User login

Cutaneous T-cell Lymphoma and Concomitant Atopic Dermatitis Responding to Dupilumab

Patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) often are diagnosed with atopic dermatitis (AD) or psoriasis before receiving their CTCL diagnosis. The effects of new biologic therapies for AD such as dupilumab, an IL-4/IL-13 antagonist, on CTCL are unknown. Dupilumab may be beneficial in CTCL given that helper T cell (TH2) cytokines are increased in advanced CTCL.1 We present a patient with definitive CTCL and concomitant AD who was safely treated with dupilumab and experienced improvement in both CTCL and AD.

Case Report

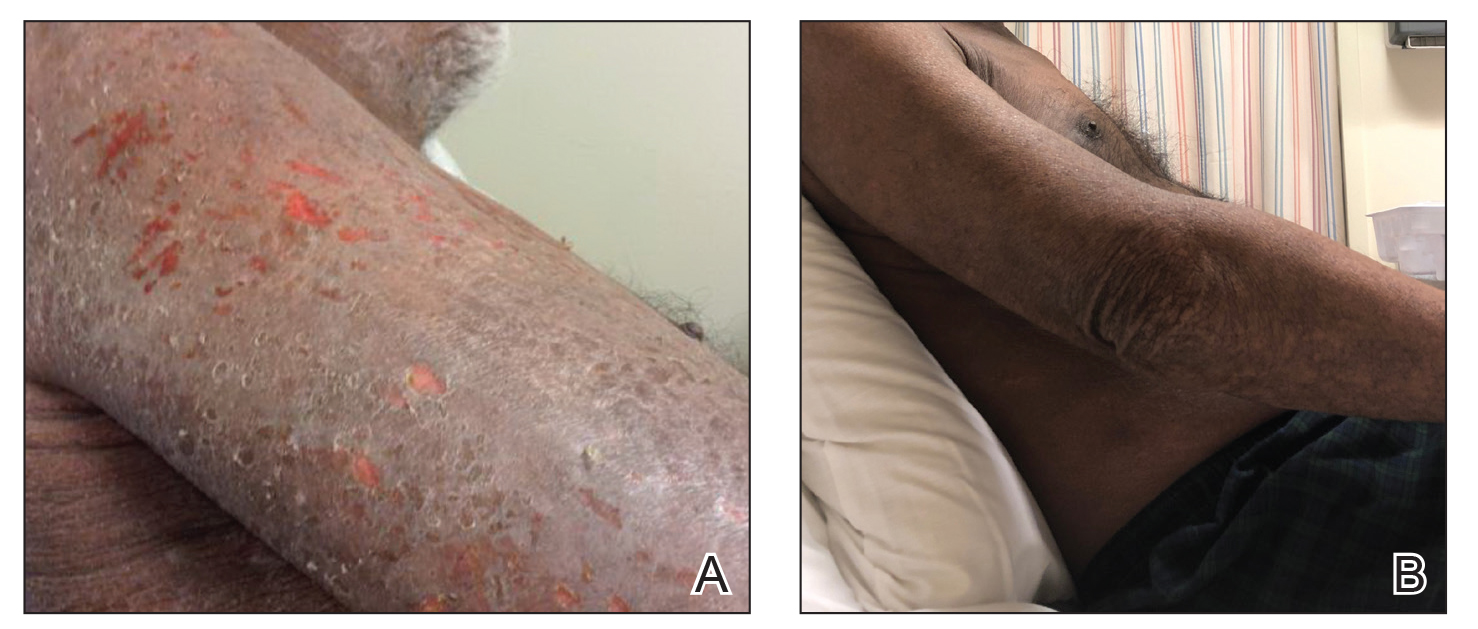

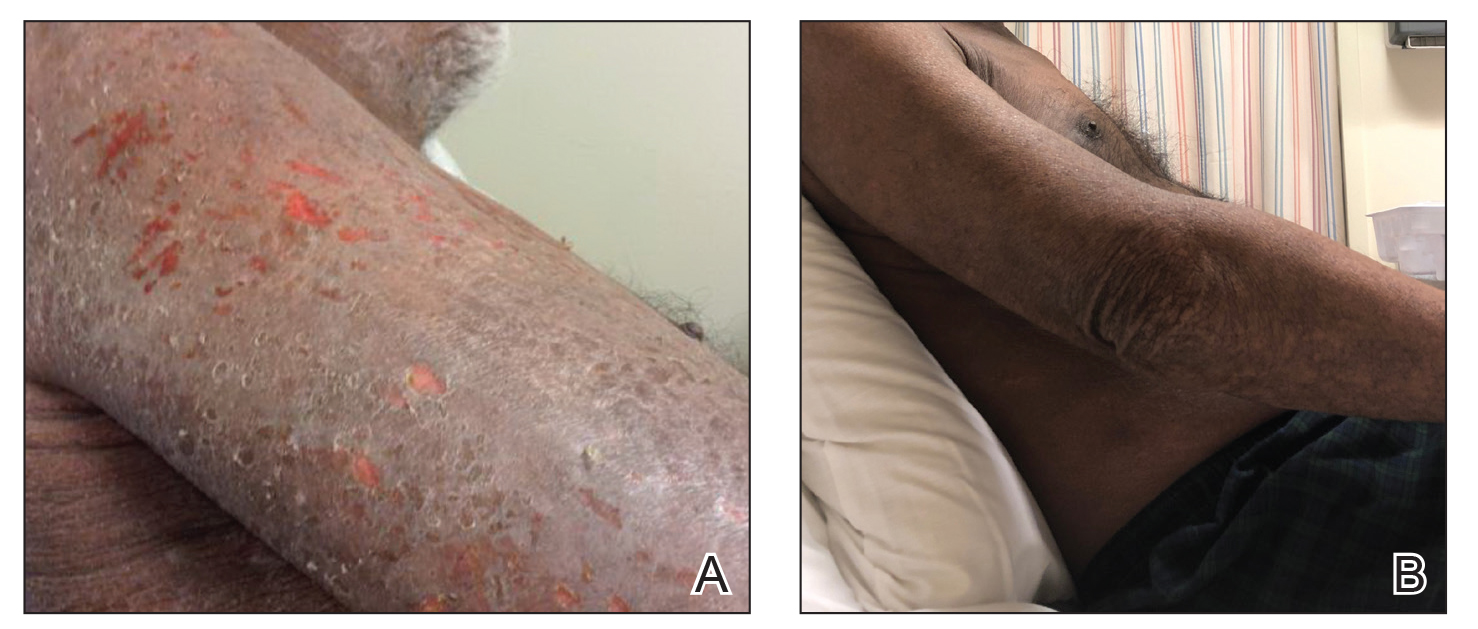

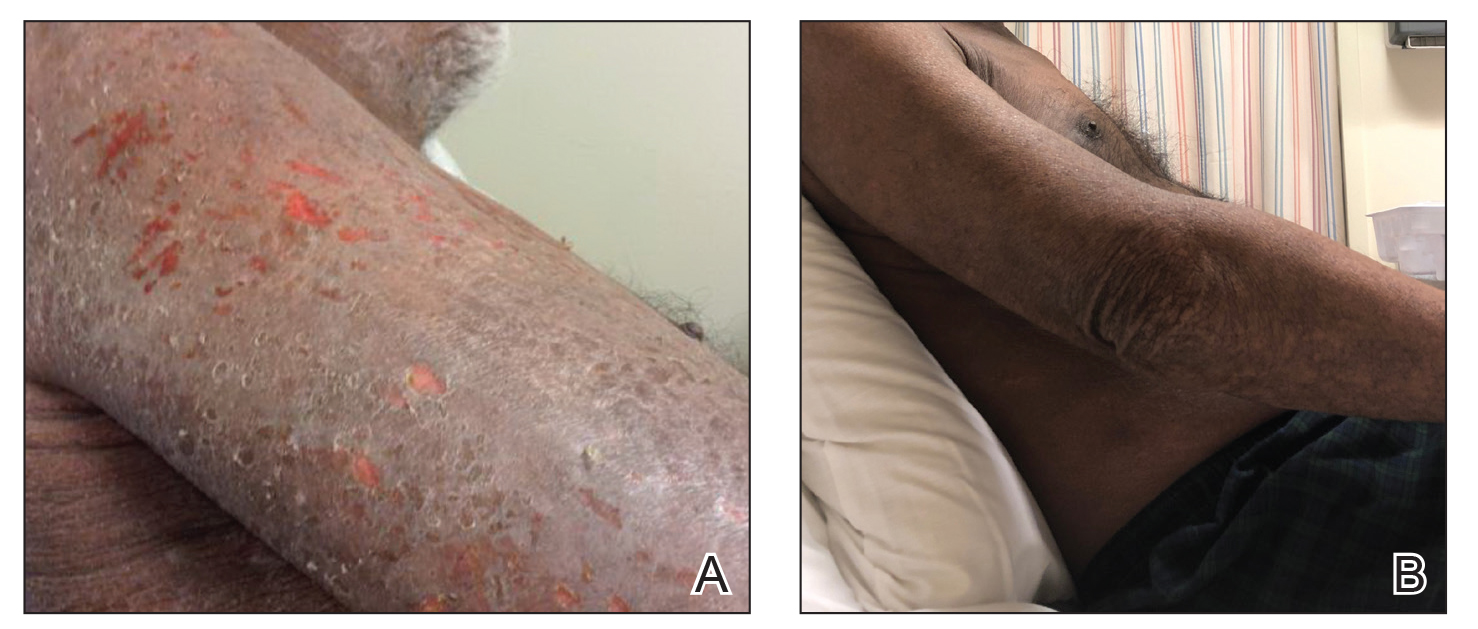

A 68-year-old man presented with increased itching from AD and a new rash on the arms, neck, chest, back, and lower extremities (Figures 1A and 2A). He had a medical history of AD and CTCL diagnosed by biopsy and peripheral blood flow cytometry (stage IVA1 [T4N0M0B2]) that was being treated with comprehensive multimodality therapy consisting of bexarotene 375 mg daily, interferon alfa-2b 3 mIU 3 times weekly, interferon gamma-1b 2 mIU 3 times weekly, total skin electron beam therapy followed by narrowband UVB twice weekly, and extracorporeal photopheresis every 4 weeks, which resulted in a partial clinical response for 6 months. A biopsy performed at the current