User login

Dyshidroticlike Contact Dermatitis and Paronychia Resulting From a Dip Powder Manicure

To the Editor:

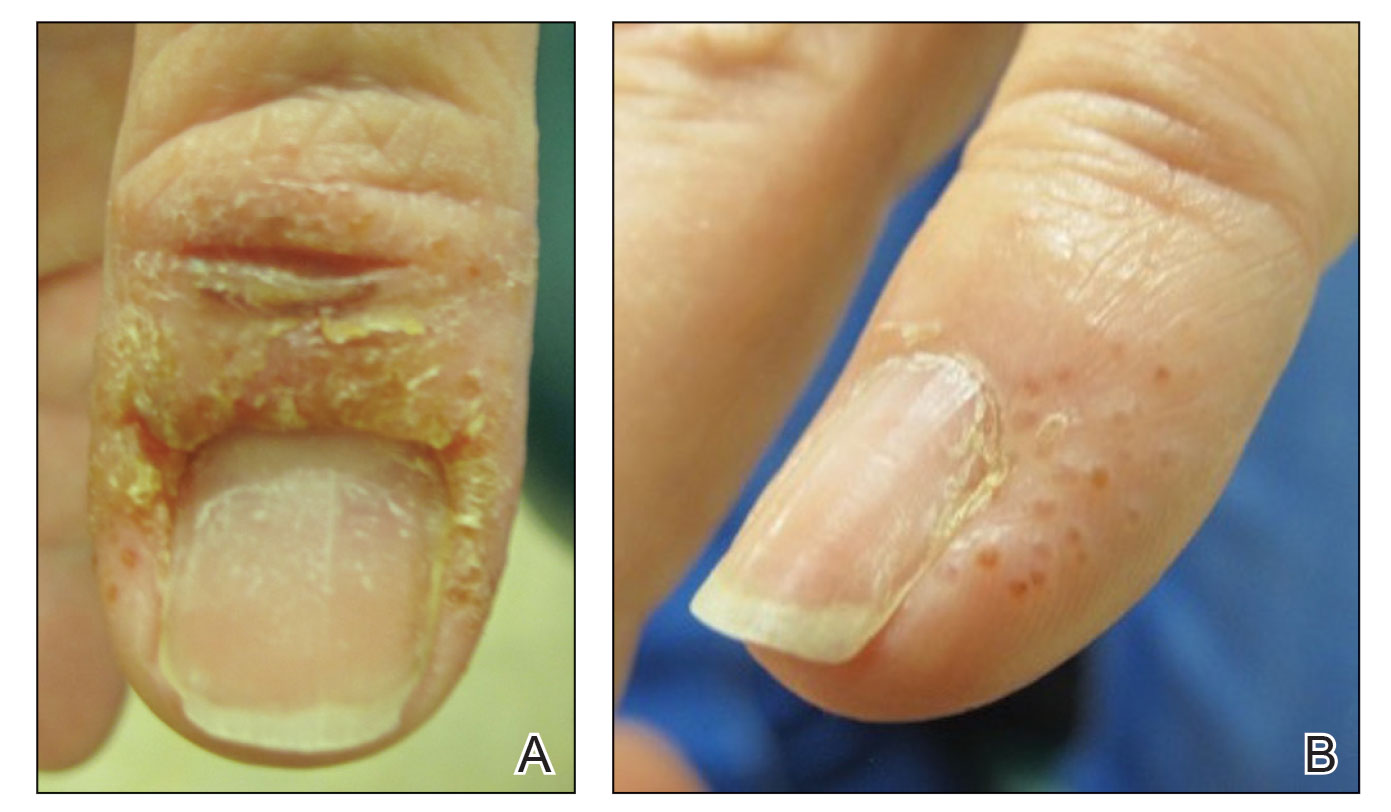

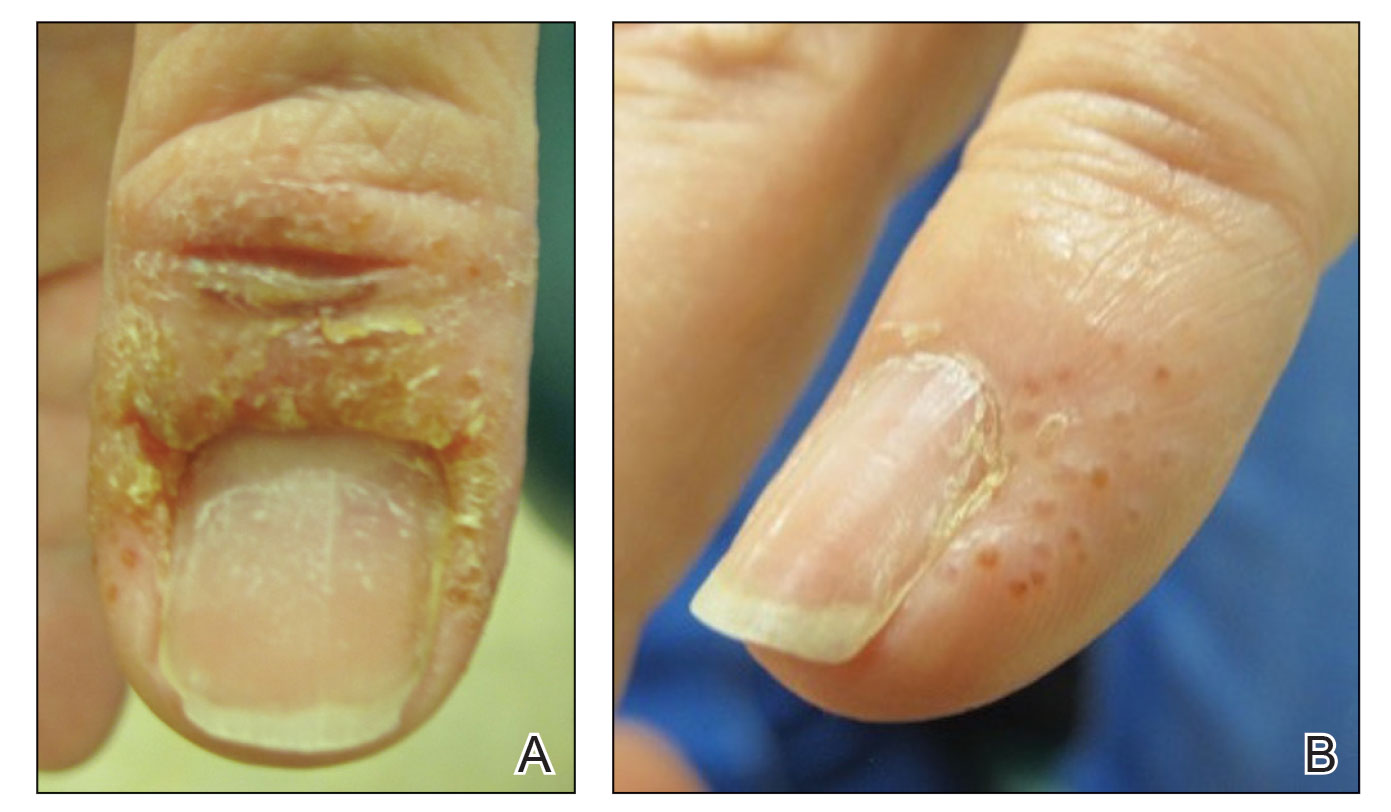

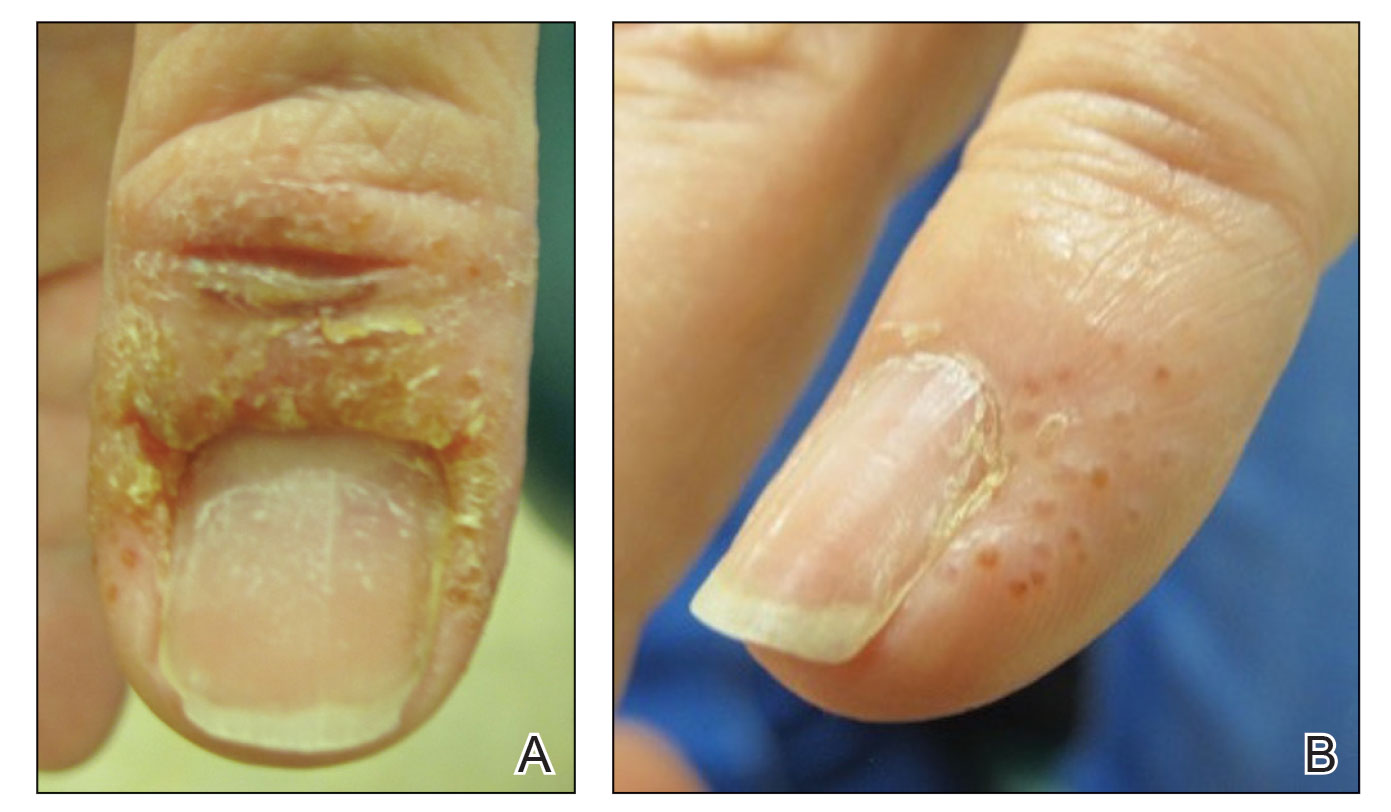

A 58-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic with a pruritic weeping eruption circumferentially on the distal digits of both hands of 5 weeks’ duration. The patient disclosed that she had been receiving dip powder manicures at a local nail salon approximately every 2 weeks over the last 3 to 6 months. She had received frequent acrylic nail extensions over the last 8 years prior to starting the dip powder manicures. Physical examination revealed well-demarcated eczematous plaques involving the lateral and proximal nail folds of the right thumb with an overlying serous crust and loss of the cuticle (Figure 1A). Erythematous plaques with firm deep-seated microvesicles also were present on the other digits, distributed distal to the distal interphalangeal joints (Figure 1B). She was diagnosed with dyshidroticlike contact dermatitis and paronychia. Treatment included phenol 1.5% colorless solution and clobetasol ointment 0.05% for twice-daily application to the affected areas. The patient also was advised to stop receiving manicures. At 1-month follow-up, the paronychia had resolved and the dermatitis had nearly resolved.

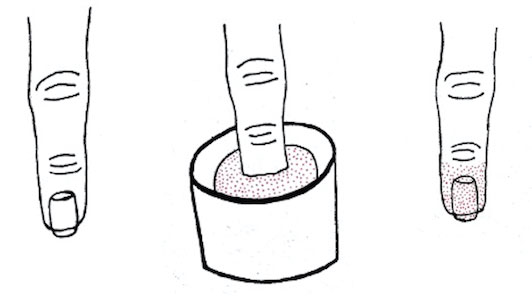

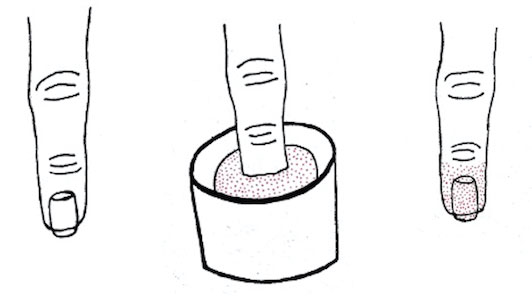

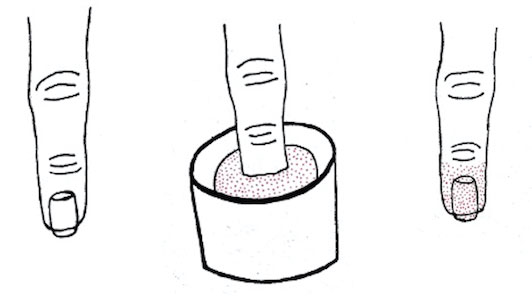

Dip powder manicures use a wet adhesive base coat with acrylic powder and an activator topcoat to initiate a chemical reaction that hardens and sets the nail polish. The colored powder typically is applied by dipping the digit up to the distal interphalangeal joint into a small container of loose powder and then brushing away the excess (Figure 2). Acrylate, a chemical present in dip powders, is a known allergen and has been associated with the development of allergic contact dermatitis and onychodystrophy in patients after receiving acrylic and UV-cured gel polish manicures.1,2 Inadequate sanitation practices at nail salons also have been associated with infection transmission.3,4 Additionally, the news media has covered the potential risk of infection due to contamination from reused dip manicure powder and the use of communal powder containers.5

To increase clinical awareness of the dip manicure technique, we describe the presentation and successful treatment of dyshidroticlike contact dermatitis and paronychia that occurred in a patient after she received a dip powder manicure. Dermatoses and infection limited to the distal phalanges will present in patients more frequently as dip powder manicures continue to increase in popularity and frequency.

- Baran R. Nail cosmetics: allergies and irritations. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3:547-555.

- Chen AF, Chimento SM, Hu S, et al. Nail damage from gel polish manicure. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2012;11:27-29.

- Schmidt AN, Zic JA, Boyd AS. Pedicure-associated Mycobacterium chelonae infection in a hospitalized patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E248-E250.

- Sniezek PJ, Graham BS, Busch HB, et al. Rapidly growing mycobacterial infections after pedicures. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:629-634.

- Joseph T. You could be risking an infection with nail dipping. NBC Universal Media, LLC. Updated July 11, 2019. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://www.nbcmiami.com/news/local/You-Could-Be-Risking-an-Infection-with-Nail-Dipping-512550372.html

To the Editor:

A 58-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic with a pruritic weeping eruption circumferentially on the distal digits of both hands of 5 weeks’ duration. The patient disclosed that she had been receiving dip powder manicures at a local nail salon approximately every 2 weeks over the last 3 to 6 months. She had received frequent acrylic nail extensions over the last 8 years prior to starting the dip powder manicures. Physical examination revealed well-demarcated eczematous plaques involving the lateral and proximal nail folds of the right thumb with an overlying serous crust and loss of the cuticle (Figure 1A). Erythematous plaques with firm deep-seated microvesicles also were present on the other digits, distributed distal to the distal interphalangeal joints (Figure 1B). She was diagnosed with dyshidroticlike contact dermatitis and paronychia. Treatment included phenol 1.5% colorless solution and clobetasol ointment 0.05% for twice-daily application to the affected areas. The patient also was advised to stop receiving manicures. At 1-month follow-up, the paronychia had resolved and the dermatitis had nearly resolved.

