User login

The Medical Liability Environment: Is It Really Any Worse for Hospitalists?

Although malpractice “crises” come and go, liability fears persist near top of mind for most physicians.1 Liability insurance premiums have plateaued in recent years, but remain at high levels, and the prospect of being reported to the National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB) or listed on a state medical board’s website for a paid liability claim is unsettling. The high-acuity setting and the absence of longitudinal patient relationships in hospital medicine may theoretically raise malpractice risk, yet hospitalists’ liability risk remains understudied.2

The contribution by Schaffer and colleagues3 in this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine is thus welcome and illuminating. The researchers examine the liability risk of hospitalists compared to that of other specialties by utilizing a large database of malpractice claims compiled from multiple insurers across a decade.3 In a field of research plagued by inadequate data, the Comparative Benchmarking System (CBS) built by CRICO/RMF is a treasure. Unlike the primary national database of malpractice claims, the NPDB, the CBS contains information on claims that did not result in a payment, as well as physicians’ specialty and detailed information on the allegations, injuries, and their causes. The CBS contains almost a third of all medical liability claims made in the United States during the study period, supporting generalizability.

Schaffer and colleagues1 found that hospitalists had a lower claims rate than physicians in emergency medicine or neurosurgery. The rate was on par with that for non-hospital general internists, even though hospitalists often care for higher-acuity patients. Although claims rates dropped over the study period for physicians in neurosurgery, emergency medicine, psychiatry, and internal medicine subspecialties, the rate for hospitalists did not change significantly. Further, the median payout on claims against hospitalists was the highest of all the specialties examined, except neurosurgery. This reflects higher injury severity in hospitalist cases: half the claims against hospitalists involved death and three-quarters were high severity.

The study is not without limitations. Due to missing data, only a fraction of the claims (8.2% to 11%) in the full dataset are used in the claims rate analysis. Regression models predicting a payment are based on a small number of payments for hospitalists (n = 363). Further, the authors advance, as a potential explanation for hospitalists’ higher liability risk, that hospitalists are disproportionately young compared to other specialists, but the dataset lacks age data. These limitations suggest caution in the authors’ overall conclusion that “the malpractice environment for hospitalists is becoming less favorable.”

Nevertheless, several important insights emerge from their analysis. The very existence of claims demonstrates that patient harm continues. The contributing factors and judgment errors found in these claims demonstrate that much of this harm is potentially preventable and a risk to patient safety. Whether or not the authors’ young-hospitalist hypothesis is ultimately proven, it is difficult to argue with more mentorship as a means to improve safety. Also, preventing or intercepting judgment errors remains a vexing challenge in medicine that undoubtedly calls for creative clinical decision support solutions. Schaffer and colleagues1 also note that hospitalists are increasingly co-managing patients with other specialties, such as orthopedic surgery. Whether this new practice model drives hospitalist liability risk because hospitalists are practicing in areas in which they have less experience (as the authors posit) or whether hospitalists are simply more likely to be named in a suit as part of a specialty team with higher liability risk remains unknown and merits further investigation.

Ultimately, regardless of whether the liability environment is worsening for hospitalists, the need to improve our liability system is clear. There is room to improve the system on a number of metrics, including properly compensating negligently harmed patients without unduly burdening providers. The system also induces defensive medicine and has not driven safety improvements as expected. The liability environment, as a result, remains challenging not just for hospitalists, but for all patients and physicians as well.

1. Sage WM, Boothman RC, Gallagher TH. Another medical malpractice crisis? Try something different. JAMA. 2020;324(14):1395-1396. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.16557

2. Schaffer AC, Puopolo AL, Raman S, Kachalia A. Liability impact of the hospitalist model of care. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(12):750-755. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2244

3. Schaffer AC, Yu-Moe CW, Babayan A, Wachter RM, Einbinder JS. Rates and characteristics of medical malpractice claims against hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(7):390-396. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3557

Although malpractice “crises” come and go, liability fears persist near top of mind for most physicians.1 Liability insurance premiums have plateaued in recent years, but remain at high levels, and the prospect of being reported to the National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB) or listed on a state medical board’s website for a paid liability claim is unsettling. The high-acuity setting and the absence of longitudinal patient relationships in hospital medicine may theoretically raise malpractice risk, yet hospitalists’ liability risk remains understudied.2

The contribution by Schaffer and colleagues3 in this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine is thus welcome and illuminating. The researchers examine the liability risk of hospitalists compared to that of other specialties by utilizing a large database of malpractice claims compiled from multiple insurers across a decade.3 In a field of research plagued by inadequate data, the Comparative Benchmarking System (CBS) built by CRICO/RMF is a treasure. Unlike the primary national database of malpractice claims, the NPDB, the CBS contains information on claims that did not result in a payment, as well as physicians’ specialty and detailed information on the allegations, injuries, and their causes. The CBS contains almost a third of all medical liability claims made in the United States during the study period, supporting generalizability.

Schaffer and colleagues1 found that hospitalists had a lower claims rate than physicians in emergency medicine or neurosurgery. The rate was on par with that for non-hospital general internists, even though hospitalists often care for higher-acuity patients. Although claims rates dropped over the study period for physicians in neurosurgery, emergency medicine, psychiatry, and internal medicine subspecialties, the rate for hospitalists did not change significantly. Further, the median payout on claims against hospitalists was the highest of all the specialties examined, except neurosurgery. This reflects higher injury severity in hospitalist cases: half the claims against hospitalists involved death and three-quarters were high severity.

The study is not without limitations. Due to missing data, only a fraction of the claims (8.2% to 11%) in the full dataset are used in the claims rate analysis. Regression models predicting a payment are based on a small number of payments for hospitalists (n = 363). Further, the authors advance, as a potential explanation for hospitalists’ higher liability risk, that hospitalists are disproportionately young compared to other specialists, but the dataset lacks age data. These limitations suggest caution in the authors’ overall conclusion that “the malpractice environment for hospitalists is becoming less favorable.”

Nevertheless, several important insights emerge from their analysis. The very existence of claims demonstrates that patient harm continues. The contributing factors and judgment errors found in these claims demonstrate that much of this harm is potentially preventable and a risk to patient safety. Whether or not the authors’ young-hospitalist hypothesis is ultimately proven, it is difficult to argue with more mentorship as a means to improve safety. Also, preventing or intercepting judgment errors remains a vexing challenge in medicine that undoubtedly calls for creative clinical decision support solutions. Schaffer and colleagues1 also note that hospitalists are increasingly co-managing patients with other specialties, such as orthopedic surgery. Whether this new practice model drives hospitalist liability risk because hospitalists are practicing in areas in which they have less experience (as the authors posit) or whether hospitalists are simply more likely to be named in a suit as part of a specialty team with higher liability risk remains unknown and merits further investigation.

Ultimately, regardless of whether the liability environment is worsening for hospitalists, the need to improve our liability system is clear. There is room to improve the system on a number of metrics, including properly compensating negligently harmed patients without unduly burdening providers. The system also induces defensive medicine and has not driven safety improvements as expected. The liability environment, as a result, remains challenging not just for hospitalists, but for all patients and physicians as well.

Although malpractice “crises” come and go, liability fears persist near top of mind for most physicians.1 Liability insurance premiums have plateaued in recent years, but remain at high levels, and the prospect of being reported to the National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB) or listed on a state medical board’s website for a paid liability claim is unsettling. The high-acuity setting and the absence of longitudinal patient relationships in hospital medicine may theoretically raise malpractice risk, yet hospitalists’ liability risk remains understudied.2

The contribution by Schaffer and colleagues3 in this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine is thus welcome and illuminating. The researchers examine the liability risk of hospitalists compared to that of other specialties by utilizing a large database of malpractice claims compiled from multiple insurers across a decade.3 In a field of research plagued by inadequate data, the Comparative Benchmarking System (CBS) built by CRICO/RMF is a treasure. Unlike the primary national database of malpractice claims, the NPDB, the CBS contains information on claims that did not result in a payment, as well as physicians’ specialty and detailed information on the allegations, injuries, and their causes. The CBS contains almost a third of all medical liability claims made in the United States during the study period, supporting generalizability.

