User login

Monoclonal Antibodies in MS

A 19-year-old man was diagnosed with relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS) at age 7 and is currently being treated with an infusible monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapy. Early in the day, he receives an infusion at an outpatient clinic. That night, he begins to experience numbness and tingling in his right upper extremity, which prompts a visit to an urgent care clinic. There, the clinician administers IV fluids to the patient. After his symptoms improve, the patient is discharged home.

The next morning, he has a new onset of left-side shoulder and neck pain with a pulsating headache. The patient reports his symptoms to his primary care provider (PCP), who instructs him to visit the emergency department (ED) for evaluation and treatment of a possible infection.

EXAMINATION

The patient arrives at the ED with a 102.4°F fever, vomiting, cough, mild congestion, diaphoresis, generalized myalgias, and chills. He also reports depression and anxiety, saying that for the past 7 days, “I haven’t felt like my normal self.”

Medical history includes moderate persistent asthma that is not well controlled, status asthmaticus, and use of an electronic vaporizing device for inhaling nicotine and marijuana/tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Besides mAb infusions, his medications include hydrocodone/acetaminophen, prochlorperazine, gabapentin, hydroxyzine, trazodone, albuterol, and montelukast.

Examination reveals vital signs within normal limits. Lab work confirms elevated white blood cell count and absolute neutrophil count. Chest x-ray shows diffuse bilateral interstitial and patchy airspace opacities. He is diagnosed with bilateral pneumonia and is admitted and started on an IV antibiotic.

Within 24 hours, a new chest x-ray shows worsening symptoms. CT of the chest with contrast reveals diffuse bilateral ground-glass and airspace opacities suggestive of acute respiratory distress syndrome; bilateral thickening of the pulmonary interstitium; trace bilateral pleural effusions; increased caliber of the main pulmonary artery; and mediastinal and right hilar lymphadenopathy.

Subsequently, the patient developed sepsis and went into acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. He is transferred to the ICU, and pulmonology is consulted. A bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) reveals neutrophil predominance; fungal, bacterial, and viral cultures are negative. The patient is started on broad-spectrum IV antibiotics and high-dose IV steroids. After 4 days, he begins to improve and is transferred out of the ICU. He is discharged with oral steroids and antibiotics.

Continue to: DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

Fortunately, the PCP and the ED provider identified risk factors that contributed to the patient’s pneumonia and its subsequent worsening to sepsis and acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. The immunosuppressive/immunomodulatory effect of mAb therapy increased the patient’s risk for infection and the severity of infection, which is why vigilant safety monitoring and surveillance is essential with mAb treatment.1 Bloodwork should be performed at least every 6 months and include a complete blood count, complete metabolic panel with differential, and JC virus antibody test. Additionally, urinalysis should be performed prior to every mAb infusion. All testing recommended in the package insert for the patient’s prescribed therapy should be performed.

The patient’s history of asthma and his chronic vaping predisposed him to respiratory infections. In mice studies, exposure to e-cigarette vapor has been shown to be cytotoxic to airway cells and to decrease macrophage and neutrophil antimicrobial function.2 Exposure also alters immunomodulating cytokines in the airway, increases inflammatory markers seen in BAL and serum samples, and increases the virulence of Staphylococcus aureus

TREATMENT AND PATIENT EDUCATION

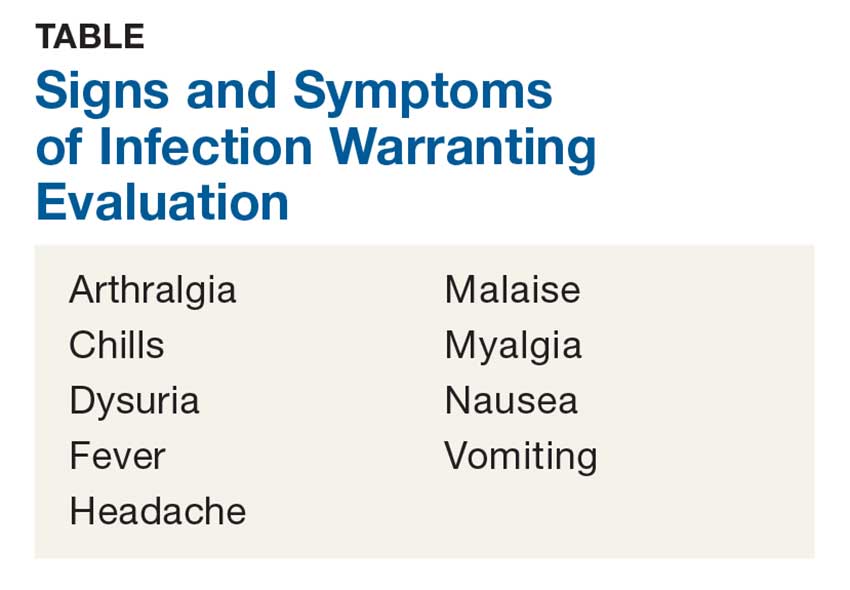

The PCP’s treatment plan included patient education about the importance of infection control measures when receiving a mAb; this includes practicing good hand and environmental hygiene, maintaining vaccinations, avoiding or reducing exposure to individuals who have infections or colds, avoiding large crowds (especially during flu season), and following recommendations for nutrition and hydration. The PCP also discussed how to recognize the early signs and symptoms of an infection—and the need for vigilant safety monitoring. The PCP described available options for smoking cessation, including nicotine replacement products, prescription non-nicotine medications, behavioral therapy, and/or counseling (individual, group or telephone) and discussed the risks associated with consuming nicotine and/or marijuana/THC and using electronic vaporizing devices.

The PCP emphasized the importance of completing the entire course of the oral antibiotics prescribed at discharge. The patient and the PCP agreed to the following plan of care: appointments with a pulmonologist and a neurologist within the next 2 weeks, and follow-up visits with the

1. Celius EG. Infections in patients with multiple sclerosis: implications for disease-modifying therapy. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;136(suppl 201):34-36.

2. Hwang JH, Lyes M, Sladewski K, et al. Electronic cigarette inhalation alters innate immunity and airway cytokines while increasing the virulence of colonizing bacteria. J Mol Med (Berl). 2016;94(6):667-679.

A 19-year-old man was diagnosed with relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS) at age 7 and is currently being treated with an infusible monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapy. Early in the day, he receives an infusion at an outpatient clinic. That night, he begins to experience numbness and tingling in his right upper extremity, which prompts a visit to an urgent care clinic. There, the clinician administers IV fluids to the patient. After his symptoms improve, the patient is discharged home.

The next morning, he has a new onset of left-side shoulder and neck pain with a pulsating headache. The patient reports his symptoms to his primary care provider (PCP), who instructs him to visit the emergency department (ED) for evaluation and treatment of a possible infection.

EXAMINATION

The patient arrives at the ED with a 102.4°F fever, vomiting, cough, mild congestion, diaphoresis, generalized myalgias, and chills. He also reports depression and anxiety, saying that for the past 7 days, “I haven’t felt like my normal self.”

Medical history includes moderate persistent asthma that is not well controlled, status asthmaticus, and use of an electronic vaporizing device for inhaling nicotine and marijuana/tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Besides mAb infusions, his medications include hydrocodone/acetaminophen, prochlorperazine, gabapentin, hydroxyzine, trazodone, albuterol, and montelukast.

Examination reveals vital signs within normal limits. Lab work confirms elevated white blood cell count and absolute neutrophil count. Chest x-ray shows diffuse bilateral interstitial and patchy airspace opacities. He is diagnosed with bilateral pneumonia and is admitted and started on an IV antibiotic.

Within 24 hours, a new chest x-ray shows worsening symptoms. CT of the chest with contrast reveals diffuse bilateral ground-glass and airspace opacities suggestive of acute respiratory distress syndrome; bilateral thickening of the pulmonary interstitium; trace bilateral pleural effusions; increased caliber of the main pulmonary artery; and mediastinal and right hilar lymphadenopathy.

Subsequently, the patient developed sepsis and went into acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. He is transferred to the ICU, and pulmonology is consulted. A bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) reveals neutrophil predominance; fungal, bacterial, and viral cultures are negative. The patient is started on broad-spectrum IV antibiotics and high-dose IV steroids. After 4 days, he begins to improve and is transferred out of the ICU. He is discharged with oral steroids and antibiotics.

Continue to: DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

Fortunately, the PCP and the ED provider identified risk factors that contributed to the patient’s pneumonia and its subsequent worsening to sepsis and acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. The immunosuppressive/immunomodulatory effect of mAb therapy increased the patient’s risk for infection and the severity of infection, which is why vigilant safety monitoring and surveillance is essential with mAb treatment.1 Bloodwork should be performed at least every 6 months and include a complete blood count, complete metabolic panel with differential, and JC virus antibody test. Additionally, urinalysis should be performed prior to every mAb infusion. All testing recommended in the package insert for the patient’s prescribed therapy should be performed.

