User login

Incidence and Characteristics

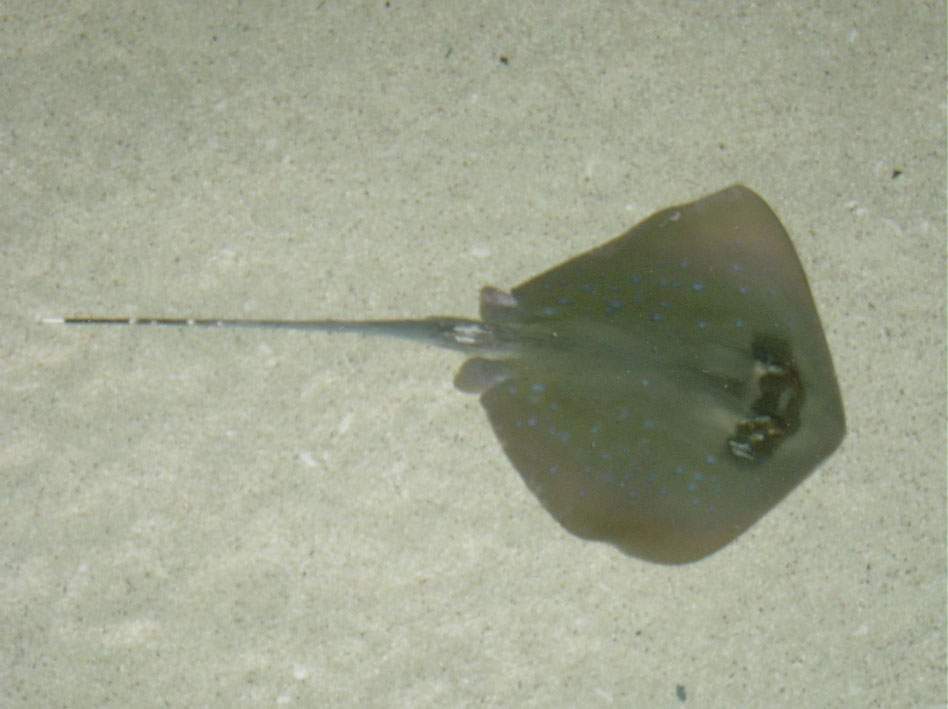

Stingrays are dorsoventrally flattened, diamond-shaped fish with light-colored ventral and dark-colored dorsal surfaces. They have strong pectoral wings that allow them to swim forward and backward and even launch off waves.3 Stingrays range in size from the palm of a human hand to 6.5 ft in width. They possess 1 or more spines (2.5 to >30 cm in length) that are disguised by much longer tails.6,7 They often are encountered accidentally because they bury themselves in the sand or mud of shallow coastal waters or rivers with only their eyes and tails exposed to fool prey and avoid predators.

Injury Clinical Presentation

Stingray injuries typically involve the lower legs, ankles, or feet after stepping on a stingray.8 Fishermen can present with injuries of the upper extremities after handling fish with their hands.9 Other rarer injuries occur when individuals are swimming alongside stingrays or when stingrays catapult off waves into moving boats.10,11 Stingrays impale victims by using their tails to direct a retroserrate barb composed of a strong cartilaginous material called vasodentin. The barb releases venom by breaking through the venom-containing integumentary sheath that encapsulates it. Stingray venom contains phosphodiesterase, serotonin, and 5′-nucleotidase. It causes severe pain, vasoconstriction, ischemia, and poor wound healing, along with systemic effects such as disorientation, syncope, seizures, salivation, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, muscle cramps or fasciculations, pruritus, allergic reaction, hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias, dyspnea, paralysis, and possibly death.1,8,12,13

