User login

Vulvar Inflammatory Dermatoses: New Approaches for Diagnosis and Treatment

Vulvar dermatoses continue to be an overlooked aspect of medical care, highlighting the necessity for enhanced diagnosis and management of these conditions. Here, we address recent advancements in understanding vulvar inflammatory dermatoses other than lichen sclerosus (LS), which was discussed in a prior Guest Editorial1—specifically vulvovaginal lichen planus (VLP), plasma cell vulvitis (PCV), and vulvar lichen simplex chronicus (LSC).

Vulvar Inflammatory Skin Disease and Quality of Life

There is an increased awareness of the impact vulvar skin disease has on quality of life and its association with anxiety and depression.2-5 Evaluating the burden of vulvar dermatoses remains an active area of research due to its significance in monitoring disease progression and assessing therapeutic effectiveness. Despite the existence of various dermatology quality-of-life assessment tools, many fail to adequately capture the unique impacts of vulvovaginal diseases, such as sexual or urinary dysfunction. The vulvar quality of life index, which was developed and validated by Saunderson et al6 in 2020, consists of a 15-item questionnaire spanning 4 domains: symptoms, anxiety, activities of daily living, and sexuality. This tool has been utilized to gauge treatment response in vulvar conditions and to compare disease burden of various vulvar dermatoses.7,8 Moving forward, integrating this tool into clinical studies on vulvar skin disease holds promise for enhancing our understanding and management of these conditions.

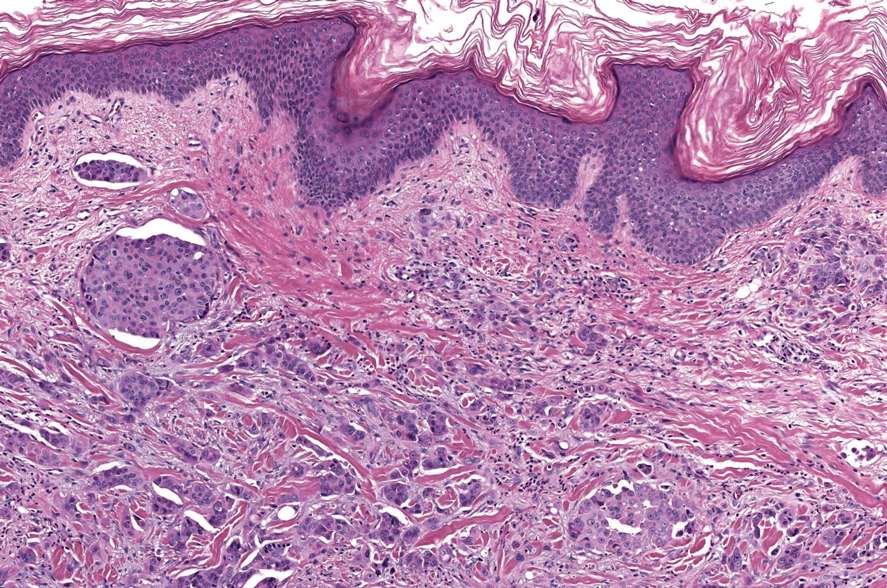

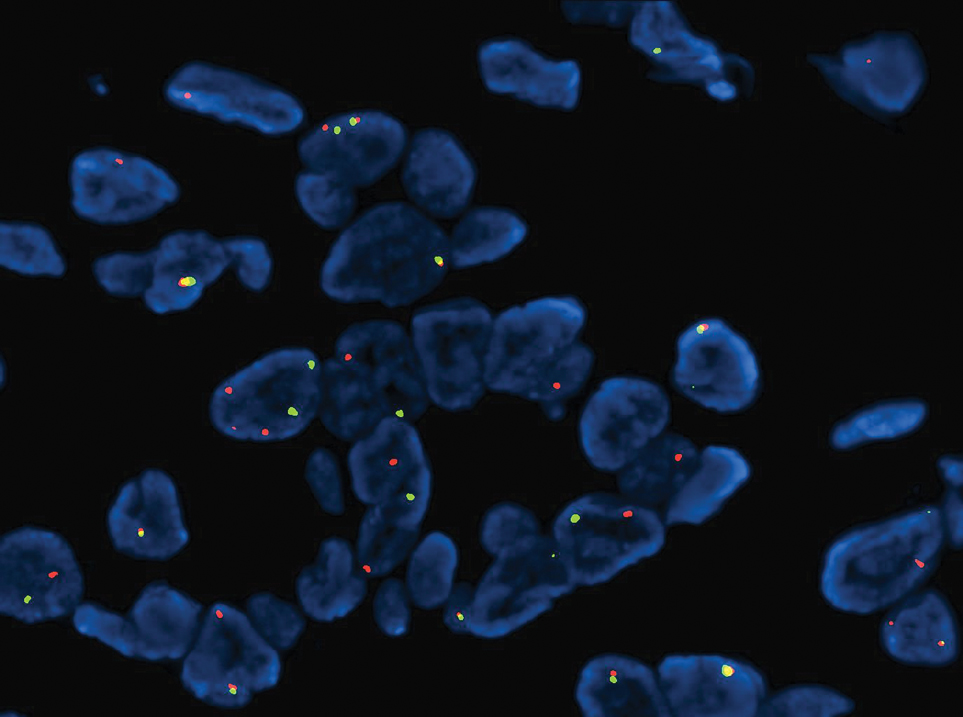

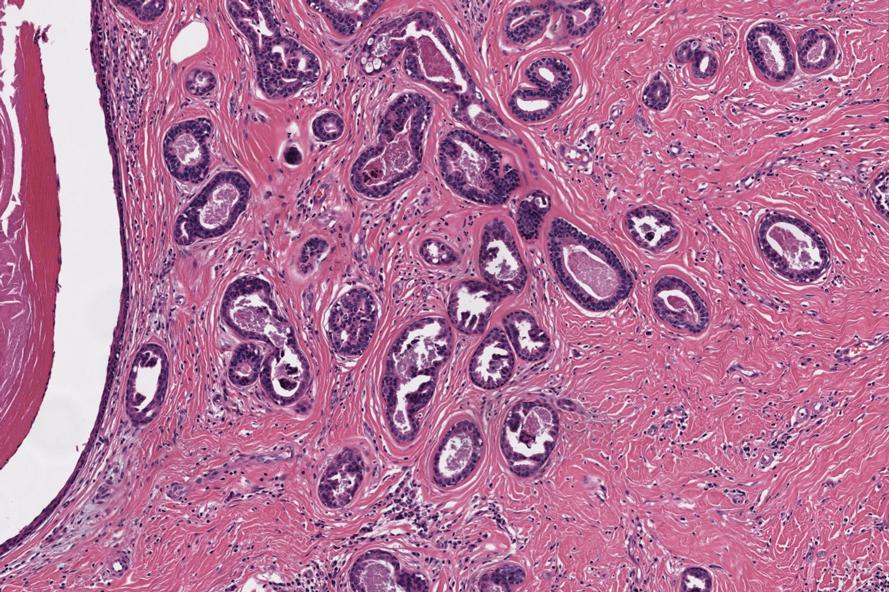

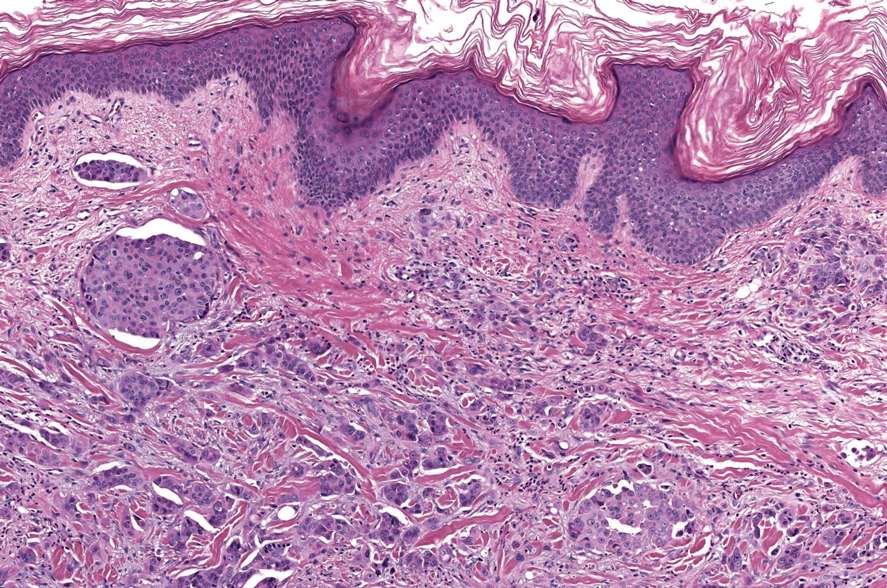

Vulvovaginal Lichen Planus

Vulvovaginal lichen planus is unique among several prevalent vulvar inflammatory skin disorders encountered by dermatologists—primarily due to its erosive form, which can extend to the vagina, resulting in noninfectious vaginitis and potential vaginal stenosis.9,10 Managing VLP poses a notable challenge, even when it is confined to the vulva, as it often proves resistant to topical therapies.11

Evaluation for Vaginal Mucosal Disease—In contrast to LS, which typically spares the vaginal mucosa, VLP can involve mucosal sites.9,12,13 Therefore, it is imperative that all patients with a diagnosis of vulvar VLP undergo evaluation for potential vaginal involvement through speculum examination, wet mount, or vaginal biopsy. Strategies to manage vaginal involvement include use of dilators and pelvic floor physical therapy, lysis of adhesions (if present), topical estrogen, and intravaginal corticosteroids—all tailored to the severity of the disease.9,11,14

Management of VLP—Approximately 20% to 40% of patients with VLP may require systemic therapy for disease management, including those who are younger, those of non-White ethnicity, and those presenting with vulvar pruritus.11 Various systemic immunosuppressants have been used for VLP, with a recent retrospective study revealing similar response rates for both methotrexate and mycophenolate mofetil in the treatment of VLP.15 Another retrospective study found hydroxychloroquine to be safe and effective for VLP but noted a slow onset of action, with approximately 70% responding at 9 months following initiation of therapy.16

Recent attention has shifted to use of targeted therapies for VLP. For instance, apremilast has shown efficacy in a single-center, nonrandomized, open-label pilot study.17 Tildrakizumab, an IL-23 inhibitor, demonstrated efficacy in a case series involving 24 patients with VLP.18 Moreover, recent case reports and series have highlighted the potential of oral Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, such as tofacitinib, in VLP treatment.19 Clinical trials are ongoing to evaluate the safety and efficacy of topical ruxolitinib and deucravacitinib (a tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor) in VLP.20-22 Systemic therapies for VLP currently are used off label, emphasizing the need for future randomized controlled trials to ascertain the optimal therapies for patients affected by erosive and nonerosive forms of this disease.

