User login

Impact of Pneumonia Guidelines

Overutilization of resources is a significant, yet underappreciated, problem in medicine. Many interventions target underutilization (eg, immunizations) or misuse (eg, antibiotic prescribing for viral pharyngitis), yet overutilization remains as a significant contributor to healthcare waste.[1] In an effort to reduce waste, the Choosing Wisely campaign created a work group to highlight areas of overutilization, specifically noting both diagnostic tests and therapies for common pediatric conditions with no proven benefit and possible harm to the patient.[2] Respiratory illnesses have been a target of many quality‐improvement efforts, and pneumonia represents a common diagnosis in pediatrics.[3] The use of diagnostic testing for pneumonia is an area where care can be optimized and aligned with evidence.

Laboratory testing and diagnostic imaging are routinely used for the management of children with community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP). Several studies have documented substantial variability in the use of these resources for pneumonia management, with higher resource use associated with a higher chance of hospitalization after emergency department (ED) evaluation and a longer length of stay among those requiring hospitalization.[4, 5] This variation in diagnostic resource utilization has been attributed, at least in part, to a lack of consensus on the management of pneumonia. There is wide variability in diagnostic testing, and due to potential consequences for patients presenting with pneumonia, efforts to standardize care offer an opportunity to improve healthcare value.

In August 2011, the first national, evidence‐based consensus guidelines for the management of childhood CAP were published jointly by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (PIDS) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA).[6] A primary focus of these guidelines was the recommendation for the use of narrow spectrum antibiotics for the management of uncomplicated pneumonia. Previous studies have assessed the impact of the publication of the PIDS/IDSA guidelines on empiric antibiotic selection for the management of pneumonia.[7, 8] In addition, the guidelines provided recommendations regarding diagnostic test utilization, in particular discouraging blood tests (eg, complete blood counts) and radiologic studies for nontoxic, fully immunized children treated as outpatients, as well as repeat testing for children hospitalized with CAP who are improving.

Although single centers have demonstrated changes in utilization patterns based on clinical practice guidelines,[9, 10, 11, 12] whether these guidelines have impacted diagnostic test utilization among US children with CAP in a larger scale remains unknown. Therefore, we sought to determine the impact of the PIDS/IDSA guidelines on the use of diagnostic testing among children with CAP using a national sample of US children's hospitals. Because the guidelines discourage repeat diagnostic testing in patients who are improving, we also evaluated the association between repeat diagnostic studies and severity of illness.

METHODS

This retrospective cohort study used data from the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) (Children's Hospital Association, Overland Park, KS). The PHIS database contains deidentified administrative data, detailing demographic, diagnostic, procedure, and billing data from 47 freestanding, tertiary care children's hospitals. This database accounts for approximately 20% of all annual pediatric hospitalizations in the United States. Data quality is ensured through a joint effort between the Children's Hospital Association and participating hospitals.

Patient Population

Data from 32 (of the 47) hospitals included in PHIS with complete inpatient and ED data were used to evaluate hospital‐level resource utilization for children 1 to 18 years of age discharged January 1, 2008 to June 30, 2014 with a diagnosis of pneumonia (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision [ICD‐9] codes 480.x‐486.x, 487.0).[13] Our goal was to identify previously healthy children with uncomplicated pneumonia, so we excluded patients with complex chronic conditions,[14] billing charges for intensive care management and/or pleural drainage procedure (IDC‐9 codes 510.0, 510.9, 511.0, 511.1, 511.8, 511.9, 513.x) on day of admission or the next day, or prior pneumonia admission in the last 30 days. We studied 2 mutually exclusive populations: children with pneumonia treated in the ED (ie, patients who were evaluated in the ED and discharged to home), and children hospitalized with pneumonia, including those admitted through the ED.

Guideline Publication and Study Periods

For an exploratory before and after comparison, patients were grouped into 2 cohorts based on a guideline online publication date of August 1, 2011: preguideline (January 1, 2008 to July 31, 2011) and postguideline (August 1, 2011 to June 30, 2014).

Study Outcomes

The measured outcomes were the monthly proportion of pneumonia patients for whom specific diagnostic tests were performed, as determined from billing data. The diagnostic tests evaluated were complete blood count (CBC), blood culture, C‐reactive protein (CRP), and chest radiograph (CXR). Standardized costs were also calculated from PHIS charges as previously described to standardize the cost of the individual tests and remove interhospital cost variation.[3]

Relationship of Repeat Testing and Severity of Illness

Because higher illness severity and clinical deterioration may warrant repeat testing, we also explored the association of repeat diagnostic testing for inpatients with severity of illness by using the following variables as measures of severity: length of stay (LOS), transfer to intensive care unit (ICU), or pleural drainage procedure after admission (>2 calendar days after admission). Repeat diagnostic testing was stratified by number of tests.

Statistical Analysis

The categorical demographic characteristics of the pre‐ and postguideline populations were summarized using frequencies and percentages, and compared using 2 tests. Continuous demographics were summarized with medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) and compared with the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Segmented regression, clustered by hospital, was used to assess trends in monthly resource utilization as well as associated standardized costs before and after guidelines publication. To estimate the impact of the guidelines overall, we compared the observed diagnostic resource use at the end of the study period with expected use projected from trends in the preguidelines period (ie, if there were no new guidelines). Individual interrupted time series were also built for each hospital. From these models, we assessed which hospitals had a significant difference between the rate observed at the end of the study and that estimated from their preguideline trajectory. To assess the relationship between the number of positive improvements at a hospital and hospital characteristics, we used Spearman's correlation and Kruskal‐Wallis tests. All analyses were performed with SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC), and P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. In accordance with the policies of the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center Institutional Review Board, this research, using a deidentified dataset, was not considered human subjects research.

RESULTS

There were 275,288 hospital admissions meeting study inclusion criteria of 1 to 18 years of age with a diagnosis of pneumonia from 2008 to 2014. Of these, 54,749 met exclusion criteria (1874 had pleural drainage procedure on day 0 or 1, 51,306 had complex chronic conditions, 1569 were hospitalized with pneumonia in the last 30 days). Characteristics of the remaining 220,539 patients in the final sample are shown in Table 1. The median age was 4 years (IQR, 27 years); a majority of the children were male (53%) and had public insurance (58%). There were 128,855 patients in the preguideline period (January 1, 2008 to July 31, 2011) and 91,684 in the post guideline period (August 1, 2011June 30, 2014).

| Overall | Preguideline | Postguideline | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| No. of discharges | 220,539 | 128,855 | 91,684 | |

| Type of encounter | ||||

| ED only | 150,215 (68.1) | 88,790 (68.9) | 61,425 (67) | <0.001 |

| Inpatient | 70,324 (31.9) | 40,065 (31.1) | 30,259 (33) | |

| Age | ||||

| 14 years | 129,360 (58.7) | 77,802 (60.4) | 51,558 (56.2) | <0.001 |

| 59 years | 58,609 (26.6) | 32,708 (25.4) | 25,901 (28.3) | |

| 1018 years | 32,570 (14.8) | 18,345 (14.2) | 14,225 (15.5) | |

| Median [IQR] | 4 [27] | 3 [27] | 4 [27] | <0.001 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 116,718 (52.9) | 68,319 (53) | 48,399 (52.8) | 00.285 |

