User login

Hypertriglyceridemia: Identifying Secondary Causes

Screening for cardiovascular (CV) risk often includes a routine serum fasting lipid profile. However, with the focus on LDL cholesterol, triglyceride measurement is frequently overlooked. Yet this element of the lipid profile is particularly important, given its strong association with not only atherosclerotic coronary heart disease but also pancreatitis.

Hypertriglyceridemia is defined as a serum triglyceride level that exceeds 150 mg/dL. In the US, an estimated 25% of patients have hypertriglyceridemia.1 Of these, 33.1% have “borderline high” triglyceride levels (150 to 199 mg/dL), 17.8% have “high” levels (200 to 499 mg/dL), and 1.7% have “very high” levels (> 500 mg/dL).1,2

Most of the time, hypertriglyceridemia is caused (or at least exacerbated) by underlying etiology. The best way to identify and manage these secondary causes is through a systematic approach.

CONSIDER THE EVIDENCE

For mild to moderately elevated (borderline high) triglyceride levels, our reflex reaction may be to recommend a triglyceride-lowering medication, such as fenofibrate. But this may not be the best answer. Although there is increasing evidence of an independent association between elevated triglyceride levels and CV risk, it remains unclear whether targeting them specifically can reduce that risk.3

In well-designed, peer-reviewed clinical trials, statins have been shown to reduce CV risk in patients with known cardiovascular disease (CVD) and those at high risk for CVD, as well as in primary prevention. However, these trials also suggest that significant residual CV risk remains after statin therapy.4

Several trials have attempted to prove residual risk reduction following combination therapy including statins—with inconclusive results:

ACCORD: Fenofibrate showed no overall macrovascular benefit when added to a statin in patients with type 2 diabetes and a triglyceride level < 204 mg/dL.3,5

AIM-HIGH: There was a 25% reduction in triglyceride levels when niacin was added to a regimen of a statin +/- ezetimibe, with an aggressive LDL treatment target (40 to 80 mg/dL). But the study was stopped early due to the lack of expected reduction in CVD events.4,6

JELIS: A reduction in major CV events was seen with 1,800 mg/d of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) supplementation plus a low-dose statin, compared to statin monotherapy. However, there was minimal change in triglyceride levels, leading the researchers to hypothesize that multiple mechanisms—such as decreasing oxidative stress, platelet aggregation, plaque formation and stabilization—contributed to the outcome.4,7

Informed by the JELIS results, the much-anticipated REDUCE-IT trial is currently in progress to address the lingering question of whether combination therapy can reduce residual CV risk. In this trial, EPA omega-3 fatty acid is being added to the regimen of statin-treated patients with persistently elevated triglycerides. Results are expected in 2017 to 2018.8

Remember that a triglyceride level of 150 mg/dL is a parameter—it does not represent a therapeutic target. There is insufficient evidence that treating to this level improves CV risk beyond LDL target recommendations.7

The National Lipid Association Expert Panel’s consensus view is that non-HDL is a better primary target than triglycerides alone or LDL. Using non-HDL as a target for intervention also simplifies the management of patients with high triglycerides (200 to 499 mg/dL). The non-HDL goal is considered to be 30 mg/dL greater than the LDL target. For patients with diabetes and those with CVD, the individualized non-HDL targets are 130 mg/dL and 100 mg/dL, respectively.9

REVIEW THE MEDICATION LIST

Several commonly used medications, including ß-blockers and thiazide diuretics, can increase triglyceride levels.10 Other medications with exacerbating effects on triglycerides include corticosteroids, retrovirals, immunosuppressants, retinoids, and some antipsychotics.10 Bile acid sequestrants (eg, colesevelam) should be avoided in patients with elevated triglycerides (> 200 mg/dL).7

In women, oral estrogen (ie, menopausal hormone replacement and oral birth control) can greatly exacerbate triglyceride levels, making transdermal delivery a better option. Tamoxifen, the hormonal medication used for breast cancer prophylaxis, can also increase triglyceride levels.11

LOOK FOR UNDERLYING CONDITIONS

Among those to consider: Hypothyroidism is common and easily ruled out by a simple blood test. Nephrotic syndrome should be ruled out, particularly in patients with concomitant renal dysfunction and peripheral edema, by checking a random urine protein-to-creatinine ratio or 24-hour urine for protein. Other factors that should be explored because of their potential effect on lipid metabolism include obesity and excessive intake of sugary beverages (ie, soda, fruit juice) and alcohol.11

High triglyceride levels occurring with low HDL are characteristic of insulin resistance and concerning for metabolic syndrome and/or polycystic ovarian syndrome.3,12 Often, patients will have underlying prediabetes (fasting glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL or random glucose ≥ 140 mg/dL with an A1C > 5.7%13) or covert type 2 diabetes. Another underdiagnosed but very common condition, obstructive sleep apnea, can greatly affect insulin sensitivity and has been associated with lipid abnormalities and metabolic syndrome.14

EXAMINE YOUR PATIENT

The physical exam is an essential component of assessment for patients with high triglycerides. As discussed, elevated triglycerides and low HDL are hallmarks for insulin resistance. As triglyceride levels are affected by obesity and body fat distribution, measuring BMI and assessing for visceral adiposity are an important part of the physical exam.4

The physical exam may also yield dermatologic clues, such as skin tags or acanthosis nigricans, a dark, velvety lesion usually found on the posterior and lateral neck creases, axillae, groin, and elbows.13 In rare cases—usually those with genetic involvement from a familial lipid metabolism disorder—patients may exhibit xanthomas. These cutaneous, lipid-rich lesions can appear as flat, yellowish plaques on various parts of the body, such as the eyelids (xanthelasma) or tendons of the hands, feet, and heels. Widespread, eruptive xanthomas, which manifest as pruritic pink papules with creamy centers, are associated with severe emergent triglyceride elevation and pancreatitis.10

CONSIDER NONPHARMACOLOGIC MANAGEMENT

In mild to moderate hypertriglyceridemia, intensive lifestyle changes are considered firstline therapy. Weight loss is recommended in obese patients; a 5% to 10% reduction in body weight can lower triglycerides by 20%.15

A quick 24-hour diet recall, including beverages, is helpful for identifying key issues. The goal should be to reduce carbohydrates—in particular, simple, high glycemic index, processed foods—as well as total and saturated fats. A substantial problem in our population is the consumption of high-fructose beverages and fruit juices. Referral to a dietitian can be very helpful, not only for initial meal planning but also for continuing counseling on successful long-term weight loss and maintenance.

Exercise is also very helpful for improving lipid parameters. A daily minimum of 30 to 60 minutes of intermittent aerobic exercise or mild resistance exercise has been shown to reduce triglyceride levels.10

PRESCRIBE APPROPRIATELY

The most important indication for treatment of hypertriglyceridemia is reduction of CVD risk. However, in patients with very high triglyceride levels (> 500 mg/dL), the goal is to decrease risk for life-threatening pancreatitis.15 Lipid-lowering medications and dietary restrictions should be promptly employed.

There are medications, as discussed earlier, that specifically lower triglycerides. Fibrates offer the most robust decrease, with a 20% to 50% reduction in triglyceride levels. Fenofibrate is considered a safer option when used in combination with a statin, due to the risk for significant muscle toxicity with gemfibrozil. There is some evidence that adding a fibrate may actually increase risk for pancreatitis; since this risk is otherwise low in patients with mild to moderate triglyceride elevation, the addition of a fibrate to their regimen should be avoided.3

Statins are the drug of choice when CV risk reduction is the goal (for patients with hypertriglyceridemia < 500 mg/dL). In addition to lowering LDL, statins can reduce triglycerides by 7% to 30%, depending on the dose.15

Other triglyceride-lowering medications include omega-3 fatty acids and niacin preparations. Prescription-strength omega-3 fatty acids have been found to lower serum triglyceride levels by 50% or more; the newest preparation, icosapent ethyl, demonstrated up to 45% reduction without significant effect on LDL levels.3 (Other preparations have been shown to substantially increase LDL in many cases.) Niacin (1,500 to 2,000 mg/d) can decrease triglycerides by 15% to 25%. However, it is no longer recommended for CV risk reduction; recent data indicate it may increase stroke risk when used in combination with statins.3,10 In April 2016, the FDA revoked its approval of the co-administration of niacin and fenofibrate with statin therapy, due to a lack of CV benefit.16

Other secondline options to consider for patients with insulin resistance or diabetes are metformin and pioglitazone. These medications have been shown to improve insulin sensitivity and decrease LDL and triglycerides in patients with prediabetes. Pioglitazone has proven beneficial in the treatment of steatohepatitis.17 Insulin is an excellent rapid triglyceride-lowering agent for patients with diabetes. It is important to reinforce that reduction of glucose is a key component in reduction of triglyceride levels.3

CONCLUSION

Hypertriglyceridemia is a complex condition that requires individualized and comprehensive management strategies. Clinicians must be able to identify and address secondary causes. Treatment options should be tailored to decrease CV and pancreatitis risk, and medication recommendations should be evidenced based and carefully selected to mitigate potential adverse effects. Patients should receive education and lifestyle management support to help motivate and equip them to employ strategies to improve their health.