Schaffer and colleagues1 found that hospitalists had a lower claims rate than physicians in emergency medicine or neurosurgery. The rate was on par with that for non-hospital general internists, even though hospitalists often care for higher-acuity patients. Although claims rates dropped over the study period for physicians in neurosurgery, emergency medicine, psychiatry, and internal medicine subspecialties, the rate for hospitalists did not change significantly. Further, the median payout on claims against hospitalists was the highest of all the specialties examined, except neurosurgery. This reflects higher injury severity in hospitalist cases: half the claims against hospitalists involved death and three-quarters were high severity.

The study is not without limitations. Due to missing data, only a fraction of the claims (8.2% to 11%) in the full dataset are used in the claims rate analysis. Regression models predicting a payment are based on a small number of payments for hospitalists (n = 363). Further, the authors advance, as a potential explanation for hospitalists’ higher liability risk, that hospitalists are disproportionately young compared to other specialists, but the dataset lacks age data. These limitations suggest caution in the authors’ overall conclusion that “the malpractice environment for hospitalists is becoming less favorable.”

Nevertheless, several important insights emerge from their analysis. The very existence of claims demonstrates that patient harm continues. The contributing factors and judgment errors found in these claims demonstrate that much of this harm is potentially preventable and a risk to patient safety. Whether or not the authors’ young-hospitalist hypothesis is ultimately proven, it is difficult to argue with more mentorship as a means to improve safety. Also, preventing or intercepting judgment errors remains a vexing challenge in medicine that undoubtedly calls for creative clinical decision support solutions. Schaffer and colleagues1 also note that hospitalists are increasingly co-managing patients with other specialties, such as orthopedic surgery. Whether this new practice model drives hospitalist liability risk because hospitalists are practicing in areas in which they have less experience (as the authors posit) or whether hospitalists are simply more likely to be named in a suit as part of a specialty team with higher liability risk remains unknown and merits further investigation.

Ultimately, regardless of whether the liability environment is worsening for hospitalists, the need to improve our liability system is clear. There is room to improve the system on a number of metrics, including properly compensating negligently harmed patients without unduly burdening providers. The system also induces defensive medicine and has not driven safety improvements as expected. The liability environment, as a result, remains challenging not just for hospitalists, but for all patients and physicians as well.

1. Sage WM, Boothman RC, Gallagher TH. Another medical malpractice crisis? Try something different. JAMA. 2020;324(14):1395-1396. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.16557

2. Schaffer AC, Puopolo AL, Raman S, Kachalia A. Liability impact of the hospitalist model of care. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(12):750-755. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2244

3. Schaffer AC, Yu-Moe CW, Babayan A, Wachter RM, Einbinder JS. Rates and characteristics of medical malpractice claims against hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(7):390-396. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3557

1. Sage WM, Boothman RC, Gallagher TH. Another medical malpractice crisis? Try something different. JAMA. 2020;324(14):1395-1396. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.16557

2. Schaffer AC, Puopolo AL, Raman S, Kachalia A. Liability impact of the hospitalist model of care. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(12):750-755. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2244

3. Schaffer AC, Yu-Moe CW, Babayan A, Wachter RM, Einbinder JS. Rates and characteristics of medical malpractice claims against hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(7):390-396. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3557

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Supporting Hospitals During a New Wave of COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has put an extraordinary strain on US hospitals.1 In spring 2020, many hospitals had to quickly adapt to treat a surge of patients, and many more had to prepare for a potential surge. Creating reserve capacity meant halting outpatient care and elective surgeries, repurposing inpatient units, and increasing critical care staffing. Hospitals again face these difficult decisions, as COVID-19 resurges and variants of SARS-CoV-2 increasingly circulate, with large financial losses projected for 2021.2 Some large hospital systems may have the financial reserves to weather this storm, but the precarious situation facing others likely requires policy action.

Hospitals’ financial stress emanates from multiple quarters. First, revenue from elective inpatient procedures and outpatient care dropped dramatically, has not fully rebounded,3,4 and is not fully offset by revenue from COVID-19 care. Second, high unemployment may force up to 20% of commercially insured Americans into lower-reimbursing public insurance or the ranks of the uninsured, generating a projected $95 billion annual loss for hospitals.5 Third, under the current payment system, the costs of preparing for a pandemic are not directly reimbursed. Yet—whether or not they ultimately experienced a large COVID-19 caseload—hospitals’ surge preparation has involved purchasing vast quantities of protective personal equipment (PPE) and other supplies and equipment, hiring additional staff, building SARS-CoV-2 testing capacity, and expanding occupational health services. Many expenses persist as “the new normal”: admissions now require SARS-CoV-2 testing, additional staff and PPE, and often, a private room. Physical distancing requirements mean hospitals’ capacity—and thus, revenue—will remain reduced.

Private insurers, by and large, are not volunteering to cover these increased costs, and it is difficult for hospitals to pass them along. Payment terms in many contracts (eg, for Medicare) are not modifiable; even where they are, renegotiating takes time. To date, federal relief payments from the CARES Act do not fully reimburse COVID-19 losses—a particular problem for smaller and safety-net hospitals without large reserves.

This situation raises ethical concerns. For example, it is ethically relevant that COVID-19 resurgence and hospitalizations are linked to states’ decisions to reopen quickly to ease economic burdens on businesses and workers. One result has been to shift some of the pandemic’s economic burden to the healthcare sector. From a fairness perspective, there should be limits on the losses hospitals are forced to shoulder to maintain COVID-19 preparedness and services. Even if hospitals have reserves, spending them threatens funding for other essential activities, such as capital investment.

The current situation is also fraught with perverse incentives that could jeopardize safe care. With elective care remaining at risk of being reduced,6 pressure intensifies to deliver as many services as possible as quickly as possible, which may not align with patients’ best interests. Across hospitals that need to maximize volume to survive, a push to keep elective services open may emerge, even as COVID-19 prevalence may favor a shutdown. Hospitals with a heavy COVID-19 caseload may have greater difficulty reopening than competitors with lower caseloads, potentially impacting quality if patients seek elective care at lower-volume centers or in ways that disrupt continuity of care.

Ethical dilemmas are also raised by the delicate balancing of interests that hospitals have been engaging in among patient groups. How should they balance the needs of COVID-19 patients against potential harms to others who must delay care?

It is wrong to ask hospitals to make such choices when policy solutions are available. With the resurgence of COVID-19 must come a fresh, sustained program of federal financial relief for hospitals. While direct government support is the swiftest path, consideration should be given to the role of private insurers, which have benefited economically from the widespread deferment and forgoing of elective care. Voluntary or mandatory investments by insurers in helping hospitals survive the pandemic and weather the new normal are consonant with insurers’ commitment to providing their members access to high-quality healthcare.

The 200-page National Strategy document released by the Biden administration on January 21, 2021, promises some important assistance to hospitals.7 It includes plans to accelerate the production of PPE and other essential supplies using the Defense Production Act and other federal authorities, to rationalize nationwide distribution of these supplies and take steps to prevent price gouging, and to deploy federal personnel and assets to help surge critical-care personnel.

These steps, if fully funded and implemented, would bring welcome respite from some of the most vexing problems hospitals have encountered during COVID-19 surges. Yet, plans for direct financial relief for hospitals are strikingly absent from the National Strategy. Nor does the recently passed $1.9 trillion federal stimulus package provide dedicated funds for hospitals, though some funds earmarked for vaccine delivery may land at hospitals. These are consequential omissions in otherwise comprehensive, thoughtful pandemic response plans.

Future legislation should include an immediate revenue infusion to reimburse hospitals’ COVID-19 preparations and lost volume and a firm commitment of ongoing financial support for preparedness through the end of the pandemic at a level sufficient to offset COVID-19–related losses. Experience with the CARES Act also suggests specific lessons for statutory design: support for hospitals should be allocated based on actual COVID-19–related burden for preparation and care, unlike CARES Act grants that were allocated based on hospitals’ past revenue and Medicare billing. This resulted in some large payments to relatively well-off hospitals and scant support for others (eg, rural or safety-net hospitals) with substantial COVID-19–related losses, a misstep that should not be repeated.

Hospitals are an integral part of the nation’s public health system. In the context of a pandemic, they should not be forced to serve as a backstop for shortcomings in other parts of the system without assistance. They, and their mission during the pandemic, are too important to fail.