| Female | 103,813 (47.1) | 60,532 (47) | 43,281 (47.2) | |

| Race | ||||

| Non‐Hispanic white | 84,423 (38.3) | 47,327 (36.7) | 37,096 (40.5) | <0.001 |

| Non‐Hispanic black | 60,062 (27.2) | 35,870 (27.8) | 24,192 (26.4) | |

| Hispanic | 51,184 (23.2) | 31,167 (24.2) | 20,017 (21.8) | |

| Asian | 6,444 (2.9) | 3,691 (2.9) | 2,753 (3) | |

| Other | 18,426 (8.4) | 10,800 (8.4) | 7,626 (8.3) | |

| Payer | ||||

| Government | 128,047 (58.1) | 70,742 (54.9) | 57,305 (62.5) | <0.001 |

| Private | 73,338 (33.3) | 44,410 (34.5) | 28,928 (31.6) | |

| Other | 19,154 (8.7) | 13,703 (10.6) | 5,451 (5.9) | |

| Disposition | ||||

| HHS | 684 (0.3) | 411 (0.3) | 273 (0.3) | <0.001 |

| Home | 209,710 (95.1) | 123,236 (95.6) | 86,474 (94.3) | |

| Other | 9,749 (4.4) | 4,962 (3.9) | 4,787 (5.2) | |

| SNF | 396 (0.2) | 246 (0.2) | 150 (0.2) | |

| Season | ||||

| Spring | 60,171 (27.3) | 36,709 (28.5) | 23,462 (25.6) | <0.001 |

| Summer | 29,891 (13.6) | 17,748 (13.8) | 12,143 (13.2) | |

| Fall | 52,161 (23.7) | 28,332 (22) | 23,829 (26) | |

| Winter | 78,316 (35.5) | 46,066 (35.8) | 32,250 (35.2) | |

| LOS | ||||

| 13 days | 204,812 (92.9) | 119,497 (92.7) | 85,315 (93.1) | <0.001 |

| 46 days | 10,454 (4.7) | 6,148 (4.8) | 4,306 (4.7) | |

| 7+ days | 5,273 (2.4) | 3,210 (2.5) | 2,063 (2.3) | |

| Median [IQR] | 1 [11] | 1 [11] | 1 [11] | 0.144 |

| Admitted patients, median [IQR] | 2 [13] | 2 [13] | 2 [13] | <0.001 |

Discharged From the ED

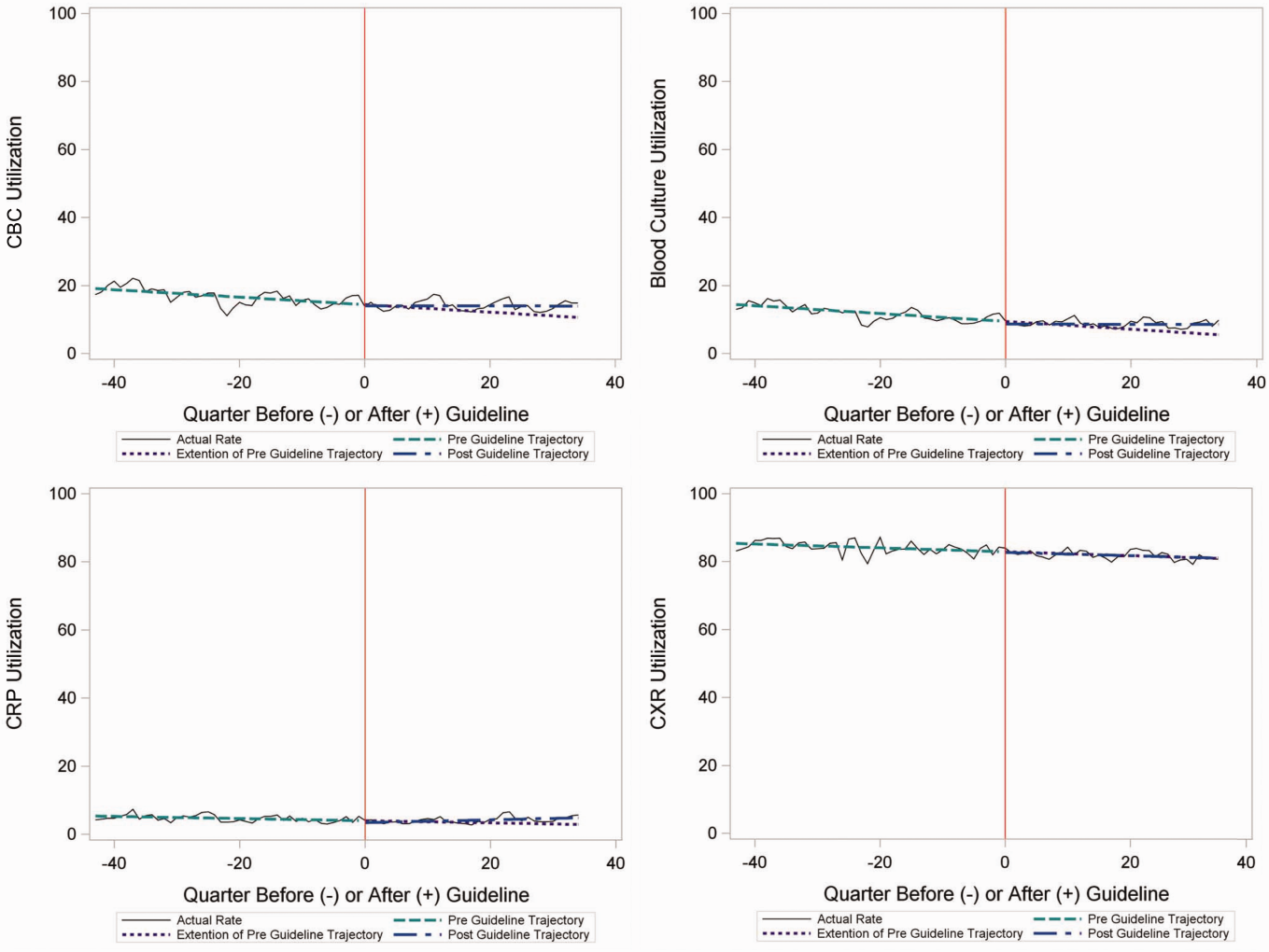

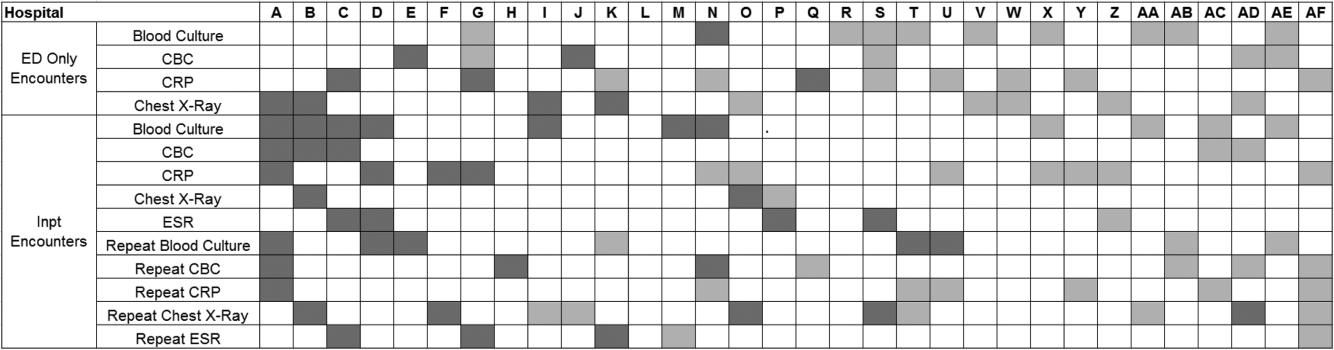

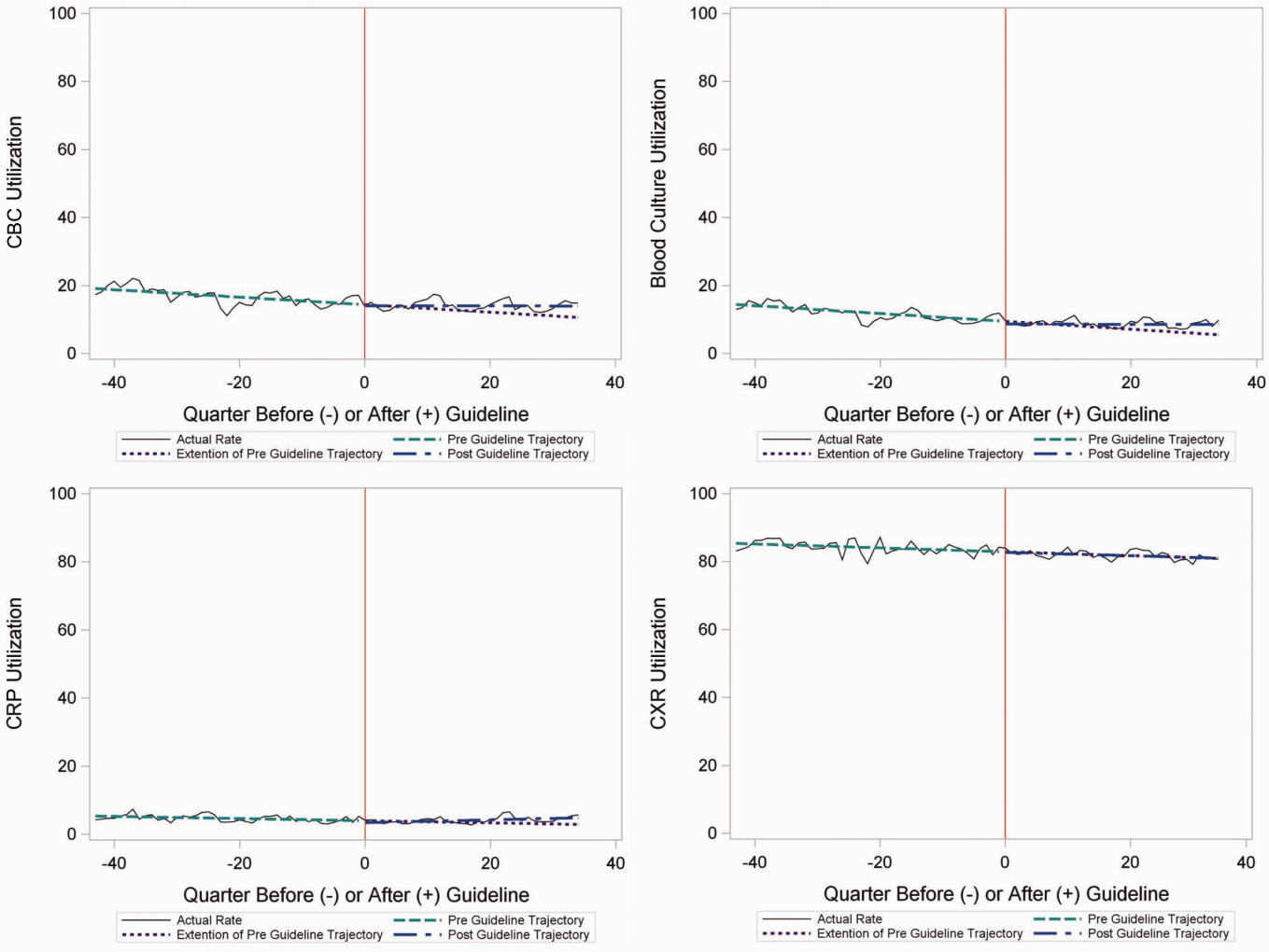

Throughout the study, utilization of CBC, blood cultures, and CRP was <20%, whereas CXR use was >75%. In segmented regression analysis, CRP utilization was relatively stable before the guidelines publication. However, by the end of the study period, the projected estimate of CRP utilization without guidelines (expected) was 2.9% compared with 4.8% with the guidelines (observed) (P < 0.05) (Figure 1). A similar pattern of higher rates of diagnostic utilization after the guidelines compared with projected estimates without the guidelines was also seen in the ED utilization of CBC, blood cultures, and CXR (Figure 1); however, these trends did not achieve statistical significance. Table 2 provides specific values. Using a standard cost of $19.52 for CRP testing, annual costs across all hospitals increased $11,783 for ED evaluation of CAP.

Baseline (%) | Preguideline Trend | Level Change at Guideline | Change in Trend After Guideline | Estimates at End of Study* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Without Guideline (%) | With Guideline (%) | P | |||||

| |||||||

| ED‐only encounters | |||||||

| Blood culture | 14.6 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 5.5 | 8.6 | NS |

| CBC | 19.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 10.7 | 14.0 | NS |

| CRP | 5.4 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 2.9 | 4.8 | <0.05 |

| Chest x‐ray | 85.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 80.9 | 81.1 | NS |

| Inpatient encounters | |||||||

| Blood culture | 50.6 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 49.2 | 41.4 | <0.05 |

| Repeat blood culture | 6.5 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 8.9 | 5.8 | NS |

| CBC | 65.2 | 0.0 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 65.0 | 62.2 | NS |

| Repeat CBC | 23.4 | 0.0 | 4.2 | 0.0 | 20.8 | 16.0 | NS |

| CRP | 25.7 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 23.8 | 23.5 | NS |

| Repeat CRP | 12.5 | 0.1 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 7.1 | 7.3 | NS |

| Chest x‐ray | 89.4 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 85.4 | 83.9 | NS |

| Repeat chest x‐ray | 25.5 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 24.1 | 17.7 | <0.05 |

