User login

Caregiver Perspectives on Communication During Hospitalization at an Academic Pediatric Institution: A Qualitative Study

Provision of high-quality, high-value medical care hinges upon effective communication. During a hospitalization, critical information is communicated between patients, caregivers, and providers multiple times each day. This can cause inconsistent and misinterpreted messages, leaving ample room for error.1 The Joint Commission notes that communication failures occurring between medical providers account for ~60% of all sentinel or serious adverse events that result in death or harm to a patient.2 Communication that occurs between patients and/or their caregivers and medical providers is also critically important. The content and consistency of this communication is highly valued by patients and providers and can affect patient outcomes during hospitalizations and during transitions to home.3,4 Still, the multifactorial, complex nature of communication in the pediatric inpatient setting is not well understood.5,6

During hospitalization, communication happens continuously during both daytime and nighttime hours. It also precedes the particularly fragile period of transition from hospital to home. Studies have shown that nighttime communication between caregivers and medical providers (ie, nurses and physicians), as well as caregivers’ perceptions of interactions that occur between nurses and physicians, may be closely linked to that caregiver’s satisfaction and perceived quality of care.6,7 Communication that occurs between inpatient and outpatient providers is also subject to barriers (eg, limited availability for direct communication)8-12; studies have shown that patient and/or caregiver satisfaction has also been tied to perceptions of this communication.13,14 Moreover, a caregiver’s ability to understand diagnoses and adhere to postdischarge care plans is intimately tied to communication during the hospitalization and at discharge. Although many improvement efforts have aimed to enhance communication during these vulnerable time periods,3,15,16 there remains much work to be done.1,10,12

The many facets and routes of communication, and the multiple stakeholders involved, make improvement efforts challenging. We believe that more effective communication strategies could result from a deeper understanding of how caregivers view communication successes and challenges during a hospitalization. We see this as key to developing meaningful interventions that are directed towards improving communication and, by extension, patient satisfaction and safety. Here, we sought to extend findings from a broader qualitative study17 by developing an in-depth understanding of communication issues experienced by families during their child’s hospitalization and during the transition to home.

METHODS

Setting

The analyses presented here emerged from the Hospital to Home Outcomes Study (H2O). The first objective of H2O was to explore the caregiver perspective on hospital-to-home transitions. Here, we present the results related to caregiver perspectives of communication, while broader results of our qualitative investigation have been published elsewhere.17 This objective informed the latter 2 aims of the H2O study, which were to modify an existing nurse-led transitional home visit (THV) program and to study the effectiveness of the modified THV on reutilization and patient-specific outcomes via a randomized control trial. The specifics of the H2O protocol and design have been presented elsewhere.18

H2O was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC), a free-standing, academic children’s hospital with ~600 inpatient beds. This teaching hospital has >800 total medical students, residents, and fellows. Approximately 8000 children are hospitalized annually at CCHMC for general pediatric conditions, with ~85% of such admissions staffed by hospitalists from the Division of Hospital Medicine. The division is composed of >40 providers who devote the majority of their clinical time to the hospital medicine service; 15 additional providers work on the hospital medicine service but have primary clinical responsibilities in another division.

Family-centered rounds (FCR) are the standard of care at CCHMC, involving family members at the bedside to discuss patient care plans and diagnoses with the medical team.19 On a typical day, a team conducting FCR is composed of 1 attending, 1 fellow, 2 to 3 pediatric residents, 2 to 3 medical students, a charge nurse or bedside nurse, and a pharmacist. Other ancillary staff, such as social workers, care coordinators, nurse practitioners, or dieticians, may also participate on rounds, particularly for children with greater medical complexity.

Population

Caregivers of children discharged with acute medical conditions were eligible for recruitment if they were English-speaking (we did not have access to interpreter services during focus groups/interviews), had a child admitted to 1 of 3 services (hospital medicine, neurology, or neurosurgery), and could attend a focus group within 30 days of the child’s discharge. The majority of participants had a child admitted to hospital medicine; however, caregivers with a generally healthy child admitted to either neurology or neurosurgery were eligible to participate in the study.

Study Design

As presented elsewhere,17,20 we used focus groups and individual in-depth interviews to generate consensus themes about patient and caregiver experiences during the transition from hospital to home. Because there is evidence suggesting that focus group participants are more willing to talk openly when among others of similar backgrounds, we stratified the sample by the family’s estimated socioeconomic status.21,22 Socioeconomic status was estimated by identifying the poverty rate in the census tract in which each participant lived. Census tracts, relatively homogeneous areas of ~4000 individuals, have been previously shown to effectively detect socioeconomic gradients.23-26 Here, we separated participants into 2 socioeconomically distinct groupings (those in census tracts where <15% or ≥15% of the population lived below the federal poverty level).26 This cut point ensured an equivalent number of eligible participants within each stratum and diversity within our sample.

Data Collection

Caregivers were recruited on the inpatient unit during their child’s hospitalization. Participants then returned to CCHMC facilities for the focus group within 30 days of discharge. Though efforts were made to enhance participation by scheduling sessions at multiple sites and during various days and times of the week, 4 sessions yielded just 1 participant; thus, the format for those became an individual interview. Childcare was provided, and participants received a gift card for their participation.

An open-ended, semistructured question guide,17 developed de novo by the research team, directed the discussion for focus groups and interviews. As data collection progressed, the question guide was adapted to incorporate new issues raised by participants. Questions broadly focused on aspects of the inpatient experience, discharge processes, and healthcare system and family factors thought to be most relevant to patient- and family-centered outcomes. Communication-related questions addressed information shared with families from the medical team about discharge, diagnoses, instructions, and care plans. An experienced moderator and qualitative research methodologist (SNS) used probes to further elucidate responses and expand discussion by participants. Sessions were held in private conference rooms, lasted ~90 minutes, were audiotaped, and were transcribed verbatim. Identifiers were stripped and transcripts were reviewed for accuracy. After conducting 11 focus groups (generally composed of 5-10 participants) and 4 individual interviews, the research team determined that theoretical saturation27 was achieved, and recruitment was suspended.

Data Analysis

An inductive, thematic approach was used for analysis.27 Transcripts were independently reviewed by a multidisciplinary team of 4 researchers, including 2 pediatricians (LGS and AFB), a clinical research coordinator (SAS), and a qualitative research methodologist (SNS). The study team identified emerging concepts and themes related to the transition from hospital to home; themes related to communication during hospitalization are presented here.

During the first phase of analysis, investigators independently read transcripts and later convened to identify and define initial concepts and themes. A preliminary codebook was then designed. Investigators continued to review and code transcripts independently, meeting regularly to discuss coding decisions collaboratively, resolving differences through consensus.28 As patterns in the data became apparent, the codebook was modified iteratively, adding, subtracting, and refining codes as needed and grouping related codes. Results were reviewed with key stakeholders, including parents, inpatient and outpatient pediatricians, and home health nurses, throughout the analytic process.27,28 Coded data were maintained in an electronic database accessible only to study personnel.

RESULTS

Participants

Resulting Themes

Analyses revealed the following 3 major communication-related themes with associated subthemes: (1) experiences that affect caregiver perceptions of communication between the inpatient medical team and families, (2) communication challenges for caregivers related to a teaching hospital environment, and (3) caregiver perceptions of communication between medical providers. Each theme (and subtheme) is explored below with accompanying verbatim quotes in the narrative and the tables.

Major Theme 1: Experiences that Affect Caregiver Perceptions of Communication Between the Inpatient Medical Team and Families

In contrast, some of the negative experiences shared by participants related to feeling excluded from discussions about their child’s care. One participant said, “They tell you…as much as they want to tell you. They don’t fully inform you on things.” Additionally, concerns were voiced about insufficient time for face-to-face discussions with physicians: “I forget what I have to say and it’s something really, really important…But now, my doctor is going, you can’t get the doctor back.” Finally, participants discussed how the use of medical jargon often made it more difficult to understand things, especially for those not in the medical field.

