User login

Diffuse Annular Plaques in an Infant

The Diagnosis: Neonatal Lupus Erythematosus

A review of the medical records of the patient’s mother from her first pregnancy revealed positive anti-Ro/SSA (Sjögren syndrome A) (>8.0 U [reference range <1.0 U]) and anti-La/SSB (Sjögren syndrome B) antibodies (>8.0 U [reference range <1.0 U]), which were reconfirmed during her pregnancy with our patient (the second child). The patient’s older brother was diagnosed with neonatal lupus erythematosus (NLE) 2 years prior at 1 month of age; therefore, the mother took hydroxychloroquine during the pregnancy with the second child to help prevent heart block if the child was diagnosed with NLE. Given the family history, positive antibodies in the mother, and clinical presentation, our patient was diagnosed with NLE. He was referred to a pediatric cardiologist and pediatrician to continue the workup of systemic manifestations of NLE and to rule out the presence of congenital heart block. The rash resolved 6 months after the initial presentation, and he did not develop any systemic manifestations of NLE.

Neonatal lupus erythematosus is a rare acquired autoimmune disorder caused by the placental transfer of anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibodies and less commonly anti-U1 ribonucleoprotein antinuclear autoantibodies.1,2 Approximately 1% to 2% of mothers with these positive antibodies will have infants affected with NLE.2 The annual prevalence of NLE in the United States is approximately 1 in 20,000 live births. Mothers of children with NLE most commonly have clinical Sjögren syndrome; however, anti-Ro/SSA and anti-LA/SSB antibodies may be present in 0.1% to 1.5% of healthy women, and 25% to 60% of women with autoimmune disease may be asymptomatic.1 As demonstrated in our case, when there is a family history of NLE in an infant from an earlier pregnancy, the risk for NLE increases to 17% to 20% in subsequent pregnancies1,3 and up to 25% in subsequent pregnancies if the initial child was diagnosed with a congenital heart block in the setting of NLE.1

Neonatal lupus erythematosus classically presents as annular erythematous macules and plaques with central scaling, telangictasia, atrophy, and pigmentary changes. It may start on the scalp and face and spread caudally.1,2 Patients may develop these lesions after UV exposure, and 80% of infants may not have dermatologic findings at birth. Importantly, 40% to 60% of mothers may be asymptomatic at the time of presentation of their child’s NLE.1 The diagnosis can be confirmed via antibody testing in the mother and/or infant. If performed, a punch biopsy shows interface dermatitis, vacuolar degeneration, and possible periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates on histopathology.1,2

Management of cutaneous NLE includes sun protection (eg, application of sunscreen) and topical corticosteroids. Most dermatologic manifestations of NLE are transient, resolving after clearance of maternal IgG antibodies in 6 to 9 months; however, some telangiectasia, dyspigmentation, and atrophic scarring may persist.1-3

Neonatal lupus erythematosus also may have hepatobiliary, cardiac, hematologic, and less commonly neurologic manifestations. Hepatobiliary manifestations usually present as hepatomegaly or asymptomatic elevated transaminases or γ-glutamyl transferase.1,3 Approximately 10% to 20% of infants with NLE may present with transient anemia and thrombocytopenia.1 Cardiac manifestations are permanent and may require pacemaker implantation.1,3 The incidence of a congenital heart block in infants with NLE is 15% to 30%.3 Cardiac NLE most commonly injures the conductive tissue, leading to a congenital atrioventricular block. The development of a congenital heart block develops in the 18th to 24th week of gestation. Manifestations of a more advanced condition can include dilation of the ascending aorta and dilated cardiomyopathy.1 As such, patients need to be followed by a pediatric cardiologist for monitoring and treatment of any cardiac manifestations.

The overall prognosis of infants affected with NLE varies. Cardiac involvement is associated with a poor prognosis, while isolated cutaneous involvement requires little treatment and portends a favorable prognosis. It is critical for dermatologists to recognize NLE to refer patients to appropriate specialists to investigate and further monitor possible extracutaneous manifestations. With an understanding of the increased risk for a congenital heart block and NLE in subsequent pregnancies, mothers with positive anti-Ro/La antibodies should receive timely counseling and screening. In expectant mothers with suspected autoimmune disease, testing for antinuclear antibodies and SSA and SSB antibodies can be considered, as administration of hydroxychloroquine or prenatal systemic corticosteroids has proven to be effective in preventing a congenital heart block.1 Our patient was followed by pediatric cardiology and was not found to have a congenital heart block.

The differential diagnosis includes other causes of annular erythema in infants, as NLE can mimic several conditions. Tinea corporis may present as scaly annular plaques with central clearing; however, it rarely is encountered fulminantly in neonates.4 Erythema multiforme is a mucocutaneous hypersensitivy reaction distinguished by targetoid morphology.5 It is an exceedingly rare diagnosis in neonates; the average pediatric age of onset is 5.6 years.6 Erythema multiforme often is associated with an infection, most commonly herpes simplex virus,5 and mucosal involvement is common.6 Urticaria multiforme (also known as acute annular urticaria) is a benign disease that appears between 2 months to 3 years of age with blanchable urticarial plaques that likely are triggered by viral or bacterial infections, antibiotics, or vaccines.6 Specific lesions usually will resolve within 24 hours. Annular erythema of infancy is a benign and asymptomatic gyrate erythema that presents as annular plaques with palpable borders that spread centrifugally in patients younger than 1 year. Notably, lesions should periodically fade and may reappear cyclically for months to years. Evaluation for underlying disease usually is negative.6

- Derdulska JM, Rudnicka L, Szykut-Badaczewska A, et al. Neonatal lupus erythematosus—practical guidelines. J Perinat Med. 2021;49:529-538. doi:10.1515/jpm-2020-0543

- Wu J, Berk-Krauss J, Glick SA. Neonatal lupus erythematosus. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:590. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0041

- Hon KL, Leung AK. Neonatal lupus erythematosus. Autoimmune Dis. 2012;2012:301274. doi:10.1155/2012/301274

- Khare AK, Gupta LK, Mittal A, et al. Neonatal tinea corporis. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:201. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.6274

- Ang-Tiu CU, Nicolas ME. Erythema multiforme in a 25-day old neonate. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:E118-E120. doi:10.1111 /j.1525-1470.2012.01873.x

