User login

Erythematous and Ulcerated Plaque on the Left Temple

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Carcinosarcoma

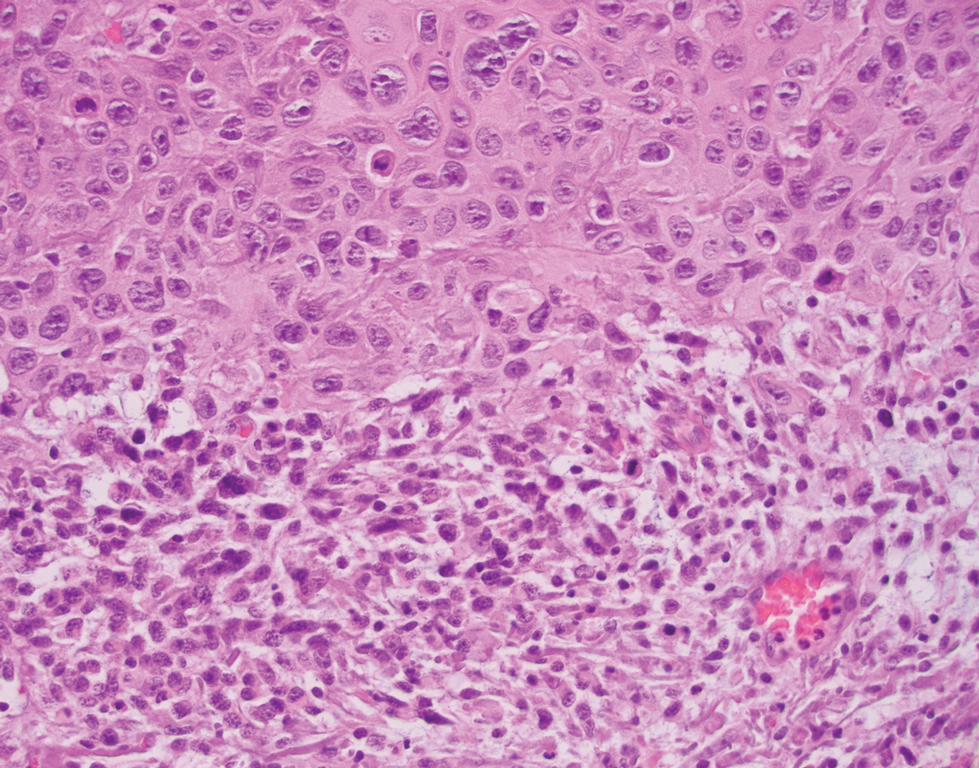

The immunohistochemical findings supported an epithelial component consistent with moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and a mesenchymal component with features consistent with a sarcoma. Consequently, the lesion was diagnosed as a primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma (PCCS).

Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma is a rare biphasic neoplasm consisting of malignant epithelial (carcinoma) and mesenchymal (sarcoma) components.1 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas are uncommon, poorly understood, primary cutaneous tumors.2,3 Characteristic of this tumor, cytokeratins highlight the epithelial component while vimentin highlights the mesenchymal component.4 Histologically, the sarcomatous components of PCCS often are highly variable, with an absence of transitional areas within the epithelial component, which frequently resembles basal cell carcinoma and/ or SCC.5-7 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma favors areas of chronic UV radiation exposure, particularly on the head and neck. Most tumors present with a slowly growing, polypoid, flesh-colored to erythematous nodule due to the infiltrative mesenchymal component.7 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma primarily is diagnosed in elderly patients, with the majority of cases diagnosed in the eighth or ninth decades of life (range, 32–98 years).1,8 Men appear to be twice as likely to be diagnosed with a PCCS compared to women.1 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas are recognized as aggressive tumors with a high propensity to metastasize and recur locally, necessitating early diagnosis and treatment.4 Accurate diagnosis of PCCSs can be challenging due to the biphasic nature of the neoplasm as well as poor differentiation or unequal proportions of the epithelial and mesenchymal components.5 Additionally, overlapping diagnostic criteria coupled with vague demarcation between soft-tissue sarcomas and distinct carcinomas also may contribute to a delay in diagnosis.9 Treatment is achieved surgically by complete wide resection, with no evidence to support the use of adjuvant or neoadjuvant external beam radiation therapy. Due to the small number of reported cases, no treatment recommendations currently exist.1

Surgical management with wide local excision has been disappointing, with recurrence rates reported as high as 33%.6 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma has an estimated overall recurrence rate of 19% and a 5-year disease-free rate of 50%.10 Risk factors associated with poorer prognosis include tumors with adnexal subtype, age less than 65 years, rapid tumor growth, a tumor greater than 20 mm at presentation, and a long-standing tumor lasting up to 30 years.2,4 Although wide local excision and Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) both have been utilized successfully, MMS has been shown to result in a cure rate of greater than 98%.6

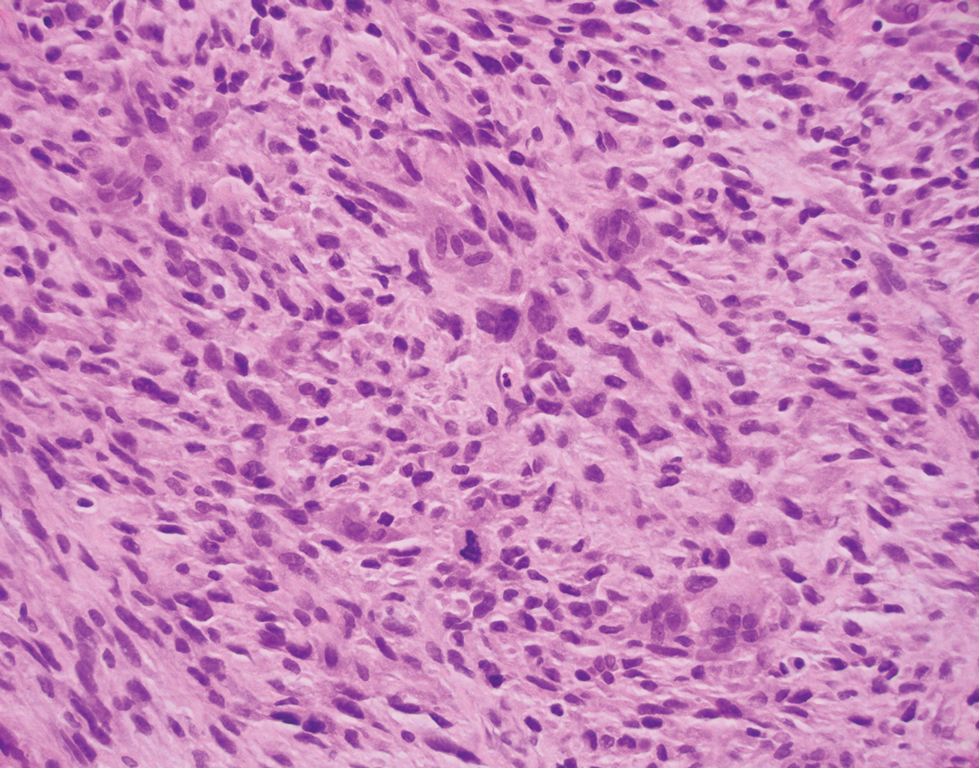

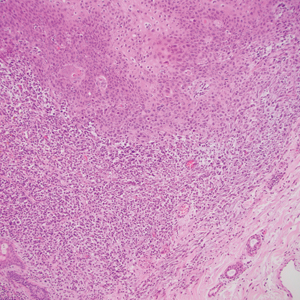

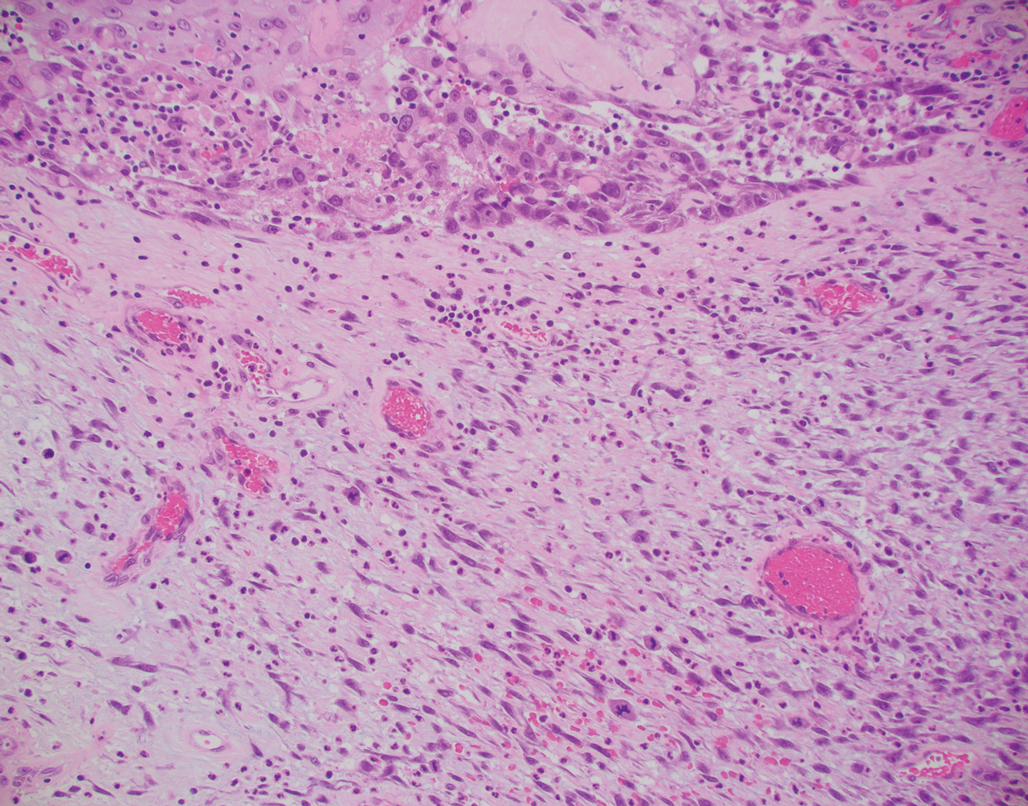

Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) is a cutaneous tumor of fibrohistiocytic mesenchymal origin that typically manifests on sun-damaged skin in elderly individuals. Clinically, it presents as a rapidly growing neoplasm that often ulcerates and bleeds. These heterogenous neoplasms have several distinct characteristics, including dense cellularity with disorganized, large, pleomorphic, and atypical-appearing spindle-shaped cells arising in the upper layers of the dermis, often disseminating into the reticular dermis and occasionally into the subcutaneous fat (Figure 1). The neoplastic cells often exhibit hyperchromic and irregular nuclei, multinucleated giant cells, and atypical mitotic figures. In most cases, negative immunohistochemical staining with SOX-10, S-100, cytokeratins, desmin, and caldesmon will allow pathologists to differentiate between AFX and other common tumors on the differential diagnosis, such as SCC, melanoma, and leiomyosarcoma. CD10 and procollagen type 1 are positive antigenic markers in AFX, but they are not specific. The standard treatment of AFX includes wide local excision or MMS for superior margin control.11

