User login

2023 Update on contraception

More US women are using IUDs than ever before. With more use comes the potential for complications and more requests related to non-contraceptive benefits. New information provides contemporary insight into rare IUD complications and the use of hormonal IUDs for treatment of HMB.

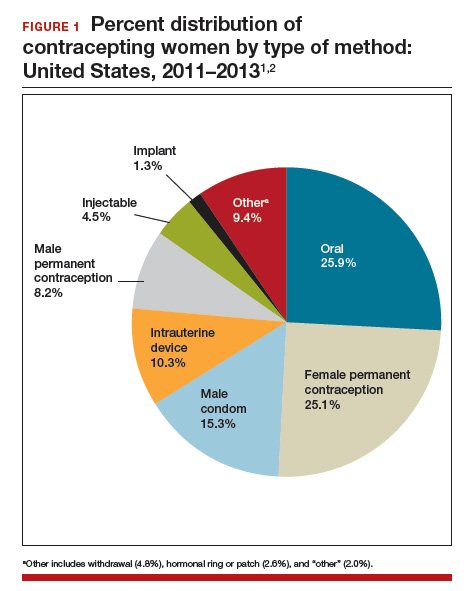

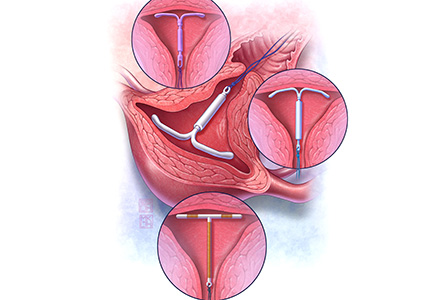

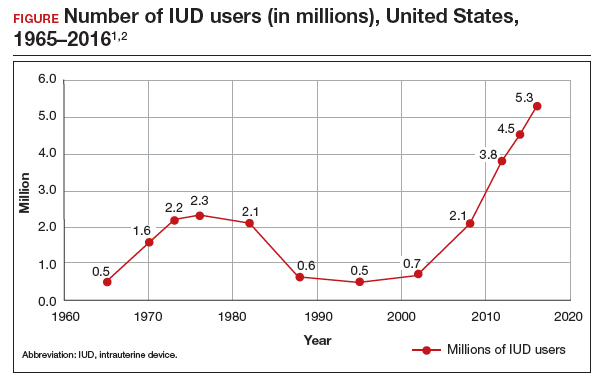

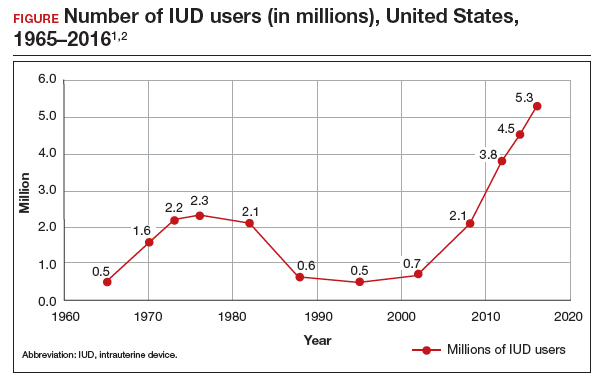

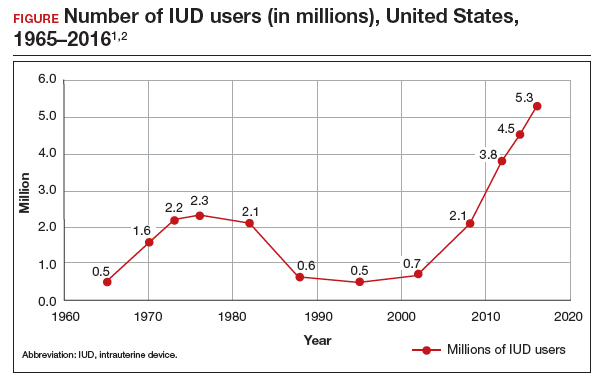

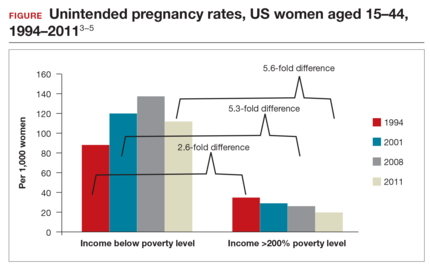

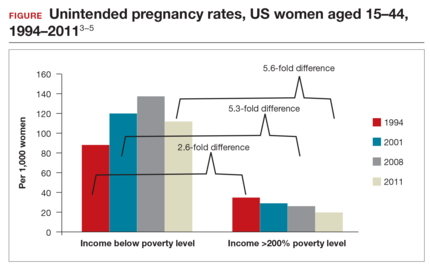

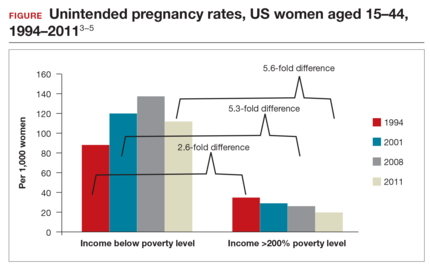

The first intrauterine device (IUD) to be approved in the United States, the Lippes Loop, became available in 1964. Sixty years later, more US women are using IUDs than ever before, and numbers are trending upward (FIGURE).1,2 Over the past year, contemporary information has become available to further inform IUD management when pregnancy occurs with an IUD in situ, as well as counseling about device breakage. Additionally, new data help clinicians expand which patients can use a levonorgestrel (LNG) 52-mg IUD for heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) treatment.

As the total absolute number of IUD users increases, so do the absolute numbers of rare outcomes, such as pregnancy among IUD users. These highly effective contraceptives have a failure rate within the first year after placement ranging from 0.1% for the LNG 52-mg IUD to 0.8% for the copper 380-mm2 IUD.3 Although the possibility for extrauterine gestation is higher when pregnancy occurs while a patient is using an IUD as compared with most other contraceptive methods, most pregnancies that occur with an IUD in situ are intrauterine.4

The high contraceptive efficacy of IUDs make pregnancy with a retained IUD rare; therefore, it is difficult to perform a study with a large enough population to evaluate management of pregnancy complicated by an IUD in situ. Clinical management recommendations for these situations are 20 years old and are supported by limited data from case reports and series with fewer than 200 patients.5,6

Intrauterine device breakage is another rare event that is poorly understood due to the low absolute number of cases. Information about breakage has similarly been limited to case reports and case series.7,8 This past year, contemporary data were published to provide more insight into both intrauterine pregnancy with an IUD in situ and IUD breakage.

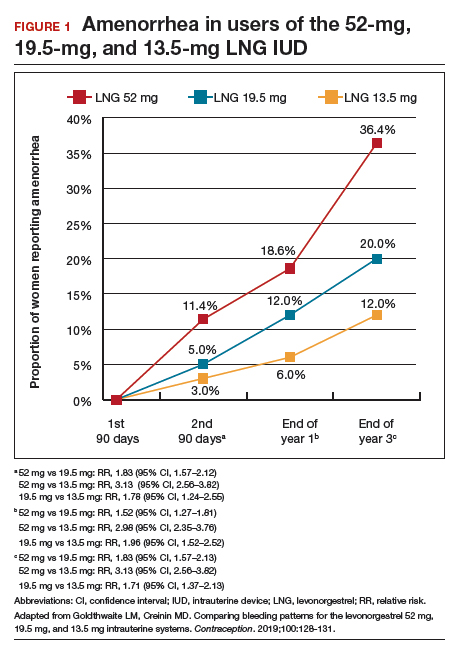

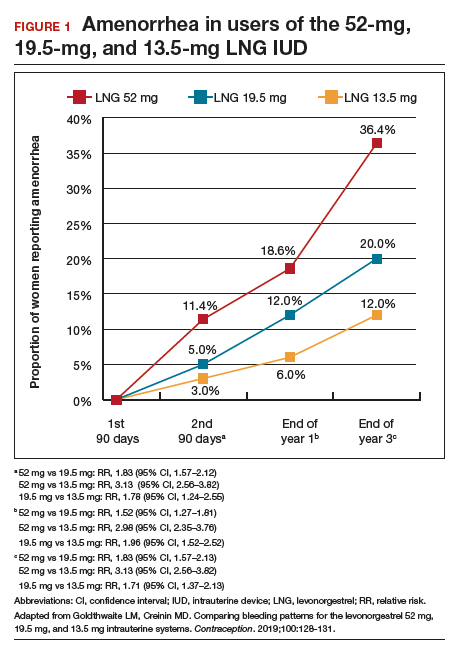

Beyond contraception, hormonal IUDs have become a popular and evidence-based treatment option for patients with HMB. The initial LNG 52-mg IUD (Mirena) regulatory approval studies for HMB treatment included data limited to parous patients and users with a body mass index (BMI) less than 35 kg/m2.9 Since that time, no studies have explored these populations. Although current practice has commonly extended use to include patients with these characteristics, we have lacked outcome data. New phase 3 data on the LNG 52-mg IUD (Liletta) included a broader range of participants and provide evidence to support this practice.

Removing retained copper 380-mm2 IUDs improves pregnancy outcomes

Panchal VR, Rau AR, Mandelbaum RS, et al. Pregnancy with retained intrauterine device: national-level assessment of characteristics and outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2023;5:101056. doi:10.1016/j.ajogmf.2023.101056

Karakuş SS, Karakuş R, Akalın EE, et al. Pregnancy outcomes with a copper 380 mm2 intrauterine device in place: a retrospective cohort study in Turkey, 2011-2021. Contraception. 2023;125:110090. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2023.110090

To update our understanding of outcomes of pregnancy with an IUD in situ, Panchal and colleagues performed a cross-sectional study using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project’s National Inpatient Sample. This data set represents 85% of US hospital discharges. The population investigated included hospital deliveries from 2016 to 2020 with an ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision) code of retained IUD. Those without the code were assigned to the comparison non-retained IUD group.

The primary outcome studied was the incidence rate of retained IUD, patient and pregnancy characteristics, and delivery outcomes including but not limited to gestational age at delivery, placental abnormalities, intrauterine fetal demise (IUFD), preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), cesarean delivery, postpartum hemorrhage, and hysterectomy.

Outcomes were worse with retained IUD, regardless of IUD removal status

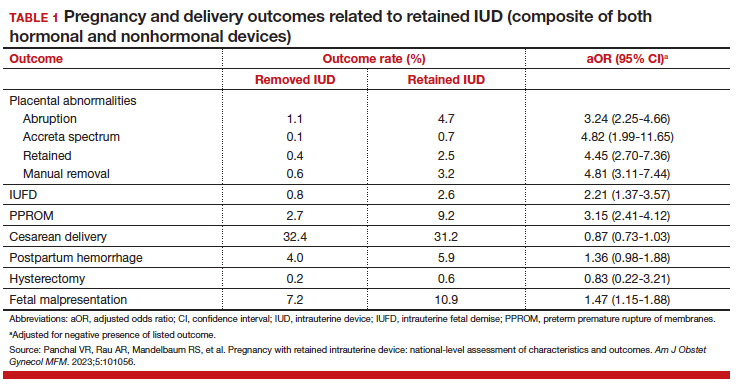

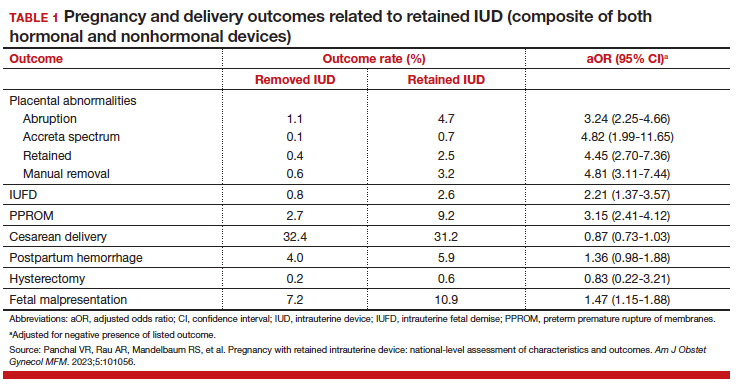

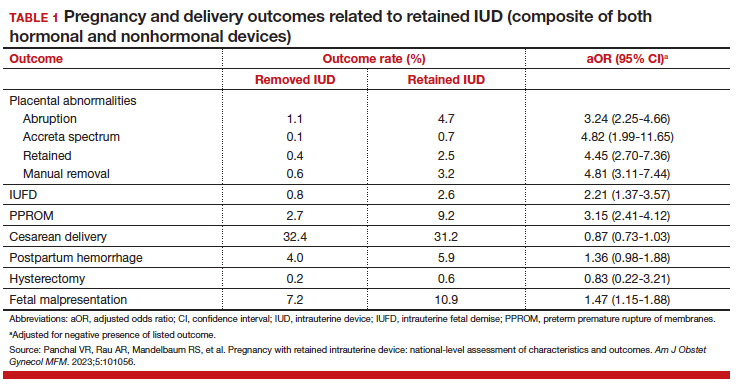

The authors found that an IUD in situ was reported in 1 out of 8,307 pregnancies and was associated with PPROM, fetal malpresentation, IUFD, placental abnormalities including abruption, accreta spectrum, retained placenta, and need for manual removal (TABLE 1). About three-quarters (76.3%) of patients had a term delivery (≥37 weeks).

