User login

A Clinical Review of Eslicarbazepine Acetate

This supplement reviews Eslicarbazepine Acetate and its effectiveness as a first-line or later adjunctive therapy in patients with partial-onset seizures.

This supplement reviews Eslicarbazepine Acetate and its effectiveness as a first-line or later adjunctive therapy in patients with partial-onset seizures.

This supplement reviews Eslicarbazepine Acetate and its effectiveness as a first-line or later adjunctive therapy in patients with partial-onset seizures.

Disparities in cardiovascular care: Past, present, and solutions

Cardiovascular disease became the leading cause of death in the United States in the early 20th century, and it accounts for nearly half of all deaths in industrialized nations.1 The mortality it inflicts was thought to be shared equally between both sexes and among all age groups and races.2 The cardiology community implemented innovative epidemiologic research, through which risk factors for cardiovascular disease were established.1 The development of coronary care units reduced in-hospital mortality from acute myocardial infarction from 30% to 15%.2–5 Further advances in pharmacology, revascularization, and imaging have aided in the detection and treatment of cardiovascular disease.6 Though cardiovascular disease remains the number-one cause of death worldwide, rates are on the decline.7

For several decades, health disparities have been recognized as a source of pathology in cardiovascular medicine, resulting in inequity of care administration among select populations. In this review, we examine whether the same forward thinking that has resulted in a decline in cardiovascular disease has had an impact on the pervasive disparities in cardiovascular medicine.

DISPARITIES DEFINED

Compared with whites, members of minority groups have a higher burden of chronic diseases, receive lower quality care, and have less access to medical care. Recognizing the potential public health ramifications, in 1999 the US Congress tasked the Institute of Medicine to study and assess the extent of healthcare disparities. This led to the landmark publication, Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care.8

The Institute of Medicine defines disparities in healthcare as racial or ethnic differences in the quality of healthcare that are not due to access-related factors, clinical needs, preferences, and appropriateness of intervention.8 Disparities can also exist according to socioeconomic status and sex.9

In an early study documenting the concept of disparities in cardiovascular disease, Stone and Vanzant10 concluded that heart disease was more common in African Americans than in whites, and that hypertension was the principal cause of cardiovascular disease mortality in African Americans.

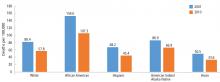

Although avoidable deaths from heart disease, stroke, and hypertensive disease declined between 2001 and 2010, African Americans still have a higher mortality rate than other racial and ethnic groups (Figure 1).11

DISPARITIES AND CARDIOVASCULAR HEALTH

The concept of cardiovascular health was established by the American Heart Association (AHA) in efforts to achieve an additional 20% reduction in cardiovascular disease-related mortality by 2020.7 Cardiovascular health is defined as the absence of clinically manifest cardiovascular disease and is measured by 7 components:

- Not smoking or abstaining from smoking for at least 1 year

- A normal body weight, defined as a body mass index less than 25 kg/m2

- Optimal physical activity, defined as 75 minutes of vigorous physical activity or 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity per week

- Regular consumption of a healthy diet

- Total cholesterol below 200 mg/dL

- Blood pressure less than 120/80 mm Hg

- Fasting blood sugar below 100 mg/dL.

Nearly 70% of the US population can claim 2, 3, or 4 of these components, but differences exist according to race,12 and 60% of adult white Americans are limited to achieving no more than 3 of these healthy metrics, compared with 70% of adult African Americans and Hispanic Americans.

Smoking

Smoking is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease.12–14

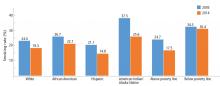

During adolescence, white males are more likely to smoke than African American and Hispanic males,12 but this trend reverses in adulthood, when African American men have a higher prevalence of smoking than white men (21.4% vs 19%).7 Rates of lifetime use are highest among American Indian or Alaskan natives and whites (75.9%), followed by African Americans (58.4%), native Hawaiians (56.8%), and Hispanics (56.7%).15 Trends for current smoking are similar (Figure 2).16 Moreover, households with lower socioeconomic status have a higher prevalence of smoking.7

Physical activity

People with a sedentary lifestyle are more likely to die of cardiovascular disease. As many as 250,000 deaths annually in the United States are attributed to lack of regular physical activity.17

Recognizing the potential public health ramifications, the AHA and the 2018 Federal Guidelines on Physical Activity recommend that children engage in 60 minutes of daily physical activity and that adults participate in 150 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous physical activity weekly.18,19

In the United States, 15.2% of adolescents reported being physically inactive, according to data published in 2016.7 Similar to most cardiovascular risk factors, minority populations and those of lower socioeconomic status had the worst profiles. The prevalence of physical inactivity was highest in African Americans and Hispanics (Figure 3).20

Studies have shown an association between screen-based sedentary behavior (computers, television, and video games) and cardiovascular disease.21–23 In the United States, 41% of adolescents used computers for activities other than homework for more than 3 hours per day on a school day.7 The pattern of use was highest in African American boys and African American girls, followed by Hispanic girls and Hispanic boys.18 Trends were similar with regard to watching television for more than 3 hours per day.

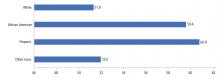

Sedentary behavior persists into adulthood, with rates of inactivity of 38.3% in African Americans, 40.1% in Hispanics, and 26.3% in white adults.7

Nutrition and obesity

Nutrition plays a major role in cardiovascular disease, specifically in the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic disease and hypertension.24 Most Americans do not meet dietary recommendations, with minority communities performing worse in specific metrics.7

Dietary patterns are reflected in the rate of obesity in this nation. Studies have shown a direct correlation between obesity and cardiovascular disease such as coronary artery disease, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation.25–28 According to data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 31% of children between the ages of 2 and 19 years are classified as obese or overweight. The highest rates of obesity are seen in Hispanic and African American boys and girls. The obesity epidemic is disproportionately rampant in children living in households with low income, low education, and high unemployment rates.7,29–31

Despite the risks associated with obesity, only 64.8% of obese adults report being informed by a doctor or health professional that they were overweight. The proportion of obese adults informed that they were overweight was significantly lower for African Americans and Hispanics compared with whites. Similar differences are seen based on socioeconomic status, as middle-income patients were less likely to be informed than those in the higher income strata (62.4% vs 70.6%).7,31

Blood pressure

Hypertension is a well-established risk factor for cardiovascular disease and stroke, and a blood pressure of 120/80 mm Hg or lower is identified as a component of ideal cardiovascular health.

In the United States the prevalence of hypertension in adults older than 20 is 32%.7 The prevalence of hypertension in African Americans is among the highest in the world.32,33 African Americans develop high blood pressure at earlier ages, and their average resting blood pressures are higher than in whites.34,35 For a 45-year-old without hypertension, the 40-year risk of developing hypertension is 92.7% for African Americans and 86% for whites.35 Hypertension is a major risk factor for stroke, and African Americans have a 1.8 times greater rate of fatal stroke than whites.7

In 2013 there were 71,942 deaths attributable to high blood pressure, and the 2011 death rate associated with hypertension was 18.9 per 100,000. By race, the death rate was 17.6 per 100,000 for white males and an alarming 47.1 per 100,000 for African American males; rates were 15.2 per 100,000 for white females and 35.1 per 100,000 for African American females.7

It is unclear what accounts for the racial difference in prevalence in hypertension. Studies have shown that African Americans are more likely than whites to have been told on more than 2 occasions that they have hypertension. And 85.7% of African Americans are aware that they have high blood pressure, compared with 82.7% of whites.14

African Americans and Hispanics have poorer hypertension control compared with whites.36,37 These observed differences cannot be attributed to access alone, as African Americans were more likely to be on higher-intensity blood pressure therapy, whereas Hispanics were more likely to be undertreated.36,38 In a meta-analysis of 13 trials, Peck et al39 showed that African Americans showed a lesser reduction in systolic and diastolic blood pressure when treated with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors.