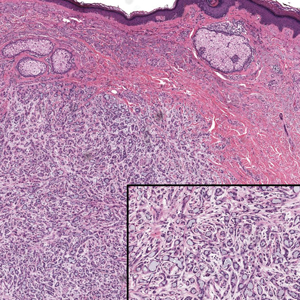

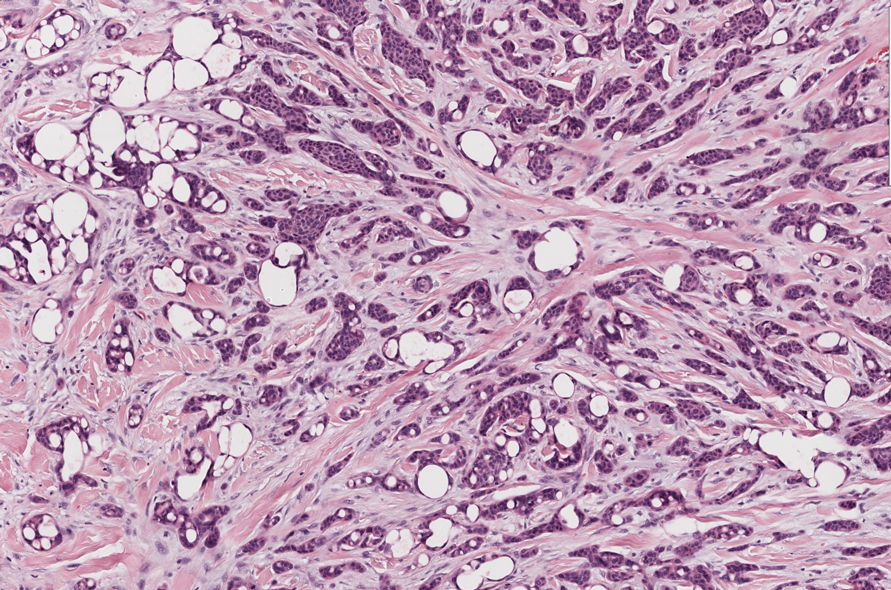

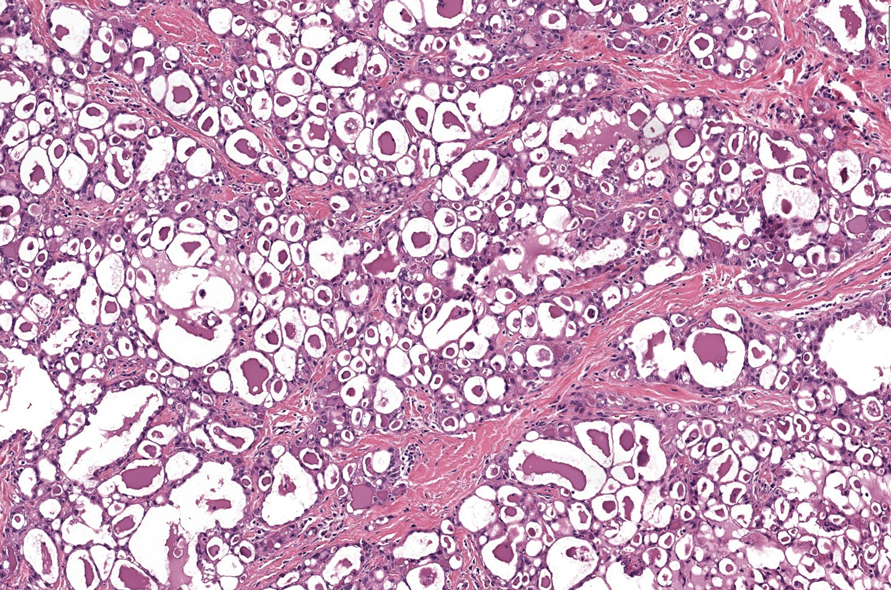

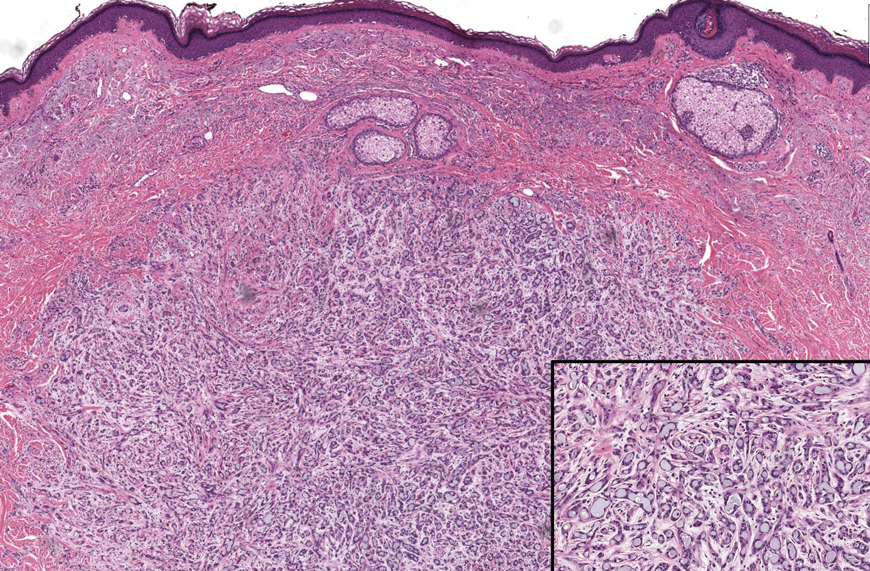

Plasma Cell Vulvitis

Plasma cell vulvitis is a chronic inflammatory disorder with an unknown etiology that some consider to be a variant of VLP.23 Others have observed an overlap with desquamative inflammatory vaginitis, categorizing PCV as a hemorrhagic vestibulovaginitis.24 Although its classification as a distinct entity remains under scrutiny, studies indicate a predilection for the nonkeratinized or partially keratinized vulva. A systematic review outlining common clinical findings reported that the most common anatomic sites included the vulvar vestibule, periurethral area, and labia minora.23 Additionally, reports have emphasized the association between PCV and other inflammatory vulvar skin conditions, including LS.25

Clinical Variants of PCV—A retrospective review proposed 2 clinical phenotypes for PCV: (1) primary non–lichen-associated PCV and (2) secondary lichen-associated PCV, which is linked to LS.26 The primary form is reported to be restricted to the vestibule, and the authors considered this a vulvar counterpart of atrophic vaginitis due to estrogen deficiency (now known as postmenopausal genitourinary syndrome). The secondary phenotype more commonly involved the vestibular and extravestibular epithelium.26

Management of PCV—Recognizing PCV in the context of LS may be important for identifying comorbid conditions and guiding treatment. However, evidence-based guidelines for PCV treatment are lacking. Commonly reported treatment modalities include clobetasol ointment 0.05% and tacrolimus ointment 0.1%.23 Successful treatment with hydrocortisone suppositories alternating with estradiol vaginal cream was reported in a recent case series.27 Crisaborole also has been reported as a treatment in 1 case of PCV.28 A recent case report found abrocitinib to be effective for the treatment of plasma cell balanitis in the setting of male genital LS,29 but there are limited data on the use of JAK inhibitors for PCV. Further research is necessary to ascertain the incidence, prevalence, clinical subtypes, and optimal management strategies for PCV to effectively treat patients with this condition.

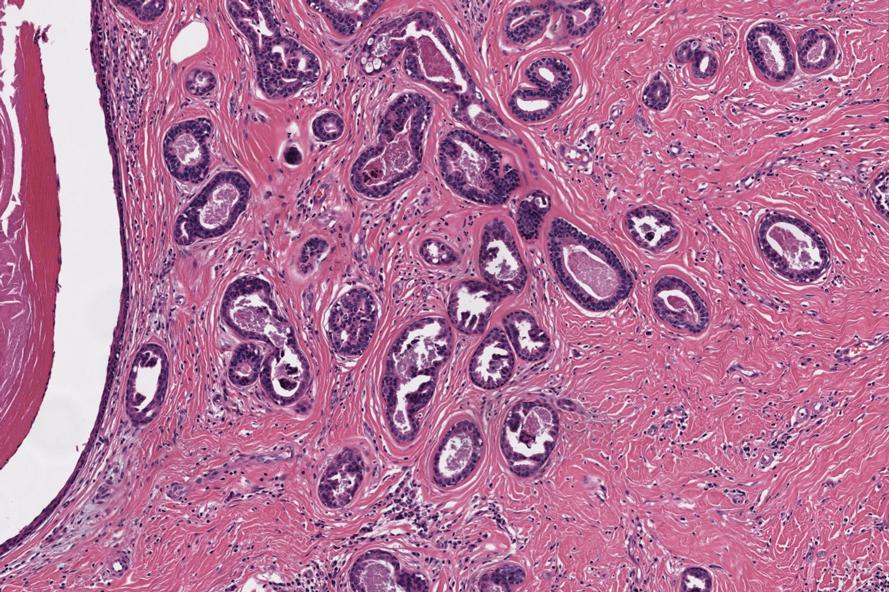

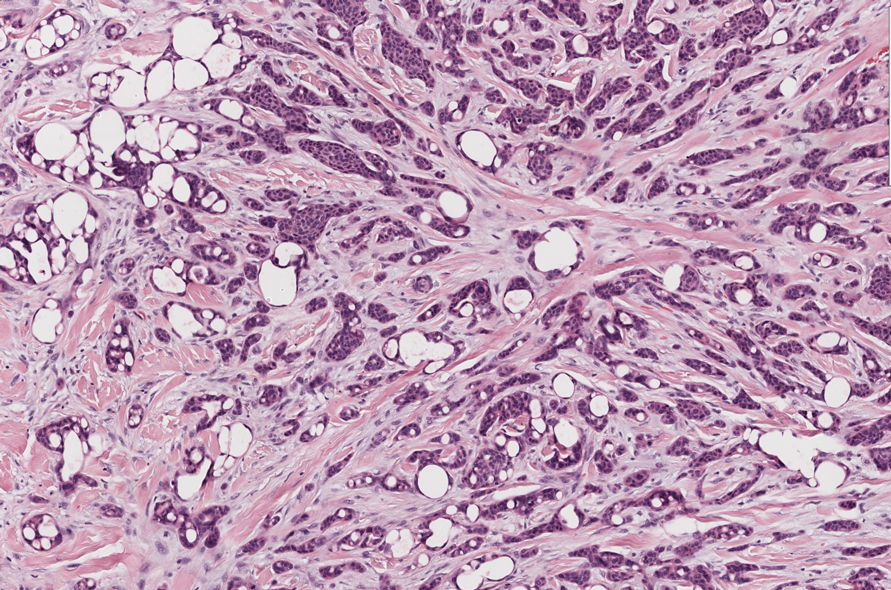

Vulvar LSC

Similar to extragenital LSC, the evaluation of vulvar LSC should prioritize identification of underlying etiologies that contribute to the itch-scratch cycle, which may include psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, neurologic conditions, and allergic or irritant contact dermatitis.30,31 Although treatment strategies may vary based on underlying conditions, we will concentrate on updates in managing vulvar LSC and pruritus associated with an atopic diathesis or resulting from chronic contact dermatitis, which is prevalent in vulvar skin areas. Finally, we highlight some emerging vulvar allergens for consideration in clinical practice.

Management of Vulvar LSC—The advent of targeted therapies, including biologics and small-molecule inhibitors, for atopic dermatitis and prurigo nodularis in recent years presents potential options for treatment of individuals with vulvar LSC. However, studies on the use of these therapies specifically for vulvar LSC are limited, necessitating thorough discussions with patients. Given the debilitating nature of vulvar pruritus that may be seen in vulvar LSC and the potential inadequacy of topical steroids as monotherapy, systemic therapies may serve as alternative options for patients with refractory disease.30

Dupilumab, a dual inhibitor of IL-4 and IL-13 signaling, has shown rapid and sustained disease improvement in patients with atopic dermatitis, prurigo nodularis, and pruritus.32,33 Although data on its role in managing vulvar LSC are scarce, a recent case series reported improvement of vulvar pruritus with dupilumab.34 Similarly, tralokinumab, an IL-13 inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for atopic dermatitis, has shown efficacy in prurigo nodularis35 and may benefit patients with vulvar LSC, though studies on cutaneous outcomes in those with genital involvement specifically are lacking. Oral JAK inhibitors such as upadacitinib and abrocitinib—both FDA approved for atopic dermatitis—have demonstrated efficacy in treating LSC and itch, potentially serving as management options for vulvar LSC in cases resistant to topical steroids or in which steroid atrophy or other steroid adverse effects may preclude continued use of such agents.36,37 Finally, IL-31 inhibitors such as nemolizumab, which reduced the signs and symptoms of prurigo nodularis in a recent phase 3 clinical trial, may hold utility in addressing vulvar LSC and associated pruritus.38

The topical JAK inhibitor ruxolitinib, which is FDA approved for atopic dermatitis and vitiligo, holds promise for managing LSC on vulvar skin while mitigating the risk for steroid-induced atrophy.39 Additionally, nonsteroidal topicals including roflumilast cream 0.3% and tapinarof cream 1%, both FDA approved for psoriasis, are being evaluated in studies for their safety and efficacy in atopic dermatitis.40,41 These agents may have the potential to improve signs and symptoms of vulvar LSC, but further studies are necessary.

