User login

Concordance Between Dermatologist Self-reported and Industry-Reported Interactions at a National Dermatology Conference

Interactions between industry and physicians, including dermatologists, are widely prevalent.1-3 Proper reporting of industry relationships is essential for transparency, objectivity, and management of potential biases and conflicts of interest. There has been increasing public scrutiny regarding these interactions.

The Physician Payments Sunshine Act established Open Payments (OP), a publicly available database that collects and displays industry-reported physician-industry interactions.4,5 For the medical community and public, the OP database may be used to assess transparency by comparing the data with physician self-disclosures. There is a paucity of studies in the literature examining the concordance of industry-reported disclosures and physician self-reported data, with even fewer studies utilizing OP as a source of industry disclosures, and none exists for dermatology.6-12 It also is not clear to what extent the OP database captures all possible dermatologist-industry interactions, as the Sunshine Act only mandates reporting by applicable US-based manufacturers and group purchasing organizations that produce or purchase drugs or devices that require a prescription and are reimbursable by a government-run health care program.5 As a result, certain companies, such as cosmeceuticals, may not be represented.

In this study we aimed to evaluate the concordance of dermatologist self-disclosure of industry relationships and those reported on OP. Specifically, we focused on interactions disclosed by presenters at the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) 73rd Annual Meeting in San Francisco, California (March 20–24, 2015), and those by industry in the 2014 OP database.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, we compared publicly available data from the OP database to presenter disclosures found in the publicly available AAD 73rd Annual Meeting program (AADMP). The AAD required speakers to disclose financial relationships with industry within the 12 months preceding the presentation, as outlined in the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education guidelines.13 All AAD presenters who were dermatologists practicing in the United States were included in the analysis, whereas residents, fellows, nonphysicians, nondermatologist physicians, and international dermatologists were excluded.

We examined general, research, and associated research payments to specific dermatologists using the 2014 OP data, which contained industry payments made between January 1 and December 31, 2014. Open Payments defined research payments as direct payment to the physician for different types of research activities and associated research payments as indirect payments made to a research institution or entity where the physician was named the principal investigator.5 We chose the 2014 database because it most closely matched the period of required disclosures defined by the AAD for the 2015 meeting. Our review of the OP data occurred after the June 2016 update and thus included the most accurate and up-to-date financial interactions.

We conducted our analysis in 2 major steps. First, we determined whether each industry interaction reported in the OP database was present in the AADMP, which provided an assessment of interaction-level concordance. Second, we determined whether all the industry interactions for any given dermatologist listed in the OP also were present in AADMP, which provided an assessment of dermatologist-level concordance.

First, to establish interaction-level concordance for each industry interaction, the company name and the type of interaction (eg, consultant, speaker, investigator) listed in the AADMP were compared with the data in OP to verify a match. Each interaction was assigned into one of the categories of concordant disclosure (a match of both the company name and type of interaction details in OP and the AADMP), overdisclosure (the presence of an AADMP interaction not found in OP, such as an additional type of interaction or company), or underdisclosure (a company name or type of interaction found in OP but not reported in the AADMP). For underdisclosure, we further classified into company present or company absent based on whether the dermatologist disclosed any relationship with a particular company in the AADMP. We considered the type of interaction to be matching if they were identical or similar in nature (eg, consulting in OP and advisory board in the AADMP), as the types of interactions are reported differently in OP and the AADMP. Otherwise, if they were not similar enough (eg, education in OP and stockholder in the AADMP), it was classified as underdisclosure. Some types of interactions reported in OP were not available on the AAD disclosure form. For example, food and beverage as well as travel and lodging were types of interactions in OP that did not exist in the AADMP. These 2 types of interactions comprised a large majority of OP payment entries but only accounted for a small percentage of the payment amount. Analysis was performed both including and excluding interactions for food, beverage, travel, and lodging (f/b/t/l) to best account for differences in interaction categories between OP and the AADMP.

Second, each dermatologist was assigned to an overall disclosure category of dermatologist-level concordance based on the status for all his/her interactions. Categories included no disclosure (no industry interactions in OP and the AADMP), concordant (all industry interactions reported in OP and the AADMP match), overdisclosure only (no industry interactions on OP but self-reported interactions present in the AADMP), and discordant (not all OP interactions were disclosed in the AADMP). The discordant category was further divided into with overdisclosure and without overdisclosure, depending on the presence or absence of industry relationships listed in the AADMP but not in OP, respectively.

To ensure uniformity, one individual (A.F.S.) reviewed and collected the data from OP and the AADMP. Information on gender and academic affiliation of study participants was obtained from information listed in the AADMP and Google searches. Data management was performed with Microsoft Excel software (Microsoft Excel 2010, Version 14.0, Microsoft Corporation). The New York University School of Medicine’s (New York, New York) institutional review board exempted this study.

Results

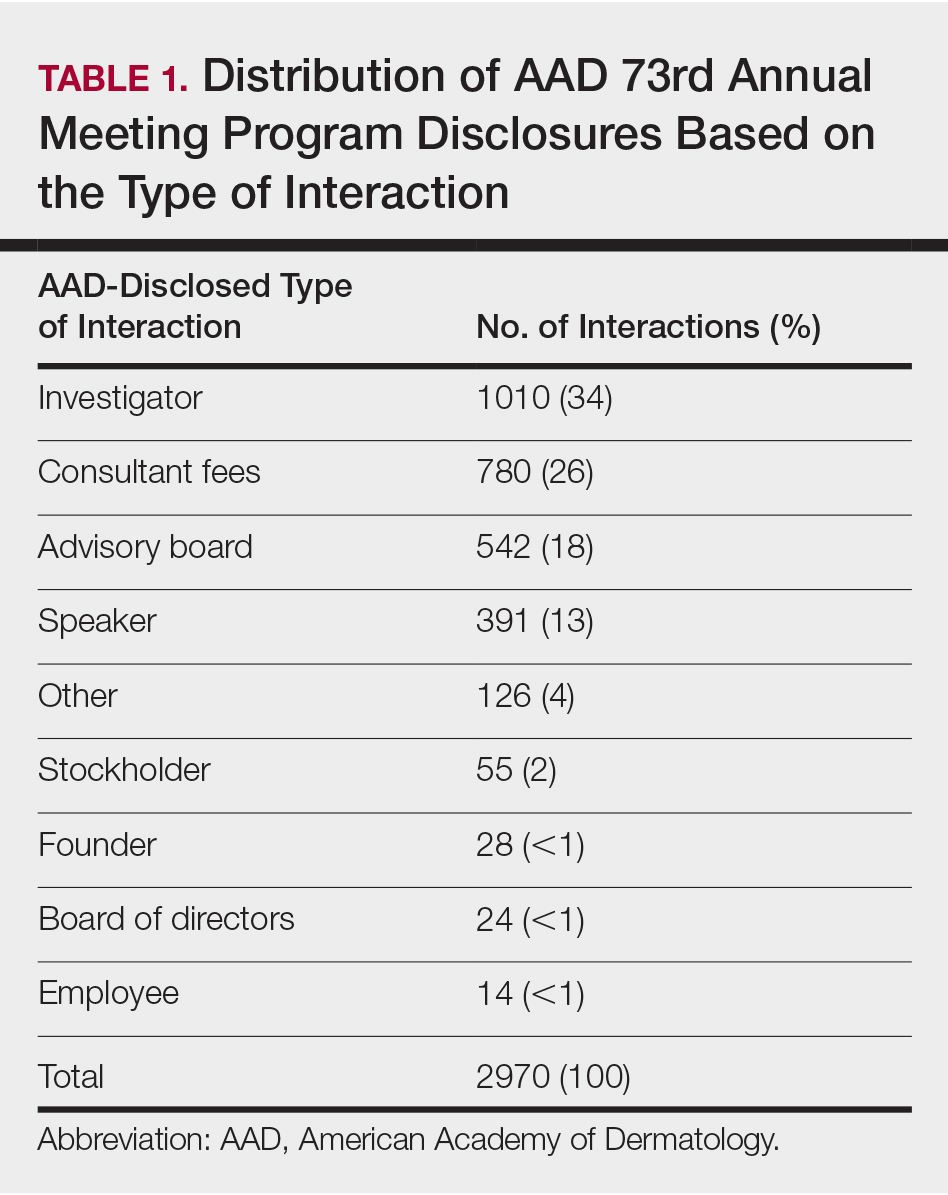

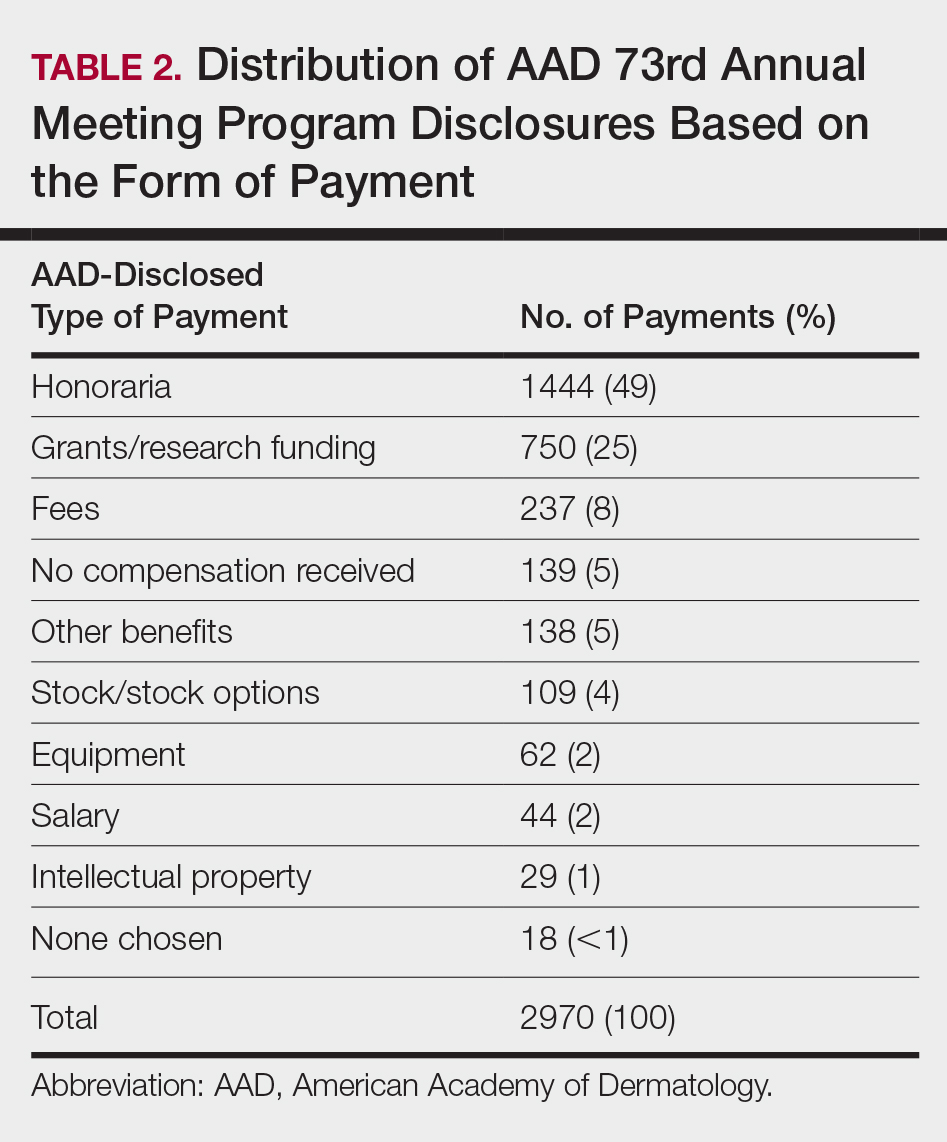

Of the 938 presenters listed in the AADMP, 768 individuals met the inclusion criteria. The most commonly cited type of relationship with industry listed in the AADMP was serving as an investigator, consultant, or advisory board member, comprising 34%, 26%, and 18%, respectively (Table 1). The forms of payment most frequently reported in the AADMP were honoraria and grants/research funding, comprising 49% and 25%, respectively (Table 2).