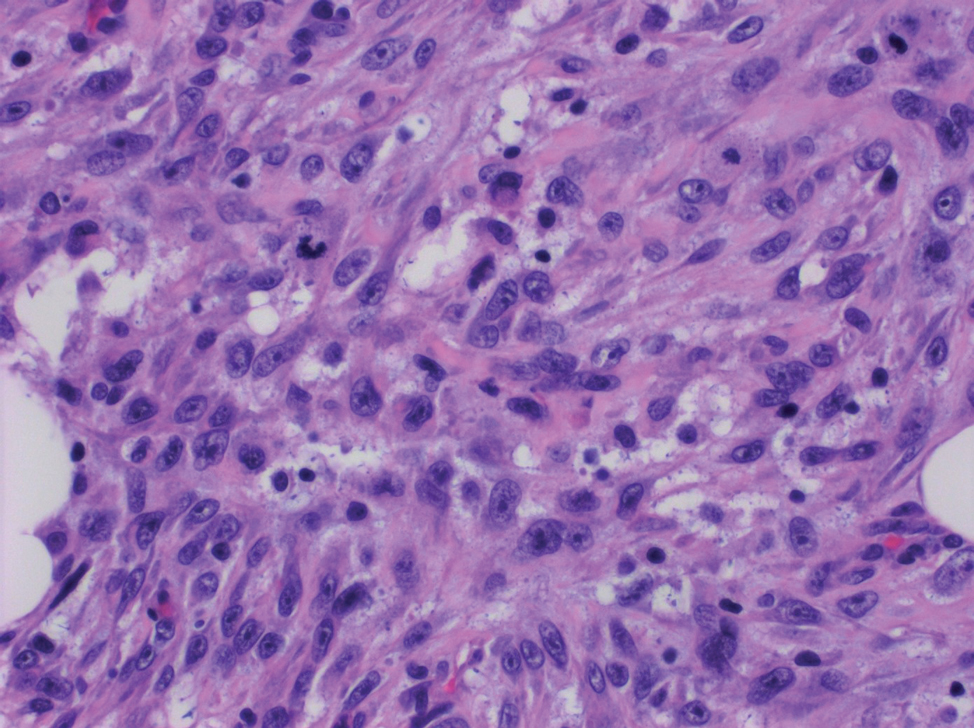

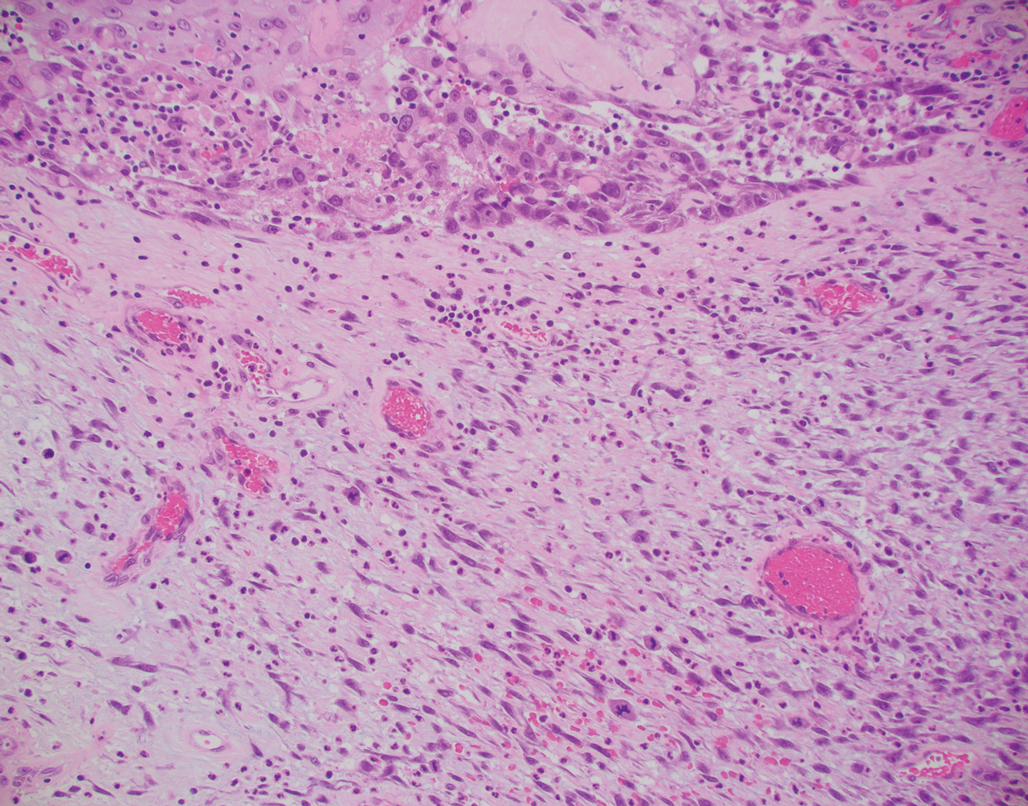

Spindle cell SCC presents as a raised or exophytic nodule, often with spontaneous bleeding and central ulceration. It usually presents on sun-damaged skin or in individuals with a history of ionizing radiation. Histologically, it is characterized by atypical spindleshaped keratinocytes in the dermis existing as single cells or cohesive nests along with keratin pearls (Figure 2). The atypical spindle cells may comprise the entire tumor or only a small portion. The use of immunohistochemical markers often is required to establish a definitive diagnosis. Spindle cell SCC stains positively, albeit frequently focally, for p63, p40, and high-molecular-weight cytokeratins such as cytokeratin 5/6, while S-100 protein, SOX-10, MART-1/Melan-A, and muscle-specific actin stains typically are negative. Wide local excision or MMS is recommended for treatment of these lesions.12

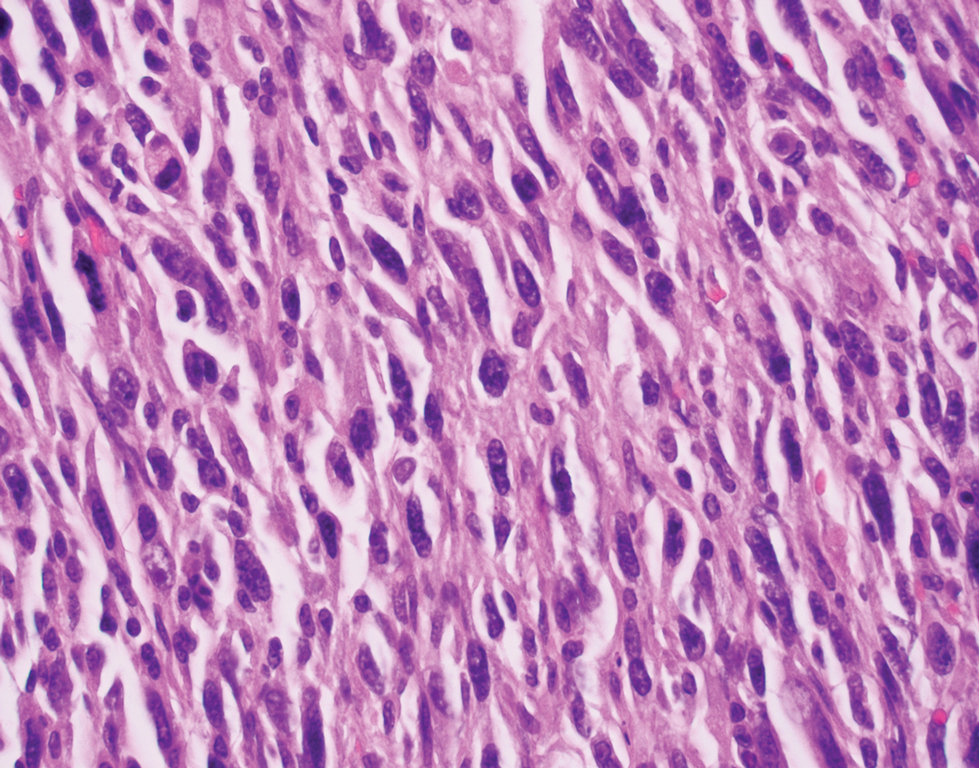

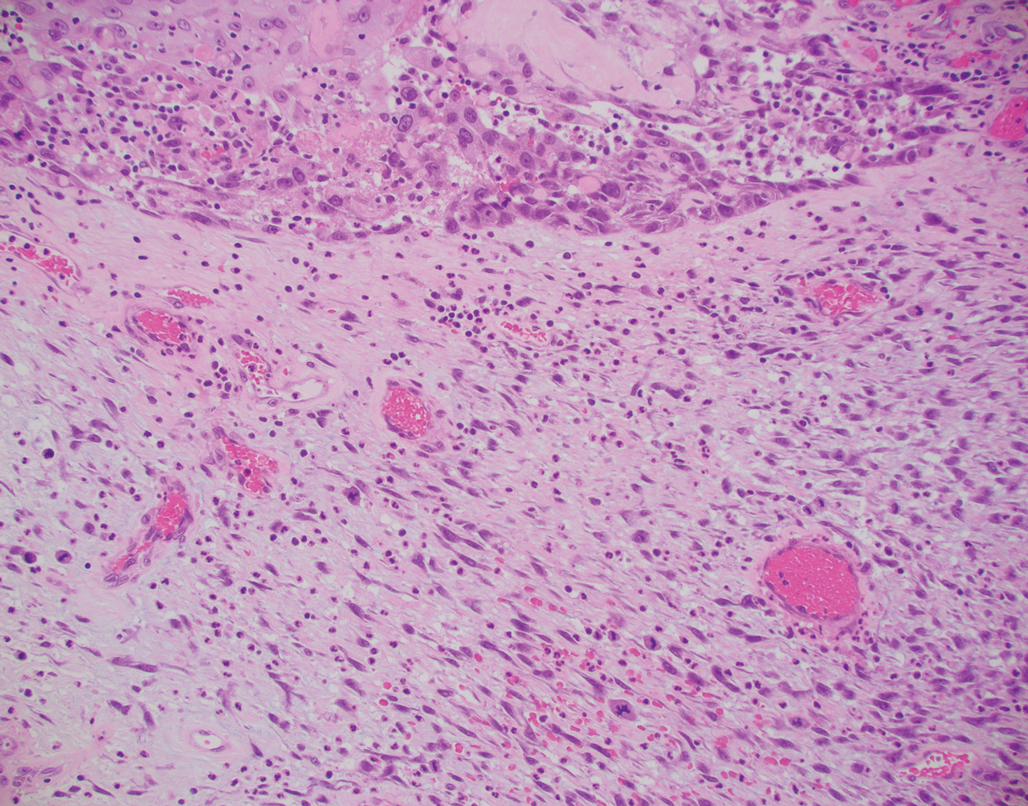

Primary cutaneous myoepithelial carcinomas are uncommon neoplasms of myoepithelial differentiation. Clinically, they often arise as soft nodular lesions on the head, neck, and lower extremities with a bimodal age distribution (50 years). Histologically cutaneous myoepithelial tumors are well-differentiated, dermal-based nodules without connection to the overlying epidermis (Figure 3). The myoepithelial cells can exhibit spindled, epithelioid, plasmacytoid, or clear cell morphologic features and show variability in cell growth patterns. One of the most common growth patterns is oval to round cells forming cords and chains in a chondromyxoid stroma. Most cases display an immunophenotyped co-expression of an epithelial cytokeratin and S-100 protein. Myoepithelial markers also may be present, including keratins, smooth muscle actin, calponin, glial fibrillary acidic protein, p63, and desmin. Surgical removal with wide local excision or MMS is essential.13