Inpatient Encounters

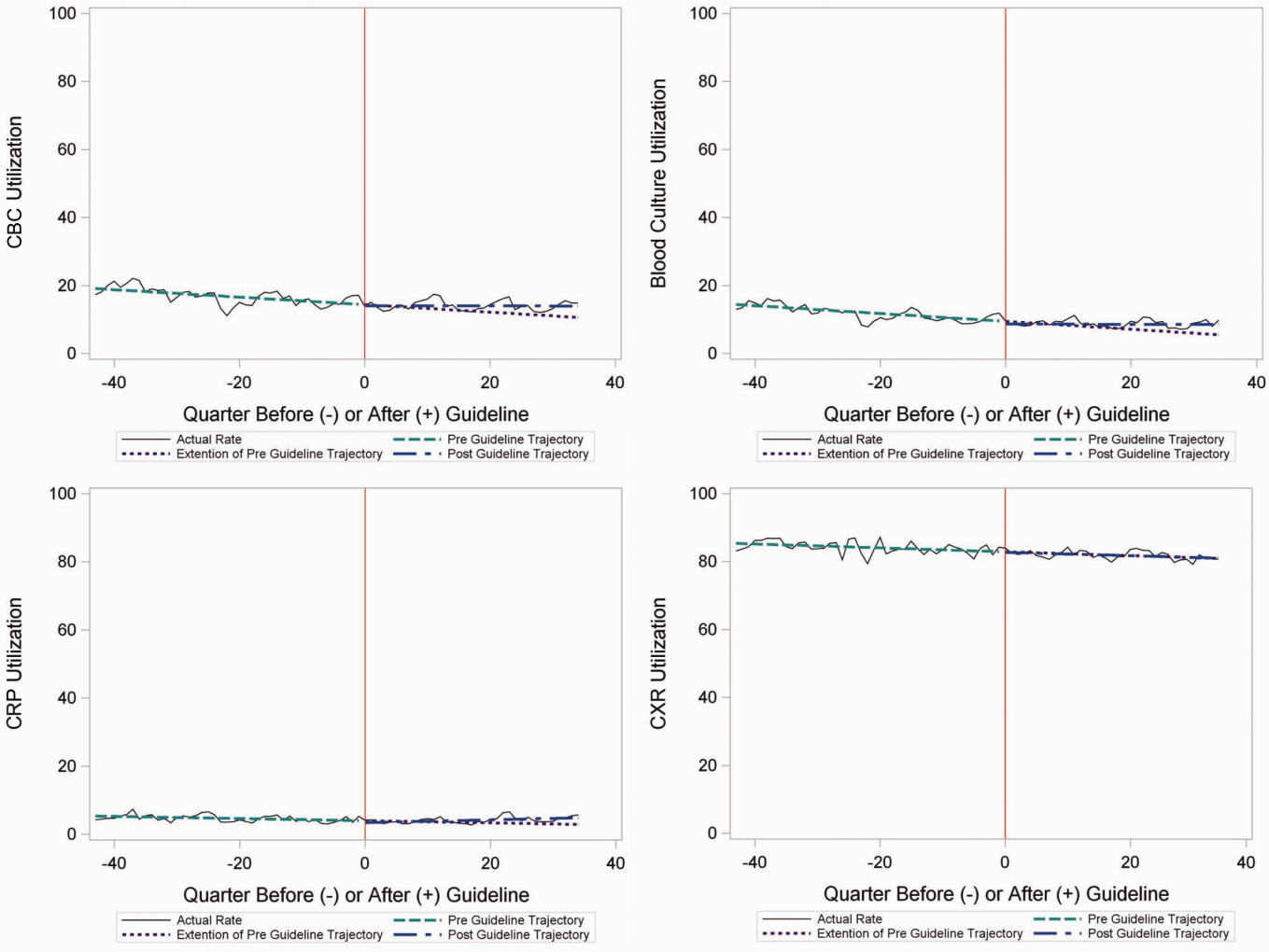

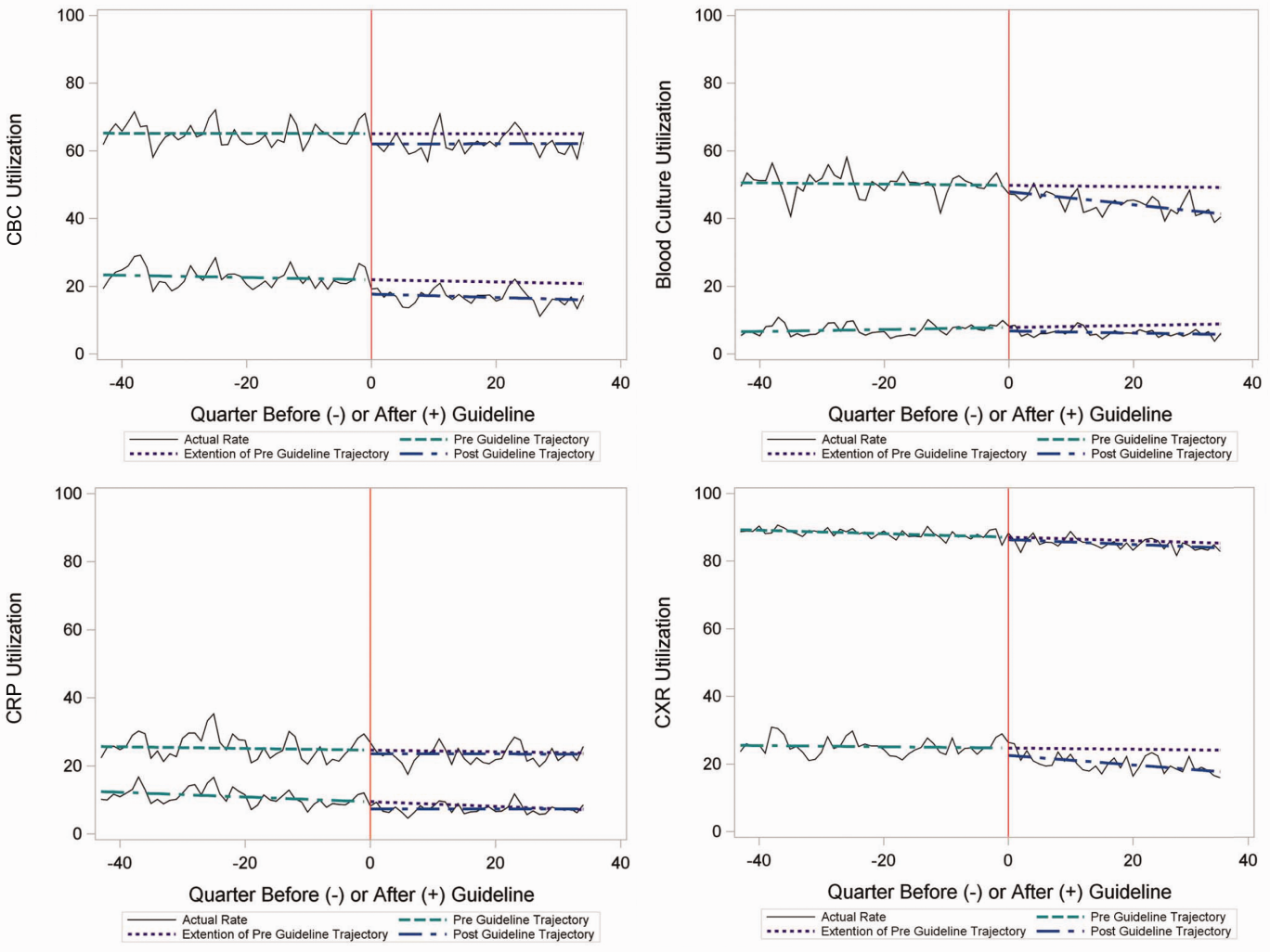

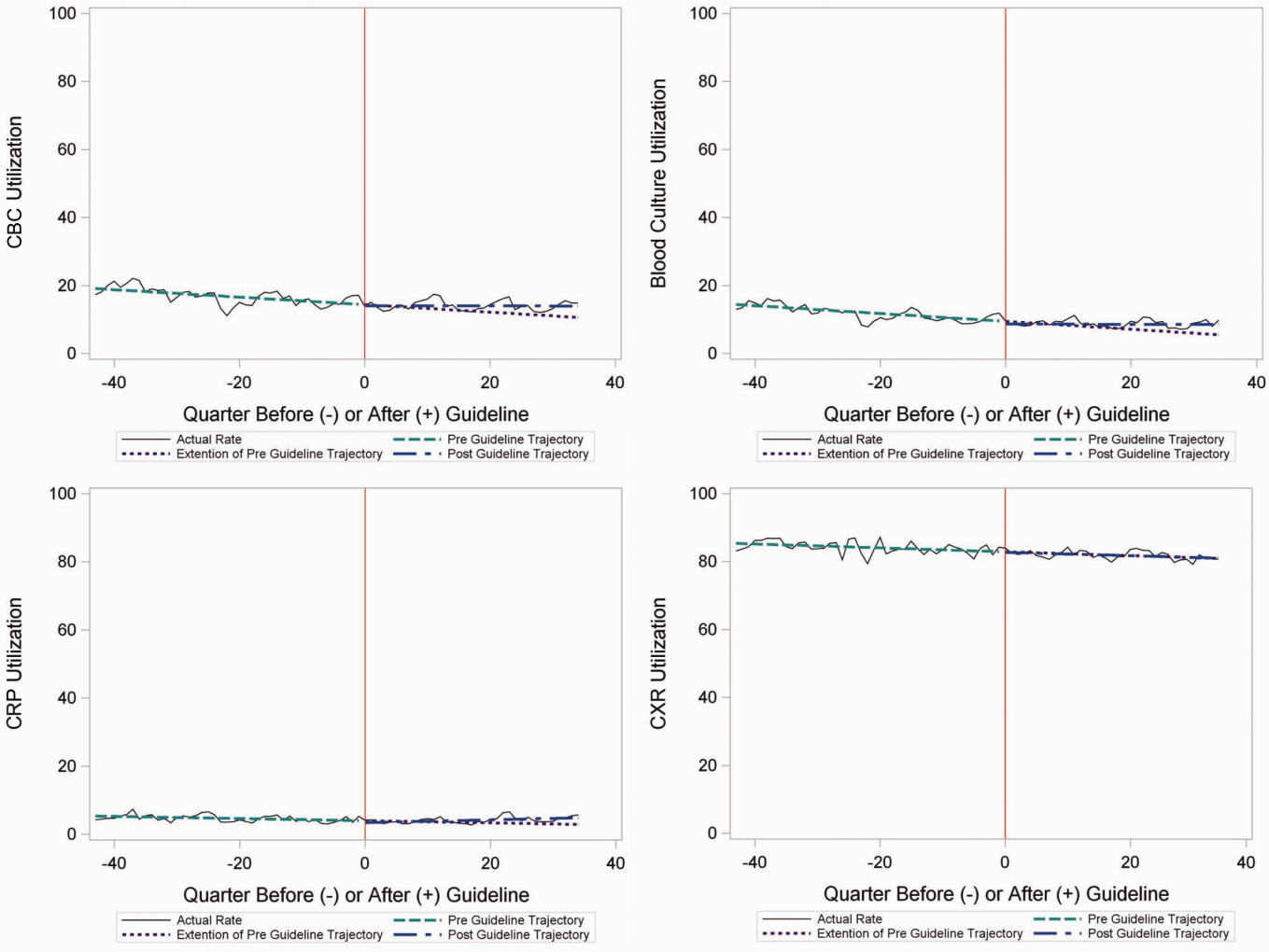

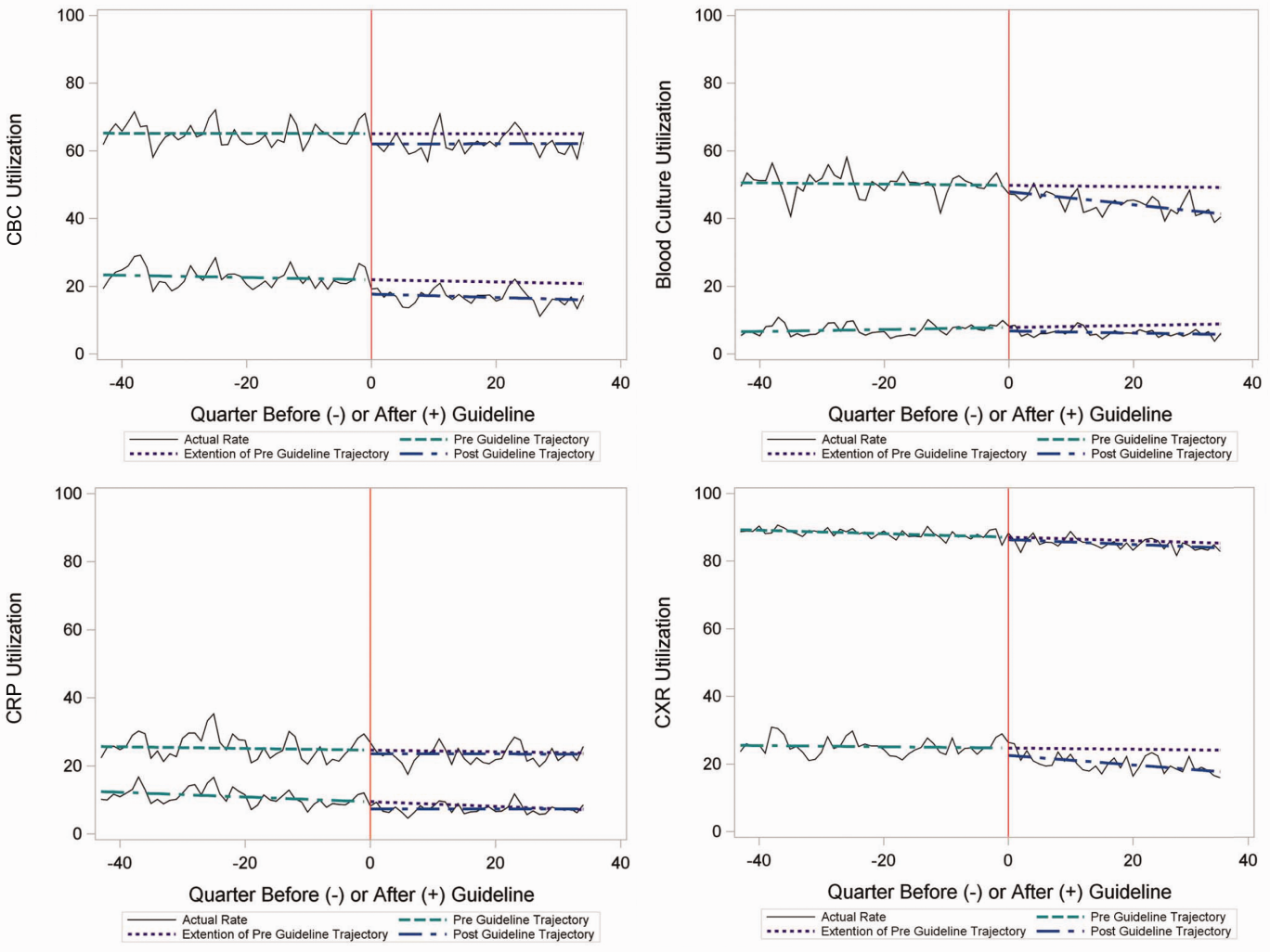

In the segmented regression analysis of children hospitalized with CAP, guideline publication was associated with changes in the monthly use of some diagnostic tests. For example, by the end of the study period, the use of blood culture was 41.4% (observed), whereas the projected estimated use in the absence of the guidelines was 49.2% (expected) (P < 0.05) (Figure 2). Table 2 includes the data for the other tests, CBC, CRP, and CXR, in which similar patterns are noted with lower utilization rates after the guidelines, compared with expected utilization rates without the guidelines; however, these trends did not achieve statistical significance. Evaluating the utilization of repeat testing for inpatients, only repeat CXR achieved statistical significance (P < 0.05), with utilization rates of 17.7% with the guidelines (actual) compared with 24.1% without the guidelines (predicted).

To better understand the use of repeat testing, a comparison of severity outcomesLOS, ICU transfer, and pleural drainage procedureswas performed between patients with no repeat testing (70%) and patients with 1 or more repeat tests (30%). Patients with repeat testing had longer LOS (no repeat testing LOS 1 [IQR, 12]) versus 1 repeat test LOS 3 ([IQR, 24] vs 2+ repeat tests LOS 5 [IQR, 38]), higher rate of ICU transfer (no repeat testing 4.6% vs 1 repeat test 14.6% vs 2+ repeat test 35.6%), and higher rate of pleural drainage (no repeat testing 0% vs 1 repeat test 0.1% vs 2+ repeat test 5.9%] (all P < 0.001).

Using standard costs of $37.57 for blood cultures and $73.28 for CXR, annual costs for children with CAP across all hospitals decreased by $91,512 due to decreased utilization of blood cultures, and by $146,840 due to decreased utilization of CXR.