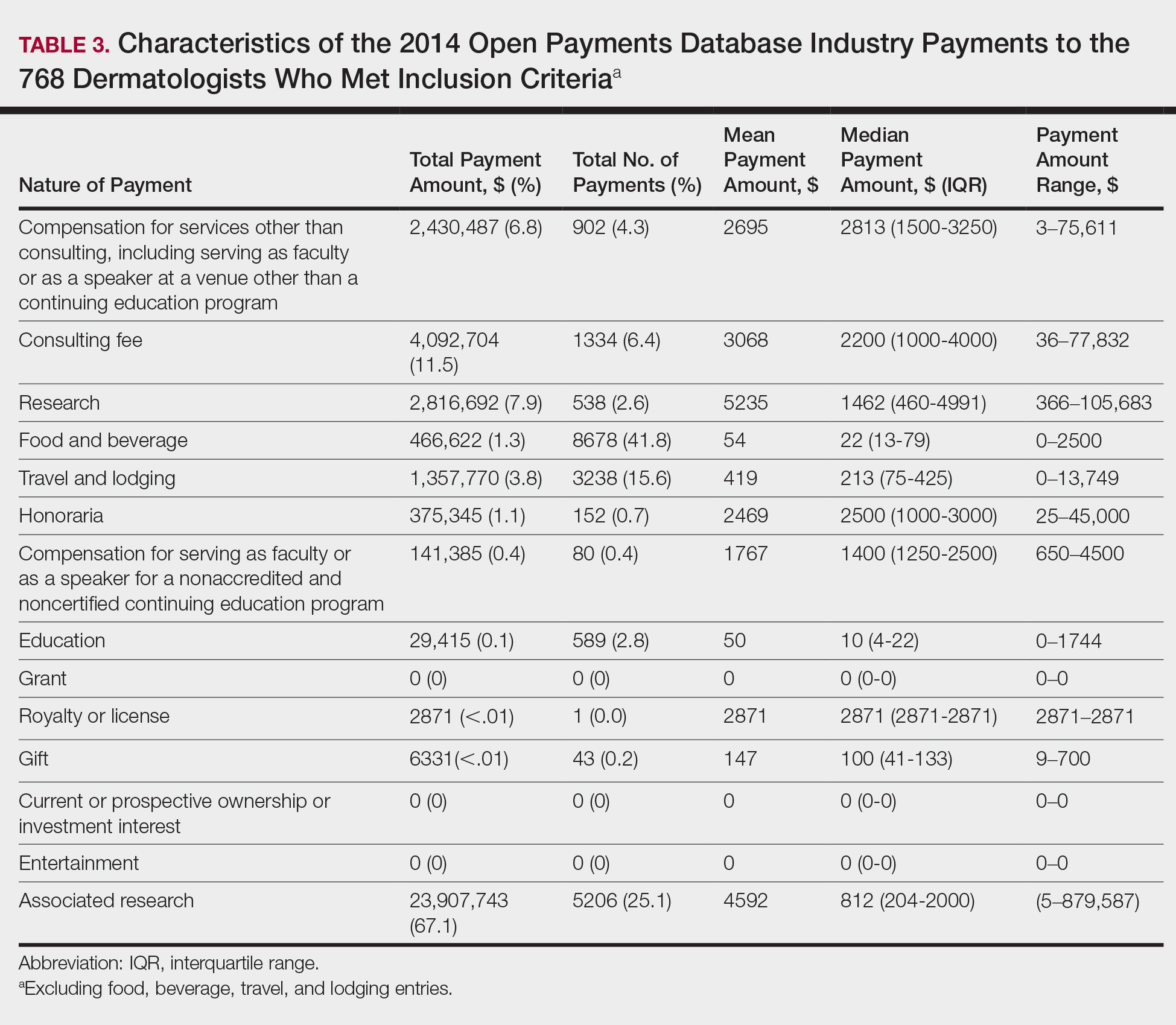

In 2014, there were a total of 20,761 industry payments totaling $35,627,365 for general, research, and associated research payments in the OP database related to the dermatologists who met inclusion criteria. There were 8678 payments totaling $466,622 for food and beverage and 3238 payments totaling $1,357,770 for travel and lodging. After excluding payments for f/b/t/l, there were 8845 payments totaling $33,802,973, with highest percentages of payment amounts for associated research (67.1%), consulting fees (11.5%), research (7.9%), and speaker fees (7.2%)(Table 3). For presenters with industry payments, the range of disbursements excluding f/b/t/l was $6.52 to $1,933,705, with a mean (standard deviation) of $107,997 ($249,941), a median of $18,247, and an interquartile range of $3422 to $97,375 (data not shown).