Dip powder manicures use a wet adhesive base coat with acrylic powder and an activator topcoat to initiate a chemical reaction that hardens and sets the nail polish. The colored powder typically is applied by dipping the digit up to the distal interphalangeal joint into a small container of loose powder and then brushing away the excess (Figure 2). Acrylate, a chemical present in dip powders, is a known allergen and has been associated with the development of allergic contact dermatitis and onychodystrophy in patients after receiving acrylic and UV-cured gel polish manicures.1,2 Inadequate sanitation practices at nail salons also have been associated with infection transmission.3,4 Additionally, the news media has covered the potential risk of infection due to contamination from reused dip manicure powder and the use of communal powder containers.5

To increase clinical awareness of the dip manicure technique, we describe the presentation and successful treatment of dyshidroticlike contact dermatitis and paronychia that occurred in a patient after she received a dip powder manicure. Dermatoses and infection limited to the distal phalanges will present in patients more frequently as dip powder manicures continue to increase in popularity and frequency.

To the Editor:

A 58-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic with a pruritic weeping eruption circumferentially on the distal digits of both hands of 5 weeks’ duration. The patient disclosed that she had been receiving dip powder manicures at a local nail salon approximately every 2 weeks over the last 3 to 6 months. She had received frequent acrylic nail extensions over the last 8 years prior to starting the dip powder manicures. Physical examination revealed well-demarcated eczematous plaques involving the lateral and proximal nail folds of the right thumb with an overlying serous crust and loss of the cuticle (Figure 1A). Erythematous plaques with firm deep-seated microvesicles also were present on the other digits, distributed distal to the distal interphalangeal joints (Figure 1B). She was diagnosed with dyshidroticlike contact dermatitis and paronychia. Treatment included phenol 1.5% colorless solution and clobetasol ointment 0.05% for twice-daily application to the affected areas. The patient also was advised to stop receiving manicures. At 1-month follow-up, the paronychia had resolved and the dermatitis had nearly resolved.

Dip powder manicures use a wet adhesive base coat with acrylic powder and an activator topcoat to initiate a chemical reaction that hardens and sets the nail polish. The colored powder typically is applied by dipping the digit up to the distal interphalangeal joint into a small container of loose powder and then brushing away the excess (Figure 2). Acrylate, a chemical present in dip powders, is a known allergen and has been associated with the development of allergic contact dermatitis and onychodystrophy in patients after receiving acrylic and UV-cured gel polish manicures.1,2 Inadequate sanitation practices at nail salons also have been associated with infection transmission.3,4 Additionally, the news media has covered the potential risk of infection due to contamination from reused dip manicure powder and the use of communal powder containers.5

To increase clinical awareness of the dip manicure technique, we describe the presentation and successful treatment of dyshidroticlike contact dermatitis and paronychia that occurred in a patient after she received a dip powder manicure. Dermatoses and infection limited to the distal phalanges will present in patients more frequently as dip powder manicures continue to increase in popularity and frequency.

- Baran R. Nail cosmetics: allergies and irritations. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3:547-555.

- Chen AF, Chimento SM, Hu S, et al. Nail damage from gel polish manicure. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2012;11:27-29.

- Schmidt AN, Zic JA, Boyd AS. Pedicure-associated Mycobacterium chelonae infection in a hospitalized patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E248-E250.

- Sniezek PJ, Graham BS, Busch HB, et al. Rapidly growing mycobacterial infections after pedicures. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:629-634.

- Joseph T. You could be risking an infection with nail dipping. NBC Universal Media, LLC. Updated July 11, 2019. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://www.nbcmiami.com/news/local/You-Could-Be-Risking-an-Infection-with-Nail-Dipping-512550372.html

- Baran R. Nail cosmetics: allergies and irritations. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3:547-555.

- Chen AF, Chimento SM, Hu S, et al. Nail damage from gel polish manicure. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2012;11:27-29.

- Schmidt AN, Zic JA, Boyd AS. Pedicure-associated Mycobacterium chelonae infection in a hospitalized patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E248-E250.

