User login

Hair Care Products Used by Women of African Descent: Review of Ingredients

In the African American and African communities, information regarding the care and treatment of hair and skin often is obtained from relatives as well as Internet videos and bloggers.1 Moreover, fewer than half of African American women surveyed believe that their physician understands African American hair.2 In addition to proficiency in the diagnosis and treatment of hair and scalp disorders in this population, dermatologists must be aware of common hair and scalp beliefs, misconceptions, care, and product use to ensure culturally competent interactions and treatment.

When a patient of African descent refers to their hair as “natural,” he/she is referring to its texture compared with hair that is chemically treated with straighteners (ie, “relaxed” or “permed” hair). Natural hair refers to hair that has not been altered with chemical treatments that permanently break and re-form disulfide bonds of the hair.1 In 2003, it was estimated that 80% of African American women treated their hair with a chemical relaxer.3 However, this preference has changed over the last decade, with a larger percentage of African American women choosing to wear a natural hairstyle.4

Regardless of preferred hairstyle, a multitude of products can be used to obtain and maintain the particular style. According to US Food and Drug Administration regulations, a product’s ingredients must appear on an information panel in descending order of predominance. Additionally, products must be accurately labeled without misleading information. However, one study found that hair care products commonly used by African American women contain mixtures of endocrine-disrupting chemicals, and 84% of detected chemicals are not listed on the label.5

Properties of Hair Care Products

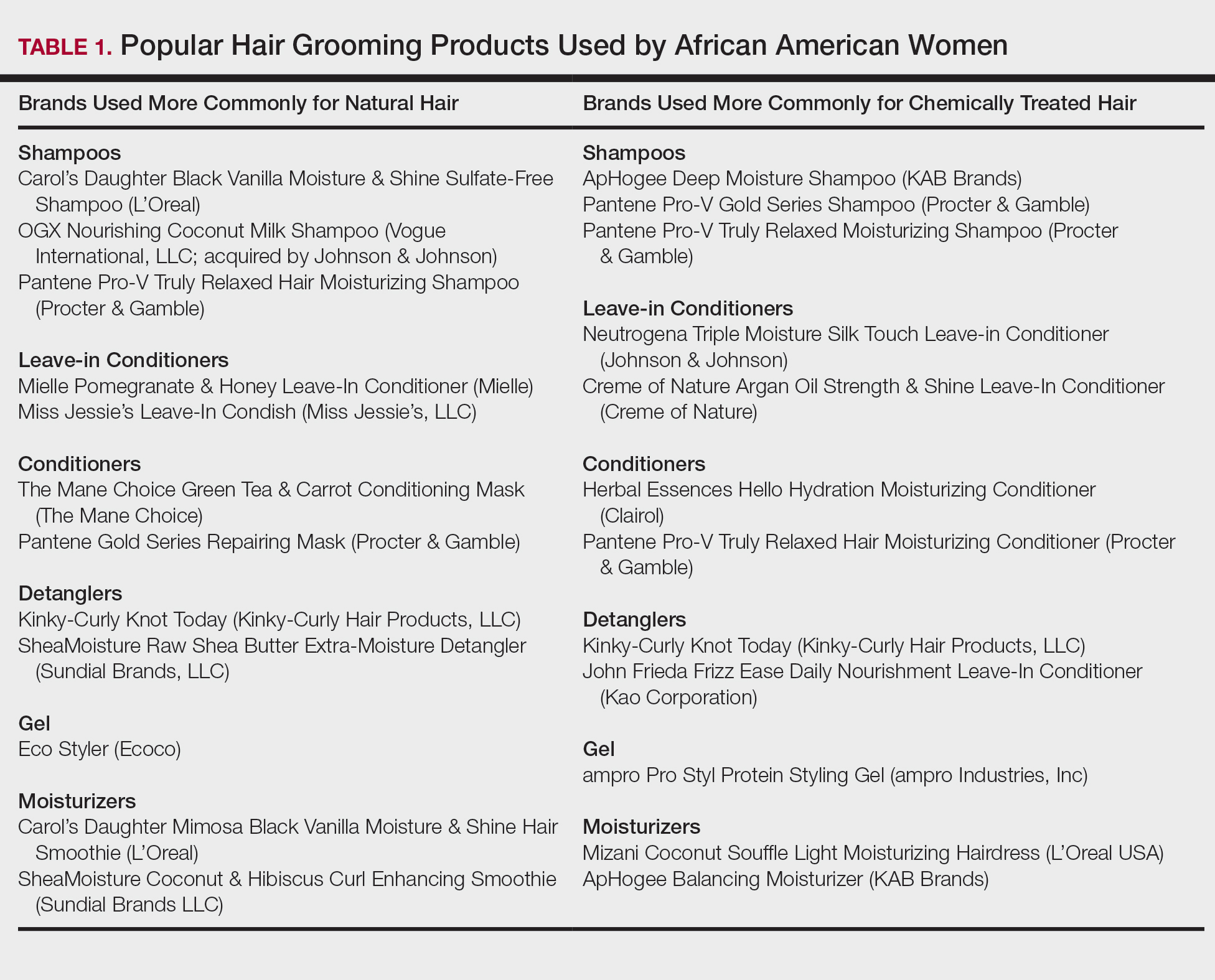

Women of African descent use hair grooming products for cleansing and moisturizing the hair and scalp, detangling, and styling. Products to achieve these goals comprise shampoos, leave-in and rinse-out conditioners, creams, pomades, oils, and gels. In August 2018 we performed a Google search of the most popular hair care products used for natural hair and chemically relaxed African American hair. Key terms used in our search included popular natural hair products, best natural hair products, top natural hair products, products for permed hair, shampoos for permed hair, conditioner for permed hair, popular detanglers for African American hair, popular products for natural hair, detanglers used for permed hair, gels for relaxed hair, moisturizers for relaxed hair, gels for natural hair, and popular moisturizers for African American hair. We reviewed all websites generated by the search and compared the most popular brands, compiled a list of products, and reviewed them for availability in 2 beauty supply stores in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; 1 Walmart in Hershey, Pennsylvania; and 1 Walmart in Willow Grove, Pennsylvania. Of the 80 products identified, we selected 57 products to be reviewed for ingredients based on which ones were most commonly seen in search results. Table 1 highlights several randomly chosen popular hair care products used by African American women to familiarize dermatologists with specific products and manufacturers.

Tightly coiled hair, common among women of African descent, is considered fragile because of decreased water content and tensile strength.6 Fragility is exacerbated by manipulation during styling, excessive heat, and harsh shampoos that strip the hair of moisture, as well as chemical treatments that lead to protein deficiency.4,6,7 Because tightly coiled hair is naturally dry and fragile, women of African descent have a particular preference for products that reduce hair dryness and breakage, which has led to the popularity of sulfate-free shampoos that minimize loss of moisture in hair; moisturizers, oils, and conditioners also are used to enhance moisture retention in hair. Conditioners also provide protein substances that can help strengthen hair.4

Consumers’ concerns about the inclusion of potentially harmful ingredients have resulted in reformulation of many products. Our review of products demonstrated that natural hair consumers used fewer products containing silicones, parabens, and sulfates, compared to consumers with chemically relaxed hair. Another tool used by manufacturers to address these concerns is the inclusion of an additional label to distinguish the product as sulfate free, silicone free, paraben free, petroleum free, or a combination of these terms. Although many patients believe that there are “good” and “bad” products, they should be made aware that there are pros and cons of ingredients frequently found in hair-grooming products. Popular ingredients in hair care products include sulfates, cationic surfactants and cationic polymers, silicone, oils, and parabens.

Sulfates

Sulfates are anion detergents in shampoo that remove sebum from the scalp and hair. The number of sulfates in a shampoo positively correlates to cleansing strength.1 However, sulfates can cause excessive sebum removal and lead to hair that is hard, rough, dull, and prone to tangle and breakage.6 Sulfates also dissolve oil on the hair, causing additional dryness and breakage.7

There are a variety of sulfate compounds with different sebum-removal capabilities. Lauryl sulfates are commonly used in shampoos for oily hair. Tightly coiled hair that has been overly cleansed with these ingredients can become exceedingly dry and unmanageable, which explains why products with lauryl sulfates are avoided. Table 1 includes only 1 product containing lauryl sulfate (Pantene Pro-V Gold Series Shampoo). Patients using a lauryl sulfate–containing shampoo can select a product that also contains a conditioning agent in the formulation.6 Alternatively, sulfate-free shampoos that contain surfactants with less detergency can be used.8 There are no published studies of the cleansing ability of sulfate-free shampoos or their effects on hair shaft fragility.9

At the opposite end of the spectrum is sodium laureth sulfate, commonly used as a primary detergent in shampoos designed for normal to dry hair.10 Sodium laureth sulfate, which provides excellent cleansing and leaves the hair better moisturized and manageable compared to lauryl sulfates,10 is a common ingredient in the products in Table 1 (ApHogee Deep Moisture Shampoo, Pantene Pro-V Gold Series Shampoo, and Pantene Pro-V Truly Relaxed Moisturizing Shampoo).

An ingredient that might be confused for a sulfate is behentrimonium methosulfate, a cationic quaternary ammonium salt that is not used to cleanse the hair, unlike sodium lauryl sulfate and sodium laureth sulfate, but serves as an antistatic conditioning agent to keep hair moisturized and frizz free.11 Behentrimonium methosulfate is found in conditioners and detanglers in Table 1 (The Mane Choice Green Tea & Carrot Conditioning Mask, Kinky-Curly Knot Today, Miss Jessie’s Leave-In Condish, SheaMoisture Raw Shea Butter Extra-Moisture Detangler, Mielle Pomegranate & Honey Leave-In Conditioner). Patients should be informed that behentrimonium methosulfate is not water soluble, which suggests that it can lead to buildup of residue.

