User login

Adherence to Topical Treatment Can Improve Treatment-Resistant Moderate Psoriasis

High-potency topical corticosteroids are first-line treatments for psoriasis, but many patients report that they are ineffective or lose effectiveness over time.1-5 The mechanism underlying the lack or loss of activity is not well characterized but may be due to poor adherence to treatment. Adherence to topical treatment is poor in the short run and even worse in the long run.6,7 We evaluated 12 patients with psoriasis resistant to topical corticosteroids to determine if they would respond to topical corticosteroids under conditions designed to promote adherence to treatment.

Methods

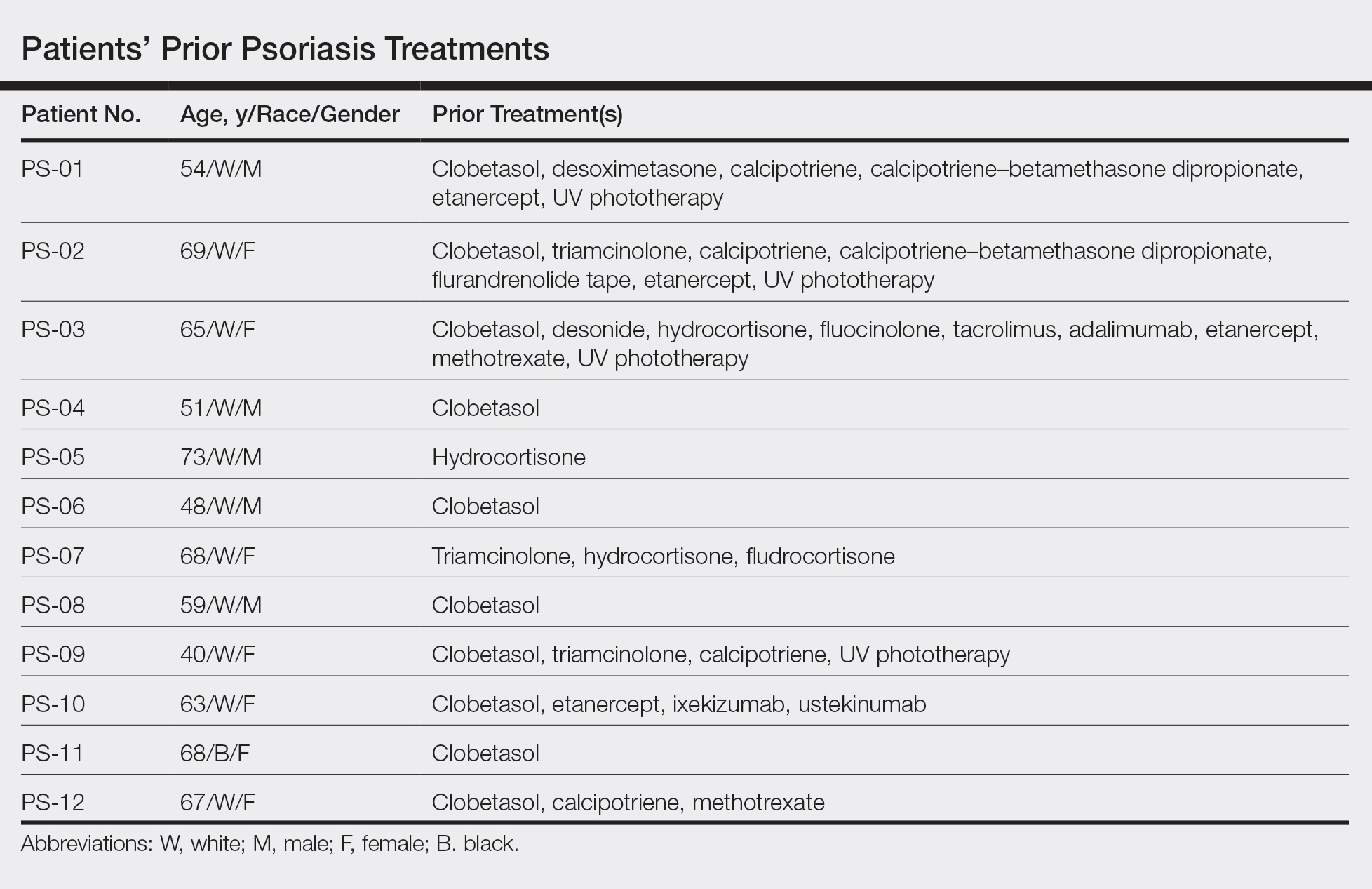

This open-label, randomized, single-center clinical study recruited 12 patients with plaque psoriasis that previously failed treatment with topical corticosteroids and other therapies (Table). We stratified disease by body surface area: mild (<3%), moderate (3%–10%), and severe (>10%). Inclusion criteria included adult patients with plaque psoriasis amenable to topical corticosteroid therapy, ability to comply with requirements of the study, and a history of failed topical corticosteroid treatment (Figure). Patients were excluded if they were pregnant, breastfeeding, had conditions that would affect adherence or potentially bias results (eg, dementia, Alzheimer disease), had a history of allergy or sensitivity to corticosteroids, and had a history of drug hypersensitivity.

All patients received desoximetasone spray 0.25% twice daily for 14 days. At the baseline visit, 6 patients were randomly selected to also receive a twice-daily reminder telephone call. Study visits occurred frequently—at baseline and on days 3, 7, and 14—to further assure good adherence to the treatment regimen.

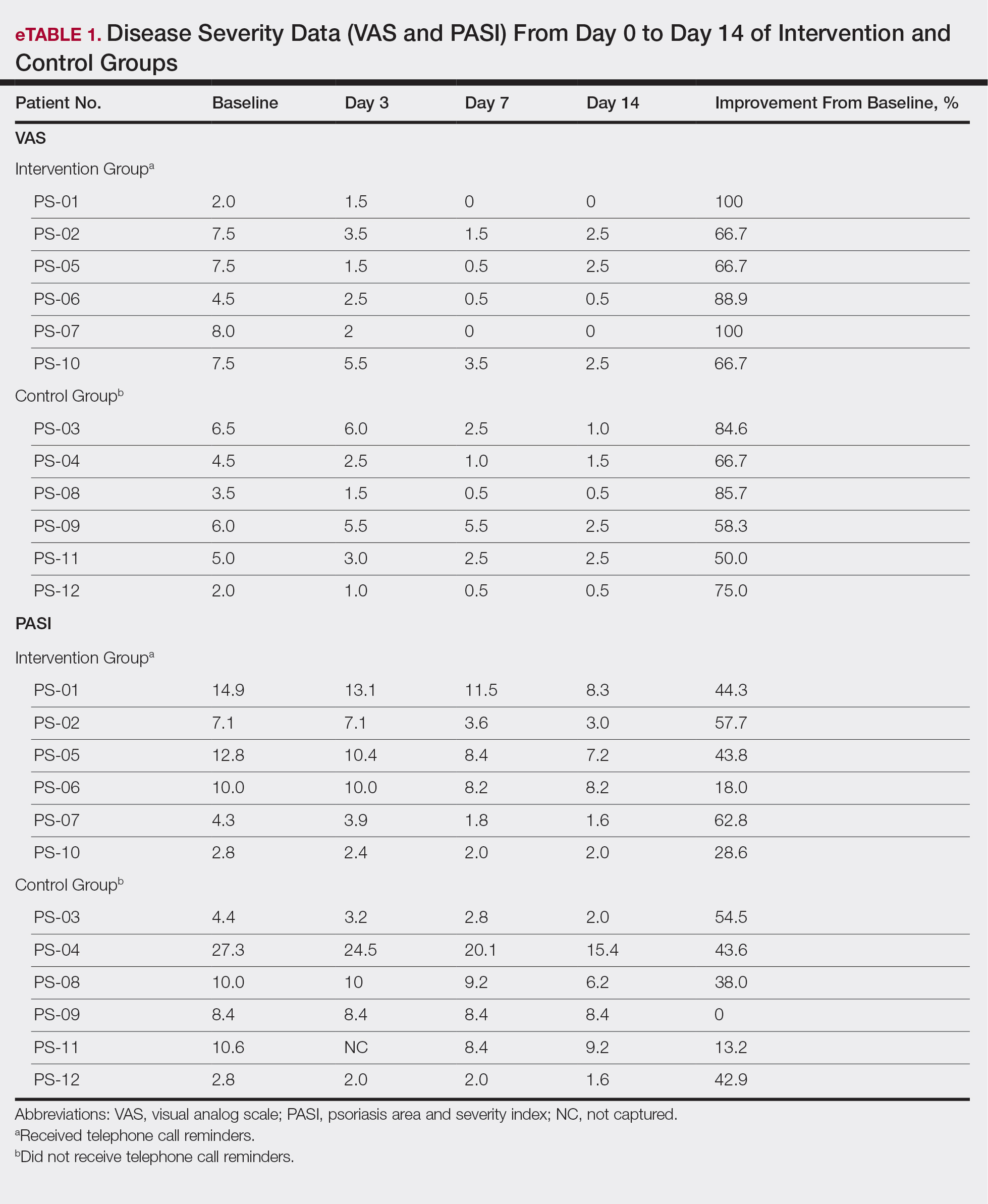

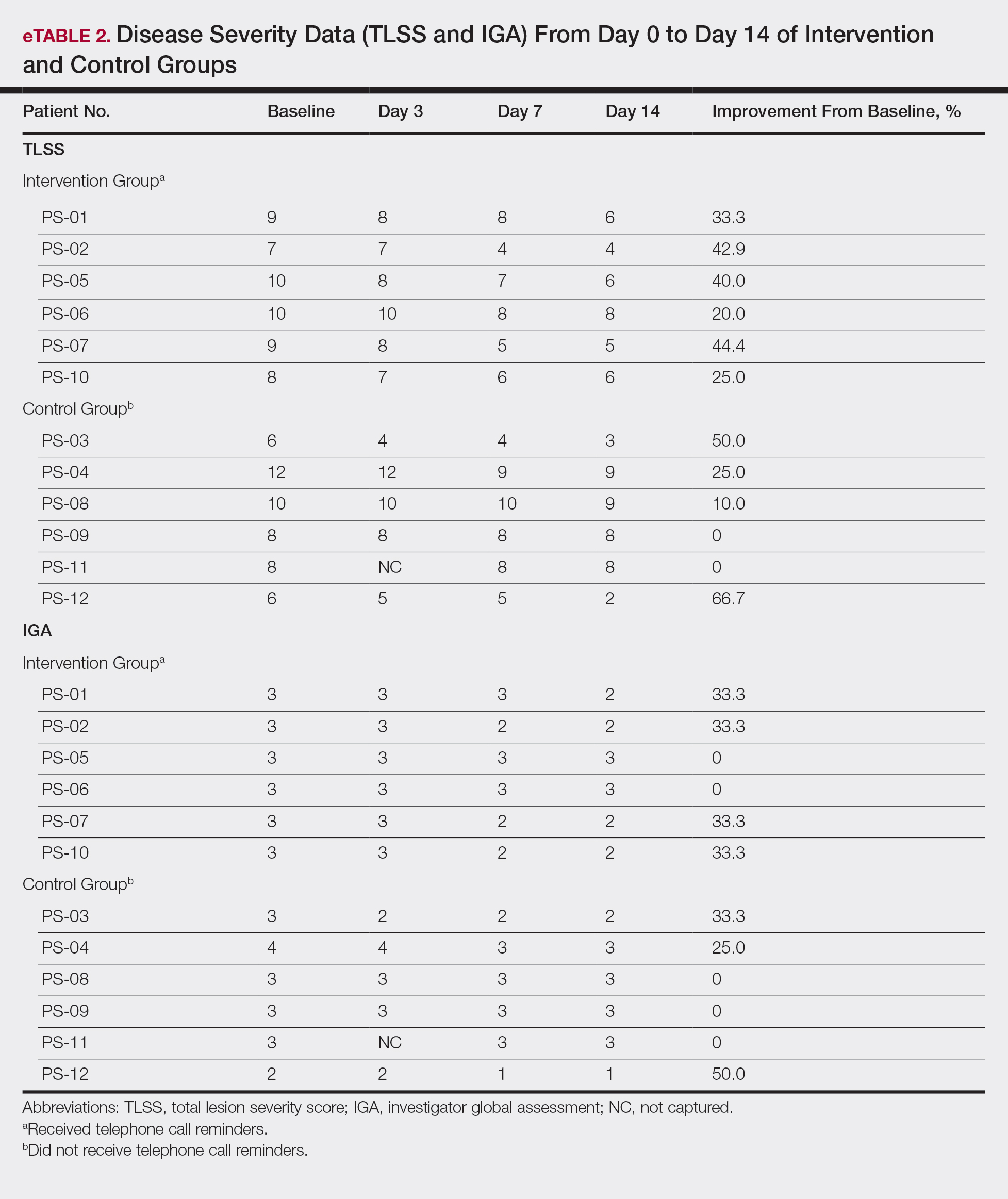

During visits, disease severity was scored using the visual analog scale for pruritus, psoriasis area and severity index (PASI), total lesion severity score (TLSS), and investigator global assessment (IGA). Descriptive statistics were used to report the outcomes for each patient.

The study was designed to assess the number of topical treatment–resistant patients who would improve with topical treatment but was not designed or powered to test if the telephone call reminders increased adherence.

Results

All patients completed the study; 10 of 12 patients (83.3%) had previously used topical clobetasol and it failed (Table). At the 2-week end-of-study visit, most patients improved on all measures. Patients who received telephone call reminders improved more than patients who did not. All 12 patients (100%) reported relief of itching; 11 of 12 (91.7%) had an improved PASI; 10 of 12 (83.3%) had an improved TLSS; and 7 of 12 (58.3%) had an improved IGA (eTables 1 and 2).

The percentage reduction in pruritus ranged from 66.7% to 100% and 50.0% to 85.7% with and without telephone call reminders, respectively. Improvement in PASI ranged from 18.0% to 62.8% and 0% to 54.5% with and without telephone call reminders, respectively. Improvement in TLSS and IGA was of lower magnitude but showed a similar pattern, with numerically greater improvement in the telephone call reminders group compared to the group that was not called (eTable 2). No patients showed a worse score for pruritus on the visual analog scale, PASI, TLSS, or IGA.

Discussion

Topical corticosteroids are highly effective for psoriasis in clinical trials, with clearance in 2 to 4 weeks in 60% to 80% of patients, a rapidity of response not matched by even the most potent biologic treatments.8,9 However, topical corticosteroids are not always effective in clinical practice. There may be primary inefficacy (they do not work at first) or secondary inefficacy (a previously effective treatment loses efficacy over time).10 Poor adherence can explain both phenomena. Primary adherence occurs when patients fill their prescription; secondary adherence occurs when patients follow the medication recommendations.11 Primary nonadherence is common in patients with psoriasis; in one study, 50% of psoriasis prescriptions were not filled.12 Secondary adherence also is poor and declines over time; electronic monitoring revealed adherence to topical treatments in psoriasis patients decreased from 85% initially to 51% at the end of 8 weeks.7 Given the high efficacy of topical corticosteroids in clinical trials and the poor adherence to topical treatment in patients with psoriasis, we anticipated that psoriasis that is resistant to topical corticosteroids would improve rapidly under conditions designed to promote adherence.

As expected, disease improved in almost every patient in this small cohort when they were given a potent topical corticosteroid, even though they previously reported that their psoriasis was resistant to potent topical corticosteroids. Although this study enrolled only a small cohort, it appears that the majority of patients with limited psoriasis that was reported to be resistant to topical treatment can see a response to topical treatment under conditions designed to encourage good adherence.

We believe that the good outcomes seen in our study were a result of good adherence. Although the desoximetasone spray 0.25% used in this study is a superpotent topical corticosteroid,8 the response to treatment was unlikely due to changing corticosteroid potency because 10 of 12 patients had tried another superpotent topical corticosteroid (clobetasol) and it failed. We chose a spray product for this study rather than an ointment to promote adherence; however, this choice limited the ability to assess adherence directly, as adherence-monitoring devices for spray delivery systems are not readily available.

Our study was limited by the small sample size and brief duration of treatment. However, the effect size is so large (ie, the topical treatment was so effective) that only a small sample size and brief treatment duration were needed to show that a high percentage of patients with psoriasis that had previously failed treatment with topical corticosteroids can in fact respond to this treatment.

We used telephone calls as reminders in 50% of patients to further encourage adherence. The study was not designed or powered to assess the effect of the telephone call reminders, but patients receiving those calls appeared to have slightly greater reduction in disease severity. Nonetheless, twice-daily telephone call reminders are unlikely to be a wanted or practical intervention; other approaches to encourage adherence are needed.

Frequent follow-up visits were incorporated in our study design to maximize adherence. Although it might not be feasible for clinical practices to schedule follow-up visits as often as in our study, other approaches such as virtual visits and electronic interaction might provide a practical alternative. Multifaceted approaches to increasing adherence include encouraging patients to participate in the treatment plan, prescribing therapy consistent with a patient’s preferred vehicle, and extensive patient education.13 If patients do not respond as expected, poor adherence can be considered. Other potential causes of poor outcomes include error in diagnosis; resistance to the prescribed treatment; concomitant infection; irritant exposure; and, in the case of biologics, antidrug antibody formation.14,15

- Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr, Cooper JZ. New topical treatments change the pattern of treatment of psoriasis: dermatologists remain the primary providers of this care. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:41-44.

- Menter A. Topical monotherapy with clobetasol propionate spray 0.05% in the COBRA trial. Cutis. 2007;80(suppl 5):12-19.