The patient’s history of asthma and his chronic vaping predisposed him to respiratory infections. In mice studies, exposure to e-cigarette vapor has been shown to be cytotoxic to airway cells and to decrease macrophage and neutrophil antimicrobial function.2 Exposure also alters immunomodulating cytokines in the airway, increases inflammatory markers seen in BAL and serum samples, and increases the virulence of Staphylococcus aureus

TREATMENT AND PATIENT EDUCATION

The PCP’s treatment plan included patient education about the importance of infection control measures when receiving a mAb; this includes practicing good hand and environmental hygiene, maintaining vaccinations, avoiding or reducing exposure to individuals who have infections or colds, avoiding large crowds (especially during flu season), and following recommendations for nutrition and hydration. The PCP also discussed how to recognize the early signs and symptoms of an infection—and the need for vigilant safety monitoring. The PCP described available options for smoking cessation, including nicotine replacement products, prescription non-nicotine medications, behavioral therapy, and/or counseling (individual, group or telephone) and discussed the risks associated with consuming nicotine and/or marijuana/THC and using electronic vaporizing devices.

The PCP emphasized the importance of completing the entire course of the oral antibiotics prescribed at discharge. The patient and the PCP agreed to the following plan of care: appointments with a pulmonologist and a neurologist within the next 2 weeks, and follow-up visits with the

A 19-year-old man was diagnosed with relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS) at age 7 and is currently being treated with an infusible monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapy. Early in the day, he receives an infusion at an outpatient clinic. That night, he begins to experience numbness and tingling in his right upper extremity, which prompts a visit to an urgent care clinic. There, the clinician administers IV fluids to the patient. After his symptoms improve, the patient is discharged home.

The next morning, he has a new onset of left-side shoulder and neck pain with a pulsating headache. The patient reports his symptoms to his primary care provider (PCP), who instructs him to visit the emergency department (ED) for evaluation and treatment of a possible infection.

EXAMINATION

The patient arrives at the ED with a 102.4°F fever, vomiting, cough, mild congestion, diaphoresis, generalized myalgias, and chills. He also reports depression and anxiety, saying that for the past 7 days, “I haven’t felt like my normal self.”

Medical history includes moderate persistent asthma that is not well controlled, status asthmaticus, and use of an electronic vaporizing device for inhaling nicotine and marijuana/tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Besides mAb infusions, his medications include hydrocodone/acetaminophen, prochlorperazine, gabapentin, hydroxyzine, trazodone, albuterol, and montelukast.

Examination reveals vital signs within normal limits. Lab work confirms elevated white blood cell count and absolute neutrophil count. Chest x-ray shows diffuse bilateral interstitial and patchy airspace opacities. He is diagnosed with bilateral pneumonia and is admitted and started on an IV antibiotic.

Within 24 hours, a new chest x-ray shows worsening symptoms. CT of the chest with contrast reveals diffuse bilateral ground-glass and airspace opacities suggestive of acute respiratory distress syndrome; bilateral thickening of the pulmonary interstitium; trace bilateral pleural effusions; increased caliber of the main pulmonary artery; and mediastinal and right hilar lymphadenopathy.

Subsequently, the patient developed sepsis and went into acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. He is transferred to the ICU, and pulmonology is consulted. A bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) reveals neutrophil predominance; fungal, bacterial, and viral cultures are negative. The patient is started on broad-spectrum IV antibiotics and high-dose IV steroids. After 4 days, he begins to improve and is transferred out of the ICU. He is discharged with oral steroids and antibiotics.

Continue to: DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

Fortunately, the PCP and the ED provider identified risk factors that contributed to the patient’s pneumonia and its subsequent worsening to sepsis and acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. The immunosuppressive/immunomodulatory effect of mAb therapy increased the patient’s risk for infection and the severity of infection, which is why vigilant safety monitoring and surveillance is essential with mAb treatment.1 Bloodwork should be performed at least every 6 months and include a complete blood count, complete metabolic panel with differential, and JC virus antibody test. Additionally, urinalysis should be performed prior to every mAb infusion. All testing recommended in the package insert for the patient’s prescribed therapy should be performed.

The patient’s history of asthma and his chronic vaping predisposed him to respiratory infections. In mice studies, exposure to e-cigarette vapor has been shown to be cytotoxic to airway cells and to decrease macrophage and neutrophil antimicrobial function.2 Exposure also alters immunomodulating cytokines in the airway, increases inflammatory markers seen in BAL and serum samples, and increases the virulence of Staphylococcus aureus

TREATMENT AND PATIENT EDUCATION

The PCP’s treatment plan included patient education about the importance of infection control measures when receiving a mAb; this includes practicing good hand and environmental hygiene, maintaining vaccinations, avoiding or reducing exposure to individuals who have infections or colds, avoiding large crowds (especially during flu season), and following recommendations for nutrition and hydration. The PCP also discussed how to recognize the early signs and symptoms of an infection—and the need for vigilant safety monitoring. The PCP described available options for smoking cessation, including nicotine replacement products, prescription non-nicotine medications, behavioral therapy, and/or counseling (individual, group or telephone) and discussed the risks associated with consuming nicotine and/or marijuana/THC and using electronic vaporizing devices.

The PCP emphasized the importance of completing the entire course of the oral antibiotics prescribed at discharge. The patient and the PCP agreed to the following plan of care: appointments with a pulmonologist and a neurologist within the next 2 weeks, and follow-up visits with the

1. Celius EG. Infections in patients with multiple sclerosis: implications for disease-modifying therapy. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;136(suppl 201):34-36.

2. Hwang JH, Lyes M, Sladewski K, et al. Electronic cigarette inhalation alters innate immunity and airway cytokines while increasing the virulence of colonizing bacteria. J Mol Med (Berl). 2016;94(6):667-679.

1. Celius EG. Infections in patients with multiple sclerosis: implications for disease-modifying therapy. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;136(suppl 201):34-36.

2. Hwang JH, Lyes M, Sladewski K, et al. Electronic cigarette inhalation alters innate immunity and airway cytokines while increasing the virulence of colonizing bacteria. J Mol Med (Berl). 2016;94(6):667-679.

Sexual Dysfunction in MS

A 37-year-old woman presents to her primary care clinic with a chief complaint of depression. She was diagnosed with relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS) at age 29 and is currently taking an injectable preventive therapy. Over the past 6 months, she has had increased marital strain secondary to losing her job because “I couldn’t mentally keep up with the work anymore.” This has caused financial difficulties for her family. In addition, she tires easily and has been napping in the afternoon. She and her husband are experiencing intimacy difficulties, and she confirms problems with vaginal dryness and a general loss of her sexual drive.

Sexual dysfunction in MS is common, affecting 40% to 80% of women and 50% to 90% of men with MS. It is an “invisible” symptom, similar to fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, and pain.1-3

