User login

Optimal Cosmetic Outcomes for Basal Cell Carcinoma: A Retrospective Study of Nonablative Laser Management

Nonablative laser therapy is emerging as an effective noninvasive treatment option for basal cell carcinoma (BCC) with reduced adverse effects and good cosmetic outcomes compared to surgery. Vascular lasers, such as the pulsed dye laser (PDL), are thought to work by selectively targeting the tumor’s vascular network while preserving normal surrounding tissue.1,2 Although high energy and multiple passes might be required, adjunctive use of dynamic cooling reduces the risk for nonselective thermal injury vs ablative lasers, which destroy the tumor itself through vaporization of tissue water.2

With no established laser management guidelines for the treatment of BCC, earlier studies using a 595-nm PDL varied highly in their protocol.3-8 Pulsed dye laser parameters ranged from a spot size of 7 to 10 mm, fluence of 7.5 to 15 J/cm2, and pulse duration of 0.5 to 3 milliseconds. Follow-up ranged from 12 days to 25 months after the final laser treatment. The number of lesions in prior studies ranged from 7 to 100 BCCs, with the clinical clearance rate ranging from 71.4% to 75% for facial BCC and 78.6% to 95% for nonfacial BCC.3-8 Studies with histologic confirmation had a clearance rate of 66.6% for facial BCC and 25% to 92.3% for nonfacial BCC.3-5,7,8 Most studies examined BCCs on the trunk and extremities with few investigating facial BCC,3-8 which is especially important given that the head and neck are the most common and cosmetically sensitive anatomic locations.9-13

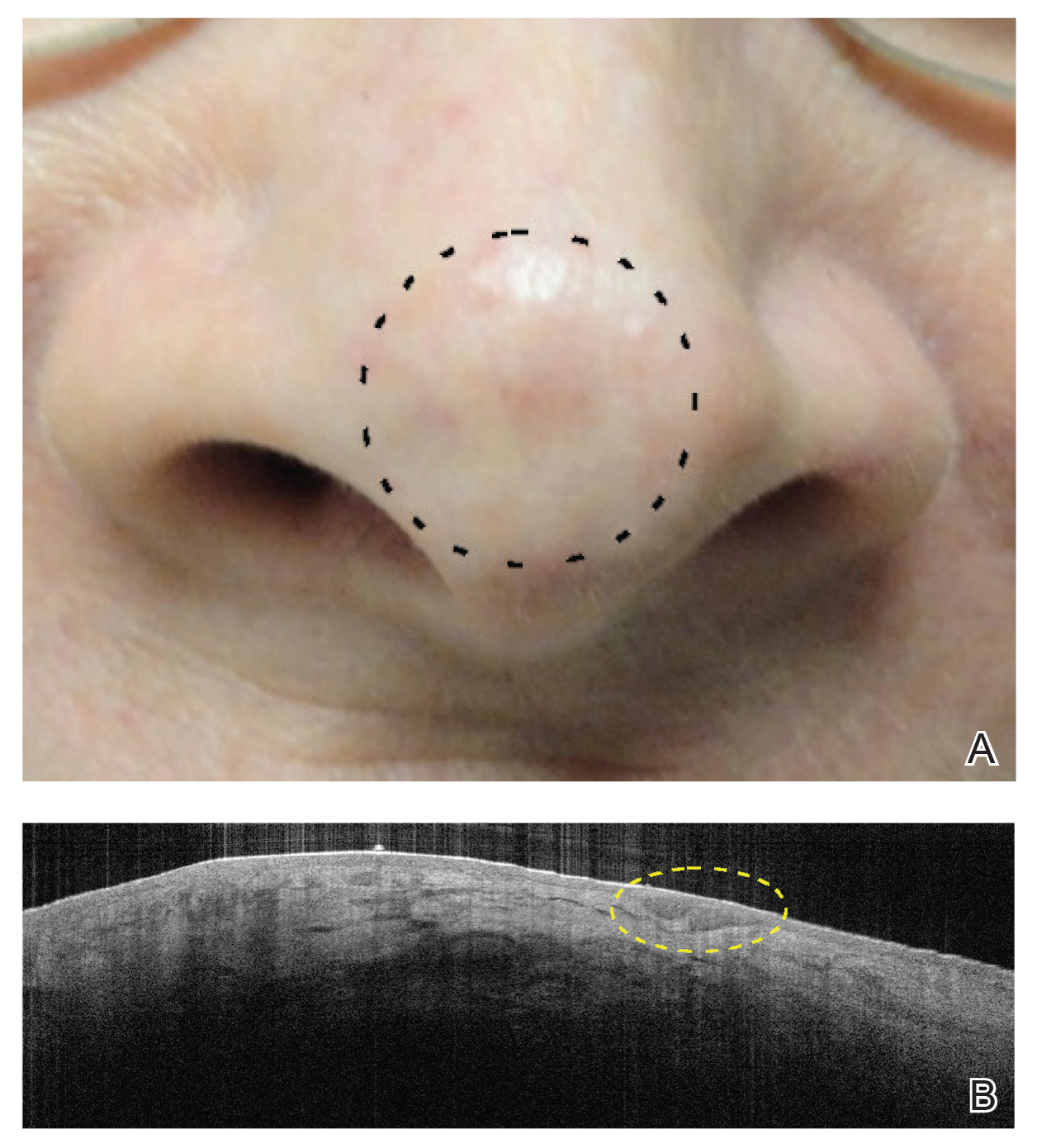

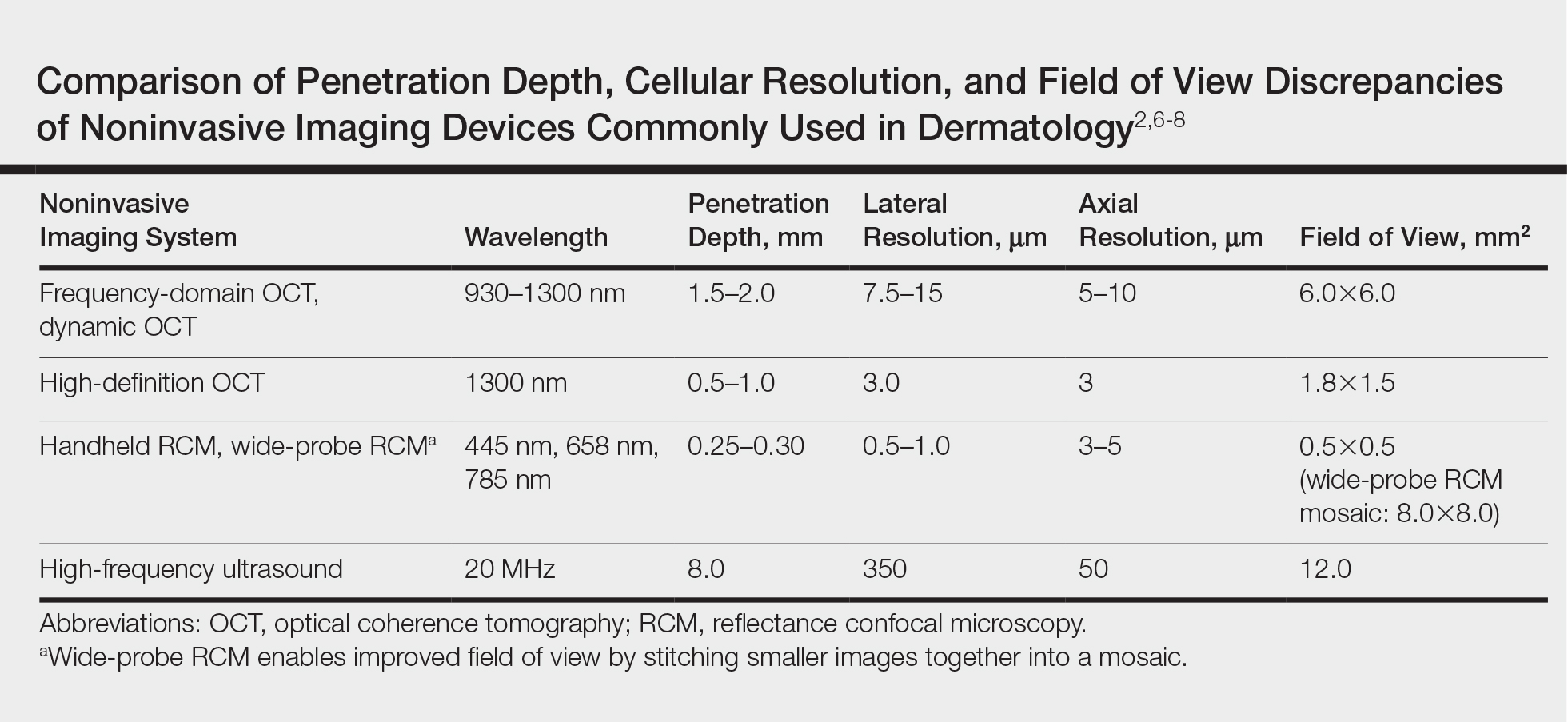

Noninvasive imaging devices, such as reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) and optical coherence tomography (OCT) can assist with the diagnosis and treatment monitoring of BCC. These devices enable in vivo visualization of tissue in both cross-sectional and en face views and therefore can reduce the need for diagnostic biopsy. Reflectance confocal microscopy enables near-histologic visualization of the epidermis and superficial dermis with a resolution of 0.5 to 1 μm.14 Optical coherence tomography uses an infrared broadband light source that allows users to view skin architecture as deep as 1.5 to 2 mm with a resolution of 5 μm.15

When used synergistically, both devices can enhance the efficacy of nonablative laser treatment. With its increased depth and wider field of view, OCT is an optimal tool for repetitive evaluation of the same site over time and for following biopsy-confirmed tumors undergoing management.16 In addition to delineating tumor margins before treatment, imaging improves the detection of residual skin cancers, despite clearance on clinical and dermoscopic examination. Noninvasive imaging and nonsurgical management with laser therapy allow the physician to leave the skin intact and avoid scar tissue that might otherwise make it more difficult to detect and manage recurrence. The ability of OCT and RCM to monitor the efficacy of nonsurgical therapies for skin cancer has been demonstrated with imiquimod, photodynamic therapy, vismodegib, and ablative laser therapy.17-20

With limited data on nonablative laser management of BCC, several gaps in the literature exist. First, in previously published studies the number of treatments was either determined to be an arbitrary set number or based on clinical clearance, which has the potential to miss residual tumor. Second, many follow-ups were limited to shortly after the final treatment, which limits the accuracy of the clearance rate, given that inflammation and scars can hide residual tumor.21-23 Third, because many studies excised the treated area, long-term follow-up for recurrence was obscured. Last, only a few studies involved facial BCC, which is the most common and cosmetically concerning anatomic location.13

Our study attempted to address these gaps by evaluating the use of noninvasive imaging to guide management of primarily facial BCC. The objective was to perform a retrospective chart review on a subgroup of patients with BCC who were treated with combined nonablative PDL and fractional laser treatment with an extended follow-up period.

Methods

Study Design

We performed a retrospective chart review of 68 patients with 93 BCCs who had been treated with nonablative laser therapy as an alternative to surgery at the Mount Sinai Faculty Practice Associates between February 2011 and December 2018. Patients were followed throughout this period for assessment of clinical and subclinical recurrence. The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Program for the Protection of Human Subjects provided institutional review board approval.

