User login

Dupilumab for the Treatment of Lichen Planus

To the Editor:

Lichen planus (LP) is an inflammatory mucocutaneous disorder that primarily affects adults aged 30 to 60 years.1 It can present across various regions such as the skin, scalp, oral cavity, genitalia, nails, and hair. It classically presents with pruritic, purple, polygonal papules or plaques. The proposed pathogenesis of this condition involves autoimmune destruction of epidermal basal keratinocytes.2 Management involves a stepwise approach, beginning with topical therapies such as corticosteroids and phototherapy and proceeding to systemic therapy including oral corticosteroids and retinoids. Additional medications with reported positive results include immunomodulators such as cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and mycophenolate mofetil.2-4 Dupilumab is a biologic immunomodulator and antagonist to the IL-4Rα on helper T cells (TH1). Although indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, this medication’s immunomodulatory properties have been shown to aid various inflammatory cutaneous conditions, including prurigo nodularis.5-9 We present a case of dupilumab therapy for treatment-refractory LP.

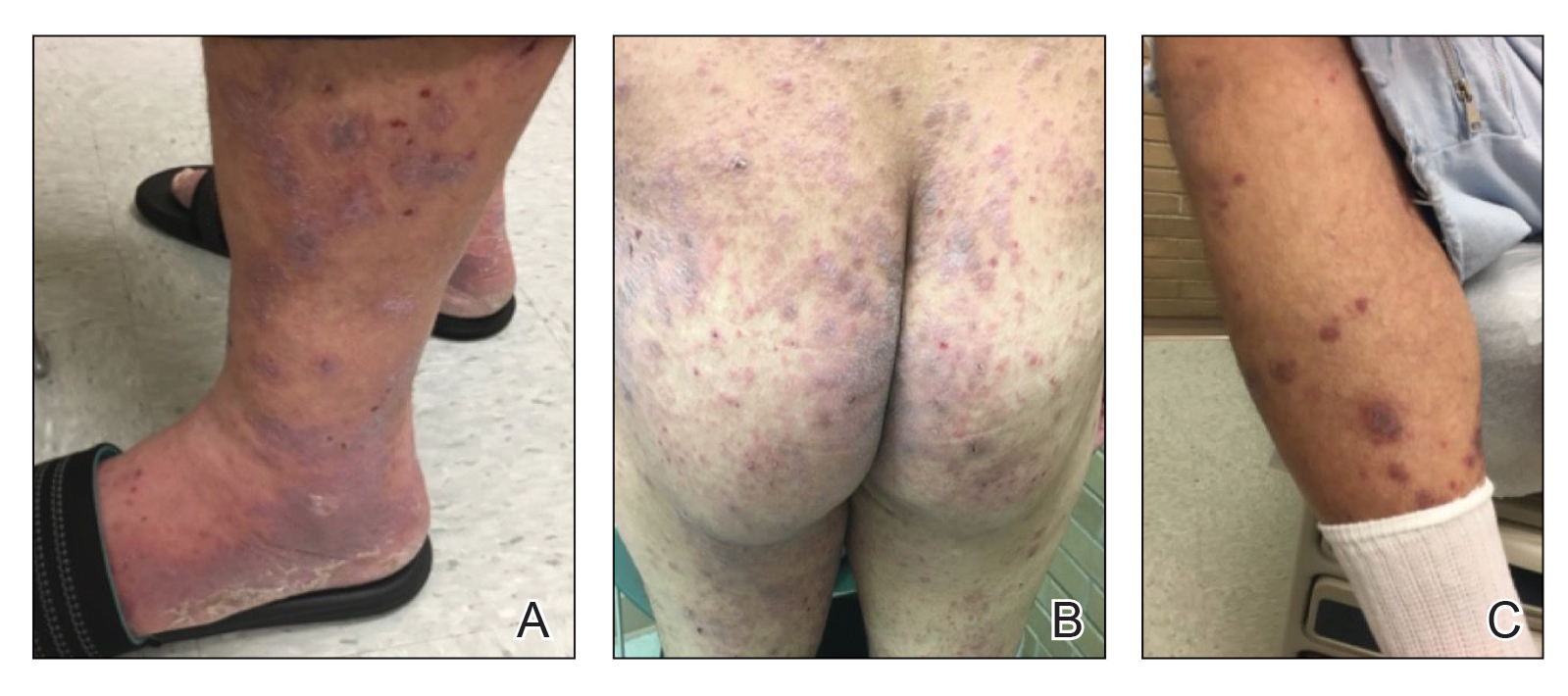

A 52-year-old man presented with a new-onset progressive rash over the prior 6 months. He reported no history of atopic dermatitis. The patient described the rash as “severely pruritic” with a numeric rating scale itch intensity of 9/10 (0 being no itch; 10 being the worst itch imaginable). Physical examination revealed purple polygonal scaly papules on the arms, hands, legs, feet, chest, and back (Figure 1).

Three biopsies were taken, all indicative of lichenoid dermatitis consistent with LP. Rapid plasma reagin as well as HIV and hepatitis C virus serology tests were negative. Halobetasol ointment, tacrolimus ointment, and oral prednisone (28-day taper starting at 40 mg) all failed. Acitretin subsequently was initiated and failed to provide any benefit. The patient was unable to come to clinic 3 times a week for phototherapy due to his work schedule.

Due to the chronic, severe, and recalcitrant nature of his condition, as well as the lack of US Food and Drug Administration–approved treatments, the patient agreed to begin off-label treatment with dupilumab. Upon documentation, the patient’s primary diagnosis was listed as LP, clearly stating all commonly accepted treatments were attempted, except off-label therapy, and failed, and the plan was to treat him with dupilumab as if he had a severe form of atopic dermatitis. Dupilumab was approved with this documentation with a minimal co-pay, as the patient was on Medicaid. At 3-month follow-up (after 4 administrations of the medication), the patient showed remarkable improvement in appearance, and his numeric rating scale itch intensity score improved to 1/10.

Lichen planus is an immune-mediated, inflammatory condition that can affect the skin, hair, nails, and oral cavity. Although its etiology is not fully understood, research supports a primarily TH1 immunologic reaction.10 These T cells promote cytotoxic CD8 T-cell differentiation and migration, leading to subsequent destruction of epidermal basal keratinocytes. An important cytokine in this pathway—tumor necrosis factor α—stimulates a series of proinflammatory factors, including IL-1α, IL-8, and IL-6. IL-6 is of particular interest, as its elevation has been identified in the serum of patients with LP, with levels correlating to disease severity.11 This increase is thought to be multifactorial and a reliable predictor of disease activity.12,13 In addition to its proinflammatory role, IL-6 promotes the activity of IL-4, an essential cytokine in TH2 T-cell differentiation.