presentation showed focal spongiosis and features of lichen simplex chronicus with no evidence suggestive of CTCL. Peripheral blood flow cytometry showed stable B1-staged disease burden (CD4/CD8, 2.6:1); CD4+/CD7−, 12% [91/µL]; CD4+/CD26−, 21% [155/µL]). Treatment with potent and superpotent topical steroids was attempted for more than 6 months and was unsuccessful in relieving the symptoms.

Given the recalcitrant nature of the patient’s rash and itching, dupilumab was added to his CTCL regimen. Prior to initiating dupilumab, the patient reported a numeric rating scale itch intensity of 7 out of 10. After 4 weeks of treatment with dupilumab, the patient reported a numeric rating scale itch intensity of 1. Over a 3-month period, the patient’s rash improved dramatically (Figures 1B and 2B), making it possible to decrease CTCL treatments—bexarotene decreased to 300 mg, interferon alfa-2b to 3 mIU twice weekly, interferon gamma-1b to 2 mIU twice weekly, extracorporeal photopheresis every 5 weeks, and narrowband UVB was discontinued completely. A comparison of the patient’s flow cytometry analysis from before treatment to 3 months after dupilumab showed an overall slight reduction in CTCL B1 blood involvement and normalization of the patient’s absolute eosinophil count and serum lactate dehydrogenase level. The patient tolerated the treatment well without any adverse events and has maintained clinical response for 6 months.