Management

Pain Relief

As with many marine envenomations, immersion in hot but not scalding water can inactivate venom and reduce symptoms.8,9 In one retrospective review, 52 of 75 (69%) patients reporting to a California poison center with stingray injuries had improvement in pain within 1 hour of hot water immersion before any analgesics were instituted.8 In another review, 65 of 74 (88%) patients presenting to a California emergency department within 24 hours of sustaining a stingray injury had complete relief of pain within 30 minutes of hot water immersion. Patients who received analgesics in addition to hot water immersion did not require a second dose.9 In concordance with these studies, we suggest immersing areas affected by stingray injuries in hot water (temperature, 43.3°C to 46.1°C [110°F–115°F]; or as close to this range as tolerated) until pain subsides.8,9,14 Ice packs are an alternative to hot water immersion that may be more readily available to patients. If pain does not resolve following hot water immersion or application of an ice pack, additional analgesics and xylocaine without epinephrine may be helpful.9,15

Infection

One major complication of stingray injuries is infection.8,9 Many bacterial species reside in stingray mucus, the marine environment, or on human skin that may be introduced during a single injury. Marine envenomations can involve organisms such as Vibrio, Aeromonas, and Mycobacterium species, which often are resistant to antibiotic prophylaxis covering common causes of soft-tissue infection such as Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species.8,9,16,17 Additionally, physicians should cover for Clostridium species and ensure patients are up-to-date on vaccinations because severe cases of tetanus following stingray injuries have been reported.18 Lastly, fungal infections including fusariosis have been reported following stingray injuries and should be considered if a patient develops an infection.19

Several authors support the use of prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics in all but mild stingray injuries.8,9,20,21 Although no standardized definition exists, mild injuries generally represent patients with superficial lacerations or less, while deeper lacerations and puncture wounds require prophylaxis. Several authors agree on the use of fluoroquinolone antibiotics (eg, ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily) for 5 to 7 days following severe stingray injuries.1,9,13,22 Other proposed antibiotic regimens include trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (160/800 mg twice daily) or tetracycline (500 mg 4 times daily) for 7 days.13 Failure of ciprofloxacin therapy after 7 days has been reported, with resolution of infection after treatment with an intravenous cephalosporin for 7 days.20 Failure of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole therapy also has been reported, with one case requiring levofloxacin for a much longer course.21 Clinical follow-up remains essential after prescribing prophylactic antibiotics, as resistance is common.

Foreign Bodies

Stingray injuries also are often complicated by foreign bodies or retained spines.3,8 Although these complications are less severe than infection, all wounds should be explored for material under local anesthesia. Furthermore, there has been support for thorough debridement of necrotic tissue with referral to a hand specialist for deeper injuries to the hands as well as referral to a foot and ankle specialist for deeper injuries of the lower extremities.23,24 More serious injuries with penetration of vital structures, such as through the chest or abdomen, require immediate exploration in an operating room.1,24

Imaging

Routine imaging of stingray injuries remains controversial. In a case series of 119 patients presenting to a California emergency department with stingray injuries, Clark et al9 found that radiographs were not helpful. This finding likely is due in part to an inability to detect hypodense material such as integumentary or glandular tissue via radiography.3 However, radiographs have been used to identify retained stingray barbs in select cases in which retained barbs are suspected.2,25 Lastly, ultrasonography potentially may offer a better first choice when a barb is not readily apparent; magnetic resonance imaging may be indicated for more involved areas and for further visualization of suspected hypodense material, though at a higher expense.2,9

Biopsy

Biopsies of stingray injuries are rarely performed, and the findings are not well characterized. One case biopsied 2 months after injury showed a large zone of paucicellular necrosis with superficial ulceration and granulomatous inflammation. The stingray venom was most likely responsible for the pattern of necrosis noted in the biopsy.21

Avoidance and Prevention

Patients traveling to areas of the world inhabited by stingrays should receive counseling on how to avoid injury. Prior to entry, individuals can throw stones or use a long stick to clear their walking or swimming areas of venomous fish.26 Polarized sunglasses may help spot stingrays in shallow water. Furthermore, wading through water with a shuffling gait can help individuals avoid stepping directly on a stingray and also warns stingrays that someone is in the area. Individuals who spend more time in coastal waters or river systems inhabited by stingrays may invest in protective stingray gear such as leg guards or specialized wading boots.26 Lastly, fishermen should be advised to avoid handling stingrays with their hands and instead cut their fishing line to release the fish.

