User login

Analysis of Online Diet Recommendations for Vitiligo

Internet platforms have become a common source of medical information for individuals with a broad range of skin conditions including vitiligo. The prevalence of vitiligo among US adults ranges from 0.76% to 1.11%, with approximately 40% of adult cases of vitiligo in the United States remaining undiagnosed.1 The vitiligo community has become more inquisitive of the relationship between diet and vitiligo, turning to online sources for suggestions on diet modifications that may be beneficial for their condition. Although there is an abundance of online information, few diets or foods have been medically recognized to definitively improve or worsen vitiligo symptoms. We reviewed the top online web pages accessible to the public regarding diet suggestions that affect vitiligo symptoms. We then compared these online results to published peer-reviewed scientific literature.

Methods

Two independent online searches were performed by Researcher 1 (Y.A.) and Researcher 2 (I.M.) using Google Advanced Search. The independent searches were performed by the reviewers in neighboring areas of Chicago, Illinois, using the same Internet browser (Google Chrome). The primary search terms were diet and vitiligo along with the optional additional terms dietary supplement(s), food(s), nutrition, herb(s), or vitamin(s). Our search included any web pages published or updated from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2021, and originally scribed in the English language. The domains “.com,” “.org,” “.edu,” and “.cc” were included.

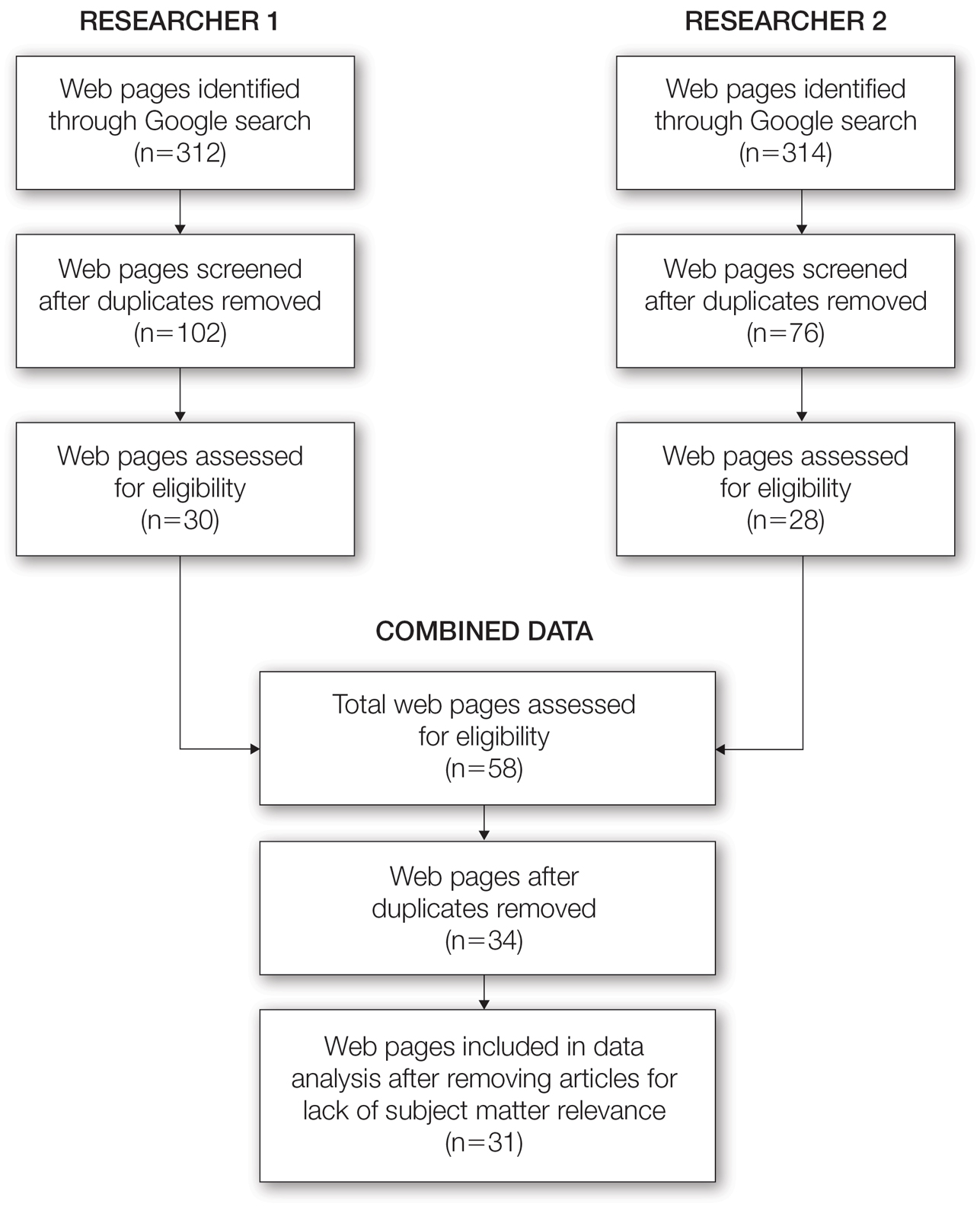

