User login

A Joint Effort to Save the Joints: What Dermatologists Need to Know About Psoriatic Arthritis

Nearly all dermatologists are aware that psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is one of the most prevalent comorbidities associated with psoriasis, yet we may lack the insight regarding how to utilize this information. After all, we specialize in the skin, not the joints, right?

When I graduated from residency in 2014, I began staffing our psoriasis clinic, where we care for the toughest, most complicated psoriasis patients, many of them struggling with both severe recalcitrant psoriasis as well as debilitating PsA. In 2016, we partnered with rheumatology to open a multidisciplinary psoriasis and PsA clinic, and I quickly began to appreciate how much PsA was being overlooked simply because patients with psoriasis were not being asked about their joints.

To start, let’s look at several facts:

- One quarter of patients with psoriasis also have PsA.1

- Skin disease most commonly develops before PsA.1

- Fifteen percent of PsA cases go undiagnosed, which dramatically increases the risk for deformed joints, erosions, osteolysis, sacroiliitis, and arthritis mutilans2 and also increases the cost of health care.3

- Everyone is crazy busy—rheumatology wait lists often are months long.

Given that dermatologists are the ones who already are seeing the majority of patients who develop PsA, we play a key role in screening for this debilitating comorbidity and starting therapy for patients with both psoriasis and PsA. We, too, are crazy busy; therefore, we need to make this process quick and efficient but also reliable. Fortunately, the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) is effective, fast, and very easy. With only 5 questions and a sensitivity and specificity of around 70%,4 this short and simple questionnaire can be incorporated into an intake form or rooming note or can just be asked during the visit. The questions include whether the patient currently has or has had a swollen joint, nail pits, heel pain, and/or dactylitis, as well as if they have been told by a physician that they have arthritis. A score of 3 or higher is considered positive and a referral to rheumatology should be considered. At the bare minimum, I highly encourage all dermatologists to incorporate the PEST screening tool into their practice.

During the physical examination itself, be sure to look at the patient’s nails and also look for joint swelling and redness, especially in the hands. When palpating a swollen joint, the presence of inflammatory arthritis will feel spongy or boggy, while the osteophytes associated with osteoarthritis will feel hard. Radiography of the affected joint may be helpful, but keep in mind that bone changes are latter sequelae of PsA, and negative radiographs do not rule out PsA.

If you highly suspect PsA after using the PEST screening tool and palpating any swollen joints, then a rheumatology referral certainly is warranted. Medication that covers both psoriasis and PsA also can be initiated. Although methotrexate often is used for joints, higher doses (ie, >15 mg/wk) usually are needed. A 2019 Cochrane review found that low-dose methotrexate (ie, ≤15 mg/wk) may be only slightly more effective then placebo5—certainly not a ringing endorsement for its use in PsA. Additionally, quality data demonstrating methotrexate’s efficacy for enthesitis or axial spondyloarthritis is lacking, and methotrexate has not demonstrated an ability to slow the radiographic progression of joints. In contrast, the anti–tumor necrosis factor agents, including adalimumab, infliximab, etanercept, and certolizumab, as well as ustekinumab and the anti–IL-17 biologics secukinumab and ixekizumab have demonstrated efficacy in American College of Rheumatology (ACR) scores, enthesitis, dactylitis, and prevention of radiographic progression of joints.6,7 Although brodalumab, an anti–IL-17 receptor inhibitor, demonstrated improvement in ACR scores, enthesitis, and dactylitis, data on its effects on radiographic progression of joints were inconclusive given the phase III trial’s premature ending due to suicidal ideation and behavior in participants.8 Several of the anti–IL-23 agents also may help PsA, with trials demonstrating improvements in ACR scores, enthesitis, and dactylitis; however, only guselkumab 100 mg every 4 weeks decreased radiographic progression of joints.9 Additionally, with the age of the Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor upon us, there are several JAK/TYK2 inhibitors that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for psoriasis (deucravacitinib) as well as for PsA (tofacitinib, upadacitinib), and there are more JAK inhibitors in the pipeline. These medications are effective; however, I do encourage caution and careful consideration in selecting the appropriate patient, as data demonstrated an increased risk for major adverse cardiovascular events and cancer in older (>50 years) rheumatoid arthritis patients who had at least 1 cardiovascular risk factor and were treated with tofacitinib.10 Although several other trials have not demonstrated this increased risk, further data are needed to determine risk for both pan-JAK inhibitors as well as selective JAK inhibitors and TYK2 inhibitors. Additionally, given psoriasis already is closely linked with many cardiovascular risk factors including heart disease, obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus,11 it will be important to have long-term safety information for JAK inhibitors in the psoriasis and PsA population.

Dermatologists are in a pivotal position to identify patients affected by PsA and start an appropriate systemic medication. We can help make an enormous impact on our patients’ lives as well as help decrease the economic impact of untreated disease. Let’s join the effort to save the joints!

- Alinaghi F, Calov M, Kristensen L, et al. Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and clinical studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:251-265.

- Villani A, Zouzaud M, Sevrain M, et al. Prevalence of undiagnosed psoriatic arthritis among psoriasis patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:242-248.

- Iragorri N, Hazlewood G, Manns B, et al. Model to determine the cost-effectiveness of screening psoriasis patients for psoriatic arthritis. Arth Car Res. 2021;73:266-274.

- Karreman M, Weel A, Van der Ven M, et al. Performance of screening tools for psoriatic arthritis: a cross-sectional study in primary care. Rheumatology. 2017;56:597-602.

- Wilsdon TD, Whittle SL, Thynne TR, et al. Methotrexate for psoriatic arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;1:CD012722. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012722.pub2

- Mourad A, Gniadecki R. Treatment of dactylitis and enthesitis in psoriatic arthritis with biologic agents: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Rheum. 2020;47:59-65.

- Wu D, Li C, Zhang S, et al. Effect of biologics on radiographic progression of peripheral joint in patients with psoriatic arthritis: meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;59:3172-3180.

- Mease P, Helliwell P, Fjellhaugen Hjuler K, et al. Brodalumab in psoriatic arthritis: results from the randomised phase III AMVISION-1 and AMVISION-2 trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:185-193.

- McInnes I, Rahman P, Gottlieb A, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of guselkumab, a monoclonal antibody specific to the p19 subunit of interleukin-23, through two years: results from a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study conducted in biologic-naïve patients with active psoriatic arthritis. Arth Rheum. 2022;74:475-485.

- Ytterberg S, Bhatt D, Mikuls T, et al. Cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:316-326.

- Miller I, Ellervik C, Yazdanyar S, et al. Meta-analysis of psoriasis, cardiovascular disease, and associated risk factors. JAAD. 2013;69:1014-1024.

Nearly all dermatologists are aware that psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is one of the most prevalent comorbidities associated with psoriasis, yet we may lack the insight regarding how to utilize this information. After all, we specialize in the skin, not the joints, right?

When I graduated from residency in 2014, I began staffing our psoriasis clinic, where we care for the toughest, most complicated psoriasis patients, many of them struggling with both severe recalcitrant psoriasis as well as debilitating PsA. In 2016, we partnered with rheumatology to open a multidisciplinary psoriasis and PsA clinic, and I quickly began to appreciate how much PsA was being overlooked simply because patients with psoriasis were not being asked about their joints.

To start, let’s look at several facts:

- One quarter of patients with psoriasis also have PsA.1

- Skin disease most commonly develops before PsA.1

- Fifteen percent of PsA cases go undiagnosed, which dramatically increases the risk for deformed joints, erosions, osteolysis, sacroiliitis, and arthritis mutilans2 and also increases the cost of health care.3

- Everyone is crazy busy—rheumatology wait lists often are months long.

Given that dermatologists are the ones who already are seeing the majority of patients who develop PsA, we play a key role in screening for this debilitating comorbidity and starting therapy for patients with both psoriasis and PsA. We, too, are crazy busy; therefore, we need to make this process quick and efficient but also reliable. Fortunately, the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) is effective, fast, and very easy. With only 5 questions and a sensitivity and specificity of around 70%,4 this short and simple questionnaire can be incorporated into an intake form or rooming note or can just be asked during the visit. The questions include whether the patient currently has or has had a swollen joint, nail pits, heel pain, and/or dactylitis, as well as if they have been told by a physician that they have arthritis. A score of 3 or higher is considered positive and a referral to rheumatology should be considered. At the bare minimum, I highly encourage all dermatologists to incorporate the PEST screening tool into their practice.

During the physical examination itself, be sure to look at the patient’s nails and also look for joint swelling and redness, especially in the hands. When palpating a swollen joint, the presence of inflammatory arthritis will feel spongy or boggy, while the osteophytes associated with osteoarthritis will feel hard. Radiography of the affected joint may be helpful, but keep in mind that bone changes are latter sequelae of PsA, and negative radiographs do not rule out PsA.

If you highly suspect PsA after using the PEST screening tool and palpating any swollen joints, then a rheumatology referral certainly is warranted. Medication that covers both psoriasis and PsA also can be initiated. Although methotrexate often is used for joints, higher doses (ie, >15 mg/wk) usually are needed. A 2019 Cochrane review found that low-dose methotrexate (ie, ≤15 mg/wk) may be only slightly more effective then placebo5—certainly not a ringing endorsement for its use in PsA. Additionally, quality data demonstrating methotrexate’s efficacy for enthesitis or axial spondyloarthritis is lacking, and methotrexate has not demonstrated an ability to slow the radiographic progression of joints. In contrast, the anti–tumor necrosis factor agents, including adalimumab, infliximab, etanercept, and certolizumab, as well as ustekinumab and the anti–IL-17 biologics secukinumab and ixekizumab have demonstrated efficacy in American College of Rheumatology (ACR) scores, enthesitis, dactylitis, and prevention of radiographic progression of joints.6,7 Although brodalumab, an anti–IL-17 receptor inhibitor, demonstrated improvement in ACR scores, enthesitis, and dactylitis, data on its effects on radiographic progression of joints were inconclusive given the phase III trial’s premature ending due to suicidal ideation and behavior in participants.8 Several of the anti–IL-23 agents also may help PsA, with trials demonstrating improvements in ACR scores, enthesitis, and dactylitis; however, only guselkumab 100 mg every 4 weeks decreased radiographic progression of joints.9 Additionally, with the age of the Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor upon us, there are several JAK/TYK2 inhibitors that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for psoriasis (deucravacitinib) as well as for PsA (tofacitinib, upadacitinib), and there are more JAK inhibitors in the pipeline. These medications are effective; however, I do encourage caution and careful consideration in selecting the appropriate patient, as data demonstrated an increased risk for major adverse cardiovascular events and cancer in older (>50 years) rheumatoid arthritis patients who had at least 1 cardiovascular risk factor and were treated with tofacitinib.10 Although several other trials have not demonstrated this increased risk, further data are needed to determine risk for both pan-JAK inhibitors as well as selective JAK inhibitors and TYK2 inhibitors. Additionally, given psoriasis already is closely linked with many cardiovascular risk factors including heart disease, obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus,11 it will be important to have long-term safety information for JAK inhibitors in the psoriasis and PsA population.

