User login

Isotretinoin Meets COVID-19: Revisiting a Fragmented Paradigm

We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.

Albert Einstein

Amidst the myriad of disruptions and corollary solutions budding from the ongoing global COVID-19 pandemic, management of acne with isotretinoin underwent a makeover. Firstly, as with any pharmaceutical prescribed in the last 1 to 2 years, patients asked the compelling question, “Will this prescription put me at higher risk for COVID-19?”, resulting in a complex set of answers from both clinical and basic science perspectives. Further, the practical use of telemedicine for clinical visits and pregnancy test reporting altered the shape of isotretinoin physician-patient communication and follow-up. Finally, the combination of these circumstances spurred us to revisit common quandaries in prescribing this drug: Can we trust what patients tell us when they are taking isotretinoin? Do we need to monitor laboratory values and follow patients on isotretinoin as closely and as frequently as we have in the past? Does the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program of iPLEDGE hold true utility?

Impact of COVID-19 on Isotretinoin Use

Isotretinoin may have varying influence on the ease of host entry and virulence of COVID-19. Because the majority of patients experience some degree of mucous membrane desiccation on isotretinoin, it originally was postulated that disruption of the nasal mucosa, thereby uncovering the basal epithelial layer where angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors are expressed, could increase the risk for viral invasion, as ACE2 is the host receptor for COVID-19 entry.1,2 On the other hand, a study of 672 medications and their effect on regulation of ACE2 levels stratified isotretinoin in the highest category of ACE2 downregulators, therefore theoretically preventing cellular entry and replication of the virus.3 In conferring with many of my colleagues and reviewing available literature, I found that these data did not summarily deter providers from initiating or continuing isotretinoin during the pandemic, and research is ongoing to particularly earmark isotretinoin as a possible COVID-19 therapy option.4,5 Despite this, and despite the lower risk for COVID-19 in the customary isotretinoin adolescent and young adult age range, an Italian study reported that 14.7% of patients (5/34) prematurely interrupted isotretinoin therapy during lockdown because of fear of COVID-19 infection.6 Data also suggest that college towns (akin to where I practice, rife with isotretinoin-eligible patients) reflected higher COVID-19 infection and death rates, likely due to dense cohabitation and intermittent migration of students and staff to and from campuses and within their communities.7 Approximately 30% of my patients on isotretinoin in the last 18 months reported having COVID-19 at some point during the pandemic, though no data exist to guide us on whether isotretinoin should be discontinued in this scenario; my patients typically continued the drug unless their primary health care team discouraged it, and in those cases, all of them resumed it after COVID-19 symptomatology resolved.

Last spring, the US Department of Health and Human Services and the US Food and Drug Administration announced that health care professionals who prescribe and/or dispense drugs subject to REMS with laboratory testing or imaging requirements should consider whether there are compelling reasons not to complete the required testing/imaging during the current public health emergency and use their best medical judgment in weighing the benefits and risks of continuing treatment in the absence of these tests. It also was stressed that prescribers should effectively communicate with their patients regarding these benefits, risks, and altered protocols.8 Further, the iPLEDGE program concurred that telemedicine was an acceptable visit type for both initiating and maintaining isotretinoin, and home pregnancy tests were valid for females of childbearing potential if an accurate testing date and results were communicated by patients to the prescriber in the required reporting windows.9 This allowed dermatologists to foster what was one of our most important roles as outpatient clinicians during the pandemic: to maintain normalcy, continuity, and support for as many patients as possible.

Isotretinoin and Telemedicine

During the pandemic, continuation of isotretinoin therapy proved easier than initiating it, given that patients could access and maintain a clear connection to the online visit platform, display understanding of the REMS mandates (along with a guardian present for a minor), perform a home pregnancy test and report the result followed by the quiz (for females), and collect the prescription in the allotted window. For new patients, the absence of a detailed in-person examination and rapport with the patient (and guardians when applicable) as well as misalignment of the date of iPLEDGE registration with the timing of the pregnancy test results and prescribing window were more onerous using digital or mailed versions of consent forms and photodocumentation of urine pregnancy test results. This tangle of requirements perpetuated missed prescribing windows, increased patient portal and phone messages, resulted in more time on the phone with the iPLEDGE help desk, and intensified angst for clinical staff.

These telemedicine visits also required validation of the patient’s geographic location to verify the billability of the visit and whether the patient was in a secure location to have a US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant conversation as well as the abstract notion that the timing and result of the pregnancy tests for females reflected a true nonpregnant state.10,11 Verification of the pregnancy tests in these situations was approached by either the patient reporting the outcome verbally or displaying the pregnancy test kit result in a video or photograph form for the medical record, all of which leave room for error, doubt, and lower sensitivity than laboratory-based collection. That being said, the increased implementation of telemedicine visits during the pandemic sustained patient access, decreased cost with less laboratory testing and reduced time away from work or school, and resulted in high patient satisfaction with their care.12 Additionally, it allowed providers to continue to more comfortably inch away from frequent in-person serologic cholesterol and hepatic testing during therapy based on mounting data that it is not indicated.13

Accordingly, the complicated concepts of trust, practicality, and sustainability for the safe and effective management of isotretinoin patients re-emerged. For example, prior to COVID-19, we trusted patients who said they were regularly taking their oral contraceptives or were truly practicing abstinence as a form of contraception. During the pandemic, we then added a layer of trust with home pregnancy test reporting. If the patient or guardian signed the isotretinoin consent form and understood the risks of the medication, ideally the physician-patient relationship fostered the optimal goals of honest conversation, adherence to the drug, safety, and clear skin. However, there is yet another trust assay: iPLEDGE, in turn, trusts that we are reporting patient data accurately, provoking us to reiterate questions we asked ourselves before the pandemic. Is the extra provider and staff clerical work and validation necessary, compounded by prior data that iPLEDGE’s capacity to limit pregnancy-related morbidity with isotretinoin has been called into question in the last decade?14 Do males need to be followed every month? Is laboratory monitoring still necessary for all isotretinoin candidates? Will post–COVID-19 data show that during various versions of the lockdown, an increased number of isotretinoin patients developed unmonitored morbidity, including transaminitis, hypertriglyceridemia, and an increase in pregnancies? How long will telemedicine visits for isotretinoin be reimbursable beyond the pandemic? Are there other models to enhance and improve isotretinoin teledermatology and compliance?15

Final Thoughts

Dermatologists’ experience managing high volumes of isotretinoin patients paired with the creativity to maintain meaningful (and truthful) patient connections and decrease administrative burden lie front and center in 2021. Because the COVID-19 pandemic remains ambient with a dearth of data to guide us, I pose the questions above as points for commiseration and catapults for future study, discussion, collaboration, and innovation. Perhaps the neo–COVID-19 world provided us with the spark we needed to metaphorically clean up the dusty isotretinoin tenets that have frayed our time and patience so we can maintain excellent care for this worthy population.

- Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis MLC, et al. Tissue disruption of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. a first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol. 2004;203:631-637.

- British Association of Dermatologists. COVID-19—isotretinoin guidance. Published March 26, 2020. Accessed June 21, 2021. https://www.bad.org.uk/shared/get-file.ashx?itemtype=document&id=6661

- Sinha S, Cheng K, Schäffer AA, et al. In vitro and in vivo identification of clinically approved drugs that modify ACE2 expression. Mol Syst Biol. 2020;16:E9628.

- Öǧüt ND, Kutlu Ö, Erbaǧcı E. Oral isotretinoin treatment in patients with acne vulgaris during the COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective cohort study in a tertiary care hospital [published online April 22, 2021]. J Cosmet Dermatol. doi:10.1111/jocd.14168

- Isotretinoin in treatment of COVID-19. National Library of Medicine website. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04361422. Updated September 23, 2020. Accessed June 21, 2021. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04361422

- Donnarumma M, Nocerino M, Lauro W, et al. Isotretinoin in acne treatment during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a retrospective analysis of adherence to therapy and side effects [published online December 22, 2020]. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14677.

- Ivory D, Gebeloff R, Mervosh S. Young people have less COVID-19 risk, but in college towns, deaths rose fast. The New York Times. December 12, 2020. Accessed June 21, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/12/us/covid-colleges-nursing-homes.html

- US Food and Drug Administration. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA provides update on patient access to certain REMS drugs during COVID-19 public health emergency. Published March 22, 2020. Accessed June 21, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-provides-update-patient-access-certain-rems-drugs-during-covid-19

- Haelle T. iPledge allows at-home pregnancy tests during pandemic. Dermatology News. Published April 3, 2020. Accessed June 28, 2021. https://www.mdedge.com/dermatology/article/220186/acne/ipledge-allows-home-pregnancy-tests-during-pandemic

- Bressler MY, Siegel DM, Markowitz O. Virtual dermatology: a COVID-19 update. Cutis. 2020;105:163-164; E2.

- Telemedicine key issues and policy. Federation of State Medical Boards website. Accessed June 28, 2021. https://www.fsmb.org/advocacy/telemedicine

- Ruggiero A, Megna M, Annunziata MC, et al. Teledermatology for acne during COVID-19: high patients’ satisfaction in spite of the emergency. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E662-E663.

- Barbieri JS, Shin DB, Wang S, et al. The clinical utility of laboratory monitoring during isotretinoin therapy for acne and changes to monitoring practices over time. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:72-79.

- Tkachenko E, Singer S, Sharma P, et al. US Food and Drug Administration reports of pregnancy and pregnancy-related adverse events associated with isotretinoin. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1175-1179.

- Das S, et al. Asynchronous telemedicine for isotretinoin management: a direct care pilot [published online January 21, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.039

We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.

Albert Einstein

Amidst the myriad of disruptions and corollary solutions budding from the ongoing global COVID-19 pandemic, management of acne with isotretinoin underwent a makeover. Firstly, as with any pharmaceutical prescribed in the last 1 to 2 years, patients asked the compelling question, “Will this prescription put me at higher risk for COVID-19?”, resulting in a complex set of answers from both clinical and basic science perspectives. Further, the practical use of telemedicine for clinical visits and pregnancy test reporting altered the shape of isotretinoin physician-patient communication and follow-up. Finally, the combination of these circumstances spurred us to revisit common quandaries in prescribing this drug: Can we trust what patients tell us when they are taking isotretinoin? Do we need to monitor laboratory values and follow patients on isotretinoin as closely and as frequently as we have in the past? Does the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program of iPLEDGE hold true utility?

Impact of COVID-19 on Isotretinoin Use

Isotretinoin may have varying influence on the ease of host entry and virulence of COVID-19. Because the majority of patients experience some degree of mucous membrane desiccation on isotretinoin, it originally was postulated that disruption of the nasal mucosa, thereby uncovering the basal epithelial layer where angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors are expressed, could increase the risk for viral invasion, as ACE2 is the host receptor for COVID-19 entry.1,2 On the other hand, a study of 672 medications and their effect on regulation of ACE2 levels stratified isotretinoin in the highest category of ACE2 downregulators, therefore theoretically preventing cellular entry and replication of the virus.3 In conferring with many of my colleagues and reviewing available literature, I found that these data did not summarily deter providers from initiating or continuing isotretinoin during the pandemic, and research is ongoing to particularly earmark isotretinoin as a possible COVID-19 therapy option.4,5 Despite this, and despite the lower risk for COVID-19 in the customary isotretinoin adolescent and young adult age range, an Italian study reported that 14.7% of patients (5/34) prematurely interrupted isotretinoin therapy during lockdown because of fear of COVID-19 infection.6 Data also suggest that college towns (akin to where I practice, rife with isotretinoin-eligible patients) reflected higher COVID-19 infection and death rates, likely due to dense cohabitation and intermittent migration of students and staff to and from campuses and within their communities.7 Approximately 30% of my patients on isotretinoin in the last 18 months reported having COVID-19 at some point during the pandemic, though no data exist to guide us on whether isotretinoin should be discontinued in this scenario; my patients typically continued the drug unless their primary health care team discouraged it, and in those cases, all of them resumed it after COVID-19 symptomatology resolved.

Last spring, the US Department of Health and Human Services and the US Food and Drug Administration announced that health care professionals who prescribe and/or dispense drugs subject to REMS with laboratory testing or imaging requirements should consider whether there are compelling reasons not to complete the required testing/imaging during the current public health emergency and use their best medical judgment in weighing the benefits and risks of continuing treatment in the absence of these tests. It also was stressed that prescribers should effectively communicate with their patients regarding these benefits, risks, and altered protocols.8 Further, the iPLEDGE program concurred that telemedicine was an acceptable visit type for both initiating and maintaining isotretinoin, and home pregnancy tests were valid for females of childbearing potential if an accurate testing date and results were communicated by patients to the prescriber in the required reporting windows.9 This allowed dermatologists to foster what was one of our most important roles as outpatient clinicians during the pandemic: to maintain normalcy, continuity, and support for as many patients as possible.

Isotretinoin and Telemedicine

During the pandemic, continuation of isotretinoin therapy proved easier than initiating it, given that patients could access and maintain a clear connection to the online visit platform, display understanding of the REMS mandates (along with a guardian present for a minor), perform a home pregnancy test and report the result followed by the quiz (for females), and collect the prescription in the allotted window. For new patients, the absence of a detailed in-person examination and rapport with the patient (and guardians when applicable) as well as misalignment of the date of iPLEDGE registration with the timing of the pregnancy test results and prescribing window were more onerous using digital or mailed versions of consent forms and photodocumentation of urine pregnancy test results. This tangle of requirements perpetuated missed prescribing windows, increased patient portal and phone messages, resulted in more time on the phone with the iPLEDGE help desk, and intensified angst for clinical staff.

These telemedicine visits also required validation of the patient’s geographic location to verify the billability of the visit and whether the patient was in a secure location to have a US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant conversation as well as the abstract notion that the timing and result of the pregnancy tests for females reflected a true nonpregnant state.10,11 Verification of the pregnancy tests in these situations was approached by either the patient reporting the outcome verbally or displaying the pregnancy test kit result in a video or photograph form for the medical record, all of which leave room for error, doubt, and lower sensitivity than laboratory-based collection. That being said, the increased implementation of telemedicine visits during the pandemic sustained patient access, decreased cost with less laboratory testing and reduced time away from work or school, and resulted in high patient satisfaction with their care.12 Additionally, it allowed providers to continue to more comfortably inch away from frequent in-person serologic cholesterol and hepatic testing during therapy based on mounting data that it is not indicated.13

Accordingly, the complicated concepts of trust, practicality, and sustainability for the safe and effective management of isotretinoin patients re-emerged. For example, prior to COVID-19, we trusted patients who said they were regularly taking their oral contraceptives or were truly practicing abstinence as a form of contraception. During the pandemic, we then added a layer of trust with home pregnancy test reporting. If the patient or guardian signed the isotretinoin consent form and understood the risks of the medication, ideally the physician-patient relationship fostered the optimal goals of honest conversation, adherence to the drug, safety, and clear skin. However, there is yet another trust assay: iPLEDGE, in turn, trusts that we are reporting patient data accurately, provoking us to reiterate questions we asked ourselves before the pandemic. Is the extra provider and staff clerical work and validation necessary, compounded by prior data that iPLEDGE’s capacity to limit pregnancy-related morbidity with isotretinoin has been called into question in the last decade?14 Do males need to be followed every month? Is laboratory monitoring still necessary for all isotretinoin candidates? Will post–COVID-19 data show that during various versions of the lockdown, an increased number of isotretinoin patients developed unmonitored morbidity, including transaminitis, hypertriglyceridemia, and an increase in pregnancies? How long will telemedicine visits for isotretinoin be reimbursable beyond the pandemic? Are there other models to enhance and improve isotretinoin teledermatology and compliance?15

Final Thoughts

Dermatologists’ experience managing high volumes of isotretinoin patients paired with the creativity to maintain meaningful (and truthful) patient connections and decrease administrative burden lie front and center in 2021. Because the COVID-19 pandemic remains ambient with a dearth of data to guide us, I pose the questions above as points for commiseration and catapults for future study, discussion, collaboration, and innovation. Perhaps the neo–COVID-19 world provided us with the spark we needed to metaphorically clean up the dusty isotretinoin tenets that have frayed our time and patience so we can maintain excellent care for this worthy population.