Retained IUD was associated with previable loss, defined as less than 22 weeks’ gestation (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 5.49; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.30–9.15) and periviable delivery, defined as 22 to 25 weeks’ gestation (aOR, 2.81; 95% CI, 1.63–4.85). Retained IUD was not associated with preterm delivery beyond 26 weeks’ gestation, cesarean delivery, postpartum hemorrhage, or hysterectomy.

Important limitations of this study are the lack of information on IUD type (copper vs hormonal) and the timing of removal or attempted removal in relation to measured pregnancy outcomes.

Continue to: Removal of copper IUD improves, but does not eliminate, poor pregnancy outcomes...

Removal of copper IUD improves, but does not eliminate, poor pregnancy outcomes

Karakus and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study of 233 patients in Turkey with pregnancies that occurred during copper 380-mm2 IUD use from 2011 to 2021. The authors reported that, at the time of first contact with the health system and diagnosis of retained IUD, 18.9% of the pregnancies were ectopic, 13.2% were first trimester losses, and 67.5% were ongoing pregnancies.

The authors assessed outcomes in patients with ongoing pregnancies based on whether or not the IUD was removed or retained. Outcomes included gestational age at delivery and adverse pregnancy outcomes, assessed as a composite of preterm delivery, PPROM, chorioamnionitis, placental abruption, and postpartum hemorrhage.

Of those with ongoing pregnancies, 13.3% chose to have an abortion, leaving 137 (86.7%) with continuing pregnancy. The IUD was able to be removed in 39.4% of the sample, with an average gestational age of 7 weeks at the time of removal.

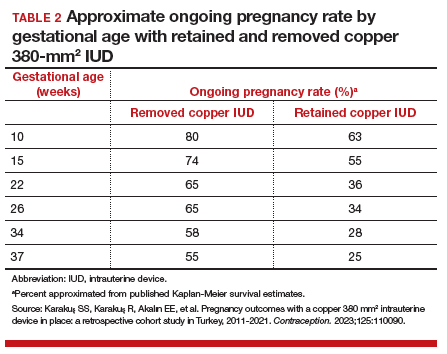

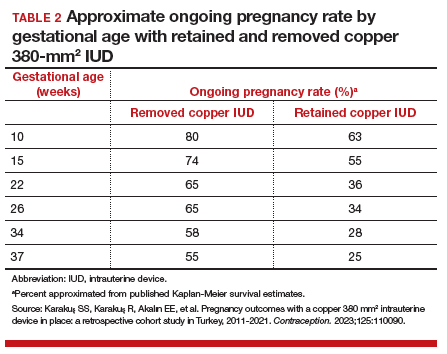

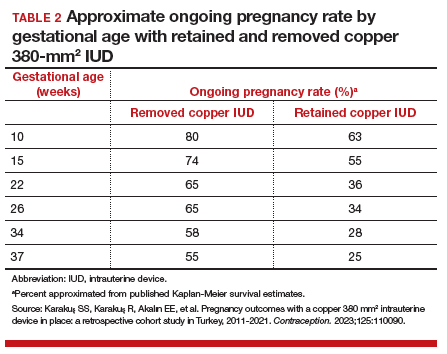

Compared with those with a retained IUD, patients in the removal group had a lower rate of pregnancy loss (33.3% vs 61.4%; P<.001) and a lower rate of the composite adverse pregnancy outcomes (53.1% vs 27.8%; P=.03). TABLE 2 shows the approximate rate of ongoing pregnancy by gestational age in patients with retained and removed copper 380-mm2 IUDs. Notably, the largest change occurred periviably, with the proportion of patients with an ongoing pregnancy after 26 weeks reducing to about half for patients with a retained IUD as compared with patients with a removed IUD; this proportion of ongoing pregnancies held through the remainder of gestation.

These studies confirm that a retained IUD is a rare outcome, occurring in about 1 in 8,000 pregnancies. Previous US national data from 2010 reported a similar incidence of 1 in 6,203 pregnancies (0.02%).10 Management and counseling depend on the patient’s desire to continue the pregnancy, gestational age, intrauterine IUD location, and ability to see the IUD strings. Contemporary data support management practices created from limited and outdated data, which include device removal (if able) and counseling those who desire to continue pregnancy about high-risk pregnancy complications. Those with a retained IUD should be counseled about increased risk of preterm or previable delivery, IUFD, and placental abnormalities (including accreta spectrum and retained placenta). Specifically, these contemporary data highlight that, beyond approximately 26 weeks’ gestation, the pregnancy loss rate is not different for those with a retained or removed IUD. Obstetric care providers should feel confident in using this more nuanced risk of extreme preterm delivery when counseling future patients. Implications for antepartum care and delivery timing with a retained IUD have not yet been defined.

Do national data reveal more breakage reports for copper 380-mm2 or LNG IUDs?

Latack KR, Nguyen BT. Trends in copper versus hormonal intrauterine device breakage reporting within the United States’ Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System. Contraception. 2023;118:109909. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2022.10.011

Latack and Nguyen reviewed postmarket surveillance data of IUD adverse events in the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) from 1998 to 2022. The FAERS is a voluntary, or passive, reporting system.

Study findings

Of the approximately 170,000 IUD-related adverse events reported to the agency during the 24-year timeframe, 25.4% were for copper IUDs and 74.6% were for hormonal IUDs. Slightly more than 4,000 reports were specific for device breakage, which the authors grouped into copper (copper 380-mm2)and hormonal (LNG 52 mg, 19.5 mg, and 13.5 mg) IUDs.

The copper 380-mm2 IUD was 6.19 times more likely to have a breakage report than hormonal IUDs (9.6% vs 1.7%; 95% CI, 5.87–6.53).

The overall proportion of IUD-related adverse events reported to the FDA was about 25% for copper and 75% for hormonal IUDs; this proportion is similar to sales figures, which show that about 15% of IUDs sold in the United States are copper and 85% are hormonal.11 However, the proportion of breakage events reported to the FDA is the inverse, with about 6 times more breakage reports with copper than with hormonal IUDs. Because these data come from a passive reporting system, the true incidence of IUD breakage cannot be assessed. However, these findings should remind clinicians to inform patients about this rare occurrence during counseling at the time of placement and, especially, when preparing for copper IUD removal. As the absolute number of IUD users increases, clinicians may be more likely to encounter this relatively rare event.

Management of IUD breakage is based on expert opinion, and recommendations are varied, ranging from observation to removal using an IUD hook, alligator forceps, manual vacuum aspiration, or hysteroscopy.7,10 Importantly, each individual patient situation will vary depending on the presence or absence of other symptoms and whether or not future pregnancy is desired.

Continue to: Data support the LNG 52-mg IUD for HMB in nulliparous and obese patients...

Data support the LNG 52-mg IUD for HMB in nulliparous and obese patients

Creinin MD, Barnhart KT, Gawron LM, et al. Heavy menstrual bleeding treatment with a levonorgestrel 52-mg intrauterine device. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:971-978. doi:10.1097AOG.0000000000005137

Creinin and colleagues conducted a study for US regulatory product approval of the LNG 52-mg IUD (Liletta) for HMB. This multicenter phase 3 open-label clinical trial recruited nonpregnant participants aged 18 to 50 years with HMB at 29 clinical sites in the United States. No BMI cutoff was used.

Baseline menstrual flow data were obtained over 2 to 3 screening cycles by collection of menstrual products and quantification of blood loss using alkaline hematin measurement. Patients with 2 cycles with a blood loss exceeding 80 mL had an IUD placement, with similar flow evaluations during the third and sixth postplacement cycles.

Treatment success was defined as a reduction in blood loss by more than 50% as compared with baseline (during screening) and measured blood loss of less than 80 mL. The enrolled population (n=105) included 28% nulliparous users, with 49% and 28% of participants having a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or higher and higher than 35 kg/m2, respectively.

Treatment highly successful in reducing blood loss

Participants in this trial had a 93% and a 98% reduction in blood loss at the third and sixth cycles of use, respectively. Additionally, during the sixth cycle of use, 19% of users had no bleeding. Treatment success occurred in about 80% of participants overall and occurred regardless of parity or BMI.

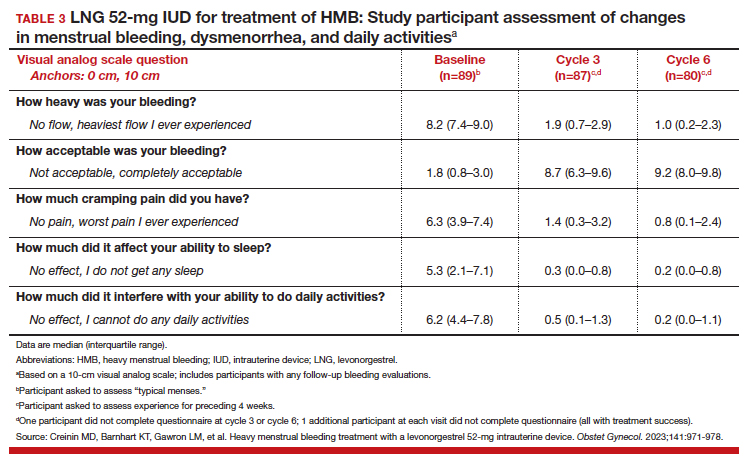

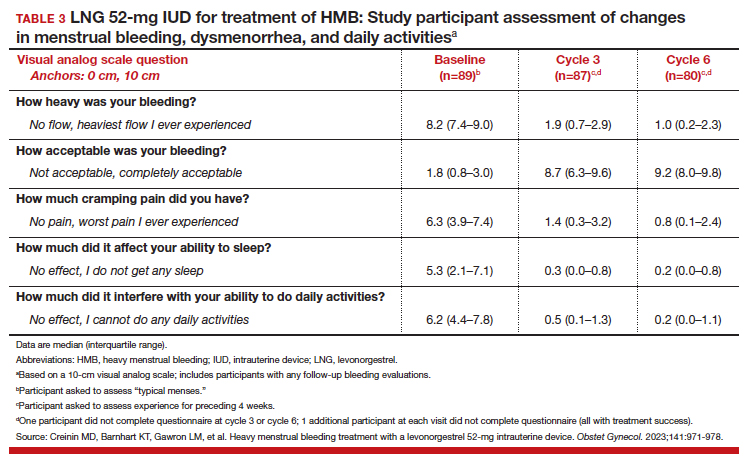

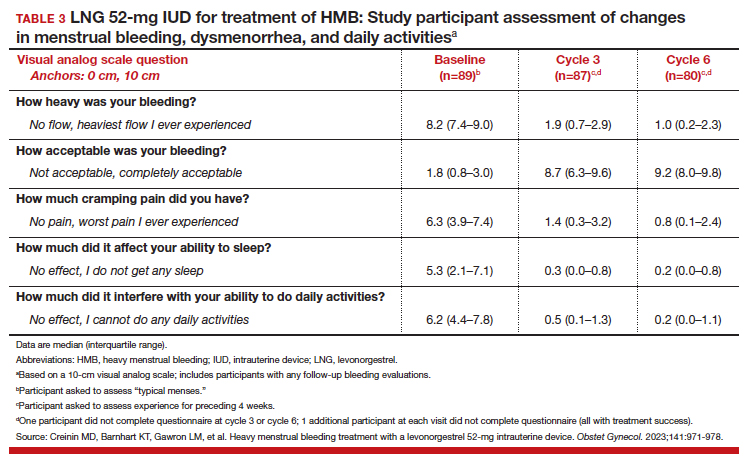

To assess a subjective measure of success, participants were asked to evaluate their menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhea severity, acceptability, and overall impact on quality of life at 3 time points: during prior typical menses, cycle 3, and cycle 6. At cycle 6, all participants reported significantly improved acceptability of bleeding and uterine pain and, importantly, decreased overall menstrual interference with the ability to complete daily activities (TABLE 3).