Cationic Surfactants and Cationic Polymers

Cationic surfactants and cationic polymers are found in many hair products and improve manageability by softening and detangling hair.6,10 Hair consists of negatively charged keratin proteins7 that electrostatically attract the positively charged polar group of cationic surfactants and cationic polymers. These surfactants and polymers then adhere to and normalize hair surface charges, resulting in improved texture and reduced friction between strands.6 For African American patients with natural hair, cationic surfactants and polymers help to maintain curl patterns and assist in detangling.6 Polyquaternium is a cationic polymer that is found in several products in Table 1 (Carol’s Daughter Black Vanilla Moisture & Shine Sulfate-Free Shampoo, OGX Nourishing Coconut Milk Shampoo, ApHogee Deep Moisture Shampoo, Pantene Pro-V Gold Series Shampoo, Neutrogena Triple Moisture Silk Touch Leave-In Conditioner, Creme of Nature Argan Oil Strength & Shine Leave-in Conditioner, and John Frieda Frizz Ease Daily Nourishment Leave-In Conditioner).

The surfactants triethanolamine and tetrasodium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) are ingredients in some styling gels and have been reported as potential carcinogens.12 However, there are inadequate human or animal data to support the carcinogenicity of either ingredient at this time. Of note, tetrasodium EDTA has been reported to increase the penetration of other chemicals through the skin, which might lead to toxicity.12

Silicone

Silicone agents can be found in a variety of hair care products, including shampoos, detanglers, hair conditioners, leave-in conditioners, and moisturizers. Of the 22 products listed in Table 1, silicones are found in 14 products. Common silicones include dimethicone, amodimethicone, cyclopentasiloxane, and dimethiconol. Silicones form hydrophobic films that create smoothness and shine.6,8 Silicone-containing products help reduce frizz and provide protection against breakage and heat damage in chemically relaxed hair.6,7 For patients with natural hair, silicones aid in hair detangling.

Frequent use of silicone products can result in residue buildup due to the insolubility of silicone in water. Preventatively, some products include water-soluble silicones with the same benefits, such as silicones with the prefixes PPG- or PEG-, laurylmethicone copolyol, and dimethicone copolyol.7 Dimethicone copolyol was found in 1 of our reviewed products (OGX Nourishing Coconut Milk Shampoo); 10 products in Table 1 contain ingredients with the prefixes PPG- or PEG-. Several products in our review contain both water-soluble and water-insoluble silicones (eg, Creme of Nature Argan Oil Strength & Shine Leave-In Conditioner).

Oils

Oils in hair care products prevent hair breakage by coating the hair shaft and sealing in moisture. There are various types of oils in hair care products. Essential oils are volatile liquid-aroma substances derived most commonly from plants through dry or steam distillation or by other mechanical processes.13 Essential oils are used to seal and moisturize the hair and often are used to produce fragrance in hair products.6 Examples of essential oils that are ingredients in cosmetics include tea tree oil (TTO), peppermint oil, rosemary oil, and thyme oil. Vegetable oils can be used to dilute essential oils because essential oils can irritate skin.14

Tea tree oil is an essential oil obtained through steam distillation of the leaves of the coastal tree Melaleuca alternifolia. The molecule terpinen-4-ol is a major component of TTO thought to exhibit antiseptic and anti-inflammatory properties.15 Pazyar et al16 reviewed several studies that propose the use of TTO to treat acne vulgaris, seborrheic dermatitis, and chronic gingivitis. Although this herbal oil seemingly has many possible dermatologic applications, dermatologists should be aware that reports have linked TTO to allergic contact dermatitis due to 1,8-cineole, another constituent of TTO.17 Tea tree oil is an ingredient in several of the hair care products that we reviewed. With growing patient interest in the benefits of TTO, further research is necessary to establish guidelines on its use for seborrheic dermatitis.

Castor oil is a vegetable oil pressed from the seeds of the castor oil plant. Its primary fatty acid group—ricinoleic acid—along with certain salts and esters function primarily as skin-conditioning agents, emulsion stabilizers, and surfactants in cosmetic products.18 Jamaican black castor oil is a popular moisturizing oil in the African American natural hair community. It differs in color from standard castor oil because of the manner in which the oil is processed. Anecdotally, it is sometimes advertised as a hair growth serum; some patients admit to applying Jamaican black castor oil on the scalp as self-treatment of alopecia. The basis for such claims might stem from research showing that ricinoleic acid exhibits anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties in some mice and guinea pig models with repeated topical application.17 Scientific evidence does not, however, support claims that castor oil or Jamaican black castor oil can treat alopecia.

Mineral oils have a lubricant base and are refined from petroleum crude oils. The composition of crude oil varies; to remove impurities, it must undergo treatment with different degrees of refinement. When products are highly treated, the result is a substantially decreased level of impurities.19 Although they are beneficial in coating the hair shaft and preventing hair damage, consumers tend to avoid products containing mineral oil because of its carcinogenic potential if untreated or mildly treated.20

Although cosmetics with mineral oils are highly treated, a study showed that mineral oil is the largest contaminant in the human body, with cosmetics being a possible source.21 Studies also have revealed that mineral oils do not prevent hair breakage compared to other oils, such as essential oils and coconut oil.22,23 Many consumers therefore choose to avoid mineral oil because alternative oils exist that are beneficial in preventing hair damage but do not present carcinogenic risk. An example of a mineral oil–free product in Table 1 is Mizani Coconut Souffle Light Moisturizing Hairdress. Only 8 of the 57 products we reviewed did not contain oil, including the following 5 included in Table 1: Carol’s Daughter Black Vanilla Moisture & Shine Sulfate-Free Shampoo, Miss Jessie’s Leave-In Condish, Kinky-Curly Knot Today (although this product did have behentrimonium made from rapeseed oil), Herbal Essences Hello Hydration Moisturizing Conditioner, and ampro Pro Styl Protein Styling Gel.

Parabens

Parabens are preservatives used to prevent growth of pathogens in and prevent decomposition of cosmetic products. Parabens have attracted a lot of criticism because of their possible link to breast cancer.24 In vitro and in vivo studies of parabens have demonstrated weak estrogenic activity that increased proportionally with increased length and branching of alkyl side chains. In vivo animal studies demonstrated weak estrogenic activity—100,000-fold less potent than 17β-estradiol.25 Ongoing research examines the relationship between the estrogenic properties of parabens, endocrine disruption, and cancer in human breast epithelial cells.5,24 The Cosmetic Ingredient Review and the US Food and Drug Administration uphold that parabens are safe to use in cosmetics.26 Several products that include parabens are listed in Table 1 (ApHogee Deep Moisture Shampoo, Neutrogena Triple Moisture Silk Touch Leave-In Conditioner, John Frieda Frizz Ease Daily Nourishment Leave-In Conditioner, and ampro Pro Styl Protein Styling Gel).

