User login

Antibody linked to spontaneous reversal of ATTR-CM

Cardiac transthyretin amyloidosis (also called ATTR amyloidosis cardiomyopathy or ATTR-CM) is a progressive disease and a cause of heart failure resulting from accumulation of the protein transthyretin, which misfolds and forms amyloid deposits on the walls of the heart, causing both systolic and diastolic dysfunction.

The condition is progressive and normally fatal within a few years of diagnosis. Treatment options are limited and aimed at slowing progression; nothing has been shown to reverse the course of the disease.

However, an international team of researchers is now reporting the discovery of three patients with ATTR-CM–associated heart failure in whom the condition resolved spontaneously, with reversion to near normal cardiac structure and function. On further investigation, it was found that these three patients had developed circulating polyclonal IgG antibodies to human ATTR amyloid.

They are hopeful that a monoclonal form of these antibodies could be developed and may represent a novel treatment, or even a cure, for the condition.

The researchers report their findings in a letter to the New England Journal of Medicine.

“We are very optimistic about this discovery of these antibodies. They could become the first treatment to clear the amyloid that causes this horribly progressive and fatal condition,” senior author Julian Gillmore, MD, head of the University College London Centre for Amyloidosis, based at the Royal Free Hospital, said in an interview.

“Obviously, there is a lot of work to do before we can say this is the case, but it is very exciting,” he added.

Dr. Gillmore explained how the antibodies were discovered. “This disease has a universally progressive course, but we had one patient who on a repeat appointment said he felt better and on detailed cardiac MRI imaging, we found that the amyloid in his heart had reduced. That is totally unheard of,” he said.

“We then looked back at our cohort of 1,663 patients with ATTR-cardiomyopathy, and we discovered two others who had also improved both on imaging and clinically,” Dr. Gillmore said.

Each of these three patients reported a reduction in symptoms, although they had not received any new or potentially disease-modifying treatments. None of the patients had had recent vaccinations, notable infections, or any clinical suggestion of myocarditis.

Clinical recovery was corroborated by substantial improvement or normalization of findings on echocardiography, serum biomarker levels, and results of cardiopulmonary exercise tests and scintigraphy.

Serial cardiac MRI scans confirmed near-complete regression of myocardial extracellular volume, coupled with remodeling to near-normal cardiac structure and function without scarring.

The researchers wondered whether the changes in these patients may have been brought about by an antibody response. On further investigation, they found antibodies in the three patients that bound specifically to ATTR amyloid deposits in a transgenic mouse model of the condition, and to synthetic ATTR amyloid. No such antibodies were present in the other 350 patients in the cohort with a typical clinical course.

“The cause and clinical significance of the anti-ATTR amyloid antibodies are intriguing and presently unclear. However, the clinical recovery of these patients establishes the unanticipated potential for reversibility of ATTR-CM and raises expectations for its treatment,” the researchers conclude.

Dr. Gillmore said they didn’t know why these three patients had these antibodies, while all the other patients did not. “There must be something different about these patients. We don’t know what that is at present, but we are looking hard.”

The researchers are hoping that after this publication, other centers caring for patients with ATTR-cardiomyopathy will look in their cohorts and see if they can identify other cases where there has been improvement.

“It is very plausible that they do have such cases, but they will be rare, as we all think of this disease as universally progressive and fatal,” Dr. Gillmore noted.

“We haven’t absolutely proven that the antibodies have caused the clearance of amyloid in these patients, but we strongly suspect this to be the case,” Dr. Gillmore said. The researchers are planning to try to confirm this by isolating the antibodies and treating the transgenic mice.

Dr. Gillmore attributed the current discovery to the development of novel imaging cardiac MRI techniques. “This allowed us to monitor closely the amyloid burden in the heart. The observation that this had diminished in these three patients was the breakthrough that led us to look for antibodies.”

Another antibody product directed against ATTR cardiomyopathy is also in development by Neurimmune, a Swiss biopharmaceutical company. A phase 1 study of this agent was recently published, suggesting that it appeared to reduce the amount of amyloid protein deposited in the heart.

Dr. Gillmore said the antibody they have detected is different from the Neurimmune product.

The research was supported by a British Heart Foundation Intermediate Clinical Research Fellowship, a Medical Research Council Career Development Award, and a project grant from the British Heart Foundation. Dr. Gillmore reports being a consultant or expert advisory board member for Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, ATTRalus, Eidos Therapeutics, Intellia Therapeutics, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Cardiac transthyretin amyloidosis (also called ATTR amyloidosis cardiomyopathy or ATTR-CM) is a progressive disease and a cause of heart failure resulting from accumulation of the protein transthyretin, which misfolds and forms amyloid deposits on the walls of the heart, causing both systolic and diastolic dysfunction.

The condition is progressive and normally fatal within a few years of diagnosis. Treatment options are limited and aimed at slowing progression; nothing has been shown to reverse the course of the disease.

However, an international team of researchers is now reporting the discovery of three patients with ATTR-CM–associated heart failure in whom the condition resolved spontaneously, with reversion to near normal cardiac structure and function. On further investigation, it was found that these three patients had developed circulating polyclonal IgG antibodies to human ATTR amyloid.

They are hopeful that a monoclonal form of these antibodies could be developed and may represent a novel treatment, or even a cure, for the condition.

The researchers report their findings in a letter to the New England Journal of Medicine.

“We are very optimistic about this discovery of these antibodies. They could become the first treatment to clear the amyloid that causes this horribly progressive and fatal condition,” senior author Julian Gillmore, MD, head of the University College London Centre for Amyloidosis, based at the Royal Free Hospital, said in an interview.

“Obviously, there is a lot of work to do before we can say this is the case, but it is very exciting,” he added.

Dr. Gillmore explained how the antibodies were discovered. “This disease has a universally progressive course, but we had one patient who on a repeat appointment said he felt better and on detailed cardiac MRI imaging, we found that the amyloid in his heart had reduced. That is totally unheard of,” he said.

“We then looked back at our cohort of 1,663 patients with ATTR-cardiomyopathy, and we discovered two others who had also improved both on imaging and clinically,” Dr. Gillmore said.

Each of these three patients reported a reduction in symptoms, although they had not received any new or potentially disease-modifying treatments. None of the patients had had recent vaccinations, notable infections, or any clinical suggestion of myocarditis.

Clinical recovery was corroborated by substantial improvement or normalization of findings on echocardiography, serum biomarker levels, and results of cardiopulmonary exercise tests and scintigraphy.

Serial cardiac MRI scans confirmed near-complete regression of myocardial extracellular volume, coupled with remodeling to near-normal cardiac structure and function without scarring.

The researchers wondered whether the changes in these patients may have been brought about by an antibody response. On further investigation, they found antibodies in the three patients that bound specifically to ATTR amyloid deposits in a transgenic mouse model of the condition, and to synthetic ATTR amyloid. No such antibodies were present in the other 350 patients in the cohort with a typical clinical course.

“The cause and clinical significance of the anti-ATTR amyloid antibodies are intriguing and presently unclear. However, the clinical recovery of these patients establishes the unanticipated potential for reversibility of ATTR-CM and raises expectations for its treatment,” the researchers conclude.

Dr. Gillmore said they didn’t know why these three patients had these antibodies, while all the other patients did not. “There must be something different about these patients. We don’t know what that is at present, but we are looking hard.”

The researchers are hoping that after this publication, other centers caring for patients with ATTR-cardiomyopathy will look in their cohorts and see if they can identify other cases where there has been improvement.

“It is very plausible that they do have such cases, but they will be rare, as we all think of this disease as universally progressive and fatal,” Dr. Gillmore noted.

“We haven’t absolutely proven that the antibodies have caused the clearance of amyloid in these patients, but we strongly suspect this to be the case,” Dr. Gillmore said. The researchers are planning to try to confirm this by isolating the antibodies and treating the transgenic mice.

Dr. Gillmore attributed the current discovery to the development of novel imaging cardiac MRI techniques. “This allowed us to monitor closely the amyloid burden in the heart. The observation that this had diminished in these three patients was the breakthrough that led us to look for antibodies.”

Another antibody product directed against ATTR cardiomyopathy is also in development by Neurimmune, a Swiss biopharmaceutical company. A phase 1 study of this agent was recently published, suggesting that it appeared to reduce the amount of amyloid protein deposited in the heart.

Dr. Gillmore said the antibody they have detected is different from the Neurimmune product.

The research was supported by a British Heart Foundation Intermediate Clinical Research Fellowship, a Medical Research Council Career Development Award, and a project grant from the British Heart Foundation. Dr. Gillmore reports being a consultant or expert advisory board member for Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, ATTRalus, Eidos Therapeutics, Intellia Therapeutics, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Cardiac transthyretin amyloidosis (also called ATTR amyloidosis cardiomyopathy or ATTR-CM) is a progressive disease and a cause of heart failure resulting from accumulation of the protein transthyretin, which misfolds and forms amyloid deposits on the walls of the heart, causing both systolic and diastolic dysfunction.

