User login

The Leaky Pipeline: A Narrative Review of Diversity in Dermatology

With a majority-minority population expected in the United States by 2044, improving diversity and cultural competency in the dermatology workforce is now more important than ever. A more diverse workforce increases the cultural competence of all providers, provides greater opportunities for mentorship and sponsorship of underrepresented minority (URM) trainees, establishes a more inclusive environment for learners, and enhances the knowledge and productivity of the workforce.1-3 Additionally, it is imperative to address clinical care disparities seen in minority patients in dermatology, including treatment of skin cancer, psoriasis, acne, atopic dermatitis, and other diseases.4-7

Despite the attention that has been devoted to improving diversity in medicine,8-10 dermatology remains one of the least diverse specialties, prompting additional calls to action within the field.11 Why does the lack of diversity still exist in dermatology, and what is the path to correcting this problem? In this article, we review the evidence of diversity barriers at different stages of medical education training that may impede academic advancement for minority learners pursuing careers in dermatology.

Undergraduate Medical Education

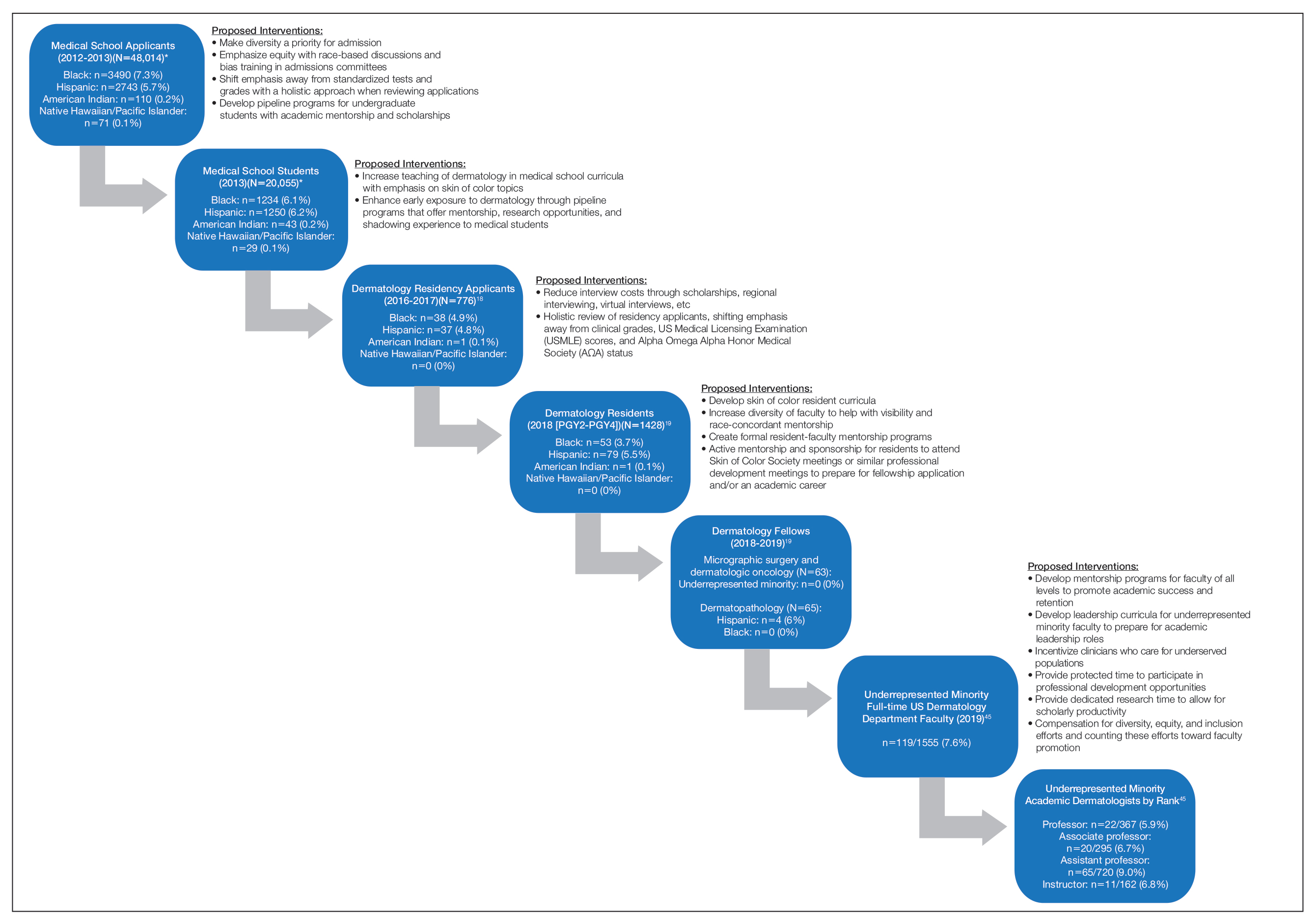

The term leaky pipeline refers to the progressive decline in the number of URMs along a given career path, including in dermatology. The Association of American Medical Colleges defines URMs as racial/ethnic populations that are “underrepresented in the medical profession relative to their numbers in the general population.”9 The first leak in the pipeline is that URMs are not applying to medical school. From 2002 and 2017, rates of both application and matriculation to medical school were lower by 30% to 70% in URM groups compared to White students, including Hispanic, Black, and American Indian/Alaska Native students.12,13 The decision not to apply to medical school was greater in URM undergraduate students irrespective of scholastic ability as measured by SAT scores.14

A striking statistic is that the number of Black men matriculating into medical school in 2014 was less than it was in 1978 despite the increase in the number of US medical schools and efforts to recruit more diverse student populations. The Association of American Medical Colleges identified potential reasons for this decline, including poor early education, lack of mentorship, negative perceptions of Black men due to racial stereotypes, and lack of financial and academic resources to support the application process.8,13,15-17 Implicit racial bias by admission committees also may play a role.

Medical School Matriculation and Applying to Dermatology Residency

There is greater representation of URM students in medical school than in dermatology residency, which means URM students are either not applying to dermatology programs or they are not matching into the specialty. In the Electronic Residency Application Service’s 2016-2017 application cycle (N=776), there were 76 (9.8%) URM dermatology residency applicants.18 In 2018, there was a notable decline in representation of Black students among residency applicants (4.9%) to matched residents (3.7%), and there were only 133 (9.3%) URM dermatology residents in total (PGY2-PGY4 classes).19 The lack of exposure to medical subspecialties and the recommendation by medical schools for URM medical students to pursue careers in primary care have been cited as reasons that these students may not apply to residency programs in specialty care.20,21 The presence of an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education dermatology residency program, fellowships, and dermatology interest groups at their medical schools correlated with higher proportions of URM students applying to dermatology programs.20

Underrepresented minority students face critical challenges during medical school, including receiving lower grades in both standardized and school-designated assessments and clerkship grades.21,22 A 2019 National Board of Medical Examiners study found that Hispanic and Black test takers scored 12.1 and 16.6 points lower than White men, respectively, on the

A recent cross-sectional study showed that lack of equitable resources, lack of support, financial constrictions, and lack of group identity were 4 barriers to URM students matching into dermatology.26 Dermatology is a competitive specialty with the highest median Electronic Residency Application Service applications submitted per US applicant (n=90)27 and an approximate total cost per US applicant of $10,781.28,29 Disadvantaged URM applicants noted relying on loans while non-URM applicants cited family financial support as being beneficial.26 In addition, an increasing number of applicants take gap years for research, which pose additional costs for finances and resources. In contrast, mentorship and participation in pipeline/enrichment programs were factors associated with URM students matching into dermatology.26

Dermatology Residency and the Transition to Advanced Dermatology Fellowships

Similar to the transition from medical school into dermatology residency, URM dermatology residents are either not applying to fellowships or are not getting in. In the 2018-2019 academic year, there were no Black, Hispanic, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, or American Indian/Alaska Native Mohs micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology fellows.19 Similarly, there were no Black, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, or American Indian/Alaska Native dermatopathology fellows. There were 4 (6%) Hispanic dermatopathology fellows.19

There also is marked underrepresentation of minority groups—and minimal growth over time—in the dermatology procedural subspecialty. Whereas the percentage of female Mohs surgeons increased considerably from 1985 to 2005 (12.7% to 40.9%, respectively), the percentage of URM Mohs surgeons remained steady from 4.2% to 4.6%, respectively, and remained at 4.5% in 2014.30

There are no available data on the race/ethnicity of fellowship applicants, as these demographic data for the application process have not been consistently or traditionally collected. The reasons why there are so few URM dermatology fellows is not known; whether this is due to a lack of mentorship or whether other factors lead to residents not applying for advanced training needs further study. Financial factors related to prolonged training, which include lower salaries and delayed loan repayment, may present barriers to applying to fellowships.