Our Recommendations

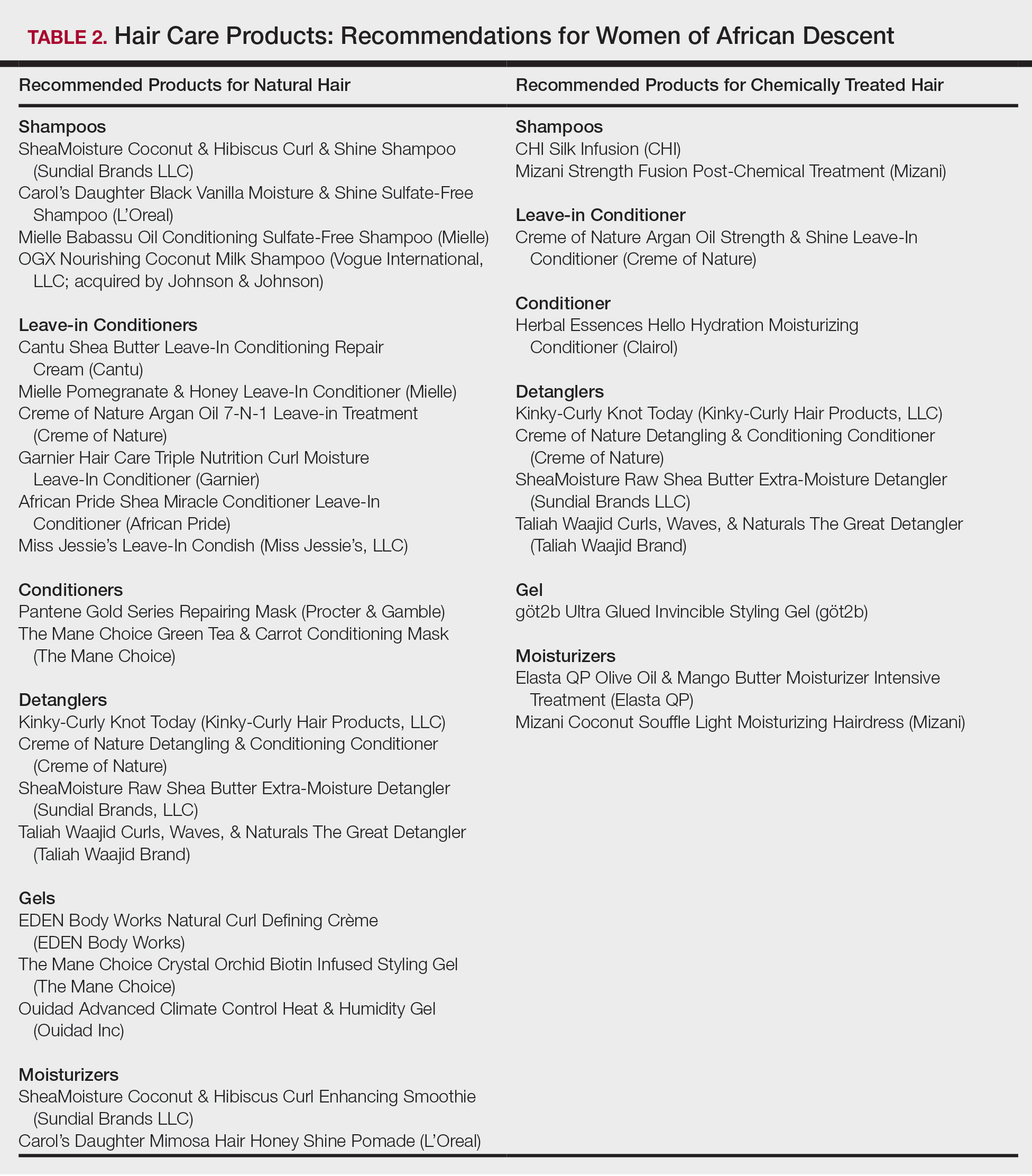

Table 2 (although not exhaustive) includes the authors’ recommendations of hair care products for individuals of African descent. Dermatologists should discuss the pros and cons of the use of products with ingredients that have controversial health effects, namely parabens, triethanolamine, tetrasodium EDTA, and mineral oils. Our recommendations do not include products that contain the prior ingredients. For many women of African descent, their hair type and therefore product use changes with the season, health of their hair, and normal changes to hair throughout their lifetime. There is no magic product for all: Each patient has specific individual styling preferences and a distinctive hair type. Decisions about which products to use can be guided with the assistance of a dermatologist but will ultimately be left up to the patient.

Conclusion

Given the array of hair and scalp care products, it is helpful for dermatologists to become familiar with several of the most popular ingredients and commonly used products. It might be helpful to ask patients which products they use and which ones have been effective for their unique hair concerns. Thus, you become armed with a catalogue of product recommendations for your patients.

- Taylor S, Kelly AP, Lim HW, et al. Taylor and Kelly’s Dermatology for Skin of Color. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009.

- Gathers RC, Mahan MG. African American women, hair care, and health barriers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:26-29.

- Quinn CR, Quinn TM, Kelly AP. Hair care practices in African American women. Cutis. 2003;72:280-282, 285-289.

- Griffin M, Lenzy Y. Contemporary African-American hair care practices. Pract Dermatol. http://practicaldermatology.com/2015/05/contemporary-african-american-hair-care-practices/. May 2015. Accessed March 19, 2020.

- Helm JS, Nishioka M, Brody JG, et al. Measurement of endocrine disrupting and asthma-associated chemicals in hair products used by black women. Environ Res. 2018;165:448-458.

- Crawford K, Hernandez C. A review of hair care products for black individuals. Cutis. 2014;93:289-293.

- Bosley RE, Daveluy S. A primer to natural hair care practices in black patients. Cutis. 2015;95:78-80, 106.

- Cline A, Uwakwe L, McMichael A. No sulfates, no parabens, and the “no-poo” method: a new patient perspective on common shampoo ingredients. Cutis. 2018;101:22-26.

- Gavazzoni Dias MFR. Hair cosmetics: an overview. Int J Trichology. 2015;7:2-15.

- Draelos ZD. Essentials of hair care often neglected: hair cleansing.Int J Trichology. 2010;2:24-29.

- Becker L, Bergfeld W, Belsito D, et al. Safety assessment of trimoniums as used in cosmetics. Int J Toxicol. 2012;31(6 suppl):296S-341S.

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Database. Edetate sodium, CID=6144. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/EDTA_

tetrasodium#section=FDA-Requirements. Accessed March 19, 2020. - Lanigan RS, Yamarik TA. Final report on the safety assessment of EDTA, calcium disodium EDTA, diammonium EDTA, dipotassium EDTA, disodium EDTA, TEA-EDTA, tetrasodium EDTA, tripotassium EDTA, trisodium EDTA, HEDTA, and trisodium HEDTA. Int J Toxicol. 2002;21(suppl 2):95-142.

- Vasireddy L, Bingle LEH, Davies MS. Antimicrobial activity of essential oils against multidrug-resistant clinical isolates of the Burkholderia cepacia complex. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0201835.

- Mondello F, De Bernardis F, Girolamo A, et al. In vivo activity of terpinen-4-ol, the main bioactive component of Melaleuca alternifolia Cheel (tea tree) oil against azole-susceptible and -resistant human pathogenic Candida species. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:158.

- Pazyar N, Yaghoobi R, Bagherani N, et al. A review of applications of tea tree oil in dermatology. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:784-790.

- Selvaag E, Eriksen B, Thune P. Contact allergy due to tea tree oil and cross-sensitization to colophony. Contact Dermatitis. 1994;31:124-125.

- Vieira C, Fetzer S, Sauer SK, et al. Pro- and anti-inflammatory actions of ricinoleic acid: similarities and differences with capsaicin. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2001;364:87-95.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer, IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans: Polynuclear Aromatic Hydrocarbons, Part 2, Carbon Blacks, Mineral Oils (Lubricant Base Oils and Derived Products) and Sorne Nitroarenes. Vol 33. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; April 1984. https://monographs.iarc.fr/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/mono33.pdf. Accessed March 19, 2020.

- Vieira C, Evangelista S, Cirillo R, et al. Effect of ricinoleic acid in acute and subchronic experimental models of inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2000;9:223-228.

- Concin N, Hofstetter G, Plattner B, et al. Evidence for cosmetics as a source of mineral oil contamination in women. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2011;20:1713-1719.

- Biedermann M, Barp L, Kornauth C, et al. Mineral oil in human tissues, part II: characterization of the accumulated hydrocarbons by comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography. Sci Total Environ. 2015;506-507:644-655.

- Ruetsch SB, Kamath YK, Rele AS, et al. Secondary ion mass spectrometric investigation of penetration of coconut and mineral oils into human hair fibers: relevance to hair damage. J Cosmet Sci. 2001;52:169-184.

- Darbre PD, Aljarrah A, Miller WR, et al. Concentrations of parabens in human breast tumours. J Appl Toxicol. 2004;24:5-13.

- Routledge EJ, Parker J, Odum J, et al. Some alkyl hydroxy benzoate preservatives (parabens) are estrogenic. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1998;153:12-19.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parabens factsheet. https://www.cdc.gov/biomonitoring/Parabens_FactSheet.html. Updated April 7, 2017. Accessed March 19, 2020.

In the African American and African communities, information regarding the care and treatment of hair and skin often is obtained from relatives as well as Internet videos and bloggers.1 Moreover, fewer than half of African American women surveyed believe that their physician understands African American hair.2 In addition to proficiency in the diagnosis and treatment of hair and scalp disorders in this population, dermatologists must be aware of common hair and scalp beliefs, misconceptions, care, and product use to ensure culturally competent interactions and treatment.

When a patient of African descent refers to their hair as “natural,” he/she is referring to its texture compared with hair that is chemically treated with straighteners (ie, “relaxed” or “permed” hair). Natural hair refers to hair that has not been altered with chemical treatments that permanently break and re-form disulfide bonds of the hair.1 In 2003, it was estimated that 80% of African American women treated their hair with a chemical relaxer.3 However, this preference has changed over the last decade, with a larger percentage of African American women choosing to wear a natural hairstyle.4

Regardless of preferred hairstyle, a multitude of products can be used to obtain and maintain the particular style. According to US Food and Drug Administration regulations, a product’s ingredients must appear on an information panel in descending order of predominance. Additionally, products must be accurately labeled without misleading information. However, one study found that hair care products commonly used by African American women contain mixtures of endocrine-disrupting chemicals, and 84% of detected chemicals are not listed on the label.5

Properties of Hair Care Products

Women of African descent use hair grooming products for cleansing and moisturizing the hair and scalp, detangling, and styling. Products to achieve these goals comprise shampoos, leave-in and rinse-out conditioners, creams, pomades, oils, and gels. In August 2018 we performed a Google search of the most popular hair care products used for natural hair and chemically relaxed African American hair. Key terms used in our search included popular natural hair products, best natural hair products, top natural hair products, products for permed hair, shampoos for permed hair, conditioner for permed hair, popular detanglers for African American hair, popular products for natural hair, detanglers used for permed hair, gels for relaxed hair, moisturizers for relaxed hair, gels for natural hair, and popular moisturizers for African American hair. We reviewed all websites generated by the search and compared the most popular brands, compiled a list of products, and reviewed them for availability in 2 beauty supply stores in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; 1 Walmart in Hershey, Pennsylvania; and 1 Walmart in Willow Grove, Pennsylvania. Of the 80 products identified, we selected 57 products to be reviewed for ingredients based on which ones were most commonly seen in search results. Table 1 highlights several randomly chosen popular hair care products used by African American women to familiarize dermatologists with specific products and manufacturers.