The condition is progressive and normally fatal within a few years of diagnosis. Treatment options are limited and aimed at slowing progression; nothing has been shown to reverse the course of the disease.

However, an international team of researchers is now reporting the discovery of three patients with ATTR-CM–associated heart failure in whom the condition resolved spontaneously, with reversion to near normal cardiac structure and function. On further investigation, it was found that these three patients had developed circulating polyclonal IgG antibodies to human ATTR amyloid.

They are hopeful that a monoclonal form of these antibodies could be developed and may represent a novel treatment, or even a cure, for the condition.

The researchers report their findings in a letter to the New England Journal of Medicine.

“We are very optimistic about this discovery of these antibodies. They could become the first treatment to clear the amyloid that causes this horribly progressive and fatal condition,” senior author Julian Gillmore, MD, head of the University College London Centre for Amyloidosis, based at the Royal Free Hospital, said in an interview.

“Obviously, there is a lot of work to do before we can say this is the case, but it is very exciting,” he added.

Dr. Gillmore explained how the antibodies were discovered. “This disease has a universally progressive course, but we had one patient who on a repeat appointment said he felt better and on detailed cardiac MRI imaging, we found that the amyloid in his heart had reduced. That is totally unheard of,” he said.

“We then looked back at our cohort of 1,663 patients with ATTR-cardiomyopathy, and we discovered two others who had also improved both on imaging and clinically,” Dr. Gillmore said.

Each of these three patients reported a reduction in symptoms, although they had not received any new or potentially disease-modifying treatments. None of the patients had had recent vaccinations, notable infections, or any clinical suggestion of myocarditis.

Clinical recovery was corroborated by substantial improvement or normalization of findings on echocardiography, serum biomarker levels, and results of cardiopulmonary exercise tests and scintigraphy.

Serial cardiac MRI scans confirmed near-complete regression of myocardial extracellular volume, coupled with remodeling to near-normal cardiac structure and function without scarring.

The researchers wondered whether the changes in these patients may have been brought about by an antibody response. On further investigation, they found antibodies in the three patients that bound specifically to ATTR amyloid deposits in a transgenic mouse model of the condition, and to synthetic ATTR amyloid. No such antibodies were present in the other 350 patients in the cohort with a typical clinical course.

“The cause and clinical significance of the anti-ATTR amyloid antibodies are intriguing and presently unclear. However, the clinical recovery of these patients establishes the unanticipated potential for reversibility of ATTR-CM and raises expectations for its treatment,” the researchers conclude.

Dr. Gillmore said they didn’t know why these three patients had these antibodies, while all the other patients did not. “There must be something different about these patients. We don’t know what that is at present, but we are looking hard.”

The researchers are hoping that after this publication, other centers caring for patients with ATTR-cardiomyopathy will look in their cohorts and see if they can identify other cases where there has been improvement.

“It is very plausible that they do have such cases, but they will be rare, as we all think of this disease as universally progressive and fatal,” Dr. Gillmore noted.

“We haven’t absolutely proven that the antibodies have caused the clearance of amyloid in these patients, but we strongly suspect this to be the case,” Dr. Gillmore said. The researchers are planning to try to confirm this by isolating the antibodies and treating the transgenic mice.

Dr. Gillmore attributed the current discovery to the development of novel imaging cardiac MRI techniques. “This allowed us to monitor closely the amyloid burden in the heart. The observation that this had diminished in these three patients was the breakthrough that led us to look for antibodies.”

Another antibody product directed against ATTR cardiomyopathy is also in development by Neurimmune, a Swiss biopharmaceutical company. A phase 1 study of this agent was recently published, suggesting that it appeared to reduce the amount of amyloid protein deposited in the heart.

Dr. Gillmore said the antibody they have detected is different from the Neurimmune product.

The research was supported by a British Heart Foundation Intermediate Clinical Research Fellowship, a Medical Research Council Career Development Award, and a project grant from the British Heart Foundation. Dr. Gillmore reports being a consultant or expert advisory board member for Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, ATTRalus, Eidos Therapeutics, Intellia Therapeutics, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Big boost in sodium excretion with HF diuretic protocol

In patients with acute heart failure, a urine sodium-guided diuretic protocol, currently recommended in guidelines from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology (HFA-ESC), led to significant increases in natriuresis and diuresis over 2 days in the prospective ENACT-HF clinical trial.

The guideline protocol was based on a 2019 HFA position paper with expert consensus, but it had not been tested prospectively, Jeroen Dauw, MD, of AZ Sint-Lucas Ghent (Belgium), explained in a presentation at HFA-ESC 2023.

“We had 282 millimoles of sodium excretion after one day, which is an increase of 64%, compared with standard of care,” Dr. Dauw told meeting attendees. “We wanted to power for 15%, so we’re way above it, with a P value of lower than 0.001.”

The effect was consistent across predefined subgroups, he said. “In addition, there’s an even higher benefit in patients with a lower eGFR [estimated glomerular filtration rate] and a higher home dose of loop diuretics, which might signal more diuretic resistance and more benefit of the protocol.”

After 2 days, the investigators saw 52% higher natriuresis and 33% higher diuresis, compared with usual care.

In an interview, Dr. Dauw said, “The protocol is feasible, safe, and very effective. Cardiologists might consider how to implement a similar protocol in their center to improve the care of their acute heart failure patients.”

Twice the oral home dose

The investigators conducted a multicenter, open-label, nonrandomized pragmatic trial at 29 centers in 18 countries globally. “We aimed to recruit 500 to detect a 15% difference in natriuresis,” Dr. Dauw said in his presentation, “but because we were a really low-budget trial, we had to stop after 3 years of recruitment.”

Therefore, 401 patients participated, 254 in the SOC arm and 147 in the protocol arm, because of the sequential nature of the study; that is, patients in the SOC arm of the two-phase study were recruited first.

Patients’ mean age was 70 years, 38% were women, and they all had at least one sign of volume overload. They were on a maintenance daily diuretic dose of 40 mg of furosemide for a month or more, and the NT-proBNP was above 1,000.

In phase 1 of the study, all centers treated 10 consecutive patients according to the local standard of care, at the discretion of the physician. In phase 2, the centers again recruited and treated at least 10 consecutive patients, this time according to the standardized diuretic protocol.

In the protocol phase, patients were treated with twice the oral home dose as an IV bolus. “This meant if, for example, you have 40 mg of furosemide at home, then you receive 80 mg as a first bolus,” Dr. Dauw told attendees. A spot urine sample was taken after 2 hours, and the response was evaluated after 6 hours. A urine sodium above 50 millimoles per liter was considered a good response.

On the second day, patients were reevaluated in the morning using urine output as a measure of diuretic response. If it was above 3 L, then the same bolus was repeated again twice daily, with 6-12 hours between administrations.

As noted, after one day, natriuresis was 174 millimoles in the SOC arm versus 282 millimoles in the protocol group – an increase of 64%. The effect was consistent across subgroups, and those with a lower eGFR and a higher home dose of loop diuretics benefited more.

Furthermore, Dr. Dauw said, there was no interaction on the endpoints with SGLT2 inhibitor use at baseline.

After two days, natriuresis was 52% higher in the protocol group and diuresis was 33% higher.

However, there was no significant difference in weight loss and no difference in the congestion score.

“We did expect to see a difference in weight loss between the study groups, as higher natriuresis and diuresis would normally be associated with higher weight loss in the protocol group,” Dr. Dauw told this news organization. “However, looking back at the study design, weight was collected from the electronic health records and not rigorously collected by study nurses. Previous studies have shown discrepancies between fluid loss and weight loss, so this is an ‘explainable’ finding.”

Participants also had a relatively high congestion score at baseline, with edema above the knee and also some pleural effusion, he told meeting attendees. Therefore, it might take more time to see a change in congestion score in those patients.

The protocol also led to a shorter length of stay – one day less in the hospital – and was very safe on renal endpoints, Dr. Dauw concluded.

A session chair asked why only patients already on diuretics were included in the study, noting that in his clinic, about half of the admissions are de novo.

Dr. Dauw said that patients already taking diuretics chronically would benefit most from the protocol. “If patients are diuretic-naive, they probably will respond well to whatever you do; if you just give a higher dose, they will respond well,” he said. “We expected that the largest benefit would be in patients already taking diuretics because they have a higher chance of not responding well.”

“There also was a big difference in the starting dose,” he added. “In the SOC arm, the baseline dose was about 60 mg, whereas we gave 120 mg, and we could already see a high difference in the effect. So, in those patients, I think the gain is bigger if you follow the protocol.”

More data coming

Looking ahead, “we only showed efficacy in the first 2 days of treatment and a shorter length of stay, probably reflecting a faster decongestion, but we don’t know for sure,” Dr. Dauw told this news organization.

“It would be important to have a study where the protocol is followed until full decongestion is reached,” he said. “That way, we can directly prove that decongestion is better and/or faster with the protocol.”