We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.

Albert Einstein

Amidst the myriad of disruptions and corollary solutions budding from the ongoing global COVID-19 pandemic, management of acne with isotretinoin underwent a makeover. Firstly, as with any pharmaceutical prescribed in the last 1 to 2 years, patients asked the compelling question, “Will this prescription put me at higher risk for COVID-19?”, resulting in a complex set of answers from both clinical and basic science perspectives. Further, the practical use of telemedicine for clinical visits and pregnancy test reporting altered the shape of isotretinoin physician-patient communication and follow-up. Finally, the combination of these circumstances spurred us to revisit common quandaries in prescribing this drug: Can we trust what patients tell us when they are taking isotretinoin? Do we need to monitor laboratory values and follow patients on isotretinoin as closely and as frequently as we have in the past? Does the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program of iPLEDGE hold true utility?

Impact of COVID-19 on Isotretinoin Use

Isotretinoin may have varying influence on the ease of host entry and virulence of COVID-19. Because the majority of patients experience some degree of mucous membrane desiccation on isotretinoin, it originally was postulated that disruption of the nasal mucosa, thereby uncovering the basal epithelial layer where angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors are expressed, could increase the risk for viral invasion, as ACE2 is the host receptor for COVID-19 entry.1,2 On the other hand, a study of 672 medications and their effect on regulation of ACE2 levels stratified isotretinoin in the highest category of ACE2 downregulators, therefore theoretically preventing cellular entry and replication of the virus.3 In conferring with many of my colleagues and reviewing available literature, I found that these data did not summarily deter providers from initiating or continuing isotretinoin during the pandemic, and research is ongoing to particularly earmark isotretinoin as a possible COVID-19 therapy option.4,5 Despite this, and despite the lower risk for COVID-19 in the customary isotretinoin adolescent and young adult age range, an Italian study reported that 14.7% of patients (5/34) prematurely interrupted isotretinoin therapy during lockdown because of fear of COVID-19 infection.6 Data also suggest that college towns (akin to where I practice, rife with isotretinoin-eligible patients) reflected higher COVID-19 infection and death rates, likely due to dense cohabitation and intermittent migration of students and staff to and from campuses and within their communities.7 Approximately 30% of my patients on isotretinoin in the last 18 months reported having COVID-19 at some point during the pandemic, though no data exist to guide us on whether isotretinoin should be discontinued in this scenario; my patients typically continued the drug unless their primary health care team discouraged it, and in those cases, all of them resumed it after COVID-19 symptomatology resolved.

Last spring, the US Department of Health and Human Services and the US Food and Drug Administration announced that health care professionals who prescribe and/or dispense drugs subject to REMS with laboratory testing or imaging requirements should consider whether there are compelling reasons not to complete the required testing/imaging during the current public health emergency and use their best medical judgment in weighing the benefits and risks of continuing treatment in the absence of these tests. It also was stressed that prescribers should effectively communicate with their patients regarding these benefits, risks, and altered protocols.8 Further, the iPLEDGE program concurred that telemedicine was an acceptable visit type for both initiating and maintaining isotretinoin, and home pregnancy tests were valid for females of childbearing potential if an accurate testing date and results were communicated by patients to the prescriber in the required reporting windows.9 This allowed dermatologists to foster what was one of our most important roles as outpatient clinicians during the pandemic: to maintain normalcy, continuity, and support for as many patients as possible.

Isotretinoin and Telemedicine

During the pandemic, continuation of isotretinoin therapy proved easier than initiating it, given that patients could access and maintain a clear connection to the online visit platform, display understanding of the REMS mandates (along with a guardian present for a minor), perform a home pregnancy test and report the result followed by the quiz (for females), and collect the prescription in the allotted window. For new patients, the absence of a detailed in-person examination and rapport with the patient (and guardians when applicable) as well as misalignment of the date of iPLEDGE registration with the timing of the pregnancy test results and prescribing window were more onerous using digital or mailed versions of consent forms and photodocumentation of urine pregnancy test results. This tangle of requirements perpetuated missed prescribing windows, increased patient portal and phone messages, resulted in more time on the phone with the iPLEDGE help desk, and intensified angst for clinical staff.

These telemedicine visits also required validation of the patient’s geographic location to verify the billability of the visit and whether the patient was in a secure location to have a US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant conversation as well as the abstract notion that the timing and result of the pregnancy tests for females reflected a true nonpregnant state.10,11 Verification of the pregnancy tests in these situations was approached by either the patient reporting the outcome verbally or displaying the pregnancy test kit result in a video or photograph form for the medical record, all of which leave room for error, doubt, and lower sensitivity than laboratory-based collection. That being said, the increased implementation of telemedicine visits during the pandemic sustained patient access, decreased cost with less laboratory testing and reduced time away from work or school, and resulted in high patient satisfaction with their care.12 Additionally, it allowed providers to continue to more comfortably inch away from frequent in-person serologic cholesterol and hepatic testing during therapy based on mounting data that it is not indicated.13

Accordingly, the complicated concepts of trust, practicality, and sustainability for the safe and effective management of isotretinoin patients re-emerged. For example, prior to COVID-19, we trusted patients who said they were regularly taking their oral contraceptives or were truly practicing abstinence as a form of contraception. During the pandemic, we then added a layer of trust with home pregnancy test reporting. If the patient or guardian signed the isotretinoin consent form and understood the risks of the medication, ideally the physician-patient relationship fostered the optimal goals of honest conversation, adherence to the drug, safety, and clear skin. However, there is yet another trust assay: iPLEDGE, in turn, trusts that we are reporting patient data accurately, provoking us to reiterate questions we asked ourselves before the pandemic. Is the extra provider and staff clerical work and validation necessary, compounded by prior data that iPLEDGE’s capacity to limit pregnancy-related morbidity with isotretinoin has been called into question in the last decade?14 Do males need to be followed every month? Is laboratory monitoring still necessary for all isotretinoin candidates? Will post–COVID-19 data show that during various versions of the lockdown, an increased number of isotretinoin patients developed unmonitored morbidity, including transaminitis, hypertriglyceridemia, and an increase in pregnancies? How long will telemedicine visits for isotretinoin be reimbursable beyond the pandemic? Are there other models to enhance and improve isotretinoin teledermatology and compliance?15

Final Thoughts

Dermatologists’ experience managing high volumes of isotretinoin patients paired with the creativity to maintain meaningful (and truthful) patient connections and decrease administrative burden lie front and center in 2021. Because the COVID-19 pandemic remains ambient with a dearth of data to guide us, I pose the questions above as points for commiseration and catapults for future study, discussion, collaboration, and innovation. Perhaps the neo–COVID-19 world provided us with the spark we needed to metaphorically clean up the dusty isotretinoin tenets that have frayed our time and patience so we can maintain excellent care for this worthy population.

- Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis MLC, et al. Tissue disruption of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. a first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol. 2004;203:631-637.

- British Association of Dermatologists. COVID-19—isotretinoin guidance. Published March 26, 2020. Accessed June 21, 2021. https://www.bad.org.uk/shared/get-file.ashx?itemtype=document&id=6661

- Sinha S, Cheng K, Schäffer AA, et al. In vitro and in vivo identification of clinically approved drugs that modify ACE2 expression. Mol Syst Biol. 2020;16:E9628.

- Öǧüt ND, Kutlu Ö, Erbaǧcı E. Oral isotretinoin treatment in patients with acne vulgaris during the COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective cohort study in a tertiary care hospital [published online April 22, 2021]. J Cosmet Dermatol. doi:10.1111/jocd.14168

- Isotretinoin in treatment of COVID-19. National Library of Medicine website. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04361422. Updated September 23, 2020. Accessed June 21, 2021. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04361422

- Donnarumma M, Nocerino M, Lauro W, et al. Isotretinoin in acne treatment during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a retrospective analysis of adherence to therapy and side effects [published online December 22, 2020]. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14677.

- Ivory D, Gebeloff R, Mervosh S. Young people have less COVID-19 risk, but in college towns, deaths rose fast. The New York Times. December 12, 2020. Accessed June 21, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/12/us/covid-colleges-nursing-homes.html

- US Food and Drug Administration. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA provides update on patient access to certain REMS drugs during COVID-19 public health emergency. Published March 22, 2020. Accessed June 21, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-provides-update-patient-access-certain-rems-drugs-during-covid-19

- Haelle T. iPledge allows at-home pregnancy tests during pandemic. Dermatology News. Published April 3, 2020. Accessed June 28, 2021. https://www.mdedge.com/dermatology/article/220186/acne/ipledge-allows-home-pregnancy-tests-during-pandemic

- Bressler MY, Siegel DM, Markowitz O. Virtual dermatology: a COVID-19 update. Cutis. 2020;105:163-164; E2.

- Telemedicine key issues and policy. Federation of State Medical Boards website. Accessed June 28, 2021. https://www.fsmb.org/advocacy/telemedicine

- Ruggiero A, Megna M, Annunziata MC, et al. Teledermatology for acne during COVID-19: high patients’ satisfaction in spite of the emergency. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E662-E663.

- Barbieri JS, Shin DB, Wang S, et al. The clinical utility of laboratory monitoring during isotretinoin therapy for acne and changes to monitoring practices over time. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:72-79.

- Tkachenko E, Singer S, Sharma P, et al. US Food and Drug Administration reports of pregnancy and pregnancy-related adverse events associated with isotretinoin. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1175-1179.

- Das S, et al. Asynchronous telemedicine for isotretinoin management: a direct care pilot [published online January 21, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.039

- Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis MLC, et al. Tissue disruption of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. a first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol. 2004;203:631-637.

- British Association of Dermatologists. COVID-19—isotretinoin guidance. Published March 26, 2020. Accessed June 21, 2021. https://www.bad.org.uk/shared/get-file.ashx?itemtype=document&id=6661

- Sinha S, Cheng K, Schäffer AA, et al. In vitro and in vivo identification of clinically approved drugs that modify ACE2 expression. Mol Syst Biol. 2020;16:E9628.

- Öǧüt ND, Kutlu Ö, Erbaǧcı E. Oral isotretinoin treatment in patients with acne vulgaris during the COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective cohort study in a tertiary care hospital [published online April 22, 2021]. J Cosmet Dermatol. doi:10.1111/jocd.14168

- Isotretinoin in treatment of COVID-19. National Library of Medicine website. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04361422. Updated September 23, 2020. Accessed June 21, 2021. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04361422

- Donnarumma M, Nocerino M, Lauro W, et al. Isotretinoin in acne treatment during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a retrospective analysis of adherence to therapy and side effects [published online December 22, 2020]. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14677.

- Ivory D, Gebeloff R, Mervosh S. Young people have less COVID-19 risk, but in college towns, deaths rose fast. The New York Times. December 12, 2020. Accessed June 21, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/12/us/covid-colleges-nursing-homes.html

- US Food and Drug Administration. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA provides update on patient access to certain REMS drugs during COVID-19 public health emergency. Published March 22, 2020. Accessed June 21, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-provides-update-patient-access-certain-rems-drugs-during-covid-19

- Haelle T. iPledge allows at-home pregnancy tests during pandemic. Dermatology News. Published April 3, 2020. Accessed June 28, 2021. https://www.mdedge.com/dermatology/article/220186/acne/ipledge-allows-home-pregnancy-tests-during-pandemic

- Bressler MY, Siegel DM, Markowitz O. Virtual dermatology: a COVID-19 update. Cutis. 2020;105:163-164; E2.

- Telemedicine key issues and policy. Federation of State Medical Boards website. Accessed June 28, 2021. https://www.fsmb.org/advocacy/telemedicine

- Ruggiero A, Megna M, Annunziata MC, et al. Teledermatology for acne during COVID-19: high patients’ satisfaction in spite of the emergency. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E662-E663.

- Barbieri JS, Shin DB, Wang S, et al. The clinical utility of laboratory monitoring during isotretinoin therapy for acne and changes to monitoring practices over time. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:72-79.

- Tkachenko E, Singer S, Sharma P, et al. US Food and Drug Administration reports of pregnancy and pregnancy-related adverse events associated with isotretinoin. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1175-1179.