Dermatologists are in a pivotal position to identify patients affected by PsA and start an appropriate systemic medication. We can help make an enormous impact on our patients’ lives as well as help decrease the economic impact of untreated disease. Let’s join the effort to save the joints!

Nearly all dermatologists are aware that psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is one of the most prevalent comorbidities associated with psoriasis, yet we may lack the insight regarding how to utilize this information. After all, we specialize in the skin, not the joints, right?

When I graduated from residency in 2014, I began staffing our psoriasis clinic, where we care for the toughest, most complicated psoriasis patients, many of them struggling with both severe recalcitrant psoriasis as well as debilitating PsA. In 2016, we partnered with rheumatology to open a multidisciplinary psoriasis and PsA clinic, and I quickly began to appreciate how much PsA was being overlooked simply because patients with psoriasis were not being asked about their joints.

To start, let’s look at several facts:

- One quarter of patients with psoriasis also have PsA.1

- Skin disease most commonly develops before PsA.1

- Fifteen percent of PsA cases go undiagnosed, which dramatically increases the risk for deformed joints, erosions, osteolysis, sacroiliitis, and arthritis mutilans2 and also increases the cost of health care.3

- Everyone is crazy busy—rheumatology wait lists often are months long.

Given that dermatologists are the ones who already are seeing the majority of patients who develop PsA, we play a key role in screening for this debilitating comorbidity and starting therapy for patients with both psoriasis and PsA. We, too, are crazy busy; therefore, we need to make this process quick and efficient but also reliable. Fortunately, the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) is effective, fast, and very easy. With only 5 questions and a sensitivity and specificity of around 70%,4 this short and simple questionnaire can be incorporated into an intake form or rooming note or can just be asked during the visit. The questions include whether the patient currently has or has had a swollen joint, nail pits, heel pain, and/or dactylitis, as well as if they have been told by a physician that they have arthritis. A score of 3 or higher is considered positive and a referral to rheumatology should be considered. At the bare minimum, I highly encourage all dermatologists to incorporate the PEST screening tool into their practice.

During the physical examination itself, be sure to look at the patient’s nails and also look for joint swelling and redness, especially in the hands. When palpating a swollen joint, the presence of inflammatory arthritis will feel spongy or boggy, while the osteophytes associated with osteoarthritis will feel hard. Radiography of the affected joint may be helpful, but keep in mind that bone changes are latter sequelae of PsA, and negative radiographs do not rule out PsA.

If you highly suspect PsA after using the PEST screening tool and palpating any swollen joints, then a rheumatology referral certainly is warranted. Medication that covers both psoriasis and PsA also can be initiated. Although methotrexate often is used for joints, higher doses (ie, >15 mg/wk) usually are needed. A 2019 Cochrane review found that low-dose methotrexate (ie, ≤15 mg/wk) may be only slightly more effective then placebo5—certainly not a ringing endorsement for its use in PsA. Additionally, quality data demonstrating methotrexate’s efficacy for enthesitis or axial spondyloarthritis is lacking, and methotrexate has not demonstrated an ability to slow the radiographic progression of joints. In contrast, the anti–tumor necrosis factor agents, including adalimumab, infliximab, etanercept, and certolizumab, as well as ustekinumab and the anti–IL-17 biologics secukinumab and ixekizumab have demonstrated efficacy in American College of Rheumatology (ACR) scores, enthesitis, dactylitis, and prevention of radiographic progression of joints.6,7 Although brodalumab, an anti–IL-17 receptor inhibitor, demonstrated improvement in ACR scores, enthesitis, and dactylitis, data on its effects on radiographic progression of joints were inconclusive given the phase III trial’s premature ending due to suicidal ideation and behavior in participants.8 Several of the anti–IL-23 agents also may help PsA, with trials demonstrating improvements in ACR scores, enthesitis, and dactylitis; however, only guselkumab 100 mg every 4 weeks decreased radiographic progression of joints.9 Additionally, with the age of the Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor upon us, there are several JAK/TYK2 inhibitors that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for psoriasis (deucravacitinib) as well as for PsA (tofacitinib, upadacitinib), and there are more JAK inhibitors in the pipeline. These medications are effective; however, I do encourage caution and careful consideration in selecting the appropriate patient, as data demonstrated an increased risk for major adverse cardiovascular events and cancer in older (>50 years) rheumatoid arthritis patients who had at least 1 cardiovascular risk factor and were treated with tofacitinib.10 Although several other trials have not demonstrated this increased risk, further data are needed to determine risk for both pan-JAK inhibitors as well as selective JAK inhibitors and TYK2 inhibitors. Additionally, given psoriasis already is closely linked with many cardiovascular risk factors including heart disease, obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus,11 it will be important to have long-term safety information for JAK inhibitors in the psoriasis and PsA population.

Dermatologists are in a pivotal position to identify patients affected by PsA and start an appropriate systemic medication. We can help make an enormous impact on our patients’ lives as well as help decrease the economic impact of untreated disease. Let’s join the effort to save the joints!

- Alinaghi F, Calov M, Kristensen L, et al. Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and clinical studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:251-265.

- Villani A, Zouzaud M, Sevrain M, et al. Prevalence of undiagnosed psoriatic arthritis among psoriasis patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:242-248.

- Iragorri N, Hazlewood G, Manns B, et al. Model to determine the cost-effectiveness of screening psoriasis patients for psoriatic arthritis. Arth Car Res. 2021;73:266-274.

- Karreman M, Weel A, Van der Ven M, et al. Performance of screening tools for psoriatic arthritis: a cross-sectional study in primary care. Rheumatology. 2017;56:597-602.

- Wilsdon TD, Whittle SL, Thynne TR, et al. Methotrexate for psoriatic arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;1:CD012722. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012722.pub2

- Mourad A, Gniadecki R. Treatment of dactylitis and enthesitis in psoriatic arthritis with biologic agents: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Rheum. 2020;47:59-65.

- Wu D, Li C, Zhang S, et al. Effect of biologics on radiographic progression of peripheral joint in patients with psoriatic arthritis: meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;59:3172-3180.

- Mease P, Helliwell P, Fjellhaugen Hjuler K, et al. Brodalumab in psoriatic arthritis: results from the randomised phase III AMVISION-1 and AMVISION-2 trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:185-193.

- McInnes I, Rahman P, Gottlieb A, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of guselkumab, a monoclonal antibody specific to the p19 subunit of interleukin-23, through two years: results from a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study conducted in biologic-naïve patients with active psoriatic arthritis. Arth Rheum. 2022;74:475-485.

- Ytterberg S, Bhatt D, Mikuls T, et al. Cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:316-326.

- Miller I, Ellervik C, Yazdanyar S, et al. Meta-analysis of psoriasis, cardiovascular disease, and associated risk factors. JAAD. 2013;69:1014-1024.

- Alinaghi F, Calov M, Kristensen L, et al. Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and clinical studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:251-265.

- Villani A, Zouzaud M, Sevrain M, et al. Prevalence of undiagnosed psoriatic arthritis among psoriasis patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:242-248.

- Iragorri N, Hazlewood G, Manns B, et al. Model to determine the cost-effectiveness of screening psoriasis patients for psoriatic arthritis. Arth Car Res. 2021;73:266-274.

- Karreman M, Weel A, Van der Ven M, et al. Performance of screening tools for psoriatic arthritis: a cross-sectional study in primary care. Rheumatology. 2017;56:597-602.

- Wilsdon TD, Whittle SL, Thynne TR, et al. Methotrexate for psoriatic arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;1:CD012722. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012722.pub2

- Mourad A, Gniadecki R. Treatment of dactylitis and enthesitis in psoriatic arthritis with biologic agents: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Rheum. 2020;47:59-65.

- Wu D, Li C, Zhang S, et al. Effect of biologics on radiographic progression of peripheral joint in patients with psoriatic arthritis: meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;59:3172-3180.

- Mease P, Helliwell P, Fjellhaugen Hjuler K, et al. Brodalumab in psoriatic arthritis: results from the randomised phase III AMVISION-1 and AMVISION-2 trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:185-193.

- McInnes I, Rahman P, Gottlieb A, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of guselkumab, a monoclonal antibody specific to the p19 subunit of interleukin-23, through two years: results from a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study conducted in biologic-naïve patients with active psoriatic arthritis. Arth Rheum. 2022;74:475-485.

- Ytterberg S, Bhatt D, Mikuls T, et al. Cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:316-326.

- Miller I, Ellervik C, Yazdanyar S, et al. Meta-analysis of psoriasis, cardiovascular disease, and associated risk factors. JAAD. 2013;69:1014-1024.

How to Advise Medical Students Interested in Dermatology: A Survey of Academic Dermatology Mentors

Dermatology remains one of the most competitive specialties in medicine. In 2022, there were 851 applicants (613 doctor of medicine seniors, 85 doctor of osteopathic medicine seniors) for 492 postgraduate year (PGY) 2 positions.1 During the 2022 application season, the average matched dermatology candidate had 7.2 research experiences; 20.9 abstracts, presentations, or publications; 11 volunteer experiences; and a US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 2 Clinical Knowledge score of 257.1 With hopes of matching into such a competitive field, students often seek advice from academic dermatology mentors. Such advice may substantially differ based on each mentor and may or may not be evidence based.

We sought to analyze the range of advice given to medical students applying to dermatology residency programs via a survey to members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) with the intent to help applicants and mentors understand how letters of intent, letters of recommendation (LORs), and Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) supplemental applications are used by dermatology programs nationwide.

