User login

Barriers to Establishing a PCS

Palliative care (PC) focuses on relieving distressing symptoms such as pain, dyspnea, fatigue, and depression; providing psychological, social, emotional, and spiritual support; and helping patients choose treatments consistent with their values.[1] Palliative care consultation services (PCSs) increase patient and family satisfaction,[2, 3] improve quality of life,[4] reduce resource utilization,[5] and decrease hospital expenditure.[2, 6] Hospitals that fund a PCS typically realize a sizable return on investment and good value, as these services provide better care at lower cost.[7] These benefits provide a strong rationale for all hospitals to establish a PCS. However, only 53% of acute care hospitals in California offer PC services, and only 37% have a hospital‐based PCS.[7] To increase access for patients with serious illness, it is necessary to understand the barriers that hinder the development of PCS. In this study, we asked leaders from hospitals without a PCS to describe these barriers and identify strategies that could overcome them and promote PCSs.

METHODS

In 2011, we surveyed all acute care hospitals in California to assess the prevalence of PCSs in the state. We defined a PCS as an interdisciplinary team that sees patients, identifies needs, makes treatment recommendations, facilitates patient and/or family decision making, and/or directly provides palliative care for patients with life‐threatening illness and their families. Hospitals that did not have a PCS were asked questions regarding plans to establish one (Is there an effort underway to establish a palliative care program in your hospital?), perceived barriers to starting one (What are 3 significant barriers or circumstances that have prevented your hospital from creating a palliative care program?), and ideas for overcoming barriers (What resources, training, policy changes would be most helpful in overcoming those barriers?). Questions that allowed for open‐ended responses were analyzed using a thematic approach.[8] Themes were initially reviewed by 1 researcher (C.J.B.), then refined and confirmed at each stage using an iterative process with other research team members (D.L.O., S.Z.P.) to reduce potential biases. Questions assessing hospital characteristics and status toward establishing a PCS provided a list of possible answers. Frequencies to these responses are reported accordingly.

RESULTS

Surveys were distributed to 376 acute care hospitals in California, of which 360 responded to the survey, resulting in a 96% response rate. Of the 360 hospitals surveyed, 46% (n=166) reported not offering any PCS. Out of the 166 that did not have PCS, 7 stated they had a PCS at some point in the last 5 years, but the program was discontinued. Hospitals without a PCS were largely for profit (75%, n=125), small with <150 beds (72%, n=120), and not affiliated with a system (63%, n=105). Overall, 34% (43/128) of hospitals reported that they had efforts underway to establish one, with 21% (9/43) expecting to start seeing patients within a year. Seventy‐two hospitals (56%, 72/128) reported that providers from local hospices aided them in providing their patients with PC, and that this approach met the needs of their patients. A total of 93 hospitals identified multiple barriers (n=186) to establishing a PCS, of which 162 responses could be categorized into 5 meaningful themes. Regarding strategies to overcome these barriers, 65 hospitals provided 72 responses that could be categorized into 5 meaningful themes (Table 1).

| Barriers and Strategies | Responses, % (n) |

|---|---|

| |

| Main barriers to establishing a PCS | 93 hospitals provided 186 barriers |

| Insufficient funding and/or resources | 31 (58) |

| Insufficient staff to support a PCS | 20 (37) |

| Perceived lack of need for a PCS | 14 (27) |

| Lack of support among nonpalliative care physicians | 13 (25) |

| Competing priorities | 8 (15) |

| Don't know/unsure | 14 (24) |

| Main strategies to overcome barriers to establishing a PCS | 65 hospitals provided 72 strategies |

| Reroute funding to establish a PCS | 28 (20) |

| Explain benefits of PCS to staff and community | 24 (17) |

| Provide a framework for how to establish a PCS | 21 (15) |

| Staff for a PCS | 18 (13) |

| Physician support | 10 (7) |

DISCUSSION

Despite citing obstacles to providing PCSs, one‐third of hospitals surveyed report that they are planning to establish a program. As an alternative, many hospitals without a PCS reported that they provide their patients with PC through partnerships with local hospice services. This approach may provide some hospitals with a practical alternative to having a PCS, especially in smaller institutions where budgets and the need for PC are proportionally small. Future surveys should account for this approach to providing PCS to patients. Sharing the strong evidence of return on investment from PCS[6, 7] with hospital leaders could help overcome the perceived barrier of cost and garner financial support. Training programs and technical assistance provided by the Palliative Care Leadership Center initiative and the Center to Advance Palliative Care have a proven track record in helping hospitals establish a PCS through mentored training,[9] and the End‐of‐Life Nursing Education Consortium has demonstrated effectiveness with nursing education.[10] These programs could provide the resources that many hospitals seek. Educating hospital leaders and clinicians about the evidence for PCSs improving care for patients with serious illness may further help to engender support for PCSs. One barrier that may be more difficult to overcome is the lack of trained PC clinicians. Efforts to educate and train generalist clinicians in primary PC may mitigate this shortfall.[1] Increasing the number of trained primary PC clinicians may also reduce fragmentation in patient care and reduce burden on specialist PC clinicians.[11] Specialty PC clinicians can also lend their expertise to hospitals seeking to start a PCS to achieve the goal of universal access to PCS.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Hospital Council of Northern and Central California, the Hospital Council of Southern California, and the Hospital Council of San Diego and Imperial Counties for their support in encouraging their members to participate. The authors also thank all of the respondents for their diligence and care in responding to the survey.

Disclosures

The California HealthCare Foundation provided funding to support the administration of the survey and analysis of findings, as well as limited dissemination of results though the foundation's communication venues. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2014.

- , , , et al. Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: a randomized control trial. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(2):180–190.

- , , , , . A systematic review of satisfaction with care at the end of life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(1):124–129.

- . Health care system factors affecting end‐of‐life care. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(suppl 1):S79–S87.

- , , . Impact of palliative care case management on resource use by patients dying of cancer at a Veterans Affairs medical center. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(1):26–35.

- , , , et al. Cost savings associated with US hospital palliative care consultation programs. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(16):1783–1790.

- , , . Two steps forward, one step back: changes in palliative care consultation services in California hospitals from 2007 to 2011. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(11):1214–1220.

- , . Using qualitative methods to explore key questions in palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(8):725–730.

- , , . Center to Advance Palliative Care palliative care consultation service metrics: consensus recommendations. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(10):1294–1298.

- , , , et al. Evaluation of the End‐of‐Life Nursing Education Consortium undergraduate faculty training program. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(1):107–114.

- , . Generalist plus specialist palliative care–creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(13):1173–1175.

Palliative care (PC) focuses on relieving distressing symptoms such as pain, dyspnea, fatigue, and depression; providing psychological, social, emotional, and spiritual support; and helping patients choose treatments consistent with their values.[1] Palliative care consultation services (PCSs) increase patient and family satisfaction,[2, 3] improve quality of life,[4] reduce resource utilization,[5] and decrease hospital expenditure.[2, 6] Hospitals that fund a PCS typically realize a sizable return on investment and good value, as these services provide better care at lower cost.[7] These benefits provide a strong rationale for all hospitals to establish a PCS. However, only 53% of acute care hospitals in California offer PC services, and only 37% have a hospital‐based PCS.[7] To increase access for patients with serious illness, it is necessary to understand the barriers that hinder the development of PCS. In this study, we asked leaders from hospitals without a PCS to describe these barriers and identify strategies that could overcome them and promote PCSs.

METHODS

In 2011, we surveyed all acute care hospitals in California to assess the prevalence of PCSs in the state. We defined a PCS as an interdisciplinary team that sees patients, identifies needs, makes treatment recommendations, facilitates patient and/or family decision making, and/or directly provides palliative care for patients with life‐threatening illness and their families. Hospitals that did not have a PCS were asked questions regarding plans to establish one (Is there an effort underway to establish a palliative care program in your hospital?), perceived barriers to starting one (What are 3 significant barriers or circumstances that have prevented your hospital from creating a palliative care program?), and ideas for overcoming barriers (What resources, training, policy changes would be most helpful in overcoming those barriers?). Questions that allowed for open‐ended responses were analyzed using a thematic approach.[8] Themes were initially reviewed by 1 researcher (C.J.B.), then refined and confirmed at each stage using an iterative process with other research team members (D.L.O., S.Z.P.) to reduce potential biases. Questions assessing hospital characteristics and status toward establishing a PCS provided a list of possible answers. Frequencies to these responses are reported accordingly.

RESULTS

Surveys were distributed to 376 acute care hospitals in California, of which 360 responded to the survey, resulting in a 96% response rate. Of the 360 hospitals surveyed, 46% (n=166) reported not offering any PCS. Out of the 166 that did not have PCS, 7 stated they had a PCS at some point in the last 5 years, but the program was discontinued. Hospitals without a PCS were largely for profit (75%, n=125), small with <150 beds (72%, n=120), and not affiliated with a system (63%, n=105). Overall, 34% (43/128) of hospitals reported that they had efforts underway to establish one, with 21% (9/43) expecting to start seeing patients within a year. Seventy‐two hospitals (56%, 72/128) reported that providers from local hospices aided them in providing their patients with PC, and that this approach met the needs of their patients. A total of 93 hospitals identified multiple barriers (n=186) to establishing a PCS, of which 162 responses could be categorized into 5 meaningful themes. Regarding strategies to overcome these barriers, 65 hospitals provided 72 responses that could be categorized into 5 meaningful themes (Table 1).

| Barriers and Strategies | Responses, % (n) |

|---|---|

| |

| Main barriers to establishing a PCS | 93 hospitals provided 186 barriers |

| Insufficient funding and/or resources | 31 (58) |

| Insufficient staff to support a PCS | 20 (37) |

| Perceived lack of need for a PCS | 14 (27) |

| Lack of support among nonpalliative care physicians | 13 (25) |

| Competing priorities | 8 (15) |

| Don't know/unsure | 14 (24) |

| Main strategies to overcome barriers to establishing a PCS | 65 hospitals provided 72 strategies |

| Reroute funding to establish a PCS | 28 (20) |

| Explain benefits of PCS to staff and community | 24 (17) |

| Provide a framework for how to establish a PCS | 21 (15) |

| Staff for a PCS | 18 (13) |

| Physician support | 10 (7) |

DISCUSSION

Despite citing obstacles to providing PCSs, one‐third of hospitals surveyed report that they are planning to establish a program. As an alternative, many hospitals without a PCS reported that they provide their patients with PC through partnerships with local hospice services. This approach may provide some hospitals with a practical alternative to having a PCS, especially in smaller institutions where budgets and the need for PC are proportionally small. Future surveys should account for this approach to providing PCS to patients. Sharing the strong evidence of return on investment from PCS[6, 7] with hospital leaders could help overcome the perceived barrier of cost and garner financial support. Training programs and technical assistance provided by the Palliative Care Leadership Center initiative and the Center to Advance Palliative Care have a proven track record in helping hospitals establish a PCS through mentored training,[9] and the End‐of‐Life Nursing Education Consortium has demonstrated effectiveness with nursing education.[10] These programs could provide the resources that many hospitals seek. Educating hospital leaders and clinicians about the evidence for PCSs improving care for patients with serious illness may further help to engender support for PCSs. One barrier that may be more difficult to overcome is the lack of trained PC clinicians. Efforts to educate and train generalist clinicians in primary PC may mitigate this shortfall.[1] Increasing the number of trained primary PC clinicians may also reduce fragmentation in patient care and reduce burden on specialist PC clinicians.[11] Specialty PC clinicians can also lend their expertise to hospitals seeking to start a PCS to achieve the goal of universal access to PCS.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Hospital Council of Northern and Central California, the Hospital Council of Southern California, and the Hospital Council of San Diego and Imperial Counties for their support in encouraging their members to participate. The authors also thank all of the respondents for their diligence and care in responding to the survey.