- Das S, et al. Asynchronous telemedicine for isotretinoin management: a direct care pilot [published online January 21, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.039

Keratotic Papule on the Abdomen

The Diagnosis: Hypergranulotic Dyscornification

Hypergranulotic dyscornification (HD) is a rarely reported reaction pattern present in benign solitary keratoses with only few reports to date. It may be an underrecognized reaction pattern based on the paucity of reported cases as well as the histologic similarities to other entities. It has been hypothesized that this pattern reflects an underlying keratin mutation or disorder of keratinization.1

Clinically, HD most commonly presents as a waxy, tan-colored, solitary keratosis generally found on the lower limbs, trunk, or back in individuals aged 20 to 60 years.1,2 Histopathology shows marked hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and clumped basophilic keratohyalin granules within the corneocytes with digitated epidermal hyperplasia. There is abnormal cornification across the entire lesion with papillomatosis and marked hypergranulosis.3 There often are homogeneous orthokeratotic mounds of large, dull, eosinophilic-staining anucleate keratinocytes that are sharply demarcated from the thickened granular layer.1,2 Within the spinous, granular, and corneal layers, there is a pale, gray-staining, basophilic, cytoplasmic substance intercellularly.1

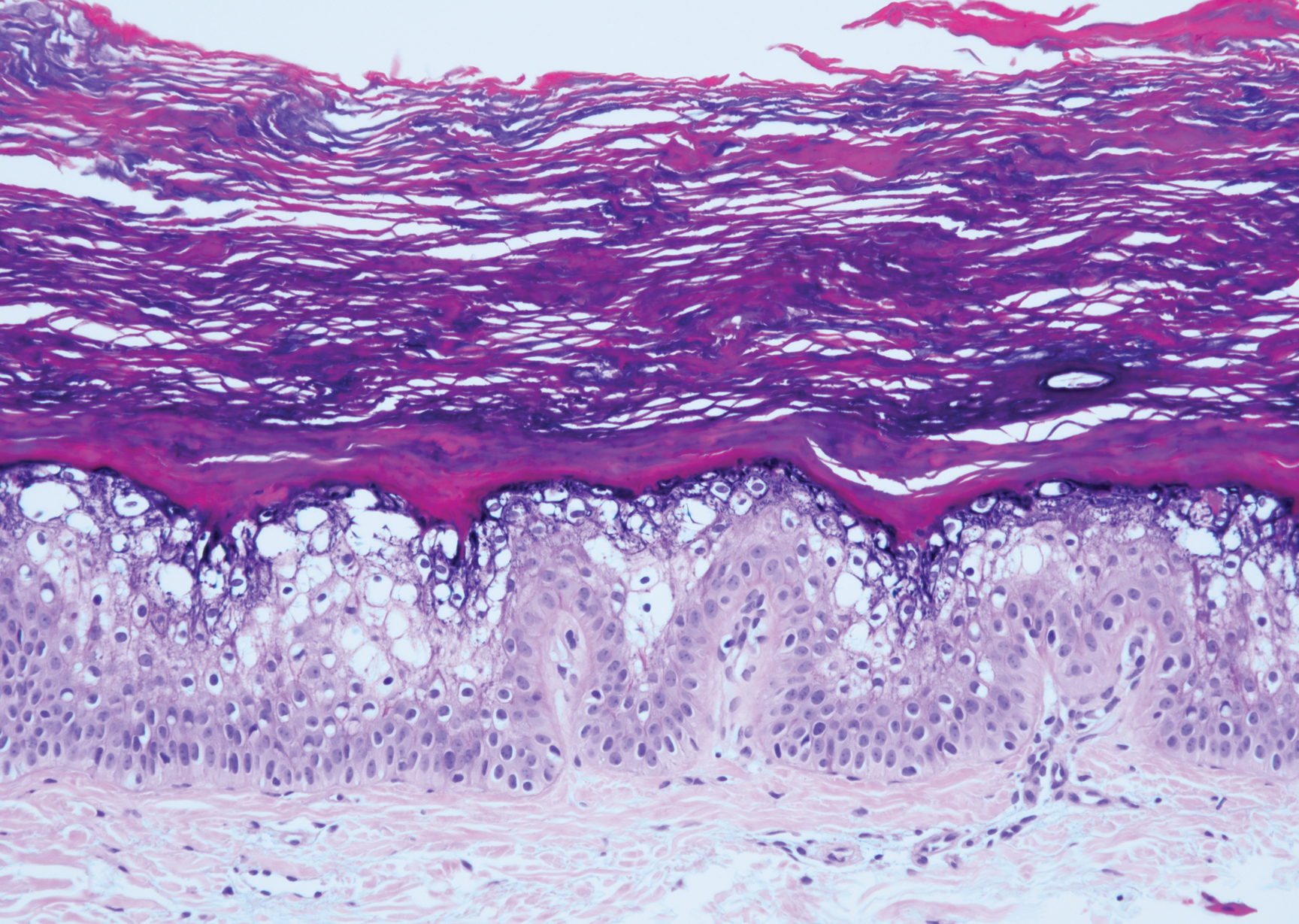

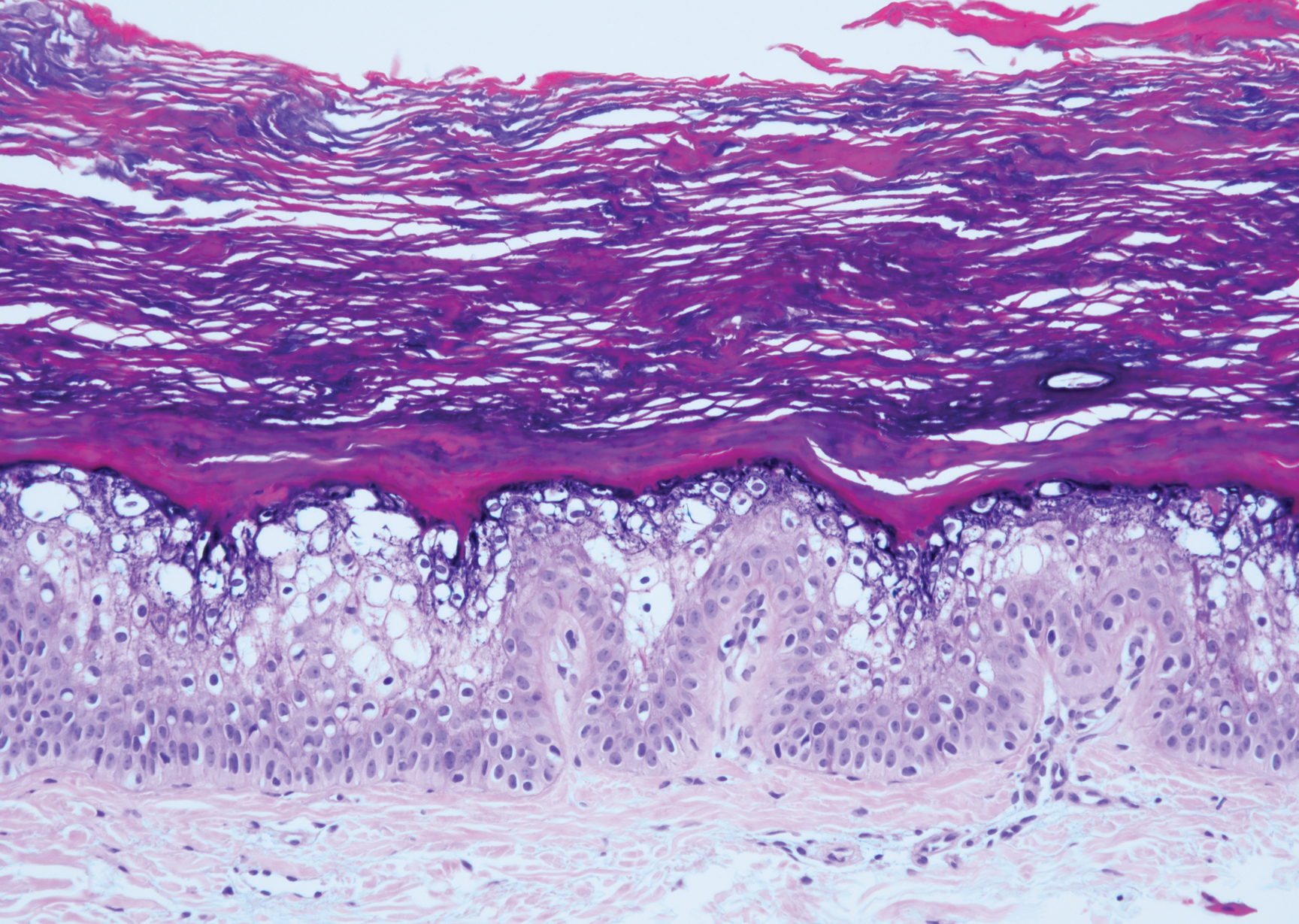

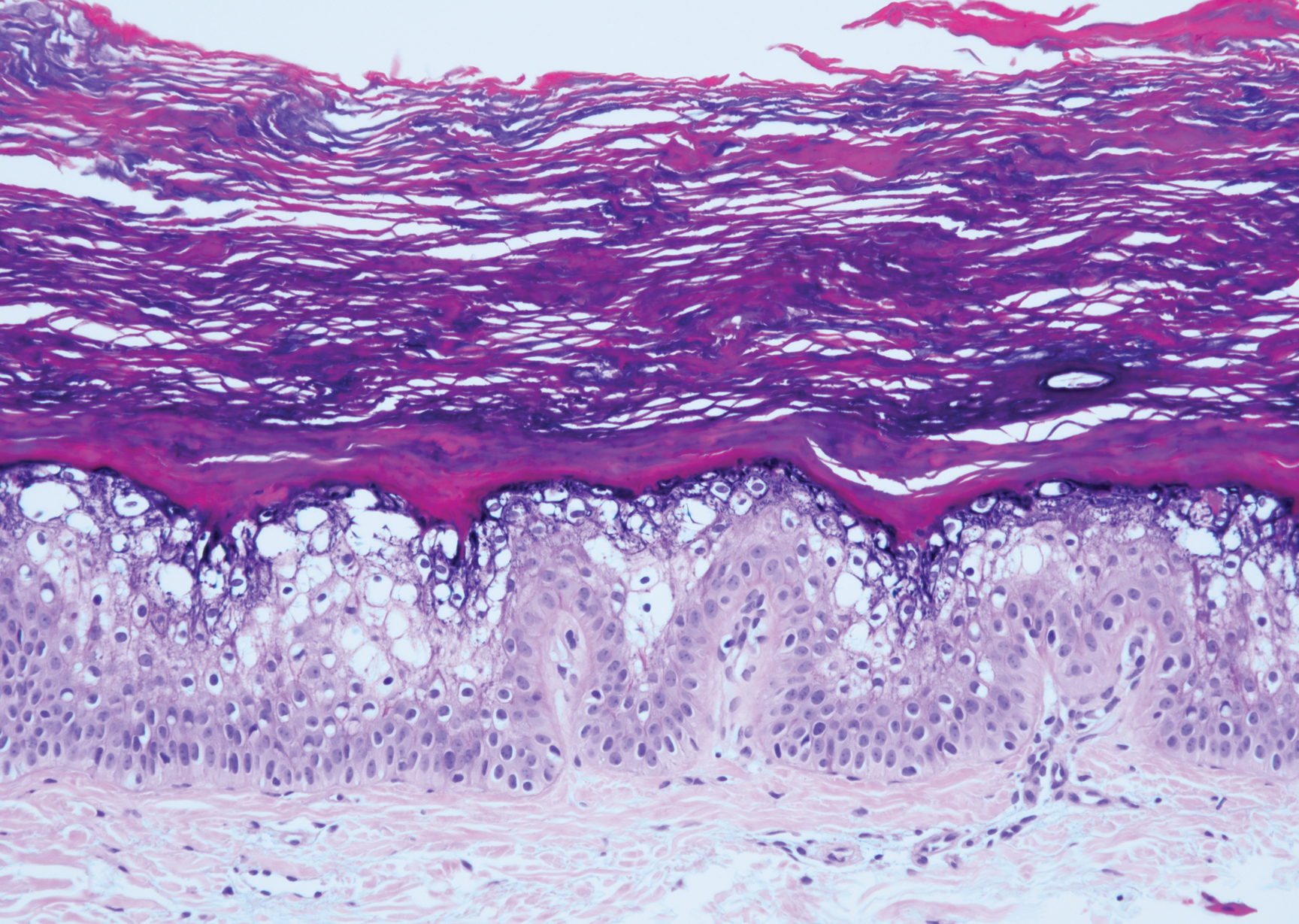

Histopathologically, HD may be mistaken for several other entities both benign and malignant.1 Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis can be a genetic disorder, an incidental finding in a variety of skin conditions, or an isolated lesion.4 The genetic syndrome, caused by mutation in keratins 1 or 10, clinically presents with hyperkeratosis, erosions, blisters, and thickening of the epidermis, often with a corrugated appearance. Epidermal nevi findings often are seen in conjunction with histologic changes of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis caused by mutation. Solitary lesions also can resemble seborrheic keratosis or verruca. In all examples of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, the histopathologic findings are identical.4 The granular layer is thickened, and coarse keratohyalin granules aggregate in the suprabasal cells.5 There is acantholysis with perinuclear vacuolization in the spinous and granular layers with characteristic pale cytoplasmic areas devoid of keratin filaments (Figure 1). The basal layer may be hyperproliferative.5