- Aurbach PS. Envenomations by aquatic vertebrates. In: Auerbach PS. Wilderness Medicine. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2007:1730-1749.

- Robins CR, Ray GC. A Field Guide to Atlantic Coast Fishes. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company; 1986.

- Diaz JH. The evaluation, management, and prevention of stingray injuries in travelers. J Travel Med. 2008;15:102-109.

- Haddad V Jr, Neto DG, de Paula Neto JB, et al. Freshwater stingrays: study of epidemiologic, clinical and therapeutic aspects based on 84 envenomings in humans and some enzymatic activities of the venom. Toxicon. 2004;43:287-294.

- Marinkelle CJ. Accidents by venomous animals in Colombia. Ind Med Surg. 1966;35:988-992.

- Last PR, White WT, Caire JN, et al. Sharks and Rays of Borneo. Collingwood VIC, Australia: CSIRO Publishing; 2010.

- Mebs D. Venomous and Poisonous Animals: A Handbook for Biologists, Toxicologists and Toxinologists, Physicians and Pharmacists. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2002.

- Clark AT, Clark RF, Cantrell FL. A retrospective review of the presentation and treatment of stingray stings reported to a poison control system. Am J Ther. 2017;24:E177-E180.

- Clark RF, Girard RH, Rao D, et al. Stingray envenomation: a retrospective review of clinical presentation and treatment in 119 cases. J Emerg Med. 2007;33:33-37.

- Mahjoubi L, Joyeux A, Delambre JF, et al. Near-death thoracic trauma caused by a stingray in the Indian Ocean. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;29:262-263.

- Parra MW, Constantini EN, Rodas EB. Surviving a transfixing cardiac injury caused by a stingray barb. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:E115-E116.

- Dos Santos JC, Grund LZ, Seibert CS, et al. Stingray venom activates IL-33 producing cardiomyocytes, but not mast cell, to promote acute neutrophil-mediated injury. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7912.

- Auerbach PS, Norris RL. Marine envenomation. In: Longo DL, Kasper SL, Jameson JL, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012:144-148.

- Cook MD, Matteucci MJ, Lall R, et al. Stingray envenomation. J Emerg Med. 2006;30:345-347.

- Bowers RC, Mustain MV. Disorders due to physical & environmental agents. In: Humphries RL, Stone C, eds. CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment Emergency Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011:835-861.

- Domingos MO, Franzolin MR, dos Anjos MT, et al. The influence of environmental bacteria in freshwater stingray wound-healing. Toxicon. 2011;58:147-153.

- Auerbach PS, Yajko DM, Nassos PS, et al. Bacteriology of the marine environment: implications for clinical therapy. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16:643-649.

- Torrez PP, Quiroga MM, Said R, et al. Tetanus after envenomations caused by freshwater stingrays. Toxicon. 2015;97:32-35.

- Hiemenz JW, Kennedy B, Kwon-Chung KJ. Invasive fusariosis associated with an injury by a stingray barb. J Med Vet Mycol. 1990;28:209-213.

- da Silva NJ Jr, Ferreira KR, Pinto RN, et al. A severe accident caused by an ocellate river stingray (Potamotrygon motoro) in central Brazil: how well do we really understand stingray venom chemistry, envenomation, and therapeutics? Toxins (Basel). 2015;7:2272-2288.

- Tartar D, Limova M, North J. Clinical and histopathologic findings in cutaneous sting ray wounds: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19261.

- Jarvis HC, Matheny LM, Clanton TO. Stingray injury to the webspace of the foot. Orthopedics. 2012;35:E762-E765.

- Trickett R, Whitaker IS, Boyce DE. Sting-ray injuries to the hand: case report, literature review and a suggested algorithm for management. J Plast Reconstruct Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:E270-E273.

- Fernandez I, Valladolid G, Varon J, et al. Encounters with venomous sea-life. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:103-112.

- O’Malley GF, O’Malley RN, Pham O, et al. Retained stingray barb and the importance of imaging. Wilderness Environ Med. 2015;26:375-379.

- How to protect yourself from stingrays. Howcast website. https://www.howcast.com/videos/228034-how-to-protect-yourself-from-stingrays/. Accessed July 12, 2018.

