User login

CAM in MS: What Works?

Q)How is complementary and alternative medicine used in multiple sclerosis, and how can I safely recommend it to my patients?

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is a non-mainstream practice used in conjunction with conventional medicine.1 Its use is prevalent among people with and without chronic illnesses, including those living with multiple sclerosis (MS). Up to 70% of Americans with MS have used some type of CAM therapy, compared with 36% of the general population.1,2 CAM use is higher in women than in men and is highest among persons ages 35 to 49—two demographics also associated with MS.3

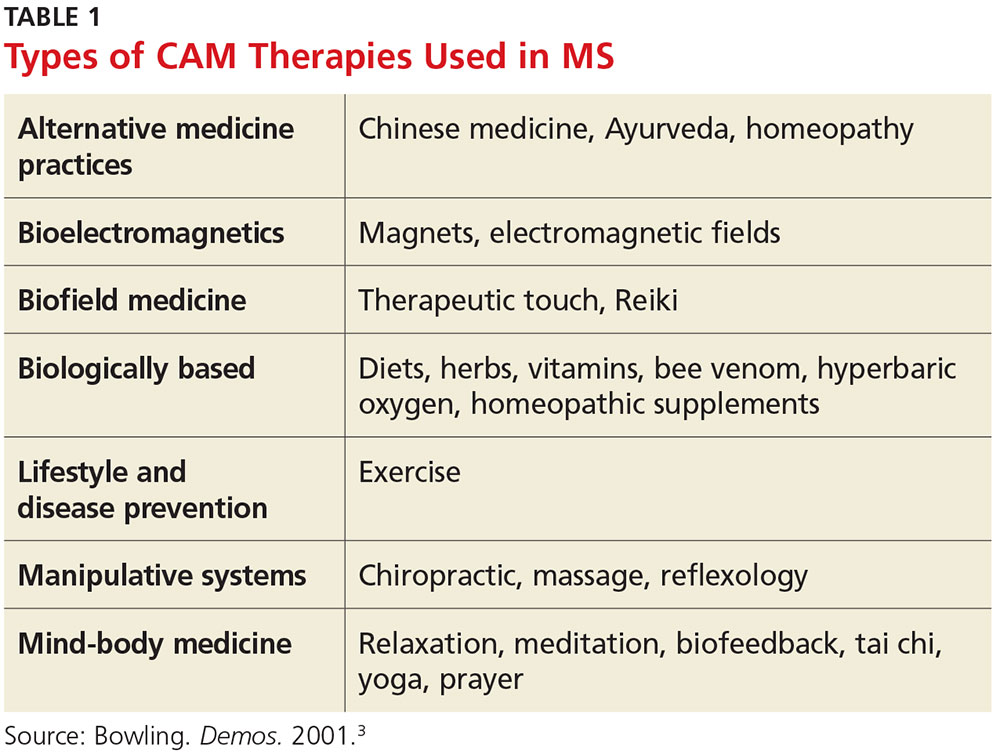

CAM practices include a myriad of therapies from different disciplines (see Table 1).3 Because most people who use CAM do not discuss it with their health care providers, it is important that providers inquire about patient use and are armed with basic safety and efficacy information.

Office visits for MS should include safety and efficacy discussions about all therapeutic treatments (disease modifying, relapse, and symptom management). Some issues—such as adverse effects—are obvious, while others, such as cost, are less so. A patient with MS may pursue an extremely expensive CAM therapy that lacks substantial evidence for the condition. Providers should therefore consider cost as part of the safety equation and be aware that while some CAM therapies have been studied in MS, most have not (or the research has been of poor quality).4

For many commonly used therapies, there is insufficient scientific evidence to support their usefulness in MS. These include acupuncture, biofeedback, Chinese medicine, chiropractic care, replacing amalgam dental fillings, equine therapy, hyperbaric oxygen treatment, low-dose naltrexone, massage therapy, tai chi, and yoga. While many of these practices are relatively safe and inexpensive, others may cause financial harm. Conversely, something considered safe and inexpensive (eg, a low-fat diet with omega-3 supplementation) may be found to be ineffective. Although recommending this type of diet for a person with MS is safe, realistic expectations must be discussed regarding its effect (or lack thereof) on the condition.4