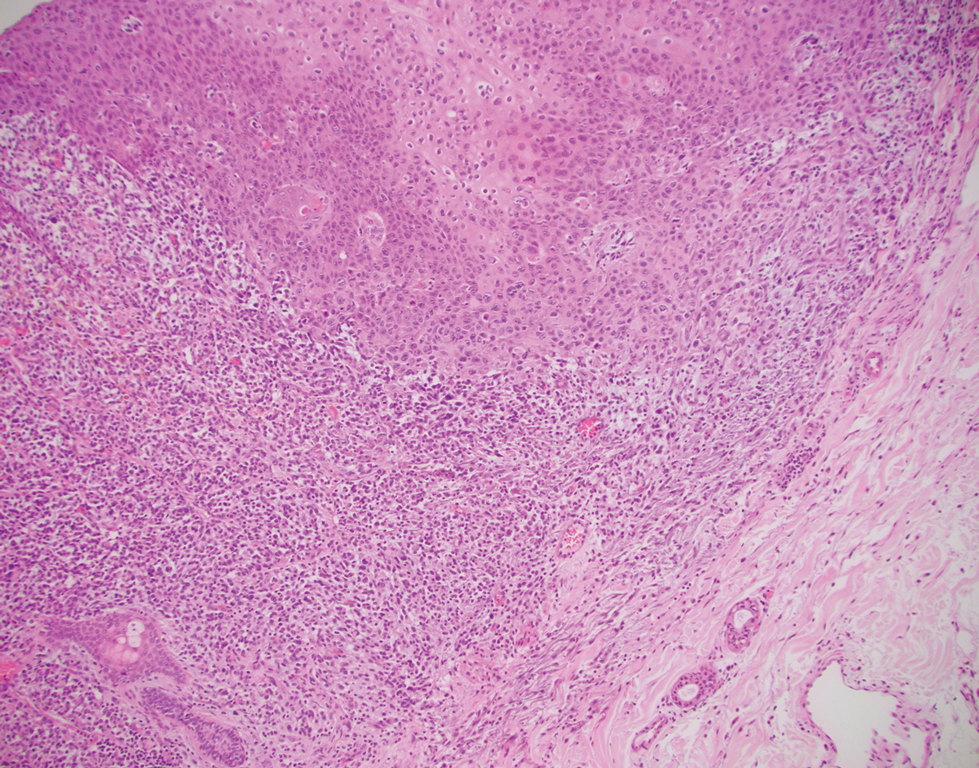

Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) is a tumor that originates from smooth muscle and rarely develops in the dermis.14 Pleomorphic LMS is a morphologic variant of LMS that has a low propensity to metastasize but commonly exhibits local recurrence.15 Leiomyosarcoma can present in any age group but most commonly manifests in individuals aged 50 to 70 years. Clinically, LMS presents as a firm solitary nodule with a smooth pink surface or a more exophytic tumor with a reddish or brown color on the extensor surface of the lower limbs; it is less common on the scalp and face.14 Histologically, most cases of pleomorphic LMS show small foci of fascicles consisting of smooth muscle tumor cells in addition to cellular pleomorphism (Figure 4).15 Many of these cells demonstrate a clear perinuclear vacuole that generally is appreciated in neoplastic smooth muscle cells.14 Pleomorphic LMS typically stains positively for at least one smooth muscle marker including desmin, h-caldesmon, muscle-specific actin, α-smooth muscle actin, or smooth muscle myosin in the leiomyosarcomatous fascicular areas.16 Complete surgical excision is the treatment of choice, and the best results are obtained with MMS.14

- Syme-Grant J, Syme-Grant NJ, Motta L, et al. Are primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas underdiagnosed? five cases and a review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:1402-1408.

- Bourgeault E, Alain J, Gagne E. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma of the basal cell subtype should be treated as a high-risk basal cell carcinoma. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19:407-411.

- West L, Srivastava D. Cutaneous carcinosarcoma of the medial canthus discovered on Mohs debulk analysis. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:1700-1702.

- Kwan JM, Satter EK. Carcinosarcoma: a primary cutaneous tumor with biphasic differentiation. Cutis. 2013;92:247-249.

- Suh KY, Lacouture M, Gerami P. p63 in primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:374‐377.

- Ruiz-Villaverde R, Aneiros-Fernandez J. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma: a cutaneous neoplasm with an exceptional presentation. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2018;18:E114-E115.

- Smart CN, Pucci RA, Binder SW, et al. Cutaneous carcinosarcoma with myoepithelial differentiation: immunohistochemical and cytogenetic analysis of a case presenting in an unusual location. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:715‐717.

- Clark JJ, Bowen AR, Bowen GM, et al. Cutaneous carcinosarcoma: a series of six cases and a review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:34‐44.

- Müller CS, Pföhler C, Schiekofer C, et al. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas: a morphological histogenetic concept revisited. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:328‐339.

- Bellew S, Del Rosso JQ, Mobini N. Primary carcinosarcoma of the ear: case report and review of the literature. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2:33‐35.

- Hong SH, Hong SJ, Lee Y, et al. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma of the shoulder: case report with literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:338-340.

- Soleymani T, Aasi SZ, Novoa R, et al. Atypical fibroxanthoma and pleomorphic dermal sarcoma: updates on classification and management. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:253-259.

- Parekh V, Seykora JT. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:503-525.

- Johnson GE, Stevens K, Morrison AO, et al. Cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma with disseminated metastases. Cutis. 2017;99:E19-E26.

- Llombart B, Serra-Guillén C, Requena C, et al. Leiomyosarcoma and pleomorphic dermal sarcoma: guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019;110:4-11.

- Oda Y, Miyajima K, Kawaguchi K, et al. Pleomorphic leiomyosarcoma: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study with special emphasis on its distinction from ordinary leiomyosarcoma and malignant fibrous histiocytoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1030-1038.

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Carcinosarcoma

The immunohistochemical findings supported an epithelial component consistent with moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and a mesenchymal component with features consistent with a sarcoma. Consequently, the lesion was diagnosed as a primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma (PCCS).

Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma is a rare biphasic neoplasm consisting of malignant epithelial (carcinoma) and mesenchymal (sarcoma) components.1 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas are uncommon, poorly understood, primary cutaneous tumors.2,3 Characteristic of this tumor, cytokeratins highlight the epithelial component while vimentin highlights the mesenchymal component.4 Histologically, the sarcomatous components of PCCS often are highly variable, with an absence of transitional areas within the epithelial component, which frequently resembles basal cell carcinoma and/ or SCC.5-7 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma favors areas of chronic UV radiation exposure, particularly on the head and neck. Most tumors present with a slowly growing, polypoid, flesh-colored to erythematous nodule due to the infiltrative mesenchymal component.7 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma primarily is diagnosed in elderly patients, with the majority of cases diagnosed in the eighth or ninth decades of life (range, 32–98 years).1,8 Men appear to be twice as likely to be diagnosed with a PCCS compared to women.1 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas are recognized as aggressive tumors with a high propensity to metastasize and recur locally, necessitating early diagnosis and treatment.4 Accurate diagnosis of PCCSs can be challenging due to the biphasic nature of the neoplasm as well as poor differentiation or unequal proportions of the epithelial and mesenchymal components.5 Additionally, overlapping diagnostic criteria coupled with vague demarcation between soft-tissue sarcomas and distinct carcinomas also may contribute to a delay in diagnosis.9 Treatment is achieved surgically by complete wide resection, with no evidence to support the use of adjuvant or neoadjuvant external beam radiation therapy. Due to the small number of reported cases, no treatment recommendations currently exist.1

Surgical management with wide local excision has been disappointing, with recurrence rates reported as high as 33%.6 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma has an estimated overall recurrence rate of 19% and a 5-year disease-free rate of 50%.10 Risk factors associated with poorer prognosis include tumors with adnexal subtype, age less than 65 years, rapid tumor growth, a tumor greater than 20 mm at presentation, and a long-standing tumor lasting up to 30 years.2,4 Although wide local excision and Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) both have been utilized successfully, MMS has been shown to result in a cure rate of greater than 98%.6

Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) is a cutaneous tumor of fibrohistiocytic mesenchymal origin that typically manifests on sun-damaged skin in elderly individuals. Clinically, it presents as a rapidly growing neoplasm that often ulcerates and bleeds. These heterogenous neoplasms have several distinct characteristics, including dense cellularity with disorganized, large, pleomorphic, and atypical-appearing spindle-shaped cells arising in the upper layers of the dermis, often disseminating into the reticular dermis and occasionally into the subcutaneous fat (Figure 1). The neoplastic cells often exhibit hyperchromic and irregular nuclei, multinucleated giant cells, and atypical mitotic figures. In most cases, negative immunohistochemical staining with SOX-10, S-100, cytokeratins, desmin, and caldesmon will allow pathologists to differentiate between AFX and other common tumors on the differential diagnosis, such as SCC, melanoma, and leiomyosarcoma. CD10 and procollagen type 1 are positive antigenic markers in AFX, but they are not specific. The standard treatment of AFX includes wide local excision or MMS for superior margin control.11

Spindle cell SCC presents as a raised or exophytic nodule, often with spontaneous bleeding and central ulceration. It usually presents on sun-damaged skin or in individuals with a history of ionizing radiation. Histologically, it is characterized by atypical spindleshaped keratinocytes in the dermis existing as single cells or cohesive nests along with keratin pearls (Figure 2). The atypical spindle cells may comprise the entire tumor or only a small portion. The use of immunohistochemical markers often is required to establish a definitive diagnosis. Spindle cell SCC stains positively, albeit frequently focally, for p63, p40, and high-molecular-weight cytokeratins such as cytokeratin 5/6, while S-100 protein, SOX-10, MART-1/Melan-A, and muscle-specific actin stains typically are negative. Wide local excision or MMS is recommended for treatment of these lesions.12