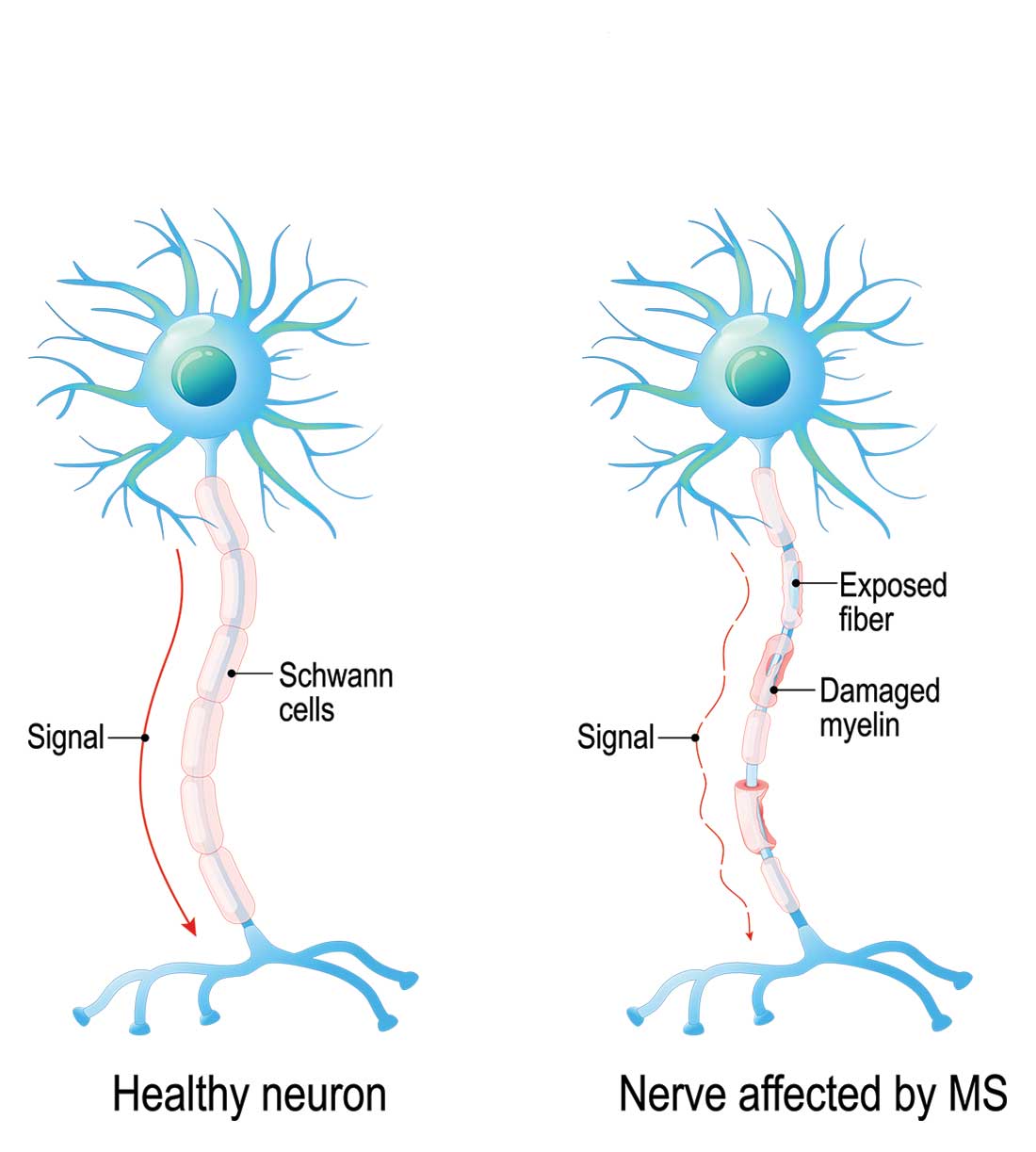

There are three ways that MS patients can be affected by sexual dysfunction, and they are categorized as primary, secondary, and tertiary. Primary sexual dysfunction results from demyelination/axonal destruction of the central nervous system, which potentially leads to altered genital sensation or paresthesia. Secondary sexual dysfunction stems from nonsexual MS symptoms, such as fatigue, spasticity, tremor, impairments in concentration/attention, and iatrogenic causes (eg, adverse effects of medication). Tertiary sexual dysfunction involves the psychosocial/cultural aspects of the disease that can impact a patient’s sexual drive.

SYMPTOMS

Like many other symptoms associated with MS, the symptoms of sexual dysfunction are highly variable. In women, the most common complaints are fatigue, decrease in genital sensation (27%-47%), decrease in libido (31%-74%) and vaginal lubrication (36%-48%), and difficulty with orgasm.4 In men with MS, in addition to erectile problems, surveys have identified decreased genital sensation, fatigue (75%), difficulty with ejaculation (18%-50%), decreased interest or arousal (39%), and anorgasmia (37%) as fairly common complaints.2

TREATMENT

Managing sexual dysfunction in a patient with MS is dependent on the underlying problem. Some examples include

- For many patients, their disease causes significant anxiety and worry about current and potentially future disability—which can make intimacy more difficult. Sometimes, referral to a mental health professional may be required to help the patient

with individual and/or couples counseling to further elucidate underlying intimacy issues. - For patients experiencing MS-associated fatigue, suggest planning for sexual activity in the morning, since fatigue is known to worsen throughout the day.

- For those who qualify for antidepressant medications, remember that some (eg, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) can further decrease libido and therefore should be avoided if possible.

- For women who have difficulty with lubrication, a nonpetroleum-based lubricant may reduce vaginal dryness, while use of a vibrator may assist with genital stimulation.

- For men who cannot maintain erection, phosphodiesterase inhibitor drugs (eg, sildenafil) can be helpful; other options include alprostadil urethral suppositories and intracavernous injections.

The patient is screened for depression using the Patient Health Questionnaire, which yields a score of 17 (moderately severe). You discuss the need for active treatment with her, and she agrees to start an antidepressant medication. Bupropion is chosen, given its effectiveness and lack of adverse effects (including sexual dysfunction). The patient also is encouraged to use nonpetroleum-based lubricants. Finally, a referral is made for couples counseling, and a 6-week follow-up appointment is scheduled.

CONCLUSION

Sexual dysfunction in MS is quite common in both women and men, and the related symptoms are often multifactorial. Strategies to address sexual dysfunction in MS require a tailored approach. Fortunately, any treatments for sexual dysfunction initiated by the patient’s primary care provider will not have an adverse effect on the patient’s outcome with MS. For more complicated cases of MS-associated sexual dysfunction, urology referral is recommended.

1. Foley FW, Sander A. Sexuality, multiple sclerosis and women. Mult Scler Manage. 1997;4:1-9.

2. Calabro RS, De Luca R, Conti-Nibali V, et al. Sexual dysfunction in male patients with multiple sclerosis: a need for counseling! Int J Neurosci. 2014;124(8):547-557.

3. Gava G, Visconti M, Salvi F, et al. Prevalence and psychopathological determinants of sexual dysfunction and related distress in women with and without multiple sclerosis. J Sex Med. 2019;16(6):833-842.

4. Cordeau D, Courtois, F. Sexual disorders in women with MS: assessment and management. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2014; 57(5):337-47.

A 37-year-old woman presents to her primary care clinic with a chief complaint of depression. She was diagnosed with relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS) at age 29 and is currently taking an injectable preventive therapy. Over the past 6 months, she has had increased marital strain secondary to losing her job because “I couldn’t mentally keep up with the work anymore.” This has caused financial difficulties for her family. In addition, she tires easily and has been napping in the afternoon. She and her husband are experiencing intimacy difficulties, and she confirms problems with vaginal dryness and a general loss of her sexual drive.

Sexual dysfunction in MS is common, affecting 40% to 80% of women and 50% to 90% of men with MS. It is an “invisible” symptom, similar to fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, and pain.1-3

There are three ways that MS patients can be affected by sexual dysfunction, and they are categorized as primary, secondary, and tertiary. Primary sexual dysfunction results from demyelination/axonal destruction of the central nervous system, which potentially leads to altered genital sensation or paresthesia. Secondary sexual dysfunction stems from nonsexual MS symptoms, such as fatigue, spasticity, tremor, impairments in concentration/attention, and iatrogenic causes (eg, adverse effects of medication). Tertiary sexual dysfunction involves the psychosocial/cultural aspects of the disease that can impact a patient’s sexual drive.

SYMPTOMS

Like many other symptoms associated with MS, the symptoms of sexual dysfunction are highly variable. In women, the most common complaints are fatigue, decrease in genital sensation (27%-47%), decrease in libido (31%-74%) and vaginal lubrication (36%-48%), and difficulty with orgasm.4 In men with MS, in addition to erectile problems, surveys have identified decreased genital sensation, fatigue (75%), difficulty with ejaculation (18%-50%), decreased interest or arousal (39%), and anorgasmia (37%) as fairly common complaints.2

TREATMENT

Managing sexual dysfunction in a patient with MS is dependent on the underlying problem. Some examples include

- For many patients, their disease causes significant anxiety and worry about current and potentially future disability—which can make intimacy more difficult. Sometimes, referral to a mental health professional may be required to help the patient

with individual and/or couples counseling to further elucidate underlying intimacy issues. - For patients experiencing MS-associated fatigue, suggest planning for sexual activity in the morning, since fatigue is known to worsen throughout the day.

- For those who qualify for antidepressant medications, remember that some (eg, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) can further decrease libido and therefore should be avoided if possible.

- For women who have difficulty with lubrication, a nonpetroleum-based lubricant may reduce vaginal dryness, while use of a vibrator may assist with genital stimulation.

- For men who cannot maintain erection, phosphodiesterase inhibitor drugs (eg, sildenafil) can be helpful; other options include alprostadil urethral suppositories and intracavernous injections.

The patient is screened for depression using the Patient Health Questionnaire, which yields a score of 17 (moderately severe). You discuss the need for active treatment with her, and she agrees to start an antidepressant medication. Bupropion is chosen, given its effectiveness and lack of adverse effects (including sexual dysfunction). The patient also is encouraged to use nonpetroleum-based lubricants. Finally, a referral is made for couples counseling, and a 6-week follow-up appointment is scheduled.

CONCLUSION

Sexual dysfunction in MS is quite common in both women and men, and the related symptoms are often multifactorial. Strategies to address sexual dysfunction in MS require a tailored approach. Fortunately, any treatments for sexual dysfunction initiated by the patient’s primary care provider will not have an adverse effect on the patient’s outcome with MS. For more complicated cases of MS-associated sexual dysfunction, urology referral is recommended.

A 37-year-old woman presents to her primary care clinic with a chief complaint of depression. She was diagnosed with relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS) at age 29 and is currently taking an injectable preventive therapy. Over the past 6 months, she has had increased marital strain secondary to losing her job because “I couldn’t mentally keep up with the work anymore.” This has caused financial difficulties for her family. In addition, she tires easily and has been napping in the afternoon. She and her husband are experiencing intimacy difficulties, and she confirms problems with vaginal dryness and a general loss of her sexual drive.