Tightly coiled hair, common among women of African descent, is considered fragile because of decreased water content and tensile strength.6 Fragility is exacerbated by manipulation during styling, excessive heat, and harsh shampoos that strip the hair of moisture, as well as chemical treatments that lead to protein deficiency.4,6,7 Because tightly coiled hair is naturally dry and fragile, women of African descent have a particular preference for products that reduce hair dryness and breakage, which has led to the popularity of sulfate-free shampoos that minimize loss of moisture in hair; moisturizers, oils, and conditioners also are used to enhance moisture retention in hair. Conditioners also provide protein substances that can help strengthen hair.4

Consumers’ concerns about the inclusion of potentially harmful ingredients have resulted in reformulation of many products. Our review of products demonstrated that natural hair consumers used fewer products containing silicones, parabens, and sulfates, compared to consumers with chemically relaxed hair. Another tool used by manufacturers to address these concerns is the inclusion of an additional label to distinguish the product as sulfate free, silicone free, paraben free, petroleum free, or a combination of these terms. Although many patients believe that there are “good” and “bad” products, they should be made aware that there are pros and cons of ingredients frequently found in hair-grooming products. Popular ingredients in hair care products include sulfates, cationic surfactants and cationic polymers, silicone, oils, and parabens.

Sulfates

Sulfates are anion detergents in shampoo that remove sebum from the scalp and hair. The number of sulfates in a shampoo positively correlates to cleansing strength.1 However, sulfates can cause excessive sebum removal and lead to hair that is hard, rough, dull, and prone to tangle and breakage.6 Sulfates also dissolve oil on the hair, causing additional dryness and breakage.7

There are a variety of sulfate compounds with different sebum-removal capabilities. Lauryl sulfates are commonly used in shampoos for oily hair. Tightly coiled hair that has been overly cleansed with these ingredients can become exceedingly dry and unmanageable, which explains why products with lauryl sulfates are avoided. Table 1 includes only 1 product containing lauryl sulfate (Pantene Pro-V Gold Series Shampoo). Patients using a lauryl sulfate–containing shampoo can select a product that also contains a conditioning agent in the formulation.6 Alternatively, sulfate-free shampoos that contain surfactants with less detergency can be used.8 There are no published studies of the cleansing ability of sulfate-free shampoos or their effects on hair shaft fragility.9

At the opposite end of the spectrum is sodium laureth sulfate, commonly used as a primary detergent in shampoos designed for normal to dry hair.10 Sodium laureth sulfate, which provides excellent cleansing and leaves the hair better moisturized and manageable compared to lauryl sulfates,10 is a common ingredient in the products in Table 1 (ApHogee Deep Moisture Shampoo, Pantene Pro-V Gold Series Shampoo, and Pantene Pro-V Truly Relaxed Moisturizing Shampoo).

An ingredient that might be confused for a sulfate is behentrimonium methosulfate, a cationic quaternary ammonium salt that is not used to cleanse the hair, unlike sodium lauryl sulfate and sodium laureth sulfate, but serves as an antistatic conditioning agent to keep hair moisturized and frizz free.11 Behentrimonium methosulfate is found in conditioners and detanglers in Table 1 (The Mane Choice Green Tea & Carrot Conditioning Mask, Kinky-Curly Knot Today, Miss Jessie’s Leave-In Condish, SheaMoisture Raw Shea Butter Extra-Moisture Detangler, Mielle Pomegranate & Honey Leave-In Conditioner). Patients should be informed that behentrimonium methosulfate is not water soluble, which suggests that it can lead to buildup of residue.

Cationic Surfactants and Cationic Polymers

Cationic surfactants and cationic polymers are found in many hair products and improve manageability by softening and detangling hair.6,10 Hair consists of negatively charged keratin proteins7 that electrostatically attract the positively charged polar group of cationic surfactants and cationic polymers. These surfactants and polymers then adhere to and normalize hair surface charges, resulting in improved texture and reduced friction between strands.6 For African American patients with natural hair, cationic surfactants and polymers help to maintain curl patterns and assist in detangling.6 Polyquaternium is a cationic polymer that is found in several products in Table 1 (Carol’s Daughter Black Vanilla Moisture & Shine Sulfate-Free Shampoo, OGX Nourishing Coconut Milk Shampoo, ApHogee Deep Moisture Shampoo, Pantene Pro-V Gold Series Shampoo, Neutrogena Triple Moisture Silk Touch Leave-In Conditioner, Creme of Nature Argan Oil Strength & Shine Leave-in Conditioner, and John Frieda Frizz Ease Daily Nourishment Leave-In Conditioner).

The surfactants triethanolamine and tetrasodium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) are ingredients in some styling gels and have been reported as potential carcinogens.12 However, there are inadequate human or animal data to support the carcinogenicity of either ingredient at this time. Of note, tetrasodium EDTA has been reported to increase the penetration of other chemicals through the skin, which might lead to toxicity.12

Silicone

Silicone agents can be found in a variety of hair care products, including shampoos, detanglers, hair conditioners, leave-in conditioners, and moisturizers. Of the 22 products listed in Table 1, silicones are found in 14 products. Common silicones include dimethicone, amodimethicone, cyclopentasiloxane, and dimethiconol. Silicones form hydrophobic films that create smoothness and shine.6,8 Silicone-containing products help reduce frizz and provide protection against breakage and heat damage in chemically relaxed hair.6,7 For patients with natural hair, silicones aid in hair detangling.

Frequent use of silicone products can result in residue buildup due to the insolubility of silicone in water. Preventatively, some products include water-soluble silicones with the same benefits, such as silicones with the prefixes PPG- or PEG-, laurylmethicone copolyol, and dimethicone copolyol.7 Dimethicone copolyol was found in 1 of our reviewed products (OGX Nourishing Coconut Milk Shampoo); 10 products in Table 1 contain ingredients with the prefixes PPG- or PEG-. Several products in our review contain both water-soluble and water-insoluble silicones (eg, Creme of Nature Argan Oil Strength & Shine Leave-In Conditioner).

Oils

Oils in hair care products prevent hair breakage by coating the hair shaft and sealing in moisture. There are various types of oils in hair care products. Essential oils are volatile liquid-aroma substances derived most commonly from plants through dry or steam distillation or by other mechanical processes.13 Essential oils are used to seal and moisturize the hair and often are used to produce fragrance in hair products.6 Examples of essential oils that are ingredients in cosmetics include tea tree oil (TTO), peppermint oil, rosemary oil, and thyme oil. Vegetable oils can be used to dilute essential oils because essential oils can irritate skin.14

Tea tree oil is an essential oil obtained through steam distillation of the leaves of the coastal tree Melaleuca alternifolia. The molecule terpinen-4-ol is a major component of TTO thought to exhibit antiseptic and anti-inflammatory properties.15 Pazyar et al16 reviewed several studies that propose the use of TTO to treat acne vulgaris, seborrheic dermatitis, and chronic gingivitis. Although this herbal oil seemingly has many possible dermatologic applications, dermatologists should be aware that reports have linked TTO to allergic contact dermatitis due to 1,8-cineole, another constituent of TTO.17 Tea tree oil is an ingredient in several of the hair care products that we reviewed. With growing patient interest in the benefits of TTO, further research is necessary to establish guidelines on its use for seborrheic dermatitis.

Castor oil is a vegetable oil pressed from the seeds of the castor oil plant. Its primary fatty acid group—ricinoleic acid—along with certain salts and esters function primarily as skin-conditioning agents, emulsion stabilizers, and surfactants in cosmetic products.18 Jamaican black castor oil is a popular moisturizing oil in the African American natural hair community. It differs in color from standard castor oil because of the manner in which the oil is processed. Anecdotally, it is sometimes advertised as a hair growth serum; some patients admit to applying Jamaican black castor oil on the scalp as self-treatment of alopecia. The basis for such claims might stem from research showing that ricinoleic acid exhibits anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties in some mice and guinea pig models with repeated topical application.17 Scientific evidence does not, however, support claims that castor oil or Jamaican black castor oil can treat alopecia.

Mineral oils have a lubricant base and are refined from petroleum crude oils. The composition of crude oil varies; to remove impurities, it must undergo treatment with different degrees of refinement. When products are highly treated, the result is a substantially decreased level of impurities.19 Although they are beneficial in coating the hair shaft and preventing hair damage, consumers tend to avoid products containing mineral oil because of its carcinogenic potential if untreated or mildly treated.20

Although cosmetics with mineral oils are highly treated, a study showed that mineral oil is the largest contaminant in the human body, with cosmetics being a possible source.21 Studies also have revealed that mineral oils do not prevent hair breakage compared to other oils, such as essential oils and coconut oil.22,23 Many consumers therefore choose to avoid mineral oil because alternative oils exist that are beneficial in preventing hair damage but do not present carcinogenic risk. An example of a mineral oil–free product in Table 1 is Mizani Coconut Souffle Light Moisturizing Hairdress. Only 8 of the 57 products we reviewed did not contain oil, including the following 5 included in Table 1: Carol’s Daughter Black Vanilla Moisture & Shine Sulfate-Free Shampoo, Miss Jessie’s Leave-In Condish, Kinky-Curly Knot Today (although this product did have behentrimonium made from rapeseed oil), Herbal Essences Hello Hydration Moisturizing Conditioner, and ampro Pro Styl Protein Styling Gel.

Parabens

Parabens are preservatives used to prevent growth of pathogens in and prevent decomposition of cosmetic products. Parabens have attracted a lot of criticism because of their possible link to breast cancer.24 In vitro and in vivo studies of parabens have demonstrated weak estrogenic activity that increased proportionally with increased length and branching of alkyl side chains. In vivo animal studies demonstrated weak estrogenic activity—100,000-fold less potent than 17β-estradiol.25 Ongoing research examines the relationship between the estrogenic properties of parabens, endocrine disruption, and cancer in human breast epithelial cells.5,24 The Cosmetic Ingredient Review and the US Food and Drug Administration uphold that parabens are safe to use in cosmetics.26 Several products that include parabens are listed in Table 1 (ApHogee Deep Moisture Shampoo, Neutrogena Triple Moisture Silk Touch Leave-In Conditioner, John Frieda Frizz Ease Daily Nourishment Leave-In Conditioner, and ampro Pro Styl Protein Styling Gel).