1. CDC. Trends in elevated triglyceride in adults: United States, 2001-2012. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db198.pdf. Accessed December 27, 2016.

2. Maki KC, Bays HE, Dicklin MR. Treatment options for the management of hypertriglyceridemia: strategies based on the best-available evidence. J Clin Lipidol. 2012;6(5):413-426.

3. Rosenson RS. Approach to the patient with hypertriglyceridemia. www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-the-patient-with-hypertriglyceridemia. Accessed December 28, 2016.

4. Talayero BG, Sacks FM. The role of triglycerides in atherosclerosis. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2011;13(6): 544-552.

5. Ginsberg HN, Elam MB, Lovato LC, et al; ACCORD Study Group. Effects of combination lipid therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010; 362(17):1563-1574.

6. AIM-HIGH Investigators. The role of niacin in raising high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to reduce cardiovascular events in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and optimally treated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Rationale and study design. The Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic syndrome with low HDL/high triglycerides: impact on Global Health outcomes (AIM-HIGH). Am Heart J. 2011;161(3):471-477.

7. Miller M, Stone NJ, Ballantyne C, et al. Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123(20):2292-2333.

8. Borow KM, Nelson JR, Mason RP. Biologic plausibility, cellular effects, and molecular mechanisms of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) in atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2015;242(1):357-366.

9. Jacobson TA, Ito MK, Maki KC, et al. National Lipid Association recommendations for patient-centered management of dyslipidemia. J Clin Lipidol. 2015;9(2):129-169.

10. Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, et al. Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012; 97(9):2969-2989.

11. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 pt B):2889-2934.

12. Amini L, Sadeghi MR, Oskuie F, Maleki H. Lipid profile in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Crescent J Med Biol Sci. 2014;1(4):147-150.

13. Mantzoros C. Insulin resistance: definition and clinical spectrum. www.uptodate.com/contents/insulin-resistance-definition-and-clinical-spectrum. Accessed December 28, 2016.

14. Lin M, Lin H, Lee P, et al. Beneficial effect of continuous positive airway pressure on lipid profiles in obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-analysis. Sleep Breath. 2015;19(3):809-817.

15. Kaur J. A comprehensive review on metabolic syndrome. Cardiol Res Pract. 2014;2014:943162.

16. FDA. Withdrawal of approval of indications related to the coadministration with statins in applications for niacin extended-release tablets and fenofibric acid delayed-release capsules. https://s3.amazonaws.com/public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2016-08887.pdf. Accessed December 28, 2016.

17. Mazza A, Fruci B, Garinis GA, et al. The role of metformin in the management of NAFLD. Exp Diabetes Res. 2012;2012: 716404.

Screening for cardiovascular (CV) risk often includes a routine serum fasting lipid profile. However, with the focus on LDL cholesterol, triglyceride measurement is frequently overlooked. Yet this element of the lipid profile is particularly important, given its strong association with not only atherosclerotic coronary heart disease but also pancreatitis.

Hypertriglyceridemia is defined as a serum triglyceride level that exceeds 150 mg/dL. In the US, an estimated 25% of patients have hypertriglyceridemia.1 Of these, 33.1% have “borderline high” triglyceride levels (150 to 199 mg/dL), 17.8% have “high” levels (200 to 499 mg/dL), and 1.7% have “very high” levels (> 500 mg/dL).1,2

Most of the time, hypertriglyceridemia is caused (or at least exacerbated) by underlying etiology. The best way to identify and manage these secondary causes is through a systematic approach.

CONSIDER THE EVIDENCE

For mild to moderately elevated (borderline high) triglyceride levels, our reflex reaction may be to recommend a triglyceride-lowering medication, such as fenofibrate. But this may not be the best answer. Although there is increasing evidence of an independent association between elevated triglyceride levels and CV risk, it remains unclear whether targeting them specifically can reduce that risk.3

In well-designed, peer-reviewed clinical trials, statins have been shown to reduce CV risk in patients with known cardiovascular disease (CVD) and those at high risk for CVD, as well as in primary prevention. However, these trials also suggest that significant residual CV risk remains after statin therapy.4

Several trials have attempted to prove residual risk reduction following combination therapy including statins—with inconclusive results:

ACCORD: Fenofibrate showed no overall macrovascular benefit when added to a statin in patients with type 2 diabetes and a triglyceride level < 204 mg/dL.3,5

AIM-HIGH: There was a 25% reduction in triglyceride levels when niacin was added to a regimen of a statin +/- ezetimibe, with an aggressive LDL treatment target (40 to 80 mg/dL). But the study was stopped early due to the lack of expected reduction in CVD events.4,6

JELIS: A reduction in major CV events was seen with 1,800 mg/d of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) supplementation plus a low-dose statin, compared to statin monotherapy. However, there was minimal change in triglyceride levels, leading the researchers to hypothesize that multiple mechanisms—such as decreasing oxidative stress, platelet aggregation, plaque formation and stabilization—contributed to the outcome.4,7

Informed by the JELIS results, the much-anticipated REDUCE-IT trial is currently in progress to address the lingering question of whether combination therapy can reduce residual CV risk. In this trial, EPA omega-3 fatty acid is being added to the regimen of statin-treated patients with persistently elevated triglycerides. Results are expected in 2017 to 2018.8

Remember that a triglyceride level of 150 mg/dL is a parameter—it does not represent a therapeutic target. There is insufficient evidence that treating to this level improves CV risk beyond LDL target recommendations.7

The National Lipid Association Expert Panel’s consensus view is that non-HDL is a better primary target than triglycerides alone or LDL. Using non-HDL as a target for intervention also simplifies the management of patients with high triglycerides (200 to 499 mg/dL). The non-HDL goal is considered to be 30 mg/dL greater than the LDL target. For patients with diabetes and those with CVD, the individualized non-HDL targets are 130 mg/dL and 100 mg/dL, respectively.9

REVIEW THE MEDICATION LIST

Several commonly used medications, including ß-blockers and thiazide diuretics, can increase triglyceride levels.10 Other medications with exacerbating effects on triglycerides include corticosteroids, retrovirals, immunosuppressants, retinoids, and some antipsychotics.10 Bile acid sequestrants (eg, colesevelam) should be avoided in patients with elevated triglycerides (> 200 mg/dL).7

In women, oral estrogen (ie, menopausal hormone replacement and oral birth control) can greatly exacerbate triglyceride levels, making transdermal delivery a better option. Tamoxifen, the hormonal medication used for breast cancer prophylaxis, can also increase triglyceride levels.11

LOOK FOR UNDERLYING CONDITIONS

Among those to consider: Hypothyroidism is common and easily ruled out by a simple blood test. Nephrotic syndrome should be ruled out, particularly in patients with concomitant renal dysfunction and peripheral edema, by checking a random urine protein-to-creatinine ratio or 24-hour urine for protein. Other factors that should be explored because of their potential effect on lipid metabolism include obesity and excessive intake of sugary beverages (ie, soda, fruit juice) and alcohol.11

High triglyceride levels occurring with low HDL are characteristic of insulin resistance and concerning for metabolic syndrome and/or polycystic ovarian syndrome.3,12 Often, patients will have underlying prediabetes (fasting glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL or random glucose ≥ 140 mg/dL with an A1C > 5.7%13) or covert type 2 diabetes. Another underdiagnosed but very common condition, obstructive sleep apnea, can greatly affect insulin sensitivity and has been associated with lipid abnormalities and metabolic syndrome.14

EXAMINE YOUR PATIENT

The physical exam is an essential component of assessment for patients with high triglycerides. As discussed, elevated triglycerides and low HDL are hallmarks for insulin resistance. As triglyceride levels are affected by obesity and body fat distribution, measuring BMI and assessing for visceral adiposity are an important part of the physical exam.4

The physical exam may also yield dermatologic clues, such as skin tags or acanthosis nigricans, a dark, velvety lesion usually found on the posterior and lateral neck creases, axillae, groin, and elbows.13 In rare cases—usually those with genetic involvement from a familial lipid metabolism disorder—patients may exhibit xanthomas. These cutaneous, lipid-rich lesions can appear as flat, yellowish plaques on various parts of the body, such as the eyelids (xanthelasma) or tendons of the hands, feet, and heels. Widespread, eruptive xanthomas, which manifest as pruritic pink papules with creamy centers, are associated with severe emergent triglyceride elevation and pancreatitis.10

CONSIDER NONPHARMACOLOGIC MANAGEMENT

In mild to moderate hypertriglyceridemia, intensive lifestyle changes are considered firstline therapy. Weight loss is recommended in obese patients; a 5% to 10% reduction in body weight can lower triglycerides by 20%.15

A quick 24-hour diet recall, including beverages, is helpful for identifying key issues. The goal should be to reduce carbohydrates—in particular, simple, high glycemic index, processed foods—as well as total and saturated fats. A substantial problem in our population is the consumption of high-fructose beverages and fruit juices. Referral to a dietitian can be very helpful, not only for initial meal planning but also for continuing counseling on successful long-term weight loss and maintenance.

