User login

Pruritic Nodules on the Breast

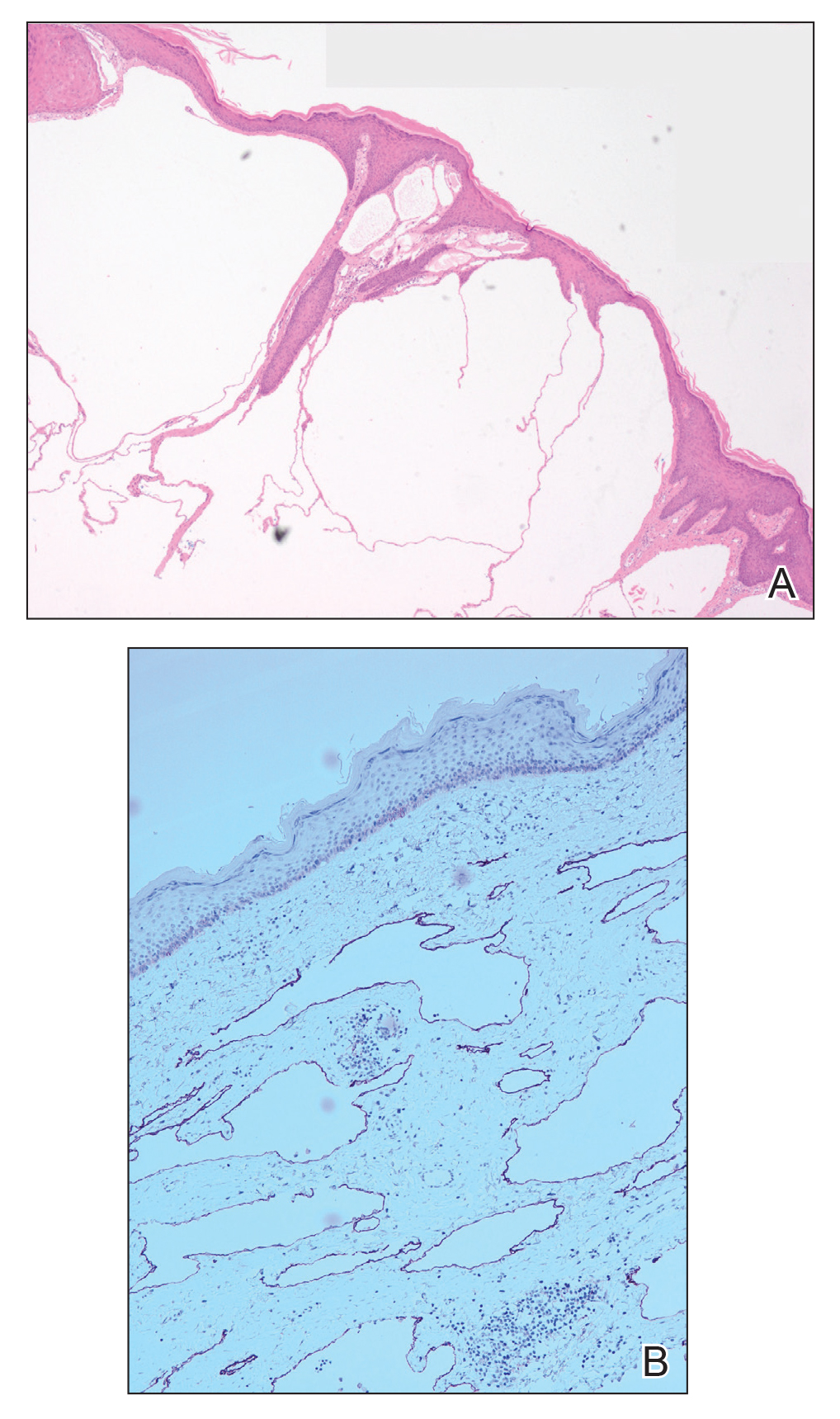

Microcystic lymphatic malformations, also known as lymphangioma circumscriptum, are rare hamartomatous lesions comprised of dilated lymphatic channels that can be both congenital and acquired.1 They often present as translucent or hemorrhagic vesicles of varying sizes that may contain lymphatic fluid and often can cluster together and appear verrucous (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis for microcystic lymphatic malformations commonly includes molluscum contagiosum, squamous cell carcinoma, verruca vulgaris, or condylomas, as well as atypical vascular lesions. They most often are found in children as congenital lesions but also may be acquired. Most acquired cases are due to chronic inflammatory and scarring processes that damage lymphatic structures, including surgery, radiation, infections, and even Crohn disease.2,3 Because the differential diagnosis is so broad and the disease can clinically mimic other common disease processes, biopsies often are performed to determine the diagnosis. On biopsy, pathologic examination revealed well-circumscribed nodular lesions with large lymphatic channels often in a background of connective tissue stroma. Increased eosinophilic material, including mast cells, also was seen (Figure 2A). On immunohistochemistry, staining showed D2-40 positivity (Figure 2B).

Damage to lymphatics from radiation and postsurgical excision of tumors are well-described causes of microcystic lymphatic malformations, as in our patient, with most instances in the literature occurring secondary to treatment of breast or cervical cancer.4-6 In these acquired cases, the pathogenesis is thought to be due to destruction and fibrosis at the layer of the reticular dermis, which causes lymphatic obstruction and subsequent dilation of superficial lymphatic channels.6

Microcystic lymphatic malformations can be difficult to distinguish from atypical vascular lesions, another common postradiation lesion. Both are benign well-circumscribed lesions that histologically do not extend into surrounding subcutaneous tissues and do not have multilayering of cells, mitosis, or hemorrhage.7 Although lymphatic lesions tend to form vesicles, atypical vascular lesions arising after radiation treatment present as erythematous or flesh-colored patches or papules. They also tend to be fairly superficial and often only involve the superficial to mid dermis. On histology they show thin-walled channels without erythrocytes that are lined by typical endothelial cells.7 Despite these differences, both clinically and histopathologically these lesions can appear similar to acquired microcystic lymphatic malformations. It is important to differentiate between these two entities, as atypical vascular lesions have a slightly higher rate of transformation into malignant tumors such as angiosarcomas.

