User login

Knowing My Limits

The records came in by fax. A patient who’d recently moved here and needed to connect with a local neurologist.

When I had time, I flipped through the records. He needed ongoing treatment for a rare neurological disease that I’d heard of, but wasn’t otherwise familiar with. It didn’t even exist in the textbooks or conferences when I was in residency. I’d never seen a case of it, just read about it here and there in journals.

I looked it up, reviewed current treatment options, monitoring, and other knowledge about it, then stared at the notes for a minute. Finally, after thinking it over, I attached a sticky note for my secretary that, if the person called, to redirect them to one of the local subspecialty neurology centers.

I have nothing against this patient, but realistically he would be better served seeing someone with time to keep up on advancements in esoteric disorders, not a general neurologist like myself.

Isn’t that why we have subspecialty centers?

Some of it is also me. There was a time in my career when keeping up on newly discovered disorders and their treatments was, well, cool. But after 25 years in practice, that changes.

It’s important to be at least somewhat aware of new developments (such as in this case) as you may encounter them, and need to know when it’s something you can handle and when to send it elsewhere.

Driving home that afternoon I thought, “I’m an old dog. I don’t want to learn new tricks.” Maybe that’s all it is. There are other neurologists my age and older who thrive on the challenge of learning about and treating new and rare disorders that were unknown when they started out. There’s nothing wrong with that.

But I’ve never pretended to be an academic or sub-sub-specialist. My patients depend on me to stay up to date on the large number of commonly seen neurological disorders, and I do my best to do that.

It ain’t easy being an old dog.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

The records came in by fax. A patient who’d recently moved here and needed to connect with a local neurologist.

When I had time, I flipped through the records. He needed ongoing treatment for a rare neurological disease that I’d heard of, but wasn’t otherwise familiar with. It didn’t even exist in the textbooks or conferences when I was in residency. I’d never seen a case of it, just read about it here and there in journals.

I looked it up, reviewed current treatment options, monitoring, and other knowledge about it, then stared at the notes for a minute. Finally, after thinking it over, I attached a sticky note for my secretary that, if the person called, to redirect them to one of the local subspecialty neurology centers.

I have nothing against this patient, but realistically he would be better served seeing someone with time to keep up on advancements in esoteric disorders, not a general neurologist like myself.

Isn’t that why we have subspecialty centers?

Some of it is also me. There was a time in my career when keeping up on newly discovered disorders and their treatments was, well, cool. But after 25 years in practice, that changes.

It’s important to be at least somewhat aware of new developments (such as in this case) as you may encounter them, and need to know when it’s something you can handle and when to send it elsewhere.

Driving home that afternoon I thought, “I’m an old dog. I don’t want to learn new tricks.” Maybe that’s all it is. There are other neurologists my age and older who thrive on the challenge of learning about and treating new and rare disorders that were unknown when they started out. There’s nothing wrong with that.

But I’ve never pretended to be an academic or sub-sub-specialist. My patients depend on me to stay up to date on the large number of commonly seen neurological disorders, and I do my best to do that.

It ain’t easy being an old dog.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

The records came in by fax. A patient who’d recently moved here and needed to connect with a local neurologist.

When I had time, I flipped through the records. He needed ongoing treatment for a rare neurological disease that I’d heard of, but wasn’t otherwise familiar with. It didn’t even exist in the textbooks or conferences when I was in residency. I’d never seen a case of it, just read about it here and there in journals.

I looked it up, reviewed current treatment options, monitoring, and other knowledge about it, then stared at the notes for a minute. Finally, after thinking it over, I attached a sticky note for my secretary that, if the person called, to redirect them to one of the local subspecialty neurology centers.

I have nothing against this patient, but realistically he would be better served seeing someone with time to keep up on advancements in esoteric disorders, not a general neurologist like myself.

Isn’t that why we have subspecialty centers?

Some of it is also me. There was a time in my career when keeping up on newly discovered disorders and their treatments was, well, cool. But after 25 years in practice, that changes.

It’s important to be at least somewhat aware of new developments (such as in this case) as you may encounter them, and need to know when it’s something you can handle and when to send it elsewhere.

Driving home that afternoon I thought, “I’m an old dog. I don’t want to learn new tricks.” Maybe that’s all it is. There are other neurologists my age and older who thrive on the challenge of learning about and treating new and rare disorders that were unknown when they started out. There’s nothing wrong with that.

But I’ve never pretended to be an academic or sub-sub-specialist. My patients depend on me to stay up to date on the large number of commonly seen neurological disorders, and I do my best to do that.

It ain’t easy being an old dog.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Losing Weight, Decreasing Alcohol, and Improving Sex Life?

Richard* was a master-of-the-universe type. He went to Wharton, ran a large hedge fund, and lived in Greenwich, Connecticut. His three children attended Ivy League schools. He played golf on the weekends and ate three healthy meals per day. There was just one issue: He had gained 90 pounds since the 1990s from consuming six to seven alcoholic beverages per day. He already had one DUI under his belt, and his marriage was on shaky ground. He had tried to address his alcohol abuse disorder on multiple occasions: He went to a yearlong class on alcoholism, saw a psychologist for cognitive-behavioral therapy, and joined Alcoholics Anonymous, all to no avail.

When I met him in December 2023, he had hit rock bottom and was willing to try anything.

At our first visit, I prescribed him weekly tirzepatide (Zepbound) off label, along with a small dose of naltrexone.

Richard shared some feedback after his first 2 weeks:

The naltrexone works great and is strong ... small dose for me effective ... I haven’t wanted to drink and when I do I can’t finish a glass over 2 hours … went from 25 drinks a week to about 4 … don’t notice other side effects … sleeping better too.

And after 6 weeks:

Some more feedback … on week 6-7 and all going well ... drinking very little alcohol and still on half tab of naltrexone ... that works well and have no side effects ... the Zepbound works well too. I do get hungry a few days after the shot but still don’t crave sugar or bad snacks … weight down 21 pounds since started … 292 to 271.

And finally, after 8 weeks:

Looking at my last text to you I see the progress … been incredible ... now down 35 pounds and at 257 … continue to feel excellent with plenty of energy … want to exercise more ... and no temptation to eat or drink unhealthy stuff ... I’m very happy this has surpassed my expectations on how fast it’s worked and I don’t feel any side effects. Marriage has never been better … all thanks to you.

Tirzepatide contains two hormones, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), that are naturally produced by our bodies after meals. Scientists recently learned that the GLP-1 system contributes to the feedback loop of addictive behaviors. Increasing synthetic GLP-1, through medications like tirzepatide, appears to minimize addictive behaviors by limiting their ability to upregulate the brain’s production of dopamine.

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter produced in the brain’s reward center, which regulates how people experience pleasure and control impulses. Dopamine reinforces the pleasure experienced by certain behaviors like drinking, smoking, and eating sweets. These new medications reduce the amount of dopamine released after these activities and thereby lower the motivation to repeat these behaviors.

Contrary to some reports in the news, the vast majority of my male patients using these medications for alcohol abuse disorder experience concurrent increases in testosterone, for two reasons: (1) testosterone increases as body mass index decreases and (2) chronic alcohol use can damage the cells in the testicles that produce testosterone and also decrease the brain’s ability to stimulate the testicles to produce testosterone.

At his most recent checkup last month, Richard’s testosterone had risen from borderline to robust levels, his libido and sleep had improved, and he reported never having felt so healthy or confident. Fingers crossed that the US Food and Drug Administration won’t wait too long before approving this class of medications for more than just diabetes, heart disease, and obesity.

*Patient’s name has been changed.

Dr. Messer is clinical assistant professor, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and associate professor, Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra University, Hempstead, New York. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Richard* was a master-of-the-universe type. He went to Wharton, ran a large hedge fund, and lived in Greenwich, Connecticut. His three children attended Ivy League schools. He played golf on the weekends and ate three healthy meals per day. There was just one issue: He had gained 90 pounds since the 1990s from consuming six to seven alcoholic beverages per day. He already had one DUI under his belt, and his marriage was on shaky ground. He had tried to address his alcohol abuse disorder on multiple occasions: He went to a yearlong class on alcoholism, saw a psychologist for cognitive-behavioral therapy, and joined Alcoholics Anonymous, all to no avail.