- Agnihotri G, Tsoukas MM. Annular skin lesions in infancy [published online February 3, 2022]. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:505-512. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.12.011

The Diagnosis: Neonatal Lupus Erythematosus

A review of the medical records of the patient’s mother from her first pregnancy revealed positive anti-Ro/SSA (Sjögren syndrome A) (>8.0 U [reference range <1.0 U]) and anti-La/SSB (Sjögren syndrome B) antibodies (>8.0 U [reference range <1.0 U]), which were reconfirmed during her pregnancy with our patient (the second child). The patient’s older brother was diagnosed with neonatal lupus erythematosus (NLE) 2 years prior at 1 month of age; therefore, the mother took hydroxychloroquine during the pregnancy with the second child to help prevent heart block if the child was diagnosed with NLE. Given the family history, positive antibodies in the mother, and clinical presentation, our patient was diagnosed with NLE. He was referred to a pediatric cardiologist and pediatrician to continue the workup of systemic manifestations of NLE and to rule out the presence of congenital heart block. The rash resolved 6 months after the initial presentation, and he did not develop any systemic manifestations of NLE.

Neonatal lupus erythematosus is a rare acquired autoimmune disorder caused by the placental transfer of anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibodies and less commonly anti-U1 ribonucleoprotein antinuclear autoantibodies.1,2 Approximately 1% to 2% of mothers with these positive antibodies will have infants affected with NLE.2 The annual prevalence of NLE in the United States is approximately 1 in 20,000 live births. Mothers of children with NLE most commonly have clinical Sjögren syndrome; however, anti-Ro/SSA and anti-LA/SSB antibodies may be present in 0.1% to 1.5% of healthy women, and 25% to 60% of women with autoimmune disease may be asymptomatic.1 As demonstrated in our case, when there is a family history of NLE in an infant from an earlier pregnancy, the risk for NLE increases to 17% to 20% in subsequent pregnancies1,3 and up to 25% in subsequent pregnancies if the initial child was diagnosed with a congenital heart block in the setting of NLE.1

Neonatal lupus erythematosus classically presents as annular erythematous macules and plaques with central scaling, telangictasia, atrophy, and pigmentary changes. It may start on the scalp and face and spread caudally.1,2 Patients may develop these lesions after UV exposure, and 80% of infants may not have dermatologic findings at birth. Importantly, 40% to 60% of mothers may be asymptomatic at the time of presentation of their child’s NLE.1 The diagnosis can be confirmed via antibody testing in the mother and/or infant. If performed, a punch biopsy shows interface dermatitis, vacuolar degeneration, and possible periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates on histopathology.1,2

Management of cutaneous NLE includes sun protection (eg, application of sunscreen) and topical corticosteroids. Most dermatologic manifestations of NLE are transient, resolving after clearance of maternal IgG antibodies in 6 to 9 months; however, some telangiectasia, dyspigmentation, and atrophic scarring may persist.1-3

Neonatal lupus erythematosus also may have hepatobiliary, cardiac, hematologic, and less commonly neurologic manifestations. Hepatobiliary manifestations usually present as hepatomegaly or asymptomatic elevated transaminases or γ-glutamyl transferase.1,3 Approximately 10% to 20% of infants with NLE may present with transient anemia and thrombocytopenia.1 Cardiac manifestations are permanent and may require pacemaker implantation.1,3 The incidence of a congenital heart block in infants with NLE is 15% to 30%.3 Cardiac NLE most commonly injures the conductive tissue, leading to a congenital atrioventricular block. The development of a congenital heart block develops in the 18th to 24th week of gestation. Manifestations of a more advanced condition can include dilation of the ascending aorta and dilated cardiomyopathy.1 As such, patients need to be followed by a pediatric cardiologist for monitoring and treatment of any cardiac manifestations.

The overall prognosis of infants affected with NLE varies. Cardiac involvement is associated with a poor prognosis, while isolated cutaneous involvement requires little treatment and portends a favorable prognosis. It is critical for dermatologists to recognize NLE to refer patients to appropriate specialists to investigate and further monitor possible extracutaneous manifestations. With an understanding of the increased risk for a congenital heart block and NLE in subsequent pregnancies, mothers with positive anti-Ro/La antibodies should receive timely counseling and screening. In expectant mothers with suspected autoimmune disease, testing for antinuclear antibodies and SSA and SSB antibodies can be considered, as administration of hydroxychloroquine or prenatal systemic corticosteroids has proven to be effective in preventing a congenital heart block.1 Our patient was followed by pediatric cardiology and was not found to have a congenital heart block.

The differential diagnosis includes other causes of annular erythema in infants, as NLE can mimic several conditions. Tinea corporis may present as scaly annular plaques with central clearing; however, it rarely is encountered fulminantly in neonates.4 Erythema multiforme is a mucocutaneous hypersensitivy reaction distinguished by targetoid morphology.5 It is an exceedingly rare diagnosis in neonates; the average pediatric age of onset is 5.6 years.6 Erythema multiforme often is associated with an infection, most commonly herpes simplex virus,5 and mucosal involvement is common.6 Urticaria multiforme (also known as acute annular urticaria) is a benign disease that appears between 2 months to 3 years of age with blanchable urticarial plaques that likely are triggered by viral or bacterial infections, antibiotics, or vaccines.6 Specific lesions usually will resolve within 24 hours. Annular erythema of infancy is a benign and asymptomatic gyrate erythema that presents as annular plaques with palpable borders that spread centrifugally in patients younger than 1 year. Notably, lesions should periodically fade and may reappear cyclically for months to years. Evaluation for underlying disease usually is negative.6

The Diagnosis: Neonatal Lupus Erythematosus

A review of the medical records of the patient’s mother from her first pregnancy revealed positive anti-Ro/SSA (Sjögren syndrome A) (>8.0 U [reference range <1.0 U]) and anti-La/SSB (Sjögren syndrome B) antibodies (>8.0 U [reference range <1.0 U]), which were reconfirmed during her pregnancy with our patient (the second child). The patient’s older brother was diagnosed with neonatal lupus erythematosus (NLE) 2 years prior at 1 month of age; therefore, the mother took hydroxychloroquine during the pregnancy with the second child to help prevent heart block if the child was diagnosed with NLE. Given the family history, positive antibodies in the mother, and clinical presentation, our patient was diagnosed with NLE. He was referred to a pediatric cardiologist and pediatrician to continue the workup of systemic manifestations of NLE and to rule out the presence of congenital heart block. The rash resolved 6 months after the initial presentation, and he did not develop any systemic manifestations of NLE.