Primary cutaneous myoepithelial carcinomas are uncommon neoplasms of myoepithelial differentiation. Clinically, they often arise as soft nodular lesions on the head, neck, and lower extremities with a bimodal age distribution (50 years). Histologically cutaneous myoepithelial tumors are well-differentiated, dermal-based nodules without connection to the overlying epidermis (Figure 3). The myoepithelial cells can exhibit spindled, epithelioid, plasmacytoid, or clear cell morphologic features and show variability in cell growth patterns. One of the most common growth patterns is oval to round cells forming cords and chains in a chondromyxoid stroma. Most cases display an immunophenotyped co-expression of an epithelial cytokeratin and S-100 protein. Myoepithelial markers also may be present, including keratins, smooth muscle actin, calponin, glial fibrillary acidic protein, p63, and desmin. Surgical removal with wide local excision or MMS is essential.13

Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) is a tumor that originates from smooth muscle and rarely develops in the dermis.14 Pleomorphic LMS is a morphologic variant of LMS that has a low propensity to metastasize but commonly exhibits local recurrence.15 Leiomyosarcoma can present in any age group but most commonly manifests in individuals aged 50 to 70 years. Clinically, LMS presents as a firm solitary nodule with a smooth pink surface or a more exophytic tumor with a reddish or brown color on the extensor surface of the lower limbs; it is less common on the scalp and face.14 Histologically, most cases of pleomorphic LMS show small foci of fascicles consisting of smooth muscle tumor cells in addition to cellular pleomorphism (Figure 4).15 Many of these cells demonstrate a clear perinuclear vacuole that generally is appreciated in neoplastic smooth muscle cells.14 Pleomorphic LMS typically stains positively for at least one smooth muscle marker including desmin, h-caldesmon, muscle-specific actin, α-smooth muscle actin, or smooth muscle myosin in the leiomyosarcomatous fascicular areas.16 Complete surgical excision is the treatment of choice, and the best results are obtained with MMS.14

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Carcinosarcoma

The immunohistochemical findings supported an epithelial component consistent with moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and a mesenchymal component with features consistent with a sarcoma. Consequently, the lesion was diagnosed as a primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma (PCCS).

Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma is a rare biphasic neoplasm consisting of malignant epithelial (carcinoma) and mesenchymal (sarcoma) components.1 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas are uncommon, poorly understood, primary cutaneous tumors.2,3 Characteristic of this tumor, cytokeratins highlight the epithelial component while vimentin highlights the mesenchymal component.4 Histologically, the sarcomatous components of PCCS often are highly variable, with an absence of transitional areas within the epithelial component, which frequently resembles basal cell carcinoma and/ or SCC.5-7 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma favors areas of chronic UV radiation exposure, particularly on the head and neck. Most tumors present with a slowly growing, polypoid, flesh-colored to erythematous nodule due to the infiltrative mesenchymal component.7 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma primarily is diagnosed in elderly patients, with the majority of cases diagnosed in the eighth or ninth decades of life (range, 32–98 years).1,8 Men appear to be twice as likely to be diagnosed with a PCCS compared to women.1 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas are recognized as aggressive tumors with a high propensity to metastasize and recur locally, necessitating early diagnosis and treatment.4 Accurate diagnosis of PCCSs can be challenging due to the biphasic nature of the neoplasm as well as poor differentiation or unequal proportions of the epithelial and mesenchymal components.5 Additionally, overlapping diagnostic criteria coupled with vague demarcation between soft-tissue sarcomas and distinct carcinomas also may contribute to a delay in diagnosis.9 Treatment is achieved surgically by complete wide resection, with no evidence to support the use of adjuvant or neoadjuvant external beam radiation therapy. Due to the small number of reported cases, no treatment recommendations currently exist.1

Surgical management with wide local excision has been disappointing, with recurrence rates reported as high as 33%.6 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma has an estimated overall recurrence rate of 19% and a 5-year disease-free rate of 50%.10 Risk factors associated with poorer prognosis include tumors with adnexal subtype, age less than 65 years, rapid tumor growth, a tumor greater than 20 mm at presentation, and a long-standing tumor lasting up to 30 years.2,4 Although wide local excision and Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) both have been utilized successfully, MMS has been shown to result in a cure rate of greater than 98%.6

Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) is a cutaneous tumor of fibrohistiocytic mesenchymal origin that typically manifests on sun-damaged skin in elderly individuals. Clinically, it presents as a rapidly growing neoplasm that often ulcerates and bleeds. These heterogenous neoplasms have several distinct characteristics, including dense cellularity with disorganized, large, pleomorphic, and atypical-appearing spindle-shaped cells arising in the upper layers of the dermis, often disseminating into the reticular dermis and occasionally into the subcutaneous fat (Figure 1). The neoplastic cells often exhibit hyperchromic and irregular nuclei, multinucleated giant cells, and atypical mitotic figures. In most cases, negative immunohistochemical staining with SOX-10, S-100, cytokeratins, desmin, and caldesmon will allow pathologists to differentiate between AFX and other common tumors on the differential diagnosis, such as SCC, melanoma, and leiomyosarcoma. CD10 and procollagen type 1 are positive antigenic markers in AFX, but they are not specific. The standard treatment of AFX includes wide local excision or MMS for superior margin control.11

Spindle cell SCC presents as a raised or exophytic nodule, often with spontaneous bleeding and central ulceration. It usually presents on sun-damaged skin or in individuals with a history of ionizing radiation. Histologically, it is characterized by atypical spindleshaped keratinocytes in the dermis existing as single cells or cohesive nests along with keratin pearls (Figure 2). The atypical spindle cells may comprise the entire tumor or only a small portion. The use of immunohistochemical markers often is required to establish a definitive diagnosis. Spindle cell SCC stains positively, albeit frequently focally, for p63, p40, and high-molecular-weight cytokeratins such as cytokeratin 5/6, while S-100 protein, SOX-10, MART-1/Melan-A, and muscle-specific actin stains typically are negative. Wide local excision or MMS is recommended for treatment of these lesions.12

Primary cutaneous myoepithelial carcinomas are uncommon neoplasms of myoepithelial differentiation. Clinically, they often arise as soft nodular lesions on the head, neck, and lower extremities with a bimodal age distribution (50 years). Histologically cutaneous myoepithelial tumors are well-differentiated, dermal-based nodules without connection to the overlying epidermis (Figure 3). The myoepithelial cells can exhibit spindled, epithelioid, plasmacytoid, or clear cell morphologic features and show variability in cell growth patterns. One of the most common growth patterns is oval to round cells forming cords and chains in a chondromyxoid stroma. Most cases display an immunophenotyped co-expression of an epithelial cytokeratin and S-100 protein. Myoepithelial markers also may be present, including keratins, smooth muscle actin, calponin, glial fibrillary acidic protein, p63, and desmin. Surgical removal with wide local excision or MMS is essential.13

Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) is a tumor that originates from smooth muscle and rarely develops in the dermis.14 Pleomorphic LMS is a morphologic variant of LMS that has a low propensity to metastasize but commonly exhibits local recurrence.15 Leiomyosarcoma can present in any age group but most commonly manifests in individuals aged 50 to 70 years. Clinically, LMS presents as a firm solitary nodule with a smooth pink surface or a more exophytic tumor with a reddish or brown color on the extensor surface of the lower limbs; it is less common on the scalp and face.14 Histologically, most cases of pleomorphic LMS show small foci of fascicles consisting of smooth muscle tumor cells in addition to cellular pleomorphism (Figure 4).15 Many of these cells demonstrate a clear perinuclear vacuole that generally is appreciated in neoplastic smooth muscle cells.14 Pleomorphic LMS typically stains positively for at least one smooth muscle marker including desmin, h-caldesmon, muscle-specific actin, α-smooth muscle actin, or smooth muscle myosin in the leiomyosarcomatous fascicular areas.16 Complete surgical excision is the treatment of choice, and the best results are obtained with MMS.14

- Syme-Grant J, Syme-Grant NJ, Motta L, et al. Are primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas underdiagnosed? five cases and a review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:1402-1408.

- Bourgeault E, Alain J, Gagne E. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma of the basal cell subtype should be treated as a high-risk basal cell carcinoma. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19:407-411.

- West L, Srivastava D. Cutaneous carcinosarcoma of the medial canthus discovered on Mohs debulk analysis. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:1700-1702.

- Kwan JM, Satter EK. Carcinosarcoma: a primary cutaneous tumor with biphasic differentiation. Cutis. 2013;92:247-249.

- Suh KY, Lacouture M, Gerami P. p63 in primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:374‐377.

- Ruiz-Villaverde R, Aneiros-Fernandez J. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma: a cutaneous neoplasm with an exceptional presentation. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2018;18:E114-E115.

- Smart CN, Pucci RA, Binder SW, et al. Cutaneous carcinosarcoma with myoepithelial differentiation: immunohistochemical and cytogenetic analysis of a case presenting in an unusual location. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:715‐717.

- Clark JJ, Bowen AR, Bowen GM, et al. Cutaneous carcinosarcoma: a series of six cases and a review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:34‐44.

- Müller CS, Pföhler C, Schiekofer C, et al. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas: a morphological histogenetic concept revisited. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:328‐339.

- Bellew S, Del Rosso JQ, Mobini N. Primary carcinosarcoma of the ear: case report and review of the literature. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2:33‐35.

- Hong SH, Hong SJ, Lee Y, et al. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma of the shoulder: case report with literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:338-340.

- Soleymani T, Aasi SZ, Novoa R, et al. Atypical fibroxanthoma and pleomorphic dermal sarcoma: updates on classification and management. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:253-259.

- Parekh V, Seykora JT. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:503-525.

- Johnson GE, Stevens K, Morrison AO, et al. Cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma with disseminated metastases. Cutis. 2017;99:E19-E26.

- Llombart B, Serra-Guillén C, Requena C, et al. Leiomyosarcoma and pleomorphic dermal sarcoma: guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019;110:4-11.

- Oda Y, Miyajima K, Kawaguchi K, et al. Pleomorphic leiomyosarcoma: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study with special emphasis on its distinction from ordinary leiomyosarcoma and malignant fibrous histiocytoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1030-1038.

- Syme-Grant J, Syme-Grant NJ, Motta L, et al. Are primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas underdiagnosed? five cases and a review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:1402-1408.

- Bourgeault E, Alain J, Gagne E. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma of the basal cell subtype should be treated as a high-risk basal cell carcinoma. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19:407-411.

- West L, Srivastava D. Cutaneous carcinosarcoma of the medial canthus discovered on Mohs debulk analysis. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:1700-1702.

- Kwan JM, Satter EK. Carcinosarcoma: a primary cutaneous tumor with biphasic differentiation. Cutis. 2013;92:247-249.