The effectiveness of medical marijuana for MS is another popular deliberation. While data suggest that several administration methods of oral cannabinoids may be effective for spasticity and pain reduction, there is inadequate evidence to support the use of smoked cannabis. The deleterious effects of cannabis on cognition also need to be considered.5

Dietary supplements (eg, vitamins, minerals, botanicals, dietary substances) are often regarded as safe by patients because they are “natural.” As clinicians, we must be direct in asking patients about everything they are taking—many dietary supplements have drug interactions and/or toxic effects and may adversely stimulate the immune system. Vitamin D, for example, is one supplement that has been heavily studied in MS; lower levels of vitamin D have been shown to increase the risk for MS, and higher levels may be associated with lower relapse and disability rates. Therefore, standard of practice is to monitor vitamin D levels and supplement accordingly.

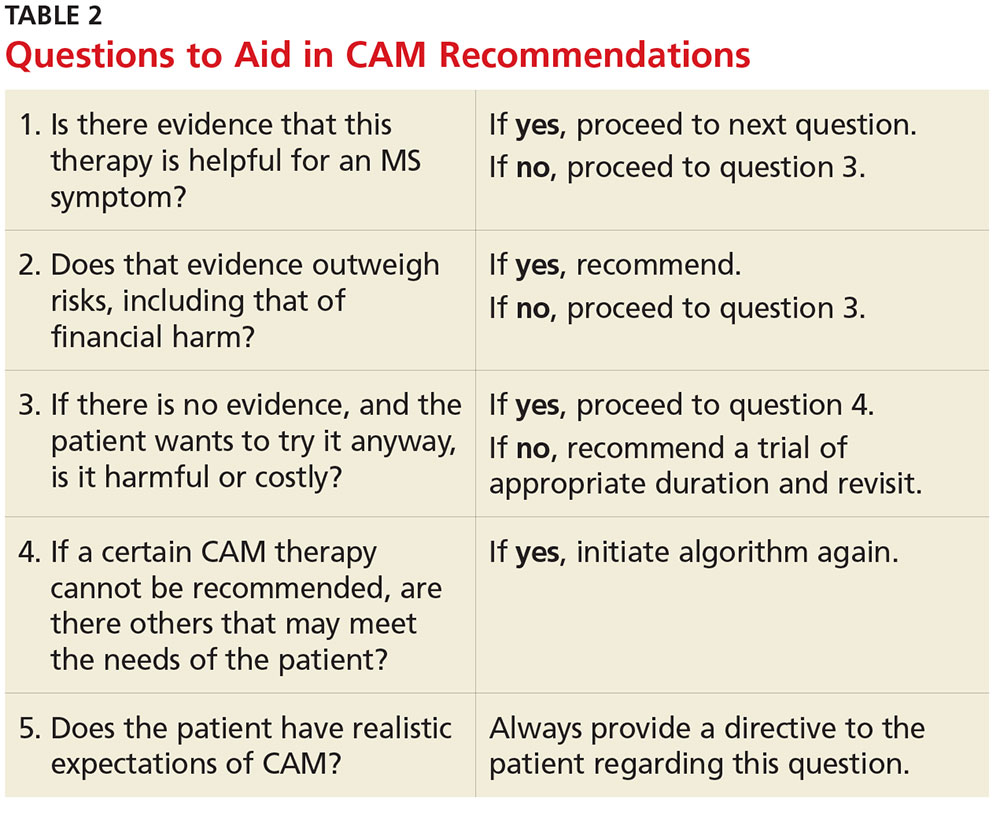

CAM can be safely and effectively recommended to people living with MS with due diligence. A question guide to aid recommendations is listed in Table 2.

Currently, no CAM therapies have been shown to modify MS, and CAM should not be recommended in place of disease-modifying treatment. However, if the proper questions are addressed, many CAM therapies can be safely recommended for common MS symptoms. Insurance coverage varies significantly among policies, but some treatments (eg, acupuncture and chiropractic care) are gaining coverage.

Finally, it is safe and a good standard of care to recommend a healthy anti-inflammatory diet, such as the Mediterranean diet, to people living with MS in order to improve general health. —MW

Megan Weigel, DNP, ARNP-C, MSCN

President of IOMSN

Baptist Neurology, Jacksonville Beach, Florida

1. CDC. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. http://nccih.nih.gov/sites/nccam.nih.gov/files/news/camstats/2002/report.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2016.