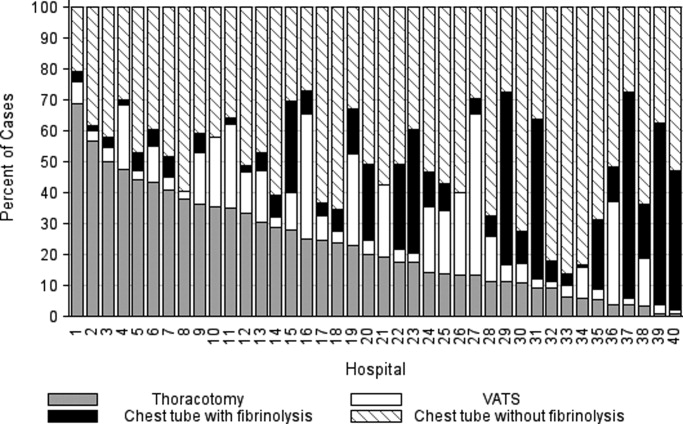

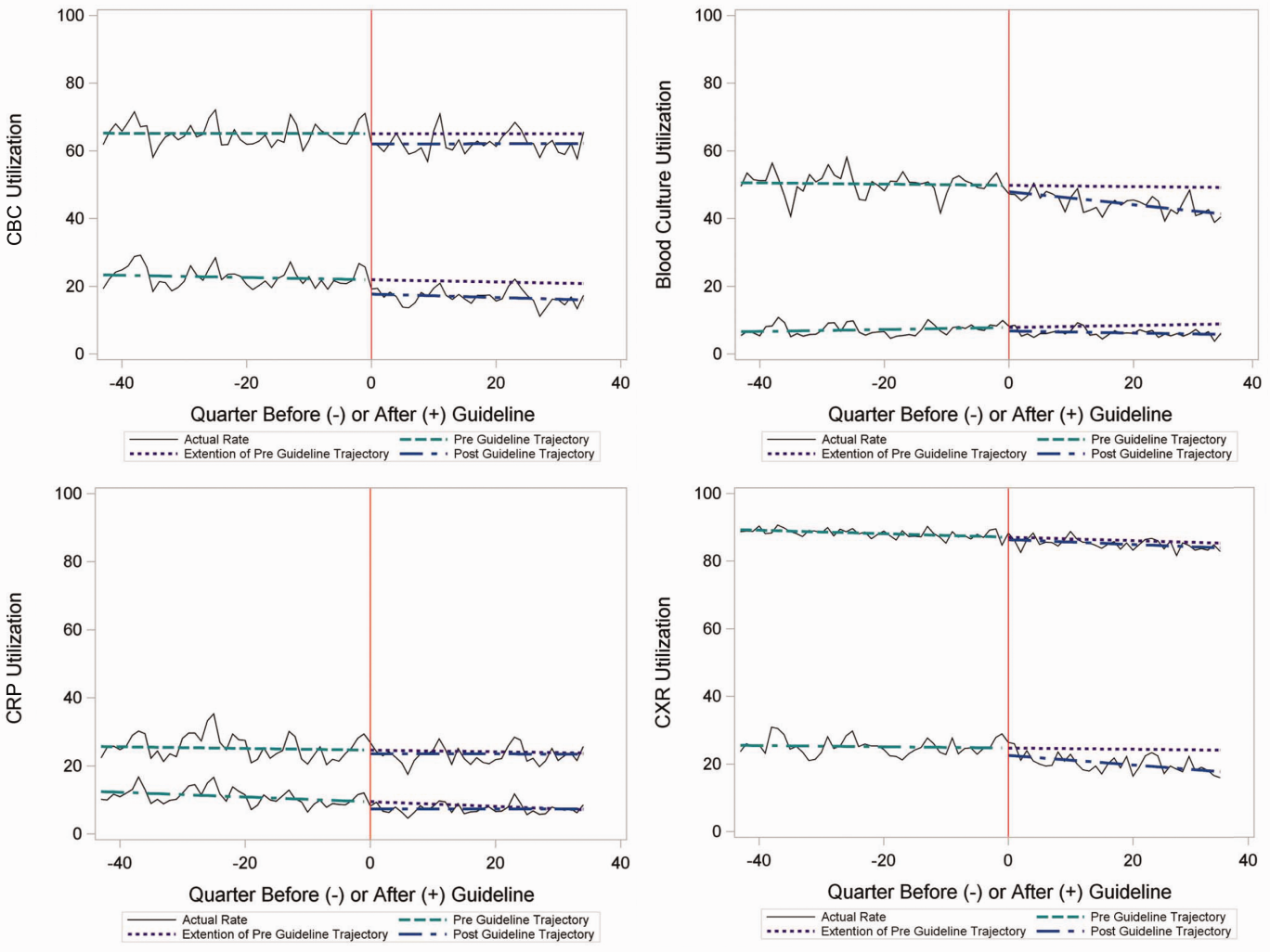

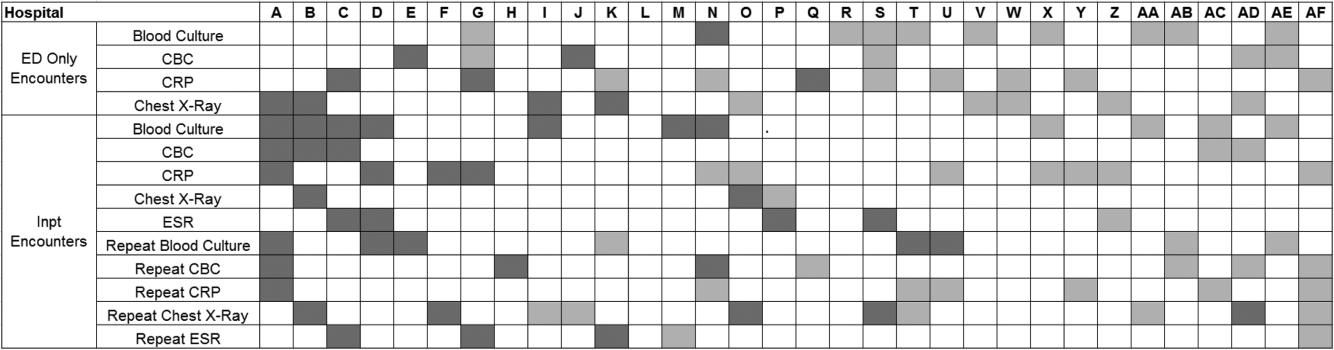

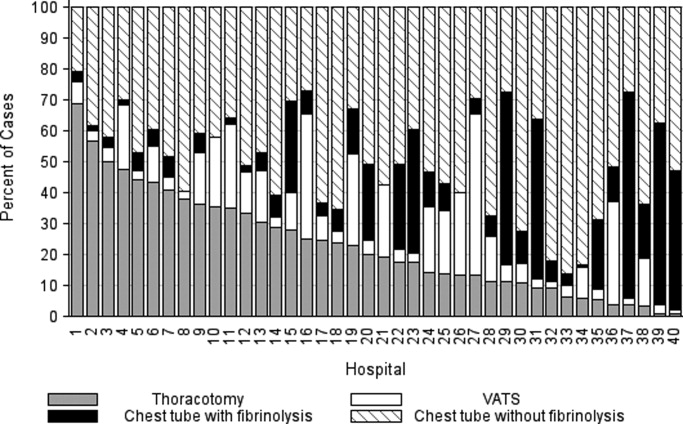

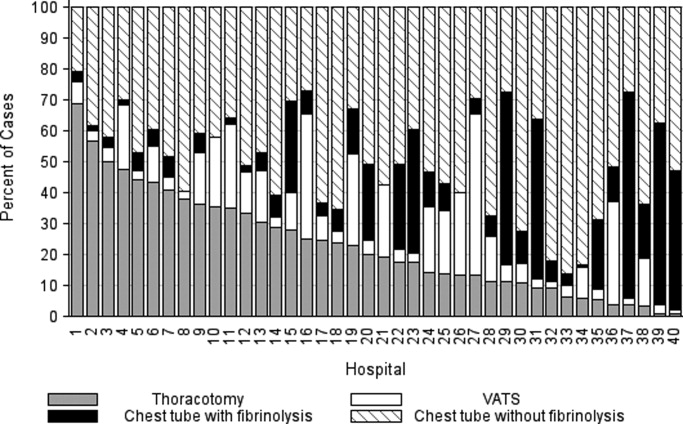

Hospital‐Level Variation in the Impact of the National Guideline

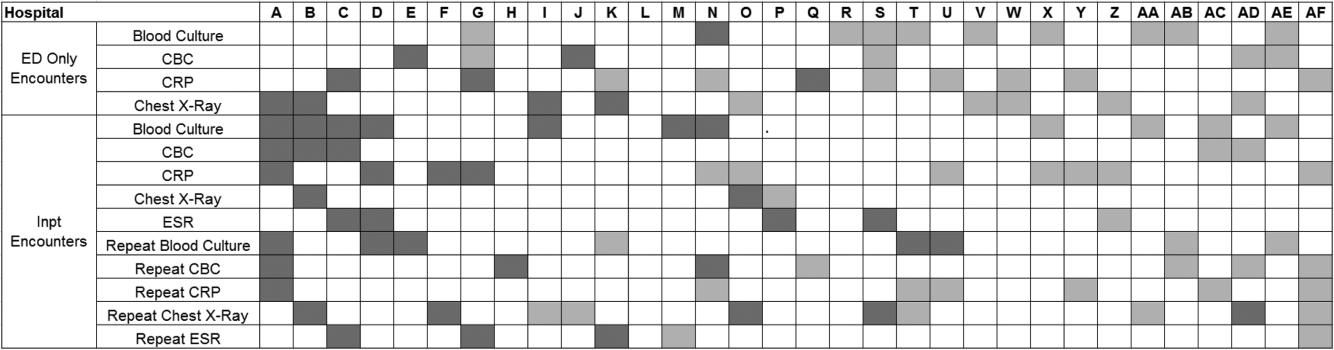

Figure 3 is a visual representation (heat map) of the impact of the guidelines at the hospital level at the end of the study from the individual interrupted time series. Based on this heat map (Figure 3), there was wide variability between hospitals in the impact of the guideline on each test in different settings (ED or inpatient). By diagnostic testing, 7 hospitals significantly decreased utilization of blood cultures for inpatients, and 5 hospitals significantly decreased utilization for repeat blood cultures and repeat CXR. Correlation between the number of positive improvements at a hospital and region (P = 0.974), number of CAP cases (P = 0.731), or percentage of public insurance (P = 0.241) were all nonsignificant.

DISCUSSION

This study complements previous assessments by evaluating the impact of the 2011 IDSA/PIDS consensus guidelines on the management of children with CAP cared for at US children's hospitals. Prior studies have shown increased use of narrow‐spectrum antibiotics for children with CAP after the publication of these guidelines.[7] The current study focused on diagnostic testing for CAP before and after the publication of the 2011 guidelines. In the ED setting, use of some diagnostic tests (blood culture, CBC, CXR, CRP) was declining prior to guideline publication, but appeared to plateau and/or increase after 2011. Among children admitted with CAP, use of diagnostic testing was relatively stable prior to 2011, and use of these tests (blood culture, CBC, CXR, CRP) declined after guideline publication. Overall, changes in diagnostic resource utilization 3 years after publication were modest, with few changes achieving statistical significance. There was a large variability in the impact of guidelines on test use between hospitals.

For outpatients, including those managed in the ED, the PIDS/IDSA guidelines recommend limited laboratory testing in nontoxic, fully immunized patients. The guidelines discourage the use of diagnostic testing among outpatients because of their low yield (eg, blood culture), and because test results may not impact management (eg, CBC).[6] In the years prior to guideline publication, there was already a declining trend in testing rates, including blood cultures, CBC, and CRP, for patients in the ED. After guideline publication, the rate of blood cultures, CBC, and CRP increased, but only the increase in CRP utilization achieved statistical significance. We would not expect utilization for common diagnostic tests (eg, CBC for outpatients with CAP) to be at or close to 0% because of the complexity of clinical decision making regarding admission that factors in aspects of patient history, exam findings, and underlying risk.[15] ED utilization of blood cultures was <10%, CBC <15%, and CRP <5% after guideline publication, which may represent the lowest testing limit that could be achieved.

CXRs obtained in the ED did not decrease over the entire study period. The rates of CXR use (close to 80%) seen in our study are similar to prior ED studies.[5, 16] Management of children with CAP in the ED might be different than outpatient primary care management because (1) unlike primary care providers, ED providers do not have an established relationship with their patients and do not have the opportunity for follow‐up and serial exams, making them less likely to tolerate diagnostic uncertainty; and (2) ED providers may see sicker patients. However, use of CXR in the ED does represent an opportunity for further study to understand if decreased utilization is feasible without adversely impacting clinical outcomes.