Patients

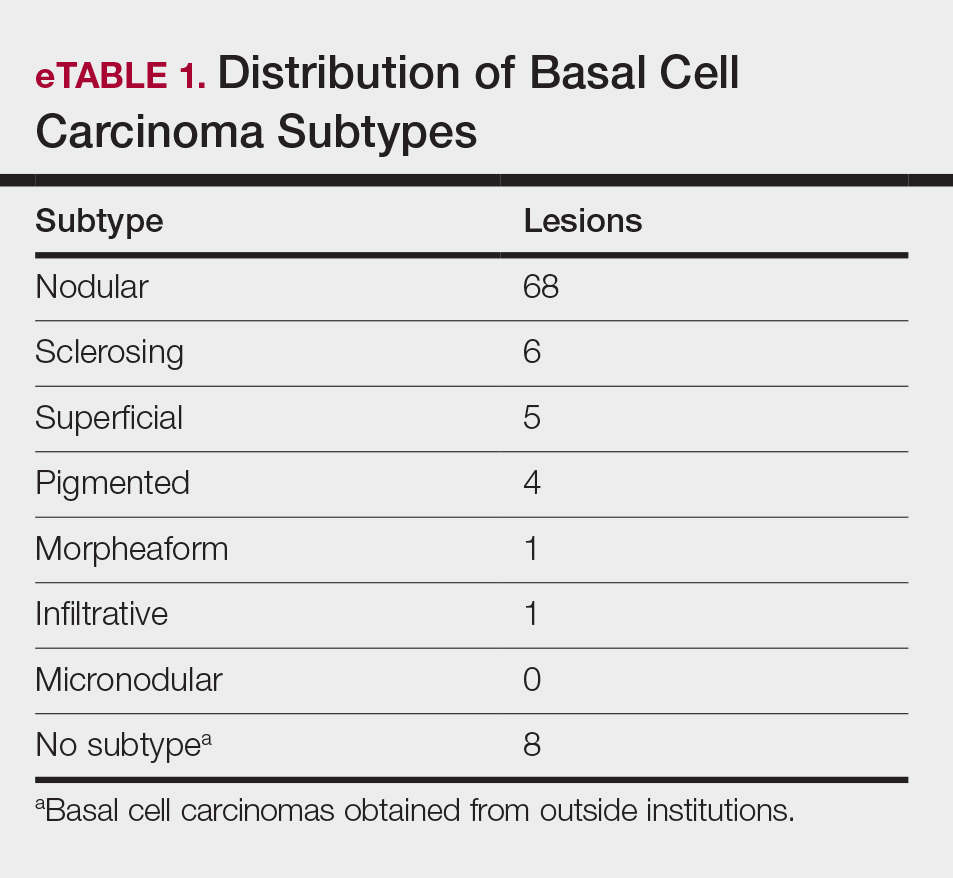

Inclusion criteria included the following: (1) BCC diagnosed by biopsy (see eTable 1 for subtypes) and (2) treated with a nonablative laser due to patient preference and eligibility by the principal investigator (PI). As a retrospective study, lesions were included irrespective of tumor subtype or size. Although the risk for perineural invasion (PNI) is extremely low with BCC (<0.2%), none of the cases demonstrated PNI on diagnostic biopsy and none exhibited clinical evidence of PNI, such as paresthesia, pain, facial paralysis, or diplopia.24

Eligibility determined by the PI included limited clinical ulceration or bleeding, or both, and a safe distance from the eye when wearing an external eye shield (ie, outside the orbital rim). Patients who had Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) or excision (or both) with recurrence at the treatment site were included. Detailed and thorough clinical and dermoscopic skin examination was critical in early detection of these cancers, allowing for treatment of less advanced tumors. The PI’s diagnostic approach utilized the published diagnostic color wheel algorithm,25 which encompasses both clinical and dermoscopic colors and patterns for early diagnosis (ie, ulceration, pink-white to white shiny areas, absence of pigmented network, leaflike structures, large blue-gray ovoid nests or globular structures, spoke wheel structures, a crystalline pattern, a singular vascular pattern of arborizing vessels), combined with OCT or RCM, when necessary.26 All lesions were imaged with OCT prior to laser treatment to confirm residual tumor following biopsy.

Although postsurgical patients were included, lesions receiving concurrent or prior nonsurgical therapy, such as a topical immunomodulator or oral hedgehog inhibitor (eg, vismodegib), were excluded.

Treatment Protocol

All patients received thorough information about the treatment, treatment alternatives, and potential adverse effects and complications. Lesions were selected based on clinical and dermoscopic findings and were biopsy confirmed. Clinical and dermoscopic photographs were taken at every visit. A camera was used for clinical photographs and a dermatoscope was attached for all contact polarized dermoscopic images. All lesions were imaged with OCT prior to laser therapy to delineate tumor margins and to confirm residual disease following biopsy to preclude biopsy-mediated regression.

Laser treatment consisted of a 595-nm PDL followed by fractional laser treatment with the 1927-nm setting. The range of PDL settings was similar to published studies of PDL for BCC (spot size, 7–10 mm; fluence, 6–15 J/cm2; pulse duration, 0.45–3 milliseconds).3-8 The fractional laser also was used at settings similar to earlier studies for actinic keratosis (fluence, 5–20 mJ; treatment density, 40%–70%).27 Laser treatment was performed by 1 of 5 medically trained providers who were fellows supervised by the PI.

All tumors received 1 to 7 treatments (average, 2.89) at 1- to 2-month intervals. Treatment end point (complete clearance) was judged on the absence of skin cancer clinically, dermoscopically on OCT, or histologically by biopsy, or a combination of these modalities. Recurrence was defined as a new histologically confirmed BCC occurring in an area that was previously documented as clear. Patients returned for follow-up 1 to 2 months after the final treatment to monitor tumor clearance and subsequently every 6 to 12 months for tumor recurrence. Posttreatment care included application of a thick emollient, such as a petrolatum-based product, until the area completely healed.

Data Collection

Clinical photographs, dermoscopic photographs, OCT scans, RCM scans, and biopsy reports were reviewed for each patient, as applicable. All patients were given an unidentifiable number; no protected health information was recorded. Data recorded for each patient included age, tumor subtype and location, tumor size, classification of the tumor as primary or a recurrence, number of treatments, treatment duration, lesion clearance, and length of follow-up.

Results

Patient and Lesion Characteristics

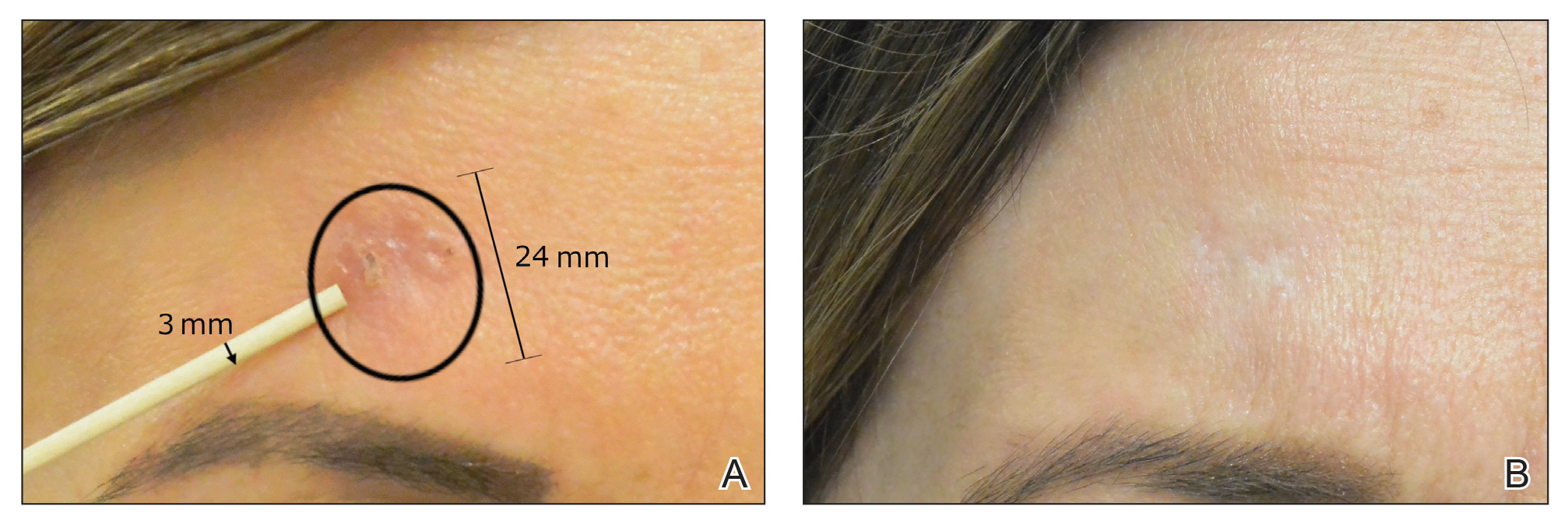

Sixty-eight patients with 93 BCCs (77 facial; 16 nonfacial) were included. The median age of patients was 70 years (range, 31–91 years). All 93 BCCs demonstrated residual tumor on OCT after diagnostic biopsy. Four BCCs had been treated earlier with MMS and were biopsy-proven recurrences. Most BCCs were of the nodular subtype; however, sclerosing, superficial, pigmented, morpheaform, and infiltrative subtypes also were included (eTable 1). Eight BCCs were obtained at outside institutions with no subtype provided. Facial BCCs had a mean (SD) clinical and dermoscopic diameter of 6.75 (4.71) mm (range, 2–24 mm). Patients were followed for 2.53 months to 6.03 years (mean follow-up, 2.43 years) and assessed for clinical and subclinical recurrence.

