User login

What’s Eating You? Cat Flea (Ctenocephalides felis) Revisited

Fleas of the order Siphonaptera are insects that feed on the blood of a mammalian host. They have no wings but jump to near 150 times their body lengths to reach potential hosts.1 An epidemiologic survey performed in 2016 demonstrated that 96% of fleas in the United States are cat fleas (Ctenocephalides felis).2 The bites often present as pruritic, nonfollicular-based, excoriated papules; papular urticaria; or vesiculobullous lesions distributed across the lower legs. Antihistamines and topical steroids may be helpful for symptomatic relief, but flea eradication is key.

Identification

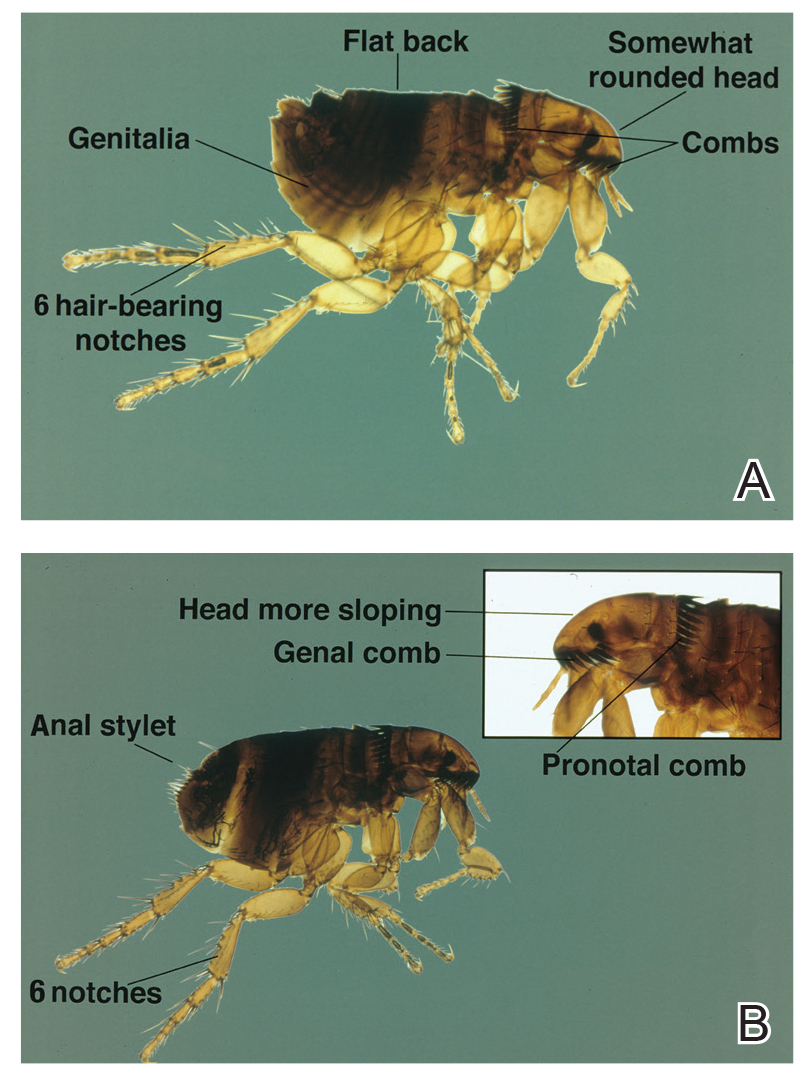

Ctenocephalides fleas, including the common cat flea and the dog flea, have a characteristic pronotal comb that resembles a mane of hair (Figure 1) and genal comb that resembles a mustache. Compared to the dog flea (Ctenocephalides canis), cat fleas have a flatter head and fewer hair-bearing notches on the dorsal hind tibia (the dog flea has 8 notches and the cat flea has 6 notches)(Figure 2).

Flea Prevention and Eradication

Effective management of flea bites requires avoidance of infested areas and eradication of fleas from the home and pets. Home treatment should be performed by a qualified specialist and a veterinarian should treat the pet, but the dermatologist must be knowledgeable about treatment options. Flea pupae can lie dormant between floorboards for extended periods of time and hatch rapidly when new tenants enter a house or apartment. Insecticidal dusts and spray formulations frequently are used to treat infested homes. It also is important to reduce flea egg numbers by vacuuming carpets and areas where pets sleep.3 Rodents often introduce fleas to households and pets, so eliminating them from the area may play an important role in flea control. Consulting with a veterinarian is important, as treatment directed at pets is critical to control flea populations. Oral agents, including fluralaner, afoxolaner, sarolaner, and spinosad, can reduce flea populations on animals by as much as 99.3% after 7 days.4,5 Fast-acting pulicidal agents, such as the combination of dinotefuran and fipronil, demonstrate curative activity as soon as 3 hours after treatment, which also may prevent reinfestation for as long as 6 weeks after treatment.6

Vector-Borne Disease

Fleas living on animals in close contact with humans, such as cats and dogs, can transmit zoonotic pathogens. Around 12,000 outpatients and 500 inpatients are diagnosed with cat scratch disease, a form of bartonellosis, annually. Ctenocephalides felis transmits Bartonella henselae from cat-to-cat and often cat-to-human through infected flea feces, causing a primary inoculation lesion and lymphadenitis. Of 3011 primary care providers surveyed from 2014 to 2015, 37.2% had treated at least 1 patient with cat scratch disease, yet knowledge gaps remain regarding the proper treatment and preventative measures for the disease.7 Current recommendations for the treatment of lymphadenitis caused by B henselae include a 5-day course of oral azithromycin.8 The preferred dosing regimen in adults is 500 mg on day 1 and 250 mg on days 2 through 5. Pediatric patients weighing less than 45.5 kg should receive 10 mg/kg on day 1 and 5 mg/kg on days 2 through 5.8 Additionally, less than one-third of the primary care providers surveyed from 2014 to 2015 said they would discuss the importance of pet flea control with immunocompromised patients who own cats, despite evidence implicating fleas in disease transmission.7 Pet-directed topical therapy with agents such as selamectin prescribed by a qualified veterinarian can prevent transmission of B henselae in cats exposed to fleas infected with the bacteria,9 which supports the importance of patient education and flea control, especially in pets owned by immunocompromised patients. Patients who are immunocompromised are at increased risk for persistent or disseminated bartonellosis, including endocarditis, in addition to cat scratch disease. Although arriving at a diagnosis may be difficult, one study found that bartonellosis in 13 renal transplant recipients was best diagnosed using both serology and polymerase chain reaction via DNA extraction of tissue specimens.10 These findings may enhance diagnostic yield for similar patients when bartonellosis is suspected.

Flea-borne typhus is endemic to Texas and Southern California.11,12 Evidence suggests that the pathogenic bacteria, Rickettsia typhi and Rickettsia felis, also commonly infect fleas in the Great Plains area.13 Opossums carry R felis, and the fleas transmit murine or endemic typhus. A retrospective case series in Texas identified 11 cases of fatal flea-borne typhus from 1985 to 2015.11 More than half of the patients reported contact with animals or fleas prior to the illness. Patients with typhus may present with fever, nausea, vomiting, rash (macular, maculopapular, papular, petechial, or morbilliform), respiratory or neurologic symptoms, thrombocytopenia, and elevated hepatic liver enzymes. Unfortunately, there often is a notable delay in initiation of treatment with the appropriate class of antibiotics—tetracyclines—and such delays can prove fatal.11 The current recommendation for nonpregnant adults is oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily continued 48 hours after the patient becomes afebrile or for 7 days, whichever therapy duration is longer.14 Because of the consequences of delayed treatment, it is important for clinicians to consider a diagnosis of vector-borne illness in a febrile patient with other associated gastrointestinal, cutaneous, respiratory, or neurologic symptoms, especially if they have animal or flea exposures. Flea control and exposure awareness remains paramount in preventing and treating this illness.