Incidence and Characteristics

Stingrays are dorsoventrally flattened, diamond-shaped fish with light-colored ventral and dark-colored dorsal surfaces. They have strong pectoral wings that allow them to swim forward and backward and even launch off waves.3 Stingrays range in size from the palm of a human hand to 6.5 ft in width. They possess 1 or more spines (2.5 to >30 cm in length) that are disguised by much longer tails.6,7 They often are encountered accidentally because they bury themselves in the sand or mud of shallow coastal waters or rivers with only their eyes and tails exposed to fool prey and avoid predators.

Injury Clinical Presentation

Stingray injuries typically involve the lower legs, ankles, or feet after stepping on a stingray.8 Fishermen can present with injuries of the upper extremities after handling fish with their hands.9 Other rarer injuries occur when individuals are swimming alongside stingrays or when stingrays catapult off waves into moving boats.10,11 Stingrays impale victims by using their tails to direct a retroserrate barb composed of a strong cartilaginous material called vasodentin. The barb releases venom by breaking through the venom-containing integumentary sheath that encapsulates it. Stingray venom contains phosphodiesterase, serotonin, and 5′-nucleotidase. It causes severe pain, vasoconstriction, ischemia, and poor wound healing, along with systemic effects such as disorientation, syncope, seizures, salivation, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, muscle cramps or fasciculations, pruritus, allergic reaction, hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias, dyspnea, paralysis, and possibly death.1,8,12,13

Management

Pain Relief

As with many marine envenomations, immersion in hot but not scalding water can inactivate venom and reduce symptoms.8,9 In one retrospective review, 52 of 75 (69%) patients reporting to a California poison center with stingray injuries had improvement in pain within 1 hour of hot water immersion before any analgesics were instituted.8 In another review, 65 of 74 (88%) patients presenting to a California emergency department within 24 hours of sustaining a stingray injury had complete relief of pain within 30 minutes of hot water immersion. Patients who received analgesics in addition to hot water immersion did not require a second dose.9 In concordance with these studies, we suggest immersing areas affected by stingray injuries in hot water (temperature, 43.3°C to 46.1°C [110°F–115°F]; or as close to this range as tolerated) until pain subsides.8,9,14 Ice packs are an alternative to hot water immersion that may be more readily available to patients. If pain does not resolve following hot water immersion or application of an ice pack, additional analgesics and xylocaine without epinephrine may be helpful.9,15

Infection

One major complication of stingray injuries is infection.8,9 Many bacterial species reside in stingray mucus, the marine environment, or on human skin that may be introduced during a single injury. Marine envenomations can involve organisms such as Vibrio, Aeromonas, and Mycobacterium species, which often are resistant to antibiotic prophylaxis covering common causes of soft-tissue infection such as Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species.8,9,16,17 Additionally, physicians should cover for Clostridium species and ensure patients are up-to-date on vaccinations because severe cases of tetanus following stingray injuries have been reported.18 Lastly, fungal infections including fusariosis have been reported following stingray injuries and should be considered if a patient develops an infection.19

Several authors support the use of prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics in all but mild stingray injuries.8,9,20,21 Although no standardized definition exists, mild injuries generally represent patients with superficial lacerations or less, while deeper lacerations and puncture wounds require prophylaxis. Several authors agree on the use of fluoroquinolone antibiotics (eg, ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily) for 5 to 7 days following severe stingray injuries.1,9,13,22 Other proposed antibiotic regimens include trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (160/800 mg twice daily) or tetracycline (500 mg 4 times daily) for 7 days.13 Failure of ciprofloxacin therapy after 7 days has been reported, with resolution of infection after treatment with an intravenous cephalosporin for 7 days.20 Failure of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole therapy also has been reported, with one case requiring levofloxacin for a much longer course.21 Clinical follow-up remains essential after prescribing prophylactic antibiotics, as resistance is common.