Methods

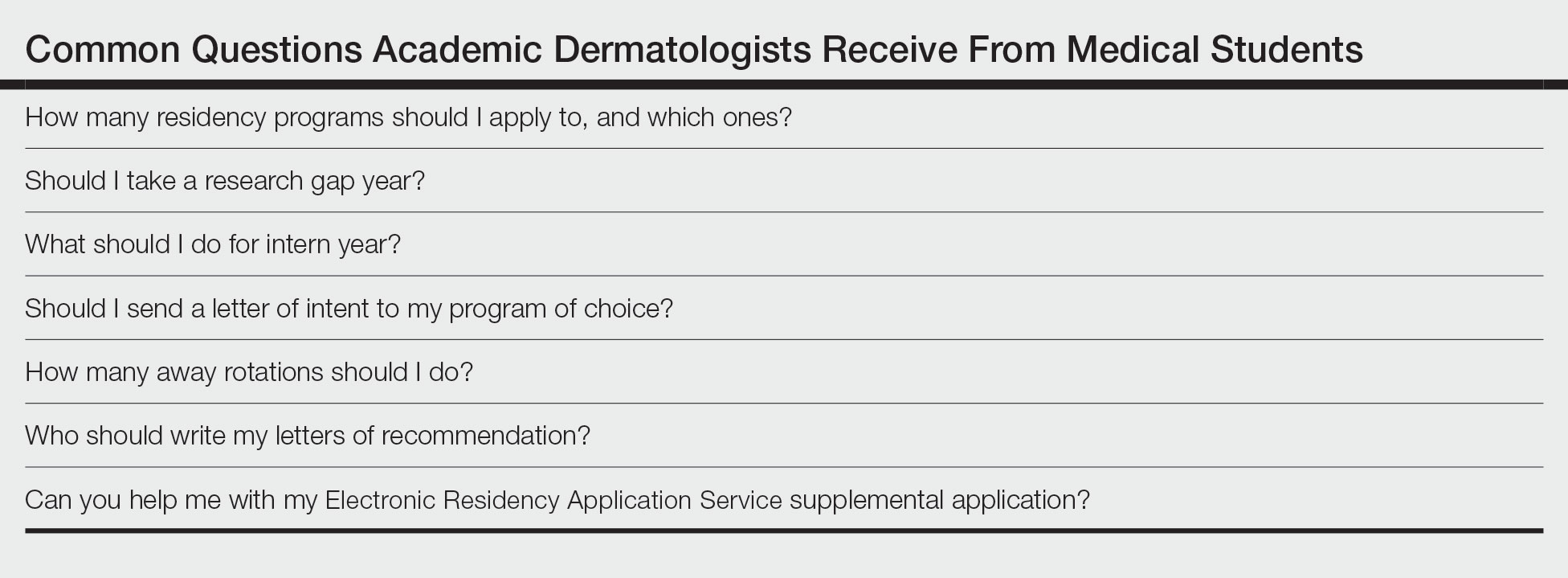

The study was reviewed by The Ohio State University institutional review board and was deemed exempt. A branching-logic survey with common questions from medical students while applying to dermatology residency programs (Table) was sent to all members of APD through the email listserve. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at The Ohio State University (Columbus, Ohio) to ensure data security.

The survey was distributed from August 28, 2022, to September 12, 2022. A total of 101 surveys were returned from 646 listserve members (15.6%). Given the branching-logic questions, differing numbers of responses were collected for each question. Descriptive statistics were utilized to analyze and report the results.

Results

Residency Program Number—Members of the APD were asked if they recommend students apply to a certain number of programs, and if so, how many programs. Of members who responded, 62.2% (61/98) either always (22.4% [22/98]) or sometimes (40.2% [39/97]) suggested students apply to a certain number of programs. When mentors made a recommendation, 54.1% (33/61) recommended applying to 59 or fewer programs, with only 9.8% (6/61) recommending students apply to 80 or more programs.

Gap Year—We queried mentors about their recommendations for a research gap year and asked which applicants should pursue this extra year. Our survey found that 74.5% of mentors (73/98) almost always (4.1% [4/98]) or sometimes (70.4% [69/98]) recommended a research gap year, most commonly for those applicants with a strong research interest (71.8% [51/71]). Other reasons mentors recommended a dedicated research year during medical school included low USMLE Step scores (50.7% [36/71]), low grades (45.1% [32/71]), little research (46.5% [33/71]), and no home program (43.7% [31/71]).

Internship Choices—Our survey results indicated that nearly two-thirds (63.3% [62/98]) of mentors did not give applicants a recommendation on type of internship (PGY-1). If a recommendation was given, academic dermatologists more commonly recommended an internal medicine preliminary year (29.6% [29/98]) over a transitional year (7.1% [7/98]).

Communication of Interest Via a Letter of Intent—We asked mentors if they recommended applicants send a letter of intent and conversely if receiving a letter of intent impacted their rank list. Nearly half (48.5% [47/97]) of mentors indicated they did not recommend sending a letter of intent, with only 15.5% (15/97) of mentors regularly recommending this practice. Additionally, 75.8% of mentors indicated that a letter of intent never (42.1% [40/95]) or rarely (33.7% [32/95]) impacted their rank list.

Rotation Choices—We queried mentors if they recommended students complete away rotations, and if so, how many rotations did they recommend. We found that 85.9% (85/99) of mentors recommended students complete an away rotation; 63.1% (53/84) of them recommended performing 2 away rotations, and 14.3% (12/84) of respondents recommended students complete 3 away rotations. More than a quarter of mentors (27.1% [23/85]) indicated their home medical schools limited the number of away rotations a medical student could complete in any 1 specialty, and 42.4% (36/85) of respondents were unsure if such a limitation existed.