Disclosures

The California HealthCare Foundation provided funding to support the administration of the survey and analysis of findings, as well as limited dissemination of results though the foundation's communication venues. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Palliative care (PC) focuses on relieving distressing symptoms such as pain, dyspnea, fatigue, and depression; providing psychological, social, emotional, and spiritual support; and helping patients choose treatments consistent with their values.[1] Palliative care consultation services (PCSs) increase patient and family satisfaction,[2, 3] improve quality of life,[4] reduce resource utilization,[5] and decrease hospital expenditure.[2, 6] Hospitals that fund a PCS typically realize a sizable return on investment and good value, as these services provide better care at lower cost.[7] These benefits provide a strong rationale for all hospitals to establish a PCS. However, only 53% of acute care hospitals in California offer PC services, and only 37% have a hospital‐based PCS.[7] To increase access for patients with serious illness, it is necessary to understand the barriers that hinder the development of PCS. In this study, we asked leaders from hospitals without a PCS to describe these barriers and identify strategies that could overcome them and promote PCSs.

METHODS

In 2011, we surveyed all acute care hospitals in California to assess the prevalence of PCSs in the state. We defined a PCS as an interdisciplinary team that sees patients, identifies needs, makes treatment recommendations, facilitates patient and/or family decision making, and/or directly provides palliative care for patients with life‐threatening illness and their families. Hospitals that did not have a PCS were asked questions regarding plans to establish one (Is there an effort underway to establish a palliative care program in your hospital?), perceived barriers to starting one (What are 3 significant barriers or circumstances that have prevented your hospital from creating a palliative care program?), and ideas for overcoming barriers (What resources, training, policy changes would be most helpful in overcoming those barriers?). Questions that allowed for open‐ended responses were analyzed using a thematic approach.[8] Themes were initially reviewed by 1 researcher (C.J.B.), then refined and confirmed at each stage using an iterative process with other research team members (D.L.O., S.Z.P.) to reduce potential biases. Questions assessing hospital characteristics and status toward establishing a PCS provided a list of possible answers. Frequencies to these responses are reported accordingly.

RESULTS

Surveys were distributed to 376 acute care hospitals in California, of which 360 responded to the survey, resulting in a 96% response rate. Of the 360 hospitals surveyed, 46% (n=166) reported not offering any PCS. Out of the 166 that did not have PCS, 7 stated they had a PCS at some point in the last 5 years, but the program was discontinued. Hospitals without a PCS were largely for profit (75%, n=125), small with <150 beds (72%, n=120), and not affiliated with a system (63%, n=105). Overall, 34% (43/128) of hospitals reported that they had efforts underway to establish one, with 21% (9/43) expecting to start seeing patients within a year. Seventy‐two hospitals (56%, 72/128) reported that providers from local hospices aided them in providing their patients with PC, and that this approach met the needs of their patients. A total of 93 hospitals identified multiple barriers (n=186) to establishing a PCS, of which 162 responses could be categorized into 5 meaningful themes. Regarding strategies to overcome these barriers, 65 hospitals provided 72 responses that could be categorized into 5 meaningful themes (Table 1).

| Barriers and Strategies | Responses, % (n) |

|---|---|

| |

| Main barriers to establishing a PCS | 93 hospitals provided 186 barriers |

| Insufficient funding and/or resources | 31 (58) |

| Insufficient staff to support a PCS | 20 (37) |

| Perceived lack of need for a PCS | 14 (27) |

| Lack of support among nonpalliative care physicians | 13 (25) |

| Competing priorities | 8 (15) |

| Don't know/unsure | 14 (24) |

| Main strategies to overcome barriers to establishing a PCS | 65 hospitals provided 72 strategies |

| Reroute funding to establish a PCS | 28 (20) |

| Explain benefits of PCS to staff and community | 24 (17) |

| Provide a framework for how to establish a PCS | 21 (15) |

| Staff for a PCS | 18 (13) |

| Physician support | 10 (7) |

DISCUSSION

Despite citing obstacles to providing PCSs, one‐third of hospitals surveyed report that they are planning to establish a program. As an alternative, many hospitals without a PCS reported that they provide their patients with PC through partnerships with local hospice services. This approach may provide some hospitals with a practical alternative to having a PCS, especially in smaller institutions where budgets and the need for PC are proportionally small. Future surveys should account for this approach to providing PCS to patients. Sharing the strong evidence of return on investment from PCS[6, 7] with hospital leaders could help overcome the perceived barrier of cost and garner financial support. Training programs and technical assistance provided by the Palliative Care Leadership Center initiative and the Center to Advance Palliative Care have a proven track record in helping hospitals establish a PCS through mentored training,[9] and the End‐of‐Life Nursing Education Consortium has demonstrated effectiveness with nursing education.[10] These programs could provide the resources that many hospitals seek. Educating hospital leaders and clinicians about the evidence for PCSs improving care for patients with serious illness may further help to engender support for PCSs. One barrier that may be more difficult to overcome is the lack of trained PC clinicians. Efforts to educate and train generalist clinicians in primary PC may mitigate this shortfall.[1] Increasing the number of trained primary PC clinicians may also reduce fragmentation in patient care and reduce burden on specialist PC clinicians.[11] Specialty PC clinicians can also lend their expertise to hospitals seeking to start a PCS to achieve the goal of universal access to PCS.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Hospital Council of Northern and Central California, the Hospital Council of Southern California, and the Hospital Council of San Diego and Imperial Counties for their support in encouraging their members to participate. The authors also thank all of the respondents for their diligence and care in responding to the survey.

Disclosures

The California HealthCare Foundation provided funding to support the administration of the survey and analysis of findings, as well as limited dissemination of results though the foundation's communication venues. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2014.

- , , , et al. Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: a randomized control trial. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(2):180–190.

- , , , , . A systematic review of satisfaction with care at the end of life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(1):124–129.

- . Health care system factors affecting end‐of‐life care. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(suppl 1):S79–S87.

- , , . Impact of palliative care case management on resource use by patients dying of cancer at a Veterans Affairs medical center. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(1):26–35.

- , , , et al. Cost savings associated with US hospital palliative care consultation programs. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(16):1783–1790.

- , , . Two steps forward, one step back: changes in palliative care consultation services in California hospitals from 2007 to 2011. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(11):1214–1220.

- , . Using qualitative methods to explore key questions in palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(8):725–730.

- , , . Center to Advance Palliative Care palliative care consultation service metrics: consensus recommendations. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(10):1294–1298.

- , , , et al. Evaluation of the End‐of‐Life Nursing Education Consortium undergraduate faculty training program. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(1):107–114.

- , . Generalist plus specialist palliative care–creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(13):1173–1175.

- Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2014.

- , , , et al. Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: a randomized control trial. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(2):180–190.

- , , , , . A systematic review of satisfaction with care at the end of life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(1):124–129.

- . Health care system factors affecting end‐of‐life care. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(suppl 1):S79–S87.

- , , . Impact of palliative care case management on resource use by patients dying of cancer at a Veterans Affairs medical center. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(1):26–35.

- , , , et al. Cost savings associated with US hospital palliative care consultation programs. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(16):1783–1790.

- , , . Two steps forward, one step back: changes in palliative care consultation services in California hospitals from 2007 to 2011. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(11):1214–1220.

- , . Using qualitative methods to explore key questions in palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(8):725–730.

- , , . Center to Advance Palliative Care palliative care consultation service metrics: consensus recommendations. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(10):1294–1298.

- , , , et al. Evaluation of the End‐of‐Life Nursing Education Consortium undergraduate faculty training program. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(1):107–114.

- , . Generalist plus specialist palliative care–creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(13):1173–1175.

Severity of Symptoms

The frequency and severity of symptoms among older hospitalized patients with chronic illnesses can have a profound negative impact on their quality of life.1, 2 Nonetheless, research examining the prevalence and management of symptoms has focused predominantly on cancer patients.3 Few studies have included patients with other serious conditions such as heart failure (HF) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),3, 4 which are very common and are major causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States.5 One longitudinal assessment of symptom severity among a group of community‐based older adults diagnosed with COPD and HF reported high rates of moderate‐to‐severe pain, dyspnea, and anxiety at baseline and follow‐up, as long as 22 months later.6 Persistent symptoms over time can have an adverse effect on an individual's physical and emotional well‐being, and highlight opportunities to improve care.3, 7 Understanding patterns of symptom change over time is a key first step in developing systems to improve quality of care for people with chronic illness.

Among hospitalized patients, pain, dyspnea, anxiety, and depression cause the greatest symptom burden, accounting for 67% of all symptoms classified as moderate to severe.8 While assessment and management of symptoms may be the reason for admission to the hospital and the focus of inpatient care, this focus may not persist after discharge, leaving patients with significant symptoms that can diminish quality of life and contribute to readmission.9 We studied a cohort of older inpatients with serious illness over time in order to determine the prevalence, severity, burden, and predictors of symptoms during the course of hospitalization and at 2 weeks after discharge.

METHODS

Setting

The study was undertaken at a large academic medical center in San Francisco.

Subjects

Participants were patients 65 years or older admitted to the medicine or cardiology services with a primary diagnosis of cancer, COPD, or HF. Participants were required to be fully oriented and English‐speaking. Patients gave written informed consent to participate. The Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco, approved this study (H8695‐35172‐01).