Foreign Bodies

Stingray injuries also are often complicated by foreign bodies or retained spines.3,8 Although these complications are less severe than infection, all wounds should be explored for material under local anesthesia. Furthermore, there has been support for thorough debridement of necrotic tissue with referral to a hand specialist for deeper injuries to the hands as well as referral to a foot and ankle specialist for deeper injuries of the lower extremities.23,24 More serious injuries with penetration of vital structures, such as through the chest or abdomen, require immediate exploration in an operating room.1,24

Imaging

Routine imaging of stingray injuries remains controversial. In a case series of 119 patients presenting to a California emergency department with stingray injuries, Clark et al9 found that radiographs were not helpful. This finding likely is due in part to an inability to detect hypodense material such as integumentary or glandular tissue via radiography.3 However, radiographs have been used to identify retained stingray barbs in select cases in which retained barbs are suspected.2,25 Lastly, ultrasonography potentially may offer a better first choice when a barb is not readily apparent; magnetic resonance imaging may be indicated for more involved areas and for further visualization of suspected hypodense material, though at a higher expense.2,9

Biopsy

Biopsies of stingray injuries are rarely performed, and the findings are not well characterized. One case biopsied 2 months after injury showed a large zone of paucicellular necrosis with superficial ulceration and granulomatous inflammation. The stingray venom was most likely responsible for the pattern of necrosis noted in the biopsy.21

Avoidance and Prevention

Patients traveling to areas of the world inhabited by stingrays should receive counseling on how to avoid injury. Prior to entry, individuals can throw stones or use a long stick to clear their walking or swimming areas of venomous fish.26 Polarized sunglasses may help spot stingrays in shallow water. Furthermore, wading through water with a shuffling gait can help individuals avoid stepping directly on a stingray and also warns stingrays that someone is in the area. Individuals who spend more time in coastal waters or river systems inhabited by stingrays may invest in protective stingray gear such as leg guards or specialized wading boots.26 Lastly, fishermen should be advised to avoid handling stingrays with their hands and instead cut their fishing line to release the fish.

Incidence and Characteristics

Stingrays are dorsoventrally flattened, diamond-shaped fish with light-colored ventral and dark-colored dorsal surfaces. They have strong pectoral wings that allow them to swim forward and backward and even launch off waves.3 Stingrays range in size from the palm of a human hand to 6.5 ft in width. They possess 1 or more spines (2.5 to >30 cm in length) that are disguised by much longer tails.6,7 They often are encountered accidentally because they bury themselves in the sand or mud of shallow coastal waters or rivers with only their eyes and tails exposed to fool prey and avoid predators.

Injury Clinical Presentation

Stingray injuries typically involve the lower legs, ankles, or feet after stepping on a stingray.8 Fishermen can present with injuries of the upper extremities after handling fish with their hands.9 Other rarer injuries occur when individuals are swimming alongside stingrays or when stingrays catapult off waves into moving boats.10,11 Stingrays impale victims by using their tails to direct a retroserrate barb composed of a strong cartilaginous material called vasodentin. The barb releases venom by breaking through the venom-containing integumentary sheath that encapsulates it. Stingray venom contains phosphodiesterase, serotonin, and 5′-nucleotidase. It causes severe pain, vasoconstriction, ischemia, and poor wound healing, along with systemic effects such as disorientation, syncope, seizures, salivation, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, muscle cramps or fasciculations, pruritus, allergic reaction, hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias, dyspnea, paralysis, and possibly death.1,8,12,13

Management

Pain Relief

As with many marine envenomations, immersion in hot but not scalding water can inactivate venom and reduce symptoms.8,9 In one retrospective review, 52 of 75 (69%) patients reporting to a California poison center with stingray injuries had improvement in pain within 1 hour of hot water immersion before any analgesics were instituted.8 In another review, 65 of 74 (88%) patients presenting to a California emergency department within 24 hours of sustaining a stingray injury had complete relief of pain within 30 minutes of hot water immersion. Patients who received analgesics in addition to hot water immersion did not require a second dose.9 In concordance with these studies, we suggest immersing areas affected by stingray injuries in hot water (temperature, 43.3°C to 46.1°C [110°F–115°F]; or as close to this range as tolerated) until pain subsides.8,9,14 Ice packs are an alternative to hot water immersion that may be more readily available to patients. If pain does not resolve following hot water immersion or application of an ice pack, additional analgesics and xylocaine without epinephrine may be helpful.9,15