Tumor Clearance

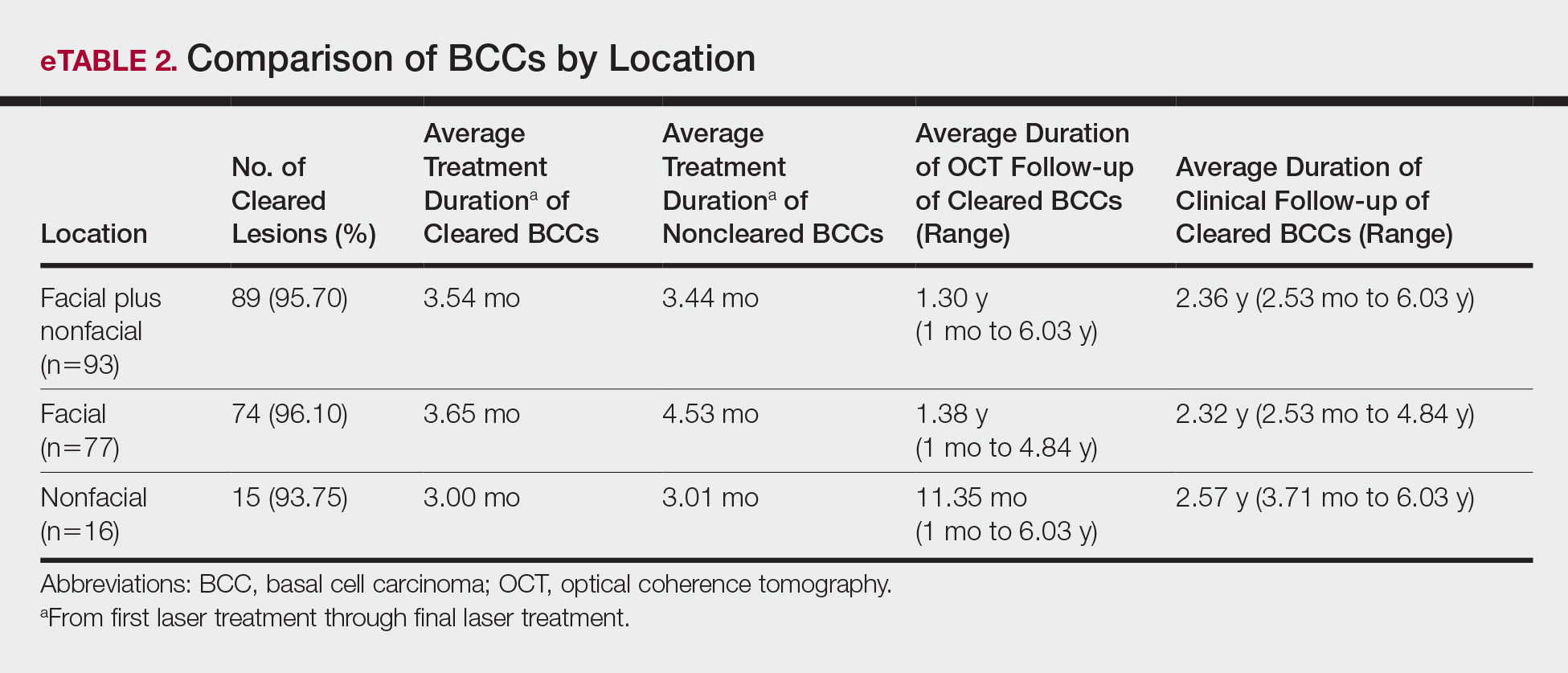

Most lesions were effectively treated, with 89 of 93 BCCs (95.70%) demonstrating complete tumor clearance. Complete tumor clearance following laser therapy was reported in 74 of 77 facial BCCs (96.10%) and 15 of 16 nonfacial BCCs (93.75%)(eTable 2). Successfully treated BCCs underwent an average of 2.88 laser treatments over a mean duration of 3.54 months (range, 1 week to 1.92 years). Four incomplete responders underwent an average of 3.25 laser treatments over a mean duration of 3.44 months (range, 1.13–6.87 months). Of the 4 lesions that did not clear, 2 were nodular, 1 was pigmented, and 1 was sclerosing.

Number of Treatments

When the clearance rate is divided into lesions that received 3 or fewer laser treatments and those that received more than 3 laser treatments, the following results were determined:

• Lesions receiving 3 or fewer treatments had a clearance rate of 96.05% (73/76) for all BCCs, 96.72% (59/61) for facial BCCs, and 93.33% (14/15) for nonfacial BCCs.

• Lesions receiving more than 3 laser treatments had a clearance rate of 94.12% (16/17) for all BCCs, 93.75% (15/16) for facial BCCs, and 100% (1/1) for nonfacial BCCs.

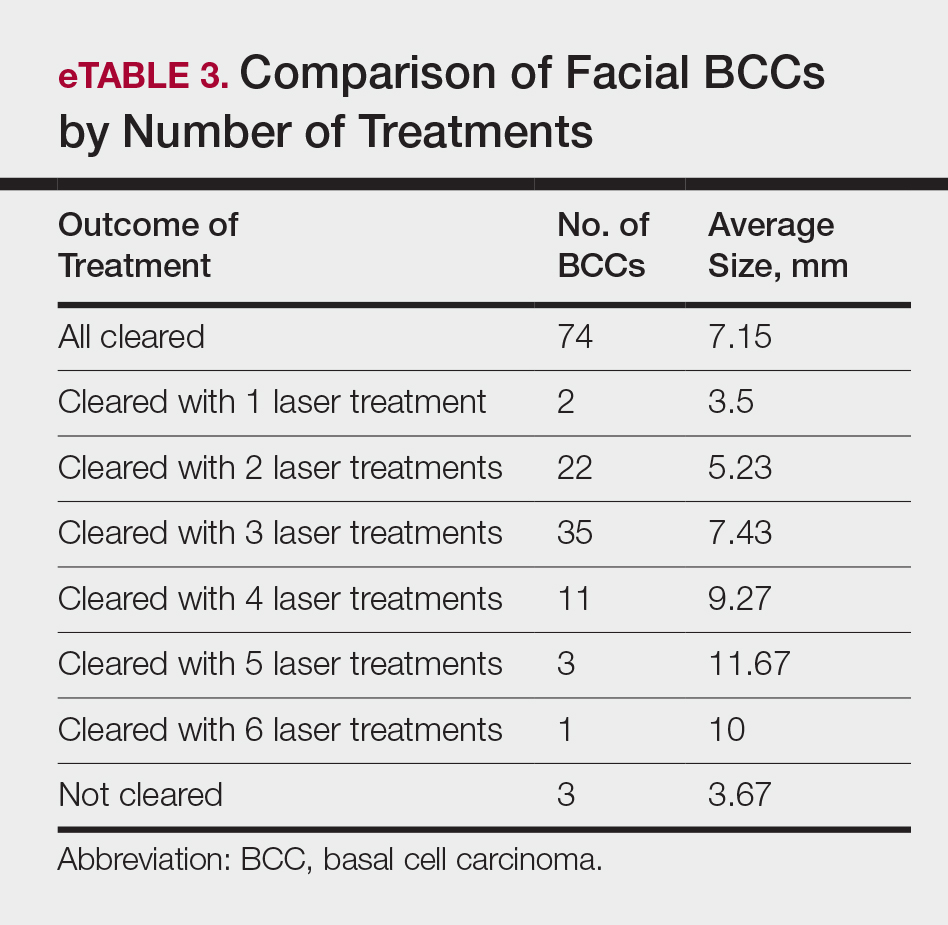

The relationship between facial BCC tumor diameter and number of treatments required for clearance had a positive correlation coefficient (Pearson r=0.319), indicating that larger BCCs required more laser treatments (eTable 3).

Tumor Recurrence

Four of 89 BCCs (4.49%)(4 of 74 facial BCCs [5.41%]) showed tumor recurrence following laser treatment, as assessed by OCT and dermoscopy. Of them, all were nodular BCCs. Prior to laser treatment, there were 4 additional patients each diagnosed with a recurrence from prior treatment with MMS; all were successfully treated with laser therapy without recurrence post–laser treatment (eFigure 1). Most of the recurrences from prior MMS required more than 3 laser treatments before clearing: 1 required 3 treatments, 2 required 4 treatments, and 1 required 6 treatments.

Of 93 lesions included in this study, 2 BCCs were deemed not clear on histologic analysis, which corresponded with residual tumor seen on OCT. Two additional lesions were determined to be not clear on OCT but were not confirmed as such on biopsy; both lesions were confirmed not clear, however, by histologic analysis on the first layer of MMS

Follow-up

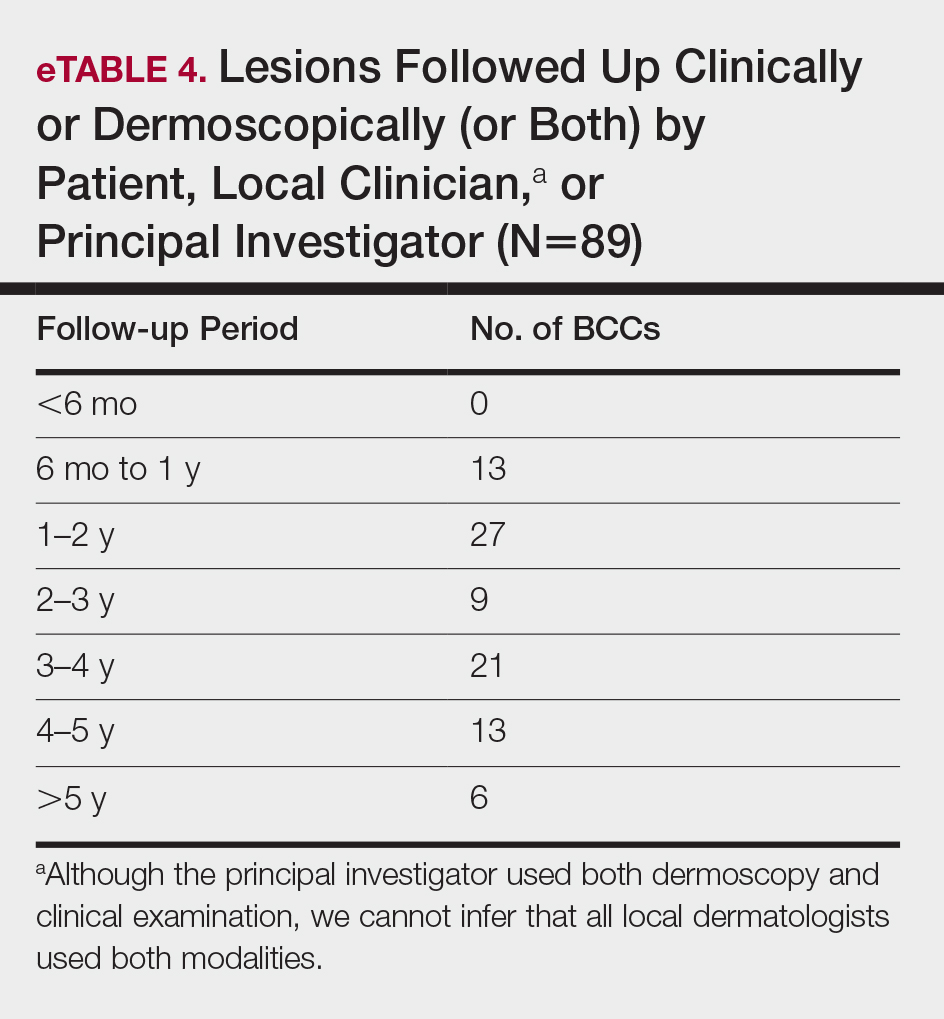

All cleared lesions (89/93) showed complete clinical response to laser treatment for 6 months or more (median follow-up, 2–3 years; mode, 1–2 years; mean, 2.66 years)(eTable 4). Although 45% of patients (40/89) have been followed clinically and/or dermoscopically (as is done for MMS follow-ups) for 3 years to more than 5 years, only 20% of patients (18/89) were followed up with OCT in combination with clinical and/or dermoscopic examination between 3 years and more than 5 years. Follow-up took on a bimodal distribution, with a peak follow-up period at 1 to 2 years and again at 3 to 4 years. Half of the lesions (45/89) were followed up with OCT in combination with clinical and dermoscopic examination at 1 to 6 months (eTable 5). Of the 2 patients with 1-month OCT follow-up, 1 died from other medical causes and the other was unable to return for further follow-up scans.