Major Theme 2: Communication Challenges for Caregivers Related to a Teaching Hospital Environment

Major Theme 3: Caregiver Perceptions of Communication Between Medical Providers

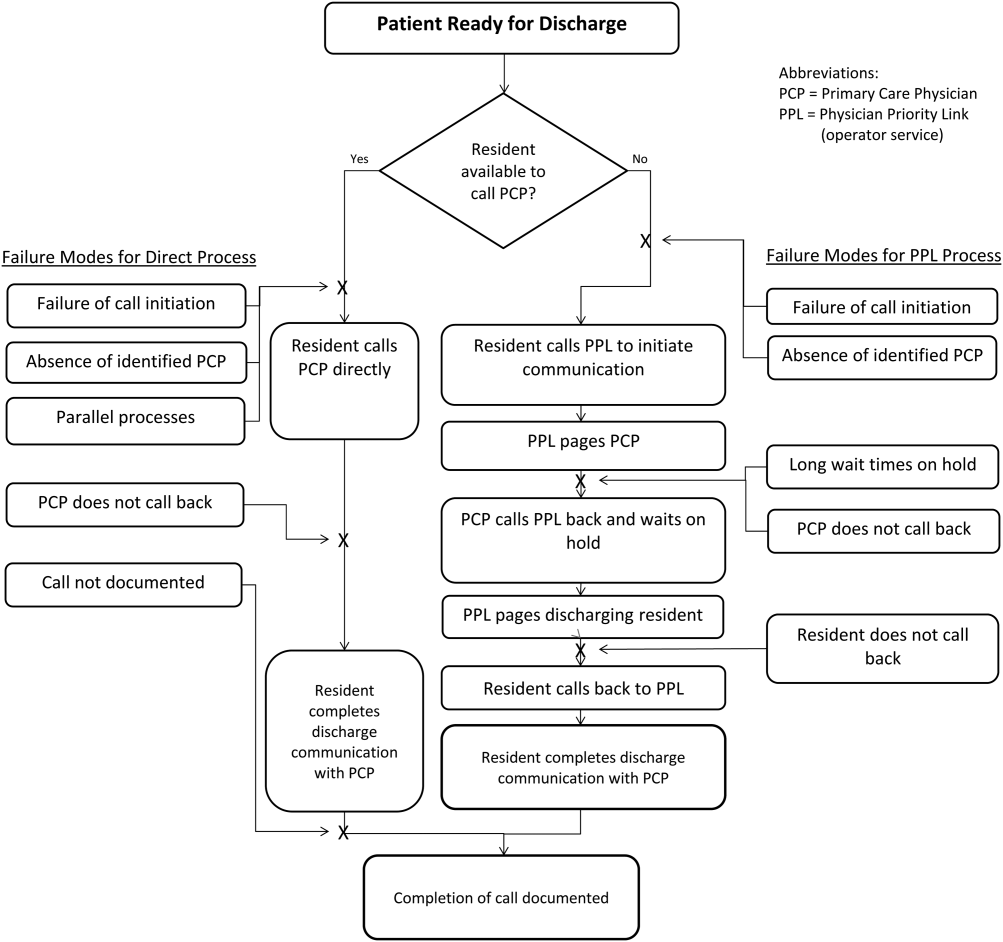

Perceptions were not isolated to the inpatient setting. Based on their experiences, caregivers similarly described their sense of how inpatient and outpatient providers were communicating with each other. In some cases, it was clear that good communication, as perceived by the participant, had occurred in situations in which the primary care physician knew “everything” about the hospitalization when they saw the patient in follow-up. One participant described, “We didn’t even realize at the time, [the medical team] had actually called our doctor and filled them in on our situation, and we got [to the follow up visit]…He already knew the entire situation.” There were others, however, who shared their uncertainty about whether the information exchange about their child’s hospitalization had actually occurred. They, therefore, voiced apprehension around who to call for advice after discharge; would their outpatient provider have their child’s hospitalization history and be able to properly advise them?

DISCUSSION

Communication during a hospitalization and at transition from hospital to home happens in both formal and informal ways; it is a vital component of appropriate, effective patient care. When done poorly, it has the potential to negatively affect a patient’s safety, care, and key outcomes.2 During a hospitalization, the multifaceted nature of communication and multidisciplinary approach to care provision can create communication challenges and make fixing challenges difficult. In order to more comprehensively move toward mitigation, it is important to gather perspectives of key stakeholders, such as caregivers. Caregivers are an integral part of their child’s care during the hospitalization and particularly at home during their child’s recovery. They are also a valued member of the team, particularly in this era of family-centered care.19,29 The perspectives of the caregivers presented here identified both successes and challenges of their communication experiences with the medical team during their child’s hospitalization. These perspectives included experiences affecting perceptions of communication between the inpatient medical team and families; communication related to the teaching hospital environment, including confusing messages associated with large multidisciplinary teams, aspects of FCR, and confusion about medical team member roles; and caregivers’ perceptions of communication between providers in and out of the hospital, including types of communication caregivers observed or believed occurred between medical providers. We believe that these qualitative results are crucial to developing better, more targeted interventions to improve communication.

Maintaining a healthy and productive relationship with patients and their caregivers is critical to providing comprehensive and safe patient care. As supported in the literature, we found that when caregivers were included in conversations, they felt appreciated and valued; in addition, when answers were not directly shared by providers or there were lingering questions, nurses often served as “interpreters.”29,30 Indeed, nurses were seen as a critical touchpoint for many participants, individuals that could not only answer questions but also be a trusted source of information. Supporting such a relationship, and helping enhance the relationship between the family and other team members, may be particularly important considering the degree to which a hospitalization can stress a patient, caregiver, and family.31-34 Developing rapport with families and facilitating relationships with the inclusion of nursing during FCR can be particularly helpful. Though this can be challenging with the many competing priorities of medical providers and the fast-paced, acute nature of inpatient care, making an effort to include nursing staff on rounds can cut down on confusion and assist the family in understanding care plans. This, in turn, can minimize the stress associated with hospitalization and improve the patient and family experience.

While academic institutions’ resources and access to subspecialties are often thought to be advantageous, there are other challenges inherent to providing care in such complex environments. Some caregivers cited confusion related to large teams of providers with, to them, indistinguishable roles asking redundant questions. These experiences affected their perceptions of FCR, generally leading to a fixation on its overwhelming aspects. Certain caregivers highlighted that FCR caused them, and their child, to feel overwhelmed and more confused about the plan for the day. It is important to find ways to mitigate these feelings while simultaneously continuing to support the inclusion of caregivers during their child’s hospitalization and understanding of care plans. Some initiatives (in addition to including nursing on FCR as discussed above) focus on improving the ways in which providers communicate with families during rounds and throughout the day, seeking to decrease miscommunications and medical errors while also striving for better quality of care and patient/family satisfaction.35 Other initiatives seek to clarify identities and roles of the often large and confusing medical team. One such example of this is the development of a face sheet tool, which provides families with medical team members’ photos and role descriptions. Unaka et al.36 found that the use of the face sheet tool improved the ability of caregivers to correctly identify providers and their roles. Thinking beyond interventions at the bedside, it is also important to include caregivers on higher level committees within the institution, such as on family advisory boards and/or peer support groups, to inform systems-wide interventions that support the tenants of family-centered care.29 Efforts such as these are worth trialing in order to improve the patient and family experience and quality of communication.

Multiple studies have evaluated the challenges with ensuring consistent and useful handoffs across the inpatient-to-outpatient transition,8-10,12 but few have looked at it from the perspective of the caregiver.13 After leaving the hospital to care for their recovering child, caregivers often feel overwhelmed; they may want, or need, to rely on the support of others in the outpatient environment. This support can be enhanced when outpatient providers are intimately aware of what occurred during the hospitalization; trust erodes if this is not the case. Given the value caregivers place on this communication occurring and occurring well, interventions supporting this communication are critical. Furthermore, as providers, we should also inform families that communication with outpatient providers is happening. Examples of efforts that have worked to improve the quality and consistency of communication with outpatient providers include improving discharge summary documentation, ensuring timely faxing of documentation to outpatient providers, and reliably making phone calls to outpatient providers.37-39 These types of interventions seek to bridge the gap between inpatient and outpatient care and facilitate a smooth transfer of information in order to provide optimal quality of care and avoid undesired outcomes (eg, emergency department revisits, readmissions, medication errors, etc) and can be adopted by institutions to address the issue of communication between inpatient and outpatient providers.

We acknowledge limitations to our study. This was done at a single academic institution with only English-speaking participants. Thus, our results may not be reflective of caregivers of children cared for in different, more ethnically or linguistically diverse settings. The patient population at CCHMC, however, is diverse both demographically and clinically, which was reflected in the composition of our focus groups and interviews. Additionally, the inclusion of participants who received a nurse home visit after discharge may limit generalizability. However, only 4 participants had a nurse home visit; thus, the overwhelming majority of participants did not receive such an intervention. We also acknowledge that those willing to participate may have differed from nonparticipants, specifically sharing more positive experiences. We believe that our sampling strategy and use of an unbiased, nonhospital affiliated moderator minimized this possibility. Recall bias is possible, as participants were asked to reflect back on a discharge experience occurring in their past. We attempted to minimize this by holding sessions no more than 30 days from the day of discharge. Finally, we present data on caregivers’ perception of communication and not directly observed communication occurrences. Still, we expect that perception is powerful in and of itself, relevant to both outcomes and to interventions.

CONCLUSION

Communication during hospitalization influences how caregivers understand diagnoses and care plans. Communication perceived as effective fosters mutual understandings and positive relationships with the potential to result in better care and improved outcomes. Communication perceived as ineffective negatively affects experiences of patients and their caregivers and can adversely affect patient outcomes. Learning from caregivers’ experiences with communication during their child’s hospitalization can help identify modifiable factors and inform strategies to improve communication, support families through hospitalization, and facilitate a smooth reentry home.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This manuscript is submitted on behalf of the H2O study group: Katherine A. Auger, MD, MSc, JoAnne Bachus, BSN, Monica L. Borell, BSN, Lenisa V. Chang, MA, PhD, Jennifer M. Gold, BSN, Judy A. Heilman, RN, Joseph A. Jabour, BS, Jane C. Khoury, PhD, Margo J. Moore, BSN, CCRP, Rita H. Pickler, PNP, PhD, Anita N. Shah, DO, Angela M. Statile, MD, MEd, Heidi J. Sucharew, PhD, Karen P. Sullivan, BSN, Heather L. Tubbs-Cooley, RN, PhD, Susan Wade-Murphy, MSN, and Christine M. White, MD, MAT.