Neonatal lupus erythematosus is a rare acquired autoimmune disorder caused by the placental transfer of anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibodies and less commonly anti-U1 ribonucleoprotein antinuclear autoantibodies.1,2 Approximately 1% to 2% of mothers with these positive antibodies will have infants affected with NLE.2 The annual prevalence of NLE in the United States is approximately 1 in 20,000 live births. Mothers of children with NLE most commonly have clinical Sjögren syndrome; however, anti-Ro/SSA and anti-LA/SSB antibodies may be present in 0.1% to 1.5% of healthy women, and 25% to 60% of women with autoimmune disease may be asymptomatic.1 As demonstrated in our case, when there is a family history of NLE in an infant from an earlier pregnancy, the risk for NLE increases to 17% to 20% in subsequent pregnancies1,3 and up to 25% in subsequent pregnancies if the initial child was diagnosed with a congenital heart block in the setting of NLE.1

Neonatal lupus erythematosus classically presents as annular erythematous macules and plaques with central scaling, telangictasia, atrophy, and pigmentary changes. It may start on the scalp and face and spread caudally.1,2 Patients may develop these lesions after UV exposure, and 80% of infants may not have dermatologic findings at birth. Importantly, 40% to 60% of mothers may be asymptomatic at the time of presentation of their child’s NLE.1 The diagnosis can be confirmed via antibody testing in the mother and/or infant. If performed, a punch biopsy shows interface dermatitis, vacuolar degeneration, and possible periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates on histopathology.1,2

Management of cutaneous NLE includes sun protection (eg, application of sunscreen) and topical corticosteroids. Most dermatologic manifestations of NLE are transient, resolving after clearance of maternal IgG antibodies in 6 to 9 months; however, some telangiectasia, dyspigmentation, and atrophic scarring may persist.1-3

Neonatal lupus erythematosus also may have hepatobiliary, cardiac, hematologic, and less commonly neurologic manifestations. Hepatobiliary manifestations usually present as hepatomegaly or asymptomatic elevated transaminases or γ-glutamyl transferase.1,3 Approximately 10% to 20% of infants with NLE may present with transient anemia and thrombocytopenia.1 Cardiac manifestations are permanent and may require pacemaker implantation.1,3 The incidence of a congenital heart block in infants with NLE is 15% to 30%.3 Cardiac NLE most commonly injures the conductive tissue, leading to a congenital atrioventricular block. The development of a congenital heart block develops in the 18th to 24th week of gestation. Manifestations of a more advanced condition can include dilation of the ascending aorta and dilated cardiomyopathy.1 As such, patients need to be followed by a pediatric cardiologist for monitoring and treatment of any cardiac manifestations.

The overall prognosis of infants affected with NLE varies. Cardiac involvement is associated with a poor prognosis, while isolated cutaneous involvement requires little treatment and portends a favorable prognosis. It is critical for dermatologists to recognize NLE to refer patients to appropriate specialists to investigate and further monitor possible extracutaneous manifestations. With an understanding of the increased risk for a congenital heart block and NLE in subsequent pregnancies, mothers with positive anti-Ro/La antibodies should receive timely counseling and screening. In expectant mothers with suspected autoimmune disease, testing for antinuclear antibodies and SSA and SSB antibodies can be considered, as administration of hydroxychloroquine or prenatal systemic corticosteroids has proven to be effective in preventing a congenital heart block.1 Our patient was followed by pediatric cardiology and was not found to have a congenital heart block.

The differential diagnosis includes other causes of annular erythema in infants, as NLE can mimic several conditions. Tinea corporis may present as scaly annular plaques with central clearing; however, it rarely is encountered fulminantly in neonates.4 Erythema multiforme is a mucocutaneous hypersensitivy reaction distinguished by targetoid morphology.5 It is an exceedingly rare diagnosis in neonates; the average pediatric age of onset is 5.6 years.6 Erythema multiforme often is associated with an infection, most commonly herpes simplex virus,5 and mucosal involvement is common.6 Urticaria multiforme (also known as acute annular urticaria) is a benign disease that appears between 2 months to 3 years of age with blanchable urticarial plaques that likely are triggered by viral or bacterial infections, antibiotics, or vaccines.6 Specific lesions usually will resolve within 24 hours. Annular erythema of infancy is a benign and asymptomatic gyrate erythema that presents as annular plaques with palpable borders that spread centrifugally in patients younger than 1 year. Notably, lesions should periodically fade and may reappear cyclically for months to years. Evaluation for underlying disease usually is negative.6

- Derdulska JM, Rudnicka L, Szykut-Badaczewska A, et al. Neonatal lupus erythematosus—practical guidelines. J Perinat Med. 2021;49:529-538. doi:10.1515/jpm-2020-0543

- Wu J, Berk-Krauss J, Glick SA. Neonatal lupus erythematosus. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:590. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0041

- Hon KL, Leung AK. Neonatal lupus erythematosus. Autoimmune Dis. 2012;2012:301274. doi:10.1155/2012/301274

- Khare AK, Gupta LK, Mittal A, et al. Neonatal tinea corporis. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:201. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.6274

- Ang-Tiu CU, Nicolas ME. Erythema multiforme in a 25-day old neonate. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:E118-E120. doi:10.1111 /j.1525-1470.2012.01873.x

- Agnihotri G, Tsoukas MM. Annular skin lesions in infancy [published online February 3, 2022]. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:505-512. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.12.011

- Derdulska JM, Rudnicka L, Szykut-Badaczewska A, et al. Neonatal lupus erythematosus—practical guidelines. J Perinat Med. 2021;49:529-538. doi:10.1515/jpm-2020-0543

- Wu J, Berk-Krauss J, Glick SA. Neonatal lupus erythematosus. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:590. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0041

- Hon KL, Leung AK. Neonatal lupus erythematosus. Autoimmune Dis. 2012;2012:301274. doi:10.1155/2012/301274

- Khare AK, Gupta LK, Mittal A, et al. Neonatal tinea corporis. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:201. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.6274

- Ang-Tiu CU, Nicolas ME. Erythema multiforme in a 25-day old neonate. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:E118-E120. doi:10.1111 /j.1525-1470.2012.01873.x

- Agnihotri G, Tsoukas MM. Annular skin lesions in infancy [published online February 3, 2022]. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:505-512. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.12.011

A 5-week-old infant boy presented with a rash at birth (left). The pregnancy was full term without complications, and he was otherwise healthy. A family history revealed that his older brother developed a similar rash 2 weeks after birth (right). Physical examination revealed polycyclic annular patches with an erythematous border and central clearing diffusely located on the trunk, extremities, scalp, and face with periorbital edema.

