User login

Asian Americans represent 4% of the population in the United States, and their share of the US population is projected to grow to 9% by 2050.1 These numbers are significant because of the high prevalence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in this community and the cultural barriers to its effective management.

Appreciating the impact of cultural barriers on health care among Asian Americans requires an understanding of the diversity of the Asian continent, which is composed of 52 countries where 100 languages and dialects are spoken. Within each region are religious, cultural, and societal differences. Asians have immigrated to the United States over the course of several generations, and the era in which they immigrated may affect their ability to understand English, integrate into American culture, and navigate the US health care system. Successful integration into American life favors those whose families immigrated several generations earlier.

The overall prevalence of HBV infection in the United States is 0.4%2; however, estimates of prevalence range from 5% to 15% in Asian American populations, and are as high as 20% in some Pacific Rim populations.3,4 The prevalence of HBV infection in Asian Americans differs by subpopulation, with the highest prevalence among immigrants from Vietnam, Laos, and China, and the lowest among those from Japan.

Of the approximately 1 million Americans estimated to be infected with HBV as of 2005, more than 750,000 had access to health care; of these, 205,000 were diagnosed with HBV infection,5 suggesting substantial underdiagnosis. Referrals to specialists were even fewer (175,000), and only about 31,000 patients chronically infected with HBV received antiviral treatment, a figure that has likely increased with greater awareness of HBV and the availability of new antiviral medications.

