User login

Recurrent Arciform Plaque on the Face

The Diagnosis: Lupus Erythematosus Tumidus

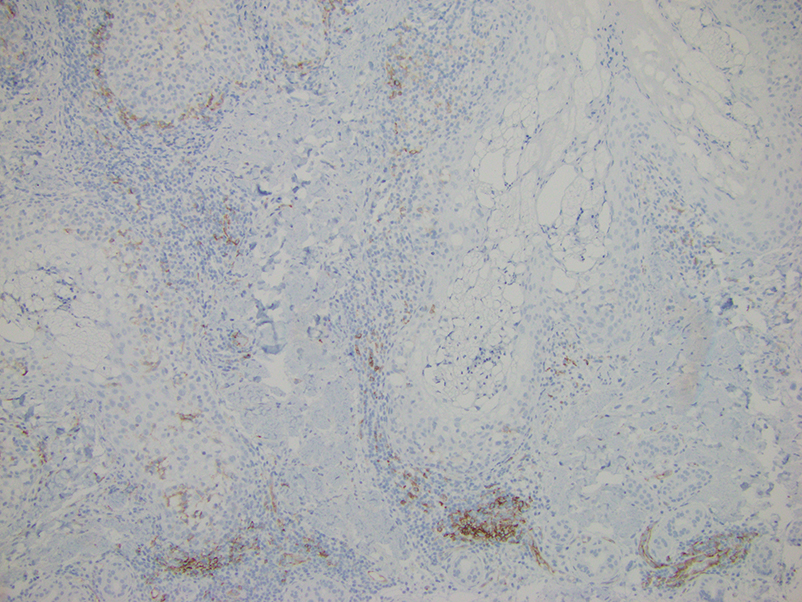

Histopathologic evaluation of a punch biopsy revealed focal dermal mucin deposition and CD123+ discrete clusters of plasmacytoid dendritic cells without interface changes (Figure 1), favoring a diagnosis of lupus erythematosus tumidus (LET) in our patient. There was no clinical improvement in symptoms when she previously was treated with topical antifungals or class III corticosteroid creams. Tacrolimus ointment 0.1% twice daily for 1 month did not result in substantial improvement in the appearance of the plaque, and it spontaneously resolved after 2 to 3 months. She declined treatment with hydroxychloroquine.