Vulvar Allergens and LSC—When assessing patients with vulvar LSC, it is crucial to recognize that allergic contact dermatitis is a common primary vulvar dermatosis but can coexist with other vulvar dermatoses such as LS.13,30 The vulvar skin’s susceptibly to allergic contact dermatitis is attributed to factors such as a higher ratio of antigen-presenting cells in the vulvar skin, the nonkeratinized nature of certain sites, and frequent contact with potential allergens.42,43 Therefore, incorporating patch testing into the diagnostic process should be considered when evaluating patients with vulvar skin conditions.43

A systemic review identified multiple vulvar allergens, including metals, topical medicaments, fragrances, preservatives, cosmetic constituents, and rubber components that led to contact dermatitis.44 Moreover, a recent analysis of topical preparations recommended by women with LS on social media found a high prevalence of known vulvar allergens in these agents, including botanical extracts/spices.45 Personal-care wipes marketed for vulvar care and hygiene are known to contain a variety of allergens, with a recent study finding numerous allergens in commercially available wipes including fragrances, scented botanicals in the form of essences, oils, fruit juices, and vitamin E.46 These findings underscore the importance of considering potential allergens when caring for patients with vulvar LSC and counseling patients about the potential allergens in many commercially available products that may be recommended on social media sites or by other sources.

Final Thoughts

Vulvar inflammatory dermatoses are becoming increasingly recognized, and there is a need to develop more effective diagnostic and treatment approaches. Recent literature has shed light on some of the challenges in the management of VLP, particularly its resistance to topical therapies and the importance of assessing and managing both cutaneous and vaginal involvement. Efforts have been made to refine the classification of PCV, with studies suggesting a variant that coexists with LS. Although evidence for vulvar-specific treatment of LSC is limited, the emergence of biologics and small-molecule inhibitors that are FDA approved for atopic dermatitis and prurigo nodularis offer promise for certain cases of vulvar LSC and vulvar pruritus. Moreover, recent developments in steroid-sparing topical agents warrant further investigation for their potential efficacy in treating vulvar LSC and possibly other vulvar inflammatory conditions in the future.

- Nguyen B, Kraus C. Vulvar lichen sclerosus: what’s new? Cutis. 2024;113:104-106. doi:10.12788/cutis.0967

- Van De Nieuwenhof HP, Meeuwis KAP, Nieboer TE, et al. The effect of vulvar lichen sclerosus on quality of life and sexual functioning. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;31:279-284. doi:10.3109/0167482X.2010.507890

- Ranum A, Pearson DR. The impact of genital lichen sclerosus and lichen planus on quality of life: a review. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2022;8:E042. doi:10.1097/JW9.0000000000000042

- Messele F, Hinchee-Rodriguez K, Kraus CN. Vulvar dermatoses and depression: a systematic review of vulvar lichen sclerosus, lichen planus, and lichen simplex chronicus. JAAD Int. 2024;15:15-20. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2023.10.009

- Choi UE, Nicholson RC, Agrawal P, et al. Involvement of vulva in lichen sclerosus increases the risk of antidepressant and benzodiazepine prescriptions for psychiatric disorder diagnoses. Int J Impot Res. Published online November 16, 2023. doi:10.1038/s41443-023-00793-3

- Saunderson R, Harris V, Yeh R, et al. Vulvar quality of life index (VQLI)—a simple tool to measure quality of life in patients with vulvar disease. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61:152-157. doi:10.1111/ajd.13235

- Wu M, Kherlopian A, Wijaya M, et al. Quality of life impact and treatment response in vulval disease: comparison of 3 common conditions using the Vulval Quality of Life Index. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:E320-E328. doi:10.1111/ajd.13898

- Kherlopian A, Fischer G. Comparing quality of life in women with vulvovaginal lichen planus treated with topical and systemic treatments using the vulvar quality of life index. Australas J Dermatol. 2023;64:E125-E134. doi:10.1111/ajd.14032

- Cooper SM, Haefner HK, Abrahams-Gessel S, et al. Vulvovaginal lichen planus treatment: a survey of current practices. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1520-1521. doi:10.1001/archderm.144.11.1520

- Chow MR, Gill N, Alzahrani F, et al. Vulvar lichen planus–induced vulvovaginal stenosis: a case report and review of the literature. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2023;11:2050313X231164216. doi:10.1177/2050313X231164216

- Kherlopian A, Fischer G. Identifying predictors of systemic immunosuppressive treatment of vulvovaginal lichen planus: a retrospective cohort study of 122 women. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:335-343. doi:10.1111/ajd.13851

- Dunaway S, Tyler K, Kaffenberger, J. Update on treatments for erosive vulvovaginal lichen planus. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:297-302. doi:10.1111/ijd.14692

- Mauskar MM, Marathe, K, Venkatesan A, et al. Vulvar diseases: conditions in adults and children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1287-1298. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.10.077

- Hinchee-Rodriguez K, Duong A, Kraus CN. Local management strategies for inflammatory vaginitis in dermatologic conditions: suppositories, dilators, and estrogen replacement. JAAD Int. 2022;9:137-138. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2022.09.004

- Hrin ML, Bowers NL, Feldman SR, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil versus methotrexate for vulvar lichen planus: a 10-year retrospective cohort study demonstrates comparable efficacy and tolerability. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:436-438. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.08.061

- Vermeer HAB, Rashid H, Esajas MD, et al. The use of hydroxychloroquine as a systemic treatment in erosive lichen planus of the vulva and vagina. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:201-203. doi:10.1111/bjd.19870

- Skullerud KH, Gjersvik P, Pripp AH, et al. Apremilast for genital erosive lichen planus in women (the AP-GELP Study): study protocol for a randomised placebo-controlled clinical trial. Trials. 2021;22:469. doi:10.1186/s13063-021-05428-w

- Kherlopian A, Fischer G. Successful treatment of vulvovaginal lichen planus with tildrakizumab: a case series of 24 patients. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:251-255. doi:10.1111/ajd.13793

- Kassels A, Edwards L, Kraus CN. Treatment of erosive vulvovaginal lichen planus with tofacitinib: a case series. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;40:14-18. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2023.08.001

- Wijaya M, Fischer G, Saunderson RB. The efficacy and safety of deucravacitinib compared to methotrexate, in patients with vulvar lichen planus who have failed topical therapy with potent corticosteroids: a study protocol for a single-centre double-blinded randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2024;25:181. doi:10.1186/s13063-024-08022-y

- Brumfiel CM, Patel MH, Severson KJ, et al. Ruxolitinib cream in the treatment of cutaneous lichen planus: a prospective, open-label study. J Invest Dermatol. 2022;142:2109-2116.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2022.01.015

- A study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib cream in participants with cutaneous lichen planus. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05593432. Updated March 12, 2024. Accessed July 12, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05593432

- Sattler S, Elsensohn AN, Mauskar MM, et al. Plasma cell vulvitis: a systematic review. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:756-762. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.04.005

- Song M, Day T, Kliman L, et al. Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis and plasma cell vulvitis represent a spectrum of hemorrhagic vestibulovaginitis. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2022;26:60-67. doi:10.1097/LGT.0000000000000637

- Saeed L, Lee BA, Kraus CN. Tender solitary lesion in vulvar lichen sclerosus. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;23:61-63. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.01.038

- Wendling J, Plantier F, Moyal-Barracco M. Plasma cell vulvitis: a classification into two clinical phenotypes. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2023;27:384-389. doi:10.1097/LGT.0000000000000771

- Prestwood CA, Granberry R, Rutherford A, et al. Successful treatment of plasma cell vulvitis: a case series. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;19:37-40. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.10.023

- He Y, Xu M, Wu M, et al. A case of plasma cell vulvitis successfully treated with crisaborole. J Dermatol. Published online April 1, 2024. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.17205

- Xiong X, Chen R, Wang L, et al. Treatment of plasma cell balanitis associated with male genital lichen sclerosus using abrocitinib. JAAD Case Rep. 2024;46:85-88. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2024.02.010

- Stewart KMA. Clinical care of vulvar pruritus, with emphasis on one common cause, lichen simplex chronicus. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:669-680. doi:10.1016/j.det.2010.08.004

- Rimoin LP, Kwatra SG, Yosipovitch G. Female-specific pruritus from childhood to postmenopause: clinical features, hormonal factors, and treatment considerations. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:157-167. doi:10.1111/dth.12034

- Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, et al; SOLO 1 and SOLO 2 Investigators. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2335-2348. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1610020

- Yosipovitch G, Mollanazar N, Ständer S, et al. Dupilumab in patients with prurigo nodularis: two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials. Nat Med. 2023;29:1180-1190. doi:10.1038/s41591-023-02320-9

- Gosch M, Cash S, Pichardo R. Vulvar pruritus improved with dupilumab. JSM Sexual Med. 2023;7:1104.

- Pezzolo E, Gambardella A, Guanti M, et al. Tralokinumab shows clinical improvement in patients with prurigo nodularis-like phenotype atopic dermatitis: a multicenter, prospective, open-label case series study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:430-432. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.04.056

- Simpson EL, Sinclair R, Forman S, et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (JADE MONO-1): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;396:255-266. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30732-7

- Simpson EL, Papp KA, Blauvelt A, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: analysis of follow-up data from the Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:404-413. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0029

- Kwatra SG, Yosipovitch G, Legat FJ, et al. Phase 3 trial of nemolizumab in patients with prurigo nodularis. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:1579-1589. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2301333

- Papp K, Szepietowski JC, Kircik L, et al. Long-term safety and disease control with ruxolitinib cream in atopic dermatitis: results from two phase 3 studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:1008-1016. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.09.060

- Lebwohl MG, Kircik LH, Moore AY, et al. Effect of roflumilast cream vs vehicle cream on chronic plaque psoriasis: the DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2022;328:1073-1084. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.15632

- Lebwohl MG, Gold LS, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2103629

- O’Gorman SM, Torgerson RR. Allergic contact dermatitis of the vulva. Dermatitis. 2013;24:64-72. doi:10.1097/DER.0b013e318284da33

- Woodruff CM, Trivedi MK, Botto N, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis of the vulva. Dermatitis. 2018;29:233-243. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000339

- Vandeweege S, Debaene B, Lapeere H, et al. A systematic review of allergic and irritant contact dermatitis of the vulva: the most important allergens/irritants and the role of patch testing. Contact Dermatitis. 2023;88:249-262. doi:10.1111/cod.14258

- Luu Y, Admani S. Vulvar allergens in topical preparations recommended on social media: a cross-sectional analysis of Facebook groups for lichen sclerosus. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2023;9:E097. doi:10.1097/JW9.0000000000000097

- Newton J, Richardson S, van Oosbre AM, et al. A cross-sectional study of contact allergens in feminine hygiene wipes: a possible cause of vulvar contact dermatitis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2022;8:E060. doi:10.1097/JW9.0000000000000060

Vulvar dermatoses continue to be an overlooked aspect of medical care, highlighting the necessity for enhanced diagnosis and management of these conditions. Here, we address recent advancements in understanding vulvar inflammatory dermatoses other than lichen sclerosus (LS), which was discussed in a prior Guest Editorial1—specifically vulvovaginal lichen planus (VLP), plasma cell vulvitis (PCV), and vulvar lichen simplex chronicus (LSC).

Vulvar Inflammatory Skin Disease and Quality of Life

There is an increased awareness of the impact vulvar skin disease has on quality of life and its association with anxiety and depression.2-5 Evaluating the burden of vulvar dermatoses remains an active area of research due to its significance in monitoring disease progression and assessing therapeutic effectiveness. Despite the existence of various dermatology quality-of-life assessment tools, many fail to adequately capture the unique impacts of vulvovaginal diseases, such as sexual or urinary dysfunction. The vulvar quality of life index, which was developed and validated by Saunderson et al6 in 2020, consists of a 15-item questionnaire spanning 4 domains: symptoms, anxiety, activities of daily living, and sexuality. This tool has been utilized to gauge treatment response in vulvar conditions and to compare disease burden of various vulvar dermatoses.7,8 Moving forward, integrating this tool into clinical studies on vulvar skin disease holds promise for enhancing our understanding and management of these conditions.