Sexual dysfunction in MS is common, affecting 40% to 80% of women and 50% to 90% of men with MS. It is an “invisible” symptom, similar to fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, and pain.1-3

There are three ways that MS patients can be affected by sexual dysfunction, and they are categorized as primary, secondary, and tertiary. Primary sexual dysfunction results from demyelination/axonal destruction of the central nervous system, which potentially leads to altered genital sensation or paresthesia. Secondary sexual dysfunction stems from nonsexual MS symptoms, such as fatigue, spasticity, tremor, impairments in concentration/attention, and iatrogenic causes (eg, adverse effects of medication). Tertiary sexual dysfunction involves the psychosocial/cultural aspects of the disease that can impact a patient’s sexual drive.

SYMPTOMS

Like many other symptoms associated with MS, the symptoms of sexual dysfunction are highly variable. In women, the most common complaints are fatigue, decrease in genital sensation (27%-47%), decrease in libido (31%-74%) and vaginal lubrication (36%-48%), and difficulty with orgasm.4 In men with MS, in addition to erectile problems, surveys have identified decreased genital sensation, fatigue (75%), difficulty with ejaculation (18%-50%), decreased interest or arousal (39%), and anorgasmia (37%) as fairly common complaints.2

TREATMENT

Managing sexual dysfunction in a patient with MS is dependent on the underlying problem. Some examples include

- For many patients, their disease causes significant anxiety and worry about current and potentially future disability—which can make intimacy more difficult. Sometimes, referral to a mental health professional may be required to help the patient

with individual and/or couples counseling to further elucidate underlying intimacy issues. - For patients experiencing MS-associated fatigue, suggest planning for sexual activity in the morning, since fatigue is known to worsen throughout the day.

- For those who qualify for antidepressant medications, remember that some (eg, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) can further decrease libido and therefore should be avoided if possible.

- For women who have difficulty with lubrication, a nonpetroleum-based lubricant may reduce vaginal dryness, while use of a vibrator may assist with genital stimulation.

- For men who cannot maintain erection, phosphodiesterase inhibitor drugs (eg, sildenafil) can be helpful; other options include alprostadil urethral suppositories and intracavernous injections.

The patient is screened for depression using the Patient Health Questionnaire, which yields a score of 17 (moderately severe). You discuss the need for active treatment with her, and she agrees to start an antidepressant medication. Bupropion is chosen, given its effectiveness and lack of adverse effects (including sexual dysfunction). The patient also is encouraged to use nonpetroleum-based lubricants. Finally, a referral is made for couples counseling, and a 6-week follow-up appointment is scheduled.

CONCLUSION

Sexual dysfunction in MS is quite common in both women and men, and the related symptoms are often multifactorial. Strategies to address sexual dysfunction in MS require a tailored approach. Fortunately, any treatments for sexual dysfunction initiated by the patient’s primary care provider will not have an adverse effect on the patient’s outcome with MS. For more complicated cases of MS-associated sexual dysfunction, urology referral is recommended.

1. Foley FW, Sander A. Sexuality, multiple sclerosis and women. Mult Scler Manage. 1997;4:1-9.

2. Calabro RS, De Luca R, Conti-Nibali V, et al. Sexual dysfunction in male patients with multiple sclerosis: a need for counseling! Int J Neurosci. 2014;124(8):547-557.

3. Gava G, Visconti M, Salvi F, et al. Prevalence and psychopathological determinants of sexual dysfunction and related distress in women with and without multiple sclerosis. J Sex Med. 2019;16(6):833-842.

4. Cordeau D, Courtois, F. Sexual disorders in women with MS: assessment and management. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2014; 57(5):337-47.

1. Foley FW, Sander A. Sexuality, multiple sclerosis and women. Mult Scler Manage. 1997;4:1-9.

2. Calabro RS, De Luca R, Conti-Nibali V, et al. Sexual dysfunction in male patients with multiple sclerosis: a need for counseling! Int J Neurosci. 2014;124(8):547-557.

3. Gava G, Visconti M, Salvi F, et al. Prevalence and psychopathological determinants of sexual dysfunction and related distress in women with and without multiple sclerosis. J Sex Med. 2019;16(6):833-842.

4. Cordeau D, Courtois, F. Sexual disorders in women with MS: assessment and management. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2014; 57(5):337-47.

MS: Partnering With Patients to Improve Health

Sharon, a 19-year-old woman, has a history of right optic neuritis and paraparesis that occurred 2 years ago. At that time, the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis (MS) was confirmed by a brain MRI and lumbar puncture. She has been taking disease-modifying therapy for 2 years and rarely misses a dose. Lately, however, she has experienced worsening symptoms and feels that her MS is progressing. Her neurologist doesn’t agree; he informs her that a recent MRI shows no changes, and her neurologic examination is within normal limits. At his suggestion, she presents to her primary care provider for an annual check-up.

HISTORY & PHYSICAL EXAM

Sharon’s height is 5 ft 2 in and her weight, 170 lb. Her blood pressure is 140/88 mm Hg and pulse, 80 beats/min and regular. Review of systems is remarkable for fatigue, visual changes when she is overheated, and weight gain of about 50 lb during the past year. Her lungs are clear to percussion and auscultation.

Her current medications include oral disease-modifying therapy, which she takes daily; an oral contraceptive (for regulation of her menstrual cycle; she says she is not sexually active); and an occasional pain reliever for headache.

CLINICAL IMPRESSION

Following history-taking and examination, the clinician notes the following impressions about Sharon’s health status:

Obesity: Examination reveals an overweight female with a BMI of 31.1.

Physical inactivity: As a legal secretary, Sharon sits at her desk most of the day. Her exercise is limited to walking to and from the bus to get to work. She has limited time for social activities due to fatigue. She spends most of her time watching television or visiting her parents.

Heat intolerance: While describing her lifestyle, Sharon notes that she does not participate in outdoor activity due to heat intolerance.

Continue to: Ambulation difficulty

Ambulation difficulty: Sharon’s walking and balance are worse than they were 6 months ago—a problem she relates to her MS, not her increased weight. She walks with a wide-based ataxic gait and transfers with difficulty, using the arms of her chair to stand up.

Poor nutritional habits: Sharon reports an irregular diet with an occasional breakfast, a sandwich for lunch, and a microwavable meal for dinner. Between meals, she snacks on nutrition bars, chocolate, and hot and cold coffee.

Smoking: Sharon smokes 1 pack of cigarettes daily.

Headache: As noted, Sharon reports occasional analgesic use for relief of headache pain.

The clinician’s impression is as follows: relapsing MS treated with disease-modifying therapy; obesity; ambulation difficulty; heat intolerance; sedentary lifestyle; and headache. In addition, the patient has the following risk factors: smoking; suboptimal activity and exercise; and poor nutritional habits.

Continue to: DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

Sharon has relapsing MS treated with disease-modifying therapy. But she also demonstrates or reports several independent risk factors, including borderline hypertension; obesity; inadequate diet; lack of activity and exercise; and possible lack of insight into her disease.1

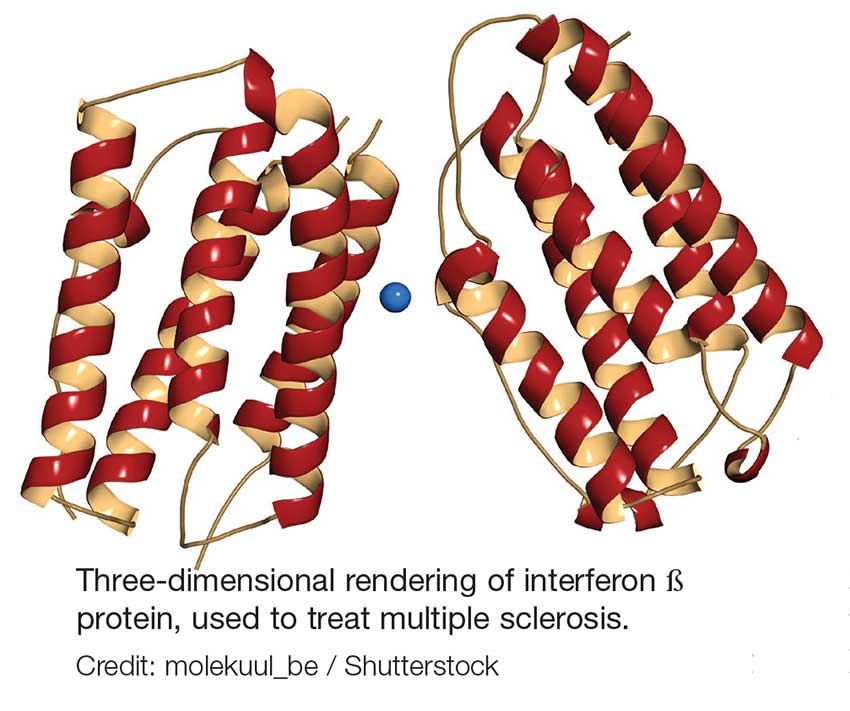

The plan of care for Sharon should include a review of her MS disease course. As this is explained, it is important to emphasize how adherence to the care plan will yield positive outcomes from the treatment. For example, the patient should understand that the underlying cause of damage in MS is related to the immune system. Providing this education might involve 1 or 2 sessions with written material, simple graphics, and explanation on how disease-modifying therapies work. Even a simple statement such as

The next step is to review Sharon’s risk factors for worsening MS, along with the impact these have on her general health. This might entail a long discussion focusing on the patient’s diet, minimal activity and exercise, and smoking. Sharon’s provider explained how all 3 factors can contribute to poor general health and have been shown to negatively affect MS. There is a general impression that wellness and neurologic diseases such as MS are disconnected. The clinician must “reconnect” the 2 through encouragement, education, and coaching.

