User login

LGBT Access to Health Care: A Dermatologist’s Role in Building a Therapeutic Relationship

The last decade has been a period of advancement for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community for legal protections and visibility. Although the journey to acceptance and equality is far from over, this progress has appropriately extended to medical academia as physicians search for ways to become more inclusive and effective care providers for their LGBT patients.1 In a recent cross-sectional study, Ginsberg et al2 examined the role for dermatologists in the care of transgender patients. The investigators concluded that dermatologists should play a larger role in a transgender patient’s physical transformation.2 It is our opinion that dermatologists need to be comfortable building rapport with LGBT patients and to become attuned to their specific needs to provide effective care.

When forging a relationship with an LGBT patient, assumptions can damage rapport. Two assumptions that should be avoided include presuming heterosexuality or, on the other hand, assuming risk for disease based on known LGBT status. A dermatologist who takes a cursory sexual history, or none at all, assuming his/her patient is heterosexual creates an environment in which a nonheterosexual patient feels uncomfortable being honest and open. Although there is enough literature to support the claim that some sexual minority groups have increased risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs),3 it is dangerous to assume a patient’s risk based solely on sexual orientation. An abstinent patient or a patient in a long-term, monogamous, same-sex relationship, for instance, may feel stereotyped by a dermatologist who wants to screen him/her for an STI. The best step in building a therapeutic relationship is to cast out these assumptions and allow LGBT patients to be open about themselves and their sexual practices. Sexual histories should be asked in nonjudgmental ways that are related to the health of the patient, leading to relevant and useful information for their care. For example, ask patients, “Do you have sex with men, women, or both?” This question should be delivered in a matter-of-fact tone, which conveys to the patient that the provider merely wants an answer to guide patient care.

Dermatologists can tailor their encounters to the specific needs of sexual minority patients. The medical literature is rich with examples of conditions that occur at greater frequency in specific sexual minority groups. Sexually transmitted infections, particularly human immunodeficiency virus, are important causes of morbidity and mortality among sexual minorities, especially men who have sex with men (MSM).3,4 Anal and penile human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and HPV-associated anal carcinoma risk are increased in MSM.5,6 The literature has remained inconclusive on the use of anal Papanicolaou tests for diagnosis; however, dermatologists have a duty to at least examine the perianal and genital area of any patient at risk for HPV-related disease or STIs.7,8 For younger patients, the HPV vaccine can help prevent certain types of HPV infection and likely reduce a patient’s risk for condyloma acuminatum and other sequelae of the virus. Guidelines have been expanded to include men aged 13 to 21 years and up to 26 years.9 More research is needed to determine if detection and prevention of these types of HPV infection using the vaccine in MSM actually leads to a decreased incidence of anal carcinoma.

Certain LGBT groups may benefit from a dermatologist’s care outside the realm of infectious diseases. One study found that increased indoor tanning use in MSM correlated with increased risk for nonmelanoma skin cancer.10 Lesbians have been found to be less likely to pursue preventative health examinations in general, including skin checks.11 Finally, transgender patients can utilize dermatologists for help with transformative procedures and side effects of hormonal treatment such as androgenic acne.1,4

Cutaneous and beyond, the future of LGBT health care in the United States is affected by the institutions that train future physicians. There is a trend toward incorporating formal LGBT curricula into medical schools and academic centers.12 The Penn Medicine Program for LGBT Health (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) is a pilot program geared toward both educating future clinicians and providing equal and unbiased care to LGBT patients.12 Programs such as this one give rise to a new generation of physicians who feel comfortable and aware of the needs of their LGBT patients.

In a time when LGBT patients are becoming more comfortable claiming their sexual and gender identities openly, there is a need for dermatologists to provide individualized unbiased care, which can best be achieved by building rapport through assumption-free history taking, performing thorough physical examinations that include the genital and perianal area, and passing these good practices on to trainees.

- Snyder JE. Trend analysis of medical publications about LGBT persons: 1950-2007. J Homosex. 2011;58:164-188.

- Ginsberg BA, Calderon M, Seminara NM, et al. A potential role for the dermatologist in the physical transformation of transgender people: a survey of attitudes and practices within the transgender community. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:303-308.

- Gee R. Primary care health issues among men who have sex with men. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2006;18:144-153.

- Katz KA, Furnish TJ. Dermatology-related epidemiologic and clinical concerns of men who have sex with men, women who have sex with women, and transgender individuals. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1303-1310.

- Fenkl EA, Jones SG, Schochet E, et al. HPV and anal cancer knowledge among HIV-infected and non-infected men who have sex with men [published online December 11, 2015]. LGBT Health. 2016;3:42-48. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2015.0086.

- Chin-Hong PV, Vittinghoff E, Cranston RD, et al. Age-related prevalence of anal cancer precursors in homosexual men: the EXPLORE Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:896-905.

- Schofield AM, Sadler L, Nelson L, et al. A prospective study of anal cancer screening in HIV-positive and negative MSM. AIDS. 2016;30:1375-1383.

- Katz MH, Katz KA, Bernestein KT, et al. We need data on anal screening effectiveness before focusing on increasing it [published online September 23, 2010]. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:2016.

- Petrosky E, Bocchini JA, Hariri S, et al. Use of 9-Valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: updated HPV vaccination recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:300-304.

- Mansh M, Katz KA, Linos E, et al. Association of skin cancer and indoor tanning in sexual minority men and women. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1308-1316.

- Conron KJ, Mimiaga MJ, Landers SJ. A population-based study of sexual orientation identity and gender differences in adult health. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1953-1960.

- Yehia BR, Calder D, Flesch JD, et al. Advancing LGBT health at an academic medical center: a case study. LGBT Health. 2015;2:362-366.

The last decade has been a period of advancement for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community for legal protections and visibility. Although the journey to acceptance and equality is far from over, this progress has appropriately extended to medical academia as physicians search for ways to become more inclusive and effective care providers for their LGBT patients.1 In a recent cross-sectional study, Ginsberg et al2 examined the role for dermatologists in the care of transgender patients. The investigators concluded that dermatologists should play a larger role in a transgender patient’s physical transformation.2 It is our opinion that dermatologists need to be comfortable building rapport with LGBT patients and to become attuned to their specific needs to provide effective care.

When forging a relationship with an LGBT patient, assumptions can damage rapport. Two assumptions that should be avoided include presuming heterosexuality or, on the other hand, assuming risk for disease based on known LGBT status. A dermatologist who takes a cursory sexual history, or none at all, assuming his/her patient is heterosexual creates an environment in which a nonheterosexual patient feels uncomfortable being honest and open. Although there is enough literature to support the claim that some sexual minority groups have increased risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs),3 it is dangerous to assume a patient’s risk based solely on sexual orientation. An abstinent patient or a patient in a long-term, monogamous, same-sex relationship, for instance, may feel stereotyped by a dermatologist who wants to screen him/her for an STI. The best step in building a therapeutic relationship is to cast out these assumptions and allow LGBT patients to be open about themselves and their sexual practices. Sexual histories should be asked in nonjudgmental ways that are related to the health of the patient, leading to relevant and useful information for their care. For example, ask patients, “Do you have sex with men, women, or both?” This question should be delivered in a matter-of-fact tone, which conveys to the patient that the provider merely wants an answer to guide patient care.

Dermatologists can tailor their encounters to the specific needs of sexual minority patients. The medical literature is rich with examples of conditions that occur at greater frequency in specific sexual minority groups. Sexually transmitted infections, particularly human immunodeficiency virus, are important causes of morbidity and mortality among sexual minorities, especially men who have sex with men (MSM).3,4 Anal and penile human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and HPV-associated anal carcinoma risk are increased in MSM.5,6 The literature has remained inconclusive on the use of anal Papanicolaou tests for diagnosis; however, dermatologists have a duty to at least examine the perianal and genital area of any patient at risk for HPV-related disease or STIs.7,8 For younger patients, the HPV vaccine can help prevent certain types of HPV infection and likely reduce a patient’s risk for condyloma acuminatum and other sequelae of the virus. Guidelines have been expanded to include men aged 13 to 21 years and up to 26 years.9 More research is needed to determine if detection and prevention of these types of HPV infection using the vaccine in MSM actually leads to a decreased incidence of anal carcinoma.