Data Collection

Data collection was undertaken from March 2001 to December 2003. This study was part of a prospective, clinical trial that compared a proactive palliative medicine consultation with usual hospital care, and has been previously described.10 Upon study enrollment, all patients completed the Inpatient Care Survey. The survey asked participants about demographic information such as date of birth, sex, education level, race, and marital status. The survey instruments also included the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) index and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS‐15). Each weekday during hospitalization, a trained research assistant asked patients to report their worst symptom level for pain, dyspnea, and anxiety in the past 24 hours using a 010 numeric rating scale, where 0 was none and 10 was the worst you can imagine. We further characterized scores into categories such that 0 was defined as none, 13 as mild, 46 as moderate, and 710 as severe. A follow‐up telephone survey, 2 weeks after discharge, reassessed patients' worst symptom levels in the past 24 hours for pain, dyspnea, and anxiety.

We also generated a composite score of symptoms to report a symptom burden score for these 3 symptoms. Using the categories of symptom severity, we assigned a score of 0 for none, 1 for mild, 2 for moderate, and 3 for severe. We summed the assigned scores for all 3 symptoms for each subject to generate a symptom burden score as follows: no symptom burden (0), mild symptom burden (13), moderate symptom burden (46), and severe symptom burden (79). In this scale, a moderate symptom burden would mean that a subject reported having at least 1 symptom at a moderate or severe level, with at least 1 other symptom present. A severe symptom burden would require the presence of all 3 symptoms, with at least 1 at a severe level.

We reviewed patient charts to assess severity of patient illness upon admission. For cancer, we recorded type; for COPD, we noted forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1); and for HF, we recorded the ejection fraction. We also queried the National Death Index to get vital statistics on all subjects.

Data Preparation

The IADL asks patients to report whether they can perform 13 daily living skills without help, with some help, or were unable to complete tasks.11 Subjects who reported needing at least some help with any of the 13 items were categorized as dependent. The GDS‐15 is a widely used, validated 15‐item scale for assessing depressive mood in the elderly.12 Scores for the GDS‐15 range from 0 to 15, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms. Based on previous research, we categorized patients as either not depressed (05) or having probable depression (6 or more).12

Statistical Analysis

Because our clinical trial had no impact on care or symptoms, we combined intervention and usual care patients for this analysis of symptom severity. Descriptive statistics, such as frequencies, means, standard deviations (SDs), and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to examine the distribution of measures. Chi‐square (2) analysis was undertaken to examine bivariate associations between categorical variables. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was undertaken to examine associations between categorical and continuous variables. Multivariate logistic regression was used to examine predictors of symptom burden at follow‐up, including patient characteristics that were significant to P 0.10 in bivariate analysis. We used KaplanMeier survival curves to examine the relationship between primary diagnosis and mortality, and assessed statistical significance using log‐rank tests (MantelCox).13 The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Mac (version 17; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL; March 11, 2009) was used to analyze these data.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

A total of 150 patients enrolled in the study. The mean length of stay was 5.4 days (SD: 5.6; range: 147 days). HF was the most common primary diagnosis (46.7%, n = 70) with 48% (n = 34) having an ejection fraction of 45% or less (mean = 43%; SD: 22); followed by cancer (30%, n = 45) with the most common type being prostate (18%, n = 8), lung (13%, n = 6), and breast (13%, n = 6); and COPD (23%, n = 35) with an average FEV1 of 1.5 L (SD: 0.94; range: 0.503.9). The mean age was 77 years (SD: 7.9; range: 6596 years). The majority of participants were men (56%, n = 83) and white (73%, n = 108), with the most being either married/partnered (43%, n = 64) or divorced/widowed (44%, n = 66). The IADL identified almost two‐thirds of participants as dependent (62%, n = 94). The GDS‐15 categorized three‐quarters of participants (n = 118) as not depressed. The only significant association between participant characteristics and their primary diagnosis was for the IADL index (Table 1), with significantly more (2 = 6.3; P = 0.04) patients with HF categorized as being dependent (72%).

| Characteristics | Primary Diagnosis | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer n = 44 | HF n = 70 | COPD n = 35 | |||

| |||||

| Length of stay | (Mean days) | 5.4 | 4.7 | 6.5 | 0.3 |

| Age | (Mean years) | 76 | 78 | 76 | 0.3 |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 47% | 37% | 57% | 0.1 | |

| Marital status | 0.2 | ||||

| Single | 16 | 9 | 17 | ||

| Married/partnered | 51 | 45 | 29 | ||

| Divorced/widowed | 33 | 46 | 54 | ||

| Race | |||||

| White | 89 | 64 | 69 | 0.1 | |

| Black/African American | 7 | 21 | 23 | ||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 5 | 10 | 9 | ||