Lack of URM Academic Faculty in Dermatology

At the academic faculty level, URM representation continues to worsen. Lett et al31 found that there is declining racial and ethnic representation in clinical academic medicine relative to US census data for 16 US medical specialties, including dermatology, with growing underrepresentation of Black and Hispanic faculty at the associate professor and full professor levels and underrepresentation in all faculty ranks. From 1970 to 2018, URM faculty in dermatology only increased from 4.8% to 7.4%, respectively. Non-URM female and male faculty members increased by 13.8 and 10.8 faculty members per year, respectively, while URM female and male faculty members increased by 1.2 and 0.8 faculty members per year, respectively.32

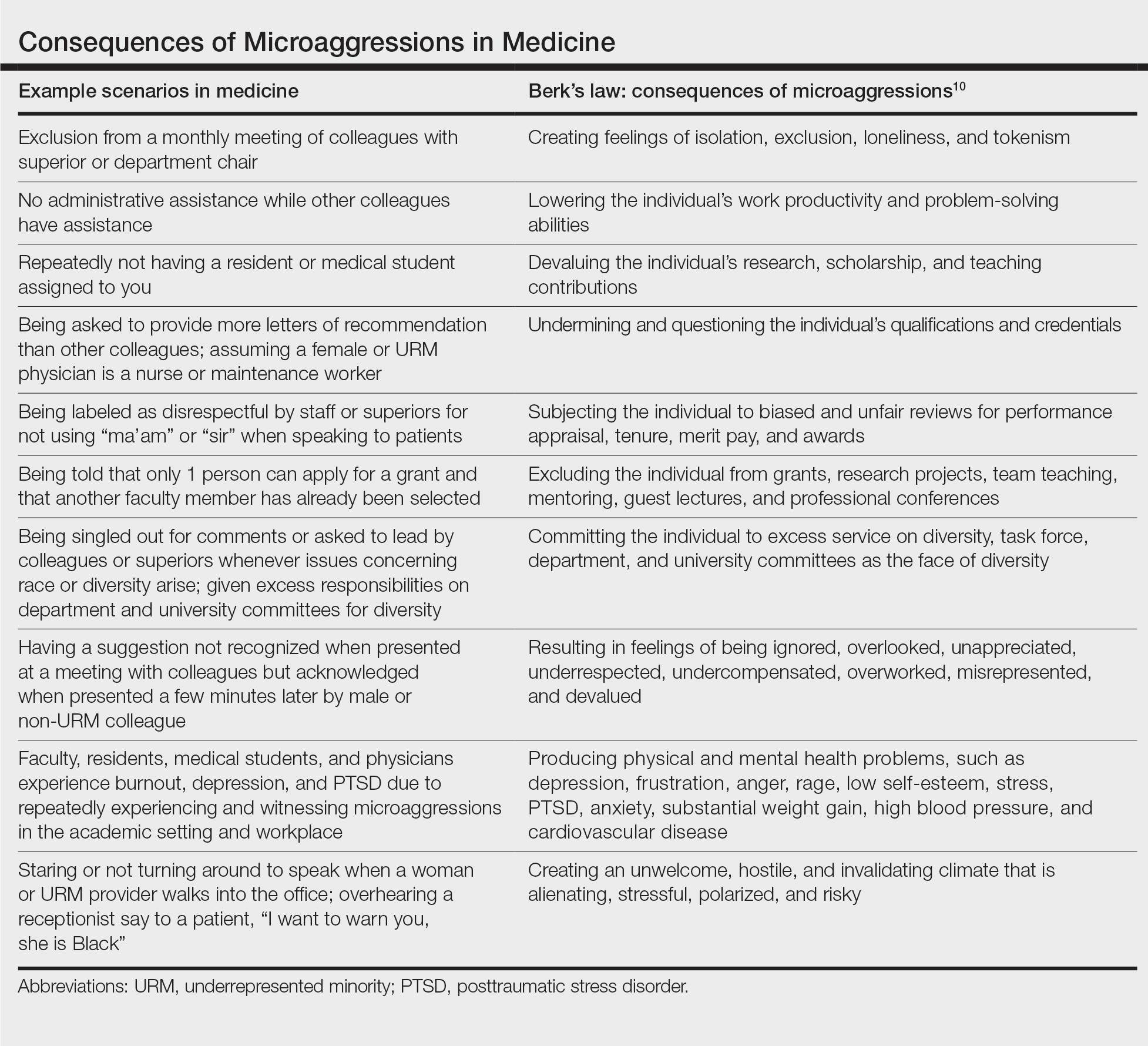

Underrepresentation of minorities seen in dermatology faculty may result from clinical demands, minority taxation (defined as the extensive service requirements uniquely experienced by URM faculty to disproportionately serve as representatives on academic committees and to mentor URM students), and barriers to academic promotion, which are challenges uniquely encountered by URMs in academic dermatology.33 Increased clinical demand may result from the fact that URM physicians are more likely to care for underserved populations, those of lower socioeconomic status, non-English–speaking patients, those on Medicaid, and those who are uninsured, which may impact renumeration. Minority tax experienced by URM faculty includes mentoring URM medical students, providing cultural expertise to departments and institutions, and participating in community service projects and outreach programs. Specifically, many institutional committees require the participation of a URM member, resulting in URM faculty members experiencing higher committee service burden. Many, if not all, of these responsibilities often are not compensated through salary or academic promotion.

A Call to Action

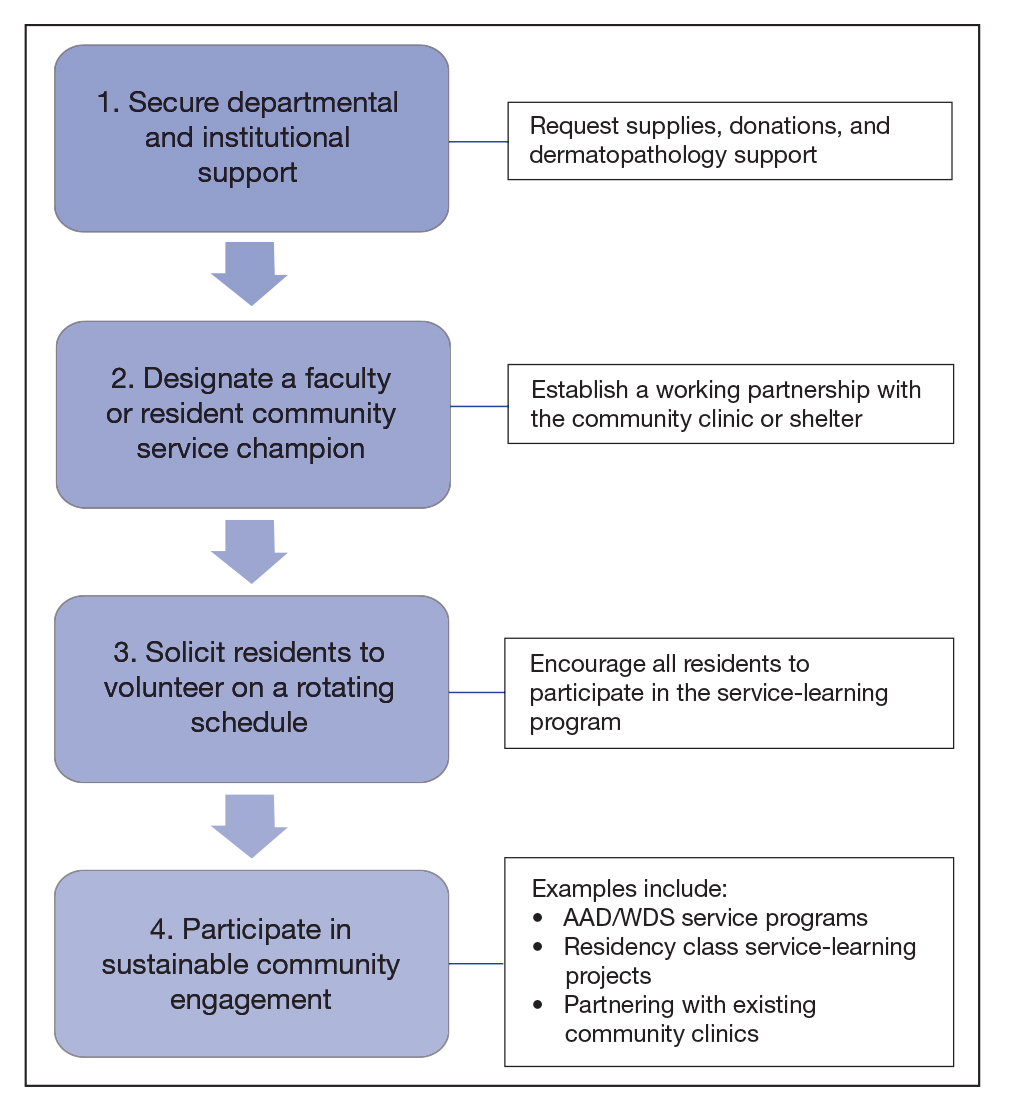

There are several steps that can be taken to create a pathway to dermatology that is inclusive, flexible, and supportive of URMs.

• Increase early exposure to dermatology in medical school. Early exposure and mentorship opportunities are associated with higher rates of students pursuing specialty field careers.34 Increased early opportunities allow for URM students to consider and explore a career in dermatology; receive mentorship; and ensure that dermatology, including topics related to skin of color (SOC), is incorporated into their learning. The American Academy of Dermatology has contributed to these efforts by its presence at every national meeting of the Student National Medical Association and Latino Medical Student Association, as well as its involvement with Nth Dimensions, which offers various educational opportunities for URM medical students.

• Implement equitable grading and holistic review processes in medical school. Racial/ethnic differences in clinical grading and standardized test scores in medical school demonstrate why holistic review of dermatology residency applicants is needed and why other metrics such as USMLE scores and AΩA status should be de-emphasized or eliminated when evaluating candidates. To support equity, many medical schools have eliminated honors grading, and some schools have eliminated AΩA distinction.

• Increase diversity of dermatology residents and residency programs. Implicit bias training for a medical school admissions committee has been shown to increase diversity in medical school enrollment.35 Whether implicit bias training and other diversity training may benefit dermatology residency selection must be examined, including study of unintended consequences, such as reduced diversity, increased microaggressions toward minority colleagues, and the illusion of fairness.36-39 Increasing representation is not sufficient—creating inclusive residency training environments is a critical parallel aim. Prioritizing diversity in dermatology residency recruitment is imperative. Creating dermatology residency positions specifically for URM residents may be an important option, as done at the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) and Duke University (Durham, North Carolina).

• Create effective programs for URM mentorship. Due to the competitive nature of dermatology residency, the need for mentors in dermatology is critically vital for URM medical students, especially those without a home dermatology program at their medical school. Further development of formal mentorship and pipeline programs is essential at both the local and national levels. Some national examples of these initiatives include diversity mentorship programs offered by the American Academy of Dermatology, Skin of Color Society, Women’s Dermatologic Society, and Student National Medical Association. Many institutional programs also offer invaluable opportunities, such as the summer research fellowship at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF); visiting clerkship grants for URMs at the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) and Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, Maryland); and integrated programs, such as the Visiting Elective Scholarship Program at UCSF, which provides funding and faculty mentorship for URM students completing an away rotation at UCSF.

