User login

Tolerance of Fragranced and Fragrance-Free Facial Cleansers in Adults With Clinically Sensitive Skin

For thousands of years, humans have used fragrances to change or affect their mood and enhance an “aura of beauty.”1 Fragrance is a primary driver in consumer choice and purchasing decisions, especially when considering personal care products.2 In addition to fragrance, consumers choose cleanser products based on compatibility with skin, cleansing properties, and sensory attributes such as viscosity and foaming.3,4 However, fragrance sensitivity is among the most common causes of allergic contact dermatitis from cosmetics and personal care products,5 and estimates of the prevalence of fragrance sensitivity range from 1.8% to 4.2%.6

A panel of 26 fragrance ingredients that frequently induce contact dermatitis in sensitive individuals has been identified.7 Since 2003, regulatory authorities in the European Union require these compounds to be listed on the labels of consumer products to protect presensitized consumers.7,8 However, manufacturers of cosmetics are not required to specify allergenic fragrance ingredients outside the European Union, and therefore it is difficult for consumers in the United States to avoid fragrance allergens.

Creation of a fragranced product for fragrance-sensitive individuals begins with careful selection of ingredients and extensive formulation testing and evaluation. This process usually is followed by testing in normal individuals to confirm that the fragranced product is well accepted and then evaluation is done in clinically confirmed fragrance-sensitive patients and those with a compromised skin barrier from atopic dermatitis, rosacea, or eczema.

Sensitive skin may be due to increased immune responsiveness, altered neurosensory input, and/or decreased skin barrier function, and presents a complex challenge for dermatologists.9 Subjective perceptions of sensitive skin include stinging, burning, pruritus, and tightness following product application. Clinically sensitive skin is defined by the presence of erythema, stratum corneum desquamation, papules, pustules, wheals, vesicles, bullae, and/or erosions.9 Although some of these symptoms may be observed immediately, others may be delayed by minutes, hours, or days following the use of an irritating product. Patients who present with subjective symptoms of sensitive skin may or may not show objective symptoms.

Gentle skin cleansing is particularly important for patients with compromised skin barrier integrity, such as those with acne, atopic dermatitis, eczema, or rosacea. Standard alkaline surfactants in skin cleansers help to remove dirt and oily soil and produce lather but can impair the skin barrier function and facilitate development of irritation.10-13 The tolerability of a cleanser is influenced by its pH, the type and amount of surfactant ingredients, the presence of moisturizing agents, and the amount of residue left on the skin after washing.11,12 Mild cleansers have been developed for patients with sensitive skin conditions and are expected to provide cleansing benefits without negatively affecting the hydration and viscoelastic properties of skin.11 Mild cleansers interact minimally with skin proteins and lipids because they usually contain nonionic synthetic surfactant mixtures; they also have a pH value close to the slightly acidic pH of normal skin, contain moisturizing agents,11,14,15 and usually produce less foam.10,16 In patients with sensitive skin, mild and fragrance-free cleansers often are recommended.17,18 Because fragrances often affect consumers’ perception of product performance19 and enhance the cleaning experience of the user, consumer compliance with clinical recommendations to use fragrance-free cleansers often is poor.

Low–molecular-weight, water-soluble, hydrophobically modified polymers (HMPs) have been used to create gentle foaming cleansers with reduced impact on the skin barrier.12,16,20 In the presence of HMPs, surfactants assemble into larger, more stable polymer-surfactant structures that are less likely to penetrate the skin.16 Hydrophobically modified polymers can potentially reduce skin irritation by lowering the concentration of free micelles in solution. Additionally, both HMPs and HMP-surfactant complexes stabilize newly formed air-water interfaces, leading to thicker, denser, and longer-lasting foams.16 A gentle, fragrance-free, foaming liquid facial test cleanser with HMPs has been shown to be well tolerated in women with sensitive skin.20

This report describes 2 studies of a new mild, HMP-containing, foaming facial cleanser with a fragrance that was free of common allergens and irritating essential oils in patients with sensitive skin. Study 1 was designed to evaluate the tolerance and acceptability of 2 variations of the HMP-containing cleanser—one fragrance free and the other with fragrance—in a small sample of healthy adults with clinically diagnosed fragrance-sensitive skin. Study 2 was a large, 2-center study of the tolerability and effectiveness of the fragranced HMP-containing cleanser compared with a benchmark dermatologist-recommended, gentle, fragrance-free, nonfoaming cleanser in women with clinically diagnosed sensitive skin.

Methods

Study 1 Design

The primary objective of this prospective, randomized, single-center, crossover study was to evaluate the tolerability of fragranced versus fragrance-free formulations of a mild, HMP-containing liquid facial cleanser in healthy male and female adults with Fitzpatrick skin types I to IV who were clinically diagnosed as having fragrance sensitivity. Fragrance sensitivity was defined as a history of positive reactions to a fragrance mixture of 8 components (fragrance mixture I) and/or a fragrance mixture of 14 fragrances (fragrance mixture II) that included balsam of Peru (Myroxylonpereirae), geraniol, jasmine oil, and oakmoss.5 All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrolling in the study, and both the study protocol and informed consent agreement were approved by an institutional review board.

Participants were instructed to wash their face twice daily, noting the time of cleansing and providing commentary about their cleansing experience in a diary. The liquid facial test cleansers contained the HMP potassium acrylates copolymer, glycerin, and a surfactant system primarily containing cocamidopropyl betaine and lauryl glucoside prepared without added fragrance (as previously described20) or with a fragrance free of common allergens and irritating essential oils.

Half of the participants used the fragranced test cleanser and half used the fragrance-free test cleanser for a 3-week treatment period (weeks 1–3). Each treatment group subsequently switched to the other test cleanser for a second 3-week treatment period (weeks 4–6). Clinicians assessed global disease severity (an overall assessment of skin condition that was independent of other evaluation criteria), itching/burning, visible irritation, erythema, and desquamation at weekly time points throughout the study and graded each clinical tolerance attribute on a 5-point scale (0=none; 1=minimal; 2=mild; 3=moderate; 4=severe). Ordinal scores at baseline and at weeks 1 and 3 were used to calculate change from baseline.

A 7-item questionnaire also was administered to participants at each visit to assess skin condition, smoothness, softness, cleanliness, radiance, satisfaction with cleansing experience, and lathering. Each item was scored on a 5-point ordinal scale (0=none; 1=minimal; 2=good; 3=excellent; 4=superior). The scores for all parameters were statistically compared with baseline values using a paired t test with a significance level of P≤.05.

Study 2 Design

This prospective, 3-week, double-blind, randomized, comparative, 2-center study to evaluate the tolerability of the fragranced, HMP-containing test cleanser from study 1 versus a benchmark gentle, fragrance-free, nonfoaming cleanser in a large population of otherwise healthy females who had been clinically diagnosed with sensitive skin (not limited to fragrance sensitivity). The study sponsor provided blinded test materials, and neither the examiner nor the recorder knew which investigational product was administered to which participants. Additionally, personnel who dispensed the test cleansers to participants or supervised their use did not participate in the evaluation to minimize potential bias. All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrolling in the study, and the study protocol and informed consent agreement were approved by an institutional review board.

Participants included women aged 18 to 65 years with mild to moderate clinical symptoms of atopic dermatitis, eczema, acne, or rosacea within the 90 days prior to the study period. They were randomized into 2 balanced treatment groups: group 1 received the mild, fragranced, HMP-containing liquid facial cleanser from study 1 and group 2 received a leading, dermatologist-recommended, gentle, fragrance-free, nonfoaming cleanser. Each treatment group used the test cleansers at least once daily for 3 weeks.

Clinicians evaluated facial skin for softness and smoothness, global disease severity (rated visually by the investigator as an overall assessment of skin condition that was independent of other evaluation criteria [as previously described20]), itching, irritation, erythema, and desquamation at baseline and at weeks 1 and 3. The effectiveness of each product to remove facial dirt, cosmetics, and sebum also was assessed; clinical grading was performed as described for study 1 using the same grading scale as in study 1 and percentage change from baseline (improvement) was calculated.

The study also included a self-assessment of skin irritation in which participants responded yes or no to the following question: Have you experienced irritation using this product? Participants also completed a questionnaire in which they were asked to select the most appropriate answer—agree strongly, agree somewhat, neither, disagree somewhat, and disagree strongly— to the following statements: the cleanser leaves no residue; cleanses deep to remove dirt, oil, and makeup; the cleanser effectively removes makeup; the cleanser leaves my skin smooth; the cleanser leaves my skin soft; the cleanser rinses completely clean; cleanser does not over dry my skin; and my skin is completely clean.

The statistical analysis was performed using a nonparametric, 2-tailed, paired Mann-Whitney U test, and statistical significance was set at P≤.05.