| Other | 0 | 4 | 0 | ||

| IADL | |||||

| Dependent | 49 | 72 | 60 | 0.04 | |

| GDS‐15 | |||||

| Probable depression | 18 | 22 | 21 | 0.9 | |

Frequency and Severity of Symptoms

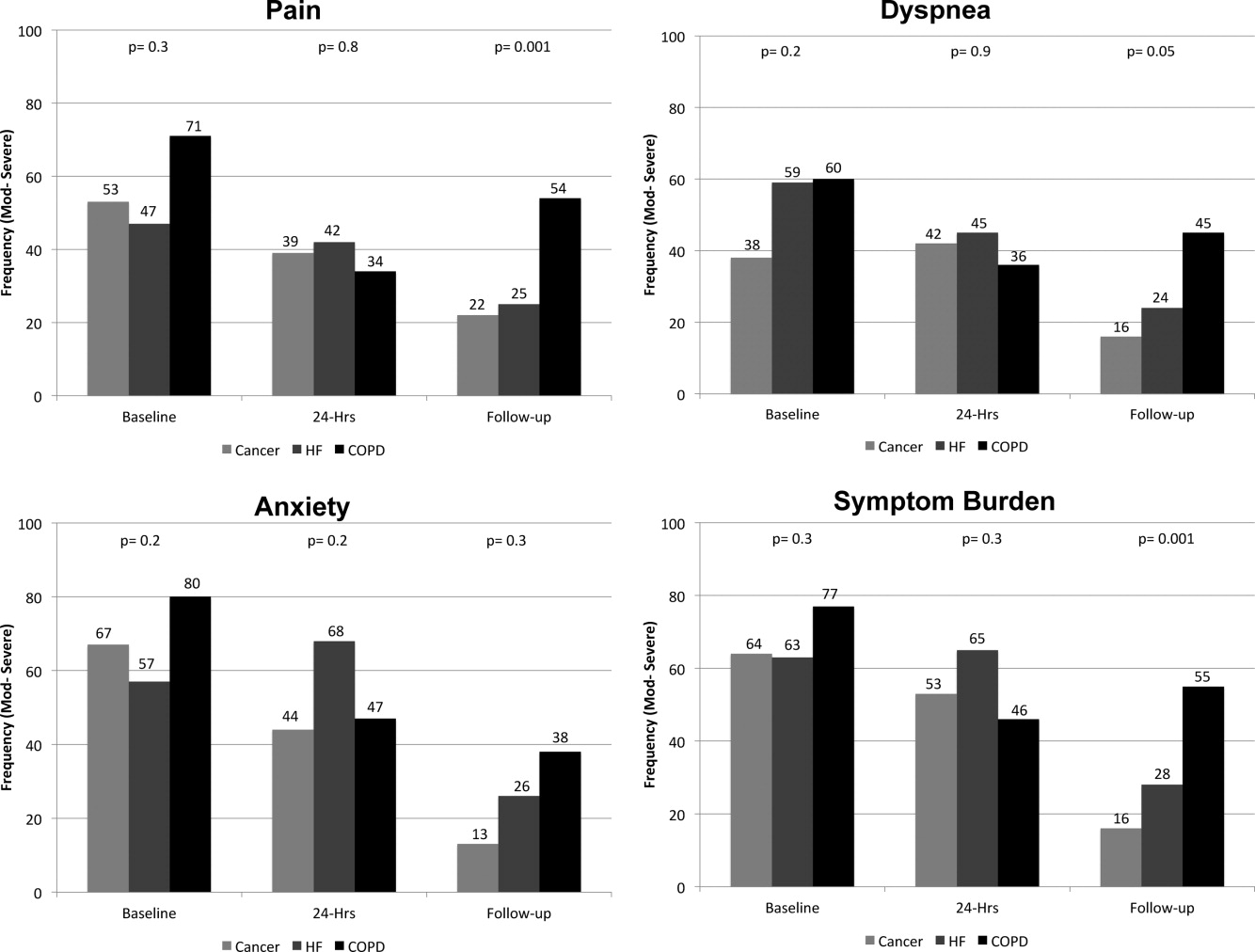

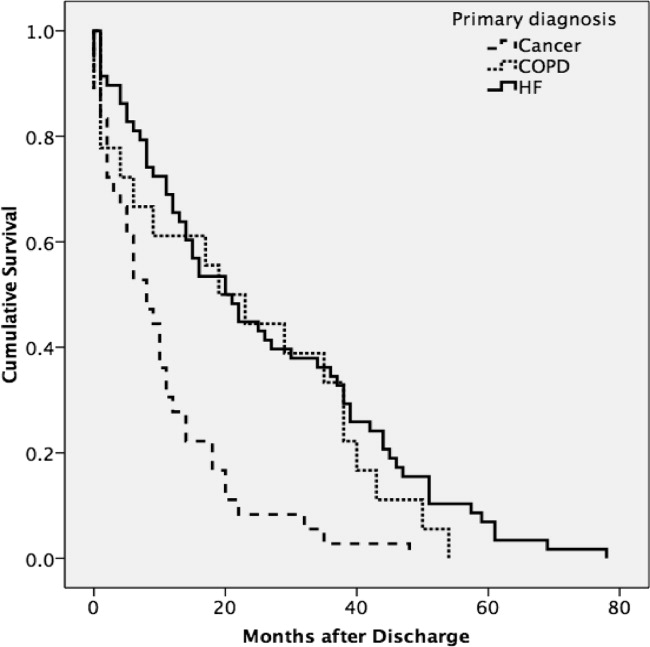

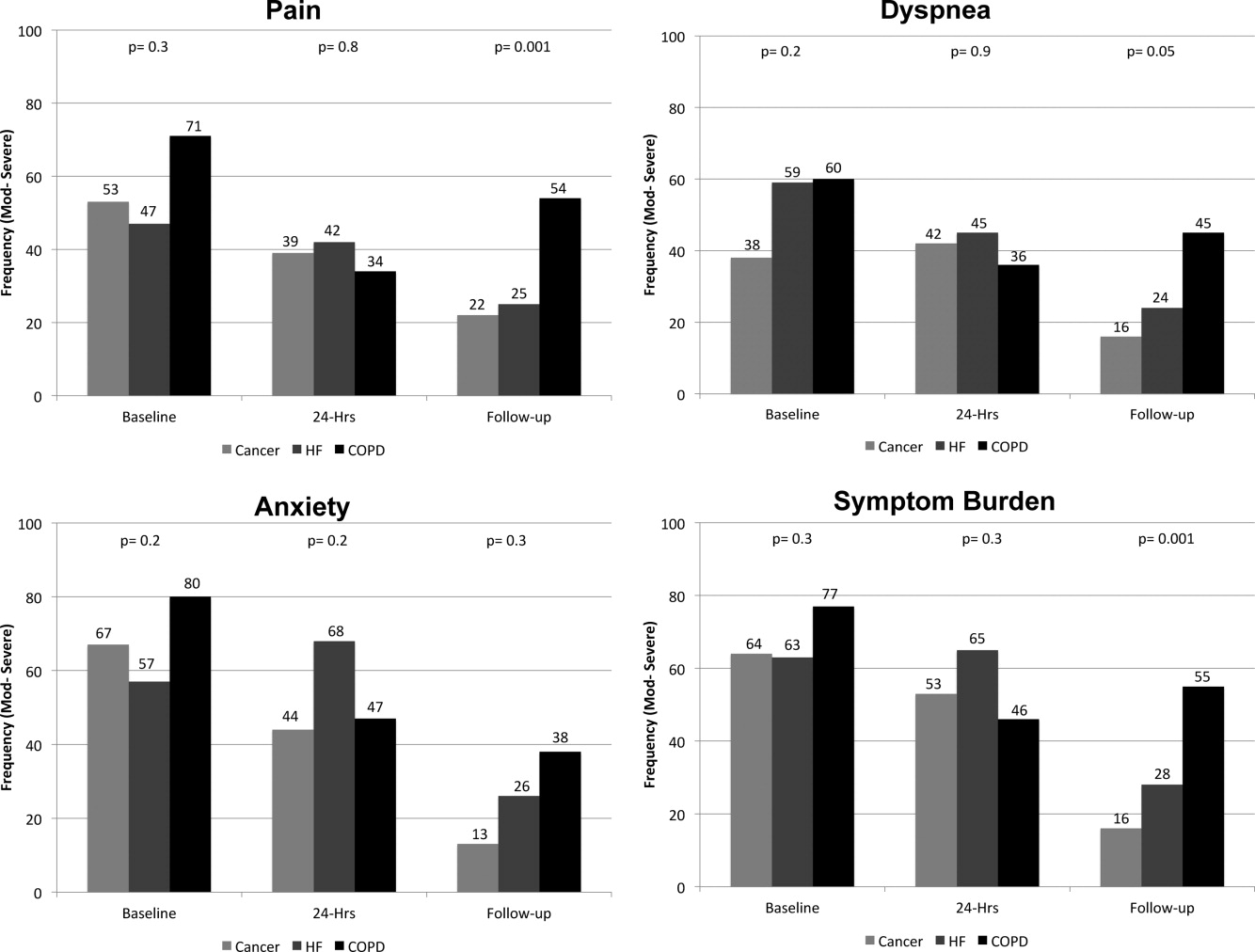

On average, the postdischarge follow‐up assessment was undertaken 24 days (median = 21.0; SD: 17.9; range: 7140 days) after the baseline assessment and 20 days after discharge (median = 15; SD: 17.0; range: 4139). At baseline, a large proportion of participants reported symptoms at a moderate‐to‐severe level for pain (54%, n = 81), dyspnea (53%, n = 79), and anxiety (63%, n = 94). The majority of patients (64%, n = 96) reported having 2 or more symptoms at a moderate‐to‐severe level and one quarter (27%, n = 41) had 3 symptoms at a moderate‐to‐severe level. While the frequency of moderate‐to‐severe symptoms decreased at the 24‐hour hospital assessment (pain = 42%, dyspnea = 45%, anxiety = 55%) and again at 2‐week follow‐up (pain = 28%, dyspnea = 27%, anxiety = 25%), a substantial symptom burden persisted with 30% (n = 36) of patients having moderate‐to‐severe levels at 2‐week follow‐up. Overall there were no differences between primary diagnosis and the frequency of symptoms at baseline or 24‐hour hospital assessment (Figure 1). However at follow‐up, those diagnosed with COPD were more likely to report moderate/severe pain (54%; 2 = 22.0; P < 0.001), dyspnea (45%; 2 = 9.3; P = 0.05), and overall symptom burden (55%; 2 = 25.9; P < 0.001) than those with cancer (pain = 22%, dyspnea = 16%, symptom burden = 16%) or HF (pain = 25%, dyspnea = 24%, symptom burden = 28%).

As symptom burden was our composite score for pain, dyspnea, and anxiety, we were interested in identifying variables in addition to primary diagnosis that might be associated with symptom burden at follow‐up. Bivariate analysis revealed that there was no significant association between symptom burden and age (2 = 1.5; P = 0.5), gender (2 = 1.3; P = 0.3), length of stay (2 = 0.4; P = 0.8), and (IADL) level of independence (2 = 0.3; P = 0.6). However, those with probable depression were more likely (2 = 11.9; P = 0.001) to have a moderate/severe symptom burden (62%, n = 13), compared to those with no depression (24%, n = 23). After adjusting for severity of symptom burden at baseline, multivariate logistic regression revealed that primary diagnosis (P = 0.01) and probable depression (OR = 4.9; 95% CI = 1.6, 14.9; P = 0.005) were associated with symptom severity. Patients with COPD had greater odds (OR = 7.0; 95% CI = 1.9, 26.2; P = 0.002) of moderate/severe symptom burden than those with cancer, while those with HF did not (OR = 2.3; 95% CI = 0.7, 7.7; P = 0.16). There was significant interaction between primary diagnosis and depression (P = 0.2).