Vulvovaginal Lichen Planus

Vulvovaginal lichen planus is unique among several prevalent vulvar inflammatory skin disorders encountered by dermatologists—primarily due to its erosive form, which can extend to the vagina, resulting in noninfectious vaginitis and potential vaginal stenosis.9,10 Managing VLP poses a notable challenge, even when it is confined to the vulva, as it often proves resistant to topical therapies.11

Evaluation for Vaginal Mucosal Disease—In contrast to LS, which typically spares the vaginal mucosa, VLP can involve mucosal sites.9,12,13 Therefore, it is imperative that all patients with a diagnosis of vulvar VLP undergo evaluation for potential vaginal involvement through speculum examination, wet mount, or vaginal biopsy. Strategies to manage vaginal involvement include use of dilators and pelvic floor physical therapy, lysis of adhesions (if present), topical estrogen, and intravaginal corticosteroids—all tailored to the severity of the disease.9,11,14

Management of VLP—Approximately 20% to 40% of patients with VLP may require systemic therapy for disease management, including those who are younger, those of non-White ethnicity, and those presenting with vulvar pruritus.11 Various systemic immunosuppressants have been used for VLP, with a recent retrospective study revealing similar response rates for both methotrexate and mycophenolate mofetil in the treatment of VLP.15 Another retrospective study found hydroxychloroquine to be safe and effective for VLP but noted a slow onset of action, with approximately 70% responding at 9 months following initiation of therapy.16

Recent attention has shifted to use of targeted therapies for VLP. For instance, apremilast has shown efficacy in a single-center, nonrandomized, open-label pilot study.17 Tildrakizumab, an IL-23 inhibitor, demonstrated efficacy in a case series involving 24 patients with VLP.18 Moreover, recent case reports and series have highlighted the potential of oral Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, such as tofacitinib, in VLP treatment.19 Clinical trials are ongoing to evaluate the safety and efficacy of topical ruxolitinib and deucravacitinib (a tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor) in VLP.20-22 Systemic therapies for VLP currently are used off label, emphasizing the need for future randomized controlled trials to ascertain the optimal therapies for patients affected by erosive and nonerosive forms of this disease.

Plasma Cell Vulvitis

Plasma cell vulvitis is a chronic inflammatory disorder with an unknown etiology that some consider to be a variant of VLP.23 Others have observed an overlap with desquamative inflammatory vaginitis, categorizing PCV as a hemorrhagic vestibulovaginitis.24 Although its classification as a distinct entity remains under scrutiny, studies indicate a predilection for the nonkeratinized or partially keratinized vulva. A systematic review outlining common clinical findings reported that the most common anatomic sites included the vulvar vestibule, periurethral area, and labia minora.23 Additionally, reports have emphasized the association between PCV and other inflammatory vulvar skin conditions, including LS.25

Clinical Variants of PCV—A retrospective review proposed 2 clinical phenotypes for PCV: (1) primary non–lichen-associated PCV and (2) secondary lichen-associated PCV, which is linked to LS.26 The primary form is reported to be restricted to the vestibule, and the authors considered this a vulvar counterpart of atrophic vaginitis due to estrogen deficiency (now known as postmenopausal genitourinary syndrome). The secondary phenotype more commonly involved the vestibular and extravestibular epithelium.26

Management of PCV—Recognizing PCV in the context of LS may be important for identifying comorbid conditions and guiding treatment. However, evidence-based guidelines for PCV treatment are lacking. Commonly reported treatment modalities include clobetasol ointment 0.05% and tacrolimus ointment 0.1%.23 Successful treatment with hydrocortisone suppositories alternating with estradiol vaginal cream was reported in a recent case series.27 Crisaborole also has been reported as a treatment in 1 case of PCV.28 A recent case report found abrocitinib to be effective for the treatment of plasma cell balanitis in the setting of male genital LS,29 but there are limited data on the use of JAK inhibitors for PCV. Further research is necessary to ascertain the incidence, prevalence, clinical subtypes, and optimal management strategies for PCV to effectively treat patients with this condition.

Vulvar LSC

Similar to extragenital LSC, the evaluation of vulvar LSC should prioritize identification of underlying etiologies that contribute to the itch-scratch cycle, which may include psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, neurologic conditions, and allergic or irritant contact dermatitis.30,31 Although treatment strategies may vary based on underlying conditions, we will concentrate on updates in managing vulvar LSC and pruritus associated with an atopic diathesis or resulting from chronic contact dermatitis, which is prevalent in vulvar skin areas. Finally, we highlight some emerging vulvar allergens for consideration in clinical practice.

Management of Vulvar LSC—The advent of targeted therapies, including biologics and small-molecule inhibitors, for atopic dermatitis and prurigo nodularis in recent years presents potential options for treatment of individuals with vulvar LSC. However, studies on the use of these therapies specifically for vulvar LSC are limited, necessitating thorough discussions with patients. Given the debilitating nature of vulvar pruritus that may be seen in vulvar LSC and the potential inadequacy of topical steroids as monotherapy, systemic therapies may serve as alternative options for patients with refractory disease.30

Dupilumab, a dual inhibitor of IL-4 and IL-13 signaling, has shown rapid and sustained disease improvement in patients with atopic dermatitis, prurigo nodularis, and pruritus.32,33 Although data on its role in managing vulvar LSC are scarce, a recent case series reported improvement of vulvar pruritus with dupilumab.34 Similarly, tralokinumab, an IL-13 inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for atopic dermatitis, has shown efficacy in prurigo nodularis35 and may benefit patients with vulvar LSC, though studies on cutaneous outcomes in those with genital involvement specifically are lacking. Oral JAK inhibitors such as upadacitinib and abrocitinib—both FDA approved for atopic dermatitis—have demonstrated efficacy in treating LSC and itch, potentially serving as management options for vulvar LSC in cases resistant to topical steroids or in which steroid atrophy or other steroid adverse effects may preclude continued use of such agents.36,37 Finally, IL-31 inhibitors such as nemolizumab, which reduced the signs and symptoms of prurigo nodularis in a recent phase 3 clinical trial, may hold utility in addressing vulvar LSC and associated pruritus.38

The topical JAK inhibitor ruxolitinib, which is FDA approved for atopic dermatitis and vitiligo, holds promise for managing LSC on vulvar skin while mitigating the risk for steroid-induced atrophy.39 Additionally, nonsteroidal topicals including roflumilast cream 0.3% and tapinarof cream 1%, both FDA approved for psoriasis, are being evaluated in studies for their safety and efficacy in atopic dermatitis.40,41 These agents may have the potential to improve signs and symptoms of vulvar LSC, but further studies are necessary.

Vulvar Allergens and LSC—When assessing patients with vulvar LSC, it is crucial to recognize that allergic contact dermatitis is a common primary vulvar dermatosis but can coexist with other vulvar dermatoses such as LS.13,30 The vulvar skin’s susceptibly to allergic contact dermatitis is attributed to factors such as a higher ratio of antigen-presenting cells in the vulvar skin, the nonkeratinized nature of certain sites, and frequent contact with potential allergens.42,43 Therefore, incorporating patch testing into the diagnostic process should be considered when evaluating patients with vulvar skin conditions.43

A systemic review identified multiple vulvar allergens, including metals, topical medicaments, fragrances, preservatives, cosmetic constituents, and rubber components that led to contact dermatitis.44 Moreover, a recent analysis of topical preparations recommended by women with LS on social media found a high prevalence of known vulvar allergens in these agents, including botanical extracts/spices.45 Personal-care wipes marketed for vulvar care and hygiene are known to contain a variety of allergens, with a recent study finding numerous allergens in commercially available wipes including fragrances, scented botanicals in the form of essences, oils, fruit juices, and vitamin E.46 These findings underscore the importance of considering potential allergens when caring for patients with vulvar LSC and counseling patients about the potential allergens in many commercially available products that may be recommended on social media sites or by other sources.

Final Thoughts

Vulvar inflammatory dermatoses are becoming increasingly recognized, and there is a need to develop more effective diagnostic and treatment approaches. Recent literature has shed light on some of the challenges in the management of VLP, particularly its resistance to topical therapies and the importance of assessing and managing both cutaneous and vaginal involvement. Efforts have been made to refine the classification of PCV, with studies suggesting a variant that coexists with LS. Although evidence for vulvar-specific treatment of LSC is limited, the emergence of biologics and small-molecule inhibitors that are FDA approved for atopic dermatitis and prurigo nodularis offer promise for certain cases of vulvar LSC and vulvar pruritus. Moreover, recent developments in steroid-sparing topical agents warrant further investigation for their potential efficacy in treating vulvar LSC and possibly other vulvar inflammatory conditions in the future.

Vulvar dermatoses continue to be an overlooked aspect of medical care, highlighting the necessity for enhanced diagnosis and management of these conditions. Here, we address recent advancements in understanding vulvar inflammatory dermatoses other than lichen sclerosus (LS), which was discussed in a prior Guest Editorial1—specifically vulvovaginal lichen planus (VLP), plasma cell vulvitis (PCV), and vulvar lichen simplex chronicus (LSC).

Vulvar Inflammatory Skin Disease and Quality of Life

There is an increased awareness of the impact vulvar skin disease has on quality of life and its association with anxiety and depression.2-5 Evaluating the burden of vulvar dermatoses remains an active area of research due to its significance in monitoring disease progression and assessing therapeutic effectiveness. Despite the existence of various dermatology quality-of-life assessment tools, many fail to adequately capture the unique impacts of vulvovaginal diseases, such as sexual or urinary dysfunction. The vulvar quality of life index, which was developed and validated by Saunderson et al6 in 2020, consists of a 15-item questionnaire spanning 4 domains: symptoms, anxiety, activities of daily living, and sexuality. This tool has been utilized to gauge treatment response in vulvar conditions and to compare disease burden of various vulvar dermatoses.7,8 Moving forward, integrating this tool into clinical studies on vulvar skin disease holds promise for enhancing our understanding and management of these conditions.

Vulvovaginal Lichen Planus

Vulvovaginal lichen planus is unique among several prevalent vulvar inflammatory skin disorders encountered by dermatologists—primarily due to its erosive form, which can extend to the vagina, resulting in noninfectious vaginitis and potential vaginal stenosis.9,10 Managing VLP poses a notable challenge, even when it is confined to the vulva, as it often proves resistant to topical therapies.11

Evaluation for Vaginal Mucosal Disease—In contrast to LS, which typically spares the vaginal mucosa, VLP can involve mucosal sites.9,12,13 Therefore, it is imperative that all patients with a diagnosis of vulvar VLP undergo evaluation for potential vaginal involvement through speculum examination, wet mount, or vaginal biopsy. Strategies to manage vaginal involvement include use of dilators and pelvic floor physical therapy, lysis of adhesions (if present), topical estrogen, and intravaginal corticosteroids—all tailored to the severity of the disease.9,11,14

Management of VLP—Approximately 20% to 40% of patients with VLP may require systemic therapy for disease management, including those who are younger, those of non-White ethnicity, and those presenting with vulvar pruritus.11 Various systemic immunosuppressants have been used for VLP, with a recent retrospective study revealing similar response rates for both methotrexate and mycophenolate mofetil in the treatment of VLP.15 Another retrospective study found hydroxychloroquine to be safe and effective for VLP but noted a slow onset of action, with approximately 70% responding at 9 months following initiation of therapy.16

Recent attention has shifted to use of targeted therapies for VLP. For instance, apremilast has shown efficacy in a single-center, nonrandomized, open-label pilot study.17 Tildrakizumab, an IL-23 inhibitor, demonstrated efficacy in a case series involving 24 patients with VLP.18 Moreover, recent case reports and series have highlighted the potential of oral Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, such as tofacitinib, in VLP treatment.19 Clinical trials are ongoing to evaluate the safety and efficacy of topical ruxolitinib and deucravacitinib (a tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor) in VLP.20-22 Systemic therapies for VLP currently are used off label, emphasizing the need for future randomized controlled trials to ascertain the optimal therapies for patients affected by erosive and nonerosive forms of this disease.

