User login

Sarcoidosis is a systemic noncaseating granulomatous disease of unknown etiology. The skin is the second most common location for disease manifestation following the lungs.1 Cutaneous sarcoidosis is present in 35% of patients with sarcoidosis and may be further subtyped by its morphologic characteristics (eg, hyperpigmented, papular, nodular, atrophic, ulcerative, psoriasiform). Cutaneous sarcoidosis has an increased tendency to occur at areas of prior injury such as surgeries or tattoos.2 Although sarcoidosis affects all races and sexes, it is more prevalent in women and in the black population.3

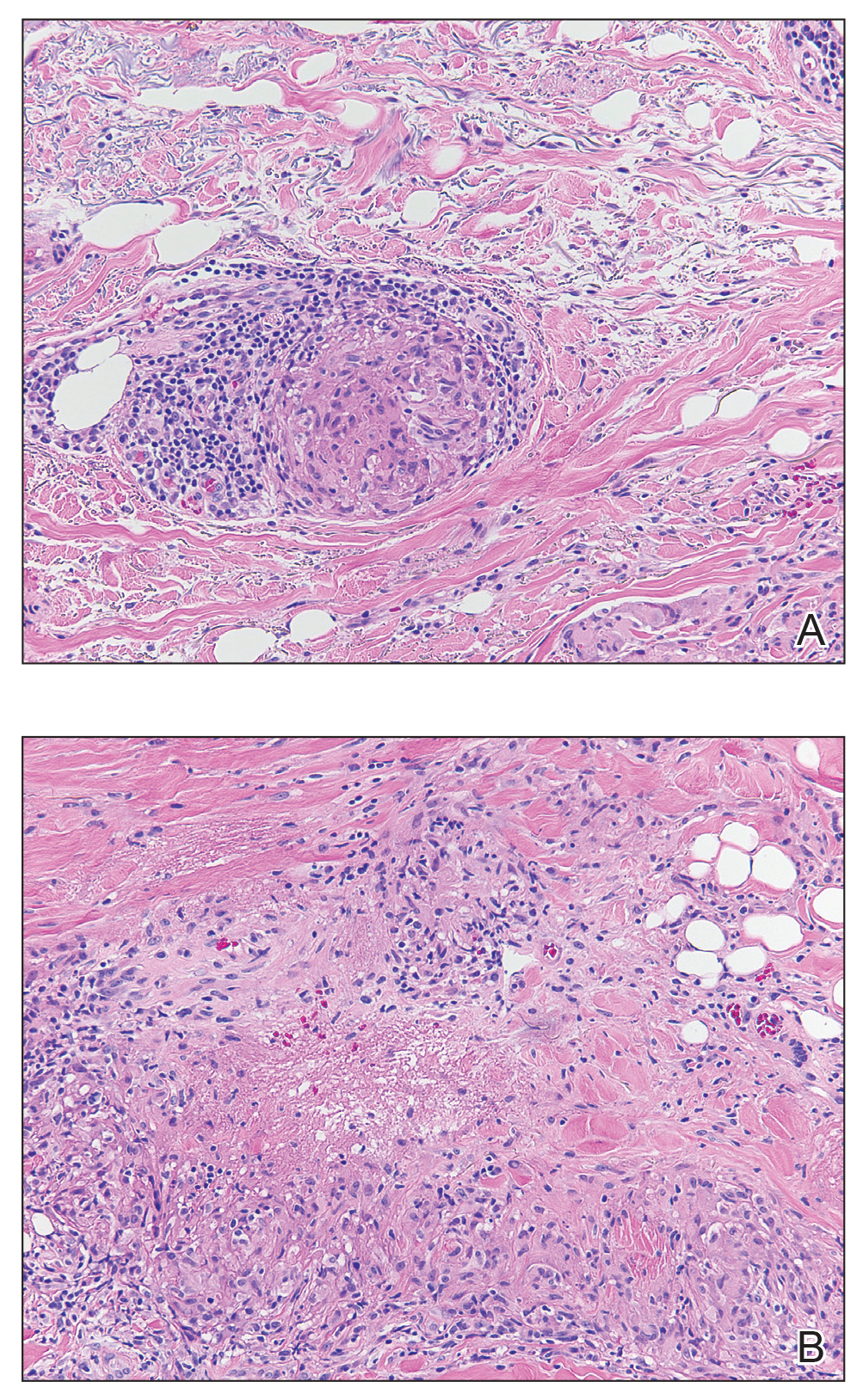

The clinical presentation of sarcoidosis is difficult due to its morphologic variation, allowing for a wide differential diagnosis. With our patient’s presentation of atrophic plaques, the differential diagnosis included granuloma annulare, necrobiosis lipoidica, tumid lupus erythematosus, leprosy, and sarcoidosis; however, biopsy is required for definitive diagnosis. The characteristic histopathology for cutaneous sarcoidosis includes noncaseating granulomas (Figure, A) composed of epithelioid histiocytes with giant cells surrounded by a lymphocytic infiltrate. Noncaseating granulomas are considered specific to sarcoidosis and are present in 71% to 89% of biopsied lesions.4 Interestingly, our patient presented with a rare subtype of atrophic ulcerative cutaneous sarcoidosis, necrobiosis lipoidica–like sarcoidosis, which is more common in females and in the black population. It is characterized by pink to violaceous plaques with depressed centers and prominent necrotizing granuloma (Figure, B) on histopathology. In a small case series, all 3 patients with necrobiosis lipoidica–like sarcoidosis were female and had systemic involvement at the time of diagnosis.5

Sarcoidosis typically is a systemic disease with only a limited number of cases presenting with isolated cutaneous findings. Therefore, patients require a systemic evaluation, which may include a chest radiograph, complete blood cell count, ophthalmologic examinations, thyroid testing, and vitamin D monitoring, as well as an echocardiogram and electrocardiogram.2