1. Khullar D, Bond AM, Schpero WL. COVID-19 and the financial health of US hospitals. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2127-2128. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6269

2. Coleman-Lochner L. Hospitals plead for bailout in face of runaway pandemic bills. February 26, 2021. Accessed March 25, 2021. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-02-26/hospitals-plead-for-bailout-in-face-of-runaway-pandemic-bills

3. American Hospital Association. Hospitals and health systems continue to face unprecedented financial challenges due to COVID-19. June 2020. Accessed February 5. 2021. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2020/06/aha-covid19-financial-impact-report.pdf

4. Birkmeyer JD, Barnato A, Birkmeyer N, Bessler R, Skinner J. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital admissions in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(11):2010-2017. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00980

5. Teasdale B, Schulman KA. Are U.S. hospitals still “recession-proof”? N Engl J Med. 2020;383(13):e82. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2018846

6. Meredith JW, High KP, Freischlag JA. Preserving elective surgeries in the COVID-19 pandemic and the future. JAMA. 2020;324(17):1725-1726. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.19594

7. Biden JR. National strategy for the COVID-19 response and pandemic preparedness. Bloomberg. January 2021. Accessed February 8, 2021. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/National-Strategy-for-the-COVID-19-Response-and-Pandemic-Preparedness.pdf

The COVID-19 pandemic has put an extraordinary strain on US hospitals.1 In spring 2020, many hospitals had to quickly adapt to treat a surge of patients, and many more had to prepare for a potential surge. Creating reserve capacity meant halting outpatient care and elective surgeries, repurposing inpatient units, and increasing critical care staffing. Hospitals again face these difficult decisions, as COVID-19 resurges and variants of SARS-CoV-2 increasingly circulate, with large financial losses projected for 2021.2 Some large hospital systems may have the financial reserves to weather this storm, but the precarious situation facing others likely requires policy action.

Hospitals’ financial stress emanates from multiple quarters. First, revenue from elective inpatient procedures and outpatient care dropped dramatically, has not fully rebounded,3,4 and is not fully offset by revenue from COVID-19 care. Second, high unemployment may force up to 20% of commercially insured Americans into lower-reimbursing public insurance or the ranks of the uninsured, generating a projected $95 billion annual loss for hospitals.5 Third, under the current payment system, the costs of preparing for a pandemic are not directly reimbursed. Yet—whether or not they ultimately experienced a large COVID-19 caseload—hospitals’ surge preparation has involved purchasing vast quantities of protective personal equipment (PPE) and other supplies and equipment, hiring additional staff, building SARS-CoV-2 testing capacity, and expanding occupational health services. Many expenses persist as “the new normal”: admissions now require SARS-CoV-2 testing, additional staff and PPE, and often, a private room. Physical distancing requirements mean hospitals’ capacity—and thus, revenue—will remain reduced.

Private insurers, by and large, are not volunteering to cover these increased costs, and it is difficult for hospitals to pass them along. Payment terms in many contracts (eg, for Medicare) are not modifiable; even where they are, renegotiating takes time. To date, federal relief payments from the CARES Act do not fully reimburse COVID-19 losses—a particular problem for smaller and safety-net hospitals without large reserves.

This situation raises ethical concerns. For example, it is ethically relevant that COVID-19 resurgence and hospitalizations are linked to states’ decisions to reopen quickly to ease economic burdens on businesses and workers. One result has been to shift some of the pandemic’s economic burden to the healthcare sector. From a fairness perspective, there should be limits on the losses hospitals are forced to shoulder to maintain COVID-19 preparedness and services. Even if hospitals have reserves, spending them threatens funding for other essential activities, such as capital investment.

The current situation is also fraught with perverse incentives that could jeopardize safe care. With elective care remaining at risk of being reduced,6 pressure intensifies to deliver as many services as possible as quickly as possible, which may not align with patients’ best interests. Across hospitals that need to maximize volume to survive, a push to keep elective services open may emerge, even as COVID-19 prevalence may favor a shutdown. Hospitals with a heavy COVID-19 caseload may have greater difficulty reopening than competitors with lower caseloads, potentially impacting quality if patients seek elective care at lower-volume centers or in ways that disrupt continuity of care.

Ethical dilemmas are also raised by the delicate balancing of interests that hospitals have been engaging in among patient groups. How should they balance the needs of COVID-19 patients against potential harms to others who must delay care?

It is wrong to ask hospitals to make such choices when policy solutions are available. With the resurgence of COVID-19 must come a fresh, sustained program of federal financial relief for hospitals. While direct government support is the swiftest path, consideration should be given to the role of private insurers, which have benefited economically from the widespread deferment and forgoing of elective care. Voluntary or mandatory investments by insurers in helping hospitals survive the pandemic and weather the new normal are consonant with insurers’ commitment to providing their members access to high-quality healthcare.

The 200-page National Strategy document released by the Biden administration on January 21, 2021, promises some important assistance to hospitals.7 It includes plans to accelerate the production of PPE and other essential supplies using the Defense Production Act and other federal authorities, to rationalize nationwide distribution of these supplies and take steps to prevent price gouging, and to deploy federal personnel and assets to help surge critical-care personnel.

These steps, if fully funded and implemented, would bring welcome respite from some of the most vexing problems hospitals have encountered during COVID-19 surges. Yet, plans for direct financial relief for hospitals are strikingly absent from the National Strategy. Nor does the recently passed $1.9 trillion federal stimulus package provide dedicated funds for hospitals, though some funds earmarked for vaccine delivery may land at hospitals. These are consequential omissions in otherwise comprehensive, thoughtful pandemic response plans.

Future legislation should include an immediate revenue infusion to reimburse hospitals’ COVID-19 preparations and lost volume and a firm commitment of ongoing financial support for preparedness through the end of the pandemic at a level sufficient to offset COVID-19–related losses. Experience with the CARES Act also suggests specific lessons for statutory design: support for hospitals should be allocated based on actual COVID-19–related burden for preparation and care, unlike CARES Act grants that were allocated based on hospitals’ past revenue and Medicare billing. This resulted in some large payments to relatively well-off hospitals and scant support for others (eg, rural or safety-net hospitals) with substantial COVID-19–related losses, a misstep that should not be repeated.

Hospitals are an integral part of the nation’s public health system. In the context of a pandemic, they should not be forced to serve as a backstop for shortcomings in other parts of the system without assistance. They, and their mission during the pandemic, are too important to fail.

The COVID-19 pandemic has put an extraordinary strain on US hospitals.1 In spring 2020, many hospitals had to quickly adapt to treat a surge of patients, and many more had to prepare for a potential surge. Creating reserve capacity meant halting outpatient care and elective surgeries, repurposing inpatient units, and increasing critical care staffing. Hospitals again face these difficult decisions, as COVID-19 resurges and variants of SARS-CoV-2 increasingly circulate, with large financial losses projected for 2021.2 Some large hospital systems may have the financial reserves to weather this storm, but the precarious situation facing others likely requires policy action.

Hospitals’ financial stress emanates from multiple quarters. First, revenue from elective inpatient procedures and outpatient care dropped dramatically, has not fully rebounded,3,4 and is not fully offset by revenue from COVID-19 care. Second, high unemployment may force up to 20% of commercially insured Americans into lower-reimbursing public insurance or the ranks of the uninsured, generating a projected $95 billion annual loss for hospitals.5 Third, under the current payment system, the costs of preparing for a pandemic are not directly reimbursed. Yet—whether or not they ultimately experienced a large COVID-19 caseload—hospitals’ surge preparation has involved purchasing vast quantities of protective personal equipment (PPE) and other supplies and equipment, hiring additional staff, building SARS-CoV-2 testing capacity, and expanding occupational health services. Many expenses persist as “the new normal”: admissions now require SARS-CoV-2 testing, additional staff and PPE, and often, a private room. Physical distancing requirements mean hospitals’ capacity—and thus, revenue—will remain reduced.

Private insurers, by and large, are not volunteering to cover these increased costs, and it is difficult for hospitals to pass them along. Payment terms in many contracts (eg, for Medicare) are not modifiable; even where they are, renegotiating takes time. To date, federal relief payments from the CARES Act do not fully reimburse COVID-19 losses—a particular problem for smaller and safety-net hospitals without large reserves.