Yersinia pestis causes the plague, an important re-emerging disease that causes infection through flea bites, inhalation, or ingestion.15 From 2000 to 2009, 56 cases and 7 deaths in the United States—New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, California, and Texas—and 21,725 cases and 1612 deaths worldwide were attributed to Y pestis. Most patients present with the bubonic form of the disease, with fever and an enlarging painful femoral or inguinal lymph node due to leg flea bites.16 Other forms of disease, including septicemic and pneumonic plague, are less common but relevant, as one-third of cases in the United States present with septicemia.15,17,18 Although molecular diagnosis and immunohistochemistry play important roles, the diagnosis of Y pestis infection often is still accomplished with culture. A 2012 survey of 392 strains from 17 countries demonstrated that Y pestis remained susceptible to the antibiotics currently used to treat the disease, including doxycycline, streptomycin, gentamicin, tetracycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and ciprofloxacin.19

Human infection with Dipylidium caninum, a dog tapeworm, has been reported after suspected accidental ingestion of cat fleas carrying the parasite.20 Children, who may present with diarrhea or white worms in their feces, are more susceptible to the infection, perhaps due to accidental flea consumption while being licked by the pet.20,21

Conclusion

Cat fleas may act as a pruritic nuisance for pet owners and even deliver deadly pathogens to immunocompromised patients. Providers can minimize their impact by educating patients on flea prevention and eradication as well as astutely recognizing and treating flea-borne diseases.

- Cadiergues MC. A comparison of jump performances of the dog flea, Ctenocephalides canis (Curtis, 1826) and the cat flea, Ctenocephalides felis (Bouché, 1835). Vet Parasitol. 2000;92:239-241.

- Blagburn B, Butler J, Land T, et al. Who’s who and where: prevalence of Ctenocephalides felis and Ctenocephalides canis in shelter dogs and cats in the United States. Presented at: American Association of Veterinary Parasitologists 61st Annual Meeting; August 6-9, 2016; San Antonio, TX. P9.

- Bitam I, Dittmar K, Parola P, et al. Fleas and flea-borne diseases. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:E667-E676.

- Dryden MW, Canfield MS, Niedfeldt E, et al. Evaluation of sarolaner and spinosad oral treatments to eliminate fleas, reduce dermatologic lesions and minimize pruritus in naturally infested dogs in west Central Florida, USA. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:389.

- Dryden MW, Canfield MS, Kalosy K, et al. Evaluation of fluralaner and afoxolaner treatments to control flea populations, reduce pruritus and minimize dermatologic lesions in naturally infested dogs in private residences in west Central Florida, USA. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:365.

- Delcombel R, Karembe H, Nare B, et al. Synergy between dinotefuran and fipronil against the cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis): improved onset of action and residual speed of kill in adult cats. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:341.

- Nelson CA, Moore AR, Perea AE, et al. Cat scratch disease: U.S. clinicians’ experience and knowledge. Zoonoses Public Health. 2018;65:67-73.

- Spach DH, Kaplan SL. Treatment of cat scratch disease. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-cat-scratch-disease?search=treatment%20of%20cat%20scratch&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~59&usage_type=default&display_rank=1.Updated June 12, 2019. Accessed August 15, 2019.

- Bouhsira E, Franc M, Lienard E, et al. The efficacy of a selamectin (Stronghold®) spot on treatment in the prevention of Bartonella henselae transmission by Ctenocephalides felis in cats, using a new high-challenge model. Parasitol Res. 2015;114:1045-1050.

- Shamekhi Amiri F. Bartonellosis in chronic kidney disease: an unrecognized and unsuspected diagnosis. Ther Apher Dial. 2017;21:430-440.

- Pieracci EG, Evert N, Drexler NA, et al. Fatal flea-borne typhus in Texas: a retrospective case series, 1985-2015. American J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;96:1088-1093.

- Maina AN, Fogarty C, Krueger L, et al. Rickettsial infections among Ctenocephalides felis and host animals during a flea-borne rickettsioses outbreak in Orange County, California. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0160604.

- Noden BH, Davidson S, Smith JL, et al. First detection of Rickettsia typhi and Rickettsia felis in fleas collected from client-owned companion animals in the Southern Great Plains. J Med Entomol. 2017;54:1093-1097.

- Sexton DJ. Murine typhus. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/murine-typhus?search=diagnosis-and-treatment-of-murine-typhus&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~21&usage_type=default&display_rank=1. Updated January 17, 2019. Accessed August 15, 2019.

- Riehm JM, Löscher T. Human plague and pneumonic plague: pathogenicity, epidemiology, clinical presentations and therapy [in German]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2015;58:721-729.

- Butler T. Plague gives surprises in the first decade of the 21st century in the United States and worldwide. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89:788-793.

- Gould LH, Pape J, Ettestad P, Griffith KS, et al. Dog-associated risk factors for human plague. Zoonoses Public Health. 2008;55:448-454.

- Margolis DA, Burns J, Reed SL, et al. Septicemic plague in a community hospital in California. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78:868-871.

- Urich SK, Chalcraft L, Schriefer ME, et al. Lack of antimicrobial resistance in Yersinia pestis isolates from 17 countries in the Americas, Africa, and Asia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:555-558.

- Jiang P, Zhang X, Liu RD, et al. A human case of zoonotic dog tapeworm, Dipylidium caninum (Eucestoda: Dilepidiidae), in China. Korean J Parasitol. 2017;55:61-64.

- Roberts LS, Janovy J Jr, eds. Foundations of Parasitology. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009.

Fleas of the order Siphonaptera are insects that feed on the blood of a mammalian host. They have no wings but jump to near 150 times their body lengths to reach potential hosts.1 An epidemiologic survey performed in 2016 demonstrated that 96% of fleas in the United States are cat fleas (Ctenocephalides felis).2 The bites often present as pruritic, nonfollicular-based, excoriated papules; papular urticaria; or vesiculobullous lesions distributed across the lower legs. Antihistamines and topical steroids may be helpful for symptomatic relief, but flea eradication is key.

Identification

Ctenocephalides fleas, including the common cat flea and the dog flea, have a characteristic pronotal comb that resembles a mane of hair (Figure 1) and genal comb that resembles a mustache. Compared to the dog flea (Ctenocephalides canis), cat fleas have a flatter head and fewer hair-bearing notches on the dorsal hind tibia (the dog flea has 8 notches and the cat flea has 6 notches)(Figure 2).

Flea Prevention and Eradication

Effective management of flea bites requires avoidance of infested areas and eradication of fleas from the home and pets. Home treatment should be performed by a qualified specialist and a veterinarian should treat the pet, but the dermatologist must be knowledgeable about treatment options. Flea pupae can lie dormant between floorboards for extended periods of time and hatch rapidly when new tenants enter a house or apartment. Insecticidal dusts and spray formulations frequently are used to treat infested homes. It also is important to reduce flea egg numbers by vacuuming carpets and areas where pets sleep.3 Rodents often introduce fleas to households and pets, so eliminating them from the area may play an important role in flea control. Consulting with a veterinarian is important, as treatment directed at pets is critical to control flea populations. Oral agents, including fluralaner, afoxolaner, sarolaner, and spinosad, can reduce flea populations on animals by as much as 99.3% after 7 days.4,5 Fast-acting pulicidal agents, such as the combination of dinotefuran and fipronil, demonstrate curative activity as soon as 3 hours after treatment, which also may prevent reinfestation for as long as 6 weeks after treatment.6

Vector-Borne Disease

Fleas living on animals in close contact with humans, such as cats and dogs, can transmit zoonotic pathogens. Around 12,000 outpatients and 500 inpatients are diagnosed with cat scratch disease, a form of bartonellosis, annually. Ctenocephalides felis transmits Bartonella henselae from cat-to-cat and often cat-to-human through infected flea feces, causing a primary inoculation lesion and lymphadenitis. Of 3011 primary care providers surveyed from 2014 to 2015, 37.2% had treated at least 1 patient with cat scratch disease, yet knowledge gaps remain regarding the proper treatment and preventative measures for the disease.7 Current recommendations for the treatment of lymphadenitis caused by B henselae include a 5-day course of oral azithromycin.8 The preferred dosing regimen in adults is 500 mg on day 1 and 250 mg on days 2 through 5. Pediatric patients weighing less than 45.5 kg should receive 10 mg/kg on day 1 and 5 mg/kg on days 2 through 5.8 Additionally, less than one-third of the primary care providers surveyed from 2014 to 2015 said they would discuss the importance of pet flea control with immunocompromised patients who own cats, despite evidence implicating fleas in disease transmission.7 Pet-directed topical therapy with agents such as selamectin prescribed by a qualified veterinarian can prevent transmission of B henselae in cats exposed to fleas infected with the bacteria,9 which supports the importance of patient education and flea control, especially in pets owned by immunocompromised patients. Patients who are immunocompromised are at increased risk for persistent or disseminated bartonellosis, including endocarditis, in addition to cat scratch disease. Although arriving at a diagnosis may be difficult, one study found that bartonellosis in 13 renal transplant recipients was best diagnosed using both serology and polymerase chain reaction via DNA extraction of tissue specimens.10 These findings may enhance diagnostic yield for similar patients when bartonellosis is suspected.