Comment

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas represent a heterogeneous group of T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders involving the skin.2 The definitive diagnosis of CTCL is challenging, as the clinical and pathologic features often are nonspecific in early disease. Frequently, undiagnosed patients are treated empirically with immunosuppressive agents. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and cyclosporine are both associated with progression or worsening of undiagnosed CTCL.3,4 Dupilumab was the first US Food and Drug Administration–approved biologic for the treatment of moderate to severe AD. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma has immunologic features, such as TH2 skewing, that overlap with AD; however, the effects of dupilumab in CTCL are not yet known.5,6 Our group has seen patients initially thought to have AD who received dupilumab without improvement and were subsequently diagnosed with CTCL, suggesting dupilumab did not affect CTCL tumor cells. Given these findings, there was concern that dupilumab might exacerbate undiagnosed CTCL. Our patient with definitive, severe, refractory CTCL noted marked improvement in both AD and underlying CTCL with the addition of dupilumab. No other treatments were added. The response was so dramatic that we were able to wean the doses and frequencies of several CTCL treatments. Our findings suggest that dupilumab may be beneficial in a certain subset of CTCL patients with a history of AD or known concomitant AD. Prospective studies are needed to fully investigate dupilumab safety and efficacy in CTCL and whether it has any primary effects on tumor burden in addition to benefit for itch and skin symptom relief.

- Guenova E, Watanabe R, Teague JE, et al. TH2 cytokines from malignant cells suppress TH1 responses and enforce a global TH2 bias in leukemic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:3755-3763.

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:151-165.

- Martinez-Escala ME, Posligua AL, Wickless H, et al. Progression of undiagnosed cutaneous lymphoma after anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1068-1076.

- Pielop JA, Jones D, Duvic M. Transient CD30+ nodal transformation of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma associated with cyclosporine treatment. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:505-511.

- Saulite I, Hoetzenecker W, Weidinger S, et al. Sézary syndrome and atopic dermatitis: comparison of immunological aspects and targets [published online May 17, 2016]. BioMed Res Int. doi:10.1155/2016/9717530.

- Sigurdsson V, Toonstra J, Bihari IC, et al. Interleukin 4 and interferon-gamma expression of the dermal infiltrate in patients with erythroderma and mycosis fungoides. an immuno-histochemical study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:429-435.

Patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) often are diagnosed with atopic dermatitis (AD) or psoriasis before receiving their CTCL diagnosis. The effects of new biologic therapies for AD such as dupilumab, an IL-4/IL-13 antagonist, on CTCL are unknown. Dupilumab may be beneficial in CTCL given that helper T cell (TH2) cytokines are increased in advanced CTCL.1 We present a patient with definitive CTCL and concomitant AD who was safely treated with dupilumab and experienced improvement in both CTCL and AD.

Case Report

A 68-year-old man presented with increased itching from AD and a new rash on the arms, neck, chest, back, and lower extremities (Figures 1A and 2A). He had a medical history of AD and CTCL diagnosed by biopsy and peripheral blood flow cytometry (stage IVA1 [T4N0M0B2]) that was being treated with comprehensive multimodality therapy consisting of bexarotene 375 mg daily, interferon alfa-2b 3 mIU 3 times weekly, interferon gamma-1b 2 mIU 3 times weekly, total skin electron beam therapy followed by narrowband UVB twice weekly, and extracorporeal photopheresis every 4 weeks, which resulted in a partial clinical response for 6 months. A biopsy performed at the current presentation showed focal spongiosis and features of lichen simplex chronicus with no evidence suggestive of CTCL. Peripheral blood flow cytometry showed stable B1-staged disease burden (CD4/CD8, 2.6:1); CD4+/CD7−, 12% [91/µL]; CD4+/CD26−, 21% [155/µL]). Treatment with potent and superpotent topical steroids was attempted for more than 6 months and was unsuccessful in relieving the symptoms.

Given the recalcitrant nature of the patient’s rash and itching, dupilumab was added to his CTCL regimen. Prior to initiating dupilumab, the patient reported a numeric rating scale itch intensity of 7 out of 10. After 4 weeks of treatment with dupilumab, the patient reported a numeric rating scale itch intensity of 1. Over a 3-month period, the patient’s rash improved dramatically (Figures 1B and 2B), making it possible to decrease CTCL treatments—bexarotene decreased to 300 mg, interferon alfa-2b to 3 mIU twice weekly, interferon gamma-1b to 2 mIU twice weekly, extracorporeal photopheresis every 5 weeks, and narrowband UVB was discontinued completely. A comparison of the patient’s flow cytometry analysis from before treatment to 3 months after dupilumab showed an overall slight reduction in CTCL B1 blood involvement and normalization of the patient’s absolute eosinophil count and serum lactate dehydrogenase level. The patient tolerated the treatment well without any adverse events and has maintained clinical response for 6 months.

Comment

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas represent a heterogeneous group of T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders involving the skin.2 The definitive diagnosis of CTCL is challenging, as the clinical and pathologic features often are nonspecific in early disease. Frequently, undiagnosed patients are treated empirically with immunosuppressive agents. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and cyclosporine are both associated with progression or worsening of undiagnosed CTCL.3,4 Dupilumab was the first US Food and Drug Administration–approved biologic for the treatment of moderate to severe AD. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma has immunologic features, such as TH2 skewing, that overlap with AD; however, the effects of dupilumab in CTCL are not yet known.5,6 Our group has seen patients initially thought to have AD who received dupilumab without improvement and were subsequently diagnosed with CTCL, suggesting dupilumab did not affect CTCL tumor cells. Given these findings, there was concern that dupilumab might exacerbate undiagnosed CTCL. Our patient with definitive, severe, refractory CTCL noted marked improvement in both AD and underlying CTCL with the addition of dupilumab. No other treatments were added. The response was so dramatic that we were able to wean the doses and frequencies of several CTCL treatments. Our findings suggest that dupilumab may be beneficial in a certain subset of CTCL patients with a history of AD or known concomitant AD. Prospective studies are needed to fully investigate dupilumab safety and efficacy in CTCL and whether it has any primary effects on tumor burden in addition to benefit for itch and skin symptom relief.

Patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) often are diagnosed with atopic dermatitis (AD) or psoriasis before receiving their CTCL diagnosis. The effects of new biologic therapies for AD such as dupilumab, an IL-4/IL-13 antagonist, on CTCL are unknown. Dupilumab may be beneficial in CTCL given that helper T cell (TH2) cytokines are increased in advanced CTCL.1 We present a patient with definitive CTCL and concomitant AD who was safely treated with dupilumab and experienced improvement in both CTCL and AD.

