User login

We Must Learn About Abortion as Primary Care Doctors

“No greater opportunity, responsibility, or obligation can fall to the lot of a human being than to become a physician. In the care of the suffering, [the physician] needs technical skill, scientific knowledge, and human understanding.”1 Internal medicine physicians have risen to this challenge for centuries. Today, it is time for us to use these skills to care for patients who need access to reproductive care — particularly medication abortion. Nationally accredited internal medicine training programs have not been required to provide abortion education, and this may evolve in the future.

However, considering the difficulty in people receiving contraception, the failure rate of contraception, the known risks from pregnancy, the increasing difficulty in accessing abortion, and the recent advocating to protect access to reproductive care by leadership of internal medicine and internal medicine subspecialty societies, we advocate that abortion must become a part of our education and practice.2

Most abortions are performed during the first trimester and can be managed with medications that are very safe.3 In fact, legal medication abortion is so safe that pregnancy in the United States has fourteen times the mortality risk as does legal medication abortion.4 Inability to access an abortion has widely documented negative health effects for women and their children.5,6

Within this context, it is important for internal medicine physicians to understand that the ability to access an abortion is the ability to access a life-saving procedure and there is no medical justification for restricting such a prescription any more than restricting any other standard medical therapy. Furthermore, the recent widespread criminalization of abortion gives new urgency to expanding the pool of physicians who understand this and are trained, able, and willing to prescribe medication abortion.

We understand that reproductive health care may not now be a component of clinical practice for some, but given the heterogeneity of internal medicine, we believe that some knowledge about medical abortion is an essential competency of foundational medical knowledge.7 The heterogeneity of practice in internal medicine lends itself to different levels of knowledge that should be embraced. Because of poor access to abortion, both ambulatory and hospital-based physicians will increasingly be required to care for patients who need abortion for medical or other reasons.

We advocate that all physicians — including those with internal medicine training — should understand counseling about choices and options (including an unbiased discussion of the options to continue or terminate the pregnancy), the safety of medication abortion in contrast to the risks from pregnancy, and where to refer someone seeking an abortion. In addition to this information, primary care physicians with a special interest in women’s health must have basic knowledge about mifepristone and misoprostol and how they work, the benefits and risks of these, and what the pregnant person seeking an abortion will experience.8

Lastly, physicians who wish to provide medication abortion — including in primary care, hospital medicine, and subspecialty care — should receive training and ongoing professional development. Such professional development should include counseling, indications, contraindications, medication regimens, navigating required documentation and reporting, and anticipating possible side effects and complications.

A major challenge to internal medicine and other primary care physicians, subspecialists, and hospitalists addressing abortion is the inadequate training in and knowledge about providing this care. However, the entire spectrum of medical education (undergraduate, graduate, and continuing education) should evolve to address this lack.

Integrating this education into medical conferences and journals is a meaningful start, possibly in partnership with medical societies that have been teaching these skills for decades. Partnering with other specialties can also help us stay current on the local legal landscape and engage in collaborative advocacy.

Specifically, some resources for training can be found at:

- www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2014/11/abortion-training-and-education

- https://prochoice.org/providers/continuing-medical-education/

- www.reproductiveaccess.org/medicationabortion/

Some may have concerns that managing the possible complications of medication abortion is a reason for internal medicine to not be involved in abortion care. However, medication abortions are safe and effective for pregnancy termination and internal medicine physicians can refer patients with complications to peers in gynecology, family medicine, and emergency medicine should complications arise.8 We have managed countless other conditions this way, including most recently during the pandemic.

We live in a country with increasing barriers to care – now with laws in many states that prevent basic health care for women. Internal medicine doctors increasingly may see patients who need care urgently, particularly those who practice in states that neighbor those that prevent this access. We are calling for all who practice internal medicine to educate themselves, optimizing their skills within the full scope of medical practice to provide possibly lifesaving care and thereby address increased needs for medical services.

We must continue to advocate for our patients. The COVID-19 pandemic has reinforced the fact that internal medicine–trained physicians are able to care for conditions that are new and, as a profession, we are capable of rapidly switching practices and learning new modalities of care. It is time for us to extend this competency to care for patients who constitute half the population and are at risk: women.

Dr. Barrett is an internal medicine hospitalist based in Albuquerque, New Mexico; she completed a medical justice in advocacy fellowship in 2022. Dr. Radhakrishnan is an internal medicine physician educator who completed an equity matters fellowship in 2022 and is based in Scottsdale, Arizona. Neither reports conflicts of interest.

References

1. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 20e. Jameson J et al., eds. McGraw Hill; 2018. Accessed Sept. 27, 2023.

2. Serchen J et al. Reproductive Health Policy in the United States: An American College of Physicians Policy Brief. Ann Intern Med.2023;176:364-6. epub 28 Feb. 2023.

3. Jatlaoui TC et al. Abortion Surveillance — United States, 2016. MMWR Surveill Summ 2019;68(No. SS-11):1-41.

4. Raymond EG and Grimes DA. The comparative safety of legal induced abortion and childbirth in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(2 Pt 1):215-9.

5. Ralph LJ et al. Self-reported Physical Health of Women Who Did and Did Not Terminate Pregnancy After Seeking Abortion Services: A Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med.2019;171:238-47. epub 11 June 2019.

6. Gerdts C et al. Side effects, physical health consequences, and mortality associated with abortion and birth after an unwanted pregnancy. Women’s Health Issues 2016;26:55-59.

7. Nobel K et al. Patient-reported experience with discussion of all options during pregnancy options counseling in the US south. Contraception. 2022;106:68-74.

8. Liu N and Ray JG. Short-Term Adverse Outcomes After Mifepristone–Misoprostol Versus Procedural Induced Abortion: A Population-Based Propensity-Weighted Study. Ann Intern Med.2023;176:145-53. epub 3 January 2023.

“No greater opportunity, responsibility, or obligation can fall to the lot of a human being than to become a physician. In the care of the suffering, [the physician] needs technical skill, scientific knowledge, and human understanding.”1 Internal medicine physicians have risen to this challenge for centuries. Today, it is time for us to use these skills to care for patients who need access to reproductive care — particularly medication abortion. Nationally accredited internal medicine training programs have not been required to provide abortion education, and this may evolve in the future.

However, considering the difficulty in people receiving contraception, the failure rate of contraception, the known risks from pregnancy, the increasing difficulty in accessing abortion, and the recent advocating to protect access to reproductive care by leadership of internal medicine and internal medicine subspecialty societies, we advocate that abortion must become a part of our education and practice.2

Most abortions are performed during the first trimester and can be managed with medications that are very safe.3 In fact, legal medication abortion is so safe that pregnancy in the United States has fourteen times the mortality risk as does legal medication abortion.4 Inability to access an abortion has widely documented negative health effects for women and their children.5,6

Within this context, it is important for internal medicine physicians to understand that the ability to access an abortion is the ability to access a life-saving procedure and there is no medical justification for restricting such a prescription any more than restricting any other standard medical therapy. Furthermore, the recent widespread criminalization of abortion gives new urgency to expanding the pool of physicians who understand this and are trained, able, and willing to prescribe medication abortion.

We understand that reproductive health care may not now be a component of clinical practice for some, but given the heterogeneity of internal medicine, we believe that some knowledge about medical abortion is an essential competency of foundational medical knowledge.7 The heterogeneity of practice in internal medicine lends itself to different levels of knowledge that should be embraced. Because of poor access to abortion, both ambulatory and hospital-based physicians will increasingly be required to care for patients who need abortion for medical or other reasons.

We advocate that all physicians — including those with internal medicine training — should understand counseling about choices and options (including an unbiased discussion of the options to continue or terminate the pregnancy), the safety of medication abortion in contrast to the risks from pregnancy, and where to refer someone seeking an abortion. In addition to this information, primary care physicians with a special interest in women’s health must have basic knowledge about mifepristone and misoprostol and how they work, the benefits and risks of these, and what the pregnant person seeking an abortion will experience.8

Lastly, physicians who wish to provide medication abortion — including in primary care, hospital medicine, and subspecialty care — should receive training and ongoing professional development. Such professional development should include counseling, indications, contraindications, medication regimens, navigating required documentation and reporting, and anticipating possible side effects and complications.

A major challenge to internal medicine and other primary care physicians, subspecialists, and hospitalists addressing abortion is the inadequate training in and knowledge about providing this care. However, the entire spectrum of medical education (undergraduate, graduate, and continuing education) should evolve to address this lack.

Integrating this education into medical conferences and journals is a meaningful start, possibly in partnership with medical societies that have been teaching these skills for decades. Partnering with other specialties can also help us stay current on the local legal landscape and engage in collaborative advocacy.

Specifically, some resources for training can be found at:

- www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2014/11/abortion-training-and-education

- https://prochoice.org/providers/continuing-medical-education/

- www.reproductiveaccess.org/medicationabortion/

Some may have concerns that managing the possible complications of medication abortion is a reason for internal medicine to not be involved in abortion care. However, medication abortions are safe and effective for pregnancy termination and internal medicine physicians can refer patients with complications to peers in gynecology, family medicine, and emergency medicine should complications arise.8 We have managed countless other conditions this way, including most recently during the pandemic.

We live in a country with increasing barriers to care – now with laws in many states that prevent basic health care for women. Internal medicine doctors increasingly may see patients who need care urgently, particularly those who practice in states that neighbor those that prevent this access. We are calling for all who practice internal medicine to educate themselves, optimizing their skills within the full scope of medical practice to provide possibly lifesaving care and thereby address increased needs for medical services.

We must continue to advocate for our patients. The COVID-19 pandemic has reinforced the fact that internal medicine–trained physicians are able to care for conditions that are new and, as a profession, we are capable of rapidly switching practices and learning new modalities of care. It is time for us to extend this competency to care for patients who constitute half the population and are at risk: women.

Dr. Barrett is an internal medicine hospitalist based in Albuquerque, New Mexico; she completed a medical justice in advocacy fellowship in 2022. Dr. Radhakrishnan is an internal medicine physician educator who completed an equity matters fellowship in 2022 and is based in Scottsdale, Arizona. Neither reports conflicts of interest.

References

1. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 20e. Jameson J et al., eds. McGraw Hill; 2018. Accessed Sept. 27, 2023.

2. Serchen J et al. Reproductive Health Policy in the United States: An American College of Physicians Policy Brief. Ann Intern Med.2023;176:364-6. epub 28 Feb. 2023.

3. Jatlaoui TC et al. Abortion Surveillance — United States, 2016. MMWR Surveill Summ 2019;68(No. SS-11):1-41.

4. Raymond EG and Grimes DA. The comparative safety of legal induced abortion and childbirth in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(2 Pt 1):215-9.

