User login

How Should a Patient with Cocaine-Associated Chest Pain be Treated?

Case

A 38-year-old man with a history of tobacco use presents to the emergency department complaining of constant substernal chest pain for three hours. His temperature is 37.7°C, his heart rate is 110 beats per minute, and his blood pressure is 155/95 mmHg. He appears anxious and diaphoretic but examination is otherwise unremarkable. He admits to cocaine use one hour before the onset of symptoms. What are the appropriate treatments for his condition?

Overview

Cocaine is the second-most-commonly used illicit drug in the U.S. and represents 31% of all ED visits related to substance abuse.1,2 According to recent survey results, 2.1 million people report recent cocaine use, and 1.6 million engage in cocaine abuse or dependence.2 Acute cardiopulmonary complaints are common in individuals who present to the ED after cocaine use, with chest pain being the most frequently reported symptom in 40%.3

Numerous etiologies for cocaine-associated chest pain (CACP) have been discovered, including musculoskeletal pain, pulmonary hypertension, cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias, and endocarditis.4 Only 0.5% of patients with aortic dissection over a four-year period had a recent history of cocaine use, making cocaine a rare cause of a rare condition.5 Cardiac chest pain remains the most frequent underlying etiology, resulting in the most common complication of myocardial infarction (MI) in up to 6% of patients.6,7

The ways in which cocaine use can cause myocardial ischemia and MI are multifactorial. A vigorous central sympathomimetic effect, coronary artery vasoconstriction, stimulation of platelets, and enhanced atherosclerosis all lead to a myocardial oxygen supply-demand imbalance.8 Other key interactions in the cardiovascular system are displayed in Figure 1. Understanding the role of these mechanisms in CACP is crucial to patient care.

Clinician goals in the management of CACP are to rapidly and accurately exclude life-threatening etiologies; assess the need for urgent acute coronary syndrome (ACS) evaluation; risk-stratify patients and ensure appropriate disposition; normalize the toxic effects of cocaine; treat resultant organ damage; and prevent long-term complications. An algorithm detailing this approach is provided in Figure 2.

Review of the Data

Diagnostic evaluation. Given potential differences in treatment regimens, it is imperative to differentiate patients who present with CACP from those whose chest pain is not associated with cocaine either by direct questioning or by screening of urine for cocaine metabolites. Once the presence of cocaine has been confirmed, guideline-based evaluation for potential ACS with serial electrocardiograms (ECG), cardiac biomarkers, and close monitoring of cardiac rhythms and hemodynamics is largely similar to standard management of all patients presenting with chest pain, with a few caveats.

Interpretation of the ECG can be challenging in the setting of cocaine. Studies have shown “abnormal” ECGs in 56% to 84% of patients, with many representing early repolarization or left ventricular hypertrophy.9,10 Likewise, patients with MI are as likely to present with normal or nonspecific ECG findings as with ischemic findings.7,11 ECG interpretation to diagnose ischemia or infarction in patients with CACP yields a sensitivity of 36% and specificity of 90%.7

Creatine kinase (CK), CK-MB fraction, and myoglobin have low specificity for the diagnosis of ischemia, as cocaine can induce skeletal muscle injury and rhabdomyolysis.9,12 Cardiac troponins demonstrate a superior specificity compared to CK and CK-MB and are thus the preferred cardiac biomarkers in diagnosing cocaine-associated MI.12

Initial management and disposition. Patients at high risk for cardiovascular events are generally admitted to a monitored bed.13 Immediate reperfusion therapy with primary percutaneous coronary intervention is recommended in patients with ST-elevation MI (STEMI). Treatment with thrombolytic agents is associated with an increased risk of intracerebral hemorrhage and lacks documented efficacy in patients with CACP. Thrombolysis should therefore only be utilized if the diagnosis of STEMI is unequivocal and an experienced cardiac catheterization laboratory is unavailable.14,15

Patients with unstable angina (UA) or non-ST-elevation MI (NSTEMI) are at higher risk for further cardiac events in a similar manner to those with ACS unrelated to cocaine. These cases might benefit from early cardiac catheterization and revascularization.16 Because of the increased risk of stent thrombosis in cocaine-users, thought to be due to recidivism, a detailed risk-benefit analysis should be undertaken prior to the implantation of cardiac stents.

Other diagnostic tests, such as stress testing and myocardial imaging, have not shown significant accuracy in diagnosing MI in this setting; moreover, these patients are at low overall risk for cardiac events and mortality. Consequently, an extensive diagnostic evaluation might not be cost-effective.7,10,13,17 Patients who have CACP without MI have a very low frequency of delayed complications.3,17 As such, cost-effective evaluation strategies, such as nine- or 12-hour observation periods in a chest pain unit, are appropriate for many of these low- to moderate-risk patients.13 For all CACP patients, the most critical post-discharge interventions are cardiac risk modification and cocaine cessation.13

Normalizing the toxic effects of cocaine with medications.

Aspirin: While no specific study has been performed in patients with CACP and aspirin, CACP guidelines, based on data supporting ACS guidelines for all patients, recommend administration of full-dose aspirin given its associated reduction in morbidity and mortality.18,19 Furthermore, given the platelet-stimulating effects of cocaine, using aspirin in this setting seems very reasonable.

Benzodiazepines: CACP guidelines support the use of benzodiazepines early in management to indirectly combat the agitation, hypertension, and tachycardia resulting from the stimulatory effects of cocaine.18,20 These recommendations are based on several animal and human studies that demonstrate significant reduction in heart rate and systemic arterial pressure with the use of these agents.21,22

Nitroglycerin: Cardiac catheterization studies have shown reversal of vasoconstriction with administration of nitroglycerin. One study demonstrated a benefit of the drug in 49% of participants.23 Additional investigation into the benefit of benzodiazepine and nitroglycerin combination therapy revealed mixed results. In one study, lorazepam plus nitroglycerin was found to be more efficacious than nitroglycerin alone.24 In another, however, use of diazepam in combination with nitroglycerin did not show benefit when evaluating pain relief, cardiac dynamics, and left ventricular function.25

Phentolamine: Phentolamine administration has been studied much less in the literature. This nonselective alpha-adrenergic antagonist exerts a dose-dependent reversal of cocaine’s vasoconstrictive properties in monkeys and humans.26,27 International guidelines for Emergency Cardiovascular Care recommend its use in treatment of cocaine-associated ACS;27 however, the AHA recommends it less strongly.18

Calcium channel blockers: Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) have not shown promise as first-line agents. While catheterization studies demonstrate the vasodilatory properties of verapamil, larger studies looking at all-cause mortality conclude that CCBs might worsen mortality rates,28 and animal studies indicate an increased risk of seizures.29 At this time, CCBs are recommended only if cardiac symptoms continue after both benzodiazepines and nitroglycerin are administered.18

The beta-blocker controversy: The use of beta-blockers in patients with CACP remains controversial given the theoretical risk of unopposed alpha-adrenergic activation. Coronary vasospasm, decreased myocardial oxygen delivery, and increased systemic vascular resistance can result from their use.30

Propranolol, a nonselective beta-blocker, was shown in catheterization studies to potentiate the coronary vasoconstriction of cocaine.31 Labetalol, a combined alpha/beta-blocker, reduced mean arterial pressure after cocaine administration during cardiac catheterization but did not reverse coronary vasoconstriction.32 This was attributed to the predominating beta greater than alpha blockade at doses administered. The selective beta-1 antagonists esmolol and metoprolol have shown no benefit in CACP.33 Carvedilol, a combined alpha/beta-blocker with both peripheral and central nervous system activity, has potential to attenuate both physiologic and behavioral response to cocaine, but it has not been well studied in this patient subset.34

The 2005 ACC/AHA STEMI guidelines recommended against beta-blockers in the setting of STEMI precipitated by cocaine use due to the potential of exacerbating coronary vasoconstriction.35 The 2007 ACC/AHA UA/NSTEMI guidelines stated that the use of a combined alpha/beta-blocker in patients with cocaine-induced ACS may be reasonable for patients with hypertension or tachycardia if pre-treated with a vasodilator.19 The 2008 ACC/AHA guidelines on the management of cocaine-related chest pain and MI recommended against the use of beta-blockers in the acute setting given the low incidence of cocaine-related MI and death.18

In a more recent study, Dattilo et al showed that beta-blockers administered to patients admitted with positive urine toxicology for cocaine significantly reduced MI and in-hospital mortality. Reduction of MI was of borderline significance in those admitted with a chief complaint of chest pain.36 Limitations of this study include unknown time of cocaine ingestion, lack of follow-up on discharge mortality, and a small sample size of 348 patients lacking statistical power.