Certain LGBT groups may benefit from a dermatologist’s care outside the realm of infectious diseases. One study found that increased indoor tanning use in MSM correlated with increased risk for nonmelanoma skin cancer.10 Lesbians have been found to be less likely to pursue preventative health examinations in general, including skin checks.11 Finally, transgender patients can utilize dermatologists for help with transformative procedures and side effects of hormonal treatment such as androgenic acne.1,4

Cutaneous and beyond, the future of LGBT health care in the United States is affected by the institutions that train future physicians. There is a trend toward incorporating formal LGBT curricula into medical schools and academic centers.12 The Penn Medicine Program for LGBT Health (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) is a pilot program geared toward both educating future clinicians and providing equal and unbiased care to LGBT patients.12 Programs such as this one give rise to a new generation of physicians who feel comfortable and aware of the needs of their LGBT patients.

In a time when LGBT patients are becoming more comfortable claiming their sexual and gender identities openly, there is a need for dermatologists to provide individualized unbiased care, which can best be achieved by building rapport through assumption-free history taking, performing thorough physical examinations that include the genital and perianal area, and passing these good practices on to trainees.

The last decade has been a period of advancement for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community for legal protections and visibility. Although the journey to acceptance and equality is far from over, this progress has appropriately extended to medical academia as physicians search for ways to become more inclusive and effective care providers for their LGBT patients.1 In a recent cross-sectional study, Ginsberg et al2 examined the role for dermatologists in the care of transgender patients. The investigators concluded that dermatologists should play a larger role in a transgender patient’s physical transformation.2 It is our opinion that dermatologists need to be comfortable building rapport with LGBT patients and to become attuned to their specific needs to provide effective care.

When forging a relationship with an LGBT patient, assumptions can damage rapport. Two assumptions that should be avoided include presuming heterosexuality or, on the other hand, assuming risk for disease based on known LGBT status. A dermatologist who takes a cursory sexual history, or none at all, assuming his/her patient is heterosexual creates an environment in which a nonheterosexual patient feels uncomfortable being honest and open. Although there is enough literature to support the claim that some sexual minority groups have increased risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs),3 it is dangerous to assume a patient’s risk based solely on sexual orientation. An abstinent patient or a patient in a long-term, monogamous, same-sex relationship, for instance, may feel stereotyped by a dermatologist who wants to screen him/her for an STI. The best step in building a therapeutic relationship is to cast out these assumptions and allow LGBT patients to be open about themselves and their sexual practices. Sexual histories should be asked in nonjudgmental ways that are related to the health of the patient, leading to relevant and useful information for their care. For example, ask patients, “Do you have sex with men, women, or both?” This question should be delivered in a matter-of-fact tone, which conveys to the patient that the provider merely wants an answer to guide patient care.

Dermatologists can tailor their encounters to the specific needs of sexual minority patients. The medical literature is rich with examples of conditions that occur at greater frequency in specific sexual minority groups. Sexually transmitted infections, particularly human immunodeficiency virus, are important causes of morbidity and mortality among sexual minorities, especially men who have sex with men (MSM).3,4 Anal and penile human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and HPV-associated anal carcinoma risk are increased in MSM.5,6 The literature has remained inconclusive on the use of anal Papanicolaou tests for diagnosis; however, dermatologists have a duty to at least examine the perianal and genital area of any patient at risk for HPV-related disease or STIs.7,8 For younger patients, the HPV vaccine can help prevent certain types of HPV infection and likely reduce a patient’s risk for condyloma acuminatum and other sequelae of the virus. Guidelines have been expanded to include men aged 13 to 21 years and up to 26 years.9 More research is needed to determine if detection and prevention of these types of HPV infection using the vaccine in MSM actually leads to a decreased incidence of anal carcinoma.

Certain LGBT groups may benefit from a dermatologist’s care outside the realm of infectious diseases. One study found that increased indoor tanning use in MSM correlated with increased risk for nonmelanoma skin cancer.10 Lesbians have been found to be less likely to pursue preventative health examinations in general, including skin checks.11 Finally, transgender patients can utilize dermatologists for help with transformative procedures and side effects of hormonal treatment such as androgenic acne.1,4

Cutaneous and beyond, the future of LGBT health care in the United States is affected by the institutions that train future physicians. There is a trend toward incorporating formal LGBT curricula into medical schools and academic centers.12 The Penn Medicine Program for LGBT Health (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) is a pilot program geared toward both educating future clinicians and providing equal and unbiased care to LGBT patients.12 Programs such as this one give rise to a new generation of physicians who feel comfortable and aware of the needs of their LGBT patients.

In a time when LGBT patients are becoming more comfortable claiming their sexual and gender identities openly, there is a need for dermatologists to provide individualized unbiased care, which can best be achieved by building rapport through assumption-free history taking, performing thorough physical examinations that include the genital and perianal area, and passing these good practices on to trainees.

- Snyder JE. Trend analysis of medical publications about LGBT persons: 1950-2007. J Homosex. 2011;58:164-188.

- Ginsberg BA, Calderon M, Seminara NM, et al. A potential role for the dermatologist in the physical transformation of transgender people: a survey of attitudes and practices within the transgender community. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:303-308.

- Gee R. Primary care health issues among men who have sex with men. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2006;18:144-153.

- Katz KA, Furnish TJ. Dermatology-related epidemiologic and clinical concerns of men who have sex with men, women who have sex with women, and transgender individuals. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1303-1310.

- Fenkl EA, Jones SG, Schochet E, et al. HPV and anal cancer knowledge among HIV-infected and non-infected men who have sex with men [published online December 11, 2015]. LGBT Health. 2016;3:42-48. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2015.0086.

- Chin-Hong PV, Vittinghoff E, Cranston RD, et al. Age-related prevalence of anal cancer precursors in homosexual men: the EXPLORE Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:896-905.

- Schofield AM, Sadler L, Nelson L, et al. A prospective study of anal cancer screening in HIV-positive and negative MSM. AIDS. 2016;30:1375-1383.

- Katz MH, Katz KA, Bernestein KT, et al. We need data on anal screening effectiveness before focusing on increasing it [published online September 23, 2010]. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:2016.

- Petrosky E, Bocchini JA, Hariri S, et al. Use of 9-Valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: updated HPV vaccination recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:300-304.

- Mansh M, Katz KA, Linos E, et al. Association of skin cancer and indoor tanning in sexual minority men and women. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1308-1316.

- Conron KJ, Mimiaga MJ, Landers SJ. A population-based study of sexual orientation identity and gender differences in adult health. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1953-1960.

- Yehia BR, Calder D, Flesch JD, et al. Advancing LGBT health at an academic medical center: a case study. LGBT Health. 2015;2:362-366.

- Snyder JE. Trend analysis of medical publications about LGBT persons: 1950-2007. J Homosex. 2011;58:164-188.

- Ginsberg BA, Calderon M, Seminara NM, et al. A potential role for the dermatologist in the physical transformation of transgender people: a survey of attitudes and practices within the transgender community. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:303-308.

- Gee R. Primary care health issues among men who have sex with men. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2006;18:144-153.

- Katz KA, Furnish TJ. Dermatology-related epidemiologic and clinical concerns of men who have sex with men, women who have sex with women, and transgender individuals. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1303-1310.

- Fenkl EA, Jones SG, Schochet E, et al. HPV and anal cancer knowledge among HIV-infected and non-infected men who have sex with men [published online December 11, 2015]. LGBT Health. 2016;3:42-48. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2015.0086.

- Chin-Hong PV, Vittinghoff E, Cranston RD, et al. Age-related prevalence of anal cancer precursors in homosexual men: the EXPLORE Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:896-905.

- Schofield AM, Sadler L, Nelson L, et al. A prospective study of anal cancer screening in HIV-positive and negative MSM. AIDS. 2016;30:1375-1383.

- Katz MH, Katz KA, Bernestein KT, et al. We need data on anal screening effectiveness before focusing on increasing it [published online September 23, 2010]. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:2016.

- Petrosky E, Bocchini JA, Hariri S, et al. Use of 9-Valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: updated HPV vaccination recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:300-304.

- Mansh M, Katz KA, Linos E, et al. Association of skin cancer and indoor tanning in sexual minority men and women. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1308-1316.