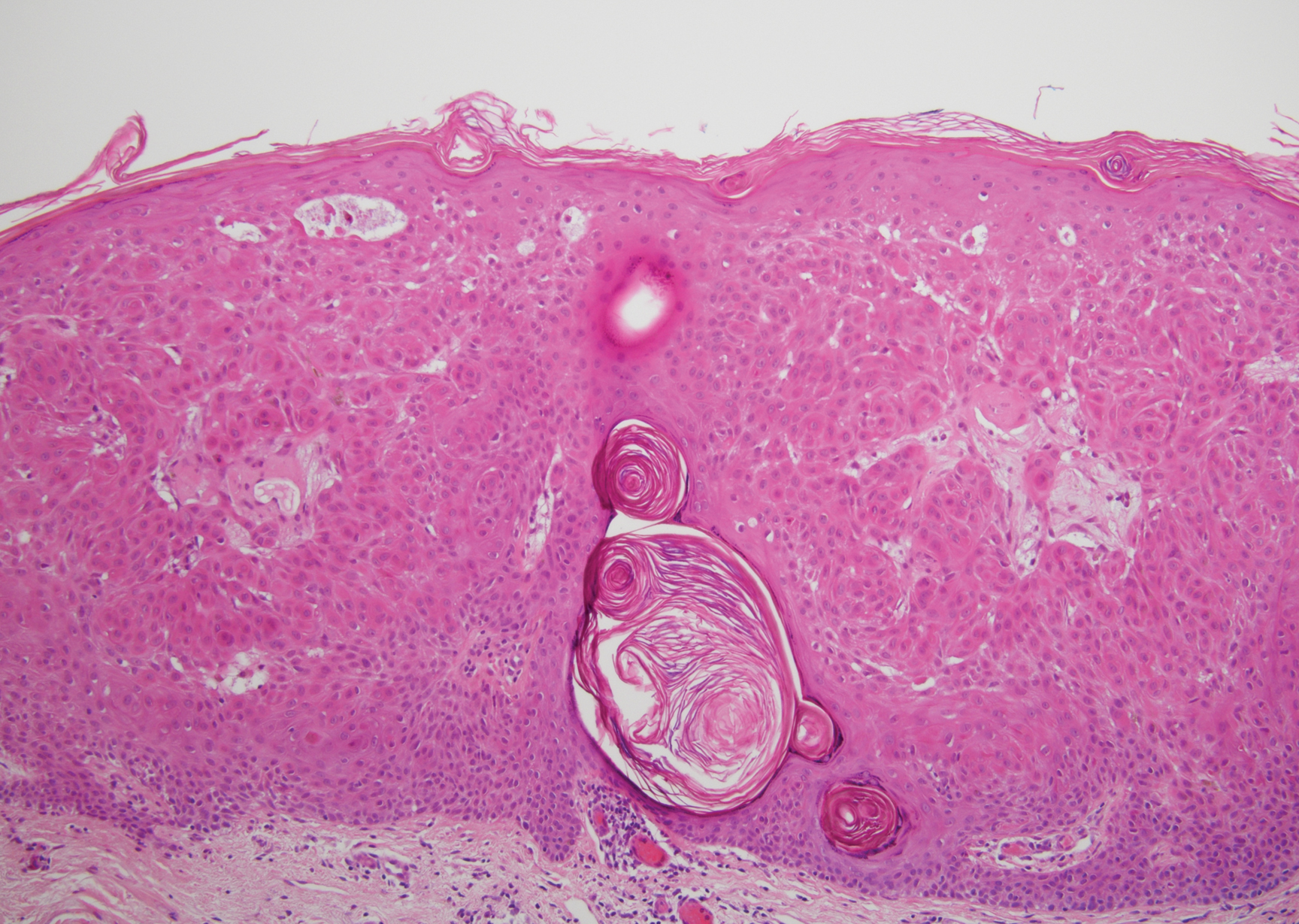

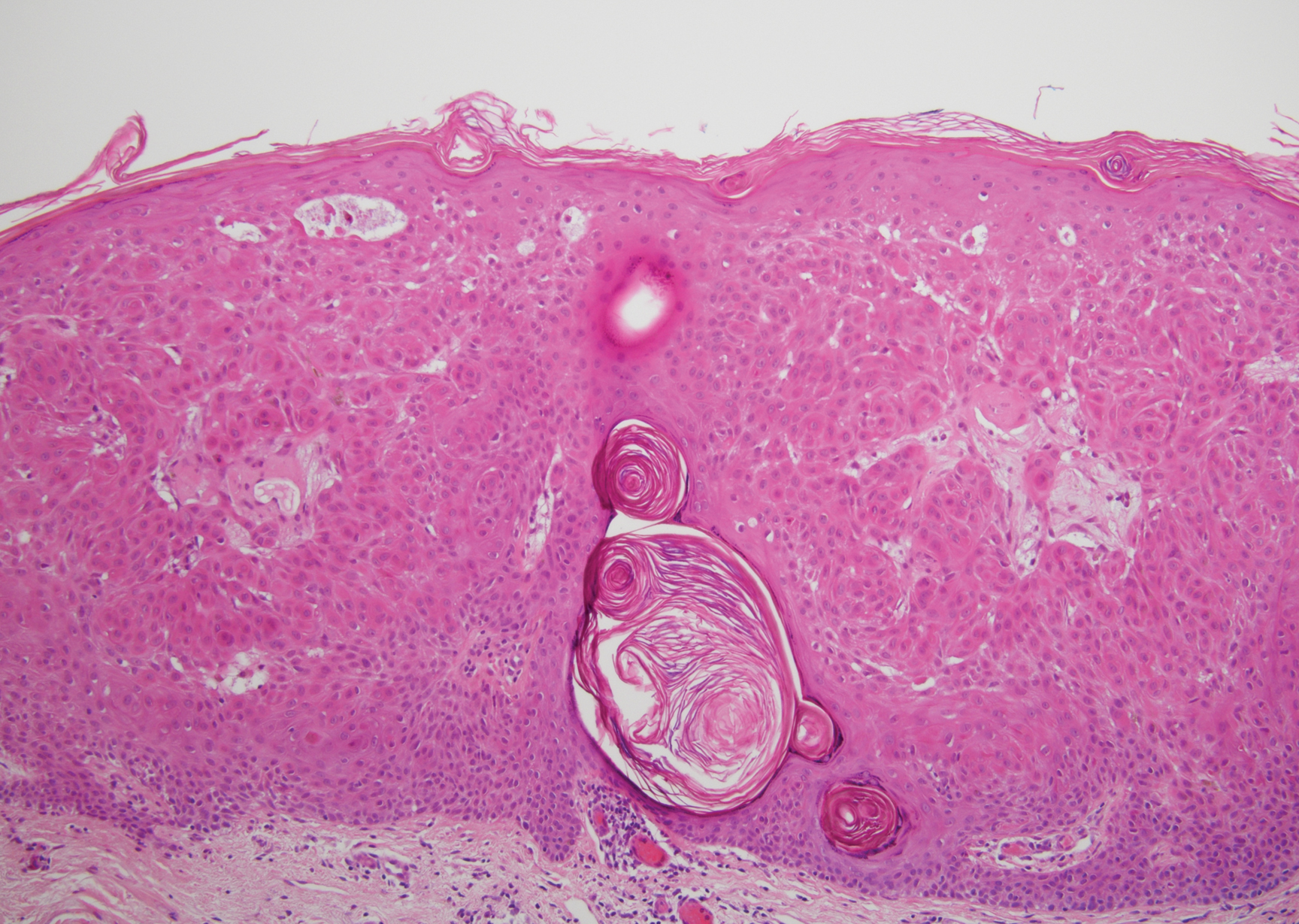

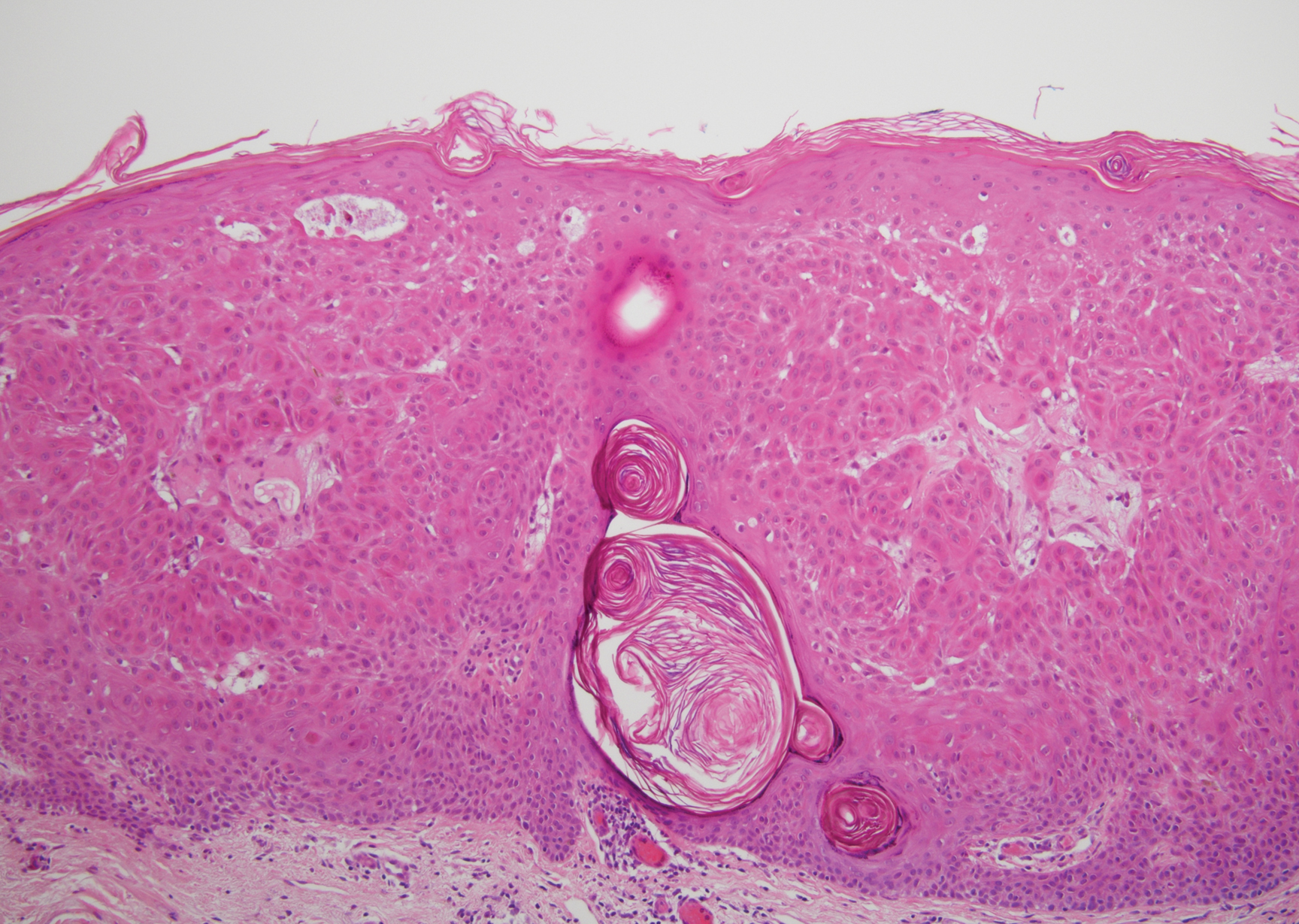

Irritated seborrheic keratosis presents as an exophytic, waxy, dark, sharply demarcated plaque with a stuck-on appearance.6 There is visible keratinization with comedolike openings, fissures and ridges, and scale; it also can contain milialike cysts. Histopathologically there is papillomatosis with prominent rete ridges, often including keratin pseudohorn cysts and squamous eddies. Enlarged capillaries can be seen in the dermal papillae. There is normal cytology with benign sheets of basaloid cells (Figure 2).7 Activating mutation in fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 leads to the growth and thickness of the epidermis that has been identified in these benign lesions.8

