89-98).

To help surgeons lower their own infection rates, Dr. Gorgun agreed to an interview at the meeting to explain exactly what was done.

There was resistance at first from surgeons who wanted to stick with their routines, but they came around once they were shown the data backing the changes. Eventually, “everyone was on board. We believe in this,” Dr. Gorgun said.

BOSTON – driven mostly by a reduction in deep organ space infections from 5.5% to 1.7%.

It was a remarkable finding that got the attention of attendees at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons. The Cleveland Clinic had been an outlier, in the wrong direction, compared with other centers, and administrators wanted a solution.

I. Emre Gorgun, MD, FACS, a colorectal surgeon and quality improvement officer at Cleveland Clinic, led the search for evidence-based interventions. Eventually, big changes were made to perioperative antibiotics, mechanical bowel prep, preop shower routines, and intraoperative procedures. The efforts paid off (Dis Colon Rectum. 2018 Jan;61[1]:89-98).

To help surgeons lower their own infection rates, Dr. Gorgun agreed to an interview at the meeting to explain exactly what was done.

There was resistance at first from surgeons who wanted to stick with their routines, but they came around once they were shown the data backing the changes. Eventually, “everyone was on board. We believe in this,” Dr. Gorgun said.

REPORTING FROM THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

A century of evolution in trauma resuscitation: The Scudder Oration 2013

WASHINGTON – The medical understanding of shock and trauma resuscitation has evolved over many decades. But cutting-edge research is revolutionizing the understanding of the mechanisms of trauma and will eventually have a profound impact on treatment models, according to Dr. Ronald V. Maier.

Dr. Maier, an ACS Fellow and the Jane and Donald D. Trunkey Professor and vice-chair of the department of surgery at the University of Washington, Seattle, delivered the Scudder Oration on Trauma during the American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress. He discussed the development of treatment models for trauma resuscitation in the 20th century, beginning with Cannon’s toxins theory of shock (Cannon WB. Traumatic Shock. New York: D. Appleton & Co; 1923), and continuing into the 1930s with Blalock’s pioneering work in developing the homeostasis theory of trauma treatment (Arch. Surg.1934;29:837-57) .

Many advancements in the theory of trauma came out of experiences on the battlefields of World War I, World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War, he said.

The progression of ideas about treatment also evolved, beginning with a minimalist approach developed during World War I to the more interventionist models involving blood transfusion developed during the Korean War era, leading to a focus on crystalloid resuscitation and oxygen deficit that became prominent during the Vietnam War.

Dr. Maier traced the progression of interventionist strategies, each supplanted by new models based on improved understanding of the mechanism of trauma and a growing realization that many of the earlier approaches amounted to overtreatment with limited improvement in survival rates.

The recent paradigm is summed up as hypotensive resuscitation, meaning damage control and supporting blood pressure without reaching normotension, taking account of the natural coagulation process that occurs in the body in response to trauma.

"The goal is to recognize that if we try to chase interventions until they’ve completely corrected the system they impact, we will end up overtreating and having all the harmful effects of the treatment," Dr. Maier said.

Dr. Maier discussed the emerging "genomic storm" model of the mechanisms of trauma that zeros in on patterns of genetic expression. "In the overall genomic response of injured patients, there is a major change in the genomic activity. After a major injury, [the expression of] 80% of the genes change significantly." Damage to the immune system is evident, especially as reflected in down regulation of T-cell pathways and responses.

Dr. Maier’s research efforts have yielded new insight into the nature of that genomic shift. "What we were able to show is that in the patients who develop major complications vs. those who do not develop complications after severe injury, there is a limited number of genes that have a marked difference in reactivity." Sixty-four genes have been identified as having a bearing on the risk of complications.

The path to recovery involves a return of those patterns to a pre-trauma state. And the pursuit of a treatment model from this new understanding of the trauma mechanism means finding a way of predicting which patients will achieve that pre-trauma pattern and which will need intervention to prevent complicated outcomes.

The next step in this line of research will involve close scrutiny of individual responses to interventions, with a focus on timing and amounts. The details of the human body’s natural response to trauma are largely unknown, so this research will be expensive and time consuming, but according to Dr. Maier, necessary if progress is to be made in treatment models.

Dr. Maier described the emerging paradigm of trauma resuscitation in terms of chaos theory. Chaos theory in the context of trauma means that for the highly complex biological system that is the human body, small early perturbations can create significant changes in outcome. An example would be a small blood transfusion early in the treatment process of a trauma patient could have a profoundly positive impact on outcomes.

Dr. Maier argued that future treatment models will involve giving patients the correct treatment at the correct time and in the correct amounts based on the particular characteristics of the patient and the injury as determined by an understanding of their genetic response pattern and timing. "We have just been funded to develop a bedside test where, with a half cc of blood, we can test the 64 genes, and hopefully, by trending the responses ... we can predict patients who are going to have numerous, severe complications vs. those patients who will not," he said.

Despite the advances that have been made, Dr. Maier acknowledged the remaining challenges in transforming trauma resuscitation. "The holy grail is to be able to identify what patient needs what therapy. That is what we are still aspiring to find, and we have not achieved it yet."

Dr. Maier stated that he had no disclosures.

WASHINGTON – The medical understanding of shock and trauma resuscitation has evolved over many decades. But cutting-edge research is revolutionizing the understanding of the mechanisms of trauma and will eventually have a profound impact on treatment models, according to Dr. Ronald V. Maier.

Dr. Maier, an ACS Fellow and the Jane and Donald D. Trunkey Professor and vice-chair of the department of surgery at the University of Washington, Seattle, delivered the Scudder Oration on Trauma during the American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress. He discussed the development of treatment models for trauma resuscitation in the 20th century, beginning with Cannon’s toxins theory of shock (Cannon WB. Traumatic Shock. New York: D. Appleton & Co; 1923), and continuing into the 1930s with Blalock’s pioneering work in developing the homeostasis theory of trauma treatment (Arch. Surg.1934;29:837-57) .

Many advancements in the theory of trauma came out of experiences on the battlefields of World War I, World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War, he said.

The progression of ideas about treatment also evolved, beginning with a minimalist approach developed during World War I to the more interventionist models involving blood transfusion developed during the Korean War era, leading to a focus on crystalloid resuscitation and oxygen deficit that became prominent during the Vietnam War.

Dr. Maier traced the progression of interventionist strategies, each supplanted by new models based on improved understanding of the mechanism of trauma and a growing realization that many of the earlier approaches amounted to overtreatment with limited improvement in survival rates.

The recent paradigm is summed up as hypotensive resuscitation, meaning damage control and supporting blood pressure without reaching normotension, taking account of the natural coagulation process that occurs in the body in response to trauma.

"The goal is to recognize that if we try to chase interventions until they’ve completely corrected the system they impact, we will end up overtreating and having all the harmful effects of the treatment," Dr. Maier said.

Dr. Maier discussed the emerging "genomic storm" model of the mechanisms of trauma that zeros in on patterns of genetic expression. "In the overall genomic response of injured patients, there is a major change in the genomic activity. After a major injury, [the expression of] 80% of the genes change significantly." Damage to the immune system is evident, especially as reflected in down regulation of T-cell pathways and responses.

Dr. Maier’s research efforts have yielded new insight into the nature of that genomic shift. "What we were able to show is that in the patients who develop major complications vs. those who do not develop complications after severe injury, there is a limited number of genes that have a marked difference in reactivity." Sixty-four genes have been identified as having a bearing on the risk of complications.

The path to recovery involves a return of those patterns to a pre-trauma state. And the pursuit of a treatment model from this new understanding of the trauma mechanism means finding a way of predicting which patients will achieve that pre-trauma pattern and which will need intervention to prevent complicated outcomes.