Exercise is also very helpful for improving lipid parameters. A daily minimum of 30 to 60 minutes of intermittent aerobic exercise or mild resistance exercise has been shown to reduce triglyceride levels.10

PRESCRIBE APPROPRIATELY

The most important indication for treatment of hypertriglyceridemia is reduction of CVD risk. However, in patients with very high triglyceride levels (> 500 mg/dL), the goal is to decrease risk for life-threatening pancreatitis.15 Lipid-lowering medications and dietary restrictions should be promptly employed.

There are medications, as discussed earlier, that specifically lower triglycerides. Fibrates offer the most robust decrease, with a 20% to 50% reduction in triglyceride levels. Fenofibrate is considered a safer option when used in combination with a statin, due to the risk for significant muscle toxicity with gemfibrozil. There is some evidence that adding a fibrate may actually increase risk for pancreatitis; since this risk is otherwise low in patients with mild to moderate triglyceride elevation, the addition of a fibrate to their regimen should be avoided.3

Statins are the drug of choice when CV risk reduction is the goal (for patients with hypertriglyceridemia < 500 mg/dL). In addition to lowering LDL, statins can reduce triglycerides by 7% to 30%, depending on the dose.15

Other triglyceride-lowering medications include omega-3 fatty acids and niacin preparations. Prescription-strength omega-3 fatty acids have been found to lower serum triglyceride levels by 50% or more; the newest preparation, icosapent ethyl, demonstrated up to 45% reduction without significant effect on LDL levels.3 (Other preparations have been shown to substantially increase LDL in many cases.) Niacin (1,500 to 2,000 mg/d) can decrease triglycerides by 15% to 25%. However, it is no longer recommended for CV risk reduction; recent data indicate it may increase stroke risk when used in combination with statins.3,10 In April 2016, the FDA revoked its approval of the co-administration of niacin and fenofibrate with statin therapy, due to a lack of CV benefit.16

Other secondline options to consider for patients with insulin resistance or diabetes are metformin and pioglitazone. These medications have been shown to improve insulin sensitivity and decrease LDL and triglycerides in patients with prediabetes. Pioglitazone has proven beneficial in the treatment of steatohepatitis.17 Insulin is an excellent rapid triglyceride-lowering agent for patients with diabetes. It is important to reinforce that reduction of glucose is a key component in reduction of triglyceride levels.3

CONCLUSION

Hypertriglyceridemia is a complex condition that requires individualized and comprehensive management strategies. Clinicians must be able to identify and address secondary causes. Treatment options should be tailored to decrease CV and pancreatitis risk, and medication recommendations should be evidenced based and carefully selected to mitigate potential adverse effects. Patients should receive education and lifestyle management support to help motivate and equip them to employ strategies to improve their health.

Screening for cardiovascular (CV) risk often includes a routine serum fasting lipid profile. However, with the focus on LDL cholesterol, triglyceride measurement is frequently overlooked. Yet this element of the lipid profile is particularly important, given its strong association with not only atherosclerotic coronary heart disease but also pancreatitis.

Hypertriglyceridemia is defined as a serum triglyceride level that exceeds 150 mg/dL. In the US, an estimated 25% of patients have hypertriglyceridemia.1 Of these, 33.1% have “borderline high” triglyceride levels (150 to 199 mg/dL), 17.8% have “high” levels (200 to 499 mg/dL), and 1.7% have “very high” levels (> 500 mg/dL).1,2

Most of the time, hypertriglyceridemia is caused (or at least exacerbated) by underlying etiology. The best way to identify and manage these secondary causes is through a systematic approach.

CONSIDER THE EVIDENCE

For mild to moderately elevated (borderline high) triglyceride levels, our reflex reaction may be to recommend a triglyceride-lowering medication, such as fenofibrate. But this may not be the best answer. Although there is increasing evidence of an independent association between elevated triglyceride levels and CV risk, it remains unclear whether targeting them specifically can reduce that risk.3

In well-designed, peer-reviewed clinical trials, statins have been shown to reduce CV risk in patients with known cardiovascular disease (CVD) and those at high risk for CVD, as well as in primary prevention. However, these trials also suggest that significant residual CV risk remains after statin therapy.4

Several trials have attempted to prove residual risk reduction following combination therapy including statins—with inconclusive results:

ACCORD: Fenofibrate showed no overall macrovascular benefit when added to a statin in patients with type 2 diabetes and a triglyceride level < 204 mg/dL.3,5

AIM-HIGH: There was a 25% reduction in triglyceride levels when niacin was added to a regimen of a statin +/- ezetimibe, with an aggressive LDL treatment target (40 to 80 mg/dL). But the study was stopped early due to the lack of expected reduction in CVD events.4,6

JELIS: A reduction in major CV events was seen with 1,800 mg/d of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) supplementation plus a low-dose statin, compared to statin monotherapy. However, there was minimal change in triglyceride levels, leading the researchers to hypothesize that multiple mechanisms—such as decreasing oxidative stress, platelet aggregation, plaque formation and stabilization—contributed to the outcome.4,7

Informed by the JELIS results, the much-anticipated REDUCE-IT trial is currently in progress to address the lingering question of whether combination therapy can reduce residual CV risk. In this trial, EPA omega-3 fatty acid is being added to the regimen of statin-treated patients with persistently elevated triglycerides. Results are expected in 2017 to 2018.8

Remember that a triglyceride level of 150 mg/dL is a parameter—it does not represent a therapeutic target. There is insufficient evidence that treating to this level improves CV risk beyond LDL target recommendations.7

The National Lipid Association Expert Panel’s consensus view is that non-HDL is a better primary target than triglycerides alone or LDL. Using non-HDL as a target for intervention also simplifies the management of patients with high triglycerides (200 to 499 mg/dL). The non-HDL goal is considered to be 30 mg/dL greater than the LDL target. For patients with diabetes and those with CVD, the individualized non-HDL targets are 130 mg/dL and 100 mg/dL, respectively.9

REVIEW THE MEDICATION LIST

Several commonly used medications, including ß-blockers and thiazide diuretics, can increase triglyceride levels.10 Other medications with exacerbating effects on triglycerides include corticosteroids, retrovirals, immunosuppressants, retinoids, and some antipsychotics.10 Bile acid sequestrants (eg, colesevelam) should be avoided in patients with elevated triglycerides (> 200 mg/dL).7

In women, oral estrogen (ie, menopausal hormone replacement and oral birth control) can greatly exacerbate triglyceride levels, making transdermal delivery a better option. Tamoxifen, the hormonal medication used for breast cancer prophylaxis, can also increase triglyceride levels.11

LOOK FOR UNDERLYING CONDITIONS

Among those to consider: Hypothyroidism is common and easily ruled out by a simple blood test. Nephrotic syndrome should be ruled out, particularly in patients with concomitant renal dysfunction and peripheral edema, by checking a random urine protein-to-creatinine ratio or 24-hour urine for protein. Other factors that should be explored because of their potential effect on lipid metabolism include obesity and excessive intake of sugary beverages (ie, soda, fruit juice) and alcohol.11

High triglyceride levels occurring with low HDL are characteristic of insulin resistance and concerning for metabolic syndrome and/or polycystic ovarian syndrome.3,12 Often, patients will have underlying prediabetes (fasting glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL or random glucose ≥ 140 mg/dL with an A1C > 5.7%13) or covert type 2 diabetes. Another underdiagnosed but very common condition, obstructive sleep apnea, can greatly affect insulin sensitivity and has been associated with lipid abnormalities and metabolic syndrome.14

EXAMINE YOUR PATIENT

The physical exam is an essential component of assessment for patients with high triglycerides. As discussed, elevated triglycerides and low HDL are hallmarks for insulin resistance. As triglyceride levels are affected by obesity and body fat distribution, measuring BMI and assessing for visceral adiposity are an important part of the physical exam.4

The physical exam may also yield dermatologic clues, such as skin tags or acanthosis nigricans, a dark, velvety lesion usually found on the posterior and lateral neck creases, axillae, groin, and elbows.13 In rare cases—usually those with genetic involvement from a familial lipid metabolism disorder—patients may exhibit xanthomas. These cutaneous, lipid-rich lesions can appear as flat, yellowish plaques on various parts of the body, such as the eyelids (xanthelasma) or tendons of the hands, feet, and heels. Widespread, eruptive xanthomas, which manifest as pruritic pink papules with creamy centers, are associated with severe emergent triglyceride elevation and pancreatitis.10

CONSIDER NONPHARMACOLOGIC MANAGEMENT

In mild to moderate hypertriglyceridemia, intensive lifestyle changes are considered firstline therapy. Weight loss is recommended in obese patients; a 5% to 10% reduction in body weight can lower triglycerides by 20%.15

A quick 24-hour diet recall, including beverages, is helpful for identifying key issues. The goal should be to reduce carbohydrates—in particular, simple, high glycemic index, processed foods—as well as total and saturated fats. A substantial problem in our population is the consumption of high-fructose beverages and fruit juices. Referral to a dietitian can be very helpful, not only for initial meal planning but also for continuing counseling on successful long-term weight loss and maintenance.

Exercise is also very helpful for improving lipid parameters. A daily minimum of 30 to 60 minutes of intermittent aerobic exercise or mild resistance exercise has been shown to reduce triglyceride levels.10

PRESCRIBE APPROPRIATELY

The most important indication for treatment of hypertriglyceridemia is reduction of CVD risk. However, in patients with very high triglyceride levels (> 500 mg/dL), the goal is to decrease risk for life-threatening pancreatitis.15 Lipid-lowering medications and dietary restrictions should be promptly employed.

