User login

The evolution of “COVIDists”

Adapting to the demands placed on hospital resources by COVID-19

The challenges posed by COVID-19 have crippled health care systems around the globe. By February 2020, the first outbreak in the United States had been set off in Washington State. We quickly became the world’s epicenter of the epidemic, with over 1.8 million patients and over 110,000 deaths.1 The rapidity of spread and the severity of the disease created a tremendous strain on resources. It blindsided policymakers and hospital administrators, which left little time to react to the challenges placed on hospital operations all over the country.

The necessity of a new care model

Although health systems in the United States are adept in managing complications of common seasonal viral respiratory illnesses, COVID-19 presented an entirely different challenge with its significantly higher mortality rate. A respiratory disease turning into a multiorgan disease that causes debilitating cardiac, renal, neurological, hematological, and psychosocial complications2 was not something we had experience managing effectively. Additional challenges included a massive surge of COVID-19 patients, a limited supply of personal protective equipment (PPE), an inadequate number of intensivists for managing the anticipated ventilated patients, and most importantly, the potential of losing some of our workforce if they became infected.

Based on the experiences in China and Italy, and various predictive models, the division of hospital medicine at Baystate Health quickly realized the necessity of a new model of care for COVID-19 patients. We came up with an elaborate plan to manage the disease burden and the strain on resources effectively. The measures we put in place could be broadly divided into three categories following the timeline of the disease: the preparatory phase, the execution phase, and the maintenance phase.

The preparatory phase: From “Hospitalists” to “COVIDists”

As in most hospitals around the country, hospitalists are the backbone of inpatient clinical operations at our health system. A focused group of 10 hospitalists who volunteered to take care of COVID-19 patients with a particular interest in the pandemic and experience in critical care were selected, and the term “COVIDists” was coined to refer to them.

COVIDists were trained in various treatment protocols and ongoing clinical trials. They were given refresher training in Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) and Fundamental Critical Care Support (FCCS) courses and were taught in critical care/ventilator management by the intensivists through rapid indoctrination in the ICU. All of them had their N-95 mask fitting updated and were trained in the safe donning and doffing of all kinds of PPE by PPE coaches. The palliative care team trained them in conducting end-of-life/code status discussions with a focus on being unable to speak with family members at the bedside. COVIDists were also assigned as Code Blue leaders for any “COVID code blue” in the hospital.

In addition to the rapid training course, COVID-related updates were disseminated daily using three different modalities: brief huddles at the start of the day with the COVIDists; a COVID-19 newsletter summarizing daily updates, new treatments, strategies, and policies; and a WhatsApp group for instantly broadcasting information to the COVIDists (Table 1).

The execution phase

All the hospitalized COVID-19 patients were grouped together to COVID units, and the COVIDists were deployed to those units geographically. COVIDists were given lighter than usual patient loads to deal with the extra time needed for donning and doffing of PPE and for coordination with specialists. COVIDists were almost the only clinicians physically visiting the patients in most cases, and they became the “eyes and ears” of specialists since the specialists were advised to minimize exposure and pursue telemedicine consults. The COVIDists were also undertaking the most challenging part of the care – talking to families about end-of-life issues and the futility of aggressive care in certain patients with preexisting conditions.

Some COVIDists were deployed to the ICU to work alongside the intensivists and became an invaluable resource in ICU management when the ICU census skyrocketed during the initial phase of the outbreak. This helped in tiding the health system over during the initial crisis. Within a short time, we shifted away from an early intubation strategy, and most of the ICU patients were managed in the intermediate care units on high flow oxygen along with the awake-proning protocol. The COVIDists exclusively managed these units. They led multidisciplinary rounds two times a day with the ICU, rapid response team (RRT), the palliative care team, and the nursing team. This step drastically decreased the number of intubations, RRT activations, reduced ICU census,3 and helped with hospital capacity and patient flow (Tables 2 and 3).

This strategy also helped build solidarity and camaraderie between all these groups, making the COVIDists feel that they were never alone and that the whole hospital supported them. We are currently evaluating clinical outcomes and attempting to identify effects on mortality, length of stay, days on the ventilator, and days in ICU.

The maintenance phase

It is already 2 months since the first devising COVIDists. There is no difference in sick callouts between COVIDists and non-COVIDists. One COVIDist and one non-COVIDist contracted the disease, but none of them required hospitalization. Although we initially thought that COVIDists would be needed for only a short period of time, the evolution of the disease is showing signs that it might be prolonged over the next several months. Hence, we are planning to continue COVIDist service for at least the next 6 months and reevaluate the need.

Hospital medicine leadership checked on COVIDists daily in regard to their physical health and, more importantly, their mental well-being. They were offered the chance to be taken off the schedule if they felt burned out, but no one wanted to come off their scheduled service before finishing their shifts. BlueCross MA recognized one of the COVIDists, Raghuveer Rakasi, MD, as a “hero on the front line.”4 In Dr. Rakasi’s words, “We took a nosedive into something without knowing its depth, and aware that we could have fatalities among ourselves. We took up new roles, faced new challenges, learned new things every day, evolving every step of the way. We had to change the way we practice medicine, finding new ways to treat patients, and protecting the workforce by limiting patient exposure, prioritizing investigations.” He added that “we have to adapt to a new normal; we should be prepared for this to come in waves. Putting aside our political views, we should stand united 6 feet apart, with a mask covering our brave faces, frequently washing our helping hands to overcome these uncertain times.”

Conclusion

The creation of a focused group of hospitalists called COVIDists and providing them with structured and rapid training (in various aspects of clinical care of COVID-19 patients, critical care/ventilator management, efficient and safe use of PPE) and daily information dissemination allowed our health system to prepare for the large volume of COVID-19 patients. It also helped in preserving the larger hospital workforce for a possible future surge.

The rapid development and implementation of the COVIDist strategy succeeded because of the intrinsic motivation of the providers to improve the outcomes of this high-risk patient population and the close collaboration of the stakeholders. Our institution remains successful in managing the pandemic in Western Massachusetts, with reserve capacity remaining even during the peak of the epidemic. A large part of this was because of creating and training a pool of COVIDists.

