User login

Scrotal Ulceration: A Complication of Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy and Subsequent Treatment With Dimethyl Sulfoxide

To the Editor:

A 54-year-old man with a history of stage IV appendiceal carcinoid adenocarcinoma treated approximately 3 months prior with intraoperative hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) presented to our clinic with scrotal pain of 5 days’ duration. He had no history of genital herpes, topical contactants, other cutaneous lesions on the body, fever, or chills. On physical examination the patient had an erythematous, purpuric, indurated, tender plaque on the left anterolateral and anterior midline of the scrotum (Figure 1). No other areas of acral purpura or livedoid cutaneous changes were identified. There was no inguinal lymphadenopathy. Biopsy was performed for histologic examination as well as tissue culture. Histology demonstrated epidermal necrosis without evidence of vasculitis. Tissue culture was unremarkable.

Two days after clinic evaluation, the patient presented to the emergency department with progression of the lesions, and he was admitted to the hospital for pain control. Computed tomography of the pelvis showed bilateral hydroceles without evidence of abscess. Ultrasonography showed scrotal thickening without abscess or fluid collection. On day 5 in the hospital, a regimen of topical 60% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was applied every 8 hours to the affected area. The patient experienced notable pain relief and a decrease in erythema within 7 hours of application (Figure 2). This regimen was continued for 7 days with improvement in surrounding erythema and pain; however, the patient’s pain persisted in the areas of necrosis. Fourteen days following completion of therapy (27 days following presentation), the patient underwent debridement and partial scrotal resection for eschar removal. Histologic examination of the debrided scrotal tissue showed necrosis extending into the dermis and no evidence of vasculitis.

Our case demonstrates a unique presentation of scrotal necrosis secondary to mitomycin C (MitC) extravasation subsequently managed with DMSO. Imaging and biopsy findings effectively ruled out infection or vasculitis and led us to consider extravasation reactions that typically occur at peripheral intravenous (IV) infusion sites. Suspected cases of scrotal necrosis following HIPEC with MitC have been reported in the literature, along with hypothesized pathophysiology.1-3

In consideration of the proposed pathophysiology, individuals with hydroceles may be more likely to experience this complication due to an abnormal but not uncommon communication between the intraperitoneal cavity and the scrotum via a patent processus vaginalis. The location of necrosis on the anterior scrotum remains unexplained. It may be a consequence of the anatomic location of the hydrocele, a collection of fluid within the tunica vaginalis. The tunica vaginalis is composed of an inner visceral and outer parietal layer, enveloping the testis at the anterior border but not the superior or posterior border. Thus, sequestration of MitC in a hydrocele would correlate anatomically to necrosis of the anterior wall of the scrotum.

Akhavan et al1 proposed the testes are unaffected because of the presence of the tough fibrous coat of the tunica albuginea that directly adheres to the testes, in addition to the adjacent visceral layer of the tunica vaginalis. These 2 layers separating the testes and the hydrocele may provide a double barrier of protection for the testes.1

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms scrotal or cutaneous, pain or ulceration, and HIPEC or hyperthermic in

Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy involves installation of high-concentration chemotherapeutics into the peritoneal cavity at the conclusion of surgical cytoreductive therapy. Cell cycle–nonspecific agents such as MitC commonly are used for this procedure.4 It is classified as a vesicant, which is the designation given to drugs known to produce the most severe extravasation reactions of skin ulceration and necrosis.5,6 Symptoms typically include an early area of localized edema, erythema, and severe pain that progresses to superficial soft tissue and skin necrosis.7 Unfortunately, no well-studied antidote exists for MitC, though empirical guidelines suggest therapeutic management with DMSO and ice packs.6,8

Dimethyl sulfoxide is thought to work as a free radical scavenger as well as a solvent that facilitates diffusion of chemotherapeutics through tissues and thus down a concentration gradient, ideal in the circumstance of an extravasation reaction.8 Topical DMSO has been studied as a nonsurgical treatment in a small number of patients to prevent progression to necrosis following MitC extravasation.5,7 However, these cases only report extravasation reactions from IV infiltration.5,7,9 Dimethyl sulfoxide is rapidly absorbed and acts as a theoretical carrier for MitC as well as other topical substances.5,10,11 Caution is advised when using topical lidocaine or steroids in combination with DMSO, as they will be rapidly absorbed systemically. Patients also should be informed about a mild local burning sensation after DMSO application and a garliclike odor of the breath, which have occurred in 5.5% and 27.5% of patients, respectively (N=144).5 Dimethyl sulfoxide has no known toxic side effects but can cause erythema, pruritus, and very rarely allergic contact dermatitis.5,12 Abdul Aziz et al2 postulated that DMSO might be used as a method to prevent the progression of necrosis in symptomatic patients following HIPEC with MitC. Reports of its use on the scrotum are absent in the current available literature.

Treatment with DMSO was attempted in our patient with limited success secondary to delayed recognition and lack of supporting literature for DMSO treatment of scrotal necrosis. Treatment was delayed by 11 days after the onset of symptoms, which is far beyond the recommendation of starting within 10 minutes.8 Irreversible tissue necrosis had already occurred as evidenced by the presence of eschar. However, it seems apparent that DMSO provided some benefit given the clear improvement in erythema and pain 7 hours after application (Figure 2). It is unknown to what extent the necrosis would have progressed if not treated with DMSO.