Plasma Cell Vulvitis

Plasma cell vulvitis is a chronic inflammatory disorder with an unknown etiology that some consider to be a variant of VLP.23 Others have observed an overlap with desquamative inflammatory vaginitis, categorizing PCV as a hemorrhagic vestibulovaginitis.24 Although its classification as a distinct entity remains under scrutiny, studies indicate a predilection for the nonkeratinized or partially keratinized vulva. A systematic review outlining common clinical findings reported that the most common anatomic sites included the vulvar vestibule, periurethral area, and labia minora.23 Additionally, reports have emphasized the association between PCV and other inflammatory vulvar skin conditions, including LS.25

Clinical Variants of PCV—A retrospective review proposed 2 clinical phenotypes for PCV: (1) primary non–lichen-associated PCV and (2) secondary lichen-associated PCV, which is linked to LS.26 The primary form is reported to be restricted to the vestibule, and the authors considered this a vulvar counterpart of atrophic vaginitis due to estrogen deficiency (now known as postmenopausal genitourinary syndrome). The secondary phenotype more commonly involved the vestibular and extravestibular epithelium.26

Management of PCV—Recognizing PCV in the context of LS may be important for identifying comorbid conditions and guiding treatment. However, evidence-based guidelines for PCV treatment are lacking. Commonly reported treatment modalities include clobetasol ointment 0.05% and tacrolimus ointment 0.1%.23 Successful treatment with hydrocortisone suppositories alternating with estradiol vaginal cream was reported in a recent case series.27 Crisaborole also has been reported as a treatment in 1 case of PCV.28 A recent case report found abrocitinib to be effective for the treatment of plasma cell balanitis in the setting of male genital LS,29 but there are limited data on the use of JAK inhibitors for PCV. Further research is necessary to ascertain the incidence, prevalence, clinical subtypes, and optimal management strategies for PCV to effectively treat patients with this condition.

Vulvar LSC

Similar to extragenital LSC, the evaluation of vulvar LSC should prioritize identification of underlying etiologies that contribute to the itch-scratch cycle, which may include psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, neurologic conditions, and allergic or irritant contact dermatitis.30,31 Although treatment strategies may vary based on underlying conditions, we will concentrate on updates in managing vulvar LSC and pruritus associated with an atopic diathesis or resulting from chronic contact dermatitis, which is prevalent in vulvar skin areas. Finally, we highlight some emerging vulvar allergens for consideration in clinical practice.

Management of Vulvar LSC—The advent of targeted therapies, including biologics and small-molecule inhibitors, for atopic dermatitis and prurigo nodularis in recent years presents potential options for treatment of individuals with vulvar LSC. However, studies on the use of these therapies specifically for vulvar LSC are limited, necessitating thorough discussions with patients. Given the debilitating nature of vulvar pruritus that may be seen in vulvar LSC and the potential inadequacy of topical steroids as monotherapy, systemic therapies may serve as alternative options for patients with refractory disease.30

Dupilumab, a dual inhibitor of IL-4 and IL-13 signaling, has shown rapid and sustained disease improvement in patients with atopic dermatitis, prurigo nodularis, and pruritus.32,33 Although data on its role in managing vulvar LSC are scarce, a recent case series reported improvement of vulvar pruritus with dupilumab.34 Similarly, tralokinumab, an IL-13 inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for atopic dermatitis, has shown efficacy in prurigo nodularis35 and may benefit patients with vulvar LSC, though studies on cutaneous outcomes in those with genital involvement specifically are lacking. Oral JAK inhibitors such as upadacitinib and abrocitinib—both FDA approved for atopic dermatitis—have demonstrated efficacy in treating LSC and itch, potentially serving as management options for vulvar LSC in cases resistant to topical steroids or in which steroid atrophy or other steroid adverse effects may preclude continued use of such agents.36,37 Finally, IL-31 inhibitors such as nemolizumab, which reduced the signs and symptoms of prurigo nodularis in a recent phase 3 clinical trial, may hold utility in addressing vulvar LSC and associated pruritus.38

The topical JAK inhibitor ruxolitinib, which is FDA approved for atopic dermatitis and vitiligo, holds promise for managing LSC on vulvar skin while mitigating the risk for steroid-induced atrophy.39 Additionally, nonsteroidal topicals including roflumilast cream 0.3% and tapinarof cream 1%, both FDA approved for psoriasis, are being evaluated in studies for their safety and efficacy in atopic dermatitis.40,41 These agents may have the potential to improve signs and symptoms of vulvar LSC, but further studies are necessary.

Vulvar Allergens and LSC—When assessing patients with vulvar LSC, it is crucial to recognize that allergic contact dermatitis is a common primary vulvar dermatosis but can coexist with other vulvar dermatoses such as LS.13,30 The vulvar skin’s susceptibly to allergic contact dermatitis is attributed to factors such as a higher ratio of antigen-presenting cells in the vulvar skin, the nonkeratinized nature of certain sites, and frequent contact with potential allergens.42,43 Therefore, incorporating patch testing into the diagnostic process should be considered when evaluating patients with vulvar skin conditions.43

A systemic review identified multiple vulvar allergens, including metals, topical medicaments, fragrances, preservatives, cosmetic constituents, and rubber components that led to contact dermatitis.44 Moreover, a recent analysis of topical preparations recommended by women with LS on social media found a high prevalence of known vulvar allergens in these agents, including botanical extracts/spices.45 Personal-care wipes marketed for vulvar care and hygiene are known to contain a variety of allergens, with a recent study finding numerous allergens in commercially available wipes including fragrances, scented botanicals in the form of essences, oils, fruit juices, and vitamin E.46 These findings underscore the importance of considering potential allergens when caring for patients with vulvar LSC and counseling patients about the potential allergens in many commercially available products that may be recommended on social media sites or by other sources.

Final Thoughts

Vulvar inflammatory dermatoses are becoming increasingly recognized, and there is a need to develop more effective diagnostic and treatment approaches. Recent literature has shed light on some of the challenges in the management of VLP, particularly its resistance to topical therapies and the importance of assessing and managing both cutaneous and vaginal involvement. Efforts have been made to refine the classification of PCV, with studies suggesting a variant that coexists with LS. Although evidence for vulvar-specific treatment of LSC is limited, the emergence of biologics and small-molecule inhibitors that are FDA approved for atopic dermatitis and prurigo nodularis offer promise for certain cases of vulvar LSC and vulvar pruritus. Moreover, recent developments in steroid-sparing topical agents warrant further investigation for their potential efficacy in treating vulvar LSC and possibly other vulvar inflammatory conditions in the future.

- Nguyen B, Kraus C. Vulvar lichen sclerosus: what’s new? Cutis. 2024;113:104-106. doi:10.12788/cutis.0967

- Van De Nieuwenhof HP, Meeuwis KAP, Nieboer TE, et al. The effect of vulvar lichen sclerosus on quality of life and sexual functioning. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;31:279-284. doi:10.3109/0167482X.2010.507890

- Ranum A, Pearson DR. The impact of genital lichen sclerosus and lichen planus on quality of life: a review. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2022;8:E042. doi:10.1097/JW9.0000000000000042

- Messele F, Hinchee-Rodriguez K, Kraus CN. Vulvar dermatoses and depression: a systematic review of vulvar lichen sclerosus, lichen planus, and lichen simplex chronicus. JAAD Int. 2024;15:15-20. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2023.10.009

- Choi UE, Nicholson RC, Agrawal P, et al. Involvement of vulva in lichen sclerosus increases the risk of antidepressant and benzodiazepine prescriptions for psychiatric disorder diagnoses. Int J Impot Res. Published online November 16, 2023. doi:10.1038/s41443-023-00793-3

- Saunderson R, Harris V, Yeh R, et al. Vulvar quality of life index (VQLI)—a simple tool to measure quality of life in patients with vulvar disease. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61:152-157. doi:10.1111/ajd.13235

- Wu M, Kherlopian A, Wijaya M, et al. Quality of life impact and treatment response in vulval disease: comparison of 3 common conditions using the Vulval Quality of Life Index. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:E320-E328. doi:10.1111/ajd.13898

- Kherlopian A, Fischer G. Comparing quality of life in women with vulvovaginal lichen planus treated with topical and systemic treatments using the vulvar quality of life index. Australas J Dermatol. 2023;64:E125-E134. doi:10.1111/ajd.14032

- Cooper SM, Haefner HK, Abrahams-Gessel S, et al. Vulvovaginal lichen planus treatment: a survey of current practices. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1520-1521. doi:10.1001/archderm.144.11.1520

- Chow MR, Gill N, Alzahrani F, et al. Vulvar lichen planus–induced vulvovaginal stenosis: a case report and review of the literature. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2023;11:2050313X231164216. doi:10.1177/2050313X231164216

- Kherlopian A, Fischer G. Identifying predictors of systemic immunosuppressive treatment of vulvovaginal lichen planus: a retrospective cohort study of 122 women. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:335-343. doi:10.1111/ajd.13851

- Dunaway S, Tyler K, Kaffenberger, J. Update on treatments for erosive vulvovaginal lichen planus. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:297-302. doi:10.1111/ijd.14692

- Mauskar MM, Marathe, K, Venkatesan A, et al. Vulvar diseases: conditions in adults and children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1287-1298. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.10.077

- Hinchee-Rodriguez K, Duong A, Kraus CN. Local management strategies for inflammatory vaginitis in dermatologic conditions: suppositories, dilators, and estrogen replacement. JAAD Int. 2022;9:137-138. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2022.09.004

- Hrin ML, Bowers NL, Feldman SR, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil versus methotrexate for vulvar lichen planus: a 10-year retrospective cohort study demonstrates comparable efficacy and tolerability. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:436-438. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.08.061

- Vermeer HAB, Rashid H, Esajas MD, et al. The use of hydroxychloroquine as a systemic treatment in erosive lichen planus of the vulva and vagina. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:201-203. doi:10.1111/bjd.19870

- Skullerud KH, Gjersvik P, Pripp AH, et al. Apremilast for genital erosive lichen planus in women (the AP-GELP Study): study protocol for a randomised placebo-controlled clinical trial. Trials. 2021;22:469. doi:10.1186/s13063-021-05428-w

- Kherlopian A, Fischer G. Successful treatment of vulvovaginal lichen planus with tildrakizumab: a case series of 24 patients. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:251-255. doi:10.1111/ajd.13793

- Kassels A, Edwards L, Kraus CN. Treatment of erosive vulvovaginal lichen planus with tofacitinib: a case series. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;40:14-18. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2023.08.001

- Wijaya M, Fischer G, Saunderson RB. The efficacy and safety of deucravacitinib compared to methotrexate, in patients with vulvar lichen planus who have failed topical therapy with potent corticosteroids: a study protocol for a single-centre double-blinded randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2024;25:181. doi:10.1186/s13063-024-08022-y

- Brumfiel CM, Patel MH, Severson KJ, et al. Ruxolitinib cream in the treatment of cutaneous lichen planus: a prospective, open-label study. J Invest Dermatol. 2022;142:2109-2116.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2022.01.015

- A study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib cream in participants with cutaneous lichen planus. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05593432. Updated March 12, 2024. Accessed July 12, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05593432

- Sattler S, Elsensohn AN, Mauskar MM, et al. Plasma cell vulvitis: a systematic review. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:756-762. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.04.005

- Song M, Day T, Kliman L, et al. Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis and plasma cell vulvitis represent a spectrum of hemorrhagic vestibulovaginitis. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2022;26:60-67. doi:10.1097/LGT.0000000000000637

- Saeed L, Lee BA, Kraus CN. Tender solitary lesion in vulvar lichen sclerosus. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;23:61-63. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.01.038

- Wendling J, Plantier F, Moyal-Barracco M. Plasma cell vulvitis: a classification into two clinical phenotypes. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2023;27:384-389. doi:10.1097/LGT.0000000000000771

- Prestwood CA, Granberry R, Rutherford A, et al. Successful treatment of plasma cell vulvitis: a case series. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;19:37-40. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.10.023

- He Y, Xu M, Wu M, et al. A case of plasma cell vulvitis successfully treated with crisaborole. J Dermatol. Published online April 1, 2024. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.17205

- Xiong X, Chen R, Wang L, et al. Treatment of plasma cell balanitis associated with male genital lichen sclerosus using abrocitinib. JAAD Case Rep. 2024;46:85-88. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2024.02.010

- Stewart KMA. Clinical care of vulvar pruritus, with emphasis on one common cause, lichen simplex chronicus. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:669-680. doi:10.1016/j.det.2010.08.004

- Rimoin LP, Kwatra SG, Yosipovitch G. Female-specific pruritus from childhood to postmenopause: clinical features, hormonal factors, and treatment considerations. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:157-167. doi:10.1111/dth.12034

- Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, et al; SOLO 1 and SOLO 2 Investigators. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2335-2348. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1610020

- Yosipovitch G, Mollanazar N, Ständer S, et al. Dupilumab in patients with prurigo nodularis: two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials. Nat Med. 2023;29:1180-1190. doi:10.1038/s41591-023-02320-9

- Gosch M, Cash S, Pichardo R. Vulvar pruritus improved with dupilumab. JSM Sexual Med. 2023;7:1104.