- Saleem MD, Negus D, Feldman SR. Topical 0.25% desoximetasone spray efficacy for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: a randomized clinical trial. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;29:32-35.

- Mraz S, Leonardi C, Colón LE, et al. Different treatment outcomes with different formulations of clobetasol propionate 0.05% for the treatment of plaque psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:354-359.

- Chiricozzi A, Pimpinelli N, Ricceri F, et al. Treatment of psoriasis with topical agents: recommendations from a Tuscany Consensus. Dermatol Ther. 2017;30:e12549.

- Carroll CL, Feldman SR, Camacho FT, et al. Adherence to topical therapy decreases during the course of an 8-week psoriasis clinical trial: commonly used methods of measuring adherence to topical therapy overestimate actual use. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:212-216.

- Alinia H, Moradi Tuchayi S, Smith JA, et al. Long-term adherence to topical psoriasis treatment can be abysmal: a 1-year randomized intervention study using objective electronic adherence monitoring. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:759-764.

- Keegan BR. Desoximetasone 0.25% spray for the relief of scaling in adults with plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:835-840.

- Beutner K, Chakrabarty A, Lemke S, et al. An intra-individual randomized safety and efficacy comparison of clobetasol propionate 0.05% spray and its vehicle in the treatment of plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:357-360.

- Mehta AB, Nadkarni NJ, Patil SP, et al. Topical corticosteroids in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:371-378.

- Blais L, Kettani FZ, Forget A, et al. Assessing adherence to inhaled corticosteroids in asthma patients using an integrated measure based on primary and secondary adherence. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;73:91-97.

- Storm A, Andersen SE, Benfeldt E, et al. One in 3 prescriptions are never redeemed: primary nonadherence in an outpatient clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:27-33.

- Zschocke I, Mrowietz U, Karakasili E, et al. Non-adherence and measures to improve adherence in the topical treatment of psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28(Suppl 2):4-9.

- Mooney E, Rademaker M, Dailey R, et al. Adverse effects of topical corticosteroids in paediatric eczema: Australasian consensus statement. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:241-251.

- Varada S, Tintle SJ, Gottlieb AB. Apremilast for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2014;7:239-250.

High-potency topical corticosteroids are first-line treatments for psoriasis, but many patients report that they are ineffective or lose effectiveness over time.1-5 The mechanism underlying the lack or loss of activity is not well characterized but may be due to poor adherence to treatment. Adherence to topical treatment is poor in the short run and even worse in the long run.6,7 We evaluated 12 patients with psoriasis resistant to topical corticosteroids to determine if they would respond to topical corticosteroids under conditions designed to promote adherence to treatment.

Methods

This open-label, randomized, single-center clinical study recruited 12 patients with plaque psoriasis that previously failed treatment with topical corticosteroids and other therapies (Table). We stratified disease by body surface area: mild (<3%), moderate (3%–10%), and severe (>10%). Inclusion criteria included adult patients with plaque psoriasis amenable to topical corticosteroid therapy, ability to comply with requirements of the study, and a history of failed topical corticosteroid treatment (Figure). Patients were excluded if they were pregnant, breastfeeding, had conditions that would affect adherence or potentially bias results (eg, dementia, Alzheimer disease), had a history of allergy or sensitivity to corticosteroids, and had a history of drug hypersensitivity.

All patients received desoximetasone spray 0.25% twice daily for 14 days. At the baseline visit, 6 patients were randomly selected to also receive a twice-daily reminder telephone call. Study visits occurred frequently—at baseline and on days 3, 7, and 14—to further assure good adherence to the treatment regimen.

During visits, disease severity was scored using the visual analog scale for pruritus, psoriasis area and severity index (PASI), total lesion severity score (TLSS), and investigator global assessment (IGA). Descriptive statistics were used to report the outcomes for each patient.

The study was designed to assess the number of topical treatment–resistant patients who would improve with topical treatment but was not designed or powered to test if the telephone call reminders increased adherence.

Results

All patients completed the study; 10 of 12 patients (83.3%) had previously used topical clobetasol and it failed (Table). At the 2-week end-of-study visit, most patients improved on all measures. Patients who received telephone call reminders improved more than patients who did not. All 12 patients (100%) reported relief of itching; 11 of 12 (91.7%) had an improved PASI; 10 of 12 (83.3%) had an improved TLSS; and 7 of 12 (58.3%) had an improved IGA (eTables 1 and 2).

The percentage reduction in pruritus ranged from 66.7% to 100% and 50.0% to 85.7% with and without telephone call reminders, respectively. Improvement in PASI ranged from 18.0% to 62.8% and 0% to 54.5% with and without telephone call reminders, respectively. Improvement in TLSS and IGA was of lower magnitude but showed a similar pattern, with numerically greater improvement in the telephone call reminders group compared to the group that was not called (eTable 2). No patients showed a worse score for pruritus on the visual analog scale, PASI, TLSS, or IGA.

Discussion

Topical corticosteroids are highly effective for psoriasis in clinical trials, with clearance in 2 to 4 weeks in 60% to 80% of patients, a rapidity of response not matched by even the most potent biologic treatments.8,9 However, topical corticosteroids are not always effective in clinical practice. There may be primary inefficacy (they do not work at first) or secondary inefficacy (a previously effective treatment loses efficacy over time).10 Poor adherence can explain both phenomena. Primary adherence occurs when patients fill their prescription; secondary adherence occurs when patients follow the medication recommendations.11 Primary nonadherence is common in patients with psoriasis; in one study, 50% of psoriasis prescriptions were not filled.12 Secondary adherence also is poor and declines over time; electronic monitoring revealed adherence to topical treatments in psoriasis patients decreased from 85% initially to 51% at the end of 8 weeks.7 Given the high efficacy of topical corticosteroids in clinical trials and the poor adherence to topical treatment in patients with psoriasis, we anticipated that psoriasis that is resistant to topical corticosteroids would improve rapidly under conditions designed to promote adherence.

As expected, disease improved in almost every patient in this small cohort when they were given a potent topical corticosteroid, even though they previously reported that their psoriasis was resistant to potent topical corticosteroids. Although this study enrolled only a small cohort, it appears that the majority of patients with limited psoriasis that was reported to be resistant to topical treatment can see a response to topical treatment under conditions designed to encourage good adherence.

We believe that the good outcomes seen in our study were a result of good adherence. Although the desoximetasone spray 0.25% used in this study is a superpotent topical corticosteroid,8 the response to treatment was unlikely due to changing corticosteroid potency because 10 of 12 patients had tried another superpotent topical corticosteroid (clobetasol) and it failed. We chose a spray product for this study rather than an ointment to promote adherence; however, this choice limited the ability to assess adherence directly, as adherence-monitoring devices for spray delivery systems are not readily available.

Our study was limited by the small sample size and brief duration of treatment. However, the effect size is so large (ie, the topical treatment was so effective) that only a small sample size and brief treatment duration were needed to show that a high percentage of patients with psoriasis that had previously failed treatment with topical corticosteroids can in fact respond to this treatment.

We used telephone calls as reminders in 50% of patients to further encourage adherence. The study was not designed or powered to assess the effect of the telephone call reminders, but patients receiving those calls appeared to have slightly greater reduction in disease severity. Nonetheless, twice-daily telephone call reminders are unlikely to be a wanted or practical intervention; other approaches to encourage adherence are needed.

Frequent follow-up visits were incorporated in our study design to maximize adherence. Although it might not be feasible for clinical practices to schedule follow-up visits as often as in our study, other approaches such as virtual visits and electronic interaction might provide a practical alternative. Multifaceted approaches to increasing adherence include encouraging patients to participate in the treatment plan, prescribing therapy consistent with a patient’s preferred vehicle, and extensive patient education.13 If patients do not respond as expected, poor adherence can be considered. Other potential causes of poor outcomes include error in diagnosis; resistance to the prescribed treatment; concomitant infection; irritant exposure; and, in the case of biologics, antidrug antibody formation.14,15

High-potency topical corticosteroids are first-line treatments for psoriasis, but many patients report that they are ineffective or lose effectiveness over time.1-5 The mechanism underlying the lack or loss of activity is not well characterized but may be due to poor adherence to treatment. Adherence to topical treatment is poor in the short run and even worse in the long run.6,7 We evaluated 12 patients with psoriasis resistant to topical corticosteroids to determine if they would respond to topical corticosteroids under conditions designed to promote adherence to treatment.

Methods

This open-label, randomized, single-center clinical study recruited 12 patients with plaque psoriasis that previously failed treatment with topical corticosteroids and other therapies (Table). We stratified disease by body surface area: mild (<3%), moderate (3%–10%), and severe (>10%). Inclusion criteria included adult patients with plaque psoriasis amenable to topical corticosteroid therapy, ability to comply with requirements of the study, and a history of failed topical corticosteroid treatment (Figure). Patients were excluded if they were pregnant, breastfeeding, had conditions that would affect adherence or potentially bias results (eg, dementia, Alzheimer disease), had a history of allergy or sensitivity to corticosteroids, and had a history of drug hypersensitivity.

All patients received desoximetasone spray 0.25% twice daily for 14 days. At the baseline visit, 6 patients were randomly selected to also receive a twice-daily reminder telephone call. Study visits occurred frequently—at baseline and on days 3, 7, and 14—to further assure good adherence to the treatment regimen.

During visits, disease severity was scored using the visual analog scale for pruritus, psoriasis area and severity index (PASI), total lesion severity score (TLSS), and investigator global assessment (IGA). Descriptive statistics were used to report the outcomes for each patient.

The study was designed to assess the number of topical treatment–resistant patients who would improve with topical treatment but was not designed or powered to test if the telephone call reminders increased adherence.

Results

All patients completed the study; 10 of 12 patients (83.3%) had previously used topical clobetasol and it failed (Table). At the 2-week end-of-study visit, most patients improved on all measures. Patients who received telephone call reminders improved more than patients who did not. All 12 patients (100%) reported relief of itching; 11 of 12 (91.7%) had an improved PASI; 10 of 12 (83.3%) had an improved TLSS; and 7 of 12 (58.3%) had an improved IGA (eTables 1 and 2).

The percentage reduction in pruritus ranged from 66.7% to 100% and 50.0% to 85.7% with and without telephone call reminders, respectively. Improvement in PASI ranged from 18.0% to 62.8% and 0% to 54.5% with and without telephone call reminders, respectively. Improvement in TLSS and IGA was of lower magnitude but showed a similar pattern, with numerically greater improvement in the telephone call reminders group compared to the group that was not called (eTable 2). No patients showed a worse score for pruritus on the visual analog scale, PASI, TLSS, or IGA.

Discussion

Topical corticosteroids are highly effective for psoriasis in clinical trials, with clearance in 2 to 4 weeks in 60% to 80% of patients, a rapidity of response not matched by even the most potent biologic treatments.8,9 However, topical corticosteroids are not always effective in clinical practice. There may be primary inefficacy (they do not work at first) or secondary inefficacy (a previously effective treatment loses efficacy over time).10 Poor adherence can explain both phenomena. Primary adherence occurs when patients fill their prescription; secondary adherence occurs when patients follow the medication recommendations.11 Primary nonadherence is common in patients with psoriasis; in one study, 50% of psoriasis prescriptions were not filled.12 Secondary adherence also is poor and declines over time; electronic monitoring revealed adherence to topical treatments in psoriasis patients decreased from 85% initially to 51% at the end of 8 weeks.7 Given the high efficacy of topical corticosteroids in clinical trials and the poor adherence to topical treatment in patients with psoriasis, we anticipated that psoriasis that is resistant to topical corticosteroids would improve rapidly under conditions designed to promote adherence.

As expected, disease improved in almost every patient in this small cohort when they were given a potent topical corticosteroid, even though they previously reported that their psoriasis was resistant to potent topical corticosteroids. Although this study enrolled only a small cohort, it appears that the majority of patients with limited psoriasis that was reported to be resistant to topical treatment can see a response to topical treatment under conditions designed to encourage good adherence.

We believe that the good outcomes seen in our study were a result of good adherence. Although the desoximetasone spray 0.25% used in this study is a superpotent topical corticosteroid,8 the response to treatment was unlikely due to changing corticosteroid potency because 10 of 12 patients had tried another superpotent topical corticosteroid (clobetasol) and it failed. We chose a spray product for this study rather than an ointment to promote adherence; however, this choice limited the ability to assess adherence directly, as adherence-monitoring devices for spray delivery systems are not readily available.

Our study was limited by the small sample size and brief duration of treatment. However, the effect size is so large (ie, the topical treatment was so effective) that only a small sample size and brief treatment duration were needed to show that a high percentage of patients with psoriasis that had previously failed treatment with topical corticosteroids can in fact respond to this treatment.

We used telephone calls as reminders in 50% of patients to further encourage adherence. The study was not designed or powered to assess the effect of the telephone call reminders, but patients receiving those calls appeared to have slightly greater reduction in disease severity. Nonetheless, twice-daily telephone call reminders are unlikely to be a wanted or practical intervention; other approaches to encourage adherence are needed.

Frequent follow-up visits were incorporated in our study design to maximize adherence. Although it might not be feasible for clinical practices to schedule follow-up visits as often as in our study, other approaches such as virtual visits and electronic interaction might provide a practical alternative. Multifaceted approaches to increasing adherence include encouraging patients to participate in the treatment plan, prescribing therapy consistent with a patient’s preferred vehicle, and extensive patient education.13 If patients do not respond as expected, poor adherence can be considered. Other potential causes of poor outcomes include error in diagnosis; resistance to the prescribed treatment; concomitant infection; irritant exposure; and, in the case of biologics, antidrug antibody formation.14,15

- Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr, Cooper JZ. New topical treatments change the pattern of treatment of psoriasis: dermatologists remain the primary providers of this care. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:41-44.

- Menter A. Topical monotherapy with clobetasol propionate spray 0.05% in the COBRA trial. Cutis. 2007;80(suppl 5):12-19.

- Saleem MD, Negus D, Feldman SR. Topical 0.25% desoximetasone spray efficacy for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: a randomized clinical trial. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;29:32-35.

- Mraz S, Leonardi C, Colón LE, et al. Different treatment outcomes with different formulations of clobetasol propionate 0.05% for the treatment of plaque psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:354-359.

- Chiricozzi A, Pimpinelli N, Ricceri F, et al. Treatment of psoriasis with topical agents: recommendations from a Tuscany Consensus. Dermatol Ther. 2017;30:e12549.

- Carroll CL, Feldman SR, Camacho FT, et al. Adherence to topical therapy decreases during the course of an 8-week psoriasis clinical trial: commonly used methods of measuring adherence to topical therapy overestimate actual use. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:212-216.

- Alinia H, Moradi Tuchayi S, Smith JA, et al. Long-term adherence to topical psoriasis treatment can be abysmal: a 1-year randomized intervention study using objective electronic adherence monitoring. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:759-764.

- Keegan BR. Desoximetasone 0.25% spray for the relief of scaling in adults with plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:835-840.

- Beutner K, Chakrabarty A, Lemke S, et al. An intra-individual randomized safety and efficacy comparison of clobetasol propionate 0.05% spray and its vehicle in the treatment of plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:357-360.

- Mehta AB, Nadkarni NJ, Patil SP, et al. Topical corticosteroids in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:371-378.

- Blais L, Kettani FZ, Forget A, et al. Assessing adherence to inhaled corticosteroids in asthma patients using an integrated measure based on primary and secondary adherence. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;73:91-97.

- Storm A, Andersen SE, Benfeldt E, et al. One in 3 prescriptions are never redeemed: primary nonadherence in an outpatient clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:27-33.

- Zschocke I, Mrowietz U, Karakasili E, et al. Non-adherence and measures to improve adherence in the topical treatment of psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28(Suppl 2):4-9.

- Mooney E, Rademaker M, Dailey R, et al. Adverse effects of topical corticosteroids in paediatric eczema: Australasian consensus statement. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:241-251.

- Varada S, Tintle SJ, Gottlieb AB. Apremilast for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2014;7:239-250.

- Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr, Cooper JZ. New topical treatments change the pattern of treatment of psoriasis: dermatologists remain the primary providers of this care. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:41-44.

- Menter A. Topical monotherapy with clobetasol propionate spray 0.05% in the COBRA trial. Cutis. 2007;80(suppl 5):12-19.

- Saleem MD, Negus D, Feldman SR. Topical 0.25% desoximetasone spray efficacy for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: a randomized clinical trial. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;29:32-35.

- Mraz S, Leonardi C, Colón LE, et al. Different treatment outcomes with different formulations of clobetasol propionate 0.05% for the treatment of plaque psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:354-359.

- Chiricozzi A, Pimpinelli N, Ricceri F, et al. Treatment of psoriasis with topical agents: recommendations from a Tuscany Consensus. Dermatol Ther. 2017;30:e12549.

- Carroll CL, Feldman SR, Camacho FT, et al. Adherence to topical therapy decreases during the course of an 8-week psoriasis clinical trial: commonly used methods of measuring adherence to topical therapy overestimate actual use. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:212-216.

- Alinia H, Moradi Tuchayi S, Smith JA, et al. Long-term adherence to topical psoriasis treatment can be abysmal: a 1-year randomized intervention study using objective electronic adherence monitoring. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:759-764.

- Keegan BR. Desoximetasone 0.25% spray for the relief of scaling in adults with plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:835-840.

- Beutner K, Chakrabarty A, Lemke S, et al. An intra-individual randomized safety and efficacy comparison of clobetasol propionate 0.05% spray and its vehicle in the treatment of plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:357-360.

- Mehta AB, Nadkarni NJ, Patil SP, et al. Topical corticosteroids in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:371-378.