The 2017 American College of Cardiology (ACC) and AHA guidelines for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults40 identifies 4 drug classes as reducing cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality: thiazide diuretics, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), and calcium channel blockers. Of these 4 classes, thiazide diuretics and calcium channel blockers have been shown to lower blood pressure more effectively in African Americans than renin-angiotensin-aldosterone inhibition with ACE inhibitors or ARBs.

Glycemic control

Type 2 diabetes mellitus secondary to insulin resistance disproportionately affects minority groups, as the prevalence of diabetes mellitus in African Americans is almost twice as high as that in whites, and 35% higher in Hispanics compared with whites.7,41 Based on NHANES data between 1984 and 2004, the prevalence of diabetes mellitus is expected to increase by 99% in whites, 107% in African Americans, and 127% in Hispanics by 2050. Alarmingly, African Americans over age 75 are expected to experience a 606% increase by 2050.42

With regard to mortality, 21.7 deaths per 100,000 population were attributable to diabetes mellitus according to reports by the AHA in 2016. The death rate in white males was 24.3 per 100,000 compared with 44.9 per 100,000 for African Americans males. The associated mortality rate for white women was 16.2 per 100,000, and 35.8 per 100,000 for African American females.7

DISPARITIES AND CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE CARE

The management of coronary artery disease has evolved from prolonged bed rest to surgical, pharmacologic, and percutaneous revascularization.2,5 Coronary revascularization procedures are now relatively common: 950,000 percutaneous coronary interventions and 397,000 coronary artery bypass procedures were performed in 2010.7

Nevertheless, despite similar clinical presentations, African Americans with acute myocardial infarction were less likely to be referred for coronary artery bypass grafting than whites.43–46 They were also less likely to be given thrombolytics47 and less likely to undergo coronary angiography with percutaneous coronary intervention.48 Similar differences have been reported when comparing Hispanics with whites.49

Some suggest that healthcare access is a key mediator of health disparities.50 In 2009, Hispanics and African Americans accounted for more than 50% of those without health insurance.51 Improved access to healthcare might mitigate the disparity in revascularizations.

Massachusetts was one of the first states to mandate that all residents obtain health insurance. As a result, the uninsured rates declined in African Americans and Hispanics in Massachusetts, but a disparity in revascularization persisted. African Americans and Hispanics were 27% and 16% less likely to undergo revascularization procedures (coronary artery bypass grafting or percutaneous coronary intervention) than whites,51 suggesting that disparities in revascularization are not solely secondary to healthcare access.

These findings are consistent with a 2004 Veterans Administration study,52 in which healthcare access was equal among races. The study showed that African Americans received fewer cardiac procedures after an acute myocardial infarction compared with whites.

Have we made progress? The largest disparity between African Americans and whites in coronary artery disease mortality existed in 1990. The disparity persisted to 2012, and although decreased, it is projected to persist to 2030.53

DISPARITIES IN HEART FAILURE

An estimated 5.7 million Americans have heart failure, and 915,000 new cases are diagnosed annually.7 Unlike coronary artery disease, heart failure is expected to increase in prevalence by 46%, to 8 million Americans with heart failure by 2030.7,54

Our knowledge of disparities in the area of heart failure is derived primarily from epidemiologic studies. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis55 showed that African Americans (4.6 per 1,000), followed by Hispanics (3.5 per 1,000) had a higher risk of developing heart failure compared with whites (2.4 per 1,000).The higher risk is in part due to disparities in socioeconomic status and prevalence of hypertension, as African Americans accounted for 75% of cases of nonischemic-related heart failure.55 African Americans also have a higher 5-year mortality rate than whites.55

Even though the 5-year mortality rate in heart failure is still 50%, the past 30 years have seen innovations in pharmacologic and device therapy and thus improved outcomes in heart failure patients. Still, significant gaps in the use of guideline-recommended therapies, quality of care, and clinical outcomes persist in contemporary practice for racial minorities with heart failure.

Disparities in inpatient care for heart failure

Patients admitted for heart failure and cared for by a cardiologist are more likely to be discharged on guideline-directed medical therapy, have fewer heart failure readmissions, and lower mortality.56,57 Breathett et al,58 in a study of 104,835 patients hospitalized in an intensive care unit for heart failure, found that primary intensive care by a cardiologist was associated with higher survival in both races. However, in the same study, white patients had a higher odds of receiving care from a cardiologist than African American patients.

Disparities and cardiac resynchronization therapy devices

In one-third of patients with heart failure, conduction delays result in dyssynchronous left ventricular contraction.59 Dyssynchrony leads to reduced cardiac performance, left ventricular remodeling, and increased mortality.56

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) was approved for clinical use in 2001, and studies have shown that it improves quality of life, exercise tolerance, cardiac performance, and morbidity and mortality rates.59–66 The 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of heart failure give a class IA recommendation (the highest) for its use in patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or less, sinus rhythm, left bundle branch block and a QRS duration of 150 ms or greater, and New York Heart Association class II, III, or ambulatory IV symptoms while on guideline-directed medical therapy.67

Despite these recommendations, racial differences are observed. A study using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database59 showed that between 2002 and 2010, a total of 374,202 CRT devices were implanted, averaging 41,578 annually. After adjusting for heart failure admissions, the study showed that CRT use was favored in men and in whites.

Another study, using the National Cardiovascular Data Registry,68 looked at patients who received implantable cardiac defibrillators (ICDs) and were eligible to receive CRT. It found that African Americans and Hispanics were less likely than whites to receive CRT, even though they were more likely to meet established criteria.

Disparities and left ventricular assist devices

The Randomized Evaluation of Mechanical Assistance for the Treatment of Congestive Heart failure (REMATCH) trial and Heart Mate II trial demonstrated that left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) were durable options for long-term support for patients with end-stage heart failure.69,70 Studies that examined the role of race and clinical outcomes after LVAD implantation have reported mixed findings.71,72 Few studies have looked at the role racial differences play in accessing LVAD therapy.

Joyce et al73 reviewed data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample from 2002 to 2003 on patients admitted to the hospital with a primary diagnosis of heart failure or cardiogenic shock. A total of 297,866 patients were included in the study, of whom only 291 underwent LVAD implantation. A multivariate analysis found that factors such as age over 65, female sex, admission to a nonacademic center, geographic region, and African American race adversely influenced access to LVAD therapy.

Breathett et al74 evaluated racial differences in LVAD implantations from 2012 to 2015, a period that corresponds to increased health insurance expansion, and found LVAD implantations increased among African American patients with advanced heart failure, but no other racial or ethnic group.

Disparities and heart transplant

For patients with end-stage heart failure, orthotopic heart transplant is the most definitive and durable option for long-term survival. According to data from the United Network for Organ Sharing, 62,508 heart transplants were performed from January 1, 1988 to December 31, 2015. Compared with transplants of other solid organs, heart transplant occurs in significantly infrequent rates.

Barriers to transplant include lack of health insurance, considered a surrogate for low socioeconomic status. Hispanics and African Americans are less likely to have private health insurance than non-Hispanic whites, and this difference is magnified among the working poor.

Despite these perceived barriers, Kilic et al75 found that African Americans comprised 16.4% of heart transplant recipients, although they make up only approximately 13% of the US population. They also had significantly shorter wait-list times than whites. On the negative side, African Americans had a higher unadjusted mortality rate than whites (15% vs 12% P = .002). African Americans also tended to receive their transplants at centers with lower transplant volumes and higher transplant mortality rates.

Several other studies also showed that African Americans compared to whites have significantly worse outcomes after transplant.76–79 What accounts for this difference? Kilic et al75 showed that African Americans had the lowest proportion of blood type matching and lowest human leukocyte antigen matching, were younger (because African Americans develop more advanced heart failure at younger ages), had higher serum creatinine levels, and were more often bridged to transplant with an LVAD.