Our Recommendations

Table 2 (although not exhaustive) includes the authors’ recommendations of hair care products for individuals of African descent. Dermatologists should discuss the pros and cons of the use of products with ingredients that have controversial health effects, namely parabens, triethanolamine, tetrasodium EDTA, and mineral oils. Our recommendations do not include products that contain the prior ingredients. For many women of African descent, their hair type and therefore product use changes with the season, health of their hair, and normal changes to hair throughout their lifetime. There is no magic product for all: Each patient has specific individual styling preferences and a distinctive hair type. Decisions about which products to use can be guided with the assistance of a dermatologist but will ultimately be left up to the patient.

Conclusion

Given the array of hair and scalp care products, it is helpful for dermatologists to become familiar with several of the most popular ingredients and commonly used products. It might be helpful to ask patients which products they use and which ones have been effective for their unique hair concerns. Thus, you become armed with a catalogue of product recommendations for your patients.

In the African American and African communities, information regarding the care and treatment of hair and skin often is obtained from relatives as well as Internet videos and bloggers.1 Moreover, fewer than half of African American women surveyed believe that their physician understands African American hair.2 In addition to proficiency in the diagnosis and treatment of hair and scalp disorders in this population, dermatologists must be aware of common hair and scalp beliefs, misconceptions, care, and product use to ensure culturally competent interactions and treatment.

When a patient of African descent refers to their hair as “natural,” he/she is referring to its texture compared with hair that is chemically treated with straighteners (ie, “relaxed” or “permed” hair). Natural hair refers to hair that has not been altered with chemical treatments that permanently break and re-form disulfide bonds of the hair.1 In 2003, it was estimated that 80% of African American women treated their hair with a chemical relaxer.3 However, this preference has changed over the last decade, with a larger percentage of African American women choosing to wear a natural hairstyle.4

Regardless of preferred hairstyle, a multitude of products can be used to obtain and maintain the particular style. According to US Food and Drug Administration regulations, a product’s ingredients must appear on an information panel in descending order of predominance. Additionally, products must be accurately labeled without misleading information. However, one study found that hair care products commonly used by African American women contain mixtures of endocrine-disrupting chemicals, and 84% of detected chemicals are not listed on the label.5

Properties of Hair Care Products

Women of African descent use hair grooming products for cleansing and moisturizing the hair and scalp, detangling, and styling. Products to achieve these goals comprise shampoos, leave-in and rinse-out conditioners, creams, pomades, oils, and gels. In August 2018 we performed a Google search of the most popular hair care products used for natural hair and chemically relaxed African American hair. Key terms used in our search included popular natural hair products, best natural hair products, top natural hair products, products for permed hair, shampoos for permed hair, conditioner for permed hair, popular detanglers for African American hair, popular products for natural hair, detanglers used for permed hair, gels for relaxed hair, moisturizers for relaxed hair, gels for natural hair, and popular moisturizers for African American hair. We reviewed all websites generated by the search and compared the most popular brands, compiled a list of products, and reviewed them for availability in 2 beauty supply stores in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; 1 Walmart in Hershey, Pennsylvania; and 1 Walmart in Willow Grove, Pennsylvania. Of the 80 products identified, we selected 57 products to be reviewed for ingredients based on which ones were most commonly seen in search results. Table 1 highlights several randomly chosen popular hair care products used by African American women to familiarize dermatologists with specific products and manufacturers.

Tightly coiled hair, common among women of African descent, is considered fragile because of decreased water content and tensile strength.6 Fragility is exacerbated by manipulation during styling, excessive heat, and harsh shampoos that strip the hair of moisture, as well as chemical treatments that lead to protein deficiency.4,6,7 Because tightly coiled hair is naturally dry and fragile, women of African descent have a particular preference for products that reduce hair dryness and breakage, which has led to the popularity of sulfate-free shampoos that minimize loss of moisture in hair; moisturizers, oils, and conditioners also are used to enhance moisture retention in hair. Conditioners also provide protein substances that can help strengthen hair.4

Consumers’ concerns about the inclusion of potentially harmful ingredients have resulted in reformulation of many products. Our review of products demonstrated that natural hair consumers used fewer products containing silicones, parabens, and sulfates, compared to consumers with chemically relaxed hair. Another tool used by manufacturers to address these concerns is the inclusion of an additional label to distinguish the product as sulfate free, silicone free, paraben free, petroleum free, or a combination of these terms. Although many patients believe that there are “good” and “bad” products, they should be made aware that there are pros and cons of ingredients frequently found in hair-grooming products. Popular ingredients in hair care products include sulfates, cationic surfactants and cationic polymers, silicone, oils, and parabens.

Sulfates

Sulfates are anion detergents in shampoo that remove sebum from the scalp and hair. The number of sulfates in a shampoo positively correlates to cleansing strength.1 However, sulfates can cause excessive sebum removal and lead to hair that is hard, rough, dull, and prone to tangle and breakage.6 Sulfates also dissolve oil on the hair, causing additional dryness and breakage.7

There are a variety of sulfate compounds with different sebum-removal capabilities. Lauryl sulfates are commonly used in shampoos for oily hair. Tightly coiled hair that has been overly cleansed with these ingredients can become exceedingly dry and unmanageable, which explains why products with lauryl sulfates are avoided. Table 1 includes only 1 product containing lauryl sulfate (Pantene Pro-V Gold Series Shampoo). Patients using a lauryl sulfate–containing shampoo can select a product that also contains a conditioning agent in the formulation.6 Alternatively, sulfate-free shampoos that contain surfactants with less detergency can be used.8 There are no published studies of the cleansing ability of sulfate-free shampoos or their effects on hair shaft fragility.9

At the opposite end of the spectrum is sodium laureth sulfate, commonly used as a primary detergent in shampoos designed for normal to dry hair.10 Sodium laureth sulfate, which provides excellent cleansing and leaves the hair better moisturized and manageable compared to lauryl sulfates,10 is a common ingredient in the products in Table 1 (ApHogee Deep Moisture Shampoo, Pantene Pro-V Gold Series Shampoo, and Pantene Pro-V Truly Relaxed Moisturizing Shampoo).

An ingredient that might be confused for a sulfate is behentrimonium methosulfate, a cationic quaternary ammonium salt that is not used to cleanse the hair, unlike sodium lauryl sulfate and sodium laureth sulfate, but serves as an antistatic conditioning agent to keep hair moisturized and frizz free.11 Behentrimonium methosulfate is found in conditioners and detanglers in Table 1 (The Mane Choice Green Tea & Carrot Conditioning Mask, Kinky-Curly Knot Today, Miss Jessie’s Leave-In Condish, SheaMoisture Raw Shea Butter Extra-Moisture Detangler, Mielle Pomegranate & Honey Leave-In Conditioner). Patients should be informed that behentrimonium methosulfate is not water soluble, which suggests that it can lead to buildup of residue.

Cationic Surfactants and Cationic Polymers

Cationic surfactants and cationic polymers are found in many hair products and improve manageability by softening and detangling hair.6,10 Hair consists of negatively charged keratin proteins7 that electrostatically attract the positively charged polar group of cationic surfactants and cationic polymers. These surfactants and polymers then adhere to and normalize hair surface charges, resulting in improved texture and reduced friction between strands.6 For African American patients with natural hair, cationic surfactants and polymers help to maintain curl patterns and assist in detangling.6 Polyquaternium is a cationic polymer that is found in several products in Table 1 (Carol’s Daughter Black Vanilla Moisture & Shine Sulfate-Free Shampoo, OGX Nourishing Coconut Milk Shampoo, ApHogee Deep Moisture Shampoo, Pantene Pro-V Gold Series Shampoo, Neutrogena Triple Moisture Silk Touch Leave-In Conditioner, Creme of Nature Argan Oil Strength & Shine Leave-in Conditioner, and John Frieda Frizz Ease Daily Nourishment Leave-In Conditioner).

The surfactants triethanolamine and tetrasodium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) are ingredients in some styling gels and have been reported as potential carcinogens.12 However, there are inadequate human or animal data to support the carcinogenicity of either ingredient at this time. Of note, tetrasodium EDTA has been reported to increase the penetration of other chemicals through the skin, which might lead to toxicity.12

Silicone

Silicone agents can be found in a variety of hair care products, including shampoos, detanglers, hair conditioners, leave-in conditioners, and moisturizers. Of the 22 products listed in Table 1, silicones are found in 14 products. Common silicones include dimethicone, amodimethicone, cyclopentasiloxane, and dimethiconol. Silicones form hydrophobic films that create smoothness and shine.6,8 Silicone-containing products help reduce frizz and provide protection against breakage and heat damage in chemically relaxed hair.6,7 For patients with natural hair, silicones aid in hair detangling.

Frequent use of silicone products can result in residue buildup due to the insolubility of silicone in water. Preventatively, some products include water-soluble silicones with the same benefits, such as silicones with the prefixes PPG- or PEG-, laurylmethicone copolyol, and dimethicone copolyol.7 Dimethicone copolyol was found in 1 of our reviewed products (OGX Nourishing Coconut Milk Shampoo); 10 products in Table 1 contain ingredients with the prefixes PPG- or PEG-. Several products in our review contain both water-soluble and water-insoluble silicones (eg, Creme of Nature Argan Oil Strength & Shine Leave-In Conditioner).