- Sniezek PJ, Graham BS, Busch HB, et al. Rapidly growing mycobacterial infections after pedicures. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:629-634.

- Joseph T. You could be risking an infection with nail dipping. NBC Universal Media, LLC. Updated July 11, 2019. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://www.nbcmiami.com/news/local/You-Could-Be-Risking-an-Infection-with-Nail-Dipping-512550372.html

Practice Points

- Manicures performed at nail salons have been associated with the development of paronychia due to inadequate sanitation practices and contact dermatitis caused by acrylates present in nail polish.

- The dip powder manicure is a relatively new manicure technique. The distribution of dermatoses and infection limited to the distal phalanges will present in patients more frequently as dip powder manicures continue to increase in popularity and are performed more frequently.

Acute onset of rash and oligoarthritis

A 29-year-old man sought treatment at our clinic for an extensive rash he’d developed the month before. The rash was on his scalp, umbilicus, glans penis, palms, and soles of his feet. He reported swelling in his left knee and his fourth toes bilaterally that was exacerbated by weight bearing. During the 2 days prior to his visit to the clinic, the patient said he’d had a fever and night sweats; he denied ocular symptoms, GI complaints, dysuria, or penile discharge.

When asked about his sexual history, the patient noted that he’d had unprotected intercourse with a woman a year earlier that resulted in pain on urination and resolved on its own. Other than a resolved case of oral thrush, the patient had a noncontributory past medical history, took no medications, and had no family history of psoriasis.

A physical exam revealed circinate, scaly, and erythematous plaques covering his entire scalp ( FIGURE 1 ). The patient’s conjunctiva and oropharynx were clear. His fingernails showed hyperkeratosis, subungual debris, and nail fold erythema, without pitting. He also had bilateral swelling of the distal interphalangeal joints of his index fingers.

The patient’s umbilicus had a scaly erythematous plaque, while there were confluent erythematous plaques in the groin area, and on the glans penis. There were also similar erythematous plaques in the axilla and inguinal folds; plaques on the lower extremities had a thicker layer of scale. The patient’s feet had crusted plaques on the plantar surface, hyperkeratotic nails with thick subungual debris, and swelling and tenderness of the fourth toes bilaterally ( FIGURE 2 ).

FIGURE 1

Circinate plaques

FIGURE 2

Hyperkeratotic nails, swollen toe

What is your diagnosis?

Diagnosis: Reiter’s syndrome

This young man had Reiter’s syndrome (RS), a form of reactive arthritis that comprises a small subset of cases within the larger family of rheumatoid factor- seronegative spondyloarthritides—conditions noted primarily for inflammation of the axial skeleton.1

Of historical interest is the fact that this diagnosis shares its name with the man who first described it, Hans Reiter, a Nazi physician who tested unapproved vaccines and performed experimental procedures on victims in concentration camps. The infamous legacy of Reiter’s name has led to the proposal that the syndrome be referred to by another, more descriptive name.2 For the sake of simplicity, we’ll refer to the syndrome by the abbreviation RS.

Look for elements of the classic triad

RS is notoriously inconsistent in its presentation. Only a third of patients will develop the “classic triad”—that is: peripheral arthritis lasting at least 1 month, urethritis (or cervicitis), and conjunctivitis. Nearly half of patients will have only a single element of the triad.3

Patients with RS will complain of generalized malaise and fever and will often describe dysuria with concomitant urethral discharge. If conjunctivitis is present, the patient will report reddened, sensitive eyes. Pain will often originate from axial bones, lower extremities (in an oligoarticular asymmetrical pattern), swollen digits, and the heels (from enthesopathy).

Skin manifestations are often very noticeable and include psoriasiform lesions ( FIGURE 3 ) on the palms, soles, and glans penis. Specifically, you’ll see keratoderma blenorrhagicum ( FIGURE 4 ), brown and red macules/papules with pustular or hyperkeratotic features, on the palmar and plantar surfaces. Erythematous and scaly lesions resembling psoriatic plaques often appear elsewhere on the body. On the uncircumcised penis, these shallow ulcerations have a micropustular, serpiginous border and are referred to as balanitis circinata. However, they may also appear psoriasiform in nature on circumcised men, as was the case with our patient.

Coincident findings include onycholysis and subungual hyperkeratosis, lesions mimicking migratory glossitis, and anterior uveitis.

FIGURE 3

Psoriasiform plaque

FIGURE 4

Keratoderma blenorrhagicum

The typical patient? A young, white man

Patients with RS are almost always Caucasian males in their early twenties and are typically HLA-B27 positive. Seronegativity for this HLA factor may portend a less severe version of the syndrome. Individuals infected with HIV show increased incidence of developing RS.3

A microbial antigen is likely responsible for the initial activation of RS. This is followed by an immune reaction involving the joints, skin, and eyes. This theory is supported by the absence of auto- antibodies, the frequent association with HLA-B27, and the fact that patients with advanced AIDS experience the same severity of RS symptoms, despite depressed CD4+ T cell function.1

Bacteria trigger syndrome via 1 of 2 pathways

The bacteria that trigger RS typically enter the body through one of 2 pathways: the genitourinary tract or the gastrointestinal tract.

- The sexual transmission pathway involves infection with Chlamydia trachomatis or Ureaplasma urealyticum 1 to 4 weeks prior to development of urethritis and possibly conjunctivitis. The arthritic component follows later.

- The gastrointestinal pathway involves an enteric pathogen, such as Salmonella enteritidis, Yersinia enterocolitica, Campylobacter fetus, or Shigella flexneri that infects the host and follows the same time frame as noted earlier, though diarrhea rather than urethritis emerges as a chief complaint.4

Various forms of arthritis comprise the differential

A number of conditions must be ruled out before the RS diagnosis is considered definitive. The most likely imposters include:

- Gonococcal arthritis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Psoriatic arthritis.

In addition, an attack of gouty arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, serum sickness, Behçet’s syndrome, rheumatic fever, Still’s disease, and HIV could also present in a similar fashion.

The lab work, detailed below, separates RS from the imposters.

Test blood and urine; check the ankles

Although there is no specific test for RS, several laboratory procedures are essential to honing in on the diagnosis. Hematological inquiry will confirm anemia, leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Though the urethral test may not be positive for a suspected organism, this procedure must be done to rule out gonococcal or chlamydial infection. This can now be done on a urine specimen rather than inserting a swab into the urethra. The urine is sent for a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test rather than a culture. If enteritis was the preceding infection, a stool culture to elucidate potential pathogens is warranted.

You’ll also need to order serological tests for antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), rheumatoid factor (RF), and HIV. As you would expect, these tests will be abnormal for systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and HIV respectively. Though these tests are often negative in RS patients, a strong association with HIV infection does exist.

Keep in mind, too, that you can differentiate gonococcal arthritis from RS based on historical features, as well as clinical features, including migratory polyarthritis with necrotic and pustular skin lesions. Patients with gonococcal arthritis will also have a positive gonococcal culture and rapid improvement with antibiotics.

If you order a biopsy, pathology is likely to find a variety of features in an RS patient, such as spongiform pustules, neutrophilic infiltrate in a perivascular pattern, and an epidermal hyperplasia that resembles psoriasis.3

Radiographic imaging for a suspected case of RS may reveal a number of signs that resemble psoriatic arthritis (pencilin-cup deformity, syndesmophytes, sacroiliitis), but enthesitis, particularly in the ankle joint region, should raise your index of suspicion for RS.6

Tx: Antibiotics, NSAIDs, and steroids

Antibiotic therapy for 3 months is indicated if a patient’s case of RS can be traced back to an infection. If a Chlamydia species is the offending organism, then doxycycline or tetracycline can be used7 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B). If the infectious agent is unknown, then ciprofloxacin can offer broad-spectrum coverage8 (SOR: B).

Though few studies have evaluated the long-term effects of NSAID treatment on RS, a regular schedule of high doses for several weeks is appropriate for inflammation and pain management. It’s most effective when given early in the disease course5 (SOR: B).

Topical corticosteroids can be used on mucosal and skin lesions. For refractory disease, immunosuppressive agents such as sulfasalazine at 2000 mg/day9 (SOR: B) or a subcutaneous injection of etanercept at 25 mg twice weekly10 (SOR: B) offer relief.

Our patient’s treatment included an NSAID and corticosteroids

Because our patient’s syndrome involved a variety of systemic manifestations, we used several medications to cover all of his symptoms. We prescribed piroxicam 20 mg daily, clobetasol 0.05% ointment applied daily to legs and feet, triamcinolone 0.1% cream applied to scalp twice daily and genitals and armpits once daily, and acitretin 25 mg daily. We consulted Rheumatology to assess and treat his joint disease. We also consulted Ophthalmology to assess for potential ocular manifestations.

Though the patient did report a history of a sexually transmitted infection, it occurred long before his visit, and we were unable to identify an infectious agent. As a result, we did not start him on any antibiotics.

We instructed the patient to return in 2 weeks. Unfortunately, he was lost to follow-up. Patients with RS, though, typically make a full recovery from their symptoms. Some patients, however—10% to 20%—may go on to have a chronic, deforming arthritis.3

1. Winchester R. Reiter’s syndrome. In Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolf K, Austen KF, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2003:1769-1776.

2. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrew’s Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: saunders elsevier; 2006.

3. Wolff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2005.

4. Colmegna I, Cuchacovich R, Espinoza LR. HLA-B27-associated reactive arthritis: pathogenetic and clinical considerations. Clin Microbiol Rev 2004;17:348-369.

5. Schachner LA, Hansen RC. Pediatric Dermatology. 2nd ed. New York, NY: churchill livingstone, Inc; 1995.

6. Gladman DD. Clinical aspects of the spondyloarthropathies. Am J Med Sci 1998;316:234-238.

7. Lauhio A, Leirisalo-Repo M, Lähdevirta J, Saikku P, Repo H. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of three-month treatment with lymecycline in reactive arthritis, with special reference to chlamydia arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1991;34:6-14.