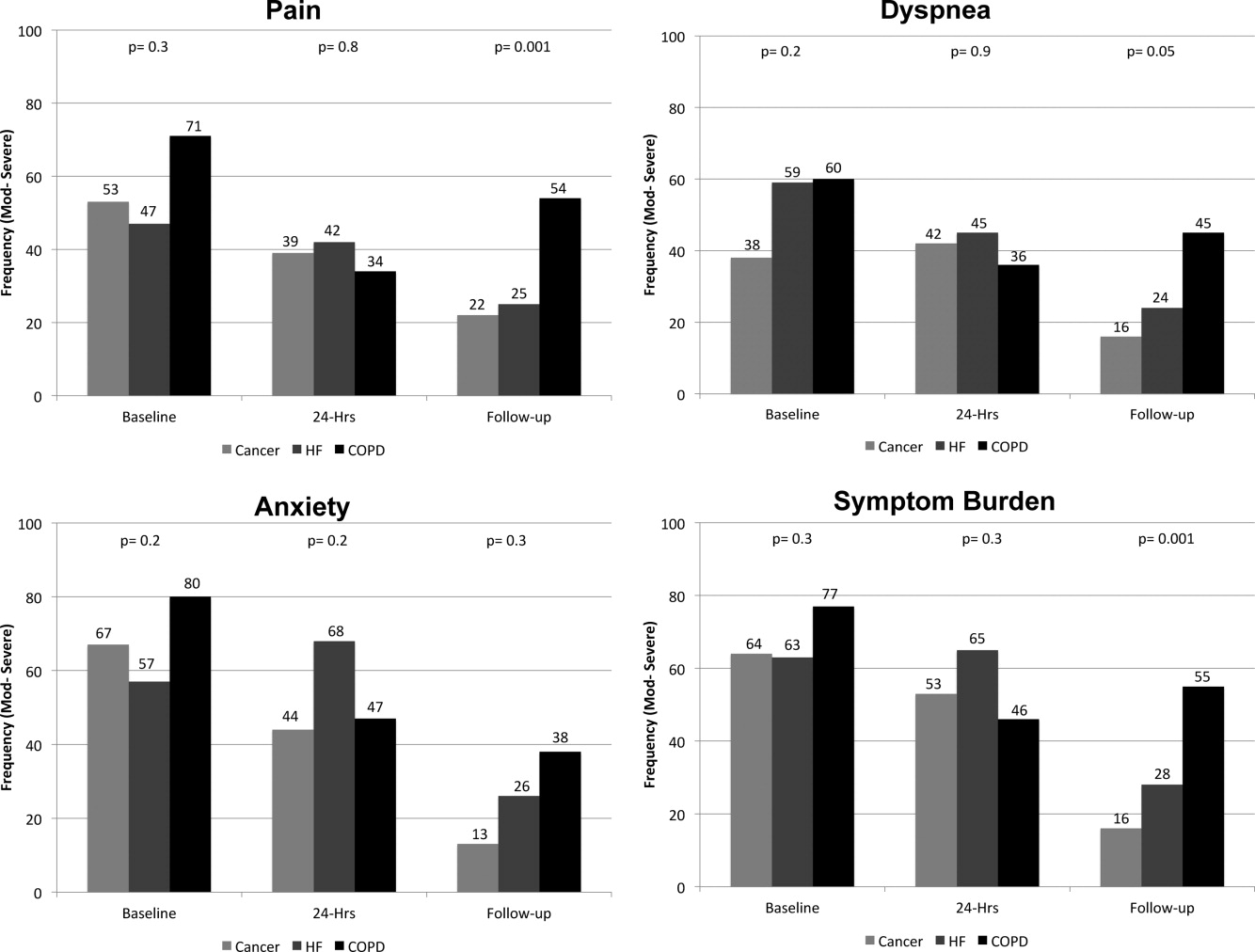

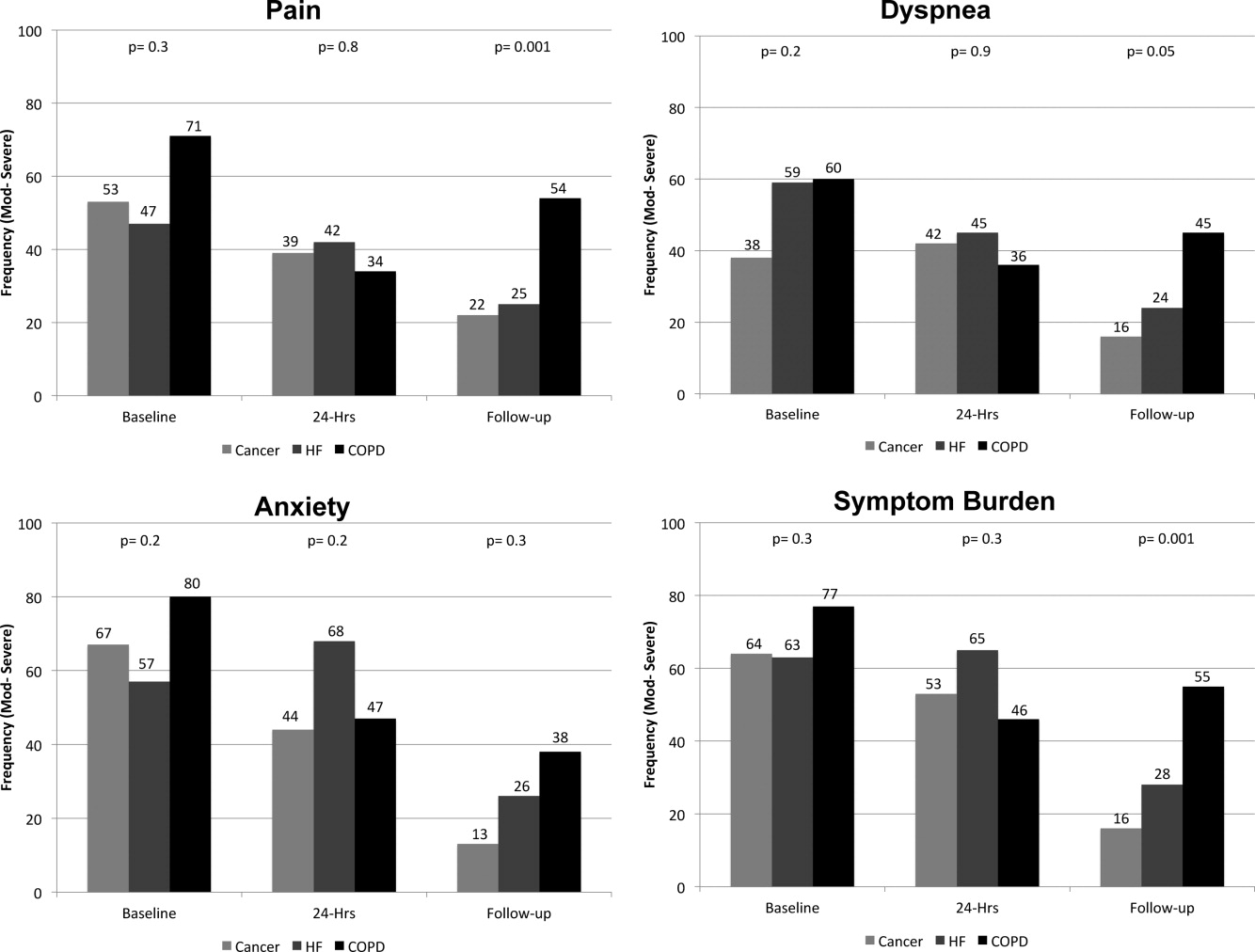

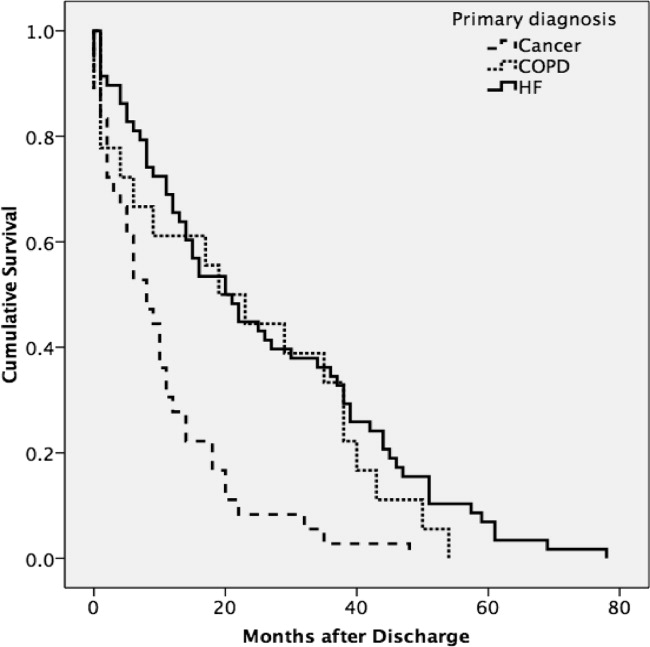

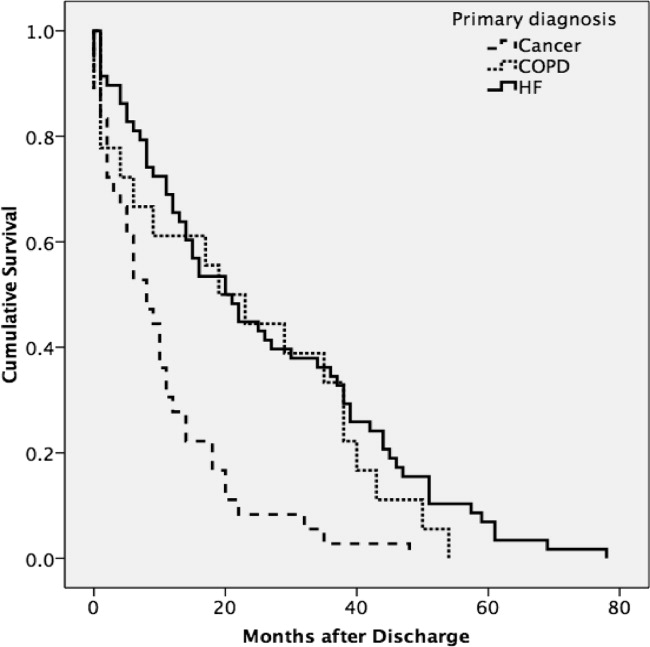

Primary Diagnosis, Symptom Burden, and Survival Time

A total of 75% of patients were identified by the National Death Index to have died between hospital discharge and December 2007, of which 47% had died within 12 months after discharge. KaplanMeier survival curves (Figure 2) revealed a significant difference (MantelCox: 2 = 19.3; df = 1; P = 0.0001) in survival time, with patients diagnosed with COPD (median = 19.0 months; 95% CI = 6.5, 31.5) and HF (median = 20.0 months; 95% CI = 12.5, 27.5) having a longer survival than those with cancer (median = 8.0 months; 95% CI = 4.1, 11.9).

We also examined the relationship between symptom burden and survival time. KaplanMeier survival curves revealed no significant difference (MantelCox: 2 = 0.2; P = 0.6) in the survival time of patients classified with a symptom burden of none/moderate (median = 15.0 months; 95% CI = 8.8, 21.2) or moderate/severe (median = 14.0 months; 95% CI = 2.6, 25.4).

DISCUSSION

In our sample of older inpatients diagnosed with cancer, HF, and COPD, a large proportion reported moderate‐to‐severe levels of pain, dyspnea, and anxiety at baseline and follow‐up. When combined, these levels represent a considerable symptom burden, with over three‐quarters of participants reporting 2 to 3 symptoms at a moderate/severe level at baseline. While symptom scores decreased at 24‐hours and 2‐week follow‐up, symptom burden remained high, with almost half of the participants reporting 23 symptoms at a moderate‐to‐severe level at 24‐hour assessment and a large minority reporting moderate‐to‐severe symptoms at follow‐up. A higher percentage of patients with COPD reported moderate‐to‐severe pain, dyspnea, and overall symptom burden at follow‐up than participants with cancer or HF who reported a similar symptom burden. We also found that patients with probable depression were more likely to have a significant symptom burden at follow‐up. These findings highlight the need to routinely assess and treat symptoms over time, including depression, and especially in patients with COPD. While we found that hospital care was seemingly effective in improving symptoms, they persist at distressing levels in many patients.

Few studies have assessed the severity of symptoms over time. One study that did, examined symptom severity among community‐based elders diagnosed with HF and COPD.6 At baseline, these participants had a lower prevalence of moderate‐to‐severe symptoms than the hospitalized patients enrolled in our study, a finding that would be anticipated, as they may not have been as ill. However, symptom severity persisted in the community‐based subjects and, in some cases, worsened over the 22‐month assessment period for pain (HF = 20% vs 42%; COPD = 27% vs 20%), dyspnea (HF = 19% vs 29%; COPD = 66% vs 76%), and anxiety (HF = 2% vs 12%; COPD = 32% vs 23%).6 In contrast, while our subjects with a primary diagnosis of HF and COPD had a higher prevalence of moderate‐to‐severe symptoms at baseline, they did experience an improvement in the severity of pain, dyspnea, and anxiety at the 2‐week follow‐up assessment. However, despite a decrease in the prevalence of moderate‐to‐severe symptoms from baseline to follow‐up, a high symptom burden persisted for many patients, particularly for those diagnosed with COPD and those with probable depression at baseline. The severity of a patient's symptoms can have a profound negative effect on health status and quality of life.14 Findings from these studies suggest that symptoms are currently not being adequately managed, and highlight an urgent need to develop coordinated strategies and systems that focus on improving the management of symptoms, including depression, over time.6

We also found that subjects recruited for this study had advanced disease, evidenced by the fact that nearly half died within 12 months. We did not use specific prognostic indices or severity of illness criteria for recruiting subjects and simply approached patients admitted with one of the target diagnoses. Our study suggests that targeting these patients for routine symptom assessment and management, including for palliative care, would be a reasonable approach given the high symptom burden and relatively high mortality at 1 year.