- Blais L, Kettani FZ, Forget A, et al. Assessing adherence to inhaled corticosteroids in asthma patients using an integrated measure based on primary and secondary adherence. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;73:91-97.

- Storm A, Andersen SE, Benfeldt E, et al. One in 3 prescriptions are never redeemed: primary nonadherence in an outpatient clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:27-33.

- Zschocke I, Mrowietz U, Karakasili E, et al. Non-adherence and measures to improve adherence in the topical treatment of psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28(Suppl 2):4-9.

- Mooney E, Rademaker M, Dailey R, et al. Adverse effects of topical corticosteroids in paediatric eczema: Australasian consensus statement. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:241-251.

- Varada S, Tintle SJ, Gottlieb AB. Apremilast for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2014;7:239-250.

Practice Points

- Most patients with psoriasis are good candidates for topical treatment.

- Topical treatment of psoriasis often is ineffective.

- Topical treatment of psoriasis can be rapidly effective, even in patients who reported disease that was resistant to topical treatment.

Topical Corticosteroids for Treatment-Resistant Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is most often treated with mid-potency topical corticosteroids.1,2 Although this option is effective, not all patients respond to treatment, and those who do may lose efficacy over time, a phenomenon known as tachyphylaxis. The pathophysiology of tachyphylaxis to topical corticosteroids has been ascribed to loss of corticosteroid receptor function,3 but the evidence is weak.3,4 Patients with severe treatment-resistant AD improve when treated with mid-potency topical steroids in an inpatient setting; therefore, treatment resistance to topical corticosteroids may be largely due to poor adherence.5

Patients with treatment-resistant AD generally improve when treated with topical corticosteroids under conditions designed to promote treatment adherence, but this improvement often is reported for study groups, not individual patients. Focusing on group data may not give a clear picture of what is happening at the individual level. In this study, we evaluated changes at an individual level to determine how frequently AD patients who were previously treated with topical corticosteroids unsuccessfully would respond to desoximetasone spray 0.25% under conditions designed to promote good adherence over a 7-day period.

Methods

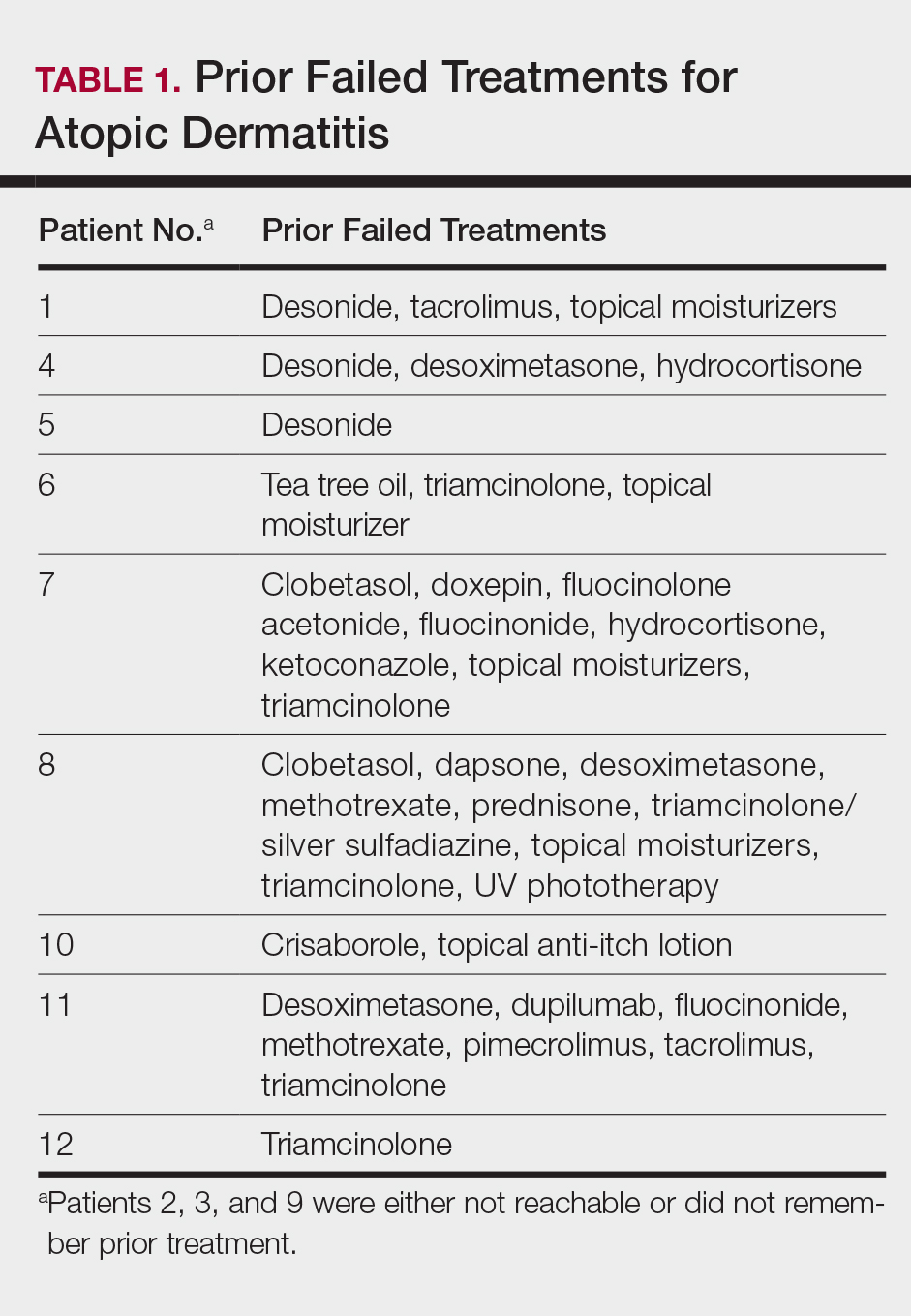

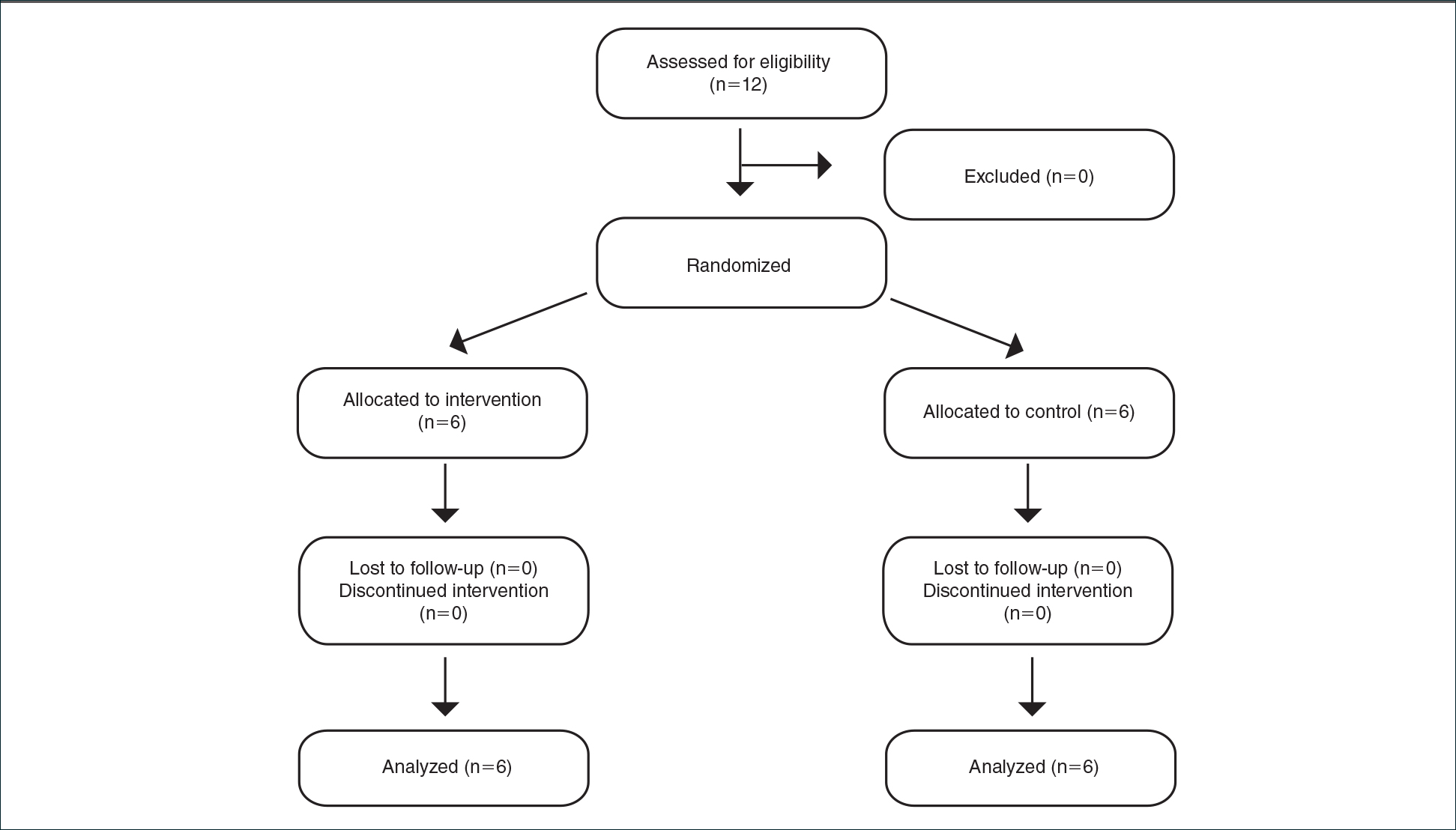

This open-label, randomized, single-center clinical study included 12 patients with AD who were previously unsuccessfully treated with topical corticosteroids in the Department of Dermatology at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center (Winston-Salem, North Carolina)(Table 1). The study was approved by the local institutional review board.

Inclusion criteria included men and women 18 years or older at baseline who had AD that was considered amenable to therapy with topical corticosteroids by the clinician and were able to comply with the study protocol (Figure). Written informed consent also was obtained from each patient. Women who were pregnant, breastfeeding, or unwilling to practice birth control during participation in the study were excluded. Other exclusion criteria included presence of a condition that in the opinion of the investigator would compromise the safety of the patient or quality of data as well as patients with no access to a telephone throughout the day. Patients diagnosed with conditions affecting adherence to treatment (eg, dementia, Alzheimer disease), those with a history of allergy or sensitivity to corticosteroids, and those with a history of drug hypersensitivity were excluded from the study.