- Conron KJ, Mimiaga MJ, Landers SJ. A population-based study of sexual orientation identity and gender differences in adult health. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1953-1960.

- Yehia BR, Calder D, Flesch JD, et al. Advancing LGBT health at an academic medical center: a case study. LGBT Health. 2015;2:362-366.

Landscape of Business Models in Teledermatology

Teledermatology remains relatively limited in practice despite strong evidence supporting its use.1 A major impediment to its adoption is nonreimbursement.2,3 We sought to characterize business models that currently are in use for teledermatology through interviews with private and academic dermatologists.

Methods

The institutional review board at the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) exempted this study from review. We contacted the email lists of the American Academy of Dermatology’s Telemedicine Task Force, the American Telemedicine Association’s Teledermatology Special Interest Group, and the Association of Professors of Dermatology to identify dermatologists who have been reimbursed for teledermatology services. Inclusion criteria were dermatologists who were currently receiving payment for teledermatology services and members of teledermatology-related professional groups. Interviews were conducted by telephone and/or email using an interview guide, which included questions on teledermatology platforms and workflow models, reimbursement structures and amounts, and referrers. Individuals, institutions, and teledermatology platforms were anonymized to encourage candid disclosure of business practices.

Results

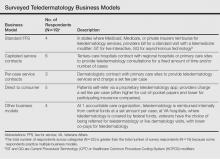

Nineteen dermatologists participated in the study. Most participants described business models fitting into 4 categories: (1) standard fee-for-service reimbursement from insurance (n=4), (2) capitated service contracts (n=6), (3) per-case service contracts (n=3), and (4) direct to consumer (n=5)(Table). There were other business models reported at Veterans Affairs hospitals and accountable care organizations (n=4).

Standard fee-for-service (FFS) teledermatology business models were frequently represented among respondents at academic institutions. With this model, providers used live interactive or store-and-forward teledermatology platforms to conduct virtual clinic visits and bill patients’ insurance companies directly. At some institutions, providers conducted live interactive teledermatology visits and also used store-and-forward teledermatology for initial screening before the patient encounter. Physician extenders at some referring sites (eg, physician assistants, nurse practitioners) were trained to photograph lesions, set up live interactive teledermatology equipment, and perform certain procedures such as skin biopsies. Referrers—often Federally Qualified Health centers, rural health clinics, or state facilities—contracted with the teledermatology site and sometimes paid a fee to join the referral network.

In another business model, teledermatology centers did not bill patients directly and instead received payment only from the centers’ participating referrers through service contracts. The subscribing institutions then could bill patients’ insurance companies appropriately. Service contracts among respondents were structured either to be capitated or reimbursed on a per-case basis. Capitated service contracts typically required subscribing institutions to pay weekly stipends of several hundred dollars or a percentage of an individual dermatologist’s salary (eg, 0.1 full-time equivalents) for consultations. Sometimes the number of consultations per time period was capped. In contrast, per-case service contracts involved per-case payments from referrers to dermatologists for teledermatology consultations. In one hybrid model, the subscribing institution paid an annual fee for a certain number of consultations per month with any additional consultations exceeding that number covered at a set fee per case.

Direct-to-consumer models, which were more common among private dermatologist respondents, used proprietary asynchronous teledermatology platforms to connect with patients. Patients generally paid out of pocket to participate, with fees ranging from $30 to $100 per case or less if the patient had participating insurance. One respondent contracted with a large private insurer to reimburse this service at a reduced fee.

Comment

Our study was limited by a small sample size; however, our goal was to detect and report different types of teledermatology business models that currently are in practice. The small number of respondents likely does not indicate poor participation; rather, it is probably reflective of our strict inclusion criteria. We sought to interview only dermatologists who were currently receiving payment for teledermatology services and members of teledermatology-related professional groups. Our strategy in this study was to cast a wide net to capture some of the few dermatologists who currently fit this requirement.

We anticipate that the standard FFS business model for teledermatology will expand slightly as more legislation incentivizing telemedicine is enacted. Currently, Medicaid reimburses for live interactive teledermatology in 47 states and for asynchronous consultations in 9 states, whereas Medicare nationally reimburses only for live interactive services in low-access areas.4 Additionally, 29 states and the District of Columbia have private insurance parity laws mandating that private plans cover and reimburse for telemedicine comparable to in-person care. Seven of those states just passed their legislation in 2015, with 8 more states currently considering proposed parity laws.5

On the other hand, the FFS model in general may actually limit the rate of adoption of teledermatology. Several of our study’s respondents pointed to dermatologists’ opportunity costs under the FFS reimbursement environment as a barrier to widespread adoption of teledermatology; providers may prefer in-person visits to teledermatology because they can perform procedures, which are more highly reimbursed. For that reason, a major driver of teledermatology adoption in the future may be the emergence of new, quality-based practice models, such as accountable care organizations.6

Because most states require that providers hold a medical license in the jurisdiction where their patient is physically located, physicians providing teledermatology services across state lines could face additional licensure requirements. However, these requirements would not be a barrier for physicians providing teledermatology services within the context of an in-state referral network. Licensure requirements generally do not restrict physician-to-physician consultations.7

Conclusion

As reimbursement models across medicine evolve and telemedicine continues to enhance delivery of care, we anticipate that quality-based reimbursement ultimately will drive successful utilization of teledermatology services. Telemedicine has been noted to be a cost-effective tool for coordinating care, maintaining quality, and improving patient satisfaction.8 Although none of the teledermatology business models surveyed currently incorporate incentives for faster case turnaround or higher patient satisfaction, we expect models to adjust as quality measures become more prevalent in the reimbursement landscape. Effective business models must be implemented to make teledermatology a feasible option for dermatologists to deliver care and patients to access care.

1. Armstrong AW, Wu J, Kovarik CL, et al. State of teledermatology programs in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:939-944.

2. Armstrong AW, Kwong MW, Ledo L, et al. Practice models and challenges in teledermatology: a study of collective experiences from teledermatologists. PLOS One. 2011;6:e28687.

3. Thomas L, Capistrant G. State telemedicine gaps analysis: coverage & reimbursement. American Telemedicine Association website. http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-source/policy/50-state-telemedicine-gaps-analysis---coverage-and-reimbursement.pdf. Published May 2015. Accessed February 19, 2016.

4. State telehealth laws and reimbursement policies: a comprehensive scan of the 50 states and District of Columbia. Center for Connected Health Policy website. http://cchpca.org/sites/default/files/resources/State%20Laws%20and%20Reimbursement%20Policies%20Report%20Feb%20%202015.pdf. Published June 2015. Accessed February 19, 2016.

5. 2015 State telemedicine legislation tracking. American Telemedicine Association website. http://www.america telemed.org/docs/default-source/policy/state-legislation-matrix_2016147931CF25A6.pdf?sfvrsn=2. Updated January 11, 2016. Accessed March 23, 2016.

6. Telehealth and ACO’s–a match made in heaven. Hands on Telehealth website. http://www.handsontelehealth.com/past-issues/159-infographic-telehealth-and-acosa-match-made-in-heaven. Accessed February 19, 2016.

7. Thomas L, Capistrant G. State telemedicine gaps analysis: physician practice standards & licensure. American Telemedicine Association website. http://www.american telemed.org/docs/default-source/policy/50-state-telemedicine-gaps-analysis--physician-practice-standards-licensure.pdf. Published May 2015. Accessed February 19, 2016.

8. Telemedicine’s impact on healthcare cost and quality. American Telemedicine Association website. http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-source/policy/examples-of-research-outcomes---telemedicine’s-impact-on-healthcare-cost-and-quality.pdf. Published April 2015. Accessed February 19, 2016.

Teledermatology remains relatively limited in practice despite strong evidence supporting its use.1 A major impediment to its adoption is nonreimbursement.2,3 We sought to characterize business models that currently are in use for teledermatology through interviews with private and academic dermatologists.

Methods

The institutional review board at the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) exempted this study from review. We contacted the email lists of the American Academy of Dermatology’s Telemedicine Task Force, the American Telemedicine Association’s Teledermatology Special Interest Group, and the Association of Professors of Dermatology to identify dermatologists who have been reimbursed for teledermatology services. Inclusion criteria were dermatologists who were currently receiving payment for teledermatology services and members of teledermatology-related professional groups. Interviews were conducted by telephone and/or email using an interview guide, which included questions on teledermatology platforms and workflow models, reimbursement structures and amounts, and referrers. Individuals, institutions, and teledermatology platforms were anonymized to encourage candid disclosure of business practices.