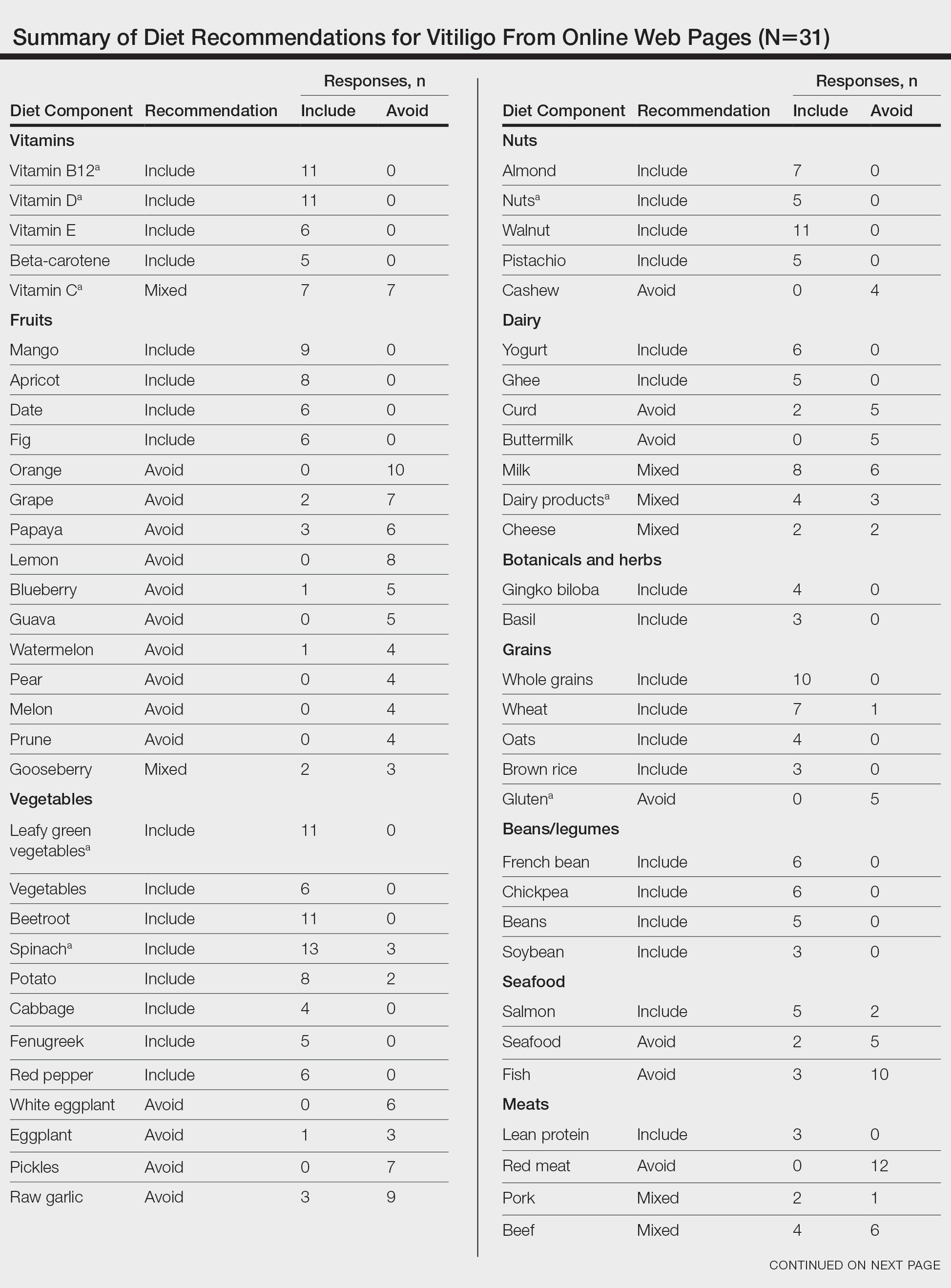

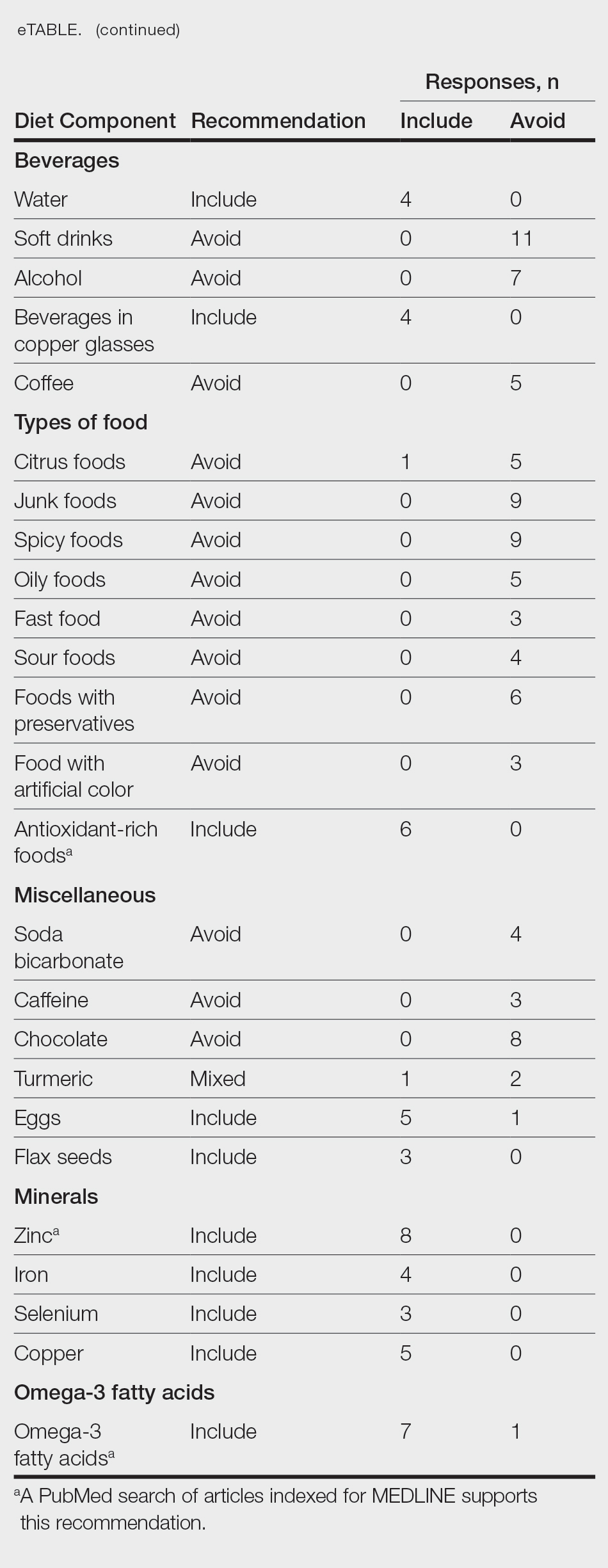

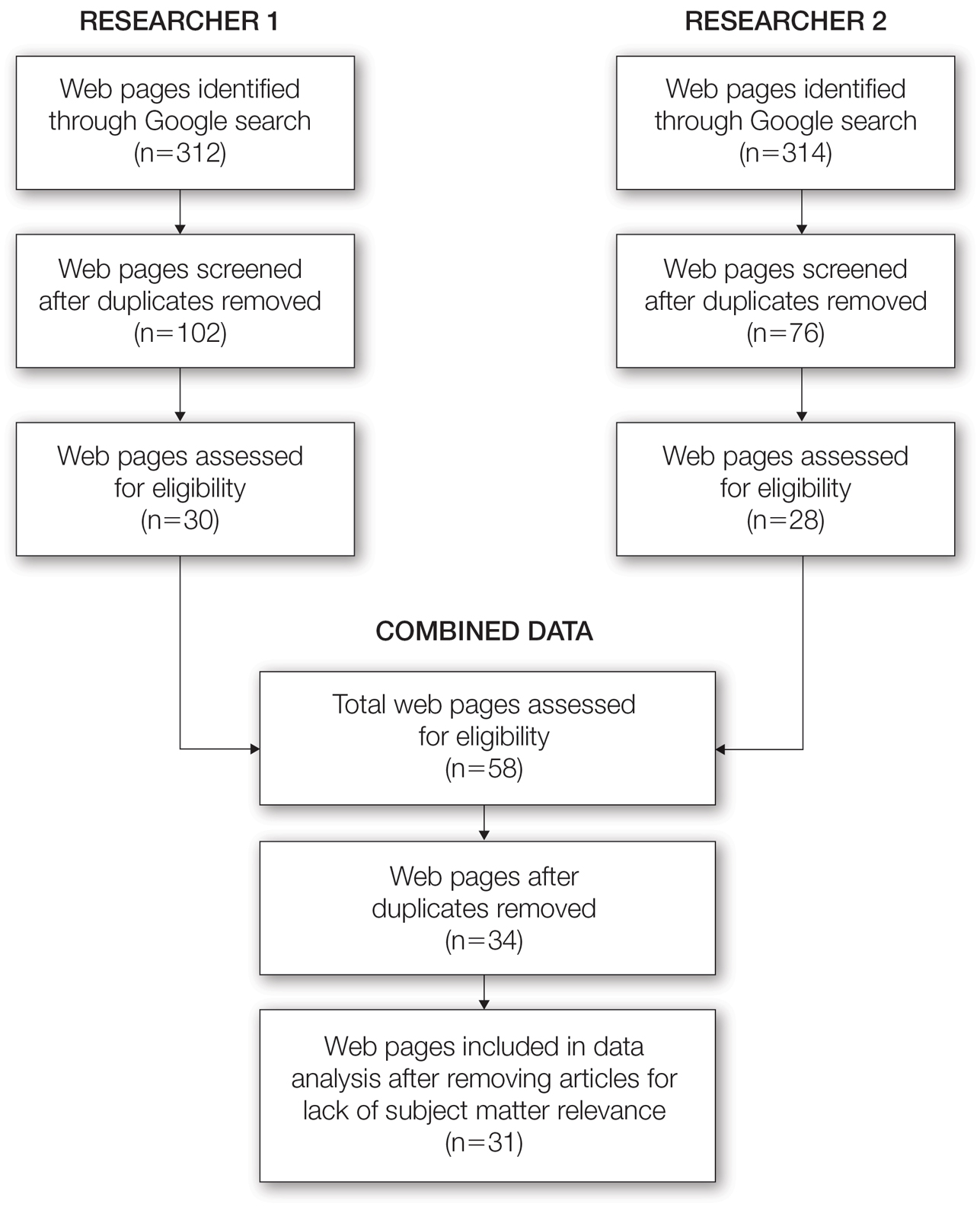

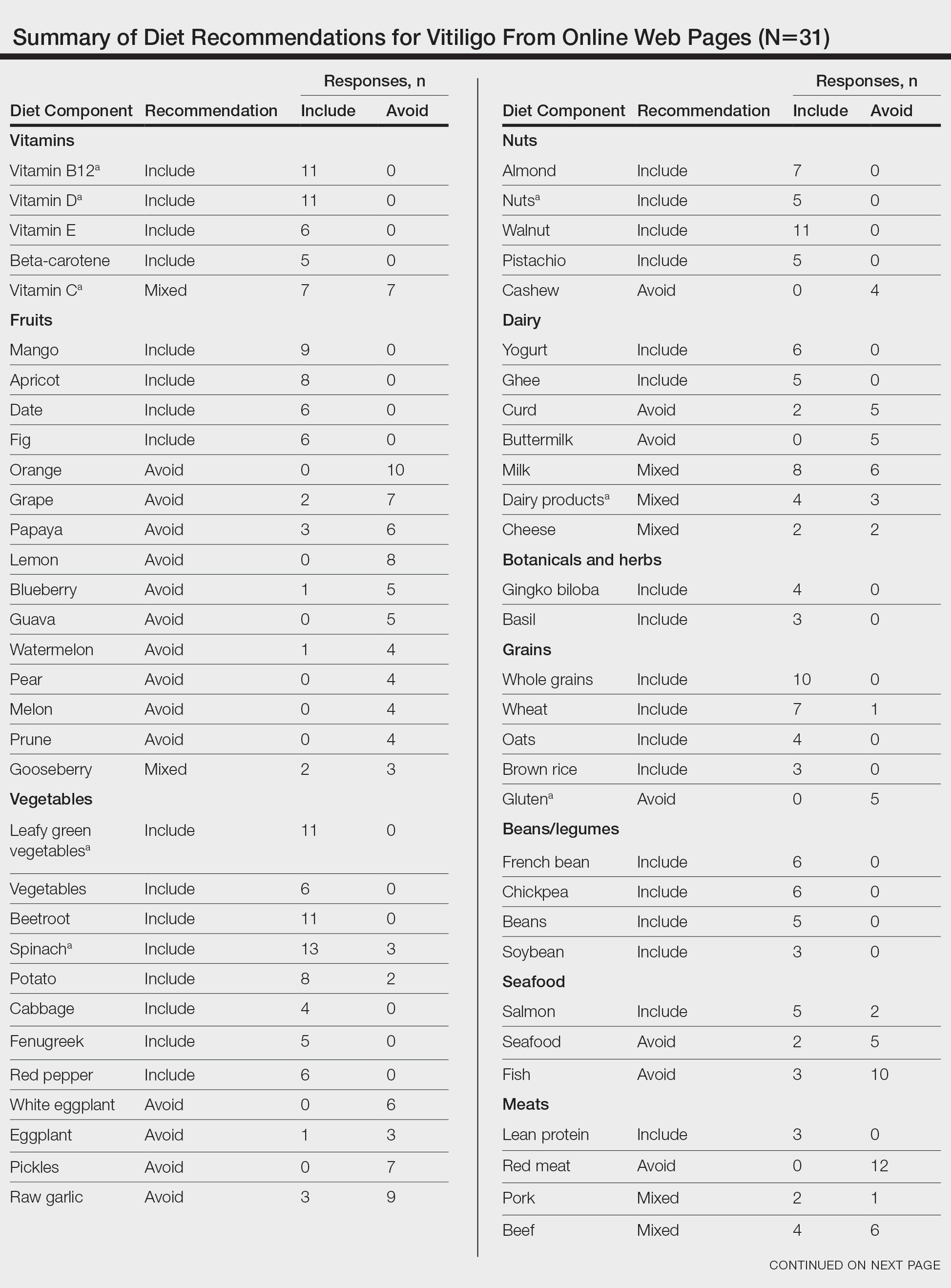

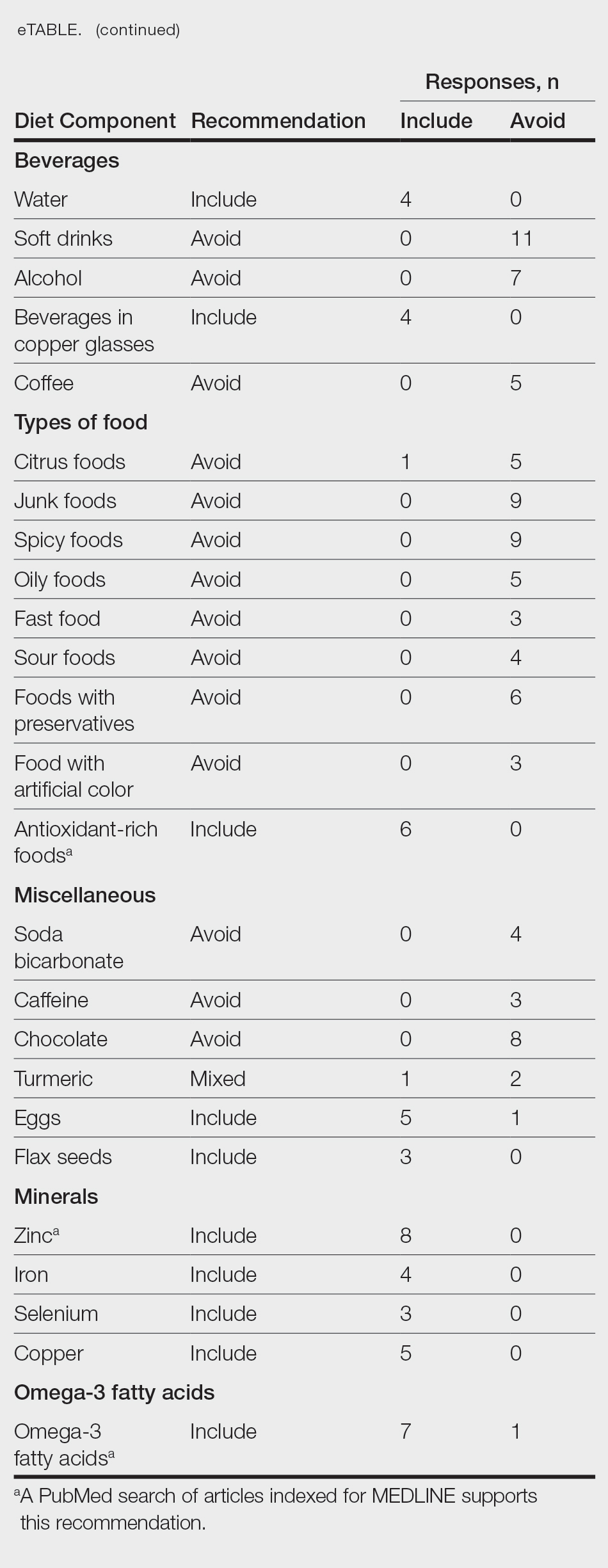

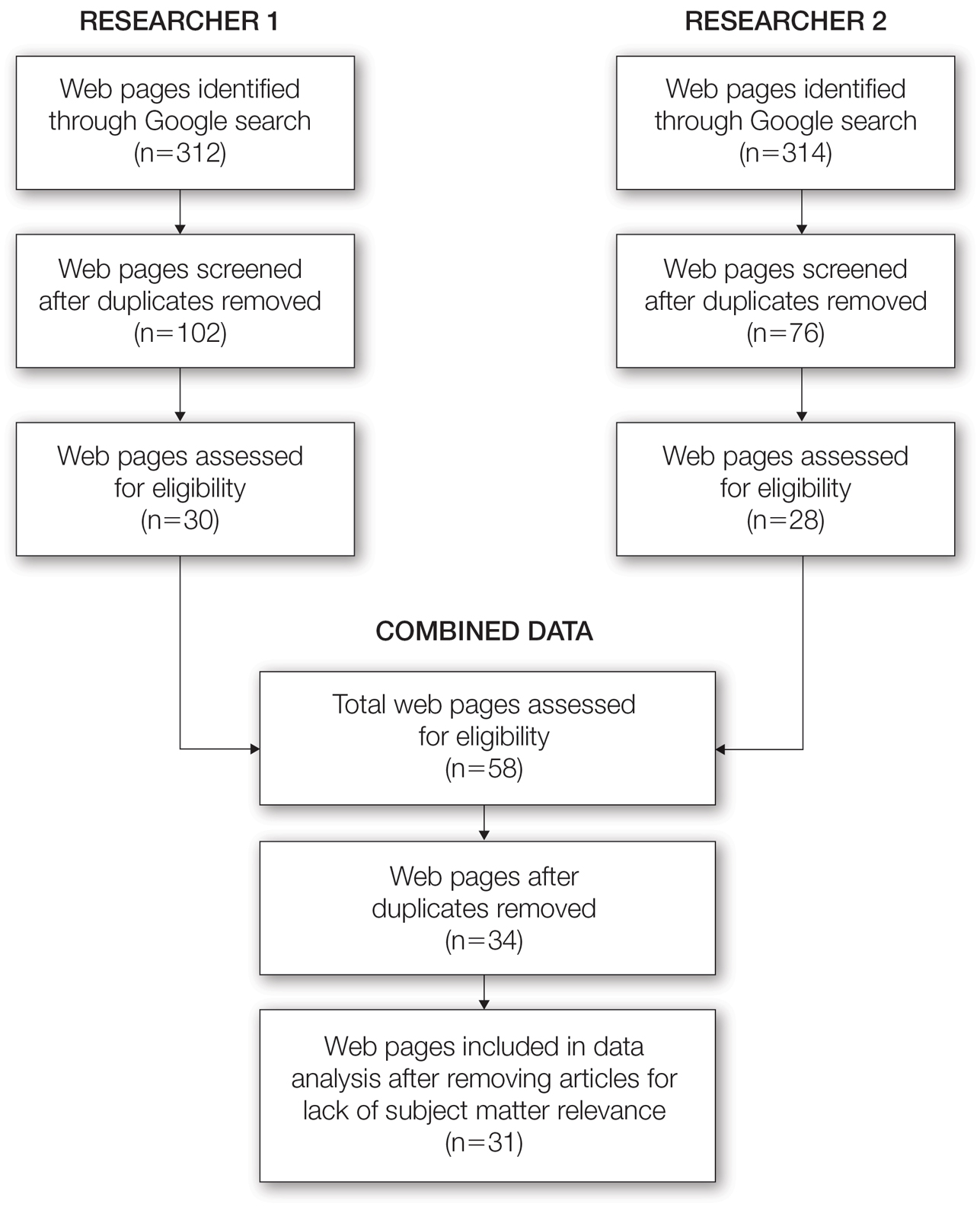

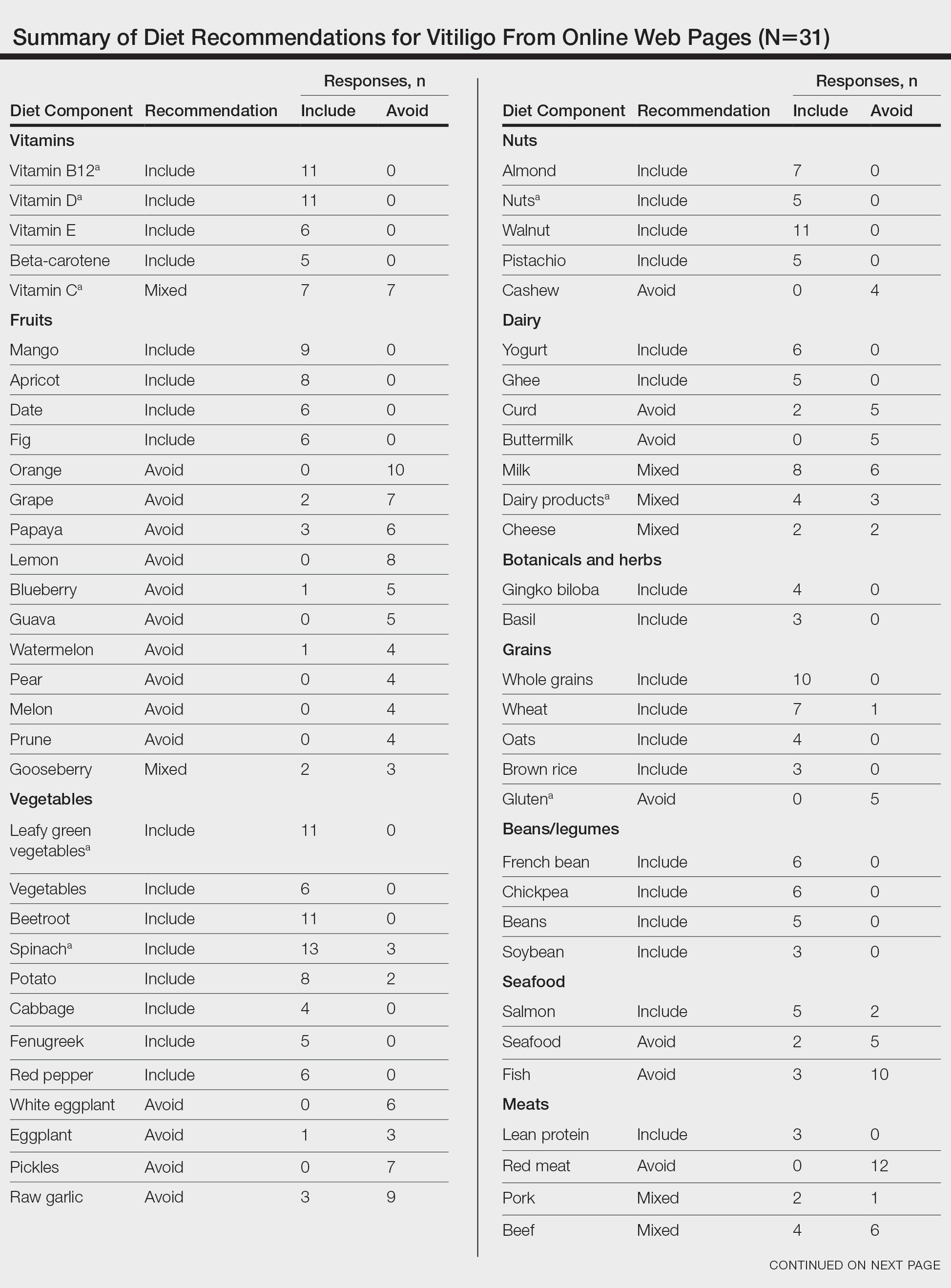

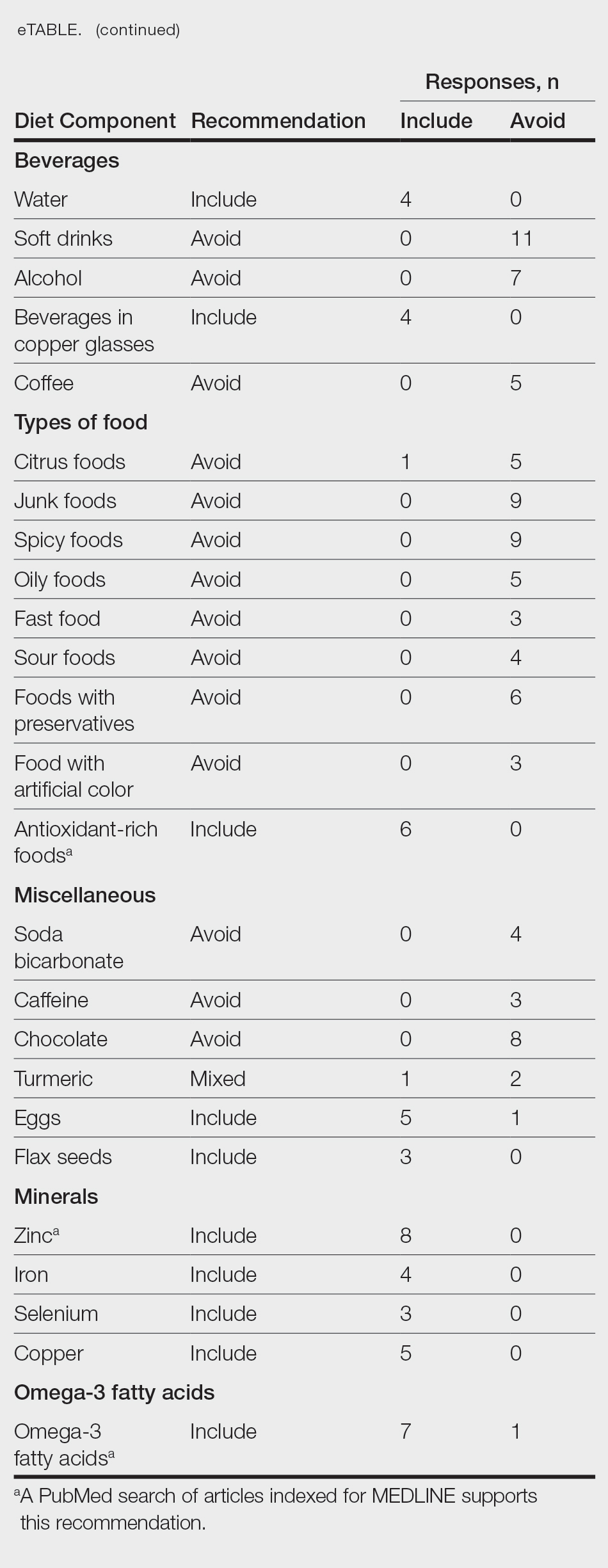

From this initial search, Researcher 1 identified 312 web pages and Researcher 2 identified 314 web pages. Each reviewer sorted their respective search results to identify the number of eligible records to be screened. Records were defined as unique web pages that met the search criteria. After removing duplicates, Researcher 1 screened 102 web pages and Researcher 2 screened 76 web pages. Of these records, web pages were excluded if they did not include any diet recommendations for vitiligo patients. Each reviewer independently created a list of eligible records, and the independent lists were then merged for a total of 58 web pages. Among these 58 web pages, there were 24 duplicate records and 3 records that were deemed ineligible for the study due to lack of subject matter relevance. A final total of 31 web pages were included in the data analysis (Figure). Of the 31 records selected, the reviewers jointly evaluated each web page and recorded the diet components that were recommended for individuals with vitiligo to either include or avoid (eTable).

For comparison and support from published scientific literature, a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted using the terms diet and vitiligo. Relevant human clinical studies published in the English-language literature were reviewed for content regarding the relationship between diet and vitiligo.