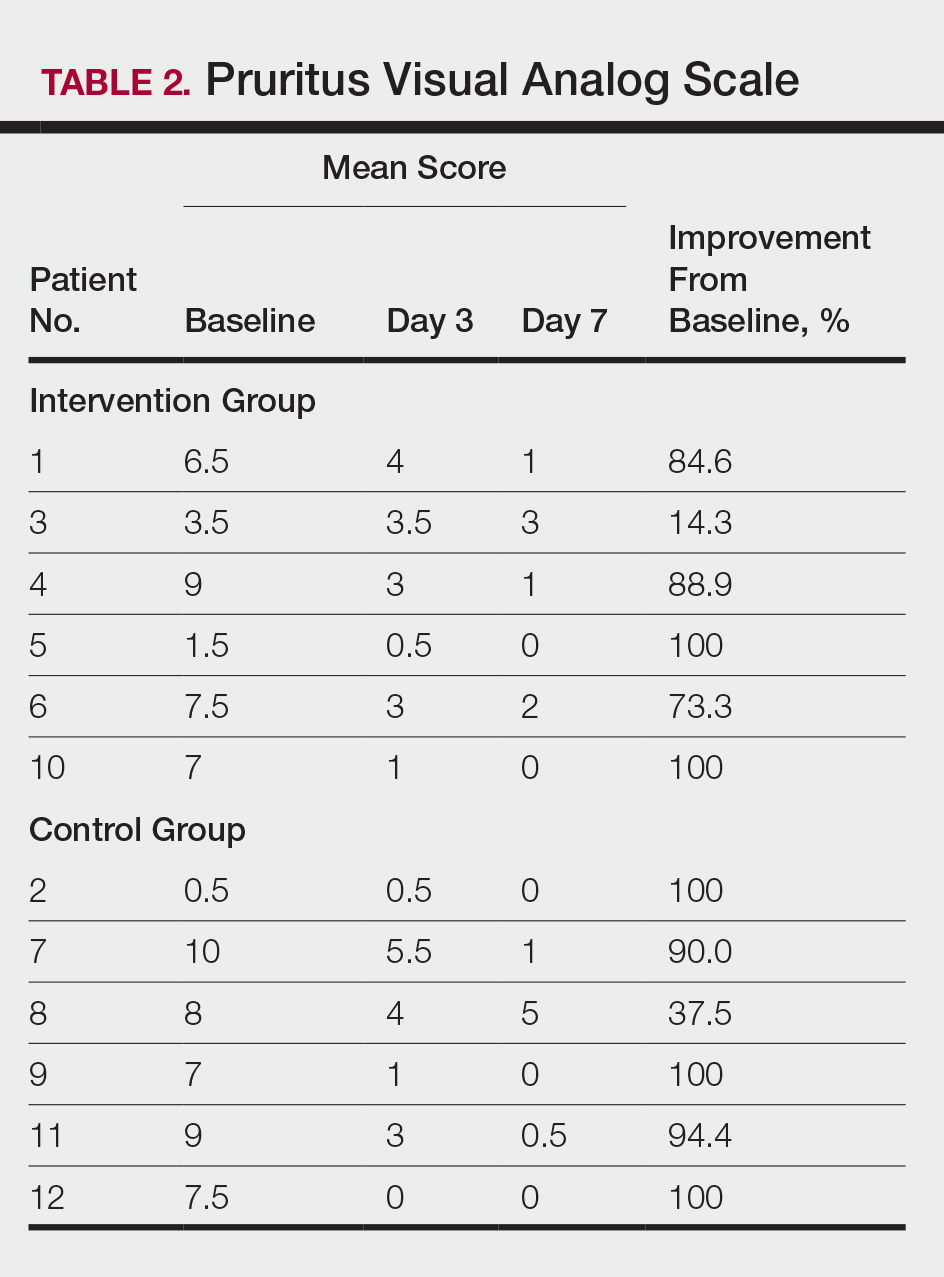

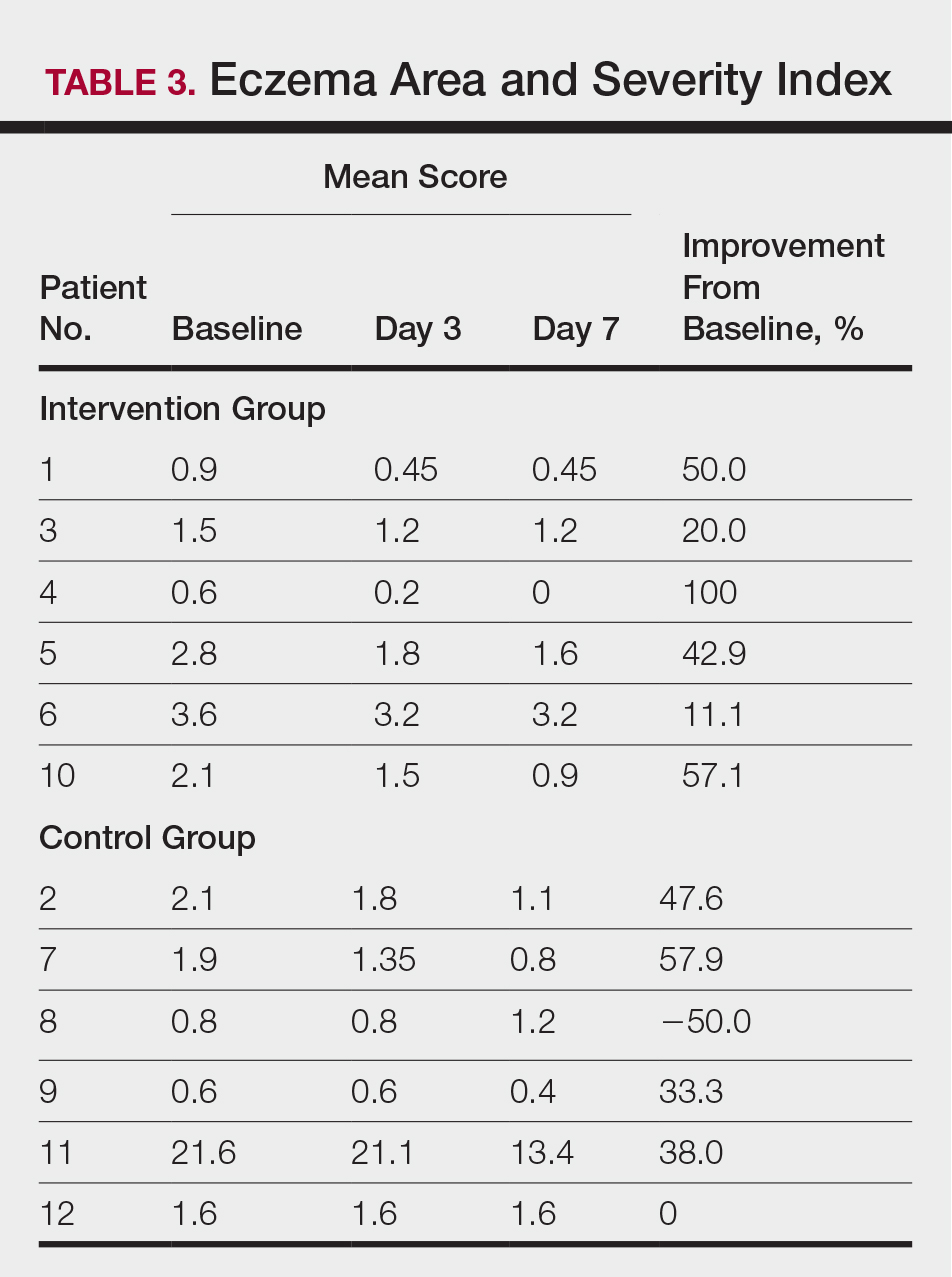

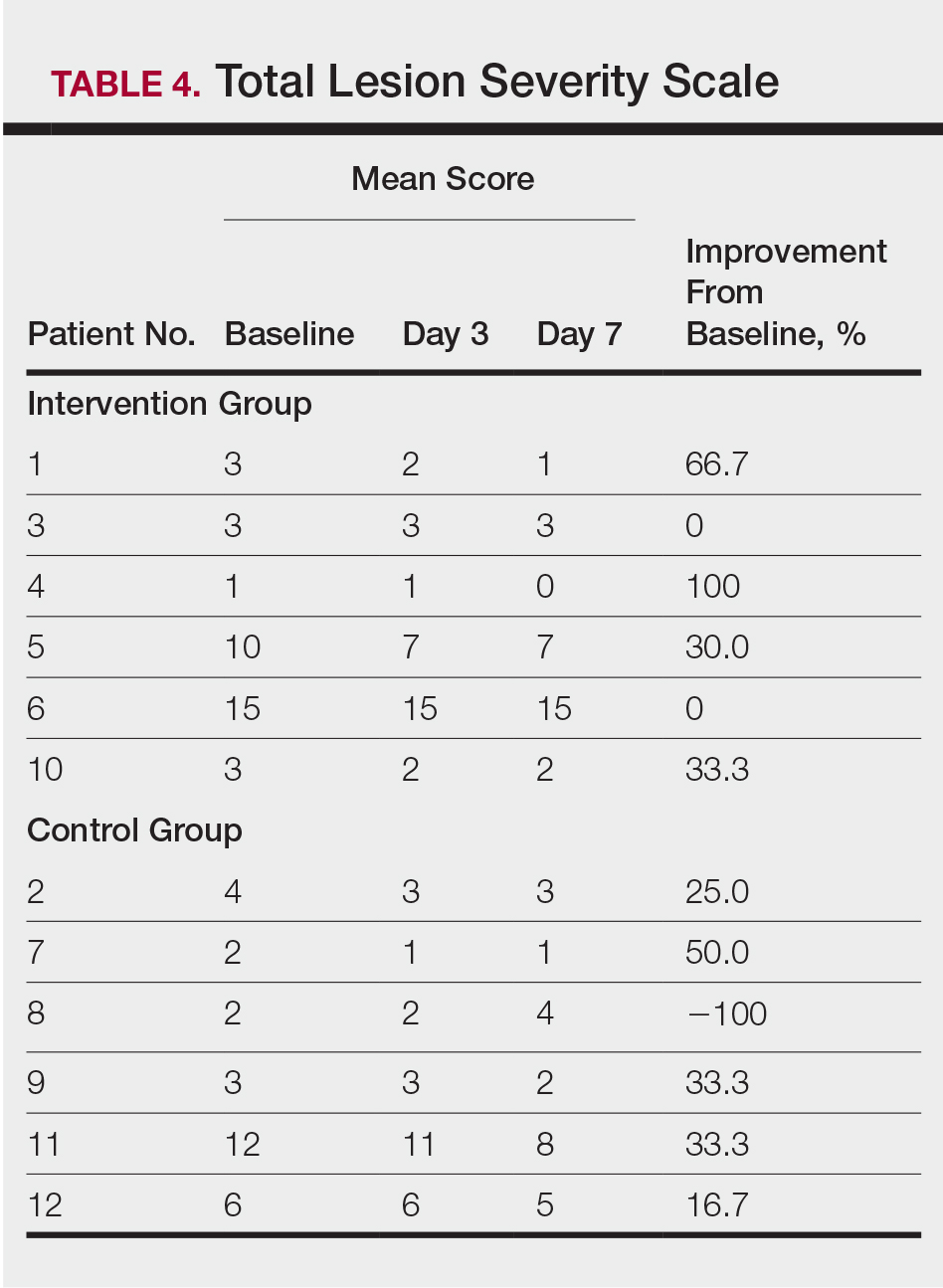

All 12 patients were treated with desoximetasone spray 0.25% for 7 days. Patients were instructed not to use other AD medications during the study period. At baseline, patients were randomized to receive either twice-daily telephone calls to discuss treatment adherence (intervention group) or no telephone calls (control) during the study period. Patients in both the intervention and control groups returned for evaluation on days 3 and 7. During these visits, disease severity was evaluated using the pruritus visual analog scale, Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), total lesion severity scale (TLSS), and investigator global assessment (IGA). Descriptive statistics were used to report the outcomes for each patient.

Results

Twelve AD patients who were previously unsuccessfully treated with topical corticosteroids were recruited for the study. Six patients were randomized to the intervention group and 6 were randomized to the control group. Fifty percent of patients were black, 50% were women, and the average age was 50.4 years. All 12 patients completed the study.