Flea-borne typhus is endemic to Texas and Southern California.11,12 Evidence suggests that the pathogenic bacteria, Rickettsia typhi and Rickettsia felis, also commonly infect fleas in the Great Plains area.13 Opossums carry R felis, and the fleas transmit murine or endemic typhus. A retrospective case series in Texas identified 11 cases of fatal flea-borne typhus from 1985 to 2015.11 More than half of the patients reported contact with animals or fleas prior to the illness. Patients with typhus may present with fever, nausea, vomiting, rash (macular, maculopapular, papular, petechial, or morbilliform), respiratory or neurologic symptoms, thrombocytopenia, and elevated hepatic liver enzymes. Unfortunately, there often is a notable delay in initiation of treatment with the appropriate class of antibiotics—tetracyclines—and such delays can prove fatal.11 The current recommendation for nonpregnant adults is oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily continued 48 hours after the patient becomes afebrile or for 7 days, whichever therapy duration is longer.14 Because of the consequences of delayed treatment, it is important for clinicians to consider a diagnosis of vector-borne illness in a febrile patient with other associated gastrointestinal, cutaneous, respiratory, or neurologic symptoms, especially if they have animal or flea exposures. Flea control and exposure awareness remains paramount in preventing and treating this illness.

Yersinia pestis causes the plague, an important re-emerging disease that causes infection through flea bites, inhalation, or ingestion.15 From 2000 to 2009, 56 cases and 7 deaths in the United States—New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, California, and Texas—and 21,725 cases and 1612 deaths worldwide were attributed to Y pestis. Most patients present with the bubonic form of the disease, with fever and an enlarging painful femoral or inguinal lymph node due to leg flea bites.16 Other forms of disease, including septicemic and pneumonic plague, are less common but relevant, as one-third of cases in the United States present with septicemia.15,17,18 Although molecular diagnosis and immunohistochemistry play important roles, the diagnosis of Y pestis infection often is still accomplished with culture. A 2012 survey of 392 strains from 17 countries demonstrated that Y pestis remained susceptible to the antibiotics currently used to treat the disease, including doxycycline, streptomycin, gentamicin, tetracycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and ciprofloxacin.19

Human infection with Dipylidium caninum, a dog tapeworm, has been reported after suspected accidental ingestion of cat fleas carrying the parasite.20 Children, who may present with diarrhea or white worms in their feces, are more susceptible to the infection, perhaps due to accidental flea consumption while being licked by the pet.20,21

Conclusion

Cat fleas may act as a pruritic nuisance for pet owners and even deliver deadly pathogens to immunocompromised patients. Providers can minimize their impact by educating patients on flea prevention and eradication as well as astutely recognizing and treating flea-borne diseases.

Fleas of the order Siphonaptera are insects that feed on the blood of a mammalian host. They have no wings but jump to near 150 times their body lengths to reach potential hosts.1 An epidemiologic survey performed in 2016 demonstrated that 96% of fleas in the United States are cat fleas (Ctenocephalides felis).2 The bites often present as pruritic, nonfollicular-based, excoriated papules; papular urticaria; or vesiculobullous lesions distributed across the lower legs. Antihistamines and topical steroids may be helpful for symptomatic relief, but flea eradication is key.

Identification

Ctenocephalides fleas, including the common cat flea and the dog flea, have a characteristic pronotal comb that resembles a mane of hair (Figure 1) and genal comb that resembles a mustache. Compared to the dog flea (Ctenocephalides canis), cat fleas have a flatter head and fewer hair-bearing notches on the dorsal hind tibia (the dog flea has 8 notches and the cat flea has 6 notches)(Figure 2).

Flea Prevention and Eradication

Effective management of flea bites requires avoidance of infested areas and eradication of fleas from the home and pets. Home treatment should be performed by a qualified specialist and a veterinarian should treat the pet, but the dermatologist must be knowledgeable about treatment options. Flea pupae can lie dormant between floorboards for extended periods of time and hatch rapidly when new tenants enter a house or apartment. Insecticidal dusts and spray formulations frequently are used to treat infested homes. It also is important to reduce flea egg numbers by vacuuming carpets and areas where pets sleep.3 Rodents often introduce fleas to households and pets, so eliminating them from the area may play an important role in flea control. Consulting with a veterinarian is important, as treatment directed at pets is critical to control flea populations. Oral agents, including fluralaner, afoxolaner, sarolaner, and spinosad, can reduce flea populations on animals by as much as 99.3% after 7 days.4,5 Fast-acting pulicidal agents, such as the combination of dinotefuran and fipronil, demonstrate curative activity as soon as 3 hours after treatment, which also may prevent reinfestation for as long as 6 weeks after treatment.6

Vector-Borne Disease

Fleas living on animals in close contact with humans, such as cats and dogs, can transmit zoonotic pathogens. Around 12,000 outpatients and 500 inpatients are diagnosed with cat scratch disease, a form of bartonellosis, annually. Ctenocephalides felis transmits Bartonella henselae from cat-to-cat and often cat-to-human through infected flea feces, causing a primary inoculation lesion and lymphadenitis. Of 3011 primary care providers surveyed from 2014 to 2015, 37.2% had treated at least 1 patient with cat scratch disease, yet knowledge gaps remain regarding the proper treatment and preventative measures for the disease.7 Current recommendations for the treatment of lymphadenitis caused by B henselae include a 5-day course of oral azithromycin.8 The preferred dosing regimen in adults is 500 mg on day 1 and 250 mg on days 2 through 5. Pediatric patients weighing less than 45.5 kg should receive 10 mg/kg on day 1 and 5 mg/kg on days 2 through 5.8 Additionally, less than one-third of the primary care providers surveyed from 2014 to 2015 said they would discuss the importance of pet flea control with immunocompromised patients who own cats, despite evidence implicating fleas in disease transmission.7 Pet-directed topical therapy with agents such as selamectin prescribed by a qualified veterinarian can prevent transmission of B henselae in cats exposed to fleas infected with the bacteria,9 which supports the importance of patient education and flea control, especially in pets owned by immunocompromised patients. Patients who are immunocompromised are at increased risk for persistent or disseminated bartonellosis, including endocarditis, in addition to cat scratch disease. Although arriving at a diagnosis may be difficult, one study found that bartonellosis in 13 renal transplant recipients was best diagnosed using both serology and polymerase chain reaction via DNA extraction of tissue specimens.10 These findings may enhance diagnostic yield for similar patients when bartonellosis is suspected.

Flea-borne typhus is endemic to Texas and Southern California.11,12 Evidence suggests that the pathogenic bacteria, Rickettsia typhi and Rickettsia felis, also commonly infect fleas in the Great Plains area.13 Opossums carry R felis, and the fleas transmit murine or endemic typhus. A retrospective case series in Texas identified 11 cases of fatal flea-borne typhus from 1985 to 2015.11 More than half of the patients reported contact with animals or fleas prior to the illness. Patients with typhus may present with fever, nausea, vomiting, rash (macular, maculopapular, papular, petechial, or morbilliform), respiratory or neurologic symptoms, thrombocytopenia, and elevated hepatic liver enzymes. Unfortunately, there often is a notable delay in initiation of treatment with the appropriate class of antibiotics—tetracyclines—and such delays can prove fatal.11 The current recommendation for nonpregnant adults is oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily continued 48 hours after the patient becomes afebrile or for 7 days, whichever therapy duration is longer.14 Because of the consequences of delayed treatment, it is important for clinicians to consider a diagnosis of vector-borne illness in a febrile patient with other associated gastrointestinal, cutaneous, respiratory, or neurologic symptoms, especially if they have animal or flea exposures. Flea control and exposure awareness remains paramount in preventing and treating this illness.