Although angiosarcomas clinically may present as erythematous patches, plaques, or nodules similar to benign postradiation lesions, they tend to be more edematous than their benign counterparts.7,8 Two other clinical factors that can help determine if a postradiation lesion is benign or malignant are the size and time of onset of the lesion. Angiosarcomas tend to be much larger than benign postradiation lesions (median size, 7.5 cm) and tend to be more multifocal in nature.8,9 They also tend to arise on average 5 to 7 years after the initial radiation treatment, while benign lesions arise sooner.9

Small, asymptomatic, acquired microcystic lymphatic malformations can be followed clinically without treatment, but these lesions do not commonly regress spontaneously. Even when asymptomatic, many clinicians will opt for treatment to prevent secondary complications such as infections, drainage, and pain. Moreover, these lesions can have notable psychosocial impacts on patients due to poor cosmetic appearance. Unfortunately, there is no gold standard of treatment, and recurrence is common, even after treatment. Historically, surgical excision was the treatment of choice, but this option carries a high risk for scarring, invasiveness, and recurrence. Recurrence rates of up to 23.1% have been reported with decreased effectiveness of resection, particularly in areas of deeper involvement.10 For these deeper lesions, CO2 laser therapy is a promising evolving therapy. It can penetrate up to the mid dermis and seems to destroy the lymphatic channels between deep and surface lymphatics, preventing the cutaneous manifestations of the disease. It has the added benefit of minimal invasiveness and fewer side effects than complete excision, with most studies reporting hyperpigmentation and scarring as the most common side effects.11 Additional emerging therapies including sclerotherapy and isotretinoin have shown benefits in case studies. Sclerotherapy causes local tissue destruction and thrombosis leading to destruction of vessel lumens and fibrosis that halts disease progression and clears existing lesions.12 Oral therapy with isotretinoin appears to work by inhibiting certain cytokines and acting as an antiangiogenic factor.13 Given the rarity of microcystic lymphatic malformations, further research must be done to determine definitive treatment.

Acquired microcystic lymphatic malformation is an important sequela of radiation therapy and surgical excision of malignancy. Despite its striking clinical appearance, it is sometimes difficult to diagnose given its rarity. It is important that clinicians are able to recognize it clinically and understand common treatment options to prevent both the mental stigma and complications, including secondary infections, drainage, and pain.

- Whimster IW. The pathology of lymphangioma circumscriptum. Br J Dermatol. 1976;94:473.

- Vlastos AT, Malpica A, Follen M. Lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva: a review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:946-954.

- Papalas JA, Robboy SJ, Burchette JL, et al. Acquired vulvar lymphangioma circumscriptum: a comparison of 12 cases with Crohn’s associated lesions or radiation therapy induced tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:958-965.

- Kaya TI, Kokturk A, Polat A, et al. A case of cutaneous lymphangiectasis secondary to breast cancer treatment. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:760-761.

- Ambrojo P, Cogolluda EF, Aguilar A, et al. Cutaneous lymphangiectases after therapy for carcinoma of the cervix. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1990;15:57-59.

- Tasdelen I, Gokgoz S, Paksoy E, et al. Acquired lymphangiectasis after breast conservation treatment for breast cancer: report of a case. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:9.

- Lucas DR. Angiosarcoma, radiation-associated angiosarcoma, and atypical vascular lesion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1804-1809.

- Brenn T, Fletcher CD. Radiation-associated cutaneous atypical vascular lesions and angiosarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:983-996.

- Gengler C, Coindre JM, Leroux A. Vascular proliferations of the skin after radiation therapy for breast cancer: clinicopathologic analysis of a series in favor of a benign process: a study from the French Sarcoma Group. Cancer. 2007;109:1584-1598.

- Ghaemmaghami F, Karimi Zarchi M, Mousavi A. Major labiaectomy as surgical management of vulvar lymphangioma circumscriptum: three cases and a review of the literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;278:57-60.

- Savas J. Carbon dioxide laser for the treatment of microcystic lymphatic malformations (lymphangioma circumscriptum): a systematic review. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1147-1157.

- Al Ghamdi KM, Mubki TF. Treatment of lymphangioma circumscriptum with sclerotherapy: an ignored effective remedy. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2011;10:156-158.

- Ayhan E. Lymphangioma circumscriptum: good clinical response to isotretinoin therapy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:E208-E209.

Microcystic lymphatic malformations, also known as lymphangioma circumscriptum, are rare hamartomatous lesions comprised of dilated lymphatic channels that can be both congenital and acquired.1 They often present as translucent or hemorrhagic vesicles of varying sizes that may contain lymphatic fluid and often can cluster together and appear verrucous (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis for microcystic lymphatic malformations commonly includes molluscum contagiosum, squamous cell carcinoma, verruca vulgaris, or condylomas, as well as atypical vascular lesions. They most often are found in children as congenital lesions but also may be acquired. Most acquired cases are due to chronic inflammatory and scarring processes that damage lymphatic structures, including surgery, radiation, infections, and even Crohn disease.2,3 Because the differential diagnosis is so broad and the disease can clinically mimic other common disease processes, biopsies often are performed to determine the diagnosis. On biopsy, pathologic examination revealed well-circumscribed nodular lesions with large lymphatic channels often in a background of connective tissue stroma. Increased eosinophilic material, including mast cells, also was seen (Figure 2A). On immunohistochemistry, staining showed D2-40 positivity (Figure 2B).

Damage to lymphatics from radiation and postsurgical excision of tumors are well-described causes of microcystic lymphatic malformations, as in our patient, with most instances in the literature occurring secondary to treatment of breast or cervical cancer.4-6 In these acquired cases, the pathogenesis is thought to be due to destruction and fibrosis at the layer of the reticular dermis, which causes lymphatic obstruction and subsequent dilation of superficial lymphatic channels.6

Microcystic lymphatic malformations can be difficult to distinguish from atypical vascular lesions, another common postradiation lesion. Both are benign well-circumscribed lesions that histologically do not extend into surrounding subcutaneous tissues and do not have multilayering of cells, mitosis, or hemorrhage.7 Although lymphatic lesions tend to form vesicles, atypical vascular lesions arising after radiation treatment present as erythematous or flesh-colored patches or papules. They also tend to be fairly superficial and often only involve the superficial to mid dermis. On histology they show thin-walled channels without erythrocytes that are lined by typical endothelial cells.7 Despite these differences, both clinically and histopathologically these lesions can appear similar to acquired microcystic lymphatic malformations. It is important to differentiate between these two entities, as atypical vascular lesions have a slightly higher rate of transformation into malignant tumors such as angiosarcomas.

Although angiosarcomas clinically may present as erythematous patches, plaques, or nodules similar to benign postradiation lesions, they tend to be more edematous than their benign counterparts.7,8 Two other clinical factors that can help determine if a postradiation lesion is benign or malignant are the size and time of onset of the lesion. Angiosarcomas tend to be much larger than benign postradiation lesions (median size, 7.5 cm) and tend to be more multifocal in nature.8,9 They also tend to arise on average 5 to 7 years after the initial radiation treatment, while benign lesions arise sooner.9

Small, asymptomatic, acquired microcystic lymphatic malformations can be followed clinically without treatment, but these lesions do not commonly regress spontaneously. Even when asymptomatic, many clinicians will opt for treatment to prevent secondary complications such as infections, drainage, and pain. Moreover, these lesions can have notable psychosocial impacts on patients due to poor cosmetic appearance. Unfortunately, there is no gold standard of treatment, and recurrence is common, even after treatment. Historically, surgical excision was the treatment of choice, but this option carries a high risk for scarring, invasiveness, and recurrence. Recurrence rates of up to 23.1% have been reported with decreased effectiveness of resection, particularly in areas of deeper involvement.10 For these deeper lesions, CO2 laser therapy is a promising evolving therapy. It can penetrate up to the mid dermis and seems to destroy the lymphatic channels between deep and surface lymphatics, preventing the cutaneous manifestations of the disease. It has the added benefit of minimal invasiveness and fewer side effects than complete excision, with most studies reporting hyperpigmentation and scarring as the most common side effects.11 Additional emerging therapies including sclerotherapy and isotretinoin have shown benefits in case studies. Sclerotherapy causes local tissue destruction and thrombosis leading to destruction of vessel lumens and fibrosis that halts disease progression and clears existing lesions.12 Oral therapy with isotretinoin appears to work by inhibiting certain cytokines and acting as an antiangiogenic factor.13 Given the rarity of microcystic lymphatic malformations, further research must be done to determine definitive treatment.