Comment

High Tumor Clearance Rates With OCT

This study yielded a clearance rate of 95.70% for all BCCs, 96.10% for facial BCCs, and 93.75% for nonfacial BCCs. This rate is higher than the clinical or histologic clearance rate (or both) of earlier studies on facial and nonfacial BCCs, which ranged from 25% to 95%.8-11 In this study, we were able to utilize OCT and histology to confirm clearance. Optical coherence tomography, which has been shown to have a high sensitivity ranging from 86% to 95.7%, is therefore optimally used in treatment monitoring.19,26,28 Optical coherence tomography has a broader specificity range of 75.3% to 98% and was not utilized for diagnostic purposes in this study. Combining OCT with a color wheel dermoscopic approach was helpful in confirming treatment efficacy of nonsurgical therapies and is significantly more accurate than clinical analysis alone (P<.01).19,26,28

We suspect that the higher clearance rates observed in our study were due to the OCT-guided treatment protocol. Optical coherence tomography was used for margination while providing a modality for tailored treatment through visualization of residual tumor on clinically and dermoscopically clear follow-ups, given that several studies found residual tumor at the lateral edge of the tumor margin on histopathologic analysis.5 Utilizing noninvasive imaging technology to delineate tumor margins before treatment can improve efficacy and limit unnecessary treatment to the surrounding normal skin (eFigure 2).29

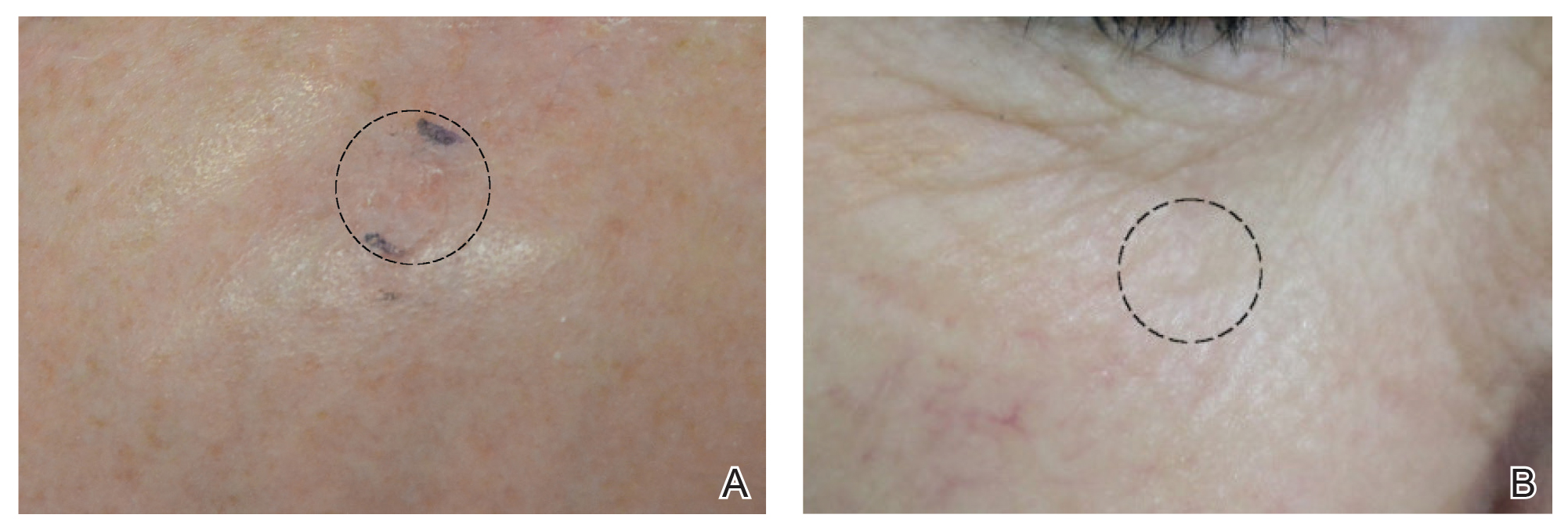

After grouping lesions by number of laser treatments, the clearance rate remained similar among facial BCCs with 3 or fewer treatments (59/61 [96.72%]), but there was a slightly decreased clearance rate for facial BCCs with more than 3 treatments (15/16 [93.75%]), which may be explained by the need for more laser treatments for larger BCCs (eTable 3). The relationship between facial BCC size and number of laser treatments was found to correlate positively (Pearson r=0.319). The largest lesion (24 mm) was successfully treated with 5 treatments (Figure). The number of nonfacial lesions was limited in this study and was not statistically significant.

there was no clinical evidence of residual BCC.

Cosmetic Outcome

Adverse effects, including erythema, purpura, blistering, and crusting, were short-term and well tolerated. Few patients had subsequent hypopigmentation in the initial months after treatment, which we consider an optimal cosmetic outcome. For example, the patient shown in the Figure would have required extensive reconstruction of the defect using bilateral rotation flaps with incisions along the hairline, grafting, or second-intention healing with partial closure to avoid brow-lifting.30 Given the relatively young age of this patient (a 45-year-old woman) and therefore limited skin laxity, secondary intention or even attempting to match grafted tissue could have resulted in a less than optimal cosmetic outcome. None of the patients experienced clinical or dermoscopic evidence of scarring from the laser treatment.

A few lesions were found to have subclinical inflammation on OCT, which might have obscured residual tumor on the 1-month follow-up scan. This condition may be similar to how pre-MMS diagnostic biopsy scars mask skin cancer during surgery, making it necessary to obtain additional layers beyond the biopsy scar tissue. This scar tissue would otherwise obscure tumor on histology during MMS, similar to subclinical inflammation obscuring residual tumor on OCT.21-23,31 Invasive and noninvasive management of skin cancers will have different healing times and therefore different optimal times to confirm clearance by histology compared to noninvasive imaging. All of the lesions in which inflammation was obscured on OCT 1-month posttreatment remained cleared. However, 1 lesion was found to be clear at a 4-week clearance scan after only 2 nonablative laser treatments and was confirmed as scar tissue on histology. Scar tissue on histology might have obscured any residual tumor. The patient appeared clinically and dermoscopically to have a milia in the same location only 5 months later; however, on OCT and histology, the lesion was confirmed to be a BCC.

Treatment Intervals

Several other studies either used a set number of treatments or determined the number of treatments based on clinical clearance.3-8 When determining the best treatment interval, we considered the period for patients to be clinically and dermoscopically healed to be 1 month. Patients came for their final follow-up scan an additional month after the final treatment in case there was any obscuring inflammation on OCT at 1 month. Given that patients responded well to nonablative laser treatment once skin clinically healed and most patients required 3 treatments, the PI began recommending a total of 3 treatments performed 4 to 6 weeks apart in clinical practice, followed by a final clearance scan 2 months after the third treatment. A period of 2 months was considered ideal for the final clearance scan because no inflammation was seen at the 2-month follow-up in the group of patients who had inflammation at the 1-month follow-up on OCT in our study. Some patients had an extended treatment duration because of noncompliance with the 4- to 6-week follow-up regimen. Although this extension of treatment duration potentially skews the clearance rate, we still included these patients, given the retrospective design of this study.

Lesions That Did Not Clear

Four BCCs did not clear, 3 of which were facial BCCs. All 4 lesions demonstrated residual tumor on OCT. Of the 3 facial lesions that did not clear:

• One was the patient who had obscuring inflammation at the 1-month follow-up and only scar tissue on histologic confirmation.

• Another was a pigmented BCC on the right cheek of a patient with Fitzpatrick skin type IV. This patient received 3 treatments without a response clinically or on OCT. (Most patients who showed complete clearance also showed reduction in tumor size after the first laser treatment. Of note, there were other patients who had lighter skin types with pigmented BCCs and all of these patients had complete response to this treatment regimen; therefore, we do not think that a pigmented BCC is an exclusion to this therapy.)

• The third was a BCC on the nose of a nonadherent patient, which may have contributed to the lack of clearance. We defined nonadherent patients as those who did not follow-up within the appropriate periods and who therefore ran the risk for tumor growth in between treatments.

The nonfacial BCC that did not clear had histologic features of focal sclerosing BCC, a more aggressive subtype of basal cell skin cancer.

Tumor Recurrence

Only 4 of 89 BCCs (4.49%) recurred, with a 5.41% (4/74) recurrence rate among facial BCCs. All recurrences lacked clinical and dermoscopic evidence of BCC but were found on follow-up OCT scan and confirmed with RCM. All recurrences were found 1.5 to 3.9 years posttreatment.

Recurrent tumors following MMS required, on average, more laser treatments than primary tumors to achieve successful tumor clearance, which we attribute to scar tissue from prior therapy obscuring recurrence, resulting in delayed diagnosis, and to inflammation and fibrosis masking residual tumors (eFigure 1). An added benefit of laser treatment is that all 4 recurrent tumors demonstrated improved cosmetic appearance of the original MMS scar.

The benefit of using OCT scans to check for recurrences is that OCT can find residual skin cancers despite the area looking clinically clear, which is especially important during clinical evaluation of a healed postsurgical scar for recurrence because OCT imaging allows us to look as deep as 2 mm under the skin. Nonsurgical treatments also enable us to leave skin intact and avoid creating scar tissue, which makes it easier to detect and manage recurrence.

Limitations

There were several important limitations of this retrospective study:

• Patients were treated by 1 of 5 medically trained fellows. Although the fellows worked under the supervision of the PI, variation in their work from one to another might have led to different end points.

• All patients who appeared clinically clear were offered biopsy to confirm clearance on histology. Some patients agreed to biopsy, but many did not because they were pleased with the cosmetic outcome, which is similar to other studies exhibiting only clinical clearance rates without providing histologic clearance following nonsurgical therapy.6 We believe that imaging with OCT circumvents this problem and offers more accurate confirmation than clinical or dermoscopic correlation alone, or the combination of the 2 modalities.

• Lack of treatment standardization and short length of follow-up can result in underestimation of the recurrence rate. In particular, most patients were followed up with OCT in less than 6 months. These are unavoidable features in a retrospective study and we are currently addressing this problem in a new prospective study.

Extended Follow-up

Although this study is not a prospective design, it does provide recurrence data over extended follow-up for the nonablative laser management of BCCs (eTables 4 and 5). Studies have demonstrated that MMS has a 5-year cure rate as high as 99% for BCC.32 Given the limited follow-up period of prior nonablative laser management studies, recurrences might not have been fully evaluated. Our study had a 4.49% recurrence rate for all BCCs and a 5.41% recurrence rate for facial BCCs but was not detectable by clinical examination combined with dermoscopic findings alone. All recurrences required the utilization of OCT or RCM or a combination of these modalities to be diagnosed. In 1 patient with recurrence, we were able to see residual tumor on both OCT and RCM without any inflammation obscuring the scan, given that 3 years had passed. Although 2 months is an optimal follow-up time for OCT, we have not found an optimal follow-up time for RCM, which is another reason why OCT might be preferable to other imaging modalities, such as RCM and high-definition OCT, that have higher resolution but provide less depth on imaging. Although only 40 of 89 patients (4.49%) had follow-up ranging from 3 years to greater than 5 years, long-term follow-up to date has been limited in prior studies.

We believe the high clearance rates and limited recurrence are secondary to the utilization of noninvasive imaging, as the majority of these recurrences would not have been diagnosed based on clinical and/or dermoscopic information alone. Additionally, the 4 biopsy-proven post-MMS recurrence patients that were treated in this study also may not have been diagnosed this early without the use of additional noninvasive imaging. In our opinion, although laser management can be used without noninvasive imaging guidance—dermoscopy, OCT, and/or RCM—this technology is critical not only for early detection but also for proper management of patients.

Conclusion

This study showed a 95.70% clearance rate for all BCCs and a 96.10% clearance rate for facial BCCs. Although we had a zero clinical recurrence rate, 4.49% of all BCCs and 5.41% of facial BCCs had recurred on subsequent monitoring with noninvasive imaging. Given the large size of the study and extended follow-up, we found nonablative laser management to be a reliable treatment alternative with improved cosmetic outcome (Figure) and minimal short-term adverse effects compared to surgery.