• Establish longitudinal skin-of-color curricula and increased opportunities for research. More robust SOC training may lead to an increasingly diverse workforce. It is important that medical student and dermatology resident and fellow education include training on SOC to ensure high-quality care to diverse patient populations, which also may enhance the knowledge of trainees, encourage clinical and research interest in this field, and reduce health care disparities. Increasing research opportunities and offering formalized longitudinal training in SOC as well as incorporating more diverse images in medical school education may foster greater interest in this field at a time when trainees are establishing their career interests. At present, there is considerable room for improvement. Nijhawan et al40 surveyed 63 dermatology chief residents and 41 program directors and found only 14.3% and 14.6%, respectively, reported having an expert who conducts clinic specializing in SOC. Only 52.4% and 65.9% reported having didactic sessions or lectures focused on SOC diseases, and 30.2% and 12.2% reported having a dedicated rotation for residents to gain experience in SOC.40 A more recent study showed that when faculty were asked to incorporate more SOC content into lectures, the most commonly identified barrier to implementation was a lack of SOC images.41 Additionally, there remains a paucity of published research on this topic, with SOC articles representing only 2.7% of the literature.42 These numbers demonstrate the continued need for a more inclusive and comprehensive curriculum in dermatology residency programs and more robust funding for SOC research.

• Recruit and support URM faculty. Increasing diversity in dermatology residency programs likely will increase the number of potential URMs pursuing additional fellowship training and academic dermatology with active career mentorship and support. In addition, promoting faculty retention by combatting the progressive loss of URMs at all faculty levels is paramount. Mentorship for URM physicians has been shown to play a key role in the decision to pursue academic medicine as well as academic productivity and job satisfaction.43,44 The visibility, cultural competency, clinical work, academic productivity, and mentorship efforts that URM faculty provide are essential to enhancing patient care, teaching diverse groups of learners, and recruiting more diverse trainees. Protected time to participate in professional development opportunities has been shown to improve recruitment and retention of URM faculty and offer additional opportunities for junior faculty to find mentors.35,36 Incentivizing clinical care of underserved populations also may augment financial stability for URM physicians who choose to care for these patients. Finally, diversity work and community service should be legitimized and count toward faculty promotion.

Conclusion

There are numerous factors that contribute to the leaky pipeline in dermatology (eFigure). Many challenges that are unique to the URM population disadvantage these students from entering medical school, applying to dermatology residency, matching into dermatology fellowships, pursuing and staying in faculty positions, and achieving faculty advancement into leadership positions. With each progressive step along this trajectory, there is less minority representation. All dermatologists, regardless of race/ethnicity, need to play an active role and must prioritize diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts at all levels of education and training for the betterment of the specialty.

- Dixon G, Kind T, Wright J, et al. Factors that influence the choice of academic pediatrics by underrepresented minorities. Pediatrics. 2019;144:E20182759. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-2759

- Yehia BR, Cronholm PF, Wilson N, et al. Mentorship and pursuit of academic medicine careers: a mixed methods study of residents from diverse backgrounds. BMC Med Educ. 2014:14:2-26. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-14-26

- Saha S, Guiton G, Wimmers PF, et al. Student body racial and ethnic composition and diversity-related outcomes in US medical schools. JAMA. 2008;300:1135-1145. doi:10.1001/jama.300.10.1135

- Hsu DY, Gordon K, Silverberg JI. The patient burden of psoriasis in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:33-41. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.03.048

- Silverberg JI. Racial and ethnic disparities in atopic dermatitis. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2015;4:44-48.

- Buster KJ, Sevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

- Barbieri JS, Shin DB, Wang S, et al. Association of race/ethnicity with differences in health care use and treatment for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:312-319. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4818

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Colburn L, et al. The Right Thing To Do, The Smart Thing to Do: Enhancing Diversity in the Health Professions. National Academies Press; 2001.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Minorities in medical education: fact and figures 2019. Accessed December 9, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/datareports/workforce/report/diversity-medicine-facts-and-figures-2019

- Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) standards on diversity. University of South Florida Health website. Accessed December 9, 2021. https://health.usf.edu/~/media/Files/Medicine/MD%20Program/Diversity/LCMEStandardsonDiversity1.ashx?la=en

- Granstein RD, Cornelius L, Shinkai K. Diversity in dermatology—a call for action. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:499-500. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0296

- Lett LA, Murdock HM, Orji W, et al. Trends in racial/ethnic representation among US medical students. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1910490. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10490

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Altering the course: Black males in medicine. Published 2015. Accessed December 8, 2021. https://store.aamc.org/downloadable/download/sample/sample_id/84/

- Barr DA, Gonzalez ME, Wanat SF. The leaky pipeline: factors associated with early decline in interest in premedical studies among underrepresented minority undergraduate students. Acad Med. 2008;83:5:503-511. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31816bda16

- Flores RL. The rising gap between rich and poor: a look at the persistence of educational disparities in the United States and why we should worry. Cogent Soc Sci. 2017;3:1323698.

- Jackson D. Why am I behind? an examination of low income and minority students’ preparedness for college. McNair Sch J. 2012;13:121-138.

- Rothstein R. The racial achievement gap, segregated schools, andsegregated neighborhoods: a constitutional insult. Race Soc Probl. 2015;7:21-30.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Residency Applicants From US MD Granting Medical Schools to ACGME-Accredited Programs by Specialty and Race/Ethnicity. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2017.

- Brotherton SE, Etzel SL. Graduate medical education, 2018-2019. JAMA. 2019;322:996-1016. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.10155

- Barnes LA, Bae GH, Nambudiri V. Sex and racial/ethnic diversity of US medical students and their exposure to dermatology programs. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:490-491. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5025

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Low D, Pollack SW, Liao Z, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in clinical grading in medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31:487-496. doi:10.1080/10401334.2019.1597724

- Rubright JD, Jodoin M, Barone MA. Examining demographics, prior academic performance and United States medical licensing examination scores. Acad Med. 2019;94;364-370. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002366

- Boatright D, Ross D, O’Connor P, et al. Racial disparities in medical student membership in the alpha omega honor society. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:659-665. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9623

- Gorouhi F, Alikhan A, Rezaei A, et al. Dermatology residency selection criteria with an emphasis on program characteristics: a national program director survey [published online March 17, 2014]. Dermatol Res Pract. doi:10.1155/2014/692760

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by underrepresented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatology residency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Results of the 2019 NRMP applicant survey by preferred specialty and applicant type. National Resident Matching Program website. Published July 2019. Accessed December 8, 2021. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Applicant-Survey-Report-2019.pdf

- Mansouri B, Walker GD, Mitchell J, et al. The cost of applying to dermatology residency: 2014 data estimates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:754-756. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.049

- Polacco MA, Lally J, Walls A, et al. Digging into debt: the financial burden associated with the otolaryngology match. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;12:1091-1096. doi:10.1177/0194599816686538

- Feng H, Feng PW, Geronemus RG. Diversity in the US Mohs micrographic surgery workforce. Dermatol Surg. 2020:46:1451-1455. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002080

- Lett LA, Orji WU, Sebro R. Declining racial and ethnic representation in clinical academic medicine: a longitudinal study of 16 US medical specialties. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0207274. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.020727432. Xierali IM, Nivet MA, Pandya AG. US Dermatology department faculty diversity trends by sex and underrepresented-in-medicine status, 1970-2018. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:280-287. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4297

- Okoye GA. Supporting underrepresented minority women in academic dermatology. Intl J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:57-60. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2019.09.009

- Bernstein J, Dicaprio MR, Mehta S. The relationship between required medical school instruction in musculoskeletal medicine and application rates to orthopaedic surgery residency programs. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:2335-2338. doi:10.2106/00004623-200410000-00031

- Capers Q, Clinchot D, McDougle L, et al. Implicit racial bias in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2017;92:365-369. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001388

- Dobbin F, Kalev A. Why diversity programs fail. Harvard Business Rev. 2016;52-60. Accessed December 8, 2021. https://hbr.org/2016/07/why-diversity-programs-fail

- Kalev A, Dobbin F, Kelly E. Best practices or best guesses? assessing the efficacy of corporate affirmative action and diversity policies. Am Sociol Rev. 2006;71:589-617.

- Sanchez JI, Medkik N. The effects of diversity awareness training on differential treatment. Group Organ Manag. 2004;29:517-536.

- Kaiser CR, Major B, Jurcevic I, et al. Presumed fair: ironic effects of organizational diversity structures. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2013;104:504-519. doi:10.1037/a0030838

- Nijhawan RI, Jacob SE, Woolery-Lloyd H. Skin of color education in dermatology residency programs: does residency training reflect the changing demographics of the United States? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:615-617.

- Jia JL, Gordon JS, Lester JC, et al. Integrating skin of color and sexual and gender minority content into dermatology residency curricula: a prospective program initiative [published online April 16, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.04.018

- Amuzie AU, Lia JL, Taylor SC, et al. Skin of color article representation in dermatology literature 2009-2019: higher citation counts and opportunities for inclusion [published online March 24, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.063

- Beech BM, Calles-Escandon J, Hairston KC, et al. Mentoring programs for underrepresented minority faculty in academic medical center: a systematic review of the literature. Acad Med. 2013;88:541-549. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828589e3

- Daley S, Wingard DL, Reznik V. Improving the retention of underrepresented minority faculty in academic medicine. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98:1435-1440. doi:10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31449-8

- Association of American Medical Colleges. US medical school faculty by sex, race/ethnicity, rank, and department, 2019. Published December 31, 2019. Accessed December 20, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/media/8476/download?attachment

With a majority-minority population expected in the United States by 2044, improving diversity and cultural competency in the dermatology workforce is now more important than ever. A more diverse workforce increases the cultural competence of all providers, provides greater opportunities for mentorship and sponsorship of underrepresented minority (URM) trainees, establishes a more inclusive environment for learners, and enhances the knowledge and productivity of the workforce.1-3 Additionally, it is imperative to address clinical care disparities seen in minority patients in dermatology, including treatment of skin cancer, psoriasis, acne, atopic dermatitis, and other diseases.4-7

Despite the attention that has been devoted to improving diversity in medicine,8-10 dermatology remains one of the least diverse specialties, prompting additional calls to action within the field.11 Why does the lack of diversity still exist in dermatology, and what is the path to correcting this problem? In this article, we review the evidence of diversity barriers at different stages of medical education training that may impede academic advancement for minority learners pursuing careers in dermatology.