When I met him in December 2023, he had hit rock bottom and was willing to try anything.

At our first visit, I prescribed him weekly tirzepatide (Zepbound) off label, along with a small dose of naltrexone.

Richard shared some feedback after his first 2 weeks:

The naltrexone works great and is strong ... small dose for me effective ... I haven’t wanted to drink and when I do I can’t finish a glass over 2 hours … went from 25 drinks a week to about 4 … don’t notice other side effects … sleeping better too.

And after 6 weeks:

Some more feedback … on week 6-7 and all going well ... drinking very little alcohol and still on half tab of naltrexone ... that works well and have no side effects ... the Zepbound works well too. I do get hungry a few days after the shot but still don’t crave sugar or bad snacks … weight down 21 pounds since started … 292 to 271.

And finally, after 8 weeks:

Looking at my last text to you I see the progress … been incredible ... now down 35 pounds and at 257 … continue to feel excellent with plenty of energy … want to exercise more ... and no temptation to eat or drink unhealthy stuff ... I’m very happy this has surpassed my expectations on how fast it’s worked and I don’t feel any side effects. Marriage has never been better … all thanks to you.

Tirzepatide contains two hormones, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), that are naturally produced by our bodies after meals. Scientists recently learned that the GLP-1 system contributes to the feedback loop of addictive behaviors. Increasing synthetic GLP-1, through medications like tirzepatide, appears to minimize addictive behaviors by limiting their ability to upregulate the brain’s production of dopamine.

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter produced in the brain’s reward center, which regulates how people experience pleasure and control impulses. Dopamine reinforces the pleasure experienced by certain behaviors like drinking, smoking, and eating sweets. These new medications reduce the amount of dopamine released after these activities and thereby lower the motivation to repeat these behaviors.

Contrary to some reports in the news, the vast majority of my male patients using these medications for alcohol abuse disorder experience concurrent increases in testosterone, for two reasons: (1) testosterone increases as body mass index decreases and (2) chronic alcohol use can damage the cells in the testicles that produce testosterone and also decrease the brain’s ability to stimulate the testicles to produce testosterone.

At his most recent checkup last month, Richard’s testosterone had risen from borderline to robust levels, his libido and sleep had improved, and he reported never having felt so healthy or confident. Fingers crossed that the US Food and Drug Administration won’t wait too long before approving this class of medications for more than just diabetes, heart disease, and obesity.

*Patient’s name has been changed.

Dr. Messer is clinical assistant professor, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and associate professor, Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra University, Hempstead, New York. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Richard* was a master-of-the-universe type. He went to Wharton, ran a large hedge fund, and lived in Greenwich, Connecticut. His three children attended Ivy League schools. He played golf on the weekends and ate three healthy meals per day. There was just one issue: He had gained 90 pounds since the 1990s from consuming six to seven alcoholic beverages per day. He already had one DUI under his belt, and his marriage was on shaky ground. He had tried to address his alcohol abuse disorder on multiple occasions: He went to a yearlong class on alcoholism, saw a psychologist for cognitive-behavioral therapy, and joined Alcoholics Anonymous, all to no avail.

When I met him in December 2023, he had hit rock bottom and was willing to try anything.

At our first visit, I prescribed him weekly tirzepatide (Zepbound) off label, along with a small dose of naltrexone.

Richard shared some feedback after his first 2 weeks:

The naltrexone works great and is strong ... small dose for me effective ... I haven’t wanted to drink and when I do I can’t finish a glass over 2 hours … went from 25 drinks a week to about 4 … don’t notice other side effects … sleeping better too.

And after 6 weeks:

Some more feedback … on week 6-7 and all going well ... drinking very little alcohol and still on half tab of naltrexone ... that works well and have no side effects ... the Zepbound works well too. I do get hungry a few days after the shot but still don’t crave sugar or bad snacks … weight down 21 pounds since started … 292 to 271.

And finally, after 8 weeks:

Looking at my last text to you I see the progress … been incredible ... now down 35 pounds and at 257 … continue to feel excellent with plenty of energy … want to exercise more ... and no temptation to eat or drink unhealthy stuff ... I’m very happy this has surpassed my expectations on how fast it’s worked and I don’t feel any side effects. Marriage has never been better … all thanks to you.

Tirzepatide contains two hormones, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), that are naturally produced by our bodies after meals. Scientists recently learned that the GLP-1 system contributes to the feedback loop of addictive behaviors. Increasing synthetic GLP-1, through medications like tirzepatide, appears to minimize addictive behaviors by limiting their ability to upregulate the brain’s production of dopamine.

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter produced in the brain’s reward center, which regulates how people experience pleasure and control impulses. Dopamine reinforces the pleasure experienced by certain behaviors like drinking, smoking, and eating sweets. These new medications reduce the amount of dopamine released after these activities and thereby lower the motivation to repeat these behaviors.

Contrary to some reports in the news, the vast majority of my male patients using these medications for alcohol abuse disorder experience concurrent increases in testosterone, for two reasons: (1) testosterone increases as body mass index decreases and (2) chronic alcohol use can damage the cells in the testicles that produce testosterone and also decrease the brain’s ability to stimulate the testicles to produce testosterone.

At his most recent checkup last month, Richard’s testosterone had risen from borderline to robust levels, his libido and sleep had improved, and he reported never having felt so healthy or confident. Fingers crossed that the US Food and Drug Administration won’t wait too long before approving this class of medications for more than just diabetes, heart disease, and obesity.

*Patient’s name has been changed.

Dr. Messer is clinical assistant professor, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and associate professor, Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra University, Hempstead, New York. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Is Semaglutide the ‘New Statin’? Not So Fast

There has been much hyperbole since the presentation of results from the SELECT cardiovascular outcomes trial (CVOT) at this year’s European Congress on Obesity, which led many to herald semaglutide as the “new statin.”

In the SELECT CVOT, participants with overweight or obesity (body mass index [BMI] ≥ 27), established cardiovascular disease (CVD), and no history of type 2 diabetes were administered the injectable glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist semaglutide (Wegovy) at a 2.4-mg dose weekly. Treatment resulted in a significant 20% relative risk reduction in major adverse CV events (a composite endpoint comprising CV death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke). Importantly, SELECT was a trial on secondary prevention of CVD.

The CV benefits of semaglutide were notably independent of baseline weight or amount of weight lost. This suggests that the underlying driver of improved CV outcomes with semaglutide extends beyond simple reduction in obesity and perhaps indicates a direct effect on vasculature and reduction in atherosclerosis, although this remains unproven.

Not All Risk Reduction Is Equal

Much of the sensationalist coverage in the lay press focused on the 20% relative risk reduction figure. This endpoint is often more impressive and headline-grabbing than the absolute risk reduction, which provides a clearer view of a treatment’s real-world impact.

In SELECT, the absolute risk reduction was 1.5 percentage points, which translated into a number needed to treat (NNT) of 67 over 34 months to prevent one primary outcome of a major adverse CV event.

Lower NNTs suggest more effective treatments because fewer people need to be treated to prevent one clinical event, such as the major adverse CV events used in SELECT.

Semaglutide vs Statins

How does the clinical effectiveness observed in the SELECT trial compare with that observed in statin trials when it comes to the secondary prevention of CVD?

The seminal 4S study published in 1994 explored the impact of simvastatin on all-cause mortality among people with previous myocardial infarction or angina and hyperlipidemia (mean baseline BMI, 26). After 5.4 years of follow-up, the trial was stopped early owing to a 3.3-percentage point absolute risk reduction in all-cause mortality (NNT, 30; relative risk reduction, 28%). The NNT to prevent one death from CV causes was 31, and the NNT to prevent one major coronary event was lower, at 15.

Other statin secondary prevention trials, such as the LIPID and MIRACL studies, demonstrated similarly low NNTs.