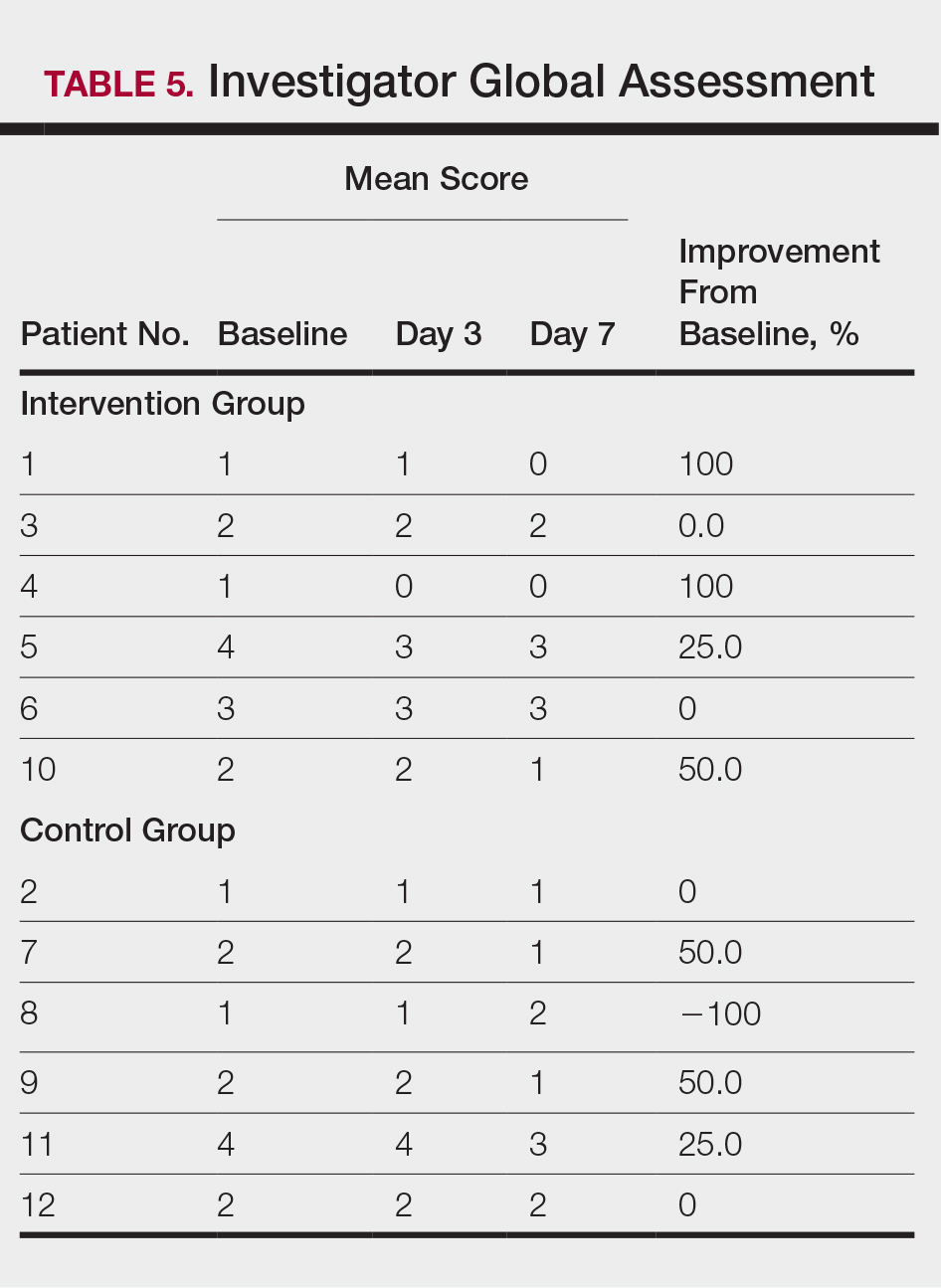

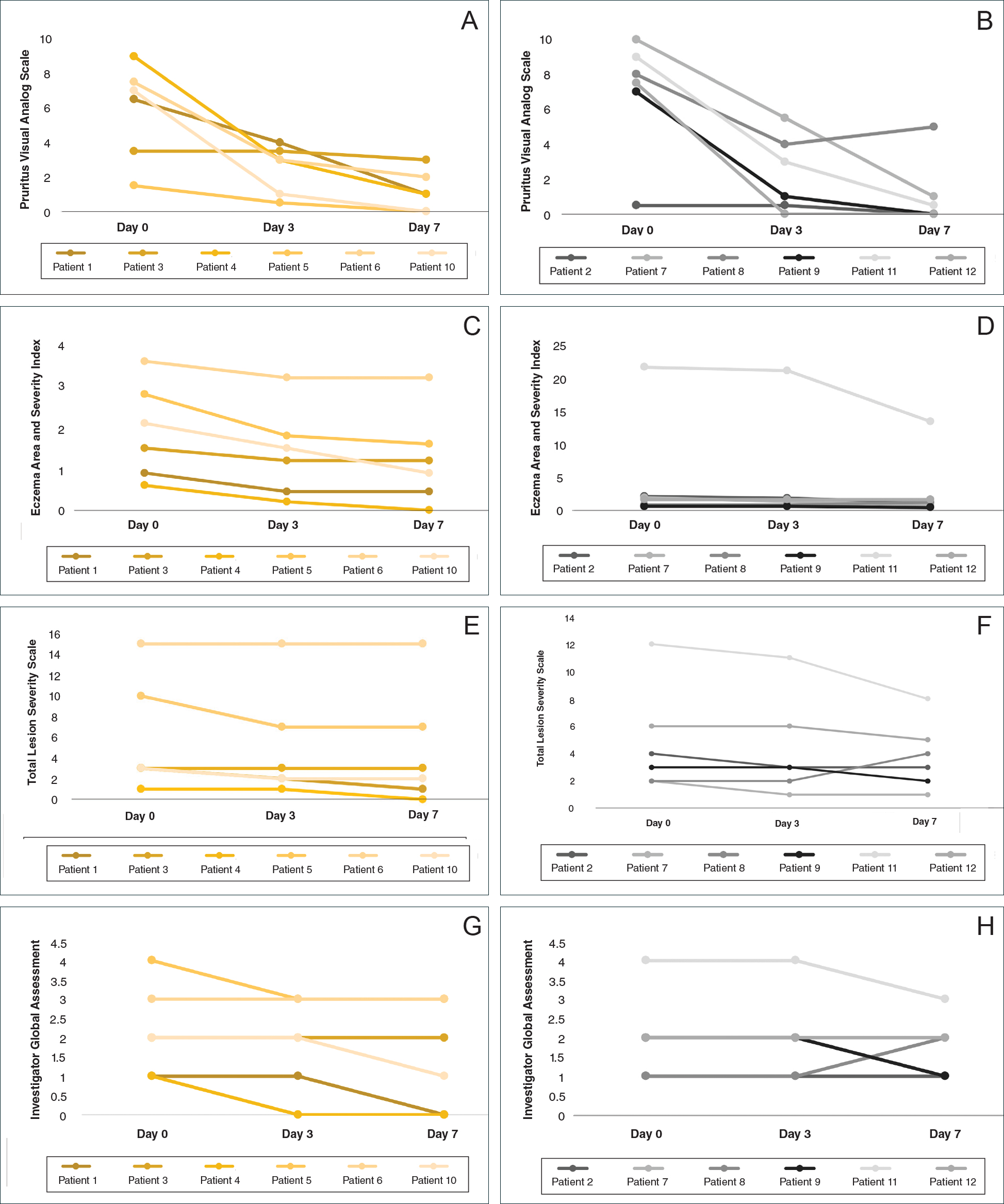

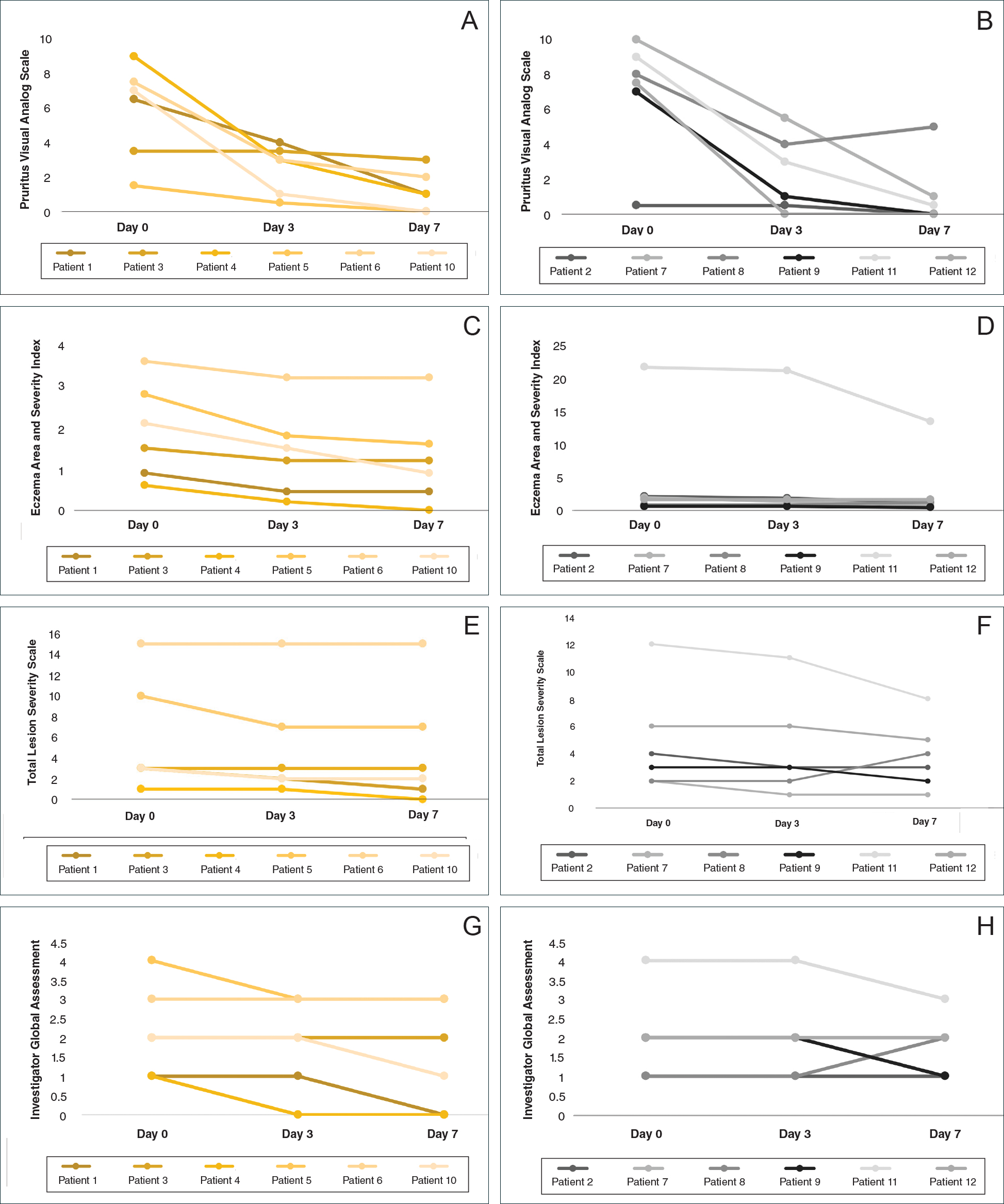

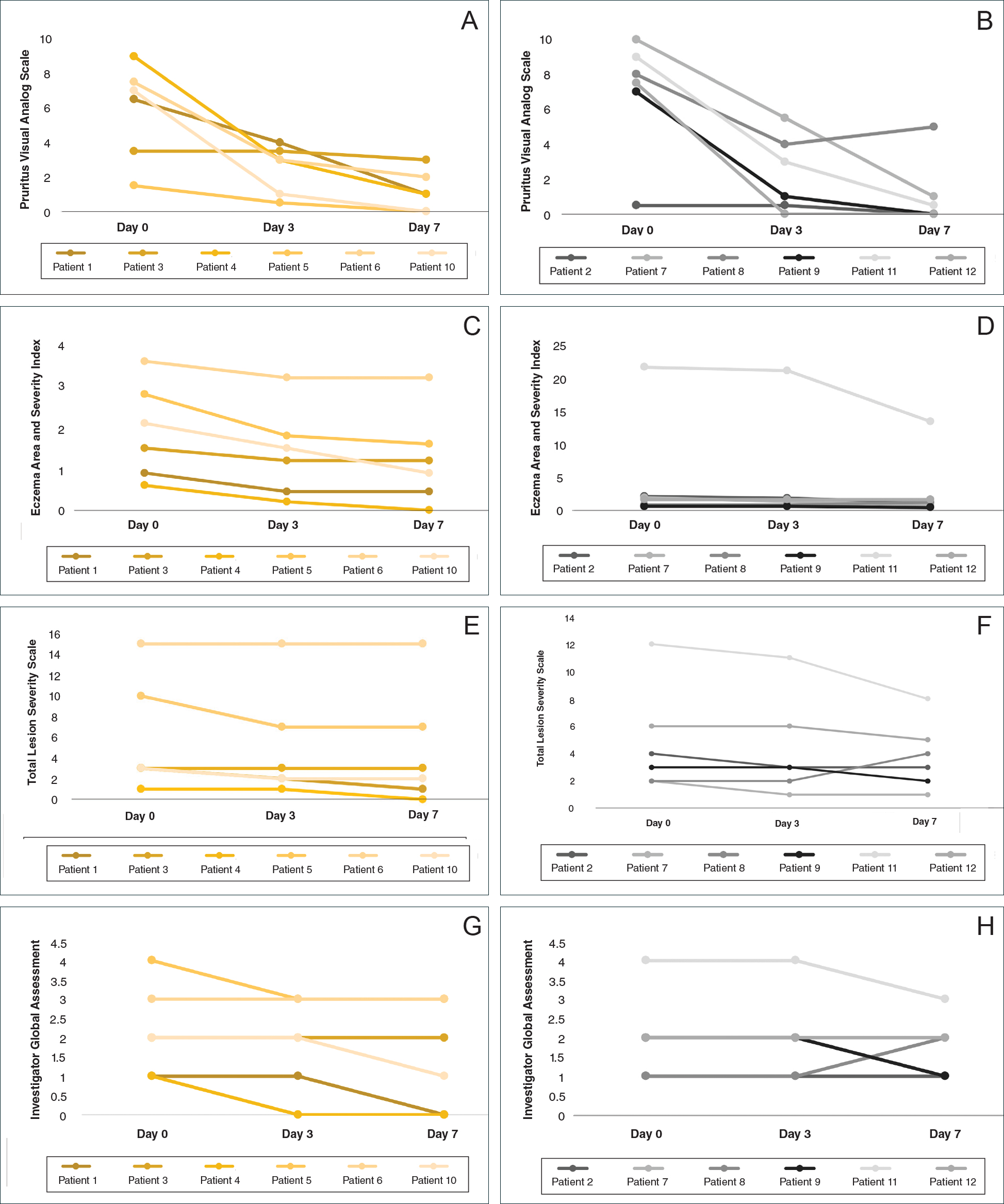

At the end of the study, most patients showed improvement in all evaluation parameters (eFigure). All 12 patients showed improvement in pruritus visual analog scores; 83.3% (10/12) showed improved EASI scores, 75.0% (9/12) showed improved TLSS scores, and 58.3% (7/12) showed improved IGA scores (Tables 2–5). Patients who received telephone calls in the intervention group showed greater improvement compared to those in the control group, except for pruritus; the mean reduction in pruritus was 76.9% in the intervention group versus 87.0% in the control group. The mean improvement in EASI score was 46.9% in the intervention group versus 21.1% in the control group. The mean improvement in TLSS score was 38.3% in the intervention group versus 9.7% in the control group. The mean improvement in IGA score was 45.8% in the intervention group versus 4.2% in the control group. Only one patient in the control group (patient 8) showed lower EASI, TLSS, and IGA scores at baseline.

Comment

Although topical corticosteroids are the mainstay for treatment of AD, many patients report treatment resistance after a period of a few doses or longer.6-9 There is strong evidence demonstrating rapid corticosteroid receptor downregulation in tissues after corticosteroid therapy, which is the accepted mechanism for tachyphylaxis, but the timing of this effect does not match up with clinical experiences. The physiologic significance of corticosteroid agonist-induced receptor downregulation is unknown and may not have any considerable effect on corticosteroid efficacy.3 A systematic review by Taheri et al3 on the development of resistance to topical corticosteroids proposed 2 theories for the underlying pathogenesis of tachyphylaxis: (1) long-term patient nonadherence, and (2) the initial maximal response during the first few weeks of therapy eventually plateaus. Because corticosteroids may plateau after a certain number of doses, natural disease flare-ups during this period may give the wrong impression of tachyphylaxis.10 The treatment “resistance” reported by the patients in our study may have been due to this plateau effect or to poor adherence.

Our finding that nearly all patients had rapid improvement of AD with the topical corticosteroid is not definitive proof but supports the notion that tachyphylaxis is largely mediated by poor adherence to treatment. Patients rapidly improved over the short study period. The short duration of treatment and multiple visits over the study period were designed to help ensure patient adherence. Rapid improvement in AD when topical corticosteroids are used should be expected, as AD patients have rapid improvement with application of topical corticosteroids in inpatient settings.11,12

Poor adherence to topical medication is common. In a Danish study, 99 of 322 patients (31%) did not redeem their AD prescriptions.13 In a single-center, 5-day, prospective study evaluating the use of fluocinonide cream 0.1% for treatment of children and adults with AD, the median percentage of prescribed doses taken was 40%, according to objective electronic monitors, even though patients reported 100% adherence in their medication diaries.Better adherence was seen on day 1 of treatment in which 66.6% (6/9) of patients adhered to their treatment strategy versus day 5 in which only 11.1% (1/9) of patients used their medication.1

Topical corticosteroids are safe and efficacious if used appropriately; however, patients commonly express fear and anxiety about using them. Topical corticosteroid phobia may stem from a misconception that these products carry the same adverse effects as their oral and systemic counterparts, which may be perpetuated by the media.1 Of 200 dermatology patients surveyed, 72.5% expressed concern about using topical corticosteroids on themselves or their children’s skin, and 24% of these patients stated they were noncompliant with their medication because of these worries. Almost 50% of patients requested prescriptions for corticosteroid-sparing medications such as tacrolimus.1 Patient education is important to help ensure treatment adherence. Other factors that can affect treatment adherence include forgetfulness; the chronic nature of AD; the need for ongoing application of topical treatments; prohibitive costs of some topical agents; and complexities in coordinating school, work, and family plans with the treatment regimen.2

We attempted to ensure good treatment adherence in our study by calling the patients in the intervention group twice daily. The mean improvement in EASI, TLSS, and IGA scores was higher in the intervention group versus the control group, which suggests that patient reminders have at least some benefit. Because AD treatment resistance appears more closely tied to nonadherence rather than loss of medication efficacy, it seems prudent to focus on interventions that would improve treatment adherence; however, such interventions generally are not well tested. Recommended interventions have included educating patients about the side effects of topical corticosteroids, avoiding use of medical jargon, and taking patient vehicle preference into account when prescribing treatments.8 Patients should be scheduled for a return visit within 1 to 2 weeks, as early return visits can augment treatment adherence.14 At the return visit, there can be a more detailed discussion of long-term management and side effects.8

Limitations of our study included a small sample size and brief treatment duration. Even though the patients had previously reported treatment failure with topical corticosteroids, all demonstrated improvement in only 1 week with a potent topical corticosteroid. The treatment resistance that initially was reported likely was due to poor adherence, but it is possible for AD patients to be resistant to treatment with topical corticosteroids due to allergic contact dermatitis. Patients could theoretically be allergic to components of the vehicle used in topical corticosteroids, which could aggravate their dermatitis; however, this effect seems unlikely in our patient population, as all the patients in our study showed improvement following treatment. Another study limitation was that adherence was not measured. The frequent follow-up visits were designed to encourage treatment adherence, but adherence was not specifically assessed. Although patients were encouraged to only use the desoximetasone spray during the study, it is not known whether patients used other products.

Conclusion

Some AD patients exhibit apparent decreased efficacy of topical corticosteroids over time, but this tachyphylaxis phenomenon is more likely due to poor treatment adherence than to loss of corticosteroid responsiveness. In our study, AD patients who reported treatment failure with topical corticosteroids improved rapidly with topical corticosteroids under conditions designed to promote good adherence to treatment. The majority of patients improved in all 4 parameters used for evaluating disease severity, with 100% of patients reporting improvement in pruritus. Intervention to improve treatment adherence may lead to better health outcomes. When AD appears resistant to topical corticosteroids, addressing adherence issues may be critical.

- Patel NU, D’Ambra V, Feldman SR. Increasing adherence with topical agents for atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:323-332.

- Mooney E, Rademaker M, Dailey R, et al. Adverse effects of topical corticosteroids in paediatric eczema: Australasian consensus statement. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:241-251.

- Taheri A, Cantrell J, Feldman SR. Tachyphylaxis to topical glucocorticoids; what is the evidence? Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18954.

- Miller JJ, Roling D, Margolis D, et al. Failure to demonstrate therapeutic tachyphylaxis to topically applied steroids in patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:546-549.

- Smith SD, Harris V, Lee A, et al. General practitioners knowledge about use of topical corticosteroids in paediatric atopic dermatitis in Australia. Aust Fam Physician. 2017;46:335-340.

- Sathishkumar D, Moss C. Topical therapy in atopic dermatitis in children. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:656-661.

- Reitamo S, Remitz A. Topical agents for atopic dermatitis. In: Bieber T, ed. Advances in the Management of Atopic Dermatitis. London, United Kingdom: Future Medicine Ltd; 2013:62-72.

- Krejci-Manwaring J, Tusa MG, Carroll C, et al. Stealth monitoring of adherence to topical medication: adherence is very poor in children with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:211-216.

- Fukaya M. Cortisol homeostasis in the epidermis is influenced by topical corticosteroids in patients with atopic dermatitis. Indian J Dermatol. 2017;62:440.

- Mehta AB, Nadkarni NJ, Patil SP, et al. Topical corticosteroids in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:371-378.

- van der Schaft J, Keijzer WW, Sanders KJ, et al. Is there an additional value of inpatient treatment for patients with atopic dermatitis? Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96:797-801.

- Dabade TS, Davis DM, Wetter DA, et al. Wet dressing therapy in conjunction with topical corticosteroids is effective for rapid control of severe pediatric atopic dermatitis: experience with 218 patients over 30 years at Mayo Clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;67:100-106.

- Storm A, Andersen SE, Benfeldt E, et al. One in 3 prescriptions are never redeemed: primary nonadherence in an outpatient clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:27-33.

- Sagransky MJ, Yentzer BA, Williams LL, et al. A randomized controlled pilot study of the effects of an extra office visit on adherence and outcomes in atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1428-1430.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is most often treated with mid-potency topical corticosteroids.1,2 Although this option is effective, not all patients respond to treatment, and those who do may lose efficacy over time, a phenomenon known as tachyphylaxis. The pathophysiology of tachyphylaxis to topical corticosteroids has been ascribed to loss of corticosteroid receptor function,3 but the evidence is weak.3,4 Patients with severe treatment-resistant AD improve when treated with mid-potency topical steroids in an inpatient setting; therefore, treatment resistance to topical corticosteroids may be largely due to poor adherence.5

Patients with treatment-resistant AD generally improve when treated with topical corticosteroids under conditions designed to promote treatment adherence, but this improvement often is reported for study groups, not individual patients. Focusing on group data may not give a clear picture of what is happening at the individual level. In this study, we evaluated changes at an individual level to determine how frequently AD patients who were previously treated with topical corticosteroids unsuccessfully would respond to desoximetasone spray 0.25% under conditions designed to promote good adherence over a 7-day period.

Methods

This open-label, randomized, single-center clinical study included 12 patients with AD who were previously unsuccessfully treated with topical corticosteroids in the Department of Dermatology at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center (Winston-Salem, North Carolina)(Table 1). The study was approved by the local institutional review board.

Inclusion criteria included men and women 18 years or older at baseline who had AD that was considered amenable to therapy with topical corticosteroids by the clinician and were able to comply with the study protocol (Figure). Written informed consent also was obtained from each patient. Women who were pregnant, breastfeeding, or unwilling to practice birth control during participation in the study were excluded. Other exclusion criteria included presence of a condition that in the opinion of the investigator would compromise the safety of the patient or quality of data as well as patients with no access to a telephone throughout the day. Patients diagnosed with conditions affecting adherence to treatment (eg, dementia, Alzheimer disease), those with a history of allergy or sensitivity to corticosteroids, and those with a history of drug hypersensitivity were excluded from the study.

All 12 patients were treated with desoximetasone spray 0.25% for 7 days. Patients were instructed not to use other AD medications during the study period. At baseline, patients were randomized to receive either twice-daily telephone calls to discuss treatment adherence (intervention group) or no telephone calls (control) during the study period. Patients in both the intervention and control groups returned for evaluation on days 3 and 7. During these visits, disease severity was evaluated using the pruritus visual analog scale, Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), total lesion severity scale (TLSS), and investigator global assessment (IGA). Descriptive statistics were used to report the outcomes for each patient.

Results

Twelve AD patients who were previously unsuccessfully treated with topical corticosteroids were recruited for the study. Six patients were randomized to the intervention group and 6 were randomized to the control group. Fifty percent of patients were black, 50% were women, and the average age was 50.4 years. All 12 patients completed the study.

At the end of the study, most patients showed improvement in all evaluation parameters (eFigure). All 12 patients showed improvement in pruritus visual analog scores; 83.3% (10/12) showed improved EASI scores, 75.0% (9/12) showed improved TLSS scores, and 58.3% (7/12) showed improved IGA scores (Tables 2–5). Patients who received telephone calls in the intervention group showed greater improvement compared to those in the control group, except for pruritus; the mean reduction in pruritus was 76.9% in the intervention group versus 87.0% in the control group. The mean improvement in EASI score was 46.9% in the intervention group versus 21.1% in the control group. The mean improvement in TLSS score was 38.3% in the intervention group versus 9.7% in the control group. The mean improvement in IGA score was 45.8% in the intervention group versus 4.2% in the control group. Only one patient in the control group (patient 8) showed lower EASI, TLSS, and IGA scores at baseline.

Comment

Although topical corticosteroids are the mainstay for treatment of AD, many patients report treatment resistance after a period of a few doses or longer.6-9 There is strong evidence demonstrating rapid corticosteroid receptor downregulation in tissues after corticosteroid therapy, which is the accepted mechanism for tachyphylaxis, but the timing of this effect does not match up with clinical experiences. The physiologic significance of corticosteroid agonist-induced receptor downregulation is unknown and may not have any considerable effect on corticosteroid efficacy.3 A systematic review by Taheri et al3 on the development of resistance to topical corticosteroids proposed 2 theories for the underlying pathogenesis of tachyphylaxis: (1) long-term patient nonadherence, and (2) the initial maximal response during the first few weeks of therapy eventually plateaus. Because corticosteroids may plateau after a certain number of doses, natural disease flare-ups during this period may give the wrong impression of tachyphylaxis.10 The treatment “resistance” reported by the patients in our study may have been due to this plateau effect or to poor adherence.

Our finding that nearly all patients had rapid improvement of AD with the topical corticosteroid is not definitive proof but supports the notion that tachyphylaxis is largely mediated by poor adherence to treatment. Patients rapidly improved over the short study period. The short duration of treatment and multiple visits over the study period were designed to help ensure patient adherence. Rapid improvement in AD when topical corticosteroids are used should be expected, as AD patients have rapid improvement with application of topical corticosteroids in inpatient settings.11,12

Poor adherence to topical medication is common. In a Danish study, 99 of 322 patients (31%) did not redeem their AD prescriptions.13 In a single-center, 5-day, prospective study evaluating the use of fluocinonide cream 0.1% for treatment of children and adults with AD, the median percentage of prescribed doses taken was 40%, according to objective electronic monitors, even though patients reported 100% adherence in their medication diaries.Better adherence was seen on day 1 of treatment in which 66.6% (6/9) of patients adhered to their treatment strategy versus day 5 in which only 11.1% (1/9) of patients used their medication.1

Topical corticosteroids are safe and efficacious if used appropriately; however, patients commonly express fear and anxiety about using them. Topical corticosteroid phobia may stem from a misconception that these products carry the same adverse effects as their oral and systemic counterparts, which may be perpetuated by the media.1 Of 200 dermatology patients surveyed, 72.5% expressed concern about using topical corticosteroids on themselves or their children’s skin, and 24% of these patients stated they were noncompliant with their medication because of these worries. Almost 50% of patients requested prescriptions for corticosteroid-sparing medications such as tacrolimus.1 Patient education is important to help ensure treatment adherence. Other factors that can affect treatment adherence include forgetfulness; the chronic nature of AD; the need for ongoing application of topical treatments; prohibitive costs of some topical agents; and complexities in coordinating school, work, and family plans with the treatment regimen.2

We attempted to ensure good treatment adherence in our study by calling the patients in the intervention group twice daily. The mean improvement in EASI, TLSS, and IGA scores was higher in the intervention group versus the control group, which suggests that patient reminders have at least some benefit. Because AD treatment resistance appears more closely tied to nonadherence rather than loss of medication efficacy, it seems prudent to focus on interventions that would improve treatment adherence; however, such interventions generally are not well tested. Recommended interventions have included educating patients about the side effects of topical corticosteroids, avoiding use of medical jargon, and taking patient vehicle preference into account when prescribing treatments.8 Patients should be scheduled for a return visit within 1 to 2 weeks, as early return visits can augment treatment adherence.14 At the return visit, there can be a more detailed discussion of long-term management and side effects.8

Limitations of our study included a small sample size and brief treatment duration. Even though the patients had previously reported treatment failure with topical corticosteroids, all demonstrated improvement in only 1 week with a potent topical corticosteroid. The treatment resistance that initially was reported likely was due to poor adherence, but it is possible for AD patients to be resistant to treatment with topical corticosteroids due to allergic contact dermatitis. Patients could theoretically be allergic to components of the vehicle used in topical corticosteroids, which could aggravate their dermatitis; however, this effect seems unlikely in our patient population, as all the patients in our study showed improvement following treatment. Another study limitation was that adherence was not measured. The frequent follow-up visits were designed to encourage treatment adherence, but adherence was not specifically assessed. Although patients were encouraged to only use the desoximetasone spray during the study, it is not known whether patients used other products.