Disclaimer

All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors, or Methodology Committee.

Disclosure

This work was (partially) supported through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (HIS-1306-0081). The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Riesenberg LA, Leitzsch J, Massucci JL, et al. Residents’ and Attending Physicians’ Handoffs: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Acad Med. 2009;84(12):1775-1787. PubMed

6. Comp D. Improving parent satisfaction by sharing the inpatient daily plan of care: an evidence review with implications for practice and research. Pediatr Nurs. 2011;37(5):237-242. PubMed

30. Latta LC, Dick R, Parry C, Tamura GS. Parental responses to involvement in rounds on a pediatric inpatient unit at a teaching hospital: a qualitative study. Acad Med. 2008;83(3):292-297. PubMed

Provision of high-quality, high-value medical care hinges upon effective communication. During a hospitalization, critical information is communicated between patients, caregivers, and providers multiple times each day. This can cause inconsistent and misinterpreted messages, leaving ample room for error.1 The Joint Commission notes that communication failures occurring between medical providers account for ~60% of all sentinel or serious adverse events that result in death or harm to a patient.2 Communication that occurs between patients and/or their caregivers and medical providers is also critically important. The content and consistency of this communication is highly valued by patients and providers and can affect patient outcomes during hospitalizations and during transitions to home.3,4 Still, the multifactorial, complex nature of communication in the pediatric inpatient setting is not well understood.5,6

During hospitalization, communication happens continuously during both daytime and nighttime hours. It also precedes the particularly fragile period of transition from hospital to home. Studies have shown that nighttime communication between caregivers and medical providers (ie, nurses and physicians), as well as caregivers’ perceptions of interactions that occur between nurses and physicians, may be closely linked to that caregiver’s satisfaction and perceived quality of care.6,7 Communication that occurs between inpatient and outpatient providers is also subject to barriers (eg, limited availability for direct communication)8-12; studies have shown that patient and/or caregiver satisfaction has also been tied to perceptions of this communication.13,14 Moreover, a caregiver’s ability to understand diagnoses and adhere to postdischarge care plans is intimately tied to communication during the hospitalization and at discharge. Although many improvement efforts have aimed to enhance communication during these vulnerable time periods,3,15,16 there remains much work to be done.1,10,12

The many facets and routes of communication, and the multiple stakeholders involved, make improvement efforts challenging. We believe that more effective communication strategies could result from a deeper understanding of how caregivers view communication successes and challenges during a hospitalization. We see this as key to developing meaningful interventions that are directed towards improving communication and, by extension, patient satisfaction and safety. Here, we sought to extend findings from a broader qualitative study17 by developing an in-depth understanding of communication issues experienced by families during their child’s hospitalization and during the transition to home.

METHODS

Setting

The analyses presented here emerged from the Hospital to Home Outcomes Study (H2O). The first objective of H2O was to explore the caregiver perspective on hospital-to-home transitions. Here, we present the results related to caregiver perspectives of communication, while broader results of our qualitative investigation have been published elsewhere.17 This objective informed the latter 2 aims of the H2O study, which were to modify an existing nurse-led transitional home visit (THV) program and to study the effectiveness of the modified THV on reutilization and patient-specific outcomes via a randomized control trial. The specifics of the H2O protocol and design have been presented elsewhere.18

H2O was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC), a free-standing, academic children’s hospital with ~600 inpatient beds. This teaching hospital has >800 total medical students, residents, and fellows. Approximately 8000 children are hospitalized annually at CCHMC for general pediatric conditions, with ~85% of such admissions staffed by hospitalists from the Division of Hospital Medicine. The division is composed of >40 providers who devote the majority of their clinical time to the hospital medicine service; 15 additional providers work on the hospital medicine service but have primary clinical responsibilities in another division.

Family-centered rounds (FCR) are the standard of care at CCHMC, involving family members at the bedside to discuss patient care plans and diagnoses with the medical team.19 On a typical day, a team conducting FCR is composed of 1 attending, 1 fellow, 2 to 3 pediatric residents, 2 to 3 medical students, a charge nurse or bedside nurse, and a pharmacist. Other ancillary staff, such as social workers, care coordinators, nurse practitioners, or dieticians, may also participate on rounds, particularly for children with greater medical complexity.

Population

Caregivers of children discharged with acute medical conditions were eligible for recruitment if they were English-speaking (we did not have access to interpreter services during focus groups/interviews), had a child admitted to 1 of 3 services (hospital medicine, neurology, or neurosurgery), and could attend a focus group within 30 days of the child’s discharge. The majority of participants had a child admitted to hospital medicine; however, caregivers with a generally healthy child admitted to either neurology or neurosurgery were eligible to participate in the study.

Study Design

As presented elsewhere,17,20 we used focus groups and individual in-depth interviews to generate consensus themes about patient and caregiver experiences during the transition from hospital to home. Because there is evidence suggesting that focus group participants are more willing to talk openly when among others of similar backgrounds, we stratified the sample by the family’s estimated socioeconomic status.21,22 Socioeconomic status was estimated by identifying the poverty rate in the census tract in which each participant lived. Census tracts, relatively homogeneous areas of ~4000 individuals, have been previously shown to effectively detect socioeconomic gradients.23-26 Here, we separated participants into 2 socioeconomically distinct groupings (those in census tracts where <15% or ≥15% of the population lived below the federal poverty level).26 This cut point ensured an equivalent number of eligible participants within each stratum and diversity within our sample.

Data Collection

Caregivers were recruited on the inpatient unit during their child’s hospitalization. Participants then returned to CCHMC facilities for the focus group within 30 days of discharge. Though efforts were made to enhance participation by scheduling sessions at multiple sites and during various days and times of the week, 4 sessions yielded just 1 participant; thus, the format for those became an individual interview. Childcare was provided, and participants received a gift card for their participation.

An open-ended, semistructured question guide,17 developed de novo by the research team, directed the discussion for focus groups and interviews. As data collection progressed, the question guide was adapted to incorporate new issues raised by participants. Questions broadly focused on aspects of the inpatient experience, discharge processes, and healthcare system and family factors thought to be most relevant to patient- and family-centered outcomes. Communication-related questions addressed information shared with families from the medical team about discharge, diagnoses, instructions, and care plans. An experienced moderator and qualitative research methodologist (SNS) used probes to further elucidate responses and expand discussion by participants. Sessions were held in private conference rooms, lasted ~90 minutes, were audiotaped, and were transcribed verbatim. Identifiers were stripped and transcripts were reviewed for accuracy. After conducting 11 focus groups (generally composed of 5-10 participants) and 4 individual interviews, the research team determined that theoretical saturation27 was achieved, and recruitment was suspended.

Data Analysis

An inductive, thematic approach was used for analysis.27 Transcripts were independently reviewed by a multidisciplinary team of 4 researchers, including 2 pediatricians (LGS and AFB), a clinical research coordinator (SAS), and a qualitative research methodologist (SNS). The study team identified emerging concepts and themes related to the transition from hospital to home; themes related to communication during hospitalization are presented here.

During the first phase of analysis, investigators independently read transcripts and later convened to identify and define initial concepts and themes. A preliminary codebook was then designed. Investigators continued to review and code transcripts independently, meeting regularly to discuss coding decisions collaboratively, resolving differences through consensus.28 As patterns in the data became apparent, the codebook was modified iteratively, adding, subtracting, and refining codes as needed and grouping related codes. Results were reviewed with key stakeholders, including parents, inpatient and outpatient pediatricians, and home health nurses, throughout the analytic process.27,28 Coded data were maintained in an electronic database accessible only to study personnel.

RESULTS

Participants

Resulting Themes

Analyses revealed the following 3 major communication-related themes with associated subthemes: (1) experiences that affect caregiver perceptions of communication between the inpatient medical team and families, (2) communication challenges for caregivers related to a teaching hospital environment, and (3) caregiver perceptions of communication between medical providers. Each theme (and subtheme) is explored below with accompanying verbatim quotes in the narrative and the tables.

Major Theme 1: Experiences that Affect Caregiver Perceptions of Communication Between the Inpatient Medical Team and Families

In contrast, some of the negative experiences shared by participants related to feeling excluded from discussions about their child’s care. One participant said, “They tell you…as much as they want to tell you. They don’t fully inform you on things.” Additionally, concerns were voiced about insufficient time for face-to-face discussions with physicians: “I forget what I have to say and it’s something really, really important…But now, my doctor is going, you can’t get the doctor back.” Finally, participants discussed how the use of medical jargon often made it more difficult to understand things, especially for those not in the medical field.

Major Theme 2: Communication Challenges for Caregivers Related to a Teaching Hospital Environment

Major Theme 3: Caregiver Perceptions of Communication Between Medical Providers

Perceptions were not isolated to the inpatient setting. Based on their experiences, caregivers similarly described their sense of how inpatient and outpatient providers were communicating with each other. In some cases, it was clear that good communication, as perceived by the participant, had occurred in situations in which the primary care physician knew “everything” about the hospitalization when they saw the patient in follow-up. One participant described, “We didn’t even realize at the time, [the medical team] had actually called our doctor and filled them in on our situation, and we got [to the follow up visit]…He already knew the entire situation.” There were others, however, who shared their uncertainty about whether the information exchange about their child’s hospitalization had actually occurred. They, therefore, voiced apprehension around who to call for advice after discharge; would their outpatient provider have their child’s hospitalization history and be able to properly advise them?

