User login

‘The pandemic within the pandemic’

The coronavirus has infected millions of Americans and killed over 174,000. But could it be worse? Maybe.

“Racism is the pandemic within the pandemic,” Marc H. Morial, president and CEO of the National Urban League, said in the 2020 “State of Black America, Unmasked” report.

“Black people with COVID-19 symptoms in February and March were less likely to get tested or treated than white patients,” he wrote.

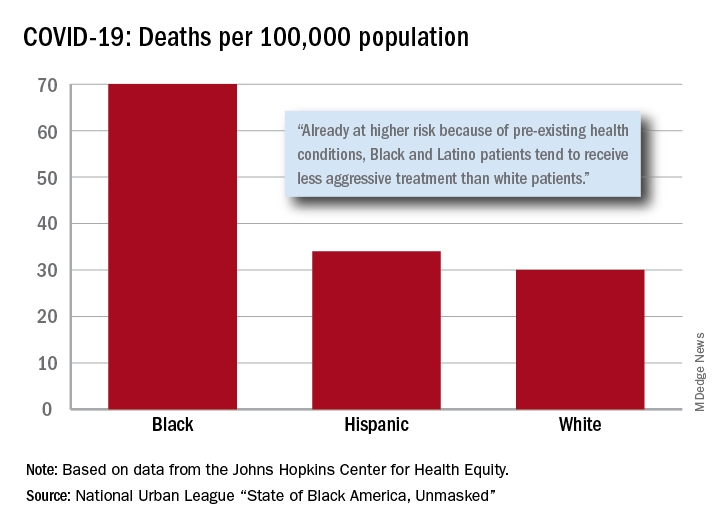

After less testing and less treatment, the next step seems inevitable. The death rate from COVID-19 is 70 per 100,000 population among Black Americans, compared with 30 per 100,000 for Whites and 34 per 100,000 for Hispanics, the league said based on data from the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Equity.

Black and Hispanic patients with COVID-19 are more likely to have preexisting health conditions, but they “tend to receive less aggressive treatment than white patients,” the report noted. The lower death rate among Hispanics may be explained by the Black population’s greater age, although Hispanic Americans have a higher infection rate (73 per 10,000) than Blacks (62 per 10,000) or Whites (23 per 10,000).

Another possible explanation for the differences in infection rates: Blacks and Hispanics are less able to work at home because they “are overrepresented in low-wage jobs that offer the least flexibility and increase their risk of exposure to the coronavirus,” the league said.

Hispanics and Blacks also are more likely to be uninsured than Whites – 19.5% and 11.5%, respectively, vs. 7.5% – so “they tend to delay seeking treatment and are sicker than white patients when they finally do,” the league said. That may account for their much higher COVID-19 hospitalization rates: 213 per 100,000 for Blacks, 205 for Hispanics, and 46 for Whites.

“The silver lining during these dark times is that this pandemic has revealed our shared vulnerability and our interconnectedness. Many people are beginning to see that when others don’t have the opportunity to be healthy, it puts all of us at risk,” Lisa Cooper, MD, James F. Fries Professor of Medicine and Bloomberg Distinguished Professor in Health Equity at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, wrote in an essay accompanying the report.

The coronavirus has infected millions of Americans and killed over 174,000. But could it be worse? Maybe.

“Racism is the pandemic within the pandemic,” Marc H. Morial, president and CEO of the National Urban League, said in the 2020 “State of Black America, Unmasked” report.

“Black people with COVID-19 symptoms in February and March were less likely to get tested or treated than white patients,” he wrote.

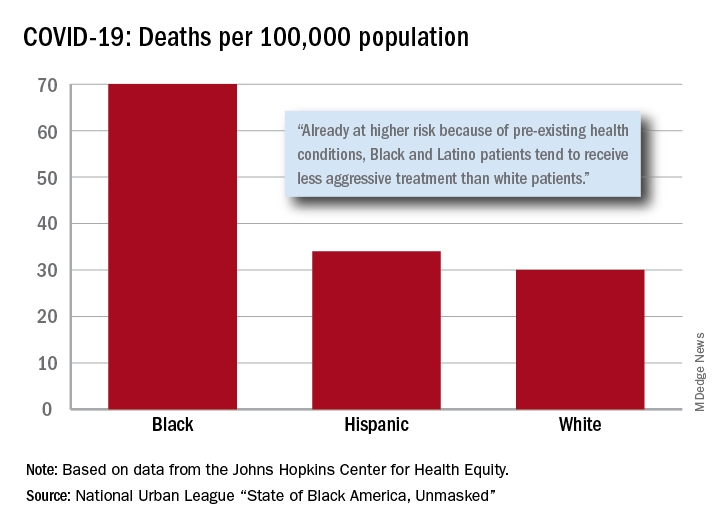

After less testing and less treatment, the next step seems inevitable. The death rate from COVID-19 is 70 per 100,000 population among Black Americans, compared with 30 per 100,000 for Whites and 34 per 100,000 for Hispanics, the league said based on data from the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Equity.

Black and Hispanic patients with COVID-19 are more likely to have preexisting health conditions, but they “tend to receive less aggressive treatment than white patients,” the report noted. The lower death rate among Hispanics may be explained by the Black population’s greater age, although Hispanic Americans have a higher infection rate (73 per 10,000) than Blacks (62 per 10,000) or Whites (23 per 10,000).

Another possible explanation for the differences in infection rates: Blacks and Hispanics are less able to work at home because they “are overrepresented in low-wage jobs that offer the least flexibility and increase their risk of exposure to the coronavirus,” the league said.

Hispanics and Blacks also are more likely to be uninsured than Whites – 19.5% and 11.5%, respectively, vs. 7.5% – so “they tend to delay seeking treatment and are sicker than white patients when they finally do,” the league said. That may account for their much higher COVID-19 hospitalization rates: 213 per 100,000 for Blacks, 205 for Hispanics, and 46 for Whites.

“The silver lining during these dark times is that this pandemic has revealed our shared vulnerability and our interconnectedness. Many people are beginning to see that when others don’t have the opportunity to be healthy, it puts all of us at risk,” Lisa Cooper, MD, James F. Fries Professor of Medicine and Bloomberg Distinguished Professor in Health Equity at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, wrote in an essay accompanying the report.

The coronavirus has infected millions of Americans and killed over 174,000. But could it be worse? Maybe.

“Racism is the pandemic within the pandemic,” Marc H. Morial, president and CEO of the National Urban League, said in the 2020 “State of Black America, Unmasked” report.

“Black people with COVID-19 symptoms in February and March were less likely to get tested or treated than white patients,” he wrote.

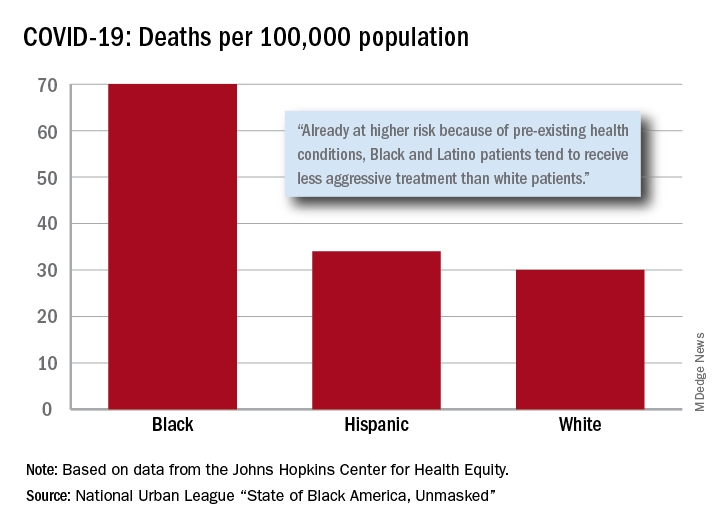

After less testing and less treatment, the next step seems inevitable. The death rate from COVID-19 is 70 per 100,000 population among Black Americans, compared with 30 per 100,000 for Whites and 34 per 100,000 for Hispanics, the league said based on data from the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Equity.