Results

Our online search revealed an abundance of information regarding various dietary modifications suggested to aid in the management of vitiligo symptoms. Most web pages (27/31 [87%]) were not authored by medical professionals or dermatologists. There were 27 diet components mentioned 8 or more times within the 31 total web pages. These diet components were selected for further review via PubMed. Each item was searched on PubMed using the term “[respective diet component] and vitiligo” among all published literature in the English language. Our study focused on summarizing the data on dietary components for which we were able to gather scientific support. These data have been organized into the following categories: vitamins, fruits, omega-3 fatty acids, grains, minerals, vegetables, and nuts.

Vitamins—The online literature recommended inclusion of vitamin supplements, in particular vitamins D and B12, which aligned with published scientific literature.2,3 Eleven of 31 (35%) web pages recommended vitamin D in vitiligo. A 2010 study analyzing patients with vitiligo vulgaris (N=45) found that 68.9% of the cohort had insufficient (<30 ng/mL) 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels.2 A prospective study of 30 individuals found that the use of tacrolimus ointment plus oral vitamin D supplementation was found to be more successful in repigmentation than topical tacrolimus alone.3 Vitamin D dosage ranged from 1500 IU/d if the patient’s serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels were less than 20 ng/mL to 3000 IU/d if the serum levels were less than 10 ng/mL for 6 months.