Dr. Medarametla is medical director, clinical operations, in the division of hospital medicine at Baystate Health, and assistant professor at University of Massachusetts, Worcester. Readers can contact him at Venkatrao.MedarametlaMD@Baystatehealth.org. Dr. Prabhakaran is unit medical director, geriatrics unit, in the division of hospital medicine at Baystate Health and assistant professor at University of Massachusetts. Dr. Bryson is associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency at Baystate Health and assistant professor at University of Massachusetts. Dr. Umar is medical director, clinical operations, in the division of hospital medicine at Baystate Health. Dr. Natanasabapathy is division chief of hospital medicine at Baystate Health and assistant professor at University of Massachusetts.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Updated Jun 10, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html.

2. Zhou F et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020 Mar 28;395(10229):1054-62.

3. Westafer LM et al. A transdisciplinary COVID-19 early respiratory intervention protocol: An implementation story. J Hosp Med. 2020 May 21;15(6):372-374.

4. Miller J. “Heroes on the front line: Dr. Raghuveer Rakasi.” Coverage. May 18, 2020. https://coverage.bluecrossma.com/article/heroes-front-line-dr-raghuveer-rakasi

Adapting to the demands placed on hospital resources by COVID-19

Adapting to the demands placed on hospital resources by COVID-19

The challenges posed by COVID-19 have crippled health care systems around the globe. By February 2020, the first outbreak in the United States had been set off in Washington State. We quickly became the world’s epicenter of the epidemic, with over 1.8 million patients and over 110,000 deaths.1 The rapidity of spread and the severity of the disease created a tremendous strain on resources. It blindsided policymakers and hospital administrators, which left little time to react to the challenges placed on hospital operations all over the country.

The necessity of a new care model

Although health systems in the United States are adept in managing complications of common seasonal viral respiratory illnesses, COVID-19 presented an entirely different challenge with its significantly higher mortality rate. A respiratory disease turning into a multiorgan disease that causes debilitating cardiac, renal, neurological, hematological, and psychosocial complications2 was not something we had experience managing effectively. Additional challenges included a massive surge of COVID-19 patients, a limited supply of personal protective equipment (PPE), an inadequate number of intensivists for managing the anticipated ventilated patients, and most importantly, the potential of losing some of our workforce if they became infected.

Based on the experiences in China and Italy, and various predictive models, the division of hospital medicine at Baystate Health quickly realized the necessity of a new model of care for COVID-19 patients. We came up with an elaborate plan to manage the disease burden and the strain on resources effectively. The measures we put in place could be broadly divided into three categories following the timeline of the disease: the preparatory phase, the execution phase, and the maintenance phase.

The preparatory phase: From “Hospitalists” to “COVIDists”

As in most hospitals around the country, hospitalists are the backbone of inpatient clinical operations at our health system. A focused group of 10 hospitalists who volunteered to take care of COVID-19 patients with a particular interest in the pandemic and experience in critical care were selected, and the term “COVIDists” was coined to refer to them.

COVIDists were trained in various treatment protocols and ongoing clinical trials. They were given refresher training in Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) and Fundamental Critical Care Support (FCCS) courses and were taught in critical care/ventilator management by the intensivists through rapid indoctrination in the ICU. All of them had their N-95 mask fitting updated and were trained in the safe donning and doffing of all kinds of PPE by PPE coaches. The palliative care team trained them in conducting end-of-life/code status discussions with a focus on being unable to speak with family members at the bedside. COVIDists were also assigned as Code Blue leaders for any “COVID code blue” in the hospital.

In addition to the rapid training course, COVID-related updates were disseminated daily using three different modalities: brief huddles at the start of the day with the COVIDists; a COVID-19 newsletter summarizing daily updates, new treatments, strategies, and policies; and a WhatsApp group for instantly broadcasting information to the COVIDists (Table 1).

The execution phase

All the hospitalized COVID-19 patients were grouped together to COVID units, and the COVIDists were deployed to those units geographically. COVIDists were given lighter than usual patient loads to deal with the extra time needed for donning and doffing of PPE and for coordination with specialists. COVIDists were almost the only clinicians physically visiting the patients in most cases, and they became the “eyes and ears” of specialists since the specialists were advised to minimize exposure and pursue telemedicine consults. The COVIDists were also undertaking the most challenging part of the care – talking to families about end-of-life issues and the futility of aggressive care in certain patients with preexisting conditions.

Some COVIDists were deployed to the ICU to work alongside the intensivists and became an invaluable resource in ICU management when the ICU census skyrocketed during the initial phase of the outbreak. This helped in tiding the health system over during the initial crisis. Within a short time, we shifted away from an early intubation strategy, and most of the ICU patients were managed in the intermediate care units on high flow oxygen along with the awake-proning protocol. The COVIDists exclusively managed these units. They led multidisciplinary rounds two times a day with the ICU, rapid response team (RRT), the palliative care team, and the nursing team. This step drastically decreased the number of intubations, RRT activations, reduced ICU census,3 and helped with hospital capacity and patient flow (Tables 2 and 3).

This strategy also helped build solidarity and camaraderie between all these groups, making the COVIDists feel that they were never alone and that the whole hospital supported them. We are currently evaluating clinical outcomes and attempting to identify effects on mortality, length of stay, days on the ventilator, and days in ICU.

The maintenance phase

It is already 2 months since the first devising COVIDists. There is no difference in sick callouts between COVIDists and non-COVIDists. One COVIDist and one non-COVIDist contracted the disease, but none of them required hospitalization. Although we initially thought that COVIDists would be needed for only a short period of time, the evolution of the disease is showing signs that it might be prolonged over the next several months. Hence, we are planning to continue COVIDist service for at least the next 6 months and reevaluate the need.

Hospital medicine leadership checked on COVIDists daily in regard to their physical health and, more importantly, their mental well-being. They were offered the chance to be taken off the schedule if they felt burned out, but no one wanted to come off their scheduled service before finishing their shifts. BlueCross MA recognized one of the COVIDists, Raghuveer Rakasi, MD, as a “hero on the front line.”4 In Dr. Rakasi’s words, “We took a nosedive into something without knowing its depth, and aware that we could have fatalities among ourselves. We took up new roles, faced new challenges, learned new things every day, evolving every step of the way. We had to change the way we practice medicine, finding new ways to treat patients, and protecting the workforce by limiting patient exposure, prioritizing investigations.” He added that “we have to adapt to a new normal; we should be prepared for this to come in waves. Putting aside our political views, we should stand united 6 feet apart, with a mask covering our brave faces, frequently washing our helping hands to overcome these uncertain times.”