Scrotal necrosis following HIPEC with MitC is a rare and incompletely understood but important chemotherapy reaction. The presentation is fairly specific with the presence of intractable and constant scrotal pain along with erythema and induration progressing to eschar. Although DMSO has been found to be effective for certain vesicant extravasation reactions at IV sites, it is not well studied for MitC, and no reports exist regarding its use on the scrotum. The presented characterization and explanation of the pathophysiology of this entity will aid in early recognition and timely institution of topical mitigating agents such as DMSO, which may prevent progression to scrotal necrosis and need for surgical debridement. More effective strategies may be geared toward prevention with thorough washout following HIPEC, preprocedural radiologic imaging or intraoperative visualization of the patent processus vaginalis, internal inguinal canal plugs, and patient education with anticipatory guidance should a reaction occur.2

- Akhavan A, Yin M, Benoit R. Scrotal ulcer after intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy. Urology. 2007;69:778.E9-E10.

- Abdul Aziz NH, Wang W, Teo MC. Scrotal pain and ulceration post HIPEC: a case report. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2015;46:60-63.

- Silva F, Avancini J, Criado P, et al. Scrotum ulcer developed after intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy with mitomycin-C [published October 21, 2012]. Bjui International. doi:10.1002/BJUIw-2012-019-web.

- González-Moreno S, González-Bayón LA, Ortega-Pérez G.Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy: rationale and technique. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;15:68-75.

- Bertelli G, Gozza A, Forno GB, et al. Topical dimethyl sulfoxide for the prevention of soft tissue injury after extravasation of vesicant cytotoxic drugs: a prospective clinical study. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2851-2855.

- Bertelli G. Prevention and management of extravasation of cytotoxic drugs. Drug Saf. 1995;12:245-255.

- Alberts DS, Dorr RT. Case report: topical DMSO for mitomycin-C-induced skin ulceration. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1991;18:693-695.

- Pérez Fidalgo JA, García Fabregat L, Cervantes A, et al; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Management of chemotherapy extravasation: ESMO-EONS Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(suppl 5):167-173.

- Ludwig CU, Stoll HR, Obrist R, et al. Prevention of cytotoxic drug induced skin ulcers with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and alpha-tocopherole. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1987;23:327-329.

- Groel JT. Dimethyl sulfoxide as a vehicle for corticosteroids. a comparison with the occlusive dressing technique. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:110-114.

- Simon LS, Grierson LM, Naseer Z. Efficacy and safety of topical diclofenac containing dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) compared with those of topical placebo, DMSO vehicle and oral diclofenac for knee osteoarthritis [published online April 19, 2009]. Pain. 2009;143:238-245.

- Nishimura M, Takano Y, Toshitani S. Systemic contact dermatitis medicamentosa occurring after intravesical dimethyl sulfoxide treatment for interstitial cystitis. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:182-183.

To the Editor:

A 54-year-old man with a history of stage IV appendiceal carcinoid adenocarcinoma treated approximately 3 months prior with intraoperative hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) presented to our clinic with scrotal pain of 5 days’ duration. He had no history of genital herpes, topical contactants, other cutaneous lesions on the body, fever, or chills. On physical examination the patient had an erythematous, purpuric, indurated, tender plaque on the left anterolateral and anterior midline of the scrotum (Figure 1). No other areas of acral purpura or livedoid cutaneous changes were identified. There was no inguinal lymphadenopathy. Biopsy was performed for histologic examination as well as tissue culture. Histology demonstrated epidermal necrosis without evidence of vasculitis. Tissue culture was unremarkable.

Two days after clinic evaluation, the patient presented to the emergency department with progression of the lesions, and he was admitted to the hospital for pain control. Computed tomography of the pelvis showed bilateral hydroceles without evidence of abscess. Ultrasonography showed scrotal thickening without abscess or fluid collection. On day 5 in the hospital, a regimen of topical 60% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was applied every 8 hours to the affected area. The patient experienced notable pain relief and a decrease in erythema within 7 hours of application (Figure 2). This regimen was continued for 7 days with improvement in surrounding erythema and pain; however, the patient’s pain persisted in the areas of necrosis. Fourteen days following completion of therapy (27 days following presentation), the patient underwent debridement and partial scrotal resection for eschar removal. Histologic examination of the debrided scrotal tissue showed necrosis extending into the dermis and no evidence of vasculitis.

Our case demonstrates a unique presentation of scrotal necrosis secondary to mitomycin C (MitC) extravasation subsequently managed with DMSO. Imaging and biopsy findings effectively ruled out infection or vasculitis and led us to consider extravasation reactions that typically occur at peripheral intravenous (IV) infusion sites. Suspected cases of scrotal necrosis following HIPEC with MitC have been reported in the literature, along with hypothesized pathophysiology.1-3

In consideration of the proposed pathophysiology, individuals with hydroceles may be more likely to experience this complication due to an abnormal but not uncommon communication between the intraperitoneal cavity and the scrotum via a patent processus vaginalis. The location of necrosis on the anterior scrotum remains unexplained. It may be a consequence of the anatomic location of the hydrocele, a collection of fluid within the tunica vaginalis. The tunica vaginalis is composed of an inner visceral and outer parietal layer, enveloping the testis at the anterior border but not the superior or posterior border. Thus, sequestration of MitC in a hydrocele would correlate anatomically to necrosis of the anterior wall of the scrotum.