8. Yli-Kerttula T, Luukkainen R, Yli-Kerttula U, et al. Effect of a three month course of ciprofloxacin on the late prognosis of reactive arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:880-884.

9. Clegg DO, Reda DJ, Weisman MH, et al. Comparison of sulfasalazine and placebo in the treatment of reactive arthritis (Reiter’s syndrome). A Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study. Arthritis Rheum 1996;39:2021-2027.

10. Flagg SD, Meador R, Hsia E, Kitumnuaypong T, Schumacher HR, Jr. Decreased pain and synovial inflammation after etanercept therapy in patients with reactive and undifferentiated arthritis: an open-label trial. Arthritis Rheum 2005;53:613-617.

A 29-year-old man sought treatment at our clinic for an extensive rash he’d developed the month before. The rash was on his scalp, umbilicus, glans penis, palms, and soles of his feet. He reported swelling in his left knee and his fourth toes bilaterally that was exacerbated by weight bearing. During the 2 days prior to his visit to the clinic, the patient said he’d had a fever and night sweats; he denied ocular symptoms, GI complaints, dysuria, or penile discharge.

When asked about his sexual history, the patient noted that he’d had unprotected intercourse with a woman a year earlier that resulted in pain on urination and resolved on its own. Other than a resolved case of oral thrush, the patient had a noncontributory past medical history, took no medications, and had no family history of psoriasis.

A physical exam revealed circinate, scaly, and erythematous plaques covering his entire scalp ( FIGURE 1 ). The patient’s conjunctiva and oropharynx were clear. His fingernails showed hyperkeratosis, subungual debris, and nail fold erythema, without pitting. He also had bilateral swelling of the distal interphalangeal joints of his index fingers.

The patient’s umbilicus had a scaly erythematous plaque, while there were confluent erythematous plaques in the groin area, and on the glans penis. There were also similar erythematous plaques in the axilla and inguinal folds; plaques on the lower extremities had a thicker layer of scale. The patient’s feet had crusted plaques on the plantar surface, hyperkeratotic nails with thick subungual debris, and swelling and tenderness of the fourth toes bilaterally ( FIGURE 2 ).

FIGURE 1

Circinate plaques

FIGURE 2

Hyperkeratotic nails, swollen toe

What is your diagnosis?

Diagnosis: Reiter’s syndrome

This young man had Reiter’s syndrome (RS), a form of reactive arthritis that comprises a small subset of cases within the larger family of rheumatoid factor- seronegative spondyloarthritides—conditions noted primarily for inflammation of the axial skeleton.1

Of historical interest is the fact that this diagnosis shares its name with the man who first described it, Hans Reiter, a Nazi physician who tested unapproved vaccines and performed experimental procedures on victims in concentration camps. The infamous legacy of Reiter’s name has led to the proposal that the syndrome be referred to by another, more descriptive name.2 For the sake of simplicity, we’ll refer to the syndrome by the abbreviation RS.

Look for elements of the classic triad

RS is notoriously inconsistent in its presentation. Only a third of patients will develop the “classic triad”—that is: peripheral arthritis lasting at least 1 month, urethritis (or cervicitis), and conjunctivitis. Nearly half of patients will have only a single element of the triad.3

Patients with RS will complain of generalized malaise and fever and will often describe dysuria with concomitant urethral discharge. If conjunctivitis is present, the patient will report reddened, sensitive eyes. Pain will often originate from axial bones, lower extremities (in an oligoarticular asymmetrical pattern), swollen digits, and the heels (from enthesopathy).

Skin manifestations are often very noticeable and include psoriasiform lesions ( FIGURE 3 ) on the palms, soles, and glans penis. Specifically, you’ll see keratoderma blenorrhagicum ( FIGURE 4 ), brown and red macules/papules with pustular or hyperkeratotic features, on the palmar and plantar surfaces. Erythematous and scaly lesions resembling psoriatic plaques often appear elsewhere on the body. On the uncircumcised penis, these shallow ulcerations have a micropustular, serpiginous border and are referred to as balanitis circinata. However, they may also appear psoriasiform in nature on circumcised men, as was the case with our patient.

Coincident findings include onycholysis and subungual hyperkeratosis, lesions mimicking migratory glossitis, and anterior uveitis.

FIGURE 3

Psoriasiform plaque

FIGURE 4

Keratoderma blenorrhagicum

The typical patient? A young, white man

Patients with RS are almost always Caucasian males in their early twenties and are typically HLA-B27 positive. Seronegativity for this HLA factor may portend a less severe version of the syndrome. Individuals infected with HIV show increased incidence of developing RS.3

A microbial antigen is likely responsible for the initial activation of RS. This is followed by an immune reaction involving the joints, skin, and eyes. This theory is supported by the absence of auto- antibodies, the frequent association with HLA-B27, and the fact that patients with advanced AIDS experience the same severity of RS symptoms, despite depressed CD4+ T cell function.1

Bacteria trigger syndrome via 1 of 2 pathways

The bacteria that trigger RS typically enter the body through one of 2 pathways: the genitourinary tract or the gastrointestinal tract.

- The sexual transmission pathway involves infection with Chlamydia trachomatis or Ureaplasma urealyticum 1 to 4 weeks prior to development of urethritis and possibly conjunctivitis. The arthritic component follows later.

- The gastrointestinal pathway involves an enteric pathogen, such as Salmonella enteritidis, Yersinia enterocolitica, Campylobacter fetus, or Shigella flexneri that infects the host and follows the same time frame as noted earlier, though diarrhea rather than urethritis emerges as a chief complaint.4

Various forms of arthritis comprise the differential

A number of conditions must be ruled out before the RS diagnosis is considered definitive. The most likely imposters include:

- Gonococcal arthritis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Psoriatic arthritis.

In addition, an attack of gouty arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, serum sickness, Behçet’s syndrome, rheumatic fever, Still’s disease, and HIV could also present in a similar fashion.

The lab work, detailed below, separates RS from the imposters.

Test blood and urine; check the ankles

Although there is no specific test for RS, several laboratory procedures are essential to honing in on the diagnosis. Hematological inquiry will confirm anemia, leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Though the urethral test may not be positive for a suspected organism, this procedure must be done to rule out gonococcal or chlamydial infection. This can now be done on a urine specimen rather than inserting a swab into the urethra. The urine is sent for a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test rather than a culture. If enteritis was the preceding infection, a stool culture to elucidate potential pathogens is warranted.

You’ll also need to order serological tests for antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), rheumatoid factor (RF), and HIV. As you would expect, these tests will be abnormal for systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and HIV respectively. Though these tests are often negative in RS patients, a strong association with HIV infection does exist.

Keep in mind, too, that you can differentiate gonococcal arthritis from RS based on historical features, as well as clinical features, including migratory polyarthritis with necrotic and pustular skin lesions. Patients with gonococcal arthritis will also have a positive gonococcal culture and rapid improvement with antibiotics.

If you order a biopsy, pathology is likely to find a variety of features in an RS patient, such as spongiform pustules, neutrophilic infiltrate in a perivascular pattern, and an epidermal hyperplasia that resembles psoriasis.3

Radiographic imaging for a suspected case of RS may reveal a number of signs that resemble psoriatic arthritis (pencilin-cup deformity, syndesmophytes, sacroiliitis), but enthesitis, particularly in the ankle joint region, should raise your index of suspicion for RS.6

Tx: Antibiotics, NSAIDs, and steroids

Antibiotic therapy for 3 months is indicated if a patient’s case of RS can be traced back to an infection. If a Chlamydia species is the offending organism, then doxycycline or tetracycline can be used7 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B). If the infectious agent is unknown, then ciprofloxacin can offer broad-spectrum coverage8 (SOR: B).

Though few studies have evaluated the long-term effects of NSAID treatment on RS, a regular schedule of high doses for several weeks is appropriate for inflammation and pain management. It’s most effective when given early in the disease course5 (SOR: B).

Topical corticosteroids can be used on mucosal and skin lesions. For refractory disease, immunosuppressive agents such as sulfasalazine at 2000 mg/day9 (SOR: B) or a subcutaneous injection of etanercept at 25 mg twice weekly10 (SOR: B) offer relief.

Our patient’s treatment included an NSAID and corticosteroids

Because our patient’s syndrome involved a variety of systemic manifestations, we used several medications to cover all of his symptoms. We prescribed piroxicam 20 mg daily, clobetasol 0.05% ointment applied daily to legs and feet, triamcinolone 0.1% cream applied to scalp twice daily and genitals and armpits once daily, and acitretin 25 mg daily. We consulted Rheumatology to assess and treat his joint disease. We also consulted Ophthalmology to assess for potential ocular manifestations.

Though the patient did report a history of a sexually transmitted infection, it occurred long before his visit, and we were unable to identify an infectious agent. As a result, we did not start him on any antibiotics.

We instructed the patient to return in 2 weeks. Unfortunately, he was lost to follow-up. Patients with RS, though, typically make a full recovery from their symptoms. Some patients, however—10% to 20%—may go on to have a chronic, deforming arthritis.3

A 29-year-old man sought treatment at our clinic for an extensive rash he’d developed the month before. The rash was on his scalp, umbilicus, glans penis, palms, and soles of his feet. He reported swelling in his left knee and his fourth toes bilaterally that was exacerbated by weight bearing. During the 2 days prior to his visit to the clinic, the patient said he’d had a fever and night sweats; he denied ocular symptoms, GI complaints, dysuria, or penile discharge.

When asked about his sexual history, the patient noted that he’d had unprotected intercourse with a woman a year earlier that resulted in pain on urination and resolved on its own. Other than a resolved case of oral thrush, the patient had a noncontributory past medical history, took no medications, and had no family history of psoriasis.

A physical exam revealed circinate, scaly, and erythematous plaques covering his entire scalp ( FIGURE 1 ). The patient’s conjunctiva and oropharynx were clear. His fingernails showed hyperkeratosis, subungual debris, and nail fold erythema, without pitting. He also had bilateral swelling of the distal interphalangeal joints of his index fingers.