Dupilumab for the Treatment of Lichen Planus

To the Editor:

Lichen planus (LP) is an inflammatory mucocutaneous disorder that primarily affects adults aged 30 to 60 years.1 It can present across various regions such as the skin, scalp, oral cavity, genitalia, nails, and hair. It classically presents with pruritic, purple, polygonal papules or plaques. The proposed pathogenesis of this condition involves autoimmune destruction of epidermal basal keratinocytes.2 Management involves a stepwise approach, beginning with topical therapies such as corticosteroids and phototherapy and proceeding to systemic therapy including oral corticosteroids and retinoids. Additional medications with reported positive results include immunomodulators such as cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and mycophenolate mofetil.2-4 Dupilumab is a biologic immunomodulator and antagonist to the IL-4Rα on helper T cells (TH1). Although indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, this medication’s immunomodulatory properties have been shown to aid various inflammatory cutaneous conditions, including prurigo nodularis.5-9 We present a case of dupilumab therapy for treatment-refractory LP.

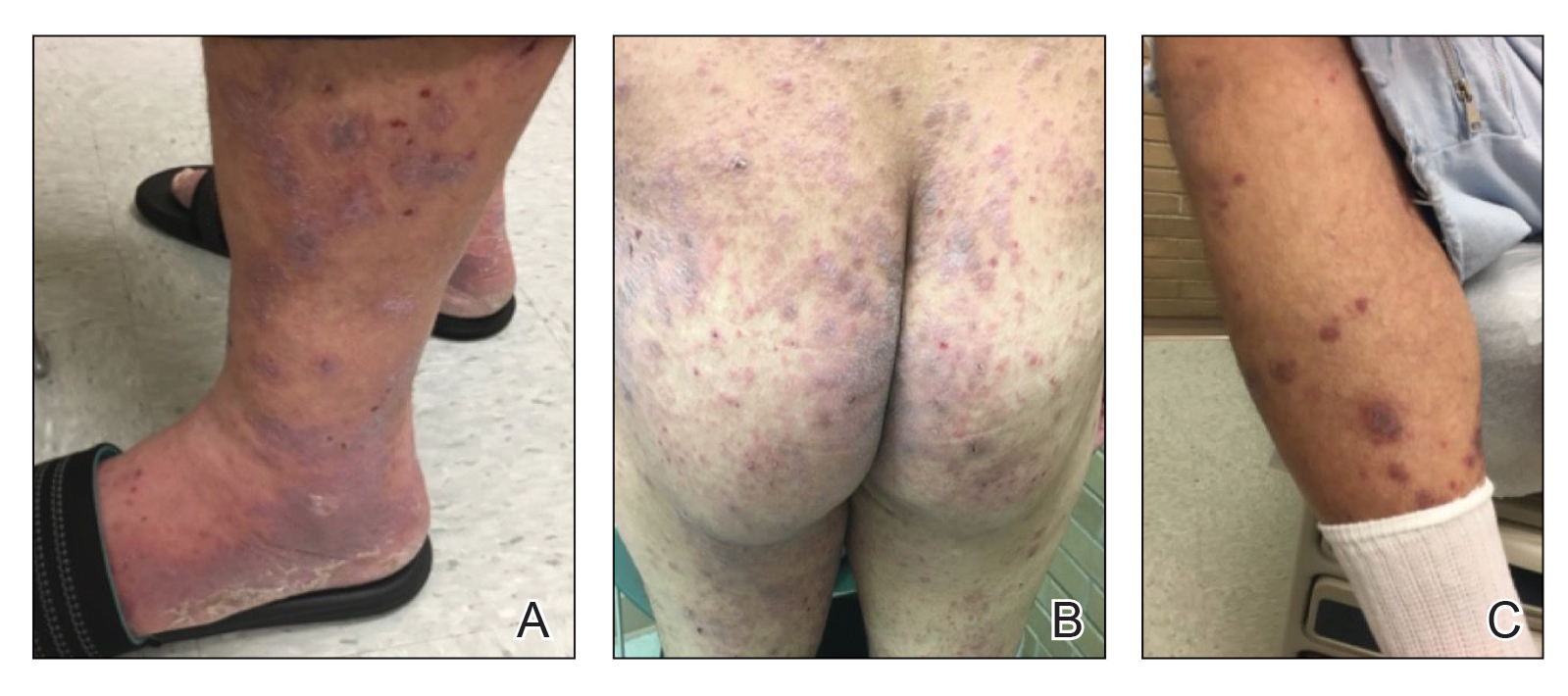

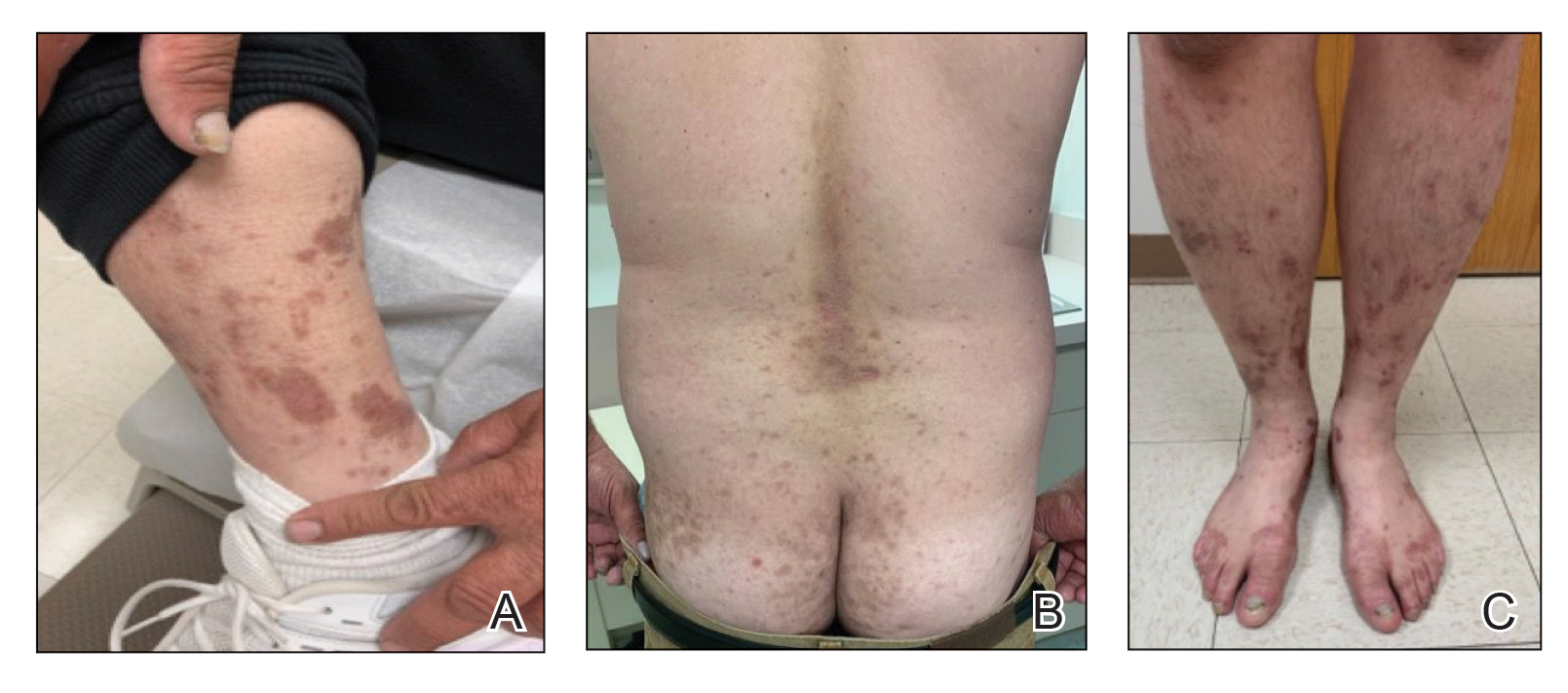

A 52-year-old man presented with a new-onset progressive rash over the prior 6 months. He reported no history of atopic dermatitis. The patient described the rash as “severely pruritic” with a numeric rating scale itch intensity of 9/10 (0 being no itch; 10 being the worst itch imaginable). Physical examination revealed purple polygonal scaly papules on the arms, hands, legs, feet, chest, and back (Figure 1).

Three biopsies were taken, all indicative of lichenoid dermatitis consistent with LP. Rapid plasma reagin as well as HIV and hepatitis C virus serology tests were negative. Halobetasol ointment, tacrolimus ointment, and oral prednisone (28-day taper starting at 40 mg) all failed. Acitretin subsequently was initiated and failed to provide any benefit. The patient was unable to come to clinic 3 times a week for phototherapy due to his work schedule.

Due to the chronic, severe, and recalcitrant nature of his condition, as well as the lack of US Food and Drug Administration–approved treatments, the patient agreed to begin off-label treatment with dupilumab. Upon documentation, the patient’s primary diagnosis was listed as LP, clearly stating all commonly accepted treatments were attempted, except off-label therapy, and failed, and the plan was to treat him with dupilumab as if he had a severe form of atopic dermatitis. Dupilumab was approved with this documentation with a minimal co-pay, as the patient was on Medicaid. At 3-month follow-up (after 4 administrations of the medication), the patient showed remarkable improvement in appearance, and his numeric rating scale itch intensity score improved to 1/10.