Black and Hispanic patients with COVID-19 are more likely to have preexisting health conditions, but they “tend to receive less aggressive treatment than white patients,” the report noted. The lower death rate among Hispanics may be explained by the Black population’s greater age, although Hispanic Americans have a higher infection rate (73 per 10,000) than Blacks (62 per 10,000) or Whites (23 per 10,000).

Another possible explanation for the differences in infection rates: Blacks and Hispanics are less able to work at home because they “are overrepresented in low-wage jobs that offer the least flexibility and increase their risk of exposure to the coronavirus,” the league said.

Hispanics and Blacks also are more likely to be uninsured than Whites – 19.5% and 11.5%, respectively, vs. 7.5% – so “they tend to delay seeking treatment and are sicker than white patients when they finally do,” the league said. That may account for their much higher COVID-19 hospitalization rates: 213 per 100,000 for Blacks, 205 for Hispanics, and 46 for Whites.

“The silver lining during these dark times is that this pandemic has revealed our shared vulnerability and our interconnectedness. Many people are beginning to see that when others don’t have the opportunity to be healthy, it puts all of us at risk,” Lisa Cooper, MD, James F. Fries Professor of Medicine and Bloomberg Distinguished Professor in Health Equity at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, wrote in an essay accompanying the report.

COVID-19 plans put to test as firefighters crowd camps for peak wildfire season

Jon Paul was leery entering his first wildfire camp of the year late last month to fight three lightning-caused fires scorching parts of a Northern California forest that hadn’t burned in 40 years.

The 54-year-old engine captain from southern Oregon knew from experience that these crowded, grimy camps can be breeding grounds for norovirus and a respiratory illness that firefighters call the “camp crud” in a normal year. He wondered what the coronavirus would do in the tent cities where hundreds of men and women eat, sleep, wash, and spend their downtime between shifts.

Mr. Paul thought about his immunocompromised wife and his 84-year-old mother back home. Then he joined the approximately 1,300 people spread across the Modoc National Forest who would provide a major test for the COVID-prevention measures that had been developed for wildland firefighters.

“We’re still first responders and we have that responsibility to go and deal with these emergencies,” he said in a recent interview. “I don’t scare easy, but I’m very wary and concerned about my surroundings. I’m still going to work and do my job.”

Mr. Paul is one of thousands of firefighters from across the United States battling dozens of wildfires burning throughout the West. It’s an inherently dangerous job that now carries the additional risk of COVID-19 transmission. Any outbreak that ripples through a camp could easily sideline crews and spread the virus across multiple fires – and back to communities across the country – as personnel transfer in and out of “hot zones” and return home.

Though most firefighters are young and fit, some will inevitably fall ill in these remote makeshift communities of shared showers and portable toilets, where medical care can be limited. The pollutants in the smoke they breathe daily also make them more susceptible to COVID-19 and can worsen the effects of the disease, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Also, one suspected or positive case in a camp will mean many other firefighters will need to be quarantined, unable to work. The worst-case scenario is that multiple outbreaks could hamstring the nation’s ability to respond as wildfire season peaks in August, the hottest and driest month of the year in the western United States.

The number of acres burned so far this year is below the 10-year average, but the fire outlook for August is above average in nine states, according to the National Interagency Fire Center. Twenty-two large fires were ignited on Monday alone after lightning storms passed through the Northwest.

A study published this month by researchers at Colorado State University and the U.S. Forest Service’s Rocky Mountain Research Station concluded that COVID outbreaks “could be a serious threat to the firefighting mission” and urged vigilant social distancing and screening measures in the camps.

“If simultaneous fires incurred outbreaks, the entire wildland response system could be stressed substantially, with a large portion of the workforce quarantined,” the study’s authors wrote.

This spring, the National Wildfire Coordinating Group’s Fire Management Board wrote – and has since been updating – protocols to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in fire camps, based on CDC guidelines. Though they can be adapted by managers at different fires and even by individual team, they center on some key recommendations, including the following:

- Firefighters should be screened for fever and other COVID symptoms when they arrive at camp.

- Every crew should insulate itself as a “module of one” for the fire season and limit interactions with other crews.

- Firefighters should maintain social distancing and wear face coverings when social distancing isn’t possible. Smaller satellite camps, known as spike camps, can be built to ensure enough space.

- Shared areas should be regularly cleaned and disinfected, and sharing tools and radios should be minimized.

The guidance does not include routine testing of newly arrived firefighters – a practice used for athletes at training camps and students returning to college campuses.

The Fire Management Board’s Wildland Fire Medical and Public Health Advisory Team wrote in a July 2 memo that it “does not recommend utilizing universal COVID-19 laboratory testing as a standalone risk mitigation or screening measure among wildland firefighters.” Rather, the group recommends testing an individual and directly exposed coworkers, saying that approach is in line with CDC guidance.

The lack of testing capacity and long turnaround times are factors, according to Forest Service spokesperson Dan Hottle.

The exception is Alaska, where firefighters are tested upon arrival at the airport and are quarantined in a hotel while awaiting results, which come within 24 hours, Mr. Hottle said.

Fire crews responding to early-season fires in the spring had some problems adjusting to the new protocols, according to assessments written by fire leaders and compiled by the Wildland Fire Lessons Learned Center.

Shawn Faiella, superintendent of the interagency “hotshot crew” – so named because they work the most challenging or “hottest” parts of wildfires – based at Montana’s Lolo National Forest, questioned the need to wear masks inside vehicles and the safety of bringing extra vehicles to space out firefighters traveling to a blaze. Parking extra vehicles at the scene of a fire is difficult in tight dirt roads – and would be dangerous if evacuations are necessary, he wrote.

“It’s damn tough to take these practices to the fire line,” Mr. Faiella wrote after his team responded to a 40-acre Montana fire in April.

One recommendation that fire managers say has been particularly effective is the “module of one” concept requiring crews to eat and sleep together in isolation for the entire fire season.

“Whoever came up with it, it is working,” said Mike Goicoechea, the Montana-based incident commander for the Forest Service’s Northern Region Type 1 team, which manages the nation’s largest and most complex wildfires and natural disasters. “Somebody may test positive, and you end up having to take that module out of service for 14 days. But the nice part is you’re not taking out a whole camp. ... It’s just that module.”

The total number of positive COVID cases among wildland firefighters among the various federal, state, local, and tribal agencies is not being tracked. Each fire agency has its own system for tracking and reporting COVID-19, said Jessica Gardetto, a spokesperson for the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the National Interagency Fire Center in Idaho.

The largest wildland firefighting agency is the Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service, with 10,000 firefighters. Another major agency is the Department of the Interior, which BLM is part of and which had more than 3,500 full-time fire employees last year. As of the first week of August, 111 Forest Service firefighters and 40 BLM firefighters (who work underneath the broader Interior Department agency) had tested positive for COVID-19, according to officials for the respective agencies.

“Considering we’ve now been experiencing fire activity for several months, this number is surprisingly low if you think about the thousands of fire personnel who’ve been suppressing wildfires this summer,” Ms. Gardetto said.

Mr. Goicoechea and his Montana team traveled north of Tucson, Arizona, on June 22 to manage a rapidly spreading fire in the Santa Catalina Mountains that required 1,200 responders at its peak. Within 2 days of the team’s arrival, his managers were overwhelmed by calls from firefighters worried or with questions about preventing the spread of COVID-19 or carrying the virus home to their families.

In an unusual move, Mr. Goicoechea called upon Montana physician – and former National Park Service ranger with wildfire experience – Harry Sibold, MD, to join the team. Physicians are rarely, if ever, part of a wildfire camp’s medical team, Mr. Goicoechea said.

Dr. Sibold gave regular coronavirus updates during morning briefings, consulted with local health officials, soothed firefighters worried about bringing the virus home to their families, and advised fire managers on how to handle scenarios that might come up.

But Dr. Sibold said he wasn’t optimistic at the beginning about keeping the coronavirus in check in a large camp in Pima County, which has the second-highest number of confirmed cases in Arizona, at the time a national COVID-19 hot spot. “I quite firmly expected that we might have two or three outbreaks,” he said.

There were no positive cases during the team’s 2-week deployment, just three or four cases in which a firefighter showed symptoms but tested negative for the virus. After the Montana team returned home, nine firefighters at the Arizona fire from other units tested positive, Mr. Goicoechea said. Contact tracers notified the Montana team, some of whom were tested. All tests returned negative.