Dairy products are a source of vitamin D.2,3 Of the web pages that mentioned dairy, a subtle majority (4/7 [57%]) recommended the inclusion of dairy products. Although many web pages did not specify whether oral vitamin D supplementation vs dietary food consumption is preferred, a 2013 controlled study of 16 vitiligo patients who received high doses of vitamin D supplementation with a low-calcium diet found that 4 patients showed 1% to 25% repigmentation, 5 patients showed 26% to 50% repigmentation, and 5 patients showed 51% to 75% repigmentation of the affected areas.4

Eleven of 31 (35%) web pages recommended inclusion of vitamin B12 supplementation in vitiligo. A 2-year study with 100 participants showed that supplementation with folic acid and vitamin B12 along with sun exposure yielded more effective repigmentation than either vitamins or sun exposure alone.5 An additional hypothesis suggested vitamin B12 may aid in repigmentation through its role in the homocysteine pathway. Although the theory is unproven, it is proposed that inhibition of homocysteine via vitamin B12 or folic acid supplementation may play a role in reducing melanocyte destruction and restoring melanin synthesis.6

There were mixed recommendations regarding vitamin C via supplementation and/or eating citrus fruits such as oranges. Although there are limited clinical studies on the use of vitamin C and the treatment of vitiligo, a 6-year prospective study from Madagascar consisting of approximately 300 participants with vitiligo who were treated with a combination of topical corticosteroids, oral vitamin C, and oral vitamin B12 supplementation showed excellent repigmentation (defined by repigmentation of more than 76% of the originally affected area) in 50 participants.7

Fruits—Most web pages had mixed recommendations on whether to include or avoid certain fruits. Interestingly, inclusion of mangoes and apricots in the diet were highly recommended (9/31 [29%] and 8/31 [26%], respectively) while fruits such as oranges, lemons, papayas, and grapes were discouraged (10/31 [32%], 8/31 [26%], 6/31 [19%], and 7/31 [23%], respectively). Although some web pages suggested that vitamin C–rich produce including citrus and berries may help to increase melanin formation, others strongly suggested avoiding these fruits. There is limited information on the effects of citrus on vitiligo, but a 2022 study indicated that 5-demethylnobiletin, a flavonoid found in sweet citrus fruits, may stimulate melanin synthesis, which can possibly be beneficial for vitiligo.8

Omega-3 Fatty Acids—Seven of 31 (23%) web pages recommended the inclusion of omega-3 fatty acids for their role as antioxidants to improve vitiligo symptoms. Research has indicated a strong association between vitiligo and oxidative stress.9 A 2007 controlled clinical trial that included 28 vitiligo patients demonstrated that oral antioxidant supplementation in combination with narrowband UVB phototherapy can significantly decrease vitiligo-associated oxidative stress (P<.05); 8 of 17 (47%) patients in the treatment group saw greater than 75% repigmentation after antioxidant treatment.10

Grains—Five of 31 (16%) web pages suggested avoiding gluten—a protein naturally found in some grains including wheat, barley, and rye—to improve vitiligo symptoms. A 2021 review suggested that a gluten-free diet may be effective in managing celiac disease, and it is hypothesized that vitiligo may be managed with similar dietary adjustments.11 Studies have shown that celiac disease and vitiligo—both autoimmune conditions—involve IL-2, IL-6, IL-7, and IL-21 in their disease pathways.12,13 Their shared immunogenic mechanism may account for similar management options.

Upon review, 2 case reports were identified that discussed a relationship between a gluten-free diet and vitiligo symptom improvement. In one report, a 9-year-old child diagnosed with both celiac disease and vitiligo saw intense repigmentation of the skin after adhering to a gluten-free diet for 1 year.14 Another case study reported a 22-year-old woman with vitiligo whose symptoms improved after 1 month of a gluten-free diet following 2 years of failed treatment with a topical steroid and phototherapy.15

Seven of 31 (23%) web pages suggested that individuals with vitiligo should include wheat in their diet. There is no published literature discussing the relationship between vitiligo and wheat. Of the 31 web pages reviewed, 10 (32%) suggested including whole grain. There is no relevant scientific evidence or hypotheses describing how whole grains may be beneficial in vitiligo.

Minerals—Eight of 31 (26%) web pages suggested including zinc in the diet to improve vitiligo symptoms. A 2020 study evaluated how different serum levels of zinc in vitiligo patients might be affiliated with interleukin activity. Fifty patients diagnosed with active vitiligo were tested for serum levels of zinc, IL-4, IL-6, and IL-17.16 The results showed that mean serum levels of zinc were lower in vitiligo patients compared with patients without vitiligo. The study concluded that zinc could possibly be used as a supplement to improve vitiligo, though the dosage needs to be further studied and confirmed.16

Vegetables—Eleven of 31 (35%) web pages recommended leafy green vegetables and 13 of 31 (42%) recommended spinach for patients with vitiligo. Spinach and other leafy green vegetables are known to be rich in antioxidants, which may have protective effects against reactive oxygen species that are thought to contribute to vitiligo progression.17,18

Nuts—Walnuts were recommended in 11 of 31 (35%) web pages. Nuts may be beneficial in reducing inflammation and providing protection against oxidative stress.9 However, there is no specific scientific literature that supports the inclusion of nuts in the diet to manage vitiligo symptoms.

Comment

With a growing amount of research suggesting that diet modifications may contribute to management of certain skin conditions, vitiligo patients often inquire about foods or supplements that may help improve their condition.19 Our review highlighted what information was available to the public regarding diet and vitiligo, with preliminary support of the following primary diet components: vitamin D, vitamin B12, zinc, and omega-3 fatty acids. Our review showed no support in the literature for the items that were recommended to avoid. It is important to note that 27 of 31 (87%) web pages from our online search were not authored by medical professionals or dermatologists. Additionally, many web pages suggested conflicting information, making it difficult to draw concrete conclusions about what diet modifications will be beneficial to the vitiligo community. Further controlled clinical trials are warranted due to the lack of formal studies that assess the relationship between diet and vitiligo.

- Gandhi K, Ezzedine K, Anastassopoulos KP, et al. Prevalence of vitiligo among adults in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:43-50. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.4724

- Silverberg JI, Silverberg AI, Malka E, et al. A pilot study assessing the role of 25 hydroxy vitamin D levels in patients with vitiligo vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:937-941. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.11.024

- Karagüzel G, Sakarya NP, Bahadır S, et al. Vitamin D status and the effects of oral vitamin D treatment in children with vitiligo: a prospective study. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2016;15:28-31. doi:10.1016/j.clnesp.2016.05.006.

- Finamor DC, Sinigaglia-Coimbra R, Neves LC, et al. A pilot study assessing the effect of prolonged administration of high daily doses of vitamin D on the clinical course of vitiligo and psoriasis. Dermatoendocrinol. 2013;5:222-234. doi:10.4161/derm.24808

- Juhlin L, Olsson MJ. Improvement of vitiligo after oral treatment with vitamin B12 and folic acid and the importance of sun exposure. Acta Derm Venereol. 1997;77:460-462. doi:10.2340/000155555577460462

- Chen J, Zhuang T, Chen J, et al. Homocysteine induces melanocytes apoptosis via PERK-eIF2α-CHOP pathway in vitiligo. Clin Sci (Lond). 2020;134:1127-1141. doi:10.1042/CS20200218

- Sendrasoa FA, Ranaivo IM, Sata M, et al. Treatment responses in patients with vitiligo to very potent topical corticosteroids combined with vitamin therapy in Madagascar. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:908-911. doi:10.1111/ijd.14510

- Wang HM, Qu LQ, Ng JPL, et al. Natural citrus flavanone 5-demethylnobiletin stimulates melanogenesis through the activation of cAMP/CREB pathway in B16F10 cells. Phytomedicine. 2022;98:153941. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2022.153941

- Ros E. Health benefits of nut consumption. Nutrients. 2010;2:652-682.

- Dell’Anna ML, Mastrofrancesco A, Sala R, et al. Antioxidants and narrow band-UVB in the treatment of vitiligo: a double-blind placebo controlled trial. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:631-636.

- Gastrointestinal microbiome and gluten in celiac disease. Ann Med. 2021;53:1797-1805. doi:10.1080/07853890.2021.1990392

- Forabosco P, Neuhausen SL, Greco L, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide linkage studies in celiac disease. Hum Hered. 2009;68:223-230. doi:10.1159/000228920

- Akbulut UE, Çebi AH, Sag˘ E, et al. Interleukin-6 and interleukin-17 gene polymorphism association with celiac disease in children. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2017;28:471-475. doi:10.5152/tjg.2017.17092

- Rodríguez-García C, González-Hernández S, Pérez-Robayna N, et al. Repigmentation of vitiligo lesions in a child with celiac disease after a gluten-free diet. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:209-210. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01388.x

- Khandalavala BN, Nirmalraj MC. Rapid partial repigmentation ofvitiligo in a young female adult with a gluten-free diet. Case Rep Dermatol. 2014;6:283-287.

- Sanad EM, El-Fallah AA, Al-Doori AR, et al. Serum zinc and inflammatory cytokines in vitiligo. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13:(12 suppl 1):S29-S33.

- Ames BN, Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM. Oxidants, antioxidants, and the degenerative diseases of aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:7915-7922. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.17.7915

- Xian D, Guo M, Xu J, et al. Current evidence to support the therapeutic potential of flavonoids in oxidative stress-related dermatoses. Redox Rep. 2021;26:134-146. doi:10.1080 /13510002.2021.1962094

- Katta R, Kramer MJ. Skin and diet: an update on the role of dietary change as a treatment strategy for skin disease. Skin Therapy Lett. 2018;23:1-5.

Internet platforms have become a common source of medical information for individuals with a broad range of skin conditions including vitiligo. The prevalence of vitiligo among US adults ranges from 0.76% to 1.11%, with approximately 40% of adult cases of vitiligo in the United States remaining undiagnosed.1 The vitiligo community has become more inquisitive of the relationship between diet and vitiligo, turning to online sources for suggestions on diet modifications that may be beneficial for their condition. Although there is an abundance of online information, few diets or foods have been medically recognized to definitively improve or worsen vitiligo symptoms. We reviewed the top online web pages accessible to the public regarding diet suggestions that affect vitiligo symptoms. We then compared these online results to published peer-reviewed scientific literature.

Methods

Two independent online searches were performed by Researcher 1 (Y.A.) and Researcher 2 (I.M.) using Google Advanced Search. The independent searches were performed by the reviewers in neighboring areas of Chicago, Illinois, using the same Internet browser (Google Chrome). The primary search terms were diet and vitiligo along with the optional additional terms dietary supplement(s), food(s), nutrition, herb(s), or vitamin(s). Our search included any web pages published or updated from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2021, and originally scribed in the English language. The domains “.com,” “.org,” “.edu,” and “.cc” were included.

From this initial search, Researcher 1 identified 312 web pages and Researcher 2 identified 314 web pages. Each reviewer sorted their respective search results to identify the number of eligible records to be screened. Records were defined as unique web pages that met the search criteria. After removing duplicates, Researcher 1 screened 102 web pages and Researcher 2 screened 76 web pages. Of these records, web pages were excluded if they did not include any diet recommendations for vitiligo patients. Each reviewer independently created a list of eligible records, and the independent lists were then merged for a total of 58 web pages. Among these 58 web pages, there were 24 duplicate records and 3 records that were deemed ineligible for the study due to lack of subject matter relevance. A final total of 31 web pages were included in the data analysis (Figure). Of the 31 records selected, the reviewers jointly evaluated each web page and recorded the diet components that were recommended for individuals with vitiligo to either include or avoid (eTable).

For comparison and support from published scientific literature, a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted using the terms diet and vitiligo. Relevant human clinical studies published in the English-language literature were reviewed for content regarding the relationship between diet and vitiligo.

Results

Our online search revealed an abundance of information regarding various dietary modifications suggested to aid in the management of vitiligo symptoms. Most web pages (27/31 [87%]) were not authored by medical professionals or dermatologists. There were 27 diet components mentioned 8 or more times within the 31 total web pages. These diet components were selected for further review via PubMed. Each item was searched on PubMed using the term “[respective diet component] and vitiligo” among all published literature in the English language. Our study focused on summarizing the data on dietary components for which we were able to gather scientific support. These data have been organized into the following categories: vitamins, fruits, omega-3 fatty acids, grains, minerals, vegetables, and nuts.