The TH2 pathway, enhanced by IL-6, increases the activity of downstream cytokines IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13. This pathway promotes IgE class switching and eosinophil maturation, pivotal factors in the development of atopic conditions such as allergic rhinitis, asthma, and atopic dermatitis. The role of IL-4 and TH2 cells in the pathogenesis of LP remains poorly understood.14 In prior basic laboratory studies, utilizing tissue sampling, RNA extraction, and real-time polymerase chain reaction assays, Yamauchi et al15 proposed that TH2-related chemokines played a pathogenic role in oral LP. Additional reports propose the pathogenic involvement of TH17, TH0, and TH2 T cells.16 These findings suggest that elevated IL-6 in those with LP may stimulate an increase in IL-4 and subsequent TH2 response. Dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets IL-4Rα found on T cells, inhibits both IL-4 and IL-13 signaling, decreasing subsequent effector cell function.17,18 Several case reports have described dupilumab successfully treating various additional dermatoses, including prurigo nodularis, chronic pruritus, and bullous pemphigoid.5-9 Our case demonstrates an example of LP responsive to dupilumab. Our findings suggest that dupilumab interacts with the pathogenic cascade of LP, potentially implicating the role of TH2 in the pathophysiology of LP.

Treatment-refractory LP remains difficult to manage for both the patient and provider. Treatment regimens remain limited to small uncontrolled studies and case reports. Although primarily considered a TH1-mediated disease, the interplay of various alternative signaling pathways has been suggested. Our case of dupilumab-responsive LP suggests an underlying pathologic role of TH2-mediated activity. Dupilumab shows promise as an effective therapy for refractory LP, as evidenced by our patient’s remarkable response. Larger studies are warranted regarding the role of TH2-mediated inflammation and the use of dupilumab in LP.

- Cleach LL, Chosidow O. Clinical practice. lichen planus. N Engl J Med. 2012;266:723-732.

- Lehman, JS, Tollefson MM, Gibson LE. Lichen planus. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:682-694.

- Frieling U, Bonsmann G, Schwarz T, et al. Treatment of severe lichen planus with mycophenolate mofetil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1063-1066.

- Cribier B, Frances C, Chosidow O. Treatment of lichen planus. an evidence-based medicine analysis of efficacy. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1521-1530.

- Calugareanu A, Jachiet C, Lepelletier C, et al. Dramatic improvement of generalized prurigo nodularis with dupilumab. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:E303-E304.

- Kaye A, Gordon SC, Deverapalli SC, et al. Dupilumab for the treatment of recalcitrant bullous pemphigoid. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1225-1226.

- Mollanazar NK, Qiu CC, Aldrich JL, et al. Use of dupilumab in HIV-positive patients: report of four cases. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:1311-1312.

- Zhai LL, Savage KT, Qiu CC, et al. Chronic pruritus responding to dupilumab—a case series. Medicines (Basel). 2019;6:72.

- Mollanazar NK, Elgash M, Weaver L, et al. Reduced itch associated with dupilumab treatment in 4 patients with prurigo nodularis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:121-122.

- Lodi G, Scully C, Carrozzo M, et al. Current controversies in oral lichen planus: report of an international consensus meeting. part 1. viral infections and etiopathogenesis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:40-51.

- Yin M, Li G, Song H, et al. Identifying the association between interleukin-6 and lichen planus: a meta-analysis. Biomed Rep. 2017;6:571-575.

- Sun A, Chia JS, Chang YF, et al. Serum interleukin-6 level is a useful marker in evaluating therapeutic effects of levamisole and Chinese medicinal herbs on patients with oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med. 2002;31:196-203.

- Rhodus NL, Cheng B, Bowles W, et al. Proinflammatory cytokine levels in saliva before and after treatment of (erosive) oral lichen planus with dexamethasone. Oral Dis. 2006;12:112-116.

- Carrozzo M. Understanding the pathobiology of oral lichen planus. Curr Oral Health Rep. 2014;1:173-179.

- Yamauchi M, Moriyama M, Hayashida JN, et al. Myeloid dendritic cells stimulated by thymic stromal lymphopoietin promote Th2 immune responses and the pathogenesis of oral lichen planus. Plos One. 2017:12:e0173017.

- Piccinni M-P, Lombardell L, Logidice F, et al. Potential pathogenetic role of Th17, Th0, and Th2 cells in erosive and reticular oral lichen planus. Oral Dis. 2013:20:212-218.

- Kidd P. Th1/Th2 balance: the hypothesis, its limitations, and implications for health and disease. Altern Med Rev. 2003;8:223-246.

- Noda S, Kruefer JG, Guttum-Yassky E. The translational revolution and use of biologics in patients with inflammatory skin diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:324-336.

To the Editor:

Lichen planus (LP) is an inflammatory mucocutaneous disorder that primarily affects adults aged 30 to 60 years.1 It can present across various regions such as the skin, scalp, oral cavity, genitalia, nails, and hair. It classically presents with pruritic, purple, polygonal papules or plaques. The proposed pathogenesis of this condition involves autoimmune destruction of epidermal basal keratinocytes.2 Management involves a stepwise approach, beginning with topical therapies such as corticosteroids and phototherapy and proceeding to systemic therapy including oral corticosteroids and retinoids. Additional medications with reported positive results include immunomodulators such as cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and mycophenolate mofetil.2-4 Dupilumab is a biologic immunomodulator and antagonist to the IL-4Rα on helper T cells (TH1). Although indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, this medication’s immunomodulatory properties have been shown to aid various inflammatory cutaneous conditions, including prurigo nodularis.5-9 We present a case of dupilumab therapy for treatment-refractory LP.

A 52-year-old man presented with a new-onset progressive rash over the prior 6 months. He reported no history of atopic dermatitis. The patient described the rash as “severely pruritic” with a numeric rating scale itch intensity of 9/10 (0 being no itch; 10 being the worst itch imaginable). Physical examination revealed purple polygonal scaly papules on the arms, hands, legs, feet, chest, and back (Figure 1).

Three biopsies were taken, all indicative of lichenoid dermatitis consistent with LP. Rapid plasma reagin as well as HIV and hepatitis C virus serology tests were negative. Halobetasol ointment, tacrolimus ointment, and oral prednisone (28-day taper starting at 40 mg) all failed. Acitretin subsequently was initiated and failed to provide any benefit. The patient was unable to come to clinic 3 times a week for phototherapy due to his work schedule.