Undergraduate Medical Education

The term leaky pipeline refers to the progressive decline in the number of URMs along a given career path, including in dermatology. The Association of American Medical Colleges defines URMs as racial/ethnic populations that are “underrepresented in the medical profession relative to their numbers in the general population.”9 The first leak in the pipeline is that URMs are not applying to medical school. From 2002 and 2017, rates of both application and matriculation to medical school were lower by 30% to 70% in URM groups compared to White students, including Hispanic, Black, and American Indian/Alaska Native students.12,13 The decision not to apply to medical school was greater in URM undergraduate students irrespective of scholastic ability as measured by SAT scores.14

A striking statistic is that the number of Black men matriculating into medical school in 2014 was less than it was in 1978 despite the increase in the number of US medical schools and efforts to recruit more diverse student populations. The Association of American Medical Colleges identified potential reasons for this decline, including poor early education, lack of mentorship, negative perceptions of Black men due to racial stereotypes, and lack of financial and academic resources to support the application process.8,13,15-17 Implicit racial bias by admission committees also may play a role.

Medical School Matriculation and Applying to Dermatology Residency

There is greater representation of URM students in medical school than in dermatology residency, which means URM students are either not applying to dermatology programs or they are not matching into the specialty. In the Electronic Residency Application Service’s 2016-2017 application cycle (N=776), there were 76 (9.8%) URM dermatology residency applicants.18 In 2018, there was a notable decline in representation of Black students among residency applicants (4.9%) to matched residents (3.7%), and there were only 133 (9.3%) URM dermatology residents in total (PGY2-PGY4 classes).19 The lack of exposure to medical subspecialties and the recommendation by medical schools for URM medical students to pursue careers in primary care have been cited as reasons that these students may not apply to residency programs in specialty care.20,21 The presence of an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education dermatology residency program, fellowships, and dermatology interest groups at their medical schools correlated with higher proportions of URM students applying to dermatology programs.20

Underrepresented minority students face critical challenges during medical school, including receiving lower grades in both standardized and school-designated assessments and clerkship grades.21,22 A 2019 National Board of Medical Examiners study found that Hispanic and Black test takers scored 12.1 and 16.6 points lower than White men, respectively, on the

A recent cross-sectional study showed that lack of equitable resources, lack of support, financial constrictions, and lack of group identity were 4 barriers to URM students matching into dermatology.26 Dermatology is a competitive specialty with the highest median Electronic Residency Application Service applications submitted per US applicant (n=90)27 and an approximate total cost per US applicant of $10,781.28,29 Disadvantaged URM applicants noted relying on loans while non-URM applicants cited family financial support as being beneficial.26 In addition, an increasing number of applicants take gap years for research, which pose additional costs for finances and resources. In contrast, mentorship and participation in pipeline/enrichment programs were factors associated with URM students matching into dermatology.26

Dermatology Residency and the Transition to Advanced Dermatology Fellowships

Similar to the transition from medical school into dermatology residency, URM dermatology residents are either not applying to fellowships or are not getting in. In the 2018-2019 academic year, there were no Black, Hispanic, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, or American Indian/Alaska Native Mohs micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology fellows.19 Similarly, there were no Black, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, or American Indian/Alaska Native dermatopathology fellows. There were 4 (6%) Hispanic dermatopathology fellows.19

There also is marked underrepresentation of minority groups—and minimal growth over time—in the dermatology procedural subspecialty. Whereas the percentage of female Mohs surgeons increased considerably from 1985 to 2005 (12.7% to 40.9%, respectively), the percentage of URM Mohs surgeons remained steady from 4.2% to 4.6%, respectively, and remained at 4.5% in 2014.30

There are no available data on the race/ethnicity of fellowship applicants, as these demographic data for the application process have not been consistently or traditionally collected. The reasons why there are so few URM dermatology fellows is not known; whether this is due to a lack of mentorship or whether other factors lead to residents not applying for advanced training needs further study. Financial factors related to prolonged training, which include lower salaries and delayed loan repayment, may present barriers to applying to fellowships.

Lack of URM Academic Faculty in Dermatology

At the academic faculty level, URM representation continues to worsen. Lett et al31 found that there is declining racial and ethnic representation in clinical academic medicine relative to US census data for 16 US medical specialties, including dermatology, with growing underrepresentation of Black and Hispanic faculty at the associate professor and full professor levels and underrepresentation in all faculty ranks. From 1970 to 2018, URM faculty in dermatology only increased from 4.8% to 7.4%, respectively. Non-URM female and male faculty members increased by 13.8 and 10.8 faculty members per year, respectively, while URM female and male faculty members increased by 1.2 and 0.8 faculty members per year, respectively.32

Underrepresentation of minorities seen in dermatology faculty may result from clinical demands, minority taxation (defined as the extensive service requirements uniquely experienced by URM faculty to disproportionately serve as representatives on academic committees and to mentor URM students), and barriers to academic promotion, which are challenges uniquely encountered by URMs in academic dermatology.33 Increased clinical demand may result from the fact that URM physicians are more likely to care for underserved populations, those of lower socioeconomic status, non-English–speaking patients, those on Medicaid, and those who are uninsured, which may impact renumeration. Minority tax experienced by URM faculty includes mentoring URM medical students, providing cultural expertise to departments and institutions, and participating in community service projects and outreach programs. Specifically, many institutional committees require the participation of a URM member, resulting in URM faculty members experiencing higher committee service burden. Many, if not all, of these responsibilities often are not compensated through salary or academic promotion.

A Call to Action

There are several steps that can be taken to create a pathway to dermatology that is inclusive, flexible, and supportive of URMs.

• Increase early exposure to dermatology in medical school. Early exposure and mentorship opportunities are associated with higher rates of students pursuing specialty field careers.34 Increased early opportunities allow for URM students to consider and explore a career in dermatology; receive mentorship; and ensure that dermatology, including topics related to skin of color (SOC), is incorporated into their learning. The American Academy of Dermatology has contributed to these efforts by its presence at every national meeting of the Student National Medical Association and Latino Medical Student Association, as well as its involvement with Nth Dimensions, which offers various educational opportunities for URM medical students.

• Implement equitable grading and holistic review processes in medical school. Racial/ethnic differences in clinical grading and standardized test scores in medical school demonstrate why holistic review of dermatology residency applicants is needed and why other metrics such as USMLE scores and AΩA status should be de-emphasized or eliminated when evaluating candidates. To support equity, many medical schools have eliminated honors grading, and some schools have eliminated AΩA distinction.

• Increase diversity of dermatology residents and residency programs. Implicit bias training for a medical school admissions committee has been shown to increase diversity in medical school enrollment.35 Whether implicit bias training and other diversity training may benefit dermatology residency selection must be examined, including study of unintended consequences, such as reduced diversity, increased microaggressions toward minority colleagues, and the illusion of fairness.36-39 Increasing representation is not sufficient—creating inclusive residency training environments is a critical parallel aim. Prioritizing diversity in dermatology residency recruitment is imperative. Creating dermatology residency positions specifically for URM residents may be an important option, as done at the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) and Duke University (Durham, North Carolina).

• Create effective programs for URM mentorship. Due to the competitive nature of dermatology residency, the need for mentors in dermatology is critically vital for URM medical students, especially those without a home dermatology program at their medical school. Further development of formal mentorship and pipeline programs is essential at both the local and national levels. Some national examples of these initiatives include diversity mentorship programs offered by the American Academy of Dermatology, Skin of Color Society, Women’s Dermatologic Society, and Student National Medical Association. Many institutional programs also offer invaluable opportunities, such as the summer research fellowship at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF); visiting clerkship grants for URMs at the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) and Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, Maryland); and integrated programs, such as the Visiting Elective Scholarship Program at UCSF, which provides funding and faculty mentorship for URM students completing an away rotation at UCSF.

• Establish longitudinal skin-of-color curricula and increased opportunities for research. More robust SOC training may lead to an increasingly diverse workforce. It is important that medical student and dermatology resident and fellow education include training on SOC to ensure high-quality care to diverse patient populations, which also may enhance the knowledge of trainees, encourage clinical and research interest in this field, and reduce health care disparities. Increasing research opportunities and offering formalized longitudinal training in SOC as well as incorporating more diverse images in medical school education may foster greater interest in this field at a time when trainees are establishing their career interests. At present, there is considerable room for improvement. Nijhawan et al40 surveyed 63 dermatology chief residents and 41 program directors and found only 14.3% and 14.6%, respectively, reported having an expert who conducts clinic specializing in SOC. Only 52.4% and 65.9% reported having didactic sessions or lectures focused on SOC diseases, and 30.2% and 12.2% reported having a dedicated rotation for residents to gain experience in SOC.40 A more recent study showed that when faculty were asked to incorporate more SOC content into lectures, the most commonly identified barrier to implementation was a lack of SOC images.41 Additionally, there remains a paucity of published research on this topic, with SOC articles representing only 2.7% of the literature.42 These numbers demonstrate the continued need for a more inclusive and comprehensive curriculum in dermatology residency programs and more robust funding for SOC research.

• Recruit and support URM faculty. Increasing diversity in dermatology residency programs likely will increase the number of potential URMs pursuing additional fellowship training and academic dermatology with active career mentorship and support. In addition, promoting faculty retention by combatting the progressive loss of URMs at all faculty levels is paramount. Mentorship for URM physicians has been shown to play a key role in the decision to pursue academic medicine as well as academic productivity and job satisfaction.43,44 The visibility, cultural competency, clinical work, academic productivity, and mentorship efforts that URM faculty provide are essential to enhancing patient care, teaching diverse groups of learners, and recruiting more diverse trainees. Protected time to participate in professional development opportunities has been shown to improve recruitment and retention of URM faculty and offer additional opportunities for junior faculty to find mentors.35,36 Incentivizing clinical care of underserved populations also may augment financial stability for URM physicians who choose to care for these patients. Finally, diversity work and community service should be legitimized and count toward faculty promotion.