“A good decongestive strategy is one that is fast, safe and effective in decreasing signs and symptoms that patients suffer from,” he added. “We believe our protocol can achieve that, but our study is only one piece of the puzzle.”

More data on natriuresis-guided decongestion is coming this year, he said, with the PUSH-AHF study from Groningen, the European DECONGEST study, and the U.S. ESCALATE study.

The study had no funding. Dr. Dauw declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In patients with acute heart failure, a urine sodium-guided diuretic protocol, currently recommended in guidelines from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology (HFA-ESC), led to significant increases in natriuresis and diuresis over 2 days in the prospective ENACT-HF clinical trial.

The guideline protocol was based on a 2019 HFA position paper with expert consensus, but it had not been tested prospectively, Jeroen Dauw, MD, of AZ Sint-Lucas Ghent (Belgium), explained in a presentation at HFA-ESC 2023.

“We had 282 millimoles of sodium excretion after one day, which is an increase of 64%, compared with standard of care,” Dr. Dauw told meeting attendees. “We wanted to power for 15%, so we’re way above it, with a P value of lower than 0.001.”

The effect was consistent across predefined subgroups, he said. “In addition, there’s an even higher benefit in patients with a lower eGFR [estimated glomerular filtration rate] and a higher home dose of loop diuretics, which might signal more diuretic resistance and more benefit of the protocol.”

After 2 days, the investigators saw 52% higher natriuresis and 33% higher diuresis, compared with usual care.

In an interview, Dr. Dauw said, “The protocol is feasible, safe, and very effective. Cardiologists might consider how to implement a similar protocol in their center to improve the care of their acute heart failure patients.”

Twice the oral home dose

The investigators conducted a multicenter, open-label, nonrandomized pragmatic trial at 29 centers in 18 countries globally. “We aimed to recruit 500 to detect a 15% difference in natriuresis,” Dr. Dauw said in his presentation, “but because we were a really low-budget trial, we had to stop after 3 years of recruitment.”

Therefore, 401 patients participated, 254 in the SOC arm and 147 in the protocol arm, because of the sequential nature of the study; that is, patients in the SOC arm of the two-phase study were recruited first.

Patients’ mean age was 70 years, 38% were women, and they all had at least one sign of volume overload. They were on a maintenance daily diuretic dose of 40 mg of furosemide for a month or more, and the NT-proBNP was above 1,000.

In phase 1 of the study, all centers treated 10 consecutive patients according to the local standard of care, at the discretion of the physician. In phase 2, the centers again recruited and treated at least 10 consecutive patients, this time according to the standardized diuretic protocol.

In the protocol phase, patients were treated with twice the oral home dose as an IV bolus. “This meant if, for example, you have 40 mg of furosemide at home, then you receive 80 mg as a first bolus,” Dr. Dauw told attendees. A spot urine sample was taken after 2 hours, and the response was evaluated after 6 hours. A urine sodium above 50 millimoles per liter was considered a good response.

On the second day, patients were reevaluated in the morning using urine output as a measure of diuretic response. If it was above 3 L, then the same bolus was repeated again twice daily, with 6-12 hours between administrations.

As noted, after one day, natriuresis was 174 millimoles in the SOC arm versus 282 millimoles in the protocol group – an increase of 64%. The effect was consistent across subgroups, and those with a lower eGFR and a higher home dose of loop diuretics benefited more.

Furthermore, Dr. Dauw said, there was no interaction on the endpoints with SGLT2 inhibitor use at baseline.

After two days, natriuresis was 52% higher in the protocol group and diuresis was 33% higher.

However, there was no significant difference in weight loss and no difference in the congestion score.

“We did expect to see a difference in weight loss between the study groups, as higher natriuresis and diuresis would normally be associated with higher weight loss in the protocol group,” Dr. Dauw told this news organization. “However, looking back at the study design, weight was collected from the electronic health records and not rigorously collected by study nurses. Previous studies have shown discrepancies between fluid loss and weight loss, so this is an ‘explainable’ finding.”

Participants also had a relatively high congestion score at baseline, with edema above the knee and also some pleural effusion, he told meeting attendees. Therefore, it might take more time to see a change in congestion score in those patients.

The protocol also led to a shorter length of stay – one day less in the hospital – and was very safe on renal endpoints, Dr. Dauw concluded.

A session chair asked why only patients already on diuretics were included in the study, noting that in his clinic, about half of the admissions are de novo.

Dr. Dauw said that patients already taking diuretics chronically would benefit most from the protocol. “If patients are diuretic-naive, they probably will respond well to whatever you do; if you just give a higher dose, they will respond well,” he said. “We expected that the largest benefit would be in patients already taking diuretics because they have a higher chance of not responding well.”

“There also was a big difference in the starting dose,” he added. “In the SOC arm, the baseline dose was about 60 mg, whereas we gave 120 mg, and we could already see a high difference in the effect. So, in those patients, I think the gain is bigger if you follow the protocol.”

More data coming

Looking ahead, “we only showed efficacy in the first 2 days of treatment and a shorter length of stay, probably reflecting a faster decongestion, but we don’t know for sure,” Dr. Dauw told this news organization.

“It would be important to have a study where the protocol is followed until full decongestion is reached,” he said. “That way, we can directly prove that decongestion is better and/or faster with the protocol.”

“A good decongestive strategy is one that is fast, safe and effective in decreasing signs and symptoms that patients suffer from,” he added. “We believe our protocol can achieve that, but our study is only one piece of the puzzle.”

More data on natriuresis-guided decongestion is coming this year, he said, with the PUSH-AHF study from Groningen, the European DECONGEST study, and the U.S. ESCALATE study.

The study had no funding. Dr. Dauw declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In patients with acute heart failure, a urine sodium-guided diuretic protocol, currently recommended in guidelines from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology (HFA-ESC), led to significant increases in natriuresis and diuresis over 2 days in the prospective ENACT-HF clinical trial.

The guideline protocol was based on a 2019 HFA position paper with expert consensus, but it had not been tested prospectively, Jeroen Dauw, MD, of AZ Sint-Lucas Ghent (Belgium), explained in a presentation at HFA-ESC 2023.

“We had 282 millimoles of sodium excretion after one day, which is an increase of 64%, compared with standard of care,” Dr. Dauw told meeting attendees. “We wanted to power for 15%, so we’re way above it, with a P value of lower than 0.001.”

The effect was consistent across predefined subgroups, he said. “In addition, there’s an even higher benefit in patients with a lower eGFR [estimated glomerular filtration rate] and a higher home dose of loop diuretics, which might signal more diuretic resistance and more benefit of the protocol.”

After 2 days, the investigators saw 52% higher natriuresis and 33% higher diuresis, compared with usual care.

In an interview, Dr. Dauw said, “The protocol is feasible, safe, and very effective. Cardiologists might consider how to implement a similar protocol in their center to improve the care of their acute heart failure patients.”

Twice the oral home dose

The investigators conducted a multicenter, open-label, nonrandomized pragmatic trial at 29 centers in 18 countries globally. “We aimed to recruit 500 to detect a 15% difference in natriuresis,” Dr. Dauw said in his presentation, “but because we were a really low-budget trial, we had to stop after 3 years of recruitment.”

Therefore, 401 patients participated, 254 in the SOC arm and 147 in the protocol arm, because of the sequential nature of the study; that is, patients in the SOC arm of the two-phase study were recruited first.

Patients’ mean age was 70 years, 38% were women, and they all had at least one sign of volume overload. They were on a maintenance daily diuretic dose of 40 mg of furosemide for a month or more, and the NT-proBNP was above 1,000.

In phase 1 of the study, all centers treated 10 consecutive patients according to the local standard of care, at the discretion of the physician. In phase 2, the centers again recruited and treated at least 10 consecutive patients, this time according to the standardized diuretic protocol.

In the protocol phase, patients were treated with twice the oral home dose as an IV bolus. “This meant if, for example, you have 40 mg of furosemide at home, then you receive 80 mg as a first bolus,” Dr. Dauw told attendees. A spot urine sample was taken after 2 hours, and the response was evaluated after 6 hours. A urine sodium above 50 millimoles per liter was considered a good response.

On the second day, patients were reevaluated in the morning using urine output as a measure of diuretic response. If it was above 3 L, then the same bolus was repeated again twice daily, with 6-12 hours between administrations.

As noted, after one day, natriuresis was 174 millimoles in the SOC arm versus 282 millimoles in the protocol group – an increase of 64%. The effect was consistent across subgroups, and those with a lower eGFR and a higher home dose of loop diuretics benefited more.

Furthermore, Dr. Dauw said, there was no interaction on the endpoints with SGLT2 inhibitor use at baseline.

After two days, natriuresis was 52% higher in the protocol group and diuresis was 33% higher.

However, there was no significant difference in weight loss and no difference in the congestion score.

“We did expect to see a difference in weight loss between the study groups, as higher natriuresis and diuresis would normally be associated with higher weight loss in the protocol group,” Dr. Dauw told this news organization. “However, looking back at the study design, weight was collected from the electronic health records and not rigorously collected by study nurses. Previous studies have shown discrepancies between fluid loss and weight loss, so this is an ‘explainable’ finding.”

