User login

Painful Plaque on the Forearm

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterium marinum Infection

A repeat excisional biopsy showed suppurative granulomatous dermatitis with negative stains for infectious organisms; however, tissue culture grew Mycobacterium marinum. The patient had a history of exposure to fish tanks, which are a potential habitat for nontuberculous mycobacteria. These bacteria can enter the body through a minor laceration or cut in the skin, which was likely due to her occupation and pet care activities.1 Her fish tank exposure combined with the cutaneous findings of a long-standing indurated plaque with proximal nodular lymphangitis made M marinum infection the most likely diagnosis.2

Due to the limited specificity and sensitivity of patient symptoms, histologic staining, and direct microscopy, the gold standard for diagnosing acid-fast bacilli is tissue culture. 3 Tissue polymerase chain reaction testing is most useful in identifying the species of mycobacteria when histologic stains identify acid-fast bacilli but repeated tissue cultures are negative.4 With M marinum, a high clinical suspicion is needed to acquire a positive tissue culture because it needs to be grown for several weeks and at a temperature of 30 °C.5 Therefore, the physician should inform the laboratory if there is any suspicion for M marinum to increase the likelihood of obtaining a positive culture.

The differential diagnosis for M marinum infection includes other skin diseases that can cause nodular lymphangitis (also known as sporotrichoid spread) such as sporotrichosis, leishmaniasis, and certain bacterial and fungal infections. Although cat scratch disease, which is caused by Bartonella henselae, can appear similar to M marinum on histopathology, it clinically manifests with a single papulovesicular lesion at the site of inoculation that then forms a central eschar and resolves within a few weeks. Cat scratch disease typically causes painful lymphadenopathy, but it does not cause nodular lymphangitis or sporotrichoid spread.6 Sporotrichosis can have a similar clinical and histologic manifestation to M marinum infection, but the patient history typically includes exposure to Sporothrix schenckii through gardening or other contact with thorns, plants, or soil.2 Cutaneous sarcoidosis can have a similar clinical appearance to M marinum infection, but nodular lymphangitis does not occur and histopathology would demonstrate noncaseating epithelioid cell granulomas.7 Lastly, although vegetative pyogenic granuloma can have some of the same histologic findings as M marinum, it typically also demonstrates sinus tract formation, which was not present in our case. Additionally, vegetative pyogenic granuloma manifests with a verrucous and pustular plaque that would not have lymphocutaneous spread.8

Treatment of cutaneous M marinum infection is guided by antibiotic susceptibility testing. One regimen is clarithromycin (500 mg twice daily9) plus ethambutol. 10 Treatment often entails a multidrug combination due to the high rates of antibiotic resistance. Other antibiotics that potentially can be used include rifampin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, minocycline, and quinolones. The treatment duration typically is more than 3 months, and therapy is continued for 4 to 6 weeks after the skin lesions resolve.11 Excision of the lesion is reserved for patients with M marinum infection that fails to respond to antibiotic therapy.5

- Wayne LG, Sramek HA. Agents of newly recognized or infrequently encountered mycobacterial diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1992;5:1-25. doi:10.1128/CMR.5.1.1

- Tobin EH, Jih WW. Sporotrichoid lymphocutaneous infections: etiology, diagnosis and therapy. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:326-332.

- van Ingen J. Diagnosis of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:103-109. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1333569

- Williamson H, Phillips R, Sarfo S, et al. Genetic diversity of PCR-positive, culture-negative and culture-positive Mycobacterium ulcerans isolated from Buruli ulcer patients in Ghana. PLoS One. 2014;9:E88007. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088007

- Aubry A, Mougari F, Reibel F, et al. Mycobacterium marinum. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.TNMI7-0038-2016

- Baranowski K, Huang B. Cat scratch disease. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated June 12, 2023. Accessed July 15, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/books/NBK482139/

- Sanchez M, Haimovic A, Prystowsky S. Sarcoidosis. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:389-416. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.006

- Borg Grech S, Vella Baldacchino A, Corso R, et al. Superficial granulomatous pyoderma successfully treated with intravenous immunoglobulin. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2021;8:002656. doi:10.12890/2021_002656

- Krooks J, Weatherall A, Markowitz S. Complete resolution of Mycobacterium marinum infection with clarithromycin and ethambutol: a case report and a review of the literature. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:48-51.

- Medel-Plaza M., Esteban J. Current treatment options for Mycobacterium marinum cutaneous infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2023;24:1113-1123. doi:10.1080/14656566.2023.2211258

- Tirado-Sánchez A, Bonifaz A. Nodular lymphangitis (sporotrichoid lymphocutaneous infections): clues to differential diagnosis. J Fungi (Basel). 2018;4:56. doi:10.3390/jof4020056

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterium marinum Infection

A repeat excisional biopsy showed suppurative granulomatous dermatitis with negative stains for infectious organisms; however, tissue culture grew Mycobacterium marinum. The patient had a history of exposure to fish tanks, which are a potential habitat for nontuberculous mycobacteria. These bacteria can enter the body through a minor laceration or cut in the skin, which was likely due to her occupation and pet care activities.1 Her fish tank exposure combined with the cutaneous findings of a long-standing indurated plaque with proximal nodular lymphangitis made M marinum infection the most likely diagnosis.2

Due to the limited specificity and sensitivity of patient symptoms, histologic staining, and direct microscopy, the gold standard for diagnosing acid-fast bacilli is tissue culture. 3 Tissue polymerase chain reaction testing is most useful in identifying the species of mycobacteria when histologic stains identify acid-fast bacilli but repeated tissue cultures are negative.4 With M marinum, a high clinical suspicion is needed to acquire a positive tissue culture because it needs to be grown for several weeks and at a temperature of 30 °C.5 Therefore, the physician should inform the laboratory if there is any suspicion for M marinum to increase the likelihood of obtaining a positive culture.

The differential diagnosis for M marinum infection includes other skin diseases that can cause nodular lymphangitis (also known as sporotrichoid spread) such as sporotrichosis, leishmaniasis, and certain bacterial and fungal infections. Although cat scratch disease, which is caused by Bartonella henselae, can appear similar to M marinum on histopathology, it clinically manifests with a single papulovesicular lesion at the site of inoculation that then forms a central eschar and resolves within a few weeks. Cat scratch disease typically causes painful lymphadenopathy, but it does not cause nodular lymphangitis or sporotrichoid spread.6 Sporotrichosis can have a similar clinical and histologic manifestation to M marinum infection, but the patient history typically includes exposure to Sporothrix schenckii through gardening or other contact with thorns, plants, or soil.2 Cutaneous sarcoidosis can have a similar clinical appearance to M marinum infection, but nodular lymphangitis does not occur and histopathology would demonstrate noncaseating epithelioid cell granulomas.7 Lastly, although vegetative pyogenic granuloma can have some of the same histologic findings as M marinum, it typically also demonstrates sinus tract formation, which was not present in our case. Additionally, vegetative pyogenic granuloma manifests with a verrucous and pustular plaque that would not have lymphocutaneous spread.8

Treatment of cutaneous M marinum infection is guided by antibiotic susceptibility testing. One regimen is clarithromycin (500 mg twice daily9) plus ethambutol. 10 Treatment often entails a multidrug combination due to the high rates of antibiotic resistance. Other antibiotics that potentially can be used include rifampin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, minocycline, and quinolones. The treatment duration typically is more than 3 months, and therapy is continued for 4 to 6 weeks after the skin lesions resolve.11 Excision of the lesion is reserved for patients with M marinum infection that fails to respond to antibiotic therapy.5

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterium marinum Infection

A repeat excisional biopsy showed suppurative granulomatous dermatitis with negative stains for infectious organisms; however, tissue culture grew Mycobacterium marinum. The patient had a history of exposure to fish tanks, which are a potential habitat for nontuberculous mycobacteria. These bacteria can enter the body through a minor laceration or cut in the skin, which was likely due to her occupation and pet care activities.1 Her fish tank exposure combined with the cutaneous findings of a long-standing indurated plaque with proximal nodular lymphangitis made M marinum infection the most likely diagnosis.2

Due to the limited specificity and sensitivity of patient symptoms, histologic staining, and direct microscopy, the gold standard for diagnosing acid-fast bacilli is tissue culture. 3 Tissue polymerase chain reaction testing is most useful in identifying the species of mycobacteria when histologic stains identify acid-fast bacilli but repeated tissue cultures are negative.4 With M marinum, a high clinical suspicion is needed to acquire a positive tissue culture because it needs to be grown for several weeks and at a temperature of 30 °C.5 Therefore, the physician should inform the laboratory if there is any suspicion for M marinum to increase the likelihood of obtaining a positive culture.

The differential diagnosis for M marinum infection includes other skin diseases that can cause nodular lymphangitis (also known as sporotrichoid spread) such as sporotrichosis, leishmaniasis, and certain bacterial and fungal infections. Although cat scratch disease, which is caused by Bartonella henselae, can appear similar to M marinum on histopathology, it clinically manifests with a single papulovesicular lesion at the site of inoculation that then forms a central eschar and resolves within a few weeks. Cat scratch disease typically causes painful lymphadenopathy, but it does not cause nodular lymphangitis or sporotrichoid spread.6 Sporotrichosis can have a similar clinical and histologic manifestation to M marinum infection, but the patient history typically includes exposure to Sporothrix schenckii through gardening or other contact with thorns, plants, or soil.2 Cutaneous sarcoidosis can have a similar clinical appearance to M marinum infection, but nodular lymphangitis does not occur and histopathology would demonstrate noncaseating epithelioid cell granulomas.7 Lastly, although vegetative pyogenic granuloma can have some of the same histologic findings as M marinum, it typically also demonstrates sinus tract formation, which was not present in our case. Additionally, vegetative pyogenic granuloma manifests with a verrucous and pustular plaque that would not have lymphocutaneous spread.8

Treatment of cutaneous M marinum infection is guided by antibiotic susceptibility testing. One regimen is clarithromycin (500 mg twice daily9) plus ethambutol. 10 Treatment often entails a multidrug combination due to the high rates of antibiotic resistance. Other antibiotics that potentially can be used include rifampin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, minocycline, and quinolones. The treatment duration typically is more than 3 months, and therapy is continued for 4 to 6 weeks after the skin lesions resolve.11 Excision of the lesion is reserved for patients with M marinum infection that fails to respond to antibiotic therapy.5

- Wayne LG, Sramek HA. Agents of newly recognized or infrequently encountered mycobacterial diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1992;5:1-25. doi:10.1128/CMR.5.1.1

- Tobin EH, Jih WW. Sporotrichoid lymphocutaneous infections: etiology, diagnosis and therapy. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:326-332.