Another retrospective cohort study examined patients admitted with chest pain and urine toxicology positive for cocaine and found that beta-blocker administration during hospitalization was not associated with increased incident mortality. Further, after a mean follow-up of 2.5 years, there was a statistically significant decrease in cardiovascular death.37 Drawbacks of this study included an older patient population, greater proportion of coronary artery disease, and higher follow-up of cardiovascular mortality rates than in previous studies, suggesting this subset might have received greater benefit from beta-blockers as a result of these characteristics.

The 2008 ACC/AHA guidelines instruct individualized consideration of the risk/benefit ratio for beta-blocker use in patients with CACP given the high rate of recidivism in cocaine abusers. The strongest indication is given to those with documented MI, left ventricular systolic dysfunction, or ventricular arrhythmias.18

It is important to note that these recommendations are based on cardiac catheterization laboratory studies, case reports, retrospective analyses, and animal experiments. No prospective controlled trials evaluating the role of beta-blockers in CACP and MI exist, and no trials regarding therapies to improve outcomes of patients sustaining a cocaine-associated MI have been reported.18

Back to the Case

This patient was experiencing cocaine-associated chest pain, which was confirmed with positive urine toxicology. Initial diagnostic workup with basic laboratory studies and cardiac biomarkers showed mild elevation in CK with troponin levels within normal limits. His ECG showed changes consistent with left ventricular hypertrophy. Chest radiograph was unremarkable.

He received aspirin, benzodiazepines, and nitroglycerin with normalization of vital signs, as well as subjective improvement in chest pain and anxiety. He was deemed to be at low risk for potential cardiac complications; thus, further cardiac testing was not pursued. Rather, he was admitted to an overnight observation unit with telemetry monitoring, where his chest pain did not recur.

He was seen in consultation with social work staff who arranged for drug abuse counseling after discharge. Given the uncertainty of relapse to cocaine use, as well as lack of known cardiac risk factors, he was not discharged on any new medications.

Bottom Line

The treatment of CACP includes normalizing the toxic systemic effects of the drug and minimizing the direct ischemic damage to the myocardium. Management varies slightly from traditional chest pain algorithms and includes benzodiazepines as well as antiplatelet agents and vasodilators to achieve this goal. Initial therapy with beta-blockers remains undefined and is largely discouraged in the acute setting. The role of beta-blockade upon discharge, however, can be beneficial in specific populations, especially those found to have underlying coronary disease.

Dr. Houchens and Dr. Czarnik are clinical instructors and Dr. Mack is a clinical lecturer at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor.

References

- Hughes A, Sathe N, Spagnola K. State Estimates of Substance Use from the 2005-2006 National Surveys on Drug Use and Health. DHHS Publication No. SMA 08-4311, NSDUH Series H-33. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2008.

- Volkow ND. Cocaine: Abuse and Addiction. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2009.

- Brody SL, Slovis CM, Wrenn KD. Cocaine-related medical problems: consecutive series of 233 patients. Am J Med. 1990;88:325-331.

- Levis JT, Garmel GM. Cocaine-associated chest pain. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2005;23:1083-1103.

- Eagle KA, Isselbacher EM, DeSanctis RW. Cocaine-related aortic dissection in perspective. Circulation. 2002;105:1529-1530.

- Feldman JA, Fish SS, Beshansky JR, Griffith JL, Woolard RH, Selker HP. Acute cardiac ischemia in patients with cocaine-associated complaints: results of a multicenter trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;36:469-476.

- Hollander JE, Hoffman RS, Gennis P, et al. Prospective multicenter evaluation of cocaine associated chest pain. Cocaine Associated Chest Pain (COCHPA) Study Group. Acad Emerg Med. 1994;1:330-339.

- Schwartz BG, Rezkalla S, Kloner RA. Cardiovascular effects of cocaine. Circulation. 2010;122:2558-2569.

- Gitter MJ, Goldsmith SR, Dunbar DN, et al. Cocaine and chest pain: clinical features and outcomes of patients hospitalized to rule out myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:277-282.

- Amin M, Gabelman G, Karpel J, et al. Acute myocardial infarction and chest pain syndromes after cocaine use. Am J Cardiol. 1990;66:1434-1437.

- Tokarski GF, Paganussi P, Urbanski R, et al. An evaluation of cocaine-induced chest pain. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19:1088-1092.

- Hollander JE, Levitt MA, Young GP, Briglia E, Wetli CV, Gawad Y. Effect of recent cocaine use on the specificity of cardiac markers for diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 1998;135(2 Pt 1):245-252.

- Weber JE, Shofer FS, Larkin GL, Kalaria AS, Hollander JE. Validation of a brief observation period for patients with cocaine-associated chest pain. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:510-517.

- Hahn IH, Hoffman RS. Diagnosis and treatment of acute myocardial infarction: cocaine use and acute myocardial infarction. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2001;19(2):1-18.

- Hoffman RS, Hollander JE. Evaluation of patients with chest pain after cocaine use. Crit Care Clin. 1997;13:809-828. Cannon CP, Weintraub WS, Demopoulos LA, et al.

- Comparison of early invasive and conservative strategies in patients with unstable coronary syndromes treated with the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor tirofiban. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1879-1887.

- Hollander JE, Hoffman RS. Cocaine-induced myocardial infarction: an analysis and review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 1992;10:169-177.

- McCord J, Jneid H, Hollander JE, et al. Management of cocaine-associated chest pain and myocardial infarction: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Acute Cardiac Care Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology. Circulation. 2008;117:1897-1907.

- Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-Elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction) developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:E1-E157.

- Hollander JE. Management of cocaine-associated myocardial ischemia. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1267-1272.

- Brubacher JR, Hoffman RS. Cocaine toxicity. Top Emerg Med. 1997;19(4):1-16.

- Catavas JD, Waters IW. Acute cocaine intoxication in the conscious dog: studies on the mechanism of lethality. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1981;217:350-356.

- Hollander JE, Hoffman RS, Gennis P, et al. Nitroglycerin in the treatment of cocaine associated chest pain—clinical safety and efficacy. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1994;32(3): 243-256.

- Honderick T, Williams D, Seaberg D, Wears R. A prospective, randomized, controlled trial of benzodiazepines and nitroglycerin or nitroglycerin alone in the treatment of cocaine-associated acute coronary syndromes. Am J Emerg Med. 2003;21(1):39-42.

- Baumann BM, Perrone J, Hornig SE, Shofer FS, Hollander JE. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of diazepam, nitroglycerin, or both for treatment of patients with potential cocaine-associated acute coronary syndromes. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:878-885.

- Schindler CW, Tella SR, Goldberg SR. Adrenoceptor mechanisms in the cardiovascular effects of cocaine in conscious squirrel monkeys. Life Sci. 1992;51(9):653-660.

- Lange RA, Cigarroa RG, Yancy CW Jr., et al. Cocaine-induced coronary-artery vasoconstriction. N Engl J Med. 1989;321(23):1557-1562.

- Furberg CD, Psaty BM, Meyer JV. Nifedipine. Dose-related increase in mortality in patients with coronary heart disease. Circulation. 1995;92:1326-1331.

- Derlet RW, Albertson TE. Potentiation of cocaine toxicity with calcium channel blockers. Am J Emerg Med. 1989;7:464-468.

- Lange RA, Hillis LD. Cardiovascular complications of cocaine use. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:351-358.

- Lange RA, Cigarroa RG, Flores ED, et al. Potentiation of cocaine-induced coronary vasoconstriction by beta-adrenergic blockade. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:897-903.

- Boehrer JD, Moliterno DJ, Willard JE, Hillis LD, Lange RA. Influence of labetalol on cocaine-induced coronary vasoconstriction in humans. Am J Med. 1993;94:608-610.

- Sand IC, Brody SL, Wrenn KD, Slovis CM. Experience with esmolol for the treatment of cocaine-associated cardiovascular complications. Am J Emerg Med. 1991;9:161-163.

- Sofuoglo M, Brown S, Babb DA, Pentel PR, Hatsukami DK. Carvedilol affects the physiological and behavioral response to smoked cocaine in humans. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;60:69-76.

- Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force of Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of patients with acute myocardial infarction). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:E1-E211.

- Dattilo PB, Hailpern SM, Fearon K, Sohal D, Nordin C. Beta-blockers are associated with reduced risk of myocardial infarction after cocaine use. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:117-125.

- Rangel C, Shu RG, Lazar LD, Vittinghoff E, Hsue PY, Marcus GM. Beta-blockers for chest pain associated with recent cocaine use. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:874-879.

Case

A 38-year-old man with a history of tobacco use presents to the emergency department complaining of constant substernal chest pain for three hours. His temperature is 37.7°C, his heart rate is 110 beats per minute, and his blood pressure is 155/95 mmHg. He appears anxious and diaphoretic but examination is otherwise unremarkable. He admits to cocaine use one hour before the onset of symptoms. What are the appropriate treatments for his condition?

Overview

Cocaine is the second-most-commonly used illicit drug in the U.S. and represents 31% of all ED visits related to substance abuse.1,2 According to recent survey results, 2.1 million people report recent cocaine use, and 1.6 million engage in cocaine abuse or dependence.2 Acute cardiopulmonary complaints are common in individuals who present to the ED after cocaine use, with chest pain being the most frequently reported symptom in 40%.3

Numerous etiologies for cocaine-associated chest pain (CACP) have been discovered, including musculoskeletal pain, pulmonary hypertension, cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias, and endocarditis.4 Only 0.5% of patients with aortic dissection over a four-year period had a recent history of cocaine use, making cocaine a rare cause of a rare condition.5 Cardiac chest pain remains the most frequent underlying etiology, resulting in the most common complication of myocardial infarction (MI) in up to 6% of patients.6,7

The ways in which cocaine use can cause myocardial ischemia and MI are multifactorial. A vigorous central sympathomimetic effect, coronary artery vasoconstriction, stimulation of platelets, and enhanced atherosclerosis all lead to a myocardial oxygen supply-demand imbalance.8 Other key interactions in the cardiovascular system are displayed in Figure 1. Understanding the role of these mechanisms in CACP is crucial to patient care.

Clinician goals in the management of CACP are to rapidly and accurately exclude life-threatening etiologies; assess the need for urgent acute coronary syndrome (ACS) evaluation; risk-stratify patients and ensure appropriate disposition; normalize the toxic effects of cocaine; treat resultant organ damage; and prevent long-term complications. An algorithm detailing this approach is provided in Figure 2.

Review of the Data

Diagnostic evaluation. Given potential differences in treatment regimens, it is imperative to differentiate patients who present with CACP from those whose chest pain is not associated with cocaine either by direct questioning or by screening of urine for cocaine metabolites. Once the presence of cocaine has been confirmed, guideline-based evaluation for potential ACS with serial electrocardiograms (ECG), cardiac biomarkers, and close monitoring of cardiac rhythms and hemodynamics is largely similar to standard management of all patients presenting with chest pain, with a few caveats.

Interpretation of the ECG can be challenging in the setting of cocaine. Studies have shown “abnormal” ECGs in 56% to 84% of patients, with many representing early repolarization or left ventricular hypertrophy.9,10 Likewise, patients with MI are as likely to present with normal or nonspecific ECG findings as with ischemic findings.7,11 ECG interpretation to diagnose ischemia or infarction in patients with CACP yields a sensitivity of 36% and specificity of 90%.7

Creatine kinase (CK), CK-MB fraction, and myoglobin have low specificity for the diagnosis of ischemia, as cocaine can induce skeletal muscle injury and rhabdomyolysis.9,12 Cardiac troponins demonstrate a superior specificity compared to CK and CK-MB and are thus the preferred cardiac biomarkers in diagnosing cocaine-associated MI.12

Initial management and disposition. Patients at high risk for cardiovascular events are generally admitted to a monitored bed.13 Immediate reperfusion therapy with primary percutaneous coronary intervention is recommended in patients with ST-elevation MI (STEMI). Treatment with thrombolytic agents is associated with an increased risk of intracerebral hemorrhage and lacks documented efficacy in patients with CACP. Thrombolysis should therefore only be utilized if the diagnosis of STEMI is unequivocal and an experienced cardiac catheterization laboratory is unavailable.14,15

Patients with unstable angina (UA) or non-ST-elevation MI (NSTEMI) are at higher risk for further cardiac events in a similar manner to those with ACS unrelated to cocaine. These cases might benefit from early cardiac catheterization and revascularization.16 Because of the increased risk of stent thrombosis in cocaine-users, thought to be due to recidivism, a detailed risk-benefit analysis should be undertaken prior to the implantation of cardiac stents.

Other diagnostic tests, such as stress testing and myocardial imaging, have not shown significant accuracy in diagnosing MI in this setting; moreover, these patients are at low overall risk for cardiac events and mortality. Consequently, an extensive diagnostic evaluation might not be cost-effective.7,10,13,17 Patients who have CACP without MI have a very low frequency of delayed complications.3,17 As such, cost-effective evaluation strategies, such as nine- or 12-hour observation periods in a chest pain unit, are appropriate for many of these low- to moderate-risk patients.13 For all CACP patients, the most critical post-discharge interventions are cardiac risk modification and cocaine cessation.13

Normalizing the toxic effects of cocaine with medications.

Aspirin: While no specific study has been performed in patients with CACP and aspirin, CACP guidelines, based on data supporting ACS guidelines for all patients, recommend administration of full-dose aspirin given its associated reduction in morbidity and mortality.18,19 Furthermore, given the platelet-stimulating effects of cocaine, using aspirin in this setting seems very reasonable.

Benzodiazepines: CACP guidelines support the use of benzodiazepines early in management to indirectly combat the agitation, hypertension, and tachycardia resulting from the stimulatory effects of cocaine.18,20 These recommendations are based on several animal and human studies that demonstrate significant reduction in heart rate and systemic arterial pressure with the use of these agents.21,22

Nitroglycerin: Cardiac catheterization studies have shown reversal of vasoconstriction with administration of nitroglycerin. One study demonstrated a benefit of the drug in 49% of participants.23 Additional investigation into the benefit of benzodiazepine and nitroglycerin combination therapy revealed mixed results. In one study, lorazepam plus nitroglycerin was found to be more efficacious than nitroglycerin alone.24 In another, however, use of diazepam in combination with nitroglycerin did not show benefit when evaluating pain relief, cardiac dynamics, and left ventricular function.25

Phentolamine: Phentolamine administration has been studied much less in the literature. This nonselective alpha-adrenergic antagonist exerts a dose-dependent reversal of cocaine’s vasoconstrictive properties in monkeys and humans.26,27 International guidelines for Emergency Cardiovascular Care recommend its use in treatment of cocaine-associated ACS;27 however, the AHA recommends it less strongly.18

Calcium channel blockers: Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) have not shown promise as first-line agents. While catheterization studies demonstrate the vasodilatory properties of verapamil, larger studies looking at all-cause mortality conclude that CCBs might worsen mortality rates,28 and animal studies indicate an increased risk of seizures.29 At this time, CCBs are recommended only if cardiac symptoms continue after both benzodiazepines and nitroglycerin are administered.18

The beta-blocker controversy: The use of beta-blockers in patients with CACP remains controversial given the theoretical risk of unopposed alpha-adrenergic activation. Coronary vasospasm, decreased myocardial oxygen delivery, and increased systemic vascular resistance can result from their use.30

Propranolol, a nonselective beta-blocker, was shown in catheterization studies to potentiate the coronary vasoconstriction of cocaine.31 Labetalol, a combined alpha/beta-blocker, reduced mean arterial pressure after cocaine administration during cardiac catheterization but did not reverse coronary vasoconstriction.32 This was attributed to the predominating beta greater than alpha blockade at doses administered. The selective beta-1 antagonists esmolol and metoprolol have shown no benefit in CACP.33 Carvedilol, a combined alpha/beta-blocker with both peripheral and central nervous system activity, has potential to attenuate both physiologic and behavioral response to cocaine, but it has not been well studied in this patient subset.34

The 2005 ACC/AHA STEMI guidelines recommended against beta-blockers in the setting of STEMI precipitated by cocaine use due to the potential of exacerbating coronary vasoconstriction.35 The 2007 ACC/AHA UA/NSTEMI guidelines stated that the use of a combined alpha/beta-blocker in patients with cocaine-induced ACS may be reasonable for patients with hypertension or tachycardia if pre-treated with a vasodilator.19 The 2008 ACC/AHA guidelines on the management of cocaine-related chest pain and MI recommended against the use of beta-blockers in the acute setting given the low incidence of cocaine-related MI and death.18

In a more recent study, Dattilo et al showed that beta-blockers administered to patients admitted with positive urine toxicology for cocaine significantly reduced MI and in-hospital mortality. Reduction of MI was of borderline significance in those admitted with a chief complaint of chest pain.36 Limitations of this study include unknown time of cocaine ingestion, lack of follow-up on discharge mortality, and a small sample size of 348 patients lacking statistical power.