Yersinia pestis causes the plague, an important re-emerging disease that causes infection through flea bites, inhalation, or ingestion.15 From 2000 to 2009, 56 cases and 7 deaths in the United States—New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, California, and Texas—and 21,725 cases and 1612 deaths worldwide were attributed to Y pestis. Most patients present with the bubonic form of the disease, with fever and an enlarging painful femoral or inguinal lymph node due to leg flea bites.16 Other forms of disease, including septicemic and pneumonic plague, are less common but relevant, as one-third of cases in the United States present with septicemia.15,17,18 Although molecular diagnosis and immunohistochemistry play important roles, the diagnosis of Y pestis infection often is still accomplished with culture. A 2012 survey of 392 strains from 17 countries demonstrated that Y pestis remained susceptible to the antibiotics currently used to treat the disease, including doxycycline, streptomycin, gentamicin, tetracycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and ciprofloxacin.19

Human infection with Dipylidium caninum, a dog tapeworm, has been reported after suspected accidental ingestion of cat fleas carrying the parasite.20 Children, who may present with diarrhea or white worms in their feces, are more susceptible to the infection, perhaps due to accidental flea consumption while being licked by the pet.20,21

Conclusion

Cat fleas may act as a pruritic nuisance for pet owners and even deliver deadly pathogens to immunocompromised patients. Providers can minimize their impact by educating patients on flea prevention and eradication as well as astutely recognizing and treating flea-borne diseases.

- Cadiergues MC. A comparison of jump performances of the dog flea, Ctenocephalides canis (Curtis, 1826) and the cat flea, Ctenocephalides felis (Bouché, 1835). Vet Parasitol. 2000;92:239-241.

- Blagburn B, Butler J, Land T, et al. Who’s who and where: prevalence of Ctenocephalides felis and Ctenocephalides canis in shelter dogs and cats in the United States. Presented at: American Association of Veterinary Parasitologists 61st Annual Meeting; August 6-9, 2016; San Antonio, TX. P9.

- Bitam I, Dittmar K, Parola P, et al. Fleas and flea-borne diseases. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:E667-E676.

- Dryden MW, Canfield MS, Niedfeldt E, et al. Evaluation of sarolaner and spinosad oral treatments to eliminate fleas, reduce dermatologic lesions and minimize pruritus in naturally infested dogs in west Central Florida, USA. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:389.

- Dryden MW, Canfield MS, Kalosy K, et al. Evaluation of fluralaner and afoxolaner treatments to control flea populations, reduce pruritus and minimize dermatologic lesions in naturally infested dogs in private residences in west Central Florida, USA. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:365.

- Delcombel R, Karembe H, Nare B, et al. Synergy between dinotefuran and fipronil against the cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis): improved onset of action and residual speed of kill in adult cats. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:341.

- Nelson CA, Moore AR, Perea AE, et al. Cat scratch disease: U.S. clinicians’ experience and knowledge. Zoonoses Public Health. 2018;65:67-73.

- Spach DH, Kaplan SL. Treatment of cat scratch disease. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-cat-scratch-disease?search=treatment%20of%20cat%20scratch&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~59&usage_type=default&display_rank=1.Updated June 12, 2019. Accessed August 15, 2019.

- Bouhsira E, Franc M, Lienard E, et al. The efficacy of a selamectin (Stronghold®) spot on treatment in the prevention of Bartonella henselae transmission by Ctenocephalides felis in cats, using a new high-challenge model. Parasitol Res. 2015;114:1045-1050.

- Shamekhi Amiri F. Bartonellosis in chronic kidney disease: an unrecognized and unsuspected diagnosis. Ther Apher Dial. 2017;21:430-440.

- Pieracci EG, Evert N, Drexler NA, et al. Fatal flea-borne typhus in Texas: a retrospective case series, 1985-2015. American J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;96:1088-1093.

- Maina AN, Fogarty C, Krueger L, et al. Rickettsial infections among Ctenocephalides felis and host animals during a flea-borne rickettsioses outbreak in Orange County, California. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0160604.

- Noden BH, Davidson S, Smith JL, et al. First detection of Rickettsia typhi and Rickettsia felis in fleas collected from client-owned companion animals in the Southern Great Plains. J Med Entomol. 2017;54:1093-1097.

- Sexton DJ. Murine typhus. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/murine-typhus?search=diagnosis-and-treatment-of-murine-typhus&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~21&usage_type=default&display_rank=1. Updated January 17, 2019. Accessed August 15, 2019.

- Riehm JM, Löscher T. Human plague and pneumonic plague: pathogenicity, epidemiology, clinical presentations and therapy [in German]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2015;58:721-729.

- Butler T. Plague gives surprises in the first decade of the 21st century in the United States and worldwide. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89:788-793.

- Gould LH, Pape J, Ettestad P, Griffith KS, et al. Dog-associated risk factors for human plague. Zoonoses Public Health. 2008;55:448-454.

- Margolis DA, Burns J, Reed SL, et al. Septicemic plague in a community hospital in California. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78:868-871.

- Urich SK, Chalcraft L, Schriefer ME, et al. Lack of antimicrobial resistance in Yersinia pestis isolates from 17 countries in the Americas, Africa, and Asia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:555-558.

- Jiang P, Zhang X, Liu RD, et al. A human case of zoonotic dog tapeworm, Dipylidium caninum (Eucestoda: Dilepidiidae), in China. Korean J Parasitol. 2017;55:61-64.

- Roberts LS, Janovy J Jr, eds. Foundations of Parasitology. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009.

- Cadiergues MC. A comparison of jump performances of the dog flea, Ctenocephalides canis (Curtis, 1826) and the cat flea, Ctenocephalides felis (Bouché, 1835). Vet Parasitol. 2000;92:239-241.

- Blagburn B, Butler J, Land T, et al. Who’s who and where: prevalence of Ctenocephalides felis and Ctenocephalides canis in shelter dogs and cats in the United States. Presented at: American Association of Veterinary Parasitologists 61st Annual Meeting; August 6-9, 2016; San Antonio, TX. P9.

- Bitam I, Dittmar K, Parola P, et al. Fleas and flea-borne diseases. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:E667-E676.

- Dryden MW, Canfield MS, Niedfeldt E, et al. Evaluation of sarolaner and spinosad oral treatments to eliminate fleas, reduce dermatologic lesions and minimize pruritus in naturally infested dogs in west Central Florida, USA. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:389.

- Dryden MW, Canfield MS, Kalosy K, et al. Evaluation of fluralaner and afoxolaner treatments to control flea populations, reduce pruritus and minimize dermatologic lesions in naturally infested dogs in private residences in west Central Florida, USA. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:365.

- Delcombel R, Karembe H, Nare B, et al. Synergy between dinotefuran and fipronil against the cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis): improved onset of action and residual speed of kill in adult cats. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:341.

- Nelson CA, Moore AR, Perea AE, et al. Cat scratch disease: U.S. clinicians’ experience and knowledge. Zoonoses Public Health. 2018;65:67-73.

- Spach DH, Kaplan SL. Treatment of cat scratch disease. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-cat-scratch-disease?search=treatment%20of%20cat%20scratch&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~59&usage_type=default&display_rank=1.Updated June 12, 2019. Accessed August 15, 2019.

- Bouhsira E, Franc M, Lienard E, et al. The efficacy of a selamectin (Stronghold®) spot on treatment in the prevention of Bartonella henselae transmission by Ctenocephalides felis in cats, using a new high-challenge model. Parasitol Res. 2015;114:1045-1050.

- Shamekhi Amiri F. Bartonellosis in chronic kidney disease: an unrecognized and unsuspected diagnosis. Ther Apher Dial. 2017;21:430-440.

- Pieracci EG, Evert N, Drexler NA, et al. Fatal flea-borne typhus in Texas: a retrospective case series, 1985-2015. American J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;96:1088-1093.

- Maina AN, Fogarty C, Krueger L, et al. Rickettsial infections among Ctenocephalides felis and host animals during a flea-borne rickettsioses outbreak in Orange County, California. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0160604.

- Noden BH, Davidson S, Smith JL, et al. First detection of Rickettsia typhi and Rickettsia felis in fleas collected from client-owned companion animals in the Southern Great Plains. J Med Entomol. 2017;54:1093-1097.

- Sexton DJ. Murine typhus. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/murine-typhus?search=diagnosis-and-treatment-of-murine-typhus&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~21&usage_type=default&display_rank=1. Updated January 17, 2019. Accessed August 15, 2019.

- Riehm JM, Löscher T. Human plague and pneumonic plague: pathogenicity, epidemiology, clinical presentations and therapy [in German]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2015;58:721-729.