Case Report

A 68-year-old man presented with increased itching from AD and a new rash on the arms, neck, chest, back, and lower extremities (Figures 1A and 2A). He had a medical history of AD and CTCL diagnosed by biopsy and peripheral blood flow cytometry (stage IVA1 [T4N0M0B2]) that was being treated with comprehensive multimodality therapy consisting of bexarotene 375 mg daily, interferon alfa-2b 3 mIU 3 times weekly, interferon gamma-1b 2 mIU 3 times weekly, total skin electron beam therapy followed by narrowband UVB twice weekly, and extracorporeal photopheresis every 4 weeks, which resulted in a partial clinical response for 6 months. A biopsy performed at the current presentation showed focal spongiosis and features of lichen simplex chronicus with no evidence suggestive of CTCL. Peripheral blood flow cytometry showed stable B1-staged disease burden (CD4/CD8, 2.6:1); CD4+/CD7−, 12% [91/µL]; CD4+/CD26−, 21% [155/µL]). Treatment with potent and superpotent topical steroids was attempted for more than 6 months and was unsuccessful in relieving the symptoms.

Given the recalcitrant nature of the patient’s rash and itching, dupilumab was added to his CTCL regimen. Prior to initiating dupilumab, the patient reported a numeric rating scale itch intensity of 7 out of 10. After 4 weeks of treatment with dupilumab, the patient reported a numeric rating scale itch intensity of 1. Over a 3-month period, the patient’s rash improved dramatically (Figures 1B and 2B), making it possible to decrease CTCL treatments—bexarotene decreased to 300 mg, interferon alfa-2b to 3 mIU twice weekly, interferon gamma-1b to 2 mIU twice weekly, extracorporeal photopheresis every 5 weeks, and narrowband UVB was discontinued completely. A comparison of the patient’s flow cytometry analysis from before treatment to 3 months after dupilumab showed an overall slight reduction in CTCL B1 blood involvement and normalization of the patient’s absolute eosinophil count and serum lactate dehydrogenase level. The patient tolerated the treatment well without any adverse events and has maintained clinical response for 6 months.

Comment

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas represent a heterogeneous group of T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders involving the skin.2 The definitive diagnosis of CTCL is challenging, as the clinical and pathologic features often are nonspecific in early disease. Frequently, undiagnosed patients are treated empirically with immunosuppressive agents. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and cyclosporine are both associated with progression or worsening of undiagnosed CTCL.3,4 Dupilumab was the first US Food and Drug Administration–approved biologic for the treatment of moderate to severe AD. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma has immunologic features, such as TH2 skewing, that overlap with AD; however, the effects of dupilumab in CTCL are not yet known.5,6 Our group has seen patients initially thought to have AD who received dupilumab without improvement and were subsequently diagnosed with CTCL, suggesting dupilumab did not affect CTCL tumor cells. Given these findings, there was concern that dupilumab might exacerbate undiagnosed CTCL. Our patient with definitive, severe, refractory CTCL noted marked improvement in both AD and underlying CTCL with the addition of dupilumab. No other treatments were added. The response was so dramatic that we were able to wean the doses and frequencies of several CTCL treatments. Our findings suggest that dupilumab may be beneficial in a certain subset of CTCL patients with a history of AD or known concomitant AD. Prospective studies are needed to fully investigate dupilumab safety and efficacy in CTCL and whether it has any primary effects on tumor burden in addition to benefit for itch and skin symptom relief.

- Guenova E, Watanabe R, Teague JE, et al. TH2 cytokines from malignant cells suppress TH1 responses and enforce a global TH2 bias in leukemic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:3755-3763.

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:151-165.

- Martinez-Escala ME, Posligua AL, Wickless H, et al. Progression of undiagnosed cutaneous lymphoma after anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1068-1076.

- Pielop JA, Jones D, Duvic M. Transient CD30+ nodal transformation of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma associated with cyclosporine treatment. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:505-511.

- Saulite I, Hoetzenecker W, Weidinger S, et al. Sézary syndrome and atopic dermatitis: comparison of immunological aspects and targets [published online May 17, 2016]. BioMed Res Int. doi:10.1155/2016/9717530.

- Sigurdsson V, Toonstra J, Bihari IC, et al. Interleukin 4 and interferon-gamma expression of the dermal infiltrate in patients with erythroderma and mycosis fungoides. an immuno-histochemical study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:429-435.

- Guenova E, Watanabe R, Teague JE, et al. TH2 cytokines from malignant cells suppress TH1 responses and enforce a global TH2 bias in leukemic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:3755-3763.

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:151-165.

- Martinez-Escala ME, Posligua AL, Wickless H, et al. Progression of undiagnosed cutaneous lymphoma after anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1068-1076.

- Pielop JA, Jones D, Duvic M. Transient CD30+ nodal transformation of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma associated with cyclosporine treatment. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:505-511.

- Saulite I, Hoetzenecker W, Weidinger S, et al. Sézary syndrome and atopic dermatitis: comparison of immunological aspects and targets [published online May 17, 2016]. BioMed Res Int. doi:10.1155/2016/9717530.

- Sigurdsson V, Toonstra J, Bihari IC, et al. Interleukin 4 and interferon-gamma expression of the dermal infiltrate in patients with erythroderma and mycosis fungoides. an immuno-histochemical study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:429-435.

Practice Points

- The diagnosis of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), particularly early-stage disease, remains challenging and often requires a combination of serial clinical evaluations as well as laboratory diagnostic examinations.

- Dupilumab and its effect on helper T cell (TH2) skewing may play a role in the future management of CTCL.