This situation raises ethical concerns. For example, it is ethically relevant that COVID-19 resurgence and hospitalizations are linked to states’ decisions to reopen quickly to ease economic burdens on businesses and workers. One result has been to shift some of the pandemic’s economic burden to the healthcare sector. From a fairness perspective, there should be limits on the losses hospitals are forced to shoulder to maintain COVID-19 preparedness and services. Even if hospitals have reserves, spending them threatens funding for other essential activities, such as capital investment.

The current situation is also fraught with perverse incentives that could jeopardize safe care. With elective care remaining at risk of being reduced,6 pressure intensifies to deliver as many services as possible as quickly as possible, which may not align with patients’ best interests. Across hospitals that need to maximize volume to survive, a push to keep elective services open may emerge, even as COVID-19 prevalence may favor a shutdown. Hospitals with a heavy COVID-19 caseload may have greater difficulty reopening than competitors with lower caseloads, potentially impacting quality if patients seek elective care at lower-volume centers or in ways that disrupt continuity of care.

Ethical dilemmas are also raised by the delicate balancing of interests that hospitals have been engaging in among patient groups. How should they balance the needs of COVID-19 patients against potential harms to others who must delay care?

It is wrong to ask hospitals to make such choices when policy solutions are available. With the resurgence of COVID-19 must come a fresh, sustained program of federal financial relief for hospitals. While direct government support is the swiftest path, consideration should be given to the role of private insurers, which have benefited economically from the widespread deferment and forgoing of elective care. Voluntary or mandatory investments by insurers in helping hospitals survive the pandemic and weather the new normal are consonant with insurers’ commitment to providing their members access to high-quality healthcare.

The 200-page National Strategy document released by the Biden administration on January 21, 2021, promises some important assistance to hospitals.7 It includes plans to accelerate the production of PPE and other essential supplies using the Defense Production Act and other federal authorities, to rationalize nationwide distribution of these supplies and take steps to prevent price gouging, and to deploy federal personnel and assets to help surge critical-care personnel.

These steps, if fully funded and implemented, would bring welcome respite from some of the most vexing problems hospitals have encountered during COVID-19 surges. Yet, plans for direct financial relief for hospitals are strikingly absent from the National Strategy. Nor does the recently passed $1.9 trillion federal stimulus package provide dedicated funds for hospitals, though some funds earmarked for vaccine delivery may land at hospitals. These are consequential omissions in otherwise comprehensive, thoughtful pandemic response plans.

Future legislation should include an immediate revenue infusion to reimburse hospitals’ COVID-19 preparations and lost volume and a firm commitment of ongoing financial support for preparedness through the end of the pandemic at a level sufficient to offset COVID-19–related losses. Experience with the CARES Act also suggests specific lessons for statutory design: support for hospitals should be allocated based on actual COVID-19–related burden for preparation and care, unlike CARES Act grants that were allocated based on hospitals’ past revenue and Medicare billing. This resulted in some large payments to relatively well-off hospitals and scant support for others (eg, rural or safety-net hospitals) with substantial COVID-19–related losses, a misstep that should not be repeated.

Hospitals are an integral part of the nation’s public health system. In the context of a pandemic, they should not be forced to serve as a backstop for shortcomings in other parts of the system without assistance. They, and their mission during the pandemic, are too important to fail.

1. Khullar D, Bond AM, Schpero WL. COVID-19 and the financial health of US hospitals. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2127-2128. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6269

2. Coleman-Lochner L. Hospitals plead for bailout in face of runaway pandemic bills. February 26, 2021. Accessed March 25, 2021. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-02-26/hospitals-plead-for-bailout-in-face-of-runaway-pandemic-bills

3. American Hospital Association. Hospitals and health systems continue to face unprecedented financial challenges due to COVID-19. June 2020. Accessed February 5. 2021. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2020/06/aha-covid19-financial-impact-report.pdf

4. Birkmeyer JD, Barnato A, Birkmeyer N, Bessler R, Skinner J. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital admissions in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(11):2010-2017. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00980

5. Teasdale B, Schulman KA. Are U.S. hospitals still “recession-proof”? N Engl J Med. 2020;383(13):e82. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2018846

6. Meredith JW, High KP, Freischlag JA. Preserving elective surgeries in the COVID-19 pandemic and the future. JAMA. 2020;324(17):1725-1726. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.19594

7. Biden JR. National strategy for the COVID-19 response and pandemic preparedness. Bloomberg. January 2021. Accessed February 8, 2021. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/National-Strategy-for-the-COVID-19-Response-and-Pandemic-Preparedness.pdf

1. Khullar D, Bond AM, Schpero WL. COVID-19 and the financial health of US hospitals. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2127-2128. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6269

2. Coleman-Lochner L. Hospitals plead for bailout in face of runaway pandemic bills. February 26, 2021. Accessed March 25, 2021. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-02-26/hospitals-plead-for-bailout-in-face-of-runaway-pandemic-bills

3. American Hospital Association. Hospitals and health systems continue to face unprecedented financial challenges due to COVID-19. June 2020. Accessed February 5. 2021. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2020/06/aha-covid19-financial-impact-report.pdf

4. Birkmeyer JD, Barnato A, Birkmeyer N, Bessler R, Skinner J. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital admissions in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(11):2010-2017. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00980

5. Teasdale B, Schulman KA. Are U.S. hospitals still “recession-proof”? N Engl J Med. 2020;383(13):e82. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2018846

6. Meredith JW, High KP, Freischlag JA. Preserving elective surgeries in the COVID-19 pandemic and the future. JAMA. 2020;324(17):1725-1726. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.19594

7. Biden JR. National strategy for the COVID-19 response and pandemic preparedness. Bloomberg. January 2021. Accessed February 8, 2021. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/National-Strategy-for-the-COVID-19-Response-and-Pandemic-Preparedness.pdf

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

The Need for Standardized Metrics to Drive Decision-making During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The rapid onset of the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic forced the US healthcare system to scramble to prepare for a health crisis with many unknowns. Early on, it was unclear exactly how the virus was transmitted, how many people would fall ill or how ill they would get, what treatments would be most efficacious, and what resources were needed to care for patients.1 Given the short window the healthcare system had to prepare, many initial and important decisions were made quickly and often at a local level, with limited coordination and standardization across localities and organizations. These decisions included what services could be offered, how best to allocate potentially scarce resources (such as personal protective equipment and ventilators), and how much surge capacity to build.2,3 In short, many of the early decisions about the pandemic were understandably varied, and the lack of standardized metrics to help guide decision-making did not help the situation.

CHALLENGES WITH MANAGING THE PANDEMIC WITHOUT STANDARDIZED METRICS

Unfortunately, as the COVID-19 pandemic continues, there has been insufficient movement toward standardizing definitions for many key measures needed to manage the public health response. Even small differences in definitions can have important implications for decision-making.4 For example, public health officials have recommended communities achieve a positivity rate of 5% or lower for 14 straight days before easing virus-related restrictions.5 In Maryland, two different entities are calculating positivity rates for the state using different methodologies and producing different results, which can have significant public health and economic implications for the state. Johns Hopkins University’s Resource Center calculates the positivity rate by comparing the number of people who tested positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) to all people who were tested. This method consistently produces a positivity rate for Maryland above the 5% threshold. In contrast, the state of Maryland calculates the positivity rate by comparing the number of positive tests for SARS-CoV-2 to the number of tests conducted, even if the same person had multiple tests (unless the tests are performed the same day at the same location). This method consistently produces a positivity rate for Maryland below the 5% threshold.6

THE POLITICIZATION OF THE DATA

The lack of standardized definitions leads not only to debate and confusion over what steps to take next, but also opens the door to politicization of pandemic data. This is readily apparent when considering mortality due to COVID-19. For example, different states use different definitions for COVID-19 mortality. Alabama defines COVID-19 mortality by only including patients who tested positive for the SARS-CoV-2 virus and the cause of death was attributed to COVID-19. In contrast, Colorado’s COVID-19 mortality definition includes those patients who are believed to have died of COVID-19, but does not require confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection by a positive test.7 Further compounding the challenge, some politicians reference the COVID-19 mortality rate as a comparison of those who died from COVID-19 with those who were sick with COVID-19, reflecting the success rate of treating patients with COVID-19, an area in which the United States has done relatively well compared with other countries. This definition of the mortality rate suits a narrative of successful pandemic management.8 However, many public health officials suggest the COVID-19 mortality rate should be defined by comparing the number of deaths from COVID-19 as a percentage of the population, which reflects the percentage of the population dying from the disease. In this regard, the United States has not done as well relative to other countries.9 These different definitions highlight how the United States lacks a standardized way to compare its performance across states and with other countries, even on a straightforward measure like mortality.