Interpretation of these findings should be mitigated by the following limitations. Because of our setting, our findings may not be generalizable to all patients with cancer, HF, and COPD. However, our subjects were admitted to general medical and cardiology services, and had common conditions, and therefore are likely similar to those presenting to other hospitals. We relied on self‐report measures to assess severity of symptoms. Patient self‐report, while potentially subject to imprecision due to poor recall and social demand biases, is considered the gold standard for symptom assessment.15 Finally, 2‐week follow‐up is relatively short, and it is possible that symptoms may have improved had we assessed them over a longer period. The longitudinal study of elders in the community that followed subjects over 22 months found that, for many patients, symptoms worsened over time and nearly half of our subjects died at 12 months, suggesting that longer follow‐up would have been unlikely to show improvement in symptoms.6

A significant minority of participants reported a substantial, persistent symptom burden, yet all symptoms assessed in our study are potentially modifiable. Recognizing and treating symptoms can be achieved through the use of targeted interventions.6 Because symptoms can occur in clusters, successful treatment of 1 symptom may also help to improve other symptoms.1 The large number of participants reporting moderate‐to‐severe levels of symptom burden at 2 weeks after discharge highlights an unmet need for improved symptom control in the outpatient setting. Unfortunately, while evidence exists for managing pain in patients with cancer, such evidence‐based practices are lacking for the management of pain and other symptoms in patients with HF and COPD. Some symptoms may require specific, disease‐oriented management. However, many symptoms may be due to common comorbidities, such as pain from degenerative joint disease, that may likely respond to proven treatments.16

Our study confirmed the significant burden of symptoms experienced by patients with serious illness and demonstrated that patients with COPD report as much symptom burden as patients with cancer and HF, if not more. While symptom severity improved over the course of the hospitalization and follow‐up, a large percentage of patients reported significant symptom burden at follow‐up. Depression was also common in these patients. Because these symptoms diminish quality of life, routine assessment and management of these symptoms is critical for improving the quality of care provided to these patients. Additional research on the best approaches to manage symptoms, including medications, interventions, and structures of care, could further improve care.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the patients who participated in this study. They thank Joanne Batt, Wren Levenberg, and Emily Philipps for their expert help as research assistants. They also thank Harold Collard, MD, for providing valuable feedback on the manuscript. Data obtained from the National Death Index assisted us in meeting our study objectives. Steven Pantilat had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

- ,,.Symptom clusters: the new frontier in symptom management research.J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr.2004(32):17–21.

- .Symptom burden: multiple symptoms and their impact as patient‐reported outcomes.J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr.2007(37):16–21.

- ,,.A comparison of symptom prevalence in far advanced cancer, AIDS, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and renal disease.J Pain Symptom Manage.2006;31(1):58–69.

- ,,, et al.Comparing three life‐limiting diseases: does diagnosis matter or is sick, sick?J Pain Symptom Manage.2011;42(3):331–341.

- ,,,,,.Deaths: final data for 2006.Natl Vital Stat Rep.2009;57(14):1–134.

- ,,,,,.Range and severity of symptoms over time among older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure.Arch Intern Med.2007;167(22):2503–2508.

- ,,,.Living with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a survey of patients' knowledge and attitudes.Respir Med.2009;103(7):1004–1012.

- ,,,,.The symptom burden of seriously ill hospitalized patients. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcome and Risks of Treatment.J Pain Symptom Manage.1999;17(4):248–255.

- ,,, et al.Relationship between early physician follow‐up and 30‐day readmission among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure.JAMA.2010;303(17):1716–1722.

- ,,,.Hospital‐based palliative medicine consultation: a randomized controlled trial.Arch Intern Med.2010;170(22):2038–2040.

- ,,,,.Studies of illness in the aged. The Index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function.JAMA.1963;185:914–919.

- ,,,.Screening for late life depression: cut‐off scores for the Geriatric Depression Scale and the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia among Japanese subjects.Int J Geriatr Psychiatry.2003;18(6):498–505.

- ,.Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations.J Am Stat Assoc.1958;53(282):457–481.

- ,,.End stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.Pneumonol Alergol Pol.2009;77(2):173–179.

- ,,,.Relationship between social desirability and self‐report in chronic pain patients.Clin J Pain.1995;11(3):189–193.

- ,,,.Etiology and severity of pain among outpatients living with HF.J Card Fail.2010;16(8):S88.

The frequency and severity of symptoms among older hospitalized patients with chronic illnesses can have a profound negative impact on their quality of life.1, 2 Nonetheless, research examining the prevalence and management of symptoms has focused predominantly on cancer patients.3 Few studies have included patients with other serious conditions such as heart failure (HF) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),3, 4 which are very common and are major causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States.5 One longitudinal assessment of symptom severity among a group of community‐based older adults diagnosed with COPD and HF reported high rates of moderate‐to‐severe pain, dyspnea, and anxiety at baseline and follow‐up, as long as 22 months later.6 Persistent symptoms over time can have an adverse effect on an individual's physical and emotional well‐being, and highlight opportunities to improve care.3, 7 Understanding patterns of symptom change over time is a key first step in developing systems to improve quality of care for people with chronic illness.

Among hospitalized patients, pain, dyspnea, anxiety, and depression cause the greatest symptom burden, accounting for 67% of all symptoms classified as moderate to severe.8 While assessment and management of symptoms may be the reason for admission to the hospital and the focus of inpatient care, this focus may not persist after discharge, leaving patients with significant symptoms that can diminish quality of life and contribute to readmission.9 We studied a cohort of older inpatients with serious illness over time in order to determine the prevalence, severity, burden, and predictors of symptoms during the course of hospitalization and at 2 weeks after discharge.

METHODS

Setting

The study was undertaken at a large academic medical center in San Francisco.

Subjects

Participants were patients 65 years or older admitted to the medicine or cardiology services with a primary diagnosis of cancer, COPD, or HF. Participants were required to be fully oriented and English‐speaking. Patients gave written informed consent to participate. The Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco, approved this study (H8695‐35172‐01).

Data Collection

Data collection was undertaken from March 2001 to December 2003. This study was part of a prospective, clinical trial that compared a proactive palliative medicine consultation with usual hospital care, and has been previously described.10 Upon study enrollment, all patients completed the Inpatient Care Survey. The survey asked participants about demographic information such as date of birth, sex, education level, race, and marital status. The survey instruments also included the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) index and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS‐15). Each weekday during hospitalization, a trained research assistant asked patients to report their worst symptom level for pain, dyspnea, and anxiety in the past 24 hours using a 010 numeric rating scale, where 0 was none and 10 was the worst you can imagine. We further characterized scores into categories such that 0 was defined as none, 13 as mild, 46 as moderate, and 710 as severe. A follow‐up telephone survey, 2 weeks after discharge, reassessed patients' worst symptom levels in the past 24 hours for pain, dyspnea, and anxiety.

We also generated a composite score of symptoms to report a symptom burden score for these 3 symptoms. Using the categories of symptom severity, we assigned a score of 0 for none, 1 for mild, 2 for moderate, and 3 for severe. We summed the assigned scores for all 3 symptoms for each subject to generate a symptom burden score as follows: no symptom burden (0), mild symptom burden (13), moderate symptom burden (46), and severe symptom burden (79). In this scale, a moderate symptom burden would mean that a subject reported having at least 1 symptom at a moderate or severe level, with at least 1 other symptom present. A severe symptom burden would require the presence of all 3 symptoms, with at least 1 at a severe level.

We reviewed patient charts to assess severity of patient illness upon admission. For cancer, we recorded type; for COPD, we noted forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1); and for HF, we recorded the ejection fraction. We also queried the National Death Index to get vital statistics on all subjects.

Data Preparation

The IADL asks patients to report whether they can perform 13 daily living skills without help, with some help, or were unable to complete tasks.11 Subjects who reported needing at least some help with any of the 13 items were categorized as dependent. The GDS‐15 is a widely used, validated 15‐item scale for assessing depressive mood in the elderly.12 Scores for the GDS‐15 range from 0 to 15, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms. Based on previous research, we categorized patients as either not depressed (05) or having probable depression (6 or more).12

Statistical Analysis

Because our clinical trial had no impact on care or symptoms, we combined intervention and usual care patients for this analysis of symptom severity. Descriptive statistics, such as frequencies, means, standard deviations (SDs), and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to examine the distribution of measures. Chi‐square (2) analysis was undertaken to examine bivariate associations between categorical variables. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was undertaken to examine associations between categorical and continuous variables. Multivariate logistic regression was used to examine predictors of symptom burden at follow‐up, including patient characteristics that were significant to P 0.10 in bivariate analysis. We used KaplanMeier survival curves to examine the relationship between primary diagnosis and mortality, and assessed statistical significance using log‐rank tests (MantelCox).13 The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Mac (version 17; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL; March 11, 2009) was used to analyze these data.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

A total of 150 patients enrolled in the study. The mean length of stay was 5.4 days (SD: 5.6; range: 147 days). HF was the most common primary diagnosis (46.7%, n = 70) with 48% (n = 34) having an ejection fraction of 45% or less (mean = 43%; SD: 22); followed by cancer (30%, n = 45) with the most common type being prostate (18%, n = 8), lung (13%, n = 6), and breast (13%, n = 6); and COPD (23%, n = 35) with an average FEV1 of 1.5 L (SD: 0.94; range: 0.503.9). The mean age was 77 years (SD: 7.9; range: 6596 years). The majority of participants were men (56%, n = 83) and white (73%, n = 108), with the most being either married/partnered (43%, n = 64) or divorced/widowed (44%, n = 66). The IADL identified almost two‐thirds of participants as dependent (62%, n = 94). The GDS‐15 categorized three‐quarters of participants (n = 118) as not depressed. The only significant association between participant characteristics and their primary diagnosis was for the IADL index (Table 1), with significantly more (2 = 6.3; P = 0.04) patients with HF categorized as being dependent (72%).

| Characteristics | Primary Diagnosis | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer n = 44 | HF n = 70 | COPD n = 35 | |||

| |||||

| Length of stay | (Mean days) | 5.4 | 4.7 | 6.5 | 0.3 |

| Age | (Mean years) | 76 | 78 | 76 | 0.3 |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 47% | 37% | 57% | 0.1 | |

| Marital status | 0.2 | ||||

| Single | 16 | 9 | 17 | ||

| Married/partnered | 51 | 45 | 29 | ||

| Divorced/widowed | 33 | 46 | 54 | ||

| Race | |||||

| White | 89 | 64 | 69 | 0.1 | |

| Black/African American | 7 | 21 | 23 | ||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 5 | 10 | 9 | ||

| Other | 0 | 4 | 0 | ||

| IADL | |||||

| Dependent | 49 | 72 | 60 | 0.04 | |

| GDS‐15 | |||||

| Probable depression | 18 | 22 | 21 | 0.9 | |

Frequency and Severity of Symptoms

On average, the postdischarge follow‐up assessment was undertaken 24 days (median = 21.0; SD: 17.9; range: 7140 days) after the baseline assessment and 20 days after discharge (median = 15; SD: 17.0; range: 4139). At baseline, a large proportion of participants reported symptoms at a moderate‐to‐severe level for pain (54%, n = 81), dyspnea (53%, n = 79), and anxiety (63%, n = 94). The majority of patients (64%, n = 96) reported having 2 or more symptoms at a moderate‐to‐severe level and one quarter (27%, n = 41) had 3 symptoms at a moderate‐to‐severe level. While the frequency of moderate‐to‐severe symptoms decreased at the 24‐hour hospital assessment (pain = 42%, dyspnea = 45%, anxiety = 55%) and again at 2‐week follow‐up (pain = 28%, dyspnea = 27%, anxiety = 25%), a substantial symptom burden persisted with 30% (n = 36) of patients having moderate‐to‐severe levels at 2‐week follow‐up. Overall there were no differences between primary diagnosis and the frequency of symptoms at baseline or 24‐hour hospital assessment (Figure 1). However at follow‐up, those diagnosed with COPD were more likely to report moderate/severe pain (54%; 2 = 22.0; P < 0.001), dyspnea (45%; 2 = 9.3; P = 0.05), and overall symptom burden (55%; 2 = 25.9; P < 0.001) than those with cancer (pain = 22%, dyspnea = 16%, symptom burden = 16%) or HF (pain = 25%, dyspnea = 24%, symptom burden = 28%).