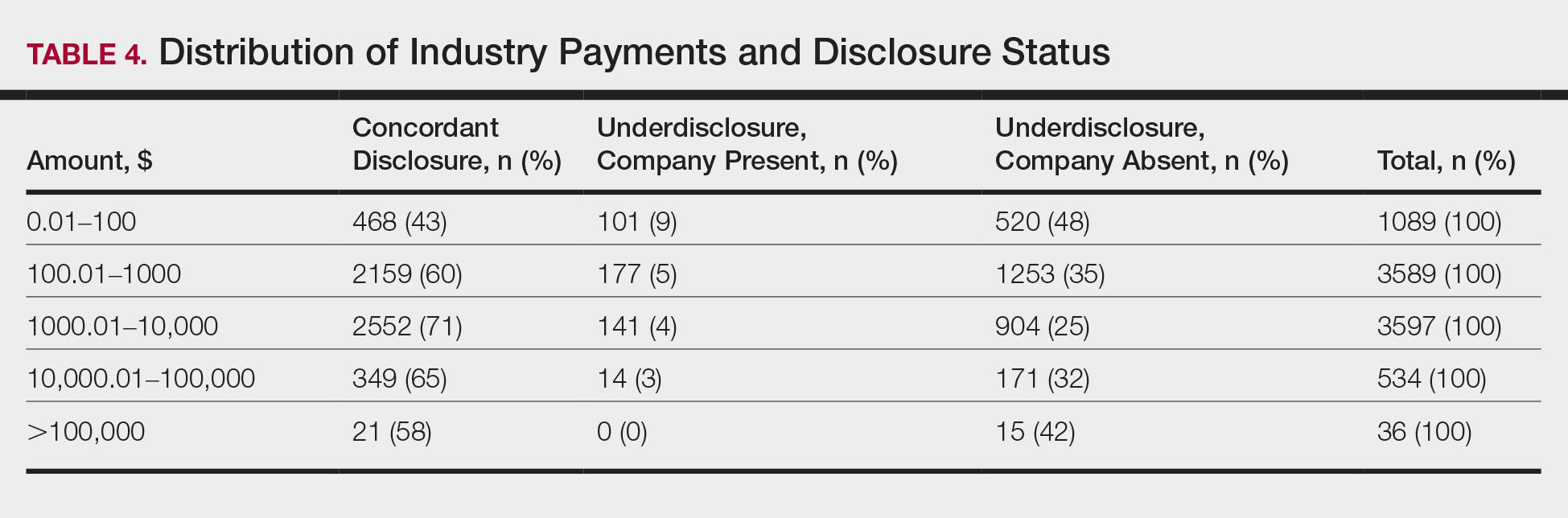

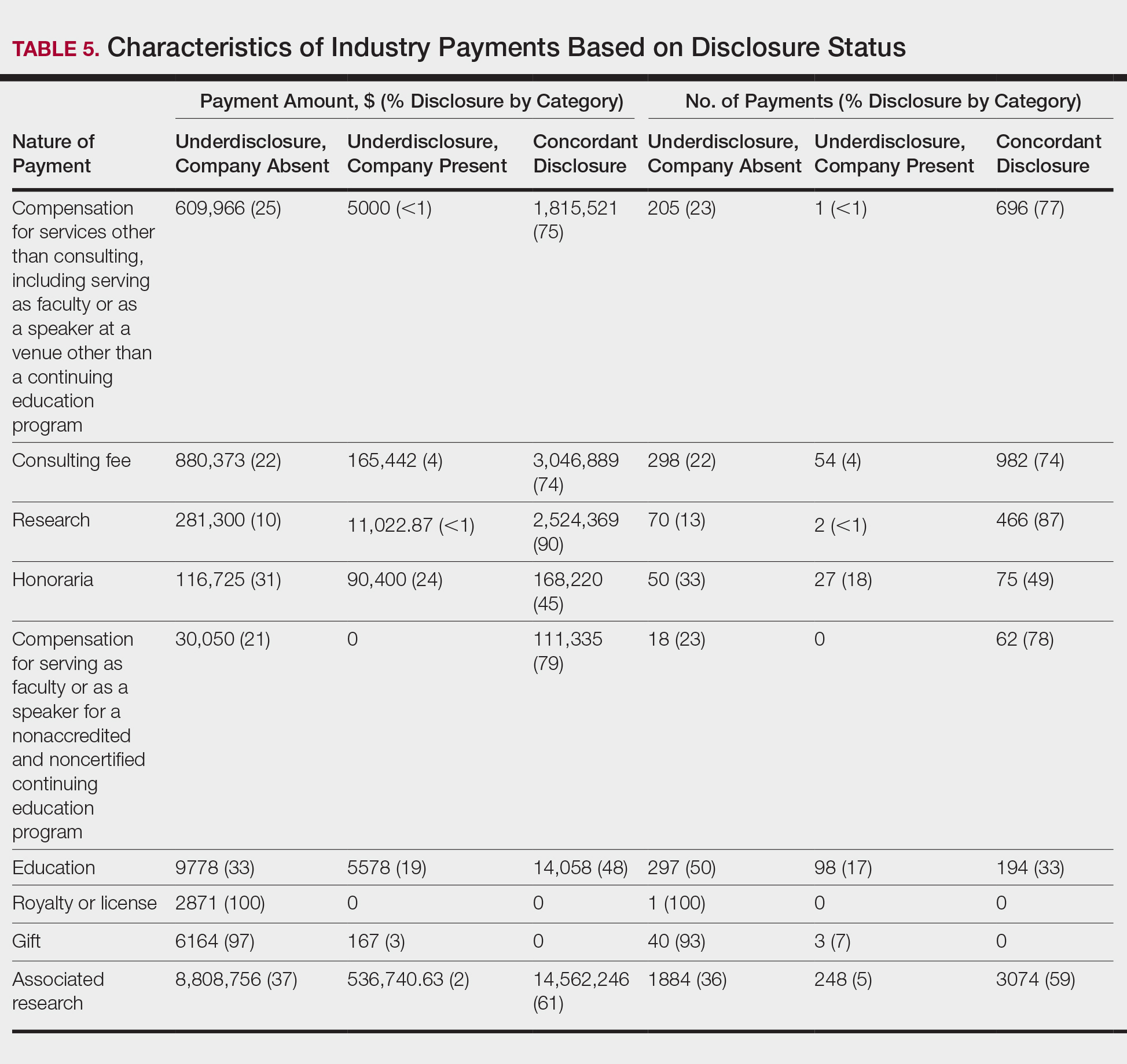

In assessing interaction-level concordance, 63% of all payment amounts in OP were classified as concordant disclosures. Regarding the number of OP payments, 27% were concordant disclosures, 34% were underdisclosures due to f/b/t/l payments, and 39% were underdisclosures due to non–f/b/t/l payments. When f/b/t/l payment entries in OP were excluded, the status of concordant disclosure for the amount and number of OP payments increased to 66% ($22,242,638) and 63% (5549), respectively. The percentage of payment entries with concordant disclosure status ranged from 43% to 71% depending on the payment amount. Payment entries at both ends of the spectrum had the lowest concordant disclosure rates, with 43% for payment entries between $0.01 and $100 and 58% for entries greater than $100,000 (Table 4). The concordance status also differed by the type of interactions. None of the OP payments for gift and royalty or license were disclosed in the AADMP, as there were no suitable corresponding categories. The proportion of payments with concordant disclosure for honoraria (45%), education (48%), and associated research (61%) was lower than the proportion of payments with concordant disclosure for research (90%), speaker fees (75%–79%), and consulting fees (74%)(Table 5).

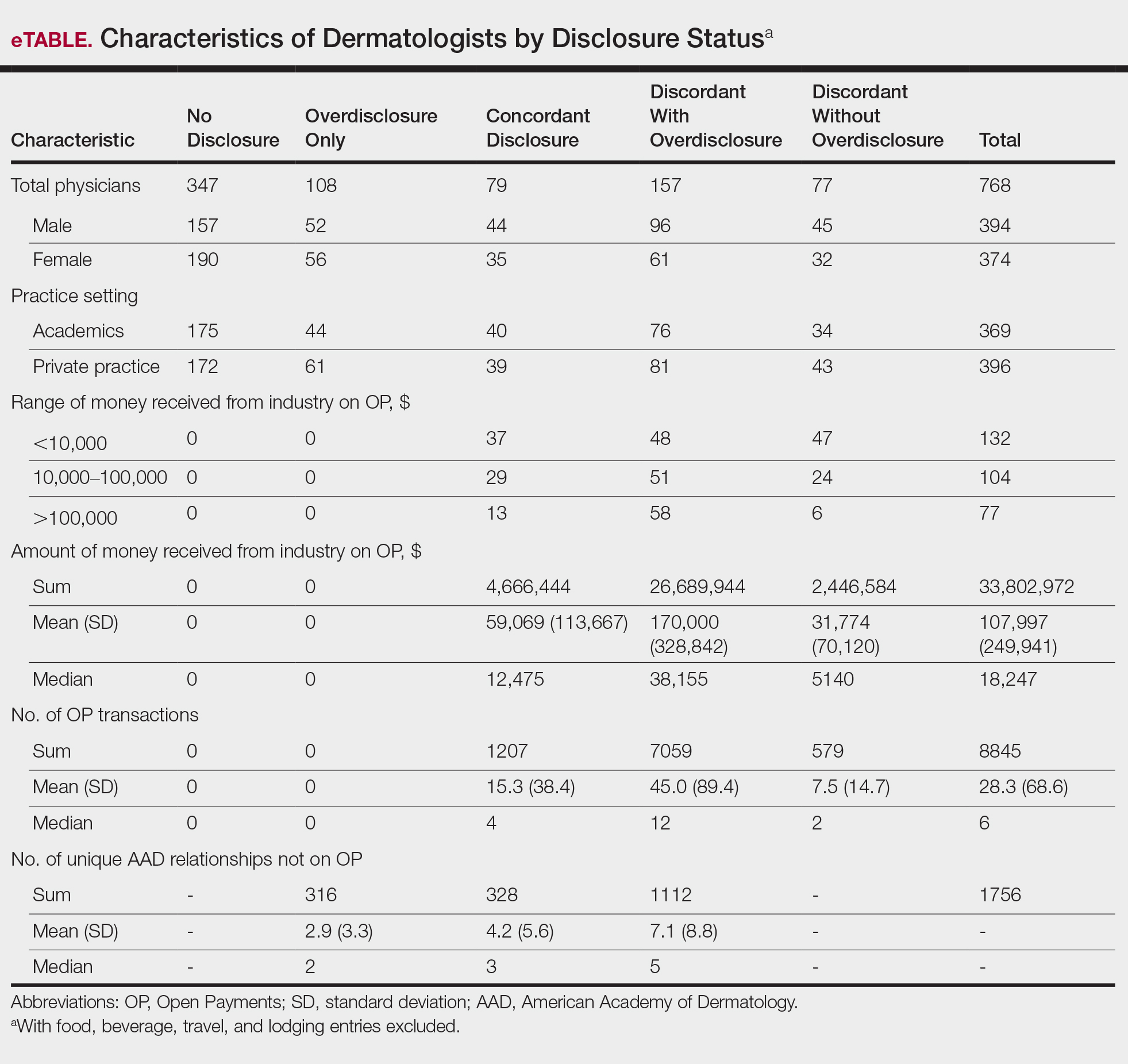

In assessing dermatologist-level concordance including all OP entries, the number of dermatologists with no disclosure, overdisclosure only, concordant disclosure, discordant with overdisclosure, and discordant without overdisclosure statuses were 234 (30%), 70 (9%), 9 (1%), 251 (33%), and 204 (27%), respectively. When f/b/t/l entries were excluded, those figures changed to 347 (45%), 108 (14%), 79 (10%), 157 (20%), and 77 (10%), respectively. The characteristics of these dermatologists and their associated industry interactions by disclosure status are shown in the eTable. Dermatologists in the discordant with overdisclosure group had the highest median number and amount of OP payments, followed by those in the concordant disclosure and discordant without overdisclosure groups. Additionally, discordant with overdisclosure dermatologists also had the highest median and mean number of unique industry interactions not on OP, followed by those in the overdisclosure only and no disclosure groups. Academic and private practice settings did not impact dermatologists’ disclosure status. The percentage of female and male dermatologists in the discordant group was 25% and 36%, respectively.

Dermatologists reported a total of 1756 unique industry relationships in the AADMP that were not found on OP. Of these, 1440 (82%) relationships were from 236 dermatologists who had industry payments on OP. The remaining 316 relationships were from 108 dermatologists who had no payments on OP. Although 114 companies reported payments to dermatologists on OP, dermatologists in the AADMP reported interactions with an additional 430 companies.

Comment

In this study, we demonstrated discordance between dermatologist self-reported financial interactions in the AADMP compared with those reported by industry via OP. After excluding f/b/t/l entries, approximately two-thirds of the total amount and number of payments in OP were disclosed, while 31% of dermatologists had discordant disclosure status.

Prior investigations in other medical fields showed high discrepancy rates between industry-reported and physician-reported relationships ranging from 23% to 62%, with studies utilizing various methodologies.6-9,11,12,14,15 Only a few studies have utilized the OP database.8,12,15 Thompson et al12 compared OP payment data with physician financial disclosure at an annual gynecology scientific meeting and found although 209 of 335 (62%) physicians had interactions listed in the OP database, only 24 (7%) listed at least 1 company in the meeting financial disclosure section. Of these 24 physicians, only 5 (21%) accurately disclosed financial relationships with all of the companies listed in OP. The investigators found 129 (38.5%) physicians and 33.7% of the $1.99 million OP payments had concordant disclosure status. When they excluded physicians who received less than $100, 53% of individuals had concordant disclosure.12 Hannon et al8 reported on inconsistencies between disclosures in the OP database and the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons Annual Meeting and found 259 (23%) of 1113 physicians meeting inclusion criteria had financial interactions listed in the OP database that were not reported in the meeting disclosures. Yee et al15 also utilized the OP database and compared it with author disclosures in 3 major ophthalmology journals.Of 670 authors, 367 (54.8%) had complete concordance, with 68 (10.1%) more reporting additional overdisclosures, leading to a discordant with underdisclosure rate of 35.1%. Additionally, $1.46 million (44.6%) of the $3.27 million OP payments had concordant disclosure status.15 Other studies compared individual companies’ online reports of physician payments with physician self-disclosures in annual meeting programs, clinical guidelines, and peer-reviewed publications.6,7,9,11,14

Our study demonstrated variation in disclosure status. Compared with other groups, dermatologists in the discordant with overdisclosure group on average had more interactions with and received higher payments from industry, which is consistent with studies in the orthopedic surgery literature.8,9 Male dermatologists had 11% more discordant disclosures than their female counterparts, which may be influenced by men having more industry interactions than women.3 Although small industry payments possessed the lowest concordant rate in our study, which has been observed,12 payments greater than $100,000 had the second-lowest concordance rate at 58%, which may be skewed by the small sample size. Rates of concordant disclosure differed among types of interactions, such as between research and associated research payments. This particular difference may be attributed to the incorrect listing of dermatologists as principal investigators or reduced awareness of payments, as associated research payments were made to the institution and not the individual.