Akhavan et al1 proposed the testes are unaffected because of the presence of the tough fibrous coat of the tunica albuginea that directly adheres to the testes, in addition to the adjacent visceral layer of the tunica vaginalis. These 2 layers separating the testes and the hydrocele may provide a double barrier of protection for the testes.1

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms scrotal or cutaneous, pain or ulceration, and HIPEC or hyperthermic in

Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy involves installation of high-concentration chemotherapeutics into the peritoneal cavity at the conclusion of surgical cytoreductive therapy. Cell cycle–nonspecific agents such as MitC commonly are used for this procedure.4 It is classified as a vesicant, which is the designation given to drugs known to produce the most severe extravasation reactions of skin ulceration and necrosis.5,6 Symptoms typically include an early area of localized edema, erythema, and severe pain that progresses to superficial soft tissue and skin necrosis.7 Unfortunately, no well-studied antidote exists for MitC, though empirical guidelines suggest therapeutic management with DMSO and ice packs.6,8

Dimethyl sulfoxide is thought to work as a free radical scavenger as well as a solvent that facilitates diffusion of chemotherapeutics through tissues and thus down a concentration gradient, ideal in the circumstance of an extravasation reaction.8 Topical DMSO has been studied as a nonsurgical treatment in a small number of patients to prevent progression to necrosis following MitC extravasation.5,7 However, these cases only report extravasation reactions from IV infiltration.5,7,9 Dimethyl sulfoxide is rapidly absorbed and acts as a theoretical carrier for MitC as well as other topical substances.5,10,11 Caution is advised when using topical lidocaine or steroids in combination with DMSO, as they will be rapidly absorbed systemically. Patients also should be informed about a mild local burning sensation after DMSO application and a garliclike odor of the breath, which have occurred in 5.5% and 27.5% of patients, respectively (N=144).5 Dimethyl sulfoxide has no known toxic side effects but can cause erythema, pruritus, and very rarely allergic contact dermatitis.5,12 Abdul Aziz et al2 postulated that DMSO might be used as a method to prevent the progression of necrosis in symptomatic patients following HIPEC with MitC. Reports of its use on the scrotum are absent in the current available literature.

Treatment with DMSO was attempted in our patient with limited success secondary to delayed recognition and lack of supporting literature for DMSO treatment of scrotal necrosis. Treatment was delayed by 11 days after the onset of symptoms, which is far beyond the recommendation of starting within 10 minutes.8 Irreversible tissue necrosis had already occurred as evidenced by the presence of eschar. However, it seems apparent that DMSO provided some benefit given the clear improvement in erythema and pain 7 hours after application (Figure 2). It is unknown to what extent the necrosis would have progressed if not treated with DMSO.

Scrotal necrosis following HIPEC with MitC is a rare and incompletely understood but important chemotherapy reaction. The presentation is fairly specific with the presence of intractable and constant scrotal pain along with erythema and induration progressing to eschar. Although DMSO has been found to be effective for certain vesicant extravasation reactions at IV sites, it is not well studied for MitC, and no reports exist regarding its use on the scrotum. The presented characterization and explanation of the pathophysiology of this entity will aid in early recognition and timely institution of topical mitigating agents such as DMSO, which may prevent progression to scrotal necrosis and need for surgical debridement. More effective strategies may be geared toward prevention with thorough washout following HIPEC, preprocedural radiologic imaging or intraoperative visualization of the patent processus vaginalis, internal inguinal canal plugs, and patient education with anticipatory guidance should a reaction occur.2

To the Editor:

A 54-year-old man with a history of stage IV appendiceal carcinoid adenocarcinoma treated approximately 3 months prior with intraoperative hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) presented to our clinic with scrotal pain of 5 days’ duration. He had no history of genital herpes, topical contactants, other cutaneous lesions on the body, fever, or chills. On physical examination the patient had an erythematous, purpuric, indurated, tender plaque on the left anterolateral and anterior midline of the scrotum (Figure 1). No other areas of acral purpura or livedoid cutaneous changes were identified. There was no inguinal lymphadenopathy. Biopsy was performed for histologic examination as well as tissue culture. Histology demonstrated epidermal necrosis without evidence of vasculitis. Tissue culture was unremarkable.

Two days after clinic evaluation, the patient presented to the emergency department with progression of the lesions, and he was admitted to the hospital for pain control. Computed tomography of the pelvis showed bilateral hydroceles without evidence of abscess. Ultrasonography showed scrotal thickening without abscess or fluid collection. On day 5 in the hospital, a regimen of topical 60% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was applied every 8 hours to the affected area. The patient experienced notable pain relief and a decrease in erythema within 7 hours of application (Figure 2). This regimen was continued for 7 days with improvement in surrounding erythema and pain; however, the patient’s pain persisted in the areas of necrosis. Fourteen days following completion of therapy (27 days following presentation), the patient underwent debridement and partial scrotal resection for eschar removal. Histologic examination of the debrided scrotal tissue showed necrosis extending into the dermis and no evidence of vasculitis.