CURRENT METRICS THAT NEED STANDARDIZATION

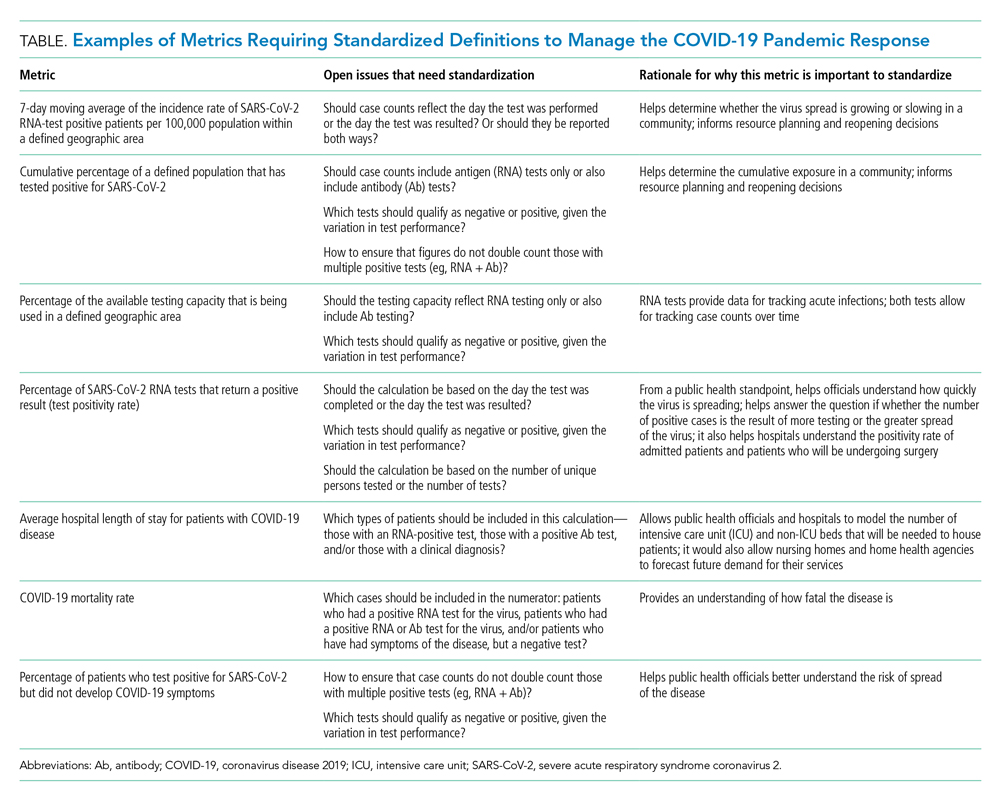

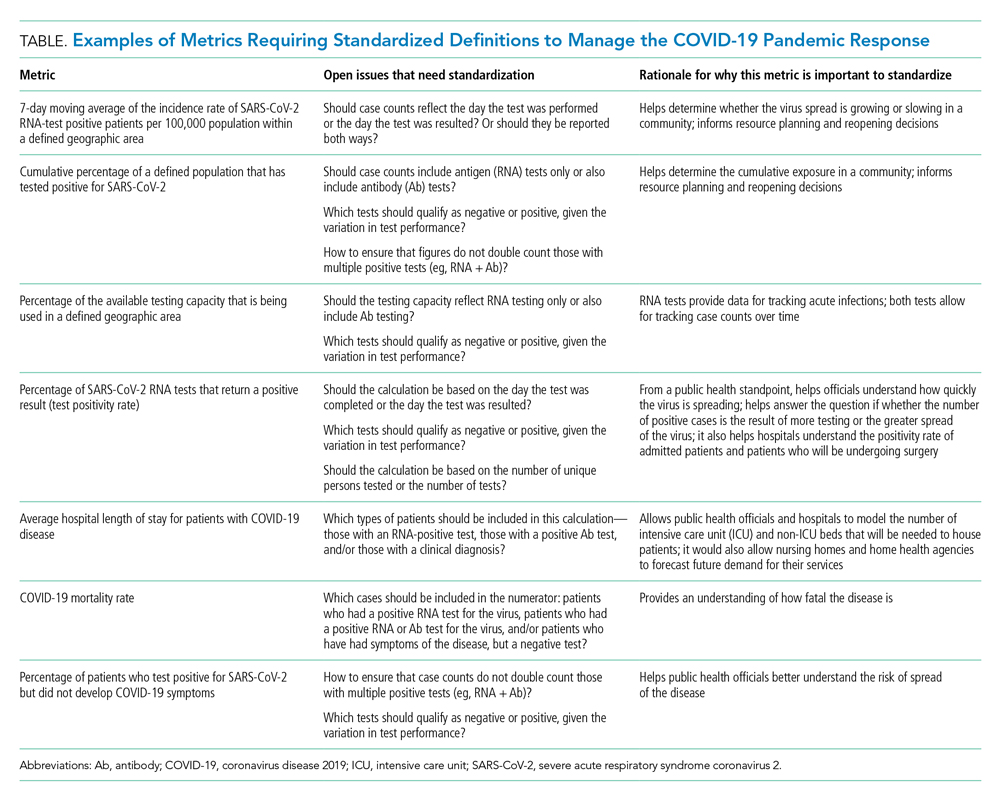

The lack of clarity on, and politicization of, pandemic data demonstrate the need to take stock of what metrics require standardization to help public health officials and health system leaders manage the pandemic response moving forward. The Table provides examples of currently used metrics that would benefit from better standardization to inform decision-making across a broad range of settings, including public health, hospitals, physician clinics, and nursing homes. For example, a commonly referenced metric during the pandemic has been a moving average of the incidence rate of positive COVID-19 cases in a defined geographic area (eg, a state).10,11 This data point is helpful to healthcare delivery organizations for understanding the change in COVID-19 cases in their cities and states, which can inform planning on whether or not to continue elective surgeries or how many beds need to be kept in reserve status for a potential surge of hospitalizations. But there has not been a consensus around whether the reporting of COVID-19 positive tests should reflect the day the test was performed or the day the test results were available. The day the test results were available can be influenced by lengthy or uneven turnaround times for the results (eg, backlogs in labs) and can paint a false picture of trends with the virus.

As another example, knowing the percentage of the population that has tested positive for COVID-19 can help inform both resource planning and reopening decisions. But there has been variation in whether counts of positive COVID-19 tests should only include antigen tests, or antibody tests as well. This exact question played out when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) made decisions that differed from those of many states about whether to include antibody tests in their publicly announced COVID-19 testing numbers,12 perhaps undermining public confidence in the reported data.

MOVING FORWARD WITH STANDARDIZING DEFINITIONS

To capture currently unstandardized metrics with broad applicability, the United States should form a consensus task force to identify and define metrics and, over time, refine them based on current science and public health priorities. The task force would require a mix of individuals with various skill sets, such as expertise in infectious diseases and epidemiology, healthcare operations, statistics, performance measurement, and public health. The US Department of Health and Human Services is likely the appropriate sponsor, with representation from the National Institutes of Health, the CDC, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, in partnership with national provider and public health group representatives.

Once standardized definitions for metrics have been agreed upon, the metric definitions will need to be made readily available to the public and healthcare organizations. Standardization will permit collection of electronic health records for quick calculation and review, with an output of dashboards for reporting. It would also prevent every public health and healthcare delivery organization from having to define its own metrics, freeing them up to focus on planning. Several metrics already have standard definitions, and those metrics have proven useful for decision-making. For example, there is agreement that the turnaround time for a SARS-CoV-2 test is measured by the difference in time between when the test was performed and when the test results were available. This standard definition allows for performance comparisons across different laboratories within the same service area and comparisons across different regions of the country. Once the metrics are standardized, public health leaders and healthcare organizations can use variation in performance and outcomes to identify leading indicators for planning.