Participants also had a relatively high congestion score at baseline, with edema above the knee and also some pleural effusion, he told meeting attendees. Therefore, it might take more time to see a change in congestion score in those patients.

The protocol also led to a shorter length of stay – one day less in the hospital – and was very safe on renal endpoints, Dr. Dauw concluded.

A session chair asked why only patients already on diuretics were included in the study, noting that in his clinic, about half of the admissions are de novo.

Dr. Dauw said that patients already taking diuretics chronically would benefit most from the protocol. “If patients are diuretic-naive, they probably will respond well to whatever you do; if you just give a higher dose, they will respond well,” he said. “We expected that the largest benefit would be in patients already taking diuretics because they have a higher chance of not responding well.”

“There also was a big difference in the starting dose,” he added. “In the SOC arm, the baseline dose was about 60 mg, whereas we gave 120 mg, and we could already see a high difference in the effect. So, in those patients, I think the gain is bigger if you follow the protocol.”

More data coming

Looking ahead, “we only showed efficacy in the first 2 days of treatment and a shorter length of stay, probably reflecting a faster decongestion, but we don’t know for sure,” Dr. Dauw told this news organization.

“It would be important to have a study where the protocol is followed until full decongestion is reached,” he said. “That way, we can directly prove that decongestion is better and/or faster with the protocol.”

“A good decongestive strategy is one that is fast, safe and effective in decreasing signs and symptoms that patients suffer from,” he added. “We believe our protocol can achieve that, but our study is only one piece of the puzzle.”

More data on natriuresis-guided decongestion is coming this year, he said, with the PUSH-AHF study from Groningen, the European DECONGEST study, and the U.S. ESCALATE study.

The study had no funding. Dr. Dauw declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM HFA-ESC 2023

First-line or BiV backup? Conduction system pacing for CRT in heart failure

Pacing as a device therapy for heart failure (HF) is headed for what is probably its next big advance.

After decades of biventricular (BiV) pacemaker success in resynchronizing the ventricles and improving clinical outcomes, relatively new conduction-system pacing (CSP) techniques that avoid the pitfalls of right-ventricular (RV) pacing using BiV lead systems have been supplanting traditional cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) in selected patients at some major centers. In fact, they are solidly ensconced in a new guideline document addressing indications for CSP and BiV pacing in HF.

But , an alternative when BiV pacing isn’t appropriate or can’t be engaged.

That’s mainly because the limited, mostly observational evidence supporting CSP in the document can’t measure up to the clinical experience and plethora of large, randomized trials behind BiV-CRT.

But that shortfall is headed for change. Several new comparative studies, including a small, randomized trial, have added significantly to evidence suggesting that CSP is at least as effective as traditional CRT for procedural, functional safety, and clinical outcomes.

The new studies “are inherently prone to bias, but their results are really good,” observed Juan C. Diaz, MD. They show improvements in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and symptoms with CSP that are “outstanding compared to what we have been doing for the last 20 years,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Diaz, Clínica Las Vegas, Medellin, Colombia, is an investigator with the observational SYNCHRONY, which is among the new CSP studies formally presented at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society. He is also lead author on its same-day publication in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology.

Dr. Diaz said that CSP, which sustains pacing via the native conduction system, makes more “physiologic sense” than BiV pacing and represents “a step forward” for HF device therapy.

SYNCHRONY compared LBB-area with BiV pacing as the initial strategy for achieving cardiac resynchronization in patients with ischemic or nonischemic cardiomyopathy.

CSP is “a long way” from replacing conventional CRT, he said. But the new studies at the HRS sessions should help extend His-bundle and LBB-area pacing to more patients, he added, given the significant long-term “drawbacks” of BiV pacing. These include inevitable RV pacing, multiple leads, and the risks associated with chronic transvenous leads.

Zachary Goldberger, MD, University of Wisconsin–Madison, went a bit further in support of CSP as invited discussant for the SYNCHRONY presentation.

Given that it improved LVEF, heart failure class, HF hospitalizations (HFH), and mortality in that study and others, Dr. Goldberger said, CSP could potentially “become the dominant mode of resynchronization going forward.”

Other experts at the meeting saw CSP’s potential more as one of several pacing techniques that could be brought to bear for patients with CRT indications.

“Conduction system pacing is going to be a huge complement to biventricular pacing,” to which about 30% of patients have a “less than optimal response,” said Pugazhendhi Vijayaraman, MD, chief of clinical electrophysiology, Geisinger Heart Institute, Danville, Pa.

“I don’t think it needs to replace biventricular pacing, because biventricular pacing is a well-established, incredibly powerful therapy,” he told this news organization. But CSP is likely to provide “a good alternative option” in patients with poor responses to BiV-CRT.

It may, however, render some current BiV-pacing alternatives “obsolete,” Dr. Vijayaraman observed. “At our center, at least for the last 5 years, no patient has needed epicardial surgical left ventricular lead placement” because CSP was a better backup option.

Dr. Vijayaraman presented two of the meeting’s CSP vs. BiV pacing comparisons. In one, the 100-patient randomized HOT-CRT trial, contractile function improved significantly on CSP, which could be either His-bundle or LBB-area pacing.

He also presented an observational study of LBB-area pacing at 15 centers in Asia, Europe, and North America and led the authors of its simultaneous publication in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“I think left-bundle conduction system pacing is the future, for sure,” Jagmeet P. Singh, MD, DPhil, told this news organization. Still, it doesn’t always work and when it does, it “doesn’t work equally in all patients,” he said.

“Conduction system pacing certainly makes a lot of sense,” especially in patients with left-bundle-branch block (LBBB), and “maybe not as a primary approach but certainly as a secondary approach,” said Dr. Singh, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who is not a coauthor on any of the three studies.

He acknowledged that CSP may work well as a first-line option in patients with LBBB at some experienced centers. For those without LBBB or who have an intraventricular conduction delay, who represent 45%-50% of current CRT cases, Dr. Singh observed, “there’s still more evidence” that BiV-CRT is a more appropriate initial approach.

Standard CRT may fail, however, even in some patients who otherwise meet guideline-based indications. “We don’t really understand all the mechanisms for nonresponse in conventional biventricular pacing,” observed Niraj Varma, MD, PhD, Cleveland Clinic, also not involved with any of the three studies.

In some groups, including “patients with larger ventricles,” for example, BiV-CRT doesn’t always narrow the electrocardiographic QRS complex or preexcite delayed left ventricular (LV) activation, hallmarks of successful CRT, he said in an interview.

“I think we need to understand why this occurs in both situations,” but in such cases, CSP alone or as an adjunct to direct LV pacing may be successful. “Sometimes we need both an LV lead and the conduction-system pacing lead.”

Narrower, more efficient use of CSP as a BiV-CRT alternative may also boost its chances for success, Dr. Varma added. “I think we need to refine patient selection.”