- Suh KY, Lacouture M, Gerami P. p63 in primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:374‐377.

- Ruiz-Villaverde R, Aneiros-Fernandez J. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma: a cutaneous neoplasm with an exceptional presentation. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2018;18:E114-E115.

- Smart CN, Pucci RA, Binder SW, et al. Cutaneous carcinosarcoma with myoepithelial differentiation: immunohistochemical and cytogenetic analysis of a case presenting in an unusual location. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:715‐717.

- Clark JJ, Bowen AR, Bowen GM, et al. Cutaneous carcinosarcoma: a series of six cases and a review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:34‐44.

- Müller CS, Pföhler C, Schiekofer C, et al. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas: a morphological histogenetic concept revisited. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:328‐339.

- Bellew S, Del Rosso JQ, Mobini N. Primary carcinosarcoma of the ear: case report and review of the literature. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2:33‐35.

- Hong SH, Hong SJ, Lee Y, et al. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma of the shoulder: case report with literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:338-340.

- Soleymani T, Aasi SZ, Novoa R, et al. Atypical fibroxanthoma and pleomorphic dermal sarcoma: updates on classification and management. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:253-259.

- Parekh V, Seykora JT. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:503-525.

- Johnson GE, Stevens K, Morrison AO, et al. Cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma with disseminated metastases. Cutis. 2017;99:E19-E26.

- Llombart B, Serra-Guillén C, Requena C, et al. Leiomyosarcoma and pleomorphic dermal sarcoma: guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019;110:4-11.

- Oda Y, Miyajima K, Kawaguchi K, et al. Pleomorphic leiomyosarcoma: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study with special emphasis on its distinction from ordinary leiomyosarcoma and malignant fibrous histiocytoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1030-1038.

A 72-year-old man with a history of nonmelanoma skin cancer and lung transplant maintained on stable doses of prednisone and tacrolimus presented with a 1.3×1.8-cm, slow-growing, well-demarcated, ulcerated, erythematous plaque with overlying serous crust on the left temple of 6 months’ duration. No cervical or axillary lymphadenopathy was appreciated on physical examination. A biopsy was performed followed by Mohs micrographic surgery. Microscopic examination of the debulking specimen revealed atypical spindle cells in the papillary and reticular dermis radiating from a central focus of a moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. The squamous cells stained positive for cytokeratin 5/6, pankeratin, and p40, while the spindle cells stained positive only for vimentin.

Communication Strategies in Mohs Micrographic Surgery: A Survey of Methods, Time Savings, and Perceived Patient Satisfaction

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) entails multiple time-consuming surgical and histological examinations for each patient. As surgical stages are performed and histological sections are processed, an efficient communication method among providers, medical assistants, histotechnologists, and patients is necessary to avoid delays. To address these and other communication issues, providers have focused on ways to increase clinic efficiency and improve patient-reported outcomes by utilizing new or repurposed communication technologies in their Mohs practice.

Prior reports have highlighted the utility of hands-free headsets that allow real-time communication among staff members as a means of increasing clinic efficiency and decreasing patient wait times.1-4 These systems may mediate a more rapid turnover between stages by mitigating the need for surgeons and support staff to assemble within a designated workspace.1,3,4 However, there is no single or standardized communication method that best suits all surgical suites and MMS practices. Our study aimed to identify the current communication strategies employed by Mohs surgeons and thereby ascertain which method(s) portend(s) the highest benefit in average daily time savings and provider-perceived patient satisfaction.

Materials and Methods

Survey Instrument

A new 10-question electronic survey was published on the SurveyMonkey website, and a link to the survey was provided in a quarterly email that originated from the American College of Mohs Surgery and was distributed to all 1735 active members. Responses were obtained from January 2019 to February 2019.

Statistical Analysis

A statistical analysis was done to determine any significant associations among the providers’ responses. P<.05 was used to determine statistical significance. A Cochran-Armitage test for trend was used to identify significant associations between the number of rooms and the communication systems that were used. Thus, 7 total tests—1 for each device (whiteboard, light system, flag system, wired intercom, wireless intercom, walkie-talkie, or headset)—were conducted. The Cochran-Armitage test also was used to determine whether the probability of using the device was affected by the number of stations/surgical rooms that were attended by the Mohs surgeons. To determine whether the communication devices used were associated with higher patient satisfaction, a χ2 test was conducted for each device (7 total tests), testing the categories of using that device (yes/no) and patient satisfaction (yes/no). A Fisher exact test of independence was used in any case where the proportion for the device and patient satisfaction was 25% or higher. To determine whether the communication method was associated with increased time savings, 7 total Cochran-Armitage tests were conducted, 1 for each device. A logistic regression model was used to determine whether there was a significant association between the number of stations and the likelihood of reporting patient satisfaction.

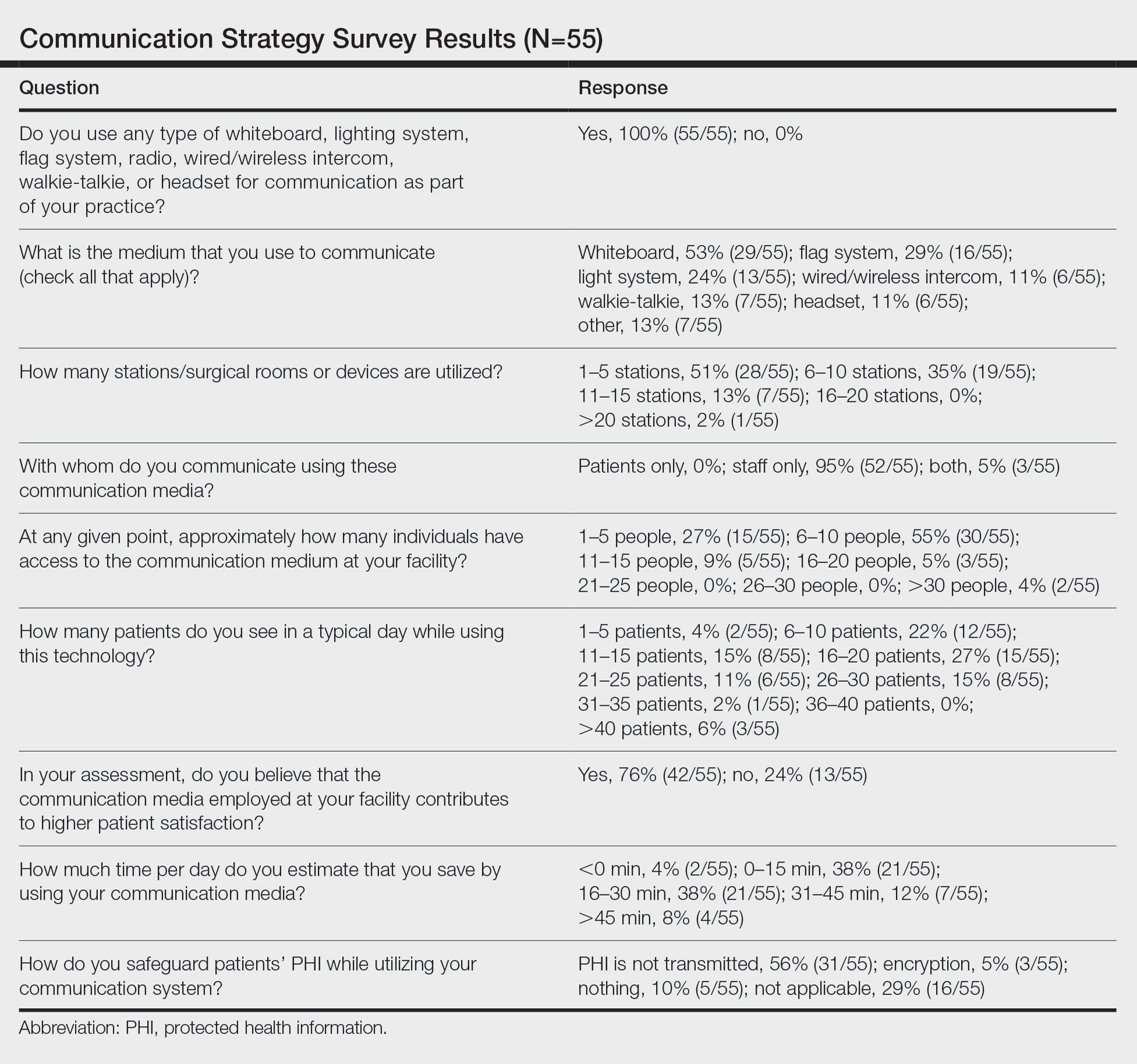

Results

Eighty-eight surgeons responded to the survey, with a response rate of 5% (88/1735). A total of 55 surgeons completed the survey in its entirety and were included in the data analysis. The most commonly used communication mediums were whiteboards (29/55 [53%]), followed by a flag system (16/55 [29%]) and a light system (13/55 [24%]). Most Mohs surgeons (52/55 [95%]) used the communication media to communicate with their staff only, and 76% (42/55) of Mohs surgeons believed that their communication media contributed to higher patient satisfaction. Overall, 58% (32/55) of Mohs surgeons stated that their communication media saved more than 15 minutes (on average) per day. The use of a whiteboard and/or flag system was reported as the least efficient method, with average daily time savings of 13 minutes. With the introduction of newer technology (wired or wireless intercoms, headsets, walkie-talkies, or internal messaging systems such as Skype) to the whiteboard and/or flag system, the time savings increased by 10 minutes per day. Nearly 25% (14/55) of surgeons utilized more than 1 communication system.