IUD expulsion and replacement rates

Although bleeding greatly decreased in all participants, 13% (n=14) discontinued before cycle 6 due to expulsion or IUD-related symptoms, with the majority citing bleeding irregularities. Expulsion occurred in 9% (n=5) of users, with the majority (2/3) occurring in the first 3 months of use and more commonly in obese and/or parous users. About half of participants with expulsion had the IUD replaced during the study. ●

Interestingly, both LNG 52-mg IUDs have been approved in most countries throughout the world for HMB treatment, and only in the United States was one of the products (Liletta) not approved until this past year. The FDA required more stringent trials than had been previously performed for approval outside of the United States. However, a benefit for clinicians is that this phase 3 study provided data in a contemporary US population. Clinicians can feel confident in counseling and offering the LNG 52-mg IUD as a first-line treatment option for patients with HMB, including those who have never been pregnant or have a BMI greater than 35 kg/m2.

Importantly, though, clinicians should be realistic with all patients that this treatment, although highly effective, is not successful for about 20% of patients by about 6 months of use. For those in whom the treatment is beneficial, the quality-of-life improvement is dramatic. Additionally, this study reminds us that expulsion risk in a population primarily using the IUD for HMB, especially if also obese and/or parous, is higher in the first 6 months of use than patients using the method for contraception. Expulsion occurs in 1.6% of contraception users through 6 months of use.12 These data highlight that IUD expulsion risk is not a fixed number, but instead is modified by patient characteristics. Patients should be counseled regarding the appropriate expulsion risk and that the IUD can be safely replaced should expulsion occur.

- Hubacher D, Kavanaugh M. Historical record-setting trends in IUD use in the United States. Contraception. 2018;98:467470. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2018.05.016

- Kavanaugh ML, Pliskin E. Use of contraception among reproductive-aged women in the United States, 2014 and 2016. F S Rep. 2020;1:83-93. doi:10.1016/j.xfre.2020.06.006

- Jensen JT, Creinin MD. Speroff & Darney’s Clinical Guide to Contraception. 6th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2020:15.

- Jensen JT, Creinin MD. Speroff & Darney’s Clinical Guide to Contraception. 6th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2020:185.

- Ozgu-Erdinc AS, Tasdemir UG, Uygur D, et al. Outcome of intrauterine pregnancies with intrauterine device in place and effects of device location on prognosis. Contraception. 2014;89:426-430. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2014.01.002

- Brahmi D, Steenland MW, Renner RM, et al. Pregnancy outcomes with an IUD in situ: a systematic review. Contraception. 2012;85:131-139. doi:10.1016/j.contraception . 2011.06.010

- Wilson S, Tan G, Baylson M, et al. Controversies in family planning: how to manage a fractured IUD. Contraception. 2013;88:599-603. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2013.07.007

- Fulkerson Schaeffer S, Gimovsky AC, Aly H, et al. Pregnancy and delivery with an intrauterine device in situ: outcomes in the National Inpatient Sample Database. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32:798-803. doi:10.1080/14767058.2017.1 391783

- Mirena. Prescribing information. Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://www .mirena-us.com/pi

- Myo MG, Nguyen BT. Intrauterine device complications and their management. Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep. 2023;12:88-95. doi.org/10.1007/s13669-023-00357-8

- National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). 2017-2019 National Survey of Family Growth. Public-Use Data File Documentation. CDC National Center for Health Statistics. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data /nsfg/NSFG-2017-2019-UG-MainText-508.pdf

- Gilliam ML, Jensen JT, Eisenberg DL, et al. Relationship of parity and prior cesarean delivery to levonorgestrel 52 mg intrauterine system expulsion over 6 years. Contraception. 2021;103:444-449. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.02.013

More US women are using IUDs than ever before. With more use comes the potential for complications and more requests related to non-contraceptive benefits. New information provides contemporary insight into rare IUD complications and the use of hormonal IUDs for treatment of HMB.

The first intrauterine device (IUD) to be approved in the United States, the Lippes Loop, became available in 1964. Sixty years later, more US women are using IUDs than ever before, and numbers are trending upward (FIGURE).1,2 Over the past year, contemporary information has become available to further inform IUD management when pregnancy occurs with an IUD in situ, as well as counseling about device breakage. Additionally, new data help clinicians expand which patients can use a levonorgestrel (LNG) 52-mg IUD for heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) treatment.

As the total absolute number of IUD users increases, so do the absolute numbers of rare outcomes, such as pregnancy among IUD users. These highly effective contraceptives have a failure rate within the first year after placement ranging from 0.1% for the LNG 52-mg IUD to 0.8% for the copper 380-mm2 IUD.3 Although the possibility for extrauterine gestation is higher when pregnancy occurs while a patient is using an IUD as compared with most other contraceptive methods, most pregnancies that occur with an IUD in situ are intrauterine.4

The high contraceptive efficacy of IUDs make pregnancy with a retained IUD rare; therefore, it is difficult to perform a study with a large enough population to evaluate management of pregnancy complicated by an IUD in situ. Clinical management recommendations for these situations are 20 years old and are supported by limited data from case reports and series with fewer than 200 patients.5,6

Intrauterine device breakage is another rare event that is poorly understood due to the low absolute number of cases. Information about breakage has similarly been limited to case reports and case series.7,8 This past year, contemporary data were published to provide more insight into both intrauterine pregnancy with an IUD in situ and IUD breakage.

Beyond contraception, hormonal IUDs have become a popular and evidence-based treatment option for patients with HMB. The initial LNG 52-mg IUD (Mirena) regulatory approval studies for HMB treatment included data limited to parous patients and users with a body mass index (BMI) less than 35 kg/m2.9 Since that time, no studies have explored these populations. Although current practice has commonly extended use to include patients with these characteristics, we have lacked outcome data. New phase 3 data on the LNG 52-mg IUD (Liletta) included a broader range of participants and provide evidence to support this practice.

Removing retained copper 380-mm2 IUDs improves pregnancy outcomes

Panchal VR, Rau AR, Mandelbaum RS, et al. Pregnancy with retained intrauterine device: national-level assessment of characteristics and outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2023;5:101056. doi:10.1016/j.ajogmf.2023.101056

Karakuş SS, Karakuş R, Akalın EE, et al. Pregnancy outcomes with a copper 380 mm2 intrauterine device in place: a retrospective cohort study in Turkey, 2011-2021. Contraception. 2023;125:110090. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2023.110090

To update our understanding of outcomes of pregnancy with an IUD in situ, Panchal and colleagues performed a cross-sectional study using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project’s National Inpatient Sample. This data set represents 85% of US hospital discharges. The population investigated included hospital deliveries from 2016 to 2020 with an ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision) code of retained IUD. Those without the code were assigned to the comparison non-retained IUD group.

The primary outcome studied was the incidence rate of retained IUD, patient and pregnancy characteristics, and delivery outcomes including but not limited to gestational age at delivery, placental abnormalities, intrauterine fetal demise (IUFD), preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), cesarean delivery, postpartum hemorrhage, and hysterectomy.

Outcomes were worse with retained IUD, regardless of IUD removal status

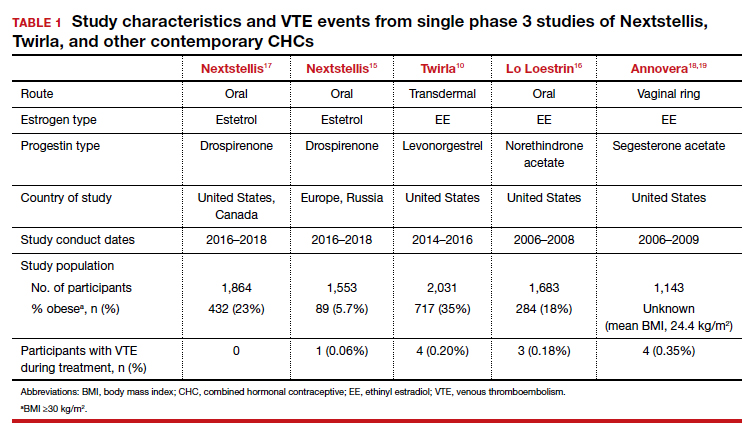

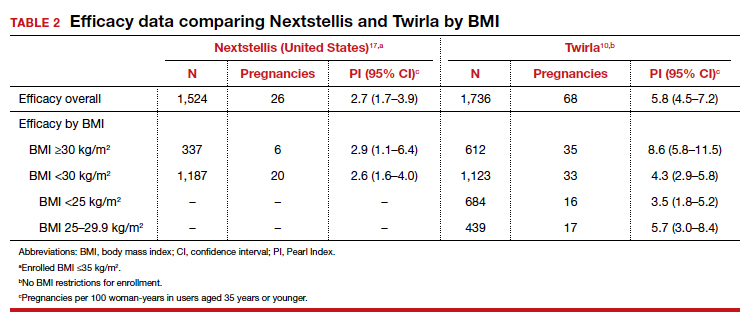

The authors found that an IUD in situ was reported in 1 out of 8,307 pregnancies and was associated with PPROM, fetal malpresentation, IUFD, placental abnormalities including abruption, accreta spectrum, retained placenta, and need for manual removal (TABLE 1). About three-quarters (76.3%) of patients had a term delivery (≥37 weeks).

Retained IUD was associated with previable loss, defined as less than 22 weeks’ gestation (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 5.49; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.30–9.15) and periviable delivery, defined as 22 to 25 weeks’ gestation (aOR, 2.81; 95% CI, 1.63–4.85). Retained IUD was not associated with preterm delivery beyond 26 weeks’ gestation, cesarean delivery, postpartum hemorrhage, or hysterectomy.

Important limitations of this study are the lack of information on IUD type (copper vs hormonal) and the timing of removal or attempted removal in relation to measured pregnancy outcomes.

Continue to: Removal of copper IUD improves, but does not eliminate, poor pregnancy outcomes...

Removal of copper IUD improves, but does not eliminate, poor pregnancy outcomes

Karakus and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study of 233 patients in Turkey with pregnancies that occurred during copper 380-mm2 IUD use from 2011 to 2021. The authors reported that, at the time of first contact with the health system and diagnosis of retained IUD, 18.9% of the pregnancies were ectopic, 13.2% were first trimester losses, and 67.5% were ongoing pregnancies.

The authors assessed outcomes in patients with ongoing pregnancies based on whether or not the IUD was removed or retained. Outcomes included gestational age at delivery and adverse pregnancy outcomes, assessed as a composite of preterm delivery, PPROM, chorioamnionitis, placental abruption, and postpartum hemorrhage.

Of those with ongoing pregnancies, 13.3% chose to have an abortion, leaving 137 (86.7%) with continuing pregnancy. The IUD was able to be removed in 39.4% of the sample, with an average gestational age of 7 weeks at the time of removal.