Conclusion

The creation of a focused group of hospitalists called COVIDists and providing them with structured and rapid training (in various aspects of clinical care of COVID-19 patients, critical care/ventilator management, efficient and safe use of PPE) and daily information dissemination allowed our health system to prepare for the large volume of COVID-19 patients. It also helped in preserving the larger hospital workforce for a possible future surge.

The rapid development and implementation of the COVIDist strategy succeeded because of the intrinsic motivation of the providers to improve the outcomes of this high-risk patient population and the close collaboration of the stakeholders. Our institution remains successful in managing the pandemic in Western Massachusetts, with reserve capacity remaining even during the peak of the epidemic. A large part of this was because of creating and training a pool of COVIDists.

Dr. Medarametla is medical director, clinical operations, in the division of hospital medicine at Baystate Health, and assistant professor at University of Massachusetts, Worcester. Readers can contact him at Venkatrao.MedarametlaMD@Baystatehealth.org. Dr. Prabhakaran is unit medical director, geriatrics unit, in the division of hospital medicine at Baystate Health and assistant professor at University of Massachusetts. Dr. Bryson is associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency at Baystate Health and assistant professor at University of Massachusetts. Dr. Umar is medical director, clinical operations, in the division of hospital medicine at Baystate Health. Dr. Natanasabapathy is division chief of hospital medicine at Baystate Health and assistant professor at University of Massachusetts.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Updated Jun 10, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html.

2. Zhou F et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020 Mar 28;395(10229):1054-62.

3. Westafer LM et al. A transdisciplinary COVID-19 early respiratory intervention protocol: An implementation story. J Hosp Med. 2020 May 21;15(6):372-374.

4. Miller J. “Heroes on the front line: Dr. Raghuveer Rakasi.” Coverage. May 18, 2020. https://coverage.bluecrossma.com/article/heroes-front-line-dr-raghuveer-rakasi

The challenges posed by COVID-19 have crippled health care systems around the globe. By February 2020, the first outbreak in the United States had been set off in Washington State. We quickly became the world’s epicenter of the epidemic, with over 1.8 million patients and over 110,000 deaths.1 The rapidity of spread and the severity of the disease created a tremendous strain on resources. It blindsided policymakers and hospital administrators, which left little time to react to the challenges placed on hospital operations all over the country.

The necessity of a new care model

Although health systems in the United States are adept in managing complications of common seasonal viral respiratory illnesses, COVID-19 presented an entirely different challenge with its significantly higher mortality rate. A respiratory disease turning into a multiorgan disease that causes debilitating cardiac, renal, neurological, hematological, and psychosocial complications2 was not something we had experience managing effectively. Additional challenges included a massive surge of COVID-19 patients, a limited supply of personal protective equipment (PPE), an inadequate number of intensivists for managing the anticipated ventilated patients, and most importantly, the potential of losing some of our workforce if they became infected.

Based on the experiences in China and Italy, and various predictive models, the division of hospital medicine at Baystate Health quickly realized the necessity of a new model of care for COVID-19 patients. We came up with an elaborate plan to manage the disease burden and the strain on resources effectively. The measures we put in place could be broadly divided into three categories following the timeline of the disease: the preparatory phase, the execution phase, and the maintenance phase.

The preparatory phase: From “Hospitalists” to “COVIDists”

As in most hospitals around the country, hospitalists are the backbone of inpatient clinical operations at our health system. A focused group of 10 hospitalists who volunteered to take care of COVID-19 patients with a particular interest in the pandemic and experience in critical care were selected, and the term “COVIDists” was coined to refer to them.

COVIDists were trained in various treatment protocols and ongoing clinical trials. They were given refresher training in Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) and Fundamental Critical Care Support (FCCS) courses and were taught in critical care/ventilator management by the intensivists through rapid indoctrination in the ICU. All of them had their N-95 mask fitting updated and were trained in the safe donning and doffing of all kinds of PPE by PPE coaches. The palliative care team trained them in conducting end-of-life/code status discussions with a focus on being unable to speak with family members at the bedside. COVIDists were also assigned as Code Blue leaders for any “COVID code blue” in the hospital.

In addition to the rapid training course, COVID-related updates were disseminated daily using three different modalities: brief huddles at the start of the day with the COVIDists; a COVID-19 newsletter summarizing daily updates, new treatments, strategies, and policies; and a WhatsApp group for instantly broadcasting information to the COVIDists (Table 1).

The execution phase

All the hospitalized COVID-19 patients were grouped together to COVID units, and the COVIDists were deployed to those units geographically. COVIDists were given lighter than usual patient loads to deal with the extra time needed for donning and doffing of PPE and for coordination with specialists. COVIDists were almost the only clinicians physically visiting the patients in most cases, and they became the “eyes and ears” of specialists since the specialists were advised to minimize exposure and pursue telemedicine consults. The COVIDists were also undertaking the most challenging part of the care – talking to families about end-of-life issues and the futility of aggressive care in certain patients with preexisting conditions.

Some COVIDists were deployed to the ICU to work alongside the intensivists and became an invaluable resource in ICU management when the ICU census skyrocketed during the initial phase of the outbreak. This helped in tiding the health system over during the initial crisis. Within a short time, we shifted away from an early intubation strategy, and most of the ICU patients were managed in the intermediate care units on high flow oxygen along with the awake-proning protocol. The COVIDists exclusively managed these units. They led multidisciplinary rounds two times a day with the ICU, rapid response team (RRT), the palliative care team, and the nursing team. This step drastically decreased the number of intubations, RRT activations, reduced ICU census,3 and helped with hospital capacity and patient flow (Tables 2 and 3).

This strategy also helped build solidarity and camaraderie between all these groups, making the COVIDists feel that they were never alone and that the whole hospital supported them. We are currently evaluating clinical outcomes and attempting to identify effects on mortality, length of stay, days on the ventilator, and days in ICU.