Reasons for discrepancies between industry-reported and dermatologist-reported disclosures may include reporting time differences, lack of physician awareness of OP, industry reporting inaccuracies, dearth of contextual information associated with individual payment entries, and misunderstandings. Prior research demonstrated that the most common reasons for physician nondisclosure included misunderstanding disclosure requirements, unintentional omission of payment, and a lack of relationship between the industry payment and presentation topic.9,12 These factors likely contributed to the disclosure inconsistencies in our study. Similarly high rates of inconsistencies across different specialties suggest systemic concerns.

We found a substantial number of dermatologist-industry interactions listed in the AADMP that were not captured by OP, with 108 dermatologists (35%) having overdisclosures even when excluding f/b/t/l entries. The number of companies in these overdisclosures approximated 4 times the number of companies on OP. Other studies have also observed physician-industry interactions not displayed on OP.8,12,15 Because the Sunshine Act requires reporting only by certain companies, interactions surrounding products such as over-the-counter merchandise, cosmetics, lasers, novel devices, and new medications are generally not included. Further, OP may not capture nonmonetary industry relationships.

There were several limitations to this study. The most notable limitation was the differences in the categorizations of industry relationships by OP and the AADMP. These differences can overemphasize some types of interactions at the expense of other types, such as f/b/t/l. As such, analyses were repeated after excluding f/b/t/l. Another limitation was the inexact overlap of time frames for OP and the AADMP, which may have led to discrepancies. However, we used the best available data and expect the vast majority of interactions to have occurred by the AAD disclosure deadline. It is possible that the presenters may have had a more updated conflict-of-interest disclosure slide at the time of the meeting presentation. The most important limitation was that we were unable to determine whether discrepancies resulted from underreporting by dermatologists or inaccurate reporting by industry. It was unlikely that OP or the AADMP alone completely represented all dermatologist-industry financial relationships.

Conclusion

With a growing emphasis on physician-industry transparency, we identified rates of differences in dermatology consistent with those in other medical fields when comparing the publicly available OP database with disclosures at national conferences. Although the differences in the categorization and requirements for disclosure between the OP database and the AADMP may account for some of the discordance, dermatologists should be aware of potentially negative public perceptions regarding the transparency and prevalence of physician-industry interactions.

Acknowledgment

The first two authors contributed equally to this research/article

- Campbell EG, Gruen RL, Mountford J, et al. A national survey of physician-industry relationships. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1742-1750.

- Marshall DC, Jackson ME, Hattangadi-Gluth JA. Disclosure of industry payments to physicians: an epidemiologic analysis of early data from the open payments program. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:84-96.

- Feng H, Wu P, Leger M. Exploring the industry-dermatologist financial relationship: insight from the open payment data. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1307-1313.

- Kirschner NM, Sulmasy LS, Kesselheim AS. Health policy basics: the physician payment Sunshine Act and the open payments program. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:519-521.

- Search Open Payment. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov. Accessed October 21, 2019.

- Buerba RA, Fu MC, Grauer JN. Discrepancies in spine surgeon conflict of interest disclosures between a national meeting and physician payment listings on device manufacturer web sites. Spine J. 2013;13:1780-1788.

- Chimonas S, Frosch Z, Rothman DJ. From disclosure to transparency: the use of company payment data. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:81-86.

- Hannon CP, Chalmers PN, Carpiniello MF, et al. Inconsistencies between physician-reported disclosures at the AAOS annual meeting and industry-reported financial disclosures in the open payments database. J Bone Joint Surg. 2016;98:E90.

- Okike K, Kocher MS, Wei EX, et al. Accuracy of conflict-of-interest disclosures reported by physicians. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1466-1474.

- Ramm O, Brubaker L. Conflicts-of-interest disclosures at the 2010 AUGS Scientific Meeting. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2012;18:79-81.

- Tanzer D, Smith K, Tanzer M. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons disclosure policy fails to accurately inform its members of potential conflicts of interest. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2015;44:E207-E210.

- Thompson JC, Volpe KA, Bridgewater LK, et al. Sunshine Act: shedding light on inaccurate disclosures at a gynecologic annual meeting. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:661.

- Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. American Academy of Dermatology and AAD Association Web site. https://aad.org/Forms/Policies/Uploads/AR/

AR%20Disclosure%20of%20Potential%20Conflicts%

20of%20Interest-2.pdf. Accessed October 21, 2019. - Hockenberry JM, Weigel P, Auerbach A, et al. Financial payments by orthopedic device makers to orthopedic surgeons. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1759-1765.

- Yee C, Greenberg PB, Margo CE, et al. Financial disclosures in academic publications and the Sunshine Act: a concordance dtudy. Br J Med Med Res. 2015;10:1-6.

Interactions between industry and physicians, including dermatologists, are widely prevalent.1-3 Proper reporting of industry relationships is essential for transparency, objectivity, and management of potential biases and conflicts of interest. There has been increasing public scrutiny regarding these interactions.

The Physician Payments Sunshine Act established Open Payments (OP), a publicly available database that collects and displays industry-reported physician-industry interactions.4,5 For the medical community and public, the OP database may be used to assess transparency by comparing the data with physician self-disclosures. There is a paucity of studies in the literature examining the concordance of industry-reported disclosures and physician self-reported data, with even fewer studies utilizing OP as a source of industry disclosures, and none exists for dermatology.6-12 It also is not clear to what extent the OP database captures all possible dermatologist-industry interactions, as the Sunshine Act only mandates reporting by applicable US-based manufacturers and group purchasing organizations that produce or purchase drugs or devices that require a prescription and are reimbursable by a government-run health care program.5 As a result, certain companies, such as cosmeceuticals, may not be represented.

In this study we aimed to evaluate the concordance of dermatologist self-disclosure of industry relationships and those reported on OP. Specifically, we focused on interactions disclosed by presenters at the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) 73rd Annual Meeting in San Francisco, California (March 20–24, 2015), and those by industry in the 2014 OP database.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, we compared publicly available data from the OP database to presenter disclosures found in the publicly available AAD 73rd Annual Meeting program (AADMP). The AAD required speakers to disclose financial relationships with industry within the 12 months preceding the presentation, as outlined in the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education guidelines.13 All AAD presenters who were dermatologists practicing in the United States were included in the analysis, whereas residents, fellows, nonphysicians, nondermatologist physicians, and international dermatologists were excluded.

We examined general, research, and associated research payments to specific dermatologists using the 2014 OP data, which contained industry payments made between January 1 and December 31, 2014. Open Payments defined research payments as direct payment to the physician for different types of research activities and associated research payments as indirect payments made to a research institution or entity where the physician was named the principal investigator.5 We chose the 2014 database because it most closely matched the period of required disclosures defined by the AAD for the 2015 meeting. Our review of the OP data occurred after the June 2016 update and thus included the most accurate and up-to-date financial interactions.

We conducted our analysis in 2 major steps. First, we determined whether each industry interaction reported in the OP database was present in the AADMP, which provided an assessment of interaction-level concordance. Second, we determined whether all the industry interactions for any given dermatologist listed in the OP also were present in AADMP, which provided an assessment of dermatologist-level concordance.

First, to establish interaction-level concordance for each industry interaction, the company name and the type of interaction (eg, consultant, speaker, investigator) listed in the AADMP were compared with the data in OP to verify a match. Each interaction was assigned into one of the categories of concordant disclosure (a match of both the company name and type of interaction details in OP and the AADMP), overdisclosure (the presence of an AADMP interaction not found in OP, such as an additional type of interaction or company), or underdisclosure (a company name or type of interaction found in OP but not reported in the AADMP). For underdisclosure, we further classified into company present or company absent based on whether the dermatologist disclosed any relationship with a particular company in the AADMP. We considered the type of interaction to be matching if they were identical or similar in nature (eg, consulting in OP and advisory board in the AADMP), as the types of interactions are reported differently in OP and the AADMP. Otherwise, if they were not similar enough (eg, education in OP and stockholder in the AADMP), it was classified as underdisclosure. Some types of interactions reported in OP were not available on the AAD disclosure form. For example, food and beverage as well as travel and lodging were types of interactions in OP that did not exist in the AADMP. These 2 types of interactions comprised a large majority of OP payment entries but only accounted for a small percentage of the payment amount. Analysis was performed both including and excluding interactions for food, beverage, travel, and lodging (f/b/t/l) to best account for differences in interaction categories between OP and the AADMP.

Second, each dermatologist was assigned to an overall disclosure category of dermatologist-level concordance based on the status for all his/her interactions. Categories included no disclosure (no industry interactions in OP and the AADMP), concordant (all industry interactions reported in OP and the AADMP match), overdisclosure only (no industry interactions on OP but self-reported interactions present in the AADMP), and discordant (not all OP interactions were disclosed in the AADMP). The discordant category was further divided into with overdisclosure and without overdisclosure, depending on the presence or absence of industry relationships listed in the AADMP but not in OP, respectively.

To ensure uniformity, one individual (A.F.S.) reviewed and collected the data from OP and the AADMP. Information on gender and academic affiliation of study participants was obtained from information listed in the AADMP and Google searches. Data management was performed with Microsoft Excel software (Microsoft Excel 2010, Version 14.0, Microsoft Corporation). The New York University School of Medicine’s (New York, New York) institutional review board exempted this study.

Results

Of the 938 presenters listed in the AADMP, 768 individuals met the inclusion criteria. The most commonly cited type of relationship with industry listed in the AADMP was serving as an investigator, consultant, or advisory board member, comprising 34%, 26%, and 18%, respectively (Table 1). The forms of payment most frequently reported in the AADMP were honoraria and grants/research funding, comprising 49% and 25%, respectively (Table 2).

In 2014, there were a total of 20,761 industry payments totaling $35,627,365 for general, research, and associated research payments in the OP database related to the dermatologists who met inclusion criteria. There were 8678 payments totaling $466,622 for food and beverage and 3238 payments totaling $1,357,770 for travel and lodging. After excluding payments for f/b/t/l, there were 8845 payments totaling $33,802,973, with highest percentages of payment amounts for associated research (67.1%), consulting fees (11.5%), research (7.9%), and speaker fees (7.2%)(Table 3). For presenters with industry payments, the range of disbursements excluding f/b/t/l was $6.52 to $1,933,705, with a mean (standard deviation) of $107,997 ($249,941), a median of $18,247, and an interquartile range of $3422 to $97,375 (data not shown).