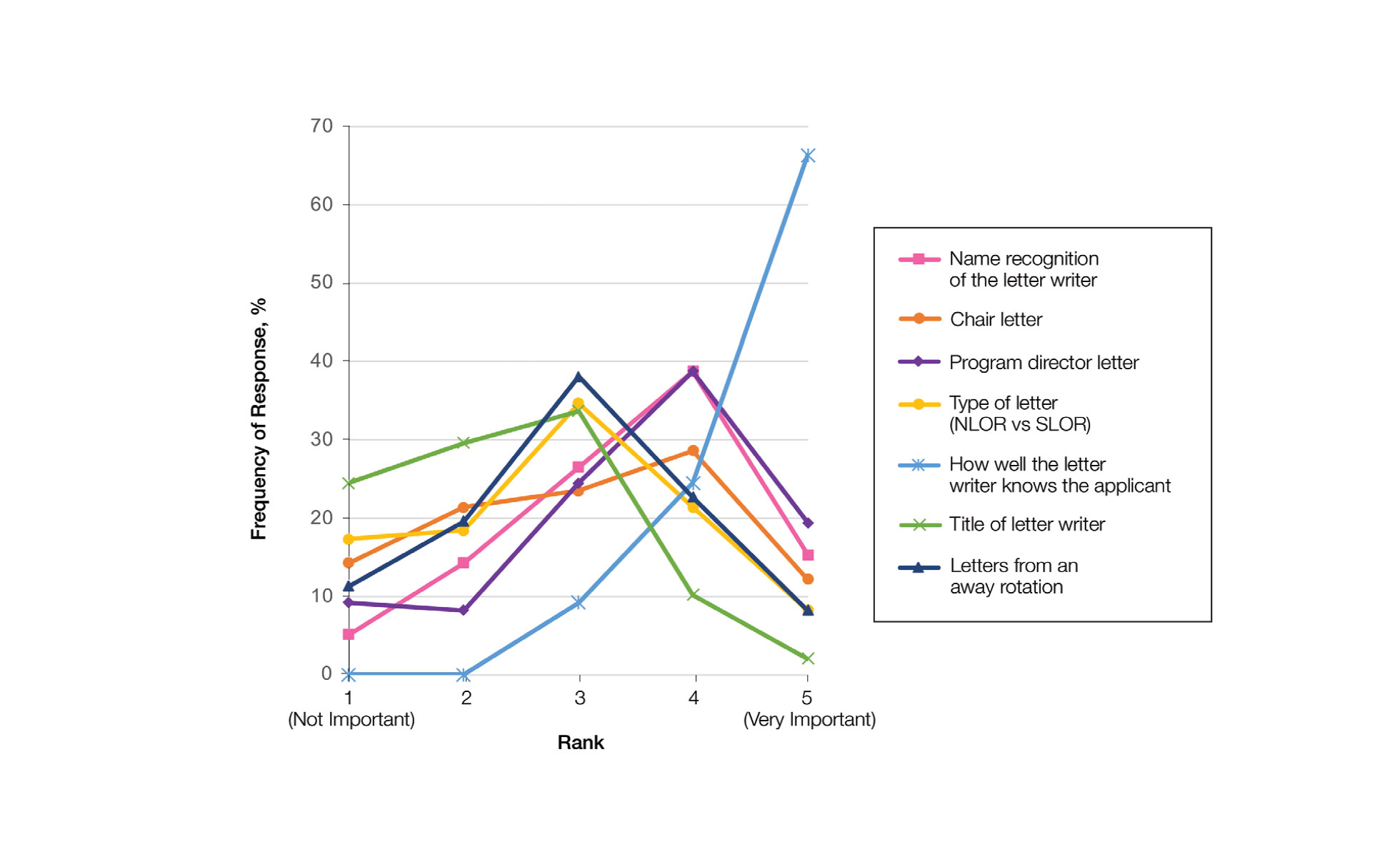

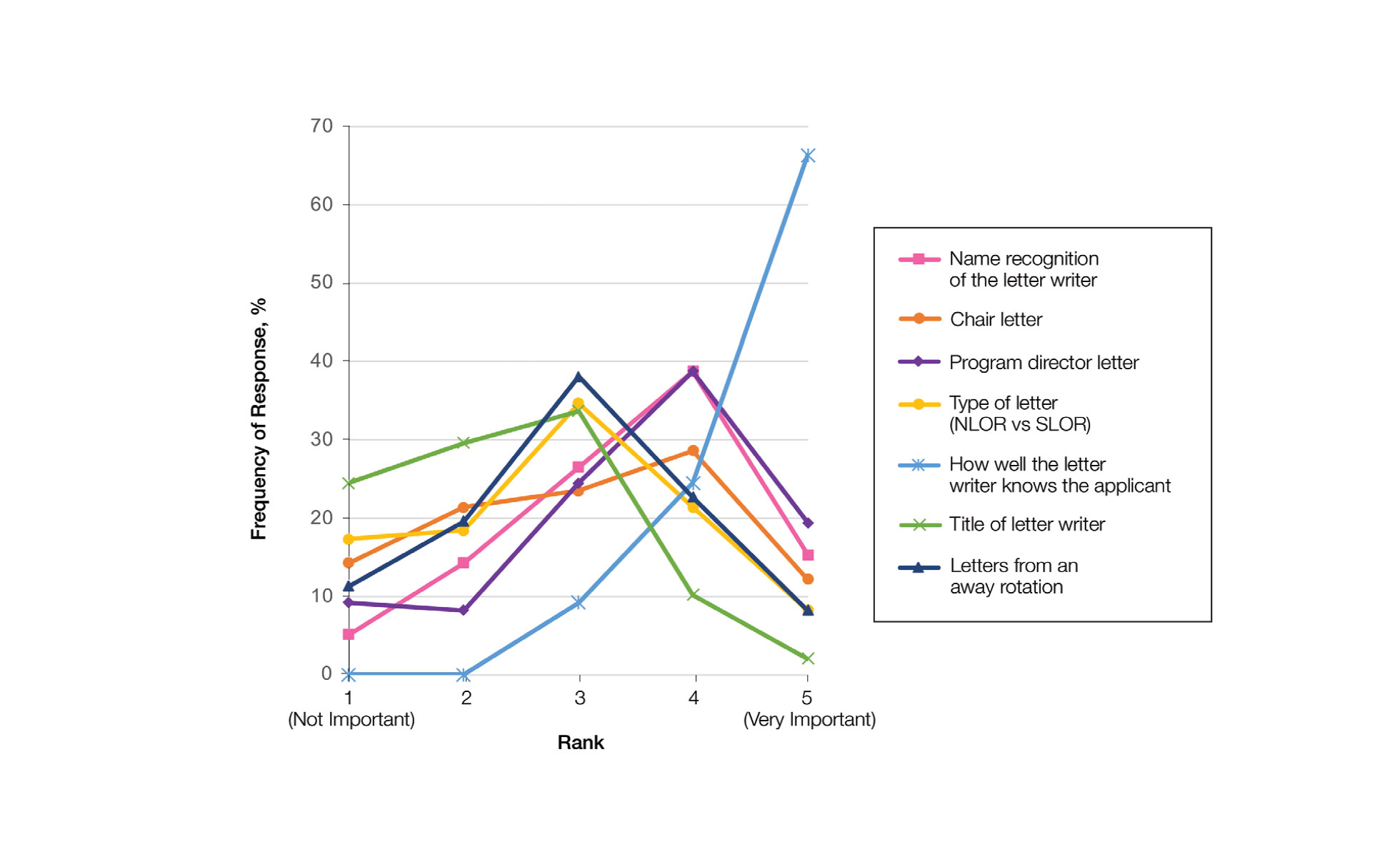

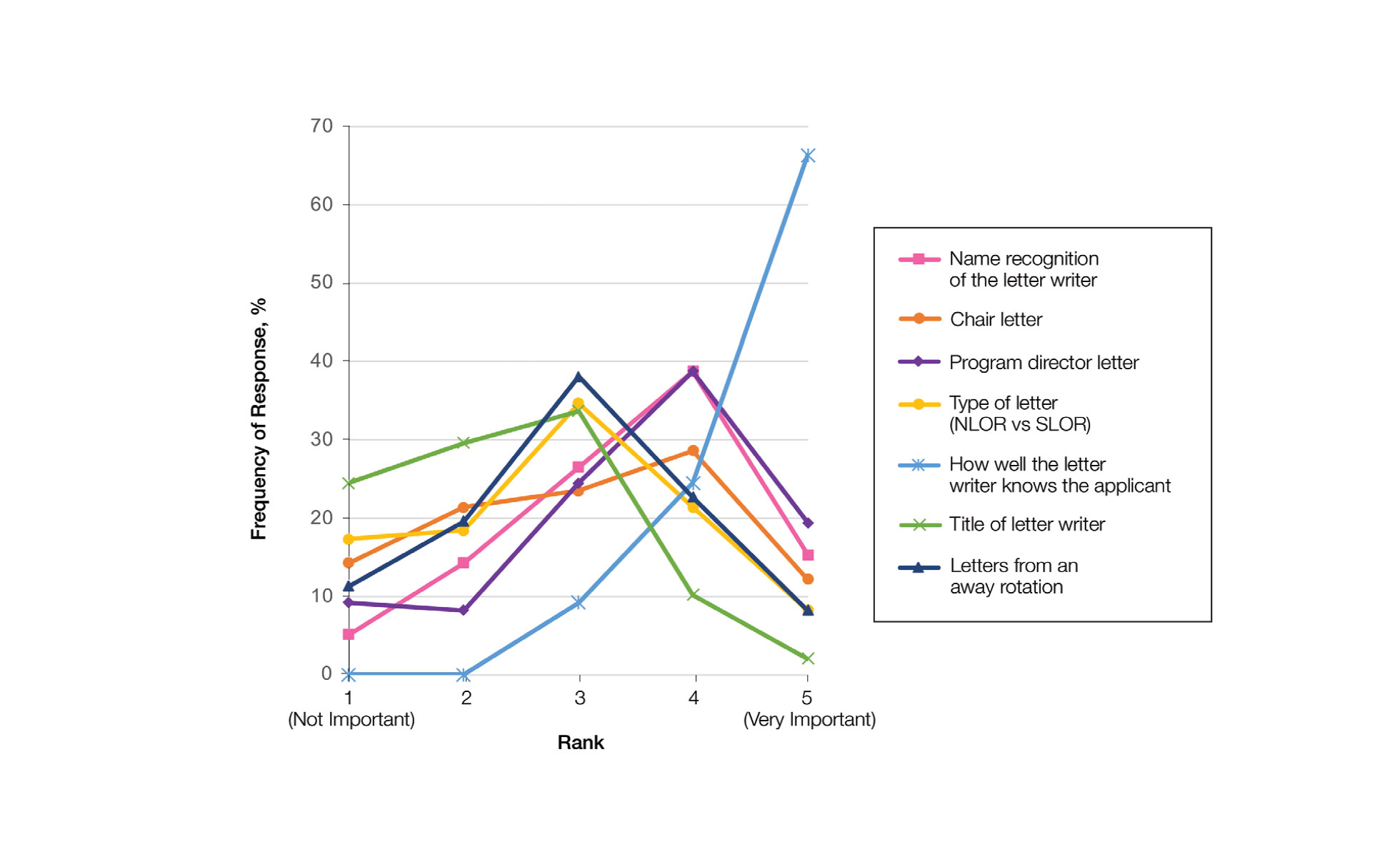

Letters of Recommendation—Our survey asked respondents to rank various factors on a 5-point scale (1=not important; 5=very important) when deciding who should write the students’ LORs. Mentors indicated that the most important factor for letter-writer selection was how well the letter writer knows the applicant, with 90.8% (89/98) of mentors rating the importance of this quality as a 4 or 5 (Figure). More than half of respondents rated the name recognition of the letter writer and program director letter as a 4 or 5 in importance (54.1% [53/98] and 58.2% [57/98], respectively). Type of letter (standardized vs nonstandardized), title of letter writer, letters from an away rotation, and chair letter scored lower, with fewer than half of mentors rating these as a 4 or 5 in importance.

Supplemental Application—When asked about the 2022 application cycle, respondents of our survey reported that the supplemental application was overall more important in deciding which applicants to interview vs which to rank highly. Prior experiences were important (ranked 4 or 5) for 58.8% (57/97) of respondents in choosing applicants to interview, and 49.4% (48/97) of respondents thought prior experiences were important for ranking. Similarly, 34.0% (33/97) of mentors indicated geographic preference was important (ranked 4 or 5) for interview compared with only 23.8% (23/97) for ranking. Finally, 57.7% (56/97) of our survey respondents denoted that program signals were important or very important in choosing which applicants to interview, while 32.0% (31/97) indicated that program signals were important in ranking applicants.

Comment

Residency Programs: Which Ones, and How Many?—The number of applications for dermatology residency programs has increased 33.9% from 2010 to 2019.2 The American Association of Medical Colleges Apply Smart data from 2013 to 2017 indicate that dermatology applicants arrive at a point of diminishing return between 37 and 62 applications, with variation within that range based on USMLE Step 1 score,3 and our data support this with nearly two-thirds of dermatology advisors recommending students apply within this range. Despite this data, dermatology residency applicants applied to more programs over the last decade (64.8 vs 77.0),2 likely to maximize their chance of matching.

Research Gap Years During Medical School—Prior research has shown that nearly half of faculty indicated that a research year during medical school can distinguish similar applicants, and close to 25% of applicants completed a research gap year.4,5 However, available data indicate that taking a research gap year has no effect on match rate or number of interview invites but does correlate with match rates at the highest ranked dermatology residency programs.6-8

Our data indicate that the most commonly recommended reason for a research gap year was an applicants’ strong interest in research. However, nearly half of dermatology mentors recommended research years during medical school for reasons other than an interest in research. As research gap years increase in popularity, future research is needed to confirm the consequence of this additional year and which applicants, if any, will benefit from such a year.

Preferences for Intern Year—Prior research suggests that dermatology residency program directors favor PGY-1 preliminary medicine internships because of the rigor of training.9,10 Our data continue to show a preference for internal medicine preliminary years over transitional years. However, given nearly two-thirds of dermatology mentors do not give applicants any recommendations on PGY-1 year, this preference may be fading.

Letters of Intent Not Recommended—Research in 2022 found that 78.8% of dermatology applicants sent a letter of intent communicating a plan to rank that program number 1, with nearly 13% sending such a letter to more than 1 program.11 With nearly half of mentors in our survey actively discouraging this process and more than 75% of mentors not utilizing this letter, the APD issued a brief statement on the 2022-2023 application cycle stating, “Post-interview communication of preference—including ‘letters of intent’ and thank you letters—should not be sent to programs. These types of communication are typically not used by residency programs in decision-making and lead to downstream pressures on applicants.”12

Away Rotations—Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, data demonstrated that nearly one-third of dermatology applicants (29%) matched at their home institution, and nearly one-fifth (18%) matched where they completed an away rotation.13 In-person away rotations were eliminated in 2020 and restricted to 1 away rotation in 2021. Restrictions regarding away rotations were removed in 2022. Our data indicate that dermatology mentors strongly supported an away rotation, with more than half of them recommending at least 2 away rotations.