5. Ralph LJ et al. Self-reported Physical Health of Women Who Did and Did Not Terminate Pregnancy After Seeking Abortion Services: A Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med.2019;171:238-47. epub 11 June 2019.

6. Gerdts C et al. Side effects, physical health consequences, and mortality associated with abortion and birth after an unwanted pregnancy. Women’s Health Issues 2016;26:55-59.

7. Nobel K et al. Patient-reported experience with discussion of all options during pregnancy options counseling in the US south. Contraception. 2022;106:68-74.

8. Liu N and Ray JG. Short-Term Adverse Outcomes After Mifepristone–Misoprostol Versus Procedural Induced Abortion: A Population-Based Propensity-Weighted Study. Ann Intern Med.2023;176:145-53. epub 3 January 2023.

“No greater opportunity, responsibility, or obligation can fall to the lot of a human being than to become a physician. In the care of the suffering, [the physician] needs technical skill, scientific knowledge, and human understanding.”1 Internal medicine physicians have risen to this challenge for centuries. Today, it is time for us to use these skills to care for patients who need access to reproductive care — particularly medication abortion. Nationally accredited internal medicine training programs have not been required to provide abortion education, and this may evolve in the future.

However, considering the difficulty in people receiving contraception, the failure rate of contraception, the known risks from pregnancy, the increasing difficulty in accessing abortion, and the recent advocating to protect access to reproductive care by leadership of internal medicine and internal medicine subspecialty societies, we advocate that abortion must become a part of our education and practice.2

Most abortions are performed during the first trimester and can be managed with medications that are very safe.3 In fact, legal medication abortion is so safe that pregnancy in the United States has fourteen times the mortality risk as does legal medication abortion.4 Inability to access an abortion has widely documented negative health effects for women and their children.5,6

Within this context, it is important for internal medicine physicians to understand that the ability to access an abortion is the ability to access a life-saving procedure and there is no medical justification for restricting such a prescription any more than restricting any other standard medical therapy. Furthermore, the recent widespread criminalization of abortion gives new urgency to expanding the pool of physicians who understand this and are trained, able, and willing to prescribe medication abortion.

We understand that reproductive health care may not now be a component of clinical practice for some, but given the heterogeneity of internal medicine, we believe that some knowledge about medical abortion is an essential competency of foundational medical knowledge.7 The heterogeneity of practice in internal medicine lends itself to different levels of knowledge that should be embraced. Because of poor access to abortion, both ambulatory and hospital-based physicians will increasingly be required to care for patients who need abortion for medical or other reasons.

We advocate that all physicians — including those with internal medicine training — should understand counseling about choices and options (including an unbiased discussion of the options to continue or terminate the pregnancy), the safety of medication abortion in contrast to the risks from pregnancy, and where to refer someone seeking an abortion. In addition to this information, primary care physicians with a special interest in women’s health must have basic knowledge about mifepristone and misoprostol and how they work, the benefits and risks of these, and what the pregnant person seeking an abortion will experience.8

Lastly, physicians who wish to provide medication abortion — including in primary care, hospital medicine, and subspecialty care — should receive training and ongoing professional development. Such professional development should include counseling, indications, contraindications, medication regimens, navigating required documentation and reporting, and anticipating possible side effects and complications.

A major challenge to internal medicine and other primary care physicians, subspecialists, and hospitalists addressing abortion is the inadequate training in and knowledge about providing this care. However, the entire spectrum of medical education (undergraduate, graduate, and continuing education) should evolve to address this lack.

Integrating this education into medical conferences and journals is a meaningful start, possibly in partnership with medical societies that have been teaching these skills for decades. Partnering with other specialties can also help us stay current on the local legal landscape and engage in collaborative advocacy.

Specifically, some resources for training can be found at:

- www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2014/11/abortion-training-and-education

- https://prochoice.org/providers/continuing-medical-education/

- www.reproductiveaccess.org/medicationabortion/

Some may have concerns that managing the possible complications of medication abortion is a reason for internal medicine to not be involved in abortion care. However, medication abortions are safe and effective for pregnancy termination and internal medicine physicians can refer patients with complications to peers in gynecology, family medicine, and emergency medicine should complications arise.8 We have managed countless other conditions this way, including most recently during the pandemic.

We live in a country with increasing barriers to care – now with laws in many states that prevent basic health care for women. Internal medicine doctors increasingly may see patients who need care urgently, particularly those who practice in states that neighbor those that prevent this access. We are calling for all who practice internal medicine to educate themselves, optimizing their skills within the full scope of medical practice to provide possibly lifesaving care and thereby address increased needs for medical services.

We must continue to advocate for our patients. The COVID-19 pandemic has reinforced the fact that internal medicine–trained physicians are able to care for conditions that are new and, as a profession, we are capable of rapidly switching practices and learning new modalities of care. It is time for us to extend this competency to care for patients who constitute half the population and are at risk: women.

Dr. Barrett is an internal medicine hospitalist based in Albuquerque, New Mexico; she completed a medical justice in advocacy fellowship in 2022. Dr. Radhakrishnan is an internal medicine physician educator who completed an equity matters fellowship in 2022 and is based in Scottsdale, Arizona. Neither reports conflicts of interest.

References

1. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 20e. Jameson J et al., eds. McGraw Hill; 2018. Accessed Sept. 27, 2023.

2. Serchen J et al. Reproductive Health Policy in the United States: An American College of Physicians Policy Brief. Ann Intern Med.2023;176:364-6. epub 28 Feb. 2023.

3. Jatlaoui TC et al. Abortion Surveillance — United States, 2016. MMWR Surveill Summ 2019;68(No. SS-11):1-41.

4. Raymond EG and Grimes DA. The comparative safety of legal induced abortion and childbirth in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(2 Pt 1):215-9.

5. Ralph LJ et al. Self-reported Physical Health of Women Who Did and Did Not Terminate Pregnancy After Seeking Abortion Services: A Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med.2019;171:238-47. epub 11 June 2019.

6. Gerdts C et al. Side effects, physical health consequences, and mortality associated with abortion and birth after an unwanted pregnancy. Women’s Health Issues 2016;26:55-59.

7. Nobel K et al. Patient-reported experience with discussion of all options during pregnancy options counseling in the US south. Contraception. 2022;106:68-74.

8. Liu N and Ray JG. Short-Term Adverse Outcomes After Mifepristone–Misoprostol Versus Procedural Induced Abortion: A Population-Based Propensity-Weighted Study. Ann Intern Med.2023;176:145-53. epub 3 January 2023.

Assessment of Same-Day Naloxone Availability in New Mexico Pharmacies

From the Department of Medicine, University of California San Diego (Dr. Haponyuk), Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Tennessee (Dr. Dejong), the Department of Family Medicine, University of New Mexico (Dr. Gutfrucht), and the Department of Internal Medicine, University of New Mexico (Dr. Barrett)

Objective: Naloxone availability can reduce the risk of death from opioid overdoses, although prescriber, legislative, and payment barriers to accessing this life-saving medication exist. A previously underreported barrier involves same-day availability, the lack of which may force patients to travel to multiple pharmacies and having delays in access or risking not filling their prescription. This study sought to determine same-day availability of naloxone in pharmacies in the state of New Mexico.

Methods: Same-day availability of naloxone was assessed via an audit survey.

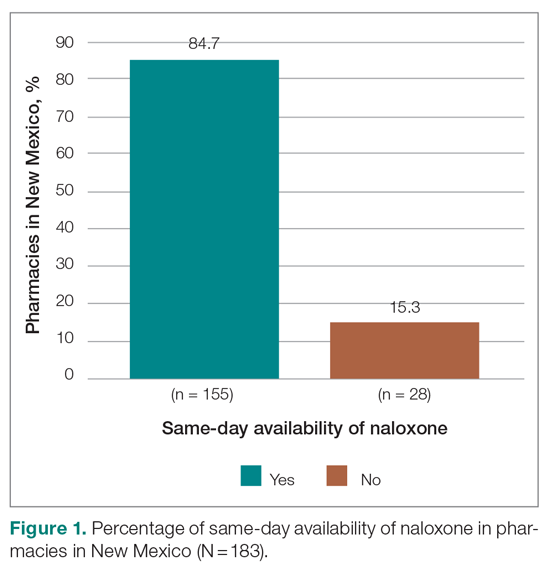

Results: Of the 183 pharamacies screened, only 84.7% had same-day availability, including only 72% in Albuquerque, the state’s most populous city/municipality.

Conclusion: These results highlight the extent of a previously underexplored challenge to patient care and barrier to patient safety, and future directions for more patient-centered care.

Keywords: naloxone; barriers to care; opioid overdose prevention.

The US is enduring an ongoing epidemic of deaths due to opioid use, which have increased in frequency since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.1 One strategy to reduce the risk of mortality from opioid use is to ensure the widespread availability of naloxone. Individual states have implemented harm reduction strategies to increase access to naloxone, including improving availability via a statewide standing order that it may be dispensed without a prescription.2,3 Such naloxone access laws are being widely adopted and are believed to reduce overdose deaths.4

There are many barriers to patients receiving naloxone despite their clinicians providing a prescription for it, including stigmatization, financial cost, and local availability.5-9 However, the stigma associated with naloxone extends to both patients and pharmacists. Pharmacists in West Virginia, for example, showed widespread concerns about having naloxone available for patients to purchase over the counter, for fear that increasing naloxone access may increase overdoses.6 A study in Tennessee also found pharmacists hesitant to recommend naloxone.7 Another study of rural pharmacies in Georgia found that just over half carried naloxone despite a state law that naloxone be available without a prescription.8 Challenges are not limited to rural areas, however; a study in Philadelphia found that more than one-third of pharmacies required a prescription to dispense naloxone, contrary to state law.9 Thus, in a rapidly changing regulatory environment, there are many evolving barriers to patients receiving naloxone.

New Mexico has an opioid overdose rate higher than the national average, coming in 15th out of 50 states when last ranked in 2018, with overdose rates that vary across demographic variables.10 Consequently, New Mexico state law added language requiring clinicians prescribing opioids for 5 days or longer to co-prescribe naloxone along with written information on how to administer the opioid antagonist.11 New Mexico is also a geographically large state with a relatively low overall population characterized by striking health disparities, particularly as related to access to care.

The purpose of this study is to describe the same-day availability of naloxone throughout the state of New Mexico after a change in state law requiring co-prescription was enacted, to help identify challenges to patients receiving it. Comprehensive examination of barriers to patients accessing this life-saving medication can advise strategies to both improve patient-centered care and potentially reduce deaths.