In assessing interaction-level concordance, 63% of all payment amounts in OP were classified as concordant disclosures. Regarding the number of OP payments, 27% were concordant disclosures, 34% were underdisclosures due to f/b/t/l payments, and 39% were underdisclosures due to non–f/b/t/l payments. When f/b/t/l payment entries in OP were excluded, the status of concordant disclosure for the amount and number of OP payments increased to 66% ($22,242,638) and 63% (5549), respectively. The percentage of payment entries with concordant disclosure status ranged from 43% to 71% depending on the payment amount. Payment entries at both ends of the spectrum had the lowest concordant disclosure rates, with 43% for payment entries between $0.01 and $100 and 58% for entries greater than $100,000 (Table 4). The concordance status also differed by the type of interactions. None of the OP payments for gift and royalty or license were disclosed in the AADMP, as there were no suitable corresponding categories. The proportion of payments with concordant disclosure for honoraria (45%), education (48%), and associated research (61%) was lower than the proportion of payments with concordant disclosure for research (90%), speaker fees (75%–79%), and consulting fees (74%)(Table 5).

In assessing dermatologist-level concordance including all OP entries, the number of dermatologists with no disclosure, overdisclosure only, concordant disclosure, discordant with overdisclosure, and discordant without overdisclosure statuses were 234 (30%), 70 (9%), 9 (1%), 251 (33%), and 204 (27%), respectively. When f/b/t/l entries were excluded, those figures changed to 347 (45%), 108 (14%), 79 (10%), 157 (20%), and 77 (10%), respectively. The characteristics of these dermatologists and their associated industry interactions by disclosure status are shown in the eTable. Dermatologists in the discordant with overdisclosure group had the highest median number and amount of OP payments, followed by those in the concordant disclosure and discordant without overdisclosure groups. Additionally, discordant with overdisclosure dermatologists also had the highest median and mean number of unique industry interactions not on OP, followed by those in the overdisclosure only and no disclosure groups. Academic and private practice settings did not impact dermatologists’ disclosure status. The percentage of female and male dermatologists in the discordant group was 25% and 36%, respectively.

Dermatologists reported a total of 1756 unique industry relationships in the AADMP that were not found on OP. Of these, 1440 (82%) relationships were from 236 dermatologists who had industry payments on OP. The remaining 316 relationships were from 108 dermatologists who had no payments on OP. Although 114 companies reported payments to dermatologists on OP, dermatologists in the AADMP reported interactions with an additional 430 companies.

Comment

In this study, we demonstrated discordance between dermatologist self-reported financial interactions in the AADMP compared with those reported by industry via OP. After excluding f/b/t/l entries, approximately two-thirds of the total amount and number of payments in OP were disclosed, while 31% of dermatologists had discordant disclosure status.

Prior investigations in other medical fields showed high discrepancy rates between industry-reported and physician-reported relationships ranging from 23% to 62%, with studies utilizing various methodologies.6-9,11,12,14,15 Only a few studies have utilized the OP database.8,12,15 Thompson et al12 compared OP payment data with physician financial disclosure at an annual gynecology scientific meeting and found although 209 of 335 (62%) physicians had interactions listed in the OP database, only 24 (7%) listed at least 1 company in the meeting financial disclosure section. Of these 24 physicians, only 5 (21%) accurately disclosed financial relationships with all of the companies listed in OP. The investigators found 129 (38.5%) physicians and 33.7% of the $1.99 million OP payments had concordant disclosure status. When they excluded physicians who received less than $100, 53% of individuals had concordant disclosure.12 Hannon et al8 reported on inconsistencies between disclosures in the OP database and the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons Annual Meeting and found 259 (23%) of 1113 physicians meeting inclusion criteria had financial interactions listed in the OP database that were not reported in the meeting disclosures. Yee et al15 also utilized the OP database and compared it with author disclosures in 3 major ophthalmology journals.Of 670 authors, 367 (54.8%) had complete concordance, with 68 (10.1%) more reporting additional overdisclosures, leading to a discordant with underdisclosure rate of 35.1%. Additionally, $1.46 million (44.6%) of the $3.27 million OP payments had concordant disclosure status.15 Other studies compared individual companies’ online reports of physician payments with physician self-disclosures in annual meeting programs, clinical guidelines, and peer-reviewed publications.6,7,9,11,14

Our study demonstrated variation in disclosure status. Compared with other groups, dermatologists in the discordant with overdisclosure group on average had more interactions with and received higher payments from industry, which is consistent with studies in the orthopedic surgery literature.8,9 Male dermatologists had 11% more discordant disclosures than their female counterparts, which may be influenced by men having more industry interactions than women.3 Although small industry payments possessed the lowest concordant rate in our study, which has been observed,12 payments greater than $100,000 had the second-lowest concordance rate at 58%, which may be skewed by the small sample size. Rates of concordant disclosure differed among types of interactions, such as between research and associated research payments. This particular difference may be attributed to the incorrect listing of dermatologists as principal investigators or reduced awareness of payments, as associated research payments were made to the institution and not the individual.

Reasons for discrepancies between industry-reported and dermatologist-reported disclosures may include reporting time differences, lack of physician awareness of OP, industry reporting inaccuracies, dearth of contextual information associated with individual payment entries, and misunderstandings. Prior research demonstrated that the most common reasons for physician nondisclosure included misunderstanding disclosure requirements, unintentional omission of payment, and a lack of relationship between the industry payment and presentation topic.9,12 These factors likely contributed to the disclosure inconsistencies in our study. Similarly high rates of inconsistencies across different specialties suggest systemic concerns.

We found a substantial number of dermatologist-industry interactions listed in the AADMP that were not captured by OP, with 108 dermatologists (35%) having overdisclosures even when excluding f/b/t/l entries. The number of companies in these overdisclosures approximated 4 times the number of companies on OP. Other studies have also observed physician-industry interactions not displayed on OP.8,12,15 Because the Sunshine Act requires reporting only by certain companies, interactions surrounding products such as over-the-counter merchandise, cosmetics, lasers, novel devices, and new medications are generally not included. Further, OP may not capture nonmonetary industry relationships.

There were several limitations to this study. The most notable limitation was the differences in the categorizations of industry relationships by OP and the AADMP. These differences can overemphasize some types of interactions at the expense of other types, such as f/b/t/l. As such, analyses were repeated after excluding f/b/t/l. Another limitation was the inexact overlap of time frames for OP and the AADMP, which may have led to discrepancies. However, we used the best available data and expect the vast majority of interactions to have occurred by the AAD disclosure deadline. It is possible that the presenters may have had a more updated conflict-of-interest disclosure slide at the time of the meeting presentation. The most important limitation was that we were unable to determine whether discrepancies resulted from underreporting by dermatologists or inaccurate reporting by industry. It was unlikely that OP or the AADMP alone completely represented all dermatologist-industry financial relationships.

Conclusion

With a growing emphasis on physician-industry transparency, we identified rates of differences in dermatology consistent with those in other medical fields when comparing the publicly available OP database with disclosures at national conferences. Although the differences in the categorization and requirements for disclosure between the OP database and the AADMP may account for some of the discordance, dermatologists should be aware of potentially negative public perceptions regarding the transparency and prevalence of physician-industry interactions.

Acknowledgment

The first two authors contributed equally to this research/article

Interactions between industry and physicians, including dermatologists, are widely prevalent.1-3 Proper reporting of industry relationships is essential for transparency, objectivity, and management of potential biases and conflicts of interest. There has been increasing public scrutiny regarding these interactions.

The Physician Payments Sunshine Act established Open Payments (OP), a publicly available database that collects and displays industry-reported physician-industry interactions.4,5 For the medical community and public, the OP database may be used to assess transparency by comparing the data with physician self-disclosures. There is a paucity of studies in the literature examining the concordance of industry-reported disclosures and physician self-reported data, with even fewer studies utilizing OP as a source of industry disclosures, and none exists for dermatology.6-12 It also is not clear to what extent the OP database captures all possible dermatologist-industry interactions, as the Sunshine Act only mandates reporting by applicable US-based manufacturers and group purchasing organizations that produce or purchase drugs or devices that require a prescription and are reimbursable by a government-run health care program.5 As a result, certain companies, such as cosmeceuticals, may not be represented.

In this study we aimed to evaluate the concordance of dermatologist self-disclosure of industry relationships and those reported on OP. Specifically, we focused on interactions disclosed by presenters at the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) 73rd Annual Meeting in San Francisco, California (March 20–24, 2015), and those by industry in the 2014 OP database.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, we compared publicly available data from the OP database to presenter disclosures found in the publicly available AAD 73rd Annual Meeting program (AADMP). The AAD required speakers to disclose financial relationships with industry within the 12 months preceding the presentation, as outlined in the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education guidelines.13 All AAD presenters who were dermatologists practicing in the United States were included in the analysis, whereas residents, fellows, nonphysicians, nondermatologist physicians, and international dermatologists were excluded.

We examined general, research, and associated research payments to specific dermatologists using the 2014 OP data, which contained industry payments made between January 1 and December 31, 2014. Open Payments defined research payments as direct payment to the physician for different types of research activities and associated research payments as indirect payments made to a research institution or entity where the physician was named the principal investigator.5 We chose the 2014 database because it most closely matched the period of required disclosures defined by the AAD for the 2015 meeting. Our review of the OP data occurred after the June 2016 update and thus included the most accurate and up-to-date financial interactions.

We conducted our analysis in 2 major steps. First, we determined whether each industry interaction reported in the OP database was present in the AADMP, which provided an assessment of interaction-level concordance. Second, we determined whether all the industry interactions for any given dermatologist listed in the OP also were present in AADMP, which provided an assessment of dermatologist-level concordance.

First, to establish interaction-level concordance for each industry interaction, the company name and the type of interaction (eg, consultant, speaker, investigator) listed in the AADMP were compared with the data in OP to verify a match. Each interaction was assigned into one of the categories of concordant disclosure (a match of both the company name and type of interaction details in OP and the AADMP), overdisclosure (the presence of an AADMP interaction not found in OP, such as an additional type of interaction or company), or underdisclosure (a company name or type of interaction found in OP but not reported in the AADMP). For underdisclosure, we further classified into company present or company absent based on whether the dermatologist disclosed any relationship with a particular company in the AADMP. We considered the type of interaction to be matching if they were identical or similar in nature (eg, consulting in OP and advisory board in the AADMP), as the types of interactions are reported differently in OP and the AADMP. Otherwise, if they were not similar enough (eg, education in OP and stockholder in the AADMP), it was classified as underdisclosure. Some types of interactions reported in OP were not available on the AAD disclosure form. For example, food and beverage as well as travel and lodging were types of interactions in OP that did not exist in the AADMP. These 2 types of interactions comprised a large majority of OP payment entries but only accounted for a small percentage of the payment amount. Analysis was performed both including and excluding interactions for food, beverage, travel, and lodging (f/b/t/l) to best account for differences in interaction categories between OP and the AADMP.