Further research is needed to determine the effect numerous away rotations have on minimizing students’ exposure to other specialties outside their chosen field. Additionally, further studies are needed to determine the impact away rotations have on economically disadvantaged students, students without home programs, and students with families. In an effort to standardize the number of away rotations, the APD issued a statement for the 2023-2024 application cycle indicating that dermatology applicants should limit away rotations to 2 in-person electives. Students without a home dermatology program could consider completing up to 3 electives.14

Who Should Write LORs?—Research in 2014 demonstrated that LORs were very important in determining applicants to interview, with a strong preference for LORs from academic dermatologists and colleagues.15 Our data strongly indicated applicants should predominantly ask for letters from writers who know them well. The majority of mentors did not give value to the rank of the letter writer (eg, assistant professor, associate professor, professor), type of letter, chair letters, or letters from an away rotation. These data may help alleviate stress many students feel as they search for letter writers.

How is the Supplemental Application Used?—In 2022, the ERAS supplemental application was introduced, which allowed applicants to detail 5 meaningful experiences, describe impactful life challenges, and indicate preferences for geographic region. Dermatology residency applicants also were able to choose 3 residency programs to signal interest in that program. Our data found that the supplemental application was utilized predominantly to select applicants to interview, which is in line with the Association of American Medical Colleges’ and APD guidelines indicating that this tool is solely meant to assist with application review.16 Further research and data will hopefully inform approaches to best utilize the ERAS supplemental application data.

Limitations—Our data were limited by response rate and sample size, as only academic dermatologists belonging to the APD were queried. Additionally, we did not track personal information of the mentors, so more than 1 mentor may have responded from a single institution, making it possible that our data may not be broadly applicable to all institutions.

Conclusion

Although there is no algorithmic method of advising medical students who are interested in dermatology, our survey data help to describe the range of advice currently given to students, which can improve and guide future recommendations. Additionally, some of our data demonstrate a discrepancy between mentor advice and current medical student practice for the number of applications and use of a letter of intent. We hope our data will assist academic dermatology mentors in the provision of advice to mentees as well as inform organizations seeking to create standards and official recommendations regarding aspects of the application process.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2022 Main Residency Match. May 2022. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/2022-Main-Match-Results-and-Data_Final.pdf

- Secrest AM, Coman GC, Swink JM, et al. Limiting residency applications to dermatology benefits nearly everyone. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:30-32.

- Apply smart for residency. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/apply-smart-residency

- Shamloul N, Grandhi R, Hossler E. Perceived importance of dermatology research fellowships. Presented at: Dermatology Teachers Exchange Group; October 3, 2020.

- Runge M, Jairath NK, Renati S, et al. Pursuit of a research year or dual degree by dermatology residency applicants: a cross-sectional study. Cutis. 2022;109:E12-E13.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role of race and ethnicity in the dermatology applicant match process. J Natl Med Assoc. 2022;113:666-670.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role research gap years play in a successful dermatology match. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:226-230.

- Ramachandran V, Nguyen HY, Dao H Jr. Does it match? analyzing self-reported online dermatology match data to charting outcomes in the Match. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:13030/qt4604h1w4.

- Hopkins C, Jalali O, Guffey D, et al. A survey of dermatology residents and program directors assessing the transition to dermatology residency. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Center). 2021;34:59-62.

- Stratman EJ, Ness RM. Factors associated with successful matching to dermatology residency programs by reapplicants and other applicants who previously graduated from medical school. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:196-202.

- Brumfiel CM, Jefferson IS, Rinderknecht FA, et al. Current perspectives of and potential reforms to the dermatology residency application process: a nationwide survey of program directors and applicants. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:595-601.

- Association of Professors of Dermatology. Residency Program Directors Section. Updated Information Regarding the 2022-2023 Application Cycle. Updated October 18, 2022. Accessed February 24, 2023. https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org/files/APD%20statement%20on%202022-2023%20application%20cycle_updated%20Oct.pdf

- Narang J, Morgan F, Eversman A, et al. Trends in geographic and home program preferences in the dermatology residency match: a retrospective cohort analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:645-647.

- Association of Professors of Dermatology Residency Program Directors Section. Recommendations Regarding Away Electives. Updated December 14, 2022. Accessed February 24, 2022. https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org/files/APD%20recommendations%20on%20away%20rotations%202023-2024.pdf

- Kaffenberger BH, Kaffenberger JA, Zirwas MJ. Academic dermatologists’ views on the value of residency letters of recommendation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:395-396.

- Supplemental ERAS Application: Guide for Residency Program. Association of American Medical Colleges; June 2022.

Dermatology remains one of the most competitive specialties in medicine. In 2022, there were 851 applicants (613 doctor of medicine seniors, 85 doctor of osteopathic medicine seniors) for 492 postgraduate year (PGY) 2 positions.1 During the 2022 application season, the average matched dermatology candidate had 7.2 research experiences; 20.9 abstracts, presentations, or publications; 11 volunteer experiences; and a US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 2 Clinical Knowledge score of 257.1 With hopes of matching into such a competitive field, students often seek advice from academic dermatology mentors. Such advice may substantially differ based on each mentor and may or may not be evidence based.

We sought to analyze the range of advice given to medical students applying to dermatology residency programs via a survey to members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) with the intent to help applicants and mentors understand how letters of intent, letters of recommendation (LORs), and Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) supplemental applications are used by dermatology programs nationwide.

Methods

The study was reviewed by The Ohio State University institutional review board and was deemed exempt. A branching-logic survey with common questions from medical students while applying to dermatology residency programs (Table) was sent to all members of APD through the email listserve. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at The Ohio State University (Columbus, Ohio) to ensure data security.

The survey was distributed from August 28, 2022, to September 12, 2022. A total of 101 surveys were returned from 646 listserve members (15.6%). Given the branching-logic questions, differing numbers of responses were collected for each question. Descriptive statistics were utilized to analyze and report the results.

Results

Residency Program Number—Members of the APD were asked if they recommend students apply to a certain number of programs, and if so, how many programs. Of members who responded, 62.2% (61/98) either always (22.4% [22/98]) or sometimes (40.2% [39/97]) suggested students apply to a certain number of programs. When mentors made a recommendation, 54.1% (33/61) recommended applying to 59 or fewer programs, with only 9.8% (6/61) recommending students apply to 80 or more programs.

Gap Year—We queried mentors about their recommendations for a research gap year and asked which applicants should pursue this extra year. Our survey found that 74.5% of mentors (73/98) almost always (4.1% [4/98]) or sometimes (70.4% [69/98]) recommended a research gap year, most commonly for those applicants with a strong research interest (71.8% [51/71]). Other reasons mentors recommended a dedicated research year during medical school included low USMLE Step scores (50.7% [36/71]), low grades (45.1% [32/71]), little research (46.5% [33/71]), and no home program (43.7% [31/71]).

Internship Choices—Our survey results indicated that nearly two-thirds (63.3% [62/98]) of mentors did not give applicants a recommendation on type of internship (PGY-1). If a recommendation was given, academic dermatologists more commonly recommended an internal medicine preliminary year (29.6% [29/98]) over a transitional year (7.1% [7/98]).

Communication of Interest Via a Letter of Intent—We asked mentors if they recommended applicants send a letter of intent and conversely if receiving a letter of intent impacted their rank list. Nearly half (48.5% [47/97]) of mentors indicated they did not recommend sending a letter of intent, with only 15.5% (15/97) of mentors regularly recommending this practice. Additionally, 75.8% of mentors indicated that a letter of intent never (42.1% [40/95]) or rarely (33.7% [32/95]) impacted their rank list.

Rotation Choices—We queried mentors if they recommended students complete away rotations, and if so, how many rotations did they recommend. We found that 85.9% (85/99) of mentors recommended students complete an away rotation; 63.1% (53/84) of them recommended performing 2 away rotations, and 14.3% (12/84) of respondents recommended students complete 3 away rotations. More than a quarter of mentors (27.1% [23/85]) indicated their home medical schools limited the number of away rotations a medical student could complete in any 1 specialty, and 42.4% (36/85) of respondents were unsure if such a limitation existed.

Letters of Recommendation—Our survey asked respondents to rank various factors on a 5-point scale (1=not important; 5=very important) when deciding who should write the students’ LORs. Mentors indicated that the most important factor for letter-writer selection was how well the letter writer knows the applicant, with 90.8% (89/98) of mentors rating the importance of this quality as a 4 or 5 (Figure). More than half of respondents rated the name recognition of the letter writer and program director letter as a 4 or 5 in importance (54.1% [53/98] and 58.2% [57/98], respectively). Type of letter (standardized vs nonstandardized), title of letter writer, letters from an away rotation, and chair letter scored lower, with fewer than half of mentors rating these as a 4 or 5 in importance.

Supplemental Application—When asked about the 2022 application cycle, respondents of our survey reported that the supplemental application was overall more important in deciding which applicants to interview vs which to rank highly. Prior experiences were important (ranked 4 or 5) for 58.8% (57/97) of respondents in choosing applicants to interview, and 49.4% (48/97) of respondents thought prior experiences were important for ranking. Similarly, 34.0% (33/97) of mentors indicated geographic preference was important (ranked 4 or 5) for interview compared with only 23.8% (23/97) for ranking. Finally, 57.7% (56/97) of our survey respondents denoted that program signals were important or very important in choosing which applicants to interview, while 32.0% (31/97) indicated that program signals were important in ranking applicants.

Comment

Residency Programs: Which Ones, and How Many?—The number of applications for dermatology residency programs has increased 33.9% from 2010 to 2019.2 The American Association of Medical Colleges Apply Smart data from 2013 to 2017 indicate that dermatology applicants arrive at a point of diminishing return between 37 and 62 applications, with variation within that range based on USMLE Step 1 score,3 and our data support this with nearly two-thirds of dermatology advisors recommending students apply within this range. Despite this data, dermatology residency applicants applied to more programs over the last decade (64.8 vs 77.0),2 likely to maximize their chance of matching.

Research Gap Years During Medical School—Prior research has shown that nearly half of faculty indicated that a research year during medical school can distinguish similar applicants, and close to 25% of applicants completed a research gap year.4,5 However, available data indicate that taking a research gap year has no effect on match rate or number of interview invites but does correlate with match rates at the highest ranked dermatology residency programs.6-8

Our data indicate that the most commonly recommended reason for a research gap year was an applicants’ strong interest in research. However, nearly half of dermatology mentors recommended research years during medical school for reasons other than an interest in research. As research gap years increase in popularity, future research is needed to confirm the consequence of this additional year and which applicants, if any, will benefit from such a year.

Preferences for Intern Year—Prior research suggests that dermatology residency program directors favor PGY-1 preliminary medicine internships because of the rigor of training.9,10 Our data continue to show a preference for internal medicine preliminary years over transitional years. However, given nearly two-thirds of dermatology mentors do not give applicants any recommendations on PGY-1 year, this preference may be fading.