Our case demonstrates a unique presentation of scrotal necrosis secondary to mitomycin C (MitC) extravasation subsequently managed with DMSO. Imaging and biopsy findings effectively ruled out infection or vasculitis and led us to consider extravasation reactions that typically occur at peripheral intravenous (IV) infusion sites. Suspected cases of scrotal necrosis following HIPEC with MitC have been reported in the literature, along with hypothesized pathophysiology.1-3

In consideration of the proposed pathophysiology, individuals with hydroceles may be more likely to experience this complication due to an abnormal but not uncommon communication between the intraperitoneal cavity and the scrotum via a patent processus vaginalis. The location of necrosis on the anterior scrotum remains unexplained. It may be a consequence of the anatomic location of the hydrocele, a collection of fluid within the tunica vaginalis. The tunica vaginalis is composed of an inner visceral and outer parietal layer, enveloping the testis at the anterior border but not the superior or posterior border. Thus, sequestration of MitC in a hydrocele would correlate anatomically to necrosis of the anterior wall of the scrotum.

Akhavan et al1 proposed the testes are unaffected because of the presence of the tough fibrous coat of the tunica albuginea that directly adheres to the testes, in addition to the adjacent visceral layer of the tunica vaginalis. These 2 layers separating the testes and the hydrocele may provide a double barrier of protection for the testes.1

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms scrotal or cutaneous, pain or ulceration, and HIPEC or hyperthermic in

Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy involves installation of high-concentration chemotherapeutics into the peritoneal cavity at the conclusion of surgical cytoreductive therapy. Cell cycle–nonspecific agents such as MitC commonly are used for this procedure.4 It is classified as a vesicant, which is the designation given to drugs known to produce the most severe extravasation reactions of skin ulceration and necrosis.5,6 Symptoms typically include an early area of localized edema, erythema, and severe pain that progresses to superficial soft tissue and skin necrosis.7 Unfortunately, no well-studied antidote exists for MitC, though empirical guidelines suggest therapeutic management with DMSO and ice packs.6,8

Dimethyl sulfoxide is thought to work as a free radical scavenger as well as a solvent that facilitates diffusion of chemotherapeutics through tissues and thus down a concentration gradient, ideal in the circumstance of an extravasation reaction.8 Topical DMSO has been studied as a nonsurgical treatment in a small number of patients to prevent progression to necrosis following MitC extravasation.5,7 However, these cases only report extravasation reactions from IV infiltration.5,7,9 Dimethyl sulfoxide is rapidly absorbed and acts as a theoretical carrier for MitC as well as other topical substances.5,10,11 Caution is advised when using topical lidocaine or steroids in combination with DMSO, as they will be rapidly absorbed systemically. Patients also should be informed about a mild local burning sensation after DMSO application and a garliclike odor of the breath, which have occurred in 5.5% and 27.5% of patients, respectively (N=144).5 Dimethyl sulfoxide has no known toxic side effects but can cause erythema, pruritus, and very rarely allergic contact dermatitis.5,12 Abdul Aziz et al2 postulated that DMSO might be used as a method to prevent the progression of necrosis in symptomatic patients following HIPEC with MitC. Reports of its use on the scrotum are absent in the current available literature.

Treatment with DMSO was attempted in our patient with limited success secondary to delayed recognition and lack of supporting literature for DMSO treatment of scrotal necrosis. Treatment was delayed by 11 days after the onset of symptoms, which is far beyond the recommendation of starting within 10 minutes.8 Irreversible tissue necrosis had already occurred as evidenced by the presence of eschar. However, it seems apparent that DMSO provided some benefit given the clear improvement in erythema and pain 7 hours after application (Figure 2). It is unknown to what extent the necrosis would have progressed if not treated with DMSO.

Scrotal necrosis following HIPEC with MitC is a rare and incompletely understood but important chemotherapy reaction. The presentation is fairly specific with the presence of intractable and constant scrotal pain along with erythema and induration progressing to eschar. Although DMSO has been found to be effective for certain vesicant extravasation reactions at IV sites, it is not well studied for MitC, and no reports exist regarding its use on the scrotum. The presented characterization and explanation of the pathophysiology of this entity will aid in early recognition and timely institution of topical mitigating agents such as DMSO, which may prevent progression to scrotal necrosis and need for surgical debridement. More effective strategies may be geared toward prevention with thorough washout following HIPEC, preprocedural radiologic imaging or intraoperative visualization of the patent processus vaginalis, internal inguinal canal plugs, and patient education with anticipatory guidance should a reaction occur.2

- Akhavan A, Yin M, Benoit R. Scrotal ulcer after intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy. Urology. 2007;69:778.E9-E10.

- Abdul Aziz NH, Wang W, Teo MC. Scrotal pain and ulceration post HIPEC: a case report. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2015;46:60-63.

- Silva F, Avancini J, Criado P, et al. Scrotum ulcer developed after intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy with mitomycin-C [published October 21, 2012]. Bjui International. doi:10.1002/BJUIw-2012-019-web.

- González-Moreno S, González-Bayón LA, Ortega-Pérez G.Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy: rationale and technique. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;15:68-75.

- Bertelli G, Gozza A, Forno GB, et al. Topical dimethyl sulfoxide for the prevention of soft tissue injury after extravasation of vesicant cytotoxic drugs: a prospective clinical study. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2851-2855.

- Bertelli G. Prevention and management of extravasation of cytotoxic drugs. Drug Saf. 1995;12:245-255.

- Alberts DS, Dorr RT. Case report: topical DMSO for mitomycin-C-induced skin ulceration. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1991;18:693-695.

- Pérez Fidalgo JA, García Fabregat L, Cervantes A, et al; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Management of chemotherapy extravasation: ESMO-EONS Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(suppl 5):167-173.