Results

Study 1 Assessment

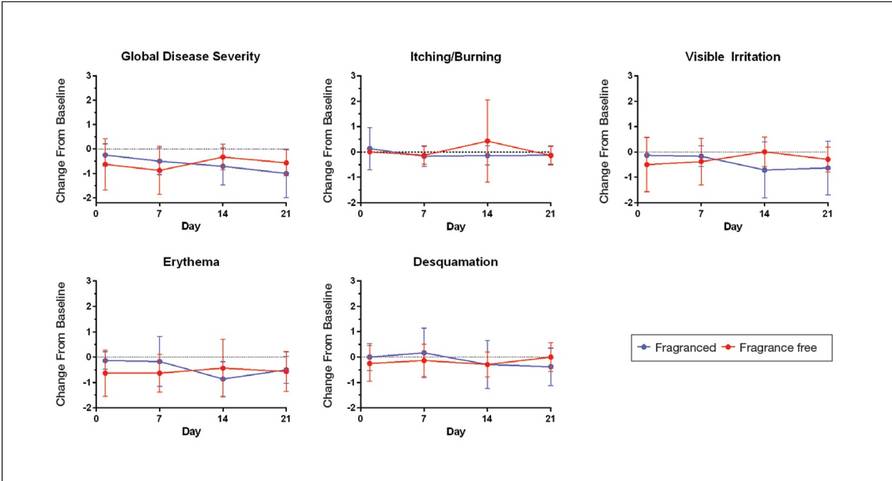

Eight female participants aged 22 to 60 years with clinically diagnosed fragrance sensitivity were enrolled in the study. After 3 weeks of use, clinician assessment showed that both the fragranced and fragrance-free test cleansers with HMPs improved several skin tolerance attributes, including global disease severity, irritation, and erythema (Figure 1). No notable differences in skin tolerance attributes were reported in the fragranced versus the fragrance-free formulations.

There were no reported differences in participant-reported cleanser effectiveness for the fragranced versus the fragrance-free cleanser either at baseline or weeks 1 or 3 (data not shown).

Study 2 Assessment

A total of 153 women aged 25 to 54 years with sensitive skin were enrolled in the study. Seventy-three participants were randomized to receive the fragranced test cleanser and 80 were randomized to receive the benchmark fragrance-free cleanser.

At week 3, there were no differences between the fragranced test cleanser and the benchmark cleanser in any of the clinician-assessed skin parameters (Figure 2). Of the parameters assessed, itching, irritation, and desquamation were the most improved from baseline in both treatment groups. Similar results were observed at week 1 (data not shown).

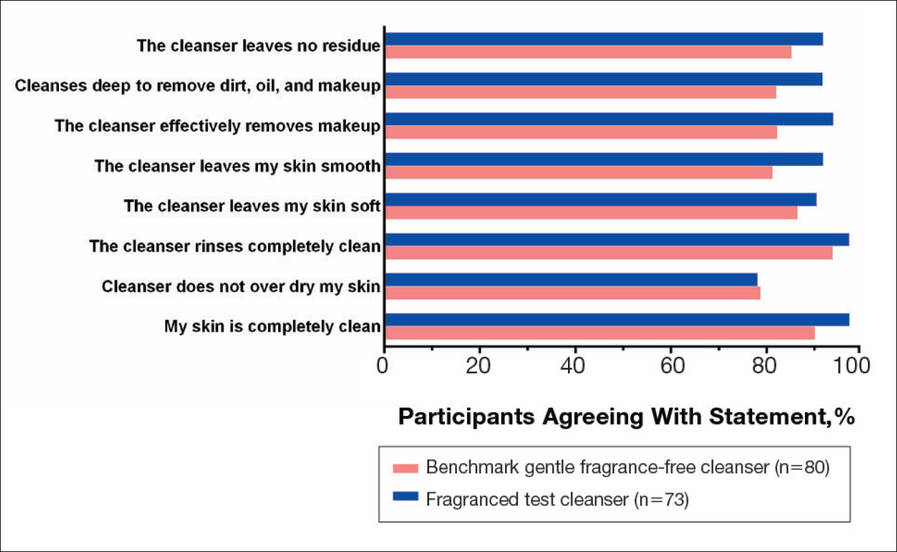

There were no apparent differences in subjective self-assessment of skin irritation between the test and benchmark cleansers at week 1 (15.7% vs 13.0%) or week 3 (24.3% vs 12.3%). When asked to respond to a series of 8 statements related to cleanser effectiveness, most participants either agreed strongly or agreed somewhat with the statements (Figure 3). There were no statistically significant differences between treatment groups, and responses to all statements indicated that participants were as satisfied with the test cleanser as they were with the benchmark cleanser.

Comment

Consumers value cleansing, fragrance, viscosity, and foaming attributes in skin care products very highly.3,4,10 Fragrances are added to personal care products to positively affect consumers’ perception of product performance and to add emotional benefits by implying social or economic prestige to the use of a product.19 In one study, shampoo formulations that varied only in the added fragrance received different consumer evaluations for cleansing effectiveness and foaming.4

Although mild nonfoaming cleansers can be effective, adult consumers generally use cleansers that foam10,16 and often judge the performance of a cleansing product based on its foaming properties.3,10 Mild cleansers with HMPs maintain the ability to foam while also reducing the likelihood of skin irritation.16 One study showed that a mild, fragrance-free, foaming cleanser containing HMPs was as effective, well tolerated, and nonirritating in patients with sensitive skin as a benchmark nonfoaming gentle cleanser.20

Results from study 1 presented here show that fragranced and fragrance-free formulations of a mild, HMP-containing cleanser are equally efficacious and well tolerated in a small sample of participants with clinically diagnosed fragrance sensitivity. Skin tolerance attributes improved with both cleansers over a 3-week period, particularly global disease severity, irritation, and erythema. These results suggest that a fragrance free of common allergens and irritating essential oils could be introduced into a mild foaming cleanser containing HMPs without causing adverse reactions, even in patients who are fragrance sensitive.

Although the populations of studies 1 and 2 both included female participants with sensitive skin, they were not identical. While study 1 assessed a limited number of participants with clinically diagnosed fragrance sensitivity, study 2 was larger and included a broader range of participants with clinically diagnosed skin sensitivity, which could include fragrance sensitivity. The well-chosen fragrance of the test cleanser containing HMPs was well tolerated; however, this does not imply that any other fragrances added to this cleanser formulation would be as well tolerated.

Conclusion

The current studies indicate that a gentle fragranced foaming cleanser with HMPs was well tolerated in a small population of participants with clinically diagnosed fragrance sensitivity. In a larger population of female participants with sensitive skin, the gentle fragranced foaming cleanser with HMPs was as effective as a leading dermatologist-recommended, fragrance-free, gentle, nonfoaming cleanser. The gentle, HMP-containing, foaming cleanser with a fragrance that does not contain common allergens and irritating essential oils offers a new cleansing option for adults with sensitive skin who may prefer to use a fragranced and foaming product.

Acknowledgments—The authors are grateful to the patients and clinicians who participated in these studies. Editorial and medical writing support was provided by Tove Anderson, PhD, and Alex Loeb, PhD, both from Evidence Scientific Solutions, Inc, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and was funded by Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc.

- Draelos ZD. To smell or not to smell? that is the question! J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;12:1-2.

- Milotic D. The impact of fragrance on consumer choice. J Consumer Behaviour. 2003;3:179-191.

- Klein K. Evaluating shampoo foam. Cosmetics & Toiletries. 2004;119:32-36.

- Herman S. Skin care: the importance of feel. GCI Magazine. December 2007:70-74.

- Larsen WG. How to test for fragrance allergy. Cutis. 2000;65:39-41.

- Schnuch A, Uter W, Geier J, et al. Epidemiology of contact allergy: an estimation of morbidity employing the clinical epidemiology and drug-utilization research (CE-DUR) approach. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;47:32-39.

- Directive 2003/15/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 February 2003 amending Council Directive 76/768/EEC on the approximation of the laws of the Member States relating to cosmetic products. Official Journal of the European Communities. 2003;L66:26-35.

- Guidance note: labelling of ingredients in Cosmetics Directive 76/768/EEC. European Commission Web site. http: //ec.europa.eu/consumers/sectors/cosmetics/files/doc/guide _labelling200802_en.pdf. Updated February 2008. Accessed September 2, 2015.

- Draelos ZD. Sensitive skin: perceptions, evaluation, and treatment. Am J Contact Dermatitis. 1997;8:67-78.

- Abbas S, Goldberg JW, Massaro M. Personal cleanser technology and clinical performance. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17(suppl 1):35-42.

- Ananthapadmanabhan KP, Moore DJ, Subramanyan K, et al. Cleansing without compromise: the impact of cleansers on the skin barrier and the technology of mild cleansing. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17(suppl 1):16-25.