2. Yadav V, Shinto L, Bourdette D. Complementary and alternative medicine for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2010;6(3):381-395.

3. Bowling AC. Alternative Medicine and Multiple Sclerosis. New York: Demos; 2001.

4. Bowling AC. Complementary and alternative medicine in MS. www.nationalmssociety.org/nationalmssociety/media/msnationalfiles/brochures/clinical_bulletin_complementary-and-alternative-medicine-in-ms.pdf. Accessed November 2, 2016.

5. Honarmand K, Tierney MC, O’Connor P, Feinstein A. Effects of cannabis on cognitive function in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2011;76(13):1153-1160.

Q)How is complementary and alternative medicine used in multiple sclerosis, and how can I safely recommend it to my patients?

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is a non-mainstream practice used in conjunction with conventional medicine.1 Its use is prevalent among people with and without chronic illnesses, including those living with multiple sclerosis (MS). Up to 70% of Americans with MS have used some type of CAM therapy, compared with 36% of the general population.1,2 CAM use is higher in women than in men and is highest among persons ages 35 to 49—two demographics also associated with MS.3

CAM practices include a myriad of therapies from different disciplines (see Table 1).3 Because most people who use CAM do not discuss it with their health care providers, it is important that providers inquire about patient use and are armed with basic safety and efficacy information.

Office visits for MS should include safety and efficacy discussions about all therapeutic treatments (disease modifying, relapse, and symptom management). Some issues—such as adverse effects—are obvious, while others, such as cost, are less so. A patient with MS may pursue an extremely expensive CAM therapy that lacks substantial evidence for the condition. Providers should therefore consider cost as part of the safety equation and be aware that while some CAM therapies have been studied in MS, most have not (or the research has been of poor quality).4

For many commonly used therapies, there is insufficient scientific evidence to support their usefulness in MS. These include acupuncture, biofeedback, Chinese medicine, chiropractic care, replacing amalgam dental fillings, equine therapy, hyperbaric oxygen treatment, low-dose naltrexone, massage therapy, tai chi, and yoga. While many of these practices are relatively safe and inexpensive, others may cause financial harm. Conversely, something considered safe and inexpensive (eg, a low-fat diet with omega-3 supplementation) may be found to be ineffective. Although recommending this type of diet for a person with MS is safe, realistic expectations must be discussed regarding its effect (or lack thereof) on the condition.4

The effectiveness of medical marijuana for MS is another popular deliberation. While data suggest that several administration methods of oral cannabinoids may be effective for spasticity and pain reduction, there is inadequate evidence to support the use of smoked cannabis. The deleterious effects of cannabis on cognition also need to be considered.5

Dietary supplements (eg, vitamins, minerals, botanicals, dietary substances) are often regarded as safe by patients because they are “natural.” As clinicians, we must be direct in asking patients about everything they are taking—many dietary supplements have drug interactions and/or toxic effects and may adversely stimulate the immune system. Vitamin D, for example, is one supplement that has been heavily studied in MS; lower levels of vitamin D have been shown to increase the risk for MS, and higher levels may be associated with lower relapse and disability rates. Therefore, standard of practice is to monitor vitamin D levels and supplement accordingly.

CAM can be safely and effectively recommended to people living with MS with due diligence. A question guide to aid recommendations is listed in Table 2.

Currently, no CAM therapies have been shown to modify MS, and CAM should not be recommended in place of disease-modifying treatment. However, if the proper questions are addressed, many CAM therapies can be safely recommended for common MS symptoms. Insurance coverage varies significantly among policies, but some treatments (eg, acupuncture and chiropractic care) are gaining coverage.

Finally, it is safe and a good standard of care to recommend a healthy anti-inflammatory diet, such as the Mediterranean diet, to people living with MS in order to improve general health. —MW

Megan Weigel, DNP, ARNP-C, MSCN

President of IOMSN

Baptist Neurology, Jacksonville Beach, Florida

Q)How is complementary and alternative medicine used in multiple sclerosis, and how can I safely recommend it to my patients?

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is a non-mainstream practice used in conjunction with conventional medicine.1 Its use is prevalent among people with and without chronic illnesses, including those living with multiple sclerosis (MS). Up to 70% of Americans with MS have used some type of CAM therapy, compared with 36% of the general population.1,2 CAM use is higher in women than in men and is highest among persons ages 35 to 49—two demographics also associated with MS.3

CAM practices include a myriad of therapies from different disciplines (see Table 1).3 Because most people who use CAM do not discuss it with their health care providers, it is important that providers inquire about patient use and are armed with basic safety and efficacy information.