There are medications, as discussed earlier, that specifically lower triglycerides. Fibrates offer the most robust decrease, with a 20% to 50% reduction in triglyceride levels. Fenofibrate is considered a safer option when used in combination with a statin, due to the risk for significant muscle toxicity with gemfibrozil. There is some evidence that adding a fibrate may actually increase risk for pancreatitis; since this risk is otherwise low in patients with mild to moderate triglyceride elevation, the addition of a fibrate to their regimen should be avoided.3

Statins are the drug of choice when CV risk reduction is the goal (for patients with hypertriglyceridemia < 500 mg/dL). In addition to lowering LDL, statins can reduce triglycerides by 7% to 30%, depending on the dose.15

Other triglyceride-lowering medications include omega-3 fatty acids and niacin preparations. Prescription-strength omega-3 fatty acids have been found to lower serum triglyceride levels by 50% or more; the newest preparation, icosapent ethyl, demonstrated up to 45% reduction without significant effect on LDL levels.3 (Other preparations have been shown to substantially increase LDL in many cases.) Niacin (1,500 to 2,000 mg/d) can decrease triglycerides by 15% to 25%. However, it is no longer recommended for CV risk reduction; recent data indicate it may increase stroke risk when used in combination with statins.3,10 In April 2016, the FDA revoked its approval of the co-administration of niacin and fenofibrate with statin therapy, due to a lack of CV benefit.16

Other secondline options to consider for patients with insulin resistance or diabetes are metformin and pioglitazone. These medications have been shown to improve insulin sensitivity and decrease LDL and triglycerides in patients with prediabetes. Pioglitazone has proven beneficial in the treatment of steatohepatitis.17 Insulin is an excellent rapid triglyceride-lowering agent for patients with diabetes. It is important to reinforce that reduction of glucose is a key component in reduction of triglyceride levels.3

CONCLUSION

Hypertriglyceridemia is a complex condition that requires individualized and comprehensive management strategies. Clinicians must be able to identify and address secondary causes. Treatment options should be tailored to decrease CV and pancreatitis risk, and medication recommendations should be evidenced based and carefully selected to mitigate potential adverse effects. Patients should receive education and lifestyle management support to help motivate and equip them to employ strategies to improve their health.

1. CDC. Trends in elevated triglyceride in adults: United States, 2001-2012. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db198.pdf. Accessed December 27, 2016.

2. Maki KC, Bays HE, Dicklin MR. Treatment options for the management of hypertriglyceridemia: strategies based on the best-available evidence. J Clin Lipidol. 2012;6(5):413-426.

3. Rosenson RS. Approach to the patient with hypertriglyceridemia. www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-the-patient-with-hypertriglyceridemia. Accessed December 28, 2016.

4. Talayero BG, Sacks FM. The role of triglycerides in atherosclerosis. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2011;13(6): 544-552.

5. Ginsberg HN, Elam MB, Lovato LC, et al; ACCORD Study Group. Effects of combination lipid therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010; 362(17):1563-1574.

6. AIM-HIGH Investigators. The role of niacin in raising high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to reduce cardiovascular events in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and optimally treated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Rationale and study design. The Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic syndrome with low HDL/high triglycerides: impact on Global Health outcomes (AIM-HIGH). Am Heart J. 2011;161(3):471-477.

7. Miller M, Stone NJ, Ballantyne C, et al. Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123(20):2292-2333.

8. Borow KM, Nelson JR, Mason RP. Biologic plausibility, cellular effects, and molecular mechanisms of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) in atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2015;242(1):357-366.

9. Jacobson TA, Ito MK, Maki KC, et al. National Lipid Association recommendations for patient-centered management of dyslipidemia. J Clin Lipidol. 2015;9(2):129-169.

10. Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, et al. Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012; 97(9):2969-2989.

11. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 pt B):2889-2934.

12. Amini L, Sadeghi MR, Oskuie F, Maleki H. Lipid profile in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Crescent J Med Biol Sci. 2014;1(4):147-150.

13. Mantzoros C. Insulin resistance: definition and clinical spectrum. www.uptodate.com/contents/insulin-resistance-definition-and-clinical-spectrum. Accessed December 28, 2016.

14. Lin M, Lin H, Lee P, et al. Beneficial effect of continuous positive airway pressure on lipid profiles in obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-analysis. Sleep Breath. 2015;19(3):809-817.

15. Kaur J. A comprehensive review on metabolic syndrome. Cardiol Res Pract. 2014;2014:943162.

16. FDA. Withdrawal of approval of indications related to the coadministration with statins in applications for niacin extended-release tablets and fenofibric acid delayed-release capsules. https://s3.amazonaws.com/public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2016-08887.pdf. Accessed December 28, 2016.

17. Mazza A, Fruci B, Garinis GA, et al. The role of metformin in the management of NAFLD. Exp Diabetes Res. 2012;2012: 716404.

1. CDC. Trends in elevated triglyceride in adults: United States, 2001-2012. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db198.pdf. Accessed December 27, 2016.

2. Maki KC, Bays HE, Dicklin MR. Treatment options for the management of hypertriglyceridemia: strategies based on the best-available evidence. J Clin Lipidol. 2012;6(5):413-426.

3. Rosenson RS. Approach to the patient with hypertriglyceridemia. www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-the-patient-with-hypertriglyceridemia. Accessed December 28, 2016.

4. Talayero BG, Sacks FM. The role of triglycerides in atherosclerosis. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2011;13(6): 544-552.

5. Ginsberg HN, Elam MB, Lovato LC, et al; ACCORD Study Group. Effects of combination lipid therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010; 362(17):1563-1574.

6. AIM-HIGH Investigators. The role of niacin in raising high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to reduce cardiovascular events in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and optimally treated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Rationale and study design. The Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic syndrome with low HDL/high triglycerides: impact on Global Health outcomes (AIM-HIGH). Am Heart J. 2011;161(3):471-477.

7. Miller M, Stone NJ, Ballantyne C, et al. Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123(20):2292-2333.

8. Borow KM, Nelson JR, Mason RP. Biologic plausibility, cellular effects, and molecular mechanisms of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) in atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2015;242(1):357-366.

9. Jacobson TA, Ito MK, Maki KC, et al. National Lipid Association recommendations for patient-centered management of dyslipidemia. J Clin Lipidol. 2015;9(2):129-169.

10. Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, et al. Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012; 97(9):2969-2989.

11. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 pt B):2889-2934.

12. Amini L, Sadeghi MR, Oskuie F, Maleki H. Lipid profile in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Crescent J Med Biol Sci. 2014;1(4):147-150.

13. Mantzoros C. Insulin resistance: definition and clinical spectrum. www.uptodate.com/contents/insulin-resistance-definition-and-clinical-spectrum. Accessed December 28, 2016.

14. Lin M, Lin H, Lee P, et al. Beneficial effect of continuous positive airway pressure on lipid profiles in obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-analysis. Sleep Breath. 2015;19(3):809-817.

15. Kaur J. A comprehensive review on metabolic syndrome. Cardiol Res Pract. 2014;2014:943162.

16. FDA. Withdrawal of approval of indications related to the coadministration with statins in applications for niacin extended-release tablets and fenofibric acid delayed-release capsules. https://s3.amazonaws.com/public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2016-08887.pdf. Accessed December 28, 2016.

17. Mazza A, Fruci B, Garinis GA, et al. The role of metformin in the management of NAFLD. Exp Diabetes Res. 2012;2012: 716404.

Kidney Disease Progression: How to Attenuate Risk

Q)I overheard a conversation at the hospital in which one of the nephrologists told an internist that allopurinol is better than other medications for treating gout because it slows the progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD). What does the data say?

CKD is a growing problem in America; the number of adults with CKD doubled from 2000 to 2008.1 Gout is considered an independent risk factor for CKD progression.2 Some randomized contr

A recent large retrospective review of Medicare charts assessed the correlation between use and dose of allopurinol and incidence of renal failure in patients older than 65.1 The researchers found that, compared with lower doses, allopurinol doses of 200 to 299 mg/d and > 300 mg/d were associated with a significantly lower hazard ratio for kidney failure, in a multivariate-adjusted model. The findings therefore suggest that doses > 199 mg may slow progression to kidney failure in the elderly.

Despite the strengths of this study, it is worth noting that it did not consider stage of kidney disease, nor did it distinguish comorbidities of the patients. The retrospective chart review format did not allow for identification of concurrent medication use (including OTC and herbal products).

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases is currently conducting an RCT to investigate the renoprotective effects of allopurinol versus placebo in diabetic patients. (Clinical Trials.gov identifier: NCT02017171). Enrollment was completed in 2014, and results are expected in June 2019.

One important proviso about allopurinol: While it is inexpensive and generally well tolerated, prescribers should be aware of rare sensitivity reactions, particularly Stevens-Johnson syndrome. —MRS

Mary Rogers Sorey, MSN

Division of Nephrology and Hypertension at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville

1. Singh JA, Yu S. Are allopurinol dose and duration of use nephroprotective in the elderly? A Medicare claims study of allopurinol use and incident renal failure. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016 Jun 13. [Epub ahead of print]

2. Roughley MJ, Belcher J, Mallen CD, Roddy E. Gout and risk of chronic kidney disease and nephrolithiasis: meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:90.