Acquired microcystic lymphatic malformation is an important sequela of radiation therapy and surgical excision of malignancy. Despite its striking clinical appearance, it is sometimes difficult to diagnose given its rarity. It is important that clinicians are able to recognize it clinically and understand common treatment options to prevent both the mental stigma and complications, including secondary infections, drainage, and pain.

Microcystic lymphatic malformations, also known as lymphangioma circumscriptum, are rare hamartomatous lesions comprised of dilated lymphatic channels that can be both congenital and acquired.1 They often present as translucent or hemorrhagic vesicles of varying sizes that may contain lymphatic fluid and often can cluster together and appear verrucous (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis for microcystic lymphatic malformations commonly includes molluscum contagiosum, squamous cell carcinoma, verruca vulgaris, or condylomas, as well as atypical vascular lesions. They most often are found in children as congenital lesions but also may be acquired. Most acquired cases are due to chronic inflammatory and scarring processes that damage lymphatic structures, including surgery, radiation, infections, and even Crohn disease.2,3 Because the differential diagnosis is so broad and the disease can clinically mimic other common disease processes, biopsies often are performed to determine the diagnosis. On biopsy, pathologic examination revealed well-circumscribed nodular lesions with large lymphatic channels often in a background of connective tissue stroma. Increased eosinophilic material, including mast cells, also was seen (Figure 2A). On immunohistochemistry, staining showed D2-40 positivity (Figure 2B).

Damage to lymphatics from radiation and postsurgical excision of tumors are well-described causes of microcystic lymphatic malformations, as in our patient, with most instances in the literature occurring secondary to treatment of breast or cervical cancer.4-6 In these acquired cases, the pathogenesis is thought to be due to destruction and fibrosis at the layer of the reticular dermis, which causes lymphatic obstruction and subsequent dilation of superficial lymphatic channels.6

Microcystic lymphatic malformations can be difficult to distinguish from atypical vascular lesions, another common postradiation lesion. Both are benign well-circumscribed lesions that histologically do not extend into surrounding subcutaneous tissues and do not have multilayering of cells, mitosis, or hemorrhage.7 Although lymphatic lesions tend to form vesicles, atypical vascular lesions arising after radiation treatment present as erythematous or flesh-colored patches or papules. They also tend to be fairly superficial and often only involve the superficial to mid dermis. On histology they show thin-walled channels without erythrocytes that are lined by typical endothelial cells.7 Despite these differences, both clinically and histopathologically these lesions can appear similar to acquired microcystic lymphatic malformations. It is important to differentiate between these two entities, as atypical vascular lesions have a slightly higher rate of transformation into malignant tumors such as angiosarcomas.

Although angiosarcomas clinically may present as erythematous patches, plaques, or nodules similar to benign postradiation lesions, they tend to be more edematous than their benign counterparts.7,8 Two other clinical factors that can help determine if a postradiation lesion is benign or malignant are the size and time of onset of the lesion. Angiosarcomas tend to be much larger than benign postradiation lesions (median size, 7.5 cm) and tend to be more multifocal in nature.8,9 They also tend to arise on average 5 to 7 years after the initial radiation treatment, while benign lesions arise sooner.9

Small, asymptomatic, acquired microcystic lymphatic malformations can be followed clinically without treatment, but these lesions do not commonly regress spontaneously. Even when asymptomatic, many clinicians will opt for treatment to prevent secondary complications such as infections, drainage, and pain. Moreover, these lesions can have notable psychosocial impacts on patients due to poor cosmetic appearance. Unfortunately, there is no gold standard of treatment, and recurrence is common, even after treatment. Historically, surgical excision was the treatment of choice, but this option carries a high risk for scarring, invasiveness, and recurrence. Recurrence rates of up to 23.1% have been reported with decreased effectiveness of resection, particularly in areas of deeper involvement.10 For these deeper lesions, CO2 laser therapy is a promising evolving therapy. It can penetrate up to the mid dermis and seems to destroy the lymphatic channels between deep and surface lymphatics, preventing the cutaneous manifestations of the disease. It has the added benefit of minimal invasiveness and fewer side effects than complete excision, with most studies reporting hyperpigmentation and scarring as the most common side effects.11 Additional emerging therapies including sclerotherapy and isotretinoin have shown benefits in case studies. Sclerotherapy causes local tissue destruction and thrombosis leading to destruction of vessel lumens and fibrosis that halts disease progression and clears existing lesions.12 Oral therapy with isotretinoin appears to work by inhibiting certain cytokines and acting as an antiangiogenic factor.13 Given the rarity of microcystic lymphatic malformations, further research must be done to determine definitive treatment.

Acquired microcystic lymphatic malformation is an important sequela of radiation therapy and surgical excision of malignancy. Despite its striking clinical appearance, it is sometimes difficult to diagnose given its rarity. It is important that clinicians are able to recognize it clinically and understand common treatment options to prevent both the mental stigma and complications, including secondary infections, drainage, and pain.

- Whimster IW. The pathology of lymphangioma circumscriptum. Br J Dermatol. 1976;94:473.

- Vlastos AT, Malpica A, Follen M. Lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva: a review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:946-954.

- Papalas JA, Robboy SJ, Burchette JL, et al. Acquired vulvar lymphangioma circumscriptum: a comparison of 12 cases with Crohn’s associated lesions or radiation therapy induced tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:958-965.

- Kaya TI, Kokturk A, Polat A, et al. A case of cutaneous lymphangiectasis secondary to breast cancer treatment. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:760-761.

- Ambrojo P, Cogolluda EF, Aguilar A, et al. Cutaneous lymphangiectases after therapy for carcinoma of the cervix. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1990;15:57-59.

- Tasdelen I, Gokgoz S, Paksoy E, et al. Acquired lymphangiectasis after breast conservation treatment for breast cancer: report of a case. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:9.

- Lucas DR. Angiosarcoma, radiation-associated angiosarcoma, and atypical vascular lesion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1804-1809.

- Brenn T, Fletcher CD. Radiation-associated cutaneous atypical vascular lesions and angiosarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:983-996.

- Gengler C, Coindre JM, Leroux A. Vascular proliferations of the skin after radiation therapy for breast cancer: clinicopathologic analysis of a series in favor of a benign process: a study from the French Sarcoma Group. Cancer. 2007;109:1584-1598.