- Walters RM, Mao G, Gunn ET, et al. Cleansing formulations that respect skin barrier integrity. Dermatol Res Pract. 2012;2012:495917.

- Saad P, Flach CR, Walters RM, et al. Infrared spectroscopic studies of sodium dodecyl sulphate permeation and interaction with stratum corneum lipids in skin. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2012;34:36-43.

- Bikowski J. The use of cleansers as therapeutic concomitants in various dermatologic disorders. Cutis. 2001;68(suppl 5):12-19.

- Walters RM, Fevola MJ, LiBrizzi JJ, et al. Designing cleansers for the unique needs of baby skin. Cosmetics & Toiletries. 2008;123:53-60.

- Fevola MJ, Walters RM, LiBrizzi JJ. A new approach to formulating mild cleansers: hydrophobically-modified polymers for irritation mitigation. In: Morgan SE, Lochhead RY, eds. Polymeric Delivery of Therapeutics. Vol 1053. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society; 2011:221-242.

- Nelson SA, Yiannias JA. Relevance and avoidance of skin-care product allergens: pearls and pitfalls. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:329-336.

- Arribas MP, Soro P, Silvestre JF. Allergic contact dermatitis to fragrances: part 2. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:29-37.

- Schroeder W. Understanding fragrance in personal care. Cosmetics & Toiletries. 2009;124:36-44.

- Draelos Z, Hornby S, Walters RM, et al. Hydrophobically-modified polymers can minimize skin irritation potential caused by surfactant-based cleansers. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;12:314-321.

For thousands of years, humans have used fragrances to change or affect their mood and enhance an “aura of beauty.”1 Fragrance is a primary driver in consumer choice and purchasing decisions, especially when considering personal care products.2 In addition to fragrance, consumers choose cleanser products based on compatibility with skin, cleansing properties, and sensory attributes such as viscosity and foaming.3,4 However, fragrance sensitivity is among the most common causes of allergic contact dermatitis from cosmetics and personal care products,5 and estimates of the prevalence of fragrance sensitivity range from 1.8% to 4.2%.6

A panel of 26 fragrance ingredients that frequently induce contact dermatitis in sensitive individuals has been identified.7 Since 2003, regulatory authorities in the European Union require these compounds to be listed on the labels of consumer products to protect presensitized consumers.7,8 However, manufacturers of cosmetics are not required to specify allergenic fragrance ingredients outside the European Union, and therefore it is difficult for consumers in the United States to avoid fragrance allergens.

Creation of a fragranced product for fragrance-sensitive individuals begins with careful selection of ingredients and extensive formulation testing and evaluation. This process usually is followed by testing in normal individuals to confirm that the fragranced product is well accepted and then evaluation is done in clinically confirmed fragrance-sensitive patients and those with a compromised skin barrier from atopic dermatitis, rosacea, or eczema.

Sensitive skin may be due to increased immune responsiveness, altered neurosensory input, and/or decreased skin barrier function, and presents a complex challenge for dermatologists.9 Subjective perceptions of sensitive skin include stinging, burning, pruritus, and tightness following product application. Clinically sensitive skin is defined by the presence of erythema, stratum corneum desquamation, papules, pustules, wheals, vesicles, bullae, and/or erosions.9 Although some of these symptoms may be observed immediately, others may be delayed by minutes, hours, or days following the use of an irritating product. Patients who present with subjective symptoms of sensitive skin may or may not show objective symptoms.

Gentle skin cleansing is particularly important for patients with compromised skin barrier integrity, such as those with acne, atopic dermatitis, eczema, or rosacea. Standard alkaline surfactants in skin cleansers help to remove dirt and oily soil and produce lather but can impair the skin barrier function and facilitate development of irritation.10-13 The tolerability of a cleanser is influenced by its pH, the type and amount of surfactant ingredients, the presence of moisturizing agents, and the amount of residue left on the skin after washing.11,12 Mild cleansers have been developed for patients with sensitive skin conditions and are expected to provide cleansing benefits without negatively affecting the hydration and viscoelastic properties of skin.11 Mild cleansers interact minimally with skin proteins and lipids because they usually contain nonionic synthetic surfactant mixtures; they also have a pH value close to the slightly acidic pH of normal skin, contain moisturizing agents,11,14,15 and usually produce less foam.10,16 In patients with sensitive skin, mild and fragrance-free cleansers often are recommended.17,18 Because fragrances often affect consumers’ perception of product performance19 and enhance the cleaning experience of the user, consumer compliance with clinical recommendations to use fragrance-free cleansers often is poor.

Low–molecular-weight, water-soluble, hydrophobically modified polymers (HMPs) have been used to create gentle foaming cleansers with reduced impact on the skin barrier.12,16,20 In the presence of HMPs, surfactants assemble into larger, more stable polymer-surfactant structures that are less likely to penetrate the skin.16 Hydrophobically modified polymers can potentially reduce skin irritation by lowering the concentration of free micelles in solution. Additionally, both HMPs and HMP-surfactant complexes stabilize newly formed air-water interfaces, leading to thicker, denser, and longer-lasting foams.16 A gentle, fragrance-free, foaming liquid facial test cleanser with HMPs has been shown to be well tolerated in women with sensitive skin.20

This report describes 2 studies of a new mild, HMP-containing, foaming facial cleanser with a fragrance that was free of common allergens and irritating essential oils in patients with sensitive skin. Study 1 was designed to evaluate the tolerance and acceptability of 2 variations of the HMP-containing cleanser—one fragrance free and the other with fragrance—in a small sample of healthy adults with clinically diagnosed fragrance-sensitive skin. Study 2 was a large, 2-center study of the tolerability and effectiveness of the fragranced HMP-containing cleanser compared with a benchmark dermatologist-recommended, gentle, fragrance-free, nonfoaming cleanser in women with clinically diagnosed sensitive skin.

Methods

Study 1 Design

The primary objective of this prospective, randomized, single-center, crossover study was to evaluate the tolerability of fragranced versus fragrance-free formulations of a mild, HMP-containing liquid facial cleanser in healthy male and female adults with Fitzpatrick skin types I to IV who were clinically diagnosed as having fragrance sensitivity. Fragrance sensitivity was defined as a history of positive reactions to a fragrance mixture of 8 components (fragrance mixture I) and/or a fragrance mixture of 14 fragrances (fragrance mixture II) that included balsam of Peru (Myroxylonpereirae), geraniol, jasmine oil, and oakmoss.5 All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrolling in the study, and both the study protocol and informed consent agreement were approved by an institutional review board.

Participants were instructed to wash their face twice daily, noting the time of cleansing and providing commentary about their cleansing experience in a diary. The liquid facial test cleansers contained the HMP potassium acrylates copolymer, glycerin, and a surfactant system primarily containing cocamidopropyl betaine and lauryl glucoside prepared without added fragrance (as previously described20) or with a fragrance free of common allergens and irritating essential oils.

Half of the participants used the fragranced test cleanser and half used the fragrance-free test cleanser for a 3-week treatment period (weeks 1–3). Each treatment group subsequently switched to the other test cleanser for a second 3-week treatment period (weeks 4–6). Clinicians assessed global disease severity (an overall assessment of skin condition that was independent of other evaluation criteria), itching/burning, visible irritation, erythema, and desquamation at weekly time points throughout the study and graded each clinical tolerance attribute on a 5-point scale (0=none; 1=minimal; 2=mild; 3=moderate; 4=severe). Ordinal scores at baseline and at weeks 1 and 3 were used to calculate change from baseline.

A 7-item questionnaire also was administered to participants at each visit to assess skin condition, smoothness, softness, cleanliness, radiance, satisfaction with cleansing experience, and lathering. Each item was scored on a 5-point ordinal scale (0=none; 1=minimal; 2=good; 3=excellent; 4=superior). The scores for all parameters were statistically compared with baseline values using a paired t test with a significance level of P≤.05.

Study 2 Design

This prospective, 3-week, double-blind, randomized, comparative, 2-center study to evaluate the tolerability of the fragranced, HMP-containing test cleanser from study 1 versus a benchmark gentle, fragrance-free, nonfoaming cleanser in a large population of otherwise healthy females who had been clinically diagnosed with sensitive skin (not limited to fragrance sensitivity). The study sponsor provided blinded test materials, and neither the examiner nor the recorder knew which investigational product was administered to which participants. Additionally, personnel who dispensed the test cleansers to participants or supervised their use did not participate in the evaluation to minimize potential bias. All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrolling in the study, and the study protocol and informed consent agreement were approved by an institutional review board.