- Ludwig CU, Stoll HR, Obrist R, et al. Prevention of cytotoxic drug induced skin ulcers with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and alpha-tocopherole. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1987;23:327-329.

- Groel JT. Dimethyl sulfoxide as a vehicle for corticosteroids. a comparison with the occlusive dressing technique. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:110-114.

- Simon LS, Grierson LM, Naseer Z. Efficacy and safety of topical diclofenac containing dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) compared with those of topical placebo, DMSO vehicle and oral diclofenac for knee osteoarthritis [published online April 19, 2009]. Pain. 2009;143:238-245.

- Nishimura M, Takano Y, Toshitani S. Systemic contact dermatitis medicamentosa occurring after intravesical dimethyl sulfoxide treatment for interstitial cystitis. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:182-183.

- Akhavan A, Yin M, Benoit R. Scrotal ulcer after intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy. Urology. 2007;69:778.E9-E10.

- Abdul Aziz NH, Wang W, Teo MC. Scrotal pain and ulceration post HIPEC: a case report. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2015;46:60-63.

- Silva F, Avancini J, Criado P, et al. Scrotum ulcer developed after intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy with mitomycin-C [published October 21, 2012]. Bjui International. doi:10.1002/BJUIw-2012-019-web.

- González-Moreno S, González-Bayón LA, Ortega-Pérez G.Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy: rationale and technique. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;15:68-75.

- Bertelli G, Gozza A, Forno GB, et al. Topical dimethyl sulfoxide for the prevention of soft tissue injury after extravasation of vesicant cytotoxic drugs: a prospective clinical study. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2851-2855.

- Bertelli G. Prevention and management of extravasation of cytotoxic drugs. Drug Saf. 1995;12:245-255.

- Alberts DS, Dorr RT. Case report: topical DMSO for mitomycin-C-induced skin ulceration. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1991;18:693-695.

- Pérez Fidalgo JA, García Fabregat L, Cervantes A, et al; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Management of chemotherapy extravasation: ESMO-EONS Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(suppl 5):167-173.

- Ludwig CU, Stoll HR, Obrist R, et al. Prevention of cytotoxic drug induced skin ulcers with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and alpha-tocopherole. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1987;23:327-329.

- Groel JT. Dimethyl sulfoxide as a vehicle for corticosteroids. a comparison with the occlusive dressing technique. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:110-114.

- Simon LS, Grierson LM, Naseer Z. Efficacy and safety of topical diclofenac containing dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) compared with those of topical placebo, DMSO vehicle and oral diclofenac for knee osteoarthritis [published online April 19, 2009]. Pain. 2009;143:238-245.

- Nishimura M, Takano Y, Toshitani S. Systemic contact dermatitis medicamentosa occurring after intravesical dimethyl sulfoxide treatment for interstitial cystitis. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:182-183.

Practice Points

- Scrotal ulceration following hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy has been reported only a few times in the literature and is likely underreported. The presentation in all reported cases was similar, with a delay in symptom onset of weeks to months, involvement of the anterior scrotum, and pain.

- Dimethyl sulfoxide, used in other vesicant reactions, may have a role in mitigating tissue damage. Alternatively, methods to prevent sequestration of vesicants in the potential space of the tunica vaginalis layers can be employed.