- Ghaemmaghami F, Karimi Zarchi M, Mousavi A. Major labiaectomy as surgical management of vulvar lymphangioma circumscriptum: three cases and a review of the literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;278:57-60.

- Savas J. Carbon dioxide laser for the treatment of microcystic lymphatic malformations (lymphangioma circumscriptum): a systematic review. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1147-1157.

- Al Ghamdi KM, Mubki TF. Treatment of lymphangioma circumscriptum with sclerotherapy: an ignored effective remedy. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2011;10:156-158.

- Ayhan E. Lymphangioma circumscriptum: good clinical response to isotretinoin therapy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:E208-E209.

- Whimster IW. The pathology of lymphangioma circumscriptum. Br J Dermatol. 1976;94:473.

- Vlastos AT, Malpica A, Follen M. Lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva: a review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:946-954.

- Papalas JA, Robboy SJ, Burchette JL, et al. Acquired vulvar lymphangioma circumscriptum: a comparison of 12 cases with Crohn’s associated lesions or radiation therapy induced tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:958-965.

- Kaya TI, Kokturk A, Polat A, et al. A case of cutaneous lymphangiectasis secondary to breast cancer treatment. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:760-761.

- Ambrojo P, Cogolluda EF, Aguilar A, et al. Cutaneous lymphangiectases after therapy for carcinoma of the cervix. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1990;15:57-59.

- Tasdelen I, Gokgoz S, Paksoy E, et al. Acquired lymphangiectasis after breast conservation treatment for breast cancer: report of a case. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:9.

- Lucas DR. Angiosarcoma, radiation-associated angiosarcoma, and atypical vascular lesion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1804-1809.

- Brenn T, Fletcher CD. Radiation-associated cutaneous atypical vascular lesions and angiosarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:983-996.

- Gengler C, Coindre JM, Leroux A. Vascular proliferations of the skin after radiation therapy for breast cancer: clinicopathologic analysis of a series in favor of a benign process: a study from the French Sarcoma Group. Cancer. 2007;109:1584-1598.

- Ghaemmaghami F, Karimi Zarchi M, Mousavi A. Major labiaectomy as surgical management of vulvar lymphangioma circumscriptum: three cases and a review of the literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;278:57-60.

- Savas J. Carbon dioxide laser for the treatment of microcystic lymphatic malformations (lymphangioma circumscriptum): a systematic review. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1147-1157.

- Al Ghamdi KM, Mubki TF. Treatment of lymphangioma circumscriptum with sclerotherapy: an ignored effective remedy. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2011;10:156-158.

- Ayhan E. Lymphangioma circumscriptum: good clinical response to isotretinoin therapy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:E208-E209.

A 51-year-old woman with a history of bilateral breast cancer presented for evaluation of lesions on the underside of the right breast. She was first diagnosed with stage II cancer of the right breast that was subsequently treated with a mastectomy and adjuvant chemotherapy 7 years prior to presentation. One year later, she developed stage IIIC adenocarcinoma of the left breast and was treated with a modified radical mastectomy, adjuvant chemotherapy, and radiation. She had been followed closely by her oncologist with regular surveillance imaging (last at 7 months prior to presentation) that had all been negative for recurrent breast cancer. She presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of lesions on the underside of the right breast that were pruritic and occasionally painful with a burning quality. These lesions had recently begun to bleed when scratched but were not otherwise growing or spreading. On physical examination she was afebrile with stable vital signs. Skin examination was notable for numerous violaceous and translucent papules and nodules underneath the right breast and axilla overlying a well-healed mastectomy scar. No lymphadenopathy was present. Shave biopsies were performed and showed well-circumscribed nodular lesions with ectatic vascular channels separated by thin fibrous walls and filled with eosinophilic proteinaceous material and scattered red blood cells. Immunohistochemical staining also showed positivity for D2-40.

Patient Satisfaction and Quality of Care: A Prospective Study at Outpatient Dermatology Clinics

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act has increased the number of insured Americans by more than 20 million individuals.1 Approximately half of the newly insured have an income at or below 138% of the poverty level and are on average younger, sicker, and more likely to report poor to fair health compared to those individuals who already had health care coverage.2 Specialties such as dermatology are faced with the challenge of expanding access to these newly insured individuals while also improving quality of care.

Because of the complexity of defining quality in medicine, patient satisfaction is being used as a proxy for quality, with physicians evaluated and reimbursed based on patient satisfaction scores. Little research has been conducted to validate the relationship between patient satisfaction and quality; however, one study showed online reviews from patients on Yelp correlated with traditional markers of quality, such as mortality and readmission rates, lending credibility to the notion that patient satisfaction equates quality of care.3 Moreover, prospective studies have found positive correlations between patient satisfaction and compliance to therapy4,5; however, these studies may not give a complete picture of the relationship between patient satisfaction and quality of care, as other studies also have illustrated that, more often than not, factors extrinsic to actual medical care (eg, time spent in the waiting room) play a considerable role in patient satisfaction scores.6-9

When judging the quality of care that is provided, one study found that patients rate physicians based on interpersonal skills and not care delivered.8 Another important factor related to patient satisfaction is the anonymity of the surveys. Patients who have negative experiences are more likely to respond to online surveys than those who have positive experiences, skewing overall ratings.6 Additionally, because of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations, physicians often are unable to respond directly to public patient reviews, resulting in an incomplete picture of the quality of care provided.

Ultimately, even if physicians do not agree that patient satisfaction correlates with quality of care, it is increasingly being used as a marker of such. Leading health care systems are embracing this new weight on patient satisfaction by increasing transparency and publishing patient satisfaction results online, allowing patients more access to physician reviews.

In dermatology, patient satisfaction serves an even more important role, as traditional markers of quality such as mortality and hospital readmission rates are not reasonable measures of patient care in this specialty, leaving patient satisfaction as one of the most accessible markers insurance companies and prospective patients can use to evaluate dermatologists. Furthermore, treatment modalities in dermatology often aim to improve quality of life, of which patient satisfaction arguably serves as an indicator. Ideally, patient satisfaction would allow physicians to identify areas where they may be better able to meet patients’ needs. However, patient satisfaction scores rarely are used as outcome measures in studies and are notoriously difficult to ascertain, as they tend to be inaccurate and may be unreliable in correlation with physician skill and training or may be skewed by patients’ desires to please their physicians.10 There also is a lack of standardized tools and scales to quantitatively judge outcomes in procedural surgeries.

Although patient satisfaction is being used as a measure of quality of care and is particularly necessary in a field such as dermatology that has outcome measures that are subjective in nature, there is a gap in the current literature regarding patient satisfaction and dermatology. To fill this gap, we conducted a prospective study of targeted interventions administered at outpatient dermatology clinics to determine if they resulted in statistically significant increases in patient satisfaction measures, particularly among Spanish-speaking patients.