DISPARITIES IN CARDIOVASCULAR RESEARCH

Although the United States has the most sophisticated and robust medical system in the world, select groups have significant differences in delivery and healthcare outcomes. There are many explanations for these differences, but a contributing factor may be the paucity of research dedicated to understand racial and ethnic differences.80

Differences observed in epidemiologic studies may be secondary to pathophysiology, genetic differences, environment, and lifestyle choices. Historically, clinical trials were conducted in homogeneous populations with respect to age (middle-aged), sex (male), and race (white), and the results were generalized to heterogeneous populations.80

Disparities in research have implications in clinical practice. Overall, the primary cause of heart failure is ischemia; however, in African Americans, the primary cause is hypertensive heart disease.81 Studies in hypertension have shown that African Americans have less of a response to neurohormonal blockade with ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers than non-African Americans.82 Nevertheless, neurohormonal blockade has become the cornerstone of heart failure treatment.

Retrospective analysis of the Vasodilator-Heart Failure trials83 showed that treatment with isosorbide dinitrate plus hydralazine, compared with placebo, conferred a survival benefit for African Americans but not whites.80 No survival advantage was noted when isosorbide dinitrate/hydralazine was compared to enalapril in African Americans, although enalapril was superior to isosorbide dinitrate in whites.45 These observations were recognized 10 to 15 years after trial completion, and were only possible because the trials included sufficient numbers of African American patients to complete analysis.

In 1993, the US Congress passed the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Revitalization Act, which established guidelines requiring NIH grant applicants to include minorities in human subject research, as they were historically underrepresented in clinical research trials.84,85

In 2001, the Beta-Blocker Evaluation of Survival Trial86 reported its results investigating whether bucindolol, a nonselective beta-blocker, would reduce mortality in patients with advanced heart failure (New York Heart Association class III or IV). This was one of the first trials to prospectively investigate racial and ethnic differences in response to treatment. Though it showed no overall benefit in the use of bucindolol in the treatment of advanced heart failure, subgroup analysis showed that whites did enjoy a benefit in terms of lower mortality, whereas African Americans did not.

Results of the Vasodilator-Heart Failure trials led to further population-directed research, most notably the African American Heart Failure Trial,87 a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial in patients who identified as African American. Patients who were randomized to receive a fixed dose of hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate had a 43% lower mortality rate, a 33% lower hospitalization rate for heart failure, and better quality of life than patients in the placebo group, leading to early termination of the trial. The outcomes suggested that the combination of isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine treats heart failure in a manner independent of pure neurohormonal blockade.

CHALLENGES IN STUDY PARTICIPATION

Recruitment of minority participants in biomedical research is a challenging task for clinical investigators.88,89 Some of the factors thought to pose potential barriers for racial and ethnic minority participation in health research include poor access to primary medical care, failure of researchers to recruit minority populations actively, and language and cultural barriers.90

Further, it is widely claimed that African Americans are less willing than nonminority individuals to participate in clinical research trials due to general distrust of the medical community as a result of the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment.91 That infamous study, conducted by the US Public Health Service between 1932 and 1972, sought to record the natural progression of untreated syphilis in poor African American men in Alabama. The participants were not informed of the true purpose of the study, and they were under the impression that they were simply receiving free healthcare from the US government. Further, they were denied appropriate treatment even after it became readily available, in order for researchers to observe the progression of the disease.

While the 1993 mandate did in fact increase pressure on researchers to develop strategies to overcome participation barriers, the issue of underrepresentation of racial minorities in clinical research, including cardiovascular research, has not been resolved and continues to be a problem today.

The overall goal of clinical research is to determine the best strategies to prevent and treat disease. But if the study population is not representative of the affected population at large, the results cannot be generalized to underrepresented subgroups. The implications of underrepresentation in research are far-reaching, and can further contribute to disparate care of minority patients such as African Americans, who have a higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and greater burden of heart failure.

PROPOSING SOLUTIONS

Between 1986 and 2018, according to a PUBMED search, 10,462 articles highlighted the presence of a health-related disparity. Solutions to address and ultimately eradicate disparities will need to eliminate healthcare bias, increase patient access, and increase diversity and inclusion in the physician work force.

Eliminating bias

Implicit bias refers to attitudes, thoughts, and feelings that exist outside of the conscious awareness.92 These biases can be triggered by race, gender, or socioeconomic status. They have manifested in society as stereotypes that men are more competent than women, women are more verbal than men, and African Americans are more athletic than whites.93

The concept of implicit bias is important, in that the populations that experience the greatest health disparities also suffer from negative cultural stereotypes.94 Healthcare professionals are not inoculated against implicit bias.95 Studies have shown that most healthcare providers have implicit biases that reflect positive attitudes toward whites and negative attitudes toward people of color.92,94,96–98

The Implicit Association Test, introduced in 1998, is widely used to measure implicit bias. It measures response time of subjects to match particular social groups to particular attributes.99 Green et al,99 using this test, showed that although physicians reported no explicit preference for white vs African American patients or differences in perceived cooperativeness, the test revealed implicit preference favoring white Americans and implicit stereotypes of African Americans as less cooperative for medical procedures and in general. This also manifested in clinical decision-making, as white Americans were more likely, and African Americans less likely, to be treated with thrombolysis.99

Sabin et al100 showed that implicit bias was present among pediatricians, although less than in society as a whole and in other healthcare professionals.

But how does one change feelings that exist outside of the conscious awareness? Green et al99 showed that making physicians aware of their susceptibility to bias changed their behavior. A subset of physicians who were made aware that bias was a focus of the study were more likely to refer African Americans for thrombolysis even if they had a high degree of implicit pro-white bias.94,100 Perhaps mandating that all healthcare providers take a self-administered and confidentially reported Implicit Association Test will lead to awareness of implicit bias and minimize healthcare behaviors that contribute to the current state of disparities.

Improving access

Common indicators of access to healthcare include health insurance status, having a usual source of healthcare, and having a regular physician.101 Health insurance does offer protection from the costs associated with illness and health maintenance.101 It is also a major contributing factor in racial and ethnic disparities.

Chen et al102 examined the effects of the Affordable Care Act and found that it was associated with reduction in the probability of being uninsured, delaying necessary care, and forgoing necessary care, and increased probability of having a physician. However, earlier studies showed that access to health insurance by itself does not equate to equitable care.103,104

Diversifying the work force

African Americans comprise 4% of physicians and Hispanic Americans 5%, despite accounting for 13% and 16% of the US population.105 This underrepresentation has led to African American and Hispanic American patients being more likely than white patients to be treated by a physician from a dissimilar racial or ethnic background.106 Studies have shown that minority patients in a race- or ethnic-concordant relationship are more likely to use needed health services, less likely to postpone seeking care, and report greater satisfaction.106,107 Minority physicians often locate and practice in neighborhoods with high minority populations, and they disproportionately care for disadvantaged patients of lower socioeconomic status and poorer health.106,108

WE ARE STILL IN THE TUNNEL, BUT THERE IS LIGHT AT THE END

The cardiovascular community has faced tremendous challenges in the past and responded with innovative research that has led to imaging that aids in the diagnosis of subclinical cardiovascular disease and invasive and pharmacologic strategies that have improved cardiovascular outcomes. One may say that there is light at the end of the tunnel; however, the existence of disparate care reminds us that we are still in the tunnel.

Disparities in cardiovascular disease management present a unique challenge for the community. There is no drug, device, or invasive procedure to eliminate this pathology. However, by acknowledging the problem and implementing changes at the system, provider, and patient level, the cardiovascular community can achieve yet another momentous achievement: the end of cardiovascular health disparities. Cardiovascular disease makes no distinction in race, sex, age, or socioeconomic status, and neither should the medical community.