“I can’t say enough about having that doctor to help,” Mr. Goicoechea said, suggesting other teams might consider doing the same. “We’re not the experts in a pandemic. We’re the experts with fire.”

That early success will be tested as the number of fires increases across the West, along with the number of firefighters responding to them. There were more than 15,000 firefighters and support personnel assigned to fires across the nation as of mid-August, and the success of those COVID-19 prevention protocols depend largely on them.

Mr. Paul, the Oregon firefighter, said that the guidelines were followed closely in camp, but less so out on the fire line. It also appeared to him that younger firefighters were less likely to follow the masking and social-distancing rules than the veterans like him. That worried him as he realized it wouldn’t take much to spark an outbreak that could sideline crews and cripple the ability to respond to a fire.

“We’re outside, so it definitely helps with mitigation and makes it simpler to social distance,” Mr. Paul said. “But I think if there’s a mistake made, it could happen.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Jon Paul was leery entering his first wildfire camp of the year late last month to fight three lightning-caused fires scorching parts of a Northern California forest that hadn’t burned in 40 years.

The 54-year-old engine captain from southern Oregon knew from experience that these crowded, grimy camps can be breeding grounds for norovirus and a respiratory illness that firefighters call the “camp crud” in a normal year. He wondered what the coronavirus would do in the tent cities where hundreds of men and women eat, sleep, wash, and spend their downtime between shifts.

Mr. Paul thought about his immunocompromised wife and his 84-year-old mother back home. Then he joined the approximately 1,300 people spread across the Modoc National Forest who would provide a major test for the COVID-prevention measures that had been developed for wildland firefighters.

“We’re still first responders and we have that responsibility to go and deal with these emergencies,” he said in a recent interview. “I don’t scare easy, but I’m very wary and concerned about my surroundings. I’m still going to work and do my job.”

Mr. Paul is one of thousands of firefighters from across the United States battling dozens of wildfires burning throughout the West. It’s an inherently dangerous job that now carries the additional risk of COVID-19 transmission. Any outbreak that ripples through a camp could easily sideline crews and spread the virus across multiple fires – and back to communities across the country – as personnel transfer in and out of “hot zones” and return home.

Though most firefighters are young and fit, some will inevitably fall ill in these remote makeshift communities of shared showers and portable toilets, where medical care can be limited. The pollutants in the smoke they breathe daily also make them more susceptible to COVID-19 and can worsen the effects of the disease, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Also, one suspected or positive case in a camp will mean many other firefighters will need to be quarantined, unable to work. The worst-case scenario is that multiple outbreaks could hamstring the nation’s ability to respond as wildfire season peaks in August, the hottest and driest month of the year in the western United States.

The number of acres burned so far this year is below the 10-year average, but the fire outlook for August is above average in nine states, according to the National Interagency Fire Center. Twenty-two large fires were ignited on Monday alone after lightning storms passed through the Northwest.

A study published this month by researchers at Colorado State University and the U.S. Forest Service’s Rocky Mountain Research Station concluded that COVID outbreaks “could be a serious threat to the firefighting mission” and urged vigilant social distancing and screening measures in the camps.

“If simultaneous fires incurred outbreaks, the entire wildland response system could be stressed substantially, with a large portion of the workforce quarantined,” the study’s authors wrote.

This spring, the National Wildfire Coordinating Group’s Fire Management Board wrote – and has since been updating – protocols to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in fire camps, based on CDC guidelines. Though they can be adapted by managers at different fires and even by individual team, they center on some key recommendations, including the following:

- Firefighters should be screened for fever and other COVID symptoms when they arrive at camp.

- Every crew should insulate itself as a “module of one” for the fire season and limit interactions with other crews.

- Firefighters should maintain social distancing and wear face coverings when social distancing isn’t possible. Smaller satellite camps, known as spike camps, can be built to ensure enough space.

- Shared areas should be regularly cleaned and disinfected, and sharing tools and radios should be minimized.

The guidance does not include routine testing of newly arrived firefighters – a practice used for athletes at training camps and students returning to college campuses.

The Fire Management Board’s Wildland Fire Medical and Public Health Advisory Team wrote in a July 2 memo that it “does not recommend utilizing universal COVID-19 laboratory testing as a standalone risk mitigation or screening measure among wildland firefighters.” Rather, the group recommends testing an individual and directly exposed coworkers, saying that approach is in line with CDC guidance.

The lack of testing capacity and long turnaround times are factors, according to Forest Service spokesperson Dan Hottle.

The exception is Alaska, where firefighters are tested upon arrival at the airport and are quarantined in a hotel while awaiting results, which come within 24 hours, Mr. Hottle said.

Fire crews responding to early-season fires in the spring had some problems adjusting to the new protocols, according to assessments written by fire leaders and compiled by the Wildland Fire Lessons Learned Center.

Shawn Faiella, superintendent of the interagency “hotshot crew” – so named because they work the most challenging or “hottest” parts of wildfires – based at Montana’s Lolo National Forest, questioned the need to wear masks inside vehicles and the safety of bringing extra vehicles to space out firefighters traveling to a blaze. Parking extra vehicles at the scene of a fire is difficult in tight dirt roads – and would be dangerous if evacuations are necessary, he wrote.

“It’s damn tough to take these practices to the fire line,” Mr. Faiella wrote after his team responded to a 40-acre Montana fire in April.

One recommendation that fire managers say has been particularly effective is the “module of one” concept requiring crews to eat and sleep together in isolation for the entire fire season.

“Whoever came up with it, it is working,” said Mike Goicoechea, the Montana-based incident commander for the Forest Service’s Northern Region Type 1 team, which manages the nation’s largest and most complex wildfires and natural disasters. “Somebody may test positive, and you end up having to take that module out of service for 14 days. But the nice part is you’re not taking out a whole camp. ... It’s just that module.”

The total number of positive COVID cases among wildland firefighters among the various federal, state, local, and tribal agencies is not being tracked. Each fire agency has its own system for tracking and reporting COVID-19, said Jessica Gardetto, a spokesperson for the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the National Interagency Fire Center in Idaho.

The largest wildland firefighting agency is the Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service, with 10,000 firefighters. Another major agency is the Department of the Interior, which BLM is part of and which had more than 3,500 full-time fire employees last year. As of the first week of August, 111 Forest Service firefighters and 40 BLM firefighters (who work underneath the broader Interior Department agency) had tested positive for COVID-19, according to officials for the respective agencies.

“Considering we’ve now been experiencing fire activity for several months, this number is surprisingly low if you think about the thousands of fire personnel who’ve been suppressing wildfires this summer,” Ms. Gardetto said.

Mr. Goicoechea and his Montana team traveled north of Tucson, Arizona, on June 22 to manage a rapidly spreading fire in the Santa Catalina Mountains that required 1,200 responders at its peak. Within 2 days of the team’s arrival, his managers were overwhelmed by calls from firefighters worried or with questions about preventing the spread of COVID-19 or carrying the virus home to their families.

In an unusual move, Mr. Goicoechea called upon Montana physician – and former National Park Service ranger with wildfire experience – Harry Sibold, MD, to join the team. Physicians are rarely, if ever, part of a wildfire camp’s medical team, Mr. Goicoechea said.

Dr. Sibold gave regular coronavirus updates during morning briefings, consulted with local health officials, soothed firefighters worried about bringing the virus home to their families, and advised fire managers on how to handle scenarios that might come up.

But Dr. Sibold said he wasn’t optimistic at the beginning about keeping the coronavirus in check in a large camp in Pima County, which has the second-highest number of confirmed cases in Arizona, at the time a national COVID-19 hot spot. “I quite firmly expected that we might have two or three outbreaks,” he said.

There were no positive cases during the team’s 2-week deployment, just three or four cases in which a firefighter showed symptoms but tested negative for the virus. After the Montana team returned home, nine firefighters at the Arizona fire from other units tested positive, Mr. Goicoechea said. Contact tracers notified the Montana team, some of whom were tested. All tests returned negative.

“I can’t say enough about having that doctor to help,” Mr. Goicoechea said, suggesting other teams might consider doing the same. “We’re not the experts in a pandemic. We’re the experts with fire.”