The patient’s umbilicus had a scaly erythematous plaque, while there were confluent erythematous plaques in the groin area, and on the glans penis. There were also similar erythematous plaques in the axilla and inguinal folds; plaques on the lower extremities had a thicker layer of scale. The patient’s feet had crusted plaques on the plantar surface, hyperkeratotic nails with thick subungual debris, and swelling and tenderness of the fourth toes bilaterally ( FIGURE 2 ).

FIGURE 1

Circinate plaques

FIGURE 2

Hyperkeratotic nails, swollen toe

What is your diagnosis?

Diagnosis: Reiter’s syndrome

This young man had Reiter’s syndrome (RS), a form of reactive arthritis that comprises a small subset of cases within the larger family of rheumatoid factor- seronegative spondyloarthritides—conditions noted primarily for inflammation of the axial skeleton.1

Of historical interest is the fact that this diagnosis shares its name with the man who first described it, Hans Reiter, a Nazi physician who tested unapproved vaccines and performed experimental procedures on victims in concentration camps. The infamous legacy of Reiter’s name has led to the proposal that the syndrome be referred to by another, more descriptive name.2 For the sake of simplicity, we’ll refer to the syndrome by the abbreviation RS.

Look for elements of the classic triad

RS is notoriously inconsistent in its presentation. Only a third of patients will develop the “classic triad”—that is: peripheral arthritis lasting at least 1 month, urethritis (or cervicitis), and conjunctivitis. Nearly half of patients will have only a single element of the triad.3

Patients with RS will complain of generalized malaise and fever and will often describe dysuria with concomitant urethral discharge. If conjunctivitis is present, the patient will report reddened, sensitive eyes. Pain will often originate from axial bones, lower extremities (in an oligoarticular asymmetrical pattern), swollen digits, and the heels (from enthesopathy).

Skin manifestations are often very noticeable and include psoriasiform lesions ( FIGURE 3 ) on the palms, soles, and glans penis. Specifically, you’ll see keratoderma blenorrhagicum ( FIGURE 4 ), brown and red macules/papules with pustular or hyperkeratotic features, on the palmar and plantar surfaces. Erythematous and scaly lesions resembling psoriatic plaques often appear elsewhere on the body. On the uncircumcised penis, these shallow ulcerations have a micropustular, serpiginous border and are referred to as balanitis circinata. However, they may also appear psoriasiform in nature on circumcised men, as was the case with our patient.

Coincident findings include onycholysis and subungual hyperkeratosis, lesions mimicking migratory glossitis, and anterior uveitis.

FIGURE 3

Psoriasiform plaque

FIGURE 4

Keratoderma blenorrhagicum

The typical patient? A young, white man

Patients with RS are almost always Caucasian males in their early twenties and are typically HLA-B27 positive. Seronegativity for this HLA factor may portend a less severe version of the syndrome. Individuals infected with HIV show increased incidence of developing RS.3

A microbial antigen is likely responsible for the initial activation of RS. This is followed by an immune reaction involving the joints, skin, and eyes. This theory is supported by the absence of auto- antibodies, the frequent association with HLA-B27, and the fact that patients with advanced AIDS experience the same severity of RS symptoms, despite depressed CD4+ T cell function.1

Bacteria trigger syndrome via 1 of 2 pathways

The bacteria that trigger RS typically enter the body through one of 2 pathways: the genitourinary tract or the gastrointestinal tract.

- The sexual transmission pathway involves infection with Chlamydia trachomatis or Ureaplasma urealyticum 1 to 4 weeks prior to development of urethritis and possibly conjunctivitis. The arthritic component follows later.

- The gastrointestinal pathway involves an enteric pathogen, such as Salmonella enteritidis, Yersinia enterocolitica, Campylobacter fetus, or Shigella flexneri that infects the host and follows the same time frame as noted earlier, though diarrhea rather than urethritis emerges as a chief complaint.4

Various forms of arthritis comprise the differential

A number of conditions must be ruled out before the RS diagnosis is considered definitive. The most likely imposters include:

- Gonococcal arthritis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Psoriatic arthritis.

In addition, an attack of gouty arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, serum sickness, Behçet’s syndrome, rheumatic fever, Still’s disease, and HIV could also present in a similar fashion.

The lab work, detailed below, separates RS from the imposters.

Test blood and urine; check the ankles

Although there is no specific test for RS, several laboratory procedures are essential to honing in on the diagnosis. Hematological inquiry will confirm anemia, leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Though the urethral test may not be positive for a suspected organism, this procedure must be done to rule out gonococcal or chlamydial infection. This can now be done on a urine specimen rather than inserting a swab into the urethra. The urine is sent for a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test rather than a culture. If enteritis was the preceding infection, a stool culture to elucidate potential pathogens is warranted.

You’ll also need to order serological tests for antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), rheumatoid factor (RF), and HIV. As you would expect, these tests will be abnormal for systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and HIV respectively. Though these tests are often negative in RS patients, a strong association with HIV infection does exist.

Keep in mind, too, that you can differentiate gonococcal arthritis from RS based on historical features, as well as clinical features, including migratory polyarthritis with necrotic and pustular skin lesions. Patients with gonococcal arthritis will also have a positive gonococcal culture and rapid improvement with antibiotics.

If you order a biopsy, pathology is likely to find a variety of features in an RS patient, such as spongiform pustules, neutrophilic infiltrate in a perivascular pattern, and an epidermal hyperplasia that resembles psoriasis.3

Radiographic imaging for a suspected case of RS may reveal a number of signs that resemble psoriatic arthritis (pencilin-cup deformity, syndesmophytes, sacroiliitis), but enthesitis, particularly in the ankle joint region, should raise your index of suspicion for RS.6

Tx: Antibiotics, NSAIDs, and steroids

Antibiotic therapy for 3 months is indicated if a patient’s case of RS can be traced back to an infection. If a Chlamydia species is the offending organism, then doxycycline or tetracycline can be used7 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B). If the infectious agent is unknown, then ciprofloxacin can offer broad-spectrum coverage8 (SOR: B).

Though few studies have evaluated the long-term effects of NSAID treatment on RS, a regular schedule of high doses for several weeks is appropriate for inflammation and pain management. It’s most effective when given early in the disease course5 (SOR: B).

Topical corticosteroids can be used on mucosal and skin lesions. For refractory disease, immunosuppressive agents such as sulfasalazine at 2000 mg/day9 (SOR: B) or a subcutaneous injection of etanercept at 25 mg twice weekly10 (SOR: B) offer relief.

Our patient’s treatment included an NSAID and corticosteroids

Because our patient’s syndrome involved a variety of systemic manifestations, we used several medications to cover all of his symptoms. We prescribed piroxicam 20 mg daily, clobetasol 0.05% ointment applied daily to legs and feet, triamcinolone 0.1% cream applied to scalp twice daily and genitals and armpits once daily, and acitretin 25 mg daily. We consulted Rheumatology to assess and treat his joint disease. We also consulted Ophthalmology to assess for potential ocular manifestations.

Though the patient did report a history of a sexually transmitted infection, it occurred long before his visit, and we were unable to identify an infectious agent. As a result, we did not start him on any antibiotics.

We instructed the patient to return in 2 weeks. Unfortunately, he was lost to follow-up. Patients with RS, though, typically make a full recovery from their symptoms. Some patients, however—10% to 20%—may go on to have a chronic, deforming arthritis.3

1. Winchester R. Reiter’s syndrome. In Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolf K, Austen KF, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2003:1769-1776.

2. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrew’s Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: saunders elsevier; 2006.

3. Wolff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2005.

4. Colmegna I, Cuchacovich R, Espinoza LR. HLA-B27-associated reactive arthritis: pathogenetic and clinical considerations. Clin Microbiol Rev 2004;17:348-369.

5. Schachner LA, Hansen RC. Pediatric Dermatology. 2nd ed. New York, NY: churchill livingstone, Inc; 1995.

6. Gladman DD. Clinical aspects of the spondyloarthropathies. Am J Med Sci 1998;316:234-238.

7. Lauhio A, Leirisalo-Repo M, Lähdevirta J, Saikku P, Repo H. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of three-month treatment with lymecycline in reactive arthritis, with special reference to chlamydia arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1991;34:6-14.

8. Yli-Kerttula T, Luukkainen R, Yli-Kerttula U, et al. Effect of a three month course of ciprofloxacin on the late prognosis of reactive arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:880-884.

9. Clegg DO, Reda DJ, Weisman MH, et al. Comparison of sulfasalazine and placebo in the treatment of reactive arthritis (Reiter’s syndrome). A Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study. Arthritis Rheum 1996;39:2021-2027.

10. Flagg SD, Meador R, Hsia E, Kitumnuaypong T, Schumacher HR, Jr. Decreased pain and synovial inflammation after etanercept therapy in patients with reactive and undifferentiated arthritis: an open-label trial. Arthritis Rheum 2005;53:613-617.

1. Winchester R. Reiter’s syndrome. In Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolf K, Austen KF, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2003:1769-1776.

2. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrew’s Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: saunders elsevier; 2006.

3. Wolff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2005.

4. Colmegna I, Cuchacovich R, Espinoza LR. HLA-B27-associated reactive arthritis: pathogenetic and clinical considerations. Clin Microbiol Rev 2004;17:348-369.

5. Schachner LA, Hansen RC. Pediatric Dermatology. 2nd ed. New York, NY: churchill livingstone, Inc; 1995.

6. Gladman DD. Clinical aspects of the spondyloarthropathies. Am J Med Sci 1998;316:234-238.

7. Lauhio A, Leirisalo-Repo M, Lähdevirta J, Saikku P, Repo H. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of three-month treatment with lymecycline in reactive arthritis, with special reference to chlamydia arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1991;34:6-14.

8. Yli-Kerttula T, Luukkainen R, Yli-Kerttula U, et al. Effect of a three month course of ciprofloxacin on the late prognosis of reactive arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:880-884.

9. Clegg DO, Reda DJ, Weisman MH, et al. Comparison of sulfasalazine and placebo in the treatment of reactive arthritis (Reiter’s syndrome). A Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study. Arthritis Rheum 1996;39:2021-2027.