- Nabel EG, Braunwald E. A tale of coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2012; 366(1):54–63. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1112570

- Braunwald E. Evolution of the management of acute myocardial infarction: a 20th century saga. Lancet 1998; 352(9142):1771–1774. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)03212-7

- Julian DG. The history of coronary care units. Br Heart J 1987; 57(6):497–502. doi:10.1136/hrt.57.6.497

- Caswell JE. A brief history of coronary care units. Public Health Rep 1967; 82(12):1105–1111. pmid:19316519

- Day HW. History of coronary care units. Am J Cardiol 1972; 30(4):405–407. pmid:4560377

- Braunwald E. Shattuck lecture—cardiovascular medicine at the turn of the millennium: triumphs, concerns, and opportunities. N Engl J Med 1997; 337(19):1360–1369. doi:10.1056/NEJM199711063371906

- Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee; Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016; 133(4):e38–e360. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350

- Nelson A. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Natl Med Assoc 2002; 94(8):666–668. pmid:12152921

- McGuire TG, Alegria M, Cook BL, Wells KB, Zaslavsky AM. Implementing the Institute of Medicine definition of disparities: an application to mental health care. Health Serv Res 2006; 41(5):1979–2005. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00583.x

- Stone CT, Vanzant FR. Heart disease as seen in a southern clinic: a clinical and pathologic survey. JAMA 1927; 89(18):1473–1480. doi:10.1001/jama.1927.02690180005002

- Centers For Disease Control And Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: avoidable deaths from heart disease, stroke, and hypertensive disease—United States, 2001–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013; 62(35):727–727. pmid:PMC4585625

- Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015; 131(4):e29–e322. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152

- Ockene IS, Miller NH. Cigarette smoking, cardiovascular disease, and stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. American Heart Association Task Force on Risk Reduction. Circulation 1997; 96(9):3243–3247. pmid:9386200

- Messner B, Bernhard D. Smoking and cardiovascular disease: mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction and early atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2014; 34(3):509–515. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.300156

- Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, et al; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018; 137(12):e67–e492. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000558

- Jamal A, Homa DM, O’Conner E, et al. Current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2005–2014. MMWR 2015; 64(44):1233–1240. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6444a2

- Myers J. Cardiology patient pages. Exercise and cardiovascular health. Circulation 2003; 107(1):e2–e5. pmid:12515760

- Shiroma EJ, Lee IM. Physical activity and cardiovascular health: lessons learned from epidemiological studies across age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Circulation 2010; 122(7):743–752. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.914721

- Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, et al. The physical activity guidelines for Americans. JAMA 2018; 320(19):2020–2028. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.14854

- Omura JD, Carlson SA, Paul P, et al. Adults eligible for cardiovascular disease prevention counseling and participation in aerobic physical activity—United States, 2013. MMWR 2015; 64(37):1047–1051. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6437a4

- Dunstan DW, Barr EL, Healy GN, et al. Television viewing time and mortality: the Australian diabetes, obesity and lifestyle study (AusDiab). Circulation 2010; 121(3):384–391. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.894824

- Warren TY, Barry V, Hooker SP, Sui X, Church TS, Blair SN. Sedentary behaviors increase risk of cardiovascular disease mortality in men. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2010; 42(5):879–885. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181c3aa7e

- Byun W, Dowda M, Pate RR. Associations between screen-based sedentary behavior and cardiovascular disease risk factors in Korean youth. J Korean Med Sci 2012; 27(4):388–394. doi:10.3346/jkms.2012.27.4.388

- Getz GS, Reardon CA. Nutrition and cardiovascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2007; 27(12):2499–2506. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.155853

- Eckel RH. Obesity and heart disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Nutrition Committee, American Heart Association. Circulation 1997; 96(9):3248–3250. pmid:9386201

- Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci E, et al. Body size and fat distribution as predictors of coronary heart disease among middle-aged and older US men. Am J Epidemiol 1995; 141(12):1117–1127. pmid:7771450

- Duflou J, Virmani R, Rabin I, Burke A, Farb A, Smialek J. Sudden death as a result of heart disease in morbid obesity. Am Heart J 1995; 130(2):306–313. pmid:7631612

- Poirier P, Giles TD, Bray GA, et al; American Heart Association; Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss: an update of the 1997 American Heart Association Scientific Statement on Obesity and Heart Disease from the Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation 2006; 113(6):898–918. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.171016

- Wang Y. Disparities in pediatric obesity in the United States. Adv Nutr 2011; 2(1):23–31. doi:10.3945/an.110.000083

- Taveras EM, Gillman MW, Kleinman KP, Rich-Edwards JW, Rifas-Shiman SL. Reducing racial/ethnic disparities in childhood obesity: the role of early life risk factors. JAMA Pediatr 2013; 167(8):731–738. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.85

- Powell-Wiley TM, Ayers CR, Banks-Richard K, et al. Disparities in counseling for lifestyle modification among obese adults: insights from the Dallas heart study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012; 20(4):849–855. doi:10.1038/oby.2011.242

- Fuchs FD. Why do black Americans have higher prevalence of hypertension?: an enigma still unsolved. Hypertension 2011; 57(3):379–380. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.163196

- Ferdinand KC, Armani AM. The management of hypertension in African Americans. Crit Pathw Cardiol 2007; 6(2):67–71. doi:10.1097/HPC.0b013e318053da59

- Voors AW, Webber LS, Berenson GS. Time course study of blood pressure in children over a three-year period. Bogalusa Heart Study. Hypertension 1980; 2(4 Pt 2):102–108. pmid:7399641

- Carson AP, Howard G, Burke GL, Shea S, Levitan EB, Muntner P. Ethnic differences in hypertension incidence among middle-aged and older adults: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Hypertension 2011; 57(6):1101–1107. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.168005

- Gu A, Yue Y, Desai RP, Argulian E. Racial and ethnic differences in antihypertensive medication use and blood pressure control among US adults with hypertension: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003 to 2012. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2017; 10(1). pii:e003166. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.116.003166

- Lackland DT. Racial differences in hypertension: implications for high blood pressure management. Am J Med Sci 2014; 348(2):135–138. doi:10.1097/MAJ.0000000000000308

- Bosworth HB, Dudley T, Olsen MK, et al. Racial differences in blood pressure control: potential explanatory factors. Am J Med 2006; 119(1):70.e9–e15. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.08.019

- Peck RN, Smart LR, Beier R, et al. Difference in blood pressure response to ACE-Inhibitor monotherapy between black and white adults with arterial hypertension: a meta-analysis of 13 clinical trials. BMC Nephrol 2013; 14:201. doi:10.1186/1471-2369-14-201

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2018; 138(17):e484–e594. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000596

- Peek ME, Cargill A, Huang ES. Diabetes health disparities: a systematic review of health care interventions. Med Care Res Rev 2007; 64(5 suppl):101S–156S. doi:10.1177/1077558707305409

- Narayan KM, Boyle JP, Geiss LS, Saaddine JB, Thompson TJ. Impact of recent increase in incidence on future diabetes burden: US, 2005–2050. Diabetes Care 2006; 29(9):2114–2116. doi:10.2337/dc06-1136

- Johnson PA, Lee TH, Cook EF, Rouan GW, Goldman L. Effect of race on the presentation and management of patients with acute chest pain. Ann Intern Med 1993; 118(8):593–601. pmid:8452325

- Hannan EL, van Ryn M, Burke J, et al. Access to coronary artery bypass surgery by race/ethnicity and gender among patients who are appropriate for surgery. Med Care 1999; 37(1):68–77. pmid:10413394

- Peterson ED, Shaw LK, DeLong ER, Pryor DB, Califf RM, Mark DB. Racial variation in the use of coronary-revascularization procedures. Are the differences real? Do they matter? N Engl J Med 1997; 336(7):480–486. doi:10.1056/NEJM199702133360706