Methods

To better understand barriers to patients obtaining naloxone, in July and August of 2019 we performed an audit (“secret shopper”) study of all pharmacies in the state, posing as patients wishing to obtain naloxone. A publicly available list of every pharmacy in New Mexico was used to identify 89 pharmacies in Albuquerque (the most populous city in New Mexico) and 106 pharmacies throughout the rest of the state.12

Every pharmacy was called via a publicly available phone number during business hours (confirmed via an internet search), at least 2 hours prior to closing. One of 3 researchers telephoned pharmacies posing as a patient and inquired whether naloxone would be available for pick up the same day. If the pharmacy confirmed it was available that day, the call concluded. If naloxone was unavailable for same day pick up, researchers asked when it would be next available. Each pharmacy was called once, and neither insurance information nor cost was offered or requested. All questions were asked in English by native English speakers.

All responses were recorded in a secure spreadsheet. Once all responses were received and reviewed, they were characterized in discrete response categories: same day, within 1 to 2 days, within 3 to 4 days, within a week, or unsure/unknown. Naloxone availability was also tracked by city/municipality, and this was compared to the state’s population distribution.

No personally identifiable information was obtained. This study was Institutional Review Board exempt.

Results

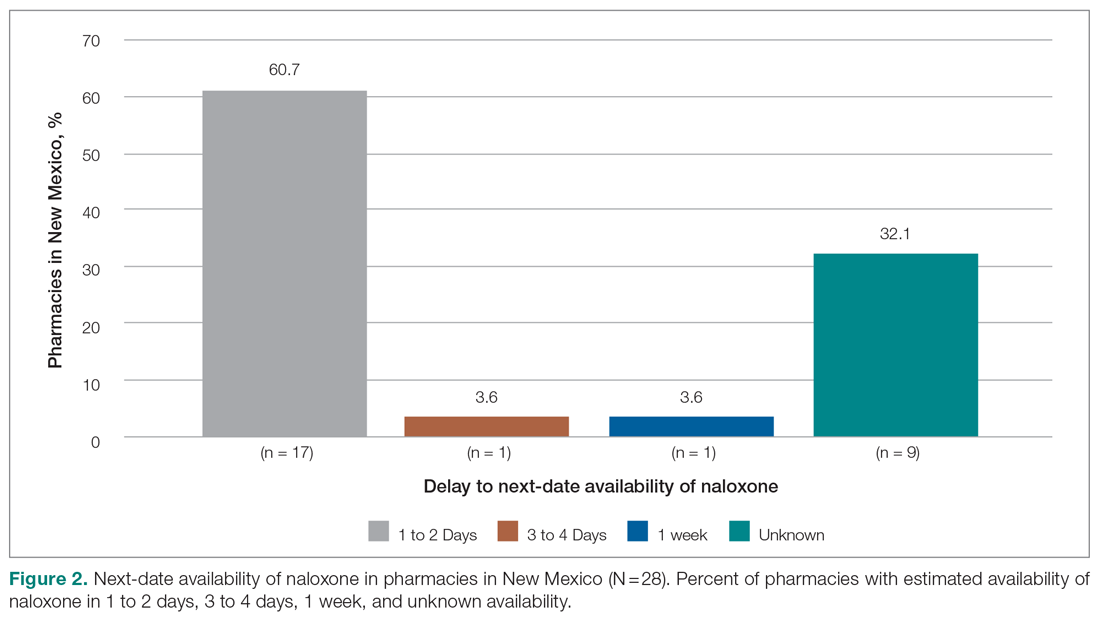

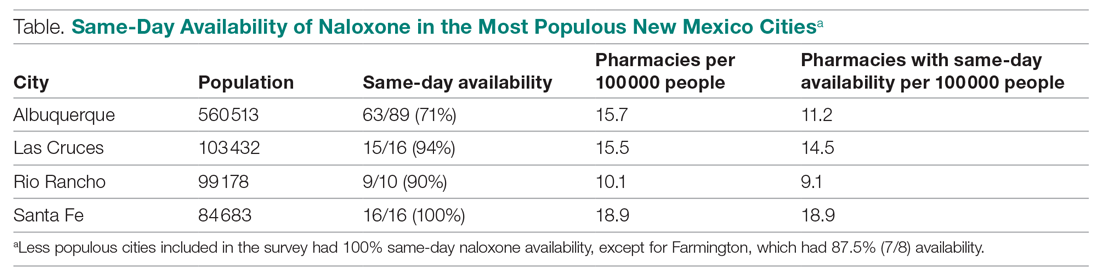

Responses were recorded from 183 pharmacies. Seventeen locations were eliminated from our analysis because their phone system was inoperable or the pharmacy was permanently closed. Of the pharmacies reached, 84.7% (155/183) reported they have naloxone available for pick up on the same day (Figure 1). Of the 15.3% (28) pharmacies that did not have same-day availability, 60.7% (17 pharmacies) reported availability in 1 to 2 days, 3.6% had availability in 3 to 4 days, 3.6% had availability in 1 week, and 32.1% were unsure of next availability (Figure 2). More than one-third of the state’s patients reside in municipalities where naloxone is immediately available in at least 72% of pharmacies (Table).13

Discussion

Increased access to naloxone at the state and community level is associated with reduced risk for death from overdose, and, consequently, widespread availability is recommended.14-17 Statewide real-time pharmacy availability of naloxone—as patients would experience availability—has not been previously reported. These findings suggest unpredictable same-day availability that may affect experience and care outcomes. That other studies have found similar challenges in naloxone availability in other municipalities and regions suggests this barrier to access is widespread,6-9 and likely affects patients throughout the country.

Many patients have misgivings about naloxone, and it places an undue burden on them to travel to multiple pharmacies or take repeated trips to fill prescriptions. Additionally, patients without reliable transportation may be unable to return at a later date. Although we found most pharmacies in New Mexico without immediate availability of naloxone reported they could have it within several days, such a delay may reduce the likelihood that patients will fill their prescription at all. It is also concerning that many pharmacies are unsure of when naloxone will be available, particularly when some of these may be the only pharmacy easily accessible to patients or the one where they regularly fill their prescriptions.

Barriers to naloxone availability requires further study due to possible negative consequences for patient safety and risks for exacerbating health disparities among vulnerable populations. Further research may focus on examining the effects on patients when naloxone dispensing is delayed or impossible, why there is variability in naloxone availability between different pharmacies and municipalities, the reasons for uncertainty when naloxone will be available, and effective solutions. Expanded naloxone distribution in community locations and in clinics offers one potential patient-centered solution that should be explored, but it is likely that more widespread and systemic solutions will require policy and regulatory changes at the state and national levels.

Limitations of this study include that the findings may be relevant for solely 1 state, such as in the case of state-specific barriers to keeping naloxone in stock that we are unaware of. However, it is unclear why that would be the case, and it is more likely that similar barriers are pervasive. Additionally, repeat phone calls, which we did not follow up with, may have yielded more pharmacies with naloxone availability. However, due to the stigma associated with obtaining naloxone, it may be that patients will not make multiple calls either—highlighting how important real-time availability is.

Conclusion

Urgent solutions are needed to address the epidemic of deaths from opioid overdoses. Naloxone availability is an important tool for reducing these deaths, resulting in numerous state laws attempting to increase access. Despite this, there are persistent barriers to patients receiving naloxone, including a lack of same-day availability at pharmacies. Our results suggest that this underexplored barrier is widespread. Improving both availability and accessibility of naloxone may include legislative policy solutions as well as patient-oriented solutions, such as distribution in clinics and hospitals when opioid prescriptions are first written. Further research should be conducted to determine patient-centered, effective solutions that can improve outcomes.

Corresponding author: Eileen Barrett, MD, MPH, Department of Internal Medicine, University of New Mexico; ebarrett@salud.unm.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Mason M, Welch SB, Arunkumar P, et al. Notes from the field: opioid overdose deaths before, during, and after an 11-week COVID-19 stay-at-home order—Cook County, Illinois, January 1, 2018–October 6, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(10):362-363. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7010a3

2. Kaiser Family Foundation. Opioid overdose death rates and all drug overdose death rates per 100,000 population (age-adjusted). Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/opioid-overdose-death

3. Sohn M, Talbert JC, Huang Z, et al. Association of naloxone coprescription laws with naloxone prescription dispensing in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(6):e196215. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.6215

4. Smart R, Pardo B, Davis CS. Systematic review of the emerging literature on the effectiveness of naloxone access laws in the United States. Addiction. 2021;116(1):6-17. doi:10.1111/add.15163

5. Mueller SR, Koester S, Glanz JM, et al. Attitudes toward naloxone prescribing in clinical settings: a qualitative study of patients prescribed high dose opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):277-283. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3895-8

6. Thornton JD, Lyvers E, Scott VGG, Dwibedi N. Pharmacists’ readiness to provide naloxone in community pharmacies in West Virginia. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2017;57(2S):S12-S18.e4. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2016.12.070

7. Spivey C, Wilder A, Chisholm-Burns MA, et al. Evaluation of naloxone access, pricing, and barriers to dispensing in Tennessee retail community pharmacies. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2020;60(5):694-701.e1. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2020.01.030

8. Nguyen JL, Gilbert LR, Beasley L, et al. Availability of naloxone at rural Georgia pharmacies, 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1921227. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.21227

9. Guadamuz JS, Alexander GC, Chaudhri T, et al. Availability and cost of naloxone nasal spray at pharmacies in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(6):e195388. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.5388

10. Edge K. Changes in drug overdose mortality in New Mexico. New Mexico Epidemiology. July 2020 (3). https://www.nmhealth.org/data/view/report/2402/

11. Senate Bill 221. 54th Legislature, State of New Mexico, First Session, 2019 (introduced by William P. Soules). Accessed October 6, 2021. https://nmlegis.gov/Sessions/19%20Regular/bills/senate/SB0221.pdf

12. GoodRx. Find pharmacies in New Mexico. Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.goodrx.com/pharmacy-near-me/all/nm

13. U.S. Census Bureau. QuickFacts: New Mexico. Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/NM

14. Linas BP, Savinkina A, Madushani RWMA, et al. Projected estimates of opioid mortality after community-level interventions. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2037259. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37259

15. You HS, Ha J, Kang CY, et al. Regional variation in states’ naloxone accessibility laws in association with opioid overdose death rates—observational study (STROBE compliant). Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(22):e20033. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000020033

16. Pew Charitable Trusts. Expanded access to naloxone can curb opioid overdose deaths. October 20, 2020. Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.