BARRIERS TO DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

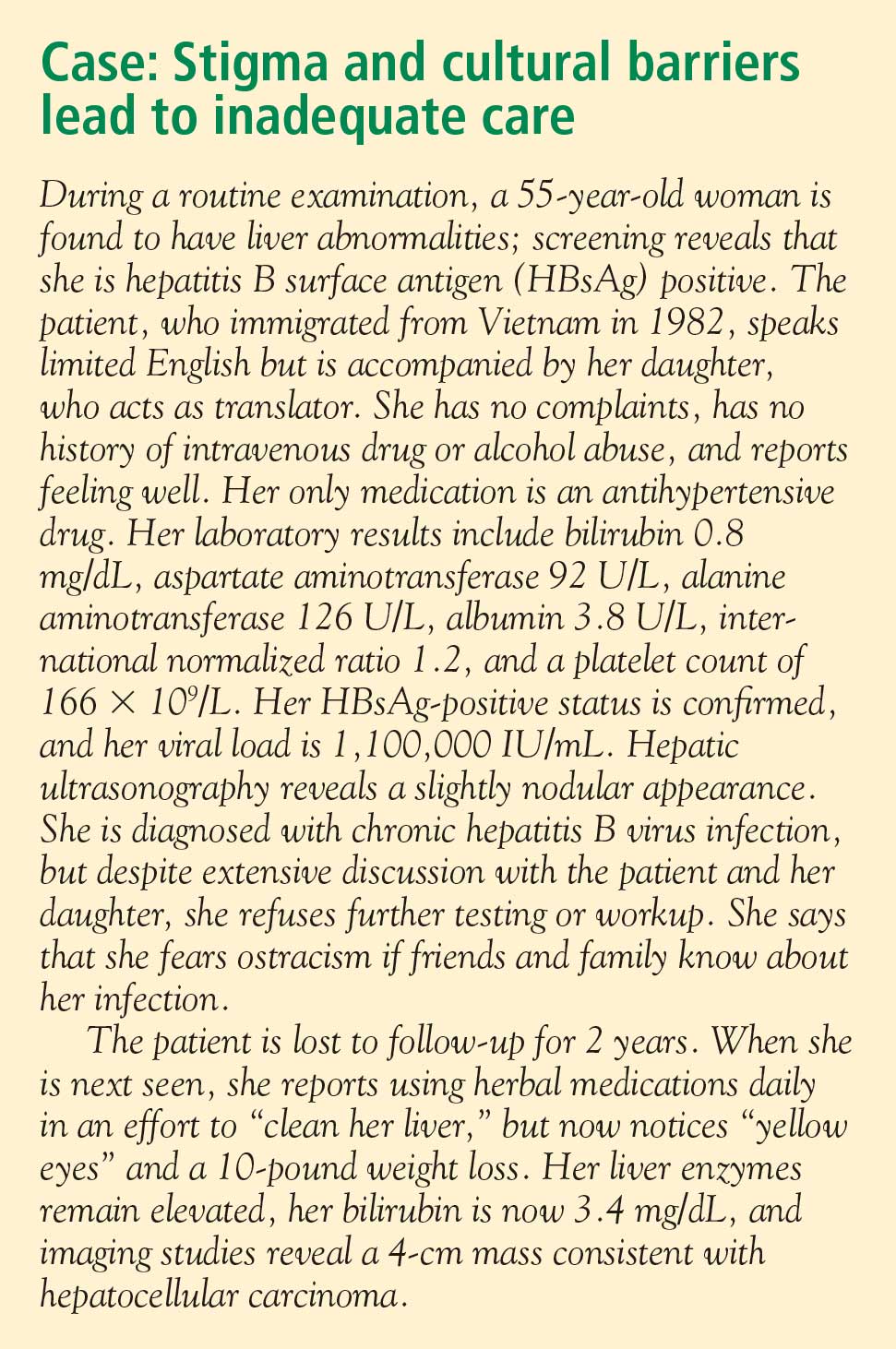

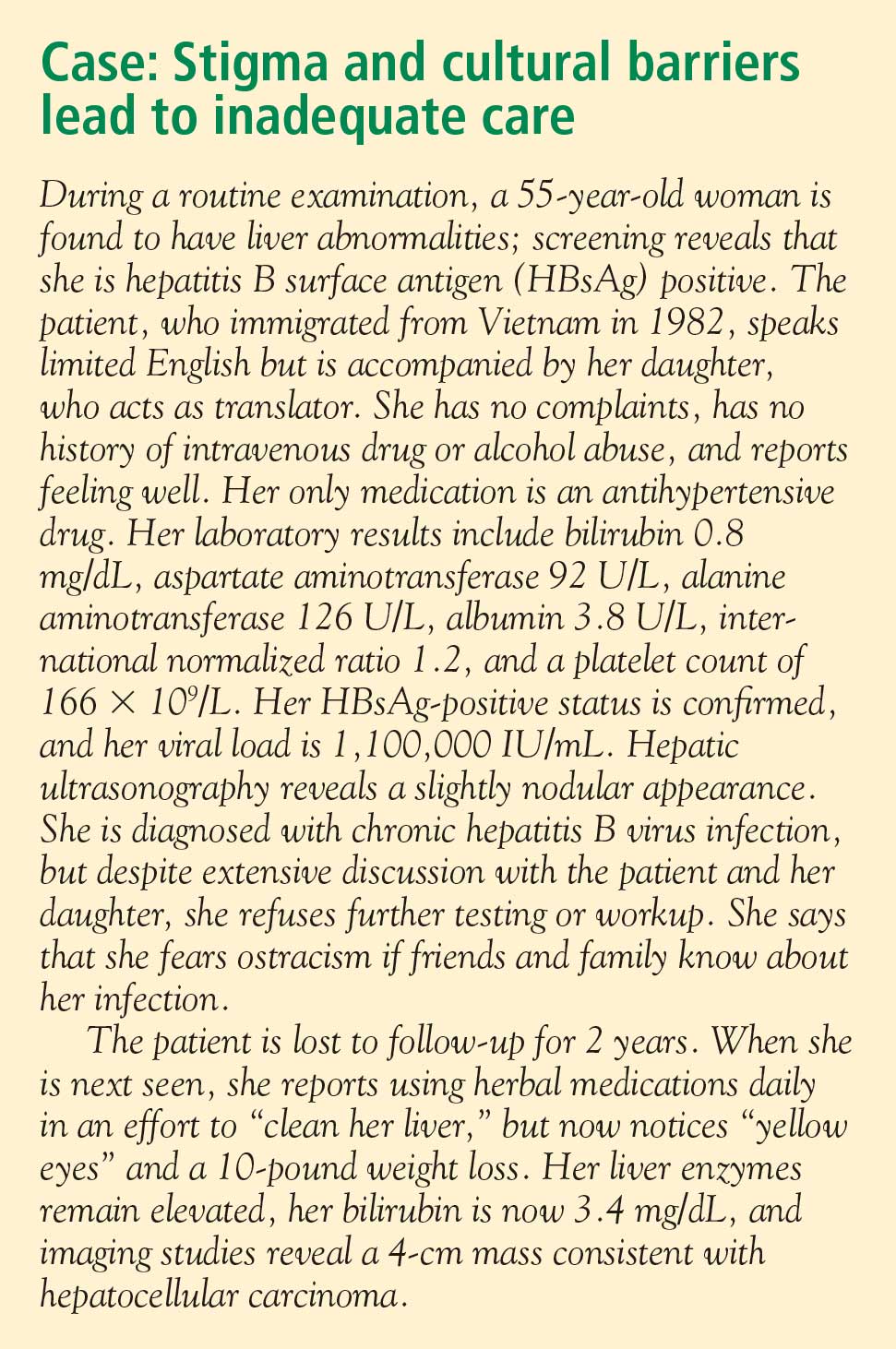

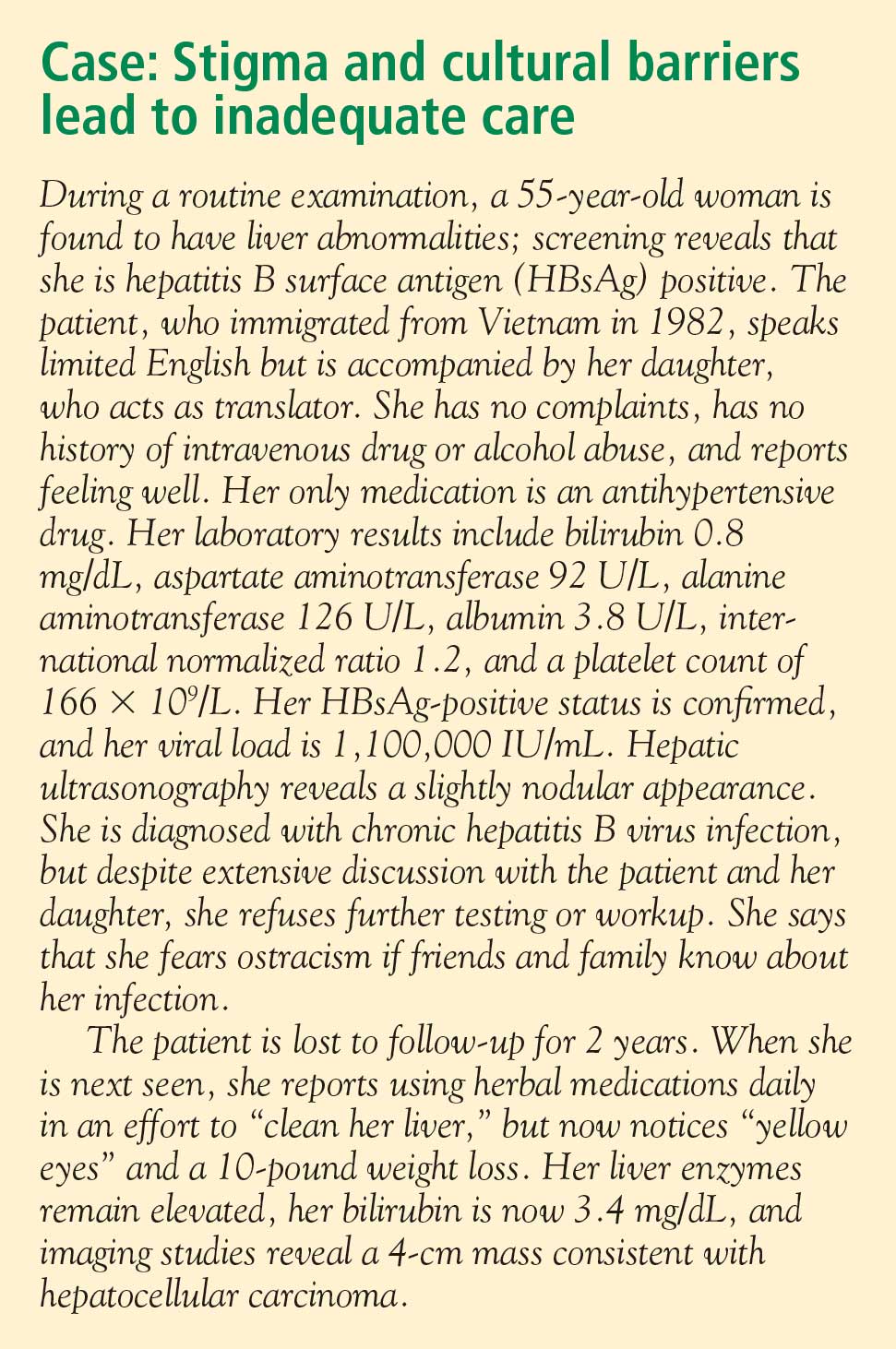

The barriers to effective management of HBV infection in Asian Americans include cultural, socioeconomic, and accessibility issues (see “Case: Stigma and cultural barriers lead to inadequate care”).

Language and linguistic isolation

Limited proficiency in English is a large, if not the largest, barrier to effective management of chronic HBV infection. According to the US Census Bureau, a person with limited English proficiency is one who does not speak English “very well.”6 This terminology has implications for allocation of federal government resources; ie, the percentage of a community’s residents with limited English proficiency is a criterion for receipt of governmental grants and other forms of assistance, including translation services.6

Linguistic isolation, another barrier to medical care, is lack of an English-speaking household member who is older than 14 years.7 By this definition, more than one-third of Korean, Taiwanese, Chinese, Hmong, and Bangladeshi households, and almost half of Vietnamese households, are linguistically isolated, with limited ability to communicate with health care providers.8

Lack of health insurance and its correlates

The high percentage of Asian immigrants without health insurance is a challenge to providing adequate health care. Health insurance coverage is lacking for about one-third of Korean immigrants, about one in five immigrants from Southeast Asia and South Asia, and about 15% of Filipino and Chinese immigrants.9

One reason for the large proportion of uninsured among these groups is the high rate of small business ownership among Asian Americans and the difficulty that small business owners have in obtaining affordable health insurance coverage. In addition, although Asian Americans are as likely as other US residents to be employed full time, their employment options may be less likely to include health insurance benefits.

Poverty affects the ability to acquire health insurance. Although the popular image of the Asian immigrant is an educated person with high earning potential, the reality is that poverty strikes immigrants from Southeast Asia at a high rate. Almost 40% of the Hmong population, for example, lives below the poverty level, and poverty rates among the Cambodian, Bangladeshi, Malaysian, and several other Asian subpopulations are nearly as high.8

Citizenship correlates with the ability to obtain health insurance; it is estimated that 42% to 57% of noncitizens lack health insurance, compared with 15% of citizens.8 Only half of Asian immigrants become naturalized citizens, with wide variability among subgroups. Two-thirds of Filipinos who immigrate to the United States eventually become naturalized compared with less than one-third of Malaysian, Japanese, Indonesian, and Hmong immigrants.8