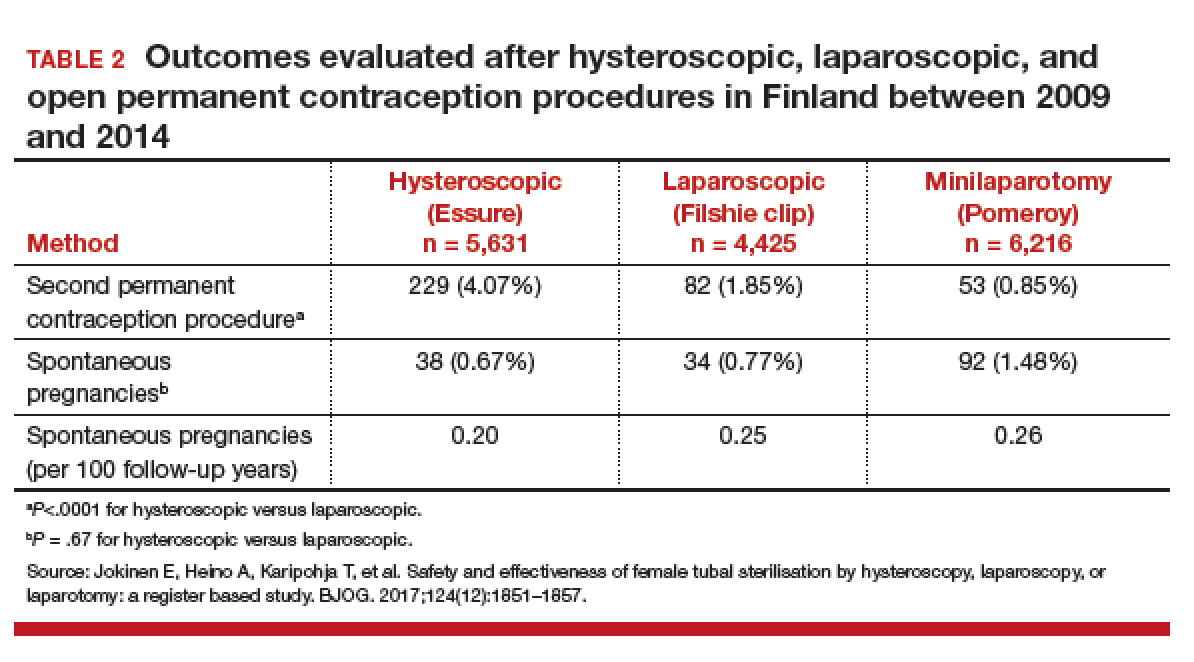

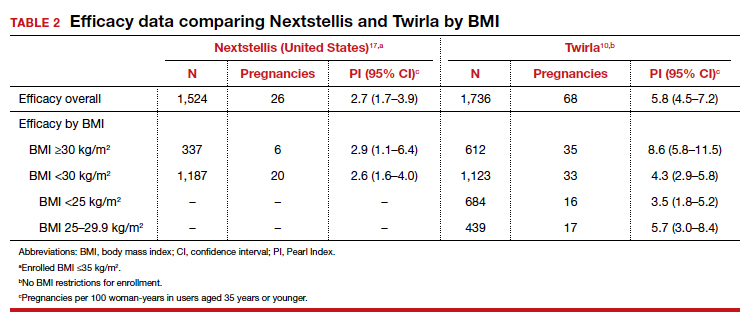

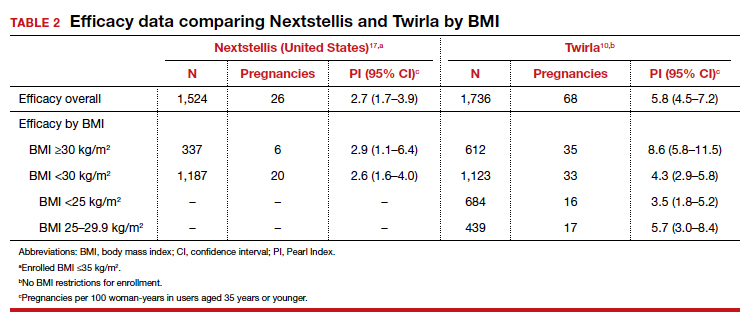

Compared with those with a retained IUD, patients in the removal group had a lower rate of pregnancy loss (33.3% vs 61.4%; P<.001) and a lower rate of the composite adverse pregnancy outcomes (53.1% vs 27.8%; P=.03). TABLE 2 shows the approximate rate of ongoing pregnancy by gestational age in patients with retained and removed copper 380-mm2 IUDs. Notably, the largest change occurred periviably, with the proportion of patients with an ongoing pregnancy after 26 weeks reducing to about half for patients with a retained IUD as compared with patients with a removed IUD; this proportion of ongoing pregnancies held through the remainder of gestation.

These studies confirm that a retained IUD is a rare outcome, occurring in about 1 in 8,000 pregnancies. Previous US national data from 2010 reported a similar incidence of 1 in 6,203 pregnancies (0.02%).10 Management and counseling depend on the patient’s desire to continue the pregnancy, gestational age, intrauterine IUD location, and ability to see the IUD strings. Contemporary data support management practices created from limited and outdated data, which include device removal (if able) and counseling those who desire to continue pregnancy about high-risk pregnancy complications. Those with a retained IUD should be counseled about increased risk of preterm or previable delivery, IUFD, and placental abnormalities (including accreta spectrum and retained placenta). Specifically, these contemporary data highlight that, beyond approximately 26 weeks’ gestation, the pregnancy loss rate is not different for those with a retained or removed IUD. Obstetric care providers should feel confident in using this more nuanced risk of extreme preterm delivery when counseling future patients. Implications for antepartum care and delivery timing with a retained IUD have not yet been defined.

Do national data reveal more breakage reports for copper 380-mm2 or LNG IUDs?

Latack KR, Nguyen BT. Trends in copper versus hormonal intrauterine device breakage reporting within the United States’ Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System. Contraception. 2023;118:109909. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2022.10.011

Latack and Nguyen reviewed postmarket surveillance data of IUD adverse events in the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) from 1998 to 2022. The FAERS is a voluntary, or passive, reporting system.

Study findings

Of the approximately 170,000 IUD-related adverse events reported to the agency during the 24-year timeframe, 25.4% were for copper IUDs and 74.6% were for hormonal IUDs. Slightly more than 4,000 reports were specific for device breakage, which the authors grouped into copper (copper 380-mm2)and hormonal (LNG 52 mg, 19.5 mg, and 13.5 mg) IUDs.

The copper 380-mm2 IUD was 6.19 times more likely to have a breakage report than hormonal IUDs (9.6% vs 1.7%; 95% CI, 5.87–6.53).

The overall proportion of IUD-related adverse events reported to the FDA was about 25% for copper and 75% for hormonal IUDs; this proportion is similar to sales figures, which show that about 15% of IUDs sold in the United States are copper and 85% are hormonal.11 However, the proportion of breakage events reported to the FDA is the inverse, with about 6 times more breakage reports with copper than with hormonal IUDs. Because these data come from a passive reporting system, the true incidence of IUD breakage cannot be assessed. However, these findings should remind clinicians to inform patients about this rare occurrence during counseling at the time of placement and, especially, when preparing for copper IUD removal. As the absolute number of IUD users increases, clinicians may be more likely to encounter this relatively rare event.

Management of IUD breakage is based on expert opinion, and recommendations are varied, ranging from observation to removal using an IUD hook, alligator forceps, manual vacuum aspiration, or hysteroscopy.7,10 Importantly, each individual patient situation will vary depending on the presence or absence of other symptoms and whether or not future pregnancy is desired.

Continue to: Data support the LNG 52-mg IUD for HMB in nulliparous and obese patients...

Data support the LNG 52-mg IUD for HMB in nulliparous and obese patients

Creinin MD, Barnhart KT, Gawron LM, et al. Heavy menstrual bleeding treatment with a levonorgestrel 52-mg intrauterine device. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:971-978. doi:10.1097AOG.0000000000005137

Creinin and colleagues conducted a study for US regulatory product approval of the LNG 52-mg IUD (Liletta) for HMB. This multicenter phase 3 open-label clinical trial recruited nonpregnant participants aged 18 to 50 years with HMB at 29 clinical sites in the United States. No BMI cutoff was used.

Baseline menstrual flow data were obtained over 2 to 3 screening cycles by collection of menstrual products and quantification of blood loss using alkaline hematin measurement. Patients with 2 cycles with a blood loss exceeding 80 mL had an IUD placement, with similar flow evaluations during the third and sixth postplacement cycles.

Treatment success was defined as a reduction in blood loss by more than 50% as compared with baseline (during screening) and measured blood loss of less than 80 mL. The enrolled population (n=105) included 28% nulliparous users, with 49% and 28% of participants having a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or higher and higher than 35 kg/m2, respectively.

Treatment highly successful in reducing blood loss

Participants in this trial had a 93% and a 98% reduction in blood loss at the third and sixth cycles of use, respectively. Additionally, during the sixth cycle of use, 19% of users had no bleeding. Treatment success occurred in about 80% of participants overall and occurred regardless of parity or BMI.

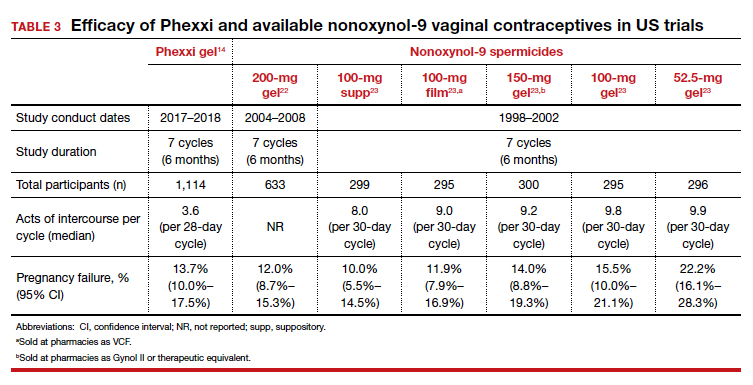

To assess a subjective measure of success, participants were asked to evaluate their menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhea severity, acceptability, and overall impact on quality of life at 3 time points: during prior typical menses, cycle 3, and cycle 6. At cycle 6, all participants reported significantly improved acceptability of bleeding and uterine pain and, importantly, decreased overall menstrual interference with the ability to complete daily activities (TABLE 3).

IUD expulsion and replacement rates

Although bleeding greatly decreased in all participants, 13% (n=14) discontinued before cycle 6 due to expulsion or IUD-related symptoms, with the majority citing bleeding irregularities. Expulsion occurred in 9% (n=5) of users, with the majority (2/3) occurring in the first 3 months of use and more commonly in obese and/or parous users. About half of participants with expulsion had the IUD replaced during the study. ●

Interestingly, both LNG 52-mg IUDs have been approved in most countries throughout the world for HMB treatment, and only in the United States was one of the products (Liletta) not approved until this past year. The FDA required more stringent trials than had been previously performed for approval outside of the United States. However, a benefit for clinicians is that this phase 3 study provided data in a contemporary US population. Clinicians can feel confident in counseling and offering the LNG 52-mg IUD as a first-line treatment option for patients with HMB, including those who have never been pregnant or have a BMI greater than 35 kg/m2.

Importantly, though, clinicians should be realistic with all patients that this treatment, although highly effective, is not successful for about 20% of patients by about 6 months of use. For those in whom the treatment is beneficial, the quality-of-life improvement is dramatic. Additionally, this study reminds us that expulsion risk in a population primarily using the IUD for HMB, especially if also obese and/or parous, is higher in the first 6 months of use than patients using the method for contraception. Expulsion occurs in 1.6% of contraception users through 6 months of use.12 These data highlight that IUD expulsion risk is not a fixed number, but instead is modified by patient characteristics. Patients should be counseled regarding the appropriate expulsion risk and that the IUD can be safely replaced should expulsion occur.

More US women are using IUDs than ever before. With more use comes the potential for complications and more requests related to non-contraceptive benefits. New information provides contemporary insight into rare IUD complications and the use of hormonal IUDs for treatment of HMB.

The first intrauterine device (IUD) to be approved in the United States, the Lippes Loop, became available in 1964. Sixty years later, more US women are using IUDs than ever before, and numbers are trending upward (FIGURE).1,2 Over the past year, contemporary information has become available to further inform IUD management when pregnancy occurs with an IUD in situ, as well as counseling about device breakage. Additionally, new data help clinicians expand which patients can use a levonorgestrel (LNG) 52-mg IUD for heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) treatment.

As the total absolute number of IUD users increases, so do the absolute numbers of rare outcomes, such as pregnancy among IUD users. These highly effective contraceptives have a failure rate within the first year after placement ranging from 0.1% for the LNG 52-mg IUD to 0.8% for the copper 380-mm2 IUD.3 Although the possibility for extrauterine gestation is higher when pregnancy occurs while a patient is using an IUD as compared with most other contraceptive methods, most pregnancies that occur with an IUD in situ are intrauterine.4

The high contraceptive efficacy of IUDs make pregnancy with a retained IUD rare; therefore, it is difficult to perform a study with a large enough population to evaluate management of pregnancy complicated by an IUD in situ. Clinical management recommendations for these situations are 20 years old and are supported by limited data from case reports and series with fewer than 200 patients.5,6

Intrauterine device breakage is another rare event that is poorly understood due to the low absolute number of cases. Information about breakage has similarly been limited to case reports and case series.7,8 This past year, contemporary data were published to provide more insight into both intrauterine pregnancy with an IUD in situ and IUD breakage.

Beyond contraception, hormonal IUDs have become a popular and evidence-based treatment option for patients with HMB. The initial LNG 52-mg IUD (Mirena) regulatory approval studies for HMB treatment included data limited to parous patients and users with a body mass index (BMI) less than 35 kg/m2.9 Since that time, no studies have explored these populations. Although current practice has commonly extended use to include patients with these characteristics, we have lacked outcome data. New phase 3 data on the LNG 52-mg IUD (Liletta) included a broader range of participants and provide evidence to support this practice.

Removing retained copper 380-mm2 IUDs improves pregnancy outcomes

Panchal VR, Rau AR, Mandelbaum RS, et al. Pregnancy with retained intrauterine device: national-level assessment of characteristics and outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2023;5:101056. doi:10.1016/j.ajogmf.2023.101056

Karakuş SS, Karakuş R, Akalın EE, et al. Pregnancy outcomes with a copper 380 mm2 intrauterine device in place: a retrospective cohort study in Turkey, 2011-2021. Contraception. 2023;125:110090. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2023.110090

To update our understanding of outcomes of pregnancy with an IUD in situ, Panchal and colleagues performed a cross-sectional study using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project’s National Inpatient Sample. This data set represents 85% of US hospital discharges. The population investigated included hospital deliveries from 2016 to 2020 with an ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision) code of retained IUD. Those without the code were assigned to the comparison non-retained IUD group.