DISCUSSION

Communication during a hospitalization and at transition from hospital to home happens in both formal and informal ways; it is a vital component of appropriate, effective patient care. When done poorly, it has the potential to negatively affect a patient’s safety, care, and key outcomes.2 During a hospitalization, the multifaceted nature of communication and multidisciplinary approach to care provision can create communication challenges and make fixing challenges difficult. In order to more comprehensively move toward mitigation, it is important to gather perspectives of key stakeholders, such as caregivers. Caregivers are an integral part of their child’s care during the hospitalization and particularly at home during their child’s recovery. They are also a valued member of the team, particularly in this era of family-centered care.19,29 The perspectives of the caregivers presented here identified both successes and challenges of their communication experiences with the medical team during their child’s hospitalization. These perspectives included experiences affecting perceptions of communication between the inpatient medical team and families; communication related to the teaching hospital environment, including confusing messages associated with large multidisciplinary teams, aspects of FCR, and confusion about medical team member roles; and caregivers’ perceptions of communication between providers in and out of the hospital, including types of communication caregivers observed or believed occurred between medical providers. We believe that these qualitative results are crucial to developing better, more targeted interventions to improve communication.

Maintaining a healthy and productive relationship with patients and their caregivers is critical to providing comprehensive and safe patient care. As supported in the literature, we found that when caregivers were included in conversations, they felt appreciated and valued; in addition, when answers were not directly shared by providers or there were lingering questions, nurses often served as “interpreters.”29,30 Indeed, nurses were seen as a critical touchpoint for many participants, individuals that could not only answer questions but also be a trusted source of information. Supporting such a relationship, and helping enhance the relationship between the family and other team members, may be particularly important considering the degree to which a hospitalization can stress a patient, caregiver, and family.31-34 Developing rapport with families and facilitating relationships with the inclusion of nursing during FCR can be particularly helpful. Though this can be challenging with the many competing priorities of medical providers and the fast-paced, acute nature of inpatient care, making an effort to include nursing staff on rounds can cut down on confusion and assist the family in understanding care plans. This, in turn, can minimize the stress associated with hospitalization and improve the patient and family experience.

While academic institutions’ resources and access to subspecialties are often thought to be advantageous, there are other challenges inherent to providing care in such complex environments. Some caregivers cited confusion related to large teams of providers with, to them, indistinguishable roles asking redundant questions. These experiences affected their perceptions of FCR, generally leading to a fixation on its overwhelming aspects. Certain caregivers highlighted that FCR caused them, and their child, to feel overwhelmed and more confused about the plan for the day. It is important to find ways to mitigate these feelings while simultaneously continuing to support the inclusion of caregivers during their child’s hospitalization and understanding of care plans. Some initiatives (in addition to including nursing on FCR as discussed above) focus on improving the ways in which providers communicate with families during rounds and throughout the day, seeking to decrease miscommunications and medical errors while also striving for better quality of care and patient/family satisfaction.35 Other initiatives seek to clarify identities and roles of the often large and confusing medical team. One such example of this is the development of a face sheet tool, which provides families with medical team members’ photos and role descriptions. Unaka et al.36 found that the use of the face sheet tool improved the ability of caregivers to correctly identify providers and their roles. Thinking beyond interventions at the bedside, it is also important to include caregivers on higher level committees within the institution, such as on family advisory boards and/or peer support groups, to inform systems-wide interventions that support the tenants of family-centered care.29 Efforts such as these are worth trialing in order to improve the patient and family experience and quality of communication.

Multiple studies have evaluated the challenges with ensuring consistent and useful handoffs across the inpatient-to-outpatient transition,8-10,12 but few have looked at it from the perspective of the caregiver.13 After leaving the hospital to care for their recovering child, caregivers often feel overwhelmed; they may want, or need, to rely on the support of others in the outpatient environment. This support can be enhanced when outpatient providers are intimately aware of what occurred during the hospitalization; trust erodes if this is not the case. Given the value caregivers place on this communication occurring and occurring well, interventions supporting this communication are critical. Furthermore, as providers, we should also inform families that communication with outpatient providers is happening. Examples of efforts that have worked to improve the quality and consistency of communication with outpatient providers include improving discharge summary documentation, ensuring timely faxing of documentation to outpatient providers, and reliably making phone calls to outpatient providers.37-39 These types of interventions seek to bridge the gap between inpatient and outpatient care and facilitate a smooth transfer of information in order to provide optimal quality of care and avoid undesired outcomes (eg, emergency department revisits, readmissions, medication errors, etc) and can be adopted by institutions to address the issue of communication between inpatient and outpatient providers.

We acknowledge limitations to our study. This was done at a single academic institution with only English-speaking participants. Thus, our results may not be reflective of caregivers of children cared for in different, more ethnically or linguistically diverse settings. The patient population at CCHMC, however, is diverse both demographically and clinically, which was reflected in the composition of our focus groups and interviews. Additionally, the inclusion of participants who received a nurse home visit after discharge may limit generalizability. However, only 4 participants had a nurse home visit; thus, the overwhelming majority of participants did not receive such an intervention. We also acknowledge that those willing to participate may have differed from nonparticipants, specifically sharing more positive experiences. We believe that our sampling strategy and use of an unbiased, nonhospital affiliated moderator minimized this possibility. Recall bias is possible, as participants were asked to reflect back on a discharge experience occurring in their past. We attempted to minimize this by holding sessions no more than 30 days from the day of discharge. Finally, we present data on caregivers’ perception of communication and not directly observed communication occurrences. Still, we expect that perception is powerful in and of itself, relevant to both outcomes and to interventions.

CONCLUSION

Communication during hospitalization influences how caregivers understand diagnoses and care plans. Communication perceived as effective fosters mutual understandings and positive relationships with the potential to result in better care and improved outcomes. Communication perceived as ineffective negatively affects experiences of patients and their caregivers and can adversely affect patient outcomes. Learning from caregivers’ experiences with communication during their child’s hospitalization can help identify modifiable factors and inform strategies to improve communication, support families through hospitalization, and facilitate a smooth reentry home.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This manuscript is submitted on behalf of the H2O study group: Katherine A. Auger, MD, MSc, JoAnne Bachus, BSN, Monica L. Borell, BSN, Lenisa V. Chang, MA, PhD, Jennifer M. Gold, BSN, Judy A. Heilman, RN, Joseph A. Jabour, BS, Jane C. Khoury, PhD, Margo J. Moore, BSN, CCRP, Rita H. Pickler, PNP, PhD, Anita N. Shah, DO, Angela M. Statile, MD, MEd, Heidi J. Sucharew, PhD, Karen P. Sullivan, BSN, Heather L. Tubbs-Cooley, RN, PhD, Susan Wade-Murphy, MSN, and Christine M. White, MD, MAT.

Disclaimer

All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors, or Methodology Committee.

Disclosure

This work was (partially) supported through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (HIS-1306-0081). The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Provision of high-quality, high-value medical care hinges upon effective communication. During a hospitalization, critical information is communicated between patients, caregivers, and providers multiple times each day. This can cause inconsistent and misinterpreted messages, leaving ample room for error.1 The Joint Commission notes that communication failures occurring between medical providers account for ~60% of all sentinel or serious adverse events that result in death or harm to a patient.2 Communication that occurs between patients and/or their caregivers and medical providers is also critically important. The content and consistency of this communication is highly valued by patients and providers and can affect patient outcomes during hospitalizations and during transitions to home.3,4 Still, the multifactorial, complex nature of communication in the pediatric inpatient setting is not well understood.5,6

During hospitalization, communication happens continuously during both daytime and nighttime hours. It also precedes the particularly fragile period of transition from hospital to home. Studies have shown that nighttime communication between caregivers and medical providers (ie, nurses and physicians), as well as caregivers’ perceptions of interactions that occur between nurses and physicians, may be closely linked to that caregiver’s satisfaction and perceived quality of care.6,7 Communication that occurs between inpatient and outpatient providers is also subject to barriers (eg, limited availability for direct communication)8-12; studies have shown that patient and/or caregiver satisfaction has also been tied to perceptions of this communication.13,14 Moreover, a caregiver’s ability to understand diagnoses and adhere to postdischarge care plans is intimately tied to communication during the hospitalization and at discharge. Although many improvement efforts have aimed to enhance communication during these vulnerable time periods,3,15,16 there remains much work to be done.1,10,12

The many facets and routes of communication, and the multiple stakeholders involved, make improvement efforts challenging. We believe that more effective communication strategies could result from a deeper understanding of how caregivers view communication successes and challenges during a hospitalization. We see this as key to developing meaningful interventions that are directed towards improving communication and, by extension, patient satisfaction and safety. Here, we sought to extend findings from a broader qualitative study17 by developing an in-depth understanding of communication issues experienced by families during their child’s hospitalization and during the transition to home.