Conclusion

There are numerous factors that contribute to the leaky pipeline in dermatology (eFigure). Many challenges that are unique to the URM population disadvantage these students from entering medical school, applying to dermatology residency, matching into dermatology fellowships, pursuing and staying in faculty positions, and achieving faculty advancement into leadership positions. With each progressive step along this trajectory, there is less minority representation. All dermatologists, regardless of race/ethnicity, need to play an active role and must prioritize diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts at all levels of education and training for the betterment of the specialty.

With a majority-minority population expected in the United States by 2044, improving diversity and cultural competency in the dermatology workforce is now more important than ever. A more diverse workforce increases the cultural competence of all providers, provides greater opportunities for mentorship and sponsorship of underrepresented minority (URM) trainees, establishes a more inclusive environment for learners, and enhances the knowledge and productivity of the workforce.1-3 Additionally, it is imperative to address clinical care disparities seen in minority patients in dermatology, including treatment of skin cancer, psoriasis, acne, atopic dermatitis, and other diseases.4-7

Despite the attention that has been devoted to improving diversity in medicine,8-10 dermatology remains one of the least diverse specialties, prompting additional calls to action within the field.11 Why does the lack of diversity still exist in dermatology, and what is the path to correcting this problem? In this article, we review the evidence of diversity barriers at different stages of medical education training that may impede academic advancement for minority learners pursuing careers in dermatology.

Undergraduate Medical Education

The term leaky pipeline refers to the progressive decline in the number of URMs along a given career path, including in dermatology. The Association of American Medical Colleges defines URMs as racial/ethnic populations that are “underrepresented in the medical profession relative to their numbers in the general population.”9 The first leak in the pipeline is that URMs are not applying to medical school. From 2002 and 2017, rates of both application and matriculation to medical school were lower by 30% to 70% in URM groups compared to White students, including Hispanic, Black, and American Indian/Alaska Native students.12,13 The decision not to apply to medical school was greater in URM undergraduate students irrespective of scholastic ability as measured by SAT scores.14

A striking statistic is that the number of Black men matriculating into medical school in 2014 was less than it was in 1978 despite the increase in the number of US medical schools and efforts to recruit more diverse student populations. The Association of American Medical Colleges identified potential reasons for this decline, including poor early education, lack of mentorship, negative perceptions of Black men due to racial stereotypes, and lack of financial and academic resources to support the application process.8,13,15-17 Implicit racial bias by admission committees also may play a role.

Medical School Matriculation and Applying to Dermatology Residency

There is greater representation of URM students in medical school than in dermatology residency, which means URM students are either not applying to dermatology programs or they are not matching into the specialty. In the Electronic Residency Application Service’s 2016-2017 application cycle (N=776), there were 76 (9.8%) URM dermatology residency applicants.18 In 2018, there was a notable decline in representation of Black students among residency applicants (4.9%) to matched residents (3.7%), and there were only 133 (9.3%) URM dermatology residents in total (PGY2-PGY4 classes).19 The lack of exposure to medical subspecialties and the recommendation by medical schools for URM medical students to pursue careers in primary care have been cited as reasons that these students may not apply to residency programs in specialty care.20,21 The presence of an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education dermatology residency program, fellowships, and dermatology interest groups at their medical schools correlated with higher proportions of URM students applying to dermatology programs.20

Underrepresented minority students face critical challenges during medical school, including receiving lower grades in both standardized and school-designated assessments and clerkship grades.21,22 A 2019 National Board of Medical Examiners study found that Hispanic and Black test takers scored 12.1 and 16.6 points lower than White men, respectively, on the

A recent cross-sectional study showed that lack of equitable resources, lack of support, financial constrictions, and lack of group identity were 4 barriers to URM students matching into dermatology.26 Dermatology is a competitive specialty with the highest median Electronic Residency Application Service applications submitted per US applicant (n=90)27 and an approximate total cost per US applicant of $10,781.28,29 Disadvantaged URM applicants noted relying on loans while non-URM applicants cited family financial support as being beneficial.26 In addition, an increasing number of applicants take gap years for research, which pose additional costs for finances and resources. In contrast, mentorship and participation in pipeline/enrichment programs were factors associated with URM students matching into dermatology.26

Dermatology Residency and the Transition to Advanced Dermatology Fellowships

Similar to the transition from medical school into dermatology residency, URM dermatology residents are either not applying to fellowships or are not getting in. In the 2018-2019 academic year, there were no Black, Hispanic, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, or American Indian/Alaska Native Mohs micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology fellows.19 Similarly, there were no Black, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, or American Indian/Alaska Native dermatopathology fellows. There were 4 (6%) Hispanic dermatopathology fellows.19

There also is marked underrepresentation of minority groups—and minimal growth over time—in the dermatology procedural subspecialty. Whereas the percentage of female Mohs surgeons increased considerably from 1985 to 2005 (12.7% to 40.9%, respectively), the percentage of URM Mohs surgeons remained steady from 4.2% to 4.6%, respectively, and remained at 4.5% in 2014.30

There are no available data on the race/ethnicity of fellowship applicants, as these demographic data for the application process have not been consistently or traditionally collected. The reasons why there are so few URM dermatology fellows is not known; whether this is due to a lack of mentorship or whether other factors lead to residents not applying for advanced training needs further study. Financial factors related to prolonged training, which include lower salaries and delayed loan repayment, may present barriers to applying to fellowships.

Lack of URM Academic Faculty in Dermatology

At the academic faculty level, URM representation continues to worsen. Lett et al31 found that there is declining racial and ethnic representation in clinical academic medicine relative to US census data for 16 US medical specialties, including dermatology, with growing underrepresentation of Black and Hispanic faculty at the associate professor and full professor levels and underrepresentation in all faculty ranks. From 1970 to 2018, URM faculty in dermatology only increased from 4.8% to 7.4%, respectively. Non-URM female and male faculty members increased by 13.8 and 10.8 faculty members per year, respectively, while URM female and male faculty members increased by 1.2 and 0.8 faculty members per year, respectively.32

Underrepresentation of minorities seen in dermatology faculty may result from clinical demands, minority taxation (defined as the extensive service requirements uniquely experienced by URM faculty to disproportionately serve as representatives on academic committees and to mentor URM students), and barriers to academic promotion, which are challenges uniquely encountered by URMs in academic dermatology.33 Increased clinical demand may result from the fact that URM physicians are more likely to care for underserved populations, those of lower socioeconomic status, non-English–speaking patients, those on Medicaid, and those who are uninsured, which may impact renumeration. Minority tax experienced by URM faculty includes mentoring URM medical students, providing cultural expertise to departments and institutions, and participating in community service projects and outreach programs. Specifically, many institutional committees require the participation of a URM member, resulting in URM faculty members experiencing higher committee service burden. Many, if not all, of these responsibilities often are not compensated through salary or academic promotion.

A Call to Action

There are several steps that can be taken to create a pathway to dermatology that is inclusive, flexible, and supportive of URMs.

• Increase early exposure to dermatology in medical school. Early exposure and mentorship opportunities are associated with higher rates of students pursuing specialty field careers.34 Increased early opportunities allow for URM students to consider and explore a career in dermatology; receive mentorship; and ensure that dermatology, including topics related to skin of color (SOC), is incorporated into their learning. The American Academy of Dermatology has contributed to these efforts by its presence at every national meeting of the Student National Medical Association and Latino Medical Student Association, as well as its involvement with Nth Dimensions, which offers various educational opportunities for URM medical students.

• Implement equitable grading and holistic review processes in medical school. Racial/ethnic differences in clinical grading and standardized test scores in medical school demonstrate why holistic review of dermatology residency applicants is needed and why other metrics such as USMLE scores and AΩA status should be de-emphasized or eliminated when evaluating candidates. To support equity, many medical schools have eliminated honors grading, and some schools have eliminated AΩA distinction.

• Increase diversity of dermatology residents and residency programs. Implicit bias training for a medical school admissions committee has been shown to increase diversity in medical school enrollment.35 Whether implicit bias training and other diversity training may benefit dermatology residency selection must be examined, including study of unintended consequences, such as reduced diversity, increased microaggressions toward minority colleagues, and the illusion of fairness.36-39 Increasing representation is not sufficient—creating inclusive residency training environments is a critical parallel aim. Prioritizing diversity in dermatology residency recruitment is imperative. Creating dermatology residency positions specifically for URM residents may be an important option, as done at the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) and Duke University (Durham, North Carolina).

• Create effective programs for URM mentorship. Due to the competitive nature of dermatology residency, the need for mentors in dermatology is critically vital for URM medical students, especially those without a home dermatology program at their medical school. Further development of formal mentorship and pipeline programs is essential at both the local and national levels. Some national examples of these initiatives include diversity mentorship programs offered by the American Academy of Dermatology, Skin of Color Society, Women’s Dermatologic Society, and Student National Medical Association. Many institutional programs also offer invaluable opportunities, such as the summer research fellowship at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF); visiting clerkship grants for URMs at the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) and Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, Maryland); and integrated programs, such as the Visiting Elective Scholarship Program at UCSF, which provides funding and faculty mentorship for URM students completing an away rotation at UCSF.

• Establish longitudinal skin-of-color curricula and increased opportunities for research. More robust SOC training may lead to an increasingly diverse workforce. It is important that medical student and dermatology resident and fellow education include training on SOC to ensure high-quality care to diverse patient populations, which also may enhance the knowledge of trainees, encourage clinical and research interest in this field, and reduce health care disparities. Increasing research opportunities and offering formalized longitudinal training in SOC as well as incorporating more diverse images in medical school education may foster greater interest in this field at a time when trainees are establishing their career interests. At present, there is considerable room for improvement. Nijhawan et al40 surveyed 63 dermatology chief residents and 41 program directors and found only 14.3% and 14.6%, respectively, reported having an expert who conducts clinic specializing in SOC. Only 52.4% and 65.9% reported having didactic sessions or lectures focused on SOC diseases, and 30.2% and 12.2% reported having a dedicated rotation for residents to gain experience in SOC.40 A more recent study showed that when faculty were asked to incorporate more SOC content into lectures, the most commonly identified barrier to implementation was a lack of SOC images.41 Additionally, there remains a paucity of published research on this topic, with SOC articles representing only 2.7% of the literature.42 These numbers demonstrate the continued need for a more inclusive and comprehensive curriculum in dermatology residency programs and more robust funding for SOC research.