That early success will be tested as the number of fires increases across the West, along with the number of firefighters responding to them. There were more than 15,000 firefighters and support personnel assigned to fires across the nation as of mid-August, and the success of those COVID-19 prevention protocols depend largely on them.

Mr. Paul, the Oregon firefighter, said that the guidelines were followed closely in camp, but less so out on the fire line. It also appeared to him that younger firefighters were less likely to follow the masking and social-distancing rules than the veterans like him. That worried him as he realized it wouldn’t take much to spark an outbreak that could sideline crews and cripple the ability to respond to a fire.

“We’re outside, so it definitely helps with mitigation and makes it simpler to social distance,” Mr. Paul said. “But I think if there’s a mistake made, it could happen.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Jon Paul was leery entering his first wildfire camp of the year late last month to fight three lightning-caused fires scorching parts of a Northern California forest that hadn’t burned in 40 years.

The 54-year-old engine captain from southern Oregon knew from experience that these crowded, grimy camps can be breeding grounds for norovirus and a respiratory illness that firefighters call the “camp crud” in a normal year. He wondered what the coronavirus would do in the tent cities where hundreds of men and women eat, sleep, wash, and spend their downtime between shifts.

Mr. Paul thought about his immunocompromised wife and his 84-year-old mother back home. Then he joined the approximately 1,300 people spread across the Modoc National Forest who would provide a major test for the COVID-prevention measures that had been developed for wildland firefighters.

“We’re still first responders and we have that responsibility to go and deal with these emergencies,” he said in a recent interview. “I don’t scare easy, but I’m very wary and concerned about my surroundings. I’m still going to work and do my job.”

Mr. Paul is one of thousands of firefighters from across the United States battling dozens of wildfires burning throughout the West. It’s an inherently dangerous job that now carries the additional risk of COVID-19 transmission. Any outbreak that ripples through a camp could easily sideline crews and spread the virus across multiple fires – and back to communities across the country – as personnel transfer in and out of “hot zones” and return home.

Though most firefighters are young and fit, some will inevitably fall ill in these remote makeshift communities of shared showers and portable toilets, where medical care can be limited. The pollutants in the smoke they breathe daily also make them more susceptible to COVID-19 and can worsen the effects of the disease, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Also, one suspected or positive case in a camp will mean many other firefighters will need to be quarantined, unable to work. The worst-case scenario is that multiple outbreaks could hamstring the nation’s ability to respond as wildfire season peaks in August, the hottest and driest month of the year in the western United States.

The number of acres burned so far this year is below the 10-year average, but the fire outlook for August is above average in nine states, according to the National Interagency Fire Center. Twenty-two large fires were ignited on Monday alone after lightning storms passed through the Northwest.

A study published this month by researchers at Colorado State University and the U.S. Forest Service’s Rocky Mountain Research Station concluded that COVID outbreaks “could be a serious threat to the firefighting mission” and urged vigilant social distancing and screening measures in the camps.

“If simultaneous fires incurred outbreaks, the entire wildland response system could be stressed substantially, with a large portion of the workforce quarantined,” the study’s authors wrote.

This spring, the National Wildfire Coordinating Group’s Fire Management Board wrote – and has since been updating – protocols to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in fire camps, based on CDC guidelines. Though they can be adapted by managers at different fires and even by individual team, they center on some key recommendations, including the following:

- Firefighters should be screened for fever and other COVID symptoms when they arrive at camp.

- Every crew should insulate itself as a “module of one” for the fire season and limit interactions with other crews.

- Firefighters should maintain social distancing and wear face coverings when social distancing isn’t possible. Smaller satellite camps, known as spike camps, can be built to ensure enough space.

- Shared areas should be regularly cleaned and disinfected, and sharing tools and radios should be minimized.

The guidance does not include routine testing of newly arrived firefighters – a practice used for athletes at training camps and students returning to college campuses.

The Fire Management Board’s Wildland Fire Medical and Public Health Advisory Team wrote in a July 2 memo that it “does not recommend utilizing universal COVID-19 laboratory testing as a standalone risk mitigation or screening measure among wildland firefighters.” Rather, the group recommends testing an individual and directly exposed coworkers, saying that approach is in line with CDC guidance.

The lack of testing capacity and long turnaround times are factors, according to Forest Service spokesperson Dan Hottle.

The exception is Alaska, where firefighters are tested upon arrival at the airport and are quarantined in a hotel while awaiting results, which come within 24 hours, Mr. Hottle said.

Fire crews responding to early-season fires in the spring had some problems adjusting to the new protocols, according to assessments written by fire leaders and compiled by the Wildland Fire Lessons Learned Center.

Shawn Faiella, superintendent of the interagency “hotshot crew” – so named because they work the most challenging or “hottest” parts of wildfires – based at Montana’s Lolo National Forest, questioned the need to wear masks inside vehicles and the safety of bringing extra vehicles to space out firefighters traveling to a blaze. Parking extra vehicles at the scene of a fire is difficult in tight dirt roads – and would be dangerous if evacuations are necessary, he wrote.

“It’s damn tough to take these practices to the fire line,” Mr. Faiella wrote after his team responded to a 40-acre Montana fire in April.

One recommendation that fire managers say has been particularly effective is the “module of one” concept requiring crews to eat and sleep together in isolation for the entire fire season.

“Whoever came up with it, it is working,” said Mike Goicoechea, the Montana-based incident commander for the Forest Service’s Northern Region Type 1 team, which manages the nation’s largest and most complex wildfires and natural disasters. “Somebody may test positive, and you end up having to take that module out of service for 14 days. But the nice part is you’re not taking out a whole camp. ... It’s just that module.”

The total number of positive COVID cases among wildland firefighters among the various federal, state, local, and tribal agencies is not being tracked. Each fire agency has its own system for tracking and reporting COVID-19, said Jessica Gardetto, a spokesperson for the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the National Interagency Fire Center in Idaho.

The largest wildland firefighting agency is the Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service, with 10,000 firefighters. Another major agency is the Department of the Interior, which BLM is part of and which had more than 3,500 full-time fire employees last year. As of the first week of August, 111 Forest Service firefighters and 40 BLM firefighters (who work underneath the broader Interior Department agency) had tested positive for COVID-19, according to officials for the respective agencies.

“Considering we’ve now been experiencing fire activity for several months, this number is surprisingly low if you think about the thousands of fire personnel who’ve been suppressing wildfires this summer,” Ms. Gardetto said.

Mr. Goicoechea and his Montana team traveled north of Tucson, Arizona, on June 22 to manage a rapidly spreading fire in the Santa Catalina Mountains that required 1,200 responders at its peak. Within 2 days of the team’s arrival, his managers were overwhelmed by calls from firefighters worried or with questions about preventing the spread of COVID-19 or carrying the virus home to their families.

In an unusual move, Mr. Goicoechea called upon Montana physician – and former National Park Service ranger with wildfire experience – Harry Sibold, MD, to join the team. Physicians are rarely, if ever, part of a wildfire camp’s medical team, Mr. Goicoechea said.

Dr. Sibold gave regular coronavirus updates during morning briefings, consulted with local health officials, soothed firefighters worried about bringing the virus home to their families, and advised fire managers on how to handle scenarios that might come up.

But Dr. Sibold said he wasn’t optimistic at the beginning about keeping the coronavirus in check in a large camp in Pima County, which has the second-highest number of confirmed cases in Arizona, at the time a national COVID-19 hot spot. “I quite firmly expected that we might have two or three outbreaks,” he said.

There were no positive cases during the team’s 2-week deployment, just three or four cases in which a firefighter showed symptoms but tested negative for the virus. After the Montana team returned home, nine firefighters at the Arizona fire from other units tested positive, Mr. Goicoechea said. Contact tracers notified the Montana team, some of whom were tested. All tests returned negative.

“I can’t say enough about having that doctor to help,” Mr. Goicoechea said, suggesting other teams might consider doing the same. “We’re not the experts in a pandemic. We’re the experts with fire.”

That early success will be tested as the number of fires increases across the West, along with the number of firefighters responding to them. There were more than 15,000 firefighters and support personnel assigned to fires across the nation as of mid-August, and the success of those COVID-19 prevention protocols depend largely on them.

