User login

Scleral Plaques in Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis

To the Editor:

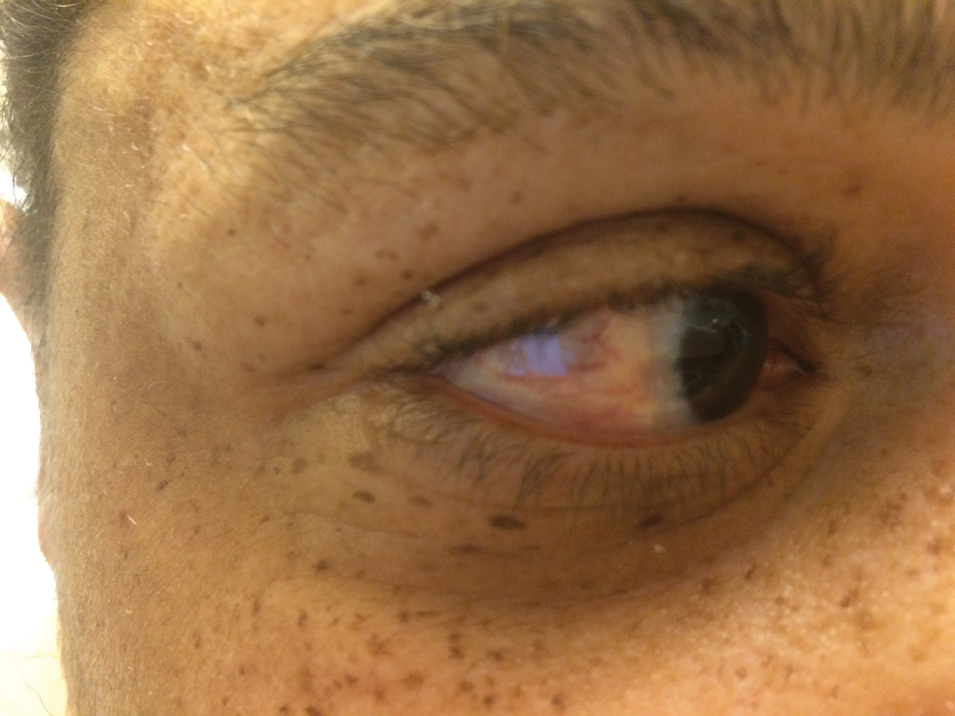

A 44-year-old man with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) complicated by lupus nephritis, end-stage renal disease, and antiphospholipid syndrome was evaluated for progressive skin tightening over the last 3 years, predominantly on the hands but also involving the feet, legs, and arms. Physical examination revealed multiple flesh-colored to hypopigmented, bound-down, indurated, fissured plaques over the distal upper and lower extremities, most prominent over the hands (Figure 1). Yellow plaques appeared on the lateral sclera of both eyes (Figure 2). A diagnosis of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) was supported by typical findings on punch biopsy, including a proliferation of dermal fibroblasts with thickened collagen bundles and mucin deposition.

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, also known as nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy, is characterized by fibrotic plaques and nodules that tend to be bilateral.1 The chronic course of this disease often is accompanied by flexion contractures. Yellow scleral plaques caused by calcium phosphate deposition are present in up to 75% of cases and are more specific to a diagnosis of NSF in patients younger than 45 years.1,2 A strong association exists between NSF and gadolinium contrast agents in patients with acute renal failure; our patient later confirmed multiple gadolinium exposures years prior. Deposits of gadolinium have even been found in NSF skin lesions.2

- Stone JH. A Clinician’s Pearls & Myths in Rheumatology. Springer London; 2009.

- Barker-Griffith A, Goldberg J, Abraham JL. Ocular pathologic features and gadolinium deposition in nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:661-663.

To the Editor:

A 44-year-old man with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) complicated by lupus nephritis, end-stage renal disease, and antiphospholipid syndrome was evaluated for progressive skin tightening over the last 3 years, predominantly on the hands but also involving the feet, legs, and arms. Physical examination revealed multiple flesh-colored to hypopigmented, bound-down, indurated, fissured plaques over the distal upper and lower extremities, most prominent over the hands (Figure 1). Yellow plaques appeared on the lateral sclera of both eyes (Figure 2). A diagnosis of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) was supported by typical findings on punch biopsy, including a proliferation of dermal fibroblasts with thickened collagen bundles and mucin deposition.

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, also known as nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy, is characterized by fibrotic plaques and nodules that tend to be bilateral.1 The chronic course of this disease often is accompanied by flexion contractures. Yellow scleral plaques caused by calcium phosphate deposition are present in up to 75% of cases and are more specific to a diagnosis of NSF in patients younger than 45 years.1,2 A strong association exists between NSF and gadolinium contrast agents in patients with acute renal failure; our patient later confirmed multiple gadolinium exposures years prior. Deposits of gadolinium have even been found in NSF skin lesions.2

To the Editor:

A 44-year-old man with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) complicated by lupus nephritis, end-stage renal disease, and antiphospholipid syndrome was evaluated for progressive skin tightening over the last 3 years, predominantly on the hands but also involving the feet, legs, and arms. Physical examination revealed multiple flesh-colored to hypopigmented, bound-down, indurated, fissured plaques over the distal upper and lower extremities, most prominent over the hands (Figure 1). Yellow plaques appeared on the lateral sclera of both eyes (Figure 2). A diagnosis of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) was supported by typical findings on punch biopsy, including a proliferation of dermal fibroblasts with thickened collagen bundles and mucin deposition.

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, also known as nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy, is characterized by fibrotic plaques and nodules that tend to be bilateral.1 The chronic course of this disease often is accompanied by flexion contractures. Yellow scleral plaques caused by calcium phosphate deposition are present in up to 75% of cases and are more specific to a diagnosis of NSF in patients younger than 45 years.1,2 A strong association exists between NSF and gadolinium contrast agents in patients with acute renal failure; our patient later confirmed multiple gadolinium exposures years prior. Deposits of gadolinium have even been found in NSF skin lesions.2

- Stone JH. A Clinician’s Pearls & Myths in Rheumatology. Springer London; 2009.