- Wenneker MB, Epstein AM. Racial inequalities in the use of procedures for patients with ischemic heart disease in Massachusetts. JAMA 1989; 261(2):253–257. pmid:2521191

- Allison JJ, Kiefe CI, Centor RM, Box JB, Farmer RM. Racial differences in the medical treatment of elderly Medicare patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Gen Intern Med 1996; 11(12):736–743. pmid:9016420

- Mickelson JK, Blum CM, Geraci JM. Acute myocardial infarction: clinical characteristics, management and outcome in a metropolitan Veterans Affairs Medical Center teaching hospital. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997; 29(5):915–925. pmid:9120176

- Yarzebski J, Bujor CF, Lessard D, Gore JM, Goldberg RJ. Recent and temporal trends (1975 to 1999) in the treatment, hospital, and long-term outcomes of Hispanic and non-Hispanic white patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction: a population-based perspective. Am Heart J 2004; 147(4):690–697. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2003.10.023

- Riley WJ. Health disparities: gaps in access, quality and affordability of medical care. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc 2012; 123:167–172. pmid:23303983

- Albert MA, Ayanian JZ, Silbaugh TS, et al. Early results of Massachusetts healthcare reform on racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in cardiovascular care. Circulation 2014; 129(24):2528–2538. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005231

- Peterson ED, Wright SM, Daley J, Thibault GE. Racial variation in cardiac procedure use and survival following acute myocardial infarction in the Department of Veterans Affairs. JAMA 1994; 271(15):1175–1180. pmid:8151875

- Pearson-Stuttard J, Guzman-Castillo M, Penalvo JL, et al. Modeling future cardiovascular disease mortality in the United States: national trends and racial and ethnic disparities. Circulation 2016; 133(10):967–978. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.019904

- Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, et al; American Heart Association Advocacy Coordinating Committee; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Stroke Council. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail 2013; 6(3):606–619. doi:10.1161/HHF.0b013e318291329a

- Bahrami H, Kronmal R, Bluemke DA, et al. Differences in the incidence of congestive heart failure by ethnicity: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168(19):2138–2145. doi:10.1001/archinte.168.19.2138

- Parmar KR, Xiu PY, Chowdhury MR, Patel E, Cohen M. In-hospital treatment and outcomes of heart failure in specialist and non-specialist services: a retrospective cohort study in the elderly. Open Heart 2015; 2(1):e000095. doi:10.1136/openhrt-2014-000095

- Avaldi VM, Lenzi J, Urbinati S, et al. Effect of cardiologist care on 6-month outcomes in patients discharged with heart failure: results from an observational study based on administrative data. BMJ Open 2017; 7(11):e018243. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018243

- Breathett K, Liu WG, Allen LA, et al. African Americans are less likely to receive care by a cardiologist during an intensive care unit admission for heart failure. JACC Heart Fail 2018; 6(5):413–420. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2018.02.015

- Sridhar AR, Yarlagadda V, Parasa S, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy: US trends and disparities in utilization and outcomes. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2016; 9(3):e003108. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.115.003108

- Abraham WT, Fisher WG, Smith AL, et al; MIRACLE Study Group. Multicenter insync randomized clinical evaluation. Cardiac resynchronization in chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2002; 346(24):1845–1853. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa013168

- Auricchio A, Stellbrink C, Sack S, et al; Pacing Therapies in Congestive Heart Failure (PATH-CHF) Study Group. Long-term clinical effect of hemodynamically optimized cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with heart failure and ventricular conduction delay. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39(12):2026–2033. pmid:12084604

- Cazeau S, Leclercq C, Lavergne T, et al; Multisite Stimulation in Cardiomyopathies (MUSTIC) Study Investigators. Effects of multisite biventricular pacing in patients with heart failure and intraventricular conduction delay. N Engl J Med 2001; 344(12):873–880. doi:10.1056/NEJM200103223441202

- Higgins SL, Hummel JD, Niazi IK, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy for the treatment of heart failure in patients with intraventricular conduction delay and malignant ventricular tachyarrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 42(8):1454–1459. pmid:14563591

- Young JB, Abraham WT, Smith AL, et al; Multicenter InSync ICD Randomized Clinical Evaluation (MIRACLE ICD) Trial Investigators. Combined cardiac resynchronization and implantable cardioversion defibrillation in advanced chronic heart failure: the MIRACLE ICD Trial. JAMA 2003; 289(20):2685–2694. doi:10.1001/jama.289.20.2685

- Sutton MG, Plappert T, Hilpisch KE, Abraham WT, Hayes DL, Chinchoy E. Sustained reverse left ventricular structural remodeling with cardiac resynchronization at one year is a function of etiology: quantitative Doppler echocardiographic evidence from the Multicenter InSync Randomized Clinical Evaluation (MIRACLE). Circulation 2006; 113(2):266–272. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.520817

- Cleland JG, Daubert JC, Erdmann E, et al; Cardiac Resynchronization-Heart Failure (CARE-HF) Study Investigators. The effect of cardiac resynchronization on morbidity and mortality in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2005; 352(15):1539–1549. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa050496

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation 2013; 128(16):e240–e327. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8776

- Farmer SA, Kirkpatrick JN, Heidenreich PA, Curtis JP, Wang Y, Groeneveld PW. Ethnic and racial disparities in cardiac resynchronization therapy. Heart Rhythm 2009; 6(3):325–331. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.12.018

- Rose EA, Gelijns AC, Moskowitz AJ, et al; Randomized Evaluation of Mechanical Assistance for the Treatment of Congestive Heart Failure (REMATCH) Study Group. Long-term use of a left ventricular assist device for end-stage heart failure. N Engl J Med 2001; 345(20):1435–1443. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa012175

- Slaughter MS, Rogers JG, Milano CA, et al; HeartMate II Investigators. Advanced heart failure treated with continuous-flow left ventricular assist device. N Engl J Med 2009; 361(23):2241–2251. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0909938

- Tsiouris A, Brewer RJ, Borgi J, Nemeh H, Paone G, Morgan JA. Continuous-flow left ventricular assist device implantation as a bridge to transplantation or destination therapy: racial disparities in outcomes. J Heart Lung Transplant 2013; 2(3):299–304. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2012.11.017

- Stulak JM, Deo S, Cowger J, et al. Do racial and sex disparities exist in clinical characteristics and outcomes for patients undergoing left ventricular assist device implantation? J Heart Lung Transplant 2013; 32(45):S279–S280.

- Joyce DL, Conte JV, Russell SD, Joyce LD, Chang DC. Disparities in access to left ventricular assist device therapy. J Surg Res 2009; 152(1):111–117. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2008.02.065

- Breathett K, Allen LA, Helmkamp L, et al. Temporal trends in contemporary use of ventricular assist devices by race and ethnicity. Circ Heart Fail 2018; 11(8):e005008. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.118.005008

- Kilic A, Higgins RS, Whitson BA, Kilic A. Racial disparities in outcomes of adult heart transplantation. Circulation 2015; 131(10):882–889. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011676

- Liu V, Bhattacharya J, Weill D, Hlatky MA. Persistent racial disparities in survival after heart transplantation. Circulation 2011; 123(15):1642–1649. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.976811

- Mahle WT, Kanter KR, Vincent RN. Disparities in outcome for black patients after pediatric heart transplantation. J Pediatr 2005; 147(6):739–743. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.07.018

- Park MH, Tolman DE, Kimball PM. The impact of race and HLA matching on long-term survival following cardiac transplantation. Transplant Proc 1997; 29(1–2):1460–1463. pmid:9123381

- Higgins RS, Fishman JA. Disparities in solid organ transplantation for ethnic minorities: facts and solutions. Am J Transplant 2006; 6(11):2556–2562. doi:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01514.x