HOT-CRT: Randomized CSP vs. BiV pacing trial

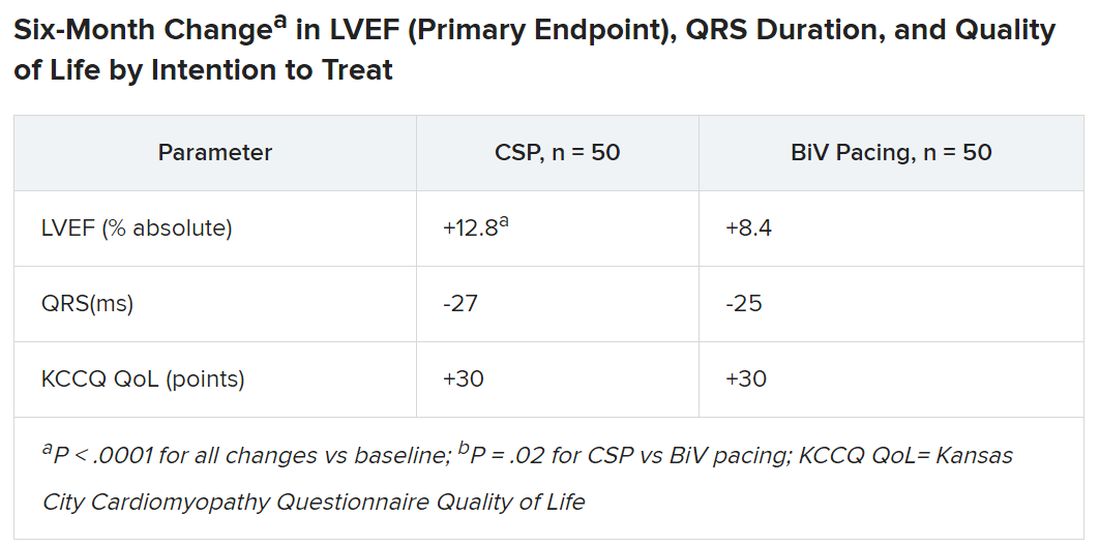

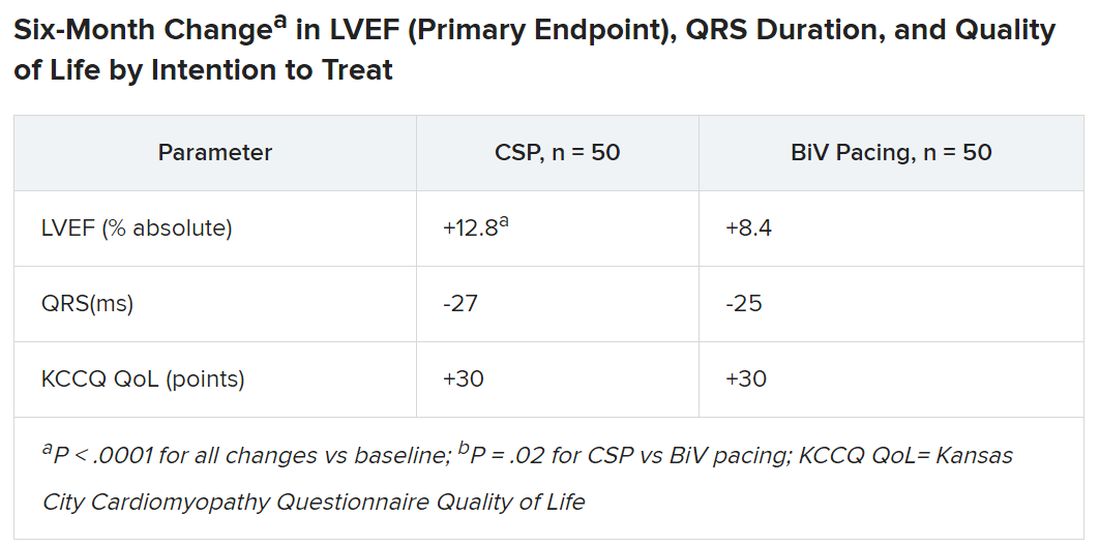

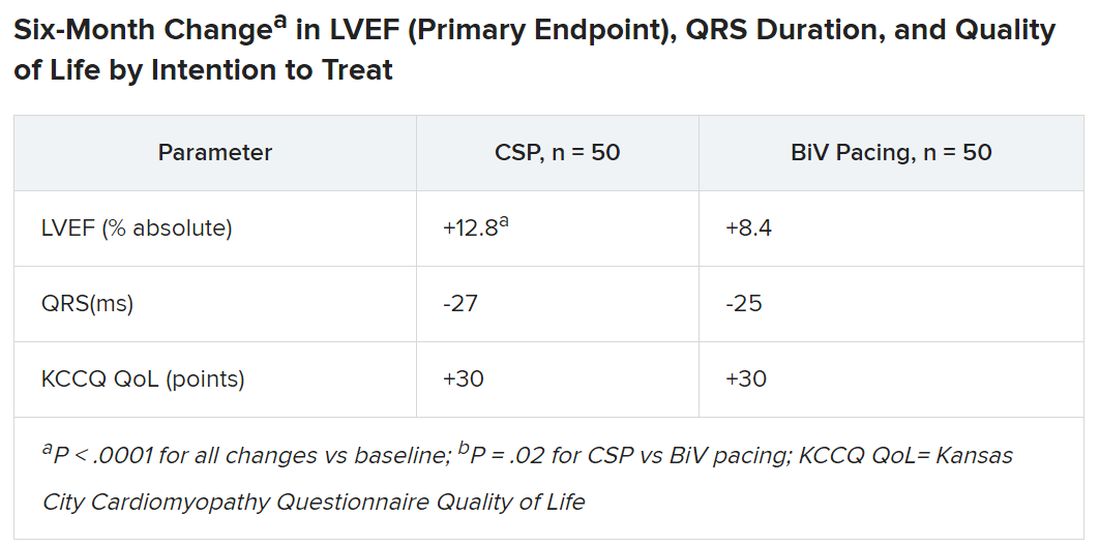

Conducted at three centers in a single health system, the His-optimized cardiac resynchronization therapy study (HOT-CRT) randomly assigned 100 patients with primary or secondary CRT indications to either to CSP – by either His-bundle or LBB-area pacing – or to standard BiV-CRT as the first-line resynchronization method.

Treatment crossovers, allowed for either pacing modality in the event of implantation failure, occurred in two patients and nine patients initially assigned to CSP and BiV pacing, respectively (4% vs. 18%), Dr. Vijayaraman reported.

Historically in trials, BiV pacing has elevated LVEF by about 7%, he said. The mean 12-point increase observed with CSP “is huge, in that sense.” HOT-CRT enrolled a predominantly male and White population at centers highly experienced in both CSP and BiV pacing, limiting its broad relevance to practice, as pointed out by both Dr. Vijayaraman and his presentation’s invited discussant, Yong-Mei Cha, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Dr. Cha, who is director of cardiac device services at her center, also highlighted the greater rate of crossover from BiV pacing to CSP, 18% vs. 4% in the other direction. “This is a very encouraging result,” because the implant-failure rate for LBB-area pacing may drop once more operators become “familiar and skilled with conduction-system pacing.” Overall, the study supports CSP as “a very good alternative for heart failure patients when BiV pacing fails.”

International comparison of CSP and BiV pacing

In Dr. Vijayaraman’s other study, the observational comparison of LBB-area pacing and BiV-CRT, the CSP technique emerged as a “reasonable alternative to biventricular pacing, not only for improvement in LV function but also to reduce adverse clinical outcomes.”

Indeed, in the international study of 1,778 mostly male patients with primary or secondary CRT indications who received LBB-area or BiV pacing (797 and 981 patients, respectively), those on CSP saw a significant drop in risk for the primary endpoint, death or HFH.

Mean LVEF improved from 27% to 41% in the LBB-area pacing group and 27% to 37% with BiV pacing (P < .001 for both changes) over a follow-up averaging 33 months. The difference in improvement between CSP and BiV pacing was significant at P < .001.

In adjusted analysis, the risk for death or HFH was greater for BiV-pacing patients, a difference driven by HFH events.

- Death or HF: hazard ratio, 1.49 (95% confidence interval, 1.21-1.84; P < .001).

- Death: HR, 1.14 (95% CI, 0.88-1.48; P = .313).

- HFH: HR, 1.49 (95% CI, 1.16-1.92; P = .002)

The analysis has all the “inherent biases” of an observational study. The risk for patient-selection bias, however, was somewhat mitigated by consistent practice patterns at participating centers, Dr. Vijayaraman told this news organization.

For example, he said, operators at six of the institutions were most likely to use CSP as the first-line approach, and the same number of centers usually went with BiV pacing.

SYNCHRONY: First-line LBB-area pacing vs. BiV-CRT

Outcomes using the two approaches were similar in the prospective, international, observational study of 371 patients with ischemic or nonischemic cardiomyopathy and standard CRT indications. Allocation of 128 patients to LBB-area pacing and 243 to BiV-CRT was based on patient and operator preferences, reported Jorge Romero Jr, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, at the HRS sessions.

Risk for the death-HFH primary endpoint dropped 38% for those initially treated with LBB-area pacing, compared with BiV pacing, primarily because of a lower HFH risk:

- Death or HFH: HR, 0.62 (95% CI, 0.41-0.93; P = .02).

- Death: HR, 0.57 (95% CI, 0.25-1.32; P = .19).

- HFH: HR, 0.61 (95% CI, 0.34-0.93; P = .02)

Patients in the CSP group were also more likely to improve by at least one NYHA (New York Heart Association) class (80.4% vs. 67.9%; P < .001), consistent with their greater absolute change in LVEF (8.0 vs. 3.9 points; P < .01).

The findings “suggest that LBBAP [left-bundle branch area pacing] is an excellent alternative to BiV pacing,” with a comparable safety profile, write Jayanthi N. Koneru, MBBS, and Kenneth A. Ellenbogen, MD, in an editorial accompanying the published SYNCHRONY report.

“The differences in improvement of LVEF are encouraging for both groups,” but were superior for LBB-area pacing, continue Dr. Koneru and Dr. Ellenbogen, both with Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center, Richmond. “Whether these results would have regressed to the mean over a longer period of follow-up or diverge further with LBB-area pacing continuing to be superior is unknown.”

Years for an answer?

A large randomized comparison of CSP and BiV-CRT, called Left vs. Left, is currently in early stages, Sana M. Al-Khatib, MD, MHS, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., said in a media presentation on two of the presented studies. It has a planned enrollment of more than 2,100 patients on optimal meds with an LVEF of 50% or lower and either a QRS duration of at least 130 ms or an anticipated burden of RV pacing exceeding 40%.

The trial, she said, “will take years to give an answer, but it is actually designed to address the question of whether a composite endpoint of time to death or heart failure hospitalization can be improved with conduction system pacing vs. biventricular pacing.”