Educational achievement is associated with attainment of financial security and health insurance. The vast majority of Taiwanese, Japanese, Filipino, and Korean Americans obtain a high school education or higher, with correspondingly higher rates of health insurance coverage. Among those from Southeast Asia (Hmong, Cambodians, Laotians, and Vietnamese), whose immigration to this country is relatively recent, fewer than half complete a high school education.8

Health care workforce representation

Certain Asian subgroups are underrepresented in the racial composition of the US health care workforce; this imbalance may affect accessibility to the health care system and adherence to medical prescriptions and instructions among underrepresented groups. Racial concordance between patient and health care provider is associated with greater patient participation in care, according to the Institute of Medicine.10 In addition to racial similarity, linguistic similarity enhances communication and adherence to instructions.

Belief systems and attitudes toward health care

An immigrant patient’s religious beliefs and cultural attitudes toward Western medicine may pose difficulties in successfully managing disease. Many Asian Americans are Buddhists, who may believe that suffering is an integral part of life; proactively seeking medical care may not be imperative for them. Confucianism, the worship of ancestors and the subjugation of the self to the well-being of the family, is a common belief system among Asians that may inhibit the desire to seek needed medical care. For example, a family elder may instruct a young man not to seek medical care for his HBV infection because this would jeopardize his siblings’ marriage prospects. Taoism involves the belief that perfection is achieved when events are allowed to take the more natural course. Intervention is therefore frowned upon.

Some belief systems may impede care because they incorporate indifference toward suffering. Many Hmong believe that the length of life is predetermined, so lifesaving care is pointless. Cultural value may be placed on stoicism, discouraging visits to health care providers. A belief that disease is caused by supernatural events rather than organic etiologies is another perception that serves as a barrier to seeking medical care.

Distrust of, or unfamiliarity with, Western medicine may delay care, and the resulting poor outcomes may be falsely attributed to Western medicine itself. In some cultures, there is a pervasive belief that a physician can touch the pulse and identify the problem. Some Laotians believe that immunizations are dangerous for a baby’s spirit, and therefore forgo immunization against HBV when it is indicated.