- Butler T. Plague gives surprises in the first decade of the 21st century in the United States and worldwide. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89:788-793.

- Gould LH, Pape J, Ettestad P, Griffith KS, et al. Dog-associated risk factors for human plague. Zoonoses Public Health. 2008;55:448-454.

- Margolis DA, Burns J, Reed SL, et al. Septicemic plague in a community hospital in California. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78:868-871.

- Urich SK, Chalcraft L, Schriefer ME, et al. Lack of antimicrobial resistance in Yersinia pestis isolates from 17 countries in the Americas, Africa, and Asia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:555-558.

- Jiang P, Zhang X, Liu RD, et al. A human case of zoonotic dog tapeworm, Dipylidium caninum (Eucestoda: Dilepidiidae), in China. Korean J Parasitol. 2017;55:61-64.

- Roberts LS, Janovy J Jr, eds. Foundations of Parasitology. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009.

Practice Points

- Cat fleas classically cause pruritic grouped papulovesicles on the lower legs of pet owners.

- Affected patients require thorough education on flea eradication.

- Cat fleas can transmit endemic typhus, cat scratch disease, and bubonic plague.

Aquatic Antagonists: Stingray Injury Update

Incidence and Characteristics

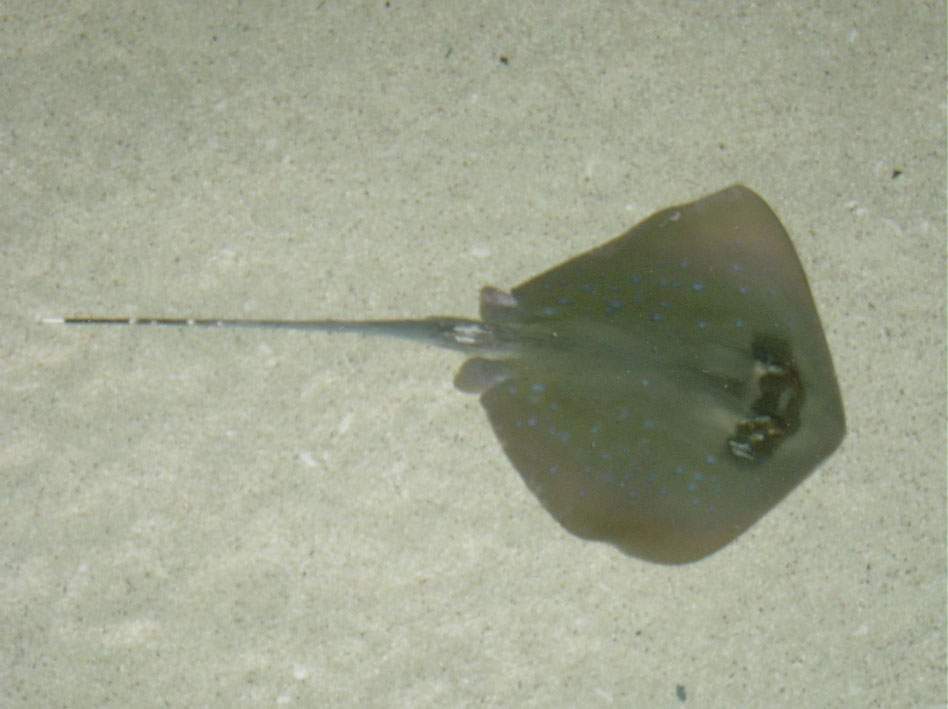

Stingrays are dorsoventrally flattened, diamond-shaped fish with light-colored ventral and dark-colored dorsal surfaces. They have strong pectoral wings that allow them to swim forward and backward and even launch off waves.3 Stingrays range in size from the palm of a human hand to 6.5 ft in width. They possess 1 or more spines (2.5 to >30 cm in length) that are disguised by much longer tails.6,7 They often are encountered accidentally because they bury themselves in the sand or mud of shallow coastal waters or rivers with only their eyes and tails exposed to fool prey and avoid predators.

Injury Clinical Presentation

Stingray injuries typically involve the lower legs, ankles, or feet after stepping on a stingray.8 Fishermen can present with injuries of the upper extremities after handling fish with their hands.9 Other rarer injuries occur when individuals are swimming alongside stingrays or when stingrays catapult off waves into moving boats.10,11 Stingrays impale victims by using their tails to direct a retroserrate barb composed of a strong cartilaginous material called vasodentin. The barb releases venom by breaking through the venom-containing integumentary sheath that encapsulates it. Stingray venom contains phosphodiesterase, serotonin, and 5′-nucleotidase. It causes severe pain, vasoconstriction, ischemia, and poor wound healing, along with systemic effects such as disorientation, syncope, seizures, salivation, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, muscle cramps or fasciculations, pruritus, allergic reaction, hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias, dyspnea, paralysis, and possibly death.1,8,12,13

Management

Pain Relief

As with many marine envenomations, immersion in hot but not scalding water can inactivate venom and reduce symptoms.8,9 In one retrospective review, 52 of 75 (69%) patients reporting to a California poison center with stingray injuries had improvement in pain within 1 hour of hot water immersion before any analgesics were instituted.8 In another review, 65 of 74 (88%) patients presenting to a California emergency department within 24 hours of sustaining a stingray injury had complete relief of pain within 30 minutes of hot water immersion. Patients who received analgesics in addition to hot water immersion did not require a second dose.9 In concordance with these studies, we suggest immersing areas affected by stingray injuries in hot water (temperature, 43.3°C to 46.1°C [110°F–115°F]; or as close to this range as tolerated) until pain subsides.8,9,14 Ice packs are an alternative to hot water immersion that may be more readily available to patients. If pain does not resolve following hot water immersion or application of an ice pack, additional analgesics and xylocaine without epinephrine may be helpful.9,15

Infection

One major complication of stingray injuries is infection.8,9 Many bacterial species reside in stingray mucus, the marine environment, or on human skin that may be introduced during a single injury. Marine envenomations can involve organisms such as Vibrio, Aeromonas, and Mycobacterium species, which often are resistant to antibiotic prophylaxis covering common causes of soft-tissue infection such as Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species.8,9,16,17 Additionally, physicians should cover for Clostridium species and ensure patients are up-to-date on vaccinations because severe cases of tetanus following stingray injuries have been reported.18 Lastly, fungal infections including fusariosis have been reported following stingray injuries and should be considered if a patient develops an infection.19

Several authors support the use of prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics in all but mild stingray injuries.8,9,20,21 Although no standardized definition exists, mild injuries generally represent patients with superficial lacerations or less, while deeper lacerations and puncture wounds require prophylaxis. Several authors agree on the use of fluoroquinolone antibiotics (eg, ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily) for 5 to 7 days following severe stingray injuries.1,9,13,22 Other proposed antibiotic regimens include trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (160/800 mg twice daily) or tetracycline (500 mg 4 times daily) for 7 days.13 Failure of ciprofloxacin therapy after 7 days has been reported, with resolution of infection after treatment with an intravenous cephalosporin for 7 days.20 Failure of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole therapy also has been reported, with one case requiring levofloxacin for a much longer course.21 Clinical follow-up remains essential after prescribing prophylactic antibiotics, as resistance is common.

Foreign Bodies

Stingray injuries also are often complicated by foreign bodies or retained spines.3,8 Although these complications are less severe than infection, all wounds should be explored for material under local anesthesia. Furthermore, there has been support for thorough debridement of necrotic tissue with referral to a hand specialist for deeper injuries to the hands as well as referral to a foot and ankle specialist for deeper injuries of the lower extremities.23,24 More serious injuries with penetration of vital structures, such as through the chest or abdomen, require immediate exploration in an operating room.1,24

Imaging

Routine imaging of stingray injuries remains controversial. In a case series of 119 patients presenting to a California emergency department with stingray injuries, Clark et al9 found that radiographs were not helpful. This finding likely is due in part to an inability to detect hypodense material such as integumentary or glandular tissue via radiography.3 However, radiographs have been used to identify retained stingray barbs in select cases in which retained barbs are suspected.2,25 Lastly, ultrasonography potentially may offer a better first choice when a barb is not readily apparent; magnetic resonance imaging may be indicated for more involved areas and for further visualization of suspected hypodense material, though at a higher expense.2,9

Biopsy

Biopsies of stingray injuries are rarely performed, and the findings are not well characterized. One case biopsied 2 months after injury showed a large zone of paucicellular necrosis with superficial ulceration and granulomatous inflammation. The stingray venom was most likely responsible for the pattern of necrosis noted in the biopsy.21

Avoidance and Prevention

Patients traveling to areas of the world inhabited by stingrays should receive counseling on how to avoid injury. Prior to entry, individuals can throw stones or use a long stick to clear their walking or swimming areas of venomous fish.26 Polarized sunglasses may help spot stingrays in shallow water. Furthermore, wading through water with a shuffling gait can help individuals avoid stepping directly on a stingray and also warns stingrays that someone is in the area. Individuals who spend more time in coastal waters or river systems inhabited by stingrays may invest in protective stingray gear such as leg guards or specialized wading boots.26 Lastly, fishermen should be advised to avoid handling stingrays with their hands and instead cut their fishing line to release the fish.