CONCLUSION

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the US healthcare system finds itself in a state of managing uncertainty for a prolonged period of time. The unprecedented nature of this crisis means that best practices will not always be clear. Providing access to clearly defined, standardized metrics will be essential to public health officials and healthcare organization leaders’ ability to manage through this pandemic. The risk of not moving in this direction means forcing leaders to make decisions without the best information available. Good data will be essential to guiding the US healthcare system through this extraordinary crisis.

- Weston S, Frieman MB. COVID-19: knowns, unknowns, and questions. mSphere. 2020;5(2):e00203-20. https://doi.org/10.1128/mSphere.00203-20

- Griffin KM, Karas MG, Ivascu NS, Lief L. Hospital preparedness for COVID-19: a practical guide from a critical care perspective. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(11):1337-1344. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202004-1037CP

- De Georgeo MR, De Georgeo JM, Egan TM, et al. Containing SARS-CoV-2 in hospitals facing finite PPE, limited testing, and physical space variability: navigating resource constrained enhanced traffic control bundling. J Microbiol Immunol. 2020;S1684-1182(20)30166-3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmii.2020.07.009

- Fischhoff B. Making decisions in a COVID-19 world. JAMA. 2020;324(2):139-140. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.10178

- Collins K. Is your state doing enough coronavirus testing? New York Times. October 14, 2020. Updated October 29, 2020. Accessed October 14, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-testing.html

- Ruiz N. Why is Maryland’s coronavirus positivity rate always lower than what Johns Hopkins says it is — and does it matter? Baltimore Sun. September 10, 2020. Accessed October 14, 2020. https://www.baltimoresun.com/coronavirus/bs-md-maryland-coronavirus-positivity-rate-hopkins-20200817-zoepxdjlxbazdm6kabrjehbemq-story.html

- Brown E, Reinhard B, Thebault R. Which deaths count toward the covid-19 death toll? It depends on the state. Washington Post. April 16, 2020. Accessed July 23, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/investigations/which-deaths-count-toward-the-covid-19-death-toll-it-depends-on-the-state/2020/04/16/bca84ae0-7991-11ea-a130-df573469f094_story.html

- Carlisle M. Here’s what Trump got wrong about America’s COVID-19 death rate. Time. August 4, 2020. Accessed October 14, 2020. https://time.com/5875411/trump-covid-19-death-rate-interview/

- Mortality analyses. Johns Hopkins University & Medicine Coronavirus Resource Center. October 14, 2020. Updated October 29, 2020. Accessed October 14, 2020. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/mortality

- COVID-19 daily case incidence rate maps. Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services. Accessed October 14, 2020. https://chfs.ky.gov/Pages/cv19maps.aspx

- COVID-19 trajectory animations. Pennsylvania Department of Health. Accessed October 14, 2020. https://www.health.pa.gov/topics/disease/coronavirus/Pages/Data-Animations.aspx

- Stolberg SG, Kaplan S, Mervosh S. CDC test counting error leaves epidemiologists ‘really baffled.’ New York Times. May 22, 2020. Updated June 3, 2020. Accessed July 23, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/22/us/politics/coronavirus-tests-cdc.html

The rapid onset of the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic forced the US healthcare system to scramble to prepare for a health crisis with many unknowns. Early on, it was unclear exactly how the virus was transmitted, how many people would fall ill or how ill they would get, what treatments would be most efficacious, and what resources were needed to care for patients.1 Given the short window the healthcare system had to prepare, many initial and important decisions were made quickly and often at a local level, with limited coordination and standardization across localities and organizations. These decisions included what services could be offered, how best to allocate potentially scarce resources (such as personal protective equipment and ventilators), and how much surge capacity to build.2,3 In short, many of the early decisions about the pandemic were understandably varied, and the lack of standardized metrics to help guide decision-making did not help the situation.

CHALLENGES WITH MANAGING THE PANDEMIC WITHOUT STANDARDIZED METRICS

Unfortunately, as the COVID-19 pandemic continues, there has been insufficient movement toward standardizing definitions for many key measures needed to manage the public health response. Even small differences in definitions can have important implications for decision-making.4 For example, public health officials have recommended communities achieve a positivity rate of 5% or lower for 14 straight days before easing virus-related restrictions.5 In Maryland, two different entities are calculating positivity rates for the state using different methodologies and producing different results, which can have significant public health and economic implications for the state. Johns Hopkins University’s Resource Center calculates the positivity rate by comparing the number of people who tested positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) to all people who were tested. This method consistently produces a positivity rate for Maryland above the 5% threshold. In contrast, the state of Maryland calculates the positivity rate by comparing the number of positive tests for SARS-CoV-2 to the number of tests conducted, even if the same person had multiple tests (unless the tests are performed the same day at the same location). This method consistently produces a positivity rate for Maryland below the 5% threshold.6

THE POLITICIZATION OF THE DATA

The lack of standardized definitions leads not only to debate and confusion over what steps to take next, but also opens the door to politicization of pandemic data. This is readily apparent when considering mortality due to COVID-19. For example, different states use different definitions for COVID-19 mortality. Alabama defines COVID-19 mortality by only including patients who tested positive for the SARS-CoV-2 virus and the cause of death was attributed to COVID-19. In contrast, Colorado’s COVID-19 mortality definition includes those patients who are believed to have died of COVID-19, but does not require confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection by a positive test.7 Further compounding the challenge, some politicians reference the COVID-19 mortality rate as a comparison of those who died from COVID-19 with those who were sick with COVID-19, reflecting the success rate of treating patients with COVID-19, an area in which the United States has done relatively well compared with other countries. This definition of the mortality rate suits a narrative of successful pandemic management.8 However, many public health officials suggest the COVID-19 mortality rate should be defined by comparing the number of deaths from COVID-19 as a percentage of the population, which reflects the percentage of the population dying from the disease. In this regard, the United States has not done as well relative to other countries.9 These different definitions highlight how the United States lacks a standardized way to compare its performance across states and with other countries, even on a straightforward measure like mortality.

CURRENT METRICS THAT NEED STANDARDIZATION

The lack of clarity on, and politicization of, pandemic data demonstrate the need to take stock of what metrics require standardization to help public health officials and health system leaders manage the pandemic response moving forward. The Table provides examples of currently used metrics that would benefit from better standardization to inform decision-making across a broad range of settings, including public health, hospitals, physician clinics, and nursing homes. For example, a commonly referenced metric during the pandemic has been a moving average of the incidence rate of positive COVID-19 cases in a defined geographic area (eg, a state).10,11 This data point is helpful to healthcare delivery organizations for understanding the change in COVID-19 cases in their cities and states, which can inform planning on whether or not to continue elective surgeries or how many beds need to be kept in reserve status for a potential surge of hospitalizations. But there has not been a consensus around whether the reporting of COVID-19 positive tests should reflect the day the test was performed or the day the test results were available. The day the test results were available can be influenced by lengthy or uneven turnaround times for the results (eg, backlogs in labs) and can paint a false picture of trends with the virus.

As another example, knowing the percentage of the population that has tested positive for COVID-19 can help inform both resource planning and reopening decisions. But there has been variation in whether counts of positive COVID-19 tests should only include antigen tests, or antibody tests as well. This exact question played out when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) made decisions that differed from those of many states about whether to include antibody tests in their publicly announced COVID-19 testing numbers,12 perhaps undermining public confidence in the reported data.

MOVING FORWARD WITH STANDARDIZING DEFINITIONS

To capture currently unstandardized metrics with broad applicability, the United States should form a consensus task force to identify and define metrics and, over time, refine them based on current science and public health priorities. The task force would require a mix of individuals with various skill sets, such as expertise in infectious diseases and epidemiology, healthcare operations, statistics, performance measurement, and public health. The US Department of Health and Human Services is likely the appropriate sponsor, with representation from the National Institutes of Health, the CDC, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, in partnership with national provider and public health group representatives.

Once standardized definitions for metrics have been agreed upon, the metric definitions will need to be made readily available to the public and healthcare organizations. Standardization will permit collection of electronic health records for quick calculation and review, with an output of dashboards for reporting. It would also prevent every public health and healthcare delivery organization from having to define its own metrics, freeing them up to focus on planning. Several metrics already have standard definitions, and those metrics have proven useful for decision-making. For example, there is agreement that the turnaround time for a SARS-CoV-2 test is measured by the difference in time between when the test was performed and when the test results were available. This standard definition allows for performance comparisons across different laboratories within the same service area and comparisons across different regions of the country. Once the metrics are standardized, public health leaders and healthcare organizations can use variation in performance and outcomes to identify leading indicators for planning.