- Taylor AL, Wright JT Jr. Should ethnicity serve as the basis for clinical trial design? Importance of race/ethnicity in clinical trials: lessons from the African-American Heart Failure Trial (A-HeFT), the African-American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK), and the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). Circulation 2005; 112(23):3654–3660. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.540443

- Yancy CW. Heart failure in African Americans: a cardiovascular engima. J Card Fail 2000; 6(3):183–186. pmid:10997742

- Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003; 289(19):2560–2572. doi:10.1001/jama.289.19.2560

- Cohn JN, Archibald DG, Ziesche S, et al. Effect of vasodilator therapy on mortality in chronic congestive heart failure. Results of a Veterans Administration cooperative study. N Engl J Med 1986; 314(24):1547–1552. doi:10.1056/NEJM198606123142404

- Chen MS Jr, Lara PN, Dang JH, Paterniti DA, Kelly K. Twenty years post-NIH Revitalization Act: enhancing minority participation in clinical trials (EMPaCT): laying the groundwork for improving minority clinical trial accrual: renewing the case for enhancing minority participation in cancer clinical trials. Cancer 2014;120(suppl 7):1091–1096. doi:10.1002/cncr.28575

- Geller SE, Koch A, Pellettieri B, Carnes M. Inclusion, analysis, and reporting of sex and race/ethnicity in clinical trials: have we made progress? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2011; 20(3):315–320. doi:10.1089/jwh.2010.2469

- Beta-Blocker Evaluation of Survival Trial Investigators; Eichhorn EJ, Domanski MJ, Krause-Steinrauf H, Bristow MR, Lavori PW. A trial of the beta-blocker bucindolol in patients with advanced chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2001; 344(22):1659–1667. doi:10.1056/NEJM200105313442202

- Taylor AL, Ziesche S, Yancy C, et al; African-American Heart Failure Trial Investigators. Combination of isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine in blacks with heart failure. N Engl J Med 2004; 351(20):2049–2057. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa042934

- Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, Moody-Ayers S. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. J Gen Intern Med 1999; 14(9):537–546. pmid:10491242

- Swanson GM, Ward AJ. Recruiting minorities into clinical trials: toward a participant-friendly system. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995; 87(23):1747–1759. doi:10.1093/jnci/87.23.1747

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care; Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2003. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK220358/. Accessed May 13, 2019.

- Fisher JA, Kalbaugh CA. Challenging assumptions about minority participation in US clinical research. Am J Public Health 2011; 101(12):2217–2222. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300279

- Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2015; 105(12):e60–e76. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.302903

- Biernat M, Manis M. Shifting standards and stereotype-based judgments. J Pers Soc Psychol 1994; 66(1):5–20. pmid:8126651

- Chapman EN, Kaatz A, Carnes M. Physicians and implicit bias: how doctors may unwittingly perpetuate health care disparities. J Gen Intern Med 2013; 28(11):1504–1510. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2441-1

- FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 2017; 18(1):19. doi:10.1186/s12910-017-0179-8

- van Ryn M, Burke J. The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians’ perceptions of patients. Soc Sci Med 2000; 50(6):813–828. pmid:10695979

- Mayo RM, Sherrill WW, Sundareswaran P, Crew L. Attitudes and perceptions of Hispanic patients and health care providers in the treatment of Hispanic patients: a review of the literature. Hisp Health Care Int 2007; 5(2):64–72.

- Blair IV, Steiner JF, Havranek EP. Unconscious (implicit) bias and health disparities: where do we go from here? Perm J 2011; 15(2):71–78. pmid:21841929

- Green AR, Carney DR, Pallin DJ, et al. Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for black and white patients. J Gen Intern Med 2007; 22(9):1231–1238. doi:10.1007/s11606-007-0258-5

- Sabin JA, Rivara FP, Greenwald AG. Physician implicit attitudes and stereotypes about race and quality of medical care. Med Care 2008; 46(7):678–685. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181653d58

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Colburn L, et al; Institute of Medicine. The Right Thing to Do, The Smart Thing to Do: Enhancing Diversity in the Health Professions: Summary of the Symposium on Diversity in Health Professions in Honor of Herbert W. Nickens, MD. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK223633/. Accessed May 13, 2019.

- Chen J, Vargas-Bustamante A, Mortensen K, Ortega AN. Racial and ethnic disparities in health care access and utilization under the Affordable Care Act. Med Care 2016; 54(2):140–146. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000467

- Saha S, Freeman M, Toure J, Tippens KM, Weeks C, Ibrahim S. Racial and ethnic disparities in the VA health care system: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2008; 23(5):654–671. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0521-4

- McCormick D, Sayah A, Lokko H, Woolhandler S, Nardin R. Access to care after Massachusetts’ health care reform: a safety net hospital patient survey. J Gen Intern Med 2012; 27(11):1548–1554. doi:10.1007/s11606-012-2173-7

- Burgos JL, Yee D, Csordas T, et al. Supporting the minority physician pipeline: providing global health experiences to undergraduate students in the United States-Mexico border region. Med Educ Online 2015; 20:27260. doi:10.3402/meo.v20.27260

- Traylor AH, Schmittdiel JA, Uratsu CS, Mangione CM, Subramanian U. The predictors of patient–physician race and ethnic concordance: a medical facility fixed-effects approach. Health Serv Res 2010; 45(3):792–805. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01086.x

- LaVeist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav 2002; 43(3):296–306. pmid:12467254

- Marrast LM, Zallman L, Woolhandler S, Bor DH, McCormick D. Minority physicians’ role in the care of underserved patients: diversifying the physician workforce may be key in addressing health disparities. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174(2):289–291. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12756

Cardiovascular disease became the leading cause of death in the United States in the early 20th century, and it accounts for nearly half of all deaths in industrialized nations.1 The mortality it inflicts was thought to be shared equally between both sexes and among all age groups and races.2 The cardiology community implemented innovative epidemiologic research, through which risk factors for cardiovascular disease were established.1 The development of coronary care units reduced in-hospital mortality from acute myocardial infarction from 30% to 15%.2–5 Further advances in pharmacology, revascularization, and imaging have aided in the detection and treatment of cardiovascular disease.6 Though cardiovascular disease remains the number-one cause of death worldwide, rates are on the decline.7

For several decades, health disparities have been recognized as a source of pathology in cardiovascular medicine, resulting in inequity of care administration among select populations. In this review, we examine whether the same forward thinking that has resulted in a decline in cardiovascular disease has had an impact on the pervasive disparities in cardiovascular medicine.

DISPARITIES DEFINED

Compared with whites, members of minority groups have a higher burden of chronic diseases, receive lower quality care, and have less access to medical care. Recognizing the potential public health ramifications, in 1999 the US Congress tasked the Institute of Medicine to study and assess the extent of healthcare disparities. This led to the landmark publication, Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care.8

The Institute of Medicine defines disparities in healthcare as racial or ethnic differences in the quality of healthcare that are not due to access-related factors, clinical needs, preferences, and appropriateness of intervention.8 Disparities can also exist according to socioeconomic status and sex.9

In an early study documenting the concept of disparities in cardiovascular disease, Stone and Vanzant10 concluded that heart disease was more common in African Americans than in whites, and that hypertension was the principal cause of cardiovascular disease mortality in African Americans.

Although avoidable deaths from heart disease, stroke, and hypertensive disease declined between 2001 and 2010, African Americans still have a higher mortality rate than other racial and ethnic groups (Figure 1).11

DISPARITIES AND CARDIOVASCULAR HEALTH

The concept of cardiovascular health was established by the American Heart Association (AHA) in efforts to achieve an additional 20% reduction in cardiovascular disease-related mortality by 2020.7 Cardiovascular health is defined as the absence of clinically manifest cardiovascular disease and is measured by 7 components:

- Not smoking or abstaining from smoking for at least 1 year

- A normal body weight, defined as a body mass index less than 25 kg/m2

- Optimal physical activity, defined as 75 minutes of vigorous physical activity or 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity per week

- Regular consumption of a healthy diet

- Total cholesterol below 200 mg/dL

- Blood pressure less than 120/80 mm Hg

- Fasting blood sugar below 100 mg/dL.