- Barker-Griffith A, Goldberg J, Abraham JL. Ocular pathologic features and gadolinium deposition in nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:661-663.

- Stone JH. A Clinician’s Pearls & Myths in Rheumatology. Springer London; 2009.

- Barker-Griffith A, Goldberg J, Abraham JL. Ocular pathologic features and gadolinium deposition in nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:661-663.

Practice Points

- It is important to examine the eyes in a patient with sclerotic skin changes on physical examination.

- The presence of yellow scleral plaques strongly is associated with a diagnosis of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis.

Symmetric Lichen Amyloidosis: An Atypical Location on the Bilateral Extensor Surfaces of the Arms

To the Editor:

Lichen amyloidosis (LA) classically presents as a pruritic, hyperkeratotic, papular eruption localized to the pretibial surface of the legs.1 Nonpruritic and generalized variants have been reported but are rare.2 Although it is the most common subtype of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis, LA is a benign condition but is difficult to eradicate.1 The precise pathophysiology is poorly understood, but chronic frictional irritation is closely associated with the eruption. We present a nongeneralized case of LA in an atypical location.

A healthy 30-year-old woman presented with an intermittent itchy rash on the elbows and knees of 2 years’ duration. The patient was first diagnosed with lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) and initially responded well to treatment with fluocinonide ointment 0.05%. Nearly 2 years after the initial presentation, she developed recurrent symptoms and sought further treatment. She reported frequent scratching in association with episodes of anxiety. Examination revealed numerous 1- to 3-mm, flesh-colored to light brown, monomorphic, dome-shaped papules over the extensor surfaces of the bilateral arms and left pretibial surface (Figure 1).

papules (1–3 mm) over the extensor surfaces of the bilateral arms.