Results

Nineteen dermatologists participated in the study. Most participants described business models fitting into 4 categories: (1) standard fee-for-service reimbursement from insurance (n=4), (2) capitated service contracts (n=6), (3) per-case service contracts (n=3), and (4) direct to consumer (n=5)(Table). There were other business models reported at Veterans Affairs hospitals and accountable care organizations (n=4).

Standard fee-for-service (FFS) teledermatology business models were frequently represented among respondents at academic institutions. With this model, providers used live interactive or store-and-forward teledermatology platforms to conduct virtual clinic visits and bill patients’ insurance companies directly. At some institutions, providers conducted live interactive teledermatology visits and also used store-and-forward teledermatology for initial screening before the patient encounter. Physician extenders at some referring sites (eg, physician assistants, nurse practitioners) were trained to photograph lesions, set up live interactive teledermatology equipment, and perform certain procedures such as skin biopsies. Referrers—often Federally Qualified Health centers, rural health clinics, or state facilities—contracted with the teledermatology site and sometimes paid a fee to join the referral network.

In another business model, teledermatology centers did not bill patients directly and instead received payment only from the centers’ participating referrers through service contracts. The subscribing institutions then could bill patients’ insurance companies appropriately. Service contracts among respondents were structured either to be capitated or reimbursed on a per-case basis. Capitated service contracts typically required subscribing institutions to pay weekly stipends of several hundred dollars or a percentage of an individual dermatologist’s salary (eg, 0.1 full-time equivalents) for consultations. Sometimes the number of consultations per time period was capped. In contrast, per-case service contracts involved per-case payments from referrers to dermatologists for teledermatology consultations. In one hybrid model, the subscribing institution paid an annual fee for a certain number of consultations per month with any additional consultations exceeding that number covered at a set fee per case.

Direct-to-consumer models, which were more common among private dermatologist respondents, used proprietary asynchronous teledermatology platforms to connect with patients. Patients generally paid out of pocket to participate, with fees ranging from $30 to $100 per case or less if the patient had participating insurance. One respondent contracted with a large private insurer to reimburse this service at a reduced fee.

Comment

Our study was limited by a small sample size; however, our goal was to detect and report different types of teledermatology business models that currently are in practice. The small number of respondents likely does not indicate poor participation; rather, it is probably reflective of our strict inclusion criteria. We sought to interview only dermatologists who were currently receiving payment for teledermatology services and members of teledermatology-related professional groups. Our strategy in this study was to cast a wide net to capture some of the few dermatologists who currently fit this requirement.

We anticipate that the standard FFS business model for teledermatology will expand slightly as more legislation incentivizing telemedicine is enacted. Currently, Medicaid reimburses for live interactive teledermatology in 47 states and for asynchronous consultations in 9 states, whereas Medicare nationally reimburses only for live interactive services in low-access areas.4 Additionally, 29 states and the District of Columbia have private insurance parity laws mandating that private plans cover and reimburse for telemedicine comparable to in-person care. Seven of those states just passed their legislation in 2015, with 8 more states currently considering proposed parity laws.5

On the other hand, the FFS model in general may actually limit the rate of adoption of teledermatology. Several of our study’s respondents pointed to dermatologists’ opportunity costs under the FFS reimbursement environment as a barrier to widespread adoption of teledermatology; providers may prefer in-person visits to teledermatology because they can perform procedures, which are more highly reimbursed. For that reason, a major driver of teledermatology adoption in the future may be the emergence of new, quality-based practice models, such as accountable care organizations.6

Because most states require that providers hold a medical license in the jurisdiction where their patient is physically located, physicians providing teledermatology services across state lines could face additional licensure requirements. However, these requirements would not be a barrier for physicians providing teledermatology services within the context of an in-state referral network. Licensure requirements generally do not restrict physician-to-physician consultations.7

Conclusion

As reimbursement models across medicine evolve and telemedicine continues to enhance delivery of care, we anticipate that quality-based reimbursement ultimately will drive successful utilization of teledermatology services. Telemedicine has been noted to be a cost-effective tool for coordinating care, maintaining quality, and improving patient satisfaction.8 Although none of the teledermatology business models surveyed currently incorporate incentives for faster case turnaround or higher patient satisfaction, we expect models to adjust as quality measures become more prevalent in the reimbursement landscape. Effective business models must be implemented to make teledermatology a feasible option for dermatologists to deliver care and patients to access care.

Teledermatology remains relatively limited in practice despite strong evidence supporting its use.1 A major impediment to its adoption is nonreimbursement.2,3 We sought to characterize business models that currently are in use for teledermatology through interviews with private and academic dermatologists.

Methods

The institutional review board at the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) exempted this study from review. We contacted the email lists of the American Academy of Dermatology’s Telemedicine Task Force, the American Telemedicine Association’s Teledermatology Special Interest Group, and the Association of Professors of Dermatology to identify dermatologists who have been reimbursed for teledermatology services. Inclusion criteria were dermatologists who were currently receiving payment for teledermatology services and members of teledermatology-related professional groups. Interviews were conducted by telephone and/or email using an interview guide, which included questions on teledermatology platforms and workflow models, reimbursement structures and amounts, and referrers. Individuals, institutions, and teledermatology platforms were anonymized to encourage candid disclosure of business practices.

Results

Nineteen dermatologists participated in the study. Most participants described business models fitting into 4 categories: (1) standard fee-for-service reimbursement from insurance (n=4), (2) capitated service contracts (n=6), (3) per-case service contracts (n=3), and (4) direct to consumer (n=5)(Table). There were other business models reported at Veterans Affairs hospitals and accountable care organizations (n=4).

Standard fee-for-service (FFS) teledermatology business models were frequently represented among respondents at academic institutions. With this model, providers used live interactive or store-and-forward teledermatology platforms to conduct virtual clinic visits and bill patients’ insurance companies directly. At some institutions, providers conducted live interactive teledermatology visits and also used store-and-forward teledermatology for initial screening before the patient encounter. Physician extenders at some referring sites (eg, physician assistants, nurse practitioners) were trained to photograph lesions, set up live interactive teledermatology equipment, and perform certain procedures such as skin biopsies. Referrers—often Federally Qualified Health centers, rural health clinics, or state facilities—contracted with the teledermatology site and sometimes paid a fee to join the referral network.

In another business model, teledermatology centers did not bill patients directly and instead received payment only from the centers’ participating referrers through service contracts. The subscribing institutions then could bill patients’ insurance companies appropriately. Service contracts among respondents were structured either to be capitated or reimbursed on a per-case basis. Capitated service contracts typically required subscribing institutions to pay weekly stipends of several hundred dollars or a percentage of an individual dermatologist’s salary (eg, 0.1 full-time equivalents) for consultations. Sometimes the number of consultations per time period was capped. In contrast, per-case service contracts involved per-case payments from referrers to dermatologists for teledermatology consultations. In one hybrid model, the subscribing institution paid an annual fee for a certain number of consultations per month with any additional consultations exceeding that number covered at a set fee per case.

Direct-to-consumer models, which were more common among private dermatologist respondents, used proprietary asynchronous teledermatology platforms to connect with patients. Patients generally paid out of pocket to participate, with fees ranging from $30 to $100 per case or less if the patient had participating insurance. One respondent contracted with a large private insurer to reimburse this service at a reduced fee.

Comment

Our study was limited by a small sample size; however, our goal was to detect and report different types of teledermatology business models that currently are in practice. The small number of respondents likely does not indicate poor participation; rather, it is probably reflective of our strict inclusion criteria. We sought to interview only dermatologists who were currently receiving payment for teledermatology services and members of teledermatology-related professional groups. Our strategy in this study was to cast a wide net to capture some of the few dermatologists who currently fit this requirement.