Mr. Paul, the Oregon firefighter, said that the guidelines were followed closely in camp, but less so out on the fire line. It also appeared to him that younger firefighters were less likely to follow the masking and social-distancing rules than the veterans like him. That worried him as he realized it wouldn’t take much to spark an outbreak that could sideline crews and cripple the ability to respond to a fire.

“We’re outside, so it definitely helps with mitigation and makes it simpler to social distance,” Mr. Paul said. “But I think if there’s a mistake made, it could happen.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Pulmonary rehab reduces COPD readmissions

Pulmonary rehabilitation reduces the likelihood that patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) will be readmitted to the hospital in the year after discharge by 33%, new research shows, but few patients participate in those programs.

In fact, in a retrospective cohort of 197,376 patients from 4446 hospitals, only 1.5% of patients initiated pulmonary rehabilitation in the 90 days after hospital discharge.

“This is a striking finding,” said Mihaela Stefan, PhD, from the University of Massachusetts Medical School–Baystate in Springfield. “Our study demonstrates that we need to increase access to rehabilitation to reduce the risk of readmissions.”

Not enough patients are initiating rehabilitation, but the onus is not only on them; the system is failing them. “We wanted to understand how much pulmonary rehabilitation lowers the readmission rate,” Stefan told Medscape Medical News.

So she and her colleagues examined the records of patients who were hospitalized for COPD in 2014 to see whether they had begun rehabilitation in the 90 days after discharge and whether they were readmitted to the hospital in the subsequent 12 months.

Patients who were unlikely to initiate pulmonary rehabilitation — such as those with dementia or metastatic cancer and those discharged to hospice care or a nursing home — were excluded from the analysis, Stefan said during her presentation at the study results at the virtual American Thoracic Society (ATS) 2020 International Conference.

The risk analysis was complex because many patients died before the year was out, and “a patient who dies has no risk of being readmitted,” she explained. Selection bias was also a factor because patients who do pulmonary rehab tend to be in better shape.

The researchers used propensity score matching and Anderson–Gill models of cumulative rehospitalizations or death at 1 year with time-varying exposure to pulmonary rehabilitation to account for clustering of individual events and adjust for covariates. “It was a complicated risk analysis,” she said.

In the year after discharge, 130,660 patients (66%) were readmitted to the hospital. The rate of rehospitalization was lower for those who initiated rehabilitation than for those who did not (59% vs 66%), as was the mean number of readmissions per patient (1.4 vs 1.8).

Rehabilitation was associated with a lower risk for readmission or death (hazard ratio, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.66 - 0.69).

“We know the referral rates are low and that pulmonary rehabilitation is effective in clinical trials,” said Stefan, and now “we see that pulmonary rehabilitation is effective when you look at patients in real life.”

From a provider perspective, “we need to make sure that hospitals get more money for pulmonary rehabilitation. Cardiac rehabilitation is paid for,” she explained. "But pulmonary rehab is not a lucrative business. I don›t know why the CMS pays more for cardiac."

A rehabilitation program generally consists of 36 sessions, held two or three times a week, and many patients can’t afford that on their own, she noted. Transportation is another huge issue.

A recent study in which semi-structured interviews were conducted with 15 COPD patients showed that the main barriers to enrollment in a pulmonary rehabilitation program are lack of awareness, family obligations, transportation, and lack of motivation, said Stefan, who was involved in that research.

Telehealth rehabilitation programs might become more available in the near future, given the COVID pandemic. But “currently, Medicare doesn’t pay for telerehab,” she said. Virtual sessions might attract more patients, but lack of computer access and training could present another barrier for some.

PAH rehab

Uptake for pulmonary rehabilitation is as low for patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) as it is for those with COPD, according to another study presented at the virtual ATS meeting.

An examination of the electronic health records of 111,356 veterans who experienced incident PAH from 2010 to 2016 showed that only 1,737 (1.6%) followed through on pulmonary rehabilitation.

“Exercise therapy is safe and effective at improving outcomes,” lead author Thomas Cascino, MD, from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, said in an ATS press release. “Recognizing that it is being underutilized is a necessary first step in working toward increasing patient access to rehab.

His group is currently working on a trial for home-based rehabilitation “using wearable technology as a means to expand access for people unable to come to center-based rehab for a variety of reasons,” he explained.

“The goal of all our treatments is to help people feel better and live longer,” Cascino added.

Stefan and Cascino have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pulmonary rehabilitation reduces the likelihood that patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) will be readmitted to the hospital in the year after discharge by 33%, new research shows, but few patients participate in those programs.

In fact, in a retrospective cohort of 197,376 patients from 4446 hospitals, only 1.5% of patients initiated pulmonary rehabilitation in the 90 days after hospital discharge.

“This is a striking finding,” said Mihaela Stefan, PhD, from the University of Massachusetts Medical School–Baystate in Springfield. “Our study demonstrates that we need to increase access to rehabilitation to reduce the risk of readmissions.”

Not enough patients are initiating rehabilitation, but the onus is not only on them; the system is failing them. “We wanted to understand how much pulmonary rehabilitation lowers the readmission rate,” Stefan told Medscape Medical News.

So she and her colleagues examined the records of patients who were hospitalized for COPD in 2014 to see whether they had begun rehabilitation in the 90 days after discharge and whether they were readmitted to the hospital in the subsequent 12 months.

Patients who were unlikely to initiate pulmonary rehabilitation — such as those with dementia or metastatic cancer and those discharged to hospice care or a nursing home — were excluded from the analysis, Stefan said during her presentation at the study results at the virtual American Thoracic Society (ATS) 2020 International Conference.

The risk analysis was complex because many patients died before the year was out, and “a patient who dies has no risk of being readmitted,” she explained. Selection bias was also a factor because patients who do pulmonary rehab tend to be in better shape.

The researchers used propensity score matching and Anderson–Gill models of cumulative rehospitalizations or death at 1 year with time-varying exposure to pulmonary rehabilitation to account for clustering of individual events and adjust for covariates. “It was a complicated risk analysis,” she said.

In the year after discharge, 130,660 patients (66%) were readmitted to the hospital. The rate of rehospitalization was lower for those who initiated rehabilitation than for those who did not (59% vs 66%), as was the mean number of readmissions per patient (1.4 vs 1.8).

Rehabilitation was associated with a lower risk for readmission or death (hazard ratio, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.66 - 0.69).

“We know the referral rates are low and that pulmonary rehabilitation is effective in clinical trials,” said Stefan, and now “we see that pulmonary rehabilitation is effective when you look at patients in real life.”

From a provider perspective, “we need to make sure that hospitals get more money for pulmonary rehabilitation. Cardiac rehabilitation is paid for,” she explained. "But pulmonary rehab is not a lucrative business. I don›t know why the CMS pays more for cardiac."

A rehabilitation program generally consists of 36 sessions, held two or three times a week, and many patients can’t afford that on their own, she noted. Transportation is another huge issue.

A recent study in which semi-structured interviews were conducted with 15 COPD patients showed that the main barriers to enrollment in a pulmonary rehabilitation program are lack of awareness, family obligations, transportation, and lack of motivation, said Stefan, who was involved in that research.

Telehealth rehabilitation programs might become more available in the near future, given the COVID pandemic. But “currently, Medicare doesn’t pay for telerehab,” she said. Virtual sessions might attract more patients, but lack of computer access and training could present another barrier for some.

PAH rehab

Uptake for pulmonary rehabilitation is as low for patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) as it is for those with COPD, according to another study presented at the virtual ATS meeting.

An examination of the electronic health records of 111,356 veterans who experienced incident PAH from 2010 to 2016 showed that only 1,737 (1.6%) followed through on pulmonary rehabilitation.

“Exercise therapy is safe and effective at improving outcomes,” lead author Thomas Cascino, MD, from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, said in an ATS press release. “Recognizing that it is being underutilized is a necessary first step in working toward increasing patient access to rehab.

His group is currently working on a trial for home-based rehabilitation “using wearable technology as a means to expand access for people unable to come to center-based rehab for a variety of reasons,” he explained.