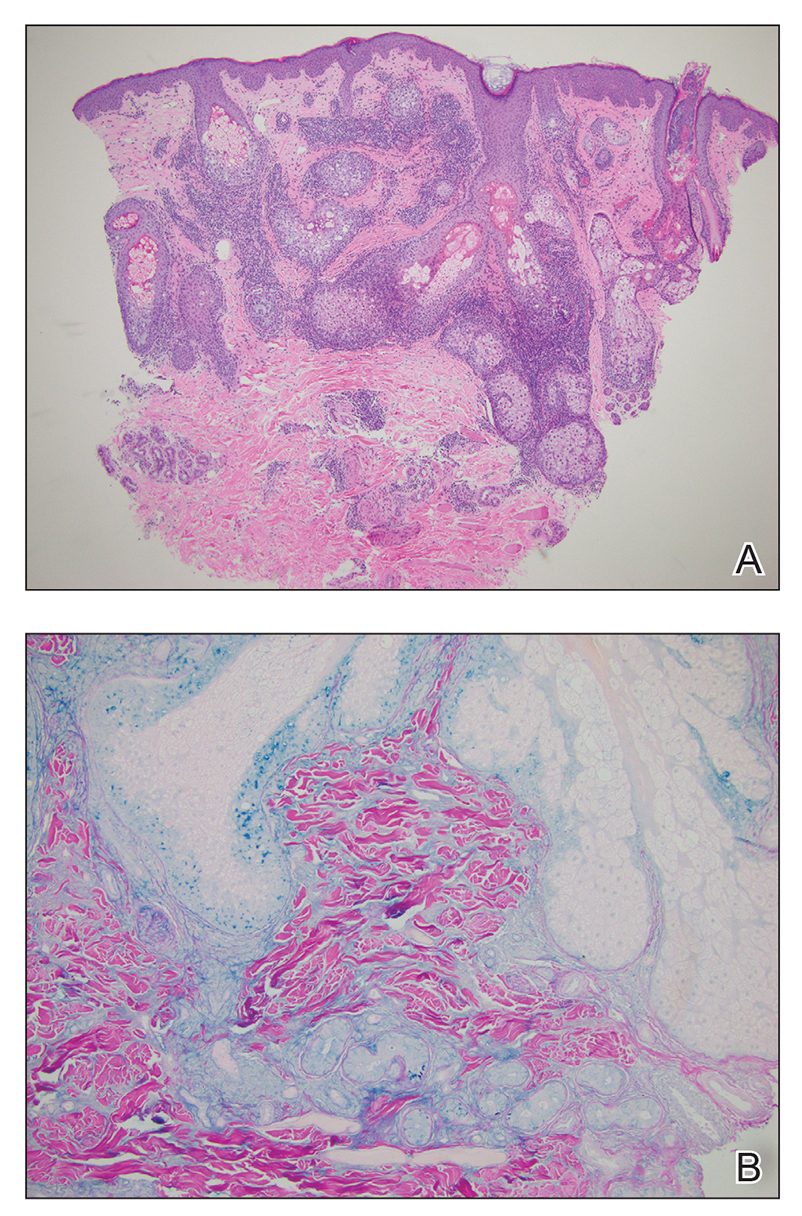

Lupus erythematosus tumidus is an uncommon subtype of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus with no distinct etiology. It is clinically characterized by edematous, urticarial, single or multiple plaques with a smooth surface affecting sun-exposed areas that can last for months to years.1 In contrast to other variations of chronic cutaneous lupus such as discoid lupus erythematosus, LET lesions lack surface papulosquamous features such as scaling, atrophy, and follicular plugging.1-4 Based solely on histologic findings, LET may be indistinguishable from reticular erythematous mucinosis and Jessner lymphocytic infiltration of the skin (JLIS) due to a similar lack of epidermal involvement and presence of a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 2).

The average age at disease onset is 36 years, nearly the same as that described in discoid lupus erythematosus.4 Lupus erythematosus tumidus has a favorable prognosis and commonly presents without other autoimmune signs, serologic abnormalities, or gender preference, with concomitant systemic lupus erythematosus sometimes reported.5

The absence of clinical and histological epidermal involvement are the most important clues to aid in the diagnosis. It has been postulated that JLIS could be an early cutaneous manifestation of LET.6 The differential diagnosis also may include erythema annulare centrifugum, granuloma annulare, and urticarial vasculitis. Lesions typically respond well to photoprotection, topical corticosteroids, and/or antimalarials. The addition of tacrolimus ointment 0.1% may result in complete regression without recurrence.7

Erythema annulare centrifugum is a reactive erythema that classically begins as a pink papule that gradually enlarges to form an annular erythematous plaque with a fine trailing scale that may recur.8 The histopathology of erythema annulare centrifugum shares features seen in LET, making the diagnosis difficult; however, secondary changes to the epidermis (eg, spongiosis, hyperkeratosis) may be seen. This condition has been associated with lymphoproliferative malignancies.8

Reticular erythematous mucinosis is clinically distinguished from LET, as it presents as reticular, rather than arciform, erythematous macules, papules, or plaques that may be asymptomatic or pruritic.9 Histopathology typically shows more superficial mucin deposition than in LET as well as superficial to mid-dermal perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates. Reticular erythematous mucinosis more frequently is reported in women in their 30s and 40s and has been associated with UV exposure and hormonal triggers, such as oral contraceptive medications and pregnancy.9

Granuloma annulare typically presents as asymptomatic, erythematous, annular plaques or papules in young women.10 There are several histologic subtypes that show focal collagen degeneration, inflammation with palisaded or interstitial histiocytes, and mucin deposition, regardless of clinical presentation. Granuloma annulare has been associated with systemic diseases including type 2 diabetes mellitus and thyroid disease. Localized granuloma annulare most commonly presents on the dorsal aspects of the hands or feet.10

We present a case of LET on the face. Although histologically similar to other dermatoses, LET often lacks epidermal involvement and presents on sun-exposed areas of the body. Jessner lymphocytic infiltration of the skin also should be considered in the differential, as there is an overlap of clinical and histopathological features; JLIS lacks mucin deposits.6 This case reinforces the importance of correlating clinical with histopathologic findings. Our patient was treated with tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, and the plaque eventually resolved in 2 to 3 months without recurrence. This condition should be included in the differential diagnosis of recurring annular plaques on sunexposed areas, particularly in middle-aged adults, even in the absence of systemic involvement.

- Liu E, Daze RP, Moon S. Tumid lupus erythematosus: a rare and distinctive variant of cutaneous lupus erythematosus masquerading as urticarial vasculitis. Cureus. 2020;12:E8305. doi:10.7759/cureus.8305

- Saleh D, Crane JS. Tumid lupus erythematosus. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- Verma P, Sharma S, Yadav P, et al. Tumid lupus erythematosus: an intriguing dermatopathological connotation treated successfully with topical tacrolimus and hydroxychloroquine combination. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:210. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.127716

- Kuhn A, Bein D, Bonsmann G. The 100th anniversary of lupus erythematosus tumidus. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;8:441-448. doi:10.1016/j. autrev.2008.12.010

- Jatwani K, Chugh K, Osholowu OS, et al. Tumid lupus erythematosus and systemic lupus erythematosus: a report on their rare coexistence. Cureus. 2020;12:E7545. doi:10.7759/cureus.7545

- Tomasini D, Mentzel T, Hantschke M, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells: an overview of their presence and distribution in different inflammatory skin diseases, with special emphasis on Jessner’s lymphocytic infiltrate of the skin and cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1132-1139. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2010.01587.x

- Patsinakidis N, Kautz O, Gibbs BF, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus: clinical perspectives. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:707-719. doi:10.2147/CCID.S166723

- Mu EW, Sanchez M, Mir A, et al. Paraneoplastic erythema annulare centrifugum eruption (PEACE). Dermatol Online J. 2015;21:13030/ qt6053h29n.