The primary outcome studied was the incidence rate of retained IUD, patient and pregnancy characteristics, and delivery outcomes including but not limited to gestational age at delivery, placental abnormalities, intrauterine fetal demise (IUFD), preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), cesarean delivery, postpartum hemorrhage, and hysterectomy.

Outcomes were worse with retained IUD, regardless of IUD removal status

The authors found that an IUD in situ was reported in 1 out of 8,307 pregnancies and was associated with PPROM, fetal malpresentation, IUFD, placental abnormalities including abruption, accreta spectrum, retained placenta, and need for manual removal (TABLE 1). About three-quarters (76.3%) of patients had a term delivery (≥37 weeks).

Retained IUD was associated with previable loss, defined as less than 22 weeks’ gestation (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 5.49; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.30–9.15) and periviable delivery, defined as 22 to 25 weeks’ gestation (aOR, 2.81; 95% CI, 1.63–4.85). Retained IUD was not associated with preterm delivery beyond 26 weeks’ gestation, cesarean delivery, postpartum hemorrhage, or hysterectomy.

Important limitations of this study are the lack of information on IUD type (copper vs hormonal) and the timing of removal or attempted removal in relation to measured pregnancy outcomes.

Continue to: Removal of copper IUD improves, but does not eliminate, poor pregnancy outcomes...

Removal of copper IUD improves, but does not eliminate, poor pregnancy outcomes

Karakus and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study of 233 patients in Turkey with pregnancies that occurred during copper 380-mm2 IUD use from 2011 to 2021. The authors reported that, at the time of first contact with the health system and diagnosis of retained IUD, 18.9% of the pregnancies were ectopic, 13.2% were first trimester losses, and 67.5% were ongoing pregnancies.

The authors assessed outcomes in patients with ongoing pregnancies based on whether or not the IUD was removed or retained. Outcomes included gestational age at delivery and adverse pregnancy outcomes, assessed as a composite of preterm delivery, PPROM, chorioamnionitis, placental abruption, and postpartum hemorrhage.

Of those with ongoing pregnancies, 13.3% chose to have an abortion, leaving 137 (86.7%) with continuing pregnancy. The IUD was able to be removed in 39.4% of the sample, with an average gestational age of 7 weeks at the time of removal.

Compared with those with a retained IUD, patients in the removal group had a lower rate of pregnancy loss (33.3% vs 61.4%; P<.001) and a lower rate of the composite adverse pregnancy outcomes (53.1% vs 27.8%; P=.03). TABLE 2 shows the approximate rate of ongoing pregnancy by gestational age in patients with retained and removed copper 380-mm2 IUDs. Notably, the largest change occurred periviably, with the proportion of patients with an ongoing pregnancy after 26 weeks reducing to about half for patients with a retained IUD as compared with patients with a removed IUD; this proportion of ongoing pregnancies held through the remainder of gestation.

These studies confirm that a retained IUD is a rare outcome, occurring in about 1 in 8,000 pregnancies. Previous US national data from 2010 reported a similar incidence of 1 in 6,203 pregnancies (0.02%).10 Management and counseling depend on the patient’s desire to continue the pregnancy, gestational age, intrauterine IUD location, and ability to see the IUD strings. Contemporary data support management practices created from limited and outdated data, which include device removal (if able) and counseling those who desire to continue pregnancy about high-risk pregnancy complications. Those with a retained IUD should be counseled about increased risk of preterm or previable delivery, IUFD, and placental abnormalities (including accreta spectrum and retained placenta). Specifically, these contemporary data highlight that, beyond approximately 26 weeks’ gestation, the pregnancy loss rate is not different for those with a retained or removed IUD. Obstetric care providers should feel confident in using this more nuanced risk of extreme preterm delivery when counseling future patients. Implications for antepartum care and delivery timing with a retained IUD have not yet been defined.

Do national data reveal more breakage reports for copper 380-mm2 or LNG IUDs?

Latack KR, Nguyen BT. Trends in copper versus hormonal intrauterine device breakage reporting within the United States’ Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System. Contraception. 2023;118:109909. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2022.10.011

Latack and Nguyen reviewed postmarket surveillance data of IUD adverse events in the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) from 1998 to 2022. The FAERS is a voluntary, or passive, reporting system.

Study findings

Of the approximately 170,000 IUD-related adverse events reported to the agency during the 24-year timeframe, 25.4% were for copper IUDs and 74.6% were for hormonal IUDs. Slightly more than 4,000 reports were specific for device breakage, which the authors grouped into copper (copper 380-mm2)and hormonal (LNG 52 mg, 19.5 mg, and 13.5 mg) IUDs.

The copper 380-mm2 IUD was 6.19 times more likely to have a breakage report than hormonal IUDs (9.6% vs 1.7%; 95% CI, 5.87–6.53).

The overall proportion of IUD-related adverse events reported to the FDA was about 25% for copper and 75% for hormonal IUDs; this proportion is similar to sales figures, which show that about 15% of IUDs sold in the United States are copper and 85% are hormonal.11 However, the proportion of breakage events reported to the FDA is the inverse, with about 6 times more breakage reports with copper than with hormonal IUDs. Because these data come from a passive reporting system, the true incidence of IUD breakage cannot be assessed. However, these findings should remind clinicians to inform patients about this rare occurrence during counseling at the time of placement and, especially, when preparing for copper IUD removal. As the absolute number of IUD users increases, clinicians may be more likely to encounter this relatively rare event.

Management of IUD breakage is based on expert opinion, and recommendations are varied, ranging from observation to removal using an IUD hook, alligator forceps, manual vacuum aspiration, or hysteroscopy.7,10 Importantly, each individual patient situation will vary depending on the presence or absence of other symptoms and whether or not future pregnancy is desired.

Continue to: Data support the LNG 52-mg IUD for HMB in nulliparous and obese patients...

Data support the LNG 52-mg IUD for HMB in nulliparous and obese patients

Creinin MD, Barnhart KT, Gawron LM, et al. Heavy menstrual bleeding treatment with a levonorgestrel 52-mg intrauterine device. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:971-978. doi:10.1097AOG.0000000000005137

Creinin and colleagues conducted a study for US regulatory product approval of the LNG 52-mg IUD (Liletta) for HMB. This multicenter phase 3 open-label clinical trial recruited nonpregnant participants aged 18 to 50 years with HMB at 29 clinical sites in the United States. No BMI cutoff was used.

Baseline menstrual flow data were obtained over 2 to 3 screening cycles by collection of menstrual products and quantification of blood loss using alkaline hematin measurement. Patients with 2 cycles with a blood loss exceeding 80 mL had an IUD placement, with similar flow evaluations during the third and sixth postplacement cycles.

Treatment success was defined as a reduction in blood loss by more than 50% as compared with baseline (during screening) and measured blood loss of less than 80 mL. The enrolled population (n=105) included 28% nulliparous users, with 49% and 28% of participants having a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or higher and higher than 35 kg/m2, respectively.

Treatment highly successful in reducing blood loss

Participants in this trial had a 93% and a 98% reduction in blood loss at the third and sixth cycles of use, respectively. Additionally, during the sixth cycle of use, 19% of users had no bleeding. Treatment success occurred in about 80% of participants overall and occurred regardless of parity or BMI.

To assess a subjective measure of success, participants were asked to evaluate their menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhea severity, acceptability, and overall impact on quality of life at 3 time points: during prior typical menses, cycle 3, and cycle 6. At cycle 6, all participants reported significantly improved acceptability of bleeding and uterine pain and, importantly, decreased overall menstrual interference with the ability to complete daily activities (TABLE 3).

IUD expulsion and replacement rates

Although bleeding greatly decreased in all participants, 13% (n=14) discontinued before cycle 6 due to expulsion or IUD-related symptoms, with the majority citing bleeding irregularities. Expulsion occurred in 9% (n=5) of users, with the majority (2/3) occurring in the first 3 months of use and more commonly in obese and/or parous users. About half of participants with expulsion had the IUD replaced during the study. ●

Interestingly, both LNG 52-mg IUDs have been approved in most countries throughout the world for HMB treatment, and only in the United States was one of the products (Liletta) not approved until this past year. The FDA required more stringent trials than had been previously performed for approval outside of the United States. However, a benefit for clinicians is that this phase 3 study provided data in a contemporary US population. Clinicians can feel confident in counseling and offering the LNG 52-mg IUD as a first-line treatment option for patients with HMB, including those who have never been pregnant or have a BMI greater than 35 kg/m2.

Importantly, though, clinicians should be realistic with all patients that this treatment, although highly effective, is not successful for about 20% of patients by about 6 months of use. For those in whom the treatment is beneficial, the quality-of-life improvement is dramatic. Additionally, this study reminds us that expulsion risk in a population primarily using the IUD for HMB, especially if also obese and/or parous, is higher in the first 6 months of use than patients using the method for contraception. Expulsion occurs in 1.6% of contraception users through 6 months of use.12 These data highlight that IUD expulsion risk is not a fixed number, but instead is modified by patient characteristics. Patients should be counseled regarding the appropriate expulsion risk and that the IUD can be safely replaced should expulsion occur.

- Hubacher D, Kavanaugh M. Historical record-setting trends in IUD use in the United States. Contraception. 2018;98:467470. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2018.05.016

- Kavanaugh ML, Pliskin E. Use of contraception among reproductive-aged women in the United States, 2014 and 2016. F S Rep. 2020;1:83-93. doi:10.1016/j.xfre.2020.06.006

- Jensen JT, Creinin MD. Speroff & Darney’s Clinical Guide to Contraception. 6th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2020:15.

- Jensen JT, Creinin MD. Speroff & Darney’s Clinical Guide to Contraception. 6th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2020:185.

- Ozgu-Erdinc AS, Tasdemir UG, Uygur D, et al. Outcome of intrauterine pregnancies with intrauterine device in place and effects of device location on prognosis. Contraception. 2014;89:426-430. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2014.01.002

- Brahmi D, Steenland MW, Renner RM, et al. Pregnancy outcomes with an IUD in situ: a systematic review. Contraception. 2012;85:131-139. doi:10.1016/j.contraception . 2011.06.010

- Wilson S, Tan G, Baylson M, et al. Controversies in family planning: how to manage a fractured IUD. Contraception. 2013;88:599-603. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2013.07.007

- Fulkerson Schaeffer S, Gimovsky AC, Aly H, et al. Pregnancy and delivery with an intrauterine device in situ: outcomes in the National Inpatient Sample Database. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32:798-803. doi:10.1080/14767058.2017.1 391783

- Mirena. Prescribing information. Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://www .mirena-us.com/pi

- Myo MG, Nguyen BT. Intrauterine device complications and their management. Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep. 2023;12:88-95. doi.org/10.1007/s13669-023-00357-8

- National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). 2017-2019 National Survey of Family Growth. Public-Use Data File Documentation. CDC National Center for Health Statistics. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data /nsfg/NSFG-2017-2019-UG-MainText-508.pdf

- Gilliam ML, Jensen JT, Eisenberg DL, et al. Relationship of parity and prior cesarean delivery to levonorgestrel 52 mg intrauterine system expulsion over 6 years. Contraception. 2021;103:444-449. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.02.013

- Hubacher D, Kavanaugh M. Historical record-setting trends in IUD use in the United States. Contraception. 2018;98:467470. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2018.05.016

- Kavanaugh ML, Pliskin E. Use of contraception among reproductive-aged women in the United States, 2014 and 2016. F S Rep. 2020;1:83-93. doi:10.1016/j.xfre.2020.06.006

- Jensen JT, Creinin MD. Speroff & Darney’s Clinical Guide to Contraception. 6th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2020:15.

- Jensen JT, Creinin MD. Speroff & Darney’s Clinical Guide to Contraception. 6th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2020:185.