The patient’s relationship with his or her health care provider is an important determinant of quality of care and willingness to continue to receive care. The best possible scenario is concordance in language and culture. Asian cultures emphasize politeness, respect for authority, filial piety, and avoidance of shame. Because Asian patients often view physicians as authority figures, they may not ask questions or voice reservations or fears about their treatment regimens; instead, they may express their agreement with physicians’ advice, but with no intent to return or follow instructions.

Infection with HBV carries a stigma about the mode of transmission that can interfere with patients’ daily lives. A study of attitudes about HBV found that HBV-infected patients feel less welcome to stay overnight or share the same bathroom at friends’ or relatives’ houses, that noninfected persons fear that the disease may be passed to them by HBV-positive friends, and that HBV-infected patients are concerned about whether their choices may have led to the infection.11

OVERCOMING BARRIERS

Sensitivity to cultural attitudes may enhance communication and the likelihood that patients will accept physicians’ recommendations. Several office visits may be necessary to confirm that a patient is receptive to the health care provider’s instructions and is adhering to them. Referral to access programs can aid communication. For example, most cities have community centers where patients can seek medical advice from physicians who speak the patients’ language; these centers also may provide native-language materials and interpreters.

Offering reassurance to patients in their own language and in a culturally sensitive setting will help break down barriers and improve care. Patients who are educated about HBV transmission and the availability of an effective vaccine may be instrumental in preventing transmission of the disease to household members.

Cultural sensitivity training will benefit health care providers and staffs whose patients include Asian Americans. Educational programs should be specific to the needs of the community, as different subpopulations have different needs. Resource materials are available for such training; for example, the federal government’s Office of Minority Health Web site (http://www.omhrc.gov/) offers links to resources for cultural training. In addition to educating themselves and their staffs, health care providers have a responsibility to advocate for funding and equal access to care, and for the creation of more cultural and community health centers that can serve as resources to overcome cultural barriers.

DISCUSSION

Robert G. Gish, MD: How often are herbal remedies tried for chronic HBV infection in the patients you see, especially in the Vietnamese population?

Tram T. Tran, MD: Once patients are diagnosed with chronic HBV infection, the use of herbal remedies is very high; it approaches 80% in my practice. Patients may not admit to it unless you ask them specifically, because they know herbal remedies may be somewhat frowned upon by Western physicians. If you are careful and ask very gently about their use of herbals, they will tell you that they do believe in herbal medicines pretty strongly.

Morris Sherman, MD, PhD: I’d like to emphasize the need to be able to communicate with patients in their own language. In Toronto, 50% of the population was born outside of Canada. We have a huge immigrant population; given the nature of hepatology, we have many patients from Southeast and South Asia, and from all over the world, who don’t speak English. My hospital has a multilingual interpreter service, which we use freely. Scarcely a day goes by without two or three interpreters coming to the clinic to talk to patients, and as a result it’s rare that I can’t make myself understood. Maybe what I’ve said hasn’t been accepted, but patients can at least understand what I’m saying.

William D. Carey, MD: I interview many applicants for our medical school, and many of them are Asians, including Hmong and Vietnamese. With the high value that most of these groups put on education and their success with educational attainment, is their access to care improving? Are we doing a better job of training nurses, allied health personnel, and physicians to deal with this problem?

Dr. Tran: I think so, yes. For instance, the Southeast Asian immigrant population arrived in two different eras. The Vietnamese who immigrated in 1975 have been in the United States longer and in general have been able to attain a higher level of education than those who came later. The group that arrived earlier is therefore more likely to have health insurance, and it has been easier to get them into the health care system. More recent immigrants have had more difficulty navigating the system. In general, their socioeconomic status and therefore access to care is directly related to how long they’ve been in the country.

- President’s Advisory Commission on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders: a people looking forward. Action for access and partnerships in the 21st century. Interim report to the president and the nation. http://permanent.access.gpo.gov/lps17931/www.aapi.gov/intreport.htm. Published January 2001. Accessed December 21, 2008.

- National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention. Hepatitis B index. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HBV/HBVfaq.htm. Updated July 8, 2008. Accessed January 21, 2009.

- Do S. The natural history of hepatitis B in Asian Americans. Asian Am Pac Isl J Health 2001; 9:141–153.

- Stanford University School of Medicine. FAQ about hepatitis B. Asian Liver Center Web site. http://liver.stanford.edu/Education/faq.html. Updated July 10, 2008. Accessed January 21, 2009.

- Di Bisceglie AM, Keeffe E, Atillasoy E, Varshneya R, Bergstein G. Management of chronic hepatitis B—an analysis of physician practices [DDW abstract M918]. Gastroenterology 2005; 128(suppl 2):A739.

- US Census Bureau. American community survey. US Census Bureau Web site. http://www.census.gov/acs/www/SBasics/SQuest/fact_pdf/P%2013%20factsheetlanguageathome2.pdf. Published January 29, 2004. Accessed January 21, 2009.

- Lestina FA. Analysis of the linguistically isolated population in Census 2000. http://www.census.gov/pred/www/rpts/A.5a.pdf. Published September 30, 2003. Accessed January 21, 2009.

- Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum. Diverse communities, diverse experiences: the status of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the U.S. http://www.apiahf.org/resources/pdf/Diverse%20Communities%20Diverse%20Experiences.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2009.

- Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum. Race, ethnicity and health care fact sheet. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation Web site. http://www.kff.org/minorityhealth/upload/7745.pdf. Published April 2008. Accessed January 21, 2009.

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds; Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, Board on Health Sciences Policy, Institute of Medicine. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?isbn=030908265X. Published 2003. Accessed January 21, 2009.

- Speigel BMR, Bollus R, Han S, et al. Development and validation of a disease-targeted quality of life instrument in chronic hepatitis B: the hepatitis B quality of life instrument, version 1.0. Hepatology 2007; 46:113–121.