- Ocanha-Xavier JP, Cola-Senra CO, Xavier-Junior JCC. Reticular erythematous mucinosis: literature review and case report of a 24-year-old patient with systemic erythematosus lupus. Lupus. 2021;30:325-335. doi:10.1177/0961203320965702 10. Keimig EL. Granuloma annulare. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:315-329. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.001

The Diagnosis: Lupus Erythematosus Tumidus

Histopathologic evaluation of a punch biopsy revealed focal dermal mucin deposition and CD123+ discrete clusters of plasmacytoid dendritic cells without interface changes (Figure 1), favoring a diagnosis of lupus erythematosus tumidus (LET) in our patient. There was no clinical improvement in symptoms when she previously was treated with topical antifungals or class III corticosteroid creams. Tacrolimus ointment 0.1% twice daily for 1 month did not result in substantial improvement in the appearance of the plaque, and it spontaneously resolved after 2 to 3 months. She declined treatment with hydroxychloroquine.

Lupus erythematosus tumidus is an uncommon subtype of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus with no distinct etiology. It is clinically characterized by edematous, urticarial, single or multiple plaques with a smooth surface affecting sun-exposed areas that can last for months to years.1 In contrast to other variations of chronic cutaneous lupus such as discoid lupus erythematosus, LET lesions lack surface papulosquamous features such as scaling, atrophy, and follicular plugging.1-4 Based solely on histologic findings, LET may be indistinguishable from reticular erythematous mucinosis and Jessner lymphocytic infiltration of the skin (JLIS) due to a similar lack of epidermal involvement and presence of a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 2).

The average age at disease onset is 36 years, nearly the same as that described in discoid lupus erythematosus.4 Lupus erythematosus tumidus has a favorable prognosis and commonly presents without other autoimmune signs, serologic abnormalities, or gender preference, with concomitant systemic lupus erythematosus sometimes reported.5

The absence of clinical and histological epidermal involvement are the most important clues to aid in the diagnosis. It has been postulated that JLIS could be an early cutaneous manifestation of LET.6 The differential diagnosis also may include erythema annulare centrifugum, granuloma annulare, and urticarial vasculitis. Lesions typically respond well to photoprotection, topical corticosteroids, and/or antimalarials. The addition of tacrolimus ointment 0.1% may result in complete regression without recurrence.7

Erythema annulare centrifugum is a reactive erythema that classically begins as a pink papule that gradually enlarges to form an annular erythematous plaque with a fine trailing scale that may recur.8 The histopathology of erythema annulare centrifugum shares features seen in LET, making the diagnosis difficult; however, secondary changes to the epidermis (eg, spongiosis, hyperkeratosis) may be seen. This condition has been associated with lymphoproliferative malignancies.8

Reticular erythematous mucinosis is clinically distinguished from LET, as it presents as reticular, rather than arciform, erythematous macules, papules, or plaques that may be asymptomatic or pruritic.9 Histopathology typically shows more superficial mucin deposition than in LET as well as superficial to mid-dermal perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates. Reticular erythematous mucinosis more frequently is reported in women in their 30s and 40s and has been associated with UV exposure and hormonal triggers, such as oral contraceptive medications and pregnancy.9

Granuloma annulare typically presents as asymptomatic, erythematous, annular plaques or papules in young women.10 There are several histologic subtypes that show focal collagen degeneration, inflammation with palisaded or interstitial histiocytes, and mucin deposition, regardless of clinical presentation. Granuloma annulare has been associated with systemic diseases including type 2 diabetes mellitus and thyroid disease. Localized granuloma annulare most commonly presents on the dorsal aspects of the hands or feet.10

We present a case of LET on the face. Although histologically similar to other dermatoses, LET often lacks epidermal involvement and presents on sun-exposed areas of the body. Jessner lymphocytic infiltration of the skin also should be considered in the differential, as there is an overlap of clinical and histopathological features; JLIS lacks mucin deposits.6 This case reinforces the importance of correlating clinical with histopathologic findings. Our patient was treated with tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, and the plaque eventually resolved in 2 to 3 months without recurrence. This condition should be included in the differential diagnosis of recurring annular plaques on sunexposed areas, particularly in middle-aged adults, even in the absence of systemic involvement.