3. Kanbay M, Huddam B, Azak A, et al. A randomized study of allopurinol on endothelial function and estimated glomerular filtration rate in asymptomatic hyperuricemic subjects with normal renal function. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(8):1887-1894.

Q)I overheard a conversation at the hospital in which one of the nephrologists told an internist that allopurinol is better than other medications for treating gout because it slows the progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD). What does the data say?

CKD is a growing problem in America; the number of adults with CKD doubled from 2000 to 2008.1 Gout is considered an independent risk factor for CKD progression.2 Some randomized contr

A recent large retrospective review of Medicare charts assessed the correlation between use and dose of allopurinol and incidence of renal failure in patients older than 65.1 The researchers found that, compared with lower doses, allopurinol doses of 200 to 299 mg/d and > 300 mg/d were associated with a significantly lower hazard ratio for kidney failure, in a multivariate-adjusted model. The findings therefore suggest that doses > 199 mg may slow progression to kidney failure in the elderly.

Despite the strengths of this study, it is worth noting that it did not consider stage of kidney disease, nor did it distinguish comorbidities of the patients. The retrospective chart review format did not allow for identification of concurrent medication use (including OTC and herbal products).

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases is currently conducting an RCT to investigate the renoprotective effects of allopurinol versus placebo in diabetic patients. (Clinical Trials.gov identifier: NCT02017171). Enrollment was completed in 2014, and results are expected in June 2019.

One important proviso about allopurinol: While it is inexpensive and generally well tolerated, prescribers should be aware of rare sensitivity reactions, particularly Stevens-Johnson syndrome. —MRS

Mary Rogers Sorey, MSN

Division of Nephrology and Hypertension at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville

Q)I overheard a conversation at the hospital in which one of the nephrologists told an internist that allopurinol is better than other medications for treating gout because it slows the progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD). What does the data say?

CKD is a growing problem in America; the number of adults with CKD doubled from 2000 to 2008.1 Gout is considered an independent risk factor for CKD progression.2 Some randomized contr

A recent large retrospective review of Medicare charts assessed the correlation between use and dose of allopurinol and incidence of renal failure in patients older than 65.1 The researchers found that, compared with lower doses, allopurinol doses of 200 to 299 mg/d and > 300 mg/d were associated with a significantly lower hazard ratio for kidney failure, in a multivariate-adjusted model. The findings therefore suggest that doses > 199 mg may slow progression to kidney failure in the elderly.

Despite the strengths of this study, it is worth noting that it did not consider stage of kidney disease, nor did it distinguish comorbidities of the patients. The retrospective chart review format did not allow for identification of concurrent medication use (including OTC and herbal products).

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases is currently conducting an RCT to investigate the renoprotective effects of allopurinol versus placebo in diabetic patients. (Clinical Trials.gov identifier: NCT02017171). Enrollment was completed in 2014, and results are expected in June 2019.

One important proviso about allopurinol: While it is inexpensive and generally well tolerated, prescribers should be aware of rare sensitivity reactions, particularly Stevens-Johnson syndrome. —MRS

Mary Rogers Sorey, MSN

Division of Nephrology and Hypertension at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville

1. Singh JA, Yu S. Are allopurinol dose and duration of use nephroprotective in the elderly? A Medicare claims study of allopurinol use and incident renal failure. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016 Jun 13. [Epub ahead of print]

2. Roughley MJ, Belcher J, Mallen CD, Roddy E. Gout and risk of chronic kidney disease and nephrolithiasis: meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:90.

3. Kanbay M, Huddam B, Azak A, et al. A randomized study of allopurinol on endothelial function and estimated glomerular filtration rate in asymptomatic hyperuricemic subjects with normal renal function. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(8):1887-1894.

1. Singh JA, Yu S. Are allopurinol dose and duration of use nephroprotective in the elderly? A Medicare claims study of allopurinol use and incident renal failure. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016 Jun 13. [Epub ahead of print]

2. Roughley MJ, Belcher J, Mallen CD, Roddy E. Gout and risk of chronic kidney disease and nephrolithiasis: meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:90.

3. Kanbay M, Huddam B, Azak A, et al. A randomized study of allopurinol on endothelial function and estimated glomerular filtration rate in asymptomatic hyperuricemic subjects with normal renal function. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(8):1887-1894.

Kidney Disease Progression: How to Calculate Risk

Q)When I diagnose patients with minor kidney disease, they often ask if they will require dialysis. I know it is unlikely, but I wish I could give them a better answer. Can you help me?

The diagnosis of chronic kidney disease (CKD) is understandably concerning for many patients. Being able to estimate CKD progression helps patients gain a better understanding of their condition while allowing clinicians to develop more personalized care plans. Tangri and colleagues developed a model that can be used to predict risk for kidney failure requiring dialysis or transplantation in patients with stage III to V CKD. This model has been validated in multiple diverse populations in North America and worldwide.1

The Kidney Failure Risk Equation (found at www.kidneyfailurerisk.com) uses four variables—age, gender, glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR)—to assess two- and five-year risk for kidney failure.1,2 For example

- A 63-year-old woman with a GFR of 45 mL/min and an ACR of 30 mg/g has a 0.4% two-year risk and a 1.3% five-year risk for progression to kidney failure requiring dialysis or transplant.1

- Alternatively, a 55-year-old man with a GFR of 38 mL/min and an ACR of 150 mg/g has a 2.9% two-year risk and a 9% five-year risk for progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD).1

Per proposed thresholds, patients with a score < 5% would be deemed “low risk”; with scores of 5% to 15%, “intermediate risk”; and with scores > 15%, “high risk.”1,2

The Kidney Failure Risk Equation can be incorporated into clinic visits to provide context for lab results. For patients with low risk for progression, optimal care and lifestyle measures can be reinforced. For those with intermediate or high risk, more intensive treatments and appropriate referrals can be initiated. (The National Kidney Foundation advises referral when a patient’s estimated GFR is 20 mL/min or the urine ACR is ≥ 300 mg/g.3) Providing a numeric risk for progression can help alleviate the patient’s uncertainty surrounding the diagnosis of CKD. —NDM

Nicole D. McCormick, MS, MBA, NP-C, CCTC

University of Colorado Renal Transplant Clinic, Aurora, Colorado

1. Tangri N, Grams ME, Levey AS, et al. Multinational assessment of accuracy of equations for predicting risk of kidney failure: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;315(2):164-174.

2. Tangri N, Stevens LA, Griffith J, et al. A predictive model for progression of chronic kidney disease to kidney failure. JAMA. 2011;305(15):1553-1559.

3. National Kidney Foundation. Renal Replacement Therapy: What the PCP Needs to Know. www.kidney.org/sites/default/files/PCP%20in%20a%20Box%20-%20Module%203.pptx. Accessed December 5, 2016.

Q)When I diagnose patients with minor kidney disease, they often ask if they will require dialysis. I know it is unlikely, but I wish I could give them a better answer. Can you help me?

The diagnosis of chronic kidney disease (CKD) is understandably concerning for many patients. Being able to estimate CKD progression helps patients gain a better understanding of their condition while allowing clinicians to develop more personalized care plans. Tangri and colleagues developed a model that can be used to predict risk for kidney failure requiring dialysis or transplantation in patients with stage III to V CKD. This model has been validated in multiple diverse populations in North America and worldwide.1

The Kidney Failure Risk Equation (found at www.kidneyfailurerisk.com) uses four variables—age, gender, glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR)—to assess two- and five-year risk for kidney failure.1,2 For example

- A 63-year-old woman with a GFR of 45 mL/min and an ACR of 30 mg/g has a 0.4% two-year risk and a 1.3% five-year risk for progression to kidney failure requiring dialysis or transplant.1

- Alternatively, a 55-year-old man with a GFR of 38 mL/min and an ACR of 150 mg/g has a 2.9% two-year risk and a 9% five-year risk for progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD).1

Per proposed thresholds, patients with a score < 5% would be deemed “low risk”; with scores of 5% to 15%, “intermediate risk”; and with scores > 15%, “high risk.”1,2

The Kidney Failure Risk Equation can be incorporated into clinic visits to provide context for lab results. For patients with low risk for progression, optimal care and lifestyle measures can be reinforced. For those with intermediate or high risk, more intensive treatments and appropriate referrals can be initiated. (The National Kidney Foundation advises referral when a patient’s estimated GFR is 20 mL/min or the urine ACR is ≥ 300 mg/g.3) Providing a numeric risk for progression can help alleviate the patient’s uncertainty surrounding the diagnosis of CKD. —NDM

Nicole D. McCormick, MS, MBA, NP-C, CCTC

University of Colorado Renal Transplant Clinic, Aurora, Colorado

Q)When I diagnose patients with minor kidney disease, they often ask if they will require dialysis. I know it is unlikely, but I wish I could give them a better answer. Can you help me?