17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Still not enough naloxone where it’s most needed. August 6, 2019. Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2019/p0806-naloxone.html

From the Department of Medicine, University of California San Diego (Dr. Haponyuk), Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Tennessee (Dr. Dejong), the Department of Family Medicine, University of New Mexico (Dr. Gutfrucht), and the Department of Internal Medicine, University of New Mexico (Dr. Barrett)

Objective: Naloxone availability can reduce the risk of death from opioid overdoses, although prescriber, legislative, and payment barriers to accessing this life-saving medication exist. A previously underreported barrier involves same-day availability, the lack of which may force patients to travel to multiple pharmacies and having delays in access or risking not filling their prescription. This study sought to determine same-day availability of naloxone in pharmacies in the state of New Mexico.

Methods: Same-day availability of naloxone was assessed via an audit survey.

Results: Of the 183 pharamacies screened, only 84.7% had same-day availability, including only 72% in Albuquerque, the state’s most populous city/municipality.

Conclusion: These results highlight the extent of a previously underexplored challenge to patient care and barrier to patient safety, and future directions for more patient-centered care.

Keywords: naloxone; barriers to care; opioid overdose prevention.

The US is enduring an ongoing epidemic of deaths due to opioid use, which have increased in frequency since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.1 One strategy to reduce the risk of mortality from opioid use is to ensure the widespread availability of naloxone. Individual states have implemented harm reduction strategies to increase access to naloxone, including improving availability via a statewide standing order that it may be dispensed without a prescription.2,3 Such naloxone access laws are being widely adopted and are believed to reduce overdose deaths.4

There are many barriers to patients receiving naloxone despite their clinicians providing a prescription for it, including stigmatization, financial cost, and local availability.5-9 However, the stigma associated with naloxone extends to both patients and pharmacists. Pharmacists in West Virginia, for example, showed widespread concerns about having naloxone available for patients to purchase over the counter, for fear that increasing naloxone access may increase overdoses.6 A study in Tennessee also found pharmacists hesitant to recommend naloxone.7 Another study of rural pharmacies in Georgia found that just over half carried naloxone despite a state law that naloxone be available without a prescription.8 Challenges are not limited to rural areas, however; a study in Philadelphia found that more than one-third of pharmacies required a prescription to dispense naloxone, contrary to state law.9 Thus, in a rapidly changing regulatory environment, there are many evolving barriers to patients receiving naloxone.

New Mexico has an opioid overdose rate higher than the national average, coming in 15th out of 50 states when last ranked in 2018, with overdose rates that vary across demographic variables.10 Consequently, New Mexico state law added language requiring clinicians prescribing opioids for 5 days or longer to co-prescribe naloxone along with written information on how to administer the opioid antagonist.11 New Mexico is also a geographically large state with a relatively low overall population characterized by striking health disparities, particularly as related to access to care.

The purpose of this study is to describe the same-day availability of naloxone throughout the state of New Mexico after a change in state law requiring co-prescription was enacted, to help identify challenges to patients receiving it. Comprehensive examination of barriers to patients accessing this life-saving medication can advise strategies to both improve patient-centered care and potentially reduce deaths.

Methods

To better understand barriers to patients obtaining naloxone, in July and August of 2019 we performed an audit (“secret shopper”) study of all pharmacies in the state, posing as patients wishing to obtain naloxone. A publicly available list of every pharmacy in New Mexico was used to identify 89 pharmacies in Albuquerque (the most populous city in New Mexico) and 106 pharmacies throughout the rest of the state.12

Every pharmacy was called via a publicly available phone number during business hours (confirmed via an internet search), at least 2 hours prior to closing. One of 3 researchers telephoned pharmacies posing as a patient and inquired whether naloxone would be available for pick up the same day. If the pharmacy confirmed it was available that day, the call concluded. If naloxone was unavailable for same day pick up, researchers asked when it would be next available. Each pharmacy was called once, and neither insurance information nor cost was offered or requested. All questions were asked in English by native English speakers.

All responses were recorded in a secure spreadsheet. Once all responses were received and reviewed, they were characterized in discrete response categories: same day, within 1 to 2 days, within 3 to 4 days, within a week, or unsure/unknown. Naloxone availability was also tracked by city/municipality, and this was compared to the state’s population distribution.

No personally identifiable information was obtained. This study was Institutional Review Board exempt.

Results

Responses were recorded from 183 pharmacies. Seventeen locations were eliminated from our analysis because their phone system was inoperable or the pharmacy was permanently closed. Of the pharmacies reached, 84.7% (155/183) reported they have naloxone available for pick up on the same day (Figure 1). Of the 15.3% (28) pharmacies that did not have same-day availability, 60.7% (17 pharmacies) reported availability in 1 to 2 days, 3.6% had availability in 3 to 4 days, 3.6% had availability in 1 week, and 32.1% were unsure of next availability (Figure 2). More than one-third of the state’s patients reside in municipalities where naloxone is immediately available in at least 72% of pharmacies (Table).13

Discussion

Increased access to naloxone at the state and community level is associated with reduced risk for death from overdose, and, consequently, widespread availability is recommended.14-17 Statewide real-time pharmacy availability of naloxone—as patients would experience availability—has not been previously reported. These findings suggest unpredictable same-day availability that may affect experience and care outcomes. That other studies have found similar challenges in naloxone availability in other municipalities and regions suggests this barrier to access is widespread,6-9 and likely affects patients throughout the country.

Many patients have misgivings about naloxone, and it places an undue burden on them to travel to multiple pharmacies or take repeated trips to fill prescriptions. Additionally, patients without reliable transportation may be unable to return at a later date. Although we found most pharmacies in New Mexico without immediate availability of naloxone reported they could have it within several days, such a delay may reduce the likelihood that patients will fill their prescription at all. It is also concerning that many pharmacies are unsure of when naloxone will be available, particularly when some of these may be the only pharmacy easily accessible to patients or the one where they regularly fill their prescriptions.

Barriers to naloxone availability requires further study due to possible negative consequences for patient safety and risks for exacerbating health disparities among vulnerable populations. Further research may focus on examining the effects on patients when naloxone dispensing is delayed or impossible, why there is variability in naloxone availability between different pharmacies and municipalities, the reasons for uncertainty when naloxone will be available, and effective solutions. Expanded naloxone distribution in community locations and in clinics offers one potential patient-centered solution that should be explored, but it is likely that more widespread and systemic solutions will require policy and regulatory changes at the state and national levels.

Limitations of this study include that the findings may be relevant for solely 1 state, such as in the case of state-specific barriers to keeping naloxone in stock that we are unaware of. However, it is unclear why that would be the case, and it is more likely that similar barriers are pervasive. Additionally, repeat phone calls, which we did not follow up with, may have yielded more pharmacies with naloxone availability. However, due to the stigma associated with obtaining naloxone, it may be that patients will not make multiple calls either—highlighting how important real-time availability is.

Conclusion

Urgent solutions are needed to address the epidemic of deaths from opioid overdoses. Naloxone availability is an important tool for reducing these deaths, resulting in numerous state laws attempting to increase access. Despite this, there are persistent barriers to patients receiving naloxone, including a lack of same-day availability at pharmacies. Our results suggest that this underexplored barrier is widespread. Improving both availability and accessibility of naloxone may include legislative policy solutions as well as patient-oriented solutions, such as distribution in clinics and hospitals when opioid prescriptions are first written. Further research should be conducted to determine patient-centered, effective solutions that can improve outcomes.

Corresponding author: Eileen Barrett, MD, MPH, Department of Internal Medicine, University of New Mexico; ebarrett@salud.unm.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Department of Medicine, University of California San Diego (Dr. Haponyuk), Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Tennessee (Dr. Dejong), the Department of Family Medicine, University of New Mexico (Dr. Gutfrucht), and the Department of Internal Medicine, University of New Mexico (Dr. Barrett)

Objective: Naloxone availability can reduce the risk of death from opioid overdoses, although prescriber, legislative, and payment barriers to accessing this life-saving medication exist. A previously underreported barrier involves same-day availability, the lack of which may force patients to travel to multiple pharmacies and having delays in access or risking not filling their prescription. This study sought to determine same-day availability of naloxone in pharmacies in the state of New Mexico.

Methods: Same-day availability of naloxone was assessed via an audit survey.

Results: Of the 183 pharamacies screened, only 84.7% had same-day availability, including only 72% in Albuquerque, the state’s most populous city/municipality.

Conclusion: These results highlight the extent of a previously underexplored challenge to patient care and barrier to patient safety, and future directions for more patient-centered care.

Keywords: naloxone; barriers to care; opioid overdose prevention.

The US is enduring an ongoing epidemic of deaths due to opioid use, which have increased in frequency since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.1 One strategy to reduce the risk of mortality from opioid use is to ensure the widespread availability of naloxone. Individual states have implemented harm reduction strategies to increase access to naloxone, including improving availability via a statewide standing order that it may be dispensed without a prescription.2,3 Such naloxone access laws are being widely adopted and are believed to reduce overdose deaths.4

There are many barriers to patients receiving naloxone despite their clinicians providing a prescription for it, including stigmatization, financial cost, and local availability.5-9 However, the stigma associated with naloxone extends to both patients and pharmacists. Pharmacists in West Virginia, for example, showed widespread concerns about having naloxone available for patients to purchase over the counter, for fear that increasing naloxone access may increase overdoses.6 A study in Tennessee also found pharmacists hesitant to recommend naloxone.7 Another study of rural pharmacies in Georgia found that just over half carried naloxone despite a state law that naloxone be available without a prescription.8 Challenges are not limited to rural areas, however; a study in Philadelphia found that more than one-third of pharmacies required a prescription to dispense naloxone, contrary to state law.9 Thus, in a rapidly changing regulatory environment, there are many evolving barriers to patients receiving naloxone.

New Mexico has an opioid overdose rate higher than the national average, coming in 15th out of 50 states when last ranked in 2018, with overdose rates that vary across demographic variables.10 Consequently, New Mexico state law added language requiring clinicians prescribing opioids for 5 days or longer to co-prescribe naloxone along with written information on how to administer the opioid antagonist.11 New Mexico is also a geographically large state with a relatively low overall population characterized by striking health disparities, particularly as related to access to care.

The purpose of this study is to describe the same-day availability of naloxone throughout the state of New Mexico after a change in state law requiring co-prescription was enacted, to help identify challenges to patients receiving it. Comprehensive examination of barriers to patients accessing this life-saving medication can advise strategies to both improve patient-centered care and potentially reduce deaths.