Infection

One major complication of stingray injuries is infection.8,9 Many bacterial species reside in stingray mucus, the marine environment, or on human skin that may be introduced during a single injury. Marine envenomations can involve organisms such as Vibrio, Aeromonas, and Mycobacterium species, which often are resistant to antibiotic prophylaxis covering common causes of soft-tissue infection such as Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species.8,9,16,17 Additionally, physicians should cover for Clostridium species and ensure patients are up-to-date on vaccinations because severe cases of tetanus following stingray injuries have been reported.18 Lastly, fungal infections including fusariosis have been reported following stingray injuries and should be considered if a patient develops an infection.19

Several authors support the use of prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics in all but mild stingray injuries.8,9,20,21 Although no standardized definition exists, mild injuries generally represent patients with superficial lacerations or less, while deeper lacerations and puncture wounds require prophylaxis. Several authors agree on the use of fluoroquinolone antibiotics (eg, ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily) for 5 to 7 days following severe stingray injuries.1,9,13,22 Other proposed antibiotic regimens include trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (160/800 mg twice daily) or tetracycline (500 mg 4 times daily) for 7 days.13 Failure of ciprofloxacin therapy after 7 days has been reported, with resolution of infection after treatment with an intravenous cephalosporin for 7 days.20 Failure of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole therapy also has been reported, with one case requiring levofloxacin for a much longer course.21 Clinical follow-up remains essential after prescribing prophylactic antibiotics, as resistance is common.

Foreign Bodies

Stingray injuries also are often complicated by foreign bodies or retained spines.3,8 Although these complications are less severe than infection, all wounds should be explored for material under local anesthesia. Furthermore, there has been support for thorough debridement of necrotic tissue with referral to a hand specialist for deeper injuries to the hands as well as referral to a foot and ankle specialist for deeper injuries of the lower extremities.23,24 More serious injuries with penetration of vital structures, such as through the chest or abdomen, require immediate exploration in an operating room.1,24

Imaging

Routine imaging of stingray injuries remains controversial. In a case series of 119 patients presenting to a California emergency department with stingray injuries, Clark et al9 found that radiographs were not helpful. This finding likely is due in part to an inability to detect hypodense material such as integumentary or glandular tissue via radiography.3 However, radiographs have been used to identify retained stingray barbs in select cases in which retained barbs are suspected.2,25 Lastly, ultrasonography potentially may offer a better first choice when a barb is not readily apparent; magnetic resonance imaging may be indicated for more involved areas and for further visualization of suspected hypodense material, though at a higher expense.2,9

Biopsy

Biopsies of stingray injuries are rarely performed, and the findings are not well characterized. One case biopsied 2 months after injury showed a large zone of paucicellular necrosis with superficial ulceration and granulomatous inflammation. The stingray venom was most likely responsible for the pattern of necrosis noted in the biopsy.21

Avoidance and Prevention

Patients traveling to areas of the world inhabited by stingrays should receive counseling on how to avoid injury. Prior to entry, individuals can throw stones or use a long stick to clear their walking or swimming areas of venomous fish.26 Polarized sunglasses may help spot stingrays in shallow water. Furthermore, wading through water with a shuffling gait can help individuals avoid stepping directly on a stingray and also warns stingrays that someone is in the area. Individuals who spend more time in coastal waters or river systems inhabited by stingrays may invest in protective stingray gear such as leg guards or specialized wading boots.26 Lastly, fishermen should be advised to avoid handling stingrays with their hands and instead cut their fishing line to release the fish.

- Aurbach PS. Envenomations by aquatic vertebrates. In: Auerbach PS. Wilderness Medicine. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2007:1730-1749.

- Robins CR, Ray GC. A Field Guide to Atlantic Coast Fishes. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company; 1986.

- Diaz JH. The evaluation, management, and prevention of stingray injuries in travelers. J Travel Med. 2008;15:102-109.