The Diagnosis: Lupus Erythematosus Tumidus

Histopathologic evaluation of a punch biopsy revealed focal dermal mucin deposition and CD123+ discrete clusters of plasmacytoid dendritic cells without interface changes (Figure 1), favoring a diagnosis of lupus erythematosus tumidus (LET) in our patient. There was no clinical improvement in symptoms when she previously was treated with topical antifungals or class III corticosteroid creams. Tacrolimus ointment 0.1% twice daily for 1 month did not result in substantial improvement in the appearance of the plaque, and it spontaneously resolved after 2 to 3 months. She declined treatment with hydroxychloroquine.

Lupus erythematosus tumidus is an uncommon subtype of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus with no distinct etiology. It is clinically characterized by edematous, urticarial, single or multiple plaques with a smooth surface affecting sun-exposed areas that can last for months to years.1 In contrast to other variations of chronic cutaneous lupus such as discoid lupus erythematosus, LET lesions lack surface papulosquamous features such as scaling, atrophy, and follicular plugging.1-4 Based solely on histologic findings, LET may be indistinguishable from reticular erythematous mucinosis and Jessner lymphocytic infiltration of the skin (JLIS) due to a similar lack of epidermal involvement and presence of a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 2).

The average age at disease onset is 36 years, nearly the same as that described in discoid lupus erythematosus.4 Lupus erythematosus tumidus has a favorable prognosis and commonly presents without other autoimmune signs, serologic abnormalities, or gender preference, with concomitant systemic lupus erythematosus sometimes reported.5

The absence of clinical and histological epidermal involvement are the most important clues to aid in the diagnosis. It has been postulated that JLIS could be an early cutaneous manifestation of LET.6 The differential diagnosis also may include erythema annulare centrifugum, granuloma annulare, and urticarial vasculitis. Lesions typically respond well to photoprotection, topical corticosteroids, and/or antimalarials. The addition of tacrolimus ointment 0.1% may result in complete regression without recurrence.7

Erythema annulare centrifugum is a reactive erythema that classically begins as a pink papule that gradually enlarges to form an annular erythematous plaque with a fine trailing scale that may recur.8 The histopathology of erythema annulare centrifugum shares features seen in LET, making the diagnosis difficult; however, secondary changes to the epidermis (eg, spongiosis, hyperkeratosis) may be seen. This condition has been associated with lymphoproliferative malignancies.8

Reticular erythematous mucinosis is clinically distinguished from LET, as it presents as reticular, rather than arciform, erythematous macules, papules, or plaques that may be asymptomatic or pruritic.9 Histopathology typically shows more superficial mucin deposition than in LET as well as superficial to mid-dermal perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates. Reticular erythematous mucinosis more frequently is reported in women in their 30s and 40s and has been associated with UV exposure and hormonal triggers, such as oral contraceptive medications and pregnancy.9

Granuloma annulare typically presents as asymptomatic, erythematous, annular plaques or papules in young women.10 There are several histologic subtypes that show focal collagen degeneration, inflammation with palisaded or interstitial histiocytes, and mucin deposition, regardless of clinical presentation. Granuloma annulare has been associated with systemic diseases including type 2 diabetes mellitus and thyroid disease. Localized granuloma annulare most commonly presents on the dorsal aspects of the hands or feet.10

We present a case of LET on the face. Although histologically similar to other dermatoses, LET often lacks epidermal involvement and presents on sun-exposed areas of the body. Jessner lymphocytic infiltration of the skin also should be considered in the differential, as there is an overlap of clinical and histopathological features; JLIS lacks mucin deposits.6 This case reinforces the importance of correlating clinical with histopathologic findings. Our patient was treated with tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, and the plaque eventually resolved in 2 to 3 months without recurrence. This condition should be included in the differential diagnosis of recurring annular plaques on sunexposed areas, particularly in middle-aged adults, even in the absence of systemic involvement.

- Liu E, Daze RP, Moon S. Tumid lupus erythematosus: a rare and distinctive variant of cutaneous lupus erythematosus masquerading as urticarial vasculitis. Cureus. 2020;12:E8305. doi:10.7759/cureus.8305

- Saleh D, Crane JS. Tumid lupus erythematosus. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- Verma P, Sharma S, Yadav P, et al. Tumid lupus erythematosus: an intriguing dermatopathological connotation treated successfully with topical tacrolimus and hydroxychloroquine combination. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:210. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.127716

- Kuhn A, Bein D, Bonsmann G. The 100th anniversary of lupus erythematosus tumidus. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;8:441-448. doi:10.1016/j. autrev.2008.12.010

- Jatwani K, Chugh K, Osholowu OS, et al. Tumid lupus erythematosus and systemic lupus erythematosus: a report on their rare coexistence. Cureus. 2020;12:E7545. doi:10.7759/cureus.7545

- Tomasini D, Mentzel T, Hantschke M, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells: an overview of their presence and distribution in different inflammatory skin diseases, with special emphasis on Jessner’s lymphocytic infiltrate of the skin and cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1132-1139. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2010.01587.x

- Patsinakidis N, Kautz O, Gibbs BF, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus: clinical perspectives. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:707-719. doi:10.2147/CCID.S166723

- Mu EW, Sanchez M, Mir A, et al. Paraneoplastic erythema annulare centrifugum eruption (PEACE). Dermatol Online J. 2015;21:13030/ qt6053h29n.