So, you can see that the NNTs for statins in secondary prevention are much lower than with semaglutide in SELECT. Furthermore, the benefits of semaglutide in preventing CVD in people living with overweight/obesity have yet to be elucidated.

In contrast, we already have published evidence showing the benefits of statins in the primary prevention of CVD, albeit with higher and more variable NNTs than in the statin secondary prevention studies.

The benefits of statins are also postulated to extend beyond their impact on lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Statins have been suggested to have anti-inflammatory and plaque-stabilizing effects, among other pleiotropic benefits.

We also currently lack evidence for the cost-effectiveness of semaglutide for CV risk reduction. Assessing economic viability and use in health care systems, such as the UK’s National Health Service, involves comparing the cost of semaglutide against the health care savings from prevented CV events. Health economic studies are vital to determine whether the benefits justify the expense. In contrast, the cost-effectiveness of statins is well established, particularly for high-risk individuals.

Advantages of GLP-1s Should Not Be Overlooked

Of course, statins don’t provide the significant weight loss benefits of semaglutide.

Additional data from SELECT presented at the 2024 European Congress on Obesity demonstrated that participants lost a mean of 10.2% body weight and 7.7 cm from their waist circumference after 4 years. Moreover, after 2 years, 12% of individuals randomized to semaglutide had returned to a normal BMI, and nearly half were no longer living with obesity.

Although the CV benefits of semaglutide were independent of weight reduction, this level of weight loss is clinically meaningful and will reduce the risk of many other cardiometabolic conditions including type 2 diabetes, metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease, and obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome, as well as improve low mood, depression, and overall quality of life. Additionally, obesity is now a risk factor for 13 different types of cancer, including bowel, breast, and pancreatic cancer, so facilitating a return to a healthier body weight will also mitigate future risk for cancer.

Sticking With Our Cornerstone Therapy, For Now

In conclusion, I do not believe that semaglutide is the “new statin.” Statins are the cornerstone of primary and secondary prevention of CVD in a wide range of comorbidities, as evidenced in multiple large and high-quality trials dating back over 30 years.

However, there is no doubt that the GLP-1 receptor agonist class is the most significant therapeutic advance for the management of obesity and comorbidities to date.

The SELECT CVOT data uniquely position semaglutide as a secondary CVD prevention agent on top of guideline-driven management for people living with overweight/obesity and established CVD. Additionally, the clinically meaningful weight loss achieved with semaglutide will impact the risk of developing many other cardiometabolic conditions, as well as improve mental health and overall quality of life.

Dr. Fernando, GP Partner, North Berwick Health Centre, North Berwick, Scotland, creates concise clinical aide-mémoire for primary and secondary care to make life easier for health care professionals and ultimately to improve the lives of patients. He is very active on social media (X handle @drkevinfernando), where he posts hot topics in type 2 diabetes and CVRM. He recently has forayed into YouTube (@DrKevinFernando) and TikTok (@drkevinfernando) with patient-facing video content. Dr. Fernando has been elected to Fellowship of the Royal College of General Practitioners, the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, and the Academy of Medical Educators for his work in diabetes and medical education. He has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for AstraZeneca; Boehringer Ingelheim; Lilly; Menarini; Bayer; Dexcom; Novartis; Novo Nordisk; Amgen; and Daiichi Sankyo; received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from AstraZeneca; Boehringer Ingelheim; Lilly; Menarini; Bayer; Dexcom; Novartis; Novo Nordisk; Amgen; and Daiichi Sankyo.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There has been much hyperbole since the presentation of results from the SELECT cardiovascular outcomes trial (CVOT) at this year’s European Congress on Obesity, which led many to herald semaglutide as the “new statin.”

In the SELECT CVOT, participants with overweight or obesity (body mass index [BMI] ≥ 27), established cardiovascular disease (CVD), and no history of type 2 diabetes were administered the injectable glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist semaglutide (Wegovy) at a 2.4-mg dose weekly. Treatment resulted in a significant 20% relative risk reduction in major adverse CV events (a composite endpoint comprising CV death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke). Importantly, SELECT was a trial on secondary prevention of CVD.

The CV benefits of semaglutide were notably independent of baseline weight or amount of weight lost. This suggests that the underlying driver of improved CV outcomes with semaglutide extends beyond simple reduction in obesity and perhaps indicates a direct effect on vasculature and reduction in atherosclerosis, although this remains unproven.

Not All Risk Reduction Is Equal

Much of the sensationalist coverage in the lay press focused on the 20% relative risk reduction figure. This endpoint is often more impressive and headline-grabbing than the absolute risk reduction, which provides a clearer view of a treatment’s real-world impact.

In SELECT, the absolute risk reduction was 1.5 percentage points, which translated into a number needed to treat (NNT) of 67 over 34 months to prevent one primary outcome of a major adverse CV event.

Lower NNTs suggest more effective treatments because fewer people need to be treated to prevent one clinical event, such as the major adverse CV events used in SELECT.

Semaglutide vs Statins

How does the clinical effectiveness observed in the SELECT trial compare with that observed in statin trials when it comes to the secondary prevention of CVD?

The seminal 4S study published in 1994 explored the impact of simvastatin on all-cause mortality among people with previous myocardial infarction or angina and hyperlipidemia (mean baseline BMI, 26). After 5.4 years of follow-up, the trial was stopped early owing to a 3.3-percentage point absolute risk reduction in all-cause mortality (NNT, 30; relative risk reduction, 28%). The NNT to prevent one death from CV causes was 31, and the NNT to prevent one major coronary event was lower, at 15.

Other statin secondary prevention trials, such as the LIPID and MIRACL studies, demonstrated similarly low NNTs.

So, you can see that the NNTs for statins in secondary prevention are much lower than with semaglutide in SELECT. Furthermore, the benefits of semaglutide in preventing CVD in people living with overweight/obesity have yet to be elucidated.

In contrast, we already have published evidence showing the benefits of statins in the primary prevention of CVD, albeit with higher and more variable NNTs than in the statin secondary prevention studies.

The benefits of statins are also postulated to extend beyond their impact on lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Statins have been suggested to have anti-inflammatory and plaque-stabilizing effects, among other pleiotropic benefits.

We also currently lack evidence for the cost-effectiveness of semaglutide for CV risk reduction. Assessing economic viability and use in health care systems, such as the UK’s National Health Service, involves comparing the cost of semaglutide against the health care savings from prevented CV events. Health economic studies are vital to determine whether the benefits justify the expense. In contrast, the cost-effectiveness of statins is well established, particularly for high-risk individuals.

Advantages of GLP-1s Should Not Be Overlooked

Of course, statins don’t provide the significant weight loss benefits of semaglutide.

Additional data from SELECT presented at the 2024 European Congress on Obesity demonstrated that participants lost a mean of 10.2% body weight and 7.7 cm from their waist circumference after 4 years. Moreover, after 2 years, 12% of individuals randomized to semaglutide had returned to a normal BMI, and nearly half were no longer living with obesity.

Although the CV benefits of semaglutide were independent of weight reduction, this level of weight loss is clinically meaningful and will reduce the risk of many other cardiometabolic conditions including type 2 diabetes, metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease, and obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome, as well as improve low mood, depression, and overall quality of life. Additionally, obesity is now a risk factor for 13 different types of cancer, including bowel, breast, and pancreatic cancer, so facilitating a return to a healthier body weight will also mitigate future risk for cancer.

Sticking With Our Cornerstone Therapy, For Now

In conclusion, I do not believe that semaglutide is the “new statin.” Statins are the cornerstone of primary and secondary prevention of CVD in a wide range of comorbidities, as evidenced in multiple large and high-quality trials dating back over 30 years.

However, there is no doubt that the GLP-1 receptor agonist class is the most significant therapeutic advance for the management of obesity and comorbidities to date.

The SELECT CVOT data uniquely position semaglutide as a secondary CVD prevention agent on top of guideline-driven management for people living with overweight/obesity and established CVD. Additionally, the clinically meaningful weight loss achieved with semaglutide will impact the risk of developing many other cardiometabolic conditions, as well as improve mental health and overall quality of life.