The next step in this line of research will involve close scrutiny of individual responses to interventions, with a focus on timing and amounts. The details of the human body’s natural response to trauma are largely unknown, so this research will be expensive and time consuming, but according to Dr. Maier, necessary if progress is to be made in treatment models.

Dr. Maier described the emerging paradigm of trauma resuscitation in terms of chaos theory. Chaos theory in the context of trauma means that for the highly complex biological system that is the human body, small early perturbations can create significant changes in outcome. An example would be a small blood transfusion early in the treatment process of a trauma patient could have a profoundly positive impact on outcomes.

Dr. Maier argued that future treatment models will involve giving patients the correct treatment at the correct time and in the correct amounts based on the particular characteristics of the patient and the injury as determined by an understanding of their genetic response pattern and timing. "We have just been funded to develop a bedside test where, with a half cc of blood, we can test the 64 genes, and hopefully, by trending the responses ... we can predict patients who are going to have numerous, severe complications vs. those patients who will not," he said.

Despite the advances that have been made, Dr. Maier acknowledged the remaining challenges in transforming trauma resuscitation. "The holy grail is to be able to identify what patient needs what therapy. That is what we are still aspiring to find, and we have not achieved it yet."

Dr. Maier stated that he had no disclosures.

WASHINGTON – The medical understanding of shock and trauma resuscitation has evolved over many decades. But cutting-edge research is revolutionizing the understanding of the mechanisms of trauma and will eventually have a profound impact on treatment models, according to Dr. Ronald V. Maier.

Dr. Maier, an ACS Fellow and the Jane and Donald D. Trunkey Professor and vice-chair of the department of surgery at the University of Washington, Seattle, delivered the Scudder Oration on Trauma during the American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress. He discussed the development of treatment models for trauma resuscitation in the 20th century, beginning with Cannon’s toxins theory of shock (Cannon WB. Traumatic Shock. New York: D. Appleton & Co; 1923), and continuing into the 1930s with Blalock’s pioneering work in developing the homeostasis theory of trauma treatment (Arch. Surg.1934;29:837-57) .

Many advancements in the theory of trauma came out of experiences on the battlefields of World War I, World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War, he said.

The progression of ideas about treatment also evolved, beginning with a minimalist approach developed during World War I to the more interventionist models involving blood transfusion developed during the Korean War era, leading to a focus on crystalloid resuscitation and oxygen deficit that became prominent during the Vietnam War.

Dr. Maier traced the progression of interventionist strategies, each supplanted by new models based on improved understanding of the mechanism of trauma and a growing realization that many of the earlier approaches amounted to overtreatment with limited improvement in survival rates.

The recent paradigm is summed up as hypotensive resuscitation, meaning damage control and supporting blood pressure without reaching normotension, taking account of the natural coagulation process that occurs in the body in response to trauma.

"The goal is to recognize that if we try to chase interventions until they’ve completely corrected the system they impact, we will end up overtreating and having all the harmful effects of the treatment," Dr. Maier said.

Dr. Maier discussed the emerging "genomic storm" model of the mechanisms of trauma that zeros in on patterns of genetic expression. "In the overall genomic response of injured patients, there is a major change in the genomic activity. After a major injury, [the expression of] 80% of the genes change significantly." Damage to the immune system is evident, especially as reflected in down regulation of T-cell pathways and responses.

Dr. Maier’s research efforts have yielded new insight into the nature of that genomic shift. "What we were able to show is that in the patients who develop major complications vs. those who do not develop complications after severe injury, there is a limited number of genes that have a marked difference in reactivity." Sixty-four genes have been identified as having a bearing on the risk of complications.

The path to recovery involves a return of those patterns to a pre-trauma state. And the pursuit of a treatment model from this new understanding of the trauma mechanism means finding a way of predicting which patients will achieve that pre-trauma pattern and which will need intervention to prevent complicated outcomes.

The next step in this line of research will involve close scrutiny of individual responses to interventions, with a focus on timing and amounts. The details of the human body’s natural response to trauma are largely unknown, so this research will be expensive and time consuming, but according to Dr. Maier, necessary if progress is to be made in treatment models.

Dr. Maier described the emerging paradigm of trauma resuscitation in terms of chaos theory. Chaos theory in the context of trauma means that for the highly complex biological system that is the human body, small early perturbations can create significant changes in outcome. An example would be a small blood transfusion early in the treatment process of a trauma patient could have a profoundly positive impact on outcomes.

Dr. Maier argued that future treatment models will involve giving patients the correct treatment at the correct time and in the correct amounts based on the particular characteristics of the patient and the injury as determined by an understanding of their genetic response pattern and timing. "We have just been funded to develop a bedside test where, with a half cc of blood, we can test the 64 genes, and hopefully, by trending the responses ... we can predict patients who are going to have numerous, severe complications vs. those patients who will not," he said.

Despite the advances that have been made, Dr. Maier acknowledged the remaining challenges in transforming trauma resuscitation. "The holy grail is to be able to identify what patient needs what therapy. That is what we are still aspiring to find, and we have not achieved it yet."

Dr. Maier stated that he had no disclosures.

A surgeon in troubled times

WASHINGTON – The political violence that plagued Northern Ireland for nearly 40 years has subsided, and the memories of those dark days in Belfast have begun to fade. But for Roy A. J. Spence, OBE, J.D., M.D., LL.D., FRCS, those years of treating trauma patients in the emergency room of the Royal Victoria Hospital in that city served as an important opportunity for learning and service.

Dr. Spence worked with a team of surgeons and other staff to treat thousands of victims of bombings, shootings, torture, kneecapping, and assault that happened in the context of clashes between two sides of a sectarian conflict and the British Army. Dr. Spence, who delivered the I.S. Ravdin Lecture in the Basic and Surgical Sciences during the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons, discussed his experiences and lessons learned.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

During the worst period of The Troubles, as the conflict is called, emergency room surgeons were treating what were essentially combat injuries in an urban hospital setting. The great majority of the injuries in Belfast occurred within 1 mile of the Royal Victoria Hospital and the Belfast City Hospital, "some at the door of the hospital, some within the hospital, and we even had one patient shot in a bed in the hospital," he said. One victim was killed in the presence of Dr. Spence in the ER.

Dr. Spence, now professor and head of the department of surgery, imaging, and perioperative medicine at Queen’s University of Belfast, stated that despite the at times overwhelming numbers of injured that flooded into the ER, 90% of patients were delivered to the ER within 30 minutes and 50% within 15 minutes. The staff developed systems to speed patients through the ER to treatment and surgery if needed. In 1972 alone, 20,000 individuals were injured in various ways, and most of these injuries occurred in Belfast.

In addition to a streamlined admission process, the surgeons developed their protocol based on lessons learned over the years.

"We had disaster plans, but, in truth, we almost never had a rehearsal. The rehearsals were for real. The rehearsals were occurring day by day."

It became clear in the early years of the conflict that, in most cases, patients were best served if the doctors stayed at the hospital to receive patients instead of rushing to the scene of a bombing or shooting. "We were almost a nuisance if we went to the scene, because there was often continuing gunfire, there were secondary explosions, and sometimes the bodies themselves were booby-trapped."

In addition, the system of handling large numbers of injured patients worked best if there was a senior surgeon and senior nurse at the door to triage patients. Those with minor injuries were taken to a separate room for treatment.

It was also important that one senior surgeon took charge of the situation and led the team. Surgeons discovered that in these crisis situations, x-raying patients could turn into a bottleneck in the treatment process, leading to dangerous delays, so at times surgery proceeded without imaging to save a patient’s life.

Dr. Spence said that the Royal Victoria distinguished itself in treating patients in the midst of a civil war by upholding the highest standards of care, documenting cases thoroughly, and treating all patients with the same level of care. Although the duty surgeons lived in the community, knew many of the victims, were aware of which group had carried out an attack, and even had family members killed in the conflict, Dr. Spence asserted that they maintained their professional standards and did not allow politics to deter them from their duties as physicians.