Methods

We conducted a prospective study evaluating patient satisfaction in the outpatient dermatology clinics of LAC+USC Medical Center in Los Angeles, California, spanning over 1 year. During this time period, patients were randomly selected to participate and were asked to complete the Short-Form Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ-18), which asked patients to rate their care experience on a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly agree; 5=strongly disagree). The survey was separated into the following 7 subscales or categories looking at different aspects of care: general satisfaction, technical quality, interpersonal manner, communication, financial aspects, time spent with physician, and accessibility and convenience. Patients were given this survey both before and after targeted interventions to improve patient satisfaction were implemented. The targeted interventions were created based on literature review in the factors affecting patient satisfaction. The change in relative satisfaction was then determined using statistical analysis. The study was approved by the University of Southern California Health Science institutional review board.

Results

Of 470 patients surveyed, the average age was 49 years. Fifty percent of respondents were male, 70% self-identified as Hispanic, 45% spoke Spanish as their native language, and 69% reported a mean annual household income of less than $15,000. When scores were stratified, English-speaking patients were significantly more satisfied than Spanish-speaking patients in the categories of technical quality (P.0340), financial aspects (P.0301), interpersonal manner (P.0037), and time spent with physician (P.0059). Specifically, in the time spent with physician category, the lowest scores were found in females, patients aged 18 to 29 years, and patients with a mean annual household income less than $15,000. These demographics correlate well with many of the newly insured and intimate the need for improved patient satisfaction, particularly in this subset of patients.

After analyzing baseline patient satisfaction scores, we implemented targeted interventions such as creating a call tree, developing multilingual disease-specific patient handouts, instituting quarterly nursing in-services, which judged interpersonal and occupational nursing skills, and recruiting bilingual staff. These interventions were implemented simultaneously and were selected with the goal of reducing the impact of the language barrier between physicians and patients and increasing accessibility to clinics. Following approximately 3 months of these interventions, performance on many categories increased in our demographics that were lowest performing when we collected baseline data. In Spanish-speaking respondents, improvement in several categories approached statistical significance, including general satisfaction (P.110), interpersonal skills (P.080), and time spent with physician (P.096). When stratifying by income and age, patients with a mean annual household income less than $15,000 demonstrated an improved technical quality (P.066) subscale score, and participants aged 18 to 29 years showed improvement in both accessibility and convenience (P.053) and financial aspects (P.056) subscales.

Comment

The categories where improvements were found are noteworthy and suggest that certain aspects of care are more important than others. Although it seems intuitive that clinical acumen and training should be important contributors to patient satisfaction, one study that analyzed 1000 online comments regarding patient satisfaction with dermatologists on the website DrScore.com found that most comments concerned physician personality and interpersonal skills rather than medical judgment and acumen,4 suggesting that a patient’s perception of the character of the physician directly affects patient satisfaction scores. This notion was reiterated by other studies, including one that found that a patient’s perception of the physician’s kindness and empathy skills, is the most important measure of quality of care scores.8 Although this perception can be intimidating to some physicians, as certain interpersonal skills are difficult to change, it is reassuring to note that external environment and cues, such as the clinic building and staff, also seem to affect interpersonal ratings. As seen in our study, patient ratings of a physician’s interpersonal skills increased after educational materials for staff and patients were created and more bilingual staff was recruited. Other environmental changes, such as spending a few more minutes with patients and sitting down when talking to patients, are relatively easy to administer and can improve patient satisfaction scores.8

Although some of the scores in our study approached but did not reach statistical significance, likely because of a small sample size, they suggest that targeted interventions can improve patient satisfaction. They also suggested that targeted interventions are particularly useful in Spanish-speaking patients, younger patients, and patients from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, which are all characteristics of the newly insured under the Patient Protection and Affordable Health Care Act.

Our study also is unique in that dermatology as a specialty is lagging in quality improvement studies. In the few studies evaluating patient satisfaction in the literature, the care provided by dermatologists was painted in a positive light.6,11 One study evaluated 45 dermatology practices and reported average patient satisfaction scores of 3.46 and 4.72 of 5 on Yelp and ZocDoc, respectively.11 Another study looking at dermatologist ratings on DrScore.com found that the majority of patients were satisfied with the care they received.6

Although these studies seem encouraging, they have several limitations. First, their results were not stratified by patient demographics and therefore may not be generalizable to low-income populations that constitute much of the newly insured. Secondly, the observational nature and limited number of studies prohibit meaningful conclusions from being drawn and leave many questions unanswered. Additionally, although the raw patient satisfaction scores seem good, dermatology is lacking compared to the patient satisfaction scores within other specialties. A study of more than 28,000 Yelp reviews of 23 specialties found that dermatology ranked second to last, ahead of only psychiatry.7 Of course, given the observational nature of this study, it is impossible to generalize, as many confounders (eg, medical comorbidities, patient age) may have skewed the dermatology ranking. Regardless, there is always room for improvement, and luckily improving patient satisfaction is not an elusive goal.

Conclusion

As dermatologists, our interventions often improve quality of life; therefore, we are positioned to be leaders in the quality improvement field. Despite the numerous limitations of using patient satisfaction as a measure for quality of care, it is used by payers to determine reimbursement and patients to select providers. Encouraging initial data from our prospective study demonstrate that small interventions can increase patient satisfaction. Continued work to maximize patient satisfaction is needed to improve outcomes for our patients, help validate the quality of care being provided, and further solidify the importance of having insurers maintain sufficient dermatologists in their networks.

- Uberoi N, Finegold K, Gee E. Health insurance coverage and the Affordable Care Act, 2010-2016. US Department of Health & Human Services website. https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/187551/ACA2010-2016.pdf. Published March 3, 2016. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- Shatzer A, Long SK, Zuckerman S. Who are the newly insured as of early March 2014? Urban Institute Health Policy Center website. http://hrms.urban.org/briefs/Who-Are-the-Newly-Insured.html. Published May 22, 2014. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- Bardach NS, Asteria-Peñaloza R, Boscardin WJ, et al. The relationship between commercial website ratings and traditional hospital performance measures in the USA. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22:194-202.

- Kincey J, Bradshaw P, Ley P. Patient satisfaction and reported acceptance of medical advice in general practice. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1975;25:558-566.

- Francis V, Korsch BM, Morris MJ. Gaps in doctor-patient communication. patients’ response to medical advice. N Engl J Med. 1969;280:535-540.

- Ali ST, Feldman SR. Patient satisfaction in dermatology: a qualitative assessment. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20. pii:doj_21534.

- Internet study: highest educated & trained doctors get poorest online reviews. Vanguard Communications website. https://vanguard communications.net/best-online-doctor-reviews/. Published April 22, 2015. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- Uhas AA, Camacho FT, Feldman SR, et al. The relationship between physician friendliness and caring, and patient satisfaction: findings from an internet-based survey. Patient. 2008;1:91-96.

- Anderson RT, Camacho FT, Balkrishnan R. Willing to wait?: the influence of patient wait time on satisfaction with primary care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:31.