Letters of Intent Not Recommended—Research in 2022 found that 78.8% of dermatology applicants sent a letter of intent communicating a plan to rank that program number 1, with nearly 13% sending such a letter to more than 1 program.11 With nearly half of mentors in our survey actively discouraging this process and more than 75% of mentors not utilizing this letter, the APD issued a brief statement on the 2022-2023 application cycle stating, “Post-interview communication of preference—including ‘letters of intent’ and thank you letters—should not be sent to programs. These types of communication are typically not used by residency programs in decision-making and lead to downstream pressures on applicants.”12

Away Rotations—Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, data demonstrated that nearly one-third of dermatology applicants (29%) matched at their home institution, and nearly one-fifth (18%) matched where they completed an away rotation.13 In-person away rotations were eliminated in 2020 and restricted to 1 away rotation in 2021. Restrictions regarding away rotations were removed in 2022. Our data indicate that dermatology mentors strongly supported an away rotation, with more than half of them recommending at least 2 away rotations.

Further research is needed to determine the effect numerous away rotations have on minimizing students’ exposure to other specialties outside their chosen field. Additionally, further studies are needed to determine the impact away rotations have on economically disadvantaged students, students without home programs, and students with families. In an effort to standardize the number of away rotations, the APD issued a statement for the 2023-2024 application cycle indicating that dermatology applicants should limit away rotations to 2 in-person electives. Students without a home dermatology program could consider completing up to 3 electives.14

Who Should Write LORs?—Research in 2014 demonstrated that LORs were very important in determining applicants to interview, with a strong preference for LORs from academic dermatologists and colleagues.15 Our data strongly indicated applicants should predominantly ask for letters from writers who know them well. The majority of mentors did not give value to the rank of the letter writer (eg, assistant professor, associate professor, professor), type of letter, chair letters, or letters from an away rotation. These data may help alleviate stress many students feel as they search for letter writers.

How is the Supplemental Application Used?—In 2022, the ERAS supplemental application was introduced, which allowed applicants to detail 5 meaningful experiences, describe impactful life challenges, and indicate preferences for geographic region. Dermatology residency applicants also were able to choose 3 residency programs to signal interest in that program. Our data found that the supplemental application was utilized predominantly to select applicants to interview, which is in line with the Association of American Medical Colleges’ and APD guidelines indicating that this tool is solely meant to assist with application review.16 Further research and data will hopefully inform approaches to best utilize the ERAS supplemental application data.

Limitations—Our data were limited by response rate and sample size, as only academic dermatologists belonging to the APD were queried. Additionally, we did not track personal information of the mentors, so more than 1 mentor may have responded from a single institution, making it possible that our data may not be broadly applicable to all institutions.

Conclusion

Although there is no algorithmic method of advising medical students who are interested in dermatology, our survey data help to describe the range of advice currently given to students, which can improve and guide future recommendations. Additionally, some of our data demonstrate a discrepancy between mentor advice and current medical student practice for the number of applications and use of a letter of intent. We hope our data will assist academic dermatology mentors in the provision of advice to mentees as well as inform organizations seeking to create standards and official recommendations regarding aspects of the application process.

Dermatology remains one of the most competitive specialties in medicine. In 2022, there were 851 applicants (613 doctor of medicine seniors, 85 doctor of osteopathic medicine seniors) for 492 postgraduate year (PGY) 2 positions.1 During the 2022 application season, the average matched dermatology candidate had 7.2 research experiences; 20.9 abstracts, presentations, or publications; 11 volunteer experiences; and a US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 2 Clinical Knowledge score of 257.1 With hopes of matching into such a competitive field, students often seek advice from academic dermatology mentors. Such advice may substantially differ based on each mentor and may or may not be evidence based.

We sought to analyze the range of advice given to medical students applying to dermatology residency programs via a survey to members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) with the intent to help applicants and mentors understand how letters of intent, letters of recommendation (LORs), and Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) supplemental applications are used by dermatology programs nationwide.

Methods

The study was reviewed by The Ohio State University institutional review board and was deemed exempt. A branching-logic survey with common questions from medical students while applying to dermatology residency programs (Table) was sent to all members of APD through the email listserve. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at The Ohio State University (Columbus, Ohio) to ensure data security.

The survey was distributed from August 28, 2022, to September 12, 2022. A total of 101 surveys were returned from 646 listserve members (15.6%). Given the branching-logic questions, differing numbers of responses were collected for each question. Descriptive statistics were utilized to analyze and report the results.

Results

Residency Program Number—Members of the APD were asked if they recommend students apply to a certain number of programs, and if so, how many programs. Of members who responded, 62.2% (61/98) either always (22.4% [22/98]) or sometimes (40.2% [39/97]) suggested students apply to a certain number of programs. When mentors made a recommendation, 54.1% (33/61) recommended applying to 59 or fewer programs, with only 9.8% (6/61) recommending students apply to 80 or more programs.

Gap Year—We queried mentors about their recommendations for a research gap year and asked which applicants should pursue this extra year. Our survey found that 74.5% of mentors (73/98) almost always (4.1% [4/98]) or sometimes (70.4% [69/98]) recommended a research gap year, most commonly for those applicants with a strong research interest (71.8% [51/71]). Other reasons mentors recommended a dedicated research year during medical school included low USMLE Step scores (50.7% [36/71]), low grades (45.1% [32/71]), little research (46.5% [33/71]), and no home program (43.7% [31/71]).

Internship Choices—Our survey results indicated that nearly two-thirds (63.3% [62/98]) of mentors did not give applicants a recommendation on type of internship (PGY-1). If a recommendation was given, academic dermatologists more commonly recommended an internal medicine preliminary year (29.6% [29/98]) over a transitional year (7.1% [7/98]).

Communication of Interest Via a Letter of Intent—We asked mentors if they recommended applicants send a letter of intent and conversely if receiving a letter of intent impacted their rank list. Nearly half (48.5% [47/97]) of mentors indicated they did not recommend sending a letter of intent, with only 15.5% (15/97) of mentors regularly recommending this practice. Additionally, 75.8% of mentors indicated that a letter of intent never (42.1% [40/95]) or rarely (33.7% [32/95]) impacted their rank list.

Rotation Choices—We queried mentors if they recommended students complete away rotations, and if so, how many rotations did they recommend. We found that 85.9% (85/99) of mentors recommended students complete an away rotation; 63.1% (53/84) of them recommended performing 2 away rotations, and 14.3% (12/84) of respondents recommended students complete 3 away rotations. More than a quarter of mentors (27.1% [23/85]) indicated their home medical schools limited the number of away rotations a medical student could complete in any 1 specialty, and 42.4% (36/85) of respondents were unsure if such a limitation existed.

Letters of Recommendation—Our survey asked respondents to rank various factors on a 5-point scale (1=not important; 5=very important) when deciding who should write the students’ LORs. Mentors indicated that the most important factor for letter-writer selection was how well the letter writer knows the applicant, with 90.8% (89/98) of mentors rating the importance of this quality as a 4 or 5 (Figure). More than half of respondents rated the name recognition of the letter writer and program director letter as a 4 or 5 in importance (54.1% [53/98] and 58.2% [57/98], respectively). Type of letter (standardized vs nonstandardized), title of letter writer, letters from an away rotation, and chair letter scored lower, with fewer than half of mentors rating these as a 4 or 5 in importance.

Supplemental Application—When asked about the 2022 application cycle, respondents of our survey reported that the supplemental application was overall more important in deciding which applicants to interview vs which to rank highly. Prior experiences were important (ranked 4 or 5) for 58.8% (57/97) of respondents in choosing applicants to interview, and 49.4% (48/97) of respondents thought prior experiences were important for ranking. Similarly, 34.0% (33/97) of mentors indicated geographic preference was important (ranked 4 or 5) for interview compared with only 23.8% (23/97) for ranking. Finally, 57.7% (56/97) of our survey respondents denoted that program signals were important or very important in choosing which applicants to interview, while 32.0% (31/97) indicated that program signals were important in ranking applicants.

Comment

Residency Programs: Which Ones, and How Many?—The number of applications for dermatology residency programs has increased 33.9% from 2010 to 2019.2 The American Association of Medical Colleges Apply Smart data from 2013 to 2017 indicate that dermatology applicants arrive at a point of diminishing return between 37 and 62 applications, with variation within that range based on USMLE Step 1 score,3 and our data support this with nearly two-thirds of dermatology advisors recommending students apply within this range. Despite this data, dermatology residency applicants applied to more programs over the last decade (64.8 vs 77.0),2 likely to maximize their chance of matching.

Research Gap Years During Medical School—Prior research has shown that nearly half of faculty indicated that a research year during medical school can distinguish similar applicants, and close to 25% of applicants completed a research gap year.4,5 However, available data indicate that taking a research gap year has no effect on match rate or number of interview invites but does correlate with match rates at the highest ranked dermatology residency programs.6-8

Our data indicate that the most commonly recommended reason for a research gap year was an applicants’ strong interest in research. However, nearly half of dermatology mentors recommended research years during medical school for reasons other than an interest in research. As research gap years increase in popularity, future research is needed to confirm the consequence of this additional year and which applicants, if any, will benefit from such a year.

Preferences for Intern Year—Prior research suggests that dermatology residency program directors favor PGY-1 preliminary medicine internships because of the rigor of training.9,10 Our data continue to show a preference for internal medicine preliminary years over transitional years. However, given nearly two-thirds of dermatology mentors do not give applicants any recommendations on PGY-1 year, this preference may be fading.

Letters of Intent Not Recommended—Research in 2022 found that 78.8% of dermatology applicants sent a letter of intent communicating a plan to rank that program number 1, with nearly 13% sending such a letter to more than 1 program.11 With nearly half of mentors in our survey actively discouraging this process and more than 75% of mentors not utilizing this letter, the APD issued a brief statement on the 2022-2023 application cycle stating, “Post-interview communication of preference—including ‘letters of intent’ and thank you letters—should not be sent to programs. These types of communication are typically not used by residency programs in decision-making and lead to downstream pressures on applicants.”12

Away Rotations—Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, data demonstrated that nearly one-third of dermatology applicants (29%) matched at their home institution, and nearly one-fifth (18%) matched where they completed an away rotation.13 In-person away rotations were eliminated in 2020 and restricted to 1 away rotation in 2021. Restrictions regarding away rotations were removed in 2022. Our data indicate that dermatology mentors strongly supported an away rotation, with more than half of them recommending at least 2 away rotations.