Another retrospective cohort study examined patients admitted with chest pain and urine toxicology positive for cocaine and found that beta-blocker administration during hospitalization was not associated with increased incident mortality. Further, after a mean follow-up of 2.5 years, there was a statistically significant decrease in cardiovascular death.37 Drawbacks of this study included an older patient population, greater proportion of coronary artery disease, and higher follow-up of cardiovascular mortality rates than in previous studies, suggesting this subset might have received greater benefit from beta-blockers as a result of these characteristics.

The 2008 ACC/AHA guidelines instruct individualized consideration of the risk/benefit ratio for beta-blocker use in patients with CACP given the high rate of recidivism in cocaine abusers. The strongest indication is given to those with documented MI, left ventricular systolic dysfunction, or ventricular arrhythmias.18

It is important to note that these recommendations are based on cardiac catheterization laboratory studies, case reports, retrospective analyses, and animal experiments. No prospective controlled trials evaluating the role of beta-blockers in CACP and MI exist, and no trials regarding therapies to improve outcomes of patients sustaining a cocaine-associated MI have been reported.18

Back to the Case

This patient was experiencing cocaine-associated chest pain, which was confirmed with positive urine toxicology. Initial diagnostic workup with basic laboratory studies and cardiac biomarkers showed mild elevation in CK with troponin levels within normal limits. His ECG showed changes consistent with left ventricular hypertrophy. Chest radiograph was unremarkable.

He received aspirin, benzodiazepines, and nitroglycerin with normalization of vital signs, as well as subjective improvement in chest pain and anxiety. He was deemed to be at low risk for potential cardiac complications; thus, further cardiac testing was not pursued. Rather, he was admitted to an overnight observation unit with telemetry monitoring, where his chest pain did not recur.

He was seen in consultation with social work staff who arranged for drug abuse counseling after discharge. Given the uncertainty of relapse to cocaine use, as well as lack of known cardiac risk factors, he was not discharged on any new medications.

Bottom Line

The treatment of CACP includes normalizing the toxic systemic effects of the drug and minimizing the direct ischemic damage to the myocardium. Management varies slightly from traditional chest pain algorithms and includes benzodiazepines as well as antiplatelet agents and vasodilators to achieve this goal. Initial therapy with beta-blockers remains undefined and is largely discouraged in the acute setting. The role of beta-blockade upon discharge, however, can be beneficial in specific populations, especially those found to have underlying coronary disease.

Dr. Houchens and Dr. Czarnik are clinical instructors and Dr. Mack is a clinical lecturer at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor.

References

- Hughes A, Sathe N, Spagnola K. State Estimates of Substance Use from the 2005-2006 National Surveys on Drug Use and Health. DHHS Publication No. SMA 08-4311, NSDUH Series H-33. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2008.

- Volkow ND. Cocaine: Abuse and Addiction. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2009.

- Brody SL, Slovis CM, Wrenn KD. Cocaine-related medical problems: consecutive series of 233 patients. Am J Med. 1990;88:325-331.

- Levis JT, Garmel GM. Cocaine-associated chest pain. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2005;23:1083-1103.

- Eagle KA, Isselbacher EM, DeSanctis RW. Cocaine-related aortic dissection in perspective. Circulation. 2002;105:1529-1530.

- Feldman JA, Fish SS, Beshansky JR, Griffith JL, Woolard RH, Selker HP. Acute cardiac ischemia in patients with cocaine-associated complaints: results of a multicenter trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;36:469-476.

- Hollander JE, Hoffman RS, Gennis P, et al. Prospective multicenter evaluation of cocaine associated chest pain. Cocaine Associated Chest Pain (COCHPA) Study Group. Acad Emerg Med. 1994;1:330-339.

- Schwartz BG, Rezkalla S, Kloner RA. Cardiovascular effects of cocaine. Circulation. 2010;122:2558-2569.

- Gitter MJ, Goldsmith SR, Dunbar DN, et al. Cocaine and chest pain: clinical features and outcomes of patients hospitalized to rule out myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:277-282.

- Amin M, Gabelman G, Karpel J, et al. Acute myocardial infarction and chest pain syndromes after cocaine use. Am J Cardiol. 1990;66:1434-1437.

- Tokarski GF, Paganussi P, Urbanski R, et al. An evaluation of cocaine-induced chest pain. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19:1088-1092.

- Hollander JE, Levitt MA, Young GP, Briglia E, Wetli CV, Gawad Y. Effect of recent cocaine use on the specificity of cardiac markers for diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 1998;135(2 Pt 1):245-252.

- Weber JE, Shofer FS, Larkin GL, Kalaria AS, Hollander JE. Validation of a brief observation period for patients with cocaine-associated chest pain. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:510-517.

- Hahn IH, Hoffman RS. Diagnosis and treatment of acute myocardial infarction: cocaine use and acute myocardial infarction. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2001;19(2):1-18.

- Hoffman RS, Hollander JE. Evaluation of patients with chest pain after cocaine use. Crit Care Clin. 1997;13:809-828. Cannon CP, Weintraub WS, Demopoulos LA, et al.

- Comparison of early invasive and conservative strategies in patients with unstable coronary syndromes treated with the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor tirofiban. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1879-1887.

- Hollander JE, Hoffman RS. Cocaine-induced myocardial infarction: an analysis and review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 1992;10:169-177.

- McCord J, Jneid H, Hollander JE, et al. Management of cocaine-associated chest pain and myocardial infarction: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Acute Cardiac Care Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology. Circulation. 2008;117:1897-1907.

- Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-Elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction) developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:E1-E157.

- Hollander JE. Management of cocaine-associated myocardial ischemia. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1267-1272.

- Brubacher JR, Hoffman RS. Cocaine toxicity. Top Emerg Med. 1997;19(4):1-16.

- Catavas JD, Waters IW. Acute cocaine intoxication in the conscious dog: studies on the mechanism of lethality. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1981;217:350-356.

- Hollander JE, Hoffman RS, Gennis P, et al. Nitroglycerin in the treatment of cocaine associated chest pain—clinical safety and efficacy. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1994;32(3): 243-256.

- Honderick T, Williams D, Seaberg D, Wears R. A prospective, randomized, controlled trial of benzodiazepines and nitroglycerin or nitroglycerin alone in the treatment of cocaine-associated acute coronary syndromes. Am J Emerg Med. 2003;21(1):39-42.

- Baumann BM, Perrone J, Hornig SE, Shofer FS, Hollander JE. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of diazepam, nitroglycerin, or both for treatment of patients with potential cocaine-associated acute coronary syndromes. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:878-885.

- Schindler CW, Tella SR, Goldberg SR. Adrenoceptor mechanisms in the cardiovascular effects of cocaine in conscious squirrel monkeys. Life Sci. 1992;51(9):653-660.

- Lange RA, Cigarroa RG, Yancy CW Jr., et al. Cocaine-induced coronary-artery vasoconstriction. N Engl J Med. 1989;321(23):1557-1562.

- Furberg CD, Psaty BM, Meyer JV. Nifedipine. Dose-related increase in mortality in patients with coronary heart disease. Circulation. 1995;92:1326-1331.

- Derlet RW, Albertson TE. Potentiation of cocaine toxicity with calcium channel blockers. Am J Emerg Med. 1989;7:464-468.

- Lange RA, Hillis LD. Cardiovascular complications of cocaine use. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:351-358.

- Lange RA, Cigarroa RG, Flores ED, et al. Potentiation of cocaine-induced coronary vasoconstriction by beta-adrenergic blockade. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:897-903.

- Boehrer JD, Moliterno DJ, Willard JE, Hillis LD, Lange RA. Influence of labetalol on cocaine-induced coronary vasoconstriction in humans. Am J Med. 1993;94:608-610.