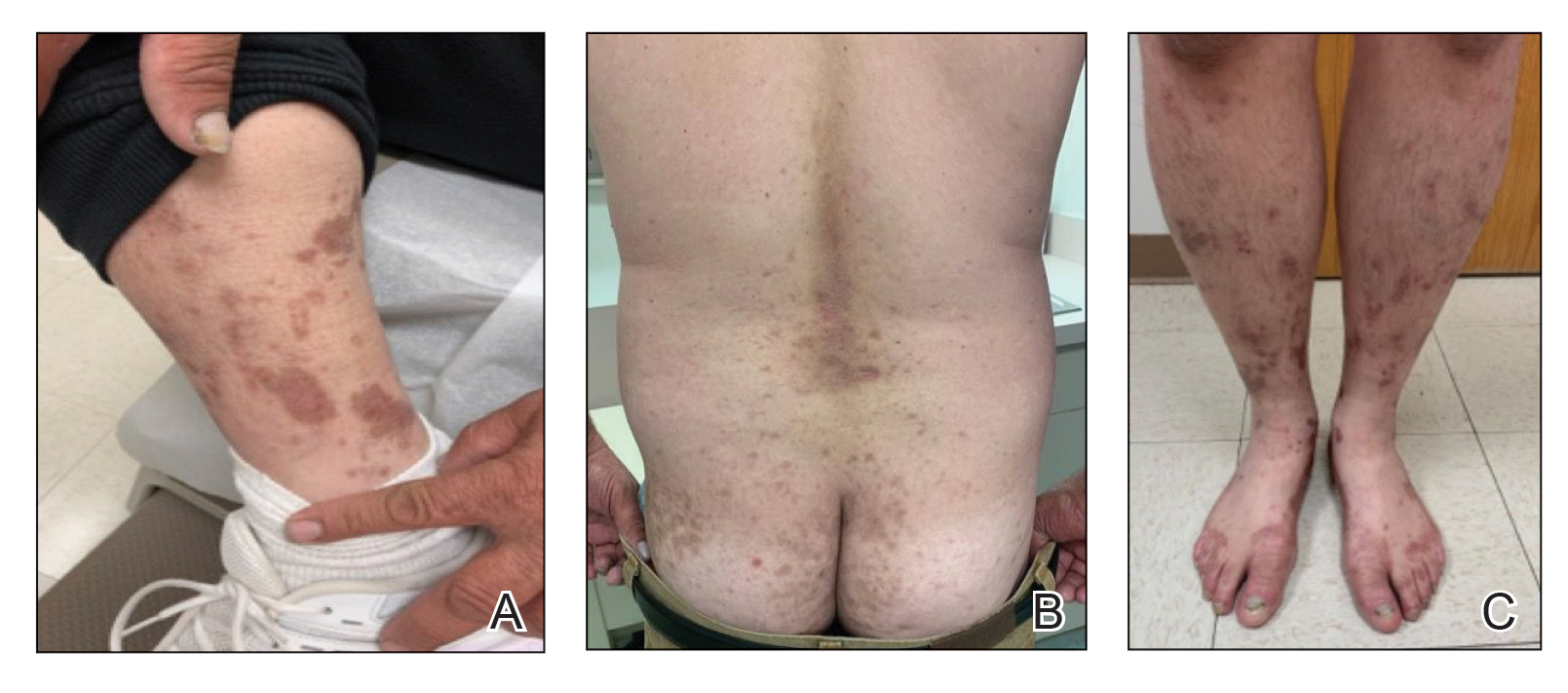

Due to the chronic, severe, and recalcitrant nature of his condition, as well as the lack of US Food and Drug Administration–approved treatments, the patient agreed to begin off-label treatment with dupilumab. Upon documentation, the patient’s primary diagnosis was listed as LP, clearly stating all commonly accepted treatments were attempted, except off-label therapy, and failed, and the plan was to treat him with dupilumab as if he had a severe form of atopic dermatitis. Dupilumab was approved with this documentation with a minimal co-pay, as the patient was on Medicaid. At 3-month follow-up (after 4 administrations of the medication), the patient showed remarkable improvement in appearance, and his numeric rating scale itch intensity score improved to 1/10.

Lichen planus is an immune-mediated, inflammatory condition that can affect the skin, hair, nails, and oral cavity. Although its etiology is not fully understood, research supports a primarily TH1 immunologic reaction.10 These T cells promote cytotoxic CD8 T-cell differentiation and migration, leading to subsequent destruction of epidermal basal keratinocytes. An important cytokine in this pathway—tumor necrosis factor α—stimulates a series of proinflammatory factors, including IL-1α, IL-8, and IL-6. IL-6 is of particular interest, as its elevation has been identified in the serum of patients with LP, with levels correlating to disease severity.11 This increase is thought to be multifactorial and a reliable predictor of disease activity.12,13 In addition to its proinflammatory role, IL-6 promotes the activity of IL-4, an essential cytokine in TH2 T-cell differentiation.

The TH2 pathway, enhanced by IL-6, increases the activity of downstream cytokines IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13. This pathway promotes IgE class switching and eosinophil maturation, pivotal factors in the development of atopic conditions such as allergic rhinitis, asthma, and atopic dermatitis. The role of IL-4 and TH2 cells in the pathogenesis of LP remains poorly understood.14 In prior basic laboratory studies, utilizing tissue sampling, RNA extraction, and real-time polymerase chain reaction assays, Yamauchi et al15 proposed that TH2-related chemokines played a pathogenic role in oral LP. Additional reports propose the pathogenic involvement of TH17, TH0, and TH2 T cells.16 These findings suggest that elevated IL-6 in those with LP may stimulate an increase in IL-4 and subsequent TH2 response. Dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets IL-4Rα found on T cells, inhibits both IL-4 and IL-13 signaling, decreasing subsequent effector cell function.17,18 Several case reports have described dupilumab successfully treating various additional dermatoses, including prurigo nodularis, chronic pruritus, and bullous pemphigoid.5-9 Our case demonstrates an example of LP responsive to dupilumab. Our findings suggest that dupilumab interacts with the pathogenic cascade of LP, potentially implicating the role of TH2 in the pathophysiology of LP.

Treatment-refractory LP remains difficult to manage for both the patient and provider. Treatment regimens remain limited to small uncontrolled studies and case reports. Although primarily considered a TH1-mediated disease, the interplay of various alternative signaling pathways has been suggested. Our case of dupilumab-responsive LP suggests an underlying pathologic role of TH2-mediated activity. Dupilumab shows promise as an effective therapy for refractory LP, as evidenced by our patient’s remarkable response. Larger studies are warranted regarding the role of TH2-mediated inflammation and the use of dupilumab in LP.

To the Editor:

Lichen planus (LP) is an inflammatory mucocutaneous disorder that primarily affects adults aged 30 to 60 years.1 It can present across various regions such as the skin, scalp, oral cavity, genitalia, nails, and hair. It classically presents with pruritic, purple, polygonal papules or plaques. The proposed pathogenesis of this condition involves autoimmune destruction of epidermal basal keratinocytes.2 Management involves a stepwise approach, beginning with topical therapies such as corticosteroids and phototherapy and proceeding to systemic therapy including oral corticosteroids and retinoids. Additional medications with reported positive results include immunomodulators such as cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and mycophenolate mofetil.2-4 Dupilumab is a biologic immunomodulator and antagonist to the IL-4Rα on helper T cells (TH1). Although indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, this medication’s immunomodulatory properties have been shown to aid various inflammatory cutaneous conditions, including prurigo nodularis.5-9 We present a case of dupilumab therapy for treatment-refractory LP.