The CAP guidelines provide a strong recommendation to obtain blood culture in moderate to severe pneumonia. Despite this, blood culture utilization declined after guideline publication. Less than 10% of children hospitalized with uncomplicated CAP have positive blood cultures, which calls into question the utility of blood cultures for all admitted patients.[17, 18, 19] The recent EPIC (Epidemiology of Pneumonia in the Community) study showed that a majority of children hospitalized with pneumonia do not have growth of bacteria in culture, but there may be a role for blood cultures in patients with a strong suspicion of complicated CAP or in the patient with moderate to severe disease.[20] In addition to blood cultures, the guidelines also recommend CBC and CXR in moderate to severely ill children. This observed decline in testing in CBC and CXR may be related to individual physician assessments of which patients are moderately to severely ill, as the guidelines do not recommend testing for children with less severe disease. Our exclusion of patients requiring intensive care management or pleural drainage on admission might have selected children with a milder course of illness, although still requiring admission.

The guidelines discourage repeat diagnostic testing among children hospitalized with CAP who are improving. In this study, repeat CXR and CBC occurred in approximately 20% of patients, but repeat blood culture and CRP was much lower. As with initial diagnostic testing for inpatients with CAP, the rates of some repeat testing decreased with the guidelines. However, those with repeat testing had longer LOS and were more likely to require ICU transfer or a pleural drainage procedure compared to children without repeat testing. This suggests that repeat testing is used more often in children with a severe presentation or a worsening clinical course, and not done routinely on hospitalized patients.

The financial impact of decreased testing is modest, because the tests themselves are relatively inexpensive. However, the lack of substantial cost savings should not preclude efforts to continue to improve adherence to the guidelines. Not only is increased testing associated with higher hospitalization rates,[5] potentially yielding higher costs and family stress, increased testing may also lead to patient discomfort and possibly increased radiation exposure through chest radiography.

Many of the diagnostic testing recommendations in the CAP guidelines are based on weak evidence, which may contribute to the lack of substantial adoption. Nevertheless, adherence to guideline recommendations requires sustained effort on the part of individual physicians that should be encouraged through institutional support.[21] Continuous education and clinical decision support, as well as reminders in the electronic medical record, would make guideline recommendations more visible and may help overcome the inertia of previous practice.[15] The hospital‐level heat map (Figure 3) included in this study demonstrates that the impact of the guidelines was variable across sites. Although a few sites had decreased diagnostic testing in many areas with no increased testing in any category, there were several sites that had no improvement in any diagnostic testing category. In addition, hospital‐level factors like size, geography, and insurance status were not associated with number of improvements. To better understand drivers of change at individual hospitals, future studies should evaluate specific strategies utilized by the rapid guideline adopters.

This study is subject to several limitations. The use of ICD‐9 codes to identify patients with CAP may not capture all patients with this diagnosis; however, these codes have been previously validated.[13] Additionally, because patients were identified using ICD‐9 coding assigned at the time of discharge, testing performed in the ED setting may not reflect care for a child with known pneumonia, but rather may reflect testing for a child with fever or other signs of infection. PHIS collects data from freestanding children's hospitals, which care for a majority of children with CAP in the US, but our findings may not be generalizable to other hospitals. In addition, we did not examine drivers of trends within individual institutions. We did not have detailed information to examine whether the PHIS hospitals in our study had actively worked to adopt the CAP guidelines. We were also unable to assess physician's familiarity with guidelines or the level of disagreement with the recommendations. Furthermore, the PHIS database does not permit detailed correlation of diagnostic testing with clinical parameters. In contrast to the diagnostic testing evaluated in this study, which is primarily discouraged by the IDSA/PIDS guidelines, respiratory viral testing for children with CAP is recommended but could not be evaluated, as data on such testing are not readily available in PHIS.

CONCLUSION

Publication of the IDSA/PIDS evidence‐based guidelines for the management of CAP was associated with modest, variable changes in use of diagnostic testing. Further adoption of the CAP guidelines should reduce variation in care and decrease unnecessary resource utilization in the management of CAP. Our study demonstrates that efforts to promote decreased resource utilization should target specific situations (eg, repeat testing for inpatients who are improving). Adherence to guidelines may be improved by the adoption of local practices that integrate and improve daily workflow, like order sets and clinical decision support tools.

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

- , . Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA. 2012;307(14):1513–1516.

- , , , et al. Choosing wisely in pediatric hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):479–485.

- , , , et al.; Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) Network. Prioritization of comparative effectiveness research topics in hospital pediatrics. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(12):1155–1164.

- , , , et al. Variability in processes of care and outcomes among children hospitalized with community‐acquired pneumonia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31(10):1036–1041.

- , , , , . Variation in emergency department diagnostic testing and disposition outcomes in pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2013;132(2):237–244.

- , , , et al.; Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. The management of community‐acquired pneumonia in infants and children older than 3 months of age: clinical practice guidelines by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(7):e25–e76.

- , , , et al., Impact of Infectious Diseases Society of America/Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society guidelines on treatment of community‐acquired pneumonia in hospitalized children. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(6):834–838.

- , , , et al. Antibiotic choice for children hospitalized with pneumonia and adherence to national guidelines. Pediatrics. 2015;136(1):44–52.

- , , , et al. Quality improvement methods increase appropriate antibiotic prescribing for childhood pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2013;131(5):e1623–e1631.

- , , , et al. Improvement methodology increases guideline recommended blood cultures in children with pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2015;135(4):e1052–e1059.

- , , , , , . Impact of a guideline on management of children hospitalized with community‐acquired pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e597–e604.

- , , , . Effectiveness of antimicrobial guidelines for community‐acquired pneumonia in children. Pediatrics. 2012;129(5):e1326–e1333.

- , , , et al. Identifying pediatric community‐acquired pneumonia hospitalizations: accuracy of administrative billing codes. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(9):851–858.

- , , , , . Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD‐10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:199.

- , . Establishing superior benchmarks of care in clinical practice: a proposal to drive achievable health care value. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(4):301–302.

- , , , . Emergency department management of childhood pneumonia in the United States prior to publication of national guidelines. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(3):240–246.

- , , , et al. Prevalence of bacteremia in hospitalized pediatric patients with community‐acquired pneumonia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(7):736–740.

- , , , , . The prevalence of bacteremia in pediatric patients with community‐acquired pneumonia: guidelines to reduce the frequency of obtaining blood cultures. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(2):92–96.

- . Do all children hospitalized with community‐acquired pneumonia require blood cultures? Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(2):177–179.

- , , , et al.; CDC EPIC Study Team. Community‐acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. children. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(9):835–845.

- , , , et al. Influence of hospital guidelines on management of children hospitalized with pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2012;130(5):e823–e830.

Overutilization of resources is a significant, yet underappreciated, problem in medicine. Many interventions target underutilization (eg, immunizations) or misuse (eg, antibiotic prescribing for viral pharyngitis), yet overutilization remains as a significant contributor to healthcare waste.[1] In an effort to reduce waste, the Choosing Wisely campaign created a work group to highlight areas of overutilization, specifically noting both diagnostic tests and therapies for common pediatric conditions with no proven benefit and possible harm to the patient.[2] Respiratory illnesses have been a target of many quality‐improvement efforts, and pneumonia represents a common diagnosis in pediatrics.[3] The use of diagnostic testing for pneumonia is an area where care can be optimized and aligned with evidence.

Laboratory testing and diagnostic imaging are routinely used for the management of children with community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP). Several studies have documented substantial variability in the use of these resources for pneumonia management, with higher resource use associated with a higher chance of hospitalization after emergency department (ED) evaluation and a longer length of stay among those requiring hospitalization.[4, 5] This variation in diagnostic resource utilization has been attributed, at least in part, to a lack of consensus on the management of pneumonia. There is wide variability in diagnostic testing, and due to potential consequences for patients presenting with pneumonia, efforts to standardize care offer an opportunity to improve healthcare value.

In August 2011, the first national, evidence‐based consensus guidelines for the management of childhood CAP were published jointly by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (PIDS) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA).[6] A primary focus of these guidelines was the recommendation for the use of narrow spectrum antibiotics for the management of uncomplicated pneumonia. Previous studies have assessed the impact of the publication of the PIDS/IDSA guidelines on empiric antibiotic selection for the management of pneumonia.[7, 8] In addition, the guidelines provided recommendations regarding diagnostic test utilization, in particular discouraging blood tests (eg, complete blood counts) and radiologic studies for nontoxic, fully immunized children treated as outpatients, as well as repeat testing for children hospitalized with CAP who are improving.

Although single centers have demonstrated changes in utilization patterns based on clinical practice guidelines,[9, 10, 11, 12] whether these guidelines have impacted diagnostic test utilization among US children with CAP in a larger scale remains unknown. Therefore, we sought to determine the impact of the PIDS/IDSA guidelines on the use of diagnostic testing among children with CAP using a national sample of US children's hospitals. Because the guidelines discourage repeat diagnostic testing in patients who are improving, we also evaluated the association between repeat diagnostic studies and severity of illness.

METHODS

This retrospective cohort study used data from the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) (Children's Hospital Association, Overland Park, KS). The PHIS database contains deidentified administrative data, detailing demographic, diagnostic, procedure, and billing data from 47 freestanding, tertiary care children's hospitals. This database accounts for approximately 20% of all annual pediatric hospitalizations in the United States. Data quality is ensured through a joint effort between the Children's Hospital Association and participating hospitals.

Patient Population

Data from 32 (of the 47) hospitals included in PHIS with complete inpatient and ED data were used to evaluate hospital‐level resource utilization for children 1 to 18 years of age discharged January 1, 2008 to June 30, 2014 with a diagnosis of pneumonia (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision [ICD‐9] codes 480.x‐486.x, 487.0).[13] Our goal was to identify previously healthy children with uncomplicated pneumonia, so we excluded patients with complex chronic conditions,[14] billing charges for intensive care management and/or pleural drainage procedure (IDC‐9 codes 510.0, 510.9, 511.0, 511.1, 511.8, 511.9, 513.x) on day of admission or the next day, or prior pneumonia admission in the last 30 days. We studied 2 mutually exclusive populations: children with pneumonia treated in the ED (ie, patients who were evaluated in the ED and discharged to home), and children hospitalized with pneumonia, including those admitted through the ED.

Guideline Publication and Study Periods

For an exploratory before and after comparison, patients were grouped into 2 cohorts based on a guideline online publication date of August 1, 2011: preguideline (January 1, 2008 to July 31, 2011) and postguideline (August 1, 2011 to June 30, 2014).

Study Outcomes

The measured outcomes were the monthly proportion of pneumonia patients for whom specific diagnostic tests were performed, as determined from billing data. The diagnostic tests evaluated were complete blood count (CBC), blood culture, C‐reactive protein (CRP), and chest radiograph (CXR). Standardized costs were also calculated from PHIS charges as previously described to standardize the cost of the individual tests and remove interhospital cost variation.[3]

Relationship of Repeat Testing and Severity of Illness

Because higher illness severity and clinical deterioration may warrant repeat testing, we also explored the association of repeat diagnostic testing for inpatients with severity of illness by using the following variables as measures of severity: length of stay (LOS), transfer to intensive care unit (ICU), or pleural drainage procedure after admission (>2 calendar days after admission). Repeat diagnostic testing was stratified by number of tests.

Statistical Analysis

The categorical demographic characteristics of the pre‐ and postguideline populations were summarized using frequencies and percentages, and compared using 2 tests. Continuous demographics were summarized with medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) and compared with the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Segmented regression, clustered by hospital, was used to assess trends in monthly resource utilization as well as associated standardized costs before and after guidelines publication. To estimate the impact of the guidelines overall, we compared the observed diagnostic resource use at the end of the study period with expected use projected from trends in the preguidelines period (ie, if there were no new guidelines). Individual interrupted time series were also built for each hospital. From these models, we assessed which hospitals had a significant difference between the rate observed at the end of the study and that estimated from their preguideline trajectory. To assess the relationship between the number of positive improvements at a hospital and hospital characteristics, we used Spearman's correlation and Kruskal‐Wallis tests. All analyses were performed with SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC), and P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. In accordance with the policies of the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center Institutional Review Board, this research, using a deidentified dataset, was not considered human subjects research.