Lichen planus is an immune-mediated, inflammatory condition that can affect the skin, hair, nails, and oral cavity. Although its etiology is not fully understood, research supports a primarily TH1 immunologic reaction.10 These T cells promote cytotoxic CD8 T-cell differentiation and migration, leading to subsequent destruction of epidermal basal keratinocytes. An important cytokine in this pathway—tumor necrosis factor α—stimulates a series of proinflammatory factors, including IL-1α, IL-8, and IL-6. IL-6 is of particular interest, as its elevation has been identified in the serum of patients with LP, with levels correlating to disease severity.11 This increase is thought to be multifactorial and a reliable predictor of disease activity.12,13 In addition to its proinflammatory role, IL-6 promotes the activity of IL-4, an essential cytokine in TH2 T-cell differentiation.

The TH2 pathway, enhanced by IL-6, increases the activity of downstream cytokines IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13. This pathway promotes IgE class switching and eosinophil maturation, pivotal factors in the development of atopic conditions such as allergic rhinitis, asthma, and atopic dermatitis. The role of IL-4 and TH2 cells in the pathogenesis of LP remains poorly understood.14 In prior basic laboratory studies, utilizing tissue sampling, RNA extraction, and real-time polymerase chain reaction assays, Yamauchi et al15 proposed that TH2-related chemokines played a pathogenic role in oral LP. Additional reports propose the pathogenic involvement of TH17, TH0, and TH2 T cells.16 These findings suggest that elevated IL-6 in those with LP may stimulate an increase in IL-4 and subsequent TH2 response. Dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets IL-4Rα found on T cells, inhibits both IL-4 and IL-13 signaling, decreasing subsequent effector cell function.17,18 Several case reports have described dupilumab successfully treating various additional dermatoses, including prurigo nodularis, chronic pruritus, and bullous pemphigoid.5-9 Our case demonstrates an example of LP responsive to dupilumab. Our findings suggest that dupilumab interacts with the pathogenic cascade of LP, potentially implicating the role of TH2 in the pathophysiology of LP.

Treatment-refractory LP remains difficult to manage for both the patient and provider. Treatment regimens remain limited to small uncontrolled studies and case reports. Although primarily considered a TH1-mediated disease, the interplay of various alternative signaling pathways has been suggested. Our case of dupilumab-responsive LP suggests an underlying pathologic role of TH2-mediated activity. Dupilumab shows promise as an effective therapy for refractory LP, as evidenced by our patient’s remarkable response. Larger studies are warranted regarding the role of TH2-mediated inflammation and the use of dupilumab in LP.

- Cleach LL, Chosidow O. Clinical practice. lichen planus. N Engl J Med. 2012;266:723-732.