By working closely with the patient and providing the education to help her make informed decisions about her health, the clinician can develop a plan to implement that has the patient’s full support. For a patient like Sharon, this includes

- Dietary modifications to improve nutrition and promote healthy weight loss

- A program of daily walking to improve stamina and support the patient’s weight loss program2

- Smoking cessation, including participation in a local support group of former smokers.3

Continue to: In Sharon's case...

In Sharon’s case, both she and her clinician agreed that it was important to meet regularly to assess progress toward their mutually agreed-upon goals. It is not enough to devise a plan—providers need to support patients in their efforts to improve their health. Meeting regularly can motivate patients to stay on track, and it gives providers an opportunity to address problems or concerns that might interfere with the patient’s progress.

1. Dalgas U, Stenager E. Exercise and disease progression in multiple sclerosis: can exercise slow down the progression of multiple sclerosis? Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2012;5(2):81-95.

2. Gianfrancesco MA, Barcellos LF. Obesity and multiple sclerosis susceptibility: a review. J Neurol Neuromedicine. 2016:1(7):1-5.

3. Healy BC, Eman A, Guttmann CRG, et al. Smoking and disease progression in multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(7):858-864.

Sharon, a 19-year-old woman, has a history of right optic neuritis and paraparesis that occurred 2 years ago. At that time, the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis (MS) was confirmed by a brain MRI and lumbar puncture. She has been taking disease-modifying therapy for 2 years and rarely misses a dose. Lately, however, she has experienced worsening symptoms and feels that her MS is progressing. Her neurologist doesn’t agree; he informs her that a recent MRI shows no changes, and her neurologic examination is within normal limits. At his suggestion, she presents to her primary care provider for an annual check-up.

HISTORY & PHYSICAL EXAM

Sharon’s height is 5 ft 2 in and her weight, 170 lb. Her blood pressure is 140/88 mm Hg and pulse, 80 beats/min and regular. Review of systems is remarkable for fatigue, visual changes when she is overheated, and weight gain of about 50 lb during the past year. Her lungs are clear to percussion and auscultation.

Her current medications include oral disease-modifying therapy, which she takes daily; an oral contraceptive (for regulation of her menstrual cycle; she says she is not sexually active); and an occasional pain reliever for headache.

CLINICAL IMPRESSION

Following history-taking and examination, the clinician notes the following impressions about Sharon’s health status:

Obesity: Examination reveals an overweight female with a BMI of 31.1.

Physical inactivity: As a legal secretary, Sharon sits at her desk most of the day. Her exercise is limited to walking to and from the bus to get to work. She has limited time for social activities due to fatigue. She spends most of her time watching television or visiting her parents.

Heat intolerance: While describing her lifestyle, Sharon notes that she does not participate in outdoor activity due to heat intolerance.

Continue to: Ambulation difficulty

Ambulation difficulty: Sharon’s walking and balance are worse than they were 6 months ago—a problem she relates to her MS, not her increased weight. She walks with a wide-based ataxic gait and transfers with difficulty, using the arms of her chair to stand up.

Poor nutritional habits: Sharon reports an irregular diet with an occasional breakfast, a sandwich for lunch, and a microwavable meal for dinner. Between meals, she snacks on nutrition bars, chocolate, and hot and cold coffee.

Smoking: Sharon smokes 1 pack of cigarettes daily.

Headache: As noted, Sharon reports occasional analgesic use for relief of headache pain.

The clinician’s impression is as follows: relapsing MS treated with disease-modifying therapy; obesity; ambulation difficulty; heat intolerance; sedentary lifestyle; and headache. In addition, the patient has the following risk factors: smoking; suboptimal activity and exercise; and poor nutritional habits.

Continue to: DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

Sharon has relapsing MS treated with disease-modifying therapy. But she also demonstrates or reports several independent risk factors, including borderline hypertension; obesity; inadequate diet; lack of activity and exercise; and possible lack of insight into her disease.1

The plan of care for Sharon should include a review of her MS disease course. As this is explained, it is important to emphasize how adherence to the care plan will yield positive outcomes from the treatment. For example, the patient should understand that the underlying cause of damage in MS is related to the immune system. Providing this education might involve 1 or 2 sessions with written material, simple graphics, and explanation on how disease-modifying therapies work. Even a simple statement such as

The next step is to review Sharon’s risk factors for worsening MS, along with the impact these have on her general health. This might entail a long discussion focusing on the patient’s diet, minimal activity and exercise, and smoking. Sharon’s provider explained how all 3 factors can contribute to poor general health and have been shown to negatively affect MS. There is a general impression that wellness and neurologic diseases such as MS are disconnected. The clinician must “reconnect” the 2 through encouragement, education, and coaching.

By working closely with the patient and providing the education to help her make informed decisions about her health, the clinician can develop a plan to implement that has the patient’s full support. For a patient like Sharon, this includes

- Dietary modifications to improve nutrition and promote healthy weight loss

- A program of daily walking to improve stamina and support the patient’s weight loss program2

- Smoking cessation, including participation in a local support group of former smokers.3

Continue to: In Sharon's case...

In Sharon’s case, both she and her clinician agreed that it was important to meet regularly to assess progress toward their mutually agreed-upon goals. It is not enough to devise a plan—providers need to support patients in their efforts to improve their health. Meeting regularly can motivate patients to stay on track, and it gives providers an opportunity to address problems or concerns that might interfere with the patient’s progress.

Sharon, a 19-year-old woman, has a history of right optic neuritis and paraparesis that occurred 2 years ago. At that time, the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis (MS) was confirmed by a brain MRI and lumbar puncture. She has been taking disease-modifying therapy for 2 years and rarely misses a dose. Lately, however, she has experienced worsening symptoms and feels that her MS is progressing. Her neurologist doesn’t agree; he informs her that a recent MRI shows no changes, and her neurologic examination is within normal limits. At his suggestion, she presents to her primary care provider for an annual check-up.

HISTORY & PHYSICAL EXAM

Sharon’s height is 5 ft 2 in and her weight, 170 lb. Her blood pressure is 140/88 mm Hg and pulse, 80 beats/min and regular. Review of systems is remarkable for fatigue, visual changes when she is overheated, and weight gain of about 50 lb during the past year. Her lungs are clear to percussion and auscultation.

Her current medications include oral disease-modifying therapy, which she takes daily; an oral contraceptive (for regulation of her menstrual cycle; she says she is not sexually active); and an occasional pain reliever for headache.

CLINICAL IMPRESSION

Following history-taking and examination, the clinician notes the following impressions about Sharon’s health status:

Obesity: Examination reveals an overweight female with a BMI of 31.1.

Physical inactivity: As a legal secretary, Sharon sits at her desk most of the day. Her exercise is limited to walking to and from the bus to get to work. She has limited time for social activities due to fatigue. She spends most of her time watching television or visiting her parents.

Heat intolerance: While describing her lifestyle, Sharon notes that she does not participate in outdoor activity due to heat intolerance.

Continue to: Ambulation difficulty

Ambulation difficulty: Sharon’s walking and balance are worse than they were 6 months ago—a problem she relates to her MS, not her increased weight. She walks with a wide-based ataxic gait and transfers with difficulty, using the arms of her chair to stand up.

Poor nutritional habits: Sharon reports an irregular diet with an occasional breakfast, a sandwich for lunch, and a microwavable meal for dinner. Between meals, she snacks on nutrition bars, chocolate, and hot and cold coffee.

Smoking: Sharon smokes 1 pack of cigarettes daily.

Headache: As noted, Sharon reports occasional analgesic use for relief of headache pain.

The clinician’s impression is as follows: relapsing MS treated with disease-modifying therapy; obesity; ambulation difficulty; heat intolerance; sedentary lifestyle; and headache. In addition, the patient has the following risk factors: smoking; suboptimal activity and exercise; and poor nutritional habits.