Second, each dermatologist was assigned to an overall disclosure category of dermatologist-level concordance based on the status for all his/her interactions. Categories included no disclosure (no industry interactions in OP and the AADMP), concordant (all industry interactions reported in OP and the AADMP match), overdisclosure only (no industry interactions on OP but self-reported interactions present in the AADMP), and discordant (not all OP interactions were disclosed in the AADMP). The discordant category was further divided into with overdisclosure and without overdisclosure, depending on the presence or absence of industry relationships listed in the AADMP but not in OP, respectively.

To ensure uniformity, one individual (A.F.S.) reviewed and collected the data from OP and the AADMP. Information on gender and academic affiliation of study participants was obtained from information listed in the AADMP and Google searches. Data management was performed with Microsoft Excel software (Microsoft Excel 2010, Version 14.0, Microsoft Corporation). The New York University School of Medicine’s (New York, New York) institutional review board exempted this study.

Results

Of the 938 presenters listed in the AADMP, 768 individuals met the inclusion criteria. The most commonly cited type of relationship with industry listed in the AADMP was serving as an investigator, consultant, or advisory board member, comprising 34%, 26%, and 18%, respectively (Table 1). The forms of payment most frequently reported in the AADMP were honoraria and grants/research funding, comprising 49% and 25%, respectively (Table 2).

In 2014, there were a total of 20,761 industry payments totaling $35,627,365 for general, research, and associated research payments in the OP database related to the dermatologists who met inclusion criteria. There were 8678 payments totaling $466,622 for food and beverage and 3238 payments totaling $1,357,770 for travel and lodging. After excluding payments for f/b/t/l, there were 8845 payments totaling $33,802,973, with highest percentages of payment amounts for associated research (67.1%), consulting fees (11.5%), research (7.9%), and speaker fees (7.2%)(Table 3). For presenters with industry payments, the range of disbursements excluding f/b/t/l was $6.52 to $1,933,705, with a mean (standard deviation) of $107,997 ($249,941), a median of $18,247, and an interquartile range of $3422 to $97,375 (data not shown).

In assessing interaction-level concordance, 63% of all payment amounts in OP were classified as concordant disclosures. Regarding the number of OP payments, 27% were concordant disclosures, 34% were underdisclosures due to f/b/t/l payments, and 39% were underdisclosures due to non–f/b/t/l payments. When f/b/t/l payment entries in OP were excluded, the status of concordant disclosure for the amount and number of OP payments increased to 66% ($22,242,638) and 63% (5549), respectively. The percentage of payment entries with concordant disclosure status ranged from 43% to 71% depending on the payment amount. Payment entries at both ends of the spectrum had the lowest concordant disclosure rates, with 43% for payment entries between $0.01 and $100 and 58% for entries greater than $100,000 (Table 4). The concordance status also differed by the type of interactions. None of the OP payments for gift and royalty or license were disclosed in the AADMP, as there were no suitable corresponding categories. The proportion of payments with concordant disclosure for honoraria (45%), education (48%), and associated research (61%) was lower than the proportion of payments with concordant disclosure for research (90%), speaker fees (75%–79%), and consulting fees (74%)(Table 5).

In assessing dermatologist-level concordance including all OP entries, the number of dermatologists with no disclosure, overdisclosure only, concordant disclosure, discordant with overdisclosure, and discordant without overdisclosure statuses were 234 (30%), 70 (9%), 9 (1%), 251 (33%), and 204 (27%), respectively. When f/b/t/l entries were excluded, those figures changed to 347 (45%), 108 (14%), 79 (10%), 157 (20%), and 77 (10%), respectively. The characteristics of these dermatologists and their associated industry interactions by disclosure status are shown in the eTable. Dermatologists in the discordant with overdisclosure group had the highest median number and amount of OP payments, followed by those in the concordant disclosure and discordant without overdisclosure groups. Additionally, discordant with overdisclosure dermatologists also had the highest median and mean number of unique industry interactions not on OP, followed by those in the overdisclosure only and no disclosure groups. Academic and private practice settings did not impact dermatologists’ disclosure status. The percentage of female and male dermatologists in the discordant group was 25% and 36%, respectively.

Dermatologists reported a total of 1756 unique industry relationships in the AADMP that were not found on OP. Of these, 1440 (82%) relationships were from 236 dermatologists who had industry payments on OP. The remaining 316 relationships were from 108 dermatologists who had no payments on OP. Although 114 companies reported payments to dermatologists on OP, dermatologists in the AADMP reported interactions with an additional 430 companies.

Comment

In this study, we demonstrated discordance between dermatologist self-reported financial interactions in the AADMP compared with those reported by industry via OP. After excluding f/b/t/l entries, approximately two-thirds of the total amount and number of payments in OP were disclosed, while 31% of dermatologists had discordant disclosure status.

Prior investigations in other medical fields showed high discrepancy rates between industry-reported and physician-reported relationships ranging from 23% to 62%, with studies utilizing various methodologies.6-9,11,12,14,15 Only a few studies have utilized the OP database.8,12,15 Thompson et al12 compared OP payment data with physician financial disclosure at an annual gynecology scientific meeting and found although 209 of 335 (62%) physicians had interactions listed in the OP database, only 24 (7%) listed at least 1 company in the meeting financial disclosure section. Of these 24 physicians, only 5 (21%) accurately disclosed financial relationships with all of the companies listed in OP. The investigators found 129 (38.5%) physicians and 33.7% of the $1.99 million OP payments had concordant disclosure status. When they excluded physicians who received less than $100, 53% of individuals had concordant disclosure.12 Hannon et al8 reported on inconsistencies between disclosures in the OP database and the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons Annual Meeting and found 259 (23%) of 1113 physicians meeting inclusion criteria had financial interactions listed in the OP database that were not reported in the meeting disclosures. Yee et al15 also utilized the OP database and compared it with author disclosures in 3 major ophthalmology journals.Of 670 authors, 367 (54.8%) had complete concordance, with 68 (10.1%) more reporting additional overdisclosures, leading to a discordant with underdisclosure rate of 35.1%. Additionally, $1.46 million (44.6%) of the $3.27 million OP payments had concordant disclosure status.15 Other studies compared individual companies’ online reports of physician payments with physician self-disclosures in annual meeting programs, clinical guidelines, and peer-reviewed publications.6,7,9,11,14

Our study demonstrated variation in disclosure status. Compared with other groups, dermatologists in the discordant with overdisclosure group on average had more interactions with and received higher payments from industry, which is consistent with studies in the orthopedic surgery literature.8,9 Male dermatologists had 11% more discordant disclosures than their female counterparts, which may be influenced by men having more industry interactions than women.3 Although small industry payments possessed the lowest concordant rate in our study, which has been observed,12 payments greater than $100,000 had the second-lowest concordance rate at 58%, which may be skewed by the small sample size. Rates of concordant disclosure differed among types of interactions, such as between research and associated research payments. This particular difference may be attributed to the incorrect listing of dermatologists as principal investigators or reduced awareness of payments, as associated research payments were made to the institution and not the individual.

Reasons for discrepancies between industry-reported and dermatologist-reported disclosures may include reporting time differences, lack of physician awareness of OP, industry reporting inaccuracies, dearth of contextual information associated with individual payment entries, and misunderstandings. Prior research demonstrated that the most common reasons for physician nondisclosure included misunderstanding disclosure requirements, unintentional omission of payment, and a lack of relationship between the industry payment and presentation topic.9,12 These factors likely contributed to the disclosure inconsistencies in our study. Similarly high rates of inconsistencies across different specialties suggest systemic concerns.

We found a substantial number of dermatologist-industry interactions listed in the AADMP that were not captured by OP, with 108 dermatologists (35%) having overdisclosures even when excluding f/b/t/l entries. The number of companies in these overdisclosures approximated 4 times the number of companies on OP. Other studies have also observed physician-industry interactions not displayed on OP.8,12,15 Because the Sunshine Act requires reporting only by certain companies, interactions surrounding products such as over-the-counter merchandise, cosmetics, lasers, novel devices, and new medications are generally not included. Further, OP may not capture nonmonetary industry relationships.

There were several limitations to this study. The most notable limitation was the differences in the categorizations of industry relationships by OP and the AADMP. These differences can overemphasize some types of interactions at the expense of other types, such as f/b/t/l. As such, analyses were repeated after excluding f/b/t/l. Another limitation was the inexact overlap of time frames for OP and the AADMP, which may have led to discrepancies. However, we used the best available data and expect the vast majority of interactions to have occurred by the AAD disclosure deadline. It is possible that the presenters may have had a more updated conflict-of-interest disclosure slide at the time of the meeting presentation. The most important limitation was that we were unable to determine whether discrepancies resulted from underreporting by dermatologists or inaccurate reporting by industry. It was unlikely that OP or the AADMP alone completely represented all dermatologist-industry financial relationships.

Conclusion

With a growing emphasis on physician-industry transparency, we identified rates of differences in dermatology consistent with those in other medical fields when comparing the publicly available OP database with disclosures at national conferences. Although the differences in the categorization and requirements for disclosure between the OP database and the AADMP may account for some of the discordance, dermatologists should be aware of potentially negative public perceptions regarding the transparency and prevalence of physician-industry interactions.

Acknowledgment

The first two authors contributed equally to this research/article

- Campbell EG, Gruen RL, Mountford J, et al. A national survey of physician-industry relationships. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1742-1750.

- Marshall DC, Jackson ME, Hattangadi-Gluth JA. Disclosure of industry payments to physicians: an epidemiologic analysis of early data from the open payments program. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:84-96.

- Feng H, Wu P, Leger M. Exploring the industry-dermatologist financial relationship: insight from the open payment data. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1307-1313.

- Kirschner NM, Sulmasy LS, Kesselheim AS. Health policy basics: the physician payment Sunshine Act and the open payments program. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:519-521.

- Search Open Payment. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov. Accessed October 21, 2019.

- Buerba RA, Fu MC, Grauer JN. Discrepancies in spine surgeon conflict of interest disclosures between a national meeting and physician payment listings on device manufacturer web sites. Spine J. 2013;13:1780-1788.

- Chimonas S, Frosch Z, Rothman DJ. From disclosure to transparency: the use of company payment data. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:81-86.

- Hannon CP, Chalmers PN, Carpiniello MF, et al. Inconsistencies between physician-reported disclosures at the AAOS annual meeting and industry-reported financial disclosures in the open payments database. J Bone Joint Surg. 2016;98:E90.