Methods

To better understand barriers to patients obtaining naloxone, in July and August of 2019 we performed an audit (“secret shopper”) study of all pharmacies in the state, posing as patients wishing to obtain naloxone. A publicly available list of every pharmacy in New Mexico was used to identify 89 pharmacies in Albuquerque (the most populous city in New Mexico) and 106 pharmacies throughout the rest of the state.12

Every pharmacy was called via a publicly available phone number during business hours (confirmed via an internet search), at least 2 hours prior to closing. One of 3 researchers telephoned pharmacies posing as a patient and inquired whether naloxone would be available for pick up the same day. If the pharmacy confirmed it was available that day, the call concluded. If naloxone was unavailable for same day pick up, researchers asked when it would be next available. Each pharmacy was called once, and neither insurance information nor cost was offered or requested. All questions were asked in English by native English speakers.

All responses were recorded in a secure spreadsheet. Once all responses were received and reviewed, they were characterized in discrete response categories: same day, within 1 to 2 days, within 3 to 4 days, within a week, or unsure/unknown. Naloxone availability was also tracked by city/municipality, and this was compared to the state’s population distribution.

No personally identifiable information was obtained. This study was Institutional Review Board exempt.

Results

Responses were recorded from 183 pharmacies. Seventeen locations were eliminated from our analysis because their phone system was inoperable or the pharmacy was permanently closed. Of the pharmacies reached, 84.7% (155/183) reported they have naloxone available for pick up on the same day (Figure 1). Of the 15.3% (28) pharmacies that did not have same-day availability, 60.7% (17 pharmacies) reported availability in 1 to 2 days, 3.6% had availability in 3 to 4 days, 3.6% had availability in 1 week, and 32.1% were unsure of next availability (Figure 2). More than one-third of the state’s patients reside in municipalities where naloxone is immediately available in at least 72% of pharmacies (Table).13

Discussion

Increased access to naloxone at the state and community level is associated with reduced risk for death from overdose, and, consequently, widespread availability is recommended.14-17 Statewide real-time pharmacy availability of naloxone—as patients would experience availability—has not been previously reported. These findings suggest unpredictable same-day availability that may affect experience and care outcomes. That other studies have found similar challenges in naloxone availability in other municipalities and regions suggests this barrier to access is widespread,6-9 and likely affects patients throughout the country.

Many patients have misgivings about naloxone, and it places an undue burden on them to travel to multiple pharmacies or take repeated trips to fill prescriptions. Additionally, patients without reliable transportation may be unable to return at a later date. Although we found most pharmacies in New Mexico without immediate availability of naloxone reported they could have it within several days, such a delay may reduce the likelihood that patients will fill their prescription at all. It is also concerning that many pharmacies are unsure of when naloxone will be available, particularly when some of these may be the only pharmacy easily accessible to patients or the one where they regularly fill their prescriptions.

Barriers to naloxone availability requires further study due to possible negative consequences for patient safety and risks for exacerbating health disparities among vulnerable populations. Further research may focus on examining the effects on patients when naloxone dispensing is delayed or impossible, why there is variability in naloxone availability between different pharmacies and municipalities, the reasons for uncertainty when naloxone will be available, and effective solutions. Expanded naloxone distribution in community locations and in clinics offers one potential patient-centered solution that should be explored, but it is likely that more widespread and systemic solutions will require policy and regulatory changes at the state and national levels.

Limitations of this study include that the findings may be relevant for solely 1 state, such as in the case of state-specific barriers to keeping naloxone in stock that we are unaware of. However, it is unclear why that would be the case, and it is more likely that similar barriers are pervasive. Additionally, repeat phone calls, which we did not follow up with, may have yielded more pharmacies with naloxone availability. However, due to the stigma associated with obtaining naloxone, it may be that patients will not make multiple calls either—highlighting how important real-time availability is.

Conclusion

Urgent solutions are needed to address the epidemic of deaths from opioid overdoses. Naloxone availability is an important tool for reducing these deaths, resulting in numerous state laws attempting to increase access. Despite this, there are persistent barriers to patients receiving naloxone, including a lack of same-day availability at pharmacies. Our results suggest that this underexplored barrier is widespread. Improving both availability and accessibility of naloxone may include legislative policy solutions as well as patient-oriented solutions, such as distribution in clinics and hospitals when opioid prescriptions are first written. Further research should be conducted to determine patient-centered, effective solutions that can improve outcomes.

Corresponding author: Eileen Barrett, MD, MPH, Department of Internal Medicine, University of New Mexico; ebarrett@salud.unm.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Mason M, Welch SB, Arunkumar P, et al. Notes from the field: opioid overdose deaths before, during, and after an 11-week COVID-19 stay-at-home order—Cook County, Illinois, January 1, 2018–October 6, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(10):362-363. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7010a3

2. Kaiser Family Foundation. Opioid overdose death rates and all drug overdose death rates per 100,000 population (age-adjusted). Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/opioid-overdose-death

3. Sohn M, Talbert JC, Huang Z, et al. Association of naloxone coprescription laws with naloxone prescription dispensing in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(6):e196215. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.6215

4. Smart R, Pardo B, Davis CS. Systematic review of the emerging literature on the effectiveness of naloxone access laws in the United States. Addiction. 2021;116(1):6-17. doi:10.1111/add.15163

5. Mueller SR, Koester S, Glanz JM, et al. Attitudes toward naloxone prescribing in clinical settings: a qualitative study of patients prescribed high dose opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):277-283. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3895-8

6. Thornton JD, Lyvers E, Scott VGG, Dwibedi N. Pharmacists’ readiness to provide naloxone in community pharmacies in West Virginia. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2017;57(2S):S12-S18.e4. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2016.12.070

7. Spivey C, Wilder A, Chisholm-Burns MA, et al. Evaluation of naloxone access, pricing, and barriers to dispensing in Tennessee retail community pharmacies. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2020;60(5):694-701.e1. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2020.01.030

8. Nguyen JL, Gilbert LR, Beasley L, et al. Availability of naloxone at rural Georgia pharmacies, 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1921227. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.21227

9. Guadamuz JS, Alexander GC, Chaudhri T, et al. Availability and cost of naloxone nasal spray at pharmacies in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(6):e195388. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.5388

10. Edge K. Changes in drug overdose mortality in New Mexico. New Mexico Epidemiology. July 2020 (3). https://www.nmhealth.org/data/view/report/2402/

11. Senate Bill 221. 54th Legislature, State of New Mexico, First Session, 2019 (introduced by William P. Soules). Accessed October 6, 2021. https://nmlegis.gov/Sessions/19%20Regular/bills/senate/SB0221.pdf

12. GoodRx. Find pharmacies in New Mexico. Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.goodrx.com/pharmacy-near-me/all/nm

13. U.S. Census Bureau. QuickFacts: New Mexico. Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/NM

14. Linas BP, Savinkina A, Madushani RWMA, et al. Projected estimates of opioid mortality after community-level interventions. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2037259. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37259

15. You HS, Ha J, Kang CY, et al. Regional variation in states’ naloxone accessibility laws in association with opioid overdose death rates—observational study (STROBE compliant). Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(22):e20033. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000020033

16. Pew Charitable Trusts. Expanded access to naloxone can curb opioid overdose deaths. October 20, 2020. Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.

17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Still not enough naloxone where it’s most needed. August 6, 2019. Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2019/p0806-naloxone.html

1. Mason M, Welch SB, Arunkumar P, et al. Notes from the field: opioid overdose deaths before, during, and after an 11-week COVID-19 stay-at-home order—Cook County, Illinois, January 1, 2018–October 6, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(10):362-363. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7010a3

2. Kaiser Family Foundation. Opioid overdose death rates and all drug overdose death rates per 100,000 population (age-adjusted). Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/opioid-overdose-death

3. Sohn M, Talbert JC, Huang Z, et al. Association of naloxone coprescription laws with naloxone prescription dispensing in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(6):e196215. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.6215

4. Smart R, Pardo B, Davis CS. Systematic review of the emerging literature on the effectiveness of naloxone access laws in the United States. Addiction. 2021;116(1):6-17. doi:10.1111/add.15163

5. Mueller SR, Koester S, Glanz JM, et al. Attitudes toward naloxone prescribing in clinical settings: a qualitative study of patients prescribed high dose opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):277-283. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3895-8

6. Thornton JD, Lyvers E, Scott VGG, Dwibedi N. Pharmacists’ readiness to provide naloxone in community pharmacies in West Virginia. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2017;57(2S):S12-S18.e4. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2016.12.070

7. Spivey C, Wilder A, Chisholm-Burns MA, et al. Evaluation of naloxone access, pricing, and barriers to dispensing in Tennessee retail community pharmacies. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2020;60(5):694-701.e1. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2020.01.030

8. Nguyen JL, Gilbert LR, Beasley L, et al. Availability of naloxone at rural Georgia pharmacies, 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1921227. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.21227

9. Guadamuz JS, Alexander GC, Chaudhri T, et al. Availability and cost of naloxone nasal spray at pharmacies in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(6):e195388. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.5388

10. Edge K. Changes in drug overdose mortality in New Mexico. New Mexico Epidemiology. July 2020 (3). https://www.nmhealth.org/data/view/report/2402/

11. Senate Bill 221. 54th Legislature, State of New Mexico, First Session, 2019 (introduced by William P. Soules). Accessed October 6, 2021. https://nmlegis.gov/Sessions/19%20Regular/bills/senate/SB0221.pdf

12. GoodRx. Find pharmacies in New Mexico. Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.goodrx.com/pharmacy-near-me/all/nm

13. U.S. Census Bureau. QuickFacts: New Mexico. Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/NM

14. Linas BP, Savinkina A, Madushani RWMA, et al. Projected estimates of opioid mortality after community-level interventions. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2037259. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37259

15. You HS, Ha J, Kang CY, et al. Regional variation in states’ naloxone accessibility laws in association with opioid overdose death rates—observational study (STROBE compliant). Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(22):e20033. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000020033

16. Pew Charitable Trusts. Expanded access to naloxone can curb opioid overdose deaths. October 20, 2020. Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.

17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Still not enough naloxone where it’s most needed. August 6, 2019. Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2019/p0806-naloxone.html

Embedding diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice in hospital medicine

A road map for success

The language of equality in America’s founding was never truly embraced, resulting in a painful legacy of slavery, racial injustice, and gender inequality inherited by all generations. However, for as long as America has fallen short of this unfulfilled promise, individuals have dedicated their lives to the tireless work of correcting injustice. Although the process has been painstakingly slow, our nation has incrementally inched toward the promised vision of equality, and these efforts continue today. With increased attention to social justice movements such as #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, our collective social consciousness may be finally waking up to the systemic injustices embedded into our fundamental institutions.