A 52-year-old man presented with a new-onset progressive rash over the prior 6 months. He reported no history of atopic dermatitis. The patient described the rash as “severely pruritic” with a numeric rating scale itch intensity of 9/10 (0 being no itch; 10 being the worst itch imaginable). Physical examination revealed purple polygonal scaly papules on the arms, hands, legs, feet, chest, and back (Figure 1).

Three biopsies were taken, all indicative of lichenoid dermatitis consistent with LP. Rapid plasma reagin as well as HIV and hepatitis C virus serology tests were negative. Halobetasol ointment, tacrolimus ointment, and oral prednisone (28-day taper starting at 40 mg) all failed. Acitretin subsequently was initiated and failed to provide any benefit. The patient was unable to come to clinic 3 times a week for phototherapy due to his work schedule.

Due to the chronic, severe, and recalcitrant nature of his condition, as well as the lack of US Food and Drug Administration–approved treatments, the patient agreed to begin off-label treatment with dupilumab. Upon documentation, the patient’s primary diagnosis was listed as LP, clearly stating all commonly accepted treatments were attempted, except off-label therapy, and failed, and the plan was to treat him with dupilumab as if he had a severe form of atopic dermatitis. Dupilumab was approved with this documentation with a minimal co-pay, as the patient was on Medicaid. At 3-month follow-up (after 4 administrations of the medication), the patient showed remarkable improvement in appearance, and his numeric rating scale itch intensity score improved to 1/10.

Lichen planus is an immune-mediated, inflammatory condition that can affect the skin, hair, nails, and oral cavity. Although its etiology is not fully understood, research supports a primarily TH1 immunologic reaction.10 These T cells promote cytotoxic CD8 T-cell differentiation and migration, leading to subsequent destruction of epidermal basal keratinocytes. An important cytokine in this pathway—tumor necrosis factor α—stimulates a series of proinflammatory factors, including IL-1α, IL-8, and IL-6. IL-6 is of particular interest, as its elevation has been identified in the serum of patients with LP, with levels correlating to disease severity.11 This increase is thought to be multifactorial and a reliable predictor of disease activity.12,13 In addition to its proinflammatory role, IL-6 promotes the activity of IL-4, an essential cytokine in TH2 T-cell differentiation.

The TH2 pathway, enhanced by IL-6, increases the activity of downstream cytokines IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13. This pathway promotes IgE class switching and eosinophil maturation, pivotal factors in the development of atopic conditions such as allergic rhinitis, asthma, and atopic dermatitis. The role of IL-4 and TH2 cells in the pathogenesis of LP remains poorly understood.14 In prior basic laboratory studies, utilizing tissue sampling, RNA extraction, and real-time polymerase chain reaction assays, Yamauchi et al15 proposed that TH2-related chemokines played a pathogenic role in oral LP. Additional reports propose the pathogenic involvement of TH17, TH0, and TH2 T cells.16 These findings suggest that elevated IL-6 in those with LP may stimulate an increase in IL-4 and subsequent TH2 response. Dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets IL-4Rα found on T cells, inhibits both IL-4 and IL-13 signaling, decreasing subsequent effector cell function.17,18 Several case reports have described dupilumab successfully treating various additional dermatoses, including prurigo nodularis, chronic pruritus, and bullous pemphigoid.5-9 Our case demonstrates an example of LP responsive to dupilumab. Our findings suggest that dupilumab interacts with the pathogenic cascade of LP, potentially implicating the role of TH2 in the pathophysiology of LP.

Treatment-refractory LP remains difficult to manage for both the patient and provider. Treatment regimens remain limited to small uncontrolled studies and case reports. Although primarily considered a TH1-mediated disease, the interplay of various alternative signaling pathways has been suggested. Our case of dupilumab-responsive LP suggests an underlying pathologic role of TH2-mediated activity. Dupilumab shows promise as an effective therapy for refractory LP, as evidenced by our patient’s remarkable response. Larger studies are warranted regarding the role of TH2-mediated inflammation and the use of dupilumab in LP.

- Cleach LL, Chosidow O. Clinical practice. lichen planus. N Engl J Med. 2012;266:723-732.

- Lehman, JS, Tollefson MM, Gibson LE. Lichen planus. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:682-694.

- Frieling U, Bonsmann G, Schwarz T, et al. Treatment of severe lichen planus with mycophenolate mofetil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1063-1066.

- Cribier B, Frances C, Chosidow O. Treatment of lichen planus. an evidence-based medicine analysis of efficacy. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1521-1530.

- Calugareanu A, Jachiet C, Lepelletier C, et al. Dramatic improvement of generalized prurigo nodularis with dupilumab. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:E303-E304.

- Kaye A, Gordon SC, Deverapalli SC, et al. Dupilumab for the treatment of recalcitrant bullous pemphigoid. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1225-1226.

- Mollanazar NK, Qiu CC, Aldrich JL, et al. Use of dupilumab in HIV-positive patients: report of four cases. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:1311-1312.

- Zhai LL, Savage KT, Qiu CC, et al. Chronic pruritus responding to dupilumab—a case series. Medicines (Basel). 2019;6:72.

- Mollanazar NK, Elgash M, Weaver L, et al. Reduced itch associated with dupilumab treatment in 4 patients with prurigo nodularis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:121-122.

- Lodi G, Scully C, Carrozzo M, et al. Current controversies in oral lichen planus: report of an international consensus meeting. part 1. viral infections and etiopathogenesis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:40-51.

- Yin M, Li G, Song H, et al. Identifying the association between interleukin-6 and lichen planus: a meta-analysis. Biomed Rep. 2017;6:571-575.

- Sun A, Chia JS, Chang YF, et al. Serum interleukin-6 level is a useful marker in evaluating therapeutic effects of levamisole and Chinese medicinal herbs on patients with oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med. 2002;31:196-203.

- Rhodus NL, Cheng B, Bowles W, et al. Proinflammatory cytokine levels in saliva before and after treatment of (erosive) oral lichen planus with dexamethasone. Oral Dis. 2006;12:112-116.

- Carrozzo M. Understanding the pathobiology of oral lichen planus. Curr Oral Health Rep. 2014;1:173-179.

- Yamauchi M, Moriyama M, Hayashida JN, et al. Myeloid dendritic cells stimulated by thymic stromal lymphopoietin promote Th2 immune responses and the pathogenesis of oral lichen planus. Plos One. 2017:12:e0173017.

- Piccinni M-P, Lombardell L, Logidice F, et al. Potential pathogenetic role of Th17, Th0, and Th2 cells in erosive and reticular oral lichen planus. Oral Dis. 2013:20:212-218.

- Kidd P. Th1/Th2 balance: the hypothesis, its limitations, and implications for health and disease. Altern Med Rev. 2003;8:223-246.