Asian Americans represent 4% of the population in the United States, and their share of the US population is projected to grow to 9% by 2050.1 These numbers are significant because of the high prevalence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in this community and the cultural barriers to its effective management.

Appreciating the impact of cultural barriers on health care among Asian Americans requires an understanding of the diversity of the Asian continent, which is composed of 52 countries where 100 languages and dialects are spoken. Within each region are religious, cultural, and societal differences. Asians have immigrated to the United States over the course of several generations, and the era in which they immigrated may affect their ability to understand English, integrate into American culture, and navigate the US health care system. Successful integration into American life favors those whose families immigrated several generations earlier.

The overall prevalence of HBV infection in the United States is 0.4%2; however, estimates of prevalence range from 5% to 15% in Asian American populations, and are as high as 20% in some Pacific Rim populations.3,4 The prevalence of HBV infection in Asian Americans differs by subpopulation, with the highest prevalence among immigrants from Vietnam, Laos, and China, and the lowest among those from Japan.

Of the approximately 1 million Americans estimated to be infected with HBV as of 2005, more than 750,000 had access to health care; of these, 205,000 were diagnosed with HBV infection,5 suggesting substantial underdiagnosis. Referrals to specialists were even fewer (175,000), and only about 31,000 patients chronically infected with HBV received antiviral treatment, a figure that has likely increased with greater awareness of HBV and the availability of new antiviral medications.

BARRIERS TO DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

The barriers to effective management of HBV infection in Asian Americans include cultural, socioeconomic, and accessibility issues (see “Case: Stigma and cultural barriers lead to inadequate care”).

Language and linguistic isolation

Limited proficiency in English is a large, if not the largest, barrier to effective management of chronic HBV infection. According to the US Census Bureau, a person with limited English proficiency is one who does not speak English “very well.”6 This terminology has implications for allocation of federal government resources; ie, the percentage of a community’s residents with limited English proficiency is a criterion for receipt of governmental grants and other forms of assistance, including translation services.6

Linguistic isolation, another barrier to medical care, is lack of an English-speaking household member who is older than 14 years.7 By this definition, more than one-third of Korean, Taiwanese, Chinese, Hmong, and Bangladeshi households, and almost half of Vietnamese households, are linguistically isolated, with limited ability to communicate with health care providers.8

Lack of health insurance and its correlates

The high percentage of Asian immigrants without health insurance is a challenge to providing adequate health care. Health insurance coverage is lacking for about one-third of Korean immigrants, about one in five immigrants from Southeast Asia and South Asia, and about 15% of Filipino and Chinese immigrants.9

One reason for the large proportion of uninsured among these groups is the high rate of small business ownership among Asian Americans and the difficulty that small business owners have in obtaining affordable health insurance coverage. In addition, although Asian Americans are as likely as other US residents to be employed full time, their employment options may be less likely to include health insurance benefits.

Poverty affects the ability to acquire health insurance. Although the popular image of the Asian immigrant is an educated person with high earning potential, the reality is that poverty strikes immigrants from Southeast Asia at a high rate. Almost 40% of the Hmong population, for example, lives below the poverty level, and poverty rates among the Cambodian, Bangladeshi, Malaysian, and several other Asian subpopulations are nearly as high.8

Citizenship correlates with the ability to obtain health insurance; it is estimated that 42% to 57% of noncitizens lack health insurance, compared with 15% of citizens.8 Only half of Asian immigrants become naturalized citizens, with wide variability among subgroups. Two-thirds of Filipinos who immigrate to the United States eventually become naturalized compared with less than one-third of Malaysian, Japanese, Indonesian, and Hmong immigrants.8

Educational achievement is associated with attainment of financial security and health insurance. The vast majority of Taiwanese, Japanese, Filipino, and Korean Americans obtain a high school education or higher, with correspondingly higher rates of health insurance coverage. Among those from Southeast Asia (Hmong, Cambodians, Laotians, and Vietnamese), whose immigration to this country is relatively recent, fewer than half complete a high school education.8

Health care workforce representation

Certain Asian subgroups are underrepresented in the racial composition of the US health care workforce; this imbalance may affect accessibility to the health care system and adherence to medical prescriptions and instructions among underrepresented groups. Racial concordance between patient and health care provider is associated with greater patient participation in care, according to the Institute of Medicine.10 In addition to racial similarity, linguistic similarity enhances communication and adherence to instructions.

Belief systems and attitudes toward health care

An immigrant patient’s religious beliefs and cultural attitudes toward Western medicine may pose difficulties in successfully managing disease. Many Asian Americans are Buddhists, who may believe that suffering is an integral part of life; proactively seeking medical care may not be imperative for them. Confucianism, the worship of ancestors and the subjugation of the self to the well-being of the family, is a common belief system among Asians that may inhibit the desire to seek needed medical care. For example, a family elder may instruct a young man not to seek medical care for his HBV infection because this would jeopardize his siblings’ marriage prospects. Taoism involves the belief that perfection is achieved when events are allowed to take the more natural course. Intervention is therefore frowned upon.

Some belief systems may impede care because they incorporate indifference toward suffering. Many Hmong believe that the length of life is predetermined, so lifesaving care is pointless. Cultural value may be placed on stoicism, discouraging visits to health care providers. A belief that disease is caused by supernatural events rather than organic etiologies is another perception that serves as a barrier to seeking medical care.

Distrust of, or unfamiliarity with, Western medicine may delay care, and the resulting poor outcomes may be falsely attributed to Western medicine itself. In some cultures, there is a pervasive belief that a physician can touch the pulse and identify the problem. Some Laotians believe that immunizations are dangerous for a baby’s spirit, and therefore forgo immunization against HBV when it is indicated.

The patient’s relationship with his or her health care provider is an important determinant of quality of care and willingness to continue to receive care. The best possible scenario is concordance in language and culture. Asian cultures emphasize politeness, respect for authority, filial piety, and avoidance of shame. Because Asian patients often view physicians as authority figures, they may not ask questions or voice reservations or fears about their treatment regimens; instead, they may express their agreement with physicians’ advice, but with no intent to return or follow instructions.