Tailored care for the individual patient is based on a variety of options and patient preference, including ease of compliance, number of follow-up visits, invasive vs noninvasive diagnosis and monitoring, and downtime for healing. The use of noninvasive imaging also allowed us to find a more standardized treatment regimen using this nonablative laser combination. We found that 3 or fewer and more than 3 treatments had similar efficacy in tumor clearance. We recommend a standard laser protocol of 3 treatments every 4 to 6 weeks with follow-up 2 months after the final treatment to assess for clearance with OCT.

Larger BCCs might require additional treatments; therefore, we caution against laser therapy without concomitant use of OCT imaging to visualize residual tumor. Utilizing other noninvasive modalities, such as dermoscopy, in combination with thorough skin examination also is critical in the early detection of skin cancers to improve the efficacy of this less-aggressive, nonablative, and cosmetically optimal treatment protocol.

Acknowledgement—We would like to acknowledge Dimitrios Karponis, BSc, from the Impirial College London, England, for his assistance with a portion of the statistical analysis.

- Campolmi P, Troiano M, Bonan P, et al. Vascular based non conventional dye laser treatment for basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:402-405.

- Soleymani T, Abrouk M, Kelly KM. An analysis of laser therapy for the treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:615-624.

- Alonso-Castro L, Ríos-Buceta L, Boixeda P, et al. The effect of pulsed dye laser on high-risk basal cell carcinomas with response control by Mohs micrographic surgery. Lasers Med Sci. 2015;30:2009-2014.

- Karsai S, Friedl H, Buhck H, et al. The role of the 595-nm pulsed dye laser in treating superficial basal cell carcinoma: outcome of a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:677-683.

- Konnikov N, Avram M, Jarell A, et al. Pulsed dye laser as a novel non-surgical treatment for basal cell carcinomas: response and follow up 12-21 months after treatment. Lasers Surg Med. 2011;43:72-78.

- Minars N, Blyumin-Karasik M. Treatment of basal cell carcinomas with pulsed dye laser: a case series. J Skin Cancer. 2012;2012:286480.

- Shah SM, Konnikov N, Duncan LM, et al. The effect of 595 nm pulsed dye laser on superficial and nodular basal cell carcinomas. Lasers Surg Med. 2009;41:417-422.

- Tran HT, Lee RA, Oganesyan G, et al. Single treatment of non-melanoma skin cancers using a pulsed-dye laser with stacked pulses. Lasers Surg Med. 2012;44:459-467.

- Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: epidemiology; pathophysiology; clinical and histological subtypes; and disease associations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:303-317.

- Silverman MK, Kopf AW, Bart RS, et al. Recurrence rates of treated basal cell carcinomas. part 3: surgical excision. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:471-476.

- Silverman MK, Kopf AW, Grin CM, et al. Recurrence rates of treated basal cell carcinomas. part 2: curettage-electrodesiccation. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1991;17:720-726.

- Dubin N, Kopf AW. Multivariate risk score for recurrence of cutaneous basal cell carcinomas. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:373-377.

- Subramaniam P, Olsen CM, Thompson BS, et al. Anatomical distributions of basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma in a population-based study in Queensland, Australia. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:175-182.

- Rajadhyaksha M, Grossman M, Esterowitz D, et al. In vivo confocal scanning laser microscopy of human skin: melanin provides strong contrast.J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104:946-952.

- Levine A, Wang K, Markowitz O. Optical coherence tomography in the diagnosis of skin cancer. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35:465-488.

- Sattler E, Kästle R, Welzel J. Optical coherence tomography in dermatology. J Biomed Opt. 2013;18:061224.

- Banzhaf CA, Themstrup L, Ring HC, et al. Optical coherence tomography imaging of non-melanoma skin cancer undergoing imiquimod therapy. Ski Res Technol. 2014;20:170-176.

- Segura S, Puig S, Carrera C, et al. Non-invasive management of non-melanoma skin cancer in patients with cancer predisposition genodermatosis: a role for confocal microscopy and photodynamic therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:819-827.

- Ulrich M, Lange-Asschenfeldt S, Gonzalez S. The use of reflectance confocal microscopy for monitoring response to therapy of skin malignancies. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2012;2:43-52.

- Couzan C, Cinotti E, Labeille B, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy identification of subclinical basal cell carcinomas during and after vismodegib treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:763-767.

- Ruiz ES, Karia PS, Morgan FC, et al. Multiple Mohs micrographic surgery is the most common reason for divergence from the appropriate use criteria: a single institution retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:830-831.

- Wagner RF Jr, Cottel WI. Multifocal recurrent basal cell carcinoma following primary tumor treatment by electrodesiccation and curettage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:1047-1049.

- Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:1582-1603.

- Lewin JM, Carucci JA. Advances in the management of basal cell carcinoma. F1000Prime Rep. 2015;7:53.

- Markowitz O. A Practical Guide to Dermoscopy. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2017.

- Markowitz O, Schwartz M, Feldman E, et al. Evaluation of optical coherence tomography as a means of identifying earlier stage basal cell carcinomas while reducing the use of diagnostic biopsy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:14-20.

- Weiss ET, Brauer JA, Anolik R, et al. 1927-nm fractional resurfacing of facial actinic keratoses: a promising new therapeutic option. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:98-102.

- Olsen J, Themstrup L, De Carvalho N, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of optical coherence tomography in actinic keratosis and basal cell carcinoma. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2016;16:44-49.

- Levine A, Siegel D, Markowitz O. Imaging in cutaneous surgery. Future Oncol. 2017;13:2329-2340.

- Gross K, Steinman H, Rapini R. Mohs Surgery: Fundamentals and Techniques. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1998.

- Suzuki HS, Serafini SZ, Sato MS. Utility of dermoscopy for demarcation of surgical margins in Mohs micrographic surgery. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:38-43.

- Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL Jr. Mohs surgery is the treatment of choice for recurrent (previously treated) basal cell carcinoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15:424-431

Nonablative laser therapy is emerging as an effective noninvasive treatment option for basal cell carcinoma (BCC) with reduced adverse effects and good cosmetic outcomes compared to surgery. Vascular lasers, such as the pulsed dye laser (PDL), are thought to work by selectively targeting the tumor’s vascular network while preserving normal surrounding tissue.1,2 Although high energy and multiple passes might be required, adjunctive use of dynamic cooling reduces the risk for nonselective thermal injury vs ablative lasers, which destroy the tumor itself through vaporization of tissue water.2

With no established laser management guidelines for the treatment of BCC, earlier studies using a 595-nm PDL varied highly in their protocol.3-8 Pulsed dye laser parameters ranged from a spot size of 7 to 10 mm, fluence of 7.5 to 15 J/cm2, and pulse duration of 0.5 to 3 milliseconds. Follow-up ranged from 12 days to 25 months after the final laser treatment. The number of lesions in prior studies ranged from 7 to 100 BCCs, with the clinical clearance rate ranging from 71.4% to 75% for facial BCC and 78.6% to 95% for nonfacial BCC.3-8 Studies with histologic confirmation had a clearance rate of 66.6% for facial BCC and 25% to 92.3% for nonfacial BCC.3-5,7,8 Most studies examined BCCs on the trunk and extremities with few investigating facial BCC,3-8 which is especially important given that the head and neck are the most common and cosmetically sensitive anatomic locations.9-13

Noninvasive imaging devices, such as reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) and optical coherence tomography (OCT) can assist with the diagnosis and treatment monitoring of BCC. These devices enable in vivo visualization of tissue in both cross-sectional and en face views and therefore can reduce the need for diagnostic biopsy. Reflectance confocal microscopy enables near-histologic visualization of the epidermis and superficial dermis with a resolution of 0.5 to 1 μm.14 Optical coherence tomography uses an infrared broadband light source that allows users to view skin architecture as deep as 1.5 to 2 mm with a resolution of 5 μm.15

When used synergistically, both devices can enhance the efficacy of nonablative laser treatment. With its increased depth and wider field of view, OCT is an optimal tool for repetitive evaluation of the same site over time and for following biopsy-confirmed tumors undergoing management.16 In addition to delineating tumor margins before treatment, imaging improves the detection of residual skin cancers, despite clearance on clinical and dermoscopic examination. Noninvasive imaging and nonsurgical management with laser therapy allow the physician to leave the skin intact and avoid scar tissue that might otherwise make it more difficult to detect and manage recurrence. The ability of OCT and RCM to monitor the efficacy of nonsurgical therapies for skin cancer has been demonstrated with imiquimod, photodynamic therapy, vismodegib, and ablative laser therapy.17-20

With limited data on nonablative laser management of BCC, several gaps in the literature exist. First, in previously published studies the number of treatments was either determined to be an arbitrary set number or based on clinical clearance, which has the potential to miss residual tumor. Second, many follow-ups were limited to shortly after the final treatment, which limits the accuracy of the clearance rate, given that inflammation and scars can hide residual tumor.21-23 Third, because many studies excised the treated area, long-term follow-up for recurrence was obscured. Last, only a few studies involved facial BCC, which is the most common and cosmetically concerning anatomic location.13

Our study attempted to address these gaps by evaluating the use of noninvasive imaging to guide management of primarily facial BCC. The objective was to perform a retrospective chart review on a subgroup of patients with BCC who were treated with combined nonablative PDL and fractional laser treatment with an extended follow-up period.

Methods

Study Design

We performed a retrospective chart review of 68 patients with 93 BCCs who had been treated with nonablative laser therapy as an alternative to surgery at the Mount Sinai Faculty Practice Associates between February 2011 and December 2018. Patients were followed throughout this period for assessment of clinical and subclinical recurrence. The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Program for the Protection of Human Subjects provided institutional review board approval.

Patients

Inclusion criteria included the following: (1) BCC diagnosed by biopsy (see eTable 1 for subtypes) and (2) treated with a nonablative laser due to patient preference and eligibility by the principal investigator (PI). As a retrospective study, lesions were included irrespective of tumor subtype or size. Although the risk for perineural invasion (PNI) is extremely low with BCC (<0.2%), none of the cases demonstrated PNI on diagnostic biopsy and none exhibited clinical evidence of PNI, such as paresthesia, pain, facial paralysis, or diplopia.24

Eligibility determined by the PI included limited clinical ulceration or bleeding, or both, and a safe distance from the eye when wearing an external eye shield (ie, outside the orbital rim). Patients who had Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) or excision (or both) with recurrence at the treatment site were included. Detailed and thorough clinical and dermoscopic skin examination was critical in early detection of these cancers, allowing for treatment of less advanced tumors. The PI’s diagnostic approach utilized the published diagnostic color wheel algorithm,25 which encompasses both clinical and dermoscopic colors and patterns for early diagnosis (ie, ulceration, pink-white to white shiny areas, absence of pigmented network, leaflike structures, large blue-gray ovoid nests or globular structures, spoke wheel structures, a crystalline pattern, a singular vascular pattern of arborizing vessels), combined with OCT or RCM, when necessary.26 All lesions were imaged with OCT prior to laser treatment to confirm residual tumor following biopsy.

Although postsurgical patients were included, lesions receiving concurrent or prior nonsurgical therapy, such as a topical immunomodulator or oral hedgehog inhibitor (eg, vismodegib), were excluded.

Treatment Protocol

All patients received thorough information about the treatment, treatment alternatives, and potential adverse effects and complications. Lesions were selected based on clinical and dermoscopic findings and were biopsy confirmed. Clinical and dermoscopic photographs were taken at every visit. A camera was used for clinical photographs and a dermatoscope was attached for all contact polarized dermoscopic images. All lesions were imaged with OCT prior to laser therapy to delineate tumor margins and to confirm residual disease following biopsy to preclude biopsy-mediated regression.