We anticipate that the standard FFS business model for teledermatology will expand slightly as more legislation incentivizing telemedicine is enacted. Currently, Medicaid reimburses for live interactive teledermatology in 47 states and for asynchronous consultations in 9 states, whereas Medicare nationally reimburses only for live interactive services in low-access areas.4 Additionally, 29 states and the District of Columbia have private insurance parity laws mandating that private plans cover and reimburse for telemedicine comparable to in-person care. Seven of those states just passed their legislation in 2015, with 8 more states currently considering proposed parity laws.5

On the other hand, the FFS model in general may actually limit the rate of adoption of teledermatology. Several of our study’s respondents pointed to dermatologists’ opportunity costs under the FFS reimbursement environment as a barrier to widespread adoption of teledermatology; providers may prefer in-person visits to teledermatology because they can perform procedures, which are more highly reimbursed. For that reason, a major driver of teledermatology adoption in the future may be the emergence of new, quality-based practice models, such as accountable care organizations.6

Because most states require that providers hold a medical license in the jurisdiction where their patient is physically located, physicians providing teledermatology services across state lines could face additional licensure requirements. However, these requirements would not be a barrier for physicians providing teledermatology services within the context of an in-state referral network. Licensure requirements generally do not restrict physician-to-physician consultations.7

Conclusion

As reimbursement models across medicine evolve and telemedicine continues to enhance delivery of care, we anticipate that quality-based reimbursement ultimately will drive successful utilization of teledermatology services. Telemedicine has been noted to be a cost-effective tool for coordinating care, maintaining quality, and improving patient satisfaction.8 Although none of the teledermatology business models surveyed currently incorporate incentives for faster case turnaround or higher patient satisfaction, we expect models to adjust as quality measures become more prevalent in the reimbursement landscape. Effective business models must be implemented to make teledermatology a feasible option for dermatologists to deliver care and patients to access care.

1. Armstrong AW, Wu J, Kovarik CL, et al. State of teledermatology programs in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:939-944.

2. Armstrong AW, Kwong MW, Ledo L, et al. Practice models and challenges in teledermatology: a study of collective experiences from teledermatologists. PLOS One. 2011;6:e28687.

3. Thomas L, Capistrant G. State telemedicine gaps analysis: coverage & reimbursement. American Telemedicine Association website. http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-source/policy/50-state-telemedicine-gaps-analysis---coverage-and-reimbursement.pdf. Published May 2015. Accessed February 19, 2016.

4. State telehealth laws and reimbursement policies: a comprehensive scan of the 50 states and District of Columbia. Center for Connected Health Policy website. http://cchpca.org/sites/default/files/resources/State%20Laws%20and%20Reimbursement%20Policies%20Report%20Feb%20%202015.pdf. Published June 2015. Accessed February 19, 2016.

5. 2015 State telemedicine legislation tracking. American Telemedicine Association website. http://www.america telemed.org/docs/default-source/policy/state-legislation-matrix_2016147931CF25A6.pdf?sfvrsn=2. Updated January 11, 2016. Accessed March 23, 2016.

6. Telehealth and ACO’s–a match made in heaven. Hands on Telehealth website. http://www.handsontelehealth.com/past-issues/159-infographic-telehealth-and-acosa-match-made-in-heaven. Accessed February 19, 2016.

7. Thomas L, Capistrant G. State telemedicine gaps analysis: physician practice standards & licensure. American Telemedicine Association website. http://www.american telemed.org/docs/default-source/policy/50-state-telemedicine-gaps-analysis--physician-practice-standards-licensure.pdf. Published May 2015. Accessed February 19, 2016.

8. Telemedicine’s impact on healthcare cost and quality. American Telemedicine Association website. http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-source/policy/examples-of-research-outcomes---telemedicine’s-impact-on-healthcare-cost-and-quality.pdf. Published April 2015. Accessed February 19, 2016.

1. Armstrong AW, Wu J, Kovarik CL, et al. State of teledermatology programs in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:939-944.

2. Armstrong AW, Kwong MW, Ledo L, et al. Practice models and challenges in teledermatology: a study of collective experiences from teledermatologists. PLOS One. 2011;6:e28687.

3. Thomas L, Capistrant G. State telemedicine gaps analysis: coverage & reimbursement. American Telemedicine Association website. http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-source/policy/50-state-telemedicine-gaps-analysis---coverage-and-reimbursement.pdf. Published May 2015. Accessed February 19, 2016.

4. State telehealth laws and reimbursement policies: a comprehensive scan of the 50 states and District of Columbia. Center for Connected Health Policy website. http://cchpca.org/sites/default/files/resources/State%20Laws%20and%20Reimbursement%20Policies%20Report%20Feb%20%202015.pdf. Published June 2015. Accessed February 19, 2016.

5. 2015 State telemedicine legislation tracking. American Telemedicine Association website. http://www.america telemed.org/docs/default-source/policy/state-legislation-matrix_2016147931CF25A6.pdf?sfvrsn=2. Updated January 11, 2016. Accessed March 23, 2016.

6. Telehealth and ACO’s–a match made in heaven. Hands on Telehealth website. http://www.handsontelehealth.com/past-issues/159-infographic-telehealth-and-acosa-match-made-in-heaven. Accessed February 19, 2016.

7. Thomas L, Capistrant G. State telemedicine gaps analysis: physician practice standards & licensure. American Telemedicine Association website. http://www.american telemed.org/docs/default-source/policy/50-state-telemedicine-gaps-analysis--physician-practice-standards-licensure.pdf. Published May 2015. Accessed February 19, 2016.

8. Telemedicine’s impact on healthcare cost and quality. American Telemedicine Association website. http://www.americantelemed.org/docs/default-source/policy/examples-of-research-outcomes---telemedicine’s-impact-on-healthcare-cost-and-quality.pdf. Published April 2015. Accessed February 19, 2016.

Practice Points

- Teledermatology services may improve access to dermatology care but are limited by lack of reimbursement.

- Different business models have been successfully implemented for use of teledermatology in different care settings.

- As more legislation incentivizing telemedicine is enacted, the standard fee-for-service business model for teledermatology likely will expand.

Access to Inpatient Dermatology Care in Pennsylvania Hospitals

Access to care is a known issue in dermatology, and many patients may experience long waiting periods to see a physician.1 Previous research has evaluated access to outpatient dermatology services, but access to dermatology in inpatient medicine is also a growing problem.2 Reports depict a decrease in dermatologist involvement in inpatient care and an increase in nondermatologist physicians caring for inpatients with dermatologic needs.2,3 This lack of access could potentially lead to missed and/or incorrect diagnoses. One study showed that most cases in which dermatology was consulted required a change in treatment once correctly diagnosed by a dermatologist.4

Despite the known trend of decreasing involvement of dermatologists in inpatient care, there remains a paucity of data quantifying the current gap in access to care for inpatients with dermatologic needs. The purpose of this study was to evaluate differential access to inpatient dermatology services across licensed hospitals within the state of Pennsylvania.

Methods

In July 2014, an invitation to participate in an anonymous online survey was mailed to all 274 hospitals throughout Pennsylvania that were currently licensed by the US Department of Health. This study was declared exempt from review by the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) institutional review board. Study data were collected and managed using electronic data capture tools hosted by the University of Pennsylvania. Hospital administrators were encouraged to report dermatology access and details regardless of current status of inpatient dermatology services in order to inform efforts to improve access to care. Invitation letters to participate in the online survey were addressed to “Administrator” according to the contact method used by the US Department of Health for accreditation of state hospitals. Addresses for accredited state hospitals were obtained from the US Department of Health Web site and were supplemented with additional addresses of Veterans Administration hospitals obtained from public listings. Three weeks after initial survey invitations were sent, reminder letters were sent to nonresponsive hospitals. Only data from hospitals currently offering inpatient services were included in the analysis; exclusion criteria included psychiatric hospitals, substance abuse treatment centers, physical rehabilitation facilities, and outpatient centers.