- Noda S, Kruefer JG, Guttum-Yassky E. The translational revolution and use of biologics in patients with inflammatory skin diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:324-336.

- Cleach LL, Chosidow O. Clinical practice. lichen planus. N Engl J Med. 2012;266:723-732.

- Lehman, JS, Tollefson MM, Gibson LE. Lichen planus. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:682-694.

- Frieling U, Bonsmann G, Schwarz T, et al. Treatment of severe lichen planus with mycophenolate mofetil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1063-1066.

- Cribier B, Frances C, Chosidow O. Treatment of lichen planus. an evidence-based medicine analysis of efficacy. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1521-1530.

- Calugareanu A, Jachiet C, Lepelletier C, et al. Dramatic improvement of generalized prurigo nodularis with dupilumab. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:E303-E304.

- Kaye A, Gordon SC, Deverapalli SC, et al. Dupilumab for the treatment of recalcitrant bullous pemphigoid. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1225-1226.

- Mollanazar NK, Qiu CC, Aldrich JL, et al. Use of dupilumab in HIV-positive patients: report of four cases. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:1311-1312.

- Zhai LL, Savage KT, Qiu CC, et al. Chronic pruritus responding to dupilumab—a case series. Medicines (Basel). 2019;6:72.

- Mollanazar NK, Elgash M, Weaver L, et al. Reduced itch associated with dupilumab treatment in 4 patients with prurigo nodularis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:121-122.

- Lodi G, Scully C, Carrozzo M, et al. Current controversies in oral lichen planus: report of an international consensus meeting. part 1. viral infections and etiopathogenesis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:40-51.

- Yin M, Li G, Song H, et al. Identifying the association between interleukin-6 and lichen planus: a meta-analysis. Biomed Rep. 2017;6:571-575.

- Sun A, Chia JS, Chang YF, et al. Serum interleukin-6 level is a useful marker in evaluating therapeutic effects of levamisole and Chinese medicinal herbs on patients with oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med. 2002;31:196-203.

- Rhodus NL, Cheng B, Bowles W, et al. Proinflammatory cytokine levels in saliva before and after treatment of (erosive) oral lichen planus with dexamethasone. Oral Dis. 2006;12:112-116.

- Carrozzo M. Understanding the pathobiology of oral lichen planus. Curr Oral Health Rep. 2014;1:173-179.

- Yamauchi M, Moriyama M, Hayashida JN, et al. Myeloid dendritic cells stimulated by thymic stromal lymphopoietin promote Th2 immune responses and the pathogenesis of oral lichen planus. Plos One. 2017:12:e0173017.

- Piccinni M-P, Lombardell L, Logidice F, et al. Potential pathogenetic role of Th17, Th0, and Th2 cells in erosive and reticular oral lichen planus. Oral Dis. 2013:20:212-218.

- Kidd P. Th1/Th2 balance: the hypothesis, its limitations, and implications for health and disease. Altern Med Rev. 2003;8:223-246.

- Noda S, Kruefer JG, Guttum-Yassky E. The translational revolution and use of biologics in patients with inflammatory skin diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:324-336.

Practice Points

- Lichen planus (LP) is an inflammatory mucocutaneous disorder that can present across various regions of the body with pruritic, purple, polygonal papules or plaques.

- The proposed pathogenesis of LP involves autoimmune destruction of epidermal basal keratinocytes.

- The immunomodulatory properties of dupilumab have been shown to aid various inflammatory cutaneous conditions.

Cutaneous T-cell Lymphoma and Concomitant Atopic Dermatitis Responding to Dupilumab

Patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) often are diagnosed with atopic dermatitis (AD) or psoriasis before receiving their CTCL diagnosis. The effects of new biologic therapies for AD such as dupilumab, an IL-4/IL-13 antagonist, on CTCL are unknown. Dupilumab may be beneficial in CTCL given that helper T cell (TH2) cytokines are increased in advanced CTCL.1 We present a patient with definitive CTCL and concomitant AD who was safely treated with dupilumab and experienced improvement in both CTCL and AD.