Medicine is not immune to these injustices. Persistent underrepresentation of women and minorities remains in medical school faculty and the broader physician workforce, and the same inequities exist in hospital medicine.1-6 The report by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) on diversity in medicine highlights the impact widespread implicit and explicit bias has on creating exclusionary environments, exemplified by research demonstrating lower promotion rates in non-White faculty.7-8 The report calls us, as physicians, to a broader mission: “Focusing solely on increasing compositional diversity along the academic continuum is insufficient. To effectively enact institutional change at academic medical centers ... leaders must focus their efforts on developing inclusive, equity-minded environments.”7

We have a clear moral imperative to correct these shortcomings for our profession and our patients. It is incumbent on our institutions and hospital medicine groups (HMGs) to embark on the necessary process of systemic institutional change to address inequality and justice within our field.

A road map for DEI and justice in hospital medicine

The policies and biases allowing these inequities to persist have existed for decades, and superficial efforts will not bring sufficient change. Our institutions require new building blocks from which the foundation of a wholly inclusive and equal system of practice can be constructed. Encouragingly, some institutions and HMGs have taken steps to modernize their practices. We offer examples and suggestions of concrete practices to begin this journey, organizing these efforts into three broad categories:

1. Recruitment and retention

2. Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

3. Community engagement and partnership.

Recruitment and retention

Improving equity and inclusion begins with recruitment. Search and hiring committees should be assembled intentionally, with gender balance, and ideally with diversity or equity experts invited to join. All members should receive unconscious bias training. For example, the University of Colorado utilizes a toolkit to ensure appropriate steps are followed in the recruitment process, including predetermined candidate selection criteria that are ranked in advance.

Job descriptions should be reviewed by a diversity expert, ensuring unbiased and ungendered language within written text. Advertisements should be wide-reaching, and the committee should consider asking applicants for a diversity statement. Interviews should include a variety of interviewers and interview types (e.g., 1:1, group, etc.). Letters of recommendation deserve special scrutiny; letters for women and minorities may be at risk of being shorter and less record focused, and may be subject to less professional respect, such as use of first names over honorifics or titles.