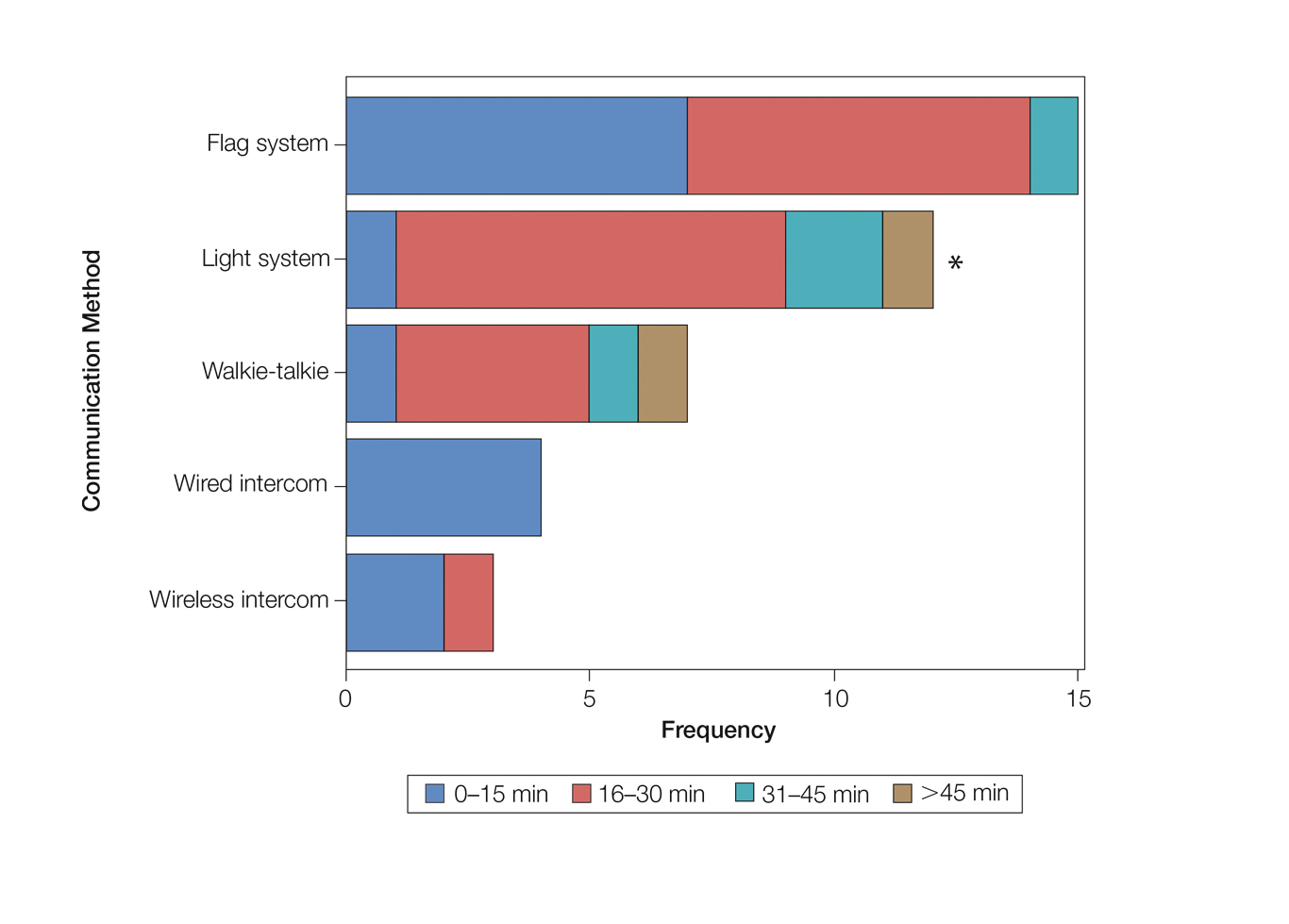

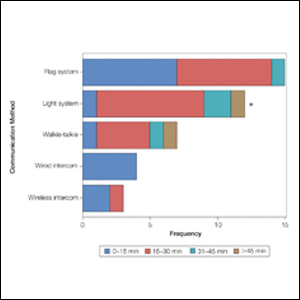

As the number of stations in an MMS suite increased, the probability of using a whiteboard to track the progress of the cases decreased. There were no statistically significant associations identified between the number of stations and the use of other communication devices (ie, flag system, light system, wireless intercom, wired intercom, walkie-talkie, headset). The stratified percentages of the amount of time savings for each communication modality are presented in the Figure (whiteboards and headsets were excluded because they did not increase time savings). The use of a light system was the only communication modality found to be statistically associated with an increase in provider-reported time savings (P=.0482; Figure). In addition, our analysis did not show an improvement in provider-reported patient satisfaction with any of the current systems used in MMS clinics.

Comment

The process of transmitting information among the medical team during MMS is a complex interplay involving the relay of crucial information, with many opportunities for the introduction of distraction and error. Despite numerous improvements in the efficiency of the preparation of histological specimens and implementation of various time-saving and tissue-saving surgical interventions, relatively little attention has been given to address the sometimes chaotic and challenging process of organizing results from each stage of multiple patients in an MMS surgical suite.5

As demonstrated by our survey, incorporation of a light-based system into an MMS clinic may improve workplace efficiency by decreasing the redundant use of support staff and allowing Mohs surgeons to transition from one station to the next seamlessly. Light-based communication systems provide an immediate notification for support staff via color-coded and/or numerically coded indicators on input switches located outside and inside the examination/surgery rooms. The switch indicators can be depressed with minimal disruption from station to station, thereby foregoing the need to interrupt an ongoing excision or closure to convey the status of the case. These systems may then permit enhanced clinic and workflow efficiency, which may help to shorten patient wait times.

Study Limitation

Although all members of the American College of Mohs Surgery were invited to participate in this online survey, only a small number (N=55) completed it in its entirety. Moreover, sample sizes for some of the communication devices were small. As a result, many of the tests might be lacking sufficient power to detect possible relationships, which might be identified in future larger-scale studies.

Conclusion

Our study supports the use of light-based communication systems in MMS suites to improve efficiency in the clinic. Based on our analysis, light-based communication methods were significantly associated with improved time savings (P=.0482). Our study did not show an improvement in provider-reported satisfaction with any of the current systems used in MMS clinics. We hope that this information will help guide providers in implementing new communication techniques to improve clinic efficiency.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. Kathy Kyler (Oklahoma City, Oklahoma) for her assistance in preparing this manuscript. Support for Dr. Chen and Mr. Stubblefield was provided through National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences [Grant 2U54GM104938-06, PI Judith James].

- Chen T, Vines L, Wanitphakdeedecha R, et al. Electronically linked: wireless, discrete, hands-free communication to improve surgical workflow in Mohs and dermasurgery clinic. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:248-252.

- Lanto AB, Yano EM, Fink A, et al. Anatomy of an outpatient visit. An evaluation of clinic efficiency in general and subspecialty clinics. Med Group Manage J. 1995;42:18-25.

- Kantor J. Application of Google Glass to Mohs micrographic surgery: a pilot study in 120 patients. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:288-289.

- Spurk PA, Mohr ML, Seroka AM, et al. The impact of a wireless telecommunication system on efficiency. J Nurs Admin. 1995;25:21-26.

- Dietert JB, MacFarlane DF. A survey of Mohs tissue tracking practices. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:514-518.

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) entails multiple time-consuming surgical and histological examinations for each patient. As surgical stages are performed and histological sections are processed, an efficient communication method among providers, medical assistants, histotechnologists, and patients is necessary to avoid delays. To address these and other communication issues, providers have focused on ways to increase clinic efficiency and improve patient-reported outcomes by utilizing new or repurposed communication technologies in their Mohs practice.

Prior reports have highlighted the utility of hands-free headsets that allow real-time communication among staff members as a means of increasing clinic efficiency and decreasing patient wait times.1-4 These systems may mediate a more rapid turnover between stages by mitigating the need for surgeons and support staff to assemble within a designated workspace.1,3,4 However, there is no single or standardized communication method that best suits all surgical suites and MMS practices. Our study aimed to identify the current communication strategies employed by Mohs surgeons and thereby ascertain which method(s) portend(s) the highest benefit in average daily time savings and provider-perceived patient satisfaction.

Materials and Methods

Survey Instrument

A new 10-question electronic survey was published on the SurveyMonkey website, and a link to the survey was provided in a quarterly email that originated from the American College of Mohs Surgery and was distributed to all 1735 active members. Responses were obtained from January 2019 to February 2019.

Statistical Analysis

A statistical analysis was done to determine any significant associations among the providers’ responses. P<.05 was used to determine statistical significance. A Cochran-Armitage test for trend was used to identify significant associations between the number of rooms and the communication systems that were used. Thus, 7 total tests—1 for each device (whiteboard, light system, flag system, wired intercom, wireless intercom, walkie-talkie, or headset)—were conducted. The Cochran-Armitage test also was used to determine whether the probability of using the device was affected by the number of stations/surgical rooms that were attended by the Mohs surgeons. To determine whether the communication devices used were associated with higher patient satisfaction, a χ2 test was conducted for each device (7 total tests), testing the categories of using that device (yes/no) and patient satisfaction (yes/no). A Fisher exact test of independence was used in any case where the proportion for the device and patient satisfaction was 25% or higher. To determine whether the communication method was associated with increased time savings, 7 total Cochran-Armitage tests were conducted, 1 for each device. A logistic regression model was used to determine whether there was a significant association between the number of stations and the likelihood of reporting patient satisfaction.

Results

Eighty-eight surgeons responded to the survey, with a response rate of 5% (88/1735). A total of 55 surgeons completed the survey in its entirety and were included in the data analysis. The most commonly used communication mediums were whiteboards (29/55 [53%]), followed by a flag system (16/55 [29%]) and a light system (13/55 [24%]). Most Mohs surgeons (52/55 [95%]) used the communication media to communicate with their staff only, and 76% (42/55) of Mohs surgeons believed that their communication media contributed to higher patient satisfaction. Overall, 58% (32/55) of Mohs surgeons stated that their communication media saved more than 15 minutes (on average) per day. The use of a whiteboard and/or flag system was reported as the least efficient method, with average daily time savings of 13 minutes. With the introduction of newer technology (wired or wireless intercoms, headsets, walkie-talkies, or internal messaging systems such as Skype) to the whiteboard and/or flag system, the time savings increased by 10 minutes per day. Nearly 25% (14/55) of surgeons utilized more than 1 communication system.

As the number of stations in an MMS suite increased, the probability of using a whiteboard to track the progress of the cases decreased. There were no statistically significant associations identified between the number of stations and the use of other communication devices (ie, flag system, light system, wireless intercom, wired intercom, walkie-talkie, headset). The stratified percentages of the amount of time savings for each communication modality are presented in the Figure (whiteboards and headsets were excluded because they did not increase time savings). The use of a light system was the only communication modality found to be statistically associated with an increase in provider-reported time savings (P=.0482; Figure). In addition, our analysis did not show an improvement in provider-reported patient satisfaction with any of the current systems used in MMS clinics.

Comment

The process of transmitting information among the medical team during MMS is a complex interplay involving the relay of crucial information, with many opportunities for the introduction of distraction and error. Despite numerous improvements in the efficiency of the preparation of histological specimens and implementation of various time-saving and tissue-saving surgical interventions, relatively little attention has been given to address the sometimes chaotic and challenging process of organizing results from each stage of multiple patients in an MMS surgical suite.5

As demonstrated by our survey, incorporation of a light-based system into an MMS clinic may improve workplace efficiency by decreasing the redundant use of support staff and allowing Mohs surgeons to transition from one station to the next seamlessly. Light-based communication systems provide an immediate notification for support staff via color-coded and/or numerically coded indicators on input switches located outside and inside the examination/surgery rooms. The switch indicators can be depressed with minimal disruption from station to station, thereby foregoing the need to interrupt an ongoing excision or closure to convey the status of the case. These systems may then permit enhanced clinic and workflow efficiency, which may help to shorten patient wait times.