Participants included women aged 18 to 65 years with mild to moderate clinical symptoms of atopic dermatitis, eczema, acne, or rosacea within the 90 days prior to the study period. They were randomized into 2 balanced treatment groups: group 1 received the mild, fragranced, HMP-containing liquid facial cleanser from study 1 and group 2 received a leading, dermatologist-recommended, gentle, fragrance-free, nonfoaming cleanser. Each treatment group used the test cleansers at least once daily for 3 weeks.

Clinicians evaluated facial skin for softness and smoothness, global disease severity (rated visually by the investigator as an overall assessment of skin condition that was independent of other evaluation criteria [as previously described20]), itching, irritation, erythema, and desquamation at baseline and at weeks 1 and 3. The effectiveness of each product to remove facial dirt, cosmetics, and sebum also was assessed; clinical grading was performed as described for study 1 using the same grading scale as in study 1 and percentage change from baseline (improvement) was calculated.

The study also included a self-assessment of skin irritation in which participants responded yes or no to the following question: Have you experienced irritation using this product? Participants also completed a questionnaire in which they were asked to select the most appropriate answer—agree strongly, agree somewhat, neither, disagree somewhat, and disagree strongly— to the following statements: the cleanser leaves no residue; cleanses deep to remove dirt, oil, and makeup; the cleanser effectively removes makeup; the cleanser leaves my skin smooth; the cleanser leaves my skin soft; the cleanser rinses completely clean; cleanser does not over dry my skin; and my skin is completely clean.

The statistical analysis was performed using a nonparametric, 2-tailed, paired Mann-Whitney U test, and statistical significance was set at P≤.05.

Results

Study 1 Assessment

Eight female participants aged 22 to 60 years with clinically diagnosed fragrance sensitivity were enrolled in the study. After 3 weeks of use, clinician assessment showed that both the fragranced and fragrance-free test cleansers with HMPs improved several skin tolerance attributes, including global disease severity, irritation, and erythema (Figure 1). No notable differences in skin tolerance attributes were reported in the fragranced versus the fragrance-free formulations.

There were no reported differences in participant-reported cleanser effectiveness for the fragranced versus the fragrance-free cleanser either at baseline or weeks 1 or 3 (data not shown).

Study 2 Assessment

A total of 153 women aged 25 to 54 years with sensitive skin were enrolled in the study. Seventy-three participants were randomized to receive the fragranced test cleanser and 80 were randomized to receive the benchmark fragrance-free cleanser.

At week 3, there were no differences between the fragranced test cleanser and the benchmark cleanser in any of the clinician-assessed skin parameters (Figure 2). Of the parameters assessed, itching, irritation, and desquamation were the most improved from baseline in both treatment groups. Similar results were observed at week 1 (data not shown).

There were no apparent differences in subjective self-assessment of skin irritation between the test and benchmark cleansers at week 1 (15.7% vs 13.0%) or week 3 (24.3% vs 12.3%). When asked to respond to a series of 8 statements related to cleanser effectiveness, most participants either agreed strongly or agreed somewhat with the statements (Figure 3). There were no statistically significant differences between treatment groups, and responses to all statements indicated that participants were as satisfied with the test cleanser as they were with the benchmark cleanser.

Comment

Consumers value cleansing, fragrance, viscosity, and foaming attributes in skin care products very highly.3,4,10 Fragrances are added to personal care products to positively affect consumers’ perception of product performance and to add emotional benefits by implying social or economic prestige to the use of a product.19 In one study, shampoo formulations that varied only in the added fragrance received different consumer evaluations for cleansing effectiveness and foaming.4

Although mild nonfoaming cleansers can be effective, adult consumers generally use cleansers that foam10,16 and often judge the performance of a cleansing product based on its foaming properties.3,10 Mild cleansers with HMPs maintain the ability to foam while also reducing the likelihood of skin irritation.16 One study showed that a mild, fragrance-free, foaming cleanser containing HMPs was as effective, well tolerated, and nonirritating in patients with sensitive skin as a benchmark nonfoaming gentle cleanser.20

Results from study 1 presented here show that fragranced and fragrance-free formulations of a mild, HMP-containing cleanser are equally efficacious and well tolerated in a small sample of participants with clinically diagnosed fragrance sensitivity. Skin tolerance attributes improved with both cleansers over a 3-week period, particularly global disease severity, irritation, and erythema. These results suggest that a fragrance free of common allergens and irritating essential oils could be introduced into a mild foaming cleanser containing HMPs without causing adverse reactions, even in patients who are fragrance sensitive.

Although the populations of studies 1 and 2 both included female participants with sensitive skin, they were not identical. While study 1 assessed a limited number of participants with clinically diagnosed fragrance sensitivity, study 2 was larger and included a broader range of participants with clinically diagnosed skin sensitivity, which could include fragrance sensitivity. The well-chosen fragrance of the test cleanser containing HMPs was well tolerated; however, this does not imply that any other fragrances added to this cleanser formulation would be as well tolerated.

Conclusion

The current studies indicate that a gentle fragranced foaming cleanser with HMPs was well tolerated in a small population of participants with clinically diagnosed fragrance sensitivity. In a larger population of female participants with sensitive skin, the gentle fragranced foaming cleanser with HMPs was as effective as a leading dermatologist-recommended, fragrance-free, gentle, nonfoaming cleanser. The gentle, HMP-containing, foaming cleanser with a fragrance that does not contain common allergens and irritating essential oils offers a new cleansing option for adults with sensitive skin who may prefer to use a fragranced and foaming product.

Acknowledgments—The authors are grateful to the patients and clinicians who participated in these studies. Editorial and medical writing support was provided by Tove Anderson, PhD, and Alex Loeb, PhD, both from Evidence Scientific Solutions, Inc, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and was funded by Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc.

For thousands of years, humans have used fragrances to change or affect their mood and enhance an “aura of beauty.”1 Fragrance is a primary driver in consumer choice and purchasing decisions, especially when considering personal care products.2 In addition to fragrance, consumers choose cleanser products based on compatibility with skin, cleansing properties, and sensory attributes such as viscosity and foaming.3,4 However, fragrance sensitivity is among the most common causes of allergic contact dermatitis from cosmetics and personal care products,5 and estimates of the prevalence of fragrance sensitivity range from 1.8% to 4.2%.6

A panel of 26 fragrance ingredients that frequently induce contact dermatitis in sensitive individuals has been identified.7 Since 2003, regulatory authorities in the European Union require these compounds to be listed on the labels of consumer products to protect presensitized consumers.7,8 However, manufacturers of cosmetics are not required to specify allergenic fragrance ingredients outside the European Union, and therefore it is difficult for consumers in the United States to avoid fragrance allergens.

Creation of a fragranced product for fragrance-sensitive individuals begins with careful selection of ingredients and extensive formulation testing and evaluation. This process usually is followed by testing in normal individuals to confirm that the fragranced product is well accepted and then evaluation is done in clinically confirmed fragrance-sensitive patients and those with a compromised skin barrier from atopic dermatitis, rosacea, or eczema.

Sensitive skin may be due to increased immune responsiveness, altered neurosensory input, and/or decreased skin barrier function, and presents a complex challenge for dermatologists.9 Subjective perceptions of sensitive skin include stinging, burning, pruritus, and tightness following product application. Clinically sensitive skin is defined by the presence of erythema, stratum corneum desquamation, papules, pustules, wheals, vesicles, bullae, and/or erosions.9 Although some of these symptoms may be observed immediately, others may be delayed by minutes, hours, or days following the use of an irritating product. Patients who present with subjective symptoms of sensitive skin may or may not show objective symptoms.

Gentle skin cleansing is particularly important for patients with compromised skin barrier integrity, such as those with acne, atopic dermatitis, eczema, or rosacea. Standard alkaline surfactants in skin cleansers help to remove dirt and oily soil and produce lather but can impair the skin barrier function and facilitate development of irritation.10-13 The tolerability of a cleanser is influenced by its pH, the type and amount of surfactant ingredients, the presence of moisturizing agents, and the amount of residue left on the skin after washing.11,12 Mild cleansers have been developed for patients with sensitive skin conditions and are expected to provide cleansing benefits without negatively affecting the hydration and viscoelastic properties of skin.11 Mild cleansers interact minimally with skin proteins and lipids because they usually contain nonionic synthetic surfactant mixtures; they also have a pH value close to the slightly acidic pH of normal skin, contain moisturizing agents,11,14,15 and usually produce less foam.10,16 In patients with sensitive skin, mild and fragrance-free cleansers often are recommended.17,18 Because fragrances often affect consumers’ perception of product performance19 and enhance the cleaning experience of the user, consumer compliance with clinical recommendations to use fragrance-free cleansers often is poor.