The maintenance phase

It is already 2 months since the first devising COVIDists. There is no difference in sick callouts between COVIDists and non-COVIDists. One COVIDist and one non-COVIDist contracted the disease, but none of them required hospitalization. Although we initially thought that COVIDists would be needed for only a short period of time, the evolution of the disease is showing signs that it might be prolonged over the next several months. Hence, we are planning to continue COVIDist service for at least the next 6 months and reevaluate the need.

Hospital medicine leadership checked on COVIDists daily in regard to their physical health and, more importantly, their mental well-being. They were offered the chance to be taken off the schedule if they felt burned out, but no one wanted to come off their scheduled service before finishing their shifts. BlueCross MA recognized one of the COVIDists, Raghuveer Rakasi, MD, as a “hero on the front line.”4 In Dr. Rakasi’s words, “We took a nosedive into something without knowing its depth, and aware that we could have fatalities among ourselves. We took up new roles, faced new challenges, learned new things every day, evolving every step of the way. We had to change the way we practice medicine, finding new ways to treat patients, and protecting the workforce by limiting patient exposure, prioritizing investigations.” He added that “we have to adapt to a new normal; we should be prepared for this to come in waves. Putting aside our political views, we should stand united 6 feet apart, with a mask covering our brave faces, frequently washing our helping hands to overcome these uncertain times.”

Conclusion

The creation of a focused group of hospitalists called COVIDists and providing them with structured and rapid training (in various aspects of clinical care of COVID-19 patients, critical care/ventilator management, efficient and safe use of PPE) and daily information dissemination allowed our health system to prepare for the large volume of COVID-19 patients. It also helped in preserving the larger hospital workforce for a possible future surge.

The rapid development and implementation of the COVIDist strategy succeeded because of the intrinsic motivation of the providers to improve the outcomes of this high-risk patient population and the close collaboration of the stakeholders. Our institution remains successful in managing the pandemic in Western Massachusetts, with reserve capacity remaining even during the peak of the epidemic. A large part of this was because of creating and training a pool of COVIDists.

Dr. Medarametla is medical director, clinical operations, in the division of hospital medicine at Baystate Health, and assistant professor at University of Massachusetts, Worcester. Readers can contact him at Venkatrao.MedarametlaMD@Baystatehealth.org. Dr. Prabhakaran is unit medical director, geriatrics unit, in the division of hospital medicine at Baystate Health and assistant professor at University of Massachusetts. Dr. Bryson is associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency at Baystate Health and assistant professor at University of Massachusetts. Dr. Umar is medical director, clinical operations, in the division of hospital medicine at Baystate Health. Dr. Natanasabapathy is division chief of hospital medicine at Baystate Health and assistant professor at University of Massachusetts.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Updated Jun 10, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html.

2. Zhou F et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020 Mar 28;395(10229):1054-62.

3. Westafer LM et al. A transdisciplinary COVID-19 early respiratory intervention protocol: An implementation story. J Hosp Med. 2020 May 21;15(6):372-374.

4. Miller J. “Heroes on the front line: Dr. Raghuveer Rakasi.” Coverage. May 18, 2020. https://coverage.bluecrossma.com/article/heroes-front-line-dr-raghuveer-rakasi

Culture: An unseen force in the hospital workplace

Parallels from the airline industry

“Workplace culture” has a profound influence on the success or failure of a team in the modern-day work environment, where teamwork and interpersonal interactions have paramount importance. Crew resource management (CRM), a technique developed originally by the airline industry, has been used as a tool to improve safety and quality in ICUs, trauma rooms, and operating rooms.1,2 This article discusses the use of CRM in hospital medicine as a tool for training and maintaining a favorable workplace culture.

Origin and evolution of CRM

United Airlines instituted the airline industry’s first crew resource management for pilots in 1981, following the 1978 crash of United Flight 173 in Portland, Ore. CRM was created based on recommendations from the National Transportation Safety Board and from a NASA workshop held subsequently.3 CRM has since evolved through five generations, and is a required annual training for most major commercial airline companies around the world. It also has been adapted for personnel training by several modern international industries.4

From the airline industry to the hospital

The health care industry is similar to the airline industry in that there is absolutely no margin of error, and that workplace culture plays a very important role. The culture being referred to here is the sum total of values, beliefs, work ethics, work strategies, strengths, and weaknesses of a group of people, and how they interact as a group. In other words, it is the dynamics of a group.

According to Donelson R. Forsyth, a social and personality psychologist at the University of Richmond (Virginia), the two key determinants of successful teamwork are a “shared mental representation of the task,” which refers to an in-depth understanding of the team and the tasks they are attempting; and “group unity/cohesion,” which means that, generally, members of cohesive groups like each other and the group, and they also are united in their pursuit of collective, group-level goals.5

Understanding the culture of a hospitalist team

Analyzing group dynamics and actively managing them toward both the institutional and global goals of health care is critical for the success of an organization. This is the core of successfully managing any team in any industry.

Additionally, the rapidly changing health care climate and insurance payment systems requires hospital medicine groups to rapidly adapt to the constantly changing health care business environment. As a result, there are a couple of ways to evaluate the effectiveness of the team:

- Measure tangible outcomes. The outcomes have to be well defined, important and measurable. These could be cost of care, quality of care, engagement of the team etc. These tangible measures’ outcome over a period of time can be used as a measure of how effective the team is.

- Simply ask your team! It is very important to know what core values the team holds dear. The best way to get that information from the team is to find out the de facto leaders of the team. They should be involved in the decision-making process, thus making them valuable to the management as well as the team.