Results

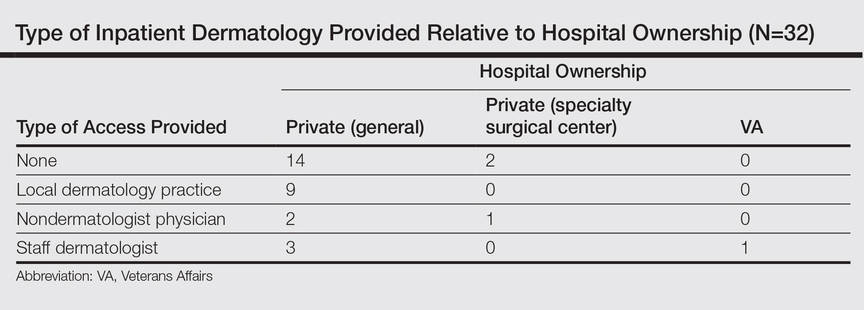

Of the 204 (74%) hospitals that met the inclusion criteria, 32 responded (16% response rate). Of the 32 hospitals that responded, 31 (97%) were privately owned facilities, 3 of which were specialty surgical centers. One (3%) hospital was a Veterans Administration hospital. Of the responders, 16 (50%) reported having any form of access to inpatient dermatology consultations. Of the 16 with reported access, 9 (56%) received their consultations through a local or private dermatology group, while 4 (25%) had a dermatologist on staff. The remaining 3 hospitals (19%) provided dermatology consultations through nondermatologist physicians on staff (a surgeon, an emergency care physician, and an internist, respectively).

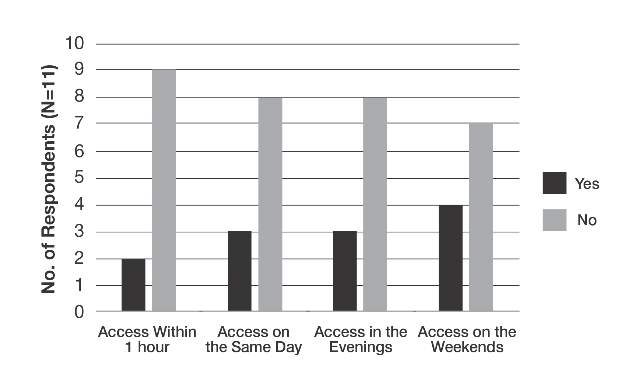

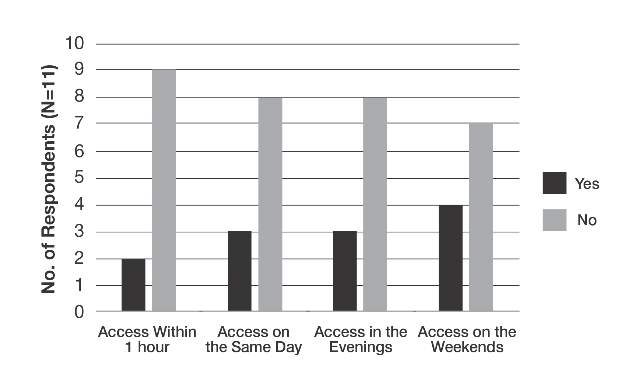

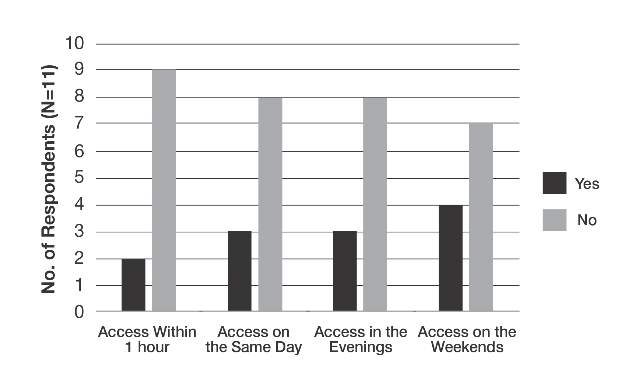

The survey also sought to gain information about the various degrees of access to inpatient dermatology care that hospitals provide. Of the 16 hospitals that reported access to inpatient dermatology services, 11 (69%) provided specific details related to access (eg, coverage, anticipated response times) of dermatology consultations (Figure). The type of access to inpatient dermatology in relation to the type of hospital ownership is shown in the Table.

Comment

The survey results indicated suboptimal access to inpatient dermatology services in Pennsylvania hospitals. Only 50% (16/32) of respondents reported providing access to dermatology consultation, the majority of which appeared to have extremely limited same-day, evening, and weekend coverage. Although our study was limited by a low response rate (16%) and represents a narrow geographic distribution, these results suggested that lack of access to inpatient dermatology consultation may be a widespread problem and may be independent of the type of hospital ownership. Furthermore, the results of this study may offer insight into the different types and availability of inpatient dermatology services offered in hospitals across the United States.

The decrease in inpatient dermatology access has been driven by many factors. First, advances in medical research and pharmacotherapy may have decreased the need for dermatologic inpatient care, as patients who formerly would have required inpatient treatments are now able to receive therapies in an outpatient setting (eg, treatment of psoriasis).5 This may create less demand for hospitals to have a dermatologist on staff. Additionally, hospitals may be less able to incentivize dermatologists to provide inpatient dermatology consultations due to low reimbursement rates, time and distance required to visit inpatient facilities (taking away from outpatient clinic time), and the perception that inpatient cases carry greater liability given their greater complexity.6-8 Together, these factors may have contributed to the current lack of inpatient dermatology services in Pennsylvania hospitals and likely in hospitals throughout the United States.

Conclusion

Although a relatively small number of academic hospitals are experiencing an emergence of dermatology hospitalists, poor access to inpatient dermatology care continues to be a problem.8 Innovation (eg, the use of teledermatology to improve access to care9) and further studies are needed to address this gap in access to inpatient dermatology care.

- Kimball AB, Resneck JS. The US dermatology workforce: a specialty remains in shortage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:741-745.

- Helms AE, Helms SE, Brodell RT. Hospital consultations: time to address an unmet need? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:308-311.

- Kirsner RS, Yang DG, Kerdel FA. The changing status of inpatient dermatology at American academic dermatology programs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:755-757.

- Nahass GT, Meyer AJ, Campbell SF, et al. Prevalence of cutaneous findings in hospitalized medical patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:207-211.

- Steinke S, Peitsch WK, Ludwig A, et al. Cost-of-illness in psoriasis: comparing inpatient and outpatient therapy. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78152.

- Swerlick RA. Declining interest in medical dermatology. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1160-1162.

- Kirsner RS, Yang DG, Kerdel FA. Inpatient dermatology: the difficulties, the reality, and the future. Dermatol Clin. 2000;18:383-390.

- Fox LP, Cotliar J, Hughey L, et al. Hospitalist dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:153-154.

- Sharma P, Kovarik CL, Lipoff JB. Teledermatology as a means to improve access to inpatient dermatology care [published online ahead of print September 16, 2015]. J Telemed Telecare. PII: 1357633X15603298.

Access to care is a known issue in dermatology, and many patients may experience long waiting periods to see a physician.1 Previous research has evaluated access to outpatient dermatology services, but access to dermatology in inpatient medicine is also a growing problem.2 Reports depict a decrease in dermatologist involvement in inpatient care and an increase in nondermatologist physicians caring for inpatients with dermatologic needs.2,3 This lack of access could potentially lead to missed and/or incorrect diagnoses. One study showed that most cases in which dermatology was consulted required a change in treatment once correctly diagnosed by a dermatologist.4

Despite the known trend of decreasing involvement of dermatologists in inpatient care, there remains a paucity of data quantifying the current gap in access to care for inpatients with dermatologic needs. The purpose of this study was to evaluate differential access to inpatient dermatology services across licensed hospitals within the state of Pennsylvania.

Methods

In July 2014, an invitation to participate in an anonymous online survey was mailed to all 274 hospitals throughout Pennsylvania that were currently licensed by the US Department of Health. This study was declared exempt from review by the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) institutional review board. Study data were collected and managed using electronic data capture tools hosted by the University of Pennsylvania. Hospital administrators were encouraged to report dermatology access and details regardless of current status of inpatient dermatology services in order to inform efforts to improve access to care. Invitation letters to participate in the online survey were addressed to “Administrator” according to the contact method used by the US Department of Health for accreditation of state hospitals. Addresses for accredited state hospitals were obtained from the US Department of Health Web site and were supplemented with additional addresses of Veterans Administration hospitals obtained from public listings. Three weeks after initial survey invitations were sent, reminder letters were sent to nonresponsive hospitals. Only data from hospitals currently offering inpatient services were included in the analysis; exclusion criteria included psychiatric hospitals, substance abuse treatment centers, physical rehabilitation facilities, and outpatient centers.