Dr. Fernando, GP Partner, North Berwick Health Centre, North Berwick, Scotland, creates concise clinical aide-mémoire for primary and secondary care to make life easier for health care professionals and ultimately to improve the lives of patients. He is very active on social media (X handle @drkevinfernando), where he posts hot topics in type 2 diabetes and CVRM. He recently has forayed into YouTube (@DrKevinFernando) and TikTok (@drkevinfernando) with patient-facing video content. Dr. Fernando has been elected to Fellowship of the Royal College of General Practitioners, the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, and the Academy of Medical Educators for his work in diabetes and medical education. He has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for AstraZeneca; Boehringer Ingelheim; Lilly; Menarini; Bayer; Dexcom; Novartis; Novo Nordisk; Amgen; and Daiichi Sankyo; received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from AstraZeneca; Boehringer Ingelheim; Lilly; Menarini; Bayer; Dexcom; Novartis; Novo Nordisk; Amgen; and Daiichi Sankyo.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There has been much hyperbole since the presentation of results from the SELECT cardiovascular outcomes trial (CVOT) at this year’s European Congress on Obesity, which led many to herald semaglutide as the “new statin.”

In the SELECT CVOT, participants with overweight or obesity (body mass index [BMI] ≥ 27), established cardiovascular disease (CVD), and no history of type 2 diabetes were administered the injectable glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist semaglutide (Wegovy) at a 2.4-mg dose weekly. Treatment resulted in a significant 20% relative risk reduction in major adverse CV events (a composite endpoint comprising CV death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke). Importantly, SELECT was a trial on secondary prevention of CVD.

The CV benefits of semaglutide were notably independent of baseline weight or amount of weight lost. This suggests that the underlying driver of improved CV outcomes with semaglutide extends beyond simple reduction in obesity and perhaps indicates a direct effect on vasculature and reduction in atherosclerosis, although this remains unproven.

Not All Risk Reduction Is Equal

Much of the sensationalist coverage in the lay press focused on the 20% relative risk reduction figure. This endpoint is often more impressive and headline-grabbing than the absolute risk reduction, which provides a clearer view of a treatment’s real-world impact.

In SELECT, the absolute risk reduction was 1.5 percentage points, which translated into a number needed to treat (NNT) of 67 over 34 months to prevent one primary outcome of a major adverse CV event.

Lower NNTs suggest more effective treatments because fewer people need to be treated to prevent one clinical event, such as the major adverse CV events used in SELECT.

Semaglutide vs Statins

How does the clinical effectiveness observed in the SELECT trial compare with that observed in statin trials when it comes to the secondary prevention of CVD?

The seminal 4S study published in 1994 explored the impact of simvastatin on all-cause mortality among people with previous myocardial infarction or angina and hyperlipidemia (mean baseline BMI, 26). After 5.4 years of follow-up, the trial was stopped early owing to a 3.3-percentage point absolute risk reduction in all-cause mortality (NNT, 30; relative risk reduction, 28%). The NNT to prevent one death from CV causes was 31, and the NNT to prevent one major coronary event was lower, at 15.

Other statin secondary prevention trials, such as the LIPID and MIRACL studies, demonstrated similarly low NNTs.

So, you can see that the NNTs for statins in secondary prevention are much lower than with semaglutide in SELECT. Furthermore, the benefits of semaglutide in preventing CVD in people living with overweight/obesity have yet to be elucidated.

In contrast, we already have published evidence showing the benefits of statins in the primary prevention of CVD, albeit with higher and more variable NNTs than in the statin secondary prevention studies.

The benefits of statins are also postulated to extend beyond their impact on lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Statins have been suggested to have anti-inflammatory and plaque-stabilizing effects, among other pleiotropic benefits.

We also currently lack evidence for the cost-effectiveness of semaglutide for CV risk reduction. Assessing economic viability and use in health care systems, such as the UK’s National Health Service, involves comparing the cost of semaglutide against the health care savings from prevented CV events. Health economic studies are vital to determine whether the benefits justify the expense. In contrast, the cost-effectiveness of statins is well established, particularly for high-risk individuals.

Advantages of GLP-1s Should Not Be Overlooked

Of course, statins don’t provide the significant weight loss benefits of semaglutide.

Additional data from SELECT presented at the 2024 European Congress on Obesity demonstrated that participants lost a mean of 10.2% body weight and 7.7 cm from their waist circumference after 4 years. Moreover, after 2 years, 12% of individuals randomized to semaglutide had returned to a normal BMI, and nearly half were no longer living with obesity.

Although the CV benefits of semaglutide were independent of weight reduction, this level of weight loss is clinically meaningful and will reduce the risk of many other cardiometabolic conditions including type 2 diabetes, metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease, and obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome, as well as improve low mood, depression, and overall quality of life. Additionally, obesity is now a risk factor for 13 different types of cancer, including bowel, breast, and pancreatic cancer, so facilitating a return to a healthier body weight will also mitigate future risk for cancer.

Sticking With Our Cornerstone Therapy, For Now

In conclusion, I do not believe that semaglutide is the “new statin.” Statins are the cornerstone of primary and secondary prevention of CVD in a wide range of comorbidities, as evidenced in multiple large and high-quality trials dating back over 30 years.

However, there is no doubt that the GLP-1 receptor agonist class is the most significant therapeutic advance for the management of obesity and comorbidities to date.

The SELECT CVOT data uniquely position semaglutide as a secondary CVD prevention agent on top of guideline-driven management for people living with overweight/obesity and established CVD. Additionally, the clinically meaningful weight loss achieved with semaglutide will impact the risk of developing many other cardiometabolic conditions, as well as improve mental health and overall quality of life.

Dr. Fernando, GP Partner, North Berwick Health Centre, North Berwick, Scotland, creates concise clinical aide-mémoire for primary and secondary care to make life easier for health care professionals and ultimately to improve the lives of patients. He is very active on social media (X handle @drkevinfernando), where he posts hot topics in type 2 diabetes and CVRM. He recently has forayed into YouTube (@DrKevinFernando) and TikTok (@drkevinfernando) with patient-facing video content. Dr. Fernando has been elected to Fellowship of the Royal College of General Practitioners, the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, and the Academy of Medical Educators for his work in diabetes and medical education. He has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for AstraZeneca; Boehringer Ingelheim; Lilly; Menarini; Bayer; Dexcom; Novartis; Novo Nordisk; Amgen; and Daiichi Sankyo; received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from AstraZeneca; Boehringer Ingelheim; Lilly; Menarini; Bayer; Dexcom; Novartis; Novo Nordisk; Amgen; and Daiichi Sankyo.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Low-Field MRIs