Dr. Al-Khatib is a coauthor on the new guideline covering both CSP and BiV-CRT in HF, as are Dr. Cha, Dr. Varma, Dr. Singh, Dr. Vijayaraman, and Dr. Goldberger; Dr. Ellenbogen is one of the reviewers.

Dr. Diaz discloses receiving honoraria or fees for speaking or teaching from Bayer Healthcare, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic. Dr. Vijayaraman discloses receiving honoraria or fees for speaking, teaching, or consulting for Abbott, Medtronic, Biotronik, and Boston Scientific; and receiving research grants from Medtronic. Dr. Varma discloses receiving honoraria or fees for speaking or consulting as an independent contractor for Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Biotronik, Impulse Dynamics USA, Cardiologs, Abbott, Pacemate, Implicity, and EP Solutions. Dr. Singh discloses receiving fees for consulting from EBR Systems, Merit Medical Systems, New Century Health, Biotronik, Abbott, Medtronic, MicroPort Scientific, Cardiologs, Sanofi, CVRx, Impulse Dynamics USA, Octagos, Implicity, Orchestra Biomed, Rhythm Management Group, and Biosense Webster; and receiving honoraria or fees for speaking and teaching from Medscape. Dr. Cha had no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Romero discloses receiving research grants from Biosense Webster; and speaking or receiving honoraria or fees for consulting, speaking, or teaching, or serving on a board for Sanofi, Boston Scientific, and AtriCure. Dr. Koneru discloses consulting for Medtronic and receiving honoraria from Abbott. Dr. Ellenbogen discloses consulting or lecturing for or receiving honoraria from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, and Abbott. Dr. Goldberger discloses receiving royalty income from and serving as an independent contractor for Elsevier. Dr. Al-Khatib discloses receiving research grants from Medtronic and Boston Scientific.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pacing as a device therapy for heart failure (HF) is headed for what is probably its next big advance.

After decades of biventricular (BiV) pacemaker success in resynchronizing the ventricles and improving clinical outcomes, relatively new conduction-system pacing (CSP) techniques that avoid the pitfalls of right-ventricular (RV) pacing using BiV lead systems have been supplanting traditional cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) in selected patients at some major centers. In fact, they are solidly ensconced in a new guideline document addressing indications for CSP and BiV pacing in HF.

But , an alternative when BiV pacing isn’t appropriate or can’t be engaged.

That’s mainly because the limited, mostly observational evidence supporting CSP in the document can’t measure up to the clinical experience and plethora of large, randomized trials behind BiV-CRT.

But that shortfall is headed for change. Several new comparative studies, including a small, randomized trial, have added significantly to evidence suggesting that CSP is at least as effective as traditional CRT for procedural, functional safety, and clinical outcomes.

The new studies “are inherently prone to bias, but their results are really good,” observed Juan C. Diaz, MD. They show improvements in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and symptoms with CSP that are “outstanding compared to what we have been doing for the last 20 years,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Diaz, Clínica Las Vegas, Medellin, Colombia, is an investigator with the observational SYNCHRONY, which is among the new CSP studies formally presented at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society. He is also lead author on its same-day publication in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology.

Dr. Diaz said that CSP, which sustains pacing via the native conduction system, makes more “physiologic sense” than BiV pacing and represents “a step forward” for HF device therapy.

SYNCHRONY compared LBB-area with BiV pacing as the initial strategy for achieving cardiac resynchronization in patients with ischemic or nonischemic cardiomyopathy.

CSP is “a long way” from replacing conventional CRT, he said. But the new studies at the HRS sessions should help extend His-bundle and LBB-area pacing to more patients, he added, given the significant long-term “drawbacks” of BiV pacing. These include inevitable RV pacing, multiple leads, and the risks associated with chronic transvenous leads.

Zachary Goldberger, MD, University of Wisconsin–Madison, went a bit further in support of CSP as invited discussant for the SYNCHRONY presentation.

Given that it improved LVEF, heart failure class, HF hospitalizations (HFH), and mortality in that study and others, Dr. Goldberger said, CSP could potentially “become the dominant mode of resynchronization going forward.”

Other experts at the meeting saw CSP’s potential more as one of several pacing techniques that could be brought to bear for patients with CRT indications.

“Conduction system pacing is going to be a huge complement to biventricular pacing,” to which about 30% of patients have a “less than optimal response,” said Pugazhendhi Vijayaraman, MD, chief of clinical electrophysiology, Geisinger Heart Institute, Danville, Pa.

“I don’t think it needs to replace biventricular pacing, because biventricular pacing is a well-established, incredibly powerful therapy,” he told this news organization. But CSP is likely to provide “a good alternative option” in patients with poor responses to BiV-CRT.

It may, however, render some current BiV-pacing alternatives “obsolete,” Dr. Vijayaraman observed. “At our center, at least for the last 5 years, no patient has needed epicardial surgical left ventricular lead placement” because CSP was a better backup option.

Dr. Vijayaraman presented two of the meeting’s CSP vs. BiV pacing comparisons. In one, the 100-patient randomized HOT-CRT trial, contractile function improved significantly on CSP, which could be either His-bundle or LBB-area pacing.

He also presented an observational study of LBB-area pacing at 15 centers in Asia, Europe, and North America and led the authors of its simultaneous publication in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“I think left-bundle conduction system pacing is the future, for sure,” Jagmeet P. Singh, MD, DPhil, told this news organization. Still, it doesn’t always work and when it does, it “doesn’t work equally in all patients,” he said.

“Conduction system pacing certainly makes a lot of sense,” especially in patients with left-bundle-branch block (LBBB), and “maybe not as a primary approach but certainly as a secondary approach,” said Dr. Singh, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who is not a coauthor on any of the three studies.

He acknowledged that CSP may work well as a first-line option in patients with LBBB at some experienced centers. For those without LBBB or who have an intraventricular conduction delay, who represent 45%-50% of current CRT cases, Dr. Singh observed, “there’s still more evidence” that BiV-CRT is a more appropriate initial approach.

Standard CRT may fail, however, even in some patients who otherwise meet guideline-based indications. “We don’t really understand all the mechanisms for nonresponse in conventional biventricular pacing,” observed Niraj Varma, MD, PhD, Cleveland Clinic, also not involved with any of the three studies.

In some groups, including “patients with larger ventricles,” for example, BiV-CRT doesn’t always narrow the electrocardiographic QRS complex or preexcite delayed left ventricular (LV) activation, hallmarks of successful CRT, he said in an interview.

“I think we need to understand why this occurs in both situations,” but in such cases, CSP alone or as an adjunct to direct LV pacing may be successful. “Sometimes we need both an LV lead and the conduction-system pacing lead.”

Narrower, more efficient use of CSP as a BiV-CRT alternative may also boost its chances for success, Dr. Varma added. “I think we need to refine patient selection.”

HOT-CRT: Randomized CSP vs. BiV pacing trial

Conducted at three centers in a single health system, the His-optimized cardiac resynchronization therapy study (HOT-CRT) randomly assigned 100 patients with primary or secondary CRT indications to either to CSP – by either His-bundle or LBB-area pacing – or to standard BiV-CRT as the first-line resynchronization method.

Treatment crossovers, allowed for either pacing modality in the event of implantation failure, occurred in two patients and nine patients initially assigned to CSP and BiV pacing, respectively (4% vs. 18%), Dr. Vijayaraman reported.

Historically in trials, BiV pacing has elevated LVEF by about 7%, he said. The mean 12-point increase observed with CSP “is huge, in that sense.” HOT-CRT enrolled a predominantly male and White population at centers highly experienced in both CSP and BiV pacing, limiting its broad relevance to practice, as pointed out by both Dr. Vijayaraman and his presentation’s invited discussant, Yong-Mei Cha, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Dr. Cha, who is director of cardiac device services at her center, also highlighted the greater rate of crossover from BiV pacing to CSP, 18% vs. 4% in the other direction. “This is a very encouraging result,” because the implant-failure rate for LBB-area pacing may drop once more operators become “familiar and skilled with conduction-system pacing.” Overall, the study supports CSP as “a very good alternative for heart failure patients when BiV pacing fails.”

International comparison of CSP and BiV pacing

In Dr. Vijayaraman’s other study, the observational comparison of LBB-area pacing and BiV-CRT, the CSP technique emerged as a “reasonable alternative to biventricular pacing, not only for improvement in LV function but also to reduce adverse clinical outcomes.”

Indeed, in the international study of 1,778 mostly male patients with primary or secondary CRT indications who received LBB-area or BiV pacing (797 and 981 patients, respectively), those on CSP saw a significant drop in risk for the primary endpoint, death or HFH.

Mean LVEF improved from 27% to 41% in the LBB-area pacing group and 27% to 37% with BiV pacing (P < .001 for both changes) over a follow-up averaging 33 months. The difference in improvement between CSP and BiV pacing was significant at P < .001.

In adjusted analysis, the risk for death or HFH was greater for BiV-pacing patients, a difference driven by HFH events.

- Death or HF: hazard ratio, 1.49 (95% confidence interval, 1.21-1.84; P < .001).