- Ocanha-Xavier JP, Cola-Senra CO, Xavier-Junior JCC. Reticular erythematous mucinosis: literature review and case report of a 24-year-old patient with systemic erythematosus lupus. Lupus. 2021;30:325-335. doi:10.1177/0961203320965702 10. Keimig EL. Granuloma annulare. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:315-329. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.001

- Liu E, Daze RP, Moon S. Tumid lupus erythematosus: a rare and distinctive variant of cutaneous lupus erythematosus masquerading as urticarial vasculitis. Cureus. 2020;12:E8305. doi:10.7759/cureus.8305

- Saleh D, Crane JS. Tumid lupus erythematosus. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- Verma P, Sharma S, Yadav P, et al. Tumid lupus erythematosus: an intriguing dermatopathological connotation treated successfully with topical tacrolimus and hydroxychloroquine combination. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:210. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.127716

- Kuhn A, Bein D, Bonsmann G. The 100th anniversary of lupus erythematosus tumidus. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;8:441-448. doi:10.1016/j. autrev.2008.12.010

- Jatwani K, Chugh K, Osholowu OS, et al. Tumid lupus erythematosus and systemic lupus erythematosus: a report on their rare coexistence. Cureus. 2020;12:E7545. doi:10.7759/cureus.7545

- Tomasini D, Mentzel T, Hantschke M, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells: an overview of their presence and distribution in different inflammatory skin diseases, with special emphasis on Jessner’s lymphocytic infiltrate of the skin and cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1132-1139. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2010.01587.x

- Patsinakidis N, Kautz O, Gibbs BF, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus: clinical perspectives. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:707-719. doi:10.2147/CCID.S166723

- Mu EW, Sanchez M, Mir A, et al. Paraneoplastic erythema annulare centrifugum eruption (PEACE). Dermatol Online J. 2015;21:13030/ qt6053h29n.

- Ocanha-Xavier JP, Cola-Senra CO, Xavier-Junior JCC. Reticular erythematous mucinosis: literature review and case report of a 24-year-old patient with systemic erythematosus lupus. Lupus. 2021;30:325-335. doi:10.1177/0961203320965702 10. Keimig EL. Granuloma annulare. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:315-329. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.001

An otherwise healthy 31-year-old woman presented with a gradual growth of a semiannular, arciform, mildly pruritic plaque around the mouth of 10 years’ duration that recurred biannually, persisted for a few months, and spontaneously remitted without residual scarring. She denied joint pain, muscle aches, sores in the mouth, personal or family history of autoimmune diseases, or other remarkable review of systems. Physical examination revealed a welldefined, edematous, smooth, arciform plaque on the face with no mucous membrane involvement. Laboratory evaluation, including complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and antinuclear antibody titer, was unremarkable. A punch biopsy was obtained.

High-Potency Topical Steroid Treatment of Multiple Keratoacanthomas Associated With Prurigo Nodularis

Practice Gap

Multiple keratoacanthomas (KAs) of the legs often are a challenge to treat, especially when these lesions appear within a field of prurigo nodules. Multiple KAs associated with prurigo nodularis is a rarer finding; more often, the condition is reported on the lower limbs of elderly women with actinically damaged skin.1,2 At times, it can be difficult to distinguish between KA and prurigo nodularis in these patients, who often report notable pruritus and might have associated eczematous dermatitis.2

Keratoacanthomas often are treated with aggressive modalities, such as Mohs micrographic surgery, excision, and electrodesiccation and curettage. Some patients are hesitant to undergo surgical treatment, however, preferring a less invasive approach. Trauma from these aggressive modalities also can be associated with recurrence of existing lesions or development of new KAs, possibly related to stimulation of a local inflammatory response and upregulation of helper T cells.2-4

Acitretin and other systemic retinoids often are considered first-line therapy for multiple KAs. Cyclosporine has been added as adjunctive treatment in cases associated with prurigo nodularis or eczematous dermatitis1,2; however, these treatments have a high rate of discontinuation because of adverse effects, including transaminitis, xerostomia, alopecia (acitretin), and renal toxicity (cyclosporine).2