- van Ingen J. Diagnosis of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:103-109. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1333569

- Williamson H, Phillips R, Sarfo S, et al. Genetic diversity of PCR-positive, culture-negative and culture-positive Mycobacterium ulcerans isolated from Buruli ulcer patients in Ghana. PLoS One. 2014;9:E88007. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088007

- Aubry A, Mougari F, Reibel F, et al. Mycobacterium marinum. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.TNMI7-0038-2016

- Baranowski K, Huang B. Cat scratch disease. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated June 12, 2023. Accessed July 15, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/books/NBK482139/

- Sanchez M, Haimovic A, Prystowsky S. Sarcoidosis. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:389-416. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.006

- Borg Grech S, Vella Baldacchino A, Corso R, et al. Superficial granulomatous pyoderma successfully treated with intravenous immunoglobulin. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2021;8:002656. doi:10.12890/2021_002656

- Krooks J, Weatherall A, Markowitz S. Complete resolution of Mycobacterium marinum infection with clarithromycin and ethambutol: a case report and a review of the literature. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:48-51.

- Medel-Plaza M., Esteban J. Current treatment options for Mycobacterium marinum cutaneous infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2023;24:1113-1123. doi:10.1080/14656566.2023.2211258

- Tirado-Sánchez A, Bonifaz A. Nodular lymphangitis (sporotrichoid lymphocutaneous infections): clues to differential diagnosis. J Fungi (Basel). 2018;4:56. doi:10.3390/jof4020056

- Wayne LG, Sramek HA. Agents of newly recognized or infrequently encountered mycobacterial diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1992;5:1-25. doi:10.1128/CMR.5.1.1

- Tobin EH, Jih WW. Sporotrichoid lymphocutaneous infections: etiology, diagnosis and therapy. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:326-332.

- van Ingen J. Diagnosis of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:103-109. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1333569

- Williamson H, Phillips R, Sarfo S, et al. Genetic diversity of PCR-positive, culture-negative and culture-positive Mycobacterium ulcerans isolated from Buruli ulcer patients in Ghana. PLoS One. 2014;9:E88007. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088007

- Aubry A, Mougari F, Reibel F, et al. Mycobacterium marinum. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.TNMI7-0038-2016

- Baranowski K, Huang B. Cat scratch disease. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated June 12, 2023. Accessed July 15, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/books/NBK482139/

- Sanchez M, Haimovic A, Prystowsky S. Sarcoidosis. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:389-416. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.006

- Borg Grech S, Vella Baldacchino A, Corso R, et al. Superficial granulomatous pyoderma successfully treated with intravenous immunoglobulin. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2021;8:002656. doi:10.12890/2021_002656

- Krooks J, Weatherall A, Markowitz S. Complete resolution of Mycobacterium marinum infection with clarithromycin and ethambutol: a case report and a review of the literature. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:48-51.

- Medel-Plaza M., Esteban J. Current treatment options for Mycobacterium marinum cutaneous infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2023;24:1113-1123. doi:10.1080/14656566.2023.2211258

- Tirado-Sánchez A, Bonifaz A. Nodular lymphangitis (sporotrichoid lymphocutaneous infections): clues to differential diagnosis. J Fungi (Basel). 2018;4:56. doi:10.3390/jof4020056

A 30-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with lesions on the right forearm of 2 years’ duration. Her medical history was unremarkable. She reported working as a chef and caring for multiple pets in her home, including 3 cats, 6 fish tanks, 3 dogs, and 3 lizards. Physical examination revealed a painful, indurated, red-violaceous plaque on the right forearm with satellite pink nodules that had been slowly migrating proximally up the forearm. An outside excisional biopsy performed 1 year prior had shown suppurative granulomatous dermatitis with negative stains for infectious organisms and negative tissue cultures. At that time, the patient was diagnosed with ruptured folliculitis; however, a subsequent lack of clinical improvement prompted her to seek a second opinion at our clinic.

Erythematous Plaques on the Dorsal Aspect of the Hand

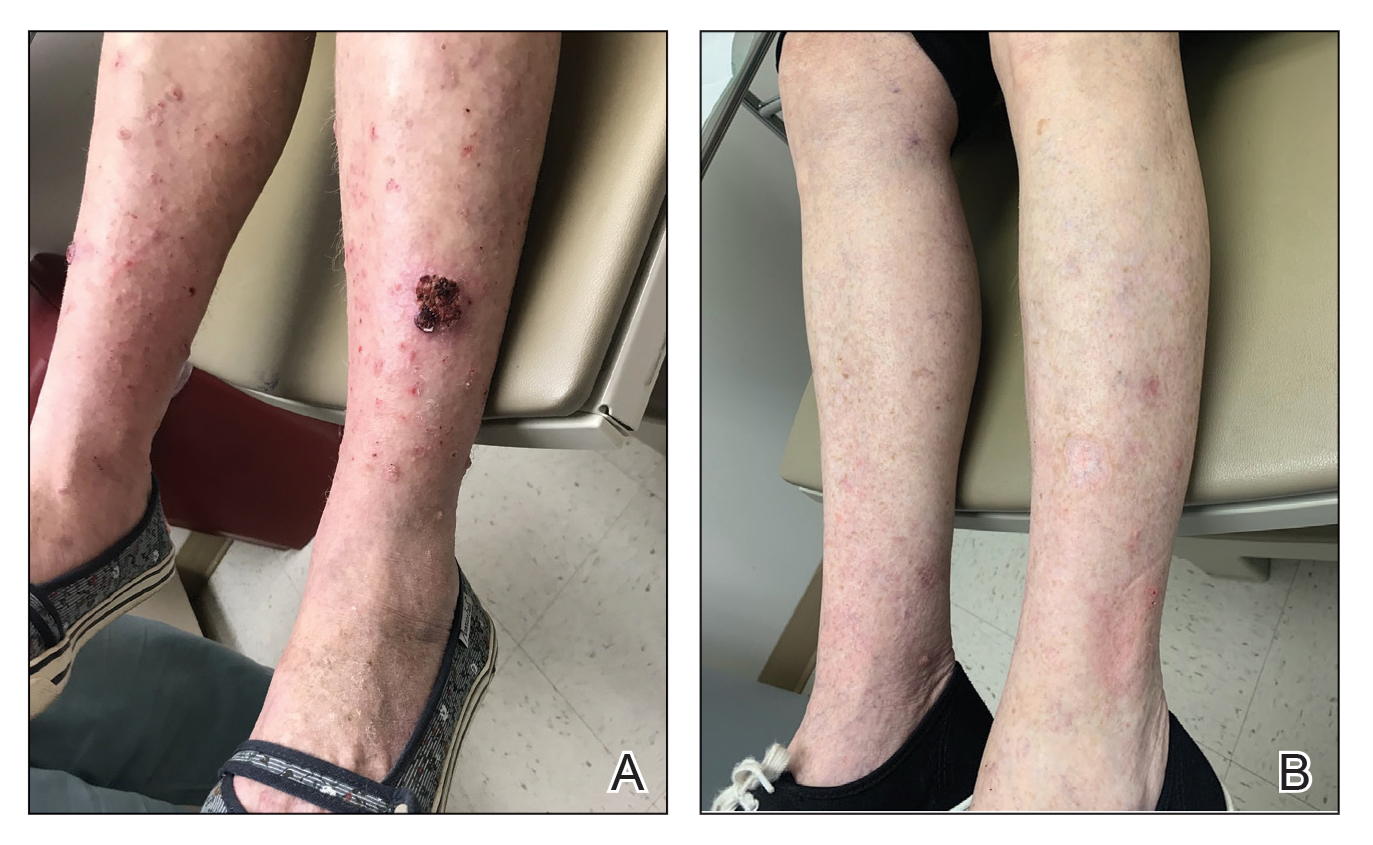

The Diagnosis: Majocchi Granuloma

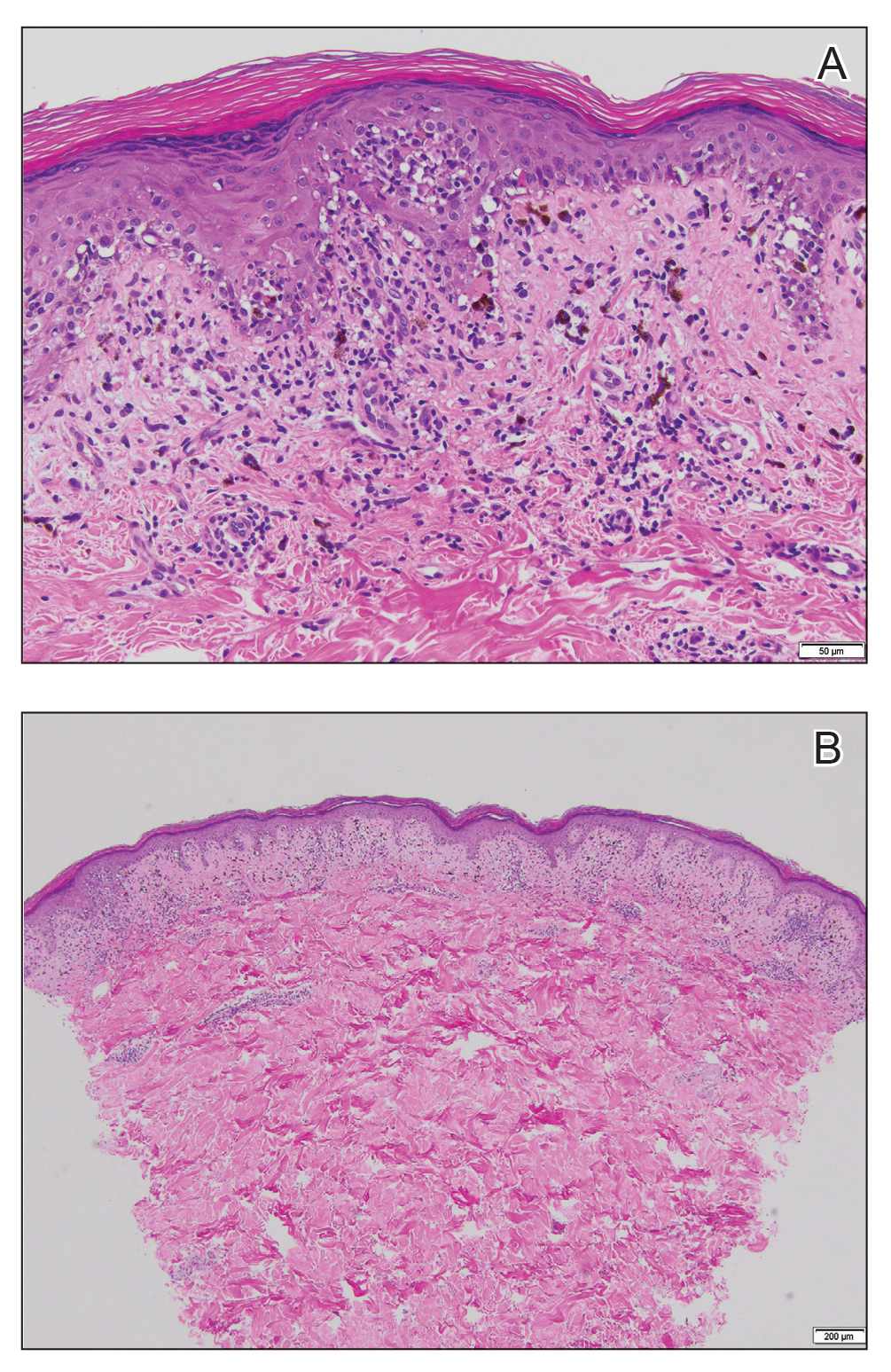

Histopathology showed rare follicular-based organisms highlighted by periodic acid–Schiff staining. This finding along with her use of clobetasol ointment on the hands led to a diagnosis of Majocchi granuloma in our patient. Clobetasol and crisaborole ointments were discontinued, and she was started on oral terbinafine 250 mg daily for 4 weeks, which resulted in resolution of the rash.