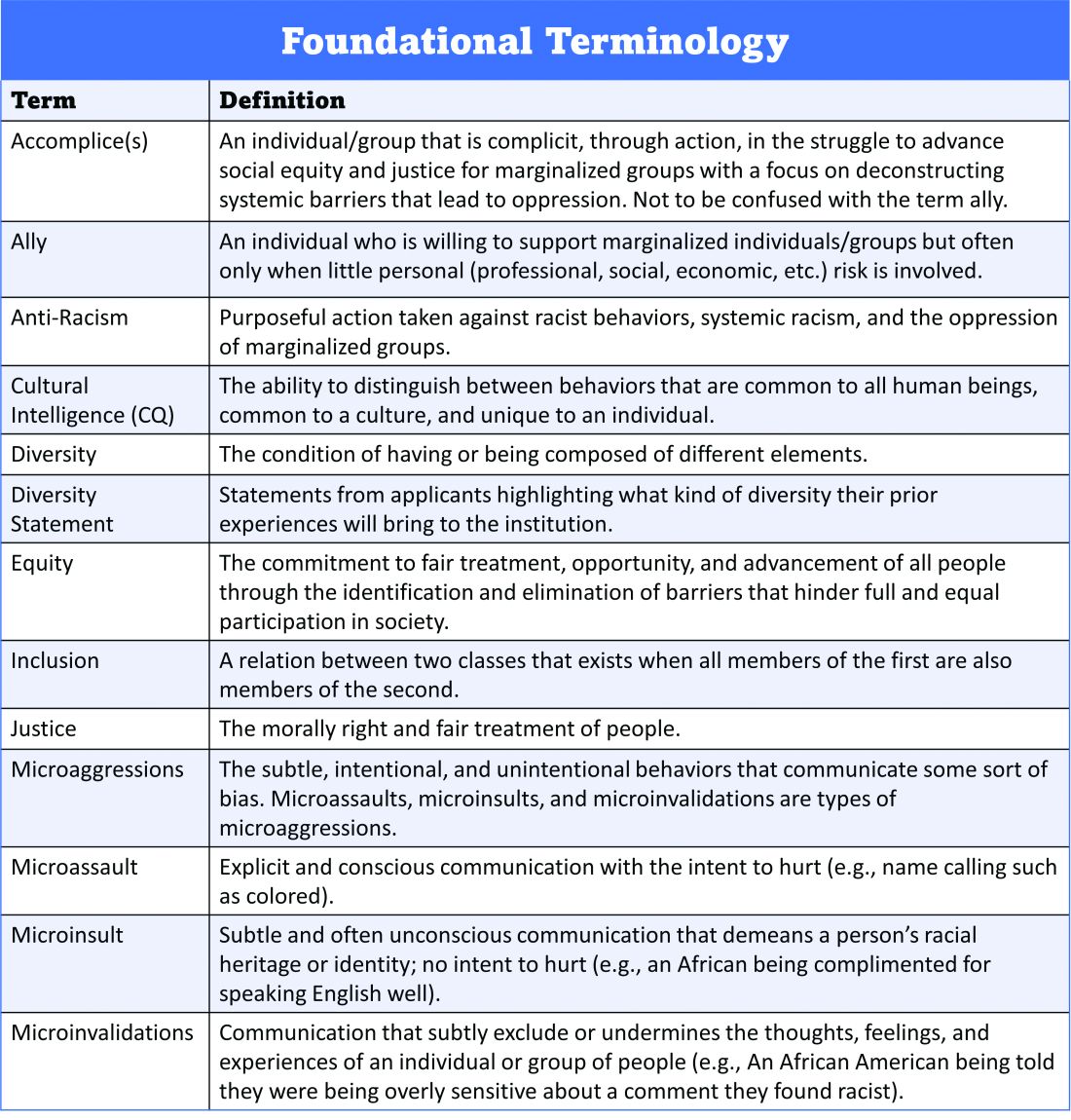

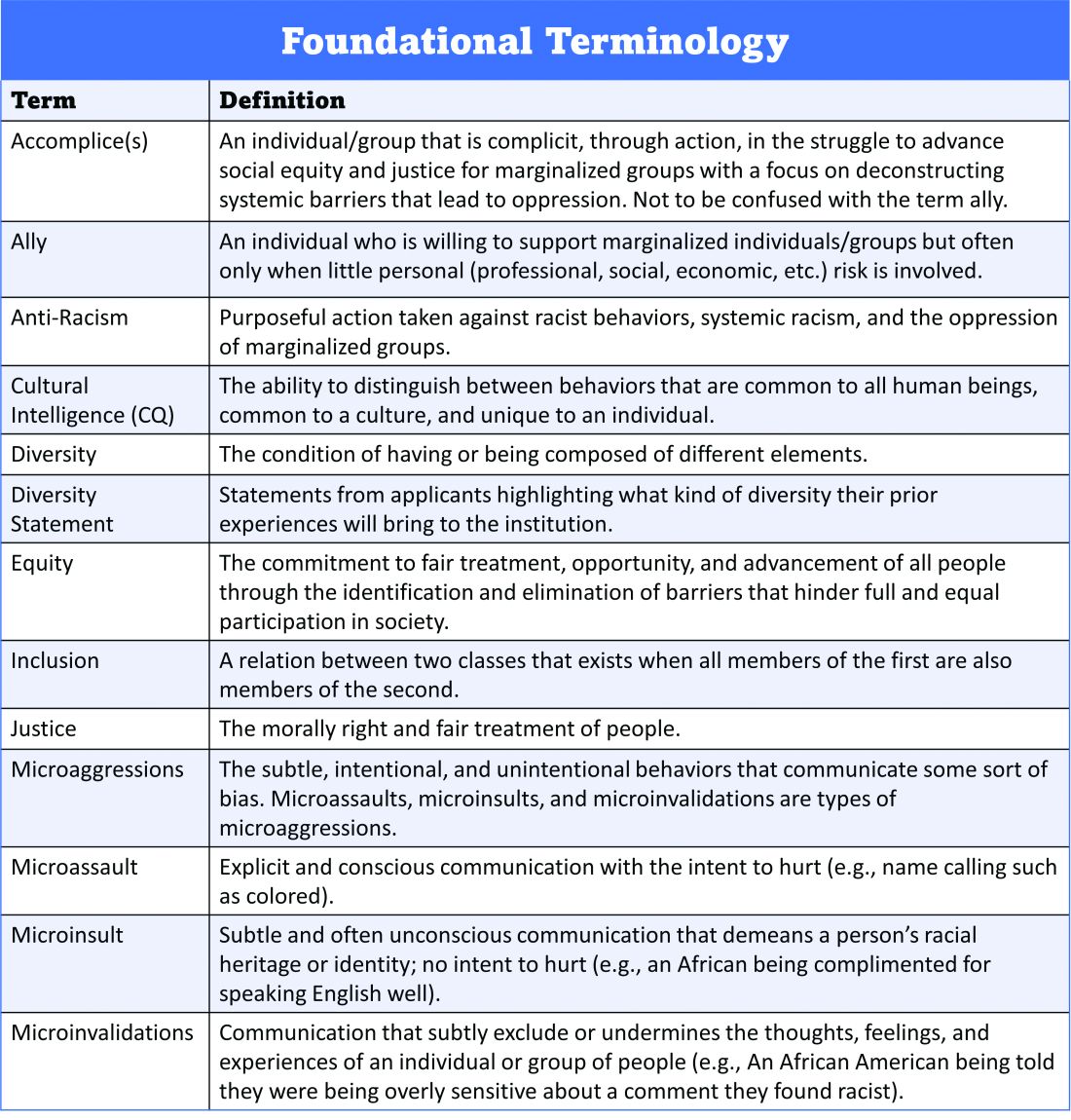

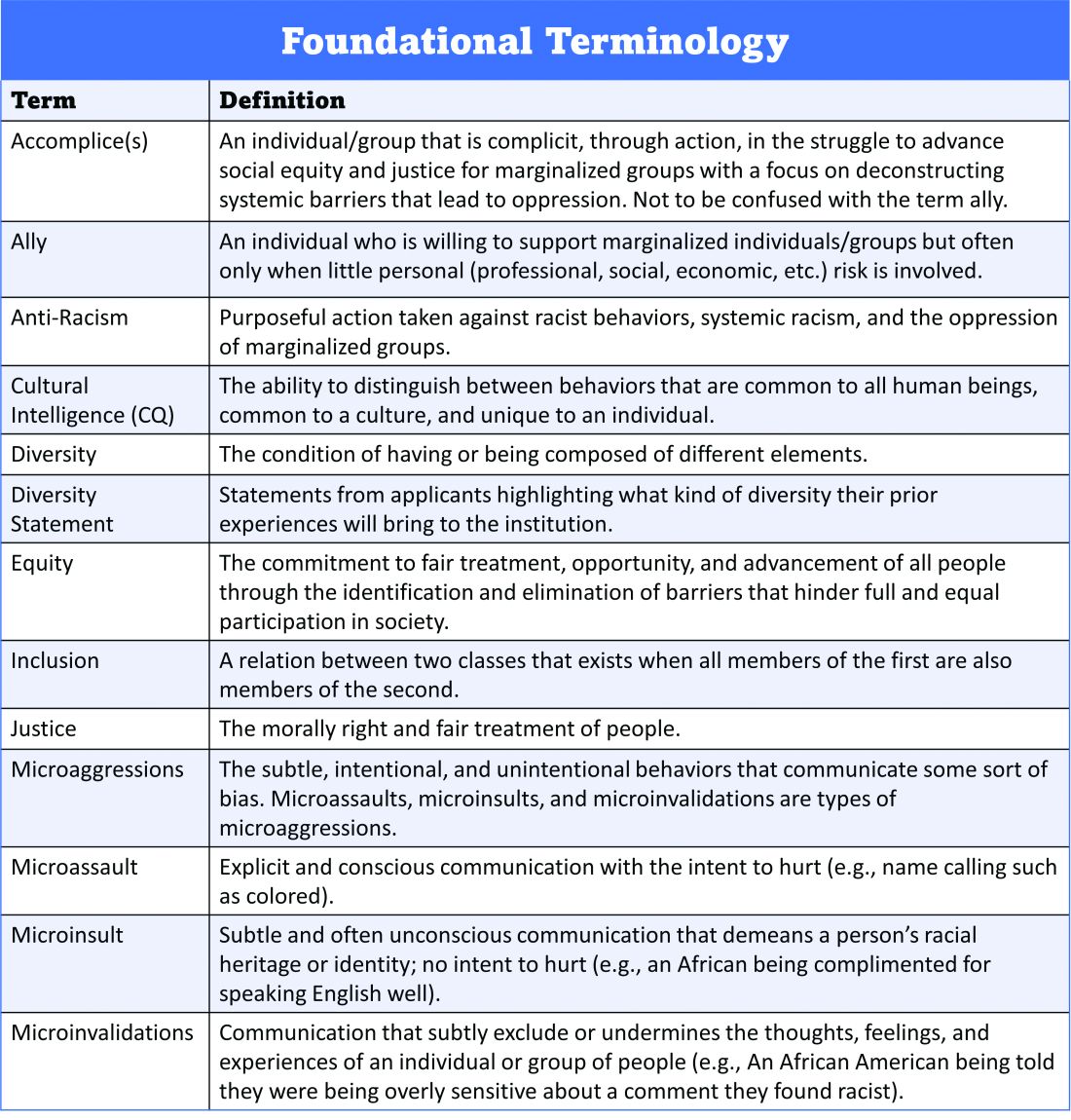

Once candidates are hired, institutions and HMGs should prioritize developing strategies to improve retention of a diverse workforce. This includes special attention to workplace culture, and thoughtfully striving for cultural intelligence within the group. Some examples may include developing affinity groups, such as underrepresented in medicine (UIM), women in medicine (WIM), or LGBTQ+ groups. Affinity groups provide a safe space for members and allies to support and uplift each other. Institutional and HMG leaders must educate themselves and their members on the importance of language (see table), and the more insidious forms of bias and discrimination that adversely affect workplace culture. Microinsults and microinvalidations, for example, can hurt and result in failure to recruit or turnover.

Conducting exit interviews when any hospitalist leaves is important to learn how to improve, but holding ‘stay’ interviews is mission critical. Stay interviews are an opportunity for HMG leaders to proactively understand why hospitalists stay, and what can be done to create more inclusive and equitable environments to retain them. This process creates psychological safety that brings challenges to the fore to be addressed, and spotlights best practices to be maintained and scaled.

Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

Women and minorities are known to be over-mentored and under-sponsored. Sponsorship is defined by Ayyala et al. as “active support by someone appropriately placed in the organization who has significant influence on decision making processes or structures and who is advocating for the career advancement of an individual and recommends them for leadership roles, awards, or high-profile speaking opportunities.”9 While the goal of mentorship is professional development, sponsorship emphasizes professional advancement. Deliberate steps to both mentor and then sponsor diverse hospitalists and future hospitalists (including trainees) are important to ensure equity.

More inclusive HMGs can be bolstered by prioritizing peer education on the professional imperative that we have a diverse workforce and equitable, just workplaces. Academic institutions may use existing structures such as grand rounds to provide education on these crucial topics, and all HMGs can host journal clubs and professional development sessions on leadership competencies that foster inclusion and equity. Sessions coordinated by women and minorities are also a form of justice, by helping overcome barriers to career advancement. Diverse faculty presenting in educational venues will result in content that is relevant to more audience members and will exemplify that leaders and experts are of all races, ethnicities, genders, ages, and abilities.

Groups should prioritize mentoring trainees and early-career hospitalists on scholarly projects that examine equity in opportunities of care, which signals that this science is valued as much as basic research. When used to demonstrate areas needing improvement, these projects can drive meaningful change. Even projects as straightforward as studying diversity in conference presenters, disparities in adherence to guidelines, or QI projects on how race is portrayed in the medical record can be powerful tools in advancing equity.

A key part of mentoring is training hospitalists and future hospitalists in how to be an upstander, as in how to intervene when a peer or patient is affected by bias, harassment, or discrimination. Receiving such training can prepare hospitalists for these nearly inevitable experiences and receiving training during usual work hours communicates that this is a valuable and necessary professional competency.

Community engagement and partnership

Institutions and HMGs should deliberately work to promote community engagement and partnership within their groups. Beyond promoting health equity, community engagement also fosters inclusivity by allowing community members to share their ideas and give recommendations to the institutions that serve them.

There is a growing body of literature that demonstrates how disadvantages by individual and neighborhood-level socioeconomic status (SES) contribute to disparities in specific disease conditions.10-11 Strategies to narrow the gap in SES disadvantages may help reduce race-related health disparities. Institutions that engage the community and develop programs to promote health equity can do so through bidirectional exchange of knowledge and mutual benefit.

An institution-specific example is Medicine for the Greater Good at Johns Hopkins. The founders of this program wrote, “health is not synonymous with medicine. To truly care for our patients and their communities, health care professionals must understand how to deliver equitable health care that meets the needs of the diverse populations we care for. The mission of Medicine for the Greater Good is to promote health and wellness beyond the confines of the hospital through an interactive and engaging partnership with the community ...” Community engagement also provides an opportunity for growing the cultural intelligence of institutions and HMGs.