Conclusion

Some AD patients exhibit apparent decreased efficacy of topical corticosteroids over time, but this tachyphylaxis phenomenon is more likely due to poor treatment adherence than to loss of corticosteroid responsiveness. In our study, AD patients who reported treatment failure with topical corticosteroids improved rapidly with topical corticosteroids under conditions designed to promote good adherence to treatment. The majority of patients improved in all 4 parameters used for evaluating disease severity, with 100% of patients reporting improvement in pruritus. Intervention to improve treatment adherence may lead to better health outcomes. When AD appears resistant to topical corticosteroids, addressing adherence issues may be critical.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is most often treated with mid-potency topical corticosteroids.1,2 Although this option is effective, not all patients respond to treatment, and those who do may lose efficacy over time, a phenomenon known as tachyphylaxis. The pathophysiology of tachyphylaxis to topical corticosteroids has been ascribed to loss of corticosteroid receptor function,3 but the evidence is weak.3,4 Patients with severe treatment-resistant AD improve when treated with mid-potency topical steroids in an inpatient setting; therefore, treatment resistance to topical corticosteroids may be largely due to poor adherence.5

Patients with treatment-resistant AD generally improve when treated with topical corticosteroids under conditions designed to promote treatment adherence, but this improvement often is reported for study groups, not individual patients. Focusing on group data may not give a clear picture of what is happening at the individual level. In this study, we evaluated changes at an individual level to determine how frequently AD patients who were previously treated with topical corticosteroids unsuccessfully would respond to desoximetasone spray 0.25% under conditions designed to promote good adherence over a 7-day period.

Methods

This open-label, randomized, single-center clinical study included 12 patients with AD who were previously unsuccessfully treated with topical corticosteroids in the Department of Dermatology at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center (Winston-Salem, North Carolina)(Table 1). The study was approved by the local institutional review board.

Inclusion criteria included men and women 18 years or older at baseline who had AD that was considered amenable to therapy with topical corticosteroids by the clinician and were able to comply with the study protocol (Figure). Written informed consent also was obtained from each patient. Women who were pregnant, breastfeeding, or unwilling to practice birth control during participation in the study were excluded. Other exclusion criteria included presence of a condition that in the opinion of the investigator would compromise the safety of the patient or quality of data as well as patients with no access to a telephone throughout the day. Patients diagnosed with conditions affecting adherence to treatment (eg, dementia, Alzheimer disease), those with a history of allergy or sensitivity to corticosteroids, and those with a history of drug hypersensitivity were excluded from the study.

All 12 patients were treated with desoximetasone spray 0.25% for 7 days. Patients were instructed not to use other AD medications during the study period. At baseline, patients were randomized to receive either twice-daily telephone calls to discuss treatment adherence (intervention group) or no telephone calls (control) during the study period. Patients in both the intervention and control groups returned for evaluation on days 3 and 7. During these visits, disease severity was evaluated using the pruritus visual analog scale, Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), total lesion severity scale (TLSS), and investigator global assessment (IGA). Descriptive statistics were used to report the outcomes for each patient.

Results

Twelve AD patients who were previously unsuccessfully treated with topical corticosteroids were recruited for the study. Six patients were randomized to the intervention group and 6 were randomized to the control group. Fifty percent of patients were black, 50% were women, and the average age was 50.4 years. All 12 patients completed the study.

At the end of the study, most patients showed improvement in all evaluation parameters (eFigure). All 12 patients showed improvement in pruritus visual analog scores; 83.3% (10/12) showed improved EASI scores, 75.0% (9/12) showed improved TLSS scores, and 58.3% (7/12) showed improved IGA scores (Tables 2–5). Patients who received telephone calls in the intervention group showed greater improvement compared to those in the control group, except for pruritus; the mean reduction in pruritus was 76.9% in the intervention group versus 87.0% in the control group. The mean improvement in EASI score was 46.9% in the intervention group versus 21.1% in the control group. The mean improvement in TLSS score was 38.3% in the intervention group versus 9.7% in the control group. The mean improvement in IGA score was 45.8% in the intervention group versus 4.2% in the control group. Only one patient in the control group (patient 8) showed lower EASI, TLSS, and IGA scores at baseline.

Comment

Although topical corticosteroids are the mainstay for treatment of AD, many patients report treatment resistance after a period of a few doses or longer.6-9 There is strong evidence demonstrating rapid corticosteroid receptor downregulation in tissues after corticosteroid therapy, which is the accepted mechanism for tachyphylaxis, but the timing of this effect does not match up with clinical experiences. The physiologic significance of corticosteroid agonist-induced receptor downregulation is unknown and may not have any considerable effect on corticosteroid efficacy.3 A systematic review by Taheri et al3 on the development of resistance to topical corticosteroids proposed 2 theories for the underlying pathogenesis of tachyphylaxis: (1) long-term patient nonadherence, and (2) the initial maximal response during the first few weeks of therapy eventually plateaus. Because corticosteroids may plateau after a certain number of doses, natural disease flare-ups during this period may give the wrong impression of tachyphylaxis.10 The treatment “resistance” reported by the patients in our study may have been due to this plateau effect or to poor adherence.

Our finding that nearly all patients had rapid improvement of AD with the topical corticosteroid is not definitive proof but supports the notion that tachyphylaxis is largely mediated by poor adherence to treatment. Patients rapidly improved over the short study period. The short duration of treatment and multiple visits over the study period were designed to help ensure patient adherence. Rapid improvement in AD when topical corticosteroids are used should be expected, as AD patients have rapid improvement with application of topical corticosteroids in inpatient settings.11,12

Poor adherence to topical medication is common. In a Danish study, 99 of 322 patients (31%) did not redeem their AD prescriptions.13 In a single-center, 5-day, prospective study evaluating the use of fluocinonide cream 0.1% for treatment of children and adults with AD, the median percentage of prescribed doses taken was 40%, according to objective electronic monitors, even though patients reported 100% adherence in their medication diaries.Better adherence was seen on day 1 of treatment in which 66.6% (6/9) of patients adhered to their treatment strategy versus day 5 in which only 11.1% (1/9) of patients used their medication.1

Topical corticosteroids are safe and efficacious if used appropriately; however, patients commonly express fear and anxiety about using them. Topical corticosteroid phobia may stem from a misconception that these products carry the same adverse effects as their oral and systemic counterparts, which may be perpetuated by the media.1 Of 200 dermatology patients surveyed, 72.5% expressed concern about using topical corticosteroids on themselves or their children’s skin, and 24% of these patients stated they were noncompliant with their medication because of these worries. Almost 50% of patients requested prescriptions for corticosteroid-sparing medications such as tacrolimus.1 Patient education is important to help ensure treatment adherence. Other factors that can affect treatment adherence include forgetfulness; the chronic nature of AD; the need for ongoing application of topical treatments; prohibitive costs of some topical agents; and complexities in coordinating school, work, and family plans with the treatment regimen.2

We attempted to ensure good treatment adherence in our study by calling the patients in the intervention group twice daily. The mean improvement in EASI, TLSS, and IGA scores was higher in the intervention group versus the control group, which suggests that patient reminders have at least some benefit. Because AD treatment resistance appears more closely tied to nonadherence rather than loss of medication efficacy, it seems prudent to focus on interventions that would improve treatment adherence; however, such interventions generally are not well tested. Recommended interventions have included educating patients about the side effects of topical corticosteroids, avoiding use of medical jargon, and taking patient vehicle preference into account when prescribing treatments.8 Patients should be scheduled for a return visit within 1 to 2 weeks, as early return visits can augment treatment adherence.14 At the return visit, there can be a more detailed discussion of long-term management and side effects.8

Limitations of our study included a small sample size and brief treatment duration. Even though the patients had previously reported treatment failure with topical corticosteroids, all demonstrated improvement in only 1 week with a potent topical corticosteroid. The treatment resistance that initially was reported likely was due to poor adherence, but it is possible for AD patients to be resistant to treatment with topical corticosteroids due to allergic contact dermatitis. Patients could theoretically be allergic to components of the vehicle used in topical corticosteroids, which could aggravate their dermatitis; however, this effect seems unlikely in our patient population, as all the patients in our study showed improvement following treatment. Another study limitation was that adherence was not measured. The frequent follow-up visits were designed to encourage treatment adherence, but adherence was not specifically assessed. Although patients were encouraged to only use the desoximetasone spray during the study, it is not known whether patients used other products.

Conclusion

Some AD patients exhibit apparent decreased efficacy of topical corticosteroids over time, but this tachyphylaxis phenomenon is more likely due to poor treatment adherence than to loss of corticosteroid responsiveness. In our study, AD patients who reported treatment failure with topical corticosteroids improved rapidly with topical corticosteroids under conditions designed to promote good adherence to treatment. The majority of patients improved in all 4 parameters used for evaluating disease severity, with 100% of patients reporting improvement in pruritus. Intervention to improve treatment adherence may lead to better health outcomes. When AD appears resistant to topical corticosteroids, addressing adherence issues may be critical.

- Patel NU, D’Ambra V, Feldman SR. Increasing adherence with topical agents for atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:323-332.

- Mooney E, Rademaker M, Dailey R, et al. Adverse effects of topical corticosteroids in paediatric eczema: Australasian consensus statement. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:241-251.

- Taheri A, Cantrell J, Feldman SR. Tachyphylaxis to topical glucocorticoids; what is the evidence? Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18954.

- Miller JJ, Roling D, Margolis D, et al. Failure to demonstrate therapeutic tachyphylaxis to topically applied steroids in patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:546-549.

- Smith SD, Harris V, Lee A, et al. General practitioners knowledge about use of topical corticosteroids in paediatric atopic dermatitis in Australia. Aust Fam Physician. 2017;46:335-340.

- Sathishkumar D, Moss C. Topical therapy in atopic dermatitis in children. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:656-661.

- Reitamo S, Remitz A. Topical agents for atopic dermatitis. In: Bieber T, ed. Advances in the Management of Atopic Dermatitis. London, United Kingdom: Future Medicine Ltd; 2013:62-72.

- Krejci-Manwaring J, Tusa MG, Carroll C, et al. Stealth monitoring of adherence to topical medication: adherence is very poor in children with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:211-216.

- Fukaya M. Cortisol homeostasis in the epidermis is influenced by topical corticosteroids in patients with atopic dermatitis. Indian J Dermatol. 2017;62:440.

- Mehta AB, Nadkarni NJ, Patil SP, et al. Topical corticosteroids in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:371-378.

- van der Schaft J, Keijzer WW, Sanders KJ, et al. Is there an additional value of inpatient treatment for patients with atopic dermatitis? Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96:797-801.

- Dabade TS, Davis DM, Wetter DA, et al. Wet dressing therapy in conjunction with topical corticosteroids is effective for rapid control of severe pediatric atopic dermatitis: experience with 218 patients over 30 years at Mayo Clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;67:100-106.

- Storm A, Andersen SE, Benfeldt E, et al. One in 3 prescriptions are never redeemed: primary nonadherence in an outpatient clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:27-33.

- Sagransky MJ, Yentzer BA, Williams LL, et al. A randomized controlled pilot study of the effects of an extra office visit on adherence and outcomes in atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1428-1430.

- Patel NU, D’Ambra V, Feldman SR. Increasing adherence with topical agents for atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:323-332.

- Mooney E, Rademaker M, Dailey R, et al. Adverse effects of topical corticosteroids in paediatric eczema: Australasian consensus statement. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:241-251.

- Taheri A, Cantrell J, Feldman SR. Tachyphylaxis to topical glucocorticoids; what is the evidence? Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18954.

- Miller JJ, Roling D, Margolis D, et al. Failure to demonstrate therapeutic tachyphylaxis to topically applied steroids in patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:546-549.

- Smith SD, Harris V, Lee A, et al. General practitioners knowledge about use of topical corticosteroids in paediatric atopic dermatitis in Australia. Aust Fam Physician. 2017;46:335-340.

- Sathishkumar D, Moss C. Topical therapy in atopic dermatitis in children. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:656-661.

- Reitamo S, Remitz A. Topical agents for atopic dermatitis. In: Bieber T, ed. Advances in the Management of Atopic Dermatitis. London, United Kingdom: Future Medicine Ltd; 2013:62-72.

- Krejci-Manwaring J, Tusa MG, Carroll C, et al. Stealth monitoring of adherence to topical medication: adherence is very poor in children with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:211-216.

- Fukaya M. Cortisol homeostasis in the epidermis is influenced by topical corticosteroids in patients with atopic dermatitis. Indian J Dermatol. 2017;62:440.

- Mehta AB, Nadkarni NJ, Patil SP, et al. Topical corticosteroids in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:371-378.

- van der Schaft J, Keijzer WW, Sanders KJ, et al. Is there an additional value of inpatient treatment for patients with atopic dermatitis? Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96:797-801.

- Dabade TS, Davis DM, Wetter DA, et al. Wet dressing therapy in conjunction with topical corticosteroids is effective for rapid control of severe pediatric atopic dermatitis: experience with 218 patients over 30 years at Mayo Clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;67:100-106.

- Storm A, Andersen SE, Benfeldt E, et al. One in 3 prescriptions are never redeemed: primary nonadherence in an outpatient clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:27-33.

- Sagransky MJ, Yentzer BA, Williams LL, et al. A randomized controlled pilot study of the effects of an extra office visit on adherence and outcomes in atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1428-1430.

Practice Points

- Mid-potency corticosteroids are the first-line treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD).

- Atopic dermatitis may fail to respond to topical corticosteroids initially or lose response over time, a phenomenon known as tachyphylaxis.

- Nonadherence to medication is the most likely cause of treatment resistance in patients with AD.

Screening for Depression in Rosacea Patients

Rosacea is a chronic skin condition that can be classified into 4 subtypes: erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous, and ocular. Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea is characterized by redness of the face and excessive blushing. Papulopustular rosacea is a more severe form of disease that is characterized by papules and pustules of the central face. If left untreated, these subtypes may progress to phymatous rosacea, which is characterized by skin thickening, fibrosis, and cosmetic disfigurement. Ocular rosacea is characterized by redness and irritation of the eyes.1 Rosacea patients often are burdened with embarrassment, social anxiety, and psychiatric comorbidities.

The Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) is a validated and reliable self-administered tool for diagnosis of depression and designation of depression severity. This instrument could prove useful in screening for depression in rosacea patients given the high incidence of psychiatric comorbidities in this patient population.2 The PHQ-9 consists of 9 questions that assess for criteria used to define depressive disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition).3 The questionnaire is brief, easy to administer, and has 88% specificity and sensitivity.4

Other studies have evaluated the relationship between rosacea and psychiatric illness, but the PHQ-9 was not used as a screening tool.7,8 Rosacea patients are at increased risk for having psychiatrist-diagnosed depression.5 In one assessment, a positive correlation between rosacea and psychiatric illness was noted using the Dermatology Life Quality Index, the rejection scale of the Questionnaire on Experience with Skin Complaints, and the German version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.6 Interpretation of Rosacea Quality of Life and Dermatology Life Quality Index scores indicated that rosacea has a negative impact on quality of life.7

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between self-assessed rosacea severity scores and level of depression using the validated rosacea self-assessment tool and the PHQ-9 questionnaire, respectively.