Case Report

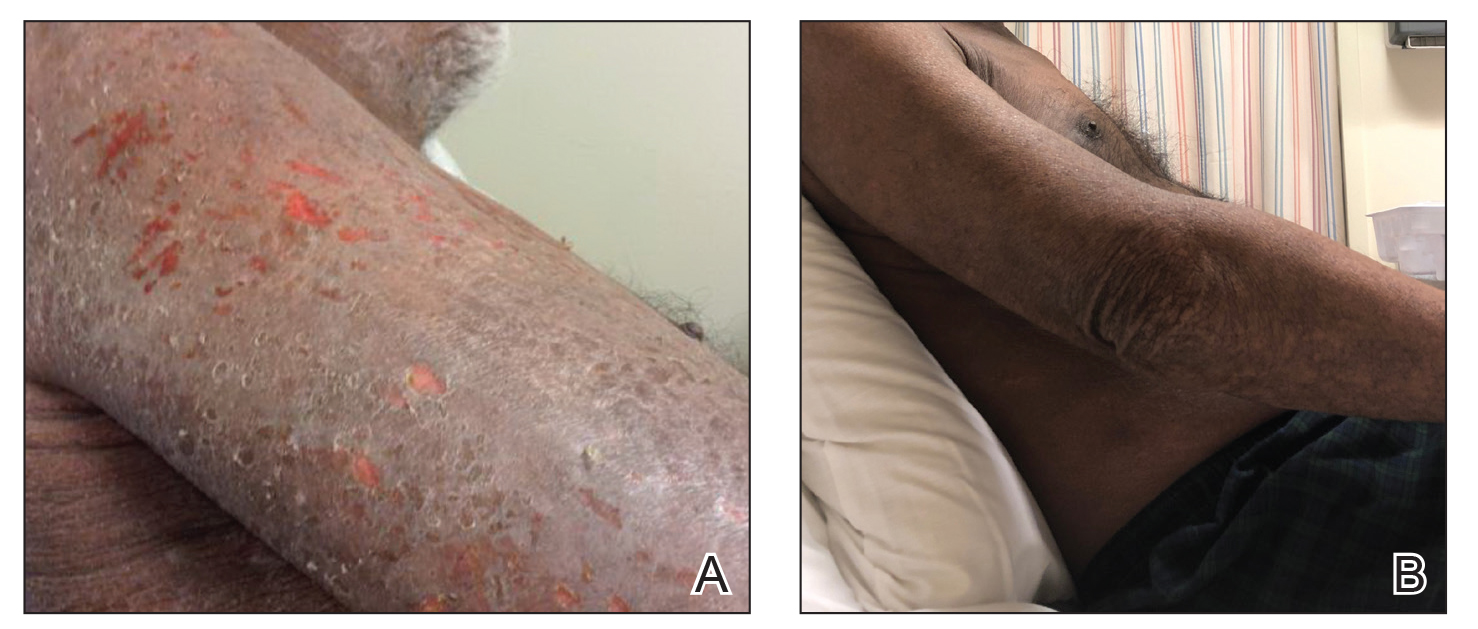

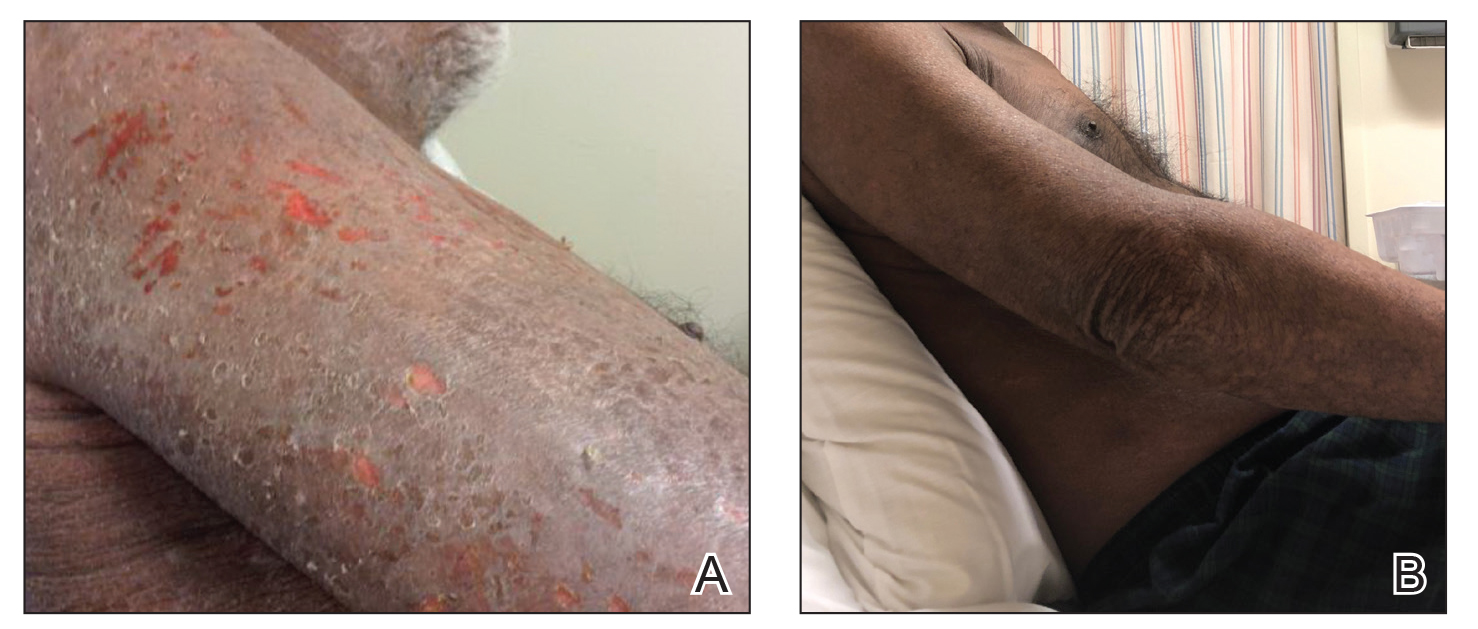

A 68-year-old man presented with increased itching from AD and a new rash on the arms, neck, chest, back, and lower extremities (Figures 1A and 2A). He had a medical history of AD and CTCL diagnosed by biopsy and peripheral blood flow cytometry (stage IVA1 [T4N0M0B2]) that was being treated with comprehensive multimodality therapy consisting of bexarotene 375 mg daily, interferon alfa-2b 3 mIU 3 times weekly, interferon gamma-1b 2 mIU 3 times weekly, total skin electron beam therapy followed by narrowband UVB twice weekly, and extracorporeal photopheresis every 4 weeks, which resulted in a partial clinical response for 6 months. A biopsy performed at the current presentation showed focal spongiosis and features of lichen simplex chronicus with no evidence suggestive of CTCL. Peripheral blood flow cytometry showed stable B1-staged disease burden (CD4/CD8, 2.6:1); CD4+/CD7−, 12% [91/µL]; CD4+/CD26−, 21% [155/µL]). Treatment with potent and superpotent topical steroids was attempted for more than 6 months and was unsuccessful in relieving the symptoms.