In the peak years of violence, the early 1970s to the early 1980s, two types of injuries – gunshot wounds to the head and kneecapping trauma – led to innovative treatment plans. The hospital established the standard of care for gunshot wounds to the head in that era, and also pioneered the use of vascular shunts to treat blast-injured limbs. The vascular shunt in particular was considered invaluable by Dr. Spence. This procedure reduced the number of amputations in cases of limb trauma from one-third to less than 10% and "allowed a very unhurried fracture reduction and external fixation."

Dr. Spence noted that general surgeons were valued in the ER because of their capacity to deal with a wide variety of injuries and because of the potentially fatal delays caused by waiting for a specialist. Although specialists were definitely needed and utilized in complex cases, most patients were treated by general surgeons. "I come from a generation that could do chest and abdominal surgery and amputations," said Dr. Spence.

Staff doctors were on call every other night and worked very long hours, a situation no longer allowed in U.K. hospitals. Surgeons worked "until the work was done" to care for all the injured and to maintain continuity of care. "There could be 100 injured people in the ER. You couldn’t just walk out at half past five."

In conclusion, Dr. Spence noted that the extended crisis of violence and trauma resulted in a close-knit "band of brothers, and occasionally, sisters" who worked in trying circumstances as colleagues. Many of those colleagues have left surgery or have died relatively young, and Dr. Spence intended his lecture to be a tribute to their service, dedication, and sacrifice in troubled times.

WASHINGTON – The political violence that plagued Northern Ireland for nearly 40 years has subsided, and the memories of those dark days in Belfast have begun to fade. But for Roy A. J. Spence, OBE, J.D., M.D., LL.D., FRCS, those years of treating trauma patients in the emergency room of the Royal Victoria Hospital in that city served as an important opportunity for learning and service.

Dr. Spence worked with a team of surgeons and other staff to treat thousands of victims of bombings, shootings, torture, kneecapping, and assault that happened in the context of clashes between two sides of a sectarian conflict and the British Army. Dr. Spence, who delivered the I.S. Ravdin Lecture in the Basic and Surgical Sciences during the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons, discussed his experiences and lessons learned.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

During the worst period of The Troubles, as the conflict is called, emergency room surgeons were treating what were essentially combat injuries in an urban hospital setting. The great majority of the injuries in Belfast occurred within 1 mile of the Royal Victoria Hospital and the Belfast City Hospital, "some at the door of the hospital, some within the hospital, and we even had one patient shot in a bed in the hospital," he said. One victim was killed in the presence of Dr. Spence in the ER.

Dr. Spence, now professor and head of the department of surgery, imaging, and perioperative medicine at Queen’s University of Belfast, stated that despite the at times overwhelming numbers of injured that flooded into the ER, 90% of patients were delivered to the ER within 30 minutes and 50% within 15 minutes. The staff developed systems to speed patients through the ER to treatment and surgery if needed. In 1972 alone, 20,000 individuals were injured in various ways, and most of these injuries occurred in Belfast.

In addition to a streamlined admission process, the surgeons developed their protocol based on lessons learned over the years.

"We had disaster plans, but, in truth, we almost never had a rehearsal. The rehearsals were for real. The rehearsals were occurring day by day."

It became clear in the early years of the conflict that, in most cases, patients were best served if the doctors stayed at the hospital to receive patients instead of rushing to the scene of a bombing or shooting. "We were almost a nuisance if we went to the scene, because there was often continuing gunfire, there were secondary explosions, and sometimes the bodies themselves were booby-trapped."

In addition, the system of handling large numbers of injured patients worked best if there was a senior surgeon and senior nurse at the door to triage patients. Those with minor injuries were taken to a separate room for treatment.

It was also important that one senior surgeon took charge of the situation and led the team. Surgeons discovered that in these crisis situations, x-raying patients could turn into a bottleneck in the treatment process, leading to dangerous delays, so at times surgery proceeded without imaging to save a patient’s life.

Dr. Spence said that the Royal Victoria distinguished itself in treating patients in the midst of a civil war by upholding the highest standards of care, documenting cases thoroughly, and treating all patients with the same level of care. Although the duty surgeons lived in the community, knew many of the victims, were aware of which group had carried out an attack, and even had family members killed in the conflict, Dr. Spence asserted that they maintained their professional standards and did not allow politics to deter them from their duties as physicians.

In the peak years of violence, the early 1970s to the early 1980s, two types of injuries – gunshot wounds to the head and kneecapping trauma – led to innovative treatment plans. The hospital established the standard of care for gunshot wounds to the head in that era, and also pioneered the use of vascular shunts to treat blast-injured limbs. The vascular shunt in particular was considered invaluable by Dr. Spence. This procedure reduced the number of amputations in cases of limb trauma from one-third to less than 10% and "allowed a very unhurried fracture reduction and external fixation."

Dr. Spence noted that general surgeons were valued in the ER because of their capacity to deal with a wide variety of injuries and because of the potentially fatal delays caused by waiting for a specialist. Although specialists were definitely needed and utilized in complex cases, most patients were treated by general surgeons. "I come from a generation that could do chest and abdominal surgery and amputations," said Dr. Spence.

Staff doctors were on call every other night and worked very long hours, a situation no longer allowed in U.K. hospitals. Surgeons worked "until the work was done" to care for all the injured and to maintain continuity of care. "There could be 100 injured people in the ER. You couldn’t just walk out at half past five."

In conclusion, Dr. Spence noted that the extended crisis of violence and trauma resulted in a close-knit "band of brothers, and occasionally, sisters" who worked in trying circumstances as colleagues. Many of those colleagues have left surgery or have died relatively young, and Dr. Spence intended his lecture to be a tribute to their service, dedication, and sacrifice in troubled times.

WASHINGTON – The political violence that plagued Northern Ireland for nearly 40 years has subsided, and the memories of those dark days in Belfast have begun to fade. But for Roy A. J. Spence, OBE, J.D., M.D., LL.D., FRCS, those years of treating trauma patients in the emergency room of the Royal Victoria Hospital in that city served as an important opportunity for learning and service.

Dr. Spence worked with a team of surgeons and other staff to treat thousands of victims of bombings, shootings, torture, kneecapping, and assault that happened in the context of clashes between two sides of a sectarian conflict and the British Army. Dr. Spence, who delivered the I.S. Ravdin Lecture in the Basic and Surgical Sciences during the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons, discussed his experiences and lessons learned.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

During the worst period of The Troubles, as the conflict is called, emergency room surgeons were treating what were essentially combat injuries in an urban hospital setting. The great majority of the injuries in Belfast occurred within 1 mile of the Royal Victoria Hospital and the Belfast City Hospital, "some at the door of the hospital, some within the hospital, and we even had one patient shot in a bed in the hospital," he said. One victim was killed in the presence of Dr. Spence in the ER.

Dr. Spence, now professor and head of the department of surgery, imaging, and perioperative medicine at Queen’s University of Belfast, stated that despite the at times overwhelming numbers of injured that flooded into the ER, 90% of patients were delivered to the ER within 30 minutes and 50% within 15 minutes. The staff developed systems to speed patients through the ER to treatment and surgery if needed. In 1972 alone, 20,000 individuals were injured in various ways, and most of these injuries occurred in Belfast.

In addition to a streamlined admission process, the surgeons developed their protocol based on lessons learned over the years.

"We had disaster plans, but, in truth, we almost never had a rehearsal. The rehearsals were for real. The rehearsals were occurring day by day."

It became clear in the early years of the conflict that, in most cases, patients were best served if the doctors stayed at the hospital to receive patients instead of rushing to the scene of a bombing or shooting. "We were almost a nuisance if we went to the scene, because there was often continuing gunfire, there were secondary explosions, and sometimes the bodies themselves were booby-trapped."