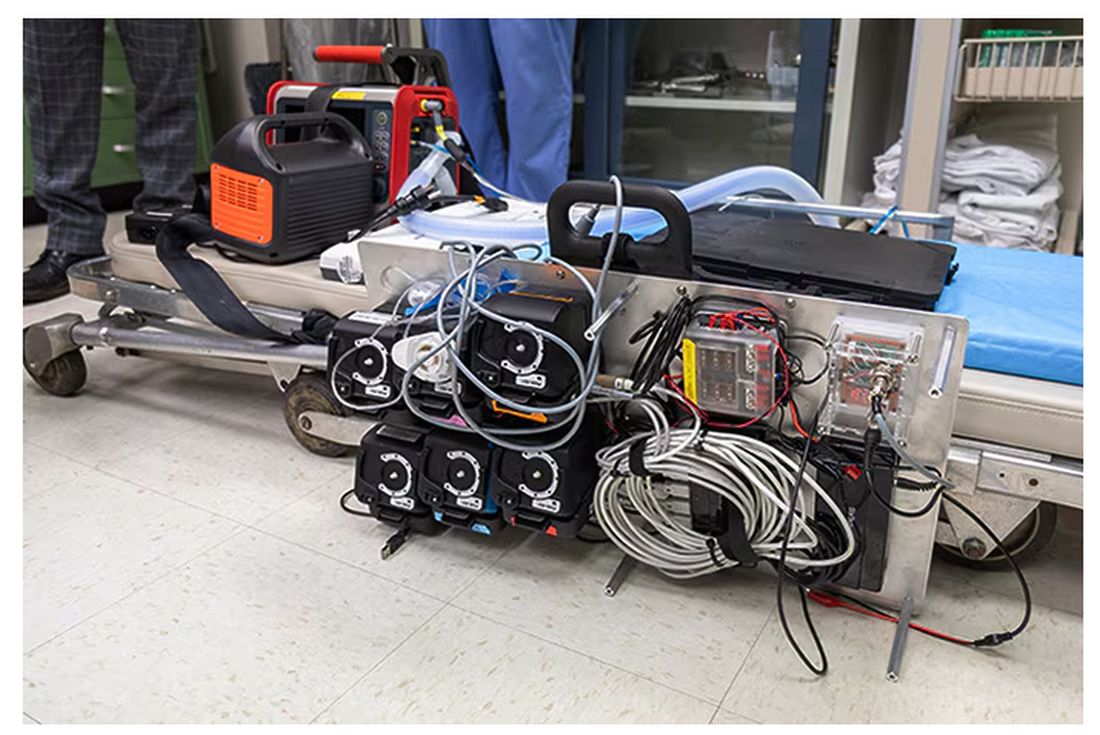

Recently, “low field” MRIs have been in the news, with the promise that they’ll be safer and easier. People can go in them with their cell phones, car keys in pockets, no ear plugs needed for the noise, etc. They’re cheaper to build and can be plugged into a standard outlet.

That’s all well and good, but what about accuracy and image quality?

That’s a big question. Even proponents of the technology say it’s not as good as what we see with 3T MRI, so they’re trying to compensate by using AI and other software protocols to enhance the pictures. Allegedly it looks good, but so far only healthy volunteers have been scanned. How will it do with a small low-grade glioma or other subtle (but important) findings? We don’t know yet.

Personally, I think having to give up your iPhone and car keys for an hour, and put in foam ear plugs, are small trade-offs to get an accurate diagnosis.

Of course, I’m also approaching this as someone who deals with brain imaging. Maybe for other structures, like a knee, that kind of detail isn’t as necessary (or maybe it is. I’m definitely not in that field).

So, as with so many things that make it into the popular press, they likely have potential, but are still not ready for prime time.

This sort of stuff always gets my office phones ringing. Patients see a blurb about it on the news or Facebook and assume it’s available now, so they want one. They seem to think the new MRI is like Bones McCoy’s tricorder. I take the scanner off my belt, wave it over them, and the answer comes up on the screen. The fact that the unit still weighs over a ton is hidden at the bottom of the blurb, if it’s even mentioned at all.

There’s also the likelihood that this sort of thing is going to be taken to the public, in the same way carotid Dopplers have been. Marketed to the worried well with celebrity endorsements and taglines like “see what your doctor won’t look for.” Of course, MRIs are chock full of things like nonspecific white matter changes, disc bulges, tiny meningiomas, and a host of other incidental findings that cause panic in cyberchondriacs. Who then call us.

But that’s another story.

I understand that for some parts of the world a comparatively inexpensive, transportable, MRI that requires less shielding and power is a HUGE deal. Its availability can make the difference between life and death.

I’m not knocking the technology. I’m sure it will be useful. But, like so much in medicine, it’s not here yet.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Recently, “low field” MRIs have been in the news, with the promise that they’ll be safer and easier. People can go in them with their cell phones, car keys in pockets, no ear plugs needed for the noise, etc. They’re cheaper to build and can be plugged into a standard outlet.

That’s all well and good, but what about accuracy and image quality?

That’s a big question. Even proponents of the technology say it’s not as good as what we see with 3T MRI, so they’re trying to compensate by using AI and other software protocols to enhance the pictures. Allegedly it looks good, but so far only healthy volunteers have been scanned. How will it do with a small low-grade glioma or other subtle (but important) findings? We don’t know yet.

Personally, I think having to give up your iPhone and car keys for an hour, and put in foam ear plugs, are small trade-offs to get an accurate diagnosis.

Of course, I’m also approaching this as someone who deals with brain imaging. Maybe for other structures, like a knee, that kind of detail isn’t as necessary (or maybe it is. I’m definitely not in that field).

So, as with so many things that make it into the popular press, they likely have potential, but are still not ready for prime time.

This sort of stuff always gets my office phones ringing. Patients see a blurb about it on the news or Facebook and assume it’s available now, so they want one. They seem to think the new MRI is like Bones McCoy’s tricorder. I take the scanner off my belt, wave it over them, and the answer comes up on the screen. The fact that the unit still weighs over a ton is hidden at the bottom of the blurb, if it’s even mentioned at all.

There’s also the likelihood that this sort of thing is going to be taken to the public, in the same way carotid Dopplers have been. Marketed to the worried well with celebrity endorsements and taglines like “see what your doctor won’t look for.” Of course, MRIs are chock full of things like nonspecific white matter changes, disc bulges, tiny meningiomas, and a host of other incidental findings that cause panic in cyberchondriacs. Who then call us.

But that’s another story.

I understand that for some parts of the world a comparatively inexpensive, transportable, MRI that requires less shielding and power is a HUGE deal. Its availability can make the difference between life and death.

I’m not knocking the technology. I’m sure it will be useful. But, like so much in medicine, it’s not here yet.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Recently, “low field” MRIs have been in the news, with the promise that they’ll be safer and easier. People can go in them with their cell phones, car keys in pockets, no ear plugs needed for the noise, etc. They’re cheaper to build and can be plugged into a standard outlet.

That’s all well and good, but what about accuracy and image quality?

That’s a big question. Even proponents of the technology say it’s not as good as what we see with 3T MRI, so they’re trying to compensate by using AI and other software protocols to enhance the pictures. Allegedly it looks good, but so far only healthy volunteers have been scanned. How will it do with a small low-grade glioma or other subtle (but important) findings? We don’t know yet.

Personally, I think having to give up your iPhone and car keys for an hour, and put in foam ear plugs, are small trade-offs to get an accurate diagnosis.

Of course, I’m also approaching this as someone who deals with brain imaging. Maybe for other structures, like a knee, that kind of detail isn’t as necessary (or maybe it is. I’m definitely not in that field).

So, as with so many things that make it into the popular press, they likely have potential, but are still not ready for prime time.

This sort of stuff always gets my office phones ringing. Patients see a blurb about it on the news or Facebook and assume it’s available now, so they want one. They seem to think the new MRI is like Bones McCoy’s tricorder. I take the scanner off my belt, wave it over them, and the answer comes up on the screen. The fact that the unit still weighs over a ton is hidden at the bottom of the blurb, if it’s even mentioned at all.

There’s also the likelihood that this sort of thing is going to be taken to the public, in the same way carotid Dopplers have been. Marketed to the worried well with celebrity endorsements and taglines like “see what your doctor won’t look for.” Of course, MRIs are chock full of things like nonspecific white matter changes, disc bulges, tiny meningiomas, and a host of other incidental findings that cause panic in cyberchondriacs. Who then call us.

But that’s another story.

I understand that for some parts of the world a comparatively inexpensive, transportable, MRI that requires less shielding and power is a HUGE deal. Its availability can make the difference between life and death.

I’m not knocking the technology. I’m sure it will be useful. But, like so much in medicine, it’s not here yet.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

The Value of Early Education

Early education is right up there with motherhood and apple pie as unarguable positive concepts. How could exposing young children to a school-like atmosphere not be a benefit, particularly in communities dominated by socioeconomic challenges? While there are some questions about the value of playing Mozart to infants, early education in the traditional sense continues to be viewed as a key strategy for providing young children a preschool foundation on which a successful academic career can be built. Several oft-cited randomized controlled trials have fueled both private and public interest and funding.