RESULTS

There were 275,288 hospital admissions meeting study inclusion criteria of 1 to 18 years of age with a diagnosis of pneumonia from 2008 to 2014. Of these, 54,749 met exclusion criteria (1874 had pleural drainage procedure on day 0 or 1, 51,306 had complex chronic conditions, 1569 were hospitalized with pneumonia in the last 30 days). Characteristics of the remaining 220,539 patients in the final sample are shown in Table 1. The median age was 4 years (IQR, 27 years); a majority of the children were male (53%) and had public insurance (58%). There were 128,855 patients in the preguideline period (January 1, 2008 to July 31, 2011) and 91,684 in the post guideline period (August 1, 2011June 30, 2014).

| Overall | Preguideline | Postguideline | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| No. of discharges | 220,539 | 128,855 | 91,684 | |

| Type of encounter | ||||

| ED only | 150,215 (68.1) | 88,790 (68.9) | 61,425 (67) | <0.001 |

| Inpatient | 70,324 (31.9) | 40,065 (31.1) | 30,259 (33) | |

| Age | ||||

| 14 years | 129,360 (58.7) | 77,802 (60.4) | 51,558 (56.2) | <0.001 |

| 59 years | 58,609 (26.6) | 32,708 (25.4) | 25,901 (28.3) | |

| 1018 years | 32,570 (14.8) | 18,345 (14.2) | 14,225 (15.5) | |

| Median [IQR] | 4 [27] | 3 [27] | 4 [27] | <0.001 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 116,718 (52.9) | 68,319 (53) | 48,399 (52.8) | 00.285 |

| Female | 103,813 (47.1) | 60,532 (47) | 43,281 (47.2) | |

| Race | ||||

| Non‐Hispanic white | 84,423 (38.3) | 47,327 (36.7) | 37,096 (40.5) | <0.001 |

| Non‐Hispanic black | 60,062 (27.2) | 35,870 (27.8) | 24,192 (26.4) | |

| Hispanic | 51,184 (23.2) | 31,167 (24.2) | 20,017 (21.8) | |

| Asian | 6,444 (2.9) | 3,691 (2.9) | 2,753 (3) | |

| Other | 18,426 (8.4) | 10,800 (8.4) | 7,626 (8.3) | |

| Payer | ||||

| Government | 128,047 (58.1) | 70,742 (54.9) | 57,305 (62.5) | <0.001 |

| Private | 73,338 (33.3) | 44,410 (34.5) | 28,928 (31.6) | |

| Other | 19,154 (8.7) | 13,703 (10.6) | 5,451 (5.9) | |

| Disposition | ||||

| HHS | 684 (0.3) | 411 (0.3) | 273 (0.3) | <0.001 |

| Home | 209,710 (95.1) | 123,236 (95.6) | 86,474 (94.3) | |

| Other | 9,749 (4.4) | 4,962 (3.9) | 4,787 (5.2) | |

| SNF | 396 (0.2) | 246 (0.2) | 150 (0.2) | |

| Season | ||||

| Spring | 60,171 (27.3) | 36,709 (28.5) | 23,462 (25.6) | <0.001 |

| Summer | 29,891 (13.6) | 17,748 (13.8) | 12,143 (13.2) | |

| Fall | 52,161 (23.7) | 28,332 (22) | 23,829 (26) | |

| Winter | 78,316 (35.5) | 46,066 (35.8) | 32,250 (35.2) | |

| LOS | ||||

| 13 days | 204,812 (92.9) | 119,497 (92.7) | 85,315 (93.1) | <0.001 |

| 46 days | 10,454 (4.7) | 6,148 (4.8) | 4,306 (4.7) | |

| 7+ days | 5,273 (2.4) | 3,210 (2.5) | 2,063 (2.3) | |

| Median [IQR] | 1 [11] | 1 [11] | 1 [11] | 0.144 |

| Admitted patients, median [IQR] | 2 [13] | 2 [13] | 2 [13] | <0.001 |

Discharged From the ED

Throughout the study, utilization of CBC, blood cultures, and CRP was <20%, whereas CXR use was >75%. In segmented regression analysis, CRP utilization was relatively stable before the guidelines publication. However, by the end of the study period, the projected estimate of CRP utilization without guidelines (expected) was 2.9% compared with 4.8% with the guidelines (observed) (P < 0.05) (Figure 1). A similar pattern of higher rates of diagnostic utilization after the guidelines compared with projected estimates without the guidelines was also seen in the ED utilization of CBC, blood cultures, and CXR (Figure 1); however, these trends did not achieve statistical significance. Table 2 provides specific values. Using a standard cost of $19.52 for CRP testing, annual costs across all hospitals increased $11,783 for ED evaluation of CAP.

Baseline (%) | Preguideline Trend | Level Change at Guideline | Change in Trend After Guideline | Estimates at End of Study* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Without Guideline (%) | With Guideline (%) | P | |||||

| |||||||

| ED‐only encounters | |||||||

| Blood culture | 14.6 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 5.5 | 8.6 | NS |

| CBC | 19.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 10.7 | 14.0 | NS |

| CRP | 5.4 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 2.9 | 4.8 | <0.05 |

| Chest x‐ray | 85.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 80.9 | 81.1 | NS |

| Inpatient encounters | |||||||

| Blood culture | 50.6 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 49.2 | 41.4 | <0.05 |

| Repeat blood culture | 6.5 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 8.9 | 5.8 | NS |

| CBC | 65.2 | 0.0 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 65.0 | 62.2 | NS |

| Repeat CBC | 23.4 | 0.0 | 4.2 | 0.0 | 20.8 | 16.0 | NS |

| CRP | 25.7 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 23.8 | 23.5 | NS |

| Repeat CRP | 12.5 | 0.1 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 7.1 | 7.3 | NS |

| Chest x‐ray | 89.4 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 85.4 | 83.9 | NS |

| Repeat chest x‐ray | 25.5 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 24.1 | 17.7 | <0.05 |

Inpatient Encounters

In the segmented regression analysis of children hospitalized with CAP, guideline publication was associated with changes in the monthly use of some diagnostic tests. For example, by the end of the study period, the use of blood culture was 41.4% (observed), whereas the projected estimated use in the absence of the guidelines was 49.2% (expected) (P < 0.05) (Figure 2). Table 2 includes the data for the other tests, CBC, CRP, and CXR, in which similar patterns are noted with lower utilization rates after the guidelines, compared with expected utilization rates without the guidelines; however, these trends did not achieve statistical significance. Evaluating the utilization of repeat testing for inpatients, only repeat CXR achieved statistical significance (P < 0.05), with utilization rates of 17.7% with the guidelines (actual) compared with 24.1% without the guidelines (predicted).

To better understand the use of repeat testing, a comparison of severity outcomesLOS, ICU transfer, and pleural drainage procedureswas performed between patients with no repeat testing (70%) and patients with 1 or more repeat tests (30%). Patients with repeat testing had longer LOS (no repeat testing LOS 1 [IQR, 12]) versus 1 repeat test LOS 3 ([IQR, 24] vs 2+ repeat tests LOS 5 [IQR, 38]), higher rate of ICU transfer (no repeat testing 4.6% vs 1 repeat test 14.6% vs 2+ repeat test 35.6%), and higher rate of pleural drainage (no repeat testing 0% vs 1 repeat test 0.1% vs 2+ repeat test 5.9%] (all P < 0.001).

Using standard costs of $37.57 for blood cultures and $73.28 for CXR, annual costs for children with CAP across all hospitals decreased by $91,512 due to decreased utilization of blood cultures, and by $146,840 due to decreased utilization of CXR.

Hospital‐Level Variation in the Impact of the National Guideline

Figure 3 is a visual representation (heat map) of the impact of the guidelines at the hospital level at the end of the study from the individual interrupted time series. Based on this heat map (Figure 3), there was wide variability between hospitals in the impact of the guideline on each test in different settings (ED or inpatient). By diagnostic testing, 7 hospitals significantly decreased utilization of blood cultures for inpatients, and 5 hospitals significantly decreased utilization for repeat blood cultures and repeat CXR. Correlation between the number of positive improvements at a hospital and region (P = 0.974), number of CAP cases (P = 0.731), or percentage of public insurance (P = 0.241) were all nonsignificant.

DISCUSSION

This study complements previous assessments by evaluating the impact of the 2011 IDSA/PIDS consensus guidelines on the management of children with CAP cared for at US children's hospitals. Prior studies have shown increased use of narrow‐spectrum antibiotics for children with CAP after the publication of these guidelines.[7] The current study focused on diagnostic testing for CAP before and after the publication of the 2011 guidelines. In the ED setting, use of some diagnostic tests (blood culture, CBC, CXR, CRP) was declining prior to guideline publication, but appeared to plateau and/or increase after 2011. Among children admitted with CAP, use of diagnostic testing was relatively stable prior to 2011, and use of these tests (blood culture, CBC, CXR, CRP) declined after guideline publication. Overall, changes in diagnostic resource utilization 3 years after publication were modest, with few changes achieving statistical significance. There was a large variability in the impact of guidelines on test use between hospitals.

For outpatients, including those managed in the ED, the PIDS/IDSA guidelines recommend limited laboratory testing in nontoxic, fully immunized patients. The guidelines discourage the use of diagnostic testing among outpatients because of their low yield (eg, blood culture), and because test results may not impact management (eg, CBC).[6] In the years prior to guideline publication, there was already a declining trend in testing rates, including blood cultures, CBC, and CRP, for patients in the ED. After guideline publication, the rate of blood cultures, CBC, and CRP increased, but only the increase in CRP utilization achieved statistical significance. We would not expect utilization for common diagnostic tests (eg, CBC for outpatients with CAP) to be at or close to 0% because of the complexity of clinical decision making regarding admission that factors in aspects of patient history, exam findings, and underlying risk.[15] ED utilization of blood cultures was <10%, CBC <15%, and CRP <5% after guideline publication, which may represent the lowest testing limit that could be achieved.

CXRs obtained in the ED did not decrease over the entire study period. The rates of CXR use (close to 80%) seen in our study are similar to prior ED studies.[5, 16] Management of children with CAP in the ED might be different than outpatient primary care management because (1) unlike primary care providers, ED providers do not have an established relationship with their patients and do not have the opportunity for follow‐up and serial exams, making them less likely to tolerate diagnostic uncertainty; and (2) ED providers may see sicker patients. However, use of CXR in the ED does represent an opportunity for further study to understand if decreased utilization is feasible without adversely impacting clinical outcomes.

The CAP guidelines provide a strong recommendation to obtain blood culture in moderate to severe pneumonia. Despite this, blood culture utilization declined after guideline publication. Less than 10% of children hospitalized with uncomplicated CAP have positive blood cultures, which calls into question the utility of blood cultures for all admitted patients.[17, 18, 19] The recent EPIC (Epidemiology of Pneumonia in the Community) study showed that a majority of children hospitalized with pneumonia do not have growth of bacteria in culture, but there may be a role for blood cultures in patients with a strong suspicion of complicated CAP or in the patient with moderate to severe disease.[20] In addition to blood cultures, the guidelines also recommend CBC and CXR in moderate to severely ill children. This observed decline in testing in CBC and CXR may be related to individual physician assessments of which patients are moderately to severely ill, as the guidelines do not recommend testing for children with less severe disease. Our exclusion of patients requiring intensive care management or pleural drainage on admission might have selected children with a milder course of illness, although still requiring admission.

The guidelines discourage repeat diagnostic testing among children hospitalized with CAP who are improving. In this study, repeat CXR and CBC occurred in approximately 20% of patients, but repeat blood culture and CRP was much lower. As with initial diagnostic testing for inpatients with CAP, the rates of some repeat testing decreased with the guidelines. However, those with repeat testing had longer LOS and were more likely to require ICU transfer or a pleural drainage procedure compared to children without repeat testing. This suggests that repeat testing is used more often in children with a severe presentation or a worsening clinical course, and not done routinely on hospitalized patients.

The financial impact of decreased testing is modest, because the tests themselves are relatively inexpensive. However, the lack of substantial cost savings should not preclude efforts to continue to improve adherence to the guidelines. Not only is increased testing associated with higher hospitalization rates,[5] potentially yielding higher costs and family stress, increased testing may also lead to patient discomfort and possibly increased radiation exposure through chest radiography.

Many of the diagnostic testing recommendations in the CAP guidelines are based on weak evidence, which may contribute to the lack of substantial adoption. Nevertheless, adherence to guideline recommendations requires sustained effort on the part of individual physicians that should be encouraged through institutional support.[21] Continuous education and clinical decision support, as well as reminders in the electronic medical record, would make guideline recommendations more visible and may help overcome the inertia of previous practice.[15] The hospital‐level heat map (Figure 3) included in this study demonstrates that the impact of the guidelines was variable across sites. Although a few sites had decreased diagnostic testing in many areas with no increased testing in any category, there were several sites that had no improvement in any diagnostic testing category. In addition, hospital‐level factors like size, geography, and insurance status were not associated with number of improvements. To better understand drivers of change at individual hospitals, future studies should evaluate specific strategies utilized by the rapid guideline adopters.