- Pezzolo E, Gambardella A, Guanti M, et al. Tralokinumab shows clinical improvement in patients with prurigo nodularis-like phenotype atopic dermatitis: a multicenter, prospective, open-label case series study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:430-432. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.04.056

- Simpson EL, Sinclair R, Forman S, et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (JADE MONO-1): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;396:255-266. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30732-7

- Simpson EL, Papp KA, Blauvelt A, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: analysis of follow-up data from the Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:404-413. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0029

- Kwatra SG, Yosipovitch G, Legat FJ, et al. Phase 3 trial of nemolizumab in patients with prurigo nodularis. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:1579-1589. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2301333

- Papp K, Szepietowski JC, Kircik L, et al. Long-term safety and disease control with ruxolitinib cream in atopic dermatitis: results from two phase 3 studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:1008-1016. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.09.060

- Lebwohl MG, Kircik LH, Moore AY, et al. Effect of roflumilast cream vs vehicle cream on chronic plaque psoriasis: the DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2022;328:1073-1084. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.15632

- Lebwohl MG, Gold LS, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2103629

- O’Gorman SM, Torgerson RR. Allergic contact dermatitis of the vulva. Dermatitis. 2013;24:64-72. doi:10.1097/DER.0b013e318284da33

- Woodruff CM, Trivedi MK, Botto N, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis of the vulva. Dermatitis. 2018;29:233-243. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000339

- Vandeweege S, Debaene B, Lapeere H, et al. A systematic review of allergic and irritant contact dermatitis of the vulva: the most important allergens/irritants and the role of patch testing. Contact Dermatitis. 2023;88:249-262. doi:10.1111/cod.14258

- Luu Y, Admani S. Vulvar allergens in topical preparations recommended on social media: a cross-sectional analysis of Facebook groups for lichen sclerosus. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2023;9:E097. doi:10.1097/JW9.0000000000000097

- Newton J, Richardson S, van Oosbre AM, et al. A cross-sectional study of contact allergens in feminine hygiene wipes: a possible cause of vulvar contact dermatitis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2022;8:E060. doi:10.1097/JW9.0000000000000060

- Nguyen B, Kraus C. Vulvar lichen sclerosus: what’s new? Cutis. 2024;113:104-106. doi:10.12788/cutis.0967

- Van De Nieuwenhof HP, Meeuwis KAP, Nieboer TE, et al. The effect of vulvar lichen sclerosus on quality of life and sexual functioning. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;31:279-284. doi:10.3109/0167482X.2010.507890

- Ranum A, Pearson DR. The impact of genital lichen sclerosus and lichen planus on quality of life: a review. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2022;8:E042. doi:10.1097/JW9.0000000000000042

- Messele F, Hinchee-Rodriguez K, Kraus CN. Vulvar dermatoses and depression: a systematic review of vulvar lichen sclerosus, lichen planus, and lichen simplex chronicus. JAAD Int. 2024;15:15-20. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2023.10.009

- Choi UE, Nicholson RC, Agrawal P, et al. Involvement of vulva in lichen sclerosus increases the risk of antidepressant and benzodiazepine prescriptions for psychiatric disorder diagnoses. Int J Impot Res. Published online November 16, 2023. doi:10.1038/s41443-023-00793-3

- Saunderson R, Harris V, Yeh R, et al. Vulvar quality of life index (VQLI)—a simple tool to measure quality of life in patients with vulvar disease. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61:152-157. doi:10.1111/ajd.13235

- Wu M, Kherlopian A, Wijaya M, et al. Quality of life impact and treatment response in vulval disease: comparison of 3 common conditions using the Vulval Quality of Life Index. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:E320-E328. doi:10.1111/ajd.13898

- Kherlopian A, Fischer G. Comparing quality of life in women with vulvovaginal lichen planus treated with topical and systemic treatments using the vulvar quality of life index. Australas J Dermatol. 2023;64:E125-E134. doi:10.1111/ajd.14032

- Cooper SM, Haefner HK, Abrahams-Gessel S, et al. Vulvovaginal lichen planus treatment: a survey of current practices. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1520-1521. doi:10.1001/archderm.144.11.1520

- Chow MR, Gill N, Alzahrani F, et al. Vulvar lichen planus–induced vulvovaginal stenosis: a case report and review of the literature. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2023;11:2050313X231164216. doi:10.1177/2050313X231164216

- Kherlopian A, Fischer G. Identifying predictors of systemic immunosuppressive treatment of vulvovaginal lichen planus: a retrospective cohort study of 122 women. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:335-343. doi:10.1111/ajd.13851

- Dunaway S, Tyler K, Kaffenberger, J. Update on treatments for erosive vulvovaginal lichen planus. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:297-302. doi:10.1111/ijd.14692

- Mauskar MM, Marathe, K, Venkatesan A, et al. Vulvar diseases: conditions in adults and children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1287-1298. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.10.077

- Hinchee-Rodriguez K, Duong A, Kraus CN. Local management strategies for inflammatory vaginitis in dermatologic conditions: suppositories, dilators, and estrogen replacement. JAAD Int. 2022;9:137-138. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2022.09.004

- Hrin ML, Bowers NL, Feldman SR, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil versus methotrexate for vulvar lichen planus: a 10-year retrospective cohort study demonstrates comparable efficacy and tolerability. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:436-438. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.08.061

- Vermeer HAB, Rashid H, Esajas MD, et al. The use of hydroxychloroquine as a systemic treatment in erosive lichen planus of the vulva and vagina. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:201-203. doi:10.1111/bjd.19870

- Skullerud KH, Gjersvik P, Pripp AH, et al. Apremilast for genital erosive lichen planus in women (the AP-GELP Study): study protocol for a randomised placebo-controlled clinical trial. Trials. 2021;22:469. doi:10.1186/s13063-021-05428-w

- Kherlopian A, Fischer G. Successful treatment of vulvovaginal lichen planus with tildrakizumab: a case series of 24 patients. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:251-255. doi:10.1111/ajd.13793

- Kassels A, Edwards L, Kraus CN. Treatment of erosive vulvovaginal lichen planus with tofacitinib: a case series. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;40:14-18. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2023.08.001

- Wijaya M, Fischer G, Saunderson RB. The efficacy and safety of deucravacitinib compared to methotrexate, in patients with vulvar lichen planus who have failed topical therapy with potent corticosteroids: a study protocol for a single-centre double-blinded randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2024;25:181. doi:10.1186/s13063-024-08022-y

- Brumfiel CM, Patel MH, Severson KJ, et al. Ruxolitinib cream in the treatment of cutaneous lichen planus: a prospective, open-label study. J Invest Dermatol. 2022;142:2109-2116.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2022.01.015

- A study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib cream in participants with cutaneous lichen planus. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05593432. Updated March 12, 2024. Accessed July 12, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05593432

- Sattler S, Elsensohn AN, Mauskar MM, et al. Plasma cell vulvitis: a systematic review. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:756-762. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.04.005

- Song M, Day T, Kliman L, et al. Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis and plasma cell vulvitis represent a spectrum of hemorrhagic vestibulovaginitis. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2022;26:60-67. doi:10.1097/LGT.0000000000000637

- Saeed L, Lee BA, Kraus CN. Tender solitary lesion in vulvar lichen sclerosus. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;23:61-63. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.01.038

- Wendling J, Plantier F, Moyal-Barracco M. Plasma cell vulvitis: a classification into two clinical phenotypes. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2023;27:384-389. doi:10.1097/LGT.0000000000000771

- Prestwood CA, Granberry R, Rutherford A, et al. Successful treatment of plasma cell vulvitis: a case series. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;19:37-40. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.10.023

- He Y, Xu M, Wu M, et al. A case of plasma cell vulvitis successfully treated with crisaborole. J Dermatol. Published online April 1, 2024. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.17205

- Xiong X, Chen R, Wang L, et al. Treatment of plasma cell balanitis associated with male genital lichen sclerosus using abrocitinib. JAAD Case Rep. 2024;46:85-88. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2024.02.010

- Stewart KMA. Clinical care of vulvar pruritus, with emphasis on one common cause, lichen simplex chronicus. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:669-680. doi:10.1016/j.det.2010.08.004

- Rimoin LP, Kwatra SG, Yosipovitch G. Female-specific pruritus from childhood to postmenopause: clinical features, hormonal factors, and treatment considerations. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:157-167. doi:10.1111/dth.12034

- Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, et al; SOLO 1 and SOLO 2 Investigators. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2335-2348. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1610020

- Yosipovitch G, Mollanazar N, Ständer S, et al. Dupilumab in patients with prurigo nodularis: two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials. Nat Med. 2023;29:1180-1190. doi:10.1038/s41591-023-02320-9

- Gosch M, Cash S, Pichardo R. Vulvar pruritus improved with dupilumab. JSM Sexual Med. 2023;7:1104.

- Pezzolo E, Gambardella A, Guanti M, et al. Tralokinumab shows clinical improvement in patients with prurigo nodularis-like phenotype atopic dermatitis: a multicenter, prospective, open-label case series study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:430-432. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.04.056

- Simpson EL, Sinclair R, Forman S, et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (JADE MONO-1): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;396:255-266. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30732-7

- Simpson EL, Papp KA, Blauvelt A, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: analysis of follow-up data from the Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:404-413. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0029

- Kwatra SG, Yosipovitch G, Legat FJ, et al. Phase 3 trial of nemolizumab in patients with prurigo nodularis. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:1579-1589. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2301333

- Papp K, Szepietowski JC, Kircik L, et al. Long-term safety and disease control with ruxolitinib cream in atopic dermatitis: results from two phase 3 studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:1008-1016. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.09.060

- Lebwohl MG, Kircik LH, Moore AY, et al. Effect of roflumilast cream vs vehicle cream on chronic plaque psoriasis: the DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2022;328:1073-1084. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.15632

- Lebwohl MG, Gold LS, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2103629

- O’Gorman SM, Torgerson RR. Allergic contact dermatitis of the vulva. Dermatitis. 2013;24:64-72. doi:10.1097/DER.0b013e318284da33

- Woodruff CM, Trivedi MK, Botto N, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis of the vulva. Dermatitis. 2018;29:233-243. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000339

- Vandeweege S, Debaene B, Lapeere H, et al. A systematic review of allergic and irritant contact dermatitis of the vulva: the most important allergens/irritants and the role of patch testing. Contact Dermatitis. 2023;88:249-262. doi:10.1111/cod.14258

- Luu Y, Admani S. Vulvar allergens in topical preparations recommended on social media: a cross-sectional analysis of Facebook groups for lichen sclerosus. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2023;9:E097. doi:10.1097/JW9.0000000000000097

- Newton J, Richardson S, van Oosbre AM, et al. A cross-sectional study of contact allergens in feminine hygiene wipes: a possible cause of vulvar contact dermatitis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2022;8:E060. doi:10.1097/JW9.0000000000000060

Optimizing Patient Care With Teledermatology: Improving Access, Efficiency, and Satisfaction

Telemedicine interest, which was relatively quiescent prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, has surged in popularity in the past few years.1 It can now be utilized seamlessly in dermatology practices to deliver exceptional patient care while reducing costs and travel time and offering dermatologists flexibility and improved work-life balance. Teledermatology applications include synchronous, asynchronous, and hybrid platforms.2 For synchronous teledermatology, patient visits are carried out in real time with audio and video technology.3 For asynchronous teledermatology—also known as the store-and-forward model—the dermatologist receives the patient’s history and photographs and then renders an assessment and treatment plan.2 Hybrid teledermatology uses real-time audio and video conferencing for history taking, assessment and treatment plan, and patient education, with photographs sent asynchronously.3 Telemedicine may not be initially intuitive or easy to integrate into clinical practice, but with time and effort, it will complement your dermatology practice, making it run more efficiently.