Treatment is guided by the severity of disease. For isolated cutaneous lesions, topical or intralesional high-potency steroids have been shown to be effective.6,7 Several studies also have shown phototherapy and laser therapy as well as surgical excision to be beneficial.8-10 Once cutaneous lesions become disfiguring or systemic involvement is found, systemic corticosteroids or other immunomodulatory medications may be warranted.11 Our patient was started on intralesional and topical high-potency steroids, which failed, and she was transitioned to methotrexate and adalimumab. Unfortunately, even with advanced therapies, our patient did not have notableresolution of the lesions.

- Mañá J, Marcoval J. Skin manifestations of sarcoidosis. Presse Med. 2012;41 (6, pt 2): E355-E374.

- Wanat KA, Rosenbach M. Cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med.2015; 36:685-702.

- Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, et al. Clinical characteristics ofpatients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(10, pt 1):1885-1889.

- Ball NJ, Kho GT, Martinka M. The histologic spectrum of cutaneous sarcoidosis: a study of twenty-eight cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004; 31:160-168.

- Mendoza V, Vahid B, Kozic H, et al. Clinical and pathologic manifestations of necrobiosis lipoidica-like skin involvement in sarcoidosis. Joint Bone Spine. 2007; 74:647-649.

- Khatri KA, Chotzen VA, Burrall BA. Lupus pernio: successful treatment with a potent topical corticosteroid. Arch Dermatol. 1995; 131:617-618.

- Singh SK, Singh S, Pandey SS. Cutaneous sarcoidosis without systemic involvement: response to intralesional corticosteroid. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1996; 62:273-274.

- Karrer S, Abels C, Wimmershoff MB, et al. Successful treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis using topical photodynamic therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2002; 138:581-584.

- Mahnke N, Medve-koenigs K, Berneburg M, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis treated with medium-dose UVA1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004; 50:978-979.

- Frederiksen LG, Jørgensen K. Sarcoidosis of the nose treated with laser surgery. Rhinology. 1996; 34:245-246.