Continue to: DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

Sharon has relapsing MS treated with disease-modifying therapy. But she also demonstrates or reports several independent risk factors, including borderline hypertension; obesity; inadequate diet; lack of activity and exercise; and possible lack of insight into her disease.1

The plan of care for Sharon should include a review of her MS disease course. As this is explained, it is important to emphasize how adherence to the care plan will yield positive outcomes from the treatment. For example, the patient should understand that the underlying cause of damage in MS is related to the immune system. Providing this education might involve 1 or 2 sessions with written material, simple graphics, and explanation on how disease-modifying therapies work. Even a simple statement such as

The next step is to review Sharon’s risk factors for worsening MS, along with the impact these have on her general health. This might entail a long discussion focusing on the patient’s diet, minimal activity and exercise, and smoking. Sharon’s provider explained how all 3 factors can contribute to poor general health and have been shown to negatively affect MS. There is a general impression that wellness and neurologic diseases such as MS are disconnected. The clinician must “reconnect” the 2 through encouragement, education, and coaching.

By working closely with the patient and providing the education to help her make informed decisions about her health, the clinician can develop a plan to implement that has the patient’s full support. For a patient like Sharon, this includes

- Dietary modifications to improve nutrition and promote healthy weight loss

- A program of daily walking to improve stamina and support the patient’s weight loss program2

- Smoking cessation, including participation in a local support group of former smokers.3

Continue to: In Sharon's case...

In Sharon’s case, both she and her clinician agreed that it was important to meet regularly to assess progress toward their mutually agreed-upon goals. It is not enough to devise a plan—providers need to support patients in their efforts to improve their health. Meeting regularly can motivate patients to stay on track, and it gives providers an opportunity to address problems or concerns that might interfere with the patient’s progress.

1. Dalgas U, Stenager E. Exercise and disease progression in multiple sclerosis: can exercise slow down the progression of multiple sclerosis? Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2012;5(2):81-95.

2. Gianfrancesco MA, Barcellos LF. Obesity and multiple sclerosis susceptibility: a review. J Neurol Neuromedicine. 2016:1(7):1-5.

3. Healy BC, Eman A, Guttmann CRG, et al. Smoking and disease progression in multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(7):858-864.

1. Dalgas U, Stenager E. Exercise and disease progression in multiple sclerosis: can exercise slow down the progression of multiple sclerosis? Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2012;5(2):81-95.

2. Gianfrancesco MA, Barcellos LF. Obesity and multiple sclerosis susceptibility: a review. J Neurol Neuromedicine. 2016:1(7):1-5.

3. Healy BC, Eman A, Guttmann CRG, et al. Smoking and disease progression in multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(7):858-864.

Cognition and MS

Cognitive changes related to multiple sclerosis (MS) were first mentioned by Jean-Martin Charcot in 1877; however, it is only within the past 25-30 years that cognitive impairment in MS has received significant clinical study. Despite a growing body of research, though, formal screening of cognitive function is not always part of routine MS clinical care.

Q)How common are cognitive symptoms in MS?

Cognitive changes affect up to 65% of patients in MS clinic samples and about one-third of pediatric MS patients.1 Cognitive deficits occur in all the MS disease courses, including clinically isolated syndrome, although they are most prevalent in secondary progressive and primary progressive disease.1 Cognitive changes have even been observed in radiographically isolated syndrome, in which MRI changes consistent with MS are observed without any neurologic symptoms or signs.2

Q)What cognitive domains are affected in MS?

Strong correlations have been demonstrated between cognitive impairment and MRI findings, including whole brain atrophy and, to some degree, overall white matter lesion burden. Cognitive changes also result from damage in specific areas, including deep gray matter and the corpus callosum, cerebral cortex, and mesial temporal lobe.3-5

The type and severity of cognitive deficits vary widely among people with MS. However, difficulties with information processing speed and short-term memory are the symptoms most commonly seen in this population. Processing speed problems affect new learning and impact memory and executive function. Other domains that can be affected are complex attention, verbal fluency, and visuospatial perception.1

Q)Are cognitive symptoms in MS progressive?

Not everyone with cognitive symptoms related to MS will show progressive changes. However, in a longitudinal study, increasing age and degree of physical disability were predictive of worsening cognitive symptoms. Also, people who demonstrate early cognitive symptoms may experience greater worsening.6

Q)What impact do cognitive symptoms have?

Changes in cognition are a common reason for someone to experience performance issues in the workplace and as such significantly affect a person’s ability to maintain employment. Impaired cognition is a primary cause of early departure from the workforceand has significant implications for self-image and self-esteem.7

Furthermore, cognitive symptoms can impact adherence to medications. They also can negatively affect daily life, through increased risk for motor vehicle accidents, difficulties with routine household tasks, and significant challenges to relationships (particularly but not exclusively those with caregivers).

Continue to: How are cognitive symptoms assessed?

Q)How are cognitive symptoms assessed?

There are several screening tools that take very little time to administer and can be used in the clinic setting. The Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT; www.wpspublish.com/store/p/2955/sdmt-symbol-digit-modalities-test) is validated in MS and takes approximately 90 s to complete. This screening instrument is proprietary and has a small fee associated with its use.8

Other possible causes of cognitive dysfunction should be investigated as well. These include an examination of medications being used—such as anticholinergics, benzodiazepines, other sedatives, cannabis, topiramate, and opioids—and consideration of other diseases and conditions, including vascular conditions, metabolic deficiencies, infection, tumor, substance abuse, early dementia, or hypothyroidism, which may contribute to or cause cognitive impairment.

Should cognitive problems be identified—either through the history, during the clinic visit, or via screening tests—more formal testing, usually performed by a neuropsychologist, may be useful in identifying the domains of function that are impaired. This information can help to identify and implement appropriate compensatory strategies, plan cognitive rehabilitation interventions, and (in the United States) assist the individual to obtain Social Security disability benefits.

Q)How are cognitive symptoms managed?

Multiple clinical trials of cognitive rehabilitation strategies have demonstrated the efficacy of computer-based programs in improving new learning, short-term memory, processing speed, and attention.9 Cognitive rehabilitation programs should be administered and/or supervised by a health care professional who is knowledgeable about MS as well as cognitive rehabilitation. Professionals such as neuropsychologists, occupational therapists, and speech language pathologists often direct cognitive training programs.

Medications that stimulate the central nervous system have been used to improve mental alertness. However, clinical trials are few and have yielded mixed results.

Continue to: In clinical trials...

In clinical trials, physical exercise has been shown to improve processing speed. More research is needed to demonstrate the type of exercise that is most beneficial and the extent of improvement in cognitive function that results.

SUMMARY

Cognitive function can be negatively impacted by MS. Activities of daily living, including employment and relationships, can be negatively impacted by changes in cognition. Regular screening of cognition is recommended by the National MS Society, using validated screening tools such as the SDMT. Additional testing is warranted for individuals reporting cognitive difficulties at home or work, or those who score below controls on screening tests. Cognitive rehabilitation may help some individuals improve their cognitive function. More research is needed to identify additional cognitive training techniques, better understand the role of physical exercise, and identify medications that may be of benefit to maintain cognitive function.

1. Amato MP, Zipoli V, Portaccio E. Cognitive changes in multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8(10):1585-1596.

2. Labiano-Fontcuberta A, Martínez-Ginés ML, Aladro Y, et al. A comparison study of cognitive deficits in radiologically and clinically isolated syndromes. Mult Scler. 2016;22(2):250-253.

3. Benedict RH, Ramasamy D, Munschauer F, et al. Memory impairment in multiple sclerosis: correlation with deep grey matter and mesial temporal atrophy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80(2):201-206.

4. Rocca MA, Amato MP, De Stefano N, et al; MAGNIMS Study Group. Clinical and imaging assessment of cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(3):302-317.

5. Rovaris M, Comi G, Filippi M. MRI markers of destructive pathology in multiple sclerosis-related cognitive dysfunction. J Neurol Sci. 2006;245(1-2):111-116.

6. Johnen A, Landmeyer NC, Bürkner PC, et al. Distinct cognitive impairments in different disease courses of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;83:568-578.

7. Rao SM, Leo GJ, Ellington L, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. II. Impact on employment and social functioning. Neurology. 1991;41(5):692-696.

8. Parmenter BA, Weinstock-Guttman B, Garg N, et al. Screening for cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis using the symbol digit modalities test. Mult Scler. 2007;13(1):52-57.

9. Goverover Y, Chiaravalloti ND, O’Brien AR, DeLuca J. Evidenced-based cognitive rehabilitation for persons with multiple sclerosis: an updated review of the literature from 2007 to 2016. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99(2):390-407.

Cognitive changes related to multiple sclerosis (MS) were first mentioned by Jean-Martin Charcot in 1877; however, it is only within the past 25-30 years that cognitive impairment in MS has received significant clinical study. Despite a growing body of research, though, formal screening of cognitive function is not always part of routine MS clinical care.

Q)How common are cognitive symptoms in MS?

Cognitive changes affect up to 65% of patients in MS clinic samples and about one-third of pediatric MS patients.1 Cognitive deficits occur in all the MS disease courses, including clinically isolated syndrome, although they are most prevalent in secondary progressive and primary progressive disease.1 Cognitive changes have even been observed in radiographically isolated syndrome, in which MRI changes consistent with MS are observed without any neurologic symptoms or signs.2

Q)What cognitive domains are affected in MS?