Culture shapes outcomes

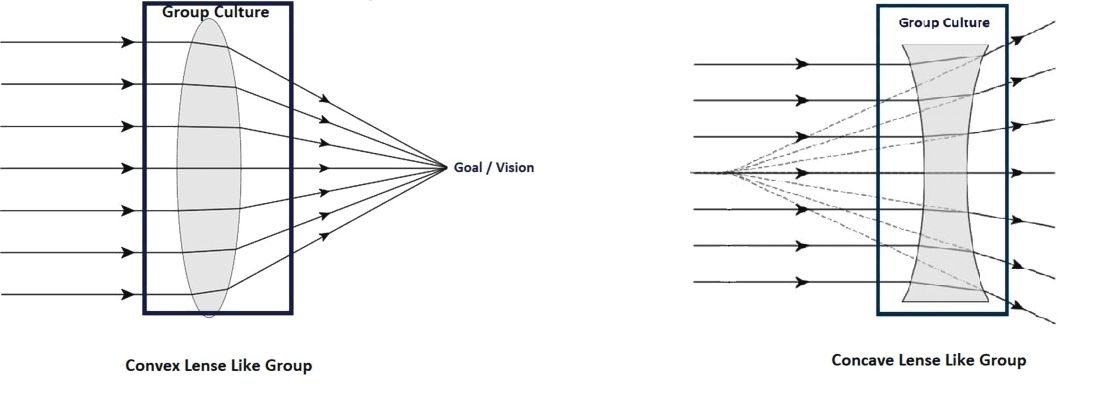

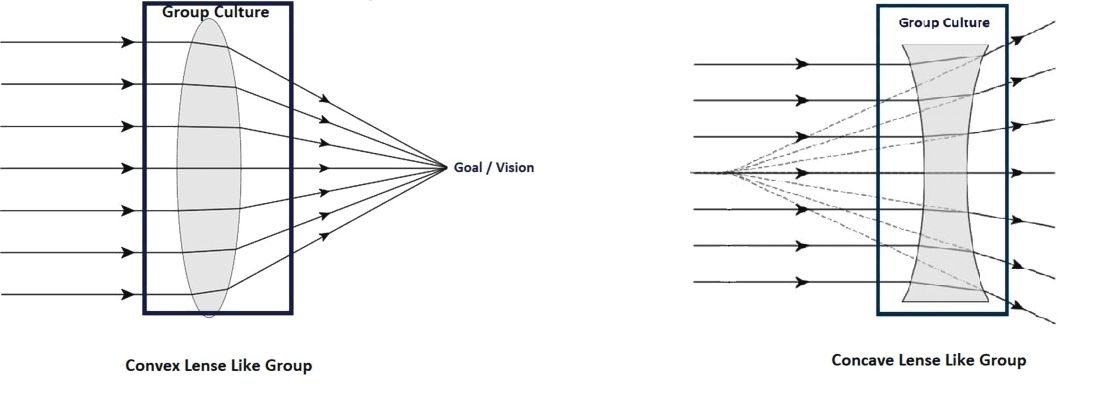

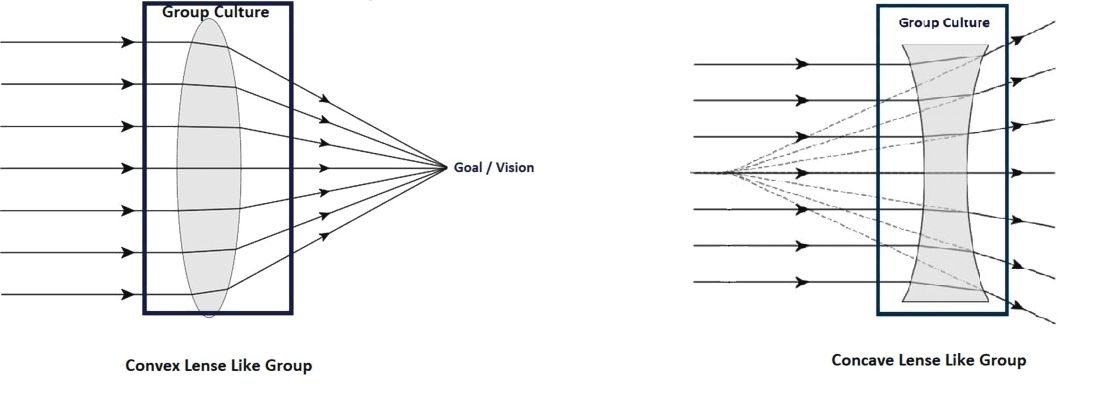

We have used the analogy of a convex and concave lens to help understand this better. A well-developed and well-coordinated team is like convex lens. A lens’ ability to converge or diverge light rays depends on certain characteristics like the curvature of surfaces and refractory index. Likewise, the culture of a group determines its ability to transform all the demands of the collective workload toward a unified goal/outcome. If it is favorable, the group will work as one and success will happen automatically.

Unfortunately, the opposite of this, (the concave lens effect), is more commonplace, where the dynamics of a team prevent the goals being achieved, as there is discordance, poor coordination of ideas and values, and team members not liking each other.

Most teams would fall somewhere within this spectrum, spanning the most favorable convex lens–like group to the least favorable concave lens–like group.

Change team dynamics using CRM principles

The concept of using CRM principles in health care is not entirely new. Such agencies as the Joint Commission and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality recommend using principles of CRM to improve communications, and as an error-prevention tool in health care.6

This approach can be broken down into four important steps:

1. Recruit right. It is important to make sure that the new recruit is the right fit for the team and that the de facto leaders and a few other team members are involved in interviewing the candidates. Their assessment should be given due consideration in making the decision to give the new recruit the job.

Every program looks for aspects like clinical competence, interpersonal communication, teamwork, etc., in a candidate, but it is even more important to make sure the candidate has the tenets that would make him/her a part of that particular team.

2. Train well. The newly recruited providers should be given focused training and the seasoned providers should be given refresher training at regular intervals. Care should be taken in designing the training programs in such a way that the providers are trained in skills that they don’t always think about, things that aren’t readily obvious, and in skills that they never get trained in during medical school and residency.

Specifically, they should be trained in:

- Values. These should include the values of both the organization and the team.

- Safety. This should include all the safety protocols that are in place in the organization - where to get help, how to report unsafe events etc.

- Communication.

Within the group: Have a mentor for the new provider, and also develop a culture where he/she feels comfortable to reach out to anyone in the team for help.

With patients and families: This training should ideally be done in a simulated environment if possible.

With other groups in the hospital: Consultants, nurses, other ancillary staff. Give them an idea about the prevailing culture in the organization with regard to these groups, so that they know what to expect when dealing with them.

- Managing perceptions. How the providers are viewed in the hospital, and how to improve it or maintain it.