- Baughman RP, Lower EE. Evidence-based therapy for cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007; 25:334-340.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic noncaseating granulomatous disease of unknown etiology. The skin is the second most common location for disease manifestation following the lungs.1 Cutaneous sarcoidosis is present in 35% of patients with sarcoidosis and may be further subtyped by its morphologic characteristics (eg, hyperpigmented, papular, nodular, atrophic, ulcerative, psoriasiform). Cutaneous sarcoidosis has an increased tendency to occur at areas of prior injury such as surgeries or tattoos.2 Although sarcoidosis affects all races and sexes, it is more prevalent in women and in the black population.3

The clinical presentation of sarcoidosis is difficult due to its morphologic variation, allowing for a wide differential diagnosis. With our patient’s presentation of atrophic plaques, the differential diagnosis included granuloma annulare, necrobiosis lipoidica, tumid lupus erythematosus, leprosy, and sarcoidosis; however, biopsy is required for definitive diagnosis. The characteristic histopathology for cutaneous sarcoidosis includes noncaseating granulomas (Figure, A) composed of epithelioid histiocytes with giant cells surrounded by a lymphocytic infiltrate. Noncaseating granulomas are considered specific to sarcoidosis and are present in 71% to 89% of biopsied lesions.4 Interestingly, our patient presented with a rare subtype of atrophic ulcerative cutaneous sarcoidosis, necrobiosis lipoidica–like sarcoidosis, which is more common in females and in the black population. It is characterized by pink to violaceous plaques with depressed centers and prominent necrotizing granuloma (Figure, B) on histopathology. In a small case series, all 3 patients with necrobiosis lipoidica–like sarcoidosis were female and had systemic involvement at the time of diagnosis.5

Sarcoidosis typically is a systemic disease with only a limited number of cases presenting with isolated cutaneous findings. Therefore, patients require a systemic evaluation, which may include a chest radiograph, complete blood cell count, ophthalmologic examinations, thyroid testing, and vitamin D monitoring, as well as an echocardiogram and electrocardiogram.2

Treatment is guided by the severity of disease. For isolated cutaneous lesions, topical or intralesional high-potency steroids have been shown to be effective.6,7 Several studies also have shown phototherapy and laser therapy as well as surgical excision to be beneficial.8-10 Once cutaneous lesions become disfiguring or systemic involvement is found, systemic corticosteroids or other immunomodulatory medications may be warranted.11 Our patient was started on intralesional and topical high-potency steroids, which failed, and she was transitioned to methotrexate and adalimumab. Unfortunately, even with advanced therapies, our patient did not have notableresolution of the lesions.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic noncaseating granulomatous disease of unknown etiology. The skin is the second most common location for disease manifestation following the lungs.1 Cutaneous sarcoidosis is present in 35% of patients with sarcoidosis and may be further subtyped by its morphologic characteristics (eg, hyperpigmented, papular, nodular, atrophic, ulcerative, psoriasiform). Cutaneous sarcoidosis has an increased tendency to occur at areas of prior injury such as surgeries or tattoos.2 Although sarcoidosis affects all races and sexes, it is more prevalent in women and in the black population.3

The clinical presentation of sarcoidosis is difficult due to its morphologic variation, allowing for a wide differential diagnosis. With our patient’s presentation of atrophic plaques, the differential diagnosis included granuloma annulare, necrobiosis lipoidica, tumid lupus erythematosus, leprosy, and sarcoidosis; however, biopsy is required for definitive diagnosis. The characteristic histopathology for cutaneous sarcoidosis includes noncaseating granulomas (Figure, A) composed of epithelioid histiocytes with giant cells surrounded by a lymphocytic infiltrate. Noncaseating granulomas are considered specific to sarcoidosis and are present in 71% to 89% of biopsied lesions.4 Interestingly, our patient presented with a rare subtype of atrophic ulcerative cutaneous sarcoidosis, necrobiosis lipoidica–like sarcoidosis, which is more common in females and in the black population. It is characterized by pink to violaceous plaques with depressed centers and prominent necrotizing granuloma (Figure, B) on histopathology. In a small case series, all 3 patients with necrobiosis lipoidica–like sarcoidosis were female and had systemic involvement at the time of diagnosis.5

Sarcoidosis typically is a systemic disease with only a limited number of cases presenting with isolated cutaneous findings. Therefore, patients require a systemic evaluation, which may include a chest radiograph, complete blood cell count, ophthalmologic examinations, thyroid testing, and vitamin D monitoring, as well as an echocardiogram and electrocardiogram.2