In addition, the system of handling large numbers of injured patients worked best if there was a senior surgeon and senior nurse at the door to triage patients. Those with minor injuries were taken to a separate room for treatment.

It was also important that one senior surgeon took charge of the situation and led the team. Surgeons discovered that in these crisis situations, x-raying patients could turn into a bottleneck in the treatment process, leading to dangerous delays, so at times surgery proceeded without imaging to save a patient’s life.

Dr. Spence said that the Royal Victoria distinguished itself in treating patients in the midst of a civil war by upholding the highest standards of care, documenting cases thoroughly, and treating all patients with the same level of care. Although the duty surgeons lived in the community, knew many of the victims, were aware of which group had carried out an attack, and even had family members killed in the conflict, Dr. Spence asserted that they maintained their professional standards and did not allow politics to deter them from their duties as physicians.

In the peak years of violence, the early 1970s to the early 1980s, two types of injuries – gunshot wounds to the head and kneecapping trauma – led to innovative treatment plans. The hospital established the standard of care for gunshot wounds to the head in that era, and also pioneered the use of vascular shunts to treat blast-injured limbs. The vascular shunt in particular was considered invaluable by Dr. Spence. This procedure reduced the number of amputations in cases of limb trauma from one-third to less than 10% and "allowed a very unhurried fracture reduction and external fixation."

Dr. Spence noted that general surgeons were valued in the ER because of their capacity to deal with a wide variety of injuries and because of the potentially fatal delays caused by waiting for a specialist. Although specialists were definitely needed and utilized in complex cases, most patients were treated by general surgeons. "I come from a generation that could do chest and abdominal surgery and amputations," said Dr. Spence.

Staff doctors were on call every other night and worked very long hours, a situation no longer allowed in U.K. hospitals. Surgeons worked "until the work was done" to care for all the injured and to maintain continuity of care. "There could be 100 injured people in the ER. You couldn’t just walk out at half past five."

In conclusion, Dr. Spence noted that the extended crisis of violence and trauma resulted in a close-knit "band of brothers, and occasionally, sisters" who worked in trying circumstances as colleagues. Many of those colleagues have left surgery or have died relatively young, and Dr. Spence intended his lecture to be a tribute to their service, dedication, and sacrifice in troubled times.

AT THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

Reengineering of care: Surgical leadership

WASHINGTON – Years of research have taught us that when it comes to heath care delivery, there is no relationship between cost and quality, according to Dr. Glenn D. Steele, the president and CEO of Geisinger Health System. Dr. Steele delivered the 2013 Commission on Cancer Oncology Lecture at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

Geisinger Health System, based in Danville, Pa., is a renowned leader in transforming health care delivery through innovative multi-institution collaboration and an emphasis on consistent use of best practices and evidence-based medicine, he said. The goal over the past decade has been to reengineer complex medical care to improve quality and reduce costs. Dr. Steele asserted that these two goals are not mutually exclusive.

"We now believe that if you look at a patient cohort – whether it is hospital based or whether it’s ambulatory care – for folks with three, four, or five chronic diseases, you find that the population with the highest costs has also the least-quality health care ... more often than not, high cost equals a less-than-optimal outcome," he said.

At the heart of the reengineering concept is the recognition that many patients in conventional treatment situations end up with what Dr. Steele referred to as "unjustified variation" in the execution of the treatment. A noted study by Little et al. showed that only half of patients treated for lung cancer, for example, receive the recommended care (Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2005;80:2051-6). The Geisinger Health System tackled the problem of unwarranted variation in treatment and "road tested" a wide range of innovations involving standardization of treatment, electronic data gathering and tracking, and institutional culture change.

The ProvenCare model was developed to incorporate all the initiatives that had been researched and tested at Geisinger, and the model was first applied in 2005 to coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). This application of ProvenCare showed that "an improvement model that embeds evidence-based medicine into the workflow, applies the principles of reliability science (standardization, error proofing, and failure mode redesign) to the care redesign process, employs effective data feedback strategies, and engages patients in their care results in the right care delivered 100% of the time with better patient outcomes" (CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2011;61:382-96). The model has since been applied to hip replacement surgery, percutaneous coronary intervention, and cataract surgery.

Dr. Steele gave an update on a recent ProvenCare project, a model for treatment of resectable non–small cell lung cancer. The project is a collaboration between Geisinger and the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer. The initial survey of lung cancer care revealed substantial room for improvement. The ProvenCare goals initially were to standardize care; build in redundancy to make sure all tasks are done; bundle related tasks; build teams, feedback protocols, and training models; move toward a multi-institutional collaboration; and achieve widespread change in institutional practices, protocol, and culture of care. The project involved an 18-month period of training and testing in the participating institutions.

Engagement of patients and a "very well-articulated set of expectations" were a critical part of the ProvenCare model. The challenge involved achieving 100% compliance across the many institutions

Geisinger has created an insurance company that has some role in controlling costs. Dr. Steele estimated that many resources spent in health care are wasted. "If we could figure out how to extract much of that 25%-30% of needless cost, we can redistribute it. ... Some of that redistribution would go to our bottom line and allow us to grow programs and make our balance sheet comfortable. ... Some of that value would go back to our insurance company and to the middle-size and small businesses that are buying our insurance premiums." This is where cost savings are reducing the cost of premiums and "giving some of that value back to consumers."

Dr. Steele said, "In most industries where you have reengineered whatever it is you are doing, you’ve got better outcomes on both the quality side and the cost side, and you are in heavy-duty competition in the consolidating market. What do you do? You lower your price. And you maintain your contribution margin. And you run your competition out of business. We don’t think that way in health care. But my bet is, in 5 years, we will think that way."

Ultimately, the drive to lower costs goes hand in hand with improving quality of care, he said. "If you believe that, and you are a professional driven to help your patients, you are much more enthusiastic about reengineering than simply working to keep costs down."

WASHINGTON – Years of research have taught us that when it comes to heath care delivery, there is no relationship between cost and quality, according to Dr. Glenn D. Steele, the president and CEO of Geisinger Health System. Dr. Steele delivered the 2013 Commission on Cancer Oncology Lecture at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

Geisinger Health System, based in Danville, Pa., is a renowned leader in transforming health care delivery through innovative multi-institution collaboration and an emphasis on consistent use of best practices and evidence-based medicine, he said. The goal over the past decade has been to reengineer complex medical care to improve quality and reduce costs. Dr. Steele asserted that these two goals are not mutually exclusive.

"We now believe that if you look at a patient cohort – whether it is hospital based or whether it’s ambulatory care – for folks with three, four, or five chronic diseases, you find that the population with the highest costs has also the least-quality health care ... more often than not, high cost equals a less-than-optimal outcome," he said.

At the heart of the reengineering concept is the recognition that many patients in conventional treatment situations end up with what Dr. Steele referred to as "unjustified variation" in the execution of the treatment. A noted study by Little et al. showed that only half of patients treated for lung cancer, for example, receive the recommended care (Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2005;80:2051-6). The Geisinger Health System tackled the problem of unwarranted variation in treatment and "road tested" a wide range of innovations involving standardization of treatment, electronic data gathering and tracking, and institutional culture change.

The ProvenCare model was developed to incorporate all the initiatives that had been researched and tested at Geisinger, and the model was first applied in 2005 to coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). This application of ProvenCare showed that "an improvement model that embeds evidence-based medicine into the workflow, applies the principles of reliability science (standardization, error proofing, and failure mode redesign) to the care redesign process, employs effective data feedback strategies, and engages patients in their care results in the right care delivered 100% of the time with better patient outcomes" (CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2011;61:382-96). The model has since been applied to hip replacement surgery, percutaneous coronary intervention, and cataract surgery.