METHODS

Setting

The analyses presented here emerged from the Hospital to Home Outcomes Study (H2O). The first objective of H2O was to explore the caregiver perspective on hospital-to-home transitions. Here, we present the results related to caregiver perspectives of communication, while broader results of our qualitative investigation have been published elsewhere.17 This objective informed the latter 2 aims of the H2O study, which were to modify an existing nurse-led transitional home visit (THV) program and to study the effectiveness of the modified THV on reutilization and patient-specific outcomes via a randomized control trial. The specifics of the H2O protocol and design have been presented elsewhere.18

H2O was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC), a free-standing, academic children’s hospital with ~600 inpatient beds. This teaching hospital has >800 total medical students, residents, and fellows. Approximately 8000 children are hospitalized annually at CCHMC for general pediatric conditions, with ~85% of such admissions staffed by hospitalists from the Division of Hospital Medicine. The division is composed of >40 providers who devote the majority of their clinical time to the hospital medicine service; 15 additional providers work on the hospital medicine service but have primary clinical responsibilities in another division.

Family-centered rounds (FCR) are the standard of care at CCHMC, involving family members at the bedside to discuss patient care plans and diagnoses with the medical team.19 On a typical day, a team conducting FCR is composed of 1 attending, 1 fellow, 2 to 3 pediatric residents, 2 to 3 medical students, a charge nurse or bedside nurse, and a pharmacist. Other ancillary staff, such as social workers, care coordinators, nurse practitioners, or dieticians, may also participate on rounds, particularly for children with greater medical complexity.

Population

Caregivers of children discharged with acute medical conditions were eligible for recruitment if they were English-speaking (we did not have access to interpreter services during focus groups/interviews), had a child admitted to 1 of 3 services (hospital medicine, neurology, or neurosurgery), and could attend a focus group within 30 days of the child’s discharge. The majority of participants had a child admitted to hospital medicine; however, caregivers with a generally healthy child admitted to either neurology or neurosurgery were eligible to participate in the study.

Study Design

As presented elsewhere,17,20 we used focus groups and individual in-depth interviews to generate consensus themes about patient and caregiver experiences during the transition from hospital to home. Because there is evidence suggesting that focus group participants are more willing to talk openly when among others of similar backgrounds, we stratified the sample by the family’s estimated socioeconomic status.21,22 Socioeconomic status was estimated by identifying the poverty rate in the census tract in which each participant lived. Census tracts, relatively homogeneous areas of ~4000 individuals, have been previously shown to effectively detect socioeconomic gradients.23-26 Here, we separated participants into 2 socioeconomically distinct groupings (those in census tracts where <15% or ≥15% of the population lived below the federal poverty level).26 This cut point ensured an equivalent number of eligible participants within each stratum and diversity within our sample.

Data Collection

Caregivers were recruited on the inpatient unit during their child’s hospitalization. Participants then returned to CCHMC facilities for the focus group within 30 days of discharge. Though efforts were made to enhance participation by scheduling sessions at multiple sites and during various days and times of the week, 4 sessions yielded just 1 participant; thus, the format for those became an individual interview. Childcare was provided, and participants received a gift card for their participation.

An open-ended, semistructured question guide,17 developed de novo by the research team, directed the discussion for focus groups and interviews. As data collection progressed, the question guide was adapted to incorporate new issues raised by participants. Questions broadly focused on aspects of the inpatient experience, discharge processes, and healthcare system and family factors thought to be most relevant to patient- and family-centered outcomes. Communication-related questions addressed information shared with families from the medical team about discharge, diagnoses, instructions, and care plans. An experienced moderator and qualitative research methodologist (SNS) used probes to further elucidate responses and expand discussion by participants. Sessions were held in private conference rooms, lasted ~90 minutes, were audiotaped, and were transcribed verbatim. Identifiers were stripped and transcripts were reviewed for accuracy. After conducting 11 focus groups (generally composed of 5-10 participants) and 4 individual interviews, the research team determined that theoretical saturation27 was achieved, and recruitment was suspended.

Data Analysis

An inductive, thematic approach was used for analysis.27 Transcripts were independently reviewed by a multidisciplinary team of 4 researchers, including 2 pediatricians (LGS and AFB), a clinical research coordinator (SAS), and a qualitative research methodologist (SNS). The study team identified emerging concepts and themes related to the transition from hospital to home; themes related to communication during hospitalization are presented here.

During the first phase of analysis, investigators independently read transcripts and later convened to identify and define initial concepts and themes. A preliminary codebook was then designed. Investigators continued to review and code transcripts independently, meeting regularly to discuss coding decisions collaboratively, resolving differences through consensus.28 As patterns in the data became apparent, the codebook was modified iteratively, adding, subtracting, and refining codes as needed and grouping related codes. Results were reviewed with key stakeholders, including parents, inpatient and outpatient pediatricians, and home health nurses, throughout the analytic process.27,28 Coded data were maintained in an electronic database accessible only to study personnel.

RESULTS

Participants

Resulting Themes

Analyses revealed the following 3 major communication-related themes with associated subthemes: (1) experiences that affect caregiver perceptions of communication between the inpatient medical team and families, (2) communication challenges for caregivers related to a teaching hospital environment, and (3) caregiver perceptions of communication between medical providers. Each theme (and subtheme) is explored below with accompanying verbatim quotes in the narrative and the tables.

Major Theme 1: Experiences that Affect Caregiver Perceptions of Communication Between the Inpatient Medical Team and Families

In contrast, some of the negative experiences shared by participants related to feeling excluded from discussions about their child’s care. One participant said, “They tell you…as much as they want to tell you. They don’t fully inform you on things.” Additionally, concerns were voiced about insufficient time for face-to-face discussions with physicians: “I forget what I have to say and it’s something really, really important…But now, my doctor is going, you can’t get the doctor back.” Finally, participants discussed how the use of medical jargon often made it more difficult to understand things, especially for those not in the medical field.

Major Theme 2: Communication Challenges for Caregivers Related to a Teaching Hospital Environment

Major Theme 3: Caregiver Perceptions of Communication Between Medical Providers

Perceptions were not isolated to the inpatient setting. Based on their experiences, caregivers similarly described their sense of how inpatient and outpatient providers were communicating with each other. In some cases, it was clear that good communication, as perceived by the participant, had occurred in situations in which the primary care physician knew “everything” about the hospitalization when they saw the patient in follow-up. One participant described, “We didn’t even realize at the time, [the medical team] had actually called our doctor and filled them in on our situation, and we got [to the follow up visit]…He already knew the entire situation.” There were others, however, who shared their uncertainty about whether the information exchange about their child’s hospitalization had actually occurred. They, therefore, voiced apprehension around who to call for advice after discharge; would their outpatient provider have their child’s hospitalization history and be able to properly advise them?

DISCUSSION

Communication during a hospitalization and at transition from hospital to home happens in both formal and informal ways; it is a vital component of appropriate, effective patient care. When done poorly, it has the potential to negatively affect a patient’s safety, care, and key outcomes.2 During a hospitalization, the multifaceted nature of communication and multidisciplinary approach to care provision can create communication challenges and make fixing challenges difficult. In order to more comprehensively move toward mitigation, it is important to gather perspectives of key stakeholders, such as caregivers. Caregivers are an integral part of their child’s care during the hospitalization and particularly at home during their child’s recovery. They are also a valued member of the team, particularly in this era of family-centered care.19,29 The perspectives of the caregivers presented here identified both successes and challenges of their communication experiences with the medical team during their child’s hospitalization. These perspectives included experiences affecting perceptions of communication between the inpatient medical team and families; communication related to the teaching hospital environment, including confusing messages associated with large multidisciplinary teams, aspects of FCR, and confusion about medical team member roles; and caregivers’ perceptions of communication between providers in and out of the hospital, including types of communication caregivers observed or believed occurred between medical providers. We believe that these qualitative results are crucial to developing better, more targeted interventions to improve communication.

Maintaining a healthy and productive relationship with patients and their caregivers is critical to providing comprehensive and safe patient care. As supported in the literature, we found that when caregivers were included in conversations, they felt appreciated and valued; in addition, when answers were not directly shared by providers or there were lingering questions, nurses often served as “interpreters.”29,30 Indeed, nurses were seen as a critical touchpoint for many participants, individuals that could not only answer questions but also be a trusted source of information. Supporting such a relationship, and helping enhance the relationship between the family and other team members, may be particularly important considering the degree to which a hospitalization can stress a patient, caregiver, and family.31-34 Developing rapport with families and facilitating relationships with the inclusion of nursing during FCR can be particularly helpful. Though this can be challenging with the many competing priorities of medical providers and the fast-paced, acute nature of inpatient care, making an effort to include nursing staff on rounds can cut down on confusion and assist the family in understanding care plans. This, in turn, can minimize the stress associated with hospitalization and improve the patient and family experience.