Oils

Oils in hair care products prevent hair breakage by coating the hair shaft and sealing in moisture. There are various types of oils in hair care products. Essential oils are volatile liquid-aroma substances derived most commonly from plants through dry or steam distillation or by other mechanical processes.13 Essential oils are used to seal and moisturize the hair and often are used to produce fragrance in hair products.6 Examples of essential oils that are ingredients in cosmetics include tea tree oil (TTO), peppermint oil, rosemary oil, and thyme oil. Vegetable oils can be used to dilute essential oils because essential oils can irritate skin.14

Tea tree oil is an essential oil obtained through steam distillation of the leaves of the coastal tree Melaleuca alternifolia. The molecule terpinen-4-ol is a major component of TTO thought to exhibit antiseptic and anti-inflammatory properties.15 Pazyar et al16 reviewed several studies that propose the use of TTO to treat acne vulgaris, seborrheic dermatitis, and chronic gingivitis. Although this herbal oil seemingly has many possible dermatologic applications, dermatologists should be aware that reports have linked TTO to allergic contact dermatitis due to 1,8-cineole, another constituent of TTO.17 Tea tree oil is an ingredient in several of the hair care products that we reviewed. With growing patient interest in the benefits of TTO, further research is necessary to establish guidelines on its use for seborrheic dermatitis.

Castor oil is a vegetable oil pressed from the seeds of the castor oil plant. Its primary fatty acid group—ricinoleic acid—along with certain salts and esters function primarily as skin-conditioning agents, emulsion stabilizers, and surfactants in cosmetic products.18 Jamaican black castor oil is a popular moisturizing oil in the African American natural hair community. It differs in color from standard castor oil because of the manner in which the oil is processed. Anecdotally, it is sometimes advertised as a hair growth serum; some patients admit to applying Jamaican black castor oil on the scalp as self-treatment of alopecia. The basis for such claims might stem from research showing that ricinoleic acid exhibits anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties in some mice and guinea pig models with repeated topical application.17 Scientific evidence does not, however, support claims that castor oil or Jamaican black castor oil can treat alopecia.

Mineral oils have a lubricant base and are refined from petroleum crude oils. The composition of crude oil varies; to remove impurities, it must undergo treatment with different degrees of refinement. When products are highly treated, the result is a substantially decreased level of impurities.19 Although they are beneficial in coating the hair shaft and preventing hair damage, consumers tend to avoid products containing mineral oil because of its carcinogenic potential if untreated or mildly treated.20

Although cosmetics with mineral oils are highly treated, a study showed that mineral oil is the largest contaminant in the human body, with cosmetics being a possible source.21 Studies also have revealed that mineral oils do not prevent hair breakage compared to other oils, such as essential oils and coconut oil.22,23 Many consumers therefore choose to avoid mineral oil because alternative oils exist that are beneficial in preventing hair damage but do not present carcinogenic risk. An example of a mineral oil–free product in Table 1 is Mizani Coconut Souffle Light Moisturizing Hairdress. Only 8 of the 57 products we reviewed did not contain oil, including the following 5 included in Table 1: Carol’s Daughter Black Vanilla Moisture & Shine Sulfate-Free Shampoo, Miss Jessie’s Leave-In Condish, Kinky-Curly Knot Today (although this product did have behentrimonium made from rapeseed oil), Herbal Essences Hello Hydration Moisturizing Conditioner, and ampro Pro Styl Protein Styling Gel.

Parabens

Parabens are preservatives used to prevent growth of pathogens in and prevent decomposition of cosmetic products. Parabens have attracted a lot of criticism because of their possible link to breast cancer.24 In vitro and in vivo studies of parabens have demonstrated weak estrogenic activity that increased proportionally with increased length and branching of alkyl side chains. In vivo animal studies demonstrated weak estrogenic activity—100,000-fold less potent than 17β-estradiol.25 Ongoing research examines the relationship between the estrogenic properties of parabens, endocrine disruption, and cancer in human breast epithelial cells.5,24 The Cosmetic Ingredient Review and the US Food and Drug Administration uphold that parabens are safe to use in cosmetics.26 Several products that include parabens are listed in Table 1 (ApHogee Deep Moisture Shampoo, Neutrogena Triple Moisture Silk Touch Leave-In Conditioner, John Frieda Frizz Ease Daily Nourishment Leave-In Conditioner, and ampro Pro Styl Protein Styling Gel).

Our Recommendations

Table 2 (although not exhaustive) includes the authors’ recommendations of hair care products for individuals of African descent. Dermatologists should discuss the pros and cons of the use of products with ingredients that have controversial health effects, namely parabens, triethanolamine, tetrasodium EDTA, and mineral oils. Our recommendations do not include products that contain the prior ingredients. For many women of African descent, their hair type and therefore product use changes with the season, health of their hair, and normal changes to hair throughout their lifetime. There is no magic product for all: Each patient has specific individual styling preferences and a distinctive hair type. Decisions about which products to use can be guided with the assistance of a dermatologist but will ultimately be left up to the patient.

Conclusion

Given the array of hair and scalp care products, it is helpful for dermatologists to become familiar with several of the most popular ingredients and commonly used products. It might be helpful to ask patients which products they use and which ones have been effective for their unique hair concerns. Thus, you become armed with a catalogue of product recommendations for your patients.

- Taylor S, Kelly AP, Lim HW, et al. Taylor and Kelly’s Dermatology for Skin of Color. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009.

- Gathers RC, Mahan MG. African American women, hair care, and health barriers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:26-29.

- Quinn CR, Quinn TM, Kelly AP. Hair care practices in African American women. Cutis. 2003;72:280-282, 285-289.

- Griffin M, Lenzy Y. Contemporary African-American hair care practices. Pract Dermatol. http://practicaldermatology.com/2015/05/contemporary-african-american-hair-care-practices/. May 2015. Accessed March 19, 2020.

- Helm JS, Nishioka M, Brody JG, et al. Measurement of endocrine disrupting and asthma-associated chemicals in hair products used by black women. Environ Res. 2018;165:448-458.

- Crawford K, Hernandez C. A review of hair care products for black individuals. Cutis. 2014;93:289-293.

- Bosley RE, Daveluy S. A primer to natural hair care practices in black patients. Cutis. 2015;95:78-80, 106.

- Cline A, Uwakwe L, McMichael A. No sulfates, no parabens, and the “no-poo” method: a new patient perspective on common shampoo ingredients. Cutis. 2018;101:22-26.

- Gavazzoni Dias MFR. Hair cosmetics: an overview. Int J Trichology. 2015;7:2-15.

- Draelos ZD. Essentials of hair care often neglected: hair cleansing.Int J Trichology. 2010;2:24-29.

- Becker L, Bergfeld W, Belsito D, et al. Safety assessment of trimoniums as used in cosmetics. Int J Toxicol. 2012;31(6 suppl):296S-341S.

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Database. Edetate sodium, CID=6144. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/EDTA_

tetrasodium#section=FDA-Requirements. Accessed March 19, 2020. - Lanigan RS, Yamarik TA. Final report on the safety assessment of EDTA, calcium disodium EDTA, diammonium EDTA, dipotassium EDTA, disodium EDTA, TEA-EDTA, tetrasodium EDTA, tripotassium EDTA, trisodium EDTA, HEDTA, and trisodium HEDTA. Int J Toxicol. 2002;21(suppl 2):95-142.

- Vasireddy L, Bingle LEH, Davies MS. Antimicrobial activity of essential oils against multidrug-resistant clinical isolates of the Burkholderia cepacia complex. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0201835.

- Mondello F, De Bernardis F, Girolamo A, et al. In vivo activity of terpinen-4-ol, the main bioactive component of Melaleuca alternifolia Cheel (tea tree) oil against azole-susceptible and -resistant human pathogenic Candida species. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:158.

- Pazyar N, Yaghoobi R, Bagherani N, et al. A review of applications of tea tree oil in dermatology. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:784-790.

- Selvaag E, Eriksen B, Thune P. Contact allergy due to tea tree oil and cross-sensitization to colophony. Contact Dermatitis. 1994;31:124-125.

- Vieira C, Fetzer S, Sauer SK, et al. Pro- and anti-inflammatory actions of ricinoleic acid: similarities and differences with capsaicin. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2001;364:87-95.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer, IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans: Polynuclear Aromatic Hydrocarbons, Part 2, Carbon Blacks, Mineral Oils (Lubricant Base Oils and Derived Products) and Sorne Nitroarenes. Vol 33. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; April 1984. https://monographs.iarc.fr/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/mono33.pdf. Accessed March 19, 2020.

- Vieira C, Evangelista S, Cirillo R, et al. Effect of ricinoleic acid in acute and subchronic experimental models of inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2000;9:223-228.

- Concin N, Hofstetter G, Plattner B, et al. Evidence for cosmetics as a source of mineral oil contamination in women. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2011;20:1713-1719.

- Biedermann M, Barp L, Kornauth C, et al. Mineral oil in human tissues, part II: characterization of the accumulated hydrocarbons by comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography. Sci Total Environ. 2015;506-507:644-655.

- Ruetsch SB, Kamath YK, Rele AS, et al. Secondary ion mass spectrometric investigation of penetration of coconut and mineral oils into human hair fibers: relevance to hair damage. J Cosmet Sci. 2001;52:169-184.

- Darbre PD, Aljarrah A, Miller WR, et al. Concentrations of parabens in human breast tumours. J Appl Toxicol. 2004;24:5-13.