Laser treatment consisted of a 595-nm PDL followed by fractional laser treatment with the 1927-nm setting. The range of PDL settings was similar to published studies of PDL for BCC (spot size, 7–10 mm; fluence, 6–15 J/cm2; pulse duration, 0.45–3 milliseconds).3-8 The fractional laser also was used at settings similar to earlier studies for actinic keratosis (fluence, 5–20 mJ; treatment density, 40%–70%).27 Laser treatment was performed by 1 of 5 medically trained providers who were fellows supervised by the PI.

All tumors received 1 to 7 treatments (average, 2.89) at 1- to 2-month intervals. Treatment end point (complete clearance) was judged on the absence of skin cancer clinically, dermoscopically on OCT, or histologically by biopsy, or a combination of these modalities. Recurrence was defined as a new histologically confirmed BCC occurring in an area that was previously documented as clear. Patients returned for follow-up 1 to 2 months after the final treatment to monitor tumor clearance and subsequently every 6 to 12 months for tumor recurrence. Posttreatment care included application of a thick emollient, such as a petrolatum-based product, until the area completely healed.

Data Collection

Clinical photographs, dermoscopic photographs, OCT scans, RCM scans, and biopsy reports were reviewed for each patient, as applicable. All patients were given an unidentifiable number; no protected health information was recorded. Data recorded for each patient included age, tumor subtype and location, tumor size, classification of the tumor as primary or a recurrence, number of treatments, treatment duration, lesion clearance, and length of follow-up.

Results

Patient and Lesion Characteristics

Sixty-eight patients with 93 BCCs (77 facial; 16 nonfacial) were included. The median age of patients was 70 years (range, 31–91 years). All 93 BCCs demonstrated residual tumor on OCT after diagnostic biopsy. Four BCCs had been treated earlier with MMS and were biopsy-proven recurrences. Most BCCs were of the nodular subtype; however, sclerosing, superficial, pigmented, morpheaform, and infiltrative subtypes also were included (eTable 1). Eight BCCs were obtained at outside institutions with no subtype provided. Facial BCCs had a mean (SD) clinical and dermoscopic diameter of 6.75 (4.71) mm (range, 2–24 mm). Patients were followed for 2.53 months to 6.03 years (mean follow-up, 2.43 years) and assessed for clinical and subclinical recurrence.

Tumor Clearance

Most lesions were effectively treated, with 89 of 93 BCCs (95.70%) demonstrating complete tumor clearance. Complete tumor clearance following laser therapy was reported in 74 of 77 facial BCCs (96.10%) and 15 of 16 nonfacial BCCs (93.75%)(eTable 2). Successfully treated BCCs underwent an average of 2.88 laser treatments over a mean duration of 3.54 months (range, 1 week to 1.92 years). Four incomplete responders underwent an average of 3.25 laser treatments over a mean duration of 3.44 months (range, 1.13–6.87 months). Of the 4 lesions that did not clear, 2 were nodular, 1 was pigmented, and 1 was sclerosing.

Number of Treatments

When the clearance rate is divided into lesions that received 3 or fewer laser treatments and those that received more than 3 laser treatments, the following results were determined:

• Lesions receiving 3 or fewer treatments had a clearance rate of 96.05% (73/76) for all BCCs, 96.72% (59/61) for facial BCCs, and 93.33% (14/15) for nonfacial BCCs.

• Lesions receiving more than 3 laser treatments had a clearance rate of 94.12% (16/17) for all BCCs, 93.75% (15/16) for facial BCCs, and 100% (1/1) for nonfacial BCCs.

The relationship between facial BCC tumor diameter and number of treatments required for clearance had a positive correlation coefficient (Pearson r=0.319), indicating that larger BCCs required more laser treatments (eTable 3).

Tumor Recurrence

Four of 89 BCCs (4.49%)(4 of 74 facial BCCs [5.41%]) showed tumor recurrence following laser treatment, as assessed by OCT and dermoscopy. Of them, all were nodular BCCs. Prior to laser treatment, there were 4 additional patients each diagnosed with a recurrence from prior treatment with MMS; all were successfully treated with laser therapy without recurrence post–laser treatment (eFigure 1). Most of the recurrences from prior MMS required more than 3 laser treatments before clearing: 1 required 3 treatments, 2 required 4 treatments, and 1 required 6 treatments.

Of 93 lesions included in this study, 2 BCCs were deemed not clear on histologic analysis, which corresponded with residual tumor seen on OCT. Two additional lesions were determined to be not clear on OCT but were not confirmed as such on biopsy; both lesions were confirmed not clear, however, by histologic analysis on the first layer of MMS

Follow-up

All cleared lesions (89/93) showed complete clinical response to laser treatment for 6 months or more (median follow-up, 2–3 years; mode, 1–2 years; mean, 2.66 years)(eTable 4). Although 45% of patients (40/89) have been followed clinically and/or dermoscopically (as is done for MMS follow-ups) for 3 years to more than 5 years, only 20% of patients (18/89) were followed up with OCT in combination with clinical and/or dermoscopic examination between 3 years and more than 5 years. Follow-up took on a bimodal distribution, with a peak follow-up period at 1 to 2 years and again at 3 to 4 years. Half of the lesions (45/89) were followed up with OCT in combination with clinical and dermoscopic examination at 1 to 6 months (eTable 5). Of the 2 patients with 1-month OCT follow-up, 1 died from other medical causes and the other was unable to return for further follow-up scans.

Comment

High Tumor Clearance Rates With OCT

This study yielded a clearance rate of 95.70% for all BCCs, 96.10% for facial BCCs, and 93.75% for nonfacial BCCs. This rate is higher than the clinical or histologic clearance rate (or both) of earlier studies on facial and nonfacial BCCs, which ranged from 25% to 95%.8-11 In this study, we were able to utilize OCT and histology to confirm clearance. Optical coherence tomography, which has been shown to have a high sensitivity ranging from 86% to 95.7%, is therefore optimally used in treatment monitoring.19,26,28 Optical coherence tomography has a broader specificity range of 75.3% to 98% and was not utilized for diagnostic purposes in this study. Combining OCT with a color wheel dermoscopic approach was helpful in confirming treatment efficacy of nonsurgical therapies and is significantly more accurate than clinical analysis alone (P<.01).19,26,28

We suspect that the higher clearance rates observed in our study were due to the OCT-guided treatment protocol. Optical coherence tomography was used for margination while providing a modality for tailored treatment through visualization of residual tumor on clinically and dermoscopically clear follow-ups, given that several studies found residual tumor at the lateral edge of the tumor margin on histopathologic analysis.5 Utilizing noninvasive imaging technology to delineate tumor margins before treatment can improve efficacy and limit unnecessary treatment to the surrounding normal skin (eFigure 2).29

After grouping lesions by number of laser treatments, the clearance rate remained similar among facial BCCs with 3 or fewer treatments (59/61 [96.72%]), but there was a slightly decreased clearance rate for facial BCCs with more than 3 treatments (15/16 [93.75%]), which may be explained by the need for more laser treatments for larger BCCs (eTable 3). The relationship between facial BCC size and number of laser treatments was found to correlate positively (Pearson r=0.319). The largest lesion (24 mm) was successfully treated with 5 treatments (Figure). The number of nonfacial lesions was limited in this study and was not statistically significant.

there was no clinical evidence of residual BCC.

Cosmetic Outcome

Adverse effects, including erythema, purpura, blistering, and crusting, were short-term and well tolerated. Few patients had subsequent hypopigmentation in the initial months after treatment, which we consider an optimal cosmetic outcome. For example, the patient shown in the Figure would have required extensive reconstruction of the defect using bilateral rotation flaps with incisions along the hairline, grafting, or second-intention healing with partial closure to avoid brow-lifting.30 Given the relatively young age of this patient (a 45-year-old woman) and therefore limited skin laxity, secondary intention or even attempting to match grafted tissue could have resulted in a less than optimal cosmetic outcome. None of the patients experienced clinical or dermoscopic evidence of scarring from the laser treatment.

A few lesions were found to have subclinical inflammation on OCT, which might have obscured residual tumor on the 1-month follow-up scan. This condition may be similar to how pre-MMS diagnostic biopsy scars mask skin cancer during surgery, making it necessary to obtain additional layers beyond the biopsy scar tissue. This scar tissue would otherwise obscure tumor on histology during MMS, similar to subclinical inflammation obscuring residual tumor on OCT.21-23,31 Invasive and noninvasive management of skin cancers will have different healing times and therefore different optimal times to confirm clearance by histology compared to noninvasive imaging. All of the lesions in which inflammation was obscured on OCT 1-month posttreatment remained cleared. However, 1 lesion was found to be clear at a 4-week clearance scan after only 2 nonablative laser treatments and was confirmed as scar tissue on histology. Scar tissue on histology might have obscured any residual tumor. The patient appeared clinically and dermoscopically to have a milia in the same location only 5 months later; however, on OCT and histology, the lesion was confirmed to be a BCC.

Treatment Intervals

Several other studies either used a set number of treatments or determined the number of treatments based on clinical clearance.3-8 When determining the best treatment interval, we considered the period for patients to be clinically and dermoscopically healed to be 1 month. Patients came for their final follow-up scan an additional month after the final treatment in case there was any obscuring inflammation on OCT at 1 month. Given that patients responded well to nonablative laser treatment once skin clinically healed and most patients required 3 treatments, the PI began recommending a total of 3 treatments performed 4 to 6 weeks apart in clinical practice, followed by a final clearance scan 2 months after the third treatment. A period of 2 months was considered ideal for the final clearance scan because no inflammation was seen at the 2-month follow-up in the group of patients who had inflammation at the 1-month follow-up on OCT in our study. Some patients had an extended treatment duration because of noncompliance with the 4- to 6-week follow-up regimen. Although this extension of treatment duration potentially skews the clearance rate, we still included these patients, given the retrospective design of this study.

Lesions That Did Not Clear

Four BCCs did not clear, 3 of which were facial BCCs. All 4 lesions demonstrated residual tumor on OCT. Of the 3 facial lesions that did not clear:

• One was the patient who had obscuring inflammation at the 1-month follow-up and only scar tissue on histologic confirmation.

• Another was a pigmented BCC on the right cheek of a patient with Fitzpatrick skin type IV. This patient received 3 treatments without a response clinically or on OCT. (Most patients who showed complete clearance also showed reduction in tumor size after the first laser treatment. Of note, there were other patients who had lighter skin types with pigmented BCCs and all of these patients had complete response to this treatment regimen; therefore, we do not think that a pigmented BCC is an exclusion to this therapy.)

• The third was a BCC on the nose of a nonadherent patient, which may have contributed to the lack of clearance. We defined nonadherent patients as those who did not follow-up within the appropriate periods and who therefore ran the risk for tumor growth in between treatments.

The nonfacial BCC that did not clear had histologic features of focal sclerosing BCC, a more aggressive subtype of basal cell skin cancer.

Tumor Recurrence

Only 4 of 89 BCCs (4.49%) recurred, with a 5.41% (4/74) recurrence rate among facial BCCs. All recurrences lacked clinical and dermoscopic evidence of BCC but were found on follow-up OCT scan and confirmed with RCM. All recurrences were found 1.5 to 3.9 years posttreatment.

Recurrent tumors following MMS required, on average, more laser treatments than primary tumors to achieve successful tumor clearance, which we attribute to scar tissue from prior therapy obscuring recurrence, resulting in delayed diagnosis, and to inflammation and fibrosis masking residual tumors (eFigure 1). An added benefit of laser treatment is that all 4 recurrent tumors demonstrated improved cosmetic appearance of the original MMS scar.