Infection with HBV carries a stigma about the mode of transmission that can interfere with patients’ daily lives. A study of attitudes about HBV found that HBV-infected patients feel less welcome to stay overnight or share the same bathroom at friends’ or relatives’ houses, that noninfected persons fear that the disease may be passed to them by HBV-positive friends, and that HBV-infected patients are concerned about whether their choices may have led to the infection.11

OVERCOMING BARRIERS

Sensitivity to cultural attitudes may enhance communication and the likelihood that patients will accept physicians’ recommendations. Several office visits may be necessary to confirm that a patient is receptive to the health care provider’s instructions and is adhering to them. Referral to access programs can aid communication. For example, most cities have community centers where patients can seek medical advice from physicians who speak the patients’ language; these centers also may provide native-language materials and interpreters.

Offering reassurance to patients in their own language and in a culturally sensitive setting will help break down barriers and improve care. Patients who are educated about HBV transmission and the availability of an effective vaccine may be instrumental in preventing transmission of the disease to household members.

Cultural sensitivity training will benefit health care providers and staffs whose patients include Asian Americans. Educational programs should be specific to the needs of the community, as different subpopulations have different needs. Resource materials are available for such training; for example, the federal government’s Office of Minority Health Web site (http://www.omhrc.gov/) offers links to resources for cultural training. In addition to educating themselves and their staffs, health care providers have a responsibility to advocate for funding and equal access to care, and for the creation of more cultural and community health centers that can serve as resources to overcome cultural barriers.

DISCUSSION

Robert G. Gish, MD: How often are herbal remedies tried for chronic HBV infection in the patients you see, especially in the Vietnamese population?

Tram T. Tran, MD: Once patients are diagnosed with chronic HBV infection, the use of herbal remedies is very high; it approaches 80% in my practice. Patients may not admit to it unless you ask them specifically, because they know herbal remedies may be somewhat frowned upon by Western physicians. If you are careful and ask very gently about their use of herbals, they will tell you that they do believe in herbal medicines pretty strongly.

Morris Sherman, MD, PhD: I’d like to emphasize the need to be able to communicate with patients in their own language. In Toronto, 50% of the population was born outside of Canada. We have a huge immigrant population; given the nature of hepatology, we have many patients from Southeast and South Asia, and from all over the world, who don’t speak English. My hospital has a multilingual interpreter service, which we use freely. Scarcely a day goes by without two or three interpreters coming to the clinic to talk to patients, and as a result it’s rare that I can’t make myself understood. Maybe what I’ve said hasn’t been accepted, but patients can at least understand what I’m saying.

William D. Carey, MD: I interview many applicants for our medical school, and many of them are Asians, including Hmong and Vietnamese. With the high value that most of these groups put on education and their success with educational attainment, is their access to care improving? Are we doing a better job of training nurses, allied health personnel, and physicians to deal with this problem?

Dr. Tran: I think so, yes. For instance, the Southeast Asian immigrant population arrived in two different eras. The Vietnamese who immigrated in 1975 have been in the United States longer and in general have been able to attain a higher level of education than those who came later. The group that arrived earlier is therefore more likely to have health insurance, and it has been easier to get them into the health care system. More recent immigrants have had more difficulty navigating the system. In general, their socioeconomic status and therefore access to care is directly related to how long they’ve been in the country.

Asian Americans represent 4% of the population in the United States, and their share of the US population is projected to grow to 9% by 2050.1 These numbers are significant because of the high prevalence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in this community and the cultural barriers to its effective management.

Appreciating the impact of cultural barriers on health care among Asian Americans requires an understanding of the diversity of the Asian continent, which is composed of 52 countries where 100 languages and dialects are spoken. Within each region are religious, cultural, and societal differences. Asians have immigrated to the United States over the course of several generations, and the era in which they immigrated may affect their ability to understand English, integrate into American culture, and navigate the US health care system. Successful integration into American life favors those whose families immigrated several generations earlier.

The overall prevalence of HBV infection in the United States is 0.4%2; however, estimates of prevalence range from 5% to 15% in Asian American populations, and are as high as 20% in some Pacific Rim populations.3,4 The prevalence of HBV infection in Asian Americans differs by subpopulation, with the highest prevalence among immigrants from Vietnam, Laos, and China, and the lowest among those from Japan.

Of the approximately 1 million Americans estimated to be infected with HBV as of 2005, more than 750,000 had access to health care; of these, 205,000 were diagnosed with HBV infection,5 suggesting substantial underdiagnosis. Referrals to specialists were even fewer (175,000), and only about 31,000 patients chronically infected with HBV received antiviral treatment, a figure that has likely increased with greater awareness of HBV and the availability of new antiviral medications.

BARRIERS TO DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

The barriers to effective management of HBV infection in Asian Americans include cultural, socioeconomic, and accessibility issues (see “Case: Stigma and cultural barriers lead to inadequate care”).

Language and linguistic isolation

Limited proficiency in English is a large, if not the largest, barrier to effective management of chronic HBV infection. According to the US Census Bureau, a person with limited English proficiency is one who does not speak English “very well.”6 This terminology has implications for allocation of federal government resources; ie, the percentage of a community’s residents with limited English proficiency is a criterion for receipt of governmental grants and other forms of assistance, including translation services.6

Linguistic isolation, another barrier to medical care, is lack of an English-speaking household member who is older than 14 years.7 By this definition, more than one-third of Korean, Taiwanese, Chinese, Hmong, and Bangladeshi households, and almost half of Vietnamese households, are linguistically isolated, with limited ability to communicate with health care providers.8

Lack of health insurance and its correlates

The high percentage of Asian immigrants without health insurance is a challenge to providing adequate health care. Health insurance coverage is lacking for about one-third of Korean immigrants, about one in five immigrants from Southeast Asia and South Asia, and about 15% of Filipino and Chinese immigrants.9

One reason for the large proportion of uninsured among these groups is the high rate of small business ownership among Asian Americans and the difficulty that small business owners have in obtaining affordable health insurance coverage. In addition, although Asian Americans are as likely as other US residents to be employed full time, their employment options may be less likely to include health insurance benefits.