CONCLUSION

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the US healthcare system finds itself in a state of managing uncertainty for a prolonged period of time. The unprecedented nature of this crisis means that best practices will not always be clear. Providing access to clearly defined, standardized metrics will be essential to public health officials and healthcare organization leaders’ ability to manage through this pandemic. The risk of not moving in this direction means forcing leaders to make decisions without the best information available. Good data will be essential to guiding the US healthcare system through this extraordinary crisis.

The rapid onset of the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic forced the US healthcare system to scramble to prepare for a health crisis with many unknowns. Early on, it was unclear exactly how the virus was transmitted, how many people would fall ill or how ill they would get, what treatments would be most efficacious, and what resources were needed to care for patients.1 Given the short window the healthcare system had to prepare, many initial and important decisions were made quickly and often at a local level, with limited coordination and standardization across localities and organizations. These decisions included what services could be offered, how best to allocate potentially scarce resources (such as personal protective equipment and ventilators), and how much surge capacity to build.2,3 In short, many of the early decisions about the pandemic were understandably varied, and the lack of standardized metrics to help guide decision-making did not help the situation.

CHALLENGES WITH MANAGING THE PANDEMIC WITHOUT STANDARDIZED METRICS

Unfortunately, as the COVID-19 pandemic continues, there has been insufficient movement toward standardizing definitions for many key measures needed to manage the public health response. Even small differences in definitions can have important implications for decision-making.4 For example, public health officials have recommended communities achieve a positivity rate of 5% or lower for 14 straight days before easing virus-related restrictions.5 In Maryland, two different entities are calculating positivity rates for the state using different methodologies and producing different results, which can have significant public health and economic implications for the state. Johns Hopkins University’s Resource Center calculates the positivity rate by comparing the number of people who tested positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) to all people who were tested. This method consistently produces a positivity rate for Maryland above the 5% threshold. In contrast, the state of Maryland calculates the positivity rate by comparing the number of positive tests for SARS-CoV-2 to the number of tests conducted, even if the same person had multiple tests (unless the tests are performed the same day at the same location). This method consistently produces a positivity rate for Maryland below the 5% threshold.6

THE POLITICIZATION OF THE DATA

The lack of standardized definitions leads not only to debate and confusion over what steps to take next, but also opens the door to politicization of pandemic data. This is readily apparent when considering mortality due to COVID-19. For example, different states use different definitions for COVID-19 mortality. Alabama defines COVID-19 mortality by only including patients who tested positive for the SARS-CoV-2 virus and the cause of death was attributed to COVID-19. In contrast, Colorado’s COVID-19 mortality definition includes those patients who are believed to have died of COVID-19, but does not require confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection by a positive test.7 Further compounding the challenge, some politicians reference the COVID-19 mortality rate as a comparison of those who died from COVID-19 with those who were sick with COVID-19, reflecting the success rate of treating patients with COVID-19, an area in which the United States has done relatively well compared with other countries. This definition of the mortality rate suits a narrative of successful pandemic management.8 However, many public health officials suggest the COVID-19 mortality rate should be defined by comparing the number of deaths from COVID-19 as a percentage of the population, which reflects the percentage of the population dying from the disease. In this regard, the United States has not done as well relative to other countries.9 These different definitions highlight how the United States lacks a standardized way to compare its performance across states and with other countries, even on a straightforward measure like mortality.

CURRENT METRICS THAT NEED STANDARDIZATION

The lack of clarity on, and politicization of, pandemic data demonstrate the need to take stock of what metrics require standardization to help public health officials and health system leaders manage the pandemic response moving forward. The Table provides examples of currently used metrics that would benefit from better standardization to inform decision-making across a broad range of settings, including public health, hospitals, physician clinics, and nursing homes. For example, a commonly referenced metric during the pandemic has been a moving average of the incidence rate of positive COVID-19 cases in a defined geographic area (eg, a state).10,11 This data point is helpful to healthcare delivery organizations for understanding the change in COVID-19 cases in their cities and states, which can inform planning on whether or not to continue elective surgeries or how many beds need to be kept in reserve status for a potential surge of hospitalizations. But there has not been a consensus around whether the reporting of COVID-19 positive tests should reflect the day the test was performed or the day the test results were available. The day the test results were available can be influenced by lengthy or uneven turnaround times for the results (eg, backlogs in labs) and can paint a false picture of trends with the virus.

As another example, knowing the percentage of the population that has tested positive for COVID-19 can help inform both resource planning and reopening decisions. But there has been variation in whether counts of positive COVID-19 tests should only include antigen tests, or antibody tests as well. This exact question played out when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) made decisions that differed from those of many states about whether to include antibody tests in their publicly announced COVID-19 testing numbers,12 perhaps undermining public confidence in the reported data.

MOVING FORWARD WITH STANDARDIZING DEFINITIONS

To capture currently unstandardized metrics with broad applicability, the United States should form a consensus task force to identify and define metrics and, over time, refine them based on current science and public health priorities. The task force would require a mix of individuals with various skill sets, such as expertise in infectious diseases and epidemiology, healthcare operations, statistics, performance measurement, and public health. The US Department of Health and Human Services is likely the appropriate sponsor, with representation from the National Institutes of Health, the CDC, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, in partnership with national provider and public health group representatives.

Once standardized definitions for metrics have been agreed upon, the metric definitions will need to be made readily available to the public and healthcare organizations. Standardization will permit collection of electronic health records for quick calculation and review, with an output of dashboards for reporting. It would also prevent every public health and healthcare delivery organization from having to define its own metrics, freeing them up to focus on planning. Several metrics already have standard definitions, and those metrics have proven useful for decision-making. For example, there is agreement that the turnaround time for a SARS-CoV-2 test is measured by the difference in time between when the test was performed and when the test results were available. This standard definition allows for performance comparisons across different laboratories within the same service area and comparisons across different regions of the country. Once the metrics are standardized, public health leaders and healthcare organizations can use variation in performance and outcomes to identify leading indicators for planning.

CONCLUSION

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the US healthcare system finds itself in a state of managing uncertainty for a prolonged period of time. The unprecedented nature of this crisis means that best practices will not always be clear. Providing access to clearly defined, standardized metrics will be essential to public health officials and healthcare organization leaders’ ability to manage through this pandemic. The risk of not moving in this direction means forcing leaders to make decisions without the best information available. Good data will be essential to guiding the US healthcare system through this extraordinary crisis.

- Weston S, Frieman MB. COVID-19: knowns, unknowns, and questions. mSphere. 2020;5(2):e00203-20. https://doi.org/10.1128/mSphere.00203-20

- Griffin KM, Karas MG, Ivascu NS, Lief L. Hospital preparedness for COVID-19: a practical guide from a critical care perspective. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(11):1337-1344. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202004-1037CP

- De Georgeo MR, De Georgeo JM, Egan TM, et al. Containing SARS-CoV-2 in hospitals facing finite PPE, limited testing, and physical space variability: navigating resource constrained enhanced traffic control bundling. J Microbiol Immunol. 2020;S1684-1182(20)30166-3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmii.2020.07.009

- Fischhoff B. Making decisions in a COVID-19 world. JAMA. 2020;324(2):139-140. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.10178

- Collins K. Is your state doing enough coronavirus testing? New York Times. October 14, 2020. Updated October 29, 2020. Accessed October 14, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-testing.html

- Ruiz N. Why is Maryland’s coronavirus positivity rate always lower than what Johns Hopkins says it is — and does it matter? Baltimore Sun. September 10, 2020. Accessed October 14, 2020. https://www.baltimoresun.com/coronavirus/bs-md-maryland-coronavirus-positivity-rate-hopkins-20200817-zoepxdjlxbazdm6kabrjehbemq-story.html

- Brown E, Reinhard B, Thebault R. Which deaths count toward the covid-19 death toll? It depends on the state. Washington Post. April 16, 2020. Accessed July 23, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/investigations/which-deaths-count-toward-the-covid-19-death-toll-it-depends-on-the-state/2020/04/16/bca84ae0-7991-11ea-a130-df573469f094_story.html

- Carlisle M. Here’s what Trump got wrong about America’s COVID-19 death rate. Time. August 4, 2020. Accessed October 14, 2020. https://time.com/5875411/trump-covid-19-death-rate-interview/