Another treatment option for patients with coexisting KA and prurigo nodularis is intralesional corticosteroids, often administered in combination with systemic retinoids.3 Topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) has been used successfully for KA, but topical treatment options are limited if 5-FU fails. Topical imiquimod and cryotherapy are thought to be of little benefit, and the appearance of new KA within imiquimod and cryotherapy treatment fields has been reported.1,2 Topical corticosteroids have been used as an adjuvant therapy for multiple KAs associated with prurigo nodularis; however, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms keratoacanthoma and steroid and keratoacanthoma and prurigo nodularis yielded no published reports of successful use of topical corticosteroids as monotherapy.2

The Technique

For patients who want to continue topical treatment of coexisting KA and prurigo nodularis after topical 5-FU fails, we have found success applying a high-potency topical corticosteroid to affected areas under occlusion nightly for 6 to 8 weeks. This treatment not only leads to resolution of KA but also simultaneously treats prurigo nodules that might be clinically difficult to distinguish from KA in some presentations. This regimen has been implemented in our practice with remarkable reduction of KA burden and relief of pruritus.

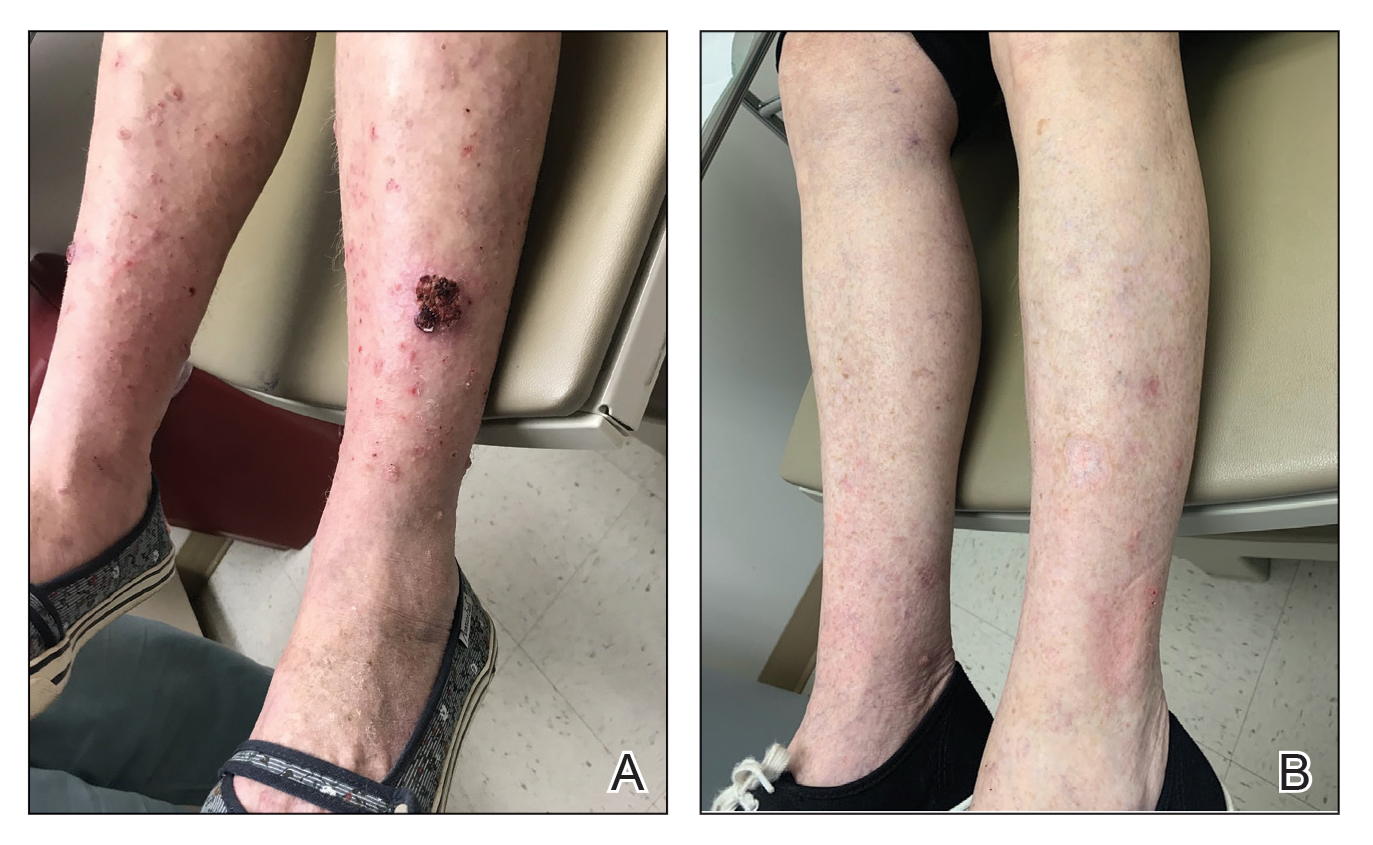

In a 68-year-old woman who was treated with this technique, multiple biopsies had shown KA (or well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma that appeared clinically as KA) on the shin (Figure, A) arising amid many lesions consistent with prurigo nodules. Topical 5-FU had failed, but the patient did not want to be treated with a more invasive modality, such as excision or injection.