Poverty affects the ability to acquire health insurance. Although the popular image of the Asian immigrant is an educated person with high earning potential, the reality is that poverty strikes immigrants from Southeast Asia at a high rate. Almost 40% of the Hmong population, for example, lives below the poverty level, and poverty rates among the Cambodian, Bangladeshi, Malaysian, and several other Asian subpopulations are nearly as high.8

Citizenship correlates with the ability to obtain health insurance; it is estimated that 42% to 57% of noncitizens lack health insurance, compared with 15% of citizens.8 Only half of Asian immigrants become naturalized citizens, with wide variability among subgroups. Two-thirds of Filipinos who immigrate to the United States eventually become naturalized compared with less than one-third of Malaysian, Japanese, Indonesian, and Hmong immigrants.8

Educational achievement is associated with attainment of financial security and health insurance. The vast majority of Taiwanese, Japanese, Filipino, and Korean Americans obtain a high school education or higher, with correspondingly higher rates of health insurance coverage. Among those from Southeast Asia (Hmong, Cambodians, Laotians, and Vietnamese), whose immigration to this country is relatively recent, fewer than half complete a high school education.8

Health care workforce representation

Certain Asian subgroups are underrepresented in the racial composition of the US health care workforce; this imbalance may affect accessibility to the health care system and adherence to medical prescriptions and instructions among underrepresented groups. Racial concordance between patient and health care provider is associated with greater patient participation in care, according to the Institute of Medicine.10 In addition to racial similarity, linguistic similarity enhances communication and adherence to instructions.

Belief systems and attitudes toward health care

An immigrant patient’s religious beliefs and cultural attitudes toward Western medicine may pose difficulties in successfully managing disease. Many Asian Americans are Buddhists, who may believe that suffering is an integral part of life; proactively seeking medical care may not be imperative for them. Confucianism, the worship of ancestors and the subjugation of the self to the well-being of the family, is a common belief system among Asians that may inhibit the desire to seek needed medical care. For example, a family elder may instruct a young man not to seek medical care for his HBV infection because this would jeopardize his siblings’ marriage prospects. Taoism involves the belief that perfection is achieved when events are allowed to take the more natural course. Intervention is therefore frowned upon.

Some belief systems may impede care because they incorporate indifference toward suffering. Many Hmong believe that the length of life is predetermined, so lifesaving care is pointless. Cultural value may be placed on stoicism, discouraging visits to health care providers. A belief that disease is caused by supernatural events rather than organic etiologies is another perception that serves as a barrier to seeking medical care.

Distrust of, or unfamiliarity with, Western medicine may delay care, and the resulting poor outcomes may be falsely attributed to Western medicine itself. In some cultures, there is a pervasive belief that a physician can touch the pulse and identify the problem. Some Laotians believe that immunizations are dangerous for a baby’s spirit, and therefore forgo immunization against HBV when it is indicated.

The patient’s relationship with his or her health care provider is an important determinant of quality of care and willingness to continue to receive care. The best possible scenario is concordance in language and culture. Asian cultures emphasize politeness, respect for authority, filial piety, and avoidance of shame. Because Asian patients often view physicians as authority figures, they may not ask questions or voice reservations or fears about their treatment regimens; instead, they may express their agreement with physicians’ advice, but with no intent to return or follow instructions.

Infection with HBV carries a stigma about the mode of transmission that can interfere with patients’ daily lives. A study of attitudes about HBV found that HBV-infected patients feel less welcome to stay overnight or share the same bathroom at friends’ or relatives’ houses, that noninfected persons fear that the disease may be passed to them by HBV-positive friends, and that HBV-infected patients are concerned about whether their choices may have led to the infection.11

OVERCOMING BARRIERS

Sensitivity to cultural attitudes may enhance communication and the likelihood that patients will accept physicians’ recommendations. Several office visits may be necessary to confirm that a patient is receptive to the health care provider’s instructions and is adhering to them. Referral to access programs can aid communication. For example, most cities have community centers where patients can seek medical advice from physicians who speak the patients’ language; these centers also may provide native-language materials and interpreters.

Offering reassurance to patients in their own language and in a culturally sensitive setting will help break down barriers and improve care. Patients who are educated about HBV transmission and the availability of an effective vaccine may be instrumental in preventing transmission of the disease to household members.

Cultural sensitivity training will benefit health care providers and staffs whose patients include Asian Americans. Educational programs should be specific to the needs of the community, as different subpopulations have different needs. Resource materials are available for such training; for example, the federal government’s Office of Minority Health Web site (http://www.omhrc.gov/) offers links to resources for cultural training. In addition to educating themselves and their staffs, health care providers have a responsibility to advocate for funding and equal access to care, and for the creation of more cultural and community health centers that can serve as resources to overcome cultural barriers.

DISCUSSION

Robert G. Gish, MD: How often are herbal remedies tried for chronic HBV infection in the patients you see, especially in the Vietnamese population?

Tram T. Tran, MD: Once patients are diagnosed with chronic HBV infection, the use of herbal remedies is very high; it approaches 80% in my practice. Patients may not admit to it unless you ask them specifically, because they know herbal remedies may be somewhat frowned upon by Western physicians. If you are careful and ask very gently about their use of herbals, they will tell you that they do believe in herbal medicines pretty strongly.