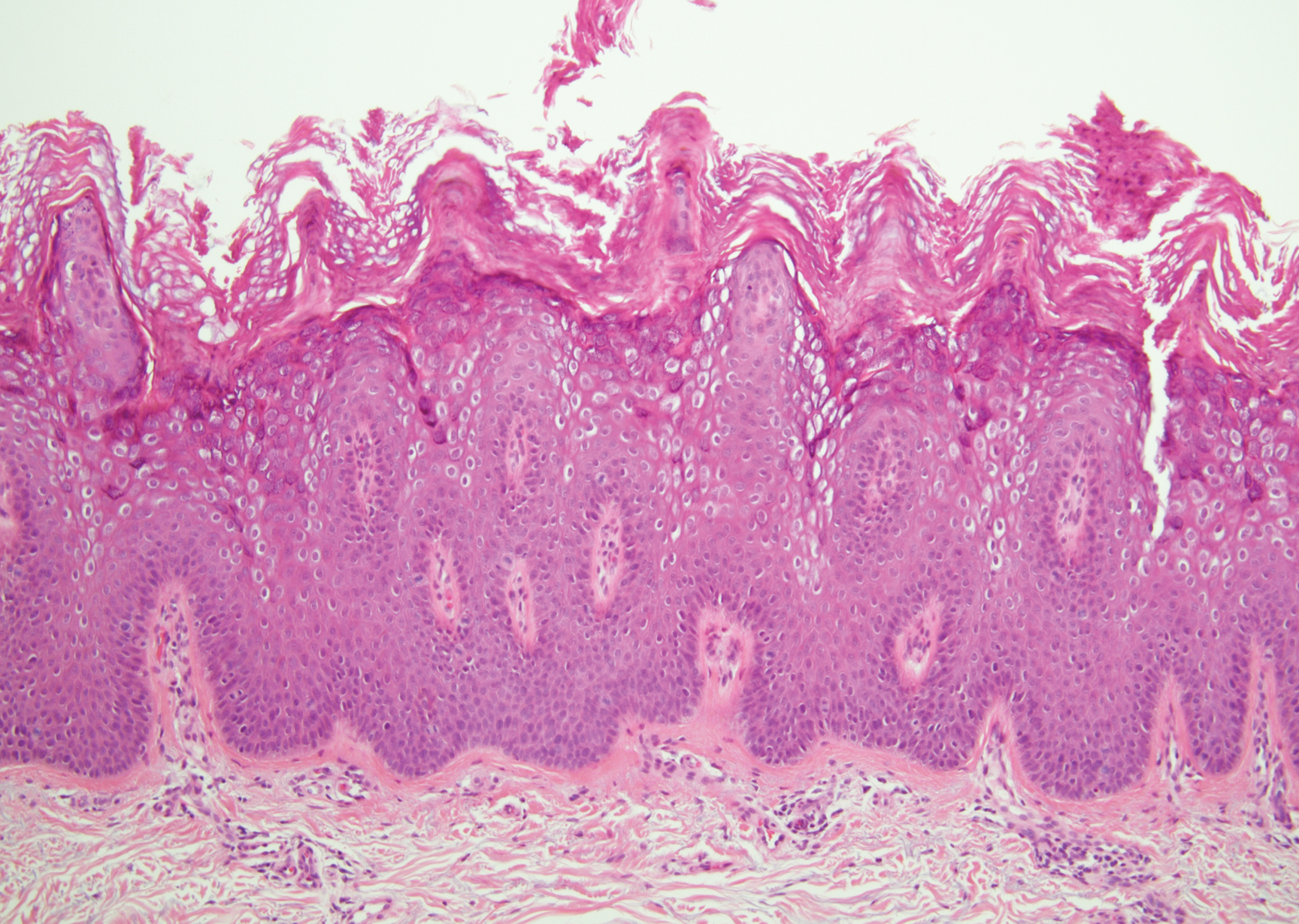

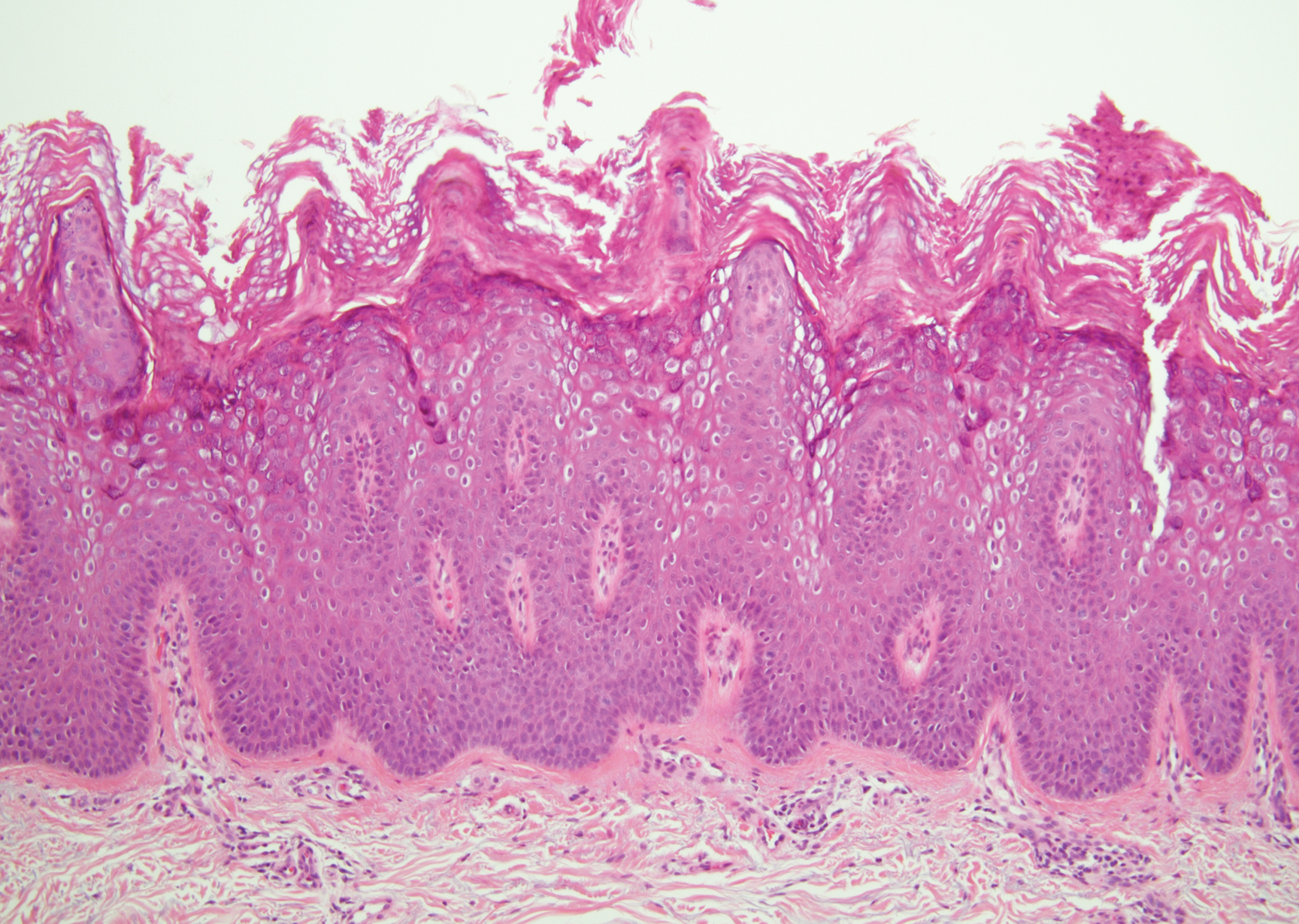

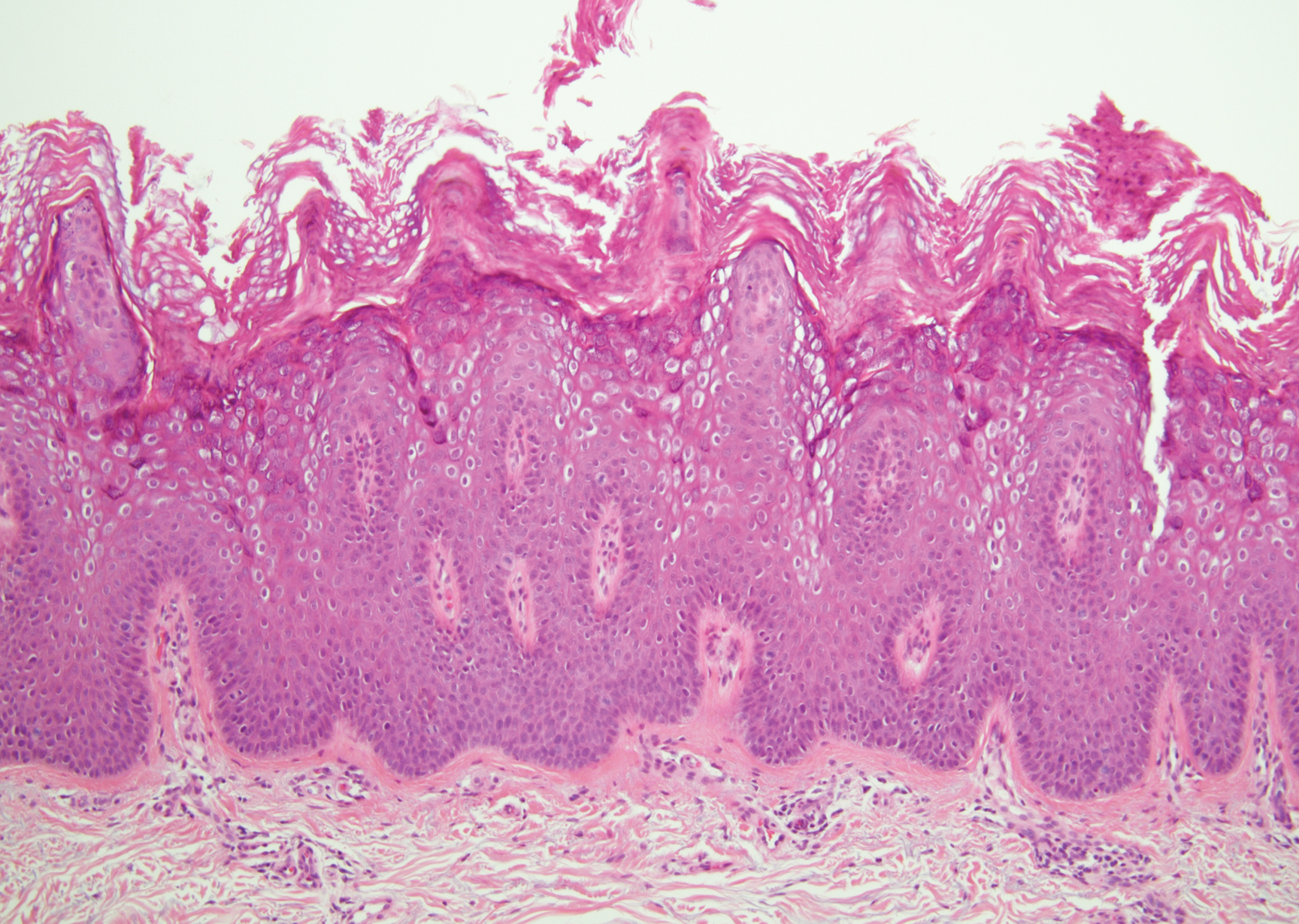

Verruca plana appears as a flesh-colored or reddish, warty, flat-topped papule that often forms clusters. Histopathologically it shows prominent hypergranulosis, thickened stratum spinosum, and vacuolized keratinocytes.9 The nuclei demonstrate a characteristic cytopathic effect of the virion, blurring the nuclear chromatin due to viral particle accumulation, known as koilocytes (Figure 3). The cause is the double-stranded DNA human papillomavirus types 2, 3, and 10.10