• Recruit and support URM faculty. Increasing diversity in dermatology residency programs likely will increase the number of potential URMs pursuing additional fellowship training and academic dermatology with active career mentorship and support. In addition, promoting faculty retention by combatting the progressive loss of URMs at all faculty levels is paramount. Mentorship for URM physicians has been shown to play a key role in the decision to pursue academic medicine as well as academic productivity and job satisfaction.43,44 The visibility, cultural competency, clinical work, academic productivity, and mentorship efforts that URM faculty provide are essential to enhancing patient care, teaching diverse groups of learners, and recruiting more diverse trainees. Protected time to participate in professional development opportunities has been shown to improve recruitment and retention of URM faculty and offer additional opportunities for junior faculty to find mentors.35,36 Incentivizing clinical care of underserved populations also may augment financial stability for URM physicians who choose to care for these patients. Finally, diversity work and community service should be legitimized and count toward faculty promotion.

Conclusion

There are numerous factors that contribute to the leaky pipeline in dermatology (eFigure). Many challenges that are unique to the URM population disadvantage these students from entering medical school, applying to dermatology residency, matching into dermatology fellowships, pursuing and staying in faculty positions, and achieving faculty advancement into leadership positions. With each progressive step along this trajectory, there is less minority representation. All dermatologists, regardless of race/ethnicity, need to play an active role and must prioritize diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts at all levels of education and training for the betterment of the specialty.

- Dixon G, Kind T, Wright J, et al. Factors that influence the choice of academic pediatrics by underrepresented minorities. Pediatrics. 2019;144:E20182759. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-2759

- Yehia BR, Cronholm PF, Wilson N, et al. Mentorship and pursuit of academic medicine careers: a mixed methods study of residents from diverse backgrounds. BMC Med Educ. 2014:14:2-26. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-14-26

- Saha S, Guiton G, Wimmers PF, et al. Student body racial and ethnic composition and diversity-related outcomes in US medical schools. JAMA. 2008;300:1135-1145. doi:10.1001/jama.300.10.1135

- Hsu DY, Gordon K, Silverberg JI. The patient burden of psoriasis in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:33-41. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.03.048

- Silverberg JI. Racial and ethnic disparities in atopic dermatitis. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2015;4:44-48.

- Buster KJ, Sevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

- Barbieri JS, Shin DB, Wang S, et al. Association of race/ethnicity with differences in health care use and treatment for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:312-319. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4818

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Colburn L, et al. The Right Thing To Do, The Smart Thing to Do: Enhancing Diversity in the Health Professions. National Academies Press; 2001.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Minorities in medical education: fact and figures 2019. Accessed December 9, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/datareports/workforce/report/diversity-medicine-facts-and-figures-2019

- Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) standards on diversity. University of South Florida Health website. Accessed December 9, 2021. https://health.usf.edu/~/media/Files/Medicine/MD%20Program/Diversity/LCMEStandardsonDiversity1.ashx?la=en

- Granstein RD, Cornelius L, Shinkai K. Diversity in dermatology—a call for action. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:499-500. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0296

- Lett LA, Murdock HM, Orji W, et al. Trends in racial/ethnic representation among US medical students. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1910490. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10490

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Altering the course: Black males in medicine. Published 2015. Accessed December 8, 2021. https://store.aamc.org/downloadable/download/sample/sample_id/84/

- Barr DA, Gonzalez ME, Wanat SF. The leaky pipeline: factors associated with early decline in interest in premedical studies among underrepresented minority undergraduate students. Acad Med. 2008;83:5:503-511. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31816bda16

- Flores RL. The rising gap between rich and poor: a look at the persistence of educational disparities in the United States and why we should worry. Cogent Soc Sci. 2017;3:1323698.

- Jackson D. Why am I behind? an examination of low income and minority students’ preparedness for college. McNair Sch J. 2012;13:121-138.

- Rothstein R. The racial achievement gap, segregated schools, andsegregated neighborhoods: a constitutional insult. Race Soc Probl. 2015;7:21-30.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Residency Applicants From US MD Granting Medical Schools to ACGME-Accredited Programs by Specialty and Race/Ethnicity. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2017.

- Brotherton SE, Etzel SL. Graduate medical education, 2018-2019. JAMA. 2019;322:996-1016. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.10155

- Barnes LA, Bae GH, Nambudiri V. Sex and racial/ethnic diversity of US medical students and their exposure to dermatology programs. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:490-491. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5025

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Low D, Pollack SW, Liao Z, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in clinical grading in medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31:487-496. doi:10.1080/10401334.2019.1597724

- Rubright JD, Jodoin M, Barone MA. Examining demographics, prior academic performance and United States medical licensing examination scores. Acad Med. 2019;94;364-370. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002366

- Boatright D, Ross D, O’Connor P, et al. Racial disparities in medical student membership in the alpha omega honor society. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:659-665. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9623

- Gorouhi F, Alikhan A, Rezaei A, et al. Dermatology residency selection criteria with an emphasis on program characteristics: a national program director survey [published online March 17, 2014]. Dermatol Res Pract. doi:10.1155/2014/692760

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by underrepresented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatology residency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Results of the 2019 NRMP applicant survey by preferred specialty and applicant type. National Resident Matching Program website. Published July 2019. Accessed December 8, 2021. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Applicant-Survey-Report-2019.pdf

- Mansouri B, Walker GD, Mitchell J, et al. The cost of applying to dermatology residency: 2014 data estimates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:754-756. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.049

- Polacco MA, Lally J, Walls A, et al. Digging into debt: the financial burden associated with the otolaryngology match. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;12:1091-1096. doi:10.1177/0194599816686538

- Feng H, Feng PW, Geronemus RG. Diversity in the US Mohs micrographic surgery workforce. Dermatol Surg. 2020:46:1451-1455. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002080

- Lett LA, Orji WU, Sebro R. Declining racial and ethnic representation in clinical academic medicine: a longitudinal study of 16 US medical specialties. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0207274. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.020727432. Xierali IM, Nivet MA, Pandya AG. US Dermatology department faculty diversity trends by sex and underrepresented-in-medicine status, 1970-2018. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:280-287. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4297

- Okoye GA. Supporting underrepresented minority women in academic dermatology. Intl J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:57-60. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2019.09.009

- Bernstein J, Dicaprio MR, Mehta S. The relationship between required medical school instruction in musculoskeletal medicine and application rates to orthopaedic surgery residency programs. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:2335-2338. doi:10.2106/00004623-200410000-00031

- Capers Q, Clinchot D, McDougle L, et al. Implicit racial bias in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2017;92:365-369. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001388

- Dobbin F, Kalev A. Why diversity programs fail. Harvard Business Rev. 2016;52-60. Accessed December 8, 2021. https://hbr.org/2016/07/why-diversity-programs-fail

- Kalev A, Dobbin F, Kelly E. Best practices or best guesses? assessing the efficacy of corporate affirmative action and diversity policies. Am Sociol Rev. 2006;71:589-617.

- Sanchez JI, Medkik N. The effects of diversity awareness training on differential treatment. Group Organ Manag. 2004;29:517-536.

- Kaiser CR, Major B, Jurcevic I, et al. Presumed fair: ironic effects of organizational diversity structures. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2013;104:504-519. doi:10.1037/a0030838

- Nijhawan RI, Jacob SE, Woolery-Lloyd H. Skin of color education in dermatology residency programs: does residency training reflect the changing demographics of the United States? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:615-617.

- Jia JL, Gordon JS, Lester JC, et al. Integrating skin of color and sexual and gender minority content into dermatology residency curricula: a prospective program initiative [published online April 16, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.04.018

- Amuzie AU, Lia JL, Taylor SC, et al. Skin of color article representation in dermatology literature 2009-2019: higher citation counts and opportunities for inclusion [published online March 24, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.063

- Beech BM, Calles-Escandon J, Hairston KC, et al. Mentoring programs for underrepresented minority faculty in academic medical center: a systematic review of the literature. Acad Med. 2013;88:541-549. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828589e3

- Daley S, Wingard DL, Reznik V. Improving the retention of underrepresented minority faculty in academic medicine. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98:1435-1440. doi:10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31449-8

- Association of American Medical Colleges. US medical school faculty by sex, race/ethnicity, rank, and department, 2019. Published December 31, 2019. Accessed December 20, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/media/8476/download?attachment

- Dixon G, Kind T, Wright J, et al. Factors that influence the choice of academic pediatrics by underrepresented minorities. Pediatrics. 2019;144:E20182759. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-2759

- Yehia BR, Cronholm PF, Wilson N, et al. Mentorship and pursuit of academic medicine careers: a mixed methods study of residents from diverse backgrounds. BMC Med Educ. 2014:14:2-26. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-14-26

- Saha S, Guiton G, Wimmers PF, et al. Student body racial and ethnic composition and diversity-related outcomes in US medical schools. JAMA. 2008;300:1135-1145. doi:10.1001/jama.300.10.1135

- Hsu DY, Gordon K, Silverberg JI. The patient burden of psoriasis in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:33-41. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.03.048

- Silverberg JI. Racial and ethnic disparities in atopic dermatitis. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2015;4:44-48.

- Buster KJ, Sevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

- Barbieri JS, Shin DB, Wang S, et al. Association of race/ethnicity with differences in health care use and treatment for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:312-319. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4818

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Colburn L, et al. The Right Thing To Do, The Smart Thing to Do: Enhancing Diversity in the Health Professions. National Academies Press; 2001.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Minorities in medical education: fact and figures 2019. Accessed December 9, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/datareports/workforce/report/diversity-medicine-facts-and-figures-2019

- Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) standards on diversity. University of South Florida Health website. Accessed December 9, 2021. https://health.usf.edu/~/media/Files/Medicine/MD%20Program/Diversity/LCMEStandardsonDiversity1.ashx?la=en

- Granstein RD, Cornelius L, Shinkai K. Diversity in dermatology—a call for action. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:499-500. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0296

- Lett LA, Murdock HM, Orji W, et al. Trends in racial/ethnic representation among US medical students. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1910490. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10490

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Altering the course: Black males in medicine. Published 2015. Accessed December 8, 2021. https://store.aamc.org/downloadable/download/sample/sample_id/84/

- Barr DA, Gonzalez ME, Wanat SF. The leaky pipeline: factors associated with early decline in interest in premedical studies among underrepresented minority undergraduate students. Acad Med. 2008;83:5:503-511. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31816bda16

- Flores RL. The rising gap between rich and poor: a look at the persistence of educational disparities in the United States and why we should worry. Cogent Soc Sci. 2017;3:1323698.