Low–molecular-weight, water-soluble, hydrophobically modified polymers (HMPs) have been used to create gentle foaming cleansers with reduced impact on the skin barrier.12,16,20 In the presence of HMPs, surfactants assemble into larger, more stable polymer-surfactant structures that are less likely to penetrate the skin.16 Hydrophobically modified polymers can potentially reduce skin irritation by lowering the concentration of free micelles in solution. Additionally, both HMPs and HMP-surfactant complexes stabilize newly formed air-water interfaces, leading to thicker, denser, and longer-lasting foams.16 A gentle, fragrance-free, foaming liquid facial test cleanser with HMPs has been shown to be well tolerated in women with sensitive skin.20

This report describes 2 studies of a new mild, HMP-containing, foaming facial cleanser with a fragrance that was free of common allergens and irritating essential oils in patients with sensitive skin. Study 1 was designed to evaluate the tolerance and acceptability of 2 variations of the HMP-containing cleanser—one fragrance free and the other with fragrance—in a small sample of healthy adults with clinically diagnosed fragrance-sensitive skin. Study 2 was a large, 2-center study of the tolerability and effectiveness of the fragranced HMP-containing cleanser compared with a benchmark dermatologist-recommended, gentle, fragrance-free, nonfoaming cleanser in women with clinically diagnosed sensitive skin.

Methods

Study 1 Design

The primary objective of this prospective, randomized, single-center, crossover study was to evaluate the tolerability of fragranced versus fragrance-free formulations of a mild, HMP-containing liquid facial cleanser in healthy male and female adults with Fitzpatrick skin types I to IV who were clinically diagnosed as having fragrance sensitivity. Fragrance sensitivity was defined as a history of positive reactions to a fragrance mixture of 8 components (fragrance mixture I) and/or a fragrance mixture of 14 fragrances (fragrance mixture II) that included balsam of Peru (Myroxylonpereirae), geraniol, jasmine oil, and oakmoss.5 All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrolling in the study, and both the study protocol and informed consent agreement were approved by an institutional review board.

Participants were instructed to wash their face twice daily, noting the time of cleansing and providing commentary about their cleansing experience in a diary. The liquid facial test cleansers contained the HMP potassium acrylates copolymer, glycerin, and a surfactant system primarily containing cocamidopropyl betaine and lauryl glucoside prepared without added fragrance (as previously described20) or with a fragrance free of common allergens and irritating essential oils.

Half of the participants used the fragranced test cleanser and half used the fragrance-free test cleanser for a 3-week treatment period (weeks 1–3). Each treatment group subsequently switched to the other test cleanser for a second 3-week treatment period (weeks 4–6). Clinicians assessed global disease severity (an overall assessment of skin condition that was independent of other evaluation criteria), itching/burning, visible irritation, erythema, and desquamation at weekly time points throughout the study and graded each clinical tolerance attribute on a 5-point scale (0=none; 1=minimal; 2=mild; 3=moderate; 4=severe). Ordinal scores at baseline and at weeks 1 and 3 were used to calculate change from baseline.

A 7-item questionnaire also was administered to participants at each visit to assess skin condition, smoothness, softness, cleanliness, radiance, satisfaction with cleansing experience, and lathering. Each item was scored on a 5-point ordinal scale (0=none; 1=minimal; 2=good; 3=excellent; 4=superior). The scores for all parameters were statistically compared with baseline values using a paired t test with a significance level of P≤.05.

Study 2 Design

This prospective, 3-week, double-blind, randomized, comparative, 2-center study to evaluate the tolerability of the fragranced, HMP-containing test cleanser from study 1 versus a benchmark gentle, fragrance-free, nonfoaming cleanser in a large population of otherwise healthy females who had been clinically diagnosed with sensitive skin (not limited to fragrance sensitivity). The study sponsor provided blinded test materials, and neither the examiner nor the recorder knew which investigational product was administered to which participants. Additionally, personnel who dispensed the test cleansers to participants or supervised their use did not participate in the evaluation to minimize potential bias. All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrolling in the study, and the study protocol and informed consent agreement were approved by an institutional review board.

Participants included women aged 18 to 65 years with mild to moderate clinical symptoms of atopic dermatitis, eczema, acne, or rosacea within the 90 days prior to the study period. They were randomized into 2 balanced treatment groups: group 1 received the mild, fragranced, HMP-containing liquid facial cleanser from study 1 and group 2 received a leading, dermatologist-recommended, gentle, fragrance-free, nonfoaming cleanser. Each treatment group used the test cleansers at least once daily for 3 weeks.

Clinicians evaluated facial skin for softness and smoothness, global disease severity (rated visually by the investigator as an overall assessment of skin condition that was independent of other evaluation criteria [as previously described20]), itching, irritation, erythema, and desquamation at baseline and at weeks 1 and 3. The effectiveness of each product to remove facial dirt, cosmetics, and sebum also was assessed; clinical grading was performed as described for study 1 using the same grading scale as in study 1 and percentage change from baseline (improvement) was calculated.

The study also included a self-assessment of skin irritation in which participants responded yes or no to the following question: Have you experienced irritation using this product? Participants also completed a questionnaire in which they were asked to select the most appropriate answer—agree strongly, agree somewhat, neither, disagree somewhat, and disagree strongly— to the following statements: the cleanser leaves no residue; cleanses deep to remove dirt, oil, and makeup; the cleanser effectively removes makeup; the cleanser leaves my skin smooth; the cleanser leaves my skin soft; the cleanser rinses completely clean; cleanser does not over dry my skin; and my skin is completely clean.

The statistical analysis was performed using a nonparametric, 2-tailed, paired Mann-Whitney U test, and statistical significance was set at P≤.05.

Results

Study 1 Assessment

Eight female participants aged 22 to 60 years with clinically diagnosed fragrance sensitivity were enrolled in the study. After 3 weeks of use, clinician assessment showed that both the fragranced and fragrance-free test cleansers with HMPs improved several skin tolerance attributes, including global disease severity, irritation, and erythema (Figure 1). No notable differences in skin tolerance attributes were reported in the fragranced versus the fragrance-free formulations.

There were no reported differences in participant-reported cleanser effectiveness for the fragranced versus the fragrance-free cleanser either at baseline or weeks 1 or 3 (data not shown).

Study 2 Assessment

A total of 153 women aged 25 to 54 years with sensitive skin were enrolled in the study. Seventy-three participants were randomized to receive the fragranced test cleanser and 80 were randomized to receive the benchmark fragrance-free cleanser.

At week 3, there were no differences between the fragranced test cleanser and the benchmark cleanser in any of the clinician-assessed skin parameters (Figure 2). Of the parameters assessed, itching, irritation, and desquamation were the most improved from baseline in both treatment groups. Similar results were observed at week 1 (data not shown).

There were no apparent differences in subjective self-assessment of skin irritation between the test and benchmark cleansers at week 1 (15.7% vs 13.0%) or week 3 (24.3% vs 12.3%). When asked to respond to a series of 8 statements related to cleanser effectiveness, most participants either agreed strongly or agreed somewhat with the statements (Figure 3). There were no statistically significant differences between treatment groups, and responses to all statements indicated that participants were as satisfied with the test cleanser as they were with the benchmark cleanser.

Comment

Consumers value cleansing, fragrance, viscosity, and foaming attributes in skin care products very highly.3,4,10 Fragrances are added to personal care products to positively affect consumers’ perception of product performance and to add emotional benefits by implying social or economic prestige to the use of a product.19 In one study, shampoo formulations that varied only in the added fragrance received different consumer evaluations for cleansing effectiveness and foaming.4

Although mild nonfoaming cleansers can be effective, adult consumers generally use cleansers that foam10,16 and often judge the performance of a cleansing product based on its foaming properties.3,10 Mild cleansers with HMPs maintain the ability to foam while also reducing the likelihood of skin irritation.16 One study showed that a mild, fragrance-free, foaming cleanser containing HMPs was as effective, well tolerated, and nonirritating in patients with sensitive skin as a benchmark nonfoaming gentle cleanser.20

Results from study 1 presented here show that fragranced and fragrance-free formulations of a mild, HMP-containing cleanser are equally efficacious and well tolerated in a small sample of participants with clinically diagnosed fragrance sensitivity. Skin tolerance attributes improved with both cleansers over a 3-week period, particularly global disease severity, irritation, and erythema. These results suggest that a fragrance free of common allergens and irritating essential oils could be introduced into a mild foaming cleanser containing HMPs without causing adverse reactions, even in patients who are fragrance sensitive.

Although the populations of studies 1 and 2 both included female participants with sensitive skin, they were not identical. While study 1 assessed a limited number of participants with clinically diagnosed fragrance sensitivity, study 2 was larger and included a broader range of participants with clinically diagnosed skin sensitivity, which could include fragrance sensitivity. The well-chosen fragrance of the test cleanser containing HMPs was well tolerated; however, this does not imply that any other fragrances added to this cleanser formulation would be as well tolerated.