Instead, we treated the patient with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% under occlusion nightly for 6 weeks. This strategy produced resolution of both KA and prurigo nodules (Figure, B). When lesions recurred after a few months, they were successfully re-treated with topical clobetasol under occlusion in a second 6-week course.

Practical Implications

Treatment of multiple KAs associated with prurigo nodularis can present a distinct challenge. For the subset of patients who want to pursue topical treatment, options reported in the literature are limited. We have found success treating multiple KAs and associated prurigo nodules with a high-potency topical corticosteroid under occlusion, with minimal or no adverse effects. We believe that a topical corticosteroid can be implemented easily in clinical practice before a more invasive surgical or intralesional modality is considered.

- Kwiek B, Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma (KA): an update and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1220-1233. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.11.033

- Wu TP, Miller K, Cohen DE, et al. Keratoacanthomas arising in association with prurigo nodules in pruritic, actinically damaged skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:426-430. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2013.03.035

- Sanders S, Busam KJ, Halpern AC, et al. Intralesional corticosteroid treatment of multiple eruptive keratoacanthomas: case report and review of a controversial therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:954-958. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2002.02069.x

- Lee S, Coutts I, Ryan A, et al. Keratoacanthoma formation after skin grafting: a brief report and pathophysiological hypothesis. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E117-E119. doi:10.1111/ajd.12501

Practice Gap

Multiple keratoacanthomas (KAs) of the legs often are a challenge to treat, especially when these lesions appear within a field of prurigo nodules. Multiple KAs associated with prurigo nodularis is a rarer finding; more often, the condition is reported on the lower limbs of elderly women with actinically damaged skin.1,2 At times, it can be difficult to distinguish between KA and prurigo nodularis in these patients, who often report notable pruritus and might have associated eczematous dermatitis.2

Keratoacanthomas often are treated with aggressive modalities, such as Mohs micrographic surgery, excision, and electrodesiccation and curettage. Some patients are hesitant to undergo surgical treatment, however, preferring a less invasive approach. Trauma from these aggressive modalities also can be associated with recurrence of existing lesions or development of new KAs, possibly related to stimulation of a local inflammatory response and upregulation of helper T cells.2-4

Acitretin and other systemic retinoids often are considered first-line therapy for multiple KAs. Cyclosporine has been added as adjunctive treatment in cases associated with prurigo nodularis or eczematous dermatitis1,2; however, these treatments have a high rate of discontinuation because of adverse effects, including transaminitis, xerostomia, alopecia (acitretin), and renal toxicity (cyclosporine).2

Another treatment option for patients with coexisting KA and prurigo nodularis is intralesional corticosteroids, often administered in combination with systemic retinoids.3 Topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) has been used successfully for KA, but topical treatment options are limited if 5-FU fails. Topical imiquimod and cryotherapy are thought to be of little benefit, and the appearance of new KA within imiquimod and cryotherapy treatment fields has been reported.1,2 Topical corticosteroids have been used as an adjuvant therapy for multiple KAs associated with prurigo nodularis; however, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms keratoacanthoma and steroid and keratoacanthoma and prurigo nodularis yielded no published reports of successful use of topical corticosteroids as monotherapy.2

The Technique

For patients who want to continue topical treatment of coexisting KA and prurigo nodularis after topical 5-FU fails, we have found success applying a high-potency topical corticosteroid to affected areas under occlusion nightly for 6 to 8 weeks. This treatment not only leads to resolution of KA but also simultaneously treats prurigo nodules that might be clinically difficult to distinguish from KA in some presentations. This regimen has been implemented in our practice with remarkable reduction of KA burden and relief of pruritus.

In a 68-year-old woman who was treated with this technique, multiple biopsies had shown KA (or well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma that appeared clinically as KA) on the shin (Figure, A) arising amid many lesions consistent with prurigo nodules. Topical 5-FU had failed, but the patient did not want to be treated with a more invasive modality, such as excision or injection.

Instead, we treated the patient with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% under occlusion nightly for 6 weeks. This strategy produced resolution of both KA and prurigo nodules (Figure, B). When lesions recurred after a few months, they were successfully re-treated with topical clobetasol under occlusion in a second 6-week course.