- Haddad V Jr, Neto DG, de Paula Neto JB, et al. Freshwater stingrays: study of epidemiologic, clinical and therapeutic aspects based on 84 envenomings in humans and some enzymatic activities of the venom. Toxicon. 2004;43:287-294.

- Marinkelle CJ. Accidents by venomous animals in Colombia. Ind Med Surg. 1966;35:988-992.

- Last PR, White WT, Caire JN, et al. Sharks and Rays of Borneo. Collingwood VIC, Australia: CSIRO Publishing; 2010.

- Mebs D. Venomous and Poisonous Animals: A Handbook for Biologists, Toxicologists and Toxinologists, Physicians and Pharmacists. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2002.

- Clark AT, Clark RF, Cantrell FL. A retrospective review of the presentation and treatment of stingray stings reported to a poison control system. Am J Ther. 2017;24:E177-E180.

- Clark RF, Girard RH, Rao D, et al. Stingray envenomation: a retrospective review of clinical presentation and treatment in 119 cases. J Emerg Med. 2007;33:33-37.

- Mahjoubi L, Joyeux A, Delambre JF, et al. Near-death thoracic trauma caused by a stingray in the Indian Ocean. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;29:262-263.

- Parra MW, Constantini EN, Rodas EB. Surviving a transfixing cardiac injury caused by a stingray barb. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:E115-E116.

- Dos Santos JC, Grund LZ, Seibert CS, et al. Stingray venom activates IL-33 producing cardiomyocytes, but not mast cell, to promote acute neutrophil-mediated injury. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7912.

- Auerbach PS, Norris RL. Marine envenomation. In: Longo DL, Kasper SL, Jameson JL, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012:144-148.

- Cook MD, Matteucci MJ, Lall R, et al. Stingray envenomation. J Emerg Med. 2006;30:345-347.

- Bowers RC, Mustain MV. Disorders due to physical & environmental agents. In: Humphries RL, Stone C, eds. CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment Emergency Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011:835-861.

- Domingos MO, Franzolin MR, dos Anjos MT, et al. The influence of environmental bacteria in freshwater stingray wound-healing. Toxicon. 2011;58:147-153.

- Auerbach PS, Yajko DM, Nassos PS, et al. Bacteriology of the marine environment: implications for clinical therapy. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16:643-649.

- Torrez PP, Quiroga MM, Said R, et al. Tetanus after envenomations caused by freshwater stingrays. Toxicon. 2015;97:32-35.

- Hiemenz JW, Kennedy B, Kwon-Chung KJ. Invasive fusariosis associated with an injury by a stingray barb. J Med Vet Mycol. 1990;28:209-213.

- da Silva NJ Jr, Ferreira KR, Pinto RN, et al. A severe accident caused by an ocellate river stingray (Potamotrygon motoro) in central Brazil: how well do we really understand stingray venom chemistry, envenomation, and therapeutics? Toxins (Basel). 2015;7:2272-2288.

- Tartar D, Limova M, North J. Clinical and histopathologic findings in cutaneous sting ray wounds: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19261.

- Jarvis HC, Matheny LM, Clanton TO. Stingray injury to the webspace of the foot. Orthopedics. 2012;35:E762-E765.

- Trickett R, Whitaker IS, Boyce DE. Sting-ray injuries to the hand: case report, literature review and a suggested algorithm for management. J Plast Reconstruct Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:E270-E273.

- Fernandez I, Valladolid G, Varon J, et al. Encounters with venomous sea-life. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:103-112.

- O’Malley GF, O’Malley RN, Pham O, et al. Retained stingray barb and the importance of imaging. Wilderness Environ Med. 2015;26:375-379.

- How to protect yourself from stingrays. Howcast website. https://www.howcast.com/videos/228034-how-to-protect-yourself-from-stingrays/. Accessed July 12, 2018.

- Aurbach PS. Envenomations by aquatic vertebrates. In: Auerbach PS. Wilderness Medicine. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2007:1730-1749.

- Robins CR, Ray GC. A Field Guide to Atlantic Coast Fishes. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company; 1986.