Scrotal Ulceration: A Complication of Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy and Subsequent Treatment With Dimethyl Sulfoxide

To the Editor:

A 54-year-old man with a history of stage IV appendiceal carcinoid adenocarcinoma treated approximately 3 months prior with intraoperative hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) presented to our clinic with scrotal pain of 5 days’ duration. He had no history of genital herpes, topical contactants, other cutaneous lesions on the body, fever, or chills. On physical examination the patient had an erythematous, purpuric, indurated, tender plaque on the left anterolateral and anterior midline of the scrotum (Figure 1). No other areas of acral purpura or livedoid cutaneous changes were identified. There was no inguinal lymphadenopathy. Biopsy was performed for histologic examination as well as tissue culture. Histology demonstrated epidermal necrosis without evidence of vasculitis. Tissue culture was unremarkable.

Two days after clinic evaluation, the patient presented to the emergency department with progression of the lesions, and he was admitted to the hospital for pain control. Computed tomography of the pelvis showed bilateral hydroceles without evidence of abscess. Ultrasonography showed scrotal thickening without abscess or fluid collection. On day 5 in the hospital, a regimen of topical 60% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was applied every 8 hours to the affected area. The patient experienced notable pain relief and a decrease in erythema within 7 hours of application (Figure 2). This regimen was continued for 7 days with improvement in surrounding erythema and pain; however, the patient’s pain persisted in the areas of necrosis. Fourteen days following completion of therapy (27 days following presentation), the patient underwent debridement and partial scrotal resection for eschar removal. Histologic examination of the debrided scrotal tissue showed necrosis extending into the dermis and no evidence of vasculitis.

Our case demonstrates a unique presentation of scrotal necrosis secondary to mitomycin C (MitC) extravasation subsequently managed with DMSO. Imaging and biopsy findings effectively ruled out infection or vasculitis and led us to consider extravasation reactions that typically occur at peripheral intravenous (IV) infusion sites. Suspected cases of scrotal necrosis following HIPEC with MitC have been reported in the literature, along with hypothesized pathophysiology.1-3

In consideration of the proposed pathophysiology, individuals with hydroceles may be more likely to experience this complication due to an abnormal but not uncommon communication between the intraperitoneal cavity and the scrotum via a patent processus vaginalis. The location of necrosis on the anterior scrotum remains unexplained. It may be a consequence of the anatomic location of the hydrocele, a collection of fluid within the tunica vaginalis. The tunica vaginalis is composed of an inner visceral and outer parietal layer, enveloping the testis at the anterior border but not the superior or posterior border. Thus, sequestration of MitC in a hydrocele would correlate anatomically to necrosis of the anterior wall of the scrotum.

Akhavan et al1 proposed the testes are unaffected because of the presence of the tough fibrous coat of the tunica albuginea that directly adheres to the testes, in addition to the adjacent visceral layer of the tunica vaginalis. These 2 layers separating the testes and the hydrocele may provide a double barrier of protection for the testes.1

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms scrotal or cutaneous, pain or ulceration, and HIPEC or hyperthermic in

Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy involves installation of high-concentration chemotherapeutics into the peritoneal cavity at the conclusion of surgical cytoreductive therapy. Cell cycle–nonspecific agents such as MitC commonly are used for this procedure.4 It is classified as a vesicant, which is the designation given to drugs known to produce the most severe extravasation reactions of skin ulceration and necrosis.5,6 Symptoms typically include an early area of localized edema, erythema, and severe pain that progresses to superficial soft tissue and skin necrosis.7 Unfortunately, no well-studied antidote exists for MitC, though empirical guidelines suggest therapeutic management with DMSO and ice packs.6,8

Dimethyl sulfoxide is thought to work as a free radical scavenger as well as a solvent that facilitates diffusion of chemotherapeutics through tissues and thus down a concentration gradient, ideal in the circumstance of an extravasation reaction.8 Topical DMSO has been studied as a nonsurgical treatment in a small number of patients to prevent progression to necrosis following MitC extravasation.5,7 However, these cases only report extravasation reactions from IV infiltration.5,7,9 Dimethyl sulfoxide is rapidly absorbed and acts as a theoretical carrier for MitC as well as other topical substances.5,10,11 Caution is advised when using topical lidocaine or steroids in combination with DMSO, as they will be rapidly absorbed systemically. Patients also should be informed about a mild local burning sensation after DMSO application and a garliclike odor of the breath, which have occurred in 5.5% and 27.5% of patients, respectively (N=144).5 Dimethyl sulfoxide has no known toxic side effects but can cause erythema, pruritus, and very rarely allergic contact dermatitis.5,12 Abdul Aziz et al2 postulated that DMSO might be used as a method to prevent the progression of necrosis in symptomatic patients following HIPEC with MitC. Reports of its use on the scrotum are absent in the current available literature.

Treatment with DMSO was attempted in our patient with limited success secondary to delayed recognition and lack of supporting literature for DMSO treatment of scrotal necrosis. Treatment was delayed by 11 days after the onset of symptoms, which is far beyond the recommendation of starting within 10 minutes.8 Irreversible tissue necrosis had already occurred as evidenced by the presence of eschar. However, it seems apparent that DMSO provided some benefit given the clear improvement in erythema and pain 7 hours after application (Figure 2). It is unknown to what extent the necrosis would have progressed if not treated with DMSO.

Scrotal necrosis following HIPEC with MitC is a rare and incompletely understood but important chemotherapy reaction. The presentation is fairly specific with the presence of intractable and constant scrotal pain along with erythema and induration progressing to eschar. Although DMSO has been found to be effective for certain vesicant extravasation reactions at IV sites, it is not well studied for MitC, and no reports exist regarding its use on the scrotum. The presented characterization and explanation of the pathophysiology of this entity will aid in early recognition and timely institution of topical mitigating agents such as DMSO, which may prevent progression to scrotal necrosis and need for surgical debridement. More effective strategies may be geared toward prevention with thorough washout following HIPEC, preprocedural radiologic imaging or intraoperative visualization of the patent processus vaginalis, internal inguinal canal plugs, and patient education with anticipatory guidance should a reaction occur.2

- Akhavan A, Yin M, Benoit R. Scrotal ulcer after intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy. Urology. 2007;69:778.E9-E10.

- Abdul Aziz NH, Wang W, Teo MC. Scrotal pain and ulceration post HIPEC: a case report. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2015;46:60-63.