- Maibach HI, Gorouhi F. Evidence-Based Dermatology. 2nd ed. Shelton, CT: People’s Medical Publishing House-USA; 2011.

- Smith R, Lipoff J. Evaluation of dermatology practice online reviews. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:153-157.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act has increased the number of insured Americans by more than 20 million individuals.1 Approximately half of the newly insured have an income at or below 138% of the poverty level and are on average younger, sicker, and more likely to report poor to fair health compared to those individuals who already had health care coverage.2 Specialties such as dermatology are faced with the challenge of expanding access to these newly insured individuals while also improving quality of care.

Because of the complexity of defining quality in medicine, patient satisfaction is being used as a proxy for quality, with physicians evaluated and reimbursed based on patient satisfaction scores. Little research has been conducted to validate the relationship between patient satisfaction and quality; however, one study showed online reviews from patients on Yelp correlated with traditional markers of quality, such as mortality and readmission rates, lending credibility to the notion that patient satisfaction equates quality of care.3 Moreover, prospective studies have found positive correlations between patient satisfaction and compliance to therapy4,5; however, these studies may not give a complete picture of the relationship between patient satisfaction and quality of care, as other studies also have illustrated that, more often than not, factors extrinsic to actual medical care (eg, time spent in the waiting room) play a considerable role in patient satisfaction scores.6-9

When judging the quality of care that is provided, one study found that patients rate physicians based on interpersonal skills and not care delivered.8 Another important factor related to patient satisfaction is the anonymity of the surveys. Patients who have negative experiences are more likely to respond to online surveys than those who have positive experiences, skewing overall ratings.6 Additionally, because of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations, physicians often are unable to respond directly to public patient reviews, resulting in an incomplete picture of the quality of care provided.

Ultimately, even if physicians do not agree that patient satisfaction correlates with quality of care, it is increasingly being used as a marker of such. Leading health care systems are embracing this new weight on patient satisfaction by increasing transparency and publishing patient satisfaction results online, allowing patients more access to physician reviews.

In dermatology, patient satisfaction serves an even more important role, as traditional markers of quality such as mortality and hospital readmission rates are not reasonable measures of patient care in this specialty, leaving patient satisfaction as one of the most accessible markers insurance companies and prospective patients can use to evaluate dermatologists. Furthermore, treatment modalities in dermatology often aim to improve quality of life, of which patient satisfaction arguably serves as an indicator. Ideally, patient satisfaction would allow physicians to identify areas where they may be better able to meet patients’ needs. However, patient satisfaction scores rarely are used as outcome measures in studies and are notoriously difficult to ascertain, as they tend to be inaccurate and may be unreliable in correlation with physician skill and training or may be skewed by patients’ desires to please their physicians.10 There also is a lack of standardized tools and scales to quantitatively judge outcomes in procedural surgeries.

Although patient satisfaction is being used as a measure of quality of care and is particularly necessary in a field such as dermatology that has outcome measures that are subjective in nature, there is a gap in the current literature regarding patient satisfaction and dermatology. To fill this gap, we conducted a prospective study of targeted interventions administered at outpatient dermatology clinics to determine if they resulted in statistically significant increases in patient satisfaction measures, particularly among Spanish-speaking patients.

Methods

We conducted a prospective study evaluating patient satisfaction in the outpatient dermatology clinics of LAC+USC Medical Center in Los Angeles, California, spanning over 1 year. During this time period, patients were randomly selected to participate and were asked to complete the Short-Form Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ-18), which asked patients to rate their care experience on a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly agree; 5=strongly disagree). The survey was separated into the following 7 subscales or categories looking at different aspects of care: general satisfaction, technical quality, interpersonal manner, communication, financial aspects, time spent with physician, and accessibility and convenience. Patients were given this survey both before and after targeted interventions to improve patient satisfaction were implemented. The targeted interventions were created based on literature review in the factors affecting patient satisfaction. The change in relative satisfaction was then determined using statistical analysis. The study was approved by the University of Southern California Health Science institutional review board.

Results

Of 470 patients surveyed, the average age was 49 years. Fifty percent of respondents were male, 70% self-identified as Hispanic, 45% spoke Spanish as their native language, and 69% reported a mean annual household income of less than $15,000. When scores were stratified, English-speaking patients were significantly more satisfied than Spanish-speaking patients in the categories of technical quality (P.0340), financial aspects (P.0301), interpersonal manner (P.0037), and time spent with physician (P.0059). Specifically, in the time spent with physician category, the lowest scores were found in females, patients aged 18 to 29 years, and patients with a mean annual household income less than $15,000. These demographics correlate well with many of the newly insured and intimate the need for improved patient satisfaction, particularly in this subset of patients.

After analyzing baseline patient satisfaction scores, we implemented targeted interventions such as creating a call tree, developing multilingual disease-specific patient handouts, instituting quarterly nursing in-services, which judged interpersonal and occupational nursing skills, and recruiting bilingual staff. These interventions were implemented simultaneously and were selected with the goal of reducing the impact of the language barrier between physicians and patients and increasing accessibility to clinics. Following approximately 3 months of these interventions, performance on many categories increased in our demographics that were lowest performing when we collected baseline data. In Spanish-speaking respondents, improvement in several categories approached statistical significance, including general satisfaction (P.110), interpersonal skills (P.080), and time spent with physician (P.096). When stratifying by income and age, patients with a mean annual household income less than $15,000 demonstrated an improved technical quality (P.066) subscale score, and participants aged 18 to 29 years showed improvement in both accessibility and convenience (P.053) and financial aspects (P.056) subscales.

Comment

The categories where improvements were found are noteworthy and suggest that certain aspects of care are more important than others. Although it seems intuitive that clinical acumen and training should be important contributors to patient satisfaction, one study that analyzed 1000 online comments regarding patient satisfaction with dermatologists on the website DrScore.com found that most comments concerned physician personality and interpersonal skills rather than medical judgment and acumen,4 suggesting that a patient’s perception of the character of the physician directly affects patient satisfaction scores. This notion was reiterated by other studies, including one that found that a patient’s perception of the physician’s kindness and empathy skills, is the most important measure of quality of care scores.8 Although this perception can be intimidating to some physicians, as certain interpersonal skills are difficult to change, it is reassuring to note that external environment and cues, such as the clinic building and staff, also seem to affect interpersonal ratings. As seen in our study, patient ratings of a physician’s interpersonal skills increased after educational materials for staff and patients were created and more bilingual staff was recruited. Other environmental changes, such as spending a few more minutes with patients and sitting down when talking to patients, are relatively easy to administer and can improve patient satisfaction scores.8

Although some of the scores in our study approached but did not reach statistical significance, likely because of a small sample size, they suggest that targeted interventions can improve patient satisfaction. They also suggested that targeted interventions are particularly useful in Spanish-speaking patients, younger patients, and patients from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, which are all characteristics of the newly insured under the Patient Protection and Affordable Health Care Act.