The benefit of using OCT scans to check for recurrences is that OCT can find residual skin cancers despite the area looking clinically clear, which is especially important during clinical evaluation of a healed postsurgical scar for recurrence because OCT imaging allows us to look as deep as 2 mm under the skin. Nonsurgical treatments also enable us to leave skin intact and avoid creating scar tissue, which makes it easier to detect and manage recurrence.

Limitations

There were several important limitations of this retrospective study:

• Patients were treated by 1 of 5 medically trained fellows. Although the fellows worked under the supervision of the PI, variation in their work from one to another might have led to different end points.

• All patients who appeared clinically clear were offered biopsy to confirm clearance on histology. Some patients agreed to biopsy, but many did not because they were pleased with the cosmetic outcome, which is similar to other studies exhibiting only clinical clearance rates without providing histologic clearance following nonsurgical therapy.6 We believe that imaging with OCT circumvents this problem and offers more accurate confirmation than clinical or dermoscopic correlation alone, or the combination of the 2 modalities.

• Lack of treatment standardization and short length of follow-up can result in underestimation of the recurrence rate. In particular, most patients were followed up with OCT in less than 6 months. These are unavoidable features in a retrospective study and we are currently addressing this problem in a new prospective study.

Extended Follow-up

Although this study is not a prospective design, it does provide recurrence data over extended follow-up for the nonablative laser management of BCCs (eTables 4 and 5). Studies have demonstrated that MMS has a 5-year cure rate as high as 99% for BCC.32 Given the limited follow-up period of prior nonablative laser management studies, recurrences might not have been fully evaluated. Our study had a 4.49% recurrence rate for all BCCs and a 5.41% recurrence rate for facial BCCs but was not detectable by clinical examination combined with dermoscopic findings alone. All recurrences required the utilization of OCT or RCM or a combination of these modalities to be diagnosed. In 1 patient with recurrence, we were able to see residual tumor on both OCT and RCM without any inflammation obscuring the scan, given that 3 years had passed. Although 2 months is an optimal follow-up time for OCT, we have not found an optimal follow-up time for RCM, which is another reason why OCT might be preferable to other imaging modalities, such as RCM and high-definition OCT, that have higher resolution but provide less depth on imaging. Although only 40 of 89 patients (4.49%) had follow-up ranging from 3 years to greater than 5 years, long-term follow-up to date has been limited in prior studies.

We believe the high clearance rates and limited recurrence are secondary to the utilization of noninvasive imaging, as the majority of these recurrences would not have been diagnosed based on clinical and/or dermoscopic information alone. Additionally, the 4 biopsy-proven post-MMS recurrence patients that were treated in this study also may not have been diagnosed this early without the use of additional noninvasive imaging. In our opinion, although laser management can be used without noninvasive imaging guidance—dermoscopy, OCT, and/or RCM—this technology is critical not only for early detection but also for proper management of patients.

Conclusion

This study showed a 95.70% clearance rate for all BCCs and a 96.10% clearance rate for facial BCCs. Although we had a zero clinical recurrence rate, 4.49% of all BCCs and 5.41% of facial BCCs had recurred on subsequent monitoring with noninvasive imaging. Given the large size of the study and extended follow-up, we found nonablative laser management to be a reliable treatment alternative with improved cosmetic outcome (Figure) and minimal short-term adverse effects compared to surgery.

Tailored care for the individual patient is based on a variety of options and patient preference, including ease of compliance, number of follow-up visits, invasive vs noninvasive diagnosis and monitoring, and downtime for healing. The use of noninvasive imaging also allowed us to find a more standardized treatment regimen using this nonablative laser combination. We found that 3 or fewer and more than 3 treatments had similar efficacy in tumor clearance. We recommend a standard laser protocol of 3 treatments every 4 to 6 weeks with follow-up 2 months after the final treatment to assess for clearance with OCT.

Larger BCCs might require additional treatments; therefore, we caution against laser therapy without concomitant use of OCT imaging to visualize residual tumor. Utilizing other noninvasive modalities, such as dermoscopy, in combination with thorough skin examination also is critical in the early detection of skin cancers to improve the efficacy of this less-aggressive, nonablative, and cosmetically optimal treatment protocol.

Acknowledgement—We would like to acknowledge Dimitrios Karponis, BSc, from the Impirial College London, England, for his assistance with a portion of the statistical analysis.

Nonablative laser therapy is emerging as an effective noninvasive treatment option for basal cell carcinoma (BCC) with reduced adverse effects and good cosmetic outcomes compared to surgery. Vascular lasers, such as the pulsed dye laser (PDL), are thought to work by selectively targeting the tumor’s vascular network while preserving normal surrounding tissue.1,2 Although high energy and multiple passes might be required, adjunctive use of dynamic cooling reduces the risk for nonselective thermal injury vs ablative lasers, which destroy the tumor itself through vaporization of tissue water.2

With no established laser management guidelines for the treatment of BCC, earlier studies using a 595-nm PDL varied highly in their protocol.3-8 Pulsed dye laser parameters ranged from a spot size of 7 to 10 mm, fluence of 7.5 to 15 J/cm2, and pulse duration of 0.5 to 3 milliseconds. Follow-up ranged from 12 days to 25 months after the final laser treatment. The number of lesions in prior studies ranged from 7 to 100 BCCs, with the clinical clearance rate ranging from 71.4% to 75% for facial BCC and 78.6% to 95% for nonfacial BCC.3-8 Studies with histologic confirmation had a clearance rate of 66.6% for facial BCC and 25% to 92.3% for nonfacial BCC.3-5,7,8 Most studies examined BCCs on the trunk and extremities with few investigating facial BCC,3-8 which is especially important given that the head and neck are the most common and cosmetically sensitive anatomic locations.9-13

Noninvasive imaging devices, such as reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) and optical coherence tomography (OCT) can assist with the diagnosis and treatment monitoring of BCC. These devices enable in vivo visualization of tissue in both cross-sectional and en face views and therefore can reduce the need for diagnostic biopsy. Reflectance confocal microscopy enables near-histologic visualization of the epidermis and superficial dermis with a resolution of 0.5 to 1 μm.14 Optical coherence tomography uses an infrared broadband light source that allows users to view skin architecture as deep as 1.5 to 2 mm with a resolution of 5 μm.15

When used synergistically, both devices can enhance the efficacy of nonablative laser treatment. With its increased depth and wider field of view, OCT is an optimal tool for repetitive evaluation of the same site over time and for following biopsy-confirmed tumors undergoing management.16 In addition to delineating tumor margins before treatment, imaging improves the detection of residual skin cancers, despite clearance on clinical and dermoscopic examination. Noninvasive imaging and nonsurgical management with laser therapy allow the physician to leave the skin intact and avoid scar tissue that might otherwise make it more difficult to detect and manage recurrence. The ability of OCT and RCM to monitor the efficacy of nonsurgical therapies for skin cancer has been demonstrated with imiquimod, photodynamic therapy, vismodegib, and ablative laser therapy.17-20

With limited data on nonablative laser management of BCC, several gaps in the literature exist. First, in previously published studies the number of treatments was either determined to be an arbitrary set number or based on clinical clearance, which has the potential to miss residual tumor. Second, many follow-ups were limited to shortly after the final treatment, which limits the accuracy of the clearance rate, given that inflammation and scars can hide residual tumor.21-23 Third, because many studies excised the treated area, long-term follow-up for recurrence was obscured. Last, only a few studies involved facial BCC, which is the most common and cosmetically concerning anatomic location.13

Our study attempted to address these gaps by evaluating the use of noninvasive imaging to guide management of primarily facial BCC. The objective was to perform a retrospective chart review on a subgroup of patients with BCC who were treated with combined nonablative PDL and fractional laser treatment with an extended follow-up period.

Methods

Study Design

We performed a retrospective chart review of 68 patients with 93 BCCs who had been treated with nonablative laser therapy as an alternative to surgery at the Mount Sinai Faculty Practice Associates between February 2011 and December 2018. Patients were followed throughout this period for assessment of clinical and subclinical recurrence. The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Program for the Protection of Human Subjects provided institutional review board approval.

Patients

Inclusion criteria included the following: (1) BCC diagnosed by biopsy (see eTable 1 for subtypes) and (2) treated with a nonablative laser due to patient preference and eligibility by the principal investigator (PI). As a retrospective study, lesions were included irrespective of tumor subtype or size. Although the risk for perineural invasion (PNI) is extremely low with BCC (<0.2%), none of the cases demonstrated PNI on diagnostic biopsy and none exhibited clinical evidence of PNI, such as paresthesia, pain, facial paralysis, or diplopia.24

Eligibility determined by the PI included limited clinical ulceration or bleeding, or both, and a safe distance from the eye when wearing an external eye shield (ie, outside the orbital rim). Patients who had Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) or excision (or both) with recurrence at the treatment site were included. Detailed and thorough clinical and dermoscopic skin examination was critical in early detection of these cancers, allowing for treatment of less advanced tumors. The PI’s diagnostic approach utilized the published diagnostic color wheel algorithm,25 which encompasses both clinical and dermoscopic colors and patterns for early diagnosis (ie, ulceration, pink-white to white shiny areas, absence of pigmented network, leaflike structures, large blue-gray ovoid nests or globular structures, spoke wheel structures, a crystalline pattern, a singular vascular pattern of arborizing vessels), combined with OCT or RCM, when necessary.26 All lesions were imaged with OCT prior to laser treatment to confirm residual tumor following biopsy.

Although postsurgical patients were included, lesions receiving concurrent or prior nonsurgical therapy, such as a topical immunomodulator or oral hedgehog inhibitor (eg, vismodegib), were excluded.

Treatment Protocol

All patients received thorough information about the treatment, treatment alternatives, and potential adverse effects and complications. Lesions were selected based on clinical and dermoscopic findings and were biopsy confirmed. Clinical and dermoscopic photographs were taken at every visit. A camera was used for clinical photographs and a dermatoscope was attached for all contact polarized dermoscopic images. All lesions were imaged with OCT prior to laser therapy to delineate tumor margins and to confirm residual disease following biopsy to preclude biopsy-mediated regression.

Laser treatment consisted of a 595-nm PDL followed by fractional laser treatment with the 1927-nm setting. The range of PDL settings was similar to published studies of PDL for BCC (spot size, 7–10 mm; fluence, 6–15 J/cm2; pulse duration, 0.45–3 milliseconds).3-8 The fractional laser also was used at settings similar to earlier studies for actinic keratosis (fluence, 5–20 mJ; treatment density, 40%–70%).27 Laser treatment was performed by 1 of 5 medically trained providers who were fellows supervised by the PI.

All tumors received 1 to 7 treatments (average, 2.89) at 1- to 2-month intervals. Treatment end point (complete clearance) was judged on the absence of skin cancer clinically, dermoscopically on OCT, or histologically by biopsy, or a combination of these modalities. Recurrence was defined as a new histologically confirmed BCC occurring in an area that was previously documented as clear. Patients returned for follow-up 1 to 2 months after the final treatment to monitor tumor clearance and subsequently every 6 to 12 months for tumor recurrence. Posttreatment care included application of a thick emollient, such as a petrolatum-based product, until the area completely healed.

Data Collection

Clinical photographs, dermoscopic photographs, OCT scans, RCM scans, and biopsy reports were reviewed for each patient, as applicable. All patients were given an unidentifiable number; no protected health information was recorded. Data recorded for each patient included age, tumor subtype and location, tumor size, classification of the tumor as primary or a recurrence, number of treatments, treatment duration, lesion clearance, and length of follow-up.