- Okike K, Kocher MS, Wei EX, et al. Accuracy of conflict-of-interest disclosures reported by physicians. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1466-1474.

- Ramm O, Brubaker L. Conflicts-of-interest disclosures at the 2010 AUGS Scientific Meeting. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2012;18:79-81.

- Tanzer D, Smith K, Tanzer M. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons disclosure policy fails to accurately inform its members of potential conflicts of interest. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2015;44:E207-E210.

- Thompson JC, Volpe KA, Bridgewater LK, et al. Sunshine Act: shedding light on inaccurate disclosures at a gynecologic annual meeting. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:661.

- Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. American Academy of Dermatology and AAD Association Web site. https://aad.org/Forms/Policies/Uploads/AR/

AR%20Disclosure%20of%20Potential%20Conflicts%

20of%20Interest-2.pdf. Accessed October 21, 2019. - Hockenberry JM, Weigel P, Auerbach A, et al. Financial payments by orthopedic device makers to orthopedic surgeons. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1759-1765.

- Yee C, Greenberg PB, Margo CE, et al. Financial disclosures in academic publications and the Sunshine Act: a concordance dtudy. Br J Med Med Res. 2015;10:1-6.

- Campbell EG, Gruen RL, Mountford J, et al. A national survey of physician-industry relationships. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1742-1750.

- Marshall DC, Jackson ME, Hattangadi-Gluth JA. Disclosure of industry payments to physicians: an epidemiologic analysis of early data from the open payments program. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:84-96.

- Feng H, Wu P, Leger M. Exploring the industry-dermatologist financial relationship: insight from the open payment data. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1307-1313.

- Kirschner NM, Sulmasy LS, Kesselheim AS. Health policy basics: the physician payment Sunshine Act and the open payments program. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:519-521.

- Search Open Payment. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov. Accessed October 21, 2019.

- Buerba RA, Fu MC, Grauer JN. Discrepancies in spine surgeon conflict of interest disclosures between a national meeting and physician payment listings on device manufacturer web sites. Spine J. 2013;13:1780-1788.

- Chimonas S, Frosch Z, Rothman DJ. From disclosure to transparency: the use of company payment data. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:81-86.

- Hannon CP, Chalmers PN, Carpiniello MF, et al. Inconsistencies between physician-reported disclosures at the AAOS annual meeting and industry-reported financial disclosures in the open payments database. J Bone Joint Surg. 2016;98:E90.

- Okike K, Kocher MS, Wei EX, et al. Accuracy of conflict-of-interest disclosures reported by physicians. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1466-1474.

- Ramm O, Brubaker L. Conflicts-of-interest disclosures at the 2010 AUGS Scientific Meeting. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2012;18:79-81.

- Tanzer D, Smith K, Tanzer M. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons disclosure policy fails to accurately inform its members of potential conflicts of interest. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2015;44:E207-E210.

- Thompson JC, Volpe KA, Bridgewater LK, et al. Sunshine Act: shedding light on inaccurate disclosures at a gynecologic annual meeting. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:661.

- Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. American Academy of Dermatology and AAD Association Web site. https://aad.org/Forms/Policies/Uploads/AR/

AR%20Disclosure%20of%20Potential%20Conflicts%

20of%20Interest-2.pdf. Accessed October 21, 2019. - Hockenberry JM, Weigel P, Auerbach A, et al. Financial payments by orthopedic device makers to orthopedic surgeons. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1759-1765.

- Yee C, Greenberg PB, Margo CE, et al. Financial disclosures in academic publications and the Sunshine Act: a concordance dtudy. Br J Med Med Res. 2015;10:1-6.

Practice Points

- There is heightening public attention to conflicts of interest since the start of the government-mandated reporting of physician-industry interactions.

- When compared with an industry-reported physician-interaction database, approximately two-thirds of dermatologists who presented at a national dermatology conference self-disclosed all interactions.

- This rate of discordance is consistent with other specialties, but it may reflect differences in the database reporting methods.

Dermoscopic Patterns of Acral Melanocytic Lesions in Skin of Color

Acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM) is a rare subtype of melanoma that occurs on the palms, soles, and nail apparatus. Unlike more common types of melanoma, ALM occurs on sun-protected areas of the skin and has distinct clinical, histologic, and genetic features. Acral lentiginous melanoma accounts for a larger proportion of melanomas in individuals with skin of color and has a worse prognosis and recurrence rate than other forms of melanoma.

Population Trends in Skin of Color

Much of the literature on malignant melanoma historically has involved non-Hispanic white patients, but the incidence in lighter-skinned populations has been increasing steadily over the last few decades.1 Although ALM can occur in any race, it disproportionately affects skin of color populations; ALM accounts for only 0.8% to 1% of all melanomas in white populations, but it constitutes 4% to 58% of melanomas in ethnic populations and is the most common melanoma subtype among black Americans.2-5 Acral lentiginous melanoma also is associated with a worse prognosis compared to other subtypes, which may indicate a more aggressive biological nature6 but also may point toward socioeconomic and cultural barriers (eg, low income or education levels, lack of insurance, lower health literacy), leading to disparities in access to care and diagnosis at advanced stages.5

Similarly, the distribution of acral melanocytic nevi appears to demonstrate an association with ethnicity and skin pigmentation. Although skin of color patients have fewer nevi than non-Hispanic whites, the proportion of acral melanocytic nevi tends to be greater.6,7 Given its grim prognosis, accurately differentiating ALM from acral nevi is of utmost importance.

Diagnostic Challenges of Acral Lesions

Due to the unique nature of the surfaces of acral sites, melanocytic lesions on the palms, soles, and nail apparatus present many diagnostic challenges. It can be difficult to distinguish acral melanoma from benign lesions using the naked eye alone. Volar surfaces are characterized by the presence of dermatoglyphics, and pigment deposition along ridges and furrows create particular dermoscopic patterns exclusive to these sites.8 Thus, dermoscopy can be useful on acral surfaces, but the dermoscopic features are different from those on the rest of the body and must be learned separately.

In addition, nearly half of patients are unaware of their acral lesions.6 Acral surfaces may not always be examined by clinicians during total-body skin examinations, leading to further possibility of overlooking a lesion. Obtaining biopsies on glabrous skin or nails also is challenging because they can be more painful and hemostasis can be more difficult, especially in the nail. Acral melanomas also may be amelanotic, including those at subungual sites.

Dermoscopic Patterns of Acral Volar Skin

Dermoscopy is a useful noninvasive tool for distinguishing between benign and malignant acral melanocytic lesions, and its efficacy in improving diagnostic accuracy and decreasing unnecessary biopsies is well-established in the literature.13,14 Acral dermoscopy allows for visualization of pigment along the dermatoglyphics that constitute the characteristic dermoscopic patterns.

Acral Lentiginous Melanoma

The hallmark dermoscopic pattern and most important finding of ALM is the parallel ridge pattern, characterized by parallel linear pigmentation along the ridges of dermatoglyphics. In the early phases of malignancy, the pattern appears light brown and involves most of the lesion; as the tumor develops, increasing melanin production results in focal areas of the parallel ridge pattern with darker bands.15,16 The sensitivity and specificity of a parallel ridge pattern for diagnosing early ALM has been shown to be 86% and 99%, respectively.15,16

A pattern of irregular diffuse pigmentation also can be observed in more advanced ALM. Dermoscopy may reveal a structureless pattern (ie, lack of identifiable structures or patterns) in a background of tan-black coloration due to more exuberant melanocyte proliferation along the epidermis.15 Sensitivity and specificity of this dermoscopic finding for invasive lesions is high at 94% and 97%, respectively.16,17 Interestingly, once ALM lesions have advanced even further, conventional melanoma-associated structures (ie, blue-white veil, polymorphous blood vessels, ulceration, irregular dots/globules or streaks) or atypical forms of typically benign acral dermoscopic patterns may be observed.15

Per a 3-step diagnostic algorithm created by Koga and Saida,18 a suspected acral lesion should first be evaluated for a parallel ridge pattern to determine the need for biopsy, as it is seen in approximately two-thirds of ALMs.19 If no parallel ridge pattern is observed, the lesion should then be checked for any of the typical dermoscopic patterns seen in benign acral nevi (eg, parallel furrow, latticelike, or fibrillar patterns).18 The maximum diameter should be measured only if the lesion does not exhibit any of the typical dermoscopic patterns. If the lesion’s diameter is greater than 7 mm in diameter, it should be biopsied; if the diameter is less than 7 mm, it should have regular clinical and dermoscopic follow-up.18

In 2015, Lallas et al20 developed the BRAAFF checklist, a scoring system of 6 variables: blotches, ridge pattern, asymmetry of structures, asymmetry of colors, parallel furrow pattern, and fibrillar pattern. The checklist also was shown to substantially improve diagnostic accuracy of dermoscopy for ALM, with sensitivity and specificity at 93.1% and 86.7%, respectively.20

Acquired Acral Nevi

Three classic dermoscopic patterns are associated with acquired acral nevi: parallel furrow pattern, latticelike pattern, and fibrillar pattern.15,21 Approximately three-quarters of all acquired acral nevi exhibit one of these patterns, roughly half exhibiting parallel furrow with tan-brown bandlike pigmentation along dermatoglyphic grooves.16,17

Latticelike patterns also are characterized by brown parallel lines along the sulci of dermatoglyphics but additionally have multiple intersecting lines. Thus, this pattern can be considered a variant of the parallel furrow pattern.15 The crisscross markings can be predominantly found in the plantar arch.22 This dermoscopic pattern comprises 15% to 25% of all acral nevi.21

Fibrillar pattern accounts for 10% to 20% of all acral melanocytic nevi.21 Dermoscopically, these lesions demonstrate parallel filamentous streaks that cross dermatoglyphics obliquely. The fibrillar pattern is predominantly found on weight-bearing areas of the sole,22 which likely is explained by pressure causing slanting of melanin columns in the horny layer.23 The fibrillar pattern has been shown to be the benign acral dermoscopic pattern that is most commonly misdiagnosed, with higher reported rates of biopsy.24

Acral Congenital Melanocytic Nevi

Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN) present at birth or appear during the first few weeks of life. Congenital melanocytic nevi can vary widely in size, shape, and color, and they are occasionally biopsied in cases of larger diameter or dermoscopic atypia to differentiate from melanoma.25 Congenital melanocytic nevi also can occur on acral volar surfaces. Possible dermoscopic patterns include parallel furrow or fibrillar patterns as well as a crista dotted pattern, defined as evenly spaced dots/globules on the ridges near the openings of eccrine ducts.26 A more commonly observed dermoscopic pattern in acral CMN is a combination of the crista dotted and parallel furrow patterns, known as the peas-in-a-pod pattern. Changes in the clinical appearance and dermoscopic features of an acral CMN are possible over time; some lesions also may fade with age.26

Final Thoughts

Acral lentiginous melanoma is a rare but potentially aggressive melanoma subtype that accounts for a larger proportion of melanomas in patients with skin of color than in white patients. Dermoscopy of acral volar skin provides invaluable diagnostic information and allows for better management of acral melanocytic lesions. Dermoscopic patterns such as the parallel ridge, parallel furrow, latticelike, fibrillar, and peas-in-a-pod patterns are unique to acral sites and can be used to differentiate between ALMs, acquired nevi, or CMNs.