Dr. Steele gave an update on a recent ProvenCare project, a model for treatment of resectable non–small cell lung cancer. The project is a collaboration between Geisinger and the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer. The initial survey of lung cancer care revealed substantial room for improvement. The ProvenCare goals initially were to standardize care; build in redundancy to make sure all tasks are done; bundle related tasks; build teams, feedback protocols, and training models; move toward a multi-institutional collaboration; and achieve widespread change in institutional practices, protocol, and culture of care. The project involved an 18-month period of training and testing in the participating institutions.

Engagement of patients and a "very well-articulated set of expectations" were a critical part of the ProvenCare model. The challenge involved achieving 100% compliance across the many institutions

Geisinger has created an insurance company that has some role in controlling costs. Dr. Steele estimated that many resources spent in health care are wasted. "If we could figure out how to extract much of that 25%-30% of needless cost, we can redistribute it. ... Some of that redistribution would go to our bottom line and allow us to grow programs and make our balance sheet comfortable. ... Some of that value would go back to our insurance company and to the middle-size and small businesses that are buying our insurance premiums." This is where cost savings are reducing the cost of premiums and "giving some of that value back to consumers."

Dr. Steele said, "In most industries where you have reengineered whatever it is you are doing, you’ve got better outcomes on both the quality side and the cost side, and you are in heavy-duty competition in the consolidating market. What do you do? You lower your price. And you maintain your contribution margin. And you run your competition out of business. We don’t think that way in health care. But my bet is, in 5 years, we will think that way."

Ultimately, the drive to lower costs goes hand in hand with improving quality of care, he said. "If you believe that, and you are a professional driven to help your patients, you are much more enthusiastic about reengineering than simply working to keep costs down."

WASHINGTON – Years of research have taught us that when it comes to heath care delivery, there is no relationship between cost and quality, according to Dr. Glenn D. Steele, the president and CEO of Geisinger Health System. Dr. Steele delivered the 2013 Commission on Cancer Oncology Lecture at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

Geisinger Health System, based in Danville, Pa., is a renowned leader in transforming health care delivery through innovative multi-institution collaboration and an emphasis on consistent use of best practices and evidence-based medicine, he said. The goal over the past decade has been to reengineer complex medical care to improve quality and reduce costs. Dr. Steele asserted that these two goals are not mutually exclusive.

"We now believe that if you look at a patient cohort – whether it is hospital based or whether it’s ambulatory care – for folks with three, four, or five chronic diseases, you find that the population with the highest costs has also the least-quality health care ... more often than not, high cost equals a less-than-optimal outcome," he said.

At the heart of the reengineering concept is the recognition that many patients in conventional treatment situations end up with what Dr. Steele referred to as "unjustified variation" in the execution of the treatment. A noted study by Little et al. showed that only half of patients treated for lung cancer, for example, receive the recommended care (Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2005;80:2051-6). The Geisinger Health System tackled the problem of unwarranted variation in treatment and "road tested" a wide range of innovations involving standardization of treatment, electronic data gathering and tracking, and institutional culture change.

The ProvenCare model was developed to incorporate all the initiatives that had been researched and tested at Geisinger, and the model was first applied in 2005 to coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). This application of ProvenCare showed that "an improvement model that embeds evidence-based medicine into the workflow, applies the principles of reliability science (standardization, error proofing, and failure mode redesign) to the care redesign process, employs effective data feedback strategies, and engages patients in their care results in the right care delivered 100% of the time with better patient outcomes" (CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2011;61:382-96). The model has since been applied to hip replacement surgery, percutaneous coronary intervention, and cataract surgery.

Dr. Steele gave an update on a recent ProvenCare project, a model for treatment of resectable non–small cell lung cancer. The project is a collaboration between Geisinger and the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer. The initial survey of lung cancer care revealed substantial room for improvement. The ProvenCare goals initially were to standardize care; build in redundancy to make sure all tasks are done; bundle related tasks; build teams, feedback protocols, and training models; move toward a multi-institutional collaboration; and achieve widespread change in institutional practices, protocol, and culture of care. The project involved an 18-month period of training and testing in the participating institutions.

Engagement of patients and a "very well-articulated set of expectations" were a critical part of the ProvenCare model. The challenge involved achieving 100% compliance across the many institutions

Geisinger has created an insurance company that has some role in controlling costs. Dr. Steele estimated that many resources spent in health care are wasted. "If we could figure out how to extract much of that 25%-30% of needless cost, we can redistribute it. ... Some of that redistribution would go to our bottom line and allow us to grow programs and make our balance sheet comfortable. ... Some of that value would go back to our insurance company and to the middle-size and small businesses that are buying our insurance premiums." This is where cost savings are reducing the cost of premiums and "giving some of that value back to consumers."

Dr. Steele said, "In most industries where you have reengineered whatever it is you are doing, you’ve got better outcomes on both the quality side and the cost side, and you are in heavy-duty competition in the consolidating market. What do you do? You lower your price. And you maintain your contribution margin. And you run your competition out of business. We don’t think that way in health care. But my bet is, in 5 years, we will think that way."

Ultimately, the drive to lower costs goes hand in hand with improving quality of care, he said. "If you believe that, and you are a professional driven to help your patients, you are much more enthusiastic about reengineering than simply working to keep costs down."

Surgery and technology: A complicated partnership

WASHINGTON – Technological innovation is transforming surgery at a rapid pace. The question, according to Dr. Mark Talamini, is how can surgeons prepare for and participate in that transformation.

Dr. Talamini delivered the Excelsior Surgical Society/Edward D. Churchill Lecture at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons. He discussed his own early interest in medical technology, the trends in technological change, and the complex issues that face surgeons in maintaining currency in training and working to develop new devices.

The most profound change in surgery in recent decades has been the insertion of high-tech devices between the surgeon and the patient. There is now most commonly a physical distance between the patient’s body and the surgeon’s hands, and "the majority of surgical procedures involve the surgeon looking at a screen." Surgical tasks of dissecting, controlling bleeding, and suturing in particular have been all but transformed by devices.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The drive to introduce new surgical devices has come up against the stringent approval process of the Food and Drug Administration and has led to public criticism of that process. Dr. Talamini, who chairs the surgery department at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, and who has worked with the FDA for more than 10 years in various capacities, argued that there must be a correct balance between innovation and regulation. "We’ve got to have both. We cannot just have instruments released to the public without understanding what the issues are regarding safety and effectiveness. For the FDA, that is the mantra: safety and effectiveness." He added, "They have a tough task to figure out the balance between getting new things to the market to benefit patients and yet maintaining overall public safety."

Dr. Talamini asserted that the growing number and complexity of surgical instruments mean that surgeons may be falling behind in their skills without realizing it. He illustrated his point by posing specific questions about the use of some recently introduced instruments and polling the audience on correct use. In response to the many wrong answers, he asserted that "we don’t know as much as we think we do about surgical technology."

To address this problem of maintaining currency and training on innovative devices, Dr. Talamini mentioned the Fundamental Use of Surgical Energy (FUSE) program created by the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. FUSE is a web-based educational and testing program for all operating room participants, including surgeons.

Dr. Talamini is particularly proud of the Center for the Future of Surgery located at the University of California, San Diego, which he was instrumental in developing. This center has a research suite for doctors and scientists to collaborate on innovative devices; training suites for the latest in surgical, robotic, laparoscopic, and microscopic techniques; and simulated operating rooms and emergency departments.

Dr. Talamini reflected on the complex relationship between innovative surgeons and device development and manufacturing companies. He cautioned the audience to consider some principles when engaging in technology development with industry. First, there would be no technological innovation without collaboration between the medical device industry and surgeons. But development and training cannot be simply a means of selling equipment. Education and sales must be clearly differentiated. In addition, disclosure and transparency are fundamental to maintaining public trust.

Finally, Dr. Talamini argued that conflict of interest in this area cannot be eliminated, but it must be managed to foster innovation.