Practical Implications

Treatment of multiple KAs associated with prurigo nodularis can present a distinct challenge. For the subset of patients who want to pursue topical treatment, options reported in the literature are limited. We have found success treating multiple KAs and associated prurigo nodules with a high-potency topical corticosteroid under occlusion, with minimal or no adverse effects. We believe that a topical corticosteroid can be implemented easily in clinical practice before a more invasive surgical or intralesional modality is considered.

Practice Gap

Multiple keratoacanthomas (KAs) of the legs often are a challenge to treat, especially when these lesions appear within a field of prurigo nodules. Multiple KAs associated with prurigo nodularis is a rarer finding; more often, the condition is reported on the lower limbs of elderly women with actinically damaged skin.1,2 At times, it can be difficult to distinguish between KA and prurigo nodularis in these patients, who often report notable pruritus and might have associated eczematous dermatitis.2

Keratoacanthomas often are treated with aggressive modalities, such as Mohs micrographic surgery, excision, and electrodesiccation and curettage. Some patients are hesitant to undergo surgical treatment, however, preferring a less invasive approach. Trauma from these aggressive modalities also can be associated with recurrence of existing lesions or development of new KAs, possibly related to stimulation of a local inflammatory response and upregulation of helper T cells.2-4

Acitretin and other systemic retinoids often are considered first-line therapy for multiple KAs. Cyclosporine has been added as adjunctive treatment in cases associated with prurigo nodularis or eczematous dermatitis1,2; however, these treatments have a high rate of discontinuation because of adverse effects, including transaminitis, xerostomia, alopecia (acitretin), and renal toxicity (cyclosporine).2

Another treatment option for patients with coexisting KA and prurigo nodularis is intralesional corticosteroids, often administered in combination with systemic retinoids.3 Topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) has been used successfully for KA, but topical treatment options are limited if 5-FU fails. Topical imiquimod and cryotherapy are thought to be of little benefit, and the appearance of new KA within imiquimod and cryotherapy treatment fields has been reported.1,2 Topical corticosteroids have been used as an adjuvant therapy for multiple KAs associated with prurigo nodularis; however, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms keratoacanthoma and steroid and keratoacanthoma and prurigo nodularis yielded no published reports of successful use of topical corticosteroids as monotherapy.2

The Technique

For patients who want to continue topical treatment of coexisting KA and prurigo nodularis after topical 5-FU fails, we have found success applying a high-potency topical corticosteroid to affected areas under occlusion nightly for 6 to 8 weeks. This treatment not only leads to resolution of KA but also simultaneously treats prurigo nodules that might be clinically difficult to distinguish from KA in some presentations. This regimen has been implemented in our practice with remarkable reduction of KA burden and relief of pruritus.

In a 68-year-old woman who was treated with this technique, multiple biopsies had shown KA (or well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma that appeared clinically as KA) on the shin (Figure, A) arising amid many lesions consistent with prurigo nodules. Topical 5-FU had failed, but the patient did not want to be treated with a more invasive modality, such as excision or injection.

Instead, we treated the patient with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% under occlusion nightly for 6 weeks. This strategy produced resolution of both KA and prurigo nodules (Figure, B). When lesions recurred after a few months, they were successfully re-treated with topical clobetasol under occlusion in a second 6-week course.

Practical Implications

Treatment of multiple KAs associated with prurigo nodularis can present a distinct challenge. For the subset of patients who want to pursue topical treatment, options reported in the literature are limited. We have found success treating multiple KAs and associated prurigo nodules with a high-potency topical corticosteroid under occlusion, with minimal or no adverse effects. We believe that a topical corticosteroid can be implemented easily in clinical practice before a more invasive surgical or intralesional modality is considered.

- Kwiek B, Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma (KA): an update and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1220-1233. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.11.033

- Wu TP, Miller K, Cohen DE, et al. Keratoacanthomas arising in association with prurigo nodules in pruritic, actinically damaged skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:426-430. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2013.03.035

- Sanders S, Busam KJ, Halpern AC, et al. Intralesional corticosteroid treatment of multiple eruptive keratoacanthomas: case report and review of a controversial therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:954-958. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2002.02069.x

- Lee S, Coutts I, Ryan A, et al. Keratoacanthoma formation after skin grafting: a brief report and pathophysiological hypothesis. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E117-E119. doi:10.1111/ajd.12501

- Kwiek B, Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma (KA): an update and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1220-1233. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.11.033

- Wu TP, Miller K, Cohen DE, et al. Keratoacanthomas arising in association with prurigo nodules in pruritic, actinically damaged skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:426-430. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2013.03.035

- Sanders S, Busam KJ, Halpern AC, et al. Intralesional corticosteroid treatment of multiple eruptive keratoacanthomas: case report and review of a controversial therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:954-958. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2002.02069.x

- Lee S, Coutts I, Ryan A, et al. Keratoacanthoma formation after skin grafting: a brief report and pathophysiological hypothesis. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E117-E119. doi:10.1111/ajd.12501