This study is subject to several limitations. The use of ICD‐9 codes to identify patients with CAP may not capture all patients with this diagnosis; however, these codes have been previously validated.[13] Additionally, because patients were identified using ICD‐9 coding assigned at the time of discharge, testing performed in the ED setting may not reflect care for a child with known pneumonia, but rather may reflect testing for a child with fever or other signs of infection. PHIS collects data from freestanding children's hospitals, which care for a majority of children with CAP in the US, but our findings may not be generalizable to other hospitals. In addition, we did not examine drivers of trends within individual institutions. We did not have detailed information to examine whether the PHIS hospitals in our study had actively worked to adopt the CAP guidelines. We were also unable to assess physician's familiarity with guidelines or the level of disagreement with the recommendations. Furthermore, the PHIS database does not permit detailed correlation of diagnostic testing with clinical parameters. In contrast to the diagnostic testing evaluated in this study, which is primarily discouraged by the IDSA/PIDS guidelines, respiratory viral testing for children with CAP is recommended but could not be evaluated, as data on such testing are not readily available in PHIS.

CONCLUSION

Publication of the IDSA/PIDS evidence‐based guidelines for the management of CAP was associated with modest, variable changes in use of diagnostic testing. Further adoption of the CAP guidelines should reduce variation in care and decrease unnecessary resource utilization in the management of CAP. Our study demonstrates that efforts to promote decreased resource utilization should target specific situations (eg, repeat testing for inpatients who are improving). Adherence to guidelines may be improved by the adoption of local practices that integrate and improve daily workflow, like order sets and clinical decision support tools.

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

Overutilization of resources is a significant, yet underappreciated, problem in medicine. Many interventions target underutilization (eg, immunizations) or misuse (eg, antibiotic prescribing for viral pharyngitis), yet overutilization remains as a significant contributor to healthcare waste.[1] In an effort to reduce waste, the Choosing Wisely campaign created a work group to highlight areas of overutilization, specifically noting both diagnostic tests and therapies for common pediatric conditions with no proven benefit and possible harm to the patient.[2] Respiratory illnesses have been a target of many quality‐improvement efforts, and pneumonia represents a common diagnosis in pediatrics.[3] The use of diagnostic testing for pneumonia is an area where care can be optimized and aligned with evidence.

Laboratory testing and diagnostic imaging are routinely used for the management of children with community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP). Several studies have documented substantial variability in the use of these resources for pneumonia management, with higher resource use associated with a higher chance of hospitalization after emergency department (ED) evaluation and a longer length of stay among those requiring hospitalization.[4, 5] This variation in diagnostic resource utilization has been attributed, at least in part, to a lack of consensus on the management of pneumonia. There is wide variability in diagnostic testing, and due to potential consequences for patients presenting with pneumonia, efforts to standardize care offer an opportunity to improve healthcare value.

In August 2011, the first national, evidence‐based consensus guidelines for the management of childhood CAP were published jointly by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (PIDS) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA).[6] A primary focus of these guidelines was the recommendation for the use of narrow spectrum antibiotics for the management of uncomplicated pneumonia. Previous studies have assessed the impact of the publication of the PIDS/IDSA guidelines on empiric antibiotic selection for the management of pneumonia.[7, 8] In addition, the guidelines provided recommendations regarding diagnostic test utilization, in particular discouraging blood tests (eg, complete blood counts) and radiologic studies for nontoxic, fully immunized children treated as outpatients, as well as repeat testing for children hospitalized with CAP who are improving.

Although single centers have demonstrated changes in utilization patterns based on clinical practice guidelines,[9, 10, 11, 12] whether these guidelines have impacted diagnostic test utilization among US children with CAP in a larger scale remains unknown. Therefore, we sought to determine the impact of the PIDS/IDSA guidelines on the use of diagnostic testing among children with CAP using a national sample of US children's hospitals. Because the guidelines discourage repeat diagnostic testing in patients who are improving, we also evaluated the association between repeat diagnostic studies and severity of illness.

METHODS

This retrospective cohort study used data from the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) (Children's Hospital Association, Overland Park, KS). The PHIS database contains deidentified administrative data, detailing demographic, diagnostic, procedure, and billing data from 47 freestanding, tertiary care children's hospitals. This database accounts for approximately 20% of all annual pediatric hospitalizations in the United States. Data quality is ensured through a joint effort between the Children's Hospital Association and participating hospitals.

Patient Population

Data from 32 (of the 47) hospitals included in PHIS with complete inpatient and ED data were used to evaluate hospital‐level resource utilization for children 1 to 18 years of age discharged January 1, 2008 to June 30, 2014 with a diagnosis of pneumonia (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision [ICD‐9] codes 480.x‐486.x, 487.0).[13] Our goal was to identify previously healthy children with uncomplicated pneumonia, so we excluded patients with complex chronic conditions,[14] billing charges for intensive care management and/or pleural drainage procedure (IDC‐9 codes 510.0, 510.9, 511.0, 511.1, 511.8, 511.9, 513.x) on day of admission or the next day, or prior pneumonia admission in the last 30 days. We studied 2 mutually exclusive populations: children with pneumonia treated in the ED (ie, patients who were evaluated in the ED and discharged to home), and children hospitalized with pneumonia, including those admitted through the ED.

Guideline Publication and Study Periods

For an exploratory before and after comparison, patients were grouped into 2 cohorts based on a guideline online publication date of August 1, 2011: preguideline (January 1, 2008 to July 31, 2011) and postguideline (August 1, 2011 to June 30, 2014).

Study Outcomes

The measured outcomes were the monthly proportion of pneumonia patients for whom specific diagnostic tests were performed, as determined from billing data. The diagnostic tests evaluated were complete blood count (CBC), blood culture, C‐reactive protein (CRP), and chest radiograph (CXR). Standardized costs were also calculated from PHIS charges as previously described to standardize the cost of the individual tests and remove interhospital cost variation.[3]

Relationship of Repeat Testing and Severity of Illness

Because higher illness severity and clinical deterioration may warrant repeat testing, we also explored the association of repeat diagnostic testing for inpatients with severity of illness by using the following variables as measures of severity: length of stay (LOS), transfer to intensive care unit (ICU), or pleural drainage procedure after admission (>2 calendar days after admission). Repeat diagnostic testing was stratified by number of tests.

Statistical Analysis

The categorical demographic characteristics of the pre‐ and postguideline populations were summarized using frequencies and percentages, and compared using 2 tests. Continuous demographics were summarized with medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) and compared with the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Segmented regression, clustered by hospital, was used to assess trends in monthly resource utilization as well as associated standardized costs before and after guidelines publication. To estimate the impact of the guidelines overall, we compared the observed diagnostic resource use at the end of the study period with expected use projected from trends in the preguidelines period (ie, if there were no new guidelines). Individual interrupted time series were also built for each hospital. From these models, we assessed which hospitals had a significant difference between the rate observed at the end of the study and that estimated from their preguideline trajectory. To assess the relationship between the number of positive improvements at a hospital and hospital characteristics, we used Spearman's correlation and Kruskal‐Wallis tests. All analyses were performed with SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC), and P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. In accordance with the policies of the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center Institutional Review Board, this research, using a deidentified dataset, was not considered human subjects research.

RESULTS

There were 275,288 hospital admissions meeting study inclusion criteria of 1 to 18 years of age with a diagnosis of pneumonia from 2008 to 2014. Of these, 54,749 met exclusion criteria (1874 had pleural drainage procedure on day 0 or 1, 51,306 had complex chronic conditions, 1569 were hospitalized with pneumonia in the last 30 days). Characteristics of the remaining 220,539 patients in the final sample are shown in Table 1. The median age was 4 years (IQR, 27 years); a majority of the children were male (53%) and had public insurance (58%). There were 128,855 patients in the preguideline period (January 1, 2008 to July 31, 2011) and 91,684 in the post guideline period (August 1, 2011June 30, 2014).

| Overall | Preguideline | Postguideline | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| No. of discharges | 220,539 | 128,855 | 91,684 | |

| Type of encounter | ||||

| ED only | 150,215 (68.1) | 88,790 (68.9) | 61,425 (67) | <0.001 |

| Inpatient | 70,324 (31.9) | 40,065 (31.1) | 30,259 (33) | |

| Age | ||||

| 14 years | 129,360 (58.7) | 77,802 (60.4) | 51,558 (56.2) | <0.001 |

| 59 years | 58,609 (26.6) | 32,708 (25.4) | 25,901 (28.3) | |

| 1018 years | 32,570 (14.8) | 18,345 (14.2) | 14,225 (15.5) | |

| Median [IQR] | 4 [27] | 3 [27] | 4 [27] | <0.001 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 116,718 (52.9) | 68,319 (53) | 48,399 (52.8) | 00.285 |

| Female | 103,813 (47.1) | 60,532 (47) | 43,281 (47.2) | |

| Race | ||||

| Non‐Hispanic white | 84,423 (38.3) | 47,327 (36.7) | 37,096 (40.5) | <0.001 |

| Non‐Hispanic black | 60,062 (27.2) | 35,870 (27.8) | 24,192 (26.4) | |

| Hispanic | 51,184 (23.2) | 31,167 (24.2) | 20,017 (21.8) | |

| Asian | 6,444 (2.9) | 3,691 (2.9) | 2,753 (3) | |

| Other | 18,426 (8.4) | 10,800 (8.4) | 7,626 (8.3) | |

| Payer | ||||

| Government | 128,047 (58.1) | 70,742 (54.9) | 57,305 (62.5) | <0.001 |

| Private | 73,338 (33.3) | 44,410 (34.5) | 28,928 (31.6) | |

| Other | 19,154 (8.7) | 13,703 (10.6) | 5,451 (5.9) | |

| Disposition | ||||

| HHS | 684 (0.3) | 411 (0.3) | 273 (0.3) | <0.001 |

| Home | 209,710 (95.1) | 123,236 (95.6) | 86,474 (94.3) | |

| Other | 9,749 (4.4) | 4,962 (3.9) | 4,787 (5.2) | |

| SNF | 396 (0.2) | 246 (0.2) | 150 (0.2) | |

| Season | ||||

| Spring | 60,171 (27.3) | 36,709 (28.5) | 23,462 (25.6) | <0.001 |

| Summer | 29,891 (13.6) | 17,748 (13.8) | 12,143 (13.2) | |

| Fall | 52,161 (23.7) | 28,332 (22) | 23,829 (26) | |

| Winter | 78,316 (35.5) | 46,066 (35.8) | 32,250 (35.2) | |

| LOS | ||||

| 13 days | 204,812 (92.9) | 119,497 (92.7) | 85,315 (93.1) | <0.001 |

| 46 days | 10,454 (4.7) | 6,148 (4.8) | 4,306 (4.7) | |

| 7+ days | 5,273 (2.4) | 3,210 (2.5) | 2,063 (2.3) | |

| Median [IQR] | 1 [11] | 1 [11] | 1 [11] | 0.144 |

| Admitted patients, median [IQR] | 2 [13] | 2 [13] | 2 [13] | <0.001 |

Discharged From the ED

Throughout the study, utilization of CBC, blood cultures, and CRP was <20%, whereas CXR use was >75%. In segmented regression analysis, CRP utilization was relatively stable before the guidelines publication. However, by the end of the study period, the projected estimate of CRP utilization without guidelines (expected) was 2.9% compared with 4.8% with the guidelines (observed) (P < 0.05) (Figure 1). A similar pattern of higher rates of diagnostic utilization after the guidelines compared with projected estimates without the guidelines was also seen in the ED utilization of CBC, blood cultures, and CXR (Figure 1); however, these trends did not achieve statistical significance. Table 2 provides specific values. Using a standard cost of $19.52 for CRP testing, annual costs across all hospitals increased $11,783 for ED evaluation of CAP.