While academic institutions’ resources and access to subspecialties are often thought to be advantageous, there are other challenges inherent to providing care in such complex environments. Some caregivers cited confusion related to large teams of providers with, to them, indistinguishable roles asking redundant questions. These experiences affected their perceptions of FCR, generally leading to a fixation on its overwhelming aspects. Certain caregivers highlighted that FCR caused them, and their child, to feel overwhelmed and more confused about the plan for the day. It is important to find ways to mitigate these feelings while simultaneously continuing to support the inclusion of caregivers during their child’s hospitalization and understanding of care plans. Some initiatives (in addition to including nursing on FCR as discussed above) focus on improving the ways in which providers communicate with families during rounds and throughout the day, seeking to decrease miscommunications and medical errors while also striving for better quality of care and patient/family satisfaction.35 Other initiatives seek to clarify identities and roles of the often large and confusing medical team. One such example of this is the development of a face sheet tool, which provides families with medical team members’ photos and role descriptions. Unaka et al.36 found that the use of the face sheet tool improved the ability of caregivers to correctly identify providers and their roles. Thinking beyond interventions at the bedside, it is also important to include caregivers on higher level committees within the institution, such as on family advisory boards and/or peer support groups, to inform systems-wide interventions that support the tenants of family-centered care.29 Efforts such as these are worth trialing in order to improve the patient and family experience and quality of communication.

Multiple studies have evaluated the challenges with ensuring consistent and useful handoffs across the inpatient-to-outpatient transition,8-10,12 but few have looked at it from the perspective of the caregiver.13 After leaving the hospital to care for their recovering child, caregivers often feel overwhelmed; they may want, or need, to rely on the support of others in the outpatient environment. This support can be enhanced when outpatient providers are intimately aware of what occurred during the hospitalization; trust erodes if this is not the case. Given the value caregivers place on this communication occurring and occurring well, interventions supporting this communication are critical. Furthermore, as providers, we should also inform families that communication with outpatient providers is happening. Examples of efforts that have worked to improve the quality and consistency of communication with outpatient providers include improving discharge summary documentation, ensuring timely faxing of documentation to outpatient providers, and reliably making phone calls to outpatient providers.37-39 These types of interventions seek to bridge the gap between inpatient and outpatient care and facilitate a smooth transfer of information in order to provide optimal quality of care and avoid undesired outcomes (eg, emergency department revisits, readmissions, medication errors, etc) and can be adopted by institutions to address the issue of communication between inpatient and outpatient providers.

We acknowledge limitations to our study. This was done at a single academic institution with only English-speaking participants. Thus, our results may not be reflective of caregivers of children cared for in different, more ethnically or linguistically diverse settings. The patient population at CCHMC, however, is diverse both demographically and clinically, which was reflected in the composition of our focus groups and interviews. Additionally, the inclusion of participants who received a nurse home visit after discharge may limit generalizability. However, only 4 participants had a nurse home visit; thus, the overwhelming majority of participants did not receive such an intervention. We also acknowledge that those willing to participate may have differed from nonparticipants, specifically sharing more positive experiences. We believe that our sampling strategy and use of an unbiased, nonhospital affiliated moderator minimized this possibility. Recall bias is possible, as participants were asked to reflect back on a discharge experience occurring in their past. We attempted to minimize this by holding sessions no more than 30 days from the day of discharge. Finally, we present data on caregivers’ perception of communication and not directly observed communication occurrences. Still, we expect that perception is powerful in and of itself, relevant to both outcomes and to interventions.

CONCLUSION

Communication during hospitalization influences how caregivers understand diagnoses and care plans. Communication perceived as effective fosters mutual understandings and positive relationships with the potential to result in better care and improved outcomes. Communication perceived as ineffective negatively affects experiences of patients and their caregivers and can adversely affect patient outcomes. Learning from caregivers’ experiences with communication during their child’s hospitalization can help identify modifiable factors and inform strategies to improve communication, support families through hospitalization, and facilitate a smooth reentry home.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This manuscript is submitted on behalf of the H2O study group: Katherine A. Auger, MD, MSc, JoAnne Bachus, BSN, Monica L. Borell, BSN, Lenisa V. Chang, MA, PhD, Jennifer M. Gold, BSN, Judy A. Heilman, RN, Joseph A. Jabour, BS, Jane C. Khoury, PhD, Margo J. Moore, BSN, CCRP, Rita H. Pickler, PNP, PhD, Anita N. Shah, DO, Angela M. Statile, MD, MEd, Heidi J. Sucharew, PhD, Karen P. Sullivan, BSN, Heather L. Tubbs-Cooley, RN, PhD, Susan Wade-Murphy, MSN, and Christine M. White, MD, MAT.

Disclaimer

All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors, or Methodology Committee.

Disclosure

This work was (partially) supported through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (HIS-1306-0081). The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Riesenberg LA, Leitzsch J, Massucci JL, et al. Residents’ and Attending Physicians’ Handoffs: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Acad Med. 2009;84(12):1775-1787. PubMed

6. Comp D. Improving parent satisfaction by sharing the inpatient daily plan of care: an evidence review with implications for practice and research. Pediatr Nurs. 2011;37(5):237-242. PubMed

30. Latta LC, Dick R, Parry C, Tamura GS. Parental responses to involvement in rounds on a pediatric inpatient unit at a teaching hospital: a qualitative study. Acad Med. 2008;83(3):292-297. PubMed

1. Riesenberg LA, Leitzsch J, Massucci JL, et al. Residents’ and Attending Physicians’ Handoffs: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Acad Med. 2009;84(12):1775-1787. PubMed

6. Comp D. Improving parent satisfaction by sharing the inpatient daily plan of care: an evidence review with implications for practice and research. Pediatr Nurs. 2011;37(5):237-242. PubMed

30. Latta LC, Dick R, Parry C, Tamura GS. Parental responses to involvement in rounds on a pediatric inpatient unit at a teaching hospital: a qualitative study. Acad Med. 2008;83(3):292-297. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Monitor Alarms in a Children's Hospital

Physiologic monitor alarms are an inescapable part of the soundtrack for hospitals. Data from primarily adult hospitals have shown that alarms occur at high rates, and most alarms are not actionable.[1] Small studies have suggested that high alarm rates can lead to alarm fatigue.[2, 3] To prioritize alarm types to target in future intervention studies, in this study we aimed to investigate the alarm rates on all inpatient units and the most common causes of alarms at a children's hospital.

METHODS

This was a cross‐sectional study of audible physiologic monitor alarms at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) over 7 consecutive days during August 2014. CCHMC is a 522‐bed free‐standing children's hospital. Inpatient beds are equipped with GE Healthcare (Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) bedside monitors (models Dash 3000, 4000, and 5000, and Solar 8000). Age‐specific vital sign parameters were employed for monitors on all units.

We obtained date, time, and type of alarm from bedside physiologic monitors using Connexall middleware (GlobeStar Systems, Toronto, Ontario, Canada).

We determined unit census using the electronic health records for the time period concurrent with the alarm data collection. Given previously described variation in hospital census over the day,[4] we used 4 daily census measurements (6:00 am, 12:00 pm, 6:00 pm, and 11:00 pm) rather than 1 single measurement to more accurately reflect the hospital census.

The CCHMC Institutional Review Board determined this work to be not human subjects research.

Statistical Analysis

For each unit and each census time interval, we generated a rate based on the number of occupied beds (alarms per patient‐day) resulting in a total of 28 rates (4 census measurement periods per/day 7 days) for each unit over the study period. We used descriptive statistics to summarize alarms per patient‐day by unit. Analysis of variance was used to compare alarm rates between units. For significant main effects, we used Tukey's multiple comparisons tests for all pairwise comparisons to control the type I experiment‐wise error rate. Alarms were then classified by alarm cause (eg, high heart rate). We summarized the cause for all alarms using counts and percentages.