As symptom burden was our composite score for pain, dyspnea, and anxiety, we were interested in identifying variables in addition to primary diagnosis that might be associated with symptom burden at follow‐up. Bivariate analysis revealed that there was no significant association between symptom burden and age (2 = 1.5; P = 0.5), gender (2 = 1.3; P = 0.3), length of stay (2 = 0.4; P = 0.8), and (IADL) level of independence (2 = 0.3; P = 0.6). However, those with probable depression were more likely (2 = 11.9; P = 0.001) to have a moderate/severe symptom burden (62%, n = 13), compared to those with no depression (24%, n = 23). After adjusting for severity of symptom burden at baseline, multivariate logistic regression revealed that primary diagnosis (P = 0.01) and probable depression (OR = 4.9; 95% CI = 1.6, 14.9; P = 0.005) were associated with symptom severity. Patients with COPD had greater odds (OR = 7.0; 95% CI = 1.9, 26.2; P = 0.002) of moderate/severe symptom burden than those with cancer, while those with HF did not (OR = 2.3; 95% CI = 0.7, 7.7; P = 0.16). There was significant interaction between primary diagnosis and depression (P = 0.2).

Primary Diagnosis, Symptom Burden, and Survival Time

A total of 75% of patients were identified by the National Death Index to have died between hospital discharge and December 2007, of which 47% had died within 12 months after discharge. KaplanMeier survival curves (Figure 2) revealed a significant difference (MantelCox: 2 = 19.3; df = 1; P = 0.0001) in survival time, with patients diagnosed with COPD (median = 19.0 months; 95% CI = 6.5, 31.5) and HF (median = 20.0 months; 95% CI = 12.5, 27.5) having a longer survival than those with cancer (median = 8.0 months; 95% CI = 4.1, 11.9).

We also examined the relationship between symptom burden and survival time. KaplanMeier survival curves revealed no significant difference (MantelCox: 2 = 0.2; P = 0.6) in the survival time of patients classified with a symptom burden of none/moderate (median = 15.0 months; 95% CI = 8.8, 21.2) or moderate/severe (median = 14.0 months; 95% CI = 2.6, 25.4).

DISCUSSION

In our sample of older inpatients diagnosed with cancer, HF, and COPD, a large proportion reported moderate‐to‐severe levels of pain, dyspnea, and anxiety at baseline and follow‐up. When combined, these levels represent a considerable symptom burden, with over three‐quarters of participants reporting 2 to 3 symptoms at a moderate/severe level at baseline. While symptom scores decreased at 24‐hours and 2‐week follow‐up, symptom burden remained high, with almost half of the participants reporting 23 symptoms at a moderate‐to‐severe level at 24‐hour assessment and a large minority reporting moderate‐to‐severe symptoms at follow‐up. A higher percentage of patients with COPD reported moderate‐to‐severe pain, dyspnea, and overall symptom burden at follow‐up than participants with cancer or HF who reported a similar symptom burden. We also found that patients with probable depression were more likely to have a significant symptom burden at follow‐up. These findings highlight the need to routinely assess and treat symptoms over time, including depression, and especially in patients with COPD. While we found that hospital care was seemingly effective in improving symptoms, they persist at distressing levels in many patients.

Few studies have assessed the severity of symptoms over time. One study that did, examined symptom severity among community‐based elders diagnosed with HF and COPD.6 At baseline, these participants had a lower prevalence of moderate‐to‐severe symptoms than the hospitalized patients enrolled in our study, a finding that would be anticipated, as they may not have been as ill. However, symptom severity persisted in the community‐based subjects and, in some cases, worsened over the 22‐month assessment period for pain (HF = 20% vs 42%; COPD = 27% vs 20%), dyspnea (HF = 19% vs 29%; COPD = 66% vs 76%), and anxiety (HF = 2% vs 12%; COPD = 32% vs 23%).6 In contrast, while our subjects with a primary diagnosis of HF and COPD had a higher prevalence of moderate‐to‐severe symptoms at baseline, they did experience an improvement in the severity of pain, dyspnea, and anxiety at the 2‐week follow‐up assessment. However, despite a decrease in the prevalence of moderate‐to‐severe symptoms from baseline to follow‐up, a high symptom burden persisted for many patients, particularly for those diagnosed with COPD and those with probable depression at baseline. The severity of a patient's symptoms can have a profound negative effect on health status and quality of life.14 Findings from these studies suggest that symptoms are currently not being adequately managed, and highlight an urgent need to develop coordinated strategies and systems that focus on improving the management of symptoms, including depression, over time.6

We also found that subjects recruited for this study had advanced disease, evidenced by the fact that nearly half died within 12 months. We did not use specific prognostic indices or severity of illness criteria for recruiting subjects and simply approached patients admitted with one of the target diagnoses. Our study suggests that targeting these patients for routine symptom assessment and management, including for palliative care, would be a reasonable approach given the high symptom burden and relatively high mortality at 1 year.

Interpretation of these findings should be mitigated by the following limitations. Because of our setting, our findings may not be generalizable to all patients with cancer, HF, and COPD. However, our subjects were admitted to general medical and cardiology services, and had common conditions, and therefore are likely similar to those presenting to other hospitals. We relied on self‐report measures to assess severity of symptoms. Patient self‐report, while potentially subject to imprecision due to poor recall and social demand biases, is considered the gold standard for symptom assessment.15 Finally, 2‐week follow‐up is relatively short, and it is possible that symptoms may have improved had we assessed them over a longer period. The longitudinal study of elders in the community that followed subjects over 22 months found that, for many patients, symptoms worsened over time and nearly half of our subjects died at 12 months, suggesting that longer follow‐up would have been unlikely to show improvement in symptoms.6

A significant minority of participants reported a substantial, persistent symptom burden, yet all symptoms assessed in our study are potentially modifiable. Recognizing and treating symptoms can be achieved through the use of targeted interventions.6 Because symptoms can occur in clusters, successful treatment of 1 symptom may also help to improve other symptoms.1 The large number of participants reporting moderate‐to‐severe levels of symptom burden at 2 weeks after discharge highlights an unmet need for improved symptom control in the outpatient setting. Unfortunately, while evidence exists for managing pain in patients with cancer, such evidence‐based practices are lacking for the management of pain and other symptoms in patients with HF and COPD. Some symptoms may require specific, disease‐oriented management. However, many symptoms may be due to common comorbidities, such as pain from degenerative joint disease, that may likely respond to proven treatments.16

Our study confirmed the significant burden of symptoms experienced by patients with serious illness and demonstrated that patients with COPD report as much symptom burden as patients with cancer and HF, if not more. While symptom severity improved over the course of the hospitalization and follow‐up, a large percentage of patients reported significant symptom burden at follow‐up. Depression was also common in these patients. Because these symptoms diminish quality of life, routine assessment and management of these symptoms is critical for improving the quality of care provided to these patients. Additional research on the best approaches to manage symptoms, including medications, interventions, and structures of care, could further improve care.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the patients who participated in this study. They thank Joanne Batt, Wren Levenberg, and Emily Philipps for their expert help as research assistants. They also thank Harold Collard, MD, for providing valuable feedback on the manuscript. Data obtained from the National Death Index assisted us in meeting our study objectives. Steven Pantilat had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The frequency and severity of symptoms among older hospitalized patients with chronic illnesses can have a profound negative impact on their quality of life.1, 2 Nonetheless, research examining the prevalence and management of symptoms has focused predominantly on cancer patients.3 Few studies have included patients with other serious conditions such as heart failure (HF) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),3, 4 which are very common and are major causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States.5 One longitudinal assessment of symptom severity among a group of community‐based older adults diagnosed with COPD and HF reported high rates of moderate‐to‐severe pain, dyspnea, and anxiety at baseline and follow‐up, as long as 22 months later.6 Persistent symptoms over time can have an adverse effect on an individual's physical and emotional well‐being, and highlight opportunities to improve care.3, 7 Understanding patterns of symptom change over time is a key first step in developing systems to improve quality of care for people with chronic illness.

Among hospitalized patients, pain, dyspnea, anxiety, and depression cause the greatest symptom burden, accounting for 67% of all symptoms classified as moderate to severe.8 While assessment and management of symptoms may be the reason for admission to the hospital and the focus of inpatient care, this focus may not persist after discharge, leaving patients with significant symptoms that can diminish quality of life and contribute to readmission.9 We studied a cohort of older inpatients with serious illness over time in order to determine the prevalence, severity, burden, and predictors of symptoms during the course of hospitalization and at 2 weeks after discharge.

METHODS

Setting

The study was undertaken at a large academic medical center in San Francisco.

Subjects

Participants were patients 65 years or older admitted to the medicine or cardiology services with a primary diagnosis of cancer, COPD, or HF. Participants were required to be fully oriented and English‐speaking. Patients gave written informed consent to participate. The Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco, approved this study (H8695‐35172‐01).

Data Collection

Data collection was undertaken from March 2001 to December 2003. This study was part of a prospective, clinical trial that compared a proactive palliative medicine consultation with usual hospital care, and has been previously described.10 Upon study enrollment, all patients completed the Inpatient Care Survey. The survey asked participants about demographic information such as date of birth, sex, education level, race, and marital status. The survey instruments also included the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) index and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS‐15). Each weekday during hospitalization, a trained research assistant asked patients to report their worst symptom level for pain, dyspnea, and anxiety in the past 24 hours using a 010 numeric rating scale, where 0 was none and 10 was the worst you can imagine. We further characterized scores into categories such that 0 was defined as none, 13 as mild, 46 as moderate, and 710 as severe. A follow‐up telephone survey, 2 weeks after discharge, reassessed patients' worst symptom levels in the past 24 hours for pain, dyspnea, and anxiety.