“The goal of all our treatments is to help people feel better and live longer,” Cascino added.

Stefan and Cascino have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pulmonary rehabilitation reduces the likelihood that patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) will be readmitted to the hospital in the year after discharge by 33%, new research shows, but few patients participate in those programs.

In fact, in a retrospective cohort of 197,376 patients from 4446 hospitals, only 1.5% of patients initiated pulmonary rehabilitation in the 90 days after hospital discharge.

“This is a striking finding,” said Mihaela Stefan, PhD, from the University of Massachusetts Medical School–Baystate in Springfield. “Our study demonstrates that we need to increase access to rehabilitation to reduce the risk of readmissions.”

Not enough patients are initiating rehabilitation, but the onus is not only on them; the system is failing them. “We wanted to understand how much pulmonary rehabilitation lowers the readmission rate,” Stefan told Medscape Medical News.

So she and her colleagues examined the records of patients who were hospitalized for COPD in 2014 to see whether they had begun rehabilitation in the 90 days after discharge and whether they were readmitted to the hospital in the subsequent 12 months.

Patients who were unlikely to initiate pulmonary rehabilitation — such as those with dementia or metastatic cancer and those discharged to hospice care or a nursing home — were excluded from the analysis, Stefan said during her presentation at the study results at the virtual American Thoracic Society (ATS) 2020 International Conference.

The risk analysis was complex because many patients died before the year was out, and “a patient who dies has no risk of being readmitted,” she explained. Selection bias was also a factor because patients who do pulmonary rehab tend to be in better shape.

The researchers used propensity score matching and Anderson–Gill models of cumulative rehospitalizations or death at 1 year with time-varying exposure to pulmonary rehabilitation to account for clustering of individual events and adjust for covariates. “It was a complicated risk analysis,” she said.

In the year after discharge, 130,660 patients (66%) were readmitted to the hospital. The rate of rehospitalization was lower for those who initiated rehabilitation than for those who did not (59% vs 66%), as was the mean number of readmissions per patient (1.4 vs 1.8).

Rehabilitation was associated with a lower risk for readmission or death (hazard ratio, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.66 - 0.69).

“We know the referral rates are low and that pulmonary rehabilitation is effective in clinical trials,” said Stefan, and now “we see that pulmonary rehabilitation is effective when you look at patients in real life.”

From a provider perspective, “we need to make sure that hospitals get more money for pulmonary rehabilitation. Cardiac rehabilitation is paid for,” she explained. "But pulmonary rehab is not a lucrative business. I don›t know why the CMS pays more for cardiac."

A rehabilitation program generally consists of 36 sessions, held two or three times a week, and many patients can’t afford that on their own, she noted. Transportation is another huge issue.

A recent study in which semi-structured interviews were conducted with 15 COPD patients showed that the main barriers to enrollment in a pulmonary rehabilitation program are lack of awareness, family obligations, transportation, and lack of motivation, said Stefan, who was involved in that research.

Telehealth rehabilitation programs might become more available in the near future, given the COVID pandemic. But “currently, Medicare doesn’t pay for telerehab,” she said. Virtual sessions might attract more patients, but lack of computer access and training could present another barrier for some.

PAH rehab

Uptake for pulmonary rehabilitation is as low for patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) as it is for those with COPD, according to another study presented at the virtual ATS meeting.

An examination of the electronic health records of 111,356 veterans who experienced incident PAH from 2010 to 2016 showed that only 1,737 (1.6%) followed through on pulmonary rehabilitation.

“Exercise therapy is safe and effective at improving outcomes,” lead author Thomas Cascino, MD, from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, said in an ATS press release. “Recognizing that it is being underutilized is a necessary first step in working toward increasing patient access to rehab.

His group is currently working on a trial for home-based rehabilitation “using wearable technology as a means to expand access for people unable to come to center-based rehab for a variety of reasons,” he explained.

“The goal of all our treatments is to help people feel better and live longer,” Cascino added.

Stefan and Cascino have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

HFNC more comfortable for posthypercapnic patients with COPD

Following invasive ventilation for severe hypercapnic respiratory failure, patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease had similar levels of treatment failure if they received high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy or noninvasive ventilation, recent research in Critical Care has suggested.

However, for patients with COPD weaned off invasive ventilation, high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) oxygen therapy was “more comfortable and better tolerated,” compared with noninvasive ventilation (NIV). In addition, “airway care interventions and the incidence of nasofacial skin breakdown associated with HFNC were significantly lower than in NIV,” according to Dingyu Tan of the Clinical Medical College of Yangzhou (China) University, Northern Jiangsu People’s Hospital, and colleagues. “HFNC appears to be an effective means of respiratory support for COPD patients extubated after severe hypercapnic respiratory failure,” they said.

The investigators screened patients with COPD and hypercapnic respiratory failure for enrollment, including those who met Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) criteria, were 85 years old or younger and caring for themselves, had bronchopulmonary infection–induced respiratory failure, and had achieved pulmonary infection control criteria. Exclusion criteria were:

- Patients under age 18 years.

- Presence of oral or facial trauma.

- Poor sputum excretion ability.

- Hemodynamic instability that would contraindicate use of NIV.

- Poor cough during PIC window.

- Poor short-term prognosis.

- Failure of the heart, brain, liver or kidney.

- Patients who could not consent to treatment.

Patients were determined to have failed treatment if they returned to invasive mechanical ventilation or switched from one treatment to another (HFNC to NIV or NIV to HFNC). Investigators also performed an arterial blood gas analysis, recorded the number of duration of airway care interventions, and monitored vital signs at 1 hour, 24 hours, and 48 hours after extubation as secondary analyses.

Overall, 44 patients randomized to receive HFNC and 42 patients randomized for NIV were available for analysis. The investigators found 22.7% of patients in the HFNC group and 28.6% in the NIV group experienced treatment failure (risk difference, –5.8%; 95% confidence interval, −23.8 to 12.4%; P = .535), with patients in the HFNC group experiencing a significantly lower level of treatment intolerance, compared with patients in the NIV group (risk difference, –50.0%; 95% CI, −74.6 to −12.9%; P = .015). There were no significant differences between either group regarding intubation (−0.65%; 95% CI, −16.01 to 14.46%), while rate of switching treatments was lower in the HFNC group but not significant (−5.2%; 95% CI, −19.82 to 9.05%).

Patients in both the HFNC and NIV groups had faster mean respiratory rates 1 hour after extubation (P < .050). After 24 hours, the NIV group had higher-than-baseline respiratory rates, compared with the HFNC group, which had returned to normal (20 vs. 24.5 breaths per minute; P < .050). Both groups had returned to baseline by 48 hours after extubation. At 1 hour after extubation, patients in the HFNC group had lower PaO2/FiO2 (P < .050) and pH values (P < .050), and higher PaCO2 values (P less than .050), compared with baseline. There were no statistically significant differences in PaO2/FiO2, pH, and PaCO2 values in either group at 24 hours or 48 hours after extubation.

Daily airway care interventions were significantly higher on average in the NIV group, compared with the HFNC group (7 vs. 6; P = .0006), and the HFNC group also had significantly better comfort scores (7 vs. 5; P < .001) as measured by a modified visual analog scale, as well as incidence of nasal and facial skin breakdown (0 vs. 9.6%; P = .027), compared with the NIV group.

Results difficult to apply to North American patients

David L. Bowton, MD, FCCP, a professor specializing in critical care at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., said in an interview the results of this trial may not be applicable for patients with infection-related respiratory failure and COPD in North America “due to the differences in common weaning practices between North America and China.”

For example, the trial used the pulmonary infection control (PIC) window criteria for extubation, which requires a significant decrease in radiographic infiltrates, improvement in quality and quantity of sputum, normalizing of leukocyte count, a synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV) rate of 10-12 breaths per minute, and pressure support less than 10-12 cm/H2O (Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:1255-67).

“The process used to achieve these measures is not standardized. In North America, daily awakening and screening for spontaneous breathing trials would be usual, but this was not reported in the current trial,” he explained.