Majocchi granuloma (also known as nodular granulomatous perifolliculitis) is a perifollicular granulomatous process caused by a dermatophyte infection of the hair follicles. Trichophyton rubrum is the most commonly implicated organism, followed by Trichophyton mentagrophytes and Epidermophyton floccosum, which also cause tinea corporis and tinea pedis.1 This condition most commonly occurs in women aged 20 to 35 years. Risk factors include trauma, occlusion of the hair follicles, immunosuppression, and use of potent topical corticosteroids in patients with tinea.2,3 Immunocompetent patients present with perifollicular papules or pustules with erythematous scaly plaques on the extremities, while immunocompromised patients may have subcutaneous nodules or abscesses on any hair-bearing parts of the body.3

Majocchi granuloma is considered a dermal fungal infection in which the disruption of hair follicles from occlusion or trauma allows fungal organisms and keratinaceous material substrates to be introduced into the dermis. The differential diagnosis is based on the types of presenting lesions. The papules of Majocchi granuloma can resemble folliculitis, acne, or insect bites, while nodules can resemble erythema nodosum or furunculosis.4 Plaques, such as those seen in our patient, can mimic cellulitis and allergic or irritant contact dermatitis.4 Additionally, the plaques may appear annular or figurate, which may resemble erythema gyratum repens or erythema annulare centrifugum.

The diagnosis of Majocchi granuloma often requires fungal culture and biopsy because a potassium hydroxide preparation is unable to distinguish between superficial and invasive dermatophytes.3 Histopathology will show perifollicular granulomatous inflammation. Fungal elements can be detected with periodic acid–Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining of the hairs and hair follicles as well as dermal infiltrates.4

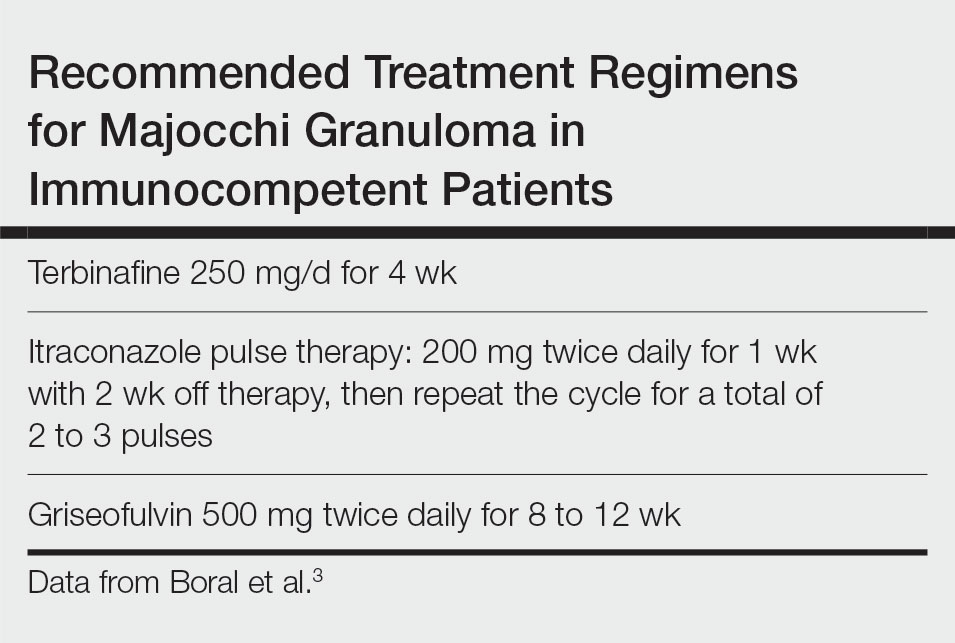

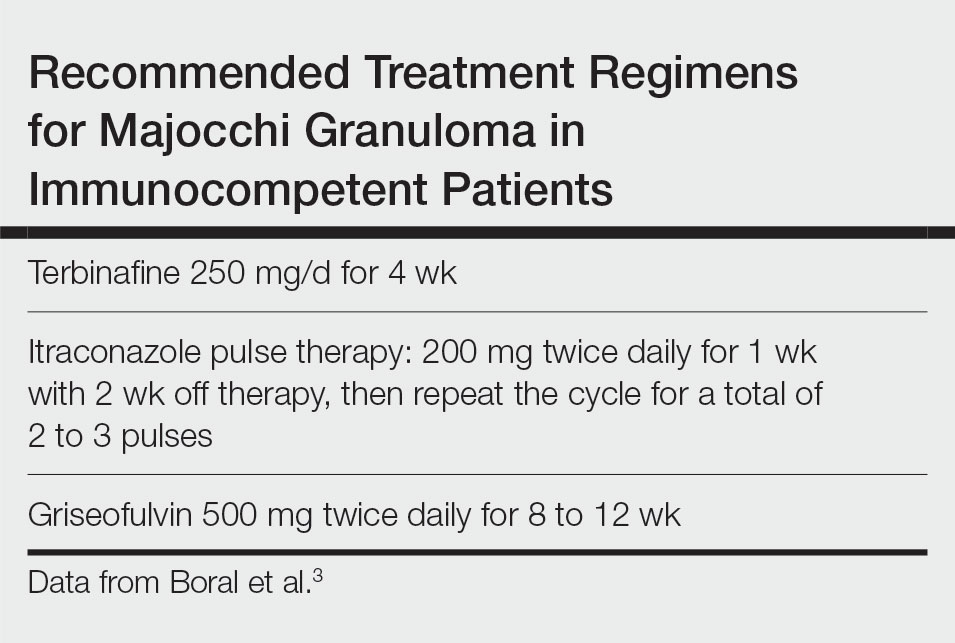

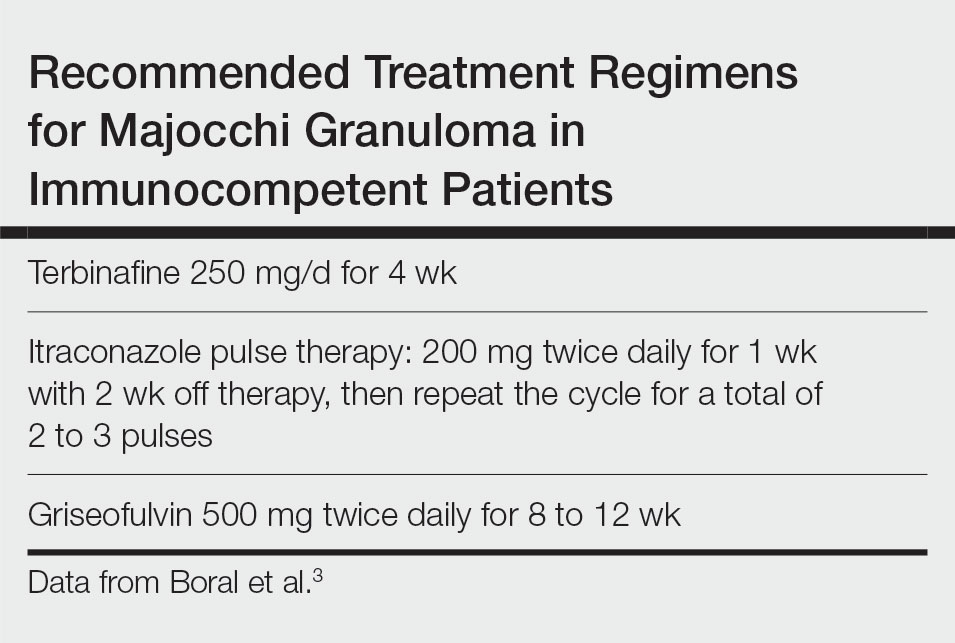

Topical corticosteroids should be discontinued. Systemic antifungals are the treatment of choice for Majocchi granuloma, as topical antifungals are not effective against deep fungal infections. Although there are no standard guidelines on duration or dosage, recommended regimens in immunocompetent patients include terbinafine 250 mg/d for 4 weeks; itraconazole pulse therapy consisting of 200 mg twice daily for 1 week with 2 weeks off therapy, then repeat the cycle for a total of 2 to 3 pulses; and griseofulvin 500 mg twice daily for 8 to 12 weeks (Table).3 For immunocompromised patients, combination therapy with more than one antifungal may be necessary.

- James WD, Berger T, Elston DM. Diseases resulting from fungi and yeasts. In: James WD, Berger T, Elston D, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2016:285-318.

- Li FQ, Lv S, Xia JX. Majocchi’s granuloma after topical corticosteroids therapy. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2014;2014:507176.

- Boral H, Durdu M, Ilkit M. Majocchi’s granuloma: current perspectives. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:751-760.

- I˙lkit M, Durdu M, Karakas¸ M. Majocchi’s granuloma: a symptom complex caused by fungal pathogens. Med Mycol. 2012;50:449-457.

The Diagnosis: Majocchi Granuloma

Histopathology showed rare follicular-based organisms highlighted by periodic acid–Schiff staining. This finding along with her use of clobetasol ointment on the hands led to a diagnosis of Majocchi granuloma in our patient. Clobetasol and crisaborole ointments were discontinued, and she was started on oral terbinafine 250 mg daily for 4 weeks, which resulted in resolution of the rash.

Majocchi granuloma (also known as nodular granulomatous perifolliculitis) is a perifollicular granulomatous process caused by a dermatophyte infection of the hair follicles. Trichophyton rubrum is the most commonly implicated organism, followed by Trichophyton mentagrophytes and Epidermophyton floccosum, which also cause tinea corporis and tinea pedis.1 This condition most commonly occurs in women aged 20 to 35 years. Risk factors include trauma, occlusion of the hair follicles, immunosuppression, and use of potent topical corticosteroids in patients with tinea.2,3 Immunocompetent patients present with perifollicular papules or pustules with erythematous scaly plaques on the extremities, while immunocompromised patients may have subcutaneous nodules or abscesses on any hair-bearing parts of the body.3

Majocchi granuloma is considered a dermal fungal infection in which the disruption of hair follicles from occlusion or trauma allows fungal organisms and keratinaceous material substrates to be introduced into the dermis. The differential diagnosis is based on the types of presenting lesions. The papules of Majocchi granuloma can resemble folliculitis, acne, or insect bites, while nodules can resemble erythema nodosum or furunculosis.4 Plaques, such as those seen in our patient, can mimic cellulitis and allergic or irritant contact dermatitis.4 Additionally, the plaques may appear annular or figurate, which may resemble erythema gyratum repens or erythema annulare centrifugum.