RESULTS

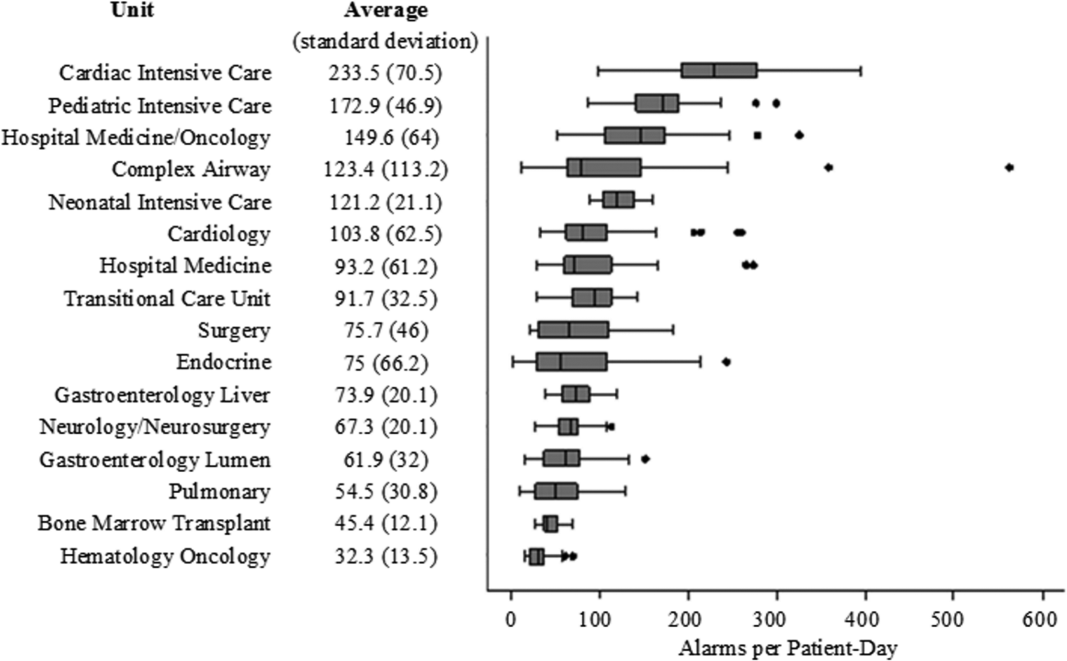

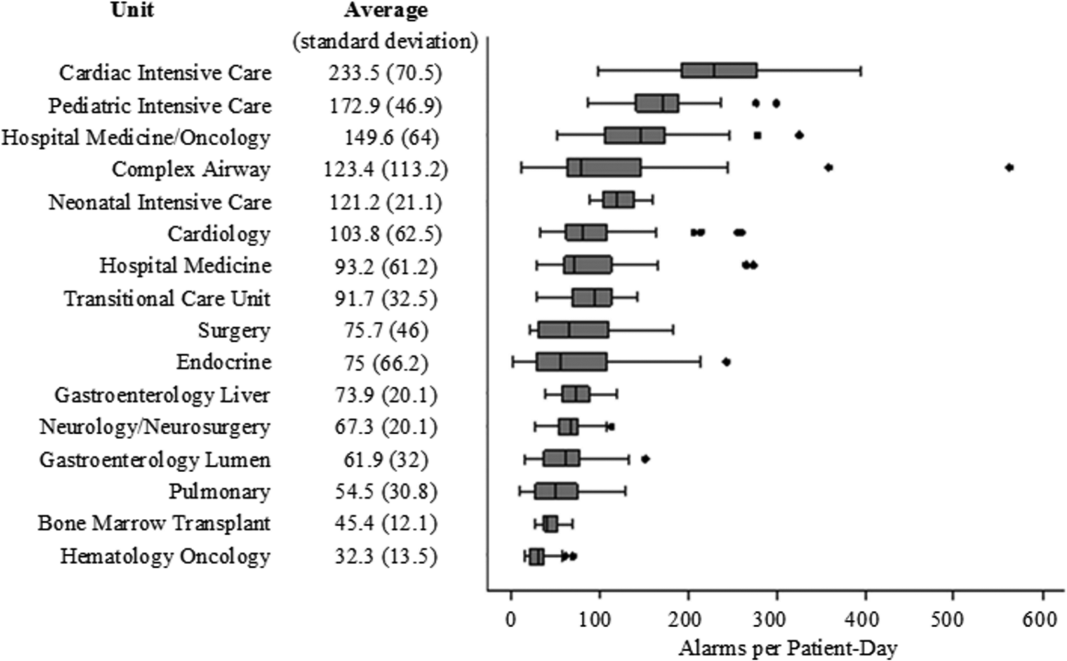

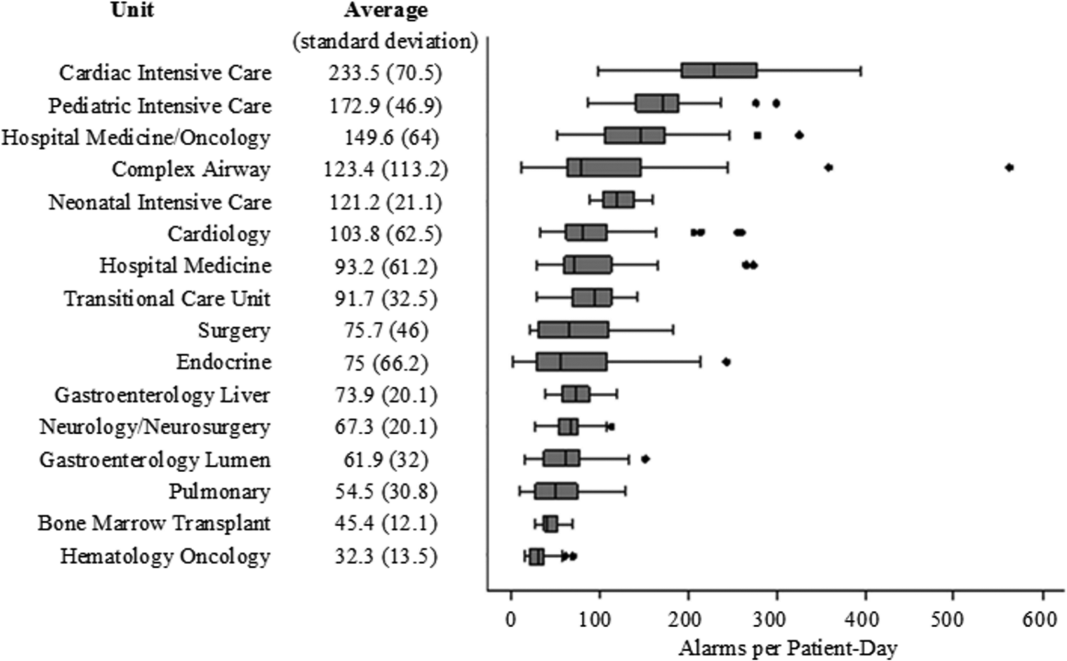

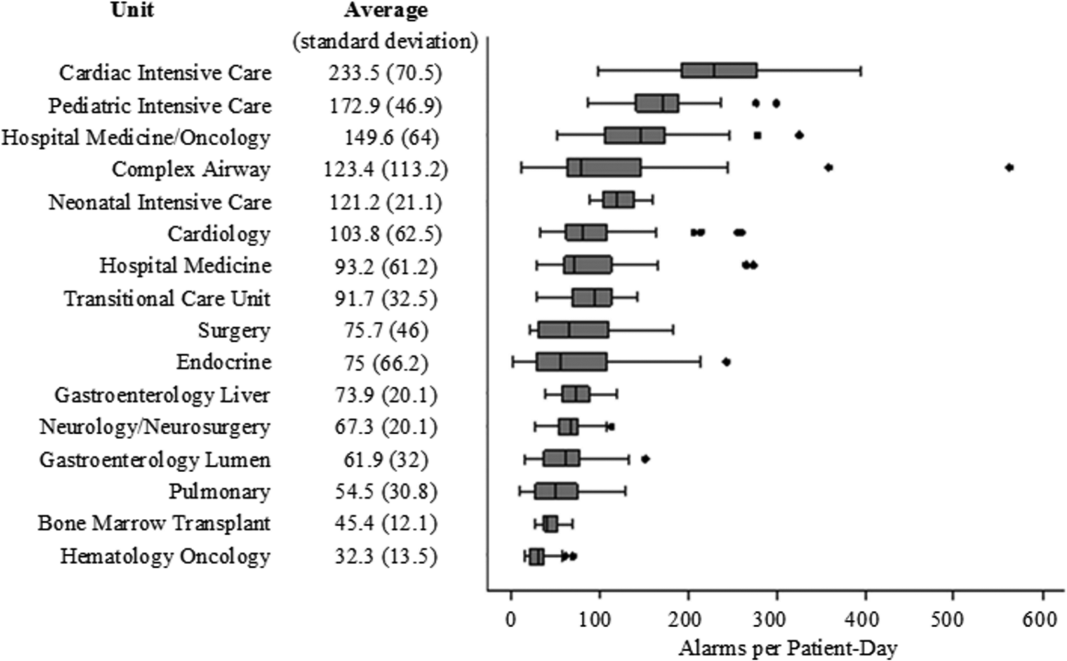

There were a total of 220,813 audible alarms over 1 week. Median alarm rate per patient‐day by unit ranged from 30.4 to 228.5; the highest alarm rates occurred in the cardiac intensive care unit, with a median of 228.5 (interquartile range [IQR], 193275) followed by the pediatric intensive care unit (172.4; IQR, 141188) (Figure 1). The average alarm rate was significantly different among the units (P < 0.01).