Strong correlations have been demonstrated between cognitive impairment and MRI findings, including whole brain atrophy and, to some degree, overall white matter lesion burden. Cognitive changes also result from damage in specific areas, including deep gray matter and the corpus callosum, cerebral cortex, and mesial temporal lobe.3-5

The type and severity of cognitive deficits vary widely among people with MS. However, difficulties with information processing speed and short-term memory are the symptoms most commonly seen in this population. Processing speed problems affect new learning and impact memory and executive function. Other domains that can be affected are complex attention, verbal fluency, and visuospatial perception.1

Q)Are cognitive symptoms in MS progressive?

Not everyone with cognitive symptoms related to MS will show progressive changes. However, in a longitudinal study, increasing age and degree of physical disability were predictive of worsening cognitive symptoms. Also, people who demonstrate early cognitive symptoms may experience greater worsening.6

Q)What impact do cognitive symptoms have?

Changes in cognition are a common reason for someone to experience performance issues in the workplace and as such significantly affect a person’s ability to maintain employment. Impaired cognition is a primary cause of early departure from the workforceand has significant implications for self-image and self-esteem.7

Furthermore, cognitive symptoms can impact adherence to medications. They also can negatively affect daily life, through increased risk for motor vehicle accidents, difficulties with routine household tasks, and significant challenges to relationships (particularly but not exclusively those with caregivers).

Continue to: How are cognitive symptoms assessed?

Q)How are cognitive symptoms assessed?

There are several screening tools that take very little time to administer and can be used in the clinic setting. The Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT; www.wpspublish.com/store/p/2955/sdmt-symbol-digit-modalities-test) is validated in MS and takes approximately 90 s to complete. This screening instrument is proprietary and has a small fee associated with its use.8

Other possible causes of cognitive dysfunction should be investigated as well. These include an examination of medications being used—such as anticholinergics, benzodiazepines, other sedatives, cannabis, topiramate, and opioids—and consideration of other diseases and conditions, including vascular conditions, metabolic deficiencies, infection, tumor, substance abuse, early dementia, or hypothyroidism, which may contribute to or cause cognitive impairment.

Should cognitive problems be identified—either through the history, during the clinic visit, or via screening tests—more formal testing, usually performed by a neuropsychologist, may be useful in identifying the domains of function that are impaired. This information can help to identify and implement appropriate compensatory strategies, plan cognitive rehabilitation interventions, and (in the United States) assist the individual to obtain Social Security disability benefits.

Q)How are cognitive symptoms managed?

Multiple clinical trials of cognitive rehabilitation strategies have demonstrated the efficacy of computer-based programs in improving new learning, short-term memory, processing speed, and attention.9 Cognitive rehabilitation programs should be administered and/or supervised by a health care professional who is knowledgeable about MS as well as cognitive rehabilitation. Professionals such as neuropsychologists, occupational therapists, and speech language pathologists often direct cognitive training programs.

Medications that stimulate the central nervous system have been used to improve mental alertness. However, clinical trials are few and have yielded mixed results.

Continue to: In clinical trials...

In clinical trials, physical exercise has been shown to improve processing speed. More research is needed to demonstrate the type of exercise that is most beneficial and the extent of improvement in cognitive function that results.

SUMMARY

Cognitive function can be negatively impacted by MS. Activities of daily living, including employment and relationships, can be negatively impacted by changes in cognition. Regular screening of cognition is recommended by the National MS Society, using validated screening tools such as the SDMT. Additional testing is warranted for individuals reporting cognitive difficulties at home or work, or those who score below controls on screening tests. Cognitive rehabilitation may help some individuals improve their cognitive function. More research is needed to identify additional cognitive training techniques, better understand the role of physical exercise, and identify medications that may be of benefit to maintain cognitive function.

Cognitive changes related to multiple sclerosis (MS) were first mentioned by Jean-Martin Charcot in 1877; however, it is only within the past 25-30 years that cognitive impairment in MS has received significant clinical study. Despite a growing body of research, though, formal screening of cognitive function is not always part of routine MS clinical care.

Q)How common are cognitive symptoms in MS?

Cognitive changes affect up to 65% of patients in MS clinic samples and about one-third of pediatric MS patients.1 Cognitive deficits occur in all the MS disease courses, including clinically isolated syndrome, although they are most prevalent in secondary progressive and primary progressive disease.1 Cognitive changes have even been observed in radiographically isolated syndrome, in which MRI changes consistent with MS are observed without any neurologic symptoms or signs.2

Q)What cognitive domains are affected in MS?

Strong correlations have been demonstrated between cognitive impairment and MRI findings, including whole brain atrophy and, to some degree, overall white matter lesion burden. Cognitive changes also result from damage in specific areas, including deep gray matter and the corpus callosum, cerebral cortex, and mesial temporal lobe.3-5

The type and severity of cognitive deficits vary widely among people with MS. However, difficulties with information processing speed and short-term memory are the symptoms most commonly seen in this population. Processing speed problems affect new learning and impact memory and executive function. Other domains that can be affected are complex attention, verbal fluency, and visuospatial perception.1

Q)Are cognitive symptoms in MS progressive?

Not everyone with cognitive symptoms related to MS will show progressive changes. However, in a longitudinal study, increasing age and degree of physical disability were predictive of worsening cognitive symptoms. Also, people who demonstrate early cognitive symptoms may experience greater worsening.6

Q)What impact do cognitive symptoms have?

Changes in cognition are a common reason for someone to experience performance issues in the workplace and as such significantly affect a person’s ability to maintain employment. Impaired cognition is a primary cause of early departure from the workforceand has significant implications for self-image and self-esteem.7

Furthermore, cognitive symptoms can impact adherence to medications. They also can negatively affect daily life, through increased risk for motor vehicle accidents, difficulties with routine household tasks, and significant challenges to relationships (particularly but not exclusively those with caregivers).

Continue to: How are cognitive symptoms assessed?

Q)How are cognitive symptoms assessed?

There are several screening tools that take very little time to administer and can be used in the clinic setting. The Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT; www.wpspublish.com/store/p/2955/sdmt-symbol-digit-modalities-test) is validated in MS and takes approximately 90 s to complete. This screening instrument is proprietary and has a small fee associated with its use.8

Other possible causes of cognitive dysfunction should be investigated as well. These include an examination of medications being used—such as anticholinergics, benzodiazepines, other sedatives, cannabis, topiramate, and opioids—and consideration of other diseases and conditions, including vascular conditions, metabolic deficiencies, infection, tumor, substance abuse, early dementia, or hypothyroidism, which may contribute to or cause cognitive impairment.

Should cognitive problems be identified—either through the history, during the clinic visit, or via screening tests—more formal testing, usually performed by a neuropsychologist, may be useful in identifying the domains of function that are impaired. This information can help to identify and implement appropriate compensatory strategies, plan cognitive rehabilitation interventions, and (in the United States) assist the individual to obtain Social Security disability benefits.

Q)How are cognitive symptoms managed?

Multiple clinical trials of cognitive rehabilitation strategies have demonstrated the efficacy of computer-based programs in improving new learning, short-term memory, processing speed, and attention.9 Cognitive rehabilitation programs should be administered and/or supervised by a health care professional who is knowledgeable about MS as well as cognitive rehabilitation. Professionals such as neuropsychologists, occupational therapists, and speech language pathologists often direct cognitive training programs.

Medications that stimulate the central nervous system have been used to improve mental alertness. However, clinical trials are few and have yielded mixed results.

Continue to: In clinical trials...

In clinical trials, physical exercise has been shown to improve processing speed. More research is needed to demonstrate the type of exercise that is most beneficial and the extent of improvement in cognitive function that results.

SUMMARY

Cognitive function can be negatively impacted by MS. Activities of daily living, including employment and relationships, can be negatively impacted by changes in cognition. Regular screening of cognition is recommended by the National MS Society, using validated screening tools such as the SDMT. Additional testing is warranted for individuals reporting cognitive difficulties at home or work, or those who score below controls on screening tests. Cognitive rehabilitation may help some individuals improve their cognitive function. More research is needed to identify additional cognitive training techniques, better understand the role of physical exercise, and identify medications that may be of benefit to maintain cognitive function.

1. Amato MP, Zipoli V, Portaccio E. Cognitive changes in multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8(10):1585-1596.

2. Labiano-Fontcuberta A, Martínez-Ginés ML, Aladro Y, et al. A comparison study of cognitive deficits in radiologically and clinically isolated syndromes. Mult Scler. 2016;22(2):250-253.

3. Benedict RH, Ramasamy D, Munschauer F, et al. Memory impairment in multiple sclerosis: correlation with deep grey matter and mesial temporal atrophy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80(2):201-206.

4. Rocca MA, Amato MP, De Stefano N, et al; MAGNIMS Study Group. Clinical and imaging assessment of cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(3):302-317.