Conclusion

The current studies indicate that a gentle fragranced foaming cleanser with HMPs was well tolerated in a small population of participants with clinically diagnosed fragrance sensitivity. In a larger population of female participants with sensitive skin, the gentle fragranced foaming cleanser with HMPs was as effective as a leading dermatologist-recommended, fragrance-free, gentle, nonfoaming cleanser. The gentle, HMP-containing, foaming cleanser with a fragrance that does not contain common allergens and irritating essential oils offers a new cleansing option for adults with sensitive skin who may prefer to use a fragranced and foaming product.

Acknowledgments—The authors are grateful to the patients and clinicians who participated in these studies. Editorial and medical writing support was provided by Tove Anderson, PhD, and Alex Loeb, PhD, both from Evidence Scientific Solutions, Inc, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and was funded by Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc.

- Draelos ZD. To smell or not to smell? that is the question! J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;12:1-2.

- Milotic D. The impact of fragrance on consumer choice. J Consumer Behaviour. 2003;3:179-191.

- Klein K. Evaluating shampoo foam. Cosmetics & Toiletries. 2004;119:32-36.

- Herman S. Skin care: the importance of feel. GCI Magazine. December 2007:70-74.

- Larsen WG. How to test for fragrance allergy. Cutis. 2000;65:39-41.

- Schnuch A, Uter W, Geier J, et al. Epidemiology of contact allergy: an estimation of morbidity employing the clinical epidemiology and drug-utilization research (CE-DUR) approach. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;47:32-39.

- Directive 2003/15/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 February 2003 amending Council Directive 76/768/EEC on the approximation of the laws of the Member States relating to cosmetic products. Official Journal of the European Communities. 2003;L66:26-35.

- Guidance note: labelling of ingredients in Cosmetics Directive 76/768/EEC. European Commission Web site. http: //ec.europa.eu/consumers/sectors/cosmetics/files/doc/guide _labelling200802_en.pdf. Updated February 2008. Accessed September 2, 2015.

- Draelos ZD. Sensitive skin: perceptions, evaluation, and treatment. Am J Contact Dermatitis. 1997;8:67-78.

- Abbas S, Goldberg JW, Massaro M. Personal cleanser technology and clinical performance. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17(suppl 1):35-42.

- Ananthapadmanabhan KP, Moore DJ, Subramanyan K, et al. Cleansing without compromise: the impact of cleansers on the skin barrier and the technology of mild cleansing. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17(suppl 1):16-25.

- Walters RM, Mao G, Gunn ET, et al. Cleansing formulations that respect skin barrier integrity. Dermatol Res Pract. 2012;2012:495917.

- Saad P, Flach CR, Walters RM, et al. Infrared spectroscopic studies of sodium dodecyl sulphate permeation and interaction with stratum corneum lipids in skin. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2012;34:36-43.

- Bikowski J. The use of cleansers as therapeutic concomitants in various dermatologic disorders. Cutis. 2001;68(suppl 5):12-19.

- Walters RM, Fevola MJ, LiBrizzi JJ, et al. Designing cleansers for the unique needs of baby skin. Cosmetics & Toiletries. 2008;123:53-60.

- Fevola MJ, Walters RM, LiBrizzi JJ. A new approach to formulating mild cleansers: hydrophobically-modified polymers for irritation mitigation. In: Morgan SE, Lochhead RY, eds. Polymeric Delivery of Therapeutics. Vol 1053. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society; 2011:221-242.

- Nelson SA, Yiannias JA. Relevance and avoidance of skin-care product allergens: pearls and pitfalls. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:329-336.

- Arribas MP, Soro P, Silvestre JF. Allergic contact dermatitis to fragrances: part 2. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:29-37.

- Schroeder W. Understanding fragrance in personal care. Cosmetics & Toiletries. 2009;124:36-44.

- Draelos Z, Hornby S, Walters RM, et al. Hydrophobically-modified polymers can minimize skin irritation potential caused by surfactant-based cleansers. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;12:314-321.

- Draelos ZD. To smell or not to smell? that is the question! J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;12:1-2.

- Milotic D. The impact of fragrance on consumer choice. J Consumer Behaviour. 2003;3:179-191.

- Klein K. Evaluating shampoo foam. Cosmetics & Toiletries. 2004;119:32-36.

- Herman S. Skin care: the importance of feel. GCI Magazine. December 2007:70-74.

- Larsen WG. How to test for fragrance allergy. Cutis. 2000;65:39-41.

- Schnuch A, Uter W, Geier J, et al. Epidemiology of contact allergy: an estimation of morbidity employing the clinical epidemiology and drug-utilization research (CE-DUR) approach. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;47:32-39.

- Directive 2003/15/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 February 2003 amending Council Directive 76/768/EEC on the approximation of the laws of the Member States relating to cosmetic products. Official Journal of the European Communities. 2003;L66:26-35.

- Guidance note: labelling of ingredients in Cosmetics Directive 76/768/EEC. European Commission Web site. http: //ec.europa.eu/consumers/sectors/cosmetics/files/doc/guide _labelling200802_en.pdf. Updated February 2008. Accessed September 2, 2015.

- Draelos ZD. Sensitive skin: perceptions, evaluation, and treatment. Am J Contact Dermatitis. 1997;8:67-78.

- Abbas S, Goldberg JW, Massaro M. Personal cleanser technology and clinical performance. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17(suppl 1):35-42.

- Ananthapadmanabhan KP, Moore DJ, Subramanyan K, et al. Cleansing without compromise: the impact of cleansers on the skin barrier and the technology of mild cleansing. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17(suppl 1):16-25.

- Walters RM, Mao G, Gunn ET, et al. Cleansing formulations that respect skin barrier integrity. Dermatol Res Pract. 2012;2012:495917.

- Saad P, Flach CR, Walters RM, et al. Infrared spectroscopic studies of sodium dodecyl sulphate permeation and interaction with stratum corneum lipids in skin. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2012;34:36-43.

- Bikowski J. The use of cleansers as therapeutic concomitants in various dermatologic disorders. Cutis. 2001;68(suppl 5):12-19.

- Walters RM, Fevola MJ, LiBrizzi JJ, et al. Designing cleansers for the unique needs of baby skin. Cosmetics & Toiletries. 2008;123:53-60.

- Fevola MJ, Walters RM, LiBrizzi JJ. A new approach to formulating mild cleansers: hydrophobically-modified polymers for irritation mitigation. In: Morgan SE, Lochhead RY, eds. Polymeric Delivery of Therapeutics. Vol 1053. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society; 2011:221-242.

- Nelson SA, Yiannias JA. Relevance and avoidance of skin-care product allergens: pearls and pitfalls. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:329-336.

- Arribas MP, Soro P, Silvestre JF. Allergic contact dermatitis to fragrances: part 2. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:29-37.

- Schroeder W. Understanding fragrance in personal care. Cosmetics & Toiletries. 2009;124:36-44.

- Draelos Z, Hornby S, Walters RM, et al. Hydrophobically-modified polymers can minimize skin irritation potential caused by surfactant-based cleansers. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;12:314-321.

Practice Points

- Fragranced and fragrance-free versions of a gentle foaming cleanser with hydrophobically modified polymers (HMPs) were similarly well tolerated in participants with clinically diagnosed fragrance sensitivity.

- In a large population of female participants with sensitive skin, the fragranced gentle foaming cleanser with HMPs was as effective as a leading dermatologist-recommended, fragrance-free, gentle, nonfoaming cleanser.

- The gentle, HMP-containing, foaming cleanser with a fragrance offers a new cleansing option for adults with sensitive skin who may prefer to use a fragranced and foaming product.

Standard Management Options for Rosacea, Part 2: Options According to Subtype

Management of Rosacea by Subtype

The management of rosacea should be tailored to address the individual signs and symptoms of each patient and often may be keyed to subtypes and levels of severity while noting that patients often experience more than one subtype concurrently.1 Using the standard grading system, primary features of each subtype are graded as mild, moderate, or severe (grades 1–3, respectively), and most secondary signs and symptoms are graded as simply present or absent (Tables 1–4, PLEASE REFER TO THE PDF TO VIEW THE TABLES). All patients should be advised of proper skin care procedures, including the use of sunscreen as well as avoidance of environmental and lifestyle factors that may affect their individual cases.

Subtype 1: Erythematotelangiectatic Rosacea

Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea is primarily characterized by flushing and persistent erythema of the central face. The appearance of telangiectases is common but not essential to the diagnosis, while burning and stinging sensations, edema, and roughness or scaling are common secondary features. Patients with this subtype often have a history of flushing alone.