Methods

Study Population

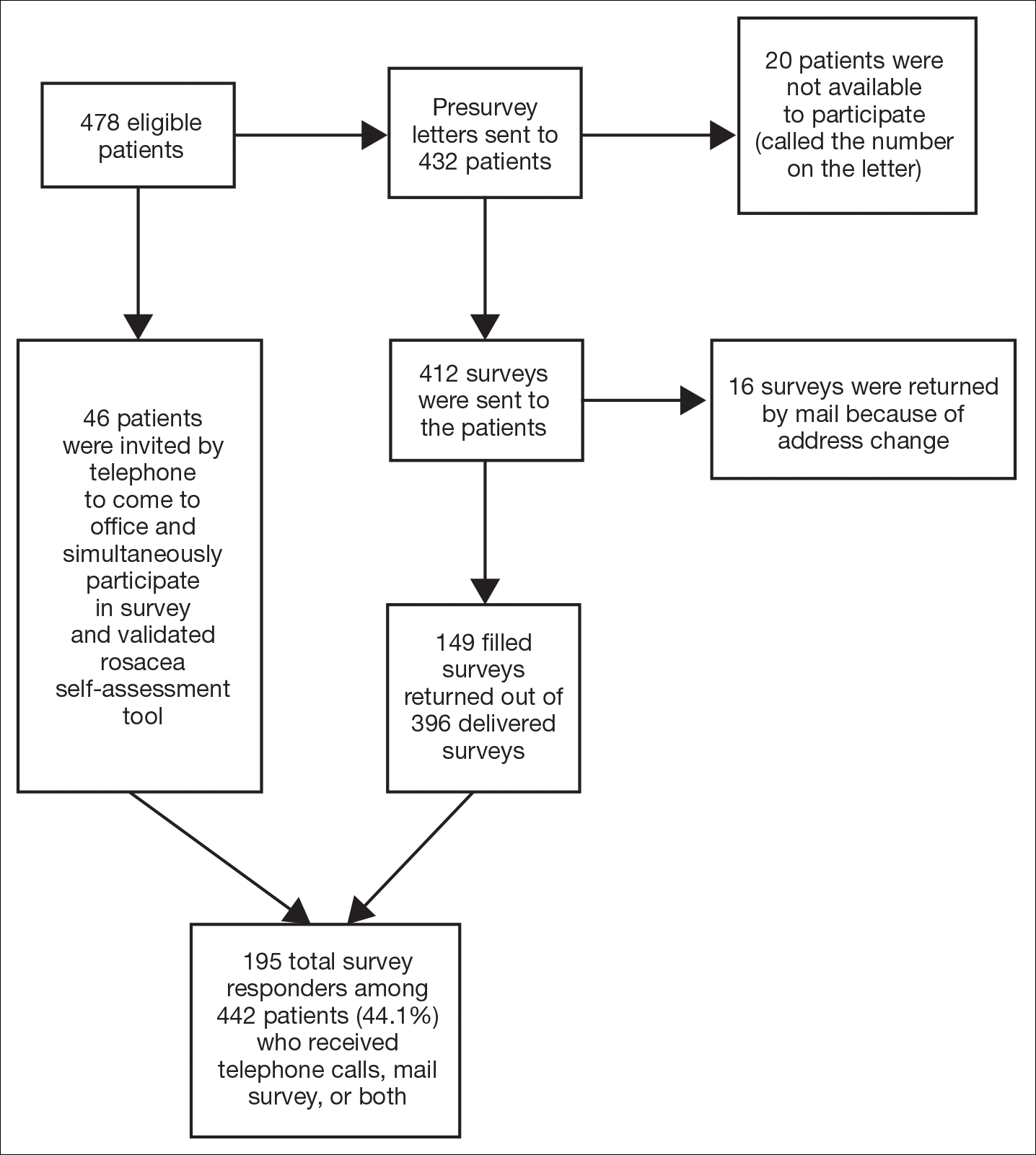

Study participants were adult patients from the Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) dermatology clinic from January 2011 to December 2014 who had received a diagnosis of rosacea (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9] code 695.3) from a Wake Forest dermatologist. Institutional review board approval was obtained prior to initiation of the study. Data collection occurred from October 2014 through February 2015. A total of 478 patients met criteria for participation in the study and were identified from the Wake Forest Baptist Hospital Transitional Data Warehouse and the electronic medical record. Because rosacea typically is not diagnosed in children and the data measures are not validated in children, this demographic group was excluded from participation.

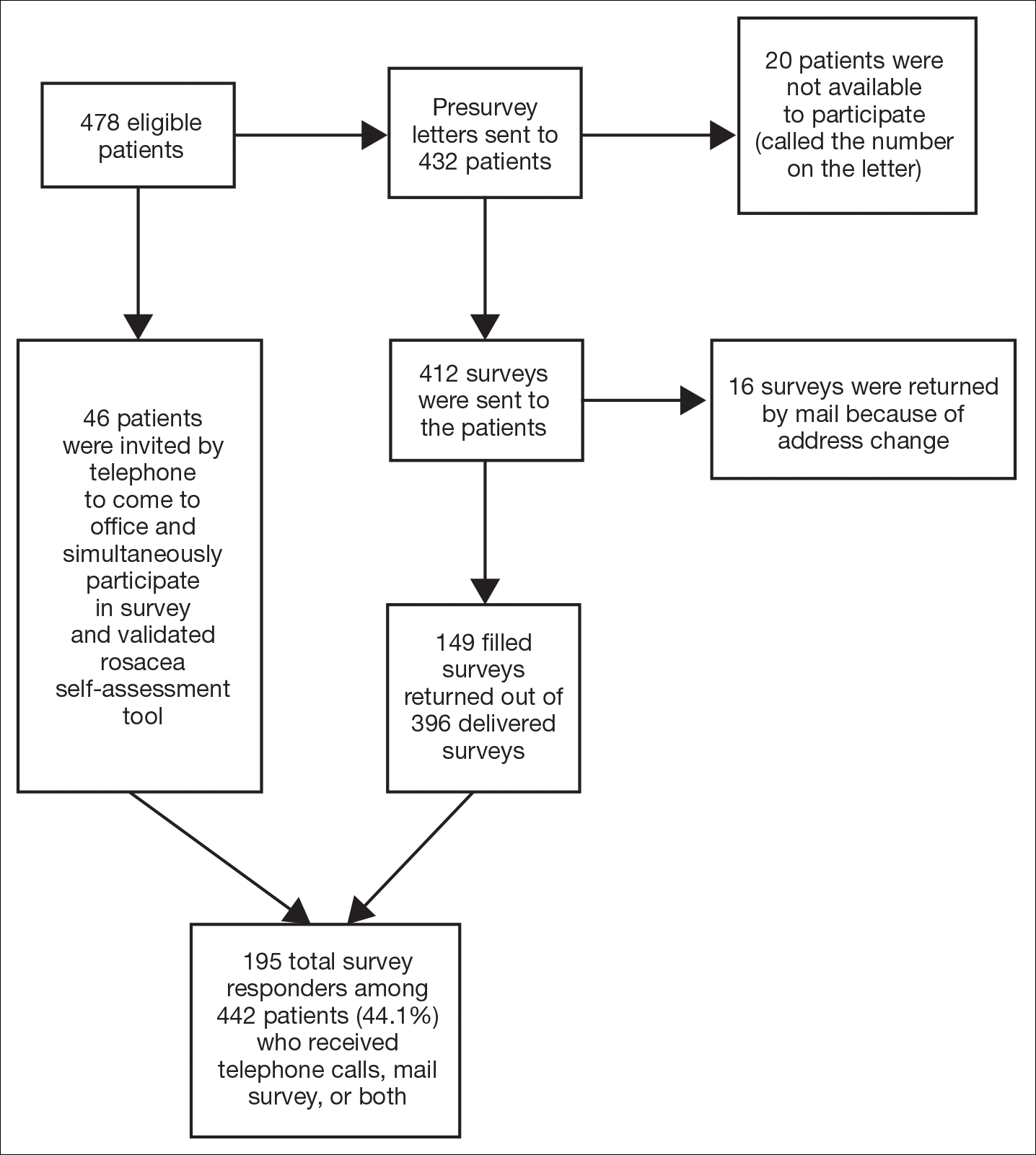

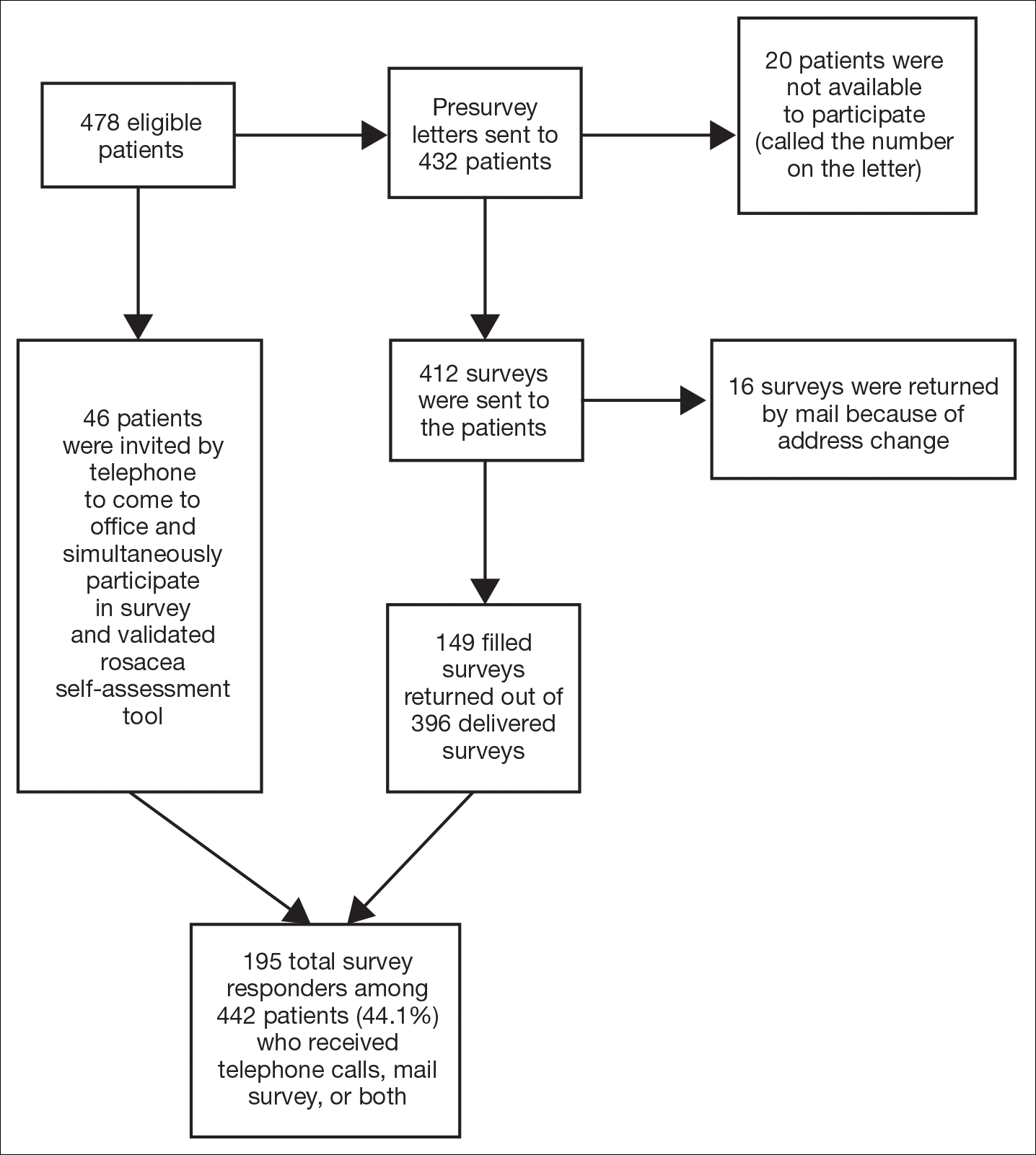

Of 478 eligible patients who were invited to participate via mail or telephone, 46 completed the rosacea self-assessment tool and PHQ-9 survey in person. A total of 432 patients were mailed a presurvey recruitment letter notifying them that they would be receiving a survey in the mail unless they contacted the study team to decline participation. An email address and telephone number for the study team was provided. Twenty patients declined to participate in the study; surveys were then mailed to the remaining 412 patients. Sixteen of the mailed surveys were returned by the post office due to an incorrect address.

Self-assessments

Patients selected images to self-identify the severity of their rosacea symptoms, including erythema, papulopustular lesions, ocular symptoms, and nasal involvement by looking at photographs on the self-assessment tool, which showed various rosacea severity levels. Scores ranged from 2 (least severe) to 8 (most severe). The PHQ-9 survey was completed by participants to assess mental health and mood.

Statistical Analysis

Results were reported using descriptive statistics. Regression analysis was performed to identify independent outcome predictors. To study the relationship between age and demographic variables, the population was divided into 2 groups: patients aged 60 years and older and patients younger than 60 years. Correlation of variables with duration of disease also was studied by creating 2 groups: patients with a disease duration of 11 years or longer and patients with a disease duration of less than 11 years. Comparisons were completed between groups using χ2 tests for proportions and t tests or analysis of variance for continuous variables. Analysis of variance was applied among all patients classified according to the following levels of depression: nondepressed, minimal depression symptoms, minor depression, major depression (moderate), and major depression (severe).