Vitamins—The online literature recommended inclusion of vitamin supplements, in particular vitamins D and B12, which aligned with published scientific literature.2,3 Eleven of 31 (35%) web pages recommended vitamin D in vitiligo. A 2010 study analyzing patients with vitiligo vulgaris (N=45) found that 68.9% of the cohort had insufficient (<30 ng/mL) 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels.2 A prospective study of 30 individuals found that the use of tacrolimus ointment plus oral vitamin D supplementation was found to be more successful in repigmentation than topical tacrolimus alone.3 Vitamin D dosage ranged from 1500 IU/d if the patient’s serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels were less than 20 ng/mL to 3000 IU/d if the serum levels were less than 10 ng/mL for 6 months.

Dairy products are a source of vitamin D.2,3 Of the web pages that mentioned dairy, a subtle majority (4/7 [57%]) recommended the inclusion of dairy products. Although many web pages did not specify whether oral vitamin D supplementation vs dietary food consumption is preferred, a 2013 controlled study of 16 vitiligo patients who received high doses of vitamin D supplementation with a low-calcium diet found that 4 patients showed 1% to 25% repigmentation, 5 patients showed 26% to 50% repigmentation, and 5 patients showed 51% to 75% repigmentation of the affected areas.4

Eleven of 31 (35%) web pages recommended inclusion of vitamin B12 supplementation in vitiligo. A 2-year study with 100 participants showed that supplementation with folic acid and vitamin B12 along with sun exposure yielded more effective repigmentation than either vitamins or sun exposure alone.5 An additional hypothesis suggested vitamin B12 may aid in repigmentation through its role in the homocysteine pathway. Although the theory is unproven, it is proposed that inhibition of homocysteine via vitamin B12 or folic acid supplementation may play a role in reducing melanocyte destruction and restoring melanin synthesis.6

There were mixed recommendations regarding vitamin C via supplementation and/or eating citrus fruits such as oranges. Although there are limited clinical studies on the use of vitamin C and the treatment of vitiligo, a 6-year prospective study from Madagascar consisting of approximately 300 participants with vitiligo who were treated with a combination of topical corticosteroids, oral vitamin C, and oral vitamin B12 supplementation showed excellent repigmentation (defined by repigmentation of more than 76% of the originally affected area) in 50 participants.7

Fruits—Most web pages had mixed recommendations on whether to include or avoid certain fruits. Interestingly, inclusion of mangoes and apricots in the diet were highly recommended (9/31 [29%] and 8/31 [26%], respectively) while fruits such as oranges, lemons, papayas, and grapes were discouraged (10/31 [32%], 8/31 [26%], 6/31 [19%], and 7/31 [23%], respectively). Although some web pages suggested that vitamin C–rich produce including citrus and berries may help to increase melanin formation, others strongly suggested avoiding these fruits. There is limited information on the effects of citrus on vitiligo, but a 2022 study indicated that 5-demethylnobiletin, a flavonoid found in sweet citrus fruits, may stimulate melanin synthesis, which can possibly be beneficial for vitiligo.8

Omega-3 Fatty Acids—Seven of 31 (23%) web pages recommended the inclusion of omega-3 fatty acids for their role as antioxidants to improve vitiligo symptoms. Research has indicated a strong association between vitiligo and oxidative stress.9 A 2007 controlled clinical trial that included 28 vitiligo patients demonstrated that oral antioxidant supplementation in combination with narrowband UVB phototherapy can significantly decrease vitiligo-associated oxidative stress (P<.05); 8 of 17 (47%) patients in the treatment group saw greater than 75% repigmentation after antioxidant treatment.10

Grains—Five of 31 (16%) web pages suggested avoiding gluten—a protein naturally found in some grains including wheat, barley, and rye—to improve vitiligo symptoms. A 2021 review suggested that a gluten-free diet may be effective in managing celiac disease, and it is hypothesized that vitiligo may be managed with similar dietary adjustments.11 Studies have shown that celiac disease and vitiligo—both autoimmune conditions—involve IL-2, IL-6, IL-7, and IL-21 in their disease pathways.12,13 Their shared immunogenic mechanism may account for similar management options.

Upon review, 2 case reports were identified that discussed a relationship between a gluten-free diet and vitiligo symptom improvement. In one report, a 9-year-old child diagnosed with both celiac disease and vitiligo saw intense repigmentation of the skin after adhering to a gluten-free diet for 1 year.14 Another case study reported a 22-year-old woman with vitiligo whose symptoms improved after 1 month of a gluten-free diet following 2 years of failed treatment with a topical steroid and phototherapy.15

Seven of 31 (23%) web pages suggested that individuals with vitiligo should include wheat in their diet. There is no published literature discussing the relationship between vitiligo and wheat. Of the 31 web pages reviewed, 10 (32%) suggested including whole grain. There is no relevant scientific evidence or hypotheses describing how whole grains may be beneficial in vitiligo.

Minerals—Eight of 31 (26%) web pages suggested including zinc in the diet to improve vitiligo symptoms. A 2020 study evaluated how different serum levels of zinc in vitiligo patients might be affiliated with interleukin activity. Fifty patients diagnosed with active vitiligo were tested for serum levels of zinc, IL-4, IL-6, and IL-17.16 The results showed that mean serum levels of zinc were lower in vitiligo patients compared with patients without vitiligo. The study concluded that zinc could possibly be used as a supplement to improve vitiligo, though the dosage needs to be further studied and confirmed.16

Vegetables—Eleven of 31 (35%) web pages recommended leafy green vegetables and 13 of 31 (42%) recommended spinach for patients with vitiligo. Spinach and other leafy green vegetables are known to be rich in antioxidants, which may have protective effects against reactive oxygen species that are thought to contribute to vitiligo progression.17,18

Nuts—Walnuts were recommended in 11 of 31 (35%) web pages. Nuts may be beneficial in reducing inflammation and providing protection against oxidative stress.9 However, there is no specific scientific literature that supports the inclusion of nuts in the diet to manage vitiligo symptoms.

Comment

With a growing amount of research suggesting that diet modifications may contribute to management of certain skin conditions, vitiligo patients often inquire about foods or supplements that may help improve their condition.19 Our review highlighted what information was available to the public regarding diet and vitiligo, with preliminary support of the following primary diet components: vitamin D, vitamin B12, zinc, and omega-3 fatty acids. Our review showed no support in the literature for the items that were recommended to avoid. It is important to note that 27 of 31 (87%) web pages from our online search were not authored by medical professionals or dermatologists. Additionally, many web pages suggested conflicting information, making it difficult to draw concrete conclusions about what diet modifications will be beneficial to the vitiligo community. Further controlled clinical trials are warranted due to the lack of formal studies that assess the relationship between diet and vitiligo.

Internet platforms have become a common source of medical information for individuals with a broad range of skin conditions including vitiligo. The prevalence of vitiligo among US adults ranges from 0.76% to 1.11%, with approximately 40% of adult cases of vitiligo in the United States remaining undiagnosed.1 The vitiligo community has become more inquisitive of the relationship between diet and vitiligo, turning to online sources for suggestions on diet modifications that may be beneficial for their condition. Although there is an abundance of online information, few diets or foods have been medically recognized to definitively improve or worsen vitiligo symptoms. We reviewed the top online web pages accessible to the public regarding diet suggestions that affect vitiligo symptoms. We then compared these online results to published peer-reviewed scientific literature.

Methods

Two independent online searches were performed by Researcher 1 (Y.A.) and Researcher 2 (I.M.) using Google Advanced Search. The independent searches were performed by the reviewers in neighboring areas of Chicago, Illinois, using the same Internet browser (Google Chrome). The primary search terms were diet and vitiligo along with the optional additional terms dietary supplement(s), food(s), nutrition, herb(s), or vitamin(s). Our search included any web pages published or updated from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2021, and originally scribed in the English language. The domains “.com,” “.org,” “.edu,” and “.cc” were included.

From this initial search, Researcher 1 identified 312 web pages and Researcher 2 identified 314 web pages. Each reviewer sorted their respective search results to identify the number of eligible records to be screened. Records were defined as unique web pages that met the search criteria. After removing duplicates, Researcher 1 screened 102 web pages and Researcher 2 screened 76 web pages. Of these records, web pages were excluded if they did not include any diet recommendations for vitiligo patients. Each reviewer independently created a list of eligible records, and the independent lists were then merged for a total of 58 web pages. Among these 58 web pages, there were 24 duplicate records and 3 records that were deemed ineligible for the study due to lack of subject matter relevance. A final total of 31 web pages were included in the data analysis (Figure). Of the 31 records selected, the reviewers jointly evaluated each web page and recorded the diet components that were recommended for individuals with vitiligo to either include or avoid (eTable).

For comparison and support from published scientific literature, a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted using the terms diet and vitiligo. Relevant human clinical studies published in the English-language literature were reviewed for content regarding the relationship between diet and vitiligo.

Results

Our online search revealed an abundance of information regarding various dietary modifications suggested to aid in the management of vitiligo symptoms. Most web pages (27/31 [87%]) were not authored by medical professionals or dermatologists. There were 27 diet components mentioned 8 or more times within the 31 total web pages. These diet components were selected for further review via PubMed. Each item was searched on PubMed using the term “[respective diet component] and vitiligo” among all published literature in the English language. Our study focused on summarizing the data on dietary components for which we were able to gather scientific support. These data have been organized into the following categories: vitamins, fruits, omega-3 fatty acids, grains, minerals, vegetables, and nuts.

Vitamins—The online literature recommended inclusion of vitamin supplements, in particular vitamins D and B12, which aligned with published scientific literature.2,3 Eleven of 31 (35%) web pages recommended vitamin D in vitiligo. A 2010 study analyzing patients with vitiligo vulgaris (N=45) found that 68.9% of the cohort had insufficient (<30 ng/mL) 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels.2 A prospective study of 30 individuals found that the use of tacrolimus ointment plus oral vitamin D supplementation was found to be more successful in repigmentation than topical tacrolimus alone.3 Vitamin D dosage ranged from 1500 IU/d if the patient’s serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels were less than 20 ng/mL to 3000 IU/d if the serum levels were less than 10 ng/mL for 6 months.

Dairy products are a source of vitamin D.2,3 Of the web pages that mentioned dairy, a subtle majority (4/7 [57%]) recommended the inclusion of dairy products. Although many web pages did not specify whether oral vitamin D supplementation vs dietary food consumption is preferred, a 2013 controlled study of 16 vitiligo patients who received high doses of vitamin D supplementation with a low-calcium diet found that 4 patients showed 1% to 25% repigmentation, 5 patients showed 26% to 50% repigmentation, and 5 patients showed 51% to 75% repigmentation of the affected areas.4

Eleven of 31 (35%) web pages recommended inclusion of vitamin B12 supplementation in vitiligo. A 2-year study with 100 participants showed that supplementation with folic acid and vitamin B12 along with sun exposure yielded more effective repigmentation than either vitamins or sun exposure alone.5 An additional hypothesis suggested vitamin B12 may aid in repigmentation through its role in the homocysteine pathway. Although the theory is unproven, it is proposed that inhibition of homocysteine via vitamin B12 or folic acid supplementation may play a role in reducing melanocyte destruction and restoring melanin synthesis.6

There were mixed recommendations regarding vitamin C via supplementation and/or eating citrus fruits such as oranges. Although there are limited clinical studies on the use of vitamin C and the treatment of vitiligo, a 6-year prospective study from Madagascar consisting of approximately 300 participants with vitiligo who were treated with a combination of topical corticosteroids, oral vitamin C, and oral vitamin B12 supplementation showed excellent repigmentation (defined by repigmentation of more than 76% of the originally affected area) in 50 participants.7

Fruits—Most web pages had mixed recommendations on whether to include or avoid certain fruits. Interestingly, inclusion of mangoes and apricots in the diet were highly recommended (9/31 [29%] and 8/31 [26%], respectively) while fruits such as oranges, lemons, papayas, and grapes were discouraged (10/31 [32%], 8/31 [26%], 6/31 [19%], and 7/31 [23%], respectively). Although some web pages suggested that vitamin C–rich produce including citrus and berries may help to increase melanin formation, others strongly suggested avoiding these fruits. There is limited information on the effects of citrus on vitiligo, but a 2022 study indicated that 5-demethylnobiletin, a flavonoid found in sweet citrus fruits, may stimulate melanin synthesis, which can possibly be beneficial for vitiligo.8

Omega-3 Fatty Acids—Seven of 31 (23%) web pages recommended the inclusion of omega-3 fatty acids for their role as antioxidants to improve vitiligo symptoms. Research has indicated a strong association between vitiligo and oxidative stress.9 A 2007 controlled clinical trial that included 28 vitiligo patients demonstrated that oral antioxidant supplementation in combination with narrowband UVB phototherapy can significantly decrease vitiligo-associated oxidative stress (P<.05); 8 of 17 (47%) patients in the treatment group saw greater than 75% repigmentation after antioxidant treatment.10

Grains—Five of 31 (16%) web pages suggested avoiding gluten—a protein naturally found in some grains including wheat, barley, and rye—to improve vitiligo symptoms. A 2021 review suggested that a gluten-free diet may be effective in managing celiac disease, and it is hypothesized that vitiligo may be managed with similar dietary adjustments.11 Studies have shown that celiac disease and vitiligo—both autoimmune conditions—involve IL-2, IL-6, IL-7, and IL-21 in their disease pathways.12,13 Their shared immunogenic mechanism may account for similar management options.