- Silva F, Avancini J, Criado P, et al. Scrotum ulcer developed after intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy with mitomycin-C [published October 21, 2012]. Bjui International. doi:10.1002/BJUIw-2012-019-web.

- González-Moreno S, González-Bayón LA, Ortega-Pérez G.Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy: rationale and technique. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;15:68-75.

- Bertelli G, Gozza A, Forno GB, et al. Topical dimethyl sulfoxide for the prevention of soft tissue injury after extravasation of vesicant cytotoxic drugs: a prospective clinical study. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2851-2855.

- Bertelli G. Prevention and management of extravasation of cytotoxic drugs. Drug Saf. 1995;12:245-255.

- Alberts DS, Dorr RT. Case report: topical DMSO for mitomycin-C-induced skin ulceration. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1991;18:693-695.

- Pérez Fidalgo JA, García Fabregat L, Cervantes A, et al; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Management of chemotherapy extravasation: ESMO-EONS Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(suppl 5):167-173.

- Ludwig CU, Stoll HR, Obrist R, et al. Prevention of cytotoxic drug induced skin ulcers with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and alpha-tocopherole. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1987;23:327-329.

- Groel JT. Dimethyl sulfoxide as a vehicle for corticosteroids. a comparison with the occlusive dressing technique. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:110-114.

- Simon LS, Grierson LM, Naseer Z. Efficacy and safety of topical diclofenac containing dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) compared with those of topical placebo, DMSO vehicle and oral diclofenac for knee osteoarthritis [published online April 19, 2009]. Pain. 2009;143:238-245.

- Nishimura M, Takano Y, Toshitani S. Systemic contact dermatitis medicamentosa occurring after intravesical dimethyl sulfoxide treatment for interstitial cystitis. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:182-183.

To the Editor:

A 54-year-old man with a history of stage IV appendiceal carcinoid adenocarcinoma treated approximately 3 months prior with intraoperative hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) presented to our clinic with scrotal pain of 5 days’ duration. He had no history of genital herpes, topical contactants, other cutaneous lesions on the body, fever, or chills. On physical examination the patient had an erythematous, purpuric, indurated, tender plaque on the left anterolateral and anterior midline of the scrotum (Figure 1). No other areas of acral purpura or livedoid cutaneous changes were identified. There was no inguinal lymphadenopathy. Biopsy was performed for histologic examination as well as tissue culture. Histology demonstrated epidermal necrosis without evidence of vasculitis. Tissue culture was unremarkable.

Two days after clinic evaluation, the patient presented to the emergency department with progression of the lesions, and he was admitted to the hospital for pain control. Computed tomography of the pelvis showed bilateral hydroceles without evidence of abscess. Ultrasonography showed scrotal thickening without abscess or fluid collection. On day 5 in the hospital, a regimen of topical 60% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was applied every 8 hours to the affected area. The patient experienced notable pain relief and a decrease in erythema within 7 hours of application (Figure 2). This regimen was continued for 7 days with improvement in surrounding erythema and pain; however, the patient’s pain persisted in the areas of necrosis. Fourteen days following completion of therapy (27 days following presentation), the patient underwent debridement and partial scrotal resection for eschar removal. Histologic examination of the debrided scrotal tissue showed necrosis extending into the dermis and no evidence of vasculitis.

Our case demonstrates a unique presentation of scrotal necrosis secondary to mitomycin C (MitC) extravasation subsequently managed with DMSO. Imaging and biopsy findings effectively ruled out infection or vasculitis and led us to consider extravasation reactions that typically occur at peripheral intravenous (IV) infusion sites. Suspected cases of scrotal necrosis following HIPEC with MitC have been reported in the literature, along with hypothesized pathophysiology.1-3

In consideration of the proposed pathophysiology, individuals with hydroceles may be more likely to experience this complication due to an abnormal but not uncommon communication between the intraperitoneal cavity and the scrotum via a patent processus vaginalis. The location of necrosis on the anterior scrotum remains unexplained. It may be a consequence of the anatomic location of the hydrocele, a collection of fluid within the tunica vaginalis. The tunica vaginalis is composed of an inner visceral and outer parietal layer, enveloping the testis at the anterior border but not the superior or posterior border. Thus, sequestration of MitC in a hydrocele would correlate anatomically to necrosis of the anterior wall of the scrotum.

Akhavan et al1 proposed the testes are unaffected because of the presence of the tough fibrous coat of the tunica albuginea that directly adheres to the testes, in addition to the adjacent visceral layer of the tunica vaginalis. These 2 layers separating the testes and the hydrocele may provide a double barrier of protection for the testes.1

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms scrotal or cutaneous, pain or ulceration, and HIPEC or hyperthermic in

Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy involves installation of high-concentration chemotherapeutics into the peritoneal cavity at the conclusion of surgical cytoreductive therapy. Cell cycle–nonspecific agents such as MitC commonly are used for this procedure.4 It is classified as a vesicant, which is the designation given to drugs known to produce the most severe extravasation reactions of skin ulceration and necrosis.5,6 Symptoms typically include an early area of localized edema, erythema, and severe pain that progresses to superficial soft tissue and skin necrosis.7 Unfortunately, no well-studied antidote exists for MitC, though empirical guidelines suggest therapeutic management with DMSO and ice packs.6,8

Dimethyl sulfoxide is thought to work as a free radical scavenger as well as a solvent that facilitates diffusion of chemotherapeutics through tissues and thus down a concentration gradient, ideal in the circumstance of an extravasation reaction.8 Topical DMSO has been studied as a nonsurgical treatment in a small number of patients to prevent progression to necrosis following MitC extravasation.5,7 However, these cases only report extravasation reactions from IV infiltration.5,7,9 Dimethyl sulfoxide is rapidly absorbed and acts as a theoretical carrier for MitC as well as other topical substances.5,10,11 Caution is advised when using topical lidocaine or steroids in combination with DMSO, as they will be rapidly absorbed systemically. Patients also should be informed about a mild local burning sensation after DMSO application and a garliclike odor of the breath, which have occurred in 5.5% and 27.5% of patients, respectively (N=144).5 Dimethyl sulfoxide has no known toxic side effects but can cause erythema, pruritus, and very rarely allergic contact dermatitis.5,12 Abdul Aziz et al2 postulated that DMSO might be used as a method to prevent the progression of necrosis in symptomatic patients following HIPEC with MitC. Reports of its use on the scrotum are absent in the current available literature.