The diagnosis of chronic kidney disease (CKD) is understandably concerning for many patients. Being able to estimate CKD progression helps patients gain a better understanding of their condition while allowing clinicians to develop more personalized care plans. Tangri and colleagues developed a model that can be used to predict risk for kidney failure requiring dialysis or transplantation in patients with stage III to V CKD. This model has been validated in multiple diverse populations in North America and worldwide.1

The Kidney Failure Risk Equation (found at www.kidneyfailurerisk.com) uses four variables—age, gender, glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR)—to assess two- and five-year risk for kidney failure.1,2 For example

- A 63-year-old woman with a GFR of 45 mL/min and an ACR of 30 mg/g has a 0.4% two-year risk and a 1.3% five-year risk for progression to kidney failure requiring dialysis or transplant.1

- Alternatively, a 55-year-old man with a GFR of 38 mL/min and an ACR of 150 mg/g has a 2.9% two-year risk and a 9% five-year risk for progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD).1

Per proposed thresholds, patients with a score < 5% would be deemed “low risk”; with scores of 5% to 15%, “intermediate risk”; and with scores > 15%, “high risk.”1,2

The Kidney Failure Risk Equation can be incorporated into clinic visits to provide context for lab results. For patients with low risk for progression, optimal care and lifestyle measures can be reinforced. For those with intermediate or high risk, more intensive treatments and appropriate referrals can be initiated. (The National Kidney Foundation advises referral when a patient’s estimated GFR is 20 mL/min or the urine ACR is ≥ 300 mg/g.3) Providing a numeric risk for progression can help alleviate the patient’s uncertainty surrounding the diagnosis of CKD. —NDM

Nicole D. McCormick, MS, MBA, NP-C, CCTC

University of Colorado Renal Transplant Clinic, Aurora, Colorado

1. Tangri N, Grams ME, Levey AS, et al. Multinational assessment of accuracy of equations for predicting risk of kidney failure: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;315(2):164-174.

2. Tangri N, Stevens LA, Griffith J, et al. A predictive model for progression of chronic kidney disease to kidney failure. JAMA. 2011;305(15):1553-1559.

3. National Kidney Foundation. Renal Replacement Therapy: What the PCP Needs to Know. www.kidney.org/sites/default/files/PCP%20in%20a%20Box%20-%20Module%203.pptx. Accessed December 5, 2016.

1. Tangri N, Grams ME, Levey AS, et al. Multinational assessment of accuracy of equations for predicting risk of kidney failure: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;315(2):164-174.

2. Tangri N, Stevens LA, Griffith J, et al. A predictive model for progression of chronic kidney disease to kidney failure. JAMA. 2011;305(15):1553-1559.

3. National Kidney Foundation. Renal Replacement Therapy: What the PCP Needs to Know. www.kidney.org/sites/default/files/PCP%20in%20a%20Box%20-%20Module%203.pptx. Accessed December 5, 2016.

MS & Pregnancy: What's Safe?

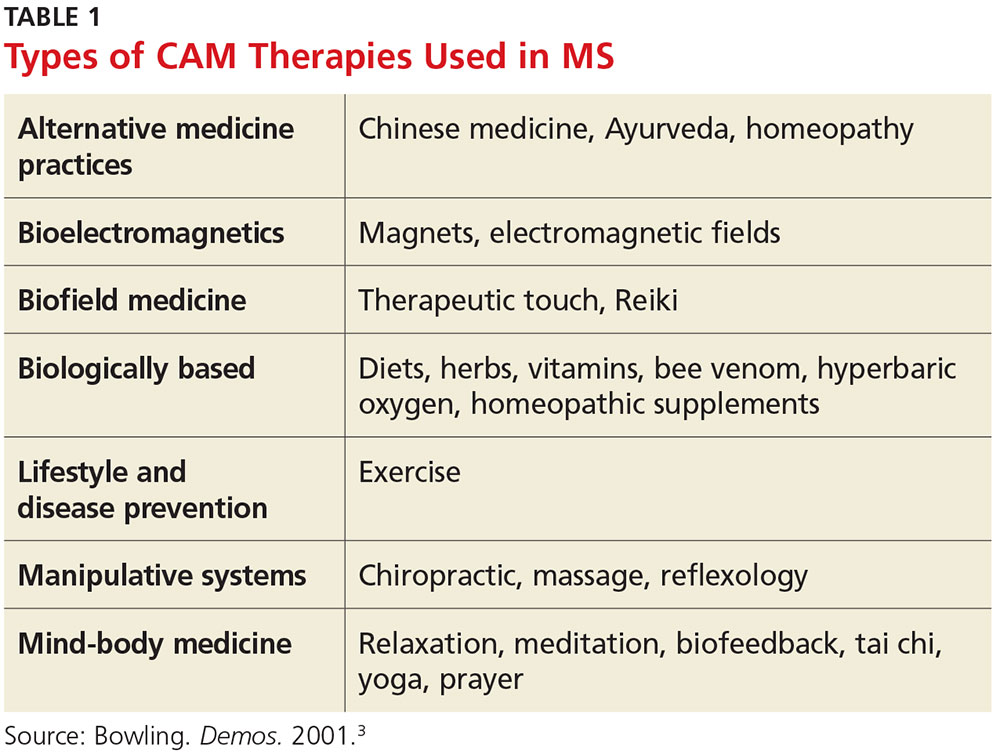

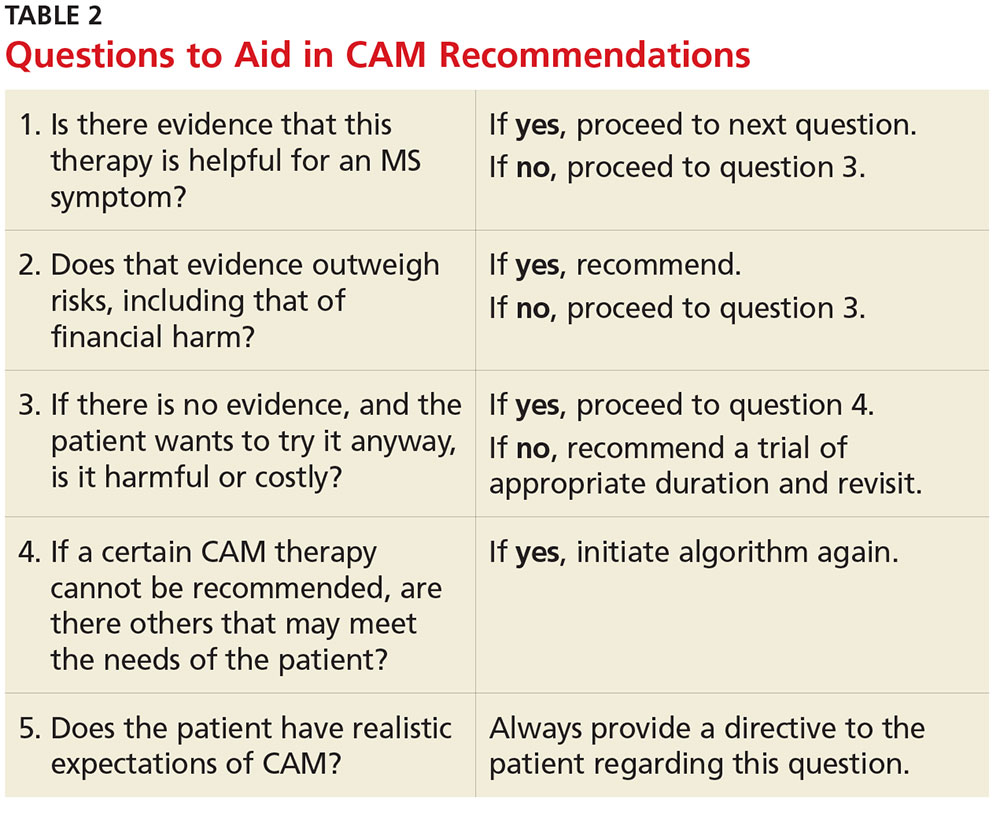

Q)What are the considerations and recommendations for pregnancy and breastfeeding in women with multiple sclerosis? When should women discontinue their disease-modifying therapies?

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory, demyelinating, degenerative disease. Three times more common in women than men, it may affect pregnancy planning and childbearing experiences.6 Evidence demonstrates a reduction in annualized relapse rate during pregnancy and the postpartum period with exclusive breastfeeding. Therefore, pregnancy and exclusive breastfeeding provide a favorable immunomodulatory effect in women with MS, which combats the increased relapse risk associated with the postpartum period.7,8

Reproductive education—including conception, pregnancy, and breastfeeding—is critical for patients with MS and their partners during a woman’s childbearing years. However, women with MS do not require special considerations during pregnancy unless they have remarkable disability. As soon as these women and their partners decide upon pregnancy, a plan should be established that includes a discussion about potential risks to the fetus due to drug exposure, as well as risks to the mother. The goal should be to minimize risk for disease activity and optimize the health of the baby.