Dr. Talamini had no disclosures.

WASHINGTON – Technological innovation is transforming surgery at a rapid pace. The question, according to Dr. Mark Talamini, is how can surgeons prepare for and participate in that transformation.

Dr. Talamini delivered the Excelsior Surgical Society/Edward D. Churchill Lecture at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons. He discussed his own early interest in medical technology, the trends in technological change, and the complex issues that face surgeons in maintaining currency in training and working to develop new devices.

The most profound change in surgery in recent decades has been the insertion of high-tech devices between the surgeon and the patient. There is now most commonly a physical distance between the patient’s body and the surgeon’s hands, and "the majority of surgical procedures involve the surgeon looking at a screen." Surgical tasks of dissecting, controlling bleeding, and suturing in particular have been all but transformed by devices.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The drive to introduce new surgical devices has come up against the stringent approval process of the Food and Drug Administration and has led to public criticism of that process. Dr. Talamini, who chairs the surgery department at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, and who has worked with the FDA for more than 10 years in various capacities, argued that there must be a correct balance between innovation and regulation. "We’ve got to have both. We cannot just have instruments released to the public without understanding what the issues are regarding safety and effectiveness. For the FDA, that is the mantra: safety and effectiveness." He added, "They have a tough task to figure out the balance between getting new things to the market to benefit patients and yet maintaining overall public safety."

Dr. Talamini asserted that the growing number and complexity of surgical instruments mean that surgeons may be falling behind in their skills without realizing it. He illustrated his point by posing specific questions about the use of some recently introduced instruments and polling the audience on correct use. In response to the many wrong answers, he asserted that "we don’t know as much as we think we do about surgical technology."

To address this problem of maintaining currency and training on innovative devices, Dr. Talamini mentioned the Fundamental Use of Surgical Energy (FUSE) program created by the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. FUSE is a web-based educational and testing program for all operating room participants, including surgeons.

Dr. Talamini is particularly proud of the Center for the Future of Surgery located at the University of California, San Diego, which he was instrumental in developing. This center has a research suite for doctors and scientists to collaborate on innovative devices; training suites for the latest in surgical, robotic, laparoscopic, and microscopic techniques; and simulated operating rooms and emergency departments.

Dr. Talamini reflected on the complex relationship between innovative surgeons and device development and manufacturing companies. He cautioned the audience to consider some principles when engaging in technology development with industry. First, there would be no technological innovation without collaboration between the medical device industry and surgeons. But development and training cannot be simply a means of selling equipment. Education and sales must be clearly differentiated. In addition, disclosure and transparency are fundamental to maintaining public trust.

Finally, Dr. Talamini argued that conflict of interest in this area cannot be eliminated, but it must be managed to foster innovation.

Dr. Talamini had no disclosures.

WASHINGTON – Technological innovation is transforming surgery at a rapid pace. The question, according to Dr. Mark Talamini, is how can surgeons prepare for and participate in that transformation.

Dr. Talamini delivered the Excelsior Surgical Society/Edward D. Churchill Lecture at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons. He discussed his own early interest in medical technology, the trends in technological change, and the complex issues that face surgeons in maintaining currency in training and working to develop new devices.

The most profound change in surgery in recent decades has been the insertion of high-tech devices between the surgeon and the patient. There is now most commonly a physical distance between the patient’s body and the surgeon’s hands, and "the majority of surgical procedures involve the surgeon looking at a screen." Surgical tasks of dissecting, controlling bleeding, and suturing in particular have been all but transformed by devices.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The drive to introduce new surgical devices has come up against the stringent approval process of the Food and Drug Administration and has led to public criticism of that process. Dr. Talamini, who chairs the surgery department at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, and who has worked with the FDA for more than 10 years in various capacities, argued that there must be a correct balance between innovation and regulation. "We’ve got to have both. We cannot just have instruments released to the public without understanding what the issues are regarding safety and effectiveness. For the FDA, that is the mantra: safety and effectiveness." He added, "They have a tough task to figure out the balance between getting new things to the market to benefit patients and yet maintaining overall public safety."

Dr. Talamini asserted that the growing number and complexity of surgical instruments mean that surgeons may be falling behind in their skills without realizing it. He illustrated his point by posing specific questions about the use of some recently introduced instruments and polling the audience on correct use. In response to the many wrong answers, he asserted that "we don’t know as much as we think we do about surgical technology."

To address this problem of maintaining currency and training on innovative devices, Dr. Talamini mentioned the Fundamental Use of Surgical Energy (FUSE) program created by the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. FUSE is a web-based educational and testing program for all operating room participants, including surgeons.

Dr. Talamini is particularly proud of the Center for the Future of Surgery located at the University of California, San Diego, which he was instrumental in developing. This center has a research suite for doctors and scientists to collaborate on innovative devices; training suites for the latest in surgical, robotic, laparoscopic, and microscopic techniques; and simulated operating rooms and emergency departments.

Dr. Talamini reflected on the complex relationship between innovative surgeons and device development and manufacturing companies. He cautioned the audience to consider some principles when engaging in technology development with industry. First, there would be no technological innovation without collaboration between the medical device industry and surgeons. But development and training cannot be simply a means of selling equipment. Education and sales must be clearly differentiated. In addition, disclosure and transparency are fundamental to maintaining public trust.

Finally, Dr. Talamini argued that conflict of interest in this area cannot be eliminated, but it must be managed to foster innovation.

Dr. Talamini had no disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

Complication gap narrows between low- and high-volume bariatric centers

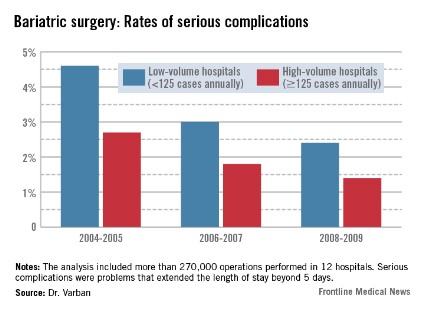

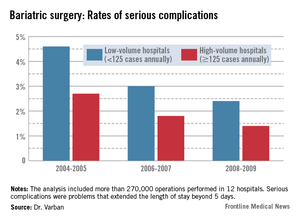

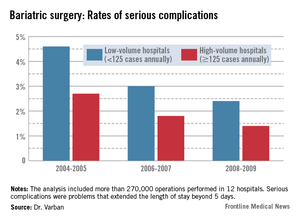

WASHINGTON – Annual case volume appears to be falling out as a safety factor in bariatric surgery, Dr. Oliver Varban said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

In the early days of the procedure, facilities that performed more than 125 operations each year had significantly better safety outcomes than did those performing fewer operations. But that difference is fading, particularly as laparoscopy continues to supplant open surgery, said Dr. Varban of the University of Michigan Health Systems, Ann Arbor.

"Over time, safety is improving in both high- and low-volume centers, with lower rates of complications, morbidity, and mortality. The inverse relationship does still persist, but that effect is attenuating."

Dr. Varban conducted a review of more than 270,000 bariatric surgery procedures performed in 12 hospitals from 2004 to 2009. He separated the hospitals by annual case volume: 125 or more and less than 125 per year.

In each year, about two-thirds of the procedures were completed in high-volume hospitals. The type of surgery also varied over the study period. During 2004-2005, laparoscopic and open procedures were about equally common. By 2006-2007, laparoscopic operations made up 65% of all bariatric procedures, and that held steady through 2008-2009.

The type of procedure evolved as well, Dr. Varban noted. In 2004-2005, gastric banding comprised about 5% of the operations. By 2006-2007, that had risen to 20%, and by 2008-2009, the number was close to 30%.

In the first era, low-volume hospitals had significantly higher rates of any complication than did high-volume centers (9.3% vs. 6%). By 2006-2007, the difference had narrowed but was still statistically significant (7% vs. 4.8%). By 2008-2009, the difference was no longer significant (5.6% vs. 4.5%).