- Jackson D. Why am I behind? an examination of low income and minority students’ preparedness for college. McNair Sch J. 2012;13:121-138.

- Rothstein R. The racial achievement gap, segregated schools, andsegregated neighborhoods: a constitutional insult. Race Soc Probl. 2015;7:21-30.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Residency Applicants From US MD Granting Medical Schools to ACGME-Accredited Programs by Specialty and Race/Ethnicity. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2017.

- Brotherton SE, Etzel SL. Graduate medical education, 2018-2019. JAMA. 2019;322:996-1016. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.10155

- Barnes LA, Bae GH, Nambudiri V. Sex and racial/ethnic diversity of US medical students and their exposure to dermatology programs. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:490-491. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5025

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Low D, Pollack SW, Liao Z, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in clinical grading in medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31:487-496. doi:10.1080/10401334.2019.1597724

- Rubright JD, Jodoin M, Barone MA. Examining demographics, prior academic performance and United States medical licensing examination scores. Acad Med. 2019;94;364-370. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002366

- Boatright D, Ross D, O’Connor P, et al. Racial disparities in medical student membership in the alpha omega honor society. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:659-665. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9623

- Gorouhi F, Alikhan A, Rezaei A, et al. Dermatology residency selection criteria with an emphasis on program characteristics: a national program director survey [published online March 17, 2014]. Dermatol Res Pract. doi:10.1155/2014/692760

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by underrepresented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatology residency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Results of the 2019 NRMP applicant survey by preferred specialty and applicant type. National Resident Matching Program website. Published July 2019. Accessed December 8, 2021. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Applicant-Survey-Report-2019.pdf

- Mansouri B, Walker GD, Mitchell J, et al. The cost of applying to dermatology residency: 2014 data estimates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:754-756. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.049

- Polacco MA, Lally J, Walls A, et al. Digging into debt: the financial burden associated with the otolaryngology match. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;12:1091-1096. doi:10.1177/0194599816686538

- Feng H, Feng PW, Geronemus RG. Diversity in the US Mohs micrographic surgery workforce. Dermatol Surg. 2020:46:1451-1455. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002080

- Lett LA, Orji WU, Sebro R. Declining racial and ethnic representation in clinical academic medicine: a longitudinal study of 16 US medical specialties. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0207274. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.020727432. Xierali IM, Nivet MA, Pandya AG. US Dermatology department faculty diversity trends by sex and underrepresented-in-medicine status, 1970-2018. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:280-287. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4297

- Okoye GA. Supporting underrepresented minority women in academic dermatology. Intl J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:57-60. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2019.09.009

- Bernstein J, Dicaprio MR, Mehta S. The relationship between required medical school instruction in musculoskeletal medicine and application rates to orthopaedic surgery residency programs. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:2335-2338. doi:10.2106/00004623-200410000-00031

- Capers Q, Clinchot D, McDougle L, et al. Implicit racial bias in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2017;92:365-369. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001388

- Dobbin F, Kalev A. Why diversity programs fail. Harvard Business Rev. 2016;52-60. Accessed December 8, 2021. https://hbr.org/2016/07/why-diversity-programs-fail

- Kalev A, Dobbin F, Kelly E. Best practices or best guesses? assessing the efficacy of corporate affirmative action and diversity policies. Am Sociol Rev. 2006;71:589-617.

- Sanchez JI, Medkik N. The effects of diversity awareness training on differential treatment. Group Organ Manag. 2004;29:517-536.

- Kaiser CR, Major B, Jurcevic I, et al. Presumed fair: ironic effects of organizational diversity structures. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2013;104:504-519. doi:10.1037/a0030838

- Nijhawan RI, Jacob SE, Woolery-Lloyd H. Skin of color education in dermatology residency programs: does residency training reflect the changing demographics of the United States? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:615-617.

- Jia JL, Gordon JS, Lester JC, et al. Integrating skin of color and sexual and gender minority content into dermatology residency curricula: a prospective program initiative [published online April 16, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.04.018

- Amuzie AU, Lia JL, Taylor SC, et al. Skin of color article representation in dermatology literature 2009-2019: higher citation counts and opportunities for inclusion [published online March 24, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.063

- Beech BM, Calles-Escandon J, Hairston KC, et al. Mentoring programs for underrepresented minority faculty in academic medical center: a systematic review of the literature. Acad Med. 2013;88:541-549. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828589e3

- Daley S, Wingard DL, Reznik V. Improving the retention of underrepresented minority faculty in academic medicine. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98:1435-1440. doi:10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31449-8

- Association of American Medical Colleges. US medical school faculty by sex, race/ethnicity, rank, and department, 2019. Published December 31, 2019. Accessed December 20, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/media/8476/download?attachment

Practice Points

- Dermatology remains the second least diverse specialty in medicine, which has important implications for the workforce and clinical excellence of the specialty.

- Barriers presenting at different stages of medical education and training result in the loss of underrepresented minority (URM) learners pursuing or advancing careers in dermatology.

- Understanding these barriers is the first step to creating and implementing important structural changes to the way we mentor, teach, and support URM students in the specialty.

Skin of Color in Preclinical Medical Education: A Cross-Institutional Comparison and A Call to Action