- Nurturing the good. Use positive reinforcements to solidify the positive aspects of group dynamics these individuals might possess.

- Weeding out the bad. Use training and feedback to alter the negative group dynamic aspects.

3. Intervene. This is necessary either to maintain the positive aspects of a team that is already high-functioning, or to transform a poorly functioning team into a well-coordinated team. This is where the principles of CRM are going to be most useful.

There are five generations of CRM, each with a different focus.6 Only the aspects relevant to hospital medicine training are mentioned here.

- Communication. Address the gaps in communication. It is important to include people who are trusted by the team in designing and executing these sessions.

- Leadership. The goal should be to encourage the team to take ownership of the program. This will make a tremendous change in the ability of a team to deliver and rise up to challenges. The organizational leadership has to be willing to elevate the leaders of the group to positions where they can meaningfully take part in managing the team and making decisions that are critical to the team.

- Burnout management. Providers getting disillusioned: having no work-life balance; not getting enough respect from management, as well as other groups of doctors/nurses/etc. in the hospital; they are subject to bad scheduling and poor pay – all of which can all lead to career-ending burnout. It is important to recognize this and mitigate the factors that cause burnout.

- Organizational culture. If the team feels valued and supported, they will, in turn, work hard toward success. Creative leadership and a willingness to accommodate what matters the most to the team is essential for achieving this.

- Simulated training. These can be done in simulation labs, or in-group sessions with the team, re-creating difficult scenarios or problems in which the whole team can come together and solve them.

- Error containment and management. The team needs to identify possible sources of error and contain them before errors happen. The group should get together if a serious event happens and brainstorm why it happened and take measures to prevent it.

4. Reevaluate. Team dynamics tend to change over time. It is important to constantly re-evaluate the team and make sure that the team’s culture remains favorable. There should be recurrent cycles of retraining and interventions to maintain the positive growth that has been attained, as depicted in the schematic below:

Conclusion

CRM is widely accepted as an effective tool in training individuals in many high performing industries. This article describes a framework in which the principles of CRM can be applied to hospital medicine to maintain positive work culture.

Dr. Prabhakaran is director of hospital medicine transitions of care, Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, Mass., and assistant professor of medicine, University of Massachusetts, Worcester. Dr. Medarametla is medical director, hospital medicine, Baystate Medical Center, and assistant professor of medicine, University of Massachusetts.

References

1. Haerkens MH et al. Crew Resource Management in the ICU: The need for culture change. Ann Intensive Care. 2012 Aug 22;2:39.

2. Haerkens MH et al. Crew Resource Management in the trauma room: A prospective 3-year cohort study. Eur J Emerg Med. 2018 Aug;25(4):281-7.

3. Malcolm Gladwell. The ethnic theory of plane crashes. Outliers: The Story of Success. (Boston: Little, Brown and Company; 2008:177-223).

4. Helmreich RL et al. The evolution of Crew Resource Management training in commercial aviation. Int J Aviat Psychol. 1999;9(1):19-32.

5. Forsyth DR. The psychology of groups. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, Ill: DEF publishers; 2017.

6. Crew Resource Management. Available at Aviation Knowledge. Accessed Dec. 20, 2017.

Parallels from the airline industry

Parallels from the airline industry

“Workplace culture” has a profound influence on the success or failure of a team in the modern-day work environment, where teamwork and interpersonal interactions have paramount importance. Crew resource management (CRM), a technique developed originally by the airline industry, has been used as a tool to improve safety and quality in ICUs, trauma rooms, and operating rooms.1,2 This article discusses the use of CRM in hospital medicine as a tool for training and maintaining a favorable workplace culture.

Origin and evolution of CRM

United Airlines instituted the airline industry’s first crew resource management for pilots in 1981, following the 1978 crash of United Flight 173 in Portland, Ore. CRM was created based on recommendations from the National Transportation Safety Board and from a NASA workshop held subsequently.3 CRM has since evolved through five generations, and is a required annual training for most major commercial airline companies around the world. It also has been adapted for personnel training by several modern international industries.4

From the airline industry to the hospital

The health care industry is similar to the airline industry in that there is absolutely no margin of error, and that workplace culture plays a very important role. The culture being referred to here is the sum total of values, beliefs, work ethics, work strategies, strengths, and weaknesses of a group of people, and how they interact as a group. In other words, it is the dynamics of a group.

According to Donelson R. Forsyth, a social and personality psychologist at the University of Richmond (Virginia), the two key determinants of successful teamwork are a “shared mental representation of the task,” which refers to an in-depth understanding of the team and the tasks they are attempting; and “group unity/cohesion,” which means that, generally, members of cohesive groups like each other and the group, and they also are united in their pursuit of collective, group-level goals.5

Understanding the culture of a hospitalist team

Analyzing group dynamics and actively managing them toward both the institutional and global goals of health care is critical for the success of an organization. This is the core of successfully managing any team in any industry.

Additionally, the rapidly changing health care climate and insurance payment systems requires hospital medicine groups to rapidly adapt to the constantly changing health care business environment. As a result, there are a couple of ways to evaluate the effectiveness of the team:

- Measure tangible outcomes. The outcomes have to be well defined, important and measurable. These could be cost of care, quality of care, engagement of the team etc. These tangible measures’ outcome over a period of time can be used as a measure of how effective the team is.

- Simply ask your team! It is very important to know what core values the team holds dear. The best way to get that information from the team is to find out the de facto leaders of the team. They should be involved in the decision-making process, thus making them valuable to the management as well as the team.

Culture shapes outcomes

We have used the analogy of a convex and concave lens to help understand this better. A well-developed and well-coordinated team is like convex lens. A lens’ ability to converge or diverge light rays depends on certain characteristics like the curvature of surfaces and refractory index. Likewise, the culture of a group determines its ability to transform all the demands of the collective workload toward a unified goal/outcome. If it is favorable, the group will work as one and success will happen automatically.

Unfortunately, the opposite of this, (the concave lens effect), is more commonplace, where the dynamics of a team prevent the goals being achieved, as there is discordance, poor coordination of ideas and values, and team members not liking each other.

Most teams would fall somewhere within this spectrum, spanning the most favorable convex lens–like group to the least favorable concave lens–like group.