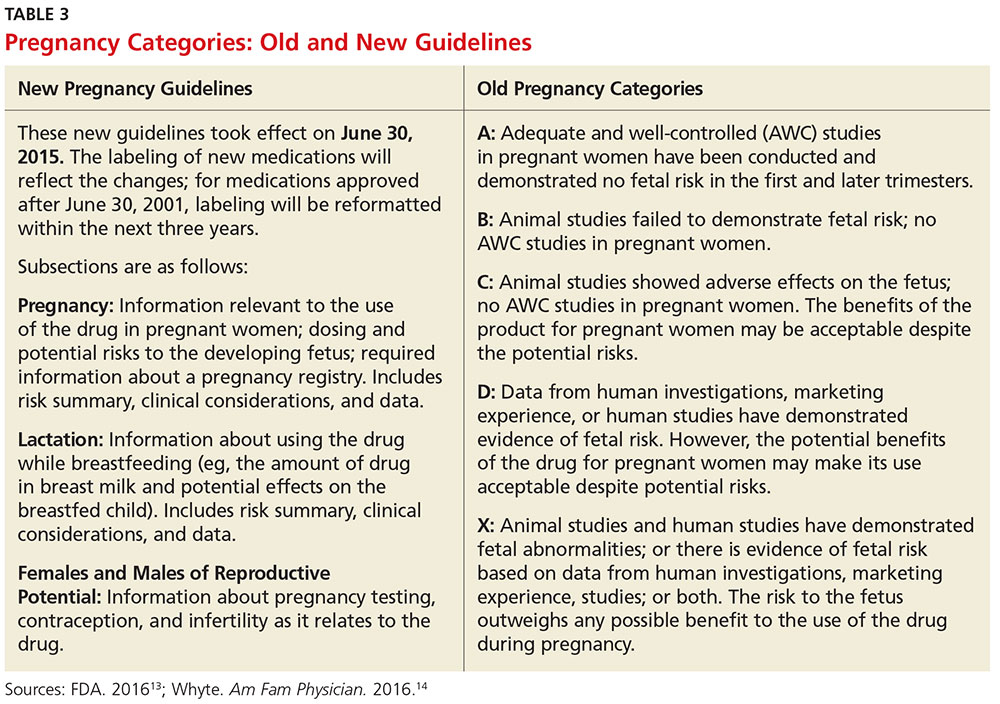

Use of DMTs during conception, pregnancy, and breastfeeding. All disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) are usually discontinued during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Common practice among MS experts is to discontinue DMTs prior to conception, with a few exceptions. There is no consensus about timing of discontinuation and washout period for each DMT. The decision is based on the half-life of each DMT, the opinions of the woman and her partner, and risk tolerance. Note: For the purposes of this discussion, the old pregnancy category designations are used, since they are familiar to clinicians. New guidelines took effect in June 2015; Table 3 outlines the change in format.

Injectables. Glatiramer acetate (GA) is the safest drug in relation to pregnancy and breastfeeding (category B). There is no evidence of congenital malformation or spontaneous abortion. The common recommendation is to discontinue the drug one to two months before conception, although some clinicians allow continuation of the injections throughout pregnancy and into breastfeeding.

Interferon-ßs are category C and therefore pose minimal risk for the fetus. The washout period before conception is two to three months, varying among clinicians. Although there is no evidence of spontaneous abortion or birth defects in humans, animal data show increased risk for abortion.9

Both GA and interferon-ßs are large molecules; there is a very minimal chance that the medication will transmit to the baby via breast milk. Thus, both DMTs are considered safe during lactation.7

Oral MS medications. The three approved MS oral medications are fingolimod, dimethyl fumarate (DMF), and teriflunomide. Fingolimod and DMF are both category C. Women on DMF must discontinue use of the medication one month prior to conception due to its short half-life. There are no reports of birth defects or spontaneous abortion in women taking DMF. Fingolimod needs to be discontinued two months prior to conception. Animal data show evidence for teratogenicity and embryolethality at lower doses of fingolimod than those used in humans.7

Teriflunomide is category X, posing high risk for the health of the fetus. It stays in the blood for approximately eight months after discontinuation of use. Animal data show teratogenicity and embryotoxicity; therefore, teriflunomide is contraindicated in pregnancy. Women on teriflunomide who plan to become pregnant need to undergo an elimination procedure with cholestyramine or charcoal.

Infusions and injections (monoclonal antibodies). The approved monoclonal antibodies include natalizumab, alemtuzumab, and daclizumab. (Currently, use of rituximab in MS is off label, and the FDA is reviewing the efficacy and safety data for ocrelizumab.) The monoclonal antibodies are category C. The recommendation is to discontinue natalizumab one to two months prior to conception and discontinue alemtuzumab four months preconception.10 There is no evidence of spontaneous abortion or birth defects in women on alemtuzumab, but there is potentially increased risk for spontaneous abortion in those on natalizumab.

The spontaneous abortion rate in daclizumab-exposed women is consistent with early pregnancy loss in the general population (12% to 26%). Data on a small number of pregnancies exposed to daclizumab did not suggest an increased risk for adverse fetal or maternal outcomes.11 However, the recommendation is to discontinue daclizumab four months prior to conception. Rituximab should be discontinued 12 months prior to conception, based on the manufacturer recommendation, although it is potentially safe to conceive when the B cell counts return to normal.

Chemotherapy agents. Mitoxantrone is the only FDA-approved chemotherapeutic drug used in MS. However, a few chemotherapy drugs—among them, azathioprine, methotrexate, and cyclophosphamide—are used off label. Chemotherapeutic agents are category D, except methotrexate (category X). Women on category D medications must use a method of birth control for three months after stopping the DMT. Often, clinicians will recommend women initiate GA or interferon during this period, in the hope of minimizing disease activity. Women on mitoxantrone and methotrexate need to use birth control for six months after stopping these immunosuppressive medications, before conceiving.12 These women likely need to switch to a safer pregnancy DMT during the long washout period.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding among women with MS require planning and decision making. The recommendations differ among clinicians and MS experts since there is no definitive evidence about the risks of the DMTs on the mother and/or the fetus. Clinicians should discuss the potential risks with women based on their knowledge and experience, and the data available based on animal research and the pregnancy registries. —ABB-Z

Aliza Bitton Ben-Zacharia, DNP, ANP

President-Elect of IOMSN

Neurology Faculty, Icahn School of Medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital System, New York, New York

6. Tullman MJ. Overview of the epidemiology, diagnosis, and disease progression associated with multiple sclerosis. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(2):S15-S20.

7. Fabian M. Pregnancy in the setting of multiple sclerosis. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2016; 22(3):837-850.

8. Vukusic S, Hutchinson M, Hours M, et al. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis (the PRIMS study): clinical predictors of post-partum relapse. Brain. 2004;127(6):1353-1360.

9. Sandberg-Wollheim M, Alteri E, Moraga MS, Kornmann G. Pregnancy outcomes in multiple sclerosis following subcutaneous interferon beta-1a therapy. Mult Scler. 2011; 17(4):423-430.

10. Coyle PK. Multiple sclerosis in pregnancy. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2014;20(1):42-59.

11. Gold SM, Voskuhl RR. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis: from molecular mechanisms to clinical application. Semin Immunopathol. 2016;38:709.

12. Vukusic S, Marignier R. Multiple sclerosis and pregnancy in the ‘treatment era’. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11(5):280-289.

13. FDA. Pregnancy and lactation labeling (drugs) final rule. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DevelopmentResources/Labeling/ucm093307.htm. Accessed November 2, 2016.

14. Whyte J. FDA implements new labeling for medications used during pregnancy and lactation. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94(1):12-13.

Q)What are the considerations and recommendations for pregnancy and breastfeeding in women with multiple sclerosis? When should women discontinue their disease-modifying therapies?

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory, demyelinating, degenerative disease. Three times more common in women than men, it may affect pregnancy planning and childbearing experiences.6 Evidence demonstrates a reduction in annualized relapse rate during pregnancy and the postpartum period with exclusive breastfeeding. Therefore, pregnancy and exclusive breastfeeding provide a favorable immunomodulatory effect in women with MS, which combats the increased relapse risk associated with the postpartum period.7,8

Reproductive education—including conception, pregnancy, and breastfeeding—is critical for patients with MS and their partners during a woman’s childbearing years. However, women with MS do not require special considerations during pregnancy unless they have remarkable disability. As soon as these women and their partners decide upon pregnancy, a plan should be established that includes a discussion about potential risks to the fetus due to drug exposure, as well as risks to the mother. The goal should be to minimize risk for disease activity and optimize the health of the baby.

Use of DMTs during conception, pregnancy, and breastfeeding. All disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) are usually discontinued during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Common practice among MS experts is to discontinue DMTs prior to conception, with a few exceptions. There is no consensus about timing of discontinuation and washout period for each DMT. The decision is based on the half-life of each DMT, the opinions of the woman and her partner, and risk tolerance. Note: For the purposes of this discussion, the old pregnancy category designations are used, since they are familiar to clinicians. New guidelines took effect in June 2015; Table 3 outlines the change in format.

Injectables. Glatiramer acetate (GA) is the safest drug in relation to pregnancy and breastfeeding (category B). There is no evidence of congenital malformation or spontaneous abortion. The common recommendation is to discontinue the drug one to two months before conception, although some clinicians allow continuation of the injections throughout pregnancy and into breastfeeding.