We also generated a composite score of symptoms to report a symptom burden score for these 3 symptoms. Using the categories of symptom severity, we assigned a score of 0 for none, 1 for mild, 2 for moderate, and 3 for severe. We summed the assigned scores for all 3 symptoms for each subject to generate a symptom burden score as follows: no symptom burden (0), mild symptom burden (13), moderate symptom burden (46), and severe symptom burden (79). In this scale, a moderate symptom burden would mean that a subject reported having at least 1 symptom at a moderate or severe level, with at least 1 other symptom present. A severe symptom burden would require the presence of all 3 symptoms, with at least 1 at a severe level.

We reviewed patient charts to assess severity of patient illness upon admission. For cancer, we recorded type; for COPD, we noted forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1); and for HF, we recorded the ejection fraction. We also queried the National Death Index to get vital statistics on all subjects.

Data Preparation

The IADL asks patients to report whether they can perform 13 daily living skills without help, with some help, or were unable to complete tasks.11 Subjects who reported needing at least some help with any of the 13 items were categorized as dependent. The GDS‐15 is a widely used, validated 15‐item scale for assessing depressive mood in the elderly.12 Scores for the GDS‐15 range from 0 to 15, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms. Based on previous research, we categorized patients as either not depressed (05) or having probable depression (6 or more).12

Statistical Analysis

Because our clinical trial had no impact on care or symptoms, we combined intervention and usual care patients for this analysis of symptom severity. Descriptive statistics, such as frequencies, means, standard deviations (SDs), and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to examine the distribution of measures. Chi‐square (2) analysis was undertaken to examine bivariate associations between categorical variables. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was undertaken to examine associations between categorical and continuous variables. Multivariate logistic regression was used to examine predictors of symptom burden at follow‐up, including patient characteristics that were significant to P 0.10 in bivariate analysis. We used KaplanMeier survival curves to examine the relationship between primary diagnosis and mortality, and assessed statistical significance using log‐rank tests (MantelCox).13 The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Mac (version 17; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL; March 11, 2009) was used to analyze these data.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

A total of 150 patients enrolled in the study. The mean length of stay was 5.4 days (SD: 5.6; range: 147 days). HF was the most common primary diagnosis (46.7%, n = 70) with 48% (n = 34) having an ejection fraction of 45% or less (mean = 43%; SD: 22); followed by cancer (30%, n = 45) with the most common type being prostate (18%, n = 8), lung (13%, n = 6), and breast (13%, n = 6); and COPD (23%, n = 35) with an average FEV1 of 1.5 L (SD: 0.94; range: 0.503.9). The mean age was 77 years (SD: 7.9; range: 6596 years). The majority of participants were men (56%, n = 83) and white (73%, n = 108), with the most being either married/partnered (43%, n = 64) or divorced/widowed (44%, n = 66). The IADL identified almost two‐thirds of participants as dependent (62%, n = 94). The GDS‐15 categorized three‐quarters of participants (n = 118) as not depressed. The only significant association between participant characteristics and their primary diagnosis was for the IADL index (Table 1), with significantly more (2 = 6.3; P = 0.04) patients with HF categorized as being dependent (72%).

| Characteristics | Primary Diagnosis | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer n = 44 | HF n = 70 | COPD n = 35 | |||

| |||||

| Length of stay | (Mean days) | 5.4 | 4.7 | 6.5 | 0.3 |

| Age | (Mean years) | 76 | 78 | 76 | 0.3 |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 47% | 37% | 57% | 0.1 | |

| Marital status | 0.2 | ||||

| Single | 16 | 9 | 17 | ||

| Married/partnered | 51 | 45 | 29 | ||

| Divorced/widowed | 33 | 46 | 54 | ||

| Race | |||||

| White | 89 | 64 | 69 | 0.1 | |

| Black/African American | 7 | 21 | 23 | ||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 5 | 10 | 9 | ||

| Other | 0 | 4 | 0 | ||

| IADL | |||||

| Dependent | 49 | 72 | 60 | 0.04 | |

| GDS‐15 | |||||

| Probable depression | 18 | 22 | 21 | 0.9 | |

Frequency and Severity of Symptoms

On average, the postdischarge follow‐up assessment was undertaken 24 days (median = 21.0; SD: 17.9; range: 7140 days) after the baseline assessment and 20 days after discharge (median = 15; SD: 17.0; range: 4139). At baseline, a large proportion of participants reported symptoms at a moderate‐to‐severe level for pain (54%, n = 81), dyspnea (53%, n = 79), and anxiety (63%, n = 94). The majority of patients (64%, n = 96) reported having 2 or more symptoms at a moderate‐to‐severe level and one quarter (27%, n = 41) had 3 symptoms at a moderate‐to‐severe level. While the frequency of moderate‐to‐severe symptoms decreased at the 24‐hour hospital assessment (pain = 42%, dyspnea = 45%, anxiety = 55%) and again at 2‐week follow‐up (pain = 28%, dyspnea = 27%, anxiety = 25%), a substantial symptom burden persisted with 30% (n = 36) of patients having moderate‐to‐severe levels at 2‐week follow‐up. Overall there were no differences between primary diagnosis and the frequency of symptoms at baseline or 24‐hour hospital assessment (Figure 1). However at follow‐up, those diagnosed with COPD were more likely to report moderate/severe pain (54%; 2 = 22.0; P < 0.001), dyspnea (45%; 2 = 9.3; P = 0.05), and overall symptom burden (55%; 2 = 25.9; P < 0.001) than those with cancer (pain = 22%, dyspnea = 16%, symptom burden = 16%) or HF (pain = 25%, dyspnea = 24%, symptom burden = 28%).

As symptom burden was our composite score for pain, dyspnea, and anxiety, we were interested in identifying variables in addition to primary diagnosis that might be associated with symptom burden at follow‐up. Bivariate analysis revealed that there was no significant association between symptom burden and age (2 = 1.5; P = 0.5), gender (2 = 1.3; P = 0.3), length of stay (2 = 0.4; P = 0.8), and (IADL) level of independence (2 = 0.3; P = 0.6). However, those with probable depression were more likely (2 = 11.9; P = 0.001) to have a moderate/severe symptom burden (62%, n = 13), compared to those with no depression (24%, n = 23). After adjusting for severity of symptom burden at baseline, multivariate logistic regression revealed that primary diagnosis (P = 0.01) and probable depression (OR = 4.9; 95% CI = 1.6, 14.9; P = 0.005) were associated with symptom severity. Patients with COPD had greater odds (OR = 7.0; 95% CI = 1.9, 26.2; P = 0.002) of moderate/severe symptom burden than those with cancer, while those with HF did not (OR = 2.3; 95% CI = 0.7, 7.7; P = 0.16). There was significant interaction between primary diagnosis and depression (P = 0.2).

Primary Diagnosis, Symptom Burden, and Survival Time

A total of 75% of patients were identified by the National Death Index to have died between hospital discharge and December 2007, of which 47% had died within 12 months after discharge. KaplanMeier survival curves (Figure 2) revealed a significant difference (MantelCox: 2 = 19.3; df = 1; P = 0.0001) in survival time, with patients diagnosed with COPD (median = 19.0 months; 95% CI = 6.5, 31.5) and HF (median = 20.0 months; 95% CI = 12.5, 27.5) having a longer survival than those with cancer (median = 8.0 months; 95% CI = 4.1, 11.9).

We also examined the relationship between symptom burden and survival time. KaplanMeier survival curves revealed no significant difference (MantelCox: 2 = 0.2; P = 0.6) in the survival time of patients classified with a symptom burden of none/moderate (median = 15.0 months; 95% CI = 8.8, 21.2) or moderate/severe (median = 14.0 months; 95% CI = 2.6, 25.4).

DISCUSSION

In our sample of older inpatients diagnosed with cancer, HF, and COPD, a large proportion reported moderate‐to‐severe levels of pain, dyspnea, and anxiety at baseline and follow‐up. When combined, these levels represent a considerable symptom burden, with over three‐quarters of participants reporting 2 to 3 symptoms at a moderate/severe level at baseline. While symptom scores decreased at 24‐hours and 2‐week follow‐up, symptom burden remained high, with almost half of the participants reporting 23 symptoms at a moderate‐to‐severe level at 24‐hour assessment and a large minority reporting moderate‐to‐severe symptoms at follow‐up. A higher percentage of patients with COPD reported moderate‐to‐severe pain, dyspnea, and overall symptom burden at follow‐up than participants with cancer or HF who reported a similar symptom burden. We also found that patients with probable depression were more likely to have a significant symptom burden at follow‐up. These findings highlight the need to routinely assess and treat symptoms over time, including depression, and especially in patients with COPD. While we found that hospital care was seemingly effective in improving symptoms, they persist at distressing levels in many patients.

Few studies have assessed the severity of symptoms over time. One study that did, examined symptom severity among community‐based elders diagnosed with HF and COPD.6 At baseline, these participants had a lower prevalence of moderate‐to‐severe symptoms than the hospitalized patients enrolled in our study, a finding that would be anticipated, as they may not have been as ill. However, symptom severity persisted in the community‐based subjects and, in some cases, worsened over the 22‐month assessment period for pain (HF = 20% vs 42%; COPD = 27% vs 20%), dyspnea (HF = 19% vs 29%; COPD = 66% vs 76%), and anxiety (HF = 2% vs 12%; COPD = 32% vs 23%).6 In contrast, while our subjects with a primary diagnosis of HF and COPD had a higher prevalence of moderate‐to‐severe symptoms at baseline, they did experience an improvement in the severity of pain, dyspnea, and anxiety at the 2‐week follow‐up assessment. However, despite a decrease in the prevalence of moderate‐to‐severe symptoms from baseline to follow‐up, a high symptom burden persisted for many patients, particularly for those diagnosed with COPD and those with probable depression at baseline. The severity of a patient's symptoms can have a profound negative effect on health status and quality of life.14 Findings from these studies suggest that symptoms are currently not being adequately managed, and highlight an urgent need to develop coordinated strategies and systems that focus on improving the management of symptoms, including depression, over time.6

We also found that subjects recruited for this study had advanced disease, evidenced by the fact that nearly half died within 12 months. We did not use specific prognostic indices or severity of illness criteria for recruiting subjects and simply approached patients admitted with one of the target diagnoses. Our study suggests that targeting these patients for routine symptom assessment and management, including for palliative care, would be a reasonable approach given the high symptom burden and relatively high mortality at 1 year.