Patient Satisfaction With Teledermatology

Studies generally have shown very high patient satisfaction rates and shorter wait times with teledermatology vs in-person visits; for example, in a systematic review of 15 teledermatology studies including 7781 patients, more than 80% of participants reported high satisfaction with their telemedicine visit, with up to 92% reporting that they would choose to do a televisit again.4 In a retrospective analysis of 615 Zocdoc physicians, 65% of whom were dermatologists, mean wait times were 2.4 days for virtual appointments compared with 11.7 days for in-person appointments.5 Similarly, in a retrospective single-institution study, mean wait times for televisits were 14.3 days compared with 34.7 days for in-person referrals.6

Follow-Up Visits for Nail Disorders Via Teledermatology

Teledermatology may be particularly well suited for treating patients with nail disorders. In a prospective observational study, Onyeka et al7 accessed 813 images from 63 dermatology patients via teledermatology over a 6-month period to assess distance, focus, brightness, background, and image quality; of them, 83% were rated as high quality. Notably, images of nail disorders, skin growths, or pigmentation disorders were rated as having better image quality than images of inflammatory skin conditions (odds ratio [OR], 4.2-12.9 [P<.005]).7 In a retrospective study of 107 telemedicine visits for nail disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic, patients with longitudinal melanonychia were recommended for in-person visits for physical examination and dermoscopy, as were patients with suspected onychomycosis, who required nail plate sampling for diagnostic confirmation; however, approximately half of visits did not require in-person follow-up, including those patients with confirmed onychomycosis.8 Onychomycosis patients could be examined for clinical improvement and counseled on medication compliance via telemedicine. Other patients who did not require in-person follow-ups were those with traumatic nail disorders such as subungual hematoma and retronychia as well as those with body‐focused repetitive behaviors, including habit-tic nail deformity, onychophagia, and onychotillomania.8