- Death: HR, 1.14 (95% CI, 0.88-1.48; P = .313).

- HFH: HR, 1.49 (95% CI, 1.16-1.92; P = .002)

The analysis has all the “inherent biases” of an observational study. The risk for patient-selection bias, however, was somewhat mitigated by consistent practice patterns at participating centers, Dr. Vijayaraman told this news organization.

For example, he said, operators at six of the institutions were most likely to use CSP as the first-line approach, and the same number of centers usually went with BiV pacing.

SYNCHRONY: First-line LBB-area pacing vs. BiV-CRT

Outcomes using the two approaches were similar in the prospective, international, observational study of 371 patients with ischemic or nonischemic cardiomyopathy and standard CRT indications. Allocation of 128 patients to LBB-area pacing and 243 to BiV-CRT was based on patient and operator preferences, reported Jorge Romero Jr, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, at the HRS sessions.

Risk for the death-HFH primary endpoint dropped 38% for those initially treated with LBB-area pacing, compared with BiV pacing, primarily because of a lower HFH risk:

- Death or HFH: HR, 0.62 (95% CI, 0.41-0.93; P = .02).

- Death: HR, 0.57 (95% CI, 0.25-1.32; P = .19).

- HFH: HR, 0.61 (95% CI, 0.34-0.93; P = .02)

Patients in the CSP group were also more likely to improve by at least one NYHA (New York Heart Association) class (80.4% vs. 67.9%; P < .001), consistent with their greater absolute change in LVEF (8.0 vs. 3.9 points; P < .01).

The findings “suggest that LBBAP [left-bundle branch area pacing] is an excellent alternative to BiV pacing,” with a comparable safety profile, write Jayanthi N. Koneru, MBBS, and Kenneth A. Ellenbogen, MD, in an editorial accompanying the published SYNCHRONY report.

“The differences in improvement of LVEF are encouraging for both groups,” but were superior for LBB-area pacing, continue Dr. Koneru and Dr. Ellenbogen, both with Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center, Richmond. “Whether these results would have regressed to the mean over a longer period of follow-up or diverge further with LBB-area pacing continuing to be superior is unknown.”

Years for an answer?

A large randomized comparison of CSP and BiV-CRT, called Left vs. Left, is currently in early stages, Sana M. Al-Khatib, MD, MHS, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., said in a media presentation on two of the presented studies. It has a planned enrollment of more than 2,100 patients on optimal meds with an LVEF of 50% or lower and either a QRS duration of at least 130 ms or an anticipated burden of RV pacing exceeding 40%.

The trial, she said, “will take years to give an answer, but it is actually designed to address the question of whether a composite endpoint of time to death or heart failure hospitalization can be improved with conduction system pacing vs. biventricular pacing.”

Dr. Al-Khatib is a coauthor on the new guideline covering both CSP and BiV-CRT in HF, as are Dr. Cha, Dr. Varma, Dr. Singh, Dr. Vijayaraman, and Dr. Goldberger; Dr. Ellenbogen is one of the reviewers.

Dr. Diaz discloses receiving honoraria or fees for speaking or teaching from Bayer Healthcare, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic. Dr. Vijayaraman discloses receiving honoraria or fees for speaking, teaching, or consulting for Abbott, Medtronic, Biotronik, and Boston Scientific; and receiving research grants from Medtronic. Dr. Varma discloses receiving honoraria or fees for speaking or consulting as an independent contractor for Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Biotronik, Impulse Dynamics USA, Cardiologs, Abbott, Pacemate, Implicity, and EP Solutions. Dr. Singh discloses receiving fees for consulting from EBR Systems, Merit Medical Systems, New Century Health, Biotronik, Abbott, Medtronic, MicroPort Scientific, Cardiologs, Sanofi, CVRx, Impulse Dynamics USA, Octagos, Implicity, Orchestra Biomed, Rhythm Management Group, and Biosense Webster; and receiving honoraria or fees for speaking and teaching from Medscape. Dr. Cha had no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Romero discloses receiving research grants from Biosense Webster; and speaking or receiving honoraria or fees for consulting, speaking, or teaching, or serving on a board for Sanofi, Boston Scientific, and AtriCure. Dr. Koneru discloses consulting for Medtronic and receiving honoraria from Abbott. Dr. Ellenbogen discloses consulting or lecturing for or receiving honoraria from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, and Abbott. Dr. Goldberger discloses receiving royalty income from and serving as an independent contractor for Elsevier. Dr. Al-Khatib discloses receiving research grants from Medtronic and Boston Scientific.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pacing as a device therapy for heart failure (HF) is headed for what is probably its next big advance.

After decades of biventricular (BiV) pacemaker success in resynchronizing the ventricles and improving clinical outcomes, relatively new conduction-system pacing (CSP) techniques that avoid the pitfalls of right-ventricular (RV) pacing using BiV lead systems have been supplanting traditional cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) in selected patients at some major centers. In fact, they are solidly ensconced in a new guideline document addressing indications for CSP and BiV pacing in HF.

But , an alternative when BiV pacing isn’t appropriate or can’t be engaged.

That’s mainly because the limited, mostly observational evidence supporting CSP in the document can’t measure up to the clinical experience and plethora of large, randomized trials behind BiV-CRT.

But that shortfall is headed for change. Several new comparative studies, including a small, randomized trial, have added significantly to evidence suggesting that CSP is at least as effective as traditional CRT for procedural, functional safety, and clinical outcomes.

The new studies “are inherently prone to bias, but their results are really good,” observed Juan C. Diaz, MD. They show improvements in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and symptoms with CSP that are “outstanding compared to what we have been doing for the last 20 years,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Diaz, Clínica Las Vegas, Medellin, Colombia, is an investigator with the observational SYNCHRONY, which is among the new CSP studies formally presented at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society. He is also lead author on its same-day publication in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology.

Dr. Diaz said that CSP, which sustains pacing via the native conduction system, makes more “physiologic sense” than BiV pacing and represents “a step forward” for HF device therapy.

SYNCHRONY compared LBB-area with BiV pacing as the initial strategy for achieving cardiac resynchronization in patients with ischemic or nonischemic cardiomyopathy.

CSP is “a long way” from replacing conventional CRT, he said. But the new studies at the HRS sessions should help extend His-bundle and LBB-area pacing to more patients, he added, given the significant long-term “drawbacks” of BiV pacing. These include inevitable RV pacing, multiple leads, and the risks associated with chronic transvenous leads.

Zachary Goldberger, MD, University of Wisconsin–Madison, went a bit further in support of CSP as invited discussant for the SYNCHRONY presentation.

Given that it improved LVEF, heart failure class, HF hospitalizations (HFH), and mortality in that study and others, Dr. Goldberger said, CSP could potentially “become the dominant mode of resynchronization going forward.”

Other experts at the meeting saw CSP’s potential more as one of several pacing techniques that could be brought to bear for patients with CRT indications.

“Conduction system pacing is going to be a huge complement to biventricular pacing,” to which about 30% of patients have a “less than optimal response,” said Pugazhendhi Vijayaraman, MD, chief of clinical electrophysiology, Geisinger Heart Institute, Danville, Pa.

“I don’t think it needs to replace biventricular pacing, because biventricular pacing is a well-established, incredibly powerful therapy,” he told this news organization. But CSP is likely to provide “a good alternative option” in patients with poor responses to BiV-CRT.

It may, however, render some current BiV-pacing alternatives “obsolete,” Dr. Vijayaraman observed. “At our center, at least for the last 5 years, no patient has needed epicardial surgical left ventricular lead placement” because CSP was a better backup option.

Dr. Vijayaraman presented two of the meeting’s CSP vs. BiV pacing comparisons. In one, the 100-patient randomized HOT-CRT trial, contractile function improved significantly on CSP, which could be either His-bundle or LBB-area pacing.

He also presented an observational study of LBB-area pacing at 15 centers in Asia, Europe, and North America and led the authors of its simultaneous publication in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“I think left-bundle conduction system pacing is the future, for sure,” Jagmeet P. Singh, MD, DPhil, told this news organization. Still, it doesn’t always work and when it does, it “doesn’t work equally in all patients,” he said.

“Conduction system pacing certainly makes a lot of sense,” especially in patients with left-bundle-branch block (LBBB), and “maybe not as a primary approach but certainly as a secondary approach,” said Dr. Singh, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who is not a coauthor on any of the three studies.

He acknowledged that CSP may work well as a first-line option in patients with LBBB at some experienced centers. For those without LBBB or who have an intraventricular conduction delay, who represent 45%-50% of current CRT cases, Dr. Singh observed, “there’s still more evidence” that BiV-CRT is a more appropriate initial approach.

Standard CRT may fail, however, even in some patients who otherwise meet guideline-based indications. “We don’t really understand all the mechanisms for nonresponse in conventional biventricular pacing,” observed Niraj Varma, MD, PhD, Cleveland Clinic, also not involved with any of the three studies.

In some groups, including “patients with larger ventricles,” for example, BiV-CRT doesn’t always narrow the electrocardiographic QRS complex or preexcite delayed left ventricular (LV) activation, hallmarks of successful CRT, he said in an interview.