- Lehman, JS, Tollefson MM, Gibson LE. Lichen planus. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:682-694.

- Frieling U, Bonsmann G, Schwarz T, et al. Treatment of severe lichen planus with mycophenolate mofetil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1063-1066.

- Cribier B, Frances C, Chosidow O. Treatment of lichen planus. an evidence-based medicine analysis of efficacy. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1521-1530.

- Calugareanu A, Jachiet C, Lepelletier C, et al. Dramatic improvement of generalized prurigo nodularis with dupilumab. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:E303-E304.

- Kaye A, Gordon SC, Deverapalli SC, et al. Dupilumab for the treatment of recalcitrant bullous pemphigoid. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1225-1226.

- Mollanazar NK, Qiu CC, Aldrich JL, et al. Use of dupilumab in HIV-positive patients: report of four cases. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:1311-1312.

- Zhai LL, Savage KT, Qiu CC, et al. Chronic pruritus responding to dupilumab—a case series. Medicines (Basel). 2019;6:72.

- Mollanazar NK, Elgash M, Weaver L, et al. Reduced itch associated with dupilumab treatment in 4 patients with prurigo nodularis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:121-122.

- Lodi G, Scully C, Carrozzo M, et al. Current controversies in oral lichen planus: report of an international consensus meeting. part 1. viral infections and etiopathogenesis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:40-51.

- Yin M, Li G, Song H, et al. Identifying the association between interleukin-6 and lichen planus: a meta-analysis. Biomed Rep. 2017;6:571-575.

- Sun A, Chia JS, Chang YF, et al. Serum interleukin-6 level is a useful marker in evaluating therapeutic effects of levamisole and Chinese medicinal herbs on patients with oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med. 2002;31:196-203.

- Rhodus NL, Cheng B, Bowles W, et al. Proinflammatory cytokine levels in saliva before and after treatment of (erosive) oral lichen planus with dexamethasone. Oral Dis. 2006;12:112-116.

- Carrozzo M. Understanding the pathobiology of oral lichen planus. Curr Oral Health Rep. 2014;1:173-179.

- Yamauchi M, Moriyama M, Hayashida JN, et al. Myeloid dendritic cells stimulated by thymic stromal lymphopoietin promote Th2 immune responses and the pathogenesis of oral lichen planus. Plos One. 2017:12:e0173017.

- Piccinni M-P, Lombardell L, Logidice F, et al. Potential pathogenetic role of Th17, Th0, and Th2 cells in erosive and reticular oral lichen planus. Oral Dis. 2013:20:212-218.

- Kidd P. Th1/Th2 balance: the hypothesis, its limitations, and implications for health and disease. Altern Med Rev. 2003;8:223-246.

- Noda S, Kruefer JG, Guttum-Yassky E. The translational revolution and use of biologics in patients with inflammatory skin diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:324-336.

To the Editor:

Lichen planus (LP) is an inflammatory mucocutaneous disorder that primarily affects adults aged 30 to 60 years.1 It can present across various regions such as the skin, scalp, oral cavity, genitalia, nails, and hair. It classically presents with pruritic, purple, polygonal papules or plaques. The proposed pathogenesis of this condition involves autoimmune destruction of epidermal basal keratinocytes.2 Management involves a stepwise approach, beginning with topical therapies such as corticosteroids and phototherapy and proceeding to systemic therapy including oral corticosteroids and retinoids. Additional medications with reported positive results include immunomodulators such as cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and mycophenolate mofetil.2-4 Dupilumab is a biologic immunomodulator and antagonist to the IL-4Rα on helper T cells (TH1). Although indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, this medication’s immunomodulatory properties have been shown to aid various inflammatory cutaneous conditions, including prurigo nodularis.5-9 We present a case of dupilumab therapy for treatment-refractory LP.

A 52-year-old man presented with a new-onset progressive rash over the prior 6 months. He reported no history of atopic dermatitis. The patient described the rash as “severely pruritic” with a numeric rating scale itch intensity of 9/10 (0 being no itch; 10 being the worst itch imaginable). Physical examination revealed purple polygonal scaly papules on the arms, hands, legs, feet, chest, and back (Figure 1).

Three biopsies were taken, all indicative of lichenoid dermatitis consistent with LP. Rapid plasma reagin as well as HIV and hepatitis C virus serology tests were negative. Halobetasol ointment, tacrolimus ointment, and oral prednisone (28-day taper starting at 40 mg) all failed. Acitretin subsequently was initiated and failed to provide any benefit. The patient was unable to come to clinic 3 times a week for phototherapy due to his work schedule.

Due to the chronic, severe, and recalcitrant nature of his condition, as well as the lack of US Food and Drug Administration–approved treatments, the patient agreed to begin off-label treatment with dupilumab. Upon documentation, the patient’s primary diagnosis was listed as LP, clearly stating all commonly accepted treatments were attempted, except off-label therapy, and failed, and the plan was to treat him with dupilumab as if he had a severe form of atopic dermatitis. Dupilumab was approved with this documentation with a minimal co-pay, as the patient was on Medicaid. At 3-month follow-up (after 4 administrations of the medication), the patient showed remarkable improvement in appearance, and his numeric rating scale itch intensity score improved to 1/10.

Lichen planus is an immune-mediated, inflammatory condition that can affect the skin, hair, nails, and oral cavity. Although its etiology is not fully understood, research supports a primarily TH1 immunologic reaction.10 These T cells promote cytotoxic CD8 T-cell differentiation and migration, leading to subsequent destruction of epidermal basal keratinocytes. An important cytokine in this pathway—tumor necrosis factor α—stimulates a series of proinflammatory factors, including IL-1α, IL-8, and IL-6. IL-6 is of particular interest, as its elevation has been identified in the serum of patients with LP, with levels correlating to disease severity.11 This increase is thought to be multifactorial and a reliable predictor of disease activity.12,13 In addition to its proinflammatory role, IL-6 promotes the activity of IL-4, an essential cytokine in TH2 T-cell differentiation.