Upon review, 2 case reports were identified that discussed a relationship between a gluten-free diet and vitiligo symptom improvement. In one report, a 9-year-old child diagnosed with both celiac disease and vitiligo saw intense repigmentation of the skin after adhering to a gluten-free diet for 1 year.14 Another case study reported a 22-year-old woman with vitiligo whose symptoms improved after 1 month of a gluten-free diet following 2 years of failed treatment with a topical steroid and phototherapy.15

Seven of 31 (23%) web pages suggested that individuals with vitiligo should include wheat in their diet. There is no published literature discussing the relationship between vitiligo and wheat. Of the 31 web pages reviewed, 10 (32%) suggested including whole grain. There is no relevant scientific evidence or hypotheses describing how whole grains may be beneficial in vitiligo.

Minerals—Eight of 31 (26%) web pages suggested including zinc in the diet to improve vitiligo symptoms. A 2020 study evaluated how different serum levels of zinc in vitiligo patients might be affiliated with interleukin activity. Fifty patients diagnosed with active vitiligo were tested for serum levels of zinc, IL-4, IL-6, and IL-17.16 The results showed that mean serum levels of zinc were lower in vitiligo patients compared with patients without vitiligo. The study concluded that zinc could possibly be used as a supplement to improve vitiligo, though the dosage needs to be further studied and confirmed.16

Vegetables—Eleven of 31 (35%) web pages recommended leafy green vegetables and 13 of 31 (42%) recommended spinach for patients with vitiligo. Spinach and other leafy green vegetables are known to be rich in antioxidants, which may have protective effects against reactive oxygen species that are thought to contribute to vitiligo progression.17,18

Nuts—Walnuts were recommended in 11 of 31 (35%) web pages. Nuts may be beneficial in reducing inflammation and providing protection against oxidative stress.9 However, there is no specific scientific literature that supports the inclusion of nuts in the diet to manage vitiligo symptoms.

Comment

With a growing amount of research suggesting that diet modifications may contribute to management of certain skin conditions, vitiligo patients often inquire about foods or supplements that may help improve their condition.19 Our review highlighted what information was available to the public regarding diet and vitiligo, with preliminary support of the following primary diet components: vitamin D, vitamin B12, zinc, and omega-3 fatty acids. Our review showed no support in the literature for the items that were recommended to avoid. It is important to note that 27 of 31 (87%) web pages from our online search were not authored by medical professionals or dermatologists. Additionally, many web pages suggested conflicting information, making it difficult to draw concrete conclusions about what diet modifications will be beneficial to the vitiligo community. Further controlled clinical trials are warranted due to the lack of formal studies that assess the relationship between diet and vitiligo.

- Gandhi K, Ezzedine K, Anastassopoulos KP, et al. Prevalence of vitiligo among adults in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:43-50. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.4724

- Silverberg JI, Silverberg AI, Malka E, et al. A pilot study assessing the role of 25 hydroxy vitamin D levels in patients with vitiligo vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:937-941. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.11.024

- Karagüzel G, Sakarya NP, Bahadır S, et al. Vitamin D status and the effects of oral vitamin D treatment in children with vitiligo: a prospective study. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2016;15:28-31. doi:10.1016/j.clnesp.2016.05.006.

- Finamor DC, Sinigaglia-Coimbra R, Neves LC, et al. A pilot study assessing the effect of prolonged administration of high daily doses of vitamin D on the clinical course of vitiligo and psoriasis. Dermatoendocrinol. 2013;5:222-234. doi:10.4161/derm.24808

- Juhlin L, Olsson MJ. Improvement of vitiligo after oral treatment with vitamin B12 and folic acid and the importance of sun exposure. Acta Derm Venereol. 1997;77:460-462. doi:10.2340/000155555577460462

- Chen J, Zhuang T, Chen J, et al. Homocysteine induces melanocytes apoptosis via PERK-eIF2α-CHOP pathway in vitiligo. Clin Sci (Lond). 2020;134:1127-1141. doi:10.1042/CS20200218

- Sendrasoa FA, Ranaivo IM, Sata M, et al. Treatment responses in patients with vitiligo to very potent topical corticosteroids combined with vitamin therapy in Madagascar. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:908-911. doi:10.1111/ijd.14510

- Wang HM, Qu LQ, Ng JPL, et al. Natural citrus flavanone 5-demethylnobiletin stimulates melanogenesis through the activation of cAMP/CREB pathway in B16F10 cells. Phytomedicine. 2022;98:153941. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2022.153941

- Ros E. Health benefits of nut consumption. Nutrients. 2010;2:652-682.

- Dell’Anna ML, Mastrofrancesco A, Sala R, et al. Antioxidants and narrow band-UVB in the treatment of vitiligo: a double-blind placebo controlled trial. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:631-636.

- Gastrointestinal microbiome and gluten in celiac disease. Ann Med. 2021;53:1797-1805. doi:10.1080/07853890.2021.1990392

- Forabosco P, Neuhausen SL, Greco L, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide linkage studies in celiac disease. Hum Hered. 2009;68:223-230. doi:10.1159/000228920

- Akbulut UE, Çebi AH, Sag˘ E, et al. Interleukin-6 and interleukin-17 gene polymorphism association with celiac disease in children. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2017;28:471-475. doi:10.5152/tjg.2017.17092

- Rodríguez-García C, González-Hernández S, Pérez-Robayna N, et al. Repigmentation of vitiligo lesions in a child with celiac disease after a gluten-free diet. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:209-210. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01388.x

- Khandalavala BN, Nirmalraj MC. Rapid partial repigmentation ofvitiligo in a young female adult with a gluten-free diet. Case Rep Dermatol. 2014;6:283-287.

- Sanad EM, El-Fallah AA, Al-Doori AR, et al. Serum zinc and inflammatory cytokines in vitiligo. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13:(12 suppl 1):S29-S33.

- Ames BN, Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM. Oxidants, antioxidants, and the degenerative diseases of aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:7915-7922. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.17.7915

- Xian D, Guo M, Xu J, et al. Current evidence to support the therapeutic potential of flavonoids in oxidative stress-related dermatoses. Redox Rep. 2021;26:134-146. doi:10.1080 /13510002.2021.1962094

- Katta R, Kramer MJ. Skin and diet: an update on the role of dietary change as a treatment strategy for skin disease. Skin Therapy Lett. 2018;23:1-5.

- Gandhi K, Ezzedine K, Anastassopoulos KP, et al. Prevalence of vitiligo among adults in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:43-50. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.4724

- Silverberg JI, Silverberg AI, Malka E, et al. A pilot study assessing the role of 25 hydroxy vitamin D levels in patients with vitiligo vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:937-941. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.11.024

- Karagüzel G, Sakarya NP, Bahadır S, et al. Vitamin D status and the effects of oral vitamin D treatment in children with vitiligo: a prospective study. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2016;15:28-31. doi:10.1016/j.clnesp.2016.05.006.

- Finamor DC, Sinigaglia-Coimbra R, Neves LC, et al. A pilot study assessing the effect of prolonged administration of high daily doses of vitamin D on the clinical course of vitiligo and psoriasis. Dermatoendocrinol. 2013;5:222-234. doi:10.4161/derm.24808

- Juhlin L, Olsson MJ. Improvement of vitiligo after oral treatment with vitamin B12 and folic acid and the importance of sun exposure. Acta Derm Venereol. 1997;77:460-462. doi:10.2340/000155555577460462

- Chen J, Zhuang T, Chen J, et al. Homocysteine induces melanocytes apoptosis via PERK-eIF2α-CHOP pathway in vitiligo. Clin Sci (Lond). 2020;134:1127-1141. doi:10.1042/CS20200218

- Sendrasoa FA, Ranaivo IM, Sata M, et al. Treatment responses in patients with vitiligo to very potent topical corticosteroids combined with vitamin therapy in Madagascar. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:908-911. doi:10.1111/ijd.14510

- Wang HM, Qu LQ, Ng JPL, et al. Natural citrus flavanone 5-demethylnobiletin stimulates melanogenesis through the activation of cAMP/CREB pathway in B16F10 cells. Phytomedicine. 2022;98:153941. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2022.153941

- Ros E. Health benefits of nut consumption. Nutrients. 2010;2:652-682.

- Dell’Anna ML, Mastrofrancesco A, Sala R, et al. Antioxidants and narrow band-UVB in the treatment of vitiligo: a double-blind placebo controlled trial. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:631-636.

- Gastrointestinal microbiome and gluten in celiac disease. Ann Med. 2021;53:1797-1805. doi:10.1080/07853890.2021.1990392

- Forabosco P, Neuhausen SL, Greco L, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide linkage studies in celiac disease. Hum Hered. 2009;68:223-230. doi:10.1159/000228920

- Akbulut UE, Çebi AH, Sag˘ E, et al. Interleukin-6 and interleukin-17 gene polymorphism association with celiac disease in children. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2017;28:471-475. doi:10.5152/tjg.2017.17092

- Rodríguez-García C, González-Hernández S, Pérez-Robayna N, et al. Repigmentation of vitiligo lesions in a child with celiac disease after a gluten-free diet. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:209-210. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01388.x

- Khandalavala BN, Nirmalraj MC. Rapid partial repigmentation ofvitiligo in a young female adult with a gluten-free diet. Case Rep Dermatol. 2014;6:283-287.

- Sanad EM, El-Fallah AA, Al-Doori AR, et al. Serum zinc and inflammatory cytokines in vitiligo. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13:(12 suppl 1):S29-S33.

- Ames BN, Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM. Oxidants, antioxidants, and the degenerative diseases of aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:7915-7922. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.17.7915

- Xian D, Guo M, Xu J, et al. Current evidence to support the therapeutic potential of flavonoids in oxidative stress-related dermatoses. Redox Rep. 2021;26:134-146. doi:10.1080 /13510002.2021.1962094

- Katta R, Kramer MJ. Skin and diet: an update on the role of dietary change as a treatment strategy for skin disease. Skin Therapy Lett. 2018;23:1-5.

Practice Points

- There are numerous online dietary and supplement recommendations that claim to impact vitiligo but most are not authored by medical professionals or dermatologists.

- Scientific evidence supporting specific dietary and supplement recommendations for vitiligo is limited.

- Current preliminary data support the potential recommendation for dietary supplementation with vitamin D, vitamin B12, zinc, and omega-3 fatty acids.