Morris Sherman, MD, PhD: I’d like to emphasize the need to be able to communicate with patients in their own language. In Toronto, 50% of the population was born outside of Canada. We have a huge immigrant population; given the nature of hepatology, we have many patients from Southeast and South Asia, and from all over the world, who don’t speak English. My hospital has a multilingual interpreter service, which we use freely. Scarcely a day goes by without two or three interpreters coming to the clinic to talk to patients, and as a result it’s rare that I can’t make myself understood. Maybe what I’ve said hasn’t been accepted, but patients can at least understand what I’m saying.

William D. Carey, MD: I interview many applicants for our medical school, and many of them are Asians, including Hmong and Vietnamese. With the high value that most of these groups put on education and their success with educational attainment, is their access to care improving? Are we doing a better job of training nurses, allied health personnel, and physicians to deal with this problem?

Dr. Tran: I think so, yes. For instance, the Southeast Asian immigrant population arrived in two different eras. The Vietnamese who immigrated in 1975 have been in the United States longer and in general have been able to attain a higher level of education than those who came later. The group that arrived earlier is therefore more likely to have health insurance, and it has been easier to get them into the health care system. More recent immigrants have had more difficulty navigating the system. In general, their socioeconomic status and therefore access to care is directly related to how long they’ve been in the country.

- President’s Advisory Commission on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders: a people looking forward. Action for access and partnerships in the 21st century. Interim report to the president and the nation. http://permanent.access.gpo.gov/lps17931/www.aapi.gov/intreport.htm. Published January 2001. Accessed December 21, 2008.

- National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention. Hepatitis B index. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HBV/HBVfaq.htm. Updated July 8, 2008. Accessed January 21, 2009.

- Do S. The natural history of hepatitis B in Asian Americans. Asian Am Pac Isl J Health 2001; 9:141–153.

- Stanford University School of Medicine. FAQ about hepatitis B. Asian Liver Center Web site. http://liver.stanford.edu/Education/faq.html. Updated July 10, 2008. Accessed January 21, 2009.

- Di Bisceglie AM, Keeffe E, Atillasoy E, Varshneya R, Bergstein G. Management of chronic hepatitis B—an analysis of physician practices [DDW abstract M918]. Gastroenterology 2005; 128(suppl 2):A739.

- US Census Bureau. American community survey. US Census Bureau Web site. http://www.census.gov/acs/www/SBasics/SQuest/fact_pdf/P%2013%20factsheetlanguageathome2.pdf. Published January 29, 2004. Accessed January 21, 2009.

- Lestina FA. Analysis of the linguistically isolated population in Census 2000. http://www.census.gov/pred/www/rpts/A.5a.pdf. Published September 30, 2003. Accessed January 21, 2009.

- Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum. Diverse communities, diverse experiences: the status of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the U.S. http://www.apiahf.org/resources/pdf/Diverse%20Communities%20Diverse%20Experiences.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2009.

- Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum. Race, ethnicity and health care fact sheet. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation Web site. http://www.kff.org/minorityhealth/upload/7745.pdf. Published April 2008. Accessed January 21, 2009.

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds; Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, Board on Health Sciences Policy, Institute of Medicine. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?isbn=030908265X. Published 2003. Accessed January 21, 2009.

- Speigel BMR, Bollus R, Han S, et al. Development and validation of a disease-targeted quality of life instrument in chronic hepatitis B: the hepatitis B quality of life instrument, version 1.0. Hepatology 2007; 46:113–121.

- President’s Advisory Commission on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders: a people looking forward. Action for access and partnerships in the 21st century. Interim report to the president and the nation. http://permanent.access.gpo.gov/lps17931/www.aapi.gov/intreport.htm. Published January 2001. Accessed December 21, 2008.

- National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention. Hepatitis B index. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HBV/HBVfaq.htm. Updated July 8, 2008. Accessed January 21, 2009.

- Do S. The natural history of hepatitis B in Asian Americans. Asian Am Pac Isl J Health 2001; 9:141–153.

- Stanford University School of Medicine. FAQ about hepatitis B. Asian Liver Center Web site. http://liver.stanford.edu/Education/faq.html. Updated July 10, 2008. Accessed January 21, 2009.

- Di Bisceglie AM, Keeffe E, Atillasoy E, Varshneya R, Bergstein G. Management of chronic hepatitis B—an analysis of physician practices [DDW abstract M918]. Gastroenterology 2005; 128(suppl 2):A739.

- US Census Bureau. American community survey. US Census Bureau Web site. http://www.census.gov/acs/www/SBasics/SQuest/fact_pdf/P%2013%20factsheetlanguageathome2.pdf. Published January 29, 2004. Accessed January 21, 2009.

- Lestina FA. Analysis of the linguistically isolated population in Census 2000. http://www.census.gov/pred/www/rpts/A.5a.pdf. Published September 30, 2003. Accessed January 21, 2009.

- Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum. Diverse communities, diverse experiences: the status of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the U.S. http://www.apiahf.org/resources/pdf/Diverse%20Communities%20Diverse%20Experiences.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2009.

- Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum. Race, ethnicity and health care fact sheet. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation Web site. http://www.kff.org/minorityhealth/upload/7745.pdf. Published April 2008. Accessed January 21, 2009.

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds; Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, Board on Health Sciences Policy, Institute of Medicine. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?isbn=030908265X. Published 2003. Accessed January 21, 2009.

- Speigel BMR, Bollus R, Han S, et al. Development and validation of a disease-targeted quality of life instrument in chronic hepatitis B: the hepatitis B quality of life instrument, version 1.0. Hepatology 2007; 46:113–121.

KEY POINTS

- Some Asian Americans have limited proficiency in English and are isolated linguistically, limiting their ability to communicate with health care providers.

- Asian Americans may view Western medicine with suspicion, causing delays in seeking care and making it difficult to successfully manage chronic HBV infection.

- Sensitivity to cultural attitudes may enhance communication and the likelihood that immigrant patients will accept health care providers’ recommendations; cultural sensitivity training may be helpful.