- Routledge EJ, Parker J, Odum J, et al. Some alkyl hydroxy benzoate preservatives (parabens) are estrogenic. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1998;153:12-19.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parabens factsheet. https://www.cdc.gov/biomonitoring/Parabens_FactSheet.html. Updated April 7, 2017. Accessed March 19, 2020.

- Taylor S, Kelly AP, Lim HW, et al. Taylor and Kelly’s Dermatology for Skin of Color. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009.

- Gathers RC, Mahan MG. African American women, hair care, and health barriers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:26-29.

- Quinn CR, Quinn TM, Kelly AP. Hair care practices in African American women. Cutis. 2003;72:280-282, 285-289.

- Griffin M, Lenzy Y. Contemporary African-American hair care practices. Pract Dermatol. http://practicaldermatology.com/2015/05/contemporary-african-american-hair-care-practices/. May 2015. Accessed March 19, 2020.

- Helm JS, Nishioka M, Brody JG, et al. Measurement of endocrine disrupting and asthma-associated chemicals in hair products used by black women. Environ Res. 2018;165:448-458.

- Crawford K, Hernandez C. A review of hair care products for black individuals. Cutis. 2014;93:289-293.

- Bosley RE, Daveluy S. A primer to natural hair care practices in black patients. Cutis. 2015;95:78-80, 106.

- Cline A, Uwakwe L, McMichael A. No sulfates, no parabens, and the “no-poo” method: a new patient perspective on common shampoo ingredients. Cutis. 2018;101:22-26.

- Gavazzoni Dias MFR. Hair cosmetics: an overview. Int J Trichology. 2015;7:2-15.

- Draelos ZD. Essentials of hair care often neglected: hair cleansing.Int J Trichology. 2010;2:24-29.

- Becker L, Bergfeld W, Belsito D, et al. Safety assessment of trimoniums as used in cosmetics. Int J Toxicol. 2012;31(6 suppl):296S-341S.

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Database. Edetate sodium, CID=6144. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/EDTA_

tetrasodium#section=FDA-Requirements. Accessed March 19, 2020. - Lanigan RS, Yamarik TA. Final report on the safety assessment of EDTA, calcium disodium EDTA, diammonium EDTA, dipotassium EDTA, disodium EDTA, TEA-EDTA, tetrasodium EDTA, tripotassium EDTA, trisodium EDTA, HEDTA, and trisodium HEDTA. Int J Toxicol. 2002;21(suppl 2):95-142.

- Vasireddy L, Bingle LEH, Davies MS. Antimicrobial activity of essential oils against multidrug-resistant clinical isolates of the Burkholderia cepacia complex. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0201835.

- Mondello F, De Bernardis F, Girolamo A, et al. In vivo activity of terpinen-4-ol, the main bioactive component of Melaleuca alternifolia Cheel (tea tree) oil against azole-susceptible and -resistant human pathogenic Candida species. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:158.

- Pazyar N, Yaghoobi R, Bagherani N, et al. A review of applications of tea tree oil in dermatology. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:784-790.

- Selvaag E, Eriksen B, Thune P. Contact allergy due to tea tree oil and cross-sensitization to colophony. Contact Dermatitis. 1994;31:124-125.

- Vieira C, Fetzer S, Sauer SK, et al. Pro- and anti-inflammatory actions of ricinoleic acid: similarities and differences with capsaicin. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2001;364:87-95.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer, IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans: Polynuclear Aromatic Hydrocarbons, Part 2, Carbon Blacks, Mineral Oils (Lubricant Base Oils and Derived Products) and Sorne Nitroarenes. Vol 33. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; April 1984. https://monographs.iarc.fr/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/mono33.pdf. Accessed March 19, 2020.

- Vieira C, Evangelista S, Cirillo R, et al. Effect of ricinoleic acid in acute and subchronic experimental models of inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2000;9:223-228.

- Concin N, Hofstetter G, Plattner B, et al. Evidence for cosmetics as a source of mineral oil contamination in women. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2011;20:1713-1719.

- Biedermann M, Barp L, Kornauth C, et al. Mineral oil in human tissues, part II: characterization of the accumulated hydrocarbons by comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography. Sci Total Environ. 2015;506-507:644-655.

- Ruetsch SB, Kamath YK, Rele AS, et al. Secondary ion mass spectrometric investigation of penetration of coconut and mineral oils into human hair fibers: relevance to hair damage. J Cosmet Sci. 2001;52:169-184.

- Darbre PD, Aljarrah A, Miller WR, et al. Concentrations of parabens in human breast tumours. J Appl Toxicol. 2004;24:5-13.

- Routledge EJ, Parker J, Odum J, et al. Some alkyl hydroxy benzoate preservatives (parabens) are estrogenic. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1998;153:12-19.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parabens factsheet. https://www.cdc.gov/biomonitoring/Parabens_FactSheet.html. Updated April 7, 2017. Accessed March 19, 2020.

Practice Points

- Dermatologists must be aware of common hair and scalp beliefs, misconceptions, care, and product use to ensure culturally competent patient interactions and treatment.

- Common ingredients in popular hair care products used by African Americans include sulfates, cationic surfactants and polymers, silicone, oils, and parabens.

Establishing the Diagnosis of Rosacea in Skin of Color Patients

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory cutaneous disorder that affects the vasculature and pilosebaceous units of the face. Delayed and misdiagnosed rosacea in the SOC population has led to increased morbidity in this patient population. 1-3 It is characterized by facial flushing and warmth, erythema, telangiectasia, papules, and pustules. The 4 major subtypes include erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous, and ocular rosacea. 4 Granulomatous rosacea is considered to be a unique variant of rosacea. Until recently, rosacea was thought to predominately affect lighter-skinned individuals of Celtic and northern European origin. 5,6 A paucity of studies and case reports in the literature have contributed to the commonly held belief that rosacea occurs infrequently in patients with skin of color (SOC). 1 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE revealed 32 results using the terms skin of color and rosacea vs 3786 using the term rosacea alone. It is possible that the nuance involved in appreciating erythema or other clinical manifestations of rosacea in SOC patients has led to underdiagnosis. Alternatively, these patients may be unaware that their symptoms represent a disease process and do not seek treatment. Many patients with darker skin will have endured rosacea for months or even years because the disease has been unrecognized or misdiagnosed. 6-8 Another factor possibly accounting for the perception that rosacea occurs infrequently in patients with SOC is misdiagnosis of rosacea as other diseases that are known to occur more commonly in the SOC population. Dermatologists should be aware that rosacea can affect SOC patients and that there are several rosacea mimickers to be considered and excluded when making the rosacea diagnosis in this patient population. To promote accurate and timely diagnosis of rosacea, we review several possible rosacea mimickers in SOC patients and highlight the distinguishing features.

Epidemiology

In 2018, a meta-analysis of published studies on rosacea estimated the global prevalence in all adults to be 5.46%.9 A multicenter study across 6 cities in Colombia identified 291 outpatients with rosacea; of them, 12.4% had either Fitzpatrick skin types IV or V.10 A study of 2743 Angolan adults with Fitzpatrick skin types V and VI reported that only 0.4% of patients had a diagnosis of rosacea.11 A Saudi study of 50 dark-skinned female patients with rosacea revealed 40% (20/50), 18% (9/50), and 42% (21/50) were Fitzpatrick skin types IV, V, and VI, respectively.12 The prevalence of rosacea in SOC patients in the United States is less defined. Data from the US National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (1993-2010) of 31.5 million rosacea visits showed that 2% of rosacea patients were black, 2.3% were Asian or Pacific Islander, and 3.9% were Hispanic or Latino.8

Clinical Features

Each of the 4 major rosacea subtypes can present in the SOC population. The granulomatous variant has been predominantly reported in black patients.13 This predilection has been attributed to either an increased susceptibility in black patients to develop this variant or a delay in diagnosis of earlier phases of inflammatory rosacea.7

In a Saudi study (N=50), severe erythematotelangiectatic rosacea was diagnosed in 42% (21/50) of patients, with the majority having Fitzpatrick skin type IV. The severe papulopustular subtype was seen in 14% (7/50) of patients, with 20% (10/50) and 14% (7/50) having Fitzpatrick skin types IV and VI, respectively.12 In a Tunisian study (N=244), erythematotelangiectatic rosacea was seen in 12% of patients, papulopustular rosacea in 69%, phymatous rosacea in 4%, and ocular rosacea in 16%. Less frequently, the granulomatous variant was seen in 3% of patients, and steroid rosacea was noted in 12% patients.14

Recognizing the signs of rosacea may be a challenge, particularly erythema and telangiectasia. Tips for making an accurate diagnosis include use of adequate lighting, blanching of the skin (Figure 1), photography of the affected area against a dark blue background, and dermatoscopic examination.3 Furthermore, a thorough medical history, especially when evaluating the presence of facial erythema and identifying triggers, may help reach the correct diagnosis. Careful examination of the distribution of papules and pustules as well as the morphology and color of the papules in SOC patients also may provide diagnostic clues.