The diagnosis of Majocchi granuloma often requires fungal culture and biopsy because a potassium hydroxide preparation is unable to distinguish between superficial and invasive dermatophytes.3 Histopathology will show perifollicular granulomatous inflammation. Fungal elements can be detected with periodic acid–Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining of the hairs and hair follicles as well as dermal infiltrates.4

Topical corticosteroids should be discontinued. Systemic antifungals are the treatment of choice for Majocchi granuloma, as topical antifungals are not effective against deep fungal infections. Although there are no standard guidelines on duration or dosage, recommended regimens in immunocompetent patients include terbinafine 250 mg/d for 4 weeks; itraconazole pulse therapy consisting of 200 mg twice daily for 1 week with 2 weeks off therapy, then repeat the cycle for a total of 2 to 3 pulses; and griseofulvin 500 mg twice daily for 8 to 12 weeks (Table).3 For immunocompromised patients, combination therapy with more than one antifungal may be necessary.

The Diagnosis: Majocchi Granuloma

Histopathology showed rare follicular-based organisms highlighted by periodic acid–Schiff staining. This finding along with her use of clobetasol ointment on the hands led to a diagnosis of Majocchi granuloma in our patient. Clobetasol and crisaborole ointments were discontinued, and she was started on oral terbinafine 250 mg daily for 4 weeks, which resulted in resolution of the rash.

Majocchi granuloma (also known as nodular granulomatous perifolliculitis) is a perifollicular granulomatous process caused by a dermatophyte infection of the hair follicles. Trichophyton rubrum is the most commonly implicated organism, followed by Trichophyton mentagrophytes and Epidermophyton floccosum, which also cause tinea corporis and tinea pedis.1 This condition most commonly occurs in women aged 20 to 35 years. Risk factors include trauma, occlusion of the hair follicles, immunosuppression, and use of potent topical corticosteroids in patients with tinea.2,3 Immunocompetent patients present with perifollicular papules or pustules with erythematous scaly plaques on the extremities, while immunocompromised patients may have subcutaneous nodules or abscesses on any hair-bearing parts of the body.3

Majocchi granuloma is considered a dermal fungal infection in which the disruption of hair follicles from occlusion or trauma allows fungal organisms and keratinaceous material substrates to be introduced into the dermis. The differential diagnosis is based on the types of presenting lesions. The papules of Majocchi granuloma can resemble folliculitis, acne, or insect bites, while nodules can resemble erythema nodosum or furunculosis.4 Plaques, such as those seen in our patient, can mimic cellulitis and allergic or irritant contact dermatitis.4 Additionally, the plaques may appear annular or figurate, which may resemble erythema gyratum repens or erythema annulare centrifugum.

The diagnosis of Majocchi granuloma often requires fungal culture and biopsy because a potassium hydroxide preparation is unable to distinguish between superficial and invasive dermatophytes.3 Histopathology will show perifollicular granulomatous inflammation. Fungal elements can be detected with periodic acid–Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining of the hairs and hair follicles as well as dermal infiltrates.4

Topical corticosteroids should be discontinued. Systemic antifungals are the treatment of choice for Majocchi granuloma, as topical antifungals are not effective against deep fungal infections. Although there are no standard guidelines on duration or dosage, recommended regimens in immunocompetent patients include terbinafine 250 mg/d for 4 weeks; itraconazole pulse therapy consisting of 200 mg twice daily for 1 week with 2 weeks off therapy, then repeat the cycle for a total of 2 to 3 pulses; and griseofulvin 500 mg twice daily for 8 to 12 weeks (Table).3 For immunocompromised patients, combination therapy with more than one antifungal may be necessary.

- James WD, Berger T, Elston DM. Diseases resulting from fungi and yeasts. In: James WD, Berger T, Elston D, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2016:285-318.

- Li FQ, Lv S, Xia JX. Majocchi’s granuloma after topical corticosteroids therapy. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2014;2014:507176.

- Boral H, Durdu M, Ilkit M. Majocchi’s granuloma: current perspectives. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:751-760.

- I˙lkit M, Durdu M, Karakas¸ M. Majocchi’s granuloma: a symptom complex caused by fungal pathogens. Med Mycol. 2012;50:449-457.

- James WD, Berger T, Elston DM. Diseases resulting from fungi and yeasts. In: James WD, Berger T, Elston D, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2016:285-318.

- Li FQ, Lv S, Xia JX. Majocchi’s granuloma after topical corticosteroids therapy. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2014;2014:507176.

- Boral H, Durdu M, Ilkit M. Majocchi’s granuloma: current perspectives. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:751-760.

- I˙lkit M, Durdu M, Karakas¸ M. Majocchi’s granuloma: a symptom complex caused by fungal pathogens. Med Mycol. 2012;50:449-457.

A 33-year-old woman presented with an asymptomatic rash on the left hand that was suspected by her primary care physician to be a flare of hand dermatitis. The patient had a history of irritant hand dermatitis diagnosed 2 years prior that was suspected to be secondary to frequent handwashing and was well controlled with clobetasol and crisaborole ointments for 1 year. Four months prior to the current presentation, she developed a flare that was refractory to these topical therapies; treatment with biweekly dupilumab 300 mg was initiated by dermatology, but the rash continued to evolve. A punch biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis.

Diffuse Papular Eruption With Erosions and Ulcerations

The Diagnosis: Immunotherapy-Related Lichenoid Drug Eruption

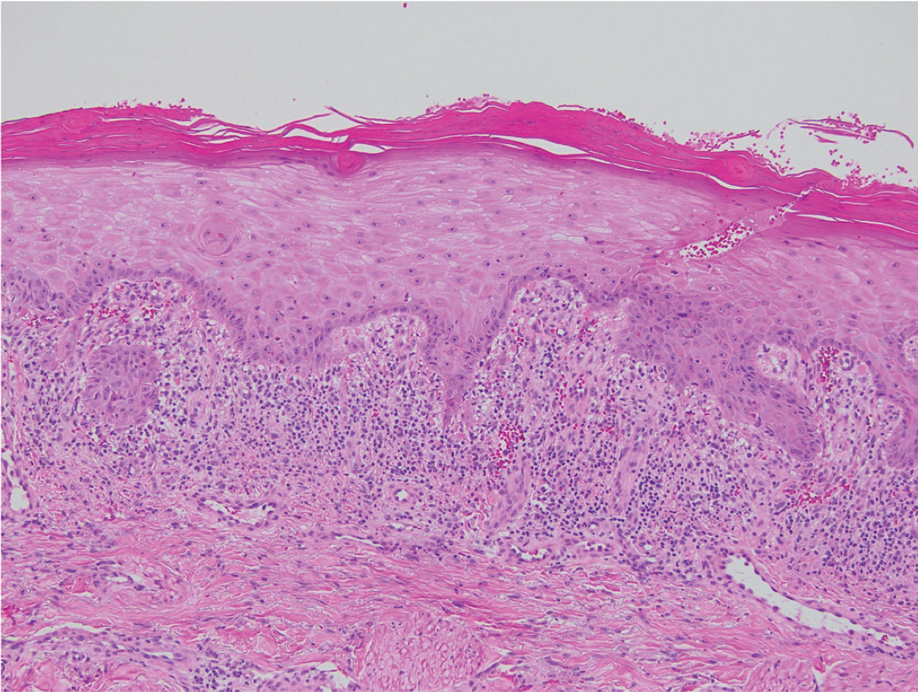

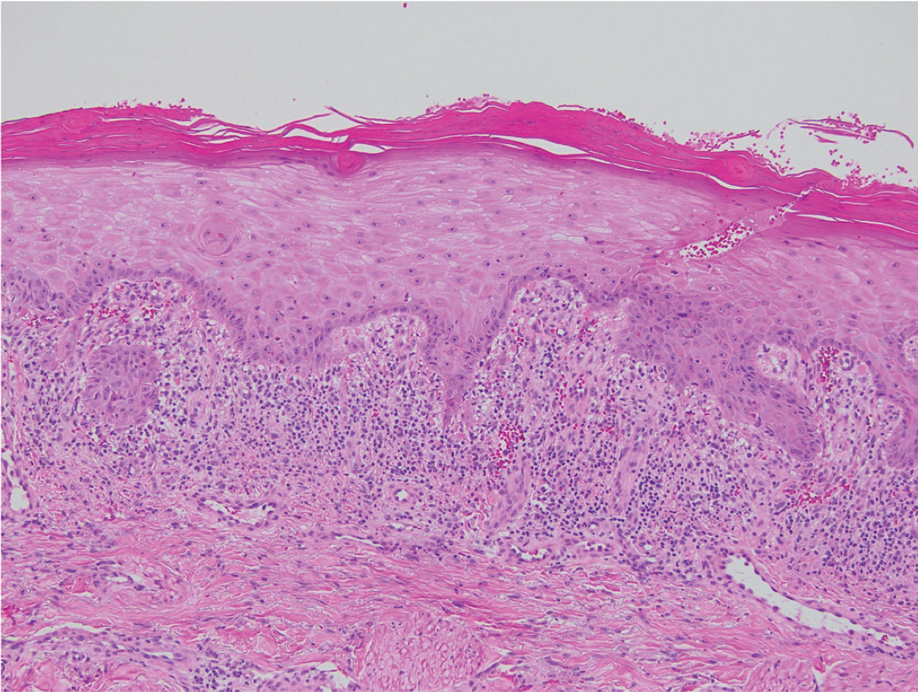

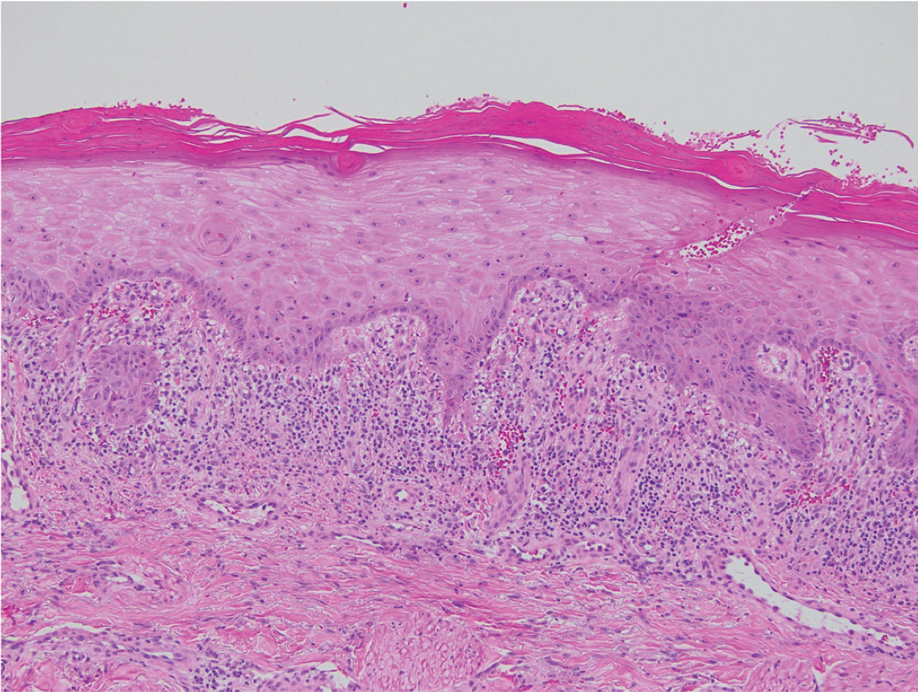

Direct immunofluorescence was negative, and histopathology revealed a lichenoid interface dermatitis, minimal parakeratosis, and saw-toothed rete ridges (Figure 1). He was diagnosed with an immunotherapyrelated lichenoid drug eruption based on the morphology of the skin lesions and clinicopathologic correlation. Bullous pemphigoid and lichen planus pemphigoides were ruled out given the negative direct immunofluorescence findings. Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS)/toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) was not consistent with the clinical presentation, especially given the lack of mucosal findings. The histology also was not consistent, as the biopsy specimen lacked apoptotic and necrotic keratinocytes to the degree seen in SJS/TEN and also had a greater degree of inflammatory infiltrate. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome was ruled out given the lack of systemic findings, including facial swelling and lymphadenopathy and the clinical appearance of the rash. No morbilliform features were present, which is the most common presentation of DRESS syndrome.