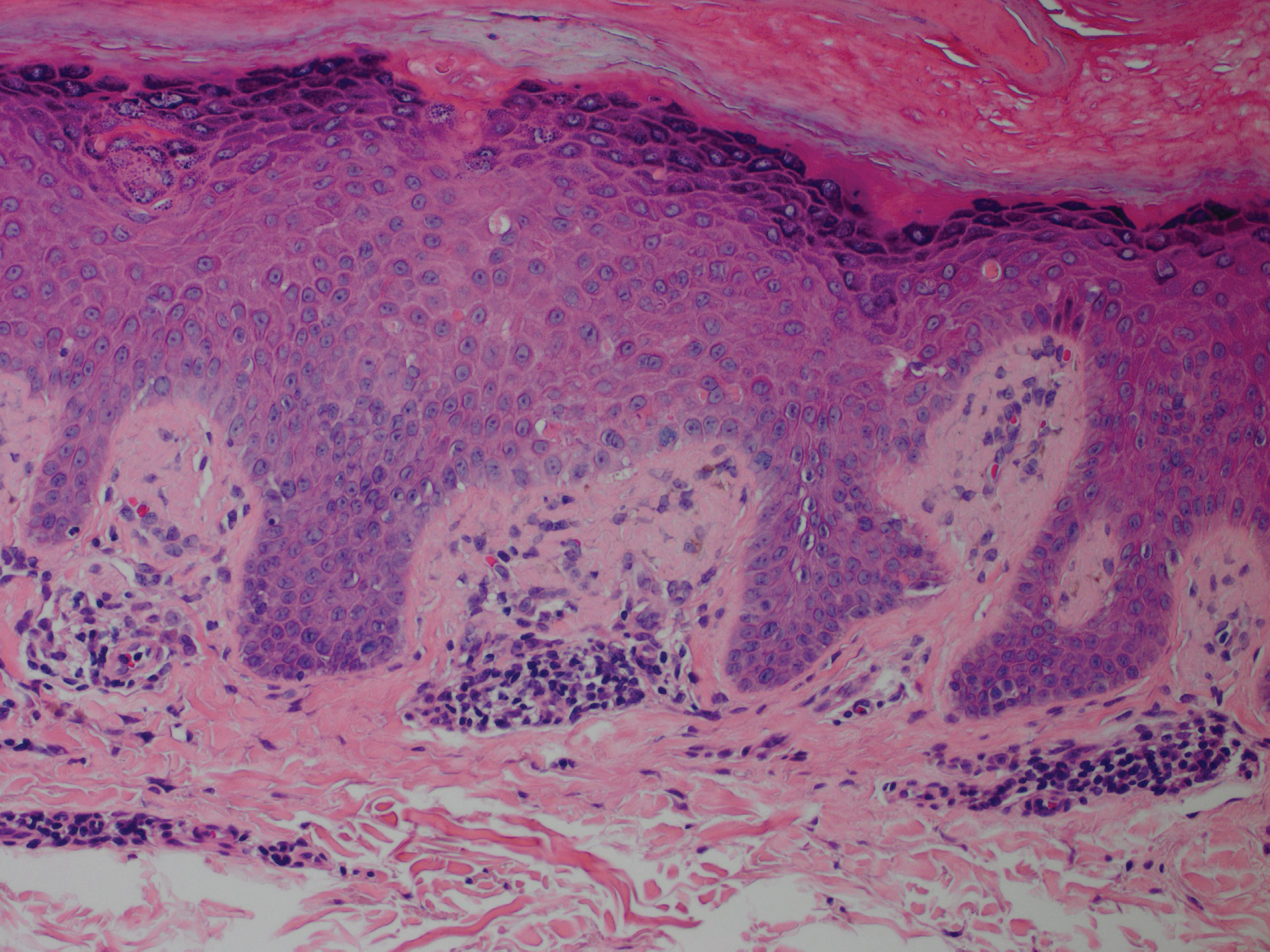

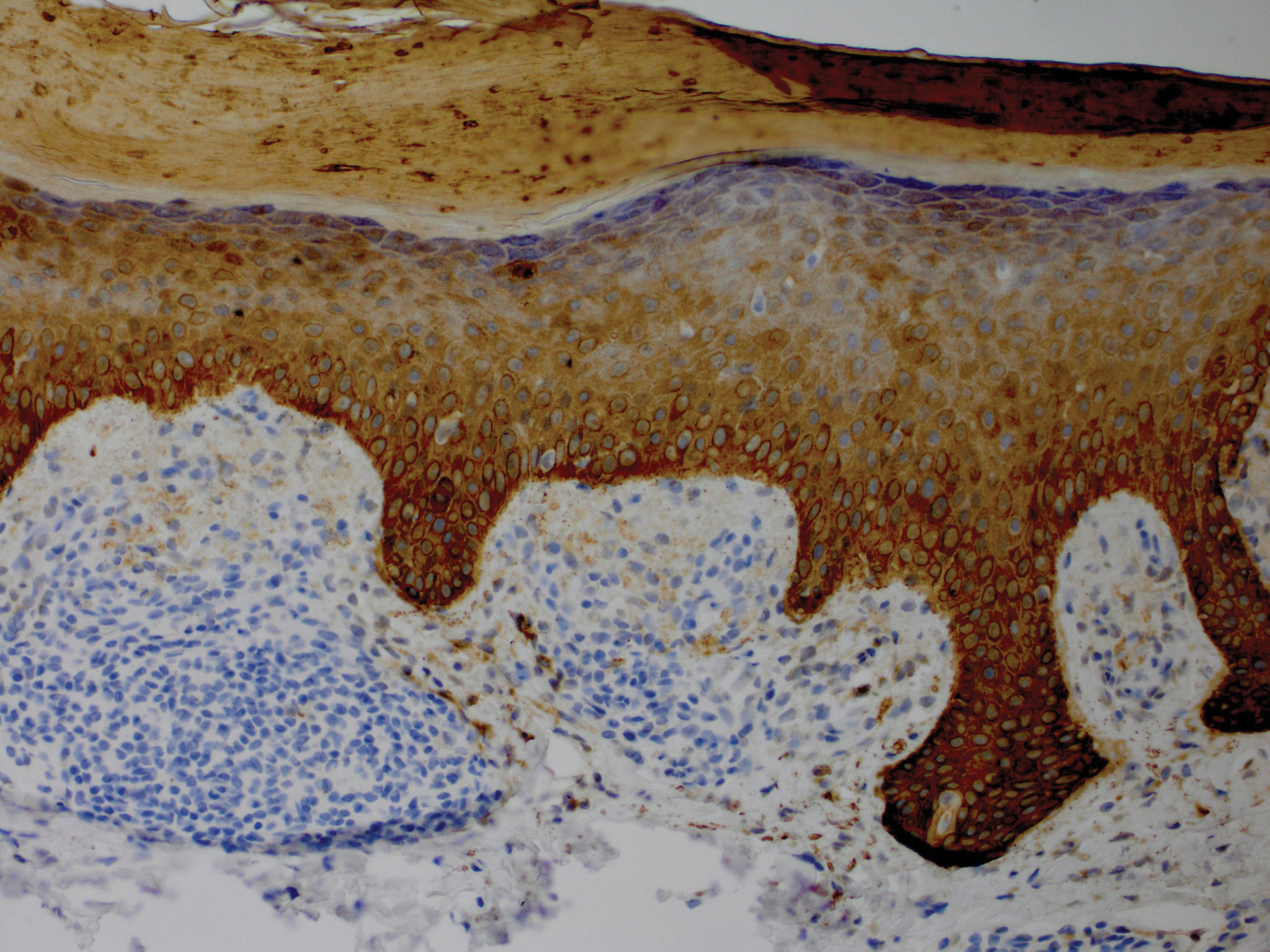

Although in an atypical location, LA was clinically suspected due to the morphology, and a biopsy was performed given the evolving nature of the lesions. The differential diagnosis included LSC, hypertrophic lichen planus, papular mucinosis, prurigo nodularis, and pretibial myxedema. Pathology revealed small eosinophilic globules in the papillary dermis (Figure 2), and cytokeratin 5/6 immunostaining showed amorphous papillary dermal deposits consistent with keratin-derived amyloid deposition (Figure 3). The deposits stained positive for Congo red and displayed apple green birefringence under polarized light. Thus, the diagnosis of LA was confirmed. After limited success with triamcinolone ointment 0.1%, the patient was transitioned to clobetasol cream 0.05% with notable physical and symptomatic improvement.

Amyloidosis is histopathologically characterized by extracellular deposits of amyloid, a polypeptide that polymerizes to form cross-β sheets.3 It is believed that the deposits seen in localized amyloidosis result from local production of amyloid, as opposed to the deposition of circulating light chains that is characteristic of systemic amyloidosis.3 Lichen amyloidosis is the most common subtype of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis.1 The amyloid in this condition has been found to react immunohistochemically with antikeratin antibody, leading to the conclusion that the amyloid is formed by degeneration of keratinocytes locally due to chronic rubbing and scratching.

4-6

The possibility remains that this patient first presented with LSC 2 years prior and secondarily developed LA due to chronic trauma. Indeed, LA has been proposed as a variant of LSC. In both conditions, scratching seems to be the most important factor in the development of lesions. It has been proposed that treatment should primarily focus on the amelioration of pruritus.5

Five percent to 10% of cases of LA have been found to have some form of upper extremity involvement.7 However, these cases typically are associated with a generalized presentation involving the trunk and arms.2,7 Our patient had no evidence of disease elsewhere. When evaluating a localized, pruritic, monomorphic, papular eruption on the extensor surfaces of the arms, LA may be an important consideration.