Interferon-ßs are category C and therefore pose minimal risk for the fetus. The washout period before conception is two to three months, varying among clinicians. Although there is no evidence of spontaneous abortion or birth defects in humans, animal data show increased risk for abortion.9

Both GA and interferon-ßs are large molecules; there is a very minimal chance that the medication will transmit to the baby via breast milk. Thus, both DMTs are considered safe during lactation.7

Oral MS medications. The three approved MS oral medications are fingolimod, dimethyl fumarate (DMF), and teriflunomide. Fingolimod and DMF are both category C. Women on DMF must discontinue use of the medication one month prior to conception due to its short half-life. There are no reports of birth defects or spontaneous abortion in women taking DMF. Fingolimod needs to be discontinued two months prior to conception. Animal data show evidence for teratogenicity and embryolethality at lower doses of fingolimod than those used in humans.7

Teriflunomide is category X, posing high risk for the health of the fetus. It stays in the blood for approximately eight months after discontinuation of use. Animal data show teratogenicity and embryotoxicity; therefore, teriflunomide is contraindicated in pregnancy. Women on teriflunomide who plan to become pregnant need to undergo an elimination procedure with cholestyramine or charcoal.

Infusions and injections (monoclonal antibodies). The approved monoclonal antibodies include natalizumab, alemtuzumab, and daclizumab. (Currently, use of rituximab in MS is off label, and the FDA is reviewing the efficacy and safety data for ocrelizumab.) The monoclonal antibodies are category C. The recommendation is to discontinue natalizumab one to two months prior to conception and discontinue alemtuzumab four months preconception.10 There is no evidence of spontaneous abortion or birth defects in women on alemtuzumab, but there is potentially increased risk for spontaneous abortion in those on natalizumab.

The spontaneous abortion rate in daclizumab-exposed women is consistent with early pregnancy loss in the general population (12% to 26%). Data on a small number of pregnancies exposed to daclizumab did not suggest an increased risk for adverse fetal or maternal outcomes.11 However, the recommendation is to discontinue daclizumab four months prior to conception. Rituximab should be discontinued 12 months prior to conception, based on the manufacturer recommendation, although it is potentially safe to conceive when the B cell counts return to normal.

Chemotherapy agents. Mitoxantrone is the only FDA-approved chemotherapeutic drug used in MS. However, a few chemotherapy drugs—among them, azathioprine, methotrexate, and cyclophosphamide—are used off label. Chemotherapeutic agents are category D, except methotrexate (category X). Women on category D medications must use a method of birth control for three months after stopping the DMT. Often, clinicians will recommend women initiate GA or interferon during this period, in the hope of minimizing disease activity. Women on mitoxantrone and methotrexate need to use birth control for six months after stopping these immunosuppressive medications, before conceiving.12 These women likely need to switch to a safer pregnancy DMT during the long washout period.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding among women with MS require planning and decision making. The recommendations differ among clinicians and MS experts since there is no definitive evidence about the risks of the DMTs on the mother and/or the fetus. Clinicians should discuss the potential risks with women based on their knowledge and experience, and the data available based on animal research and the pregnancy registries. —ABB-Z

Aliza Bitton Ben-Zacharia, DNP, ANP

President-Elect of IOMSN

Neurology Faculty, Icahn School of Medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital System, New York, New York

Q)What are the considerations and recommendations for pregnancy and breastfeeding in women with multiple sclerosis? When should women discontinue their disease-modifying therapies?

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory, demyelinating, degenerative disease. Three times more common in women than men, it may affect pregnancy planning and childbearing experiences.6 Evidence demonstrates a reduction in annualized relapse rate during pregnancy and the postpartum period with exclusive breastfeeding. Therefore, pregnancy and exclusive breastfeeding provide a favorable immunomodulatory effect in women with MS, which combats the increased relapse risk associated with the postpartum period.7,8

Reproductive education—including conception, pregnancy, and breastfeeding—is critical for patients with MS and their partners during a woman’s childbearing years. However, women with MS do not require special considerations during pregnancy unless they have remarkable disability. As soon as these women and their partners decide upon pregnancy, a plan should be established that includes a discussion about potential risks to the fetus due to drug exposure, as well as risks to the mother. The goal should be to minimize risk for disease activity and optimize the health of the baby.

Use of DMTs during conception, pregnancy, and breastfeeding. All disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) are usually discontinued during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Common practice among MS experts is to discontinue DMTs prior to conception, with a few exceptions. There is no consensus about timing of discontinuation and washout period for each DMT. The decision is based on the half-life of each DMT, the opinions of the woman and her partner, and risk tolerance. Note: For the purposes of this discussion, the old pregnancy category designations are used, since they are familiar to clinicians. New guidelines took effect in June 2015; Table 3 outlines the change in format.

Injectables. Glatiramer acetate (GA) is the safest drug in relation to pregnancy and breastfeeding (category B). There is no evidence of congenital malformation or spontaneous abortion. The common recommendation is to discontinue the drug one to two months before conception, although some clinicians allow continuation of the injections throughout pregnancy and into breastfeeding.

Interferon-ßs are category C and therefore pose minimal risk for the fetus. The washout period before conception is two to three months, varying among clinicians. Although there is no evidence of spontaneous abortion or birth defects in humans, animal data show increased risk for abortion.9

Both GA and interferon-ßs are large molecules; there is a very minimal chance that the medication will transmit to the baby via breast milk. Thus, both DMTs are considered safe during lactation.7

Oral MS medications. The three approved MS oral medications are fingolimod, dimethyl fumarate (DMF), and teriflunomide. Fingolimod and DMF are both category C. Women on DMF must discontinue use of the medication one month prior to conception due to its short half-life. There are no reports of birth defects or spontaneous abortion in women taking DMF. Fingolimod needs to be discontinued two months prior to conception. Animal data show evidence for teratogenicity and embryolethality at lower doses of fingolimod than those used in humans.7

Teriflunomide is category X, posing high risk for the health of the fetus. It stays in the blood for approximately eight months after discontinuation of use. Animal data show teratogenicity and embryotoxicity; therefore, teriflunomide is contraindicated in pregnancy. Women on teriflunomide who plan to become pregnant need to undergo an elimination procedure with cholestyramine or charcoal.

Infusions and injections (monoclonal antibodies). The approved monoclonal antibodies include natalizumab, alemtuzumab, and daclizumab. (Currently, use of rituximab in MS is off label, and the FDA is reviewing the efficacy and safety data for ocrelizumab.) The monoclonal antibodies are category C. The recommendation is to discontinue natalizumab one to two months prior to conception and discontinue alemtuzumab four months preconception.10 There is no evidence of spontaneous abortion or birth defects in women on alemtuzumab, but there is potentially increased risk for spontaneous abortion in those on natalizumab.

The spontaneous abortion rate in daclizumab-exposed women is consistent with early pregnancy loss in the general population (12% to 26%). Data on a small number of pregnancies exposed to daclizumab did not suggest an increased risk for adverse fetal or maternal outcomes.11 However, the recommendation is to discontinue daclizumab four months prior to conception. Rituximab should be discontinued 12 months prior to conception, based on the manufacturer recommendation, although it is potentially safe to conceive when the B cell counts return to normal.

Chemotherapy agents. Mitoxantrone is the only FDA-approved chemotherapeutic drug used in MS. However, a few chemotherapy drugs—among them, azathioprine, methotrexate, and cyclophosphamide—are used off label. Chemotherapeutic agents are category D, except methotrexate (category X). Women on category D medications must use a method of birth control for three months after stopping the DMT. Often, clinicians will recommend women initiate GA or interferon during this period, in the hope of minimizing disease activity. Women on mitoxantrone and methotrexate need to use birth control for six months after stopping these immunosuppressive medications, before conceiving.12 These women likely need to switch to a safer pregnancy DMT during the long washout period.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding among women with MS require planning and decision making. The recommendations differ among clinicians and MS experts since there is no definitive evidence about the risks of the DMTs on the mother and/or the fetus. Clinicians should discuss the potential risks with women based on their knowledge and experience, and the data available based on animal research and the pregnancy registries. —ABB-Z

Aliza Bitton Ben-Zacharia, DNP, ANP

President-Elect of IOMSN

Neurology Faculty, Icahn School of Medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital System, New York, New York

6. Tullman MJ. Overview of the epidemiology, diagnosis, and disease progression associated with multiple sclerosis. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(2):S15-S20.

7. Fabian M. Pregnancy in the setting of multiple sclerosis. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2016; 22(3):837-850.

8. Vukusic S, Hutchinson M, Hours M, et al. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis (the PRIMS study): clinical predictors of post-partum relapse. Brain. 2004;127(6):1353-1360.

9. Sandberg-Wollheim M, Alteri E, Moraga MS, Kornmann G. Pregnancy outcomes in multiple sclerosis following subcutaneous interferon beta-1a therapy. Mult Scler. 2011; 17(4):423-430.

10. Coyle PK. Multiple sclerosis in pregnancy. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2014;20(1):42-59.

11. Gold SM, Voskuhl RR. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis: from molecular mechanisms to clinical application. Semin Immunopathol. 2016;38:709.

12. Vukusic S, Marignier R. Multiple sclerosis and pregnancy in the ‘treatment era’. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11(5):280-289.

13. FDA. Pregnancy and lactation labeling (drugs) final rule. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DevelopmentResources/Labeling/ucm093307.htm. Accessed November 2, 2016.