Results

Of the 204 (74%) hospitals that met the inclusion criteria, 32 responded (16% response rate). Of the 32 hospitals that responded, 31 (97%) were privately owned facilities, 3 of which were specialty surgical centers. One (3%) hospital was a Veterans Administration hospital. Of the responders, 16 (50%) reported having any form of access to inpatient dermatology consultations. Of the 16 with reported access, 9 (56%) received their consultations through a local or private dermatology group, while 4 (25%) had a dermatologist on staff. The remaining 3 hospitals (19%) provided dermatology consultations through nondermatologist physicians on staff (a surgeon, an emergency care physician, and an internist, respectively).

The survey also sought to gain information about the various degrees of access to inpatient dermatology care that hospitals provide. Of the 16 hospitals that reported access to inpatient dermatology services, 11 (69%) provided specific details related to access (eg, coverage, anticipated response times) of dermatology consultations (Figure). The type of access to inpatient dermatology in relation to the type of hospital ownership is shown in the Table.

Comment

The survey results indicated suboptimal access to inpatient dermatology services in Pennsylvania hospitals. Only 50% (16/32) of respondents reported providing access to dermatology consultation, the majority of which appeared to have extremely limited same-day, evening, and weekend coverage. Although our study was limited by a low response rate (16%) and represents a narrow geographic distribution, these results suggested that lack of access to inpatient dermatology consultation may be a widespread problem and may be independent of the type of hospital ownership. Furthermore, the results of this study may offer insight into the different types and availability of inpatient dermatology services offered in hospitals across the United States.

The decrease in inpatient dermatology access has been driven by many factors. First, advances in medical research and pharmacotherapy may have decreased the need for dermatologic inpatient care, as patients who formerly would have required inpatient treatments are now able to receive therapies in an outpatient setting (eg, treatment of psoriasis).5 This may create less demand for hospitals to have a dermatologist on staff. Additionally, hospitals may be less able to incentivize dermatologists to provide inpatient dermatology consultations due to low reimbursement rates, time and distance required to visit inpatient facilities (taking away from outpatient clinic time), and the perception that inpatient cases carry greater liability given their greater complexity.6-8 Together, these factors may have contributed to the current lack of inpatient dermatology services in Pennsylvania hospitals and likely in hospitals throughout the United States.

Conclusion

Although a relatively small number of academic hospitals are experiencing an emergence of dermatology hospitalists, poor access to inpatient dermatology care continues to be a problem.8 Innovation (eg, the use of teledermatology to improve access to care9) and further studies are needed to address this gap in access to inpatient dermatology care.

Access to care is a known issue in dermatology, and many patients may experience long waiting periods to see a physician.1 Previous research has evaluated access to outpatient dermatology services, but access to dermatology in inpatient medicine is also a growing problem.2 Reports depict a decrease in dermatologist involvement in inpatient care and an increase in nondermatologist physicians caring for inpatients with dermatologic needs.2,3 This lack of access could potentially lead to missed and/or incorrect diagnoses. One study showed that most cases in which dermatology was consulted required a change in treatment once correctly diagnosed by a dermatologist.4

Despite the known trend of decreasing involvement of dermatologists in inpatient care, there remains a paucity of data quantifying the current gap in access to care for inpatients with dermatologic needs. The purpose of this study was to evaluate differential access to inpatient dermatology services across licensed hospitals within the state of Pennsylvania.

Methods

In July 2014, an invitation to participate in an anonymous online survey was mailed to all 274 hospitals throughout Pennsylvania that were currently licensed by the US Department of Health. This study was declared exempt from review by the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) institutional review board. Study data were collected and managed using electronic data capture tools hosted by the University of Pennsylvania. Hospital administrators were encouraged to report dermatology access and details regardless of current status of inpatient dermatology services in order to inform efforts to improve access to care. Invitation letters to participate in the online survey were addressed to “Administrator” according to the contact method used by the US Department of Health for accreditation of state hospitals. Addresses for accredited state hospitals were obtained from the US Department of Health Web site and were supplemented with additional addresses of Veterans Administration hospitals obtained from public listings. Three weeks after initial survey invitations were sent, reminder letters were sent to nonresponsive hospitals. Only data from hospitals currently offering inpatient services were included in the analysis; exclusion criteria included psychiatric hospitals, substance abuse treatment centers, physical rehabilitation facilities, and outpatient centers.

Results

Of the 204 (74%) hospitals that met the inclusion criteria, 32 responded (16% response rate). Of the 32 hospitals that responded, 31 (97%) were privately owned facilities, 3 of which were specialty surgical centers. One (3%) hospital was a Veterans Administration hospital. Of the responders, 16 (50%) reported having any form of access to inpatient dermatology consultations. Of the 16 with reported access, 9 (56%) received their consultations through a local or private dermatology group, while 4 (25%) had a dermatologist on staff. The remaining 3 hospitals (19%) provided dermatology consultations through nondermatologist physicians on staff (a surgeon, an emergency care physician, and an internist, respectively).

The survey also sought to gain information about the various degrees of access to inpatient dermatology care that hospitals provide. Of the 16 hospitals that reported access to inpatient dermatology services, 11 (69%) provided specific details related to access (eg, coverage, anticipated response times) of dermatology consultations (Figure). The type of access to inpatient dermatology in relation to the type of hospital ownership is shown in the Table.

Comment

The survey results indicated suboptimal access to inpatient dermatology services in Pennsylvania hospitals. Only 50% (16/32) of respondents reported providing access to dermatology consultation, the majority of which appeared to have extremely limited same-day, evening, and weekend coverage. Although our study was limited by a low response rate (16%) and represents a narrow geographic distribution, these results suggested that lack of access to inpatient dermatology consultation may be a widespread problem and may be independent of the type of hospital ownership. Furthermore, the results of this study may offer insight into the different types and availability of inpatient dermatology services offered in hospitals across the United States.

The decrease in inpatient dermatology access has been driven by many factors. First, advances in medical research and pharmacotherapy may have decreased the need for dermatologic inpatient care, as patients who formerly would have required inpatient treatments are now able to receive therapies in an outpatient setting (eg, treatment of psoriasis).5 This may create less demand for hospitals to have a dermatologist on staff. Additionally, hospitals may be less able to incentivize dermatologists to provide inpatient dermatology consultations due to low reimbursement rates, time and distance required to visit inpatient facilities (taking away from outpatient clinic time), and the perception that inpatient cases carry greater liability given their greater complexity.6-8 Together, these factors may have contributed to the current lack of inpatient dermatology services in Pennsylvania hospitals and likely in hospitals throughout the United States.

Conclusion

Although a relatively small number of academic hospitals are experiencing an emergence of dermatology hospitalists, poor access to inpatient dermatology care continues to be a problem.8 Innovation (eg, the use of teledermatology to improve access to care9) and further studies are needed to address this gap in access to inpatient dermatology care.

- Kimball AB, Resneck JS. The US dermatology workforce: a specialty remains in shortage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:741-745.

- Helms AE, Helms SE, Brodell RT. Hospital consultations: time to address an unmet need? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:308-311.

- Kirsner RS, Yang DG, Kerdel FA. The changing status of inpatient dermatology at American academic dermatology programs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:755-757.

- Nahass GT, Meyer AJ, Campbell SF, et al. Prevalence of cutaneous findings in hospitalized medical patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:207-211.

- Steinke S, Peitsch WK, Ludwig A, et al. Cost-of-illness in psoriasis: comparing inpatient and outpatient therapy. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78152.

- Swerlick RA. Declining interest in medical dermatology. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1160-1162.

- Kirsner RS, Yang DG, Kerdel FA. Inpatient dermatology: the difficulties, the reality, and the future. Dermatol Clin. 2000;18:383-390.

- Fox LP, Cotliar J, Hughey L, et al. Hospitalist dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:153-154.

- Sharma P, Kovarik CL, Lipoff JB. Teledermatology as a means to improve access to inpatient dermatology care [published online ahead of print September 16, 2015]. J Telemed Telecare. PII: 1357633X15603298.

- Kimball AB, Resneck JS. The US dermatology workforce: a specialty remains in shortage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:741-745.

- Helms AE, Helms SE, Brodell RT. Hospital consultations: time to address an unmet need? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:308-311.

- Kirsner RS, Yang DG, Kerdel FA. The changing status of inpatient dermatology at American academic dermatology programs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:755-757.