- Ozgu-Erdinc AS, Tasdemir UG, Uygur D, et al. Outcome of intrauterine pregnancies with intrauterine device in place and effects of device location on prognosis. Contraception. 2014;89:426-430. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2014.01.002

- Brahmi D, Steenland MW, Renner RM, et al. Pregnancy outcomes with an IUD in situ: a systematic review. Contraception. 2012;85:131-139. doi:10.1016/j.contraception . 2011.06.010

- Wilson S, Tan G, Baylson M, et al. Controversies in family planning: how to manage a fractured IUD. Contraception. 2013;88:599-603. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2013.07.007

- Fulkerson Schaeffer S, Gimovsky AC, Aly H, et al. Pregnancy and delivery with an intrauterine device in situ: outcomes in the National Inpatient Sample Database. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32:798-803. doi:10.1080/14767058.2017.1 391783

- Mirena. Prescribing information. Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://www .mirena-us.com/pi

- Myo MG, Nguyen BT. Intrauterine device complications and their management. Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep. 2023;12:88-95. doi.org/10.1007/s13669-023-00357-8

- National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). 2017-2019 National Survey of Family Growth. Public-Use Data File Documentation. CDC National Center for Health Statistics. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data /nsfg/NSFG-2017-2019-UG-MainText-508.pdf

- Gilliam ML, Jensen JT, Eisenberg DL, et al. Relationship of parity and prior cesarean delivery to levonorgestrel 52 mg intrauterine system expulsion over 6 years. Contraception. 2021;103:444-449. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.02.013

2022 Update on contraception

On June 24, 2022, the US Supreme Court ruled in Dobbs v Jackson to overturn the landmark Roe v Wade decision, deeming that abortion is not protected by statutes that provide the right to privacy, liberty, or autonomy. With this historic ruling, other rights founded on the same principles, including the freedom to use contraception, may be called into question in the future. Clinics that provide abortion care typically play a vital role in providing contraception services. Due to abortion restriction across the country, many of these clinics are predicted to close and many have already closed. Within one month of the Dobbs decision, 43 clinics in 11 states had shut their doors to patients, reducing access to basic contraception services.1 It is more important now than ever that clinicians address barriers and lead the effort to improve and ensure that patients have access to contraceptive services.

In this Update, we review recent evidence that may help aid patients in obtaining contraception more easily and for longer periods of time. We review strategies demonstrated to improve contraceptive access, including how to increase prescribing rates of 1-year contraceptive supplies and pharmacist-prescribed contraception. We also review new data on extended use of the levonorgestrel 52 mg intrauterine device (LNG 52 mg IUD).

One-year prescribing of hormonal contraception decreases an access barrier

Uhm S, Chen MJ, Cutler ED, et al. Twelve-month prescribing of contraceptive pill, patch, and ring before and after a standardized electronic medical record order change. Contraception. 2021;103:60-63.

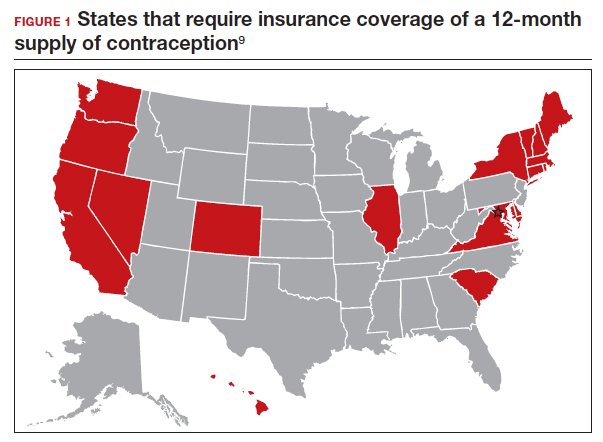

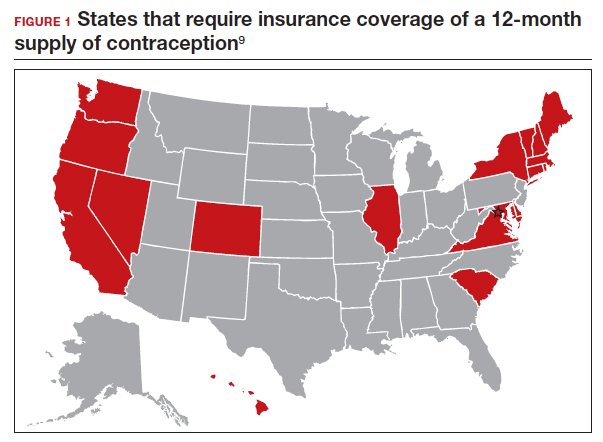

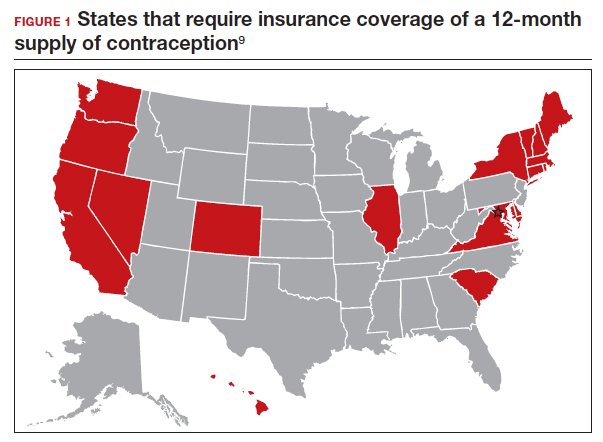

Providing a 1-year supply of self-administered contraception can lead to higher likelihood of continued use and is associated with reduced cost, unintended pregnancy, and abortion rates.2-4 Although some patients may not use a full year’s supply of pills, rings, or patches under such programs, the lower rates of unintended pregnancy result in significant cost savings as compared with the unused contraceptives.2,3 Accordingly, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advises dispensing a 1-year supply of self-administered hormonal contraception.5 Insurance coverage and providers’ prescribing practices can be barriers to patients obtaining a year’s supply of hormonal contraception. Currently, 18 states and the District of Columbia legally require insurers to cover a 12-month supply of prescription contraceptives (FIGURE 1). Despite these laws and the CDC recommendation, studies show that most people continue to receive only a 1- to 3-month supply.6-8 One strategy to increase the number of 1-year supplies of self-administered contraception is institutional changes to default prescription orders.

Study design

In California, legislation enacted in January 2017 required commercial and medical assistance health plans to cover up to 12 months of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved self-administered hormonal contraceptives dispensed at 1 time as prescribed or requested. To better serve patients, a multidisciplinary team from the University of California Davis Health worked with the institution’s pharmacy to institute an electronic medical record (EMR) default order change from dispensing 1-month with refills to dispensing 12-month quantities for all combined and progestin-only pills, patches, and rings on formulary.

After this EMR order change in December 2019, Uhm and colleagues conducted a retrospective pre-post study using outpatient prescription data that included nearly 5,000 contraceptive pill, patch, and ring prescriptions over an 8-month period. They compared the frequency of 12-month prescriptions for each of these methods 4 months before and 4 months after the default order change. They compared the proportion of 12-month prescriptions by prescriber department affiliation and by clinic location. Department affiliation was categorized as obstetrics-gynecology or non–obstetrics-gynecology. Clinic location was categorized as medical center campus or community clinics.

Increase in 12-month prescriptions

The authors found an overall increase in 12-month prescriptions, from 11% to 27%, after the EMR order change. Prescribers at the medical center campus clinics more frequently ordered a 12-month supply compared with prescribers at community clinics both before (33% vs 4%, respectively) and after (53% vs 19%, respectively) the EMR change. The only group of providers without a significant increase in 12-month prescriptions was among obstetrics-gynecology providers at community clinics (4% before vs 6% after).

The system EMR change modified only the standard facility order settings and did not affect individual favorite orders, which may help explain the differences in prescribing practices. While this study found an increase in 12-month prescriptions, there were no data on the actual number of supplies a patient received or on reimbursement.

The study by Uhm and colleagues showed that making a relatively simple change to default EMR orders can increase 12-month contraception prescribing and lead to greater patient-centered care. Evidence shows that providers and pharmacists are not necessarily aware of laws that require 12-month supply coverage and routinely prescribe smaller supplies.6,7,9 For clinicians in states that have these laws (FIGURE 1), we urge you to provide as full a supply of contraceptives as possible as this approach is both evidence based and patient centered. Although this study shows the benefit of universal system change to the EMR, individual clinicians also must be sure to modify personal order preferences. In addition, pharmacists can play an important role by updating policies that comply with these laws and by increasing pharmacy stocks of contraception supplies.7 For those living in states that do not currently have these laws, we encourage you to reach out to your legislators to advocate for similar laws as the data show clear medical and cost benefits for patients and society.

Continue to: Pharmacist prescription of hormonal contraception is safe and promotes continuation...

Pharmacist prescription of hormonal contraception is safe and promotes continuation

Rodriguez MI, Skye M, Edelman AB, et al. Association of pharmacist prescription and 12-month contraceptive continuation rates. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:647.e1-647.e9.

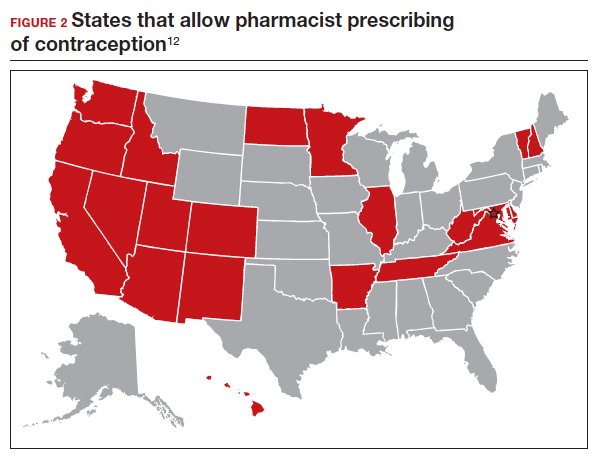

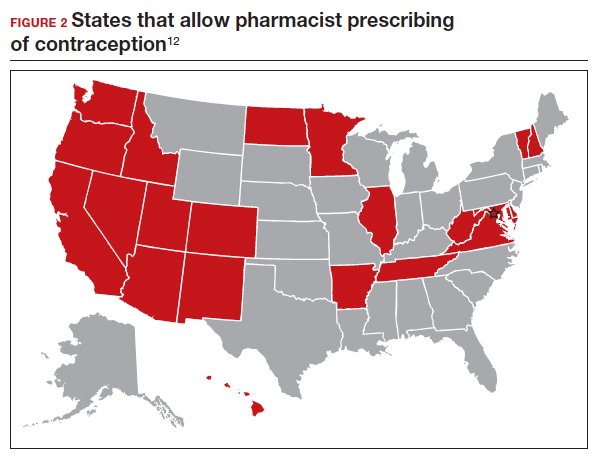

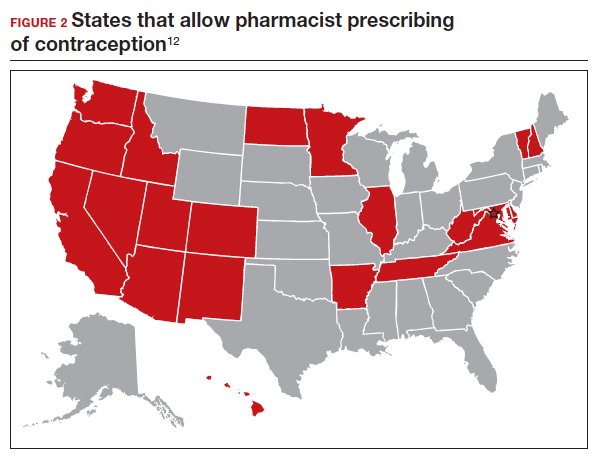

Patients often face difficulty obtaining both new and timely refills of self-administered contraception.10,11 To expand contraception access, Oregon became the first state (in 2016) to enact legislation to authorize direct pharmacist prescribing of hormonal contraceptives.12 Currently, 17 states and the District of Columbia have protocols for pharmacist prescribing privileges (FIGURE 2), and proposed legislation is pending in another 14 states.10,12 These protocols vary, but basic processes include screening, documentation, monitoring, and referrals when necessary. Typically, protocols require a pharmacist to review a patient’s medical history, pregnancy status, medication use, and blood pressure, followed by contraceptive counseling.10 Pharmacies are generally located in the community they serve, have extended hours, and usually do not require an appointment.8,13,14

Pharmacist prescribing increases the number of new contraceptive users, and pharmacists are more likely to prescribe a 6-month or longer supply of contraceptives compared with clinicians.8,13,15 Also, pharmacist prescribing is safe, with adherence rates to the CDC’s US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use similar to those of prescriptions provided by a clinician.13

Authors of a recent multi-state study further assessed the impact of pharmacist prescribing by evaluating 12-month continuation and perfect use rates.

Study design

Rodriguez and colleagues evaluated the results of a 1-year prospective cohort study conducted in 2019 that included 388 participants who sought contraception in California, Colorado, Hawaii, and Oregon. All these states had laws permitting pharmacist prescribing and 12-month supply of hormonal contraception. Participants received prescriptions directly from a pharmacist at 1 of 139 pharmacies (n = 149) or filled a prescription provided by a clinician (n = 239). The primary outcomes were continuation of an effective method and perfect use of contraception across 12 months.