- Sand IC, Brody SL, Wrenn KD, Slovis CM. Experience with esmolol for the treatment of cocaine-associated cardiovascular complications. Am J Emerg Med. 1991;9:161-163.

- Sofuoglo M, Brown S, Babb DA, Pentel PR, Hatsukami DK. Carvedilol affects the physiological and behavioral response to smoked cocaine in humans. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;60:69-76.

- Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force of Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of patients with acute myocardial infarction). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:E1-E211.

- Dattilo PB, Hailpern SM, Fearon K, Sohal D, Nordin C. Beta-blockers are associated with reduced risk of myocardial infarction after cocaine use. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:117-125.

- Rangel C, Shu RG, Lazar LD, Vittinghoff E, Hsue PY, Marcus GM. Beta-blockers for chest pain associated with recent cocaine use. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:874-879.

Case

A 38-year-old man with a history of tobacco use presents to the emergency department complaining of constant substernal chest pain for three hours. His temperature is 37.7°C, his heart rate is 110 beats per minute, and his blood pressure is 155/95 mmHg. He appears anxious and diaphoretic but examination is otherwise unremarkable. He admits to cocaine use one hour before the onset of symptoms. What are the appropriate treatments for his condition?

Overview

Cocaine is the second-most-commonly used illicit drug in the U.S. and represents 31% of all ED visits related to substance abuse.1,2 According to recent survey results, 2.1 million people report recent cocaine use, and 1.6 million engage in cocaine abuse or dependence.2 Acute cardiopulmonary complaints are common in individuals who present to the ED after cocaine use, with chest pain being the most frequently reported symptom in 40%.3

Numerous etiologies for cocaine-associated chest pain (CACP) have been discovered, including musculoskeletal pain, pulmonary hypertension, cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias, and endocarditis.4 Only 0.5% of patients with aortic dissection over a four-year period had a recent history of cocaine use, making cocaine a rare cause of a rare condition.5 Cardiac chest pain remains the most frequent underlying etiology, resulting in the most common complication of myocardial infarction (MI) in up to 6% of patients.6,7

The ways in which cocaine use can cause myocardial ischemia and MI are multifactorial. A vigorous central sympathomimetic effect, coronary artery vasoconstriction, stimulation of platelets, and enhanced atherosclerosis all lead to a myocardial oxygen supply-demand imbalance.8 Other key interactions in the cardiovascular system are displayed in Figure 1. Understanding the role of these mechanisms in CACP is crucial to patient care.

Clinician goals in the management of CACP are to rapidly and accurately exclude life-threatening etiologies; assess the need for urgent acute coronary syndrome (ACS) evaluation; risk-stratify patients and ensure appropriate disposition; normalize the toxic effects of cocaine; treat resultant organ damage; and prevent long-term complications. An algorithm detailing this approach is provided in Figure 2.

Review of the Data

Diagnostic evaluation. Given potential differences in treatment regimens, it is imperative to differentiate patients who present with CACP from those whose chest pain is not associated with cocaine either by direct questioning or by screening of urine for cocaine metabolites. Once the presence of cocaine has been confirmed, guideline-based evaluation for potential ACS with serial electrocardiograms (ECG), cardiac biomarkers, and close monitoring of cardiac rhythms and hemodynamics is largely similar to standard management of all patients presenting with chest pain, with a few caveats.

Interpretation of the ECG can be challenging in the setting of cocaine. Studies have shown “abnormal” ECGs in 56% to 84% of patients, with many representing early repolarization or left ventricular hypertrophy.9,10 Likewise, patients with MI are as likely to present with normal or nonspecific ECG findings as with ischemic findings.7,11 ECG interpretation to diagnose ischemia or infarction in patients with CACP yields a sensitivity of 36% and specificity of 90%.7

Creatine kinase (CK), CK-MB fraction, and myoglobin have low specificity for the diagnosis of ischemia, as cocaine can induce skeletal muscle injury and rhabdomyolysis.9,12 Cardiac troponins demonstrate a superior specificity compared to CK and CK-MB and are thus the preferred cardiac biomarkers in diagnosing cocaine-associated MI.12

Initial management and disposition. Patients at high risk for cardiovascular events are generally admitted to a monitored bed.13 Immediate reperfusion therapy with primary percutaneous coronary intervention is recommended in patients with ST-elevation MI (STEMI). Treatment with thrombolytic agents is associated with an increased risk of intracerebral hemorrhage and lacks documented efficacy in patients with CACP. Thrombolysis should therefore only be utilized if the diagnosis of STEMI is unequivocal and an experienced cardiac catheterization laboratory is unavailable.14,15

Patients with unstable angina (UA) or non-ST-elevation MI (NSTEMI) are at higher risk for further cardiac events in a similar manner to those with ACS unrelated to cocaine. These cases might benefit from early cardiac catheterization and revascularization.16 Because of the increased risk of stent thrombosis in cocaine-users, thought to be due to recidivism, a detailed risk-benefit analysis should be undertaken prior to the implantation of cardiac stents.

Other diagnostic tests, such as stress testing and myocardial imaging, have not shown significant accuracy in diagnosing MI in this setting; moreover, these patients are at low overall risk for cardiac events and mortality. Consequently, an extensive diagnostic evaluation might not be cost-effective.7,10,13,17 Patients who have CACP without MI have a very low frequency of delayed complications.3,17 As such, cost-effective evaluation strategies, such as nine- or 12-hour observation periods in a chest pain unit, are appropriate for many of these low- to moderate-risk patients.13 For all CACP patients, the most critical post-discharge interventions are cardiac risk modification and cocaine cessation.13

Normalizing the toxic effects of cocaine with medications.

Aspirin: While no specific study has been performed in patients with CACP and aspirin, CACP guidelines, based on data supporting ACS guidelines for all patients, recommend administration of full-dose aspirin given its associated reduction in morbidity and mortality.18,19 Furthermore, given the platelet-stimulating effects of cocaine, using aspirin in this setting seems very reasonable.

Benzodiazepines: CACP guidelines support the use of benzodiazepines early in management to indirectly combat the agitation, hypertension, and tachycardia resulting from the stimulatory effects of cocaine.18,20 These recommendations are based on several animal and human studies that demonstrate significant reduction in heart rate and systemic arterial pressure with the use of these agents.21,22

Nitroglycerin: Cardiac catheterization studies have shown reversal of vasoconstriction with administration of nitroglycerin. One study demonstrated a benefit of the drug in 49% of participants.23 Additional investigation into the benefit of benzodiazepine and nitroglycerin combination therapy revealed mixed results. In one study, lorazepam plus nitroglycerin was found to be more efficacious than nitroglycerin alone.24 In another, however, use of diazepam in combination with nitroglycerin did not show benefit when evaluating pain relief, cardiac dynamics, and left ventricular function.25

Phentolamine: Phentolamine administration has been studied much less in the literature. This nonselective alpha-adrenergic antagonist exerts a dose-dependent reversal of cocaine’s vasoconstrictive properties in monkeys and humans.26,27 International guidelines for Emergency Cardiovascular Care recommend its use in treatment of cocaine-associated ACS;27 however, the AHA recommends it less strongly.18

Calcium channel blockers: Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) have not shown promise as first-line agents. While catheterization studies demonstrate the vasodilatory properties of verapamil, larger studies looking at all-cause mortality conclude that CCBs might worsen mortality rates,28 and animal studies indicate an increased risk of seizures.29 At this time, CCBs are recommended only if cardiac symptoms continue after both benzodiazepines and nitroglycerin are administered.18

The beta-blocker controversy: The use of beta-blockers in patients with CACP remains controversial given the theoretical risk of unopposed alpha-adrenergic activation. Coronary vasospasm, decreased myocardial oxygen delivery, and increased systemic vascular resistance can result from their use.30

Propranolol, a nonselective beta-blocker, was shown in catheterization studies to potentiate the coronary vasoconstriction of cocaine.31 Labetalol, a combined alpha/beta-blocker, reduced mean arterial pressure after cocaine administration during cardiac catheterization but did not reverse coronary vasoconstriction.32 This was attributed to the predominating beta greater than alpha blockade at doses administered. The selective beta-1 antagonists esmolol and metoprolol have shown no benefit in CACP.33 Carvedilol, a combined alpha/beta-blocker with both peripheral and central nervous system activity, has potential to attenuate both physiologic and behavioral response to cocaine, but it has not been well studied in this patient subset.34

The 2005 ACC/AHA STEMI guidelines recommended against beta-blockers in the setting of STEMI precipitated by cocaine use due to the potential of exacerbating coronary vasoconstriction.35 The 2007 ACC/AHA UA/NSTEMI guidelines stated that the use of a combined alpha/beta-blocker in patients with cocaine-induced ACS may be reasonable for patients with hypertension or tachycardia if pre-treated with a vasodilator.19 The 2008 ACC/AHA guidelines on the management of cocaine-related chest pain and MI recommended against the use of beta-blockers in the acute setting given the low incidence of cocaine-related MI and death.18

In a more recent study, Dattilo et al showed that beta-blockers administered to patients admitted with positive urine toxicology for cocaine significantly reduced MI and in-hospital mortality. Reduction of MI was of borderline significance in those admitted with a chief complaint of chest pain.36 Limitations of this study include unknown time of cocaine ingestion, lack of follow-up on discharge mortality, and a small sample size of 348 patients lacking statistical power.