A multivariate analysis that controlled for type of surgery and patient demographics found a similar trend. The risk of any complication remained significantly elevated at low-volume centers during all three periods (odds ratio, 1.33 in 2004-2005; 1.35 in 2006-2007; and 1.21 in 2008-2009).

The pattern of serious complications (problems that extended the length of stay beyond 5 days) was similar, with a rate of 4.6% vs. 2.7% in the early era; 3% vs. 1.8% in the middle era; and 2.4% vs. 1.4% in the final era. The risk of serious complications was significantly higher in the low-volume group in every era (OR 1.35, 1.43, and 1.44, respectively).

The rates of reoperation were higher in low-volume centers in every era, and declined as time went on. However, the difference between low- and high-volume centers in terms of reoperation rates was nonsignificant at every time point (1.5% vs. 1.06%; 1% vs. 0.75%; 0.78% vs. 0.67%). Similarly, the adjusted odds ratios were nonsignificant (OR 1.22, 1.28, and 1.20).

Although overall the mortality rates were low and remained low, they declined significantly in both groups over the study period (from 0.22% vs. 0.1% and 0.09% vs. 0.04%). Only in the first era was the difference statistically significant, with an adjusted OR of 1.71.

Dr. Varban had no financial disclosures.

WASHINGTON – Annual case volume appears to be falling out as a safety factor in bariatric surgery, Dr. Oliver Varban said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

In the early days of the procedure, facilities that performed more than 125 operations each year had significantly better safety outcomes than did those performing fewer operations. But that difference is fading, particularly as laparoscopy continues to supplant open surgery, said Dr. Varban of the University of Michigan Health Systems, Ann Arbor.

"Over time, safety is improving in both high- and low-volume centers, with lower rates of complications, morbidity, and mortality. The inverse relationship does still persist, but that effect is attenuating."

Dr. Varban conducted a review of more than 270,000 bariatric surgery procedures performed in 12 hospitals from 2004 to 2009. He separated the hospitals by annual case volume: 125 or more and less than 125 per year.

In each year, about two-thirds of the procedures were completed in high-volume hospitals. The type of surgery also varied over the study period. During 2004-2005, laparoscopic and open procedures were about equally common. By 2006-2007, laparoscopic operations made up 65% of all bariatric procedures, and that held steady through 2008-2009.

The type of procedure evolved as well, Dr. Varban noted. In 2004-2005, gastric banding comprised about 5% of the operations. By 2006-2007, that had risen to 20%, and by 2008-2009, the number was close to 30%.

In the first era, low-volume hospitals had significantly higher rates of any complication than did high-volume centers (9.3% vs. 6%). By 2006-2007, the difference had narrowed but was still statistically significant (7% vs. 4.8%). By 2008-2009, the difference was no longer significant (5.6% vs. 4.5%).

A multivariate analysis that controlled for type of surgery and patient demographics found a similar trend. The risk of any complication remained significantly elevated at low-volume centers during all three periods (odds ratio, 1.33 in 2004-2005; 1.35 in 2006-2007; and 1.21 in 2008-2009).

The pattern of serious complications (problems that extended the length of stay beyond 5 days) was similar, with a rate of 4.6% vs. 2.7% in the early era; 3% vs. 1.8% in the middle era; and 2.4% vs. 1.4% in the final era. The risk of serious complications was significantly higher in the low-volume group in every era (OR 1.35, 1.43, and 1.44, respectively).

The rates of reoperation were higher in low-volume centers in every era, and declined as time went on. However, the difference between low- and high-volume centers in terms of reoperation rates was nonsignificant at every time point (1.5% vs. 1.06%; 1% vs. 0.75%; 0.78% vs. 0.67%). Similarly, the adjusted odds ratios were nonsignificant (OR 1.22, 1.28, and 1.20).

Although overall the mortality rates were low and remained low, they declined significantly in both groups over the study period (from 0.22% vs. 0.1% and 0.09% vs. 0.04%). Only in the first era was the difference statistically significant, with an adjusted OR of 1.71.

Dr. Varban had no financial disclosures.

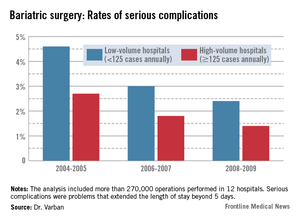

WASHINGTON – Annual case volume appears to be falling out as a safety factor in bariatric surgery, Dr. Oliver Varban said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

In the early days of the procedure, facilities that performed more than 125 operations each year had significantly better safety outcomes than did those performing fewer operations. But that difference is fading, particularly as laparoscopy continues to supplant open surgery, said Dr. Varban of the University of Michigan Health Systems, Ann Arbor.

"Over time, safety is improving in both high- and low-volume centers, with lower rates of complications, morbidity, and mortality. The inverse relationship does still persist, but that effect is attenuating."

Dr. Varban conducted a review of more than 270,000 bariatric surgery procedures performed in 12 hospitals from 2004 to 2009. He separated the hospitals by annual case volume: 125 or more and less than 125 per year.

In each year, about two-thirds of the procedures were completed in high-volume hospitals. The type of surgery also varied over the study period. During 2004-2005, laparoscopic and open procedures were about equally common. By 2006-2007, laparoscopic operations made up 65% of all bariatric procedures, and that held steady through 2008-2009.

The type of procedure evolved as well, Dr. Varban noted. In 2004-2005, gastric banding comprised about 5% of the operations. By 2006-2007, that had risen to 20%, and by 2008-2009, the number was close to 30%.

In the first era, low-volume hospitals had significantly higher rates of any complication than did high-volume centers (9.3% vs. 6%). By 2006-2007, the difference had narrowed but was still statistically significant (7% vs. 4.8%). By 2008-2009, the difference was no longer significant (5.6% vs. 4.5%).

A multivariate analysis that controlled for type of surgery and patient demographics found a similar trend. The risk of any complication remained significantly elevated at low-volume centers during all three periods (odds ratio, 1.33 in 2004-2005; 1.35 in 2006-2007; and 1.21 in 2008-2009).

The pattern of serious complications (problems that extended the length of stay beyond 5 days) was similar, with a rate of 4.6% vs. 2.7% in the early era; 3% vs. 1.8% in the middle era; and 2.4% vs. 1.4% in the final era. The risk of serious complications was significantly higher in the low-volume group in every era (OR 1.35, 1.43, and 1.44, respectively).

The rates of reoperation were higher in low-volume centers in every era, and declined as time went on. However, the difference between low- and high-volume centers in terms of reoperation rates was nonsignificant at every time point (1.5% vs. 1.06%; 1% vs. 0.75%; 0.78% vs. 0.67%). Similarly, the adjusted odds ratios were nonsignificant (OR 1.22, 1.28, and 1.20).

Although overall the mortality rates were low and remained low, they declined significantly in both groups over the study period (from 0.22% vs. 0.1% and 0.09% vs. 0.04%). Only in the first era was the difference statistically significant, with an adjusted OR of 1.71.

Dr. Varban had no financial disclosures.

AT THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

Major finding: From 2004 to 2009, the rates of serious complications, reoperation, and mortality improved in low-volume hospitals, bringing their results closer to those seen in high-volume centers.

Data source: The study included data on more than 270,000 bariatric surgical procedures.

Disclosures: Dr. Varban had no financial disclosures.