Crusted Plaque in the Umbilicus

The Diagnosis: Sister Mary Joseph Nodule

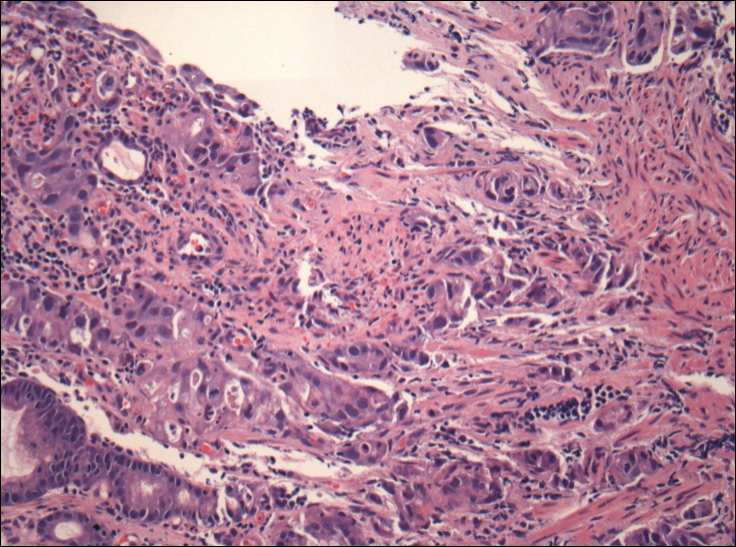

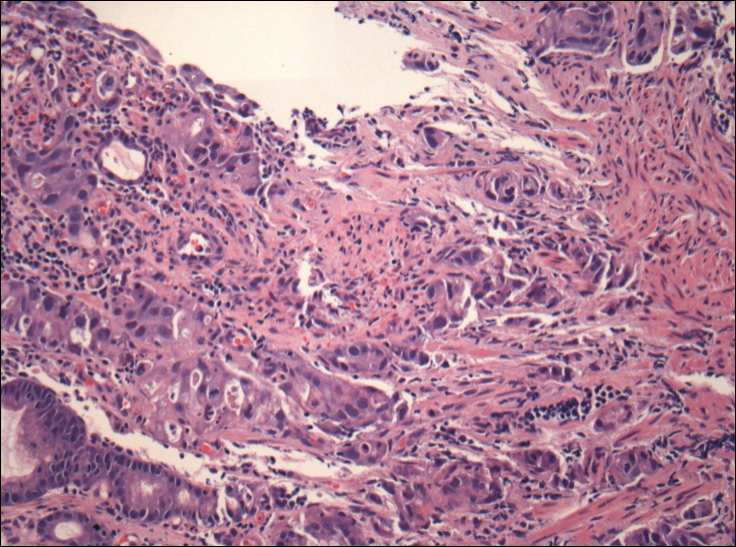

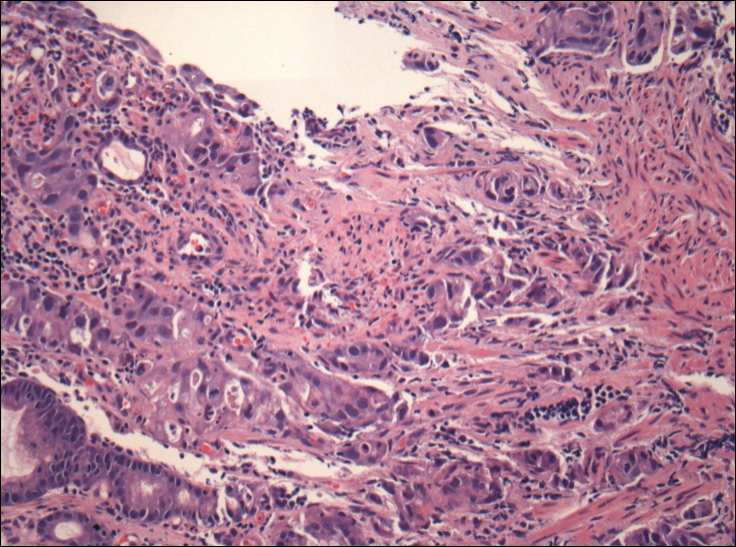

The umbilical skin biopsy revealed a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma (Figure) that was positive for cytokeratin 20 and CDX2 and negative for cytokeratin 7 and transcription termination factor 1. The patient subsequently underwent computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis, which showed multiple soft-tissue nodules on the greater omentum, a soft-tissue density at the umbilicus, and thickening of the gastric mucosa. An upper endoscopy was then performed, which revealed a large fungating ulcerated mass in the stomach. Biopsy of this mass showed an invasive moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, which was ERBB2 (formerly HER2) negative. Histopathologically, these pleomorphic glands looked similar to the glands seen in the original skin biopsy. With this diagnosis of metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma, our patient chose palliative chemotherapy but declined precipitously and died 2 months after the initial skin biopsy of the umbilical lesion.

When encountering a patient with an umbilical lesion, it is important to consider benign and malignant lesions in the differential diagnosis. A benign lesion may include scar, cyst, pyogenic granuloma, hemangioma, umbilical hernia, endometriosis, polyp, abscess, or the presence of an omphalith.1 Inflammatory dermatoses such as psoriasis or eczema also should be considered. Malignant lesions could be either primary or secondary, with metastatic disease being the most common.2 Sister Mary Joseph nodule (SMJN) is the eponymgiven to an umbilical lesion representing metastatic disease. Sister Mary Joseph was a nurse and surgical assistant to Dr. William Mayo in Rochester, Minnesota, in what is now known as the Mayo Clinic. She is credited to be the first to observe and note the association between an umbilical nodule and intra-abdominal malignancy. Metastasis to the umbilicus is thought to occur by way of contiguous, hematogenous, lymphatic, or direct spread through embryologic remnants from primary cancers of nearby gastrointestinal or pelvic viscera. It is a rare cutaneous sign of internal malignancy, with an estimated prevalence of 1% to 3%.3 The most common primary cancer is gastric adenocarcinoma, though cases of metastasis from pancreatic, endometrial, and less commonly hematopoietic or supradiaphragmatic cancers have been reported.4 It is more common in women, likely due to the addition of gynecologic malignancies.1

The use of dermoscopy has been advocated as an adjuvant tool in delineating benign and malignant umbilical lesions when an atypical polymorphous vascular pattern indicating neovascularization has been observed with neoplastic growth.5 Once a suspicious umbilical lesion is identified, the first step should be to obtain a skin biopsy or to use fine needle aspiration for cytology.6 Biopsy is especially relevant in the background of cancer history because SMJN may present with cancer recurrence.3 Once one of these is obtained, histological and immunohistochemical analysis will guide further workup and diagnosis of the umbilical lesion.

The importance of reviewing such cases lies in the variable presentation of cutaneous metastases such as SMJN and the grim prognosis that accompanies this finding. It presents as a firm indurated plaque or nodule that may present with systemic symptoms suggestive of malignancy, though in 30% of cases it is the sole initial sign.7 The nodule may be painful if ulcerated or fissured. Bloody, serous, or purulent discharge may be present. After diagnosis of an SMJN, most patients succumb to the disease within 12 months. Thus, it is vital for dermatologists to investigate umbilical lesions with great caution and a high index of suspicion.