Results

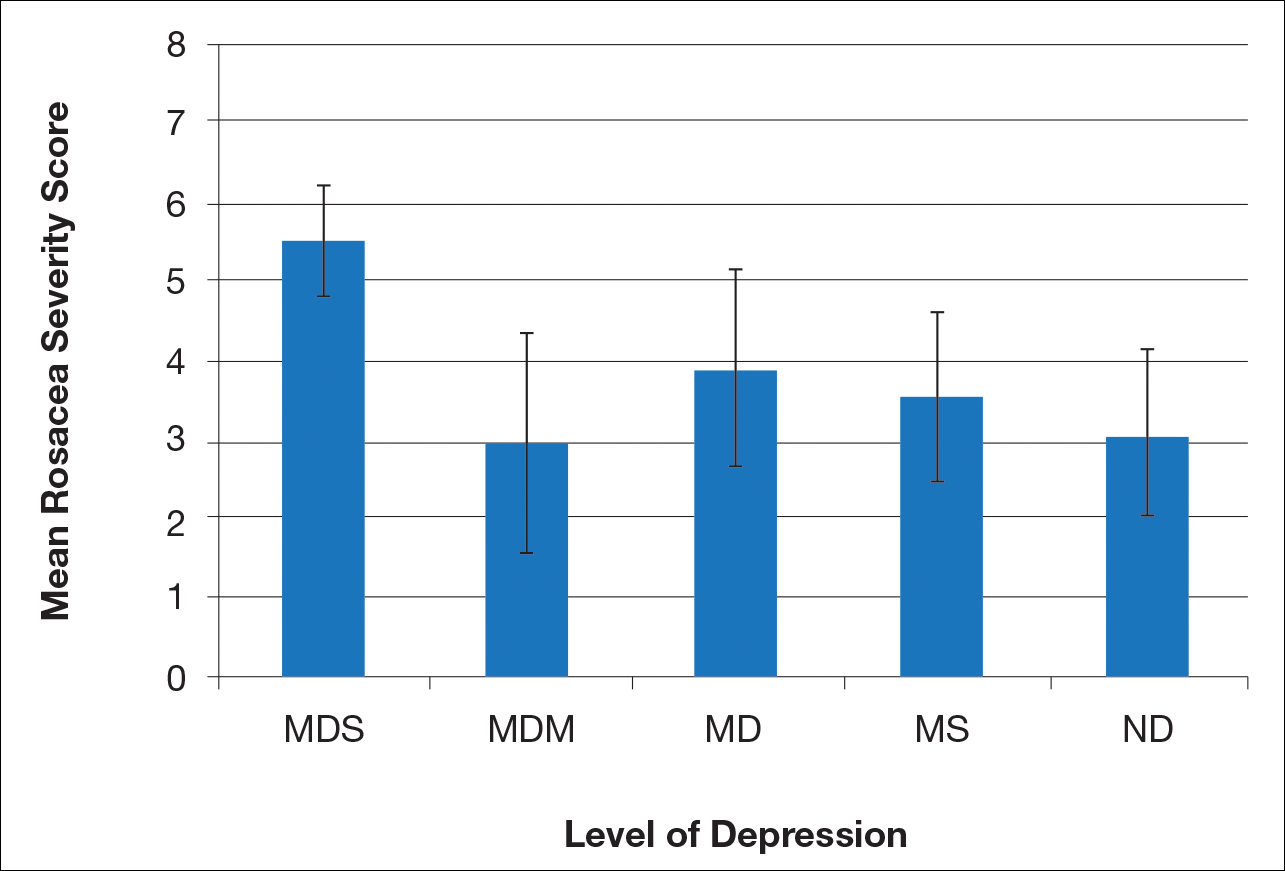

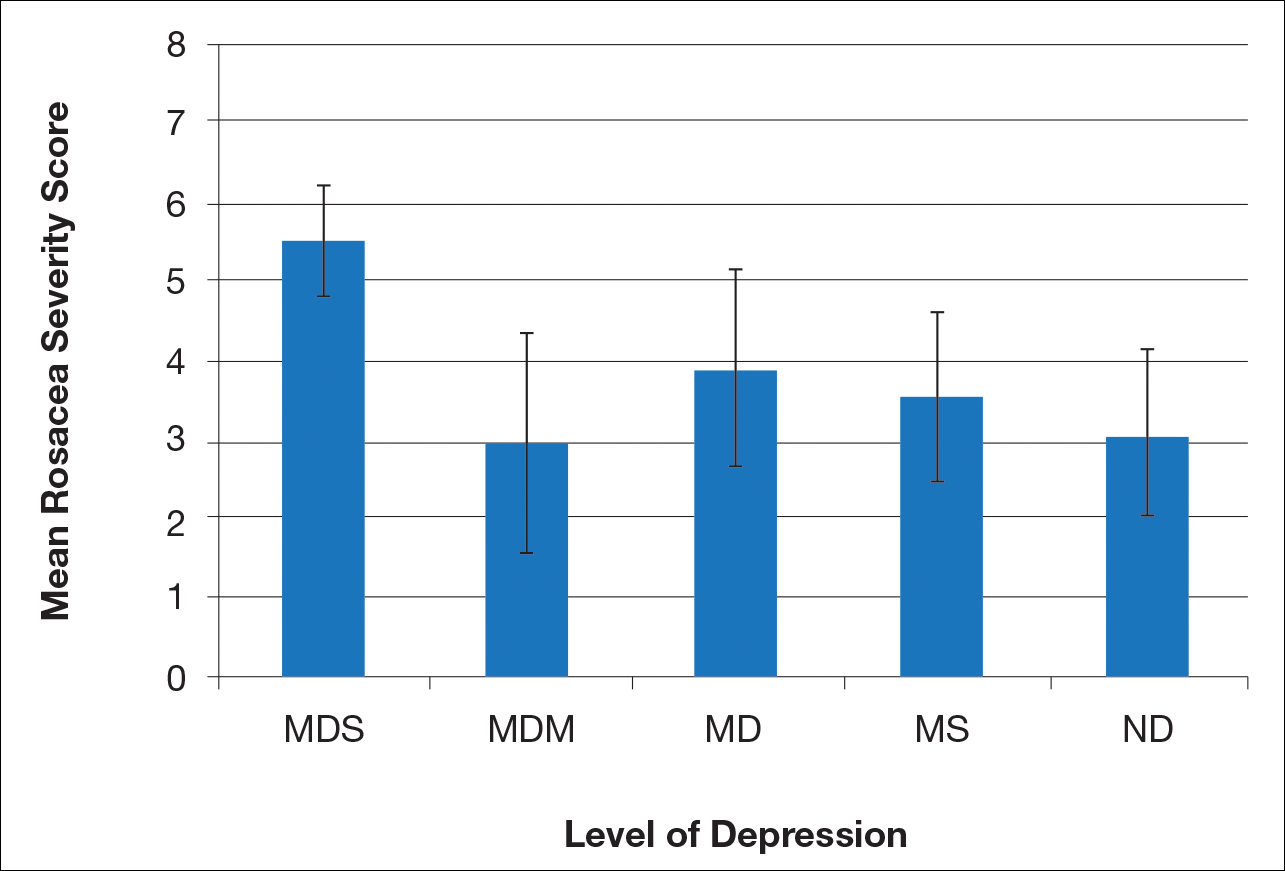

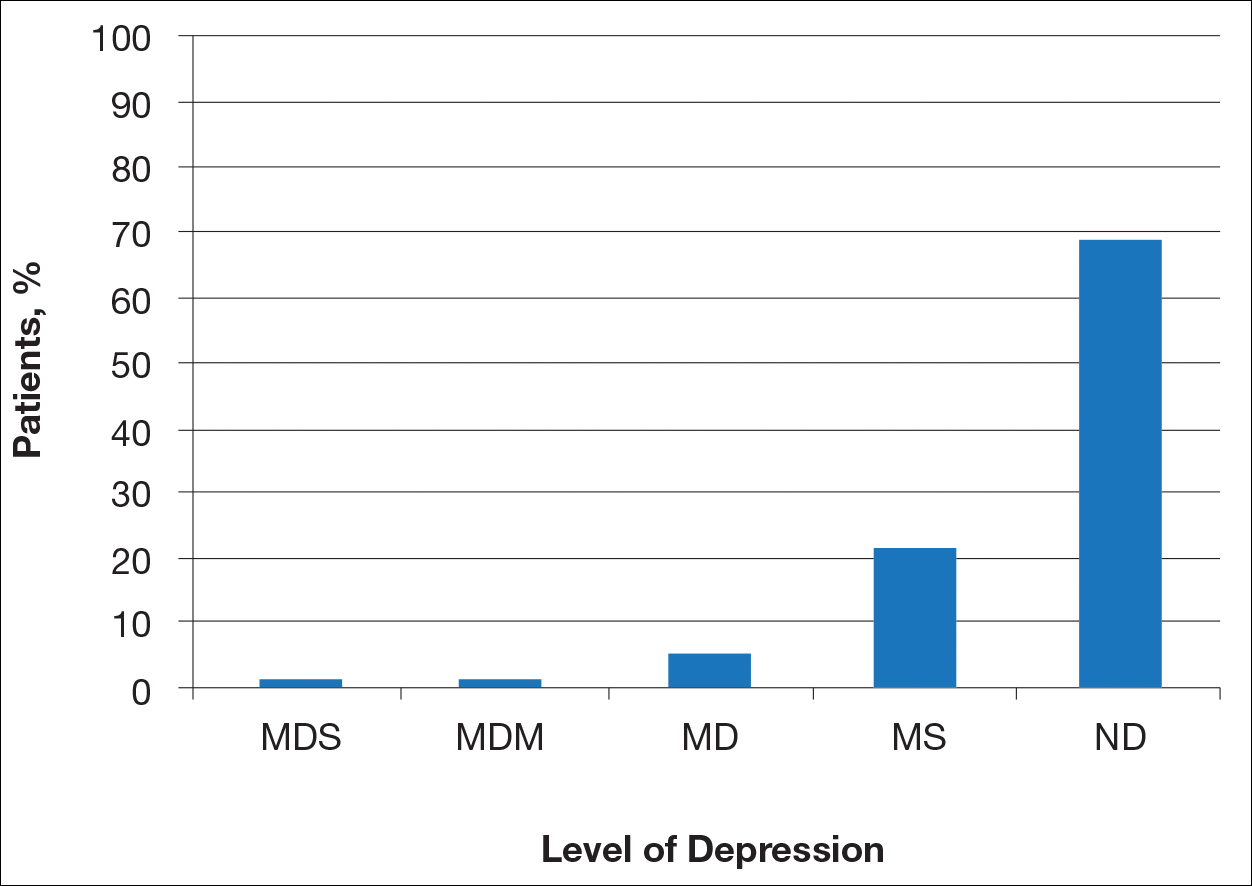

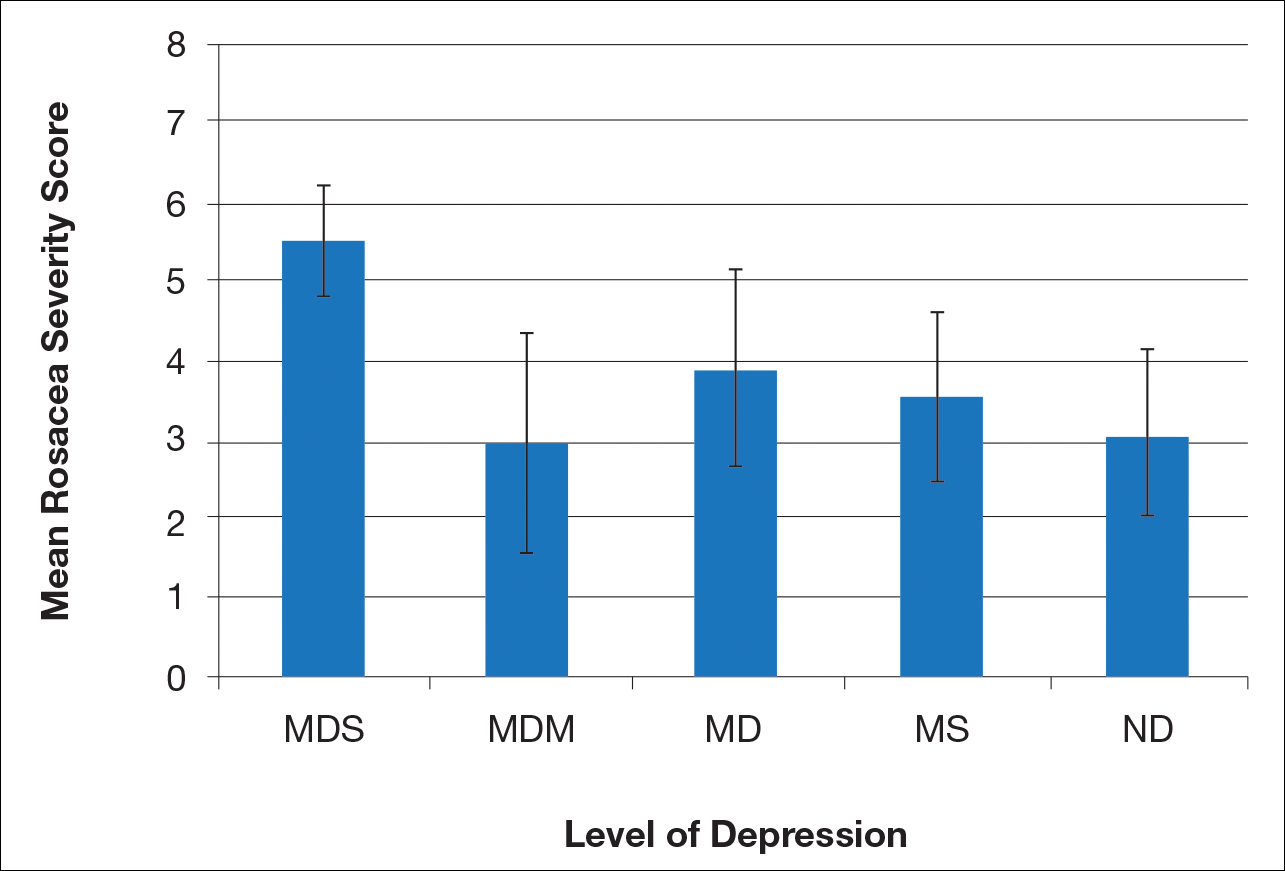

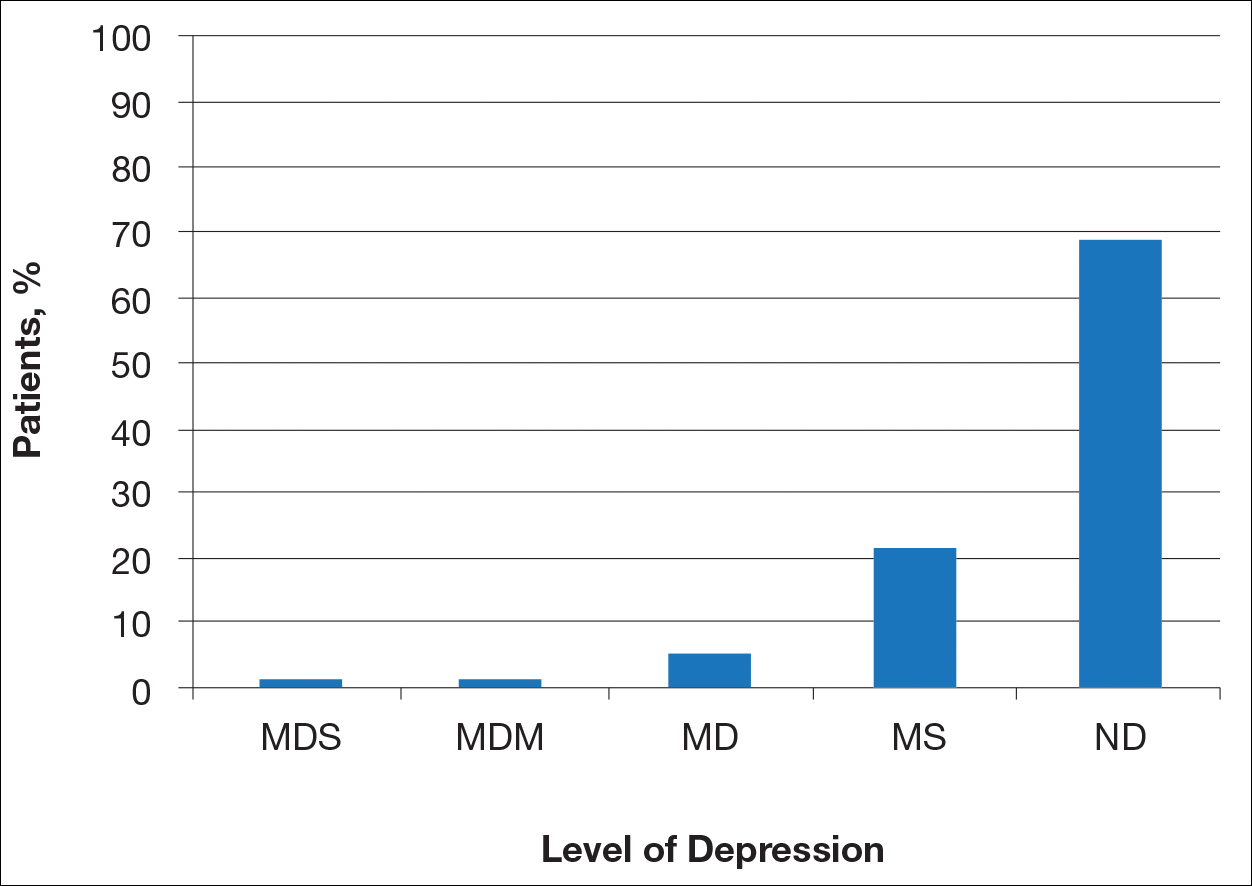

There is a direct relationship between rosacea severity and depression when comparing across the following levels of depression: nondepressed, minimal depression symptoms, minor depression, major depression (moderate), and major depression (severe)(P=.006; F=5.18; N=183)

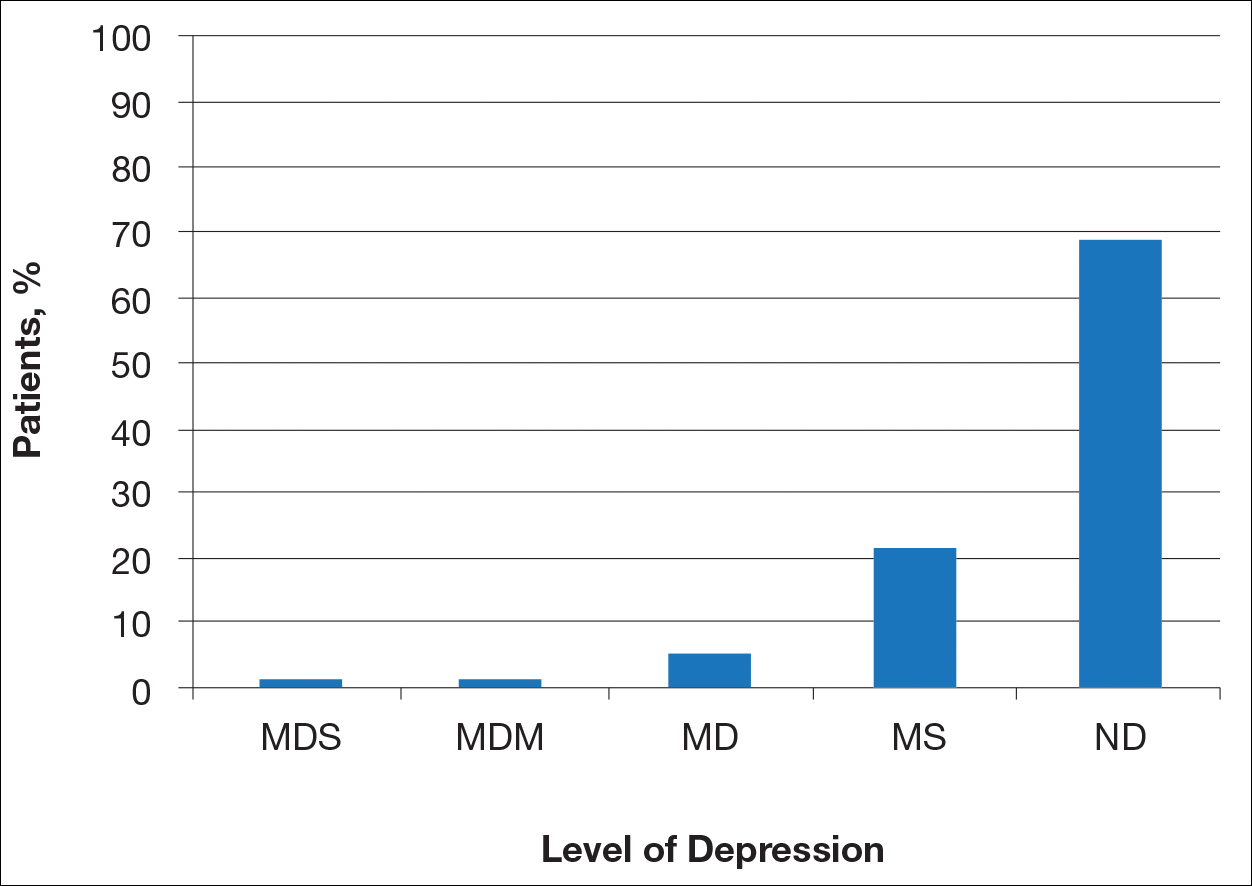

Most patients reported they were nondepressed (68.9%). As measured by the PHQ-9, 31.1% of patients experienced some level of depression: 21.9% reported minimal depression symptoms, 7.1% reported minor depression, 1.1% reported major depression (moderate), and 1.1% reported major depression (severe)(Table).

Comment

There is a direct relationship between rosacea severity and level of depression. In our study, nearly one-third of patients reported some degree of depression. The reason for this correlation may be due to disease stigmatization and decreased quality of life due to the somatic symptoms of rosacea. Our study reinforced the results of other studies evaluating the psychosocial impact of rosacea.8,9 Depression is associated with poor treatment adherence and poor outcomes in rosacea patients; therefore, depression may serve as an important outcome measure.10 The psychosocial impact of rosacea can be severe, but with disease improvement, there often is an improvement in the patient’s psychosocial status.7

There are several limitations to our study. The study population consisted of patients at a university dermatology clinic who may not be representative of patients in the general population; however, our hospital system does not require referral and provides care to a large percentage of the surrounding community.

Clinical implementation of the validated rosacea self-assessment tool and PHQ-9 may have several benefits. Patient-assessed rosacea severity and psychosocial impact obtained via use of these tools would provide physicians with information to fine-tune rosacea treatment regimens. Patients with the greatest social impact may require a more aggressive treatment approach. Early detection of depression in the rosacea population is important in informing treatment strategy and improving outcomes. Physicians should pay close attention to signs of depression in rosacea patients and determine if psychiatric treatment or referral for psychiatric evaluation is indicated. The correlation between rosacea and depression underscores the importance of treating this highly impactful disease; however, the low number of responders from the major depression (moderate) subgroup prevented us from making any strong conclusion about this specific subgroup.

- Steinhoff M, Schauber J, Leyden JJ. New insights into rosacea pathophysiology: a review of recent findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6, suppl 1):S15-S26.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychol Ann. 2002;32:509-515.

- America Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-613.