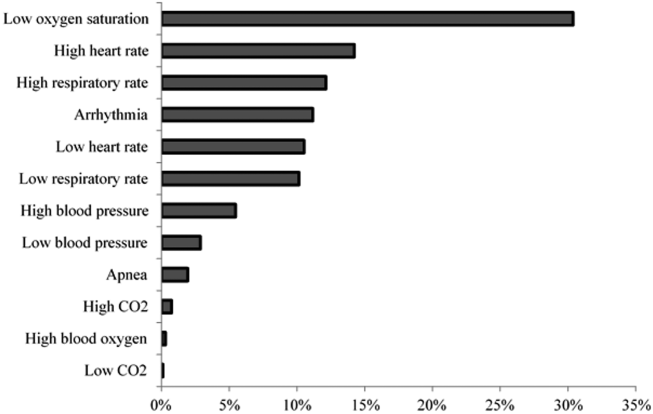

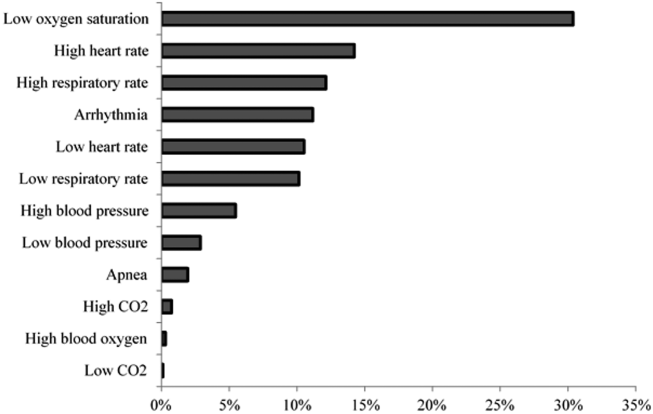

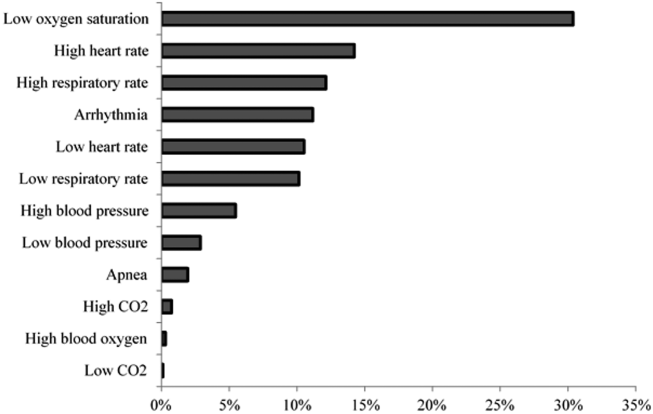

Technical alarms (eg, alarms for artifact, lead failure), comprised 33% of the total number of alarms. The remaining 67% of alarms were for clinical conditions, the most common of which was low oxygen saturation (30% of clinical alarms) (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

We described alarm rates and causes over multiple units at a large children's hospital. To our knowledge, this is the first description of alarm rates across multiple pediatric inpatient units. Alarm counts were high even for the general units, indicating that a nurse taking care of 4 monitored patients would need to process a physiologic monitor alarm every 4 minutes on average, in addition to other sources of alarms such as infusion pumps.

Alarm rates were highest in the intensive care unit areas, which may be attributable to both higher rates of monitoring and sicker patients. Importantly, however, alarms were quite high and variable on the acute care units. This suggests that factors other than patient acuity may have substantial influence on alarm rates.

Technical alarms, alarms that do not indicate a change in patient condition, accounted for the largest percentage of alarms during the study period. This is consistent with prior literature that has suggested that regular electrode replacement, which decreases technical alarms, can be effective in reducing alarm rates.[5, 6] The most common vital sign change to cause alarms was low oxygen saturation, followed by elevated heart rate and elevated respiratory rate. Whereas in most healthy patients, certain low oxygen levels would prompt initiation of supplemental oxygen, there are many conditions in which elevated heart rate and respiratory rate may not require titration of any particular therapy. These may be potential intervention targets for hospitals trying to improve alarm rates.

Limitations

There are several limitations to our study. First, our results are not necessarily generalizable to other types of hospitals or those utilizing monitors from other vendors. Second, we were unable to include other sources of alarms such as infusion pumps and ventilators. However, given the high alarm rates from physiologic monitors alone, these data add urgency to the need for further investigation in the pediatric setting.

CONCLUSION

Alarm rates at a single children's hospital varied depending on the unit. Strategies targeted at reducing technical alarms and reducing nonactionable clinical alarms for low oxygen saturation, high heart rate, and high respiratory rate may offer the greatest opportunity to reduce alarm rates.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Melinda Egan for her assistance in obtaining data for this study and Ting Sa for her assistance with data management.

Disclosures: Dr. Bonafide is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number K23HL116427. Dr. Bonafide also holds a Young Investigator Award grant from the Academic Pediatric Association evaluating the impact of a data‐driven monitor alarm reduction strategy implemented in safety huddles. Dr. Brady is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality under award number K08HS23827. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. This study was funded by the Arnold W. Strauss Fellow Grant, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

- , , , et al. Systematic review of physiologic monitor alarm characteristics and pragmatic interventions to reduce alarm frequency. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(2):136–144.

- , , , et al. Association between exposure to nonactionable physiologic monitor alarms and response time in a children's hospital. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(6):345–351.

- , , , et al. Pulse oximetry desaturation alarms on a general postoperative adult unit: a prospective observational study of nurse response time. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(10):1351–1358.

- , , , , . Traditional measures of hospital utilization may not accurately reflect dynamic patient demand: findings from a children's hospital. Hosp Pediatr. 2012;2(1):10–18.

- , , , et al. A team‐based approach to reducing cardiac monitor alarms. Pediatrics. 2014;134(6):e1686–e1694.

- , , , . Daily electrode change and effect on cardiac monitor alarms: an evidence‐based practice approach. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013;28(3):265–271.

Physiologic monitor alarms are an inescapable part of the soundtrack for hospitals. Data from primarily adult hospitals have shown that alarms occur at high rates, and most alarms are not actionable.[1] Small studies have suggested that high alarm rates can lead to alarm fatigue.[2, 3] To prioritize alarm types to target in future intervention studies, in this study we aimed to investigate the alarm rates on all inpatient units and the most common causes of alarms at a children's hospital.

METHODS

This was a cross‐sectional study of audible physiologic monitor alarms at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) over 7 consecutive days during August 2014. CCHMC is a 522‐bed free‐standing children's hospital. Inpatient beds are equipped with GE Healthcare (Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) bedside monitors (models Dash 3000, 4000, and 5000, and Solar 8000). Age‐specific vital sign parameters were employed for monitors on all units.

We obtained date, time, and type of alarm from bedside physiologic monitors using Connexall middleware (GlobeStar Systems, Toronto, Ontario, Canada).

We determined unit census using the electronic health records for the time period concurrent with the alarm data collection. Given previously described variation in hospital census over the day,[4] we used 4 daily census measurements (6:00 am, 12:00 pm, 6:00 pm, and 11:00 pm) rather than 1 single measurement to more accurately reflect the hospital census.

The CCHMC Institutional Review Board determined this work to be not human subjects research.

Statistical Analysis

For each unit and each census time interval, we generated a rate based on the number of occupied beds (alarms per patient‐day) resulting in a total of 28 rates (4 census measurement periods per/day 7 days) for each unit over the study period. We used descriptive statistics to summarize alarms per patient‐day by unit. Analysis of variance was used to compare alarm rates between units. For significant main effects, we used Tukey's multiple comparisons tests for all pairwise comparisons to control the type I experiment‐wise error rate. Alarms were then classified by alarm cause (eg, high heart rate). We summarized the cause for all alarms using counts and percentages.

RESULTS

There were a total of 220,813 audible alarms over 1 week. Median alarm rate per patient‐day by unit ranged from 30.4 to 228.5; the highest alarm rates occurred in the cardiac intensive care unit, with a median of 228.5 (interquartile range [IQR], 193275) followed by the pediatric intensive care unit (172.4; IQR, 141188) (Figure 1). The average alarm rate was significantly different among the units (P < 0.01).

Technical alarms (eg, alarms for artifact, lead failure), comprised 33% of the total number of alarms. The remaining 67% of alarms were for clinical conditions, the most common of which was low oxygen saturation (30% of clinical alarms) (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

We described alarm rates and causes over multiple units at a large children's hospital. To our knowledge, this is the first description of alarm rates across multiple pediatric inpatient units. Alarm counts were high even for the general units, indicating that a nurse taking care of 4 monitored patients would need to process a physiologic monitor alarm every 4 minutes on average, in addition to other sources of alarms such as infusion pumps.

Alarm rates were highest in the intensive care unit areas, which may be attributable to both higher rates of monitoring and sicker patients. Importantly, however, alarms were quite high and variable on the acute care units. This suggests that factors other than patient acuity may have substantial influence on alarm rates.

Technical alarms, alarms that do not indicate a change in patient condition, accounted for the largest percentage of alarms during the study period. This is consistent with prior literature that has suggested that regular electrode replacement, which decreases technical alarms, can be effective in reducing alarm rates.[5, 6] The most common vital sign change to cause alarms was low oxygen saturation, followed by elevated heart rate and elevated respiratory rate. Whereas in most healthy patients, certain low oxygen levels would prompt initiation of supplemental oxygen, there are many conditions in which elevated heart rate and respiratory rate may not require titration of any particular therapy. These may be potential intervention targets for hospitals trying to improve alarm rates.

Limitations

There are several limitations to our study. First, our results are not necessarily generalizable to other types of hospitals or those utilizing monitors from other vendors. Second, we were unable to include other sources of alarms such as infusion pumps and ventilators. However, given the high alarm rates from physiologic monitors alone, these data add urgency to the need for further investigation in the pediatric setting.

CONCLUSION

Alarm rates at a single children's hospital varied depending on the unit. Strategies targeted at reducing technical alarms and reducing nonactionable clinical alarms for low oxygen saturation, high heart rate, and high respiratory rate may offer the greatest opportunity to reduce alarm rates.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Melinda Egan for her assistance in obtaining data for this study and Ting Sa for her assistance with data management.