5. Rovaris M, Comi G, Filippi M. MRI markers of destructive pathology in multiple sclerosis-related cognitive dysfunction. J Neurol Sci. 2006;245(1-2):111-116.

6. Johnen A, Landmeyer NC, Bürkner PC, et al. Distinct cognitive impairments in different disease courses of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;83:568-578.

7. Rao SM, Leo GJ, Ellington L, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. II. Impact on employment and social functioning. Neurology. 1991;41(5):692-696.

8. Parmenter BA, Weinstock-Guttman B, Garg N, et al. Screening for cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis using the symbol digit modalities test. Mult Scler. 2007;13(1):52-57.

9. Goverover Y, Chiaravalloti ND, O’Brien AR, DeLuca J. Evidenced-based cognitive rehabilitation for persons with multiple sclerosis: an updated review of the literature from 2007 to 2016. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99(2):390-407.

1. Amato MP, Zipoli V, Portaccio E. Cognitive changes in multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8(10):1585-1596.

2. Labiano-Fontcuberta A, Martínez-Ginés ML, Aladro Y, et al. A comparison study of cognitive deficits in radiologically and clinically isolated syndromes. Mult Scler. 2016;22(2):250-253.

3. Benedict RH, Ramasamy D, Munschauer F, et al. Memory impairment in multiple sclerosis: correlation with deep grey matter and mesial temporal atrophy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80(2):201-206.

4. Rocca MA, Amato MP, De Stefano N, et al; MAGNIMS Study Group. Clinical and imaging assessment of cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(3):302-317.

5. Rovaris M, Comi G, Filippi M. MRI markers of destructive pathology in multiple sclerosis-related cognitive dysfunction. J Neurol Sci. 2006;245(1-2):111-116.

6. Johnen A, Landmeyer NC, Bürkner PC, et al. Distinct cognitive impairments in different disease courses of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;83:568-578.

7. Rao SM, Leo GJ, Ellington L, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. II. Impact on employment and social functioning. Neurology. 1991;41(5):692-696.

8. Parmenter BA, Weinstock-Guttman B, Garg N, et al. Screening for cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis using the symbol digit modalities test. Mult Scler. 2007;13(1):52-57.

9. Goverover Y, Chiaravalloti ND, O’Brien AR, DeLuca J. Evidenced-based cognitive rehabilitation for persons with multiple sclerosis: an updated review of the literature from 2007 to 2016. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99(2):390-407.

Identifying and Managing MS Relapse

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, autoimmune-mediated disorder of the central nervous system that affects more than 40,000 people in the United States. About 85% of cases are categorized as relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS), based on the clinical and radiographic pattern of focal demyelination in different regions of the brain and spinal cord over time. Though not fully understood, the pathophysiology of RRMS involves axonal degeneration and inflammatory demyelination; the latter is considered a relapse in patients with an established MS diagnosis.

OVERVIEW

MS relapse can have a significant impact on patients’ short- and long-term function, quality of life, and finances. Relapse may be identified via

- New neurologic symptoms reported by the patient

- New neurologic findings on physical examination

- New radiographic findings on contrast-enhanced MRI of the central nervous system, or

- Abnormal results of cerebrospinal fluid analysis.

Patient-reported symptoms and abnormal signs identified on physical exam should correspond with the area of the central nervous system affected. In some cases, patients may have radiographic evidence of relapse without symptoms or signs.

It is essential for health care providers to identify relapse, as it is an important marker of disease activity that may warrant treatment—particularly if symptoms are impacting function or if there is optic neuritis. MS relapse is also an indicator of suboptimal response to disease-modifying therapies.

Treatment of relapse is one component of RRMS management, which also includes symptom management and use of disease-modifying therapy to reduce risk for disease activity and decline in function.

DIAGNOSING RELAPSE

Because risk for MS relapse cannot be predicted, both patients and providers need to have a high index of suspicion in the setting of new neurologic symptoms or decline in function. Relapse should be considered when these symptoms last longer than 24 hours in the absence of fever or infection. The clinical features of relapse should have corresponding radiographic evidence of active demyelination on contrast-enhanced MRI.

A pseudo-relapse is characterized by new or worsening neurologic symptoms lasting longer than 24 hours with concurrent fever, infection, or other metabolic derangement. Pseudo-relapse does not show radiographic evidence of active demyelination on contrast-enhanced MRI.

Continue to: Aggravation of longstanding neurologic symptoms...

Aggravation of longstanding neurologic symptoms is not considered a relapse, as no new radiographic evidence of disease progression will be seen on MRI. Factors that may contribute to aggravation of established symptoms include an increase in core body temperature, sleep deprivation, and psychosocial stress.

When a patient with suspected or diagnosed RRMS presents with new neurologic symptoms of more than 24 hours’ duration, the first step is to conduct a physical exam to assess for objective evidence of neurologic deficits and signs of infection, including fever. The provider should also order select laboratory testing—including a complete blood cell count and urinalysis with culture—to exclude infection. In certain cases, contrast-enhanced MRI of the brain and/or spine may be ordered; however, this may delay treatment initiation if the study cannot be promptly scheduled.

Evaluation and management should involve communication, if not face-to-face consultation, with the patient’s neurology provider who is responsible for MS management.

IMMEDIATE MANAGEMENT

Acute relapses are managed with anti-inflammatory agents. For some patients, treatment may provide symptomatic relief, shorten the recovery phase, and improve motor function. Long-term benefits have not been demonstrated, except in patients with optic neuritis.

Firstline therapy for MS relapse is high-dose corticosteroids, which can be administered at home, at an ambulatory infusion center, or (in some cases) in a hospital setting. The preferred regimen is methylprednisolone (1 g IV for 3-5 d), with or without prednisone taper. Another option is dexamethasone (80 mg bid for 3-5 d), with or without prednisone taper.1-3

Continue to: Common adverse effects of corticosteroids include...

Common adverse effects of corticosteroids include headache, emotional lability, insomnia, glucose intolerance, hypertension, dyspepsia, and exacerbation of psychiatric conditions; drug interactions should also be considered. Patients with diabetes may need to be admitted to the hospital for glycemic monitoring and control.

High-dose corticosteroids are associated with a rare, non–dose-dependent risk for aseptic femoral necrosis. For patients who are refractory to or not candidates for corticosteroids, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) gel (80 U/d IM or subQ daily for 10 d) is an option. This medication may be better tolerated, although it is much more expensive than corticosteroids. Plasmapheresis and IV immunoglobulin are also options for patients with refractory symptoms or contraindications to recommended therapies.1-3

ONGOING MANAGEMENT

Once a treatment plan is initiated, providers should carefully follow the patient’s response in terms of adverse effects, symptom improvement, and functional recovery. Those with refractory symptoms may need additional doses of the initial therapy or an alternative therapy.

The relapse recovery period may last several months and be complete or incomplete, so providers may also need to manage neurologic symptoms and functional deficits (with pharmacologic and/or nonpharmacologic options). Patients who have had a relapse should also meet with their neurology provider to discuss their disease-modifying therapy plan, since relapse indicates a suboptimal response to current therapy.

1. Bevan C, Gelfand JM. Therapeutic management of severe relapses in multiple sclerosis. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2015;17(4):17.

2. Frohman TC, O’Donoghue DL, Northrop D, eds. Multiple Sclerosis for the Physician Assistant. National Multiple Sclerosis Society. 2011.

3. Giesser B, ed. Primer on Multiple Sclerosis . 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press ; 2015.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, autoimmune-mediated disorder of the central nervous system that affects more than 40,000 people in the United States. About 85% of cases are categorized as relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS), based on the clinical and radiographic pattern of focal demyelination in different regions of the brain and spinal cord over time. Though not fully understood, the pathophysiology of RRMS involves axonal degeneration and inflammatory demyelination; the latter is considered a relapse in patients with an established MS diagnosis.

OVERVIEW

MS relapse can have a significant impact on patients’ short- and long-term function, quality of life, and finances. Relapse may be identified via

- New neurologic symptoms reported by the patient

- New neurologic findings on physical examination

- New radiographic findings on contrast-enhanced MRI of the central nervous system, or

- Abnormal results of cerebrospinal fluid analysis.

Patient-reported symptoms and abnormal signs identified on physical exam should correspond with the area of the central nervous system affected. In some cases, patients may have radiographic evidence of relapse without symptoms or signs.

It is essential for health care providers to identify relapse, as it is an important marker of disease activity that may warrant treatment—particularly if symptoms are impacting function or if there is optic neuritis. MS relapse is also an indicator of suboptimal response to disease-modifying therapies.

Treatment of relapse is one component of RRMS management, which also includes symptom management and use of disease-modifying therapy to reduce risk for disease activity and decline in function.

DIAGNOSING RELAPSE

Because risk for MS relapse cannot be predicted, both patients and providers need to have a high index of suspicion in the setting of new neurologic symptoms or decline in function. Relapse should be considered when these symptoms last longer than 24 hours in the absence of fever or infection. The clinical features of relapse should have corresponding radiographic evidence of active demyelination on contrast-enhanced MRI.