However, a recent commentary published in Science suggests that all programs are “not unequivocally positive and much more research is needed.” “Worrisome results in Tennessee,” “Success in Boston,” and “Largely null results for Headstart” are just a few of the article’s section titles and convey a sense of the inconsistency the investigators found as they reviewed early education systems around the country.

While there may be some politicians who may attempt to use the results of this investigation as a reason to cancel public funding of underperforming early education programs, the authors avoid this baby-and-the-bathwater conclusion. Instead, they urge more rigorous research “to understand how effective programs can be designed and implemented.”

The kind of re-thinking and brainstorming these investigators suggest takes time. While we’re waiting for this process to gain traction, this might be a good time to consider some of the benefits of early education that we don’t usually consider when our focus is on academic metrics.

A recent paper in Children’s Health Care by investigators at the Boston University Medical Center and School of Medicine considered the diet of children attending preschool. Looking at the dietary records of more than 300 children attending 30 childcare centers, the researchers found that the children’s diets before arrival at daycare was less healthy than while they were in daycare. “The hour after pickup appeared to be the least healthful” of any of the time periods surveyed. Of course, we will all conjure up images of what this chaotic post-daycare pickup may look like and cut the harried parents and grandparents some slack when it comes to nutritional choices. However, the bottom line is that for the group of children surveyed being in preschool or daycare protected them from a less healthy diet they were being provided outside of school hours.

Our recent experience with pandemic-related school closures provides more evidence that being in school was superior to any remote experience academically. School-age children and adolescents gained weight when school closures were the norm. Play patterns for children shifted from outdoor play to indoor play — often dominated by more sedentary video games. Both fatal and non-fatal gun-related injuries surged during the pandemic and, by far, the majority of these occur in the home and not at school.

Stepping back to look at this broader picture that includes diet, physical activity, and safety — not to mention the benefits of socialization — leads one to arrive at the unfortunate conclusion that Of course there will be those who point to the belief that schools are petri dishes putting children at greater risk for respiratory infections. On the other hand, we must accept that schools haven’t proved to be a major factor in the spread of COVID that many had feared.

The authors of the study in Science are certainly correct in recommending a more thorough investigation into the academic benefits of preschool education. However, we must keep in mind that preschool offers an environment that can be a positive influence on young children.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Early education is right up there with motherhood and apple pie as unarguable positive concepts. How could exposing young children to a school-like atmosphere not be a benefit, particularly in communities dominated by socioeconomic challenges? While there are some questions about the value of playing Mozart to infants, early education in the traditional sense continues to be viewed as a key strategy for providing young children a preschool foundation on which a successful academic career can be built. Several oft-cited randomized controlled trials have fueled both private and public interest and funding.

However, a recent commentary published in Science suggests that all programs are “not unequivocally positive and much more research is needed.” “Worrisome results in Tennessee,” “Success in Boston,” and “Largely null results for Headstart” are just a few of the article’s section titles and convey a sense of the inconsistency the investigators found as they reviewed early education systems around the country.

While there may be some politicians who may attempt to use the results of this investigation as a reason to cancel public funding of underperforming early education programs, the authors avoid this baby-and-the-bathwater conclusion. Instead, they urge more rigorous research “to understand how effective programs can be designed and implemented.”

The kind of re-thinking and brainstorming these investigators suggest takes time. While we’re waiting for this process to gain traction, this might be a good time to consider some of the benefits of early education that we don’t usually consider when our focus is on academic metrics.

A recent paper in Children’s Health Care by investigators at the Boston University Medical Center and School of Medicine considered the diet of children attending preschool. Looking at the dietary records of more than 300 children attending 30 childcare centers, the researchers found that the children’s diets before arrival at daycare was less healthy than while they were in daycare. “The hour after pickup appeared to be the least healthful” of any of the time periods surveyed. Of course, we will all conjure up images of what this chaotic post-daycare pickup may look like and cut the harried parents and grandparents some slack when it comes to nutritional choices. However, the bottom line is that for the group of children surveyed being in preschool or daycare protected them from a less healthy diet they were being provided outside of school hours.

Our recent experience with pandemic-related school closures provides more evidence that being in school was superior to any remote experience academically. School-age children and adolescents gained weight when school closures were the norm. Play patterns for children shifted from outdoor play to indoor play — often dominated by more sedentary video games. Both fatal and non-fatal gun-related injuries surged during the pandemic and, by far, the majority of these occur in the home and not at school.

Stepping back to look at this broader picture that includes diet, physical activity, and safety — not to mention the benefits of socialization — leads one to arrive at the unfortunate conclusion that Of course there will be those who point to the belief that schools are petri dishes putting children at greater risk for respiratory infections. On the other hand, we must accept that schools haven’t proved to be a major factor in the spread of COVID that many had feared.

The authors of the study in Science are certainly correct in recommending a more thorough investigation into the academic benefits of preschool education. However, we must keep in mind that preschool offers an environment that can be a positive influence on young children.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Early education is right up there with motherhood and apple pie as unarguable positive concepts. How could exposing young children to a school-like atmosphere not be a benefit, particularly in communities dominated by socioeconomic challenges? While there are some questions about the value of playing Mozart to infants, early education in the traditional sense continues to be viewed as a key strategy for providing young children a preschool foundation on which a successful academic career can be built. Several oft-cited randomized controlled trials have fueled both private and public interest and funding.

However, a recent commentary published in Science suggests that all programs are “not unequivocally positive and much more research is needed.” “Worrisome results in Tennessee,” “Success in Boston,” and “Largely null results for Headstart” are just a few of the article’s section titles and convey a sense of the inconsistency the investigators found as they reviewed early education systems around the country.

While there may be some politicians who may attempt to use the results of this investigation as a reason to cancel public funding of underperforming early education programs, the authors avoid this baby-and-the-bathwater conclusion. Instead, they urge more rigorous research “to understand how effective programs can be designed and implemented.”

The kind of re-thinking and brainstorming these investigators suggest takes time. While we’re waiting for this process to gain traction, this might be a good time to consider some of the benefits of early education that we don’t usually consider when our focus is on academic metrics.

A recent paper in Children’s Health Care by investigators at the Boston University Medical Center and School of Medicine considered the diet of children attending preschool. Looking at the dietary records of more than 300 children attending 30 childcare centers, the researchers found that the children’s diets before arrival at daycare was less healthy than while they were in daycare. “The hour after pickup appeared to be the least healthful” of any of the time periods surveyed. Of course, we will all conjure up images of what this chaotic post-daycare pickup may look like and cut the harried parents and grandparents some slack when it comes to nutritional choices. However, the bottom line is that for the group of children surveyed being in preschool or daycare protected them from a less healthy diet they were being provided outside of school hours.

Our recent experience with pandemic-related school closures provides more evidence that being in school was superior to any remote experience academically. School-age children and adolescents gained weight when school closures were the norm. Play patterns for children shifted from outdoor play to indoor play — often dominated by more sedentary video games. Both fatal and non-fatal gun-related injuries surged during the pandemic and, by far, the majority of these occur in the home and not at school.

Stepping back to look at this broader picture that includes diet, physical activity, and safety — not to mention the benefits of socialization — leads one to arrive at the unfortunate conclusion that Of course there will be those who point to the belief that schools are petri dishes putting children at greater risk for respiratory infections. On the other hand, we must accept that schools haven’t proved to be a major factor in the spread of COVID that many had feared.

The authors of the study in Science are certainly correct in recommending a more thorough investigation into the academic benefits of preschool education. However, we must keep in mind that preschool offers an environment that can be a positive influence on young children.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Calcium and CV Risk: Are Supplements and Vitamin D to Blame?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Tricia Ward: Hi. I’m Tricia Ward, from theheart.org/Medscape Cardiology. I’m joined today by Dr Matthew Budoff. He is professor of medicine at UCLA and the endowed chair of preventive cardiology at the Lundquist Institute. Welcome, Dr Budoff.

Matthew J. Budoff, MD: Thank you.