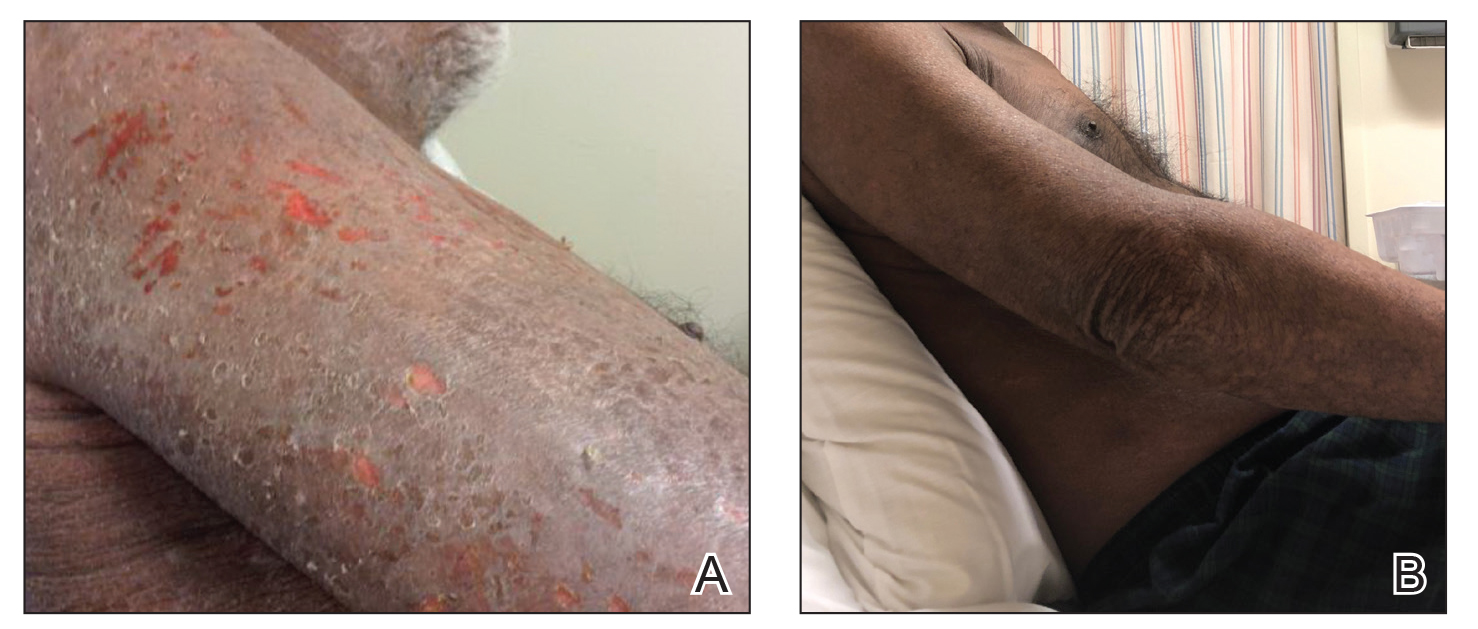

Given the recalcitrant nature of the patient’s rash and itching, dupilumab was added to his CTCL regimen. Prior to initiating dupilumab, the patient reported a numeric rating scale itch intensity of 7 out of 10. After 4 weeks of treatment with dupilumab, the patient reported a numeric rating scale itch intensity of 1. Over a 3-month period, the patient’s rash improved dramatically (Figures 1B and 2B), making it possible to decrease CTCL treatments—bexarotene decreased to 300 mg, interferon alfa-2b to 3 mIU twice weekly, interferon gamma-1b to 2 mIU twice weekly, extracorporeal photopheresis every 5 weeks, and narrowband UVB was discontinued completely. A comparison of the patient’s flow cytometry analysis from before treatment to 3 months after dupilumab showed an overall slight reduction in CTCL B1 blood involvement and normalization of the patient’s absolute eosinophil count and serum lactate dehydrogenase level. The patient tolerated the treatment well without any adverse events and has maintained clinical response for 6 months.

Comment

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas represent a heterogeneous group of T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders involving the skin.2 The definitive diagnosis of CTCL is challenging, as the clinical and pathologic features often are nonspecific in early disease. Frequently, undiagnosed patients are treated empirically with immunosuppressive agents. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and cyclosporine are both associated with progression or worsening of undiagnosed CTCL.3,4 Dupilumab was the first US Food and Drug Administration–approved biologic for the treatment of moderate to severe AD. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma has immunologic features, such as TH2 skewing, that overlap with AD; however, the effects of dupilumab in CTCL are not yet known.5,6 Our group has seen patients initially thought to have AD who received dupilumab without improvement and were subsequently diagnosed with CTCL, suggesting dupilumab did not affect CTCL tumor cells. Given these findings, there was concern that dupilumab might exacerbate undiagnosed CTCL. Our patient with definitive, severe, refractory CTCL noted marked improvement in both AD and underlying CTCL with the addition of dupilumab. No other treatments were added. The response was so dramatic that we were able to wean the doses and frequencies of several CTCL treatments. Our findings suggest that dupilumab may be beneficial in a certain subset of CTCL patients with a history of AD or known concomitant AD. Prospective studies are needed to fully investigate dupilumab safety and efficacy in CTCL and whether it has any primary effects on tumor burden in addition to benefit for itch and skin symptom relief.

- Guenova E, Watanabe R, Teague JE, et al. TH2 cytokines from malignant cells suppress TH1 responses and enforce a global TH2 bias in leukemic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:3755-3763.

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:151-165.

- Martinez-Escala ME, Posligua AL, Wickless H, et al. Progression of undiagnosed cutaneous lymphoma after anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1068-1076.

- Pielop JA, Jones D, Duvic M. Transient CD30+ nodal transformation of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma associated with cyclosporine treatment. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:505-511.

- Saulite I, Hoetzenecker W, Weidinger S, et al. Sézary syndrome and atopic dermatitis: comparison of immunological aspects and targets [published online May 17, 2016]. BioMed Res Int. doi:10.1155/2016/9717530.

- Sigurdsson V, Toonstra J, Bihari IC, et al. Interleukin 4 and interferon-gamma expression of the dermal infiltrate in patients with erythroderma and mycosis fungoides. an immuno-histochemical study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:429-435.

Patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) often are diagnosed with atopic dermatitis (AD) or psoriasis before receiving their CTCL diagnosis. The effects of new biologic therapies for AD such as dupilumab, an IL-4/IL-13 antagonist, on CTCL are unknown. Dupilumab may be beneficial in CTCL given that helper T cell (TH2) cytokines are increased in advanced CTCL.1 We present a patient with definitive CTCL and concomitant AD who was safely treated with dupilumab and experienced improvement in both CTCL and AD.

Case Report

A 68-year-old man presented with increased itching from AD and a new rash on the arms, neck, chest, back, and lower extremities (Figures 1A and 2A). He had a medical history of AD and CTCL diagnosed by biopsy and peripheral blood flow cytometry (stage IVA1 [T4N0M0B2]) that was being treated with comprehensive multimodality therapy consisting of bexarotene 375 mg daily, interferon alfa-2b 3 mIU 3 times weekly, interferon gamma-1b 2 mIU 3 times weekly, total skin electron beam therapy followed by narrowband UVB twice weekly, and extracorporeal photopheresis every 4 weeks, which resulted in a partial clinical response for 6 months. A biopsy performed at the current presentation showed focal spongiosis and features of lichen simplex chronicus with no evidence suggestive of CTCL. Peripheral blood flow cytometry showed stable B1-staged disease burden (CD4/CD8, 2.6:1); CD4+/CD7−, 12% [91/µL]; CD4+/CD26−, 21% [155/µL]). Treatment with potent and superpotent topical steroids was attempted for more than 6 months and was unsuccessful in relieving the symptoms.

Given the recalcitrant nature of the patient’s rash and itching, dupilumab was added to his CTCL regimen. Prior to initiating dupilumab, the patient reported a numeric rating scale itch intensity of 7 out of 10. After 4 weeks of treatment with dupilumab, the patient reported a numeric rating scale itch intensity of 1. Over a 3-month period, the patient’s rash improved dramatically (Figures 1B and 2B), making it possible to decrease CTCL treatments—bexarotene decreased to 300 mg, interferon alfa-2b to 3 mIU twice weekly, interferon gamma-1b to 2 mIU twice weekly, extracorporeal photopheresis every 5 weeks, and narrowband UVB was discontinued completely. A comparison of the patient’s flow cytometry analysis from before treatment to 3 months after dupilumab showed an overall slight reduction in CTCL B1 blood involvement and normalization of the patient’s absolute eosinophil count and serum lactate dehydrogenase level. The patient tolerated the treatment well without any adverse events and has maintained clinical response for 6 months.