Nearly 70% of the US population can claim 2, 3, or 4 of these components, but differences exist according to race,12 and 60% of adult white Americans are limited to achieving no more than 3 of these healthy metrics, compared with 70% of adult African Americans and Hispanic Americans.

Smoking

Smoking is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease.12–14

During adolescence, white males are more likely to smoke than African American and Hispanic males,12 but this trend reverses in adulthood, when African American men have a higher prevalence of smoking than white men (21.4% vs 19%).7 Rates of lifetime use are highest among American Indian or Alaskan natives and whites (75.9%), followed by African Americans (58.4%), native Hawaiians (56.8%), and Hispanics (56.7%).15 Trends for current smoking are similar (Figure 2).16 Moreover, households with lower socioeconomic status have a higher prevalence of smoking.7

Physical activity

People with a sedentary lifestyle are more likely to die of cardiovascular disease. As many as 250,000 deaths annually in the United States are attributed to lack of regular physical activity.17

Recognizing the potential public health ramifications, the AHA and the 2018 Federal Guidelines on Physical Activity recommend that children engage in 60 minutes of daily physical activity and that adults participate in 150 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous physical activity weekly.18,19

In the United States, 15.2% of adolescents reported being physically inactive, according to data published in 2016.7 Similar to most cardiovascular risk factors, minority populations and those of lower socioeconomic status had the worst profiles. The prevalence of physical inactivity was highest in African Americans and Hispanics (Figure 3).20

Studies have shown an association between screen-based sedentary behavior (computers, television, and video games) and cardiovascular disease.21–23 In the United States, 41% of adolescents used computers for activities other than homework for more than 3 hours per day on a school day.7 The pattern of use was highest in African American boys and African American girls, followed by Hispanic girls and Hispanic boys.18 Trends were similar with regard to watching television for more than 3 hours per day.

Sedentary behavior persists into adulthood, with rates of inactivity of 38.3% in African Americans, 40.1% in Hispanics, and 26.3% in white adults.7

Nutrition and obesity

Nutrition plays a major role in cardiovascular disease, specifically in the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic disease and hypertension.24 Most Americans do not meet dietary recommendations, with minority communities performing worse in specific metrics.7

Dietary patterns are reflected in the rate of obesity in this nation. Studies have shown a direct correlation between obesity and cardiovascular disease such as coronary artery disease, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation.25–28 According to data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 31% of children between the ages of 2 and 19 years are classified as obese or overweight. The highest rates of obesity are seen in Hispanic and African American boys and girls. The obesity epidemic is disproportionately rampant in children living in households with low income, low education, and high unemployment rates.7,29–31

Despite the risks associated with obesity, only 64.8% of obese adults report being informed by a doctor or health professional that they were overweight. The proportion of obese adults informed that they were overweight was significantly lower for African Americans and Hispanics compared with whites. Similar differences are seen based on socioeconomic status, as middle-income patients were less likely to be informed than those in the higher income strata (62.4% vs 70.6%).7,31

Blood pressure

Hypertension is a well-established risk factor for cardiovascular disease and stroke, and a blood pressure of 120/80 mm Hg or lower is identified as a component of ideal cardiovascular health.

In the United States the prevalence of hypertension in adults older than 20 is 32%.7 The prevalence of hypertension in African Americans is among the highest in the world.32,33 African Americans develop high blood pressure at earlier ages, and their average resting blood pressures are higher than in whites.34,35 For a 45-year-old without hypertension, the 40-year risk of developing hypertension is 92.7% for African Americans and 86% for whites.35 Hypertension is a major risk factor for stroke, and African Americans have a 1.8 times greater rate of fatal stroke than whites.7

In 2013 there were 71,942 deaths attributable to high blood pressure, and the 2011 death rate associated with hypertension was 18.9 per 100,000. By race, the death rate was 17.6 per 100,000 for white males and an alarming 47.1 per 100,000 for African American males; rates were 15.2 per 100,000 for white females and 35.1 per 100,000 for African American females.7

It is unclear what accounts for the racial difference in prevalence in hypertension. Studies have shown that African Americans are more likely than whites to have been told on more than 2 occasions that they have hypertension. And 85.7% of African Americans are aware that they have high blood pressure, compared with 82.7% of whites.14

African Americans and Hispanics have poorer hypertension control compared with whites.36,37 These observed differences cannot be attributed to access alone, as African Americans were more likely to be on higher-intensity blood pressure therapy, whereas Hispanics were more likely to be undertreated.36,38 In a meta-analysis of 13 trials, Peck et al39 showed that African Americans showed a lesser reduction in systolic and diastolic blood pressure when treated with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors.

The 2017 American College of Cardiology (ACC) and AHA guidelines for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults40 identifies 4 drug classes as reducing cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality: thiazide diuretics, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), and calcium channel blockers. Of these 4 classes, thiazide diuretics and calcium channel blockers have been shown to lower blood pressure more effectively in African Americans than renin-angiotensin-aldosterone inhibition with ACE inhibitors or ARBs.

Glycemic control

Type 2 diabetes mellitus secondary to insulin resistance disproportionately affects minority groups, as the prevalence of diabetes mellitus in African Americans is almost twice as high as that in whites, and 35% higher in Hispanics compared with whites.7,41 Based on NHANES data between 1984 and 2004, the prevalence of diabetes mellitus is expected to increase by 99% in whites, 107% in African Americans, and 127% in Hispanics by 2050. Alarmingly, African Americans over age 75 are expected to experience a 606% increase by 2050.42

With regard to mortality, 21.7 deaths per 100,000 population were attributable to diabetes mellitus according to reports by the AHA in 2016. The death rate in white males was 24.3 per 100,000 compared with 44.9 per 100,000 for African Americans males. The associated mortality rate for white women was 16.2 per 100,000, and 35.8 per 100,000 for African American females.7

DISPARITIES AND CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE CARE

The management of coronary artery disease has evolved from prolonged bed rest to surgical, pharmacologic, and percutaneous revascularization.2,5 Coronary revascularization procedures are now relatively common: 950,000 percutaneous coronary interventions and 397,000 coronary artery bypass procedures were performed in 2010.7

Nevertheless, despite similar clinical presentations, African Americans with acute myocardial infarction were less likely to be referred for coronary artery bypass grafting than whites.43–46 They were also less likely to be given thrombolytics47 and less likely to undergo coronary angiography with percutaneous coronary intervention.48 Similar differences have been reported when comparing Hispanics with whites.49

Some suggest that healthcare access is a key mediator of health disparities.50 In 2009, Hispanics and African Americans accounted for more than 50% of those without health insurance.51 Improved access to healthcare might mitigate the disparity in revascularizations.

Massachusetts was one of the first states to mandate that all residents obtain health insurance. As a result, the uninsured rates declined in African Americans and Hispanics in Massachusetts, but a disparity in revascularization persisted. African Americans and Hispanics were 27% and 16% less likely to undergo revascularization procedures (coronary artery bypass grafting or percutaneous coronary intervention) than whites,51 suggesting that disparities in revascularization are not solely secondary to healthcare access.

These findings are consistent with a 2004 Veterans Administration study,52 in which healthcare access was equal among races. The study showed that African Americans received fewer cardiac procedures after an acute myocardial infarction compared with whites.