The TH2 pathway, enhanced by IL-6, increases the activity of downstream cytokines IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13. This pathway promotes IgE class switching and eosinophil maturation, pivotal factors in the development of atopic conditions such as allergic rhinitis, asthma, and atopic dermatitis. The role of IL-4 and TH2 cells in the pathogenesis of LP remains poorly understood.14 In prior basic laboratory studies, utilizing tissue sampling, RNA extraction, and real-time polymerase chain reaction assays, Yamauchi et al15 proposed that TH2-related chemokines played a pathogenic role in oral LP. Additional reports propose the pathogenic involvement of TH17, TH0, and TH2 T cells.16 These findings suggest that elevated IL-6 in those with LP may stimulate an increase in IL-4 and subsequent TH2 response. Dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets IL-4Rα found on T cells, inhibits both IL-4 and IL-13 signaling, decreasing subsequent effector cell function.17,18 Several case reports have described dupilumab successfully treating various additional dermatoses, including prurigo nodularis, chronic pruritus, and bullous pemphigoid.5-9 Our case demonstrates an example of LP responsive to dupilumab. Our findings suggest that dupilumab interacts with the pathogenic cascade of LP, potentially implicating the role of TH2 in the pathophysiology of LP.

Treatment-refractory LP remains difficult to manage for both the patient and provider. Treatment regimens remain limited to small uncontrolled studies and case reports. Although primarily considered a TH1-mediated disease, the interplay of various alternative signaling pathways has been suggested. Our case of dupilumab-responsive LP suggests an underlying pathologic role of TH2-mediated activity. Dupilumab shows promise as an effective therapy for refractory LP, as evidenced by our patient’s remarkable response. Larger studies are warranted regarding the role of TH2-mediated inflammation and the use of dupilumab in LP.

To the Editor:

Lichen planus (LP) is an inflammatory mucocutaneous disorder that primarily affects adults aged 30 to 60 years.1 It can present across various regions such as the skin, scalp, oral cavity, genitalia, nails, and hair. It classically presents with pruritic, purple, polygonal papules or plaques. The proposed pathogenesis of this condition involves autoimmune destruction of epidermal basal keratinocytes.2 Management involves a stepwise approach, beginning with topical therapies such as corticosteroids and phototherapy and proceeding to systemic therapy including oral corticosteroids and retinoids. Additional medications with reported positive results include immunomodulators such as cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and mycophenolate mofetil.2-4 Dupilumab is a biologic immunomodulator and antagonist to the IL-4Rα on helper T cells (TH1). Although indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, this medication’s immunomodulatory properties have been shown to aid various inflammatory cutaneous conditions, including prurigo nodularis.5-9 We present a case of dupilumab therapy for treatment-refractory LP.

A 52-year-old man presented with a new-onset progressive rash over the prior 6 months. He reported no history of atopic dermatitis. The patient described the rash as “severely pruritic” with a numeric rating scale itch intensity of 9/10 (0 being no itch; 10 being the worst itch imaginable). Physical examination revealed purple polygonal scaly papules on the arms, hands, legs, feet, chest, and back (Figure 1).

Three biopsies were taken, all indicative of lichenoid dermatitis consistent with LP. Rapid plasma reagin as well as HIV and hepatitis C virus serology tests were negative. Halobetasol ointment, tacrolimus ointment, and oral prednisone (28-day taper starting at 40 mg) all failed. Acitretin subsequently was initiated and failed to provide any benefit. The patient was unable to come to clinic 3 times a week for phototherapy due to his work schedule.

Due to the chronic, severe, and recalcitrant nature of his condition, as well as the lack of US Food and Drug Administration–approved treatments, the patient agreed to begin off-label treatment with dupilumab. Upon documentation, the patient’s primary diagnosis was listed as LP, clearly stating all commonly accepted treatments were attempted, except off-label therapy, and failed, and the plan was to treat him with dupilumab as if he had a severe form of atopic dermatitis. Dupilumab was approved with this documentation with a minimal co-pay, as the patient was on Medicaid. At 3-month follow-up (after 4 administrations of the medication), the patient showed remarkable improvement in appearance, and his numeric rating scale itch intensity score improved to 1/10.

Lichen planus is an immune-mediated, inflammatory condition that can affect the skin, hair, nails, and oral cavity. Although its etiology is not fully understood, research supports a primarily TH1 immunologic reaction.10 These T cells promote cytotoxic CD8 T-cell differentiation and migration, leading to subsequent destruction of epidermal basal keratinocytes. An important cytokine in this pathway—tumor necrosis factor α—stimulates a series of proinflammatory factors, including IL-1α, IL-8, and IL-6. IL-6 is of particular interest, as its elevation has been identified in the serum of patients with LP, with levels correlating to disease severity.11 This increase is thought to be multifactorial and a reliable predictor of disease activity.12,13 In addition to its proinflammatory role, IL-6 promotes the activity of IL-4, an essential cytokine in TH2 T-cell differentiation.

The TH2 pathway, enhanced by IL-6, increases the activity of downstream cytokines IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13. This pathway promotes IgE class switching and eosinophil maturation, pivotal factors in the development of atopic conditions such as allergic rhinitis, asthma, and atopic dermatitis. The role of IL-4 and TH2 cells in the pathogenesis of LP remains poorly understood.14 In prior basic laboratory studies, utilizing tissue sampling, RNA extraction, and real-time polymerase chain reaction assays, Yamauchi et al15 proposed that TH2-related chemokines played a pathogenic role in oral LP. Additional reports propose the pathogenic involvement of TH17, TH0, and TH2 T cells.16 These findings suggest that elevated IL-6 in those with LP may stimulate an increase in IL-4 and subsequent TH2 response. Dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets IL-4Rα found on T cells, inhibits both IL-4 and IL-13 signaling, decreasing subsequent effector cell function.17,18 Several case reports have described dupilumab successfully treating various additional dermatoses, including prurigo nodularis, chronic pruritus, and bullous pemphigoid.5-9 Our case demonstrates an example of LP responsive to dupilumab. Our findings suggest that dupilumab interacts with the pathogenic cascade of LP, potentially implicating the role of TH2 in the pathophysiology of LP.

Treatment-refractory LP remains difficult to manage for both the patient and provider. Treatment regimens remain limited to small uncontrolled studies and case reports. Although primarily considered a TH1-mediated disease, the interplay of various alternative signaling pathways has been suggested. Our case of dupilumab-responsive LP suggests an underlying pathologic role of TH2-mediated activity. Dupilumab shows promise as an effective therapy for refractory LP, as evidenced by our patient’s remarkable response. Larger studies are warranted regarding the role of TH2-mediated inflammation and the use of dupilumab in LP.