- Nahass GT, Meyer AJ, Campbell SF, et al. Prevalence of cutaneous findings in hospitalized medical patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:207-211.

- Steinke S, Peitsch WK, Ludwig A, et al. Cost-of-illness in psoriasis: comparing inpatient and outpatient therapy. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78152.

- Swerlick RA. Declining interest in medical dermatology. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1160-1162.

- Kirsner RS, Yang DG, Kerdel FA. Inpatient dermatology: the difficulties, the reality, and the future. Dermatol Clin. 2000;18:383-390.

- Fox LP, Cotliar J, Hughey L, et al. Hospitalist dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:153-154.

- Sharma P, Kovarik CL, Lipoff JB. Teledermatology as a means to improve access to inpatient dermatology care [published online ahead of print September 16, 2015]. J Telemed Telecare. PII: 1357633X15603298.

Practice Points

- Changes in inpatient dermatology care over the past few decades have led to barriers in patient access to care.

- Many hospitals currently lack access to inpatient dermatology care, and those that do provide access often have no same-day, evening, or weekend coverage or may only provide access to dermatology care via nondermatologist physicians.

- Intervention by a dermatologist may be essential in making correct dermatologic diagnoses and treatment recommendations in inpatient settings.

Solitary Nodular Lesion on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Pilomatricoma

Pilomatricoma, first described by Malherbe and Chenantais1 in 1880, is a benign appendageal tumor derived from hair follicle matrix cells. It classically manifests as a solitary, asymptomatic, firm dermal nodule with a normal overlying epidermis. Less common morphologic variants include perforating, lymphagiectatic, keratoacanthomalike, pigmented, and anetodermalike surface changes.2 Inflammation and erosion through the skin surface are observed in the rare perforating variant, as seen in our patient. The average size is 1 cm, and it rarely exceeds 3 cm in diameter.3 The tumors predominantly occur on the head, neck, and upper extremities, with only 9.5% on the scalp.2 It may occur at any age, though it has a bimodal distribution with peaks in childhood and in adults older than 60 years. A slight preponderance in females has been observed with a female to male ratio of 1.5 to 1.2 Although our patient is black, most reported cases have occurred in individuals of European descent. Because cases of pilomatricoma are not systematically reported, it is uncertain if this finding represents a publication bias or if race is an actual risk factor. Multiple pilomatricomas and familial cases have been described in association with myotonic dystrophy, Turner syndrome, Gardner syndrome, Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, polyfactorial coagulopathy, trisomy 9, xeroderma pigmentosum, and basal cell nevus syndrome.2,4

It has been shown that the proliferating cells of pilomatricomas stain with antibodies directed against Lef1 (lymphoid enhancer binding factor 1), a marker from hair matrix cells, providing biochemical evidence for the morphologic appearance of these neoplasms.5 Pilomatricomas have been associated with B-cell/chronic lymphocytic leukemia lymphoma 2 gene, BCL2, expression, a proto-oncogene that suppresses apoptosis in benign and malignant neoplasms, which may contribute to the pathogenesis of these tumors.6 Pilomatricomas also have been associated with β-catenin mutation, expression of Bmp2 (bone morphogenetic protein 2), and human hair keratin basic 1.7-9

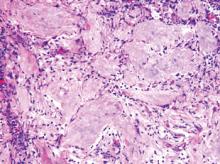

Definitive diagnosis is obtained through biopsy, looking for characteristic histopathologic findings. The lesion usually is found in the lower dermis and subcutaneous fat. However, in the perforating variant, the lesion is more superficial, located in the papillary and mid dermis, as seen in our patient.10

Pilomatricomas are sharply demarcated, often surrounded by a connective-tissue capsule. Histopathologic analysis reveals islands of epithelial cells comprised of 3 subtypes: basophilic cells with scant cytoplasm, shadow cells with a central pallor (Figure), and transitional cells between the former 2 cellular types.11 The number of basophilic and transitional cells is inversely related to the number of shadow cells. In older lesions, the shadow cells predominate, while the basophilic cells are few in number or absent. Calcium deposits are seen in 80% of lesions with von Kossa staining.12

Transformation into malignancy, known as pilomatrical carcinoma, is rare. These malignant neoplasms are characterized by aggressive biologic behavior such as recurrence, diffuse spread, or metastasis, or by cytologic abnormalities such as poor cellular organization, squamous differentiation, and conspicuous mitotic activity.13 The recent growth of the long-standing lesion in our patient might be interpreted as a sign of malignant transformation. However, this observation may be related to the intense inflammatory reaction supported by the histopathology.

Pilomatricomas are not associated with mortality. Pilomatrical carcinomas are uncommon but are locally invasive and can cause visceral metastases and death. Spontaneous regression has never been observed and medical treatment is ineffective. The treatment of choice is incision and curettage or surgical excision.14 Although recurrence has only been reported in 2.6% of cases from a large case series (N=228), patients should be monitored after surgical excision.12

1. Malherbe A, Chenantais J. Note sur l'epithelioma calcifie des glandes sebacees. Prog Med. 1880;8:826-828.

2. Julian CG, Bowers PW. A clinical review of 209 pilomatricomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2, pt 1):191-195.

3. Lozzi GP, Soyer HP, Fruehauf J, et al. Giant pilomatricoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:286-289.

4. Hubbard VG, Whittaker SJ. Multiple familial pilomatricomas: an unusual case. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:281-283.

5. Kizawa K, Toyoda M, Ito M, et al. Aberrantly differentiated cells in benign pilomatrixoma reflect the normal hair follicle: immunohistochemical analysis of Ca-binding S100A2, S100A3 and S100A6 proteins. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:314-320.

6. Farrier S, Morgan M. bcl-2 expression in pilomatricoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:254-257.

7. Park SW, Suh KS, Wang HY, et al. Beta-catenin expression in the transitional cell zone of pilomatricoma. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:624-629.

8. Kurokawa I, Kusumoto K, Bessho K, et al. Immunohistochemical expression of bone morphogenetic protein-2 in pilomatricoma. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:754-758.

9. Cribier B, Asch PH, Regnier C, et al. Expression of human hair keratin basic 1 in pilomatrixoma: a study of 128 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:600-604.

10. Bayle P, Bazex J, Lamant L, et al. Multiple perforating and non perforating pilomatricomas in a patient with Churg-Strauss syndrome and Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:607-610.

11. Elder D, Elenitsas R, Ragsdale BD. Pilomatricoma. In: Elder D, Elenitsas R, Jaworsky C, et al, eds. Histopathology of the Skin. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1997:757-759.

12. Forbis R Jr, Helwig EB. Pilomatrixoma (calcifying epithelioma). Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:606-618.

13. Wood MG, Parhizgar B, Beerman H. Malignant pilomatricoma. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:770-773.

14. Thomas RW, Perkins JA, Ruegemer JL, et al. Surgical excision of pilomatrixoma of the head and neck: a retrospective review of 26 cases. Ear Nose Throat J. 1999;78:541, 544-546, 548.

The Diagnosis: Pilomatricoma

Pilomatricoma, first described by Malherbe and Chenantais1 in 1880, is a benign appendageal tumor derived from hair follicle matrix cells. It classically manifests as a solitary, asymptomatic, firm dermal nodule with a normal overlying epidermis. Less common morphologic variants include perforating, lymphagiectatic, keratoacanthomalike, pigmented, and anetodermalike surface changes.2 Inflammation and erosion through the skin surface are observed in the rare perforating variant, as seen in our patient. The average size is 1 cm, and it rarely exceeds 3 cm in diameter.3 The tumors predominantly occur on the head, neck, and upper extremities, with only 9.5% on the scalp.2 It may occur at any age, though it has a bimodal distribution with peaks in childhood and in adults older than 60 years. A slight preponderance in females has been observed with a female to male ratio of 1.5 to 1.2 Although our patient is black, most reported cases have occurred in individuals of European descent. Because cases of pilomatricoma are not systematically reported, it is uncertain if this finding represents a publication bias or if race is an actual risk factor. Multiple pilomatricomas and familial cases have been described in association with myotonic dystrophy, Turner syndrome, Gardner syndrome, Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, polyfactorial coagulopathy, trisomy 9, xeroderma pigmentosum, and basal cell nevus syndrome.2,4