Further research is needed to determine the effect numerous away rotations have on minimizing students’ exposure to other specialties outside their chosen field. Additionally, further studies are needed to determine the impact away rotations have on economically disadvantaged students, students without home programs, and students with families. In an effort to standardize the number of away rotations, the APD issued a statement for the 2023-2024 application cycle indicating that dermatology applicants should limit away rotations to 2 in-person electives. Students without a home dermatology program could consider completing up to 3 electives.14

Who Should Write LORs?—Research in 2014 demonstrated that LORs were very important in determining applicants to interview, with a strong preference for LORs from academic dermatologists and colleagues.15 Our data strongly indicated applicants should predominantly ask for letters from writers who know them well. The majority of mentors did not give value to the rank of the letter writer (eg, assistant professor, associate professor, professor), type of letter, chair letters, or letters from an away rotation. These data may help alleviate stress many students feel as they search for letter writers.

How is the Supplemental Application Used?—In 2022, the ERAS supplemental application was introduced, which allowed applicants to detail 5 meaningful experiences, describe impactful life challenges, and indicate preferences for geographic region. Dermatology residency applicants also were able to choose 3 residency programs to signal interest in that program. Our data found that the supplemental application was utilized predominantly to select applicants to interview, which is in line with the Association of American Medical Colleges’ and APD guidelines indicating that this tool is solely meant to assist with application review.16 Further research and data will hopefully inform approaches to best utilize the ERAS supplemental application data.

Limitations—Our data were limited by response rate and sample size, as only academic dermatologists belonging to the APD were queried. Additionally, we did not track personal information of the mentors, so more than 1 mentor may have responded from a single institution, making it possible that our data may not be broadly applicable to all institutions.

Conclusion

Although there is no algorithmic method of advising medical students who are interested in dermatology, our survey data help to describe the range of advice currently given to students, which can improve and guide future recommendations. Additionally, some of our data demonstrate a discrepancy between mentor advice and current medical student practice for the number of applications and use of a letter of intent. We hope our data will assist academic dermatology mentors in the provision of advice to mentees as well as inform organizations seeking to create standards and official recommendations regarding aspects of the application process.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2022 Main Residency Match. May 2022. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/2022-Main-Match-Results-and-Data_Final.pdf

- Secrest AM, Coman GC, Swink JM, et al. Limiting residency applications to dermatology benefits nearly everyone. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:30-32.

- Apply smart for residency. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/apply-smart-residency

- Shamloul N, Grandhi R, Hossler E. Perceived importance of dermatology research fellowships. Presented at: Dermatology Teachers Exchange Group; October 3, 2020.

- Runge M, Jairath NK, Renati S, et al. Pursuit of a research year or dual degree by dermatology residency applicants: a cross-sectional study. Cutis. 2022;109:E12-E13.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role of race and ethnicity in the dermatology applicant match process. J Natl Med Assoc. 2022;113:666-670.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role research gap years play in a successful dermatology match. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:226-230.

- Ramachandran V, Nguyen HY, Dao H Jr. Does it match? analyzing self-reported online dermatology match data to charting outcomes in the Match. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:13030/qt4604h1w4.

- Hopkins C, Jalali O, Guffey D, et al. A survey of dermatology residents and program directors assessing the transition to dermatology residency. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Center). 2021;34:59-62.

- Stratman EJ, Ness RM. Factors associated with successful matching to dermatology residency programs by reapplicants and other applicants who previously graduated from medical school. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:196-202.

- Brumfiel CM, Jefferson IS, Rinderknecht FA, et al. Current perspectives of and potential reforms to the dermatology residency application process: a nationwide survey of program directors and applicants. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:595-601.

- Association of Professors of Dermatology. Residency Program Directors Section. Updated Information Regarding the 2022-2023 Application Cycle. Updated October 18, 2022. Accessed February 24, 2023. https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org/files/APD%20statement%20on%202022-2023%20application%20cycle_updated%20Oct.pdf

- Narang J, Morgan F, Eversman A, et al. Trends in geographic and home program preferences in the dermatology residency match: a retrospective cohort analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:645-647.

- Association of Professors of Dermatology Residency Program Directors Section. Recommendations Regarding Away Electives. Updated December 14, 2022. Accessed February 24, 2022. https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org/files/APD%20recommendations%20on%20away%20rotations%202023-2024.pdf

- Kaffenberger BH, Kaffenberger JA, Zirwas MJ. Academic dermatologists’ views on the value of residency letters of recommendation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:395-396.

- Supplemental ERAS Application: Guide for Residency Program. Association of American Medical Colleges; June 2022.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2022 Main Residency Match. May 2022. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/2022-Main-Match-Results-and-Data_Final.pdf

- Secrest AM, Coman GC, Swink JM, et al. Limiting residency applications to dermatology benefits nearly everyone. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:30-32.

- Apply smart for residency. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/apply-smart-residency

- Shamloul N, Grandhi R, Hossler E. Perceived importance of dermatology research fellowships. Presented at: Dermatology Teachers Exchange Group; October 3, 2020.

- Runge M, Jairath NK, Renati S, et al. Pursuit of a research year or dual degree by dermatology residency applicants: a cross-sectional study. Cutis. 2022;109:E12-E13.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role of race and ethnicity in the dermatology applicant match process. J Natl Med Assoc. 2022;113:666-670.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role research gap years play in a successful dermatology match. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:226-230.

- Ramachandran V, Nguyen HY, Dao H Jr. Does it match? analyzing self-reported online dermatology match data to charting outcomes in the Match. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:13030/qt4604h1w4.

- Hopkins C, Jalali O, Guffey D, et al. A survey of dermatology residents and program directors assessing the transition to dermatology residency. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Center). 2021;34:59-62.

- Stratman EJ, Ness RM. Factors associated with successful matching to dermatology residency programs by reapplicants and other applicants who previously graduated from medical school. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:196-202.

- Brumfiel CM, Jefferson IS, Rinderknecht FA, et al. Current perspectives of and potential reforms to the dermatology residency application process: a nationwide survey of program directors and applicants. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:595-601.

- Association of Professors of Dermatology. Residency Program Directors Section. Updated Information Regarding the 2022-2023 Application Cycle. Updated October 18, 2022. Accessed February 24, 2023. https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org/files/APD%20statement%20on%202022-2023%20application%20cycle_updated%20Oct.pdf

- Narang J, Morgan F, Eversman A, et al. Trends in geographic and home program preferences in the dermatology residency match: a retrospective cohort analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:645-647.

- Association of Professors of Dermatology Residency Program Directors Section. Recommendations Regarding Away Electives. Updated December 14, 2022. Accessed February 24, 2022. https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org/files/APD%20recommendations%20on%20away%20rotations%202023-2024.pdf

- Kaffenberger BH, Kaffenberger JA, Zirwas MJ. Academic dermatologists’ views on the value of residency letters of recommendation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:395-396.

- Supplemental ERAS Application: Guide for Residency Program. Association of American Medical Colleges; June 2022.

Practice Points

- Dermatology mentors recommend students apply to 60 or fewer programs, with only a small percentage of faculty routinely recommending students apply to more than 80 programs.

- Dermatology mentors strongly recommend that students should not send a letter of intent to programs, as it rarely is used in the ranking process.

- Dermatology mentors encourage students to ask for letters of recommendation from writers who know them the best, irrespective of the letter writer’s rank or title. The type of letter (standardized vs nonstandardized), chair letter, or letters from an away rotation do not hold as much importance.

Periorbital Lupuslike Presentation of Graft-versus-host Disease

To the Editor:

A 79-year-old man presented with a scaling eruption in the periorbital area, on the bilateral forearms, and on the chest of 4 weeks’ duration. The patient denied systemic symptoms including lethargy, muscle weakness, and fevers. His medical history was notable for blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm, a form of acute myeloid leukemia, diagnosed 3 years prior to presentation. The patient received an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant 8 months later. His posttransplant course was complicated by gastrointestinal graft-versus-host disease (GVHD); progressive graft loss requiring a donor lymphocyte infusion after 1 month; and leukemia cutis, which spontaneously resolved after 1 month. The patient was taken off all immunosuppressive therapy 5 months after the transplant and had been doing well for 2 years with only mild mucosal GVHD affecting the oral mucosa and the head of the penis.