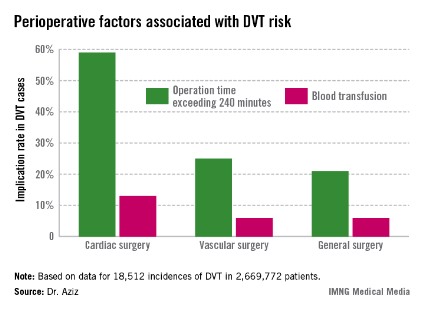

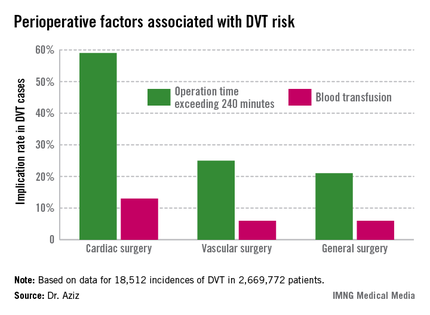

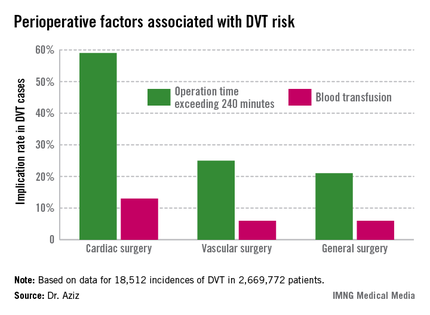

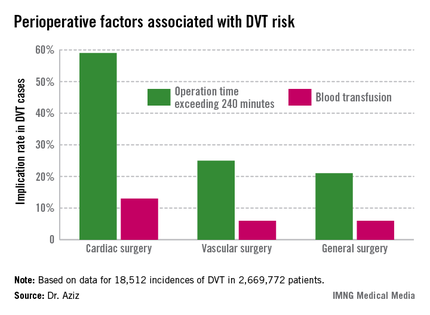

DVT risk higher in cardiac and vascular surgery patients

WASHINGTON – Cardiac and vascular surgery patients are at higher risk for deep vein thrombosis than are general surgery patients, according to data presented at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

In a retrospective analysis of 2,669,772 patients with a median age of 64 years, 43% of whom were males, in the ACS-National Surgery Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) during 2005-2009, Dr. Faisal Aziz of Penn State Hershey (Pa.) Heart and Vascular Institute and his colleagues sought to determine the actual rate of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) during revascularization procedures, compared with general surgery. They also investigated the relationship between the type of operation and the DVT incidence rate.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality considers the incidence rate of DVT a patient safety indicator. Dr. Aziz cited data indicating that one in four patients who develop DVT postoperatively before discharge has an additional venous thromboembolic event–related event in the subsequent 21 months requiring hospitalization, at a cost of approximately $15,000, or roughly 21% higher than the original DVT event (J. Manag. Care. Pharm. 2007;13:475-86).

The researchers sorted patients according to DVT risk factors such as age, gender, body mass index over 40 kg/m2, and whether the surgery was acute. They then assessed intraoperative factors such as total time to completion and its American Society of Anesthesiology score. They then considered the postoperative factors associated with DVT, such as blood transfusions, return to the operating room, deep wound infection, cardiac arrest, and mortality.

Dr. Aziz and his team determined that there were 18,512 incidences of DVT, equaling 0.69% of all patients studied. Of those, 0.66% occurred during general surgery, 2.08% occurred during cardiac surgery, and 1% occurred during vascular surgery.

"The implications of our study are that, contrary to popular belief, the incidence of postoperative DVT is actually higher after cardiac surgery and vascular surgery procedures," he said.

The cardiac surgery procedures associated with the highest DVT incidence rate were tricuspid valve replacement (8%), thoracic endovascular aortic repair (5%), thoracic aortic graft replacement (4%), and pericardial window (4%).

In a comparison of cardiac procedures, tricuspid valve replacement vs. aortic valve replacement had a risk ratio of 3.5 (P < .001). In tricuspid valve replacement vs. coronary artery bypass, the former had a risk ratio of 11.24 (P < .001).

Vascular surgeries with the highest DVT incidence rates were peripheral bypass (1%), amputation (trans-metatarsal, 0.75%; below knee, 1%; above the knee, 1%), and ruptured aortic aneurysms (3.5%), Dr. Aziz reported.

Intra-and postoperative factors associated with DVT risk included operation times exceeding 240 minutes and previous DVT. Compared with 21% of general surgery patients, operation time was implicated in 59% of cardiac surgery patients (relative risk, 2.72; P < .001) and 25% of vascular surgery patients (RR, 1.14; P <.001). Blood transfusions affected 13% of cardiac surgery patients (RR, 2.3; P < .001), 6% of vascular surgery patients (RR, 1.3; P < .001), and 6% of general surgery patients.

Compared with 24% for general surgery patients, returning to the operating room was implicated in 27% of cardiac patients (RR, 1.4; P = .27) and 32% of vascular surgery patients (RR, 1.3; P < .001).

"Procedures and perioperative factors associated with high risk of postoperative DVT should be identified, and adequate DVT prophylaxis should be ensured for these patients," he concluded.

Dr. Aziz and his associates had no disclosures.

WASHINGTON – Cardiac and vascular surgery patients are at higher risk for deep vein thrombosis than are general surgery patients, according to data presented at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

In a retrospective analysis of 2,669,772 patients with a median age of 64 years, 43% of whom were males, in the ACS-National Surgery Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) during 2005-2009, Dr. Faisal Aziz of Penn State Hershey (Pa.) Heart and Vascular Institute and his colleagues sought to determine the actual rate of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) during revascularization procedures, compared with general surgery. They also investigated the relationship between the type of operation and the DVT incidence rate.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality considers the incidence rate of DVT a patient safety indicator. Dr. Aziz cited data indicating that one in four patients who develop DVT postoperatively before discharge has an additional venous thromboembolic event–related event in the subsequent 21 months requiring hospitalization, at a cost of approximately $15,000, or roughly 21% higher than the original DVT event (J. Manag. Care. Pharm. 2007;13:475-86).

The researchers sorted patients according to DVT risk factors such as age, gender, body mass index over 40 kg/m2, and whether the surgery was acute. They then assessed intraoperative factors such as total time to completion and its American Society of Anesthesiology score. They then considered the postoperative factors associated with DVT, such as blood transfusions, return to the operating room, deep wound infection, cardiac arrest, and mortality.

Dr. Aziz and his team determined that there were 18,512 incidences of DVT, equaling 0.69% of all patients studied. Of those, 0.66% occurred during general surgery, 2.08% occurred during cardiac surgery, and 1% occurred during vascular surgery.

"The implications of our study are that, contrary to popular belief, the incidence of postoperative DVT is actually higher after cardiac surgery and vascular surgery procedures," he said.

The cardiac surgery procedures associated with the highest DVT incidence rate were tricuspid valve replacement (8%), thoracic endovascular aortic repair (5%), thoracic aortic graft replacement (4%), and pericardial window (4%).

In a comparison of cardiac procedures, tricuspid valve replacement vs. aortic valve replacement had a risk ratio of 3.5 (P < .001). In tricuspid valve replacement vs. coronary artery bypass, the former had a risk ratio of 11.24 (P < .001).

Vascular surgeries with the highest DVT incidence rates were peripheral bypass (1%), amputation (trans-metatarsal, 0.75%; below knee, 1%; above the knee, 1%), and ruptured aortic aneurysms (3.5%), Dr. Aziz reported.

Intra-and postoperative factors associated with DVT risk included operation times exceeding 240 minutes and previous DVT. Compared with 21% of general surgery patients, operation time was implicated in 59% of cardiac surgery patients (relative risk, 2.72; P < .001) and 25% of vascular surgery patients (RR, 1.14; P <.001). Blood transfusions affected 13% of cardiac surgery patients (RR, 2.3; P < .001), 6% of vascular surgery patients (RR, 1.3; P < .001), and 6% of general surgery patients.

Compared with 24% for general surgery patients, returning to the operating room was implicated in 27% of cardiac patients (RR, 1.4; P = .27) and 32% of vascular surgery patients (RR, 1.3; P < .001).