- Cleach LL, Chosidow O. Clinical practice. lichen planus. N Engl J Med. 2012;266:723-732.

- Lehman, JS, Tollefson MM, Gibson LE. Lichen planus. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:682-694.

- Frieling U, Bonsmann G, Schwarz T, et al. Treatment of severe lichen planus with mycophenolate mofetil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1063-1066.

- Cribier B, Frances C, Chosidow O. Treatment of lichen planus. an evidence-based medicine analysis of efficacy. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1521-1530.

- Calugareanu A, Jachiet C, Lepelletier C, et al. Dramatic improvement of generalized prurigo nodularis with dupilumab. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:E303-E304.

- Kaye A, Gordon SC, Deverapalli SC, et al. Dupilumab for the treatment of recalcitrant bullous pemphigoid. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1225-1226.

- Mollanazar NK, Qiu CC, Aldrich JL, et al. Use of dupilumab in HIV-positive patients: report of four cases. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:1311-1312.

- Zhai LL, Savage KT, Qiu CC, et al. Chronic pruritus responding to dupilumab—a case series. Medicines (Basel). 2019;6:72.

- Mollanazar NK, Elgash M, Weaver L, et al. Reduced itch associated with dupilumab treatment in 4 patients with prurigo nodularis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:121-122.

- Lodi G, Scully C, Carrozzo M, et al. Current controversies in oral lichen planus: report of an international consensus meeting. part 1. viral infections and etiopathogenesis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:40-51.

- Yin M, Li G, Song H, et al. Identifying the association between interleukin-6 and lichen planus: a meta-analysis. Biomed Rep. 2017;6:571-575.

- Sun A, Chia JS, Chang YF, et al. Serum interleukin-6 level is a useful marker in evaluating therapeutic effects of levamisole and Chinese medicinal herbs on patients with oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med. 2002;31:196-203.

- Rhodus NL, Cheng B, Bowles W, et al. Proinflammatory cytokine levels in saliva before and after treatment of (erosive) oral lichen planus with dexamethasone. Oral Dis. 2006;12:112-116.

- Carrozzo M. Understanding the pathobiology of oral lichen planus. Curr Oral Health Rep. 2014;1:173-179.

- Yamauchi M, Moriyama M, Hayashida JN, et al. Myeloid dendritic cells stimulated by thymic stromal lymphopoietin promote Th2 immune responses and the pathogenesis of oral lichen planus. Plos One. 2017:12:e0173017.

- Piccinni M-P, Lombardell L, Logidice F, et al. Potential pathogenetic role of Th17, Th0, and Th2 cells in erosive and reticular oral lichen planus. Oral Dis. 2013:20:212-218.

- Kidd P. Th1/Th2 balance: the hypothesis, its limitations, and implications for health and disease. Altern Med Rev. 2003;8:223-246.

- Noda S, Kruefer JG, Guttum-Yassky E. The translational revolution and use of biologics in patients with inflammatory skin diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:324-336.

- Cleach LL, Chosidow O. Clinical practice. lichen planus. N Engl J Med. 2012;266:723-732.

- Lehman, JS, Tollefson MM, Gibson LE. Lichen planus. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:682-694.

- Frieling U, Bonsmann G, Schwarz T, et al. Treatment of severe lichen planus with mycophenolate mofetil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1063-1066.

- Cribier B, Frances C, Chosidow O. Treatment of lichen planus. an evidence-based medicine analysis of efficacy. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1521-1530.

- Calugareanu A, Jachiet C, Lepelletier C, et al. Dramatic improvement of generalized prurigo nodularis with dupilumab. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:E303-E304.

- Kaye A, Gordon SC, Deverapalli SC, et al. Dupilumab for the treatment of recalcitrant bullous pemphigoid. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1225-1226.

- Mollanazar NK, Qiu CC, Aldrich JL, et al. Use of dupilumab in HIV-positive patients: report of four cases. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:1311-1312.

- Zhai LL, Savage KT, Qiu CC, et al. Chronic pruritus responding to dupilumab—a case series. Medicines (Basel). 2019;6:72.

- Mollanazar NK, Elgash M, Weaver L, et al. Reduced itch associated with dupilumab treatment in 4 patients with prurigo nodularis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:121-122.

- Lodi G, Scully C, Carrozzo M, et al. Current controversies in oral lichen planus: report of an international consensus meeting. part 1. viral infections and etiopathogenesis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:40-51.

- Yin M, Li G, Song H, et al. Identifying the association between interleukin-6 and lichen planus: a meta-analysis. Biomed Rep. 2017;6:571-575.

- Sun A, Chia JS, Chang YF, et al. Serum interleukin-6 level is a useful marker in evaluating therapeutic effects of levamisole and Chinese medicinal herbs on patients with oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med. 2002;31:196-203.

- Rhodus NL, Cheng B, Bowles W, et al. Proinflammatory cytokine levels in saliva before and after treatment of (erosive) oral lichen planus with dexamethasone. Oral Dis. 2006;12:112-116.

- Carrozzo M. Understanding the pathobiology of oral lichen planus. Curr Oral Health Rep. 2014;1:173-179.

- Yamauchi M, Moriyama M, Hayashida JN, et al. Myeloid dendritic cells stimulated by thymic stromal lymphopoietin promote Th2 immune responses and the pathogenesis of oral lichen planus. Plos One. 2017:12:e0173017.

- Piccinni M-P, Lombardell L, Logidice F, et al. Potential pathogenetic role of Th17, Th0, and Th2 cells in erosive and reticular oral lichen planus. Oral Dis. 2013:20:212-218.

- Kidd P. Th1/Th2 balance: the hypothesis, its limitations, and implications for health and disease. Altern Med Rev. 2003;8:223-246.

- Noda S, Kruefer JG, Guttum-Yassky E. The translational revolution and use of biologics in patients with inflammatory skin diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:324-336.

Practice Points

- Lichen planus (LP) is an inflammatory mucocutaneous disorder that can present across various regions of the body with pruritic, purple, polygonal papules or plaques.

- The proposed pathogenesis of LP involves autoimmune destruction of epidermal basal keratinocytes.

- The immunomodulatory properties of dupilumab have been shown to aid various inflammatory cutaneous conditions.