Because this subtype of rosacea may be difficult to treat, identification and avoidance of environmental and lifestyle triggers to minimize flushing and irritation of the skin may be especially important.1

Although no drugs to reduce flushing have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), off-label use of certain medications may potentially have a moderating effect for grades 2 and 3 flushing. It should be noted, however, that there are no broad-spectrumantiflushing medications, and those specific to the cause of the flushing should be chosen.

Flushing is a phenomenon of vasodilation that can be considered an abnormality of cutaneous vascular smooth muscle control. Vascular smooth muscle is controlled by circulating vasoactive agents or by autonomic nerves.

Circulating vasoactive agents are associated with dry flushing and may be exogenous (eg, alcohol, calcium channel-blocking agents, and nicotinic acid [niacin]) or endogenous (eg, histamine and prostaglandins). Management options to mediate flushing caused by endogenous agents may include aspirin, indomethacin, or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs that also may reduce erythema. Antihistamines may be prescribed to reduce flushing related to histamines produced endogenously or exogenously by certain foods.2

When vasodilation is controlled by autonomic nerves, it is accompanied by sweating.2 This flushing usually results from heat in the ambient surroundings or from exercise or hot drinks, for example. In this case, flushing may be reduced by cooling the neck and face with a cold wet towel or a fan. Ice chips held in the mouth and ingestion of ice water may be effective.2 Flushing also may be diminished, of course, by avoidance of other potential environmental and lifestyle factors.1

In severe cases, the alpha 2 agonist clonidine or a beta-blocker such as nadolol may sometimes reduce neurally mediated flushing.2 For women with menopausal flushing, hormone replacement therapy prescribed by a gynecologist or primary care physician could be considered but should be used with caution.

Flushing also may have emotional origins for some patients, and these individuals may additionally benefit from psychological counseling or biofeedback.

Telangiectases and background erythema are commonly treated with laser therapy,3-8 including long-pulsed dye, potassium-titanyl-phosphate, and diode lasers, which have been associated with little or no purpura.4 They also may be reduced by intense pulsed light therapy,7,9 and electrocautery is an additional option for telangiectasia. Although published clinical data are limited, lasers and intense pulsed light also may be used to reduce flushing.6

The appearance of flushing, erythema, and telangiectases also may be concealed with cosmetics.1 In addition, burning, stinging, roughness, and/or scaling may be minimized by selecting appropriate over-the-counter products, including nonirritating cosmetics, nonsoap cleansers, moisturizers, and appropriate cleansing techniques. Sunblocks or sunscreens may be particularly important.

Subtype 2: Papulopustular Rosacea

This subtype is characterized by persistent central facial erythema with transient central facial papules or pustules, or both (Figure, PLEASE REFER TO THE PDF TO VIEW THE FiGURE). In these patients, topical therapies and oral antibiotics are prescribed, though the modes of action have not been definitively established.

Topical therapies FDA approved for the treatment of rosacea including metronidazole and azelaic acid as well as topical sodium sulfacetamide–sulfur may be used alone or in conjunction with oral therapy administered initially or at any point during treatment. A controlled-release formulation of oral doxycycline is FDA approved for rosacea with low plasma levels that do not exert antimicrobial effects while retaining anti-inflammatory activity.10 Topical therapy and/or a controlled-release oral therapy for rosacea may be used for grades 1 and 2 disease. For grade 3, an oral antibiotic may be used initially with a topical therapy to bring the disorder under immediate control. Once remission has been achieved, it often may be maintained on a long-term basis with a topical or controlled-release agent alone for an indefinite period.11

In some cases, oral drug therapy for grades 2 and 3and/or in patients with ocular involvement may consist of off-label systemic tetracycline (or other members of the tetracycline family) administered as 1 g/d in divided doses for 2 to 3 weeks, followed by 0.5 g/d for 2 to 3 weeks.12 Some physicians may prescribe higher doses, longer courses, or other tetracyclines such as doxycycline or minocycline.

In refractory cases, off label oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim alone, metronidazole, erythromycin, ampicillin, clindamycin, or dapsone may be prescribed. Off-label isotretinoin reportedly may be effective, especially in otherwise refractory cases or when the patulous follicles of incipient rhinophyma are present. Use of isotretinoin requires careful monitoring, and long-lasting remission is not common.

Additional off-label alternatives for refractory rosacea may include other antibacterial agents, mild topical retinoids, or adapalene.13,14 It also has been suggested in isolated reports that drugs eradicating Demodex folliculorum may play a role in treating certain cases of papulopustular rosacea, including topical permethrin; systemic ivermectin; and topical crotamiton, sulfur, and lindane.15 Use on the face for patients with rosacea is off label, and if prescribed, patients should be cautioned about the irritation potential of these agents.

While there was historical speculation on the treatment of Helicobacter pylori to manage rosacea, studies found no substantial difference in the abatement of rosacea following H pylori treatment compared with patients in placebo control groups.16,17

In certain exceptional cases, short-term use of a low-strength topical steroid may be considered for rapid resolution of inflammation. However, long-term use of these agents often produces rosacealike manifestations, commonly called steroid-induced rosacea, and therefore should be avoided. Topical calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus and pimecrolimus also may be of value in treating erythema from active inflammation,12 though they have been reported to induce a rosacealike eruption.18-21 Topical retinoids have been recommended by some to repair the dermis by decreasing abnormal elastin, increasing collagen, increasing glycosaminoglycan, and decreasing telangiectases.22

Possible burning and stinging sensations may be dealt with as described for erythematotelangiectatic rosacea.

Subtype 3: Phymatous Rosacea

In addition to a primary feature of rosacea (flushing, erythema, telangiectases, papules or pustules), phymatous rosacea may include skin thickening, irregular surface nodularities, and patulous follicles. Enlargement commonly occurs on the nose (rhinophyma), though other affected locations may include the chin, forehead, cheeks, and ears.

Management options for grade 1 phymatous rosacea, with patulous follicles but no contour changes, include topical and systemic antibiotics if inflammatory lesions are present. Isotretinoin has been demonstrated to decrease nasal volume in rhinophyma, especially in younger patients with less advanced disease, though volume may increase again after therapy is stopped.22,23 During isotretinoin therapy, numerous large sebaceous glands were reported to be diminished in size and number.22 There also is evidence that topical retinoids may decrease fibrosis, elastosis, and sebaceous gland hypertrophy.24-26

Grades 2—change in contour without a nodular component—and 3—change in contour with a nodular component—phymatous rosacea may require surgical therapy, such as cryosurgery, radiofrequency ablation, electrosurgery, heated scalpel, electrocautery, tangential excision combined with scissor sculpturing, skin grafting, and dermabrasion. CO2 or erbium:YAG lasers may be used as a bloodless scalpel to remove excess tissue and recontour the nose. Fractional resurfacing can be of value in mild cases.

Subtype 4: Ocular Rosacea

The common presentations of ocular rosacea are a watery or bloodshot appearance, foreign body sensation, burning or stinging, dryness, itching, light sensitivity, and blurred vision. A history of styes (chalazion, hordeolum) is a strong indication, as well as dry eye, recurrent conjunctivitis, or blepharitis. Telangiectases of the eyelid margins or lid and periocular erythema also may be present.

The meibomian glands typically are obstructed and often may be blocked. The formation of collarettes, narrow rims of loosened keratin around the base of the eyelashes, is common. A gritty granular symptom indicates damage to the ocular surface. Undiagnosed ocular rosacea may present with recurring inflammation such as episcleritis, iritis,

and keratitis.

Ocular rosacea may appear in advance of the cutaneous form, and more than 60% of patients with cutaneous rosacea also may have ocular involvement. Treatment of cutaneous rosacea alone may be inadequate in lessening the risk for vision loss resulting from ocular rosacea, and referral to an ophthalmologist may be needed.

Treatment of grades 1 and 2 ocular rosacea may initially include artificial tears, and on a long-term basis, the patient should apply a warm compress and cleanse the eyelashes twice daily with baby shampoo on a wet washcloth rubbed onto the upper and lower eyelashes of the closed eyes. Antibiotic ointment may be appropriate to decrease the presence of Propionibacterium acnes, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Staphylococcus aureus, and to soften any collarettes, allowing easy removal by the patient during eyelash hygiene. An oral tetracycline such as low-dose doxycycline may be necessary, and for grade 3 ocular rosacea, a topical steroid, cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion, or alternative oral medications may be prescribed by the ophthalmologist. Any corneal ulceration requires immediate attention by an ophthalmologist, as it may involve loss of visual acuity.

Conclusion

Managing the various potential signs and symptoms of rosacea calls for consideration of a broad spectrum of care, and a more precise selection of therapeutic options may become increasingly possible as their mechanisms of action are more definitively known and the etiology and pathogenesis of rosacea are more completely understood. Meanwhile, however, the classification of rosacea by its morphologic features and grading by severity may serve as an appropriate guide for its effective management.