Results

Patient and Lesion Characteristics

Sixty-eight patients with 93 BCCs (77 facial; 16 nonfacial) were included. The median age of patients was 70 years (range, 31–91 years). All 93 BCCs demonstrated residual tumor on OCT after diagnostic biopsy. Four BCCs had been treated earlier with MMS and were biopsy-proven recurrences. Most BCCs were of the nodular subtype; however, sclerosing, superficial, pigmented, morpheaform, and infiltrative subtypes also were included (eTable 1). Eight BCCs were obtained at outside institutions with no subtype provided. Facial BCCs had a mean (SD) clinical and dermoscopic diameter of 6.75 (4.71) mm (range, 2–24 mm). Patients were followed for 2.53 months to 6.03 years (mean follow-up, 2.43 years) and assessed for clinical and subclinical recurrence.

Tumor Clearance

Most lesions were effectively treated, with 89 of 93 BCCs (95.70%) demonstrating complete tumor clearance. Complete tumor clearance following laser therapy was reported in 74 of 77 facial BCCs (96.10%) and 15 of 16 nonfacial BCCs (93.75%)(eTable 2). Successfully treated BCCs underwent an average of 2.88 laser treatments over a mean duration of 3.54 months (range, 1 week to 1.92 years). Four incomplete responders underwent an average of 3.25 laser treatments over a mean duration of 3.44 months (range, 1.13–6.87 months). Of the 4 lesions that did not clear, 2 were nodular, 1 was pigmented, and 1 was sclerosing.

Number of Treatments

When the clearance rate is divided into lesions that received 3 or fewer laser treatments and those that received more than 3 laser treatments, the following results were determined:

• Lesions receiving 3 or fewer treatments had a clearance rate of 96.05% (73/76) for all BCCs, 96.72% (59/61) for facial BCCs, and 93.33% (14/15) for nonfacial BCCs.

• Lesions receiving more than 3 laser treatments had a clearance rate of 94.12% (16/17) for all BCCs, 93.75% (15/16) for facial BCCs, and 100% (1/1) for nonfacial BCCs.

The relationship between facial BCC tumor diameter and number of treatments required for clearance had a positive correlation coefficient (Pearson r=0.319), indicating that larger BCCs required more laser treatments (eTable 3).

Tumor Recurrence

Four of 89 BCCs (4.49%)(4 of 74 facial BCCs [5.41%]) showed tumor recurrence following laser treatment, as assessed by OCT and dermoscopy. Of them, all were nodular BCCs. Prior to laser treatment, there were 4 additional patients each diagnosed with a recurrence from prior treatment with MMS; all were successfully treated with laser therapy without recurrence post–laser treatment (eFigure 1). Most of the recurrences from prior MMS required more than 3 laser treatments before clearing: 1 required 3 treatments, 2 required 4 treatments, and 1 required 6 treatments.

Of 93 lesions included in this study, 2 BCCs were deemed not clear on histologic analysis, which corresponded with residual tumor seen on OCT. Two additional lesions were determined to be not clear on OCT but were not confirmed as such on biopsy; both lesions were confirmed not clear, however, by histologic analysis on the first layer of MMS

Follow-up

All cleared lesions (89/93) showed complete clinical response to laser treatment for 6 months or more (median follow-up, 2–3 years; mode, 1–2 years; mean, 2.66 years)(eTable 4). Although 45% of patients (40/89) have been followed clinically and/or dermoscopically (as is done for MMS follow-ups) for 3 years to more than 5 years, only 20% of patients (18/89) were followed up with OCT in combination with clinical and/or dermoscopic examination between 3 years and more than 5 years. Follow-up took on a bimodal distribution, with a peak follow-up period at 1 to 2 years and again at 3 to 4 years. Half of the lesions (45/89) were followed up with OCT in combination with clinical and dermoscopic examination at 1 to 6 months (eTable 5). Of the 2 patients with 1-month OCT follow-up, 1 died from other medical causes and the other was unable to return for further follow-up scans.

Comment

High Tumor Clearance Rates With OCT

This study yielded a clearance rate of 95.70% for all BCCs, 96.10% for facial BCCs, and 93.75% for nonfacial BCCs. This rate is higher than the clinical or histologic clearance rate (or both) of earlier studies on facial and nonfacial BCCs, which ranged from 25% to 95%.8-11 In this study, we were able to utilize OCT and histology to confirm clearance. Optical coherence tomography, which has been shown to have a high sensitivity ranging from 86% to 95.7%, is therefore optimally used in treatment monitoring.19,26,28 Optical coherence tomography has a broader specificity range of 75.3% to 98% and was not utilized for diagnostic purposes in this study. Combining OCT with a color wheel dermoscopic approach was helpful in confirming treatment efficacy of nonsurgical therapies and is significantly more accurate than clinical analysis alone (P<.01).19,26,28

We suspect that the higher clearance rates observed in our study were due to the OCT-guided treatment protocol. Optical coherence tomography was used for margination while providing a modality for tailored treatment through visualization of residual tumor on clinically and dermoscopically clear follow-ups, given that several studies found residual tumor at the lateral edge of the tumor margin on histopathologic analysis.5 Utilizing noninvasive imaging technology to delineate tumor margins before treatment can improve efficacy and limit unnecessary treatment to the surrounding normal skin (eFigure 2).29

After grouping lesions by number of laser treatments, the clearance rate remained similar among facial BCCs with 3 or fewer treatments (59/61 [96.72%]), but there was a slightly decreased clearance rate for facial BCCs with more than 3 treatments (15/16 [93.75%]), which may be explained by the need for more laser treatments for larger BCCs (eTable 3). The relationship between facial BCC size and number of laser treatments was found to correlate positively (Pearson r=0.319). The largest lesion (24 mm) was successfully treated with 5 treatments (Figure). The number of nonfacial lesions was limited in this study and was not statistically significant.

there was no clinical evidence of residual BCC.

Cosmetic Outcome

Adverse effects, including erythema, purpura, blistering, and crusting, were short-term and well tolerated. Few patients had subsequent hypopigmentation in the initial months after treatment, which we consider an optimal cosmetic outcome. For example, the patient shown in the Figure would have required extensive reconstruction of the defect using bilateral rotation flaps with incisions along the hairline, grafting, or second-intention healing with partial closure to avoid brow-lifting.30 Given the relatively young age of this patient (a 45-year-old woman) and therefore limited skin laxity, secondary intention or even attempting to match grafted tissue could have resulted in a less than optimal cosmetic outcome. None of the patients experienced clinical or dermoscopic evidence of scarring from the laser treatment.

A few lesions were found to have subclinical inflammation on OCT, which might have obscured residual tumor on the 1-month follow-up scan. This condition may be similar to how pre-MMS diagnostic biopsy scars mask skin cancer during surgery, making it necessary to obtain additional layers beyond the biopsy scar tissue. This scar tissue would otherwise obscure tumor on histology during MMS, similar to subclinical inflammation obscuring residual tumor on OCT.21-23,31 Invasive and noninvasive management of skin cancers will have different healing times and therefore different optimal times to confirm clearance by histology compared to noninvasive imaging. All of the lesions in which inflammation was obscured on OCT 1-month posttreatment remained cleared. However, 1 lesion was found to be clear at a 4-week clearance scan after only 2 nonablative laser treatments and was confirmed as scar tissue on histology. Scar tissue on histology might have obscured any residual tumor. The patient appeared clinically and dermoscopically to have a milia in the same location only 5 months later; however, on OCT and histology, the lesion was confirmed to be a BCC.

Treatment Intervals

Several other studies either used a set number of treatments or determined the number of treatments based on clinical clearance.3-8 When determining the best treatment interval, we considered the period for patients to be clinically and dermoscopically healed to be 1 month. Patients came for their final follow-up scan an additional month after the final treatment in case there was any obscuring inflammation on OCT at 1 month. Given that patients responded well to nonablative laser treatment once skin clinically healed and most patients required 3 treatments, the PI began recommending a total of 3 treatments performed 4 to 6 weeks apart in clinical practice, followed by a final clearance scan 2 months after the third treatment. A period of 2 months was considered ideal for the final clearance scan because no inflammation was seen at the 2-month follow-up in the group of patients who had inflammation at the 1-month follow-up on OCT in our study. Some patients had an extended treatment duration because of noncompliance with the 4- to 6-week follow-up regimen. Although this extension of treatment duration potentially skews the clearance rate, we still included these patients, given the retrospective design of this study.

Lesions That Did Not Clear

Four BCCs did not clear, 3 of which were facial BCCs. All 4 lesions demonstrated residual tumor on OCT. Of the 3 facial lesions that did not clear:

• One was the patient who had obscuring inflammation at the 1-month follow-up and only scar tissue on histologic confirmation.

• Another was a pigmented BCC on the right cheek of a patient with Fitzpatrick skin type IV. This patient received 3 treatments without a response clinically or on OCT. (Most patients who showed complete clearance also showed reduction in tumor size after the first laser treatment. Of note, there were other patients who had lighter skin types with pigmented BCCs and all of these patients had complete response to this treatment regimen; therefore, we do not think that a pigmented BCC is an exclusion to this therapy.)

• The third was a BCC on the nose of a nonadherent patient, which may have contributed to the lack of clearance. We defined nonadherent patients as those who did not follow-up within the appropriate periods and who therefore ran the risk for tumor growth in between treatments.

The nonfacial BCC that did not clear had histologic features of focal sclerosing BCC, a more aggressive subtype of basal cell skin cancer.

Tumor Recurrence

Only 4 of 89 BCCs (4.49%) recurred, with a 5.41% (4/74) recurrence rate among facial BCCs. All recurrences lacked clinical and dermoscopic evidence of BCC but were found on follow-up OCT scan and confirmed with RCM. All recurrences were found 1.5 to 3.9 years posttreatment.

Recurrent tumors following MMS required, on average, more laser treatments than primary tumors to achieve successful tumor clearance, which we attribute to scar tissue from prior therapy obscuring recurrence, resulting in delayed diagnosis, and to inflammation and fibrosis masking residual tumors (eFigure 1). An added benefit of laser treatment is that all 4 recurrent tumors demonstrated improved cosmetic appearance of the original MMS scar.

The benefit of using OCT scans to check for recurrences is that OCT can find residual skin cancers despite the area looking clinically clear, which is especially important during clinical evaluation of a healed postsurgical scar for recurrence because OCT imaging allows us to look as deep as 2 mm under the skin. Nonsurgical treatments also enable us to leave skin intact and avoid creating scar tissue, which makes it easier to detect and manage recurrence.

Limitations

There were several important limitations of this retrospective study:

• Patients were treated by 1 of 5 medically trained fellows. Although the fellows worked under the supervision of the PI, variation in their work from one to another might have led to different end points.

• All patients who appeared clinically clear were offered biopsy to confirm clearance on histology. Some patients agreed to biopsy, but many did not because they were pleased with the cosmetic outcome, which is similar to other studies exhibiting only clinical clearance rates without providing histologic clearance following nonsurgical therapy.6 We believe that imaging with OCT circumvents this problem and offers more accurate confirmation than clinical or dermoscopic correlation alone, or the combination of the 2 modalities.

• Lack of treatment standardization and short length of follow-up can result in underestimation of the recurrence rate. In particular, most patients were followed up with OCT in less than 6 months. These are unavoidable features in a retrospective study and we are currently addressing this problem in a new prospective study.

Extended Follow-up