Another retrospective cohort study examined patients admitted with chest pain and urine toxicology positive for cocaine and found that beta-blocker administration during hospitalization was not associated with increased incident mortality. Further, after a mean follow-up of 2.5 years, there was a statistically significant decrease in cardiovascular death.37 Drawbacks of this study included an older patient population, greater proportion of coronary artery disease, and higher follow-up of cardiovascular mortality rates than in previous studies, suggesting this subset might have received greater benefit from beta-blockers as a result of these characteristics.

The 2008 ACC/AHA guidelines instruct individualized consideration of the risk/benefit ratio for beta-blocker use in patients with CACP given the high rate of recidivism in cocaine abusers. The strongest indication is given to those with documented MI, left ventricular systolic dysfunction, or ventricular arrhythmias.18

It is important to note that these recommendations are based on cardiac catheterization laboratory studies, case reports, retrospective analyses, and animal experiments. No prospective controlled trials evaluating the role of beta-blockers in CACP and MI exist, and no trials regarding therapies to improve outcomes of patients sustaining a cocaine-associated MI have been reported.18

Back to the Case

This patient was experiencing cocaine-associated chest pain, which was confirmed with positive urine toxicology. Initial diagnostic workup with basic laboratory studies and cardiac biomarkers showed mild elevation in CK with troponin levels within normal limits. His ECG showed changes consistent with left ventricular hypertrophy. Chest radiograph was unremarkable.

He received aspirin, benzodiazepines, and nitroglycerin with normalization of vital signs, as well as subjective improvement in chest pain and anxiety. He was deemed to be at low risk for potential cardiac complications; thus, further cardiac testing was not pursued. Rather, he was admitted to an overnight observation unit with telemetry monitoring, where his chest pain did not recur.

He was seen in consultation with social work staff who arranged for drug abuse counseling after discharge. Given the uncertainty of relapse to cocaine use, as well as lack of known cardiac risk factors, he was not discharged on any new medications.

Bottom Line

The treatment of CACP includes normalizing the toxic systemic effects of the drug and minimizing the direct ischemic damage to the myocardium. Management varies slightly from traditional chest pain algorithms and includes benzodiazepines as well as antiplatelet agents and vasodilators to achieve this goal. Initial therapy with beta-blockers remains undefined and is largely discouraged in the acute setting. The role of beta-blockade upon discharge, however, can be beneficial in specific populations, especially those found to have underlying coronary disease.

Dr. Houchens and Dr. Czarnik are clinical instructors and Dr. Mack is a clinical lecturer at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor.

References

- Hughes A, Sathe N, Spagnola K. State Estimates of Substance Use from the 2005-2006 National Surveys on Drug Use and Health. DHHS Publication No. SMA 08-4311, NSDUH Series H-33. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2008.

- Volkow ND. Cocaine: Abuse and Addiction. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2009.

- Brody SL, Slovis CM, Wrenn KD. Cocaine-related medical problems: consecutive series of 233 patients. Am J Med. 1990;88:325-331.

- Levis JT, Garmel GM. Cocaine-associated chest pain. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2005;23:1083-1103.

- Eagle KA, Isselbacher EM, DeSanctis RW. Cocaine-related aortic dissection in perspective. Circulation. 2002;105:1529-1530.

- Feldman JA, Fish SS, Beshansky JR, Griffith JL, Woolard RH, Selker HP. Acute cardiac ischemia in patients with cocaine-associated complaints: results of a multicenter trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;36:469-476.

- Hollander JE, Hoffman RS, Gennis P, et al. Prospective multicenter evaluation of cocaine associated chest pain. Cocaine Associated Chest Pain (COCHPA) Study Group. Acad Emerg Med. 1994;1:330-339.

- Schwartz BG, Rezkalla S, Kloner RA. Cardiovascular effects of cocaine. Circulation. 2010;122:2558-2569.

- Gitter MJ, Goldsmith SR, Dunbar DN, et al. Cocaine and chest pain: clinical features and outcomes of patients hospitalized to rule out myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:277-282.

- Amin M, Gabelman G, Karpel J, et al. Acute myocardial infarction and chest pain syndromes after cocaine use. Am J Cardiol. 1990;66:1434-1437.

- Tokarski GF, Paganussi P, Urbanski R, et al. An evaluation of cocaine-induced chest pain. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19:1088-1092.

- Hollander JE, Levitt MA, Young GP, Briglia E, Wetli CV, Gawad Y. Effect of recent cocaine use on the specificity of cardiac markers for diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 1998;135(2 Pt 1):245-252.

- Weber JE, Shofer FS, Larkin GL, Kalaria AS, Hollander JE. Validation of a brief observation period for patients with cocaine-associated chest pain. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:510-517.

- Hahn IH, Hoffman RS. Diagnosis and treatment of acute myocardial infarction: cocaine use and acute myocardial infarction. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2001;19(2):1-18.

- Hoffman RS, Hollander JE. Evaluation of patients with chest pain after cocaine use. Crit Care Clin. 1997;13:809-828. Cannon CP, Weintraub WS, Demopoulos LA, et al.

- Comparison of early invasive and conservative strategies in patients with unstable coronary syndromes treated with the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor tirofiban. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1879-1887.

- Hollander JE, Hoffman RS. Cocaine-induced myocardial infarction: an analysis and review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 1992;10:169-177.

- McCord J, Jneid H, Hollander JE, et al. Management of cocaine-associated chest pain and myocardial infarction: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Acute Cardiac Care Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology. Circulation. 2008;117:1897-1907.

- Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-Elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction) developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:E1-E157.

- Hollander JE. Management of cocaine-associated myocardial ischemia. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1267-1272.

- Brubacher JR, Hoffman RS. Cocaine toxicity. Top Emerg Med. 1997;19(4):1-16.

- Catavas JD, Waters IW. Acute cocaine intoxication in the conscious dog: studies on the mechanism of lethality. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1981;217:350-356.

- Hollander JE, Hoffman RS, Gennis P, et al. Nitroglycerin in the treatment of cocaine associated chest pain—clinical safety and efficacy. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1994;32(3): 243-256.

- Honderick T, Williams D, Seaberg D, Wears R. A prospective, randomized, controlled trial of benzodiazepines and nitroglycerin or nitroglycerin alone in the treatment of cocaine-associated acute coronary syndromes. Am J Emerg Med. 2003;21(1):39-42.

- Baumann BM, Perrone J, Hornig SE, Shofer FS, Hollander JE. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of diazepam, nitroglycerin, or both for treatment of patients with potential cocaine-associated acute coronary syndromes. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:878-885.

- Schindler CW, Tella SR, Goldberg SR. Adrenoceptor mechanisms in the cardiovascular effects of cocaine in conscious squirrel monkeys. Life Sci. 1992;51(9):653-660.

- Lange RA, Cigarroa RG, Yancy CW Jr., et al. Cocaine-induced coronary-artery vasoconstriction. N Engl J Med. 1989;321(23):1557-1562.

- Furberg CD, Psaty BM, Meyer JV. Nifedipine. Dose-related increase in mortality in patients with coronary heart disease. Circulation. 1995;92:1326-1331.

- Derlet RW, Albertson TE. Potentiation of cocaine toxicity with calcium channel blockers. Am J Emerg Med. 1989;7:464-468.

- Lange RA, Hillis LD. Cardiovascular complications of cocaine use. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:351-358.