10. Flagg SD, Meador R, Hsia E, Kitumnuaypong T, Schumacher HR, Jr. Decreased pain and synovial inflammation after etanercept therapy in patients with reactive and undifferentiated arthritis: an open-label trial. Arthritis Rheum 2005;53:613-617.

Blisters during pregnancy—just with the second husband

A 33-year-old Hispanic woman who was 5 months pregnant came to the hospital complaining of nausea and vomiting. She had a history of anticardiolipin antibody syndrome, diagnosed originally in 1993 after 2 spontaneous abortions. She had stopped taking warfarin (Coumadin) at the start of her pregnancy, and had been taking heparin for 3 months.

After 4 days of close monitoring, the patient had labor induced for severe life-threatening pre-eclampsia. One day after induction and delivery of a stillborn fetus, she began to develop painful swelling of both hands and feet along with targetoid, urticarial, edematous, deep pink, slightly dusky papules and plaques on her hands, abdomen, lower extremities, and proximal thighs. Some of the edematous sites began to form vesicles and bullae (FIGURE 1 AND 2). When asked about this eruption, the patient mentioned having a similar rash after delivery of one of her children about 10 years before.

Interestingly, she noted that she only experienced these cutaneous findings during pregnancies with her second husband and not with her first. Biopsies were performed and showed prominent eosinophils in the dermis and a subepidermal vesicle (FIGURE 3).

FIGURE 1

Blisters on the wrist…

FIGURE 2

…and the abdomen

FIGURE 3

Biopsy results

What is your diagnosis?

Diagnosis: Pemphigoid gestationis

The patient had pemphigoid gestationis, also known as herpes gestationis, a rare autoimmune bullous disease of pregnancy and the puerperium.1 Clinically and immunopathologically, pemphigoid gestationis is related to the pemphigoid group of disorders and is not virally mediated.2

In the United States, pemphigoid gestationis has an incidence of 1:10,000 to 1:50,000 pregnancies.3 Clinically, it manifests during the second or third trimester, with a sudden onset of extremely pruritic urticarial papules and plaques usually located around the umbilicus. These lesions often progress to tense vesicles and blisters and spread peripherally to the trunk, often sparing the face, palms, and soles.4 Worsening of the lesions at the time of delivery occurs in 75% of cases, and usually recurs with subsequent pregnancies.5 Occasionally, however, subsequent pregnancies are unaffected, so-called “skip pregnancies.”6 This occurs most often when there has been a change in paternity.7

The exact cause of pemphigoid gestationis is unknown. Investigative efforts lead to the identification of an immunoglobulin G (IgG) autoantibody, which binds to bullous pemphigoid (BP) antigen 2, also called BP180, which is a protein associated with hemidesmosomes of basal keratinocytes.8-10 These hemidesmosomes form the central portion of the dermalepidermal anchoring complex, whose function is to establish a connection between the basal keratinocytes and the upper dermis.11,12 This is critical for maintaining dermal-epidermal adhesion. It is hypothesized that binding of autoantibodies to BP180 initiates an inflammatory reaction, leading to blister formation at the dermal-epidermal junction.13

Pathology and immunology

Histopathologic findings demonstrate subepidermal vesicles, spongiosis, and perivascular lymphocyte, and histiocyte infiltrates with a preponderance of eosinophils.3 The sine qua non of the disease, though, is the demonstration through direct immunofluorescence of complement deposition and IgG in a linear band along the basement membrane.14

There appears to be a genetic predisposition toward the development of pemphigoid gestationis. Associations with human leukocyte antigens (HLAs) DR3 (61%–85%), DR4 (52%), or both (43%–50%) have been reported.3,15,16 Interestingly, 85% of persons with a history of pemphigoid gestationis were found to have anti-HLA antibodies, some of which were directed against paternal HLAs expressed in their placentae.17 These findings raised speculation about a possible immunologic insult against placental antigens during pregnancy. Evidence suggests that circulating autoantibodies in patients with pemphigoid gestationis bind to the dermal-epidermal junction of skin and amnion in which BP180 antigen is also present.18-20

It has been demonstrated that in patients with pemphigoid gestationis the cells of the placenta stroma express abnormal major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules.21,22 This lead to the proposition of 2 possible mechanisms for the initiation of an autoimmune response in pemphigoid gestationis. The first proposes that placental BP180 is presented to the maternal immune system in association with abnormal MHC molecules, which then trigger the production of autoantibodies that cross-react with the skin. Alternatively, the placental stromal cells may evoke an allogeneic reaction against the BP180 antigen presented by paternal MHC molecules of the placental stroma, which then cross-reacts with the skin.23 The latter theory supports the findings in this patient, who developed pemphigoid gestationis during the 2 pregnancies with her second husband and not during the pregnancies with her first husband.

Differential diagnosis

It is important to differentiate the prebullous stage of pemphigoid gestationis from other pregnancy-related dermatoses. These include polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (PEP), pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP), erythema multiforme, prurigo annularis, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, and impetigo herpetiformis. Impetigo herpetiformis is not related to bacterial or viral causes, but is rather a manifestation of pustular psoriasis during pregnancy. The target lesions that form in pemphigoid gestationis look just like the target lesions of erythema multiforme.

When there is no blister formation, it is impossible to distinguish pemphigoid gestationis from many of the other cutaneous eruptions of pregnancy. If uncertain, the clinician should perform punch biopsies of the involved skin, with one specimen sent for immunofluoresence studies. The biopsy should not pass directly through a bullae, due to risk of losing the overlying epidermis in the specimen. Do the punch biopsy at the edge of the bulla including some normal skin. Other important laboratory exams to perform would include liver function tests to look for an upward trend associated with intrahepatic cholestasis, and herpes simplex virus antibody testing for the association with erythema multiforme. The cutaneous findings and pertinent tests are listed in the table below in order of increasing potential as a life-threatening dermatosis (TABLE).

TABLE

Differential diagnosis for blisters in pregnancy

| DISEASE | ASSOCIATIONS | DIAGNOSIS | TREATMENT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymorphous eruption of pregnancy | Nonspecific pruritic eruption of pregnancy | Biopsy to differentiate from prebullous stage of pemphigoid (herpes) gestationis | Mild to mid-potency topical steroids, oral antihistamines |

| Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy | Occur in stretch marks, spare umbilicus; more often in primigravidas | Unless history is very clear, biopsy to differentiate from prebullous stage of pemphigoid gestationis | Emollients, pulse-dye laser during violaceous stage of striae, topical steroids, oral antihistamines |

| Erythema multiforme | Can involve mucous membranes, targetoid lesions, absence of pruritus, centripetal spread, favors palms/soles | Viral, bacterial, or drug-related eruption. Most often with herpes simplex I or II virus. Biopsy to differentiate from pemphigoid gestationis | Acyclovir, valacyclovir if HSV-related, treatment of bacterial infection, or removal of offending drug |

| Pemphigoid gestationis | Blistering, urticarial papules/plaques, pruritus | Biopsy sent for histologic diagnosis and immunofluorescence | Prednisone for short course starting at 1 mg/kg, then tapering over 2–3 months, topical steroids |

| Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy | +/- jaundice, otherwise no cutaneous findings other than generalized pruritus, risk of preterm birth | Elevation in liver function tests, cholesterol, triglycerides, dark urine, right upper quadrant pain, nausea, greasy stools | Ursodeoxycholic acid, S-adenosyl-L-methionine |

| Impetigo herpetiformis (pustular psoriasis of pregnancy) | Extremely ill with fever, chills, nausea, vascular instability, pustules rather than vesicles | Biopsy if uncertain, pustules sterile, risk of hypocalcemia, hypoparathyroidism | High dose oral steroids or cyclosporine |

Treatment

Pemphigoid gestationis should resolve spontaneously within 2 to 3 months of delivery. Treatment is aimed at preventing new blisters and relieving pruritus, with topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines in mild cases.2,25 In advanced lesions as seen in this case, 0.3 to 0.5 mg/kg of prednisolone daily is usually sufficient.3,25 Alternative medications include sulfapyridine, dapsone, and cyclosporine, though disease response is variable and their safety is questionable.3

When the skin condition began, the patient was treated with oral antihistamines and topical steroids. On day 2, the diagnosis of pemphigoid gestationis was clear, and she was started on oral prednisone at 60 mg/d, which resulted in rapid symptom improvement in her lesions and swelling. New lesions stopped forming, and systemic steroids were tapered off over the 3 months after delivery. The skin lesions healed and she was given supportive counseling to help her cope with her pregnancy loss.

Conclusion

We have described a rare case of a patient with no cutaneous eruptions during her pregnancies with her first husband, who developed pemphigoid gestationis in 2 pregnancies with her second husband. While it is interesting that our patient also had the anticardiolipin syndrome, most patients do not have both conditions.

Our patient had the classic findings of pemphigoid gestationis with many characteristic lesions (including the umbilicus) making the diagnosis possible before biopsy confirmation. This was fortunate for her because her painful swelling responded quickly to the corticosteroids. When cases are less clinically obvious, biopsy for histopathology and immunofluorescence facilitates differentiation of pemphigoid gestationis from other dermatoses of pregnancy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard P. Usatine, MD, University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900. E-mail: usatine@uthscsa.edu

1. Coupe RL. Herpes gestationis. Arch Dermatol 1965;91:633-636.

2. Jenkins RE, Hern S, Black MM. Clinical features and management of 87 patients with pemphigoid gestationis. Clin Exp Dermatol 1999;24:255-259.

3. Al-Fouzan AW, Galadari I, Oumeish I, et al. Herpes gestationis (Pemphigoid gestationis). Clinics Dermatology 2006;24:109-112.

4. Shornick JK. Herpes gestationis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1987;17:539-556.

5. Holmes RC, Black MM, Dann J, et al. A comparative study of toxic erythema of pregnancy and herpes gestationis. Br J Dermatol 1982;106:499-510.

6. Cozzani E, Basso M, Parodi A, Rebora A. Pemphigoid gestationis post partum after changing husband. Intn J Dermatol 2005;44:1057-1058.