Our study also is unique in that dermatology as a specialty is lagging in quality improvement studies. In the few studies evaluating patient satisfaction in the literature, the care provided by dermatologists was painted in a positive light.6,11 One study evaluated 45 dermatology practices and reported average patient satisfaction scores of 3.46 and 4.72 of 5 on Yelp and ZocDoc, respectively.11 Another study looking at dermatologist ratings on DrScore.com found that the majority of patients were satisfied with the care they received.6

Although these studies seem encouraging, they have several limitations. First, their results were not stratified by patient demographics and therefore may not be generalizable to low-income populations that constitute much of the newly insured. Secondly, the observational nature and limited number of studies prohibit meaningful conclusions from being drawn and leave many questions unanswered. Additionally, although the raw patient satisfaction scores seem good, dermatology is lacking compared to the patient satisfaction scores within other specialties. A study of more than 28,000 Yelp reviews of 23 specialties found that dermatology ranked second to last, ahead of only psychiatry.7 Of course, given the observational nature of this study, it is impossible to generalize, as many confounders (eg, medical comorbidities, patient age) may have skewed the dermatology ranking. Regardless, there is always room for improvement, and luckily improving patient satisfaction is not an elusive goal.

Conclusion

As dermatologists, our interventions often improve quality of life; therefore, we are positioned to be leaders in the quality improvement field. Despite the numerous limitations of using patient satisfaction as a measure for quality of care, it is used by payers to determine reimbursement and patients to select providers. Encouraging initial data from our prospective study demonstrate that small interventions can increase patient satisfaction. Continued work to maximize patient satisfaction is needed to improve outcomes for our patients, help validate the quality of care being provided, and further solidify the importance of having insurers maintain sufficient dermatologists in their networks.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act has increased the number of insured Americans by more than 20 million individuals.1 Approximately half of the newly insured have an income at or below 138% of the poverty level and are on average younger, sicker, and more likely to report poor to fair health compared to those individuals who already had health care coverage.2 Specialties such as dermatology are faced with the challenge of expanding access to these newly insured individuals while also improving quality of care.

Because of the complexity of defining quality in medicine, patient satisfaction is being used as a proxy for quality, with physicians evaluated and reimbursed based on patient satisfaction scores. Little research has been conducted to validate the relationship between patient satisfaction and quality; however, one study showed online reviews from patients on Yelp correlated with traditional markers of quality, such as mortality and readmission rates, lending credibility to the notion that patient satisfaction equates quality of care.3 Moreover, prospective studies have found positive correlations between patient satisfaction and compliance to therapy4,5; however, these studies may not give a complete picture of the relationship between patient satisfaction and quality of care, as other studies also have illustrated that, more often than not, factors extrinsic to actual medical care (eg, time spent in the waiting room) play a considerable role in patient satisfaction scores.6-9

When judging the quality of care that is provided, one study found that patients rate physicians based on interpersonal skills and not care delivered.8 Another important factor related to patient satisfaction is the anonymity of the surveys. Patients who have negative experiences are more likely to respond to online surveys than those who have positive experiences, skewing overall ratings.6 Additionally, because of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations, physicians often are unable to respond directly to public patient reviews, resulting in an incomplete picture of the quality of care provided.

Ultimately, even if physicians do not agree that patient satisfaction correlates with quality of care, it is increasingly being used as a marker of such. Leading health care systems are embracing this new weight on patient satisfaction by increasing transparency and publishing patient satisfaction results online, allowing patients more access to physician reviews.

In dermatology, patient satisfaction serves an even more important role, as traditional markers of quality such as mortality and hospital readmission rates are not reasonable measures of patient care in this specialty, leaving patient satisfaction as one of the most accessible markers insurance companies and prospective patients can use to evaluate dermatologists. Furthermore, treatment modalities in dermatology often aim to improve quality of life, of which patient satisfaction arguably serves as an indicator. Ideally, patient satisfaction would allow physicians to identify areas where they may be better able to meet patients’ needs. However, patient satisfaction scores rarely are used as outcome measures in studies and are notoriously difficult to ascertain, as they tend to be inaccurate and may be unreliable in correlation with physician skill and training or may be skewed by patients’ desires to please their physicians.10 There also is a lack of standardized tools and scales to quantitatively judge outcomes in procedural surgeries.

Although patient satisfaction is being used as a measure of quality of care and is particularly necessary in a field such as dermatology that has outcome measures that are subjective in nature, there is a gap in the current literature regarding patient satisfaction and dermatology. To fill this gap, we conducted a prospective study of targeted interventions administered at outpatient dermatology clinics to determine if they resulted in statistically significant increases in patient satisfaction measures, particularly among Spanish-speaking patients.

Methods

We conducted a prospective study evaluating patient satisfaction in the outpatient dermatology clinics of LAC+USC Medical Center in Los Angeles, California, spanning over 1 year. During this time period, patients were randomly selected to participate and were asked to complete the Short-Form Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ-18), which asked patients to rate their care experience on a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly agree; 5=strongly disagree). The survey was separated into the following 7 subscales or categories looking at different aspects of care: general satisfaction, technical quality, interpersonal manner, communication, financial aspects, time spent with physician, and accessibility and convenience. Patients were given this survey both before and after targeted interventions to improve patient satisfaction were implemented. The targeted interventions were created based on literature review in the factors affecting patient satisfaction. The change in relative satisfaction was then determined using statistical analysis. The study was approved by the University of Southern California Health Science institutional review board.

Results

Of 470 patients surveyed, the average age was 49 years. Fifty percent of respondents were male, 70% self-identified as Hispanic, 45% spoke Spanish as their native language, and 69% reported a mean annual household income of less than $15,000. When scores were stratified, English-speaking patients were significantly more satisfied than Spanish-speaking patients in the categories of technical quality (P.0340), financial aspects (P.0301), interpersonal manner (P.0037), and time spent with physician (P.0059). Specifically, in the time spent with physician category, the lowest scores were found in females, patients aged 18 to 29 years, and patients with a mean annual household income less than $15,000. These demographics correlate well with many of the newly insured and intimate the need for improved patient satisfaction, particularly in this subset of patients.

After analyzing baseline patient satisfaction scores, we implemented targeted interventions such as creating a call tree, developing multilingual disease-specific patient handouts, instituting quarterly nursing in-services, which judged interpersonal and occupational nursing skills, and recruiting bilingual staff. These interventions were implemented simultaneously and were selected with the goal of reducing the impact of the language barrier between physicians and patients and increasing accessibility to clinics. Following approximately 3 months of these interventions, performance on many categories increased in our demographics that were lowest performing when we collected baseline data. In Spanish-speaking respondents, improvement in several categories approached statistical significance, including general satisfaction (P.110), interpersonal skills (P.080), and time spent with physician (P.096). When stratifying by income and age, patients with a mean annual household income less than $15,000 demonstrated an improved technical quality (P.066) subscale score, and participants aged 18 to 29 years showed improvement in both accessibility and convenience (P.053) and financial aspects (P.056) subscales.