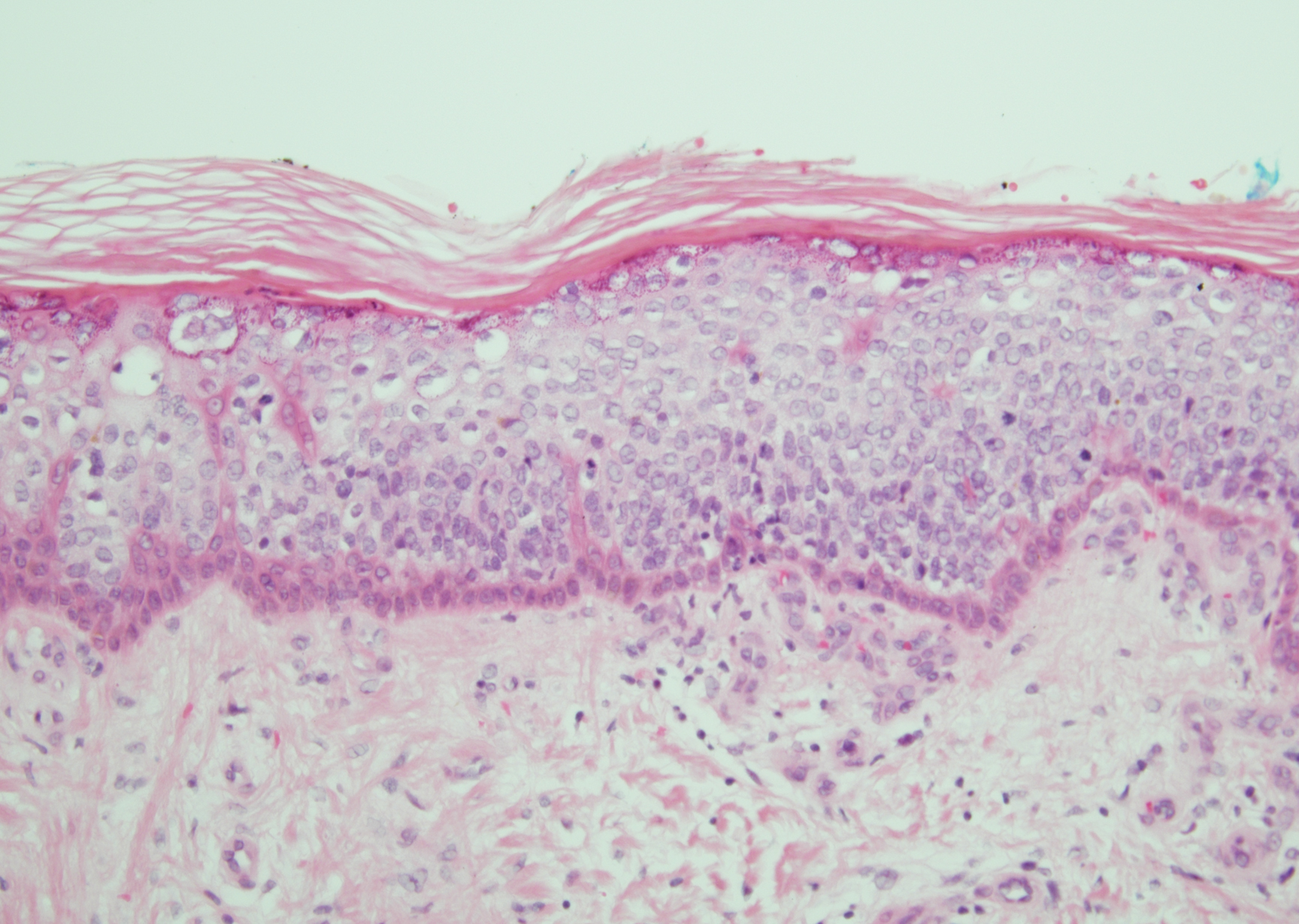

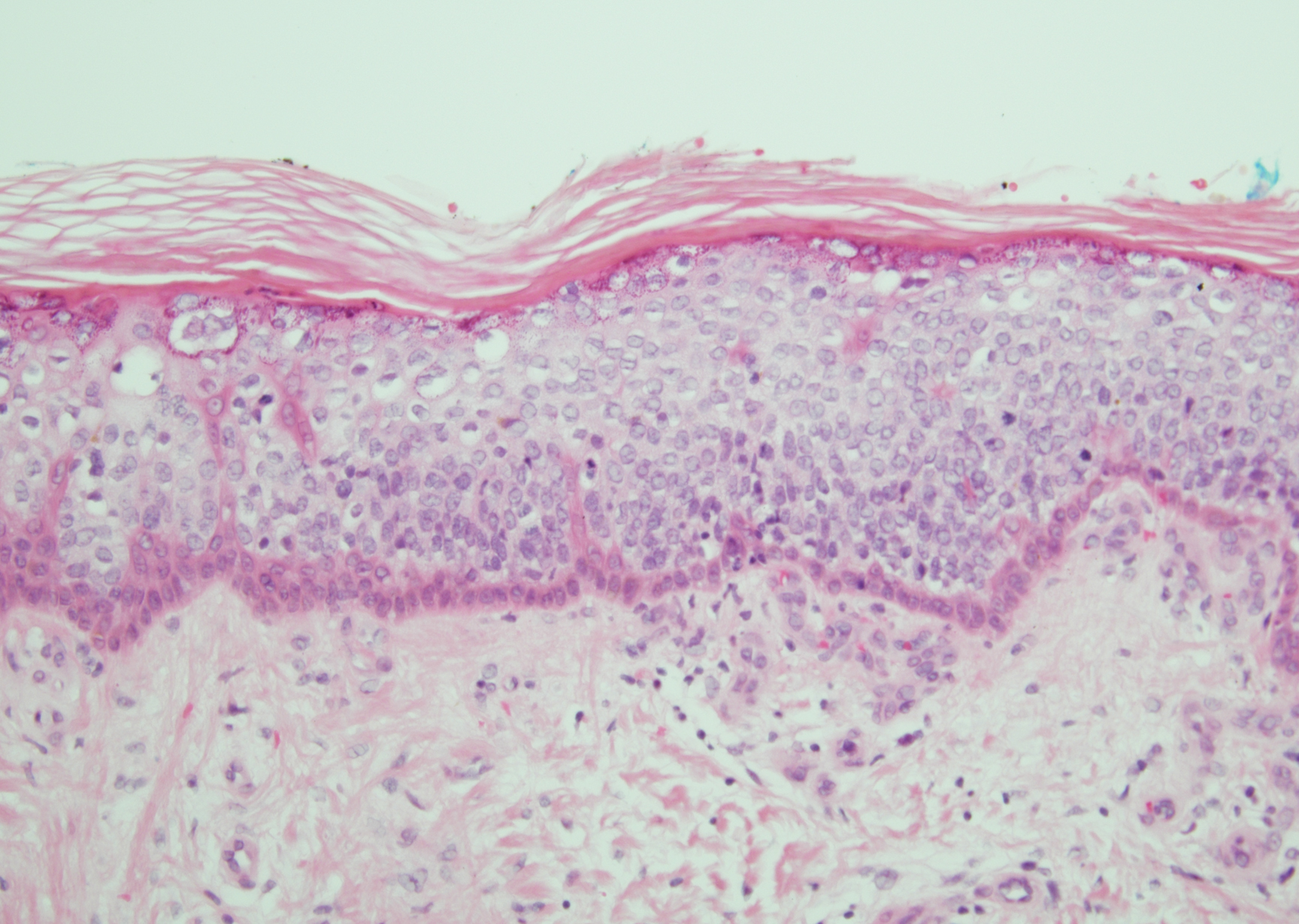

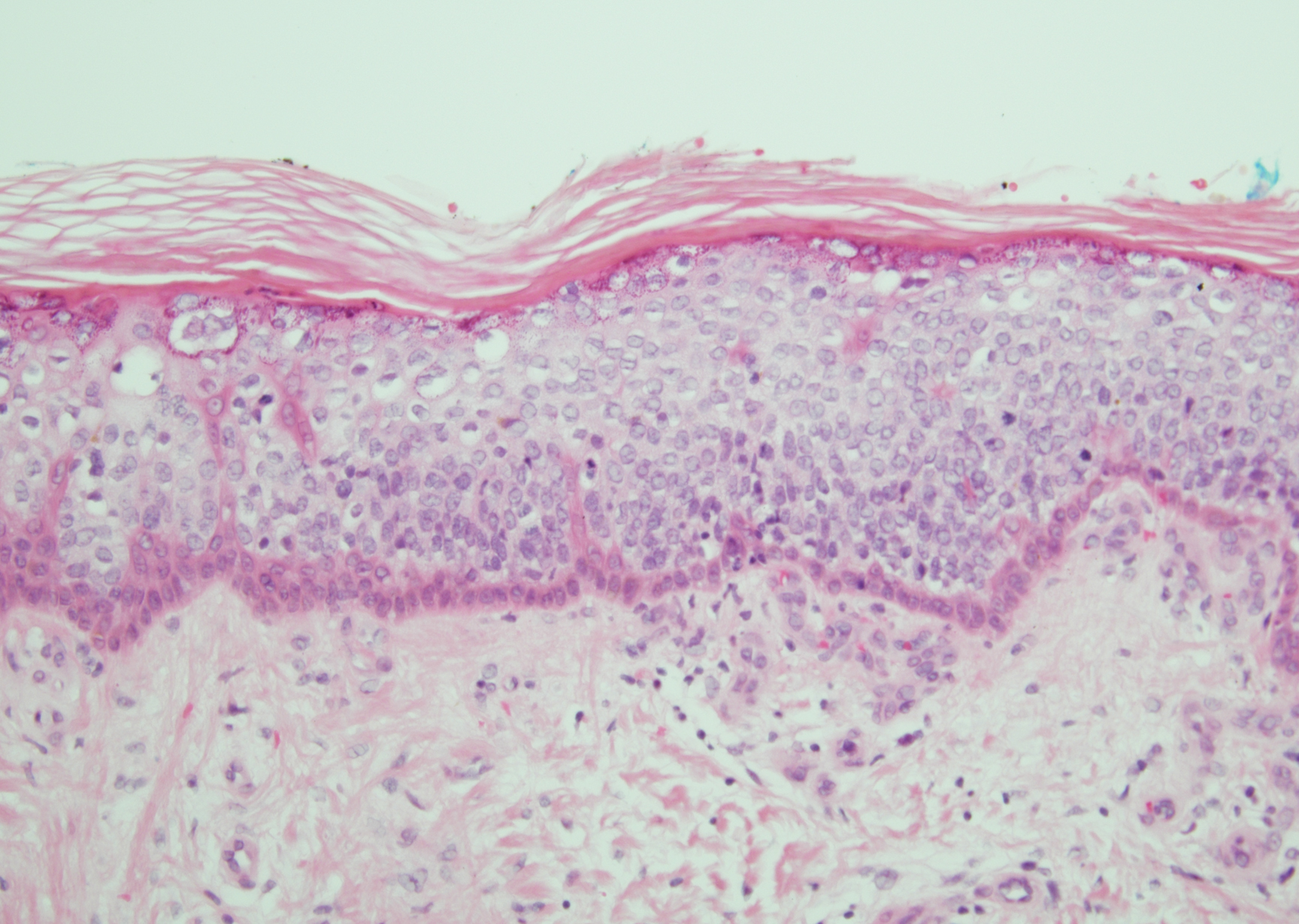

Bowen disease is a form of squamous cell carcinoma in situ characterized by an enlarging, well-demarcated, erythematous plaque with an irregular border and crusting or scaling. Histopathology reveals pleomorphic epidermal keratinization that becomes incorporated in the stratum corneum as parakeratotic nuclei. There is acanthosis, elongation of the rete ridges, and disorganized keratinocytes with atypia.11 The granular and spinous layers show an atypical honeycomb pattern with atypical cellular morphology (Figure 4).12 Bowen disease is a malignant lesion commonly found in older adults on sun-exposed skin that can evolve into invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

- Roy SF, Ko CJ, Moeckel GW, et al. Hypergranulotic dyscornification: 30 cases of a striking epithelial reaction pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:742-747.

- Dohse L, Elston D, Lountzis N, et al. Benign hypergranulotic keratosis with dyscornification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:AB52.

- Reichel M. Hypergranulotic dyscornification. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:21-24.

- Kumar P, Kumar R, Kumar Mandal RK, et al. Systematized linear epidermolytic hyperkeratosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:21248.

- Peter Rout D, Nair A, Gupta A, et al. Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis: clinical update. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:333-344.

- Ingraffea A. Benign skin neoplasms. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2013;21:21-32.

- Braun R. Dermoscopy of pigmented seborrheic keratosis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1556.

- Duperret EK, Oh SJ, McNeal A, et al. Activating FGFR3 mutations cause mild hyperplasia in human skin, but are insufficient to drive benign or malignant skin tumors. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:1551-1559.

- Liu H, Chen S, Zhang F, et al. Seborrheic keratosis or verruca plana? a pilot study with confocal laser scanning microscopy. Skin Res Technol. 2010;16:408-412.

- Prieto-Granada CN, Lobo AZC, Mihm MC. Skin infections. In: Kradin RL, ed. Diagnostic Pathology of Infectious Disease. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2010:519-616.

- DeCoste R, Moss P, Boutilier R, et al. Bowen disease with invasive mucin-secreting sweat gland differentiation: report of a case and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:425-430.

- Ulrich M, Kanitakis J, González S, et al. Evaluation of Bowen disease by in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2011;166:451-453.

The Diagnosis: Hypergranulotic Dyscornification

Hypergranulotic dyscornification (HD) is a rarely reported reaction pattern present in benign solitary keratoses with only few reports to date. It may be an underrecognized reaction pattern based on the paucity of reported cases as well as the histologic similarities to other entities. It has been hypothesized that this pattern reflects an underlying keratin mutation or disorder of keratinization.1

Clinically, HD most commonly presents as a waxy, tan-colored, solitary keratosis generally found on the lower limbs, trunk, or back in individuals aged 20 to 60 years.1,2 Histopathology shows marked hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and clumped basophilic keratohyalin granules within the corneocytes with digitated epidermal hyperplasia. There is abnormal cornification across the entire lesion with papillomatosis and marked hypergranulosis.3 There often are homogeneous orthokeratotic mounds of large, dull, eosinophilic-staining anucleate keratinocytes that are sharply demarcated from the thickened granular layer.1,2 Within the spinous, granular, and corneal layers, there is a pale, gray-staining, basophilic, cytoplasmic substance intercellularly.1

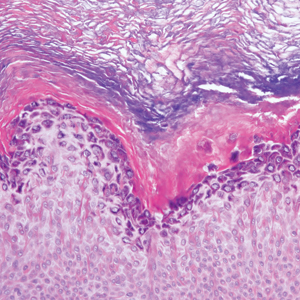

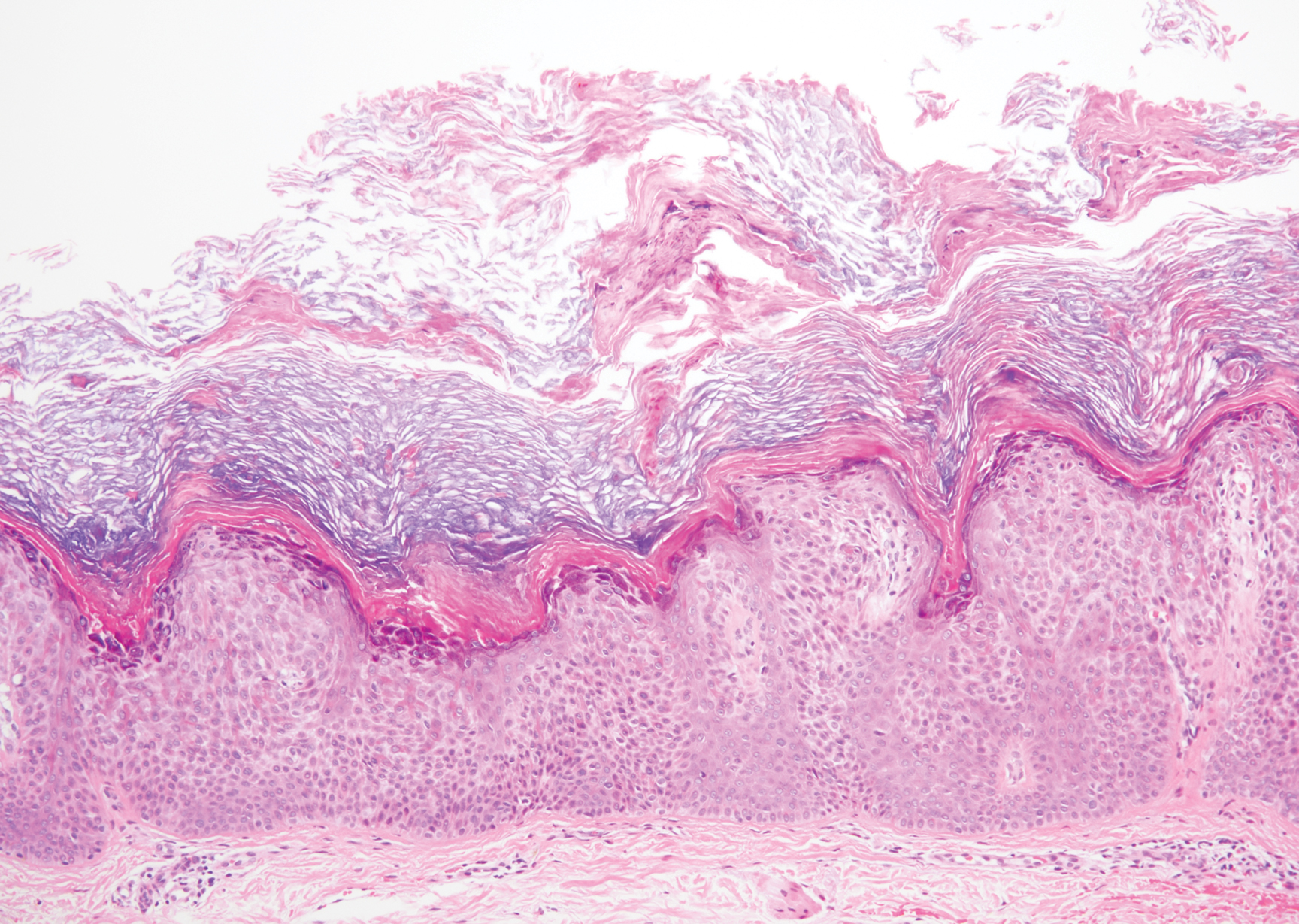

Histopathologically, HD may be mistaken for several other entities both benign and malignant.1 Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis can be a genetic disorder, an incidental finding in a variety of skin conditions, or an isolated lesion.4 The genetic syndrome, caused by mutation in keratins 1 or 10, clinically presents with hyperkeratosis, erosions, blisters, and thickening of the epidermis, often with a corrugated appearance. Epidermal nevi findings often are seen in conjunction with histologic changes of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis caused by mutation. Solitary lesions also can resemble seborrheic keratosis or verruca. In all examples of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, the histopathologic findings are identical.4 The granular layer is thickened, and coarse keratohyalin granules aggregate in the suprabasal cells.5 There is acantholysis with perinuclear vacuolization in the spinous and granular layers with characteristic pale cytoplasmic areas devoid of keratin filaments (Figure 1). The basal layer may be hyperproliferative.5