Study Limitation

Although all members of the American College of Mohs Surgery were invited to participate in this online survey, only a small number (N=55) completed it in its entirety. Moreover, sample sizes for some of the communication devices were small. As a result, many of the tests might be lacking sufficient power to detect possible relationships, which might be identified in future larger-scale studies.

Conclusion

Our study supports the use of light-based communication systems in MMS suites to improve efficiency in the clinic. Based on our analysis, light-based communication methods were significantly associated with improved time savings (P=.0482). Our study did not show an improvement in provider-reported satisfaction with any of the current systems used in MMS clinics. We hope that this information will help guide providers in implementing new communication techniques to improve clinic efficiency.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. Kathy Kyler (Oklahoma City, Oklahoma) for her assistance in preparing this manuscript. Support for Dr. Chen and Mr. Stubblefield was provided through National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences [Grant 2U54GM104938-06, PI Judith James].

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) entails multiple time-consuming surgical and histological examinations for each patient. As surgical stages are performed and histological sections are processed, an efficient communication method among providers, medical assistants, histotechnologists, and patients is necessary to avoid delays. To address these and other communication issues, providers have focused on ways to increase clinic efficiency and improve patient-reported outcomes by utilizing new or repurposed communication technologies in their Mohs practice.

Prior reports have highlighted the utility of hands-free headsets that allow real-time communication among staff members as a means of increasing clinic efficiency and decreasing patient wait times.1-4 These systems may mediate a more rapid turnover between stages by mitigating the need for surgeons and support staff to assemble within a designated workspace.1,3,4 However, there is no single or standardized communication method that best suits all surgical suites and MMS practices. Our study aimed to identify the current communication strategies employed by Mohs surgeons and thereby ascertain which method(s) portend(s) the highest benefit in average daily time savings and provider-perceived patient satisfaction.

Materials and Methods

Survey Instrument

A new 10-question electronic survey was published on the SurveyMonkey website, and a link to the survey was provided in a quarterly email that originated from the American College of Mohs Surgery and was distributed to all 1735 active members. Responses were obtained from January 2019 to February 2019.

Statistical Analysis

A statistical analysis was done to determine any significant associations among the providers’ responses. P<.05 was used to determine statistical significance. A Cochran-Armitage test for trend was used to identify significant associations between the number of rooms and the communication systems that were used. Thus, 7 total tests—1 for each device (whiteboard, light system, flag system, wired intercom, wireless intercom, walkie-talkie, or headset)—were conducted. The Cochran-Armitage test also was used to determine whether the probability of using the device was affected by the number of stations/surgical rooms that were attended by the Mohs surgeons. To determine whether the communication devices used were associated with higher patient satisfaction, a χ2 test was conducted for each device (7 total tests), testing the categories of using that device (yes/no) and patient satisfaction (yes/no). A Fisher exact test of independence was used in any case where the proportion for the device and patient satisfaction was 25% or higher. To determine whether the communication method was associated with increased time savings, 7 total Cochran-Armitage tests were conducted, 1 for each device. A logistic regression model was used to determine whether there was a significant association between the number of stations and the likelihood of reporting patient satisfaction.

Results

Eighty-eight surgeons responded to the survey, with a response rate of 5% (88/1735). A total of 55 surgeons completed the survey in its entirety and were included in the data analysis. The most commonly used communication mediums were whiteboards (29/55 [53%]), followed by a flag system (16/55 [29%]) and a light system (13/55 [24%]). Most Mohs surgeons (52/55 [95%]) used the communication media to communicate with their staff only, and 76% (42/55) of Mohs surgeons believed that their communication media contributed to higher patient satisfaction. Overall, 58% (32/55) of Mohs surgeons stated that their communication media saved more than 15 minutes (on average) per day. The use of a whiteboard and/or flag system was reported as the least efficient method, with average daily time savings of 13 minutes. With the introduction of newer technology (wired or wireless intercoms, headsets, walkie-talkies, or internal messaging systems such as Skype) to the whiteboard and/or flag system, the time savings increased by 10 minutes per day. Nearly 25% (14/55) of surgeons utilized more than 1 communication system.

As the number of stations in an MMS suite increased, the probability of using a whiteboard to track the progress of the cases decreased. There were no statistically significant associations identified between the number of stations and the use of other communication devices (ie, flag system, light system, wireless intercom, wired intercom, walkie-talkie, headset). The stratified percentages of the amount of time savings for each communication modality are presented in the Figure (whiteboards and headsets were excluded because they did not increase time savings). The use of a light system was the only communication modality found to be statistically associated with an increase in provider-reported time savings (P=.0482; Figure). In addition, our analysis did not show an improvement in provider-reported patient satisfaction with any of the current systems used in MMS clinics.

Comment

The process of transmitting information among the medical team during MMS is a complex interplay involving the relay of crucial information, with many opportunities for the introduction of distraction and error. Despite numerous improvements in the efficiency of the preparation of histological specimens and implementation of various time-saving and tissue-saving surgical interventions, relatively little attention has been given to address the sometimes chaotic and challenging process of organizing results from each stage of multiple patients in an MMS surgical suite.5

As demonstrated by our survey, incorporation of a light-based system into an MMS clinic may improve workplace efficiency by decreasing the redundant use of support staff and allowing Mohs surgeons to transition from one station to the next seamlessly. Light-based communication systems provide an immediate notification for support staff via color-coded and/or numerically coded indicators on input switches located outside and inside the examination/surgery rooms. The switch indicators can be depressed with minimal disruption from station to station, thereby foregoing the need to interrupt an ongoing excision or closure to convey the status of the case. These systems may then permit enhanced clinic and workflow efficiency, which may help to shorten patient wait times.

Study Limitation

Although all members of the American College of Mohs Surgery were invited to participate in this online survey, only a small number (N=55) completed it in its entirety. Moreover, sample sizes for some of the communication devices were small. As a result, many of the tests might be lacking sufficient power to detect possible relationships, which might be identified in future larger-scale studies.

Conclusion

Our study supports the use of light-based communication systems in MMS suites to improve efficiency in the clinic. Based on our analysis, light-based communication methods were significantly associated with improved time savings (P=.0482). Our study did not show an improvement in provider-reported satisfaction with any of the current systems used in MMS clinics. We hope that this information will help guide providers in implementing new communication techniques to improve clinic efficiency.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. Kathy Kyler (Oklahoma City, Oklahoma) for her assistance in preparing this manuscript. Support for Dr. Chen and Mr. Stubblefield was provided through National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences [Grant 2U54GM104938-06, PI Judith James].

- Chen T, Vines L, Wanitphakdeedecha R, et al. Electronically linked: wireless, discrete, hands-free communication to improve surgical workflow in Mohs and dermasurgery clinic. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:248-252.

- Lanto AB, Yano EM, Fink A, et al. Anatomy of an outpatient visit. An evaluation of clinic efficiency in general and subspecialty clinics. Med Group Manage J. 1995;42:18-25.

- Kantor J. Application of Google Glass to Mohs micrographic surgery: a pilot study in 120 patients. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:288-289.

- Spurk PA, Mohr ML, Seroka AM, et al. The impact of a wireless telecommunication system on efficiency. J Nurs Admin. 1995;25:21-26.

- Dietert JB, MacFarlane DF. A survey of Mohs tissue tracking practices. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:514-518.

- Chen T, Vines L, Wanitphakdeedecha R, et al. Electronically linked: wireless, discrete, hands-free communication to improve surgical workflow in Mohs and dermasurgery clinic. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:248-252.

- Lanto AB, Yano EM, Fink A, et al. Anatomy of an outpatient visit. An evaluation of clinic efficiency in general and subspecialty clinics. Med Group Manage J. 1995;42:18-25.

- Kantor J. Application of Google Glass to Mohs micrographic surgery: a pilot study in 120 patients. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:288-289.

- Spurk PA, Mohr ML, Seroka AM, et al. The impact of a wireless telecommunication system on efficiency. J Nurs Admin. 1995;25:21-26.

- Dietert JB, MacFarlane DF. A survey of Mohs tissue tracking practices. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:514-518.

Practice Points

- There are limited studies evaluating the efficacy of different communication methods in Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) clinics.

- This study suggests that incorporation of a light-based system into an MMS clinic improves workplace efficiency.

Successful Treatment of Refractory Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita With Intravenous Immunoglobulin and Dapsone

To the Editor:

Evidence-based recommendations for optimal medical management of patients with immunobullous diseases prior to elective surgery are sparse.1,2 There is an uncertain balance between the use of immunomodulators and immunosuppressants, and implementation of these agents is heavily weighted against an increased infection risk from both active disease with denuded skin and suboptimal wound healing due to iatrogenic immunosuppression.1-5 Historically, clinical management of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) seldomly has resulted in substantial disease resolution.1,3,4 Herein, we describe a case of recalcitrant EBA that was treated with a combination of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and dapsone, which resulted in a favorable clinical response and successful hip arthroplasty without cutaneous complications.

A 66-year-old man presented to an outside clinic with nonhealing ulcers on the oral mucosa, hands, groin, and feet. He was treated with systemic steroids after a histologic examination suggested bullous pemphigoid, but the lesions did not exhibit any appreciable improvement after several months of treatment. Despite the lack of improvement, the patient was continued on systemic steroids with a waxing and waning disease course.

Within a year, the patient presented to an orthopedist at our institution with severe left hip pain that had been limiting his mobility and had become unresponsive to conservative therapy. Radiologic investigations suggested advanced osteoarthritis and avascular necrosis of the left hip. Surgical intervention was delayed, as his orthopedist expressed concern that the extent of the body surface area affected by cutaneous denudation placed him at an unacceptable risk for infection. The orthopedic surgeon then referred the patient to our clinic for evaluation of the lesions. Physical examination revealed numerous crusted erosions in various stages of healing on the oral mucosa, palms, groin, and soles. Repeat biopsy of a denuded ulcer on the patient’s arm was obtained by our providers (nearly 1 year after the first biopsy by the outside physician). Histologic examination showed a pauci-immune subepidermal blister without acantholysis, which in combination with the clinical presentation of tense bullae on trauma-prone surfaces led to a favored diagnosis of EBA.

The patient began trials of several immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive agents, both in isolation and in combination, including systemic steroids, mycophenolate mofetil, four 1000-mg infusions of rituximab, and dapsone. Although results were suboptimal, dapsone 150 mg once daily for 3 months yielded the greatest clinical improvement with subsequent granulation and/or re-epithelialization of the chronic ulcers. After discussion during our department’s Grand Rounds, it was determined that the patient should undergo a trial of IVIG infusions, which were initiated with a loading dose of 2000 mg/kg over 5 consecutive days, followed by once-monthly maintenance infusion doses of 1200 mg/kg for 4 consecutive months. While receiving IVIG, he was maintained on a once-daily dose of dapsone 150 mg

Following this treatment regimen, he was noted to have marked improvement with only few scattered healing erosions. Upon completion of his last IVIG infusion, his cutaneous and mucosal manifestations of EBA were greatly minimized, demonstrating the best level of control that had been achieved during the disease course (Figure 1). This therapy completely cleared the cutaneous and mucosal ulcerations, thus permitting the patient to undergo a total left hip arthroplasty without complications (Figure 2).