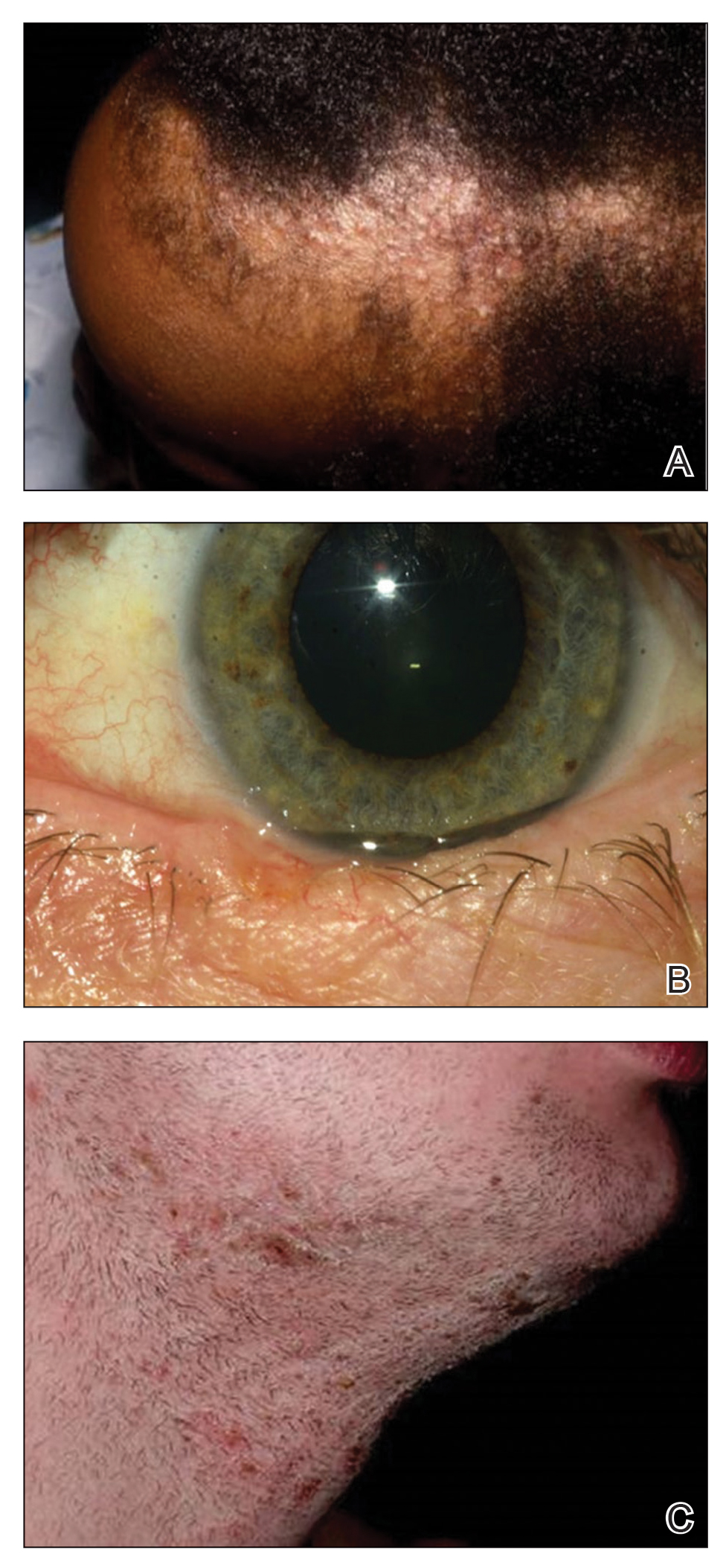

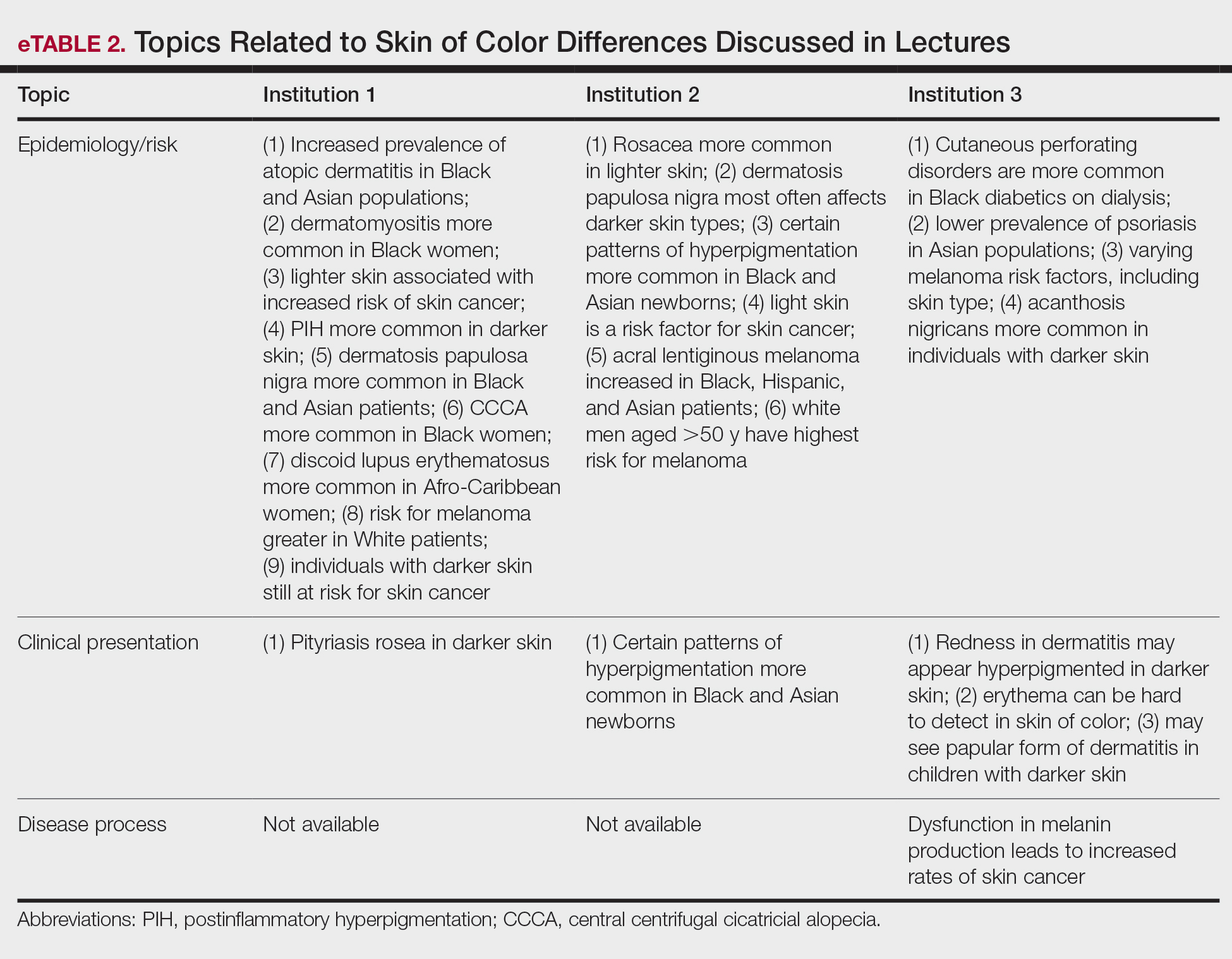

A ccording to the US Census Bureau, more than half of all Americans are projected to belong to a minority group, defined as any group other than non-Hispanic White alone, by 2044. 1 Consequently, the United States rapidly is becoming a country in which the majority of citizens will have skin of color. Individuals with skin of color are of diverse ethnic backgrounds and include people of African, Latin American, Native American, Pacific Islander, and Asian descent, as well as interethnic backgrounds. 2 Throughout the country, dermatologists along with primary care practitioners may be confronted with certain cutaneous conditions that have varying disease presentations or processes in patients with skin of color. It also is important to note that racial categories are socially rather than biologically constructed, and the term skin of color includes a wide variety of diverse skin types. Nevertheless, the current literature thoroughly supports unique pathophysiologic differences in skin of color as well as variations in disease manifestation compared to White patients. 3-5 For example, the increased lability of melanosomes in skin of color patients, which increases their risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, has been well documented. 5-7 There are various dermatologic conditions that also occur with higher frequency and manifest uniquely in people with darker, more pigmented skin, 7-9 and dermatologists, along with primary care physicians, should feel prepared to recognize and address them.

Extensive evidence also indicates that there are unique aspects to consider while managing certain skin diseases in patients with skin of color.8,10,11 Consequently, as noted on the Skin of Color Society (SOCS) website, “[a]n increase in the body of dermatological literature concerning skin of color as well as the advancement of both basic science and clinical investigational research is necessary to meet the needs of the expanding skin of color population.”2 In the meantime, current knowledge regarding cutaneous conditions that diversely or disproportionately affect skin of color should be actively disseminated to physicians in training. Although patients with skin of color should always have access to comprehensive care and knowledgeable practitioners, the current changes in national and regional demographics further underscore the need for a more thorough understanding of skin of color with regard to disease pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment.

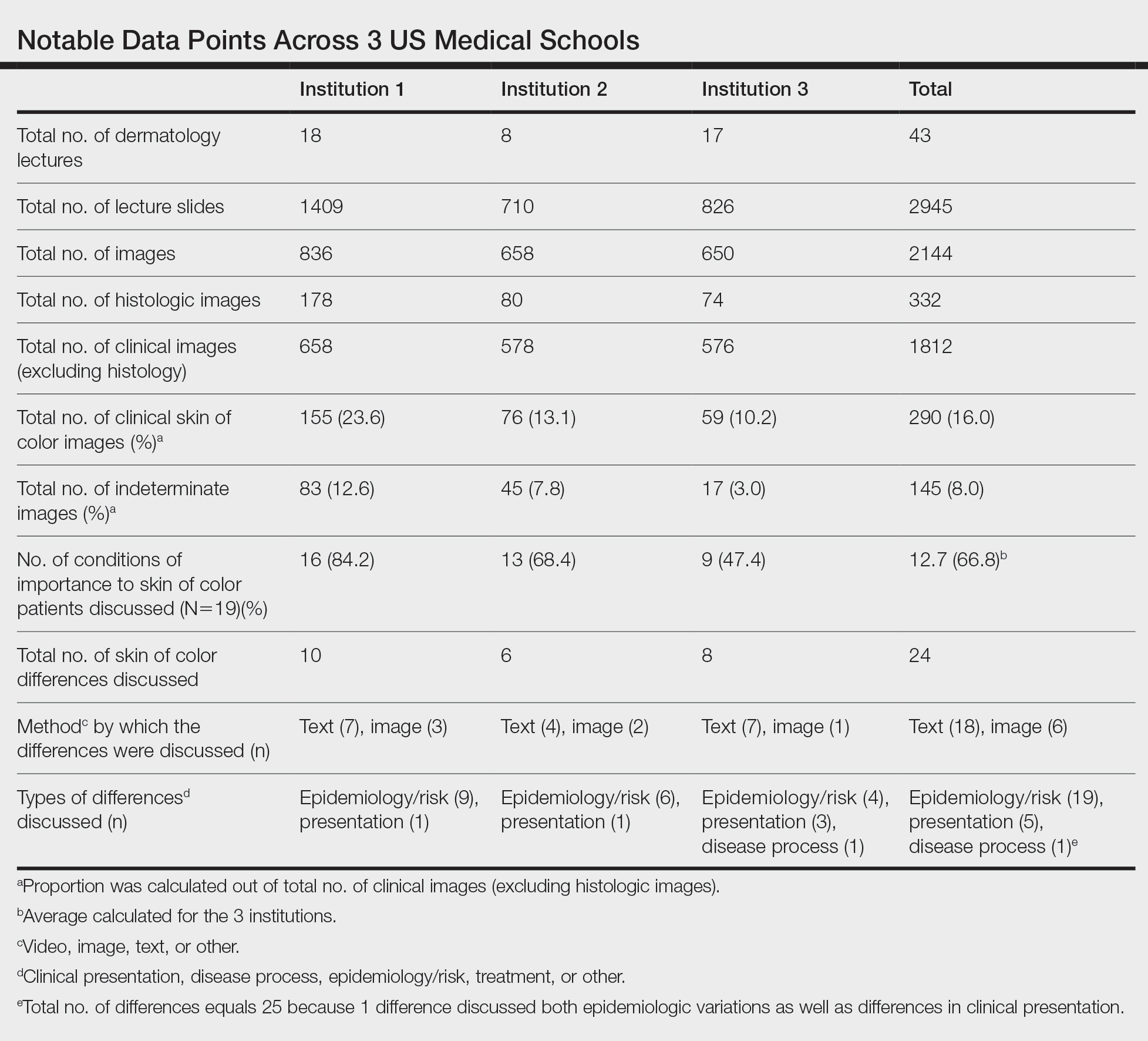

Several studies have found that medical students in the United States are minimally exposed to dermatology in general compared to other clinical specialties,12-14 which can easily lead to the underrecognition of disorders that may uniquely or disproportionately affect individuals with pigmented skin. Recent data showed that medical schools typically required fewer than 10 hours of dermatology instruction,12 and on average, dermatologic training made up less than 1% of a medical student’s undergraduate medical education.13,15,16 Consequently, less than 40% of primary care residents felt that their medical school curriculum adequately prepared them to manage common skin conditions.14 Although not all physicians should be expected to fully grasp the complexities of skin of color and its diagnostic and therapeutic implications, both practicing and training dermatologists have acknowledged a lack of exposure to skin of color. In one study, approximately 47% of dermatologists and dermatology residents reported that their medical training (medical school and/or residency) was inadequate in training them on skin conditions in Black patients. Furthermore, many who felt their training was lacking in skin of color identified the need for greater exposure to Black patients and training materials.15 The absence of comprehensive medical education regarding skin of color ultimately can be a disadvantage for both practitioners and patients, resulting in poorer outcomes. Furthermore, underrepresentation of skin of color may persist beyond undergraduate and graduate medical education. There also is evidence to suggest that noninclusion of skin of color pervades foundational dermatologic educational resources, including commonly used textbooks as well as continuing medical education disseminated at national conferences and meetings.17 Taken together, these findings highlight the need for more diverse and representative exposure to skin of color throughout medical training, which begins with a diverse inclusive undergraduate medical education in dermatology.

The objective of this study was to determine if the preclinical dermatology curriculum at 3 US medical schools provided adequate representation of skin of color patients in their didactic presentation slides.

Methods