Tools for advancing comprehensive change – Repurposing PDSA cycles

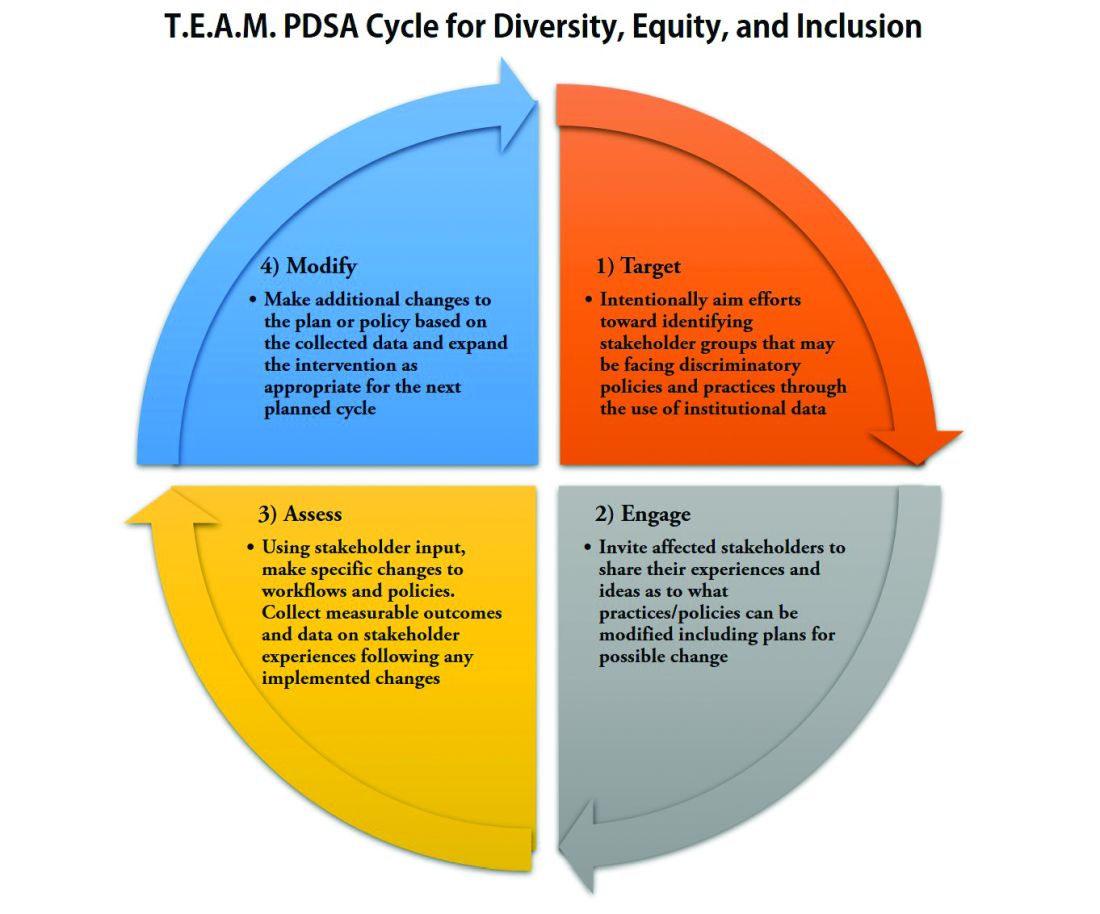

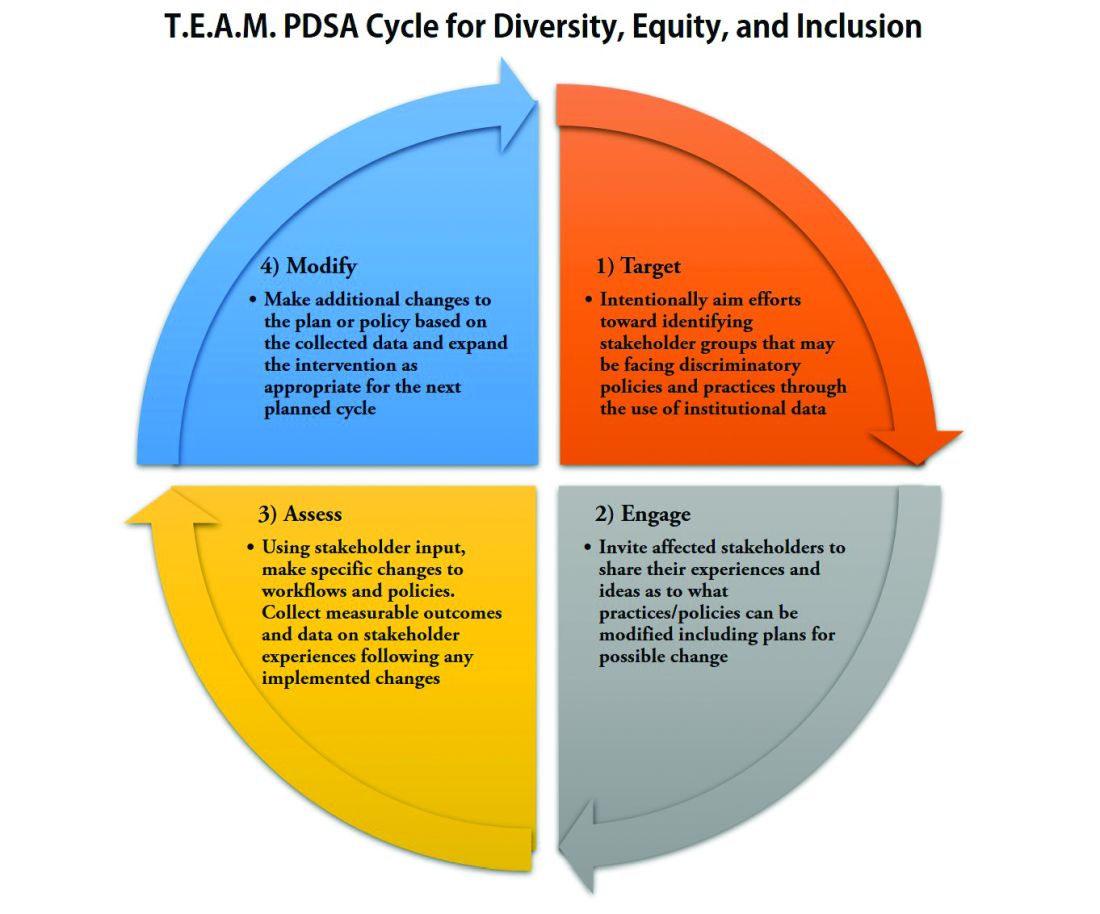

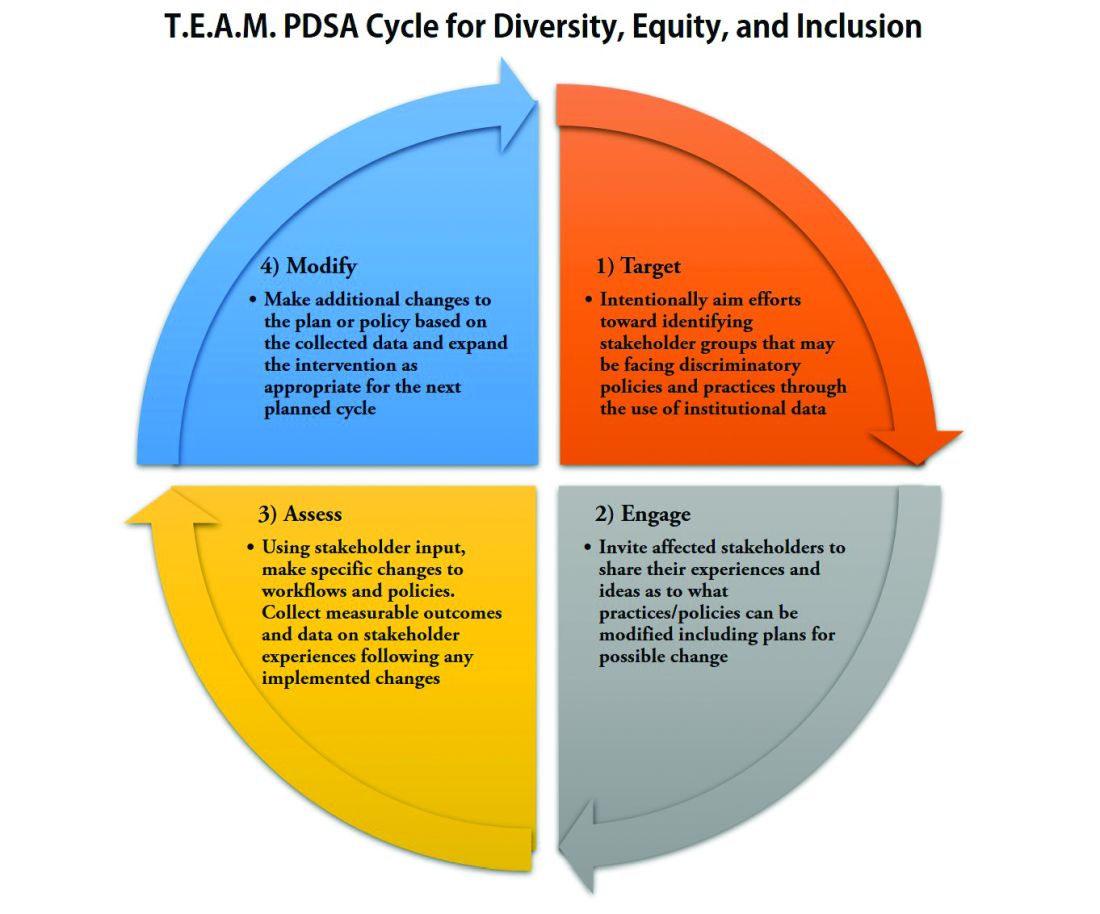

Whether institutions and HMGs are at the beginning of their journey or further along in the work of reducing disparities, having a systematic approach for implementing and refining policies and procedures can cultivate more inclusive and equitable environments. Thankfully, hospitalists are already equipped with the fundamental tools needed to advance change across their institutions – QI processes in the form of Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles.

They allow a continuous cycle of successful incremental change based on direct evidence and experience. Any efforts to deconstruct systematic bias within our organizations must also be a continual process. Our female colleagues and colleagues of color need our institutions to engage unceasingly to bring about the equality they deserve. To that end, PDSA cycles are an apt tool to utilize in this work as they can naturally function in a never-ending process of improvement.

With PDSA as a model, we envision a cycle with steps that are intentionally purposed to fit the needs of equitable institutional change: Target-Engage-Assess-Modify. As highlighted (see graphic), these modifications ensure that stakeholders (i.e., those that unequal practices and policies affect the most) are engaged early and remain involved throughout the cycle.

As hospitalists, we have significant work ahead to ensure that we develop and maintain a diverse, equitable and inclusive workforce. This work to bring change will not be easy and will require a considerable investment of time and resources. However, with the strategies and tools that we have outlined, our institutions and HMGs can start the change needed in our profession for our patients and the workforce. In doing so, we can all be accomplices in the fight to achieve racial and gender equity, and social justice.

Dr. Delapenha and Dr. Kisuule are based in the department of internal medicine, division of hospital medicine, at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. Dr. Martin is based in the department of medicine, section of hospital medicine at the University of Chicago. Dr. Barrett is a hospitalist in the department of internal medicine, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

References

1. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019: Figure 19. Percentage of physicians by sex, 2018. AAMC website.

2. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 16. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by sex and race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

3. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 15. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

4. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 6. Percentage of acceptees to U.S. medical schools by race/ethnicity (alone), academic year 2018-2019. AAMC website.

5. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019 Figure 18. Percentage of all active physicians by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

6. Herzke C et al. Gender issues in academic hospital medicine: A national survey of hospitalist leaders. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(6):1641-6.

7. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Fostering diversity and inclusion. AAMC website.

8. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Executive summary. AAMC website.

9. Ayyala MS et al. Mentorship is not enough: Exploring sponsorship and its role in career advancement in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2019;94(1):94-100.

10. Ejike OC et al. Contribution of individual and neighborhood factors to racial disparities in respiratory outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021 Apr 15;203(8):987-97.

11. Galiatsatos P et al. The effect of community socioeconomic status on sepsis-attributable mortality. J Crit Care. 2018 Aug;46:129-33.

A road map for success

A road map for success

The language of equality in America’s founding was never truly embraced, resulting in a painful legacy of slavery, racial injustice, and gender inequality inherited by all generations. However, for as long as America has fallen short of this unfulfilled promise, individuals have dedicated their lives to the tireless work of correcting injustice. Although the process has been painstakingly slow, our nation has incrementally inched toward the promised vision of equality, and these efforts continue today. With increased attention to social justice movements such as #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, our collective social consciousness may be finally waking up to the systemic injustices embedded into our fundamental institutions.

Medicine is not immune to these injustices. Persistent underrepresentation of women and minorities remains in medical school faculty and the broader physician workforce, and the same inequities exist in hospital medicine.1-6 The report by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) on diversity in medicine highlights the impact widespread implicit and explicit bias has on creating exclusionary environments, exemplified by research demonstrating lower promotion rates in non-White faculty.7-8 The report calls us, as physicians, to a broader mission: “Focusing solely on increasing compositional diversity along the academic continuum is insufficient. To effectively enact institutional change at academic medical centers ... leaders must focus their efforts on developing inclusive, equity-minded environments.”7

We have a clear moral imperative to correct these shortcomings for our profession and our patients. It is incumbent on our institutions and hospital medicine groups (HMGs) to embark on the necessary process of systemic institutional change to address inequality and justice within our field.

A road map for DEI and justice in hospital medicine

The policies and biases allowing these inequities to persist have existed for decades, and superficial efforts will not bring sufficient change. Our institutions require new building blocks from which the foundation of a wholly inclusive and equal system of practice can be constructed. Encouragingly, some institutions and HMGs have taken steps to modernize their practices. We offer examples and suggestions of concrete practices to begin this journey, organizing these efforts into three broad categories:

1. Recruitment and retention

2. Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

3. Community engagement and partnership.

Recruitment and retention

Improving equity and inclusion begins with recruitment. Search and hiring committees should be assembled intentionally, with gender balance, and ideally with diversity or equity experts invited to join. All members should receive unconscious bias training. For example, the University of Colorado utilizes a toolkit to ensure appropriate steps are followed in the recruitment process, including predetermined candidate selection criteria that are ranked in advance.