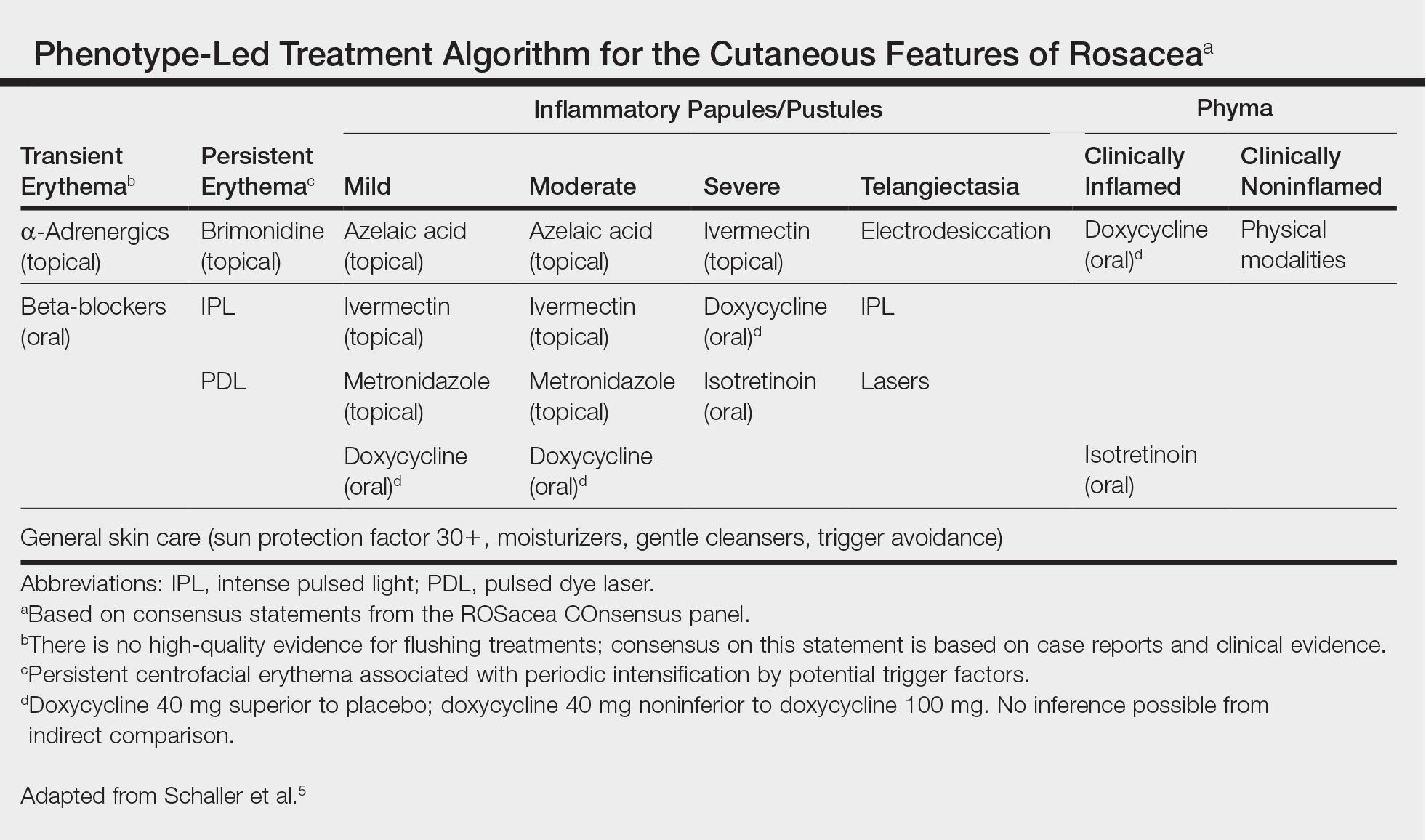

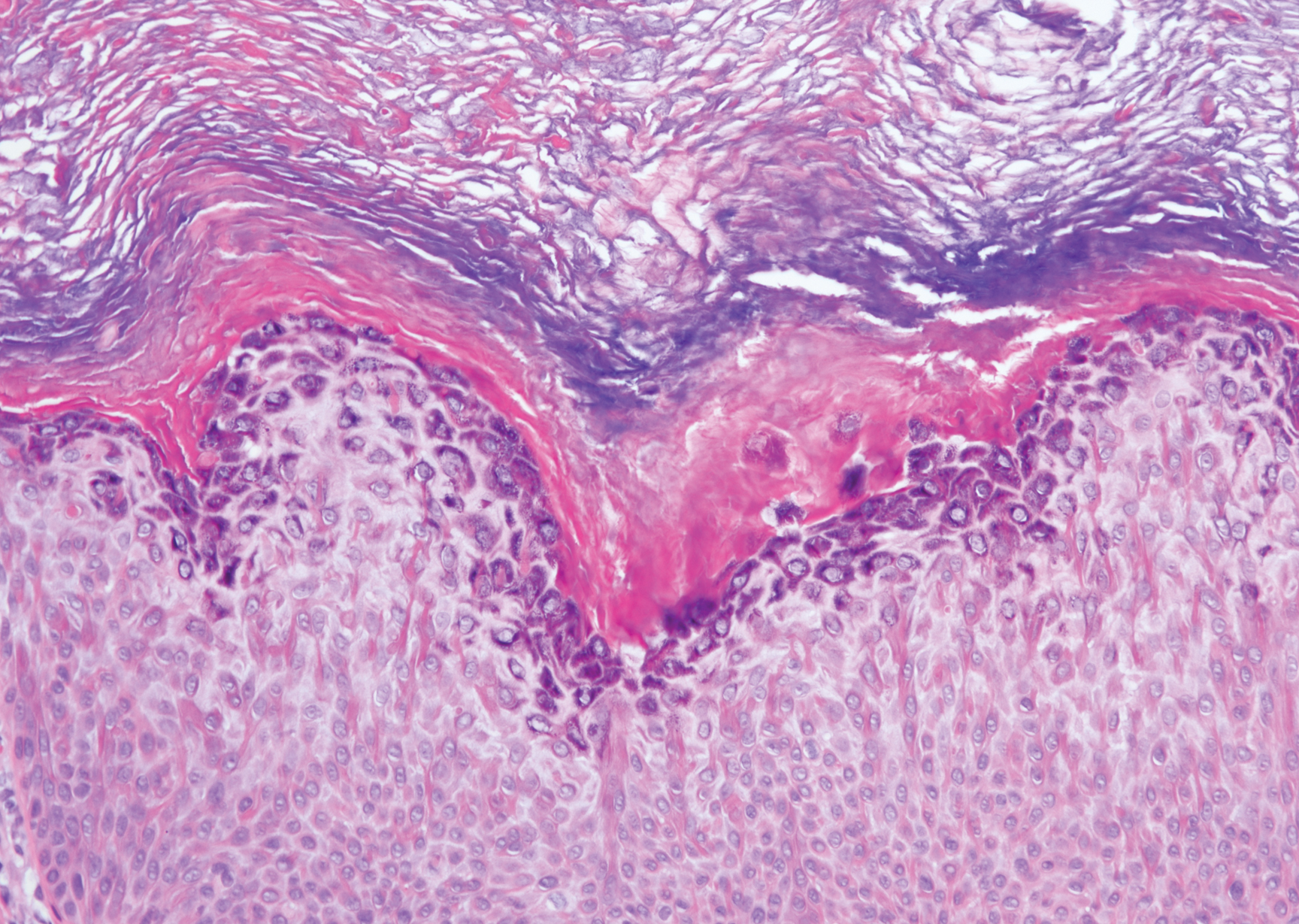

Irritated seborrheic keratosis presents as an exophytic, waxy, dark, sharply demarcated plaque with a stuck-on appearance.6 There is visible keratinization with comedolike openings, fissures and ridges, and scale; it also can contain milialike cysts. Histopathologically there is papillomatosis with prominent rete ridges, often including keratin pseudohorn cysts and squamous eddies. Enlarged capillaries can be seen in the dermal papillae. There is normal cytology with benign sheets of basaloid cells (Figure 2).7 Activating mutation in fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 leads to the growth and thickness of the epidermis that has been identified in these benign lesions.8

Verruca plana appears as a flesh-colored or reddish, warty, flat-topped papule that often forms clusters. Histopathologically it shows prominent hypergranulosis, thickened stratum spinosum, and vacuolized keratinocytes.9 The nuclei demonstrate a characteristic cytopathic effect of the virion, blurring the nuclear chromatin due to viral particle accumulation, known as koilocytes (Figure 3). The cause is the double-stranded DNA human papillomavirus types 2, 3, and 10.10

Bowen disease is a form of squamous cell carcinoma in situ characterized by an enlarging, well-demarcated, erythematous plaque with an irregular border and crusting or scaling. Histopathology reveals pleomorphic epidermal keratinization that becomes incorporated in the stratum corneum as parakeratotic nuclei. There is acanthosis, elongation of the rete ridges, and disorganized keratinocytes with atypia.11 The granular and spinous layers show an atypical honeycomb pattern with atypical cellular morphology (Figure 4).12 Bowen disease is a malignant lesion commonly found in older adults on sun-exposed skin that can evolve into invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

The Diagnosis: Hypergranulotic Dyscornification

Hypergranulotic dyscornification (HD) is a rarely reported reaction pattern present in benign solitary keratoses with only few reports to date. It may be an underrecognized reaction pattern based on the paucity of reported cases as well as the histologic similarities to other entities. It has been hypothesized that this pattern reflects an underlying keratin mutation or disorder of keratinization.1

Clinically, HD most commonly presents as a waxy, tan-colored, solitary keratosis generally found on the lower limbs, trunk, or back in individuals aged 20 to 60 years.1,2 Histopathology shows marked hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and clumped basophilic keratohyalin granules within the corneocytes with digitated epidermal hyperplasia. There is abnormal cornification across the entire lesion with papillomatosis and marked hypergranulosis.3 There often are homogeneous orthokeratotic mounds of large, dull, eosinophilic-staining anucleate keratinocytes that are sharply demarcated from the thickened granular layer.1,2 Within the spinous, granular, and corneal layers, there is a pale, gray-staining, basophilic, cytoplasmic substance intercellularly.1

Histopathologically, HD may be mistaken for several other entities both benign and malignant.1 Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis can be a genetic disorder, an incidental finding in a variety of skin conditions, or an isolated lesion.4 The genetic syndrome, caused by mutation in keratins 1 or 10, clinically presents with hyperkeratosis, erosions, blisters, and thickening of the epidermis, often with a corrugated appearance. Epidermal nevi findings often are seen in conjunction with histologic changes of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis caused by mutation. Solitary lesions also can resemble seborrheic keratosis or verruca. In all examples of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, the histopathologic findings are identical.4 The granular layer is thickened, and coarse keratohyalin granules aggregate in the suprabasal cells.5 There is acantholysis with perinuclear vacuolization in the spinous and granular layers with characteristic pale cytoplasmic areas devoid of keratin filaments (Figure 1). The basal layer may be hyperproliferative.5

Irritated seborrheic keratosis presents as an exophytic, waxy, dark, sharply demarcated plaque with a stuck-on appearance.6 There is visible keratinization with comedolike openings, fissures and ridges, and scale; it also can contain milialike cysts. Histopathologically there is papillomatosis with prominent rete ridges, often including keratin pseudohorn cysts and squamous eddies. Enlarged capillaries can be seen in the dermal papillae. There is normal cytology with benign sheets of basaloid cells (Figure 2).7 Activating mutation in fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 leads to the growth and thickness of the epidermis that has been identified in these benign lesions.8

Verruca plana appears as a flesh-colored or reddish, warty, flat-topped papule that often forms clusters. Histopathologically it shows prominent hypergranulosis, thickened stratum spinosum, and vacuolized keratinocytes.9 The nuclei demonstrate a characteristic cytopathic effect of the virion, blurring the nuclear chromatin due to viral particle accumulation, known as koilocytes (Figure 3). The cause is the double-stranded DNA human papillomavirus types 2, 3, and 10.10

Bowen disease is a form of squamous cell carcinoma in situ characterized by an enlarging, well-demarcated, erythematous plaque with an irregular border and crusting or scaling. Histopathology reveals pleomorphic epidermal keratinization that becomes incorporated in the stratum corneum as parakeratotic nuclei. There is acanthosis, elongation of the rete ridges, and disorganized keratinocytes with atypia.11 The granular and spinous layers show an atypical honeycomb pattern with atypical cellular morphology (Figure 4).12 Bowen disease is a malignant lesion commonly found in older adults on sun-exposed skin that can evolve into invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

- Roy SF, Ko CJ, Moeckel GW, et al. Hypergranulotic dyscornification: 30 cases of a striking epithelial reaction pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:742-747.

- Dohse L, Elston D, Lountzis N, et al. Benign hypergranulotic keratosis with dyscornification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:AB52.

- Reichel M. Hypergranulotic dyscornification. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:21-24.

- Kumar P, Kumar R, Kumar Mandal RK, et al. Systematized linear epidermolytic hyperkeratosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:21248.

- Peter Rout D, Nair A, Gupta A, et al. Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis: clinical update. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:333-344.

- Ingraffea A. Benign skin neoplasms. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2013;21:21-32.

- Braun R. Dermoscopy of pigmented seborrheic keratosis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1556.

- Duperret EK, Oh SJ, McNeal A, et al. Activating FGFR3 mutations cause mild hyperplasia in human skin, but are insufficient to drive benign or malignant skin tumors. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:1551-1559.

- Liu H, Chen S, Zhang F, et al. Seborrheic keratosis or verruca plana? a pilot study with confocal laser scanning microscopy. Skin Res Technol. 2010;16:408-412.

- Prieto-Granada CN, Lobo AZC, Mihm MC. Skin infections. In: Kradin RL, ed. Diagnostic Pathology of Infectious Disease. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2010:519-616.

- DeCoste R, Moss P, Boutilier R, et al. Bowen disease with invasive mucin-secreting sweat gland differentiation: report of a case and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:425-430.

- Ulrich M, Kanitakis J, González S, et al. Evaluation of Bowen disease by in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2011;166:451-453.

- Roy SF, Ko CJ, Moeckel GW, et al. Hypergranulotic dyscornification: 30 cases of a striking epithelial reaction pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:742-747.

- Dohse L, Elston D, Lountzis N, et al. Benign hypergranulotic keratosis with dyscornification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:AB52.

- Reichel M. Hypergranulotic dyscornification. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:21-24.

- Kumar P, Kumar R, Kumar Mandal RK, et al. Systematized linear epidermolytic hyperkeratosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:21248.

- Peter Rout D, Nair A, Gupta A, et al. Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis: clinical update. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:333-344.

- Ingraffea A. Benign skin neoplasms. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2013;21:21-32.

- Braun R. Dermoscopy of pigmented seborrheic keratosis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1556.

- Duperret EK, Oh SJ, McNeal A, et al. Activating FGFR3 mutations cause mild hyperplasia in human skin, but are insufficient to drive benign or malignant skin tumors. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:1551-1559.

- Liu H, Chen S, Zhang F, et al. Seborrheic keratosis or verruca plana? a pilot study with confocal laser scanning microscopy. Skin Res Technol. 2010;16:408-412.

- Prieto-Granada CN, Lobo AZC, Mihm MC. Skin infections. In: Kradin RL, ed. Diagnostic Pathology of Infectious Disease. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2010:519-616.

- DeCoste R, Moss P, Boutilier R, et al. Bowen disease with invasive mucin-secreting sweat gland differentiation: report of a case and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:425-430.

- Ulrich M, Kanitakis J, González S, et al. Evaluation of Bowen disease by in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2011;166:451-453.

A 59-year-old woman with a history of basal cell carcinoma, uterine and ovarian cancer, and verrucae presented with an asymptomatic 3-mm lesion on the left side of the lower abdomen. Physical examination revealed a waxy, tan-colored, solitary keratosis. A shave biopsy was performed. Histopathology showed hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, papillomatosis, and marked hypergranulosis with pale gray cytoplasm of the spinous-layer keratinocytes.

"Doctor, Do I Need a Skin Check?"

What does your patient need to know at the first visit?

A patient may be scheduled for a total-body skin examination (TBSE) through several routes: primary care referral, continued cancer screening for an at-risk patient or patient transfer, or patient-directed scheduling for general screening regardless of risk factors. At the patient's first visit, it is imperative that the course of the appointment is smooth and predictable for patient comfort and for a thorough and effective examination. The nurse initially solicits salient medical history, particularly personal and family history of skin cancer, current medications, and any acute concerns. The nurse then prepares the patient for the logistics of the TBSE, namely to undress, don a gown that ties and opens in the back, and be seated on the examination table. When I enter the room, the conversation commences with me seated across from the patient, reviewing specifics about his/her history and risk factors. Then the TBSE is executed from head to toe.

Do you broadly recommend TBSE?

Firstly, TBSE is a safe clinical tool, supported by data outlining a lack of notable patient morbidity during the examination, including psychosocial factors, and it is generally well-received by patients (Risica et al). In 2016, the US Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) outlined its recommendations regarding screening for skin cancer, concluding that there is insufficient evidence to broadly recommend TBSE. Unfortunately, USPSTF findings amassed data from all types of screenings, including those by nondermatologists, and did not extract specialty-specific benefits and risks to patients. The recommendation also did not outline the influence of TBSE on morbidity and mortality for at-risk groups. The guidelines target primary care practice trends; therefore, specialty societies such as the American Academy of Dermatology issued statements following the USPSTF recommendation outlining these salient clarifications, namely that TBSE detects melanoma and keratinocyte carcinomas earlier than in patients who are not screened. Randomized controlled trials to prove this observation are lacking, particularly because of the ethics of withholding screening from a prospective study group. However, in 2017, Johnson et al outlined the best available survival data in concert with the USPSTF statement to arrive at the most beneficial screening recommendations for patients, specifically targeting risk groups--those with a history of skin cancer, immunosuppression, indoor tanning and/or many blistering sunburns, and several other genetic parameters--for at least annual TBSE.

The technique and reproducibility of TBSE also are not standardized, though they seem to have been endearingly apprenticed but variably implemented through generations of dermatology residents going forward into practice. As it is, depending on patient body surface area, mobility, willingness to disrobe, and adornments (eg, tattoos, hair appliances), multiple factors can restrict full view of a patient's skin. Recently, Helm et al proposed standardizing the TBSE sequence to minimize omitted areas of the body, which may become an imperative tool for streamlined resident teaching and optimal screening encounters.

How do you keep patients compliant with TBSE?

During and following TBSE, I typically outline any lesions of concern and plan for further testing, screening, and behavioral prevention strategies. Frequency of TBSE and importance of compliance are discussed during the visit and reinforced at checkout where the appointment templates are established a year in advance for those with skin cancer. Further, for those with melanoma, their appointment slots are given priority status so that any cancellations or delays are rescheduled preferentially. Particularly during the discussion about TBSE frequency, I emphasize the comparison and importance of this visit akin to other recommended screenings, such as mammograms and colonoscopies, and that we, as dermatologists, are part of their cancer surveillance team.

What do you do if patients refuse your recommendations?

Some patients refuse a gown or removal of certain clothing items (eg, undergarments, socks, wigs). Some patients defer a yearly TBSE upon checkout and schedule an appointment only when a lesion of concern arises. My advice is not to shame patients and to take advantage of as much as the patient is able and comfortable to show us and be present for, welcoming that we have the opportunity to take care of them and screen for cancer in any capacity. In underserved or limited budget practice regions, lesion-directed examination vs TBSE may be the only screening method utilized and may even attract more patients to a screening facility (Hoorens et al).