7. Shornick JK, Black MM. Fetal risks in herpes gestationis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992;26:63-68.

8. Diaz LA, Ratrie H, III, Saunders WS, et al. Isolation of a human epidermal cDNA corresponding to the 180-kD autoantigen recognized by bullous pemphigoid and herpes gestationis sera. Immunolocalization of this protein to the hemidesmosome. J Clin Invest 1990;86:1088-1094.

9. Giudice GJ, Emery DJ, Diaz LA. Cloning and primary structural analysis of the bullous pemphigoid autoantigen BP180. J Invest Dermatol 1992;99:243-250.

10. Zillikens D, Giudice GJ. BP180/typeXVIII collagen: its role in acquired and inherited disorders of the dermal-epidermal junction. Arch Dermatol Res 1999;291:187-194.

11. Borradori L, Sonnenberg A. Hemidesmosomes: roles in adhesion, signaling and human diseases. Curr Opin Cell Biol 1996;8:647-656.

12. Zillikens D. Acquired skin disease of hemidesmosomes. J Dermatol Sci 1999;20:134-154.

13. Schmidt E, Zillikens D. Autoimmune and inherited subepidermal blistering diseases: advances in the clinic and the laboratory. Adv Dermatol 2000;16:113-157.

14. Shornick JD. Dermatoses of pregnancy. Semin Cutan Med Surg 1998;17:172-181.

15. Holmes RC, Black MM, Jurecka W, et al. Clues to the aetiology and pathogenesis of herpes gestationis. Br J Dermatol 1983;109:131-139.

16. Shornick JK, Stastny P, Gilliam JN. High frequency of histocompatibility antigens DR3 and DR4 in herpes gestationis. J Clin Invest 1981;68:553-555.

17. Shornick JK, Stastny P, Gilliam JN. Paternal histocompatibility (HLA) antigens and maternal anti-HLA antibodies in herpes gestationis. J Invest Dermatol 1983;81:407-409.

18. Ortonne JP, Hsi BL, Verrando P, et al. Herpes gestationis factor reacts with the amniotic epithelial basement membrane. Br J Dermatol 1987;117:147-154.

19. Kelly SE, Bhogal BS, Wojnarowska F, Black MM. Expression of a pemphigoid gestationis-related antigen by human placenta. Br J Dermatol 1988;118:605-611.

20. Fairley JA, Heintz PW, Neuburg M, et al. Expression pattern of the bullous pemphigoid-180 antigen in normal and neoplastic epithelia. Br J Dermatol 1995;133:385-391.

21. Kelly SE, Black MM, Fleming S. Antigen-presenting cells in the skin and placenta in pemphigoid gestationis. Br J Dermatol 1990;122:593-599.

22. Borthwick GM, Holmes RC, Stirrat GM. Abnormal expression of class II MHC antigens in placentae from patients with pemphigoid gestationis. Placenta 1988;9:81-94.

23. Kelly SE, Black MM, Fleming S. Pemphigoid gestationis: a unique mechanism of initiation of an autoimmune response by MHC class II molecules. J Pathol 1989;158:81-82.

24. Borradori L, Saurat JH. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy. Toward a comprehensive view. Arch Dermatol 1994;130:778-780.

25. Shimanovich I, Bröcker EB, Zillikens D. Pemphigoid gestationis: new insights into the pathogenesis lead to novel diagnostic tools. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2002;109:970-976.

A 33-year-old Hispanic woman who was 5 months pregnant came to the hospital complaining of nausea and vomiting. She had a history of anticardiolipin antibody syndrome, diagnosed originally in 1993 after 2 spontaneous abortions. She had stopped taking warfarin (Coumadin) at the start of her pregnancy, and had been taking heparin for 3 months.

After 4 days of close monitoring, the patient had labor induced for severe life-threatening pre-eclampsia. One day after induction and delivery of a stillborn fetus, she began to develop painful swelling of both hands and feet along with targetoid, urticarial, edematous, deep pink, slightly dusky papules and plaques on her hands, abdomen, lower extremities, and proximal thighs. Some of the edematous sites began to form vesicles and bullae (FIGURE 1 AND 2). When asked about this eruption, the patient mentioned having a similar rash after delivery of one of her children about 10 years before.

Interestingly, she noted that she only experienced these cutaneous findings during pregnancies with her second husband and not with her first. Biopsies were performed and showed prominent eosinophils in the dermis and a subepidermal vesicle (FIGURE 3).

FIGURE 1

Blisters on the wrist…

FIGURE 2

…and the abdomen

FIGURE 3

Biopsy results

What is your diagnosis?

Diagnosis: Pemphigoid gestationis

The patient had pemphigoid gestationis, also known as herpes gestationis, a rare autoimmune bullous disease of pregnancy and the puerperium.1 Clinically and immunopathologically, pemphigoid gestationis is related to the pemphigoid group of disorders and is not virally mediated.2

In the United States, pemphigoid gestationis has an incidence of 1:10,000 to 1:50,000 pregnancies.3 Clinically, it manifests during the second or third trimester, with a sudden onset of extremely pruritic urticarial papules and plaques usually located around the umbilicus. These lesions often progress to tense vesicles and blisters and spread peripherally to the trunk, often sparing the face, palms, and soles.4 Worsening of the lesions at the time of delivery occurs in 75% of cases, and usually recurs with subsequent pregnancies.5 Occasionally, however, subsequent pregnancies are unaffected, so-called “skip pregnancies.”6 This occurs most often when there has been a change in paternity.7

The exact cause of pemphigoid gestationis is unknown. Investigative efforts lead to the identification of an immunoglobulin G (IgG) autoantibody, which binds to bullous pemphigoid (BP) antigen 2, also called BP180, which is a protein associated with hemidesmosomes of basal keratinocytes.8-10 These hemidesmosomes form the central portion of the dermalepidermal anchoring complex, whose function is to establish a connection between the basal keratinocytes and the upper dermis.11,12 This is critical for maintaining dermal-epidermal adhesion. It is hypothesized that binding of autoantibodies to BP180 initiates an inflammatory reaction, leading to blister formation at the dermal-epidermal junction.13

Pathology and immunology

Histopathologic findings demonstrate subepidermal vesicles, spongiosis, and perivascular lymphocyte, and histiocyte infiltrates with a preponderance of eosinophils.3 The sine qua non of the disease, though, is the demonstration through direct immunofluorescence of complement deposition and IgG in a linear band along the basement membrane.14

There appears to be a genetic predisposition toward the development of pemphigoid gestationis. Associations with human leukocyte antigens (HLAs) DR3 (61%–85%), DR4 (52%), or both (43%–50%) have been reported.3,15,16 Interestingly, 85% of persons with a history of pemphigoid gestationis were found to have anti-HLA antibodies, some of which were directed against paternal HLAs expressed in their placentae.17 These findings raised speculation about a possible immunologic insult against placental antigens during pregnancy. Evidence suggests that circulating autoantibodies in patients with pemphigoid gestationis bind to the dermal-epidermal junction of skin and amnion in which BP180 antigen is also present.18-20

It has been demonstrated that in patients with pemphigoid gestationis the cells of the placenta stroma express abnormal major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules.21,22 This lead to the proposition of 2 possible mechanisms for the initiation of an autoimmune response in pemphigoid gestationis. The first proposes that placental BP180 is presented to the maternal immune system in association with abnormal MHC molecules, which then trigger the production of autoantibodies that cross-react with the skin. Alternatively, the placental stromal cells may evoke an allogeneic reaction against the BP180 antigen presented by paternal MHC molecules of the placental stroma, which then cross-reacts with the skin.23 The latter theory supports the findings in this patient, who developed pemphigoid gestationis during the 2 pregnancies with her second husband and not during the pregnancies with her first husband.

Differential diagnosis

It is important to differentiate the prebullous stage of pemphigoid gestationis from other pregnancy-related dermatoses. These include polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (PEP), pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP), erythema multiforme, prurigo annularis, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, and impetigo herpetiformis. Impetigo herpetiformis is not related to bacterial or viral causes, but is rather a manifestation of pustular psoriasis during pregnancy. The target lesions that form in pemphigoid gestationis look just like the target lesions of erythema multiforme.

When there is no blister formation, it is impossible to distinguish pemphigoid gestationis from many of the other cutaneous eruptions of pregnancy. If uncertain, the clinician should perform punch biopsies of the involved skin, with one specimen sent for immunofluoresence studies. The biopsy should not pass directly through a bullae, due to risk of losing the overlying epidermis in the specimen. Do the punch biopsy at the edge of the bulla including some normal skin. Other important laboratory exams to perform would include liver function tests to look for an upward trend associated with intrahepatic cholestasis, and herpes simplex virus antibody testing for the association with erythema multiforme. The cutaneous findings and pertinent tests are listed in the table below in order of increasing potential as a life-threatening dermatosis (TABLE).