Have we made progress? The largest disparity between African Americans and whites in coronary artery disease mortality existed in 1990. The disparity persisted to 2012, and although decreased, it is projected to persist to 2030.53

DISPARITIES IN HEART FAILURE

An estimated 5.7 million Americans have heart failure, and 915,000 new cases are diagnosed annually.7 Unlike coronary artery disease, heart failure is expected to increase in prevalence by 46%, to 8 million Americans with heart failure by 2030.7,54

Our knowledge of disparities in the area of heart failure is derived primarily from epidemiologic studies. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis55 showed that African Americans (4.6 per 1,000), followed by Hispanics (3.5 per 1,000) had a higher risk of developing heart failure compared with whites (2.4 per 1,000).The higher risk is in part due to disparities in socioeconomic status and prevalence of hypertension, as African Americans accounted for 75% of cases of nonischemic-related heart failure.55 African Americans also have a higher 5-year mortality rate than whites.55

Even though the 5-year mortality rate in heart failure is still 50%, the past 30 years have seen innovations in pharmacologic and device therapy and thus improved outcomes in heart failure patients. Still, significant gaps in the use of guideline-recommended therapies, quality of care, and clinical outcomes persist in contemporary practice for racial minorities with heart failure.

Disparities in inpatient care for heart failure

Patients admitted for heart failure and cared for by a cardiologist are more likely to be discharged on guideline-directed medical therapy, have fewer heart failure readmissions, and lower mortality.56,57 Breathett et al,58 in a study of 104,835 patients hospitalized in an intensive care unit for heart failure, found that primary intensive care by a cardiologist was associated with higher survival in both races. However, in the same study, white patients had a higher odds of receiving care from a cardiologist than African American patients.

Disparities and cardiac resynchronization therapy devices

In one-third of patients with heart failure, conduction delays result in dyssynchronous left ventricular contraction.59 Dyssynchrony leads to reduced cardiac performance, left ventricular remodeling, and increased mortality.56

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) was approved for clinical use in 2001, and studies have shown that it improves quality of life, exercise tolerance, cardiac performance, and morbidity and mortality rates.59–66 The 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of heart failure give a class IA recommendation (the highest) for its use in patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or less, sinus rhythm, left bundle branch block and a QRS duration of 150 ms or greater, and New York Heart Association class II, III, or ambulatory IV symptoms while on guideline-directed medical therapy.67

Despite these recommendations, racial differences are observed. A study using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database59 showed that between 2002 and 2010, a total of 374,202 CRT devices were implanted, averaging 41,578 annually. After adjusting for heart failure admissions, the study showed that CRT use was favored in men and in whites.

Another study, using the National Cardiovascular Data Registry,68 looked at patients who received implantable cardiac defibrillators (ICDs) and were eligible to receive CRT. It found that African Americans and Hispanics were less likely than whites to receive CRT, even though they were more likely to meet established criteria.

Disparities and left ventricular assist devices

The Randomized Evaluation of Mechanical Assistance for the Treatment of Congestive Heart failure (REMATCH) trial and Heart Mate II trial demonstrated that left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) were durable options for long-term support for patients with end-stage heart failure.69,70 Studies that examined the role of race and clinical outcomes after LVAD implantation have reported mixed findings.71,72 Few studies have looked at the role racial differences play in accessing LVAD therapy.

Joyce et al73 reviewed data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample from 2002 to 2003 on patients admitted to the hospital with a primary diagnosis of heart failure or cardiogenic shock. A total of 297,866 patients were included in the study, of whom only 291 underwent LVAD implantation. A multivariate analysis found that factors such as age over 65, female sex, admission to a nonacademic center, geographic region, and African American race adversely influenced access to LVAD therapy.

Breathett et al74 evaluated racial differences in LVAD implantations from 2012 to 2015, a period that corresponds to increased health insurance expansion, and found LVAD implantations increased among African American patients with advanced heart failure, but no other racial or ethnic group.

Disparities and heart transplant

For patients with end-stage heart failure, orthotopic heart transplant is the most definitive and durable option for long-term survival. According to data from the United Network for Organ Sharing, 62,508 heart transplants were performed from January 1, 1988 to December 31, 2015. Compared with transplants of other solid organs, heart transplant occurs in significantly infrequent rates.

Barriers to transplant include lack of health insurance, considered a surrogate for low socioeconomic status. Hispanics and African Americans are less likely to have private health insurance than non-Hispanic whites, and this difference is magnified among the working poor.

Despite these perceived barriers, Kilic et al75 found that African Americans comprised 16.4% of heart transplant recipients, although they make up only approximately 13% of the US population. They also had significantly shorter wait-list times than whites. On the negative side, African Americans had a higher unadjusted mortality rate than whites (15% vs 12% P = .002). African Americans also tended to receive their transplants at centers with lower transplant volumes and higher transplant mortality rates.

Several other studies also showed that African Americans compared to whites have significantly worse outcomes after transplant.76–79 What accounts for this difference? Kilic et al75 showed that African Americans had the lowest proportion of blood type matching and lowest human leukocyte antigen matching, were younger (because African Americans develop more advanced heart failure at younger ages), had higher serum creatinine levels, and were more often bridged to transplant with an LVAD.

DISPARITIES IN CARDIOVASCULAR RESEARCH

Although the United States has the most sophisticated and robust medical system in the world, select groups have significant differences in delivery and healthcare outcomes. There are many explanations for these differences, but a contributing factor may be the paucity of research dedicated to understand racial and ethnic differences.80

Differences observed in epidemiologic studies may be secondary to pathophysiology, genetic differences, environment, and lifestyle choices. Historically, clinical trials were conducted in homogeneous populations with respect to age (middle-aged), sex (male), and race (white), and the results were generalized to heterogeneous populations.80

Disparities in research have implications in clinical practice. Overall, the primary cause of heart failure is ischemia; however, in African Americans, the primary cause is hypertensive heart disease.81 Studies in hypertension have shown that African Americans have less of a response to neurohormonal blockade with ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers than non-African Americans.82 Nevertheless, neurohormonal blockade has become the cornerstone of heart failure treatment.

Retrospective analysis of the Vasodilator-Heart Failure trials83 showed that treatment with isosorbide dinitrate plus hydralazine, compared with placebo, conferred a survival benefit for African Americans but not whites.80 No survival advantage was noted when isosorbide dinitrate/hydralazine was compared to enalapril in African Americans, although enalapril was superior to isosorbide dinitrate in whites.45 These observations were recognized 10 to 15 years after trial completion, and were only possible because the trials included sufficient numbers of African American patients to complete analysis.

In 1993, the US Congress passed the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Revitalization Act, which established guidelines requiring NIH grant applicants to include minorities in human subject research, as they were historically underrepresented in clinical research trials.84,85

In 2001, the Beta-Blocker Evaluation of Survival Trial86 reported its results investigating whether bucindolol, a nonselective beta-blocker, would reduce mortality in patients with advanced heart failure (New York Heart Association class III or IV). This was one of the first trials to prospectively investigate racial and ethnic differences in response to treatment. Though it showed no overall benefit in the use of bucindolol in the treatment of advanced heart failure, subgroup analysis showed that whites did enjoy a benefit in terms of lower mortality, whereas African Americans did not.

Results of the Vasodilator-Heart Failure trials led to further population-directed research, most notably the African American Heart Failure Trial,87 a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial in patients who identified as African American. Patients who were randomized to receive a fixed dose of hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate had a 43% lower mortality rate, a 33% lower hospitalization rate for heart failure, and better quality of life than patients in the placebo group, leading to early termination of the trial. The outcomes suggested that the combination of isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine treats heart failure in a manner independent of pure neurohormonal blockade.

CHALLENGES IN STUDY PARTICIPATION

Recruitment of minority participants in biomedical research is a challenging task for clinical investigators.88,89 Some of the factors thought to pose potential barriers for racial and ethnic minority participation in health research include poor access to primary medical care, failure of researchers to recruit minority populations actively, and language and cultural barriers.90