- Aurbach PS. Envenomations by aquatic vertebrates. In: Auerbach PS. Wilderness Medicine. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2007:1730-1749.

- Robins CR, Ray GC. A Field Guide to Atlantic Coast Fishes. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company; 1986.

- Diaz JH. The evaluation, management, and prevention of stingray injuries in travelers. J Travel Med. 2008;15:102-109.

- Haddad V Jr, Neto DG, de Paula Neto JB, et al. Freshwater stingrays: study of epidemiologic, clinical and therapeutic aspects based on 84 envenomings in humans and some enzymatic activities of the venom. Toxicon. 2004;43:287-294.

- Marinkelle CJ. Accidents by venomous animals in Colombia. Ind Med Surg. 1966;35:988-992.

- Last PR, White WT, Caire JN, et al. Sharks and Rays of Borneo. Collingwood VIC, Australia: CSIRO Publishing; 2010.

- Mebs D. Venomous and Poisonous Animals: A Handbook for Biologists, Toxicologists and Toxinologists, Physicians and Pharmacists. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2002.

- Clark AT, Clark RF, Cantrell FL. A retrospective review of the presentation and treatment of stingray stings reported to a poison control system. Am J Ther. 2017;24:E177-E180.

- Clark RF, Girard RH, Rao D, et al. Stingray envenomation: a retrospective review of clinical presentation and treatment in 119 cases. J Emerg Med. 2007;33:33-37.

- Mahjoubi L, Joyeux A, Delambre JF, et al. Near-death thoracic trauma caused by a stingray in the Indian Ocean. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;29:262-263.

- Parra MW, Constantini EN, Rodas EB. Surviving a transfixing cardiac injury caused by a stingray barb. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:E115-E116.

- Dos Santos JC, Grund LZ, Seibert CS, et al. Stingray venom activates IL-33 producing cardiomyocytes, but not mast cell, to promote acute neutrophil-mediated injury. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7912.

- Auerbach PS, Norris RL. Marine envenomation. In: Longo DL, Kasper SL, Jameson JL, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012:144-148.

- Cook MD, Matteucci MJ, Lall R, et al. Stingray envenomation. J Emerg Med. 2006;30:345-347.

- Bowers RC, Mustain MV. Disorders due to physical & environmental agents. In: Humphries RL, Stone C, eds. CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment Emergency Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011:835-861.

- Domingos MO, Franzolin MR, dos Anjos MT, et al. The influence of environmental bacteria in freshwater stingray wound-healing. Toxicon. 2011;58:147-153.

- Auerbach PS, Yajko DM, Nassos PS, et al. Bacteriology of the marine environment: implications for clinical therapy. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16:643-649.

- Torrez PP, Quiroga MM, Said R, et al. Tetanus after envenomations caused by freshwater stingrays. Toxicon. 2015;97:32-35.

- Hiemenz JW, Kennedy B, Kwon-Chung KJ. Invasive fusariosis associated with an injury by a stingray barb. J Med Vet Mycol. 1990;28:209-213.

- da Silva NJ Jr, Ferreira KR, Pinto RN, et al. A severe accident caused by an ocellate river stingray (Potamotrygon motoro) in central Brazil: how well do we really understand stingray venom chemistry, envenomation, and therapeutics? Toxins (Basel). 2015;7:2272-2288.

- Tartar D, Limova M, North J. Clinical and histopathologic findings in cutaneous sting ray wounds: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19261.

- Jarvis HC, Matheny LM, Clanton TO. Stingray injury to the webspace of the foot. Orthopedics. 2012;35:E762-E765.

- Trickett R, Whitaker IS, Boyce DE. Sting-ray injuries to the hand: case report, literature review and a suggested algorithm for management. J Plast Reconstruct Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:E270-E273.

- Fernandez I, Valladolid G, Varon J, et al. Encounters with venomous sea-life. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:103-112.

- O’Malley GF, O’Malley RN, Pham O, et al. Retained stingray barb and the importance of imaging. Wilderness Environ Med. 2015;26:375-379.

- How to protect yourself from stingrays. Howcast website. https://www.howcast.com/videos/228034-how-to-protect-yourself-from-stingrays/. Accessed July 12, 2018.

Incidence and Characteristics

Stingrays are dorsoventrally flattened, diamond-shaped fish with light-colored ventral and dark-colored dorsal surfaces. They have strong pectoral wings that allow them to swim forward and backward and even launch off waves.3 Stingrays range in size from the palm of a human hand to 6.5 ft in width. They possess 1 or more spines (2.5 to >30 cm in length) that are disguised by much longer tails.6,7 They often are encountered accidentally because they bury themselves in the sand or mud of shallow coastal waters or rivers with only their eyes and tails exposed to fool prey and avoid predators.

Injury Clinical Presentation

Stingray injuries typically involve the lower legs, ankles, or feet after stepping on a stingray.8 Fishermen can present with injuries of the upper extremities after handling fish with their hands.9 Other rarer injuries occur when individuals are swimming alongside stingrays or when stingrays catapult off waves into moving boats.10,11 Stingrays impale victims by using their tails to direct a retroserrate barb composed of a strong cartilaginous material called vasodentin. The barb releases venom by breaking through the venom-containing integumentary sheath that encapsulates it. Stingray venom contains phosphodiesterase, serotonin, and 5′-nucleotidase. It causes severe pain, vasoconstriction, ischemia, and poor wound healing, along with systemic effects such as disorientation, syncope, seizures, salivation, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, muscle cramps or fasciculations, pruritus, allergic reaction, hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias, dyspnea, paralysis, and possibly death.1,8,12,13

Management

Pain Relief

As with many marine envenomations, immersion in hot but not scalding water can inactivate venom and reduce symptoms.8,9 In one retrospective review, 52 of 75 (69%) patients reporting to a California poison center with stingray injuries had improvement in pain within 1 hour of hot water immersion before any analgesics were instituted.8 In another review, 65 of 74 (88%) patients presenting to a California emergency department within 24 hours of sustaining a stingray injury had complete relief of pain within 30 minutes of hot water immersion. Patients who received analgesics in addition to hot water immersion did not require a second dose.9 In concordance with these studies, we suggest immersing areas affected by stingray injuries in hot water (temperature, 43.3°C to 46.1°C [110°F–115°F]; or as close to this range as tolerated) until pain subsides.8,9,14 Ice packs are an alternative to hot water immersion that may be more readily available to patients. If pain does not resolve following hot water immersion or application of an ice pack, additional analgesics and xylocaine without epinephrine may be helpful.9,15

Infection

One major complication of stingray injuries is infection.8,9 Many bacterial species reside in stingray mucus, the marine environment, or on human skin that may be introduced during a single injury. Marine envenomations can involve organisms such as Vibrio, Aeromonas, and Mycobacterium species, which often are resistant to antibiotic prophylaxis covering common causes of soft-tissue infection such as Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species.8,9,16,17 Additionally, physicians should cover for Clostridium species and ensure patients are up-to-date on vaccinations because severe cases of tetanus following stingray injuries have been reported.18 Lastly, fungal infections including fusariosis have been reported following stingray injuries and should be considered if a patient develops an infection.19

Several authors support the use of prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics in all but mild stingray injuries.8,9,20,21 Although no standardized definition exists, mild injuries generally represent patients with superficial lacerations or less, while deeper lacerations and puncture wounds require prophylaxis. Several authors agree on the use of fluoroquinolone antibiotics (eg, ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily) for 5 to 7 days following severe stingray injuries.1,9,13,22 Other proposed antibiotic regimens include trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (160/800 mg twice daily) or tetracycline (500 mg 4 times daily) for 7 days.13 Failure of ciprofloxacin therapy after 7 days has been reported, with resolution of infection after treatment with an intravenous cephalosporin for 7 days.20 Failure of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole therapy also has been reported, with one case requiring levofloxacin for a much longer course.21 Clinical follow-up remains essential after prescribing prophylactic antibiotics, as resistance is common.