Participant demographics were similar between the 2 groups except for education and insurance status. Participants who received a prescription from a clinician reported higher levels of education. A greater proportion of uninsured participants received a prescription from a pharmacist (11%) compared with from a clinician (3%).

Contraceptive continuation rates

Participants were surveyed 3 times during the 12-month study about their current contraceptive method, if they had switched methods, or if they had any missed days of contraception.

Overall, 340 participants (88%) completed a full 12 months of follow-up. Continuation rates were similar between the 2 groups: 89% in the clinician-prescribed and 90% in the pharmacist-prescribed group (P=.86). Participants in the 2 groups also reported similar rates of perfect use (no missed days: 54% and 47%, respectively [P=.69]). Additionally, the authors reported that 29 participants changed from a tier 2 (pill, patch, ring, injection) to a tier 1 (intrauterine device or implant) method during follow-up, with no difference in switch rates for participants who received care from a clinician (10%) or a pharmacist (7%).

Patients have difficulties in obtaining both an initial contraceptive prescription and refills in time to avoid breaks in coverage.16 Pharmacist prescription of contraception is a proven strategy to increase access to contraception for new users or to promote continuation among current users. This practice is evidence based, decreases unintended pregnancy rates, and is safe.8,13,15,17

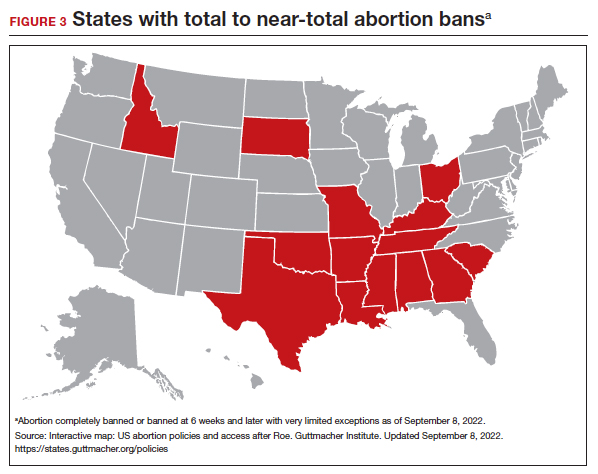

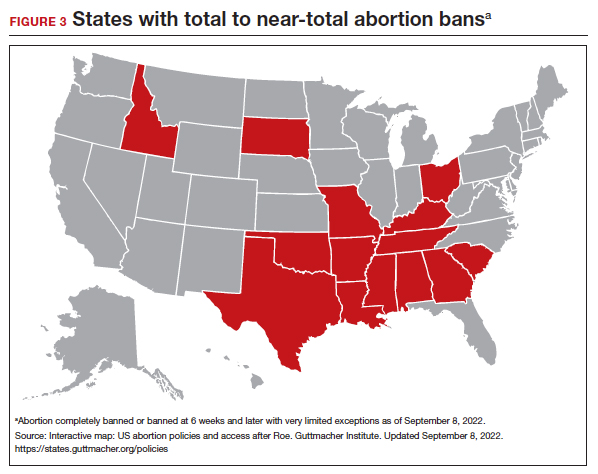

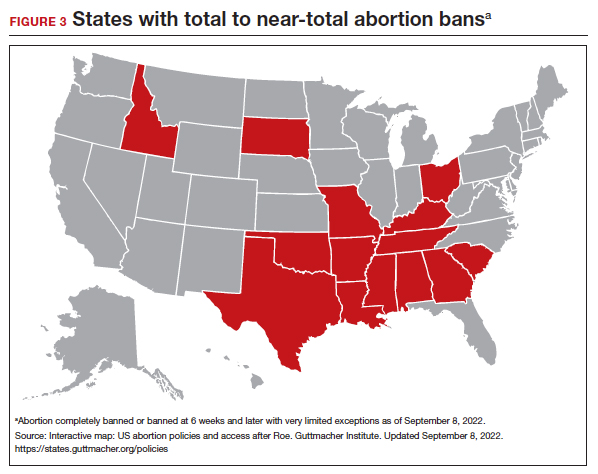

Promoting universal pharmacist prescribing is even more important given the overruling of Roe v Wade. With abortion restrictions, many family planning clinics that also play a vital role in providing contraception will close. Most states that are limiting abortion care (FIGURE 3) are the same states without pharmacist-prescribing provisions (FIGURE 2). As patient advocates, we need to continue to support this evidence-based practice in states where it is available and push legislators in states where it is not. Pharmacists should receive support to complete the training and certification needed to not only provide this service but also to receive appropriate reimbursements. Restrictions, such as requiring patients to be 18 years or older or to have prior consultation with a physician, should be limited as these are not necessary to provide self-administered contraception safely. Clinicians and pharmacists should inform patients, in states where this is available, that they can access initial or refill prescriptions at their local pharmacy if that is more convenient or their preference. Clinicians who live in states without these laws can advocate for their community by encouraging their legislators to pass laws that allow this evidence-based practice.

Continue to: LNG 52 mg IUD demonstrates efficacy and safety through 8 years of use...

LNG 52 mg IUD demonstrates efficacy and safety through 8 years of use

Creinin MD, Schreiber CA, Turok DK, et al. Levonorgestrel 52 mg intrauterine system efficacy and safety through 8 years of use. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;S00029378(22)00366-0.

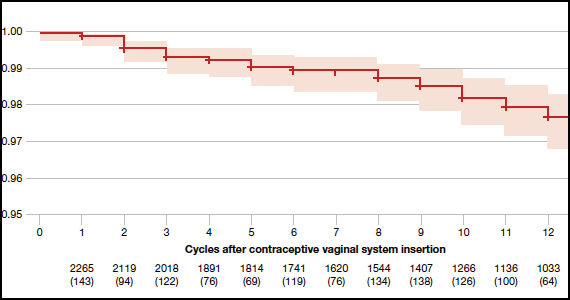

Given the potential difficulty accessing contraceptive and abortion services due to state restrictions, patients may be more motivated to maintain long-acting reversible contraceptives for maximum periods of time. The LNG 52 mg IUD was first marketed as a 5-year product, but multiple studies suggested that it had potential longer duration of efficacy and safety.18,19 The most recent clinical trial report shows that the LNG 52 mg IUD has at least 8 years of efficacy and safety.

Evidence supports 8 years’ use

The ACCESS IUS (A Comprehensive Contraceptive Efficacy and Safety Study of an IUS) phase 3 trial was designed to assess the safety and efficacy of a LNG 52 mg IUD (Liletta) for up to 10 years of use. The recent publication by Creinin and colleagues extends the available data from this study from 6 to 8 years.

Five-hundred and sixty-nine participants started year 7; 478 completed year 7 and 343 completed year 8 by the time the study was discontinued. Two pregnancies occurred in year 7 and no pregnancies occurred in year 8. One of the pregnancies in year 7 was determined by ultrasound examination to have implantation on day 4 after LNG IUD removal. According to the FDA, any pregnancy that occurs within 7 days of discontinuation is included as on-treatment, whereas the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has a 2-day cutoff. Over 8 years, 11 pregnancies occurred. The cumulative life-table pregnancy rate in the primary efficacy population through year 8 was 1.32% (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.69–2.51) under FDA rules and 1.09% (95% CI, 0.56–2.13) according to EMA guidance.

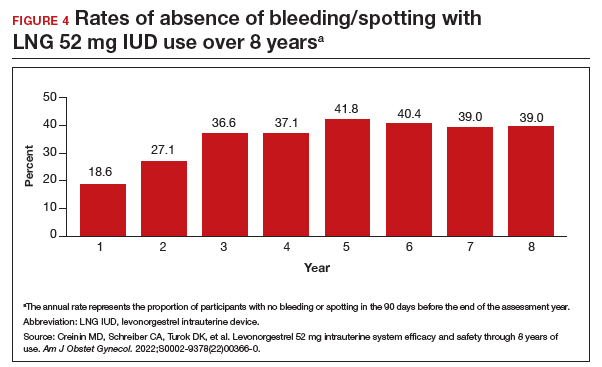

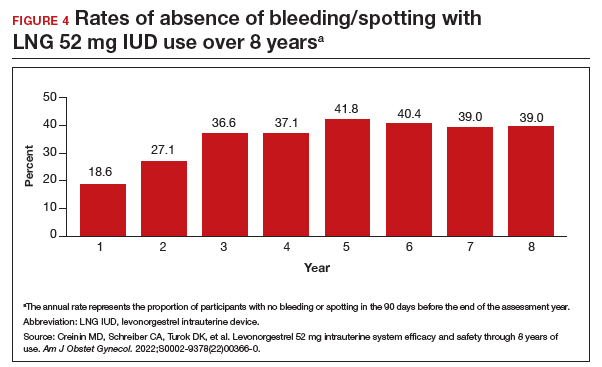

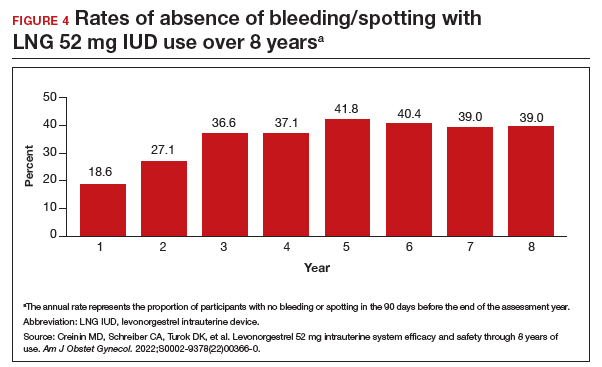

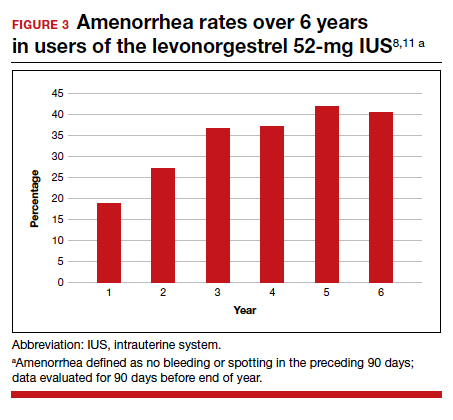

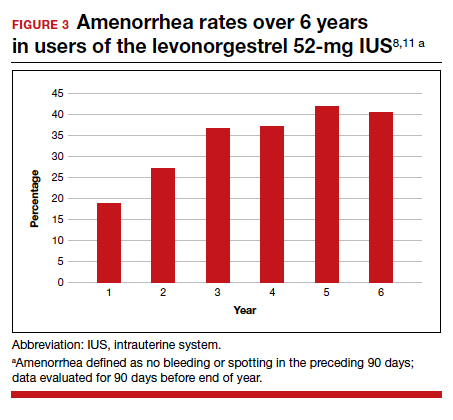

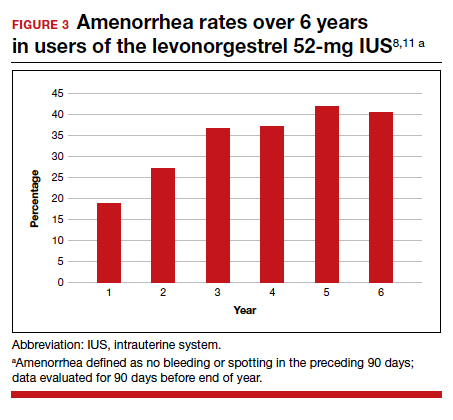

Absence of bleeding/spotting rates and adverse events

Rates of absence of bleeding/spotting remained relatively stable in years 7 and 8 at around 40%, similar to the rates during years 3 to 8 (FIGURE 4). Overall, only 2.6% of participants discontinued LNG IUD use because of bleeding problems, with a total of 4 participants discontinuing for this reason in years 7 and 8. Expulsion rates remained low at a rate of approximately 0.5% in years 7 and 8. Vulvovaginal infections were the most common adverse effect during year 7–8 of use. These findings are consistent with those found at 6 years.20 ●

As abortion and contraception services become more difficult to access, patients may be more motivated to initiate or maintain an intrauterine device for longer. The ACCESS IUS trial provides contemporary data that are generalizable across the US population. Clinicians should educate patients about the efficacy, low incidence of new adverse events, and the steady rate at which patients experience absence of bleeding/spotting. The most recent data analysis supports continued use of LNG 52 mg IUD products for up to 8 years with an excellent extended safety profile. While some providers may express concern that patients may experience more bleeding with prolonged use, this study demonstrated low discontinuation rates due to bleeding in years 7 and 8. Perforations were diagnosed only during the first year, meaning that they most likely are related to the insertion process. Additionally, in this long-term study, expulsions occurred most frequently in the first year after placement. This study, which shows that the LNG IUD can continue to be used for longer than before, is important because it means that many patients will need fewer removals and reinsertions over their lifetime, reducing a patient’s risks and discomfort associated with these procedures. Sharing these data is important, as longer LNG IUD retention may reduce burdens faced by patients who desire long-acting reversible contraception.