- Tay CH, Dacosta JL. Lichen amyloidosis. clinical study of 40 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:129-136.

- Kandhari R, Ramesh V, Singh A. A generalized, non-pruritic variant of lichen amyloidosis: a case report and a brief review. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:328.

- Biewend ML, Menke DM, Calamia KT. The spectrum of localized amyloidosis: a case series of 20 patients and review of the literature. Amyloid. 2006;13:135-142.

- Jambrosic J, From L, Hanna W. Lichen amyloidosus. ultrastructure and pathogenesis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1984;6:151-158.

- Weyers W, Weyers I, Bonczkowitz M, et al. Lichen amyloidosis: a consequence of scratching. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:923-928.

- Kumakiri M, Hashimoto K. Histogenesis of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis: sequential change of epidermal keratinocytes to amyloid via filamentous degeneration. J Invest Dermatol. 1979;73:150-162.

- Salim T, Shenoi SD, Balachandran C, et al. Lichen amyloidosus: a study of clinical, histopathologic and immunofluorescence findings in 30 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:166-169.

To the Editor:

Lichen amyloidosis (LA) classically presents as a pruritic, hyperkeratotic, papular eruption localized to the pretibial surface of the legs.1 Nonpruritic and generalized variants have been reported but are rare.2 Although it is the most common subtype of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis, LA is a benign condition but is difficult to eradicate.1 The precise pathophysiology is poorly understood, but chronic frictional irritation is closely associated with the eruption. We present a nongeneralized case of LA in an atypical location.

A healthy 30-year-old woman presented with an intermittent itchy rash on the elbows and knees of 2 years’ duration. The patient was first diagnosed with lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) and initially responded well to treatment with fluocinonide ointment 0.05%. Nearly 2 years after the initial presentation, she developed recurrent symptoms and sought further treatment. She reported frequent scratching in association with episodes of anxiety. Examination revealed numerous 1- to 3-mm, flesh-colored to light brown, monomorphic, dome-shaped papules over the extensor surfaces of the bilateral arms and left pretibial surface (Figure 1).

papules (1–3 mm) over the extensor surfaces of the bilateral arms.

Although in an atypical location, LA was clinically suspected due to the morphology, and a biopsy was performed given the evolving nature of the lesions. The differential diagnosis included LSC, hypertrophic lichen planus, papular mucinosis, prurigo nodularis, and pretibial myxedema. Pathology revealed small eosinophilic globules in the papillary dermis (Figure 2), and cytokeratin 5/6 immunostaining showed amorphous papillary dermal deposits consistent with keratin-derived amyloid deposition (Figure 3). The deposits stained positive for Congo red and displayed apple green birefringence under polarized light. Thus, the diagnosis of LA was confirmed. After limited success with triamcinolone ointment 0.1%, the patient was transitioned to clobetasol cream 0.05% with notable physical and symptomatic improvement.

Amyloidosis is histopathologically characterized by extracellular deposits of amyloid, a polypeptide that polymerizes to form cross-β sheets.3 It is believed that the deposits seen in localized amyloidosis result from local production of amyloid, as opposed to the deposition of circulating light chains that is characteristic of systemic amyloidosis.3 Lichen amyloidosis is the most common subtype of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis.1 The amyloid in this condition has been found to react immunohistochemically with antikeratin antibody, leading to the conclusion that the amyloid is formed by degeneration of keratinocytes locally due to chronic rubbing and scratching.

4-6

The possibility remains that this patient first presented with LSC 2 years prior and secondarily developed LA due to chronic trauma. Indeed, LA has been proposed as a variant of LSC. In both conditions, scratching seems to be the most important factor in the development of lesions. It has been proposed that treatment should primarily focus on the amelioration of pruritus.5

Five percent to 10% of cases of LA have been found to have some form of upper extremity involvement.7 However, these cases typically are associated with a generalized presentation involving the trunk and arms.2,7 Our patient had no evidence of disease elsewhere. When evaluating a localized, pruritic, monomorphic, papular eruption on the extensor surfaces of the arms, LA may be an important consideration.

To the Editor:

Lichen amyloidosis (LA) classically presents as a pruritic, hyperkeratotic, papular eruption localized to the pretibial surface of the legs.1 Nonpruritic and generalized variants have been reported but are rare.2 Although it is the most common subtype of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis, LA is a benign condition but is difficult to eradicate.1 The precise pathophysiology is poorly understood, but chronic frictional irritation is closely associated with the eruption. We present a nongeneralized case of LA in an atypical location.

A healthy 30-year-old woman presented with an intermittent itchy rash on the elbows and knees of 2 years’ duration. The patient was first diagnosed with lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) and initially responded well to treatment with fluocinonide ointment 0.05%. Nearly 2 years after the initial presentation, she developed recurrent symptoms and sought further treatment. She reported frequent scratching in association with episodes of anxiety. Examination revealed numerous 1- to 3-mm, flesh-colored to light brown, monomorphic, dome-shaped papules over the extensor surfaces of the bilateral arms and left pretibial surface (Figure 1).

papules (1–3 mm) over the extensor surfaces of the bilateral arms.

Although in an atypical location, LA was clinically suspected due to the morphology, and a biopsy was performed given the evolving nature of the lesions. The differential diagnosis included LSC, hypertrophic lichen planus, papular mucinosis, prurigo nodularis, and pretibial myxedema. Pathology revealed small eosinophilic globules in the papillary dermis (Figure 2), and cytokeratin 5/6 immunostaining showed amorphous papillary dermal deposits consistent with keratin-derived amyloid deposition (Figure 3). The deposits stained positive for Congo red and displayed apple green birefringence under polarized light. Thus, the diagnosis of LA was confirmed. After limited success with triamcinolone ointment 0.1%, the patient was transitioned to clobetasol cream 0.05% with notable physical and symptomatic improvement.