How to Obtain a Dermatology Residency: A Guide Targeted to Underrepresented in Medicine Medical Students

There has been increasing attention focused on the lack of diversity within dermatology academic and residency programs.1-6 Several factors have been identified as contributing to this narrow pipeline of qualified applicants, including lack of mentorship, delayed exposure to the field, implicit bias, and lack of an overall holistic review of applications with overemphasis on board scores.1,5 In an effort to provide guidance to underrepresented in medicine (UIM) students who are interested in dermatology, the Skin of Color Society (SOCS) has created a detailed, step-by-step guide on how to obtain a position in a dermatology residency program,7 which was modeled after a similar resource created by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.8 Here, we highlight the main SOCS recommendations to help guide medical students through a systematic approach to becoming successful applicants for dermatology residency.

Start Early

Competitive fields such as dermatology require intentional efforts starting at the beginning of medical school. Regardless of what specialty is right for you, begin by constructing a well-rounded application for residency immediately. Start by shadowing dermatologists and attending Grand Rounds held in your institution’s dermatology department to ensure that this field is right for you. Students are encouraged to meet with academic advisors and upperclassmen to seek guidance on gaining early exposure to dermatology at their home institutions (or nearby programs) during their first year. As a platform for learning about community-based dermatology activities, join your school’s Dermatology Interest Group, keeping in mind that an executive position in such a group can help foster relationships with faculty and residents of the dermatology department. A long-term commitment to community service also contributes to your depth as an applicant. Getting involved early helps students uncover health disparities in medicine and allows time to formulate ideas to implement change. Forming a well-rounded application mandates maintaining good academic standing, and students should prioritize mastering the curriculum, excelling in clinical rotations, and studying for the US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE).

Choose a Mentor

The summer between your first and second years of medical school is an opportune time to explore research opportunities. Students successfully complete research by taking ownership of a project, efficiently meeting deadlines, maintaining contact with research mentors by quickly responding to emails, and producing quality work. Research outside of dermatology also is valued. Research mentors often provide future letters of recommendation, so commit to doing an outstanding job. For those finding it difficult to locate a mentor, consider searching the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD)(https://www.aad.org/mentorship/) or SOCS (https://skinofcolorsociety.org/) websites. The AAD has an established Diversity Mentorship Program (https://www.aad.org/member/career/volunteer/diversity-mentorship) that provides members with direct guidance from dermatologists for 4 weeks. Students use this time to conduct research, learn more about the specialty, and foster a relationship with their mentor. Students can apply any year of medical school; however, the typical awardee usually is a third-year or fourth-year student. The AAD may provide a stipend to help offset expenses.

Prepare for Boards

Second year is a continuation of the agenda set forth in first year, now with the focus shifting toward board preparation and excelling in clinical core didactics and rotations. According to data from the 2018 National Resident Matching Program,9 the mean USMLE Step 1 score for US allopathic senior medical students who matched into dermatology was 249 compared to 241 who did not match into dermatology. However, the mean score is just that—a mean—and people have matched with lower scores. Do not be intimidated by this number; instead, be driven to commit the time and resources to master the content and do your personal best on the USMLE Step examinations. Given the shift in some programs for earlier clinical exposure and postponement of boards until the third year, the recommendations in this timeline can be catered to fit a medical student’s specific situation.

Build Your Application

The third year of medical school is a busy year. Prepare for third-year clinical rotations by speaking with upperclassmen and clinical preceptors as you progress through your rotations. Evaluations and recommendations are weighed heavily by residency program directors, as this information is used to ascertain your clinical abilities. Seek feedback from your preceptors early and often with a sincere attempt to integrate suggested improvements. Schedule a dermatology rotation at your home institution after completing the core rotations. Although they are not required, applicants may complete away rotations early in their fourth year; the application period for visiting student learning opportunities typically opens April 1 of the third year, if not earlier. Free resources are available to help prepare for your dermatology rotations. Start by reviewing the Basic Dermatology Curriculum on the AAD website (https://www.aad.org/member/education/residents/bdc). Make contributions to

Interviewing for Residency

During your fourth year of medical school, you will be completing dermatology rotations, submitting your applications through the Electronic Residency Application Service, and interviewing with residency programs. When deciding which programs to apply to, consider referencing the American Medical Association Residency and Fellowship Database (https://freida.ama-assn.org/Freida/#/). Also keep in mind that, depending on your competitiveness, you should expect to receive 1 interview for every 10 programs you apply to, thus the application process can be quite costly. It is highly encouraged that you ask for letters of recommendation prior to August 15 and that you submit your applications by September 15. Complete mock interviews with a mentor and research commonly asked questions. Prior to your interview day, you want to spend time researching the program, browsing faculty publications, and reviewing your application. Dress in a comfortable suit, shoes, and minimal accessories; arrive early knowing that your interview begins even before you meet your interviewer, so treat everyone you meet with respect. Refrain from speaking to anyone in a casual way and have questions prepared to ask each interviewer. After your interviews, be sure to write thank you notes or emails if a program does not specifically discourage postinterview communication. Continuous efforts will improve your success in obtaining a dermatology residency position.

Final Thoughts

Recent articles have underscored and emphasized the importance of diversity in our field, with a call to action to find meaningful and overdue solutions.2,6 We acknowledge the important role that mentors play in providing timely, honest, and encouraging guidance to UIM students interested in careers in dermatology. We hope to provide readily available and detailed guidance to these students on how they can present themselves as excellent and qualified applicants through this summary and other platforms.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the members of the SOCS Diversity Task Force for their assistance in creating the original guide.

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants—turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260.

- Granstein RD, Cornelius L, Shinkai K. Diversity in dermatology—a call for action. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:499-500.

- Imadojemu S, James WD. Increasing African American representation in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:15-16.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Pritchett EN, Pandya AG, Ferguson NN, et al. Diversity in dermatology: roadmap for improvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:337-341.

- Taylor SC. Meeting the unique dermatologic needs of black patients [published online August 21, 2019]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1963.

- Skin of Color Society. How to obtain a position in a dermatology residency program. https://skinofcolorsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/How-to-Obtain-a-Position-in-a-Dermatology-Residency-Program-10-08-2019.pdf. Accessed June 24, 2020.

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. How to obtain an orthopedic residency by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. https://www.aaos.org/globalassets/about/diversity/how-to-obtain-an-orthopaedic-residency.pdf. Accessed June 24, 2020.

- Results and Data—2018 Main Residency Match. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; 2018. Published April 2018. Accessed June 24, 2020.

There has been increasing attention focused on the lack of diversity within dermatology academic and residency programs.1-6 Several factors have been identified as contributing to this narrow pipeline of qualified applicants, including lack of mentorship, delayed exposure to the field, implicit bias, and lack of an overall holistic review of applications with overemphasis on board scores.1,5 In an effort to provide guidance to underrepresented in medicine (UIM) students who are interested in dermatology, the Skin of Color Society (SOCS) has created a detailed, step-by-step guide on how to obtain a position in a dermatology residency program,7 which was modeled after a similar resource created by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.8 Here, we highlight the main SOCS recommendations to help guide medical students through a systematic approach to becoming successful applicants for dermatology residency.

Start Early

Competitive fields such as dermatology require intentional efforts starting at the beginning of medical school. Regardless of what specialty is right for you, begin by constructing a well-rounded application for residency immediately. Start by shadowing dermatologists and attending Grand Rounds held in your institution’s dermatology department to ensure that this field is right for you. Students are encouraged to meet with academic advisors and upperclassmen to seek guidance on gaining early exposure to dermatology at their home institutions (or nearby programs) during their first year. As a platform for learning about community-based dermatology activities, join your school’s Dermatology Interest Group, keeping in mind that an executive position in such a group can help foster relationships with faculty and residents of the dermatology department. A long-term commitment to community service also contributes to your depth as an applicant. Getting involved early helps students uncover health disparities in medicine and allows time to formulate ideas to implement change. Forming a well-rounded application mandates maintaining good academic standing, and students should prioritize mastering the curriculum, excelling in clinical rotations, and studying for the US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE).

Choose a Mentor

The summer between your first and second years of medical school is an opportune time to explore research opportunities. Students successfully complete research by taking ownership of a project, efficiently meeting deadlines, maintaining contact with research mentors by quickly responding to emails, and producing quality work. Research outside of dermatology also is valued. Research mentors often provide future letters of recommendation, so commit to doing an outstanding job. For those finding it difficult to locate a mentor, consider searching the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD)(https://www.aad.org/mentorship/) or SOCS (https://skinofcolorsociety.org/) websites. The AAD has an established Diversity Mentorship Program (https://www.aad.org/member/career/volunteer/diversity-mentorship) that provides members with direct guidance from dermatologists for 4 weeks. Students use this time to conduct research, learn more about the specialty, and foster a relationship with their mentor. Students can apply any year of medical school; however, the typical awardee usually is a third-year or fourth-year student. The AAD may provide a stipend to help offset expenses.

Prepare for Boards

Second year is a continuation of the agenda set forth in first year, now with the focus shifting toward board preparation and excelling in clinical core didactics and rotations. According to data from the 2018 National Resident Matching Program,9 the mean USMLE Step 1 score for US allopathic senior medical students who matched into dermatology was 249 compared to 241 who did not match into dermatology. However, the mean score is just that—a mean—and people have matched with lower scores. Do not be intimidated by this number; instead, be driven to commit the time and resources to master the content and do your personal best on the USMLE Step examinations. Given the shift in some programs for earlier clinical exposure and postponement of boards until the third year, the recommendations in this timeline can be catered to fit a medical student’s specific situation.

Build Your Application

The third year of medical school is a busy year. Prepare for third-year clinical rotations by speaking with upperclassmen and clinical preceptors as you progress through your rotations. Evaluations and recommendations are weighed heavily by residency program directors, as this information is used to ascertain your clinical abilities. Seek feedback from your preceptors early and often with a sincere attempt to integrate suggested improvements. Schedule a dermatology rotation at your home institution after completing the core rotations. Although they are not required, applicants may complete away rotations early in their fourth year; the application period for visiting student learning opportunities typically opens April 1 of the third year, if not earlier. Free resources are available to help prepare for your dermatology rotations. Start by reviewing the Basic Dermatology Curriculum on the AAD website (https://www.aad.org/member/education/residents/bdc). Make contributions to

Interviewing for Residency

During your fourth year of medical school, you will be completing dermatology rotations, submitting your applications through the Electronic Residency Application Service, and interviewing with residency programs. When deciding which programs to apply to, consider referencing the American Medical Association Residency and Fellowship Database (https://freida.ama-assn.org/Freida/#/). Also keep in mind that, depending on your competitiveness, you should expect to receive 1 interview for every 10 programs you apply to, thus the application process can be quite costly. It is highly encouraged that you ask for letters of recommendation prior to August 15 and that you submit your applications by September 15. Complete mock interviews with a mentor and research commonly asked questions. Prior to your interview day, you want to spend time researching the program, browsing faculty publications, and reviewing your application. Dress in a comfortable suit, shoes, and minimal accessories; arrive early knowing that your interview begins even before you meet your interviewer, so treat everyone you meet with respect. Refrain from speaking to anyone in a casual way and have questions prepared to ask each interviewer. After your interviews, be sure to write thank you notes or emails if a program does not specifically discourage postinterview communication. Continuous efforts will improve your success in obtaining a dermatology residency position.

Final Thoughts

Recent articles have underscored and emphasized the importance of diversity in our field, with a call to action to find meaningful and overdue solutions.2,6 We acknowledge the important role that mentors play in providing timely, honest, and encouraging guidance to UIM students interested in careers in dermatology. We hope to provide readily available and detailed guidance to these students on how they can present themselves as excellent and qualified applicants through this summary and other platforms.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the members of the SOCS Diversity Task Force for their assistance in creating the original guide.

There has been increasing attention focused on the lack of diversity within dermatology academic and residency programs.1-6 Several factors have been identified as contributing to this narrow pipeline of qualified applicants, including lack of mentorship, delayed exposure to the field, implicit bias, and lack of an overall holistic review of applications with overemphasis on board scores.1,5 In an effort to provide guidance to underrepresented in medicine (UIM) students who are interested in dermatology, the Skin of Color Society (SOCS) has created a detailed, step-by-step guide on how to obtain a position in a dermatology residency program,7 which was modeled after a similar resource created by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.8 Here, we highlight the main SOCS recommendations to help guide medical students through a systematic approach to becoming successful applicants for dermatology residency.