Our report is novel in that it supports a combination of IVIG and dapsone as a viable presurgical therapy for patients with EBA, and this treatment also may be applicable for other primary immunobullous disorders.2,5 Our case was particularly challenging in that the severity of the patient’s bullous disease precluded him from an elective orthopedic joint replacement due to the risk for wound dehiscence and surgical site infection.2 We determined that IVIG and dapsone would be the most optimal combination therapy to facilitate superior disease control and concurrently allow for appropriate wound healing without impairing the host immune response. This report is unique from a clinical perspective in that a balance was successfully achieved between immune suppression, with avoidance of associated side effects, and disease activity.

- Ahmed AR, Gürcan HM. Treatment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita with intravenous immunoglobulin in patients non-responsive to conventional therapy: clinical outcome and post-treatment long-term follow-up [published online August 8, 2011]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1074-1083.

- Rubin J, Touloei K, Favreau T, et al. Mohs surgery in patients immunobullous diseases: should prednisone be increased prior to surgery? J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:45-46.

- Ishii N, Hamada T, Dainichi T, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: what’s new? J Dermatol. 2010;37:220-230.

- Mosqueira CB, Furlani Lde A, Xavier AF, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin for treatment of severe acquired bullous epidermolysis refractory to conventional immunosuppressive therapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:521-524.

- Ludwig RJ. Clinical presentation, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of EBA. ISRN Dermatology. 2013;2013:812029.

To the Editor:

Evidence-based recommendations for optimal medical management of patients with immunobullous diseases prior to elective surgery are sparse.1,2 There is an uncertain balance between the use of immunomodulators and immunosuppressants, and implementation of these agents is heavily weighted against an increased infection risk from both active disease with denuded skin and suboptimal wound healing due to iatrogenic immunosuppression.1-5 Historically, clinical management of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) seldomly has resulted in substantial disease resolution.1,3,4 Herein, we describe a case of recalcitrant EBA that was treated with a combination of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and dapsone, which resulted in a favorable clinical response and successful hip arthroplasty without cutaneous complications.

A 66-year-old man presented to an outside clinic with nonhealing ulcers on the oral mucosa, hands, groin, and feet. He was treated with systemic steroids after a histologic examination suggested bullous pemphigoid, but the lesions did not exhibit any appreciable improvement after several months of treatment. Despite the lack of improvement, the patient was continued on systemic steroids with a waxing and waning disease course.

Within a year, the patient presented to an orthopedist at our institution with severe left hip pain that had been limiting his mobility and had become unresponsive to conservative therapy. Radiologic investigations suggested advanced osteoarthritis and avascular necrosis of the left hip. Surgical intervention was delayed, as his orthopedist expressed concern that the extent of the body surface area affected by cutaneous denudation placed him at an unacceptable risk for infection. The orthopedic surgeon then referred the patient to our clinic for evaluation of the lesions. Physical examination revealed numerous crusted erosions in various stages of healing on the oral mucosa, palms, groin, and soles. Repeat biopsy of a denuded ulcer on the patient’s arm was obtained by our providers (nearly 1 year after the first biopsy by the outside physician). Histologic examination showed a pauci-immune subepidermal blister without acantholysis, which in combination with the clinical presentation of tense bullae on trauma-prone surfaces led to a favored diagnosis of EBA.

The patient began trials of several immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive agents, both in isolation and in combination, including systemic steroids, mycophenolate mofetil, four 1000-mg infusions of rituximab, and dapsone. Although results were suboptimal, dapsone 150 mg once daily for 3 months yielded the greatest clinical improvement with subsequent granulation and/or re-epithelialization of the chronic ulcers. After discussion during our department’s Grand Rounds, it was determined that the patient should undergo a trial of IVIG infusions, which were initiated with a loading dose of 2000 mg/kg over 5 consecutive days, followed by once-monthly maintenance infusion doses of 1200 mg/kg for 4 consecutive months. While receiving IVIG, he was maintained on a once-daily dose of dapsone 150 mg

Following this treatment regimen, he was noted to have marked improvement with only few scattered healing erosions. Upon completion of his last IVIG infusion, his cutaneous and mucosal manifestations of EBA were greatly minimized, demonstrating the best level of control that had been achieved during the disease course (Figure 1). This therapy completely cleared the cutaneous and mucosal ulcerations, thus permitting the patient to undergo a total left hip arthroplasty without complications (Figure 2).

Our report is novel in that it supports a combination of IVIG and dapsone as a viable presurgical therapy for patients with EBA, and this treatment also may be applicable for other primary immunobullous disorders.2,5 Our case was particularly challenging in that the severity of the patient’s bullous disease precluded him from an elective orthopedic joint replacement due to the risk for wound dehiscence and surgical site infection.2 We determined that IVIG and dapsone would be the most optimal combination therapy to facilitate superior disease control and concurrently allow for appropriate wound healing without impairing the host immune response. This report is unique from a clinical perspective in that a balance was successfully achieved between immune suppression, with avoidance of associated side effects, and disease activity.

To the Editor:

Evidence-based recommendations for optimal medical management of patients with immunobullous diseases prior to elective surgery are sparse.1,2 There is an uncertain balance between the use of immunomodulators and immunosuppressants, and implementation of these agents is heavily weighted against an increased infection risk from both active disease with denuded skin and suboptimal wound healing due to iatrogenic immunosuppression.1-5 Historically, clinical management of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) seldomly has resulted in substantial disease resolution.1,3,4 Herein, we describe a case of recalcitrant EBA that was treated with a combination of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and dapsone, which resulted in a favorable clinical response and successful hip arthroplasty without cutaneous complications.

A 66-year-old man presented to an outside clinic with nonhealing ulcers on the oral mucosa, hands, groin, and feet. He was treated with systemic steroids after a histologic examination suggested bullous pemphigoid, but the lesions did not exhibit any appreciable improvement after several months of treatment. Despite the lack of improvement, the patient was continued on systemic steroids with a waxing and waning disease course.

Within a year, the patient presented to an orthopedist at our institution with severe left hip pain that had been limiting his mobility and had become unresponsive to conservative therapy. Radiologic investigations suggested advanced osteoarthritis and avascular necrosis of the left hip. Surgical intervention was delayed, as his orthopedist expressed concern that the extent of the body surface area affected by cutaneous denudation placed him at an unacceptable risk for infection. The orthopedic surgeon then referred the patient to our clinic for evaluation of the lesions. Physical examination revealed numerous crusted erosions in various stages of healing on the oral mucosa, palms, groin, and soles. Repeat biopsy of a denuded ulcer on the patient’s arm was obtained by our providers (nearly 1 year after the first biopsy by the outside physician). Histologic examination showed a pauci-immune subepidermal blister without acantholysis, which in combination with the clinical presentation of tense bullae on trauma-prone surfaces led to a favored diagnosis of EBA.

The patient began trials of several immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive agents, both in isolation and in combination, including systemic steroids, mycophenolate mofetil, four 1000-mg infusions of rituximab, and dapsone. Although results were suboptimal, dapsone 150 mg once daily for 3 months yielded the greatest clinical improvement with subsequent granulation and/or re-epithelialization of the chronic ulcers. After discussion during our department’s Grand Rounds, it was determined that the patient should undergo a trial of IVIG infusions, which were initiated with a loading dose of 2000 mg/kg over 5 consecutive days, followed by once-monthly maintenance infusion doses of 1200 mg/kg for 4 consecutive months. While receiving IVIG, he was maintained on a once-daily dose of dapsone 150 mg

Following this treatment regimen, he was noted to have marked improvement with only few scattered healing erosions. Upon completion of his last IVIG infusion, his cutaneous and mucosal manifestations of EBA were greatly minimized, demonstrating the best level of control that had been achieved during the disease course (Figure 1). This therapy completely cleared the cutaneous and mucosal ulcerations, thus permitting the patient to undergo a total left hip arthroplasty without complications (Figure 2).

Our report is novel in that it supports a combination of IVIG and dapsone as a viable presurgical therapy for patients with EBA, and this treatment also may be applicable for other primary immunobullous disorders.2,5 Our case was particularly challenging in that the severity of the patient’s bullous disease precluded him from an elective orthopedic joint replacement due to the risk for wound dehiscence and surgical site infection.2 We determined that IVIG and dapsone would be the most optimal combination therapy to facilitate superior disease control and concurrently allow for appropriate wound healing without impairing the host immune response. This report is unique from a clinical perspective in that a balance was successfully achieved between immune suppression, with avoidance of associated side effects, and disease activity.

- Ahmed AR, Gürcan HM. Treatment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita with intravenous immunoglobulin in patients non-responsive to conventional therapy: clinical outcome and post-treatment long-term follow-up [published online August 8, 2011]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1074-1083.

- Rubin J, Touloei K, Favreau T, et al. Mohs surgery in patients immunobullous diseases: should prednisone be increased prior to surgery? J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:45-46.

- Ishii N, Hamada T, Dainichi T, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: what’s new? J Dermatol. 2010;37:220-230.

- Mosqueira CB, Furlani Lde A, Xavier AF, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin for treatment of severe acquired bullous epidermolysis refractory to conventional immunosuppressive therapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:521-524.

- Ludwig RJ. Clinical presentation, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of EBA. ISRN Dermatology. 2013;2013:812029.

- Ahmed AR, Gürcan HM. Treatment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita with intravenous immunoglobulin in patients non-responsive to conventional therapy: clinical outcome and post-treatment long-term follow-up [published online August 8, 2011]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1074-1083.

- Rubin J, Touloei K, Favreau T, et al. Mohs surgery in patients immunobullous diseases: should prednisone be increased prior to surgery? J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:45-46.

- Ishii N, Hamada T, Dainichi T, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: what’s new? J Dermatol. 2010;37:220-230.

- Mosqueira CB, Furlani Lde A, Xavier AF, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin for treatment of severe acquired bullous epidermolysis refractory to conventional immunosuppressive therapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:521-524.

- Ludwig RJ. Clinical presentation, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of EBA. ISRN Dermatology. 2013;2013:812029.

Practice Points

- Treatment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) is difficult, and most treatment regimens are based on anecdotal reports.

- Systemic corticosteroids have been the mainstay of therapy for severe or extensive disease but impose an increased risk for postoperative complications including surgical site infections.

- A steroid-sparing regimen of intravenous immunoglobulin and systemic dapsone may be used when rapid clearance of EBA is needed prior to elective surgery.