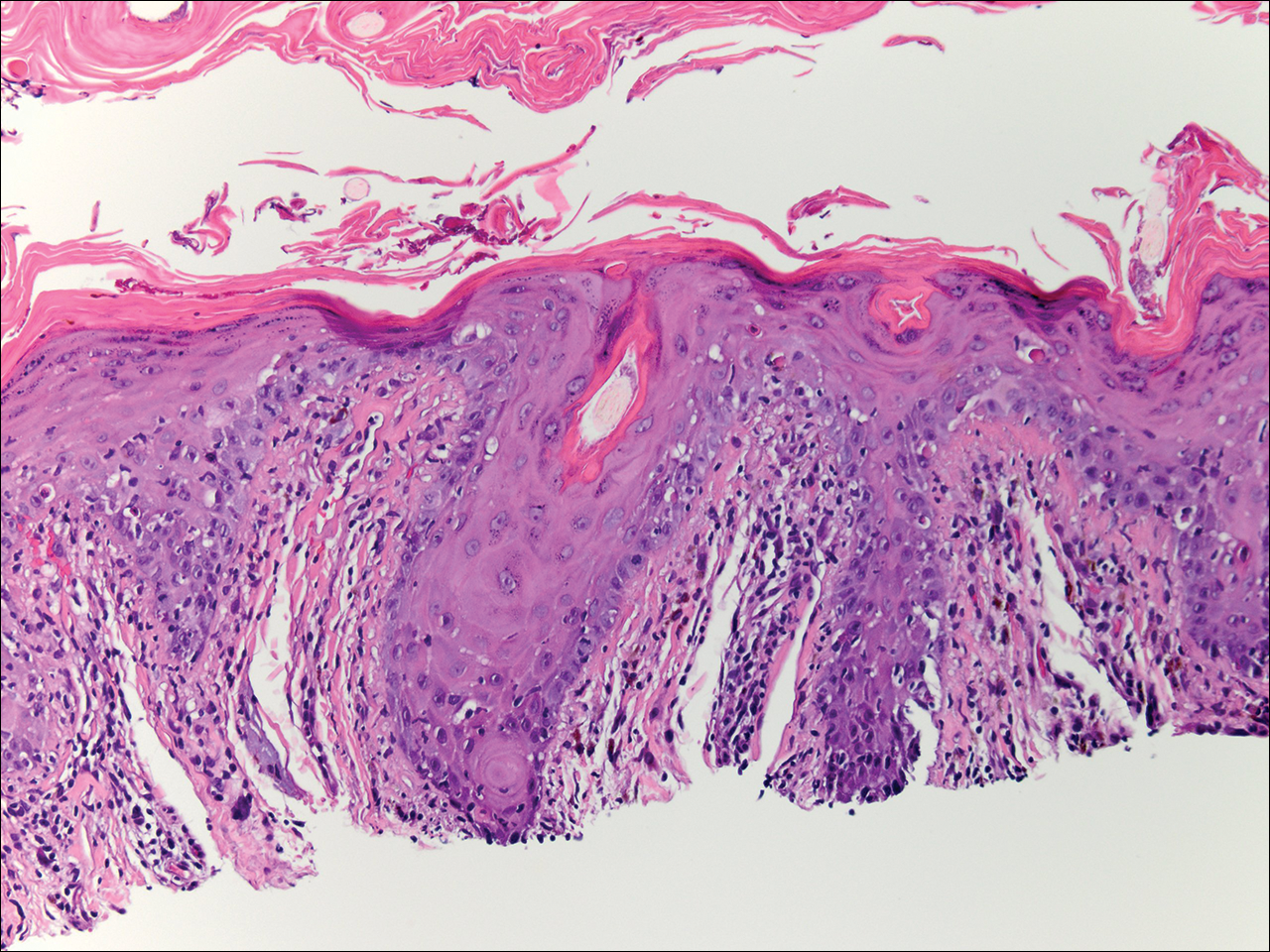

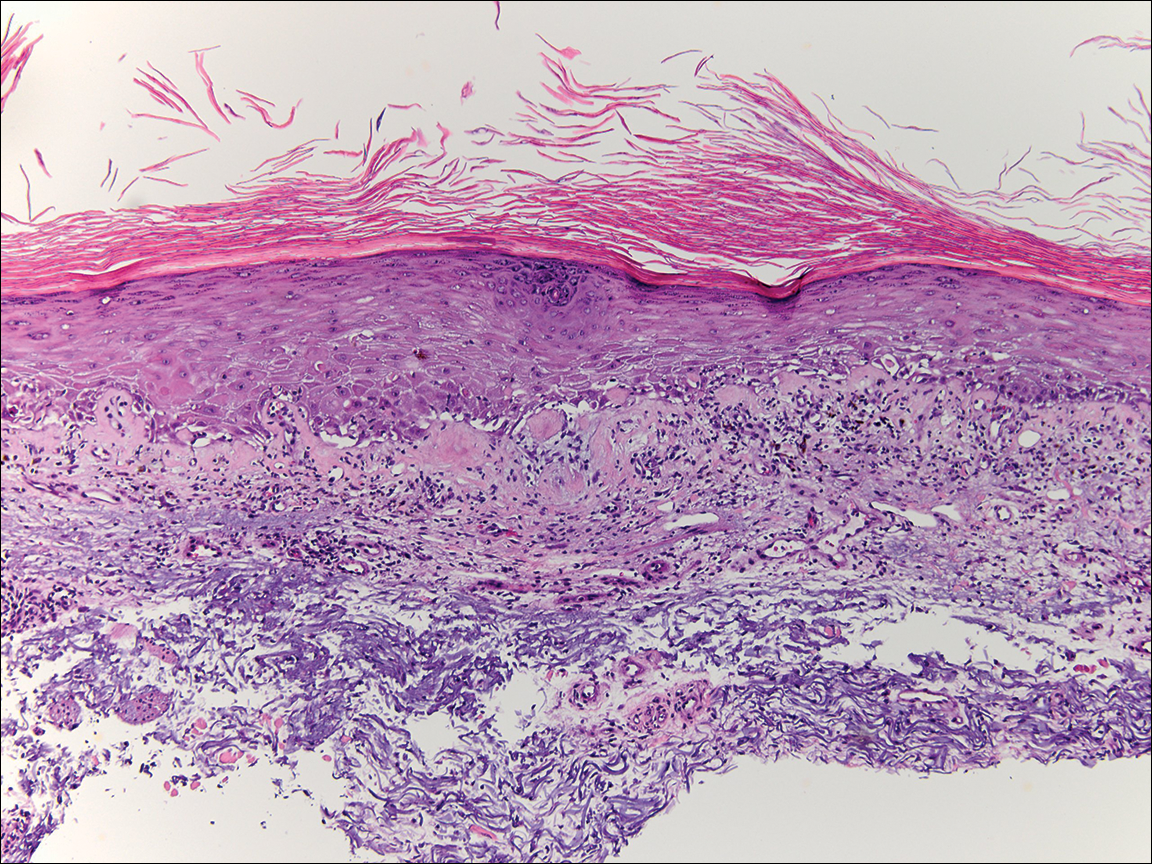

Physical examination at the current presentation revealed linear, atrophic, scaling, purplish plaques with adherent white scale on the upper and lower eyelids (Figure 1). The patient also had scattered purple scaling patches on the bilateral forearms and chest. Laboratory tests including complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and lactate dehydrogenase demonstrated no gross abnormalities. Two shave biopsies of the right lower eyelid (Figure 2) and left arm (Figure 3) were performed for histologic examination and revealed basket weave hyperkeratosis, irregular acanthosis, sawtooth rete ridges, and scattered dyskeratotic cells. Vacuolar changes and smudging of the basement membrane zone along with a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the upper dermis also were noted in both biopsies. A diagnosis of lupuslike grade 1 GVHD was made.

Graft-versus-host disease remains a notable cause of morbidity and mortality in allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients.1 Skin manifestations represent the most common manifestation of GVHD and have been reclassified as acute or chronic disease based on clinical and histologic findings rather than time of onset. Although acute GVHD classically presents as diffuse morbilliform papules and macules, chronic GVHD has a large range of clinical presentations most commonly mimicking the skin findings of lichen planus, morphea, scleroderma, or lichen sclerosus.1

Lupuslike GVHD is a rarely reported manifestation of chronic GVHD that predominantly affects the lower eyelids and malar regions.2,3 Our case documents extensive involvement of both the upper and lower eyelids. A lupuslike manifestation of GVHD may portend a poor prognosis. In a case series of 5 patients with chronic GVHD presenting as facial lupuslike plaques, 1 patient died from a relapse of leukemia and 3 patients developed sclerodermatous GVHD. The fifth patient was lost to follow-up.2 In another case series, a retrospective analysis discovered that 3 of 7 patients with sclerodermatous GVHD initially presented with hyperpigmented periorbital plaques.4 Resolution of skin findings with topical steroids and oral tacrolimus was reported in a case of GVHD presenting with periorbital lupuslike plaques.3 Although further reports are needed to validate the relationship, a lupuslike presentation of chronic GVHD may be an important harbinger for the development of extensive sclerodermatous GVHD.

A diagnosis of lupuslike GVHD is made based on the correlation of a comprehensive medical history, clinical examination, and histopathologic findings. Although other cases of chronic GVHD resembling dermatomyositis presented with purple periorbital plaques, these patients demonstrated dermatomyositislike systemic symptoms including muscle weakness and fatigue, which were not present in our patient.5,6 Antinuclear antibody (ANA) testing is unlikely to be helpful in the diagnosis of this uncommon presentation, as 65% (41/63) of chronic GVHD patients developed ANA antibodies in one study.7 Also, other patients with lupuslike GVHD who progressed to sclerodermatous GVHD have had both positive and negative ANA serology.2 The histopathology of GVHD and lupus erythematosus can exhibit overlapping features, such as lymphocytic infiltrate with interface changes; however, in lupus erythematosus, mucin usually is present, the infiltrate usually is denser and deeper, and a thickened basement membrane zone may be present. Necrotic keratinocytes also usually are not seen in lupus erythematosus unless the patient’s photosensitivity has led to a sunburn reaction.

After his initial presentation, our patient’s mucosal GVHD flared in the mouth and on the penis, and he was started on prednisone 50 mg once daily and mycophenolate mofetil 1 g twice daily. With this treatment, our patient’s periorbital scaling plaques resolved to residual hyperpigmentation along with remarkable improvement of the mucosal GVHD. He has not manifested any signs of leukemia relapse or sclerodermatous GVHD; however, he remains under close clinical evaluation.

This case highlights an unusual presentation of GVHD with periorbital plaques mimicking hypertrophic lupus erythematous. A greater recognition of this rare entity is essential to further elucidate its prognosis and its relationship with sclerodermatous GVHD.

- Hymes SR, Alousi AM, Cowen EW. Graft-versus-host disease: part I. pathogenesis and clinical manifestations of graft-versus-host disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:515.e1-5.15e18; quiz 533-534.

- Goiriz R, Peñas PF, Delgado-Jiménez Y, et al. Cutaneous lichenoid graft-versus-host disease mimicking lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2008;17:591-595.

- Hu SW, Myskowski PL, Papadopoulos EB, et al. Chronic cutaneous graft-versus host disease simulating hypertrophic lupus erythematosus—a case report of a new morphologic variant of graft-versus-host disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:E81-E83.

- Chosidow O, Bagot M, Vernant JP, et al. Sclerodermatous chronic graft-versus-host disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:49-55.

- Ollivier I, Wolkenstein P, Gherardi R, et al. Dermatomyositis-like graft-versus-host disease. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:558-559.

- Arin MJ, Scheid C, Hübel K, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host disease with skin signs suggestive of dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:141-143.

- Patriarca F, Skert C, Sperotto A, et al. The development of autoantibodies after allogeneic stem cell transplantation is related with chronic graft-vs-host disease and immune recovery. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:389-396.

To the Editor:

A 79-year-old man presented with a scaling eruption in the periorbital area, on the bilateral forearms, and on the chest of 4 weeks’ duration. The patient denied systemic symptoms including lethargy, muscle weakness, and fevers. His medical history was notable for blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm, a form of acute myeloid leukemia, diagnosed 3 years prior to presentation. The patient received an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant 8 months later. His posttransplant course was complicated by gastrointestinal graft-versus-host disease (GVHD); progressive graft loss requiring a donor lymphocyte infusion after 1 month; and leukemia cutis, which spontaneously resolved after 1 month. The patient was taken off all immunosuppressive therapy 5 months after the transplant and had been doing well for 2 years with only mild mucosal GVHD affecting the oral mucosa and the head of the penis.