Amyloidosis is histopathologically characterized by extracellular deposits of amyloid, a polypeptide that polymerizes to form cross-β sheets.3 It is believed that the deposits seen in localized amyloidosis result from local production of amyloid, as opposed to the deposition of circulating light chains that is characteristic of systemic amyloidosis.3 Lichen amyloidosis is the most common subtype of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis.1 The amyloid in this condition has been found to react immunohistochemically with antikeratin antibody, leading to the conclusion that the amyloid is formed by degeneration of keratinocytes locally due to chronic rubbing and scratching.

4-6

The possibility remains that this patient first presented with LSC 2 years prior and secondarily developed LA due to chronic trauma. Indeed, LA has been proposed as a variant of LSC. In both conditions, scratching seems to be the most important factor in the development of lesions. It has been proposed that treatment should primarily focus on the amelioration of pruritus.5

Five percent to 10% of cases of LA have been found to have some form of upper extremity involvement.7 However, these cases typically are associated with a generalized presentation involving the trunk and arms.2,7 Our patient had no evidence of disease elsewhere. When evaluating a localized, pruritic, monomorphic, papular eruption on the extensor surfaces of the arms, LA may be an important consideration.

- Tay CH, Dacosta JL. Lichen amyloidosis. clinical study of 40 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:129-136.

- Kandhari R, Ramesh V, Singh A. A generalized, non-pruritic variant of lichen amyloidosis: a case report and a brief review. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:328.

- Biewend ML, Menke DM, Calamia KT. The spectrum of localized amyloidosis: a case series of 20 patients and review of the literature. Amyloid. 2006;13:135-142.

- Jambrosic J, From L, Hanna W. Lichen amyloidosus. ultrastructure and pathogenesis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1984;6:151-158.

- Weyers W, Weyers I, Bonczkowitz M, et al. Lichen amyloidosis: a consequence of scratching. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:923-928.

- Kumakiri M, Hashimoto K. Histogenesis of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis: sequential change of epidermal keratinocytes to amyloid via filamentous degeneration. J Invest Dermatol. 1979;73:150-162.

- Salim T, Shenoi SD, Balachandran C, et al. Lichen amyloidosus: a study of clinical, histopathologic and immunofluorescence findings in 30 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:166-169.

- Tay CH, Dacosta JL. Lichen amyloidosis. clinical study of 40 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:129-136.

- Kandhari R, Ramesh V, Singh A. A generalized, non-pruritic variant of lichen amyloidosis: a case report and a brief review. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:328.

- Biewend ML, Menke DM, Calamia KT. The spectrum of localized amyloidosis: a case series of 20 patients and review of the literature. Amyloid. 2006;13:135-142.

- Jambrosic J, From L, Hanna W. Lichen amyloidosus. ultrastructure and pathogenesis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1984;6:151-158.

- Weyers W, Weyers I, Bonczkowitz M, et al. Lichen amyloidosis: a consequence of scratching. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:923-928.

- Kumakiri M, Hashimoto K. Histogenesis of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis: sequential change of epidermal keratinocytes to amyloid via filamentous degeneration. J Invest Dermatol. 1979;73:150-162.

- Salim T, Shenoi SD, Balachandran C, et al. Lichen amyloidosus: a study of clinical, histopathologic and immunofluorescence findings in 30 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:166-169.

Practice Points

- Lichen amyloidosis (LA) classically presents as a pruritic and papular eruption localized to the pretibial surface of the legs.

- Nonpruritic and generalized variants are rare.

- This case represents a pruritic and nongeneralized

case located on the arms; LA should be considered

for any localized and pruritic eruption on the arms.

Bothersome Blisters: Localized Epidermolysis Bullosa Simplex

To the Editor:

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) was first described in 1886, with the first classification scheme proposed in 1962 utilizing transmission electron microscopy (TEM) findings to delineate categories: epidermolytic (EB simplex [EBS]), lucidolytic (junctional EB), and dermolytic (dystrophic EB).1 Localized EBS (EBS-loc) is an autosomal-dominant disorder caused by negative mutations in keratin-5 and keratin-14, proteins expressed in the intermediate filaments of basal keratinocytes, which result in fragility of the skin in response to minor trauma.2 The incidence of EBS-loc is approximately 10 to 30 cases per million live births, with the age of presentation typically between the first and third decades of life.3,4 Because EBS-loc is the most common and often mildest form of EB, not all patients present for medical evaluation and true prevalence may be underestimated.4 We report a case of EBS-loc.

A 26-year-old woman with no notable medical history presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of skin blisters that had been intermittently present since infancy. The blisters primarily occurred on the feet, but she did occasionally develop blisters on the hands, knees, and elbows and at sites of friction or trauma (eg, bra line, medial thighs) following exercise. The blisters were worsened by heat and tight-fitting shoes. Because of the painful nature of the blisters, she would lance them with a needle. On the medial thighs, she utilized nonstick and gauze bandage roll dressings to minimize friction. A review of systems was positive for hyperhidrosis. Her family history revealed multiple family members with blisters involving the feet and areas of friction or trauma for 4 generations with no known diagnosis.