Treatment with DMSO was attempted in our patient with limited success secondary to delayed recognition and lack of supporting literature for DMSO treatment of scrotal necrosis. Treatment was delayed by 11 days after the onset of symptoms, which is far beyond the recommendation of starting within 10 minutes.8 Irreversible tissue necrosis had already occurred as evidenced by the presence of eschar. However, it seems apparent that DMSO provided some benefit given the clear improvement in erythema and pain 7 hours after application (Figure 2). It is unknown to what extent the necrosis would have progressed if not treated with DMSO.

Scrotal necrosis following HIPEC with MitC is a rare and incompletely understood but important chemotherapy reaction. The presentation is fairly specific with the presence of intractable and constant scrotal pain along with erythema and induration progressing to eschar. Although DMSO has been found to be effective for certain vesicant extravasation reactions at IV sites, it is not well studied for MitC, and no reports exist regarding its use on the scrotum. The presented characterization and explanation of the pathophysiology of this entity will aid in early recognition and timely institution of topical mitigating agents such as DMSO, which may prevent progression to scrotal necrosis and need for surgical debridement. More effective strategies may be geared toward prevention with thorough washout following HIPEC, preprocedural radiologic imaging or intraoperative visualization of the patent processus vaginalis, internal inguinal canal plugs, and patient education with anticipatory guidance should a reaction occur.2

To the Editor:

A 54-year-old man with a history of stage IV appendiceal carcinoid adenocarcinoma treated approximately 3 months prior with intraoperative hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) presented to our clinic with scrotal pain of 5 days’ duration. He had no history of genital herpes, topical contactants, other cutaneous lesions on the body, fever, or chills. On physical examination the patient had an erythematous, purpuric, indurated, tender plaque on the left anterolateral and anterior midline of the scrotum (Figure 1). No other areas of acral purpura or livedoid cutaneous changes were identified. There was no inguinal lymphadenopathy. Biopsy was performed for histologic examination as well as tissue culture. Histology demonstrated epidermal necrosis without evidence of vasculitis. Tissue culture was unremarkable.

Two days after clinic evaluation, the patient presented to the emergency department with progression of the lesions, and he was admitted to the hospital for pain control. Computed tomography of the pelvis showed bilateral hydroceles without evidence of abscess. Ultrasonography showed scrotal thickening without abscess or fluid collection. On day 5 in the hospital, a regimen of topical 60% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was applied every 8 hours to the affected area. The patient experienced notable pain relief and a decrease in erythema within 7 hours of application (Figure 2). This regimen was continued for 7 days with improvement in surrounding erythema and pain; however, the patient’s pain persisted in the areas of necrosis. Fourteen days following completion of therapy (27 days following presentation), the patient underwent debridement and partial scrotal resection for eschar removal. Histologic examination of the debrided scrotal tissue showed necrosis extending into the dermis and no evidence of vasculitis.

Our case demonstrates a unique presentation of scrotal necrosis secondary to mitomycin C (MitC) extravasation subsequently managed with DMSO. Imaging and biopsy findings effectively ruled out infection or vasculitis and led us to consider extravasation reactions that typically occur at peripheral intravenous (IV) infusion sites. Suspected cases of scrotal necrosis following HIPEC with MitC have been reported in the literature, along with hypothesized pathophysiology.1-3

In consideration of the proposed pathophysiology, individuals with hydroceles may be more likely to experience this complication due to an abnormal but not uncommon communication between the intraperitoneal cavity and the scrotum via a patent processus vaginalis. The location of necrosis on the anterior scrotum remains unexplained. It may be a consequence of the anatomic location of the hydrocele, a collection of fluid within the tunica vaginalis. The tunica vaginalis is composed of an inner visceral and outer parietal layer, enveloping the testis at the anterior border but not the superior or posterior border. Thus, sequestration of MitC in a hydrocele would correlate anatomically to necrosis of the anterior wall of the scrotum.

Akhavan et al1 proposed the testes are unaffected because of the presence of the tough fibrous coat of the tunica albuginea that directly adheres to the testes, in addition to the adjacent visceral layer of the tunica vaginalis. These 2 layers separating the testes and the hydrocele may provide a double barrier of protection for the testes.1

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms scrotal or cutaneous, pain or ulceration, and HIPEC or hyperthermic in

Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy involves installation of high-concentration chemotherapeutics into the peritoneal cavity at the conclusion of surgical cytoreductive therapy. Cell cycle–nonspecific agents such as MitC commonly are used for this procedure.4 It is classified as a vesicant, which is the designation given to drugs known to produce the most severe extravasation reactions of skin ulceration and necrosis.5,6 Symptoms typically include an early area of localized edema, erythema, and severe pain that progresses to superficial soft tissue and skin necrosis.7 Unfortunately, no well-studied antidote exists for MitC, though empirical guidelines suggest therapeutic management with DMSO and ice packs.6,8

Dimethyl sulfoxide is thought to work as a free radical scavenger as well as a solvent that facilitates diffusion of chemotherapeutics through tissues and thus down a concentration gradient, ideal in the circumstance of an extravasation reaction.8 Topical DMSO has been studied as a nonsurgical treatment in a small number of patients to prevent progression to necrosis following MitC extravasation.5,7 However, these cases only report extravasation reactions from IV infiltration.5,7,9 Dimethyl sulfoxide is rapidly absorbed and acts as a theoretical carrier for MitC as well as other topical substances.5,10,11 Caution is advised when using topical lidocaine or steroids in combination with DMSO, as they will be rapidly absorbed systemically. Patients also should be informed about a mild local burning sensation after DMSO application and a garliclike odor of the breath, which have occurred in 5.5% and 27.5% of patients, respectively (N=144).5 Dimethyl sulfoxide has no known toxic side effects but can cause erythema, pruritus, and very rarely allergic contact dermatitis.5,12 Abdul Aziz et al2 postulated that DMSO might be used as a method to prevent the progression of necrosis in symptomatic patients following HIPEC with MitC. Reports of its use on the scrotum are absent in the current available literature.