As with the standard classification and grading systems, the options described here are provisional and subject to modification with the development of new therapies, increase in scientific knowledge, and testing of their relevance and applicability by investigators and clinicians. Also, as with any consensus document, these options do not necessarily reflect the views of any single individual and not all comments were incorporated.

Acknowledgments—The committee thanks the following individuals who reviewed and contributed to this document: Joel Bamford, MD, Duluth, Minnesota; Mats Berg, MD, Uppsala, Sweden; James Del Rosso, DO, Las Vegas, Nevada; Roy Geronemus, MD, New York, New York; David Goldberg, MD, JD, Hackensack, New Jersey; Richard Granstein, MD, New York, New York; William James, MD, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Albert Kligman, MD, PhD, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Mark Mannis, MD, Davis, California; Ronald Marks, MD, Cardiff, United Kingdom; Michelle Pelle, MD, San Diego, California; Noah Scheinfeld, MD, JD, New York, New York; Bryan Sires, MD, PhD, Kirkland, Washington; Helen Torok, MD, Medina, Ohio; John Wolf, MD, Houston, Texas; and Mina Yaar, MD, Boston, Massachusetts.

- Odom R, Dahl M, Dover J, et al; National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the Classification and Staging of Rosacea. Standard management options for rosacea, part 1: overview and broad spectrum of care. Cutis. 2009;84:43-47.

- Wilkin JK. The red face: flushing disorders. Clin Dermatol. 1993;11:211-223.

- Jasim ZF, Woo WK, Handley JM. Long-pulsed (6-ms) pulsed dye laser treatment of rosacea-associated telangiectasia using subpurpuric clinical threshold. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:37-40.

- Alam M, Dover JS, Arndt KA. Treatment of facial telangiectasia with variable-pulse high-fluence pulsed-dye laser: comparison of efficacy with fluences immediately above and below the purpura threshold. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:681-685.

- Schroeter CA, Haaf-von Below S, Neumann HA. Effective treatment of rosacea using intense pulsed light systems. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1285-1289.

- Clark SM, Lanigan SW, Marks R. Laser treatment of erythema and telangiectasia associated with rosacea. Lasers Med. 2002;17:26-33.

- Alster T, Anderson RR, Bank DE, et al. The use of photodynamic therapy in dermatology: results of a consensus conference. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:140-154.

- Rohrer TE, Chatrath V, Iyengar V. Does pulse stacking improve the results of treatment with variable-pulse pulsed-dye lasers? Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:163-167.

- Mark KA, Sparacio RM, Voigt A, et al. Objective and quantitative improvement of rosacea-associated erythema after intense pulsed light treatment. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:600-604.

- Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, Jackson M, et al. Two randomized phase III clinical trials evaluating anti-inflammatory dose doxycycline (40-mg doxycycline, USP capsules) administered once daily for treatment of rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:791-802.

- Dahl MV, Katz HI, Krueger GG, et al. Topical metronidazole maintains remissions of rosacea. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:679-683.

- Bikowski JB. The pharmacologic therapy of rosacea: a paradigm shift in progress. Cutis. 2005;75(suppl 3):27-32.

- Altinyazar HC, Koca R, Tekin NS, et al. Adapalene vs. metronidazole gel for the treatment of rosacea. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:252-255.

- Scheinfeld NS. Rosacea. Skinmed. 2006;5:191-194.

- Scheinfeld N. When rosacea resists standard therapies. Skin & Aging. 2006;8:46-48.

- Bamford JT, Tilden RL, Blankush JL, et al. Effect of treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection on rosacea. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:659-663.

- Herr H, You CH. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori and rosacea: it may be a myth. J Korean Med Sci. 2000;15:551-554.

- Gorman CR, White SW. Rosaceiform dermatitis as a complication of treatment of facial seborrheic dermatitis with 1% pimecrolimus cream [letter]. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1168.

- El Sayed F, Ammoury A, Dhaybi R, et al. Rosaceiform eruption to pimecrolimus [letter]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;54:548-550.

- Antille C, Saurat JH, Lübbe J. Induction of rosaceiform dermatitis during treatment of facial inflammatory dermatoses with tacrolimus ointment. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:457-460.

- Bernard LA, Cunningham BB, Al-Suwaidan S, et al. A rosacea-like granulomatous eruption in a patient using tacrolimus ointment for atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:229-231.

- Pelle MT, Crawford GH, James WD. Rosacea: II. therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:499-512.

- Wilkin JK. Rosacea: pathophysiology and treatment. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:359-362.

- Daly TJ, Weston WL. Retinoid effects on fibroblast proliferation and collagen synthesis in vitro and on fibrotic disease in vivo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15(4, pt 2):900-902.

- Schmidt JB, Gebhart W, Raff M, et al. 13-cis-retinoic acid in rosacea. clinical and laboratory findings. Acta Derm Venereol. 1984;64:15-21.

- Yamamoto O, Bhawan J, Solares G, et al. Ultrastructural effects of topical tretinoin on dermo-epidermal junction and papillary dermis in photodamaged skin. a controlled study. Exp Dermatol. 1995;4:146-154.

Management of Rosacea by Subtype

The management of rosacea should be tailored to address the individual signs and symptoms of each patient and often may be keyed to subtypes and levels of severity while noting that patients often experience more than one subtype concurrently.1 Using the standard grading system, primary features of each subtype are graded as mild, moderate, or severe (grades 1–3, respectively), and most secondary signs and symptoms are graded as simply present or absent (Tables 1–4, PLEASE REFER TO THE PDF TO VIEW THE TABLES). All patients should be advised of proper skin care procedures, including the use of sunscreen as well as avoidance of environmental and lifestyle factors that may affect their individual cases.

Subtype 1: Erythematotelangiectatic Rosacea

Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea is primarily characterized by flushing and persistent erythema of the central face. The appearance of telangiectases is common but not essential to the diagnosis, while burning and stinging sensations, edema, and roughness or scaling are common secondary features. Patients with this subtype often have a history of flushing alone.

Because this subtype of rosacea may be difficult to treat, identification and avoidance of environmental and lifestyle triggers to minimize flushing and irritation of the skin may be especially important.1

Although no drugs to reduce flushing have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), off-label use of certain medications may potentially have a moderating effect for grades 2 and 3 flushing. It should be noted, however, that there are no broad-spectrumantiflushing medications, and those specific to the cause of the flushing should be chosen.

Flushing is a phenomenon of vasodilation that can be considered an abnormality of cutaneous vascular smooth muscle control. Vascular smooth muscle is controlled by circulating vasoactive agents or by autonomic nerves.

Circulating vasoactive agents are associated with dry flushing and may be exogenous (eg, alcohol, calcium channel-blocking agents, and nicotinic acid [niacin]) or endogenous (eg, histamine and prostaglandins). Management options to mediate flushing caused by endogenous agents may include aspirin, indomethacin, or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs that also may reduce erythema. Antihistamines may be prescribed to reduce flushing related to histamines produced endogenously or exogenously by certain foods.2

When vasodilation is controlled by autonomic nerves, it is accompanied by sweating.2 This flushing usually results from heat in the ambient surroundings or from exercise or hot drinks, for example. In this case, flushing may be reduced by cooling the neck and face with a cold wet towel or a fan. Ice chips held in the mouth and ingestion of ice water may be effective.2 Flushing also may be diminished, of course, by avoidance of other potential environmental and lifestyle factors.1

In severe cases, the alpha 2 agonist clonidine or a beta-blocker such as nadolol may sometimes reduce neurally mediated flushing.2 For women with menopausal flushing, hormone replacement therapy prescribed by a gynecologist or primary care physician could be considered but should be used with caution.

Flushing also may have emotional origins for some patients, and these individuals may additionally benefit from psychological counseling or biofeedback.

Telangiectases and background erythema are commonly treated with laser therapy,3-8 including long-pulsed dye, potassium-titanyl-phosphate, and diode lasers, which have been associated with little or no purpura.4 They also may be reduced by intense pulsed light therapy,7,9 and electrocautery is an additional option for telangiectasia. Although published clinical data are limited, lasers and intense pulsed light also may be used to reduce flushing.6

The appearance of flushing, erythema, and telangiectases also may be concealed with cosmetics.1 In addition, burning, stinging, roughness, and/or scaling may be minimized by selecting appropriate over-the-counter products, including nonirritating cosmetics, nonsoap cleansers, moisturizers, and appropriate cleansing techniques. Sunblocks or sunscreens may be particularly important.

Subtype 2: Papulopustular Rosacea

This subtype is characterized by persistent central facial erythema with transient central facial papules or pustules, or both (Figure, PLEASE REFER TO THE PDF TO VIEW THE FiGURE). In these patients, topical therapies and oral antibiotics are prescribed, though the modes of action have not been definitively established.