Dietary Calcium vs Coronary Calcium

Ms. Ward: The reason I wanted to talk to you today is because there have been some recent studies linking calcium supplements to an increased risk for cardiovascular disease. I’m old enough to remember when we used to tell people that dietary calcium and coronary calcium weren’t connected and weren’t the same. Were we wrong?

Dr. Budoff: I think there’s a large amount of mixed data out there still. The US Preventive Services Task Force looked into this a number of years ago and said there’s no association between calcium supplementation and increased risk for cardiovascular disease.

As you mentioned, there are a couple of newer studies that point us toward a relationship. I think that we still have a little bit of a mixed bag, but we need to dive a little deeper into that to figure out what’s going on.

Ms. Ward: Does it appear to be connected to calcium in the form of supplements vs calcium from foods?

Dr. Budoff: We looked very carefully at dietary calcium in the MESA study, the multiethnic study of atherosclerosis. There is no relationship between dietary calcium intake and coronary calcium or cardiovascular events. We’re talking mostly about supplements now when we talk about this increased risk that we’re seeing.

Does Vitamin D Exacerbate Risk?

Ms. Ward: Because it’s seen with supplements, is that likely because that’s a much higher concentration of calcium coming in or do you think it’s something inherent in its being in the form of a supplement?

Dr. Budoff: I think there are two things. One, it’s definitely a higher concentration all at once. You get many more milligrams at a time when you take a supplement than if you had a high-calcium food or drink.

Also, most supplements have vitamin D as well. I think vitamin D and calcium work synergistically. When you give them both together simultaneously, I think that may have more of a potentiating effect that might exacerbate any potential risk.

Ms. Ward: Is there any reason to think there might be a difference in type of calcium supplement? I always think of the chalky tablet form vs calcium chews.

Dr. Budoff: I’m not aware of a difference in the supplement type. I think the vitamin D issue is a big problem because we all have patients who take thousands of units of vitamin D — just crazy numbers. People advocate really high numbers and that stays in the system.

Personally, I think part of the explanation is that with very high levels of vitamin D on top of calcium supplementation, you now absorb it better. You now get it into the bone, but maybe also into the coronary arteries. If you’re very high in vitamin D and then are taking a large calcium supplement, it might be the calcium/vitamin D combination that’s giving us some trouble. I think people on vitamin D supplements really need to watch their levels and not get supratherapeutic.

Ms. Ward: With the vitamin D?

Dr. Budoff: With the vitamin D.

Diabetes and Renal Function

Ms. Ward: In some of the studies, there seems to be a higher risk in patients with diabetes. Is there any reason why that would be?

Dr. Budoff: I can’t think of a reason exactly why with diabetes per se, except for renal disease. Patients with diabetes have more intrinsic renal disease, proteinuria, and even a reduced eGFR. We’ve seen that the kidney is very strongly tied to this. We have a very strong relationship, in work I’ve done a decade ago now, showing that calcium supplementation (in the form of phosphate binders) in patients on dialysis or with advanced renal disease is linked to much higher coronary calcium progression.

We did prospective, randomized trials showing that calcium intake as binders to reduce phosphorus led to more coronary calcium. We always thought that was just relegated to the renal population, and there might be an overlap here with the diabetes and more renal disease. I have a feeling that it has to do with more of that. It might be regulation of parathyroid hormone as well, which might be more abnormal in patients with diabetes.

Avoid Supratherapeutic Vitamin D Levels

Ms. Ward:: What are you telling your patients?

Dr. Budoff: I tell patients with normal kidney function that the bone will modulate 99.9% of the calcium uptake. If they have osteopenia or osteoporosis, regardless of their calcium score, I’m very comfortable putting them on supplements.

I’m a little more cautious with the vitamin D levels, and I keep an eye on that and regulate how much vitamin D they get based on their levels. I get them into the normal range, but I don’t want them supratherapeutic. You can even follow their calcium score. Again, we’ve shown that if you’re taking too much calcium, your calcium score will go up. I can just check it again in a couple of years to make sure that it’s safe.

Ms. Ward:: In terms of vitamin D levels, when you’re saying “supratherapeutic,” what levels do you consider a safe amount to take?

Dr. Budoff: I’d like them under 100 ng/mL as far as their upper level. Normal is around 70 ng/mL at most labs. I try to keep them in the normal range. I don’t even want them to be high-normal if I’m going to be concomitantly giving them calcium supplements. Of course, if they have renal insufficiency, then I’m much more cautious. We’ve even seen calcium supplements raise the serum calcium, which you never see with dietary calcium. That’s another potential proof that it might be too much too fast.

For renal patients, even in mild renal insufficiency, maybe even in diabetes where we’ve seen a signal, maybe aim lower in the amount of calcium supplementation if diet is insufficient, and aim a little lower in vitamin D targets, and I think you’ll be in a safer place.

Ms. Ward: Is there anything else you want to add?

Dr. Budoff: The evidence is still evolving. I’d say that it’s interesting and maybe a little frustrating that we don’t have a final answer on all of this. I would stay tuned for more data because we’re looking at many of the epidemiologic studies to try to see what happens in the real world, with both dietary intake of calcium and calcium supplementation.

Ms. Ward: Thank you very much for joining me today.

Dr. Budoff: It’s a pleasure. Thanks for having me.

Dr. Budoff disclosed being a speaker for Amarin Pharma.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Tricia Ward: Hi. I’m Tricia Ward, from theheart.org/Medscape Cardiology. I’m joined today by Dr Matthew Budoff. He is professor of medicine at UCLA and the endowed chair of preventive cardiology at the Lundquist Institute. Welcome, Dr Budoff.

Matthew J. Budoff, MD: Thank you.

Dietary Calcium vs Coronary Calcium

Ms. Ward: The reason I wanted to talk to you today is because there have been some recent studies linking calcium supplements to an increased risk for cardiovascular disease. I’m old enough to remember when we used to tell people that dietary calcium and coronary calcium weren’t connected and weren’t the same. Were we wrong?

Dr. Budoff: I think there’s a large amount of mixed data out there still. The US Preventive Services Task Force looked into this a number of years ago and said there’s no association between calcium supplementation and increased risk for cardiovascular disease.

As you mentioned, there are a couple of newer studies that point us toward a relationship. I think that we still have a little bit of a mixed bag, but we need to dive a little deeper into that to figure out what’s going on.

Ms. Ward: Does it appear to be connected to calcium in the form of supplements vs calcium from foods?

Dr. Budoff: We looked very carefully at dietary calcium in the MESA study, the multiethnic study of atherosclerosis. There is no relationship between dietary calcium intake and coronary calcium or cardiovascular events. We’re talking mostly about supplements now when we talk about this increased risk that we’re seeing.

Does Vitamin D Exacerbate Risk?

Ms. Ward: Because it’s seen with supplements, is that likely because that’s a much higher concentration of calcium coming in or do you think it’s something inherent in its being in the form of a supplement?

Dr. Budoff: I think there are two things. One, it’s definitely a higher concentration all at once. You get many more milligrams at a time when you take a supplement than if you had a high-calcium food or drink.

Also, most supplements have vitamin D as well. I think vitamin D and calcium work synergistically. When you give them both together simultaneously, I think that may have more of a potentiating effect that might exacerbate any potential risk.

Ms. Ward: Is there any reason to think there might be a difference in type of calcium supplement? I always think of the chalky tablet form vs calcium chews.

Dr. Budoff: I’m not aware of a difference in the supplement type. I think the vitamin D issue is a big problem because we all have patients who take thousands of units of vitamin D — just crazy numbers. People advocate really high numbers and that stays in the system.

Personally, I think part of the explanation is that with very high levels of vitamin D on top of calcium supplementation, you now absorb it better. You now get it into the bone, but maybe also into the coronary arteries. If you’re very high in vitamin D and then are taking a large calcium supplement, it might be the calcium/vitamin D combination that’s giving us some trouble. I think people on vitamin D supplements really need to watch their levels and not get supratherapeutic.

Ms. Ward: With the vitamin D?

Dr. Budoff: With the vitamin D.