- Diaz JH. The evaluation, management, and prevention of stingray injuries in travelers. J Travel Med. 2008;15:102-109.

- Haddad V Jr, Neto DG, de Paula Neto JB, et al. Freshwater stingrays: study of epidemiologic, clinical and therapeutic aspects based on 84 envenomings in humans and some enzymatic activities of the venom. Toxicon. 2004;43:287-294.

- Marinkelle CJ. Accidents by venomous animals in Colombia. Ind Med Surg. 1966;35:988-992.

- Last PR, White WT, Caire JN, et al. Sharks and Rays of Borneo. Collingwood VIC, Australia: CSIRO Publishing; 2010.

- Mebs D. Venomous and Poisonous Animals: A Handbook for Biologists, Toxicologists and Toxinologists, Physicians and Pharmacists. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2002.

- Clark AT, Clark RF, Cantrell FL. A retrospective review of the presentation and treatment of stingray stings reported to a poison control system. Am J Ther. 2017;24:E177-E180.

- Clark RF, Girard RH, Rao D, et al. Stingray envenomation: a retrospective review of clinical presentation and treatment in 119 cases. J Emerg Med. 2007;33:33-37.

- Mahjoubi L, Joyeux A, Delambre JF, et al. Near-death thoracic trauma caused by a stingray in the Indian Ocean. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;29:262-263.

- Parra MW, Constantini EN, Rodas EB. Surviving a transfixing cardiac injury caused by a stingray barb. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:E115-E116.

- Dos Santos JC, Grund LZ, Seibert CS, et al. Stingray venom activates IL-33 producing cardiomyocytes, but not mast cell, to promote acute neutrophil-mediated injury. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7912.

- Auerbach PS, Norris RL. Marine envenomation. In: Longo DL, Kasper SL, Jameson JL, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012:144-148.

- Cook MD, Matteucci MJ, Lall R, et al. Stingray envenomation. J Emerg Med. 2006;30:345-347.

- Bowers RC, Mustain MV. Disorders due to physical & environmental agents. In: Humphries RL, Stone C, eds. CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment Emergency Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011:835-861.

- Domingos MO, Franzolin MR, dos Anjos MT, et al. The influence of environmental bacteria in freshwater stingray wound-healing. Toxicon. 2011;58:147-153.

- Auerbach PS, Yajko DM, Nassos PS, et al. Bacteriology of the marine environment: implications for clinical therapy. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16:643-649.

- Torrez PP, Quiroga MM, Said R, et al. Tetanus after envenomations caused by freshwater stingrays. Toxicon. 2015;97:32-35.

- Hiemenz JW, Kennedy B, Kwon-Chung KJ. Invasive fusariosis associated with an injury by a stingray barb. J Med Vet Mycol. 1990;28:209-213.

- da Silva NJ Jr, Ferreira KR, Pinto RN, et al. A severe accident caused by an ocellate river stingray (Potamotrygon motoro) in central Brazil: how well do we really understand stingray venom chemistry, envenomation, and therapeutics? Toxins (Basel). 2015;7:2272-2288.

- Tartar D, Limova M, North J. Clinical and histopathologic findings in cutaneous sting ray wounds: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19261.

- Jarvis HC, Matheny LM, Clanton TO. Stingray injury to the webspace of the foot. Orthopedics. 2012;35:E762-E765.

- Trickett R, Whitaker IS, Boyce DE. Sting-ray injuries to the hand: case report, literature review and a suggested algorithm for management. J Plast Reconstruct Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:E270-E273.

- Fernandez I, Valladolid G, Varon J, et al. Encounters with venomous sea-life. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:103-112.

- O’Malley GF, O’Malley RN, Pham O, et al. Retained stingray barb and the importance of imaging. Wilderness Environ Med. 2015;26:375-379.

- How to protect yourself from stingrays. Howcast website. https://www.howcast.com/videos/228034-how-to-protect-yourself-from-stingrays/. Accessed July 12, 2018.

Practice Points

- Acute pain associated with stingray injuries can be treated with hot water immersion.

- Stingray injuries are prone to secondary infection and poor wound healing.