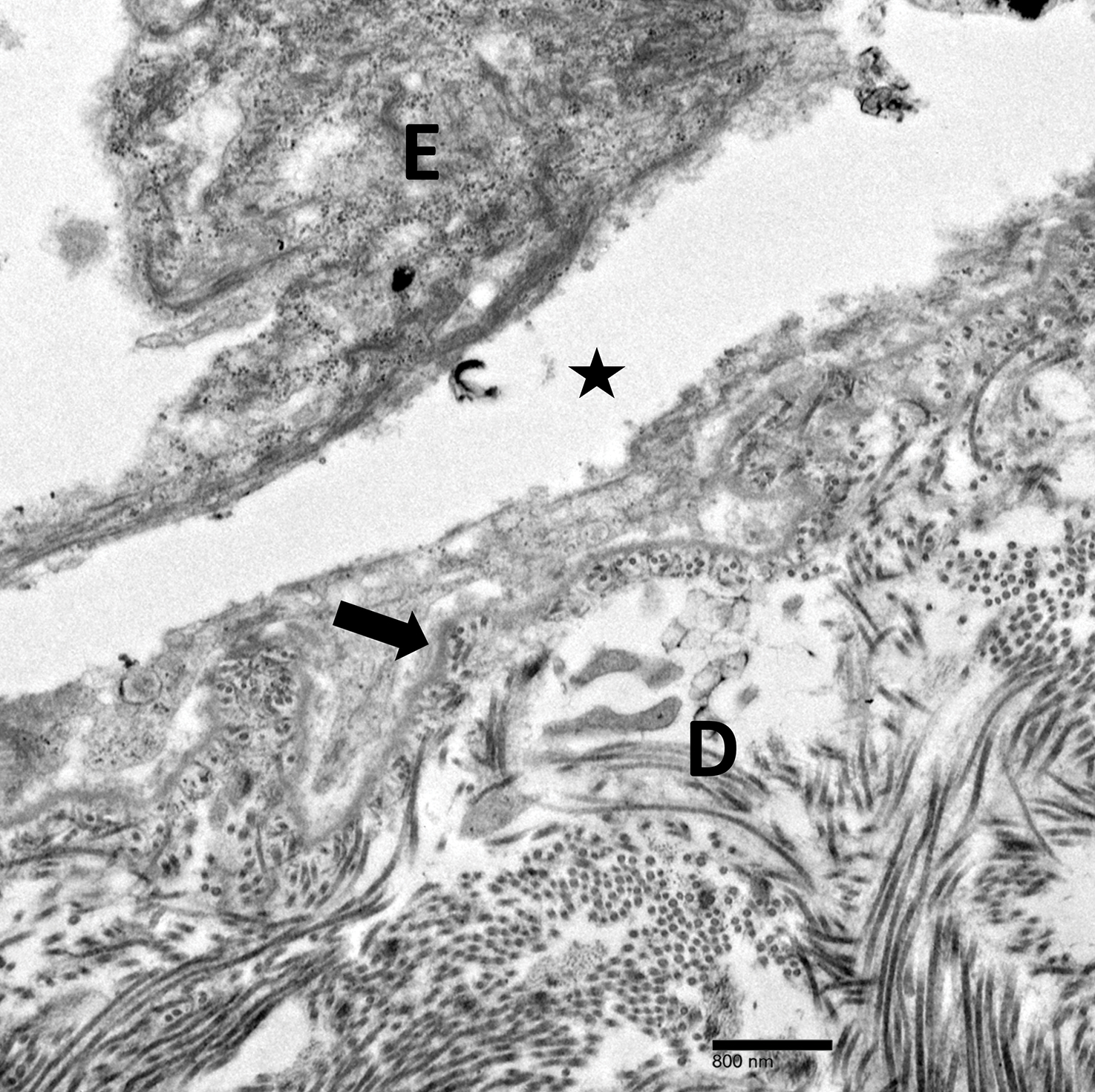

Physical examination revealed multiple tense bullae and calluses scattered over the bilateral plantar and distal dorsal feet with a few healing, superficially eroded, erythematous papules and plaques on the bilateral medial thighs (Figure 1). A biopsy from an induced blister on the right dorsal second toe was performed and sent in glutaraldehyde to the Epidermolysis Bullosa Clinic at Stanford University (Redwood City, California) for electron microscopy, which revealed lysis within the basal keratinocytes through the tonofilaments with continuous and intact lamina densa and lamina lucida (Figure 2). In this clinical context with the relevant family history, the findings were consistent with the diagnosis of EBS-loc (formerly Weber-Cockayne syndrome).2

Skin manifestations of EBS-loc typically consist of friction-induced blisters, erosions, and calluses primarily on the palms and soles, often associated with hyperhidrosis and worsening of symptoms in summer months and hot temperatures.3 Milia, atrophic scarring, and dystrophic nails are uncommon.1 Extracutaneous involvement is rare with the exception of oral cavity erosions, which typically are asymptomatic and usually are only seen during infancy.1

Light microscopy does not have a notable role in diagnosis of classic forms of inherited EB unless another autoimmune blistering disorder is suspected.2,5 Both TEM and immunofluorescence mapping are used to diagnose EB.1 DNA mutational analysis is not considered a first-line diagnostic test for EB given it is a costly labor-intensive technique with limited access at present, but it may be considered in settings of prenatal diagnosis or in vitro fertilization.1 Biopsy of a freshly induced blister should be performed, as early reepithelialization of an existing blister makes it difficult to establish the level of cleavage.5 Applying firm pressure using a pencil eraser and rotating it on intact skin induces a subclinical blister. Two punch biopsies (4 mm) at the edge of the blister with one-third lesional and two-thirds perilesional skin should be obtained, with one biopsy sent for immunofluorescence mapping in Michel fixative and the other for TEM in glutaraldehyde.3,5 Transmission electron microscopy of an induced blister in EBS-loc shows cleavage within the most inferior portion of the basilar keratinocyte.2 Immunofluorescence mapping with anti–epidermal basement membrane monoclonal antibodies can distinguish between EB subtypes and assess expression of specific skin-associated proteins on both a qualitative or semiquantitative basis, providing insight on which structural protein is mutated.1,5

No specific treatments are available for EBS-loc. Mainstays of treatment include prevention of mechanical trauma and secondary infection. Hyperhidrosis of thepalms and soles may be treated with topical aluminum chloride hexahydrate or injections of botulinum toxin type A.2,6 Patients have normal life expectancy, though some cases may have complications with substantial morbidity.1 Awareness of this disease, its clinical course, and therapeutic options will allow physicians to more appropriately counsel patients on the disease process.