Differences in patient population also make the application of the results difficult, Dr. Bowton said. “Only 60% of the patients had spirometrically confirmed COPD and fewer than half were on at least dual inhaled therapy prior to hospitalization with only one-third taking beta agonists or anticholinergic agents,” he noted. “The cause of respiratory failure was infectious, requiring an infiltrate on chest radiograph; thus, patients with hypercarbic respiratory failure without a new infiltrate were excluded from the study. On average, patients were hypercarbic, yet alkalemic at the time of extubation; the PaCO2 and pH at the time of intubation were not reported.

“This study suggests that in some patients with COPD and respiratory failure requiring invasive mechanical ventilation, HFO [high-flow oxygen] may be better tolerated and equally effective as NIPPV [noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation] at mitigating the need for reintubation following extubation. In this patient population where hypoxemia prior to extubation was not severe, the mechanisms by which HFO is beneficial remain speculative,” he said.

This study was funded by the Rui E special fund for emergency medicine research and the Yangzhou Science and Technology Development Plan. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest. Dr. Bowton reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Tan D et al. Crit Care. 2020 Aug 6. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03214-9.

Following invasive ventilation for severe hypercapnic respiratory failure, patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease had similar levels of treatment failure if they received high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy or noninvasive ventilation, recent research in Critical Care has suggested.

However, for patients with COPD weaned off invasive ventilation, high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) oxygen therapy was “more comfortable and better tolerated,” compared with noninvasive ventilation (NIV). In addition, “airway care interventions and the incidence of nasofacial skin breakdown associated with HFNC were significantly lower than in NIV,” according to Dingyu Tan of the Clinical Medical College of Yangzhou (China) University, Northern Jiangsu People’s Hospital, and colleagues. “HFNC appears to be an effective means of respiratory support for COPD patients extubated after severe hypercapnic respiratory failure,” they said.

The investigators screened patients with COPD and hypercapnic respiratory failure for enrollment, including those who met Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) criteria, were 85 years old or younger and caring for themselves, had bronchopulmonary infection–induced respiratory failure, and had achieved pulmonary infection control criteria. Exclusion criteria were:

- Patients under age 18 years.

- Presence of oral or facial trauma.

- Poor sputum excretion ability.

- Hemodynamic instability that would contraindicate use of NIV.

- Poor cough during PIC window.

- Poor short-term prognosis.

- Failure of the heart, brain, liver or kidney.

- Patients who could not consent to treatment.

Patients were determined to have failed treatment if they returned to invasive mechanical ventilation or switched from one treatment to another (HFNC to NIV or NIV to HFNC). Investigators also performed an arterial blood gas analysis, recorded the number of duration of airway care interventions, and monitored vital signs at 1 hour, 24 hours, and 48 hours after extubation as secondary analyses.

Overall, 44 patients randomized to receive HFNC and 42 patients randomized for NIV were available for analysis. The investigators found 22.7% of patients in the HFNC group and 28.6% in the NIV group experienced treatment failure (risk difference, –5.8%; 95% confidence interval, −23.8 to 12.4%; P = .535), with patients in the HFNC group experiencing a significantly lower level of treatment intolerance, compared with patients in the NIV group (risk difference, –50.0%; 95% CI, −74.6 to −12.9%; P = .015). There were no significant differences between either group regarding intubation (−0.65%; 95% CI, −16.01 to 14.46%), while rate of switching treatments was lower in the HFNC group but not significant (−5.2%; 95% CI, −19.82 to 9.05%).

Patients in both the HFNC and NIV groups had faster mean respiratory rates 1 hour after extubation (P < .050). After 24 hours, the NIV group had higher-than-baseline respiratory rates, compared with the HFNC group, which had returned to normal (20 vs. 24.5 breaths per minute; P < .050). Both groups had returned to baseline by 48 hours after extubation. At 1 hour after extubation, patients in the HFNC group had lower PaO2/FiO2 (P < .050) and pH values (P < .050), and higher PaCO2 values (P less than .050), compared with baseline. There were no statistically significant differences in PaO2/FiO2, pH, and PaCO2 values in either group at 24 hours or 48 hours after extubation.

Daily airway care interventions were significantly higher on average in the NIV group, compared with the HFNC group (7 vs. 6; P = .0006), and the HFNC group also had significantly better comfort scores (7 vs. 5; P < .001) as measured by a modified visual analog scale, as well as incidence of nasal and facial skin breakdown (0 vs. 9.6%; P = .027), compared with the NIV group.

Results difficult to apply to North American patients

David L. Bowton, MD, FCCP, a professor specializing in critical care at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., said in an interview the results of this trial may not be applicable for patients with infection-related respiratory failure and COPD in North America “due to the differences in common weaning practices between North America and China.”

For example, the trial used the pulmonary infection control (PIC) window criteria for extubation, which requires a significant decrease in radiographic infiltrates, improvement in quality and quantity of sputum, normalizing of leukocyte count, a synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV) rate of 10-12 breaths per minute, and pressure support less than 10-12 cm/H2O (Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:1255-67).

“The process used to achieve these measures is not standardized. In North America, daily awakening and screening for spontaneous breathing trials would be usual, but this was not reported in the current trial,” he explained.

Differences in patient population also make the application of the results difficult, Dr. Bowton said. “Only 60% of the patients had spirometrically confirmed COPD and fewer than half were on at least dual inhaled therapy prior to hospitalization with only one-third taking beta agonists or anticholinergic agents,” he noted. “The cause of respiratory failure was infectious, requiring an infiltrate on chest radiograph; thus, patients with hypercarbic respiratory failure without a new infiltrate were excluded from the study. On average, patients were hypercarbic, yet alkalemic at the time of extubation; the PaCO2 and pH at the time of intubation were not reported.

“This study suggests that in some patients with COPD and respiratory failure requiring invasive mechanical ventilation, HFO [high-flow oxygen] may be better tolerated and equally effective as NIPPV [noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation] at mitigating the need for reintubation following extubation. In this patient population where hypoxemia prior to extubation was not severe, the mechanisms by which HFO is beneficial remain speculative,” he said.

This study was funded by the Rui E special fund for emergency medicine research and the Yangzhou Science and Technology Development Plan. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest. Dr. Bowton reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Tan D et al. Crit Care. 2020 Aug 6. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03214-9.

Following invasive ventilation for severe hypercapnic respiratory failure, patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease had similar levels of treatment failure if they received high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy or noninvasive ventilation, recent research in Critical Care has suggested.

However, for patients with COPD weaned off invasive ventilation, high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) oxygen therapy was “more comfortable and better tolerated,” compared with noninvasive ventilation (NIV). In addition, “airway care interventions and the incidence of nasofacial skin breakdown associated with HFNC were significantly lower than in NIV,” according to Dingyu Tan of the Clinical Medical College of Yangzhou (China) University, Northern Jiangsu People’s Hospital, and colleagues. “HFNC appears to be an effective means of respiratory support for COPD patients extubated after severe hypercapnic respiratory failure,” they said.

The investigators screened patients with COPD and hypercapnic respiratory failure for enrollment, including those who met Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) criteria, were 85 years old or younger and caring for themselves, had bronchopulmonary infection–induced respiratory failure, and had achieved pulmonary infection control criteria. Exclusion criteria were:

- Patients under age 18 years.

- Presence of oral or facial trauma.

- Poor sputum excretion ability.

- Hemodynamic instability that would contraindicate use of NIV.

- Poor cough during PIC window.

- Poor short-term prognosis.

- Failure of the heart, brain, liver or kidney.

- Patients who could not consent to treatment.

Patients were determined to have failed treatment if they returned to invasive mechanical ventilation or switched from one treatment to another (HFNC to NIV or NIV to HFNC). Investigators also performed an arterial blood gas analysis, recorded the number of duration of airway care interventions, and monitored vital signs at 1 hour, 24 hours, and 48 hours after extubation as secondary analyses.

Overall, 44 patients randomized to receive HFNC and 42 patients randomized for NIV were available for analysis. The investigators found 22.7% of patients in the HFNC group and 28.6% in the NIV group experienced treatment failure (risk difference, –5.8%; 95% confidence interval, −23.8 to 12.4%; P = .535), with patients in the HFNC group experiencing a significantly lower level of treatment intolerance, compared with patients in the NIV group (risk difference, –50.0%; 95% CI, −74.6 to −12.9%; P = .015). There were no significant differences between either group regarding intubation (−0.65%; 95% CI, −16.01 to 14.46%), while rate of switching treatments was lower in the HFNC group but not significant (−5.2%; 95% CI, −19.82 to 9.05%).