- Whiteman DC, Green AC, Olsen CM. The growing burden of invasive melanoma: projections of incidence rates and numbers of new cases in six susceptible populations through 2031. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:1161-1171.

- Bradford PT, Goldstein AM, McMaster ML, et al. Acral lentiginous melanoma: incidence and survival patterns in the United States, 1986-2005. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:427-434.

- Nakamura Y, Fujisawa Y. Diagnosis and management of acral lentiginous melanoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2018;19:42.

- Cormier JN, Xing Y, Ding M, et al. Ethnic differences among patients with cutaneous melanoma. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1907-1914.

- Wang Y, Zhao Y, Ma S. Racial differences in six major subtypes of melanoma: descriptive epidemiology. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:691.

- Madankumar R, Gumaste PV, Martires K, et al. Acral melanocytic lesions in the United States: prevalence, awareness, and dermoscopic patterns in skin-of-color and non-Hispanic white patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:724.e1-730.e1.

- Palicka GA, Rhodes AR. Acral melanocytic nevi: prevalence and distribution of gross morphologic features in white and black adults. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1085-1094.

- Thomas L, Phan A, Pralong P, et al. Special locations dermoscopy: facial, acral, and nail. Dermatol Clin. 2013;31:615-624.

- Gong HZ, Zheng HY, Li J. Amelanotic melanoma [published online January 21, 2019]. Melanoma Res. doi:10.1097/CMR.0000000000000571.

- Ise M, Yasuda F, Konohana I, et al. Acral melanoma with hyperkeratosis mimicking a pigmented wart. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2013;3:37-39.

- Serarslan G, Akçaly CM, Atik E. Acral lentiginous melanoma misdiagnosed as tinea pedis: a case report. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:37-38.

- Gumaste P, Penn L, Cohen N, et al. Acral lentiginous melanoma of the foot misdiagnosed as a traumatic ulcer. a cautionary case. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2015;105:189-194.

- Carli P, de Giorgi V, Chiarugi A, et al. Addition of dermoscopy to conventional naked-eye examination in melanoma screening: a randomized study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:683-689.

- Carli P, de Giorgi V, Crocetti E, et al. Improvement of malignant/benign ratio in excised melanocytic lesions in the ‘dermoscopy era’: a retrospective study 1997-2001. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:687-692.

- Saida T, Koga H, Uhara H. Key points in dermoscopic differentiation between early acral melanoma and acral nevus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:25-34.

- Ishihara Y, Saida T, Miyazaki A, et al. Early acral melanoma in situ: correlation between the parallel ridge pattern on dermoscopy and microscopic features. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:21-27.

- Saida T, Miyazaki A, Oguchi S, et al. Significance of dermoscopic patterns in detecting malignant melanoma on acral volar skin: results of a multicenter study in Japan. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1233-1238.

- Koga H, Saida T. Revised 3-step dermoscopic algorithm for the management of acral melanocytic lesions. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:741-743.

- Lallas A, Sgouros D, Zalaudek I, et al. Palmar and plantar melanomas differ for sex prevalence and tumor thickness but not for dermoscopic patterns. Melanoma Res. 2014;24:83-87.

- Lallas A, Kyrgidis A, Koga H, et al. The BRAAFF checklist: a new dermoscopic algorithm for diagnosing acral melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1041-1049.

- Saida T, Koga H. Dermoscopic patterns of acral melanocytic nevi: their variations, changes, and significance. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1423-1426.

- Miyazaki A, Saida T, Koga H, et al. Anatomical and histopathological correlates of the dermoscopic patterns seen in melanocytic nevi on the sole: a retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:230-236.

- Watanabe S, Sawada M, Ishizaki S, et al. Comparison of dermatoscopic images of acral lentiginous melanoma and acral melanocytic nevus occurring on body weight-bearing areas. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:47-50.

- Costello CM, Ghanavatian S, Temkit M, et al. Educational and practice gaps in the management of volar melanocytic lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:1450-1455.

- Alikhan A, Ibrahimi OA, Eisen DB. Congenital melanocytic nevi: where are we now? part I. clinical presentation, epidemiology, pathogenesis, histology, malignant transformation, and neurocutaneous melanosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:495.e1-495.e17; quiz 512-514.

- Minagawa A, Koga H, Saida T. Dermoscopic characteristics of congenital melanocytic nevi affecting acral volar skin. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:809-813.

Acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM) is a rare subtype of melanoma that occurs on the palms, soles, and nail apparatus. Unlike more common types of melanoma, ALM occurs on sun-protected areas of the skin and has distinct clinical, histologic, and genetic features. Acral lentiginous melanoma accounts for a larger proportion of melanomas in individuals with skin of color and has a worse prognosis and recurrence rate than other forms of melanoma.

Population Trends in Skin of Color

Much of the literature on malignant melanoma historically has involved non-Hispanic white patients, but the incidence in lighter-skinned populations has been increasing steadily over the last few decades.1 Although ALM can occur in any race, it disproportionately affects skin of color populations; ALM accounts for only 0.8% to 1% of all melanomas in white populations, but it constitutes 4% to 58% of melanomas in ethnic populations and is the most common melanoma subtype among black Americans.2-5 Acral lentiginous melanoma also is associated with a worse prognosis compared to other subtypes, which may indicate a more aggressive biological nature6 but also may point toward socioeconomic and cultural barriers (eg, low income or education levels, lack of insurance, lower health literacy), leading to disparities in access to care and diagnosis at advanced stages.5

Similarly, the distribution of acral melanocytic nevi appears to demonstrate an association with ethnicity and skin pigmentation. Although skin of color patients have fewer nevi than non-Hispanic whites, the proportion of acral melanocytic nevi tends to be greater.6,7 Given its grim prognosis, accurately differentiating ALM from acral nevi is of utmost importance.

Diagnostic Challenges of Acral Lesions

Due to the unique nature of the surfaces of acral sites, melanocytic lesions on the palms, soles, and nail apparatus present many diagnostic challenges. It can be difficult to distinguish acral melanoma from benign lesions using the naked eye alone. Volar surfaces are characterized by the presence of dermatoglyphics, and pigment deposition along ridges and furrows create particular dermoscopic patterns exclusive to these sites.8 Thus, dermoscopy can be useful on acral surfaces, but the dermoscopic features are different from those on the rest of the body and must be learned separately.

In addition, nearly half of patients are unaware of their acral lesions.6 Acral surfaces may not always be examined by clinicians during total-body skin examinations, leading to further possibility of overlooking a lesion. Obtaining biopsies on glabrous skin or nails also is challenging because they can be more painful and hemostasis can be more difficult, especially in the nail. Acral melanomas also may be amelanotic, including those at subungual sites.

Dermoscopic Patterns of Acral Volar Skin

Dermoscopy is a useful noninvasive tool for distinguishing between benign and malignant acral melanocytic lesions, and its efficacy in improving diagnostic accuracy and decreasing unnecessary biopsies is well-established in the literature.13,14 Acral dermoscopy allows for visualization of pigment along the dermatoglyphics that constitute the characteristic dermoscopic patterns.

Acral Lentiginous Melanoma

The hallmark dermoscopic pattern and most important finding of ALM is the parallel ridge pattern, characterized by parallel linear pigmentation along the ridges of dermatoglyphics. In the early phases of malignancy, the pattern appears light brown and involves most of the lesion; as the tumor develops, increasing melanin production results in focal areas of the parallel ridge pattern with darker bands.15,16 The sensitivity and specificity of a parallel ridge pattern for diagnosing early ALM has been shown to be 86% and 99%, respectively.15,16

A pattern of irregular diffuse pigmentation also can be observed in more advanced ALM. Dermoscopy may reveal a structureless pattern (ie, lack of identifiable structures or patterns) in a background of tan-black coloration due to more exuberant melanocyte proliferation along the epidermis.15 Sensitivity and specificity of this dermoscopic finding for invasive lesions is high at 94% and 97%, respectively.16,17 Interestingly, once ALM lesions have advanced even further, conventional melanoma-associated structures (ie, blue-white veil, polymorphous blood vessels, ulceration, irregular dots/globules or streaks) or atypical forms of typically benign acral dermoscopic patterns may be observed.15

Per a 3-step diagnostic algorithm created by Koga and Saida,18 a suspected acral lesion should first be evaluated for a parallel ridge pattern to determine the need for biopsy, as it is seen in approximately two-thirds of ALMs.19 If no parallel ridge pattern is observed, the lesion should then be checked for any of the typical dermoscopic patterns seen in benign acral nevi (eg, parallel furrow, latticelike, or fibrillar patterns).18 The maximum diameter should be measured only if the lesion does not exhibit any of the typical dermoscopic patterns. If the lesion’s diameter is greater than 7 mm in diameter, it should be biopsied; if the diameter is less than 7 mm, it should have regular clinical and dermoscopic follow-up.18

In 2015, Lallas et al20 developed the BRAAFF checklist, a scoring system of 6 variables: blotches, ridge pattern, asymmetry of structures, asymmetry of colors, parallel furrow pattern, and fibrillar pattern. The checklist also was shown to substantially improve diagnostic accuracy of dermoscopy for ALM, with sensitivity and specificity at 93.1% and 86.7%, respectively.20

Acquired Acral Nevi

Three classic dermoscopic patterns are associated with acquired acral nevi: parallel furrow pattern, latticelike pattern, and fibrillar pattern.15,21 Approximately three-quarters of all acquired acral nevi exhibit one of these patterns, roughly half exhibiting parallel furrow with tan-brown bandlike pigmentation along dermatoglyphic grooves.16,17

Latticelike patterns also are characterized by brown parallel lines along the sulci of dermatoglyphics but additionally have multiple intersecting lines. Thus, this pattern can be considered a variant of the parallel furrow pattern.15 The crisscross markings can be predominantly found in the plantar arch.22 This dermoscopic pattern comprises 15% to 25% of all acral nevi.21