- Lange RA, Cigarroa RG, Flores ED, et al. Potentiation of cocaine-induced coronary vasoconstriction by beta-adrenergic blockade. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:897-903.

- Boehrer JD, Moliterno DJ, Willard JE, Hillis LD, Lange RA. Influence of labetalol on cocaine-induced coronary vasoconstriction in humans. Am J Med. 1993;94:608-610.

- Sand IC, Brody SL, Wrenn KD, Slovis CM. Experience with esmolol for the treatment of cocaine-associated cardiovascular complications. Am J Emerg Med. 1991;9:161-163.

- Sofuoglo M, Brown S, Babb DA, Pentel PR, Hatsukami DK. Carvedilol affects the physiological and behavioral response to smoked cocaine in humans. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;60:69-76.

- Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force of Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of patients with acute myocardial infarction). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:E1-E211.

- Dattilo PB, Hailpern SM, Fearon K, Sohal D, Nordin C. Beta-blockers are associated with reduced risk of myocardial infarction after cocaine use. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:117-125.

- Rangel C, Shu RG, Lazar LD, Vittinghoff E, Hsue PY, Marcus GM. Beta-blockers for chest pain associated with recent cocaine use. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:874-879.

Nosocomial Pneumonia

(This chapter has been reprinted with permission from Williams MV, Hayward R: Comprehensive Hospital Medicine, 1st edition. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, in press.)

Background

Nosocomial pneumonia (NP) is the leading cause of mortality among patients who die from hospital-acquired infections. Defined as pneumonia occurring 48 hours or more after hospital admission, NP also includes the subset of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), defined as pneumonia developing 48 to 72 hours after initiation of mechanical ventilation. The incidence of NP is between 5 and 15 cases per 1000 hospital admissions. Healthcare-associated pneumonia (HCAP), part of the continuum of NP, describes an increasingly common proportion of pneumonia developing outside the hospital (Table I) (1). Typically afflicting people in a nursing home or assisted living setting, these patients are at risk for antibiotic-resistant-organisms and should be approached similarly to cases of nosocomial pneumonia rather than community-acquired pneumonia. Most of the data informing our diagnostic and treatment decisions about NP come from studies performed in mechanically ventilated patients and are extrapolated to make recommendations for non-ventilated patients.

Mortality attributable to NP is debated, but may be as high as 30%. The presence of nosocomial pneumonia increases hospital length of stay an average of 7–10 days, and in the case of VAP, is estimated to cost between $10,000 and $40,000 per case (2).

Assessment

Clinical Presentation

Signs and Symptoms

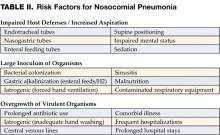

Nosocomial pneumonia is usually diagnosed based on clinical grounds. Typical symptoms and signs consist of fever, cough with sputum, and shortness of breath in the setting of hypoxia and a new infiltrate on chest radiograph (CXR). In the elderly, signs may be more subtle and delirium, fever, or leukocytosis in the absence of cough should trigger its consideration. The likelihood of NP increases among patients with risk factors for microaspiration, oropharyngeal colonization, or overgrowth of resistant organisms (Table II) (3).

Differential Diagnosis

Prior to settling on a diagnosis of NP, alternative causes of fever, hypoxia, and pulmonary infiltrates should be considered. Most commonly, these include pulmonary embolus, pulmonary edema, or atelectasis. Alternative infectious sources, such as urinary tract, skin and soft-tissue infections, and device-related infections (i.e., central venous catheters) are common in hospitalized patients and should be ruled out before diagnosing nosocomial pneumonia.

Diagnosis

Diagnostic strategies for NP seek to confirm the diagnosis and identify an etiologic pathogen, thus allowing timely, effective, and streamlined antibiotic therapy. Unfortunately, no consensus exists on the best approach to diagnosing nosocomial pneumonia. After obtaining a complete blood count and blood cultures, you can choose between a clinical or microbiologic diagnostic approach to diagnosis. A clinical diagnosis relies on a new or progressive radiographic infiltrate along with signs of infection such as fever, leukocytosis, or purulent sputum. Clinical diagnosis is sensitive, but is likely to lead to antibiotic overuse. The microbiologic approach requires sampling of secretions from the respiratory tract and may reduce inappropriate antibiotic use, but takes longer and may not be available in all hospitals.

Preferred Studies

The microbiologic approach to diagnosis relies on the use of quantitative or semi-quantitative cultures to create thresholds for antibiotic treatment. Bacterial cultures that demonstrate a level of growth above the thresholds described below warrant treatment, while those below it should trigger withholding or discontinuation of antibiotics.

Bronchoscopic Approaches: Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) with a cutoff of 10 (4) organisms/mL or protected specimen brush (PSB) with a cutoff of 10 (3) organisms/mL are felt to be the most specific diagnostic tests when performed prior to initiating antibiotics, or prior to changing antibiotics if a patient is already receiving them. In clinically stable patients, antibiotics can be safely discontinued if bacterial growth falls below the thresholds. If cultures are positive, antibiotic therapy should be tailored to target the organism identified. The bronchoscopic approach is favored in patients who are mechanically ventilated, develop their pneumonia late in the hospital stay (>5–7 days), are at risk for unusual pathogens, are failing therapy or suspected of having an alternative diagnosis.

Non-Bronchoscopic Approaches: Qualitative endotracheal aspirates (ETA) have been shown to be quite sensitive in ventilated patients, regularly identify organisms that may be subsequently found by BAL or PSB, and if negative, should result in withholding antibiotics. Quantitative endotracheal aspirates with a cutoff of 10 (6) organisms/mL are often encouraged to reduce antibiotic overuse, but results should be interpreted cautiously as they only have a sensitivity and specificity of about 75% (1). Consideration should be given to withholding antibiotics in a clinically stable patient with a negative quantitative ETA if antibiotics have not been changed in the preceding 72 hours. Many ICUs have begun to perform blinded sampling of lower respiratory tract secretions with suction catheters (blind PSB, blind mini-BAL). These techniques can be performed at all hours by trained respiratory therapists or nurses, provide culture data similar to that of bronchoscopy, and may be safer and less costly than bronchoscopy. In general, non-bronchoscopic techniques are preferred in patients who are not mechanically ventilated. Sputum sampling, while easy to obtain, has not been well studied in NP. However, in patients in whom bronchoscopic or other non-bronchoscopic techniques are not feasible, sputum sampling may be performed to identify potentially resistant organisms and help tailor therapy.

Alternative Options

Clinical Pulmonary Infection Score—Combining Clinical and Microbiologic Approaches

The clinical diagnosis of nosocomial pneumonia (new infiltrate + fever, leukocytosis, or purulent sputum) likely leads to antibiotic overuse, yet pursuing a bronchoscopic diagnosis is invasive, costly, and requires technical expertise. The quantitative ETA, blind PSB, and blind BAL discussed above are examples of some compromises that avoid the need for bronchoscopy, yet add microbiologic data in an attempt to prevent excess antibiotic therapy. Formally combining diagnostic approaches (clinical + microbiologic) may also be useful. One such option is the use of the clinical pulmonary infection score (CPIS), which combines clinical, radiographic, physiological, and microbiologic data into a numerical result. Scores >6 have been shown to correlate well with quantitative BAL (4). More recent studies, however, have suggested a lower specificity which could still result in antibiotic overuse, but this approach remains more accurate than a general clinical approach. Using the CPIS serially at the time NP is suspected and again at 72 hours may be more useful. Patients with an initial low clinical suspicion for pneumonia (CPIS of 6 or less) could have antibiotics safely discontinued at 72 hours if the CPIS remains low (5). Such a strategy may be useful in settings where more sophisticated diagnostic modalities are not available.

Multiple studies of biological markers of infection have attempted to find a non-invasive, rapid, accurate means of determining who needs antibiotics for presumed NP. Unfortunately, the results have largely been disappointing. More recently, measurement of a soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells (sTREM-1) that is upregulated in the setting of infection has been shown to improve our ability to diagnose NP accurately. Measurement of sTREM-1 was 98% sensitive and 90% specific for the diagnosis of pneumonia in mechanically ventilated patients (6). While promising, more data is needed before this test can be recommended for routine use.