“I think we need to understand why this occurs in both situations,” but in such cases, CSP alone or as an adjunct to direct LV pacing may be successful. “Sometimes we need both an LV lead and the conduction-system pacing lead.”

Narrower, more efficient use of CSP as a BiV-CRT alternative may also boost its chances for success, Dr. Varma added. “I think we need to refine patient selection.”

HOT-CRT: Randomized CSP vs. BiV pacing trial

Conducted at three centers in a single health system, the His-optimized cardiac resynchronization therapy study (HOT-CRT) randomly assigned 100 patients with primary or secondary CRT indications to either to CSP – by either His-bundle or LBB-area pacing – or to standard BiV-CRT as the first-line resynchronization method.

Treatment crossovers, allowed for either pacing modality in the event of implantation failure, occurred in two patients and nine patients initially assigned to CSP and BiV pacing, respectively (4% vs. 18%), Dr. Vijayaraman reported.

Historically in trials, BiV pacing has elevated LVEF by about 7%, he said. The mean 12-point increase observed with CSP “is huge, in that sense.” HOT-CRT enrolled a predominantly male and White population at centers highly experienced in both CSP and BiV pacing, limiting its broad relevance to practice, as pointed out by both Dr. Vijayaraman and his presentation’s invited discussant, Yong-Mei Cha, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Dr. Cha, who is director of cardiac device services at her center, also highlighted the greater rate of crossover from BiV pacing to CSP, 18% vs. 4% in the other direction. “This is a very encouraging result,” because the implant-failure rate for LBB-area pacing may drop once more operators become “familiar and skilled with conduction-system pacing.” Overall, the study supports CSP as “a very good alternative for heart failure patients when BiV pacing fails.”

International comparison of CSP and BiV pacing

In Dr. Vijayaraman’s other study, the observational comparison of LBB-area pacing and BiV-CRT, the CSP technique emerged as a “reasonable alternative to biventricular pacing, not only for improvement in LV function but also to reduce adverse clinical outcomes.”

Indeed, in the international study of 1,778 mostly male patients with primary or secondary CRT indications who received LBB-area or BiV pacing (797 and 981 patients, respectively), those on CSP saw a significant drop in risk for the primary endpoint, death or HFH.

Mean LVEF improved from 27% to 41% in the LBB-area pacing group and 27% to 37% with BiV pacing (P < .001 for both changes) over a follow-up averaging 33 months. The difference in improvement between CSP and BiV pacing was significant at P < .001.

In adjusted analysis, the risk for death or HFH was greater for BiV-pacing patients, a difference driven by HFH events.

- Death or HF: hazard ratio, 1.49 (95% confidence interval, 1.21-1.84; P < .001).

- Death: HR, 1.14 (95% CI, 0.88-1.48; P = .313).

- HFH: HR, 1.49 (95% CI, 1.16-1.92; P = .002)

The analysis has all the “inherent biases” of an observational study. The risk for patient-selection bias, however, was somewhat mitigated by consistent practice patterns at participating centers, Dr. Vijayaraman told this news organization.

For example, he said, operators at six of the institutions were most likely to use CSP as the first-line approach, and the same number of centers usually went with BiV pacing.

SYNCHRONY: First-line LBB-area pacing vs. BiV-CRT

Outcomes using the two approaches were similar in the prospective, international, observational study of 371 patients with ischemic or nonischemic cardiomyopathy and standard CRT indications. Allocation of 128 patients to LBB-area pacing and 243 to BiV-CRT was based on patient and operator preferences, reported Jorge Romero Jr, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, at the HRS sessions.

Risk for the death-HFH primary endpoint dropped 38% for those initially treated with LBB-area pacing, compared with BiV pacing, primarily because of a lower HFH risk:

- Death or HFH: HR, 0.62 (95% CI, 0.41-0.93; P = .02).

- Death: HR, 0.57 (95% CI, 0.25-1.32; P = .19).

- HFH: HR, 0.61 (95% CI, 0.34-0.93; P = .02)

Patients in the CSP group were also more likely to improve by at least one NYHA (New York Heart Association) class (80.4% vs. 67.9%; P < .001), consistent with their greater absolute change in LVEF (8.0 vs. 3.9 points; P < .01).

The findings “suggest that LBBAP [left-bundle branch area pacing] is an excellent alternative to BiV pacing,” with a comparable safety profile, write Jayanthi N. Koneru, MBBS, and Kenneth A. Ellenbogen, MD, in an editorial accompanying the published SYNCHRONY report.

“The differences in improvement of LVEF are encouraging for both groups,” but were superior for LBB-area pacing, continue Dr. Koneru and Dr. Ellenbogen, both with Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center, Richmond. “Whether these results would have regressed to the mean over a longer period of follow-up or diverge further with LBB-area pacing continuing to be superior is unknown.”

Years for an answer?

A large randomized comparison of CSP and BiV-CRT, called Left vs. Left, is currently in early stages, Sana M. Al-Khatib, MD, MHS, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., said in a media presentation on two of the presented studies. It has a planned enrollment of more than 2,100 patients on optimal meds with an LVEF of 50% or lower and either a QRS duration of at least 130 ms or an anticipated burden of RV pacing exceeding 40%.

The trial, she said, “will take years to give an answer, but it is actually designed to address the question of whether a composite endpoint of time to death or heart failure hospitalization can be improved with conduction system pacing vs. biventricular pacing.”

Dr. Al-Khatib is a coauthor on the new guideline covering both CSP and BiV-CRT in HF, as are Dr. Cha, Dr. Varma, Dr. Singh, Dr. Vijayaraman, and Dr. Goldberger; Dr. Ellenbogen is one of the reviewers.

Dr. Diaz discloses receiving honoraria or fees for speaking or teaching from Bayer Healthcare, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic. Dr. Vijayaraman discloses receiving honoraria or fees for speaking, teaching, or consulting for Abbott, Medtronic, Biotronik, and Boston Scientific; and receiving research grants from Medtronic. Dr. Varma discloses receiving honoraria or fees for speaking or consulting as an independent contractor for Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Biotronik, Impulse Dynamics USA, Cardiologs, Abbott, Pacemate, Implicity, and EP Solutions. Dr. Singh discloses receiving fees for consulting from EBR Systems, Merit Medical Systems, New Century Health, Biotronik, Abbott, Medtronic, MicroPort Scientific, Cardiologs, Sanofi, CVRx, Impulse Dynamics USA, Octagos, Implicity, Orchestra Biomed, Rhythm Management Group, and Biosense Webster; and receiving honoraria or fees for speaking and teaching from Medscape. Dr. Cha had no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Romero discloses receiving research grants from Biosense Webster; and speaking or receiving honoraria or fees for consulting, speaking, or teaching, or serving on a board for Sanofi, Boston Scientific, and AtriCure. Dr. Koneru discloses consulting for Medtronic and receiving honoraria from Abbott. Dr. Ellenbogen discloses consulting or lecturing for or receiving honoraria from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, and Abbott. Dr. Goldberger discloses receiving royalty income from and serving as an independent contractor for Elsevier. Dr. Al-Khatib discloses receiving research grants from Medtronic and Boston Scientific.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM HEART RHYTHM 2023

Dapagliflozin matches non–loop diuretic for congestion in AHF: DAPA-RESIST

suggests a new randomized trial. The drugs were given to the study’s loop diuretic–resistant patients on top of furosemide.

Changes in volume status and measures of pulmonary congestion and risk for serious adverse events were similar for those assigned to take dapagliflozin, an SGLT2 inhibitor, or metolazone, a quinazoline diuretic. Those on dapagliflozin zone ultimately received a larger cumulative furosemide dose in the 61-patient trial, called DAPA-RESIST.

“The next steps are to assess whether a strategy of using SGLT2 inhibitors up front in patients with HF reduces the incidence of diuretic resistance, and to test further combinations of diuretics such as thiazide or thiazide-like diuretics, compared with acetazolamide, when used in addition to an IV loop diuretic and SGLT2 inhibitors together,” Ross T. Campbell, MBChB, PhD, University of Glasgow and Queen Elizabeth University Hospital, also in Glasgow, said in an interview.

Dr. Campbell presented the findings at the annual meeting of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology and is senior author on its simultaneous publication in the European Heart Journal.

The multicenter trial randomly assigned 61 patients with AHF to receive dapagliflozin at a fixed dose of 10 mg once daily or metolazone 5 mg or 10 mg (starting dosage at physician discretion) once daily for 3 days of treatment on an open-label basis.

Patients had entered the trial on furosemide at a mean daily dosage of 260 mg in the dapagliflozin group and 229 mg for those assigned metolazone; dosages for the loop diuretic in the trial weren’t prespecified.

Their median age was 79 and 54% were women; 44% had HF with reduced ejection fraction. Their mean glomerular filtration rate was below 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in 26%, 90% had chronic kidney disease, 98% had peripheral edema, and 46% had diabetes.