Localized EBS may be more common than previously thought, as not all patients seek medical care. Given its impact on patient quality of life, it is important for clinicians to recognize EBS-loc. Although no specific treatments are available, wound care counseling and explanation of the genetics of the disease should be provided to patients.

- Fine JD, Eady RA, Bauer EA, et al. The classification of inherited epidermolysis bullosa (EB): report of the Third International Consensus Meeting on Diagnosis and Classification of EB. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:931-950.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2012.

- Eichenfield LF, Frieden IJ, Mathes EF, et al, eds. Neonatal and Infant Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2015.

- Spitz JL. Genodermatoses: A Clinical Guide to Genetic Skin Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

- Epidermolysis bullosa. Stanford Medicine website. http://med.stanford.edu/dermatopathology/dermpath-services/epiderm.html. Accessed April 3, 2019.

- Abitbol RJ, Zhou LH. Treatment of epidermolysis bullosa simplex, Weber-Cockayne type, with botulinum toxin type A. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:13-15.

To the Editor:

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) was first described in 1886, with the first classification scheme proposed in 1962 utilizing transmission electron microscopy (TEM) findings to delineate categories: epidermolytic (EB simplex [EBS]), lucidolytic (junctional EB), and dermolytic (dystrophic EB).1 Localized EBS (EBS-loc) is an autosomal-dominant disorder caused by negative mutations in keratin-5 and keratin-14, proteins expressed in the intermediate filaments of basal keratinocytes, which result in fragility of the skin in response to minor trauma.2 The incidence of EBS-loc is approximately 10 to 30 cases per million live births, with the age of presentation typically between the first and third decades of life.3,4 Because EBS-loc is the most common and often mildest form of EB, not all patients present for medical evaluation and true prevalence may be underestimated.4 We report a case of EBS-loc.

A 26-year-old woman with no notable medical history presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of skin blisters that had been intermittently present since infancy. The blisters primarily occurred on the feet, but she did occasionally develop blisters on the hands, knees, and elbows and at sites of friction or trauma (eg, bra line, medial thighs) following exercise. The blisters were worsened by heat and tight-fitting shoes. Because of the painful nature of the blisters, she would lance them with a needle. On the medial thighs, she utilized nonstick and gauze bandage roll dressings to minimize friction. A review of systems was positive for hyperhidrosis. Her family history revealed multiple family members with blisters involving the feet and areas of friction or trauma for 4 generations with no known diagnosis.

Physical examination revealed multiple tense bullae and calluses scattered over the bilateral plantar and distal dorsal feet with a few healing, superficially eroded, erythematous papules and plaques on the bilateral medial thighs (Figure 1). A biopsy from an induced blister on the right dorsal second toe was performed and sent in glutaraldehyde to the Epidermolysis Bullosa Clinic at Stanford University (Redwood City, California) for electron microscopy, which revealed lysis within the basal keratinocytes through the tonofilaments with continuous and intact lamina densa and lamina lucida (Figure 2). In this clinical context with the relevant family history, the findings were consistent with the diagnosis of EBS-loc (formerly Weber-Cockayne syndrome).2

Skin manifestations of EBS-loc typically consist of friction-induced blisters, erosions, and calluses primarily on the palms and soles, often associated with hyperhidrosis and worsening of symptoms in summer months and hot temperatures.3 Milia, atrophic scarring, and dystrophic nails are uncommon.1 Extracutaneous involvement is rare with the exception of oral cavity erosions, which typically are asymptomatic and usually are only seen during infancy.1

Light microscopy does not have a notable role in diagnosis of classic forms of inherited EB unless another autoimmune blistering disorder is suspected.2,5 Both TEM and immunofluorescence mapping are used to diagnose EB.1 DNA mutational analysis is not considered a first-line diagnostic test for EB given it is a costly labor-intensive technique with limited access at present, but it may be considered in settings of prenatal diagnosis or in vitro fertilization.1 Biopsy of a freshly induced blister should be performed, as early reepithelialization of an existing blister makes it difficult to establish the level of cleavage.5 Applying firm pressure using a pencil eraser and rotating it on intact skin induces a subclinical blister. Two punch biopsies (4 mm) at the edge of the blister with one-third lesional and two-thirds perilesional skin should be obtained, with one biopsy sent for immunofluorescence mapping in Michel fixative and the other for TEM in glutaraldehyde.3,5 Transmission electron microscopy of an induced blister in EBS-loc shows cleavage within the most inferior portion of the basilar keratinocyte.2 Immunofluorescence mapping with anti–epidermal basement membrane monoclonal antibodies can distinguish between EB subtypes and assess expression of specific skin-associated proteins on both a qualitative or semiquantitative basis, providing insight on which structural protein is mutated.1,5

No specific treatments are available for EBS-loc. Mainstays of treatment include prevention of mechanical trauma and secondary infection. Hyperhidrosis of thepalms and soles may be treated with topical aluminum chloride hexahydrate or injections of botulinum toxin type A.2,6 Patients have normal life expectancy, though some cases may have complications with substantial morbidity.1 Awareness of this disease, its clinical course, and therapeutic options will allow physicians to more appropriately counsel patients on the disease process.

Localized EBS may be more common than previously thought, as not all patients seek medical care. Given its impact on patient quality of life, it is important for clinicians to recognize EBS-loc. Although no specific treatments are available, wound care counseling and explanation of the genetics of the disease should be provided to patients.

To the Editor:

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) was first described in 1886, with the first classification scheme proposed in 1962 utilizing transmission electron microscopy (TEM) findings to delineate categories: epidermolytic (EB simplex [EBS]), lucidolytic (junctional EB), and dermolytic (dystrophic EB).1 Localized EBS (EBS-loc) is an autosomal-dominant disorder caused by negative mutations in keratin-5 and keratin-14, proteins expressed in the intermediate filaments of basal keratinocytes, which result in fragility of the skin in response to minor trauma.2 The incidence of EBS-loc is approximately 10 to 30 cases per million live births, with the age of presentation typically between the first and third decades of life.3,4 Because EBS-loc is the most common and often mildest form of EB, not all patients present for medical evaluation and true prevalence may be underestimated.4 We report a case of EBS-loc.