Baseline (%) | Preguideline Trend | Level Change at Guideline | Change in Trend After Guideline | Estimates at End of Study* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Without Guideline (%) | With Guideline (%) | P | |||||

| |||||||

| ED‐only encounters | |||||||

| Blood culture | 14.6 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 5.5 | 8.6 | NS |

| CBC | 19.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 10.7 | 14.0 | NS |

| CRP | 5.4 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 2.9 | 4.8 | <0.05 |

| Chest x‐ray | 85.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 80.9 | 81.1 | NS |

| Inpatient encounters | |||||||

| Blood culture | 50.6 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 49.2 | 41.4 | <0.05 |

| Repeat blood culture | 6.5 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 8.9 | 5.8 | NS |

| CBC | 65.2 | 0.0 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 65.0 | 62.2 | NS |

| Repeat CBC | 23.4 | 0.0 | 4.2 | 0.0 | 20.8 | 16.0 | NS |

| CRP | 25.7 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 23.8 | 23.5 | NS |

| Repeat CRP | 12.5 | 0.1 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 7.1 | 7.3 | NS |

| Chest x‐ray | 89.4 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 85.4 | 83.9 | NS |

| Repeat chest x‐ray | 25.5 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 24.1 | 17.7 | <0.05 |

Inpatient Encounters

In the segmented regression analysis of children hospitalized with CAP, guideline publication was associated with changes in the monthly use of some diagnostic tests. For example, by the end of the study period, the use of blood culture was 41.4% (observed), whereas the projected estimated use in the absence of the guidelines was 49.2% (expected) (P < 0.05) (Figure 2). Table 2 includes the data for the other tests, CBC, CRP, and CXR, in which similar patterns are noted with lower utilization rates after the guidelines, compared with expected utilization rates without the guidelines; however, these trends did not achieve statistical significance. Evaluating the utilization of repeat testing for inpatients, only repeat CXR achieved statistical significance (P < 0.05), with utilization rates of 17.7% with the guidelines (actual) compared with 24.1% without the guidelines (predicted).

To better understand the use of repeat testing, a comparison of severity outcomesLOS, ICU transfer, and pleural drainage procedureswas performed between patients with no repeat testing (70%) and patients with 1 or more repeat tests (30%). Patients with repeat testing had longer LOS (no repeat testing LOS 1 [IQR, 12]) versus 1 repeat test LOS 3 ([IQR, 24] vs 2+ repeat tests LOS 5 [IQR, 38]), higher rate of ICU transfer (no repeat testing 4.6% vs 1 repeat test 14.6% vs 2+ repeat test 35.6%), and higher rate of pleural drainage (no repeat testing 0% vs 1 repeat test 0.1% vs 2+ repeat test 5.9%] (all P < 0.001).

Using standard costs of $37.57 for blood cultures and $73.28 for CXR, annual costs for children with CAP across all hospitals decreased by $91,512 due to decreased utilization of blood cultures, and by $146,840 due to decreased utilization of CXR.

Hospital‐Level Variation in the Impact of the National Guideline

Figure 3 is a visual representation (heat map) of the impact of the guidelines at the hospital level at the end of the study from the individual interrupted time series. Based on this heat map (Figure 3), there was wide variability between hospitals in the impact of the guideline on each test in different settings (ED or inpatient). By diagnostic testing, 7 hospitals significantly decreased utilization of blood cultures for inpatients, and 5 hospitals significantly decreased utilization for repeat blood cultures and repeat CXR. Correlation between the number of positive improvements at a hospital and region (P = 0.974), number of CAP cases (P = 0.731), or percentage of public insurance (P = 0.241) were all nonsignificant.

DISCUSSION

This study complements previous assessments by evaluating the impact of the 2011 IDSA/PIDS consensus guidelines on the management of children with CAP cared for at US children's hospitals. Prior studies have shown increased use of narrow‐spectrum antibiotics for children with CAP after the publication of these guidelines.[7] The current study focused on diagnostic testing for CAP before and after the publication of the 2011 guidelines. In the ED setting, use of some diagnostic tests (blood culture, CBC, CXR, CRP) was declining prior to guideline publication, but appeared to plateau and/or increase after 2011. Among children admitted with CAP, use of diagnostic testing was relatively stable prior to 2011, and use of these tests (blood culture, CBC, CXR, CRP) declined after guideline publication. Overall, changes in diagnostic resource utilization 3 years after publication were modest, with few changes achieving statistical significance. There was a large variability in the impact of guidelines on test use between hospitals.

For outpatients, including those managed in the ED, the PIDS/IDSA guidelines recommend limited laboratory testing in nontoxic, fully immunized patients. The guidelines discourage the use of diagnostic testing among outpatients because of their low yield (eg, blood culture), and because test results may not impact management (eg, CBC).[6] In the years prior to guideline publication, there was already a declining trend in testing rates, including blood cultures, CBC, and CRP, for patients in the ED. After guideline publication, the rate of blood cultures, CBC, and CRP increased, but only the increase in CRP utilization achieved statistical significance. We would not expect utilization for common diagnostic tests (eg, CBC for outpatients with CAP) to be at or close to 0% because of the complexity of clinical decision making regarding admission that factors in aspects of patient history, exam findings, and underlying risk.[15] ED utilization of blood cultures was <10%, CBC <15%, and CRP <5% after guideline publication, which may represent the lowest testing limit that could be achieved.

CXRs obtained in the ED did not decrease over the entire study period. The rates of CXR use (close to 80%) seen in our study are similar to prior ED studies.[5, 16] Management of children with CAP in the ED might be different than outpatient primary care management because (1) unlike primary care providers, ED providers do not have an established relationship with their patients and do not have the opportunity for follow‐up and serial exams, making them less likely to tolerate diagnostic uncertainty; and (2) ED providers may see sicker patients. However, use of CXR in the ED does represent an opportunity for further study to understand if decreased utilization is feasible without adversely impacting clinical outcomes.

The CAP guidelines provide a strong recommendation to obtain blood culture in moderate to severe pneumonia. Despite this, blood culture utilization declined after guideline publication. Less than 10% of children hospitalized with uncomplicated CAP have positive blood cultures, which calls into question the utility of blood cultures for all admitted patients.[17, 18, 19] The recent EPIC (Epidemiology of Pneumonia in the Community) study showed that a majority of children hospitalized with pneumonia do not have growth of bacteria in culture, but there may be a role for blood cultures in patients with a strong suspicion of complicated CAP or in the patient with moderate to severe disease.[20] In addition to blood cultures, the guidelines also recommend CBC and CXR in moderate to severely ill children. This observed decline in testing in CBC and CXR may be related to individual physician assessments of which patients are moderately to severely ill, as the guidelines do not recommend testing for children with less severe disease. Our exclusion of patients requiring intensive care management or pleural drainage on admission might have selected children with a milder course of illness, although still requiring admission.

The guidelines discourage repeat diagnostic testing among children hospitalized with CAP who are improving. In this study, repeat CXR and CBC occurred in approximately 20% of patients, but repeat blood culture and CRP was much lower. As with initial diagnostic testing for inpatients with CAP, the rates of some repeat testing decreased with the guidelines. However, those with repeat testing had longer LOS and were more likely to require ICU transfer or a pleural drainage procedure compared to children without repeat testing. This suggests that repeat testing is used more often in children with a severe presentation or a worsening clinical course, and not done routinely on hospitalized patients.

The financial impact of decreased testing is modest, because the tests themselves are relatively inexpensive. However, the lack of substantial cost savings should not preclude efforts to continue to improve adherence to the guidelines. Not only is increased testing associated with higher hospitalization rates,[5] potentially yielding higher costs and family stress, increased testing may also lead to patient discomfort and possibly increased radiation exposure through chest radiography.

Many of the diagnostic testing recommendations in the CAP guidelines are based on weak evidence, which may contribute to the lack of substantial adoption. Nevertheless, adherence to guideline recommendations requires sustained effort on the part of individual physicians that should be encouraged through institutional support.[21] Continuous education and clinical decision support, as well as reminders in the electronic medical record, would make guideline recommendations more visible and may help overcome the inertia of previous practice.[15] The hospital‐level heat map (Figure 3) included in this study demonstrates that the impact of the guidelines was variable across sites. Although a few sites had decreased diagnostic testing in many areas with no increased testing in any category, there were several sites that had no improvement in any diagnostic testing category. In addition, hospital‐level factors like size, geography, and insurance status were not associated with number of improvements. To better understand drivers of change at individual hospitals, future studies should evaluate specific strategies utilized by the rapid guideline adopters.

This study is subject to several limitations. The use of ICD‐9 codes to identify patients with CAP may not capture all patients with this diagnosis; however, these codes have been previously validated.[13] Additionally, because patients were identified using ICD‐9 coding assigned at the time of discharge, testing performed in the ED setting may not reflect care for a child with known pneumonia, but rather may reflect testing for a child with fever or other signs of infection. PHIS collects data from freestanding children's hospitals, which care for a majority of children with CAP in the US, but our findings may not be generalizable to other hospitals. In addition, we did not examine drivers of trends within individual institutions. We did not have detailed information to examine whether the PHIS hospitals in our study had actively worked to adopt the CAP guidelines. We were also unable to assess physician's familiarity with guidelines or the level of disagreement with the recommendations. Furthermore, the PHIS database does not permit detailed correlation of diagnostic testing with clinical parameters. In contrast to the diagnostic testing evaluated in this study, which is primarily discouraged by the IDSA/PIDS guidelines, respiratory viral testing for children with CAP is recommended but could not be evaluated, as data on such testing are not readily available in PHIS.

CONCLUSION

Publication of the IDSA/PIDS evidence‐based guidelines for the management of CAP was associated with modest, variable changes in use of diagnostic testing. Further adoption of the CAP guidelines should reduce variation in care and decrease unnecessary resource utilization in the management of CAP. Our study demonstrates that efforts to promote decreased resource utilization should target specific situations (eg, repeat testing for inpatients who are improving). Adherence to guidelines may be improved by the adoption of local practices that integrate and improve daily workflow, like order sets and clinical decision support tools.

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

- , . Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA. 2012;307(14):1513–1516.

- , , , et al. Choosing wisely in pediatric hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):479–485.

- , , , et al.; Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) Network. Prioritization of comparative effectiveness research topics in hospital pediatrics. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(12):1155–1164.

- , , , et al. Variability in processes of care and outcomes among children hospitalized with community‐acquired pneumonia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31(10):1036–1041.

- , , , , . Variation in emergency department diagnostic testing and disposition outcomes in pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2013;132(2):237–244.

- , , , et al.; Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. The management of community‐acquired pneumonia in infants and children older than 3 months of age: clinical practice guidelines by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(7):e25–e76.

- , , , et al., Impact of Infectious Diseases Society of America/Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society guidelines on treatment of community‐acquired pneumonia in hospitalized children. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(6):834–838.

- , , , et al. Antibiotic choice for children hospitalized with pneumonia and adherence to national guidelines. Pediatrics. 2015;136(1):44–52.

- , , , et al. Quality improvement methods increase appropriate antibiotic prescribing for childhood pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2013;131(5):e1623–e1631.

- , , , et al. Improvement methodology increases guideline recommended blood cultures in children with pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2015;135(4):e1052–e1059.

- , , , , , . Impact of a guideline on management of children hospitalized with community‐acquired pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e597–e604.

- , , , . Effectiveness of antimicrobial guidelines for community‐acquired pneumonia in children. Pediatrics. 2012;129(5):e1326–e1333.

- , , , et al. Identifying pediatric community‐acquired pneumonia hospitalizations: accuracy of administrative billing codes. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(9):851–858.

- , , , , . Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD‐10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:199.

- , . Establishing superior benchmarks of care in clinical practice: a proposal to drive achievable health care value. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(4):301–302.

- , , , . Emergency department management of childhood pneumonia in the United States prior to publication of national guidelines. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(3):240–246.

- , , , et al. Prevalence of bacteremia in hospitalized pediatric patients with community‐acquired pneumonia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(7):736–740.

- , , , , . The prevalence of bacteremia in pediatric patients with community‐acquired pneumonia: guidelines to reduce the frequency of obtaining blood cultures. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(2):92–96.

- . Do all children hospitalized with community‐acquired pneumonia require blood cultures? Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(2):177–179.

- , , , et al.; CDC EPIC Study Team. Community‐acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. children. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(9):835–845.

- , , , et al. Influence of hospital guidelines on management of children hospitalized with pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2012;130(5):e823–e830.

- , . Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA. 2012;307(14):1513–1516.

- , , , et al. Choosing wisely in pediatric hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):479–485.

- , , , et al.; Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) Network. Prioritization of comparative effectiveness research topics in hospital pediatrics. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(12):1155–1164.

- , , , et al. Variability in processes of care and outcomes among children hospitalized with community‐acquired pneumonia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31(10):1036–1041.

- , , , , . Variation in emergency department diagnostic testing and disposition outcomes in pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2013;132(2):237–244.

- , , , et al.; Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. The management of community‐acquired pneumonia in infants and children older than 3 months of age: clinical practice guidelines by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(7):e25–e76.

- , , , et al., Impact of Infectious Diseases Society of America/Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society guidelines on treatment of community‐acquired pneumonia in hospitalized children. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(6):834–838.

- , , , et al. Antibiotic choice for children hospitalized with pneumonia and adherence to national guidelines. Pediatrics. 2015;136(1):44–52.