Foreign Bodies

Stingray injuries also are often complicated by foreign bodies or retained spines.3,8 Although these complications are less severe than infection, all wounds should be explored for material under local anesthesia. Furthermore, there has been support for thorough debridement of necrotic tissue with referral to a hand specialist for deeper injuries to the hands as well as referral to a foot and ankle specialist for deeper injuries of the lower extremities.23,24 More serious injuries with penetration of vital structures, such as through the chest or abdomen, require immediate exploration in an operating room.1,24

Imaging

Routine imaging of stingray injuries remains controversial. In a case series of 119 patients presenting to a California emergency department with stingray injuries, Clark et al9 found that radiographs were not helpful. This finding likely is due in part to an inability to detect hypodense material such as integumentary or glandular tissue via radiography.3 However, radiographs have been used to identify retained stingray barbs in select cases in which retained barbs are suspected.2,25 Lastly, ultrasonography potentially may offer a better first choice when a barb is not readily apparent; magnetic resonance imaging may be indicated for more involved areas and for further visualization of suspected hypodense material, though at a higher expense.2,9

Biopsy

Biopsies of stingray injuries are rarely performed, and the findings are not well characterized. One case biopsied 2 months after injury showed a large zone of paucicellular necrosis with superficial ulceration and granulomatous inflammation. The stingray venom was most likely responsible for the pattern of necrosis noted in the biopsy.21

Avoidance and Prevention

Patients traveling to areas of the world inhabited by stingrays should receive counseling on how to avoid injury. Prior to entry, individuals can throw stones or use a long stick to clear their walking or swimming areas of venomous fish.26 Polarized sunglasses may help spot stingrays in shallow water. Furthermore, wading through water with a shuffling gait can help individuals avoid stepping directly on a stingray and also warns stingrays that someone is in the area. Individuals who spend more time in coastal waters or river systems inhabited by stingrays may invest in protective stingray gear such as leg guards or specialized wading boots.26 Lastly, fishermen should be advised to avoid handling stingrays with their hands and instead cut their fishing line to release the fish.

Incidence and Characteristics

Stingrays are dorsoventrally flattened, diamond-shaped fish with light-colored ventral and dark-colored dorsal surfaces. They have strong pectoral wings that allow them to swim forward and backward and even launch off waves.3 Stingrays range in size from the palm of a human hand to 6.5 ft in width. They possess 1 or more spines (2.5 to >30 cm in length) that are disguised by much longer tails.6,7 They often are encountered accidentally because they bury themselves in the sand or mud of shallow coastal waters or rivers with only their eyes and tails exposed to fool prey and avoid predators.

Injury Clinical Presentation

Stingray injuries typically involve the lower legs, ankles, or feet after stepping on a stingray.8 Fishermen can present with injuries of the upper extremities after handling fish with their hands.9 Other rarer injuries occur when individuals are swimming alongside stingrays or when stingrays catapult off waves into moving boats.10,11 Stingrays impale victims by using their tails to direct a retroserrate barb composed of a strong cartilaginous material called vasodentin. The barb releases venom by breaking through the venom-containing integumentary sheath that encapsulates it. Stingray venom contains phosphodiesterase, serotonin, and 5′-nucleotidase. It causes severe pain, vasoconstriction, ischemia, and poor wound healing, along with systemic effects such as disorientation, syncope, seizures, salivation, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, muscle cramps or fasciculations, pruritus, allergic reaction, hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias, dyspnea, paralysis, and possibly death.1,8,12,13

Management

Pain Relief

As with many marine envenomations, immersion in hot but not scalding water can inactivate venom and reduce symptoms.8,9 In one retrospective review, 52 of 75 (69%) patients reporting to a California poison center with stingray injuries had improvement in pain within 1 hour of hot water immersion before any analgesics were instituted.8 In another review, 65 of 74 (88%) patients presenting to a California emergency department within 24 hours of sustaining a stingray injury had complete relief of pain within 30 minutes of hot water immersion. Patients who received analgesics in addition to hot water immersion did not require a second dose.9 In concordance with these studies, we suggest immersing areas affected by stingray injuries in hot water (temperature, 43.3°C to 46.1°C [110°F–115°F]; or as close to this range as tolerated) until pain subsides.8,9,14 Ice packs are an alternative to hot water immersion that may be more readily available to patients. If pain does not resolve following hot water immersion or application of an ice pack, additional analgesics and xylocaine without epinephrine may be helpful.9,15

Infection

One major complication of stingray injuries is infection.8,9 Many bacterial species reside in stingray mucus, the marine environment, or on human skin that may be introduced during a single injury. Marine envenomations can involve organisms such as Vibrio, Aeromonas, and Mycobacterium species, which often are resistant to antibiotic prophylaxis covering common causes of soft-tissue infection such as Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species.8,9,16,17 Additionally, physicians should cover for Clostridium species and ensure patients are up-to-date on vaccinations because severe cases of tetanus following stingray injuries have been reported.18 Lastly, fungal infections including fusariosis have been reported following stingray injuries and should be considered if a patient develops an infection.19

Several authors support the use of prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics in all but mild stingray injuries.8,9,20,21 Although no standardized definition exists, mild injuries generally represent patients with superficial lacerations or less, while deeper lacerations and puncture wounds require prophylaxis. Several authors agree on the use of fluoroquinolone antibiotics (eg, ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily) for 5 to 7 days following severe stingray injuries.1,9,13,22 Other proposed antibiotic regimens include trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (160/800 mg twice daily) or tetracycline (500 mg 4 times daily) for 7 days.13 Failure of ciprofloxacin therapy after 7 days has been reported, with resolution of infection after treatment with an intravenous cephalosporin for 7 days.20 Failure of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole therapy also has been reported, with one case requiring levofloxacin for a much longer course.21 Clinical follow-up remains essential after prescribing prophylactic antibiotics, as resistance is common.

Foreign Bodies

Stingray injuries also are often complicated by foreign bodies or retained spines.3,8 Although these complications are less severe than infection, all wounds should be explored for material under local anesthesia. Furthermore, there has been support for thorough debridement of necrotic tissue with referral to a hand specialist for deeper injuries to the hands as well as referral to a foot and ankle specialist for deeper injuries of the lower extremities.23,24 More serious injuries with penetration of vital structures, such as through the chest or abdomen, require immediate exploration in an operating room.1,24

Imaging

Routine imaging of stingray injuries remains controversial. In a case series of 119 patients presenting to a California emergency department with stingray injuries, Clark et al9 found that radiographs were not helpful. This finding likely is due in part to an inability to detect hypodense material such as integumentary or glandular tissue via radiography.3 However, radiographs have been used to identify retained stingray barbs in select cases in which retained barbs are suspected.2,25 Lastly, ultrasonography potentially may offer a better first choice when a barb is not readily apparent; magnetic resonance imaging may be indicated for more involved areas and for further visualization of suspected hypodense material, though at a higher expense.2,9

Biopsy

Biopsies of stingray injuries are rarely performed, and the findings are not well characterized. One case biopsied 2 months after injury showed a large zone of paucicellular necrosis with superficial ulceration and granulomatous inflammation. The stingray venom was most likely responsible for the pattern of necrosis noted in the biopsy.21

Avoidance and Prevention

Patients traveling to areas of the world inhabited by stingrays should receive counseling on how to avoid injury. Prior to entry, individuals can throw stones or use a long stick to clear their walking or swimming areas of venomous fish.26 Polarized sunglasses may help spot stingrays in shallow water. Furthermore, wading through water with a shuffling gait can help individuals avoid stepping directly on a stingray and also warns stingrays that someone is in the area. Individuals who spend more time in coastal waters or river systems inhabited by stingrays may invest in protective stingray gear such as leg guards or specialized wading boots.26 Lastly, fishermen should be advised to avoid handling stingrays with their hands and instead cut their fishing line to release the fish.