Checkpoint inhibitor (CPI) therapy has become the cornerstone in management of certain advanced malignancies.1 Checkpoint inhibitors block cytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4, programmed cell death-1, and/or programmed cell death ligand-1, allowing activated T cells to infiltrate the tumor microenvironment and destroy malignant cells. Checkpoint inhibitors are approved for the treatment of melanoma, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma and are being investigated in various other cutaneous and soft tissue malignancies.1-3

Although CPIs have shown substantial efficacy in the management of advanced malignancies, immune-related adverse events (AEs) are common due to nonspecific immune activation.2 Immune-related cutaneous AEs are the most common immune-related AEs, occurring in 30% to 50% of patients who undergo treatment.2-5 Common immune-related cutaneous AEs include maculopapular, psoriasiform, and lichenoid dermatitis, as well as pruritus without dermatitis.2,3,6 Other reactions include but are not limited to bullous pemphigoid, vitiligolike depigmentation, and alopecia.2,3 Immune-related cutaneous AEs usually are self-limited; however, severe life-threatening reactions such as the spectrum of SJS/TEN and DRESS syndrome also can occur.2-4 Immune-related cutaneous AEs are graded based on the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events: grade 1 reactions are asymptomatic and cover less than 10% of the patient’s body surface area (BSA), grade 2 reactions have mild symptoms and cover 10% to 30% of the patient’s BSA, grade 3 reactions have moderate to severe symptoms and cover greater than 30% of the patient’s BSA, and grade 4 reactions are life-threatening.2,3 With prompt recognition and adequate treatment, mild to moderate immune-related cutaneous AEs—grades 1 and 2—largely are reversible, and less than 5% require discontinuation of therapy.2,3,6 It has been suggested that immune-related cutaneous AEs may be a positive prognostic factor in the treatment of underlying malignancy, indicating adequate immune activation targeting the malignant cells.6

Although our patient had some typical violaceous, flat-topped papules and plaques with Wickham striae, he also had atypical findings for a lichenoid reaction. Given the endorsement of blisters, it is possible that some of these lesions initially were bullous and subsequently ruptured, leaving behind erosions. However, in other areas, there also were eroded papules and ulcerations without a reported history of excoriation, scratching, picking, or prior bullae, including difficult-to-reach areas such as the back. It is favored that these lesions represented a robust lichenoid dermatitis leading to erosive and ulcerated lesions, similar to the formation of bullous lichen planus. Lichenoid eruptions secondary to immunotherapy are well-known phenomena, but a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms ulcer, lichenoid, and immunotherapy revealed only 2 cases of ulcerative lichenoid eruptions: a localized digital erosive lichenoid dermatitis and a widespread ulcerative lichenoid drug eruption without true erosions.7,8 However, widespread erosive and ulcerated lichenoid reactions are rare.

Lichenoid eruptions most strongly are associated with anti–programmed cell death-1/ programmed cell death ligand-1 therapy, occurring in 20% of patients undergoing treatment.3 Lichenoid eruptions present as discrete, pruritic, erythematous, violaceous papules and plaques on the chest and back and rarely may involve the limbs, palmoplantar surfaces, and oral mucosa.2,3,6 Histopathologic features include a dense bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis with scattered apoptotic keratinocytes in the basal layer of the epidermis.2,4,6 Grades 1 to 2 lesions can be managed with high-potency topical corticosteroids without CPI dose interruption, with more extensive grade 2 lesions requiring systemic corticosteroids.2,6,9 Lichenoid eruptions grade 3 or higher also require systemic corticosteroid therapy CPI therapy cessation until the eruption has receded to grade 0 to 1.2 Alternative treatment options for high-grade toxicity include phototherapy and acitretin.2,4,9

Our patient was treated with cessation of immunotherapy and initiation of a systemic corticosteroid taper, acitretin, and narrowband UVB therapy. After 6 weeks of treatment, the pain and pruritus improved and the rash had resolved in some areas while it had taken on a more classic lichenoid appearance with violaceous scaly papules and plaques (Figure 2) in areas of prior ulcers and erosions. He no longer had any bullae, erosions, or ulcers.

- Barrios DM, Do MH, Phillips GS, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors to treat cutaneous malignancies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1239-1253. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.131

- Geisler AN, Phillips GS, Barrios DM, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related dermatologic adverse events. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1255-1268. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.132

- Tattersall IW, Leventhal JS. Cutaneous toxicities of immune checkpoint inhibitors: the role of the dermatologist. Yale J Biol Med. 2020;93:123-132.

- Si X, He C, Zhang L, et al. Management of immune checkpoint inhibitor-related dermatologic adverse events. Thorac Cancer. 2020;11:488-492. doi:10.1111/1759-7714.13275

- Eggermont AMM, Kicinski M, Blank CU, et al. Association between immune-related adverse events and recurrence-free survival among patients with stage III melanoma randomized to receive pembrolizumab or placebo: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:519-527. doi:10.1001 /jamaoncol.2019.5570

- Sibaud V, Meyer N, Lamant L, et al. Dermatologic complications of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Curr Opin Oncol. 2016;28:254-263. doi:10.1097/CCO.0000000000000290

- Martínez-Doménech Á, García-Legaz Martínez M, Magdaleno-Tapial J, et al. Digital ulcerative lichenoid dermatitis in a patient receiving anti-PD-1 therapy. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt8sm0j7t7.

- Davis MJ, Wilken R, Fung MA, et al. Debilitating erosive lichenoid interface dermatitis from checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt3vq6b04v.

- Apalla Z, Papageorgiou C, Lallas A, et al. Cutaneous adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a literature review [published online January 29, 2021]. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2021;11:E2021155. doi:10.5826/dpc.1101a155

The Diagnosis: Immunotherapy-Related Lichenoid Drug Eruption

Direct immunofluorescence was negative, and histopathology revealed a lichenoid interface dermatitis, minimal parakeratosis, and saw-toothed rete ridges (Figure 1). He was diagnosed with an immunotherapyrelated lichenoid drug eruption based on the morphology of the skin lesions and clinicopathologic correlation. Bullous pemphigoid and lichen planus pemphigoides were ruled out given the negative direct immunofluorescence findings. Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS)/toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) was not consistent with the clinical presentation, especially given the lack of mucosal findings. The histology also was not consistent, as the biopsy specimen lacked apoptotic and necrotic keratinocytes to the degree seen in SJS/TEN and also had a greater degree of inflammatory infiltrate. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome was ruled out given the lack of systemic findings, including facial swelling and lymphadenopathy and the clinical appearance of the rash. No morbilliform features were present, which is the most common presentation of DRESS syndrome.

Checkpoint inhibitor (CPI) therapy has become the cornerstone in management of certain advanced malignancies.1 Checkpoint inhibitors block cytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4, programmed cell death-1, and/or programmed cell death ligand-1, allowing activated T cells to infiltrate the tumor microenvironment and destroy malignant cells. Checkpoint inhibitors are approved for the treatment of melanoma, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma and are being investigated in various other cutaneous and soft tissue malignancies.1-3

Although CPIs have shown substantial efficacy in the management of advanced malignancies, immune-related adverse events (AEs) are common due to nonspecific immune activation.2 Immune-related cutaneous AEs are the most common immune-related AEs, occurring in 30% to 50% of patients who undergo treatment.2-5 Common immune-related cutaneous AEs include maculopapular, psoriasiform, and lichenoid dermatitis, as well as pruritus without dermatitis.2,3,6 Other reactions include but are not limited to bullous pemphigoid, vitiligolike depigmentation, and alopecia.2,3 Immune-related cutaneous AEs usually are self-limited; however, severe life-threatening reactions such as the spectrum of SJS/TEN and DRESS syndrome also can occur.2-4 Immune-related cutaneous AEs are graded based on the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events: grade 1 reactions are asymptomatic and cover less than 10% of the patient’s body surface area (BSA), grade 2 reactions have mild symptoms and cover 10% to 30% of the patient’s BSA, grade 3 reactions have moderate to severe symptoms and cover greater than 30% of the patient’s BSA, and grade 4 reactions are life-threatening.2,3 With prompt recognition and adequate treatment, mild to moderate immune-related cutaneous AEs—grades 1 and 2—largely are reversible, and less than 5% require discontinuation of therapy.2,3,6 It has been suggested that immune-related cutaneous AEs may be a positive prognostic factor in the treatment of underlying malignancy, indicating adequate immune activation targeting the malignant cells.6

Although our patient had some typical violaceous, flat-topped papules and plaques with Wickham striae, he also had atypical findings for a lichenoid reaction. Given the endorsement of blisters, it is possible that some of these lesions initially were bullous and subsequently ruptured, leaving behind erosions. However, in other areas, there also were eroded papules and ulcerations without a reported history of excoriation, scratching, picking, or prior bullae, including difficult-to-reach areas such as the back. It is favored that these lesions represented a robust lichenoid dermatitis leading to erosive and ulcerated lesions, similar to the formation of bullous lichen planus. Lichenoid eruptions secondary to immunotherapy are well-known phenomena, but a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms ulcer, lichenoid, and immunotherapy revealed only 2 cases of ulcerative lichenoid eruptions: a localized digital erosive lichenoid dermatitis and a widespread ulcerative lichenoid drug eruption without true erosions.7,8 However, widespread erosive and ulcerated lichenoid reactions are rare.

Lichenoid eruptions most strongly are associated with anti–programmed cell death-1/ programmed cell death ligand-1 therapy, occurring in 20% of patients undergoing treatment.3 Lichenoid eruptions present as discrete, pruritic, erythematous, violaceous papules and plaques on the chest and back and rarely may involve the limbs, palmoplantar surfaces, and oral mucosa.2,3,6 Histopathologic features include a dense bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis with scattered apoptotic keratinocytes in the basal layer of the epidermis.2,4,6 Grades 1 to 2 lesions can be managed with high-potency topical corticosteroids without CPI dose interruption, with more extensive grade 2 lesions requiring systemic corticosteroids.2,6,9 Lichenoid eruptions grade 3 or higher also require systemic corticosteroid therapy CPI therapy cessation until the eruption has receded to grade 0 to 1.2 Alternative treatment options for high-grade toxicity include phototherapy and acitretin.2,4,9

Our patient was treated with cessation of immunotherapy and initiation of a systemic corticosteroid taper, acitretin, and narrowband UVB therapy. After 6 weeks of treatment, the pain and pruritus improved and the rash had resolved in some areas while it had taken on a more classic lichenoid appearance with violaceous scaly papules and plaques (Figure 2) in areas of prior ulcers and erosions. He no longer had any bullae, erosions, or ulcers.