Change team dynamics using CRM principles

The concept of using CRM principles in health care is not entirely new. Such agencies as the Joint Commission and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality recommend using principles of CRM to improve communications, and as an error-prevention tool in health care.6

This approach can be broken down into four important steps:

1. Recruit right. It is important to make sure that the new recruit is the right fit for the team and that the de facto leaders and a few other team members are involved in interviewing the candidates. Their assessment should be given due consideration in making the decision to give the new recruit the job.

Every program looks for aspects like clinical competence, interpersonal communication, teamwork, etc., in a candidate, but it is even more important to make sure the candidate has the tenets that would make him/her a part of that particular team.

2. Train well. The newly recruited providers should be given focused training and the seasoned providers should be given refresher training at regular intervals. Care should be taken in designing the training programs in such a way that the providers are trained in skills that they don’t always think about, things that aren’t readily obvious, and in skills that they never get trained in during medical school and residency.

Specifically, they should be trained in:

- Values. These should include the values of both the organization and the team.

- Safety. This should include all the safety protocols that are in place in the organization - where to get help, how to report unsafe events etc.

- Communication.

Within the group: Have a mentor for the new provider, and also develop a culture where he/she feels comfortable to reach out to anyone in the team for help.

With patients and families: This training should ideally be done in a simulated environment if possible.

With other groups in the hospital: Consultants, nurses, other ancillary staff. Give them an idea about the prevailing culture in the organization with regard to these groups, so that they know what to expect when dealing with them.

- Managing perceptions. How the providers are viewed in the hospital, and how to improve it or maintain it.

- Nurturing the good. Use positive reinforcements to solidify the positive aspects of group dynamics these individuals might possess.

- Weeding out the bad. Use training and feedback to alter the negative group dynamic aspects.

3. Intervene. This is necessary either to maintain the positive aspects of a team that is already high-functioning, or to transform a poorly functioning team into a well-coordinated team. This is where the principles of CRM are going to be most useful.

There are five generations of CRM, each with a different focus.6 Only the aspects relevant to hospital medicine training are mentioned here.

- Communication. Address the gaps in communication. It is important to include people who are trusted by the team in designing and executing these sessions.

- Leadership. The goal should be to encourage the team to take ownership of the program. This will make a tremendous change in the ability of a team to deliver and rise up to challenges. The organizational leadership has to be willing to elevate the leaders of the group to positions where they can meaningfully take part in managing the team and making decisions that are critical to the team.

- Burnout management. Providers getting disillusioned: having no work-life balance; not getting enough respect from management, as well as other groups of doctors/nurses/etc. in the hospital; they are subject to bad scheduling and poor pay – all of which can all lead to career-ending burnout. It is important to recognize this and mitigate the factors that cause burnout.

- Organizational culture. If the team feels valued and supported, they will, in turn, work hard toward success. Creative leadership and a willingness to accommodate what matters the most to the team is essential for achieving this.

- Simulated training. These can be done in simulation labs, or in-group sessions with the team, re-creating difficult scenarios or problems in which the whole team can come together and solve them.

- Error containment and management. The team needs to identify possible sources of error and contain them before errors happen. The group should get together if a serious event happens and brainstorm why it happened and take measures to prevent it.

4. Reevaluate. Team dynamics tend to change over time. It is important to constantly re-evaluate the team and make sure that the team’s culture remains favorable. There should be recurrent cycles of retraining and interventions to maintain the positive growth that has been attained, as depicted in the schematic below:

Conclusion

CRM is widely accepted as an effective tool in training individuals in many high performing industries. This article describes a framework in which the principles of CRM can be applied to hospital medicine to maintain positive work culture.

Dr. Prabhakaran is director of hospital medicine transitions of care, Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, Mass., and assistant professor of medicine, University of Massachusetts, Worcester. Dr. Medarametla is medical director, hospital medicine, Baystate Medical Center, and assistant professor of medicine, University of Massachusetts.

References

1. Haerkens MH et al. Crew Resource Management in the ICU: The need for culture change. Ann Intensive Care. 2012 Aug 22;2:39.

2. Haerkens MH et al. Crew Resource Management in the trauma room: A prospective 3-year cohort study. Eur J Emerg Med. 2018 Aug;25(4):281-7.

3. Malcolm Gladwell. The ethnic theory of plane crashes. Outliers: The Story of Success. (Boston: Little, Brown and Company; 2008:177-223).

4. Helmreich RL et al. The evolution of Crew Resource Management training in commercial aviation. Int J Aviat Psychol. 1999;9(1):19-32.

5. Forsyth DR. The psychology of groups. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, Ill: DEF publishers; 2017.

6. Crew Resource Management. Available at Aviation Knowledge. Accessed Dec. 20, 2017.

“Workplace culture” has a profound influence on the success or failure of a team in the modern-day work environment, where teamwork and interpersonal interactions have paramount importance. Crew resource management (CRM), a technique developed originally by the airline industry, has been used as a tool to improve safety and quality in ICUs, trauma rooms, and operating rooms.1,2 This article discusses the use of CRM in hospital medicine as a tool for training and maintaining a favorable workplace culture.

Origin and evolution of CRM

United Airlines instituted the airline industry’s first crew resource management for pilots in 1981, following the 1978 crash of United Flight 173 in Portland, Ore. CRM was created based on recommendations from the National Transportation Safety Board and from a NASA workshop held subsequently.3 CRM has since evolved through five generations, and is a required annual training for most major commercial airline companies around the world. It also has been adapted for personnel training by several modern international industries.4

From the airline industry to the hospital

The health care industry is similar to the airline industry in that there is absolutely no margin of error, and that workplace culture plays a very important role. The culture being referred to here is the sum total of values, beliefs, work ethics, work strategies, strengths, and weaknesses of a group of people, and how they interact as a group. In other words, it is the dynamics of a group.

According to Donelson R. Forsyth, a social and personality psychologist at the University of Richmond (Virginia), the two key determinants of successful teamwork are a “shared mental representation of the task,” which refers to an in-depth understanding of the team and the tasks they are attempting; and “group unity/cohesion,” which means that, generally, members of cohesive groups like each other and the group, and they also are united in their pursuit of collective, group-level goals.5

Understanding the culture of a hospitalist team

Analyzing group dynamics and actively managing them toward both the institutional and global goals of health care is critical for the success of an organization. This is the core of successfully managing any team in any industry.