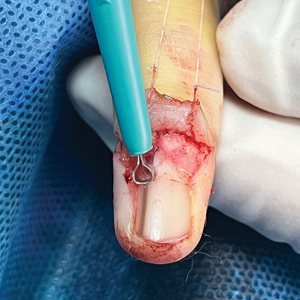

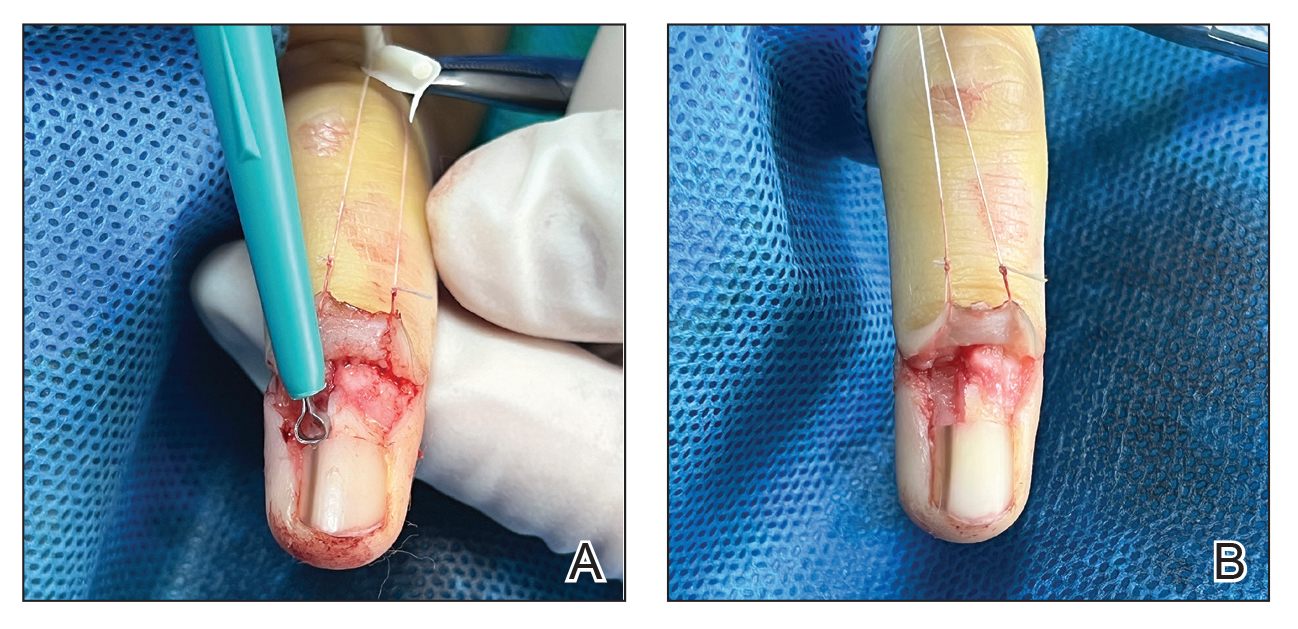

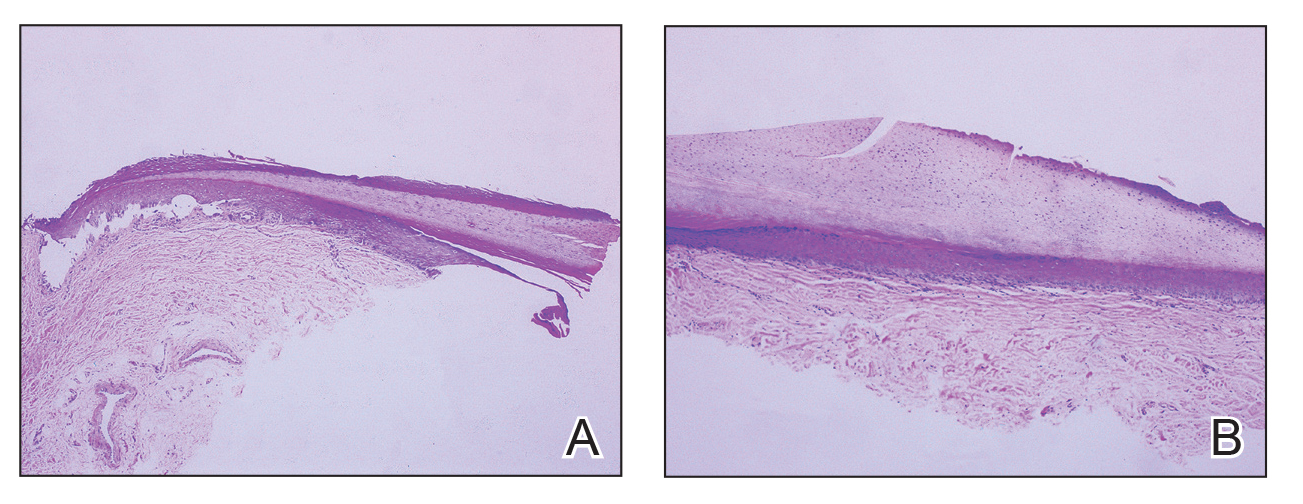

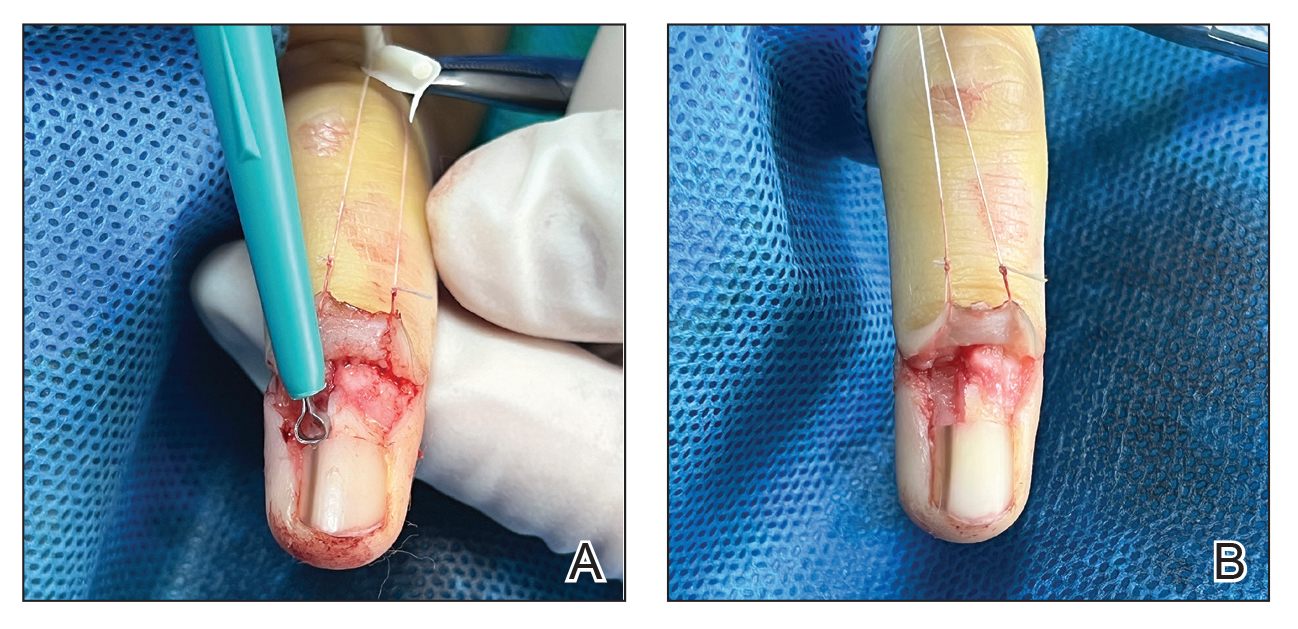

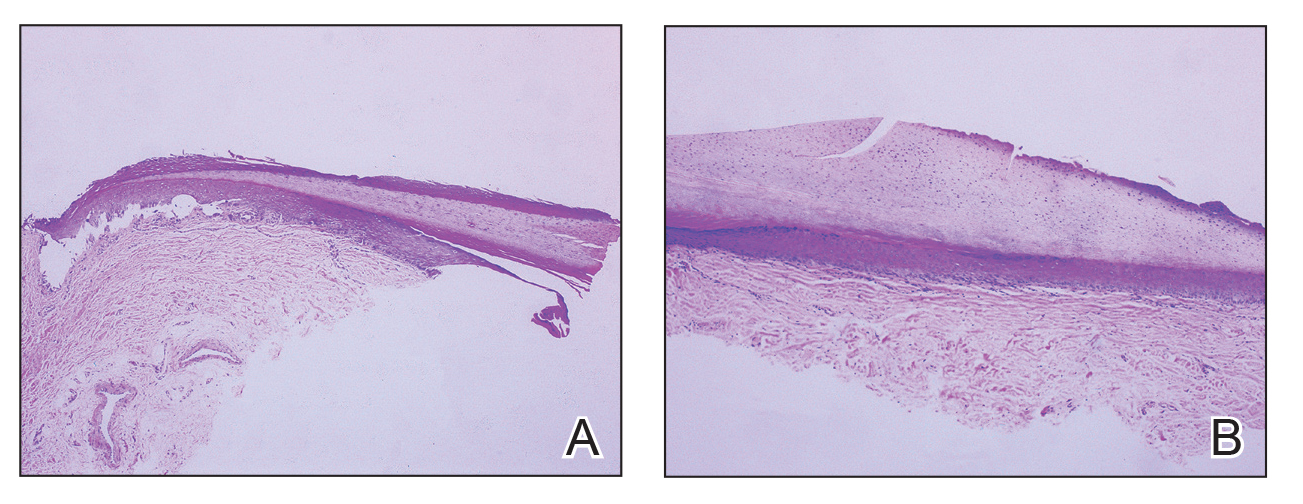

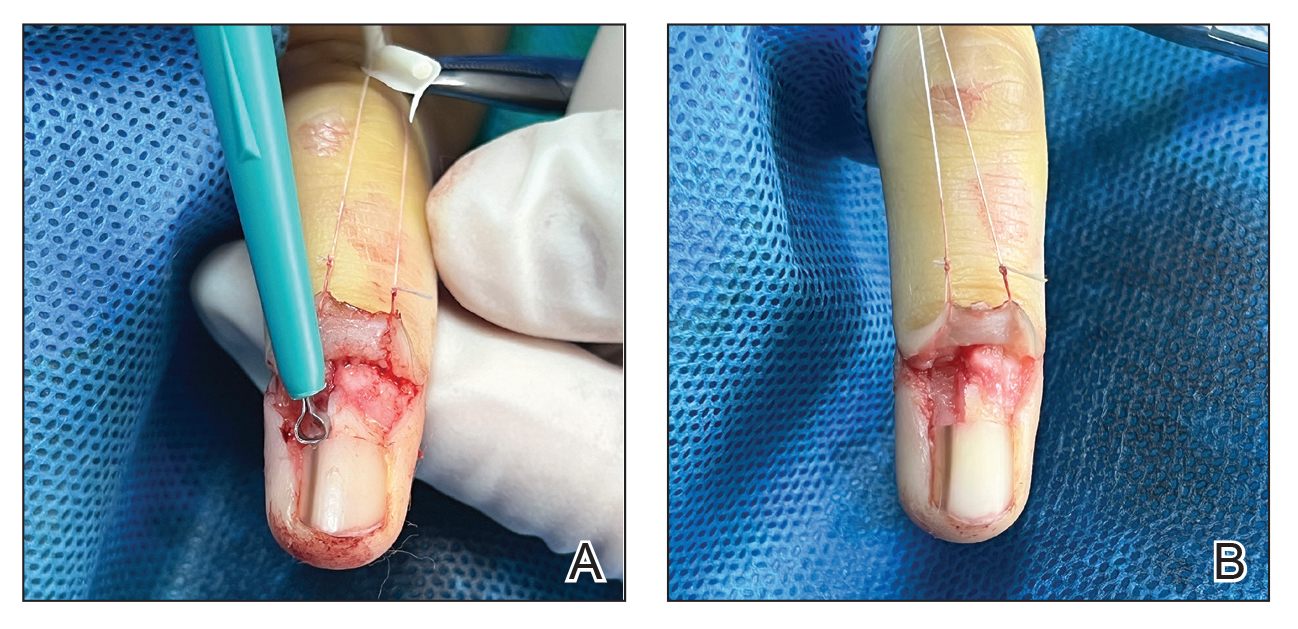

Patients undergoing nail biopsies to rule out malignancies or to diagnose inflammatory nail disorders also may be managed via telemedicine. Patients for whom nail biopsies are recommended often are anxious about the procedure, which may be due to portrayal of nail trauma in the media9 or lack of accurate information on nail biopsies online.10 Therefore, counseling via telemedicine about the details of the procedure in a patient-friendly way (eg, showing an animated video and narrating it11) can allay anxiety without the inconvenience, cost, and time missed from work associated with traveling to an in-person visit. In addition, postoperative counseling ideally is performed via telemedicine because complications following nail procedures are uncommon. In a retrospective study of 502 patients who underwent a nail biopsy at a single academic center, only 14 developed surgical site infections within 8 days on average (range, 5–13 days), with a higher infection risk in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (P<.0003).12

Advantages and Limitations

There are many benefits to incorporating telemedicine into dermatology practices, including reduced overhead costs, convenience and time saved for patients, and flexibility and improved work-life balance for dermatologists. In addition, because the number of in-person visits seen generally is fixed due to space constraints and work-hour restrictions, delegating follow-up visits to telemedicine can free up in-person slots for new patients and those needing procedures. However, there also are some inherent limitations to telemedicine: technology access, vision or hearing difficulties or low digital health literacy, or language barriers. In the prospective observational study by Onyeka et al7 analyzing 813 teledermatology images, patients aged 65 to 74 years sent in more clinically useful images (OR, 7.9) and images that were more often in focus (OR, 2.6) compared with patients older than 85 years.

Final Thoughts

Incorporation of telemedicine into dermatologic practice is a valuable tool for triaging patients with acute issues, improving patient care and health care access, making practices more efficient, and improving dermatologist flexibility and work-life balance. Further development of teledermatology to provide access to underserved populations prioritizing dermatologist reimbursement and progress on technologic innovations will make teledermatology even more useful in the coming years.

- He A, Ti Kim T, Nguyen KD. Utilization of teledermatology services for dermatological diagnoses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:1059-1062.

- Lee JJ, English JC 3rd. Teledermatology: a review and update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:253-260.

- Wang RH, Barbieri JS, Kovarik CL, et al. Synchronous and asynchronous teledermatology: a narrative review of strengths and limitations. J Telemed Telecare. 2022;28:533-538.

- Miller J, Jones E. Shaping the future of teledermatology: a literature review of patient and provider satisfaction with synchronous teledermatology during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:1903-1909.

- Gu L, Xiang L, Lipner SR. Analysis of availability of online dermatology appointments during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:517-520.

- Wang RF, Trinidad J, Lawrence J, et al. Improved patient access and outcomes with the integration of an eConsult program (teledermatology) within a large academic medical center. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;83:1633-1638.

- Onyeka S, Kim J, Eid E, et al. Quality of images submitted by older patients to a teledermatology platform. Abstract presented at the Society of Investigative Dermatology Annual Meeting; May 15-18, 2024; Dallas, TX.

- Chang MJ, Stewart CR, Lipner SR. Retrospective study of nail telemedicine visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14630.

- Albucker SJ, Falotico JM, Lipner SR. A real nail biter: a cross-sectional study of 75 nail trauma scenes in international films and television series. J Cutan Med Surg. 2023;27:288-291.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. Evaluating the impact and educational value of YouTube videos on nail biopsy procedures. Cutis. 2020;105:148-149, E1.

- Hill RC, Ho B, Lipner SR. Assuaging patient anxiety about nail biopsies with an animated educational video. J Am Acad Dermatol. Published online March 29, 2024. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2024.03.031.

- Axler E, Lu A, Darrell M, et al. Surgical site infections are uncommon following nail biopsies in a single-center case-control study of 502 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. Published online May 15, 2024. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2024.05.017

Telemedicine interest, which was relatively quiescent prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, has surged in popularity in the past few years.1 It can now be utilized seamlessly in dermatology practices to deliver exceptional patient care while reducing costs and travel time and offering dermatologists flexibility and improved work-life balance. Teledermatology applications include synchronous, asynchronous, and hybrid platforms.2 For synchronous teledermatology, patient visits are carried out in real time with audio and video technology.3 For asynchronous teledermatology—also known as the store-and-forward model—the dermatologist receives the patient’s history and photographs and then renders an assessment and treatment plan.2 Hybrid teledermatology uses real-time audio and video conferencing for history taking, assessment and treatment plan, and patient education, with photographs sent asynchronously.3 Telemedicine may not be initially intuitive or easy to integrate into clinical practice, but with time and effort, it will complement your dermatology practice, making it run more efficiently.

Patient Satisfaction With Teledermatology

Studies generally have shown very high patient satisfaction rates and shorter wait times with teledermatology vs in-person visits; for example, in a systematic review of 15 teledermatology studies including 7781 patients, more than 80% of participants reported high satisfaction with their telemedicine visit, with up to 92% reporting that they would choose to do a televisit again.4 In a retrospective analysis of 615 Zocdoc physicians, 65% of whom were dermatologists, mean wait times were 2.4 days for virtual appointments compared with 11.7 days for in-person appointments.5 Similarly, in a retrospective single-institution study, mean wait times for televisits were 14.3 days compared with 34.7 days for in-person referrals.6

Follow-Up Visits for Nail Disorders Via Teledermatology

Teledermatology may be particularly well suited for treating patients with nail disorders. In a prospective observational study, Onyeka et al7 accessed 813 images from 63 dermatology patients via teledermatology over a 6-month period to assess distance, focus, brightness, background, and image quality; of them, 83% were rated as high quality. Notably, images of nail disorders, skin growths, or pigmentation disorders were rated as having better image quality than images of inflammatory skin conditions (odds ratio [OR], 4.2-12.9 [P<.005]).7 In a retrospective study of 107 telemedicine visits for nail disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic, patients with longitudinal melanonychia were recommended for in-person visits for physical examination and dermoscopy, as were patients with suspected onychomycosis, who required nail plate sampling for diagnostic confirmation; however, approximately half of visits did not require in-person follow-up, including those patients with confirmed onychomycosis.8 Onychomycosis patients could be examined for clinical improvement and counseled on medication compliance via telemedicine. Other patients who did not require in-person follow-ups were those with traumatic nail disorders such as subungual hematoma and retronychia as well as those with body‐focused repetitive behaviors, including habit-tic nail deformity, onychophagia, and onychotillomania.8

Patients undergoing nail biopsies to rule out malignancies or to diagnose inflammatory nail disorders also may be managed via telemedicine. Patients for whom nail biopsies are recommended often are anxious about the procedure, which may be due to portrayal of nail trauma in the media9 or lack of accurate information on nail biopsies online.10 Therefore, counseling via telemedicine about the details of the procedure in a patient-friendly way (eg, showing an animated video and narrating it11) can allay anxiety without the inconvenience, cost, and time missed from work associated with traveling to an in-person visit. In addition, postoperative counseling ideally is performed via telemedicine because complications following nail procedures are uncommon. In a retrospective study of 502 patients who underwent a nail biopsy at a single academic center, only 14 developed surgical site infections within 8 days on average (range, 5–13 days), with a higher infection risk in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (P<.0003).12

Advantages and Limitations

There are many benefits to incorporating telemedicine into dermatology practices, including reduced overhead costs, convenience and time saved for patients, and flexibility and improved work-life balance for dermatologists. In addition, because the number of in-person visits seen generally is fixed due to space constraints and work-hour restrictions, delegating follow-up visits to telemedicine can free up in-person slots for new patients and those needing procedures. However, there also are some inherent limitations to telemedicine: technology access, vision or hearing difficulties or low digital health literacy, or language barriers. In the prospective observational study by Onyeka et al7 analyzing 813 teledermatology images, patients aged 65 to 74 years sent in more clinically useful images (OR, 7.9) and images that were more often in focus (OR, 2.6) compared with patients older than 85 years.

Final Thoughts

Incorporation of telemedicine into dermatologic practice is a valuable tool for triaging patients with acute issues, improving patient care and health care access, making practices more efficient, and improving dermatologist flexibility and work-life balance. Further development of teledermatology to provide access to underserved populations prioritizing dermatologist reimbursement and progress on technologic innovations will make teledermatology even more useful in the coming years.

Telemedicine interest, which was relatively quiescent prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, has surged in popularity in the past few years.1 It can now be utilized seamlessly in dermatology practices to deliver exceptional patient care while reducing costs and travel time and offering dermatologists flexibility and improved work-life balance. Teledermatology applications include synchronous, asynchronous, and hybrid platforms.2 For synchronous teledermatology, patient visits are carried out in real time with audio and video technology.3 For asynchronous teledermatology—also known as the store-and-forward model—the dermatologist receives the patient’s history and photographs and then renders an assessment and treatment plan.2 Hybrid teledermatology uses real-time audio and video conferencing for history taking, assessment and treatment plan, and patient education, with photographs sent asynchronously.3 Telemedicine may not be initially intuitive or easy to integrate into clinical practice, but with time and effort, it will complement your dermatology practice, making it run more efficiently.

Patient Satisfaction With Teledermatology