Differential Diagnosis and Distinguishing Features

Several disorders are included in the differential diagnosis of rosacea and may confound a correct rosacea diagnosis, including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), seborrheic dermatitis, dermatomyositis, acne vulgaris, sarcoidosis, and steroid dermatitis. Many of these disorders also occur more commonly in patients with SOC; therefore, it is important to clearly distinguish these entities from rosacea in this population.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus is an autoimmune disease that commonly presents with erythema as well as erythematous inflammatory facial lesions similar to rosacea. The classic clinical appearance of SLE is the butterfly or malar rash, an erythematous macular eruption on the malar region of the face that also may involve the nose. This rash can appear similar to rosacea; however, the malar rash classically spares the nasolabial folds, while erythema of rosacea often involves this anatomic boundary. Although the facial erythema in both SLE and early stages of rosacea may be patchy and similar in presentation, the presence of papules and pustules rarely occurs in SLE and may help to differentiate SLE from certain variants of rosacea.15

Both SLE and rosacea may be exacerbated by sun exposure, and patients may report burning and stinging.16-18 Performing a complete physical examination, performing a skin biopsy with hematoxylin and eosin and direct immunofluorescence, and checking serologies including antinuclear antibody (ANA) can assist in making the diagnosis. It is important to note that elevated ANA, albeit lower than what is typically seen in SLE, has been reported in rosacea patients.19 If ANA is elevated, more specific SLE antibodies should be tested (eg, double-stranded DNA). Additionally, SLE can be differentiated on histology by a considerably lower CD4:CD8 ratio, fewer CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells, and more CD123+ plasmacytoid dendritic cells compared to rosacea.20

Seborrheic Dermatitis

Seborrheic dermatitis is a frequent cause of facial erythema linked to the Malassezia yeast species in susceptible individuals. Seborrheic dermatitis has a notable prevalence in women of African descent and often is considered normal by these patients.21 Rosacea and seborrheic dermatitis are relatively common dermatoses and therefore can present concurrently. In both diseases, facial erythema may be difficult to discern upon cursory inspection. Seborrheic dermatitis may be distinguished from rosacea by the clinical appearance of erythematous patches and plaques involving the scalp, anterior and posterior hairlines, preauricular and postauricular areas, and medial eyebrows. Both seborrheic dermatitis and rosacea may involve the nasolabial folds, but the presence of scale in seborrheic dermatitis is a distinguishing feature. Scale may vary in appearance from thick, greasy, and yellowish to fine, thin, and whitish.22 In contrast to rosacea, the erythematous lesions of seborrheic dermatitis often are annular in configuration. Furthermore, postinflammatory hypopigmentation and, to a lesser extent, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation are key clinical components of seborrheic dermatitis in SOC patients but are not as commonly observed in rosacea.

Dermatomyositis

Dermatomyositis is a systemic autoimmune disease characterized by progressive and symmetric proximal musculoskeletal weakness and cutaneous findings. Facial erythema in the malar and nasolabial folds can be seen in patients with dermatomyositis18; however, the facial erythema seen in dermatomyositis, known as heliotrope rash, has a violaceous dusky quality and also involves the periorbital region. The violaceous hue and periorbital involvement are distinguishing features from rosacea. Okiyama et al23 described facial macular violaceous erythema with scale and edema in Japanese patients with dermatomyositis on the nasolabial folds, eyebrows, chin, cheeks, and ears; they also described mild atrophy with telangiectasia. Other clinical signs to help distinguish rosacea from dermatomyositis are the presence of edema of the face and extremities, Gottron papules, and poikiloderma. Dermatomyositis is a disease that affects all races; however, it is 4 times more common in black vs white patients,24 making it even more important to be able to distinguish between these conditions.

Acne Vulgaris

Acne vulgaris, the most commonly diagnosed dermatosis in patients with SOC, is characterized by papules, pustules, cysts, nodules, open and closed comedones, and hyperpigmented macules on the face, chest, and back.25,26 The absence of comedonal lesions and the presence of hyperpigmented macules distinguishes acne vulgaris from rosacea in this population.1 In addition, the absence of telangiectasia and flushing are important distinguishing factors when making the diagnosis of acne vulgaris.

Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem inflammatory disease characterized histologically by the presence of noncaseating granulomas in sites such as the lungs, lymph nodes, eyes, nervous system, liver, spleen, heart, and skin.27 Cutaneous sarcoidosis is known as a great mimicker of many other dermatoses, as it may present with multiple morphologic features. Cutaneous sarcoidosis most typically presents as papules, but nodules, plaques, lupus pernio, subcutaneous infiltrates, and infiltration of scars also have been identified.28 Sarcoid papules typically are 1 to 5 mm in size on the face, neck, and periorbital skin29; they are initially orange or yellow-brown in color, turn brownish red or violaceous, then involute to form faint macules.30 Papular lesions may either resolve or evolve into plaques, particularly on the extremities, face, scalp, back, and buttocks. Additionally, there are a few case reports of patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis presenting with large bulbous nasal masses initially thought to be rhinophyma.31-33 Finally, it may be difficult to distinguish sarcoidosis from granulomatous rosacea, which is characterized by firm yellow, brown, violaceous, red, or flesh-colored monomorphic papules or nodules affecting the perioral, periocular, medial, and/or lateral areas of the face (Figure 2).4,34 Patients also can have unilateral disease.35 Patients with granulomatous rosacea lack flushing and erythema as seen in more characteristic presentations of rosacea. They may report pain, pruritus, or burning, or they may be asymptomatic.36 Features that distinguish granulomatous rosacea from sarcoidosis include the absence of nodules, plaques, lupus pernio, subcutaneous infiltrates, and infiltration of scars. Clinical, histological, and radiographic evaluation are necessary to make the diagnosis of sarcoidosis over rosacea.

Steroid Dermatitis

Steroid dermatitis involving the face may mimic rosacea. It is caused by the application of a potent corticosteroid to the facial skin for a prolonged period of time. In a report from a teaching hospital in Baghdad, the duration of application was 0.25 to 10 years on average.37 Reported characteristics of steroid dermatitis included facial erythema, telangiectasia, papules, pustules, and warmth to the touch. Distinguishing features from rosacea may be the presence of steroid dermatitis on the entire face, whereas rosacea tends to occur on the center of the face. Diagnosis of steroid dermatitis is made based on a history of chronic topical steroid use with rebound flares upon discontinuation of steroid.

Final Thoughts

Rosacea has features common to many other facial dermatoses, making the diagnosis challenging, particularly in patients with SOC. This difficulty in diagnosis may contribute to an underestimation of the prevalence of this disease in SOC patients. An understanding of rosacea, its nuances in clinical appearance, and its mimickers in SOC patients is important in making an accurate diagnosis.

References

- Alexis AF. Rosacea in patients with skin of color: uncommon but not rare. Cutis. 2010;86:60-62.

- Kim NH, Yun SJ, Lee JB. Clinical features of Korean patients with rhinophyma. J Dermatol. 2017;44:710-712.

- Hua TC, Chung PI, Chen YJ, et al. Cardiovascular comorbidities in patients with rosacea: a nationwide case-control study from Taiwan. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:249-254.

- Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, et al. Standard classification of rosacea: report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the Classification and Staging of Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:584-587.

- Elewski BE, Draelos Z, Dreno B, et al. Global diversity and optimized outcome: proposed international consensus from the Rosacea International Expert Group. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:188-200.

- Alexis AF, Callender VD, Baldwin HE, et al. Global epidemiology and clinical spectrum of rosacea, highlighting skin of color: review and clinical practice experience [published online September 19, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1722-1729.e7.

- Dlova NC, Mosam A. Rosacea in black South Africans with skin phototypes V and VI. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:670-673.

- Al-Dabagh A, Davis SA, McMichael AJ, et al. Rosacea in skin of color: not a rare diagnosis [published online October 15, 2014]. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20. pii:13030/qt1mv9r0ss.

- Gether L, Overgaard LK, Egeberg A, et al. Incidence and prevalence of rosacea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:282-289.

- Rueda LJ, Motta A, Pabon JG, et al. Epidemiology of rosacea in Colombia. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:510-513.

- De Luca DA, Maianski Z, Averbukh M. A study of skin disease spectrum occurring in Angola phototype V-VI population in Luanda. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:849-855.

- Al Balbeesi AO, Halawani MR. Unusual features of rosacea in Saudi females with dark skin. Ochsner J. 2014;14:321-327.

- Rosen T, Stone MS. Acne rosacea in blacks. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:70-73.

- Khaled A, Hammami H, Zeglaoui F, et al. Rosacea: 244 Tunisian cases. Tunis Med. 2010;88:597-601.

- Usatine RP, Smith MA, Chumley HS, et al. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2013.

- O'Gorman SM, Murphy GM. Photoaggravated disorders. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:385-398, ix.

- Foering K, Chang AY, Piette EW, et al. Characterization of clinical photosensitivity in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:205-213.

- Saleem MD, Wilkin JK. Evaluating and optimizing the diagnosis of erythematotelangiectatic rosacea. Dermatol Clin. 2018;36:127-134.

- Black AA, McCauliffe DP, Sontheimer RD. Prevalence of acne rosacea in a rheumatic skin disease subspecialty clinic. Lupus. 1992;1:229-237.

- Brown TT, Choi EY, Thomas DG, et al. Comparative analysis of rosacea and cutaneous lupus erythematosus: histopathologic features, T-cell subsets, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:100-107.

- Taylor SC, Barbosa V, Burgess C, et al. Hair and scalp disorders in adult and pediatric patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2017;100:31-35.

- Gary G. Optimizing treatment approaches in seborrheic dermatitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:44-49.

- Okiyama N, Kohsaka H, Ueda N, et al. Seborrheic area erythema as a common skin manifestation in Japanese patients with dermatomyositis. Dermatology. 2008;217:374-377.

- Taylor SC, Kyei A. Defining skin of color. In: Taylor SC, Kelly AP, Lim HW, et al, eds. Taylor and Kelly's Dermatology for Skin of Color. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2016:9-15.