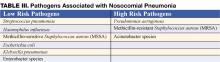

Management

Initial Treatment

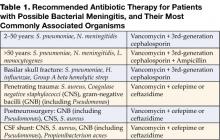

Early initiation of adequate empiric antibiotic therapy (i.e., the antibiotics administered are shown to be active against all organisms isolated) is associated with improved survival compared with initial inadequate therapy (1,7). Antibiotics should be started immediately after obtaining blood and sputum samples for culture and should not be withheld in the event of delay in diagnostic testing. The need to choose antibiotics quickly and expeditiously drives the use of broad spectrum antibiotics. In an effort to avoid unnecessary overuse of broad spectrum antibiotics, therapy should be based on risk for multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens. Identifying patients at low risk for MDR pathogens by clinical criteria allows for more narrow, but effective, antibiotic therapy. Low risk patients include those who develop their pneumonia early in the hospitalization (<5–7 days), are not immunocompromised, have not had prior broad spectrum antibiotics, and do not have risk factors for HCAP (Table I) (1,7). In these patients antibiotics should target common community-acquired organisms (Table III–low risk pathogens). Appropriate initial antibiotic therapy could include a third generation cephalosporin or a beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor. In some communities or hospital wards the incidence of methicillin-resistance among Staphylococcus aureus isolates (MRSA) may be high enough to warrant initial empiric therapy with vancomycin or linezolid.

Unfortunately, today’s increasingly complex hospitalized patients are unlikely to be “low risk,” especially in intensive care units.

Patients not meeting low risk criteria are considered to be at high risk for MDR pathogens (Table III–high risk pathogens). Initial empiric therapy needs to be broad and should include one antipseudomonal agent (cefepime or imipenem or beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor) plus a fluoroquinolone or aminoglycoside plus vancomycin or linezolid. The specific initial empiric therapy should be dictated by local resistance patterns, cost, and availability of preferred agents. When such broad spectrum therapy is initiated, it becomes imperative that antibiotics are “de-escalated” to limit antibiotic overuse. De-escalation therapy focuses on narrowing the antibiotic spectrum based on culture results, and limiting the overall duration of therapy. Hospitalists should aim to accomplish such de-escalation within 48–72 hours of initiating broad-spectrum antibiotics.

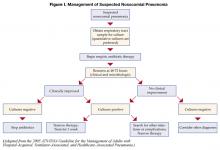

Subsequent Treatment

Patients started on initial empiric antibiotic therapy for presumed nosocomial pneumonia should be reassessed at 48–72 hours. Specifically, cultures should be checked and the clinical response to treatment evaluated. Figure I describes an algorithm for guiding treatment (1). In patients who are clinically stable and have negative lower respiratory tract cultures, antibiotics can be stopped. Patients with positive cultures should have antibiotics tailored, or “de-escalated” based on the organisms identified. In general, the most narrow spectrum antibiotic that is active against the bacteria isolated should be used. The use of combination therapy for gram negative organisms (two or more antibiotics active against a bacterial isolate) is widely practiced to achieve synergy, or prevent the development of resistance. However, in the absence of neutropenia, combination therapy has not been shown to be superior to monotherapyy (8), and monotherapy is preferred. The isolation of MRSA from a respiratory sample should also result in use of monotherapy. While some studies have suggested that linezolid may be superior to vancomycin for MRSA pneumonia, this finding needs validation in prospective studies.

A second component of de-escalation is shortening the total duration of therapy. The CPIS may be used to shorten the duration of therapy in patients at low risk for pneumonia. Investigators at a Veterans Affairs medical center randomized patients suspected of having NP, but who had a CPIS score < 6, to either treatment for 10–21 days, or short course therapy. Patients receiving short course therapy were reassessed at day 3, and if their CPIS score remained < 6, antibiotics were stopped (5). The short course therapy group had no difference in mortality when compared to the standard treatment group, but had less antibiotic use, shorter ICU stays, and was less likely to develop a superinfection or infection with a resistant organism. If the CPIS is not used, or if patients are felt to be at higher risk or convincingly demonstrated to have NP, a shorter course of therapy may still be preferred. A large randomized trial showed that 8 days of antibiotic therapy for patients with VAP resulted in similar clinical outcomes when compared to 15 days of therapy. Additionally, shorter duration antibiotic therapy was associated with lower likelihood of developing subsequent infections with multi-resistant pathogens. A subset of patients in the 8 day treatment group infected with non-fermenting gram negative bacilli (e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa) did have a higher pulmonary infection recurrence rate, but due to aggressive surveillance, this did not translate into a higher mortality risk in this subset of patients (9).

In summary, treatment of patients with suspected NP starts with immediate initiation of antibiotics and collection of respiratory secretions. While low risk patients can receive narrower spectrum therapy, most patients will require broad initial empiric therapy. The antibiotic regimen, however, should be narrowed at 48–72 hours based on microbiological results if the patient is improving. Overall treatment duration of 1 week is safe and effective with less chance of promoting growth of resistant organisms. In the subset of patients with pseudomonal infections, treatment of 1 week duration should be followed by active surveillance for recurrence, or alternatively, treatment can be extended to two weeks.

Prognosis

Once treatment for NP is initiated, clinical improvement is usually seen by 48–72 hours. There is little support for following either microbiologic response (clearance of positive cultures) or the response by chest radiography. The chest radiograph often lags behind the clinical response, however, a markedly worsening CXR (>50% increase in infiltrate) within the first 48 hours may indicate treatment failure. Clinical resolution as measured by temperature, white blood cell count, and oxygenation usually occurs by 6–7 days (10). Failure of oxygenation to improve by 72 hours has been shown to be predictive of treatment failure.

The overall mortality in patients with NP is as high as 30–70%, largely due to severe comorbid disease in the at risk population. Higher mortality rates are seen in patients with VAP and resistant organisms. The mortality attributable to the episode of NP is about 30%, and can be reduced to <15% with appropriate antibiotic therapy (1).

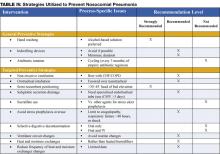

Prevention

Preventive strategies are either directed at reducing the overall incidence of infectious complications in hospitalized patients, or they are specifically targeted at reducing the incidence of nosocomial pneumonia (3). The majority of the data supporting preventive strategies is limited to patients in the ICU, and in particular, patients receiving mechanical ventilation. However, many of the preventive principles can be extrapolated to the non-ICU population. The preventive strategies are highlighted in Table IV (page 18).

General Preventive Strategies

General preventive strategies aim to avoid contamination of patients with antimicrobial resistant organisms that exist in hospitals, or mitigating the emergence of antimicrobial resistant organisms in the first place. Preventing iatrogenic spread of resistant organisms depends on careful hand hygiene. Hand washing before and after patient contact reduces the incidence of nosocomial infection. Alcohol-based hand rinses placed at the bedside may actually be superior to soap and water, and in addition, improve compliance with hand hygiene.

Minimizing the use of indwelling devices (central lines, urinary catheters) also reduces the emergence of resistant organisms. When these devices are necessary, focusing on their timely removal is critical. The control of antibiotic use has been central to many preventive strategies. Prolonged or unnecessary use of broad-spectrum antibiotics is strongly associated with development and colonization of resistant organisms. Strategies that focus on aggressive antibiotic de-escalation (described above) are a key preventive tool. Some institutions have had success with antibiotic restriction or rotation, but long term data on the effectiveness of these techniques are lacking.

Targeted Preventive Strategies

Preventive strategies to lower the incidence of NP focus on reducing risk factors for oropharyngeal or gastric colonization and subsequent aspiration of contaminated oropharyngeal or gastric secretions (1,3,7,11).

Endotracheal intubation is one of the most important risk factors for NP in patients requiring ventilatory support. The use of non-invasive ventilation (NIV) or positive pressure mask ventilation in selected groups of patients has been effective in preventing nosocomial pneumonia. Non-invasive ventilation has been most successful in patients with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and pulmonary edema secondary to congestive heart failure (CHF) and should be considered in appropriately selected patients. When intubation is required the use of nasotracheal intubation should be avoided due higher rates of NP when compared to orotracheal intubation.

Supine positioning may contribute to the development of NP, likely due to an increased risk of gastric reflux and subsequent aspiration. Studies of semi-recumbent positioning (elevation of the head of the bed >45 degrees) have shown less reflux, less aspiration, and in one recent randomized control trial, a significant reduction in the rate of VAP (12). Elevation of the head of the bed is clearly indicated in mechanically ventilated patients and is also likely to benefit all patients at risk for aspiration and subsequent NP, although this technique has not been well studied in non-ventilated patients.