Treatment with DMSO was attempted in our patient with limited success secondary to delayed recognition and lack of supporting literature for DMSO treatment of scrotal necrosis. Treatment was delayed by 11 days after the onset of symptoms, which is far beyond the recommendation of starting within 10 minutes.8 Irreversible tissue necrosis had already occurred as evidenced by the presence of eschar. However, it seems apparent that DMSO provided some benefit given the clear improvement in erythema and pain 7 hours after application (Figure 2). It is unknown to what extent the necrosis would have progressed if not treated with DMSO.

Scrotal necrosis following HIPEC with MitC is a rare and incompletely understood but important chemotherapy reaction. The presentation is fairly specific with the presence of intractable and constant scrotal pain along with erythema and induration progressing to eschar. Although DMSO has been found to be effective for certain vesicant extravasation reactions at IV sites, it is not well studied for MitC, and no reports exist regarding its use on the scrotum. The presented characterization and explanation of the pathophysiology of this entity will aid in early recognition and timely institution of topical mitigating agents such as DMSO, which may prevent progression to scrotal necrosis and need for surgical debridement. More effective strategies may be geared toward prevention with thorough washout following HIPEC, preprocedural radiologic imaging or intraoperative visualization of the patent processus vaginalis, internal inguinal canal plugs, and patient education with anticipatory guidance should a reaction occur.2

- Akhavan A, Yin M, Benoit R. Scrotal ulcer after intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy. Urology. 2007;69:778.E9-E10.

- Abdul Aziz NH, Wang W, Teo MC. Scrotal pain and ulceration post HIPEC: a case report. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2015;46:60-63.

- Silva F, Avancini J, Criado P, et al. Scrotum ulcer developed after intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy with mitomycin-C [published October 21, 2012]. Bjui International. doi:10.1002/BJUIw-2012-019-web.

- González-Moreno S, González-Bayón LA, Ortega-Pérez G.Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy: rationale and technique. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;15:68-75.

- Bertelli G, Gozza A, Forno GB, et al. Topical dimethyl sulfoxide for the prevention of soft tissue injury after extravasation of vesicant cytotoxic drugs: a prospective clinical study. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2851-2855.

- Bertelli G. Prevention and management of extravasation of cytotoxic drugs. Drug Saf. 1995;12:245-255.

- Alberts DS, Dorr RT. Case report: topical DMSO for mitomycin-C-induced skin ulceration. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1991;18:693-695.

- Pérez Fidalgo JA, García Fabregat L, Cervantes A, et al; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Management of chemotherapy extravasation: ESMO-EONS Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(suppl 5):167-173.

- Ludwig CU, Stoll HR, Obrist R, et al. Prevention of cytotoxic drug induced skin ulcers with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and alpha-tocopherole. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1987;23:327-329.

- Groel JT. Dimethyl sulfoxide as a vehicle for corticosteroids. a comparison with the occlusive dressing technique. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:110-114.

- Simon LS, Grierson LM, Naseer Z. Efficacy and safety of topical diclofenac containing dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) compared with those of topical placebo, DMSO vehicle and oral diclofenac for knee osteoarthritis [published online April 19, 2009]. Pain. 2009;143:238-245.

- Nishimura M, Takano Y, Toshitani S. Systemic contact dermatitis medicamentosa occurring after intravesical dimethyl sulfoxide treatment for interstitial cystitis. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:182-183.

- Akhavan A, Yin M, Benoit R. Scrotal ulcer after intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy. Urology. 2007;69:778.E9-E10.

- Abdul Aziz NH, Wang W, Teo MC. Scrotal pain and ulceration post HIPEC: a case report. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2015;46:60-63.

- Silva F, Avancini J, Criado P, et al. Scrotum ulcer developed after intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy with mitomycin-C [published October 21, 2012]. Bjui International. doi:10.1002/BJUIw-2012-019-web.

- González-Moreno S, González-Bayón LA, Ortega-Pérez G.Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy: rationale and technique. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;15:68-75.

- Bertelli G, Gozza A, Forno GB, et al. Topical dimethyl sulfoxide for the prevention of soft tissue injury after extravasation of vesicant cytotoxic drugs: a prospective clinical study. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2851-2855.

- Bertelli G. Prevention and management of extravasation of cytotoxic drugs. Drug Saf. 1995;12:245-255.

- Alberts DS, Dorr RT. Case report: topical DMSO for mitomycin-C-induced skin ulceration. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1991;18:693-695.

- Pérez Fidalgo JA, García Fabregat L, Cervantes A, et al; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Management of chemotherapy extravasation: ESMO-EONS Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(suppl 5):167-173.

- Ludwig CU, Stoll HR, Obrist R, et al. Prevention of cytotoxic drug induced skin ulcers with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and alpha-tocopherole. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1987;23:327-329.

- Groel JT. Dimethyl sulfoxide as a vehicle for corticosteroids. a comparison with the occlusive dressing technique. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:110-114.

- Simon LS, Grierson LM, Naseer Z. Efficacy and safety of topical diclofenac containing dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) compared with those of topical placebo, DMSO vehicle and oral diclofenac for knee osteoarthritis [published online April 19, 2009]. Pain. 2009;143:238-245.

- Nishimura M, Takano Y, Toshitani S. Systemic contact dermatitis medicamentosa occurring after intravesical dimethyl sulfoxide treatment for interstitial cystitis. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:182-183.

Practice Points

- Scrotal ulceration following hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy has been reported only a few times in the literature and is likely underreported. The presentation in all reported cases was similar, with a delay in symptom onset of weeks to months, involvement of the anterior scrotum, and pain.

- Dimethyl sulfoxide, used in other vesicant reactions, may have a role in mitigating tissue damage. Alternatively, methods to prevent sequestration of vesicants in the potential space of the tunica vaginalis layers can be employed.