Patients in both the HFNC and NIV groups had faster mean respiratory rates 1 hour after extubation (P < .050). After 24 hours, the NIV group had higher-than-baseline respiratory rates, compared with the HFNC group, which had returned to normal (20 vs. 24.5 breaths per minute; P < .050). Both groups had returned to baseline by 48 hours after extubation. At 1 hour after extubation, patients in the HFNC group had lower PaO2/FiO2 (P < .050) and pH values (P < .050), and higher PaCO2 values (P less than .050), compared with baseline. There were no statistically significant differences in PaO2/FiO2, pH, and PaCO2 values in either group at 24 hours or 48 hours after extubation.

Daily airway care interventions were significantly higher on average in the NIV group, compared with the HFNC group (7 vs. 6; P = .0006), and the HFNC group also had significantly better comfort scores (7 vs. 5; P < .001) as measured by a modified visual analog scale, as well as incidence of nasal and facial skin breakdown (0 vs. 9.6%; P = .027), compared with the NIV group.

Results difficult to apply to North American patients

David L. Bowton, MD, FCCP, a professor specializing in critical care at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., said in an interview the results of this trial may not be applicable for patients with infection-related respiratory failure and COPD in North America “due to the differences in common weaning practices between North America and China.”

For example, the trial used the pulmonary infection control (PIC) window criteria for extubation, which requires a significant decrease in radiographic infiltrates, improvement in quality and quantity of sputum, normalizing of leukocyte count, a synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV) rate of 10-12 breaths per minute, and pressure support less than 10-12 cm/H2O (Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:1255-67).

“The process used to achieve these measures is not standardized. In North America, daily awakening and screening for spontaneous breathing trials would be usual, but this was not reported in the current trial,” he explained.

Differences in patient population also make the application of the results difficult, Dr. Bowton said. “Only 60% of the patients had spirometrically confirmed COPD and fewer than half were on at least dual inhaled therapy prior to hospitalization with only one-third taking beta agonists or anticholinergic agents,” he noted. “The cause of respiratory failure was infectious, requiring an infiltrate on chest radiograph; thus, patients with hypercarbic respiratory failure without a new infiltrate were excluded from the study. On average, patients were hypercarbic, yet alkalemic at the time of extubation; the PaCO2 and pH at the time of intubation were not reported.

“This study suggests that in some patients with COPD and respiratory failure requiring invasive mechanical ventilation, HFO [high-flow oxygen] may be better tolerated and equally effective as NIPPV [noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation] at mitigating the need for reintubation following extubation. In this patient population where hypoxemia prior to extubation was not severe, the mechanisms by which HFO is beneficial remain speculative,” he said.

This study was funded by the Rui E special fund for emergency medicine research and the Yangzhou Science and Technology Development Plan. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest. Dr. Bowton reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Tan D et al. Crit Care. 2020 Aug 6. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03214-9.

FROM CRITICAL CARE

Send kids to school safely if possible, supplement virtually

The abrupt transition to online learning for American children in kindergarten through 12th grade has left educators and parents unprepared, but virtual learning can be a successful part of education going forward, according to a viewpoint published in JAMA Pediatrics. However, schools also can reopen safely if precautions are taken, and students would benefit in many ways, according to a second viewpoint.

“As policy makers, health care professionals, and parents prepare for the fall semester and as public and private schools grapple with how to make that possible, a better understanding of K-12 virtual learning options and outcomes may facilitate those difficult decisions,” wrote Erik Black, PhD, of the University of Florida, Gainesville; Richard Ferdig, PhD, of Kent State University, Ohio; and Lindsay A. Thompson, MD, of the University of Florida, Gainesville.

“Importantly, K-12 virtual schooling is not suited for all students or all families.”

In a viewpoint published in JAMA Pediatrics, the authors noted that virtual schooling has existed in the United States in various forms for some time. “Just like the myriad options that are available for face-to-face schooling in the U.S., virtual schooling exists in a complex landscape of for-profit, charter, and public options.”

Not all virtual schools are equal

Consequently, not all virtual schools are created equal, they emphasized. Virtual education can be successful for many students when presented by trained online instructors using a curriculum designed to be effective in an online venue.

“Parents need to seek reviews and ask for educational outcomes from each virtual school system to assess the quality of the provided education,” Dr. Black, Dr. Ferdig, and Dr. Thompson emphasized.

Key questions for parents to consider when faced with online learning include the type of technology needed to participate; whether their child can maintain a study schedule and complete assignments with limited supervision; whether their child could ask for help and communicate with teachers through technology including phone, text, email, or video; and whether their child has the basic reading, math, and computer literacy skills to engage in online learning, the authors said. Other questions include the school’s expectations for parents and caregivers, how student information may be shared, and how the virtual school lines up with state standards for K-12 educators (in the case of options outside the public school system).

“The COVID-19 pandemic offers a unique challenge for educators, policymakers, and health care professionals to partner with parents to make the best local and individual decisions for children,” Dr. Black, Dr. Ferdig, and Dr. Thompson concluded.

Schools may be able to open safely

Children continue to make up a low percentage of COVID-19 cases and appear less likely to experience illness, wrote C. Jason Wang, MD, PhD, and Henry Bair, BS, of Stanford (Calif.) University in a second viewpoint also published in JAMA Pediatrics. The impact of long-term school closures extends beyond education and can “exacerbate socioeconomic disparities, amplify existing educational inequalities, and aggravate food insecurity, domestic violence, and mental health disorders,” they wrote.

Dr. Wang and Mr. Bair proposed that school districts “engage key stakeholders to establish a COVID-19 task force, composed of the superintendent, members of the school board, teachers, parents, and health care professionals to develop policies and procedures,” that would allow schools to open safely.

The authors outlined strategies including adapting teaching spaces to accommodate physical distance, with the addition of temporary modular buildings if needed. They advised assigned seating on school buses, and acknowledged the need for the availability of protective equipment, including hand sanitizer and masks, as well as the possible use of transparent barriers on the sides of student desks.

“As the AAP [American Academy of Pediatrics] guidance suggests, teachers who must work closely with students with special needs or with students who are unable to wear masks should wear N95 masks if possible or wear face shields in addition to surgical masks,” Dr. Wang and Mr. Bair noted. Other elements of the AAP guidance include the creation of fixed cohorts of students and teachers to limit virus exposure.

“Even with all the precautions in place, COVID-19 outbreaks within schools are still likely,” they said. “Therefore, schools will need to remain flexible and consider temporary closures if there is an outbreak involving multiple students and/or staff and be ready to transition to online education.”

The AAP guidance does not address operational approaches to identifying signs and symptoms of COVID-19, the authors noted. “To address this, we recommend that schools implement multilevel screening for students and staff.”

“In summary, to maximize health and educational outcomes, school districts should adopt some or all of the measures of the AAP guidance and prioritize them after considering local COVID-19 incidence, key stakeholder input, and budgetary constraints,” Dr. Wang and Mr. Bair concluded.

Schools opening is a regional decision

“The mission of the AAP is to attain optimal physical, mental, and social health and well-being for all infants, children, adolescents, and young adults,” Howard Smart, MD, said in an interview. The question of school reopening “is of national importance, and the AAP has a national role in making recommendations regarding national policy affecting the health of the children.”

“The decision to open schools will be made regionally, but it is important for a nonpolitical national voice to make expert recommendations,” he emphasized.

“Many of the recommendations are ideal goals,” noted Dr. Smart, chairman of the department of pediatrics at the Sharp Rees-Stealy Medical Group in San Diego. “It will be difficult, for example, to implement symptom screening every day before school, no matter where it is performed. Some of the measures may be quite costly, and take time to implement, or require expansion of school staff, for which there may be no budget.”

In addition, “[n]ot all students are likely to comply with masking, distance, and hand-washing recommendations. One student who is noncompliant will be able to infect many other students and staff, as has been seen in other countries.” Also, parental attitudes toward control measures are likely to affect student attitudes, he noted.