Office visits for MS should include safety and efficacy discussions about all therapeutic treatments (disease modifying, relapse, and symptom management). Some issues—such as adverse effects—are obvious, while others, such as cost, are less so. A patient with MS may pursue an extremely expensive CAM therapy that lacks substantial evidence for the condition. Providers should therefore consider cost as part of the safety equation and be aware that while some CAM therapies have been studied in MS, most have not (or the research has been of poor quality).4

For many commonly used therapies, there is insufficient scientific evidence to support their usefulness in MS. These include acupuncture, biofeedback, Chinese medicine, chiropractic care, replacing amalgam dental fillings, equine therapy, hyperbaric oxygen treatment, low-dose naltrexone, massage therapy, tai chi, and yoga. While many of these practices are relatively safe and inexpensive, others may cause financial harm. Conversely, something considered safe and inexpensive (eg, a low-fat diet with omega-3 supplementation) may be found to be ineffective. Although recommending this type of diet for a person with MS is safe, realistic expectations must be discussed regarding its effect (or lack thereof) on the condition.4

The effectiveness of medical marijuana for MS is another popular deliberation. While data suggest that several administration methods of oral cannabinoids may be effective for spasticity and pain reduction, there is inadequate evidence to support the use of smoked cannabis. The deleterious effects of cannabis on cognition also need to be considered.5

Dietary supplements (eg, vitamins, minerals, botanicals, dietary substances) are often regarded as safe by patients because they are “natural.” As clinicians, we must be direct in asking patients about everything they are taking—many dietary supplements have drug interactions and/or toxic effects and may adversely stimulate the immune system. Vitamin D, for example, is one supplement that has been heavily studied in MS; lower levels of vitamin D have been shown to increase the risk for MS, and higher levels may be associated with lower relapse and disability rates. Therefore, standard of practice is to monitor vitamin D levels and supplement accordingly.

CAM can be safely and effectively recommended to people living with MS with due diligence. A question guide to aid recommendations is listed in Table 2.

Currently, no CAM therapies have been shown to modify MS, and CAM should not be recommended in place of disease-modifying treatment. However, if the proper questions are addressed, many CAM therapies can be safely recommended for common MS symptoms. Insurance coverage varies significantly among policies, but some treatments (eg, acupuncture and chiropractic care) are gaining coverage.

Finally, it is safe and a good standard of care to recommend a healthy anti-inflammatory diet, such as the Mediterranean diet, to people living with MS in order to improve general health. —MW

Megan Weigel, DNP, ARNP-C, MSCN

President of IOMSN

Baptist Neurology, Jacksonville Beach, Florida

1. CDC. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. http://nccih.nih.gov/sites/nccam.nih.gov/files/news/camstats/2002/report.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2016.

2. Yadav V, Shinto L, Bourdette D. Complementary and alternative medicine for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2010;6(3):381-395.

3. Bowling AC. Alternative Medicine and Multiple Sclerosis. New York: Demos; 2001.

4. Bowling AC. Complementary and alternative medicine in MS. www.nationalmssociety.org/nationalmssociety/media/msnationalfiles/brochures/clinical_bulletin_complementary-and-alternative-medicine-in-ms.pdf. Accessed November 2, 2016.

5. Honarmand K, Tierney MC, O’Connor P, Feinstein A. Effects of cannabis on cognitive function in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2011;76(13):1153-1160.

1. CDC. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. http://nccih.nih.gov/sites/nccam.nih.gov/files/news/camstats/2002/report.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2016.

2. Yadav V, Shinto L, Bourdette D. Complementary and alternative medicine for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2010;6(3):381-395.

3. Bowling AC. Alternative Medicine and Multiple Sclerosis. New York: Demos; 2001.

4. Bowling AC. Complementary and alternative medicine in MS. www.nationalmssociety.org/nationalmssociety/media/msnationalfiles/brochures/clinical_bulletin_complementary-and-alternative-medicine-in-ms.pdf. Accessed November 2, 2016.

5. Honarmand K, Tierney MC, O’Connor P, Feinstein A. Effects of cannabis on cognitive function in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2011;76(13):1153-1160.