The Diagnosis: Immunotherapy-Related Lichenoid Drug Eruption

Direct immunofluorescence was negative, and histopathology revealed a lichenoid interface dermatitis, minimal parakeratosis, and saw-toothed rete ridges (Figure 1). He was diagnosed with an immunotherapyrelated lichenoid drug eruption based on the morphology of the skin lesions and clinicopathologic correlation. Bullous pemphigoid and lichen planus pemphigoides were ruled out given the negative direct immunofluorescence findings. Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS)/toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) was not consistent with the clinical presentation, especially given the lack of mucosal findings. The histology also was not consistent, as the biopsy specimen lacked apoptotic and necrotic keratinocytes to the degree seen in SJS/TEN and also had a greater degree of inflammatory infiltrate. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome was ruled out given the lack of systemic findings, including facial swelling and lymphadenopathy and the clinical appearance of the rash. No morbilliform features were present, which is the most common presentation of DRESS syndrome.

Checkpoint inhibitor (CPI) therapy has become the cornerstone in management of certain advanced malignancies.1 Checkpoint inhibitors block cytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4, programmed cell death-1, and/or programmed cell death ligand-1, allowing activated T cells to infiltrate the tumor microenvironment and destroy malignant cells. Checkpoint inhibitors are approved for the treatment of melanoma, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma and are being investigated in various other cutaneous and soft tissue malignancies.1-3

Although CPIs have shown substantial efficacy in the management of advanced malignancies, immune-related adverse events (AEs) are common due to nonspecific immune activation.2 Immune-related cutaneous AEs are the most common immune-related AEs, occurring in 30% to 50% of patients who undergo treatment.2-5 Common immune-related cutaneous AEs include maculopapular, psoriasiform, and lichenoid dermatitis, as well as pruritus without dermatitis.2,3,6 Other reactions include but are not limited to bullous pemphigoid, vitiligolike depigmentation, and alopecia.2,3 Immune-related cutaneous AEs usually are self-limited; however, severe life-threatening reactions such as the spectrum of SJS/TEN and DRESS syndrome also can occur.2-4 Immune-related cutaneous AEs are graded based on the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events: grade 1 reactions are asymptomatic and cover less than 10% of the patient’s body surface area (BSA), grade 2 reactions have mild symptoms and cover 10% to 30% of the patient’s BSA, grade 3 reactions have moderate to severe symptoms and cover greater than 30% of the patient’s BSA, and grade 4 reactions are life-threatening.2,3 With prompt recognition and adequate treatment, mild to moderate immune-related cutaneous AEs—grades 1 and 2—largely are reversible, and less than 5% require discontinuation of therapy.2,3,6 It has been suggested that immune-related cutaneous AEs may be a positive prognostic factor in the treatment of underlying malignancy, indicating adequate immune activation targeting the malignant cells.6

Although our patient had some typical violaceous, flat-topped papules and plaques with Wickham striae, he also had atypical findings for a lichenoid reaction. Given the endorsement of blisters, it is possible that some of these lesions initially were bullous and subsequently ruptured, leaving behind erosions. However, in other areas, there also were eroded papules and ulcerations without a reported history of excoriation, scratching, picking, or prior bullae, including difficult-to-reach areas such as the back. It is favored that these lesions represented a robust lichenoid dermatitis leading to erosive and ulcerated lesions, similar to the formation of bullous lichen planus. Lichenoid eruptions secondary to immunotherapy are well-known phenomena, but a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms ulcer, lichenoid, and immunotherapy revealed only 2 cases of ulcerative lichenoid eruptions: a localized digital erosive lichenoid dermatitis and a widespread ulcerative lichenoid drug eruption without true erosions.7,8 However, widespread erosive and ulcerated lichenoid reactions are rare.

Lichenoid eruptions most strongly are associated with anti–programmed cell death-1/ programmed cell death ligand-1 therapy, occurring in 20% of patients undergoing treatment.3 Lichenoid eruptions present as discrete, pruritic, erythematous, violaceous papules and plaques on the chest and back and rarely may involve the limbs, palmoplantar surfaces, and oral mucosa.2,3,6 Histopathologic features include a dense bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis with scattered apoptotic keratinocytes in the basal layer of the epidermis.2,4,6 Grades 1 to 2 lesions can be managed with high-potency topical corticosteroids without CPI dose interruption, with more extensive grade 2 lesions requiring systemic corticosteroids.2,6,9 Lichenoid eruptions grade 3 or higher also require systemic corticosteroid therapy CPI therapy cessation until the eruption has receded to grade 0 to 1.2 Alternative treatment options for high-grade toxicity include phototherapy and acitretin.2,4,9

Our patient was treated with cessation of immunotherapy and initiation of a systemic corticosteroid taper, acitretin, and narrowband UVB therapy. After 6 weeks of treatment, the pain and pruritus improved and the rash had resolved in some areas while it had taken on a more classic lichenoid appearance with violaceous scaly papules and plaques (Figure 2) in areas of prior ulcers and erosions. He no longer had any bullae, erosions, or ulcers.

- Barrios DM, Do MH, Phillips GS, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors to treat cutaneous malignancies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1239-1253. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.131

- Geisler AN, Phillips GS, Barrios DM, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related dermatologic adverse events. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1255-1268. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.132

- Tattersall IW, Leventhal JS. Cutaneous toxicities of immune checkpoint inhibitors: the role of the dermatologist. Yale J Biol Med. 2020;93:123-132.

- Si X, He C, Zhang L, et al. Management of immune checkpoint inhibitor-related dermatologic adverse events. Thorac Cancer. 2020;11:488-492. doi:10.1111/1759-7714.13275

- Eggermont AMM, Kicinski M, Blank CU, et al. Association between immune-related adverse events and recurrence-free survival among patients with stage III melanoma randomized to receive pembrolizumab or placebo: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:519-527. doi:10.1001 /jamaoncol.2019.5570

- Sibaud V, Meyer N, Lamant L, et al. Dermatologic complications of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Curr Opin Oncol. 2016;28:254-263. doi:10.1097/CCO.0000000000000290

- Martínez-Doménech Á, García-Legaz Martínez M, Magdaleno-Tapial J, et al. Digital ulcerative lichenoid dermatitis in a patient receiving anti-PD-1 therapy. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt8sm0j7t7.

- Davis MJ, Wilken R, Fung MA, et al. Debilitating erosive lichenoid interface dermatitis from checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt3vq6b04v.

- Apalla Z, Papageorgiou C, Lallas A, et al. Cutaneous adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a literature review [published online January 29, 2021]. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2021;11:E2021155. doi:10.5826/dpc.1101a155

- Barrios DM, Do MH, Phillips GS, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors to treat cutaneous malignancies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1239-1253. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.131

- Geisler AN, Phillips GS, Barrios DM, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related dermatologic adverse events. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1255-1268. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.132

- Tattersall IW, Leventhal JS. Cutaneous toxicities of immune checkpoint inhibitors: the role of the dermatologist. Yale J Biol Med. 2020;93:123-132.

- Si X, He C, Zhang L, et al. Management of immune checkpoint inhibitor-related dermatologic adverse events. Thorac Cancer. 2020;11:488-492. doi:10.1111/1759-7714.13275

- Eggermont AMM, Kicinski M, Blank CU, et al. Association between immune-related adverse events and recurrence-free survival among patients with stage III melanoma randomized to receive pembrolizumab or placebo: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:519-527. doi:10.1001 /jamaoncol.2019.5570

- Sibaud V, Meyer N, Lamant L, et al. Dermatologic complications of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Curr Opin Oncol. 2016;28:254-263. doi:10.1097/CCO.0000000000000290

- Martínez-Doménech Á, García-Legaz Martínez M, Magdaleno-Tapial J, et al. Digital ulcerative lichenoid dermatitis in a patient receiving anti-PD-1 therapy. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt8sm0j7t7.

- Davis MJ, Wilken R, Fung MA, et al. Debilitating erosive lichenoid interface dermatitis from checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt3vq6b04v.

- Apalla Z, Papageorgiou C, Lallas A, et al. Cutaneous adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a literature review [published online January 29, 2021]. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2021;11:E2021155. doi:10.5826/dpc.1101a155

A 70-year-old man presented with a painful, pruritic, diffuse eruption on the trunk, legs, and arms of 2 months’ duration. He had a history of stage IV pleomorphic cell sarcoma of the retroperitoneum and was started on pembrolizumab therapy 6 weeks prior to the eruption. Physical examination revealed violaceous papules and plaques with shiny reticulated scaling as well as multiple scattered eroded papules and shallow ulcerations. The oral mucosa and genitals were spared. The patient endorsed blisters followed by open sores that were both itchy and painful. He denied self-infliction. Both the patient and his wife denied scratching. Two biopsies for direct immunofluorescence and histopathology were performed.

Progressive Axillary Hyperpigmentation

The Diagnosis: Dowling-Degos Disease

Histopathology demonstrated elongation of the epidermal rete ridges with increased basal pigmentation, suprapapillary epithelial thinning, dermal melanophages, and a mild lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure). Given the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of Dowling-Degos disease (DDD) was made. The patient was counseled on the increased risk for her children developing DDD. Treatment with the erbium:YAG (Er:YAG) laser subsequently was initiated.