- Kirstein M, Jones RK, Philbin J. One month post-Roe: at least 43 abortion clinics across 11 states have stopped offering abortion care. Guttmacher Institute. July 28, 2022. Accessed September 14, 2022. https://www.guttmacher.org /article/2022/07/one-month-post-roe-least-43-abortion-clinics-across -11-states-have-stopped-offering

- Foster DG, Hulett D, Bradsberry M, et al. Number of oral contraceptive pill packages dispensed and subsequent unintended pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:566-572.

- Foster DG, Parvataneni R, de Bocanegra HT, et al. Number of oral contraceptive pill packages dispensed, method continuation, and costs. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:1107-114.

- Niu F, Cornelius J, Aboubechara N, et al. Real world outcomes related to providing an annual supply of short-acting hormonal contraceptives. Contraception. 2022;107:58-61.

- Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. US selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-66.

- Women’s sexual and reproductive health services: key findings from the 2017 Kaiser Women’s Health Survey. KFF: Kaiser Family Foundation. March 13, 2018. Accessed September 14, 2022. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy /issue-brief/womens-sexual-and-reproductive-health-services-key-findings -from-the-2017-kaiser-womens-health-survey/

- Nikpour G, Allen A, Rafie S, et al. Pharmacy implementation of a new law allowing year-long hormonal contraception supplies. Pharmacy (Basel). 2020;8:E165.

- Rodriguez MI, Edelman AB, Skye M, et al. Association of pharmacist prescription with dispensed duration of hormonal contraception. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e205252.

- Insurance coverage of contraceptives. Guttmacher Institute. Updated August 1, 2022. Accessed September 14, 2022. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy /explore/insurance-coverage-contraceptives

- Chim C, Sharma P. Pharmacists prescribing hormonal contraceptives: a status update. US Pharm. 2021;46:45-49.

- Rodriguez MI, Hersh A, Anderson LB, et al. Association of pharmacist prescription of hormonal contraception with unintended pregnancies and Medicaid costs. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:1238-1246.

- Pharmacist-prescribed contraceptives. Guttmacher Institute. Updated August 1, 2022. Accessed September 14, 2022. https://www.guttmacher.org/state -policy/explore/pharmacist-prescribed-contraceptives

- Anderson L, Hartung DM, Middleton L, et al. Pharmacist provision of hormonal contraception in the Oregon Medicaid population. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:1231-1237.

- Rodriguez MI, Edelman AB, Skye M, et al. Reasons for and experience in obtaining pharmacist prescribed contraception. Contraception. 2020;102:259-261.

- Rodriguez MI, Manibusan B, Kaufman M, et al. Association of pharmacist prescription of contraception with breaks in coverage. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:781-787.

- Pittman ME, Secura GM, Allsworth JE, et al. Understanding prescription adherence: pharmacy claims data from the Contraceptive CHOICE Project. Contraception. 2011;83:340-345.

- Rodriguez MI, Skye M, Edelman AB, et al. Association of pharmacist prescription and 12-month contraceptive continuation rates. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:647.e1-647.e9.

- Secura GM, Allsworth JE, Madden T, et al. The Contraceptive CHOICE Project: reducing barriers to long-acting reversible contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:115.e1-7.

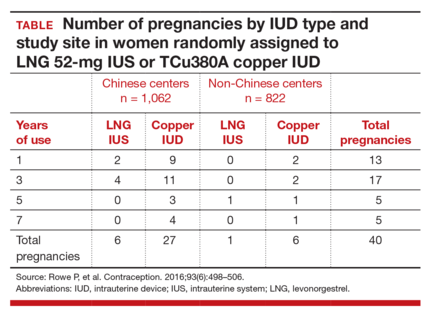

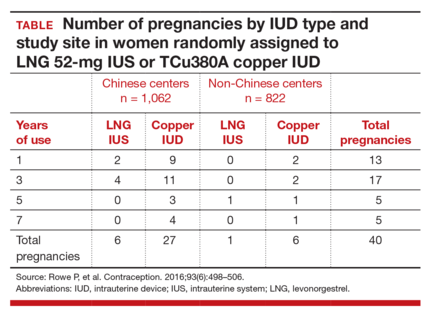

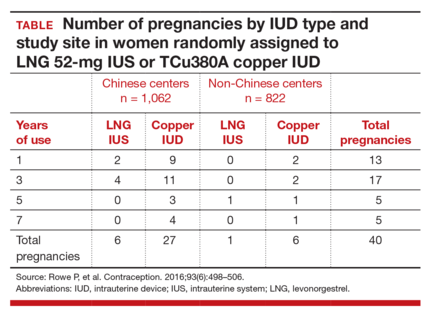

- Rowe P, Farley T, Peregoudov A, et al. Safety and efficacy in parous women of a 52-mg levonorgestrel-medicated intrauterine device: a 7-year randomized comparative study with the TCu380A. Contraception. 2016;93:498-506.

- Westhoff CL, Keder LM, Gangestad A, et al. Six-year contraceptive efficacy and continued safety of a levonorgestrel 52 mg intrauterine system. Contraception. 2020;101:159-161.

On June 24, 2022, the US Supreme Court ruled in Dobbs v Jackson to overturn the landmark Roe v Wade decision, deeming that abortion is not protected by statutes that provide the right to privacy, liberty, or autonomy. With this historic ruling, other rights founded on the same principles, including the freedom to use contraception, may be called into question in the future. Clinics that provide abortion care typically play a vital role in providing contraception services. Due to abortion restriction across the country, many of these clinics are predicted to close and many have already closed. Within one month of the Dobbs decision, 43 clinics in 11 states had shut their doors to patients, reducing access to basic contraception services.1 It is more important now than ever that clinicians address barriers and lead the effort to improve and ensure that patients have access to contraceptive services.

In this Update, we review recent evidence that may help aid patients in obtaining contraception more easily and for longer periods of time. We review strategies demonstrated to improve contraceptive access, including how to increase prescribing rates of 1-year contraceptive supplies and pharmacist-prescribed contraception. We also review new data on extended use of the levonorgestrel 52 mg intrauterine device (LNG 52 mg IUD).

One-year prescribing of hormonal contraception decreases an access barrier

Uhm S, Chen MJ, Cutler ED, et al. Twelve-month prescribing of contraceptive pill, patch, and ring before and after a standardized electronic medical record order change. Contraception. 2021;103:60-63.

Providing a 1-year supply of self-administered contraception can lead to higher likelihood of continued use and is associated with reduced cost, unintended pregnancy, and abortion rates.2-4 Although some patients may not use a full year’s supply of pills, rings, or patches under such programs, the lower rates of unintended pregnancy result in significant cost savings as compared with the unused contraceptives.2,3 Accordingly, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advises dispensing a 1-year supply of self-administered hormonal contraception.5 Insurance coverage and providers’ prescribing practices can be barriers to patients obtaining a year’s supply of hormonal contraception. Currently, 18 states and the District of Columbia legally require insurers to cover a 12-month supply of prescription contraceptives (FIGURE 1). Despite these laws and the CDC recommendation, studies show that most people continue to receive only a 1- to 3-month supply.6-8 One strategy to increase the number of 1-year supplies of self-administered contraception is institutional changes to default prescription orders.

Study design

In California, legislation enacted in January 2017 required commercial and medical assistance health plans to cover up to 12 months of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved self-administered hormonal contraceptives dispensed at 1 time as prescribed or requested. To better serve patients, a multidisciplinary team from the University of California Davis Health worked with the institution’s pharmacy to institute an electronic medical record (EMR) default order change from dispensing 1-month with refills to dispensing 12-month quantities for all combined and progestin-only pills, patches, and rings on formulary.

After this EMR order change in December 2019, Uhm and colleagues conducted a retrospective pre-post study using outpatient prescription data that included nearly 5,000 contraceptive pill, patch, and ring prescriptions over an 8-month period. They compared the frequency of 12-month prescriptions for each of these methods 4 months before and 4 months after the default order change. They compared the proportion of 12-month prescriptions by prescriber department affiliation and by clinic location. Department affiliation was categorized as obstetrics-gynecology or non–obstetrics-gynecology. Clinic location was categorized as medical center campus or community clinics.

Increase in 12-month prescriptions

The authors found an overall increase in 12-month prescriptions, from 11% to 27%, after the EMR order change. Prescribers at the medical center campus clinics more frequently ordered a 12-month supply compared with prescribers at community clinics both before (33% vs 4%, respectively) and after (53% vs 19%, respectively) the EMR change. The only group of providers without a significant increase in 12-month prescriptions was among obstetrics-gynecology providers at community clinics (4% before vs 6% after).

The system EMR change modified only the standard facility order settings and did not affect individual favorite orders, which may help explain the differences in prescribing practices. While this study found an increase in 12-month prescriptions, there were no data on the actual number of supplies a patient received or on reimbursement.

The study by Uhm and colleagues showed that making a relatively simple change to default EMR orders can increase 12-month contraception prescribing and lead to greater patient-centered care. Evidence shows that providers and pharmacists are not necessarily aware of laws that require 12-month supply coverage and routinely prescribe smaller supplies.6,7,9 For clinicians in states that have these laws (FIGURE 1), we urge you to provide as full a supply of contraceptives as possible as this approach is both evidence based and patient centered. Although this study shows the benefit of universal system change to the EMR, individual clinicians also must be sure to modify personal order preferences. In addition, pharmacists can play an important role by updating policies that comply with these laws and by increasing pharmacy stocks of contraception supplies.7 For those living in states that do not currently have these laws, we encourage you to reach out to your legislators to advocate for similar laws as the data show clear medical and cost benefits for patients and society.

Continue to: Pharmacist prescription of hormonal contraception is safe and promotes continuation...

Pharmacist prescription of hormonal contraception is safe and promotes continuation

Rodriguez MI, Skye M, Edelman AB, et al. Association of pharmacist prescription and 12-month contraceptive continuation rates. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:647.e1-647.e9.

Patients often face difficulty obtaining both new and timely refills of self-administered contraception.10,11 To expand contraception access, Oregon became the first state (in 2016) to enact legislation to authorize direct pharmacist prescribing of hormonal contraceptives.12 Currently, 17 states and the District of Columbia have protocols for pharmacist prescribing privileges (FIGURE 2), and proposed legislation is pending in another 14 states.10,12 These protocols vary, but basic processes include screening, documentation, monitoring, and referrals when necessary. Typically, protocols require a pharmacist to review a patient’s medical history, pregnancy status, medication use, and blood pressure, followed by contraceptive counseling.10 Pharmacies are generally located in the community they serve, have extended hours, and usually do not require an appointment.8,13,14

Pharmacist prescribing increases the number of new contraceptive users, and pharmacists are more likely to prescribe a 6-month or longer supply of contraceptives compared with clinicians.8,13,15 Also, pharmacist prescribing is safe, with adherence rates to the CDC’s US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use similar to those of prescriptions provided by a clinician.13

Authors of a recent multi-state study further assessed the impact of pharmacist prescribing by evaluating 12-month continuation and perfect use rates.

Study design

Rodriguez and colleagues evaluated the results of a 1-year prospective cohort study conducted in 2019 that included 388 participants who sought contraception in California, Colorado, Hawaii, and Oregon. All these states had laws permitting pharmacist prescribing and 12-month supply of hormonal contraception. Participants received prescriptions directly from a pharmacist at 1 of 139 pharmacies (n = 149) or filled a prescription provided by a clinician (n = 239). The primary outcomes were continuation of an effective method and perfect use of contraception across 12 months.

Participant demographics were similar between the 2 groups except for education and insurance status. Participants who received a prescription from a clinician reported higher levels of education. A greater proportion of uninsured participants received a prescription from a pharmacist (11%) compared with from a clinician (3%).

Contraceptive continuation rates

Participants were surveyed 3 times during the 12-month study about their current contraceptive method, if they had switched methods, or if they had any missed days of contraception.

Overall, 340 participants (88%) completed a full 12 months of follow-up. Continuation rates were similar between the 2 groups: 89% in the clinician-prescribed and 90% in the pharmacist-prescribed group (P=.86). Participants in the 2 groups also reported similar rates of perfect use (no missed days: 54% and 47%, respectively [P=.69]). Additionally, the authors reported that 29 participants changed from a tier 2 (pill, patch, ring, injection) to a tier 1 (intrauterine device or implant) method during follow-up, with no difference in switch rates for participants who received care from a clinician (10%) or a pharmacist (7%).