- Aurbach PS. Envenomations by aquatic vertebrates. In: Auerbach PS. Wilderness Medicine. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2007:1730-1749.

- Robins CR, Ray GC. A Field Guide to Atlantic Coast Fishes. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company; 1986.

- Diaz JH. The evaluation, management, and prevention of stingray injuries in travelers. J Travel Med. 2008;15:102-109.

- Haddad V Jr, Neto DG, de Paula Neto JB, et al. Freshwater stingrays: study of epidemiologic, clinical and therapeutic aspects based on 84 envenomings in humans and some enzymatic activities of the venom. Toxicon. 2004;43:287-294.

- Marinkelle CJ. Accidents by venomous animals in Colombia. Ind Med Surg. 1966;35:988-992.

- Last PR, White WT, Caire JN, et al. Sharks and Rays of Borneo. Collingwood VIC, Australia: CSIRO Publishing; 2010.

- Mebs D. Venomous and Poisonous Animals: A Handbook for Biologists, Toxicologists and Toxinologists, Physicians and Pharmacists. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2002.

- Clark AT, Clark RF, Cantrell FL. A retrospective review of the presentation and treatment of stingray stings reported to a poison control system. Am J Ther. 2017;24:E177-E180.

- Clark RF, Girard RH, Rao D, et al. Stingray envenomation: a retrospective review of clinical presentation and treatment in 119 cases. J Emerg Med. 2007;33:33-37.

- Mahjoubi L, Joyeux A, Delambre JF, et al. Near-death thoracic trauma caused by a stingray in the Indian Ocean. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;29:262-263.

- Parra MW, Constantini EN, Rodas EB. Surviving a transfixing cardiac injury caused by a stingray barb. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:E115-E116.

- Dos Santos JC, Grund LZ, Seibert CS, et al. Stingray venom activates IL-33 producing cardiomyocytes, but not mast cell, to promote acute neutrophil-mediated injury. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7912.

- Auerbach PS, Norris RL. Marine envenomation. In: Longo DL, Kasper SL, Jameson JL, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012:144-148.

- Cook MD, Matteucci MJ, Lall R, et al. Stingray envenomation. J Emerg Med. 2006;30:345-347.

- Bowers RC, Mustain MV. Disorders due to physical & environmental agents. In: Humphries RL, Stone C, eds. CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment Emergency Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011:835-861.

- Domingos MO, Franzolin MR, dos Anjos MT, et al. The influence of environmental bacteria in freshwater stingray wound-healing. Toxicon. 2011;58:147-153.

- Auerbach PS, Yajko DM, Nassos PS, et al. Bacteriology of the marine environment: implications for clinical therapy. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16:643-649.

- Torrez PP, Quiroga MM, Said R, et al. Tetanus after envenomations caused by freshwater stingrays. Toxicon. 2015;97:32-35.

- Hiemenz JW, Kennedy B, Kwon-Chung KJ. Invasive fusariosis associated with an injury by a stingray barb. J Med Vet Mycol. 1990;28:209-213.

- da Silva NJ Jr, Ferreira KR, Pinto RN, et al. A severe accident caused by an ocellate river stingray (Potamotrygon motoro) in central Brazil: how well do we really understand stingray venom chemistry, envenomation, and therapeutics? Toxins (Basel). 2015;7:2272-2288.

- Tartar D, Limova M, North J. Clinical and histopathologic findings in cutaneous sting ray wounds: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19261.

- Jarvis HC, Matheny LM, Clanton TO. Stingray injury to the webspace of the foot. Orthopedics. 2012;35:E762-E765.

- Trickett R, Whitaker IS, Boyce DE. Sting-ray injuries to the hand: case report, literature review and a suggested algorithm for management. J Plast Reconstruct Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:E270-E273.

- Fernandez I, Valladolid G, Varon J, et al. Encounters with venomous sea-life. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:103-112.

- O’Malley GF, O’Malley RN, Pham O, et al. Retained stingray barb and the importance of imaging. Wilderness Environ Med. 2015;26:375-379.

- How to protect yourself from stingrays. Howcast website. https://www.howcast.com/videos/228034-how-to-protect-yourself-from-stingrays/. Accessed July 12, 2018.

- Aurbach PS. Envenomations by aquatic vertebrates. In: Auerbach PS. Wilderness Medicine. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2007:1730-1749.

- Robins CR, Ray GC. A Field Guide to Atlantic Coast Fishes. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company; 1986.

- Diaz JH. The evaluation, management, and prevention of stingray injuries in travelers. J Travel Med. 2008;15:102-109.

- Haddad V Jr, Neto DG, de Paula Neto JB, et al. Freshwater stingrays: study of epidemiologic, clinical and therapeutic aspects based on 84 envenomings in humans and some enzymatic activities of the venom. Toxicon. 2004;43:287-294.

- Marinkelle CJ. Accidents by venomous animals in Colombia. Ind Med Surg. 1966;35:988-992.

- Last PR, White WT, Caire JN, et al. Sharks and Rays of Borneo. Collingwood VIC, Australia: CSIRO Publishing; 2010.

- Mebs D. Venomous and Poisonous Animals: A Handbook for Biologists, Toxicologists and Toxinologists, Physicians and Pharmacists. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2002.

- Clark AT, Clark RF, Cantrell FL. A retrospective review of the presentation and treatment of stingray stings reported to a poison control system. Am J Ther. 2017;24:E177-E180.

- Clark RF, Girard RH, Rao D, et al. Stingray envenomation: a retrospective review of clinical presentation and treatment in 119 cases. J Emerg Med. 2007;33:33-37.

- Mahjoubi L, Joyeux A, Delambre JF, et al. Near-death thoracic trauma caused by a stingray in the Indian Ocean. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;29:262-263.

- Parra MW, Constantini EN, Rodas EB. Surviving a transfixing cardiac injury caused by a stingray barb. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:E115-E116.

- Dos Santos JC, Grund LZ, Seibert CS, et al. Stingray venom activates IL-33 producing cardiomyocytes, but not mast cell, to promote acute neutrophil-mediated injury. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7912.

- Auerbach PS, Norris RL. Marine envenomation. In: Longo DL, Kasper SL, Jameson JL, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012:144-148.

- Cook MD, Matteucci MJ, Lall R, et al. Stingray envenomation. J Emerg Med. 2006;30:345-347.

- Bowers RC, Mustain MV. Disorders due to physical & environmental agents. In: Humphries RL, Stone C, eds. CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment Emergency Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011:835-861.

- Domingos MO, Franzolin MR, dos Anjos MT, et al. The influence of environmental bacteria in freshwater stingray wound-healing. Toxicon. 2011;58:147-153.

- Auerbach PS, Yajko DM, Nassos PS, et al. Bacteriology of the marine environment: implications for clinical therapy. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16:643-649.

- Torrez PP, Quiroga MM, Said R, et al. Tetanus after envenomations caused by freshwater stingrays. Toxicon. 2015;97:32-35.

- Hiemenz JW, Kennedy B, Kwon-Chung KJ. Invasive fusariosis associated with an injury by a stingray barb. J Med Vet Mycol. 1990;28:209-213.

- da Silva NJ Jr, Ferreira KR, Pinto RN, et al. A severe accident caused by an ocellate river stingray (Potamotrygon motoro) in central Brazil: how well do we really understand stingray venom chemistry, envenomation, and therapeutics? Toxins (Basel). 2015;7:2272-2288.

- Tartar D, Limova M, North J. Clinical and histopathologic findings in cutaneous sting ray wounds: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19261.

- Jarvis HC, Matheny LM, Clanton TO. Stingray injury to the webspace of the foot. Orthopedics. 2012;35:E762-E765.

- Trickett R, Whitaker IS, Boyce DE. Sting-ray injuries to the hand: case report, literature review and a suggested algorithm for management. J Plast Reconstruct Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:E270-E273.

- Fernandez I, Valladolid G, Varon J, et al. Encounters with venomous sea-life. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:103-112.

- O’Malley GF, O’Malley RN, Pham O, et al. Retained stingray barb and the importance of imaging. Wilderness Environ Med. 2015;26:375-379.

- How to protect yourself from stingrays. Howcast website. https://www.howcast.com/videos/228034-how-to-protect-yourself-from-stingrays/. Accessed July 12, 2018.

Practice Points

- Acute pain associated with stingray injuries can be treated with hot water immersion.

- Stingray injuries are prone to secondary infection and poor wound healing.