A 26-year-old woman with no notable medical history presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of skin blisters that had been intermittently present since infancy. The blisters primarily occurred on the feet, but she did occasionally develop blisters on the hands, knees, and elbows and at sites of friction or trauma (eg, bra line, medial thighs) following exercise. The blisters were worsened by heat and tight-fitting shoes. Because of the painful nature of the blisters, she would lance them with a needle. On the medial thighs, she utilized nonstick and gauze bandage roll dressings to minimize friction. A review of systems was positive for hyperhidrosis. Her family history revealed multiple family members with blisters involving the feet and areas of friction or trauma for 4 generations with no known diagnosis.

Physical examination revealed multiple tense bullae and calluses scattered over the bilateral plantar and distal dorsal feet with a few healing, superficially eroded, erythematous papules and plaques on the bilateral medial thighs (Figure 1). A biopsy from an induced blister on the right dorsal second toe was performed and sent in glutaraldehyde to the Epidermolysis Bullosa Clinic at Stanford University (Redwood City, California) for electron microscopy, which revealed lysis within the basal keratinocytes through the tonofilaments with continuous and intact lamina densa and lamina lucida (Figure 2). In this clinical context with the relevant family history, the findings were consistent with the diagnosis of EBS-loc (formerly Weber-Cockayne syndrome).2

Skin manifestations of EBS-loc typically consist of friction-induced blisters, erosions, and calluses primarily on the palms and soles, often associated with hyperhidrosis and worsening of symptoms in summer months and hot temperatures.3 Milia, atrophic scarring, and dystrophic nails are uncommon.1 Extracutaneous involvement is rare with the exception of oral cavity erosions, which typically are asymptomatic and usually are only seen during infancy.1

Light microscopy does not have a notable role in diagnosis of classic forms of inherited EB unless another autoimmune blistering disorder is suspected.2,5 Both TEM and immunofluorescence mapping are used to diagnose EB.1 DNA mutational analysis is not considered a first-line diagnostic test for EB given it is a costly labor-intensive technique with limited access at present, but it may be considered in settings of prenatal diagnosis or in vitro fertilization.1 Biopsy of a freshly induced blister should be performed, as early reepithelialization of an existing blister makes it difficult to establish the level of cleavage.5 Applying firm pressure using a pencil eraser and rotating it on intact skin induces a subclinical blister. Two punch biopsies (4 mm) at the edge of the blister with one-third lesional and two-thirds perilesional skin should be obtained, with one biopsy sent for immunofluorescence mapping in Michel fixative and the other for TEM in glutaraldehyde.3,5 Transmission electron microscopy of an induced blister in EBS-loc shows cleavage within the most inferior portion of the basilar keratinocyte.2 Immunofluorescence mapping with anti–epidermal basement membrane monoclonal antibodies can distinguish between EB subtypes and assess expression of specific skin-associated proteins on both a qualitative or semiquantitative basis, providing insight on which structural protein is mutated.1,5

No specific treatments are available for EBS-loc. Mainstays of treatment include prevention of mechanical trauma and secondary infection. Hyperhidrosis of thepalms and soles may be treated with topical aluminum chloride hexahydrate or injections of botulinum toxin type A.2,6 Patients have normal life expectancy, though some cases may have complications with substantial morbidity.1 Awareness of this disease, its clinical course, and therapeutic options will allow physicians to more appropriately counsel patients on the disease process.

Localized EBS may be more common than previously thought, as not all patients seek medical care. Given its impact on patient quality of life, it is important for clinicians to recognize EBS-loc. Although no specific treatments are available, wound care counseling and explanation of the genetics of the disease should be provided to patients.

- Fine JD, Eady RA, Bauer EA, et al. The classification of inherited epidermolysis bullosa (EB): report of the Third International Consensus Meeting on Diagnosis and Classification of EB. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:931-950.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2012.

- Eichenfield LF, Frieden IJ, Mathes EF, et al, eds. Neonatal and Infant Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2015.

- Spitz JL. Genodermatoses: A Clinical Guide to Genetic Skin Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

- Epidermolysis bullosa. Stanford Medicine website. http://med.stanford.edu/dermatopathology/dermpath-services/epiderm.html. Accessed April 3, 2019.

- Abitbol RJ, Zhou LH. Treatment of epidermolysis bullosa simplex, Weber-Cockayne type, with botulinum toxin type A. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:13-15.

- Fine JD, Eady RA, Bauer EA, et al. The classification of inherited epidermolysis bullosa (EB): report of the Third International Consensus Meeting on Diagnosis and Classification of EB. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:931-950.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2012.

- Eichenfield LF, Frieden IJ, Mathes EF, et al, eds. Neonatal and Infant Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2015.

- Spitz JL. Genodermatoses: A Clinical Guide to Genetic Skin Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

- Epidermolysis bullosa. Stanford Medicine website. http://med.stanford.edu/dermatopathology/dermpath-services/epiderm.html. Accessed April 3, 2019.

- Abitbol RJ, Zhou LH. Treatment of epidermolysis bullosa simplex, Weber-Cockayne type, with botulinum toxin type A. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:13-15.

Practice Points

- Localized epidermolysis bullosa simplex (formerly Weber-Cockayne syndrome) presents with flaccid bullae and erosions predominantly on the hands and feet, most commonly related to mechanical friction and heat.

- It is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion with defects in keratin-5 and keratin-14.

- Biopsy of a freshly induced blister should be examined by transmission electron microscopy or immunofluorescence mapping.

- Treatment is focused on wound management and infection control of the blisters.