Comment

The categories where improvements were found are noteworthy and suggest that certain aspects of care are more important than others. Although it seems intuitive that clinical acumen and training should be important contributors to patient satisfaction, one study that analyzed 1000 online comments regarding patient satisfaction with dermatologists on the website DrScore.com found that most comments concerned physician personality and interpersonal skills rather than medical judgment and acumen,4 suggesting that a patient’s perception of the character of the physician directly affects patient satisfaction scores. This notion was reiterated by other studies, including one that found that a patient’s perception of the physician’s kindness and empathy skills, is the most important measure of quality of care scores.8 Although this perception can be intimidating to some physicians, as certain interpersonal skills are difficult to change, it is reassuring to note that external environment and cues, such as the clinic building and staff, also seem to affect interpersonal ratings. As seen in our study, patient ratings of a physician’s interpersonal skills increased after educational materials for staff and patients were created and more bilingual staff was recruited. Other environmental changes, such as spending a few more minutes with patients and sitting down when talking to patients, are relatively easy to administer and can improve patient satisfaction scores.8

Although some of the scores in our study approached but did not reach statistical significance, likely because of a small sample size, they suggest that targeted interventions can improve patient satisfaction. They also suggested that targeted interventions are particularly useful in Spanish-speaking patients, younger patients, and patients from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, which are all characteristics of the newly insured under the Patient Protection and Affordable Health Care Act.

Our study also is unique in that dermatology as a specialty is lagging in quality improvement studies. In the few studies evaluating patient satisfaction in the literature, the care provided by dermatologists was painted in a positive light.6,11 One study evaluated 45 dermatology practices and reported average patient satisfaction scores of 3.46 and 4.72 of 5 on Yelp and ZocDoc, respectively.11 Another study looking at dermatologist ratings on DrScore.com found that the majority of patients were satisfied with the care they received.6

Although these studies seem encouraging, they have several limitations. First, their results were not stratified by patient demographics and therefore may not be generalizable to low-income populations that constitute much of the newly insured. Secondly, the observational nature and limited number of studies prohibit meaningful conclusions from being drawn and leave many questions unanswered. Additionally, although the raw patient satisfaction scores seem good, dermatology is lacking compared to the patient satisfaction scores within other specialties. A study of more than 28,000 Yelp reviews of 23 specialties found that dermatology ranked second to last, ahead of only psychiatry.7 Of course, given the observational nature of this study, it is impossible to generalize, as many confounders (eg, medical comorbidities, patient age) may have skewed the dermatology ranking. Regardless, there is always room for improvement, and luckily improving patient satisfaction is not an elusive goal.

Conclusion

As dermatologists, our interventions often improve quality of life; therefore, we are positioned to be leaders in the quality improvement field. Despite the numerous limitations of using patient satisfaction as a measure for quality of care, it is used by payers to determine reimbursement and patients to select providers. Encouraging initial data from our prospective study demonstrate that small interventions can increase patient satisfaction. Continued work to maximize patient satisfaction is needed to improve outcomes for our patients, help validate the quality of care being provided, and further solidify the importance of having insurers maintain sufficient dermatologists in their networks.

- Uberoi N, Finegold K, Gee E. Health insurance coverage and the Affordable Care Act, 2010-2016. US Department of Health & Human Services website. https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/187551/ACA2010-2016.pdf. Published March 3, 2016. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- Shatzer A, Long SK, Zuckerman S. Who are the newly insured as of early March 2014? Urban Institute Health Policy Center website. http://hrms.urban.org/briefs/Who-Are-the-Newly-Insured.html. Published May 22, 2014. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- Bardach NS, Asteria-Peñaloza R, Boscardin WJ, et al. The relationship between commercial website ratings and traditional hospital performance measures in the USA. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22:194-202.

- Kincey J, Bradshaw P, Ley P. Patient satisfaction and reported acceptance of medical advice in general practice. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1975;25:558-566.

- Francis V, Korsch BM, Morris MJ. Gaps in doctor-patient communication. patients’ response to medical advice. N Engl J Med. 1969;280:535-540.

- Ali ST, Feldman SR. Patient satisfaction in dermatology: a qualitative assessment. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20. pii:doj_21534.

- Internet study: highest educated & trained doctors get poorest online reviews. Vanguard Communications website. https://vanguard communications.net/best-online-doctor-reviews/. Published April 22, 2015. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- Uhas AA, Camacho FT, Feldman SR, et al. The relationship between physician friendliness and caring, and patient satisfaction: findings from an internet-based survey. Patient. 2008;1:91-96.

- Anderson RT, Camacho FT, Balkrishnan R. Willing to wait?: the influence of patient wait time on satisfaction with primary care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:31.

- Maibach HI, Gorouhi F. Evidence-Based Dermatology. 2nd ed. Shelton, CT: People’s Medical Publishing House-USA; 2011.

- Smith R, Lipoff J. Evaluation of dermatology practice online reviews. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:153-157.

- Uberoi N, Finegold K, Gee E. Health insurance coverage and the Affordable Care Act, 2010-2016. US Department of Health & Human Services website. https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/187551/ACA2010-2016.pdf. Published March 3, 2016. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- Shatzer A, Long SK, Zuckerman S. Who are the newly insured as of early March 2014? Urban Institute Health Policy Center website. http://hrms.urban.org/briefs/Who-Are-the-Newly-Insured.html. Published May 22, 2014. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- Bardach NS, Asteria-Peñaloza R, Boscardin WJ, et al. The relationship between commercial website ratings and traditional hospital performance measures in the USA. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22:194-202.

- Kincey J, Bradshaw P, Ley P. Patient satisfaction and reported acceptance of medical advice in general practice. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1975;25:558-566.

- Francis V, Korsch BM, Morris MJ. Gaps in doctor-patient communication. patients’ response to medical advice. N Engl J Med. 1969;280:535-540.

- Ali ST, Feldman SR. Patient satisfaction in dermatology: a qualitative assessment. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20. pii:doj_21534.

- Internet study: highest educated & trained doctors get poorest online reviews. Vanguard Communications website. https://vanguard communications.net/best-online-doctor-reviews/. Published April 22, 2015. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- Uhas AA, Camacho FT, Feldman SR, et al. The relationship between physician friendliness and caring, and patient satisfaction: findings from an internet-based survey. Patient. 2008;1:91-96.

- Anderson RT, Camacho FT, Balkrishnan R. Willing to wait?: the influence of patient wait time on satisfaction with primary care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:31.

- Maibach HI, Gorouhi F. Evidence-Based Dermatology. 2nd ed. Shelton, CT: People’s Medical Publishing House-USA; 2011.

- Smith R, Lipoff J. Evaluation of dermatology practice online reviews. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:153-157.

Practice Points

- It is becoming increasingly important, particularly in the field of dermatology, to both measure and work to improve patient satisfaction scores.

- Preliminary research has found that simple interventions, such as providing disease-specific handouts and interpreter services, can improve satisfaction scores, making patient satisfaction an achievable goal.