- Chalya PL, Mabula JB, Rambau PF, et al. Sister Mary Joseph's nodule at a University teaching hospital in northwestern Tanzania: a retrospective review of 34 cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:151.

- Papalas JA, Selim MA. Metastatic vs primary malignant neoplasms affecting the umbilicus: clinicopathologic features of 77 tumors. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2011;15:237-242.

- Palaniappan M, Jose WM, Mehta A, et al. Umbilical metastasis: a case series of four Sister Joseph nodules from four different visceral malignancies. Curr Oncol. 2010;17:78-81.

- Zhang YL, Selvaggi SM. Metastatic islet cell carcinoma to the umbilicus: diagnosis by fine-needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;29:91-94.

- Mun JH, Kim JM, Ko HC, et al. Dermoscopy of a Sister Mary Joseph nodule. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:e190-e192.

- Handa U, Garg S, Mohan H. Fine-needle aspiration of Sister Mary Joseph's (paraumbilical) nodules. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:348-350.

- Abu-Hilal M, Newman JS. Sister Mary Joseph and her nodule: historical and clinical perspective. Am J Med Sci. 2009;337:271-273.

The Diagnosis: Sister Mary Joseph Nodule

The umbilical skin biopsy revealed a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma (Figure) that was positive for cytokeratin 20 and CDX2 and negative for cytokeratin 7 and transcription termination factor 1. The patient subsequently underwent computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis, which showed multiple soft-tissue nodules on the greater omentum, a soft-tissue density at the umbilicus, and thickening of the gastric mucosa. An upper endoscopy was then performed, which revealed a large fungating ulcerated mass in the stomach. Biopsy of this mass showed an invasive moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, which was ERBB2 (formerly HER2) negative. Histopathologically, these pleomorphic glands looked similar to the glands seen in the original skin biopsy. With this diagnosis of metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma, our patient chose palliative chemotherapy but declined precipitously and died 2 months after the initial skin biopsy of the umbilical lesion.

When encountering a patient with an umbilical lesion, it is important to consider benign and malignant lesions in the differential diagnosis. A benign lesion may include scar, cyst, pyogenic granuloma, hemangioma, umbilical hernia, endometriosis, polyp, abscess, or the presence of an omphalith.1 Inflammatory dermatoses such as psoriasis or eczema also should be considered. Malignant lesions could be either primary or secondary, with metastatic disease being the most common.2 Sister Mary Joseph nodule (SMJN) is the eponymgiven to an umbilical lesion representing metastatic disease. Sister Mary Joseph was a nurse and surgical assistant to Dr. William Mayo in Rochester, Minnesota, in what is now known as the Mayo Clinic. She is credited to be the first to observe and note the association between an umbilical nodule and intra-abdominal malignancy. Metastasis to the umbilicus is thought to occur by way of contiguous, hematogenous, lymphatic, or direct spread through embryologic remnants from primary cancers of nearby gastrointestinal or pelvic viscera. It is a rare cutaneous sign of internal malignancy, with an estimated prevalence of 1% to 3%.3 The most common primary cancer is gastric adenocarcinoma, though cases of metastasis from pancreatic, endometrial, and less commonly hematopoietic or supradiaphragmatic cancers have been reported.4 It is more common in women, likely due to the addition of gynecologic malignancies.1

The use of dermoscopy has been advocated as an adjuvant tool in delineating benign and malignant umbilical lesions when an atypical polymorphous vascular pattern indicating neovascularization has been observed with neoplastic growth.5 Once a suspicious umbilical lesion is identified, the first step should be to obtain a skin biopsy or to use fine needle aspiration for cytology.6 Biopsy is especially relevant in the background of cancer history because SMJN may present with cancer recurrence.3 Once one of these is obtained, histological and immunohistochemical analysis will guide further workup and diagnosis of the umbilical lesion.

The importance of reviewing such cases lies in the variable presentation of cutaneous metastases such as SMJN and the grim prognosis that accompanies this finding. It presents as a firm indurated plaque or nodule that may present with systemic symptoms suggestive of malignancy, though in 30% of cases it is the sole initial sign.7 The nodule may be painful if ulcerated or fissured. Bloody, serous, or purulent discharge may be present. After diagnosis of an SMJN, most patients succumb to the disease within 12 months. Thus, it is vital for dermatologists to investigate umbilical lesions with great caution and a high index of suspicion.

The Diagnosis: Sister Mary Joseph Nodule

The umbilical skin biopsy revealed a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma (Figure) that was positive for cytokeratin 20 and CDX2 and negative for cytokeratin 7 and transcription termination factor 1. The patient subsequently underwent computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis, which showed multiple soft-tissue nodules on the greater omentum, a soft-tissue density at the umbilicus, and thickening of the gastric mucosa. An upper endoscopy was then performed, which revealed a large fungating ulcerated mass in the stomach. Biopsy of this mass showed an invasive moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, which was ERBB2 (formerly HER2) negative. Histopathologically, these pleomorphic glands looked similar to the glands seen in the original skin biopsy. With this diagnosis of metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma, our patient chose palliative chemotherapy but declined precipitously and died 2 months after the initial skin biopsy of the umbilical lesion.