TABLE

Differential diagnosis for blisters in pregnancy

| DISEASE | ASSOCIATIONS | DIAGNOSIS | TREATMENT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymorphous eruption of pregnancy | Nonspecific pruritic eruption of pregnancy | Biopsy to differentiate from prebullous stage of pemphigoid (herpes) gestationis | Mild to mid-potency topical steroids, oral antihistamines |

| Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy | Occur in stretch marks, spare umbilicus; more often in primigravidas | Unless history is very clear, biopsy to differentiate from prebullous stage of pemphigoid gestationis | Emollients, pulse-dye laser during violaceous stage of striae, topical steroids, oral antihistamines |

| Erythema multiforme | Can involve mucous membranes, targetoid lesions, absence of pruritus, centripetal spread, favors palms/soles | Viral, bacterial, or drug-related eruption. Most often with herpes simplex I or II virus. Biopsy to differentiate from pemphigoid gestationis | Acyclovir, valacyclovir if HSV-related, treatment of bacterial infection, or removal of offending drug |

| Pemphigoid gestationis | Blistering, urticarial papules/plaques, pruritus | Biopsy sent for histologic diagnosis and immunofluorescence | Prednisone for short course starting at 1 mg/kg, then tapering over 2–3 months, topical steroids |

| Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy | +/- jaundice, otherwise no cutaneous findings other than generalized pruritus, risk of preterm birth | Elevation in liver function tests, cholesterol, triglycerides, dark urine, right upper quadrant pain, nausea, greasy stools | Ursodeoxycholic acid, S-adenosyl-L-methionine |

| Impetigo herpetiformis (pustular psoriasis of pregnancy) | Extremely ill with fever, chills, nausea, vascular instability, pustules rather than vesicles | Biopsy if uncertain, pustules sterile, risk of hypocalcemia, hypoparathyroidism | High dose oral steroids or cyclosporine |

Treatment

Pemphigoid gestationis should resolve spontaneously within 2 to 3 months of delivery. Treatment is aimed at preventing new blisters and relieving pruritus, with topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines in mild cases.2,25 In advanced lesions as seen in this case, 0.3 to 0.5 mg/kg of prednisolone daily is usually sufficient.3,25 Alternative medications include sulfapyridine, dapsone, and cyclosporine, though disease response is variable and their safety is questionable.3

When the skin condition began, the patient was treated with oral antihistamines and topical steroids. On day 2, the diagnosis of pemphigoid gestationis was clear, and she was started on oral prednisone at 60 mg/d, which resulted in rapid symptom improvement in her lesions and swelling. New lesions stopped forming, and systemic steroids were tapered off over the 3 months after delivery. The skin lesions healed and she was given supportive counseling to help her cope with her pregnancy loss.

Conclusion

We have described a rare case of a patient with no cutaneous eruptions during her pregnancies with her first husband, who developed pemphigoid gestationis in 2 pregnancies with her second husband. While it is interesting that our patient also had the anticardiolipin syndrome, most patients do not have both conditions.

Our patient had the classic findings of pemphigoid gestationis with many characteristic lesions (including the umbilicus) making the diagnosis possible before biopsy confirmation. This was fortunate for her because her painful swelling responded quickly to the corticosteroids. When cases are less clinically obvious, biopsy for histopathology and immunofluorescence facilitates differentiation of pemphigoid gestationis from other dermatoses of pregnancy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard P. Usatine, MD, University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900. E-mail: usatine@uthscsa.edu

A 33-year-old Hispanic woman who was 5 months pregnant came to the hospital complaining of nausea and vomiting. She had a history of anticardiolipin antibody syndrome, diagnosed originally in 1993 after 2 spontaneous abortions. She had stopped taking warfarin (Coumadin) at the start of her pregnancy, and had been taking heparin for 3 months.

After 4 days of close monitoring, the patient had labor induced for severe life-threatening pre-eclampsia. One day after induction and delivery of a stillborn fetus, she began to develop painful swelling of both hands and feet along with targetoid, urticarial, edematous, deep pink, slightly dusky papules and plaques on her hands, abdomen, lower extremities, and proximal thighs. Some of the edematous sites began to form vesicles and bullae (FIGURE 1 AND 2). When asked about this eruption, the patient mentioned having a similar rash after delivery of one of her children about 10 years before.

Interestingly, she noted that she only experienced these cutaneous findings during pregnancies with her second husband and not with her first. Biopsies were performed and showed prominent eosinophils in the dermis and a subepidermal vesicle (FIGURE 3).

FIGURE 1

Blisters on the wrist…

FIGURE 2

…and the abdomen

FIGURE 3

Biopsy results

What is your diagnosis?

Diagnosis: Pemphigoid gestationis

The patient had pemphigoid gestationis, also known as herpes gestationis, a rare autoimmune bullous disease of pregnancy and the puerperium.1 Clinically and immunopathologically, pemphigoid gestationis is related to the pemphigoid group of disorders and is not virally mediated.2

In the United States, pemphigoid gestationis has an incidence of 1:10,000 to 1:50,000 pregnancies.3 Clinically, it manifests during the second or third trimester, with a sudden onset of extremely pruritic urticarial papules and plaques usually located around the umbilicus. These lesions often progress to tense vesicles and blisters and spread peripherally to the trunk, often sparing the face, palms, and soles.4 Worsening of the lesions at the time of delivery occurs in 75% of cases, and usually recurs with subsequent pregnancies.5 Occasionally, however, subsequent pregnancies are unaffected, so-called “skip pregnancies.”6 This occurs most often when there has been a change in paternity.7

The exact cause of pemphigoid gestationis is unknown. Investigative efforts lead to the identification of an immunoglobulin G (IgG) autoantibody, which binds to bullous pemphigoid (BP) antigen 2, also called BP180, which is a protein associated with hemidesmosomes of basal keratinocytes.8-10 These hemidesmosomes form the central portion of the dermalepidermal anchoring complex, whose function is to establish a connection between the basal keratinocytes and the upper dermis.11,12 This is critical for maintaining dermal-epidermal adhesion. It is hypothesized that binding of autoantibodies to BP180 initiates an inflammatory reaction, leading to blister formation at the dermal-epidermal junction.13

Pathology and immunology

Histopathologic findings demonstrate subepidermal vesicles, spongiosis, and perivascular lymphocyte, and histiocyte infiltrates with a preponderance of eosinophils.3 The sine qua non of the disease, though, is the demonstration through direct immunofluorescence of complement deposition and IgG in a linear band along the basement membrane.14

There appears to be a genetic predisposition toward the development of pemphigoid gestationis. Associations with human leukocyte antigens (HLAs) DR3 (61%–85%), DR4 (52%), or both (43%–50%) have been reported.3,15,16 Interestingly, 85% of persons with a history of pemphigoid gestationis were found to have anti-HLA antibodies, some of which were directed against paternal HLAs expressed in their placentae.17 These findings raised speculation about a possible immunologic insult against placental antigens during pregnancy. Evidence suggests that circulating autoantibodies in patients with pemphigoid gestationis bind to the dermal-epidermal junction of skin and amnion in which BP180 antigen is also present.18-20

It has been demonstrated that in patients with pemphigoid gestationis the cells of the placenta stroma express abnormal major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules.21,22 This lead to the proposition of 2 possible mechanisms for the initiation of an autoimmune response in pemphigoid gestationis. The first proposes that placental BP180 is presented to the maternal immune system in association with abnormal MHC molecules, which then trigger the production of autoantibodies that cross-react with the skin. Alternatively, the placental stromal cells may evoke an allogeneic reaction against the BP180 antigen presented by paternal MHC molecules of the placental stroma, which then cross-reacts with the skin.23 The latter theory supports the findings in this patient, who developed pemphigoid gestationis during the 2 pregnancies with her second husband and not during the pregnancies with her first husband.

Differential diagnosis

It is important to differentiate the prebullous stage of pemphigoid gestationis from other pregnancy-related dermatoses. These include polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (PEP), pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP), erythema multiforme, prurigo annularis, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, and impetigo herpetiformis. Impetigo herpetiformis is not related to bacterial or viral causes, but is rather a manifestation of pustular psoriasis during pregnancy. The target lesions that form in pemphigoid gestationis look just like the target lesions of erythema multiforme.

When there is no blister formation, it is impossible to distinguish pemphigoid gestationis from many of the other cutaneous eruptions of pregnancy. If uncertain, the clinician should perform punch biopsies of the involved skin, with one specimen sent for immunofluoresence studies. The biopsy should not pass directly through a bullae, due to risk of losing the overlying epidermis in the specimen. Do the punch biopsy at the edge of the bulla including some normal skin. Other important laboratory exams to perform would include liver function tests to look for an upward trend associated with intrahepatic cholestasis, and herpes simplex virus antibody testing for the association with erythema multiforme. The cutaneous findings and pertinent tests are listed in the table below in order of increasing potential as a life-threatening dermatosis (TABLE).

TABLE

Differential diagnosis for blisters in pregnancy

| DISEASE | ASSOCIATIONS | DIAGNOSIS | TREATMENT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymorphous eruption of pregnancy | Nonspecific pruritic eruption of pregnancy | Biopsy to differentiate from prebullous stage of pemphigoid (herpes) gestationis | Mild to mid-potency topical steroids, oral antihistamines |

| Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy | Occur in stretch marks, spare umbilicus; more often in primigravidas | Unless history is very clear, biopsy to differentiate from prebullous stage of pemphigoid gestationis | Emollients, pulse-dye laser during violaceous stage of striae, topical steroids, oral antihistamines |

| Erythema multiforme | Can involve mucous membranes, targetoid lesions, absence of pruritus, centripetal spread, favors palms/soles | Viral, bacterial, or drug-related eruption. Most often with herpes simplex I or II virus. Biopsy to differentiate from pemphigoid gestationis | Acyclovir, valacyclovir if HSV-related, treatment of bacterial infection, or removal of offending drug |

| Pemphigoid gestationis | Blistering, urticarial papules/plaques, pruritus | Biopsy sent for histologic diagnosis and immunofluorescence | Prednisone for short course starting at 1 mg/kg, then tapering over 2–3 months, topical steroids |

| Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy | +/- jaundice, otherwise no cutaneous findings other than generalized pruritus, risk of preterm birth | Elevation in liver function tests, cholesterol, triglycerides, dark urine, right upper quadrant pain, nausea, greasy stools | Ursodeoxycholic acid, S-adenosyl-L-methionine |

| Impetigo herpetiformis (pustular psoriasis of pregnancy) | Extremely ill with fever, chills, nausea, vascular instability, pustules rather than vesicles | Biopsy if uncertain, pustules sterile, risk of hypocalcemia, hypoparathyroidism | High dose oral steroids or cyclosporine |

Treatment

Pemphigoid gestationis should resolve spontaneously within 2 to 3 months of delivery. Treatment is aimed at preventing new blisters and relieving pruritus, with topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines in mild cases.2,25 In advanced lesions as seen in this case, 0.3 to 0.5 mg/kg of prednisolone daily is usually sufficient.3,25 Alternative medications include sulfapyridine, dapsone, and cyclosporine, though disease response is variable and their safety is questionable.3