Treatment is guided by the severity of disease. For isolated cutaneous lesions, topical or intralesional high-potency steroids have been shown to be effective.6,7 Several studies also have shown phototherapy and laser therapy as well as surgical excision to be beneficial.8-10 Once cutaneous lesions become disfiguring or systemic involvement is found, systemic corticosteroids or other immunomodulatory medications may be warranted.11 Our patient was started on intralesional and topical high-potency steroids, which failed, and she was transitioned to methotrexate and adalimumab. Unfortunately, even with advanced therapies, our patient did not have notableresolution of the lesions.

- Mañá J, Marcoval J. Skin manifestations of sarcoidosis. Presse Med. 2012;41 (6, pt 2): E355-E374.

- Wanat KA, Rosenbach M. Cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med.2015; 36:685-702.

- Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, et al. Clinical characteristics ofpatients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(10, pt 1):1885-1889.

- Ball NJ, Kho GT, Martinka M. The histologic spectrum of cutaneous sarcoidosis: a study of twenty-eight cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004; 31:160-168.

- Mendoza V, Vahid B, Kozic H, et al. Clinical and pathologic manifestations of necrobiosis lipoidica-like skin involvement in sarcoidosis. Joint Bone Spine. 2007; 74:647-649.

- Khatri KA, Chotzen VA, Burrall BA. Lupus pernio: successful treatment with a potent topical corticosteroid. Arch Dermatol. 1995; 131:617-618.

- Singh SK, Singh S, Pandey SS. Cutaneous sarcoidosis without systemic involvement: response to intralesional corticosteroid. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1996; 62:273-274.

- Karrer S, Abels C, Wimmershoff MB, et al. Successful treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis using topical photodynamic therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2002; 138:581-584.

- Mahnke N, Medve-koenigs K, Berneburg M, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis treated with medium-dose UVA1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004; 50:978-979.

- Frederiksen LG, Jørgensen K. Sarcoidosis of the nose treated with laser surgery. Rhinology. 1996; 34:245-246.

- Baughman RP, Lower EE. Evidence-based therapy for cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007; 25:334-340.

- Mañá J, Marcoval J. Skin manifestations of sarcoidosis. Presse Med. 2012;41 (6, pt 2): E355-E374.

- Wanat KA, Rosenbach M. Cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med.2015; 36:685-702.

- Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, et al. Clinical characteristics ofpatients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(10, pt 1):1885-1889.

- Ball NJ, Kho GT, Martinka M. The histologic spectrum of cutaneous sarcoidosis: a study of twenty-eight cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004; 31:160-168.

- Mendoza V, Vahid B, Kozic H, et al. Clinical and pathologic manifestations of necrobiosis lipoidica-like skin involvement in sarcoidosis. Joint Bone Spine. 2007; 74:647-649.

- Khatri KA, Chotzen VA, Burrall BA. Lupus pernio: successful treatment with a potent topical corticosteroid. Arch Dermatol. 1995; 131:617-618.

- Singh SK, Singh S, Pandey SS. Cutaneous sarcoidosis without systemic involvement: response to intralesional corticosteroid. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1996; 62:273-274.

- Karrer S, Abels C, Wimmershoff MB, et al. Successful treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis using topical photodynamic therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2002; 138:581-584.

- Mahnke N, Medve-koenigs K, Berneburg M, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis treated with medium-dose UVA1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004; 50:978-979.

- Frederiksen LG, Jørgensen K. Sarcoidosis of the nose treated with laser surgery. Rhinology. 1996; 34:245-246.

- Baughman RP, Lower EE. Evidence-based therapy for cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007; 25:334-340.

A 57-year-old woman presented with several lesions on the left extensor forearm of 10 years’ duration. A single annular indurated lesion with central atrophy initially developed near a prior surgical site. The lesions were pruritic with no associated pain or bleeding. Over 5 years, similar lesions had developed extending up the arm. No benefit was seen with low-potency topical steroid application. Biopsy for histopathologic examination was performed to confirm the diagnosis.