Dowling-Degos disease (also known as reticulate pigmented anomaly of the flexures) is an uncommon autosomal-dominant condition characterized by reticular hyperpigmentation involving the flexural and intertriginous sites. Classic DDD commonly is caused by lossof-function mutations in the keratin 5 gene, KRT51; however, DDD also may result from loss-of-function mutations in the protein O-fucosyltransferase 1, POFUT1, and protein O-glucosyltransferase 1, POGLUT1, genes.2

Rare cases of DDD associated with hidradenitis suppurativa are caused by mutations in the presenilin enhancer protein 2 gene, PSENEN.3

Of note, a missense mutation in KRT5 is implicated in epidermolysis bullosa simplex with mottled pigmentation. Onset of DDD typically occurs during the third to fourth decades of life. Reticulated hyperpigmented macules initially occur in the axillae and groin and progressively increase over time to involve the neck, inframammary folds, trunk, and flexural surfaces of the arms and thighs. Patients additionally may present with pitted perioral scars, comedolike lesions on the back and neck, epidermoid cysts, and hidradenitis suppurativa. Keratoacanthoma and squamous cell carcinoma rarely have been reported in association with classic DDD.4,5

Dowling-Degos disease usually is asymptomatic, though pruritus seldom may occur in the affected flexural areas. Histologically, the epidermal rete ridges are elongated in a filiform or antlerlike pattern with increased pigmentation of the basal layer and thinning of the suprapapillary epithelium. Dermal melanosis and a mild perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate also are present with no increase in the number of melanocytes.6,7 Galli-Galli disease is a variant of DDD that shares similar clinical and histologic features of DDD but is distinguished from DDD by suprabasilar nondyskeratotic acantholysis on histology.8

Regarding other differential diagnoses for our patient, acanthosis nigricans may be distinguished clinically by the presence of velvety and/or verrucous plaques, commonly in the neck folds and axillae. Histologically, acanthosis nigricans is distinct from DDD and involves hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and epidermal papillomatosis. Our patient had no history of diabetes mellitus or insulin resistance. Granular parakeratosis presents with hyperpigmented hyperkeratotic papules and plaques classically confined to the axillary region; however, the involvement of other intertriginous areas may occur. Histologically, granular parakeratosis demonstrates compact parakeratosis with small bluish keratohyalin granules within the stratum corneum. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis presents with red-brown keratotic papules that initially appear in the intermammary region and spread laterally forming a reticulated pattern. Histology is similar to acanthosis nigricans and demonstrates hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis. Inverse psoriasis presents with symmetric and sharply demarcated, erythematous, nonscaly plaques in the intertriginous areas. The plaques of inverse psoriasis may be pruritic and/or sore and occasionally may become macerated. Inverse psoriasis shares similar histologic findings compared to classic plaque psoriasis but may have less confluent parakeratosis.

Treatment of DDD essentially is reserved for cosmetic reasons. Topical hydroquinone, tretinoin, and corticosteroids have been used with limited to no success.5,9 Beneficial results after treatment with the Er:YAG laser have been reported.10

- Betz RC, Planko L, Eigelshoven S, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the keratin 5 gene lead to Dowling-Degos disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:510-519.

- Basmanav FB, Oprisoreanu AM, Pasternack SM, et al. Mutations in POGLUT1, encoding protein O-glucosyltransferase 1, cause autosomaldominant Dowling-Degos disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94:135-143.

- Pavlovsky M, Sarig O, Eskin-Schwartz M, et al. A phenotype combining hidradenitis suppurativa with Dowling-Degos disease caused by a founder mutation in PSENEN. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:502-508.

- Ujihara M, Kamakura T, Ikeda M, et al. Dowling-Degos disease associated with squamous cell carcinomas on the dappled pigmentation. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:568-571.

- Weber LA, Kantor GR, Bergfeld WF. Reticulate pigmented anomaly of the flexures (Dowling-Degos disease): a case report associated with hidradenitis suppurativa and squamous cell carcinoma. Cutis. 1990;45:446-450.

- Jones EW, Grice K. Reticulate pigmented anomaly of the flexures. Dowing Degos disease, a new genodermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1150-1157.

- Kim YC, Davis MD, Schanbacher CF, et al. Dowling-Degos disease (reticulate pigmented anomaly of the flexures): a clinical and histopathologic study of 6 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999; 40:462-467.

- Reisenauer AK, Wordingham SV, York J, et al. Heterozygous frameshift mutation in keratin 5 in a family with Galli-Galli disease. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1362-1365.

- Oppolzer G, Schwarz T, Duschet P, et al. Dowling-Degos disease: unsuccessful therapeutic trial with retinoids [in German]. Hautarzt. 1987;38:615-618.

- Wenzel G, Petrow W, Tappe K, et al. Treatment of Dowling-Degos disease with Er:YAG-laser: results after 2.5 years. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:1161-1162.

The Diagnosis: Dowling-Degos Disease

Histopathology demonstrated elongation of the epidermal rete ridges with increased basal pigmentation, suprapapillary epithelial thinning, dermal melanophages, and a mild lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure). Given the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of Dowling-Degos disease (DDD) was made. The patient was counseled on the increased risk for her children developing DDD. Treatment with the erbium:YAG (Er:YAG) laser subsequently was initiated.

Dowling-Degos disease (also known as reticulate pigmented anomaly of the flexures) is an uncommon autosomal-dominant condition characterized by reticular hyperpigmentation involving the flexural and intertriginous sites. Classic DDD commonly is caused by lossof-function mutations in the keratin 5 gene, KRT51; however, DDD also may result from loss-of-function mutations in the protein O-fucosyltransferase 1, POFUT1, and protein O-glucosyltransferase 1, POGLUT1, genes.2

Rare cases of DDD associated with hidradenitis suppurativa are caused by mutations in the presenilin enhancer protein 2 gene, PSENEN.3

Of note, a missense mutation in KRT5 is implicated in epidermolysis bullosa simplex with mottled pigmentation. Onset of DDD typically occurs during the third to fourth decades of life. Reticulated hyperpigmented macules initially occur in the axillae and groin and progressively increase over time to involve the neck, inframammary folds, trunk, and flexural surfaces of the arms and thighs. Patients additionally may present with pitted perioral scars, comedolike lesions on the back and neck, epidermoid cysts, and hidradenitis suppurativa. Keratoacanthoma and squamous cell carcinoma rarely have been reported in association with classic DDD.4,5

Dowling-Degos disease usually is asymptomatic, though pruritus seldom may occur in the affected flexural areas. Histologically, the epidermal rete ridges are elongated in a filiform or antlerlike pattern with increased pigmentation of the basal layer and thinning of the suprapapillary epithelium. Dermal melanosis and a mild perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate also are present with no increase in the number of melanocytes.6,7 Galli-Galli disease is a variant of DDD that shares similar clinical and histologic features of DDD but is distinguished from DDD by suprabasilar nondyskeratotic acantholysis on histology.8

Regarding other differential diagnoses for our patient, acanthosis nigricans may be distinguished clinically by the presence of velvety and/or verrucous plaques, commonly in the neck folds and axillae. Histologically, acanthosis nigricans is distinct from DDD and involves hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and epidermal papillomatosis. Our patient had no history of diabetes mellitus or insulin resistance. Granular parakeratosis presents with hyperpigmented hyperkeratotic papules and plaques classically confined to the axillary region; however, the involvement of other intertriginous areas may occur. Histologically, granular parakeratosis demonstrates compact parakeratosis with small bluish keratohyalin granules within the stratum corneum. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis presents with red-brown keratotic papules that initially appear in the intermammary region and spread laterally forming a reticulated pattern. Histology is similar to acanthosis nigricans and demonstrates hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis. Inverse psoriasis presents with symmetric and sharply demarcated, erythematous, nonscaly plaques in the intertriginous areas. The plaques of inverse psoriasis may be pruritic and/or sore and occasionally may become macerated. Inverse psoriasis shares similar histologic findings compared to classic plaque psoriasis but may have less confluent parakeratosis.

Treatment of DDD essentially is reserved for cosmetic reasons. Topical hydroquinone, tretinoin, and corticosteroids have been used with limited to no success.5,9 Beneficial results after treatment with the Er:YAG laser have been reported.10

The Diagnosis: Dowling-Degos Disease

Histopathology demonstrated elongation of the epidermal rete ridges with increased basal pigmentation, suprapapillary epithelial thinning, dermal melanophages, and a mild lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure). Given the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of Dowling-Degos disease (DDD) was made. The patient was counseled on the increased risk for her children developing DDD. Treatment with the erbium:YAG (Er:YAG) laser subsequently was initiated.

Dowling-Degos disease (also known as reticulate pigmented anomaly of the flexures) is an uncommon autosomal-dominant condition characterized by reticular hyperpigmentation involving the flexural and intertriginous sites. Classic DDD commonly is caused by lossof-function mutations in the keratin 5 gene, KRT51; however, DDD also may result from loss-of-function mutations in the protein O-fucosyltransferase 1, POFUT1, and protein O-glucosyltransferase 1, POGLUT1, genes.2

Rare cases of DDD associated with hidradenitis suppurativa are caused by mutations in the presenilin enhancer protein 2 gene, PSENEN.3

Of note, a missense mutation in KRT5 is implicated in epidermolysis bullosa simplex with mottled pigmentation. Onset of DDD typically occurs during the third to fourth decades of life. Reticulated hyperpigmented macules initially occur in the axillae and groin and progressively increase over time to involve the neck, inframammary folds, trunk, and flexural surfaces of the arms and thighs. Patients additionally may present with pitted perioral scars, comedolike lesions on the back and neck, epidermoid cysts, and hidradenitis suppurativa. Keratoacanthoma and squamous cell carcinoma rarely have been reported in association with classic DDD.4,5

Dowling-Degos disease usually is asymptomatic, though pruritus seldom may occur in the affected flexural areas. Histologically, the epidermal rete ridges are elongated in a filiform or antlerlike pattern with increased pigmentation of the basal layer and thinning of the suprapapillary epithelium. Dermal melanosis and a mild perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate also are present with no increase in the number of melanocytes.6,7 Galli-Galli disease is a variant of DDD that shares similar clinical and histologic features of DDD but is distinguished from DDD by suprabasilar nondyskeratotic acantholysis on histology.8

Regarding other differential diagnoses for our patient, acanthosis nigricans may be distinguished clinically by the presence of velvety and/or verrucous plaques, commonly in the neck folds and axillae. Histologically, acanthosis nigricans is distinct from DDD and involves hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and epidermal papillomatosis. Our patient had no history of diabetes mellitus or insulin resistance. Granular parakeratosis presents with hyperpigmented hyperkeratotic papules and plaques classically confined to the axillary region; however, the involvement of other intertriginous areas may occur. Histologically, granular parakeratosis demonstrates compact parakeratosis with small bluish keratohyalin granules within the stratum corneum. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis presents with red-brown keratotic papules that initially appear in the intermammary region and spread laterally forming a reticulated pattern. Histology is similar to acanthosis nigricans and demonstrates hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis. Inverse psoriasis presents with symmetric and sharply demarcated, erythematous, nonscaly plaques in the intertriginous areas. The plaques of inverse psoriasis may be pruritic and/or sore and occasionally may become macerated. Inverse psoriasis shares similar histologic findings compared to classic plaque psoriasis but may have less confluent parakeratosis.

Treatment of DDD essentially is reserved for cosmetic reasons. Topical hydroquinone, tretinoin, and corticosteroids have been used with limited to no success.5,9 Beneficial results after treatment with the Er:YAG laser have been reported.10

- Betz RC, Planko L, Eigelshoven S, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the keratin 5 gene lead to Dowling-Degos disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:510-519.

- Basmanav FB, Oprisoreanu AM, Pasternack SM, et al. Mutations in POGLUT1, encoding protein O-glucosyltransferase 1, cause autosomaldominant Dowling-Degos disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94:135-143.

- Pavlovsky M, Sarig O, Eskin-Schwartz M, et al. A phenotype combining hidradenitis suppurativa with Dowling-Degos disease caused by a founder mutation in PSENEN. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:502-508.

- Ujihara M, Kamakura T, Ikeda M, et al. Dowling-Degos disease associated with squamous cell carcinomas on the dappled pigmentation. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:568-571.