Comment

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas represent a heterogeneous group of T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders involving the skin.2 The definitive diagnosis of CTCL is challenging, as the clinical and pathologic features often are nonspecific in early disease. Frequently, undiagnosed patients are treated empirically with immunosuppressive agents. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and cyclosporine are both associated with progression or worsening of undiagnosed CTCL.3,4 Dupilumab was the first US Food and Drug Administration–approved biologic for the treatment of moderate to severe AD. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma has immunologic features, such as TH2 skewing, that overlap with AD; however, the effects of dupilumab in CTCL are not yet known.5,6 Our group has seen patients initially thought to have AD who received dupilumab without improvement and were subsequently diagnosed with CTCL, suggesting dupilumab did not affect CTCL tumor cells. Given these findings, there was concern that dupilumab might exacerbate undiagnosed CTCL. Our patient with definitive, severe, refractory CTCL noted marked improvement in both AD and underlying CTCL with the addition of dupilumab. No other treatments were added. The response was so dramatic that we were able to wean the doses and frequencies of several CTCL treatments. Our findings suggest that dupilumab may be beneficial in a certain subset of CTCL patients with a history of AD or known concomitant AD. Prospective studies are needed to fully investigate dupilumab safety and efficacy in CTCL and whether it has any primary effects on tumor burden in addition to benefit for itch and skin symptom relief.

Patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) often are diagnosed with atopic dermatitis (AD) or psoriasis before receiving their CTCL diagnosis. The effects of new biologic therapies for AD such as dupilumab, an IL-4/IL-13 antagonist, on CTCL are unknown. Dupilumab may be beneficial in CTCL given that helper T cell (TH2) cytokines are increased in advanced CTCL.1 We present a patient with definitive CTCL and concomitant AD who was safely treated with dupilumab and experienced improvement in both CTCL and AD.

Case Report

A 68-year-old man presented with increased itching from AD and a new rash on the arms, neck, chest, back, and lower extremities (Figures 1A and 2A). He had a medical history of AD and CTCL diagnosed by biopsy and peripheral blood flow cytometry (stage IVA1 [T4N0M0B2]) that was being treated with comprehensive multimodality therapy consisting of bexarotene 375 mg daily, interferon alfa-2b 3 mIU 3 times weekly, interferon gamma-1b 2 mIU 3 times weekly, total skin electron beam therapy followed by narrowband UVB twice weekly, and extracorporeal photopheresis every 4 weeks, which resulted in a partial clinical response for 6 months. A biopsy performed at the current presentation showed focal spongiosis and features of lichen simplex chronicus with no evidence suggestive of CTCL. Peripheral blood flow cytometry showed stable B1-staged disease burden (CD4/CD8, 2.6:1); CD4+/CD7−, 12% [91/µL]; CD4+/CD26−, 21% [155/µL]). Treatment with potent and superpotent topical steroids was attempted for more than 6 months and was unsuccessful in relieving the symptoms.

Given the recalcitrant nature of the patient’s rash and itching, dupilumab was added to his CTCL regimen. Prior to initiating dupilumab, the patient reported a numeric rating scale itch intensity of 7 out of 10. After 4 weeks of treatment with dupilumab, the patient reported a numeric rating scale itch intensity of 1. Over a 3-month period, the patient’s rash improved dramatically (Figures 1B and 2B), making it possible to decrease CTCL treatments—bexarotene decreased to 300 mg, interferon alfa-2b to 3 mIU twice weekly, interferon gamma-1b to 2 mIU twice weekly, extracorporeal photopheresis every 5 weeks, and narrowband UVB was discontinued completely. A comparison of the patient’s flow cytometry analysis from before treatment to 3 months after dupilumab showed an overall slight reduction in CTCL B1 blood involvement and normalization of the patient’s absolute eosinophil count and serum lactate dehydrogenase level. The patient tolerated the treatment well without any adverse events and has maintained clinical response for 6 months.

Comment

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas represent a heterogeneous group of T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders involving the skin.2 The definitive diagnosis of CTCL is challenging, as the clinical and pathologic features often are nonspecific in early disease. Frequently, undiagnosed patients are treated empirically with immunosuppressive agents. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and cyclosporine are both associated with progression or worsening of undiagnosed CTCL.3,4 Dupilumab was the first US Food and Drug Administration–approved biologic for the treatment of moderate to severe AD. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma has immunologic features, such as TH2 skewing, that overlap with AD; however, the effects of dupilumab in CTCL are not yet known.5,6 Our group has seen patients initially thought to have AD who received dupilumab without improvement and were subsequently diagnosed with CTCL, suggesting dupilumab did not affect CTCL tumor cells. Given these findings, there was concern that dupilumab might exacerbate undiagnosed CTCL. Our patient with definitive, severe, refractory CTCL noted marked improvement in both AD and underlying CTCL with the addition of dupilumab. No other treatments were added. The response was so dramatic that we were able to wean the doses and frequencies of several CTCL treatments. Our findings suggest that dupilumab may be beneficial in a certain subset of CTCL patients with a history of AD or known concomitant AD. Prospective studies are needed to fully investigate dupilumab safety and efficacy in CTCL and whether it has any primary effects on tumor burden in addition to benefit for itch and skin symptom relief.

- Guenova E, Watanabe R, Teague JE, et al. TH2 cytokines from malignant cells suppress TH1 responses and enforce a global TH2 bias in leukemic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:3755-3763.

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:151-165.

- Martinez-Escala ME, Posligua AL, Wickless H, et al. Progression of undiagnosed cutaneous lymphoma after anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1068-1076.

- Pielop JA, Jones D, Duvic M. Transient CD30+ nodal transformation of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma associated with cyclosporine treatment. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:505-511.

- Saulite I, Hoetzenecker W, Weidinger S, et al. Sézary syndrome and atopic dermatitis: comparison of immunological aspects and targets [published online May 17, 2016]. BioMed Res Int. doi:10.1155/2016/9717530.

- Sigurdsson V, Toonstra J, Bihari IC, et al. Interleukin 4 and interferon-gamma expression of the dermal infiltrate in patients with erythroderma and mycosis fungoides. an immuno-histochemical study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:429-435.

- Guenova E, Watanabe R, Teague JE, et al. TH2 cytokines from malignant cells suppress TH1 responses and enforce a global TH2 bias in leukemic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:3755-3763.

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:151-165.

- Martinez-Escala ME, Posligua AL, Wickless H, et al. Progression of undiagnosed cutaneous lymphoma after anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1068-1076.

- Pielop JA, Jones D, Duvic M. Transient CD30+ nodal transformation of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma associated with cyclosporine treatment. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:505-511.

- Saulite I, Hoetzenecker W, Weidinger S, et al. Sézary syndrome and atopic dermatitis: comparison of immunological aspects and targets [published online May 17, 2016]. BioMed Res Int. doi:10.1155/2016/9717530.

- Sigurdsson V, Toonstra J, Bihari IC, et al. Interleukin 4 and interferon-gamma expression of the dermal infiltrate in patients with erythroderma and mycosis fungoides. an immuno-histochemical study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:429-435.

Practice Points

- The diagnosis of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), particularly early-stage disease, remains challenging and often requires a combination of serial clinical evaluations as well as laboratory diagnostic examinations.

- Dupilumab and its effect on helper T cell (TH2) skewing may play a role in the future management of CTCL.