Diabetes and Renal Function

Ms. Ward: In some of the studies, there seems to be a higher risk in patients with diabetes. Is there any reason why that would be?

Dr. Budoff: I can’t think of a reason exactly why with diabetes per se, except for renal disease. Patients with diabetes have more intrinsic renal disease, proteinuria, and even a reduced eGFR. We’ve seen that the kidney is very strongly tied to this. We have a very strong relationship, in work I’ve done a decade ago now, showing that calcium supplementation (in the form of phosphate binders) in patients on dialysis or with advanced renal disease is linked to much higher coronary calcium progression.

We did prospective, randomized trials showing that calcium intake as binders to reduce phosphorus led to more coronary calcium. We always thought that was just relegated to the renal population, and there might be an overlap here with the diabetes and more renal disease. I have a feeling that it has to do with more of that. It might be regulation of parathyroid hormone as well, which might be more abnormal in patients with diabetes.

Avoid Supratherapeutic Vitamin D Levels

Ms. Ward:: What are you telling your patients?

Dr. Budoff: I tell patients with normal kidney function that the bone will modulate 99.9% of the calcium uptake. If they have osteopenia or osteoporosis, regardless of their calcium score, I’m very comfortable putting them on supplements.

I’m a little more cautious with the vitamin D levels, and I keep an eye on that and regulate how much vitamin D they get based on their levels. I get them into the normal range, but I don’t want them supratherapeutic. You can even follow their calcium score. Again, we’ve shown that if you’re taking too much calcium, your calcium score will go up. I can just check it again in a couple of years to make sure that it’s safe.

Ms. Ward:: In terms of vitamin D levels, when you’re saying “supratherapeutic,” what levels do you consider a safe amount to take?

Dr. Budoff: I’d like them under 100 ng/mL as far as their upper level. Normal is around 70 ng/mL at most labs. I try to keep them in the normal range. I don’t even want them to be high-normal if I’m going to be concomitantly giving them calcium supplements. Of course, if they have renal insufficiency, then I’m much more cautious. We’ve even seen calcium supplements raise the serum calcium, which you never see with dietary calcium. That’s another potential proof that it might be too much too fast.

For renal patients, even in mild renal insufficiency, maybe even in diabetes where we’ve seen a signal, maybe aim lower in the amount of calcium supplementation if diet is insufficient, and aim a little lower in vitamin D targets, and I think you’ll be in a safer place.

Ms. Ward: Is there anything else you want to add?

Dr. Budoff: The evidence is still evolving. I’d say that it’s interesting and maybe a little frustrating that we don’t have a final answer on all of this. I would stay tuned for more data because we’re looking at many of the epidemiologic studies to try to see what happens in the real world, with both dietary intake of calcium and calcium supplementation.

Ms. Ward: Thank you very much for joining me today.

Dr. Budoff: It’s a pleasure. Thanks for having me.

Dr. Budoff disclosed being a speaker for Amarin Pharma.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Tricia Ward: Hi. I’m Tricia Ward, from theheart.org/Medscape Cardiology. I’m joined today by Dr Matthew Budoff. He is professor of medicine at UCLA and the endowed chair of preventive cardiology at the Lundquist Institute. Welcome, Dr Budoff.

Matthew J. Budoff, MD: Thank you.

Dietary Calcium vs Coronary Calcium

Ms. Ward: The reason I wanted to talk to you today is because there have been some recent studies linking calcium supplements to an increased risk for cardiovascular disease. I’m old enough to remember when we used to tell people that dietary calcium and coronary calcium weren’t connected and weren’t the same. Were we wrong?

Dr. Budoff: I think there’s a large amount of mixed data out there still. The US Preventive Services Task Force looked into this a number of years ago and said there’s no association between calcium supplementation and increased risk for cardiovascular disease.

As you mentioned, there are a couple of newer studies that point us toward a relationship. I think that we still have a little bit of a mixed bag, but we need to dive a little deeper into that to figure out what’s going on.

Ms. Ward: Does it appear to be connected to calcium in the form of supplements vs calcium from foods?

Dr. Budoff: We looked very carefully at dietary calcium in the MESA study, the multiethnic study of atherosclerosis. There is no relationship between dietary calcium intake and coronary calcium or cardiovascular events. We’re talking mostly about supplements now when we talk about this increased risk that we’re seeing.

Does Vitamin D Exacerbate Risk?

Ms. Ward: Because it’s seen with supplements, is that likely because that’s a much higher concentration of calcium coming in or do you think it’s something inherent in its being in the form of a supplement?

Dr. Budoff: I think there are two things. One, it’s definitely a higher concentration all at once. You get many more milligrams at a time when you take a supplement than if you had a high-calcium food or drink.

Also, most supplements have vitamin D as well. I think vitamin D and calcium work synergistically. When you give them both together simultaneously, I think that may have more of a potentiating effect that might exacerbate any potential risk.

Ms. Ward: Is there any reason to think there might be a difference in type of calcium supplement? I always think of the chalky tablet form vs calcium chews.

Dr. Budoff: I’m not aware of a difference in the supplement type. I think the vitamin D issue is a big problem because we all have patients who take thousands of units of vitamin D — just crazy numbers. People advocate really high numbers and that stays in the system.

Personally, I think part of the explanation is that with very high levels of vitamin D on top of calcium supplementation, you now absorb it better. You now get it into the bone, but maybe also into the coronary arteries. If you’re very high in vitamin D and then are taking a large calcium supplement, it might be the calcium/vitamin D combination that’s giving us some trouble. I think people on vitamin D supplements really need to watch their levels and not get supratherapeutic.

Ms. Ward: With the vitamin D?

Dr. Budoff: With the vitamin D.

Diabetes and Renal Function

Ms. Ward: In some of the studies, there seems to be a higher risk in patients with diabetes. Is there any reason why that would be?

Dr. Budoff: I can’t think of a reason exactly why with diabetes per se, except for renal disease. Patients with diabetes have more intrinsic renal disease, proteinuria, and even a reduced eGFR. We’ve seen that the kidney is very strongly tied to this. We have a very strong relationship, in work I’ve done a decade ago now, showing that calcium supplementation (in the form of phosphate binders) in patients on dialysis or with advanced renal disease is linked to much higher coronary calcium progression.

We did prospective, randomized trials showing that calcium intake as binders to reduce phosphorus led to more coronary calcium. We always thought that was just relegated to the renal population, and there might be an overlap here with the diabetes and more renal disease. I have a feeling that it has to do with more of that. It might be regulation of parathyroid hormone as well, which might be more abnormal in patients with diabetes.

Avoid Supratherapeutic Vitamin D Levels

Ms. Ward:: What are you telling your patients?

Dr. Budoff: I tell patients with normal kidney function that the bone will modulate 99.9% of the calcium uptake. If they have osteopenia or osteoporosis, regardless of their calcium score, I’m very comfortable putting them on supplements.

I’m a little more cautious with the vitamin D levels, and I keep an eye on that and regulate how much vitamin D they get based on their levels. I get them into the normal range, but I don’t want them supratherapeutic. You can even follow their calcium score. Again, we’ve shown that if you’re taking too much calcium, your calcium score will go up. I can just check it again in a couple of years to make sure that it’s safe.

Ms. Ward:: In terms of vitamin D levels, when you’re saying “supratherapeutic,” what levels do you consider a safe amount to take?

Dr. Budoff: I’d like them under 100 ng/mL as far as their upper level. Normal is around 70 ng/mL at most labs. I try to keep them in the normal range. I don’t even want them to be high-normal if I’m going to be concomitantly giving them calcium supplements. Of course, if they have renal insufficiency, then I’m much more cautious. We’ve even seen calcium supplements raise the serum calcium, which you never see with dietary calcium. That’s another potential proof that it might be too much too fast.

For renal patients, even in mild renal insufficiency, maybe even in diabetes where we’ve seen a signal, maybe aim lower in the amount of calcium supplementation if diet is insufficient, and aim a little lower in vitamin D targets, and I think you’ll be in a safer place.

Ms. Ward: Is there anything else you want to add?