Start Early

Competitive fields such as dermatology require intentional efforts starting at the beginning of medical school. Regardless of what specialty is right for you, begin by constructing a well-rounded application for residency immediately. Start by shadowing dermatologists and attending Grand Rounds held in your institution’s dermatology department to ensure that this field is right for you. Students are encouraged to meet with academic advisors and upperclassmen to seek guidance on gaining early exposure to dermatology at their home institutions (or nearby programs) during their first year. As a platform for learning about community-based dermatology activities, join your school’s Dermatology Interest Group, keeping in mind that an executive position in such a group can help foster relationships with faculty and residents of the dermatology department. A long-term commitment to community service also contributes to your depth as an applicant. Getting involved early helps students uncover health disparities in medicine and allows time to formulate ideas to implement change. Forming a well-rounded application mandates maintaining good academic standing, and students should prioritize mastering the curriculum, excelling in clinical rotations, and studying for the US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE).

Choose a Mentor

The summer between your first and second years of medical school is an opportune time to explore research opportunities. Students successfully complete research by taking ownership of a project, efficiently meeting deadlines, maintaining contact with research mentors by quickly responding to emails, and producing quality work. Research outside of dermatology also is valued. Research mentors often provide future letters of recommendation, so commit to doing an outstanding job. For those finding it difficult to locate a mentor, consider searching the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD)(https://www.aad.org/mentorship/) or SOCS (https://skinofcolorsociety.org/) websites. The AAD has an established Diversity Mentorship Program (https://www.aad.org/member/career/volunteer/diversity-mentorship) that provides members with direct guidance from dermatologists for 4 weeks. Students use this time to conduct research, learn more about the specialty, and foster a relationship with their mentor. Students can apply any year of medical school; however, the typical awardee usually is a third-year or fourth-year student. The AAD may provide a stipend to help offset expenses.

Prepare for Boards

Second year is a continuation of the agenda set forth in first year, now with the focus shifting toward board preparation and excelling in clinical core didactics and rotations. According to data from the 2018 National Resident Matching Program,9 the mean USMLE Step 1 score for US allopathic senior medical students who matched into dermatology was 249 compared to 241 who did not match into dermatology. However, the mean score is just that—a mean—and people have matched with lower scores. Do not be intimidated by this number; instead, be driven to commit the time and resources to master the content and do your personal best on the USMLE Step examinations. Given the shift in some programs for earlier clinical exposure and postponement of boards until the third year, the recommendations in this timeline can be catered to fit a medical student’s specific situation.

Build Your Application

The third year of medical school is a busy year. Prepare for third-year clinical rotations by speaking with upperclassmen and clinical preceptors as you progress through your rotations. Evaluations and recommendations are weighed heavily by residency program directors, as this information is used to ascertain your clinical abilities. Seek feedback from your preceptors early and often with a sincere attempt to integrate suggested improvements. Schedule a dermatology rotation at your home institution after completing the core rotations. Although they are not required, applicants may complete away rotations early in their fourth year; the application period for visiting student learning opportunities typically opens April 1 of the third year, if not earlier. Free resources are available to help prepare for your dermatology rotations. Start by reviewing the Basic Dermatology Curriculum on the AAD website (https://www.aad.org/member/education/residents/bdc). Make contributions to

Interviewing for Residency

During your fourth year of medical school, you will be completing dermatology rotations, submitting your applications through the Electronic Residency Application Service, and interviewing with residency programs. When deciding which programs to apply to, consider referencing the American Medical Association Residency and Fellowship Database (https://freida.ama-assn.org/Freida/#/). Also keep in mind that, depending on your competitiveness, you should expect to receive 1 interview for every 10 programs you apply to, thus the application process can be quite costly. It is highly encouraged that you ask for letters of recommendation prior to August 15 and that you submit your applications by September 15. Complete mock interviews with a mentor and research commonly asked questions. Prior to your interview day, you want to spend time researching the program, browsing faculty publications, and reviewing your application. Dress in a comfortable suit, shoes, and minimal accessories; arrive early knowing that your interview begins even before you meet your interviewer, so treat everyone you meet with respect. Refrain from speaking to anyone in a casual way and have questions prepared to ask each interviewer. After your interviews, be sure to write thank you notes or emails if a program does not specifically discourage postinterview communication. Continuous efforts will improve your success in obtaining a dermatology residency position.

Final Thoughts

Recent articles have underscored and emphasized the importance of diversity in our field, with a call to action to find meaningful and overdue solutions.2,6 We acknowledge the important role that mentors play in providing timely, honest, and encouraging guidance to UIM students interested in careers in dermatology. We hope to provide readily available and detailed guidance to these students on how they can present themselves as excellent and qualified applicants through this summary and other platforms.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the members of the SOCS Diversity Task Force for their assistance in creating the original guide.

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants—turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260.

- Granstein RD, Cornelius L, Shinkai K. Diversity in dermatology—a call for action. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:499-500.

- Imadojemu S, James WD. Increasing African American representation in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:15-16.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Pritchett EN, Pandya AG, Ferguson NN, et al. Diversity in dermatology: roadmap for improvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:337-341.

- Taylor SC. Meeting the unique dermatologic needs of black patients [published online August 21, 2019]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1963.

- Skin of Color Society. How to obtain a position in a dermatology residency program. https://skinofcolorsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/How-to-Obtain-a-Position-in-a-Dermatology-Residency-Program-10-08-2019.pdf. Accessed June 24, 2020.

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. How to obtain an orthopedic residency by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. https://www.aaos.org/globalassets/about/diversity/how-to-obtain-an-orthopaedic-residency.pdf. Accessed June 24, 2020.

- Results and Data—2018 Main Residency Match. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; 2018. Published April 2018. Accessed June 24, 2020.

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants—turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260.

- Granstein RD, Cornelius L, Shinkai K. Diversity in dermatology—a call for action. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:499-500.

- Imadojemu S, James WD. Increasing African American representation in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:15-16.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Pritchett EN, Pandya AG, Ferguson NN, et al. Diversity in dermatology: roadmap for improvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:337-341.

- Taylor SC. Meeting the unique dermatologic needs of black patients [published online August 21, 2019]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1963.

- Skin of Color Society. How to obtain a position in a dermatology residency program. https://skinofcolorsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/How-to-Obtain-a-Position-in-a-Dermatology-Residency-Program-10-08-2019.pdf. Accessed June 24, 2020.

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. How to obtain an orthopedic residency by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. https://www.aaos.org/globalassets/about/diversity/how-to-obtain-an-orthopaedic-residency.pdf. Accessed June 24, 2020.

- Results and Data—2018 Main Residency Match. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; 2018. Published April 2018. Accessed June 24, 2020.

Practice Points

- Students interested in dermatology are encouraged to seek mentorship, strive for their academic best, and maintain their unique personal interests that make them a well-rounded applicant.

- Increasing diversity in dermatology requires initiative from students as well as dermatologists who are willing to mentor and sponsor.

Photosensitivity Reaction From Dronedarone for Atrial Fibrillation

To the Editor:

A 61-year-old woman with a history of atrial fibrillation, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia presented with an erythematous, edematous, pruritic eruption on the chest, neck, and arms of 2 weeks’ duration. The patient had no history of considerable sun exposure or reports of photosensitivity. One month prior to presentation she had started taking dronedarone for improved control of atrial fibrillation. She had no known history of drug allergies. Other medications included valsartan, digoxin, pioglitazone, simvastatin, aspirin, hydrocodone, and zolpidem, all of which were unchanged for years. There were no changes in topical products used.

Physical examination revealed confluent, well-demarcated, erythematous and edematous papules and plaques over the anterior aspect of the neck, bilateral forearms, and dorsal aspect of the hands, with a v-shaped distribution on the chest (Figure). There was notable sparing of the submental region, upper arms, abdomen, back, and legs. Dronedarone was discontinued and she was started on fluocinonide ointment 0.05% and oral hydroxyzine for pruritus. Her rash resolved within the following few weeks.

|

|

| Confluent, well-demarcated, erythematous and edematous papules and plaques in a v-shaped distribution on the chest (A) and dorsal aspect of the hands (B). |

Dronedarone is a noniodinated benzofuran derivative. It is structurally similar to and shares the antiarrhythmic properties of amiodarone,1 and thus it is used in the treatment of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter. However, the pulmonary and thyroid toxicities sometimes associated with amiodarone have not been observed with dronedarone. The primary side effect of dronedarone is gastrointestinal distress, specifically nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Dronedarone has been associated with severe liver injury and hepatic failure.2 Cutaneous reactions appear to be an uncommon side effect of dronedarone therapy. Across 5 clinical studies (N=6285), adverse events involving skin and subcutaneous tissue including eczema, allergic dermatitis, pruritus, and nonspecific rash occurred in 5% of dronedarone and 3% of placebo patients. Photosensitivity reactions occurred in less than 1% of dronedarone recipients.3

Although the lack of a biopsy leaves the possibility of a contact or photocontact dermatitis, our patient demonstrated the potential for dronedarone to cause a photodistributed drug eruption that resolved after cessation of the medication.

1. Hoy SM, Keam SJ. Dronedarone. Drugs. 2009;69:1647-1663.

2. In brief: FDA warning on dronedarone (Multaq). Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2011;53:17.

3. Multaq [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: sanofi-aventis; 2009.

To the Editor:

A 61-year-old woman with a history of atrial fibrillation, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia presented with an erythematous, edematous, pruritic eruption on the chest, neck, and arms of 2 weeks’ duration. The patient had no history of considerable sun exposure or reports of photosensitivity. One month prior to presentation she had started taking dronedarone for improved control of atrial fibrillation. She had no known history of drug allergies. Other medications included valsartan, digoxin, pioglitazone, simvastatin, aspirin, hydrocodone, and zolpidem, all of which were unchanged for years. There were no changes in topical products used.

Physical examination revealed confluent, well-demarcated, erythematous and edematous papules and plaques over the anterior aspect of the neck, bilateral forearms, and dorsal aspect of the hands, with a v-shaped distribution on the chest (Figure). There was notable sparing of the submental region, upper arms, abdomen, back, and legs. Dronedarone was discontinued and she was started on fluocinonide ointment 0.05% and oral hydroxyzine for pruritus. Her rash resolved within the following few weeks.

|

|

| Confluent, well-demarcated, erythematous and edematous papules and plaques in a v-shaped distribution on the chest (A) and dorsal aspect of the hands (B). |

Dronedarone is a noniodinated benzofuran derivative. It is structurally similar to and shares the antiarrhythmic properties of amiodarone,1 and thus it is used in the treatment of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter. However, the pulmonary and thyroid toxicities sometimes associated with amiodarone have not been observed with dronedarone. The primary side effect of dronedarone is gastrointestinal distress, specifically nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Dronedarone has been associated with severe liver injury and hepatic failure.2 Cutaneous reactions appear to be an uncommon side effect of dronedarone therapy. Across 5 clinical studies (N=6285), adverse events involving skin and subcutaneous tissue including eczema, allergic dermatitis, pruritus, and nonspecific rash occurred in 5% of dronedarone and 3% of placebo patients. Photosensitivity reactions occurred in less than 1% of dronedarone recipients.3

Although the lack of a biopsy leaves the possibility of a contact or photocontact dermatitis, our patient demonstrated the potential for dronedarone to cause a photodistributed drug eruption that resolved after cessation of the medication.

To the Editor:

A 61-year-old woman with a history of atrial fibrillation, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia presented with an erythematous, edematous, pruritic eruption on the chest, neck, and arms of 2 weeks’ duration. The patient had no history of considerable sun exposure or reports of photosensitivity. One month prior to presentation she had started taking dronedarone for improved control of atrial fibrillation. She had no known history of drug allergies. Other medications included valsartan, digoxin, pioglitazone, simvastatin, aspirin, hydrocodone, and zolpidem, all of which were unchanged for years. There were no changes in topical products used.