In the opposite corner are those patients who deem the recommended TBSE interval as too infrequent, which poses a delicate dilemma. In my opinion, these situations present another cohort of risks. Namely, the patient may become (or continue to be) overly fixated on the small details of every skin lesion, and in my experience, they tend to develop the habit of expecting at least 1 biopsy at each visit, typically of a lesion of their choosing. Depending on the validity of this expectation vs my clinical examination, it can lead to a difficult discussion with the patient about oversampling lesions and the potential for many scars, copious reexcisions for ambiguous lesion pathology, and a trend away from prudent clinical care. In addition, multiple visits incur more patient co-pays and time away from school, work, or home. To ease the patient's mind, I advise to call our office for a more acute visit if there is a lesion of concern; I additionally recommend taking a smartphone photograph of a concerning lesion and monitoring it for changes or sending the photograph to our patient portal messaging system so we can evaluate its acuity.

What take-home advice do you give to patients?

As the visit ends, I further explain that home self-examination or examination by a partner between visits is intuitively a valuable screening adjunct for skin cancer. In 2018, the USPSTF recommended behavioral skin cancer prevention counseling and self-examination only for younger-age cohorts with fair skin (6 months to 24 years), but its utility in specialty practice must be qualified. The American Academy of Dermatology Association subsequently issued a statement to support safe sun-protective practices and diligent self-screening for changing lesions, as earlier detection and management of skin cancer can lead to decreased morbidity and mortality from these neoplasms.

Resources for Patients

American Academy of Dermatology's SPOT Skin Cancer

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: What Screening Tests Are There?

Suggested Readings

AAD statement on USPSTF recommendation on skin cancer screening. Schaumburg, IL: American Academy of Dermatology; July 26, 2016. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/aad-statement-on-uspstf. Accessed April 26, 2019.

AADA responds to USPSTF recommendation on skin cancer prevention counseling. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Dermatology Association; March 20, 2018. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/skin-cancer-prevention-counseling. Accessed April 26, 2019.

Helm MF, Hallock KK, Bisbee E, et al. Optimizing the total body skin exam: an observational cohort study [published online February 15, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.028.

Hoorens I, Vossaert K, Pil L, et al. Total-body examination vs lesion-directed skin cancer screening. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:27-34.

Johnson MM, Leachman SA, Aspinwall LG, et al. Skin cancer screening: recommendations for data-driven screening guidelines and a review of the US Preventive Services Task Force controversy. Melanoma Manag. 2017;4:13-37.

Risica PM, Matthews NH, Dionne L, et al. Psychosocial consequences of skin cancer screening. Prev Med Rep. 2018;10:310-316.

US Preventive Services Task Force, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. Screening for skin cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316:429-435.

US Preventive Services Task Force, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Behavioral counseling to prevent skin cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319:1134-1142.

What does your patient need to know at the first visit?

A patient may be scheduled for a total-body skin examination (TBSE) through several routes: primary care referral, continued cancer screening for an at-risk patient or patient transfer, or patient-directed scheduling for general screening regardless of risk factors. At the patient's first visit, it is imperative that the course of the appointment is smooth and predictable for patient comfort and for a thorough and effective examination. The nurse initially solicits salient medical history, particularly personal and family history of skin cancer, current medications, and any acute concerns. The nurse then prepares the patient for the logistics of the TBSE, namely to undress, don a gown that ties and opens in the back, and be seated on the examination table. When I enter the room, the conversation commences with me seated across from the patient, reviewing specifics about his/her history and risk factors. Then the TBSE is executed from head to toe.

Do you broadly recommend TBSE?

Firstly, TBSE is a safe clinical tool, supported by data outlining a lack of notable patient morbidity during the examination, including psychosocial factors, and it is generally well-received by patients (Risica et al). In 2016, the US Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) outlined its recommendations regarding screening for skin cancer, concluding that there is insufficient evidence to broadly recommend TBSE. Unfortunately, USPSTF findings amassed data from all types of screenings, including those by nondermatologists, and did not extract specialty-specific benefits and risks to patients. The recommendation also did not outline the influence of TBSE on morbidity and mortality for at-risk groups. The guidelines target primary care practice trends; therefore, specialty societies such as the American Academy of Dermatology issued statements following the USPSTF recommendation outlining these salient clarifications, namely that TBSE detects melanoma and keratinocyte carcinomas earlier than in patients who are not screened. Randomized controlled trials to prove this observation are lacking, particularly because of the ethics of withholding screening from a prospective study group. However, in 2017, Johnson et al outlined the best available survival data in concert with the USPSTF statement to arrive at the most beneficial screening recommendations for patients, specifically targeting risk groups--those with a history of skin cancer, immunosuppression, indoor tanning and/or many blistering sunburns, and several other genetic parameters--for at least annual TBSE.

The technique and reproducibility of TBSE also are not standardized, though they seem to have been endearingly apprenticed but variably implemented through generations of dermatology residents going forward into practice. As it is, depending on patient body surface area, mobility, willingness to disrobe, and adornments (eg, tattoos, hair appliances), multiple factors can restrict full view of a patient's skin. Recently, Helm et al proposed standardizing the TBSE sequence to minimize omitted areas of the body, which may become an imperative tool for streamlined resident teaching and optimal screening encounters.

How do you keep patients compliant with TBSE?

During and following TBSE, I typically outline any lesions of concern and plan for further testing, screening, and behavioral prevention strategies. Frequency of TBSE and importance of compliance are discussed during the visit and reinforced at checkout where the appointment templates are established a year in advance for those with skin cancer. Further, for those with melanoma, their appointment slots are given priority status so that any cancellations or delays are rescheduled preferentially. Particularly during the discussion about TBSE frequency, I emphasize the comparison and importance of this visit akin to other recommended screenings, such as mammograms and colonoscopies, and that we, as dermatologists, are part of their cancer surveillance team.

What do you do if patients refuse your recommendations?

Some patients refuse a gown or removal of certain clothing items (eg, undergarments, socks, wigs). Some patients defer a yearly TBSE upon checkout and schedule an appointment only when a lesion of concern arises. My advice is not to shame patients and to take advantage of as much as the patient is able and comfortable to show us and be present for, welcoming that we have the opportunity to take care of them and screen for cancer in any capacity. In underserved or limited budget practice regions, lesion-directed examination vs TBSE may be the only screening method utilized and may even attract more patients to a screening facility (Hoorens et al).

In the opposite corner are those patients who deem the recommended TBSE interval as too infrequent, which poses a delicate dilemma. In my opinion, these situations present another cohort of risks. Namely, the patient may become (or continue to be) overly fixated on the small details of every skin lesion, and in my experience, they tend to develop the habit of expecting at least 1 biopsy at each visit, typically of a lesion of their choosing. Depending on the validity of this expectation vs my clinical examination, it can lead to a difficult discussion with the patient about oversampling lesions and the potential for many scars, copious reexcisions for ambiguous lesion pathology, and a trend away from prudent clinical care. In addition, multiple visits incur more patient co-pays and time away from school, work, or home. To ease the patient's mind, I advise to call our office for a more acute visit if there is a lesion of concern; I additionally recommend taking a smartphone photograph of a concerning lesion and monitoring it for changes or sending the photograph to our patient portal messaging system so we can evaluate its acuity.

What take-home advice do you give to patients?

As the visit ends, I further explain that home self-examination or examination by a partner between visits is intuitively a valuable screening adjunct for skin cancer. In 2018, the USPSTF recommended behavioral skin cancer prevention counseling and self-examination only for younger-age cohorts with fair skin (6 months to 24 years), but its utility in specialty practice must be qualified. The American Academy of Dermatology Association subsequently issued a statement to support safe sun-protective practices and diligent self-screening for changing lesions, as earlier detection and management of skin cancer can lead to decreased morbidity and mortality from these neoplasms.

Resources for Patients

American Academy of Dermatology's SPOT Skin Cancer

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: What Screening Tests Are There?

What does your patient need to know at the first visit?

A patient may be scheduled for a total-body skin examination (TBSE) through several routes: primary care referral, continued cancer screening for an at-risk patient or patient transfer, or patient-directed scheduling for general screening regardless of risk factors. At the patient's first visit, it is imperative that the course of the appointment is smooth and predictable for patient comfort and for a thorough and effective examination. The nurse initially solicits salient medical history, particularly personal and family history of skin cancer, current medications, and any acute concerns. The nurse then prepares the patient for the logistics of the TBSE, namely to undress, don a gown that ties and opens in the back, and be seated on the examination table. When I enter the room, the conversation commences with me seated across from the patient, reviewing specifics about his/her history and risk factors. Then the TBSE is executed from head to toe.

Do you broadly recommend TBSE?

Firstly, TBSE is a safe clinical tool, supported by data outlining a lack of notable patient morbidity during the examination, including psychosocial factors, and it is generally well-received by patients (Risica et al). In 2016, the US Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) outlined its recommendations regarding screening for skin cancer, concluding that there is insufficient evidence to broadly recommend TBSE. Unfortunately, USPSTF findings amassed data from all types of screenings, including those by nondermatologists, and did not extract specialty-specific benefits and risks to patients. The recommendation also did not outline the influence of TBSE on morbidity and mortality for at-risk groups. The guidelines target primary care practice trends; therefore, specialty societies such as the American Academy of Dermatology issued statements following the USPSTF recommendation outlining these salient clarifications, namely that TBSE detects melanoma and keratinocyte carcinomas earlier than in patients who are not screened. Randomized controlled trials to prove this observation are lacking, particularly because of the ethics of withholding screening from a prospective study group. However, in 2017, Johnson et al outlined the best available survival data in concert with the USPSTF statement to arrive at the most beneficial screening recommendations for patients, specifically targeting risk groups--those with a history of skin cancer, immunosuppression, indoor tanning and/or many blistering sunburns, and several other genetic parameters--for at least annual TBSE.

The technique and reproducibility of TBSE also are not standardized, though they seem to have been endearingly apprenticed but variably implemented through generations of dermatology residents going forward into practice. As it is, depending on patient body surface area, mobility, willingness to disrobe, and adornments (eg, tattoos, hair appliances), multiple factors can restrict full view of a patient's skin. Recently, Helm et al proposed standardizing the TBSE sequence to minimize omitted areas of the body, which may become an imperative tool for streamlined resident teaching and optimal screening encounters.

How do you keep patients compliant with TBSE?

During and following TBSE, I typically outline any lesions of concern and plan for further testing, screening, and behavioral prevention strategies. Frequency of TBSE and importance of compliance are discussed during the visit and reinforced at checkout where the appointment templates are established a year in advance for those with skin cancer. Further, for those with melanoma, their appointment slots are given priority status so that any cancellations or delays are rescheduled preferentially. Particularly during the discussion about TBSE frequency, I emphasize the comparison and importance of this visit akin to other recommended screenings, such as mammograms and colonoscopies, and that we, as dermatologists, are part of their cancer surveillance team.

What do you do if patients refuse your recommendations?

Some patients refuse a gown or removal of certain clothing items (eg, undergarments, socks, wigs). Some patients defer a yearly TBSE upon checkout and schedule an appointment only when a lesion of concern arises. My advice is not to shame patients and to take advantage of as much as the patient is able and comfortable to show us and be present for, welcoming that we have the opportunity to take care of them and screen for cancer in any capacity. In underserved or limited budget practice regions, lesion-directed examination vs TBSE may be the only screening method utilized and may even attract more patients to a screening facility (Hoorens et al).

In the opposite corner are those patients who deem the recommended TBSE interval as too infrequent, which poses a delicate dilemma. In my opinion, these situations present another cohort of risks. Namely, the patient may become (or continue to be) overly fixated on the small details of every skin lesion, and in my experience, they tend to develop the habit of expecting at least 1 biopsy at each visit, typically of a lesion of their choosing. Depending on the validity of this expectation vs my clinical examination, it can lead to a difficult discussion with the patient about oversampling lesions and the potential for many scars, copious reexcisions for ambiguous lesion pathology, and a trend away from prudent clinical care. In addition, multiple visits incur more patient co-pays and time away from school, work, or home. To ease the patient's mind, I advise to call our office for a more acute visit if there is a lesion of concern; I additionally recommend taking a smartphone photograph of a concerning lesion and monitoring it for changes or sending the photograph to our patient portal messaging system so we can evaluate its acuity.

What take-home advice do you give to patients?

As the visit ends, I further explain that home self-examination or examination by a partner between visits is intuitively a valuable screening adjunct for skin cancer. In 2018, the USPSTF recommended behavioral skin cancer prevention counseling and self-examination only for younger-age cohorts with fair skin (6 months to 24 years), but its utility in specialty practice must be qualified. The American Academy of Dermatology Association subsequently issued a statement to support safe sun-protective practices and diligent self-screening for changing lesions, as earlier detection and management of skin cancer can lead to decreased morbidity and mortality from these neoplasms.

Resources for Patients

American Academy of Dermatology's SPOT Skin Cancer

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: What Screening Tests Are There?

Suggested Readings

AAD statement on USPSTF recommendation on skin cancer screening. Schaumburg, IL: American Academy of Dermatology; July 26, 2016. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/aad-statement-on-uspstf. Accessed April 26, 2019.

AADA responds to USPSTF recommendation on skin cancer prevention counseling. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Dermatology Association; March 20, 2018. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/skin-cancer-prevention-counseling. Accessed April 26, 2019.

Helm MF, Hallock KK, Bisbee E, et al. Optimizing the total body skin exam: an observational cohort study [published online February 15, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.028.

Hoorens I, Vossaert K, Pil L, et al. Total-body examination vs lesion-directed skin cancer screening. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:27-34.

Johnson MM, Leachman SA, Aspinwall LG, et al. Skin cancer screening: recommendations for data-driven screening guidelines and a review of the US Preventive Services Task Force controversy. Melanoma Manag. 2017;4:13-37.

Risica PM, Matthews NH, Dionne L, et al. Psychosocial consequences of skin cancer screening. Prev Med Rep. 2018;10:310-316.

US Preventive Services Task Force, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. Screening for skin cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316:429-435.

US Preventive Services Task Force, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Behavioral counseling to prevent skin cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319:1134-1142.

Suggested Readings

AAD statement on USPSTF recommendation on skin cancer screening. Schaumburg, IL: American Academy of Dermatology; July 26, 2016. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/aad-statement-on-uspstf. Accessed April 26, 2019.

AADA responds to USPSTF recommendation on skin cancer prevention counseling. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Dermatology Association; March 20, 2018. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/skin-cancer-prevention-counseling. Accessed April 26, 2019.

Helm MF, Hallock KK, Bisbee E, et al. Optimizing the total body skin exam: an observational cohort study [published online February 15, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.028.

Hoorens I, Vossaert K, Pil L, et al. Total-body examination vs lesion-directed skin cancer screening. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:27-34.

Johnson MM, Leachman SA, Aspinwall LG, et al. Skin cancer screening: recommendations for data-driven screening guidelines and a review of the US Preventive Services Task Force controversy. Melanoma Manag. 2017;4:13-37.

Risica PM, Matthews NH, Dionne L, et al. Psychosocial consequences of skin cancer screening. Prev Med Rep. 2018;10:310-316.

US Preventive Services Task Force, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. Screening for skin cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316:429-435.