- Mortality analyses. Johns Hopkins University & Medicine Coronavirus Resource Center. October 14, 2020. Updated October 29, 2020. Accessed October 14, 2020. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/mortality

- COVID-19 daily case incidence rate maps. Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services. Accessed October 14, 2020. https://chfs.ky.gov/Pages/cv19maps.aspx

- COVID-19 trajectory animations. Pennsylvania Department of Health. Accessed October 14, 2020. https://www.health.pa.gov/topics/disease/coronavirus/Pages/Data-Animations.aspx

- Stolberg SG, Kaplan S, Mervosh S. CDC test counting error leaves epidemiologists ‘really baffled.’ New York Times. May 22, 2020. Updated June 3, 2020. Accessed July 23, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/22/us/politics/coronavirus-tests-cdc.html

- Weston S, Frieman MB. COVID-19: knowns, unknowns, and questions. mSphere. 2020;5(2):e00203-20. https://doi.org/10.1128/mSphere.00203-20

- Griffin KM, Karas MG, Ivascu NS, Lief L. Hospital preparedness for COVID-19: a practical guide from a critical care perspective. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(11):1337-1344. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202004-1037CP

- De Georgeo MR, De Georgeo JM, Egan TM, et al. Containing SARS-CoV-2 in hospitals facing finite PPE, limited testing, and physical space variability: navigating resource constrained enhanced traffic control bundling. J Microbiol Immunol. 2020;S1684-1182(20)30166-3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmii.2020.07.009

- Fischhoff B. Making decisions in a COVID-19 world. JAMA. 2020;324(2):139-140. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.10178

- Collins K. Is your state doing enough coronavirus testing? New York Times. October 14, 2020. Updated October 29, 2020. Accessed October 14, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-testing.html

- Ruiz N. Why is Maryland’s coronavirus positivity rate always lower than what Johns Hopkins says it is — and does it matter? Baltimore Sun. September 10, 2020. Accessed October 14, 2020. https://www.baltimoresun.com/coronavirus/bs-md-maryland-coronavirus-positivity-rate-hopkins-20200817-zoepxdjlxbazdm6kabrjehbemq-story.html

- Brown E, Reinhard B, Thebault R. Which deaths count toward the covid-19 death toll? It depends on the state. Washington Post. April 16, 2020. Accessed July 23, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/investigations/which-deaths-count-toward-the-covid-19-death-toll-it-depends-on-the-state/2020/04/16/bca84ae0-7991-11ea-a130-df573469f094_story.html

- Carlisle M. Here’s what Trump got wrong about America’s COVID-19 death rate. Time. August 4, 2020. Accessed October 14, 2020. https://time.com/5875411/trump-covid-19-death-rate-interview/

- Mortality analyses. Johns Hopkins University & Medicine Coronavirus Resource Center. October 14, 2020. Updated October 29, 2020. Accessed October 14, 2020. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/mortality

- COVID-19 daily case incidence rate maps. Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services. Accessed October 14, 2020. https://chfs.ky.gov/Pages/cv19maps.aspx

- COVID-19 trajectory animations. Pennsylvania Department of Health. Accessed October 14, 2020. https://www.health.pa.gov/topics/disease/coronavirus/Pages/Data-Animations.aspx

- Stolberg SG, Kaplan S, Mervosh S. CDC test counting error leaves epidemiologists ‘really baffled.’ New York Times. May 22, 2020. Updated June 3, 2020. Accessed July 23, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/22/us/politics/coronavirus-tests-cdc.html

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Email: jmaustin@jhmi.edu; Telephone: 832-816-5618; Twitter: @JMatthewAustin.

Perception of Resources Spent on Defensive Medicine and History of Being Sued Among Hospitalists: Results from a National Survey

Annual healthcare costs in the United States are over $3 trillion and are garnering significant national attention.1 The United States spends approximately 2.5 times more per capita on healthcare when compared to other developed nations.2 One source of unnecessary cost in healthcare is defensive medicine. Defensive medicine has been defined by Congress as occurring “when doctors order tests, procedures, or visits, or avoid certain high-risk patients or procedures, primarily (but not necessarily) because of concern about malpractice liability.”3

Though difficult to assess, in 1 study, defensive medicine was estimated to cost $45 billion annually.4 While general agreement exists that physicians practice defensive medicine, the extent of defensive practices and the subsequent impact on healthcare costs remain unclear. This is especially true for a group of clinicians that is rapidly increasing in number: hospitalists. Currently, there are more than 50,000 hospitalists in the United States,5 yet the prevalence of defensive medicine in this relatively new specialty is unknown. Inpatient care is complex and time constraints can impede establishing an optimal therapeutic relationship with the patient, potentially raising liability fears. We therefore sought to quantify hospitalist physician estimates of the cost of defensive medicine and assess correlates of their estimates. As being sued might spur defensive behaviors, we also assessed how many hospitalists reported being sued and whether this was associated with their estimates of defensive medicine.

METHODS

Survey Questionnaire

In a previously published survey-based analysis, we reported on physician practice and overuse for 2 common scenarios in hospital medicine: preoperative evaluation and management of uncomplicated syncope.6 After responding to the vignettes, each physician was asked to provide demographic and employment information and malpractice history. In addition, they were asked the following: In your best estimation, what percentage of healthcare-related resources (eg, hospital admissions, diagnostic testing, treatment) are spent purely because of defensive medicine concerns? __________% resources

Survey Sample & Administration

The survey was sent to a sample of 1753 hospitalists, randomly identified through the Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM) database of members and annual meeting attendees. It is estimated that almost 30% of practicing hospitalists in the United States are members of the SHM.5 A full description of the sampling methodology was previously published.6 Selected hospitalists were mailed surveys, a $20 financial incentive, and subsequent reminders between June and October 2011.

The study was exempted from institutional review board review by the University of Michigan and the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System.

Variables

The primary outcome of interest was the response to the “% resources” estimated to be spent on defensive medicine. This was analyzed as a continuous variable. Independent variables included the following: VA employment, malpractice insurance payer, employer, history of malpractice lawsuit, sex, race, and years practicing as a physician.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Descriptive statistics were first calculated for all variables. Next, bivariable comparisons between the outcome variables and other variables of interest were performed. Multivariable comparisons were made using linear regression for the outcome of estimated resources spent on defensive medicine. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Of the 1753 surveys mailed, 253 were excluded due to incorrect addresses or because the recipients were not practicing hospitalists. A total of 1020 were completed and returned, yielding a 68% response rate (1020 out of 1500 eligible). The hospitalist respondents were in practice for an average of 11 years (range 1-40 years). Respondents represented all 50 states and had a diverse background of experience and demographic characteristics, which has been previously described.6

Resources Estimated Spent on Defensive Medicine

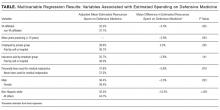

Hospitalists reported, on average, that they believed defensive medicine accounted for 37.5% (standard deviation, 20.2%) of all healthcare spending. Results from the multivariable regression are presented in the Table. Hospitalists affiliated with a VA hospital reported 5.5% less in resources spent on defensive medicine than those not affiliated with a VA hospital (32.2% VA vs 37.7% non-VA, P = 0.025). For every 10 years in practice, the estimate of resources spent on defensive medicine decreased by 3% (P = 0.003). Those who were male (36.4% male vs 39.4% female, P = 0.023) and non-Hispanic white (32.5% non-Hispanic white vs 44.7% other, P ≤ 0.001) also estimated less resources spent on defensive medicine. We did not find an association between a hospitalist reporting being sued and their perception of resources spent on defensive medicine.

Risk of Being Sued

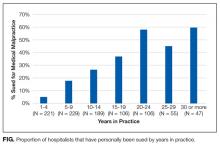

Over a quarter of our sample (25.6%) reported having been sued at least once for medical malpractice. The proportion of hospitalists that reported a history of being sued generally increased with more years of practice (Figure). For those who had been in practice for at least 20 years, more than half (55%) had been sued at least once during their career.

DISCUSSION

In a national survey, hospitalists estimated that almost 40% of all healthcare-related resources are spent purely because of defensive medicine concerns. This estimate was affected by personal demographic and employment factors. Our second major finding is that over one-quarter of a large random sample of hospitalist physicians reported being sued for malpractice.