Additionally, the rapidly changing health care climate and insurance payment systems requires hospital medicine groups to rapidly adapt to the constantly changing health care business environment. As a result, there are a couple of ways to evaluate the effectiveness of the team:

- Measure tangible outcomes. The outcomes have to be well defined, important and measurable. These could be cost of care, quality of care, engagement of the team etc. These tangible measures’ outcome over a period of time can be used as a measure of how effective the team is.

- Simply ask your team! It is very important to know what core values the team holds dear. The best way to get that information from the team is to find out the de facto leaders of the team. They should be involved in the decision-making process, thus making them valuable to the management as well as the team.

Culture shapes outcomes

We have used the analogy of a convex and concave lens to help understand this better. A well-developed and well-coordinated team is like convex lens. A lens’ ability to converge or diverge light rays depends on certain characteristics like the curvature of surfaces and refractory index. Likewise, the culture of a group determines its ability to transform all the demands of the collective workload toward a unified goal/outcome. If it is favorable, the group will work as one and success will happen automatically.

Unfortunately, the opposite of this, (the concave lens effect), is more commonplace, where the dynamics of a team prevent the goals being achieved, as there is discordance, poor coordination of ideas and values, and team members not liking each other.

Most teams would fall somewhere within this spectrum, spanning the most favorable convex lens–like group to the least favorable concave lens–like group.

Change team dynamics using CRM principles

The concept of using CRM principles in health care is not entirely new. Such agencies as the Joint Commission and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality recommend using principles of CRM to improve communications, and as an error-prevention tool in health care.6

This approach can be broken down into four important steps:

1. Recruit right. It is important to make sure that the new recruit is the right fit for the team and that the de facto leaders and a few other team members are involved in interviewing the candidates. Their assessment should be given due consideration in making the decision to give the new recruit the job.

Every program looks for aspects like clinical competence, interpersonal communication, teamwork, etc., in a candidate, but it is even more important to make sure the candidate has the tenets that would make him/her a part of that particular team.

2. Train well. The newly recruited providers should be given focused training and the seasoned providers should be given refresher training at regular intervals. Care should be taken in designing the training programs in such a way that the providers are trained in skills that they don’t always think about, things that aren’t readily obvious, and in skills that they never get trained in during medical school and residency.

Specifically, they should be trained in:

- Values. These should include the values of both the organization and the team.

- Safety. This should include all the safety protocols that are in place in the organization - where to get help, how to report unsafe events etc.

- Communication.

Within the group: Have a mentor for the new provider, and also develop a culture where he/she feels comfortable to reach out to anyone in the team for help.

With patients and families: This training should ideally be done in a simulated environment if possible.

With other groups in the hospital: Consultants, nurses, other ancillary staff. Give them an idea about the prevailing culture in the organization with regard to these groups, so that they know what to expect when dealing with them.

- Managing perceptions. How the providers are viewed in the hospital, and how to improve it or maintain it.

- Nurturing the good. Use positive reinforcements to solidify the positive aspects of group dynamics these individuals might possess.

- Weeding out the bad. Use training and feedback to alter the negative group dynamic aspects.

3. Intervene. This is necessary either to maintain the positive aspects of a team that is already high-functioning, or to transform a poorly functioning team into a well-coordinated team. This is where the principles of CRM are going to be most useful.

There are five generations of CRM, each with a different focus.6 Only the aspects relevant to hospital medicine training are mentioned here.

- Communication. Address the gaps in communication. It is important to include people who are trusted by the team in designing and executing these sessions.

- Leadership. The goal should be to encourage the team to take ownership of the program. This will make a tremendous change in the ability of a team to deliver and rise up to challenges. The organizational leadership has to be willing to elevate the leaders of the group to positions where they can meaningfully take part in managing the team and making decisions that are critical to the team.

- Burnout management. Providers getting disillusioned: having no work-life balance; not getting enough respect from management, as well as other groups of doctors/nurses/etc. in the hospital; they are subject to bad scheduling and poor pay – all of which can all lead to career-ending burnout. It is important to recognize this and mitigate the factors that cause burnout.

- Organizational culture. If the team feels valued and supported, they will, in turn, work hard toward success. Creative leadership and a willingness to accommodate what matters the most to the team is essential for achieving this.

- Simulated training. These can be done in simulation labs, or in-group sessions with the team, re-creating difficult scenarios or problems in which the whole team can come together and solve them.

- Error containment and management. The team needs to identify possible sources of error and contain them before errors happen. The group should get together if a serious event happens and brainstorm why it happened and take measures to prevent it.

4. Reevaluate. Team dynamics tend to change over time. It is important to constantly re-evaluate the team and make sure that the team’s culture remains favorable. There should be recurrent cycles of retraining and interventions to maintain the positive growth that has been attained, as depicted in the schematic below:

Conclusion

CRM is widely accepted as an effective tool in training individuals in many high performing industries. This article describes a framework in which the principles of CRM can be applied to hospital medicine to maintain positive work culture.

Dr. Prabhakaran is director of hospital medicine transitions of care, Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, Mass., and assistant professor of medicine, University of Massachusetts, Worcester. Dr. Medarametla is medical director, hospital medicine, Baystate Medical Center, and assistant professor of medicine, University of Massachusetts.

References

1. Haerkens MH et al. Crew Resource Management in the ICU: The need for culture change. Ann Intensive Care. 2012 Aug 22;2:39.

2. Haerkens MH et al. Crew Resource Management in the trauma room: A prospective 3-year cohort study. Eur J Emerg Med. 2018 Aug;25(4):281-7.

3. Malcolm Gladwell. The ethnic theory of plane crashes. Outliers: The Story of Success. (Boston: Little, Brown and Company; 2008:177-223).

4. Helmreich RL et al. The evolution of Crew Resource Management training in commercial aviation. Int J Aviat Psychol. 1999;9(1):19-32.

5. Forsyth DR. The psychology of groups. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, Ill: DEF publishers; 2017.

6. Crew Resource Management. Available at Aviation Knowledge. Accessed Dec. 20, 2017.