When encountering a patient with an umbilical lesion, it is important to consider benign and malignant lesions in the differential diagnosis. A benign lesion may include scar, cyst, pyogenic granuloma, hemangioma, umbilical hernia, endometriosis, polyp, abscess, or the presence of an omphalith.1 Inflammatory dermatoses such as psoriasis or eczema also should be considered. Malignant lesions could be either primary or secondary, with metastatic disease being the most common.2 Sister Mary Joseph nodule (SMJN) is the eponymgiven to an umbilical lesion representing metastatic disease. Sister Mary Joseph was a nurse and surgical assistant to Dr. William Mayo in Rochester, Minnesota, in what is now known as the Mayo Clinic. She is credited to be the first to observe and note the association between an umbilical nodule and intra-abdominal malignancy. Metastasis to the umbilicus is thought to occur by way of contiguous, hematogenous, lymphatic, or direct spread through embryologic remnants from primary cancers of nearby gastrointestinal or pelvic viscera. It is a rare cutaneous sign of internal malignancy, with an estimated prevalence of 1% to 3%.3 The most common primary cancer is gastric adenocarcinoma, though cases of metastasis from pancreatic, endometrial, and less commonly hematopoietic or supradiaphragmatic cancers have been reported.4 It is more common in women, likely due to the addition of gynecologic malignancies.1

The use of dermoscopy has been advocated as an adjuvant tool in delineating benign and malignant umbilical lesions when an atypical polymorphous vascular pattern indicating neovascularization has been observed with neoplastic growth.5 Once a suspicious umbilical lesion is identified, the first step should be to obtain a skin biopsy or to use fine needle aspiration for cytology.6 Biopsy is especially relevant in the background of cancer history because SMJN may present with cancer recurrence.3 Once one of these is obtained, histological and immunohistochemical analysis will guide further workup and diagnosis of the umbilical lesion.

The importance of reviewing such cases lies in the variable presentation of cutaneous metastases such as SMJN and the grim prognosis that accompanies this finding. It presents as a firm indurated plaque or nodule that may present with systemic symptoms suggestive of malignancy, though in 30% of cases it is the sole initial sign.7 The nodule may be painful if ulcerated or fissured. Bloody, serous, or purulent discharge may be present. After diagnosis of an SMJN, most patients succumb to the disease within 12 months. Thus, it is vital for dermatologists to investigate umbilical lesions with great caution and a high index of suspicion.

- Chalya PL, Mabula JB, Rambau PF, et al. Sister Mary Joseph's nodule at a University teaching hospital in northwestern Tanzania: a retrospective review of 34 cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:151.

- Papalas JA, Selim MA. Metastatic vs primary malignant neoplasms affecting the umbilicus: clinicopathologic features of 77 tumors. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2011;15:237-242.

- Palaniappan M, Jose WM, Mehta A, et al. Umbilical metastasis: a case series of four Sister Joseph nodules from four different visceral malignancies. Curr Oncol. 2010;17:78-81.

- Zhang YL, Selvaggi SM. Metastatic islet cell carcinoma to the umbilicus: diagnosis by fine-needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;29:91-94.

- Mun JH, Kim JM, Ko HC, et al. Dermoscopy of a Sister Mary Joseph nodule. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:e190-e192.

- Handa U, Garg S, Mohan H. Fine-needle aspiration of Sister Mary Joseph's (paraumbilical) nodules. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:348-350.

- Abu-Hilal M, Newman JS. Sister Mary Joseph and her nodule: historical and clinical perspective. Am J Med Sci. 2009;337:271-273.

- Chalya PL, Mabula JB, Rambau PF, et al. Sister Mary Joseph's nodule at a University teaching hospital in northwestern Tanzania: a retrospective review of 34 cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:151.

- Papalas JA, Selim MA. Metastatic vs primary malignant neoplasms affecting the umbilicus: clinicopathologic features of 77 tumors. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2011;15:237-242.

- Palaniappan M, Jose WM, Mehta A, et al. Umbilical metastasis: a case series of four Sister Joseph nodules from four different visceral malignancies. Curr Oncol. 2010;17:78-81.

- Zhang YL, Selvaggi SM. Metastatic islet cell carcinoma to the umbilicus: diagnosis by fine-needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;29:91-94.

- Mun JH, Kim JM, Ko HC, et al. Dermoscopy of a Sister Mary Joseph nodule. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:e190-e192.

- Handa U, Garg S, Mohan H. Fine-needle aspiration of Sister Mary Joseph's (paraumbilical) nodules. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:348-350.

- Abu-Hilal M, Newman JS. Sister Mary Joseph and her nodule: historical and clinical perspective. Am J Med Sci. 2009;337:271-273.

A 74-year-old man presented to our outpatient dermatology clinic with an asymptomatic umbilical lesion of unknown duration. The patient believed the lesion was a scar resulting from a prior laparoscopic repair of an umbilical hernia. However, the patient reported epigastric abdominal pain and diarrhea of 1 month's duration that he believed was due to the stomach flu. The patient denied fever, chills, loss of appetite, or weight loss. History was remarkable for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease, and emphysema. The patient had a surgical history of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty in addition to the laparoscopic umbilical hernia repair. The patient's medications included pantoprazole, ondansetron, diphenoxylate-atropine as needed, amlodipine, lisinopril-hydrochlorothiazide, simvastatin, and aspirin. Physical examination revealed a 1×2-cm pink, nodular, firm plaque with crust at the umbilicus that was tender on palpation. A shave biopsy of the umbilicus was performed and sent for both pathological and immunohistochemical analysis.