- Weber LA, Kantor GR, Bergfeld WF. Reticulate pigmented anomaly of the flexures (Dowling-Degos disease): a case report associated with hidradenitis suppurativa and squamous cell carcinoma. Cutis. 1990;45:446-450.

- Jones EW, Grice K. Reticulate pigmented anomaly of the flexures. Dowing Degos disease, a new genodermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1150-1157.

- Kim YC, Davis MD, Schanbacher CF, et al. Dowling-Degos disease (reticulate pigmented anomaly of the flexures): a clinical and histopathologic study of 6 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999; 40:462-467.

- Reisenauer AK, Wordingham SV, York J, et al. Heterozygous frameshift mutation in keratin 5 in a family with Galli-Galli disease. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1362-1365.

- Oppolzer G, Schwarz T, Duschet P, et al. Dowling-Degos disease: unsuccessful therapeutic trial with retinoids [in German]. Hautarzt. 1987;38:615-618.

- Wenzel G, Petrow W, Tappe K, et al. Treatment of Dowling-Degos disease with Er:YAG-laser: results after 2.5 years. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:1161-1162.

- Betz RC, Planko L, Eigelshoven S, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the keratin 5 gene lead to Dowling-Degos disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:510-519.

- Basmanav FB, Oprisoreanu AM, Pasternack SM, et al. Mutations in POGLUT1, encoding protein O-glucosyltransferase 1, cause autosomaldominant Dowling-Degos disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94:135-143.

- Pavlovsky M, Sarig O, Eskin-Schwartz M, et al. A phenotype combining hidradenitis suppurativa with Dowling-Degos disease caused by a founder mutation in PSENEN. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:502-508.

- Ujihara M, Kamakura T, Ikeda M, et al. Dowling-Degos disease associated with squamous cell carcinomas on the dappled pigmentation. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:568-571.

- Weber LA, Kantor GR, Bergfeld WF. Reticulate pigmented anomaly of the flexures (Dowling-Degos disease): a case report associated with hidradenitis suppurativa and squamous cell carcinoma. Cutis. 1990;45:446-450.

- Jones EW, Grice K. Reticulate pigmented anomaly of the flexures. Dowing Degos disease, a new genodermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1150-1157.

- Kim YC, Davis MD, Schanbacher CF, et al. Dowling-Degos disease (reticulate pigmented anomaly of the flexures): a clinical and histopathologic study of 6 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999; 40:462-467.

- Reisenauer AK, Wordingham SV, York J, et al. Heterozygous frameshift mutation in keratin 5 in a family with Galli-Galli disease. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1362-1365.

- Oppolzer G, Schwarz T, Duschet P, et al. Dowling-Degos disease: unsuccessful therapeutic trial with retinoids [in German]. Hautarzt. 1987;38:615-618.

- Wenzel G, Petrow W, Tappe K, et al. Treatment of Dowling-Degos disease with Er:YAG-laser: results after 2.5 years. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:1161-1162.

A 50-year-old Hispanic woman presented with asymptomatic, progressive, brown hyperpigmentation involving the axillae, neck, upper back, and inframammary areas of 5 years’ duration. She had no other notable medical history; family history was unremarkable. She had been treated with topical hydroquinone and tretinoin by an outside physician without improvement. Physical examination revealed reticulated hyperpigmented macules and patches involving the inverse regions of the neck, axillae, and inframammary regions. Additionally, acneform pitted scars involving the perioral region were seen. A 4.0-mm punch biopsy of the right axilla was performed.

Hyperpigmentation on the Head and Neck

The Diagnosis: Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia Overlapping With Lichen Planus Pigmentosus

Microscopic examination revealed focal dermal pigmentation, papillary fibrosis, and epidermal atrophy. These clinical and histologic findings indicated a diagnosis of fully developed lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP) overlapping with frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA). Other cases have demonstrated an association between LPP and FFA.1,2

Lichen planus pigmentosus is considered an uncommon variant of lichen planus, as it has similar histopathologic findings and occasional coexistence.3,4 It is characterized by hyperpigmented macules primarily located in sun-exposed and flexural areas of the skin. First described in India,5 this disease has a predilection for darker skin (Fitzpatrick skin types III-V),6,7 and it has been reported in other racial and ethnic groups including Latin Americans, Middle Eastern populations, Japanese, and Koreans.4,8 Typically, lesions initially appear as ill-defined, blue-grey, round to oval macules that coalesce into hyperpigmented patches. Involvement most commonly begins at the forehead and temples, which are affected in nearly all patients. Infrequently, LPP can be generalized or affect the oral mucosa; involvement of the palms, soles, and nails does not occur. Patients may be asymptomatic, but some experience mild pruritus and burning. The disease course is chronic and insidious, with new lesions appearing over time and old lesions progressively darkening and expanding.6,7,9

Although the pathogenesis of LPP is unknown, several exposures have been implicated, such as amla oil, mustard oil, henna, hair dye, and environmental pollutants.7 Because lesions characteristically occur in sun-exposed areas, UV light also may be involved. In addition, studies have suggested that LPP is associated with endocrinopathies such as diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemias, as in our patient, as well as autoimmune conditions such as vitiligo and systemic lupus erythematosus.10,11

Histopathologic findings are characterized by vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer in the epidermis as well as perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltration and the presence of melanophages in the dermis.3,9 Lichen planus pigmentosus is difficult to treat, as no consistently effective modality has been established. Topical tacrolimus, topical corticosteroids, oral retinoids, lasers, and sun protection have been implemented with underwhelming results.12

Frontal fibrosing alopecia is a variant of lichen planopilaris that predominantly affects postmenopausal women and presents with frontotemporal hair loss in a bandlike distribution.5,13 Both terminal and vellus hairs are affected. Involvement of multiple hair-bearing sites of the skin have been reported, including the entire scalp, eyebrows, and eyelashes. Affected areas may display hypopigmentation and be accompanied by pruritus and trichodynia.14,15 The pathogenesis currently is under investigation, with studies demonstrating autoimmune, genetic, and possibly even endocrine predispositions.16-18 Biopsies of lesions are indistinguishable from lichen planopilaris, which shows follicular lymphocytic infiltration, perifollicular fibrosis, interface dermatitis of the follicular infundibulum and isthmus, and vertical fibrous tracks.5 Patients with FFA have demonstrated variable responses to treatments, with one study showing improvement with oral finasteride or dutasteride.14 Topical and intralesional corticosteroids have yielded suboptimal effects. Other modalities include hydroxychloroquine and mycophenolate mofetil.15,19

Co-occurrence of LPP and FFA primarily is seen in postmenopausal women with darker skin,14,15 as in our patient, though premenopausal cases have been reported. Lichen planus pigmentosus may serve as a harbinger in most patients.1,2 In a similar fashion, our patient presented with hyperpigmented macular lesions prior to the onset of frontotemporal hair loss.

Our patient was started on finasteride 2.5 mg daily, minoxidil foam 5%, clobetasol solution 0.05%, triamcinolone ointment 0.1%, and hydrocortisone ointment 2.5%. She was instructed to commence treatment and follow up in 6 months.

The differential diagnosis includes dermatologic conditions that mimic both LPP and FFA. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and fixed drug reaction were unlikely based on the patient's history. The lesions of ashy dermatosis are characteristically gray erythematous macules on the trunk and limbs. Riehl melanosis is a rare pigmented contact dermatitis that is associated with a history of repeated contact with sensitizing allergens. Although Hori nevus is characterized by small, blue-gray or brown macules on the face, lesions predominantly occur on the bony prominences of the cheeks. Melasma also presents with dark to gray macules that affect the face and less commonly the neck, as in our patient.2

Early discoid lupus erythematosus presents with round erythematous plaques with overlying scale extending into the hair follicles. In pseudopalade of Brocq, an idiopathic cicatricial alopecia, lesions typically are flesh colored. Biopsy also shows epidermal atrophy with additional dermal sclerosis and fibrosis. Folliculitis decalvans is a scarring form of alopecia associated with erythema and pustules, findings that were not present in our patient. Keratosis follicularis spinulosa decalvans is a rare, X-linked inherited ichthyosis manifesting as scarring alopecia with follicular depressions and papules on the scalp in younger males. Photophobia and other manifestations may be present. Alopecia mucinosa is a nonscarring alopecia with grouped follicular erythematous patches or plaques. Mucin sometimes can be squeezed from affected areas, and histopathologic examination shows mucin accumulation.4

- Dlova NC. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and lichen planus pigmentosus: is there a link? Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:439-442.

- Pirmez R, Duque-Estrada B, Donati A, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features of lichen planus pigmentosus in 37 patients with frontal fibrosing alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:1387-1390.

- Rieder E, Kaplan J, Kamino H, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20713.

- Kashima A, Tajiri A, Yamashita A, et al. Two Japanese cases of lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:740-742.

- Bhutani L, Bedi T, Pandhi R. Lichen planus pigmentosus. Dermatologica. 1974;149:43-50.

- Ross EK, Tan E, Shapiro J. Update on primary cicatricial alopecias. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1-37.

- Kanwa AJ, Dogra S, Handa S, et al. A study of 124 Indian patients with lichen planus pigmentosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:481-485.

- Al-Mutairi N, El-Khalawany M. Clinicopathological characteristics of lichen planus pigmentosus and its response to tacrolimus ointment: an open label, non-randomized, prospective study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:535-540.

- Vega ME, Waxtein L, Arenas R, et al. Ashy dermatosis and lichen planus pigmentosus: a clinicopathologic study of 31 cases. Int J Dermatol. 1992;31:90-94.

- Robles-Méndez JC, Rizo-Frías P, Herz-Ruelas ME, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus and its variants: review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:505-514.

- Torres J, Guadalupe A, Reyes E, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus in patients with endocrinopathies and hepatitis C. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:AB139.

- Kim JE, Won CH, Chang S, et al. Linear lichen planus pigmentosus of the forehead treated by neodymium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet laser and topical tacrolimus. J Dermatol. 2012;39:189-191.

- Kossard S. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia: scarring alopecia in a pattern distribution. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:770-774.

- Vano-Galvan S, Molina-Ruiz AM, Serrano-Falcon C, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a multicenter review of 355 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:670-678.

- MacDonald A, Clark C, Holmes S. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a review of 60 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:955-961.

- Harries MJ, Meyer K, Chaudhry I, et al. Lichen planopilaris is characterized by immune privilege collapse of the hair follicle's epithelial stem cell niche. J Pathol. 2013;231:236-247.

- Karnik P, Tekeste Z, McCormick TS, et al. Hair follicle stem cell-specific PPARgamma deletion causes scarring alopecia. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1243-1257.

- Rodriguez-Bayona B, Ruchaud S, Rodriguez C, et al. Autoantibodies against the chromosomal passenger protein INCENP found in a patient with Graham Little-Piccardi-Lassueur syndrome. J Autoimmune Dis. 2007;4:1.

- Rácz E, Gho C, Moorman PW, et al. Treatment of frontal fibrosing alopecia and lichen planopilaris: a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1461-1470.

The Diagnosis: Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia Overlapping With Lichen Planus Pigmentosus